FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Google LLC (No 2) [2021] FCA 367

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent GOOGLE AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties confer with a view to providing within 14 days agreed orders reflecting the conclusions reached by the Court and appropriate further steps.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

1. Limited parts of these reasons for judgment have been redacted to give effect to non-publication orders made on 4 and 10 December 2020.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THAWLEY J:

[1] | |

[19] | |

[20] | |

[28] | |

Collection, storage and use of personal data about a user’s location | [33] |

[39] | |

[45] | |

[46] | |

[50] | |

[50] | |

[65] | |

[77] | |

[77] | |

[78] | |

[87] | |

[99] | |

[121] | |

[136] | |

[141] | |

[142] | |

[151] | |

[153] | |

[158] | |

[159] | |

[164] | |

[166] | |

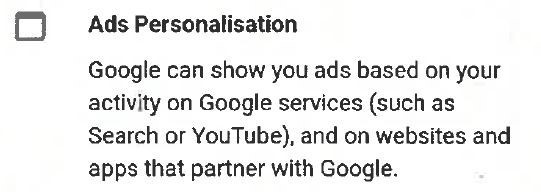

[213] | |

[229] | |

[230] | |

[239] | |

[241] | |

[244] | |

[245] | |

[251] | |

[256] | |

[265] | |

[275] | |

[278] | |

[279] | |

[282] | |

[289] | |

[290] | |

[293] | |

[298] | |

[299] | |

[301] | |

[302] | |

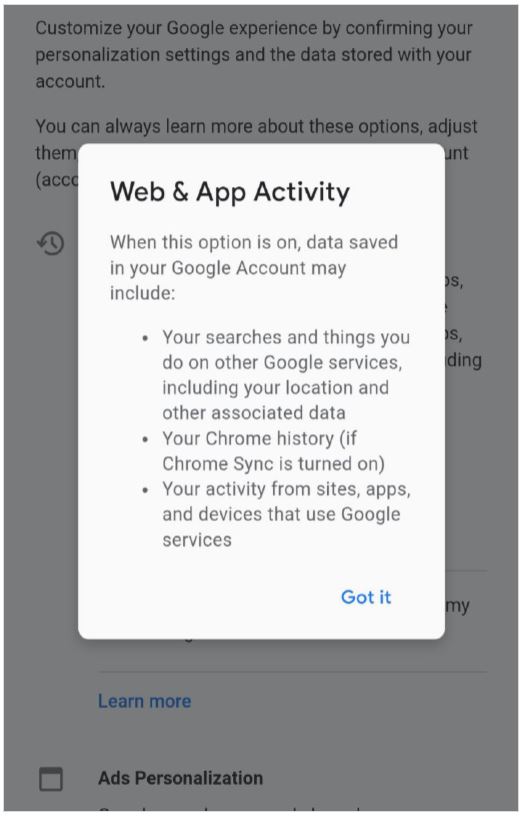

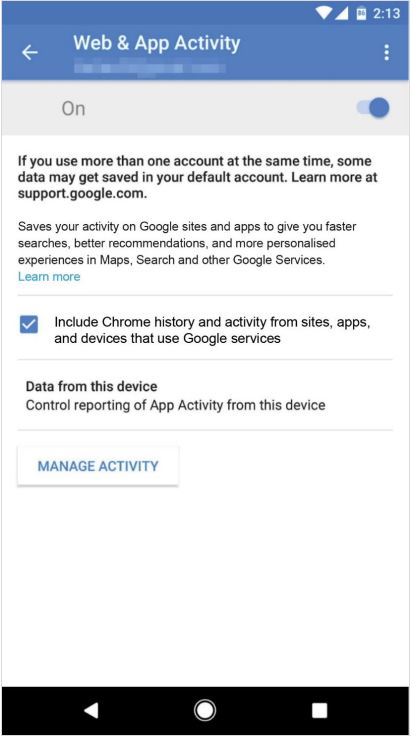

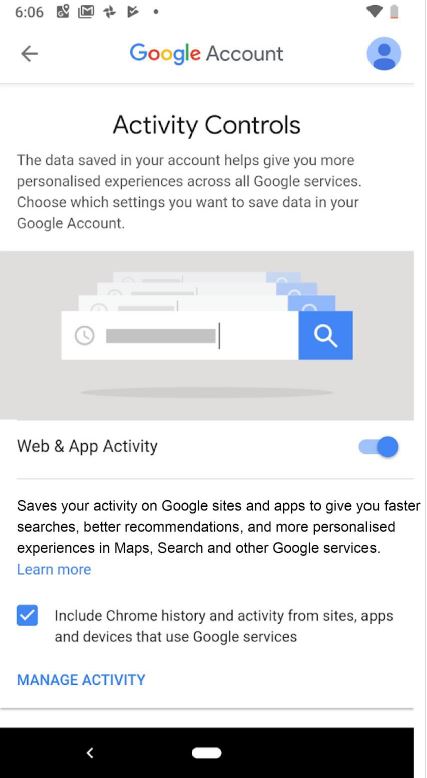

SCENARIO 3: USERS CONSIDERING WHETHER TO TURN WEB & APP ACTIVITY “OFF” | [303] |

[304] | |

[309] | |

[317] | |

[318] | |

[323] | |

[327] | |

[327] | |

[328] | |

[329] | |

[334] | |

[341] |

1 The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) alleges that Google LLC and Google Australia Pty Ltd (GAPL) contravened ss 18, 29 and 33 or 34 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). Google LLC is incorporated in the United States of America. GAPL is incorporated in Australia. They are referred to collectively in these reasons as Google.

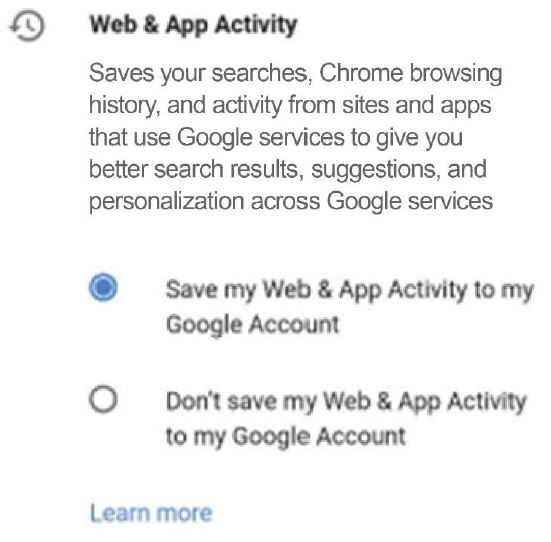

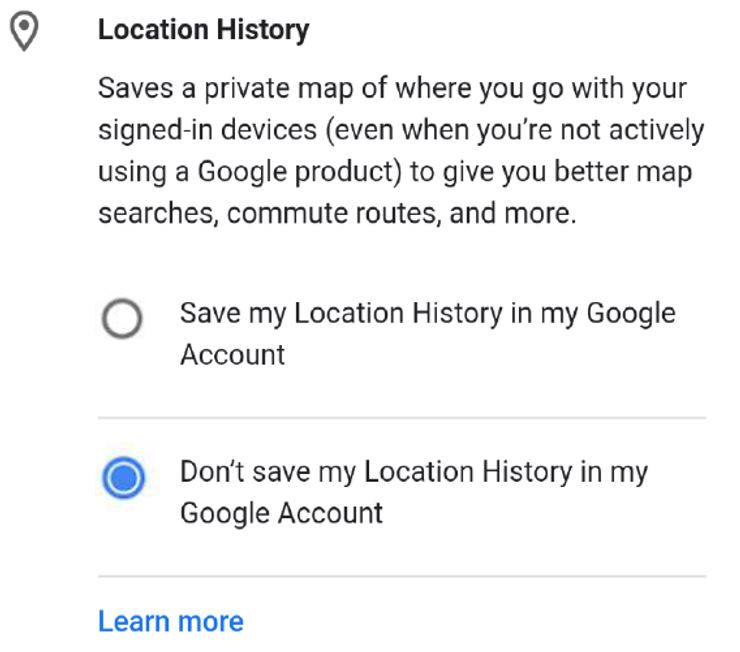

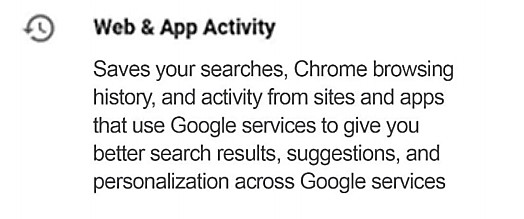

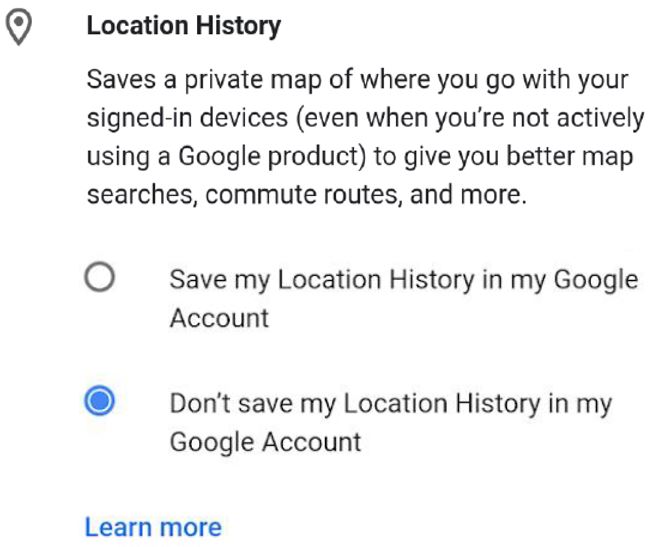

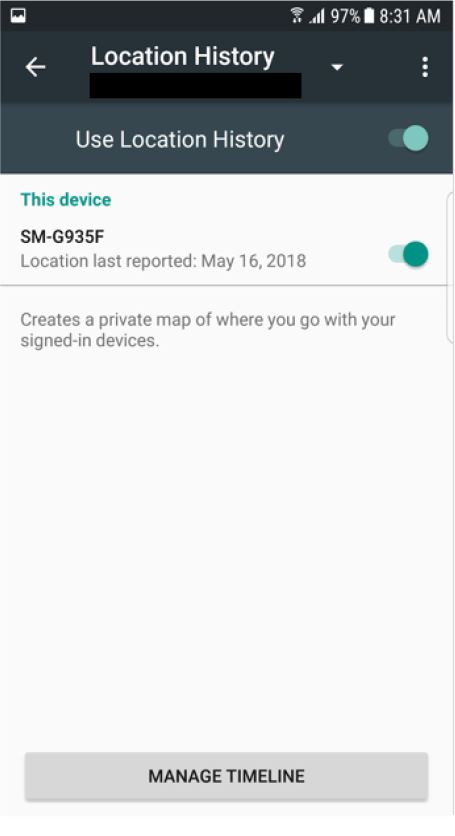

2 The ACCC’s case was that particular users of mobile devices with Android operating systems (Android OS) were misled by reason of the content of various screens those users saw on their devices. Two settings were central to the ACCC’s case: “Web & App Activity” and “Location History”. When setting up a device relevant to the proceedings, Web & App Activity was defaulted to “on” and Location History was defaulted to “off”. These default settings meant that Google LLC could obtain, retain and use personal location data when a user was using various apps, including Google services such as Google Maps. At the core of the ACCC’s case was the contention that there were users who were misled or likely to have been misled by what was, and what was not, stated or shown on various relevant screens on the users’ devices; there were users who, acting reasonably, would have been led into thinking that, with Location History “off”, Google LLC would not obtain, retain and use personal data about a user’s location, and that this was not relevantly changed by the fact that Web & App Activity was “on”.

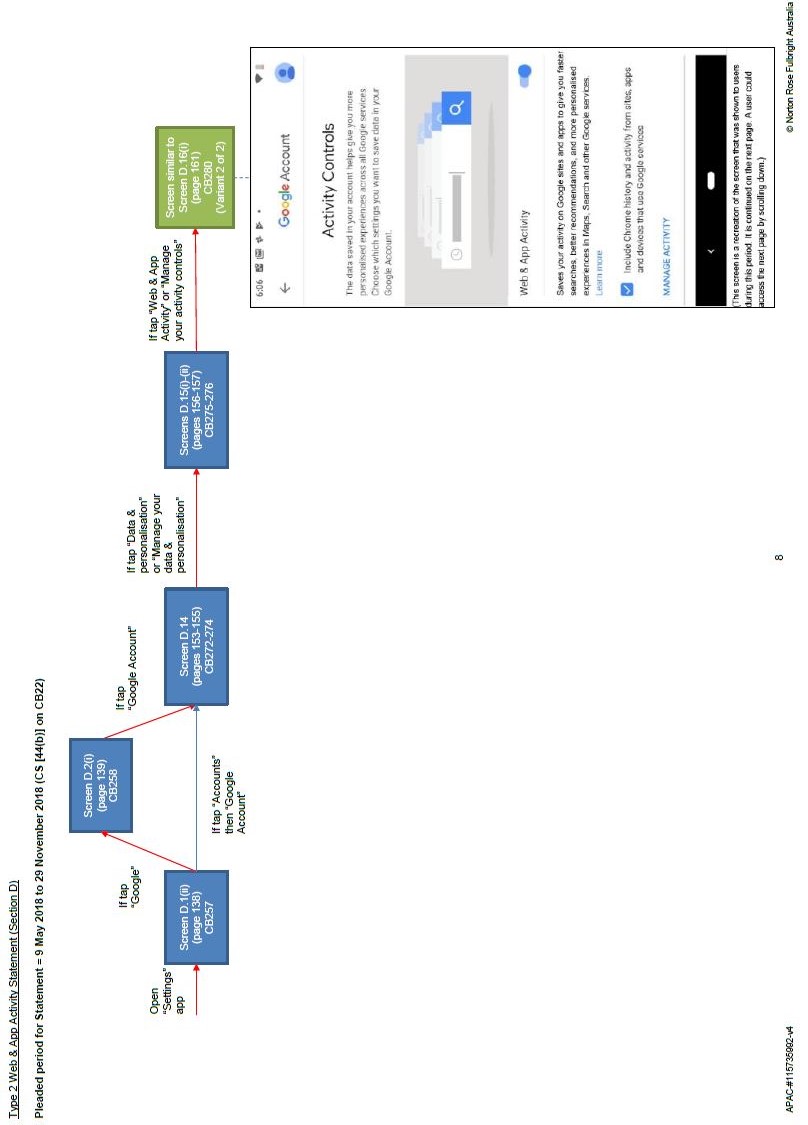

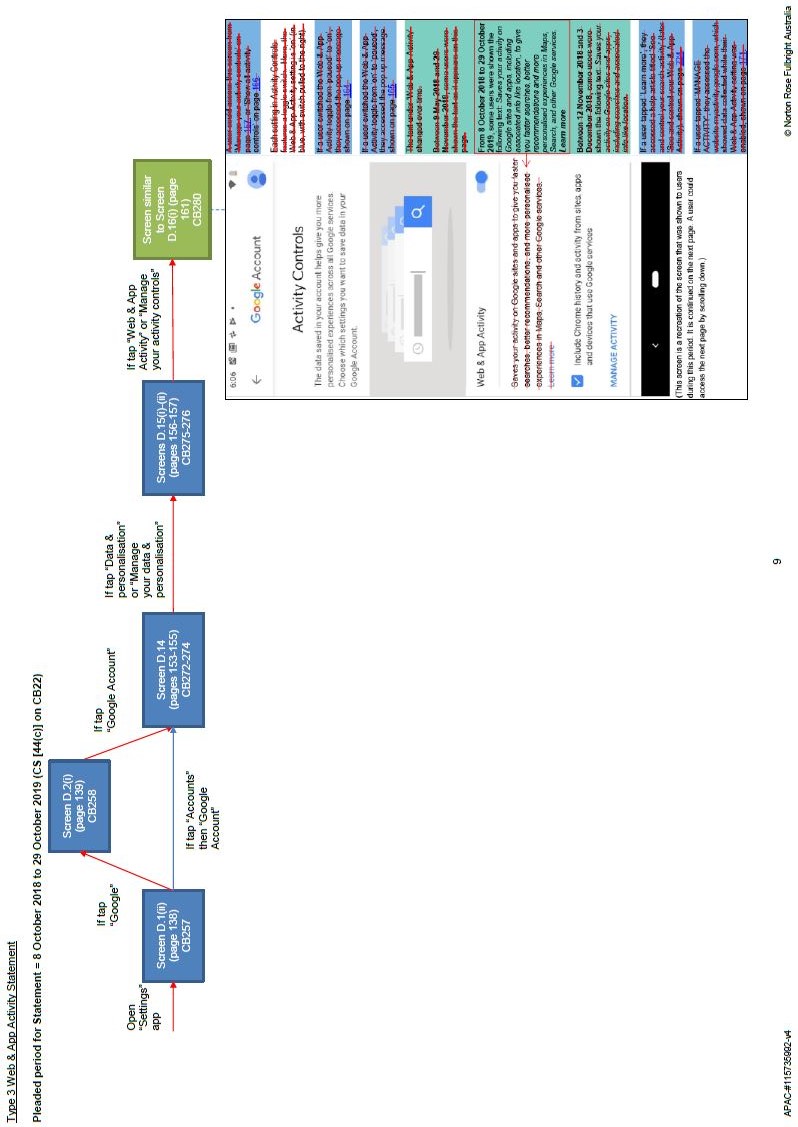

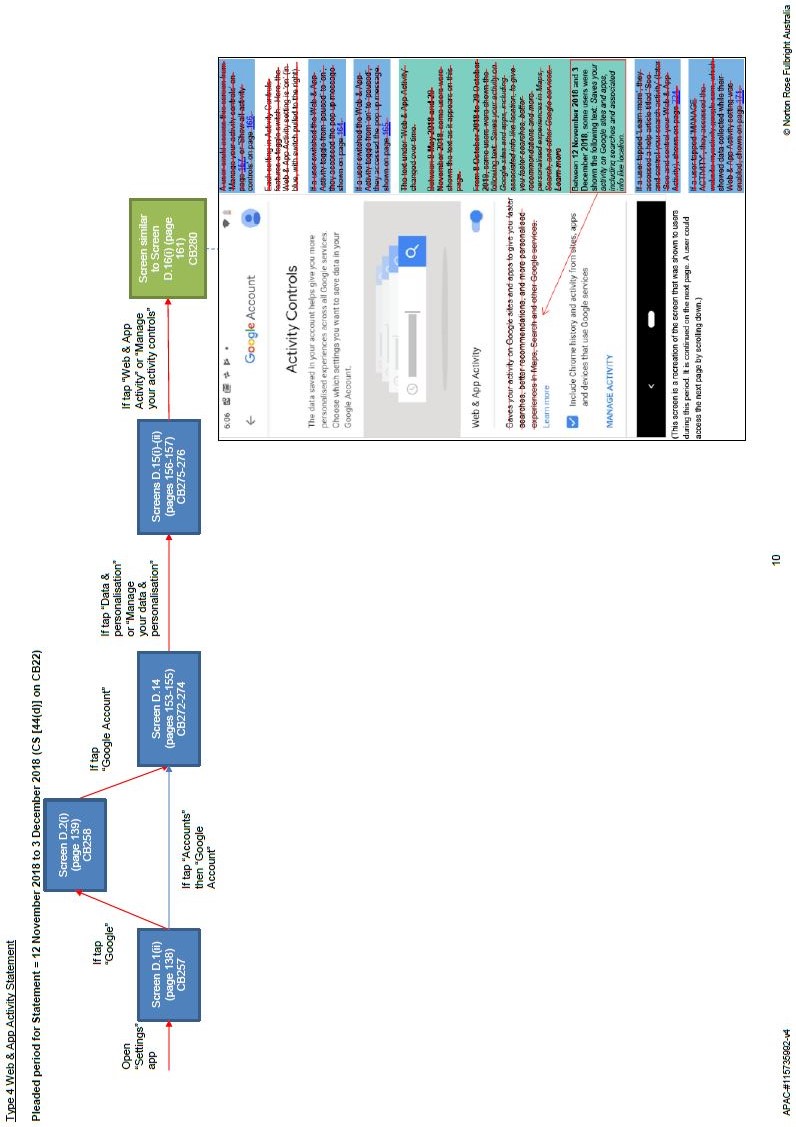

3 The ACCC ran its case by reference to particular classes of users in three different scenarios, confined to particular time periods. The classes of users in each scenario were quite specifically identified and identified in a way which necessarily carried an implication that the relevant users had certain characteristics.

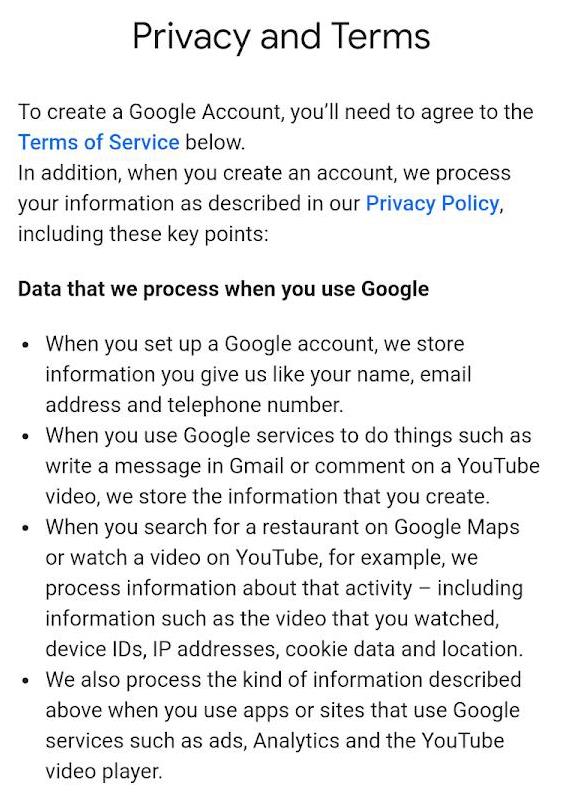

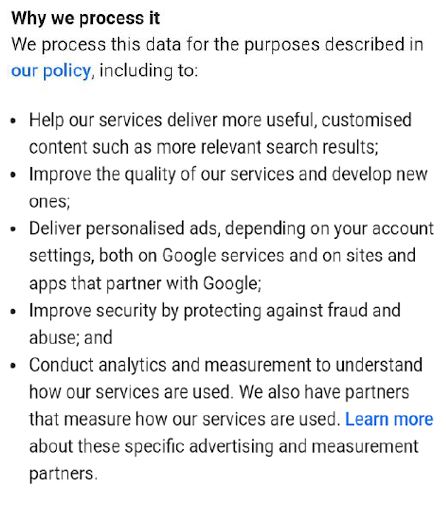

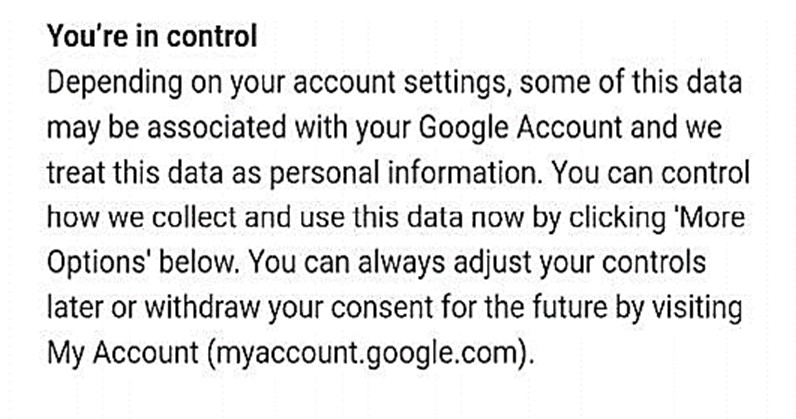

4 Scenario 1 concerned users who:

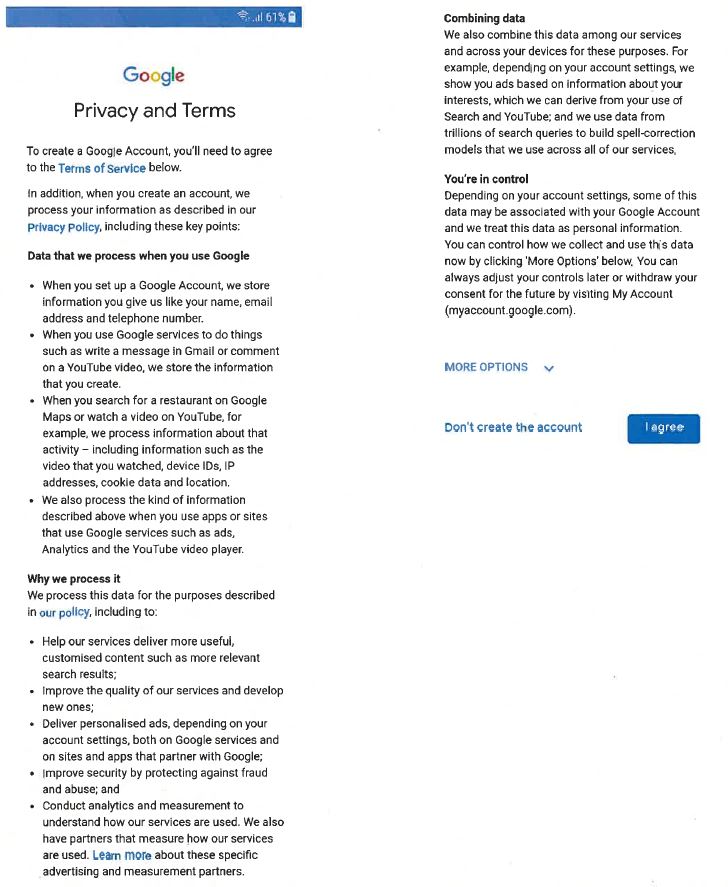

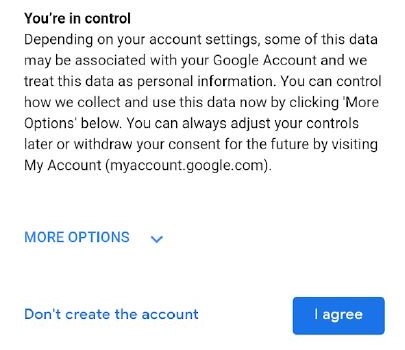

(1) used an Android OS on a mobile device, between 30 April 2018 and 19 December 2018, to set-up his or her Google Account;

(2) when viewing the Privacy and Terms screen (Annexure A to these reasons), chose to click on “More Options” rather than “I agree” or “Don’t create the account” and were accordingly, shown the More Options screen (Annexure B to these reasons).

5 The ACCC’s case in relation to Scenario 1 was not that Google should have given some general warning to all users at the commencement of setting up a Google Account. On the ACCC’s case and the evidence, the vast majority of users would not have clicked on “More Options” and would not have reached the More Options screen. One reason a user may have clicked on “More Options” was that the user had a concern about privacy generally or, more specifically, about personal data concerning the user’s location being obtained or used. Such a user would be expected to pay more attention to material relevant to his or her privacy concerns and perhaps also to seek out further information. The extent to which that would be so is addressed later.

6 At its simplest, the ACCC’s case in relation to Scenario 1 was that, as a result of what users saw on the Privacy and Terms screen (Annexure A) and the More Option screen (Annexure B), users would have been misled into thinking that Google LLC would not obtain, retain and use personal location data whilst Location History was defaulted to “off”. In fact, however, Google would continue to obtain, retain and use location data when a user used Google products or services because Web & App Activity was “on”.

7 Scenario 2 concerned events after the initial set-up of the device and the opening of a Google Account. Scenario 2 concerned users who:

(1) either during set-up or at some other time had turned the Location History setting to “on”, from its default position of “off”; and

(2) had then later made a decision to turn Location History back to “off”.

8 The class of users was confined to users who had already made a decision to turn Location History “off”. That decision must have been made for a reason, presumably connected with what the user knew or thought about the function of the Location History setting. This class of user had a specific objective beyond simply setting up their Google Account.

9 In summary, the ACCC’s case was that Google LLC incorrectly represented to certain users who had decided to turn Location History “off” that:

(1) Google LLC would not continue to obtain, retain and use personal data about the user’s location after the Location History setting was turned “off”; and

(2) Google LLC would only obtain, retain and use personal data about location for the user’s purposes, not for Google’s purposes.

10 In fact Google LLC could obtain, retain and use personal data about location whilst Web & App Activity was “on”, even when Location History was “off”. That data would be used both for Google’s purposes and the user’s purposes.

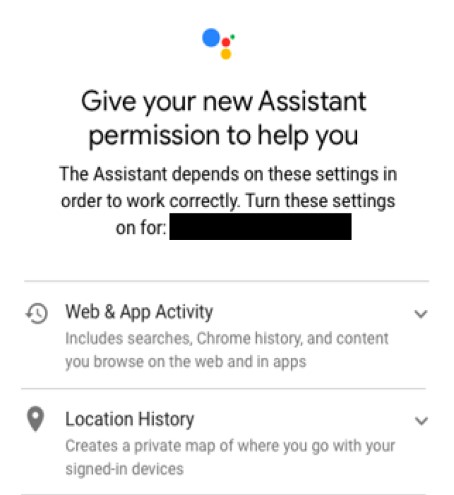

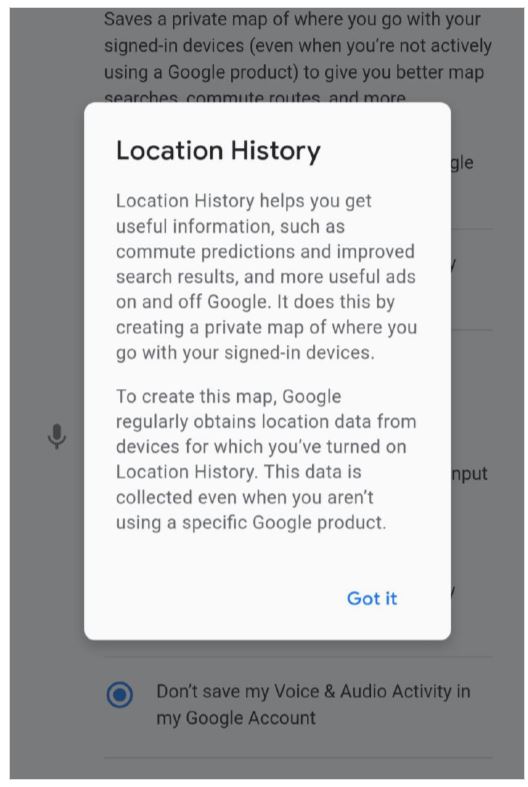

11 Scenario 3 concerned users considering whether to turn the Web & App Activity setting “off”. Although this could occur during the set-up process, the case was argued on the basis of this occurring after set-up of the device and the opening of a Google Account.

12 The class of persons to whom Scenario 3 applied was stated to be confined to users considering whether to turn Web & App Activity “off”. The relevant users must have been considering whether to turn the setting off for some reason, presumably connected with what the person knew or thought about the function of the Web & App Activity setting. The relevant user identified by the ACCC was someone who had an objective, namely to make a decision about something that the user had decided to look into.

13 In summary, the ACCC’s case in relation to Scenario 3 was that Google incorrectly represented to certain users considering whether to turn Web & App Activity “off” that:

(1) having Web & App Activity “on” would not allow personal data in relation to the users’ location being obtained, retained and used by Google LLC; and

(2) Google LLC would only obtain, retain and use personal data about location for the users’ purposes, not for Google’s purposes.

14 Whilst Google did not dispute that the ACCC could run its case by reference to users in the classes and scenarios identified by the ACCC, Google disputed that it breached any of the relevant provisions of the ACL.

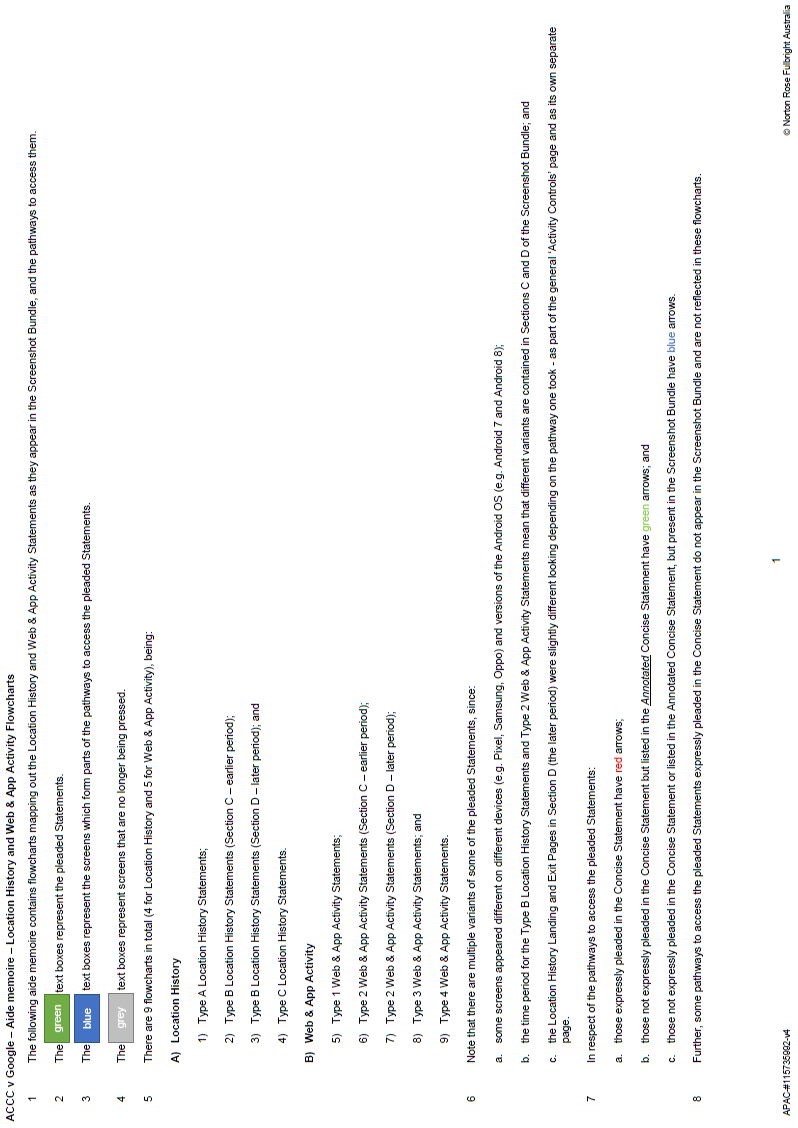

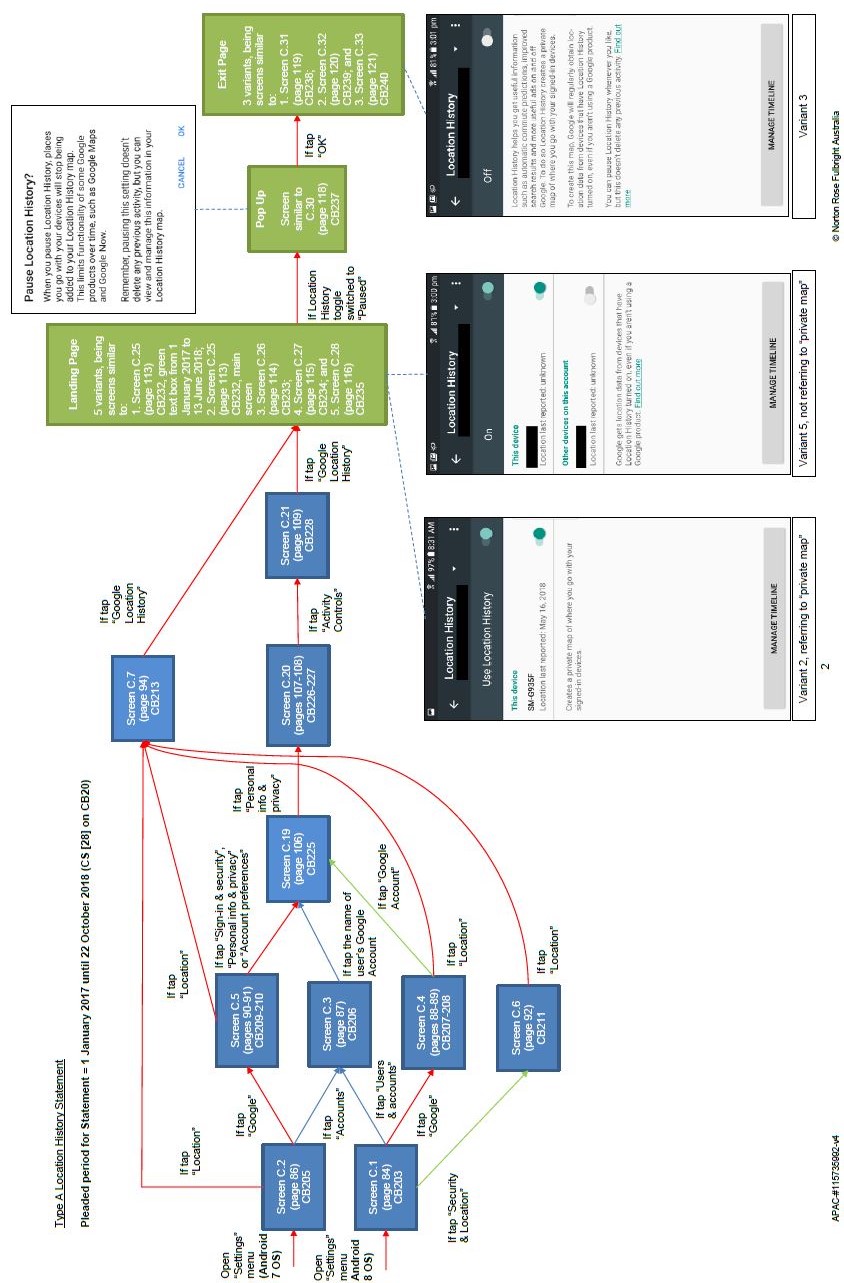

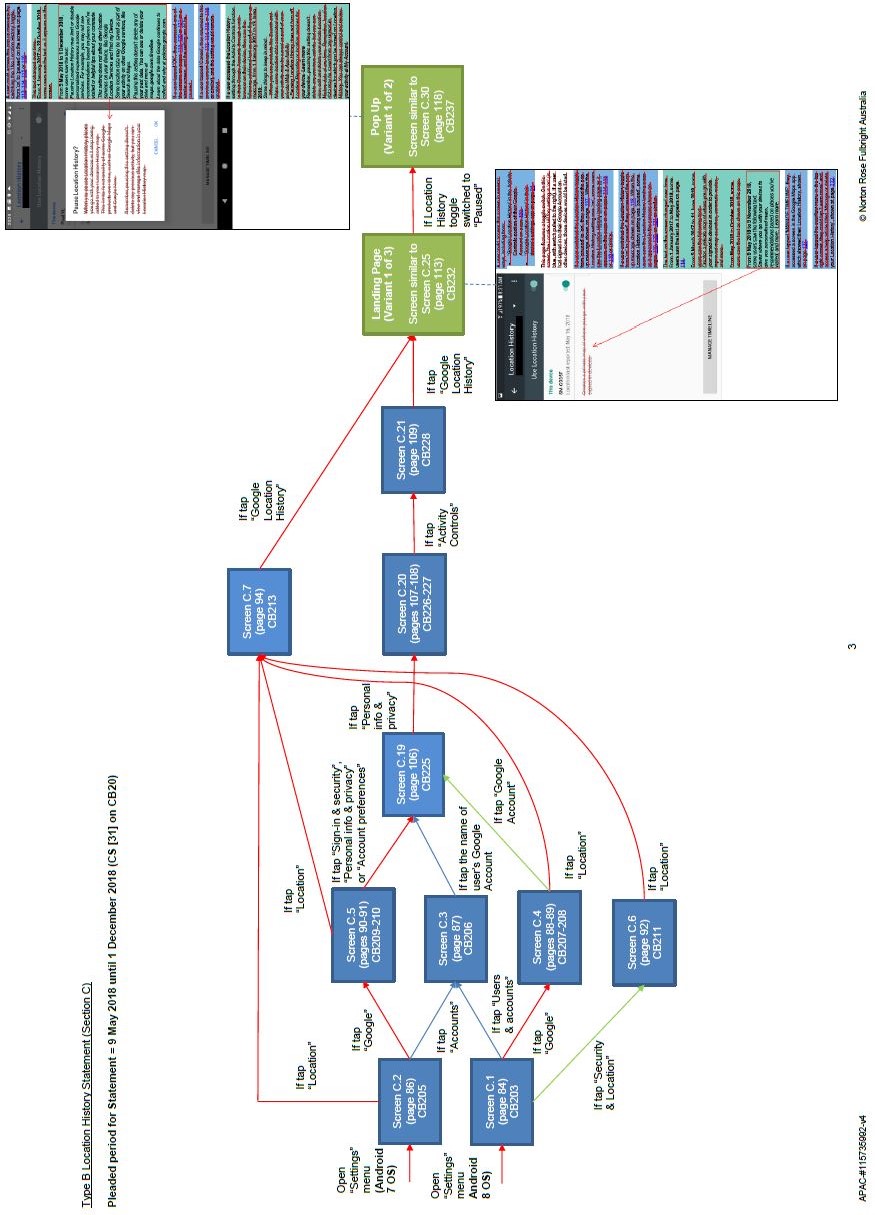

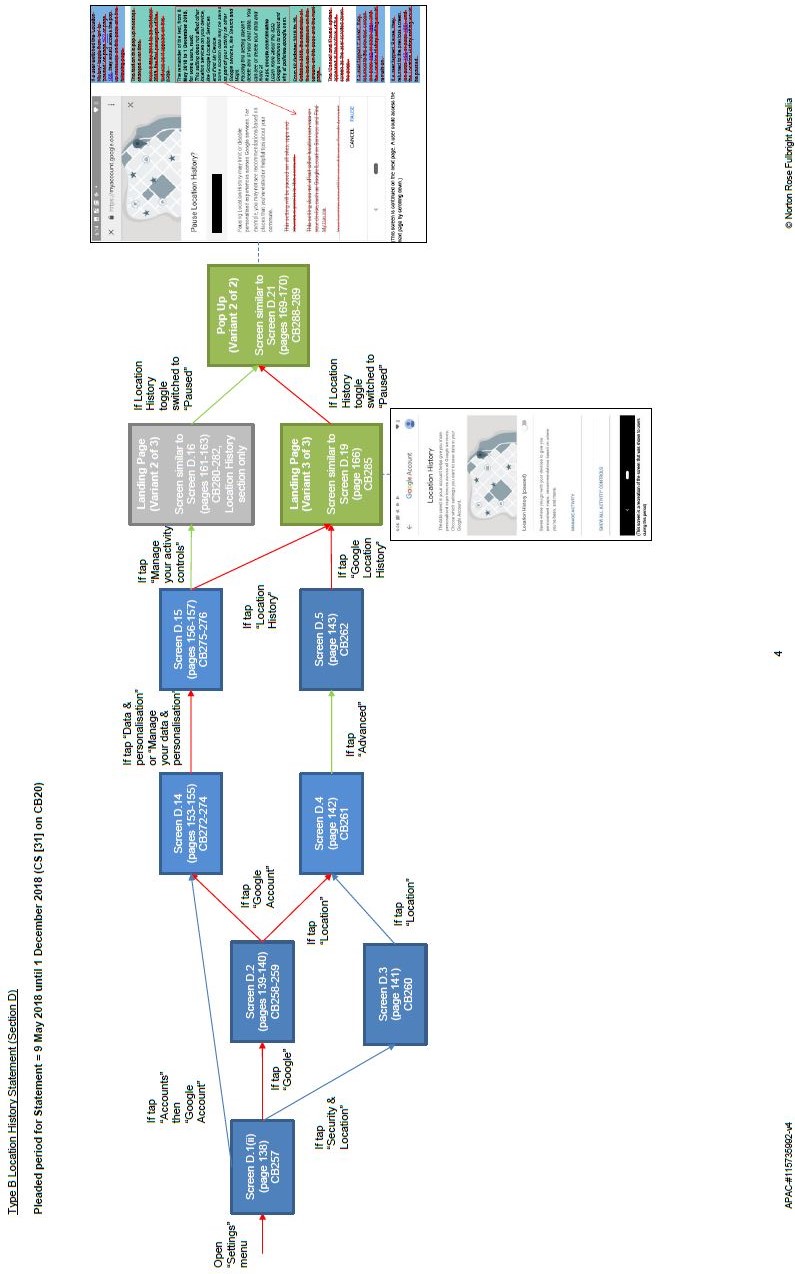

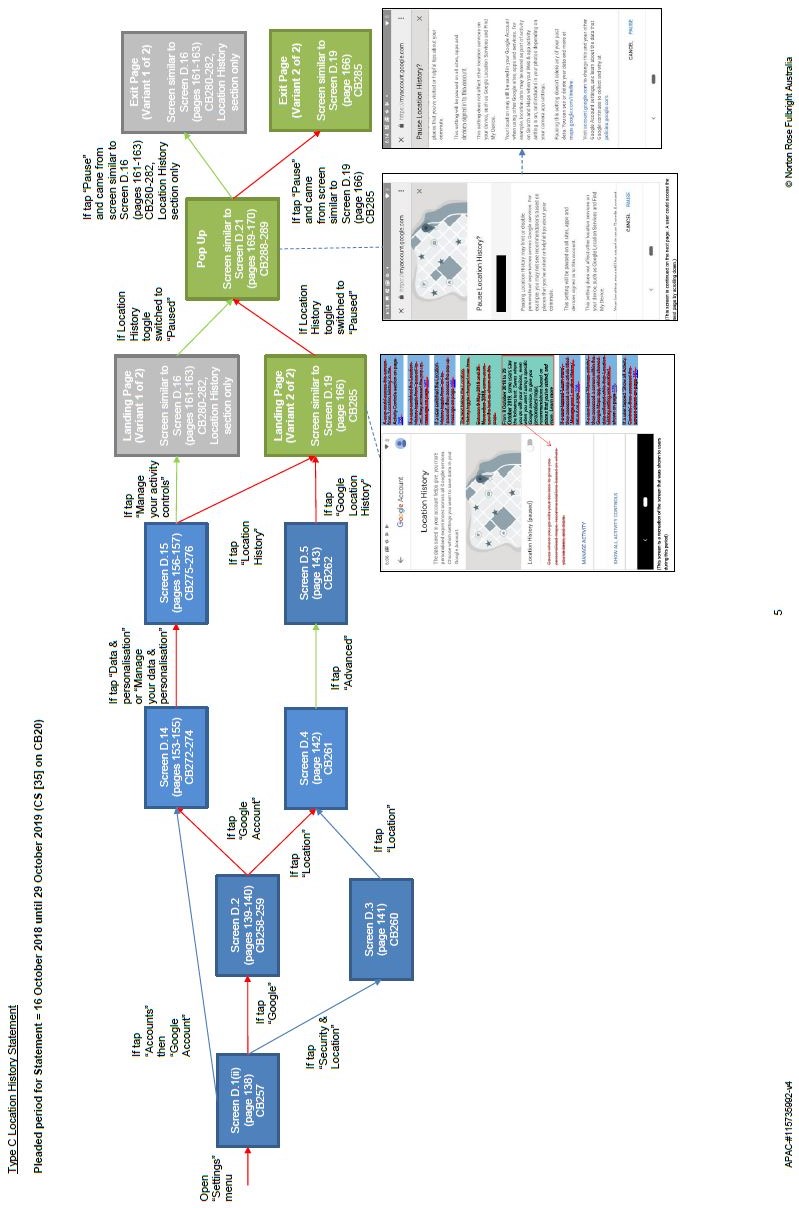

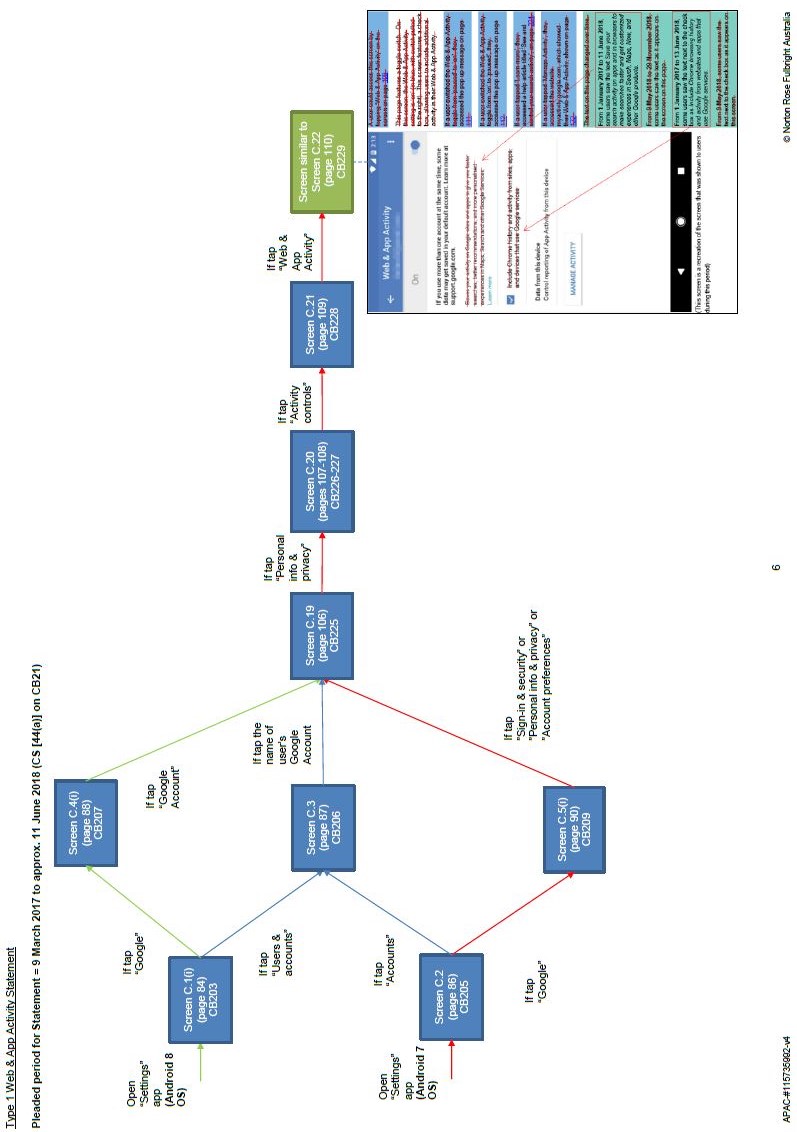

15 The ACCC ran its case on the basis of numerous variations of screens presented to users over various and overlapping time periods. The possible permutations of precisely what users might have seen was not reasonably calculable. Ultimately, the case was run by reference to an amended aide memoire identifying representative screens. This was a reasonable way to deal with the issues in an appropriate manner. The aide memoire, updated after closing submissions, is MFI 3 (Annexure C to these reasons).

16 One matter of principle which divided the parties was whether, within each class, the Court had to assess the case by reference to a single hypothetical user having only one possible reaction or response to the material presented to the user by the screens. Google submitted that the law was to that effect. For the reasons given below, I reject that submission. So far as concerns s 18 of the ACL, it is sufficient for the ACCC to establish that Google’s conduct was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive ordinary or reasonable members of the relevant class, extreme or fanciful responses being disregarded.

17 For the reasons which follow, I have concluded that the ACCC’s case under s 18 of the ACL is partially made out in respect of each of the three scenarios. Google’s conduct would not have misled all reasonable users in the classes identified; but Google’s conduct misled or was likely to mislead some reasonable users within the particular classes identified. The number or proportion of reasonable users who were misled, or were likely to have been misled, does not matter for the purposes of establishing contraventions.

18 I have also concluded that the ACCC’s case under ss 29(1)(g) and 34 of the ACL is partially made out in respect of each scenario.

19 Many of the facts were agreed between the parties for the purposes of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). The following account of the facts is drawn largely from the “Further Amended Statement of Agreed Facts” and the “Further Agreed Facts”.

Overview of Google’s services in Australia

20 Google LLC supplied a range of software products and services to consumers in Australia, referred to in these reasons as “Google services”, including:

(a) the “Google Play Store”, a mobile app and online entertainment store;

(b) “Google Search”, an internet search engine;

(c) “Google Chrome”, a web browser;

(d) “Google Maps”, a mapping app;

(e) “Gmail”, an email service and app; and

(f) “YouTube”, an online video platform.

21 From at least 1 January 2017, Google supplied:

(1) various goods and services to consumers in Australia, including certain Google services;

(2) the Android OS (which is not comprised within the Google services), namely a mobile operating system developed by Google LLC which it regularly updated. Google LLC permitted the Android OS to be used by other companies on an “open source” basis.

22 Google Accounts are accounts available to individual users. Use of some Google services (such as Google Search, Google Maps and YouTube) does not require a Google Account. Other Google services, such as the Google Play Store, require the user to be signed into his or her Google Account. Some product features in certain Google services are not available if the user does not sign into a Google Account (for example, some features of YouTube and Google Maps).

23 The content of the Android OS was available to millions of Australian users in the relevant period. Around 6.3 million Australian users set-up a new Google Account on devices using the Android OS between January 2017 and August 2019.

24 Third-party manufacturers of mobile devices that used the Android OS may have also licensed Google Mobile Services (GMS) from Google LLC and pre-installed GMS on their mobile devices. GMS is a set of Google apps (including the Google Play Store, Google Search, Google Chrome and YouTube) and application programming interfaces used on mobile devices running on the Android OS.

25 Google LLC required licensees of GMS to meet certain requirements, including that no modifications were made to the Google Account settings on devices with GMS pre-installed. The significant majority of third-party manufacturers who used the Android OS for mobile devices supplied in Australia also licensed GMS.

26 The Pixel is a mobile phone which Google LLC caused to be manufactured by third-parties before October 2018. Google LLC has manufactured the Pixel since October 2018. Around 280,000 Pixels were sold in Australia either indirectly by third-party resellers or directly by GAPL in financial years 2017 to 2019.

27 GAPL supplied Pixels to third-party suppliers of mobile devices in Australia at all material times and, since around June 2018, also supplied Pixels directly to consumers in Australia. The Pixels supplied by GAPL to third-party suppliers and consumers in Australia were pre-installed with the Android OS and GMS. GAPL was not responsible for the Google services, Google Accounts or the Android OS.

28 The parties referred to a “user” as a person who:

(a) had a mobile device which used the Android OS and on which GMS was installed; and

(i) either had a Google Account and was signed into his or her Google Account on a mobile device which used the Android OS and on which GMS was installed (those devices being referred to as Linked Devices); or

(ii) alternatively, was in the process of setting up a Google Account on the mobile device.

29 The parties referred to personal data as data which is identifiable as being associated with the holder of a particular Google Account. For the purposes of this proceeding, the parties agreed that IP address data is not personal data in relation to or about a user’s location.

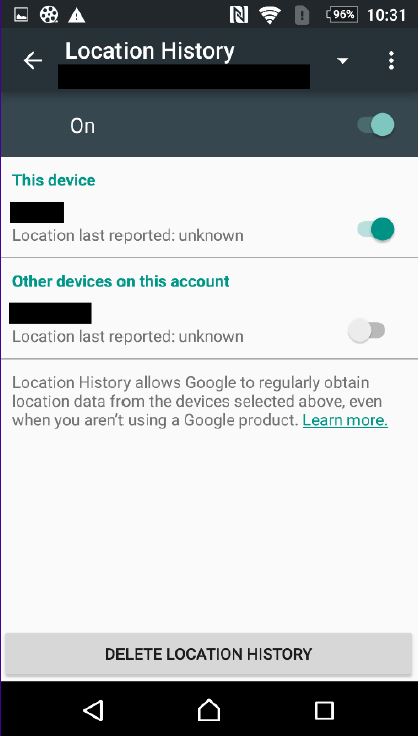

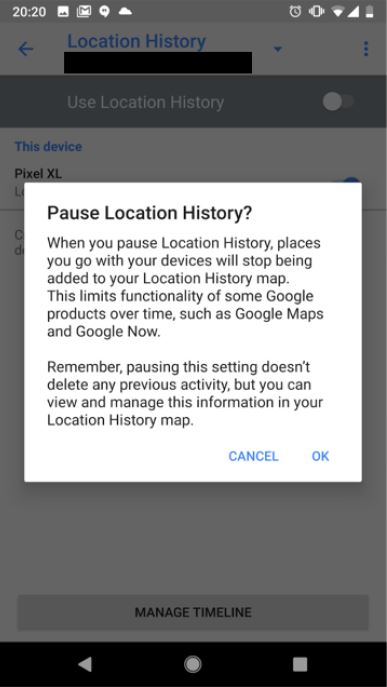

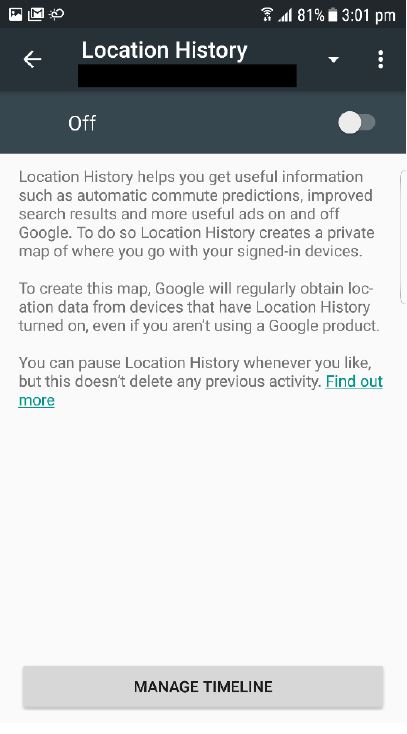

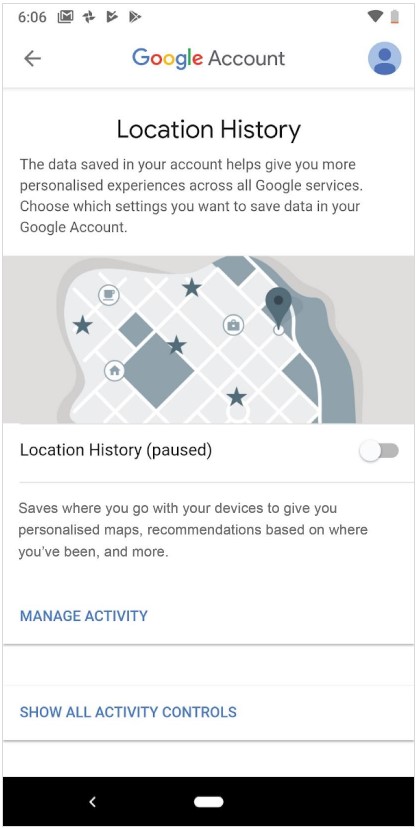

30 From 1 January 2017 to 29 October 2019, the settings within users’ Google Accounts included Location History and Web & App Activity.

31 At all relevant times, the default setting when a user set-up a Google Account was that the Location History setting was turned “off” (or “paused” or “disabled”).

32 At all relevant times, the default setting when a user set-up a Google Account was that the Web & App Activity setting was turned “on” (or “enabled”).

Collection, storage and use of personal data about a user’s location

33 Google LLC collected and stored personal data about a user’s location from a Linked Device if the “Device-level Location Setting” (described in paragraphs 39 to 44 below) was enabled, the user was signed in to their Google Account, and either or both of the following applied:

(1) the Web & App Activity setting was enabled and the user had used certain Google services (for example Google Maps or Google Search); and

(2) the Location History setting was enabled.

34 Further, some apps, such as Google Photos, included settings that permitted data from the use of that app to be associated with the user’s Google Account. These discrete app settings were not the subject of these proceedings. Leaving this aside, Google LLC did not collect or store personal data about a user’s location except in the circumstances identified immediately above.

35 The personal data about a user’s location that Google LLC collected from the user’s Linked Device in the circumstances described at [33(1)] above was stored by Google LLC in association with the user’s Google Account and was accessible to the user in the “My Activity” feature of their Google Account.

36 The personal data about a user’s location that Google LLC collected from the user’s Linked Device in the circumstances described at [33(2)] above was stored by Google LLC in association with the user’s Google Account and was accessible to the user in the “Timeline” feature of Google Maps.

37 The Location History and Web & App Activity settings could be enabled or paused:

(a) between 1 January 2017 and 30 April 2018: at any time after the set-up of a Google Account; and

(b) after 30 April 2018: at any time during or after the set-up of a Google Account.

38 Google LLC collected, stored and used personal data (including personal data in relation to a user’s location) for purposes including the following:

(a) the user’s use of Google services;

(b) to personalise advertisements for the user;

(c) in an anonymised form, to personalise advertisements for any other user or users;

(d) in an anonymised form, to infer demographic information;

(e) in an anonymised form, to measure the performance of advertisements;

(f) in an anonymised, aggregated form, to promote, offer to supply or supply advertising services to third parties; and

(g) to produce anonymised, aggregated statistics (such as store visit conversions statistics) and sharing those statistics with advertisers.

39 Whether location data might have be collected from a Pixel depended upon whether the “Use Location” or “Location” setting on that Pixel was enabled. Similar settings were available on other Android devices, but may have been labelled differently. The parties referred to these device settings as the Device-level Location Setting.

40 At all relevant times when a user set-up their Linked Device, the user was presented with an option to disable the Device-level Location Setting, which was enabled by default.

41 The location data collected by Google LLC when the Device-level Location Setting was enabled was not personal data unless the circumstances described at [33] above applied, namely Web & App Activity and/or Location History was enabled. This is because the data was not identifiable as being associated with the holder of a particular Google Account.

42 If a user disabled the Device-level Location Setting, no apps (whether Google apps or third-party apps) were able to access the location of the user’s Linked Device (even if either or both of Location History or Web & App Activity were enabled).

43 Where the Device-level Location Setting was disabled, some product features in certain apps (including some Google services) were not available to the user. In circumstances where those features would otherwise be available to the user, the relevant apps (including some Google services) might prompt the user to enable the Device-level Location Setting on the Linked Device. Where, in response to such a prompt in certain apps (including some Google services), the user chose to enable the Device-level Location Setting, that had the effect of toggling a particular switch to “on”. For example, with the Device-level Location Setting disabled, Google Maps would:

(a) not show the user their location on a map or give directions using the user’s current location (but could give point-to-point directions between two specified locations); and

(b) prompt the user to enable the Device-level Location Setting on that Linked Device.

44 Where the user chose to enable the Device-level Location Setting in this example that had the effect of toggling a particular switch to “on”.

45 The “Further Amended Statement of Agreed Facts” referred to a “Screenshot Bundle” (SB) and “Supplementary Screenshot Bundle”, which the parties agreed formed part of the agreed facts. It contained screenshots, typically from a Pixel device, which were representative of screens shown to users of Android devices running the then-current versions of the Android OS in the period 1 January 2017 to 29 October 2019. The Screenshot Bundle was divided into sections in relation to setting controls presented during “Set-up”, and post set-up “Settings”.

46 During the period 1 January 2017 to 29 October 2019, the screens that a user would see during the set-up of their Linked Devices varied. This depended on, for example, the device used and the point in time at which the user was setting up the Linked Device.

47 When setting up a new Linked Device, a user could select the following options:

(a) create a new Google Account;

(b) sign in to an existing Google Account; or

(c) skip signing in to or creating a Google Account.

48 A user’s options in the period 1 January 2017 to 29 April 2018 were shown at pages 8 – 9 of the Screenshot Bundle. A user’s options in the period 30 April 2018 to 29 October 2019 were shown at pages 47 – 50 of the Screenshot Bundle.

49 The various permutations of what would be seen depending on what link or option a user chose are not practical to put in writing. They are referred to below in resolving the issues raised in the proceedings and can be partially seen by an examination of MFI 3 at Annexure C.

50 The ACCC and Google relied on evidence of distinguished economists with particular expertise in behavioural economics. The ACCC relied on evidence from Professor Robert Slonim, a professor at the School of Economics at the University of Sydney. Google relied on evidence from Professor John List, a professor of economics at the University of Chicago. Professor Slonim prepared the first report filed in the proceedings, Professor List responded and Professor Slonim prepared a report in reply. In addition, Professors Slonim and List prepared a joint report. I was impressed and assisted by both professors.

51 The expert evidence was to the effect that the appropriate framework for understanding how users approached the process of navigating the relevant screens involved a cost-benefit analysis, subject to certain behavioural biases. At any point in the navigation process, if users perceived the marginal benefit of navigating or searching further exceeded the marginal cost, the user would continue. Conversely, users would not search or navigate further where they perceived the marginal cost to exceed the marginal benefit. A user may have known that information was available but rationally chose not to read it. If a user was particularly concerned to know about a particular topic, all other things being equal, such a user was more likely to look for that information. But even a person interested in a topic may have reached a point where he or she would stop notwithstanding that the person knew there was more information available.

52 Professor Slonim and Professor List drew a distinction between traditional economic models of decision making and that indicated by the field of behavioural economics. At its most severe, traditional economic modelling answers what should be the result by analysing the decision which would be made by a person who, to adopt Professor List’s language, “is unswervingly rational, completely selfish, analytical, reliable, and can effortlessly and costlessly solve even the most difficult optimization problems”. Behavioural economics recognises that actual human behaviour deviates from the traditional rational model in predictable ways. Behavioural economics starts from the premise that people are time constrained, do not have all (or even most) information easily accessible and have cognitive capacity with serious limits in processing information when making choices. These constraints cause people to use short-cuts (referred to as “heuristics”) to make choices. The heuristics are subject to many biases, which result in systematic and predictable deviations from making the optimal choices which would be assumed in the traditional economic approach. Behavioural economists would say that people are “boundedly rational”.

53 Professor Slonim and Professor List agreed that people are generally subject to a number of behavioural biases. These include the following.

54 First, risk aversion: This refers to a bias whereby people prefer the expected value of a risky prospect rather than the risky prospect. Professor List gave the following example:

To understand risk aversion, consider a simple example in which a decision maker has to value a lottery that pays either $100 or $0, both with a 50% probability. This might reflect a random draw from an urn with 5 red balls and 5 black balls, where drawing a red ball results in a payment of $100 and a black ball results in no payment. The expected value of this lottery is $50 (= 0.5*$100 + 0.5*0). Risk aversion implies that a person prefers a certain $50 payment to this lottery and thus would be willing to pay less than $50 to participate in the lottery.

55 The point in its application to the present case, is that risk aversion will reduce the value to the user if the outcome is unknown to some value below the expected value.

56 Secondly, ambiguity aversion: This refers to a bias whereby people prefer a risky choice with known probabilities to an ambiguous choice where the probabilities are unknown. Ambiguity aversion and risk aversion are usefully considered together, because it often happens that people do not know the actual probabilities associated with outcomes. Professor List explained (footnotes omitted):

In many situations, however, people do not know the actual probabilities associated with outcomes. For example, consider the above example of a lottery determined by an urn filled with red and black balls, but where the number of balls of each color is unknown. This problem is referred to as an “ambiguous” choice in contrast to the “risky” choice involving known probabilities. In 1961, Daniel Ellsberg showed that people preferred a risky choice (with known probabilities) to ambiguous choices and hence are willing to pay less for ambiguous choices than risky ones. This preference is known as “ambiguity aversion”.

57 Thirdly, present bias: This refers to a bias causing people to place an inordinate amount of weight on costs or benefits that affect them in the present when compared to future costs or benefits. Both experts agreed that present bias could have affected users’ decisions regarding effort that they expended in navigating the screens.

58 Fourthly, status quo bias: Status quo bias refers to a common preference people have for the existing state of affairs rather than choosing an alternative. This applies in a variety of situations, including a preference for items people already own, current service providers, current insurance policies and default options. Status quo bias implies that default settings – for example Location History switched “off” and Web & App Activity switched “on” – may play an important role in user decisions regarding privacy settings. Referring to literature addressing online choices and technology more generally, Professor List stated (footnotes omitted):

Economic literature recognizes that the use of defaults can be efficient in the sense that in their absence Users would face more complex and demanding choices, potentially resulting in greater confusion and more frequent “mistakes”. The use of defaults is ubiquitous in the [technology] industry.

59 Fifthly, loss aversion: Loss aversion refers to the tendency for people to dislike losing more than they like winning. For example, Professor Slonim explained that participants in many experiments demanded much more money to give up an item than they were willing to pay to obtain the same item. In traditional economics, it would be assumed that people determine the correct value of alternatives and choose the better option. It is well established that this does not in fact occur in decision-making because people often bypass a sure win in order to avoid a possible, equivalently sized, loss.

60 The experts also addressed other issues. The experts referred to “cognitive cost”, which recognises that a person has limited mental resources to evaluate all possible options. Both experts considered the cognitive costs that users faced in navigating the various screens, particularly those involved in the set-up process. The amount of effort a user might be prepared to expend depends on a number of matters including how important a particular issue is to the person. A person with a particular concern about privacy might be prepared to expend greater mental resources on the topic than someone who did not have such a concern.

61 The experts agreed that there is a technological trade-off between privacy and service quality. This was described by Professor List in the following way (footnotes omitted):

Digital platforms and their users face a technological tradeoff between privacy and service quality. The use of personal data enables Google to offer a variety of personalized services based on individuals’ historical locations, travel patterns, web search and browsing activity, etc. Personal data enables Google to tailor advertisements to Users’ interests and enables Google to generate higher revenues and better serve advertisers. The tradeoff between privacy and service quality is central to the value proposition that Google offers its users and Google has been enormously successful. In 2017, for example, Google’s Android operating system was used in 65% of smartphones in Australia. Google’s market share of Australian search queries has averaged approximately 94% since 2014.

The tradeoff between privacy and service quality is well understood in the economics literature. In a paper that summarizes theoretical and empirical research on the economics of privacy, Acquisti et al. (2016) conclude that:

[I]ndividuals and organizations face complex, often ambiguous, and sometimes intangible trade-offs. Individuals can benefit from protecting the security of their data to avoid the misuse of information they share with other entities. However, they also benefit from the sharing of information with peers and third parties that results in mutually satisfactory interactions.

62 The experts referred to “choice architecture”. This refers to the entirety of the design of the screens. The experts agreed that this can affect whether, how much and how carefully users will invest effort to read and understand the content as well as affect the paths they will use to navigate through the screens.

63 The experts referred to “salience” and addressed the role of headings on the screens. On the basis that people have limited time and energy, a heading or some “salient” feature may capture the audience’s attention and perhaps also divert attention from some other aspect of the screen.

64 Professor Slonim and Professor List accepted that the various biases pulled in different directions. Some implied that users would spend more time assessing the content of the various screens; some implied that the user would spend less time. The experts ultimately agreed in their Joint Report that “[b]ehavioural economics … yields ambiguous predictions regarding the effort users will put into reading and navigating” the screens. As both parties ultimately submitted, in short, the economists agreed that behavioural economics alone could not predict how users’ decision-making would be affected by the screens. Nevertheless, the various points the experts made, which accord with common-sense, are useful in considering how a user faced with the various screens referred to in the proceedings might have reacted.

65 Google relied on the evidence of Mr David Monsees, a Senior Product Manager at Google LLC. Mr Monsees was responsible for the user-facing aspect of user data controls (UDC) or “UDC settings”, which included the Location History and Web & App Activity settings.

66 Mr Monsees gave evidence about Google’s products and accounts, and more specifically about the Location History and Web & App Activity settings and how those settings functioned.

67 In cross-examination, Mr Monsees was taken to a number of internal Google documents, which disclosed ongoing discussions regarding the Location History and Web & App Activity settings. The ACCC submitted that those documents demonstrated that Google employees considered the information provided to users in respect of Location History and Web & App Activity to be wholly deficient.

68 The first of these documents was a document labelled “go/ul2017”, and associated emails about the go/ul2017 document. The go/ul2017 document was a document prepared by Mr Lopyrev, the head engineer for Location History, and Mr Lopyrev’s team. XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX:

XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX

69 The go/ul2017 document had been sent to Mr Horling, Mr Monsees’ boss, on 23 February 2017, and forwarded to Mr Monsees by Mr Horling three days later. In his email to Mr Horling on 23 February 2017, Mr Lopyrev stated that the user story in relation to Location History and Web & App Activity was “crazy confusing”:

… I have two more topics for us:

- there was a plan to merge LH [Location History] and WAAH [Web & App Activity] - where did we land on this? should we consider it again (now that LH and WAAH world have so much overlap, our user story is crazy confusing - see go/ul2017)

- can you tell me the latest on Context Manager / Footprints ?

70 Mr Monsees replied to Mr Horling’s email, stating “that go/ul2017 doc from Mike is very unsettling”. Mr Monsees gave evidence that when he wrote that the go/ul2017 document was “very unsettling”, he was referring to XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX. Whilst acknowledging that at the time he read the document he would have understood that XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XXXX XX, Mr Monsees stated that this was not what “unsettled” him about the document.

71 Mr Monsees also gave evidence about internal Google communications regarding an article entitled “AP Exclusive: Google tracks your movements, like it or not” published by the Associated Press on or around 13 August 2018 (AP Article). The AP Article criticised the fact that Google retained users’ location information, even after a user had “paused” the Location History setting. The AP Article included:

An Associated Press investigation found that many Google services on Android devices and iPhones store your location data even if you’ve used privacy settings that say they will prevent it from doing so.

…

Google’s support page on the subject states: “You can turn off Location History at any time. With Location History off, the places you go are no longer stored.”

That isn’t true. Even with Location History paused, some Google apps automatically store timestamped location data without asking.

…

To stop Google from saving these location markers, the company says, users can turn off another setting, one that does not specifically reference location information. Called “Web and App Activity” and enabled by default, that setting stores a variety of information from Google apps and websites to your Google account.

When paused, it will prevent activity on any device from being saved to your account. But leaving “Web & App Activity” on and turning “Location History” off only prevents Google from adding your movements to the “timeline,” its visualization of your daily travels. It does not stop Google’s collection of other location markers …

72 After the publication of the AP Article, an urgent meeting was held between various Google employees, where the AP Article was discussed. It was referred to internally as the “Oh Shit” meeting. In response to the AP Article and following the meeting, Google’s Director of Communication & Public Affairs circulated a document entitled “Making Location History simple”, which referred to works being carried out to “reduce user confusion re: how location is used across our products and services”. The document was sent to Mr Monsees, who added information to the document regarding Location History projects that had been previously discussed or were already in progress.

73 Mr Monsees was also taken to a number of communications regarding the AP Article on “Industryinfo”, an internal Google platform used for discussion of tech industry news. A number of Google staff members commented about the AP Article on Industryinfo. For example, a Staff Software Engineer said (emphasis and use of word “redacted” in original):

I agree with the article. Location off should mean location off; not except for this case or that case.

The current UI [User Interface] feels like it is designed to make things possible, yet difficult enough that people won’t figure it out. New exceptions, defaulted to on, silently appearing in settings menus you may never see is <redacted>.

74 A Senior Technical Solutions Consultant also said:

Although I know how it works and what the difference between “Location” and “Location History” is, I did not know Web and App Activity had anything to do with location.

Also seems like we are not very good at explaining this to users.

75 Internal Google documents showed that following the publication of the AP Article, there was at least a 500% increase in the number of users disabling Location History and Web & App Activity.

76 It is not clear that the settings referred to in the documents to which Mr Monsees was taken, or to which the AP Article referred, were the same as the settings which were the subject of these proceedings, although I infer that there is likely to have been broad similarities. Mr Monsees’ evidence, and the documents to which he was taken do not establish, or assist in establishing in any meaningful way, that Google’s conduct in the specific respects pleaded in the present proceedings was misleading or likely to be so to the particular classes identified. Accordingly, I have not placed any reliance on this evidence.

77 Section 18(1) of the ACL provides that:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

78 The relevant general principles may be stated as follows.

79 First, because s 18 is focussed on “conduct” that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive, it is critical to commence consideration of whether the section applies by first identifying the relevant conduct with precision: Campbell v Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 CLR 304 at [32] (French CJ); Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 249 CLR 435 at [89] (Hayne J).

80 Secondly, it is necessary to consider whether the identified conduct was conduct “in trade or commerce”. In the present case, there is no dispute that the conduct was in trade or commerce.

81 Thirdly, it is necessary to consider whether the conduct as a whole, and in context, was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive: Campbell at [102]; Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne v Powell (2015) 330 ALR 67 at [172].

82 Where conduct includes the making of express representations or where it is alleged that conduct gives rise to representations being made, it is necessary to bear in mind that “[r]eferences to misrepresentation or reliance must not be permitted to obscure the need to identify contravening conduct”: Campbell at [102]. The relevant “conduct is not to be pigeon-holed into the framework or language of representation”: Comité Interprofessionnel at [172].

83 The following further observations should be made in relation to cases, such as the present, where it is asserted that conduct gave rise to representations which were misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive:

representations may be express or they may be implied from words or conduct: Given v Pryor (1979) 24 ALR 442 at 446; Aqua-Marine Marketing Pty Ltd v Pacific Reef Fisheries (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 5) [2012] FCA 908 at [78];

it is necessary to determine whether the representations were in fact conveyed by the relevant conduct as a whole, assessed in context; examining only isolated parts of the conduct, for example individual express representations, “invites error”: Butcher v Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Limited (2004) 218 CLR 592 at [109] per McHugh J; approved in Campbell at [102];

where a Court is concerned to ascertain the overall impression created by a number of express and implied representations conveyed by one communication, or by a series of representations made during an online process or presentation, it is wrong simply to analyse the separate effect of each representation;

where a publication, or online process or presentation, contains a misleading statement in one place, but contains material which corrects or explains the misleading statement in another, the question is one of overall assessment of the whole publication or online process: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2020) 381 ALR 507 at [25]; a variety of considerations will be relevant, including the prominence of the various statements and the likelihood of the consumer reading or absorbing any neutralising material;

the conduct must ultimately be assessed as a whole and this means that individual representations must be assessed in the context of the whole of the conduct: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 199; Butcher at [39]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 (ACCC v TPG) at [52].

84 Fourthly, it is necessary to determine whether the conduct was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. Conduct will be misleading or deceptive if it induces or is capable of inducing error or has a tendency to lead into error. In ACCC v TPG at [39], French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ stated:

… Conduct is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, if it has a tendency to lead into error. That is to say there must be a sufficient causal link between the conduct and error on the part of persons exposed to it [Elders Trustee and Executor Co Ltd v E G Reeves Pty Ltd (1987) 78 ALR 193 at 241 (Gummow J)].

85 Conduct which merely causes confusion or uncertainty or wonderment is not necessarily misleading or deceptive: Google Inc at [8]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 317 ALR 73 at [39] (Allsop CJ).

86 The Court must put itself in the position of the relevant consumer. There is no question that the more one pores over the relevant screens, the more one notices matters of detail, the more one appreciates the literal meaning rather than what might first have been understood and the more one sees nuances and subtleties which might have been overlooked by the consumer. The relevant consumers in the classes identified by the ACCC would have read the material in a manner consistent with the consumer’s context. The question is not whether, on close analysis of written material by the Court after detailed argument, the various screens can be seen to be strictly accurate. The question is whether Google’s conduct as a whole, including what was and what was not stated on the various screens, was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive reasonable members of the class of consumers likely to be affected by the conduct. The consumers in the relevant classes are in a different position to the Court.

Principles where conduct directed to a class of persons

87 Where the question whether conduct is misleading or deceptive arises in relation to a particular class of persons, as opposed to specified individuals, the Court must assess whether the conduct is likely to mislead or deceive by reference to the ordinary or reasonable members of that class, namely the “class of consumers likely to be affected by the conduct”: Puxu at 199; see also: Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [102]; Google Inc at [7]; TPG Internet at [23].

88 It was common ground between the parties that there is no “not insignificant number” test – that is, it is not necessary for an applicant to prove that a “not insignificant number” of people within the class were likely to be misled: TPG Internet at [23] and Trivago NV v Australian Competition and Consumer Commissioner (2020) 384 ALR 496 at [192].

89 During oral argument, Google submitted that:

(1) the law requires the identification of a single hypothetical person within the relevant class of users to test, by reference to that hypothetical person, whether the members of the class would have been misled by the conduct;

(2) the question is whether that hypothetical person would have been misled, the hypothetical person being capable of only one response.

90 Google relied upon what the High Court stated in Campomar at [103] (footnotes omitted; Google’s emphasis added):

Where the persons in question are not identified individuals to whom a particular misrepresentation has been made or from whom a relevant fact, circumstance or proposal was withheld, but are members of a class to which the conduct in question was directed in a general sense, it is necessary to isolate by some criterion a representative member of that class. The inquiry thus is to be made with respect to this hypothetical individual why the misconception complained has arisen or is likely to arise if no injunctive relief be granted. In formulating this inquiry, the courts have had regard to what appears to be the outer limits of the purpose and scope of the statutory norm of conduct fixed by s 52. Thus, in Puxu, Gibbs CJ observed that conduct not intended to mislead or deceive and which was engaged in “honestly and reasonably” might nevertheless contravene s 52. Having regard to these “heavy burdens” which the statute created, his Honour concluded that, where the effect of conduct on a class of persons, such as consumers, was in issue, the section must be “regarded as contemplating the effect of the conduct on reasonable members of the class”.

91 I do not accept that in all misleading or deceptive conduct cases where the conduct is directed to the public at large, or a segment of the public, it is necessary to isolate one hypothetical person within the class to determine whether there has been a contravention. It may be necessary to isolate a number of hypothetical persons within the class, assuming the variable characteristics of the reasonable members of the class suggest that such an approach is appropriate. As was made clear in Campomar at [99], cases should not be considered in the abstract; regard must be had to the circumstances of the particular case and the remedy sought in respect of the contravention alleged to have occurred. I do not read Campomar at [103] as requiring the identification of only one hypothetical person in all cases. The final sentence of [103] recognises that “where the effect of conduct on a class of persons, such as consumers, was in issue, the section must be ‘regarded as contemplating the effect of the conduct on reasonable members of the class’”, citing Puxu at 199. It may be that reasonable members of the class cannot be distilled into a single hypothetical reasonable person.

92 In any event, even if there must be an identification of a single hypothetical member of the class, it does not follow that in all cases the identified hypothetical person is only capable of one response or reaction. There may well be situations where a hypothetical person might reasonably have been misled and might reasonably not have been misled. The law recognises that there may be a number of different “reasonable” responses to conduct. Indeed, the High Court in Campomar expressly so concluded at [105] (footnotes omitted; emphasis added):

Nevertheless, in an assessment of the reactions or likely reactions of the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of the class of prospective purchasers of a mass-marketed product for general use, such as athletic sportswear or perfumery products, the court may well decline to regard as controlling the application of s 52 those assumptions by persons whose reactions are extreme or fanciful. For example, the evidence of one witness in the present case, a pharmacist, was that he assumed that “Australian brand name laws would have restricted anybody else from putting the NIKE name on a product other than that endorsed by the [Nike sportswear company]”. Further, the assumption made by this witness extended to the marketing of pet food and toilet cleaner. Such assumptions were not only erroneous but extreme and fanciful. They would not be attributed to the “ordinary” or “reasonable” members of the classes of prospective purchasers of pet food and toilet cleaners. The initial question which must be determined is whether the misconceptions, or deceptions, alleged to arise or to be likely to arise are properly to be attributed to the ordinary or reasonable members of the classes of prospective purchasers.

93 In National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2004) 49 ACSR 369, Dowsett J stated at [24]:

While it is true that members of a class may differ in personal capacity and experience, that is usually the case whenever a test of reasonableness is applied. Such a test does not necessarily postulate only one reasonable response in the particular circumstances. Frequently, different persons, acting reasonably, will respond in different ways to the same objective circumstances. The test of reasonableness involves the recognition of the boundaries within which reasonable responses will fall, not the identification of a finite number of acceptable reasonable responses.

94 In Comité Interprofessionnel at [171], Beach J accepted that there was scope for different responses:

[W]here the issue is the effect of conduct on a class of persons such as consumers (rather than identified individuals to whom a particular misrepresentation has been made or particular conduct directed), the effect of the conduct or representations upon ordinary or reasonable members of that class must be considered (Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [102] and [103]). This hypothetical construct avoids using the very ignorant or the very knowledgeable to assess effect or likely effect; it also avoids using those credited with habitual caution or exceptional carelessness; it also avoids considering the assumptions of persons which are extreme or fanciful. Further, the objective characteristics that one attributes to ordinary or reasonable members of the relevant class may differ depending on the medium for communication being considered. There is scope for diversity of response both within the same medium and across different media.

95 In other areas of the law where a hypothetical reasonable individual is considered, the Court might be bound to land upon one response. For example, the determination of whether a published matter conveys a pleaded imputation requires the Court to identify one meaning, despite the obvious truth that the publication is likely to mean different things to different people. As Diplock LJ stated in Slim v Daily Telegraph Ltd [1968] 2 QB 157 at 173:

[When] words are published to the millions of readers of a popular newspaper, the chances are that if the words are reasonably capable of being understood as bearing more than one meaning, some readers will have understood them as bearing one of those meanings and some will have understood them as bearing others of those meanings. But none of this matters. What does matter is what the adjudicator at the trial thinks is the one and only meaning that the readers as reasonable men should have collectively understood the words to bear. That is “the natural and ordinary meaning” of words in an action for libel.

96 This principle is one developed in respect of a private action for the tort of defamation. Applying such an approach to assessing alleged misleading or deceptive conduct might, on many occasions, fail to protect ordinary or reasonable consumers, an outcome that is unlikely given the ACL is directed at broad consumer protections. One would not condone misleading conduct directed to the public at large just because 51% of consumers, or an even greater majority, of consumers would not be misled. The law in the consumer protection field does not confine a hypothetical member of the class to one response. As Allsop CJ stated in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 327 ALR 540 at [95]: “[t]he fact that some people may not be misled is not the point”.

97 In summary, the test was accurately stated by the Full Court in TPG Internet at [22(e)]:

[W]here the impugned conduct is directed to the public generally or a section of the public, the question whether the conduct is likely to mislead or deceive has to be approached at a level of abstraction where the Court must consider the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the relevant class to whom the conduct is directed and consider the likely effect of the conduct on ordinary or reasonable members of the class, disregarding reactions that might be regarded as extreme or fanciful: Campomar at [101]-[105]; Google at [7] per French CJ and Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

98 If there were a requirement to land upon a single response by a hypothetical person, this would provide significant tension, if not be inconsistent, with the proposition advanced by both parties that it is not necessary for an applicant to prove that a “not insignificant number” of people within the class were likely to be misled. If one had to land upon one response, this would naturally invite consideration of the response of the majority of reasonable members of the class. If the majority were not misled, then the case would fail notwithstanding that the conduct misled (a not insignificant number of) reasonable members of the class.

99 Section 29(1)(g) of the ACL provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services: …

(g) make a false or misleading representation that goods or services have sponsorship, approval, performance characteristics, accessories, uses or benefits;

100 It was not in dispute that, if the pleaded representations were made, then they were made “in trade or commerce”. It follows that, to establish a breach of s 29(1)(g), the ACCC must establish that Google, “in connection with the supply or … promotion … of goods or services”, made a “representation that goods or services have … performance characteristics … uses or benefits” which was “false or misleading”.

101 The words “in connection with” in this context are broad; see also [340] below. The various pleaded representations, if made, were made “in connection with” the supply or promotion of the Android OS, the Pixel phone and various Google services. Google did not submit that this requirement was not made out in relation to Google LLC. The ACCC relied upon a number of performance characteristics, uses and benefits – see: letter from Norton Rose Fulbright to Corrs Chambers Westgarth dated 21 July 2020. It is not necessary to set these out in detail. By way of example, it was alleged that Google represented that the Android OS had “performance characteristics” which it did not have including that the Location History setting controlled whether Google would obtain personal data about a user’s location and that if the setting was “off” Google would not obtain personal data about a user’s location from a linked device or use that data. Equivalent particulars were provided with respect to “uses” and “benefits” of the Android OS.

102 A comparison of the text of ss 18 and 29 suggest potentially significant differences in their respective operation. For example:

(1) First, the legislative drafter has chosen quite different language with “misleading or deceptive” and “false or misleading”. Ordinarily, this might be thought to indicate a different test was intended. However, as will be explained below, the different wording simply reflects the fact that the provisions were drawn from different origins and it was probably not intended from the choice of words to indicate substantially different tests. This result is also suggested by the fact that both tests cover conduct or representations which are “misleading”.

(2) Secondly, s 18 includes the words “likely to mislead or deceive” which reflects an amendment to s 52 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (TPA) made in 1977; these words do not have a counterpart in s 29 and did not have a counterpart in s 53 of the TPA (from which s 29 of the ACL was drawn).

(3) Thirdly, s 18 is concerned with “conduct” and s 29 is concerned with “representations”.

103 Section 18 of the ACL was based on s 52 of the TPA. Section 52 of the TPA, headed “misleading or deceptive conduct” enacted a generally applicable minimum standard, applicable to any conduct in trade or commerce. Section 52 of the TPA (and now s 18 of the ACL) only ever carried civil consequences. Section 52 reflected, at least in the Australian context, a new regulatory approach. It was based at least in part on s 5 of the US Federal Trade Commission Act 1914 although there were significant differences, in particular s 52 did not prohibit “unfair” practices – see: Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 226-227.

104 Section 29 of the ACL was based on s 53 of the TPA. Section 53 of the TPA, as enacted in 1974, was headed “false representations” and created criminal offences in respect of specifically enumerated false representations and “false or misleading statements”. Section 53, being specific in its focus and carrying criminal consequences, was by no means novel. At least in part, it was modelled on or influenced by State and UK legislation including the Consumer Affairs Act 1972 (Vic), the Trade Descriptions Act 1968 (UK) and the Merchandise Marks Act 1887 (UK).

105 Whilst ss 52 and 53 were both within Div 1 of the TPA, entitled “Unfair practices”, the purpose of s 53 was to create specific offences carrying criminal consequences, whereas the purpose of s 52 was to create a minimum standard of conduct, breach of which – through other provisions – would carry civil consequences. It has been said that “ACL s 29 (formerly TPA s 53) supports ACL s 18 [formerly TPA s 52] by enumerating specific types of conduct which, if engaged in trade or commerce in connection with the promotion or supply of goods or services, will give rise to a breach of the Act”: Miller RV, Miller’s Australian Competition and Consumer Law Annotated (43rd ed, Thomson Reuters, 2021) at [ACL.29.20]. It is important, however, to appreciate that the provisions have different origins, objectives and operation even if s 29 can be described as “supporting” s 18 or it can be seen that there is partial overlap in purpose.

106 In considering the operation of s 52, it has been said that the provisions of Part V of the TPA (which included ss 52 and 53) are “remedial” and should, accordingly, be given a liberal construction: Accounting Systems 2000 (Developments) Pty Ltd v CCH Australia Ltd (1993) 42 FCR 470 at 503. That proposition has been stated in relation to ss 18 and 29 of the ACL: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Private Networks Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 384 at [15]. Authority establishes that “remedial” legislation should be construed so as to give the fullest relief which the fair meaning of its language will allow, even where a person contravening the provision will be liable to a penalty: Devenish v Jewel Food Stores Pty Ltd (1991) 172 CLR 32 at 44 (Mason CJ). It should also be recognised, however, that there is a distinction between s 18 and s 29 which is evident from the statutory language and purpose. Section 29 has a penal operation and s 18 does not. There is nothing unusual in a provision having more than one purpose – cf: Rich v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2004) 220 CLR 129 at [35]; New South Wales Aboriginal Land Council v Minister Administering the Crown Lands Act (2016) 260 CLR 232 at [92]. The ordinary rules of construction apply to a “penal” provision: Beckwith v The Queen (1976) 135 CLR 569 at 576. The ordinary rules of construction also apply to “remedial” or “beneficial” legislation. Underlying the observations which are made from time to time that penal provisions should be construed strictly, remedial provisions liberally, or beneficial provisions beneficially, is the simple proposition that, where different constructions are available, a legislative provision should receive a construction which promotes its purpose over one which does not. The labelling of a provision as “penal”, “remedial” or “beneficial” merely reflects a conclusion about purpose as revealed by the statutory text read in context. A label can be unhelpful if it disguises that a provision might have multiple purposes or if it leads to an assumption that the purpose is to be pursued at all cost.

107 Ultimately, it is the terms of the particular provision which must be applied to the facts. There are differences between ss 18 and 29 which might be important in particular cases. First, as mentioned, s 29 is a civil penalty provision – see: s 224 of the ACL. In a civil proceeding, the court must find the case of a party proved if it is satisfied that the case has been proved on the balance of probabilities: s 140(1) of the Evidence Act. Section 140(2) of the Evidence Act provides:

Without limiting the matters that the court may take into account in deciding whether it is so satisfied, it is to take into account:

(a) the nature of the cause of action or defence; and

(b) the nature of the subject-matter of the proceeding; and

(c) the gravity of the matters alleged.

108 Whilst s 140(2) applies according to its terms, it is appropriate to observe that s 140(2)(c) reflects the common law position that the more serious the allegation, the less likely it might be expected, all other things being equal, that a respondent would have committed the relevant act: Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336. The Court must have regard to the gravity of what is sought to be established in assessing whether the party bearing the onus (the ACCC) has discharged that onus: Patrick Stevedores Holdings Pty Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (2019) 286 IR 52 at [17]-[18] (Lee J).

109 Secondly, s 29 revolves around the making of representations. Whilst it may be accepted that representations can arise through conduct, the application of s 18 requires identification of “conduct” and s 29 requires the identification of “representations”. A representation is a statement about or related to a matter of fact, which might be made in writing, orally, pictorially or through conduct: Given v Pryor at 445-446 (Franki J).

110 Thirdly, unlike s 18, there is no express reference in s 29 to a concept of “likely to mislead”. Google submitted that, by reason of the lack of reference in s 29 to the concept of something being “likely to mislead”, the ACCC had to prove to the requisite standard that Google made representations that were actually false or misleading; it was not sufficient for the ACCC to prove that it was likely, or that there was a real or not remote chance or possibility, that relevant users would be misled. This would be sufficient for s 18, but not for s 29. For the reasons which follow, I accept this submission.

111 The words “likely to mislead or deceive” were introduced in 1977 into what was then s 52 of the TPA. This followed a recommendation made by the Swanson Committee in its August 1976 report: Trade Practices Act Review Committee, Report to the Minister for Business and Consumer Affairs (Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1976). The Swanson Committee explained at [9.55]:

A number of submissions also suggested to the Committee that it was not certain whether section 52 required proof of actual damage or whether the mere possibility of damage were sufficient to invoke the section. The Committee considers that the section should apply to conduct which is likely to mislead or deceive, without requiring proof that the conduct has mislead or deceived, but should not apply to conduct which has merely a tendency to mislead or deceive. We recommend that section 52 should be amended to make it clear that it applies only to conduct ‘that is, or is likely to be, misleading or deceptive’.

112 In relation to s 53 of the TPA (upon which s 29 is based), the Committee stated at [9.64]:

… [T]he Committee would like to express the general view that it should not be the function of section 53, which has criminal law sanctions, to prohibit as wide a sweep of false and misleading conduct as possible. Section 53 should deal only with conduct which has demonstrably led to abuses and involves a real potential for harm. Section 52, which has sanctions of a civil nature, provides a more appropriate approach to a general prohibition of undesirable practices.

113 A number of cases have recognised that, although s 29 of the ACL uses the term “false or misleading” rather than “misleading or deceptive” as used in s 18, there is no meaningful difference between the two phrases; indeed, it is at least implicitly suggested in some of the cases that there is no meaningful difference between a representation being “false or misleading” and conduct being “likely to mislead or deceive”. This line of authority, at least in the recent past, starts with the decision of Gordon J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682. At [14] and [15] her Honour stated:

In relation to the first element, s 53(e) [of the TPA] requires the representation to be “false or misleading” as opposed to “misleading or deceptive” (in s 52). I was not taken to, and I have not found, any authority which attributes a meaningful difference to this dichotomy for the purposes of the TPA. (For a discussion of the phrase “false and misleading” under a different Act, see Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v Hadkiss (2007) 160 FCR 151). Indeed, the vast majority of cases that discuss an alleged breach of s 53(e) couple it with a breach of s 52 and deal with the “false or misleading” and “misleading or deceptive” aspect of the conduct mutatis mutandis: see Foxtel Management Pty Ltd (2005) 214 ALR 554 at [94]; ACCC v Target Australia Pty Ltd (2001) ATPR 41-840; ACCC v Harbin Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1792; ACCC v Prouds Jewellers Pty Ltd [2008] FCAFC 199 at [42].

That is not altogether surprising. The purpose of s 53 has been described as being to “[support] s 52 by enumerating specific types of conduct which, if engaged in by a corporation in trade or commerce in connection with the promotion or supply of goods or services, [would] give rise to a breach of the Act”: see R Miller, Miller’s Annotated Trade Practices Act (30th ed, 2009), [1.53.5]. Accordingly, and in the absence of any submission to the contrary, I see no reason why the application of s 53(e) should not fall to be determined upon the conclusions I reach in relation to s 52 – namely that the representations were misleading and deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive.

114 In Coles Supermarkets at [38] to [40], Allsop CJ stated:

For the enquiry under s 18, it is necessary to identify the impugned conduct and then to consider whether that conduct, considered as a whole and in context, is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive: Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (2013) 249 CLR 435; 294 ALR 404; 99 IPR 197; [2013] HCA 1 at [89], [102] and [118]; and Campomar Sociedad Limitada v Nike International (2000) 202 CLR 45; 169 ALR 677; 46 IPR 481; [2000] HCA 12 at [100]–[101] (Campomar). The same applies to the enquiry as to representations and conduct under ss 29(1)(a) and 33, respectively.

Conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive if it has the tendency to lead into error, if there is a sufficient causal link between the conduct and the error on the part of the person exposed to the conduct: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640; 304 ALR 186; 96 ACSR 475; [2013] HCA 54 at [39] (TPG). The causing of confusion or questioning is insufficient; it is necessary to establish that the ordinary or reasonable consumer is likely to be led into error.

There is no meaningful difference between the words and phrases “misleading or deceptive” and “mislead or deceive” (s 18), “false or misleading” (s 29(1)(a)) and “mislead” (s 33): Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14].

115 In Comité Interprofessionnel at [170], Beach J accepted that there “is no meaningful difference” between the words and phrases “misleading or deceptive”, “mislead or deceive” or “false or misleading”, citing Dukemaster at [14] and Coles Supermarkets at [40].

116 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v HJ Heinz Co Australia Ltd (2018) 363 ALR 136 at [37], White J stated:

The principles which the Court applies when considering alleged contraventions of s 29(1) and s 33 of the ACL are settled. Section 29 of the ACL is the counterpart to s 53 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). It was common ground that the case law developed in relation to s 53 may be applied in relation to s 29. It was also common ground that, despite the slight differences in language between the terms “misleading or deceptive” and “mislead or deceive” used in s 18 of the ACL and the term “false or misleading” used in s 29(1), the terms have the same meaning: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14], cited with approval by Allsop CJ in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; (2015) 317 ALR 73 at [40]. It has, however, been held that conduct which is “liable to mislead” (being the term used in s 33) applies to a narrower range of conduct than does conduct which is “likely to mislead or deceive” (being the term used in s 18): Coles Supermarkets at [44] and the cases cited therein. Under s 33, what is required is that there be an actual probability that the public would be misled: Trade Practices Commission v J&R Enterprises Pty Ltd (1991) 99 ALR 325 at 339.

117 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd (2019) 371 ALR 396 at [6] and [7], Bromwich J stated:

The three pleaded provisions have aspects in common, and to that extent overlap, but also some important areas of difference. There is no material difference in the factual inquiry as between s 18 and s 29(1)(g) in this case because:

(1) there is no meaningful distinction between “misleading or deceptive” and “false or misleading”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14]–[15]; and

(2) the conduct, both admitted and denied, is by way of the same express or implied representations in relation to both provisions, even though s 18 is general in its scope and does not attract any civil penalty consequences, while s 29(1)(g) is specific in its focus and does have civil penalty consequences.

Section 33 is in a somewhat different category, because the requirement to establish that the impugned conduct was “liable to mislead the public” as to characteristics or suitability is both narrower than “likely to mislead or deceive” in s 18, and requires proof of an actual probability that the public would be misled: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited (2014) 317 ALR 73; [2014] FCA 634 (ACCC v Coles) at [44] and the cases there cited.

118 The Full Court in TPG Internet at [21] stated:

Although s 18 takes a different form to s 29, the prohibitions are similar in nature. Whilst s 29 uses the phrase “false or misleading” rather than “misleading or deceptive”, it has been said that there is no material difference in the two expressions: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14] per Gordon J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2014) 317 ALR 73; [2014] FCA 634 at [40] per Allsop CJ; Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne v Powell (2015) 330 ALR 67; 115 IPR 269; [2015] FCA 1110 at [170] per Beach J.

119 The amendment which was made in 1977 to s 52 of the TPA was apparently motivated by an intention to make clear that, in order to establish a contravention of s 52, it was not necessary to adduce evidence that someone had actually sustained loss or was in fact misled: see [111] above. It may be questioned whether the amendment was strictly necessary. Section 52 set a standard of conduct. It is not necessary to establish loss in order to establish a failure to meet a certain standard of conduct. It would have been necessary to prove loss if a person sought a remedy in respect of contravening conduct, and the relevant remedy was premised on loss being suffered (for example under s 82 of the TPA). Further, leaving loss to one side, if the proper inference to draw is that a reasonable person was likely to have been misled by relevant conduct, the Court would ordinarily conclude that the conduct was “misleading or deceptive”. Nevertheless, the amendment to s 52 indicates, both textually and as a matter of legislative history, that there is a difference in what may be described as the “purposes” (and operation) of s 52 (s 18 of the ACL) and s 53 (s 29 of the ACL).

120 Section 29(1)(g) requires that a representation be “false or misleading”. The representation must actually be “false or misleading”. It is not necessary to adduce evidence that a reasonable person in the relevant class was in fact misled. That is an inference which the Court can draw from the objective circumstances. In my view, it is an inference the Court would have to draw, having regard to the correct standard of proof, in order to be satisfied that there had been a contravention of s 29(1)(g). If the Court only considered that there was a “real or not remote chance or possibility” that a reasonable person in the relevant class was in fact misled, but was not prepared to conclude that any person was in fact misled, then a contravention of s 29(1)(g) would not be established even though that might be sufficient to establish a breach of s 18 – see: Global Sportsman Pty Ltd v Mirror Newspapers Pty Ltd (1984) 2 FCR 82 at 87. If the proper inference to draw is that the representation was “false or misleading” to some members of the class acting reasonably, but not to other reasonable members, the fact that some reasonable members of the class would not have been misled can be taken into account in determining an appropriate penalty, but a contravention will still have been established.

121 Section 33 – which relates to goods – provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the manufacturing process, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any goods.

122 Section 34 – which relates to services – provides:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any services.

123 To establish a breach of ss 33 or 34, the ACCC must establish that:

(1) in trade or commerce;

(2) Google engaged in conduct that was “liable to mislead”;

(3) the conduct was liable to mislead “the public”;

(4) the conduct was liable to mislead as to the nature, characteristics or suitability for purpose of the goods (s 33) or services (s 34).

124 The first matter was not in dispute.

125 As to the second matter, “liable to mislead” is a higher standard than “likely to mislead or deceive” under s 18. The ACCC is required to demonstrate that there was an “actual probability that the public would be misled”: Coles Supermarkets at [44]. In Coles Supermarkets at [44], Allsop CJ stated:

While the words and phrases “misleading or deceptive”, “mislead or deceive”, “false or misleading” and “mislead” are synonymous, the authorities reveal that a distinction is to be made between “likely to mislead or deceive” (in s 18) and “liable to mislead” (in s 33). The latter has been said to apply to a narrower range of conduct: Westpac Banking Corporation v Northern Metals Pty Ltd (1989) 14 IPR 499 at 502; Trade Practices Commission v J & R Enterprises Pty Ltd (1991) 99 ALR 325 at 338–9 (J & R Enterprises); and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Turi Foods Pty Ltd (No 4) [2013] FCA 665 at [79]. Under s 33, what is required is that there be an actual probability that the public would be misled: J & R Enterprises at 339. (This citation of J & R Enterprises at 338–9 should not be taken to endorse the comments of O’Loughlin J as to a burden beyond reasonable doubt at 339.)

126 In GlaxoSmithKline at [7], Bromwich J accepted that s 33 required proof of an actual probability that the public would be misled, referring to Coles Supermarkets at [44].

127 As to the third matter, a representation will be made to the public if the approach is general and the number of people who are approached is sufficiently large or if the approach is to all within a sufficient segment of the community at large. In Trade Practices Commission v J & R Enterprises (1991) 99 ALR 325 at 347-348, O’Loughlin J said:

The word “public” is not to be taken as meaning the world at large or the whole community. There will be a sufficient approach to the public if, first, the approach is general and at random and secondly, the number of people who are approached is sufficiently large. In dealing with the phrase “invitation to the public”, Barwick CJ said in Lee v Evans (1964) 112 CLR 276 at 285:

… the basic concept is that the invitation, though maybe not universal, is general; that it is an invitation to all and sundry of some segment of the community at large. This does not mean that it must be an invitation to all the public either everywhere, or in any particular community.

128 As to Scenario 1, concerning the set-up of a device, the relevant users became Google Account holders during the set-up process, assuming that they so agreed. I am satisfied that, if any conduct otherwise breached ss 33 or 34, the requirement that the conduct mislead “the public” is satisfied.