Federal Court of Australia

Murphy v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 381

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | NATIONWIDE NEWS PTY LTD ACN 008 438 828 First Respondent MS ANNETTE SHARP Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 19 April 2021 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The matter be listed for further hearing and entry of orders at 10am on 21 April 2021.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[5] | |

[11] | |

[11] | |

[15] | |

[21] | |

[24] | |

[34] | |

[38] | |

[39] | |

[40] | |

[47] | |

[47] | |

[50] | |

[64] | |

[70] | |

[77] | |

[77] | |

[77] | |

[83] | |

[83] | |

[91] | |

[97] | |

[98] | |

[100] | |

[100] | |

[104] | |

[107] | |

[111] | |

[112] | |

[113] |

LEE J:

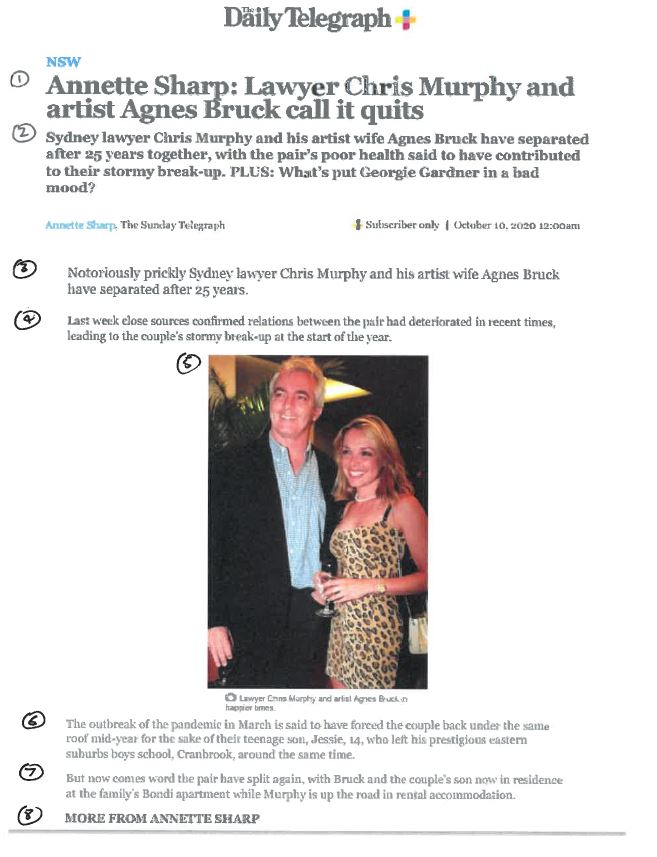

1 On 10 October last year the second respondent, Ms Annette Sharp, wrote an article published by the first respondent (News) in The Daily Telegraph newspaper (print article) and on associated websites. When published on the internet, the article had a different title and lead paragraph, and included additional photographs (internet article), but unless it is necessary to distinguish between the two publications, I will refer to them below collectively as the “article”.

2 The print article was entitled “Portrait of the artist as an estranged wife”. To anyone familiar with the early work of James Joyce (before, as Evelyn Waugh memorably said, that “poor, dotty Irishman” descended into gibberish) the nod in the print article’s heading to the seminal portrait of a renegade Catholic artist is discordant and somewhat perplexing. Upon examination, the article was largely a gossipy and intrusive piece about the applicant, Mr Christopher Murphy and his separated, painter wife. For reasons not explained in the evidence, the internet article had a more prosaic and accurate title: “Annette Sharp: Lawyer Chris Murphy and artist Agnes Bruck call it quits”.

3 Mr Murphy, a well-known Sydney solicitor, says the article conveyed a number of defamatory imputations, and he seeks relief by way of damages and an order that News and Ms Sharp be enjoined from continuing to publish the imputations or from publishing them in the future.

4 Mr Murphy is entitled to some relief and in explaining why this is so, the balance of my reasons will be divided into the following headings:

B The Imputations and the “Variant” Imputation;

C The Issue of Meaning;

D The Defence;

E Relief; and

F Orders.

B THE IMPUTATIONS AND THE “VARIANT” IMPUTATION

5 Both the print article and the internet article are reproduced at Schedule A and Schedule B to these reasons.

6 Mr Murphy alleges that the article carried the following five imputations, each of which he says is defamatory of him:

(1) Mr Murphy, despite holding himself out as a competent lawyer, was in fact so ravaged by age and deafness as to be unfit to practice (Imputation A);

(2) Mr Murphy, despite holding himself out as a competent lawyer, was in fact so ravaged by age and deafness as to be unable to represent his clients in court (Imputation B);

(3) Mr Murphy as a lawyer was incapable of representing his client’s interests by reason of the ravages of age and associated deafness (Imputation C);

(4) Mr Murphy as a lawyer was incapable of representing his client’s interests in court by reason of the ravages of age and associated deafness (Imputation D);

(5) Mr Murphy has so physically deteriorated that he is no longer fit to practice as a lawyer (Imputation E).

7 News and Ms Sharp deny that any of these imputations were conveyed. They further contend that if conveyed:

(1) as to all imputations, no imputation is defamatory;

(2) as to Imputation B, Imputation C and Imputation D, that if defamatory, the imputation is substantially true, giving rise to a defence under s 25 of the Defamation Act 2005 (NSW) (Act); and

(3) as to all imputations, that if defamatory, the imputation is defensible at common law because the article carried a “variant imputation that is not substantially different from, nor more injurious than” the imputation conveyed, being: “[t]he Applicant, a lawyer, has been affected by deafness in the past year that has kept him from representing his clients in court” (Variant Imputation).

8 Before turning to the logically anterior questions as to what pleaded imputation was conveyed and its character, it is convenient to pause to say something about the Variant Imputation and the apparent legal premise upon which it has been pleaded.

9 The Full Court (Besanko, Bromwich and Wheelahan JJ) made it plain in Australian Broadcasting Corporation v Chau Chak Wing [2019] FCAFC 125; (2019) 271 FCR 632 (at 642–3 [22]), that contrary to the decision of the majority of the Victorian Court of Appeal (Warren CJ and Ashley JJA) in Setka v Abbott [2014] VSCA 287; (2014) 44 VR 352, there never was any separate “Hore-Lacy [David Syme & Co Ltd v Hore-Lacy [2000] VSCA 24; (2000) 1 VR 667] defence” and there is no such separate defence now. As the Full Court explained (at 643 [22]–[23]):

The foundation for pleading justification of permissible variant imputations is statute, namely the rules of pleading which in this Court relevantly include rr 16.02, 16.08, and 16.41 of the Federal Court Rules. Those rules are calculated to avoid trial by ambush, and to promote the precise identification of the issues that are before the Court, and as such, may require a respondent to plead any variant of a meaning alleged by an applicant that the respondent proposes to justify at trial. However, whatever the shape of a defence of justification as permissibly pleaded, in order that a justification defence succeed at trial in respect of the publication of a matter, the common law requires that a respondent establish the substantial truth of all the meanings that are fairly within the imputations that are the subject of the applicant’s claim and which are found by the Court to have been conveyed and to have been defamatory of the applicant.

In this case, the parties accepted that it was open to a respondent in this Court to plead a common law justification defence consistently with the principles essayed in Hore-Lacy. The dispute, however, turned on whether in applying those principles the respondents’ variant imputations of the existence of reasonable grounds for belief were permissible variants of, and therefore responsive to the applicant’s pleaded meanings.

(Citation omitted).

10 The requirements of pleadings are informed by considerations of procedural fairness which, obviously enough, depend upon the circumstances of the case. The Variant Imputation is of no utility in this case. For reasons explained below, Imputation D was conveyed; it was defamatory; and News and Ms Sharp have failed to establish that it was substantially true. When it is borne in mind that the common law requires that the substantial truth of all the meanings fairly within the pleaded imputations is to be proved, this finding is not only determinative of the defence under s 25 of the Act, but also the common law justification defence as pleaded.

11 Mr Murphy submits that the most important aspects of the print article were the photographs and the “key paragraphs” being:

[3] Notoriously prickly Sydney lawyer Chris Murphy and his artist wife Agnes Bruck have separated after 25 years.

[8] According to well-placed sources, contributing further to the collapse of the couple’s rocky union has been the recent poor health of both Murphy and Bruck.

[10] Murphy, who will be 72 this month, continues to battle the ravages of age and with it the associated deafness that has kept him from representing his famous clients in court during the past year.

[11] That responsibility has increasingly gone to his less-bullish second-in-command, Bryan Wrench who this week was in court for another of Murphy’s clients, one-time South Sydney pin-up boy Sam Burgess.

12 The internet article is in substantially identical terms (including each of the impugned paragraphs) and also refers to Mr Murphy’s “poor health” in the subheading.

13 The notion that Mr Murphy holds himself out as a competent lawyer (see Imputation A and Imputation B) is said to be carried by the references to Mr Murphy’s practice, including his list of what were described as his “famous” clients. It was further submitted that it should be inferred “that a person with such a practice holds himself out as competent – as every lawyer must”.

14 There is no need to detail, yet again, the well-known relevant principles as to meaning. I recently summarised them in Stead v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 15 (at [14]–[15]). Each party accepted the correctness of that summary. It is appropriate to move directly to the imputations.

15 These imputations can be dealt with together because they suffer the same vice.

16 The notion that the article conveyed facts “despite” Mr Murphy “holding himself out as a competent lawyer” carries with it the idea that what was conveyed by the article was that there was an implied or inferred representation being made by Mr Murphy as to his competence that was somehow falsified by the true position. Nothing was conveyed about how Mr Murphy held himself out to the public. The hypothetical referee does not engage in over-elaborate analysis in search of hidden meanings, nor do they engage in a complicated process of inferential reasoning. The meanings alleged are, in this respect, strained or forced interpretations.

17 Further, as to Imputation A, the notion that the article conveyed that Mr Murphy was “unfit to practice” puts the matter far too highly. This seems to suggest that he could not do any work as a solicitor at all and, it would necessarily follow, should not be able to hold himself out as a lawyer. As [10] makes clear, the difficulties said to be suffered by Mr Murphy had kept him, it was said, from appearing in court. This aspect of his work was, it was suggested, taken over by his “second-in-command”; obviously enough, a second-in-command necessarily implies that Mr Murphy remained the lawyer primarily in command (or, as Mr Murphy would put it, the “boss”). The reference to “his famous clients” (at [10]) suggests an ongoing and continuing relationship with those clients whereby Mr Murphy does play a role, albeit one that does not involve him appearing in court.

18 The additional headline, lead paragraph and images in the internet article, which are said in some way to convey the notion of some unfitness to work generally, make no mention of Mr Murphy’s capacity to practice law simpliciter and do not distinguish the position from the print article.

19 Taken as a whole, the article does not convey the suggestion that Mr Murphy is unable (or unfit) to continue as a legal practitioner at all; rather it conveys something about his present ability to perform what would be perceived by an ordinary reader to be an important aspect or function of his work, being representing his clients in court.

20 Neither of these imputations were conveyed.

21 It is worth dealing next with this imputation because, like Imputation A, it carries with it the notion that the article conveyed that Mr Murphy “is no longer fit to practice as a lawyer”.

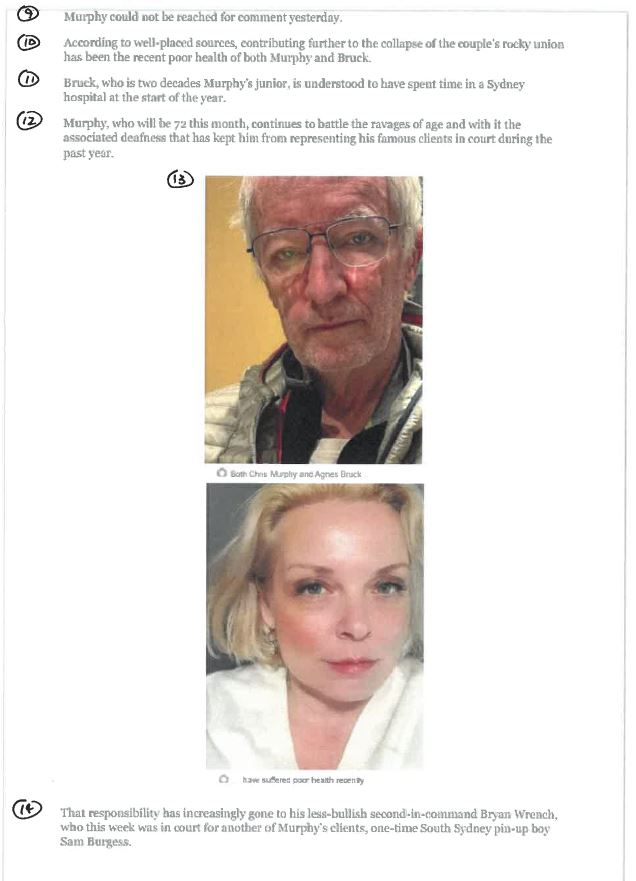

22 Imputation E was said to be carried because “age” and “associated deafness” are permanent conditions and the juxtaposition of the photos of a younger Mr Murphy with a recent photograph of a dishevelled and considerably older man conveys a physical deterioration. Further, the suggestion that he is “no longer fit to practice as a lawyer” was said to be carried by reason of the contents of [10] of the article. Mr Murphy submits that the central point is that he is said to have been “kept” from his practice in court (and therefore, as a lawyer) by reason of matters that the ordinary reasonable reader would consider permanent and irreversible.

23 For the reasons identified (at [17]–[19]) above, I do not consider Imputation E was conveyed.

24 These imputations do not contain the vice identified (at [16]) above.

25 Mr Murphy submits that Imputation D is the most straightforward and can be sourced directly from [10] of the print article, which is repeated in the internet article. That passage refers specifically to Mr Murphy being: (a) a lawyer; (b) “ravaged by age and associated deafness”; and (c) “kept” from representing his clients in court by reason of (b).

26 It was accepted by Mr Murphy that Imputation C differs from Imputation D in that it is broader and is not limited in its concern with Mr Murphy’s ability to represent his client’s interests in court, but rather in a more general sense. Although I have largely dealt with this point (at [17]–[19]) above, it is appropriate to descend into some further detail here to do justice to the submissions made in support of Imputation C being conveyed.

27 Mr Murphy is identified as a criminal lawyer in [12]–[13] of the print article. It was submitted by Mr Murphy that the ordinary reasonable reader (being a layman and not a lawyer) is a person whose knowledge of the legal system, and specifically the criminal justice element of the legal system, associates criminal lawyers with in-court advocacy of the kind seen in the television programmes “Law and Order”, “Rumpole of the Bailey” or “Perry Mason”, or the film “A Few Good Men” (depending on the vintage of the ordinary reasonable reader).

28 Reference was made to the oft-quoted words of Lord Devlin in Lewis v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1964] AC 234 (at 277):

… the natural and ordinary meaning of words ought in theory to be the same for the lawyer as for the layman, because the lawyer’s first rule of construction is that words are to be given their natural and ordinary meaning as popularly understood. The proposition that ordinary words are the same for the lawyer as for the layman is as a matter of pure construction undoubtedly true. But it is very difficult to draw the line between pure construction and implication, and the layman’s capacity for implication is much greater than the lawyer’s. The lawyer’s rule is that the implication must be necessary as well as reasonable. The layman reads in an implication much more freely; and unfortunately, as the law of defamation has to take into account, is especially prone to do so when it is derogatory.”

(Emphasis added).

29 It was submitted that if sufficient regard is had to the attributes of the ordinary reasonable reader, a reference to a criminal lawyer who is being “kept” from representing his clients in court, is a reference to a criminal lawyer who is being “kept” from representing his client’s interests at all. To find otherwise, Mr Murphy submitted, would be to make far too much of the use of the word “court” in the article.

30 Much emphasis was placed on the notion that an ordinary reasonable reader would not know that the scope of a solicitor’s work extends, as it does, to a wide range of tasks beyond appearing in a court room. It was stressed that nowhere in the article was the word “solicitor” used and that it would be artificial to consider that an ordinary reasonable reader would understand that Mr Murphy, as a solicitor, would be understood to have work away from the perceived essence of his role as a criminal lawyer – appearing primarily in the Local or District Courts doing mentions, pleas and summary hearings.

31 I accept the true scope and nature of the work done by solicitors acting exclusively in criminal matters may be somewhat obscure to an ordinary reader. Further, the hypothetical referee would not have a lawyer’s appreciation of distinctions between the work of barristers and solicitors and it is noteworthy that the word used throughout the article to describe Mr Murphy was “lawyer”. Despite this, as I have already explained in the context of Imputation A above, when one reads the article as a whole, including [10] and [11] together (as it appears in the print article), what is said to the ordinary reasonable reader is that: (a) Mr Murphy’s difficulties had kept him from appearing in court; (b) he had a role which included him presently having a “second-in-command”; and (c) he continued to have clients (and hence some work as a lawyer).

32 Although I consider Imputation D was clearly conveyed, Imputation C was not conveyed.

33 It follows that it is next necessary to determine whether the only imputation that was conveyed (Imputation D) was defamatory.

34 An imputation will be defamatory of a person if it would cause the ordinary reasonable reader to think the less of the person when applying the ordinary reader’s general knowledge and their knowledge of standards held by the general community: JWR Productions Australia Pty Ltd v Duncan-Watt (No 2) [2020] FCA 236; (2020) 377 ALR 467 (at 541 [387] per Thawley J).

35 More particularly, given the nature of Imputation D, a person’s business or professional reputation can be damaged without reflecting on his character, as is the case here. This issue was discussed by Gleeson CJ and Crennan J in John Fairfax Publications Pty Ltd v Gacic [2007] HCA 28; (2007) 230 CLR 291 (at 294 [2], see also 295 [6]), which was a case that:

… concern[ed] that form of defamation which involves injury to business reputation, that is, the publication of imputations that have a tendency to injure a person in his or her business, trade, or profession. That the law of defamation affords such protection is not surprising. Suppose someone says: “X is a thoroughly decent person, but he is showing signs of age; his eyesight is poor, and his hands tremble.” That would not be a reflection on X’s character. It would be likely to evoke sympathy rather than hatred, ridicule or contempt. If, however, X were a surgeon, the statement could be damaging. To say that someone is a good person, but a dangerously incompetent surgeon, is clearly likely to injure the person’s professional reputation. That is an established form of defamation, and it was not called in question by the parties to the present appeal.

(Emphasis added).

36 As Mr Murphy notes, these observations were cited with apparent approval and further explained by French CJ, Gummow, Kiefel and Bell JJ in Radio 2UE Pty Ltd v Chesterton [2009] HCA 16; (2009) 238 CLR 460 (at 472–3 [23], see also 477 [36] and 479–81 [45]–[50]). Counsel for News and Ms Sharp, Mr Sibtain, correctly accepted that an imputation that a professional person was associated with a condition which the ordinary reasonable reader might regard as sufficient to render that professional less competent, capable, or effective than other professionals in their field, would be defamatory. However, it was submitted that the attributes of age and deafness do not strike at the capacity of Mr Murphy to perform the functions required of him in his profession. I disagree. Imputation D was an imputation of the type contemplated in Gacic. Although not reflecting on Mr Murphy’s character, what was conveyed would be perceived by the hypothetical referee to go to an important aspect or function of his professional work, and was defamatory of him as a professional.

37 It follows it is necessary to deal with the defence of News and Ms Sharp.

38 News and Ms Sharp contend that Imputation D (Mr Murphy as a lawyer was incapable of representing his client’s interests in court by reason of the ravages of age and associated deafness) was true in substance.

D.1 The Particulars of the Justification Defence

39 Particulars of justification were pleaded. Out of these particulars of justification set out below, it was only the underlined H2, I1(b)–(g), J and K that remained in dispute by the end of the trial:

A. At all material times, [Mr Murphy] has been a lawyer.

B. [Mr Murphy] is the founder of a law firm now trading under the name Murphy’s Lawyers Inc (MLI).

C. [Mr Murphy] has provided legal services as a principal of MLI, or its predecessors, since about 1972.

D. Since at least 2012, Mr Bryan Wrench has been a lawyer at MLI.

E. Since at least August 2019, Mr Wrench has been the lawyer at MLI responsible for the management and oversight of MLI’s clients’ cases in court. Mr Wrench is described in promotional material for that firm as its Managing Lawyer.

F. Since at least 2016, Mr Wrench has appeared for and/or represented clients of MLI in numerous court proceedings. Reports of those appearances and/or that representation have been published on the website operated by MLI.

G. MLI has not published on its website any reports of [Mr Murphy] appearing in court for clients of MLI since at least 12 April 2017.

H. At all material times, but since at least 2012, [Mr Murphy] has suffered from severe to profound hearing loss. Since at least 2014, [Mr Murphy] has used powerful hearing aids to assist him with his hearing, without which he is able to hear very little.

H1. Since at least 2014, [Mr Murphy] has experienced difficulties hearing:

(a) from a distance; or

(b) with softly spoken people; or

(c) in background noise,

with the use of his behind-the-ear hearing devices.

H2. At some time prior to April 2020, [Mr Murphy] began using remote microphone devices to assist his hearing at distances of greater than one metre. However, [Mr Murphy] has continued to experience difficulties hearing:

(a) where there is background noise; or

(b) when he is unable to follow visual cues; or

(c) where the speaker does not have a clear voice; or

(d) where the speaker has an accent.

H3. Since around March 2020, many courts in New South Wales have conducted hearings via audio visual or telephone link in response to the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic.

H4. During the period since March 2020, [Mr Murphy] has had risk factors for severe illness from COVID-19 being his age, the fact that he suffers from type II diabetes and the fact that he has advanced heart disease.

I. In or about April 2020, [Mr Murphy] applied for the adjournment of proceedings to which he was a party, being proceedings 2017/00327881 in the District Court of New South Wales. In support of that application, [Mr Murphy] sought an adjournment of a hearing using an audio visual link for reasons that included that he was suffering from severe to profound hearing loss in both ears that would prevent him from participating in that hearing.

I1. In or about February 2021, the hearing of the proceedings referred to in particular I above was conducted in person in the District Court of New South Wales. At that hearing:

(a) [Mr Murphy], by his legal representatives, requested various persons, including his instructing solicitor, the barristers and the presiding Judge, to put on or use amplification devices and submitted that [Mr Murphy] had severe hearing loss and could not hear from 1 to 1.5 metres away, even with high powered hearing devices;

(b) [Mr Murphy] complained, during the hearing, that the Judge could not be heard because of the way in which he was wearing his amplification device;

(c) [Mr Murphy], by his counsel, requested the return of an amplification device which was losing its charge and said that the amplification device needed to be charged after an hour or two’s use;

(d) [Mr Murphy] required the return of the amplification devices on several occasions so that the devices could be recharged;

(e) [Mr Murphy] did not notice that his mobile telephone emitted a loud noise which was heard by others in Court;

(f) [Mr Murphy] experienced hearing difficulties when communicating with his instructing solicitor when the latter was not wearing or using an amplification device;

(g) the Court officer administering the oath did not have an amplification device and had to speak loudly and close to [Mr Murphy].

J. It may be inferred from the foregoing that, since at least August 2019, [Mr Murphy] has refrained from representing clients of MLI in court because of the difficulties experienced by him arising from his hearing loss, and, since March 2020, his age.

K. Further, it may be inferred from the foregoing that, since at least August 2019, [Mr Murphy] has been unable or unwilling to represent clients of MLI in court because of his age and hearing loss.

D.2 Five Preliminary Observations

40 Before coming to the specific contest as to whether those remaining parts of the particulars were made out, it is appropriate to frame the inquiry by making five important preliminary points.

41 First, News and Ms Sharp bear the onus of proving that every material part of the imputations pleaded by Mr Murphy is substantially true.

42 Secondly, consistently with s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), when the law requires proof of any fact, the tribunal of fact “must feel an actual persuasion of its occurrence or existence before it can be found”: Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 (at 361). It follows that News and Ms Sharp, as the parties bearing the onus, will not succeed unless the whole of the evidence establishes a “reasonable satisfaction” on the preponderance of probabilities such as to sustain the relevant issue (Axon v Axon (1937) 59 CLR 395 (at 403 and 407)); and the “facts proved must form a reasonable basis for a definite conclusion affirmatively drawn of the truth of which the tribunal of fact may reasonably be satisfied”: Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 (at 305).

43 Thirdly, News and Ms Sharp are bound by their pleaded case, set out at [39] above, in relation to justifying all the meanings that are fairly within Imputation D.

44 Fourthly, it is convenient to break down the factual contest on the justification defence into two related aspects of Imputation D, being:

(1) Mr Murphy’s alleged incapacity of representing his client’s interests in court (Incapacity Issue); and

(2) Whether Mr Murphy not appearing for clients in court was the result of “the ravages of age and associated deafness” (Non Appearance Issue).

45 Fifthly, directly relevant to both issues, is that when one comes to a consideration of the evidence, it must be assessed against the reality that in this case a special jury, in the form a referee, has inquired into and reported upon questions as to Mr Murphy’s hearing and the reports of the referee have been adopted (ultimately without objection). As I explained in CPB Contractors Pty Limited v Celsus Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 2112; 268 FCR 590 (at 604–5 [55]–[62]), the reference procedure provided for by s 54A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and Div 28.6 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR) creates a procedure, which has as a central aspect the necessity for a report of the referee to be adopted in whole or in part before it has any legal effect. The process provides for the referee, under the control of a judge, participating in a special mode of inquiry and, upon adoption of a report emerging from the inquiry, it is the court which makes findings of fact, either explicitly or implicitly, by adopting the report.

46 With these matters in mind, I will proceed initially to record findings resulting from the reference, then make some further findings (particularly relevant to the Non Appearance Issue) and finally consider whether News and Ms Sharp have made out those parts of their justification particulars that remain in dispute.

D.3 The Evidence Generally Relevant to Justification

47 As noted above, on 18 December 2020, an order was made that a referee audiologist, Ms Sarah Platt-Hepworth, inquire into and report upon four questions relevant to Mr Murphy’s hearing and his hearing capacity. The inquiry was to be conducted in such a manner as the referee considered would, without undue formality or delay, enable a just, efficient, timely and cost-effective resolution of the reference, and Mr Murphy was directed to make himself available for an examination or examinations as directed by the referee and to provide to the referee any medical records or other information or documents as directed by the referee.

48 The process of the inquiry occurred efficiently and without incident, but when the report of the referee (Report) was provided to the Court and the parties, it left open the possibility that the referee had not been provided with some relevant recent reports from Mr Murphy’s audiologist, and noted the history of Mr Murphy’s use of two different types of hearing aids during 2020. Accordingly, on 11 February 2021, pursuant to FCR 28.67(1), without opposition, the Report was adopted subject to the preparation of a supplementary report (Supplementary Report) by the referee. The Supplementary Report was prepared promptly, and without any opposition by the parties, on 2 March 2021, the Supplementary Report was adopted. Relevantly, upon (and by the process of) adoption, the following was found by the Court:

1. What is the current state of hearing of Mr Murphy?

Mr Murphy has a severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss in both ears. The hearing loss is permanent. When compared with previous hearing test results (conducted by Sydney Adult and Children’s Ear Nose Throat Centre) provided by Mr Murphy, there has been no significant change in hearing levels since 2012. Without the use of hearing aids it would be expected that Mr Murphy would have great difficulty with auditory communication in all situations.

2. Without limiting question 1, with the assistance of any hearing assistance technology to which Mr Murphy has access, what is the state of Mr Murphy’s ability to hear in a room of the size and configuration of a standard courtroom?

Mr Murphy has access to hearing aids and other technology that has been shown to be appropriate for the degree of hearing loss. Mr Murphy has demonstrated proficiency in the use of this equipment. Aided speech tests demonstrate that with the use of his hearing aids it is likely that Mr Murphy can communicate effectively in a room the size and configuration of a standard courtroom. This is particularly the case when Mr Murphy utilises the remote microphone devices that he is in possession of. Using live voice rather than a recording which is closer in replicating the sound environment of the court Mr Murphy was able to score 100% in the auditory visual condition and in the auditory alone condition, using his hearing aids alone. His ability to hear clearly at a distance was demonstrated when using the Roger clip. Mr Murphy was able to score 90% correct. It must be emphasised that the material used for test purposes, places more focus on auditory ability alone than would be the case in a courtroom. In the courtroom Mr Murphy would also have the advantage of understanding the context of what is being communicated.

3. How would the answer to question 2 be affected by the acoustics and level of ambient noise in a courtroom.

Mr Murphy utilises a Roger Pen or Roger Clip to overcome the increased challenges provided by poor acoustics, reverberation, ambient noise and increased distance from the speaker.

The main purpose of the Roger Pen or Clip is to pick up the speaker’s voice by being placed close to the sound source (in most cases the mouth), and in this way reduce the ambient noise. The Roger device transmits the speech closest to it directly to the hearing aids and is capable of transmitting the signal for up to 10 metres. Mr Murphy reports that he frequently either places the Roger device close to the sound source or gives it to the speaker. It can therefore be concluded that the acoustics and ambient noise in the court room have very little effect on Mr Murphy’s ability to hear, provided that he uses the Roger device(s) as he has reported. This was also demonstrated in the clinic with standardised test sentences.

In the event that Mr Murphy does not use the Roger devices when in court and is relying on his hearing aids alone, it is my opinion that Mr Murphy may experience more difficulty hearing and understanding speech. It is likely that Mr Murphy would need to focus more effort in understanding speech particularly if the speaker does not have a clear voice, is not clearly visible or is at a considerable distance. Ambient noise may also interfere with Mr Murphy’s ability to understand speech when not using the Roger devices. However, Mr Murphy’s hearing aids do have the ability to enhance any speech signal above the level of ambient noise. Hearing aids such as those worn by Mr Murphy contain multi-adaptive directional microphones which are automatically activated in noisy situations. Test results demonstrated that Mr Murphy’s aided hearing is sufficient for effective communication in various conditions with his hearing aids alone. It is also likely that given Mr Murphy’s long standing hearing loss he has become adept at utilising visual cues to aid communication. His familiarity with the Court environment and his knowledge of the context of the material being discussed would also lessen the disability associated with the degree of hearing loss.

4. Is Mr Murphy’s current state of hearing (including his ability to hear in a room of the size and configuration of a standard courtroom), likely to have been materially different at an earlier date during 2020 and, if so, in what way?

Mr Murphy provided copies of previous hearing test results dating from 2012 to 2020. These tests were carried out by Sydney Adult and Children’s Ear Nose and Throat Centre. There has been no significant change in Mr Murphy’s hearing levels during this period or when compared to tests carried out for the purposes of this report. On this basis, I consider that it is unlikely that Mr Murphy’s hearing was materially different at any earlier date in 2020.

49 As to the questions the subject of the Supplementary Report:

5. What differences in use or effectiveness, if any, exist in the ordinary use by a person with Mr Murphy’s current state of hearing between the Phonak Naida M90 SP BTE (Behind-the-ear) hearing aids (second device) and the Phonak Naida Q90-UP hearing aids (first device)?

The Naida Q90 UP and M90 SP are both suitable devices for Mr Murphy’s degree of hearing loss. They are premium devices with comparable high power outputs and 20 digital channels. There are some technical differences in performance of the hearing aids. These differences relate to the introduction of enhanced digital processing and more sophisticated algorithms enabling the automatic functioning of the hearing aids. In addition the Naida M90 SP introduced the use of direct Bluetooth wireless technology as opposed to the Naida Q90 which required the use of an additional Bluetooth streaming accessory.

It is my opinion that the Naida Q90 and M90s are essentially equally effective in quiet situations when used by a person with Mr Murphy’s degree of hearing loss and listening skills. Both devices would give appropriate amplification to enable the user to hear speech. In situations where there is a significant amount of background noise it is likely that the Naida M90 SP would provide enhanced noise reduction, improving the clarity of speech in noise and therefore reducing the listening effort required. It is likely that the Naida Q90 UP would require more use of visual and contextual cues. In summary it is my opinion that it may be easier and require less auditory effort for someone with Mr Murphy’s degree of hearing loss to hear speech when using the Naida M90 SP compared to the Naida Q90 UP.

6. Is there any difference between the first device and second device as to how they can operate effectively with the Phonak Roger Remote Microphone Pens and the Roger Remote Microphone Clip referred to in the Report?

There is a difference in the practical use of the Roger devices between the Naida Q90 and the Naida M90. The Q90 series requires the use of a Bluetooth streaming accessory to be worn by the hearing impaired person in addition to their hearing aids. It also requires the manual activation of a streaming program by pushing a button on the accessory. The M90 series has the Bluetooth receiver built into the hearing aid. There is no requirement to wear an additional accessory or to manually activate the device. Once the Roger transmitter (Roger remote microphone pen or microphone clip) is switched on it will stream the signal directly to the hearing aids.

The aim of the Roger devices is to reduce interference from noise by essentially improving the proximity to the sound source. This occurs equally when the Roger devices are used correctly with either the Naida Q90 or the Naida M90. Therefore in my opinion there is likely to be no significant difference in the effectiveness of the Roger devices when used with the first device and the second device.

7. Was the Referee provided with, and took into account in the preparation of the Report, the Sydney Audiology reports annexed to this order dated 29 April 2020 and 18 December 2020 (Sydney Audiology Reports) and if they were not taken into account by the Referee, do the tests and opinions expressed in the Sydney Audiology Reports alter the opinions expressed in the Report and, if so, how?

I was not provided with and therefore did not take into account the Sydney Audiology reports dated 29 April 2020 and 18 December 2020. The tests and opinions expressed in the Sydney Audiology Reports do not alter the opinions I expressed in the Report provided to the Court.

The Sydney Audiology report is in keeping with the opinions I have previously expressed. It states that Mr Murphy has a severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss bilaterally. To summarise both Sydney Audiology reports also state that his hearing devices will assist him to communicate 1:1, he will have more difficulty in noise, benefits from visual cues and that he utilises Bluetooth streaming and remote microphones. Other than the Audiogram there are no test results in the Sydney Audiology reports to directly support the views expressed (although these views are consistent with the degree of hearing loss).

In summary, having reviewed the Sydney Audiology reports, there is no change to the opinions I have expressed in the original report provided to the Court.

(Numbering adjusted to be consecutive).

Further Findings as to the Incapacity Issue

50 In addition to these findings, as was noted above (at [39]), there was little left in any dispute as to the Incapacity Issue by the end of the trial. It was an agreed fact pursuant to s 191 of the Evidence Act that Mr Murphy was not capable of appearing as an advocate in court, or as an instructing solicitor in court, without the use of his hearing aids and Roger devices: T93.19–22 and T95.35–45.

51 On each occasion he has appeared in court since 2014, Mr Murphy has used Roger devices: affidavit of Mr Murphy affirmed 26 February 2021 (Murphy 2) (at [12]). When he takes part in legal proceedings, he or his Counsel will seek permission to utilise the Roger devices and these requests have never been met with resistance from the judiciary. They are recharged during breaks and he brings additional charged devices to Court in case one runs out of power: Murphy 2 (at [15]–[16]). Other than by News and Ms Sharp’s attempt to isolate exchanges with the judge overseeing a District Court proceeding in which Mr Murphy was a plaintiff (Mould proceeding) in order to construct a narrative of “practical challenges” occasioned by the use of the Roger devices in court, this evidence was not the subject of challenge and I accept it. Mr Laycock also gave uncontested evidence that Mr Murphy will always use the available technology where necessary to facilitate his hearing: affidavit of Mr Laycock affirmed 2 February 2021 (at [15]).

52 With respect, there was a good deal of irrelevant cross-examination of Mr Murphy as to the question of incapacity in the light of the adoption of the reports of the referee and the consistent position of Mr Murphy as to the state of his hearing and the unchallenged evidence as to the use of his devices. In fairness to Mr Sibtain, however, the position as to the extent of Mr Murphy’s unassisted incapacity to appear or instruct in court was clarified, during the cross-examination, by Mr Murphy accepting the terms of the agreed fact.

53 Residual issues were raised about “fragmenting” and “body block” being occasioned by the use of the technology. No doubt there are some limitations. It may involve Mr Murphy missing some words if participants in a hearing talk simultaneously, and it is conceivable that if someone wearing a Roger device is blocked by another person Mr Murphy may experience some transient, mild difficulties.

54 It is not only in Equity that one comes across whispering practitioners. Diffident, timorous and maffling practitioners and witnesses are not unknown – even in the more robust surrounds of the criminal law. The acoustics of some courtrooms are, to put it mildly, suboptimal. In country New South Wales, it might be thought there is an inverse relationship between the age and beauty of the courthouse and the ease by which an advocate can hear the judge or magistrate. In any event, it is a commonplace that participants in court proceedings, be they litigants or practitioners, will miss words spoken by the Bench, a witness or a fellow practitioner from time to time. If words are sometimes missed, they can be repeated. The notion that Mr Murphy could appear and represent clients in court provided he obtained the assistance of hearing aids and Roger devices is one I find persuasive.

55 In this regard, the fact that Mr Murphy wears his hearing aids was again not really disputed. Mr Murphy gave evidence he wore the Phonak Naida Q90-UP BTE hearing aids from 2018 until November 2020. He found the device worked well and allowed him to hear people and participate in conversations: Murphy 2 (at [10]). Since November 2020 Mr Murphy has worn the Phonak Naida M90 SP BTE, which he has found works well and is equally good when used with the Roger devices: Murphy 2 (at [11]). This was not challenged in cross-examination, is not inherently incredible, and I accept it.

56 There was some suggestion made from time to time by News and Ms Sharp that because Mr Murphy requires Roger devices, this fact, in and of itself, meant he was “unable” to appear in court. I reject that submission. As anyone experienced in litigation would be aware, many barristers and judges, including a recent highly distinguished judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, have had significant hearing difficulties. Other participants in court proceedings just need to adjust. To suggest persons with hearing difficulties are unable to appear is a little like saying that someone with infirmity of sight is unable to appear. There have also been famous blind barristers and judges. Sir John Wall was a notable Deputy Master of the Chancery Division of the High Court of Justice in the 1990s. John Mortimer QC in his play “A Voyage Round My Father”, memorably describes his father, a barrister, continuing to practise after he went blind.

57 What Mr Murphy said about the co-operation of others involved in the court process utilising the Roger devices is unsurprising. If it was drawn to the attention of a judicial officer that a practitioner needed others to wear a Roger device, it seems to me inconceivable that the presiding officer would not make the necessary arrangements. This occurred during the course of the proceeding before me and caused no disruption or inconvenience.

58 This conclusion, which accords with commonsense, is also consistent with the evidence of Mr Kalantzis (a highly experienced litigator with nearly 30 years’ experience: T198.45–199.9). He gave evidence of acting for Mr Murphy in the Mould proceeding. He stated that he communicated in a normal fashion with Mr Murphy, that the use of the devices did not disrupt the trial (T201.14–33), and that he did not recall any relevant resistance by the judge to wearing the devices once the need for them (as opposed to a hearing loop) was explained: T198.27–35.

59 Indeed, it was obvious that during the hearing, Mr Murphy, when utilising his hearing aids and through the use of Roger devices, experienced no difficulty in hearing what was going on. In fact, he was even able to hear the oral evidence of the far from cacophonous Mr Boulten SC, who did not have a Roger device in the witness box for the majority of his cross-examination: T87.21–2.

60 Counsel for Mr Murphy makes the wry but accurate point that it was counsel for News and Ms Sharp, who cross-examined Mr Murphy, who:

… appeared to mishear things a number of times throughout (see, eg, Day 2, T149.15-19, T166.46-167.11; and generally during the cross-examination of Mr Jarratt on Day 3). To be clear, the Applicant is not suggesting (as the logic of the Respondents’ defence might appear to suggest) that Counsel for the Respondents is “unable” to represent clients in court. The point is simply made that Court is a human process, in which fallible and imperfect beings participate, and where any participant can mishear or miss things – whether or not they happen to have a diagnosed condition. The respondents have simply failed to demonstrate that, with the support of his hearing aids and Roger devices, Mr Murphy is at any relevant disadvantage to practitioners without a hearing impairment that might render him “unable” to represent clients as a lawyer or advocate (cf Particular K).

(Mr Murphy’s emphasis).

61 With no disrespect to Mr Sibtain, I agree.

62 For completeness, I should deal with the attempt of News and Ms Sharp to rely on Mr Murphy’s concerns about using Microsoft Teams for the Mould proceeding, relatively early in the period when in-person court hearings were disrupted by the pandemic in early 2020.

63 Mr Murphy gave evidence that he experienced some technical difficulties with the video conferencing technology: Murphy 2 (at [20(b)]–[20(c)]). Mr Kalantzis, Mr Murphy’s solicitor in the Mould proceeding who was present at the relevant Microsoft Teams conference when these problems were experienced, confirmed that the problem was with “feedback”: T200.34 and T202.27–30. It is apparent that Mr Murphy became capable of using videoconferencing technology with his impairment. He has attended all case management conferences in this proceeding via Microsoft Teams without incident or difficulty: Murphy 2 (at [36]). In any event, as Mr Murphy correctly submits, a one-off inability to attend for a specific reason like feedback on video software would not suffice to prove the sting of the imputations which require an ongoing inability to represent clients in court to be proved.

Findings as to the Non Appearance Issue

64 It is then necessary to turn to whether it has been established that Mr Murphy’s absence from court was the result of “the ravages of age and associated deafness” or for some other reason. This requires me to either accept or reject the evidence of Mr Murphy. Because of this, it is appropriate to pause and say something about the evidence of Mr Murphy generally.

65 Although Mr Murphy is a highly experienced advocate who has no doubt prepared countless witnesses for cross-examination over the course of his long career, he often seemed to either forget or to ignore the advice I have little doubt he would have conveyed. He was often non-responsive, long-winded, argumentative and, once or twice, somewhat rude to the cross-examiner. Despite this, there was a certain rakish charm about his performance in the witness box and despite my misgivings about his manner of giving evidence, he generally told the truth and the most important aspects of his evidence were corroborated or coincided with the inherent probabilities. I will return to his manner of giving evidence when it comes to damages.

66 I am presently concerned, however, with the evidence of Mr Murphy by which he explained that the reason he has appeared in court very rarely in the last 10 years was because he had changed his role in the firm: affidavit of Mr Murphy affirmed 29 January 2021 (Murphy 1) (at [12]). This aspect of his evidence was repeated in a forceful manner, numerous times in cross-examination: see, for example, T153.12–7 and T157.9–17.

67 This evidence was said to be corroborated, but I do not think much can be made of this. Mr Boulten specifically denied that Mr Murphy did not appear in court because of challenges associated with his hearing (T67.3–5) and, without objection, gave evidence of his understanding that neither his health nor his age were the reasons he understood Mr Murphy did not appear in court: T68.3–5. Similar evidence was given by Mr Thomas and Mr Houda to the effect that Mr Murphy’s reduced appearances in court are the product of choice. Having noted this, with no disrespect to these witnesses, evidence as to their subjective understanding of Mr Murphy’s mental processes is beside the point and of no real utility.

68 On balance, I am prepared to accept Mr Murphy’s evidence as to his rationale for non-appearance, despite any general concerns I have as to: (a) the manner of his giving of his evidence; and (b) that Mr Murphy’s pattern of infrequent appearance in court seems to be co-incident with the diminution of his hearing ability. In particular, I accept that he has chosen to assume the role of a “rainmaker” for his firm, while continuing to be closely involved in cases, including by conferring with counsel, conducting research, preparation and making tactical decisions: Murphy 1 (at [23]). Much was made of the fact that Mr Wrench, the second-in-command to the self-described “overlord” (T144.21–2), is promoted heavily on the Murphy’s Lawyers website. But this is beside the point: Mr Wrench is the one going to court, along with two other solicitors, and Mr Murphy now considers himself “the strategist” and “the tactician”: T144.21–2. What matters is whether these arrangements were the product of inability or, as I have found, choice.

69 I am fortified in this conclusion by reason of the fact that when he does want to appear in court for what he perceives to be an important reason, he does so. It was uncontroversial that Mr Murphy has appeared a number of times in the past 10 years for what he described as “high-profile” matters: Murphy 2 (at [9]). This appears to have been for some sort of protective or pastoral reason for at least some clients; for others, it may have been because of the increased publicity that these appearances generated (it is unnecessary to determine the reasons for his appearance in each of these special cases).

Conclusion on the Disputed Particulars

70 The findings I have made as to the Incapacity Issue and the Non Appearance Issue are sufficient to dispose of most of the disputed particulars.

71 I do accept that at some time prior to April 2020, Mr Murphy began using remote microphone devices to assist his hearing at distances of greater than one metre but that he has continued to experience some difficulties hearing: (a) where there is background noise; (b) when he is unable to follow visual cues; (c) where the speaker does not have a clear voice; or (d) where the speaker has an accent: see Particular H2. This is all consistent with the agreed fact that Mr Murphy is not capable of appearing as an advocate in court, or as an instructing solicitor in court, without the use of his hearing aids and Roger devices. But, as I found above, with the use of his hearing aids and Roger devices, he is capable of appearing in court.

72 As to Particular I1, it was alleged that earlier this year Mr Murphy experienced various difficulties during a hearing of the Mould proceeding. The precise sub-particulars are set out (at [39]) above. As to:

(1) Particular (a): I accept that Mr Murphy, by his legal representatives, requested participants use Roger devices because of Mr Murphy’s severe hearing loss, but this is entirely consistent with the findings of the evidence as to the Incapacity Issue. In any event, this particular was accepted by Mr Murphy: T280.32.

(2) Particulars (b), (c) and (d): although the use of Roger devices requires some instruction (as is evident from particular (a)), this is innocuous; similarly, the notion (that seems to be the substance of particulars (c) and (d)) that the Roger devices need to be charged is hardly surprising. Mr Murphy confirmed that the devices have an eight hour battery life: T117.41–4.

(3) Particular (e): was denied in cross-examination; the transcript is unclear and I do not think the evidence is such as to allow a finding to be made that Mr Murphy did not notice that his mobile telephone emitted a loud noise which was heard by others in court: T118.3–19.

(4) Particulars (f) and (g): that Mr Murphy experienced hearing difficulties when communicating with his instructing solicitor when he was not wearing a Roger device and the Court officer had to speak loudly and close to Mr Murphy when administering the oath, goes nowhere; the first difficulty is that these allegations were not put to Mr Murphy; the second is that no evidence to this effect was elicited in chief from Mr Kalantzis, Mr Murphy’s solicitor, who was called in the case of News and Ms Sharp; and the third is that even if these particulars were proved (which they were not), this would not be inconsistent with the agreed fact and my findings as to the Incapacity Issue – it is uncontroversial that Mr Murphy needs to wear Roger devices to participate fully in court proceedings (although this admission was made in the context of Mr Murphy appearing in Court, rather than participating as a litigant).

73 As to Particulars J and K, for reasons I have explained, I do not accept that the inferences should be drawn that since at least August 2019, Mr Murphy has refrained from representing clients in court because of his hearing loss or has been unable or unwilling to represent clients in court for the same reason.

74 Finally, I have not dealt yet directly with the issue of Mr Murphy’s age. It will be recalled that Imputation D was that Mr Murphy as a lawyer was incapable of representing his client’s interests in court by reason of the ravages of age and associated deafness. The conjunction “and” is of significance. That is because justification of the pleaded imputation can only be proved if the deafness element is also proved, which it is not. Further, the only attempt to prove the ravages of age element of the imputation was to raise Mr Murphy’s concern about attending an in-person hearing of the Mould proceeding in April 2020 (at the commencement of the lockdown). This does not assist News or Ms Sharp because I accept Mr Murphy’s evidence that he would have appeared in court if he wanted and was allowed to do so: T162.28–39. As he correctly submits, Mr Murphy was in no different position to any other person in a COVID risk category – which includes a substantial number of solicitors, barristers and judges. One would not say that all such persons were “kept” from appearing in court (during part but not all of 2020) by the “ravages of age”.

75 There was some evidence as to Mr Murphy having a heart condition (described as atrial fibrillation or advanced heart disease). But the evidence is that he has had this condition since 1989 and it has not kept him from appearing in court.

76 For the above reasons, the defence must be rejected, which requires me to turn to the issue of relief.

Principles and Preliminary Observations

77 The damages sought by Mr Murphy are for non-economic loss comprising general damages (damages for injury to reputation and hurt to feelings) and, if found to be relevant, aggravated damages (damages for non-economic loss, which are said to have been increased by some illegitimate conduct of News and Ms Sharp).

78 The relevant principles were not in dispute, and the following explanation is taken from my recent judgment in Stead (at [229]–[230] and [238]).

79 The award of damages is governed by the provisions of Pt 4 Div 3 of the Act. By s 34 of the Act, the Court is required “to ensure that there is an appropriate and rational relationship” between the harm sustained and the amount of damages awarded. Further, by reason of the operation of s 35(1) of the Act and by declaration of the Minister pursuant to s 35(3), the maximum amount of damages for non-economic loss that may be awarded – the so-called “cap” – is currently $421,000. This cap may only be exceeded if the Court is satisfied that the circumstances of the publication of the defamatory matter are such as to warrant an award of aggravated damages: s 35(2).

80 In considering this appropriate and rational relationship, it is necessary to bear in mind that reputation is not a commodity having a market value and because the available remedy is damages, courts can and must have regard to what is allowed as damages for other kinds of non-economic injury: see Rogers v Nationwide News Pty Ltd [2003] HCA 522; (2003) 216 CLR 327 (at 349–51 [66]–[70] per Hayne J). Because the only measure or yardstick against which the required relationship may be measured are decisions placing a value by way of an award of damages to harm to reputation (and awards of damages for other forms of non-economic loss occasioned by other types of wrongs), there is a need to have some regard to “comparables”. This not only allows the Court to fix upon a sum which reflects the necessary statutory relationship, but serves the allied purpose of providing some consistency in damages between closely comparable cases.

81 The three purposes of an award are: (a) consolation for the personal distress and hurt caused by the publication; (b) reparation for the harm done to the person’s reputation; and (3) vindication of reputation. The assessment is an intuitive, evaluative process “at large”, but is subject to the provisions of Pt 4 Div 3 of the Act.

82 I will deal with the evidence and my findings relevant to general damages under the following headings: (a) hurt to feelings; (b) Mr Murphy’s reputation; (c) the nature and gravity of Imputation D; and (d) the extent of publication.

Findings Relevant to General Damages

83 Mr Murphy is a 72 year old solicitor, who has been practicing for 49 years. He is not a man wracked by self-doubt or vexed by a lack of confidence in his ability as a lawyer.

84 He gave evidence that when he was informed about the article, he was immediately shocked and he is still upset at the untruths published about him – including in the internet article (which remains online): Murphy 1 (at [25]). The fact that the internet article remains online makes Mr Murphy feel like he is “drowning in lies”: T75.18–20.

85 He gave evidence that he fears that his position in the legal profession has been destroyed by an article that described “a person who was not who I am”: Murphy 1 (at [32]). Particular emphasis was placed on his evidence that nothing had upset him more in his legal career: Murphy 1 (at [41]). He stated (Murphy 1 (at [32])) that:

I am not easily perturbed. I have lived with the emotions of clients and their families since 1970 and tried to calm and console the suffering they endured. However, this article hit an emotional vulnerability in an area where I could not conceive of such a blow occurring. It has caused me continuing sleeplessness and stress and still does. I had always thought my childhood inoculated me to endure the behaviour of others but for once I apply the word “traumatised” to the impact this article had.

(Mr Murphy’s emphasis).

86 Mr Murphy further said that as a boy he had grown up with disabled family members, and the fact someone had selected his deafness as “an axe for [his] career” was particularly upsetting: T70.44–T71.8 and T73.17–9.

87 In these circumstances, Mr Murphy is, and remains, worried that a person in need of a criminal solicitor will refrain from doing so because of the false allegations (Murphy 1 (at [40])) and that (at T76.20–2):

I feel very, very bad about it, and very angry still, as I sit here at this moment, and I don’t know how I will ever wash it away, because I have the sort of mind that focuses.

88 He said he has also been disturbed by the extent of publication. He gave evidence he was upset that a practitioner of the stature of Mr Boulten had read the article: Murphy 1 (at [34(b)]). Similarly, he said he has become upset on each occasion that he has discussed the matter with Mr Houda, a former employee: Murphy 1 (at [34(c)]). He also asserted that he had been upset by a relatively random member of the public approaching him about the article: Murphy 1 (at [34(h)]).

89 Consistently with Mr Murphy being upset, Mr Kalantzis saw him very shortly after he became aware of the article. He gave evidence that Mr Murphy was “quite distressed”, and upset about “the connotation that he’s somehow past his prime and that he can’t do his job”: T203.27–36.

90 Mr Murphy is a proud man. Indeed, he is a self-described “robust alpha male”: T169.24–5. Far from uniquely, I suspect he feels a general sense of disquiet arising from the inexorable march of time. His hearing loss understandably bothers him such that any mention of it in the media, however benign, would disturb his equilibrium. Like most people, he would also have been upset about the publication of details of the breakdown of his marriage. But what matters for present purposes, assessing the evidence as a whole, is that Mr Murphy was hurt and angry about the article and took particular offence at the article conveying the wrongheaded notion that he suffered an inability to appear in court. Having formed this impression, I do consider that some of the evidence he gave as to the extent of his subjective hurt was a tad exaggerated. The evidence that the article affected him as profoundly as he asserted did not become more compelling by the way Mr Murphy advocated for his own cause; nor did it get more persuasive upon repetition.

91 It was not, of course, necessary for Mr Murphy to prove good reputation as it is assumed in his favour; but notwithstanding News and Ms Sharp did not put reputation in issue, evidence was adduced.

92 That evidence establishes that Mr Murphy enjoyed a prior reputation as a well-known criminal defence solicitor who has acted for many high profile clients. This reputation has allowed him to become the “rainmaker” for his firm, with clients engaging his firm because of his reputation.

93 A highly experienced leader of the New South Wales Bar, Mr Boulten, gave the following evidence in his affidavit affirmed 29 January 2021 (at [15]), which I accept:

[Mr] Murphy has, for many years, had a reputation as one of Sydney’s leading criminal lawyers. His firm is a major criminal law firm, both in the sense of the number of cases that the firm undertakes and the significance of the issues involved in many of those cases. Prior to publication of the [article], Mr Murphy personally had a reputation as a skilful and savvy legal adviser to people accused of the whole range of criminal offences and he was known to be an effective criminal lawyer who often succeeds on his clients’ behalf.

94 Other witnesses (Mr Deirmendjian, an artist, and Mr Houda, another criminal defence solicitor) gave evidence consistent with that of Mr Boulten.

95 Mr Kalantzis, a fellow solicitor (being a witness called by News and Ms Sharp), explained that he had known Mr Murphy for 15 or 16 years, saw him five to six times a week, and that he knew Mr Murphy’s reputation as “an astute, dedicated, fearless advocate and, also, a very loyal and generous man”: T201.35–7 and T202.13–4. Mr Kalantzis told the Court that whenever his practice was approached by a client with a criminal matter, he would refer that client to Mr Murphy because he “trust[ed] Mr Murphy and his team to do the best job possible”: T202.20–5.

96 I find Mr Murphy had a widely known reputation as a leading and effective criminal solicitor.

The Nature and Gravity of Imputation D

97 I have already explained why I think Imputation D was conveyed and, in doing so, have touched upon its nature. To convey that a leading criminal solicitor was incapable of representing his client’s interests in court by reason of the ravages of age and associated deafness is an imputation of some seriousness. It reflected upon an important part of Mr Murphy’s professional life in an inaccurate and misleading way. It is possible to conceive easily of far worse defamations than saying a solicitor was rendered incapable of performing an important part of his function by reason of factors outside the solicitor’s control. The article did not suggest Mr Murphy was incompetent (in the sense of being negligent or lacking professional skill); nor did it suggest any character flaw or moral turpitude. But notwithstanding this, it is a far from trivial thing to convey about a person such as Mr Murphy.

98 Attached to these reasons is Schedule C. This sets out the uncontested facts concerning the extent of the publication of both the print article and the internet article. It demonstrates that publication was very extensive.

99 A bowdlerised version of the internet article remains accessible.

Findings Relevant to Aggravated Damages

100 The nature of defamation, formalism and the accumulated lore of defamation practice has detached this area of the law from the mainstream of the law of torts in a number of respects. One aspect where this is evident is the laser-like focus on seeking aggravated damages. The reason is obvious and has already been touched upon: the statutory cap of damages can be exceeded if the Court is satisfied that the circumstances of the publication are such as to call for aggravated damages: s 35(2).

101 At the risk of stating the obvious, it is useful to start with some fundamentals: (a) aggravated compensatory damages do not constitute a separate head of damage but involve an increase in compensatory damages as a result of conduct by the wrongdoer increasing the harm suffered; (b) in defamation, they may be awarded by way of compensation for injury resulting from the circumstances and manner of a respondent publisher’s wrongdoing but a respondent’s conduct after publication may also be relevantly taken into account as improperly aggravating injury done to the applicant; and (c) they can only be awarded where the relevant conduct meets the threshold of being unjustified, improper or lacking bona fides.

102 Mr Murphy relies upon no less that thirteen matters which can be broken down as between the circumstances of publication and post-publication conduct. As to the former, Mr Murphy relies upon the following circumstances:

(1) the failure to make proper inquiries or investigate prior to publication;

(2) the promotion of the matters complained of on social media to boost publication (Murphy 1 (at [37]));

(3) the republication of the internet article by News on the websites of its interstate newspapers (Murphy 2 (at [8]));

(4) the motivation of Ms Sharp to seek retribution for earlier proceedings brought by Mr Murphy (Murphy 1 (at [36])); this was alleged to be malicious and improper;

(5) the presentation of the matters complained of in an over sensationalised manner indicating an intent to injure Mr Murphy;

(6) the failure of News and Ms Sharp to ever respond to, or act upon, the letter of demand (Murphy 1 (at [39])); and

(7) the continued publication online.

103 Additionally, the following post-publication matters are relied upon:

(8) the denial of publication by Ms Sharp (even during the trial when a further amended defence was filed) despite admitting to authoring almost the entirety of the article;

(9) the maintenance of a so-called Hore-Lacy defence seeking to prove an unpleaded defamatory imputation;

(10) the maintenance of the justification defence despite the adoption of the referee reports and it being self-evidently hopeless;

(11) the failure to apologise;

(12) the conduct of Ms Sharp in publishing the allegations in circumstances where, it can be inferred from drafts of the article, that the opinion of Ms Sharp was contrary to, or inconsistent with, the allegations made about Mr Murphy;

(13) the affidavit of Marlia Saunders affirmed 18 March 2020, that deposes to the fact that the internet article (and the various instances of republication on other websites controlled by News) was amended on 9 March 2021; relevantly, the revisions remove any reference to the “critical paragraph” ([10] of the print article and [12] in the internet article); in particular, the original version was: “Murphy, who will be 72 this month, continues to battle the ravages of age and with it the associated deafness that has kept him from representing his famous clients in court during the past year”; whereas the revised version now reads: “Murphy, who will be 72 this month, continues to manage matters for his firm’s famous clients, but hasn’t been seen to represent them in court as much in recent times”; it is said that this revision constitutes an admission by News which is aggravating in two respects: (a) delay; and (b) the persistence with the justification defence which was said to be “in many respects indistinguishable from an exercise in disability shaming” and, in the face of the effective admission as to the defamatory nature of the article, “is baffling”.

104 I accept that Mr Murphy gave evidence that each of these circumstances aggravated his subjective hurt. But this aspect of Mr Murphy’s claim can be resolved even without determining whether that evidence can be accepted in all respects. There are two overriding difficulties with the thirteen circumstances relied upon by Mr Murphy: first, in significant respects, Mr Murphy overstates the significance of the conduct that he relies upon (or mischaracterises an ordinary incident of contested litigation as something more); and secondly, none of the conduct, properly analysed, reaches the requisite level of being conduct which was unjustified, improper or lacking in bona fides.

105 Taking the circumstances in turn, I find as follows:

(1) As to the failure to make proper inquiries, there was nothing unjustifiable, improper or lacking in bona fides in Ms Sharp not undertaking further investigation prior to publication; the article was inaccurate in an important and material sense; but not every such mistake is relevantly unjustified or improper.

(2) As to publicising the article on social media or “interstate” websites, this conduct, by itself, is not improper nor unjustifiable, it is an ordinary incident of the way in which newspapers seek to publicise published material.

(3) As to the motivations of Ms Sharp, I am not satisfied in accordance with s 140(1) of the Evidence Act that Ms Sharp was motivated by any malicious or improper intention as submitted. A deliberately unattractive photo of Mr Murphy was selected and the article publicised aspects of Mr Murphy’s life which it is difficult to see had any real public interest. Among other things, it was an unpleasant and invasive article. But despite this, a party bearing the onus will not succeed unless the whole of the evidence establishes a reasonable satisfaction on the preponderance of probabilities. I am a long way short of having a reasonable basis for a conclusion affirmatively drawn that Ms Sharp was motivated as alleged. As it happens, to the extent that there is any real evidence of motivation, it tends to point in a different direction: the initial versions of the article were more anodyne. In the absence of any other evidence, this seems to be arguably inconsistent with the notion that the author was motivated by some prior malicious intent.

(4) As to the notion that the article was “over-sensationalised”, although the article is an appropriate target of the criticism I have made of it, it does not present as being very different from articles of a similar nature published in tabloid newspapers; it would be going too far to regard its manner of presentation as relevantly improper.

(5) The failure to respond to the letter of demand does not, in and of itself, provide a circumstance which is of a character to warrant an award of aggravated damages; News and Ms Sharp took the view, which was not irrational, that the article could arguably be defensible. In this regard, there was no suggestion that the defence was pleaded improperly (the maintenance of the defence will be considered separately below).

(6) As to the denial of publication, this always seemed to me to be a tempest in a teapot. It is unclear as to why Ms Sharp denied that she was a publisher, save as to provide some specificity as to those parts of the article for which she was directly responsible and those parts that were a product of others. It may be accepted that this did not address the legal question of publication (and no submission was persisted at the trial in opposition to the substantive allegation of publication). Although the pleading was somewhat curious in this respect, it is nowhere near conduct of the character so as to justify aggravated damages.

(7) Much the same thing could be said about the so called “Hore-Lacy defence”. As I have explained above, although there is no separate Hore-Lacy defence, this does not necessarily mean that in certain circumstances the pleading of variant imputations cannot serve to provide procedural fairness as to the way in which a respondent is to defend allegations as to meaning. Although the pleading of a variant imputation may have been unnecessary in the circumstances of this case, it is again putting the matter far too highly to suggest that this provides any conceivable basis for an award of aggravated damages.

(8) Although it became weak, the maintenance of the justification defence was not unjustifiable, improper or lacking in bona fides. Notwithstanding the findings that were made upon adoption of the reports of the referee, there was still a good faith dispute as to Mr Murphy’s ability to hear in court, which required consideration of the evidence given by him (and others) as to the wearing of hearing aids and Roger devices. The reality is that without the use of these devices, Mr Murphy could not appear in court (as was reflected in the agreed fact). Although I accept that parts of the cross-examination of Mr Murphy were unnecessary (by reason of the findings made upon adoption of the reports of the referee), the cross-examination was conducted professionally and inoffensively. In all the circumstances, I do not consider the maintenance of the justification defence to have been conducted improperly and hence it does not ground an award of aggravated damages.

(9) I do not consider the failure to apologise was improper or lacking in bona fides. It is difficult to understand why a failure to apologise would have this character in circumstances where a justification defence was being pursued and there was a legitimate argument including as to the meanings pleaded. There was nothing about this conduct which was relevantly improper.

(10) As to the conduct of Ms Sharp, I have already explained above that I do not think that it has been proved that she was behaving in some form of malicious manner. To the extent relevant, it is most likely that during the preparation of the articles Ms Sharp came across further information, and that the article was changed into its final form (meaning, unwisely, it conveyed Imputation D). This conduct does not in and of itself suggest improper or unjustifiable conduct of the type necessary to ground an award of aggravated damages.

(11) As to the last matter relied upon, News and Ms Sharp might be forgiven for thinking that they are damned if they do and damned if they don’t. On the one hand they are criticised for continuing the publication of an article said to convey a defamatory imputation. On the other hand they are criticised for taking steps to remove the most objectionable part of the article. Although the delay in removing the article in its original form is relevant, it is not surprising that during the course of the proceeding it became increasingly apparent that the justification defence was weaker than may have first been anticipated. These sorts of vicissitudes are hardly novel in contested litigation and in circumstances where the conduct of the litigation was otherwise conducted appropriately, it does not constitute conduct of a character as suggested by Mr Murphy.

106 It follows that no circumstances are present (either individually or in a combination) such as to mean that any compensatory award made to Mr Murphy should relate to aggravated damages.

107 Although I have explained the principles relevant to the impressionistic process of fixing upon an appropriate solatium for hurt to feelings, damage to reputation and vindication in one lump sum, in the present case, it is worth stressing two aspects which have particular importance.

108 This is an example of a case where the damage to reputation has occurred in circumstances where a person’s professional standing is affected (although there is no reflection on the integrity of Mr Murphy).

109 Having said this, the appropriate and rational relationship between the harm sustained and the amount of damages awarded should reflect the widespread publication, the fact that the law places a high value upon reputation, that Mr Murphy is entitled to vindication of reputation, and that he did experience a significant degree of subjective hurt to feelings.

110 It is difficult to identify comparables, but in considering the appropriate and rational relationship between the harm and the amount, I have had regard to the general tenor of awards as part of the process of synthesis of the relevant matters to which I have referred. Weighing up all the factors, I have concluded that the appropriate amount for non-economic loss comprising general damages is an award of $110,000.

111 There were no submissions made concerning interest on any award of damages and the matter has been brought on for hearing very quickly. If relevant, when I deal with the entry of final orders, I will hear any submissions relating to interest.

112 Given the recent developments in the amendment of the internet article, my preliminary view is that this case does not seem to me to be one where any relief in the form of an injunction should be granted. Having said this, if Mr Murphy persists in his application for this relief then I will hear oral submissions at the time I make final orders.