Federal Court of Australia

Fair Work Ombudsman v IE Enterprises Pty Ltd [2021] FCA 60

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | IE ENTERPRISES PTY LTD (ACN 151 469 877) First Respondent EYAL ISRAEL Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to the declarations and orders made by Justice Anderson on 18 June 2020 (Default Orders):

(a) the First Respondent pay pecuniary penalties in an amount of $215,000 for its contraventions as declared in orders 1(a) to (k) of the Default Orders, pursuant to subsection 546(1) of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act);

(b) the Second Respondent pay pecuniary penalties in an amount of $41,000 for his involvement in the First Respondent’s contraventions, as declared in orders 2 and 1(a) to (e) and (g) to (k) of the Default Orders, pursuant to subsection 546(1) of the FW Act;

(c) pursuant to subsection 546(3) of the FW Act, the First Respondent and the Second Respondent pay their respective penalty amounts to the Consolidated Revenue Fund of the Commonwealth within 28 days of these Orders.

2. The Applicant has liberty to apply on seven days’ notice in the event that any of the preceding orders are not complied with.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ANDERSON J:

INTRODUCTION

1 On 18 June 2020, I granted partial default judgment and made various declarations and orders against the Respondents in this proceeding: see Fair Work Ombudsman v IE Enterprises Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 848.

2 This judgment concerns the civil penalties which the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) seeks against the Respondents as a consequence of the contraventions found to be proven by the Court in these proceedings.

3 Ms Fiona Knowles of counsel appeared on behalf of the FWO. There was no appearance by or on behalf of the Respondents, nor was there any submissions filed by the Respondents. I am satisfied on the evidence tendered by the FWO that the Respondents have been put on notice of this penalty proceeding. That evidence includes:

(1) an affidavit of a Senior Lawyer employed by the Fair Work Ombudsman, Ms Claire Toner, sworn 16 April 2020 (First Toner Affidavit);

(2) a second affidavit of Ms Toner sworn 15 June 2020 (Second Toner Affidavit);

(3) a third affidavit of Ms Toner sworn 15 June 2020 (Third Toner Affidavit); and

(4) a fourth affidavit of Ms Toner sworn 27 August 2020 (Fourth Toner Affidavit), (collectively, the Toner Affidavits).

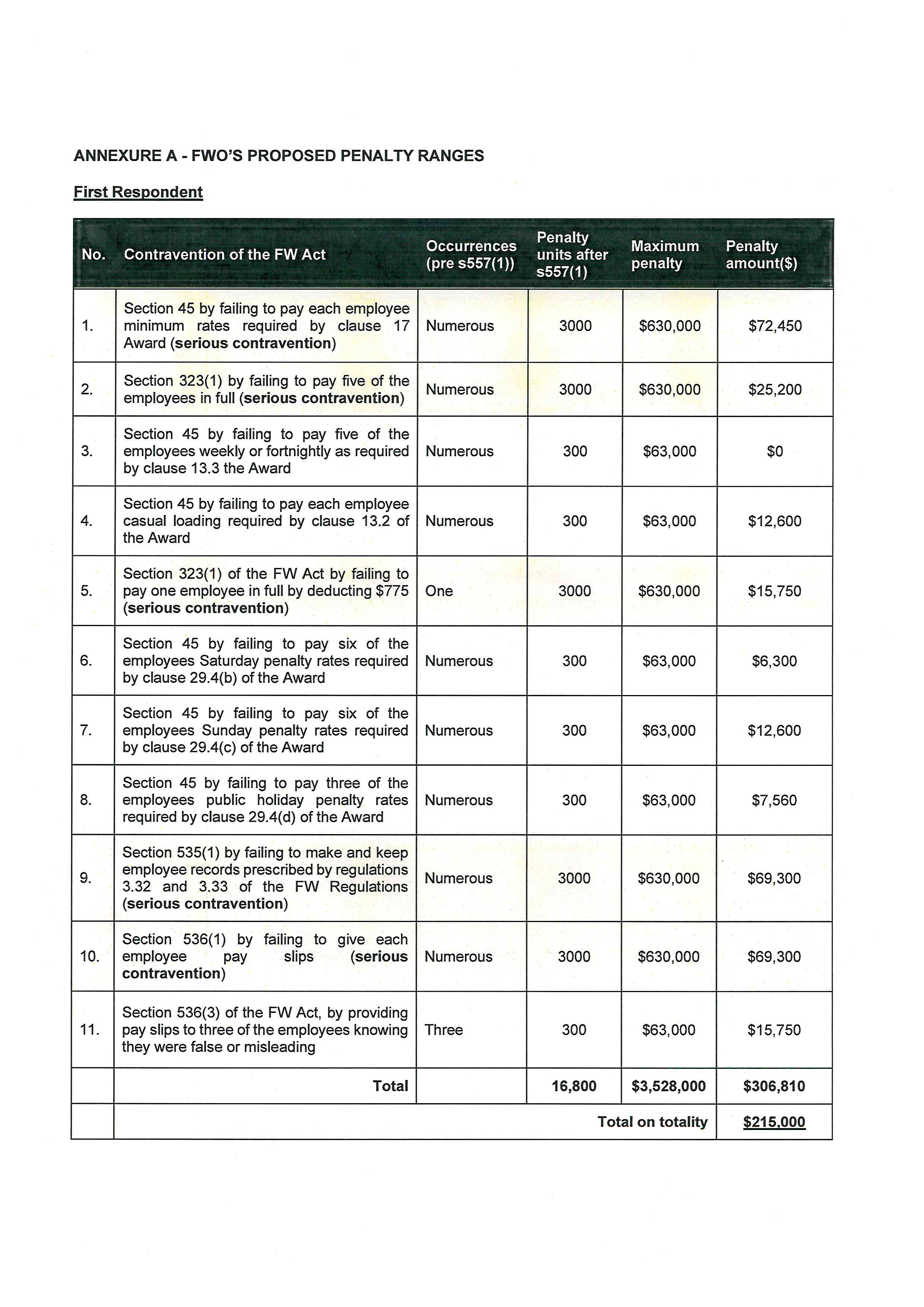

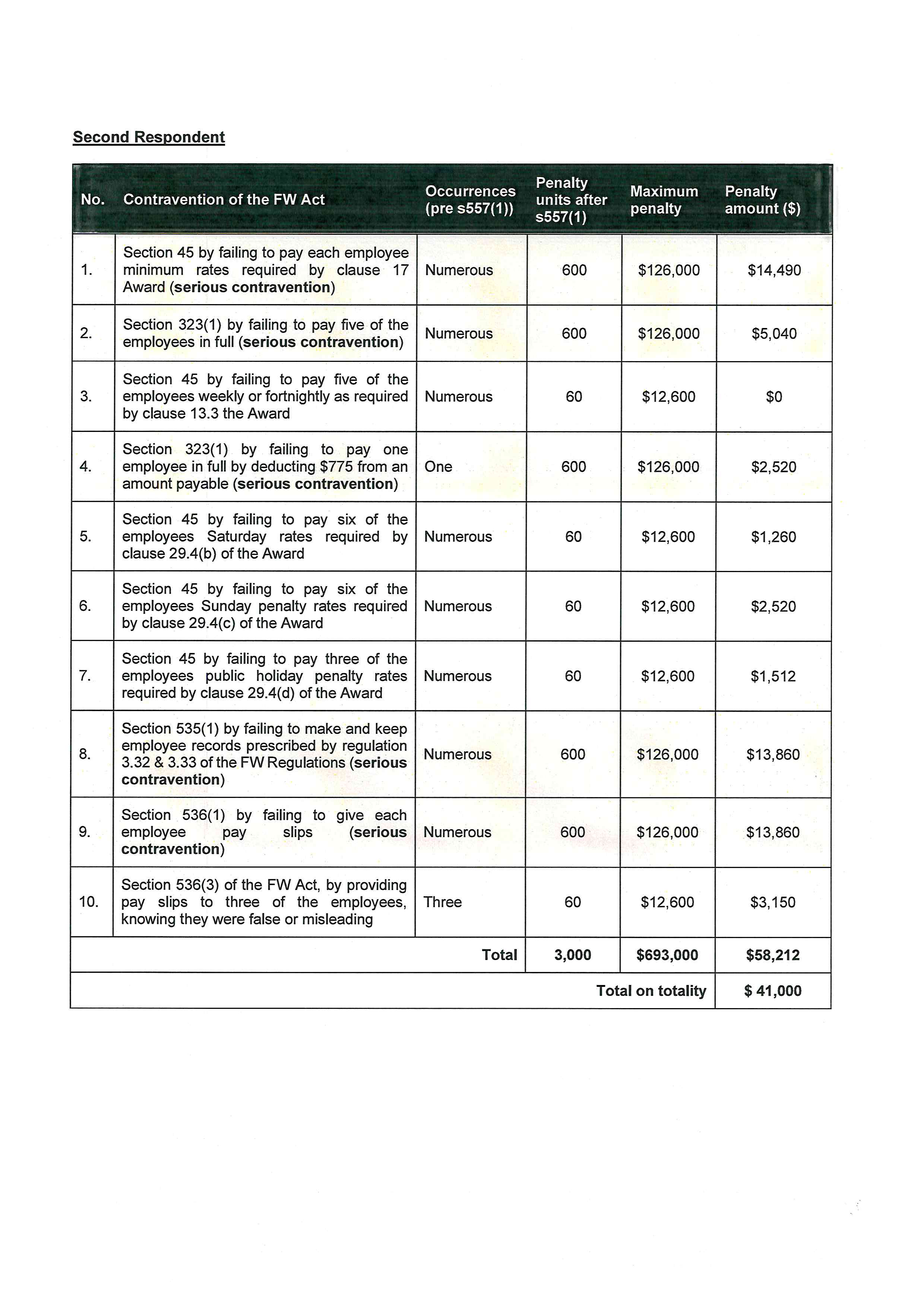

4 The FWO seeks the imposition of the following penalties (which are detailed in Annexure A to this judgment):

(1) $215,000 against the First Respondent, IE Enterprises Pty Ltd, trading as Uncle Toys (Uncle Toys); and

(2) $41,000 against the Second Respondent, Mr Eyal Israel.

5 For the reasons that follow, Orders will be made which impose those penalties on each of the Respondents.

BACKGROUND

6 Uncle Toys engaged eight employees to work on a casual basis at its “pop up” kiosks during the 2017/2018 Christmas season for varying periods from 23 October 2017 to 2 January 2018 (Assessed Employment Period). Uncle Toys sold toys and other recreational goods at shopping centres in Victoria. At all relevant times, the Second Respondent, Mr Israel, was the sole director of Uncle Toys and responsible for its overall direction, control, and management.

7 On 18 June 2020, this Court handed down its liability decision in default. The Court made:

(1) declarations that, consequent upon its default, Uncle Toys had committed eleven contraventions of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act) and the General Retail Industry Award 2010, including five serious contraventions (within the meaning of s 557A of the FW Act) (collectively, the contraventions);

(2) declarations that, consequent upon his default, Mr Israel was involved in ten of Uncle Toys’ contraventions, including the five serious contraventions; and

(3) orders that Uncle Toys and Mr Israel pay the relevant employees their outstanding entitlements of $21,749.19, which remain unpaid,

(collectively, the Liability Orders).

8 In addition to the Toner Affidavits referred to above, the FWO also tendered and relied upon the following unchallenged affidavits:

(1) an affidavit of a Fair Work Inspector, Ms Claudia Zeballos, affirmed 31 August 2020 (Zeballos Affidavit); and

(2) affidavits of three employees, namely:

(a) an affidavit of Mr Julian Mizzi affirmed 18 January 2021 (Mizzi Affidavit);

(b) an affidavit of Ms Jium Ku affirmed 22 January 2021 (Ku Affidavit); and

(c) an affidavit of Ms Seoin Park affirmed 22 January 2021 (Park Affidavit).

PRINCIPLES ON THE DETERMINATION OF PENALTY

9 A primary purpose of civil penalties is to promote compliance by putting a price on contraventions that is sufficiently high to act as a deterrent, both to the contravener, and to others who may be tempted to contravene the relevant legislation: Commonwealth of Australia v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 (Cth v FWBII) at [55] per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ and at [110] per Keane J. In Cth v FWBII, French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ stated at [55]:

… the purpose of a civil penalty, as French J explained in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd, is primarily if not wholly protective in promoting the public interest in compliance:

“Punishment for breaches of the criminal law traditionally involves three elements: deterrence, both general and individual, retribution and rehabilitation. Neither retribution nor rehabilitation, within the sense of the Old and New Testament moralities that imbue much of our criminal law, have any part to play in economic regulation of the kind contemplated by Pt IV [of the Trade Practices Act] … The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act.”

(Citations omitted.)

10 Justice Keane stated at [110]:

… in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd, French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ approved the statement by the Full Court of the Federal Court in Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission that a civil penalty for a contravention of the law:

“must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not such as to be regarded by [the] offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business.”

(Citations omitted.)

11 The authorities establish that the Court has a discretion to assess the appropriate penalty: Fair Work Ombudsman v Jetstar Airways Ltd [2014] FCA 33 at [28] citing A & L Silvestri Pty Ltd v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2008] FCA 466 at [6] per Gyles J. In Fair Work Ombudsman v NSH North Pty Ltd trading as New Shanghai Charlestown [2017] FCA 1301; 275 1R 148 (NSH North) at [36], Justice Bromwich summarised how the discretion is to be approached:

(1) the first step is to identify the separate contraventions involved. Each breach of each separate obligation found in the FW Act and Award is a separate contravention of a civil remedy provision for the purposes of s 539(2) of the FW Act;

(2) the second step is to consider whether any of the contraventions constitute a single course of conduct such that they are treated as a single contravention under s 557(1) of the FW Act;

(3) the third step is to consider whether there should be further adjustment to ensure that, to the extent of any overlap between groups of separate aggregated contraventions, there is no double penalty imposed, and that the penalty is an appropriate response to what each respondent did;

(4) the fourth step is to consider the appropriate penalty in respect of each final individual group of contraventions, taken in isolation, having regard to all the circumstances of the case and the maximum penalties available for each contravention; and

(5) the final step is, having fixed an appropriate penalty for each contravention (or, if relevant, each group of contraventions), to consider the overall penalties arrived at and apply the totality principle to ensure that the penalties for each respondent are appropriate and proportionate to the conduct viewed as a whole: Kelly v Fitzpatrick [2007] FCA 1080 (Kelly) at [30]; Australian Ophthalmic Supplies Pty Ltd v McAlary Smith [2008] FCAFC 8; 165 FCR 560 (Ophthalmic Supplies) at [23] per Gray J and [71] and [102] per Graham J.

APPLICATION OF section 557 OF THE FW ACT

12 Section 557(1) of the FW Act provides that, for specified contraventions of the FW Act, two or more contraventions of the same civil remedy provision will be treated as a single contravention where they were committed by the same person and “arose out of a course of conduct by the person”.

13 In this case, on each occasion a provision is breached in respect of the 11 declared contraventions, that is a separate civil remedy provision for the purposes of s 557 of the FW Act: Rocky Holdings Pty Limited v Fair Work Ombudsman [2014] FCAFC 62; 221 FCR 153 at [12]-[18] per North, Flick and Jagot JJ; Fair Work Ombudsman v Lohr [2018] FCA 5; 356 ALR 424 (Lohr) at [29]-[34] per Bromwich J; Fair Work Ombudsman v Siner Enterprises Pty Ltd and Anors (No 2) [2018] FCCA 589 at [16]-[18] per Lucev J; Fair Work Ombudsman v Blue Impression Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCCA 2797; 274 IR 374 (Blue Impression) at [32]-[36] (this finding was not disturbed on appeal in EZY Accounting 123 Pty Ltd v Fair Work Ombudsman [2018] FCAFC 134; 360 ALR 261).

14 The FWO accepts that the Respondents are entitled to the benefit of s 557(1) to group multiple contraventions of the same term of the Award or section of the FW Act, and to treat them as a single course of conduct where those breaches relate to multiple employees or occurred on multiple occasions.

15 The FWO submits that, after the application of s 557(1) of the FW Act, there are 11 contraventions committed by Uncle Toys and 10 contraventions committed by Mr Israel: see columns 1, 2 and 3 in Annexure A to this judgment.

CONSIDERATION OF COMMON ELEMENTS

16 In addition to the statutory course of conduct in s 557, the Court may impose a single penalty in respect of multiple contraventions where treating contraventions separately would give rise to a danger that the Respondents would be penalised twice for essentially the same conduct: Fair Work Ombudsman v Construction, Forestry, Mining, Maritime and Energy Union [2019] FCAFC 69 at [181] per Rangiah J; see also Ross J at [90]-[92]; Ophthalmic Supplies at [46] per Graham J.

17 The FWO submits it would not be appropriate to further group the contraventions, as each contravention arises from separate and distinct obligations and to do so would give insufficient weight to the separate legal character of the obligations: Lohr at [29]-[34] per Bromwich J.

18 The FWO referred to Uncle Toys’ conduct in failing to pay Debora Van Hattem, Jean-Brieuc Gicquel, Julian Mizzi, Seoin (Jessica) Park and Thomas Gatt:

(1) in full, in contravention of s 323(1) of the FW Act (a serious contravention); and

(2) at the end of every contravention engagement, weekly or fortnightly per cl 13.3 of the Award, in contravention of s 45 of the FW Act.

19 The FWO accepts that this conduct arose from essentially the same conduct, namely a failure to pay those five employees at all for their last period of work, being:

(1) three weeks for Ms Van Hatten;

(2) two weeks for Mr Gicquel;

(3) one week for Ms Park; and

(4) the last day for each of Mr Mizzi and Mr Gatt.

20 On that basis, and to ensure there is no overlap, the FWO submits that the Court should not penalise the Respondents for the contravention of s 45 of the FW Act for breaching cl 13.3 of the Award.

21 The FWO submits that failure to pay the five employees during their last periods of work resulted in underpayments to those five employees in respect of their minimum hourly rates, casual loading, Saturday penalty rates, Sunday penalty rates and public holiday penalty rates, which were pleaded separately. The FWO submits that the contraventions in respect of the failure to pay in full and the failure to pay at the end of every engagement, weekly or fortnightly arose from distinct conduct and decisions to not pay at all or on time, rather than as a result of the decision to pay the employees insufficient flat rates of pay.

MAXIMUM PENALTIES

22 It is appropriate for the Court to consider “the maximum penalty as a yardstick rather than using particular cases for that purpose, as so to do can divert attention from the ordained maximum”: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v J Hutchinson Pty Ltd T/A Hutchinson Builders [2019] FCA 667 at [35]; see also Ophthalmic Supplies at [108] per Buchanan J. In Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25; 228 CLR 357, Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ stated at [31]:

… careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick.

23 In this proceeding, the maximum penalties are calculated by reference to the penalty units in the tables in s 539(2) of the FW Act.

Increased penalties for serious contraventions and for record keeping and pay slip contraventions

24 From 15 September 2017, the Fair Work Amendment (Protecting Vulnerable Workers) Act 2017 (PVW Act) introduced “serious contraventions” in the FW Act, which increased maximum penalties for certain civil penalty contraventions. The maximum penalties were increased to a penalty ten times higher than penalties for other contraventions.

25 The explanatory memorandum to the Fair Work Amendment (Protecting Vulnerable Workers) Bill 2017 (PVW Bill) stated:

The Bill also addresses concerns that civil penalties under the Fair Work Act are currently too low to effectively deter unscrupulous employers who exploit vulnerable workers because the costs associated with being caught are seen as an acceptable cost of doing business. The Bill will increase relevant civil penalties to an appropriate level so the threat of being fined acts as an effective deterrent to potential wrongdoers.

26 The Regulation Impact Statement to the PVW Bill stated that the amendments were informed by the Senate Standing Committee on Education and Employment’s report titled “A National Disgrace: The Exploitation of Temporary Work Visa Holders”. That report stated at [9.273]:

The current maximum civil penalties under the FW Act are $54 000 for a corporation or $10 800 for an individual. By contrast, the penalties under other Commonwealth legislation such as the Corporations Act 2001 and the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 are an order of magnitude higher. The maximum civil penalty under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 is in the region of $500 000 for an individual and $10 million for a corporation.

27 The report stated at [9.276]-[9.278]:

… the current penalty regime under the FW Act almost invites unscrupulous employers to treat the law with impunity. The current penalties on company directors under the FW Act operate as the equivalent of a parking fine for some of the unscrupulous 7-Eleven franchisees, and directors of labour hire companies, who have built the systematic exploitation of visa workers into their business models.

Furthermore, even when the FWO has secured a conviction, employers that deliberately set out to avoid their legislative obligations have evaded the full consequences of the existing penalty regime through various forms of corporate restructuring, asset shifting, and liquidating the company.

The derisory penalties under the FW Act therefore undermine the enforcement activity of the FWO by sending the wrong signal to unscrupulous employers. Furthermore, they offer no comfort to legitimate businesses whose operations are undercut by dodgy operators. In addition, because the penalties obtained from directors are insufficient to cover the total amount of underpayments, vulnerable employees who have been ripped off, and have taken their case to the authorities, are left out-of-pocket. This further discourages other employees from coming forward with evidence of unlawful activity.

28 The PVW Act also increased the penalties for record keeping and pay slip contraventions. The Explanatory Memorandum to the PVW Bill stated:

The new maximum penalties also extend to false or misleading employee records or payslips, which the contravening employer knows to be false or misleading. The prohibition was previously provided for under regulation 3.44 of the Fair Work Regulations. The maximum penalty for these contraventions increases from 20 penalty units under the Regulations to 60 penalty units under the new provisions for individuals, and from 100 to 300 penalty units for bodies corporate.

The increase to these maximum penalties recognises that the current penalty levels for these contraventions are too low compared to other civil penalty provisions within the Act. This also acknowledges the important role employee records and payslips play in determining compliance under the Act; without reliable employee records, employees may be unable to prove their case and recover their minimum entitlements at law.

29 The PVW Act introduced a new offence of providing employees with false or misleading pay slips under s 536(3) of the FW Act.

30 The FWO submits that the Court should consider where the contraventions sit in the spectrum of offending conduct for the relevant type of contravention. In the case of serious contraventions – that is, conduct which is done knowingly and as part of a systematic pattern of conduct – this includes taking into account the increase in penalties as an indication of the legislature’s view of the seriousness of the conduct, as well as the totality principle.

Total maximum penalties

31 In this case, five of Uncle Toys’ and five of Mr Israel’s contraventions are “serious contraventions” and attract a higher maximum penalty under s 539(2) of the FW Act.

32 If the Court accepts the FWO’s proposed approach to course of conduct and grouping, the maximum penalties that the Court could impose are:

(1) $3,528,000 in respect of Uncle Toys; and

(2) $693,000 in respect of Mr Israel.

FACTORS RELEVANT TO PENALTY

33 Justice Tracey in Kelly set out a non-exhaustive list of factors relevant to the imposition of penalties. Justice Tracey referred to the following relevant considerations at [14]:

(1) the nature and extent of the conduct which led to the breaches;

(2) the circumstances in which that conduct took place;

(3) the nature and extent of any loss or damage sustained as a result of the breaches;

(4) whether there had been similar previous conduct by the respondent;

(5) whether the breaches were properly distinct or arose out of the one course of conduct;

(6) the size of the business enterprise involved;

(7) whether or not the breaches were deliberate;

(8) whether senior management was involved in the breaches;

(9) whether the party committing the breach had exhibited contrition;

(10) whether the party committing the breach had taken corrective action;

(11) whether the party committing the breach had cooperated with the enforcement authorities;

(12) the need to ensure compliance with minimum standards by provision of an effective means for investigation and enforcement of employee entitlements; and

(13) the need for specific and general deterrence.

34 Recently, in Pattinson v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2020] FCAFC 177; 384 ALR 75 (Pattinson), Allsop CJ, White and Wigney JJ stated at [99]-[100]:

The appropriate penalty

The kinds of consideration to be taken into account to which French J referred in CSR (1991) ATPR ¶41-076 at 52,152–52,153 were:

1. The nature and extent of the contravening conduct.

2. The amount of loss or damage caused.

3. The circumstances in which the conduct took place.

4. The size of the contravening company.

5. The degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market.

6. The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended.

7. Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level.

8. Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention.

9. Whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

Other cases have similarly expressed lists of possible relevant considerations: see for example, Santow J in Australian Securities and Investment Commission v Adler [2002] NSWSC 483; 42 ACSR 80 at [126] and Tracey J in Kelly v Fitzpatrick [2007] FCA 1080; 166 IR 14 at 18–19 [14]. To the list of French J may be added, to the extent that it is not inherent within his Honour’s list, the apparent attitude of the contravenor to compliance with the relevant law of Parliament. Such lists are (unless found in a relevant statutory provision) not legal check lists. They are judicial descriptions of likely relevant considerations applicable to the task of coming to an appropriate penalty in the circumstances of varied cases, for the object of deterrence of contraventions of like kind set against the statutory maximum penalty. As Buchanan J said in Australian Ophthalmic Supplies Pty Ltd v McAlary-Smith [2008] FCAFC 8; 165 FCR 560 at 580 [91] such lists are useful as long as they “do not become transformed into a rigid catalogue of matters for attention. … [T]he task of the Court is to fix a penalty that pays appropriate regard to the circumstances in which the contraventions have occurred and the need to sustain public confidence in the statutory regime which imposes the obligations”. As Gyles J said in A & L Silvestri Pty Limited v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2008] FCA 466 at [6] the factors are not mandatory criteria and can lead to over-elaborate reasoning for a task that is a discretion at large as to what is appropriate to the object concerned.

The setting out of such factors is of assistance, however, not only in capturing relevant matters, but also in providing the necessary focus: that it is to the contravention in question to which the penalty is directed. This is not because there is a retributive principle that there must be equality between act and punishment for the crime, but because the contravention (and its nature, quality and seriousness) must be considered and understood such that the appropriate penalty be imposed to deter such a contravention in the future. The features of the contravention that can be seen to be relevant to its seriousness will find their place, not in the operation of some freestanding retributively-derived principle of proportionality, but in understanding the degree of deterrence necessary to be reflected in the size of the penalty: Flight Centre Limited v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 53; 260 FCR 68 at 86 [71]. Importantly, however, the imposition of an appropriate penalty, given the object of deterrence, does not authorise and empower the imposition of an oppressive penalty that is one that is more than is appropriate to deter a contravention of the kind before the court. The primacy of the object of deterrence does not unmoor or untether the consideration of appropriateness from the circumstances and the contravention before the court and what is reasonably necessary to deter contraventions of the kind before the court. Notions of reasonableness inhering in statutes as part of the principle of legality would deny a construction that sought to do so, at least without the clearest language. Any such construction would entail the risk of personal predilection, not principle, guiding the imposition of penal sanction with necessary attendant problems of inconsistency, a consequence not to be attributed to Parliament. As Burchett and Kiefel JJ said in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; 71 FCR 285 at 293:

As Smithers J emphasised in Stihl Chain Saws (at 17,896), insistence upon the deterrent quality of a penalty should be balanced by insistence that it “not be so high as to be oppressive”. Plainly, if deterrence is the object, the penalty should not be greater than is necessary to achieve this object; severity beyond that would be oppression.

(Bold text in the original.)

35 Their Honours stated at [103]:

The question is what can reasonably be thought to be appropriate to serve as a real deterrent and “must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is such as not to be regarded … as an acceptable cost of doing business”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 at 659 [66] referring to Singtel Optus 287 ALR at 265 [62]–[63].

36 Their Honours further stated at [109]:

Notwithstanding the continued relevance of the notion of proportionality in considering and fixing an appropriate penalty for a contravention with the object of deterrence, the recognition of the irrelevance of considerations such as retribution, denunciation and rehabilitation in the context of possible loss of liberty, and the recognition that the imposition of the penalty is the setting of a price to dissuade the contravenor and others from contravening in like manner in the future makes clearer the whole overall process of arriving at the evaluative conclusion of an appropriate penalty to fulfil the object of deterrence. The process is whole and discretionary, and evaluative in character, to which objective aspects of the contravention and what might be called the subjective characteristics of the contravenor, indeed all considerations that rationally touch on or inform deterrence, are relevant. As Charlesworth J said in Robinson above, the mental attitude of the contravenor is relevant: whether innocent, or whether reflective of a determined refusal to comply with, or of a determination to be disobedient to, the law, or whether some other characteristic relevant in some other way that can be seen to bear on the assessment of the need for, and required degree of, deterrence.

37 Having regard to those principles, I turn to consider the factors which are relevant to evaluating the appropriate penalties in this case.

Nature and extent of the conduct and loss

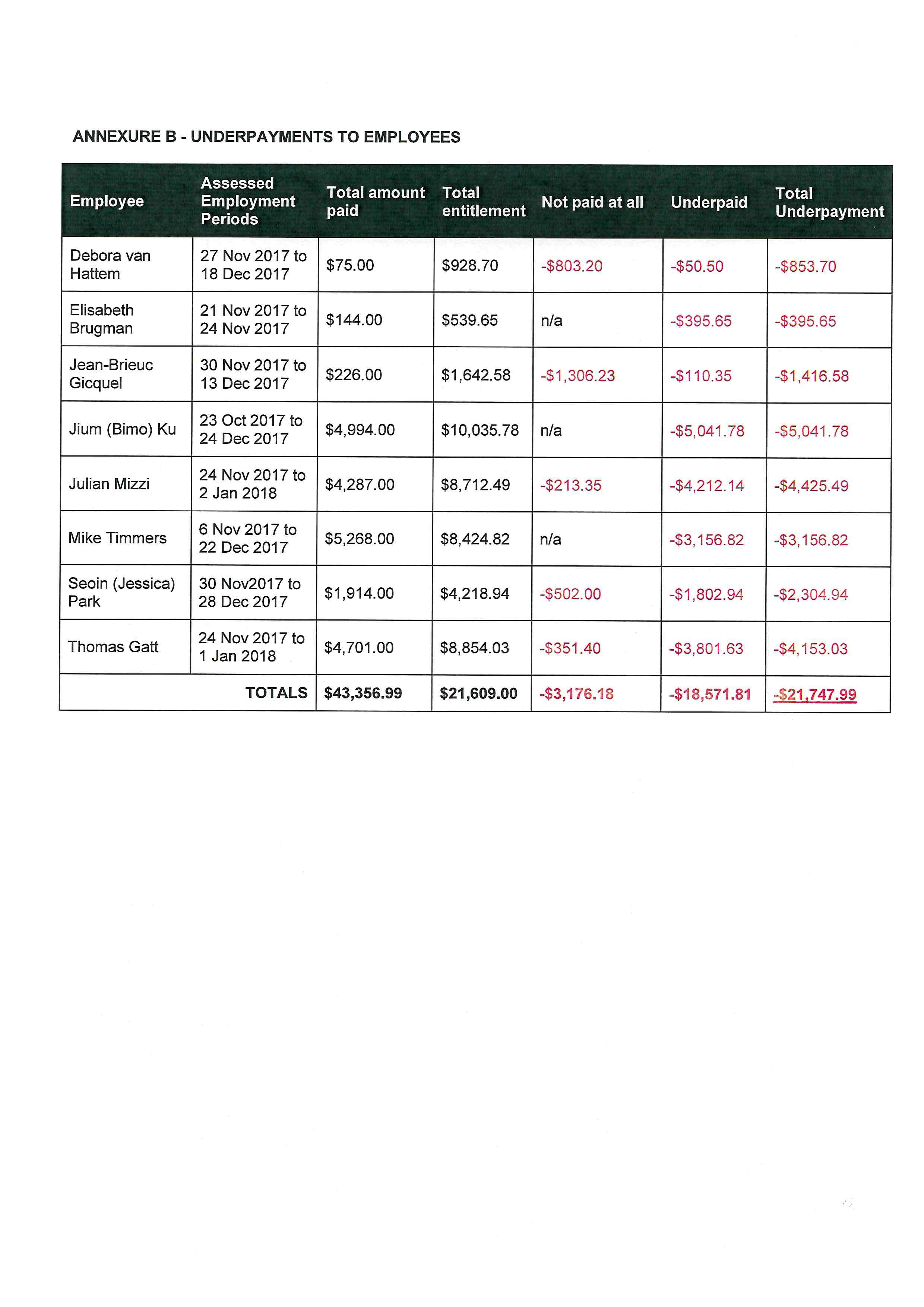

38 During the Assessed Employment Period, the eight employees were underpaid by a total of $21,749.19 during periods of one to nine weeks. These underpayments were significant over such a short period of time, representing 37.47% to 91.92% of the wages to which the employees were entitled (detailed in Annexure B to this judgment).

39 Despite the Second Respondent, Mr Israel, informing the employees that they would be paid $17.00 per hour, plus a $10 bonus each time they sold over $1,000 worth of stock in a shift, Uncle Toys paid them far less and, in respect of five employees during some pay periods, not at all.

40 The unchallenged affidavit evidence tendered by the FWO sets out the hardship the relevant employees experienced as a result of the Respondents’ conduct. By way of example, Ms Park deposes that she borrowed money from a friend in Korea to afford basic living expenses. Ms Ku deposes that she was “very worried” about how she would afford to pay for food and accommodation, and that the combination of trying to recover her underpayments and looking for another job was “exhausting”. Mr Mizzi deposes that:

Because I was only paid $14.50 per hour (which I had thought was because of the 15% “tax” [Mr Israel] said Uncle Toys was going to withhold …), I had to work very long hours to afford my rent and living expenses in Australia. This was exhausting, for example between 12 December 2017 and 24 December 2017 I worked 13 days straight, without a day off. Of those 13 shifts, seven were 12 hours or longer.

41 Mr Mizzi deposes that he was afraid that, if he resigned, he would not receive his previous week’s wages, and that he “felt exploited and helpless”.

42 Furthermore, the Respondents failed to make and keep records as required in respect of any of the employees, gave three employees pay slips containing false or misleading information about Uncle Toys’ name and Australian Business Number, and otherwise failed to provide the employees with pay slips at all. The significance of pay slips in helping employees to recover their minimum entitlements was recognised in the Explanatory Memorandum of the PVW Bill which also introduced the false and misleading pay slips contravention in s 536(3) of the FW Act.

Position of the employees

43 At the time the contraventions occurred, the employees were young (aged from 23 and 27 years old) and foreign nationals subject to visa conditions. The FWO submits that young visa workers are particularly vulnerable to exploitation. Three of the employees have deposed that this was their first job in Australia and that they were not aware of the rates of pay to which they were legally entitled.

44 According to reports annexed to the Zeballos Affidavit tendered by the FWO, which were prepared by the FWO’s Strategic Research, Analysis and Reporting Team during the 2017-2018 financial year:

(1) visa holders accounted for 5% of the workforce in Australia, but 20% of FWO disputes;

(2) subclass 417 working holiday visas accounted for 6.8% of FWO disputes; and

(3) the most common age for visa holders who brought a dispute to the FWO was 25.

45 The FWO submits that the employees were vulnerable given their age, inexperience and visa status and that the Court can infer that Uncle Toys and Mr Israel exploited this vulnerability by paying very low rates of pay and not paying five of them at all in their last periods of employment, when the Respondents no longer required them to work after the Christmas or New Year’s trading period.

Deliberateness

46 The serious contraventions occurred as a result of deliberate and systematic conduct by the Respondents, undertaken in full knowledge that Uncle Toys was breaching its obligations under the FW Act and Award. Additionally, and despite not being “serious contraventions”, the failure to pay casual loading and other penalties arose despite the Respondents having prior knowledge of Uncle Toys’ obligations under the Award.

47 The Assessed Employment Period took place during the fourth Christmas trading season in which the FWO received complaints from employees alleging underpayments. The FWO raised the first two complaints in December 2013 and December 2014 with Mr Israel, but he did not respond.

48 From 8 January to 24 February 2015, the FWO received a further six complaints. During that time, the FWO contacted Mr Israel by telephone and email, and provided educational materials including fact sheets regarding the FWO’s role, minimum wages, obligations in respect of record keeping and pay slips, hyperlinks to the Award, advice on minimum casual rates and a “Pay and Conditions Guide”.

49 The following year, the FWO received another complaint, and from 17 December 2015 to 22 January 2016, the FWO again engaged with the Respondents to provide the same education material. On 22 January 2016, the FWO issued a formal “Letter of Caution”.

50 By the Assessed Employment Period, Mr Israel and Uncle Toys were aware that the Award applied to employees engaged by Uncle Toys, that the Award set minimum rates of pay in relation to casuals, Saturdays, Sundays or public holidays, and that Uncle Toys was required to keep records and give employees pay slips.

51 In the Assessed Employment Period, Uncle Toys paid the employees flat rates well below their minimum entitlements, unlawfully deducted a large amount from one employee’s wages, failed to keep employee records as required, provided three employees with pay slips containing false or misleading information regarding Uncle Toys’ name and ABN, and otherwise failed to provide the employees with pay slips at all.

52 The FWO accepts that the Respondents have not previously been the subject of court proceedings. However, the FWO submits that the Respondents’ complete failure to amend their behaviour in response to the FWO’s previous education attempts, which included a “Letter of Caution”, are indicative of their wilful disregard for Uncle Toys’ legal obligations. I agree.

Need to ensure compliance with minimum standards

53 One of the principal objects of the FW Act is to ensure “a guaranteed safety net of fair, relevant and enforceable minimum terms and conditions …”: FW Act, s 3(b). By failing to adhere to the Award, Uncle Toys undermined this objective.

54 The Respondents’ pay slip and record keeping contraventions also undermined the FWO’s capacity to monitor and enforce compliance, and for the employees to check and recover their entitlements. This Court has recognised that “the requirement for the provision of pay slips is an important means of guarding against the exploitation of vulnerable workers”: Fair Work Ombudsman v Group Property Services (No 2) [2017] FCA 557 at [548]; see also Fair Work Ombudsman v Han Investments Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 623 at [114]-[115]; and Tomvald v Toll Transport Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1208 at [120].

55 The FWO submits that the Court should impose meaningful penalties to show that Uncle Toys’ contraventions have serious consequences.

Involvement of senior management

56 The contraventions involved senior management, namely the Second Respondent, Mr Israel. At all material times, Mr Israel was the directing mind and will of Uncle Toys and personally responsible for the conduct which resulted in the contraventions. His conduct and decisions were inextricably intertwined with Uncle Toys’ contraventions.

Corrective action, cooperation with authorities and contrition

57 The Respondents have shown no contrition, no cooperation and taken no corrective action. A corporate respondent’s expression of contrition can be represented by that corporation taking steps to correct its wrongdoing and change its behaviour. In this proceeding, when confronted by the FWO with evidence of Uncle Toys’ wrongdoing, Mr Israel responded with statements to the effect that:

(1) the employees were “trying to squeeze money” out of him; and

(2) the FWO “can send whatever you like, but [Mr Israel was] not going to co-operate and [was] not going to send [the FWO] anything”, and Mr Israel was “prepared to go to court to fight” the employees.

58 A failure to actively engage in proceedings has been recognised as a relevant factor: see eg Pattinson at [99]; Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v Gibson (No 3) [2017] FCA 1148 at [83]-[84]. The Respondents refused to co-operate with the FWO during the investigation, and failed to engage with the proceedings or comply with their obligations, despite being aware of the proceedings. Despite the Respondents being aware of the Liability Orders, they have also failed to rectify the underpayments in contravention of those orders.

Size and financial circumstances of the business enterprise

59 When considering the appropriate amount of a penalty, the size and financial circumstances of the contravener is a relevant factor: Fair Work Ombudsman v Australian Workers’ Union [2020] FCA 60 at [44]-[45]; Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v Hocking Stuart (Richmond) Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1184 at [29].

60 The FWO accepts that Uncle Toys’ business is small, and the Assessed Employment Period was not lengthy. Mr Israel has claimed that he and Uncle Toys are unable to pay the outstanding amounts due to the employees. However, the Respondents have not provided any evidence in relation to their financial position, assets or inability to pay any penalty awarded by the Court.

61 In addition, “capacity to pay is less relevant than general deterrence”: NSH North at [107]. In NSH North, Bromwich J stated the following at [106]-[107]:

As was pointed out in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Leahy Petroleum Pty Ltd (No 2) [2005] FCA 254; 215 ALR 281 at [9]:

The size of the contravening companies and their respective capacities to pay a penalty were relied upon as factors in mitigation in the present case. Plainly, such factors can be relevant to the penalty that is necessary to deter the company from contravening the Act in the future. Size may also be relevant to general deterrence because other potential contraveners are likely to take notice of penalties imposed on companies of a similar size. However, a contravening company’s capacity to pay a penalty is of less relevance to the objective of general deterrence because that objective is not concerned with whether the penalties imposed have been paid. Rather, it involves a penalty being fixed that will deter others from engaging in similar contravening conduct in the future. Thus, general deterrence will depend more on the expected quantum of the penalty for the offending conduct, rather than on a past offender’s capacity to pay a previous penalty. I therefore respectfully agree with the observation of Smithers J, referred to by Burchett and Kiefel JJ in NW Frozen Foods, to the effect that, a penalty that is no greater than is necessary to achieve the object of general deterrence, will not be oppressive. I have approached the issue of corporate penalties on that basis. The penalties in relation to the individuals may need to be tempered by personal considerations.

The above principle quoted from Leahy Petroleum was summarised and endorsed by Heerey J in Jordan v Mornington Inn Pty Ltd [2007] FCA 1384; 166 IR 33 at [99], who noted that capacity to pay is less relevant than general deterrence. The Full Court endorsed that conclusion in Mornington Inn Pty Ltd v Jordan [2008] FCAFC 70; 168 FCR 383 at [69], and it has been applied many times since then. It may be regarded as settled law.

DETERRENCE

62 It is well established that the need for specific and general deterrence are central purposes underlying the imposition of a penalty under the FW Act: see eg Ponzio v B & P Caelli Constructions Pty Ltd [2007] FCAFC 65 (Ponzio) at [93] and [97].

Specific deterrence

63 In Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 (ACCC v TPG), French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ stated at [64]:

In Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, it was rightly said by the Full Court of the Federal Court that the court, in fixing a penalty, must “make[] it clear to [the contravener], and to the market, that the cost of courting a risk of contravention … cannot be regarded as [an] acceptable cost of doing business”.

(Citations omitted.)

64 Specific deterrence “is directed to ensuring that the contraveners are not prepared to embark upon the risk of re-offending”: Fair Work Ombudsman v AJR Nominees Pty Ltd (No.2) [2014] FCA 128 at [50]. In Pattinson at [191], Allsop CJ, White and Wigney JJ observed:

The assessment of the character of the contravention includes all factors that can rationally go to its gravity and seriousness, bearing in mind that the object of the imposition is deterrence. That includes an attitude of displayed and continuing disobedience to the law, as part of a characterisation of the nature and character of what was done.

65 Evidence of prior conduct may demonstrate the culture of the organisation as to compliance or contravention and a need for specific deterrence: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining, and Energy Union (Syme Library Case) (No 2) [2019] FCA 1555 at [81]; see also Blue Impression at [59]. In this respect, courts have recognised that previous complaints made to the FWO about a respondent may indicate a need for specific deterrence and may be weighed in considering an appropriate penalty in relation to a respondent: Fair Work Ombudsman v Cuts Only The Original Barber Pty Ltd [2014] FCCA 2381 at [174]; Blue Impression at [59].

66 Uncle Toys’ failure to amend its behaviour in response to the FWO’s education attempts demonstrates that the action taken by the FWO was insufficient to deter the Respondents from continuing the same conduct, thus necessitating a more severe penalty, and that penalties must be set at a meaningful level in order to achieve compliance: ACCC v TPG, [64]; Fair Work Ombudsman v Yogurberry World Square Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 1290, [24]-[25].

General deterrence

67 The High Court in Cth v FWBII (at [55] and [59] (per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ) and at [102] (per Keane J)), confirmed the importance of civil penalties in promoting the public interest in compliance with Commonwealth workplace laws through general deterrence, and this has recently been affirmed by the Full Court in Pattinson (at [191] per Allsop CJ, White and Wigney JJ). To be effective as a general deterrent, the Court should fix a penalty to ensure the contravening conduct is not regarded as “an acceptable cost of doing business”: Cth v FWBII at [110] (per Keane J) citing ACCC v TPG at [66] and Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20; 287 ALR 249 at [62]-[63].

68 There is a need for a strong deterrent penalty in respect of the record keeping contraventions and false and misleading pay slip contraventions in these proceedings. The impact of this conduct undermines the system of workplace compliance. A strong deterrent penalty should emphasise that the provision of false information to employees is inexcusable.

69 General deterrence can be of particular importance in the retail industry. Courts have recognised that particular characteristics of the retail industry underscore the heightened need for general deterrence. For example, the retail industry is a large industry, which can employ unskilled labour, and, in such circumstances, may be more likely to attract young, overseas workers engaged in casual work: Fair Work Ombudsman v Mai Pty Ltd & Anor [2016] FCCA 1481 at [143] per Jarrett J; Fair Work Ombudsman v EA Fuller & Sons Pty Ltd & Anor [2013] FCCA 5 at [113] per Driver J.

70 The FWO submits that the Court should have regard to the message sent to employers and the community generally when imposing penalties. The FWO submits that the message must make it clear that obligations to workers cannot be avoided or abrogated, and deter other employers in the retail industry, and of young workers, from similar conduct.

TOTALITY

71 Having examined an appropriate penalty for each contravention, the Court must examine the aggregate penalty to determine whether it is an appropriate response to the conduct that led to the breaches: Kelly at [30] per Tracey J; Ophthalmic Supplies at [23] (per Gray J), [71] (per Graham J) and [102] (per Buchanan J). The totality “principle is designed to ensure that the aggregate of the penalties imposed is not such as to be oppressive or crushing”: Kelly at [30]. The penalty must also be commensurate with the seriousness of the conduct engaged in by the Respondents taking into account the increase in penalties provided by the PVW Act.

72 Taking these factors into consideration, the FWO submits that a discount on totality is warranted in this case as set out in Annexure A to this judgment.

73 Taking all of the above matters into account, the FWO submits that it is appropriate and reasonable that the Court impose the following aggregate penalties:

(1) $215,000 against Uncle Toys; and

(2) $41,000 against Mr Israel.

DISPOSITION

74 Having considered the FWO’s submissions and the evidence tendered by the FWO, I am satisfied that, when viewed as a whole, the conduct in these proceedings – particularly in relation to the low rates of pay, the failure to pay employees anything at all for their final periods of work and the issuing of false and misleading pay slips – is serious and warrants the Court’s strong disapproval.

75 The contravening conduct spanned a range of entitlements, affected multiple employees and continued notwithstanding the prior attempts of the FWO to educate the Respondents as to their obligations to their employees.

76 I am satisfied on the evidence that the Respondents’ conduct was deliberate and systematic and had a significant impact on the relevant employees.

77 Underpayment of employees and the exploitation of vulnerable employees undermines core principles of the Australian workplace relations system. Those core principles include an enforceable and fair safety net of employment terms and conditions. It is, in my view, fundamental to the effectiveness of workplace regulation in Australia that this safety net is extended to all employees, regardless of their youth or visa status.

78 In considering the submissions made by the FWO on the appropriate penalties to be imposed upon the Respondents, I am mindful of French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ’s observations in Cth v FWBII at [60]. Their Honours observed that “it is the function of the relevant regulator to regulate the industry in order to achieve compliance and, accordingly, it is to be expected” that a regulator, such as the FWO, “will be in a position to offer informed submissions as to the effects of contravention on the industry and the level of penalty necessary to achieve compliance”.

79 In Cth v FWBII at [64], French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ further stated that:

… the phenomenon of a regulator making submissions as to the terms and quantum of a civil penalty does not lead to and is not likely to lead to erroneous views about the importance of the regulator’s opinion in the setting of appropriate penalties … [I]t is consistent with the purposes of civil penalty regimes …, and therefore with the public interest, that the regulator take an active role in attempting to achieve the penalty which the regulator considers to be appropriate and thus that the regulator’s submissions as to the terms and quantum of a civil penalty be treated as a relevant consideration.

80 In light of these principles, having considered the evidence and the submissions advanced by the FWO, for the reasons given, I am satisfied that it is appropriate and reasonable that the Court impose the following aggregate penalties:

(1) $215,000 against Uncle Toys; and

(2) $41,000 against Mr Israel.

81 Calculations underpinning these penalties were submitted by the FWO, and are annexed to this judgment as Annexure A.

82 I have made Orders to that effect.

I certify that the preceding eighty-two (82) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Anderson. |

Associate: