Federal Court of Australia

KD (deceased) on behalf of the Mirning People v State of Western Australia [2021] FCA 10

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

A. The Applicant in proceeding WAD 48 of 2019 has made a native title determination application (Mirning Application Part B).

B. The Applicant in the Mirning Application Part B and the State of Western Australia (the State) have reached an agreement as to the terms of the determination which is to be made in relation to the land and waters covered by the Mirning Application Part B (the Determination Area). The external boundaries of the Determination Area are described in Schedule One to the determination.

C. Pursuant to s 87(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), the parties have filed with this Court an agreement in writing setting out the terms of the agreement reached by the parties in relation to the Mirning Application Part B.

D. The terms of the agreement involve the making of consent orders for a determination pursuant to s 87 and s 94A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) that native title does not exist in relation to the land and waters of the Determination Area.

E. Pursuant to s 87(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth), the parties have requested that the Court determine the proceedings that relate to the Determination Area without holding a hearing.

BEING SATISFIED that a determination of native title in the terms set out in Attachment A would be within the power of the Court and, it appearing to the Court appropriate to do so, pursuant to s 87 and s 94A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) and by the consent of the parties:

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. There be a determination of native title in WAD 48 of 2019 in terms of the determination as set out in Attachment A.

2. Order 1 is to take effect on the date that the State files a notice that the Mirning Part B Indigenous Land Use Agreement (Mirning Part B ILUA) has been Conclusively Registered (as defined in the Mirning Part B ILUA) on the Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements.

3. If the Conclusive Registration Date does not occur on or before 31 December 2022, or such other date as the Court may order, Order 1 will not take effect and the proceedings are to be listed for further directions.

4. There be no order as to costs.

5. There be liberty to any party to apply within 21 days to vary those parts of these orders which depart form the form of consent provided by the parties to the making of these orders.

NOTING THAT IN THESE ORDERS:

Conclusive Registration means, once this Agreement has been registered, that this Agreement remains registered:

(a) at a date that is 60 Business Days after the date on which a decision is made to register this Agreement, provided that no legal proceedings have been commenced in respect of such registration; or

(b) otherwise, at a date that is 40 Business Days following the exhaustion and determination of the final available legal proceedings in respect of such legal proceedings,

and Conclusively Registered has a corresponding meaning.

Conclusive Registration Date means the date that the State has issued the Parties with a notice confirming when this Agreement has been Conclusively Registered.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ATTACHMENT A

DETERMINATION

THE COURT ORDERS, DECLARES AND DETERMINES THAT:

Existence of native title (s 225 Native Title Act)

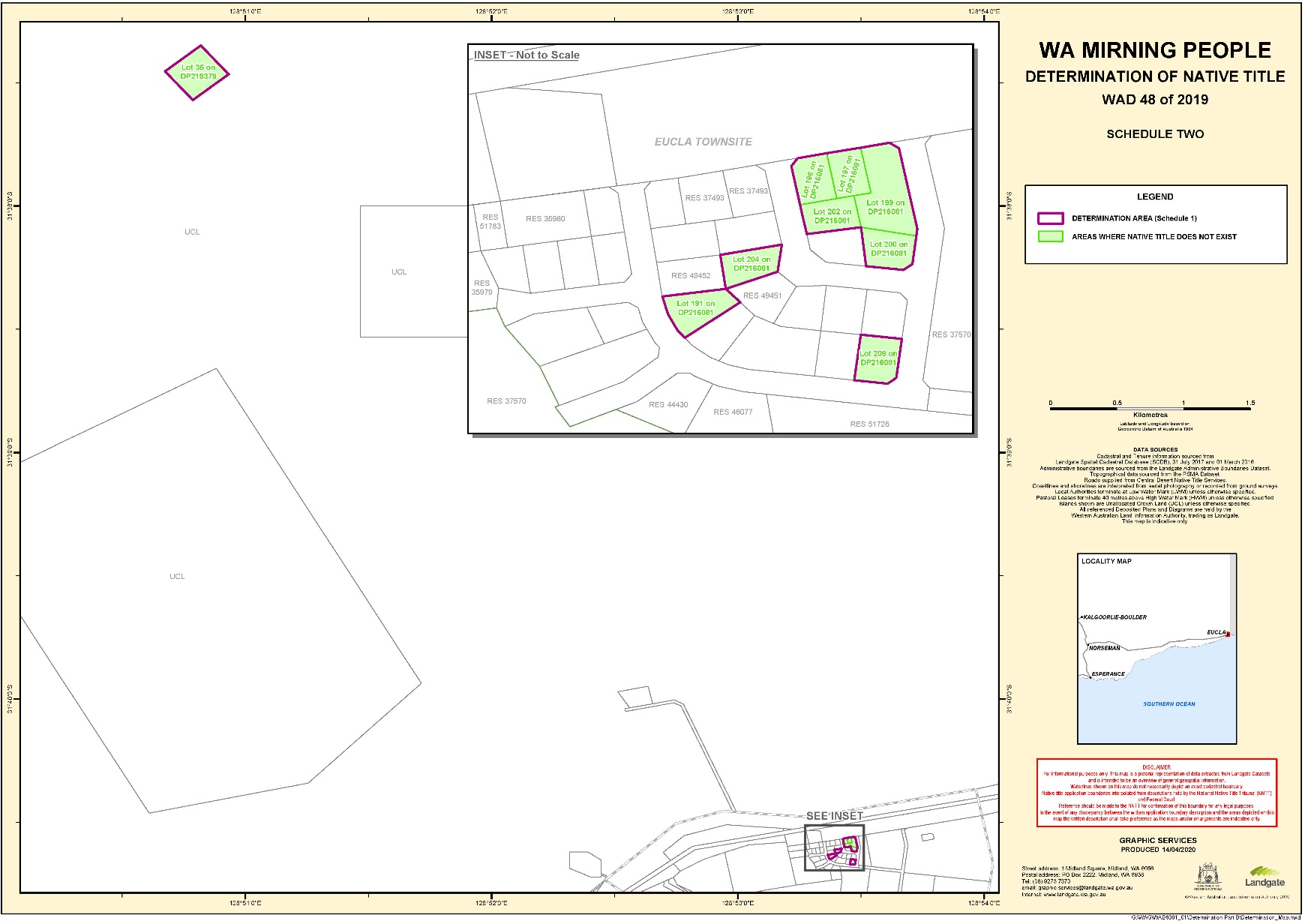

1. By reason of surrender, native title does not exist in the Determination Area, being the land and waters described in Schedule One and depicted on the maps at Schedule Two.

SCHEDULE ONE

DETERMINATION AREA

The Determination Area, generally shown as bordered in purple on the maps at Schedule Two, is all that land and waters comprising:

(a) Lot 191 on Deposited Plan 216081, being the whole of the land comprised in Certificate of Title 2220/326;

(b) Lot 196 on Deposited Plan 216081, being the whole of the land comprised in Certificate of Title LR3138/787;

(c) Lot 197 on Deposited Plan 216081, being the whole of the land comprised in Certificate of Title 2220/328;

(d) Lot 199 on Deposited Plan 216081, being the whole of the land comprised in Certificate of Title 2188/429;

(e) Lot 200 on Deposited Plan 216081, being the whole of the land comprised in Certificate of Title 2635/517;

(f) Lot 202 on Deposited Plan 216081, being the whole of the land comprised in Certificate of Title 2220/329;

(g) Lot 204 on Deposited Plan 216081, being the whole of the land comprised in Certificate of Title 2540/865;

(h) Lot 209 on Deposited Plan 216081, being the whole of the land comprised in Certificate of Title 2600/96; and

(i) Lot 36 on Deposited Plan 219379, Reserve 45847, being the whole of the land comprised in Certificate of Title LR3123/652.

SCHEDULE TWO

MAPS OF THE DETERMINATION AREA

COLVIN J:

1 The Court is asked to make a consent determination as to the balance of the land the subject of an application by the Mirning People for determination of native title. The present application concerns eight lots located in the town of Eucla and one lot located northwest of the town referred to together by the parties as the Part B land. The rest of the land the subject of the original application (being Part A) was the subject of a consent determination made on 24 October 2017: KD (deceased) on behalf of the Mirning People v State of Western Australia (No 4) [2017] FCA 1225.

2 At the time that the determination of native title was made as to Part A, the parties agreed to exclude Part B to allow time for continued discussions. Those discussions have now resulted in agreement and joint submissions from the applicant and the State of Western Australia as to the making of a consent determination as to Part B.

3 The proposed orders would involve the making of a determination pursuant to s 225 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) that native title does not exist in the Part B land. The agreement that has been reached contemplates that such a determination would be made to take effect once the State is satisfied that an indigenous land use agreement (ILUA) (in terms that have been negotiated) is 'Conclusively Registered' (a term that is itself defined in the proposed ILUA).

4 In joint submissions, the applicant and the State describe the reason for proceeding in this way in the following terms:

A determination that native title does not exist cannot take effect until the non-exclusive native title rights and interests that are extant over the 9 areas comprising…Part B…are surrendered. The terms of an Area Agreement ILUA pursuant to Part 2, Division 3, Subdivision C of the Native Title Act have been agreed between the Applicant and the State. The ILUA provides for a cash and land package to be held in trust in exchange for the surrender of the native title rights and interests, and validation of the acts done by the State over the 9 areas.

5 It is proposed that if registration of the ILUA does not occur before 31 December 2022, or such other date as the Court may order, then the proceedings are to be listed for further directions.

6 Reliance is placed upon the making of similar orders by Mortimer J in Taylor on behalf of the Yamatji Nation Claim v State of Western Australia [2020] FCA 42. In that case, her Honour made orders to reflect the terms of a settlement that included determinations of native title as to some land and the surrender of native title as to other land as part of an ILUA process. The negotiated outcome had taken some four years to conclude. The orders were made on the basis that they would not take effect unless the State was satisfied that the registration of the ILUA had occurred. Therefore, the orders looked forward to a point in time when, if the contemplated ILUA was arranged, the native title as to part of the land would be surrendered and a determination of native title would then be made on the basis that there was no native title as to that part.

7 In making the orders, Mortimer J observed at [34]:

I accept those orders, while unusual, are necessary and appropriate to address the circumstances of this particular settlement, involving as it does both a determination that native title exists in respect of some parcels of land in the SPA, and an ILUA which confers a range of benefits and compensation, and also involves the surrender of native title over the majority of the SPA, by way of the agreement to a negative determination. The course of events that has occurred in relation to the Noongar settlement (for a summary, see the recent decision of the Full Court of this Court in McGlade v South West Aboriginal Land & Sea Aboriginal Corporation (No 2) [2019] FCAFC 238 at [1]-[15], [37]-[85]) provides an example of the challenges which may be brought. While all those involved no doubt hope that the Yamatji Nation settlement does not follow the same course, the orders proposed, which the Court accepts should be made, are designed to reflect some of the potential uncertainties in the short term.

8 So, the form of orders proposed in these proceedings reflects the fact that terms agreed as to surrender of title to be the subject of the ILUA may be the subject of challenges as part of the process of registering the ILUA even though all parties who have been joined in the present application (after notification as required by the Native Title Act) are in agreement. There are costs and delay involved in undertaking the ILUA process. In those circumstances, it is understandable that the parties may wish to have some certainty as to the nature of the determination of native title that will take effect if, as expected, the ILUA is registered.

9 The Court has power to make a determination as to the outcome of an application for native title where the parties have reached agreement as to the terms in which the application should be determined: see s 87(1A) of the Native Title Act. In the present case, the determination made in 2017 as to Part A resulted in an amendment to the application which means that the whole of the application now relates to Part B and the proposed orders are sought on that basis. A consent determination may be made to the effect that native title does not exist: Bullen on behalf of the Esperance Nyungar People v State of Western Australia [2014] FCA 197 (McKerracher J).

10 The following conditions must be met before a determination of native title may be made pursuant to s 87 of the Native Title Act based upon the agreement of the parties. They are:

(1) Notice of the application for determination of native title must have been given as required by s 66 of the Native Title Act and the notice period must have expired.

(2) The agreement of the parties must relate to an area which is included in the area covered by the application.

(3) The terms of the proposed agreement must be in writing and signed by or on behalf of each of the parties and filed with the Court.

(4) There must have been no previous determination of the extent of native title over the area (or the order must be justified as a variation of the previous determination pursuant to s 13(1)(b) of the Native Title Act).

(5) The Court must be satisfied that an order in the proposed terms would be within the power of the Court. In that regard, the Federal Court has jurisdiction as to matters arising under the Native Title Act and must make any determination of native title in accordance with the procedures in the Act (see s 213). Those procedures require any determination of native title to set out the matters stated in s 225 (see s 94A). They require the determination to reflect the state of the common law as to the nature and extent of such interests and for there to be a factual basis for the making of an order and the determination must specify:

(a) the persons, or each group of persons, holding the common or group rights comprising native title;

(b) the nature and extent of the native title rights and interests;

(c) the nature and extent of any other interests;

(d) the relationship between the native title interests and any other interests;

(e) whether the native title rights and interests confer possession, occupation, use and enjoyment to the exclusion of all others.

(6) It must appear to the Court that it is appropriate to make the order.

(7) If a determination of the existence of native title is to be made based on agreement then (as required by s 55 of the Native Title Act) the Court must at the same time or as soon as practicable thereafter make the determination required by s 56 as to how the native title interest will be held.

11 In addition to making a determination of native title in agreed terms, the Court may also make an order that gives effect to terms of an agreement that involve matters other than native title: s 87(5).

12 I am satisfied as to the matters listed in subparagraphs (1) to (5) of [10] of these reasons. They are supported by the affidavit material filed in support of the application. I am also satisfied that there has been a detailed process in which experienced lawyers acting for the applicant and the State have negotiated and reached agreement.

13 However, as noted in subparagraph (6) of [10], before making the proposed orders the Court must also be satisfied that it is appropriate to make a determination, in effect, that there is no native title (or will be if the existing native title interests are surrendered as part of the process to approve the ILUA). It is asked to make that determination at a time when, on the material before the Court, native title does exist but an agreement has been reached for its surrender. In effect, the Court is asked to make a conditional determination that will take effect in the future only in the event that surrender occurs.

14 A determination of native title is a determination 'whether or not native title exists': s 225. As the determination as proposed will only be made in the event that native title has been surrendered as agreed, for the following reasons I agree with Mortimer J that orders in the terms proposed may be made where they are necessary and appropriate and will take effect only if and when certain specified events occur. I would make clear in the orders that the determination is on the basis of the surrender (to take effect on registration of the ILUA). As the orders will depart from those proposed by consent I will reserve liberty to any party to apply within 21 days to vary those orders.

Is it appropriate to make the proposed determination?

15 The approach to be adopted by the Court when considering whether to make a determination of native title in terms that have been agreed was carefully considered by Mortimer J in Freddie v Northern Territory [2017] FCA 867 and in Agius v South Australia (No 6) [2018] FCA 358 (Agius). As has been noted, the Court may make such an order if it considers it to be appropriate to do so.

16 In Cronin on behalf of the Butchulla People (land & sea claim #2) v State of Queensland [2019] FCA 2082, O'Bryan J summarised the reasoning of Mortimer J in the following terms (at [14]) (citations omitted):

(a) The s 87(1A) role is quite different from the Court's role in contested hearings. The Court's focus is on the agreement between the parties.

(b) Satisfaction as to appropriateness must take into account the nature of the rights sought to be recognised in the determination, having operation against the whole world, including rights in rem. The orders should be clear in their terms and the process one which observes procedural fairness and is supported by the State's agreement that a 'credible and rational basis' for the determination has been made out.

(c) The discretion as to appropriateness is wide but the Court must focus on the individual circumstances of each determination.

(d) The Court must also consider ss 37M and 37N of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and pursue the objectives of those provisions promoting the just resolution of disputes, according to law, and as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible.

(e) There must be some probative material to allow the Court to satisfy itself that the requirements of s 225 of the Act are met. However, there is no requirement to file all of the material as the determination is based on the agreement entered into on a free and informed basis.

(f) The Court is not required to conduct an enquiry on the merits, but must still be satisfied that the State made a reasonable and rational decision in entering the s 87 agreement.

(g) The Court should be satisfied that the State came to the agreement after discharging its public responsibilities to the community it represents, including the claimants.

(h) The public interest in a settled outcome as opposed to an exhaustive contested process is considerable.

(i) The flexibility of a settled outcome allows the State to take into account a wide range of matters including, for instance, the history of dispossession.

17 The extent to which there must be probative factual material (and legal reasoning) disclosed to support the application has been the subject of judicial observations expressed in somewhat different terms.

18 In Ward v Western Australia [2006] FCA 1848 at [8] it was said that the Court may make a determination under s 87 without receiving evidence or embarking upon its own inquiry.

19 In an oft quoted passage in Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474, North J stated at [37]:

…when the court is examining the appropriateness of an agreement, it is not required to examine whether the agreement is grounded on a factual basis which would satisfy the Court at a hearing of the application. The primary consideration of the Court is to determine whether there is an agreement and whether it was freely entered into on an informed basis... Insofar as this latter consideration applies to a State party, it will require the Court to be satisfied that the State party has taken steps to satisfy itself that there is a credible basis for an application.

20 In King on behalf of the Eringa Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia [2011] FCA 1386, Keane CJ said at [19]:

More recently, the Court has been prepared to rely upon the processes of the relevant State or Territory about the requirements of s 223 being met to be satisfied that the making of the agreed orders is appropriate. That is because each State and Territory has developed a protocol or procedure by which it determines whether native title (as defined in s 223) has been established. It acts in the public interest and as the public guardian in doing so. It has access to anthropological, and where appropriate, archaeological, historical and linguistic expertise. It has a legal team to manage and supervise the testing as to the existence of native title in the claimant group. Although the Court must, of course, preserve to itself the question whether it is satisfied that the proposed orders are appropriate in the circumstances of each particular application, generally the Court reaches the required satisfaction by reliance upon those processes. They are commonly explained in the joint submissions of the parties in support of the orders agreed. That is the case in this instance.

21 Not long thereafter, Mansfield J summarised the state of the authorities in Lander v State of South Australia [2012] FCA 427 at [11]-[13]:

The focus of the Court in considering whether the orders sought are appropriate under s 87 is on the making of the agreement by the parties. In Lovett on behalf of the Gunditjmara People v State of Victoria [2007] FCA 474 North J stated at [36]-[37] that:

The Act [Native Title Act] is designed to encourage parties to take responsibility for resolving proceeding without the need for litigation. Section 87 must be construed in this context. The power must be exercised flexibly and with regard to the purpose for which the section is designed.

In this context, when the court is examining the appropriateness of an agreement, it is not required to examine whether the agreement is grounded on a factual basis which would satisfy the Court at a hearing of the application. The primary consideration of the Court is to determine whether there is an agreement and whether it was freely entered into on an informed basis: Nangkiriny v State of Western Australia (2002) 117 FCR 6; [2002] FCA 660, Ward v State of Western Australia [2006] FCA 1848. Insofar as this latter consideration applies to a State party, it will require the Court to be satisfied that the State party has taken steps to satisfy itself that there is a credible basis for an application: Munn v Queensland (2001) 115 FCR 109; [2001] FCA 1229.

Therefore, the Court does not need to embark on its own inquiry of the merits of the claim made in the application to be satisfied that the orders sought are supportable and in accordance with the law: Cox on behalf of the Yungngora People v State of Western Australia [2007] FCA 588 at [3] per French J. However, it might consider that evidence for the limited purpose of being satisfied that the State is acting in good faith and rationally: Munn for and on behalf of the Gunggari People v State of Queensland (2001) 115 FCR 109 at [29]-[30] per Emmett J. See also Smith v State of Western Australia [2000] FCA 1249; (2000) 104 FCR 494 at [38] per Madgwick J:

State governments are necessarily obliged to subject claims for native title over lands and waters owned and occupied by the State and State agencies, to scrutiny just as carefully as the community would expect in relation to claims by non-Aborigines to significant rights over such land.

I note also the observations of Reeves J in Nelson v Northern Territory of Australia (2010) 190 FCR 344; [2010] FCA 1343 at [12]-[13]:

It is appropriate to make some comments about the difficult balance a State party needs to strike between its role in protecting the community’s interests, including the stringency of the process it follows in assessing the underlying evidence going to the existence of native title, and its role in the native title system as a whole, to ensure that it, like the Court and all other parties, takes a flexible approach that is aimed at facilitating negotiation and achieving agreement. In Lovett North J commented:

...There is a question as to how far a State party is required to investigate in order to satisfy itself of a credible basis for an application. One reason for the often inordinate time taken to resolve some of these cases is the overly demanding nature of the investigation conducted by State parties. The scope of these investigations demanded by some States is reflected in the complex connection guidelines published by some States.

The power conferred by the Act on the Court to approve agreements is given in order to avoid lengthy hearings before the Court. The Act does not intend to substitute a trial, in effect, conducted by State parties for a trial before the Court. Thus, something significantly less than the material necessary to justify a judicial determination is sufficient to satisfy a State party of a credible basis for an application. The Act contemplates a more flexible process than is often undertaken in some cases.

I respectfully agree with North J in these observations. In my view, it would be perverse to replace a trial before the Court with a trial conducted by a State party respondent and I do not consider that is what is intended by the provisions of s 87 of the Act.

22 It is to be noted that in King on behalf of the Eringa Native Title Claim Group, Keane CJ had observed (at [24]):

In this matter, the Court has had the benefit of the joint submissions. They confirm that the State is satisfied that the agreed determination is a proper one. It has had the benefit of a thorough examination of the available evidentiary material. The joint submission in turn refers at considerable length to the material on which it has relied.

23 Therefore, his Honour was not concerned with an instance where the State simply presented matters without any engagement with the available evidentiary material that formed the basis for the formation by the State of the view that the proposed determination was a proper one.

24 Recently in Widjabul Wia-Bal v Attorney General of New South Wales [2020] FCAFC 34; (2020) 274 FCR 577, the Court considered what was needed to demonstrate a factual basis for mediating a claim with a view to reaching an agreement through a process of mediation that might result in the Court being invited to make a determination of native title on the basis that it was appropriate to do so in the terms as agreed. In that context, three judges with considerable experience in dealing with such matters (Reeves, Jagot and Mortimer JJ) said at [51] (referring to the Native Title Act as the NT Act):

Before considering the facts of the present case it is necessary to say something about the Court's power to make a determination of native title in accordance with an agreement. The Court must be satisfied that it is appropriate to make the orders specified in the agreement and that there is power to do so: ss 87(1)(c) and 87A(4) of the NT Act. It has been stated that it is sufficient for a party in the position of the State to satisfy itself that there is a credible basis for the application…To fulfil its function under the NT Act, in the context of a mediation with a view to entering an agreement under ss 87 or 87A, the State is not required to obtain proof from an applicant which would demonstrate to the civil standard of proof, on the balance of probabilities, that the native title rights claimed by the applicant exist. Indeed, for the State to seek more from an applicant than such material as establishes a credible basis for the existence of the native title rights sought in the determination would be inconsistent with the obligation in s 94E(5) to act in good faith in the conduct of the mediation. It cannot be an act in good faith in the conduct of a mediation to require an applicant to provide the State with more than that which is legally necessary for the State to be in a position to inform the Court that, from the State's perspective, it is appropriate for the Court to make the determination of native title in orders giving effect to the terms of an agreement as provided for in s 87 or 87A of the NT Act. To place such an unwarranted burden on an applicant would be fundamentally inconsistent with the scheme of the NT Act and in particular the provisions identified above which constitute the 'special procedure', which the Preamble to the statute recognises is required for the 'just and proper ascertainment of native title rights and interests'. Such an act would readily be characterised as an act not in good faith in the conduct of a mediation.

25 In Western Bundjalung People v Attorney General of New South Wales [2017] FCA 992, Jagot J considered the role of the State where the Court was invited to make determinations of native title based upon agreement in the context of legislation that expressly encourages resolution by mediation. As her Honour noted at [17], [20]:

Against this background, the duty to which we are all subject, to ensure that issues arising under the NTA are resolved according to law and in a manner which is efficient, timely and at a cost which is proportionate to the importance and complexity of the matters in dispute, is of the utmost importance. The discharge of its duty by the State party is particularly critical. It is the State party which is the landed successor to the dispossession of Aboriginal peoples. It is the State party with whom the principal negotiations about native title claims must take place. It is within the power of the State party to agree to resolve a claim by an applicant without the need for contested litigation and in a manner which is timely, efficient and does not involve disproportionate resources. It is the State party which is subject not only to the duties imposed by the NTA and the Court Act but also by the obligations of a model litigant. Unless the State party is both vigilant about discharging all of its duties in good faith, recognising the objects of the NTA and its unique role, and committed to taking responsibility for driving sensible and fair outcomes in a timely manner, there is no real prospect of other parties or the Court being able to effectively discharge their and its duties. There is also no prospect of matters being resolved in a manner which is consistent with the objects of the NTA.

…

It is also apparent from the authorities that the Court recognises that the State party is effectively the guardian of all of the interests of its people in a native title claim. It should go without saying that the people to whom the State owes a duty include the Aboriginal people who are the claimants. Thus it would be wrong for the State to conceive of its role as merely a gatekeeper through which cogent claims may ultimately be permitted to pass if the claim is one that comes to be supported by so much material that, in all probability, the claim would succeed before the Court if litigated; in particular, ensuring prima facie cogent claims are resolved by agreement in a timely and fair manner, at a reasonable and proportionate cost to claimant groups, is an important part of the public interest the State is intended to protect and promote.

26 As to the above matters, see also Taylor on behalf of the Yamatji Nation Claim at [8].

27 I noted in Hobbs on behalf of the Ngurrara D2 Claim Group v State of Western Australia [2020] FCA 624 at [24] that:

A determination of native title must be made in accordance with the procedures in the Native Title Act: s 213(1). As the determination, if made, will have consequences beyond the parties who give their consent, heightened scrutiny is warranted: CG (Deceased) on behalf of the Badimia People v State of Western Australia [2016] FCAFC 67; (2016) 240 FCR 466 at [48] (North, Mansfield, Jagot and Mortimer JJ). The same concern pertains when the Court is invited to make a consent determination: Freddie v Northern Territory [2017] FCA 867 at [18] (Mortimer J). In effect there is a broader public interest in the determination because it may affect third parties who do not presently have an interest in the area and may have unforeseen consequences well into the future. It is also has an intergenerational character.

28 In Drury v Western Australia [2020] FCAFC 69 the Court was concerned with whether an order for determination of native title by consent may result in the appointment of two prescribed bodies corporate in respect of the same land on the basis that there were overlapping native title interests. In that context, Mortimer J and I explained that in such an instance particular factual information may be required to support the existence of overlapping native title due to the significance of making such an order. In doing so, we said (at [92]-[94]):

Where there is a significant area of overlap between two native titles that are proposed to be determined by consent, the Court may consider that aspect to be a reason why it is not appropriate for the purposes of s 87(1A) to make the orders without some form of hearing. A hearing may be appropriate to consider whether there is a sufficient basis to make the two overall determinations of native title given the practical consequences for the operation of the Act of the kind already considered.

Further, the absence of any evidence concerning the nature and extent of traditional laws about the interaction between the rights and interests of the two societies with native title over the same land may be a reason for a hearing. In such a case, the Court may wish to consider whether there should be greater detail in the proposed order, appropriate to reflect some of the complexities which (a) give rise to such determinations; and (b) may arise if there are two PBCs for the same land and waters.

For those reasons, it is to be expected that a party seeking a determination by consent that there are overlapping native titles will demonstrate that there is an appropriate basis for such a determination or articulate why it is submitted that it is appropriate to make the determinations by consent without any hearing even though the proposed consent determinations will recognise overlapping native titles.

29 It can be seen that emphasis has been placed upon both the significance of the agreement reached between the parties and the obligation of the State to be acting in good faith and rationally and in circumstances where there is probative material to support the basis for the view that native title in the terms proposed does exist (or in the present case that native title does not exist). The Court does not undertake its own inquiry as to the facts. However, the due discharge of the State's obligation must be established where the Court is asked to make a determination as to native title by consent. The Court relies upon both the agreement of the parties and the discharge by the State of its role as a party acting in the public interest in bringing native title claims to conclusion by consensus where possible as the basis for a conclusion that orders proposed by consent are within jurisdiction and appropriate.

30 Accordingly, it is no part of the State's role to present to the Court for agreement a proposal that invites the Court to make a determination as to native title in terms that are not supported by the available evidence viewed through the lens of a party seeking to reach a reasonable compromise in the public interest (or to frustrate such outcomes by insisting upon proof of a particular kind where there is material upon which a reasonable party would base a compromise). The Court may be more readily persuaded as to the due discharge of the State's obligation where it is satisfied that there has been a genuine process by which the parties have engaged in negotiation and the applicant has been legally represented by competent lawyers with requisite experience. However, that is not to say that in the circumstances of a particular case that the Court may consider it appropriate for some information to be provided to demonstrate the basis for a reasonable view that there is (or is not) native title.

31 Therefore, it is not enough that there is bare evidence that the parties consent to the terms of a determination and that, on its face, the proposed determination is in a form that would be recognised by the Court if there were facts to support such a determination. Rather, the Court acts upon the agreement between the parties as well as the discharge by the State of its role in acting in the public interest as itself establishing that there is a factual basis for a determination of native title in the terms proposed. If the Court has concerns as to whether the State has properly discharged its role or as to whether there is a proper factual basis for the proposed declaration then it is not appropriate for the orders to be made. A bare assertion by the parties by way of agreed submission that the State, acting on behalf of the community generally and having regard to the terms of the Native Title Act is satisfied that the determination is justified will not be sufficient in most cases where a determination of native title based upon agreement of the parties is proposed.

32 So, whilst the Court does not inquire into the correctness of the factual matters that form the foundation for the view that there is native title, there must be some demonstration to the Court that there is such a factual basis that has been accepted through the negotiation process before it would be appropriate for a determination of native title to be made by agreement (whether it be a determination in the affirmative or the negative). The Court does not act upon a fiction that arises from an assertion (even by agreement) of such a factual basis. Therefore, it is to be expected that the parties will provide to the Court whether by way of joint submissions or a statement of facts agreed between the applicant and the State sufficient material to enable the Court to be satisfied that there is a credible and rational basis in fact and law for the conclusion that there is native title in the terms agreed. In many instances that may be done by describing the steps that have been taken or by referring to the analysis of such claims in related matters rather than presentation of the detail. However, there must be a basis put forward. Otherwise, the statutory requirement that the Court be satisfied that it is appropriate for such a determination to be made would be devoid of any real content. There would be no real scrutiny or oversight by the Court and determinations of considerable importance to the community and future generations could be made without any real foundation.

33 These matters are important given the nature of the interests involved. Neither the present holders of native title nor the State acting at the point in time where agreement may be reached are themselves acting in their own interest or even existing interests. Both act in a representative capacity, in effect as trustees, settling important matters for future generations.

34 In the above context, the joint submissions filed by the applicant and the State in the present case, make the following statements as to connection to Country that includes the nine lots that comprise Area B:

In reaching agreement with the MNC, the State has taken into account the connection of the Mirning native title holders to their country.

The Applicant provided the First Respondent with the following material (connection material) in support of the Mirning native title claimants' connection to Mirning Country (collectively, the Part A Determination Area and the Part B Application Area):

a) Mirning Native Title Claim WAD 6001/001 WC01/1 Anthropologist's Report by Dr Kingsley Palmer dated 2013 (Palmer Report);

b) Appendix B: Genealogies to the Anthropologist's Report dated July 2009;

c) Witness statement of James Schultz dated 3 June 2017;

d) Witness statements of Raelene Peel dated 16 June 2017 and 13 July 2017;

e) Witness statements of John Graham dated 7 June 2017 and 13 July 2017;

f) Witness statement of James Peel dated 16 June 2017;

g) Witness statement of Lennard Walker dated 2 June 2017;

h) Witness statement of Fred Grant dated 2 June 2017;

i) Witness statement of Ethan Hansen dated 2 June 2017;

j) Witness statement of Troy Hansen dated 2 June 2017;

k) Witness statement of Mervyn Reynolds dated 13 July 2017;

l) Witness statement of April Lawrie dated 14 July 2017; and

m) Witness statement of Clem Lawrie dated 19 July 2017.

The traditional country of the Mirning native title claimants is located at the far south eastern extremity of Western Australia. It comprises a strip of coastal country, which includes high cliffs of the western portions of the Great Australian Bight, as well as extensive coastal dunes. To the north the area includes portions of the limestone plateau and parts of the Nullarbor Plain. The eastern boundary of Mirning Country is the South Australian border.

The Mirning native title claimants are:

i. persons who are descendants of named apical ancestors (either by birth or adoption in accordance with Mirning traditional law and custom) and are recognised by other native title holders as having realised their rights in accordance with traditional law and custom through knowledge, association and familiarity with the Determination Area; and

ii. those persons, including members of the Spinifex people, who hold mythical or ritual totemic knowledge and experience of Tjukurpa associated with any part of the Determination Area so as to give rise to rights and responsibilities in relation to such part(s) of the Determination Area and are recognised by other holders of ritual totemic knowledge as having native title rights and interests within the Determination Area by virtue of that knowledge and experience.

The Mirning native title claimants are bound together by a normative system of laws and customs which, on the basis of known facts and reasonable inference, has continued to be observed in a substantially uninterrupted manner since prior to the declaration of sovereignty over Western Australia. The concepts of the Dreaming (Tjukurpa) and the Law are central to the belief system of the Mirning native title claimants and give rise to the normative system which governs customary behaviour and the possession of rights and interests in land.

The Mirning native title claimants' rights and interests in Mirning Country arise from descent (either by birth or adoption) from a named apical ancestor, together with knowledge, association and familiarity with Mirning Country, and also from mythical and ritual totemic knowledge of the Tjukurpa associated with Mirning Country.

Whilst all of the Mirning native title claimants currently live outside of Mirning Country, they continue to access the area as often as they are able, to take and use resources and to teach their children about the area. There is a shared acknowledgement that under traditional law and custom the permission of the Mirning native title claimants is needed to enter Mirning Country in order to avoid danger to persons and to country.

Evidence of continued occupation and traditional use of Mirning Country is set out in the witness statements listed at [42] above. Some particular examples are set out in the paragraphs that follow, but these are neither exhaustive nor provided in any particular order of priority.

John Graham states that it is my right to hunt all over Mirning country and fish along the coast because my grandparents and great grandparents are Mirning. That is what I was taught by the old people. When you go into country you call out to old people and make a fire. When smoke blows it calms them down. When you leave then you walk through fire so they can’t follow you. Spirits don’t like smoke. You have to tell the spirits that you are on the country and that you are Mirning and you can tell them who you are.

Raelene Peel talks about travelling through Mirning Country with her husband and children. When we are on land we will take kangaroo, wombats, and bush medicines. Different areas have different things. For example you might go along and see a prickly bush like spear leaves, they are the best ones to get for a rub. We take a lot of the little branches, strip the leaves, rub it in our hand and you can smell it. You boil those little branches with a bit of oil and then you crush it. You find that plant on Mirning country south of the Transline. We get emu on the WA side of Mirning country when the dad emu is not around to protect the younger ones. That is also the best time of year to get emu eggs.

James Schultz states that [w]hen strangers come into Mirning country they need to speak to Mirning people especially if they are going near a sacred place. If people don’t ask permission of Mirning people like they are supposed to and they take something from country then they can get sick for breaking the rules. The Spinifex men are Law men so they have a lot of access to the Mirning [country] – Mirning people know they are there. They don’t need permission to come onto Mirning country to look after the dreaming story sites.

Lennard Walker is an Anangu man who lives at Tjuntjuntjara in Spinifex country. He states that there are not enough Mirning people in the Law to look after the Tjukurkpa story and sites in their country by themselves so me and other Law men are helping out.

The Applicant and the State have reached an agreement as to the terms of the Minute and ILUA, recognising that the acts done on the 9 areas comprising the Mirning Part B Application area were invalid to the extent that they affected native title (section 24OA Native Title Act) and that to enable validation of those acts, the Mirning native title claimants have agreed to surrender their native title rights and interests.

35 The above material is of a kind that properly would be provided to support an affirmative determination of native title. However, the Court is invited to make a determination that there is no native title in anticipation of the approval of an ILUA that will surrender native title interests.

36 The Court has not been provided with a copy of the ILUA nor with any explanation as to the nature of its terms. The process for its registration will allow for its scrutiny if appropriate. The determination that the Court is invited to make presumes, in effect, that the surrender of native title through that process has occurred. Therefore, that fact is both sufficient of itself and is the only fact advanced to justify the making of the order.

37 In the above circumstances, in my view, two matters should be made clear in making orders of the kind proposed. First, it should be made abundantly clear that the determination only takes effect in the event that the ILUA is approved and I will make a small amendment to the proposed orders to reflect that position. Second, the form of determination of native title should be expressly made on the basis that the native title interests have been surrendered. As I have indicated, I will reserve liberty to any party to apply to vary those aspects of the orders which depart from the consent of the parties.

38 For those reasons, in all the circumstances, I am satisfied that it is appropriate to make the determination in the terms proposed.

I certify that the preceding thirty-eight (38) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Colvin. |

Associate: