FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Gardiner v Taungurung Land and Waters Council [2021] FCA 80

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 9 February 2021 |

THE COURT DIRECTS THAT:

1. The parties provide submissions on the question of the appropriate relief in light of the Court’s reasons for judgment, limited to 5 pages each, including submissions as to costs, and whether the question of relief should be determined on the papers or after a further oral hearing.

2. The respondents each file and serve submissions, limited to 5 pages, by 4pm on 23 February 2021.

3. The applicants file and serve submissions, limited to 5 pages, by 4pm on 9 March 2021.

4. The respondents file and serve any submissions in reply, limited to 3 pages, by 4pm on 16 March 2021.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MORTIMER J:

1 This is an application for judicial review of a decision by a delegate of the Native Title Registrar dated 30 April 2020, to register the Taungurung Settlement Indigenous Land Use Agreement under s 24CK(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). The Taungurung ILUA is an “area ILUA” under the Native Title Act and is a key component of a wider settlement under the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic). While the parties did not address in detail the precise effect of the ILUA according to its terms, it is apparent that the ILUA provides for the surrender of native title over the area it covers in certain circumstances and the extinguishment of that title; that no native title is being recognised by the agreement; and that no compensation is payable under the Native Title Act. In return the State of Victoria has agreed to provide a range of economic and non-economic benefits to those who fall within the definition of the “traditional owner group” in the ILUA, through a corporation established as part of the settlement. It is not in dispute that the ILUA is intended to preclude any future claims for, and determination of, native title over the ILUA area.

2 The applicants are each persons who claim to hold native title in parts of the ILUA area. An affidavit in support of the application described the applicants as follows:

(a) the first Applicant, Ms Margaret Gardiner, is a Ngurai Illum Wurrung, indigenous elder as well as Waywurru elder, for present purposes;

(b) the second Applicant, Mr Gary Murray, is also a Dhudhuroa, indigenous elder as well as an elder of the Yorta Yorta People;

(c) the third Applicant, Mr Vincent Peters, is a Ngurai Illum Wurrung, indigenous elder; and

(d) the fourth Applicant, Ms Elizabeth Thorpe, is a Ngurai Illum Wurrung, indigenous elder as well as Waywurru.

The application is supported by two affidavits from David Shaw, the solicitor for the applicants, the second correcting an omission in his first affidavit. Mr Shaw’s affidavits were not affirmed at the time of their filing on 11 June 2020 and 7 July 2020 respectively, but were accepted for filing in accordance with practice note SMIN-1, Special Measures in Response to COVID-19. Mr Shaw’s affidavits were subsequently affirmed on 17 June 2020 and 9 December 2020 and refiled on 9 December 2020.

3 For the reasons set out below, the judicial review application will be upheld on some grounds, but not all of them. The parties will have an opportunity to be heard on the question of appropriate relief after they have considered the Court’s reasons.

Background

4 The ILUA in dispute is the product of negotiations between the first respondent and the State that occurred for some years prior to its registration on 30 April 2020. It is part of a package of agreements between the Taungurung People and the State of Victoria forming part of a recognition and settlement agreement, entered into under s 4 of the TOS Act. As noted by Richards J in a decision in a related proceeding, Gardiner v Attorney-General [2020] VSC 224 (at [3]):

The settlement package is yet to be fully implemented. If and when that occurs, it will confer significant benefits on the Taungurung and its members. In particular, if the ILUA is registered, it will bind all persons holding native title in relation to any of the land or waters in the agreement area, who are not already parties to the agreement. Its effect will be to settle all native title claims in respect of the agreement area.

5 The first respondent, The Taungurung Land and Waters Council, is represented by First Nations Legal and Research Services. First Nations Legal is the Native Title Representative Body for Victoria, and receives Commonwealth funding to undertake this role pursuant to s 203FE of the Native Title Act. First Nations Legal is, accordingly, also a body which can certify the authorisation of an ILUA under s 203BE of the Act.

6 The ILUA was entered into on 26 October 2018. On 30 November 2018, First Nations Legal certified that the requirements in s 203BE(5)(a) and (b) had been met by the process leading to the agreement of the ILUA. The application for registration of the ILUA was made on 17 December 2018.

7 On 20 March 2019, the National Native Title Tribunal gave notification of the application to register the ILUA, in accordance with s 24CH of the Native Title Act.

8 On 6 June 2019, the solicitors for the applicants and certain other people, whom I will refer to as the objectors, wrote to First Nations Legal, stating that they intended to object to the registration on the bases that:

(a) the certification of the ILUA was “indistinguishable from the one held in Quall not to be a certification for the purposes of ss 24CG(3) and 203BE of the NT Act”, referring to the decision of the Full Court in Northern Land Council v Quall [2019] FCAFC 77; and

(b) the ILUA had not been authorised as required by s 251A of the Native Title Act, and so could not meet the conditions for proper certification under s 203BE of the Act.

The applicants requested that the application for registration be withdrawn.

9 On 20 June 2019, the applicants provided a letter of objection to the registration of the ILUA to the Native Title Registrar, noting in detail the objections they had previously provided to First Nations Legal.

10 First Nations Legal and the State each provided submissions to the Registrar in response to the objectors. These submissions are before the Court and are summarised below in the context of the summary of the delegate’s decision.

11 On 28 November 2019, the objectors submitted four affidavits, which had been filed in a related proceeding commenced in the Supreme Court of Victoria, to which I refer below.

12 On 30 April 2020, the Registrar’s delegate registered the ILUA under s 24CK of the Native Title Act. It remained registered at the time of trial and the time of the publication of these reasons for judgment. There was no challenge to the delegation by the Registrar of the exercise of power under s 24CK.

Related proceeding in the Supreme Court of Victoria

13 Prior to, and then concurrently with, the proceedings in this Court, judicial review proceedings were instituted in the Supreme Court of Victoria in relation to the recognition and settlement agreement. Three of the four plaintiffs in that proceeding are applicants in this proceeding. Consistently with their case in this proceeding, and amongst other claims, the applicants in the Supreme Court dispute that the Taungurung are the correct traditional owners (and native title holders) of the entire area covered by the recognition and settlement agreement. On 18 August 2020, Richards J determined that the Supreme Court proceeding be stayed until after the determination of the proceeding filed in this Court: Gardiner v Attorney-General (No 3) [2020] VSC 516.

Part A Threshold Statement request

14 As part of the process under the TOS Act, First Nations Legal’s predecessor, Native Title Services Victoria, on behalf of the Taungurung People, had prepared a Part A Threshold Statement under that Act and provided it to the State. That document was subject to a notice to produce in the Supreme Court proceeding, and became subject to an interlocutory judgment after the State refused to produce the document because it had been provided on a confidential basis: Gardiner VSC. Richards J described the document as follows (at [16]-[17]):

The Statement was prepared for and submitted on behalf of the Taungurung to formally initiate negotiations with the State for an agreement under the Settlement Act. It was prepared as required by the ‘Threshold Guidelines for Victorian traditional owner groups seeking a settlement under the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010’, published in 2013 by the Native Title Unit of the then Department of Justice. The Guidelines set out a process for traditional owner groups to seek entry into negotiations with the State towards a settlement under the Settlement Act, by lodgement of a threshold statement. They also set out the threshold matters to be addressed, and the process for the State’s consideration of a threshold statement.

The Guidelines contemplate that a threshold statement will be prepared in two parts. The Part A threshold statement is to contain six items:

A1. Statement of intent to negotiate

A2. Traditional owner group statement of association to country

A3. Description and basis of traditional owner group

A4. Description and basis of proposed agreement area

A5. Research process overview, chronology and findings

A6. Traditional owner group decision-making

(Footnotes omitted.)

15 Richards J made orders dated 1 May 2020 that the Part A Threshold Statement be provided to the Supreme Court, with leave to be given to the solicitors for the plaintiffs in the Supreme Court proceeding to inspect and copy the statement. The orders required that if the document was provided to the plaintiffs, they be required to undertake to maintain the confidentiality of the document and to not use the document or the information in it other than for the purposes of the Supreme Court proceeding. The result is that, at the time of the hearing in this Court, the applicants are aware of the contents of the Part A Threshold Statement, but the document is not before the Court in this proceeding.

16 The applicants did not however have access to the contents of this document at the time of the delegate’s decision on 30 April 2020. They did have access to a summary version. In 2014, a “summary threshold statement” was prepared, and published by the Victorian Department of Justice, inviting responses from the Victorian traditional owner community. There was no dispute in this proceeding that the applicants have had access to the summary threshold statement and it is before the Court in this proceeding.

17 During the ILUA notification period, on 7 November 2019, the solicitors for the applicants wrote to the Registrar, providing the applicants’ objections to the registration of the ILUA. Among other things, the letter noted that the Part A Threshold Statement was (at that time) subject to a notice to produce in the Supreme Court proceeding and that the State had resisted production. The applicants’ solicitors submitted that

the Registrar should request FNLRS and the State of Victoria to produce the Part A Threshold Statement and, on its provision, allow the objectors an opportunity to comment on its contents.

18 The letter submitted that the Part A Threshold Statement was

the fundamental document upon which the proponents of the ILUA must rely to assert that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the area covered by the agreement have been identified.

19 The letter also made the following submissions:

In our view, the production of the Part A Threshold Statement would demonstrate the extent and quality of the research underpinning the ILUA in question and the efforts made to identify the Native Title claimants. As matters stand, apart from assertions made on behalf of the Taungurung Group and the brief research paper enclosed with the submissions made by FNLRS, no research material has been put before the Registrar to enable the Registrar to be satisfied that ‘all reasonable efforts’ have, in fact, been made.

Further, in considering whether ‘all reasonable efforts’ have been made for the purposes of s 203BE(5)(a) and (b) of the NTA, in light of White J’s comments in Bright extracted above to the effect that each case must be determined by its own circumstances, the Registrar, we submit, must bear in mind that the proposed Taungurung ILUA covers in excess of 8% of the land mass of the State of Victoria, i.e. an area of 20,210 square kilometres. The proponents of the Taungurung ILUA rely on the efforts of the respective proponents of the ILUA in the Bright and Kemppi cases to suggest that what amounted to ‘all reasonable efforts’ in those cases should be sufficient in this case. In our submission, this is misleading. The ILUA in issue in Bright concerned an area of land 10 square kilometres. The ILUA in issue in Kemppi concerned an area of land about 27.5 square kilometres. In this case, the proponents must, in light of the sheer size of the agreement area and the considerable implications for so many Victorian traditional owners, be held to a higher standard than was acceptable in the small agreement areas in the Bright and Kemppi cases.

20 The cases referred to in this extract are Bright v Northern Land Council [2018] FCA 752 and Kemppi v Adani Mining Pty Ltd (No 2) [2019] FCAFC 117.

21 The delegate noted this submission in her reasons at [94]. She stated:

I note that some objectors have suggested I should require First Nations to produce the Threshold Statement that was provided to the State on a confidential and without prejudice basis during the Settlement Act negotiations, and the information contained in the database maintained by First Nations. Further, there are assertions that the database does not distinguish between Taungurung and Ngurai Illum and that there is no evidence about how the database was compiled and what steps were taken to test the claims made by the people that they had native title over the land. As mentioned earlier, the onus here is on the objectors to satisfy me that the requirements of s 203BE(5)(a) are not met, and not on First Nations or any other party. I also note that First Nations has done extensive research into the composition of the Taungurung group, holds a genealogical register, and has also indicated that membership required more than blood descent for a person to retain rights and interests over a particular area. I understand that those people on the database met these criteria or have been verified through these means.

Finding

22 I find that the applicants were not provided with the Part A Threshold Statement at any time prior to the decision of Richards J on 1 May 2020, and so did not have access to a copy of the Part A Threshold Statement during the notification and objection process in 2019. I find also that the applicants made clear submissions to the Registrar that the document was central to the Registrar’s task, and to their ability properly to exercise their rights under s 24CI of the Native Title Act to object to the registration of the ILUA.

Application for extension of time

23 On 11 June 2020, the applicants filed an application for an extension of time under r 31.02 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) to lodge an application for review under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth). The application was accompanied by a supporting affidavit affirmed by Kylie Maree Rodman on 10 June 2020. It is unnecessary to consider at length the grounds for the application for extension of time, because the extension sought was of only four minutes. Ms Rodman’s affidavit stated that this brief delay in filing the application for judicial review was due to delays caused by her working from home, without access to the usual IT infrastructure of her office, also as a result, I infer, of the COVID-19 pandemic.

24 On 8 July 2020, I made orders extending the time for filing the originating application under s 11 of the ADJR Act. The application was subsequently filed on 17 July 2020.

The legislative scheme

25 For an ILUA to be registered, a decision such as that under review in this proceeding is required by ss 24CJ and 24CK of the Native Title Act, which provide:

24CJ Decision about registration

The Registrar must, after the end of the notice period, decide whether or not to register an agreement covered by an application under this Subdivision on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements. However, in a case where section 24CL is to be applied, the Registrar must not do so until all persons covered by paragraph (2)(b) of that section are known.

24CK Registration of area agreements certified by representative bodies

Registration only if conditions satisfied

(1) If the application for registration of the agreement was certified by representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies for the area (see paragraph 24CG(3)(a)) and the conditions in this section are satisfied, the Registrar must register the agreement. If the conditions are not satisfied, the Registrar must not register the agreement.

First condition

(2) The first condition is that:

(a) no objection under section 24CI against registration of the agreement was made within the notice period; or

(b) one or more objections under section 24CI against registration of the agreement were made within the notice period, but they have all been withdrawn; or

(c) one or more objections under section 24CI against registration of the agreement were made within the notice period, all of them have not been withdrawn, but none of the persons making them has satisfied the Registrar that the requirements of paragraphs 203BE(5)(a) and (b) were not satisfied in relation to the certification of the application by any of the representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies concerned.

Second condition

(3) The second condition is that if, when the Registrar proposes to register the agreement, there is a registered native title body corporate in relation to any land or waters in the area covered by the agreement, that body corporate is a party to the agreement.

Matters to be taken into account

(4) In deciding whether he or she is satisfied as mentioned in paragraph (2)(c), the Registrar must take into account any information given to the Registrar in relation to the matter by:

(a) the persons making the objections mentioned in that paragraph; and

(b) the representative Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander bodies that certified the application;

and may, but need not, take into account any other matter or thing.

26 Thus, the Registrar or her delegate has a binary choice under s 24CK. If the statutory conditions are met, she must register the ILUA. If they are not, she must not register the ILUA.

27 The certification function to which s 24CK(1) refers is, relevantly, the following part of s 203BE:

Certification of applications for registration of indigenous land use agreements

(5) A representative body must not certify under paragraph (1)(b) an application for registration of an indigenous land use agreement unless it is of the opinion that:

(a) all reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that all persons who hold or may hold native title in relation to land or waters in the area covered by the agreement have been identified; and

(b) all the persons so identified have authorised the making of the agreement.

28 The meaning of the condition in s 24CK(2)(c), and its application to the facts, is central to the applicants’ arguments on judicial review.

The Delegate’s Decision

29 The decision of the delegate of the Registrar set out the chronology prior to the registration decision as follows (at [2]-[9]):

On 20 October 2018, a meeting was held at Camp Jungai in Rubicon, Victoria to authorise the Taungurung Settlement ILUA (authorisation meeting).

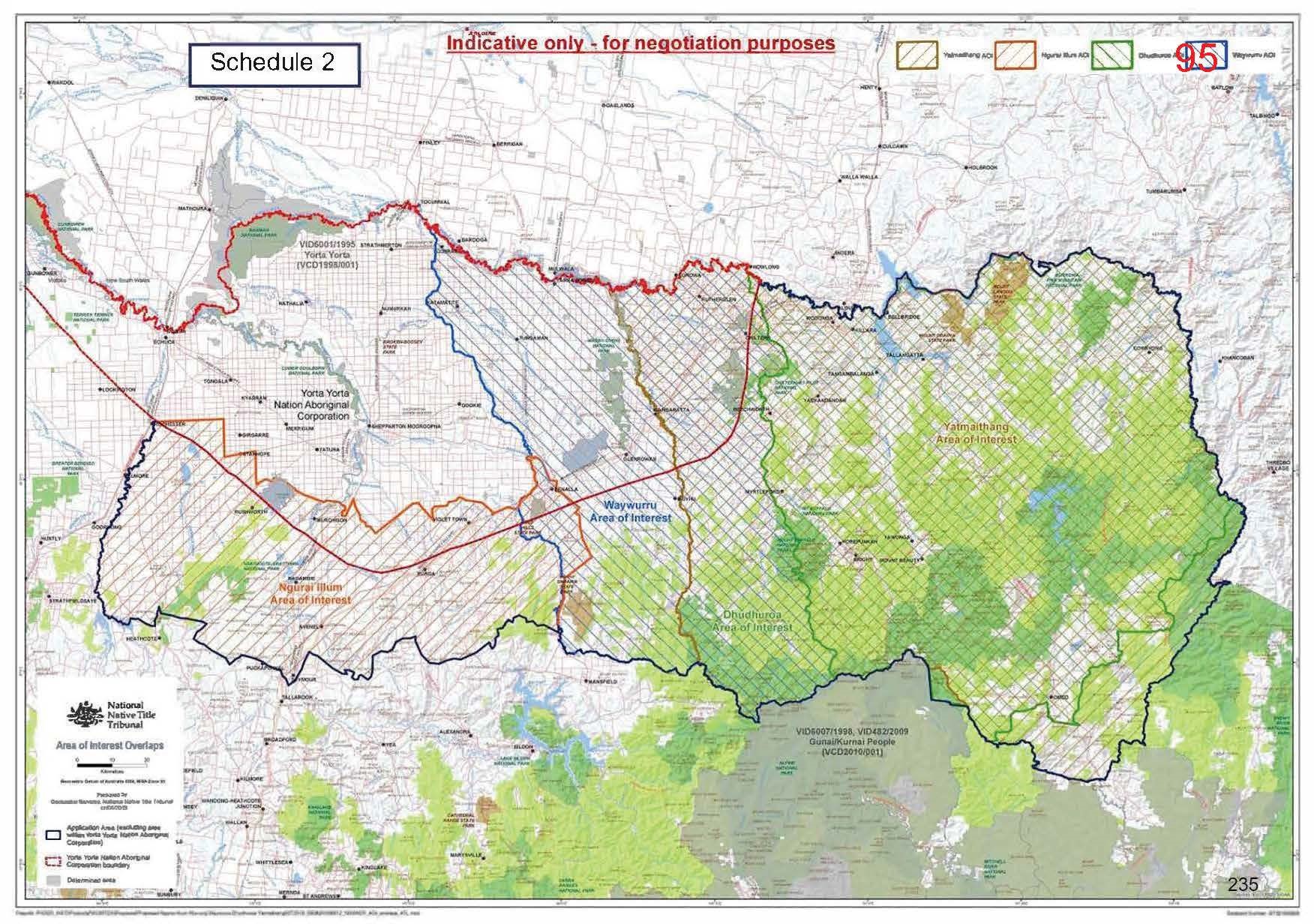

On 17 December 2018, an application was made to the Registrar, pursuant to s 24CG(1) of the Act, for the registration of the Taungurung Settlement ILUA as an area agreement ILUA (see ss 24CA to 24CE). The area covers about 20,210 square kilometres and comprises land and waters south of the Murray River from Rochester to Wangaratta to the Great Dividing Range.

On 25 February 2019, I decided that the Registrar was required to give notice of the agreement, pursuant to s 24CH, because the procedural requirements for notification of the agreement had been met. It is not disputed that the application complied with the procedural requirements for notification and that the Registrar was thus obliged to notify the agreement.

The notice period commenced on 20 March 2019, and between 24 April to 20 June 2019, objections against the registration of the agreement were received from persons claiming to hold native title in the agreement area.

On 20 May 2019, the objectors and the parties were advised that the Registrar was considering the impact of the Full Federal Court’s decision in Northern Land Council v Quall [2019] FCAFC 77 (Quall) and that while undertaking such consideration, the delegate would stay the procedural fairness process in relation to each objection received. The parties were advised that the delegate was of the view that she was required to continue to assess the validity of any further objections that were made and that the procedural fairness for any prima facie valid objection would also be stayed. The parties were also requested to advise the delegate of their proposed course of action if they considered the Full Court’s decision would adversely affect the ability of the agreement being registered as an ILUA.

On 20 June 2019, the notice period for the agreement ended.

In the period from 2 August 2019 to 28 February 2020, the procedural fairness steps outlined in Attachment A were taken.

In November 2019, December 2019 and February 2020, the objectors and the parties were advised that, in my view, a fair opportunity had been provided for all relevant persons to comment on the objections and the responses received in relation to them, and that I would proceed to make a decision.

(Footnotes omitted.)

30 Some of the objections referred to in paragraph [5] of the delegate’s decision were objections raised on behalf of the applicants in this proceeding. The “procedural fairness steps” taken by the delegate were described in Attachment A to the delegate’s decision:

• On 24 April 2019, the Registrar received an objection against registration of the agreement from Mr Freddie Dowling.

• On 25 April 2019, the Registrar received an objection from Dr Judith Crispin.

• On 9 May 2019, the Registrar received an objection from Ms Michelle Carlon.

• On 20 May 2019, the objection by Dr Crispin was provided to First Nations as the native title service provider and the representative of the Taungurung Signatories and the Taungurung Clans Aboriginal Corporation, and the Victorian Government Solicitor’s Office as the representative of the State of Victoria. First Nations and the State of Victoria were also informed, by a separate letter of the objection by Mr Dowling but were advised that he had been given an opportunity to provide additional information to support his objection and that his legal representative, Mr Matthew Pudovskis had requested a copy of the application for registration to progress the objection.

• On 22 May 2019, the Victorian Government Solicitor’s Office confirmed that the parties agreed to only a copy of the certification of the application to be provided to Mr Dowling’s representative. The Victorian Government Solicitor’s Office also queried whether there would be a change to the registration process being undertaken in relation to the application following the decision of the Full Federal Court in Quall handed down on 20 May 2019.

• On 24 May 2019, the objectors and the parties to the agreement were informed that the application for registration may be affected by the Full Court’s decision in Quall and that the procedural fairness process had been stayed in relation to each objection until the Registrar had considered the implications of the decision. The parties were also informed that the delegate would continue to assess the validity of any further objections received and objections that were prima facie valid would also be stayed. The parties were requested to advise their proposed course of action if they considered the Full Court’s decision would adversely affect the ability of the agreement being registered as an ILUA.

• On 11 June 2019, the Registrar received an objection from Mr Darren Atkinson.

• On 17 June 2019, the Registrar received an objection from Mr Alan Dowling.

• On 19 June 2019, objections were received from Ms Nicole Atkinson, Ms Porsha Atkinson and Mr Kevin Atkinson.

• On 20 June 2019, objections were received from Mr Robert Nicholls and Professor Henry Atkinson.

• On 2 August 2019, the objections and supporting material, including letters of support of some of the objections, were provided to First Nations and the Victorian Government Solicitor’s Office.

• On 30 August 2019, in response to the objections, three submissions were received from First Nations responding to the objection of Mr Freddie Dowling, the objectors represented by Holding Redlich and other objectors (collectively the Bangerang and Wollithiga objectors).

On 10 September 2019, the State responded to the objections, also providing three submissions. A copy of the responses by First Nations and the State were provided to the objectors on 3 and 10 September 2019. The objectors were also provided with a copy of First Nations’ certificate pursuant to s 203BE of the Act which accompanies the application for registration.

• On 23 September 2019, Mr Alan Dowling provided a response to the submissions by First Nations, the State’s Comments and Attachment B to the State’s Comments (A Dowling’s Response).

• On 23 September 2019, Mr Kevin Atkinson, Mr Darren Atkinson, Ms Nicole Atkinson, and Ms Porsha Atkinson provided a document titled ‘Response to State of Victoria’s Comments on the Bangerang and Wollithica Objections’ (Atkinson’s response to State’s Comments) and a Parliament of Victoria First Session response by the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs.

• On 24 September 2019, Mr Kevin Atkinson, Mr Darren Atkinson, Ms Nicole Atkinson, and Ms Porsha Atkinson provided a document titled ‘Our Objectors Responses\To the FNLRS Response’ (Atkinson’s response to First Nations).

• The material received on 23 and 24 September 2019 was not provided to First Nations and the State for further comment as in my view the objectors did not raise new matters that required comment and a fair opportunity had been provided for all relevant persons to comment on these objections.

• On 7 October 2019, Mr Matthew Pudovskis provided a submission on behalf Mr Freddie Dowling, responding to the matters raised by First Nations and the State in their responses.

• On 7 November 2019, Holding Redlich provided a submission on behalf of its clients responding to submissions from the First Nations and the State.

• The objectors and the parties were advised that in my view the objectors represented by Holding Redlich did not raise new matters within the additional material provided that required further comment and that a fair opportunity had been provided for all relevant persons to comment on the objections. There was further correspondence in relation to this, and on 28 November 2019, Holding Redlich provided a letter enclosing four affidavits filed and served in the Supreme Court of Victoria proceeding.

• On 22 November 2019, the State provided comments in response to the submissions made on behalf of Mr Freddie Dowling.

• On 6 December 2019, First Nations provided a response to the submissions made on behalf of Mr Freddie Dowling.

• In response to these submissions, further submissions was provided by Mr Pudovskis on behalf of Mr Dowling on 21 January 2020.

• The parties were asked whether they wished to comment on the recent decision in McGlade No 2 and any other matter. The State and First Nations provided responses on 10 and 18 February 2020 respectively.

• On 28 February 2020, Mr Pudovskis provided submissions on behalf of Mr Dowling in response to the parties’ submissions.

• This material received in support of Mr Freddie Dowling’s objection was not provided to First Nations and the State for further comment as in my view the objectors did not raise new matters within the additional material provided requiring comment and because a fair opportunity had been provided for all relevant persons to comment on the objection.

31 From [10]-[13] the delegate considered the information to which she must have regard. From [14]-[17] the delegate set out the relevant text of ss 24CJ and 24CK.

32 The delegate considered (from [18]-[26]) the threshold question of whether the agreement was an ILUA within the meaning of that term in the Native Title Act. At [27], she concluded the agreement met the requirements of ss 24CB to 24CE and was an ILUA within the meaning of s 24CA of the Native Title Act. The applicants do not dispute that this was the correct conclusion.

33 The delegate then went on to consider the two conditions required by s 24CK, the first condition being that in s 24CK(2), (set out above at [25]). The delegate noted the mandatory nature of the requirement in s 24CK at [28]:

If the conditions of s 24CK(2) and (3) are satisfied, I must register the agreement and if they are not satisfied, I must not register the agreement: see s 24CK(1).

The first condition: s 24CK(2)

34 This condition is concerned with objections against registration of the agreement. From [31]-[37], the delegate considered whether the objections made were valid, and concluded that each objection was valid. From [38]-[45] the delegate considered the nature of the task required by s 24CK(2)(c) and stated:

I understand that the condition in s 24CK(2)(c) will be met unless the Registrar is satisfied that the requirements of paragraphs 203BE(5)(a) and (b) were not satisfied in relation to the certification.

[Having set out s 203BE(5)]

Although s 203BE(5) states that ‘[a] representative body must not certify under paragraph 1(b) an application for registration of an indigenous land use agreement unless it is of the opinion that …’, the relevant test is at s 24CK(2)(c).

35 The delegate then considered a number of authorities of this Court, in particular the decisions in Corunna v South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council [2015] FCA 491; 235 FCR 40 at [61]; Bright at [49] and Kemppi at [79] and [84]. The delegate described these decisions as having the effect that “the objectors have the onus of satisfying the Registrar that one or both of the requirements in s 203BE(5)(a) and (b) were not met”. The delegate noted the objectors’ submission

that the onus is on the Taungurung claim group and the State to demonstrate that ‘all reasonable efforts’ were made to identify persons who hold or may hold native title in the agreement area. There have been other similar assertions.

(Footnotes omitted.)

36 On the basis of the authorities cited above, the delegate rejected this submission and confirmed her view that “the test at s 24CK(2)(c) directs the Registrar specifically to paragraphs 203BE(5)(a) and (b) and their substantive provisions”.

37 The delegate then turned to consider whether there was valid certification as required by s 203BE(5). At [48], the delegate set out a detailed summary of the assertions made by objectors challenging the validity of the certification. Many concerned the application of the decision in Quall FCAFC. At [49] the delegate set out a summary of the State and the TLWC’s alternative contentions. The delegate concluded at [50]-[51]:

Following the Full Federal Court’s decision in Quall, the validity of the certification of the agreement has been brought to my attention. However, the subsequent decision of the Full Court in Kemppi FC has confirmed that when an objection to the registration of an agreement as an ILUA is made, the task before the Registrar is to consider afresh whether the requirement of s 203BE(5)(a) and (b) have been satisfied. The task is not to review the certification generally. In particular, the Full Court stated:

The validity or correctness of the certificate that QSNTS [the relevant representative body] gave under s 203BE(5) and (6) was not a statutory condition of the Registrar’s power and duty to register the Adani ILUA if, as occurred here, there was an objection under s 24CI. That is because in such a case, s 24CK(2)(c) required the delegate to consider whether “in relation to the certification”, she was satisfied that the requirements of s 203BE(5)(a) and (b) had not been met. In other words, the Registrar, under s 24CK(2)(c), is not considering the opinion of the representative body, but only whether he or she is satisfied that the requirements of each of pars (a) and (b) in s 203BE(5) have not been met.

Accordingly, I do not consider it my task to determine the validity of the certification.

38 The delegate then considered each of the elements of s 203BE(5)(a) and (b) and asked whether the objectors had satisfied her that the requirements of those paragraphs were in fact not met. Not all of the objections made are relevant to the grounds of review in this proceeding.

Sub-s 203BE(5)(a)

39 Relevantly, the delegate summarised the objectors’ submissions (referring to them as the “Holding Redlich objectors”) at [69]. The delegate set out in some detail the objectors’ claims to hold native title in the area, and their claims that the TLWC and First Nations Legal failed to make reasonable efforts to ensure that all persons who hold or may hold native title in the agreement area were identified. The delegate’s summary was:

• First Nations’ database does not distinguish persons identifying themselves as Taungurung or Ngurai Illum. The objectors and their family members attended the authorisation meeting with proxies from 186 people who were descendants of the Taungurung apical ancestors and who were unable to attend in person. Following the motion to accept the proxies being defeated, First Nations took no steps to make enquiries with the 186 people who wished to be involved in the agreement making process. By restricting the agreement making process to approximately 150 people on its database, First Nations prevented others who hold or may hold native title from being identified.

• Ms Thorpe, Mr Peters and Ms Layton, and their families, were not contacted by First Nations and did not see any notice of the authorisation meeting. Mr Peters and Ms Layton’s attempts to engage with First Nations about the Taungurung claim, such as their research of inclusion of apical ancestors, have been disregarded, and after hearing of the meeting from a third party, Ms Layton attempted to contact representatives of the Taungurung claim group who refused to engage with her.

• The notices given of meetings were not published in a way which reached interested parties and did not alert the Ngurai Illum that the proposed agreement applied to them.

40 At [70] the delegate set out First Nations Legal’s response to these objections:

• The contention that First Nations’ database did not distinguish between people identifying as Taungurung and Ngurai Illum is irrelevant. The particulars of their identity or purported membership of a particular group is not a requirement of the Act.

• Contrasting the number of proxies collected as opposed to the number of people on the database does not indicate whether ‘reasonable efforts’ were made to identify native title holders as the database was not the only basis through which First Nations sought to comply with s 203BE(5)(a). The meeting was publically advertised in relevant newspapers to reach potential native title holders beyond the database.

• The database has been developed through a period of research, from which approximately 150 entrants were identified, with most having a long association with the Taungurung group. Approximately 100 people attended the authorisation meeting, who were required to go through a registration process identifying their lines of descent before they could enter. This was done with the assistance of First Nations research staff and with reference to a genealogical register, and where any dispute or uncertainty arose, other Taungurung people were on hand to assist and verify lines of connection.

• The identity of those who purportedly provided proxies have not been provided and no explanation has been provided how their identity or descent were verified or could be verified, or how they are reasonably considered to hold or may hold native title rights. The objection provides no details beyond descent from an apical ancestor, when traditional owner groups (including the Taungurung) commonly require more than blood descent to retain rights and interests over a particular area. Those persons have also not separately made objections.

• The proxies may provide some probative value as to the efforts made to identify native holders. The objectors made considerable efforts to identify native title holders by:

• Contacting at least 186 people who they considered may hold native title rights, advising them of the meeting, and then obtaining their proxy if they declined to attend;

• Actively promoted the meeting on Facebook, and encouraged attendance in support of their position opposing the recognition and settlement agreement; and

• Arranged for the hire of a coach to drive from Melbourne to the location of the authorisation meeting (with funding provided by First Nations).

• These efforts did not result in the attendance of substantial numbers of native title holders who supported their position but did increase the awareness of potential native title holders, giving them the opportunity to participate. This contradicts the assertions that the authorisation meeting was improperly notified or that it proceeded without the knowledge of a large group of native title holders. First Nations was entitled to take these efforts into account when assessing if ‘all reasonable efforts’ had been made, although the efforts of the objectors are legally insignificant compared with the efforts of TLWC ensuring notice was provided to its approximately 300 members.

• It was unlikely that there was any reasonable expectation the proxies would be accepted, making attendance in person was necessary, as the reliance on the proxies was not advised until 4:48pm the afternoon prior to the authorisation meeting. To First Nations’ knowledge, proxies have never been accepted in any meeting dealing with rights and interests, and in any event ILUAs must be authorised using a decision making process under s 251A. The map in the public notice showed that the proposed agreement area overlaps the area claimed by the Ngurai Illum by about 30 – 40%, making it apparent that the proposed agreement may impact upon those interests asserted by the objectors on behalf of the Ngurai Illum. In addition, it is clear that each of the objectors were subjectively so aware.

• Ms Thorpe, Mr Peters and Ms Layton were all aware of the authorisation meeting, and attended and participated, despite not being on the database or seeing the public notifications. Mr Peters also attended several information sessions held before the authorisation meeting, and with Ms Thorpe, he met with Taungurung representatives, the lawyer with carriage of the matter, and the principal researcher on 12 October 2018 at First Nations’ offices. Ms Thorpe and Ms Layton also actively participated in the decision making process at the authorisation meeting, although they opposed the decision that was made.

• First Nations, the Taungurung, and others made significant efforts over many years, which included research and open full group meetings, the public notification and objection process under the Settlement Act, public and personal notification of the authorisation meeting, and efforts of the objectors to notify 186 people directly and on social media. This contributed to the widespread knowledge of the proposed ILUA, and the ability of people who hold or may hold native title to participate in the authorisation process.

41 At [71] the delegate set out the State’s response to the objections, which noted that the State had also made an attempt to contact Ms Gardiner and Mr Murray, through letters sent to them as individuals and also to Dhudhuroa Waywurru Aboriginal Corporation (of which Mr Murray is Chairperson).

42 At [72] the delegate summarised the objectors’ responses to the submissions by the First Nations Legal and the State. The objectors’ response relevantly included contentions that:

(a) the Registrar should require the Part A Threshold Statement and First Nations Legal’s database to be produced to them.

(b) that the ILUA should be distinguished from those considered in Bright and Kemppi FC because the area of land in question is significantly larger, and so the standard for “all reasonable efforts” ought to be higher.

(c) the status of the objectors as representatives of their families and groups was important, and that inferences of opposition to the ILUA could be drawn from the existence of the 186 attempted proxy votes.

(d) the onus was on those seeking registration of the ILUA to demonstrate that all reasonable efforts were made to identify native title holders.

43 After setting out the submissions regarding further objections by individuals not involved in this proceeding, the delegate considered whether, in light of the objections, the requirement that “all reasonable efforts” be made to identify people who hold or may hold native title had been satisfied. Relying on the reasons of White J in Bright, the delegate found that whether the criterion was satisfied was a question of fact, to be determined by reference to the circumstances. Citing QGC Pty Ltd v Bygrave (No 3) [2011] FCA 1457; 199 FCR 94 the delegate stated (at [82]):

the expression ‘persons who hold or may hold native title’ in s 24CG(3)(b)(i) is directed ‘to all of the different sets of native title rights and interests that may be held in the area covered by the agreement’ and may refer to those rights and interests that have been recognised formally and those that have no formal recognition. This can include persons who ‘by any means makes a claim to hold native title’. His Honour considered that the expression ‘in s 24CG(3)(b)(i) is to be construed expansively and inclusively’ however it must be ‘reasonable to conclude that person, group, or community holds native title, in any part of the area covered by the agreement [emphasis added]’.

44 Having considered other authorities on the interpretation of s 203BE(5)(a), the delegate concluded at [85]:

In light of the above, I understand the requirement is that ‘all reasonable efforts have been made’, which directs s 203BE(5)(a) to the efforts made and whether they can be considered reasonable in the circumstances. I am not required to consider whether all potential native title holders have been identified or whether I agree with the views formed by the representative body about ‘all persons who hold or may hold native title’ in relation to the land and waters covered by the agreement area. Rather, it is whether the material shows that those views were shaped as a consequence of reasonable efforts. To satisfy me that all reasonable efforts have not been made would require the objectors to show that the efforts to ensure all persons who hold or may hold native title in the area have been identified were wanting such that the efforts and subsequent views cannot be said to be reasonably based.

45 At [86]-[99] of her reasons, the delegate applied this understanding of the test to the circumstances before her. This included her response regarding the objectors’ request that the Part A Threshold Statement be made available to them, as discussed above. The delegate noted that First Nations Legal had undertaken “substantial anthropological, archival, historical and genealogical research” into “consideration of the composition of the landowning group and the apical ancestors of the group” (at [86]). She found that this process included:

(a) a detailed notification and consultation process under the TOS Act, including contacting various aboriginal and traditional owner entities by letter;

(b) notification of the authorisation meeting in five newspapers; and

(c) requiring that the people who attended the authorisation meeting undergo a registration process before attending, identifying their lines of descent.

46 The delegate then found (at [96]-[99]:

It is also asserted that some of the objectors were not given an opportunity to decide whether to be included in the Taungurung claim and to engage in any research undertaken by First Nations. I consider that opportunities were provided during the Settlement Act process where the objectors or the bodies that represent their interests were invited to participate, and have their submissions considered and investigated. The objectors were also given an opportunity to engage by attending meetings of the Taungurung, including the authorisation meeting.

On the basis of the efforts outlined above, First Nations formed the view that ‘all persons who hold or may hold native title’ in relation to the agreement area include members of the Taungurung People.

In the circumstances here, the claims to hold native title over the area were the subject of reasonable and comprehensive enquiries by First Nations which resulted in that body identifying the Taungurung People. The persons who therefore needed to be identified for the purpose of authorising the agreement were the Taungurung People. The objectors have therefore not satisfied me that all reasonable efforts were not made by First Nations in the circumstances here.

It follows that the objectors have not satisfied me that the requirements of paragraph 203BE(5)(a) were not satisfied.

Sub-s 203BE(5)(b)

47 The delegate then asked herself if the objectors had shown that the requirements of s 203BE(5)(b) were not satisfied.

48 Section 203BE(5)(b) requires that the persons identified under s 203BE(5)(a) authorised the making of the agreement. At [102], the delegate extracted the relevant statements from First Nations Legal’s certificate:

All the persons so identified have authorised the making of the agreement: 203BE(5)(b)

17. During negotiations with the State of Victoria, First Nations sent updates to the people listed on the Database for the Taungurung native title claim group, and presented at meetings of the native title group, in relation to the progress of those negotiations (particularly during 2017 and 2018, leading up to finalisation of negotiations).

18. First Nations also arranged five information sessions during the month prior to the authorisation meeting to provide an opportunity for the people who hold, or may hold, native title in the proposed Taungurung ILUA area to learn about the proposed settlement package (including the terms of the Taungurung ILUA) and to ask questions. Details of the information sessions were contained in the same notice in which the authorisation meeting was notified on 24 September 2018, and again in the reminder notices of 3 October 2018, and 11 October 2018.

19. In addition First Nations produced a forty-eight page plain-English guide to the proposed settlement. A copy of this document was sent to every person on the Database along with the reminder notification sent 3 October 2018, and further copies were available at the information sessions and the authorisation meeting.

20. First Nations also produced a further six page plain-English short-form guide to the settlement. A copy of this document was sent to every person on the Database along with the reminder notification sent 11 October 2018, and further copies were available at the remaining information session and the authorisation meeting.

21. First Nations staff arranged, attended and presented at the authorisation meeting held on 20 October 2018 in Rubicon for entry into the Taungurung ILUA and other agreements.

22. First Nations offered reasonable travel assistance for people to attend the meeting.

23. Those in attendance at the authorisation meeting resolved to employ an agreed and adopted decision making process to authorise entry into the Taungurung ILUA and other agreements.

24. The Taungurung ILUA and other agreements were authorised in accordance with the agreed and adopted decision making process, including a direction to the Taungurung Signatories to execute the Taungurung ILUA.

49 The delegate then summarised the objectors’ contentions, including, from [104], the contentions of the applicants:

In the objection of 20 June 2019, the following assertions are made:

• There was a defect in the authorisation of the agreement by TLWC, which is currently the subject of proceedings before the Supreme Court of Victoria.

• It was incorrectly decided at meetings on 14 July 2012 and 10 August 2013 that the Ngurai Illum should be treated as a subgroup of the Taungurung and their ancestors, including Tooterie, be added as Taungurung ancestors. Tooterie previously was not considered a Taungurung ancestor.

• The proposed recognition and settlement agreement, together with the proposed ILUA, provided that the Taungurung People consist of persons descended from 12 apical ancestors, including Tooterie, associated with Taungurung country.

• The draft minutes from the 20 October 2018 authorisation meeting record the following:

• Verification of attendees entitled to participate in the authorisation meeting as descendants of the 12 apical ancestors checked against a genealogy (item 6);

• Adoption of an agreed decision making process (resolution 2);

• Removal of Tooterie as an apical ancestor (resolution 10);

• Authorisation of the making of the ILUA and the recognition and settlement agreement, and of an application to have the ILUA registered under the Act (resolution 13);

• Authorisation of TCAC to be the traditional owner group entity, on behalf of persons who hold or may hold native title in the area, for the purposes of managing benefits under the ILUA and Settlement Act, and to formally enter into the agreements (resolution 15).

• The minutes record that no action was taken to limit authorisation to the descendants of the remaining 11 apical ancestors or to reduce the agreement area by Tooterie’s country.

• Accordingly, there was not a single group, as required under the Settlement Act, in relation to who may authorise the ILUA under s 251A of the Act. Therefore, there was not, within the meaning in s 251A, a single authorising decision as purported to occur at the authorisation meeting, binding both the Taungurung and Ngurai Illum.

• Alternatively, those in the reconstituted Taungurung group descended from 11 apical ancestors could not comprise all the persons who hold or may hold native title in the area who may authorise the making of an ILUA under s 251A. If Tooterie descendants are not persons who hold or may hold native title in the area, then authorisation of the ILUA was purportedly given by persons other than those who hold or may hold native title.

• A number of the objectors have been aware of the Taungurung agreement making process for some time. They have attempted to engage with the Taungurung to voice their objections, however, First Nations has not facilitated that process and the Taungurung has rejected the objections. Since at least 2011, a number of the objectors have attempted to raise their objections to the boundaries of the agreement area and/or inclusion of their ancestors as Taungurung ancestors, including by attending Taungurung full group meetings or through the Settlement Act process, but such concerns have been met with hostility and/or disregarded.

• Since October 2017, Holding Redlich has corresponded with the Department of Justice and Regulation, First Nations, the Hon Martin Pakula MP (then Victorian Attorney-General), the Victorian Government Solicitor’s Office and the Hon Jill Hennessy MP (Victorian Attorney-General) to express the objectors’ concerns about the agreement making process. The overwhelming response has been that they are ‘too late’ to raise concerns. Further, the objectors have also been denied access to documents and information that would enable them to better understand the process that has occurred to date.

• At the authorisation meeting, the majority of people who identify as Ngurai Illum (whether as an independent group or as a Taungurung clan) supported the motion to remove Ngurai Illum land and ancestors from the Taungurung claim, however, the motion was defeated on the basis of votes from the broader Taungurung claim group.

• The objectors who attended the authorisation meeting and were not directed to leave, requested that the Chair, accept proxies from 186 traditional owners. The proxy forms were divided into groups based on relevant apical ancestors. Following a letter from Holding Redlich to First Nations dated 19 October 2018, Taungurung were on notice that proxies would be brought by the objectors. All proxies authorised the holder to vote against the authorisation, but a motion to accept the proxies was defeated. No action was taken to notify the persons giving proxies of the recognition and settlement agreement and Taungurung ILUA before or after it had been authorised by the persons present.

• The notice invited all persons who hold or may hold native title in the land and waters shown in the map and Mr Murray attended the authorisation meeting on the basis that the map showed an area of land including Dhudhuroa country. Mr Murray was excluded from the meeting on the basis that, as a Dhudhuroa person, he did not have standing to vote in a Taungurung meeting, and he was therefore prevented, as a person who holds or may hold native title in the area, from participating in the authorisation process.

(Footnotes omitted.)

50 The delegate then summarised First Nations Legal’s response at [105]:

• The objectors’ comments about authorisation under s 251A where there are two groups is understood to be based on the decision in Kemp v Native Title Registrar [2006] FCA 939, where it was held that there must be separate processes for each group, and that each group must make a separate authorisation decision.

• From research undertaken since 1997 in relation to the traditional ownership of the agreement area and in support of Taungurung’s negotiations under the Settlement Act, the Ngurai Illum is understood as a clan or subgroup within Taungurung, and not an independent or separate traditional owner group. Attachment B is a brief research paper supporting this. First Nations requested, including prior to the authorisation meeting, that the objectors provide any evidence or reasoning in support of their view but they have not done so.

• Tooterie was an Aboriginal woman associated with the agreement area, who was born into the Ngurai Illum. She married into the Wurundjeri-Woi Wurrung and all her known descendants identify as Wurundjeri-Woi Wurrung. One of the objectors, Ms Xiberras, attended the authorisation meeting and challenged the inclusion of Tooterie as a Taungurung ancestor. In her view, Tooterie was more correctly identified as a Wurundjeri-Woi Wurrung ancestor. Given no known person was expressing a Taungurung identity solely on descent from Tooterie, and her inclusion may cause offence to Ms Xiberras and other Wurundjeri-Woi Wurrung people, the resolution to remove Tooterie was strongly supported. This action did not bring into existence some second native title group at the authorisation meeting. Tooterie was not removed based on her Ngurai Illum characteristics, and there are several other Ngurai Illum ancestors who remain as Taungurung apical ancestors.

• No resolution was made to exclude Tooterie’s descendants from continued participation in the meeting as no such resolution was put to the floor and considered by the meeting. The meeting also had no cause to consider whether by including Tooterie’s descendants, authorisation was given by non-native title holders, as the only two participants asserting descent solely through Tooterie (being Ms Xiberras and her brother) voluntarily left on the basis of no further interest or business in the meeting following removal of Tooterie.

• The minutes of the meeting on 14 July 2012 show that the Taungurung did not ‘decide’ to include Ngurai Illum at that meeting, and were not of the view that Ngurai Illum were a Taungurung clan prior to the meeting. Instead, in response to objections raised by Ms Gardiner, the Taungurung established a working group to examine the issue and to seek mediation with Ms Gardiner. After several attempts to arrange a mediation, those purporting to represent Ngurai Illum stopped returning calls and mediation could not proceed. On advice of the working group, having considered Taungurung oral tradition that Ngurai Illum was a Taungurung clan, the fact they spoke the same language, and those purporting a separate Ngurai Illum identity were not engaging, the full group resolved to ‘confirm’ Ngurai Illum as a Taungurung clan and to continue attempts to meet with those asserting a separate identity.

• Tooterie was added as a Taungurung apical ancestor at a subsequent meeting on 10 August 2013. Given native title rights are common or group rights held by a collective traditional owner group or society, the Taungurung claim to Ngurai Illum lands was not reliant on the inclusion of Tooterie or any individual apical ancestor, and did not mean that the agreement area was expanded nor did it provide any benefit to the existing Taungurung members. The sole effect was to make the group more expansive and inclusive, giving those descendants a pathway to enjoy native title rights on Taungurung country. This remained the position until Ms Xiberras, on behalf of her Wurundjeri-Woi Wurrung people, requested at the authorisation meeting that Tooterie be removed.

• First Nations refute the assertions it had not facilitated engagement between the objectors and the Taungurung, or that the Taungurung have met these concerns with hostility.

• Each objector asserting a Ngurai Illum identity participated in the authorisation process.

• Section 251A, and the Act in general, do not provide any right to proxies.

• Mr Murray was not permitted entry because he is not a descendant of an ancestor associated with the ILUA area, is not accepted by the wider Taungurung group as a native title holder, and research indicates he is not someone who may reasonably be considered to hold native title within the ILUA area. Mr Murray claims his traditional owner group, identified as Dhudhuroa, has native title interests in the east of the agreement area. However, he has never provided the basis for this claim, and the objection remains silent beyond his own assertion.

(Footnotes omitted.)

51 At [106] the delegate set out the State’s response to the objectors:

• The existence of the Supreme Court of Victoria proceeding does not assist the Registrar to be satisfied that the requirements of s 203BE(5)(a) and (b) have not been met.

• The Taungurung people see themselves as comprised of a number of clans with similar dialects and as part of a broader Kulin alliance. Some members identify with a particular area or clan and others identify with the group’s country as a whole.

• As a result of oral history, a common language and a lack of engagement on the issue from those who may assert a separate identity for the Ngurai Illum, it was resolved at a Taungurung group meeting on 14 July 2012 that the Ngurai-Illum is a Taungurung clan.

• Country associated with the Ngurai Illum therefore formed part of the proposed agreement area. Tooterie was not identified as an apical ancestor at that point and she was not a reason for the inclusion of the Ngurai Illum as a Taungurung clan.

• During the Settlement Act process, the State received anthropological and historical information from NTSV on behalf of the Taungurung, which concluded that the Ngurai Illum and the Taungurung had common language, laws and customs. The State considered this information and accepted that it was reasonable to include country associated with the Ngurai Illum in the proposed ILUA area.

• The inclusion of Ngurai Illum country was not reliant on the identification of Tooterie as a Taungurung apical ancestor.

• Before receiving the Threshold Statement, the State had material from the Taungurung which did not include Tooterie as an identified apical ancestor. The Taungurung resolved to add Tooterie at a full group meeting on 10 August 2013. When the Threshold Statement was received, one of the people regarded by the Taungurung as an ancestor was Tooterie. The State accepted that the Threshold Statement provided sufficient evidence to support a group description that included Tooterie, and that known descendants of Tooterie identified as Wurundjeri.

• In 2014, as part of the Settlement Act process, the State published the Summary Threshold Statement and invited submissions. Some of the submissions raised concerns about the inclusion of Tooterie as a Taungurung ancestor. The Taungurung, represented by NTSV, provided the State with a response addressing in detail submissions which had raised, among other matters, concerns about the inclusion of Tooterie. After considering the submissions and any responses to them, the State formed the view that who was regarded as a Taungurung ancestor was largely a matter for the Taungurung. The State was content that the inclusion or exclusion of Tooterie was a matter of ongoing consideration by the Taungurung and could be subject to change in the future. The State remained of the view, after becoming aware of the removal of Tooterie as an apical ancestor at the authorisation meeting, that this was a matter for the Taungurung as part of defining and redefining group membership over time.

• The exclusion of Tooterie did not change who was a member of the Taungurung group as no person in the group claimed descent only from Tooterie.

• In relation to the proxies provided, Kemppi FC provides that s 203BE(5)(b) will be satisfied if all those who hold or may hold native title are given a reasonable opportunity to attend the authorisation meeting.

(Footnotes omitted.)

52 At [107], the delegate set out the objectors’ response to what was put by both First Nations Legal and the State:

• The objectors and their families did not take part in the research undertaken in support of the Taungurung claim and therefore the research has not been subjected to outside scrutiny.

• First Nations failed to properly represent the interests of people from the Ngurai Illum, Waywurru and Dhudhuroa nations and were not receptive to attempts made by the objectors to put forward a contrary position.

• Even if representatives of the Ngurai Illum stopped returning calls, First Nations were obligated to assist all Aboriginal Victorians to ensure that the interests of Ngurai Illum, Waywurru and Dhudhuroa descendants were effectively represented.

• The Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages produced a map of Victorian Aboriginal languages displaying Ngurai Illum as a separate language group to Taungurung.

• There is no evidence that First Nations facilitated engagement between the objectors and the Taungurung or that the Taungurung did not meet the objectors’ concerns with hostility.

• The Ngurai Illum had no opportunity to opt in or out of the Taungurung claim other than by attending the authorisation meeting where, although more Ngurai Illum sought to vote against authorisation, they were outnumbered by other Taungurung members.

• Mr Murray asserts that the Taungurung claim group has not established any connection between the Taungurung apical ancestors and the Ovens Valley area in the region of Bright and the surrounding areas. The Dhudhuroa claim to the contested area around Bright is based on evidence that a Dhudhuroa ancestor Jilbino lived in that area.

• Mr Murray does not alone have the obligation to establish the basis for the Dhudhuroa claim over the disputed area. First Nations has not offered to assist Mr Murray to engage an anthropologist to review his own research. Any failure to provide the basis of his claim cannot justify the Taungurung claim into the disputed area without any external scrutiny.

• First Nations has not produced evidence to show that the Taungurung apical ancestors had any connection with the land in question, disputed that the Dhudhuroa apical ancestor Jilbino had a connection with the land in question, or attempted to trace the descendants of Jilbino for the purposes of discharging their ‘all reasonable efforts’ obligations.

• Given the facts are disputed and the outcome has such a profound impact on the objectors, their families and future generations, all parties should be required to submit evidence to enable the Registrar to make findings of fact before exercising her statutory powers.

53 From [110]-[113] the delegate considered the proper construction of the phrase “all the persons” in s 203BE(5)(b). Relying on the Full Court’s finding in McGlade v South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Corporation (No 2) [2019] FCAFC 238; 374 ALR 329, the delegate concluded that “all the persons” is a reference to the persons identified in s 203BE(5)(a). The delegate found these persons to be the Taungurung People. Therefore, the delegate reasoned, the persons who must have authorised the making of the ILUA are those identified as Taungurung People.

54 From [114]-[119] the delegate assessed the applicable decision making process under s 251A. She stated that s 251A “provides for an ILUA to be authorised using a traditional decision making process, or an agreed to and adopted process”. At [115]-[116] the delegate noted that the certificate states, and draft minutes of the authorisation meeting record, that the ILUA was authorised in accordance was an agreed and adopted decision making process. The delegate continued:

I note there is information before me that indicates that there has been research undertaken in relation to the identification of the decision making processes. In my view, there is no information which disputes that an agreed and adopted process should not have been used and that there instead exists a traditional decision making process under s 251A.

(Footnotes omitted.)

55 The delegate then noted the objectors’ contention that

there should have been two decision making processes under s 251A used in relation to the authorisation of the making of the ILUA as there were two distinct groups present, namely the Ngurai Illum and the Taungurung.

56 The delegate rejected this contention and instead accepted the submissions of First Nations Legal and the State that Ngurai Illum Wurrung is a subgroup or clan of the Taungurung, a position she found was supported by “a brief research paper”. This was a paper entitled “NTSV Ngurai-illam-wurung/Taungurung Research Position Paper”, and states it was prepared by three people: one identified as a “senior anthropologist” and two identified as “research historians”. The paper describes its purpose in the following terms:

This position paper is in response to issues raised by the Department of Justice (DOJ) in relation to the status of the Ngurai-illam-wurrung as portrayed in the Threshold Statement of the Taungurung people (supported by the NTSV) under the Traditional Owner Settlement Act (TOSA).

57 Relying in part on this research paper, the delegate concluded that the process agreed to and adopted by those who identified as Taungurung People was sufficient.

58 From [120]-[142], the delegate considered whether the Taungurung People had in fact authorised the making of the ILUA in accordance with the agreed to and adopted process. Having reviewed the authorities which deal with s 251A and s 251B, the delegate found:

(a) that a reasonable opportunity must be given to participate in the adoption of the particular process and the making of decisions pursuant to that process (at [121]-[123]);

(b) that where a reasonable opportunity was given to participate, it could be inferred that those who did not participate chose not to be involved in the making of the decision (at [125]-[126]); and

(c) that it is therefore not necessary for all native title claimants or holders to participate in the authorisation process. Citing McGlade (No 2), she found that the authorisation process “should not be scrutinised in an overly technical or pedantic way” (at [127]-[128]).

59 The delegate at [129] identified the objectors’ contentions that

some of the objectors appear to assert that a reasonable opportunity was not given as they were not identified and therefore not invited or consulted, and therefore their people have not given free, prior and informed consent to the Taungurung ILUA. In addition, Mr Murray says he was excluded from the authorisation meeting and therefore not given an opportunity to participate. There are also assertions that the 186 proxies provided were not taken into consideration.

60 However the delegate found that, given the steps taken by First Nations Legal, the objectors had not satisfied her “that a reasonable opportunity was not afforded ‘to participate in the adoption of a particular process and the making of decisions pursuant to that process’”: at [134].

61 Finally, the delegate turned to the conduct of the meeting and the process of authorisation of the agreement. At [136]-[137] the delegate found:

I consider the decision of Ward v Northern Territory [2002] FCA 171 (Ward) to be relevant to my consideration in relation to the conduct at the authorisation meeting. In Ward, O’Loughlin J identified deficiencies in the information provided in that matter regarding the authorisation process and listed a number of questions which in substance were required to be addressed. The questions identified by O’Loughlin J, which do not need to be answered in any formal way, are:

Who convened it and why was it convened? To whom was notice given and why was it given? What was the agenda for the meeting? Who attended the meeting? What was the authority of those who attended? Who chaired the meeting or otherwise controlled the proceedings of the meeting? By what right did that person have control of the meeting? Was there a list of attendees compiled, and if so by whom and when? Was the list verified by a second person? What resolutions were passed or decisions made? Were they unanimous, and if not, what was the voting for and against a particular resolution? Were there any apologies recorded?

O’Loughlin J considered that it was only necessary for the substance of these questions to be addressed. In my view, the substance of those questions has been addressed in the material provided.

(Footnotes omitted.)

62 The delegate proceeded to answer, in broad terms, the questions posed by O’Loughlin J in Ward extracted above, based largely on information provided in the notice of the authorisation meeting, which is also before the Court. At [140] the delegate stated:

In my view, the conduct of the meeting was such that those present resolved to use the agreed and adopted decision making process, and, while the specific details of the process has not been provided, it is indicative that the actual process was participative and inclusive, allowing those present an opportunity to participate. For instance, the persons who were present were able to consider the proposed resolutions that were put to the floor, and participate by deciding whether or not to pass the resolutions. I also consider that the members of the Taungurung people voted in support of the resolutions to authorise the ILUA.

63 Accordingly, the delegate concluded that the first condition of s 24CK was met.

The second condition: s 24CK(3)

64 The second condition was dealt with briefly by the delegate, who found (at [144]-[148]):

The second condition for registration of an area agreement is contained in s 24CK(3), which provides:

The second condition is that if, when the Registrar proposes to register the agreement, there is a registered native title body corporate in relation to any land or waters in the area covered by the agreement, that body corporate is a party to the agreement.

The requirements of this provision are to be considered at the time the Registrar proposes to register the agreement.

The geospatial end of notification overlap analysis does not identify any registered native title bodies corporate in relation to any area subject to the agreement. My own searches of the Tribunal’s databases confirm this.

I am satisfied that there are no registered native title bodies corporate in relation to the agreement area.

I find that the second condition of s 24CK is met.

65 This conclusion is not disputed by the applicants and is not subject to any ground of review.

Application for judicial review

The grounds of review

66 The application for judicial review contains seven grounds:

2. The decision and the reasons for decision involved the following error or errors of law:

2.1 the Applicants were denied procedural fairness in being denied access to the Threshold Statement (reasons [94]).

2.2 The Delegate erred in law in imposing the onus upon the Objectors. The Delegate correctly cited authority that her task was “to consider whether all reasonable efforts had been made to ensure that those who hold or may hold native title over [the agreement area] have been identified” (reasons [83]) but did not consider all the evidence relevant to that question and that the Delegate was bound to consider in making her decision. Instead, the Delegate placed an onus upon the Applicants to satisfy her “that all reasonable efforts have not been made would require the objectors to show that the efforts to ensure all persons who hold or may hold native title in the area have been identified were wanting such that the efforts and subsequent views cannot be said to be reasonably based” (reasons [85]). In so doing, she misconstrued what the notion of “onus” means in the law relating to administrative decisions and imposed on the Applicants a stringent requirement of disproof which was impermissible.

2.3 The Delegate asked herself the wrong questions, by accepting as determinative, the reliance of First Nations for its notification and certification functions upon its Database of more than 150 people (reasons [88], and [94], and notice being sent to only to those people (reasons [130] and [131]) in circumstances where, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Act, the correct question on which the Delegate had to be satisfied was whether “all reasonable efforts” were made to notify to all persons who hold or may hold Native Title. There was a live and central factual issue that was required to be determined by the Delegate as to whether there were a group or groups of indigenous people not on the Database but who reasonably claimed to hold native tile rights and interests over parts for the area the subject of the ILUA that had been ignored or overlooked in the authorisation process. The Delegate failed to engage this issue or determine it.

2.4 The Delegate erred in accepting the submissions of First Nations as to research into the composition of the landowning group and the apical ancestors of the group (reasons [86] and [87]) as determinative of whether a broader definition that of “all persons who hold or may hold Native Title” was the correct enquiry. That enquiry was required to be conducted on the basis of evidence which was not put before the Delegate and on which the Applicants were given no opportunity (as procedural fairness required) to address in their submissions.

2.5 The Delegate erred in categorising the Applicants’ Affidavit evidence as “assertions” when that evidence was “sworn evidence” and was not challenged (reasons [69]). That Affidavit evidence was directly relevant to the identity of the 180 people who had provided proxies (Gardiner Affidavit [23], [32]), Peters Affidavit [42], Thorpe Affidavit [26]) the validity of some of the identified Ancestors and their acknowledged areas of country (Gardiner Affidavit [20] , Peters Affidavit [36], [37], [52], [54], [55], Thorpe [5], [12], [19] ) the deficiencies of the notice process for the Authorisation meeting (Peters Affidavit [31], [41], [46] Gardiner Affidavit [29], Thorpe Affidavit [14], [24], [39]. By reason of the approach to those affidavits taken by the Delegate she failed to take the information contained in them into account in any realistic sense, as she was bound to do.

2.6 The Delegate erred in accepting submissions from First Nations as to the conduct of the authorisation meeting without any or any reliable evidence noting that “specific details of the process has not been provided” (reasons [140]) and not taking into account as relevant considerations the Affidavit evidence of the Applicants with respect to that process.

2.7 The Delegate’s decision was also both unreasonable and irrational.

(Footnotes omitted.)

The applicants’ submissions in summary

67 A recurring theme of the applicants’ submissions is that First Nations Legal has failed to consider and represent them as persons who may hold separate native title from the Taungurung over parts of the area covered by the ILUA, and that this failure was not appropriately addressed by the delegate in the registration process.

68 In their written submissions from [7]-[11], the applicants set out the role of First Nations Legal as a representative body under the Act, by reference to the decisions in Kemppi and Quall FCAFC. They then summarise their contentions (as I understand they contend they put to the Registrar) as to their claimed native title in the area central to the dispute at [12]:

a) Taungurung country is on the Upper Goulburn, upstream from Seymour, including the towns of Alexandra, Yea, Mansfield, Seymour and Broadford;