Federal Court of Australia

Universal Music Publishing Pty Ltd v Palmer (No 2) [2021] FCA 434

ORDERS

UNIVERSAL MUSIC PUBLISHING PTY LTD First Applicant SONGS OF UNIVERSAL, INC. Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The sound recording of the song “Aussies Not Gonna Cop It”, referred to in paragraph 9 of the applicants’ statement of claim filed on 6 February 2019 (UAP recording), and the video advertisements for the United Australia Party to which the UAP recording was synchronised, referred to in paragraph 10 of the statement of claim (UAP videos), each contain a reproduction of a substantial part of each of the musical work comprised in the song We’re Not Gonna Take It, composed by Daniel (“Dee”) Snider (the Musical Work), and the lyrics of that song, also composed by Mr Snider ( the Literary Work).

2. The respondent infringed the second applicant’s copyright in each of the Musical Work and Literary Work by:

(a) reproducing;

(b) authorising the reproduction of;

(c) communicating; and

(d) authorising the communication of

a substantial part of those works in Australia without the licence of the applicants.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

3. The respondent, whether by himself, his servants, agents or otherwise be permanently restrained from:

(a) reproducing;

(b) authorising the reproduction of;

(c) communicating to the public; and

(d) authorising the communication to the public of

the whole or a substantial part of the Musical Work or the Literary Work in Australia without the licence of the applicants.

4. The respondent take all necessary steps to:

(a) cause any and all reproductions of the UAP recording, including the UAP videos and any other video or audio recording that embodies the UAP recording, to be removed from all online locations controlled by the respondent or the United Australia Party (including on the websites YouTube and Facebook); and

(b) cause the communication of the UAP recording, including the UAP videos and any other video or audio recording that embodies the UAP recording, (including in advertisements for the United Australia Party) to cease.

5. The respondent deliver up to the applicants all unauthorised reproductions of the Musical Work or the Literary Work in his possession, power, custody or control, including the UAP recording and UAP videos.

6. Pursuant to s 115(2) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), the respondent pay the applicants damages of $500,000.

7. Pursuant to s 115(4) of the Copyright Act, the respondent pay the applicants $1,000,000 in additional damages.

8. Within 14 days, the parties confer with a view to reaching agreement on the amount of interest payable on the damages pursuant to s 51A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth).

9. In the event that the parties are unable to agree on the amount of interest, the applicants file and serve submissions on the point by 28 May 2021 and the respondents file and serve submissions in response by 11 June 2021, no submissions to exceed three (3) pages.

10. The respondent pay the applicants’ costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Table of Contents

[1] | |

The relevant statutory provisions and some general principles | [9] |

[25] | |

[29] | |

[31] | |

[45] | |

[46] | |

[58] | |

[62] | |

Negotiations with Universal for a licence to use a “re-recording” of WNGTI | [66] |

The development of the lyrics to ANGCI and the UAP recording | [97] |

The evidence of Mr Wright and some further contemporaneous documents | [97] |

[110] | |

[116] | |

[120] | |

[123] | |

[136] | |

[154] | |

[169] | |

[170] | |

[171] | |

Step 2: What was taken, derived or copied from the works in suit? | [174] |

[178] | |

[194] | |

Step 3: Do the impugned works reproduce a substantial part of the copyright works? | [224] |

[224] | |

[233] | |

Was the copied part a substantial part of the literary work? | [279] |

[286] | |

[287] | |

[287] | |

[314] | |

Were Palmer’s dealings fair for the purpose of parody or satire? | [321] |

[356] | |

[358] | |

[359] | |

[359] | |

[365] | |

[369] | |

[398] | |

[451] | |

[453] | |

[481] | |

[481] | |

[490] | |

[496] | |

[527] | |

[532] |

KATZMANN J:

1 Daniel (known as Dee) Snider is the lead singer of Twisted Sister, a heavy metal band based in the United States of America. Mr Snider is also a composer and songwriter. Perhaps his most famous song, and certainly his most popular, is “We’re Not Gonna Take It” (WNGTI), which was first released in 1984. Clive Palmer is an Australian businessman with a keen interest in politics and the founder and leader of the United Australia Party (UAP).

2 The two men have little in common.

3 During the 2019 Australian elections, the UAP campaign featured the song “Aussies Not Gonna Cop It” (ANGCI). In about November 2018 Mr Palmer authorised the creation of a recording of that song (the UAP recording). He also authorised the synchronisation of the UAP recording with at least 12 video advertisements for the UAP (the UAP videos).

4 The music and lyrics of the WNGTI and ANGCI have a good deal in common.

5 The substantive issue in this case is whether, by authorising the creation or the recording and its synchronisation with the video advertisements, Mr Palmer infringed the copyright in WNGTI.

6 At all relevant times the owner of the copyright in both the music and the lyrics of WNGTI was Songs of Universal Inc., the second applicant in this proceeding. The first applicant, Universal Music Publishing Pty Ltd (UMP), is and was at all relevant times the exclusive licensee, that is to say, the holder of a written licence signed on behalf of the owner of the copyright authorising it, to the exclusion of all others, to do an act that, but for the licence, the owner would have the exclusive right to do: Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), s 10(1). In this judgment, unless it is necessary to distinguish between them, I shall refer to both applicants as Universal.

7 Although it was not his original position, Mr Palmer now admits that copyright subsists in the music of WNGTI as an original musical work and that copyright also subsists in the lyrics of the song as an original literary work.

8 It is common ground that, if the UAP recording contains a reproduction of a substantial part of the music and/or lyrics of WNGTI, then Mr Palmer has infringed Universal’s copyright unless he has a defence. He relied on the defence of fair dealing for the purpose of parody or satire.

The relevant statutory provisions and some general principles

9 Copyright is a form of property, commonly referred to as intellectual property although it is also a form of industrial property. Copyright in music was described uncontroversially in evidence in this case as a commercial asset from which income can be earned, among other things, through licensing for use in advertisements.

10 Copyright law protects the particular form of expression of an original work, namely a work which is “the product of the labour, skill and capital” of its creator: IceTV Pty Ltd v Nine Network Australia Pty Ltd (2009) 239 CLR 458 at [28] (French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ, citing Macmillan and Co Ltd v Cooper (1923) 93 LJPC 113 at 117–118 per Lord Atkinson); at [70] (Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ). The general policy of copyright is to prevent unauthorised copying of particular material forms of expression that are the result of “intellectual exertions of the human mind”: Sawkins v Hyperion Records Ltd [2005] EWCA Civ 565; [2005] 3 All ER 636; [2005] 1 WLR 3281 at [28] (Mummery LJ). But the protection is subject to numerous qualifications, exceptions, restrictions and defences, reflecting the purpose of copyright law, which is “to balance the public interest in promoting the encouragement of ‘literary’, ‘dramatic’, ‘musical’ and ‘artistic works’, as defined, by providing a just reward for the creator, with the public interest in maintaining a robust public domain in which further works are produced”: IceTV at [71] (Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ).

11 WNGTI was first published in the United Kingdom on 25 May 1984. Even so, as the UK is a party to the Berne Convention (the International Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works concluded at Berne on 9 September 1886), the provisions of the Copyright Act apply in relation to it in the same way as they apply in relation to works first published in Australia and as if it had first been published in Australia: Copyright (International Protection) Regulations 1969 (Cth), reg 4(1).

12 Part III Division 1 of the Copyright Act deals with the nature, duration and ownership of copyright in works, Division 2 with infringement.

13 The nature of copyright in original works is described in s 31, which relevantly provides:

(1) For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, copyright, in relation to a work, is the exclusive right:

(a) in the case of a literary … or musical work, to do all or any of the following acts:

(i) to reproduce the work in a material form;

(ii) to publish the work;

(iii) to perform the work in public;

(iv) to communicate the work to the public;

(v) to make an adaptation of the work

(vi) to do, in relation to a work that is an adaptation of the first mentioned work, any of the acts specified in relation to the first-mentioned work in subparagraphs (i) to (iv), inclusive[.]

…

(2) The generality of subparagraph (1)(a)(i) is not affected by subparagraph (1)(a)(vi).

…

14 “Musical work” is not defined in the Copyright Act, save for certain unrelated purposes. In Sawkins at [53] Mummery LJ observed:

In the absence of a special statutory definition of music, ordinary usage assists: as indicated in the dictionaries, the essence of music is combining sounds for listening to. Music is not the same as mere noise. The sound of music is intended to produce effects of some kind on the listener’s emotions and intellect. The sounds may be produced by an organised performance on instruments played from a musical score, though that is not essential for the existence of the music or of copyright in it. Music must be distinguished from the fact and form of its fixation as a record of a musical composition. The score is the traditional and convenient form of fixation of the music and conforms to the requirement that a copyright work must be recorded in some material form. But the fixation in the written score or on a record is not in itself the music in which copyright subsists. There is no reason why, for example, a recording of a person’s spontaneous singing, whistling or humming or improvisations of sounds by a group of people with or without musical instruments should not be regarded as “music” for copyright purposes.

15 Later, at [56], his Lordship said that it was “wrong in principle to single out the notes as uniquely significant for copyright purposes and to proceed to deny copyright to the other elements that make some contribution to the sound of the music when performed, such as performing indications, tempo and performance practice indicators, if they are the product of a person’s effort, skill and time”.

16 A “literary work” is simply a written or printed work irrespective of its literary merit or lack of it: University of London Press Ltd v University Tutorial Press Ltd [1916] 2 Ch 601 at 608 (which concerned examination papers); cited with approval in numerous cases including Computer Edge Pty Ltd v Apple Computer Inc. (1986) 161 CLR 171 at [11]. That point is underscored by s 10 of the Copyright Act in which literary work is defined to include a table or compilation expressed in words, figures or symbols and a computer program or a compilation of computer programs.

17 “Adaptation” is relevantly defined, also in s 10, in relation to a literary work in a non-dramatic form, as: a version of the work in a dramatic form and vice versa; a translation of the work; or a version of the work in which a story or action is conveyed solely or principally by means of pictures. “Adaptation” in relation to a musical work is relevantly defined in the same section to mean “an arrangement or transcription of the work”.

18 For the purposes of the Act, a literary or musical work is deemed to have been reproduced in a material form if a sound or “cinematograph film” recording is made of the work. Similarly, any record embodying such a recording and any copy of such a film is deemed to be a reproduction of the work: see s 21(1). This provision applies in relation to an adaptation of the work in the same way it applies in relation to the work itself: s 21(2).

19 “Reproduction” means copying and does not include the production of a substantially similar result by independent work, without copying: EMI Songs Australia Pty Ltd v Larrikin Music Publishing Pty Ltd (2011) 191 FCR 444 at [49]–[50], [121] (Emmett J) (EMI v Larrikin) citing Francis Day & Hunter Ltd v Bron [1963] Ch 587 at 618 and 623-624 and SW Hart & Co Pty Ltd v Edwards Hot Water Systems (1985) 159 CLR 466 at 472.

20 Section 14 relevantly provides that, unless the contrary intention appears, any reference in the Copyright Act to the doing of an act in relation to a work or a reproduction, adaptation or copy of a work is to be read as including a reference to a substantial part of the work.

21 As for infringement, s 36 is applicable. Insofar as it is relevant, it states:

(1) Subject to this Act, the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia, or authorizes the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright.

(1A) In determining, for the purposes of subsection (1), whether or not a person has authorised the doing in Australia of any act comprised in the copyright in a work, without the licence of the owner of the copyright, the matters that must be taken into account include the following:

(a) the extent (if any) of the person’s power to prevent the doing of the act concerned;

(b) the nature of any relationship existing between the person and the person who did the act concerned;

(c) whether the person took any reasonable steps to prevent or avoid the doing of the act, including whether the person complied with any relevant industry codes of practice.

22 In other words, unless the Act otherwise provides, anyone who is not the owner or licensee of the copyright in a work who reproduces (copies) that work in a material form, publishes it, performs or communicates it in public, or adapts it will infringe the copyright.

23 The Act provides for exceptions for fair dealing with works for certain purposes including, relevantly, parody or satire. Those exceptions are contained in Division 3. The exception for fair dealing for the purpose of parody or satire is covered by s 41A.

24 Remedies are dealt with in Part V, remedies for infringement in s 115.

25 The defence was filed on 20 March 2019. It was amended nearly 16 months later, on 28 July 2020, well after Universal’s evidence in chief had been served.

26 In the first iteration Mr Palmer denied that copyright subsisted in the musical work comprised in the song WNGTI. He contended that the musical work was “not an original musical work within the meaning of the Act” and denied that copyright subsisted in the literary work alleging that the UAP recording and videos use original lyrics and do not reproduce the literary work. In the alternative, he denied that copyright subsisted in the literary work on the ground that “the incorporation and reproduction of such works is fair dealing for the purpose of parody or satire” within the meaning of s 41A. He denied the allegations of copyright infringement on the same basis. He admitted that a licence was required for the use of the literary work, but denied it was required for the use of the musical work, and asserted that he had not used the literary work.

27 His position altered significantly with the filing of the amended defence.

28 In the amended defence Mr Palmer withdrew his assertion that the musical work was not an original musical work within the meaning of the Copyright Act and admitted all allegations relating to the subsistence and ownership of the copyright in both works. Nevertheless, he claimed that the UAP recording and videos did not incorporate a substantial part of the musical work or the literary work and therefore did not infringe Universal’s copyright. In the alternative, he claimed that the UAP recording and videos did not infringe Universal’s copyright because the incorporation or reproduction of the musical and literary works constituted “fair dealing for the purpose of parody or satire” within s 41A.

29 On 4 December 2019 I ordered that the parties file an agreed statement of facts and issues. A document answering that description was filed on 3 March 2020. An amended version was tendered at the hearing.

30 The final version of the agreed statement identifies the following questions for determination:

(1) Did the UAP recording and UAP videos contain a reproduction of a substantial part of the music and/or lyrics of WNGTI?

(2) If so, did any such reproduction fall within s 41A of the Copyright Act because it was fair in all the circumstances and made for the purpose of parody or satire?

(3) What relief should be granted if Universal’s copyright is found to have been infringed in the music or the lyrics or both, including:

(a) in what sum general damages should be awarded;

(b) should additional damages be awarded under s 115(4) of the Copyright Act and, if so, in what amount; and

(c) should injunctive relief be granted; and, if so, in what form?

31 Evidence was given on Universal’s behalf by Mr Snider, four Universal executives, one of its lawyers, a musicologist and a music industry expert.

32 Mr Snider affirmed four affidavits, one in support of an interlocutory application, and three in connection with the substantive dispute. In two affidavits affirmed on 1 February 2019 and 23 April 2019, Mr Snider discussed the history of the composition of WNGTI; the sale of the copyright to Universal; the approval process for the use of his songs in advertising; and the manner in which he became aware of, and his reaction to, the UAP advertisements. The fourth affidavit was affirmed during the course of the trial. It concerned a social media post by Mr Palmer after Mr Snider had testified. Mr Snider’s credit was not called into question in cross-examination and no submission was made that his evidence should not be accepted. He impressed me as a witness of truth.

33 The Universal executives from whom affidavits were taken were Karen Ann Don, UMP’s Senior Vice-President (Legal & Business Affairs); Karina Jean Masters, UMP’s Director of Synchronisation & Marketing; Andrew Richard Charles Jenkins, the President of the Australia and Asia-Pacific region for Universal’s corporate group and a director of UMP; and Thomas Herbert Eaton, the Senior Vice-President of Music for Advertising of Universal’s corporate group. Their evidence covered a range of topics including the nature of the applicants’ businesses; Universal’s rights in WNGTI; action taken by Universal after becoming aware of the UAP advertisements; and Mr Palmer’s response; the considerations relevant to the licensing of music in advertising; correspondence with UMP on Mr Palmer’s behalf about licensing WNGTI; the approval process for use of US songs in advertising; and a hypothetical licence fee for the use of WNGTI in the UAP advertisements.

34 Sebastien David Tonkin, a solicitor, affirmed a number of affidavits in the proceeding, not all of which were read at the final hearing. Two of the affidavits read at the final hearing annexed or exhibited the UAP advertisements and various publications including media articles and social media posts about UAP’s advertising campaign, UAP advertisements, and this proceeding. Two other affidavits related to Mr Palmer’s non-compliance with discovery orders. The last in time, filed on 13 October 2020, detailed some of the information gleaned from the discovery and subpoenaed documents.

35 An affidavit was also provided by Karl Richter, the founder of an Australian music supervision (procurement) company which assists clients with selecting and sourcing music for use in various projects and which has been involved in sourcing music for advertisements for a wide range of products. Mr Richter gave independent expert evidence on a hypothetical licence fee for use of WNGTI in UAP advertising.

36 All these affidavits were read and all witnesses, with the exception of Ms Don and Mr Tonkin, attended for cross-examination.

37 Universal’s musicologist was Professor Andrew Ford, a composer, writer, broadcaster, and music scholar who has enjoyed a long academic career. He affirmed two affidavits, both of which were read, and was the co-author of a joint expert report. He also gave evidence in concurrent session with the musicologist retained by Mr Palmer.

38 Mr Palmer gave evidence. He affirmed two affidavits precisely one year apart and was extensively cross-examined. His musicologist was Dr Robert Davidson, a composer, double bass player, researcher, senior lecturer in music at the University of Queensland. Dr Davidson affirmed an affidavit on 14 August 2019 and was the co-author of the joint expert report.

39 Mr Palmer also relied on evidence from David Wright and James McDonald. Mr Wright swore two affidavits, Mr McDonald one. Mr McDonald was the National Director of the UAP during the relevant period. Mr Wright is the director of Creative Division Pty Ltd (trading as Atomic Pixel). He was engaged by the UAP to provide production services for its advertising campaign in the 2019 federal election. He was involved in the development of the UAP advertisements and deposed, among other things, to discussions with Mr Palmer and correspondence with Universal about a licence. In cross-examination it emerged that he had also run as a candidate for the UAP in the 2019 election.

40 During the course of the hearing, Mr Palmer’s solicitor, Sameh Morris Iskander, filed an affidavit. Annexed to that affidavit were documents which should have been discovered by Mr Palmer.

41 All the affidavits were read and, with the exception of Mr Iskander, each deponent was required for cross-examination. Unusually, Mr Palmer testified after the other two lay witnesses, Mr McDonald and Mr Wright. No explanation was offered but it is reasonable to assume that this unusual course had at least something to do with the fact that the hearing took place during the week before the Queensland election in which the UAP was fielding candidates in every seat.

42 While Mr McDonald was concerned to protect the UAP, I found him to be generally honest.

43 Mr Wright’s affidavits were not full and frank. On occasions during his oral evidence, his answers were punctuated by inappropriate giggles. I formed the view that these were nervous giggles. For the most part, however, I concluded that his oral evidence was truthful.

44 Mr Palmer, on the other hand, was a most unimpressive witness. In significant respects his evidence was inconsistent with the contemporaneous records and the evidence of both Mr Wright and Mr McDonald. I deal with his evidence at some length later in these reasons. It is sufficient to observe at this point that he was an unreliable witness whose evidence was at times incredible.

45 Many of the relevant facts were either admitted or not in dispute. Unless otherwise indicated, none of the facts set out below was controversial and I make findings accordingly. A good deal of the narrative is drawn from Universal’s meticulous written submissions which in these respects were not contradicted.

46 The WNGTI music is an original musical work and the WNGTI lyrics are an original literary work within the meaning of those terms in the Copyright Act.

47 Mr Snider is the author and composer of WNGTI. He started writing it in 1980. He finished it in 1984.

48 Mr Snider joined Twisted Sister in 1976 as its lead singer. He was also the band’s sole songwriter. Twisted Sister was active until 1987, when it broke up. It reunited in 1988 and its members continued to work together and perform publicly throughout the 2000s. It disbanded in 2016, shortly after the death of its drummer. Since then, Mr Snider has continued touring, both on his own and with a backup band, playing Twisted Sister songs as well as songs from his solo work. Mr Snider has also been involved in many solo projects, including hosting radio programs, appearing on several reality TV shows, and doing voice-over work for television, animation and computer games.

49 Until 1987, Mr Snider wrote all the music and lyrics to the songs he performed. Thereafter he wrote a number of albums in partnership with other songwriters. He gave unchallenged evidence, which I accept, that songwriting always came naturally to him. He explained that he felt he had something to say and knew how to say it. He also gave unchallenged evidence, which I also accept, that the integrity of his songwriting was, and remains, very important to him.

50 Mr Snider’s songwriting process almost always began with two elements: a title, which usually features prominently in the lyrics, and a short melodic idea, which is the first thing he would record. He would then flesh out the rest of the song musically, on a guitar, and write the other lyrics, which were strongly inspired by its title.

51 The process involved in the writing of WNGTI was no different. Mr Snider deposed:

In my usual process, working from a list of potential song titles that I had thought up, I sang the entire chorus of We’re Not Gonna Take It into a tape recorder – that is, the words “We’re not gonna take it. No we ain’t gonna take it. We’re not gonna take it, anymore”. At that point I could not come up with a satisfactory verse and bridge for the song so I put it to one side for future development and use. I knew I had something special in this song (even telling my band and our producer at the time Eddie Kramer that I had a “hit” in the works), so I needed to make sure the rest of the song was as strong as the chorus.

Over the next few years, whenever I was working on new song ideas, I would return to the chorus I had written for We’re Not Gonna Take It and try again to finish it properly. It was only in the winter of 1982 that I finally was able to complete it. Generally, while Twisted Sister was recording one release, I would be working on the songs for the following album. Throughout 1982 and 1983, I continued to “flesh out” We’re Not Gonna Take It (along with all the other songs for what was to become the album Stay Hungry, released in 1984). I did not present the song to the rest of the band until late in 1983, when we began demoing new songs for Stay Hungry. At no stage did any other person (including the other members of Twisted Sister) contribute to writing the music and lyrics of We’re Not Gonna Take It.

As with all my songs, the combination of words in the title of We’re Not Gonna Take It inspired everything else about the song, especially its lyrical content. As an angry, frustrated, younger man (I was 25 in 1980) I wanted to write a song to express not only my emotional state, but one which I felt was shared by our audience. I wanted it to be an anthem that everyone could sing or shout along to when they heard it.

52 Mr Snider’s musical influences are many and varied. He is unaware of ever having consciously copied a musical work or lyrics. As he readily acknowledged, however, he was inspired by others. At the time he wrote WNGTI, he recalls deriving inspiration from the Def Leppard 1983 album, Pyromania; such hard rock albums as Alice Cooper’s School’s Out; and the pop/rock anthems of the English rock band, Slade.

53 WNGTI was first released as a single on 27 April 1984 and then appeared on Twisted Sister’s third album, Stay Hungry, which was released on 10 May 1984. It was an immediate international commercial success. It reached no. 21 on the US Billboard Hot 100 singles chart, no. 6 in Australia, no. 5 in Canada and no. 2 in New Zealand. It was certified as a gold record in Mexico, Sweden and the US (where the Stay Hungry album achieved platinum status three times) and platinum eight times in Canada. It is generally regarded as Twisted Sister’s best and most popular song and its popularity has grown over the years, so much so, according to Mr Snider, that these days it is “practically a folk song”. It was Mr Snider’s most commercially successful song.

54 WNGTI has been licensed for use in musical theatre, films, and television, including the Broadway musical and film productions of Rock of Ages; advertisements for the film Charlotte’s Web (2006); films such as The Emoji Movie (2017) and Ready Player One (2018); and several television series such as Young Sheldon and Person of Interest. It has also been used for advertising purposes on many occasions and in various parts of the world. And Mr Snider has been asked to perform the song for major events on numerous occasions to diverse audiences and for a variety of causes.

55 As Mr Snider observed, WNGTI has “a strong message of defiance, but the lyrics are quite non-specific”. It was important to him that the message not be directed to any particular authority figures or causes. He believes that this generic quality contributes to the song’s enduring appeal. He has heard it played at sporting events, rallies, and protests “of all kinds”. According to Mr Snider, many people consider it one of the greatest songs of rebellion ever written. It has appeared on many lists on the subject.

56 Several American politicians have used WNGTI in their election campaigns. Mr Snider performed it for Arnold Schwarzenegger’s gubernatorial campaign, although to his knowledge it was not licensed for any recorded advertisements in the campaign. In 2012 Paul Ryan, then a candidate for president in the Republican primaries, used it at one of his campaign rallies, albeit without Mr Snider’s permission, but ceased to use it at Mr Snider’s request because Mr Snider did not want his song to be associated with Mr Ryan or his views and policies. Mr Snider believes that, more than any other of his songs, his image and personality are very closely associated with WNGTI.

57 In 2015 WNGTI was used as the theme song for Donald Trump’s first presidential campaign, initially with Mr Snider’s permission, which he said he granted because of his then-friendship with Mr Trump. Mr Snider explained that they had been involved in several charity projects together and he had appeared a number of times on Mr Trump’s reality television show, Celebrity Apprentice, and through them he came to like Mr Trump and his family. But when he found he was unable to agree with many of Mr Trump’s positions and policies and did not want others to think that he approved or endorsed his campaign, he asked him to stop using the song and Mr Trump obliged.

Universal Music Publishing and Songs of Universal

58 UMP and Songs are members of the global corporate conglomerate known as the Universal Music Publishing Group (UMPG). UMPG administers and in many cases (including licensing songs for use in advertising) controls as exclusive licensee the copyright in the songs in the UMPG catalogue. On 1 January 2019 UMP became the exclusive licensee in Australia of the copyright in WNGTI, with rights to sue for infringements before that date.

59 Universal has published Mr Snider’s music since the 1980s. He has always enjoyed a very good relationship with Universal which, he said, was built on years of trust.

60 In 2015 Mr Snider assigned the copyright in his songs, including WNGTI, to Songs, although he retained his interest in the so-called “writers share” or performing rights. Before and after the assignment of the copyright, Universal sought his approval for the synchronisation of his songs with visual material, such as in advertising or films. That was important to Mr Snider. As he explained it:

The song-writing process is a very emotional process for me; it comes from the heart. It would be devastating to me if any of my songs – but particularly We're Not Gonna Take It – were licensed for a purpose that I consider to be offensive or contrary to my beliefs, because I would feel like I was supporting a cause against my will. I want to prevent my music being used in association with products, companies or messages which I find objectionable. I view this as a fundamental and valuable part of my rights as a performer and songwriter.

Whenever I approve the use of one of my songs, I have to be satisfied that the proposed use would not damage my reputation or my commercial interests. Universal usually provides me or my management team with details about the proposed use, including who the prospective advertiser is, in order for me to make an informed decision. If I need more information, I ask for it.

That said, I try to take a pragmatic approach to potential licensing requests and am open to maximising the value of my songs. In the past, when I have been presented with a licensing opportunity that is not immediately attractive to me, I have looked for the positive characteristics of the brand or company and considered whether any such characteristics are sufficient to overcome my initial reluctance. This is particularly so if the licensing opportunity is for a significant sum of money.

61 Since the assignment of the copyright in 2015, Universal has regularly notified Mr Snider’s management of requests to use WNGTI, although the agreement with Songs does not require it.

62 Mr Palmer is a well-known Australian businessman. It is an agreed fact that he has a net worth exceeding AUD1 billion. Mr Palmer has been in business for over 40 years. He also has a keen interest in politics and has long been involved in it. He was a member of the National Party for nearly 40 years and for four years, following its amalgamation in Queensland with the Liberal Party, the Liberal National Party, before founding and leading the Palmer United Party. It is common knowledge that Mr Palmer served as a member of the House of Representatives in the Australian Parliament for the Queensland seat of Fairfax between 2013 and 2016 and that he was a candidate for the Senate on the UAP ticket in the last federal election.

63 In February 2018 Mr Palmer announced that the Palmer United Party would contest the 2019 election. In July 2018 the party was rebranded the UAP and registered with the Australian Election Commission. At all the relevant times Mr Palmer was its registered officer.

64 In around July 2018 the UAP began a nationwide media campaign in preparation for the 2019 election. To win support, it deployed various forms of media, including print, radio, television and online advertising, and text messaging. It also distributed T-shirts, worn by its members and supporters, upon the back of which the words “Aussie’s Aren’t Gonna Cop It Anymore” were printed. It fielded candidates in every seat in the House of Representatives and the Senate.

65 Although there is no direct evidence on the point, it is possible that Mr Palmer knew that the song had been used in the Trump campaign in 2016. Having regard to his long business career and keen interest in politics, Mr Palmer is likely to have followed the Trump campaign and may well have drawn inspiration from it. There is some support in the evidence for this. An appearance by Mr Palmer on the Nine Network’s Today program featured in a segment on the American television show, Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, which found its way into evidence in an exhibit to one of Mr Tonkin’s affidavits, admitted without objection. It is sufficient to refer to the opening:

OLIVER: But perhaps the most eye catching candidate is Clive Palmer, head of his own United Australia party. He’s a brash businessman who’s pushing a populist anti-establishment platform. If that’s already reminding you of someone, just wait till you hear him yelling at a news anchor.

[Cuts to clip from the “Today” show on Channel 9. Clive Palmer is on the Gold Coast and is wearing a suit with a red tie.]

PALMER: “We’ve got to stop about the fake news people attacking individuals. As I said, my wealth is $4,000 million dollars. Do you think I give a stuff about what you personally think or anyone else I might care about this country? God bless Australia. Put Australians first.”

OLIVER: Wow. That’s all pretty Trumpy right there. Arrogance, check, Red tie, check. He even has billboards with his campaign slogan “Make Australia Great”, which notably doesn’t say “Make Australia Great, again”.

[An image of Palmer sporting the thumbs up sign appears behind Oliver in front of billboard “Make AUSTRALIA GREAT!!”]

Negotiations with Universal for a licence to use a “re-recording” of WNGTI

66 In October 2018, Mr Palmer instructed Mr Wright to approach Universal to negotiate a licence to use in advertisements for the UAP a “re-recorded version” of the Twisted Sister track with possible lyric changes. It is an agreed fact that in his dealings with Universal Mr Wright was acting as Mr Palmer’s agent.

67 On 11 October 2018 Mr Wright emailed UMP with the following inquiry:

We have a major client that wishes to produce a local talent cover version of the Dee Snider track “We’re not gonna take it”. The usage would be specially for a national TVC campaign, and only a portion of the track would be used. I understand that UMPG acquired all rights to Twisted Sister back in 2015. Given that Dee Snider wrote the track I am making you the first port of call for this. I understand you may have rights to the recorded works, and the mechanical usage rights may differ.

Can you advise if you can help with this enquiry, or refer us to the entity that can help?

(Emphasis added.)

68 The “major client” was Mr Palmer.

69 The next day Selina Meuross replied, copying in Ms Masters, who was her supervisor. Ms Meuross confirmed Mr Wright’s understanding and invited him to complete an advertising licence request form which she attached to her email.

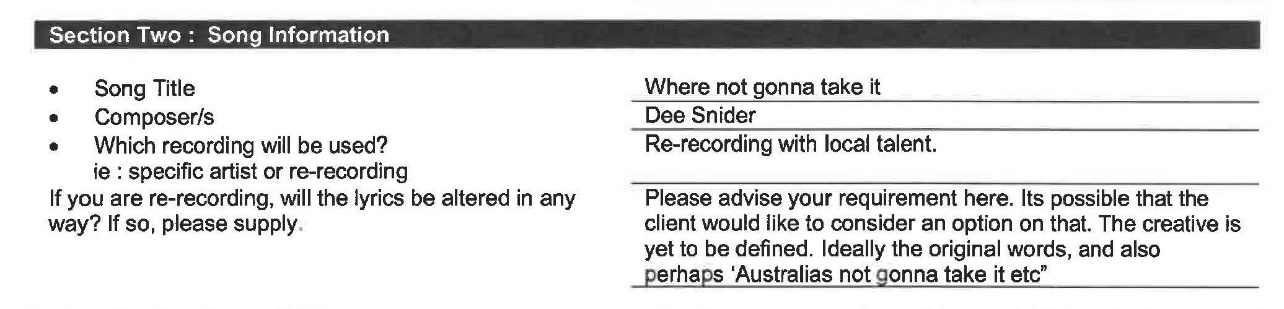

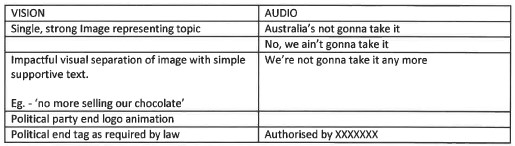

70 Later that day Mr Wright submitted a completed form, identifying his client as the UAP and the product being advertised as “United Australia Party – workers rising up concepts”. The term of the proposed licence was “ASAP until June next year”. The proposal was that the song would be used on the ABC, the internet, including the UAP website, and YouTube. The form provided the following information about the song:

71 On 16 October 2018, based on that limited information, Ms Meuross quoted a licence fee of $150,000+GST for eight months, subject to a signed contract and the approval of Mr Snider. The quote was valid for 30 days. But there was a proviso. Ms Meuross stipulated:

Please note that this is very much subject to writer approval, and before we send it off for clearance we will need the full creative, lyric changes, and name of the local artist that will be covering the song. The cover must strictly not be a sound-alike.

72 Mr Wright responded within the hour. He said that he would speak with “the client” and get back to her soon. He said he was “fine with not being a sound alike”, adding: “I had only gone down that path [that is, opted for a sound-alike] as I assumed it might be more difficult to get approval of the original recorded version with the original artists”. I interpolate that Ms Masters’ evidence was that a “sound-alike” in this context is a re-recording that sounds like the original master recording, the rights in which may be owned by an unrelated third party.

73 Mr Wright then inquired:

Is there any chance we can access that for a larger fee?

74 Ms Meuross replied:

Hi David, if you would like to use the original Twisted Sister master recording you will have to contact the master owner/record label (Warner Music) and liaise with them separately for a quote to use their recording. Of course if you do choose to use the original recording you won’t be able to change the lyrics/re-record your own version. We’ll also have to re-quote so let me know what the client decides to do.

As for the timeline, it’s really difficult to determine as it’s different for every case. Once we have the final terms laid out we will put it to the writers for approval straight away, and it can take up to a week or more for us to get feedback from them. If there is a tight deadline for this I would advise that the client decides what to do re the recording asap.

75 I interpolate that in cross-examination Mr Wright said that he understood from this email that Universal was now saying that they did not own 100% of the copyright and/or that “they were fishing for more fees”. It is clear that he understood the difference between publishing rights (the right to use the music), held by Universal, and mechanical rights (the right to use the master recording). Yet he purported to be taken aback by Ms Meuross’s reply. I do not consider this evidence credible in the light of his opening remark to Universal in his initial email, which indicated that he was aware of the possibility that Universal did not hold all the rights, in particular “the mechanical usage rights”.

76 In a subsequent email, also sent on 16 October 2018, Ms Meuross explained that the quoted fee reflected the fact that “this is a nationwide political advertising campaign that will use a premium song from our catalogue” and “the fact that it is a re-record”, albeit with lyric changes, “further increases the fee”. She asked Mr Wright to bear in mind that, if he did use “the master”, UMP’s fee would be lower but he would also have to pay Warner Music a separate fee on top of UMP’s publishing fee.

77 Ultimately, however, nothing came of either inquiry. Mr Palmer baulked at paying the licence fee. Mr Wright made a counter-offer of $35,000. UMP rejected the counter-offer and negotiations broke down.

78 Cross-examination of Mr Wright revealed that in the meantime he was developing some videos which incorporated WNGTI.

79 On 23 October 2018 Mr Wright sent an email to “Terry Smith” the text of which began with the words “Here is a new one for WNGTI” and contained a series of hyperlinks to “new and “revised videos for/of WNGTI”.

80 On 25 October 2018 Mr Wright sent another email addressed to “Terry Smith”, carrying the subject line: “FW: Current versions of WNGTI including WA GSt”. This email contained hyperlinks to the videos hyperlinked to the 23 October email as well as other emails with different themes.

81 On 27 and 29 October 2018 Mr Wright sent two further emails to “Terry Smith” containing hyperlinks to videos.

82 Not all the hyperlinks in the emails worked by the time of the trial. Mr Wright was cross-examined about this but was unable to offer a reason. Some of the hyperlinked videos were in evidence. They were tendered by Universal. Each of those videos featured Twisted Sister’s original recording of WNGTI synchronised to images and text urging the viewer to “VOTE [1] UNITED AUSTRALIA PARTY”. Universal submitted that, given the references in the emails to “WNGTI”, it should be inferred that the other videos also featured the Twisted Sister recording of WNGTI. The inference is a reasonable one. No argument to the contrary was advanced. In the circumstances that is the inference I draw. It is also reasonable to infer that at this point in time Mr Palmer was contemplating using the original recording in the UAP videos.

83 Mr Wright testified that “Terry Smith” was an alias for Mr Palmer. Evidence admitted without objection, included in an exhibit to Mr Tonkin’s second affidavit, indicates that this was a name Mr Palmer used while acting as a shadow director of Queensland Nickel. The reason Mr Palmer felt that he needed to conduct this correspondence by concealing his true identity was not explored in cross-examination. But it is self-evident that he felt he had something to hide.

84 On the morning of 29 October 2019 Mr Wright apparently had a conversation with Ms Meuross in which she reiterated the position she had taken in her last email. Later that morning Mr Wright followed up on that conversation with an email.

85 In the email to Ms Meuross Mr Wright explained that the nature of political advertising is such that he was not able to divulge “our strategy in an open manner”, lest “the integrity of the campaign” be compromised. He went on to say:

I understand that you require some information. What I can reveal is the following; there would be nothing racist, sexist or misogynistic, religious, or anti LGBTI etc, and that the topics will be more about fiscal debate for equality and fairness for the masses within the various demographic’s [sic] areas. The intent is simple clean messaging with no spoken words.

15 Second EXAMPLE:

If we approve your requested fee of $150,000 fee, we need it to cover off until the election. We will need to extend the usage until 12 months to cover off in the unlikely case that they will call it very late. There are reasons that this is unlikely, regardless we need to cover off on that.

A high-quality combined artist session would be the basis of the recording. The members form a very strong 11-piece high energy power ballad band. It would not be a shabby rendition.

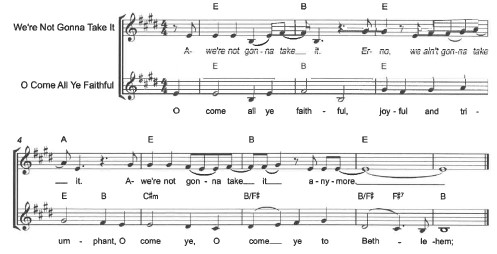

86 Once again the only change proposed to the lyrics of the chorus to WNGTI was in the first line (from “We’re” to “Australia’s”).

87 Ms Meuross replied early that afternoon. She said she was happy to make the term 12 months but would have to push the fee up to $160,000 to cover the extra four months. She also sought more information about the “strong images” that would be used. She said that once she received that information she would be happy to put the request before the writer (Mr Snider) for approval. She emphasised, however, that “the writer will need to see the final video or at least a final storyboard”, that this was Universal’s invariable practice and it was “non-negotiable”.

88 At 5.57pm Mr Wright emailed “Terry Smith” with hyperlinks to a number of videos including three “with word change”, presumably from “We’re” to “Australia’s” and four advertisements on various subjects “as approved”.

89 At 9.46am the next day, 30 October 2019, Mr Wright wrote back to Ms Meuross:

A little effort could be made to ensure client satisfaction. As the suggested fee is a premium for political use, it must come with the liberties and freedoms that are required for the short sharp turn around of a political campaign. No agreement can be considered to have the campaign vetted by an offshore writer/musician that is receiving a fee for license, or the fee receiving artists management. Even if your demand was not perceived as unreasonable for a political campaign, there is not enough time for such a drawn-out process.

This is a national campaign that is extended the courtesy of political due process by law.

The fiscal offer is as previously stated.

$150k for up to 12 months.

There is no agreement to third party entities approving our campaign elements. This is non-negotiable.

Please return by 3pm Friday the 2/11/18 with an approval if you would like to be considered for the new business. A decision will be made between the tracks that are being explored, and the ease of working with the supplier involved. To earn the account, there is a requirement that a supplier is working for us to streamline processes.

90 As Universal observed in their submissions several observations can be made about this email. First, Mr Wright was adamant that Universal and Mr Snider would not be permitted to approve the advertising in advance. Second, although Mr Wright referred to other tracks “being explored”, no evidence was given of what those tracks were and, if other songs were being considered, none was eventually selected for the UAP videos presumably because none of the possible alternatives had the benefits that WNGTI offered. Third, prior approval from the songwriter remained a sticking point for Universal. In cross-examination Mr Wright did not accept that this had led to an impasse in the negotiations. He purported to be unconcerned about the issue, saying “I knew that we were in a negotiation pattern, as one does in business …”. He testified, based on his experience, that even that would have been negotiable for the right price.

91 At this point Ms Masters entered the fray. Until then she had only been indirectly involved, having been copied into the correspondence. This time it was she who replied to Mr Wright, advising that the approval of the writer was “standard procedure for any synchronization use”, irrespective of the nature of the campaign; that Universal had the right to negotiate terms and quote on fees for the publishing rights they considered acceptable, based on terms and variations he might supply; and that if Mr Wright did not find those terms acceptable, he could select other music that was “easier to clear” for the proposed use. To this end she offered to put him “in touch” with Universal’s production music arm.

92 Two hours later Mr Wright replied:

Thank you for your response. We are hearing verbatim about the hurdles and obstacles set out in a pattern that leads to a high budget, but no client satisfaction. What we require is some initiative and an attempt to ensure client satisfaction is performed in a streamlined, non-intrusive, fair and reasonable manner.

Political strategy campaigns do not fall under the normal banner. Hence the additional fee loading you are proposing. If a premium is paid because it’s a political campaign, the fee covers certain considerations. To charge a premium because of something, and not allow consideration of that very thing can easily be seen as unconscionable and is definitely unreasonable.

The rights you refer to are the basis of an internal agreement with yourself and an artist and are not rights with your client. This is new business. With a client, you are at liberty to see if an agreement can be met where a fair and reasonable price for a usage, based on a given set of control parameters. If you have no client, you are not acting in the commercial interest of the firm, nor the artist.

Could you have some thought on how one could appease the ‘system’ that does not appear to be designed for Political Strategy campaigns, and still forge a relationship with a new business client and raise the annual turnover slightly.

Might I suggest we provide 1 x example mock up, and are given no go zones that the Writer feels he does not want the re-recorded, word altered version to represent? This to my mind still seems unreasonable considering we are being charged at the political rate, but it might be a valid lateral way of moving beyond your current hurdle, assuming you are actually interested in securing the business?

93 Ms Masters was unmoved. She told Mr Wright in a return email why UMP required “clear and precise creative details” and that the licence fee was not just affected by “the political context of the use” but also by the fact that the proposed use was for a “re-record” with a change in the lyrics. She said that these were “all fair and standard conditions of any licence” in which Universal enters, whether with a music supervisor, advertising agency, TV or film production company, or short-film maker. She also said that the writer was entitled “to view and approve the final creative as to how the song will be used” but at this stage she indicated that “[a] proposed storyboard would be fine”. If the client was not comfortable with this, she suggested he look at an alternative song that might be easier to clear.

94 This email went unanswered. It is an agreed fact that it was at this point that the negotiations broke down.

95 That evening Mr Wright emailed Mr Palmer (“Terry Smith”). In that email he provided the following “copyright update”:

Universal are still being sticklers for their rules regarding us showing all our concepts to the writer in order to seek approval for his music. Whilst that’s not an issue for soap powder, it’s a big issue for us because we don’t want to expose our deck to anyone too early. I doubt he has any political alliances within Australia, but we could not assume the same with the music publishers. At least I would not assume that.

I note that It [sic] was used for Schwarzenegger’s campaign and Dee Snider agreed with the usage in 2003. In 2012 Snider asked Republican vice-presidential running mate Paul Ryan’s camp not to play his hit song in their campaign. Its also been used for a teacher strikes and for and Pro-Choice campaigns, which he approved.

I also noted that he is also a performer for hire, and this is managed via a different agent. Perhaps this is another avenue to communicate with him, but the final negotiation here in AU appears to sit with Universal.

Interestingly, he is doing a smaller sized tour here in Australia from January to audiences ranging from 550-1000 PAX, which I understand are sold out since August this year.

96 Mr Wright claimed in evidence that his only concern was that the UAP’s proposal might “leak”. But the email indicates that he was also keen to secure Mr Snider’s approval. At the same time his evidence revealed that he was also concerned that obtaining his approval would have “delayed the process” and delays in a political campaign are undesirable.

The development of the lyrics to ANGCI and the UAP recording

The evidence of Mr Wright and some further contemporaneous documents

97 In his first affidavit Mr Wright said nothing about the development of either ANGCI or the UAP recording. In his second affidavit he said that ANGCI, as used in the advertisements, was performed by session musicians he had arranged to perform it. He deposed to telling these musicians in “a couple of short telephone conversations” not to take their performance too seriously, to give the song “a good belt”, to sing it “like an old 80’s rocker” and to “have some fun with it”. He also deposed that he told them that the performance style should be “in your face” but that “it should not be an exact sound-alike of the vocals in We’re Not Gonna Take It”, consistent with the request made by Universal.

98 A somewhat different picture emerged in cross-examination, a cross-examination apparently based on discovered documents. The failure to provide a full and frank account of the history in evidence in chief reflects adversely on his credit.

99 For a start, Mr Wright did not arrange for the session musicians to perform ANGCI.

100 Rather, the cross-examination revealed that Mr Wright instructed local session musicians to perform a number of takes of (the chorus of) WNGTI with variations. It is not clear when those instructions were given or the order in which the takes were recorded. But the recordings were completed by 13 November 2018, within two weeks of the breakdown in negotiations for the licence. Mr Wright testified that there were 14 takes and 14 recordings were tendered. The effect of Mr Wright’s evidence is that he regarded “cop” as a variation of “take”.

101 Mr Wright sent the recordings to Mr Palmer for his approval on 13 and 14 November 2018. They were dispatched in two emails to the “Terry Smith” account.

102 The first email began in this way:

Hi Clive,

MUSIC

Here is a link to a series of takes for ‘we ain’t gonna take it’. They are about 8 megs each so I could not easily email them as clips, but you can right click and download from each file here.

The hyperlink to the files followed.

103 The second email attached another hyperlink and included this message (without alteration):

I am not sure the cop it one is the best as it sounds like ‘we’re not going to carpet’. Good if we were advertising floor tiles. You can’t unhear this now.

104 In their submissions Universal described the evolution of ANGCI from WNGTI in the following way, based on the electronic files which became Exhibit E. Mr Palmer did not take issue with the description. Version 1 below is virtually identical to the chorus of WNGTI. Version 6 is the one upon which Mr Palmer settled.

V1_LYRIC_1.WAV / V2_LYRIC _1.wav (Version 1)

We’re not gonna take it

Oh no, we ain’t gonna take it

We’re not gonna take it

Anymore

(x2)

V1_LYRIC_5.wav / V2_LYRIC _5.wav

We’re not gonna take it

[You know] we’re not gonna take it

We’re not gonna take it

Anymore

(x2)

V1_LYRIC_4.wav / V2_LYRIC _4.wav

Australia ain’t gonna take it

No Aussies are not gonna take it

We’re not gonna take it

Anymore

(x2)

V1_LYRIC_7.wav / V2_LYRIC _7.wav

Australia’s not gonna take it

Aussies not gonna take it

We’re not gonna take it

At all

(x2)

V1_LYRIC_6.wav / V2_LYRIC _6.wav

Australia ain’t gonna take it

Australians are not gonna take it

Aussies not gonna take it

At all

(x2)

V1_LYRIC_2.WAV / V2_LYRIC _2.wav (Version 6)

Australia ain’t gonna cop it

No Australia’s not gonna cop it

Aussies not gonna cop it

Anymore

(x2)

V1_LYRIC_3.wav / V2_LYRIC _3.wav

Australia ain’t gonna cop it

No Australia’s not gonna cop it

Aussies not gonna cop it

At all

(x2)

105 On 16 November 2018, and with apparent indifference to the want of a licence, Mr Palmer authorised the creation of the UAP recording, which Universal described as “a cover version” of WNGTI.

106 That day, Mr Wright emailed Mr Palmer, again to the account of “Terry Smith”, with the subject line:

WGTI Daves remix version – raised vocals

107 Mr Wright informed Mr Palmer that he had “done a remix of this at [his] end to broadcast – 12 mastering lever, and raised the voice a little in the process”. He asked Mr Palmer whether that was an improvement as far as he was concerned and indicated his view that “this version sounds quite a lot better ...”. The body of the email also contained a hyperlink which was not working at the time of the trial. Mr Palmer responded within hours: “Well done that it [sic]”.

108 A couple of hours later, Mr Wright sent another email to Mr Palmer with the subject line:

WNGTI with COP in graphics and Musician reimbursement

The email contained a hyperlink to “a tester version with the word ‘cop’ in the graphic to match” and sought authorisation for the musicians to be reimbursed. The hyperlink was inaccessible. In cross-examination Mr Wright accepted that the subject line was a reference to WNGTI “with the lyric variation whereby ‘cop’ is substituted for ‘take’” and the word “cop” also appeared in the graphics. Mr Wright conceded, in effect, that Mr Palmer had approved the change.

109 In cross-examination Mr McDonald confirmed that ANGCI was an evolution from WNGTI. He testified that, before he sent the letter to Universal on 8 January 2019, Mr Palmer told him that he had written the words to ANGCI by taking words used in the chorus of WNGTI and changing them. Mr Palmer did not deny that he had said this to Mr McDonald or suggest that Mr McDonald was mistaken. He merely claimed not to remember saying so.

110 Mr Palmer said nothing in either of his affidavits about the source of the music used in the UAP recording or his involvement in the production of the UAP recording.

111 In his first affidavit Mr Palmer gave the following account of the creation of the impugned works:

In or about September 2018, I was sitting at home preparing for the upcoming Federal election and what the party was trying to achieve for ordinary Australians. While deep in contemplation, I wrote the words for “Aussies Ain’t Gonna Cop It”; that is, the words:

“Australia ain’t gonna cop it;

No Australia’s not gonna cop it;

Aussies not gonna cop it, anymore.

The words instantly resonated with me and the views and values of the UAP. The party was formed because of the disenfranchisement with the major party duopoly in Australia and the views many Australians hold — that there is a lack of proper representation in government. The words perfectly supported the values of the party and members of the party agreed.

112 He acknowledged no debt to Mr Snider or WNGTI. In cross-examination he denied any such connection.

113 In his first affidavit, presumably to underscore the point he wanted to make, namely that ANGCI was an original work which he had composed (no other relevant purpose being evident), under the heading “original works” Mr Palmer waxed lyrical about his creative side. While his counsel elected not to read this passage, much of it was cross-examined into evidence. Mr Palmer professed to have “a keen interest in the publication of original poetic works”. He claimed to have “regularly published poetic works”, and to have been invited to share his poetic works at the Queensland Poetry Festival, works he said were “considered to be very moving and genuine” (according to his wife).

114 In a non-responsive answer to a question he was asked in cross-examination, he volunteered the following explanation for his source:

I remember seeing the Peter Finch movie, where he said, “we’re not gonna take it anymore”, in one of those scenes. And he repeatedly stated that in a scene in the movie – “we’re not gonna take it anymore, we’re not gonna take it anymore”, because he – I think – before he committed suicide on the TV station he was supposed to beat. This was in the movie, Network, that was produced about 1977. So from that, I developed the idea – Australians are not prepared to accept it – I thought that was a similar type thing that I worked that back, and ended up with these words.

(Emphasis added)

115 This evidence appeared to take everyone else in the virtual courtroom by surprise.

116 At least 12 UAP videos were made and used in the UAP’s advertising campaign. The effect of Mr Wright’s evidence is that the form and content of the UAP advertisements were finalised sometime between 16 November and 2 December 2018. Mr McDonald testified that one of the advertisements was “run” on YouTube in November. Having regard to the evidence above regarding the creation of the UAP videos, in all probability they were all finalised by the second half of November. The UAP videos were first broadcast on television on 2 December 2018.

117 Those videos contain the following slogans: (a) “AUSTRALIANS TO RUN AUSTRALIA / FOR AUSTRALIANS”; (b) “BANKING RIP OFFS / WE’RE NOT GONNA COP IT”; (c) “$55 Billion spent on NBN / STILL DOESN’T WORK”; (d) “Getting 80% of GST back! / WA PEOPLE ARE WORTH 100%”; (e) “LABOR & LIBERAL HAVE SPENT $55 BILLION ON THE NBN / NOTHING TO FEED YOUR ANIMALS”; (f) “NETWORK AND POWER RIP OFFS / WE’RE NOT GONNA COP IT”; (g) “NEW ZEALANDER OF THE YEAR”; (h) “NO MORE FOREIGN CONTROL OF POLITICIANS”; (i) “NO MORE WASTE OF TAXPAYERS’ MONEY / STOP POLITICAL PERKS!”; (j) “SOD OFF SHORTEN’S TAXES / WE’RE NOT GOING TO COP IT”; (k) “STOP THE SALE”; and (l) “WANT STABILITY?”.

118 The UAP videos have the following common features. First, the UAP recording is played throughout and it is the only audio in the videos apart from minor sound effects and the authorisation statement at the end. Second, the authorisation statement “[a]uthorised by Clive Palmer for the United Australia Party, Brisbane” appears on the screen. Third, before the authorisation statement, the videos conclude with an animated version of the UAP logo mark and the tag line: “VOTE [1] UNITED AUSTRALIA PARTY”.

119 On YouTube and Facebook, each UAP video is shown on a webpage with accompanying text which often contains a message to support or join the UAP or to vote for the UAP at the forthcoming election.

The UAP’s advertising campaign

120 Mr Palmer authorised the broadcast and communication of the UAP recording and videos on television, radio and online streaming.

121 According to Mr McDonald, total expenditure on the UAP advertising campaign was “something in the order of $80 million”. As at 11 January 2019 prepaid expenditure on broadcast advertising was $12 million. Documents discovered by Mr Palmer indicate that the UAP videos were broadcast on television over 18,600 times, constituting some 20.6% of total broadcasts in the campaign. Mr Tonkin’s unchallenged evidence, given in his first affidavit sworn on 17 April 2019, was that in total the UAP videos had been viewed on YouTube and Facebook more than 17.5 million times.

122 The UAP videos published on the internet were not geo-locked to Australia and could therefore be accessed from overseas.

123 Mr Snider became aware through social media of the UAP videos/advertisements. He first became aware of the UAP advertisements on 31 December 2018 because his Twitter followers were up in arms about them. Numerous tweets were annexed to his second affidavit, such as:

• @deesnider Just interested to know: Did you and / or your recording company give permission to Australia's Clive Palmer’s United Party to use the melody to “We’re Not Going To Take It” with revised lyrics? Just saw Palmer's ad on Aussie tv.

• It’s cringeworthy. Please get it taken off the air.

• @deesnider did you know that Australian political party @UnitedAusParty is using a parody of “We’re Not Gonna Take It” in their political commercials? It’s not a good look.

• @deesnider Hey mate just wondering if you know that we’re not gunna take it is being used for a right wing political party in Australia

• He’s the last bloke on earth you’d want to be associated with.

• @deesnider Have you authorised Clive Palmer to use your song for his political party in Australia?

• @deesnider Gday Dee from Australia I'm not sure if you know we have a politician (Clive Palmer) that is very much like Trump doing political advertising with your song “We’re not gonna take it” I’m not sure if he and his party have permission to use it ...

• @deesnider @BoyGeorge ok gents, time to fire legal teams up and put a-stop to this Clive Palmer nonsense @clivepalmerm It’s destroying your music for thinking Australians!!!

• Please @deesnider tell us you know nothing about @PalmerUtdParty butchering “We’re Not Gonna Take It” for their horrendous political commercial. @CliveFPalmer is well known for not paying bills so odds are he didn’t pay #twistedsister either

124 At around the same time, Twisted Sister’s guitarist and manager, John “Jay Jay” French, told Mr Snider that the band’s website and social media were being bombarded with objections to them “letting” Mr Palmer use their song. Mr Snider deposed that their Australian fans were “incensed”. Five emails to Twisted Sister were annexed to Mr Snider’s second affidavit, the substance of which read as follows (without alteration):

• Are you aware that your tune is being used for a political campaign (TV) here in Australia?

If you are, good luck to you!

If not, this guy has a habit of leaving employees, contractors and suppliers out of pocket. Be warned.

In either case, this does not put your band in a great light.

Sorry I can not post a link to the ads, they appear to be on TV only.

[A link to the UAP website was included.]

• Did you really give permission to Clive Palmer’s ‘United Australia Party’ to use your song ‘We’re Not Gonna Take It’ (with altered words) in their election advertising or has he just helped himself to it as he seems to feel entitled to do whatever he wants? No need to reply to this email. Just wanted to make you aware.

• Query from a concerned fan – is the band aware that a narrow minded, bigoted political party in Australia called the United Australia Party led by entitled rich man Clive Palmer is using their song (or a differently worded version) for their political campaign? I thought “We’re not gonna take it” is about fighting the man? Clive Palmer and his party are by definition the oppressive man with their boot on the neck of those in need or who are different .... I really hope Twisted Sister do not endorse them.

• Hi we got someone using one of your songs in their political advertising. He’s a real piece of work that’s screwed over works. If you do have an agreement I was wondering if he disclosed his bad reputation before getting this association. However if there is no agreement for the royalties of where not going to take it. I’m more than happy to tell you who to send the cease and desist to.

• Hi there ...

I was just writing to express some ... well ‘A’ concern!

A complete scum of the earth politician by the name of Clive Palmer is using ‘We’re Not Gonna Take It’ for his campaign here in Australia. Do the band know this?

Either way (they do or they don’t), then they should know that this politician is a complete sleeze bag who has only two interests .... 1) getting power; and 2) in getting wealthier (he is already extremely wealthy!!!) Not the kind of person TS should would want to be associated with!!!

Please don’t let this creep get away with this crap!!!

125 The complaints continued even after the dispute with Universal became public.

126 Mr Snider deposed that, after he became aware of the videos, he immediately watched one of the advertisements. He was “horrified” to hear the use of WNGTI “with slightly revised lyrics”. He proceeded to explain why:

Not only was my song being misappropriated and misrepresented, but the production of the advertisement on every level was horrendous: the poor lyrics, the poor quality vocals and the poor production values as well as the context of what appears to be a cheap advertisement for a party whose values I knew nothing about. I think the vocal style used by the singer in the advertisements is trying to emulate mine, and that the whole audio recording is a low-quality ‘sound-a-like’ of the original recording …

127 Media coverage of the dispute between Universal and Mr Palmer and this proceeding attracted more tweets like the ones set out above. Some of them were also annexed to Mr Snider’s second affidavit. Mr Snider is concerned that, for the foreseeable future, WNGTI will primarily be associated in the minds of the Australian public with Mr Palmer’s political campaign and that people who are not aware of the proceeding may think he supports Mr Palmer or allowed his music to be used in low quality advertising — or both. Mr Snider is “deeply [upset]” by the use of WNGTI without his permission and regards it as “a direct misappropriation”, not merely of his song, but also of the years of labour that went into its creation.

128 Mr Snider came to learn that there were a number of advertisements with the same audio but different visuals. Since he had not approved any licence for political advertising in Australia, he immediately instructed his management to contact Universal to see whether they had granted a licence. He deposed that he “would have been very surprised and shocked” if they had because he trusted them to seek his approval first, as he believed they had always done.

129 Mr Snider had never heard of Mr Palmer or the UAP before he learned about the advertisements. Once he became aware of their “general political stance”, he read media articles concerning Mr Palmer, including allegations that he had shut down his nickel mining business causing the loss of hundreds of jobs and improperly used its assets to fund his political campaign. Mr Snider said he did not know whether those allegations were true but the media coverage “taken together” suggested to him that Mr Palmer was not a person with whom he wanted to be associated and he did not want his song to be associated with him.

130 After he became aware of the UAP advertisements and, although he referred the matter to Universal “with instructions to take action”, Mr Snider decided to reach out to Mr Palmer directly via Twitter and ask him to stop. Part of his purpose was to reassure fans that he had not given permission for the use of the song in the advertisements.

131 On 1 January 2019 Mr Snider tweeted:

“We’re Not Gonna Take It” is a song about EVERYONE’S right to free choice.

“We’ve got the right to choose and there ain’t no way we’ll lose it!” The FIRST LINE of the first verse! Clive Palmer and the @PalmerUtdParty are NOT pro choice ... so THIS AIN’T HIS SONG!

132 Mr Palmer responded:

We believe in everyone’s right to choose and freedom of speech. Why try to stop us promoting freedom of speech & free choice?

133 This exchange provoked a number of tweets, all hostile to Mr Palmer, including the following two, which read (without alteration):

• Nothing worse than when politicians bastardise songs in an attempt to be hip. Especially without artists permission.

• You “believe ...” WTF?! Same reason kids can’t pull shit off Wikipedia to turn in as their own on a homework assignment. If you don’t know how free speech and free choice work, you shouldn’t be running for a public office. Cause you’re either too stupid and/or or too deceitful.

134 On 1 January 2019 Mr French tweeted and Mr Snider retweeted:

Twisted Sister does not endorse Australian politician Clive Palmer, never heard of him and was never informed of Clive Palmer’s use of a re -written version of our song Were Not Gonna Take It.

We receive no money from its use and we are investigating how we can stop it.

135 In the early hours of 2 January 2019 (AEDST) Mr French wrote to Mr Eaton complaining about the advertisements:

I have never received so much negative email blow back on the use of a re written version of Were Not Gonna Take It by an Australian politician named Clive Palmer.

He is hated and the use is on a tv commercial with changed lyrics.

If the use is unauthorized then please have it stopped immediately.

If Universal actually issued a license, I want to know the name of the idiot who allowed this to happen.

We need to inoculate the band from this very very bad association with this known racist as Dee will be touring soon and really doesn’t need all the bad press that may come of it [w]hich can affect his ticket sales, his new solo album sales and, in a much larger concern, our long term CD, video, vinyl and streaming income.

I await you official comment.

136 On 3 January 2019 Universal sent a letter of demand to Mr Palmer and the UAP, copied to Mr Wright, demanding, amongst other things, that the use of the UAP recording and the UAP videos cease.

137 Later that day an unidentified person in the Brisbane office of the UAP replied, advising that Mr Palmer was “currently travelling” and the letter would be raised with him as a matter of priority on his return.

138 On 5 January 2020, in response to a further tweet by Mr Snider about the dispute, a person named Kevin Morgan (with the Twitter handle @kevinmorgantas) posted the following tweet:

Why did u steal the melody from the chef and velvet underground then rip off come holy faithful [sic] and the sell out to universal u got no rights no copywriter you are a fraud and Clive will expose you

139 On 8 January 2020 Mr McDonald replied to Universal’s letter of demand, asserting that Universal’s position was devoid of merit. Despite Mr Palmer’s request to licence the copyright in WNGTI, he insisted that Universal prove ownership. He repeated the allegation in Mr Morgan’s tweet that WNGTI was a “rip off” of O Come All Ye Faithful. He denied that the musical work was written by Mr Snider. He asserted that:

The music was originally arranged as an a capella piece by a songsmith who was part of a ghost-writing system (working with the velvet underground which was run in the United States of America). Others may have documented the instrumentation, but the melody was already present. As Twisted Sister never remunerated the original arranger, we do not understand how they have had at any time any claim to copyright for anything. It seems your company may have been misled at the time you paid Mr. Snider money for something he never owned. We suggest you either commence proceedings against Mr. Snider or seek a refund of any money you may have paid him.

140 Mr McDonald claimed that Mr Palmer had “composed”, and owned copyright in, the lyrics used in the UAP recording and videos. He also claimed that the UAP’s use was “fair use under the Copyright Act” apparently because the music used in the commercials “runs for approximately 11 seconds and is used to criticize [sic]”.

141 I interpolate that this is the first time Mr Palmer or any of his agents had made such allegations to Universal and the evidence indicates that no such allegations had previously been made in any of Mr Palmer’s social media posts.

142 In anticipation of an application by Universal for an interlocutory injunction, Mr McDonald threatened to seek $10 million by way of security from Universal, which he estimated would be the value of damages on the usual undertaking required as a condition of the grant of such an injunction. He asserted that Mr Snider had “threatened violence” against Mr Palmer, based solely on a tweet in which Mr Snider said that he would “deal” with the dispute himself. On that basis, Mr McDonald foreshadowed that “they”, presumably the UAP, would write to the relevant Minister objecting to the grant of a visa to Mr Snider, who was due to embark on an Australian tour.

143 In cross-examination Mr McDonald testified that the letter was based on what Mr Palmer had told him and that Mr Palmer had “signed off” on its contents, in other words that Mr Palmer had reviewed the letter in draft and approved it before it was sent. Mr McDonald also testified that Mr Palmer had directed him to use the word “composed” but that before he sent the letter Mr Palmer had told him that he had “written” the lyrics in the UAP recording by taking the words of WNGTI and changing them. He conceded that it was misleading to say that Mr Palmer “composed” the lyrics.

144 The same day, 8 January 2020, the UAP issued the following media release, which was published on its Facebook page: