Federal Court of Australia

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Telstra Corporation Limited [2021] FCA 502

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | TELSTRA CORPORATION LIMITED (ACN 051 775 556) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth):

(a) Between at least 1 January 2016 and about 27 August 2018 (Relevant Period), sales staff at Telstra Licensed Stores (TLS) located in Arndale in South Australia, Broome in Western Australia, and Casuarina, Palmerston and Alice Springs in the Northern Territory (Relevant Stores) entered into contracts on behalf of Telstra for the supply of goods and services to 108 Indigenous Australian consumers identified in Annexure A, many of who were from regional and remote Indigenous communities, and who were subjected to the exploitative practices described in paragraph 1(c) and subsequently incurred significant debt (Affected Consumers).

(b) The Affected Consumers possessed one or more of the following characteristics:

(i) many spoke English as a second, third or fourth language;

(ii) many had difficulties with reading, writing and understanding financial concepts and had limited or no ability to read or comprehend the terms of Telstra’s written contracts that they would be bound by and other documentation related to the transaction which, for these consumers, was confusing and difficult to understand; and

(iii) many were unemployed and relied on government benefits or pensions as the primary source of their limited income.

(c) When entering the Affected Consumers into contracts for post-paid mobile products and services, TLS sales staff:

(i) entered the Affected Consumers into more than one contract for post-paid mobile products and services on a single day;

(ii) in some instances, having regard to the specific circumstances of the Affected Consumers, engaged in unfair tactics by not giving full and proper explanation of matters such as:

A. the terms of the contracts, including the way in which data usage was charged;

B. the nature and monthly base costs of the contract;

C. the consumer’s total minimum monthly liability for all post-paid products and services; and

D. the risk of incurring potentially unlimited excess data charges under the contracts;

(iii) in some instances, falsely represented or created the false or misleading impression that consumers could or would receive a device or devices for “free”;

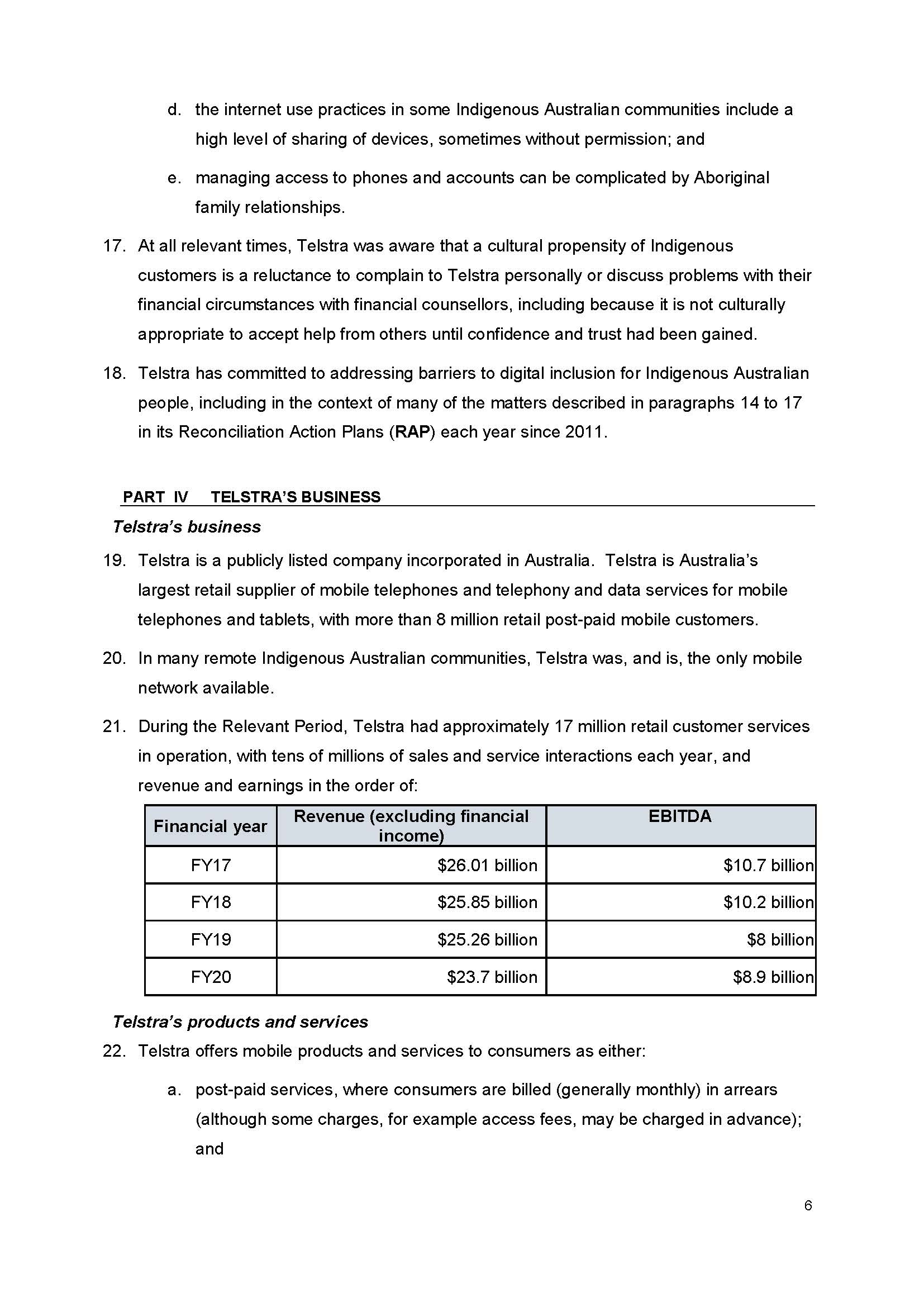

(iv) in many instances, manipulated credit assessments, so as to be able to enter into post-paid contracts with consumers who would otherwise have failed Telstra’s credit assessment process and not have been approved for credit;

(v) in some instances, sold consumers extra add ons that they did not want or that sales staff falsely represented would be “free”, or would provide benefits to customers they could not otherwise obtain, when some of those benefits were otherwise available free of charge;

(vi) having regard to the specific circumstances of the Affected Consumers, did not take adequate steps to determine whether the cost of the post-paid mobile products and services were affordable for the particular consumer, including when sales staff were aware the consumer was unemployed or receiving a government benefit or pension;

(vii) exploited the consumer’s lack of understanding of the terms applying to the transaction and/or took advantage of a cultural propensity for Indigenous Australian people to express agreement as a means of avoiding conflict,

(collectively referred to as the Improper Sales Practices).

(d) The conduct of the TLS sales staff referred to in paragraphs 1(a) and 1(c) above is taken to have been engaged by Telstra pursuant to s 139B(2) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA), and Telstra, by virtue of that conduct, thereby engaged in trade or commerce, in conduct in relation to each of the Affected Consumers that was, in all the circumstances, unconscionable in breach of s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), which is contained in Schedule 2 to the CCA, the occurrence and impact of which was all the more serious as a result of the matters set out in paragraphs 1(e) and 1(f) below.

(e) The Improper Sales Practices took place in circumstances where, during the Relevant Period, Telstra was aware of:

(i) the unique cultural needs of, and issues faced by, many Indigenous Australian people;

(ii) various aspects of the Improper Sales Practices that had occurred, and reoccurred, in the Relevant Stores from the ongoing reports of such conduct received through various channels, including its own Credit Risk Office;

(iii) the risk of some Indigenous Australian consumers incurring significant charges from excess data charges, within a short time period, including due to how devices were used and shared within some Indigenous Australian communities, which meant that large excess data charges could be incurred over a short period of time without adequate warning upfront of the costs involved for the account holder; and

(iv) the possible impact that any sales staff incentives paid by the licensees of the Relevant Stores to their sales staff could have had in positively encouraging Improper Sales Practices.

(f) Despite knowledge of the matters in paragraph 1(e), Telstra did not, during the Relevant Period:

(i) have, or implement, effective systems or processes to ensure that the risk and magnitude of additional significant excess usage fees if customers exceeded the included usage allowances of a post-paid contract for mobile services was explained fully and properly to Affected Consumers at the Relevant Stores;

(ii) take effective steps to ensure that TLS sales staff identified the products or the services most suited to the Affected Consumers’ means and circumstances;

(iii) have, or implement, effective systems or processes that would have prevented the Affected Consumers from being sold inappropriate and unaffordable post-paid products and services without understanding what they were signing up for, the base cost of those contracts and potential excess data charges;

(iv) have, or implement, effective systems and processes to detect and prevent TLS sales staff engaging in credit assessment manipulation;

(v) change its processes for referring or selling debts of consumers who had purchased products and services from the Relevant Stores to third party debt collectors, who pursued many of the Affected Consumers for the debt they owed to Telstra;

(vi) offer Indigenous Australian cultural awareness training to sales staff until May 2017, did not adequately focus such training on how sales staff may need to adjust the way they engaged with Indigenous Australian consumers in a sales environment and, in any case, did not require all sales staff, including those at the Relevant Stores, to undertake the Indigenous Australian cultural awareness training;

(vii) have, or implement, effective systems or processes to provide assistance to Indigenous Australian consumers who did not speak English as a first language or who had limited financial or literacy skills to understand the contracts for the post-paid mobile products and services; and

(viii) have in place, or implement, an effective remediation program to respond comprehensively to complaints made by or on behalf of the Affected Consumers.

AND THE COURT ORDERS BY CONSENT THAT:

2. Pursuant to s 224(1)(a)(i) of the ACL, within 30 days of the date of this Order, the Respondent pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty in the sum of $50 million.

3. The Respondent pay the Applicant’s costs of and incidental to the proceeding.

4. A copy of the reasons for judgment, with the seal of the Court affixed thereon, be retained on the Court file for the purposes of s 137H(3) of the CCA.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MORTIMER J:

1 The respondent, Telstra Corporation Limited, is a publicly listed company incorporated in Australia. It is Australia’s largest retail supplier of mobile telephones and telephony and data services for mobile telephones and tablets. By orders made today, and as a result of contraventions of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), which Telstra has admitted, the Court has imposed significant penalties on Telstra, as well as granting declaratory relief and ordering Telstra to pay the costs. The contraventions involve unconscionable conduct engaged in by sales staff at five Telstra licensed stores (the Telstra stores), in connection with contracts for the supply of post-paid mobile products and services to 108 consumers (the affected consumers). Those consumers are all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, who – for a variety of reasons – were vulnerable to unconscionable sales practices employed by the staff employed at the Telstra stores. The affected consumers were also exposed to serious financial hardship and distress through becoming liable for expenses that they could not afford to pay, and which some had not understood they were incurring. Telstra’s approach to complaints about the sales practices, and its delay in accepting responsibility for the conduct, as well as some of its debt recovery practices, are aggravating factors.

2 For the reasons set out below, there will be orders in the terms proposed by the parties.

Background

3 On 26 November 2020, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission commenced proceedings in this Court against Telstra in respect of allegedly unconscionable conduct that occurred in the period 1 January 2016 to 27 August 2018, and was alleged to be contrary to s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law, which is found in sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act. It was apparent that Telstra admitted this conduct in full. On 3 December 2021, the parties filed an affidavit of Mr James Rutherford Docherty affirmed on that date. The affidavit annexed a joint statement of agreed facts and admissions, which was admitted pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), and a proposed minute of consent orders sought by the parties. The statement of agreed facts and admissions is annexed to these reasons for judgment.

4 The parties also provided a document described as “Confidential Annexure A” to the originating application and agreed facts. Part A of this document lists the names of the affected consumers, details of the store which sold them the products and services, and the number of contracts they each entered. Part B of annexure A is a list of affected consumers who, as a result of the contraventions, incurred debts to Telstra, and whose debts were sold by Telstra to third party debt collectors. On 21 December 2020 the Court made suppression orders pursuant to s 37AF(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) in relation to the personal names and “CIDN / CAC” (being the number used to identify the consumer in Telstra’s system) contained in annexure A. Annexure A is accordingly not included in the copy of the agreed facts annexed to these reasons.

5 On 31 March 2021, the Court conducted a hearing in relation to the proposed orders and the quantum of the financial penalty which should be imposed.

The factual setting for the agreed CONTRAVENTIONS

6 It is an agreed fact that at the time of the admitted contraventions, Telstra was and remains the only service provider whose mobile network is available in many remote Indigenous Australian communities. That fact becomes relevant to the absence of any real bargaining power in the affected consumers. If they wanted mobile phones or tablets which could work in the communities where they lived, they had to purchase those services from Telstra.

7 The category of products and services in question were “post-paid services”, where consumers are billed in arrears. This is in contrast to “pre-paid services” where consumers purchase credit in advance which is used to pay for mobile services as they are used. The contraventions also involved the sale of “add ons”, which are described in the agreed facts as products or services that were attached to post-paid services and most of which attracted periodic charges additional to the core post-paid contract, such as subscriptions to music streaming services. Devices such as iPads were also sold to the affected consumers on the post-paid contracts.

8 The five stores in which the contraventions occurred were what are described as “Telstra licensed stores” that held “Telstra Dealership Agreements” with Telstra. The exact nature of the contractual or licensing arrangements between Telstra and the stores was not clear on the agreed facts, but Telstra admits that the conduct of the staff employed in the relevant stores was conduct engaged in on behalf of Telstra. For that reason I have described them as “Telstra stores”. In the statement of agreed facts and admissions, there are referred to as the “TLS”, for “Telstra Licensed Stores”.

9 During the relevant period, and as part of the contractual process carried out in the Telstra stores, Telstra required consumers to verify their identity and to pass a “credit assessment” before post-paid products and services were supplied. The credit assessments were designed to evaluate the credit risk of the consumer to Telstra, based on a number of criteria such as the consumer’s payment history with Telstra, and information provided by the consumer about their occupation and employment status. A number of limited circumstances might lead to a consumer not receiving approval, such as the consumer having not met prior payment obligations and/or having outstanding debt to Telstra, having an unfavourable credit rating with an external credit reporting body, or not providing sufficient identification. It is an agreed fact that customers typically received an approved credit assessment outcome.

10 An “approved” rating was required before a consumer could enter into a post-paid contract. But approval also meant consumers could enter into more than one such contract, for up to three devices without any further limits being triggered and with no limit on the total minimum base cost of the relevant contracts. The joint submission at [51] described the problems with the credit assessment process:

The information required in that process served to highlight the financial vulnerability of consumers (eg where they had an unfavourable credit rating or history, or where they were unemployed and/or receiving government benefits or pensions). However, the system was able to be readily manipulated by sales staff by creating different customer identifications or falsely indicating that the person was employed. The result was that consumers were approved for credit, limited only by reference to the number of devices, that was unaffordable by them: see SAFA at [29]-[36], [48]-[50], [52]-[54].

11 This kind of credit manipulation practice formed part of the contravening conduct. The applicable telecommunications regulations did not require, and Telstra did not request, that consumers provide detailed financial information. Nor was there any consideration during the credit assessment of what proportion of a consumer’s income would be required to cover the cost of post-paid products and services. During the relevant period Telstra’s credit assessment system did not have mechanisms in place to prevent the kinds of credit manipulation described in the extracted paragraph above.

12 The agreed facts disclose that the Telstra stores, and the staff employed in them, were incentivised to secure post-paid contracts with people such as the affected consumers. Telstra set performance and sales targets under the terms of the Telstra Dealership Agreements held by each of the Telstra stores, which the stores were required to meet. Telstra also provided financial incentives in the form of one-off payments to licensees for the supply of services, the incentive for post-paid services being greater than the amount for pre-paid services. Telstra was aware the licensees in turn set sales targets and provided financial incentives to sales staff. It is agreed that therefore Telstra was aware the combined effect of this incentivising was to

encourage its agents and representatives, including in the Relevant Stores, to engage with consumers at the point of sale in ways that would increase the volume and value of Post−Paid Products and Services supplied.

13 It was also agreed that:

Telstra was in a substantially stronger bargaining position than the Affected Consumers, because the Affected Consumers possessed one or more of the following characteristics:

a. many spoke English as a second, third or fourth language;

b. many had difficulties with reading, writing and understanding financial concepts and had limited or no ability to read or comprehend the terms of Telstra’s written contracts that they would be bound by and other documentation related to the transaction which, for these consumers, was confusing and difficult to understand; and

c. many were unemployed and relied on government benefits or pensions as the primary source of their limited income.

14 To this can be added, as I have already noted, that Telstra was the only service provider available in many remote communities. The affected consumers had little or no choice but to use the Telstra stores.

Telstra’s admissions and the proposed relief

15 Telstra has made the following admissions:

When entering the Affected Consumers into contracts for Post-Paid Products and Services, TLS sales staff:

a. entered Affected Consumers into more than one contract for Post-Paid Products and Services on a single day;

b. in some instances, having regard to the specific circumstances of the Affected Consumers, engaged in unfair tactics by not giving a full and proper explanation of matters such as:

i. the terms of the contracts, including the way in which data usage was charged;

ii. the nature and monthly base costs of the contract;

iii. the consumer’s total minimum monthly liability for all Post-Paid Products and Services; and

iv. the risk of incurring potentially unlimited Excess Data Charges … under the contracts;

c. in some instances, falsely represented or created the false or misleading impression that consumers could or would receive a device or devices for ‘free’;

d. in some instances, sold consumers extra Add ons that they did not want or that sales staff falsely represented or created the false or misleading impression would be ‘free’, would provide benefits to consumers they could not otherwise obtain or needed to be purchased when some of the relevant benefits (being technical support services) were otherwise available free of charge;

e. having regard to the specific circumstances of the Affected Consumers, did not take adequate steps to determine whether the cost of the Post-Paid Products and Services were affordable for the particular consumer, including when sales staff were aware the consumer was unemployed or receiving a government benefit or pension;

f. exploited the consumer’s lack of understanding of the terms applying to the transaction (arising in part from the characteristics outlined in paragraph 46) and/or took advantage of a cultural propensity for Indigenous Australian people to express agreement as a means of avoiding conflict,

(collectively referred to as Improper Sales Practices).

16 While it is agreed that this conduct was conducted on Telstra’s behalf, it is also an agreed fact that Telstra did not “direct, intend, approve or authorise” these practices. I take that distinction to be intended to convey that neither Telstra’s Board, nor its senior executives, consciously set out to have staff at Telstra stores engage in such practices, but the Board (at least) accepts the deliberate conduct of the staff members at the Telstra stores is properly seen as capable in law of being attributed to Telstra itself. Further, there are agreed facts which establish that Telstra became “increasingly aware” of various aspects of the improper practices over the relevant period, starting from at least 6 December 2016.

17 It was unclear to the Court what was meant in the agreed facts when the term “Telstra” was used in a context referable to a state of mind. After an inquiry of counsel at the hearing, the matter was clarified.

18 Senior counsel for Telstra submitted at the hearing that “awareness” in the statement of agreed facts should be understood in light of the fact agreed at [12] that “neither Telstra’s board nor senior executives were aware of the improper sales practices at the time they occurred”. He submitted that the word “awareness” was used to refer to “the awareness of responsible managers within the relevant arm of the organisation to whom information came”. Senior counsel for the ACCC accepted this description. I accept that is an appropriate inference to draw. That is the sense in which I use the term in these reasons.

19 The post-paid products and services sold to the affected consumers involved standard form contracts that included standard minimum monthly charges of up to $786 and averaging $322, and unlimited, automatic charges for data usage that exceeded the monthly data allowances included in the contract. These amounts usually represented a substantial proportion of the income of affected consumers, who on the agreed facts were generally in receipt of some kind of government support payment as their principal form of income.

20 While the affected consumers were saddled with obligations that would lead them to incur considerable debts, the licensees of the five Telstra stores received an average financial bonus of $24,492 in respect of the affected consumers. It is an agreed fact that individual sales staff at the five Telstra stores were also likely to have been paid incentive payments by the relevant licensee for their work in encouraging the affected consumers to enter into these contracts.

21 As I have noted above, in numerous cases the individual sales staff at the Telstra stores also manipulated aspects of Telstra’s credit assessment process and represented (falsely) to affected consumers that they had passed the assessment. This manipulation meant affected consumers were approved for post-paid products and services when they otherwise would not have been, if accurate information had been used. It is agreed this was done in the way described at [10] above and by:

b. slightly altering the name of the consumer or changing the consumer’s date of birth in order to make applications against multiple CIDNs rather than multiple applications against the correct CIDN to avoid potentially negative credit history under the consumer’s real name;

c. adding or removing driver licence details;

d. amending the residential status and address; and

e. amending the duration of residence,

(collectively referred to as Credit Assessment Manipulation).

22 It is an agreed fact this manipulation was done “without Telstra’s knowledge”. I infer what is meant by that agreed fact is that while the staff and management in the relevant stores who engaged in the conduct were aware of what they were doing, at the time of the conduct neither Telstra’s Board nor its senior executives had knowledge the conduct was occurring. Further, other staff within Telstra became aware over time, but the agreed facts do not permit the inference such staff knew about the conduct at the time it was occurring. Senior counsel for Telstra submitted the agreed fact that this manipulation occurred “without Telstra’s knowledge” was intended to refer to:

relevant members of the Telstra employee group within the organisation who had responsibility, for instance, such as dealing with the TIO first inquiry, obtained some information by that route. Likewise, those involved in the CRO investigations and reports obtained the knowledge revealed by those reports. Those who received complaints had the knowledge conveyed by those complaints. So you have a wide range of employees who gained some knowledge. But it’s a mistake to assume that a complete picture was possessed as time unfolded within the organisation about the list of improper practices that we now see in the originating application, your Honour.

23 However, as I explain below and as this submission acknowledges, those with responsibilities for compliance within Telstra did become aware of this practice of manipulating credit assessments, and initially the only steps taken were steps to protect Telstra’s position, rather than steps to assist the affected consumers.

24 All of the affected consumers consequently incurred significant debts to Telstra, ranging from $1,600 to $19,524, the average being $7,461. Some of these debts, as noted above, were sold by Telstra to third party debt collectors. Telstra has subsequently waived all the debts owed by the affected consumers, and refunded all amounts paid to it by the affected consumers (including interest) in respect of sales arising from the improper sales practices and credit assessment manipulation. The total debt waived and refunds provided by Telstra is $979,507. What happened about the transactions with the third party debt collectors is not covered by the agreed facts, although it is apparent that Telstra bought back at least some of the debts owed by affected consumers.

25 On the basis of the agreed facts, Telstra has admitted to contravening s 21 of the ACL which provides:

21 Unconscionable conduct in connection with goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with:

(a) the supply or possible supply of goods or services to a person; or

(b) the acquisition or possible acquisition of goods or services from a person;

engage in conduct that is, in all the circumstances, unconscionable.

(2) This section does not apply to conduct that is engaged in only because the person engaging in the conduct:

(a) institutes legal proceedings in relation to the supply or possible supply, or in relation to the acquisition or possible acquisition; or

(b) refers to arbitration a dispute or claim in relation to the supply or possible supply, or in relation to the acquisition or possible acquisition.

(3) For the purpose of determining whether a person has contravened subsection (1):

(a) the court must not have regard to any circumstances that were not reasonably foreseeable at the time of the alleged contravention; and

(b) the court may have regard to conduct engaged in, or circumstances existing, before the commencement of this section.

(4) It is the intention of the Parliament that:

(a) this section is not limited by the unwritten law relating to unconscionable conduct; and

(b) this section is capable of applying to a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour, whether or not a particular individual is identified as having been disadvantaged by the conduct or behaviour; and

(c) in considering whether conduct to which a contract relates is unconscionable, a court’s consideration of the contract may include consideration of:

(i) the terms of the contract; and

(ii) the manner in which and the extent to which the contract is carried out;

and is not limited to consideration of the circumstances relating to formation of the contract.

26 The parties have submitted joint proposed orders. Aside from some consequential orders, the principal components of the relief proposed are:

(a) a declaration describing

(i) the nature of the unconscionable conduct, being the improper sales practices and credit manipulation practices;

(ii) the context of that conduct;

(iii) that Telstra was aware of the specific vulnerabilities of the affected consumers; and

(iv) that despite that knowledge, Telstra did not implement or take steps to implement appropriate processes to protect against or remediate the effects of the unconscionable conduct.

(b) an order that Telstra pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty in the amount of $50 million.

27 Prior to the commencement of this proceeding, Telstra had also agreed to enter into an enforceable undertaking, pursuant to s 87B of the Competition and Consumer Act, with a term of five years. The undertaking takes effect 30 days from the date of the Court’s orders. The undertaking covers further steps by way of remediation to be taken by Telstra, in relation to other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander consumers who may have been affected by “substantially similar” conduct to that which is the subject of the s 21 contravention in this proceeding, including refunds and waiving of any debts incurred by those other consumers. This aspect of the remediation scheme will be advertised, and promoted at Telstra’s own expense, I infer to ensure as many additional consumers as possible are made aware of the remediation scheme. Telstra has also undertaken to initiate a compliance program, to review and adjust its “Indigenous Hotline” so that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander complainants are better able to be assisted, including by speaking to Indigenous consultants and interpreters. The hotline will be promoted by signage at point of sale locations.

28 Further, Telstra has undertaken to enhance the “digital literacy training” programs it runs, at its own expense. Specific locations, and nominated Aboriginal communities, are identified in Annexure B to the undertaking. This training will include topics that relate to practical management and usage of mobile phone plans and devices, how to use the internet, the difference between pre-paid and post-paid mobile phone plans, managing costs associated with owning a mobile phone; identifying relevant government agencies, and how to contact them for issues about telecommunications service providers; and the role of financial counsellors.

29 The undertaking given by Telstra will be publicly available on the ACCC website, and is annexure B to the agreed facts annexed to these reasons. As the parties submit, the undertaking by Telstra is an important part of the resolution of the proceeding.

Applicable principles

The applicable penalty is a matter for the Court

30 Although the parties have jointly submitted that $50 million is an appropriate penalty, the parties accept that the Court is not bound to give effect to that submission. Nevertheless, the Court generally ought to give effect to agreed submissions as to appropriate remedy: Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 (Commonwealth v DFWBII); NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v ACCC [1996] FCA 1134; 71 FCR 285 and Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; ATPR 41-993. In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bupa Aged Care Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 602 at [18]-[19], I said:

Wigney J made a different but consistent observation in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2016] FCA 1516; 118 ACSR 124 at [104]:

In considering whether the proposed agreed penalty is an appropriate penalty, the Court should … generally recognise that there is no single appropriate penalty and that an agreed penalty may be an appropriate penalty if it falls within a range within which any of the figures could be considered to be appropriate having regard to all relevant circumstances. The Court should also recognise that the agreed penalty is most likely the result of compromise and pragmatism on the part of the Commission, and to reflect, amongst other things, the Commission’s considered estimation of the risks and expense of the litigation had it not been settled.

I respectfully agree with Wigney J’s observations, although it is important to emphasise that considerations of pragmatism and compromise on the part of the regulator do not absolve the Court from forming its own opinion that the proposed penalty is, on the evidence, within an appropriate range and proportionate to the conduct constituting the contraventions.

31 I adhere to those views.

32 The parties submitted that this principle is not confined to agreed submissions on pecuniary penalties but also applies to agreement on other forms of relief, including agreed positions on declarations, injunctions and the like.

33 The parties cited ACCC v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1405 at [72] and [75]; ACCC v Real Estate Institute of Western Australia Inc [1999] FCA 1387; 95 FCR 114 at [1], [20]-[21] and [29]; ACCC v Target Australia Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1326 at [24]; ACCC v Virgin Mobile Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2002] FCA 1548 at [2] and ACCC v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2006] FCA 1730; [2007] ATPR 42-140 at [4] for this proposition. I accept the Court generally adopts an agreed position by the parties on other forms of relief as well. The underlying rationale for doing so is the same. Nevertheless, the question of appropriateness remains one for judicial determination.

34 The nature of the task for the Court where the parties agree as to appropriate penalty was considered by the Full Court in Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft v ACCC [2021] FCAFC 49, an appeal from a decision of this Court in which the primary judge found that the agreed penalty was not appropriate within the meaning of s 224(1) of the ACL. In response to a submission that the Court’s task in determining an appropriate penalty is not discretionary, the Full Court said (at [123], [130]-[131]):

The starting point, even where an agreed or jointly proposed civil penalty is put to the Court as part of a settlement, is s 224(1) of the Consumer Law, which provides that, if the Court is satisfied that a person has contravened a relevant provision of the Consumer Law, the Court may order the person to pay such pecuniary penalty “as the court determines to be appropriate”. Subsection 224(2) of the Consumer Law provides that in “determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters”, including those matters specified in subpars (a), (b) and (c). These provisions make it clear that it is always a matter for the Court to determine the appropriate penalty having regard to all relevant matters.

…

The Commission’s submission that the Court’s determination of a penalty pursuant to s 224(1) of the Consumer Law does not involve the exercise of discretion where a penalty has been jointly proposed by the parties appears to proceed on the basis that the Court’s task in such a case is limited to determining whether the proposed penalty is or is not an appropriate penalty. That determination in turn depends on whether the proposed penalty is within the permissible range of penalties. It is on that basis that the Commission submitted that, to succeed on the appeal, Volkswagen need only demonstrate that the primary judge erred in concluding that the jointly proposed penalty was not an appropriate penalty, in the sense that it was not within the permissible range. The suggestion appeared to be that there was only one correct answer to that question; that the primary judge’s determination that the agreed penalty was not within the permissible range was either right or wrong.

The Commission’s characterisation of the Court’s task in cases involving agreed and jointly proposed penalties is, however, overly simplistic and inaccurate. The Court’s task in such cases is not limited to simply determining whether the jointly proposed penalty is within the permissible range, though that might be expected to be a highly relevant and perhaps determinative consideration. Nor is the Court necessarily compelled to accept and impose the proposed penalty if it is found to be within the acceptable range, though the public policy consideration of predictability of outcome would generally provide a compelling reason for the Court to accept the proposed penalty in those circumstances. The overriding statutory directive is for the Court to impose a penalty which is determined to be appropriate having regard to all relevant matters. The fact that the regulator and the contravener have agreed and jointly proposed a penalty is plainly a relevant and important matter which the Court must have regard to in determining an appropriate penalty. It does not follow, however, that the determination is not discretionary in nature.

35 At [128], in the context of explaining what is meant by propositions in authorities to the effect that a penalty may be appropriate if it falls within a “permissible range”, the Full Court said:

It should be emphasised in this context, however, that even though the process in determining whether an agreed and jointly proposed penalty is an appropriate penalty involves or includes determining whether that penalty falls within the permissible range of penalties, having regard to all the relevant facts and circumstances, it does not follow that the Court’s task can be said to amount to no more than determining whether the proposed penalty falls within the permissible range, as the Commission’s submission tended to suggest. Nor can it be said that the Court is bound to start with the proposed penalty and to then limit itself to considering whether that penalty is within the permissible range: Mobil Oil at 48,627; [54].

36 I respectfully agree with all of the observations set out above.

Deterrence

37 The question of the purposes for which penalties are to be imposed, and therefore the range of factors which might be permissibly considered, was the subject of some differences of judicial opinion, or at least of emphasis, in a series of decisions in this Court which were traced recently by the Full Court in Pattinson v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2020] FCAFC 177; 299 IR 404 at [25]-[37] (Allsop CJ, White and Wigney JJ). As the plurality in Pattinson observed at [35], the High Court’s decision in Commonwealth v DFWBII settled the question, and determined that

retribution and rehabilitation have no part to play as objects of the imposition of civil penalties: the object of civil penalties being entirely protective in promoting compliance, through deterrence (specific and general).

38 In Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2018] HCA 3; 262 CLR 157 at [116], the plurality (Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ) emphasised that in order for civil penalties to have this deterrent effect, there should be a sufficient “sting or burden” in the penalty amount:

Other things being equal, it is assumed that the greater the sting or burden of the penalty, the more likely it will be that the contravener will seek to avoid the risk of subjection to further penalties and thus the more likely it will be that the contravener is deterred from further contraventions; likewise, the more potent will be the example that the penalty sets for other would-be contraveners and therefore the greater the penalty’s general deterrent effect. Conversely, the less the sting or burden that a penalty imposes on a contravener, the less likely it will be that the contravener is deterred from further contraventions and the less the general deterrent effect of the penalty. Ultimately, if a penalty is devoid of sting or burden, it may not have much, if any, specific or general deterrent effect, and so it will be unlikely, or at least less likely, to achieve the specific and general deterrent effects that are the raison d’être of its imposition.

39 At [39] in Pattinson, the plurality said:

If one recognises that the imposition of the civil penalty or the imposition of punishment in the nature of a civil penalty has only one object or purpose: the protection of society in promoting the public interest by compliance with the relevant law by putting a price on contravention sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor or by others who might be tempted to contravene, then perhaps little utility and no error can be seen in viewing a civil penalty as a form of punishment. Given, however, the clarity of the view of the majority in the Agreed Penalties Case (HC) as to the object of imposition of a civil penalty, to avoid confusion and the risk of error, it is better not to describe the function of the imposition of a civil penalty as punishment, lest notions of retribution intrude. Also, the nature of the provision, contravention of which may result in the imposition of a civil penalty, is relevant to consider. As French J said in CSR at 52,151 the provisions of Pt IV of the Trade Practices Act are “of a regulatory rather than penal character”. Whilst the remedy is a penalty, and so correctly to be called penal, the purpose or object of its imposition is protective to bring about regulatory compliance by deterrence. The same may be said about the substantive provisions of industrial relations legislation, such as the Fair Work Act, as Parliament’s expression of the appropriate rules of engagement of the community in the labour market, to be regulated in accordance with the statute.

40 Similar observations can be made about Parliament’s prescriptions in the Competition and Consumer Act and the ACL about the appropriate rules of engagement in matters of trade and commerce.

41 No different approach is to be taken to the imposition of penalties for unconscionable conduct under the ACL: ACCC v Acquire Learning and Careers Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 602, [51]-[53]; ACCC v Get Qualified Australia Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2017] FCA 1018, [28]; ACCC v Cornerstone Investment Aust Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 5) [2019] FCA 1544, [41]; ACCC v Ford Motor Company of Australia Ltd [2018] FCA 703; 360 ALR 124, [40]-[44]; ASIC v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 3) [2018] FCA 1701; 131 ACSR 585, [120].

42 I respectfully adopt the explanation given by Allsop CJ (Besanko and Middleton JJ agreeing) in Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd [2015] FCAFC 50; 236 FCR 199 at [296]. A prohibition on unconscionable conduct involves

recognition of the deep and abiding requirement of honesty in behaviour; a rejection of trickery or sharp practice; fairness when dealing with consumers; the central importance of the faithful performance of bargains and promises freely made; the protection of those whose vulnerability as to the protection of their own interests places them in a position that calls for a just legal system to respond for their protection, especially from those who would victimise, predate or take advantage; a recognition that inequality of bargaining power can (but not always) be used in a way that is contrary to fair dealing or conscience; the importance of a reasonable degree of certainty in commercial transactions; the reversibility of enrichments unjustly received; the importance of behaviour in a business and consumer context that exhibits good faith and fair dealing; and the conduct of an equitable and certain judicial system that is not a harbour for idiosyncratic or personal moral judgment and exercise of power and discretion based thereon.

43 As noted above, there was no debate between the parties in this proceeding that the conduct for which Telstra is to be held legally responsible was unconscionable conduct within the meaning of s 21 of the ACL. I accept it is appropriate to characterise the conduct as unconscionable.

Maximum penalty

44 The parties submitted that the applicable principles about the role of a maximum penalty in fixing an appropriate penalty are those set out in Markarian v the Queen [2005] HCA 25; 228 CLR 357. As the joint submissions acknowledged, those principles were stated in the context of criminal sentencing, but the parties contended, and I accept, the same principles apply in the civil penalty context.

45 In Pattinson at [105], the plurality said:

The setting of a maximum penalty by Parliament is a part of such a notion of proportionality. Parliament is to be taken to be setting the maximum penalty for cases in which the need for deterrence is strongest, as it is in crime intended for the worst type of case. If the penalty is to be appropriate for the object of deterrence in relation to contravention of the kind before the court the various considerations that bear on the question must display such features as warrant the evaluative conclusion that the penalty is appropriate. The place of the maximum penalty was discussed by the Full Court in Reckitt Benckiser (after the Agreed Penalties Case (HC)), as follows at [154]-[156]:

154 In considering the sufficiency of a proposed civil penalty, regard must ordinarily be had to the maximum penalty. In Markarian, a criminal sentencing context, it was observed at [31] that:

careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick.

155 The reasoning in Markarian about the need to have regard to the maximum penalty when considering the quantum of a penalty has been accepted to apply to civil penalties in numerous decisions of this Court both at first instance and on appeal (Director of Consumer Affairs, Victoria v Alpha Flight Services Pty Ltd [2015] FCAFC 118 at [43]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v BAJV Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 52 at [50]-[52]; Setka v Gregor (No 2) (2011) 195 FCR 203; [2011] FCAFC 90 at [46]; McDonald v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner (2011) 202 IR 467; [2011] FCAFC 29 at [28]-[29]). As Markarian makes clear, the maximum penalty, while important, is but one yardstick that ordinarily must be applied.

156 Care must be taken to ensure that the maximum penalty is not applied mechanically, instead of it being treated as one of a number of relevant factors, albeit an important one. Put another way, a contravention that is objectively in the mid-range of objective seriousness may not, for that reason alone, transpose into a penalty range somewhere in the middle between zero and the maximum penalty. Similarly, just because a contravention is towards either end of the spectrum of contraventions of its kind does not mean that the penalty must be towards the bottom or top of the range respectively. However, ordinarily there must be some reasonable relationship between the theoretical maximum and the final penalty imposed.

46 The maximum penalty for a single contravention by a company of s 21 during the relevant period was $1.1 million: see item 2 of s 224(3) of the ACL. The parties submitted that “each occasion that one of the Affected Consumers entered into a contract with Telstra through the improper sales practices” constituted a separate contravention. There were 119 such occasions, affecting 108 consumers. I accept that submission.

47 The parties therefore submitted that the total statutory maximum applicable was $130.9 million, being 119 times $1.1 million.

48 While each occasion might be properly characterised as a separate contravention arising from separate acts, the parties submitted than in a case such as this, where contraventions are “inextricably interrelated”, they may be grouped as a “course of conduct” for penalty purposes: ACCC v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; 262 FCR 243 at [234]. The parties contended that in this case, the contraventions should be grouped into five courses of conduct; one course of conduct for each of the Telstra stores. They submitted that the penalty sums for each course of conduct should reflect differences in wrongdoing at each of the relevant stores. As I explain below, they submitted a spectrum of penalties should apply to each store, generally based upon the number of occurrences of unconscionable conduct at each store, measured largely by the number of affected consumers who attended each store.

49 In circumstances where liability was contested, and evidence adduced and cross-examined, it may well have been the case that the conduct occurring at each store might not properly be classified as a single course of conduct. The course of conduct principle is applied to ensure an offender is not punished twice for the “same criminality”: see Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; 194 IR 461 at [39], Middleton and Gordon JJ. With more detailed evidence it may have been more obvious that the conduct in relation to each affected consumer – revolving as it did around individual representations to each consumer in a store and individual contracts – might not have been characterised as the “same criminality”. However, on the agreed facts as they are presented to the Court, read with the joint submissions, I accept there is a rational basis to characterise what the staff at each store did as the “same criminality” in terms of their dealings with the affected consumers, particularly given the agreed facts about the directions given to staff by store management, and the incentivising of staff which occurred at each store.

50 Relatedly, the parties submitted an application of the totality principle to the facts did not warrant any alteration (up or down) to the proposed penalty sum, because of the significant overlap in wrongdoing. I accept that submission.

Matters relevant to the quantum of a civil penalty

51 The principles governing the imposition of a penalty are well settled. Section 224(2) of the ACL provides:

In determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the court must have regard to all relevant matters including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

52 In Bupa at [21]-[23], I summarised some of the factors referred to in other authorities, and emphasised the importance of not treating any of these factors as some kind of exhaustive checklist. That is especially important when dealing with unconscionable conduct, which is a wide concept, with its character being heavily fact-dependent in each given case. The factors to which I referred in Bupa (by reference also to those set out in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 762; [1991] ATPR 41-076 at 52,152-52,153) are not to be applied mechanically or mathematically by the Court. Rather they are to be applied through what the authorities describe as a process of “instinctive synthesis”, being a weighing of all relevant factors, rather than starting from a predetermined figure and making adjustments for each separate factor: see Pattinson at [109]-[112].

53 The parties submitted that the nature, extent and duration of the conduct was “extremely serious”. The conduct must be understood in the context that it continued to occur over a period of more than two and a half years, in five different stores that were located in South Australia, Northern Territory and Western Australia. It was geographically widespread, and it was systematic. The affected consumers were particularly vulnerable, and sales staff took advantage of their vulnerabilities and Telstra’s comparatively superior bargaining power to engage in the unconscionable conduct. During oral argument, senior counsel for the ACCC accepted that the conduct of the staff in each store could be described as dishonest.

54 As to the relevant circumstances surrounding the conduct, including the role of management, the parties submitted that although Telstra’s Board and senior executives were not aware of the improper sales practices at the time they were occurring, there are some relevant facts about the state of mind of Telstra’s Board and senior executives at the time of the contraventions which “exacerbated the unconscionable conduct”. The joint submissions identified three sets of circumstances. I accept those circumstances do exacerbate the unconscionable conduct because they reveal how Telstra’s lack of adequate systems and supervision contributed to the perpetuation of the improper sales and contractual behaviour by the staff at Telstra stores. Those circumstances were:

(a) Senior Telstra management understood the various challenges and vulnerabilities of Indigenous Australians that were relevant to Telstra’s business, including vulnerabilities which the staff at the Telstra stores took advantage of during the contravening conduct. Telstra did not have or implement effective systems or training to prevent the improper sales practices, or to properly respond when complaints were subsequently made. The manipulation of the credit assessment process was a particular illustration of these failings.

(b) The system of sales targets and financial incentives for Telstra stores required, and incentivised, greater numbers of sales of post-paid services than pre-paid services. Rewards typically increased with the increasing number and monthly base cost of post-paid services sold. Telstra was aware that its licensees paid financial rewards to sales staff and that this system had the potential to encourage the improper sales practices. This risk was raised with senior Telstra executives from at least March 2017.

(c) Telstra management personnel were put on notice of aspects of the improper sales practices through reports prepared by its credit risk office. The reports identified that credit assessment manipulation had been occurring at each of the relevant stores, and “that there were inherent issues with the customer demographics of the relevant stores”. A detailed summary of the notice provided to Telstra of the improper sales practices is provided in the agreed facts from [63]-[97] and in the joint submission at [56]. It is sufficient to emphasise that notice of some aspects of the improper sales practices was first given to Telstra in December 2016, and Telstra’s awareness of the practices gradually increased from that time. For example, in 2017, Telstra received the first of at least 33 Consumer Complaints in relation to improper sales practices at the Alice Springs Telstra store. The complaints came from financial counsellors and other representatives such as MoneyMob Talkabout, North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency, and Anglicare NT. Despite this, improper practices continued to occur until about 27 August 2018.

55 During this same period, and in the face of this knowledge about the way some of its customers may have incurred their debts, Telstra sold the debts of consumers who had purchased products and services at four of the relevant stores. During this period, it did not take steps to change its policy on selling debt, or to buy back the debt despite being notified about the financial distress caused to the affected consumers.

56 The loss and damage caused to the affected consumers varied, but the parties submit it “was of a serious kind”. I agree with that description. Some of those debts might well have been avoided altogether had the improper sales practices not occurred. The harm caused is summarised in the agreed facts at [53]-[62], and in the joint submission at [60]. It included the accrual of debts of amounts that were very significant to the affected consumers. The effects on those consumers are set out at [59] of the agreed facts, which bears setting out in full:

Thirdly, the exploitative and deceptive nature of the sales practices had the potential to bear directly upon the dignity of the individual Affected Consumers who were subjected to them. Those individuals included consumers of limited education, consumers with extremely limited English language skills, consumers with cultural propensities to avoid confrontation and conflict particularly in a commercial environment such as the sale of mobile phone plans and devices, and consumers with very severe physical and mental health difficulties. Rather than treating these consumers in ways that were appropriate and sensitive to these vulnerabilities, it appears that the sales staff pursued the greater incentives that were likely available for the sale of the Post-Paid Products and Services and, in doing so, took action which risked diminishing the basic dignity of the consumers. Affected Consumers may have felt a real sense of cultural shame and embarrassment, which is particularly significant to Indigenous Australian people.

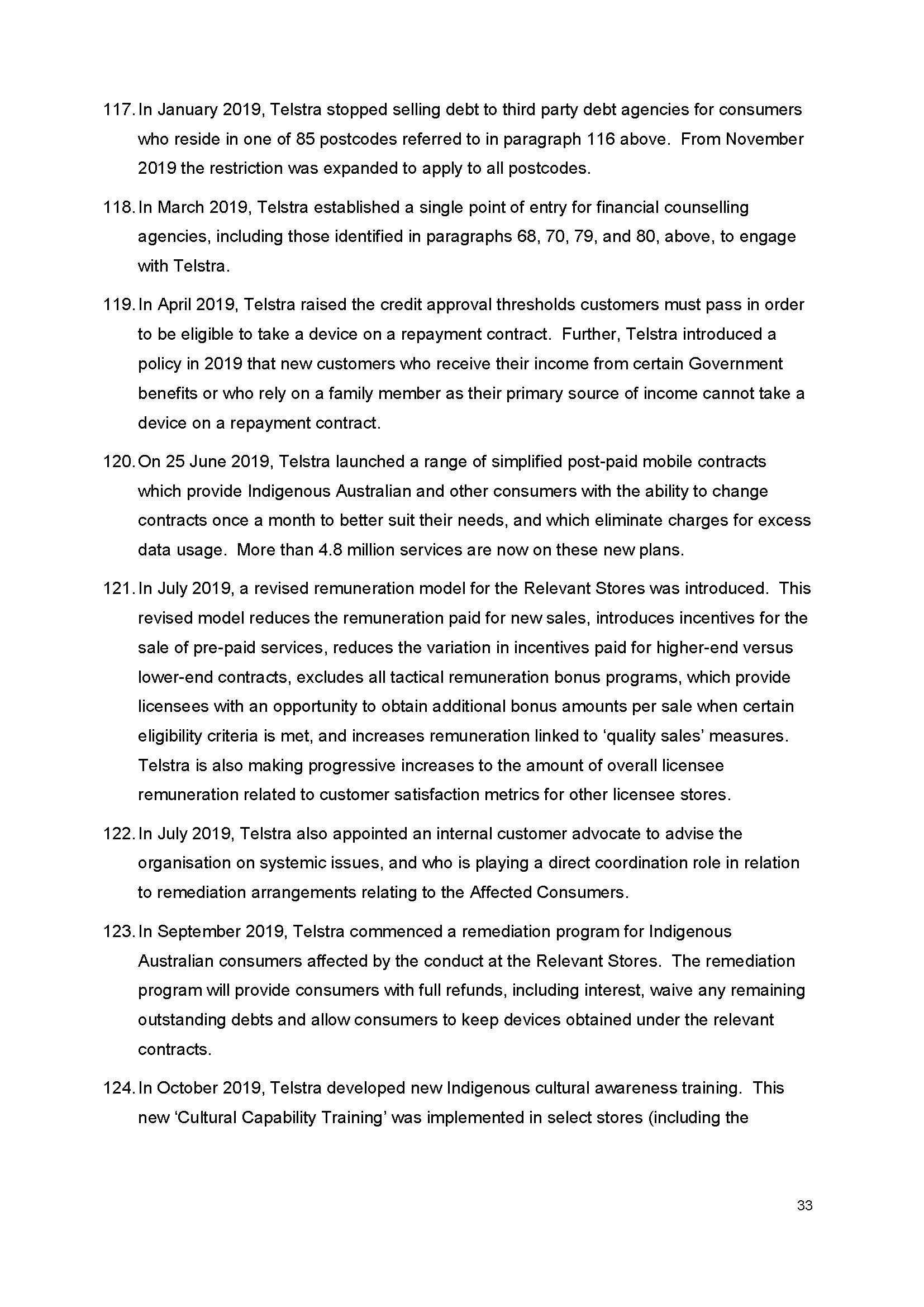

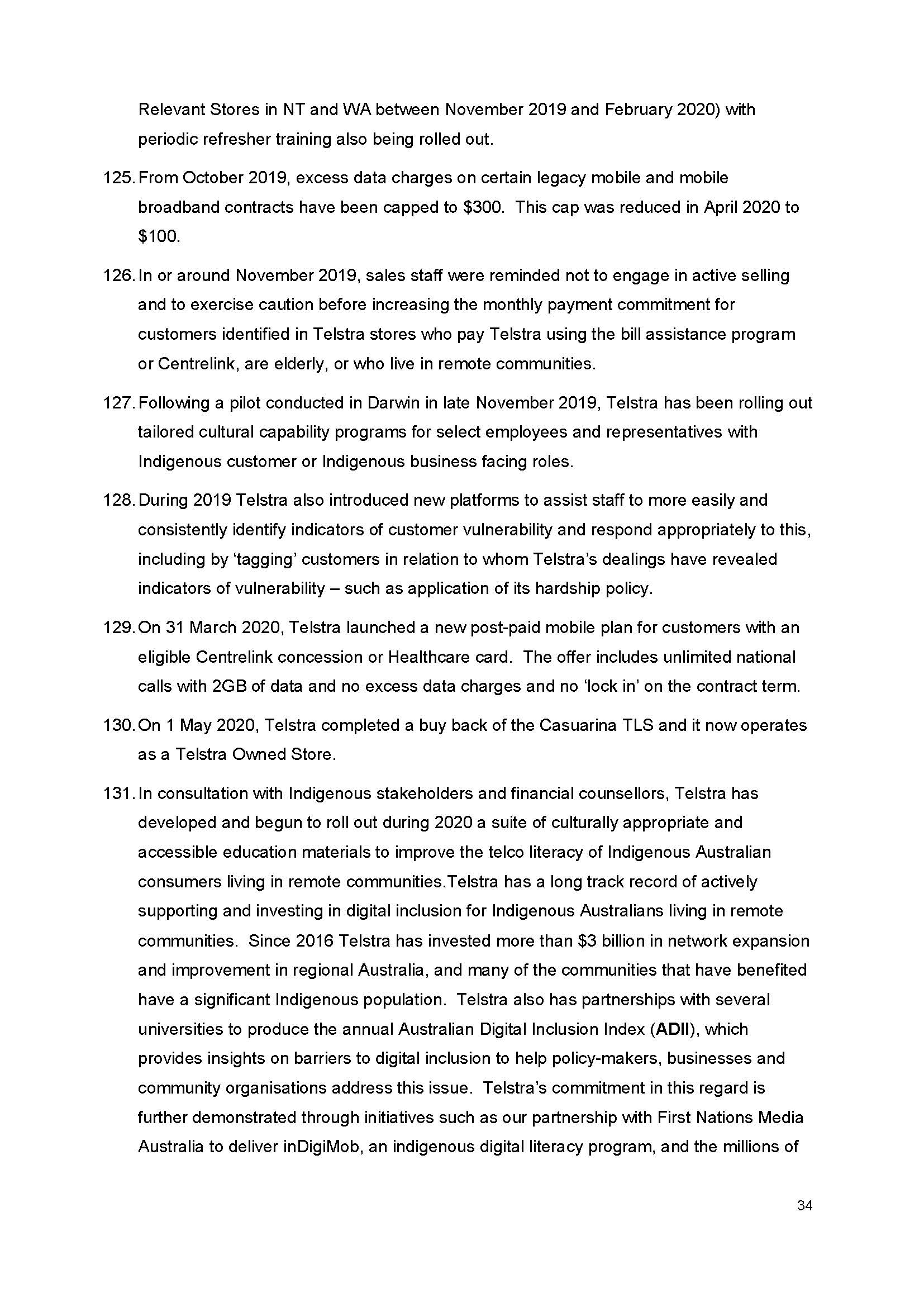

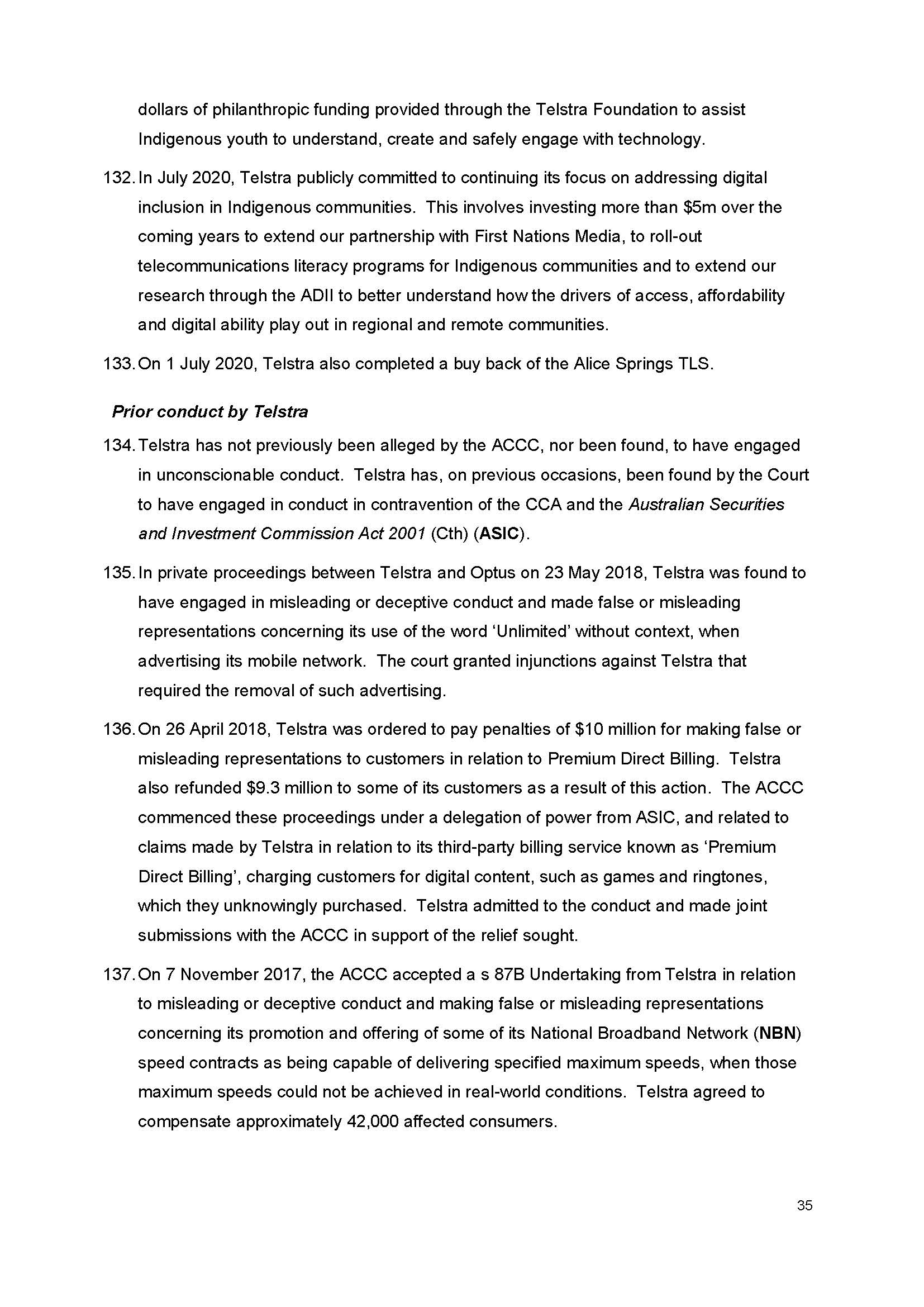

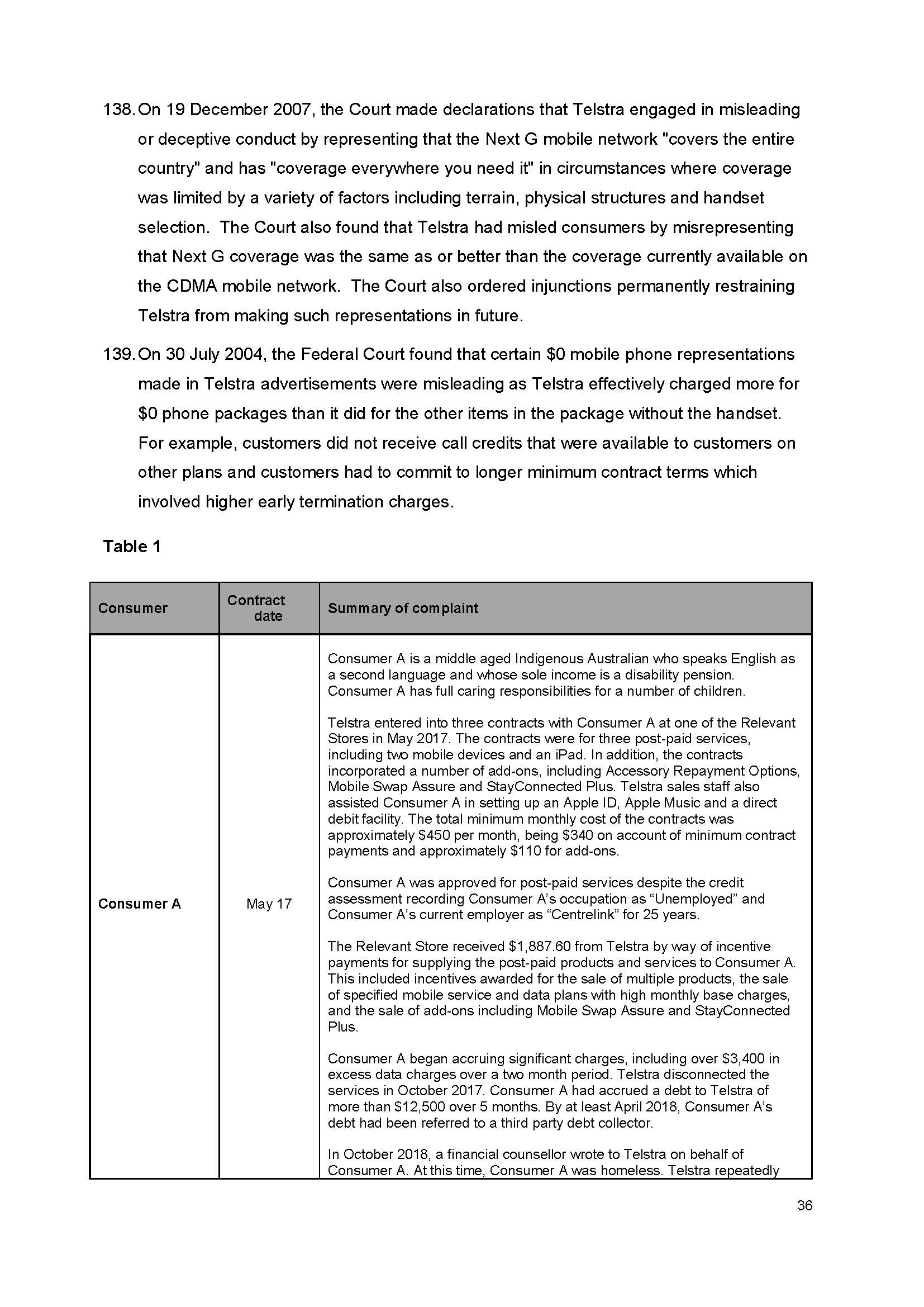

57 The effects on individual affected consumers are also apparent from Table 1 of the agreed facts. As I said to counsel during the hearing, Telstra’s agreement to the facts in this Table, and its agreement to submitting such a Table to the Court, demonstrate the high level of its cooperation in this proceeding, and its commitment, by the time of this proceeding, to transparency about the contravening conduct. Those factors should be given weight in its favour in fixing an appropriate penalty.

58 Consumer C is one of the four consumers whose contracts with Telstra, and whose experiences having entered into those contracts, are described in Table 1.

Consumer C is an Indigenous Australian who has severe mental health issues and is on a disability pension. Consumer C has extremely limited English skills and Consumer C’s speech is incoherent.

Telstra entered into three contracts with Consumer C at a Relevant Store in June 2017. The contracts were for three post-paid services, including one mobile device and one iPad. In addition, the contracts also incorporated a number of add-ons including Accessory Repayment Options and/or Mobile Swap Assure. The third post-paid service was for the subscription service “Telstra Platinum Service”. The total minimum monthly cost of the contracts was approximately $220 per month, being $145 on account of minimum contract payments and $75 for add-ons.

Consumer C was approved to enter into post-paid products and services with a total minimum base cost of up to $10,000, despite having incurred a previous debt to Telstra.

The Relevant Store received $759.20 from Telstra by way of incentive payments for supplying post-paid products and services to Consumer C. This included incentives awarded for the sale of multiple products, the sale of specified post-paid mobile service and data plans with high monthly base charges, and the sale of the add-on Mobile Swap Assure.

Telstra disconnected the services in November 2017. Consumer C had accrued a debt to Telstra of more than $4,600 over five months. By at least November 2017, Consumer C’s debt was referred to a third party debt collector.

Consumer C was worried sick and very concerned about how repayment could be made of even a fraction of the Telstra debt given Consumer C’s low income. In April 2018, a financial counsellor wrote to Telstra on behalf of Consumer C requesting a full debt waiver. Telstra initially refused to waive the debt in full and deemed the “acquisition of the mobile services was conducted in a proper manner” despite receiving detailed information about the vulnerabilities of the consumer.

In June 2018, Telstra waived Consumer C’s debt in full and Consumer C was not required to return the devices. In August 2020, Telstra issued a refund to Consumer C of more than $1,000, by way of cheque, for all amounts paid in respect of Telstra services and interest.

59 This is simply by way of example. The narratives recounted in relation to each of the four consumers in Table 1 reveal egregious behaviour, not only by the local staff in the Telstra stores, but by Telstra itself in its insistence on the return of devices, and in its refusal over many months to waive debts even after being presented with information which should have caused any corporation acting reasonably to do so. These factual narratives also reveal the level of Telstra’s self-interest, at the expense of affected consumers in conduct such as seeking to recover (and retain) incentive payments paid to its licensees, but yet not agreeing to waive debts to affected consumers, even though the circumstances involved the same unconscionable conduct.

60 The evidence is that, eventually, Telstra waived all debts owed by the affected consumers and refunded all amounts paid to it by the affected consumers in respect of sales arising from the improper sales conduct and credit manipulation. Although this process took much longer than it should have, and involved unreasonable refusals at various stages by Telstra, I accept that ultimately is a factor which weighs in favour of Telstra on the question of appropriate penalty.

61 As the parties submitted, Telstra is a “major company with wide reach in the telecommunications sector”. It has an annual revenue exceeding $25 billion. Telstra’s size increased the power imbalance between it and the affected consumers, including by allowing it to rely on standard form contracts that it did not negotiate. The parties submitted and I accept that Telstra’s size is also relevant to the size of the penalty necessary to ensure an appropriate deterrent effect.

62 Telstra has not previously been alleged to have, nor been found to have engaged in, unconscionable conduct, although it has been found by this Court to have contravened the Competition and Consumer Act in other respects. The parties submitted that this was a factor supporting the large penalty proposed.

63 Telstra’s cooperation with the ACCC has been substantial, and the parties submitted that the proposed penalty is smaller than it otherwise might be to reflect this cooperation, citing Commonwealth v DFWBII at [46]; NW Frozen Foods at 293-294; Mobil Oil at [55] and Pattinson at [207]-[209]. I accept that Telstra has taken significant remedial and corrective action, which is described at [110]-[133] of the agreed facts and summarised at [70] of the joint submission.

64 Telstra has also given an enforceable undertaking to the ACCC, which was provided as annexure B to the agreed facts. I place considerable weight on the terms of enforceable undertaking, and I accept, as senior counsel for Telstra submitted, that the implementation of the enforceable undertaking will occur at significant cost (in monetary and resource terms) to Telstra. In addition, notable amongst Telstra’s remediation and corrective action are:

(a) No longer selling debt to third-party agencies;

(b) Introducing new arrangements for post-paid contracts. This includes new, simplified post-paid mobile contracts which allow consumers to change contracts once a month to better suit their needs, and which eliminate charges for excess data usage. These new contracts are “no lock in” in nature, allowing consumers to leave without service termination charges (and just pay out any associated device charges). Telstra has also capped excess data charges on certain legacy mobile and mobile broadband contracts at $100.

(c) In consultation with Indigenous stakeholders and financial counsellors, developing culturally appropriate and accessible education materials to improve the “telco literacy” of Indigenous Australian consumers living in remote communities; and

(d) Buying back the Casuarina and Alice Springs stores, which accounted for the majority of the sales to the affected consumers.

65 The timing of Telstra’s cooperation deserves recognition, as well as its fulsomeness. On the evidence, Telstra had cooperated significantly with the ACCC prior to these proceedings being instituted, to the extent that as part of the originating process an agreed position was put to the Court. That is cooperation in a full sense. Telstra’s level of cooperation also discloses a willingness to be transparent from the start with the Court, and therefore with the community as a whole. It has maximised the savings in public funds and resources, both to the ACCC and the Court.

66 Senior Counsel for Telstra was also instructed to make a direct apology to the Court:

Lastly, your Honour, I did want to say this: I have instructions on behalf of Telstra and its chief executive officer to apologise for these serious contraventions and the impact that it had on customers and communities. Telstra is remorseful that this conduct occurred, and was not fully rectified more quickly than, in fact, occurred. But it does point out it has taken steps to fully remediate all of the customers, and has taken other significant steps to change its processes, policies and sales practices to ensure that the risk of similar conduct has been fully addressed, and such conduct does not occur in the future.

67 An apology given on a public and serious occasion such as the final hearing in this proceeding demonstrates contrition. I give weight to Telstra’s apology.

68 The parties submit that this level of cooperation indicates a lesser need for specific deterrence, and to an extent I agree. However, Telstra’s conduct prior to agreement being reached with the ACCC, but after complaints were made to it on behalf of affected consumers, and after internal and external investigations began to detect the improper sales practices, indicates that the appropriate penalty will be one which does address specific deterrence. In my opinion the penalty must be such that Telstra understands it needs to react differently, more proactively and more promptly to complaints and investigations, especially where those drawing its attention to problems are reputable organisations, including reputable consumer organisations.

69 There are no agreed facts about what, if anything, has happened to the staff who engaged, on the ground, in this conduct on behalf of Telstra. As individuals, they bear considerable personal responsibility for the unconscionable conduct, for the predicaments then experienced by affected consumers, and at least in many cases, the distress, embarrassment and anxiety caused by the accrual of debts which on view were very large for these consumers.

70 Whether or not individuals acting on behalf of telecommunications service providers such as Telstra will be in any way deterred by the penalties and other orders in this case was also not a matter addressed by the parties. Nevertheless, it is important to state the obvious: none of these contraventions can occur without individuals deciding, or agreeing, to be the ones who unconscionably encourage, persuade or cajole vulnerable consumers to enter into such contracts, with or without false representations. The Court deprecates the behaviour of the individual staff members at the Telstra stores, even if the legal responsibility for the unconscionable conduct has been assumed by Telstra itself.

The penalty figure and how it is calculated

71 On the basis that the unconscionable conduct at each Telstra store should be seen as one course of conduct, the parties submitted it was appropriate to calculate the penalty amounts for the conduct at each store so as to reflect the differences in the gravity and frequency of the conduct. The two factors which guided the parties’ proposals, and which I accept are relevant, are the number of consumers affected, and the continuation of the improper sales practices after the risk reports. It is appropriate to highlight those factors, and to fix greater penalties for conduct at some of the Telstra stores accordingly. The parties described the conduct at the five stores in the following way, which I accept as an accurate and appropriate description:

Casuarina TLS: The conduct at this store is the most serious of all the stores. On [51] separate occasions over the course of almost two years, 45 of the 108 Affected Consumers were entered into a total of 122 contracts through the unconscionable sales. Starting from 1 September 2017, at least 48 complaints were made to Telstra regarding the improper practices at the Casuarina TLS, many by financial counsellors and support agencies. The First Casuarina CRO report was submitted to various Telstra management personnel with responsibilities connected with State, regional or local areas or major partners on 1 December 2017. Despite the recommendations in this report to cease credit assessment manipulation and the subsequent clawback of remuneration paid to the Casuarina TLS in respect of the sales identified to have been impacted by credit assessment manipulation, the improper sales practices were engaged in on a further 12 occasions and the debts arising were the subject of referral or sale on 63 occasions. The maximum penalty for this course of conduct is $56.1 million (ie 51 times $1.1 million). Making significant allowance for cooperation and corrective action, an appropriate total penalty for this course of conduct is $23 million.

Alice Springs TLS: On 34 separate occasions over the course of nearly two and half years, 32 of the 108 Affected Consumers were entered into a total of 78 contracts through the unconscionable sales. Starting from 11 August 2017, at least 33 complaints were made to Telstra regarding the improper practices at the Alice Springs store, many by financial counsellors and support agencies. The Alice Springs CRO report was submitted to various Telstra management personnel with responsibilities connected with State, regional or local areas or major partners on 22 May 2018. Despite the recommendations in this report to cease credit assessment manipulation and the subsequent clawback of remuneration paid to the Alice Springs TLS in respect of the sales identified to have been impacted by credit assessment manipulation the improper sales practices were engaged in on a further four occasions and the debts arising were the subject of referral or sale on 26 occasions. The maximum penalty for this course of conduct is $37.4 million (ie 34 times $1.1 million). Making significant allowance for cooperation and corrective action, an appropriate total penalty for this course of conduct is $15 million.

Broome TLS: On 22 separate occasions over the course of around 9 months, 22 of the 108 Affected Consumers were entered into a total of 52 contracts through the unconscionable sales. The Broome CRO report was submitted to various Telstra management personnel with responsibilities connected with State, regional or local areas or major partners on 17 January 2018 and on 22 February 2018 a bulk complaint was received from a counselling agency on behalf of 21 consumers in relation to the improper sales conduct at the Broome TLS. The improper sales practices were not engaged in after the Broome CRO Report was provided, but the resulting debts arising were the subject of referral or sale on a further 18 occasions. In June 2018, Telstra waived the entirety of the outstanding debts for all of the 21 consumers that were part of the bulk complaint referred to above. The maximum penalty for this course of conduct is $24.2 million (ie 22 times $1.1 million). Making significant allowance for cooperation and corrective action, an appropriate total penalty for this course of conduct is $8 million.

Arndale TLS: On nine separate occasions over the course of almost a year, seven of the 108 Affected Consumers were entered into a total of 19 contracts through the unconscionable sales. There was no CRO report for Arndale. The last of the contract sales was on 8 February 2018 and debts were referred or sold on 12 occasions between January and December 2018. The maximum penalty for this course of conduct is $9.9 million (ie nine times $1.1 million). Making significant allowance for cooperation and corrective action, an appropriate total penalty for this course of conduct is $3 million.

Palmerston TLS: On three separate occasions in 2017, two of the 108 Affected Consumers were entered into a total of five contracts through the unconscionable sales. The Palmerston CRO report was submitted to various Telstra management personnel with responsibilities connected with State, regional or local areas or major partners on around 5 December 2017. No improper sales were made after this time and no debts were referred or sold to third parties. The maximum penalty for this course of conduct is $3.3 million (ie three times $1.1 million). Making significant allowance for cooperation and corrective action, an appropriate total penalty for this course of conduct is $1 million.

72 This brings the total penalty to $50 million. The parties submitted this total figure was a “just” one, and did not require any further alteration in accordance with the totality principle.

73 I accept that the calculations by which the parties reached different figures for different stores appropriately reflected the different circumstances at each store, and were appropriately proportionate to the statutory maximums. I also accept that the single penalty figure of $50 million is “an” appropriate figure. A significant penalty is necessary to send a strong and clear message to all those who might be tempted to take advantage of vulnerable consumers in similar ways. A strong and clear message must also be sent to those who might then be slow to remediate their conduct out of self-interest. Both the unconscionability and any delay in remediation are likely to be firmly and heavily punished. Further, given I have found there is some need for specific deterrence, in order to ensure Telstra itself does not repeat this kind of conduct, I am satisfied the figure of $50 million is appropriate to achieve this specific deterrence as well. Even for a corporation the size of Telstra, it is a significant sum.

The appropriateness of the declaratory relief

74 It is uncontroversial that this Court has a wide discretionary power to make declarations under s 21 of the Federal Court Act. In ACCC v Coles Gordon J said (at [75]-[76]):

Where a declaration is sought with the consent of the parties, the Court’s discretion is not supplanted, but nor will the Court refuse to give effect to terms of settlement by refusing to make orders where they are within the Court’s jurisdiction and are otherwise unobjectionable: see, for example, Econovite at [11].

However, before making declarations, three requirements should be satisfied:

(1) The question must be a real and not a hypothetical or theoretical one;

(2) The applicant must have a real interest in raising it; and

(3) There must be a proper contradictor: Forster v Jododex at 437-8.

75 I accept the parties’ submissions that these conditions are made out, for the following reasons:

There is a real and not a hypothetical question: There is a direct and important question as to whether Telstra contravened the provisions of the ACL in engaging in the unconscionable conduct.

The applicant has a real interest in raising it: The ACCC has an obvious interest, as the statutory regulator discharging its functions in the public interest, in bringing the proceedings.

There is a proper contradictor and real consequences: Telstra, as the entity declared to have contravened the law, has an interest in opposing the relief. This remains so notwithstanding its admissions and agreement.

76 The declaratory relief now jointly sought by the parties substantively reflects that sought by the ACCC in its originating application.

Conclusion

77 Taking into account all of the circumstances, including the enforceable undertaking, the corrective and remediation action, Telstra’s public apology and its high level of cooperation in these proceedings from the start, I am satisfied the penalty of $50 million is an appropriate penalty, and that the declaratory relief sought is also appropriate. I also take into account the enforceable undertaking, and the agreed proposal for Telstra to pay a contribution towards the legal costs of the ACCC.

I certify that the preceding seventy-seven (77) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Mortimer. |

Associate:

Annexure