Federal Court of Australia

Juno Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Celgene Corporation [2021] FCA 236

ORDERS

First Applicant NATCO PHARMA LIMITED Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

OTHER MATTERS:

Upon the applicants undertaking to the Court and to the respondent that, until such time as the Court delivers its reasons for judgment at first instance in this proceeding on the validity of claims 1, 4 and 9 of Australian patent no 715779 or the proceeding is earlier terminated or until further order, they will give to the respondent at least four months’ written notice prior to, in Australia,:

(a) offering to supply;

(b) supplying; or

(c) achieving listing on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme of,

any pharmaceutical product containing lenalidomide as the active pharmaceutical ingredient.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicants have leave nunc pro tunc to file and serve amended particulars of invalidity in the form previously delivered to the respondent.

2. The respondent’s application seeking summary dismissal of parts of the applicants’ amended particulars of invalidity be dismissed.

3. The applicants’ application to strike out parts of the respondent’s cross-claim be dismissed.

4. The respondent’s application to amend its cross-claim be refused.

5. The applicants be excused from complying with the respondent’s notices to produce dated 4 December 2020 and 15 December 2020.

6. There be an expedited trial in August 2021 of the applicants’ challenge to the validity of claims 1, 4 and 9 of Australian patent no. 715779 together with so much of the respondent’s cross-claim as relates to the infringement of that patent.

7. Costs reserved.

8. Liberty to apply.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 The applicants, Juno Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd and Natco Pharma Ltd, have instituted the present patent proceeding against the respondent, Celgene Corporation, in order to clear the way for the future launch of their generic pharmaceutical products.

2 They challenge the validity of three claims of the principal patent in suit.

3 The respondent has cross-claimed for infringement of not only that patent, but also of six method of treatment patents and an additional patent which I will describe as the MCL patent; I have listed these later in my reasons. The applicants do not challenge the validity of these other patents in the present proceeding, at least for the moment.

4 Before me are competing interlocutory applications.

5 The respondent has sought to summarily dismiss the applicants’ grounds of invalidity concerning the alleged failure to disclose the best method and false suggestion. That application fails.

6 The applicants have sought to strike out parts of the cross-claim. That application also fails, as does the respondent’s cross-application to add a further declaration to the cross-claim.

7 The applicants have also sought an expedited trial of their invalidity challenge to the principal patent in suit and those parts of the cross-claim concerning that patent, but not the method of treatment patents or the MCL patent. They do so to clear the way for their launch. That application is granted, even though their strategic objective may not be fully met even if they are successful on questions concerning the principal patent in suit. I will fix the matter for trial at a time convenient to the parties in August this year. The expectation of the parties is that I will deliver judgment the following month, all being well.

8 In addition to these interlocutory applications, there were other questions between the parties concerning discovery and notices to produce. With some encouragement from me at an earlier hearing, the discovery question has now been resolved, conditional only upon the outcome of my ruling concerning the respondent’s summary dismissal application. As for the applicants’ application to set aside the respondent’s notices to produce, I will dispose of that lesser order question later.

9 Let me begin with the principal patent in suit, putting to one side the other patents.

The principal patent

10 The principal patent in suit, which is Australian patent no 715779, concerns the compounds substituted 2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-phthalimides and -1-oxoisoindolines, and methods of reducing tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) levels. Its earliest priority date is 24 July 1996.

11 The patentee and original applicant is the present respondent.

12 It is necessary to draw attention to various features of the specification.

13 The specification states (p 1 lines 6 to 9):

The present invention relates to substituted 2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)phthalimides and substituted 2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1-oxoisoindolines, the method of reducing levels of tumor necrosis factor α in a mammal through the administration thereof, and pharmaceutical compositions of such derivatives.

14 The following background is then given (p 1 line 11 to p 2 line 19):

Tumor necrosis factor α, or TNFα, is a cytokine which is released primarily by mononuclear phagocytes in response to a number immunostimulators. When administered to animals or humans, it causes inflammation, fever, cardiovascular effects, hemorrhage, coagulation, and acute phase responses similar to those seen during acute infections and shock states. Excessive or unregulated TNFα production thus has been implicated in a number of disease conditions. These include endotoxemia and/or toxic shock syndrome {Tracey et al., Nature 330, 662-664 (1987) and Hinshaw et al., Circ. Shock 30, 279-292 (1990)}; cachexia {Dezube et al., Lancet, 335 (8690), 662 (1990)} and Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome where TNFα concentration in excess of 12,000 pg/mL have been detected in pulmonary aspirates from ARDS patients {Millar et al., Lancet 2 (8665), 712-714 (1989)}. Systemic infusion of recombinant TNFα also resulted in changes typically seen in ARDS {Ferrai-Baliviera et al., Arch. Surg. 124(12), 1400-1405 (1989)}.

TNFα appears to be involved in bone resorption diseases, including arthritis. When activated, leukocytes will produce bone-resorption, an activity to which the data suggest TNFα contributes. {Bertolini et al., Nature 319, 516-518 (1986) and Johnson et al., Endocrinology 124(3), 1424-1427 (1989).} TNFα also has been shown to stimulate bone resorption and inhibit bone formation in vitro and in vivo through stimulation of osteoclast formation and activation combined with inhibition of osteoblast function. Although TNFα may be involved in many bone resorption diseases, including arthritis, the most compelling link with disease is the association between production of TNFα by tumor or host tissues and malignancy associated hypercalcemia {Calci. Tissue Int. (US) 46(Suppl.), S3-10 (1990)}. In Graft versus Host Reaction, increased serum TNFα levels have been associated with major complication following acute allogenic bone marrow transplants {Holler et al., Blood, 75(4), 1011-1016 (1990)}.

Cerebral malaria is a lethal hyperacute neurological syndrome associated with high blood levels of TNFα and the most severe complication occurring in malaria patients. Levels of serum TNFα correlated directly with the severity of disease and the prognosis in patients with acute malaria attacks {Grau et al., N Engl. J Med. 320(24), 1586-1591 (1989)}.

Macrophage-induced angiogenesis TNFα is known to be mediated by TNFα Leibovich et al. {Nature, 329, 630-632 (1987)} showed TNFα induces in vivo capillary blood vessel formation in the rat cornea and the developing chick chorioallantoic membranes at very low doses and suggest TNFα is a candidate for inducing angiogenesis in inflammation, wound repair, and tumor growth. TNFα production also has been associated with cancerous conditions, particularly induced tumors {Ching et al., Brit. J. Cancer, (1955) 72, 339-343, and Koch, Progress in Medicinal Chemistry, 22, 166-242 (1985)}.

TNFα also plays a role in the area of chronic pulmonary inflammatory diseases.

15 It is also stated (p 3 lines 12 to 32):

TNFα blockage with monoclonal anti-TNFα antibodies has been shown to be beneficial in rheumatoid arthritis {Elliot et al., Int. J. Pharmac. 1995 17(2), 141-145} and Crohn’s disease {von Dullemen et al., Gastroenterology, 1995 109(1), 129-135}

Moreover, it now is known that TNFα is a potent activator of retrovirus replication including activation of HIV-1. {Duh et al., Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 86, 5974-5978 (1989); Poll et al., Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 87, 782-785 (1990); Monto et al., Blood 79, 2670 (1990); Clouse et al., J. Immunol. 142, 431-438 (1989); Poll et al., AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovirus, 191-197 (1992)}. AIDS results from the infection of T lymphocytes with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). At least three types or strains of HIV have been identified, i.e., HIV-1, HIV-2 and HIV-3. As a consequence of HIV infection, T-cell mediated immunity is impaired and infected individuals manifest severe opportunistic infections and/or unusual neoplasms. HIV entry into the T lymphocyte requires T lymphocyte activation. Other viruses, such as HIV-1, HIV-2 infect T lymphocytes after T cell activation and such virus protein expression and/or replication is mediated or maintained by such T cell·activation. Once an activated T lymphocyte is infected with HIV, the T lymphocyte must continue to be maintained in an activated state to permit HIV gene expression and/or HIV replication. Cytokines, specifically TNFα, are implicated in activated T-cell mediated HIV protein expression and/or virus replication by playing a role in maintaining T lymphocyte activation. Therefore, interference with cytokine activity such as by prevention or inhibition of cytokine production, notably TNFα, in an HIV-infected individual assists in limiting the maintenance of T lymphocyte caused by HIV infection.

16 Further, it is said (p 5 line 20 to p 6 line 3):

Decreasing TNFα levels and/or increasing cAMP levels thus constitutes a valuable therapeutic strategy for the treatment of many inflammatory, infectious, immunological, and malignant diseases. These include but are not restricted to septic shock, sepsis, endotoxic shock, hemodynamic shock and sepsis syndrome, post ischemic reperfusion injury, malaria, mycobacterial infection, meningitis, psoriasis, congestive heart failure, fibrotic disease, cachexia, graft rejection, oncogenic or cancerous conditions, asthma, autoimmune disease, opportunistic infections in AIDS, rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatoid spondylitis, osteoarthritis, other arthritic conditions, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythrematosis, ENL in leprosy, radiation damage, oncogenic conditions, and hyperoxic alveolar injury. Prior efforts directed to the suppression of the effects of TNFα have ranged from the utilization of steroids such as dexamethasone and prednisolone to the use of both polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies {Beutler et al., Science 234, 470-474 (1985); WO 92/11383}.

The present invention is based on the discovery that certain classes of non-polypeptide compounds more fully described herein decrease the levels of TNFα.

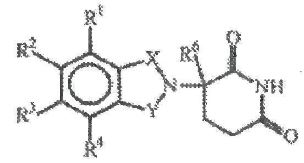

In particular, the invention pertains to (i) compounds of the formula:

…

17 The claims in suit are claims 1, 4 and 9 and deal with compounds. They are the following:

1. A 2,6-dioxopiperidine selected from the group consisting of (a) a compound of the formula:

in which:

one of X and Y is C=O and the other of X and Y is C=O or CH2;

(i) each of R1, R2, R3, and R4, independently of the others, is halo, alkyl of 1 to 4 carbon atoms, or alkoxy of 1 to 4 carbon atoms or (ii) one of R1, R2, R3, and R4 is - NHR5 and the remaining of R1, R2, R3, and R4 are hydrogen;

R5 is hydrogen or alkyl of 1 to 8 carbon atoms;

R6 is hydrogen, alkyl of 1 to 8 carbon atoms, benzyl, or halo;

provided that R6 is other than hydrogen if X and Y are C=O and (i) each of R1, R2, R3, and R4 is fluoro or (ii) one of R1, R2, R3, or R4 is amino; and

(b) the acid addition salts of said compounds which contain a nitrogen atom capable of being protonated.

…

4. A compound according to claim 1 which is 1-oxo-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl) 5-aminoisoindoline, l-oxo-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-y1)-4-aminoisoindoline, 1-oxo-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-y1)-6-aminoisoindoline, 1-oxo-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-7-aminoisoindoline, l-oxo-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-4,5,6,7-tetrafluoroisoindoline, 1-oxo-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-4,5,6,7-tetrachloroisoindoline, 1-oxo-2-(2,6-dioxo-piperidin-3-yl)-4,5,6,7-tetramethylisoindoline, 1-oxo-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-4,5,6,7-tetramethoxyisoindoline, 3-(1-oxo-4-aminoisoindolin-1-yl)-3-methylpiperidine-2,6-dione, 3-(l-oxo-4-aminoisoindolin-l-y1)-3-ethylpiperidine-2,6-dione, 3-(l-oxo-4-aminoisoindolin-l-yl)-3-propylpiperidine-2,6-dione, or 3-(3-aminophthalimi-do)-3-methylpiperidine-2,6-dione.

…

9. A compound which is 1-oxo-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-4-aminoisoindoline.

…

18 The chemical compound 1-oxo-2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-4-aminoisoindoline, which is referred to specifically in claim 9 and embraced within the broader claims 1 and 4, is also known as “lenalidomide”.

19 I should also set out claim 5 by way of contrast:

5. The method of reducing undesirable levels of TNFα in a mammal which comprises administering thereto an effective amount of a compound according to claim 1.

20 It will be appreciated that unlike claims 1, 4 and 9, claim 5 refers expressly to reducing levels of TNFα. The definition of the invention and the absence of such an integer in claims 1, 4 and 9 is relevant to one of the asserted grounds of invalidity that I will return to shortly.

The challenge to the grounds of invalidity

21 The amended particulars of invalidity address three grounds, being lack of inventive step, failure to disclose the best method, and false suggestion. For the moment it is only necessary to deal with the second and third grounds, which are sought by the respondent to be summarily dismissed or struck out under s 31A of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and rr 16.21 and 26.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

22 The second ground is expressed as follows:

4 The Patent does not comply with subsection 40(2)(a) of the Act because the complete specification does not describe the best method known to the Respondent of performing the alleged invention.

Particulars

(a) The specification asserts that the patentee discovered that the non-polypeptide compounds described in the Patent, when administered, decrease levels of TNFα.

(b) The specification does not disclose which of those compounds had been identified by, or was known to, the patentee, as at the date on which it filed the complete specification, to most effectively perform the invention by decreasing levels of TNFα when administered.

23 The third ground is expressed as follows:

5 Each of claims 1, 4 and 9 of the Patent should be revoked pursuant to subsection 138(3)(d) of the Act on the ground that the Patent was obtained by false suggestion or misrepresentation.

Particulars

(a) If, in the alternative to the allegation in paragraph 4 above, the patentee did not conduct testing to determine whether the members of the classes of non-polypeptide compounds described in the Patent decrease the levels of TNFα, the representation at page 6 lines 1 to 2 that such a discovery had been made was a false suggestion and was a misrepresentation because it falsely represented that such testing had been conducted.

(b) The representation in paragraph (a) above materially contributed to the Commissioner’s decision to grant the Patent.

24 In terms of the relevant principles concerning summary dismissal, particularly concerning patent litigation, I need do little more than note what was said in Upaid Systems Ltd v Telstra Corporation Ltd (2016) 122 IPR 190 by Perram, Jagot and Beach JJ at [44] to [53]:

The primary judge made an order for summary dismissal invoking s 31A of the Federal Court Act 1976 (Cth) and r 26.01 of the Federal Court Rules 2011. It is not necessary to separately discuss r 26.01. Section 31A(2) and (3) provide as follows:

Summary judgment

(1) [...]

(2) The Court may give judgment for one party against another in relation to the whole or any part of a proceeding if:

(a) the first party is defending the proceeding or that part of the proceeding; and

(b) the Court is satisfied that the other party has no reasonable prospect of successfully prosecuting the proceeding or that part of the proceeding.

(3) For the purposes of this section, a defence or a proceeding or part of a proceeding need not be:

(a) hopeless; or

(b) bound to fail;

for it to have no reasonable prospect of success.

[...]

His Honour discussed the parties’ submissions concerning the question of “reasonable prospect of success” and his own conclusions at [496] to [516]. The relevant principles were not in doubt. A number of propositions may be stated.

First, a proceeding or claim need not be “hopeless” or “bound to fail” for it to have no reasonable prospect of success (s 31A(3)).

Second, s 31A(2) may justify summary dismissal where, inter alia, there is unanswerable or unanswered evidence of a fact fatal to the pleaded case or any permissible modification (Spencer v Commonwealth (2010) 241 CLR 118; 269 ALR 233; [2010] HCA 28 (Spencer) at [22] per French CJ and Gummow J).

Third, the exercise of power under s 31A(2) should be used with caution, particularly where complex questions of fact or law are involved. The present case concerns questions of construction of claim 1 of the 853 patent which are legal questions although to some extent informed by factual considerations.

Fourth, as was said in Spencer at [59] per Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ:

In many cases where a plaintiff has no reasonable prospect of prosecuting a proceeding, the proceeding could be described (with or without the addition of intensifying epithets like “clearly”, “manifestly” or “obviously”) as “frivolous”, “untenable”, “groundless” or “faulty”. But none of those expressions (alone or in combination) should be understood as providing a sufficient chart of the metes and bounds of the power given by s 31A. Nor can the content of the word “reasonable”, in the phrase “no reasonable prospect”, be sufficiently, let alone completely, illuminated by drawing some contrast with what would be a “frivolous”, “untenable”, “groundless” or “faulty” claim.

Fifth, the fact that one is dealing with a patent infringement claim does not make it immune from a summary dismissal order. But where the technology is complex or the Court is not able to confidently construe the relevant claim, then summary determination may not be appropriate.

In Virgin Atlantic Airways Ltd v Delta Air Lines Inc [2011] RPC 18; [2011] EWCA Civ 162 at [13], [14], Jacob LJ observed:

... Whilst the general rules as to summary judgment apply equally to patent cases as to other types of case, there can be difficulties, particularly in cases where the technology is complex. If it is, the court may not be able, on a summary application, to form a confident view about the claim or its construction, particularly about the understanding of the skilled man. On the other hand in a case such as the present, where the technology is relatively simple to understand, there is really no good reason why summary procedure cannot be invoked. No one should assume that summary judgment is not for patent disputes. It all depends on the nature of the dispute. That can cut both ways, of course. If the court is able to grasp the case well enough to resolve the point, then it can and should do so — whether in favour of the patentee or the alleged infringer.

These observations were approved of by Floyd LJ in Nampak Plastics Europe Ltd v Alpla UK Ltd [2015] FSR 11; [2014] EWCA Civ 1293 at [7], who also made the following further observations at [9] to [11]:

It is clear that the fact that a dispute involves the resolution of an issue of construction of a patent does not automatically render it unsuitable for summary judgment. However it is necessary to proceed with caution given that the court is not being called upon, when construing a patent, to decide what the words of the patent mean to it, but what they would have been understood to mean by the person skilled in the art: see per Lord Hoffmann in Kirin-Amgen Inc v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd (2004) 64 IPR 444; [2005] 1 All ER 667; [2004] UKHL 46 at [32], [33]. Such an exercise is dependent upon the identity of the person skilled in the art and the knowledge and assumptions which one attributes to him or her.

That said, it remains the law that expert evidence is not admitted as to the meaning of ordinary English words which have no special or technical meaning in the art. Once equipped with evidence as to the knowledge and assumptions of the person skilled in the art, the determination of the meaning which the words used in a patent claim would convey to one skilled in the art is for the court.

It follows from what I have said that, on a summary judgment application such as this, it is necessary for a party who claims that the court is inadequately equipped to decide an issue of construction to identify, perhaps in only quite general terms, the nature of the evidence of the common general knowledge which he proposes to adduce, and to be in a position to explain why that evidence might reasonably be expected to have an impact on the issue of construction. If that party is not able to do so, it is open to the court to conclude that he is simply hoping that “something may turn up” and that his defence does not have the necessary “reality” to avoid summary judgment under Pt 24.

Generally speaking, we agree with these observations. Indeed, we would also note that the UK test of “no real prospect” of success is more stringent than the s 31A test (see Spencer at [51]) which refers to “no reasonable prospect”, thereby perhaps permitting greater ambit for summary dismissal under s 31A(2) of a patent infringement claim than under the UK analogue.

25 Of course, in the present context concerning the respondent’s summary dismissal application, I am concerned with patent invalidity issues rather than patent infringement issues, although construction questions can arise under either category. Indeed, in the present context concerning the lack of disclosure of the best method, questions of the scope of claims 1, 4 and 9 arise relating to the boundaries and content of the invention.

26 As regards the principles concerning strike out applications, these are also well known and I hardly need linger on their detail. It is sufficient to refer to and adopt the observations of Kenny J in Polar Aviation Pty Ltd v Civil Aviation Safety Authority (No 4) (2011) 203 FCR 293 at [7] to [18], including to note the distinction between a strike out application and a summary dismissal application.

27 Let me then turn to the first ground of challenge.

Best method

28 Section 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) in the form applicable at the relevant time required that a complete specification describe “the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention”.

29 Of course, that requires an ascertainment of “the invention”.

30 Now it appears that the applicants’ case is based on a characterisation of the invention the subject of the 779 patent as non-polypeptide compounds that when administered decrease TNFα levels.

31 Accordingly, the applicants contend that the best method requirement can only be met by way of a disclosure of which of the compounds had been identified or was known to the respondent to “most effectively” decrease levels of TNFα.

32 But according to the respondent, and with which I agree, it is strongly arguable that the applicants’ case is based on a mischaracterisation of the invention so far as claims 1, 4 and 9 are concerned.

33 It is strongly arguable that the invention of the 779 patent is a newly discovered class of non-polypeptide compounds, one of which is lenalidomide. And if this be accepted, then as the respondent points out, it seems that the 779 patent discloses the best method of making lenalidomide.

34 Further, on the current state of the authorities, the specification need not expressly identify the best method as the best method. As the Full Court explained in Pfizer Overseas Pharmaceuticals v Eli Lilly and Company (2005) 225 ALR 416 at [374] per French and Lindgren JJ, the best method known to the patentee need not be identified as such in the specification. But I accept that this statement was obiter.

35 So, according to the respondent, the ground of best method as advanced by the applicants has no reasonable prospect of success and should be summarily dismissed. In the alternative, it is said that it should be struck out.

36 Now the applicants take issue with the respondent’s contentions.

37 First, they point out that the best method requirement forms part of the bargain between the patentee and the State. I agree. This was described by the Full Court in Firebelt Pty Ltd v Brambles Australia Ltd (2000) 51 IPR 531 as follows at [48] per Spender, Drummond and Mansfield JJ:

This requirement is to ensure good faith on the part of the patentee, and to protect the public against a patentee who deliberately keeps to himself something novel and not previously published which he knows of or has found out gives the best results, with a view to getting the benefit of monopoly without giving to the public the corresponding consideration of knowledge of the best method of performing the invention.

38 Second, they point out that the best method requirement applies to all patents, whether they contain product claims or method claims or both. I also agree. In Les Laboratoires Servier v Apotex Pty Ltd (2016) 247 FCR 61 at [108], Bennett, Besanko and Beach JJ said:

The nature and extent of the disclosure required to satisfy the best method requirement will depend on the nature of the invention itself. Accordingly, a distinction between products and processes that ignores the specific features of the invention claimed is unhelpful.

39 Third, the applicants say that the argument that they seek to advance at trial has a parallel with the lack of best method argument that was upheld in Servier. I disagree. But let me for the moment just set out how the applicants put their argument.

40 In that case, claim 1 was to the arginine salt of perindopril and its hydrates. The claim covered all crystalline forms of perindopril arginine, and the particular crystalline form that was made depended on variables in the steps of manufacture, including the solvent used and the temperature. So far, so good.

41 It was said that Servier had shown by the experiments in the specification that a particular crystalline form that it had made had useful storage properties. But it did not disclose which crystalline form it had made and tested out of the various crystalline forms falling within the scope of claim 1, which was unlimited as to crystalline form.

42 So, on the facts of that case, it was said that Servier was obliged to disclose the steps that it used to make the compound in order to disclose which member of the class of claimed products it had established had the desirable useful shelf-life properties.

43 Now the applicants’ analysis is in some respects superficial. But pressing on.

44 Fourth, the applicants say that in the present case, the respondent developed a broad class of compounds, defined by the Markush “Formula I” on page 6 of the specification and in claim 1, which I have reproduced earlier. That claim covers around 18,000 different compounds. On pages 6 (lines 2 to 3) and 7 (lines 8 to 9), the 779 patent discloses that compounds falling within Formula I decrease the levels of TNFα. Yet the applicants say that no testing or data is provided in the 779 patent as to the degree to which any of the thousands of compounds actually decreased levels of TNFα or which compound or compounds achieved the best results. I accept for present purposes that there is no such testing or data disclosed in the specification.

45 I should note for convenience at this point that if no testing was undertaken, then the applicants contend that the respondent made a misrepresentation to the Patent Office; hence their asserted third ground of invalidity which I will discuss later. Let me return to the applicants’ arguments concerning best method.

46 Fifth, the applicants say that disclosure of which compound the respondent knew had the best properties in reducing levels of TNFα of those that it had tested was necessary in order to satisfy the best method requirement.

47 The applicants referred to Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd v Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC (2016) 117 IPR 252 where Jagot J found that relevant claims were insufficient both because the compounds could not readily be made, and also because the person skilled in the art could not readily select which compounds, from the millions of compounds within the scope of those claims, would have the required anti-viral activity.

48 The applicants then sought to buff their argument by reference to Idenix Pharmaceuticals LLC v Gilead Sciences Pty Ltd (2017) 134 IPR 1 at [238] where Nicholas, Beach and Burley JJ approved of the reasoning of Jagot J at [620] to [625], and rejected the contention that those passages went solely to utility.

49 Sixth, it is said that to the extent that the respondent contends that lenalidomide was the best compound, the applicants say that a claim for lenalidomide specifically was added only by amendment after grant.

50 In my view, the applicants are in difficulty with this asserted ground of invalidity.

51 The nature of the disclosure required to satisfy the best method requirement will depend on the nature of the invention. But each of claims 1, 4 and 9, being the claims in suit, are to a compound simpliciter.

52 There are no integers of these claims which relate to the reduction of levels of TNFα. Accordingly, the applicants’ position is based on a problematic construction of the claims.

53 Indeed, arguably the applicants have strayed into issues regarding utility, although lack of utility is not pleaded. And of course the grounds of invalidity themselves are conceptually distinct.

54 Further, in my view, and as the respondent correctly pointed out, the present case is not analogous with Servier.

55 In Servier, the claim was to an arginine salt. But Servier did not disclose the best method of preparing the arginine salt.

56 In that case, the specification disclosed the “classical method of salification of organic chemistry”. But this was insufficiently specific although attractively expressed.

57 There were various ways of preparing the claimed salt and the form of the resulting substance may have varied as a result. It was for that reason that Servier was required to disclose the best method of making the arginine salt that it had used. Disclosure of the methods of synthesis actually employed by Servier would have avoided leaving the skilled addressee at risk of possible dead ends and false starts that may have resulted from the attempt to identify an appropriate classical salification method. Servier’s failure to disclose that method amounted to a failure to disclose the best method of performing the invention.

58 But in the matter before me, the respondent has a strong case for saying that the skilled addressee would be able to make lenalidomide or the other compounds claimed using standard techniques and methodologies.

59 Further, there does not appear to be any suggestion that there are different ways of making the various compounds claimed, including most relevantly, lenalidomide, that avoid any particular pitfalls or difficulties in the synthetic process.

60 Further, there also appears to be no suggestion that the respondent failed to disclose the best method of synthesis known to it at the relevant time.

61 Further, on the face of claims 1, 4 and 9, there is nothing to require the compound to have a particular level of activity against levels of TNFα as a feature of the invention; this may be contrasted with the form of claim 5.

62 And as the respondent points out, if it is correct on “the invention”, the best method requirement is met if the best method of making the claimed compound(s) is disclosed. In this respect, Servier says (at [103]):

It is necessary to understand the invention itself in order to appreciate what is required of an inventor by way of disclosure in the specification in order to secure a monopoly from the public. In some cases, the claim to a product will require no description of the method of obtaining it and it can be left to the skilled worker (as in AMP v Utilux). In other cases, the product claim, properly understood, will require sufficient directions in order to obtain the monopoly.

63 Further, I agree with the respondent that Gilead does not assist the applicants.

64 In that case, Jagot J accepted that the disclosure in relation to claims to compounds simpliciter was sufficient, even if the disclosure did not enable the skilled person to identify whether those compounds had the activity described in the patent. Contrastingly, it was only claims which incorporated an additional integer expressly directed to the biological activity of the claimed compounds (an integer which is absent in the present case) where a relevant lack of sufficiency was established by the absence of disclosure of biological data (see [620] to [625]).

65 Consistently with the way Jagot J approached the matter in Gilead, in an analogous exercise in Bluescope Steel Ltd v Dongkuk Steel Mill Co Ltd (No 2) (2019) 152 IPR 195 concerning claims dealing with coating thickness variations, I held there to be a failure to disclose the best method.

66 Let me deal with the other question.

67 I agree with the respondent that a patent does not need to identify the best method as being the best method. In Pfizer at [374], French and Lindgren JJ cited C Van Der Lely NV v Ruston’s Engineering Co Ltd [1993] RPC 45 at 56 for the proposition that the best method need not be identified as such in the specification. Now I accept that this was obiter. It was not in dispute in that case that the specification as amended disclosed the best method. What was disputed was whether the pre-amendment specification could be considered. But in my view it is obiter which I should apply at my level.

68 Further, in Servier the Full Court referred to the primary judge’s statement that the best method need not be identified as such, and then said (at [37]):

Depending on the invention, that requirement may be satisfied in different ways, such as a detailed description of a preferred embodiment, reference to drawings or structures, or specific process conditions or chemical formulations (Firebelt Pty Ltd v Brambles Australia Ltd (2000) 51 IPR 531 at [53]).

69 So, a patentee may in substance satisfy the best method requirement without expressly stating that a method is the best method.

70 Further, as the Full Court in Servier made clear at [103], the best method in respect of a product claim will usually be met by disclosing how to make the product. Further, there is no requirement to provide the biological or other data that the applicants’ case is premised on.

71 Now the applicants wish to contend at trial that:

(a) there must nevertheless be a fair disclosure of that method, for example by disclosure as a preferred embodiment;

(b) the disclosure must be sufficient to satisfy the patent applicant’s consideration for the grant of the monopoly, by putting the public in possession of the full benefit of the disclosed invention; and

(c) the particular requirements for disclosure of the best method will depend on the relevant patent.

72 I have no difficulty with such statements at the level of generality with which they have been expressed, but they do not negate the powerful points made in the respondent’s favour.

73 Further, the applicants submit that the best method requirement is to be assessed by reference to the form that the specification took at either the date of filing or the date of grant, and in that respect the decision in Pfizer that any subsequently amended form of the specification is relevant to consideration of the best method requirement was wrongly decided. Now they may submit this, but on this aspect Pfizer controls.

74 Further, the applicants say that for a patent that involves a claim to thousands of compounds, if the respondent had actually tested compounds and found them to reduce levels of TNFα then it should disclose which compound or compounds it found was most effective in doing so. That avoids the need for the public to itself conduct such testing, including potentially of a large number of compounds, in order to discern that which the respondent itself knew. That sounds all very sensible, but the precise legal requirement is another matter.

75 Further, the applicants say that the respondent provides no basis for its assertion that lenalidomide is the best compound. At this point let me say a little more about lenalidomide.

76 Lenalidomide is a drug for treating, in particular, multiple myeloma, as well as transfusion-dependent anaemia due to a certain myelodysplastic syndrome and mantle cell lymphoma. It has achieved Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) listing for the treatment of multiple myeloma and transfusion-dependent anaemia due to myelodysplastic syndrome. But the applicants say that none of those indications are mentioned in the 779 patent.

77 The applicants say that if lenalidomide was the best compound that the respondent tested for decreasing levels of TNFα, as distinct from treating multiple myeloma, it is said that no basis is established for that assumption and there is no disclosure within the specification to support it.

78 But in my view the respondent is not required to demonstrate that lenalidomide was in fact at some undefined time the best compound that it tested in decreasing levels of TNFα. And the fact is that this compound was disclosed. And as I have said, its method of synthesis is not what is in issue.

79 In my view the respondent is strong on the legal questions that I have discussed. But this is not definitive.

80 This ground depends on the boundaries and content of “the invention” and the construction of claims 1, 4 and 9. Clearly there is no express purpose or effect integer concerning the required biological activity. Nevertheless I cannot deny the possibility of something implicit, and notwithstanding that other claims make the point explicit (for example, claim 5) where it is intended.

81 In my view it is arguable that given the nature of the invention described in the 779 patent, the respondent did not satisfy its obligations in respect of the best method requirement and I cannot say that this ground has no reasonable prospect of success.

82 But even if there was a basis for otherwise finding, there are discretionary reasons that would justify me in not summarily dismissing or striking out the ground at this stage.

83 First, there needs to be a trial on the question of inventive step anyway which will involve substantial technical and expert evidence.

84 Second, if I take the best method point off the table now and consequently have no evidence led on the topic, and ultimately on appeal I turn out to be wrong after I had completed the trial on inventive step and other matters, there would have to be a new trial on the question with new evidence led. That would be an unsatisfactory outcome.

85 Third, I will need to consider the boundaries and content of “the invention” for the ground of lack of inventive step. It would be unsatisfactory to summarily dispose of such questions now and to possibly reach a different or modified view later in the context of the other ground(s).

86 Fourth, the relative additional time at trial in dealing with the best method point is not so great that it is worth procuring a saving by now getting rid of the point. But I should say that I may grant indemnity costs to the respondent if it ultimately wins on this point anyway.

87 For these reasons, I will not summarily dismiss or strike out this ground at this stage.

False suggestion

88 The respondent complains that in the amended particulars of invalidity the pleading of the case on false suggestion is deficient.

89 It is said that the pleading does not identify any suggestion which was false and which was relevant to the grant of the 779 patent.

90 Further, the allegation depends on speculation that the patentee may not have tested the relevant compounds. But no material to support that speculation is identified.

91 It is said that the allegation of false suggestion should be summarily dismissed. In the alternative, that it should be struck out.

92 These submissions also have some force although the relevant “suggestion” has been identified (see p 6 lines 1 and 2 of the specification). But as an exercise of discretion I will not strike this ground out or summarily dismiss it.

93 I am leaving the best method ground in. Further, there will be limited discovery on that question. That being so, I would expect that the applicants should then be able to give further particulars of the false suggestion ground, although I should say for completeness that the applicants are entitled to plead in the alternative.

Expedition and the cross-claim – some further background

94 It is now necessary to deal with the question of the applicants’ application for expedition concerning a trial of all issues on invalidity and infringement concerning the 779 patent and their strike out application concerning the cross-claim.

95 But before dealing with these questions head on, I need to set out some further background.

Future supply by the applicants and the limited revocation case

96 Each of the applicants is involved in the supply of pharmaceutical products. Each presently has an intention to supply a product covered by the 779 patent to the Australian market and therefore seeks a timely ruling from me regarding the validity of claims 1, 4 and 9 of the 779 patent. The first and second applicants entered into an agreement with effect from 8 May 2020 regarding the prospective supply of lenalidomide in Australia.

97 Now it is not commercially viable to supply a pharmaceutical product in Australia unless that product is listed on the PBS. But the process of obtaining listing on the PBS usually takes about two to three months.

98 Unless the applicants are able to obtain a first instance decision as to the validity of claims 1, 4 and 9 of the 779 patent by the end of the third quarter of this year, the applicants say that they would be deprived of the practical benefit of establishing that those claims are invalid.

99 Let me say something more about the applicants’ case.

100 The complete specification for the 779 patent was filed on 24 July 1997, and its 20-year term would therefore have ordinarily expired on 24 July 2017.

101 But a five-year extension of term was granted on 12 September 2008, and so the term will expire on 24 July 2022. The extension of term was based on a regulatory approval date of 20 December 2007, which was for lenalidomide.

102 Because of the operation of s 78 of the Patents Act, the exclusive rights of the respondent during the extended term of the 779 patent are confined. Accordingly, the applicants’ revocation case has been confined to challenging the validity of the product claims 1, 4 and 9 only. Moreover, the invalidity issues are identical for each of those three claims given that the applicants only seek to establish that the claims are invalid insofar as they encompass the specific compound included in claim 9, which is lenalidomide.

103 Let me say something more about the three grounds of alleged invalidity.

104 The lack of inventive step case is based on thalidomide having well-known pharmacological properties, with the development of analogues being well-known, and with specific analogues of thalidomide including EM-12 and pomalidomide being disclosed as being useful in the prior art. Lenalidomide is structurally related to thalidomide.

105 Now the applicants rely on four separate pieces of prior art, which in essence deal with analogues of thalidomide: Robert J D’Amato et al, Thalidomide is an inhibitor of angiogenesis, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci, Vol 91, pp 4082 – 4085, April 1994 published on 26 April 1994 (the D’Amato article), WO1994020085, filed on 24 February 1994, published on 15 September 1994 (the D’Amato patent), He W et al., ‘Synthesis of thalidomide and analogues and their biological potential for treatment of graft versus host disease’ poster presentation from the 206th American Chemical Society National Meeting, 1993 published on or before 22 August 1993 (the He poster) and WO1992/014455, filed on 14 February 1992, published on 3 September 1992 (the Kaplan patent). They also rely on the combination of the D’Amato patent and the Kaplan patent.

106 The other two grounds, which I have addressed earlier being lack of best method and false suggestion, are raised in the alternative and are confined in scope. They principally turn on the factual question of whether the respondent tested any of the compounds that it claimed and, if it did, the results of such testing.

107 Let me now say something about the respondent’s product(s).

Revlimid

108 The respondent has registered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) a number of products containing lenalidomide known as “Revlimid”. The Revlimid products are also listed on the PBS for certain indications.

109 The approved indications for Revlimid (see the Revlimid product information sheet) are:

(a) “Multiple myeloma” (the MM indication) where it is used for:

(i) newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: in combination with other medicines (bortezomib and/or dexamethasone) or as a monotherapy depending on patient condition, and disease state and progression;

(ii) previously treated multiple myeloma: in combination with dexamethasone in certain circumstances;

(b) “Myelodysplastic syndromes” (the MDS indication) where it is used for “transfusion-dependent anaemia due to low- or intermediate-1 risk myelodysplastic syndromes associated with a deletion 5q cytogenetic abnormality with our without additional cytogenetic abnormalities”; and

(c) “the treatment of patients with relapsed and/or refractory mantle cell lymphoma” (the MCL indication).

110 Multiple myeloma is a cancer that forms in certain white blood cells known as plasma cells. The cancerous plasma cells multiply and collect as tumors in various parts of the body including in the bone marrow and on the bone surface.

111 Transfusion-dependent anaemia is a blood condition caused by various diseases, here the transfusion-dependent anaemia is associated with certain myelodysplastic syndromes. The condition results in the patient’s dependence on regular blood transfusions.

112 Mantle cell lymphoma is a rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which affects the “mantle zone” of B-cells causing them to mutate and build up in the lymphatic system.

113 Patients being treated for each of the MM indication, the MDS indication, and the MCL indication will all generally be treated by a haematologist.

114 According to the Revlimid product information sheet, the dosage regime for Revlimid varies from patient to patient, depending on the indication being treated and other factors including whether or not the patient is experiencing renal impairment.

115 Let me now say something about the respondent’s other patents that are the subject of its cross-claim for infringement against the applicants.

The method of treatment patents and the MCL patent

116 The respondent has raised six method of treatment patents as being potentially infringed by any future supply by the applicants of lenalidomide in Australia.

117 There is also a seventh patent that I will describe as the MCL patent.

118 The priority date for the method of treatment patents is six years after that for the 779 patent, and the field of expertise is different. The alleged invention in those six patents relates to methods of administering a known drug, lenalidomide, to treat blood cancers and so the issues will draw upon the skills of a haematologist or related medical practitioner.

119 Those six patents relate to methods of treating particular conditions (myelodysplastic syndrome, multiple myeloma, mantle cell lymphoma) by administering lenalidomide in particular dosage amounts, administering in a cyclical manner, and administering together with other active ingredients.

120 Before I proceed further, it is useful to set out details of the method of treatment patents and the MCL patent as follows:

Australian patent number | Title of patents | Priority date | Expiry date |

2003228508 MoT (508) | Methods of using and compositions comprising immunomodulatory compounds for the treatment and management of myelodysplastic syndromes | 15 October 2002 | 13 April 2023 |

2012201727 MoT (727) | Methods of using and compositions comprising immunomodulatory compounds for the treatment and management of myelodysplastic syndromes | 15 October 2002 | 13 April 2023 |

2003234626 MoT (626) | Methods and compositions using immunomodulatory compounds for treatment and management of cancers and other diseases | 17 May 2002 | 16 May 2023 |

2006202316 MoT (316) | Methods and compositions using immunomodulatory compounds for treatment and management of cancers and other diseases | 17 May 2002 | 16 May 2023 |

2012254881 MoT (881) | Methods and compositions using immunomodulatory compounds for treatment and management of cancers and other diseases | 17 May 2002 | 16 May 2023 |

2013263799 MoT (799) | Methods and compositions using immunomodulatory compounds for treatment and management of cancers and other diseases | 17 May 2002 | 16 May 2023 |

2007282027 MCL (027) | Use of 3- (4-amino-1-oxo-1,3-dihydro-isoindol-2-yl)-piperidine-2,6-dione for the treatment of mantle cell lymphomas | 3 August 2006 | 2 August 2027 |

121 For the most part I can put the MCL patent to one side and just address the six method of treatment patents.

122 In relation to the expiry dates of the method of treatment patents, the method of treatment patents can be divided into two patent families expiring one month apart from each other.

123 There are patents expiring on 13 April 2023 being the first family of patents with the earliest priority date of 15 October 2002, relating to a method of treating myelodysplastic syndromes, namely, the 508 patent and the 727 patent.

124 There are patents expiring on 16 May 2023 being the second family of patents with an earliest priority date of 17 May 2002, relating to a method of treating:

(a) multiple myeloma, metastatic melanoma, and prostate cancer (the 626 patent);

(b) “a cancer” being lung cancer, cancer of the blood, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, renal cancer, amyloidosis, and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (the 316 patent); and

(c) newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (the 881 patent and the 799 patent).

125 In relation to the Revlimid product information sheet, the method of treatment patents can be broken into four sub-groups.

126 There is one patent which appears not to read onto any approved indication on the Revlimid product information sheet, and which the applicants say therefore will not be infringed by the sale of a generic lenalidomide product, being the 508 patent. The applicants say that all claims of the 508 patent relate to “a method of treating myelodysplastic syndrome” whereas the Revlimid product information sheet includes the MDS indication. There appears to be a difference between treating the root disease (myelodysplastic syndrome) and treating another disease (anaemia) associated with a certain type of the root disease (myelodysplastic syndromes associated with a deletion 5q (q31 to 33) cytogenetic abnormality). The 508 patent does not appear to be relevant to approved indications on the Revlimid product information sheet, or the supply of a generic lenalidomide product.

127 There is one patent which arguably reads onto the MDS indication, but which can be avoided by a carve out of the MDS indication, leaving the MM indication and the MCL indication “on-label”. This applies to the 727 patent.

128 There are three patents which arguably read onto the MM indication, but which can be avoided by a carve out of the MM indication, leaving the MCL indication and the MDS indication “on-label”. This applies to the 626 patent, the 881 patent, and the 799 patent.

129 There is one patent which arguably reads onto the MCL indication and the MM indication (the 316 patent) but which can be avoided by a carve out of the MCL indication and the MM indication leaving the MDS indication “on-label”.

130 The subsets of the method of treatment patents that will be relevant to the supply of any lenalidomide product in Australia will depend on the product label, and the PBS reimbursement profile secured.

131 Now the 779 patent covers a different alleged invention to the method of treatment patents. The 779 patent relates to an invention which is said to arise from the discovery of new compounds and their properties, and the relevant expert is therefore likely to involve a medicinal chemist, whether working alone or as part of a team. The 779 patent does not disclose or relate to methods of treating patients.

132 The 779 patent states that the patentee has discovered a new group of chemical compounds that reduces levels of TNFα. The applicants’ lack of inventive step case asserts that it was obvious to develop analogues of thalidomide that would share its known pharmacological properties, including the reduction of TNFα levels. That case will focus on expert evidence from, inter-alia, a medicinal chemist as to the development of analogues of a known drug.

133 The earliest priority date of the 779 patent is 24 June 1996. After this date, there is a gap of:

(a) just under six years to the earliest priority date of the second family of the method of treatment patents (the 626 patent, the 316 patent, the 881 patent, and the 799 patent) in May 2002; and

(b) more than six years to the earliest priority date of the first family of the method of treatment patents (the 508 patent and the 727 patent) in October 2002.

134 Further, it was accepted by the parties before me that the prior art that was cited in the international search reports (ISR) and by the Australian examiners for the six method of treatment patents does not overlap with the prior art cited in this proceeding.

135 Accordingly, there is no substantive prospect for overlap in the lack of inventive step issues that would be considered in this proceeding, and in a proceeding addressing any of the method of treatment patents.

136 Ms Naomi Pearce, the solicitor and patent attorney for the applicants, gave evidence as to the prior art included in the World Intellectual Property Organization ISR for each application and the prior art referenced by the Australian examiner in the course of examining the patent. An ISR is the results of the search conducted by the International Searching Authority as part of the process for examination of a patent application filed under the Patent Cooperation Treaty. Typically, prior art referenced in the ISR will be the start point for examiners when the patent application enters national phase, and the examiners will carry out their own searches and supplement the ISR with additional art.

137 No family member of the 779 patent was listed in the ISRs or raised by the IP Australia examiner as prior art to any of the method of treatment patents.

138 None of the inventive step art pleaded in relation to the 779 patent was raised in any ISR or by the Australian examiner as relevant to the examination of any of the method of treatment patents.

139 Let me return now to discussing in more detail the question of the products the applicants intend to supply and the question of the potential infringement of the method of treatment patents.

140 But before doing so, I should note that counsel for the respondent sought leave to cross-examine Ms Pearce on her instructions. But this was not justified in context and risked trespassing into privilege territory beyond the boundaries of any waiver that might already have occurred. Further, any answers would not likely have sufficiently assisted me concerning the strike out of the cross-claim or the justification for expedition sought by the applicants such as to warrant leave.

The applicants’ products will be generic products

141 The applicants’ lenalidomide products will be generic products.

142 Sponsors of generic products apply for registration on the ARTG on the basis of bioequivalence to a reference innovator product, in this case the Revlimid products.

143 Once bioequivalence is established, sponsors of generic drugs are able to rely upon the safety and efficacy data including clinical trial data submitted by the sponsor of the innovator product to support the indications for which listing is sought.

144 For this reason, sponsors of generic drugs do not typically seek to conduct any additional clinical trials, but instead rely on the clinical data of the sponsor.

145 Given the reliance on the innovator data including clinical trial data, the generic product can only be registered for the same indications and dosing regimen for which the innovator product is listed on the ARTG, as set out in the product information sheet for the innovator product, or a sub-set thereof; for instance a generic might have a more limited range of doses compared to the innovator product, which may mean that certain dosing regimens cannot be approved.

146 In this regard, the applicants’ products are generic products which will be registered by reference to the respondent’s Revlimid products.

147 Given this, according to the view expressed by Ms Lisa Taliadoros, the solicitor for the respondent, the applicants’ products can only be for the Revlimid indications as set out in the Revlimid product information sheet for the Revlimid products or a sub-set thereof.

148 Furthermore, as the PBS listing of a product is referable to its ARTG listing and product information sheet, and therefore the PBS listing of a generic product will closely reflect that of the innovator product. This includes any restrictions relating to the indications and clinical criteria for which a PBS listed product can be prescribed, such as those which apply to a product that is listed under the “authority script” regime.

149 Based on the above matters, in Ms Taliadoros’ view the applicants can only achieve PBS listing of their products for the same indications, dosage regimen and clinical criteria which apply to the Revlimid products or a sub-set thereof. And in her view, the supply of lenalidomide for each of the Revlimid indications would fall within the scope of at least one of the method of treatment patents, namely, the 316, 626, 727, 799 and 881 patents.

150 Accordingly, she expressed the view that the sale and supply of the applicants’ products for the Revlimid indications would infringe at least one claim of each of the 316, 626, 727, 799 and 881 patents.

151 Now it would seem that the applicants may launch their generic lenalidomide products in late 2021. But there is no evidence as to whether the applicants have made an application for registration on the ARTG of any such products.

152 According to Ms Taliadoros’ evidence, the period between application and Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) approval may be in the order of ten to twelve months. So, she inferred that the applicants had already lodged an application with the TGA for regulatory approval of their generic lenalidomide products. And she expressed the view that this application would likely include information concerning the indications, dosage form, dosage, treatment regimen, and concomitant therapy in respect of the products.

153 She also inferred that the applicants had applied for registration of products for each of the Revlimid indications and corresponding dose forms for which the Revlimid products were listed on the ARTG.

154 On this basis, she asserted that there existed a threat to infringe at least one claim of the 316, 626, 727, 799 and 881 patents.

155 Let me turn to the question of indication carve outs.

156 When an application for approval of a generic product is filed with the TGA, it is not clear which indications (or sets of indications) will be approved by the TGA. The indications to be included in the final product information sheet is not something which a generic applicant needs to resolve or finally determine by the time that they file their application for TGA approval, and this may not be resolved until one of the final steps in the regulatory review process.

157 Indication “carve outs” is a routine approach taken by generics companies in Australia for many reasons, including commercial reasons and patent reasons. Carving out an indication (or multiple indications) is a step that can be done at any stage in the regulatory review process in Australia. It is not uncommon for generic applicants to seek to amend the designated indications at various stages of the regulatory review process, typically as one of the final steps prior to approval of the generic medicine.

158 It is also not uncommon for generic applicants to seek approval of multiple parallel applications with the TGA at the same time, which are otherwise identical save for the different indication combinations being sought, so that there are no delays to approval associated with any “last minute” indication amendments.

159 Prior to TGA approval, it is uncertain which indications the TGA will approve for the applicants’ proposed lenalidomide product.

160 The evidence before me indicates that there has been no decision made regarding the launch indications for the applicants’ proposed Australian lenalidomide product.

161 I also accept that the applicants will not make a decision regarding the launch indications for the proposed generic product until just prior to TGA approval, factoring in any feedback received from the TGA, together with other considerations including avoiding potential patent infringement proceedings.

162 Ms Taliadoros also dealt with the question of carve outs that she understood the applicants were raising as a means of avoiding infringement of one or more of the respondent’s patents. In her view, by the carve outs suggested in the applicants’ evidence, the applicants could not avoid infringing all of the method of treatment patents. She expressed the following views.

163 First, there are patents that “read on” to each of the Revlimid indications in the sense that:

(a) the MM indication reads onto the 626 patent, 881 patent, 799 patent and 316 patent;

(b) the MCL indication reads onto the 316 patent; and

(c) the MDS indication reads onto the 727 patent.

164 Second, even if the applicants were to seek to carve out only one of the three indications, the remaining two indications would be captured by at least one or more of the respondent’s method of treatment patents. So:

(a) carving out the MDS indication to avoid the claims of the 727 patent would still leave the MM and MCL indications (that is, the 626 patent, 881 patent, 799 patent and 316 patent);

(b) carving out the MM indication to avoid the claims of the 626 patent, 881 patent, and the 799 patent would still leave the MCL and MDS indications (that is, the 316 patent, and 727 patent); and

(c) carving out the MCL indication and the MM indication to avoid the claims of the 316 patent would still leave the MDS indication (that is, the 727 patent).

165 Third, if the applicants were to seek to carve out any two of the three indications, one or more of the method of treatment patents would still be infringed. So:

(a) if the applicants were to carve out the MCL indication and the MM indication, the product would still be listed on the ARTG and PBS for the MDS indication, and at least the 727 patent would be infringed;

(b) if the applicants were to carve out the MCL indication and the MDS indication, the applicants’ product would still be listed on the ARTG and PBS for the MM indication, and hence at least the 626 patent, 881 patent, 799 patent and 316 patent would be infringed; and

(c) if the applicants were to carve out the MM indication and MDS indication, the product would still be listed on the ARTG for the MCL indication, and hence at least the 316 patent would be infringed.

166 Therefore, in her opinion, the only way for the applicants to avoid infringement altogether would be to carve out each of the Revlimid indications. But this would not leave any of the indications for which the Revlimid product is listed on the ARTG. That is, there would be no scope for a generic product based on the Revlimid product as the innovator product.

167 I do not need to rule on these views whether definitively or as a matter of likelihood at this stage. These issues at present are hypothetical. Moreover, the respondent will be protected by the undertaking that the applicants propose to give.

168 Having set all this out, I can now turn to the applicants’ strike out application concerning the cross-claim.

The cross-claim

169 The respondent by its cross-claim seeks a declaration that the applicants have threatened to infringe the 779 patent, the method of treatment patents and the MCL patent, an injunction restraining the applicants from infringing, damages or an account of profits, additional damages, a declaration that the applicants have threatened to contravene s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, an injunction restraining the applicants from breaching the Australian Consumer Law, damages, costs and interest.

170 On 11 February 2021 the applicants filed an interlocutory application seeking that identified parts of certain paragraphs of the respondent’s statement of cross-claim be struck out. Those paragraphs set out the allegations that the respondent makes by reference to the six method of treatment patents and the MCL patent, being a patent registered by the respondent relating to the use of lenalidomide to treat mantle cell lymphoma. For the purposes of the discussion that follows I will refer to the method of treatment patents and the MCL patent together as the seven patents.

171 The applicants submit that the respondent’s allegations of infringement of each of the seven patents is premature and brought in circumstances where there is no justiciable dispute in existence.

172 The applicants say that they are not offering and cannot offer any lenalidomide products for sale in Australia, and the respondent is unable to particularise any facts establishing any clear and immediate intention to do so.

173 They say that the respondent is seeking to have me adjudicate, and requiring the applicants to defend, full infringement proceedings on not only the 779 patent but on the other seven patents, including on every claim contained in each of the seven patents. They say that the seven patent claims assert a monopoly over several different methods of treatment, when there is no basis for contending, in relation to any claim of any of the seven patents, that the applicants will seek registration from the TGA to sell any product for a method of treatment coming within the scope of any such valid claim.

174 It is said that the hypothetical character of the cross-claim is exemplified by the scope of many of the claims of the seven patents. Many of the claims of those patents do not encompass the “on-label” indications. And the applicants cannot seek registration from the TGA to sell any product for a method of treatment coming within the scope of any claim that does not encompass an “on-label” indication. Accordingly, it is said that there is no risk of the applicants infringing such claims, even with a full label, and so there is no justiciable issue arising in relation to them.

175 Further, the applicants say that such proceedings must also, of necessity, require the applicants to litigate the validity of every claim on the basis of no more than mere speculation that the applicants might seek to obtain authorisation from the TGA for selling in Australia lenalidomide for any such methods of treatment.

176 Further, the applicants point out that by operation of s 119A of the Patents Act, steps taken to seek inclusion of the relevant products on the ARTG cannot amount to infringement.

177 Accordingly, it is said that the basis of each of the paragraphs of the cross-claim which the applicants seek to strike out is hypothetical.

178 Further, it is said that such a hypothetical claim cannot be justified on the basis that there may come a time when the respondent would suffer irreparable harm if the matters are not determined early, should there come a time when the applicants do decide to obtain TGA approval to supply lenalidomide for a method of treatment coming within the scope of any claims of any of the seven patents.

179 First, it is pointed out that the applicants have proffered an undertaking to enable the respondent to institute infringement proceedings on any or all of the seven patents, should the applicants ever seek to sell lenalidomide in Australia prior to patent expiry, an undertaking which includes selling lenalidomide for use in any claimed method.

180 Second, it is said that because lenalidomide is listed as a “complex authority required drug” and is designated as “authority required”, a lenalidomide product can only be supplied under an authority script under which authority is granted to a named patient for a specified indication if PBS reimbursement is to be obtained. Accordingly, the drug cannot be sold in circumstances which do not exactly match the narrow PBS authority script conditions. And in this context, to obtain PBS reimbursement, each named patient and known condition must be identified, registered and tracked through the authority script regime and a patient risk management program. Accordingly, the scope and extent of sales is recorded and capable of being compensated for by monetary damages.

181 Further, it is said that the respondent’s pleading of the cross-claim in respect of the seven patents also prevents any of the current re-examination requests from proceeding before the Patent Office by reason of s 97(4) of the Patents Act. That prevents the low-cost procedure provided for by Ch 9 of the Patents Act from proceeding at a time when there is no threat of infringement giving rise to a basis for enforcement of those patents to be undertaken.

182 Accordingly, it is said that I should strike out the relevant paragraphs of the cross-claim relating to the seven patents.

183 I would reject the strike out application concerning the seven patents.

184 The respondent’s cross-claim is in some respects hypothetical but not sufficiently hypothetical to warrant summary disposition.

185 Now although the cross-claim concerns conduct that has not yet taken place, it is based on conduct that the applicants intend to undertake during the term of the seven patents.

186 The fact that the applicants have not yet marketed their lenalidomide products does not render the cross-claim egregiously hypothetical concerning the seven patents.

187 Now there is no doubt that the applicants are not currently offering lenalidomide products and cannot do so until they obtain regulatory approval. But that does not mean that they have no intention to offer those products for sale after such approval is obtained, and prior to the expiry of the seven patents. Indeed, it is clear that they do have such an intention.

188 Further, the applicants do not say that there is no intention to offer lenalidomide products during the term of the seven patents (the last of which expires in 2027), only that there is no intention to offer those products before the issue of the validity of the 779 patent is determined.

189 Further, I should also say that I agree with counsel for the respondent that the reliance by the applicants on s 119A provides no answer to the point that steps taken by the applicants concerning inclusion on the ARTG are potentially relevant to the question of the applicants’ intention as to steps beyond that point that could potentially amount to infringement.

190 But let me return to what I have before me, which is a strike out application rather than a summary dismissal application. I make that point because whether issues are hypothetical or too hypothetical is not something that I necessarily need to deal with at this stage. All that I need to consider is whether the relevant paragraphs of the cross-claim on their face give rise to a reasonable arguable cause of action justifying the relief sought.

191 On that question, the central paragraphs of the cross-claim are the following which provide:

9 The Cross-Respondents intend to, inter alia, import, offer to supply, supply and sell a generic version of each of the REVLIMID products in Australia prior to the expiry of the [779 patent] (Natco/Juno Products). In order to engage in such activities, the Cross-Respondents require the Natco/Juno products to be registered on the ARTG. The Cross-Respondents will also seek PBS listing for the products.

10 The Natco/Juno Products will contain lenalidomide as the active ingredient.

11 The Cross-Respondents intend that the Natco/Juno Products will be registered on the ARTG for the treatment of MM, MDS and MCL and be PBS listed for the treatment of MM and MDS.

Particulars

(a) Pearce IP’s letter to the Registrar dated 9 November 2020.

(b) The affidavit of Naomi Kate Pearce affirmed 9 November 2020 at [20], [21], and [22].

(c) The affidavit of Naomi Kate Pearce affirmed 9 December 2020 at [15], [16], and [20].

(d) Transcript of Case Management Conference on 24 November 2020 at T23.1-4.

(e) Transcript of Case Management Conference on 23 December 2020 at T5.12-24; T7.36-41; and T8.42-43.

12 It is not possible for the Cross-Respondents to supply a product as described in paragraphs 9 to 11 for the treatments referred to in paragraph 11 without infringing the [779 patent] and each of the method of treatment patents, namely the 508 Patent, 727 Patent, 626 Patent, 316 Patent, 881 Patent, 799 Patent and 027 Patent (as defined below).

13 The Natco/Juno Products will be supplied with product information that reflects the treatment regimens set out in the REVLIMID Product Information, and the PBS Listing (for the MM and MDS REVLIMID Indications).

Particulars

The Particulars to paragraphs 9 to 11 above are hereby repeated.

14 The Cross-Respondents have not proffered an undertaking that they will not infringe the [779 patent] and the method of treatment patents, namely the 508 Patent, 727 Patent, 626 Patent, 316 Patent, 881 Patent, 799 Patent and 027 Patent (as defined below) during their term.

Particulars

(a) Letter from Pearce IP to Jones Day dated 8 December 2020.

(b) Transcript of Case Management Conference on 24 November 2020 T23.1-4.

(c) Transcript of Case Management Conference on 23 December 2020 T5.12-24.

15 The Cross-Respondents have not proffered an undertaking not to make an application to revoke the 508 Patent, 727 Patent, 626 Patent, 316 Patent, 881 Patent, 799 Patent and 027 Patent (as defined below).

Particulars

The Particulars to paragraph 14 above are hereby repeated.

192 There is no basis for striking out these paragraphs, particularly [11] and [13], or other paragraphs which depend upon them. The relevant factual questions on their face are clear and supported by the particulars. As I say, I am not dealing with a summary dismissal application.

193 Accordingly, I will not strike out any part of the cross-claim, nor at this stage order any temporary stay of the non-779 patent questions. I should also say that I am not troubled by the applicants’ s 97(4) point. If that is the consequence, so be it.

194 The real question concerns which parts of the cross-claim should be dealt with at trial at this stage, a matter that I will address in a moment when discussing the question of expedition.

195 Let me make one final point on the form of the cross-claim. The respondent also seeks leave to amend its notice of cross-claim to seek the following relief:

A declaration that it is not possible for the Cross-Respondents to offer to supply, supply or sell a generic version of any of the Second Cross-Claimant’s ‘REVLIMID’® products in Australia for the treatment of MM, MDS and MCL (as defined in the accompanying Statement of Claim dated 29 January 2021) and be listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme for the treatment of MM and MDS, without infringing Australian Patent Nos. 2003228508, 2012201727, 2003234626, 2006202316, 2012254881, 2013263799, and 2007282027, during their term.

196 I will not grant leave to amend. Such a proposed declaration is contrived in its manifest strategic objective and it is also bad in form. It is also unnecessary as the current declarations and other relief sought in the cross-claim should be sufficient.

Expedition

197 The applicants have filed their evidence in chief on invalidity on 29 January 2021. This comprised affidavits from two expert witnesses and an affidavit from a “searcher” witness.

198 They seek expedition concerning a trial on all issues concerning the 779 patent. I agree that this is justified.

199 The validity of the 779 patent should be determined first. Any issues in relation to the method of treatment patents and the MCL patent should be determined later. Those later-filed patents raise distinct and separate issues as I have already endeavoured to explain in some detail.