Federal Court of Australia

Onus v Minister for the Environment [2020] FCA 1807

ORDERS

First Applicant MARJORIE THORPE Second Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The decision of the respondent dated 6 August 2020 not to make a declaration under s 12 of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth) is set aside from the date it was made.

2. The application dated 17 June 2018, insofar as it relates to s 12 of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth), be remitted to the Minister with a direction that she refer the application for reconsideration and determination according to law by another Minister with responsibility for administering the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth).

3. The respondent pay the applicants’ costs of the application, as agreed or taxed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

GRIFFITHS J:

1 By an amended originating application for judicial review, the applicants challenge the lawfulness of the Minister’s decision dated 6 August 2020 not to make declarations under ss 10 and 12 of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth) (the Act).

2 The Minister’s refusal decision related to applications by nine traditional owners of the Djab Wurrung Country (which included the two applicants in the present proceeding), for declarations to be made for:

(a) the protection and preservation of a significant Aboriginal area from injury or desecration (s 10); and

(b) the protection and preservation of specified significant Aboriginal objects, being six trees with cultural significance, from injury or desecration (s 12).

3 The applicants’ primary concerns relate to the effect of the construction and alignment of a section of the Western Highway between Ararat and Buangor in Victoria on the area and certain trees, which are said to have particular significance for Aboriginals.

4 The judicial review challenge relies on the Court’s jurisdiction under both the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (ADJR Act) and s 39B of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth).

5 For the following reasons, I consider that the Minister’s decision in respect of the application for a declaration under s 12 of the Act is invalid in law and should be set aside. I dismiss the applicants’ challenge to the lawfulness of the Minister’s decision in relation to the application for a declaration under s 10 of the Act.

6 It is desirable to outline the lengthy procedural history leading up to the current proceeding, noting that this is not the first occasion this matter has come before the Court. Indeed, this is the fourth such occasion (three of which relate to the Ministerial decisions refusing to make declarations under ss 10 and 12, while the other involved an unsuccessful challenge to the Minister’s decision not to grant a s 9 declaration). There has also been related litigation in other Courts, including a recent decision dated 3 December 2020 in the Supreme Court of Victoria by Forbes J, in which the Court granted an interlocutory injunction in relation to the area which is the same as the area in the present proceeding (see Thorpe v Head, Transport for Victoria [2020] VSC 804).

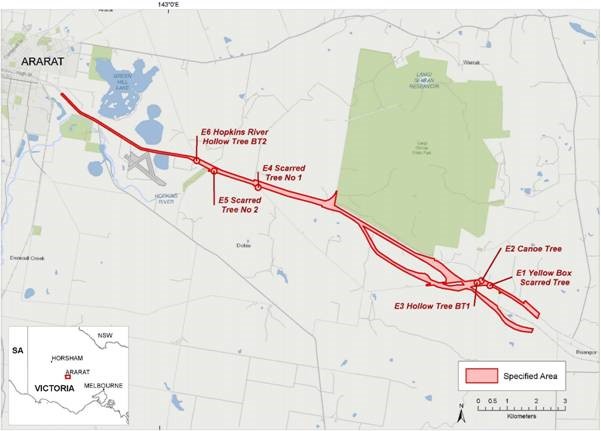

7 By a letter dated 17 June 2018, the then Minister for the Environment and Energy (the Hon Josh Frydenberg MP) was asked to make declarations under ss 9, 10 and 12 of the Act to protect the same significant Aboriginal area and six trees as are the subject of the present proceeding. Attached to the application was a report by Dr Heather Builth entitled “Desktop Report on Culturally Modified Trees along Planned Road Works of Southern Deviation Route of Option 1 for the Western Highway between Ararat and Beaufort, Victoria” (2017 Builth Report). Additional information in support of the urgent application was provided on 5 July 2018. This included confirmation that the s 10 application sought protection over an area described as the “Maximum Construction Footprint” of the planned roadworks as shown in maps and by GPS coordinates which were attached to that correspondence (the Specified Area) and that the s 12 application sought protection of particular objects, being the following six trees, including a 100m protection buffer:

a. E1 (Yellow Box Scarred Tree) [GDA94 Coordinates: (688430E 5864681N)];

b. E2 (Canoe Tree) [GDA94 Coordinates: (688126E 5864844N)];

c. E3 (Hollow Tree BT1) [GDA94 Coordinates: (687991 E 5864773N)];

d. E4 (Scarred Tree No 1) [GDA94 Coordinates: (680435E 5868058N)];

e. E5 (Scarred Tree No 2) [GDA94 Coordinates: (678917E 5868624N)]; and

f. E6 (Hopkins River Hollow Tree BT2) [GDA94 Coordinates: (678320E 5868983N)].

8 The following map, which was before the Minister, identifies the Specified Area by pink shading within a red boundary line. Notably, the map does not show the highway alignment at all, although it may be assumed that the alignment is somewhere in the Specified Area. The scale of the map is such that the map fails to identify with any precision the physical proximity of each of the six trees to the assumed highway alignment. As will shortly emerge, the Minister did not have before her any map which precisely identified the proposed highway alignment as at the date of her decision:

9 On 18 July 2018, Minister Frydenberg appointed Ms Susan Phillips as a reporter pursuant to s 10(1)(c) of the Act (the Reporter). Ms Phillips’ report, which was completed on 7 September 2018, was received by the Minister on 13 September 2018 (Phillips Report). It, together with the 17 June 2018 application and the 5 July 2018 email which provided additional information, was among the voluminous material which was before the current Minister for the Environment (the Hon Sussan Ley MP) when she made the decision which is the subject of the current proceeding. It might also be noted that the material before the Minister included a second report dated August 2018 by Dr Builth (2018 Builth Report). Another document before the Minister was a report dated December 2018 by On Country Heritage and Consulting (On Country Report).

10 On 12 September 2018, the then Minister for the Environment (the Hon Melissa Price MP) refused to make the emergency declaration sought under s 9 of the Act as she was not satisfied that the specified area was under serious and immediate threat of injury or desecration.

11 Subsequently, on 19 December 2018, Minister Price refused to make the declarations sought under ss 10 and 12 of the Act. That decision was quashed by consent by the Court’s orders dated 12 April 2019 in VID 168 of 2019. The matter was remitted to the Minister for redetermination according to law.

12 On 16 July 2019, Minister Ley (who had succeeded Minister Price as Minister) purported to make a decision again refusing to make the ss 10 and 12 declarations. That decision was quashed on 6 December 2019 following proceedings before Robertson J in which it was held that the Minister’s decision was invalid (see Clark v Minister for the Environment [2019] FCA 2027; 274 FCR 99). The Minister was directed once again to redetermine the matter according to law. In separate reasons for judgment delivered on the same day, Robertson J dismissed a separate application for an interlocutory injunction by the same applicants (Clark v Minister for the Environment (No 2) [2019] FCA 2028).

13 After the matter was remitted for reconsideration for the second time, the Minister sought and was provided with additional material by both the applicants and Major Road Projects Victoria (MRPV, which I will use to describe both that body and its predecessor body, the Major Roads Projects Authority), which had overall responsibility for the Western Highway project. The Minister was also provided with material from the Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation (EMAC), which body had a statutory role under the Victorian Aboriginal heritage protection framework, to which MRP was bound.

14 It will be necessary to expand upon this summary of background matters in due course.

15 On 6 August 2020, the Minister made the decision which is the subject of the present proceeding. On the same day the Minister provided a detailed statement of reasons for her decision. This is the third Ministerial decision rejecting the 17 June 2018 application for declarations under ss 10 and 12 of the Act.

The Minister’s statement of reasons summarised

16 The statement of reasons totals 35 pages, together with multiple attachments. The attachments are voluminous and total approximately 5,250 pages (not all of which were put in evidence in the present proceeding). To avoid adding unduly to the length of these reasons for judgment, I will defer summarising the relevant attachments until addressing each of the six grounds of judicial review.

17 For current purposes, it is sufficient to set out section 6 of the Minister’s statement of reasons, which identifies the reasons for her ultimate findings and decision in respect of both ss 10 and 12 of the Act (it will be necessary later to address other relevant parts of the Minister’s statement of reasons with specific reference to the six individual grounds of judicial review):

6. Reasons for decision

6.1 To make a declaration under section 12 of the ATSIHP Act in relation to the Six Trees, I must be satisfied that the Six Trees are significant Aboriginal objects and are under threat of injury or desecration.

6.2 I was not satisfied that Tree E1 is a significant Aboriginal object. In reaching my conclusion, I placed significant weight on my finding that Aboriginal opinion is divided on the question of whether Tree E1 is of cultural significance. I also placed weight on my finding that the reports commissioned in relation to the Six Trees are inconclusive with respect to the significance of Tree E1, and did not provide detail about the uses or beliefs centred on Tree E1 (in contrast to the other trees subject to the Application).

6.3 I was satisfied that Trees E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6 are significant Aboriginal objects. However, I was not satisfied that those trees are under threat of injury or desecration. In reaching this conclusion, I accepted that MRPV has made a commitment to avoid Trees E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6 as part of the Western Highway upgrade and has developed the Framework for identifying and monitoring trees. Although it is unlikely to be legally binding, I accepted that MRPV can reasonably be expected to honour this commitment. I was further satisfied that the commitment of MRPV and the Framework provide adequate protection against possible use or treatment of the trees in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition, over and above protection against physical removal or destruction of the trees. For these reasons, I was satisfied that the procedures described above mean that the trees are not likely to be used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition within the meaning of section 3(1) of the ATSIHP Act and, accordingly, they are not under threat of injury or desecration as defined.

6.4 To make a declaration under section 10 of the ATSIHP Act in relation to the Specified Area, I must be satisfied that the Specified Area is a significant Aboriginal area and is under threat of injury or desecration. I accepted that, on balance, the Specified Area is a significant Aboriginal area. I also accepted that the Specified Area is under threat of injury or desecration within the meaning of section 10(1)(b)(ii) of the ATSIHP Act. I also received a report under section 10(4) of the ATSIHP Act (Section 10 Report), and I considered that report and the representations attached to that report. I was therefore satisfied that the preconditions for making a declaration under section 10 were met.

6.5 I also considered ‘other matters’ that I consider to be relevant under section 10(1)(d), including:

a. the effects on pecuniary interests of third parties;

b. considerations relating to health and safety; and

c. the extent to which the area is protected under State legislation.

6.6 Overall, I considered that considerations in favour of making a declaration under section 10 to protect and preserve the Specified Area from injury or desecration were outweighed by the considerations against the making of such a declaration. I acknowledged that the Specified Area for which protection is sought retains cultural value and connection to Country for the Applicants and the Djab Wurrung people. Having regard to the materials before me, I acknowledged that the Specified Area is of particular significance to Aboriginal people and I accepted that there is a threat of injury or desecration to the Specified Area.

6.7 Nevertheless, these findings did not remove the need to weigh up competing considerations before making any decision pursuant to section 10. The need for this balancing exercise is inherent in the fact that section 10 of the ATSIHP Act does not compel me to make a declaration in circumstances where I found that the Specified Area is a significant Aboriginal area and is under threat of desecration or injury, and instead allowed me to consider ‘other relevant matters’ before deciding whether to make a declaration.

6.8 With respect to the interests of third parties, I accepted that a declaration under section 10 of the ATSIHP Act would have a detrimental impact upon the pecuniary interests of the Victorian Government because of the significant ongoing financial costs resulting from the delay in commencement of construction, the termination of the relevant contract and the additional cost that would be incurred in pursuing an alternative route. I considered that this matter weighed substantially against making a declaration under section 10.

6.9 I also found that the making of a declaration would have had some impact on the pecuniary interests of commercial communities who are likely to benefit from the improved transport efficiency the Project is expected to deliver. However, in the absence of any modelling as to the predicted extent of these benefits, I accorded low weight to the pecuniary interests of the community.

6.10 With respect to health and safety considerations, I found that there are likely to be community road safety benefits in the construction of the Western Highway upgrade. In this regard, I accepted that the Project would have a positive impact on a broad section of the community. I consider that this matter weighs substantially against making a declaration under section 10, which would at the very least substantially defer or delay such community road safety benefits.

6.11 With respect to the extent to which the area is protected under State legislation, I was satisfied that any area of Victoria which is of cultural heritage is protected from harm by the Aboriginal Heritage Act if it satisfies the definition of an Aboriginal place. I accorded significant weight to the fact that a CHMP under the Aboriginal Heritage Act was approved on 18 October 2013 by Martang as the relevant RAP and that it is an offence for a sponsor of an approved CHMP to knowingly, recklessly or negligently fail to comply with the conditions of the CHMP. I also placed some weight on the specific measures contained in the CHMP for the management of Aboriginal cultural heritage likely to be affected by the activity relating to the Project. I also accepted that MRPV has made a commitment in good faith to avoid five of the Six Trees (Trees E2, E3, E4, E5, E6).

6.12 Accordingly, although I acknowledged the views of the Applicants on the CHMP and the role of Martang, I was satisfied that the Victorian Aboriginal heritage protection regime provides some degree of protection for the Specified Area. However, given that I accepted that the Specified Area is nevertheless under threat of injury or desecration, I considered that the extent to which this matter weighed against making a declaration under section 10 is slight.

6.13 For these reasons discussed in paragraphs 6.5 to 6.12, I concluded that there was sufficient evidence to allow me reasonably to form the view that the impact on the pecuniary interests of third parties, the health and safety considerations supporting the Western Highway upgrade, and the extent to which the area is protected under State legislation outweighed the loss of Aboriginal heritage value in the Specified Area.

6.14 Based on the material presented to me and for reasons set out above, I found that:

a. I received an application for the purposes of section 10(1)(a) and section 12(1)(a) of the ATSIHP Act;

b. I was not satisfied that Tree E1 is a significant Aboriginal object for the purposes of section 12(1)(b)(i) of the ATSIHP Act;

c. on balance, I was satisfied that the Trees E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6 are significant Aboriginal objects for the purposes of section 12(1)(b)(i) of the ATSIHP Act;

d. I was not satisfied that there is a threat of injury or desecration to Trees E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6 for the purposes of section 12(1)(b)(ii) of the ATSIHP Act;

e. I was satisfied that the Specified Area is a significant Aboriginal area for the purposes of section 10(1)(b)(i) of the ATSIHP Act;

f. I was satisfied that there is a threat of injury or desecration to the Specified Area for the purposes of section 10(1)(b)(ii) of the ATSIHP Act;

g. I received a report under section 10(4) of the ATSIHP Act in relation to the Specified Area (the Section 10 Report) and considered the report and all representations attached to the report;

h. after considering other matters that I considered to be relevant for the purposes of section 10(1)(d) of the ATSIHP Act, and carefully considering information and submissions to the contrary, I found that the following matters weighed against the exercise of my discretion to make a declaration under section 10:

(i) a declaration would have had a detrimental impact upon the pecuniary interests of the Victorian Government;

(ii) a declaration is likely to have had a negative impact, to some extent, on the pecuniary interests of the commercial communities who stand to benefit from the improved transport efficiency the Project is expected to deliver;

(iii) a declaration would have had a detrimental impact on the significant community road safety benefits which are expected to arise from the construction of the Western Highway upgrade;

(iv) the measures under the Aboriginal Heritage Act, the CHMP, and the commitment of MRPV, provide some degree of protection for the Specified Area and some mitigation of the impact of the Project on Aboriginal heritage across the Specified Area; and

i. I found that, on balance, the matters that weighed against making a declaration under section 10 outweighed those matters which weighed in favour of making such a declaration.

6.15 In light of these findings, and for the reasons above, I decided not to make declarations under section 10 and section 12 of the ATSIHP Act.

The applicants’ six judicial review grounds

18 By the amended originating application filed on 8 October 2020, the applicants raised the following six grounds of judicial review (without alteration save for deleting underlining):

The Applicants rely on the following grounds of review in lieu of the grounds set out in the originating application filed on 4 September 2020.

1. The Respondent failed to comply with a procedural condition for the decision, namely the obligation in s 10(1)(c) to of the Act to commission and receive a report in relation to the area from a person nominated by her.

Particulars

(a) The previous Minister appointed a Reporter under s 10(1)(c) of the Act on 18 July 2018. The report was completed and provided to the Minister on 7 September 2018.

(b) The Respondent discounted the report provided to the previous Minister because the Reporter’s observations about the injury and desecration of the trees and the area containing the trees were no longer relevant in light of the draft “Framework” proposed by Major Road Projects Victoria (’MRPV’) in April or May 2019.

(c) Insofar as the 2019 draft Framework altered the proposed works that had been assessed in the 7 September 2018 report that report did not deal with the matters prescribed by s 10(4) of the Act relevant to the consideration of the applications by the Respondent on 6 August 2020.

(d) The receipt and consideration by the Respondent of a report that complies with s 10(4) of the Act is a condition enlivening the power ins 10(1) of the Act.

2. The Respondent’s decision was affected by an unreasonable failure to exercise or consider exercising the power to obtain an up-to-date report pursuant to s 10(4) of the Act.

Particulars

(a) Particulars (a) and (b) of ground 1 are repeated.

(b) Given the Respondent’s view that the draft “Framework” proposed by MRPV in April or May 2019 materially changed the nature of the works that had been assessed by the Reporter in her 7 September 2018 report, it was unreasonable for the Respondent not to obtain an updated report that addressed the works relevant to the assessment of the Respondent’s decision on 6 August 2020.

3. The Respondent based her decision on the existence of a fact that did not exist, namely that MRPV had given an undertaking that would have the effect that trees E2 – E6 would not be “used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition due to works related to the Western Highway upgrade.”

Particulars

(a) The draft Framework before the Respondent was no more than a proposal and could not in itself result in the protection of trees E2-E6 from injury or desecration.

(b) The draft Framework suggested according lesser protection to trees E2-E6 than was required by the relevant Australian standard, compliance with which was a contractual requirement where trees were required to be protected.

(c) In any case, the non-removal of a tree pursuant to the draft Framework does not equate to using or treating the area and the trees in a manner not inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition.

4. The Respondent failed to take into account relevant considerations, in that she failed to give proper consideration to certain submissions that were made to the Reporter and included in the report or were made in response to the notice published in the Gazette, or alternatively, the Respondent made an error of law in wrongly treating certain submissions as “irrelevant considerations”.

Particulars

(a) Section 10(1)(c) of the Act requires the Minister to consider a report under s 10(4) and any representations contained in the report.

(b) Section 10(3)(b) of the Act requires the Minister to give due consideration to any representations furnished in response to a notice published in the Gazette under s 10(3).

(c) The Respondent failed to give adequate consideration to representations that raised biodiversity or conservation issues, asserting that such issues were “irrelevant considerations”.

(d) Further and alternatively, the Respondent made an error of law by treating biodiversity and conservation issues as irrelevant considerations for the purposes of her decisions under ss 10 and 12 of the Act.

5. The Respondent based her decision on the existence of a fact that did not exist, or alternatively, the Respondent’s decision was affected by jurisdictional error because it was based on reasoning that was irrational, in that the Respondent’s finding that it was reasonable to expect that an alternative route would have similar impacts on Aboriginal cultural heritage was not rationally open on the basis of the information before the Respondent considered as a whole.

Particulars

(a) The letter of the Major Road Projects Authority (‘MRPA’, the predecessor to MRPV) dated 7 November 2018, on which the Respondent relied, noted that the proposed northern alignment generally followed the route of the existing highway and that the new carriageway in the proposed northern alignment generally followed an existing powerline easement along the south side of the existing highway.

(b) The Respondent erred in stating that there was no evidence before her that the Applicants’ proposed alternative northern route was free of Aboriginal cultural heritage issues.

(c) The Respondent failed to consider the evidence before her, both in the report of the Reporter provided under s 10 and in the report prepared by Dr Heather Builth dated August 2018, that the route proposed by the Applicants had already been cleared of significant trees and “requires no protection for Aboriginal significance under the ATSIHP Act.”

(d) It was not rationally open to the Minister to conclude that the Applicants’ alternative route could be expected to have similar impacts on Aboriginal cultural heritage to the approved route.

6. The Respondent took into account irrelevant considerations, or alternatively, the Respondent’s decision was affected by jurisdictional error because it was based on reasoning that was irrational, in that the Respondent’s conclusion that making the declaration(s) sought by the Applicants would cause significant detrimental impact on the pecuniary interests of the Victorian government was based on the cost estimates of an “alternate northern alignment” that was not possible to construct by the time of the Respondent’s decision on 6 August 2020 and which in any case had not been proposed by the Applicants or anyone else and was not indicative of the cost of making the declaration(s) sought.

Particulars

(a) The Respondent compared the costs of the MRPV approved option (‘Option 1’) with an alternative option described in the Respondent’s Reasons as the “alternate northern alignment”, being the option that had previously been assessed by MRPA in the 2012 Environmental Effects Statement as Option 2, for “indicative comparison” despite the Respondent’s acknowledgement that the “alternate northern alignment” (‘Option 2’) was not the same as the Applicants’ proposed “Northern Option”.

(b) By the time of the Respondent’s decision on 6 August 2020, it was no longer possible to construct Option 2, due to a section of the project having been constructed along Option 1 past the point where the Option 1 and Option 2 routes diverged, which was completed in or around April 2016.

(c) It was clear, and the Respondent acknowledged, that the result of the Respondent granting either or both of the declarations sought would not be to construct the project in accordance with Option 2, but to construct it along an alternative route.

(d) The “indicative” comparison relied upon by the Respondent could not rationally support the conclusion that making the declaration(s) sought would have significant detrimental impact on the pecuniary interests of the Victorian government.

The applicants’ submissions summarised

19 The applicants’ submissions, both in chief and in reply, on each of the six grounds of judicial review may be summarised as follows.

(i) Ground 1: Failure to commission and receive a report under s 10(1)(c) of the Act relating to the application

20 The applicants complain that although the Phillips Report was before the Minister when she made her decision, she effectively put it to one side as no longer being relevant to the matters she had to determine. This was because she treated the draft Framework as fundamentally altering the nature of the threat to the significant area as reviewed by the Reporter. The applicants pointed to [5.56] of the Minister’s statement of reasons:

I consider the Reporter’s statement that “based on the description of the activity to occur in the Specified Area as set out in Part 1 of the CHMP, it appears that the area and objects, the subject of the Application, will be completely altered and the trees destroyed”. However, this observation was made prior to MRPV’s commitment in its letter of 29 May 2019 to avoid five of the Six Trees in the manner set out above.

21 The letter dated 29 May 2019 described and attached the draft Framework which is referred to by the Minister in her statement of reasons as “the Framework”.

22 The applicants contended that if the Minister was correct to approach the Framework as having fundamentally altered the nature of the threat or injury post the Phillips Report, that Report did not deal with the matters required by s 10(4). In other words, given this fundamental change, those parts of the Report which addressed, as at September 2018, the nature of the threat of injury or desecration and the prohibitions and restrictions to be made could not have dealt with those matters as they applied to things as they stood on 6 August 2020. The applicants contended that, on the Minister’s own assessment, those parts of the Phillips Report dealing with the impact of the planned road works on the significant Aboriginal area (in which Ms Phillips had concluded that “the area and objects the subject of the Application will be completely altered”) were no longer relevant in light of MRPV’s stated commitment to avoid five of the six trees. The applicants added that to the extent that other matters in the Phillips Report (such as the extent of the area that should be protected or the prohibitions or restrictions to be made with respect to the area) flowed from Ms Phillips’ conclusions about the Specified Area being completely altered, the Minister did not have before her as at 6 August 2020 a report that relevantly addressed those matters.

23 The applicants contended that, in light of MRPV’s commitment which caused the road route to be changed post the Phillips Report, the Minister had to assess the threat of injury or desecration to the Specified Area caused by the new route.

24 The applicants contended that the requirements of s 10(4) were essential preconditions to the Minister’s power to determine the application.

(ii) Ground 2: Unreasonable failure to exercise the power to obtain an up-to-date report

25 Ground 2 was in the alternative to ground 1. The applicants contended that even if the Phillips Report constituted a report for the purposes of s 10(4), the Minister should have obtained an additional report or, at least, an update to the Phillips Report, which addressed the matters which the Minister viewed as having been made redundant by MRPV’s commitment in the letter dated 29 May 2019. The applicants contended that the purpose of a s 10(4) report is to provide the Minister with an independent objective analysis of the issues specified in that provision, including the submissions received by the reporter, so as to inform the Minister’s decision. They contended that the Minister’s power under s 10(1)(c) to obtain a report was a power which had to be exercised reasonably in the legal sense, citing Minister for Immigration v Li [2013] HCA 18; 249 CLR 332 at [63] per Hayne, Kiefel and Bell JJ.

26 In support of this contention, the applicants emphasised the importance of the fact that, under the statutory scheme, the s 10(4) report “is the principal means of informing the Minister about the issues she is required to consider in making the decision”. Thus it was critical that the s 10(4) report be current and address the matters which the Minister was required to consider. The applicants contended that the Minister’s failure to exercise the power to obtain an updated or additional report was unreasonable “in the manner of s 5(2)(g) of the ADJR Act”.

(iii) Ground 3: Error in the treatment of the MRPV draft Framework

27 The applicants challenged the Minister’s assessment of the commitment given by MRPV, which commitment was at the heart of the Minister’s conclusion that five of the six trees were not at risk of injury or desecration. They contended that the Minister’s reasoning on this issue was flawed because:

(a) the commitment was set out in a document entitled “draft Framework”, which was no more than a proposal (emphasis added);

(b) the suggested level of protection under the draft Framework was less than that required by the relevant Australian standard, which was the minimum standard for protection of trees imposed by MRPV on its own contractors; and/or

(c) the Minister treated the mere non-removal of a tree as entirely removing the threat of injury or desecration.

28 The applicants contended that if the draft Framework was binding and effective to prevent destruction of the relevant five trees, the Minister then had to consider whether the treatment of the trees under that Framework, together with construction of the highway along the proposed route, amounted to treatment of the trees that was inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition having regard to the terms of s 3(2)(b) of the Act (which provided that an object is taken to be injured or desecrated if it is treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition). They contended that because the significance of the trees to the Djab Wurrung people extended to their ability to interact with the trees and the surrounding landscape, mere non-destruction of the trees did not address that additional aspect of their significance to Aboriginal tradition. Because the Minister had not engaged with the extent to which those traditions would be impeded by construction of the highway through the area if the trees were not physically removed or harmed, the applicants contended that the Minister had effectively repeated the error identified by Robertson J in Clark at [146] ff.

29 The applicants submitted that this claimed error by the Minister provided the basis for Forbes J’s recent decision in Thorpe to grant an interim injunction restraining the roadworks notwithstanding MRPV’s commitment. In particular, they pointed to what her Honour said at [77]-[78] (emphasis added):

77 The difficulty that is presented by the defendants’ undertaking is the same difficulty identified by Robertson J in his review of the Minister’s reasons. It would result in restraint that is limited to protection of a number of individual trees without due regard for the broader elements of how those trees hold cultural significance within their landscape. Would relocating a living tree, whether it be a distance of metres or kilometres, to preserve the tree if it were possible to do so, preserve some or all of its social or other significance in accordance with Aboriginal tradition? Put another way, if the tree is preserved but the landscape surrounding it altered by substantial roadworks, how is the impact on the significance of the tree being managed in accordance with the Act?

78 Without understanding the significance of each tree in all the ways embodied in the definition of cultural heritage significance, there is a danger that such an approach may be unnecessarily broad or unduly restrictive in application. This approach is not the same exercise as creating a buffer to protect the health of the tree as a living organism to ensure its root system and canopy is protected from compaction or other disturbance. That buffer is necessary to protect the tree itself rather than necessarily protecting the cultural heritage associated with it.

30 The applicants contended that, contrary to the Minister’s statement in [5.61] that the applicants had failed clearly to describe how the “functions and attributes of the trees are under threat of injury or desecration apart from their physical removal or harm”, there was such material before the Minister. This material related to the cultural significance of the trees, which extended beyond their mere existence and emphasised their connection with the landscape. The applicants added that the Minister should have addressed this material. They identified the material as including the On Country Report and the 2018 Builth Report.

31 The applicants described the Minister’s error as involving the Minister basing her decision on a fact that did not exist (namely that the draft Framework effectively ensured the protection of the five trees) within the meaning of s 5(3)(b) of the ADJR Act. Alternatively, the error was described as a misunderstanding or misapplication of the Minister’s statutory task.

(iv) Ground 4: Failure to take into account relevant considerations, namely submissions

32 Having regard to the terms of ss 10(1)(c) and 10(3)(b) of the Act, the applicants contended that the reference in the former provision to “any representations attached to the report” is to representations received by the Reporter following the publication of a notice in the Gazette inviting submissions from interested persons which must be given due consideration, as required by the latter provision.

33 The applicants focussed on the Minister’s statement in [5.28] of the statement of reasons where she said that many of the representations “additionally raised irrelevant considerations, such as biodiversity conservation issues”. Relying upon the Full Court’s decision in Tickner v Chapman [1995] FCAFC 1726; 57 FCR 451, the applicants contended that the Minister was obliged to consider all the representations (referring in particular to what Kiefel J said in Tickner at 495). The applicants also relied upon the statement in Tickner concerning the meaning of the obligation to “consider”, as recently approved in Carrascalao v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] FCAFC 107; 252 FCR 352 at [36]-[46].

34 The applicants contended that the Minister could not simply dismiss representations regarding biodiversity and conservation issues where there was an express statutory obligation to consider all the representations. This required the Minister to reflect upon them and then decide what weight to give them. The applicants contended that the representations regarding biodiversity and conservations issues were not irrelevant considerations, contrary to the Minister’s view.

(v) Ground 5: Erroneous finding that an alternative route would have similar Aboriginal heritage protection issues

35 This ground relates to an alternative route for the highway proposed by the applicants, commonly referred to as the “Northern Option”. The Northern Option generally followed the existing carriageway of the Western Highway and an existing powerline easement adjacent to it.

36 In the 2018 Builth Report, Dr Builth regarded the powerline corridor on the northern side of the highway as “a largely cleared and previously disturbed area” which was “highly suitable for development as a road because [Dr Builth] found no culturally modified trees or related artefacts”.

37 The Phillips Report noted at [128] that Dr Builth considered that VicRoads should investigate this option “as it requires no protection for Aboriginal significance” under the Act.

38 The applicants referred to [5.114] of the Minister’s statement of reasons in which she said (emphasis added):

… I considered it possible that there could be other additional obstacles to the Applicants’ proposed ‘Northern Option’, such as Aboriginal heritage areas or objects, which had not yet been considered. There was no evidence before me that the Applicants’ proposed ‘Northern Option’ is free of such issues.

39 The applicants complained that the Minister’s statement that there was no evidence before her that the Northern Option “is free of such issues” was “plainly false”. That was because both the Phillips Report and the 2018 Builth Report contained evidence to that effect.

40 The applicants contended that because the Minister based her decision in part on a fact that did not exist (namely the absence of any evidence that the proposed Northern Option would not raise Aboriginal heritage protection issues), this amounted to a reviewable error under s 5(3)(a) of the ADJR Act. Alternatively, they contended that the Minister’s decision was affected by jurisdictional error because it was based on irrational reasoning (citing inter alia Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZMDS [2010] HCA 16; 240 CLR 611 at [135] per Crennan and Bell JJ).

(vi) Ground 6: Error in the treatment of cost estimates

41 The applicants described this error as involving the Minister’s assessment of costs which had been prepared for an entirely different route (namely Option 2) in considering the pecuniary interests of the Victorian Government if a declaration were made and assuming that the effect of making such a declaration would be to require an alternative route to construct the section of duplicated highway. The applicants contended that the Minister’s reliance on costings provided by MRPV in its letter dated 7 November 2018 involved the Minister taking into irrelevant considerations contrary to s 5(2)(b) of the ADJR Act.

42 The applicant’s contentions on this issue had the following elements.

(a) In its letter dated 7 November 2018, MRPV provided to the Minister costings drawn from an environmental effects statement prepared earlier in the process, comparing what was then labelled Option 1 (being the route that was ultimately approved) and Option 2 (being a route that was not available post April 2016). Neither option resembled the applicants’ proposed Northern Option. The Minister noted that the cost comparisons had been “provided for indicative comparison.”

(b) Despite the Minister’s caveat that the references in the MRPV letter to the “northern alignment” (that is, the previous Option 2) was not and did not claim to be the same as the applicants’ proposed Northern Option, the Minister at [5.109] invoked the MRPV cost estimates of Option 2, then on the basis of that material, concluded that “I was satisfied that the alternative northern alignment would cost significantly more than the cost of the approved alignment.”

(c) The Minister rejected an engineer’s analysis of the likely costs of the Northern Option (including that it may be cheaper than the approved option because it was shorter and less challenging in engineering terms) that had been provided by the applicants, because the Minister “prefer[red] the economic statistics and design information provided by MRPV” in the environmental effects statement that had compared Option 1 and Option 2 in 2012.

(d) By the time of the Minister’s decision on 6 August 2020, it was no longer possible to build Option 2 because a section of the project beyond the point where the proposed Options 1 and 2 diverged had already been constructed by around April 2016. Accordingly, there was no possibility that granting the declarations sought by the applicants could result in the construction of the road along the Option 2 route.

(e) In circumstances where, as the Minister herself acknowledged, Option 2 (referred to in the MRPV letter as the “alternate northern alignment”) was not the same as the Northern Option proposed by the applicants, and where it was not even possible for Option 2 to be pursued instead of the approved route if the declarations were made, the costings relating to Option 2 were irrelevant to the Minister’s consideration of the declarations under the Act.

43 Alternatively, the applicants contended that the Minister’s finding regarding the costs of making the declarations was irrational and amounted to jurisdictional error.

The Minister’s submissions summarised

(i) Ground 1: Failure to commission and receive a report under s 10(1)(c) of the Act relating to the application

44 The Minister submitted that she did not “discount” the Phillips Report; rather she observed that it had been overtaken by MRPV’s more recent commitment. She further submitted that, as a matter of statutory construction, a report which satisfied the relevant statutory requirements did not cease to be a report for the purposes of s 10(1)(c) even if events subsequently changed. In support of that submission the Minister relied upon the following matters:

(a) although a s 10 report has the purpose of assisting the Minister in making a decision, the Minister is free to depart from it;

(b) the Minister is able to consider not only such a report, but other matters that he or she considers relevant (see s 10(1)(d));

(c) the legislative regime envisages that the Minister may consult with such persons as he or she considers appropriate with a view to resolving the matter to which the application relates (s 13(3)), which further supports the particular role played by a s 10 report; and

(d) it would be unrealistic not to expect details of a project to evolve over time and it is unlikely that the Parliament intended that the Minister would have to go back to a s 10 reporter.

(ii) Ground 2: Unreasonable failure to exercise the power to obtain an up-to-date report

45 As to the applicants’ claim that the Minister had failed unreasonably in a legal sense to exercise the power to obtain an updated report, the Minister submitted that the claim should be rejected for the following reasons:

(a) Without denying the importance of a s 10(4) report, there is nothing in the legislative scheme to indicate that it needed to be updated to encompass new information or changes in the nature of any threat.

(b) The Minister is entitled to inform himself or herself on relevant matters other than those set out in a s 10 report and it is for the Minister to decide what weight should be given to the reporter’s view.

(c) It would be time consuming to seek a further report, particularly taking into account any procedural fairness obligations under s 10(3).

(d) The change to the nature of the threat in this case was of a kind that can be expected in a significant and complex project.

(e) That relevant changes mitigated the threat to the Specified Area and did not introduce any new element of threat which the Reporter had not addressed.

(iii) Ground 3: Error in the treatment of the MRPV draft Framework

46 The Minister acknowledged that the effect of Clark was that she was required under s 12 to ask herself whether the trees were, or were likely to be, used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition, even if the trees were not destroyed. She added that this was the way in which she approached the matter in conducting the redetermination, referring to [5.52] of her statement of reasons. She emphasised her finding at [5.62] of her statement of reasons that she could not identify any Aboriginal tradition in relation to the use or treatment of Trees E2 to E6 with which the Western Highway upgrade was likely to be inconsistent, whether by reason of their physical proximity or otherwise. The Minister submitted that she did not treat MRPV’s commitment as fully answering the statutory test of injury or desecration as she went on to consider whether there was evidence of any Aboriginal tradition that would be affected by the works if the trees were retained.

47 In addition, the Minister submitted that the relevant Australian standard did not bind her. Rather, it was a matter for her assessment whether the Framework would in fact result in the trees being spared from harm.

48 As to the applicants’ claim that the draft Framework was merely a proposal and not a binding commitment, the Minister said that she was justified in understanding that MRPV had committed to protecting the five trees by realigning the highway.

(iv) Ground 4: Failure to take into account relevant considerations, namely submissions

49 The Minister submitted that she was not obliged to consider representations regarding biodiversity and conservation issues because, having regard to the subject matter, scope and purpose of the legislation, those representations were not mandatory considerations. The Minister emphasised that those representations “raised matters unrelated to Aboriginal heritage”.

(v) Ground 5: Erroneous finding that an alternative route would have similar Aboriginal heritage protection issues

50 The Minister emphasised the following three points with respect to her reasoning about possible Aboriginal heritage issues affecting the Northern Option:

(a) her conclusion with respect to that matter was a “peripheral comment” and was one of a matrix of factors supporting her ultimate conclusion;

(b) that conclusion was no more than the identification of a possibility and did not constitute reliance on any particular “fact”; and

(c) thus there was no “fact” to attract a complaint of no evidence.

51 The Minister added that her conclusion was consistent with Dr Builth’s report, which noted that the Northern Option route had not yet been part of a heritage survey under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 (Vic).

(vi) Ground 6: Error in the treatment of cost estimates

52 The Minister submitted that she did not make any findings about the costs of construction of an alternative route which would be required if such a declaration was made. Rather, she said that she referred to the indicative costings of the Northern Option because that alternative had been considered by MRPV (see [5.108] of the statement of reasons). She emphasised that she did not state that it was still an option.

53 As to her comments at [5.110] of the statement of reasons, the Minister submitted that they were simply responsive to an apparent misapprehension by the applicants’ expert (Mr Vocale) that MRPV had compared the costs of the approved alignment and the Northern Option.

54 While acknowledging that one of the matters relied upon by the Minister in deciding not to make the declarations was because they would have a significant impact on the pecuniary interests of the Victorian government, the Minister submitted that that finding was based not on the costings of alternative routes, but on wasted planning and assessment costs and termination costs.

Consideration and determination

(a) The relevant legislative provisions

55 The purposes of the Act are set out in s 4. They are stated to be “the preservation and protection from injury or desecration of areas and objects in Australia and in Australian waters, being areas and objects that are of particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal tradition”.

56 Division 1 of Pt II empowers the Minister to make declarations. Section 9 provides for the Minister to make, by legislative instrument, an emergency declaration in relation to an area where the Minister has received an application by or on behalf of Aboriginals seeking preservation or protection of the area from injury and desecration. Another condition of the power to make an emergency declaration is that the Minister must be satisfied that the area is a significant Aboriginal area and that it is under serious and immediate threat of injury or desecration.

57 Section 10 empowers the Minister to make other kinds of declarations in relation to an area. It provides as follows:

10 Other declarations in relation to areas

(1) Where the Minister:

(a) receives an application made orally or in writing by or on behalf of an Aboriginal or a group of Aboriginals seeking the preservation or protection of a specified area from injury or desecration;

(b) is satisfied:

(i) that the area is a significant Aboriginal area; and

(ii) that it is under threat of injury or desecration;

(c) has received a report under subsection (4) in relation to the area from a person nominated by him or her and has considered the report and any representations attached to the report; and

(d) has considered such other matters as he or she thinks relevant;

he or she may, by legislative instrument, make a declaration in relation to the area.

(2) Subject to this Part, a declaration under subsection (1) has effect for such period as is specified in the declaration.

(3) Before a person submits a report to the Minister for the purposes of paragraph (1)(c), he or she shall:

(a) publish, in the Gazette, and in a local newspaper, if any, circulating in any region concerned, a notice:

(i) stating the purpose of the application made under subsection (1) and the matters required to be dealt with in the report;

(ii) inviting interested persons to furnish representations in connection with the report by a specified date, being not less than 14 days after the date of publication of the notice in the Gazette; and

(iii) specifying an address to which such representations may be furnished; and

(b) give due consideration to any representations so furnished and, when submitting the report, attach them to the report.

(4) For the purposes of paragraph (1)(c), a report in relation to an area shall deal with the following matters:

(a) the particular significance of the area to Aboriginals;

(b) the nature and extent of the threat of injury to, or desecration of, the area;

(c) the extent of the area that should be protected;

(d) the prohibitions and restrictions to be made with respect to the area;

(e) the effects the making of a declaration may have on the proprietary or pecuniary interests of persons other than the Aboriginal or Aboriginals referred to in paragraph (1)(a);

(f) the duration of any declaration;

(g) the extent to which the area is or may be protected by or under a law of a State or Territory, and the effectiveness of any remedies available under any such law;

(h) such other matters (if any) as are prescribed.

58 The Minister is empowered under s 12 of the Act to make declarations in relation to objects (as opposed to areas). It provides as follows:

12 Declarations in relation to objects

(1) Where the Minister:

(a) receives an application made orally or in writing by or on behalf of an Aboriginal or a group of Aboriginals seeking the preservation or protection of a specified object or class of objects from injury or desecration;

(b) is satisfied:

(i) that the object is a significant Aboriginal object or the class of objects is a class of significant Aboriginal objects; and

(ii) that the object or the whole or part of the class of objects, as the case may be, is under threat of injury or desecration;

(c) has considered any effects the making of a declaration may have on the proprietary or pecuniary interests of persons other than the Aboriginal or Aboriginals referred to in paragraph (1)(a); and

(d) has considered such other matters as he or she thinks relevant;

he or she may, by legislative instrument, make a declaration in relation to the object or the whole or that part of the class of objects, as the case may be.

(2) Subject to this Part, a declaration under subsection (1) has effect for such period as is specified in the declaration.

(3) A declaration under subsection (1) in relation to an object or objects shall:

(a) describe the object or objects with sufficient particulars to enable the object or objects to be identified; and

(b) contain provisions for and in relation to the protection and preservation of the object or objects from injury or desecration.

(3A) A declaration under subsection (1) cannot prevent the export of an object if there is a certificate in force under section 12 of the Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act 1986 authorising its export.

(4) A declaration under subsection (1) in relation to Aboriginal remains may include provisions ordering the delivery of the remains to:

(a) the Minister; or

(b) an Aboriginal or Aboriginals entitled to, and willing to accept, possession, custody or control of the remains in accordance with Aboriginal tradition.

59 It may be noted that a significant difference between the making of a declaration under s 10 as opposed to s 12 is that, in relation to the former provision (which is concerned with areas) but not the latter provision (which is concerned with objects), the Minister must receive and consider a report from a person nominated by the Minister.

60 Mention should also be made of s 13. It not only requires the Minister to consult with appropriate Ministers of a State or Territory before making a declaration (s 13(2)), specific provision is also made in s 13(3) for the Minister to conduct consultations with any person with a view to resolving to the satisfaction of an applicant and the Minister any matter to which the application relates. Accordingly, the Act contemplates that an application may be resolved without the necessity for the Minister to make a declaration.

61 Some key statutory concepts and terms are defined in s 3 of the Act. “[S]ignificant Aboriginal object” is defined in s 3(1) as “an object (including Aboriginal remains) of particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal tradition”.

62 “[S]ignificant Aboriginal area” is relevantly defined in s 3(1) as “an area of land in Australia… of particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal tradition”.

63 Under s 3(2), an area or object is taken to be injured or desecrated if:

(a) in the case of an area;

(i) it is used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition;

(ii) by reason of anything done in, on or near the area, the use or significance of the area in accordance with Aboriginal tradition is adversely affected; or

(iii) passage through or over, or entry upon, the area by any person occurs in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition; or

(b) in the case of an object, it is used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition.

64 Sub-section 3(2) provides another significant difference between a significant Aboriginal area and a significant Aboriginal object. The circumstances in which an area is taken to be injured or desecrated are wider than is the case with an object. In both cases, however, an area or object is taken to be injured or desecrated if it is used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition.

65 The effect of s 3(3) is to deem an area or object to be under threat of injury or desecration if it is, or is likely to be, injured or desecrated.

66 As is evident from the provisions described above, the concept of “Aboriginal tradition” is a central concept in the statutory regime. “Aboriginal tradition” is defined in s 3(1) as “the body of traditions, observances, customs and beliefs of Aboriginals generally or of a particular community or group of Aboriginals, and includes any such traditions, observances, customs or beliefs relating to particular persons, areas, objects or relationships”.

67 As Robertson J observed in Clark at [147] that defined expression has both “breadth” and “subtlety”. The defined expression is also complex and requires a proper understanding of Aboriginal traditions, observances, customs or beliefs. The Minister’s previous understanding and application of the concept was found by Robertson J in Clark to be legally flawed. One of the key issues in the present proceeding is whether, in reconsidering and redetermining the application, the Minister has adopted and applied a legally correct understanding and application of key statutory concepts, particularly “Aboriginal tradition” and “injury and desecration”.

68 Where the Minister refuses to make a declaration under Div 1 of Pt II, he or she is required by s 16 to take reasonable steps to notify the applicant or applicants of the decision.

69 The Act provides for consultation by the Minister with the appropriate Minister of the relevant State (as noted above) and for revocation of a declaration where the Minister is satisfied that the law of a State makes effective provision for the protection of the area, object or objects (see ss 13(2) and (5), together with s 7). This is important. As von Doussa J observed in Chapman v Luminis (No 4) [2001] FCA 1106; 123 FCR 62 at [256], the Act is “a protective mechanism of last resort where State or Territory legislation is ineffective or inadequate to protect the heritage areas or objects. This intention finds expression in particular in ss 7 and 13 …” (see also Bropho at 211 per French J, referred to at [71] below).

70 A declaration relating to a significant Aboriginal area or object has the force of law and contravention of the terms of such a declaration is an indictable offence carrying substantial penalties (see ss 22 and 23 respectively). The Court has a broad power under s 26 to grant, on the Minister’s application, an injunction restraining conduct that constitutes or would constitute a contravention of a declaration made under Pt II (which includes ss 10 and 12) and to restrain related conduct.

71 It is desirable to say something more about the purposes and history of the Act, drawing heavily on French J’s informative reasons for judgment in Tickner v Bropho (1993) 40 FCR 183 at 211 ff. First, the Act was enacted with the express purpose of preserving and protecting from injury or desecration areas and objects in Australia that are of particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal tradition. It was envisaged that it would be used as a protective mechanism of last resort where State or Territory legislation was ineffective or inadequate to protect heritage areas or objects. The need for Commonwealth legislation on this subject matter was tied to the perceived inadequacy or non-enforcement of State laws, as acknowledged by the then Minister for Aboriginal Affairs in the Second Reading Speech to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage (Interim Protection) Bill 1984 (Cth) when introducing that Bill (which was the genesis of the current Act):

Time and again the Commonwealth has been powerless to take legal action where State or Territory laws were inadequate, not enforced or non-existent, despite its clear constitutional responsibility.

72 Secondly, the beneficial nature of the legislation was expressly acknowledged in the conclusion to that Second Reading Speech when it was described as (emphasis added):

…beneficial legislation, as other legislation remedying social disadvantage has been. Aboriginals and Islanders will be secure in the knowledge that areas and objects of particular significance to them can be preserved and protected. Where the remains of ancestors were stolen from graves and shamefully abused, this Bill will allow those remains to be returned to them. ... But the benefit will not be confined to those local Aboriginals and Islanders whose areas and objects received the direct protection of the law. In a wider and very real sense, the benefit will be felt by the whole community. The preservation and protection of this ancient and significant culture from the destructive processes which have been operating at different rates across this country can only enrich the heritage of all Australians.

73 Thirdly, when the legislation was amended in 1986 and its title changed to its current form, the policy underlying the legislation was described by the then Minister for Aboriginal Affairs in the Second Reading Speech as follows:

Where an Aboriginal community closely identifies with an area which has historical, cultural or spiritual significance, the Commonwealth Act provides a means of protecting that area from actions which may destroy, injure or desecrate it. The Act cannot and will not be used where a State or Territory government has given assurances, or taken action, to protect such an area.

…

The Act, in effect, provides a means whereby Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders can use the Commonwealth to review decisions by State and Territory governments. It gives the Commonwealth authority to bring affected parties together to conciliate, mediate and negotiate in order to remove a threat of injury to a significant Aboriginal area or object. Declarations are needed only where such mediation fails to resolve the problem of a threat. The Act has been used in this way during the past two years.

74 Fourthly, it is important to note that under both ss 10 and 12, the Minister has an ultimate discretion whether or not to make a declaration even if he or she is satisfied that a significant Aboriginal area or object is under threat of injury or desecration, as is reflected in the use of the word “may” in the concluding part of both ss 10(1) and 12(1).

75 Fifthly, as French J observed in Bropho at 223-224, the Act (emphasis added):

… was enacted for the benefit of the whole community to preserve what remains of a beautiful and intricate culture and mythology. Its protection is a matter of public interest. There will, however, be occasions on which that objective will conflict with other public interests. The public interest in the provision of safe, convenient and economic utilities may in some cases only be advanced at the expense of areas of significance to Aboriginals. The question whether a declaration should be made which would adversely affect the public or private interests is a matter within the discretion of the Minister who is required to evaluate the competing considerations and make a decision accordingly. It follows that the statutory purpose does not extend to unqualified protection for areas of significance to Aboriginals. The Act provides a mechanism by which such protection can be made available. Over and above that it accords a high value to such protection for heritage areas threatened with injury or desecration. That high statutory value is a factor required to be given substantial weight in the exercise of ministerial discretion under s 10.

Those same observations apply to the exercise of ministerial discretion under s 12.

76 Finally, in Bropho at 191 Black CJ described the Act as being “clear in its purposes, broad in its application and powerful in the provision it makes for the achievement of its purposes”.

(c) The applicants’ six judicial review grounds

77 It is convenient to now address each of the six judicial review grounds.

(i) Ground 1: Failure to commission and receive a report under s 10(1)(c) of the Act relating to the application

78 This ground is only relevant to that part of the Minister’s decision in which she refused to make a declaration under s 10 in respect of the Specified Area. As noted, there is no requirement under s 12 of the Act for the Minister to obtain and consider a report in making a decision concerning a significant Aboriginal object.

79 For the following reasons, I reject the applicants’ claim that the Minister failed to commission and receive a report under s 10(1)(c) having regard to the particular circumstances here. The gravamen of the applicants’ complaint is that while the Phillips Report may have been a report for the purposes of s 10(1)(c) at the time it was provided to the Minister, this changed when the Minister received MRPV’s commitment in its letter dated 29 May 2019 to avoid five of the six trees. The applicants say that this fundamental change meant that the Phillips Report was no longer relevant. I did not understand the applicants to claim that the Phillips Report was not a valid report for the purposes of s 10 at the time it was provided to the Minister. Rather, their complaint is that it ceased to be a valid report because of the fundamental change provided by MRPV’s commitment, which change necessarily affected many of the matters specified in s 10(4) which had to be dealt with in a report.

80 I accept the Minister’s submission that the applicants’ position is inconsistent with various aspects of the statutory context. That context includes that procedural fairness requirements are likely to operate to provide the Minister with relevant material even where there is a fundamental change to the conduct which provides the threat of injury or desecration, as occurred here post the Phillips Report with the commitment given by MRPV. The applicants made no complaint of procedural unfairness. It is evident from the Minister’s statement of reasons that the applicants and other interested parties were given multiple opportunities to respond to various developments which post-dated the Phillips Report and they availed themselves of those opportunities.

81 Another aspect of the statutory context is the power conferred upon the Minister by s 13(3) which enables him or her to consult with various persons with a view to resolving an application without having to make a declaration. Again, it is evident that the Minister availed herself of this avenue here, albeit without success. The simple point is not that such consultation failed, but rather that the Act recognises various ways by which the Minister can obtain information relevant to the Minister’s decision-making task from various sources and need not obtain a further s 10(4) report in the events that occurred here.

82 It is also notable that the legislation is silent on the question whether the Minister has the power to direct a reporter to provide an updated report. Perhaps more significantly, the relevant provisions in s 10 are expressed in terms which indicate that the matters which have to be dealt with in a report are matters as they stand at the time the report is submitted to the Minister (see in particular s 10(4)).

83 Finally, I do not accept the applicants’ submission that their position is supported by what Lockhart J said in Bropho at 209. His Honour referred there to the possibility of a reporter being required by the Minister to prepare “a further report”. But that was said in the context of a hypothetical situation where the Minister was faced with two separate applications by different Aboriginal people or groups. Nothing said by his Honour was directed to the circumstances in the present proceeding where there was only one application, one s 10(4) report and a significant subsequent development.

(ii) Ground 2: Unreasonable failure to exercise the power to obtain an up-to-date report

84 This ground is also rejected for the following reasons. First, putting to one side any difference between the concept of “unreasonableness” under the ADJR Act and under the Judiciary Act, the Minister’s failure not to obtain an up-to-date s 10(4) report was not unreasonable. Assuming, without deciding, that the Minister had such a power, it was not unreasonable for the Minister not to exercise that power having regard to the matters relied upon above in rejecting ground 1.

85 Secondly, there is nothing in the statutory scheme which indicates that the Minister is required to obtain a further s 10(4) report whenever there is a significant change in the conduct which is being assessed against the relevant statutory provisions. Perhaps that is unsurprising given the time and resources involved in producing such a report. Moreover, as has been emphasised, other aspects of the statutory scheme provide the Minister with the power to obtain up-to-date and relevant information from a variety of sources. Those powers would need to be exercised reasonably.

(iii) Ground 3: Error in the treatment of the MRPV draft Framework

86 As this ground focuses upon the Minister’s state of satisfaction under s 12(1)(b)(ii) of the Act, it is desirable to say something about the legal character of that state of satisfaction and the extent to which it is amenable to judicial review.

A. Judicial review of the Minister’s state of satisfaction under s 12(1)(b)(ii) of the Act

87 It is notable that the Minister’s power to make a declaration under s 12 is subject to various preconditions, namely:

(a) receipt of an application from specified persons;

(b) that the Minister must be satisfied not only that the object sought to be preserved or protected is a significant Aboriginal object but also that the object is under threat of injury or desecration;

(c) that the Minister must consider the effects of making a declaration on the proprietary or pecuniary interests of third parties; and

(d) that the Minister must consider such other matters as he or she thinks relevant.

88 The pre-condition in paragraph (b) is of a different nature to those in the other paragraphs. That is because the pre-condition turns on whether or not the Minister has attained a particular state of satisfaction in relation to the two matters identified therein. The other pre-conditions are objective and do not turn upon the Minister’s state of satisfaction, with the possible exception of paragraph (d).

89 The pre-condition in paragraph (b) is properly regarded in law as a subjective jurisdictional fact in the sense in which that concept was described, for example, by the Full Court in Ali v Minister for Home Affairs [2020] FCAFC 109; 380 ALR 393 at [41] with reference to the Minister’s state of satisfaction under s 501CA(4)(b)(ii) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth).

90 In Ali, the Full Court described the scope of judicial review of a subjective jurisdictional fact with reference to cases such as Avon Downs Pty Ltd v Federal Commissioner of Taxation [1949] HCA 26; 78 CLR 353 per Dixon J; Minister for Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs v SGLB [2004] HCA 32; 78 ALJR 992 at [38] per Gummow and Hayne JJ; Goundar v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2016] FCA 1203; 160 ALD 123 at [53]-[54] per Robertson J and SZMDS. Other relevant cases include R v Connell; Ex parte Hetton Bellbird Collieries Ltd [1944] HCA 42; 69 CLR 407; Wei v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2015] HCA 51; 257 CLR 21 at [33] per Gageler and Keane JJ; Graham v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2017] HCA 33; 263 CLR 1 at [57] per Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler, Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ and Ibrahim v Minister for Home Affairs [2019] FCAFC 89; 270 FCR 12 at [51]-[56] per White, Perry and Charlesworth JJ. Those authorities stand for the proposition that a state of satisfaction (which is a jurisdictional fact) must be attained reasonably and on a correct understanding of the law. Mr Kennett SC (who together with Ms Wright appeared for the Minister) acknowledged that this was a correct statement of legal principle.

91 Accordingly, an assessment of ground 3 of the applicants’ challenge here raises the question as to whether the Minister’s conclusion that she was not satisfied that five of the six trees were under threat of injury or desecration was a state of satisfaction which was attained reasonably and with a correct understanding of the law.

92 For the reasons that follow, I consider that the Minister’s state of satisfaction was attained unreasonably and/or without a correct understanding of the law.

93 Before explaining why that is so, it is desirable to say something more about both the background to the matter and relevant parts of the Minister’s statement of reasons.

B. The Minister’s statement of reasons and some background matters

94 As noted above, the application for the making of the declarations is dated 17 June 2018. Relevantly, the application stated (emphasis added):

Starting from 18 June 2018 there are proposed road works planned which will lead to the desecration of significant sites and objects, in particular, highly culturally significant trees. The significant Aboriginal areas and objects on Djab Wurrung country close to the Victorian town of Buangor on the VicRoads planned upgrade to the Western Highway.

Attached to this application is a desktop report on the culturally modified trees along the planned road works (‘Report’).

Of particular significance are hollow trees ‘E3’ and ‘E6’ detailed in the report, with photos attached [sic] at the end of this letter. E6 has been used by our people for over 50 generations.

E3 & E6 are two highly culturally significant ancient hollow trees, which sit in a [sic] extremely significant area at the basin of the Hopkins river, and are connected to our songlines and stories that reach from Langi Ghiran, our black cockatoo dreaming site and also along the Hopkins river which is connected to our eel dreaming. VicRoads intends to physically destroy and remove these ancient trees that are particularly culturally significant to our women.

These trees have been used by our ancestors for hundreds of years, over 50 generations, and have had multiple uses over time. They are extremely rare examples and the last remnants of such trees, most similar trees in the area have already been destroyed over the course of history. We are fighting to maintain and preserve what we have left, as these trees have played an important role in the health of our country and the wellbeing of our people for countless generations. They are living beings that embody our stories throughout this significant landscape. These old trees are named ‘Delgug’ meaning ‘tall person’. These trees are our ancestors and we must protect them to the best of our ability. Destroying them is severely upsetting, and brings bad fortune.

…

95 It is significant that the claimed cultural significance of the trees was not confined to their connection to the Specified Area (being the “Maximum Construction Footprint”), but extended beyond that to include songlines and stories reaching from Langi Ghiran (the Djab Wurrung people’s black cockatoo dreaming site) which is outside the Specified Area, as well as the Hopkins River (connected to Djab Wurrung people’s eel dreaming) which is outside the Specified Area).

96 It is also to be noted from the application that the claimed cultural significance of the trees focused not only upon the physical use of those trees by Aboriginals over hundreds of years but also on their spiritual quality because they were viewed as embodying Aboriginal ancestors. These claims are vivid examples of the complex and nuanced nature of Aboriginal tradition.

97 I have set out at [17] above the particular paragraphs from the Minister’s statement of reasons dated 6 August 2020 which summarise her reasons and ultimate findings in declining to make a declaration under either ss 10 or 12 of the Act. The Minister’s summary of her findings and reasons in respect of her decision not to make a declaration under s 12 in respect of Trees E2 to E6 are contained in [6.3].

98 It is now appropriate to refer to other parts of the Minister’s statement of reasons which explain why she declined to make a s 12 declaration in respect of those trees (which the Minister found to be “significant Aboriginal objects”, but not at threat of injury or desecration). They are principally contained in [5.52] to [5.63] of the statement of reasons (and noting that the applicants do not challenge the findings concerning tree E1):