FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Bandjalang People No 3 v Attorney-General of New South Wales [2021] FCA 386

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 30 April 2021 |

BEING SATISFIED that a determination of native title in the terms sought by the parties is within the power of the Court, and it appearing appropriate to do so by consent of the parties and pursuant to ss 87(2) and (5) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth):

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. On 2 December 2013 the Federal Court made the consent determination in Bandjalang People No 1 and No 2 v Attorney-General of New South Wales [2013] FCA 1278.

B. On 24 March 2016, the Applicant made a native title determination application in accordance with ss 13(1) and 61 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) to the Federal Court of Australia (proceedings number NSD 426 of 2016) in relation to a number of parcels of land (the Bandjalang No 3 Application).

C. On 1 February 2019, the Applicant comprising the same individuals as the Applicant for the Bandjalang No 3 Application made a further native title determination application in accordance with ss 13(1) and 61 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) to the Federal Court of Australia (proceedings number NSD 122 of 2019) in relation to three parcels of land (the Bandjalang No 4 Application).

D. On 26 August 2019, the Court made an order, pursuant to s 64(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) that the Bandjalang No 3 Application and Bandjalang No 4 Application be combined and dealt with together by the Court within the Bandjalang No 3 Application. In this determination, the Bandjalang No 3 and Bandjalang No 4 Applications are referred to together as the Application.

E. The parties have reached an agreement as to the terms of a determination to be made by consent in relation to all land and waters subject to the Application (the Determination Area), being a determination that:

(i) native title exists in relation to part of the Determination Area (the Native Title Area); and

(ii) native title has been extinguished in relation to the balance of the Determination Area (the Extinguished Area).

(the Agreement)

F. The Determination Area is within the external boundary of the claim area determined in Bandjalang People No 1 and No 2 v Attorney General of New South Wales [2013] FCA 1278 (proceedings number NSD 6107 of 1998)]

G. The terms of the Agreement involve the making of orders by consent for a determination pursuant to s 87, and in accordance with s 94A, of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

H. In accordance with s 87(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), the parties have filed a Minute of Proposed Consent Determination of Native Title which reflects the terms of the Agreement.

I. The Applicant has nominated Bandjalang Aboriginal Corporation Prescribed Body Corporate RNTBC ICN 7930 to hold the determined native title in trust for the common law holders in accordance with s 56(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

J. Bandjalang Aboriginal Corporation Prescribed Body Corporate RNTBC ICN 7930 has consented in writing to hold the determined rights and interests comprising the native title in trust for the common law holders and to perform the functions of a registered native title body corporate under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be a determination of native title in the terms set out below (the Determination).

2. The native title be held on trust.

3. Bandjalang Aboriginal Corporation Prescribed Body Corporate RNTBC ICN 7930:

(a) be the prescribed body corporate for the purposes of s 57(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth); and

(b) perform the functions set out in s 57(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and the Native Title (Prescribed Body Corporate) Regulations 1999 (Cth).

4. There be no order as to costs.

THE COURT DETERMINES THAT:

Existence of Native Title

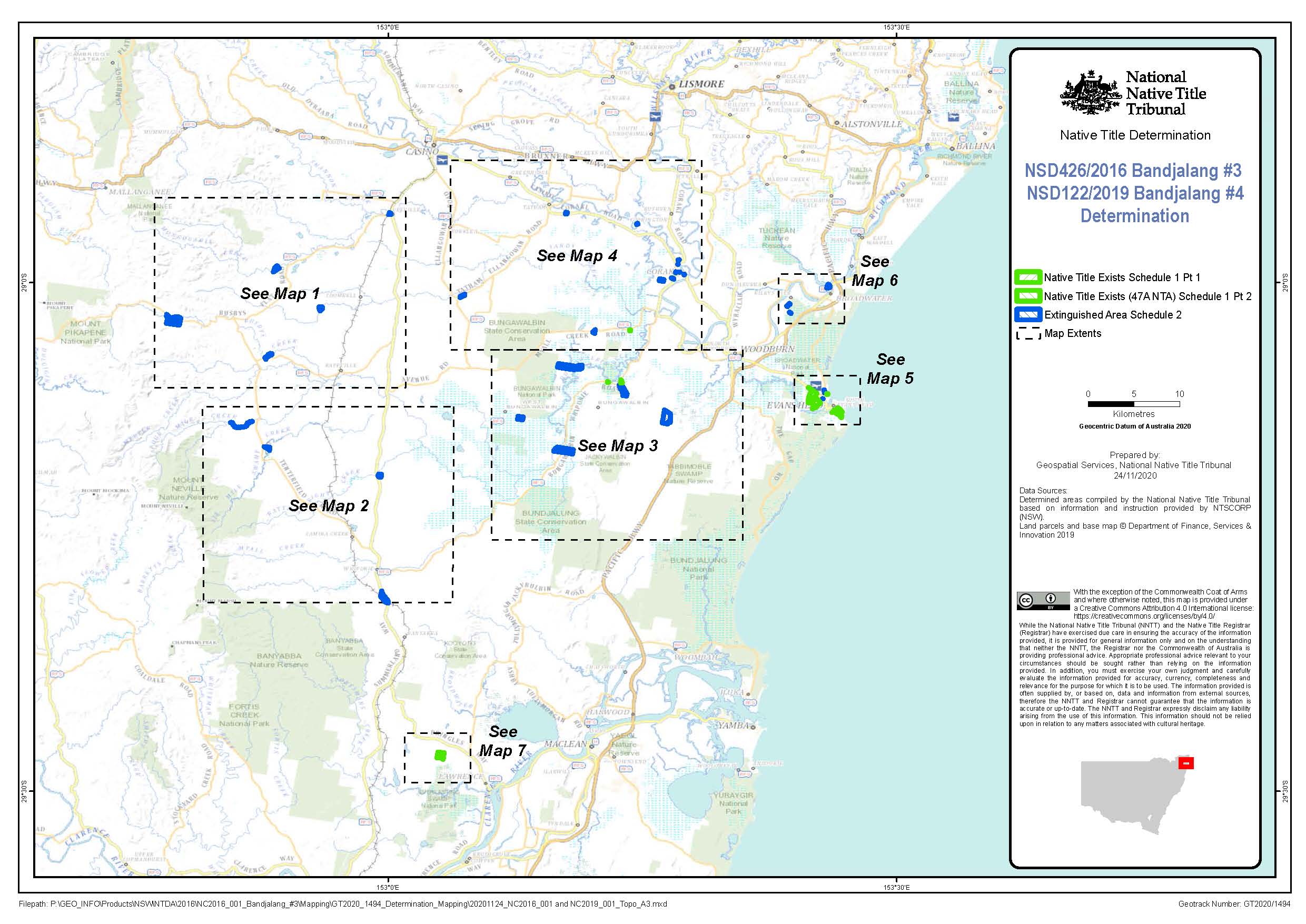

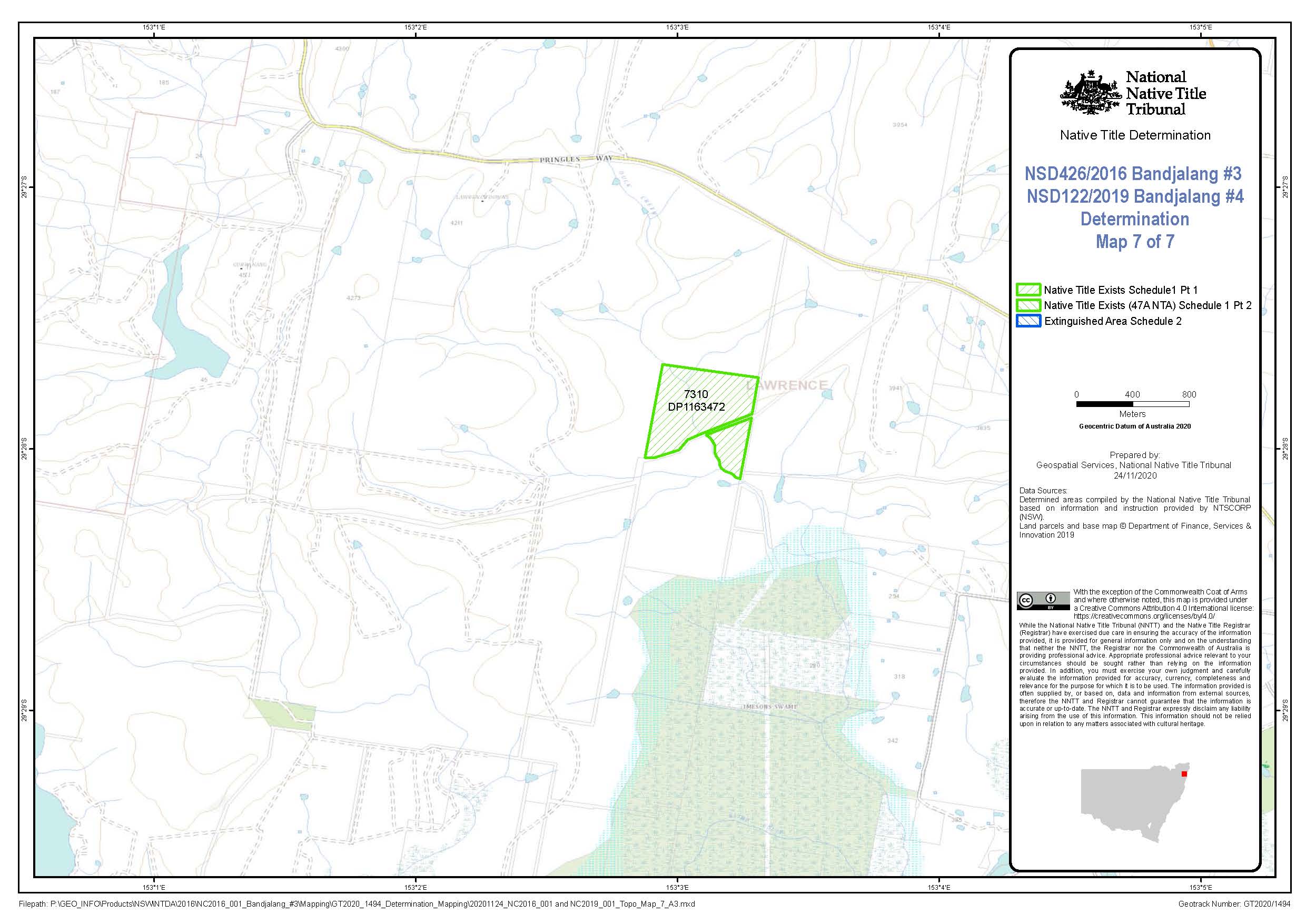

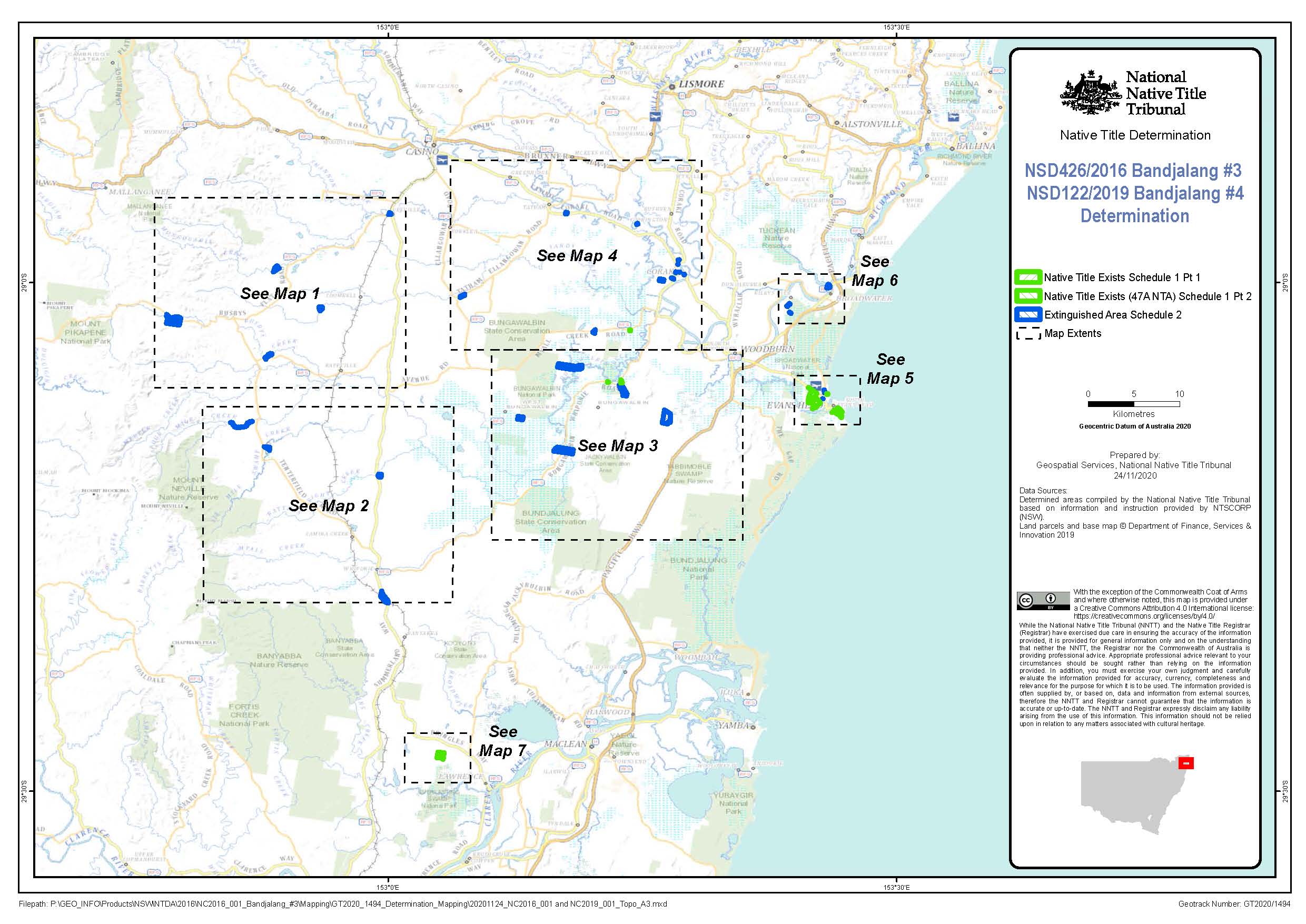

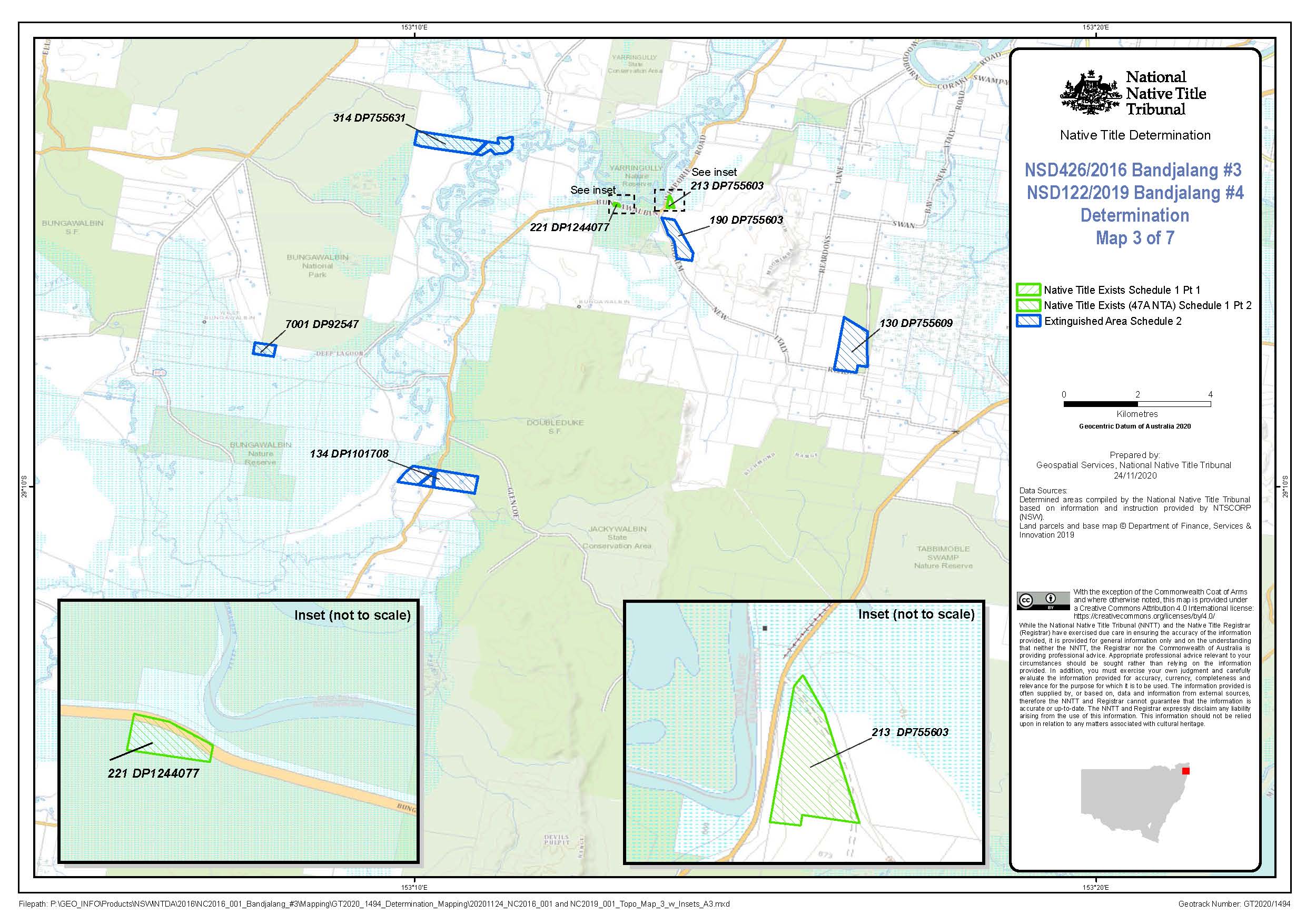

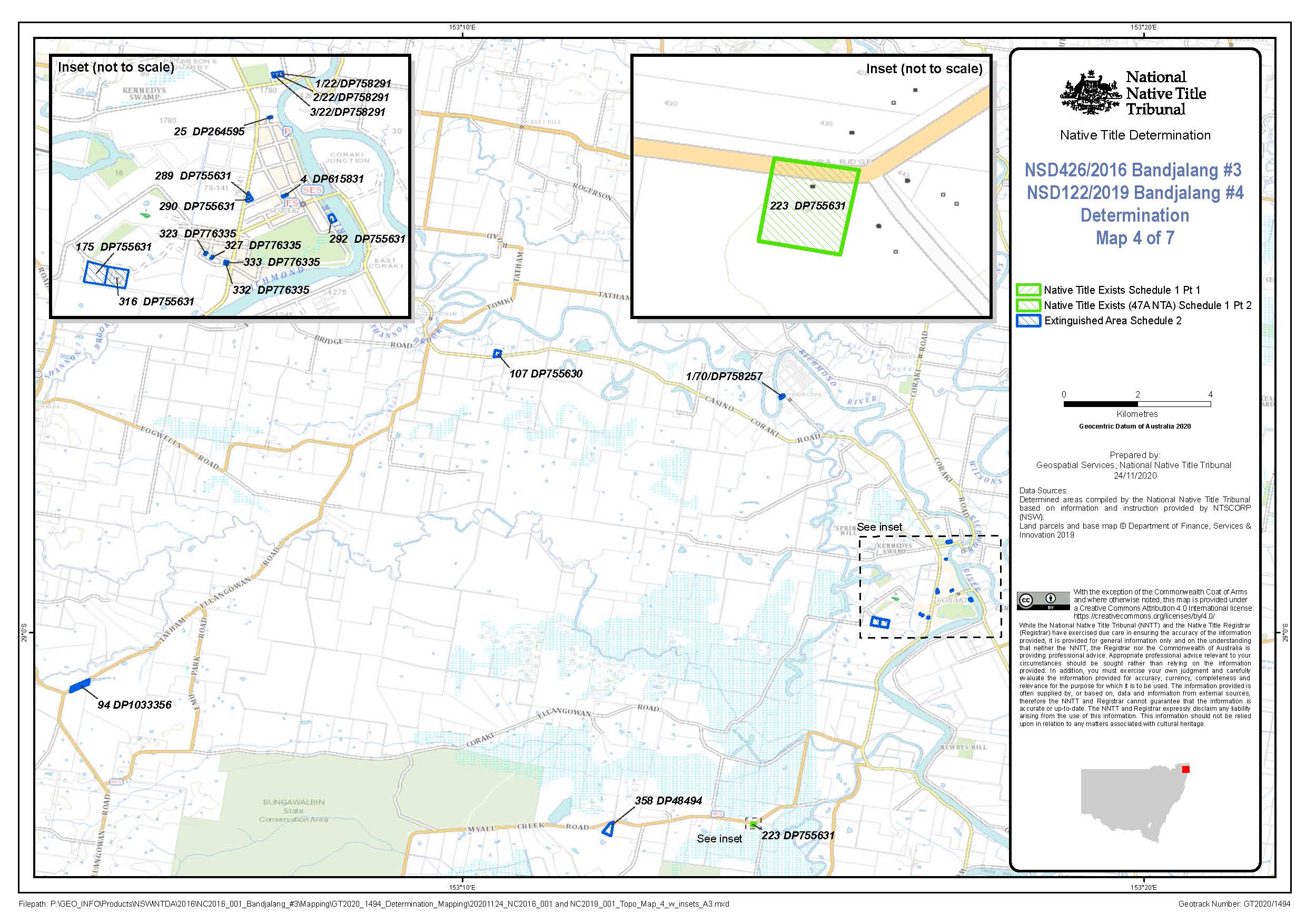

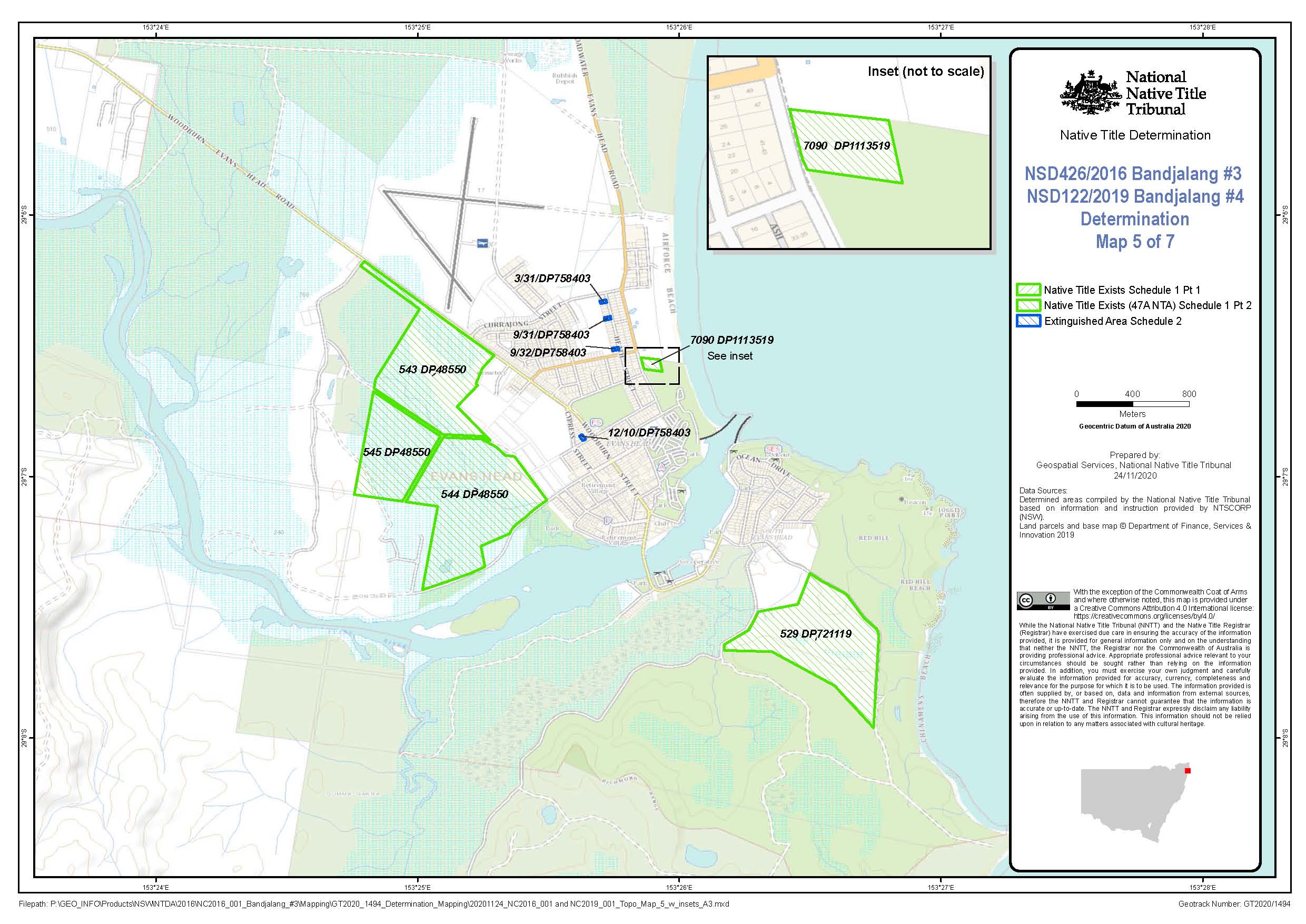

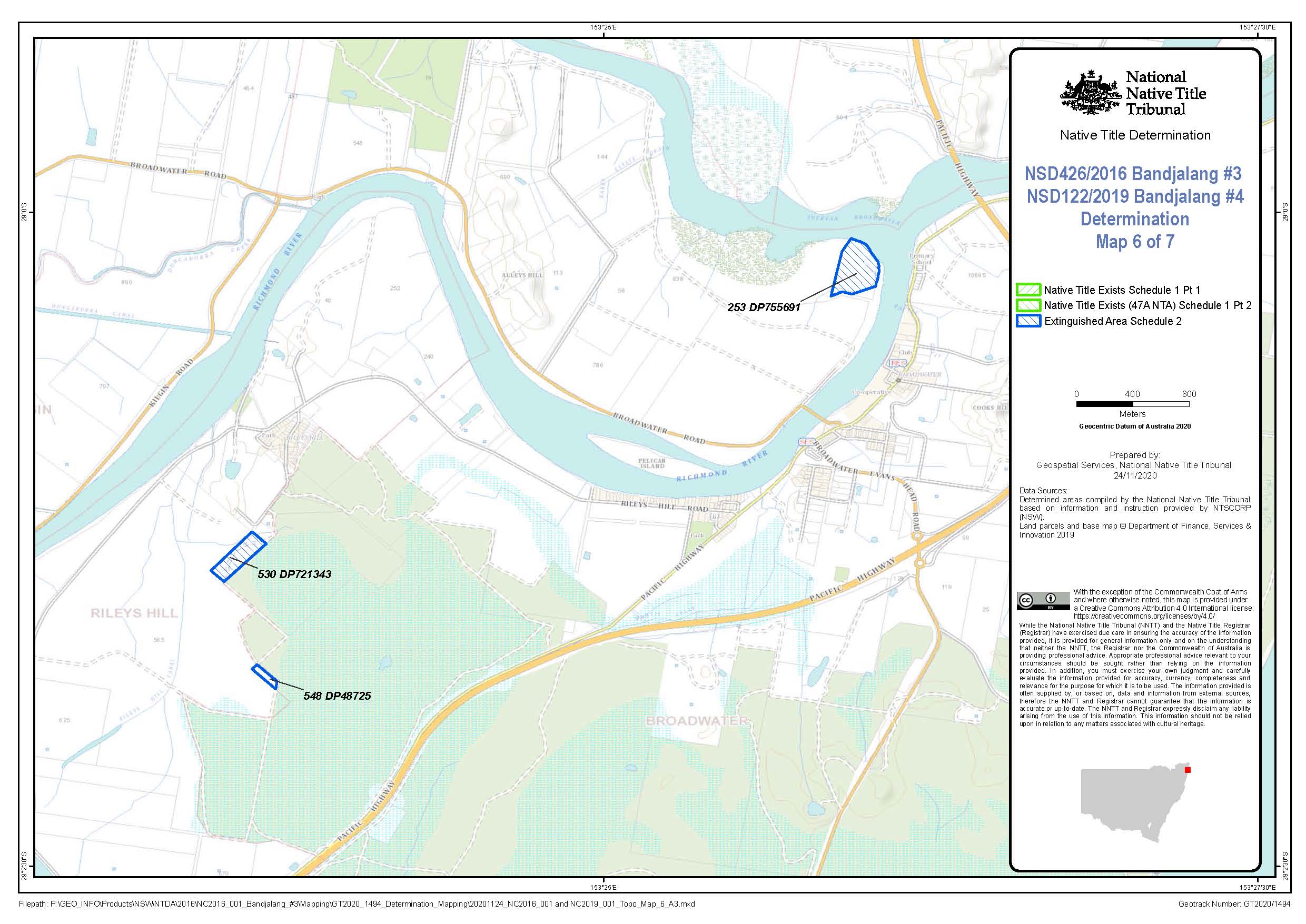

1. Native title exists in relation to the Native Title Area described in Parts 1 and 2 of Part A of Schedule One and depicted on the maps at Part B of Schedule One.

2. Native title is extinguished in relation to the Extinguished Area described in Part A of Schedule Two and depicted on the maps at Part B of Schedule Two.

3. To the extent of any inconsistency between the written description in Part A of Schedules One and Two and the maps at Part B of those Schedules, the written description prevails.

Native title holders

4. Native title in relation to the Native Title Area is held by the Bandjalang People who are Aboriginal persons who are:

(a) the biological descendants of:

(i) King Harry;

(ii) Jack Wilson;

(iii) Susannah mother of Frank Jock Jnr;

(iv) Michael ‘Mundoon’ Wilson;

(v) George James;

(vi) Eliza Breckenridge;

(vii) Jack Breckenridge;

(viii) Frank Jock Jnr;

(ix) Ada Jock;

(x) Gibson Robinson;

(xi) Grace Bond; and

(b) persons adopted or incorporated into the families of those persons (and the biological descendants of any such adopted or incorporated persons) and who identify as and are accepted as Bandjalang People in accordance with Bandjalang traditional laws and customs.

Nature and extent of non-exclusive native title rights and interests

5. Subject to paragraphs 6, 7 and 8, the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests in the Native Title Area are the non-exclusive native title rights set out below:

(a) the right to hunt, fish and gather the traditional natural resources of the Native Title Area for non-commercial personal, domestic and communal use;

(b) the right to take and use waters on or in the Native Title Area;

(c) the right to access and camp on the Native Title Area;

(d) the right to do the following activities on the land:

(i) conduct ceremonies;

(ii) teach the physical, cultural and spiritual attributes of places and areas of importance on or in the land and waters; and

(iii) to have access to, maintain and protect from physical harm, sites in the Native Title Area which are of significance to the Bandjalang people under traditional laws and customs.

General qualifications on native title rights and interests

6. Native title does not exist in:

(a) minerals as defined in the Mining Act 1992 (NSW) and the Mining Regulation 2010 (NSW); and

(b) petroleum as defined in the Petroleum (Onshore) Act 1991 (NSW) and the Petroleum (Submerged Lands) Act 1982 (NSW).

7. The native title rights and interests described in paragraph 5 are exercised for personal, domestic and non-commercial communal purposes and do not confer possession, occupation, use or enjoyment to the exclusion of all others. The native title rights and interests do not confer any right to control public access or use the land and waters in the Native Title Area.

8. The native title rights and interests in relation to the land or waters in the Native Title Area are subject to and exercisable in accordance with:

(a) the laws of the State of New South Wales and of the Commonwealth, including the common law; and

(b) the traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed by the Bandjalang people.

Nature and extent of any other rights and interests

9. The nature and extent of Other Interests in relation to the Native Title Area are described in Schedule Three.

Relationship between native title rights and interests and other rights and interests

10. Subject to paragraphs 11 and 12, the relationship between the native title rights and interests in relation to land and waters in the Native Title Area described in paragraph 5 and the Other Interests described in Schedule Three is that:

(a) the Other Interests continue to have effect; and

(b) the Other Interests co-exist with the native title rights and interests;

(c) the Native Title Holders do not have the right to control access to or the use of the land and waters within the Native Title Area by the holders of the Other Interests; and

(d) to the extent of any inconsistency between the Other Interests and the native title rights and interests, the Other Interests and any activity that is required or permitted by or in exercise of a right conferred or held under the Other Interests, while they are in existence, prevail over but do not extinguish the native title rights and interests and any exercise of those native title rights and interests.

11. The relationship between the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters described in Part 2 of Part A of Schedule One (land or waters in relation to which s 47A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applies) and the Other Interests described at item 1(a) of Schedule Three is that:

(a) the Other Interests continue to have effect;

(b) the non-extinguishment principle described in s 238 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applies to the grant or vesting of the Other Interests or any prior interest in relation to the area in accordance with s 47A(3)(b) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth);

(c) the native title rights and interests continue to exist in their entirety, but have no effect in relation to the Other Interests;

(d) the Other Interests, and any activity that is required or permitted by or in exercise of a right conferred or held under and done in accordance with the Other Interests, may be exercised and enjoyed in their entirety notwithstanding the existence of the native title rights and interests;

(e) the native title rights and interests may not be exercised on land or waters the subject of the Other Interests while those Other Interests exist;

(f) if the Other Interests or their effects are wholly removed or otherwise wholly cease to operate, the native title rights and interests again have full effect; and

(g) if the Other Interests or their effects are removed only to an extent, or otherwise cease to operate only to an extent, the native title rights and interests again have effect to that extent.

12. The relationship between the native title rights and interests in relation to the land and waters described in Part 1 of Part A of Schedule One and the Other Interests described at item (1)(b) of Schedule Three is that:

(a) pursuant to section 36(9) of the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), the Other Interests shall be subject to the native title rights and interests; and

(b) the land and waters may only be dealt with by the Aboriginal Land Council that holds the Other Interests in accordance with the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) and the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

Definitions

13. In these orders, unless the contrary intention appears:

‘Aboriginal Land Council’ means New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council and any Local Aboriginal Land Council constituted under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW) for a Local Aboriginal Land Council area, within the meaning of that Act, that is within the Native Title Area, and includes Bogal Local Aboriginal Land Council, Casino Boolangle Local Aboriginal Land Council, Jali Local Aboriginal Land Council, Ngulingah Local Aboriginal Land Council and Yaegl Local Aboriginal Land Council.

‘Bandjalang People’ has the same meaning as Native Title Holders.

‘Determination Area’ means the Native Title Area together with the Extinguished Area.

‘Extinguished Area’ means the land and waters described in Schedule Two.

‘land’ has the same meaning as in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

‘laws of the State of New South Wales and of the Commonwealth’ means statutes, regulations, other subordinate legislation and the common law operating in the State of New South Wales and the Commonwealth of Australia.

‘Native Title Area’ means the land and waters described in Schedule One.

‘Native Title Holders’ means the persons described in paragraph 4.

‘native title rights and interests’ means the rights and interests described in paragraph 5.

‘Other Interests’ means the rights and interests described in Schedule Three.

‘waters’ has the same meaning as in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

14. If a word or expression is not defined in these orders or this Determination, but is defined in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) or the Native Title (New South Wales) Act 1994 (NSW), it has the meaning given to it in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) or the Native Title (New South Wales) Act 1994 (NSW).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SCHEDULE ONE – NATIVE TITLE AREA

A. Description of Native Title Area

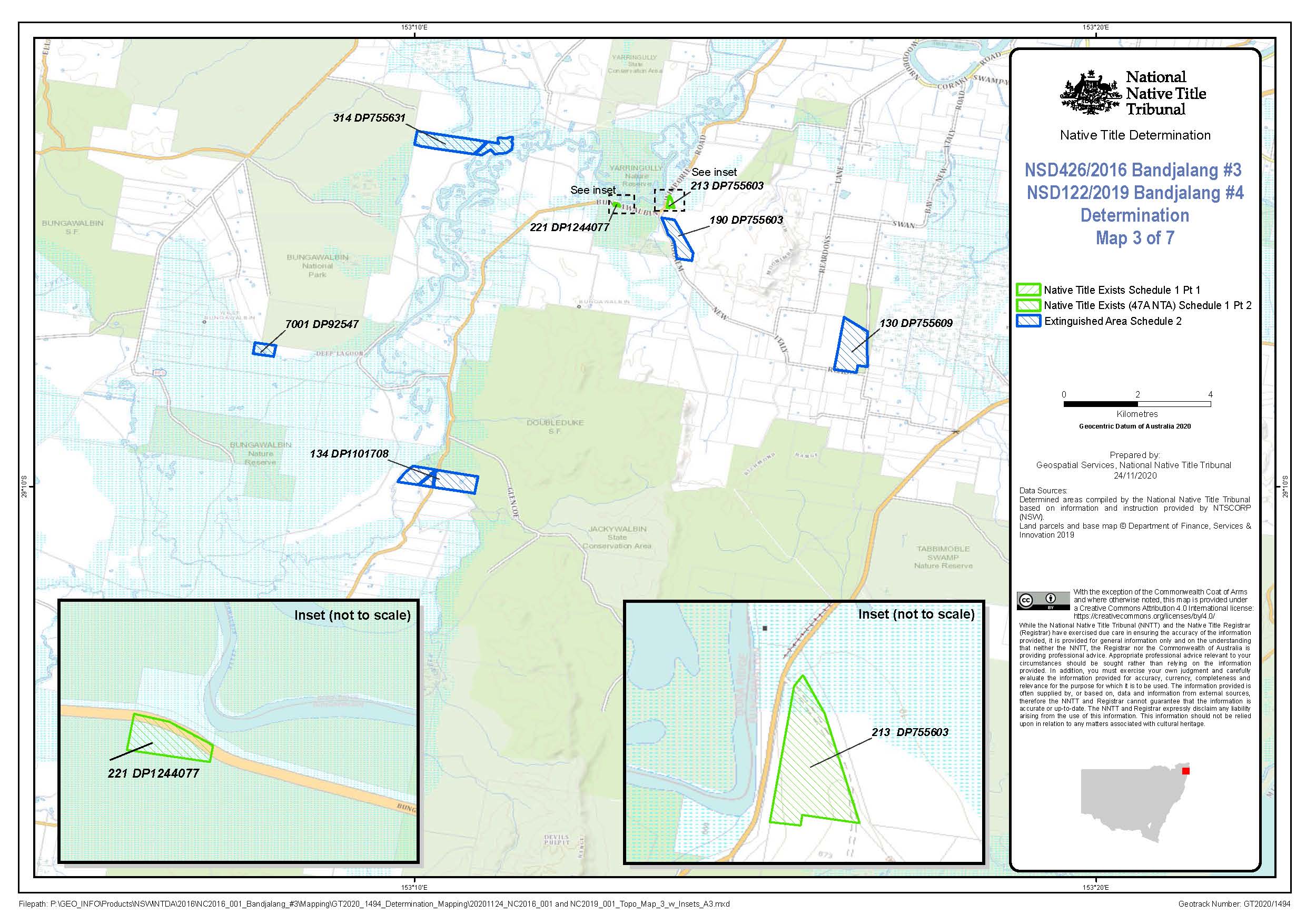

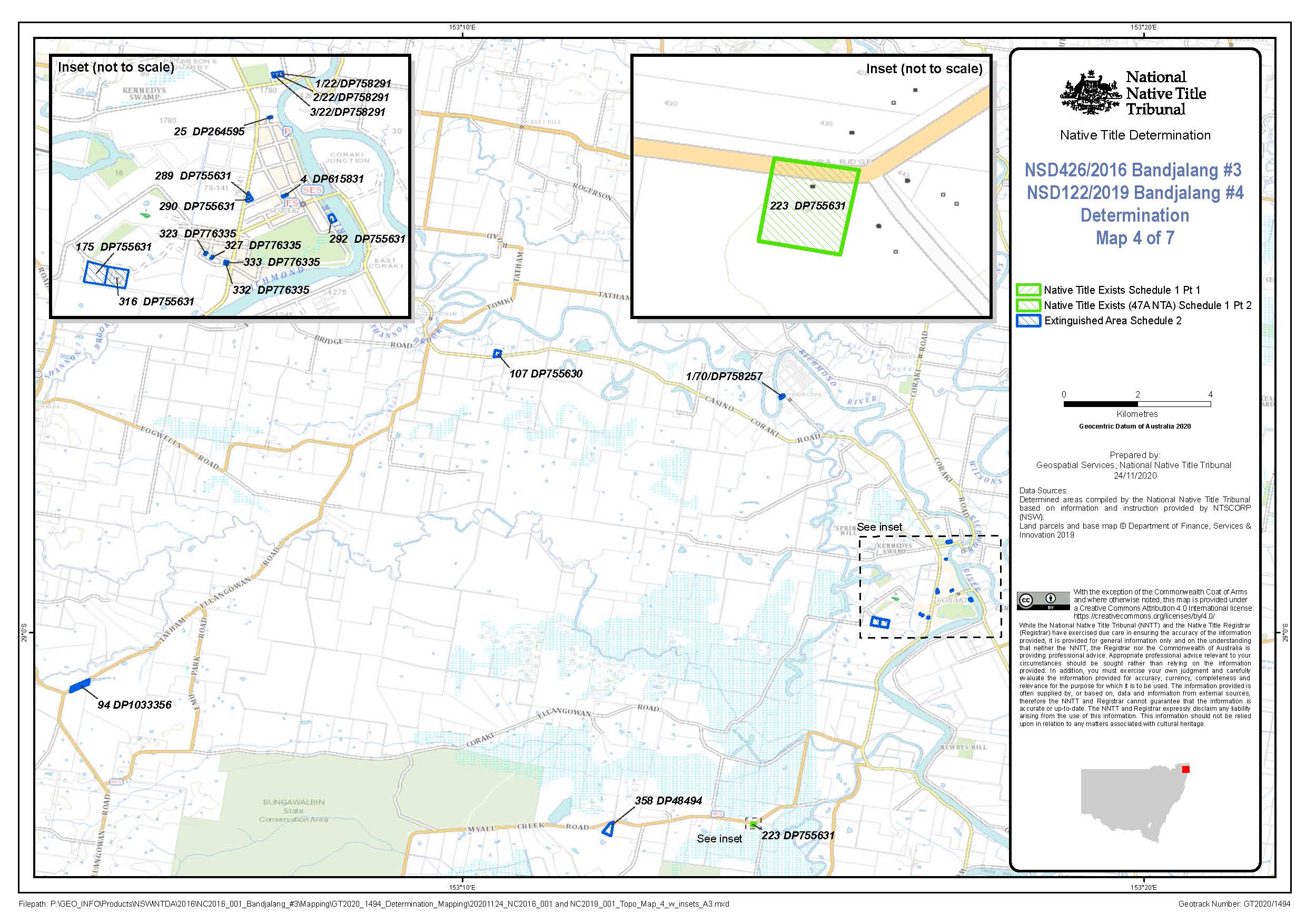

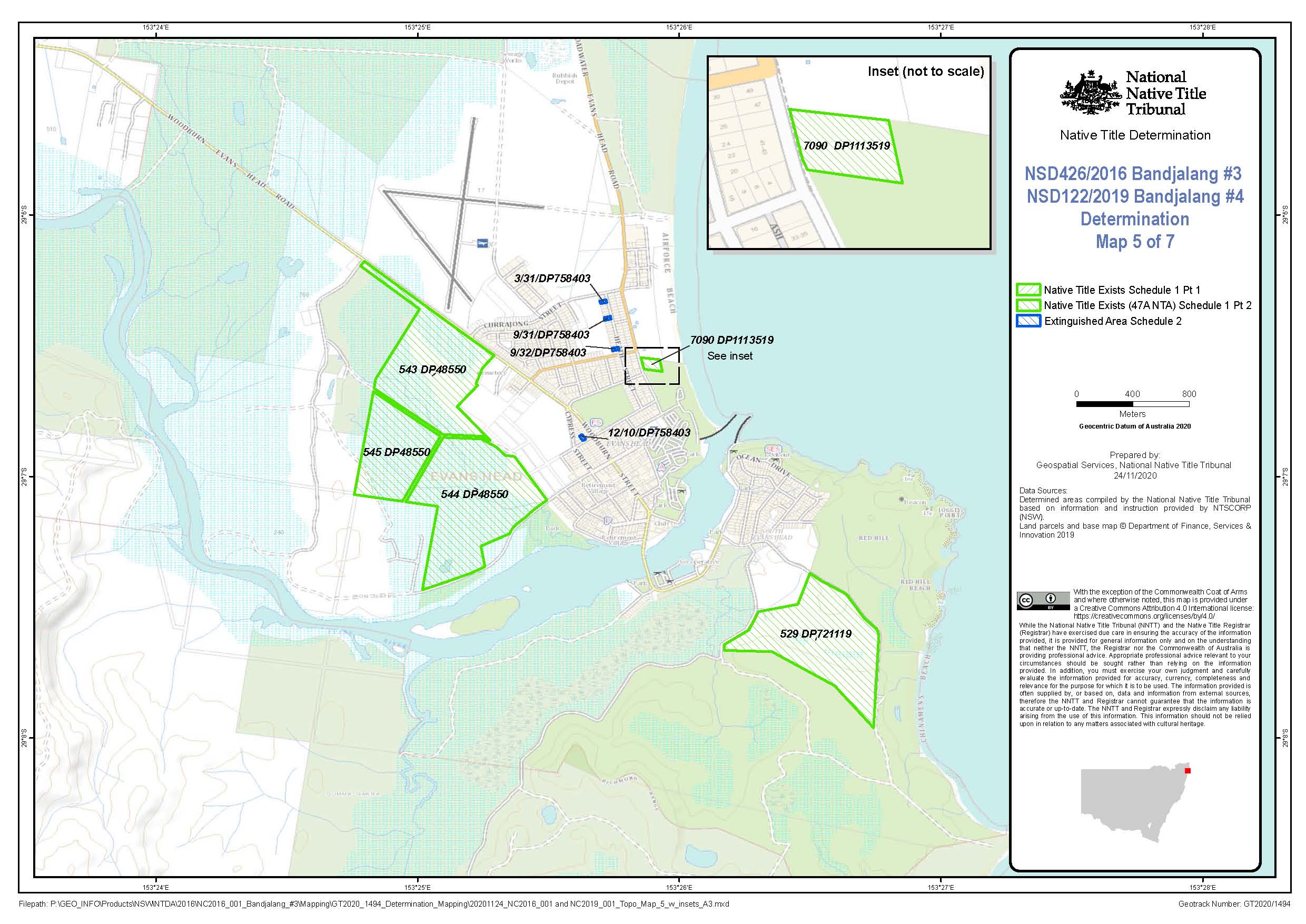

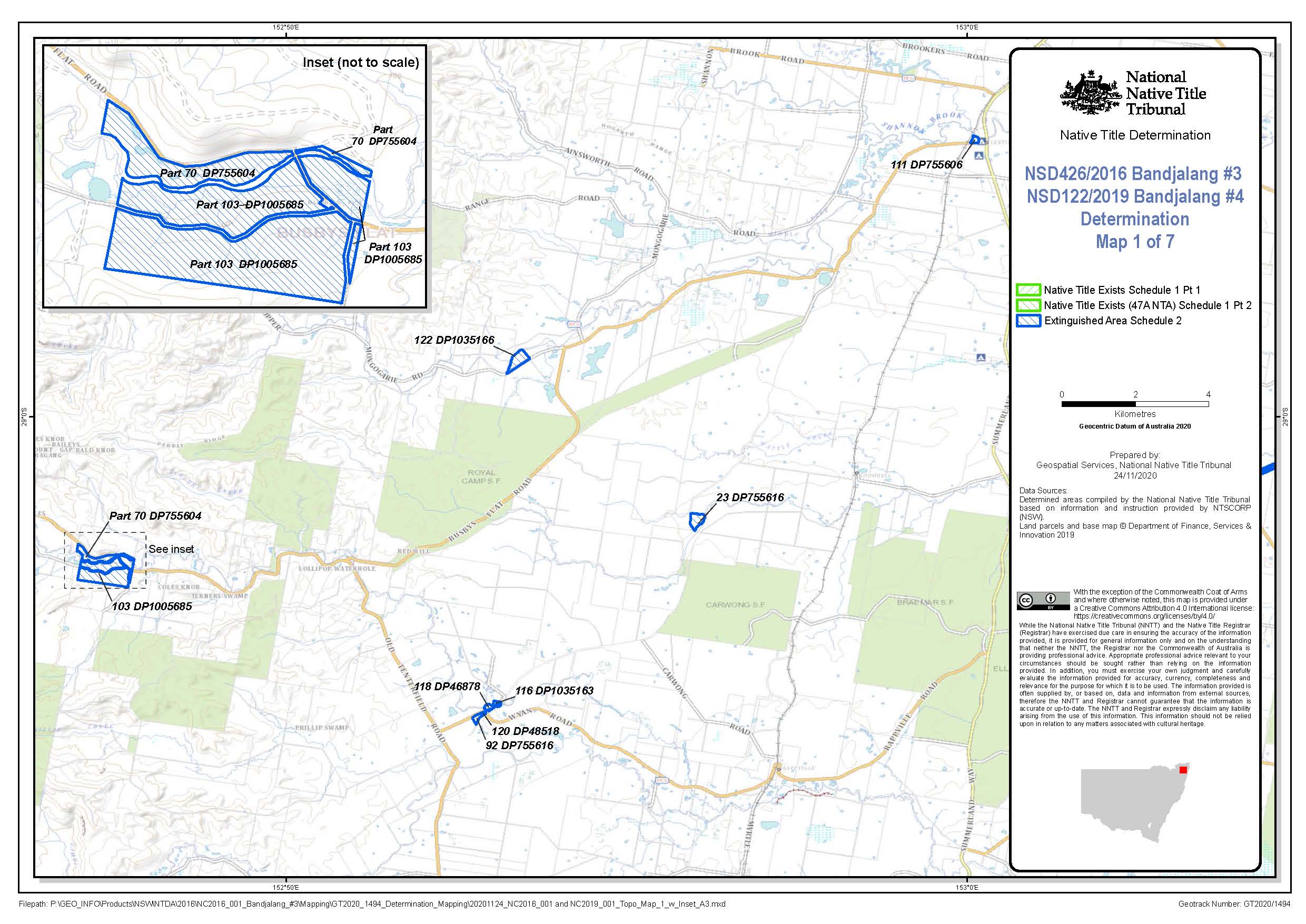

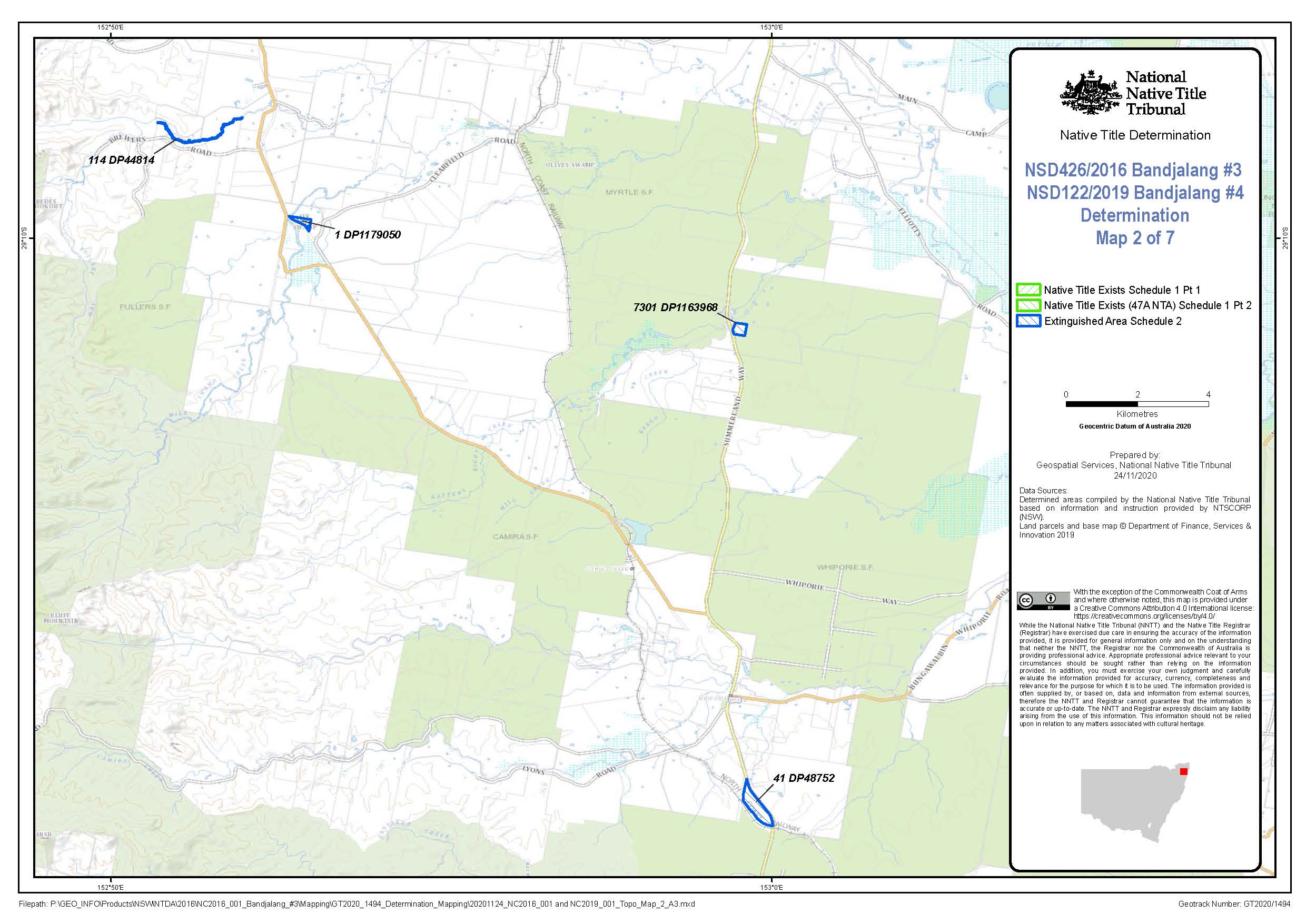

Subject to Schedule Two, Part A(a) and (b), the Native Title Area comprises all the land and waters described in Part 1 and Part 2 below and which is depicted on the maps at Part B of this Schedule.

Part 1 - Land or waters where native title has not been wholly extinguished

All the land and waters described as Lot 7310 DP 1163472 and depicted on the maps at Part B of this Schedule hatched in green (with hatching running diagonally upwards from right to left).

Part 2 - Land and waters in relation to which s 47A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) applies

All land and waters described in the following table and depicted on the maps at Part B of this Schedule hatched in green (with hatching running diagonally upwards from left to right).

Aboriginal Land Council | Areas over which freehold title held | Mapsheet |

Bogal Local Aboriginal Land Council | Lot 213 DP 755603 | Map 3 Inset |

Lot 221 DP 1244077 | Map 3 Inset | |

Lot 223 DP 755631 | Map 4 Inset | |

New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council | Lot 7090 DP 1113519 | Map 5 Inset |

Bogal Local Aboriginal Land Council, Jali Local Aboriginal Land Council and Ngulingah Local Aboriginal Land Council | Lot 529 DP 721119 | Map 5 |

Lot 543 DP 48550 | Map 5 | |

Lot 544 DP 48550 | Map 5 | |

Lot 545 DP 48550 | Map 5 |

B. Maps of the Native Title Area

SCHEDULE TWO – EXTINGUISHED AREA

A. Description of Extinguished Area

(a) any land or waters upon which a road, which is or was a public work, was commenced to be constructed or established, on or before 23 December 1996;

(b) any land or waters upon which a public road was dedicated or established under statute or common law on or before 23 December 1996; and

(c) the land and waters described in the following list and depicted on the map in Part B of this Schedule hatched in blue (with hatching running diagonally upwards from left to right):

Description | Map sheet |

Lot 1 DP 1179050 | Map 2 |

Lot 1 Section 22 DP 758291 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 1 Section 70 DP 758257 | Map 4 |

Lot 103 DP 1005685 | Map 1 |

Lot 107 DP 755630 | Map 4 |

Lot 111 DP 755606 | Map 1 |

Lot 114 DP 44814 | Map 2 |

Lot 116 DP 1035163 | Map 1 |

Lot 118 DP 46878 | Map 1 |

Lot 12 Section 10 DP 758403 | Map 5 |

Lot 120 DP 48518 | Map 1 |

Lot 122 DP 1035166 | Map 1 |

Lot 130 DP 755609 | Map 3 |

Lot 134 DP 1101708 | Map 3 |

Lot 175 DP 755631 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 190 DP 755603 | Map 3 |

Lot 2 Section 22 DP 758291 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 23 DP 755616 | Map 1 |

Lot 25 DP 264595 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 253 DP 755691 | Map 6 |

Lot 289 DP 755631 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 290 DP 755631 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 292 DP 755631 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 3 Section 22 DP 758291 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 3 Section 31 DP 758403 | Map 5 |

Lot 314 DP 755631 | Map 3 |

Lot 316 DP 755631 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 323 DP 776335 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 327 DP 776335 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 332 DP 776335 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 333 DP 776335 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 358 DP 48494 | Map 4 |

Lot 4 DP 615831 | Map 4 Inset |

Lot 41 DP 48752 | Map 2 |

Lot 530 DP 721343 | Map 6 |

Lot 548 DP 48725 | Map 6 |

Part Lot 70 DP 755604 (Southern Severances) | Map 1 Inset |

Lot 7001 DP 92547 | Map 3 |

Lot 7301 DP 1163968 | Map 2 |

Lot 9 Section 31 DP 758403 | Map 5 |

Lot 9 Section 32 DP 758403 | Map 5 |

Lot 92 DP 755616 | Map 1 |

Lot 94 DP 1033356 | Map 4 |

B. Maps of Extinguished Area

SCHEDULE THREE – OTHER INTERESTS IN THE NATIVE TITLE AREA

The Other Interests are as follows:

1. Aboriginal Land Council Interests

(a) The rights and interests of each of the Aboriginal Land Councils listed in the table below as the holder of a freehold title, which includes the rights of each Aboriginal Land Council to use, manage, control, hold or dispose of, or otherwise deal with, land vested in it in accordance with the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW):

Current Holder of Land | Land |

Bogal Local Aboriginal Land Council | Lot 213 DP 755603 Lot 221 DP 1244077 Lot 223 DP 755631 |

Bogal Local Aboriginal Land Council, Jali Local Aboriginal Land Council and Ngulingah Local Aboriginal Land Council | Lot 529 DP 721119 Lot 543 DP 48550 Lot 544 DP 48550 Lot 545 DP 48550 |

New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council | Lot 7090 DP 1113519 |

(b) The rights and interests of Yaegl Local Aboriginal Land Council as the holder of freehold title in relation to Lot 7310 DP 1163472.

2. Energy Interests

(a) The rights and interests of an electricity supply authority within the meaning of the Gas and Electricity (Consumer Safety) Act 2017 and the Energy Services Corporations Act 1995 (NSW) in exercising functions, powers or rights in accordance with the laws of the State of New South Wales or of the Commonwealth and as either or both owner and operator of facilities for the transmission of electricity and other forms of energy and associated infrastructure situated on the Native Title Area, including but not limited to rights under the Gas and Electricity (Consumer Safety) Act 2017 (NSW) and the Energy Services Corporations Act 1995 (NSW) to enter the Native Title Area in order to access, use, maintain, repair, replace, upgrade or otherwise deal with existing facilities and infrastructure.

(b) The rights and interests of:

(i) a network operator within the meaning of the Electricity Supply Act 1995 (NSW); or

(ii) for the purposes of any privatisation transaction, any lessor or lessee of a transmission system or person who owns or is authorised to control or operate a transmission system within the meaning of the Electricity Supply Act 1995 (NSW);

in exercising functions, powers or rights in accordance with the laws of the State of New South Wales or of the Commonwealth as the operator of facilities for the transmission of electricity and other forms of energy and associated infrastructure situated on the Native Title Area including but not limited to rights under the Electricity Supply Act 1995 (NSW) to enter the Native Title Area in order to access, use, maintain, repair, replace, upgrade or otherwise deal with existing facilities and infrastructure.

3. Local Government Interests

The rights and interests of Richmond Valley Council and Clarence Valley Council as local councils under the Local Government Act 1993 (NSW) and as entities exercising statutory powers in respect of the land or waters within their local government areas

(a) Any rights interests, including licences and permits, granted by the Crown in right of the State of New South Wales or of the Commonwealth pursuant to statute or under regulations made pursuant to such legislation.

(b) Any rights and interests held or conferred by reason of the force and operation of the laws of the State of New South Wales or the Commonwealth.

(c) Rights and interests of members of the public arising under the common law or statute.

(d) So far as confirmed pursuant to ss 16 and 18 of the Native Title (New South Wales) Act 1994 (NSW), any other existing public access to and enjoyment of:

(i) waterways;

(ii) the beds and banks or foreshores of waterways;

(iii) coastal waters and beaches;

(iv) stock routes; and

(v) areas that were public places at the end of 31 December 1993.

(e) The rights of:

(i) an employee, agent or instrumentality of the State of New South Wales;

(ii) an employee, agent or instrumentality of the Commonwealth;

(iii) an employee, agent or instrumentality of any Local Government Authority;

to access the Native Title Area and carry out actions as required in the performance of his, her or its statutory or common law duties.

RARES J:

1 It is particularly fitting to acknowledge and pay respect to the traditional custodians of the land on which the Court sits today, the Bandjalang people and their elders past, present and emerging. On 2 December 2013, the Court made a determination under the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the 2013 determination) to recognise the Bandjalang people’s non-exclusive native title rights and interests over their traditional lands and waters here on the north coast of New South Wales at and around Evans Head. The Bandjalang people have possessed and been connected to those lands and waters since before European settlement under their traditional laws and customs that they have continued to acknowledge and observe for all that time: Bandjalang People No 1 and No 2 v Attorney-General of New South Wales [2013] FCA 1278.

2 On that occasion over 7 years ago, Jagot J described the determined effort that the Bandjalang people had made to achieve that significant, and long delayed, recognition by the law of Australia, of what they and their ancestors have always known and treasured.

3 The making of this determination today by consent arises out of two proceedings that the applicant filed respectively on 24 March 2016 (No 3) (NSD426/2016) and on 1 February 2019 (No 4) (NSD122/2019). On 21 August 2019, the Court ordered that both proceedings be consolidated into proceeding No 3. The determination today will complete the process of legal recognition of the Bandjalang people’s non-exclusive native title rights and interests over an additional 52 small, but significant, parcels of land covering in total about 7.2 square kilometres within the boundaries of the existing determination area.

Background

4 Despite the disruptions caused by European settlement over more than two centuries, the evidence in support of the current determination includes examples of some of the richness of the Bandjalang people’s significant connection to their country. The dirrawang or goanna is an important julebi or totem for the Bandjalang people. The Goanna Headland, near Evans Head, was included in the existing determination area. It is a site of particular significance in their tradition. The dirrawang at the Goanna Headland is lying down protectively, facing out to sea where it laid its eggs.

5 One of the parcels of land that today’s determination will restore to the Bandjalang people’s non-exclusive possession is the site of the old public school at Bora Ridge, near Casino (the old school site). That school closed in 1974. The locality takes its name from a bora ring that is a circular mound in the south-eastern corner of the school yard.

6 On 1 October 2020, two members of the claim group, Afzal Khan, who is also a member of the applicant, and Simone Barker, gave affidavit evidence to me in a hearing about the significance of the bora ground. I will say more about that hearing later in these reasons. Mr Khan was born in 1978. He said that his grandmother, his mother (who was a Bandjalang woman) and his aunties had indicated that the bora ground was in the south-east corner of the site. They told him that he was not to go there unless he was with one of his uncles. Mr Khan said that all his female relatives stayed away and would not go anywhere near the bora ground. He said that ever since he was a child, the edge of the bora ground had been marked out with a wooden fence of treated pine logs. Mr Khan said that his elders taught him that the bora ground was a place where male elders of the clan would introduce younger boys to undertake initiation and be circumcised. He said that as a Bandjalang man he believed the spirits of his old people were still at the bora ground and that it was the home of a particular spirit called a “clever man”, or Kadartji man.

7 Ms Barker was born in 1964 and her father was a Bandjalang man. She grew up on Bandjalang country at Spring Hill. She said that her father had first told her that a bora ring was on the land and that it was a men’s site. He warned her not to go to where the bora ring was because he was frightened that something might happen to her if she went closer to it than the location of the old school building.

8 The founding teacher at the school when it opened in January 1900 was Michael Byrne. On 21 July 1951, Mr Byrne wrote to the Lismore newspaper, The Northern Star, to explain some history of the site and the school. He recalled that the local tribes had held corroborees at the bora ring.

The s 87 agreement

9 On 26 March 2021, the solicitors for all of the parties entered into an agreement under s 87 of the Act (the s 87 agreement). The parties are:

the applicant, comprised of Veronica Wilson, Rebecca Cowan, Gwen Hickling, Nahrina Yuke and Afzal Khan, who bring this proceeding on behalf of the Bandjalang people with their authorisation;

the Attorney-General on behalf of the State of New South Wales;

six land councils, namely Bogal, Casino Boolangle, Jali, Ngulingah and Yaegl Local Aboriginal Land Councils and the New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council, which hold between them interests in the 52 parcels of land; and

two electricity providers, Essential Energy and Transgrid.

10 The s 87 agreement contained orders that the parties ask the Court to make today. The parties have agreed that the Court should determine, by consent, that the Bandjalang people have the following non-exclusive rights over the 52 parcels of land:

the right to hunt, fish and gather the traditional natural resources of the area for non-commercial personal, domestic and communal use;

the right to take and use waters;

to access and camp;

to conduct ceremonies, teach the physical, cultural and spiritual attributes of places and areas of importance;

to have access, to maintain and protect from physical harm, sites that are of significance to them under their traditional laws and customs.

11 The s 87 agreement also recorded several other matters, including acknowledging that other rights and interests exist alongside, and in some places, in place of, the Bandjalang people’s non-exclusive rights and interests over their land and waters.

The legal context

12 A consent determination like this is a very important proceeding. It establishes for the whole Australian community that an indigenous people has legally enforceable native title rights and interests over the land and waters that it covers. I have summarised some of the important matters for all of those involved in a consent determination in earlier decisions and will draw on those in what I now say (see Lampton on behalf of the Juru People v State of Queensland [2014] FCA 736 at [4]–[6]).

13 The recognition and protection of native title by our nation’s common law in the landmark decision of Mabo v State of Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 and by the Parliament of the Commonwealth when it passed the Act enabled Indigenous Australians and their descendants to satisfy the very human desire to identify with, enjoy and feel a part of their cultural heritage on land and waters with which they have, and feel, a spiritual and emotional connection. When the Court makes an order for a determination of native title, it exercises the judicial power of the Commonwealth, on behalf of the whole of the Australian community, to recognise the indigenous claimants’ rights and interests as having the force of law in both social systems: cf Long v Northern Territory of Australia [2011] FCA 571 at [6] per Mansfield J.

14 A determination by the Court that native title exists serves many important purposes, as the preamble to the Act acknowledges. These include the recognition of the entitlement of Indigenous Australians to enjoy rights and interests in their land and waters, in accordance with their peoples’ traditional laws and customs. Those rights and interests were not previously recognised, following European settlement and the displacement and frequent dispossession of Indigenous Australians. However, from today, the rights and interests of the Bandjalang people in the 52 parcels will be protected by the force of law so that the current and future descendants of the original indigenous inhabitants before the 1840s will enjoy rights and interests that their ancestors had.

15 The different land councils held all of the 52 parcels under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW). Because there are differences between the rights under that Act and the rights of native title holders under the Native Title Act, some difficult issues arose when the parties were negotiating for the 2013 determination. As a result, those parcels could not be included in the 2013 determination. The land councils and their legal representatives have engaged co-operatively with the applicant and the State in arriving at the terms of the s 87 agreement and today’s consent determination.

16 The Court has not had a hearing of the applicant’s claim on its merits. Even so, the Court has an important power to make a determination that native title over land and waters exists under s 87 of the Act once all of the parties have signed a written agreement, and provided that certain other conditions are met. In these proceedings, the Attorney-General of New South Wales, as the responsible Minister of State, has consented to the making of the determination of native title. Before the Court can make the orders recognising native title, it must be satisfied that the consent determination has been reached after proper consideration by the parties, particularly the State, of all of the matters that the Act requires be established. This consensual process depends upon the executive government of each State and Territory in whose jurisdiction the claim is made taking an active role in the litigation. The government must scrutinise carefully any claim for native title in order to seek to protect the interests of the whole community that it represents: Munn (for and on behalf of the Gunggari People) v Queensland (2001) 115 FCR 109 at 115 [29] per Emmett J.

17 I will now deal with the legal and factual issues that I must decide in order to make the consent determination. Under ss 87(1A) and (2) of the Act, the Court has a special power to make an order to recognise native title rights and interests in, or consistent with, the terms of the parties’ agreement if it appears to the Court to be appropriate to do so. The power must be exercised having regard to the beneficial purpose of the Act and its moral foundation that is declared in the words of its preamble: Northern Territory of Australia v Alyawarr, Kaytetye, Warumungu, Wakaya Native Title Claim Group (2005) 145 FCR 442 at 461 [63] per Wilcox, French and Weinberg JJ.

18 In making a determination that native title exists, even by consent and without a hearing, the Court must set out details of the matters mentioned in s 225 (s 94A). Accordingly, if the Court is asked to make a consent determination, it must be satisfied that there is sufficient evidence before it that would make it appropriate to do so. However, it is not necessary for the parties to tender evidence as if they were still contesting the proceedings. That is not the purpose for which such evidence is required. Rather, as a former Chief Justice of Australia explained, it may be necessary to reassure the Court that a proper basis exists for the determination because “… the agreement is rooted in reality” (The Hon R.S. French AC, Native Title – A Constitutional Shift?, published in: H.P. Lee and P. Gerangelos (ed), Constitutional Advancement in a Frozen Continent: Essays in Honour of George Winterton, The Federation Press, 2009, pp 126–154).

19 What evidence will be sufficient will vary from case to case, but it must show that the orders have a substantive and real foundation. Anthropological evidence is often tendered so as to assist the Court in arriving at this degree of satisfaction. Evidence is relevant for the Court to satisfy itself that the parties had a real basis to arrive at their consent. Indeed, in the first place, because of its cogency, the same evidence is likely to have induced the respondents, especially the Government, to consent to the making of the determination of native title.

20 However, I must still be satisfied that the parties’ agreement to include the Bandjalang people’s native title rights and interests in the old school site in the orders that I am asked to make today would be within the power of the Court (s 87(1)(c)).

Would it be within the power of the Court to make a determination about the old school site?

21 On 15 March 1985, the State transferred the ownership of the old school site (Lot 223 in DP755631 in the parish of West Coraki, County of Richmond in the District of Grafton) to the Bogal Land Council under the Aboriginal Land Rights Act. As a result, the Bogal Land Council holds that site for the benefit of Aboriginal people within the meaning of s 47A(1)(b) of the Native Title Act, and it can be included in the consent determination if I am satisfied that it would be within the power of the Court to disregard, under s 47A(2), the earlier act that extinguished native title.

22 The October 2020 hearing was about whether the construction and establishment of the Bora Ridge Public School in 1899 as a public work by the then Colonial Government of New South Wales and later extensions of it in 1919 and 1925, wholly or partly extinguished native title. If that had happened, then s 47A of the Act may not have enabled the Court to make any orders about the old school site because it had been used as a public work: see ss 23B(7), 23E and 47A(2)(b): s 20 of the Native Title (New South Wales) Act 1994 (NSW) and Erubam Le (Darnley Islander) #1 v Queensland (2003) 134 FCR 155. It is not necessary to explain the legal issues in any detail.

23 In 1899, the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney Ltd (the bank) was the owner of the freehold title in the school site. The bank then leased the site to the Department of Public Instruction in 1899, so that the school could be constructed and established. The later construction and establishment of the teacher’s residence occurred in 1919. All of those events happened after the bank had been granted complete ownership. During the hearing, I suggested that the parties’ concerns with the lease and subsequent dealings with the old school site by the Colonial and later State Governments appeared to be irrelevant because all native title in that land had been extinguished before 1899 when the bank received its grant of the freehold estate. That is the effect of both s 237A of the Native Title Act and the common law, as the High Court decided in Fejo (on behalf of Larrakia People) v Northern Territory (1998) 195 CLR 96 at 126 [43] and 128 [46]–[47] per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ.

24 Thus it appeared that all subsequent dealings by the bank, Colony and State had occurred on the basis of the validity of the grant of freehold to the bank, and s 47A(3) preserved the validity of those dealings as facts. Therefore, when the State transferred its title in the old school site to Bogal Land Council in 1985, s 47A(2) had the legal consequence that the earlier extinguishment of native title rights and interests that occurred prior to 1899, when the bank acquired the freehold title in the land, could be disregarded and it did not matter that later the old school site became a public work. Section 47A(3) preserves the validity of all intermediate dealings in land between the act extinguishing native title that s 47A(2) requires to be disregarded and the present owner of that land.

25 On that basis, and the agreement of the parties, there is a real and substantive foundation to conclude that it would be within the power of the Court to determine that, pursuant to s 47A(2), any prior extinguishment of the Bandjalang people’s native title rights and interests in the old school site can be disregarded (s 87(1)(c)). Thus, the Court would have power to determine that the Bandjalang people can again exercise, at least, non-exclusive native title rights and interests and use the bora ring and surrounding land on that site in accordance with their traditional laws and customs.

Authorisation for the s 87 agreement under s 251A of the Act

26 Helen Orr, a solicitor employed by NTSCORP, the representative body, is the solicitor for the applicant with day-to-day responsibility for this consolidated proceeding. In her affidavit, affirmed on 7 April 2021, she described the background to the parties entering into the signed s 87 agreement that was filed on 27 March 2021. She said that the applicant and the State supported the Court acting on that agreement and that they had filed joint written submissions that I have found helpful.

27 Ms Orr explained that on 5 November 2020, she prepared a notice of a meeting of the claim group calling an authorisation meeting under s 251A of the Act to seek the claim group’s authorisation of the then proposed s 87 agreement and the nomination of Bandjalang Aboriginal Corporation Prescribed Body Corporate RNTBC (Bandjalang RNTBC) as the prescribed body corporate to hold on trust for the Bandjalang people the native title rights and interests that will be recognised by the consent determination in accordance with s 56 of the Act.

28 The notice set the meeting for 7 December 2020 at 10:30am at the Woodburn Evans Head RSL Club. The notice of meeting identified the composition of the claim group and the proposed consent determination area. It included an agenda that provided for the meeting to, first, update attendees on the proposed consent determination, secondly, confirm a decision-making process for the meeting to follow, thirdly, authorise and make decisions in relation to the proposed consent determination that would recognise or, in some cases, extinguish the Bandjalang people’s native title rights and interests in some parcels of land and, fourthly, consider and make decisions about nominating and authorising Bandjalang RNTBC to hold as trustee the Bandjalang people’s native title rights and interests in relation this proceeding. The notice required persons proposing to attend to register in advance of the meeting because the venue had a maximum capacity prescribed under public health regulations operating to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. The notice of meeting advised that NTSCORP would consider providing financial assistance to persons who needed it to attend the meeting.

29 Ms Orr caused the notice of the authorisation meeting to be advertised in the Koori Mail edition of 18 November 2020, and she and other NTSCORP staff arranged for copies to be posted to 201 addressees being the 156 members of Bandjalang RNTBC and others known to NTSCORP as members of the Bandjalang people whose addresses it maintained on its mailing list. I am satisfied by Ms Orr’s evidence that the notice of the authorisation meeting was sufficient, given appropriately and that NTSCORP assisted those members of the claim group who wished to attend but had to travel long distances to do so with sustenance, travel and accommodation expenses.

The authorisation meeting of 7 December 2020

30 The meeting occurred on 7 December 2020 with about 31 members of the Bandjalang people in attendance whom Ms Orr considered were representative of families constituting the claim group. She outlined the background on the progress of the claim and went through with them the terms of the proposed consent determination and s 87 agreement, answering questions, together with Alexander Chalmers, deputy principal solicitor of NTSCORP, as she progressed. At times the meeting discussed and clarified issues during this process. Ms Orr said that the terms of the then proposed consent determination were substantially the same as the current ones that I will make today.

31 The meeting resolved that:

those present were sufficiently representative of the Bandjalang people to be able to make authoritative decisions about this proceeding and that there had been adequate notice of the meeting;

the description of the claim group in the proposed consent determination be confirmed;

the Bandjalang people had no particular decision-making process under their traditional laws and customs and the meeting would proceed with discussion led or guided by family representatives to seek a consensus that would then be put to the meeting for acceptance in a clearly worded resolution and decided on by the votes of the majority, being the same process used in earlier authorisation meetings on 7 October 2015 and 15 June 2018;

the applicant be authorised to deal with all matters arising in the proceedings and to enter into the s 87 agreement on the basis that the then form of the agreement and proposed consent determination could be the subject of minor amendments;

Bandjalang RNTBC would hold the Bandjalang people’s native title rights and interests the subject of the proposed consent determination on trust and that Rebecca Cowan and Nahrina Yuke were authorised to sign the confirmation of that nomination which is in evidence.

Bandjalang RNTBC accepts the nomination

32 On 13 January 2021, NTSCORP posted notices of the annual general meeting of Bandjalang RNTBC to be held at Woodburn Evans Head RSL Club on 9 and 10 February 2021. Ms Orr attended the meeting and observed that the members present, who formed a quorum, passed a resolution that Bandjalang RNTBC agreed to hold, on trust for the common law holders, the native title rights and interests of the Bandjalang people the subject of the proposed consent determination.

33 I am satisfied on the evidence, in accordance with s 56(2)(b) of the Act, that Bandjalang RNTBC has been authorised by the Bandjalang people, being the common law holders of their native title rights and interests, to hold on trust for them those rights and interests the subject of the consent determination to be made today.

Jurisdictional findings

34 Negotiations that lead to consent orders, such as the ones I am making today, resolve the whole or significant parts of litigation and have a very important place in our court system. They enable the parties to achieve results that are acceptable to all of them but that may not have been available to one or more of the parties if the Court had to decide the dispute. And, of course, such agreements also enable the Court to deal more quickly with other people’s cases.

35 A determination of native title affects the status of the land and waters to which it relates because it recognises rights and interests in them that, subject to the Act and the terms of the determination itself, the holders can exercise forever after against any other person, including the Commonwealth and the State: cf Alyawarr 145 FCR at 463 [70]. Because a consent determination, just as a determination after a fully contested hearing, creates this status, the Court must be careful to ensure that the State, as representative of the community generally, has itself played an active role in carefully evaluating the material and evidence on which its consent is based.

36 Here, the Court has already made the 2013 determination of the Bandjalang people’s native title rights and interests over the whole of land mass within which the 52 lots are physically located, by consent. The Court was then satisfied that the State had fulfilled its responsibilities, and acted in reliance on the affidavit of Janet Moss, affirmed on 25 November 2013, who was the solicitor acting for the State: see Bandjalang [2013] FCA 1278 at [18].

37 The State’s evidence demonstrated that it has undertaken that responsibility appropriately. The State relied on the affidavit of Caitlin Fegan affirmed on 6 April 2021 which annexed the affidavit of Ms Moss affirmed 25 November 2013 in support of the Court making the 2013 determination. Ms Fegan said that the Attorney-General was satisfied, on the basis of what Ms Moss had explained about the extensive research and advice that the State had considered when consenting to the 2013 determination, that there was a credible basis to do so again for present purposes.

38 Ms Moss explained that in the time since the first proceeding had commenced on 17 May 1996, the applicant and the State had done extensive work in investigating, preparing and exchanging evidence. That included participating in taking preservation evidence on-country before the late Hely J in October 2002, reviewing expert anthropological reports by Dr John Morton, on which the applicant relied, and a review of it and other material that Dr Lee Sackett conducted as the State’s expert. The applicant provided extensive affidavit evidence from members of the claim group and others, together with expert linguistic and archaeological reports. The State relied on its in-house researchers before briefing senior and junior counsel in 2009 to make a full assessment of all the material that had been obtained to date in respect of the applicant’s then current amended claims.

39 The State’s counsel advised on 7 September 2009 that the State could be satisfied that there was a cogent and credible basis for a consent determination that recognised that the Bandjalang people had non-exclusive native title rights and interests in the land and waters now covered by the Court’s 2013 determination.

40 Ms Fegan said that the then Attorney-General had accepted that the applicant’s material was sufficiently credible to support the continuity of connection between the Bandjalang people and the land and waters covered by the areas claimed in the 2013 determination. That area necessarily included the residual areas now claimed in this proceeding and on 6 June 2017 the Attorney-General filed a notice that this was still the State’s position.

41 Ms Fegan said that, based on the evidence referred to in Ms Moss’ affidavit and the 2013 determination, the current Attorney-General is also satisfied that there is a sufficiently credible basis to justify the State agreeing to the Court making the proposed consent determination in accordance with the s 87 agreement that the State signed on 26 March 2021.

42 I am satisfied that, first, all of the parties to both proceedings Nos. 3 and 4 signed the agreement under s 87 of the Act on 25 and 26 March 2021, secondly, it resolves both proceedings and, thirdly, an order in, or consistent with, the terms of that agreement would be within the power of the Court because:

each of the original and amended Form 1 applications filed in proceedings Nos. 3 and 4 was valid and made in accordance with the Act (ss 61, 64 and 81);

the Native Title Registrar registered proceeding No 3 on 25 August 2016 under s 190A of the Act and the notification period under s 66 ran between 19 October 2016 and 18 January 2017;

the Registrar registered proceeding No 4 on 29 March 2019 under s 190A of the Act and the notification period under s 66 ran between 8 May 2019 and 7 August 2019;

on 29 August 2019, Jagot J ordered that both proceedings Nos. 3 and 4 be consolidated;

the applications in proceedings Nos. 3 and 4 and the consolidated application relate to areas (being the 52 lots) in respect of which there is no approved determination of native title (ss 13(1)(a) and 61A(1)); and

the proposed orders comply with the requirements of ss 94A and 225 because they set out, in relation to the land and waters specified, the group of persons holding the common or group rights comprising the native title, the nature and extent of each of the native title and other rights and interests, the relationship between those native title and other rights and interests, and those orders acknowledge that the Bandjalang people’s native title rights and interests to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of the land and waters will not be to the exclusion of others.

Conclusion

43 For these reasons, I am satisfied that it is appropriate to make the consent determination in the terms proposed. The Court congratulates the parties on achieving a resolution that gives the Bandjalang people rights and interests in the 52 parcels of land that will henceforward be protected by both their own system of law and the orders of this Court made today pursuant to the judicial power of the Commonwealth under the Constitution of Australia.

I certify that the preceding forty-three (43) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Rares. |

Associate:

NSD 426 of 2016 | |

GWEN HICKLING | |

Fifth Applicant: | NAHRINA YUKE |

Sixth Applicant: | AFZAL KHAN |

JALI LOCAL ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL | |

Fifth Respondent: | NGULINGAH LOCAL ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL |

Sixth Respondent: | NSW ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL |

Seventh Respondent: | YAEGL LOCAL ABORIGINAL LAND COUNCIL |

Eighth Respondent: | ESSENTIAL ENERGY |

Ninth Respondent: | TRANSGRID |