Federal Court of Australia

Impiombato v BHP Group Limited (No 2) [2020] FCA 1720

ORDERS

First Applicant KLEMWEB NOMINEES PTY LTD (AS TRUSTEE FOR THE KLEMWEB SUPERANNUATION FUND) Second Applicant | ||

AND: | BHP GROUP LIMITED (ACN 004 028 077) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicants’ application, made by email dated 25 November 2020, for leave to refer the Court to a recent judgment of the High Court of Justice in England, be refused.

2. The respondent’s interlocutory application dated 12 May 2020 be dismissed.

3. Within 14 days, each party file a written submission (of no more than two pages) on the costs of the interlocutory application.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MOSHINSKY J:

Introduction

1 These reasons deal with an interlocutory application filed by the respondent, BHP Group Limited (BHP Ltd), formerly BHP Billiton Limited, dated 12 May 2020. Before outlining BHP Ltd’s contentions and the relief sought, the following background matters are noted.

2 The proceeding is a representative proceeding under Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). Following the consolidation of the proceeding with another proceeding, the joint applicants are: Mr Vince Impiombato; and Klemweb Nominees Pty Ltd (as trustee for the Klemweb Superannuation Fund). A new pleading – the consolidated statement of claim – was prepared following the consolidation of the two proceedings. At the hearing of BHP Ltd’s interlocutory application, the applicants applied for leave to amend the pleading to make some adjustments to address points raised by BHP Ltd. The application for leave to amend was not opposed, and leave to amend was granted. The amended pleading is the amended consolidated statement of claim (the statement of claim).

3 The applicants and the persons they represent (the Group Members) are all persons who or which:

(a) during the period from 8 August 2012 to the close of trade on 9 November 2015 inclusive (the Relevant Period) entered into a contract to acquire an interest in fully paid up ordinary shares in:

(i) BHP Ltd on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) (the BHP ASX Shares);

(ii) BHP Group Plc, formerly named BHP Billiton Plc (BHP Plc), a company registered in England and Wales, on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) (the BHP LSE Shares); and/or

(iii) BHP Plc on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) (the BHP JSE Shares);

(b) do not fall within certain exclusions or exceptions (which need not be set out); and

(c) are alleged to have suffered loss or damage by, or which resulted from, the conduct of BHP Ltd as pleaded in the statement of claim.

4 At all material times, BHP Ltd and BHP Plc had a dual listed company structure pursuant to which they operated as if they were a single unified economic entity pursuant to a dual listed company structure agreement. At the material times, this was the DLC Structure Sharing Agreement dated 29 June 2001 (the DLC Structure Sharing Agreement). In the statement of claim, the expression “BHP” is used to refer to the notional single unified economic entity comprising BHP Ltd and BHP Plc. The expression “BHP” will be used in the same way in these reasons.

5 At all material times, BHP Ltd and BHP Plc (or BHP Ltd alone – see further below), through a wholly-owned subsidiary, BHP Billiton Brasil Ltda (BHP Brasil), a company registered in Brazil, held a 50% interest in Samarco Mineração SA (Samarco), a company registered in Brazil. The other 50% of the shares in Samarco was held by Vale SA, a company registered in Brazil. At all material times, Samarco owned and operated the Germano complex in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, comprising an iron ore mine, several concentrators and the Fundão Dam (the Germano Complex). At all material times, Samarco had a board of directors that was comprised of representatives appointed by Vale and BHP Brasil respectively.

6 At around 3.30 pm on 5 November 2015 in Brazil (around 4.30 am AEST on 6 November 2015 in Australia), the Fundão Dam failed, releasing a significant volume of tailings, and resulting in loss of life and other consequences. It is alleged in the statement of claim that these included: the shutdown of the Germano Complex; BHP’s future iron ore production capabilities being revised downwards; BHP’s iron ore cash flow and/or earnings generated by Samarco mining operations being lost or significantly reduced for a substantial period of time; and BHP being exposed to substantial remediation costs and significant reputational damage. On 6 November 2015, BHP Ltd made an announcement on the ASX that there had been a serious incident at Samarco. On 9 November 2015, BHP Ltd made a further announcement, referring to the failure of the Fundão Dam and some of the consequences of that failure. Following those announcements, the price of the BHP ASX Shares, the BHP LSE Shares and the BHP JSE Shares declined significantly.

7 In broad terms, the applicants allege that in the period August 2012 to November 2015, BHP Ltd was aware of certain information and risks relating to the Fundão Dam, and was obliged by Rule 3.1 of the ASX Listing Rules and s 674(2) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) to immediately inform the ASX of that information and those risks. It is alleged that BHP Ltd did not inform the ASX of those matters at any time prior to 9 November 2015, and thereby contravened Rule 3.1 of the ASX Listing Rules and s 674(2) of the Corporations Act. The applicants also allege that BHP Ltd engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive in contravention of s 12DA(1) of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) (the ASIC Act) and s 1041H(1) of the Corporations Act by making certain alleged representations concerning the safety of its people, and the safety and sustainability of the environment and the communities in which BHP, and its subsidiaries, carried on business.

8 The applicants allege that those contraventions caused them loss. In relation to the BHP ASX Shares, it is alleged that, during the Relevant Period, the contraventions caused the price at which BHP ASX Shares traded on the ASX to be higher than their true value and/or the market price that would have prevailed but for the contraventions. Further or in the alternative, it is alleged that the applicants and some of the Group Members who acquired BHP ASX Shares during the Relevant Period would not have acquired those shares if the contraventions had not occurred.

9 In relation to the BHP LSE Shares, the causal path is more complicated. It is alleged that:

(a) during the Relevant Period, the market for BHP LSE Shares was a market in which the price at which BHP LSE Shares traded on the LSE was, and was reasonably expected to have been, influenced by material information concerning BHP that became publicly available to the market for BHP LSE Shares;

(b) during the Relevant Period, material information concerning BHP disclosed by BHP Ltd to the ASX became publicly available to the market for BHP LSE Shares;

(c) further or in the alternative, during the Relevant Period, the market for BHP LSE Shares was a market in which the price at which BHP LSE Shares traded was influenced by the price and/or movements in the price of BHP ASX Shares; and

(d) by reason of these matters, during the Relevant Period, the contraventions caused the price at which BHP LSE Shares traded on the LSE to be higher than their true value and/or the market price that would have prevailed but for the contraventions.

10 Further or in the alternative, it is alleged that some of the Group Members who acquired BHP LSE Shares during the Relevant Period would not have acquired those shares if the contraventions had not occurred.

11 Comparable allegations are made in relation to the BHP JSE Shares.

12 By its interlocutory application dated 12 May 2020, BHP Ltd advances three main contentions and seeks associated relief:

(a) First, BHP Ltd contends that, on its proper construction, Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act does not apply to the claims brought by the applicants on behalf of shareholders of BHP Ltd and/or BHP Plc who are not residents of Australia (non-resident Group Members). BHP Ltd seeks a declaration to this effect and an order that the non-resident Group Members be excluded from the class of persons defined as Group Members in the proceeding. BHP relies on the presumption that legislation is not intended to operate extraterritorially and submits that that presumption is engaged in relation to Pt IVA and has not been displaced.

(b) Secondly, if the Court does not accept its first contention, BHP Ltd contends that, as a matter of discretion, pursuant to s 23 or 33ZF of the Federal Court of Australia Act, the Court should exclude certain categories of Group Members from the proceeding. BHP Ltd seeks the exclusion of either:

(iv) all non-resident Group Members; alternatively all shareholders of BHP Plc who are not residents of Australia (non-resident shareholders of BHP Plc); or

(v) all non-resident Group Members who do not register to participate in the proceeding.

BHP Ltd submits that the Court should make such an order to ameliorate the prejudice faced by BHP Ltd and BHP Plc by virtue of non-resident Group Members having claims prosecuted on their behalf in this proceeding without the concomitant extinguishment of rights over the same subject-matter in the jurisdictions in which BHP Plc’s shares are traded, noting that the vast majority of non-resident Group Members are holders of shares in BHP Plc rather than BHP Ltd.

(c) Thirdly, and independently of the first and second contentions, BHP Ltd contends that the causes of action pleaded on behalf of Group Members who acquired shares in BHP Plc (as distinct from BHP Ltd) are not viable and ought to be struck out. BHP Ltd submits that the alleged contraventions by BHP Ltd, even if established, cannot have caused loss to persons acquiring shares in a different, foreign company (BHP Plc) on a foreign stock exchange.

13 For the reasons that follow, in my view, the application should be dismissed. In brief summary:

(a) I do not accept the contention that Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act cannot apply to claims brought on behalf of persons who are not resident in Australia.

(b) Assuming there is power to do so, I do not consider it appropriate to make an order, in the exercise of the discretion, excluding all non-resident Group Members, or all non-resident shareholders of BHP Plc, from the represented group in this proceeding. Further, I do not consider it appropriate, at least at this stage (before a defence has even been filed), to exclude non-resident Group Members who do not register to participate in the proceeding.

(c) In my view, the pleaded facts, at least arguably, establish a causal link for the purposes of the relevant statutory provisions between BHP Ltd’s alleged contraventions and the losses claimed to have been suffered by shareholders of BHP Plc. Beyond this, I do not consider it appropriate to determine, at a preliminary stage, and without a full factual context, whether the losses claimed to have been suffered by the shareholders of BHP Plc are within the contemplation of the relevant statutory provisions, which is a complex and novel question of statutory construction.

BHP Ltd’s interlocutory application

14 In support of its interlocutory application, BHP Ltd relies on the following affidavit and expert reports:

(a) an affidavit of Jason Betts, a partner of Herbert Smith Freehills, the solicitors for BHP Ltd, dated 4 September 2020, relating to the composition of shareholders of BHP Ltd and BHP Plc;

(b) an expert report dated 25 June 2020 and a reply expert report dated 3 September 2020 prepared by Alexander Layton QC, relating to English law;

(c) an expert report dated 26 June 2020 of Monye Anyadike-Danes QC, relating to Northern Ireland law;

(d) an expert report dated 26 June 2020 of Dr Kirsty Hood QC, relating to Scots law; and

(e) an expert report dated 1 July 2020 and a reply expert report filed on 4 September 2020 of Frank Snyckers SC, relating to South African law.

15 In response, the applicants rely on the following affidavits and expert reports:

(a) affidavits of Brett Spiegel, a principal lawyer in the firm, Phi Finney McDonald, the solicitors (together with Maurice Blackburn) for the applicants, dated 14 August 2020 and 4 September 2020 – the first affidavit annexed a copy of the DLC Structure Sharing Agreement; the second affidavit related to the application for leave to amend the pleading, which was dealt with at the hearing;

(b) an expert report dated 13 August 2020 of Hugh Mercer QC, relating to English law; and

(c) an expert report dated 13 August 2020 (signed on 31 August 2020) of Paul Farlam SC, relating to South African law.

16 There was no cross-examination.

17 The hearing took place using Microsoft Teams video-conferencing software due to the restrictions in place during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mr Spiegel adopted his affidavit, which had been provided in unsworn form (consistently with the Court’s practice guidelines during the pandemic), during the hearing. Detailed outlines of submissions were provided by the parties in advance of the hearing.

18 On 25 November 2020, while judgment on BHP Ltd’s interlocutory application was reserved, the applicants sent an email to my associate seeking leave to refer the Court to a recent judgment of the High Court of Justice in England. The email stated that the judgment related to an application by BHP Plc and BHP Ltd in that jurisdiction to strike out proceedings brought in England on behalf of Brazilian applicants. The email stated that the applicants sought leave to refer to the judgment, in particular to the abuse of process principles set out in the judgment. The email noted that BHP Ltd objected to the judgment being provided to the Court because it constituted, BHP Ltd submitted, an attempt by the applicants to adduce fresh evidence, after the hearing of the application and while judgment was reserved. In my view, in circumstances where the content of English law is a question of fact, the applicants are in substance seeking to re-open their case to adduce further evidence. I do not consider it appropriate to permit the applicants to do so. Both sides have adduced extensive evidence on the relevant principles of English law. In that context, it is not shown that I would be assisted by receiving this further judgment. In particular, I would be receiving it without the benefit of any analysis about it by the experts on English law who have already given evidence in connection with the present interlocutory application. Accordingly, I refuse the applicants’ application for leave to refer the Court to the judgment.

The statement of claim

19 In this section of these reasons, I provide an overview of the pleading, and set out the particular paragraphs of the statement of claim that are the subject of BHP Ltd’s strike-out application. In setting out extracts from the statement of claim, the amendments for which leave was granted at the hearing have been incorporated without mark up.

20 Paragraph 3 of the statement of claim contains the description of the Group Members. It states (omitting the particulars and the exclusion of certain categories of persons in paragraph (b)):

3. The Joint Applicants and the persons they represent (the Group Members) are all persons who or which:

(a) during the period from 8 August 2012 to the close of trade on 9 November 2015 inclusive (Relevant Period) entered into a contract (whether themselves or by an agent or trustee) to acquire an interest in fully paid up ordinary shares in:

(i) the Respondent, formerly BHP Billiton Limited (BHP Ltd), on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX), a financial market operated by ASX Limited (the BHP ASX Shares);

(ii) BHP Group Plc, formerly BHP Billiton Plc (BHP Plc), a company registered in England and Wales, on the London Stock Exchange (LSE), a financial market operated by the London Stock Exchange Group Plc (the BHP LSE Shares); and/or

(iii) BHP Plc on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE), a financial market operated by the Johannesburg Stock Exchange Limited (the BHP JSE Shares);

(b) were not … ; and

(c) are alleged to have suffered loss or damage by, or which resulted from, the conduct of BHP Ltd as pleaded in this statement of claim.

21 In paragraph 7 of the statement of claim, it is alleged that, at all material times, BHP Ltd was obliged by s 111AP(1) and/or s 674(2) of the Corporations Act and/or Rule 3.1 of the ASX Listing Rules, once it became aware of any information concerning BHP Ltd that a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect on the price or value of BHP ASX Shares, to tell the ASX that information immediately, unless any of the exceptions in Rule 3.1A of the ASX Listing Rules applied.

22 Paragraph 8 of the statement of claim relates to BHP Plc and is in the following terms:

8. At all material times, BHP Plc has had on issue:

(a) BHP LSE Shares which were and are:

(i) traded on the LSE under the designation “BLT”; and

(ii) able to be acquired and sold by investors and potential investors in BHP LSE Shares on the LSE (BHP LSE Share Market); and

(b) BHP JSE Shares which were and are:

(i) traded on the JSE under the designation “BIL”; and

(ii) able to be acquired and sold by investors and potential investors in BHP JSE Shares on the JSE (BHP JSE Share Market).

23 Paragraphs 9 and 10 of the statement of claim relate to the dual listed company structure:

9. At all material times, BHP Ltd and BHP Plc had a dual listed company structure (DLC Structure).

Particulars

DLC Structure Sharing Agreement, recital A and cl 2.

10. Pursuant to the DLC Structure, BHP Ltd and BHP Plc operated as if they were a single unified economic entity (BHP) through:

(a) identical boards of directors which comprised the same individuals; and

Particulars

DLC Structure Sharing Agreement, cl 2(b).

(b) a single unified management team; including a single Group Management Committee, being BHP’s most senior executive body (BHP GMC);

Particulars

BHP annual report for the 2011 financial year (FY) (being the period between 1 July 2010 and 30 June 2011), page 127; BHP FY2012 annual report, page 131; BHP FY2013 annual report, page 151; BHP FY2014 annual report, page 172; BHP FY2015 annual report, page 160.

At all material times, the purpose of the GMC was inter alia to: (i) assist the Chief Executive Officer in pursuing BHP’s corporate purpose; (ii) provide leadership to the BHP Group, determine its priorities and guide its operations; and (iii) provide a forum to debate high-level matters [and] ensure consistent development of the BHP Group’s strategy.

(c) the economic and voting interests in BHP resulting from holding one share in BHP Ltd were equivalent to the economic and voting interests resulting from holding one share in BHP Plc.

Particulars

DLC Structure Sharing Agreement, cl 3.

24 Paragraphs 11 to 18 of the statement of claim identify the relevant officers of BHP Ltd and allege that any information of which any of those officers became aware or which ought reasonably have come into their possession, in the course of carrying out their duties, was information of which BHP Ltd was aware within the meaning of Rule 3.1 and Rule 19.12 of the ASX Listing Rules.

25 Paragraphs 19 to 30 of the statement of claim contain pleadings about Samarco, including, at paragraph 26, the composition of its board of directors.

26 The statement of claim sets out, at paragraphs 31-39, allegations regarding the design, location and construction of the Fundão Dam. The statement of claim then sets out, at paragraphs 40-43, allegations concerning problems with the Fundão Dam at various times between August 2012 and November 2015. The statement of claim uses the following expressions to define the information concerning the problems with the Fundão Dam at the various times:

(a) the August 2012 Information;

(b) the September 2012 Information;

(c) the Pre-August 2014 Information; and

(d) the Post-August 2014 Information.

27 The statement of claim also contains allegations concerning the likely consequences of a failure of the Fundão Dam, defined as the “General Consequential Risks” (paragraph 44). Certain alleged, more specific consequences are defined as the “BHP Consequential Risks” (paragraph 45).

28 The allegations concerning contraventions of continuous disclosure obligations are set out in Section H (paragraphs 46-53) of the statement of claim.

29 It is alleged, at paragraph 48, that BHP Ltd was aware (within the meaning of Rule 19.12 of the ASX Listing Rules):

(a) by no later than 8 August 2012, of the August 2012 Information;

(b) by no later than 30 September 2012, of the September 2012 Information;

(c) by no later than in the period from 30 September 2012, until around 27 August 2014, of the Pre-August 2014 Information;

(d) at all material times from no later than around 27 August 2014, until 5 October 2015 (Brazilian time), of the Post-August 2014 Information; and

(e) at all material times, of the General Consequential Risks and the BHP Consequential Risks.

30 It is alleged, at paragraph 49, that by reason of these matters, BHP Ltd was aware, for the purposes of Rule 3.1 of the ASX Listing Rules and s 674(2) of the Corporations Act, of the information and risks referred to above, at the respective times set out above. It is alleged, at paragraphs 50-53, that BHP Ltd failed to make continuous disclosure of the relevant information and thus contravened s 674(2) of the Corporations Act.

31 The next section of the statement of claim (Section I, comprising paragraphs 54-63) contains allegations based on the misleading or deceptive conduct provisions of the ASIC Act and the Corporations Act. On the basis of statements contained in BHP’s annual reports for the 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015 financial years, it is alleged at paragraph 59 that BHP Ltd represented, from and throughout the Relevant Period, that:

(a) the primary consideration in every aspect of BHP’s business was the safety of its people and the safety and sustainability of the environment and the communities in which it, and its subsidiaries, carried on business; and

(b) it had effective systems and processes in place to identify and effectively manage risks to the safety of its people and the safety and sustainability of the environment and the communities in which it, and its subsidiaries, carried on business, including the Samarco mining operation,

(defined as the “Representations” in the statement of claim).

32 It is alleged, at paragraph 62, that by no later than 8 August 2012 and at all times thereafter until the end of the Relevant Period, the Representations were misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. It is alleged (in paragraph 63) that BHP Ltd contravened s 12DA(1) of the ASIC Act and s 1041H(1) of the Corporations Act.

33 Paragraph 64 of the statement of claim describes the failure of the Fundão Dam on 5 November 2015.

34 Paragraphs 65 to 67 of the statement of claim describe the disclosure of information following the failure of the Fundão Dam and the share price impacts:

65. On 6 November 2015, BHP Ltd made an announcement on the ASX that there had been a serious incident at Samarco (the 6 November 2015 Announcement).

Particulars

BHP ASX release entitled “INCIDENT AT SAMARCO” dated 6 November 2015.

66. On 9 November 2015, BHP Ltd made an announcement on the ASX about the failure of the Fundão Dam and some of the consequences of that failure (the 9 November 2015 Announcement).

Particulars

BHP ASX release entitled “UPDATE: INCIDENT AT SAMARCO” dated 9 November 2015.

67. Following the 6 November 2015 Announcement and/or the 9 November 2015 Announcement, the price of:

(a) the BHP ASX Shares;

(b) the BHP LSE Shares; and/or

(c) the BHP JSE Shares,

declined significantly.

Particulars

The price of the BHP ASX Shares declined from a closing price of $23.28 on 5 November 2015 to a closing price of $18.09 on 30 November 2015.

The price of the BHP LSE Shares declined from a closing price of GBP 10.34 on 5 November 2015 to a closing price of GBP 7.96 on 30 November 2015.

The price of the BHP JSE Shares declined from a closing price of ZAR 221.59 on 5 November 2015 to a closing price of ZAR 170.30 on 30 November 2015.

It is convenient to note at this point that the particulars to paragraph 67 indicate a comparable percentage decline in the price of BHP Ltd shares and BHP Plc shares.

35 The next section of the statement of claim (Section L, comprising paragraphs 68-80) deals with causation of loss. First, at paragraphs 68-70, there are allegations relating to the BHP ASX Shares. Secondly, at paragraphs 71-75, allegations concerning the BHP LSE Shares are set out. Thirdly, allegations concerning the BHP JSE Shares are set out at paragraphs 76-80. By its strike-out application, BHP Ltd seeks to strike out paragraphs 71-80. Although the strike-out application does not challenge paragraphs 68-70, I set out those paragraphs (as well as paragraphs 71-80) in order to provide context. I note also that paragraphs 71-80 of the statement of claim were the subject of a number of the amendments in respect of which leave to amend was granted at the hearing of BHP Ltd’s interlocutory application. Those amendments, which are incorporated but not marked up in the extract below, sought to address some of the points made by BHP Ltd in its written submissions. Section L of the statement of claim is in the following terms:

L. CONTRAVENTIONS CAUSED LOSS

L.1 BHP ASX Shares

68. During the Relevant Period, the BHP ASX Share Market was a market:

(a) regulated by, inter alia, ss 674(2) and 1041H of the Corporations Act, Rule 3.1 of the Listing Rules and s 12DA of the ASIC Act;

(b) in which the price at which BHP ASX Shares traded on the ASX was, and was reasonably expected to have been, influenced by the material information concerning BHP that was published on the ASX or that otherwise became publicly available;

(c) in which material information, namely the August 2012 Information, September 2012 Information, Pre-August 2014 Information, Post-August 2014 Information, General Consequential Risks and BHP Consequential Risks, had not been disclosed, which a reasonable person would expect, had it been disclosed, would have had a material adverse effect on the price or value of the BHP ASX Shares; and

(d) in which misleading or deceptive conduct, namely the Representations, had occurred, which a reasonable person would expect to have a material effect on the price or value of BHP ASX Shares.

69. During the Relevant Period:

(a) the Continuous Disclosure Contraventions; and

(b) the Misrepresentations Contraventions,

(collectively, the Contraventions) caused the price at which BHP ASX Shares traded on the ASX to be higher than their true value and/or the market price that would have prevailed but for the Contraventions (or any of them).

Particulars

This is to be inferred from paragraphs 64-67 above and the particulars subjoined thereto.

Particulars of the extent to which the Contraventions caused the price at which BHP ASX Shares traded on the ASX to be higher than their true value and/or the market price that would have prevailed but for the Contraventions (or any of them) will be provided after the filing of expert reports.

70. Further or in the alternative to paragraphs 68 and 69 above, the Joint Applicants and some of the Group Members who acquired an interest in BHP ASX Shares during the Relevant Period would not have acquired an interest in the BHP ASX Shares if the Contraventions that had occurred at the time of their acquisition (or any of them) had not occurred.

Particulars

The Joint Applicants and some Group Members acquired an interest in the BHP ASX Shares in reliance upon the Representations.

The Joint Applicants would not have acquired an interest in the BHP ASX Shares had the information the subject of the Required Disclosures (or any of them) been disclosed, or had the Representations been retracted, corrected or qualified prior to such acquisition.

The identities of all those Group Members which or who would not have acquired an interest in BHP ASX Shares had information the subject of the Required Disclosures (or any of them) been disclosed or had the Representations been retracted, corrected or qualified prior to such acquisition, will be obtained and provided following opt out, the determination of the Joint Applicants’ claims and identified common issues at an initial trial and if, and when, it is necessary for a determination to be made of the individual claims of those Group Members.

L.2 BHP LSE Shares

71. During the Relevant Period, the BHP LSE Share Market was a market in which the price at which BHP LSE Shares traded on the LSE was, and was reasonably expected to have been, influenced by material information concerning BHP that became publicly available to the BHP LSE Share Market.

72. During the Relevant Period, material information concerning BHP disclosed by BHP Ltd to the ASX became publicly available to the BHP LSE Share Market.

Particulars

Material information concerning BHP disclosed by BHP Ltd to the ASX became publicly available to the BHP LSE Share Market by reason of the fact that company announcements disclosed to the ASX became publicly available on the ASX website www.asx.com.au

Further particulars may be provided after discovery.

73. Further and in the alternative to paragraphs 71 and/or 72 above, during the Relevant Period, the BHP LSE Share Market was a market in which the price at which BHP LSE Shares traded on the LSE was influenced by the price and/or movements in the price of BHP ASX Shares.

Particulars

This is to be inferred from paragraphs 9, 10 and/or 67 above and the particulars subjoined thereto.

Further particulars will be provided after the filing of expert reports.

74. By reason of the matters pleaded at paragraphs 71, 72 and/or 73 above, during the Relevant Period, the Contraventions caused the price at which BHP LSE Shares traded on the LSE to be higher than their true value and/or the market price that would have prevailed but for the Contraventions (or any of them).

Particulars

This is to be inferred from paragraphs 9, 10, 65, 66, 67, 71, 72 and/or 73 above [and] the particulars subjoined thereto.

Particulars of the extent to which the Contraventions caused the price at which BHP LSE Shares traded on the LSE to be higher than their true value and/or the market price that would have prevailed but for the Contraventions (or any of them) will be provided following service of expert quantum evidence.

75. Further or in the alternative to paragraph 74 above, some of the Group Members who acquired an interest in BHP LSE Shares during the Relevant Period would not have acquired an interest in the BHP LSE Shares if the Contraventions that had occurred at the time of their acquisition (or any of them) had not occurred.

Particulars

The identities of all those Group Members which or who would not have acquired an interest in BHP LSE Shares had the Required Disclosures (or any of them) been disclosed or had the Representations been retracted, corrected or qualified prior to such acquisition, will be obtained and provided following opt out, the determination of the Joint Applicants’ claims and identified common issues at an initial trial and if, and when, it is necessary for a determination to be made of the individual claims of those Group Members.

L.3 BHP JSE Shares

76. During the Relevant Period, the BHP JSE Share Market was a market in which the price at which BHP JSE Shares traded on the JSE was, and was reasonably expected to have been, influenced by material information concerning BHP that became publicly available to the BHP JSE Share Market.

77. During the Relevant Period, material information disclosed by BHP Ltd to the ASX became publicly available to the BHP JSE Share Market.

Particulars

Material information concerning BHP disclosed by BHP Ltd to the ASX became publicly available to the BHP JSE Share Market by reason of the fact that company announcements disclosed to the ASX became publicly available on the ASX website www.asx.com.au

Further particulars may be provided after discovery.

78. Further or in the alternative to paragraphs 76 and/or 77 above, during the Relevant Period, the BHP JSE Share Market was a market in which the price at which BHP JSE Shares traded on the JSE was influenced by the price and/or movements in the price of BHP ASX Shares.

Particulars

This is to be inferred from paragraphs 9, 10 and/or 67 above and the particulars subjoined thereto.

Further particulars will be provided upon service of the Joint Applicants’ expert quantum evidence.

79. By reason of the matters pleaded at paragraphs 76, 77 and/or 78 above, during the Relevant Period, the Contraventions caused the price at which BHP JSE Shares traded on the JSE to be higher than their true value and/or the market price that would have prevailed but for the Contraventions (or any of them).

Particulars

This is to be inferred from the matters set out at paragraphs 9, 10, 65, 66, 67, 76, 77 and/or 78 above the particulars subjoined thereto.

Particulars of the extent to which the Contraventions caused the price at which BHP JSE Shares traded on the JSE to be higher than their true value and/or the market price that would have prevailed but for the Contraventions (or any of them) will be provided after the filing of expert reports.

80. Further or in the alternative to paragraph 79 above, some of the Group Members who acquired an interest in BHP JSE Shares during the Relevant Period would not have acquired an interest in the BHP JSE Shares if the Contraventions that had occurred at the time of their acquisition (or any of them) had not occurred.

Particulars

The identities of all those Group Members which or who would not have acquired an interest in BHP JSE Shares had the Required Disclosures (or any of them) been disclosed or had the Representations been retracted, corrected or qualified prior to such acquisition, will be obtained and provided following opt out, the determination of the Joint Applicants’ claim and identified common issues at an initial trial and if, and when, it is necessary for a determination to be made of the individual claims of those Group Members.

36 The final section of the pleading (Section M, comprising paragraphs 81-83) contains allegations concerning loss and damage. Paragraph 81 alleges that the applicants suffered loss and/or damage in relation to their interests in BHP ASX Shares by and resulting from the contraventions. Paragraph 82 (omitting particulars) states:

82. Group Members who acquired an interest in:

(a) BHP ASX Shares;

(b) BHP LSE Shares; and/or

(c) BHP JSE Shares,

during the Relevant Period have suffered loss and/or damage in relation to their interests in those shares by and resulting from the Contraventions (or any one or combination of the Contraventions).

Factual material before the Court

37 The parties have placed a limited amount of factual material before the Court for the purposes of resolving BHP Ltd’s interlocutory application. I now set out a summary of that material.

Material concerning the shareholdings in BHP Ltd and BHP Plc

38 In Mr Betts’s affidavit he stated that: BHP Ltd and BHP Plc operate as a dual listed company; the two entities exist as separate companies; both companies have a unified Board of Directors comprising the same individuals; and the companies are run by a unified management team and operate as if they were a single economic entity (referred to as “BHP” in these reasons). He stated that BHP Ltd’s shares are listed on the ASX and BHP Plc’s shares are listed on the LSE and the JSE.

39 Mr Betts stated that he caused a solicitor to examine data in respect of the volume of shares traded in BHP Ltd and BHP Plc during the Relevant Period. That data showed that the number of shares traded during the Relevant Period was:

(a) in BHP Ltd on the ASX – approximately 6.3 billion;

(b) in BHP Plc on the LSE – approximately 6.1 billion; and

(c) in BHP Plc on the JSE – approximately 2.1 billion.

40 It follows from that trading data that:

(a) a total of approximately 14.5 billion shares in BHP Ltd and BHP Plc were traded during the Relevant Period;

(b) approximately 43.4% of the total volume of shares traded were traded in BHP Ltd; and

(c) approximately 56.6% of the total volume of shares traded were traded in BHP Plc.

41 Mr Betts referred in his affidavit to information in the annual reports published by BHP during the Relevant Period regarding the geographical distribution of shareholders. Based on that information, Mr Betts observed that:

(a) about 97.8% of the registered shareholders in BHP Ltd, and less than 0.1% of registered shareholders in BHP Plc, appeared to be resident in Australia; and

(b) about 2.2% of registered shareholders in BHP Ltd, and more than 99.9% of registered shareholders in BHP Plc, appeared to be resident outside Australia.

42 Mr Betts also provided information concerning the top 20 shareholders (by shareholdings) in BHP Ltd and BHP Plc during the Relevant Period.

43 Mr Betts stated that he was informed by Andrew Gunn, Practice Lead, Investor Relations at BHP, and believed that:

(a) many of the largest legal registered shareholders of BHP Ltd and BHP Plc (by number of shares held) are nominees or custodians, who typically hold shares on behalf of others;

(b) approximately 51 of the 65 shareholders in BHP Ltd and BHP Plc listed in paragraph 12 of his affidavit (i.e. the largest shareholders during the years comprising the Relevant Period) are nominees or custodians holding shares on behalf of others;

(c) BHP has some information regarding:

(i) beneficial owners of shares held by registered legal holders; and

(ii) the investment managers or persons who make decisions to buy and sell those shares (decision makers),

as a result of responses to tracing notices issued under ss 672A and 672B of the Corporations Act (and analogous mechanisms in foreign jurisdictions);

(d) BHP has partial point-in-time information from August 2012, August 2013, August 2014 and August 2015 (in other words, around the time BHP published its annual reports for each of the 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015 financial years), as to the geographical location of certain beneficial owners of (and decision makers in respect of) shares held by:

(iii) the top 200 registered shareholders of BHP Ltd;

(iv) the top 200 registered shareholders of BHP Plc shares listed on the JSE; and

(v) the registered shareholders of BHP Plc shares listed on the LSE with more than 500,000 shares,

(the Analysed Registered Shareholders);

(e) the shares held by the Analysed Registered Shareholders represent 62-64% of the shares issued by BHP Ltd and 92-93% of the shares issued by BHP Plc;

(f) the information BHP has about the decision makers and beneficial owners referrable to the Analysed Registered Shareholders extends to name, country, and in some instances city, but not address;

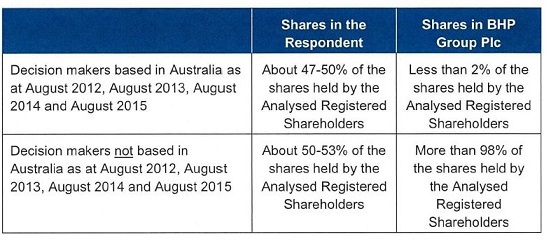

(g) of the shares held by the Analysed Registered Shareholders, the geographical split of the decision makers in respect of those shares was as follows:

(h) of the shares held by the Analysed Registered Shareholders in around August 2014 and August 2015 (in other words, around the time BHP published its annual reports for each of the 2014 and 2015 financial years), the geographical split of beneficial owners was as follows:

(i) BHP Ltd does not hold comparable information to that set out at paragraphs (g) and (h) above in respect of shareholders other than the Analysed Registered Shareholders;

(j) there may be additional persons with interests in BHP’s shares sitting behind the beneficial owners referred to in paragraph (h) above; in other words, the beneficial owners referred to in paragraph (h) above may be holding the shares on behalf of others; where that is the case, it is not possible for BHP to identify the ultimate beneficial owners of its shares;

(k) given that information in respect of the Analysed Registered Shareholders above covers only part of BHP’s share registers, depending on the year:

(vi) between about 36% and 38% of BHP Ltd’s shares were not analysed;

(vii) between about 7% and 8% of BHP Plc’s shares were not analysed; and

(l) of the shares in BHP Ltd that were not analysed, a large number of these are likely to be Australian retail investors because of the small size of their holdings; for example, in BHP’s annual reports for each of the 2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015 financial years, more than 21% of shares were held by shareholders with 10,000 or fewer shares.

The DLC Structure Sharing Agreement

44 A copy of the DLC Structure Sharing Agreement was in evidence, annexed to Mr Spiegel’s affidavit dated 14 August 2020. Also annexed to that affidavit was a copy of a later version of that agreement, which had effect from 23 November 2015. That version can be put to one side for present purposes.

45 The DLC Structure Sharing Agreement is an agreement between BHP Ltd (then named BHP Limited) and BHP Plc (then named Billiton Plc) dated 29 June 2001.

46 The Recital to the agreement stated that BHP Ltd and BHP Plc had agreed to establish a dual listed companies structure for the purposes of the future conduct of their combined businesses. It was stated that, accordingly, the implementation, management and operation of their combined businesses and affairs would be undertaken in accordance with the terms of the agreement and, in particular, the “DLC Equalisation Principles” and the “DLC Structure Principles” as defined later in the agreement.

47 The DLC Structure Principles were set out in clause 2, which was in the following terms:

2. DLC Structure Principles

[BHP Ltd] and [BHP Plc] agree that the following principles are essential to the implementation, management and operation of the DLC Structure:

(a) [BHP Ltd] and [BHP Plc] must operate as if they were a single unified economic entity, through boards of directors which comprise the same individuals and a unified senior executive management;

(b) the directors of [BHP Ltd] and [BHP Plc] shall, in addition to their duties to the company concerned, have regard to the interests of the holders of [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Shares and the holders of [BHP Plc] Ordinary Shares as if the two companies were a single unified economic entity and for that purpose the directors of each company shall take into account in the exercise of their powers the interests of the shareholders of the other; and

(c) the DLC Equalisation Principles must be observed,

and [BHP Ltd] and [BHP Plc] agree to pursue, and agree to procure (to the extent that it is appropriate to do so) that each member of its respective Group and BHP Billiton Executive Services Company will pursue, the DLC Structure Principles.

48 The expression “DLC Structure”, which was used in clause 2, was defined in clause 1.1 to mean “the arrangement whereby, inter alia, [BHP Ltd] and [BHP Plc] have a unified management structure and the business of both [BHP Ltd] and [BHP Plc] are managed on a unified basis in accordance with the provisions of this Agreement”.

49 The DLC Equalisation Principles were set out in clause 3. It is sufficient for present purposes to set out clause 3.1:

3.1 DLC Equalisation Principles

Subject to Clause 3.2, the following principles shall be observed in relation to the rights of the [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Shares and the [BHP Plc] Ordinary Shares:

(a) the Equalisation Ratio shall govern the economic rights of one [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Share relative to one [BHP Plc] Ordinary Share (and vice versa) and the relative voting rights of one [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Share and one [BHP Plc] Ordinary Share on Joint Electorate Actions so that, where the Equalisation Ratio is 1:1, a holder of one [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Share and a holder of one [BHP Plc] Ordinary Share shall, as far as practicable:

(i) receive equivalent economic returns; and

(ii) enjoy equivalent rights as to voting in relation to Joint Electorate Actions,

and otherwise such returns and rights as between a [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Share and a [BHP Plc] Ordinary Share will be in proportion to the then prevailing Equalisation Ratio;

(b) where an Action by [BHP Ltd] or [BHP Plc] is proposed such that the Action would result in the ratio of the economic returns on, or voting rights (in relation to Joint Electorate Actions) of, a [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Share to a [BHP Plc] Ordinary Share not being the same as the then prevailing Equalisation Ratio, or which would benefit the holders of Ordinary Shares in one party relative to the holders of Ordinary Shares in the other party, then:

(i) unless the Boards of [BHP Ltd] and [BHP Plc] determine that it is not appropriate or practicable, a Matching Action shall be undertaken; or

(ii) if no Matching Action is to be undertaken, an appropriate adjustment to the Equalisation Ratio shall be made,

in order to ensure that there is equitable treatment (having regard to the then prevailing Equalisation Ratio) as between the holder of one [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Share and the holder of one [BHP Plc] Ordinary Share. However, if the Boards of [BHP Ltd] and [BHP Plc] determine that it is not appropriate or practicable to undertake a Matching Action and that an adjustment to the Equalisation Ratio would not be appropriate or practicable in relation to an Action, then such Action may be undertaken provided it has been approved as a Class Rights Action.

50 The expression “Equalisation Ratio” was defined in clause 1.1 as follows:

Equalisation Ratio means the ratio for the time being of (a) the dividend, capital and (in relation to Joint Electorate Actions) voting rights per [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Share to (b) the dividend, capital and (in relation to Joint Electorate Actions) voting rights per [BHP Plc] Ordinary Share in the Combined Group (which shall initially be 1:1).

51 The expression “Action” was defined as:

Action means any distribution or any action affecting the amount or nature of issued share capital, including any dividend, distribution in specie, offer by way of rights, bonus issue, repayment of capital, sub-division or consolidation, buy-back or amendment of the rights of any shares or a series of one or more of such actions.

52 The expression “Matching Action” was defined as:

Matching Action means any Action in relation to either the holders of [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Shares or the holders of [BHP Plc] Ordinary Shares whose overall effect is such that, when taken together with an Action taken or to be taken in relation to the holders of [BHP Plc] Ordinary Shares or of [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Shares (as the case may be), is such as to ensure that the economic returns and voting rights of a [BHP Ltd] Ordinary Share and of a [BHP Plc] Ordinary Share are maintained in proportion to the Equalisation Ratio.

Ownership of shares in BHP Brasil

53 I note for completeness that, at the hearing, I sought clarification from the parties as to whether BHP Brasil was a wholly-owned subsidiary of both BHP Ltd and BHP Plc or of BHP Ltd alone. The statement of claim refers to BHP Brasil as a wholly-owned subsidiary of “BHP”, that is, the notional single unified economic entity (see the particulars to paragraph 21 and the definition of “BHP” in paragraph 10). This does not make the position clear. In oral submissions, senior counsel for the applicants stated that he was instructed that the relevant assets were jointly owned by BHP Plc and BHP Ltd. Senior counsel for BHP Ltd submitted that the interest in BHP Brasil was held by BHP Ltd alone, referring to paragraph 9 of an affidavit of Anna Sutherland, a partner of Herbert Smith Freehills, dated 20 September 2018 (filed in connection with an earlier interlocutory application). In that paragraph, Ms Sutherland stated: “At all material times, Samarco was a 50/50 contractual joint venture between a subsidiary of the Respondent, BHP Billiton Brasil Ltda (BHP Brasil), and a Brazilian company, Companhia Vale do Rio Dace S.A. (Vale).” It is not necessary for present purposes to resolve this factual point.

Findings relating to foreign law

54 In this section of these reasons, I set out my findings (of fact) in relation to foreign law, based on the expert evidence filed by the parties. These findings are made for the purposes of resolving BHP Ltd’s interlocutory application; if it is necessary to deal with the same or similar issues of foreign law on a subsequent occasion (eg, at trial), the material before the Court may be different and the findings may not be the same.

55 There is a large measure of agreement between the foreign law experts. To the extent that there are areas of disagreement, in the absence of cross-examination I have made findings based on my assessment of the reasoning expressed in the expert reports. Ultimately, however, I do not consider any of the points of disagreement to be determinative of BHP Ltd’s interlocutory application.

English law

56 In relation to English law, BHP Ltd relies on the first report and the reply report of Mr Layton QC, and the applicants rely on the report of Mr Mercer QC.

57 In his first report, Mr Layton addressed four questions, each of which related to a scenario in which a new proceeding raising the same issues is commenced in the courts of England and Wales following the conclusion of the present proceeding. Questions 1, 2 and 3 related to a new proceeding against BHP Ltd, while question 4 related to a new proceeding against BHP Plc. The issue to which Mr Layton’s report was directed was whether a judgment or order of this Court in the present proceeding would be recognised by a court of England and Wales if such a new proceeding were commenced. Questions 1, 2 and 3 related to three different types of judgment or order in the present proceeding, namely (i) a judgment addressing the common questions on liability, (ii) an order for damages in favour of all Group Members, and (iii) an order approving a settlement. Ultimately, Mr Layton’s opinions did not differ depending on the type of judgment or order. Thus, the distinction between the three different types of judgment or order can be put to one side for present purposes.

58 At paragraphs 11-18 of his first report, Mr Layton set out the principles of English law concerning the recognition and enforcement of Australian judgments in England. Mr Mercer agreed with that exposition of the principles (see paragraph 13 of his report). I therefore accept those paragraphs of Mr Layton’s first report.

59 At paragraphs 19-28 of his report, Mr Layton set out the principles relating to res judicata, issue estoppel and preclusive effect in the particular context of foreign judgments. There does not appear to be any substantive disagreement regarding those principles (see Mr Mercer’s report at paragraphs 29, 32) and I accept Mr Layton’s statement of these principles. It is unnecessary to resolve the differences of view highlighted in paragraphs 15 and 16 of Mr Layton’s reply report.

60 At paragraphs 39-41 of his first report, Mr Layton discussed jurisdiction based on presence. Mr Mercer indicated his agreement at paragraph 13 of his report. I accept that description of the principles relating to jurisdiction based on presence in Mr Layton’s report.

61 Although their reasoning differed, both Mr Layton and Mr Mercer agreed that if a new proceeding were commenced against BHP Ltd by (i) the applicants or (ii) a Group Member who registered to participate in a settlement of the present proceeding (following the distribution of notices with respect to the same) and who did not subsequently opt out of the present proceeding, the court of England and Wales would recognise the judgment of this Court in the present proceeding: see Mr Layton’s first report at paragraphs 10, 31-38, 54; and Mr Mercer’s report at paragraphs 14, 34-52. I accept that conclusion, which is common ground between the experts.

62 The experts differed, however, regarding the other questions addressed in Mr Layton’s first report.

63 In relation to a new proceeding against BHP Ltd brought by (i) a Group Member who did not register to participate in a settlement of the present proceeding and did not opt out of the present proceeding (following the receipt of notices with respect to the same), or (ii) a Group Member who did not register and did not opt out and who did not receive notices with respect to participation in any settlement, Mr Layton’s view was that, while it is not possible to be categoric, the court of England and Wales would not recognise the judgment of this Court in the present proceeding: see Mr Mercer’s first report, paragraphs 10, 44-47, 54. Contrastingly, Mr Mercer’s opinion was that Mr Layton was too firm in his conclusions with respect to these Group Members: see Mr Mercer’s report, paragraph 15. In Mr Mercer’s view it was “arguable” that an English court “could well” reach the opposite conclusion in relation to a Group Member who received notices but did not opt out of the present proceeding or register to participate in a settlement. In addition, in Mr Mercer’s view, there were grounds to consider that an English court would reach the same conclusion in relation to Group Members who did not receive notice, although he considered this to be more difficult. In his reply report at paragraph 6, Mr Layton stated that he does not agree with Mr Mercer’s views on these matters and stated:

As is apparent from both my original Opinion and Mr Mercer’s Opinion, this is largely uncharted territory in English law and the questions have to be considered by extrapolation from existing law and principles. So, while I can agree that it is “arguable” that an English court “could” (not “could well”) recognise a judgment as against such a group member, I do not consider that it would do so. This would be a big departure from existing law and precedent, and the Supreme Court has shown itself to be cautious in this sort of area.

(Footnote omitted.)

64 On the basis of the reports, I find that there is considerable uncertainty as to whether or not a court of England and Wales would recognise a judgment of this Court in this proceeding if a new proceeding were commenced against BHP Ltd by a Group Member who did not register to participate in a settlement of the present proceeding and did not opt out of the present proceeding (following the receipt of notices with respect to the same). There is both uncertainty as to the applicable principles of English law, as well as uncertainty pertaining to the factual context in which any such issue may arise. I find that there is, at least, some risk that the court would not recognise a judgment of this Court in such circumstances. As to whether or not a court of England and Wales would recognise a judgment of this Court in this proceeding if a new proceeding were commenced against BHP Ltd by a Group Member who did not register and did not opt out and who did not receive notices with respect to participation in any settlement, I find that there is a higher risk that the court would not recognise a judgment of this Court in such circumstances.

65 In relation to a new proceeding against BHP Plc, Mr Layton’s view was that a court of England in Wales would not recognise the judgment of this Court in the present proceeding, whether the new proceeding was commenced by (i) the applicants, (ii) a Group Member who registered to participate in any settlement of the present proceeding and who did not opt out of the proceeding, (iii) a Group Member who did not register to participate in any settlement of the present proceeding and did not opt out of the proceeding (following the receipt of notices with respect to the same), or (iv) a Group Member who did not register and did not opt out, and who did not receive notices regarding participation in any settlement of the present proceeding: see Mr Layton’s first report, paragraphs 10, 48-53, 54. Mr Mercer agreed with Mr Layton’s analysis in connection with piercing the corporate veil at paragraphs 50-51 of Mr Layton’s first report: see Mr Mercer’s report, paragraph 16. I therefore accept those paragraphs of Mr Layton’s first report as correctly stating the applicable principles of English law. However, Mr Mercer did not agree with Mr Layton’s discussion of the principles of privity at paragraphs 52-53 of his first report: see Mr Mercer’s report, paragraphs 35-39. Further, Mr Mercer stated that there is a body of English case law that does not require privity of interest before precluding proceedings, namely the doctrine of abuse of process where there is a collateral attack on the decision of a court of competent jurisdiction: see Mr Mercer’s report, 14, 47-52. In his reply report, Mr Layton stated that he did not agree with Mr Mercer’s opinion on the application of the doctrines of privity or abuse of process. However, I do not understand the reply report to indicate any clear disagreement as regards Mr Mercer’s statements of the applicable principles. Insofar as Mr Mercer set out the principles relating to privity (in paragraphs 35-39 of his report), I accept those statements as accurate statements of English law. However, it is difficult to predict how those principles would be applied to a hypothetical new proceeding against BHP Plc, and I find the application of those principles to such a proceeding to be quite uncertain. Insofar as Mr Mercer set out principles relating to abuse of process (in paragraphs 47-52 of his report), I accept those statements as accurate statements of English law. However, again, it is difficult to predict how those principles would be applied to a hypothetical new proceeding against BHP Plc, and I find the application of those principles to such a proceeding to be quite uncertain. I find that there is, at least, some risk that a new proceeding against BHP Plc would not be precluded by a judgment of this Court in this proceeding.

66 In paragraphs 20-25 of Mr Mercer’s report, he described the principles relating to representative actions in England and Wales. In his reply report at paragraph 8, Mr Layton stated that, subject to two points of clarification, he agreed with that description. I accept Mr Mercer’s description of the principles relating to representative actions in England and Wales, subject to the two points of clarification raised by Mr Layton.

67 Mr Mercer discussed principles relating to limitation of actions in his report. A paragraph 27.2 he stated that ss 90 and 90A of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (UK) (the FSMA) are the primary mechanisms available to shareholders to bring claims against issuers for untrue or misleading statements or omissions in England, and are the closest equivalent to the claims brought by the applicants under Australian law in the present proceeding. He stated that the relevant time limit for breach of the statutory provisions is governed by the tort provisions in the Limitation Act 1980 (UK), s 2, which provides: “An action founded on a tort shall not be brought after the expiration of six years from the date on which the cause of action accrued.” Mr Mercer stated that he understood that the events that gave rise to the present proceeding took place in or before 2015, and therefore there would appear in his view to be a substantial chance that proceedings commenced after the conclusion of the present proceeding (which he understood to be at an early stage) would be time-barred. In his reply report, Mr Layton stated at paragraph 11 that, while he agreed that a claim brought under s 90 and/or s 90A of the FSMA would be subject to a six-year limitation period under s 2 of the Limitation Act, a comparable claim would most probably be available for negligent misstatement, which would attract the provisions of ss 14A and 14B of the Limitation Act. Mr Layton stated that s 14A provides an extended time limit for negligence actions (except for personal injury or death) where facts relevant to the cause of action were not known to the claimant at the date of accrual of the cause of action. In such a case, time expires after either six years from the date of accrual of the cause of action, or after three years from the date of “the knowledge required for bringing an action for damages in respect of the relevant damage”, whichever is later. I accept the statements of principle relating to limitation of actions in Mr Mercer’s report and Mr Layton’s reply report. Having regard to the matters stated in Mr Layton’s reply report, I find that there is some risk that a limitation defence will not be available with respect to a new proceeding against BHP Ltd or BHP Plc.

Scots law and Northern Ireland law

68 It is not necessary for present purposes to refer in detail to the reports of Dr Hood QC (relating to Scots law) and Ms Anyadike-Danes QC (relating to Northern Ireland law). In each case, the expert was asked to address substantially the same questions as Mr Layton. While the principles of law were not the same as those of English law, each expert reached conclusions that were broadly the same as those reached by Mr Layton. The applicants did not file any responding evidence relating to Scots law or Northern Ireland law. In his report, Mr Mercer stated at paragraph 17 that he did not profess to have the requisite specialist knowledge of Scots law or Northern Ireland law to address the reports of Dr Hood and Ms Anyadike-Danes. In the absence of any responding evidence, I accept the opinions of Dr Hood and Mr Anyadike-Danes.

69 Mr Mercer, in paragraph 18 of his report, addressed the practical question whether he would expect a class action against a London listed entity such as BHP Plc to occur in Northern Ireland or Scotland as opposed to London. He stated that, in his experience, if there were to be a UK group action against BHP Plc, notwithstanding Australian proceedings, it is overwhelmingly likely that there would only be a single group action and that it would take place in London. See also paragraph 19 of Mr Mercer’s report. BHP Ltd did not file any reply evidence in relation to those paragraphs. In the absence of any reply evidence, I accept those paragraphs of Mr Mercer’s report.

South African law

70 Mr Snyckers SC was instructed to answer four questions that were substantially the same as the four questions addressed in Mr Layton’s report. Each of the questions related to a scenario in which a new proceeding raising the same issues is commenced in a court in the Republic of South Africa following the conclusion of the present proceeding. Questions 1, 2 and 3 related to a new proceeding against BHP Ltd, while question 4 related to a new proceeding against BHP Plc. The issue to which the report was directed was whether a judgment or order of this Court in the present proceeding would be recognised by a court of South Africa if such a new proceeding were commenced. Questions 1, 2 and 3 related to three different types of judgment or order in the present proceeding, namely (i) a judgment addressing the common questions on liability, (ii) an order for damages in favour of all Group Members, and (iii) an order approving a settlement. Ultimately, Mr Snyckers’s opinions did not differ depending on the type of judgment or order. It follows that the distinction between the three different types of judgment or order can be put to one side.

71 The expert report of Mr Farlam did not express any clear disagreement with the contents of Mr Snyckers’s report. In these circumstances, I accept the statements of principle and the opinions expressed in Mr Snyckers’s first report as an accurate statement of South African law in relation to the questions addressed in the report.

72 Mr Snyckers’s first report proceeded on the assumption that the South African court has assumed both subject-matter and personal jurisdiction over BHP Ltd (see paragraph 24.5). In paragraph 26 of his first report, Mr Snyckers stated there are two main ways in which the present proceeding outcomes could preclude or restrain the contemplated plaintiffs’ actions in South Africa, namely by the court upholding a defence of res iudicata (or issue estoppel) raised against the action, or by the court entertaining the claim but still recognising the present proceeding outcomes (by taking into account any benefit received by such plaintiff as a result of the present proceeding and deducting it from any benefit awarded in South Africa). Mr Snyckers discussed the principles of res iudicata at paragraphs 29 to 35 of his first report.

73 Mr Snyckers considered the potential applicability of the Protection of Businesses Act 99 of 1978 (SA) (the PBA) at paragraphs 36-66 of his first report. Section 1F of the PBA (set out at paragraph 38 of the report) deals with a foreign judgment constituting res iudicata. Mr Snyckers stated at paragraph 66:

I therefore conclude that –

1. Section 1F of the PBA would apply to the same cause of action advanced in South Africa by the Applicants as against BHP Ltd, but would not apply in any proceedings brought by any Group Member, whether against BHP Ltd or BHP Plc; and

2. Section 1F would not preclude the application of the common law principles of res iudicata to claims brought by Group Members, whether against BHP Ltd or against BHP Plc, and these fall to be considered as to when and how they would apply to such claims.

74 Mr Snyckers considered the application of the South African common law doctrine of res iudicata (and extensions to that doctrine) at paragraphs 67 to 84 of his first report.

75 Mr Snyckers considered the principles relating to submission to jurisdiction at paragraphs 85 to 93 of his first report.

76 In relation to a new proceeding brought by the applicants against BHP Ltd, Mr Snyckers concluded that, if the cause of action is the same as that advanced in the present proceeding, then s 1F of the PBA would preclude the applicants from advancing that same cause of action in South Africa, and this would be so probably even if the relief sought in South Africa differed from the relief sought in the present proceeding. However, if and to the extent that the cause of action is not the same, the common law principles would apply: see paragraph 98 of Mr Snyckers’s first report.

77 Mr Snyckers then considered a new proceeding against BHP Ltd commenced by Group Members who register to participate in a settlement of this proceeding following distribution of notices with respect to the same, and who do not subsequently opt out (referred to in the report as the “registered group”). Mr Snyckers expressed the view at paragraph 107 that the Group Members’ position is akin to that of a defendant who is not the initiating party but is joined to legal proceedings by the initiating party and ends up bound to the outcome of the proceedings. Mr Snyckers expressed the view at paragraph 108 that a South African court would find that, by not opting out of the present proceeding and by taking the positive step of registering their interest to participate in any settlement, after receipt of a notice explaining the consequences of registration and not opting out, considered objectively the members of the registered group manifested an intention to be bound by the outcome of the present proceeding, which would be sufficient to conclude that the registered group subjected themselves to the jurisdiction of the Federal Court of Australia in the present proceeding. Mr Snyckers concluded in relation to the registered group at paragraph 113 as follows:

Accordingly, in my view, it should be accepted that the members of the registered group would be precluded from bringing the same action against BHP Ltd in South Africa, or be precluded from adjudicating issues that were essential to the outcome in the Question 1 judgment, save that there might be some limited potential for declining to do so on equitable grounds where the relief sought in South Africa was materially different from that sought in the AU action.

78 Mr Snyckers next considered a new proceeding against BHP Ltd commenced by Group Members who do not register to participate in a settlement of the present proceeding and who do not opt out, following the receipt of notices with respect to the same (referred to in the report as the “first no-opt out group”). As noted in paragraph 114 of the report, the question was whether, given the judgment, a South African court would preclude or restrain a member of the first no-opt out group from bringing in the South African court the same or similar subject-matter claim to that brought by the applicants in the present proceeding. This required consideration of whether objectively (i.e. adjudged from the perspective of a reasonable person) the conduct of the first no-opt out group was consistent only with the conclusion, on the balance of probabilities, that they intended to be bound by the outcome of the present proceeding (see paragraph 118 of the report). Mr Snyckers’s view, expressed at paragraph 119, was that, on the assumption that it can be demonstrated on the balance of probabilities that the member in question received and read the notice, and was in a position to understand its import, a failure to opt out or to register an interest to participate would be held as supporting a conclusion of submission. Mr Snyckers expressed the view at paragraph 133 that, as long as a court (of South Africa) was satisfied of submission, there would, save for the case where the relief sought was materially different, be no reason to decline to uphold a defence of res iudicata in relation to issues that were tried in, or essential to the outcome of, the judgment in the present proceeding, against members of the first no-opt out group. I note that, in respect of this category of Group Members, Mr Snyckers’s conclusion in relation to South African law differs from the conclusion of Mr Layton in relation to English law.

79 Mr Snyckers then considered a new proceeding against BHP Ltd commenced by Group Members who did not receive any notice relating to opting out of or registering an interest to participate in any settlement in the present proceeding, and who did not register to participate in a settlement of the present proceeding and did not opt out (referred to in the report as the “second no-opt out group”). Mr Snyckers’s view, as stated in paragraph 140, was that, in the absence of special facts suggesting that members of the second no-opt out group became sufficiently aware of the contents of the notice or at least of the consequences of inaction, despite not receiving the notice, to warrant the inference that they must have submitted to jurisdiction, a South African court would not find there to have been submission, and would accordingly not apply the principle of res iudicata to preclude a claim by any such member against BHP Ltd in South Africa.

80 In relation to a new proceeding against BHP Plc, after careful and considered discussion of the issues, Mr Snyckers concluded at paragraph 172:

On balance, although this is a difficult question on which to reach a firm conclusion, I believe a South African court would allow an action against BHP Plc to proceed in South Africa, even if the issues and facts were substantially identical to those in the [present proceeding] against BHP Ltd that yielded a judgment or settlement, yet subject to the fact that it would be wary of allowing overcompensation of the relevant plaintiffs. Should a defendant be able to demonstrate that the only relief sought was in fact already fully compensated in the [present proceeding] as flowing from the same wrong (albeit committed by another party, or partly by another party), that may be sufficient to cause the court not to allow the action to proceed.

81 In the last section of his report, Mr Snyckers noted and discussed the different considerations that may apply when the action being brought in South Africa is a class action, and the question arises whether members who were Group Members in the present proceeding should be included in a class certified in an action against BHP Ltd or BHP Plc in South Africa.

82 I turn now to consider the matters discussed in Mr Farlam’s report and the reply report of Mr Snyckers.

83 Mr Farlam was instructed to consider two questions relating to extinctive prescription (or limitation of actions) under South African law, with reference to a hypothetical claim brought in South Africa under South African law, arising from disclosure and misrepresentation contraventions, against BHP Ltd and/or BHP Plc (referred to in the report as the “South African BHP claim”). Mr Farlam was instructed to assume that the South African claim was a delictual claim based on misrepresentation (as posited in Mr Snyckers’s report). Mr Farlam was asked to advise on the following questions:

(a) What, if any, limitation period(s) would be applicable to such a claim in South Africa?

(b) What is the effect of any applicable limitation period expiring on a claimant’s ability to litigate such a claim in South Africa?

84 In his reply report, Mr Snyckers stated at paragraph 10 that he considered Mr Farlam’s report to be an accurate, well-reasoned and reliable report on the issues on which it expresses views. In these circumstances, I accept the statements of principle and opinions expressed in Mr Farlam’s report as an accurate statement of South African law in relation to the questions addressed in the report. Although Mr Snyckers made some additional observations in his reply report, these do not affect the substance of the opinions expressed in Mr Farlam’s report.

85 In relation to the first question, Mr Farlam stated at paragraph 32 that prescription is generally governed by the Prescription Act, 68 of 1969 (SA). Sections 11 and 12 of that Act were particularly germane to the present question. He stated at paragraph 35 that a delictual claim is a claim in respect of an “other debt” as referred to in s 11(d) of that Act. Accordingly, a limitation period of three years would apply to the South African BHP claim. Mr Farlam stated that, under s 12, subject to exceptions, prescription runs as soon as the debt is due. As set out in paragraph 39 of the report, under s 12(3) of the Act, a debt shall not be deemed to be due until the creditor has knowledge of the identity of the debtor and of the facts from which the debt arises; provided that a creditor shall be deemed to have such knowledge if he could have acquired it by exercising reasonable care. Mr Farlam then discussed the case law regarding that test, including in the context of a claim reliant on a delictual cause of action involving negligent misstatement. Mr Farlam noted, at paragraph 50, that the completion of the three-year limitation period can be delayed or interrupted, pursuant to s 13 or 14 of the Prescription Act. This had potential application to BHP Ltd (as distinct from BHP Plc) as it was not registered as an external company in South Africa (see paragraph 57 of the report).

86 In relation to the second question, Mr Farlam stated at paragraph 59 that this issue was directly addressed by s 10(1) of the Prescription Act, which provides that “a debt shall be extinguished by prescription after the lapse of the period which in terms of the relevant law applies in respect of the prescription of such debt”. Mr Farlam explained that this meant the debt was nullified and not merely rendered unenforceable.

87 In his reply report, Mr Snyckers discussed some additional matters, in particular choice-of-law issues that may arise. I accept Mr Snyckers’s reply report as accurately stating the principles of South African law relating to choice-of-law issues.

The first contention

88 BHP Ltd contends that, on its proper construction, Pt IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act does not apply to the claims brought by the applicants on behalf of shareholders of BHP Ltd and/or BHP Plc who are not residents of Australia. BHP Ltd seeks a declaration to this effect and an order that the non-resident Group Members be excluded from the class of persons defined as Group Members in the proceeding. BHP relies on the presumption that legislation is not intended to operate extraterritorially and submits that that presumption is engaged in relation to Pt IVA and has not been displaced.

89 In its interlocutory application, BHP Ltd sought a declaration in the following terms:

1. A declaration that Part IVA of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Act) does not apply to the claims brought by the Joint Applicants on behalf of shareholders of BHP Group Limited and/or BHP Group plc who are not residents of Australia and who:

a. are not an applicant in proceedings brought under that Part; or

b. have not otherwise submitted to the jurisdiction of the Court for the purpose of such proceedings.

90 However, in the course of oral submissions, senior counsel for BHP Ltd focussed on the proposition that, on its proper construction, Pt IVA does not apply to claims brought on behalf of persons who are not residents of Australia, without the qualifications expressed in sub-paragraphs (a) and (b) of paragraph 1 of the interlocutory application. Consistently with the way the argument was presented orally, senior counsel for BHP Ltd then indicated that BHP Ltd did not press sub-paragraphs (a) and (b) of the declaration sought in paragraph 1 of the interlocutory application. Thus, BHP Ltd’s contention is that Pt IVA does not apply to the claims brought by the applicants on behalf of shareholders of BHP Ltd and/or BHP Plc who are not residents of Australia.