Federal Court of Australia

State Street Global Advisors Trust Company v Maurice Blackburn Pty Ltd (No 2) [2021] FCA 137

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days of these orders, the applicants file and serve short submissions (limited to 5 pages) and minutes of proposed orders to give effect to these reasons concerning:

(a) the future display in Melbourne of the replica of the Fearless Girl statue owned by the first respondent with or without a disclaimer;

(b) other final orders; and

(c) costs.

2. Within 14 days of the receipt of such submissions and minutes, the first respondent file and serve responding submissions (limited to 5 pages) and minutes of proposed orders on such topics.

3. To the extent necessary, any orders previously made under s 37AI of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) shall be varied so as to exclude any clauses of the master agreement or its annexures reproduced in these reasons.

4. Liberty to apply.

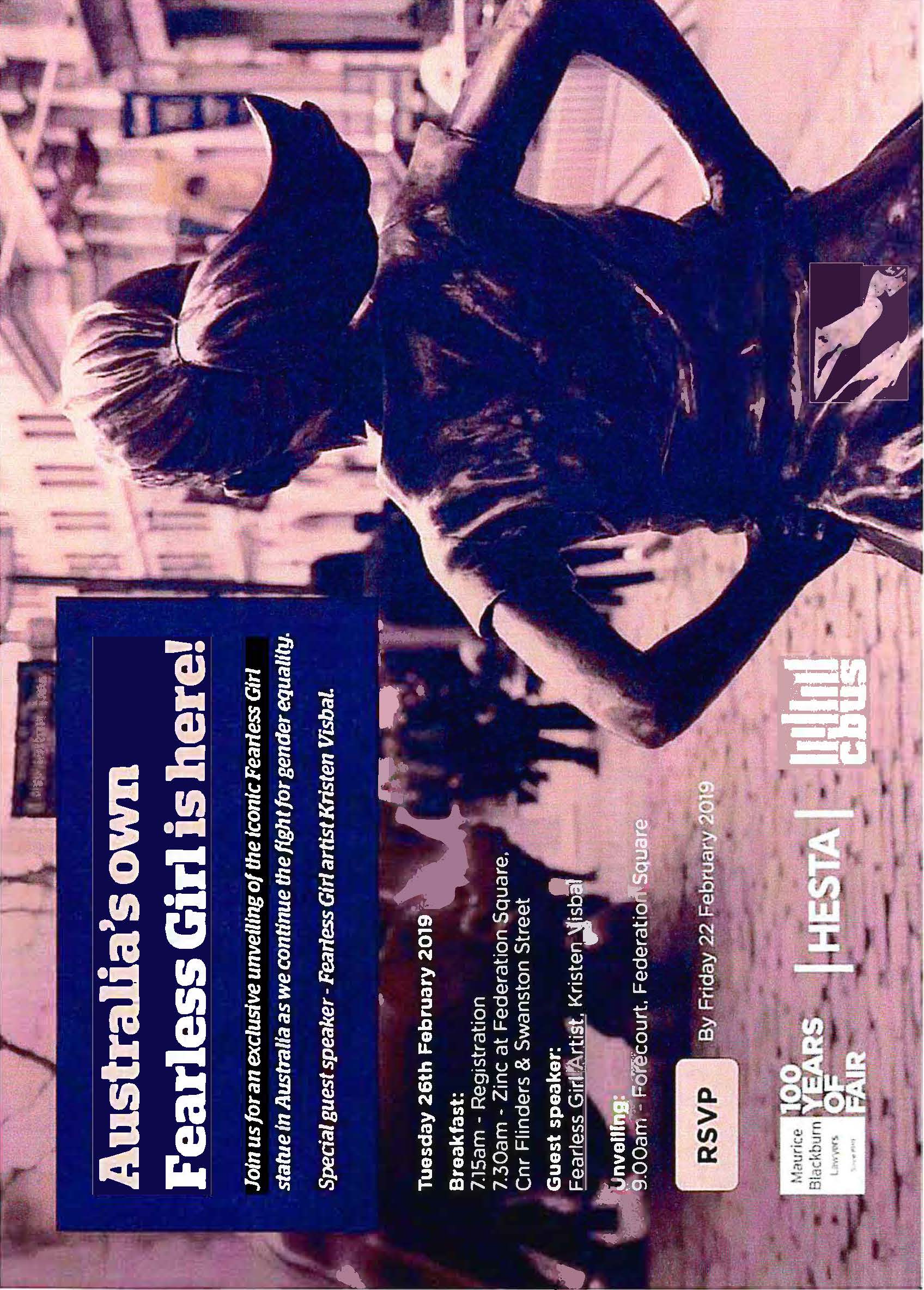

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BEACH J:

1 The applicants, State Street Global Advisors Trust Company and its subsidiary, State Street Global Advisors Australia Ltd, claim that Maurice Blackburn lawyers (MBL) has infringed their rights concerning the display and use of the life-size bronze statue known as “Fearless Girl”. I will refer to the applicants as SSGA collectively and as State Street (US) and State Street (Australia) for the holding company and subsidiary respectively.

2 SSGA has also sued United Super Pty Ltd (Cbus) and H.E.S.T. Australia Ltd (HESTA), but the claims against them have now been settled.

3 The background to SSGA’s claims can be shortly stated.

4 On 6 February 2019, MBL entered into an agreement with Ms Kristen Visbal (the artist), to purchase and use a limited-edition reproduction of Fearless Girl for an Australian campaign concerning workplace gender equality including equal pay for women (the art agreement). The original statue had been commissioned from the artist by State Street (US) and is currently located in front of the New York Stock Exchange (the New York statue).

5 The art agreement had been negotiated by MBL’s then National Brand and Social Media Manager, Ms Rebecca Hanlan and MBL’s external solicitor, Mr Ian McDonald of Simpsons solicitors on the one hand, and the artist and her New York lawyer, Ms Nancy Wolff on the other hand.

6 In late 2017, Ms Hanlan proposed that MBL establish a campaign to promote workplace gender equality issues. Apparently, gender equality had long been a key value of MBL. It had previously advocated on behalf of clients and independently on issues of workplace sexual harassment, gender discrimination in hiring, and the gender pay gap. Ms Hanlan’s proposal for the campaign involved promoting workplace wage equality to address the gender pay gap (the MBL campaign). And she was concerned to make the MBL campaign of interest to the media so that the campaign would get attention and generate more discussion on such issues.

7 In April 2018, a member of Ms Hanlan’s team, Ms Pia Chaudhuri, an external consultant and former employee of One Green Bean, a “creative” agency engaged by MBL, formulated a proposal setting out a vision for the campaign. Ms Chaudhuri’s proposal suggested an event on Equal Pay Day in September 2018. The idea was that MBL would collaborate with an Australian sculptor and create a statue to unveil on Equal Pay Day in order to launch the campaign. The intention was that the statue would embody the concept of a life-size woman standing next to a stack of bank notes representing the amount that women were paid less than men that year. Further, the desire was to place the statue somewhere in the Melbourne CBD with high foot traffic and as would befit the status of such a symbol. Further, the intention was to have unions and other organisations approached to get behind the campaign.

8 In late May 2018, another member of Ms Hanlan’s team, Mr Neil Pharaoh, a former lawyer who was working as a consultant at the time, drafted an overview document for the purpose of asking the Victorian Parliament to approve placement of the proposed statue on Parliament grounds.

9 In early June 2018, Ms Hanlan contacted various sculptors about creating the statue. But it became apparent to her that the design and creation of an original artwork would not be possible within the timeframe anticipated. Accordingly, she then had the idea of approaching the artist who had created the New York statue in order to buy a replica of the New York statue for the campaign.

10 Ms Hanlan contacted the artist about the possibility of buying a replica of the New York statue for the MBL campaign (the replica), and communications then took place between Ms Hanlan, Mr McDonald, the artist and Ms Wolff.

11 After reaching an understanding with the artist to acquire the replica, albeit that the art agreement was not signed until 6 February 2019, MBL looked for sponsors to join the MBL campaign. MBL contacted companies in a wide range of industry sectors. Ultimately, only two superannuation funds, HESTA and Cbus, joined with MBL.

12 MBL proposed to hold an event to launch the public unveiling of the replica at ZINC, an events venue at Federation Square in Melbourne’s CBD, on 26 February 2019. That date was close to International Women’s Day on 8 March 2019.

13 On 12 February 2019, MBL sent out formal invitations to the launch event to approximately 1,870 people. The invitation list for the launch event was largely compiled from MBL’s existing contact lists, together with groups of invitees proposed by HESTA and Cbus. The list included clients and those who referred work to MBL, union representatives, members of the media, and representatives from women’s advocacy and other associated interest groups.

14 On 14 February 2019, MBL sent additional invitations to a further group of invitees.

15 On the same day, SSGA commenced the present proceeding and obtained from another judge interim injunctions preventing MBL from publicly installing, showing or displaying the replica in Australia and requiring MBL to cease all marketing and promotion of the replica.

16 On 21 February 2019, I heard SSGA’s application for interlocutory injunctions seeking relief in similar terms to extend the interim injunctions. I discharged the interim injunctions and refused to grant the interlocutory relief sought by SSGA.

17 On 25 February 2019, MBL sent additional invitations to a further group of invitees.

18 On 26 February 2019, MBL hosted the launch event at ZINC in Federation Square. There were around 200 attendees including school children that had also been invited. At the event there were electronic billboards and signs of various sizes containing images of a Fearless Girl statue and the name “Fearless Girl” in connection with MBL, HESTA and Cbus. The artist made two speeches at the event. Further, there was a panel discussion involving representatives of MBL, HESTA and Cbus, which included comments about gender issues. There were also interviews given by the artist to Australian media outlets.

19 I should say now that the launch event had little if anything to do with the finance industry or promoting financial services or products. And those present hardly represented the typical demographic that one would expect to find at a cocktail function for financial players. Further, very few of those present at the launch event would ever have heard of State Street (US), State Street (Australia) or their operations. They were not well known at the time in Victoria at least by members of the public. They had no retail operations in Victoria. And their offerings in Victoria of financial products were available more to institutional or wholesale investors.

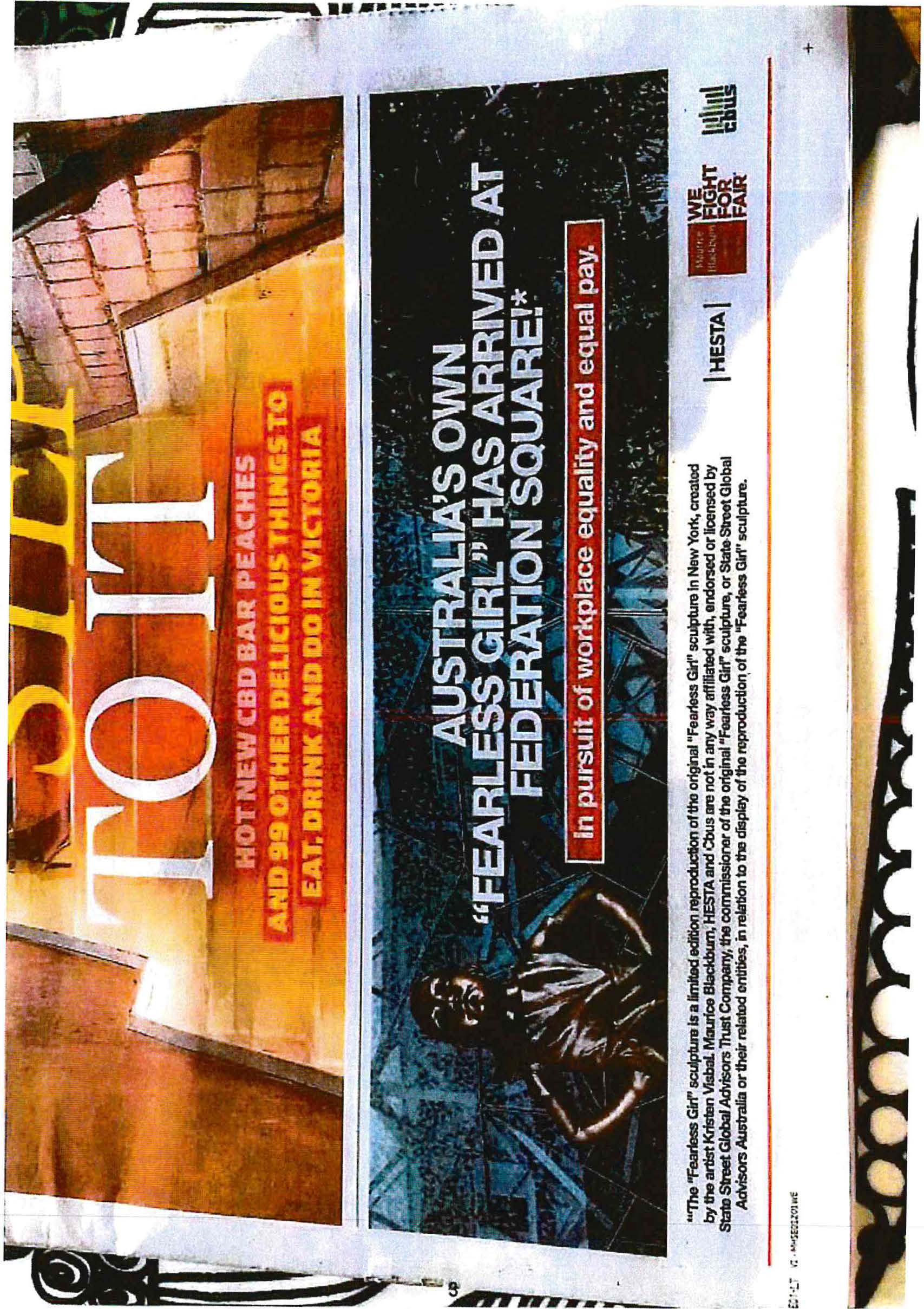

20 After the launch event, the replica and MBL’s and the other sponsors’ association with it was promoted by two paid advertisements. There was a wrap-around cover published on 2 March 2019 in the Herald Sun newspaper, including an image of the replica and reference to MBL, HESTA and Cbus. Further, there was a full-page advertisement published on 10 March 2019 in the Stellar magazine, including an image of the replica and reference to MBL, HESTA and Cbus. Copies of the first, second and third invitations, the wrap-around cover and the Stellar advertisement are annexed to these reasons; I will return to them later.

21 Now in this proceeding, SSGA has made various statutory claims that MBL by its conduct engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct contrary to ss 18 and 29(1)(a), (g) and (h) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) (sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)), trade mark infringement contrary to ss 120(1) and (2) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), and infringement of copyright contrary to s 36 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).

22 Further, SSGA has made various tort claims. First, SSGA asserts that MBL engaged in the tort of passing off. Second, State Street (US) has put a case of interference with contractual relations in that MBL induced the artist to breach the agreement that she had entered into with State Street (US) relating to the creation, ongoing use, display and promotion of the New York statue, the Fearless Girl trade mark and the artwork embodied by the New York statue. I will refer to the agreement between the artist and State Street (US) as the “master agreement” and the artwork embodied by the New York statue as the “artwork”.

23 Generally, SSGA has sought to weave its web of statutory and tort claims in such a fashion as to effectively assert monopoly rights in an icon that it does not have. There is considerable disparity between what it paid for and what it now asserts it is entitled to protect. But Australian statute law and tort law cannot fill that gap.

24 For the reasons that follow, I would reject the claims made by SSGA except insofar as the question of the future display of the replica is concerned and whether any disclaimer is required to be used with the replica. I will hear the parties further on such questions including whether any orders need to be made or undertakings given.

25 It is convenient to divide my reasons into the following sections:

(a) Fearless Girl ([27] to [62]);

(b) The master agreement ([63] to [75]);

(c) MBL’s conduct and involvement ([76] to [406]);

(d) Interference with contractual relations ([407] to [680]);

(e) ACL claims and passing off ([681] to [955]);

(f) Trade mark infringement ([956] to [1084]);

(g) Copyright infringement ([1085] to [1187]); and

(h) Conclusion ([1188] to [1191]).

26 I should make one other preliminary point. Because of the inconvenience caused by the COVID-19 restrictions, I cancelled oral closing addresses. As a consequence, the parties provided to me extensive written closing submissions that were of considerable assistance.

FEARLESS GIRL

27 Before getting into the detail of SSGA’s claims and the evidence, it is important to make some observations concerning the New York statue and its commissioning, and the master agreement.

28 In 2016, State Street (US) engaged its advertising agency, McCann, to develop a campaign to promote the SPDR SSGA Gender Diversity Index ETF (the SHE fund), which is an exchange traded fund listed on the NYSE’s Arca exchange. The SHE fund tracks against the SSGA Gender Diversity Index, which measures the performance of US large capitalisation companies that are “gender diverse”, being companies that exhibit gender diversity in their senior leadership positions. In late 2016, McCann commissioned the artist to help create a bronze statue of a strong and confident girl that would stand opposite the Charging Bull statue at Bowling Green Park on Wall Street in the Financial District of Manhattan, New York City.

29 In the evening of 7 March 2017, State Street (US) installed the New York statue at Bowling Green Park. This was the night before International Women’s Day. A plaque was placed beneath the statue that stated “Know the power of women in leadership. SHE makes a difference” with the SSGA logo. The reference to “SHE” was a reference to both the gender of the girl and the ticker symbol of the SHE fund. I note that the plaque was subsequently removed and replaced with a sign which also referred to State Street (US).

30 To accompany the unveiling of the New York statue, State Street (US) launched an integrated marketing campaign (the Fearless Girl campaign). Installation of the statue was timed to coincide with a public announcement made by State Street (US), in which it called on 3,500 companies in the US, UK and Australia representing more than US$30 trillion in market capitalisation to increase the number of women on their boards.

31 The New York statue was apparently intended by State Street (US) to celebrate women leaders in business, but also to inspire the next generation of leaders in business. Apparently, it was to be a symbol of State Street (US)’s messaging regarding the importance of gender diversity in senior business leadership.

32 The Fearless Girl campaign was widely reported by global news agencies and was discussed extensively on major social media platforms. The Fearless Girl campaign resulted in:

(a) over 4.6 billion Twitter impressions in the first 12 weeks of the campaign;

(b) approximately 745 million Instagram impressions in the first 12 weeks of the campaign;

(c) approximately 2,400 print and digital articles with 140.5 million impressions which involved mentions of State Street (US) and the New York statue in the first three weeks of the campaign;

(d) 1,676 US broadcast mentions of State Street (US) and the New York statue, with audiences of 43.4 million viewers in the first three weeks of the campaign;

(e) an approximate 650% increase in @StateStreet Twitter handle impressions;

(f) an approximate 90% increase in views of State Street (US)’s website; and

(g) an approximate 450% increase in views of the SHE fund webpage on State Street (US)’s website.

33 Further, during the period 7 March 2017 to 4 April 2017, there was an increase in average daily trading volume in the SHE fund of 170%.

34 The media and social media coverage of the Fearless Girl campaign also had a significant impact on State Street (US)’s “share of voice” (SOV), which is a marketing industry measure used to assess the news media exposure a brand gets compared to its competitors. State Street (US)’s SOV in key publications increased from 7.8% for the period from 1 December 2016 to 3 March 2017 to 37.4% for the period from 7 March 2017 to 31 March 2017.

35 In April 2018, State Street (US) and the City of New York announced that the New York statue would be moved to a prominent location in front of the NYSE. The move to the new location was completed in December 2018. The New York statue currently stands in front of the NYSE with a new sign that incorporates State Street (US)’s logo and a description of its purpose.

36 Let me extrapolate from State Street (US) to SSGA more generally.

37 The Fearless Girl campaign has had a measurable impact on SSGA achieving its goal of promoting and bringing awareness to SSGA’s efforts to promote gender diversity in corporate governance.

38 In particular, from the launch of the Fearless Girl campaign until September 2018, 301 of the 1,228 companies which SSGA identified as having no female board members had added a female director, including 21 of the 45 companies identified in Australia. Further, by March 2019, 423 of the 1,265 companies which SSGA identified as having no female board members had added a female director, including 26 of the 56 companies identified in Australia.

39 Further, Fearless Girl has been important to SSGA’s asset stewardship campaign, in particular the board governance initiative to drive greater gender diversity at the corporate level, which is international. Further, there is an annual report which is available to a wide variety of stakeholders.

40 Further, Fearless Girl has been used by SSGA to draw attention to SSGA’s environmental, social and corporate governance investing capabilities, in particular with the SHE fund.

41 In evidence were various marketing and promotional documents of SSGA.

42 First, I was taken to a document titled “Drive Change: SPDR SSGA Gender Diversity Index ETF” published in March 2018, which appeared to have an expiry date of 31 December 2019, concerning the SHE fund. Undoubtedly this was a document used to promote an investment product, structured to promote gender diverse leadership. A selling point was that at the time of its publication, the SHE fund was sold to investors as “the least expensive thematic large-cap US equity ETF in the market today”. On one of the 12 pages is a reference to Fearless Girl and State Street (US)’s placement of the New York statue. This was said to be done “to amplify our message” concerning gender diversity on boards or perhaps a little more broadly women in corporate leadership positions. To be clear, this all had little to do with MBL’s broader campaign themes of equal pay, equal opportunity and gender equality across all levels of employment in all sectors. Further, MBL’s campaign was also directed, inter-alia, to young and younger women, rather than finance or investment types with ready cash to invest.

43 There is also something further to note. SSGA’s audience was substantially companies in the SHE fund, target companies that it was looking to add, and actual or potential investors in the SHE fund. Further, it would seem that only US companies were invested in so far as the fund was concerned.

44 Second, in evidence was an Annual Stewardship Report for 2017, which was published by SSGA in July 2018.

45 I will not go through it in detail, but several features can be noted. There was a photograph of the New York statue on the front cover. And further reference to Fearless Girl was made on pages 42 to 44 (see also page 32) with another photograph. Again, the placement of the New York statue was described as being “to raise awareness about the importance of gender diversity in corporate leadership”.

46 Admittedly, the report has broader themes than this. Further, there was reference to some Australian activity. So, it was said (page 49):

Gender Diversity (Australia, United Kingdom and United States) In 2017, we adopted voting guidelines designed to address our concerns over the levels of gender diversity on boards of companies in Australia, the UK and the US. During 2017, we reached out to 787 companies to share our concerns about the absence of female directors on the board.

In response to our engagement in this area, 152 companies subsequently added a woman to their board. Of these companies, 129 companies (84 percent) were based in the US, 16 companies (10 percent) were Australian and seven companies (4 percent) were from the UK. Consequently, we took voting action against 511 companies for failing to demonstrate sufficient progress on board diversity.

47 In addition to raising awareness of issues concerning gender diversity at a corporate level, another of the purposes of the commissioning of the New York statue was to promote SSGA, its business and its product and service offerings. It achieved this purpose through a coordinated and targeted social media campaign, which tied the launch of the New York statue to SSGA and its gender diversity initiatives.

48 Now SSGA has sought to maintain and protect the integrity of the New York statue and the Fearless Girl campaign’s message. SSGA has granted requests from both within SSGA and externally to use the Fearless Girl image and replicas of the New York statue where there is a clear association between the use of the image and replicas with gender diversity and asset stewardship initiatives. But it has also refused many such requests.

49 Further, SSGA’s continuing public efforts to promote the New York statue since her relocation to the NYSE have included installation of a replica in London, ongoing reporting on SSGA’s overall progress in promoting greater gender diversity at the board level, promotion on SSGA’s websites and frequent social media postings. State Street (US)’s website, for example, contains examples of ongoing use of the Fearless Girl name and image, including a section describing the genesis of the New York statue and the Fearless Girl campaign.

50 I do not need to elaborate further on SSGA’s marketing activities in the US or the reputation that it may have acquired in the US as being associated with the New York statue or Fearless Girl. The more relevant question, particularly concerning the ACL claims and passing off, is its activities and reputation in Australia. On that topic, SSGA is on a much more flimsy foundation.

51 Now SSGA says that it has engaged in extensive marketing and promotional activities in Australia under and by reference to the name and mark “Fearless Girl” in connection with the Fearless Girl campaign that has used images of the New York statue. In particular, SSGA says that it has used Fearless Girl in Australia in various ways, which I accept.

52 First, it has used it in some marketing materials to SSGA’s Australian institutional clients, including in marketing emails and external presentations delivered to a variety of clients including those in the superannuation industry.

53 Second, it has used it in a limited way on State Street (Australia)’s websites, which have included information about the Fearless Girl campaign and SSGA’s asset stewardship initiatives. I will discuss State Street (Australia)’s promotion of the New York statue and the Fearless Girl campaign via its websites in more detail later in my reasons.

54 Third, it has used it in some presentations to researchers, dealer groups and financial advisors.

55 Fourth, it has used it through presentations delivered at some industry events which were attended by financial advisors in the Australian market and prospective clients like superannuation funds, investment companies and banks. It has used it in several presentations directed at the role of women in the financial services industry and in executive positions. It used it in the international keynote presentation at Mumbrella360 in June 2018.

56 Fifth, since March 2017, the New York statue and the Fearless Girl campaign have also been included in some articles published:

(a) in Australian newspapers such as the Sydney Morning Herald, the Age, the Herald Sun, the Brisbane Times, the Advertiser, the Mercury, and the Canberra Times;

(b) on Australian financial industry websites such as the Australian Financial Review, Yahoo Finance, Business Insider Australia and Top1000Funds;

(c) in syndicated media services in regional areas of Australia such as the Gold Coast Bulletin, the Geelong Advertiser, the Perth Now and WAtoday;

(d) on other Australian news websites such as the ABC News and 9News sites; and

(e) on marketing industry websites such as AdNews, Mumbrella and B&T.

57 Sixth, in Australia, following the success of its Fearless Girl campaign, SSGA won the 2017 Social Media Campaign of the Year award at the Marketing Advertising and Sales Excellence Awards.

58 I will return to the question of SSGA’s and Fearless Girl’s reputation in Australia later.

59 Let me say something about SSGA’s witnesses.

60 Mr John Brockelman, SSGA’s Global Head of Brand Marketing & Communications, gave evidence that the SHE fund invests in companies that not only have a higher percentage of women at the board level, but also at the senior leadership levels. More generally, he gave evidence in relation to SSGA’s global operations, the development of SSGA’s Fearless Girl campaign including the commissioning of the New York statue, the impact of that campaign, the media attention attracted by the campaign, and State Street (US)’s agreement with the artist, namely, the master agreement. He was cross-examined, and for the most part was a forthright witness. He had significant experience in the field of marketing. But whatever his opinions, the reputation of SSGA, the New York statue and the iconography associated with Fearless Girl in Australia generally and Victoria in particular were really matters for me to determine, even if one clothed some of his opinions as being in the nature of an in-house expert. Further, some of his opinions were in any event problematic for reasons that I will briefly refer to later.

61 I should say that Mr James MacNevin, the Head of Asia Pacific at SSGA, also gave evidence. Mr MacNevin gave evidence in relation to SSGA’s operations in Australia, including some use of Fearless Girl in promotions to SSGA’s clients, in communications via SSGA’s websites, in presentations at industry events and in general marketing used by SSGA. He was also cross-examined, and I found him to be honest and for the most part helpful, although some aspects of his evidence had their difficulties which I will briefly identify later.

62 Other affidavit evidence was also tendered. Ms Rebecca Smith was a solicitor employed by SSGA’s solicitors, Gilbert + Tobin, who attended the launch event on 26 February 2019. She described what she observed, but was not cross-examined. Mr Aditya Vasudevan was a solicitor employed by Gilbert + Tobin who purported to describe how information relating to Fearless Girl was accessible via State Street (Australia)’s website. He was not cross-examined. I will return to his written evidence later.

MASTER AGREEMENT

63 Let me now say something about the master agreement between State Street (US) and the artist and its terms. I will discuss the art agreement between MBL and the artist later.

64 State Street (US) did not enter into a formal agreement at the time of the creation of the New York statue or before its unveiling. Later, on 12 May 2017, State Street (US) and the artist entered into the master agreement, which as I have said related to the creation, ongoing use, display and promotion of the New York statue, Fearless Girl trade mark and the artwork.

65 The master agreement contains terms that granted State Street (US), described in the agreement as SSGA, various rights and limited the artist’s rights. It is necessary that I set out some of these provisions. I should say that generally speaking its terms are confidential. Nevertheless, what I have set out are not sufficiently confidential as to justify not setting them out in a publicly available copy of my reasons.

66 Key terms of the master agreement include the following:

(a) Clause 1(d) provided:

Artist agrees that any two-dimensional or three-dimensional reproductions of the Artwork that are provided by Artist to any third party as part of any promotional or corporate event, conference, ceremony, banquet, retreat, awards dinner, or the like, shall give attribution to SSGA as follows: “Statue commissioned by SSGA” provided, however, that Artist may request that SSGA waive such attribution requirement with respect to any particular gift or award proposed by the Artist.

(b) Clause 3 provided:

a) The Parties acknowledge and agree that SSGA shall have the exclusive right, pursuant to a license set forth in Exhibit A hereto, to display and distribute two-dimensional copies, and three-dimensional Artist-sanctioned copies, of the Artwork to promote (i) gender diversity issues in corporate governance and in the financial services sector, and (ii) SSGA and the products and services it offers. Notwithstanding, Artist is free to discuss issues involving Gender Diversity Goals in connection with the Artwork, provided the Artwork is not used to promote any third party.

b) All uses not licensed to SSGA hereunder are reserved to Artist, subject to the restrictions set forth in Paragraphs 6, 7, 12 and 13 below.

c) SSGA may not use images of the Artwork as a “logo,” which the Parties understand and agree is a stylized two- or three-dimensional image used consistently with SSGA’s corporate name, goods, or services to identify SSGA as the source of such goods or services. The Parties understand and agree that the display of the Artwork in photographs or holograms by SSGA, in connection with SSGA marketing communications or otherwise, in any medium or format now known or hereafter developed, shall not be considered use of the Artwork as a “logo.”

(c) Clause 6 provided:

a) Artist shall use commercially reasonable efforts to ensure that the Artwork is never exploited under authority of Artist in a manner that could tarnish or dilute the SSGA brand or SSGA’s high-quality reputation.

…

c) Subject to the restrictions set forth in Paragraph 7 below, Artist may exploit the Artwork for the following pre-approved uses (the “Pre-Approved Uses”) in a manner consistent with the principles set forth in Paragraphs 6(a) and 6(b)(ii) above:

i. create an exact reproduction, i.e., a three-dimensional “artist proof” of the Artwork, for auction;

ii. create, display, and distribute two-dimensional copies of the Artwork for Artist’s portfolio, in all formats and media (e.g. websites);

iii. create, display, and distribute three-dimensional copies of the Artwork in various mediums and sizes in keeping with the present high quality of Artist’s work;

iv. create, display, and distribute two-dimensional copies of the Artwork (A) for “fine art” purposes or (B) pursuant to Paragraph 7(c)(i)(B) below;

v. create, display, and distribute two-dimensional copies of the Artwork in children’s books;

vi. create, display, and distribute miniature three-dimensional copies of the Artwork as charms, pendants, or other jewelry;

vii. create, display, and distribute three-dimensional copies of the Artwork in the form of dolls, ornaments, and other three-dimensional merchandise;

viii. create, display, and distribute two-dimensional copies of the Artwork for merchandise where the depiction of the Artwork is merely ornamentation and not branding.

…

f) With respect to any proposed use by Artist that does not constitute a Pre-Approved Use as set forth above, is not set forth in Paragraph 7 below, or is not otherwise set forth herein, the Parties agree to review and discuss them in good faith and SSGA shall provide a response to Artist no more than three (3) weeks from her request. Artist may request an expedited approval process, from time to time, for a two-week review for time sensitive requests.

(d) Clauses 7(a) to (c) provided:

a) The Parties acknowledge and agree that use or exploitation of the Artwork by certain third parties, such as third party financial institutions, corporations, or individuals that may not share the Parties’ Gender Diversity Goals may dilute, tarnish, or otherwise damage SSGA, the SSGA brand, Artist’s reputation, or the integrity of the Artwork.

b) The Parties agree that the Artwork shall never be authorized for use by any third party as a logo or brand, including, without limitation, the display of the Artwork on third party “branded” merchandise (including statuettes) that is designed to promote a third party, its products, or services. … Unless otherwise agreed in writing between the Parties, the foregoing restriction on use for any branding purpose as set out in Exhibit C hereto, shall be incorporated as a condition of Artist’s sale of copies of the Artwork to third parties.

c) The Parties agree that the following uses of the Artwork do not constitute Pre-Approved Uses and require both Parties’ prior written approval, on a case-by-case basis, such that Artist, Artist’s designated representative, or Artist’s agent, may not knowingly:

i. sell, license, or distribute copies of the Artwork in any medium or size to any financial institution for any commercial and/or corporate purpose (whether internal or external-facing), such as in connection with a conference, event, ceremony, banquet, retreat, awards dinner of the like…

ii. sell, license, or distribute copies of the Artwork in any medium or size to any third party to use in connection with gender diversity issues in corporate governance or in the financial services sector; or

iii. sell, license, or distribute copies of the Artwork in any medium or size to any political party, politician, activist, or activist group…

(e) Clauses 11(a) to (c) provided:

a) The Parties acknowledge and agree that SSGA filed an intent-to-use application to register the term “Fearless Girl” as a trademark (the “Mark”) in the United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “US PTO”), and may file further trademark applications to register the Mark in the US PTO, and abroad.

b) The Parties acknowledge and agree that SSGA is the exclusive owner of the Mark, and will, subject to its good faith business judgment, monitor and police infringement of the Mark worldwide.

c) SSGA acknowledges that certain use of the Mark by Artist as the name of the Statue may be nominative fair use, or not a trademark use…but use of the Mark on a label, packaging, or advertising or promotional materials in connection with the sale, offer for sale, license, or distribution of reproductions of the Artwork, in any medium, other than as merely and only describing the Artwork as created by Kristen Visbal, shall be subject to the Trademark License Agreement annexed hereto as Exhibit D. For the avoidance of doubt, use of the Mark on labels, packaging, and advertising associated with jewelry, series of books, dolls, ornaments, and other merchandise will require a trademark sub-license agreement, but use of the Mark on art prints that display the Trademark to refer to the Statue does not.

67 At this point I should note that in the preamble clauses to the master agreement:

(a) the “Statue” was defined as “an original bronze statue for International Women’s Day, which is now known as the ‘Fearless Girl’”; and

(b) the “Artwork” was defined as “the work of visual art that is embodied by the Statue”.

68 Exhibit A to the master agreement is a copyright licence agreement. I will set out the relevant provisions later in these reasons. Exhibit B is not directly relevant for present purposes.

69 Exhibit C to the master agreement is a “No Branding Provision” and provided:

Except as otherwise agreed between the Parties, the following clause shall be included in all agreements entered into by Artist with all third parties in connection with the use of the Artwork:

The Artwork shall never be used, or authorized for use, as a logo or brand. The Artwork shall never be displayed on “branded” material, in any medium now know or hereafter devised, including without limitation any merchandise, products, or printed or electronic material, that features a trademark, service mark, trade name, tagline, logo, or other indicia identifying a person or entity except for Kristen Visbal or State Street Global Advisors or its affiliates.

Notwithstanding the above “no branding” requirement, a reproduction of the Artwork may be depicted in labels, on merchandise, on packaging for merchandise, and in promotion or advertising collateral, which also display the name of a third-party manufacturer or retailer of the merchandise being promoted/advertised.

70 Exhibit D to the master agreement is a trademark licence agreement. I will set out the relevant provisions later in these reasons.

71 State Street (US) asserts that the master agreement preserves for State Street (US) the exclusive right to use the artwork in relation to promoting gender diversity in corporate governance and in the financial services sector. Correspondingly, it says that the master agreement limits the artist’s ability to deal with the rights in the artwork, particularly in connection with gender diversity issues in corporate governance or in the financial services sector and limits her permitted uses of the Fearless Girl trade mark.

72 State Street (US) says that the master agreement secures subject matter exclusivity for State Street (US) in the New York statue, artwork and the Fearless Girl trade mark in relation to promoting gender diversity in corporate governance and in the financial services sector.

73 Further, it points out that the master agreement also acknowledges that use of the artwork by third party financial institutions, corporations or individuals may dilute, tarnish or otherwise damage State Street (US) and the State Street (US) brand, consistent with the preservation of rights in relation to the financial services sector to State Street (US).

74 Now only one significant construction issue concerning the master agreement has been raised before me. I will dispose of it later.

75 Let me now turn to MBL’s conduct and involvement.

MBL’S CONDUCT AND INVOLVEMENT

76 Let me begin by saying something briefly about MBL’s witnesses.

77 MBL adduced evidence from Ms Hanlan, who was cross-examined. She gave evidence about the development of the MBL campaign from its inception, her contact with the artist, negotiations with the artist and Ms Wolff, broader aspects of the MBL campaign such as obtaining partners, publicity for the campaign and launch event, and events subsequent to the launch event. I will discuss her evidence in more detail in a moment, which was generally reliable.

78 Further, MBL called Mr McDonald, who was also cross-examined. Mr McDonald was a solicitor at Simpsons solicitors, the specialist firm retained by MBL to advise on the purchase of the replica and who represented MBL in these proceedings. He gave evidence concerning his role in negotiating with the artist and Ms Wolff in relation to MBL’s purchase of the replica, and his dealings with Ms Hanlan in relation to the purchase. I will also discuss his evidence in some detail later, none of which was successfully impugned.

79 Further, MBL adduced evidence from Ms Kara Sheehan, who was cross-examined. She was the General Counsel and Company Secretary of MBL. She gave evidence about her limited role in relation to the purchase of the replica. There was no reason to doubt any of her evidence and it was not meaningfully challenged.

80 Further, MBL adduced expert evidence from Mr Geoffrey Edwards, who was cross-examined. Mr Edwards was a freelance consultant and adviser on sculpture to public and private collections throughout Australia. Mr Edwards had been the Senior Curator of Sculpture at the National Gallery of Victoria and later, Director of the Geelong Art Gallery. He gave evidence about how works produced in editions (multiples) were referred to or titled, and the connection between the commissioning of a work and the work itself including how the work was generally viewed or treated. Mr Edwards addressed these issues to the New York statue. I had no reason to doubt any of the opinions that he expressed although his evidence had its obvious limitations which I will discuss later.

81 Finally, MBL adduced evidence from Mr Sebastian Tonkin, who was a solicitor at Simpsons. He had compiled various articles in the media concerning the statue, and USBs containing a video presentation about the New York statue and a recording from the launch event.

82 Let me at this point discuss in detail the evidence given by Ms Hanlan and Mr McDonald, the subject matter of which goes principally to the claim concerning the tort of interference with contractual relations.

The dealings involving Ms Hanlan

83 Ms Hanlan was the National Brand and Social Media Manager at MBL from 2012 until August 2019. Her previous roles included being a Senior Manager, Corporate Brand Usage and Management at Standard Chartered Bank (Singapore) in 2011, Group Marketing Manager at Shape Australia from 2009 to 2010 and National Brand Manager at Australia Post from 2006 to 2009.

84 As the National Brand and Social Media Manager, Ms Hanlan was responsible for overseeing MBL’s marketing, communications, advertising and media requirements. Her team was responsible for implementing MBL’s advertising campaigns directed at prospective clients in its practice areas, like employment and personal injury law.

85 One of her key objectives was to maintain MBL’s reputation as a leading law firm, not just for individual plaintiff claims but in the area of social justice more broadly. To this end, as well as direct marketing efforts directed to prospective clients, her role involved the development and execution of broader campaigns intended to elevate MBL’s brand and reach audiences outside its ordinary client base. She said that whilst it was desirable for these brand campaigns to intersect in some way with MBL’s existing practice areas, the main focus was for MBL to participate in, and be seen to be participating in, conversations of relevance to the broader public and media.

86 She said that gender equality had long been a key value of MBL. MBL had advocated, both on behalf of its clients and independently, on the issues of workplace sexual harassment, gender discrimination in hiring and the gender pay gap. MBL worked, together with union clients, throughout the 1950s and 1960s on issues relating to equal pay leading up to 1972, when the principle of equal pay for equal work became law. Apparently, MBL itself had a particular internal focus on diversity and inclusivity in hiring decisions. MBL regarded itself as a leader in this field in legal and broader commercial circles.

87 In late 2017, she had a discussion with Ms Liberty Sanger, one of MBL’s principal lawyers who had recently been appointed as chair of the Victorian Government’s Equal Workplaces Advisory Council, about whether MBL should consider focusing on workplace gender equality issues and try to bring about change in that area.

88 Ms Hanlan then engaged Mr Pharaoh to conduct research into how the media portrayed gender equality issues. The purpose of commissioning Mr Pharaoh to do this research was to understand how equal pay issues were being discussed and framed in the media and how MBL might progress this cause.

89 The development of the campaign began with discussions between Ms Hanlan and external consultants with expertise in relation to the creation and strategy for advertising or community campaigns. Ms Hanlan had a prior relationship with Ms Chaudhuri. She also had a prior relationship with Mr Carl Ratcliff, formerly head of strategy for One Green Bean (OGB).

90 In early January 2018, Ms Hanlan had a phone call with Ms Chaudhuri about the starting point for a campaign and sent her an email setting out her thoughts. At that stage Ms Hanlan envisioned a broad campaign in relation to gender equality in the workplace encompassing issues of workplace safety, workplace equal opportunity and representation, which Ms Hanlan referred to as gender parity and wage equality. According to Ms Hanlan, building a campaign with the aim of improving workplaces for women would align with MBL’s values and core client base.

91 One of the central pillars of Ms Hanlan’s proposal was wage equality, also known as the gender pay gap. According to her, the gender pay gap was an issue that had been bubbling along for some time and was by then gaining some momentum in the media. She thought that a campaign to highlight the issue and make people more aware of it, with a call to the Victorian government to take more enforcement action, was worth considering.

92 By mid-March 2018, Mr Ratcliff, Ms Chaudhuri and Ms Hanlan had developed some ideas for an equal pay campaign and decided that they needed to commission some research to assist them to identify key messages and language for the campaign. Ms Hanlan engaged the research company Forward Scout to undertake qualitative and quantitative research to inform and develop MBL’s strategic approach to the gender pay gap.

93 In mid-April 2018, Forward Scout prepared an initial report on its qualitative research in mid-April 2018 followed by a more detailed research debrief in May 2018.

94 By mid-to-late April 2018, Ms Hanlan had the benefit of Mr Pharaoh’s report on how the media had presented gender pay equality issues and Forward Scout’s qualitative research findings, so she wanted to find a way to leverage those findings into a campaign that would be of interest to the media. The reason for needing media interest in the campaign was so that the campaign would get attention and generate more discussion, which would then hopefully generate more calls for change.

95 Ms Chaudhuri created a creative proposal setting out the vision for the campaign, based on what they had learned from the research and their discussions to date.

96 Ms Chaudhuri’s proposal suggested the campaign would have several assets, being discrete elements that would each contribute to the overall campaign. These were a “campaign film”, a microsite (meaning a small, topic-focused website), a moment (being, a day on which the campaign would hit the public in a newsworthy way) and a partner pack (to encourage other organisations to support the campaign). The campaign would also ask the community to commit to the cause by signing up to a pledge. Under moment, Ms Chaudhuri’s presentation suggested an event on Equal Pay Day in September 2018. Her suggestion was that they would collaborate with an Australian sculptor and create a statue to unveil on Equal Pay Day. Her report included a picture of a statue. The intention was that the statue would embody the concept of a life-size woman standing next to a stack of notes representing the exact amount that women were paid less than men that year. That figure was to be based on statistics released by the Australian Government’s Workplace Gender Equality Agency (WGEA). The picture in Ms Chaudhuri’s presentation was indicative only and Ms Hanlan did not expect the ultimate statue would look like that. Ms Chaudhuri’s presentation also included a name for the campaign, namely “We’ve Earned It”.

97 Ms Hanlan and Ms Chaudhuri were still considering possible dates for the launch of the campaign and were factoring in other key dates of relevance to the campaign, being:

(a) the Victorian election cycle, with the election scheduled for 24 November 2018; and

(b) Equal Pay Day, being the date on which the WGEA published its data about gender pay equality, expected in around September 2018.

98 At around that time, Ms Hanlan engaged an external public relations company, Callidus PR, to work with them on the campaign. She knew Ms Louise Nealon, who worked at Callidus PR.

99 In early May 2018, Ms Hanlan met with Ms Nealon and others for a discussion about the campaign. Ms Chaudhuri presented an updated version of the creative proposal and a treatment for the campaign film. Ms Nealon presented a proposal for a PR strategy.

100 Ms Hanlan presented the research and the campaign ideas to a small group of key people within MBL, including Ms Sanger.

101 Ms Hanlan also contacted Mr Michael Harms at Consumedia, MBL’s media buying agency, to enlist his support for finding potential partners for the campaign. Mr Harms was well-connected in the media industry and she thought he would be well-placed to introduce them to potential partners. She told Mr Harms that MBL wanted to approach companies that had signed up to the WGEA and therefore were already aligned with the purpose of the campaign. She sent him a list of WGEA accredited brands that included companies in a wide range of industries.

102 Later in May 2018, she had a discussion by email with the creative team about whether and when to go ahead with commissioning a statue and where it might be located. She had hoped that it would be located in the Melbourne CBD, somewhere with high foot traffic and befitting of a symbol of such an important issue.

103 At around this time in late May 2018, Mr Pharaoh drafted an overview document for the purpose of asking the Victorian Parliament to approve placement of a statue on Parliament grounds. Mr Pharaoh also developed wording for communications to several municipal locations seeking permission to have a statue erected in one of those locations.

104 On 8 June 2018, MBL was notified that placement of a statue in the gardens of Parliament House would not be possible. Ms Hanlan’s focus then turned to the City of Melbourne Council and as she thought it, in particular the Lord Mayor, Ms Sally Capp, would be able to assist in finding a similarly prominent public location.

105 In early June 2018, Ms Hanlan started contacting artists, by email or by phone, about commissioning a statue. Ms Hanlan mentioned the New York statue in some of these communications. Whilst she did not consider that the New York statue would be generally known to the public, she did think that it would likely be known to artists involved in public art and sculpture. By referring to it, she was trying to convey the general idea that they were seeking an artwork to symbolise a social issue in an easily understood (not abstract) way.

106 From around June 2018, Ms Hanlan was also searching for a media partner for the campaign. A media partner provided more than just advertising space. It provided a platform to spread content via many different channels, including editorial and PR, as well as advertising space. The campaign team ultimately came to the view that a partnership with News Corp in Victoria, publisher of the Herald Sun newspaper, might be more valuable and expose the campaign to a broader audience than a partnership with Fairfax, then the publisher of the other major Victorian daily newspaper, the Age.

107 Ms Hanlan could not recall when or how she first heard about the New York statue, but she believed that when she did first learn about it, she only took in its appearance and its name, Fearless Girl, and that it had been installed opposite the statue of the Charging Bull in support of gender equality on International Women’s Day in 2017. In around October 2017, she read in the media an article that the company that commissioned the New York statue had settled a dispute in relation to allegations that it had underpaid its female staff. She believed that was the first time she became aware of the identity of the commissioner of the New York statue, although the name of the commissioner, State Street, meant nothing to her at the time.

108 In around early June 2018, she raised with her creative team whether they should investigate whether they could buy a replica of the New York statue for the campaign. She did not consider, nor did anyone else in her team suggest that they considered, that Fearless Girl was already associated with another company or a particular industry. She thought it was worth considering further so she set about trying to find out who the artist behind the New York statue was and how she could contact him or her.

109 She read an article by Danielle Wiener-Bronner for CNNMoney (New York) titled “‘Fearless Girl’ artist wants her message spread beyond Wall Street”, first published online on 19 April 2018. Having read that article, she understood that:

(a) Ms Kristen Visbal was the name of the artist who had created the New York statue;

(b) the artist was offering for sale replicas of the New York statue;

(c) the artist had already sold three replicas, one of which had been unveiled in Oslo, Norway;

(d) the artist wanted the replicas to be placed in public places “so that the statue can continue spreading a message of gender equality”;

(e) State Street (US) held the Fearless Girl trade mark;

(f) State Street (US) was not involved in the replicas;

(g) Fearless Girl had been criticised in relation to State Street (US)’s settlement of allegations that it underpaid its female and black employees; and

(h) the artist saw Fearless Girl as a “much-needed symbol” and said “[t]he message may have begun as a statement about Wall Street [but the statue] has taken on a life of her own”.

110 Upon reading that article, she was hopeful that MBL might be able to purchase a replica.

111 By the time she decided to contact the artist, Ms Hanlan and her team had been working on the campaign for nearly six months. As far as she can recall, in all of that time she did not ever suggest, nor did any else suggest to her, that the campaign focus on pay inequality or gender diversity in the financial services industry over any other industry, or on pay inequality or gender diversity of company’s boards. Indeed, she always intended that the campaign be a broad campaign across a wide range of industries and at all levels of seniority to maximise the number of people who might be interested in the campaign and bring about real change.

112 On 7 June 2018, she sent an email to the artist. At the end of the email she said to the artist that she wanted to assure her that MBL’s planned campaign and its use of the replica would not be a “corporate branding exercise”. She said this because she wanted to convey to the artist that MBL was an organisation that was genuinely committed to promoting equal pay and workplace equality, and that MBL was not seeking to use Fearless Girl as an advertisement for its services.

113 On 12 June 2018, she sent a follow-up email to the artist as she had not received a response from her. In her response later that day, the artist stated that Australia was on her list for potential placement of the work.

114 Following that email correspondence, Ms Hanlan had a telephone conversation with the artist on 13 June 2018. The conversation lasted for approximately 40 minutes. In that call, Ms Hanlan told the artist about MBL. She recalled saying to the artist words to the effect of:

(a) MBL is one of Australia’s leading social justice law firms;

(b) when Maurice Blackburn started the firm nearly 100 years ago, his goal was to help ordinary Australians access the law;

(c) Maurice Blackburn’s goal to provide access to justice for all Australians, not just those who can afford it, was still very much the driving force behind the firm; and

(d) MBL was heavily involved in cases involving workers’ rights, asylum seeker rights, gender equality, and workplace discrimination.

115 Ms Hanlan told the artist about the campaign that MBL was planning. She recalled saying to the artist words to the effect of:

(a) MBL wanted to launch a campaign about wage equality;

(b) Ms Sanger was keen to help drive change in this area and that she would be MBL’s spokesperson for the campaign; and

(c) MBL was looking to build a coalition of organisations who would support the campaign. She said that they wanted the campaign to be bigger than just a MBL campaign and that with more organisations involved the campaign would reach a wider audience. She could not recall whether she specified the identities of the organisations or the types of organisations that she had hoped would be in the coalition.

116 She told the artist about the intended timing for the campaign. She said to the artist that they were planning to launch the campaign on Equal Pay Day in August or September 2018, and she said that Equal Pay Day was significant because it represented the additional days in the next financial year until Australian women’s wages reached the same level that Australian men had earned in the previous financial year.

117 During that call, the artist said to Ms Hanlan words to the following effect:

(a) she had made Fearless Girl and that the statue was important to her because her goal was to bring about equality between men and women, and she saw Fearless Girl as an inclusive symbol and that it was not about excluding men from the conversation, but creating a better society where both men and women were equally valued;

(b) she liked the idea of Fearless Girl being associated with an equal pay campaign;

(c) State Street (US) had unveiled the New York statue and had acquired two additional replicas, although it later became apparent that State Street (US) had acquired three additional replicas;

(d) she thought one of State Street (US)’s replicas was planned for London and the other was planned for Tokyo or Hong Kong;

(e) she thought the power of the Fearless Girl message would be strengthened if it was not connected with just one organisation, but with a wider range of organisations. Ms Hanlan assumed the artist’s reference to “one organisation” meant State Street (US) as she had just told her that it had unveiled the New York statue and had acquired two more replicas;

(f) she owned copyright in the artwork;

(g) State Street (US) owned a trade mark; she did not;

(h) she wanted to sell replicas of the New York statue to spread the word about gender equality;

(i) she had sold a replica to a hotel in Oslo, Norway and that it faced the parliament building there;

(j) she was in talks with a boarding school in Africa about creating a replica for that school;

(k) she had been previously contacted by Plan International Australia, an Australian charity that works to improve children’s rights and equality for girls, but it had decided not to purchase a replica due to the high cost;

(l) the cost of a full-size replica was US$250,000, which she acknowledged was expensive, and said that there could be no negotiation on the price; and

(m) the replica had to be pitched as a gift to the Australian people and it had to be installed in a public place.

118 As far as Ms Hanlan can recall, the artist did not tell her that she had an agreement with State Street (US), or that she was under any limitations or restrictions as to what she or a purchaser could or could not do with the replicas, other than she had mentioned State Street (US)’s trade mark.

119 Based on that telephone conversation with the artist, Ms Hanlan was left with the impression that she had plans to expand her message of gender equality around the world and that she was already gaining momentum through sales of the other replicas. As regards her statement that the replica must be “a gift to the Australian people”, Ms Hanlan understood that the artist did not want replicas of the New York statue to be promoted as being owned by a company and that they must be installed in public places.

120 After having made contact with the artist and confirmed that MBL could, in principle, purchase the replica for the campaign, the most pressing task was to find other organisations to support the campaign. In around mid-June 2018, the creative team and Ms Hanlan pulled together a long list of potential contacts and companies to approach regarding the campaign. The list included companies and contacts operating in the following fields: professional services, accountancy, property, energy, superannuation, private health funds, retail banking, legal, education, construction and other industries.

121 Ms Hanlan and others from the core campaign team started having conversations with their contacts at potential partner organisations. On 18 June 2018, Mr Pharaoh confirmed to her by email that HESTA had indicated that it would join the campaign.

122 Also on 18 June 2018, the artist sent her an email which repeated some of the comments she had made during their earlier phone conversation. The email stated:

I am very excited at the prospect of placing Fearless Girl in Melbourne and the figure couldn’t be more perfectly suited to your event. As we discussed, formally speaking, Fearless Girl stands for supporting women in leadership positions, equality, equality of pay, education of women, education in the work place for the prevention of prejudice and the general well being of women. Marking the day when women work for free certainly will drive home the discrepancy in pay between men and women. Fearless Girl is a perfect fit.

As discussed, I am quietly creating and placing a limited edition of 25 of the full size Fearless Girl. We unveiled her in front of the Grand Hotel in Oslo, Norway last March and she faces the Parliament building. Another European unveiling is scheduled for October and, in August, we will unveil at a boarding school representing 27 countries. Three other unveilings are scheduled. I am targeting public placement, educational facilities or corporate campuses in order to continue to spread the messages behind Fearless Girl as well as the key message of the enlightened path forward as being the collaboration between men and women for better decisions and a better environment.

State Street Global Advisors of Boston, Massachusetts owns the trademark for supporting women in leadership positions under the Fearless Girl name. I own the copyright on the work. The Australian coalition is able to freely announce that the sculpture has been gifted to the people of Australia. The restriction is that the group would not be able to use the figure as a brand identity.

…

With 6 parties chipping in for purchase, I think your group could make a dream of the Plan International group come true! I would be happy to speak with you and others in the coalition on the phone again once you’ve had the opportunity to digest all of this. Regarding trademark, if you have any questions, we can also schedule a call with my lawyer Nancy Wolff.

123 The artist’s email attached a draft agreement and some notes for purchase that the artist’s lawyer had drafted for another client. This draft agreement subsequently became what I have described as the art agreement. Ms Hanlan skimmed the draft art agreement at the time, but she does not recall reading it or the notes for purchase carefully as she knew that she would be asking a lawyer to review them and advise her. She did recall that she formed the impression that MBL would not be able to “lock up” the Fearless Girl name or image with its brand or logo. Lock up is a marketing term; it involves taking one element (a name, logo, symbol or picture) and mixing it with another element (name, logo, symbol or picture) to create a new lock up, or brand. In this context, she thought they could not use the image as part of MBL’s trade mark, nor could they advertise, for example, “Maurice Blackburn Fearless Girl legal services”. She considered that would not be a problem as she had no intention of doing that. It was never her intention that the replica would be used to advertise MBL’s legal services or as a brand for MBL. The replica was solely for use as part of the MBL campaign.

124 On 18 June 2018, she also received the quantitative debrief of Forward Scout’s research. The next step was for that research to form part of a corporate engagement, white paper-style report to a range of corporations in order to seek their engagement with the campaign.

125 On 20 June 2018, and before she had sought any legal advice or input on the documents the artist had sent to her, Ms Hanlan sent an email to the artist. In that email she told her, inter-alia, that MBL was looking for coalition members for the campaign, including global consulting firms, superannuation funds, City of Melbourne Council, health fund providers, unions and financial services. In relation to superannuation funds, Ms Hanlan explained her justification for their identification in terms of “as they are big supporters [of] women planning for their financial future etc”.

126 The artist responded on the same day and said “This rounds to the picture for me quite well”. The artist also said “Please let me know if you or your legal team needs to schedule a call with my lawyer Nancy Wolff”. After reading that email, the impression Ms Hanlan had was that the artist was happy with their proposed campaign and they could move forward.

127 On or around 21 June 2018, Ms Hanlan approached Ms Sheehan, who had just started in the role of General Counsel at MBL, about the campaign and the draft art agreement. She asked her whether Ms Sheehan would review the draft art agreement herself or whether she would brief an external lawyer. During that discussion or in a subsequent conversation shortly afterwards, Ms Sheehan told Ms Hanlan that she thought this matter should be dealt with by a specialist lawyer.

128 A friend of Ms Hanlan’s had, until shortly before that time, been employed as a lawyer at Simpsons. Through her, Ms Hanlan knew that Simpsons specialised in arts law and she asked her friend for the name of a person that she could contact to assist her with the review of the draft agreement. On 22 June 2018, she sent her an email introducing Ms Hanlan to Mr McDonald.

129 Ms Hanlan then emailed Ms Sheehan with Mr McDonald’s details, copying him in. Separately, she sent Ms Sheehan an email briefly outlining what she saw as MBL’s requirements for the purchase, including what she wanted to be able to do with the replica.

130 Shortly afterwards, also on 22 June 2018, Ms Hanlan was copied on an email from Ms Sheehan to Mr McDonald in which she attached the draft art agreement and the notes for purchase that Ms Hanlan had received from the artist as well as a copy of Ms Hanlan’s earlier email to her outlining MBL’s requirements.

131 Ms Hanlan wanted to ensure that MBL could use the replica for the purposes of the MBL campaign. Whilst she had not made a final decision about every element of the campaign, she did at that time know that MBL would want to install the replica in a public place and use the replica and its image as part of the campaign. It was never her intention that the replica would be used to advertise MBL’s legal services or as a brand for MBL. The replica was solely for use as part of the campaign. Given the significant cost of the replica and its part of the campaign, she needed to guarantee that they could use it for the planned purposes. If they could not use it for their purposes there would be no point in continuing to negotiate an agreement with the artist to purchase the replica.

132 On 27 June 2018, she received an email from Mr McDonald attaching his comments on the draft art agreement.

133 On 29 June 2018, she emailed Mr McDonald and asked him “So we’re happy that we’d be able to use the fearless girl the way we needed to and also for our partners?”. She asked that question because, whilst by that stage she had skimmed the draft art agreement, she didn’t feel qualified to comment on the drafting of the clauses. She simply wanted to ensure MBL could use the replica for the purposes of the campaign.

134 Later that day, Mr McDonald responded to her question, saying that:

Our deletions to subclause (1) of the clause on page 4 in relation to “No-Branding Use” remove the issue about referring to the work in (among other things) MB or other newsletters or on an MB website, each of which would clearly be branded with the firm’s name and logo.

The additional wording after subclause (3) is to remove any ambiguity as to what MB or the co-contributors are permitted to do with the work, but let us know if there is anything extra you want to specify here. Note also our comment inserted as “IMcD3” at the end of subclause (2), including that MB may want to negotiate for the deletion of this subclause.

The amendments we have suggested reflect our instructions, but we particularly look forward to your assessment of whether there is anything else that should be included (or excluded) here.

Kara: particularly look forward to any comments from you on this or any of the other amendments we have suggested.

135 Later that afternoon, Ms Sheehan emailed Ms Hanlan and suggested that she call Mr McDonald to discuss his queries. At that time, Ms Hanlan was overseas so rather than calling Mr McDonald, on 3 July 2018, she emailed him and Ms Sheehan.

136 In an email, she wrote that the “no branding use” clause was her “biggest concern” and suggested that it should be removed or clarified. She said this because she did not really understand the wording of that clause and, more specifically, she wanted to be sure MBL would be able to partner with superannuation funds, which she assumed would be considered financial services companies. Her email stated:

My responses to the specific questions are below- can you review and forward to Ian. I’m in Greece at the moment so not picking up my v/m

• the cost and payment schedule (p.2) – I agree a % should be held back until delivery;

Happy for you to make a recommendation on this

• the no branding use (p.3) – see comments re (2) – do you or the potential contributors have any issues with the limitation?;

as per my earlier email this is my biggest concern – I think we need to ask her if we can a) remove it or B have her explain what the intent is here ie what is corp governance and what is fin service s- we will have superannuation providers contribute and are they tech fin services etc

• Credit (p.3) – Ian’s proposed clause looks ok, but if you want MB’s logo and contributors logos on the plaque, can you let Ian know?;

I want to make sure that we can put our logos on the plaque – MB and any other contributors – this is very important as we need to be able to show who has brought the girl to Melbourne and why.

• Photography (p.5) – do we want the artist to provide a photographer or will we have our own at the Event?;

Part of the offer is that the artist will include the McCann photographer who did the work for the NYC fearless Girl – this ensures consistency in creative presentation.

137 Mr McDonald replied to her stating that he would make changes to the draft art agreement in light of her comments. There were then some further emails between Mr McDonald, Ms Sheehan and Ms Hanlan regarding the payment schedule in the draft art agreement.

138 On 4 July 2018, she received another amended version of the draft art agreement from Mr McDonald and, in a separate document, a table that she had requested explaining the amendments he had made. She did not recall looking at the draft art agreement but she did look at the table of amendments as she wanted to be sure that they were telling the artist how MBL wanted to promote the campaign and the replica. Shortly afterwards, Ms Sheehan emailed Ms Hanlan to say that Mr McDonald’s documents looked fine to forward on to the artist.

139 On 4 July 2018, Ms Hanlan sent Mr McDonald’s revised version of the draft art agreement and the table of amendments to the artist.

140 She received emails from the artist on 5 and 10 July 2018, in which the artist, inter-alia, said that she had provided the documents to her lawyer, namely, Ms Wolff, for review.

141 On 14 July 2018, Ms Hanlan received an email from the artist copied to Ms Wolff attaching a revised draft art agreement. The email stated:

We did note that your legal team removed the no branding clause which we have replaced. I am under contractual obligation with State Street to include that language in our agreement and the clause will have to remain. For your protection, any promotion of the work and your event should emphasize that the work is a “gift” to the people of Australia and is being used to highlight the 15.3% gender discrepancy in pay. The required no branding clause would prohibit logo use in conjunction with the work but, certainly, the name of each and every contributor should be clearly spelled out.

Remember that Fearless Girl stands for supporting women in leadership positions, equality of women, equal pay, education of women, education in the work place for the prevention of prejudice and the general wellbeing of women. I am thrilled you are planning to tour with the work but, ask that in all cases she be used to promote these same gender diversity goals.

In regard to relative size of the artwork, Fearless Girl is 50 inches high and I am 5’9”.

Note that Fearless Girl is being produced in a limited edition of 25 as we discussed but, I also will make two Artist Proofs which will travel on loan. The Artist Proofs have been noted in the agreement.

On page 5, we’ve asked that I be apprised of the ceremony plans and that mention of the initial casting placed by State Street in New York. If I am speaking, I will handle that aspect.

142 She did not recall reading the revised draft art agreement on the basis that MBL’s lawyer would be dealing with that, but she did read the covering email. She recalled reading the artist’s comments that she was under an obligation with State Street (US) to include certain language in the draft art agreement, but Ms Hanlan did not understand the artist to be telling her that MBL could not use the replica in its campaign as planned. Ms Hanlan took the artist’s comments to mean that there would need to be some changes to the wording of the draft art agreement but that she was happy to go ahead with the sale to MBL.

143 Ms Hanlan saw the artist’s comment “The required no branding clause would prohibit logo use in conjunction with the work but, certainly, the name of each and every contributor should be clearly spelled out” and she wanted to clarify what she meant by that. Ms Hanlan expected MBL would want to use its logo and the logos of its partners in connection with the campaign, including on the plaque.

144 Ms Hanlan understood that the replica should be used to promote the gender diversity goals listed in the artist’s email, being “supporting women in leadership positions, equality of women, equal pay, education of women, education in the workplace for the prevention of prejudice and the general wellbeing of women”. Whilst MBL’s campaign was focused on gender pay parity, Ms Hanlan considered that all of the goals identified by the artist were parts of the same puzzle and that promoting each of those goals would assist with the aim of achieving equal pay.

145 Ms Hanlan was fine with the artist mentioning in her speech that the New York statue had been commissioned by State Street (US).

146 Ms Hanlan forwarded the artist’s email to Ms Sheehan on 17 July 2018. Ms Sheehan responded on 18 July 2018 to say she would have Mr McDonald review the amendments to the draft art agreement. The email stated:

I will ask Ian to look at this, but one thing I want to point out is the changes around use of the statue with branded material.

Below is a highlighted clause of what has been inserted, which will prevent us from using images of the statue on branded material – based on this wording we will not be able to use the image on our branded website or in brochures.

The artist says this is based on its contractual arrangements with State Street.

If not sure if this is going to be acceptable – can you please have a think about it?

I’ll copy you into my correspondence with Ian.

(1) The Artwork shall never be used, or authorized for use, as a logo or brand or on or in merchandising. The Artwork shall never be displayed on “branded” material, in any medium now know or hereafter devised, including without limitation any merchandise, products, or printed or electronic material, that features a trademark, service mark, trade name, tagline, logo, or other indicia identifying a person or entity except for Kristen Visbal or State Street Global Advisors or its affiliates.

(2) The Artwork may not be used in connection with gender diversity issues in corporate governance or in the financial services sector.

(3) The Artwork may notbe used by the Client for the promotion of any political party, politician, activist, or activist group.

For clarity, however: nothing in this clause prevents the Client or co-contributors to the cost of the Artwork from:

a. talking about the Artwork (including why it was purchased, what it represents to them, who has partnered with the purchase and how their purchase of the Artwork supports gender diversity goals); or

b. taking the Artwork on a roadshow within Australia and showing and discussing the Artwork in public (and particularly in regional and rural schools and communities).

147 Ms Sheehan drew her attention to wording in the draft art agreement that she thought would prevent MBL using images of the replica on its website or in brochures and asked her to consider if that would be acceptable. After reading Ms Sheehan’s email, Ms Hanlan thought that they needed to be really clear on how MBL wanted to promote the replica. Ms Hanlan thought that the best way forward was to put the onus back on the artist and set out in the draft agreement what MBL wanted to do with the replica to check if she would permit those uses.

148 On 18 July 2018, Ms Sheehan sent the artist’s email and attachments to Mr McDonald, copied to Ms Hanlan. The email stated:

Please see the attached response. Could you please review for us?

Rebecca is going to let us know her views on the changes to the branding clause – this may be a problem for us. Apart from this, can you please advise of any other significant changes?

149 Ms Hanlan followed with an email requesting clarity on what would be permitted under the revised draft art agreement.

150 Later that day, Mr McDonald responded saying that he thought the amendments would be “tricky” for MBL and its campaign partners, and suggested that Ms Hanlan provide examples of the ways in which MBL and its campaign partners would want to use the replica. He stated the following:

My initial reaction, however, is that the clause she (or State Street) is insisting upon is going to be tricky for you and the other organisations, and perhaps one way to respond might be to give examples of what you want to do and ask whether these would be OK under her view of the clause.

151 Sometime in the week commencing 23 July 2018, Ms Hanlan had a telephone conversation with the artist. Ms Hanlan could not recall the date of that call and she does not generally make file notes of her calls. However, she did recall some matters. The artist told her words to the effect that MBL would not be able to use the replica in a way that adopted Fearless Girl as its own brand or the brand of a campaign partner. Consistent with Ms Hanlan’s earlier views, her take on this was that MBL was not permitted to lock up its logo with the replica or images of it or use the words Fearless Girl to advertise its products or services. Ms Hanlan said to the artist that MBL intended to use the replica as part of its campaign, including promoting it on social media, putting it on the MBL website, using it in internal communications, creating a press release and promotional materials for an event or events and touring regionally and, potentially, nationally. Further, Ms Hanlan said that MBL had no intention of using the replica or the words Fearless Girl on products or to advertise its legal services. And the artist said to Ms Hanlan that she thought that should be fine.