Federal Court of Australia

Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions v Wallenius Wilhelmsen Ocean AS [2021] FCA 52

ORDERS

COMMONWEALTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC PROSECUTIONS Prosecutor | ||

AND: | Accused | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Wallenius Wilhelmsen Ocean AS is convicted of the offence of, between about 1 June 2011 and about 31 July 2012, in Japan and elsewhere, in connection with the transport of vehicles to Australia, intentionally giving effect to cartel provisions in an arrangement or understanding reached with others in relation to the supply of ocean shipping services, knowing or believing that the arrangement or understanding contained cartel provisions contrary to s 44ZZRG(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

2. Wallenius Wilhelmsen Ocean AS is fined the sum $24 million in relation to that offence.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

WIGNEY J:

1 Wallenius Wilhelmsen Ocean AS (WWO) is a large Norwegian company which supplies global shipping services, including the shipment of motor vehicles, trucks, buses and other commercial vehicles on routes to Australia. It ostensibly competed with other large global shipping companies who also supplied shipping services in that market. From at least July 2009, however, WWO (then known as Wallenius Wilhelmsen Logistics AS) and a number of other global shipping companies gave effect to provisions in an arrangement or understanding which had the effect of limiting or distorting that competition. That arrangement or understanding only came to an end in September 2012 when action was taken by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) and the United States Department of Justice (DOJ). The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) subsequently conducted an investigation into the conduct of WWO and the other shipping companies. That investigation culminated in the laying of criminal charges against three of the companies.

2 On 3 August 2017, Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha (NYK) was convicted of intentionally giving effect to cartel provisions contrary to s 44ZZRG(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA). NYK was fined the sum of $25 million: Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions v Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha (2017) 254 FCR 235 (CDPP v NYK).

3 On 2 August 2019, Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd (K-Line) was convicted of the same offence. K-Line was fined the sum of $34.5 million: Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions v Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha Ltd [2019] FCA 1170; 137 ACSR 575 (CDPP v K-Line).

4 On 18 June 2020, WWO pleaded guilty to a single rolled-up charge of intentionally giving effect to cartel provisions contrary to s 44ZZRG of the CCA. That charge, which was in terms that essentially mirrored the charges against NYK and K-Line, was in the following terms:

Between about 1 June 2011 and about 31 July 2012, in Japan and elsewhere, in connection with the transport of vehicles to Australia, Wallenius Wilhelmsen Logistics AS (now Wallenius Wilhelmsen Ocean AS) intentionally gave effect to cartel provisions in an arrangement made or understanding reached with others in relation to the supply of ocean shipping services, knowing or believing that the arrangement or understanding contained cartel provisions contrary to section 44ZZRG(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

5 The facts of the offence to which WWO has pleaded guilty are, in summary, that on a number of occasions over a period of just over a year, WWO intentionally gave effect to a cartel provision in an arrangement or understanding it had reached with some of its ostensible competitors in the market for the supply of ocean shipping services. WWO’s conduct in giving effect to the cartel provision involved at least two other parties to the arrangement or understanding: NYK and Mitsui OSK Lines Ltd (MOL). The arrangement or understanding involved or included what was said to be a “rule of respect” or “guiding principle” the effect of which was that the parties to the arrangement or understanding would seek to allocate certain customers between themselves on certain international shipping routes, including routes to Australia, and would not attempt to win each other’s existing business. They thereby sought to ensure that their existing market shares were not altered. The arrangement or understanding has been referred to generally as the Respect Arrangement.

6 Needless to say, the conduct engaged in by WWO in giving effect to the cartel provision in the Respect Arrangement amounted to a very serious offence against Australia’s laws prohibiting cartel conduct.

7 The task for the Court is to impose a penalty that is of a severity appropriate in all the circumstances. The maximum penalty for the offence, in WWO’s circumstances, is a fine not exceeding $48,532,493. While the central issue in sentencing WWO is the size of the fine that it should be ordered to pay having regard to, inter alia, the objective seriousness of the offence and WWO’s subjective circumstances, consideration must also be given to the issue of parity with the fines which have previously been imposed on NYK and K-Line.

Facts relating to the offence

8 The primary facts relating to the offence upon which WWO is to be sentenced were and are not in dispute. The prosecutor, the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions, tendered a Statement of Agreed Facts which was made for the purposes of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

9 The Statement of Agreed Facts is a detailed and comprehensive document. It is obviously unnecessary to refer verbatim to all of the facts referred to in it. Following is a summary or distillation of the material facts.

Overview of the offending conduct

10 WWO is a large Norwegian shipping company.

11 The shipping services supplied by WWO included the shipment of motor vehicles, trucks, buses, commercial vehicles and agricultural, mining and construction equipment. It supplied those services to a number of customers, including the manufacturers of those vehicles and equipment, on a number of routes, including routes from Europe, Turkey and the Americas to Australia.

12 WWO competed with a number of other shipping companies for the supply of those ocean shipping services. From at least July 2009, however, WWO and some of its competitors, relevantly including NYK and MOL, applied what was said to be a “rule of respect” or “guiding principle” to their ostensible competition. The substance and effect of that rule or principle was that they would “respect” each other’s businesses by endeavouring to allocate between themselves the business for certain customers on certain routes and by not attempting to “win” or secure shipping contracts which were held by one of the other companies when those contracts came up for tender or renewal. They thereby sought to ensure that their existing shares of the relevant market for ocean shipping services were not materially altered.

13 As has already been noted, the rule or principle which was applied by, relevantly, WWO, NYK and MOL, has been referred to as the Respect Arrangement. The Respect Arrangement constituted or comprised an arrangement or understanding between the relevant carriers for the purposes of the CCA. It also contained a cartel provision within the meaning of s 44ZZRD(3)(b)(i) of the CCA because it relevantly had the purpose of directly or indirectly “allocating between any or all of the parties to the arrangement or understanding the persons or classes of persons who have acquired, or who are likely to acquire, goods or services from any or all of the parties to the arrangement or understanding”. The relevant cartel provision in the Respect Arrangement may conveniently be called the market allocation provision.

14 The parties to the Respect Arrangement, including WWO, would from time to time engage in conduct which gave effect to the Respect Arrangement and the market allocation provision. In general terms, that conduct included the following types of conduct.

15 First, the sharing of information between the parties about the freight rates for the supply of services to customers on particular routes to and from Australia, including information about the rates that were charged, the rates that were proposed to be charged, or the changes or proposed changes to those rates.

16 Second, the reaching of agreements, arrangements or understandings about what freight rates, or approximate freight rates or changes to freight rates, each of the parties would bid, quote, submit or otherwise communicate to customers or potential customers in respect of the supply of services on particular routes to and from Australia. On occasion, the agreement would include that one or more of the parties would not bid or submit for the relevant business.

17 Third, the submission, or non-submission, as the case may be, of bids or quotes to customers or potential customers of freight rates, or approximate freight rates or changes to freight rates, in respect of the supply of services on particular routes to and from Australia in accordance with agreements, arrangements or understandings entered into or arrived at between the parties.

18 The charge to which WWO ultimately pleaded guilty involved six specific incidents of conduct of that nature by officers or employees of WWO which gave effect to the market allocation provision of the Respect Arrangement. That conduct occurred between 1 June 2011 and 31 July 2012.

19 WWO also admitted that it had committed two other offences of giving effect to the market allocation provision in the Respect Arrangement. The specific incidents of conduct constituting those offences occurred in 2009. With the agreement of the Director, WWO asked that the Court take those offences into account in passing sentence for the offence of which it had been convicted in accordance with s 16BA of the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth).

20 The following table summarises the six incidents of conduct which are the subject of the offence of which WWO has pleaded guilty and will be convicted and the two additional incidents which are the subject of the offences to be taken into account in accordance with s 16BA of the Crimes Act.

Incident | Customer | Route(s) | Year |

1 – charged conduct | Renault Nissan | United States to Australia | 2011 |

2 – charged conduct | Renault Nissan | Europe and Turkey to Australia | 2012 |

3 – charged conduct | Fiat Chrysler | Europe to Australia – cars | 2011 |

4 – charged conduct | Fiat Chrysler | Europe to Australia – trucks | 2012 |

5 – charged conduct | Fiat Chrysler | Europe to Australia – mid-contract period | 2012 |

6 – charged conduct | Toyota | United States to Australia | 2012 |

7 – s 16BA offence | Toyota | United States to Australia | 2009 |

8 – s 16BA offence | Mitsubishi | Europe and Turkey to Australia | 2009 |

21 The specific facts relating to each of these incidents will be detailed later.

22 There is no evidence that WWO continued to give effect to the Respect Arrangement after 31 July 2012.

WWO

23 WWO is a global organisation, with offices and agents in Europe, Africa, North East Asia, South East Asia, Japan, North America, Central and South America, India, Middle East and Oceania, including Australia. Its major offices are in Tokyo, Japan, and New Jersey, United States of America (US). WWO currently operates globally a fleet of more than 55 pure car carriers and pure car truck carriers.

24 In Australia, WWO provides logistical services for the processing and distribution of “roll-on, roll-off” vehicles and breakbulk cargo imported from the US and Europe. It has offices and agents in each major port, including Brisbane, Fremantle, Melbourne, Newcastle, Port Kembla and Sydney.

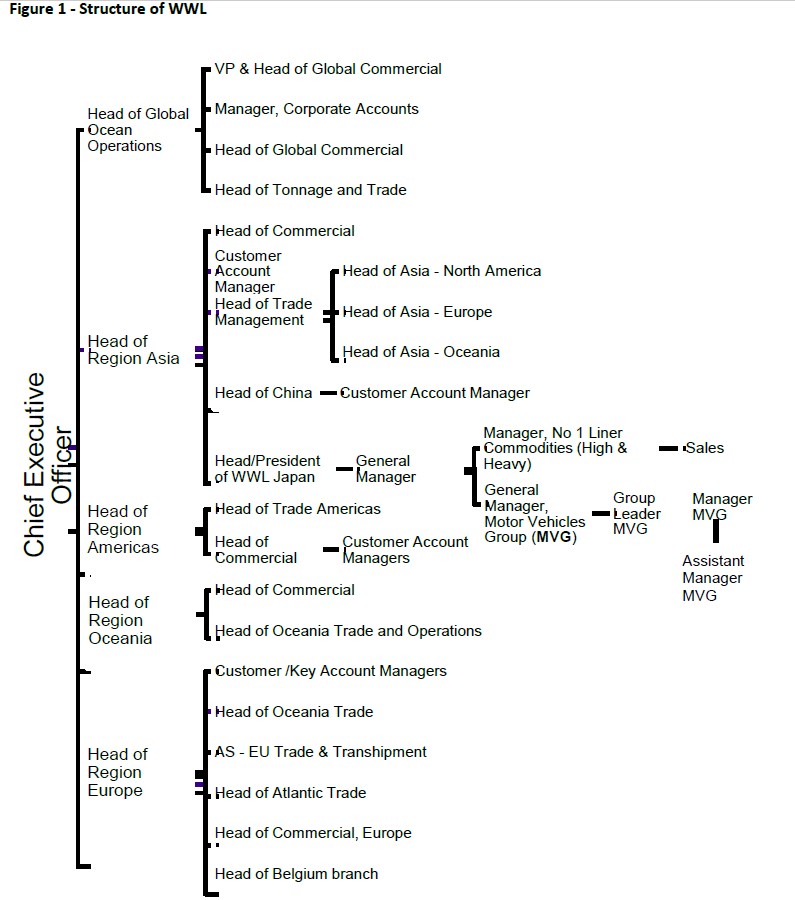

25 Between 2009 and 2012, part of the relevant corporate or managerial structure of WWO was as described in Figure 1 below:

26 WWO’s regional offices had authority to enter into agreements with customers in their respective regions up to a spending limit of US$50 million.

Services on routes to Australia

27 In 2012, approximately 1.1 million new motor vehicles, including passenger vehicles, SUVs, light trucks and heavy vehicles, were sold in Australia. The total value of automotive imports to Australia for that year was $34.8 billion, consisting of both vehicle imports ($26.4 billion) and component imports ($8.4 billion). Automotive imports from Japan comprised the largest share of total automotive imports (30%) with a value of $10,565 million, followed by Europe ($7,582 million), North America ($5,936 million), South East Asia ($5,075 million), Korea ($2,740 million) and China ($1,546 million).

28 Between 2009 and 2012, approximately 80% of sales of new passenger vehicles to private and fleet purchasers in Australia were passenger motor vehicles that had been imported into Australia.

29 Eight companies supplied ocean transport services globally during the charge period. Those companies were NYK, K-Line, WWO, MOL, Nissan Motor Car Carrier Co. Ltd (Nissan MCC), Eukor Car Carriers Inc, Höegh Autolines Holdings AS and Toyofuji Shipping Co. Toyofuji was majority owned and controlled by Toyota Motor Corporation. Nissan MCC was originally owned and controlled by Nissan Motor Co Ltd, but during the charge period was majority owned by MOL.

30 During the charge period, WWO’s global share of capacity for “roll-on, roll-off” services, based on the number of specialised car carriers, was between 8.2% and 10.5%. NYK’s share of capacity was between 15.5% and 17.2%, K-Line’s share was between 11.6% and 11.9% and MOL’s share was between 12.1% and 14.1%. The market shares of the other participants in the market were: between 10.9% and 11.6% for Eukor; between 6.3% and 8.8% for Höegh; between 0.9% and 1.0% for Toyofuji; and between 1.9% and 2.8% for Nissan MCC.

31 Between 2009 and August 2012, WWO shipped 645,740 motor vehicles to Australia, including 114,953 vehicles in 2009, 146,868 vehicles in 2010, 159,987 vehicles in 2011, 190,425 vehicles in 2012 and 33,507 vehicles by August 2012. During this same period, it shipped 3,707 motor vehicles from Australia, including 874 vehicles in 2009, 517 vehicles in 2010, 1,372 vehicles in 2011, 871 vehicles in 2011 and 73 vehicles by August 2012.

32 Between 2009 and 2012, the revenue generated by WWO from the shipping services provided by it and its related entity (Wallenius Wilhelmsen Logistics Australia Pty Ltd) for each financial year was: US$219,344,708 in 2009; US$312,619,748 in 2010; US$462,559,434 in 2011; and US$581,382,231 in 2012. WWO’s revenue generated from its logistical services provided by WWO and the same related entity for each financial year totalled US$31,562,665 in 2009, US$37,049,091 in 2010, US$42,506,092 in 2011 and US$48,746,727 in 2012. WWO’s total revenue (the addition of the preceding amounts) totalled $301,425,490 in 2009, $377,642,346 in 2010, $485,324,934 in 2011 and $606,330,486 in 2012.

General operation of the Respect Arrangement

33 The overarching arrangement or understanding which has been referred to as the Respect Arrangement was in existence from at least July 2009. The general nature and effect of the Respect Arrangement, including the market allocation provision, was referred to earlier. The specific incidents where WWO gave effect to the Respect Arrangement are detailed later. Following is a more detailed description of the general operation of the Respect Arrangement.

34 The shipping companies or carriers who were parties to the Respect Arrangement engaged in a range of conduct in order to give effect to the market allocation provision. The conduct often occurred in the context of requests for tenders or bids, or contract renewals or renegotiations, by a freight customer for a particular route or routes. The conduct was often instigated by the incumbent carrier who had the business for that route or routes. It included the following types of conduct.

35 First, the incumbent carrier would, in some cases, confirm or reach an agreement, or endeavour to reach an agreement, with one or more of the other carriers to the effect that they would not respond to a tender or request for freight rates by a customer.

36 Second, the incumbent carrier, in some cases, would discuss freight rates with the other carriers, determine what it considered to be the appropriate freight rates, or approximate freight rates or range of freight rates, for each of the other carriers to bid to the customer. The incumbent carrier would then take the lead in reaching agreement with each carrier about how they would respond to the customer.

37 Third, in some cases, the incumbent carrier would discuss with other carriers whether the existing freight rates on a route for a particular manufacturer should either generally remain unchanged, or be increased by an amount or approximate amount or decreased by an amount or approximate amount. The incumbent carrier would then seek to reach an agreement with some or all of the carriers to the effect that they would respond accordingly to a tender or request for freight rates by the manufacturer, without necessarily disclosing the actual rates at which each carrier would provide in response to the tender or request for prices.

38 Where none of the carriers who were party to the Respect Arrangement had existing business with a particular customer or a particular route, or a new route was proposed or introduced, that business was considered to be “new business”. In those circumstances, the carriers might do their best to obtain as much of that business as they could in competition with each other. After the initial contract had been awarded, however, that business would generally then be considered to be business to which the Respect Arrangement would apply.

39 While the carriers who were party to the Respect Arrangement were sometimes unable to reach an agreement in order to adhere or give effect to the market allocation provision, those occasions of non-adherence were unusual. In any event, as will be seen, that that was not the case for WWO in respect of the six specific incidents of conduct encompassed by the offence of which it has pleaded guilty, or the two incidents of conduct relevant to the two s 16BA offences.

40 There was also evidence, referred to in the agreed facts, concerning WWO’s general adherence to the Respect Arrangement, albeit that that evidence specifically related to WWO’s conduct in respect of routes that did not involve Australia. In respect of routes from Japan to Europe, for example, the evidence of the Senior Managing Executive Officer of MOL’s Car Carrier Division was that WWO almost never violated the Respect Arrangement. Similarly, the evidence of the General Manager of NYK’s Car Carrier Group, again in the context of routes from Japan to Europe, was that he could not recall a single occasion between 2011 and 2012 when WWO did not act in accordance with the Respect Arrangement, or where there was disagreement between the carriers that required the carriers’ counterparts to be contacted in order to discuss the issue and reach agreement.

WWO’s knowledge of antitrust law

41 From at least June 2003, WWO provided competition law training for its employees. Further training was offered to its staff in 2004, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2012 and 2013.

42 WWO’s competition law training comprised face-to-face training sessions or e-learning modules. This training material included: a manual which set out employees’ obligations in the event the JFTC searched WWO’s offices without prior notice; WWO’s 2003 Code of Ethics for the Asia Region, which contained a general obligation to observe the law and outlined possible disciplinary actions for staff who failed to comply; and WWO’s 2007 Code of Conduct, which included a specific obligation to not “engage in anti-competitive behaviour” and informed WWO employees that “[WWO] is committed to complying fully with all applicable laws relating to fair competition, fair pricing and consumer protection”.

43 The compliance training and procedures which WWO had in place at the time of the offending, and put in place after the offending, were the subject of evidence adduced by WWO. That evidence is discussed in detail later.

44 It should perhaps be noted in this context that, despite the clear reference in the 2003 Code of Ethics to disciplinary action for staff who failed to comply with the obligation to observe the law, none of the WWO staff identified in connection with the six specific incidents of conduct were subjected to disciplinary action as a result of their conduct.

WWO’s conduct in giving effect to the Respect Arrangement – Specific incidents

45 WWO gave effect to the market allocation provision in the Respect Arrangement from time to time through face-to-face and telephone discussions between manager-level employees or senior executives of WWO and their counterparts at the other carriers who were party to the arrangement. As adverted to earlier, the offence for which WWO is to be sentenced involved or encompassed six specific incidents in which it gave effect to the market allocation provision. WWO also requested the Court to take into account two additional offences which involved specific incidents in which it gave effect to the market allocation provision in 2009. Following is the relevant details of each of the eight incidents.

Incident 1: Renault Nissan – US to Australia

46 In mid-2011, Renault Nissan Purchasing Organisation (RNPO) issued a global tender. The tender included a request for bids for the provision of shipping services on the US to Australia route. The tender required a response by 11 October 2011.

47 On or around 7 October 2011, WWO’s Vice President and Head of Global Commercial (VP), Oslo, telephoned the Group Leader of the Motor Vehicle Group (MVG) of WWO Japan, and requested information about MOL’s position. On the same date, the Group Leader of the MVG sent an email to a number of people, including the Manager of the MVG, which requested that information about MOL’s approach to the tender be passed on to the VP. The subject line of the email included the words “Destroy after reading”. The Manager of the MVG sent an email response to the Group Leader of the MVG which stated that he had made enquiries with MOL and expected to receive an answer from MOL in relation to its position concerning the tender on 11 October 2011.

48 Between 7 October and 11 October 2011, the Manager of the MVG had a number of conversations with the Assistant Manager or the Manager of the Cross Trade Team in MOL’s Car Carrier Division. During those conversations, the WWO manager said words to the effect that WWO considered the US to Australia route to be an important trade route for WWO, that Nissan cargo was classified as WWO cargo and that WWO did not want MOL to be aggressive for new trade on that route. During one of the conversations, the relevant MOL manager said that he considered the tender to be “new business” and that MOL would therefore be competing for it. The WWO manager replied that WWO would retaliate if MOL sought to compete for this business.

49 Following those conversations, the Manager of the MVG telephoned the Assistant Manager of the Cross Trade Team in MOL’s Car Carrier Division. During that conversation, the Manager of the MVG disclosed the freight rate that WWO would be submitting in response to the tender and said that MOL should submit a rate “higher than the market rate” that WWO intended to submit. The MOL manager agreed.

50 On 11 October 2011, the Manager of the MVG emailed the President of WWO Japan. One of the emails informed the President that MOL considered the business to be “new business” and provided a comparison of WWO’s and MOL’s shipping services on the US to Australia route. The other reported that MOL was planning to submit a freight rate in response to the tender.

51 WWO submitted its bid for cargo from the US to Australia in response to the Nissan tender on 12 October 2011.

52 WWO was awarded 100% of the Nissan cargo from the US to Australia.

53 WWO shipped 6,083 Nissan passenger vehicles over the relevant contract period. It generated revenue of US$6,305,008 but that revenue ultimately resulted in a loss of US$1,233,446.

Incident 2: Renault Nissan – Europe and Turkey to Australia

54 In mid-2011, RNPO issued a global tender which included a request for bids for the provision of shipping services on routes from Europe to Australia and Turkey to Australia for the 2012-2013 contract period.

55 In about May or June 2011, the Manager of the MVG of WWO Japan and the Manager of the Cross Trade Team of NYK had a telephone conversation and meeting concerning the tender. During a conversation which occurred either over the telephone or at the meeting, the WWO manager told the NYK manager the freight rates that WWO was proposing to submit to RNPO for the route from Europe to Australia for cars, light commercial vehicles and vans (being US$855, US$990 and US$1615, respectively) and the NYK manager provided the WWO manager with NYK’s proposed freight rate for the Turkey to Australia route (being US$930/unit). He also requested that WWO bid higher than this rate. The WWO manager said that he understood NYK’s request.

56 On 15 November 2011, WWO submitted freight rate quotations to RNPO for the Europe to Australia route which were identical to the rates that its manager had told the NYK manager that it would submit. It also submitted a rate of US$1250/unit for the Nissan cargo on the Turkey to Australia route.

57 No Nissan cargo was shipped by WWO on the routes from Europe to Australia or Turkey to Australia for the 2012-2013 contract period.

Incidents 3-5: Fiat Chrysler – Europe to Australia

58 In or around early August 2011, Fiat issued a request for quotation, which included Fiat passenger vehicle cargo and Iveco truck cargo on the Europe to Australia route to commence in 2012. NYK was Fiat’s existing carrier for passenger vehicle cargo. WWO did not have a contract with Fiat, or provide any services to Fiat, in respect of Fiat passenger vehicle cargo on the Europe to Australia route.

Incident 3: Europe to Australia – cars

59 In or about August 2011, following Fiat’s request for quotation, the Manager of the Cross Trade Team within NYK’s Car Carrier Division contacted the Manager of the MVG of WWO Japan. A conversation took place between those two managers in relation to quotations for the Fiat passenger vehicle cargo. During that conversation, the NYK manager provided the WWO manager with the details of the freight rate level which NYK wanted WWO to bid. The WWO manager said that he understood the request.

60 WWO subsequently submitted a freight rate around the level that had been communicated by NYK.

61 In 2012, NYK entered into an agreement with Fiat for the provision of shipping services, including for the shipping of Fiat passenger vehicles on the Europe to Australia route.

Incident 4: Europe to Australia – trucks

62 In or around early August 2011, after receiving Fiat’s request for quotation, the Manager of the MVG of WWO Japan contacted the Manager of the Cross Trade Team within NYK’s Car Carrier Division. A conversation took place between those two managers in relation to quotations for the Iveco truck cargo. During that conversation, the WWO manager told the NYK manager a particular freight rate and requested that NYK submit a freight rate above that rate. The NYK manager agreed.

63 Following the submission of bids in response to Fiat’s request, NYK retained all of its existing Fiat business.

Incident 5: Europe to Australia – mid-contract period

64 In or around 1 May 2012, Chrysler Australia Pty Ltd took over the distribution of Fiat and Alfa Romeo vehicles in Australia. At that time, NYK was Fiat’s existing carrier for Fiat’s passenger vehicle cargo on the Europe to Australia route.

65 On or around 23 April 2012, an officer of Chrysler Australia approached a WWO Contract Manager for Business Development Oceania in Australia. The Chrysler Australia officer indicated that Chrysler Australia wanted to change service providers from NYK and asked the WWO manager to provide WWO’s proposed freight rate for the Europe to Australia route.

66 On or around 4 May 2012, WWO’s Australian office provided Fiat Chrysler with a freight rate quotation for shipping services on the Europe to Australia route.

67 On or around 21 May 2012, two senior WWO managers, WWO’s Key Account Manager (Europe) and Head of Commercial (Europe), met with Fiat Group Automobiles S.p.A’s (FGA) representatives. During that meeting, discussions took place concerning the supply of shipping services and rates for shipping certain vehicle models on the Europe to Australia route. The FGA representatives advised the WWO managers that Fiat was very interested in changing service provider on this route as NYK was transhipping units in Singapore and did not have good frequency and transit time.

68 On or around 24 May 2012, WWO’s Head of Commercial (Europe) emailed WWO executives including WWO’s Key Account Manager (Europe). The email stated that, in the past, WWO had stayed away from Fiat’s business due to “rate levels” and “in order to avoid retaliation from NYK”. The manager indicated, however, that a number of things had changed that may lead WWO to pursue the business.

69 On or around 16 July 2012, a representative of Chrysler Australia contacted a WWO representative and asked whether WWO could provide shipping services from Europe to Australia at a rate lower than the rate it quoted in May 2012. WWO provided a further revised freight rate quotation in response to that request on 24 July 2012.

70 On or around 25 July 2012, the Manager of the MVG of WWO Japan had a conversation with the Head of Oceania Trade in the WWO Europe Office. During that conversation, the Manager of the MVG said that he had heard from NYK and from within WWO that WWO was seeking to obtain Fiat Chrysler as a customer on routes to Australia. He said that given the Fiat volumes in question were still under contract to NYK, if WWO proceeded with that course, it would interfere with NYK’s current contract and NYK would want WWO to respect its existing business. The Manager of the MVG reiterated that if WWO took any of the Fiat cargo from NYK on the Europe to Australia route, WWO would be contravening the arrangement between the carriers to “respect” each other’s customers, which would lead to repercussions and retaliation by NYK. In that context, he requested the Head of Oceania Trade to provide him with the freight rate figures so he could speak to his counterpart at NYK in Japan. The Head of Oceania Trade informed the Manager of the MVG that he was aware of the arrangement between WWO and NYK to “respect” each other’s customers.

71 On or around 26 July 2012, the Manager of the MVG sent an email to WWO’s VP. The email noted that the Fiat cargo on the Europe to Australia route was historically very important business for NYK and he was afraid of NYK’s reaction if WWO went after that business.

72 On 27 July 2012, the Manager of the MVG sent an email to the President regarding Chrysler Australia’s request. The email explained that it was a serious situation as WWO’s Key Account Manager (Europe) had already submitted a freight rate quotation. He proposed that WWO’s Oslo office stop the Key Account Manager from continuing.

73 The President replied to that email on the same date. In that email, the President indicated that he would intervene if the Manager of MVG could not handle the situation. In an email in reply, the Manager of the MVG told the President that, regardless of what Fiat had said, WWO would not attempt to win this business and that he would “lead the FIAT business to reach the point that [WWO] will answer No Space … and not accept any booking” and that “whatever the customer says [WWO] shouldn’t touch NYK business”.

74 On about 30 July 2012, the Manager of the MVG had a telephone conversation with the Deputy Manager of the Global Marketing and Cross Trade team in NYK’s Car Carrier Group. During that conversation, NYK’s manager said that he had heard a rumour that WWO had made a competitive rate offer to Fiat Chrysler for NYK’s business on the Europe to Australia route, that this business was still under contract to NYK and that, as a result, WWO was interfering with NYK’s current contract. He said that NYK wanted WWO’s respect for this business and requested that WWO submit a new quote with increased rates. The WWO manager said, in reply, that Chrysler Australia had approached WWO for a freight rate quotation for Fiat cargo on the Europe to Australia route and that WWO did not want to interfere with NYK’s Fiat business. He indicated, however, that WWO would be responding to Chrysler with a quote because of its relationship with Fiat on other routes.

75 On 30 July 2012, the Manager of the MVG sent an email to WWO’s VP. A copy of that email was sent to the President. In the email, the Manager of the MVG requested information concerning WWO’s freight rate for the Fiat cargo on the Europe to Australia route, noted that urgent action was required and requested that he and WWO’s VP have a telephone discussion about the matter.

76 Following that email, the Manager of the MVG and WWO’s VP had a telephone conversation. During that conversation, the Manager of the MVG conveyed that he or his supervisor had spoken to his counterpart at NYK, that the situation with NYK was serious, that NYK would retaliate if WWO did not revise its quote to Chrysler Australia and that he would speak to his counterpart at NYK to provide the freight rates that WWO had submitted to Chrysler Australia.

77 In an email sent on 31 July 2012, WWO’s VP stated that WWO “will not offer rates on any other models due to space constraints”. On the same day, the Manager of the MVG sent an email to the President. The Manager of the MVG stated that he had advised WWO’s VP of the seriousness of the situation and that he had obtained the freight rate that WWO had quoted to Fiat. He also informed the President that Fiat was considering terminating its contract with NYK and that he believed that, although WWO’s freight rate submitted to Fiat was relatively high, in light of the situation and NYK’s requested increased freight rate for this cargo, there was a possibility that WWO’s rate would not be considered too high by Fiat. The Manager of the MVG also noted that he had an upcoming meeting with NYK about the matter.

78 Shortly afterwards, NYK’s Deputy Manager telephoned the Manager of the MVG. During the ensuing conversation, the WWO manager told the NYK manager the rates that WWO had quoted to Chrysler Australia. The WWO manager also told the NYK manager that it would be difficult for WWO to increase the freight rate immediately, but that WWO would tell Fiat that it did not have space to carry Fiat cargo on the Europe to Australia route.

79 On 31 July 2012, the Manager of the MVG met with NYK’s Deputy Manager and the Manager of the Global Marketing and Cross Trade Team of NYK’s Car Carrier Division in a conference room at NYK’s headquarters in Tokyo. During that meeting, the WWO manager told the NYK manager the rates that WWO had quoted to Fiat, which were higher than the rates that NYK charged to Fiat.

80 On the same date, WWO confirmed to FGA that its rates quoted on 24 July 2012 for two specific vehicle models were valid and that WWO could not quote for further models or volumes because of space constraints.

Incident 6: Toyota – US to Australia

81 On or about 16 February 2012, Toyota Logistic Services (TLS), a company based in the US, issued a request for quotations as part of a feasibility study, including quotations for the provision of shipping services for Toyota Highlander cargo (known in Australia as the “Kluger”) on the US to Australia route. Until this time, Klugers were not transported from North America to Australia, and NYK was the incumbent carrier of Toyota cargo for the Japan to Australia route.

82 On or about 29 February 2012, the Manager of the MVG telephoned the Deputy Manager of the Global Marketing and Cross Trade team in NYK’s Car Carrier Group. During this conversation, the WWO manager told the NYK manager that WWO intended to submit a bid for the Kluger cargo but, in doing so, did not want to interfere with NYK for this business. He indicated that WWO’s intended rate was in the range of US$50/m3 and US$70/m3. The NYK manager asked WWO not to submit a quote with rates within that range and to instead quote a rate that was much higher. The NYK manager informed the WWO manager that NYK was proposing to submit a freight rate of US$105/m3. In response, the WWO manager asked whether a rate of US$90/m3 or US$95/m3 would be acceptable to NYK. The NYK manager replied that a quote of US$95/m3 would be acceptable. The WWO manager told the NYK manager that WWO management would be consulted about the quote to be submitted to TLS.

83 In February 2012, WWO responded to TLS’ feasibility study with a freight rate of approximately US$40/m3 plus a bunker adjustment factor (BAF).

84 On 17 May 2012, TLS sent an email to bid participants. The email referred to a TLS tender and the TLS system for submitting bids, including the bids for the provision of shipping services for Kluger cargo on the US to Australia route.

85 After receiving that email, NYK’s Deputy Manager of the Global Marketing and Cross Trade team telephoned the Manager of the MVG. The NYK manager asked the WWO manager whether WWO would allow NYK to charter space on the WWO direct service from the US to Australia. The WWO manager said, in reply, that WWO would support NYK and offer space on its direct service if WWO could carry some part of the Kluger business on its own bill of lading.

86 On 28 May 2012, the Deputy Manager and Manager of NYK’s Global Marketing and Cross Trade team met with the Manager of the MVG at NYK’s Tokyo offices to discuss the Kluger tender. During that meeting, the WWO manager informed the NYK manager of WWO’s proposed freight rates to be submitted to the TLS tender.

87 On 30 May 2012, the Manager of the MVG had a telephone conversation with the Deputy Manager of NYK’s Global Marketing and Cross Trade team. During that conversation, the WWO manager informed the NYK manager that WWO proposed to offer a rate of US$80/m3 in response to the TLS tender on the US to Australia route. That was lower than the rate that WWO had submitted in response to the TLS feasibility study.

88 In June 2012, WWO submitted to the TLS tender a base freight rate of US$69.80/m3 plus BAF and other surcharges for routes from the US to Australia. In July 2012, WWO submitted a revised base freight rate of US$61.80/m3 to the TLS tender for the US to Australia routes.

Incidents 7-8: the s 16BA offences

89 As has already been noted, Incidents 7 and 8 did not occur within the charge period and are not part of the conduct the subject of the offence of which WWO has pleaded guilty. These incidents constitute the two offences that WWO has requested the Court to take into account, pursuant to s 16BA of the Crimes Act, in sentencing it for the offence of which it has pleaded guilty. The manner in which these offences and the incidents they encompass are to be taken into account in sentencing WWO will be considered in more detail later.

Incident 7: Toyota – US to Australia (2009)

90 On or around 18 November 2009, the Assistant Manager of the MVG had a conversation with the Manager of the America Team in NYK. During that conversation, the NYK manager said that he had been contacted by a customer in relation to the provision of shipping services on the US to Australia route. He asked the WWO manager, in that context, what freight rate he should quote. The WWO manager said, in reply, that NYK should submit freight rates higher than US$90/m3 – US$100/m3.

91 On or about 25 November 2009, Toyota issued a request for quotation to WWO as part of a feasibility study for the shipment of Klugers from the US to Australia. It became apparent to WWO, as a result of the issuing of this request, that Toyota was the customer referred to by the NYK manager during the telephone call with the WWO manager on 18 November 2009.

92 On 26 November 2009, the President emailed the Assistant Manager of the MVG. The President suggested that the quote that WWO proposed to submit to Toyota should be discussed with NYK in accordance with the Respect Arrangement. He indicated that he would speak to NYK the next day.

93 No cargo was ultimately shipped by Toyota on the US to Australia route.

Incident 8: Mitsubishi – Europe and Turkey to Australia (2009)

94 In around May or June each year, Mitsubishi sought annual freight rate renewals and occasionally ad hoc quotations on specific routes from shipping carriers.

95 On or just prior to 12 November 2009, Mitsubishi contacted NYK and requested that it submit freight rate quotations, including for the routes from Europe to Australia and Turkey to Australia.

96 After receiving that request, on 12 November 2009, the Deputy General Manager of NYK, who was responsible for Europe Trade and Cross Trade within NYK’s Car Carrier Division at the time, telephoned his counterpart at WWO.

97 During that conversation, the NYK manager said that Mitsubishi had requested a freight rate quotation for the aforementioned routes and told the WWO manager the freight rates NYK had provided. He indicated to the WWO manager that if WWO was contacted by Mitsubishi, it should provide rates “in line with” NYK’s freight rates.

98 WWO did not have a contract with Mitsubishi at this time. Nor did it provide shipping services to Mitsubishi on the Europe to Australia or Turkey to Australia routes.

elements of the offence

99 The elements of the offence created by s 44ZZRG of the CCA were analysed in some detail in CDPP v NYK at [171]-[188] and CDPP v K-Line at [171]-[185]. It is unnecessary to repeat that detail here. It suffices to observe again that, while the offence provision in s 44ZZRG may at first blush appear to be beguilingly straightforward, the devil is in the detailed and complex definition of the term “cartel provision” in s 44ZZRD of the CCA. It is also necessary to have regard to other relevant definitional provisions in s 4F and s 44ZZRB of the CCA, as well as provisions of the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) which provide for, inter alia, the fault elements applicable to federal criminal offences, including those in the CCA. It should also be noted, in this context, that since WWO committed the charged offence, the relevant offence provisions have been renumbered; relevantly, the former s 44ZZRG is now s 45AG of the CCA. The content of the provision, however, remains unchanged.

100 In short and simple terms relevant to the particulars of the offence to which WWO has pleaded guilty, the relevant elements of the offence are as follows.

101 First, there was in existence a contract, arrangement or understanding that contained a “cartel provision”: s 44ZZRG(1)(a) of the CCA.

102 The Respect Arrangement was, relevantly, an arrangement or understanding for the purposes of s 44ZZRG(1)(a) of the CCA.

103 A provision is a “cartel provision” if, relevantly: it has the purpose of directly or indirectly allocating between any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding the persons or classes of persons who have acquired, or who are likely to acquire, goods or services from any or all of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding; and at least two of the parties to the contract, arrangement or understanding are or are likely to be, or but for any contract, arrangement or understanding would be or would be likely to be, in competition with each other in relation to the supply, or likely supply, of goods or services: ss 44ZZRD(1), (3)(b)(i) and (4)(a), (b) and (c) of the CCA.

104 The Respect Arrangement relevantly contained a cartel provision because it contained a provision, the market allocation provision, which had the purpose of allocating the supply of shipping services, including shipping services to Australia, between the parties to the Respect Arrangement who were in competition with each other in relation to the supply of such services.

105 Second, the accused corporation knew or believed that the relevant contract, arrangement or understanding contained a cartel provision: s 44ZZRG(2) of the CCA; see also s 5.3 of the Criminal Code which defines the fault element of knowledge.

106 It is implicit in WWO’s plea of guilty that it knew or believed that the Respect Arrangement contained the market allocation provision which was a cartel provision.

107 Third, the corporation gave effect to the cartel provision: s 44ZZRG(1)(b) of the CCA.

108 WWO gave effect to the relevant cartel provision in the particularised six incidents in which its officers or employees engaged in communications with officers or employees of other parties to the Respect Arrangement, specifically NYK and MOL, in relation to the freight rates that the respective companies would bid in response to requests for bids by motor vehicle manufacturers for the shipping of motor vehicles to Australia.

109 Fourth, the corporation intended to give effect to the cartel provision. No fault element is specified in relation to s 44ZZRG(1)(b) of the CCA. Section 5.6(1) of the Criminal Code provides that, where the fault element for a physical element of an offence that consists only of conduct is not specified, the fault element is intention.

110 It is implicit in WWO’s plea of guilty that it intended to give effect to the market allocation provision.

111 It should also be noted, in this context, that s 5 of the CCA provides that the provisions of, inter alia, Pt IV of the CCA extend to, relevantly, engaging in conduct outside Australia by bodies corporate incorporated or carrying on business in Australia. WWO was not incorporated in Australia; however, it is an agreed fact that WWO carried on business in Australia. It is on that basis that s 44ZZRG of the CCA extends to WWO’s offending conduct. That is important because all of the offending conduct otherwise occurred outside Australia. All of the collusive arrangements and discussions, and all of the contracts that resulted from them, were engaged in or entered into overseas. None of the WWO managers who were involved in the relevant conduct were Australian citizens or residents.

maximum penalty

112 The penalty for an offence against s 44ZZRG(1) is set out in s 44ZZRG(3) of the CCA.

113 In simple terms, the maximum penalty is the greater of three amounts: first, the sum of $10,000,000; second, an amount consisting of three times the total benefits that were obtained from the commission of the offence, if those benefits can be determined; third, if the benefits cannot be determined, an amount consisting of 10% of the corporation’s annual turnover during the 12-month period ending at the end of the month in which the corporation committed, or began committing, the offence. The expression “annual turnover” is defined in s 44ZZRB of the CCA as the sum of the values of all the supplies that the corporation, or any related corporation, made or was likely to have made during the relevant 12-month period, other than certain specific types of supplies, including supplies that are not connected with Australia.

114 It was common ground that the total value of the benefits obtained by WWO which were attributable to the commission of the offence could not be determined.

115 It was an agreed fact for the purpose of this proceeding that WWO’s annual turnover, as defined, in the relevant 12-month period from 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2011, was approximately $485,324,934. The Director accepted that the annual turnover calculated by WWO provided an appropriate basis for the calculation of the maximum penalty pursuant to s 44ZZRG(3) of the CCA.

116 Accordingly, the maximum penalty in respect of the offence committed by WWO is $48,532,493.

Evidence adduced by wwo

117 WWO adduced affidavit evidence from Ms Marianne Frisell Schreuder, a senior legal counsel of WWO.

118 Ms Schreuder had been employed by WWO since 1996 and had worked in many different roles and positions. She took up a role as Legal Counsel Region Asia & Oceania in the Global Legal & Ocean Services division in 2002 and remained in that role until 2012. During that time, she was based in Tokyo from 2002 to 2006 and again from 2010 to 2012. In that role, she was responsible for providing legal advice, support and training for WWO’s Asia and Oceania business activities, including advice on competition law matters. In 2013, she was promoted to the role of Head of Global & Legal Compliance and Global Compliance Officers in WWO, a new position within the organisation. In that role, she was part of WWO’s Global Leadership Team and reported directly to the Chief Executive Officer. She held that role for almost four years.

119 In April 2017, following a company restructure, Ms Schreuder was appointed to her current role as Senior Legal Counsel. In that role, she is responsible for managing WWO’s regulatory and legal response to ongoing investigations by various competition authorities around the world. Ms Schreuder noted that she has now worked for WWO for over 20 years in both a legal and compliance role.

120 Ms Schreuder’s evidence focused on WWO’s compliance training and procedures and the penalties paid by WWO in other jurisdictions. Ms Schreduer was not cross-examined and her evidence was not challenged.

Compliance training and procedures

121 Ms Schreuder’s evidence was that from at least June 2003, WWO employees have been required to attend compliance and code of conduct training in accordance with WWO’s Compliance Program. That training was provided in various countries where WWO carried on business, including Australia, and included training sessions concerning the local competition laws that applied in the relevant country.

122 WWO also had a Code of Conduct from at least June 2003. That Code was most recently updated in 2016. Ms Schreuder’s evidence concerning the Code of Conduct included the following:

The Code of Conduct stipulates that no employee should engage in anti-competitive behaviour, including the disclosure of information about the company, a customer or competitor not publically known, and all employees should be aware that the penalties for non-compliance are severe. The Code of Conduct notes that violations of the Code of Conduct or applicable laws may result in disciplinary action as well as termination of employment and legal proceedings.

123 Ms Schreuder also gave evidence that from 2012 to 2015, WWO implemented a revised global Compliance Program. The revised program included: the creation of a Global Compliance Policy; the creation of a compliance section within WWO, including the appointment of a Global Compliance Officer and other key compliance managers; updated jurisdiction-specific compliance manuals and policies; jurisdiction-specific compliance training; separation of the commercial and operational departments within WWO; the introduction of an Alert Line; and regular auditing to ensure compliance with the revised program.

124 The Global Compliance Policy was introduced in or around 2012 to 2013 and outlined the organisational structure, responsibilities and reporting lines for the implementation of WWO’s revised Compliance Program. It included a statement of commitment by management to compliance with relevant competition laws. Responsibility for the policy’s implementation rested with the Chief Executive Officer, the Heads of Division and Heads of the Regional Market Performance Areas.

125 Ms Schreduer’s evidence was that from around September 2012 to February 2020, more than 100 competition law training sessions with WWO employees have been conducted globally, with eight sessions specific to competition compliance in Australia delivered to employees in Australia. She further stated that in her role as Global Compliance Officer, she delivered approximately 14 of those sessions. Ms Schreuder’s evidence concerning the training sessions included the following:

From around 2014, all of [WWO’s] workforce have been required to complete in-person training and/or e-learning programs from time to time. These training and e-learning programs form part of the compliance training program and are targeted at the prevention of anti-competitive practices and anti-bribery and anti-corruption practices. In 2015, employees were required to complete an e-learning program specifically focused on anti-competitive practices. For completeness, I note that the [WWO] employees who did not complete this program were those production employees involved in the provision of land-based services.

126 Ms Schreuder also noted that from 2013, WWO made a number of significant changes to its senior management personnel, including the President and CEO, Chief Commercial Officer, Chief Operating Officer for Ocean Services and the President of WWO’s Japan office. None of the new personnel that were appointed had prior involvement with the conduct the subject of this proceeding.

127 Finally, Ms Schreuder stated that in June 2014, WWO established a new department with sole responsibility for ocean operations that was functionally separate from the company’s commercial department. It also established an anonymous hotline in 2013 to encourage the reporting of anti-competitive behaviour or conduct otherwise in breach of the Code of Conduct or other WWO policies.

128 Two matters should perhaps be noted in the context of considering Ms Schreuder’s evidence concerning WWO’s compliance training and programs. First, it is self-evident that the training and programs that were in place before 2012 were plainly either deficient, ineffective or perhaps both. Either the WWO managers and executives who engaged in the conduct which gave effect to the Respect Arrangement were unaware that their conduct was unlawful anti-competitive conduct which breached WWO’s Code of Conduct, in which case the training and programs were manifestly deficient, or the managers and executives knew that their conduct was unlawful and contrary to the Code of Conduct, but engaged in that conduct anyway, in which case the training and programs were manifestly ineffective. As discussed later, the latter is more likely to have been the case.

129 Second, the significant changes to WWO’s compliance training and programs in and after 2012 can largely be explained by, or were the product of, the JFTC and DOJ raids. Although Ms Schreuder’s evidence does not make this link expressly or directly, it is difficult to avoid the inference that the new measures implemented by WWO in and after 2012 were a result of the fact that the competition authorities had discovered and exposed its participation in the global cartel.

Penalties paid in other jurisdictions

130 Ms Schreuder’s evidence also included the following detail concerning fines paid by WWO in other jurisdictions as a matter of public record. The relevance of the imposition of those penalties and the appropriate weight to be given to them in the exercise of the sentencing discretion is addressed later.

United States

131 In October 2011, WWO entered into a Compromise Agreement with the US Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) and paid an agreed administrative penalty of US$800,000 in relation to alleged conduct concerning the transportation of automobiles and other motorised vehicles by “roll-on, roll-off” specialised car carrier vessels. That conduct occurred pursuant to agreements that were not filed with the FMC.

132 On 11 July 2016, WWO agreed to plead guilty and pay a criminal fine of US$98.9 million in the US in relation to its participation in a combination and conspiracy to suppress and eliminate competition by allocating customers and routes, rigging bids and fixing prices for international ocean shipping services for “roll-on, roll-off” cargo to and from the Port of Baltimore and other locations in the US during the period February 2000 until February 2012. This fine related in part to conduct affecting certain volumes of commerce on routes to Australia, though the extent to which that was the case is unclear.

133 In November 2016, three WWO employees were indicted on charges of conspiring with competitors to allocate certain customers between routes, rig bids and fix prices for the sale of international ocean shipments of “roll-on, roll-off” cargo to and from the US and elsewhere.

Europe

134 On 21 February 2018, the European Commission fined WWO and three other maritime car carriers for participating in a cartel concerning intercontinental maritime transportation of vehicles in breach of European Union antitrust rules. WWO was fined EUR207,335,000 (approximately US$171 million at that time) in relation to conduct on various routes to and from the European Economic Area during the period 18 October 2006 to 6 September 2012. The conduct for which WWO was fined by the European Commission included some conduct which affected volumes of commerce on routes to Australia, though the extent to which that was the case is again unclear.

Japan

135 On 18 March 2014, the JFTC found WWO and other carriers had illegally coordinated their responses to requests for prices from customers in breach of Japanese legislation. WWO was issued with an administrative surcharge payment order in the amount of JPY3,495,710,000 (approximately US$33 million at that time) in relation to the North America to Japan route and Europe to Japan route from mid-January 2008 until 6 September 2012.

China

136 On 15 December 2015, China’s National Development and Reform Commission fined eight carriers for reaching and implementing monopoly agreements which eliminated and restricted competition in the car carrying industry. WWO was fined CNY45,061,269 (approximately US$7 million at that time) in relation to conduct occurring between 2008 to September 2012 involving import and export ocean shipping on routes between China and North America, Japan, Europe and Turkey.

South Africa

137 On 13 August 2015, the Competition Tribunal of South Africa approved a settlement agreement filed by the South African Competition Commission and WWO. The conduct by WWO which was the subject of that settlement agreement included it entering into, and giving effect to, agreements to fix prices, divide markets and collude on tenders issued by vehicle, equipment, rolling construction and agricultural machinery manufacturers with its competitors for the transportation of motor vehicles to and from South Africa by sea. WWO agreed to pay an administrative penalty of ZAR95,695,529 (approximately US$6.4 million at that time) for conduct occurring from 2008 to September 2012 in relation to certain volumes of commerce on routes between South Africa and Europe, North Africa, North America and Asia including Japan, Thailand and Indonesia, and conduct occurring from 1999 to 2012 in relation to certain volumes of commerce on the Thailand to South Africa route.

Mexico

138 On 9 June 2017, Mexico’s Federal Economic Competition Commission fined WWO and six other carriers for entering into collusive agreements to allocate between them portions of the car carrier and “high and heavy” carrier markets in Mexico. The fine of approximately US$4.2 million at that time concerned WWO’s conduct in 2012 in relation to certain volumes of commerce on the route from Europe to Mexico.

Brazil

139 On 9 November 2016, WWO agreed to pay fines totalling BRL28,627,814.01 (approximately US$4.1 million at that time) to Brazil’s Administrative Council for Economic Defence following an investigation into alleged anti-competitive behaviour in the car carrying industry.

South Korea

140 On 1 September 2017, the Korean Fair Trade Commission issued a total fine of KRW43 billion (approximately $47.68 million at that time) on WWO and eight other international shipping companies for agreeing to and implementing conduct having an anti-competitive effect on the automobile marine transport market for exports and imports of automobiles from or into Korea between 2002 and 2012. WWO was also fined KRW5,515,000,000 (approximately US$3.6 million at that time) in relation to conduct occurring from 2005 to 2012 in relation to certain volumes of commerce on routes between South Korea and North, Central and South America, Europe and the Mediterranean and the rest of Asia including Japan.

Contrition

141 It is noteworthy that Ms Schreuder’s evidence did not include an express or even implicit apology or statement of contrition and remorse on behalf of WWO. Nor was there any other direct evidence of contrition or remorse, though as discussed later, WWO’s early indication that it would plead guilty to the offence is demonstrative of some measure of contrition.

Guilty plea

142 On 23 August 2019, the Director filed an indictment in this Court ex officio pursuant to s 23AB(1)(b) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). That indictment contained one rolled-up offence under s 44ZZRG of the CCA.

143 On 29 August 2019, at the first case management hearing in this matter, the Court was advised that the matter would proceed by way of a plea of guilty and sentencing hearing.

144 On 20 February 2020, following two additional case management hearings that focused largely on the delays in finalising the Statement of Agreed Facts, the matter was listed for a sentencing hearing on 18 June 2020 with an estimate of one day. The Director noted that WWO, at that time, had not formally entered a plea of guilty. The parties agreed that the plea could and would be entered at the commencement of the sentencing hearing, with neither party anticipating any change in the plea.

145 A formal plea of guilty to the indictment containing the single rolled up charge under s 44ZZRG of the CCA was eventually entered on 18 June 2020.

the appropriate sentence

146 WWO, a corporation convicted of a federal offence, is to be sentenced in accordance with Pt 1B of the Crimes Act. The relevant provisions of Pt 1B and the applicable sentencing principles were considered at length in CDPP v NYK and CDPP v K-Line. Given the obvious similarities and connections between the offending behaviour of NYK, K-Line and WWO, the following discussion largely repeats or reiterates much of what was said in the sentencing judgment in those matters. Where appropriate, however, relevant distinguishing facts or features will be highlighted.

147 Section 16A(1) of the Crimes Act states that the “overarching principle” of Pt 1B is that any sentence imposed by the Court must be of a “severity appropriate in all the circumstances of the offence”: see CDPP v NYK at [202]; CDPP v K-Line at [264].

148 Section 16A(2) details the matters that the Court must take into account so far as they are relevant and known to the Court. Those matters relevantly include: the nature and the circumstances of the offence; other offences (if any) that are required or permitted to be taken into account; if the offence forms part of a course of conduct, that course of conduct; the personal circumstances of any victim of the offence; any injury, loss or damage resulting from the offence; the degree to which the offender has shown contrition for the offence; if the offender has pleaded guilty, that fact; the degree to which the offender has co-operated with law enforcement agencies in the investigation of the offence and other offences; the deterrent effect of any sentence on the offender or any other person; the need to ensure that the offender is adequately punished for the offence; the character and antecedents of the offender; and the prospect of rehabilitation of the offender.

149 The “checklist” of matters detailed in s 16A(2) does not, however, exclude other relevant considerations, including common law sentencing principles: Direction of Public Prosecutions (Cth) v El Karhani (1990) 21 NSWLR 370 at 377-8; Bui v Director of Public Prosecutions (Cth) (2012) 244 CLR 638 at [18]; Johnson v The Queen [2004] HCA 15; 78 ALJR 616 at [15]. Sentencing principles such as parity and proportionality are important considerations in fixing a sentence of a severity appropriate in all the circumstances: Hili v The Queen (2010) 242 CLR 520 at [25]; Wong v The Queen (2001) 207 CLR 584 at [78].

150 The following is a more detailed consideration of the relevant matters set out in s 16A(2) and other matters insofar as they are relevant to the offence committed by WWO and WWO’s particular circumstances.

Section 16A(2)(a) of the Crimes Act – The nature and circumstances of the offence

151 As has already been noted, the offence committed by WWO was, on any view, a very serious offence which requires condign punishment. WWO did not contend otherwise. A number features of the offence and the offending conduct compel that conclusion.

Course of conduct – a “rolled-up” offence

152 WWO has pleaded guilty to a single offence in contravention of s 44ZZRG(1) of the CCA. That should not, however, detract from the fact that, strictly speaking, WWO committed multiple offences against s 44ZZRG(1). A separate offence against s 44ZZRG(1) is committed each time a corporation engages in conduct which gives effect to a cartel provision. The agreed facts disclose that WWO engaged in conduct between June 2011 and July 2012 which gave effect to a cartel provision on six separate occasions. Each of those occasions could have been charged as a separate offence. WWO also committed two other offences which it has requested the Court to take into account, pursuant to s 16BA of the Crimes Act, in sentencing it for the offence of which it has pleaded guilty.

153 Notwithstanding that the facts reveal that WWO committed multiple offences, it is permissible for the Director to present an indictment containing a “rolled-up” charge on a plea (or expected plea) of guilty for a federal offence. A “rolled-up” charge is a charge in which more than one contravention of the relevant offence provision, or more than one episode of criminality, is particularised as part of the charge. A rolled-up charge would, but for the accused’s plea of guilty and consent, be liable to be quashed on the basis that it would offend the rule against duplicity: see CDPP v NYK at [206] and CDPP v K-Line at [269], both citing Environment Protection Authority v Truegrain Pty Ltd (2013) 85 NSWLR 125 at [31]-[52].

154 The relevant principles regarding rolled-up charges were summarised as follows in CDPP v K-Line at [270] (see also CDPP v NYK at [207]):

In sentencing a rolled-up charge, the Court is required to assess the criminality of an offender’s conduct as particularised. The issue for the Court on sentence is the criminality disclosed by the offence, not the number of charges: R v Knight [2004] NSWCCA 145 at [25]-[26]. The more contraventions or episodes of criminality that form part of the rolled-up charge, the more objectively serious the offence is likely to be: R v Richard [2011] NSWSC 866 at [65(f)]; R v Glynatsis [2013] NSWCCA 131; 230 A Crim R 99 at [66]; R v De Leeuw [2015] NSWCCA 183 at [116]. That said, the maximum penalty for the rolled-up charge is the maximum penalty for one offence, not the aggregate of the penalties for what could have been charged as separate offences: R v Richard at [105]; R v Donald [2013] NSWCCA 238 at [85].

155 Putting aside the fact that the offence to which WWO has pleaded guilty is a “rolled-up” offence, it is, in any event, relevant in assessing the nature and seriousness of the offence that WWO’s offending involved a course of conduct over a lengthy period of time. The scale and duration of the offending is discussed in more detail later.

The maximum penalty

156 The maximum penalty for the one offence committed by WWO is $48,532,493.

157 The maximum penalty for an offence is often viewed as a “guidepost” or “yardstick” that bears on the ultimate discretionary determination of the sentence for the offence: Elias v The Queen (2013) 248 CLR 483 at [27]. It can also be taken to represent the legislature’s assessment of the seriousness of the offence: Muldrock v The Queen (2011) 244 CLR 120 at [31]. It is, however, only one of many factors that may or must be taken into account when determining the appropriate sentence. Indeed, in some cases and in some circumstances it may provide little to no assistance: Markarian v The Queen (2005) 228 CLR 357 at [65], citing R v Geddes (1936) 36 SR (NSW) 554 at 555-556. As the High Court has observed, “[i]t is wrong to suggest that the court is constrained, by reason of the maximum penalty, to impose an inappropriately severe sentence on an offender for the offence for which he or she has been convicted”: Elias at [27].

158 The maximum penalty for an offence against s 44ZZRG of the CCA is not a single, specified sum or formula. The provision instead provides for alternative maximum penalties. The Director submitted that this “flexibility” indicates the seriousness with which the Parliament views cartel conduct.

159 As discussed earlier, the maximum penalty in WWO’s circumstances is based on its annual turnover, as defined in s 44ZZRB of the CCA. That is because, as was agreed by the parties, it was impossible to determine the total value of the benefits obtained by one or more persons that were reasonably attributable to the commission of the offence and 10% of WWO’s agreed annual turnover was greater than the sum of $10,000,000: see s 44ZZRG(3) of the CCA.

160 The relevance of this basis of assessment of the maximum penalty was explained in CDPP v K-Line at [274] as follows (see also CDPP v NYK at [211]):

One can readily comprehend why the legislature chose to include a maximum penalty for cartel offences which may be based on the offending corporation’s annual turnover. Specific deterrence is a major consideration in determining the appropriate size of the fine to impose in relation to a cartel offence. The fine should be such as to ensure that the penalty is not to be regarded by the offender or others as an acceptable cost of doing business. The sum required to achieve that objective will generally be larger where the offending corporation is a very large corporation, as may be reflected in its annual turnover. That said, in some cases a maximum penalty based on the offending corporation’s annual turnover may not provide a realistic guide to the objective seriousness of the offending conduct or criminality involved in the offence. It is, for example, possible to imagine a case where a large corporation with a very high annual turnover committed a single relatively minor offence against s 44ZZRG of the [CCA].

161 WWO submitted that this was a case in which “the offending corporation’s annual turnover may not provide a realistic guide to the objective seriousness of the offending conduct”. It referred, in that regard, to the facts of “Instance 1”: the shipment of 6,083 Nissan passenger vehicles by WWO from the US to Australia at a loss of US$1,233,446. The fact it had made a loss, rather than a profit, was said by WWO to be “itself significant”, suggesting that annual turnover as a “point of reference … must be applied with great caution”. The effect of WWO’s submission was that the maximum penalty should be treated with circumspection because there was a level of disconnect between WWO’s size and the seriousness of its offending conduct based on the fact that it had not been shown to have directly profited from it.

162 It may be accepted, essentially for the reasons given in the passage from CDPP v K-Line just cited, that where the maximum penalty for an offence against s 44ZZRG of the CCA is calculated by reference to the offending corporation’s annual turnover, some degree of caution or circumspection should generally be applied in treating the maximum penalty as a relevant “guidepost” or “yardstick” in determining the appropriate penalty. It cannot, however, be accepted that there was any relevant disconnect between WWO’s size, reflected in its annual turnover, and the seriousness of its offending, such that the maximum penalty of $48,532,493 provides no useful or reliable guidepost or yardstick in determining the appropriate penalty. WWO’s submission to that effect is based on an overly simplistic and flawed approach to the assessment of the seriousness of cartel offences generally and the offence committed by it specifically.

163 While the profit that a corporation derived from cartel conduct may be one indication of the seriousness of that offending conduct, it is by no means the only measure of the seriousness of the offending conduct. It is obviously not always possible to quantify accurately the profits that may be derived from a cartel offence. That is no doubt why the maximum penalty prescribed for such offences provides for alternative methods by which to calculate the penalty if the benefits attributable to the offence cannot be ascertained. The fact that it cannot be demonstrated that a corporation derived a direct financial benefit from giving effect to a cartel provision does not mean that the offence was not serious. Nor does the fact that the corporation can be shown to have made a loss from one incident of giving effect to the cartel provision.

164 The benefits that a corporation may derive from a cartel offence are clearly not limited to profits. Indeed, the benefits that a corporation may derive from a cartel are not limited to quantifiable financial benefits of any kind, but include more intangible, but nonetheless extremely valuable, benefits. That is no doubt why the concept of benefit in s 44ZZRG(3) is not limited to profits or other direct financial benefits.

165 This is a case in point. There could be little doubt that WWO benefited from its participation in the Respect Arrangement and its giving effect to the market allocation provision specifically. The very point or purpose of the Respect Arrangement and market allocation provision was the maintenance of stable market shares amongst the parties and the absence of effective price competition or other competitive pressures. The agreed facts reveal that those objectives were largely achieved. The maintenance of a stable market share, the maintenance of its existing business and the absence of effective price competition in the market were undoubtedly benefits that WWO derived from its offending conduct.

166 The seriousness of a cartel offence is also not to be measured simply on the basis of the benefits derived by the offender. A cartel offence committed by a corporation may undoubtedly also be considered to be a serious offence if the benefits from that offending mainly flowed to the other participants in the cartel. This again is a case in point. There could be no doubt that the other participants in the cartel, in particular NYK, benefited from some of the specific incidents in which WWO gave effect to the cartel arrangement. That is because those incidents involved WWO showing “respect” to NYK by not attempting to submit a bid or competitive bid in respect of customers or routes where NYK was the incumbent carrier. That allowed NYK to retain that business at freight rates that were likely to have been higher than would have been the case if there had been any effective price competition.

167 Finally, it is in any event overly simplistic to approach the analysis of the seriousness of cartel offending solely by reference to the benefits that can be shown to have been derived by the offender and other participants in the cartel. That would largely ignore the serious economic damage that may be caused by such anti-competitive conduct, particularly anti-competitive conduct engaged in by a very large corporation in a strategically important market. This case is again a case in point. WWO was undoubtedly a large corporation and the market for ocean shipping services was undoubtedly an important market for an island nation such as Australia. To assess the seriousness of WWO’s offending conduct solely on the basis of the profit or loss it may have derived from that offending would ignore the serious deleterious effects that its conduct had, or was likely to have had, on competition in that important market.

168 It is no doubt of some relevance in assessing the seriousness of WWO’s offending that it incurred a small loss from one of the shipping contracts which was affected by its conduct and that there is no evidence that it derived any direct financial benefit from any of the other incidents by which it gave effect to the market allocation provision. It perhaps overstates the position, however, to say that that fact is “itself significant”. More importantly, it provides no sound basis for WWO’s submission that there was a disconnect between WWO’s size, as reflected in its relevant annual turnover in the period prior to the offending, and the seriousness of its offending, nor any sound basis for the submission that the maximum penalty applicable in WWO’s case should not be considered to be a relevant or reliable guidepost in the assessment of the appropriate penalty.

169 Finally, it should perhaps be reiterated that, in any event, the maximum penalty is no more than a guidepost or yardstick. It is but one of the many relevant considerations in fixing the appropriate penalty.

Cartel offences generally

170 It is trite to observe that cartel conduct generally involves anti-competitive conduct of a very serious nature that should be emphatically condemned and deterred by the imposition of appropriately stern penalties. Prior to 2009, cartel conduct attracted only civil penalties. The fact that cartel conduct was criminalised in 2009 no doubt reflects the fact that Parliament regarded it sufficiently serious as to attract “opprobrium and societal condemnation in a way that the imposition of a civil penalty cannot”: CDPP v NYK at [215]-[216], also at [1] which reproduces the Minister’s Second Reading Speech; CDPP v K-Line at [275], [278].

171 While WWO is to be sentenced for a criminal offence, as opposed to being punished for contravention of a civil penalty provision, it is nonetheless useful to consider what has been said concerning the objective seriousness of cartel conduct in the civil penalty context. Much of what has been said about the seriousness of cartel conduct in that context applies equally in the criminal context.