FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

McCallum, in the Matter of Re Holdco Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) (No 2) [2021] FCA 377

File number: | VID 285 of 2020 |

Judgment of: | O'BRYAN J |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords: | BANKRUPTCY AND INSOLVENCY – where administrators have disposed of property used or in the possession of companies under administration by way of sale pursuant to orders of the Court made under s 44C(2)(c) of the Corporations Act 2010 (Cth) – where the proceeds of sale have been retained to meet the claims of persons who assert ownership or security interests in the property sold – where the administrators claim their costs out of the retained proceeds of sale – where a number of interested parties have made claims to ownership or security interests in the property sold – determination of the relative value of the property sold by administrators – consideration of different valuation methodologies proposed by expert valuers – proper approach to valuation – whether unaccepted offers to purchase an asset are admissible as direct evidence of market value of that asset INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY – whether works done pursuant to technology and marketing services agreements created copyright works – whether the copyright works were sold as part of the property used or in the possession of companies under administration so as to generate some of the sale proceeds – whether relevant services agreements contained a retention of title clause which was a security interest within the meaning of section 12 of the Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (Cth) – whether ownership of copyright works, the subject of the retention of title clause, vested in grantor of the interest EQUITY – whether a vendor’s equitable lien arose under a share purchase agreement which provided for the payment of an initial purchase price and the remainder of the purchase price was deferred to a later date – where the share purchase agreement was subsequently varied – whether variations to the share purchase agreement evince an intention to exclude, abandon or waive the lien |

Legislation: | Copyright Act 1958 (Cth) ss 10, 32(2), 35(2), 35(6), 36(1), 47AB, 196, 197 Corporations Act 2010 (Cth) ss 429(2), 442C, 436A, 436C, 446A, 447A, 513C, 556(1), 1305 Corporations Act 2010 (Cth) Schedule 2 (Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations) para 60-10(1)(c) Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) ss 59, 69 Goods Act 1958 (Vic) s 6 Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (Cth) ss 3, 12, 19(5), 21, 267 Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) r 40.02(b) |

Cases cited: | 674921 BC Ltd v Advanced Wing Technologies Corp (2006) 9 PPSA (d) 43; 263 DLR (4th) 290 Albert Life Assurance Co, Ex parte Western Life Assurance Society (1870) LR 11 Eq 164 Aluminium Industrie Vaassen BV v Romalpa Aluminium Ltd [1976] 1 WLR 676 Armour v Thyssen Edelstahlwerke AG [1991] 2 AC 339 Auxil Pty Ltd v Terranova [2009] WASCA 163; 260 ALR 164 Baiyai Pty Ltd v Guy [2009] NSWCA 65 Barclays Bank v Estates & Commercial Ltd [1997] 1 WLR 415 Barker v Cox (1876) 4 Ch D 464 Beale v Trinkler [2008] NSWSC 347 Benzlaw & Associates Pty Ltd v Medi-Aid Centre Foundation Ltd [2007] QSC 233 BP Refinery (Westernport) Pty Ltd v Shire of Hastings (1994) 180 CLR 266 Caruana v Port Macquarie-Hastings Council [2007] NSWLEC 109; 210 LGERA 1 Commonwealth of Australia v Amann Aviation Pty Ltd (1991) 174 CLR 64 Cordelia Holdings Pty Ltd v Newkey Investments Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 48 Crawley v Short [2009] NSWCA 410; 262 ALR 654 Dura (Australia) Constructions Pty Ltd v Hue Boutique Living Pty Ltd (2014) 49 VR 86 Elderly Citizens Homes of SA Inc v Balnaves (1998) 72 SASR 210 ET-China.com International Holdings v Cheung [2019] NSWSC 1874; 142 ACSR 121 Evans v McLean (No 2) [1987] WAR 110; (1985) 9 ACLR 796 Goold v Commonwealth (1993) 42 FCR 51 Hannam v Lamney (1926) 43 WN (NSW) 68 Hewett v Court (1983) 149 CLR 639 Jafari v 23 Developments Pty Ltd [2018] VSC 404 Langen & Wind Ltd v Bell [1972] Ch 685 Mackreth v Symmons (1808) 33 ER 778 McCallum, in the Matter of Re Holdco Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) [2020] FCA 666; 145 ACSR 243 McDonald v Federal Commissioner of Land Tax (1915) 20 CLR 231 MMAL Rentals Pty Ltd v Bruning (2004) 63 NSWLR 167 Re Maiden Civil (P&E) Pty Ltd; Albarran v Queensland Excavation Services Pty Ltd [2013] NSWSC 852; 277 FLR 337 Reliance Finance Corporation Pty Ltd v Heid [1982] 1 NSWLR 466 Rodney Jane Racing Pty Ltd v Monster Energy Company [2019] FCA 923; 370 ALR 140 State Government Insurance Office (Qld) v Rees (1979) 144 CLR 549 Wossidlo v Catt (1934) 52 CLR 301 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | Victoria |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | General and Personal Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | 325 |

27-29 January; 1, 4 February 2021 | |

Counsel for the Plaintiff: | D F McAloon |

Solicitor for the Plaintiff: | Gilbert + Tobin |

Counsel for the First Interested Party: | J Slattery QC with L Currie |

Solicitor for the First Interested Party: | Clayton Utz |

Counsel for the Second and Third Interested Parties: | H N G Austin QC with A C Roe |

Solicitor for the Second and Third Interested Parties: | Ashurst |

Counsel for the Fourth Interested Party: | O Bigos QC |

Solicitor for the Fourth Interested Party: | Minter Ellison |

Counsel for the Fifth and Sixth Interested Parties: | P Crutchfield QC with B McLachlan |

Solicitor for the Fifth and Sixth Interested Parties: | Arnold Bloch Leibler |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The claim made by the plaintiffs in respect of items 11 and 12 of the plaintiffs' amended notice of claim is dismissed.

2. The claim made by the first interested party (Westpac) in the proceeding is upheld to the extent determined in the accompanying reasons of the Court, namely that Westpac is entitled to a proportionate share of the balance of the Retained Proceeds (after payment of all other amounts pursuant to previous orders of the Court) of 65.5%.

3. The claim made by the second and third interested parties (Sargon Capital and Taiping) in the proceeding is upheld to the extent determined in the accompanying reasons of the Court, namely that Sargon Capital is entitled to a proportionate share of the balance of the Retained Proceeds (after payment of all other amounts pursuant to previous orders of the Court) of 13.1%.

4. The claims made by the fourth interested party (GrowthOps) and the fifth and sixth interested parties (Diversa and OneVue) in the proceeding are dismissed.

5. The plaintiffs, Westpac, and Sargon Capital and Taiping have liberty to apply to the Court for:

(a) a final order that gives effect to orders 1 to 4 herein by specifying the dollar amounts to be paid to each of them from the Retained Proceeds;

(b) any other order consequential upon the accompanying reasons of the Court.

6. By 19 May 2021, any party (costs applicant) that seeks an order for the payment of the whole or part of its costs of the proceeding by another party (costs respondent) is to file and serve any evidence relied on and a written submission of no more than 5 pages which specifies the amount claimed in a lump sum.

7. By 16 June 2021, any costs respondent is to file and serve any evidence relied on and a written submission of no more than 5 pages in response.

8. Subject to further order, any costs awarded in the proceeding will be awarded in a lump sum pursuant to rule 40.02(b) of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

9. The Court will determine the award of costs on the papers unless any party gives notice in its written submission that it seeks a hearing on the question of costs.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SCHEDULE OF INTERESTED PARTIES

First Interested Party | Westpac Banking Corporation (ACN 007 457 141) |

Second Interested Party | Sargon Capital Pty Ltd (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (In Liquidation) (ACN 608 799 873) |

Third Interested Party | Taiping Trustees Limited |

Fourth Interested Party | GrowthOps Services Pty Ltd (ACN 626 208 777) |

Fifth Interested Party | Diversa Pty Ltd (ACN 079 201 835) |

Sixth Interested Party | OneVue Holdings Limited (ACN 108 221 870) |

A. INTRODUCTION | [1] |

[22] | |

[27] | |

[30] | |

[49] | |

[51] | |

[54] | |

G.1 The claims to ownership of intellectual property assets made by or on behalf of Sargon Capital and Sargon Services | [54] |

[54] | |

[60] | |

[74] | |

[80] | |

[84] | |

[84] | |

[85] | |

[107] | |

[112] | |

[140] | |

[141] | |

[154] | |

[158] | |

[181] | |

[181] | |

[190] | |

[197] | |

[198] | |

[210] | |

[219] | |

[226] | |

[230] | |

[233] | |

[253] | |

[254] | |

[257] | |

[277] | |

Conclusion with respect to the fair market value of the BSA assets | [279] |

[281] | |

[284] | |

[287] | |

[303] | |

[309] | |

[312] | |

[313] | |

[316] | |

Conclusion on the fair market value of the Sale Subsidiaries | [318] |

[320] | |

[321] |

O’BRYAN J:

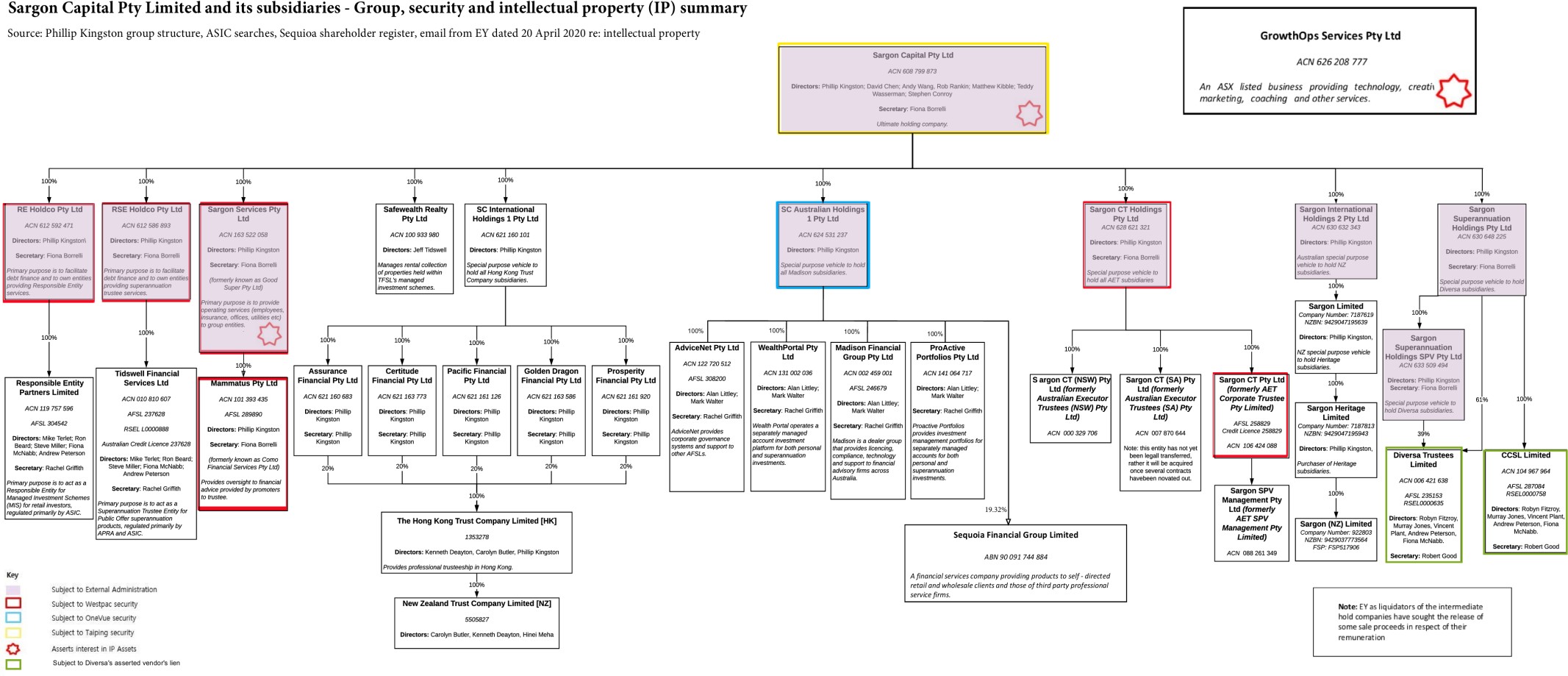

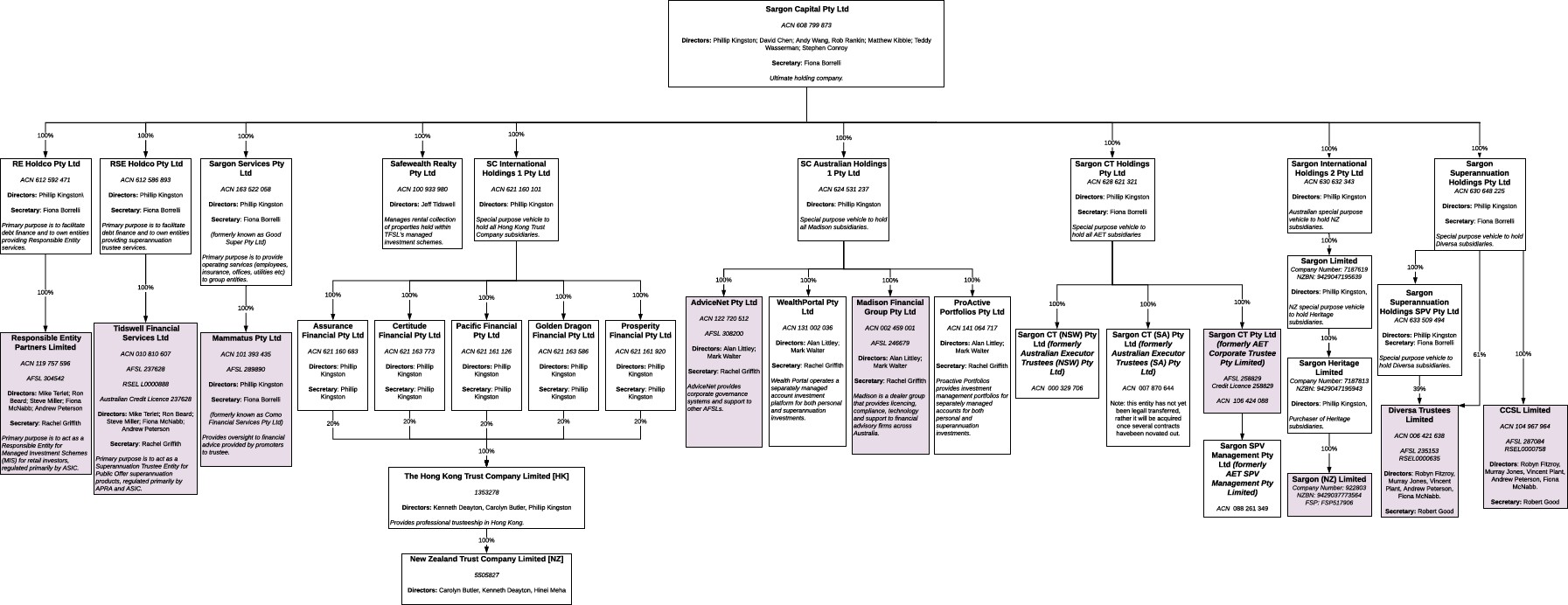

1 The Sargon Group was a corporate group consisting of approximately 39 companies which conducted a series of financial planning, corporate trustee, responsible entity, superannuation and related financial services businesses. Sargon Capital Pty Ltd (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (In Liquidation) ACN 608 799 873 (Sargon Capital) was at all relevant times the ultimate holding company of the Sargon Group. The corporate structure of the Sargon Group as at 4 May 2020, as relevant to these proceedings, is set out in Appendix A to these reasons (which has been extracted from Annexure A to the Joint Statement of Agreed Facts tendered by the parties and which is reproduced below).

2 External administration of Sargon Group entities commenced on 29 January 2020 with the appointment of Mr Shaun Fraser and Mr Jason Preston of McGrathNicol as joint and several receivers and managers of Sargon Capital by secured creditor Taiping Trustees Limited (Taiping). Subsequently, on 8 March 2020, Joseph Hayes and Andrew McCabe of Wexted Advisors were appointed to act as administrators of Sargon Capital pursuant to s 436C of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) and, on 8 April 2020, Messrs Hayes and McCabe were appointed joint and several liquidators of Sargon Capital.

3 The plaintiffs in this proceeding, Stewart McCallum and Adam Nikitins of Ernst & Young, were appointed as joint and several voluntary administrators of the following Sargon Group entities on 4 February 2020:

(a) Re Holdco Pty Ltd ACN 612 592 471 (Re Holdco);

(b) RSE Holdco Pty Ltd ACN 612 586 893 (RSE Holdco);

(c) Sargon Services Pty Ltd ACN 163 522 058 (Sargon Services);

(d) Sargon CT Holdings Pty Ltd ACN 628 621 321 (Sargon CT Holdings);

(e) SC International Holdings 2 Pty Ltd ACN 630 632 343 (SCIH2);

(f) Sargon Superannuation Holdings Pty Ltd ACN 630 648 225 (Sargon SH); and

(g) Sargon Superannuation Holdings SPV Pty Ltd ACN 633 509 494 (Sargon SPV),

(which I will refer to collectively as the Sargon VA Entities).

4 The plaintiffs were also appointed as joint and several voluntary administrators of SC Australian Holdings 1 Pty Ltd (SCAH1). However, on 4 February 2020, Mr Daniel Walley and Mr Christopher Hill of PricewaterhouseCoopers were appointed as joint and several receivers and managers of SCAH1. As a result, the plaintiffs did not seek to deal with SCAH1 and it is not directly relevant to this proceeding.

5 Subsequently, on 14 May 2020, the plaintiffs were appointed as liquidators of the Sargon VA Entities.

6 Between the date of their appointment as administrators and the end of April 2020, the plaintiffs negotiated a sale of certain of the businesses and assets of the Sargon VA Entities to the Cloverhill Group (Cloverhill Sale). The sale was complicated by disputes over the ownership of, and security interests held over, certain of the assets to be sold. As a result of those disputes, on 30 April 2020 the plaintiffs sought urgent relief from the Court under ss 442C and 447A of the Corporations Act. Specifically, under s 442C(2)(c), the plaintiffs sought leave of the Court to dispose of:

(a) all intellectual property used or in the possession of Sargon Services (including, but not limited to, intellectual property in relation to the software systems known as "Arcadia", "Sentinel", "Metropolis", "API Impact" and "Sargon Pay", and in relation to the trademarks and domain names set out in the annexure to the originating process); and

(b) such property of the Sargon VA Entities as is (or may be) subject to a security interest (including under the Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (Cth)),

in connection with, and as part of, the sale of the property of the Sargon VA Entities pursuant to the Cloverhill Sale. The plaintiffs also sought orders as to the treatment of the proceeds of the sale for the purposes of satisfying the requirement in s 442C(3) to make arrangements for the adequate protection of the interests of the owners of the intellectual property and the security interest holders. Under s 447A of the Corporations Act, the plaintiffs sought orders as to how Part 5.3A of the Corporations Act was to operate in relation to the proceeds of sale so as to preserve the rights of the owners of the intellectual property and the security interest holders as between themselves.

7 On 1 May 2020, I made orders under ss 442C and 447A to facilitate the Cloverhill Sale as sought by the plaintiffs. On 19 May 2020, I published reasons for making those orders: McCallum, in the Matter of Re Holdco Pty Ltd (Administrators Appointed) [2020] FCA 666; 145 ACSR 243 (Re Holdco).

8 One of the orders made at that time was an order that, upon the completion of the Cloverhill Sale, all proceeds of the Cloverhill Sale (excluding the sum of $400,000 representing consideration for the sale of ancillary assets belonging to the "Decimal Entities") (Retained Proceeds) were to be deposited into a separate controlled, interest-bearing monies account to be maintained by the plaintiffs and which could only be accessed or disbursed by the plaintiffs in accordance with an order or direction of the Court. The Retained Proceeds were to be retained for the purpose of meeting claims that any party had in respect of the property of the Sargon VA Entities directly or indirectly sold pursuant to the Cloverhill Sale including (but not limited to):

(a) any claim by the plaintiffs to recover from the Retained Proceeds amounts in respect of remuneration, fees and expenses properly incurred in their capacity as voluntary administrators of the Sargon VA Entities;

(b) claims of the first interested party, Westpac Banking Corporation (Westpac), including its rights under security interests registered on the Personal Property Securities Register prior to completion of the Cloverhill Sale;

(c) any claim that the second and third interested parties, Sargon Capital and Taiping, and/or the fourth interested party, GrowthOps Services Pty Ltd (GrowthOps), may have to recover from the Retained Proceeds amounts by reference to a claimed interest in, or in respect of, the intellectual property that was sold; and

(d) any claim that the fifth and sixth interested parties, Diversa Pty Ltd (Diversa) and its parent company OneVue Holdings Limited (OneVue), may have pursuant to any equitable lien or other security interest over the shares held by Sargon SH and Sargon SPV in Diversa Trustees Limited ACN 006 421 638 (DTL) and CCSL Limited ACN 104 967 964 (CCSL).

9 This proceeding concerns the resolution of the above claims. The task being undertaken by the Court is a task required by the orders made on 1 May 2020 pursuant to s 442C of the Corporations Act, which is to apply the Retained Proceeds for the purpose of meeting claims that any party has as owners of, or security holders in, the property that was sold. In meeting claims, the Court is carrying into effect the requirement of s 442C(3) to protect adequately the interests of such parties (to the extent the Court has found that they are owners or security holders in respect of the property that was sold).

10 The method of apportioning the sale proceeds across the various claims of the plaintiffs and interested parties was described in Re Holdco as follows (at [67]):

Under the proposed arrangements, the retained sale proceeds would not simply be apportioned across claimants according to the amount of their respective claims. Rather, the retained proceeds would be apportioned across the different asset classes in respect of which parties claim interests by reference to the relative value of each asset class to the sale proceeds. Once that allocation has been done, all persons who have claims in respect of each asset class will have that claim determined and receive their entitlement to the apportioned sale proceeds. The properly incurred expenses of the administrators will be deducted rateably across the asset classes, and the reasonableness of the expenses will also need to be established.

11 In this proceeding, no party sought to contradict or vary that method of apportioning the sale proceeds. The relative values of different asset classes will ultimately be expressed as a percentage, so that the monetary entitlements of successful claimants can be calculated by applying the relevant percentage to the balance of the Retained Proceeds after deducting the plaintiffs’ properly incurred expenses. The parties agreed that that method would give effect to the requirement stipulated in s 442C(3) to protect adequately the interests of each secured party. The dispute between the interested parties concerned the existence of ownership or security interests in different asset classes and the method by which the relative value of different asset classes should be determined.

12 The Cloverhill Sale was effected by the execution of a Business Sale Agreement dated 4 May 2020 (Business Sale Agreement) and separate Share Sale Agreements dated 4 May 2020 for the sale of all the shares in the following subsidiaries of the Sargon VA Entities:

(a) Responsible Entity Partners Ltd (REP);

(b) Tidswell Financial Services Ltd (Tidswell);

(c) Mammatus Pty Ltd (Mammatus);

(d) Sargon CT Pty Ltd (Sargon CT);

(e) Sargon CT (NSW) Pty Ltd (Sargon CT NSW);

(f) Sargon Limited (NZ) (Sargon NZ);

(g) CCSL; and

(h) DTL,

(which I will refer to collectively as the Sale Subsidiaries).

13 The purchasers were Pacific Infrastructure Services Pty Ltd and Pacific Infrastructure Holdings Pty Ltd (collectively, Pacific Infrastructure). The overall total consideration for the Cloverhill Sale (paid pursuant to the Business Sale Agreement and the Share Sale Agreements) was $29,600,000 (being the $30,000,000 gross proceeds less $400,000 payable to the Decimal entities).

14 On 15 May 2020, the plaintiffs and each of the interested parties filed and served notices of their claims to the Retained Proceeds in accordance with the orders of the Court made on 1 May 2020. On 18 December 2020 (as an annexure to their written submissions), the plaintiffs served an amended notice of claim.

15 In accordance with the orders made on 1 May 2020, various deductions have been made from the Retained Proceeds from time to time, including:

(a) $351,884 paid to the Australian Taxation Office pursuant to orders dated 4 August 2020;

(b) $19,470 paid to the mediator for conducting the mediation of the proceeding pursuant to orders dated 4 August 2020;

(c) $120,653.25 paid to the Victorian and New South Wales State Revenue Offices pursuant to orders dated 15 September 2020; and

(d) $38,219.79 paid to Intralinks, Inc pursuant to orders dated 16 December 2020;

(e) $14,492.84 paid to Gilbert + Tobin, solicitors to the plaintiffs, on account of disbursements pursuant to orders dated 16 March 2021;

(f) $8,205.00 paid to the Federal Court of Australia on account of setting down and hearing fees pursuant to orders dated 16 March 2021; and

(g) $3,625.57 paid to Gilbert + Tobin, solicitors to the plaintiffs, on account of disbursements pursuant to orders dated 19 April 2021.

16 On 27 August 2020, the plaintiffs filed an interlocutory application under paragraph 60-10(1)(c) of the Insolvency Practice Schedule (Corporations) (being Schedule 2 to the Corporations Act) seeking determination of the remuneration that the plaintiffs are entitled to receive for work performed in the voluntary administrations and liquidations of the Sargon VA Entities. That application was referred to a Registrar of the Federal Court for determination.

17 On 20 January 2021, I made an order by consent concerning the plaintiffs’ notice of claim in this proceeding, which resolved almost the entirety of the plaintiffs’ claim (other than items 11 and 12 of the plaintiffs' amended notice of claim). That order was as follows:

The following amounts may be withdrawn by the Plaintiffs from the Retained Proceeds (as defined in the orders made in this proceeding on 1 May 2020 (1 May 2020 Orders)) and applied in full and final satisfaction of any claim by the Plaintiffs to the Retained Proceeds for reimbursement of the Plaintiffs’ remuneration, costs and expenses including counsel fees (excluding any other costs and expenses, including counsel fees, of the Plaintiffs as agreed between the parties by consent or as approved by order of the Court to be paid from the Retained Proceeds):

(a) such amount, up to a maximum of $1,259,721.80, as is determined by the Federal Court of Australia pursuant to the interlocutory process filed by the Plaintiffs on 27 August 2020 on account of the Plaintiffs’ remuneration incurred in the voluntary administrations and liquidations of the Sargon VA Entities (as defined in the 1 May 2020 Orders);

(b) the amount of $336,904.70 on account of the remuneration incurred in connection with the voluntary administration of Sargon Services Pty Ltd (In Liquidation) as approved by the creditors at the reconvened second meeting of creditors on 14 May 2020 (Reconvened Second Meeting);

(c) the amount of $536,825.69 on account of the remuneration incurred in connection with the voluntary administration of Sargon CT Holdings Pty Ltd (In Liquidation) as approved by the creditors at the Reconvened Second Meeting; and

(d) the amount of $2,653,570.97 on account of the Plaintiffs’ reasonable costs and expenses incurred in the voluntary administrations and liquidations of the Sargon VA Entities.

18 The above consent order gives priority to the majority of the plaintiffs’ claim out of the Retained Proceeds. As stated above, after deducting the plaintiffs’ claim, the balance of the Retained Proceeds will be apportioned between the interested parties which are able to establish a claim to particular asset classes (by reason of an ownership or security interest) by reference to the relative value of that asset class (expressed as a percentage).

19 The conclusions I have reached are as follows:

(a) the claim made by the plaintiffs in respect of items 11 and 12 of the plaintiffs' amended notice of claim is dismissed;

(b) the claim made by Westpac is upheld and it is entitled to a proportionate share of the balance of the Retained Proceeds reflecting the relative value of the assets of Sargon Services sold pursuant to the Business Sale Agreement and the shares in REP, Tidswell, Mammatus, Sargon CT and Sargon CT NSW, which I have determined to be 65.5%;

(c) the claim made by Sargon Capital and Taiping is upheld and they are entitled to a proportionate share of the balance of the Retained Proceeds reflecting the relative value of the assets of Sargon Capital sold pursuant to the Business Sale Agreement which I have determined to be 13.1%; and

(d) the claims made by GrowthOps, and Diversa and OneVue, in the proceeding are dismissed.

20 For completeness, I have determined that the relative value of DTL and CCSL is 21.4% and the relative value of Sargon NZ is nil.

21 For the avoidance of doubt, the amounts payable to Westpac and Sargon Capital from the Retained Proceeds are to be calculated and paid only after the amounts due to the plaintiff have been paid in accordance with the order of the Court made on 20 January 2021 (including the final determination of amounts due in respect of paragraph 1(a) of that order).

22 The plaintiffs filed a claim on 15 May 2020 and served an amended notice of claim on 18 December 2020. As stated above, almost the entirety of the plaintiffs’ claim was resolved by the consent order made on 20 January 2021, including the plaintiffs’ claim for their reasonable remuneration, costs and expenses. The unresolved claim, being items 11 and 12 of the amended notice of claim, is a claim for pre-appointment priority employee entitlements owing by Sargon Services under ss 556(1)(e)-(h) of the Corporations Act. The plaintiffs contend that, by reason of s 561 of the Corporations Act, those entitlements are required to be met from that proportion of the Retained Proceeds that reflects the value of Sargon Services’ circulating assets that were sold pursuant to the Business Sale Agreement (and must be paid in priority to Westpac’s security interests over those circulating assets).

23 Westpac filed a claim on 15 May 2020. Westpac claims to be owed some $32,000,000 under loan facilities granted to Re Holdco, RSE Holdco and Sargon CT Holdings and facilities for bank guarantees to Sargon Services. Those facilities were secured by general security agreements over the assets of those entities and Mammatus. The Mammatus general security agreement was released on 4 May 2020, but the rights of Westpac as against the Retained Proceeds were preserved in relation to security over the assets of Mammatus due to paragraph 6 of the orders made on 1 May 2020. Westpac therefore claims that proportion of the Retained Proceeds that reflects the value of:

(a) the assets of Sargon Services sold pursuant to the Business Sale Agreement; and

(b) the shares in REP, Tidswell, Mammatus, Sargon CT and Sargon CT NSW,

up to the amounts owing to Westpac under each relevant facility.

24 Sargon Capital and Taiping filed a notice of claim on 15 May 2020. Sargon Capital claims an ownership interest in certain assets which were sold pursuant to the Business Sale Agreement comprising software, website, trade marks and domain names. Taiping has a registered security interest against Sargon Capital on the Personal Property Securities Register comprising a general security deed. Under that deed, Taiping holds a security interest over all of the present and after-acquired property of Sargon Capital including a charge over intellectual property. Sargon Capital and Taiping therefore claim that proportion of the Retained Proceeds that reflects the value of the intellectual property owned by Sargon Capital and sold pursuant to the Business Sale Agreement. As the interests of Sargon Capital and Taiping are aligned, references in these reasons to the interests and submissions of Sargon Capital should be understood as including Taiping.

25 GrowthOps filed a notice of claim on 15 May 2020. In the notice, GrowthOps claimed an interest in two categories of assets sold pursuant to the Business Sale Agreement. The first was an ownership interest in intellectual property created by GrowthOps under the Technology Master Services Agreement (having a commencement date of 1 July 2019) (Technology MSA) and the Master Services Agreement (Creative, Marketing, Coaching & Leadership) (having a commencement date of 2 September 2019) (Marketing MSA) and provided to Sargon Capital, but for which GrowthOps had not been paid (being an amount of $1,854,621.11 as at 13 May 2020 with costs and interest continuing to accrue in accordance with the terms of the Technology MSA and Marketing MSA). Such intellectual property is referred to in those agreements as the “Developed IP”. The second category was an interest, as licensor, of the royalty free licence of “GrowthOps Background IP” granted to Sargon Capital pursuant to the Technology MSA. The claim for the second category of asset was not pressed by GrowthOps at the hearing. GrowthOps therefore claims that proportion of the Retained Proceeds that reflects the value of the Developed IP sold pursuant to the Business Sale Agreement (up to the total amount owing under the Technology MSA and Marketing MSA).

26 Diversa filed a notice of claim on 15 May 2020. In the notice, Diversa claims a vendor's equitable lien over the shares in CCSL and DTL to the extent that it has not been paid the purchase price for its sale of those shares to Sargon SH and Sargon SPV pursuant to a Share Purchase Agreement dated 20 December 2018. The total purchase price under the Share Purchase Agreement (as varied) was $43 million, to be paid by way of an initial purchase price of $12 million and then a deferred purchase price of $31 million. The initial purchase price has been paid. The deferred purchase price, which became immediately payable on 3 February 2020 when administrators were appointed to Sargon SH and Sargon SPV, remains largely unpaid. Diversa has undertaken to limit its claim as a secured creditor to no more than $8 million of the proceeds of the Cloverhill Sale. Diversa therefore claims that proportion of the Retained Proceeds that reflects the value of the shares in CCSL and DTL up to $8 million. As the interests of Diversa and OneVue are aligned, references in these reasons to the interests and submissions of Diversa should be understood as including OneVue.

27 In accordance with orders made on 31 August 2020, the parties filed a joint statement of the questions to be determined by the Court on the notified claims. As these reasons address each of the questions as framed by the parties, it is appropriate to set out that statement in full:

JOINT STATEMENT OF QUESTIONS TO BE DETERMINED BY THE COURT

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 On 4 May 2020, certain property of the Sargon Group (but some of which is claimed to have been owned by GrowthOps), was sold to Pacific Infrastructure Services Pty Ltd and Pacific Infrastructure Holdings Pty Ltd (Cloverhill Sale) pursuant to orders made under section 442C of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

1.2 This document is filed in respect of paragraph 2(b) of the orders of the Federal Court of Australia made on 31 August 2020 which provided that the parties confer and seek to agree and file with the Court a joint statement of the questions to be determined on the Claims as defined in those orders.

1.3 In this document:

(a) Developed IP has the meaning in paragraphs 15 and 19 of the McMenamin Affidavit.

(b) McMenamin Affidavit means the affidavit of Craig McMenamin filed in this proceeding and dated 12 June 2020.

(c) Marketing MSA, Quarterly Growth Plans, Statements of Work, Systems and Technology MSA all have the same meaning as in the McMenamin Affidavit.

2. VALUATION DATE AND BASIS OF VALUATION

2.1 On what basis should:

(a) the shares; and

(b) the assets

sold under the Cloverhill Sale be valued; for example, a fair market value basis?

2.2 On what date should:

(a) the shares; and

(b) assets

sold under the Cloverhill Sale be valued?

3. OWNERSHIP OF ASSETS

Sargon Capital and Sargon Services

3.1 As at the date of the Cloverhill Sale (being 4 May 2020), did Sargon Capital Pty Ltd (Sargon Capital) or Sargon Services Pty Ltd (Sargon Services) own:

(a) the domain name, www.sargon.com;

(b) the business name, Good Super;

(c) the trademarks listed in items 1 to 7 of part A of schedule 8 of the Business Sale Agreement [being the agreement dated 4 May 2020 between Sargon Services, Pacific Infrastructure Services Pty Ltd, Stewart McCallum, Adam Nikitins and the entities listed in schedule 2 of that agreement];

(d) the domain names listed in items 8 to 14 and 17 to 32 of part B of schedule 8 of the Business Sale Agreement; and

(e) the domain names listed in items 15 and 16 and 33 to 35 of part B of schedule 8 of the Business Sale Agreement?

Other intellectual property

3.2 How should any value attributed to the "Sargon Trustee Cloud Software", as referred to in the expert reports of Jeff Hall, be divided between Sargon Capital, Sargon Services and GrowthOps?

3.3 How should any value attributed to the "Software technology", as referred to in the expert reports of Antony Samuel, be divided between Sargon Capital, Sargon Services and GrowthOps?

3.4 What part, if any, of the Additional IP comprises intellectual property rights in software that GrowthOps developed in relation to the following systems:

(a) Arcadia;

(b) Pay;

(c) Impact;

(d) Sentinel; and

(e) Metropolis,

and which it describes as Developed IP?

3.5 As at the date of the Cloverhill Sale (being 4 May 2020), was the Developed IP (or any part of it) owned by Sargon Capital, Sargon Services or GrowthOps?

3.6 Was the Developed IP sold as part of the Cloverhill Sale so as to generate part of the Retained Proceeds?

3.7 To the extent (if any) to which GrowthOps does not own the Developed IP, is it entitled to any compensation with respect to its claim that it has granted a licence in favour of Pacific Infrastructure Services Pty Ltd for the Background IP, as referred to in paragraph 35 of the McMenamin Affidavit?

3.8 If the answer to question 3.7 is yes, is GrowthOps' claim to compensation for the Background IP secured by any asset that was sold as part of the Cloverhill Sale?

Diversa

3.9 Does Diversa Pty Ltd have a vendor's equitable lien over the shares of CCSL Limited and Diversa Trustees Limited to the extent that it has not been paid the purchase price for the sale of those shares to Sargon Superannuation Holdings Pty Ltd and Sargon Superannuation Holdings SPV Pty Ltd?

4. VALUATION AND ATTRIBUTION

4.1 What is the proportion of the Retained Proceeds that should be attributed to each of:

(a) the shares in each of:

(i) the Responsible Entity Partners Limited;

(ii) Tidswell Financial Services Ltd;

(iii) Mammatus Pty Ltd;

(iv) Sargon CT (NSW) Pty Ltd;

(v) Sargon CT Pty Ltd;

(vi) Sargon Limited (a company registered in New Zealand);

(vii) Diversa Trustees Limited; and

(viii) CCSL Limited; and

(b) the assets sold under the Business Sale Agreement and, in particular:

(i) the domain name www.sargon.com;

(ii) the intellectual property comprising the computer programs Arcadia, Pay, Impact, Sentinel and Metropolis;

(iii) intellectual property rights in software that GrowthOps claims to have developed in relation to the following systems: (a) Arcadia, (b) Pay, (c) Impact, (d) Sentinel and (e) Metropolis, and which it describes as Developed IP,

(iv) the following two alternatives:

(A) "Sargon Trustee Cloud Software", as referred to in the expert reports of Jeff Hall, including what proportion of this asset, if any, comprises Developed IP; or

(B) the "Website" and "Software technology", as referred to in the expert reports of Antony Samuel, including what proportion of this asset, if any, comprises Developed IP;

(v) the plant and equipment of Sargon Services;

(vi) the business name, Good Super;

(vii) the trademarks listed in items 1 to 7 of part A of schedule 8 of the Business Sale Agreement;

(viii) the domain names listed in items 8 to 14 and 17 to 32 of part B of schedule 8 of the Business Sale Agreement;

(ix) the domain names listed in items 15 and 16 and 33 to 35 of part B of schedule 8 of the Business Sale Agreement; and

(x) any licence in respect of the Background IP with respect to which GrowthOps claims an entitlement to the Retained Proceeds?

4.2 What amount should be allocated to the Plaintiffs from the Retained Proceeds for their reasonable remuneration, costs and expenses, including in accordance with the principles set out in Re Universal Distributing Co Ltd (in liq) (1933) 48 CLR 171 and how should that be allocated to the shares and assets referred to in paragraph 4.1 above?

4.3 In light of the matters in paragraphs 4.1 and 4.2, what amounts should be allocated to each of the Interested Parties from the Retained Proceeds?

5. COSTS

5.1 What orders should be made in relation to costs?

28 For the reasons expressed earlier in respect of the notified claims, questions 3.7, 3.8, 4.1(b)(x) and 4.2 do not require answers in this proceeding.

29 In relation to the unresolved aspect of the plaintiffs’ claim, being items 11 and 12 of the plaintiffs’ amended notice of claim, the plaintiffs seek the Court to determine, in connection with question 4.1(b), the proportion of the Retained Proceeds that should be attributed to Sargon Services’ receivables sold pursuant to the Business Sale Agreement.

Joint Statement of Agreed Facts

30 The parties have filed and tendered a Joint Statement of Agreed Facts which sets out the background to the issues to be resolved in this proceeding. The Joint Statement of Agreed Facts is reproduced in full in Section E below.

31 The plaintiffs read the affidavits of Stewart Alexander McCallum dated 30 April 2020, 1 May 2020 and 29 May 2020. Mr McCallum is one of the plaintiffs. He is a partner of Ernst & Young (EY) and is a chartered accountant and a Registered Liquidator of the Supreme Court of Victoria and the Federal Court of Australia. He has in excess of 20 years’ experience in corporate insolvency, restructuring and forensic accounting. Mr McCallum gave evidence about the administration of the Sargon VA Entities and the Cloverhill Sale, including the claims that have been made by the plaintiffs and the respondents to the proceeds of the sale. Mr McCallum was cross-examined. There was no challenge to his credit and I accept his evidence.

32 Westpac read an affidavit of Peter Gage Sise dated 12 June 2020. Mr Sise is a solicitor employed by the solicitors for Westpac in this proceeding, Clayton Utz. Mr Sise was not cross-examined.

33 Westpac also read an affidavit of John Gregory McKillop dated 12 June 2020. Mr McKillop is employed by Westpac as a Senior Account Manager—Credit Restructuring. Mr McKillop gave evidence about the loan facilities provided by Westpac to certain of the Sargon VA Entities and the securities given in respect of those loans. Mr McKillop was not cross-examined.

34 Westpac also read an affidavit of Sophia Alice Griffiths-Mark dated 24 July 2020. At the time of swearing her affidavit, Ms Griffiths-Mark was a graduate-at-law employed by the solicitors for Westpac in this proceeding, Clayton Utz. Ms Griffiths-Mark gave evidence about internet searches conducted by her to seek to identify the registrant of certain domain names relevant to the proceeding. Ms Griffiths-Mark was not cross examined.

Sargon Capital / Taiping witness

35 Sargon Capital and Taiping read two affidavits of Shaun Fraser dated 12 June 2020 and 14 August 2020. Mr Fraser is a Registered Liquidator and a partner in McGrathNicol, a firm of chartered accountants who provide restructuring and advisory services. Mr Fraser is one of the receivers and managers appointed to Sargon Capital (together with Mr Jason Preston). Mr Fraser gave evidence concerning Sargon Capital and its business and Taiping’s loan to, and security interest over, Sargon Capital. Mr Fraser was not cross-examined.

36 GrowthOps read two affidavits of Craig McMenamin dated 12 June 2020 and 24 July 2020. Mr McMenamin is the Chief Financial Officer and Company Secretary of the parent company of GrowthOps and is also the company secretary of GrowthOps. Mr McMenamin was not cross-examined.

37 Diversa read an affidavit of Ashley Mark Fenton dated 24 July 2020. Mr Fenton is the Chief Financial Officer of OneVue and a Company Secretary of Diversa. Mr Fenton was not cross-examined.

38 Expert valuation reports were tendered on behalf of each of Westpac, Sargon Capital and Taiping, and Diversa.

39 Westpac tendered a report dated 24 July 2020 and a supplementary report dated 14 August 2020 of Jeffrey Lewis Hall. Mr Hall holds a B.Sc. (Summa Cum Laude) in Accounting from Kansas State University and a Master of Commerce in Finance from the University of New South Wales. He is a Chartered Financial Analyst and a member of the CFA Society, a Certified Public Accountant and a member of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants and a Chartered Accountant and member of the Australian Institute of Chartered Accountants. Mr Hall was a founder of Sumner Hall Associates Pty Ltd and has been a director since 2002 and is currently the Managing Director. Sumner Hall Associates is a specialist advisory firm providing corporate advisory services in relation to mergers and acquisitions, divestments, capital raisings, corporate restructuring and financial matters generally. One of the principal activities of the firm is the preparation of corporate and business valuations. Between 1989 and 2001, Mr Hall was Executive Director and shareholder of Grant Samuel & Associates Pty Limited, an investment banking firm.

40 Sargon Capital and Taiping tendered a report dated 24 July 2020 and a supplementary report dated 14 August 2020 of Antony Bryn Samuel. Mr Samuel holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree from the University of Western Australia and is a Chartered Accountant (Australia). He is Managing Director of Sapere Research Group Limited, leading Sapere’s forensic accounting and valuation team, and is a former partner of PwC in London and Sydney with over 20 years of experience as an accountant.

41 Diversa tendered a report dated 24 July prepared by Campbell Jaski, a Partner in the Corporate Value Advisory practice at PwC. Mr Jaski has over 25 years of experience in corporate finance, valuation and business management. He studied corporate finance and valuation theory at the Stern School of Business, New York University and Melbourne Business School, Melbourne University. He is an accredited Business Valuation Specialist with Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand and is a Fellow of the Financial Services Institute of Australasia. He is also a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators. For the past 12 years, Mr Jaski has specialised in the valuation of businesses, shares, intangible assets, projects and financial instruments. Prior to this, Mr Jaski worked for Rio Tinto Limited.

42 In accordance with orders of the Court, the parties prepared a Joint Statement of Questions for Expert Valuers which was filed on 5 November 2020. The valuation experts conferred before trial and prepared a joint report dated 1 December 2020 (Joint Expert Report). The Joint Expert Report summarises the experts’ areas of agreement and disagreement in relation to the Joint Statement of Questions for Expert Valuers and the basis of those opinions.

43 The expert valuers were cross-examined concurrently. None of the witnesses changed their opinions in the course of cross-examination, but the cross-examination helped to distil and explain the differences in approach that had been taken by each of the experts.

44 In my view, each of the experts is suitably qualified to express opinions on the relative values of the shares and assets sold as part of the Cloverhill Sale. Further, I consider that each of the experts had a reasoned basis for the opinions they expressed. While the conclusions reached by each expert as to relative value generally favoured the party that had called the expert, that circumstance did not cause me to doubt the sincerity with which the opinions were advanced. Many of the issues debated between the experts involved matters of judgment for which no answer could be said to be right or wrong in an absolute sense. Ultimately, though, I have formed the judgment that certain approaches to the issues in dispute are preferable, which I explain below.

45 Various business records were tendered by the parties. I made rulings on evidentiary objections during the hearing. Only one objection was the subject of substantive argument, being the admissibility of an announcement published on the Sargon website following the Cloverhill Sale (Sale Announcement). The relevant parts of the Sale Announcement were as follows:

Pacific Infrastructure Partners (‘PIP’), a new entity formed for the purpose of investing in technology-enabled financial services, today announces the completion of the acquisition of key operating entities and assets of the Sargon Capital group of companies (‘Sargon’).

New York-based financiers Teddy Wasserman and Australian Matthew Kibble led the transaction through Cloverhill Group LLC and Kibble Holdings LLC respectively. They are joined as equity shareholders in PIP by Vista Credit Partners (‘VCP’), who also provided financing for the transaction. VCP is a strategic credit investor and financing partner offering a variety of capital solutions to the enterprise software, data and technology market. VCP is the credit-lending arm of Vista Equity Partners (‘Vista’), a leading global technology investor.

Cloverhill Group Managing Partner, Teddy Wasserman said, “We believe the proprietary next-generation trustee infrastructure that Sargon has developed to be world-class technology. …”

The cloud-based platform developed by Sargon delivers clients greater transparency over funds and reduces costs and complexity, while at the same time providing more scalable and reliable operations.

David Flannery, President of Vista Credit Partners, said, “This is a tremendous asset class and Australia is recognised as having one of the best models of superannuation and retirement savings in the world. Vista and VCP have a long and proud track-record of backing companies like Pacific Infrastructure Partners, which are at the forefront of digital transformation and have the intellectual property capable of winning on a global stage.

…

Pacific Infrastructure Partners (PIP) is a new entity formed for the purpose of investing in the financial services industry to support the delivery of strong, independent, technology-enabled trustee solutions. In May 2020, PIP completed the acquisition of the key operating entities and assets of financial technology and infrastructure company, Sargon, including Sargon’s trustee, corporate trust and responsible entity operations, and its proprietary technology infrastructure. …

46 Sargon Capital and Taiping sought to tender the Sale Announcement as evidence relevant to the assessment of the value of the intellectual property sold as part of the sale. The relevant facts asserted in the announcement include that the new owners of the Sargon business that was sold held the opinion that the trustee infrastructure (software) developed by Sargon is “world-class technology”.

47 The evidence is hearsay under s 59 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act) and is inadmissible unless an exception applies. I allowed the evidence as a business record within s 69 of the Evidence Act. As I stated in Rodney Jane Racing Pty Ltd v Monster Energy Company [2019] FCA 923; 370 ALR 140 at [178], whether a webpage can be shown to be a business record within the meaning of s 69 depends upon the content of the webpage and what is able to be established (whether directly or by inference) about the content of the page. In the present case, I am satisfied that the Sale Announcement:

(a) forms part of the records belonging to that part of the business of the Sargon Group that was sold (the sale included the Sargon website);

(b) was made for the purposes of that business, to inform (amongst others) present and prospective customers of the sale; and

(c) was made by a person who might reasonably be supposed to have had personal knowledge of the relevant facts asserted in the announcement because the statements were made by the representatives of the purchasers about their opinions of the assets that were purchased.

48 While the Sale Announcement is admissible evidence, I do not place significant weight on the evidence. The opinions expressed in the announcement are stated at a high level of generality and do not greatly assist in seeking to attribute a value to the software relative to the other assets sold in the Cloverhill Sale. The opinions must also be discounted to some extent in recognition that a purchaser of a business will likely wish to promote the acquisition that has been made.

E. JOINT STATEMENT OF AGREED FACTS

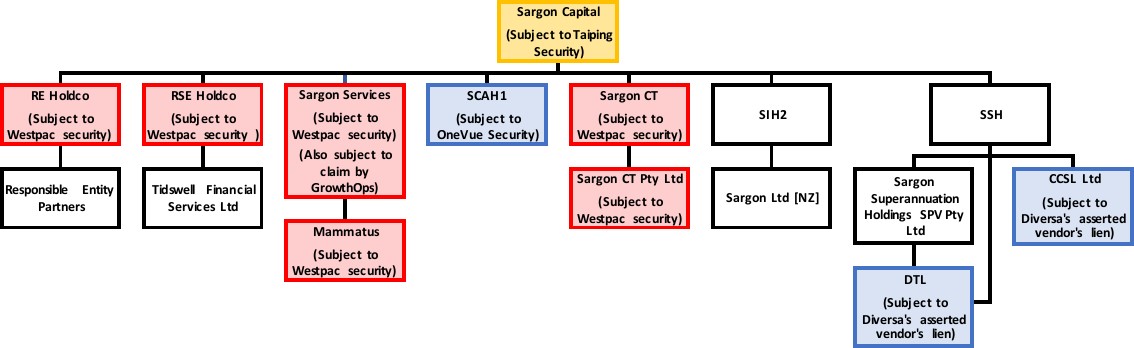

49 The parties tendered a Joint Statement of Agreed Facts. It is convenient to reproduce that statement in full because it sets out the primary background facts which were not controversial. Annexures A and B to the Joint Statement of Agreed Facts, which contain diagrams of the corporate structure of the Sargon Group and security interests held or claimed by the parties, are reproduced at the end of these reasons.

PROPOSED JOINT STATEMENT OF AGREED FACTS

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 This document is filed in respect of paragraph 2(a) of the Orders of the Federal Court of Australia made on 31 August 2020 which provided that the parties confer and seek to agree and file with the Court a statement of agreed facts in relation to the Claims as defined in those orders.

2.1 The Sargon Group was a corporate group consisting of approximately 39 companies which conducted a series of financial planning, corporate trustee, responsible entity, superannuation and related financial services businesses (Sargon Group).

2.2 Sargon Capital Pty Ltd (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (In Liquidation) ACN 608 799 873 (Sargon Capital) was at all relevant times, the ultimate holding company of the Sargon Group, but did not itself engage in any trading activities.

2.3 Sargon Capital was at all relevant times the sole shareholder of each of the following ten Intermediate Holding Companies:

(a) RE Holdco Pty Ltd ACN 612 592 471 (RE Holdco);

(b) RSE Holdco Pty Ltd ACN 612 586 893 (RSE Holdco);

(c) Sargon Services Pty Ltd ACN 163 522 058 (Sargon Services);

(d) Safewealth Realty Pty Ltd ACN 100 933 980 (Safewealth);

(e) SC International Holdings 1 Pty Ltd ACN 621 160 101 (SCIH1);

(f) SC Australian Holdings 1 Pty Ltd ACN 624 531 237 (SCAH1);

(g) Sargon CT Holdings Pty Ltd ACN 628 621 321 (Sargon CT);

(h) Sargon International Holdings 2 Pty Ltd ACN 630 632 343 (SIH2);

(i) Sargon Superannuation Holdings Pty Ltd ACN 630 648 225 (SSH), which in turn was the sole shareholder of Sargon Superannuation Holdings SPV Pty Ltd ACN 633 509 494 (Sargon SPV); and

(j) Decimal Software Pty Ltd ACN 009 235 956 (Decimal).

2.4 Each of the above Intermediate Holding Companies (with the exception of Safewealth) was in turn a parent company of at least one subsidiary entity. These subsidiary entities along with Sargon Services were the operating business entities of the Sargon Group (Operating Subsidiaries).

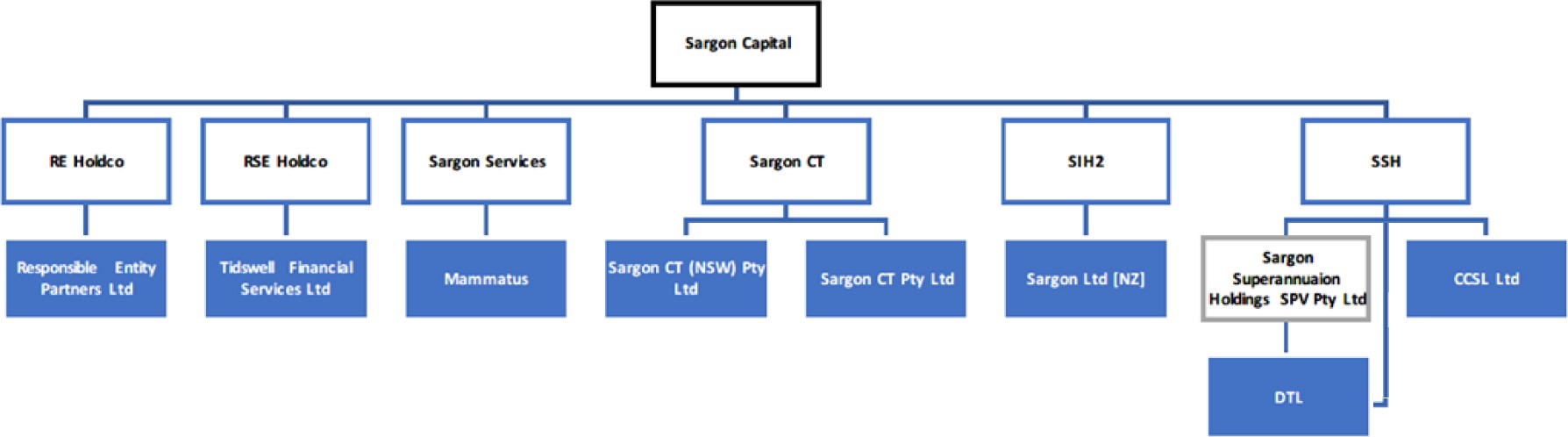

2.5 The diagram below provides an overview of the Relevant Operating Subsidiaries (as defined at 2.6 below) within the Sargon Group (shaded in blue). A larger and more detailed structure diagram of the Sargon Group is provided at Annexure A.

2.6 The Operating Subsidiaries that are the subject of the Cloverhill Proceedings and the Cloverhill Sale (defined below) are:

(a) CCSL Ltd ACN 104 967 964 (CCSL) (a subsidiary of SSH );

(b) Diversa Trustees Ltd ACN 006 421 638 (DTL) (3,142,333 shares in which were owned by SSH and 2,000,000 shares in which were owned by Sargon SPV);

(c) Mammatus Pty Ltd ACN 101 393 435 (Mammatus) (a subsidiary of Sargon Services);

(d) Responsible Entity Partners Limited ACN 119 757 596 (a subsidiary of RE Holdco);

(e) Sargon CT (NSW) Pty Ltd ACN 000 329 706 (Sargon CT (NSW)) (a subsidiary of Sargon CT);

(f) Sargon CT Pty Ltd ACN 106 424 088 (a subsidiary of Sargon CT);

(g) Sargon Ltd NZBN 9429047195639 (a subsidiary of SIH2); and

(h) Tidswell Financial Services Ltd ACN 010 810 607 (a subsidiary of RSE Holdco).

(Collectively, Relevant Operating Subsidiaries).

2.7 Sargon Services provided a number of the Operating Subsidiaries (save for SSH and its Relevant Operating Subsidiaries, CCSL and DTL, up until 1 January 2020) with labour and administrative services under various services agreements. Sargon Services provided labour and administrative services for SSH and its Relevant Operating Subsidiaries, CCSL and DTL, from 1 January 2020 onwards.

3. PROPERTY OF THE SARGON GROUP

3.1 The assets of each of the Sargon Group's operating businesses were held by the various Operating Subsidiaries or by Sargon Capital itself.

3.2 The property of the Sargon Group that is the subject of the Cloverhill Proceedings is as follows:

(a) much of the business and general assets of the Sargon Group, including all of the assets of each of the Relevant Sargon Entities (defined at 7.2 below);

(b) the share capital of the Relevant Operating Subsidiaries; and

(c) the intellectual property associated with the Sargon Group (noting that GrowthOps claims an interest in a subset of the intellectual property).

3.3 As described in more detail in section 9 below, the above property was sold by a number of the Intermediate Holding Companies to Pacific Infrastructure Services Pty Ltd ACN 640 130 712 (Pacific Services) and Pacific Infrastructure Holdings Pty Ltd ACN 640 129 479 (Pacific Holdings) as part of a complete sale of the business to the Cloverhill Group (Cloverhill Sale).

4. THE PARTIES TO THE CLOVERHILL PROCEEDINGS

4.1 There are seven active parties in proceeding VID 285/2020 (Cloverhill Proceedings), being:

(a) the Plaintiffs (Stewart McCallum and Adam Nikitins of Ernst & Young) (Administrators);

(b) Westpac Banking Corporation ACN 007 457 141 (Westpac) (the First Interested Party);

(c) Sargon Capital (the Second Interested Party);

(d) Taiping Trustees Limited (A company registered in Hong Kong) (Trade Register number 0821942) (Taiping) (the Third Interested Party);

(e) GrowthOps Services Pty Ltd ACN 626 208 777 (GrowthOps) (the Fourth Interested Party);

(f) Diversa Pty Ltd ACN 079 201 835 (Diversa) (the Fifth Interested Party); and

(g) OneVue Holdings Limited ACN 108 221 870 (OneVue) (the Sixth Interested Party).

4.2 The interests of the Second and Third Interested Parties are aligned such that there is no need to distinguish between them. The same applies to the Fifth and Six Interested Parties.

5.1 In this section, the facts relevant to the circumstances in which each of the parties came to have interests in the Cloverhill Proceedings are set out, in as close to a chronological order as is possible, except in the case of Westpac's loan facilities and security interests where they are set out according to the Operating Subsidiary, which is more convenient given Westpac had numerous lending arrangements with several entities.

5.2 An overview of the claimed security interests of the parties over the relevant entities to the Cloverhill Proceedings is set out in the following diagram. A larger and more detailed structure diagram of the structure of the Sargon Group is provided at Annexure B.

Taiping's Secured Promissory Note, Guarantee and Indemnity and GSD

5.3 Taiping was incorporated on 15 November 2002 under the laws of Hong Kong. Taiping is a subsidiary of the China Taiping Group, of which China Taiping Insurance Group Limited is the ultimate holding company. China Taiping Insurance Group Limited is a Chinese state-owned financial and insurance group that is headquartered in Hong Kong and has been listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange since 2000.

5.4 Phillip Kingston was both a managing director of Sargon Capital and the sole director of Trimantium Investment Management Pty Ltd (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (In Liquidation) ACN 624 073 196 (TTIM).

5.5 On 9 February 2018, Taiping and TTIM entered into a Secured Promissory Note, under which Taiping agreed to advance to TTIM a total of HKD $500,000,000 (approximately AUD $81,000,000) (Secured Promissory Note).

5.6 The Secured Promissory Note was also executed by Sargon Capital as obligor.

5.7 To further secure the performance of the obligations of TTIM, Sargon Capital provided the following security documents in favour of Taiping:

(a) a Guarantee and Indemnity dated 27 April 2018 (Sargon Capital Guarantee); and

(b) a General Security Deed dated 27 April 2018 (Sargon Capital GSD).

5.8 The Sargon Capital GSD was registered on the Personal Property Securities Register (PPSR) (Registration Number 201804090021528) on 9 April 2018.

5.9 Under the terms of the Sargon Capital GSD, Taiping was granted a security interest over all of the present and after-acquired property of Sargon Capital. In particular, Taiping was granted a charge over any intellectual property, including:

(a) a patent, trademark or service mark, copyright, registered design, trade secret or confidential information; or

(b) a licence or other right to use or to grant the use of any of the above, or to be the registered proprietor or user of any of the above.

Westpac

RE Holdco

5.10 On or about 15 October 2018, Westpac provided a loan facility to RE Holdco with a limit of $5,000,000. The loan facility is secured by:

(a) an unlimited guarantee and indemnity granted by Sargon Services in favour of Westpac dated 30 October 2018;

(b) an unlimited interlocking guarantee and indemnity granted by RSE Holdco, RE Holdco and Sargon CT in favour of Westpac dated 30 October 2018 (Interlocking Guarantee and Indemnity);

(c) an unlimited guarantee and indemnity granted by Mammatus in favour of Westpac dated 30 October 2018 which was released on 4 May 2020;

(d) a general security agreement granted by Sargon Services in favour of Westpac dated 30 October 2018 with PPSR registration number 201811010064791 (Sargon Services GSA);

(e) a general security agreement granted by RSE Holdco in favour of Westpac dated 4 July 2016 with PPSR registration number 201607080019959 (RSE Holdco GSA);

(f) a general security agreement granted by RE Holdco in favour of Westpac dated 4 July 2016 with PPSR registration number 201607080019786 (RE Holdco GSA);

(g) a general security agreement granted by Sargon CT in favour of Westpac dated 30 October 2018 with PPSR registration number 201811010067224 (Sargon CT GSA); and

(h) a general security agreement granted by Mammatus in favour of Westpac dated 30 October 2018 formerly with PPSR registration number 201811010064988 (Mammatus GSA). The Mammatus GSA was released on 4 May 2020.

RSE Holdco

5.11 On or about 15 October 2018, Westpac provided a loan facility to RSE Holdco with a limit of $600,000. The loan facility is secured by:

(a) an unlimited guarantee and indemnity granted by Sargon Services in favour of Westpac dated 30 October 2018;

(b) the Interlocking Guarantee and Indemnity;

(c) an unlimited guarantee and indemnity granted by Mammatus in favour of Westpac dated 30 October 2018 which was released on 4 May 2020;

(d) the Sargon Services GSA;

(e) the RSE Holdco GSA;

(f) the RE Holdco GSA;

(g) the Sargon CT GSA; and

(h) the Mammatus GSA. The Mammatus GSA was released on 4 May 2020.

Sargon CT

5.12 On or about 15 October 2018, Westpac provided two loan facilities to Sargon CT with limits of $12,000,000 and $10,000,000 respectively.

5.13 On or about 24 December 2019, Westpac provided another loan facility to Sargon CT with a limit of $6,000,000.

5.14 The loan facilities provided to Sargon CT are secured by:

(a) an unlimited guarantee and indemnity granted by Sargon Services in favour of Westpac dated 30 October 2018;

(b) the Interlocking Guarantee and Indemnity;

(c) an unlimited guarantee and indemnity granted by Mammatus in favour of Westpac dated 30 October 2018 which was released on 4 May 2020;

(d) the Sargon Services GSA;

(e) the RSE Holdco GSA;

(f) the RE Holdco GSA;

(g) the Sargon CT GSA; and

(h) the Mammatus GSA. The Mammatus GSA was released on 4 May 2020.

Sargon Services

5.15 Westpac provided the following facilities for bank guarantees in respect of Sargon Services:

(a) on or about 7 June 2018, a bank guarantee in favour of Circuit Recruitment Group (Vic) Pty Ltd ACN 141 687 747 for the amount of $60,942.04;

(b) on or about 5 July 2019, a bank guarantee in favour of BGH (287 Collins) Pty Ltd ACN 623 369 899 for the amount of $111,839.00; and

(c) on or about 20 August 2019, a bank guarantee in favour of IPAR Rehabilitation Pty Ltd ACN 104 234 317 for the amount of $59,417.88.

5.16 The bank guarantees remain outstanding and therefore the full amounts (as specified above) were contingently owing.

5.17 These facilities are each secured by the Sargon Services GSA.

Diversa Share Purchase Agreement

5.18 Diversa was incorporated in New South Wales on 3 July 1997 and provides superannuation trustee services. It is a wholly owned subsidiary of OneVue, an ASX listed company (ASX:OVH) that is a wholesale service provider to the wealth management industry.

5.19 Pursuant to a Share Purchase Agreement dated 20 December 2018 and its subsequent variations (Diversa SPA), Diversa sold:

(a) all of the shares it held in CCSL to SSH;

(b) 3,142,333 of the shares it held in DTL to SSH; and

(c) 2,000,000 of the shares it held in DTL to Sargon SPV.

5.20 Pursuant to the Diversa SPA, the total consideration payable was $43 million to be paid by way of an Initial Purchase Price of $12 million and then a Deferred Purchase Price of $31 million, with the Deferred Purchase Price payable by SSH and Sargon SPV in proportion to the number of CCSL and DTL shares each received under the Diversa SPA.

5.21 Sargon Capital guaranteed to Diversa performance of the obligations of SSH and SPV under the Diversa SPA.

5.22 The Initial Purchase Price component of the consideration for the DTL and CCSL shares has been paid. However, taking into account realisations to date, $28,365,386.31 of the Deferred Purchase Price component of the consideration (and accrued interest owing under the Diversa SPA) remains outstanding.

GrowthOps Technology MSA, Marketing MSA and invoices issued 30 July 2019 – 31 January 2020

5.23 GrowthOps was incorporated in Victoria on 17 May 2018. GrowthOps is a wholly owned subsidiary of the ASX listed company Trimantium GrowthOps Limited ACN 621 067 678 (ASX:TGO) (TGO). Both GrowthOps and TGO provide management consulting, technology, advertising, creative, coaching and leadership services.

5.24 On or around 30 August 2019, GrowthOps and Sargon Capital entered into a Technology Master Services Agreement, with a commencement date of 1 July 2019 (Technology MSA). Significant clauses include 7.1(a), (c) and (d). Clause 7.1(a) provided that "all Intellectual Property Rights in the Services and Deliverables (Developed IP), except any GrowthOps Background IP or its service methodology and knowledge, vests in Sargon immediately upon payment to GrowthOps for same, and GrowthOps hereby assigns, and must procure that its personnel assign, all Intellectual Property Rights in the Developed IP To Sargon. GrowthOps agrees to do all things which may be necessary for these ownership rights to pass to Sargon. At Sargon's request, GrowthOps must provide, and ensure that its personnel or sub-contractors provide consents to or waivers of any moral rights in specific Developed IP. This clause does not in any way derogate from the ability for GrowthOps to utilise the same service methodology for other clients"

5.25 On or around 2 September 2019, GrowthOps and Sargon Capital entered into a Master Services Agreement (Creative, Marketing, Coaching & Leadership), with a commencement date of 2 September 2019 (Marketing MSA). Significant clauses include 7.1(a), (c) and (d). Clause 7.1(a) provided that "all Intellectual Property Rights in the Services and Deliverables (Developed IP), except any GrowthOps Background IP or its service methodology and knowledge, vests in Sargon immediately upon payment to GrowthOps for same, and GrowthOps hereby assigns, and must procure that its personnel assign, all Intellectual Property Rights in the Developed IP To Sargon. GrowthOps agrees to do all things which may be necessary for these ownership rights to pass to Sargon. At Sargon’s request, GrowthOps must provide, and ensure that its personnel or sub-contractors provide consents to or waivers of any moral rights in specific Developed IP. This clause does not in any way derogate from the ability for GrowthOps to utilise the same service methodology for other clients."

5.26 Between 30 July 2019 and 31 January 2020, GrowthOps issued 24 invoices to Sargon Capital totalling $1,649,402.85 (excluding GST). The invoices were described to relate to various technology, creative, marketing, coaching and leadership services to Sargon Capital under the Technology MSA and the Marketing MSA spanning the period 1 July 2019 to 31 January 2020.

5.27 To date, Sargon Capital has only paid two of those invoices, which amount to the sum of $314,128.50 (excluding GST). The balance of the invoices ($1,335,274.35) remains unpaid.

Letters of demand and appointment of the Administrators

5.28 On 2 December 2019, Taiping's solicitors Ashurst issued a letter to TTIM and Sargon Capital stating that TTIM had committed an Event of Default (as defined in the Secured Promissory Note).

5.29 On 19 December 2019, Ashurst sent a further letter on behalf of Taiping to Mr Kingston in his capacity as the sole director of TTIM and as a director of Sargon Capital. The letter notified Mr Kingston that TTIM had failed to pay the interest that was due and payable to Taiping.

5.30 On 20 January 2020, Taiping's solicitors Ashurst issued letters of demand to TTIM and Sargon Capital stating that as at 20 January 2020, the amount of HKD $512,964,934.61 was immediately due and payable, pursuant to the terms of the Sargon Capital Guarantee and Sargon Capital GSD. Both TTIM and Sargon Capital failed to comply with the demands made by Taiping.

5.31 On 3 February 2020, the Administrators were appointed as voluntary administrators to eight of the Intermediate Holding Companies.

5.32 Between 3 February 2020 and 14 May 2020, the Administrators conducted the voluntary administration of the Relevant Sargon Entities (defined at 7.2 below), which culminated in the complete sale of the business to the Cloverhill Group (Cloverhill Sale).

5.33 Further detail about the Administrators' appointment and the Cloverhill Sale is set out in paragraphs 7.2 and 9.1 - 9.21 respectively.

5.34 On 23 April 2020, Clayton Utz (acting on behalf of Westpac) issued notices of demand to (i) Sargon CT for $20,492,044.83, (ii) RSE Holdco for $605,366.68 and (iii) Sargon Services for $20,492,044.83. On 28 May 2020, Clayton Utz issued further notices of demand to (iv) Sargon CT for $6,146,653.62, (v) RE Holdco for $5,074,393.95, (vi) Sargon Services for $60,942.04 and (vii) $111,839. Some of the amounts claimed overlap.

6.1 On 15 May 2020, the active parties in this matter filed notices of claim. Each of the amounts claimed below are “as at” that date.

6.2 In its notice of claim, Taiping claims that the total amount owing to it is no less than $4,000,000. There is no dispute that this amount is owing.

6.3 In its notice of claim, GrowthOps claims compensation for the sale of intellectual property in which it claims an interest, in an amount equal at least to the unpaid invoices referred to at paragraphs 5.26 - 5.27, together with compensation for the perpetual, irrevocable and royalty free licence in respect of the GrowthOps Background IP (as defined in each of the Technology MSA and the Marketing MSA). GrowthOps claims $1,854,621.11 as at 13 May 2020, including GST, and interest and costs which continue to accrue. There is no dispute that this amount is owing.

6.4 In its notice of claim, Westpac claims that the amount owing to it in respect of the facilities referred to at paragraphs 5.10 - 5.17 is $32,019,961.81 (plus recovery costs and interest accruing after 30 April 2020). There is no dispute that this amount is owing.

6.5 In its notice of claim, Diversa claims that the total amount owing to it in respect of the Diversa SPA is $28,365,386.31. There is no dispute that this amount is owing.

6.6 In their notice of claim, the Administrators claim that the total amount owing to them is $4,255,562.67 (plus further amounts that are subject to quantification and Court approval), pursuant to remuneration, costs, expenses (both current and prospective) and pre-appointment priority employee entitlements owing by Sargon Services. The Administrators’ notice of claim was revised in the third affidavit of Stewart McCallum dated 29 May 2020 and the Administrators’, now Liquidators’ remuneration, costs and expenses in connection with the liquidations of the Relevant Operating Subsidiaries, including in connection with the Cloverhill Proceedings, continues to accrue.

7. EXTERNAL ADMINISTRATION OF THE SARGON GROUP

7.1 On 29 January 2020, Shaun Fraser and Jason Preston were appointed by Taiping as joint and several receivers and managers of Sargon Capital (Sargon Capital Receivers), and a further two other related companies (Trimantium Capital Funds Management Pty Ltd (Receivers and Managers Appointed) (In Liquidation) ACN 602 329 902 (TCFM) and TTIM.

7.2 On 3 February 2020, Phillip Kingston in his capacity as the sole director of nine of the Intermediate Holding Companies passed resolutions pursuant to section 436A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corporations Act) appointing the Administrators as the voluntary administrators of the following seven Intermediate Holding Companies (plus an eighth Intermediate Holding Company, SCAH1, the assets of which were not sold as part of the Cloverhill Sale):

(a) Re Holdco;

(b) RSE Holdco;

(c) Sargon Services;

(d) SCIH1;

(e) Sargon CT;

(f) SIH2; and

(g) SSH.

(Collectively, Relevant Sargon Entities).

7.3 Safewealth was not placed into administration.

7.4 As a result of their appointment, the Administrators took control of all of the shares owned by the Sargon Group in the Operating Subsidiaries and all of the employees and documents of the Sargon Group.

7.5 On 3 and 4 February 2020, Matthew Byrnes and David Hodgson of Grant Thornton were appointed as joint and several voluntary administrators of:

(a) Decimal;

(b) Decimal Technology and Systems Pty Ltd ACN 118 370 291;

(c) Decimal Pty Ltd ACN 135 979 743; and

(d) Simpla Pty Ltd ACN 159 982 671.

(Collectively, Decimal Entities).

7.6 On 4 February 2020, Daniel Walley and Christopher Hill of PricewaterhouseCoopers were appointed as joint and several receivers and managers of SCAH1 by Diversa. SCAH1 and its assets do not form part of the Cloverhill Proceedings.

7.7 On 8 March 2020, Joseph Hayes and Andrew McCabe of Wexted Advisors were appointed as joint and several administrators of Sargon Capital, TTIM and TCFM pursuant to section 436C of the Corporations Act.

7.8 On 10 March 2020, Mr Byrnes and Mr Hodgson were appointed as the liquidators of the Decimal Entities.

7.9 On 8 April 2020, at the second meeting of the creditors of Sargon Capital, it was resolved to wind up Sargon Capital, and Mr Hayes and Mr McCabe were appointed as liquidators pursuant to section 446A of the Corporations Act.

7.10 On 14 May 2020, at the second meeting of creditors of the Sargon Entities, it was resolved to wind up the Relevant Sargon Entities and Mr McCallum and Mr Nikitins were appointed as liquidators (defined in this document as the Administrators: see paragraph 4.1(a) above) pursuant to section 446A of the Corporations Act.

8. SARGON SERVICES

8.1 Sargon Services employed many of the employees who worked for the Sargon Group, including employees who provided services to the Intermediate Holding Companies and the Operating Subsidiaries. Sargon Services also rented offices that were used by other entities in the Sargon Group.

8.2 The services provided by Sargon Services to Responsible Entity Partners Limited, Tidswell Financial Services Ltd, Sargon CT and Sargon CT (NSW) (for the period of five years starting on 8 May 2019) were in the following categories:

(a) governance, risk and compliance;

(b) human resources;

(c) finance;

(d) information technology;

(e) legal;

(f) product; and

(g) corporate trustee.

8.3 The services provided by Sargon Services to DTL and CCSL (for the period of one year starting on 19 January 2020, subject to a three-month extension) were in the following categories:

(a) governance, risk and compliance;

(b) human resources;

(c) finance;

(d) information technology;

(e) legal; and

(f) product.

8.4 From 28 June 2019 to 31 December 2019, DTL and CCSL received services of the following kind from OneVue Services Pty Ltd (OneVue Services) pursuant to a Transitional Services Agreement dated 28 June 2019 instead of Sargon Services. DTL and CCSL paid a monthly fee to OneVue Services for those services. The services provided under the Transitional Services Agreement included:

(a) accounting and financial management (for which DTL and CCSL paid $20,000 per month);

(b) human resources;

(c) information technology and cyber security (for which DTL and CCSL paid $20,000 per month);

(d) legal and litigation support; and

(e) product development and marketing.

8.5 DTL and CCSL paid $20,000 per month under the Transitional Services Agreement for the services provided by OneVue Services other than accounting and financial management services and information technology and cyber security services (for which the separate monthly fees identified above were paid).

8.6 The total monthly fee paid by DTL and CCSL from July to September was $60,000 (ex GST) per month. In October, November and December 2019, OneVue Services did not provide information technology and cyber security services to DTL and CCSL, so DTL and CCSL paid $40,000 (ex GST) for each of those months.

8.7 After and before the Administrators were appointed:

(a) on 18 February 2020, Sargon Services entered into an agreement with DTL and CCSL, pursuant to which Sargon Services agreed to provide services to DTL and CCSL in exchange for a fee of $92,000 per month for one year from 19 January 2020 subject to a three-month extension; and

(b) on 8 May 2019, Sargon Services, Tidswell, Sargon CT (NSW), Sargon CT and REP entered into an agreement pursuant to which Sargon Services agreed to provide each other party to that agreement with services in exchange for a fee fixed at the cost incurred by Sargon Services in providing those services plus a margin of 10% for a period of 5 years, subject to early termination.

8.8 For the period July 2018 to December 2019, Sargon Services incurred the following expenses (as recorded on its profit and loss statement):

(a) $14,267,649.36 in salary package costs;

(b) $2,187,131.05 in staff expenses;

(c) $793,794.11 in professional services expenses; and

(d) $962,937.72 in occupancy costs;

totalling $18,211,512.24. The total of all of Sargon Services’ expenses for that period was $20,215,913.87.

9. CLOVERHILL SALE

9.1 Following their appointment on 3 February 2020, the Administrators commenced a sale process in which they advertised all of the shares owned by the Intermediate Holding Companies in the Operating Subsidiaries (other than SCAH1's shares).

9.2 On 10 February 2020, the Administrators provided the Sargon Capital Receivers with a copy of Sargon Capital's balance sheet as at the end of December 2019, which stated that Sargon Capital held, amongst other things, the following assets:

(a) intercompany loans (with a book value of AUD$115,991,605.11);

(b) "Intangible tech - Sargon" (with a book value of AUD$5,797,293.90); and

(c) domain name (with a book value of AUD$237,696.49).

9.3 The balance sheet for Sargon Services as at the end of December 2019 recorded $1,037,554.95 for "Intangible tech - Sargon" which comprised $549,583 for Sargon Technology, $1,053,694.39 for "Website" and -$565,722.44 for "Amortisation of Website".

9.4 Between 17 February 2020 and 10 March 2020, substantial correspondence was exchanged and various conversations occurred between the Sargon Capital Receivers and the Administrators concerning the sale process.

9.5 Between 4 February 2020 and 25 March 2020, the Sargon Capital Receivers made several requests of the Administrators to provide access to Sargon Capital’s books and records, and information relevant to the proposed Cloverhill Sale. The majority of the information requested was not provided to the Sargon Capital Receivers, in part, due to a confidentiality agreement between the Administrators and the Cloverhill Group.

9.6 On or around 18 February 2020, the Cloverhill Group made an offer to the Administrators to purchase all of the assets of some of the Relevant Sargon Entities (among other entities), including the share capital in the Relevant Operating Subsidiaries (among other entities).

9.7 On or about 4 March 2020, a written offer dated 4 March 2020 was made by the Cloverhill Group to purchase all of the assets of each of the Relevant Sargon Entities (among other entities), including the share capital in the Relevant Operating Subsidiaries (among other entities), subject to the fulfilment of various conditions precedent.

9.8 On 10 March 2020, the Sargon Capital Receivers sought confirmation from the Administrators that the proposed sale did not include any assets or property of Sargon Capital, in particular, any intellectual property.

9.9 On 28 March 2020, GrowthOps and the Administrators reached an in-principle agreement that GrowthOps would transfer any rights that it had in the Developed IP (as that term is defined in the Technology MSA and Marketing MSA) to the Cloverhill Group for an agreed payment contingent on the completion of the Cloverhill Sale (Administrators' Proposed Agreement).