Federal Court of Australia

Ross, in the matter of Print Mail Logistics (International) Pty Ltd (in liq) v Elias [2021] FCA 419

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The plaintiffs’ originating application filed on 10 April 2019 is dismissed.

2. The plaintiffs pay the defendants’ costs of the proceeding to be taxed failing agreement.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

REEVES J:

INTRODUCTION

1 Mr David Ross and Mr Blair Pleash, the first plaintiffs, are the Liquidators of the second plaintiff, Print Mail Logistics (International) Pty Ltd (PMLI or the company). In this proceeding, they have sought relief under various provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act) against present and past directors of PMLI. Their claim for this relief revolves around two loan transactions: the Armstrong Unsecured Loan Agreement (the Armstrong Agreement) which was allegedly made on or about 14 July 2015; and the Wellington Secured Loan Agreement (the Wellington Agreement) which was made about two weeks later.

2 The Liquidators allege that, under the Wellington Agreement, PMLI took responsibility for the personal debts of Mr Nigel Elias, the first defendant, including a debt of $100,000 allegedly due under the Armstrong Agreement and that it became insolvent by entering into that agreement. With respect to the former, that is, the transfer of personal liabilities allegation, the Liquidators allege in their fourth further amended statement of claim (4FASC) that the defendants, as directors of PMLI, entered into an unreasonable director-related transaction (s 588FDA of the Act) and in the process breached their duties as directors of PMLI (ss 180, 181 and 182 of the Act). With respect to the latter, that is, the insolvency allegation, they alleged that the defendants entered into an insolvent transaction in breach of s 588G of the Act and entered into an uncommercial transaction (s 588FB of the Act). Consequently, they claimed that the defendants were liable to pay PMLI compensation under ss 588FF(1)(a), 588M(2) and/or 1317H(1) of the Act.

3 Prior to closing submissions at the trial, the parties agreed that there were three closely interconnected factual issues in dispute. The first related to the existence of the Armstrong Agreement and the other two related to the effect of the Wellington Agreement. The Liquidators bear the onus on all three issues. For the reasons that follow, I do not consider the evidence that they adduced at trial was sufficient to discharge their onus on any of those issues. Their originating application will therefore be dismissed with costs.

4 PMLI was registered on 19 February 2010. It was then known as PML Media Pty Ltd. Mr Elias was a director of the company from the outset and remains so. The other three defendants served as directors of the company from time to time. They were: Mr Luis Garcia (the second defendant) from 3 March 2014 to 4 August 2017; Mr John Woods (the third defendant) from 24 March 2010 to 1 December 2016; and Mr Adrian Pereira (the fourth defendant) from 19 February 2010 to 24 June 2016.

5 PMLI was a subsidiary of Print Mail Logistics Limited (PML) and a part of the PML group of companies. PML was also incorporated on 19 February 2010. It was, at all relevant times, a public company listed on the National Stock Exchange (NSX). It operated a printing and mailing business which it conducted from an address at Dowsing Point in Tasmania.

6 There are three other companies that are not parties to this proceeding but which have nonetheless figured in the events to which it relates. They are:

(a) Wellington Capital Pty Ltd (Wellington), which has since changed its name to Southland Stokers Pty Ltd (Southland Stokers);

(b) Armstrong Registry Services Limited (Armstrong) which is now deregistered; and

(c) Babylon Nominees Pty Ltd (Babylon).

During the period pertinent to this proceeding, all of these companies were controlled by Ms Jennifer Hutson. In these reasons, they will generally be referred to collectively as “the Hutson entities”.

7 Armstrong provided advisory services to PML and this formed the basis of the relationship that developed between Armstrong and the PML Group. Consequently, at least up until the end of 2015, there was a good relationship between the principals of each group of companies, Ms Hutson and Mr Elias; so much so that each of Wellington, Armstrong and Babylon, from time to time, advanced funds to the PML group and/or Mr Elias to assist them to conduct their business activities.

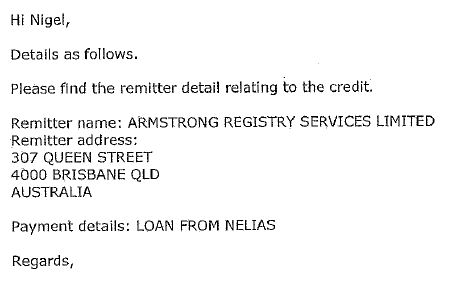

8 As a part of that process, on 21 December 2011, Armstrong loaned the sum of $50,000 to Mr Elias pursuant to a secured loan agreement which was signed and dated on that date. It is not in dispute that that sum was loaned to Mr Elias in his personal capacity and that the amount of interest that was outstanding on that loan as at 29 July 2015 was $11,980.01.

9 In 2012, PMLI purchased some vacant land at an address in Cambridge, Tasmania (the property). The intention was that the whole of PML’s printing and mailing business would move to that site. The property was purchased in two tranches and was valued in PMLI’s books at $922,517.61. The purchase was financed, in part, with loan funds obtained from the Maitland Mutual Building Society, which loan was secured against the property. Since PMLI did not trade, its principal source of income to meet its financial obligations, including its loan repayments to the Maitland Mutual Building Society, was the financial support provided to it by PML. For this purpose, PMLI and PML maintained a running inter-company loan account.

10 At about the time the property was purchased, there was also the prospect of PMLI being able to purchase a third adjoining block of vacant land. However, that purchase became the subject of litigation between PMLI and the vendor. That litigation was settled in late 2015. As a result, the vendor repaid PMLI the $10,000 deposit it had paid, together with a further sum of $40,000. The adjoining block was never purchased.

11 As mentioned at the outset, the Armstrong Agreement was allegedly made on or about 14 July 2015. Under that agreement, Armstrong was alleged to have loaned a further sum of $100,000 to Mr Elias at an interest rate of 8% per annum and to be repaid on or before the termination date of 14 August 2015.

12 As also mentioned at the outset, on or about 29 July 2015, PMLI entered into the Wellington Agreement. There is no dispute in this proceeding that, under that agreement, Wellington loaned $420,000 to PMLI. The agreement was in writing and was comprised of:

(a) a secured loan agreement between PMLI and Wellington dated 29 July 2015;

(b) a fixed and floating charge over the assets of PMLI dated 29 July 2015 and registered on the Personal Property Security Register (PPSR) on 13 August 2015; and

(c) a second mortgage over the property dated 4 August 2015 and registered on 11 September 2015.

13 On the same date, Wellington, PMLI and PML also entered into a deed whereby PML guaranteed to pay to Wellington any monies due and payable in the event of a default by PMLI under the Wellington Agreement.

14 To complete the chronology, the original repayment date for the loan made under the Wellington Agreement was 31 January 2016. It was not paid by that date. Subsequently, however, on 29 February 2016, PMLI and Wellington agreed on an extension of the repayment date to 1 July 2017. At the same time, in return for a payment of $1,000, Wellington agreed to release PML from its guarantee obligations mentioned above with respect to any default by PMLI under the Wellington Agreement.

15 On 2 October 2018, PMLI was placed in voluntary administration. By resolution passed at its second meeting of creditors on 5 November 2018, it was placed in liquidation and the Liquidators were appointed.

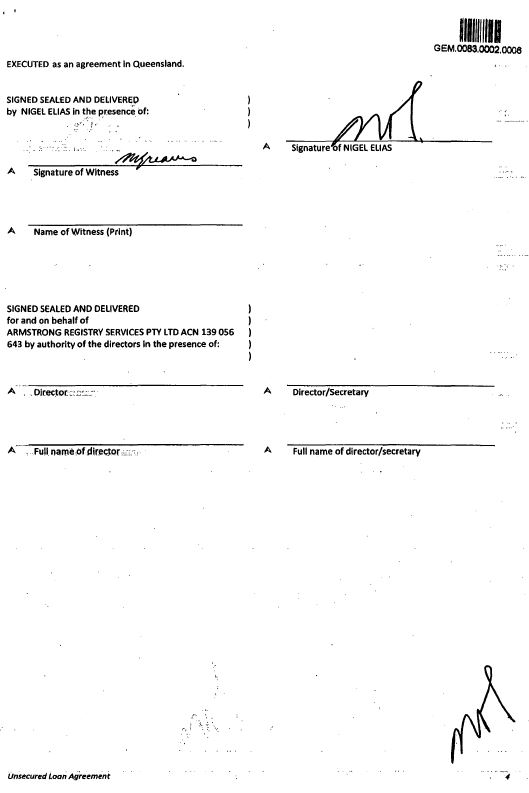

THE ISSUES

16 As already mentioned, prior to closing submissions at the trial, counsel for the parties agreed that the following three factual issues fell to be determined in this matter:

[Issue 1]

Did Mr Elias and Armstrong enter into [the Armstrong Agreement] on or about 14 July 2015 in respect of an advance of $100,000 to Mr Elias?

[Issue 2]

On 29 July 2015, did PMLI become liable for debts of Mr Elias owing to Armstrong at that time, being

(a) [a] debt of $100,000 [alleged] by the plaintiffs to be owing pursuant to [the Armstrong Agreement]; and

(b) a debt of $11,980.01 [agreed] to be owing as interest by Mr Elias [to Armstrong] on [the] personal loan [advanced in December 2011 (see at [8] above)].

[Issue 3]

[Did] PMLI [become] insolvent on 29 July 2015 by virtue of its entry into the [Wellington Agreement]?

ISSUE 1 – DID MR ELIAS AND ARMSTRONG ENTER INTO THE ARMSTRONG AGREEMENT?

Introduction

17 To establish that Mr Elias entered into the Armstrong Agreement, the Liquidators relied on the following records and documents:

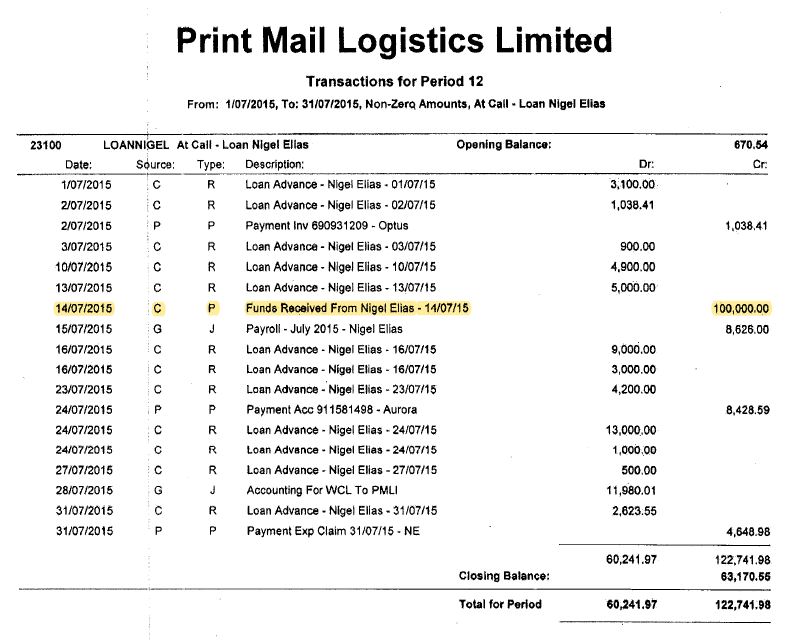

(a) first, the PML ledger for the period 1 July 2015 to 31 July 2015 which records a credit of $100,000 on 14 July 2015, together with the notation “funds received from Nigel Elias”;

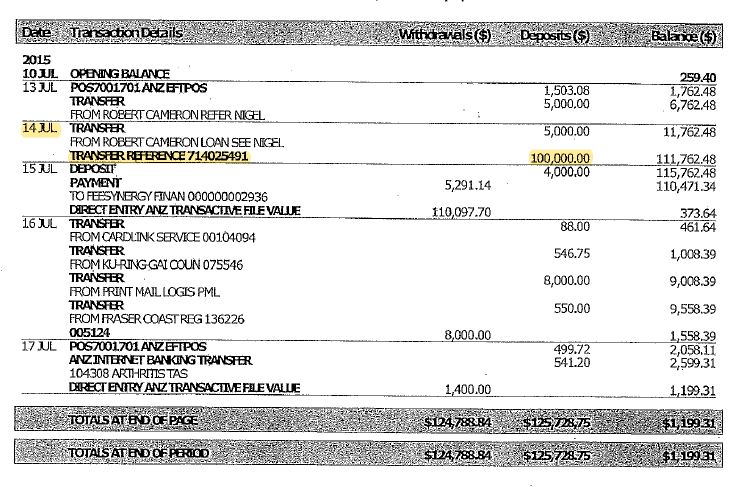

(b) secondly, the Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (ANZ Bank) bank statement relating to PML’s bank account which shows a credit of $100,000 on the same date;

(c) thirdly, a document, of which there are at least three copies, entitled “Unsecured Loan Agreement”, namely the Armstrong Agreement, apparently signed by Mr Elias and witnessed by Ms Greaves.

18 It is convenient to begin with the two records described at [17(a)] and [17(b)] above. They are recorded in the evidence as exhibits D31 and P20, respectively, as follows:

(a) The PML ledger

(Emphasis added)

(b) The ANZ Bank statement

19 In respect of these records, Mr Elias said in his outline of evidence:

…

62. I am … aware that there is a record of me paying $100,000 to PML on or about 14 July 2015. I do not recall where these funds came from. Regardless, this payment is between PML and myself, and Armstrong is evidently not a party to it.

63. I have never transferred any personal obligation of my own to PML or to PMLI.

…

20 In cross-examination at the trial, Mr Elias said, among other things, that he had “no idea” what the ledger entry related to. He claimed he had no responsibility for that entry. He also stated that the funds concerned did not come from him and he had no knowledge as to where they came from. When asked whether he had investigated the source of the funds, he said:

I found that the proposition that I had somehow paid in $100,000 into PML’s account or PMLI’s account or any other account, was unadulterated nonsense. I went to the ANZ bank, and I asked them to produce whatever they could produce in respect of this $100,000 that appeared in PML’s account. And a lady at the ANZ bank in Hobart, produced a piece of paper which – I’m really stretching my memory now, basically said that this money came from Armstrong into PML’s account. And there was reference in that to – the reference was Elias.

21 He added that he was told by the ANZ Bank that the reference to “Elias” was information provided by Armstrong. This evidence was supported by an email dated 13 August 2019 (Exh P7) that Mr Elias received from Ms Jennie Fox, Assistant Manager, Retail, at the Hobart branch of the ANZ Bank. In that email, Ms Fox stated:

22 When pressed about these answers on the footing that PML was “strapped for cash, in July 2015 [and therefore he] would have been aware of [the] receipt of $100,000”, Mr Elias said:

I can’t recall that I would – I assume that I would know about the receipt of $100,000 from whichever source. And I would’ve assumed – I don’t take any exception to the proposition that Armstrong paid PML, Print Mail Logistics Limited, $100,000. I take considerably [sic] exception and know nothing about the insertion of the word, Elias, into that.

23 Mr Pereira, who is a Chartered Accountant and was in 2015 PML’s Chief Financial Officer, gave the following evidence about this transaction. First, in his affidavit filed 13 June 2019, he said that (at [37(b)]:

… I know nothing about a loan of $100,000.00 to [Mr Elias] from Armstrong on 14 July 2015. Further no loan of that amount was recorded in the records of PML as received at that time or, so far as l am aware, thereafter. However, PML did in fact owe Armstrong such a sum as at 30 June 2015, and up to 29 July 2015, as the then capital balance of a running loan which had existed since May 2014, details of which, on the capital side, are as follows:

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

All of these amounts are recorded in the financial records of PML and are evidenced in PML’s bank statements.

…

24 Secondly, by the time Mr Pereira made his written outline of evidence in this proceeding in May 2020, he had attended a public examination conducted by the Liquidators in August 2019. Having, through that process, obtained some further information about the transaction, he gave the following evidence in that outline:

62. On 14 July 2015, PML received $100,000.00 from Armstrong. This amount was recorded in the books and records of PML as a loan from Elias to PML.

63. In my affidavit sworn on 11 June 2019 and filed with the Court on 14 June 2019, I swore at paragraph 37 (b) that I knew nothing about a loan of $100,000.00 to Elias from Armstrong.

64. In the days leading up to my public examination on 19 August 2019, I was made aware of the fact that PML had received the sum of $100,000.00 from Armstrong on or about 14 July 2015 and I was provided a copy of PML’s bank statement evidencing the receipt of $100,000.00 on that day. I disclosed that fact and provided a copy of the relevant bank statement at the public examination of 19 August 2019.

65. Regardless of the fact that PML received $100,000.00 from Armstrong on 14 July 2015, PML did not repay that actual sum to Armstrong on behalf of Elias on 29 July 2015 from the proceeds of the [Wellington Agreement].

66. On 29 July 2015, PML repaid to Armstrong the $100,000.00 that it already owed in cash advances and repayments (i.e. the running loan account) between 14 May 2014 and 21 August 2014 as described at paragraph 37 (b) of my affidavit sworn on 11 June 2019 and filed with the Court on 14 June 2019.

67. The Liquidators claim that on 29 July 2015, PMLI paid a personal liability of $100,000.00 owing by Elias to Armstrong. I consider this allegation to be untrue and not supported by the evidence. Firstly, PMLI did not make any payment to Armstrong on behalf of Elias. Secondly, while PML did make a payment to Armstrong that included the sum of $100,000, it was in repayment of the running loan account between it (PML) and Armstrong and was unrelated to any liability of Elias to Armstrong.

68. The Liquidators allege that Elias entered into a loan agreement with Armstrong on or about 14 July 2015 in the sum of $100,000.00. I am aware that Elias strongly disputes that allegation.

69. The running loan account between PML and Armstrong comprised the following:

|

| ||

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

All of these amounts are recorded in the financial records of PML and are evidenced in PML’s bank statements …

25 Mr Pereira gave similar evidence during his cross-examination at the trial of this matter. In particular, he said about the “genesis of that transaction” that:

Yes. So what I then knew was that by receiving a copy of PMLs ANZ bank account statement for that time, that $100,000 did turn up, and then – and inquiry had been made by [Mr Elias] to understand through the ANZ what that $100,000 was, and then that the remittance detail provided to the ANZ show the remitter as being Armstrong registry, and a reference to [Mr Elias] as well.

(Errors in original)

26 The Armstrong Agreement mentioned at [17(c)] above is the third record or document relied upon by the Liquidators in respect of this issue. As already mentioned, there are at least three copies of that agreement in evidence. They are all annexed to the affidavit of Ms Greaves, the person who allegedly witnessed Mr Elias’ signature on the agreement. While the details of the differences between the three copies of the agreement are set out in Ms Greaves’ evidence below (see at [39]), the broad differences are as follows.

27 The first page of the first copy of the Agreement bears the notations “Not dated Not signed by Armstrong” and “safe custody Armstrong. Box 1/2015 Packet #3”. It also contains a bar code on the top right hand corner below which appears the letters and number “GEM.0083.0002.0001”. On the subsequent pages, the last number of the bar code increases sequentially 2, 3, etc up to 6.

28 Each page of that copy of the agreement bears an initial in the bottom right hand corner as follows:

29 On the bottom left hand corner of the Table of Contents page of that copy (the second page), there appears the symbol and number “#13442”. Consistent with the notation on the first page, there is a blank beside the words “Agreement” and “Dated” on the third page of that copy.

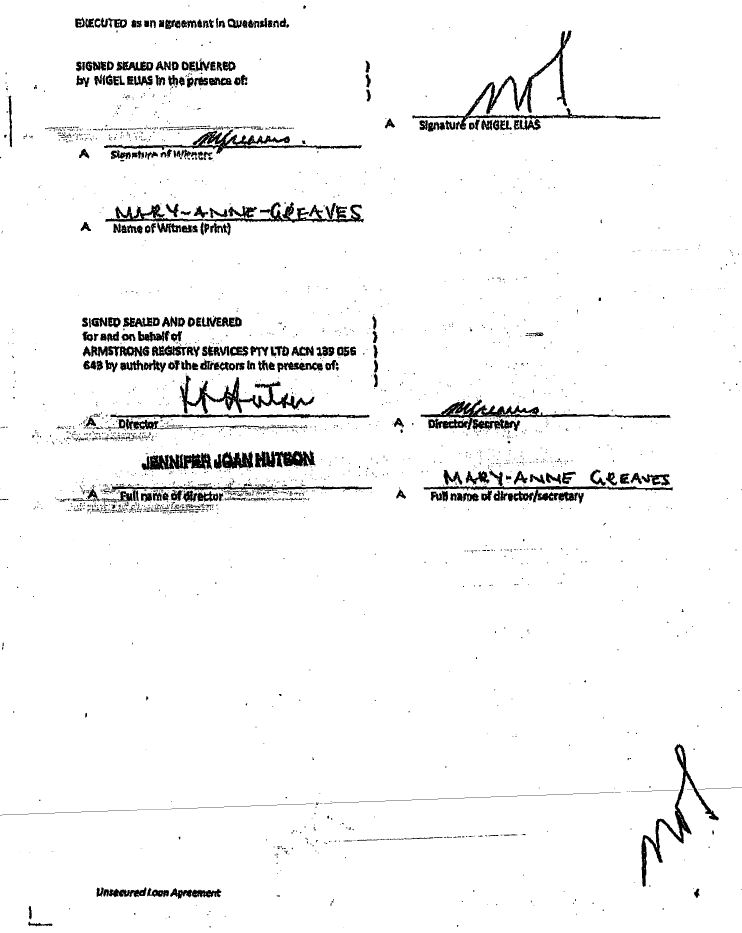

30 Finally, the execution page of that copy of the agreement is in the following form:

31 Except that the second copy of the Armstrong Agreement bears no notations on the first page and the bar code on the top right hand corner is: “GEM.0083.0002.0007”; and, on the subsequent pages, the last number increases sequentially (8, 9, etc up to 12), that copy is in essentially the same form as the first copy of the Agreement described above.

32 The third copy of the Agreement is, however, quite different in several respects. First, it bears no notations or bar codes at all. Secondly, beside the words “Agreement” and “Dated” on the third page of that copy, there appears the handwritten date “14 July 2015”. As already noted, this part of the other two copies is blank. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, the execution page of that copy is in the following form:

33 With respect to the Armstrong Agreement, Mr Elias said in his outline of evidence that:

I am aware that the plaintiffs allege that Armstrong lent me $100,000 in a separate unsecured loan. I have seen the loan document upon which they make that allegation. I have no recollection of that document. The signature on the document appears to be mine, but I do not recollect signing it.

34 In his oral evidence he reiterated his agreement that the signature on the execution page of each copy of that agreement looked “very similar to my signature”. Despite this acknowledgement, he gave the following reasons why he did not believe he actually signed that agreement:

… First of all, I have absolutely no recollection of signing this document. Secondly, it’s axiomatic that I therefore have no recollection of Mary-Anne Greaves’ signature witnessing a signature that I can’t recall. Thirdly, I would have total recall, absolutely 100 per cent recall in the event that I executed a document for which I was personal [sic] liable for $100,000. Fourthly, there is no direction to pay at all that has been tendered by nobody to my knowledge, because it doesn’t exist, in respect of $100,000 and fifthly, there is no $100,000 that appears in any bank account of mine.

(Errors in original)

Further, when he was asked later in his cross-examination whether it was possible he had signed it, he said: “[i]t is not possible”.

35 During his cross-examination, Mr Elias was taken to the execution page of the third copy of the agreement (see at [32] above) and it was put to him that “this document was executed on about 14 July 2015”. He replied “It may have been executed by them – by whoever, but I have no recollection, I repeat, of executing any document of this nature, whichever version you’re referring to … on or around 14 July. Or any other date for that matter” . He added that “[t]he only thing I can add to that is that the handwriting for the date is – I would, from my dealings with her, would know it was Jennifer Hutson’s handwriting for the date. That’s all” . Given that the other two copies of the agreement are not dated, I infer that this evidence refers to the handwritten date on the third copy as mentioned above at [32].

36 Mr Elias agreed in cross-examination that he attended a meeting with Ms Greaves in Sydney on or about 13 July 2015. However, he denied signing the Armstrong Agreement on that date. With respect to that meeting, he said “There was no documentation executed other than the documentation that was presented to me by the young lawyer, whose name I have forgotten, who was sitting in and – in the board – one of the boardrooms of McCullough Robertson in Sydney”. He then denied that documentation related to the affairs of PML.

37 As already mentioned, Ms Greaves was the person who, on the face of each copy of the Armstrong Agreement, witnessed Mr Elias’ signature. She was called as a witness by the defendants. Ms Greaves holds a Master of Laws degree and was admitted as a solicitor in Queensland in 2004. By the time she gave her evidence at the trial, she had held a practising certificate for 16 years. She joined Wellington in 2005 and left it in 2016. Initially her role with Wellington was as a Compliance Officer. Thereafter she variously served as Assistant Company Secretary, as Company Secretary, as a Company Director and as the company’s General Counsel. She also served as the Company Secretary of Armstrong. She said in her evidence that throughout the period of her employment with Wellington she acted on the instructions of Ms Jennifer Hutson who, as already mentioned (see at [6]), was the principal of the Hutson entities.

38 Ms Greaves’ evidence-in-chief was confined to adopting her outline of evidence and advancing a further reason why she doubted the authenticity of at least the third copy of the Armstrong Agreement. She did that by answering the following question in the negative: “[D]o you ever write your name with a hyphen between the word ‘Anne’ and the word ‘Greaves’?”. This evidence refers to her name as it is written below her signature where it first appears on the third copy of the agreement (see at [32] above).

39 In her written outline of evidence, Ms Greaves gave the following evidence with respect to the three copies of the Armstrong Agreement:

(a) First copy [see at [27] above]

7. This document has the words “safe custody Armstrong. Box 1/2015 Packet#” written on the first page.

8. I understand that the [Liquidators have] referred to this document as a counterpart.

9. This document purports to bear my signature as witness to Nigel Elias’ signature.

10. I dispute that this is my signature for the following reasons:

a. in my career as a solicitor I would always use my stamp to verify my name. If I did not have my stamp with me at the time, I would write my full name in my own handwriting. On this document I note there is simply a signature and nothing else. I consider that that is highly unusual.

b. I believe that quite possibly this an electronic signature;

c. I have no recollection of witnessing an undated Loan Agreement between [Armstrong]and Mr Elias.

11. Further I note the Table of Contents page bears document number #13442.

12. I recall that [Armstrong]would always have the document numbering on all pages of the documents except for the cover page. which would follow through on every page of a document created by [Armstrong]. It strikes me as highly unusual that the document numbering only appears on the Table of Contents page. This causes me to question the authenticity of this document.

(Errors in original)

(b) Second copy [see at [31] above]

13. When reviewing this document it is apparent that the signature (purporting to belong to Mr Elias) on the bottom right hand corner of the page with the word “Agreement” at the top left hand corner is different to the signature in the same position on “MG1”. It is apparent that there is a loop at the commencement of the signature on “MG1” that is not found at the commencement of the signature on “MG2”.

14. When reviewing this document it is apparent that the signature (purporting to belong to Mr Elias) at the bottom right hand corner of page “2” is different to the signature in the same position on “MG1”. Again there appears to be a loop at the commencement of the signature on “MG2” that is not found on “MG1”. Further it is apparent that there are other clearly noticeable differences which indicate that it is not the same signature.

15. When reviewing this document it is apparent that the signature (purporting to belong to Mr Elias) at the bottom right hand corner of page “3” is different to the signature in the same position on “MG1”. There are clearly noticeable differences which indicate that they are not the same signature.

16. When reviewing this document it is apparent that my signature on the last page as “witness” is different between the two documents. I note that “MG2” contains what appears to be a full stop and the other document does not.

17. My signature on “MG1” is further away from the words ‘Signature of Witness’ below the line than in “MG2”.

(c) Third copy [see at [32] above]

18. When reviewing this document I note that in the signing clauses my signature when allegedly witnessing Mr Elias’ signature is different to that of my signature when allegedly signing in my capacity as Director/Secretary of [Armstrong].

19. I note that in my signature witnessing Mr Elias the G for “Greaves” appears to show under the line and the other signature on this document does not go below the line. This seems very unusual to me.

20. Further I note that my name is hand written on both signing clauses.

21. As I stated earlier in this witness statement and also at the public examination held on 19 August 2019 that in my experience as a solicitor I always applied my stamp as opposed to writing my name.

22. Further, I am very familiar with Jennifer Hutson’s hand writing and the hand written words stating “MARY-ANNE-GREAVES” and ‘MARY-ANNE GREAVES” appear to be Ms Hutson’s hand writing.

23. I have no recollection of witnessing this document.

24. I recall that my recollection or otherwise of allegedly witnessing Mr Elias’ signature on 14 July 2015 was raised at the public examination and I denied witnessing Mr Elias’ signature in that regard.

25. I recall that I left the employment of [Armstrong]and Jennifer Hutson in general on or about the 7 July 2016. I commenced work as Company Secretary at Michael Hill on 11 July 2016.

26. I recall that at some date in or about July 2016 Jennifer Hutson requested and arranged to meet me at the coffee shop near my office and asked me to sign a number of documents. I do not recall what documents they were now and she effectively placed them before me and demanded that I sign. Regrettably I did affix my signature to a number of documents without first enquiring as to their purpose. I believe that there is a possibility that if my original signature is shown to be on any of the documents as “MG1”, “MG2” or “MG3” then quite possibly they were procured this way.

40 In cross-examination, Ms Greaves said that she first met Mr Elias in 2009. At about that time, she said Mr Elias would, from time to time, borrow money from Wellington or Armstrong on behalf of PML. She said that, so far as she was aware, Ms Hutson and Mr Elias had a “good working relationship, at least up until about 2015”. While she did not specifically recall this happening, she accepted that, on occasions, she would “formalise loan documents, after advances had been made”. When taken to the copies of the Wellington Agreement annexed to her outline of evidence, she agreed that she had signed that agreement on behalf of Wellington. However, she said she did not recall doing that. Nonetheless, she said that she recalled drawing the agreement at the request of Ms Hutson. She also said that, because the transaction concerned was quite involved, she remembered discussing it with Ms Hutson.

41 Ms Greaves said that she could not remember a loan of $100,000 being made by Armstrong to Mr Elias some 14 days before the Wellington Agreement. She said she did, however, recall one instance where Mr Elias borrowed money for the purposes of making a payroll tax payment, but she did not “believe it was for that amount, that high, no”. She said that, if such an advance were made, Mr Ted Savage, the company’s Finance Controller, would have been involved in processing it. She also said that, if a person had borrowed monies from Armstrong or Wellington and directed that those monies be paid to a third party, she personally would not have been willing to accept such a direction because “under anti-money laundering, you shouldn’t pay it to a third party”.

42 Ms Greaves was cross-examined at some length with respect to her claims about the discrepancies in the three copies of the Armstrong Agreement set out above (see at [39]). To begin with, she agreed that she had no expertise as a handwriting expert. Next, she confirmed that she had no recollection of signing any of the three copies of that agreement. Then she was asked about her statement at [26] in her outline of evidence set out above at [39].

43 With respect to this statement, she reiterated that she could remember signing documents at the meeting in July 2016, but she did not know what those documents were. She agreed it was possible that those documents were the various copies of the Armstrong Agreement. Ms Greaves said she “usually … tried to” be quite careful about witnessing documents of this kind. She was then asked a series of questions on that subject as follows:

And you would have understood, as a solicitor practicing in compliance, the importance of properly witnessing documents?---Yes.

And you would have understood that it would have been a breach of your ethical obligations if you were to witness a document not in the presence of the deponent or the person executing it. That’s correct?---Yes.

And can I suggest to you that that’s something that you would not have been likely to do?---You can suggest it, but at the time when Jenny came to meet me in 2016, I was very vulnerable and in a very bad way. So it was possible I did do something like that.

Can I suggest to you that it’s not likely? Can I suggest to you - - -?---Yes, yes.

Can I suggest to you that the more likely scenario is that you actually did the right thing, as a prudent lawyer, and when a document was witnessed it was witnessed in the presence of the witness. Here, Mr Elias?---Yes, you can suggest that.

Do you agree with that?---Yes, you can suggest that. Yes.

I know I can suggest it, but what I’m asking is do you agree with me that that is the more likely scenario? That you witnessed the document?---Yes, yes.

So when I go to the first document, can I suggest to you that the most likely scenario is that you did, in fact, witness Mr Elias’ signature?---Yes.

Okay. And in terms of witnessing Mr Elias’ signature, what I’m putting to you is that the most likely scenario is that you did witness Mr Elias’ signature?---Yes.

And that you wouldn’t have written your name in the witness section later on at a later date, because you would have understood that was a breach of your obligations?---Yes, I just don’t understand why I would have witnessed his signature and not written my name.

Okay. But putting that aside, you wouldn’t have witnessed a signature after the event. You would have only done that in the presence of the person?---Yes, in 99.9 per cent of cases, yes.

45 When asked about her signature above the words “Director/Secretary” on the execution page of the third copy of the agreement (see at [32] above), she said:

… So can I suggest to you that the most likely scenario is that you did execute that document?---I don’t recall executing that document, and I always write – stamp my name. If I don’t have my stamp, I write it, and I didn’t write my name or use my stamp.

Yes, I think in your evidence, you thought it might have been Ms Hutson that filled in your name?---Correct.

Yes. But can I ask you about the execution. What I’m putting to you is that the most likely scenario is that you did, in fact, execute that document yourself?---I can’t agree with that.

You can’t agree, or you don’t remember?---I don’t remember.

46 With respect to the notations and bar codes appearing on the top right hand corner of the first copy of the agreement (see at [27] above), she gave the following evidence:

Does that mean anything to you? Could you explain that to me please?---I wrote Safe Custody Armstrong, so it normally goes into – goes to somebody else who looks after our Safe Custody.

Okay, so is that when you get the document back signed, and it goes away into archives to be stored and looked after the original? Is that right?---Yes, for – yes, for safe-keeping – yes.

Okay, so does box 1/2015 – does that mean that it would have gone into Safe Custody in – when – 2015?---I would have thought so.

Okay, so doesn’t that weigh against the suggestion that it might have been in about July 2016 that you attested the document?---Sorry, can you just repeat that?

Doesn’t that weigh against the likelihood that it was in 2016 that you completed the execution of the document?---Well, no – it wasn’t signed by Armstrong at that point.

Well, I’m suggesting that before you put it in Safe Custody, wouldn’t you have ensured that it was executed by all parties?---Not necessarily. The person who does Safe Custody should have arranged that.

But that’s your writing there – Safe Custody Armstrong – that’s correct?---Yes. The rest of it’s not my writing.

But you wouldn’t write that on the document until the document was complete – would you – in the usual course?---In the usual course – yes.

47 Ms Greaves said she could recall having lunch with Mr Elias in Sydney in June/July 2015. She said the purpose of that lunch was “[j]ust to catch up on what [PML] was doing … what they were doing”. She said she did not recall taking any documents to that meeting. She also said that she had other meetings with Mr Elias in Sydney at the offices of McCullough Robertson Lawyers. However, she said she did not recall witnessing any documents at any of those meetings.

48 Finally, Ms Greaves confirmed that she gave evidence in the Magistrates Court at Brisbane when a copy of the Armstrong Agreement was shown to her. However, she said she did not know whether, or not, the copy that she was shown was the original of that agreement.

49 Before concluding this review of the evidence in respect of this first issue, it is important to record the following matters. First, as already noted, despite the fact that she was a former officer of two of the Hutson entities, Ms Greaves was called by the defendants at the trial of this proceeding. Secondly, in his oral evidence, Mr Pleash, one of the Liquidators, revealed that the liquidation, and therefore this proceeding, was being funded by a secured creditor of PMLI, called Southland Stokers. As already noted, Southland Stokers is Wellington’s current name (see [6(a)] above. Thirdly, despite this connection with the plaintiffs, Ms Hutson did not give evidence at the trial. In this respect, Mr Elias gave evidence that, so far as he was aware, Ms Hutson was alive and living somewhere in Brisbane. Fourthly, the plaintiffs did not call any other former officer or employee of Armstrong to give evidence about its document record system, including the significance of the bar codes that appear on the top of the first and second copies of the Armstrong Agreement.

The contentions

50 While the Liquidators accepted that Mr Pereira “presented as a credible and helpful witness at all times”, they contended that Mr Elias’ explanations for the first two records above (at [17(a)] and [17(b)] was “unlikely”. In support of the latter contention, they claimed that Mr Elias “denied being aware that such a significant sum had being [sic] received at the time and denied that he had arranged the advance. Notwithstanding this, the monies were utilised immediately by PML and at a time when it was in financial difficulty”. Additionally, they contended that Mr Elias’ claim that he had no knowledge of the $100,000 transfer was “not credible in circumstances where the whole of the $100,000 was used on 15 July 2015 to meet the majority of the $110,097.70 payroll payment the day after its receipt”. They also contended that Mr Elias was evasive when cross-examined about these issues and that his claim to have no recollection of signing the Armstrong Agreement “was convenient to him”. Further, they contended he was “guarded when it suited him and less than candid” and that “his evidence should be weighed accordingly”.

51 Relying on the New South Wales Court of Appeal judgment in Manly Council v Byrne [2004] NSWCA 123 (Manly Council), the Liquidators contended that the rule in Jones v Dunkel did not apply to allow an inference to be drawn with respect to Ms Hutson’s absence as a witness at the trial because her evidence was “relevant to” the case advanced by the defendants and that she was equally available to be called by both parties. However, they contended that an inference should be drawn against the defendants arising from their failure to adduce evidence from the other directors of PMLI, Mr Woods and Mr Garcia.

52 In summary, the Liquidators contended that this Court should find that Mr Elias and Armstrong entered into the Armstrong Agreement on or about 14 July 2015 based upon inferences being drawn from some, or all, of the following matters:

(a) the denial of Mr Elias in relation to all 4 intonations of the Unsecured Loan Agreement includes the copy of the original certified as such by Senior Registrar Mahoney of the Magistrates Court, which the Court should accept was an original signed by Mr Elias and Ms Greaves in circumstances where Mr Elias and Ms Greaves accept that the signature looks like their respective signature, it is submitted that it is right for the Court to conclude that it is on the basis that a certified original has been provided;

(b) Mr Elias and Ms Greaves were together in Sydney on 13 July 2015, and it is probable, despite their lack of recollection that this is when Mr Elias signed in the presence of Ms Greaves as witness;

(c) $100,000 was deposited in PMLI’s account by Armstrong on 14 July 2015 with a notation that it related to Mr Elias;

(d) the accounts of PML prepared by the finance team supervised by CFO Mr Pereira record and account for this $100,000 as “Funds received from Nigel Elias”;

(e) the $100,000 has never been disputed or queried by Mr Elias or returned to Armstrong and the accounting records of PML which is a public company have not been adjusted nor has the money been returned following enquiries made by both Mr Elias and Mr Pereira about this $100,000 that confirmed the remitter was Armstrong;

(f) the evidence of Mr Elias at paragraph 62 of his statement where he says “this payment is between PML and myself and Armstrong is evidently not a part of it” is false on his own evidence.

Finally, the Liquidators sought to emphasise Ms Greaves’ evidence in cross-examination (set out at [43]-[45] above) that the most likely scenario was that she did actually witness Mr Elias signing the Armstrong Agreement.

53 In response, first, with respect to the first two records above (at [17(a)] and [17(b)]), the defendants contended that there was no evidence that Mr Elias had ever personally received $100,000 from Armstrong and they pointed to Mr Elias’ denial that he had any association with the transaction to which those two records related. Further, they contended that there was no evidence that Mr Elias knew about that transaction until August 2019 when he received the information set out earlier from Ms Fox at the ANZ Bank in Hobart (see at [21] above).

54 They also contended that, as a Director of Armstrong, Ms Hutson was in a position to give evidence about that transaction and since she had not done so, a Jones v Dunkel inference should be drawn that her evidence would not have assisted the plaintiffs. In this respect, they contended that “Ms Hutson is well-known to the plaintiffs as she is funding the liquidation of PMLI”. With respect to the plaintiffs’ assertion that the $100,000 deposit was immediately used by PML to pay its payroll tax, the defendants pointed to the fact that both Mr Elias and Mr Pereira had denied this. Furthermore, they contended that there was no evidence from anyone “with contemporary knowledge of PML’s financial position in July 2015” that it was in financial distress at that time.

55 With respect to the Armstrong Agreement, they contended that, because of the following factors, “the only safe conclusion … to draw” was that Mr Elias did not sign it:

(a) Mr Elias’ evidence that he did not sign the document;

(b) Ms Greaves’ evidence that she does not recall signing the document;

(c) the peculiar features of the similarities between [the second copy] (only partly signed) and [the third copy] (dated and fully signed), which might suggest that [the second copy] was later changed by Ms Hutson in order to create [the third copy];

(d) the physical evidence that Ms Greaves’ name is mis-spelled;

(e) the failure to make the original of [the third copy] available for inspection; and

(f) the Jones v Dunkel inference to be drawn from the plaintiff’s failure to lead evidence from Ms Hutson,

The relevant principles

56 Both parties have relied extensively on inferences to prove their case. For instance, the Liquidators have sought to draw inferences from the contents of the accounting and banking records at [17(a)] and [17(b)] above and the presence of the signatures of both Mr Elias, as the borrower, and Ms Greaves, as the witness, on all three copies of the Armstrong Agreement. For their part, the defendants have sought to rely on the rule in Jones v Dunkel to draw inferences from the failure of Ms Hutson to give evidence at the trial of this matter. It is therefore appropriate to begin by reviewing the relevant principles bearing on the drawing of inferences.

57 The process of drawing an inference was described by Brennan and McHugh JJ in G v H (1994) 181 CLR 387 at 390 in the following terms:

An inference is a tentative or final assent to the existence of a fact which the drawer of the inference bases on the existence of some other fact or facts. The drawing of an inference is an exercise of the ordinary powers of human reason in the light of human experience; it is not affected directly by any rule of law.

58 The manner in which a party may rely upon an inference to prove an aspect of their case was outlined by Gageler J (dissenting on the outcome) in Henderson v State of Queensland (2014) 255 CLR 1; [2014] HCA 52 (Henderson) as follows (at [89]):

Generally speaking, and subject always to statutory modification, a party who bears the legal burden of proving the happening of an event or the existence of a state of affairs on the balance of probabilities can discharge that burden by adducing evidence of some fact the existence of which, in the absence of further evidence, is sufficient to justify the drawing of an inference that it is more likely than not that the event occurred or that the state of affairs exists. The threshold requirement for the party bearing the burden of proof to adduce evidence at least to establish some fact which provides the basis for such a further inference was explained by Kitto J in Jones v Dunkel:

“One does not pass from the realm of conjecture into the realm of inference until some fact is found which positively suggests, that is to say provides a reason, special to the particular case under consideration, for thinking it likely that in that actual case a specific event happened or a specific state of affairs existed.”

(Footnote omitted)

The process of inferential reasoning involved in drawing inferences from facts proved by evidence adduced in a civil proceeding cannot be reduced to a formula. The process when undertaken judicially is nevertheless informed by principles of long standing which reflect systemic values and experience. One such principle, forming “a fundamental precept of the adversarial system of justice”, is that “all evidence is to be weighed according to the proof which it was in the power of one side to have produced, and in the power of the other to have contradicted”. Another such principle, “reflecting a conventional perception that members of our society do not ordinarily engage in fraudulent or criminal conduct”, is that “a court should not lightly make a finding that, on the balance of probabilities, a party to civil litigation has been guilty of such conduct”. The reluctance of a court to infer fraudulent or criminal conduct is ordinarily somewhat stronger in respect of a person who is not a party to litigation and who is for that reason denied an opportunity to explain and justify his or her conduct as consistent with the conventional perception.

(Footnotes omitted)

It is to be noted that his Honour cited, among other authorities, Blatch v Archer (1774) 98 ER 969 (Blatch) at 970 for the first principle above (at [91] of Henderson) and Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 362 for the second.

60 In Chetcuti v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2019) 270 FCR 335; [2019] FCAFC 112 (Chetcuti), the majority of the Full Court (Murphy and Rangiah JJ) identified the connection between the rule in Jones v Dunkel and Blatch in the following terms (at [89]):

The rule in Jones v Dunkel has been described as an application of the principle in Blatch v Archer (1774) 1 Cowp 63 at 65; 98 ER 969 at 970 that, “All evidence is to be weighed according to the proof which was in the power of one side to have produced, and in the power of the other to have contradicted”. It was entirely within the knowledge of the Minister and his advisors as to when he began his consideration of the material, and it was within his power to produce direct evidence as to that matter.

See also the discussion in Fair Work Ombudsman v Hu (2019) 289 IR 240; [2019] FCAFC 133 at [50]-[52] per Flick and Reeves JJ.

61 In Kuhl v Zurich Financial Services Australia Ltd (2011) 243 CLR 361; [2011] HCA 11, the plurality explained the context of the rule in the following terms (at [63]-[64]):

The rule in Jones v Dunkel is that the unexplained failure by a party to call a witness may in appropriate circumstances support an inference that the uncalled evidence would not have assisted the party’s case. That is particularly so where it is the party which is the uncalled witness. The failure to call a witness may also permit the court to draw, with greater confidence, any inference unfavourable to the party that failed to call the witness, if that uncalled witness appears to be in a position to cast light on whether the inference should be drawn …

The rule in Jones v Dunkel permits an inference, not that evidence not called by a party would have been adverse to the party, but that it would not have assisted the party.

(Citations omitted.)

62 However, in Chetcuti, their Honours did identify two limits to the application of the rule. The first was that “although the rule allows the Court to draw with greater confidence an inference unfavourable to the party that failed to call the witness, it cannot be used to fill evidentiary gaps or convert conjecture into inference” (at [91]). The second was that “the facts proved must give rise to a reasonable and definite inference, not merely to conflicting inferences of equal degree of probability so that the choice between them is a mere matter of conjecture” (at [95]). See also Lithgow City Council v Jackson (2011) 244 CLR 352; [2011] HCA 36 at [94] per Crennan J; Ashby v Slipper (2014) 219 FCR 322; [2014] FCAFC 15 at [71]-[73] per Mansfield and Gilmour JJ and Kumar v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (2020) 274 FCR 646; [2020] FCAFC 16 at [123]-[124] per Derrington and Thawley JJ.

63 A number of other limits were identified in the judgment of Manly Council which was relied upon by the Liquidators. In that judgment, Campbell J (with whom Beazley JA and Pearlman AJA agreed) identified the following limits:

(a) there must first be direct evidence of facts from which the inference is open to be drawn (at [54]);

(b) the inference may not be drawn where the evidence adduced is already sufficient to prove the case for the party who failed to call the witness (at [55]);

(c) the rule does not require a party to call “comparatively unimportant”, or “merely cumulative”, or “inferior” evidence which has been dispensed “on general grounds of expense and inconvenience”, although this does not justify a party deliberately choosing to call less favourable witnesses (at [61], [64] and [65]); and

(d) where the witness is equally available to both parties, however, that may still not be sufficient to avoid an inference being drawn against either or both parties (at [71]).

Consideration

64 With these principles in mind, I turn to consider the inferences upon which the Liquidators sought to rely to prove that Mr Elias and Armstrong entered into the Armstrong Agreement on or about 14 July 2015. Dealing first with the accounting and banking records at [17(a)] and [17(b)] above, two things are clear on the face of those records (see at [18] above). First, that $100,000 was paid into PML’s bank account on 14 July 2015. Secondly, that PML’s ledger entitled “At Call - Loan Nigel Elias” shows a credit entry for 14 July 2015 of $100,000 with the notation “Funds Received From Nigel Elias – 14/07/2015”. Given the identical dates and amounts recorded in these two records, it can be readily inferred that they both relate to the same transaction. However, the critical question on this issue is whether it can be further inferred that that transaction was connected with the Armstrong Agreement whereby Armstrong allegedly loaned $100,000 to Mr Elias.

65 The first difficulty with drawing that inference is that the accounting record, namely the ledger entry at [17(a)] above, records funds being received by PML from Mr Elias. Even assuming the fact that entry appears in Mr Elias’ “At Call - Loan” ledger and therefore may evidence a loan, the receipt of the funds by PML from Mr Elias can only, by itself, (see further below) support the inference that the loan concerned was one made by Mr Elias to PML. Conversely, on that assumption, that ledger entry does not provide a basis for inferring that a loan in that amount was made by Armstrong to Mr Elias. It follows that the payment recorded by that entry is, as Mr Elias said in his outline of evidence, “between PML and myself, and Armstrong is evidently not a party to it”. For these reasons, I reject the Liquidators’ contentions at [52(d)] and [52(f)] above with respect to this ledger entry and the falsity of Mr Elias’ evidence concerning it.

66 The second difficulty with drawing that inference is that the banking record, namely the 14 July transfer shown on the ANZ Bank statement at [17(b)] above, relates to a payment that was made by Armstrong to PML. That fact is established by the contents of the email from the ANZ Bank dated 13 August 2019 (set out at [21] above). That email also records the payment details as “LOAN FROM NELIAS”. Putting aside a direction by Mr Elias to Armstrong to pay those monies to PML, that payment does not therefore evidence a loan payment by Armstrong to Mr Elias. The possibility that the payment was made by direction can also be put aside for a number of reasons. First, no such direction was pleaded by the Liquidators in their 4FASC. Secondly, and in any event, Mr Elias denied any such direction existed (see at [34] above). Thirdly, and most importantly, the Liquidators have not adduced any evidence that any such direction was ever given. For these reasons, assuming the Liquidators’ contention at [52(c)] above was intended to refer to PML, rather than PMLI, I also reject that submission.

67 The third difficulty with drawing that inference concerns Ms Hutson’s absence as a witness at the trial of this proceeding. On this aspect, I reject the Liquidators’ submission that no Jones v Dunkel inference should be drawn as a result of their failure to call Ms Hutson as a witness (see at [51] above). I do so for the following reasons. To begin with, as already noted, through the current manifestation of Wellington, namely Southland Stokers, Ms Hutson is funding the Liquidators in their pursuit of this proceeding. In my view, that state of affairs places her firmly in the same camp as the Liquidators (see Claremont Petroleum NL v Cummings (1992) 110 ALR 239 at 259 per Wilcox J and Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australian Lending Centre Pty Ltd (No 3) (2012) 213 FCR 380; [2012] FCA 43 at [153] per Perram J). Furthermore, as the principal of Armstrong in July 2015, Ms Hutson was very likely to be able to explain why Armstrong transferred $100,000 to PML on 14 July 2015 such that it could be inferred that the records described above were connected with that transaction and, therefore, the loan Armstrong allegedly made to Mr Elias as reflected by the Armstrong Agreement. Put differently and expressed in Blatch terminology, that evidence was peculiarly within Ms Hutson’s power to produce and it was plainly pertinent to the question whether the Armstrong Agreement was made as the Liquidators allege and the defendants deny.

68 Having regard to the principles relating to the rule in Jones v Dunkel outlined earlier, I therefore consider that two things follow from Ms Hutson’s absence as a witness at the trial of this matter. First, I infer that her evidence would not have assisted the Liquidators’ case on the matters mentioned above. Secondly, in the absence of her evidence on those matters, I am not willing to draw the inference advanced by the Liquidators to connect the 14 July 2015 transfer with the Armstrong Agreement loan.

69 These conclusions also affect the inferences that the Liquidators seek to have drawn in respect of the third document upon which they rely, namely the Armstrong Agreement. First, with respect to their contention at [52(a)] above, so far as I can ascertain, the certification of the Senior Registrar of the Magistrates Court was not tendered in evidence at the trial of this matter. Even if it were, without further information as to the circumstances of the hearing before the Magistrates Court, I do not see how it can be inferred that the document produced under subpoena from that Court is the original copy of the Armstrong Agreement. This is supported by the fact that, in her evidence, Ms Greaves was not able to say whether or not the copy of that document shown to her during the Magistrates Court hearing was the original copy of that agreement (see at [48] above).

70 Secondly, and in any event, the crucial version of the Armstrong Agreement, for the purposes of inferring that Armstrong and Mr Elias entered into that agreement, is the third copy. That is so because only that copy purportedly bears the date of the agreement and the duly witnessed signatures of all the parties to the agreement, namely Mr Elias on his own behalf and Ms Hutson and Ms Greaves on behalf of Armstrong. It therefore contains the essential evidence from which an inference may be drawn that an agreement in the terms of that document was reached between those parties on that date. On the other hand, since the first and second copies do not contain all that essential evidence, they do not, in my view, permit of that inference. However, for the following reasons, I do not consider the third copy of that agreement provides evidence of the requisite facts upon which that inference could be drawn. The first concern relates to the handwritten date “14 July 2015” which appears beside the words “Agreement made” on the third page of that copy of the document and none of the other copies (see at [32] above). The evidence of Mr Elias, which I accept, is that that handwriting is Ms Hutson’s. That being so, if she had given evidence at the trial, Ms Hutson should have been able to confirm that she wrote that date on the document on or about 14 July 2015 and she should have been able to describe the circumstances in which she came to do that. In her absence, I infer that her evidence on these matters would not have assisted the Liquidators’ case.

71 The second concern relates to the discrepancies in that copy of the agreement highlighted by Ms Greaves in her evidence (see at [39] above). They include the absence of her personal stamp verifying her signature and the fact that her name is instead written on that copy in Ms Hutson’s handwriting. In this respect, I should add that I reject the proposition inferentially raised during Ms Greaves’ cross-examination that she had to have some expertise as a handwriting expert to identify those deficiencies. Accordingly, if she had given evidence at the trial, Ms Hutson should have been able to explain some, or all, of these discrepancies. That includes the circumstances in which she came to sign that third copy of the agreement. Again, in her absence, I infer that her evidence on these matters would not have assisted the Liquidators’ case. Conversely, in Ms Hutson’s absence as a witness at the trial of this matter, I am not willing to draw an inference in the Liquidators’ favour that the Armstrong Agreement was duly executed and made by all of the relevant parties on or about 14 July 2015 as may be reflected by that copy.

72 The third concern arises from Mr Elias’ denials that he entered into the Armstrong Agreement on or about 14 July 2015, or at all. The first thing to be said about those denials is that they are plainly self-serving and that they need to be weighed accordingly. That said, for the following reasons, I do not consider there is a reliable basis for accepting the Liquidators’ submissions that I should reject those denials because Mr Elias’ evidence is variously false, lacking in credibility or evasive. First, the Liquidators have not produced any contemporaneous record which directly contradicts Mr Elias’ evidence. Secondly, there is the fact that Mr Elias elected to give evidence at the trial of this matter and thereby subjected himself to cross-examination by the Liquidators’ counsel. Thirdly, based on my observations of Mr Elias’ demeanour in the witness box, I consider he withstood that cross-examination reasonably well and that he was generally endeavouring to give his evidence truthfully. Accordingly, I do not accept the Liquidators’ submissions at [50] above that I should reject Mr Elias’ denials concerning the Armstrong Agreement.

73 Finally, having regard to these conclusions and the fact that the Liquidators submitted that Mr Pereira should be accepted as a credible and reliable witness (see at [50] above), which submissions I accept, I therefore also accept the defendants’ contentions on two other matters. First, I consider that both Mr Elias and Mr Pereira should be accepted on their evidence that they did not become aware of the 14 July 2015 transfer into PML’s bank account until at or about the time of the public examination into the affairs of PMLI, when Mr Elias made the inquiry of the ANZ Bank described earlier (at [21] above), that is in August 2019. Secondly, I also consider that Mr Pereira should be accepted on his evidence that PML was not in financial distress in or about July 2015 and that it did not require the sum of $100,000 to meet its payroll tax liabilities. For these reasons, and conversely, I reject the Liquidators’ contentions at [50] and [52(a)] above.

74 That leaves the Liquidators’ contentions at [52(b)] and [52(e)] above. I reject those contentions for the following reasons:

(a) As to [52(b)], first, as already mentioned, Mr Elias denied ever having signed the Armstrong Agreement and he gave reasons to support that denial (see at [36] above). He also particularly denied signing that agreement during his meeting with Ms Greaves in Sydney in July 2015. For her part, Ms Greaves did not recall witnessing any documents at her meetings with Mr Elias in June/July 2015 (see at [47] above). She also said she did not believe she witnessed Mr Elias’ signature on the Armstrong Agreement (see at [39(c)], point 23, above). To counter this evidence, the Liquidators have pointed to the concession that Ms Greaves made in cross-examination that the most likely scenario was that she did actually witness Mr Elias’ signature on that document (see at [43]-[45] above). In this respect, I note that, from my observations of her evidence, Ms Greaves was ambivalent in her acceptance of this proposition (see at [44] above). The Liquidators also relied upon Mr Elias’ acceptance that the signature on all copies of the Armstrong Agreement looked like his (see at [33] above). Nonetheless, weighing these competing pieces of evidence, I am not persuaded to draw the inference advanced by the Liquidators. That is to say, I am not persuaded it is more likely than not that the event concerning the signing of the Armstrong Agreement occurred as described in [52(b)] above.

(b) As to [52(e)], insofar as Mr Elias is concerned, at least until about August 2019, his failure to investigate the 14 July 2015 transfer is explained by the conclusion I have already reached above (at [73]) that both he and Mr Pereira first became aware of that transfer to PML at about that time. In those circumstances, given Mr Elias’ denials that he entered into the Armstrong Agreement, it is unsurprising that he has not personally paid the sum of $100,000 to Armstrong. Further, given Armstrong was the source of the information about that transfer and that information is contentious in this proceeding, it is difficult to see why PML needed to adjust its records to reflect it. On this aspect, it is also worth noting that, despite the loan under the alleged Armstrong Agreement falling due for repayment on or before 14 August 2015, there is no evidence of Armstrong having taken any action to recover it. I therefore reject the Liquidators’ contentions at [52(e)] above.

75 Finally, since Mr Elias and Mr Pereira were the defendants most directly involved in the issues in this proceeding and there is nothing to suggest that either of Mr Garcia or Mr Woods was directly involved in any of the relevant events, I consider their evidence falls into the “merely cumulative” category identified in the Manly Council decision (see at [63(c)] above). This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that the Liquidators did not identify, even in general terms, the evidence that either Mr Garcia or Mr Woods could have given nor the issue to which that evidence may have related. I therefore reject the Liquidators’ contention that any Jones v Dunkel inference should be drawn as a result of their failure to give evidence at the trial of this proceeding.

Conclusion

76 For these reasons, the Liquidators have failed to adduce the evidence necessary to establish facts sufficient to justify the drawing of the inferences necessary to discharge their onus to prove on the balance of probabilities that Mr Elias and Armstrong entered into the Armstrong Agreement on or about 14 July 2015 pursuant to which Armstrong allegedly loaned $100,000 to Mr Elias.

ISSUE 2 – ON 29 JULY 2015, DID PMLI BECOME LIABLE FOR THE SPECIFIED DEBTS OF MR ELIAS OWING, OR ALLEGED TO BE OWING, TO ARMSTRONG?

Introduction

77 This is the first of two issues which concern the effect of the Wellington Agreement. By this issue, the Liquidators contend that, as a consequence of the Wellington Agreement, the existence of which is not in dispute, the defendants caused PMLI to accept liability for two debts owed personally by Mr Elias to Armstrong:

(a) a debt of $100,000 allegedly owing pursuant to the Armstrong Agreement; and

(b) a debt of $11,980.01 acknowledged to be owing as interest on the loan of $50,000 that Armstrong made to Mr Elias in December 2011.

78 For the reasons set out above, the Liquidators have failed to establish that the Armstrong Agreement was entered into and, therefore, that the debt referred to in (a) above existed. Even if that were not so, for the reasons provided later (see at [87] and [93] below), there is a separate cogent explanation for the sum of $100,000 which was included in the transactions associated with the Wellington Agreement. On both of these footings, the Liquidators have failed to prove their case on (a) above. That being so, this issue essentially reduces to the question whether, under the Wellington Agreement, PMLI accepted liability for Mr Elias’ acknowledged interest debt of $11,980.01.

The evidence

79 As already noted, the Wellington Agreement was dated 29 July 2015 and executed by Mr Elias and Mr Pereira for PMLI and Ms Hutson and Ms Greaves for Wellington. Under its terms, Wellington loaned $420,000 to PMLI at an interest rate of 8% per annum to be repaid on the termination date of 31 January 2016.

80 In his outline of evidence, Mr Elias described the background to the Wellington Agreement in the following terms:

38. The background to this transaction was as follows:

a. PMLI had a loan from PML of a little over $427,000, which had been used to fund the purchase of the Property. This loan was unsecured and at call. PML was not pressing PMLI for payment.

b. PML had various loans from Hutson-related entities (Armstrong, Babylon and Wellington), totalling a little under $420,000. These had initially been unsecured, but Hutson had arranged a form of security … being shareholdings in PML’s subsidiary PMLI. She now wished that form of security to be replaced.

39. Hutson proposed that Wellington lend $420,000 to PMLI, which would enable PMLI to pay out its loan from PML in that amount. This in turn would provide $420,000 to PML, which it would use to pay out its loans from Hutson-related entities. There would be a small surplus left in PML, as these loans were less than $420,000.

40. That is what happened. Wellington lent $420,000 to PMLI, secured as set out in the [Wellington Agreement] and guaranteed by PML, and due for repayment on 31 January 2016. PMLI on-paid those funds to PML in almost complete discharge of its loan from PML. PML then used the $420,000 it received from PMLI to make the following payments:

a. $165,242.19 to Armstrong in repayment of various loans;

b. $13,500 to Wellington in repayment of its loan;

c. $225,000 to Babylon in repayment of its loan; and

d. the sum of $16,257.81 thereby remaining was then paid as to $11,980.01 to me in reduction of a loan from me to PML, and the balance of $4,277.80 was retained by PML.

81 In his oral evidence, Mr Elias insisted that the Wellington Agreement was Ms Hutson’s idea and he emphatically denied it was his. He also said that, in early June 2015, Ms Hutson sent him a series of letters in which she sought various payments from him, or PML, as follows:

(a) payment of a $100,000 loan from Armstrong to PML plus interest owing of $7,725.07;

(b) payment of a $40,000 loan from Armstrong to PML;

(c) payment of an amount totalling $236,000 as consideration for a number of holdings of PML’s shares held by Wellington and a Hutson entity called Babylon;

(d) payment of a $50,000 loan from Armstrong to Mr Elias plus interest owing of $11,980.01.

82 On 1 and 11 June 2015, Mr Elias sent two emails to Ms Hutson and Ms Greaves (the former copied to others) in which he confirmed his understanding as to how the transactions associated with the Wellington Agreement were to proceed. The second of those emails (11 June 2015) was in the following form:

Dear Jenny,

This email shall serve to confirm the understandings reached during our recent meeting at the offices of [Wellington].

1. Wellington or its nominee (“Wellington”) will advance $420,000-00 to [PMLI]. This advance will be secured by way of (i) a second ranking charge over the assets and undertaking of PMLI (ii) a second ranking mortgage over real property owned by PMLI and (iii) the guarantee of [PML].

The advance shall be repayable no later than January 31, 2016 and bear interest at 8% per annum provided however that if the advance is repaid in full on or prior to January 31, 2016 then the interest rate shall be 2% per annum.

2. PMLI will issue Wellington a direction to pay to pay [sic] the proceeds of the advance to PML in settlement of part or all of the indebtedness of PMLI to PML.

3. PML will issue PMLI a direction to pay the proceeds of the funds which it will receive to such Wellington related entities as PML may be indebted to (note: this shall specifically include the acquisition by PML of PMLI shares owned by Wellington related entities)

4. Contemporaneously with #1-#3 above PML will provide an undertaking to Wellington or its nominee to ensure that $50,000-00 anticipated to be released in consequence of the changes in the security requirements of the premises of PML will be directed to discharge the residual indebtedness of PML to Wellington.

Kindest regards,

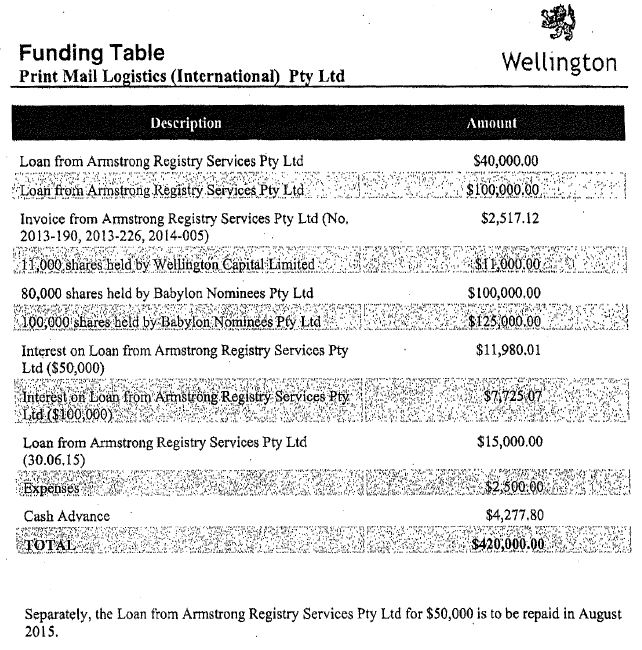

Nigel

83 On 19 June 2015, Ms Greaves sent an email to Mr Elias attaching a Funding Table which detailed the various transactions that were to be undertaken. That table was as follows:

84 Mr Elias said in his oral evidence that the transactions associated with the Wellington Agreement happened as described in this Funding Table. However, he added that there was “one unusual feature” involving, what he described as, “cyber cheques” as follows:

Could you now tell us what actually happened in that transaction?---What happened was exactly what was proposed, with one unusual feature. And I’ve never seen this before, but Hutson was quite insistence [sic] on it. And rather than actual monies moving around, as contemplated, she produced and requested that the PML Group produce cheques, and that we would swap these as cyber cheques. And except for a very small amount, there was no money that was going to change hands.

85 Pursuant to this “swap … [of] cyber cheques”, three sets of cheques were drawn on 28 July 2015, all of which were either for the sum of $420,000, or totalled that amount. They were as follows:

(a) Wellington drew a cheque in favour of PMLI in the sum of $420,000;

(b) PMLI drew a cheque in favour of PML in the sum of $420,000;

(c) PML drew three cheques totalling $420,000 in favour of three Hutson entities as follows:

(i) Wellington – the sum of $13,500;

(ii) Babylon – the sum of $225,000; and

(iii) Armstrong – the sum of $181,500.

86 The last three cheques (described in (c) above) corresponded to the 11 items in the Funding Table in [83] above, two of which related to Babylon, two of which related to Wellington and seven of which related to Armstrong, as follows:

(a) Wellington

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(b) Babylon

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(c) Armstrong

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

87 This issue relates to items [86(c)(ii)] and [86(c)(iv)] above. With respect to item (c)(ii), the separate cogent explanation alluded to above is contained in the evidence of Mr Pereira. He described how the sum of $100,000 came to be owing by PML to Armstrong. He said it was “the then capital balance of a running loan which had existed since May 2014”. He also said that “[a]ll of these amounts are recorded in the financial records of PML and are evidenced in PML’s bank statements” (see his affidavit of 13 June 2019 set out at [23] above and his outline of evidence of May 2020 outlined at [24(66)] and [24(69)] above).

88 As for item (c)(iv) above, in his outline of evidence, Mr Elias described how that item was treated. He said:

In relation to PML’s reduction in its loan balance to me by $11,980.01, I directed PML to pay that amount directly to Armstrong, in reduction of a loan balance between myself and Armstrong. In other words, this was not an assumption by PML of my personal obligation to Armstrong, but rather it was a payment between PML and myself made according to the manner of my direction, and had the effect of reducing PML’s indebtedness to me.

89 Finally, it is appropriate to record two events that occurred after the Wellington Agreement was executed on 29 July 2015. The first was the extension to the termination date in that agreement from 31 January 2016 to 1 July 2017. Mr Elias described the circumstances of that event in his outline of evidence in the following terms:

43. On or about 29 February 2016, Wellington and PMLI agreed by letter to extend the due date for repayment of the Wellington Secured Loan to 1 July 2017 for consideration of $1000.

…

45. At the same time, by letter dated 29 February 2016 Wellington released PML from its obligation under the guarantee, for consideration of $1000.

90 The second event occurred in early 2016. At that time, Mr Elias met Ms Hutson in Brisbane and Ms Hutson told him that she had written off the loans from Wellington to PMLI. That event is recorded in Mr Elias’ outline of evidence in the following terms:

47. On a date I cannot now recall in early 2016, possibly as late as April 2016, I met with Hutson at a coffee shop on Ann Street near her offices in Brisbane. During that meeting, we talked about the loans from Wellington to PMLI and to me, amongst other things. We had a conversation to the following effect:

ME: What about the loans Wellington has extended to PMLI and myself?

HUTSON: Forget about them – I’ve written them off. My concerns now revolve around ASIC.

48. At the time, I was aware from Hutson that she was being investigated by ASIC in relation to dealings she had had with and through a number of companies unrelated to PMLI.

49. Hutson was the managing director of Wellington, and it was clear to me that she had the authority to treat the $420,000 loan from Wellington as being written off. If the loan was written off, or would otherwise not be enforced, then there was no need for PML to guarantee PMLI’s obligations under it.

50. It was my understanding from the above events that:

a. Wellington did not intend to enforce the [Wellington Agreement];

b. Wellington would not seek repayment of the $420,000 it had lent to PMLI; and

c. Wellington did not require PML to guarantee that loan (consistent with its intention not to enforce the loan and its release of PML from the written guarantee).

The contentions

91 The Liquidators’ submissions on this issue focused on the two items in the Funding Table identified above (at [87]). For the reasons already given, I reject their contentions with respect to item (c)(ii). With respect to item (c)(iv), they made the curious contention that that “transaction was in fact a ruse in the sense that the monies were never actually advanced to PMLI and then onforwarded to PML. In fact, nothing was advanced to PMLI excepted [sic] for the sum of $4277.80”. They contended that the result of the series of transactions associated with the Wellington Agreement was that PMLI became indebted to Wellington for the sum of $420,000, which included the $11,980.01 interest that Mr Elias owed to Armstrong. Further, they contended that Mr Elias provided no consideration to PMLI to take on this personal liability of his.

92 In summary, the defendants contended that all of the pertinent payments were, in fact, made by PML and none was made by PMLI. Further, they contended that the $100,000 loan payment related to a debt that was in fact due by PML to Armstrong, as recorded in PML’s accounts. Finally, they contended that the $11,980.01 interest payment was a partial reduction of PML’s indebtedness to Mr Elias on its running loan account with him and it did not involve PMLI accepting responsibility for Mr Elias’ personal debts.

Consideration

93 This second issue can be disposed of relatively briefly. First, to reiterate, I accept Mr Pereira’s evidence (see at [87] above) that the $100,000 loan mentioned in the Funding Table was a loan that PML owed to Armstrong dating from May 2014, as recorded in PML’s books of account. Accordingly, even if the Armstrong Agreement was made between Armstrong and Mr Elias and, as a result, Mr Elias owed $100,000 to Armstrong, that loan is not the loan mentioned in the first item of the Funding Table. It necessarily follows that, as a result of the transactions associated with the Wellington Agreement, PMLI did not accept Mr Elias’ personal liability for that loan, even assuming it existed.

94 Secondly, as for the amount of $11,980.01 of interest owing on the $50,000 loan that Mr Elias acknowledged he owed to Armstrong, for the following reasons I reject the Liquidators’ contentions that, under the Wellington Agreement, PMLI accepted liability for that personal debt of Mr Elias. First, as the defendants have correctly observed, in the course of the transactions associated with the Wellington Agreement, PMLI did not actually pay anything to Armstrong. Instead, it paid all of the $420,000 sum it received from Wellington to PML. Secondly, as between Mr Elias and PML, I accept his evidence and the defendants’ contentions that the sum of $11,980.01 was applied in reduction of the balance of the running loan account between PML and him.

Conclusion

95 For these reasons, the Liquidators have failed to prove, on the balance of probabilities, that, on 29 July 2015, PMLI became liable for the personal debts either allegedly owed (the $100,000 loan), or admitted to be owed (the $11,980.01 interest), by Mr Elias to Armstrong.

ISSUE 3 – DID PMLI BECOME INSOLVENT ON 29 JULY 2015 BY VIRTUE OF ITS ENTRY INTO THE WELLINGTON AGREEMENT?

The insolvency allegation as pleaded

96 This issue concerns the insolvency allegation which is pleaded at [41] of the Liquidators’ 4FASC. There, the Liquidators allege that: