Federal Court of Australia

Sharma by her litigation representative Sister Marie Brigid Arthur v Minister for the Environment [2021] FCA 560

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicants’ application for an interlocutory injunction is dismissed.

2. The claims made by each of the applicants (other than those made on behalf of the represented persons) for a quia timet injunction, are dismissed.

3. The parties consult and, on or before 3 June 2021, file proposed orders addressing the matters dealt with at paragraph 520 of the Court’s reasons for judgment.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BROMBERG J:

[4] | |

[18] | |

[29] | |

3.1 The Effect of Greenhouse Gases upon Earth’s Surface Temperature | [37] |

3.2 The Earth System, Carbon Sinks, Feedbacks, the Tipping Cascade and ‘Hothouse Earth’ | [44] |

[54] | |

[55] | |

[67] | |

[68] | |

[69] | |

[70] | |

[74] | |

[91] | |

4.1 Ascertaining whether a Novel Duty Exists – the Applicable Legal Principles | [96] |

4.2 The Law’s Adaptation to Altering Social Conditions – The Early Environmental Cases | [116] |

[138] | |

[143] | |

[149] | |

[184] | |

[184] | |

[205] | |

[226] | |

[236] | |

[237] | |

[247] | |

[258] | |

[289] | |

[316] | |

6.1 Coherence of the Posited Duty with the Statutory Scheme and Administrative Law | [316] |

[428] | |

[474] | |

[490] | |

[492] | |

[513] |

1 The applicants claim that the first respondent, the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment (Minister) owes them and other Australian children a duty of care. They also claim an injunction to restrain an apprehended breach of that duty. In assessing whether a duty of care exists, the law of negligence focuses upon the foreseeability of harm and the relationship between the person who has caused or contributed to the harm (or will do so) and the persons who have or may be harmed.

2 That is the focus of these reasons. They commence with an introduction to the parties, their respective cases and the conduct which the applicants say is subject to a duty of care – a decision by the Minister made under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) to approve the extraction of coal from a coal mine. Details about the application for approval are then given in Section 2 of these reasons. In Section 3, my reasons turn to consider the evidence about the degree of risk and the magnitude of the risk of harm feared by the applicants. The foreseeability and likelihood of that harm arising and being caused or contributed to by carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the Earth’s atmosphere generated by the combustion of coal from the coal mine is also considered.

3 Section 4 of these reasons addresses the legal principles applicable to establishing the existence of a duty of care and the statutory scheme in which the Minister is empowered to approve or not approve a “controlled action” such as the expansion of a coal mine. My reasons then divide to consider reasonable foreseeability of harm and those features of the relations between the Minister and Australian children which support a finding that a duty of care exists (Section 5 – The Affirmative Salient Features) and those features that do not (Section 6 – The Negative Salient Features). In Section 7, I conclude that the existence of a duty of care is established and should be recognised by the law of negligence. In Section 8, I deal with and reject the application for an injunction to restrain an asserted apprehended breach of the duty of care by the Minister. The further necessary steps to finalise this litigation are then addressed in Section 9.

1. The Parties and their Claims

4 The applicants in this proceeding are eight Australian children: Anjali Sharma, Isolde Shanti Raj-Seppings, Ambrose Malachy Hayes, Tomas Webster Arbizu, Bella Paige Burgemeister, Laura Fleck Kirwan, Ava Princi and Luca Gwyther Saunders (the applicants). The applicants are all children residing in Australia. As a consequence of their youth, the proceeding is brought by their litigation representative Sister Marie Brigid Arthur, a Sister of the Brigidine Order of Victoria. The applicants bring the proceeding on their own behalf and as a representative proceeding under Division 9.2 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), representing children who ordinarily reside in Australia (the Represented Children) as well as “other Represented Children”, being children residing anywhere in the world. During the course of the hearing the applicants confined their claims for relief to themselves and the Represented Children, that is, the Australian Children. I will refer to the applicants and the Represented Children collectively as the Children.

5 The Minister is an officer of the Commonwealth within the meaning of s 75(v) of the Constitution, and relevantly, the Minister responsible for administering the EPBC Act.

6 The second respondent is Vickery Coal Pty Ltd, a wholly owned subsidiary of Whitehaven Coal Pty Ltd. Whitehaven holds development consent under the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (NSW) (EPA Act) for a coal mine in northern New South Wales, known as the Vickery Coal Project (the Approved Project). Although approved some time ago, coal production from the Approved Project is yet to commence. The Approved Project occupies a site within the Gunnedah and Narrabri local government areas, approximately 25 kilometres north of Gunnedah in New South Wales.

7 On or around 11 February 2016, Whitehaven applied to the Minister to expand and extend the Approved Project in accordance with s 68 of the EPBC Act (the Extension Project). Vickery replaced Whitehaven as the proponent of the Extension Project on 17 July 2018. If approved, the Extension Project would, amongst other things, increase total coal extraction from the mine site from 135 to 168 million tonnes (Mt). When combusted, the additional coal extracted from the Extension Project will produce about 100 Mt of CO2.

8 The Minister has before her the decision to approve or refuse the Extension Project under s 130(1) and s 133 of the EPBC Act. This proceeding concerns that decision.

9 In this proceeding the applicants claim that the Minister owes each of the Children a duty to exercise her power under s 130 and s 133 of the EPBC Act with reasonable care so as not to cause them harm. That duty of care is said to arise by reason of the existence of a legal relationship between the Minister and the Children recognised by the law of negligence.

10 The applicants apprehend that the Minister will fail to discharge the duty by exercising her discretion in favour of the approval of the Extension Project. The applicants seek declaratory and injunctive relief designed to preclude the Minister from failing to discharge the duty of care they claim she has.

11 The particular harm relevant to the alleged duty of care is mental or physical injury, including ill-health or death, as well as economic and property loss. The applicants assert that the Children are likely to suffer those injuries in the future as a consequence of their likely exposure to climatic hazards induced by increasing global surface temperatures driven by the further emission of CO2 into the Earth’s atmosphere. The feared climatic hazards include more, longer and more intense bushfires, storm surges, coastal flooding, inland flooding, cyclones and other extreme weather events.

12 The applicants allege that such harm will occur in the future and mainly towards the end of this century when global average surface temperatures are forecast to be significantly higher than they are currently. Broadly speaking, it is at that time that, unlike today’s adults, today’s children will be alive and will be the class of persons most susceptible to the harms in question. Indeed, the applicants say that today’s children will live on Earth during a period in which, if CO2 concentration continues to increase, some harm is very probable, serious harm is likely and cataclysmal harm is possible. This seems to be the basis for the proceeding being directed to providing relief to children, as distinct from all persons. On this basis, the applicants say that the Children are vulnerable to a known, foreseeable risk of serious harm, which the Minister can control, but they cannot. In addition, the applicants say that by her position in the Commonwealth Executive, the Minister has special responsibilities to Australian children.

13 The applicants say that if the Minister approves the Extension Project, carbon presently stored safely underground at the mine site of the Extension Project will be extracted, combusted and emitted as CO2 into the Earth’s atmosphere and will materially contribute to CO2 concentration.

14 The applicants accept that by this proceeding they seek that the Court recognise a novel duty of care. They say that the salient features of the relationship between the Minister and the Children support the recognition of the posited duty. Further, they say that such a duty raises a natural extension of the historical development of the law of tort in making responsible a person with the ability to cause or control harm to their “neighbour”. They say today’s adults have gained both previously unimaginable power to harm tomorrow’s adults, and the ability to control that harm. The applicants seek the aid of the Court to impose a correlative responsibility to protect them from what they say is a serious threat of irreversible future harm.

15 The Minister does not dispute that climate change presents serious threats and challenges to the environment, the Australian community and the world at large. However, the Minister denies the existence of a duty of care as alleged. The Minister denies that injury to the Children from the approval of the Extension Project is reasonably foreseeable and says that the relevant salient features point overwhelmingly against the recognition of the novel duty of care contended for by the applicants. Additionally, the Minister contends that if a duty of care exists, there is no reasonable apprehension that the duty will be breached and for that and other reasons no proper basis to grant injunctive relief. The Minister contends that the proceeding should be dismissed.

16 The applicants also sought an interlocutory injunction to restrain the Minister from exercising her power under s 130 and s 133 of the EPBC Act pending the hearing and determination of the proceeding. It was only in relation to this limited aspect of the applicants’ claim that Vickery sought to be joined as a respondent to the proceeding and participate at the hearing.

17 As a matter of case management, and with the consent of the parties, the hearing of the interlocutory injunction was adjourned to, and heard in conjunction with, the final hearing. This course was facilitated by the Minister providing an undertaking to the Court not to make a decision under s 130 and s 133 of the EPBC Act before the conclusion of the final hearing. The Minister later extended that undertaking to effectively facilitate the publication of these reasons. Ultimately, it has not been necessary for me to determine the application for an interlocutory injunction and for that reason I will dismiss that application.

2. The Application for Approval to Extend the Coal Mine

18 The relevant background to the Approved Project and the Extension Project was not in dispute and I have drawn the following account from the Statement of Agreed Facts filed by the parties and the from parties’ respective submissions.

19 An initial proposal to develop the coal mine north of Gunnedah was made by Whitehaven in 2014 under the EPA Act. This is the Approved Project, and it was approved as a ‘State Significant Development’ within the meaning of s 89C(1) (now s 4.36(1)) of the EPA Act on 19 September 2014). That initial application did not invoke the operation of the EPBC Act. That is because on 17 May 2012, a delegate of the Minister determined that the proposed action was not a ‘controlled action’ under s 75 of the EPBC Act, if implemented in a particular manner. It therefore did not require the Minister’s approval under the EPBC Act.

20 The Approved Project sought to extract further coal buried deeper in the ground than in past mining activities on the site. It had ambitions of extracting of 135 Mt of coal over a 30-year period, at a rate of up to 4.5 Mt of run-of-mine (ROM) coal per year. In addition, associated developments were proposed which would facilitate the transportation of ROM coal on public roads to Whitehaven’s existing coal handling and preparation plant (CHPP). This facility enables coal to be processed and loaded onto trains for rail transport to the Port of Newcastle.

21 Despite these ambitions, coal production at the mine has not yet commenced.

22 As set out above, on or around 10 February 2016, Whitehaven applied to the Minister to extend the Approved Project in accordance with s 68 of the EPBC Act. The focus of this proceeding is the application for the Extension Project. The proposed actions of the Extension Project include:

(i) an increase in the total coal extraction from the site of the Approved Project from 135 to 168 Mt;

(ii) an increase in the peak annual extraction rate from 4.5 to 10 Mt per annum (Mtpa) of coal and an additional disturbance area of 776 hectares; and

(iii) the development of a new CHPP and train-load-out facility at the site of the Approved Project (both of which would process coal from other nearby mines), which would involve:

(a) stockpiling and processing a total of 13 Mtpa of ROM coal;

(b) production of up to 11.5 Mtpa of metallurgical and thermal coal products;

(c) transportation of up to 11.5 Mtpa of coal from the rail load facility, the rail spur line and via the public rail network to Newcastle for export to other countries;

(d) development of a new rail spur to connect the load out facility to the main Werris Creek to Mungindi Railway line;

(e) construction of a water supply borefield and associated infrastructure; and

(f) changes to the final landform in certain specified ways relating to the overburden emplacement areas and pit lake void.

23 The Extension Project will cause, directly or indirectly, emissions of greenhouse gases, particularly CO2. These estimated emissions are referred to in terms of CO2 equivalent (CO2-e) emissions. Direct greenhouse gas emissions occur from sources that are owned or controlled by the relevant entity or development (referred to as Scope 1 emissions). Indirect greenhouse gas emissions arise from the generation of purchased energy products (principally electricity) by the relevant entity or development (referred to as Scope 2 emissions). Other indirect greenhouse gas emissions arise from sources that are not owned or controlled by the relevant entity or development but are nonetheless a consequence of its mining activity (referred to as Scope 3 emissions).

24 Over the course of its life, the Extension Project will, compared with the Approved Project, lead to the following levels of greenhouse gas emissions:

(i) an overall reduction of approximately 1 Mt of CO2-e in Scope 1 emissions;

(ii) an overall increase of approximately 0.15 Mt CO2-e in Scope 2 emissions; and

(iii) an overall increase of approximately 100 Mt CO2-e in Scope 3 emissions.

25 Those actions will take place over a period of 26 years, with one year projected for construction. In this context, the Minister’s delegate determined that the Extension Project constituted a ‘controlled action’ under s 75(1) of the EPBC Act. The relevant controlling provisions were s 18 and s 18A, and s 24D and s 24E (relating to listed threatened species and communities and water resources respectively). As a consequence of declaring the Extension Project a ‘controlled action’, the Minister is required to assess the application under s 130(1) and s 133 of the EPBC Act. Section 130(2) of the EPBC Act prescribes that the proposed action is assessed either pursuant to a bilateral agreement or pursuant to Pt 8 of the Act. The Extension Project was assessed pursuant to a bilateral agreement between the Commonwealth and the State of NSW (Bilateral Agreement) which accredits the assessment process under the EPA Act.

26 In May 2020, the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (NSW Department) provided its assessment report (NSW Department Report) in accordance with the Bilateral Agreement. A number of environmental, social and economic factors were considered in the NSW Department Report. It found that the possible adverse environmental impacts associated with the Extension Project were outweighed by the public interest in granting its approval. On balance, the NSW Department Report concluded that the Extension Project was acceptable under certain conditions.

27 Given the status of the Extension Project as a ‘State Significant Development’ under the EPA, the extension application was also assessed by the NSW Independent Planning Commission (IPC) for development consent. The IPC is the designated development consent authority of the Extension Project site under cl 8A of the State Environmental Planning Policy (State and Regional Development) 2011 and s 4.5(a) of the EPA Act. On 12 August 2020, the IPC granted development consent for the extension project, subject to certain conditions (Development Consent) and published its Statement of Reasons for Decision (IPC Report).

28 The Development Consent and the NSW Department Report were provided to the Minister on 14 August 2020. Generally, the receipt of the assessment report provides the Minister with 30 business days, or such longer period as she specifies in writing, to decide whether to approve the application. However, on 9 December 2020, a delegate of the Minister extended this time to 30 April 2021 pursuant to s 130(1A) of the EPBC Act. Further and as previously indicated, in the context of this proceeding the undertaking given by the Minister was further extended.

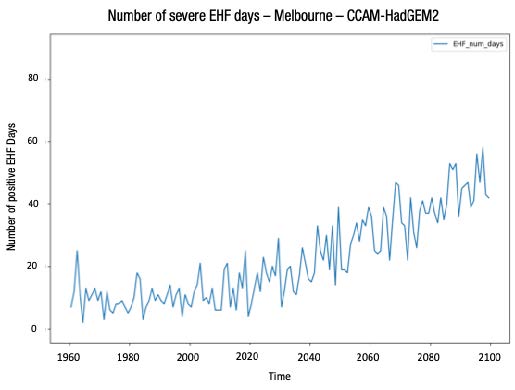

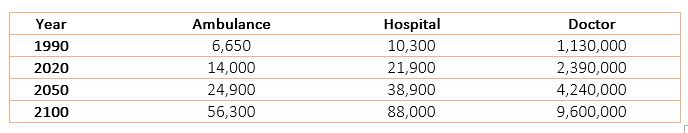

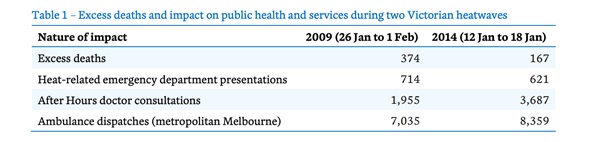

29 The relief the applicants seek depends upon the Court being satisfied that the approval of the Extension Project by the Minister involves a risk of future injury to each of the Children. The risk of injury alleged by the applicants extends to many forms of what may broadly be described as climatic hazards. Each of these hazards, bushfires being one example, are alleged to be events which climate change will induce in terms of either frequency, ferocity or geographical spread. The risk of harm in question in this case is therefore harm induced by climate change and, more specifically, harm induced by increases in the Earth’s average surface temperature. The applicants alleged that such harm will occur in the future and mainly towards the end of this century when global surface temperatures are forecast to be significantly higher than they are currently.

30 In a nutshell, the applicants’ case is that the scientific evidence demonstrates the plausible possibility that the effects of climate change will bring about a future world in which the Earth’s average surface temperature (currently at about 1.1°C above pre-industrial temperature levels) will reach about 4°C above pre-industrial temperature levels by about 2100. Supported by unchallenged expert evidence, the applicants contended that a 4°C future world may come about in one of two ways: first, where the greenhouse effect upon the Earth’s increasing temperature is driven by an approximately linear relationship between increased human emissions of CO2 and increased temperatures, and second, in circumstances where continuing human emissions of CO2 will result in ‘Earth System’ changes, which diminish the Earth’s current ability to reflect heat, absorb CO2, and retain CO2 currently held in carbon sinks, triggering ‘tipping cascades’ which propel the Earth into a 4°C trajectory. That scenario was referred to in the evidence as “Hothouse Earth”. Under this scenario, humans will lose the capacity to control climate change and global surface temperatures will continue warming even if human emissions of CO2 are curtailed.

31 Further, the unchallenged evidence of the applicants is that the best available outcome that climate change mitigation measures can now achieve is a stabilised global average surface temperature of 2°C above pre-industrial levels. However, at that temperature and beyond, there is an exponentially increasing risk of the Earth being propelled into an irreversible 4°C trajectory because of ‘Earth System’ changes.

32 Given the plausible prospect of Earth’s temperature stabilising at 4°C or greater if stabilisation at 2°C is not achieved, the applicants contended that 100 Mt of CO2 emissions, attributable to the Extension Project, will be significant and material to future increased global average surface temperatures. This, in turn, will expose the Children to a greater risk of injury.

33 To enable an understanding of the different climate scenarios or the “future worlds” in which that risk of harm to the Children is to be assessed, it is necessary to consider the evidence relevant to those elements of the applicants’ case to which I have just referred.

34 Most of the evidence to which I will refer was given by Professor Steffen in his report dated 7 December 2020. Professor Steffen is an eminent specialist with over 30 years’ experience in climate and ‘Earth System’ science research and teaching. Neither his expertise nor the opinions he gave were challenged. A brief account of his experience and expertise is set out in the Schedule to these reasons.

35 The opinions which Professor Steffen gave were sourced in both his own substantial research and that of other specialists in the field. To a large extent, his evidence relied upon the research and climate change modelling published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). As a factsheet published by the Minister’s Department states, the IPCC is the leading international body for assessing scientific research on climate change and is acknowledged by governments around the world as the most reliable source of advice on climate change. The IPCC was established in 1988 to provide the world with a clear scientific view on the current state of knowledge on climate change and its potential environmental and socio-economic impacts. The IPCC is organised into three working groups and a taskforce that focuses on greenhouse gas emissions. The main role of each working group is to summarise the state of knowledge on climate change in reports published by the IPCC, known as IPCC Assessment Reports. To ensure that those reports are credible, transparent and objective, the reports must pass through a rigorous two-stage scientific and technical review process before being accepted by the IPCC Plenary which is constituted by representatives of member countries of the United Nations and the World Meteorological Organisation.

36 The following account of the evidence is also taken from reports prepared by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BoM). Neither the expertise of the relevant authors of the CSIRO or BoM publications, nor the opinions contained therein, were in contest.

3.1 The Effect of Greenhouse Gases upon Earth’s Surface Temperature

37 The greenhouse effect describes the relationship between the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases and global average surface temperature. The Earth’s surface absorbs energy from the sun in the form of visible and ultraviolet radiation, and discharges some of this energy back into space in the form of infrared radiation (heat). CO2 is a greenhouse gas. CO2 absorbs a significant proportion of the outgoing radiation and re-radiates some of it back into the lower atmosphere (troposphere) and into the Earth’s surface, thus warming the surface and lower atmosphere.

38 It is well-established that, when burned to produce energy, fossil fuels such as coal produce greenhouse gases, particularly CO2.

39 Emissions of CO2 from industrial sources (currently about 90%) and land-use change (currently about 10%) have raised the atmospheric concentration of CO2 and the global average surface temperature by 1.1℃ compared to pre-industrial levels. From pre-industrial levels to the present, the combustion of coal by humans is estimated to have produced around 1,000 gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2 out of a total of 2,180 Gt emitted by human activity generally. That is, the combustion of coal has contributed about 46% of the total emission of CO2. Professor Steffen estimates that this has contributed about 0.5℃ of the total of 1.1℃ temperature rise from the reference date up to the present date. The commonly used reference date for climate change related parameters as defined by the IPCC is the 1850-1900 average, or, where data is available for individual years, 1876. This is referred to as “pre-industrial”.

40 Increasing emissions of CO2 from the Earth’s surface increase the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere, which intensifies the greenhouse effect. In other words, the more outgoing infrared radiation (heat) is trapped and re-radiated by CO2, the more the Earth’s surface and lower atmosphere are warmed. Other greenhouse gases such as methane and nitrous oxide also influence global average surface temperature.

41 Professor Steffen opined that there is an approximately linear relationship between human emissions of CO2 from all sources and the increase in global average surface temperature (subject to the non-linear impact of feedbacks, which are discussed below). In the absence of the non-linear effects of feedbacks, further emissions of CO2 from human activities (combustion of fossil fuels and land use) will increase the global average surface temperature at a rate of about 1℃ for every 1,800 Gt of CO2 emitted).

42 The concentration of atmospheric CO2 is currently rising at a rate of about 2.5 ppm (parts per million) per year and this is driving increasing temperatures at the rate of 0.24℃ per five-year period or nearly 0.5℃ per decade. If this rate continues throughout this century, by 2100 the global average surface temperature will reach about 5℃ above the pre-industrial level.

43 At some point in the future, increases in global average surface temperature will likely slow and then stabilise for a multi-decadal period. The rate at which global surface temperature will stabilise depends upon a number of factors. These include, the cumulative CO2 emitted by human activities since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and also the feedbacks within the ‘Earth System’ that strengthen or weaken the trajectories of CO2 and temperature. I turn then to explain the ‘Earth System’, feedback processes and what Professor Steffen referred to as the “tipping cascade”.

3.2 The Earth System, Carbon Sinks, Feedbacks, the Tipping Cascade and ‘Hothouse Earth’

44 Professor Steffen described the Earth as a single complex system in which the biosphere, and increasingly human activities, play a vital role in the stable functioning of the planet as a whole. He explained that the ‘Earth System’ (a conceptual construct developed to explain the processes on Earth which cycle materials and energy) is defined as “the suite of interlinked physical, chemical, biological and human processes that cycle (transport and transform) materials and energy in complex, dynamic ways within the system” (Earth System).

45 As explained by Professor Steffen, within the Earth System there are numerous natural ‘sub-systems’ which:

(i) filter most of the damaging ultraviolet radiation from the sun, allowing life to flourish on the surface of the Earth;

(ii) facilitate the movement of freshwater around the Earth, providing the necessary rainfall for ecosystems to flourish; and

(iii) absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, which regulates the Earth’s energy balance. Plants perform this role as they photosynthesise.

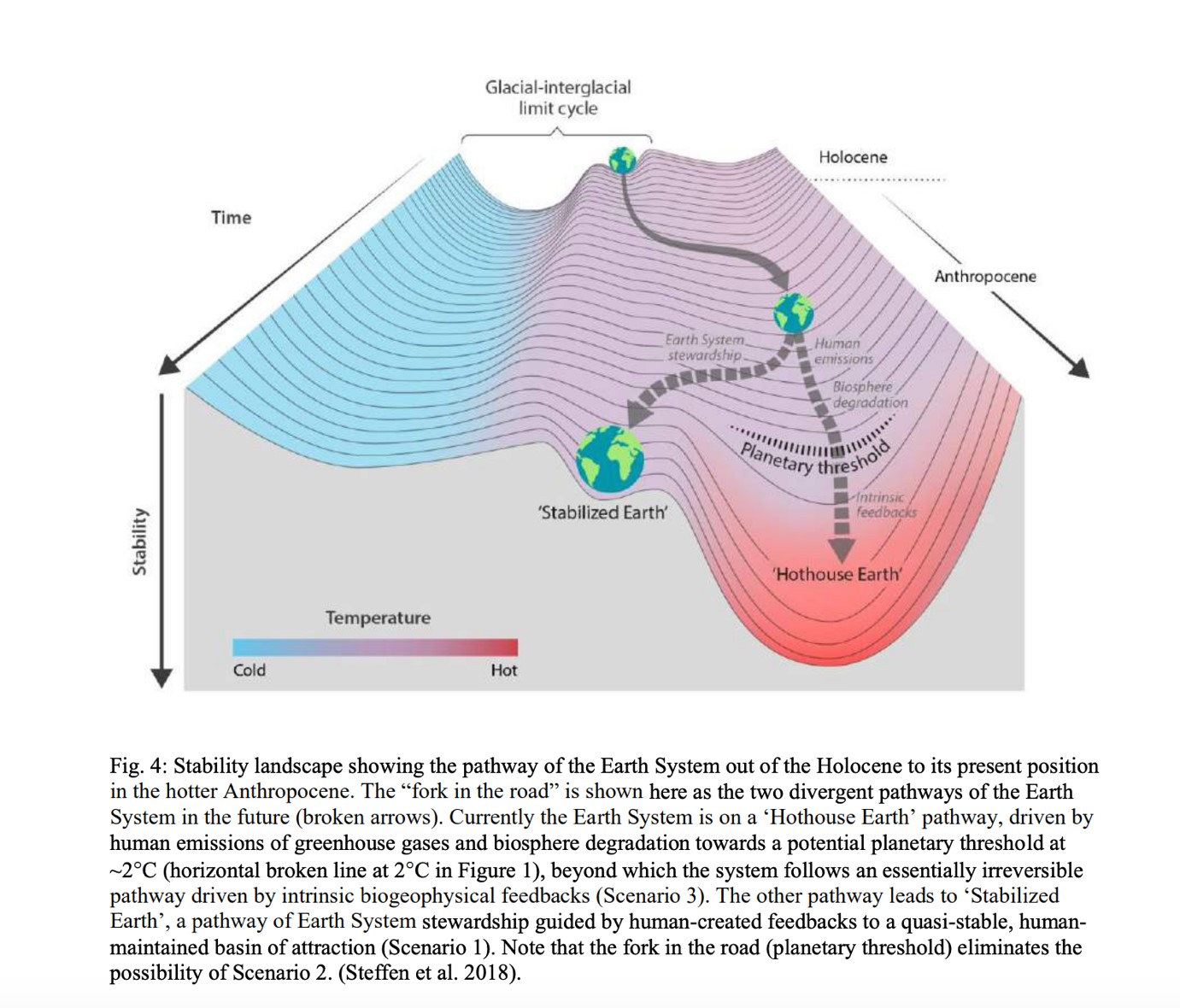

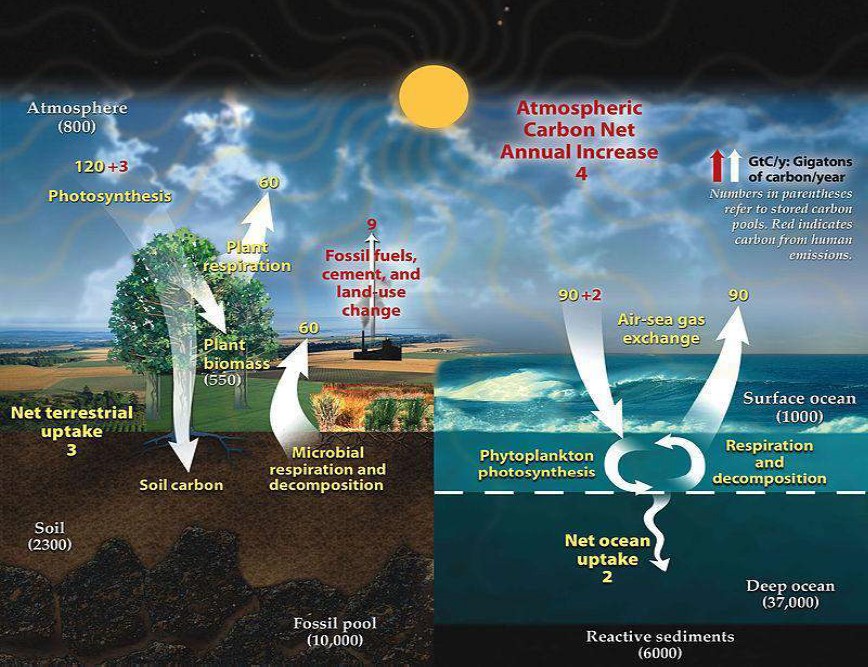

46 The role of atmospheric CO2 in the Earth System is that it acts as the thermal regulator, a fundamental controller of the surface temperature of the planet. The ‘carbon cycle’ describes the movement of carbon between land, atmosphere and oceans. It is shown in Figure 2 in Professor Steffen’s report, replicated here:

The global carbon cycle showing the movement of carbon between land, atmosphere and oceans in billions of tons (gigatonnes - Gt) of carbon per year. Yellow numbers are natural fluxes, red are human-driven fluxes, and white are stored carbon.

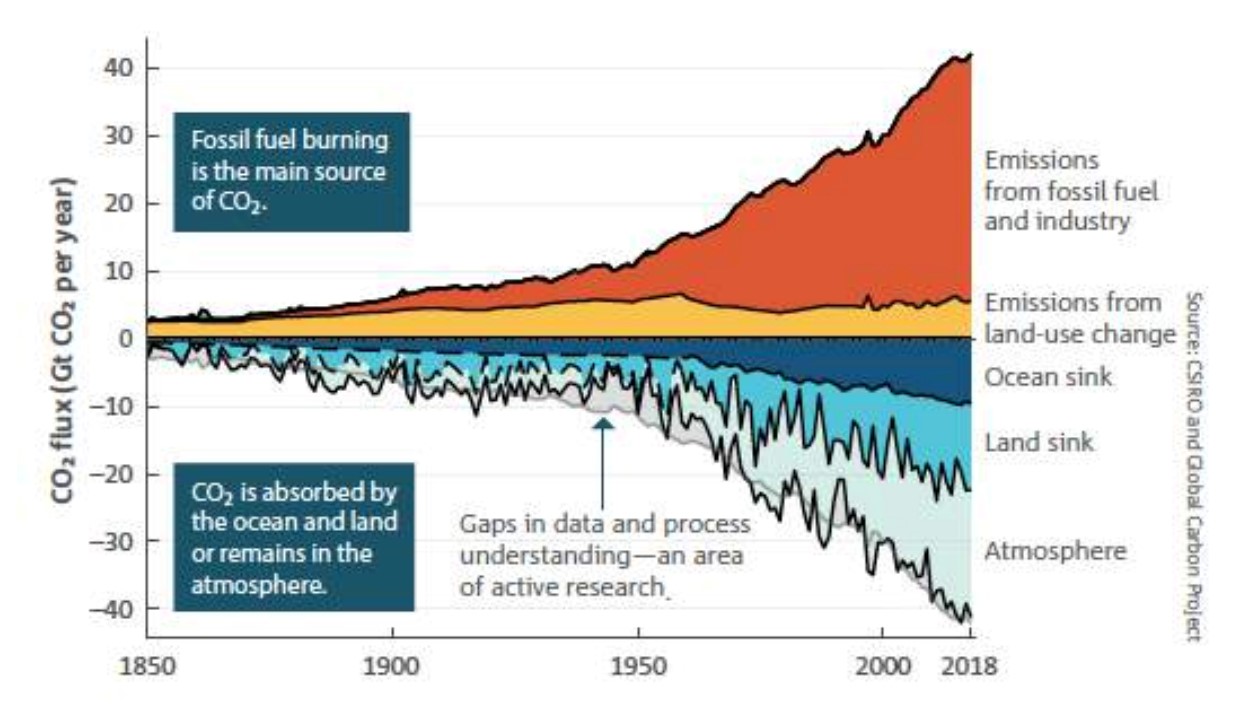

47 As is depicted in Figure 2, there are natural features of the environment, including the oceans and land-based sources (eg the Amazon rainforest), which absorb more CO2 than they produce (referred to as “carbon sinks”). About 55% of human emissions of CO2 are absorbed by land and ocean carbon sinks. The remaining 45% that is left in the atmosphere is the primary driver of the increasing global average surface temperature. Land and ocean carbon sinks “fall far short” of absorbing the increased burden on the system caused by human emissions of CO2. This is depicted by Figure 3 of Professor Steffen’s report and is consistent with the joint report prepared by the CSIRO and BoM, entitled State of the Climate: 2020 (CSIRO and BoM report). Figure 3 shows human emissions of CO2 from 1850 to 2018 and the partitioning of this additional CO2 in the Earth System among the atmosphere, the land (vegetation and soils) and the ocean:

The human emissions of CO2, primarily from the combustion of fossil fuels, are partitioned among the atmosphere and carbon sinks on land and in the ocean. The “imbalance” between the total emissions and total sinks reflects imprecisions in our measurements and understanding, primarily of the land and ocean sinks. Source Friedlingstein et al. (2019) and CSIRO and BoM (2020).

49 It is important to understand that within the carbon cycle there are processes known as ‘feedbacks’ which accelerate, and have the potential to further accelerate, the warming of the Earth’s average surface temperature. Examples include:

melting ice, including the melting of Arctic sea ice and the loss of ice from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. Melting Arctic sea ice will uncover darker seawater, which absorbs more sunlight and accelerates warming. Melting permafrost also releases CO2 and methane into the atmosphere;

forest dieback, which concerns degradation through drought, heat and fire affecting large biomes such as the Amazon rainforest and boreal forests in Siberia and Canada. Increasing drought and heat will increase fire frequency, causing bushfires that will emit CO2 presently stored in the Earth’s forest systems; and

changes in circulation patterns, such as the Atlantic Ocean circulation of the northern hemisphere jet stream. A warming ocean affects global ocean and atmospheric circulation, global and regional sea levels and uptake of anthropogenic CO2 and causes losses in oxygen and impacts on marine ecosystems.

50 According to Professor Steffen and the IPCC, feedback processes accelerate the warming of the Earth System by destroying the Earth’s ability to absorb CO2 or reflect heat. These feedback processes thus compound climate change arising from human emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases, producing a non-linear trajectory of increasing temperatures.

51 As the global average surface temperature rises towards 2℃ and beyond, the risk of such feedbacks being activated increases. Because many feedback processes are interconnected, triggering one feedback process may have a rippling effect on others. Professor Steffen referred to this as a tipping cascade. If this tipping cascade is activated, Professor Steffen opined that humans will lose the capacity to control the trajectory of climate change, leading to a much hotter Earth. He refers to this as the Hothouse Earth scenario.

52 Hothouse Earth is one of the future world scenarios that I will shortly explain. Before I do that, there are a few other matters to note which Professor Steffen’s report addressed.

53 Assuming that the stabilisation of CO2 is not affected by non-human factors such as ‘feedback processes’, the stabilisation of CO2 in the Earth’s atmosphere requires that human emissions of CO2 reach net zero. Professor Steffen stated that reaching net zero is a pre-requisite for global average surface temperature to stabilise. However, there will be a lag between global average surface temperature stabilising and the stabilisation of atmospheric CO2 of several decades at least and possibly up to a century. That is because of the time needed for the heat content of the major components of the Earth System – land, ocean, ice and atmosphere – to equilibrate, with a net transfer of heat from the ocean to the atmosphere.

3.3 Effects to Date of Human Emissions of CO2

54 Professor Steffen was asked to describe the effects to date of human emissions of CO2 in Australia and globally. His evidence was as follows:

The human emissions of CO2 (and other greenhouse gases, although CO2 is the most important) have already changed Earth’s climate in very many significant ways. As an overview, the planet’s atmosphere and ocean are heating at an increasing rate, polar ice is melting, extreme weather events are becoming more extreme, sea levels are rising, and ecosystems and species are being lost or degraded.

(a) The most important impacts of climate change to date on Australia include the following (CSIRO and BoM 2020):

• Australia’s climate has warmed on average by 1.44 ± 0.24°C since national records began in 1910, leading to an increase in the frequency of extreme heat events. Summer extreme temperatures are increasingly breaching 35°C and even 40°C in most of our capital cities and many regional centres.

• There has been a decline of around 16 per cent in April to October rainfall in the southwest of Australia since 1970. Across the same region, May–July rainfall has seen the largest decrease, by around 20 per cent since 1970.

• In the southeast of Australia there has been a decline of around 12 per cent in April to October rainfall since the late 1990s.

• There has been a decrease in streamflow at the majority of streamflow gauges across southern Australia since 1975.

• Rainfall and streamflow have increased across parts of northern Australia since the 1970s.

• There has been an increase in extreme fire weather, and in the length of the fire season, across large parts of the country since the 1950s, especially in southern Australia.

• There has been a decrease in the number of tropical cyclones observed in the Australian region since 1982.

• Oceans around Australia are acidifying and have warmed by around 1°C since 1910, contributing to longer and more frequent marine heatwaves.

• Sea levels are rising around Australia, including more frequent extremes, that are increasing the risk of inundation and damage to coastal infrastructure and communities.

(b) The effects of climate change are clear and unequivocal around the planet - on every continent and in every ocean basin. The most important impacts of climate change to date globally include the following (IPCC 2013):

• Warmer and/or fewer cold days and nights over most land areas.

• Warmer and/or more frequent hot days and nights over most land areas.

• Increases in the frequency and/or duration of heat waves in many regions.

• Increase in the frequency, intensity and/or amount of heavy precipitation (more land areas with increases than with decreases).

• Increases in intensity and/or duration of drought in many regions since 1970.

• Increases in intense tropical cyclone activity in the North Atlantic since 1970.

• Increased incidence and/or magnitude of extreme high sea levels.

Global observational evidence published since the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report in 2013 reinforce these trends. For example:

• Measurements from satellite altimeters show a climate-change driven acceleration of mean global sea level over the past 25 years (Nerem et al. 2018). Averaged globally over the past 27 years, sea level has been rising at 3.2mm/year. But for the past five years, the rate was 4.8mm/year, and for the 5-year period before that the rate was 4.1mm year (Canadell and Jackson 2020, based on data from the European Space Agency and Copernicus Marine Service).

• Climate change is rapidly increasing the thermal stress for coral reefs as measured at 100 coral reef locations around the world. The level of thermal stress during the 2015-2016 El Niño was unprecedented over the period 1871-2017 (Lough et al. 2018).

• Intense tropical cyclone activity has increased from 1980 to 2016. Storms of 200 km/hr have doubled in number, and storms of 250 km/hr have tripled in number (Rahmstorf et al. 2018).

3.4 Future Effects – The Future World Scenarios

55 In his evidence, Professor Steffen outlined the approach adopted by climate scientists to project how continued CO2 emissions from human activity might affect the Earth System in the future and what the impacts of any such change (including on the level at which Earth’s surface temperatures stabilise) might be:

(a) The most common approach involves quantitative projections by reference to Earth System models based on mathematical descriptions of the major features of the Earth System and their interactions.

(b) The models are driven by projected human emissions of greenhouse gases and land-use change, as well as natural drivers of climate change such as solar radiation.

(c) The outputs of the models provide insight into the risks presented by different levels of climate change, often characterised by changes in global average surface temperature.

(d) The analysis is supplemented by evidence from past changes in the Earth System (such as the melting of the ice caps during previous warm periods) which may provide insights as to how the Earth System might change in the future.

56 One such model is the representative concentration pathway (RCP), which accounts for the full suite of greenhouse gases and land use over time. RCPs are framed in terms of “radiative forcing”, which refers to the change in energy levels in the Earth system due to particular drivers of climate change. Radiative forcings which are larger than zero indicate global warming, while radiative forcings which are smaller than zero indicate global cooling.

57 The IPCC has published four RCPs: RCP 2.6, RCP 4.5, RCP 6.0 and RCP 8.5. The numbers refer to the radiative forcing in the year 2100. Each RCP consists of a data set which includes a set of starting values and the estimated emissions up to 2100. Each data set is based on historic information and a set of plausible assumptions about future economic activity, energy sources, population growth and other socio-economic factors. The four RCPs cover a range of emission scenarios with and without climate mitigation policies. For example, RCP 8.5 is based on minimal effort to reduce emissions. RCP 2.6 requires strong mitigation efforts, with early participation from all emitters followed by active removal of atmospheric CO2. RCP 2.6 is described by the IPCC Synthesis Report (2014) as a stringent mitigation scenario. RCP 4.5 and RCP 6.0 are described as “intermediate scenarios” and RCP 8.5 as a scenario with “very high emissions of greenhouse gases”. The IPCC stated that scenarios without additional efforts to constrain greenhouse gas emissions lead to pathways ranging between RCP 6.0 and RCP 8.5.

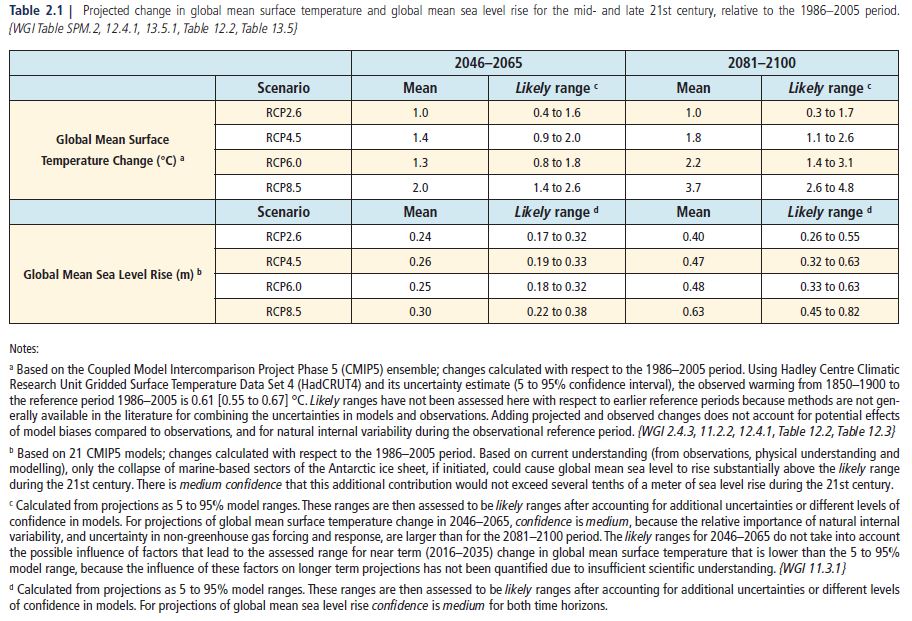

58 Professor Steffen stated that the lowest RCP (2.6) would result in a global average surface temperature rise of below 2°C by the year 2100, while the highest RCP (8.5) would lead to a temperature rise of 4°C or more by 2100. The continuum of projected increasing global average surface temperature under each scenario from 2046 to 2100 is shown in Table 2.1 of the IPCC Synthesis Report (2014). It should be noted, however, that the reference point used here is not the pre-industrial level. Instead, changes in temperature have been calculated by reference to the 1986-2005 period:

59 In his evidence, Professor Steffen proposed three possible climate futures, which he correlated to the IPCC RCPs as I will later explain. First, it is convenient to give an outline of the main characteristics of each of Professor Steffen’s three scenarios. “Scenario 1” forecasts that global average surface temperature will stabilise in the second half of this century “at, or very close to, 2°C” above the pre-industrial level. The Minister contended that there was some ambiguity in Professor Steffen’s specification of the temperature at which global average surface temperatures would stabilise for “Scenario 1” and contended that he really meant below 2°C and around 1.8°C. For the reasons later given, I do not accept that contention. I will call Professor Steffen’s “Scenario 1” – a “2°C Future World”. It is equivalent to the RCP 4.5 scenario. Each of those scenarios are based on a linear relationship between future emissions of CO2 and increased global average surface temperature.

60 Under Professor Steffen’s “Scenario 2”, it is projected that global average surface temperature will stabilise late this century but more likely early into the 22nd century at, or very close to, 3°C, above the pre-industrial level. I will call this Scenario “3°C Future World”. According to Professor Steffen, that Scenario is approximately equivalent to the upper end of RCP 6.0 envelope of temperature scenarios. The scenario is premised on present national policy settings guiding future emissions trajectories.

61 “Scenario 3” forecasts that global average surface temperature will continue to rise throughout this century with a temperature of about 4°C above the pre-industrial level by late this century, but with the surface temperature likely continuing to rise into the 22nd century. Professor Steffen called this Scenario Hothouse Earth. For convenience and consistency, I will call it a “4°C Future World”. In terms of temperature outcomes at or around the end of this century, this scenario corresponds with the IPCC’s RCP 8.5 which forecasts a 4°C or more temperature rise by the end of this century.

62 However, the two scenarios differ in the paths they each take to reach a similar conclusion about temperature at the end of this century. RCP 8.5 is based on human emissions of CO2 being the dominant driver of temperature rise, whereas Professor Steffen’s scenario is non-linear by reference to the impact of human CO2 emissions and is premised upon feedback processes being activated and adding significant amounts of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere and playing an important role in the ultimate temperature rise.

63 Professor Steffen did not propose a possible scenario of his own which correlated with RCP 2.6. He did however give consideration to that scenario. He stated that RCP 2.6 is consistent with the Paris Agreement signed within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2015 (“Paris Agreement”) target of limiting temperatures to well below 2℃ with the ambition to limit temperature to 1.5°C above the pre-industrial average. Professor Steffen predicts that the target of 1.5℃ is now very likely to be “inaccessible without significant overshoot” (temperatures rising above 1.5℃) followed by a drawdown of CO₂ from the atmosphere by natural means (such as reforestation), industrial means (such as carbon capture and storage) or both.

64 In this context which includes consideration by Professor Steffen of some six years’ worth of data about emissions since the IPCC published its RCPs, Professor Steffen opined that the lowest temperature increase that can realistically be contemplated today is that the global average surface temperature will stabilise at, or very close to, 2°C above pre-industrial levels. This is Professor Steffen’s “Scenario 1” and what I have called a 2°C Future World and reflects RCP 4.5.

65 Professor Steffen’s analysis essentially contemplated that there are only two future worlds now likely to be accessible: either a 2°C Future World or a 4°C Future World. In Professor Steffen’s opinion, RCP 8.5 appears to be increasingly unlikely as renewable energies become cheaper and begin to replace fossil fuels at large scales. However, as indicated already, Professor Steffen opined that essentially the same temperature level (about 4°C by about 2100) envisaged by RCP 8.5 will be reached if the 4°C Future World scenario becomes the reality. Professor Steffen considered a 4°C Future World as plausible given sufficient levels of human emissions of CO₂. However, if certain mitigation measures are taken, Professor Steffen suggested that a 2°C Future World is also plausible. Although Professor Steffen identified a 3°C Future World as a possibility, he opined that there is a “very significant risk” that a 3°C Future World is not accessible because there is a danger that “strongly non-linear feedbacks will be activated by a 3°C warning”. In other words, Professor Steffen forecasts that a tipping cascade will likely be activated by a 3°C temperature rise. He stated that that could occur at “even lower” temperatures, noting that a 2°C temperature rise could trigger a 4°C Future World trajectory but the probability of such a scenario was “much lower” for a 2°C rise than for a 3°C rise. He alternatively expressed this by saying there was “a small (but non-zero) probability of initiating a tipping cascade at a 2°C temperature rise”. Professor Steffen’s assessment is supported by the IPCC’s projection of a “moderate” risk of feedback processes being triggered at a 2°C temperature rise. Professor Steffen opined that this risk will undoubtedly rise with a 3°C temperature increase.

66 A fundamental point made by Professor Steffen’s analysis is that if sufficient measures are not taken to reduce human emissions of CO2 so as to stabilise surface temperature at 2°C, global average surface temperatures will then enter an irreversible 4°C Future World or Hothouse Earth trajectory. Professor Steffen opined that ‘feedback processes’ will be activated by a 3°C (or even lower) temperature rise with a consequent “significant risk” that a tipping cascade will be triggered taking the global average surface temperature beyond 3°C and onto the 4°C Future World trajectory. That is depicted in Figure 4 of Professor Steffen’s report.

3.4.1 Effects of a 2℃ Future World

67 In relation to each of the three scenarios postulated by Professor Steffen, he described the projected global impacts followed by a description of the impacts in Australia. He noted that the risks and impacts described were linked to the stabilisation of the global average surface temperature for each of the three scenarios. He emphasised that stabilisation will take multiple decades at a minimum and stated that, therefore, the risks and impacts described were relevant to the current generation of children and the following generation or two.

Scenario 1: Stabilisation at a rise in global average surface temperature of about 2℃ above the pre-industrial level (IPCC 2018).

• 37% of the global population will be exposed to extreme heat at least once every five years. This will have severe impacts on human health and wellbeing, as well as on worker productivity.

• Sea-level will rise by 0.46 m by 2100, leading to large increases in coastal flooding, saltwater intrusion in low-lying areas, and more damaging storm surges. The most vulnerable countries include small island states, Bangladesh, low-lying Southeast Asian cities and settlements, and many regions along the African coast.

• 99% of coral reefs will be dead from severe bleaching; this means that the Great Barrier Reef will cease to exist as we know it today, as well as other coral reefs around the world.

• A decline of 3 million tonnes in marine fisheries, with the most severe impacts on developing countries that rely on marine fish for a large fraction of protein in their diets.

• Ecosystems will shift to a new biome on 13% of Earth’s land, leading to large rates of extinctions as well as a surge in invasive species as individual organisms migrate in response to a changing climate.

• 6.6 million square kilometres of Arctic permafrost will thaw, releasing large amounts of CO2 and methane to the atmosphere, accelerating the warming trend.

• 7% reduction in maize harvests in the tropics, with the poorest countries suffering the most damaging impacts.

• 16% of plant species will lose at least half of their current range, leading to significant within-ecosystem changes as well as an increase in extinction rates.

For Australia, Scenario 1 would significantly increase the likelihood in any given year of extreme weather events (King et al. 2017): (i) 77% likelihood of severe heatwaves, power blackouts and bushfires; and 74% likelihood of severe droughts, water restrictions and reduced crop yields. More generally, CSIRO and BoM 2020, have used simulations from the latest generation of climate models to project changes to Australia’s climate over the next few decades. These projections would thus be relevant for a 1.5-2℃ world, and thus provide useful insights for Scenario 1:

• Continued warming, with more extremely hot days and fewer extremely cool days.

• A decrease in cool season rainfall across many regions of the south and east, likely leading to more time spent in drought.

• A longer fire season for the south and east and an increase in the number of dangerous fire weather days.

• More intense short-duration heavy rainfall events throughout the country.

• Fewer tropical cyclones, but a greater proportion projected to be of high intensity, with ongoing large variations from year to year.

• Fewer east coast lows particularly during the cooler months of the year. For events that do occur, sea level rise will increase the severity of some coastal impacts.

• More frequent, extensive, intense and longer-lasting marine heatwaves leading to increased risk of more frequent and severe bleaching events for coral reefs, including the Great Barrier and Ningaloo reefs.

• Continued warming and acidification of its surrounding oceans.

• Ongoing sea level rise. Recent research on potential ice loss from the Antarctic ice sheet suggests that the upper end of projected global mean sea level rise could be higher than previously assessed (as high as 0.61 to 1.10 m global average by the end of the century for a high emissions pathway, although these changes vary by location).

• More frequent extreme sea levels. For most of the Australian coast, extreme sea levels that had a probability of occurring once in a hundred years are projected to become an annual event by the end of this century with lower emissions, and by mid-century for higher emissions.

3.4.2 Effects of a 3℃ Future World

68 The effects forecast by Professor Steffen for a 3℃ Future World were as follows:

Scenario 2: Stabilisation at a rise in global average surface temperature of about 3℃ above the pre-industrial level. Here I focus on projected impacts on Australia of this scenario, based on a recent assessment by the Australian Academy of Sciences (Hoegh-Guldberg et al. 2020, and references therein):

• Many of Australia’s ecological systems, such as coral reefs and forests, would be unrecognisable, accelerating the decline or Australia’s natural resources through the loss or change in the distribution of thousands of species and ecological processes. (As noted for scenario 1, the Great Barrier Reef will no longer exist at temperature rises of 2℃ or more).

• Much larger climate change-driven changes to water resources are likely, leading to increasingly contested supplies for natural flows, irrigated agriculture and other uses.

• At 3℃, living in many Australian cities and towns would be extremely challenging due to more frequent and severe extreme weather events, including much higher temperatures and more severe water shortages.

• Sea levels will rise by 0.4 to 0.8 metres by 2100 and by many metres over subsequent centuries. These changes will cost hundreds of billions of dollars over coming decades as coastal inundation and storm surge increasingly impact Australia’s coastal communities, infrastructure and businesses. Between 160,000 and 250,000 properties are at risk of flooding when sea levels rise to 1 metre above pre-industrial.

• The probability of large-scale extreme events, such as large storms, floods, droughts, hail storms, tropical cyclones, heatwaves and other climate-related phenomena will increase rapidly.

• High fire danger weather will increase significantly, leading to more catastrophic fire seasons such as the 2019/2020 Black Summer fires.

• Grain, fruit and vegetable crops will suffer more severe reductions in yields in a 3℃ world, and rising heat stress will negatively affect extensive and intensive livestock systems.

• Rural communities will face increasingly harsh living conditions due to increasing debt from diminishing crop yields, insurance losses from worsening extreme weather events, and more challenging working conditions due to increasing extreme heat.

• Australia at 3℃ will be hotter, drier and more water stressed with impacts on water security, availability, quality, economies, human health and ecosystems. Many locations in Australia in a 3℃ world would be very difficult to inhabit due to projected water shortages.

• Multiple impacts of a 3℃ world would damage the health and wellbeing of Australians. These include escalating heat stress, more frequent and intense bushfires, reduced access to food and water, increasing risk of infectious disease, and deteriorating mental health and general wellbeing.

3.4.3 Effects of a 4℃ Future World

69 The projected effects of a 4℃ Future World were described by Professor Steffen as follows:

Scenario 3: The Hothouse Earth scenario, with stabilisation in the 22nd century at a global average surface temperature level at least 4℃, and probably higher, above the pre-industrial level. There has been much less research on the impacts of a 4-5℃ temperature rise in global average surface temperature. However, a few of the potential impacts that could arise from such a high level of warming were summarised in Steffen et al. (2018: Supplementary Information). These include:

• Multiple impacts on agricultural regions, including depletion of soil fertility, changes in water availability and loss of coastal agricultural lands, with the risk of widespread starvation in the most vulnerable regions and/or large migrations out of those regions, increasing the risk of conflict elsewhere.

• Destruction of coral reefs from ocean warming and acidification, and consequent loss of livelihoods for those communities and societies dependent on reefs.

• Amazon rainforest at risk of conversion to savanna from both climate and land-use change. This would lead to large releases of CO2 to the atmosphere as well as large increases in extinction rates of species that depend on the rainforest.

• Tropical drylands at risk of becoming too hot and dry for agriculture, and too hot for human habitation. This has very large implications for many regions in Africa in particular, but also parts of Asia and much of Australia (see below).

• Very large risks from coastal flooding to transport, infrastructure and coastal ecosystems. Economic damages could trigger regional or global economic collapse as major coastal cities on all continents become uninhabitable.

• Reliability of South Asian (Indian) Monsoon vulnerable to high aerosol loading and to the warming of the Indian Ocean and adjacent land. Well over 1 billion people in south Asia depend on a reliable monsoon system. Failure of the monsoon would very likely lead to large-scale starvation, migration and conflict.

• Mountain glaciers melting at rapid rates, changing amount and timing of run-off. Freshwater resources of over 1 billion people at risk.

• Large changes to riparian and wetlands, with loss of water of some places and increased flooding in others.

For Australia, the corresponding impacts (harms) of Scenario 3 are:

• Much of Australia’s inland areas (savanna and semi-arid zones) will become uninhabitable for humans, except for artificial enclosed environments.

• The southeast and southwest agricultural zones will become largely unviable, due to extreme heat and a reduction in cool season rainfall. This would lead to a large depopulation of regional Australia.

• Australia’s large coastal cities (Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth) will suffer increasing inundation and flooding from storm surges as sea level rises to metres above its pre-industrial level over the coming centuries. This will drive severe economic challenges, both because of direct damage from flooding and the large costs of adaptation.

• The Great Barrier Reef will no longer exist.

• Most of the eastern broadleafed (eucalypt forests) will no longer exist due to repeated, severe bushfires.

3.4.4 What Needs to Be Done to Achieve a 2℃ Future World

70 Professor Steffen’s evidence also addressed the probability of a 2℃ Future World and what would need to be done to achieve it and thus (on his analysis) avoid a 4℃ Future World.

71 Professor Steffen opined that there is a 67% probability of achieving a 2℃ Future World if cumulative CO2 emissions from 2021 onwards are restricted to about 855 Gt of CO2 (equivalent to about 20 years of emissions at 2019 rates). That would require net-zero emissions by 2050 by all major emitting countries.

72 Professor Steffen referred to research by McGlade and Ekins (2015) which, using a ‘carbon budget framework’, concluded that there was a 50% probability of the world meeting a 2℃ temperature target if a global CO2 emissions budget of 1,100 Gt of CO2 was achieved for the 2011-2050 period. Professor Steffen noted that this carbon budget was somewhat higher than the budget of 855 Gt of CO2 which he had used in his own analysis (on the basis of a 67% probability). McGlade and Ekins analysed the available global fossil fuel “reserves” and “resources”, defining “resources” as all of the fossil fuels that are known to exist and “reserves” as a subset of “resources”, being those fossil fuels that are currently “economically and technologically viable to exploit”. McGlade and Ekins showed that if all of the world’s existing fossil fuel “reserves” were burnt, about 2,860 Gt of CO2 would be emitted and that about 2,000 Gt of these emissions would come from the combustion of coal. This level of emissions is about 2.5 times greater than the allowable carbon budget for reaching a 2℃ temperature target. On that basis, McGlade and Ekins concluded that globally, 62% of the world’s existing fossil fuel reserves need to be left in the ground, unburnt, and, having performed a regional analysis, it was concluded that over 90% of Australia’s existing coal reserves cannot be burnt to be consistent with a 2℃ temperature target.

73 The definition of “reserves” used by McGlade and Ekins would appear to include the 100 Mt of coal from the Extension Project, it being “economically and technologically viable to exploit now”. On the basis of the carbon budget analysis used by McGlade and Ekins to predict a 50% probability of meeting a 2℃ Future World, Professor Steffen offered this conclusion:

The obvious conclusion from the carbon budget analysis above is that currently operating coal mines must be phased out as soon as possible (preferably no later than 2030), and that no new coal mines, or extensions to existing coal mines, can be allowed.

3.5 Deliberation and Conclusions

74 The following plausible scenarios were demonstrated by that evidence:

(i) the Paris Agreement target of limiting global average surface temperature to well below 2°C, with the ambition to limit temperature to 1.5°C above the pre-industrial level, is now unlikely to be achieved without significant overshoot;

(ii) the best future stabilised global average surface temperature which can be realistically contemplated today, is 2°C above the pre-industrial level; and

(iii) if the global average surface temperature increases beyond 2°C, there is a risk, moving from very small (at about 2°C) to very substantial (at about 3°C), that Earth’s natural systems will propel global surface temperatures into an irreversible 4°C trajectory, resulting in global average surface temperature reaching about 4°C above the pre-industrial level by about 2100.

75 Furthermore, the evidence demonstrates that the risk of harm to the Children from climatic hazards brought about by increased global average surface temperatures, is on a continuum in which both the degree of risk and the magnitude of the potential harm will increase exponentially if the Earth moves beyond a global average surface temperature of 2°C, towards 3°C and then to 4°C above the pre-industrial level.

76 The applicants also seek to establish propositions which are in contest. Those propositions are directed to the extent that 100 Mt of CO2 from the Extension Project will materially contribute to the Children’s risk of being injured by one or more of the hazards induced by climate change.

77 Whether the emission of 100 Mt of CO2 from the Extension Project would increase the risk of harm to the Children is relevant to two aspects of the case. First, it bears on whether a duty of care should be recognised and, in particular, to the question of whether it is reasonably foreseeable that the emission of the 100 Mt of CO2 will increase the risk of the Children being harmed. Second, it is relevant to whether I should grant the injunction the applicants seek. For that purpose, I will need to be satisfied (to the extent later discussed) that it is likely that the emission of the 100 Mt of CO2 will cause the Children harm which, relevantly, is an inquiry as to whether it is likely that the emissions will materially contribute to that harm.

78 As French CJ said in Amaca Pty Ltd v Booth (2011) 246 CLR 36 at [41], “[t]he risk of an occurrence and the cause of an occurrence are quite different things”. Ordinarily, risk is assessed prospectively and causation is assessed retrospectively. However, because, for the purposes of the injunction, I may need to address the prospect of the Minister’s conduct causing harm to the Children, any causation assessment will necessarily be prospective rather than retrospective.

79 The submissions of the parties as to the prospective connection between the Minister’s impugned conduct (the emission of 100 Mt of CO2) and the increased risk of harm to the Children, were largely made by reference to a causation inquiry and not particularly directed to the risk-focused assessment required by the reasonable foreseeability inquiry. Despite that, the following discussion will assist in determining each of the inquiries I may need to make. My conclusions as to foreseeability inquiry and the causation inquiry (in so far as it has been necessary to come to a conclusion) are given later.

80 The applicants contended that the 100 Mt of CO2 from the Extension Project would make a material contribution to future increases in the global surface temperature and thus the degree and magnitude of the risk of harm faced by the Children. That was put in two ways although primary reliance was placed on the second. First, the applicants contended that the approval, extraction, export and combustion of carbon from the Extension Project will emit a material quantity of CO2 into the atmosphere. They contended that the more CO2 that is emitted, the higher the level of CO2 concentration will be before it reaches its zenith. The higher the level of CO2 concentration when it reaches its zenith, the worse the harm to today’s children will be.

81 The Minister responded to that contention by quantifying the increase in global temperature that 100 Mt of CO2 would cause. Assuming a purely linear relationship between increased emissions of CO2 and increased temperature, the calculation was available by reference to Professor Steffen’s evidence that further emissions will increase global average surface temperature at a rate of about 1℃ for every 1,800 Gt of CO2 emitted. The emission of 100 Mt of CO2 would therefore result in an increase of one eighteen-thousandth of a degree Celsius.

82 The Minister contended that an increase of that magnitude was de minimis, which I take to mean negligible (see Bonnington Castings Ltd v Wardlaw [1956] 1 All ER 615 at 618-619 (Lord Reid)). To make good that contention, the Minister contended by way of example that if it were to be assumed that global average surface temperature would otherwise stabilise at 2℃, it would logically follow that, with the addition of 100 Mt of CO2, the temperature would instead stabilise at 2.00005℃. It was then said that there was simply no evidence before the Court about what that magnitude of increase meant in terms of measurable risk. It was suggested that climate change modelling does not operate at a sufficient level of specificity to provide an answer.

83 The wealth of scientific knowledge demonstrated by the evidence before me suggests that science is likely capable of providing that answer. However, I am unable to say that the evidence itself demonstrates the extent, if any, that a fractional increase in average global temperature of the kind in question poses an additional risk of harm to the Children. But that conclusion does not answer the way in which the applicants put their case. They argue that it is the accumulation of CO2 which causes exposure to the risk of harm and accumulated CO2, including the contribution to that accumulation which the 100 Mt of CO2 will make, that will bring about increased temperatures and the harm that the evidence demonstrates will follow. In that way, the applicants say there will be a material contribution to injury.

84 The second way the case was put by the applicants was to adopt what an economist might call a marginal analysis. This contention was made by reference to the contribution that 100 Mt of CO2 may have on the level at which the global average surface temperature will stabilise. In that respect, the applicants first relied on Professor Steffen’s evidence that CO2 emissions from the Extension Project “would increase the level at which atmospheric CO2 concentration is eventually stabilised, and thus would increase the level at which the global average surface temperature is eventually stabilised”. The applicants then relied on the Future World scenarios identified already and the propositions set out at [74] above including that there is a risk, moving in degree from very small to very substantial as the global average surface temperature increases from 2℃ to 3℃ above the pre-industrial level, that a ‘tipping cascade’ will trigger a 4℃ Future World trajectory. The applicants contended that once global average surface temperatures reach or exceed 2℃ above the pre-industrial level, the risk of a 4℃ Future World increases exponentially and that with that heightened realm of risk in prospect, the emission of an additional 100 Mt of CO2 is material. On that basis and given that the evidence demonstrates an increase in both the degree and magnitude of risk of harm to the Children as between a 2℃ Future World and a 4℃ Future World, the applicants contended that the emission of 100 Mt of CO2 in the context of the risk profile just described, is a material contribution to the risk of exposure to harm.

85 The Minister sought to challenge that submission in a number of ways. First, the Minister characterised the applicants’ case as dependent upon demonstrating that the 100 Mt of CO2 from the Extension Project would be emitted outside the available budget of emissions necessary to meet a 2℃ target. The Minister contended that it is likely that the 100 Mt of CO2 would be emitted compliantly with the Paris Agreement and thus within a lower than 2℃ target.

86 Putting aside for the moment what I think is a mischaracterisation of the applicants’ case, there is not sufficient evidence before me on which I could conclude that there is no real prospect of the 100 Mt of CO2 being burnt outside the available fossil fuel budget necessary to meet a 2℃ target. The Minister called no evidence. The Minister essentially contended that the Court should infer that the 100 Mt of CO2 would likely be emitted in accordance with the Paris Agreement. There is no sufficient basis for that inference. The Minister relied upon little else than speculation, in circumstances where the evidence showed that at least one of the potential consumers of the coal is not a signatory to the Paris Agreement.

87 Further and in any event, there is evidence before me which tends to support the proposition that the 100 Mt of CO2 will not be emitted as part of the available carbon budget necessary to achieve a 2℃ target. Professor Steffen’s opinion was that it was “obvious” from the carbon budget analysis, that “no new coal mines, or extensions to existing coal mines, can be allowed”. There can be no doubt that in making that statement Professor Steffen had the Extension Project in mind. True it is that he did not go on to explain why, but to say it is “obvious” by reference to the carbon budget analysis he relied on implies that the reason is to be found in his prior reliance on the study made by McGlade and Ekins, who had analysed the position for Australia and had calculated that over 90% of Australia’s existing coal reserves cannot be burnt to meet a 2℃ target. That observation reveals the logic behind Professor Steffen’s conclusion and it is logic which may be relied upon irrespective of whether the conclusion he proffered was based upon his specialist expertise. If there is no capacity to include 90% of existing Australian reserves of coal in the carbon budget, it seems unlikely that a capacity for new reserves to be included exists. Even “existing” reserves, by which Professor Steffen must have meant those already being exploited, logically have only a 1 in 10 chance of being included in the budget. There is no evidence sufficient to support a contention that the 100 Mt of CO2 from the Extension Project is earmarked for some priority treatment relative to other coal sufficient to put it in the top 10% of candidates for inclusion in the budget.

88 I should say that, whilst the applicants’ contention about risk is stronger on the basis of there being a real prospect of the 100 Mt of CO2 being emitted on or after average surface temperature has reached 2℃, the contention does not depend upon that. The contention depends upon the plausible prospect that surface temperature will reach a point where a ‘tipping cascade’ will be triggered even by a fractional increase in temperature. As that fractional increase will be the product of an accumulation of CO2, it is not essential to the applicants’ contention that the 100 Mt of CO2 is emitted outside of the ‘carbon budget’. What is essential is that the emission does not occur after the ‘tipping cascade’ is triggered. No one contended for that proposition and, on the evidence I do not think it was available.

89 The Minister also suggested that the applicants’ position relied upon demonstrating that a 2℃ Future World was the most likely scenario and that the applicants had overstated Professor Steffen’s evidence on that point because, when properly analysed, Professor Steffen was really saying that a stabilised average global temperature of about 1.8℃ was the most likely scenario. There are some differences in the way that Professor Steffen has described the stabilised average global temperature for his “Scenario 1”. It is variously described as “at, or very close to, 2℃”, “around 2℃”, “approximately 2℃”, “a 2℃ target”, and on one occasion he said “approximately equivalent to, or slightly higher than the upper Paris [A]ccord target of ‘well below 2℃’”. Read in context, the better view is that when Professor Steffen was referring to the stabilised average global temperature for his “Scenario 1” he meant 2℃ or slightly lower but not “well below 2℃” and not the upper target of the Paris Agreement.

90 In any event, the applicants did not say that a 2℃ Future World is the most likely scenario. Their contention was that a 2℃ Future World is a plausible possibility in circumstances where at temperatures at or slightly lower than 2℃, there is a small (but non-zero) probability that a tipping cascade will trigger a 4℃ Future World trajectory. Professor Steffen’s unchallenged evidence establishes that trajectory as a plausible scenario, should the global average surface temperature exceed 2℃ or slightly lower. That was a necessary element of the applicants’ contention and it was established.

4. Does the Minister owe the Children a DUTY OF CARE?

91 The applicants, who are all less than 18 years of age, contend that the Minister owes a duty of care to them and the class of persons they represent. The class description was originally identified as children born before the date the proceeding was filed who ordinarily reside in Australia or elsewhere, but during the course of the proceeding the applicants limited the relief sought to children residing in Australia. I have therefore proceeded on the basis that the relief claimed, including the scope of the duty of care claimed, is limited to Australian children including the applicants.

92 Although formulated a little differently by the applicants’ Amended Concise Statement (and with my adjustment to take into account that relief is now limited to Australian children), the content of the posited duty as described by the applicants’ submissions is the duty of the Minister to exercise her power under s 130 and s 133 of the EPBC Act with reasonable care to not cause the Children harm resulting from the extraction of coal and emission of CO2 into the Earth’s atmosphere. The type of harm that the applicants assert the duty should cover is mental or physical injury, including ill health or death, as well as damage to property and economic loss.

93 As formulated by the applicants, the duty would extend to any decision under s 130 and s 133 of the EPBC Act involving the extraction of any amount of coal. However, the evidence and submissions made were not directed to any extraction of coal but were focused specifically on the Extension Project and the Minister’s prospective decision to approve or not approve the extraction of 33 Mt of coal and the consequent emission of 100 Mt of CO2, which the applicants assert will make a reasonably foreseeable contribution to climate change and the risk of harm that the applicants fear. The applicants’ case cannot support the establishment of a duty in respect of the Minister’s approval of the extraction of any amount of coal, no matter how small. That is because reasonable foreseeability of harm is an essential pre-condition to the existence of a duty of care. It was not the applicants’ case that it is reasonably foreseeable that the extraction and combustion of any amount of coal would cause the Children injury. The description of the asserted duty was not limited to the Extension Project and was not expressly limited by a reasonable foreseeability requirement. Such a requirement must, however, be implicit in the applicants’ description of the duty of care asserted.

94 I will proceed on the basis that the duty of care asserted is not confined to the approval of the Extension Project but extends to an approval of the extraction of coal which foreseeably exposes the Children to harm. However, I can only conveniently assess whether such a duty exists by reference to the evidence and that evidence and, in particular, the evidence going to the reasonable foreseeability inquiry is specific to the Extension Project. I will therefore confine the findings I will make about the existence of a duty of care to the approval of the Extension Project. If those findings give rise to a duty of care that can be described in terms which extend beyond the Extension Project, I will consider a wider description after further submissions are made by the parties as envisaged by my concluding remarks in Section 9. For present purposes I will refer to the duty of care asserted by the applicants as “the posited duty of care” meaning a duty on the Minister to take reasonable care in the exercise of her statutory powers not to cause the Children harm arising from the extraction of coal from the Extension Project and the consequent emission of CO2 into the Earth’s atmosphere.

95 The existence of a duty of care is a necessary condition of liability in negligence: Brookfield Multiplex Ltd v Owners Corporation Strata Plan 61288 (2014) 254 CLR 185 at [19] (French CJ). The applicants do not identify any authority holding that the posited duty of care exists in directly comparable factual circumstances. They ask the Court to find what is in such circumstances referred to as a “novel” duty of care.

4.1 Ascertaining whether a Novel Duty Exists – the Applicable Legal Principles

96 Whether a novel duty of care exists is to be ascertained by reference to a multi-factorial assessment in which considerations (salient features) relevant to the appropriateness of imputing a legal duty upon the putative tortfeasor are assessed and weighed. I discussed the appropriate approach to the ascertainment of a novel duty of care in Plaintiff S99/2016 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2016) 243 FCR 17 at [201]-[229]. The principles there discussed are not in contest and were relied upon by the parties. For convenience the discussion of those principles is here updated but largely repeated.

97 A salient features approach was adopted by Allsop P (with whom Simpson J agreed) as applicable to determining whether a novel duty of care exists in Caltex Refineries (Qld) Pty Ltd v Stavar (2009) 75 NSWLR 649, at [102]. Relevantly, his Honour said this (emphasis added):