FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Smart Corporation Pty Ltd (No 3) [2021] FCA 347

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

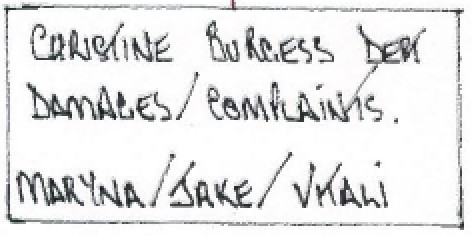

AND: | SMART CORPORATION PTY LTD (ACN 134 192 297) First Respondent VITALI ROESCH Second Respondent MARYNA KOSUKHINA Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

PENAL NOTICE

IF YOU (BEING THE PERSON BOUND BY THIS ORDER):

(A) REFUSE OR NEGLECT TO DO ANY ACT WITHIN THE TIME SPECIFIED IN THIS ORDER FOR THE DOING OF THE ACT; OR

(B) DISOBEY THE ORDER BY DOING AN ACT WHICH THE ORDER REQUIRES YOU NOT TO DO,

YOU WILL BE LIABLE TO IMPRISONMENT, SEQUESTRATION OF PROPERTY OR OTHER PUNISHMENT. ANY OTHER PERSON WHO KNOWS OF THIS ORDER AND DOES ANYTHING WHICH HELPS OR PERMITS YOU TO BREACH THE TERMS OF THIS ORDER MAY BE SIMILARLY PUNISHED.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The first respondent:

(a) during the period January 2014 to August 2019, made a representation to consumers, via the publication of statements made on its website, australian4wdhire.com.au that:

(i) all A4WD's rental vehicles had the benefit of being insured for off-road use; and

(ii) if any damage occurred to the vehicle while being hired, including while being used on unsealed roads, it would be insured under A4WD's insurance policies,

(together, the Insurance Coverage Representation),

when in fact in not all instances would consumers have the benefit of the rental vehicle being insured for damage to it, and in cases of a single vehicle incident where the vehicle was insured, the consumer would at the first respondent's sole discretion be liable under the first respondent's standard form contract for either the costs of rectifying the damage to the vehicle, the vehicle's replacement value or the payout figure under the first respondent's finance contract for the vehicle; and

the first respondent, thereby, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of rental vehicles:

(b) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, contained in Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL); and

(c) made a false or misleading representation that the rental vehicles had characteristics or benefits which they did not have, in contravention of s 29(1)(g) of the ACL.

2. The terms in the various standard form contracts between the first respondent and consumers, as set out in Annexure A, are declared pursuant to s 250 of the ACL to be unfair terms within the meaning of s 24 of the ACL, and are also declared to be void pursuant to s 23 of the ACL, because they included terms to the following effect:

(a) GPS Provisions under which, taken together:

(i) the first respondent was permitted to use global positioning system (GPS) tracking data on the hired vehicle to monitor where the vehicle was driven, the times when the vehicle was being driven and how fast it was being driven;

(ii) the first respondent could use this GPS data to conclude that a consumer had operated the vehicle in a manner which was a Prohibited Operation (defined in the contract to include, among other things, driving in contravention of any traffic laws, driving outside of built-up areas between sunset and dawn and driving during periods of low visibility including but not limited to fog and heavy rain);

(iii) the consumer acknowledged that engaging in a Prohibited Operation will or may cause excessive wear and tear and would likely cause other damage to the vehicle (defined as Driver Behaviour Damage); and

(iv) in the event that the GPS data evidenced that a Prohibited Operation had occurred, the consumer would be liable to compensate the first respondent for the deemed Driver Behaviour Damage in amounts which could authorise the first respondent to deduct part or all of the consumer's security bond;

(b) an Insurance Discretion Clause which provided that in the event of a single vehicle accident, the first respondent had the sole discretion to elect not to submit an insurance claim to its insurers for damage caused to the vehicle, the consequence of which was that the consumer was then liable to pay for the costs of rectifying the damage, the vehicle's replacement value or the payout figure under the first respondent's finance contract, even in circumstances where the vehicle was in fact insured for the damage; and

(c) a Non-Disparagement Clause which required consumers to act at all times in the first respondent's best interests,

in circumstances where each of the GPS Clause, the Insurance Discretion Clause and the Non-Disparagement Clause:

(d) caused a significant imbalance between the rights and obligations of consumers and the first respondent;

(e) were not reasonably necessary to protect the legitimate interests of the first respondent as the party advantaged by the terms; and

(f) caused financial and non-financial detriment to consumers.

3. Between April 2017 and August 2019, the first respondent engaged in conduct in trade or commerce that was, in all the circumstances unconscionable in breach of s 21 of the ACL, by:

(a) in respect of each of the 31 identified consumers (listed at Annexure B), sending each consumer an email that contained language that was intimidating and threatening:

(i) claiming misleadingly and in bad faith that information contained in a document produced by its GPS data provider (Driver Behaviour Report), was evidence that the consumer had incurred large numbers of 'speeding violations' or had otherwise engaged in a Prohibited Operation when using the vehicle, which was a serious breach of contract; and

(ii) saying that the first respondent would be retaining part or all of the security bond because the consumer engaged in a Prohibited Operation;

(b) in respect of 25 of the 31 identified consumers (listed at Annexure C), also relying on a consumer's alleged Prohibited Operation of the vehicle, as purportedly evidenced by the Driver Behaviour Report, to deduct an amount of the consumer's security bond for what it described as 'excessive wear and tear' or 'night driving' irrespective of whether there had been any damage done to the vehicle;

(c) in respect of 18 of the 31 identified consumers (listed at Annexure D), also sending other intimidatory correspondence containing intemperate language that was intimidating and threatening, and which was sent in order to deter and discourage the consumer from:

(i) raising legitimate concerns about the accuracy of the Driver Behaviour Report; and

(ii) disputing the first respondent's allegations that they had engaged in a Prohibited Operation when using the hire vehicle; and

(d) in respect of three of the 31 identified consumers (listed at Annexure E), falsely alleging that the police had issued speeding fines in respect of the consumer's driving of the hired vehicle.

4. The second and third respondents, each of whom caused the first respondent to engage in the conduct described at paragraphs 1 and 3 above, were each knowingly concerned in and a party to, the contraventions of the first respondent declared in those paragraphs within the meaning of s 224(1)(e) of the ACL.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Non-party consumer redress

5. Pursuant to s 239 of the ACL, and within 21 days of the date that this order is served by email on the second and third respondents (at the addresses set out in Annexure F), the second and third respondents must jointly and severally pay to the applicant, on behalf of each of the consumers named in Annexure G, the amount identified in Annexure G for that consumer.

Disqualification orders

6. Pursuant to s 248 of the ACL, the second respondent is disqualified from managing a corporation for a period of three years from the date that this order is served on the second respondent by email (at the address set out in Annexure F).

7. Pursuant to s 248 of the ACL, the third respondent is disqualified from managing a corporation for a period of three years from the date that this order is served on the third respondent by email (at the address set out in Annexure F).

Pecuniary penalties

8. Pursuant to s 224 of the ACL, the first respondent must pay to the Commonwealth of Australia, within 21 days of the date that this order is served by email on the first respondent (at the address set out in Annexure F), $870,000 by way of pecuniary penalty, in respect of the contraventions of s 21 and 29(1)(g) of the ACL referred to in paragraphs 1 and 3 above.

9. Pursuant to s 224 of the ACL, the second respondent must pay to the Commonwealth of Australia, within 21 days of the date that this order is served by email on the second respondent (at the address set out in Annexure F), $179,000 by way of pecuniary penalty in respect of the second respondent's involvement in the first respondent's contraventions of s 21 and 29(1)(g) of the ACL as declared in paragraph 4 above.

10. Pursuant to s 224 of the ACL, the third respondent must pay to the Commonwealth of Australia, within 21 days of the date that this order is served by email on the third respondent (at the address set out in Annexure F), $174,000 by way of pecuniary penalty in respect of the third respondent's involvement in the first respondent's contraventions of s 21 and 29(1)(g) of the ACL as declared in paragraph 4 above, such penalty to become payable only after payment of the non-party consumer redress set out in paragraph 5 above and only on the last day of the month following the month in which the third respondent is discharged from bankruptcy.

Other orders

11. The reasons for judgment with a seal of the court affixed thereon be retained on the court file for the purposes of s 137H(3) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

12. The second and third respondents must pay the applicant's costs of the proceeding to be taxed, if not agreed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Annexure A

The terms in the various standard form contracts between the first respondent and consumers that are unfair terms, and are therefore void:

Dates standard contract terms in force | Void terms |

From January 2014 to some time before 31 March 2016 | Clause 4(d) Clause 19(d) |

From at least 31 March 2016 to at least 24 May 2017 | Clause 4(d) Clause 20(d) |

From at least 24 May 2017 to some time before 3 April 2018 | Clause 4(d) Clause 17 (second and third paragraphs only) Clause 20(d) |

From at least 3 April 2018 to some time before July 2018 | Clause 4(d) Clause 13(f) Clause 17 (second and third paragraphs only) Clause 20(d) |

At some time between April 2018 and July 2018 until at least September 2018 | Clause 5(c), (j) Clause 8 (d)-(i) Clause 17(g), (h) |

From at least 24 September 2018 until May 2019 | Clause 5(c), (j) Clause 8(d)-(j) Clause 17(g), (h) |

From at least May 2019 | Clause 5(c), (j) Clause 8(h), (j) Clause 17(g), (h) |

Annexure B

The 31 identified consumers who received emails from the first respondent as described in paragraph 3(a) of these orders:

No. | Customer name(s) |

1. | Benjimen Bomford |

2. | Kenneth Hitchcock |

3. | John Moriarty |

4. | Matthew Roach |

5. | Ian Davison and Jane-Marie Forrest |

6. | AK |

7. | BP |

8. | CL |

9. | DB |

10. | GS |

11. | HY |

12. | JL |

13. | JH |

14. | JK |

15. | LM |

16. | MV |

17. | MM |

18. | NC |

19. | PF |

20. | PH |

21. | RW |

22. | SL |

23. | SM |

24. | VV |

25. | WR |

26. | CM |

27. | DM |

28. | MK |

29. | NJ |

30. | TM |

31. | TMcC |

Annexure C

List of 25 consumers who were charged for 'excessive wear and tear' and/or 'night driving' as described in paragraph 3(b) of these orders:

No. | Customer name(s) | Amounts deducted for 'excessive wear and tear' and/or 'night driving' |

1. | Benjimen Bomford | $4,710 |

2. | Kenneth Hitchcock | $3,002.15 |

3. | John Moriarty | $500 |

4. | Matthew Roach | $500 and $500 for 'night driving' |

5. | Ian Davison and Jane-Marie Forrest | $1,000 |

6. | AK | $1,000 |

7. | BP | $500 |

8. | CL | $500 |

9. | DB | $1,000 for 'night driving' |

10. | GS | $500 |

11. | HY | $1,164.66 |

12. | JL | $500 |

13. | JH | $500 |

14. | JK | $500 |

15. | LM | $500 |

16. | MV | $500 |

17. | MM | $193.81 |

18. | NC | $500 |

19. | PF | $500 |

20. | PH | $500 |

21. | RW | $500 |

22. | SL | $500 |

23. | SM | $70 |

24. | VV | $4,390 |

25. | WR | $500 |

Annexure D

List of 18 consumers who received other intimidatory correspondence from A4WD as described in paragraph 3(c) of these orders:

No. | Customer name(s) |

1. | Benjimen Bomford |

2. | Kenneth Hitchcock |

3. | John Moriarty |

4. | Matthew Roach |

5. | Ian Davison and Jane-Marie Forrest |

6. | CL |

7. | DB |

8. | GS |

9. | HY |

10. | JH |

11. | LM |

12. | MV |

13. | MK |

14. | PF |

15. | PH |

16. | SM |

17. | WR |

18. | CM |

Annexure E

List of three customers who were falsely told that the police had issued speeding fines in respect of the consumer's driving of the hired vehicle as described in paragraph 3(d) of these orders.

1. | Benjimen Bomford |

2. | Kenneth Hitchcock |

3. | Matthew Roach |

Annexure F

A copy of these orders must be served on the first, second and third respondents at the following email addresses:

Respondent | Contact Name | Email Address |

First respondent | Matthew Bookless (SV Partners) | Matthew.Bookless@svp.com.au |

Second respondent | Vitali Roesch | vitaliroesch@gmail.com |

Third respondent | Maryna Kosukhina | marynakosukhina@gmail.com |

Annexure G

The second and third respondents pay to the ACCC the following amounts for the benefit of the following consumers:

Hirer name(s) | Amount (deducted by the respondents for 'excessive wear and tear' and processing/administration fees) |

Ian Davison and Jane-Marie Forrest | $1,200 |

John Moriarty | $550 |

Benjimen Bomford | $4,760 |

Kenneth Hitchcock | $3,052.15 |

[1] | |

[6] | |

Misleading or deceptive conduct and false or misleading representations | [8] |

[11] | |

[14] | |

[15] | |

[16] | |

Misleading or deceptive conduct or false or misleading representations | [23] |

[23] | |

[26] | |

[35] | |

Were the Insurance Representations misleading or deceptive and false or misleading? | [46] |

[59] | |

[63] | |

[63] | |

[74] | |

[75] | |

[88] | |

[113] | |

[120] | |

[127] | |

[127] | |

[141] | |

[167] | |

[174] | |

[181] | |

[182] | |

[193] | |

[193] | |

Extent of Mr Roesch's and Ms Kosukhina's knowing involvement | [198] |

[203] | |

[209] | |

[215] | |

[220] | |

[234] | |

[235] | |

[239] | |

[247] | |

[248] | |

[250] | |

[253] | |

Matters to which the court will have regard in fixing penalty | [269] |

[271] | |

The size of A4WD and its financial position and those of Mr Roesch and Ms Kosukhina | [271] |

[280] | |

[281] | |

[282] | |

Whether the respondent has engaged in similar conduct in the past | [286] |

False or misleading representations - specific penalty factors | [287] |

[287] | |

[293] | |

The deliberateness of the contraventions, and whether they were systematic and/or covert | [295] |

[298] | |

[298] | |

The deliberateness of the contraventions, and whether they were systematic and/or covert | [302] |

[304] | |

[315] | |

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

JACKSON J:

1 In this proceeding, the applicant (ACCC) seeks declarations as to breaches of Schedule 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), known as the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), by the first respondent, Smart Corporation Pty Ltd, which formerly traded as Australian 4WD Hire (A4WD). The ACCC also seeks a pecuniary penalty against A4WD. The second respondent, Vitali Roesch, and the third respondent, Maryna Kosukhina, are former directors and employees of the company. The ACCC seeks declarations, non-party redress orders, injunctions, disqualification from managing corporations and pecuniary penalties against Mr Roesch and Ms Kosukhina based on what is said to be their knowing involvement in A4WD's breaches of the ACL. The ACCC also seeks declarations that certain terms in what were A4WD's standard conditions for the hire of vehicles are unfair contract terms for the purposes of s 23 of the ACL.

2 This proceeding was commenced in April 2019. The respondents were initially represented by a solicitor, filed a concise statement in response to the ACCC's concise statement, and opposed the remedies sought. Then A4WD went into liquidation on 23 December 2019. Ms Kosukhina became bankrupt on 26 February 2020. The court gave the ACCC leave to proceed against the company, subject to an undertaking by the ACCC that it will not enforce any pecuniary penalties or costs orders against the company without the leave of the court. The liquidators indicated that they did not want A4WD to take any further part in the proceeding. The lawyer who had been on the record for all three respondents ceased to act after the company went into liquidation, and no notice of acting or notice of address for service has since been filed for any of the respondents. The ACCC has not communicated with Ms Kosukhina's trustee in bankruptcy.

3 In those circumstances, orders were made to ensure that the respondents had notice of the hearing of the matter and the possible consequences for them if they did not take part. But none of the respondents appeared at the hearing, which proceeded in their absence on 29 September 2020. The ACCC adduced evidence, largely by affidavit, and made submissions in favour of the relief sought.

4 The court received supplementary written submissions from the ACCC on 30 September 2020 and 22 February 2021. During the preparation of these reasons it became apparent that the decision of the Full Court in an appeal which the ACCC brought in relation to Quantum Housing Group Ltd was likely to be relevant to questions of unconscionable conduct in this proceeding. My Chambers raised with the ACCC whether I should await the Full Court's decision in that case before delivering these reasons, the ACCC submitted that I should, and so I have done so. That decision came down on 19 March 2021: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Quantum Housing Group Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 40.

5 For the reasons that follow, I have decided substantially to grant the relief the ACCC seeks.

The alleged bases of the remedies sought under the ACL

6 A4WD was in the business of hiring out four wheel drive vehicles. It appears that its customers were typically tourists who wanted to drive the vehicles in remote places, including off sealed roads.

7 There are three sets of allegations made against A4WD. They concern misleading or deceptive conduct and false or misleading representations, unfair contract terms, and unconscionable conduct.

Misleading or deceptive conduct and false or misleading representations

8 The ACCC makes allegations of breach of the ACL concerning statements about insurance coverage for hired vehicles which A4WD made on its website (australian4wdhire.com.au) and in emails to potential customers between January 2014 and August 2019. According to the ACCC, these were representations to consumers that all of A4WD's vehicles had the benefit of being insured for off-road use, and that if any damage to the vehicle occurred when it was being hired, including when it was being used on unsealed roads, it would be covered by insurance policies taken out by A4WD.

9 The ACCC alleges that those representations were false, because not all of A4WD's vehicles were insured for damage caused by single vehicle accidents. A4WD's standard terms and conditions required the hirer to reimburse the company for the cost of repairs in that situation. Also, those terms also gave A4WD the sole discretion not to make a claim on its insurers for single vehicle accidents even if the vehicle was insured, but to instead recover repair costs from the hirer.

10 Accordingly, the ACCC says that the statements made by A4WD on its website and in its emails involved misleading or deceptive conduct in breach of s 18 of the ACL. The ACCC also claims that the statements were false or misleading representations that goods, namely the hired vehicles, had benefits which they did not have, in breach of s 29(1)(g) of the ACL.

11 The ACCC alleges that certain provisions which appeared in A4WD's standard terms and conditions are unfair contract terms within the meaning of Part 2-3 of the ACL.

12 The standard terms varied from time to time, but the alleged effect of the relevant provisions can be summarised as follows:

(1) Through Global Positioning System (GPS) tracking data on the hired vehicle, A4WD could prepare a Driver Behaviour Report (DBR) which could show that the hirer had engaged in a 'Prohibited Operation' as defined in the contract, for example by driving over the speed limit. That would make the hirer liable to compensate A4WD for deemed 'Driver Behaviour Damage', and A4WD could deduct the compensation from the hirer's security bond. The ACCC submits that these provisions are unfair contract terms because they imposed financial penalties on the hirer without a causal connection between the hirer's behaviour and any loss to A4WD.

(2) If the hired vehicle was damaged in a single vehicle incident, A4WD had the sole discretion to elect not to submit an insurance claim to its insurers for damage, loss or replacement of the hire vehicle. The consumer would then be liable to pay for the costs of rectifying the damage, the vehicle's replacement value, or the pay-out figure under A4WD's finance contract, even in circumstances where the vehicle was in fact insured for the damage. This is the same provision which is said to falsify the representations about insurance.

(3) Hirers were obligated to act at all times in the best interests of A4WD's business and interests and not defame or denigrate A4WD following the return of the vehicle, including by placing misleading, deceptive or defamatory negative reviews on any website or other form of online forum. The ACCC says that this created a significant imbalance because there were no corresponding obligations that A4WD owed to the customer. This clause prevented the customer from denigrating A4WD even when the customer's views were honestly and genuinely held, and it exposed the customer to liability to A4WD for allegedly failing to act in the company's best interests.

13 The ACCC alleges that the above terms are unfair contract terms within the meaning of s 23 of the ACL and so should be declared to be unfair under s 250.

14 The allegations of unconscionable conduct arise out of A4WD's behaviour in relation to some 31 customers, after they had returned their hired vehicles. The conduct took place in a period from about April 2017 to about August 2019. It typically started with an email the customers would receive after the vehicle had been returned which alleged on the basis of the DBR that the customers had engaged in numerous speeding violations, in the order of hundreds. That was in circumstances where the hirers had paid substantial security bonds (of between $1,500 and $5,000) and the contracts they had signed purportedly entitled A4WD to deduct money from the bond for each violation. The language of the emails is said to have been intemperate, intimidating and threatening, and some customers who tried to dispute the matters received further emails which the ACCC characterises in the same way. After these emails, A4WD deducted money from the security bonds of 25 of the customers for 'excessive wear and tear' or as a 'night driving fee'. Six customers did not receive any part of their bonds back. This is all said to be in breach of the prohibition in s 21 of the ACL on engaging in conduct that is, in all the circumstances, unconscionable.

Involvement of Mr Roesch and Ms Kosukhina

15 Mr Roesch was a director of A4WD from November 2008 until October 2015 and its sole director for nearly all of that time. He became bankrupt in 2016. Ms Kosukhina was a director of the company from September 2015 until January 2020, and sole registered director for nearly all of that time. The ACCC alleges that Mr Roesch continued as a shadow director from October 2015. It says that Mr Roesch and Ms Kosukhina were jointly and severally responsible for the actions of A4WD and so should be liable in respect of its alleged breaches of the ACL and subject to pecuniary penalties, injunctions and disqualification orders.

Preliminary issue - proceeding against Ms Kosukhina

16 While the ACCC has obtained leave to proceed against A4WD as a company in liquidation, it has not sought any comparable leave to proceed against Ms Kosukhina, a bankrupt. It submits that it is not required to do so because it is not seeking to proceed against her in respect of a provable debt.

17 Section 58(3)(b) of the Bankruptcy Act 1966 (Cth) relevantly provides that after a debtor has become bankrupt, it is not competent for a creditor to take any fresh step in a legal proceeding in respect of a provable debt, except with the leave of the court. As to what is a provable debt, s 82(1) provides that subject to Part VI Division 1 of the Bankruptcy Act:

all debts and liabilities, present or future, certain or contingent, to which a bankrupt was subject at the date of the bankruptcy, or to which he or she may become subject before his or her discharge by reason of an obligation incurred before the date of the bankruptcy, are provable in his or her bankruptcy.

18 Section 82(3) provides that penalties or fines imposed by a court in respect of an 'offence against a law' are not provable in bankruptcy.

19 The monetary remedies the ACCC seeks against Ms Kosukhina are pecuniary penalties, non-party consumer redress orders and the costs of the proceedings. As to the penalties, there is a question about whether s 82(3) applies, because it is arguable that the reference to an 'offence' is only to a criminal offence, and here the ACCC seeks civil penalty orders. In Mathers v Commonwealth of Australia [2004] FCA 217; (2004) 134 FCR 135 at [29]-[30], Heerey J held that civil penalties which the ACCC was pursuing under s 76 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) came within the meaning of 'penalties or fines imposed by a court in respect of an offence against a law' and so were not admissible to proof against an insolvent company under s 553B of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). But a similar result does not necessarily follow in relation to s 82 of the Bankruptcy Act. That is because s 82(3AA) expressly provides that civil penalties under the Corporations Act are not provable debts, which might suggest that civil penalties under other legislation such as the ACL may be provable. There was no provision in the Corporations Act comparable to s 82(3AA) of the Bankruptcy Act which was drawn to Heerey J's attention; in fact, s 553B(1), in providing that pecuniary penalty orders under the Proceeds of Crime Act 1987 (Cth) were admissible to proof, points in the opposite direction to s 82(3AA).

20 But it is not necessary to decide the issue on that basis, because I consider that the monetary remedies, if ordered, are neither debts or liabilities to which Ms Kosukhina was subject at the time of her bankruptcy, nor debts or liabilities to which she may become subject before her discharge by reason of an obligation incurred before the date of the bankruptcy. For Ms Kosukhina to become liable to pay a pecuniary penalty, it will be necessary for this court to determine that she has breached relevant civil penalty provisions and to exercise a discretion that she should be liable for a penalty. For her to be liable for non-party redress orders, the court will have to determine that she was involved in contraventions of relevant provisions of the ACL and to exercise a discretion to make the redress orders: see ACL s 239. A costs order will similarly require the exercise of the court's discretion. None of those matters constitute debts or liabilities to which Ms Kosukhina was subject at the time of the bankruptcy or liabilities to which she will become subject by reason of an obligation incurred before that time. At most, there was a vulnerability to a determination that A4WD had breached the ACL, that Ms Kosukhina had been involved in those breaches, and that the court's discretion should be exercised in a way giving rise to monetary obligations on her part: see Gaffney v Federal Commissioner of Taxation (1998) 81 FCR 574 at 581; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Black on White Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 363; (2004) 138 FCR 314 at [34]-[35]; Foots v Southern Cross Mine Management Pty Ltd [2007] HCA 56; (2007) 234 CLR 52 at [35]-[36].

21 Another possible reason why any liability would not be provable in the bankruptcy is that the ACCC, the party proceeding in this court, is not a 'creditor' so that s 58(3) of the Bankruptcy Act does not apply to it in respect of that liability. Pecuniary penalties are payable to the Commonwealth (or a State or Territory), not to the ACCC (ACL s 224(1)), and prima facie, if liability had been imposed by non-party consumer redress orders at the commencement of the bankruptcy, it would have been liability to the consumers, not to the ACCC. But basing the result on that ground might be anomalous, as it may be inconsistent with the policy of s 58(3) to ensure that relevant monetary claims are realised and discharged through the bankruptcy process rather than through the courts: see Re Sharpe; Ex parte Tietyens Investments Pty Ltd (in liq) v Official Trustee (Unreported, Federal Court of Australia, 26 October 1998) at 6-7 (Weinberg J). In the absence of full argument on the point it is preferable not to resolve it on that ground.

22 I conclude that the potential monetary liabilities which will be imposed on Ms Kosukhina if the ACCC is successful in this proceeding will not be debts provable in the bankruptcy, so that s 58(3) does not require the ACCC to obtain the leave of the court before continuing to prosecute its claims against her.

Misleading or deceptive conduct or false or misleading representations

23 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2020] FCAFC 130; (2020) 381 ALR 507 at [22] the Full Court summarised the principles to be applied to the prohibition on misleading or deceptive conduct and closely related prohibitions as follows (citations removed):

The central question is whether the impugned conduct, viewed as a whole, has a sufficient tendency to lead a person exposed to the conduct into error (that is, to form an erroneous assumption or conclusion about some fact or matter). A number of subsidiary principles, directed to the central question, have been developed:

(a) First, conduct is likely to mislead or deceive if there is a real or not remote chance or possibility of it doing so.

(b) Second, it is not necessary to prove an intention to mislead or deceive.

(c) Third, it is unnecessary to prove that the conduct in question actually deceived or misled anyone. Evidence that a person has in fact formed an erroneous conclusion is admissible and may be persuasive but is not essential. Such evidence does not itself establish that conduct is misleading or deceptive within the meaning of the statute. The question whether conduct is misleading or deceptive is objective and the Court must determine the question for itself.

(d) Fourth, it is not sufficient if the conduct merely causes confusion.

(e) Fifth, where the impugned conduct is directed to the public generally or a section of the public, the question whether the conduct is likely to mislead or deceive has to be approached at a level of abstraction where the Court must consider the likely characteristics of the persons who comprise the relevant class to whom the conduct is directed and consider the likely effect of the conduct on ordinary or reasonable members of the class, disregarding reactions that might be regarded as extreme or fanciful.

24 The Full Court also indicated (at [23]) that a requirement that a significant number of persons to whom the conduct is directed would be led into error is no part of the test under s 18 of the ACL: see also Trivago N.V. v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2020] FCAFC 185; (2020) 384 ALR 496 at [192].

25 As far as the prohibition on false or misleading representations in s 29 of the ACL goes, a representation is a statement, which may be conveyed by words or conduct, explicitly or by implication: Aqua-Marine Marketing Pty Ltd v Pacific Reef Fisheries (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 5) [2012] FCA 908 at [78]. It is doubtful whether there is any material difference between the requirement in s 29 that the representation be 'false or misleading' and the phrase used in s 18, 'misleading or deceptive': see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14]; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; (2014) 317 ALR 73 at [40].

26 The ACCC has adduced evidence of captures of A4WD's website, australian4wdhire.com.au at various times.

27 As at 3 August 2017 the home page of the website made the following statement (all errors in original):

Our 4WD's And Bush Campers

For the recreational 4WD and Camper Hire we provide wide range of Small 4WD, Medium 4WD, Large 4WD, Extra Large 4WD, Dual Cabs with Canopy, Troop Carriers, Luxury 4WD as well as various types of Bush Campers. Our 4WD and Bush Camper range was designed predominantly for the self-drive 4WD Tourism & Travel where travelers can experience top quality 4WD and equipment to go for a cruise around the Country Side or to explore the Australian Outback and to have the access and flexibility for their destinations and enjoy their holidays at their own pace. Vehicles of this category are properly insured and equipped and are suitable for this type of travel.

Area of Use, Insurance & Roadside Assistance

Australian 4WD Hire has Off-Road Insurance for all vehicles and we allow you to travel on unsealed roads as long as they are on HEMA MAPS, (aka gazetted road) and are open and safe for passage and you have disclosed your remote Area of Use if applicable. All our vehicles are covered by Manufacturers Warranties and Roadside Assistance. In the unlikely event of vehicle failure, a replacement vehicle will be provided to you subject to availability.

HEMA Maps is a company that produces maps, atlases, guides and digital navigation products.

28 The above text was displayed prominently near the top of the home page. Further down under the heading 'We Offer' there were a number of bullet points, one of which said 'All Vehicles Off-Road Insured'. The statement 'Australian 4WD Hire has Off-Road Insurance and we allow you to travel on unsealed roads as long as they are on HEMA MAPS, (aka gazetted road) and are open and safe for passage' was repeated towards the bottom of the page. Similar statements appeared in web captures taken regularly up to September 2018.

29 From July 2018, the home page, after photographs of vehicles available for hire and a booking form, contained another section headed 'Why Australian 4WD Hire?'. One of the answers to that question under a graphic of a 4WD vehicle was 'All Vehicles Off-Road Insured'. Another, under a graphic indicating an online map was 'Off-Road OK as long as on HEMA MAPS'.

30 Further down the home page as it appeared from July 2018 under a heading '4 x 4 Rental For Any Purpose' or 'Off-Road 4 x 4 Rental For Any Purpose' and a sub-heading 'Freedom and Peace of Mind', the following statement was made: 'Choosing your own adventure while enjoying peace of mind is the ultimate in off-road travel. All Australian 4WD Hire Vehicles are insured for Off-Road use, allowing you to travel worry free on any unsealed roads found on Hema Maps (aka gazetted, open to the public and safe for passage)'.

31 The ACCC has provided page captures for subsequent dates from which it can be inferred that the home page made these representations throughout the period (at least) to 21 August 2019. At some time between then and the next web capture, which was taken on 9 September 2019, references to vehicles being insured for off-road use were removed.

32 While the respondents did not appear at trial, their position on these and other matters can be found in their responses to compulsory notices for the production of information which the ACCC served under s 155 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CACA). The ACCC's first s 155 notice was dated 8 November 2018 and contained requirements for information that were divided into a Schedule 1 and a Schedule 2. On 29 November 2018, A4WD gave separate responses to each schedule (Sch 1 Response and Sch 2 Response). On 21 December 2018, the ACCC sought clarification of some of the company's previous answers. A4WD responded to this on 1 February 2019 (February Response). In the Sch 1 Response, A4WD said (emphasis and errors in original):

A4WD WEBSITE

7. The Australian 4Wd Hire website, under the current Entity was published in January 2014.

8. a,b,c, - All of the statements you have highlighted have appeared on the website pretty much since the business' inception. It appears that you may be forgot or deliberately choose not to mention that all these statements are also subject to our T&Cs which are published on our website 24/7.

The only alteration in that regard has been made to any of these statements is the removal of 2 words, 'Fully Comprehensively', which appeared before 'Insured' on the website and was removed from all text on the website and terms and conditions sometime between September and November 2017.

The decision to remove these 2 specific words came following meetings with the Office of Fair Trading, also correspondence with ACCC on and before 6th of October of 2017 and our Legal Representatives, who advised that, even though Legal Liability Cover as Fully Comprehensively Insured does extend to our customers, subject to our T&C's, the web advertising may give the customer a false sense of security or perception in believing that, no matter the cause, or nature of the incident that they would have no liability in event of damage, and of course this is not the case with any insurer in Australia.

We concluded that by using these 2 specific words, we were not only risking the genuine interests of our business, but also our customers. Given this advice we made the decision to remove these 2 specific words and simply advertise vehicles as 'Off-Road Insured', however the Legal Liability Cover as Fully Comprehensively Insured subject to our T&C's on all our vehicle has not changed.

33 In the February Response, A4WD clarified the timing of the representations to make it clear that they had appeared on its website since January 2014. From this, it is clear that statements to the effect of those set out above were made on the website from that time until August 2019. Until at least September 2017 they were made with particular emphasis by saying that the vehicles were 'Fully Comprehensively' insured.

34 In addition, emails which A4WD sent to potential customers who had requested quotes on the website said:

WE OFFER - ANY TIME - ANY WHERE

THE RIGHT VEHICLE FOR THE RIGHT PURPOSE WITH RIGHT EQUIPMENT

…

• All Vehicles Off-Road Insured

• Off-Road OK as long as on HEMA MAPS

…

There are examples of these emails in evidence that are dated 2 April 2017, 22 December 2017 and 7 February 2018. It can be inferred from the standardised wording and formatting of the emails that many more such emails were sent to potential customers between at least April 2017 and February 2018.

The representations thereby made

35 There was no specific evidence about the characteristics of the class of people who were exposed to these statements by way of the website. But from the affidavit evidence provided by specific customers, and the nature and evident intended audience of the website itself, it may be inferred that the class was comprised of a potentially wide range of individuals who were considering or planning holidays in remote and regional areas of Australia. It is likely that they had some familiarity with using the internet to acquire and reserve goods and services but they may not have ever done so for the purpose of hiring a vehicle. There were members of the class who were not Australian citizens and lived overseas.

36 There is no reason to limit that class to people with any particular background, or level of education or experience, so it may be inferred that the class would be made up of people with varying levels of experience in hiring vehicles, varying familiarity with 4WD vehicles and varying levels of knowledge about the insurance arrangements common in the vehicle hire industry, ranging from detailed knowledge to no knowledge at all. Some members of the class may never have hired a vehicle at all before, and many would never have done so in Australia.

37 The ACCC alleges that the statements set out above represented that all of A4WD's vehicles had the benefit of being insured for off-road use. The respondents have admitted this in their concise statement filed on 21 May 2019. That allegation is made out for the period January 2014 to August 2019.

38 The ACCC also contends that the statements represented to consumers that should any damage occur to the vehicle while being hired, including while being used on unsealed roads, it would be insured under A4WD's insurance policies. The respondents' concise statement denies this.

39 Obviously the statements I have set out above did represent that all vehicles that could be hired from A4WD were insured for off-road use. The issue appears to be whether they represented that they were insured for any damage.

40 It seems that from January 2014 up until at least September 2017, they did make that representation. By the Sch 1 Response as quoted above, A4WD has admitted that the website said that the vehicles were 'fully comprehensively' insured. Mr Roesch and Ms Kosukhina have admitted that too, as they each were named on both Sch 1 and Sch 2 Responses as having signed it.

41 I am also satisfied that in the form the website appears to have taken from September 2017 to September 2018, a representation that any damage would be insured was made. The statement that the vehicles are 'properly insured' and are 'suitable for this type of travel' together with unqualified statements that A4WD has off-road insurance for all vehicles, and allows travel on unsealed roads, conveyed that the vehicles were insured for any damage. The statements were made on a website with the evident purpose of persuading potential customers to hire the vehicles. In the absence of any express qualification, they are likely to have led at least some ordinary, reasonable members of the class of users of the website to believe that any damage to the vehicle, including any damage sustained off-road, would be covered by insurance.

42 The representation that any damage was insured was also made on another part of the web site in the form it appears to have taken from July 2018 to at least August 2019. The heading 'Freedom and Peace of Mind', and the statement that, due to A4WD being insured, the customer could 'travel worry free on any unsealed roads found on Hema Maps' conveyed that any damage on those roads would be covered by the company's insurance. If there had been gaps in that insurance, the hirer would not necessarily be 'worry free'.

43 Finally, from April 2017 to February 2018, the emails received, in the context of the website (which it appears all recipients of the emails had used before receiving the emails), also conveyed that any damage which occurred to the vehicle while it was being hired would be insured under A4WD's policies.

44 I therefore find that both alleged representations were made, that is, that all of A4WD's vehicles had the benefit of being insured for off-road use, and that if any damage occurred to the vehicle while being hired it would be insured under A4WD's insurance policies (Insurance Representations). They were made on the website as it stood from least January 2014 to August 2019, and by emails from April 2017 to February 2018. Many ordinary and reasonable users of the website would understand the insurance mentioned in both of these representations to refer to insurance provided by an insurance company. And the insurance in question would not just mean the existence of an indemnity under an insurance policy which may or may not be called upon. In common experience and in ordinary parlance, to say that a vehicle is 'insured' implies that if damage to the vehicle occurs, or the vehicle is stolen or lost, an insurance company will pay for the cost of repairing or replacing the vehicle. That was reinforced by the context of the statements on the website, which were viewed by people considering whether to hire a vehicle from A4WD and so would be understood as advancing a reason why they should do so, namely because if any damage to the vehicle occurs, they will not be liable for it. That would be especially important to potential customers who may be considering taking the vehicle off sealed roads, where the risk of single vehicle accidents may be perceived to be greater.

45 In the respondents' concise statement they seem to try to minimise the extent to which it is likely that anyone was misled by noting, in effect, that the hirer always took the risk of such matters as excesses and exclusions, as well as mechanical damage. But while it can be accepted that most people are familiar with such common limitations to vehicle insurance, that does not detract from the main thrust of what the statements conveyed, as described above.

Were the Insurance Representations misleading or deceptive and false or misleading?

46 The ACCC relies on four matters said to falsify the Insurance Representations. The first matter is that not all of A4WD's rental vehicles were insured for damage caused in single vehicle accidents. The respondents admitted in their concise statement an allegation that approximately 46% of the vehicles hired by A4WD were not insured for accidents causing damage to the rental vehicle (i.e. they were not comprehensively insured). But that admission followed a statement that, 'Originally, A4WD advertised that all vehicles were comprehensively insured. When they cease [sic] to be comprehensively insured, A4WD changed the wording of the representation to reflect that fact.' From this and from the Sch 1 Response as set out above, it appears that any admission made by the respondents only relates to the period after September to November 2017. It is implicit in the concise statement that at that time, or perhaps some time before it, all vehicles were insured for all damage.

47 The ACCC also relies on a schedule of insurances dated 26 November 2018 which shows that approximately half of A4WB's vehicles were insured for third party property damage only. This tends to confirm the admission but it does not contain any dates on which insurance ceased and so does not shed any light on whether the vehicles were comprehensively insured before November 2018. There are individual certificates of comprehensive insurance but these all date from the end of 2018.

48 The Sch 2 Response dated 29 November 2018 explains A4WD's policy on insuring vehicles as follows (errors in original):

Once a vehicle reaches a certain age (2-3 years) or travels over 100,000 km, it is no longer commercially viable to insure them comprehensively through a 3rd party insurer, at which time they are transferred to a The 3rd Party Property Damages cover and the Comprehensive Cover is then extended through us as I hire company, subject to, our customers adhering to our Terms and Conditions.

The response asserts that 'we do extend Full Comprehensive Cover on all our vehicles subject to, our customers adhering to our Terms and Conditions'. But it is clear that to the extent that the 'Comprehensive Cover' relates to damage to the hired vehicle, it refers to a 'self-insurance policy'. In my view these passages in the Sch 2 Response also confirm the admission in the concise statement, but they do not indicate whether it relates to the period before September to November 2017.

49 Since over half of the vehicles had only third party damage insurance as at November 2018, and since the Sch 2 Response seems to indicate this was the result of a policy that depended on the age of the vehicle, and so was applied progressively over the fleet, it may be inferred that there were a number of vehicles that were uninsured before November 2018. But it is not clear from the admission when that policy began to be applied, it is not possible to say how many vehicles were insured at any given time, and, in particular, it is not possible to conclude on the balance of probabilities that any vehicles were uninsured before September to November 2017, that being the subject of the admission.

50 The second matter on which the ACCC relies to falsify the Insurance Representations is that if there was a single vehicle accident, there was a possibility that a vehicle hired from A4WD would not be insured for accidental damage. This also relies on the statements about self-insurance in both of the Sch 1 and Sch 2 Responses that are described above and does not add to the first matter on which the ACCC relies.

51 The third matter relied on by the ACCC is that if an A4WD rental vehicle was damaged in a single vehicle accident while being used by the hirer, the costs of repairing the damage to the vehicle might not necessarily have been insured and in that circumstance the hirer would be required to reimburse A4WD for the cost of repairing the damage to the vehicle. The fourth matter relied on is that there was a possibility that even if A4WD's rental vehicle was insured for the damage to it, the hirer would still be required to pay for the cost of repairing the damage, because A4WD's hire contract gave it the sole discretion to elect not to submit an insurance claim to its insurers for damage caused in single vehicle accidents and, instead, A4WD could claim the costs of the repairs from the hirer.

52 Those two matters are each said to follow from A4WD 's standard hiring terms and conditions, as they varied from time to time. The periods in which each different version of the standard terms was in use is difficult to establish from the evidence. The only sure evidence of the relevant periods comes from examples of signed and dated contracts with customers. The earliest of these in evidence is dated 24 May 2017. Before then, it is necessary to rely on dates given for three versions of the standard terms in the s 155 responses. It is clear from comparing those versions to actual signed contracts that the version history given by A4WD in the s 155 responses is unreliable. Nevertheless, I accept the ACCC's submission that what it says is the first version was in use from January 2014. That is because A4WD admits as much in the Sch 1 Response and confirms the same in the February Response, no actual signed contract or other evidence contradicts that admission, and from observing the history of ongoing elaboration of the standard terms - a history of terms being added or being amended so as to become more detailed - it can be inferred that the version which the ACCC says is the first version was indeed the earliest one in use. For example, that version does not contain a provision about GPS tracking, which appears to have first appeared in the standard terms in around March 2016.

53 The significance of the above for present purposes is that this first version of the standard terms contained the clause concerning insurance and single vehicle incidents which, the ACCC says, falsifies the Insurance Representations. Hence I find that this clause appeared in all versions of A4WD's standard terms, dating from January 2014. Clause 4(d) of the terms as they stood as at January 2014 was:

In the event of a single vehicle incident the Company may at its sole discretion, depending on the extent of the damage to the Vehicle, elect not to submit a claim to its insurer for damage, loss or replacement of the Vehicle. Should the Company elect not to lodge a claim with in [sic] its insurer in a single vehicle incident, the Company may instead hold the Hirer/Joint-Hirer and/or Authorised Driver/s of the vehicle jointly and severally liable for:

i. the total amount necessary to rectify all Vehicle damage in order to repair the Vehicle to a standard to be determined by the Company; or

ii. the Vehicle's replacement value as assessed by the Company's insurer; or

iii. the sum required to fully satisfy any vehicle pay-out figure under a contract of finance between the Company and a financier whichever is the greater of these three figures and at the sole discretion of the Company. In the event the Company elects not to submit a claim to its insurer for any such rectification of Vehicle damage or Vehicle replacement, the Hirer / Joint Hirer and/or Authorised Driver/s hereby acknowledge and agree that the quantum associated with the repair or replacement of the Vehicle, or the Vehicle's payout figure with the Company's financier, will be payable to the Company as liquidated damages immediately upon written demand by the Company or its legal representatives.

That term was substantially unchanged in various iterations of the standard conditions running through to 2019. I will refer to the terms to that effect collectively as the Insurance Discretion Clause.

54 To summarise, then, my findings about the matters said to falsify the Insurance Representations: the evidence set out above satisfies me that from at least November 2017 until August 2019, some of the vehicles hired out by A4WD were not subject to policies of insurance taken out with third party insurers which provided coverage for any damage to the vehicle. From November 2018, the date of the schedule of insurance to which I have referred, the proportion of such vehicles was a little over half. For those vehicles, single vehicle accidents where there was no damage to third party property would not be insured by any third party insurer at all. In view of what was conveyed by the statements on the website and in the emails, as I have found above, those statements were misleading or deceptive and false or misleading from November 2017.

55 Given the lack of evidence regarding the true position as to the insurance of the vehicles before September to November 2017, the ACCC has not established that some of A4WD's vehicles were not comprehensively insured before that time. I do not find that the statements were misleading, deceptive or false for that reason before November 2017.

56 As for the Insurance Discretion Clause, under it the benefit of any insurance policy could be denied to the customer at A4WD's absolute discretion. That is a significant qualification to the unqualified statements that all vehicles were insured, including for off-road use. The respondents' concise statement asserts that all vehicles were the subject of insurance policies for at least third party damage, so that the statements to the effect that the vehicles were insured were correct. But whether or not those statements were literally true when understood in that light, I have found that they would be understood by reasonable users of the website and recipients of the emails to be saying that if damage to the vehicle occurred, or the vehicle was stolen or lost, an insurance company would pay for the cost of repairing or replacing the vehicle. In failing to refer to the fact that this would depend on whether A4WD exercised its contractual discretion against lodging a claim, and that if it did then the customer would be liable to indemnify the company for any loss, the statements were misleading. The presence of the Insurance Discretion Clause from January 2014 means that they were misleading from that date on.

57 The respondents' concise statement argues that since the contract contained a security bond clause, and the hirers had to pay the bond, it must have been apparent to them that the insurance did not cover all damage or other losses. There are three answers to this. First, it is likely that many users of the website viewed the statements on the website before deciding to hire a vehicle, before turning their minds to matters such as a security bond, before being informed of the requirement for the bond, and before paying it. It has long been recognised that a contravention of s 18 of the ACL may occur at the point where members of the target audience have been enticed into 'the marketing web' by an erroneous belief caused by the respondent, even if the consumer may come to appreciate the true position before a transaction is concluded: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [50]. The second answer is that not all consumers were likely to make the connection between the existence of a security bond and insurance coverage which supports the inference on which the respondents relied. Failing to make that connection and inference does not, in my view, take a user of the website outside the class of ordinary and reasonable users. The third answer is that even if an ordinary reasonable user did make that connection, they could nevertheless understand the security bond to cover matters which one would not ordinarily expect to be covered by comprehensive insurance, such as deliberate damage or an excess.

58 The Sch 1 Response also refers to the availability of the terms and conditions on the website. Whether or not qualifying material of that nature is effective to neutralise an otherwise misleading or deceptive statement is a matter for determination in the specific circumstances of any particular case, and the qualifying material must be sufficiently prominent to prevent the primary statement from being misleading and deceptive: Medical Benefits Fund of Australia Ltd v Cassidy [2003] FCAFC 289; (2003) 135 FCR 1 at [37] (Stone J, Moore and Mansfield JJ agreeing). In the present case, there was little to indicate to users of the website that the statements were qualified by terms and conditions. There was no statement to that effect made immediately after the misleading statements, or any other device designed to draw the user's attention to the fact that those statements were qualified by the company's standard terms and conditions. A link to the terms and conditions is found near the bottom of the home page, behind an asterisk referable to the hire fees, not to the misleading statements. The link is in the same size print as the rest of the normal block text, three paragraphs below the statement about driving 'worry free'. It just says 'Terms and conditions apply' - it is not specifically connected with the statements about insurance coverage. And the terms themselves are the usual finely and densely printed mass of detailed provisions, in which the Insurance Discretion Clause can be found as an unlabelled sub-clause, or at least it can if one is looking for it. It is unlikely that an ordinary, reasonable user of the website, devoting a reasonable but not excessive amount of time to his or her review of it for the purposes of possibly hiring a vehicle, would find the Insurance Discretion Clause, read it, and understand it to qualify the prominent statements made on the website home page. Despite the fact that it was possible to find the standard terms and conditions, the website was still misleading.

59 There can be no issue that the publication of the website and the sending of the quotation emails to potential customers was conduct in trade or commerce.

60 For the reasons given, in making the statements on its website that I have described above between January 2014 and August 2019 (both inclusive), A4WD engaged in conduct that was misleading and deceptive. The company therefore contravened s 18 of the ACL during that period. The ACCC has established that from January 2014, the website and emails were misleading because of statements they made which obscured the existence and effect of the Insurance Discretion Clause. From November 2017, they were also misleading because not all of the company's hire vehicles were insured for damage to the vehicle.

61 As for s 29(1)(g) of the ACL, the respondents' concise statement admits that A4WD has represented to consumers, via the publication of statements made on its website, that all A4WD's rental vehicles have the benefit of being 'insured for off-road use'. In the circumstances, and as I have explained, that statement conveyed that all the vehicles also had the benefit that if damage occurred or the vehicle was stolen or lost, an insurance company would pay for the cost of repairing or replacing it. Given that this was not true for some of the vehicles from at least November 2017 (as at November 2018, over half of them), that statement was false. And given that it omitted to refer to the potentially significant qualification to the statement which arose from the Insurance Discretion Clause, it was also misleading from January 2014.

62 The Insurance Representations were false or misleading representations that the goods supplied had benefits. They were made in connection with the supply of goods and the promotion of the supply of goods; when used as a verb, 'supply' includes supply by way of hire and when used as a noun it has a corresponding meaning: ACL s 2(1). So from January 2014until August 2019, in making the Insurance Representations, A4WD contravened s 29(1)(g) of the ACL.

63 Section 23(1) of the ACL relevantly provides that a term of a consumer contract is void if it is unfair, and the contract is a standard form contract. A consumer contract includes a contract for the supply of goods to an individual whose acquisition of the goods is wholly or predominantly for personal, domestic or household use or consumption: s 23(3).

64 Section 24 of the ACL provides:

(1) A term of a consumer contract or small business contract is unfair if:

(a) it would cause a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations arising under the contract; and

(b) it is not reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term; and

(c) it would cause detriment (whether financial or otherwise) to a party if it were to be applied or relied on.

(2) In determining whether a term of a contract is unfair under subsection (1), a court may take into account such matters as it thinks relevant, but must take into account the following:

(a) the extent to which the term is transparent;

(b) the contract as a whole.

(3) A term is transparent if the term is:

(a) expressed in reasonably plain language; and

(b) legible; and

(c) presented clearly; and

(d) readily available to any party affected by the term.

(4) For the purposes of subsection (1)(b), a term of a contract is presumed not to be reasonably necessary in order to protect the legitimate interests of the party who would be advantaged by the term, unless that party proves otherwise.

65 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v CLA Trading Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 377 at [54], Gilmour J set out the following principles (citations removed) about the application of Part 2, Division 2, Subdivision BA of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (ASIC Act). For present purposes that Part is not materially different to Part 2-3 of the ACL, which contains s 23 and s 24:

(a) the underlying policy of unfair contract terms legislation respects true freedom of contract and seeks to prevent the abuse of standard form consumer contracts which, by definition, will not have been individually negotiated;

(b) the requirement of a 'significant imbalance' directs attention to the substantive unfairness of the contract;

(c) it is useful to assess the impact of an impugned term on the parties' rights and obligations by comparing the effect of the contract with the term and the effect it would have without it;

(d) the 'significant imbalance' requirement is met if a term is so weighted in favour of the supplier as to tilt the parties' rights and obligations under the contract significantly in its favour - this may be by the granting to the supplier of a beneficial option or discretion or power, or by the imposing on the consumer of a disadvantageous burden or risk or duty;

(e) significant in this context means 'significant in magnitude', or 'sufficiently large to be important', 'being a meaning not too distant from substantial';

(f) the legislation proceeds on the assumption that some terms in consumer contracts, especially in standard form consumer contracts, may be inherently unfair, regardless of how comprehensively they might be drawn to the consumer's attention; and

(g) in considering 'the contract as a whole', not each and every term of the contract is equally relevant, or necessarily relevant at all. The main requirement is to consider terms that might reasonably be seen as tending to counterbalance the term in question.

66 It can be relevant in assessing whether a term would cause a significant imbalance to consider whether any burden that the contract imposes on the consumer is matched by a corresponding right or (as a correlative) a corresponding duty on the supplier: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Chrisco Hampers Australia Limited [2015] FCA 1204; (2015) 239 FCR 33 at [53]-[58] (Edelman J).

67 As for what is reasonably necessary to protect the legitimate interests of the supplier, it is not appropriate to attempt to define 'legitimate interest' as it will depend on the nature of the particular business of the relevant supplier, the particular circumstances of the business, and the context of the contract as a whole. A legitimate interest may not be purely monetary and may not be confined to reimbursement of expenses directly occasioned by the customer's default. It may be intangible and unquantifiable. The court may take into account options that might be available to the supplier in terms of protecting its business interests, other than the impugned contract terms: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Ashley & Martin Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1436 at [48]-[49], [51], [53] (Banks-Smith J). Here, the ACCC relies on the presumption under s 24(4), which requires A4WD to prove that the impugned terms are reasonably necessary in order to protect its legitimate interests.

68 The third element in s 24(1) is detriment to the consumer. Lord Steyn said of a similar provision applicable in the United Kingdom that this element 'may not add much': Director General of Fair Trading v First National Bank plc [2002] UKHL 52; [2002] 1 AC 481 at [36]. In my view that element simply requires that the application of or reliance on the unfair contract term will be disadvantageous to the consumer in some way. Under s 23(1)(c), the detriment may be financial or otherwise. It can include the imposition of liability in circumstances where the consumer would otherwise not be liable, or allowing the company to charge the consumer for damage for breach of contract where that breach did not cause or contribute to the damage: Ashley & Martin at [63]. Both of those are instances where the contract causes detriment because it imposes a disadvantage which would not be imposed in its absence.

69 As to transparency, s 24(2)(a) only requires the Court to consider transparency in relation to the particular term that is said to be unfair and only in relation to the matters concerning that term in s 24(1)(a) to (c): Chrisco at [43]. The meaning of 'transparency' in this context is explicit in s 24(3) (see [64] above). But it is not immediately apparent how the transparency of a term, or lack of it, can affect the question of whether the term is unfair.

70 The difficulty arises because of the nature of the evaluation required by Part 2-3. It does not involve the exercise of a discretion. Section 23 provides that a term of a relevant consumer contract is void if it is unfair. The term will be unfair if the three elements in s 24(1) are satisfied. Whether that is so is an objective question requiring the application of the specified criteria to the facts. Section 24(2) describes it as a determination. No order of the court is required for s 24(2) to have effect. The court may make a declaration under s 250 which can have further remedial consequences (see below), and that involves a discretion. But that is a different thing to the determination contemplated by s 24(2).

71 That being so, it is hard to see how the transparency of the provision can affect the objective question of whether the three criteria in s 24(1) are satisfied. With one qualification, whether a term would cause a significant imbalance, is reasonably necessary to protect legitimate interests of a party, or would cause detriment to another party depends on what the impugned term means, that is, on its proper construction. Those matters depend on the effect of the term, on other relevant characteristics of the contract as a whole, and on the factual question of whether the term is reasonably necessary to protect legitimate interests. They do not depend on how the impugned term is presented. If, for example, it is buried in fine print, that may affect its legibility, but it will make no difference to the effect it will have on the parties if it is relied on. So, as Edelman J pointed out in Chrisco at [43], the Explanatory Memorandum to the Trade Practices Amendment (Australian Consumer Law) Bill (No 2) 2010 (Cth) on the introduction of what is now Part 2-3 of the ACL says that if a term is not transparent it does not mean that it is unfair and if a term is transparent it does not mean that it is not unfair: see also Gilmour J's observation in CLA Trading at [54(f)] (quoted above).

72 The one qualification emerges from the judgment of Banks-Smith J in Ashley & Martin. At [157] her Honour referred to obscurity in the way a particular provision was drafted. The obscurity meant that it was hard to know how the clause would apply in a particular situation: see [113]-[115]. Her Honour observed that this increased the degree of difficulty for consumers in identifying their contractual rights and thus added to the significant imbalance which the provision caused. This was still a question of the terms in which the provision was cast, not the way in which it was presented. I do not suggest that this is the only way that transparency (or lack thereof) can contribute to unfairness. It will depend on the circumstances of the case. But in the circumstances of this case, no other ways spring to mind.

73 As to having regard to the contract as a whole, an impugned term cannot be assessed in a vacuum which ignores the practical considerations that attach to the carrying out of contractual obligations: Ashley & Martin at [66].

Standard form consumer contracts

74 The respondents have admitted in their concise statement that 'consumers' - by implication persons who wanted to hire vehicles from A4WD - were required to enter into a standard form contract as the ACCC alleges. There are numerous examples of contracts in the evidence which contain the terms that the applicant says are unfair contract terms. It is inherent in the likely purpose of each vehicle hire, namely use by people who are on holiday, that the goods were being acquired for personal use (there is a definition of 'acquire' in s 2(1) of the ACL which confirms that it encompasses the hire of goods). The contracts here meet the definition of 'consumer contracts' in s 23(3) and were 'standard form contracts' for the purposes of Part 2-3 and s 250 of the ACL.

75 The first set of terms which the ACCC says are unfair concern the GPS tracking of the hired vehicles, the DBR that could be prepared on the basis of the GPS data, and the consequences for the hirer if that DBR revealed breaches of the contract. These standard terms varied somewhat over time and it is necessary to trace the changes.

76 I have described above the combination of admissions in the s 155 responses and the ongoing development of A4WD's standard terms, which permits different versions of the standard terms to be dated. That process establishes that as at 31 March 2016, the standard terms contained a cl 17 (First GPS Clause), as follows:

GPS Tracking of Vehicles

Australian 4WD Hire reserve the right to use GPS tracking to record speed, area, and time of use, however use of GPS tracking is not limited to this. Should any data received show any breach of speed limits or area or time of use, it will be considered as Negligence and regardless of circumstances, will constitute a breach of these Terms and Conditions.

Notwithstanding the capitalisation, 'Negligence' is not a defined term.

77 Subsequent versions of the contracts made between May 2017 and April 2018 contained an expanded version of cl 17 (Second GPS Clause). The ACCC submitted that this version of the GPS Clause should be dated from 1 January 2017, but that relies on admissions in the s 155 responses which I have found to be unreliable because they do not correspond with other signed and dated customer contracts which are in evidence. Those contracts are the surest way of dating the various versions of the clauses from 2017 on. The Second GPS Clause is:

You hereby acknowledge that the Company uses GPS systems to track and monitor the vehicles including, but not limited to, speed, time, driver behaviour, location and routes of travel. At any time, the Company may at its sole discretion prepare a GPS Driver Behaviour Report ('DBR') in respect of the Vehicle indicating the aforementioned matters in addition to other matters the Company at its discretion considers necessary.

In the event the DBR evidences that you:

a. have driven the Vehicle in excess of legal speed limits and/or driven the Vehicle more than 60 kilometres per hour on unsealed roads or tracks;

b. at the reasonable assessment of the Company your driver behaviour has caused damage and/or excessive wear and tear to the Vehicle;

c. the Vehicle has been driven on a road or track which has not been either open or safe for passage or permitted by Company;

You acknowledge that such acts have caused damage and/or excessive wear and tear to the vehicle either seen or unseen and that the Company has suffered loss and damage ('Driver Behaviour Damage'). In respect of the Driver Behaviour Damage you hereby irrevocably authorise the Company, at its sole discretion, to deduct your security bond or part of it by way of liquidated damages ('the Liquidated Damages'). You hereby acknowledge that the Liquidated Damages are a genuine pre-estimate of the loss that the Company will suffer in relation to Driver Behaviour Damage. This clause (17) does not limit the rights and/or remedies available to the Company pursuant to these Terms and Conditions, at law or in equity.

78 From at least 3 April 2018 until sometime before July 2018, a further clause was inserted into the standard terms at cl 13(f), which provided (Third GPS Clause):

The Hirer/Joint Hirer and Authorised Driver being jointly and severally liable for any and all loss or damage whosoever caused to the vehicle or the Company as a result of any breach of the terms and conditions herein, acknowledge, consent and agree to the following:

…

f. That when travelling outside built up areas you are not permitted to drive between sunset and dawn or during any period of reduced visibility, including but not limited to fog, dust storms, heavy rain and hirer accepts that minimum penalty of $500.00 per incident will apply

79 Under these standard terms, the amount of the security bond varied between $1,500 and $5,000, depending on the age of the driver, whether the customer chose to pay a daily amount of between $25 and $50, and (at A4WD's discretion) whether the customer intended to drive the vehicle to any remote areas: see cl 12.

80 At some time between April 2018 and July 2018, the terms concerning GPS tracking were moved to cl 5(c) and cl 8 of the standard terms (Fourth GPS Clause). Under cl 8(a), the hirer acknowledged 'that the Company monitors the areas the Vehicle was driven, when the Vehicle was driven and how fast the Vehicle was driven using GPS'. Under cl 8(b), A4WD could, at its discretion, prepare a DBR for the Vehicle. It is clear from acknowledgments in cl 8(c) that GPS data supplied by a third party provider called CTRACK was to be used to compile the DBR.

81 In this version of the contract, cl 3(i) obligated the hirer to prevent the vehicle from being operated in a manner that was a 'Prohibited Operation'. Clause 1(w) contained a long and detailed definition of what was a Prohibited Operation. It included operating the vehicle outside any agreed or disclosed area of use. It also included (among many other things):

(1) operation in contravention of any traffic laws;

(2) operation outside built up areas between sunset and dawn;

(3) operation 'during any period of reduced visibility, including but not limited to fog, dust storms and heavy rain';

(4) 'driving the Vehicle at a speed higher than 60km per hour on an unsealed road or track, unless the conditions (including but not limited to the road conditions) and the Traffic Laws permit otherwise'; and

(5) 'driving the Vehicle above the indicated speed limit'.