FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Hood v Bush Pharmacy Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1686

Table of Corrections | |

Para [283] fourth sentence delete the words “the bottles supplied by Ms Levinson and Heritage Oils with” | |

Para [308] second sentence delete the word “not” | |

Para [344] second sentence replace the word “application” with the word “applicable” | |

Para [388] fourth sentence replace the words “cannot assume or infer” with the words “cannot be assumed or inferred that” | |

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | BUSH PHARMACY PTY LTD (ACN 149 740 741) Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | BUSH PHARMACY PTY LTD (ACN 149 740 741) Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | Cross-Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant file and serve a proposed minute of order within 7 days.

2. The proceeding be listed for any argument in relation to the form of the orders (including in relation to costs) at a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1271 of 2017 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | JOHN JAMES DAVID HOOD Applicant | |

AND: | DOWN UNDER ENTERPRISES INTERNATIONAL PTY LIMITED (ACN 127 755 971) Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | DOWN UNDER ENTERPRISES INTERNATIONAL PTY LIMITED (ACN 127 755 971) Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | JOHN JAMES DAVID HOOD Cross-Respondent | |

JUDGE: | NICHOLAS J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 November 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant file and serve a proposed minute of order within 7 days.

2. The proceeding be listed for any argument in relation to the form of the orders (including in relation to costs) at a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 1272 of 2017 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | JOHN JAMES DAVID HOOD Applicant | |

AND: | NEW DIRECTIONS AUSTRALIA PTY. LIMITED (ACN 052 973 743) Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | NEW DIRECTIONS AUSTRALIA PTY. LIMITED (ACN 052 973 743) Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | JOHN JAMES DAVID HOOD Cross-Respondent | |

JUDGE: | NICHOLAS J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 november 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant file and serve a proposed minute of order within 7 days.

2. The proceeding be listed for any argument in relation to the form of the orders (including in relation to costs) at a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 2175 of 2017 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | JOHN JAMES DAVID HOOD Applicant | |

AND: | NATIVE OILS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 154 612 487) Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | NATIVE OILS AUSTRALIA PTY LTD (ACN 154 612 487) Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | JOHN JAMES DAVID HOOD Cross-Respondent | |

JUDGE: | NICHOLAS J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 november 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant file and serve a proposed minute of order within 7 days.

2. The proceeding be listed for any argument in relation to the form of the orders (including in relation to costs) at a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ORDERS

NSD 2176 of 2017 | ||

| ||

BETWEEN: | JOHN JAMES DAVID HOOD Applicant | |

AND: | HERITAGE OILS PTY LTD (612 556 626) First Respondent JULIA GAY LEVINSON Second Respondent | |

AND BETWEEN: | HERITAGE OILS PTY LTD (612 556 626) Cross-Claimant | |

AND: | JOHN JAMES DAVID HOOD Cross-Respondent | |

JUDGE: | NICHOLAS J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 23 november 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The applicant file and serve a proposed minute of order within 7 days.

2. The proceeding be listed for any argument in relation to the form of the orders (including in relation to costs) at a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[9] | |

[9] | |

[15] | |

Down Under Enterprises International Pty Limited (NSD 1271 of 2017) | [17] |

[18] | |

[19] | |

Heritage Oils Pty Ltd / Julia Gay Levinson (NSD 2176 of 2017) | [20] |

[22] | |

[24] | |

[36] | |

[36] | |

[36] | |

[41] | |

[45] | |

[48] | |

[50] | |

[51] | |

[51] | |

[55] | |

[58] | |

[59] | |

[59] | |

[62] | |

[74] | |

[82] | |

[82] | |

[84] | |

[87] | |

[114] | |

[119] | |

[154] | |

Is Kunzea ambigua essential oil a staple commercial product? | [174] |

[190] | |

[207] | |

[224] | |

[255] | |

[270] | |

[281] | |

[302] | |

[312] | |

[322] | |

[332] | |

[338] | |

[347] | |

[360] | |

[367] | |

[374] | |

[384] | |

[391] |

NICHOLAS J:

1 Before me are five proceedings for patent infringement, trade mark infringement and contravention of s 18 and s 29 of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”). The trade mark case against all respondents was abandoned by the applicant during the course of the hearing.

2 The patent in suit (Standard Patent No 721156) expired on 20 October 2017 almost a year before the hearing of the proceedings commenced. It is common ground that the priority date of the claims is 23 October 1996 (“the Priority Date”) based on a provisional application filed on that date.

3 In its broadest form, the invention, as defined in claim 1, is “[a]n essential oil derived from shrubs of the genus Kunzea”. The claims include various other product claims (claims 2-4) together with various method of treatment claims (claims 5-13) that use such an oil.

4 The validity of the claims of the patent on which the respondents are sued is challenged by the respondents who seek orders revoking all such claims. The applicant now accepts that the product claims 1-4 (inclusive) are invalid.

5 The respondents say that none of the method of treatment claims are valid and, if they are, then they have not been infringed. The infringement case is based solely on s 117 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (“the Act”).

6 The applicant claims pecuniary relief for infringements of the patent that are alleged to have occurred during the six year period prior to the commencement of each proceeding and up to the expiry date. He also claims additional damages under s 122(1A) of the Act.

7 The trial of the proceedings was confined to questions of liability and any entitlement on the part of the applicant to additional damages (but not the quantum thereof) with all questions concerning the quantification of any pecuniary relief being deferred for consideration at a later date.

8 Also before me is an application by the applicant to amend the claims of the patent.

9 Mr Hood, the applicant, is the named inventor and the patentee. He made a number of affidavits and was cross-examined. He describes himself as a farmer and an inventor.

10 Mr Hood purchased a farm in 1986 which was called the “DuCane Estate”. The farm is approximately 400 hectares in size and is situated in North East Tasmania, around 34 kilometres east of Bridport. In 1990 Mr Hood went to Western Australia to work in a gold refinery. He returned to Tasmania in December 1990. He said that it was at this time that he first paid attention to the native shrubs growing on his property including Kunzea ambigua.

11 Mr Hood did not know the name Kunzea ambigua until sometime in 1993 or 1994 when he asked a botanist at the Queen Victoria Museum in Launceston to identify a sample of the shrub from his farm. The botanist, Ms Mary Cameron, identified the shrub as Kunzea ambigua. She also identified a number of other shrubs, Melaleuca squarrosa (lemon scented tea tree), Melaleuca ericifolia (swamp paperbark, or lavender tea tree), and Leptospermum lanigerum (woolly tea tree), which were also growing on Mr Hood’s property at the time.

12 Mr Hood learnt about Kunzea ambigua from various botanical books which he borrowed from friends in the Launceston area and from conversations with them, including Mr Peter Duckworth, a retired forester. From the reading and the conversations, Mr Hood came to understand that it was the German botanist, Gustav Kunze, that discovered the genus Kunzea and it was given its botanical name after him in 1851 or thereabouts. From this same research, Mr Hood came to understand that it was George Claridge Druce who identified Kunzea ambigua in 1917.

13 In March 1995 Mr Hood sent samples of Kunzea ambigua, Melaleuca squarrosa and Melaleuca ericifolia to Professor Bob Menary at the University of Tasmania (“UTAS”). According to Mr Hood, he asked Professor Menary to see if any of the shrubs he had provided contained oils that might have a commercial use. He later received a telephone call from one of Professor Menary’s assistants who told Mr Hood that they “… had identified 23.3% 1,8-cineole in the Kunzea ambigua shrub, young regrowth and 15.3% 1,8-cineole in mature regrowth (being shrubs of 2-3 feet in height)”. The assistant also said that “the highest percentage of all the shrubs that [Mr Hood] provided to the University of Tasmania was 39.9% 1,8-cineole was from Melaleuca squarrosa and next was Melaleuca ericifolia with 39%”.

14 It was not until 23 October 1996 that Mr Hood filed his provisional specification. The complete specification was filed on 20 October 1997 and was first open to public inspection on 15 May 1998. The obvious errors in the claims to which I refer later in these reasons all appear in the complete specification as filed on 20 October 1997.

Bush Pharmacy Pty Ltd (NSD 1267 of 2017)

15 Bush Pharmacy Pty Ltd (“Bush Pharmacy”) is a company that operates a farm on Flinders Island, Tasmania, where it harvests wild growing flora which it distils into essential oils. The essential oils that Bush Pharmacy has extracted and sold include those derived from Kunzea ambigua.

16 Bush Pharmacy sells Kunzea ambigua essential oil to commercial customers in Australia and overseas and has done so since in or about April 2016. It does not supply Kunzea ambigua to consumers. Mr Stephen Backhaus, a director of Bush Pharmacy, made two affidavits and was cross-examined.

Down Under Enterprises International Pty Limited (NSD 1271 of 2017)

17 Down Under Enterprises International Pty Ltd (“Down Under”) was established by Dee-Ann Seccombe Prather and her husband, Phillip Prather, in or about September 2007. Between June 2016 and January 2017 Down Under sold to various customers located outside Australia 1kg and 2kg packets containing Kunzea ambigua essential oil. Ms Prather, who is the sole director of Down Under, made two affidavits and was cross-examined.

New Directions Australia Pty Limited (NSD 1272 of 2017)

18 New Directions Australia Pty Ltd (“New Directions”) is a wholesaler of natural skin products and natural raw materials including essential oils. New Directions has sold Kunzea ambigua essential oils since about 2004. The majority of New Directions’ customers are commercial customers. Mr Domenic Ardino is a director of New Directions. He made two affidavits and was cross-examined.

Native Oils Australia Pty Ltd (NSD 2175 of 2017)

19 Native Oils Australia Pty Ltd (“Native Oils”) was incorporated in 2011, but did not commence trading until 2013. Mr David Johnson, the Managing Director of Native Oils, made two affidavits, and was cross-examined. He gave evidence concerning sales of Kunzea ambigua essential oil made by Native Oils the first of which occurred in or about April 2014.

Heritage Oils Pty Ltd / Julia Gay Levinson (NSD 2176 of 2017)

20 Heritage Oils Pty Ltd (“Heritage Oils”) sold bottles of Kunzea ambigua essential oils and various other products that contained Kunzea ambigua essential oil, in the period 27 December 2012 to 18 May 2017. In that period, approximately 36.7 kgs of Kunzea ambigua was sold by Heritage Oils to customers in Australia. Ms Julia Gay Levinson, who is also a respondent in the proceeding against Heritage Oils, is a director of that company. She previously carried on business as a sole trader under the name Heritage Oils until the company took over her business. The claim against her relates to trading activities carried on by her prior to that time. Ms Levinson made two affidavits and was also cross-examined. Another director of Heritage Oils, Mr David Brocklehurst, also gave evidence for that company. He made one affidavit and was cross-examined.

21 At the hearing Mr Hood was represented by Mr M Green SC, who appeared with Ms B Oliak, Dr G O’Shea and Mr B Cameron. Mr A Fox, with Mr S Hallahan, appeared for Bush Pharmacy, Down Under and New Directions. Mr S Reuben and Ms J Whitaker appeared for Native Oils, Heritage Oils and Ms Levinson.

The Therapeutic Goods Act LISTING

22 Mr Hood caused “DUCANE KUNZEA OIL Kunzea ambigua” in 1mL/ml liquid multipurpose bottles to be listed on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (“ARTG”) maintained pursuant to s 9A of the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) (“the TG Act”). This listing, numbered 72143, and effective from 3 July 2002, is for the following standard indications:

Relief of the symptoms of influenza/flu.

Temporary relief of the pain of arthritis. (or) Temporary relief of arthritic pain.

Helps relieve nervous tension, stress and mild anxiety.

Relief of muscular aches and pains.

Temporary relief of the pain of rheumatism. [or] Temporary relief of rheumatic pain.

23 According to the public summary of the registration, the active ingredient of the medicine is Kunzea ambigua 1mL/mL. The dosage form is shown as “Liquid-multipurpose” and the route of administration is shown as “Inhalation”.

24 The patent is entitled “Essential oil and methods of use”.

25 The specification acknowledges that essential oils have been used for medicinal purposes for many hundreds of years. It also acknowledges that essential oils have been extracted in a number of different ways, most often by steam distillation.

26 The specification states that the object of the invention is to provide “a new essential oil which has beneficial properties”. The invention “in its broader sense” is said to include an essential oil derived from plants of the genus “Kunzea”. According to the specification:

More specifically, it relates to the essential oil derived from the shrub Kunzea ambigua. The essential oil is adapted for treatment of ailments of the human body, and is applied topically to relieve pain, minimize bruising and to assist in healing, and may be used either pure or in a carrier.

…

The shrub from which the oil is obtained, a member of the Myrtaceae family, genus Kunzea, species ambigua.

27 The specification does not suggest that Mr Hood was the first to “discover” Kunzea ambigua. As is apparent from the passage just quoted, at the time the specification (and the provisional specification) was prepared Kunzea ambigua was a known plant species that had already been classified as a member of a known family (the Myrtaceae family) and a known genus (the Kunzea genus). This is also borne out by Mr Hood’s dealings with Ms Cameron, the botanist, who identified for Mr Hood the sample of the plant obtained by him from his farm. It is also borne out by other evidence to which I will refer later in these reasons.

28 The specification describes the area in Tasmania in which Kunzea ambigua is found and the manner in which it may be harvested. This is followed by a brief description of a known process that may be used to extract the essential oil from the plant.

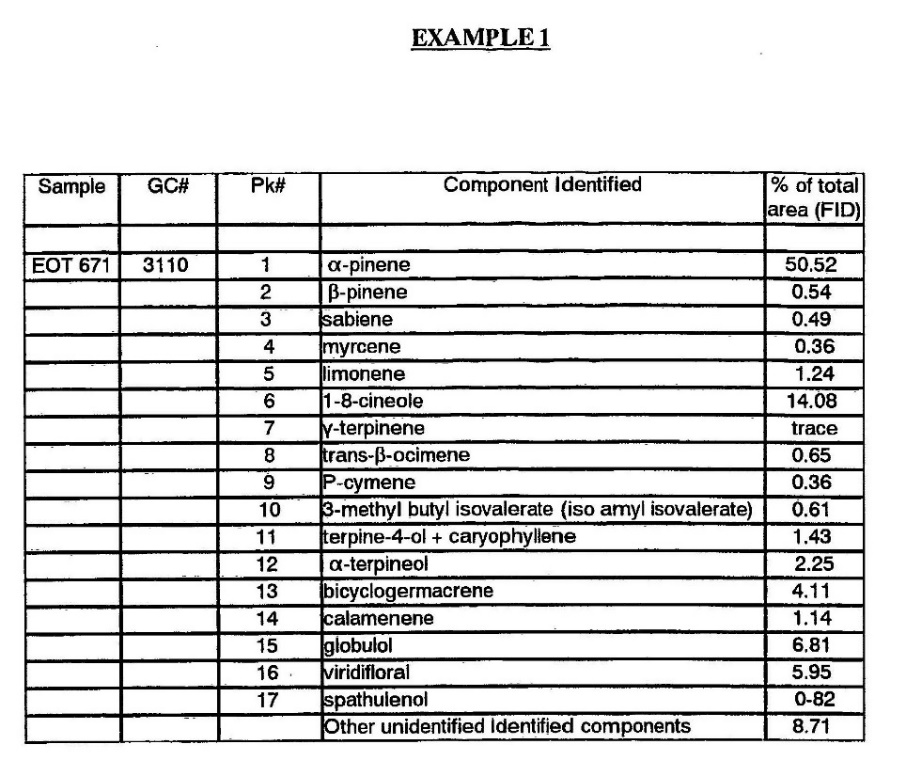

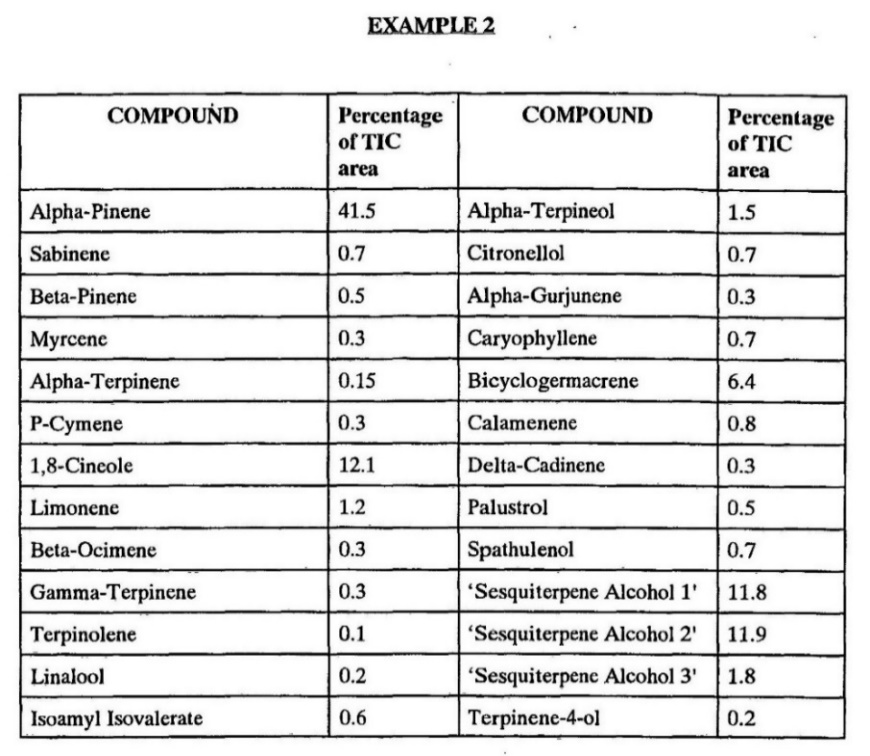

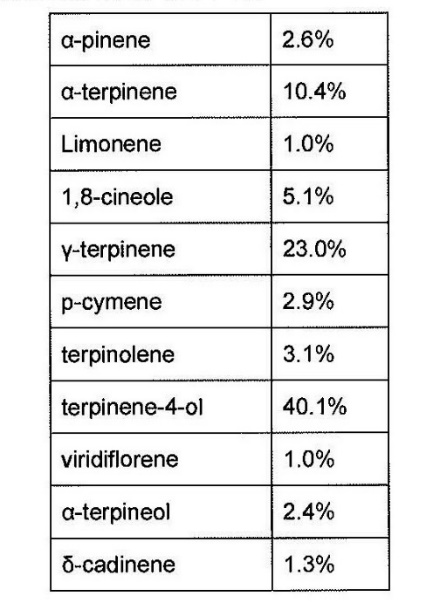

29 The specification also includes a discussion of the chemical composition of the oil obtained from Kunzea ambigua based on gas chromatograph analysis with reference to examples. The specification states:

The attached examples show the results of gas chromatograph analysis of the oil made from the shrub, and it will be seen that its principal components in each example are mono- and sesqui-terpenes.

Considering Example 1, the largest components are α pinene, 50.52 per cent, 1-8-cineole, 14.08 per cent, and sesquiterpene alcohols, globulol, 6.81 per cent, and viridiflorol, 5.96 per cent.

In Example 2, again the largest components are α pinene, 41.5 per cent, 1-8-cineole, 12.1 per cent and in this case, there are identified 3 sesquiterpene alcohols which together are 25.5 per cent.

Whilst other analyses of the oils have varied in absolute percentage, the relative percentages of the various components are very similar, with a preponderance of the above components.

30 A comparison of Example 1 and Example 2 (set out below) shows that there are some significant differences in the composition of the different samples. However, what both Examples have in common is that their largest components are alpha-pinene and 1-8-cineole which are present in quantities of about 40-50% and 12-14% respectively. The results of the gas chromatograph analysis as set out in the specification are as follows:

31 The specification also includes a discussion of the “trials” that Mr Hood conducted. Mr Hood does not purport to have conducted any scientific tests (for example, any form of randomised trial) and the evidence referred to in the specification is essentially anecdotal. According to the specification:

I have had trials done with the oil in a number of therapeutic applications, and although full trials has not been completed, I have found, qualitatively, that the oil has the ability to reduce pain caused by muscle and tendon strain and impact trauma, and it has also been found to reduce pain from gout, headache and bites, particularly insect and spider bites.

It has also had positive results in the treatment of rashes, skin irritations and acne.

It also seems to provide a positive result in relieving sinus congestion and as a result of this, aids in the return of the senses of smell and taste.

It also appears to have an ability to prevent the progress of cold sores, although to date the results in treating genital herpes have not been so positive.

One area which has provided a surprising reaction is in the treatment of bruising.

If applied to the area after the trauma and before bruising has started or is only incipient, I have found that it is almost completely ameliorated.

The oil appears to have no strongly adverse reaction with the skin, although as with all essential oils, people with sensitive skin should be careful before they apply it at full strength, but it can readily be applied, diluted in a carrier oil, preferably a pure vegetable oil, a lotion which can be an aqueous suspension, or an ointment, which can often be a petroleum emulsifying ointment base.

Where the Kunzea ambigua oil is applied, either pure or in a carrier oil or a lotion, the oil seems to pass through the skin relatively quickly, so no doubt it has a molecular size to enable this to occur, although to date I have not studied the size of the molecule.

…

Apart from its pharmaceutical benefits, the oil can be used in other ways.

32 Pausing there, it can be seen that the specification discloses that the oil may be applied topically either in undiluted form or using a carrier, preferably a pure vegetable oil, a lotion, or an ointment. While the specification clearly contemplates that the oil may be applied in these ways, it is also clear that the function of the carrier is to facilitate the topical application of the Kunzea ambigua oil in diluted form. In my view the specification is not in this passage contemplating the use of the Kunzea oil as part of a blend of different essential oils (except in so far as any other oil acts as a carrier). Nor do I understand this passage to be suggesting the use of Kunzea oil, or Kunzea ambigua oil, in blended products that include other active ingredients, the function of which is to cleanse or hydrate the body.

33 The specification also states that the oil may be used as “an oil disseminator”, “a very good rust inhibitor”, and a timber polish. The specification then continues as follows:

Whilst I have described the oil itself, its method of production and various uses, it is to be understood that these may be developed as the use of the oil continues.

Whilst in the above embodiment, I have described the use of the oil derived from the shrub Kunzea ambigua, it is believed that the oils derived from other plants of the genus Kunzea may have similar properties.

34 There are 18 claims. Claims 1-4 and claims 16-17 are product claims. Claims 5-13 are method of treatment claims. There is also a claim for the use of the essential oil as an insect repellent (claim 14) and as a rust inhibitor (claim 15). Claims 16 and 18 are omnibus claims and claim 17 is a claim based on the Examples.

35 The claims of the patent are as follows:

1. An essential oil derived from shrubs of the genus Kunzea.

2. The essential oil as claimed in claim 1 which oil is derived from the shrub Kunzea ambigua.

3. The essential oil of claim 1 in which the oil is obtained from the distillation of the green matter of the shrub.

4. The essential oil of claim 2 wherein the distillation is by steam distillation.

5. A method of treatment in which the essential oil as claimed in any one of claims 1 to 4 is applied topically as a treatment to relieve pain, minimize bruising, or to assist in healing.

6. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 4 wherein the pain relieved is pain from muscle and tendon strain, impact trauma, gout, headaches and insect and other bites.

7. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 4 wherein the use of the essential oil relieves sinus congestion.

8. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 4 wherein the essential oil limits the progress of cold sores, dries up dermatitis and aids in the healing of contusions.

9. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 4 wherein the essential oil assists in treatment of rashes, skin irritations and acne.

10. A method as claimed in any of claims 4 to 7 wherein the essential oil is applied in a carrier.

11. A method as claimed in claim 8 wherein the carrier is a vegetable oil.

12. A method as claimed in claim 8 wherein the carrier is a lotion.

13. A method as claimed in claim 8 wherein the carrier is an ointment.

14. The essential oil of any one of claims 1 to 3 wherein the oil is used as an insect repellent.

15. The essential oil of any one of claims 1 to 3 wherein the oil is used as a rust inhibitor.

16. An essential oil substantially as hereinbefore described.

17. An essential oil having an analysis substantially as described in relation to the Examples.

18. The use of the essential oil as claimed in any one of claims 1 to 4 and 15, substantially as hereinbefore described.

The Applicant’s expert witnesses

36 Professor Robert Menary OAM is Emeritus Professor in the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture at UTAS. He has undertaken research and teaching in the field of horticultural science over a long career commencing in 1967 when he was first employed as a Senior Lecturer at UTAS. He has published extensively and supervised a large number of PhD students. He also supervised the Master’s thesis (discussed later in these reasons) of Valerie Dragar (now Dr Dragar) as part of her work toward the degree of Master of Agricultural Science.

37 Professor Menary gave evidence of his dealings with Mr Hood in the mid-1990’s which broadly corroborated Mr Hood’s evidence. According to Professor Menary, he provided the sample Kunzea ambigua oil from Mr Hood to Dr Davies who performed a gas chromatographic analysis, the results of which were then provided to Mr Hood. The evidence indicates that this type of analysis was routine and was typically employed at the Priority Date to ascertain the composition of oil extracted from plant matter.

38 Professor Menary said that he did not have any particular knowledge or experience in relation to therapeutic uses or qualities of essential oils and, on that basis, did not comment on any aspects of the patent (including claims 5 to 13) which related to the therapeutic uses for Kunzea ambigua oil. His knowledge and experience focused on the flavours and fragrances of essential oils rather than their therapeutic uses.

39 One matter upon which Professor Menary gave evidence was that relating to the ascertainability of two documents that were relied upon by the respondents and which were said to contain information made relevant pursuant to s 7(3) of the Act. The respondents abandoned reliance upon those documents as s 7(3) information in closing submissions.

40 Professor Menary provided a written report which includes a response to Dr Carson’s affidavit evidence. However, I did not find this response of much assistance due to its lack of specificity. In particular, it failed to engage with Dr Carson’s evidence as to what was commonly and generally known by people working in the field of essential oils as at the Priority Date. I believe this most likely reflects the fact that Professor Menary’s knowledge and experience was, as I have said, focused on fragrances and flavours of essential oils.

41 Dr Narkowicz is an academic in the School of Medicine at UTAS. He teaches and performs research, primarily in the area of pharmaceutical product evaluation. He obtained a Bachelor of Science (Hons) in 1985 majoring in chemistry. His Honours thesis was on Tasmanian marine natural products, including terpendoids from soft corals. In 2003 he was awarded a Doctor of Philosophy which focused on the isolation and characterisation of marine natural products with anti-parasitic activity.

42 He has since led investigations at the School of Pharmacy at UTAS on Tasmanian natural products with potential pharmaceutical applications. These included two formulations containing Kunzea oil that were developed by a Tasmanian pharmacist from Launceston for treating psoriasis and greasy heel in horses.

43 With respect to Kunzea oil, Dr Narkowicz has led investigations into the constituents of Kunzea oil and variations in Kunzea oil constituents. In particular, he has researched the antibacterial and antifungal activity of Kunzea oil and different fractions of Kunzea oil. He has conducted clinical trials of formulations containing Kunzea oil for psoriasis in humans, greasy heel in horses and onychomycosis (toenail infection) in humans. He was part of a team that successfully obtained a RIRDC grant for the onychomycosis study. Mr Narkowicz has also lead projects investigating other essential oils.

44 Since 2009, Dr Narkowicz has been the Director and CEO of Xderma Pty Ltd. Xdera was created to commercialise Greasy Heel KO, a pharmaceutical product containing Kunzea oil for use on horses. This product was released into the market in 2010 under a minor use permit. Full registration for the product was sought but ultimately refused. The company is currently pursuing the commercialisation of other topical skin care products. He is also associated with a company that has obtained a TGA listing for a product that incorporates Kunzea ambigua oil into a product which “may assist with the management of toenail fungal infections such as onychomycosis”.

45 Dr Southwell is a plant research chemist. He is an Adjunct Professor of Plant Science at Southern Cross University. He was awarded a Bachelor of Science (Hons) from the University of Sydney in 1967. He subsequently completed a Masters of Science in 1972 and was then awarded a Doctor of Philosophy in 1982 from the University of Manchester. He then returned to Australia and took up a position as Head of the Essential Oil Research Unit at the Wollongbar Agricultural Institute and progressed to Senior Research Scientist in 1984 and Principal Research Scientist in 1991. As a plant research chemist, he conducted research into new, unusual and commercial secondary metabolites present in flora. Given the commercial importance of tea tree and eucalyptus, he has performed a significant amount of work using these oils.

46 Since 1995, Dr Southwell has been a Committee Member of Standards Australia’s CH/21 Essential Oil Committee. From around the same time, he has been a delegate to the International Standards Organisation’s TC54 Essential Oil Committee. In both committees, Dr Southwell has participated in the development of new standards and voted on changes to existing standards. The standards developed by the TC54 Committee are used by oil traders to establish acceptable baselines for the quality and authenticity of various traded essential oils. Through this work, Dr Southwell is familiar with the specifications of significant commercial essential oils.

47 In 2005 Dr Southwell set up his own consulting company called Phytoquest which advises on the chemistry of volatile constituents including essential oils and insect and plant chemistry ecology.

48 Mr Archer was an executive with the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration. He has over 17 years’ experience at a senior level. He began as Head of the OTC Medicines Section and then took up a variety of other positions including Secretary of the Medicines Evaluation Committee and Secretary of the Therapeutics Goods Committee. He is now the Director of Archer Emergy & Associates which is an independent consulting group providing advice and assistance to companies that import, manufacture or sell medicines, medical devices, cosmetics and foods in Australia and New Zealand. Mr Archer was not cross-examined.

49 Large parts of the expert report made by Mr Archer which was tendered by the applicant were rejected on the basis that they constituted expressions of opinion about the meaning and effect of various statutory provisions or were irrelevant to any issue in the case.

50 As I have mentioned, Mr Hood gave evidence and was cross-examined. His solicitor, Mr Stephen Sharpe, also gave evidence, but was not cross-examined. Mr Sharpe’s evidence was mostly directed to proof of documents relating to the prosecution history of the patent and included the file obtained from the patent attorney firm A Tatlock & Associates (which acted for Mr Hood in connection with his patent application), various search results, trap purchases, webpages and letters of demand, some of which are documents I will make reference to later in these reasons.

The Respondents’ expert witnesses

51 Dr Carson is a Research Associate in the School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Western Australia. She is a microbiologist. She completed a Bachelor of Science (Honours) at the University of Western Australia in 1989 and which was conferred in 1990. After completing that degree, Dr Carson commenced working towards a PhD focused on antimicrobial agents derived from plants which she completed in 2001. The title of her PhD thesis was “Antimicrobial activity of Melaleuca alternifolia Oil”.

52 Melaleuca alternifolia is one of a number of plants which have commonly been referred to as tea tree. The essential oil derived from Melaleuca alternifolia is commonly referred to as tea tree oil.

53 In 1994, Dr Carson commenced working as a member of a research group funded by what was then known as the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation in relation to the study of the antimicrobial activity of tea tree oil. Her research work during the period from 1994 to 2014 was primarily in relation to tea tree oil. Dr Carson completed her PhD research (which she completed on a part-time basis) in 2001. In 1993, Dr Carson published a review paper co-written with Professor Thomas Riley entitled “Antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia” in Letters in Applied Microbiology, 1993.

54 Dr Carson was an impressive witness. I consider she is well qualified by reason of her training and experience to give evidence as to the content of the common general knowledge as at the Priority Date.

55 Dr Clark is an ethnobotanist and anthropologist. In 1982 he completed a Bachelor of Science at the University of Adelaide majoring in botany and zoology. As part of that degree, he studied the biochemistry and taxonomy of plants. From 1990 to 1995 he undertook doctoral research in social anthropology and human geography at the University of Adelaide and was awarded a Doctor of Philosophy in 1995.

56 From 1982 to 2011 he was employed at the South Australian Museum. He held various positions at the South Australian Museum, including Registrar and then Senior Collection Manager of the Anthropology Division. This role involved organising and managing approximately 30000 artefacts and conducting field work relevant to the collection. In 1992 he became a Curator of Anthropology and from 1994 he was the Senior Curator of Aboriginal Collections. In 1998 he became Principal Curator of the Australian Aboriginal Cultures Gallery Project. In 2000 he became Head of Science at the Museum, and shortly after, Head of Anthropology/Manager of Sciences.

57 Since 2011 he has been self-employed as a consultant and an author. Some of his publications relate to Aboriginal uses of plants as medicines and foods. He has also been consulted from time to time by chemists who are interested in plants with potential therapeutic uses.

The Respondents’ lay witnesses

58 As previously noted, Mr Backhaus, Ms Prather, Mr Ardino, Mr Johnson, Ms Levinson and Mr Brocklehurst gave evidence. The only other lay witness for the respondents was Ms Debra Wilson, a senior librarian at UTAS. She gave evidence as to the public availability of the Dragar Thesis and the Morrison article both of which are discussed later in these reasons. Ms Wilson was not required for cross-examination.

59 The skilled addressee is a notional person skilled in the relevant art who may have an interest in using the products or methods of the invention, making the products of the invention, or making products used to carry out the methods of the invention either alone or in collaboration with others having such interest: see Aristocrat Technologies Australia Pty Ltd v Konami Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 114 IPR 28 at [26], Apotex Pty Ltd v Warner-Lambert Company LLC (No 2) (2016) 122 IPR 17 at [27]. The notional skilled addressee may, in an appropriate case, consist of a team of persons having different fields of expertise: General Tire & Rubber Co Ltd v Firestone Tyre & Rubber Co Ltd [1972] RPC 457 at 485, Root Quality Pty Ltd v Root Control Technologies Pty Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 225 at [71]. The notional skilled addressee may be, depending on the field of the invention, highly qualified, but lacks the capacity for invention. For this reason the notional skilled addressee is sometimes referred to as the hypothetical “non-inventive worker in the field”: Wellcome Foundation Ltd v VR Laboratories (Aust) Pty Ltd (1981) 148 CLR 262 (“Wellcome”) at 270. In the present case I will refer to this notional person as the person skilled in the art.

60 In the present case it was common ground that Mr Hood, even though he was the inventor, was not a person skilled in the art.

61 Counsel for Mr Hood submitted that the person skilled in the art in this case consisted of a team of persons possessing a number of different skills including a botanist, a plant or organic chemist, pharmacologists and, “… persons involved in regulatory compliance and marketing research”. I think this description of the notional team is too broad. I accept that the notional team may include a plant or organic chemist, a microbiologist and a horticultural scientist, all with training and experience in the field of the use of essential oils. It may also include pharmacologists, pharmacists and dermatologists but it will not include persons involved in the regulatory or marketing fields. Of those that gave relevant expert evidence, it seems to me that Dr Carson (a microbiologist), Dr Southwell (a plant chemist) and, to a lesser extent, Professor Menary (a horticultural scientist) are most likely to reflect the combined knowledge and experience of the person skilled in the art as at the Priority Date. I say to a lesser extent in the case of Professor Menary because, as he clearly acknowledged in his evidence, his considerable experience in the field of essential oils was focused on the flavour and fragrance of essential oils rather than any therapeutic use.

62 There was no dispute between the parties as to the relevant principles of construction. These were summarised by the Full Court (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) in Jupiters Ltd v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 222 ALR 155 at [67]. I do not think it necessary to set out their Honours’ often quoted summary.

63 It is alleged by the respondents that each of claims 6-9 lack clarity because they refer to a method of treatment as claimed in claim 4 in circumstances where claim 4 does not claim a method of treatment. There is no doubt that the reference in these claims to claim 4 is an obvious drafting error and that they should refer instead to claim 5. Of course, the error would be readily corrected by an amendment substituting the reference to claim 4 with a reference to claim 5 in each of claims 6-9.

64 In closing submissions the applicant initially submitted that there was no error in claim 7 and that it was indeed intended to refer to claim 4. The difficulty with that submission is that, while claim 7 refers to a method of treatment as claimed in claim 4, there is no method of treatment referred to in claim 4. In my view claim 7, if read in that way, makes no sense at all and is liable to be revoked on the ground that it lacks clarity.

65 If claim 7 is read with claim 5, then the method of treatment referred to in claim 7 must be one in which the essential oil is applied topically to relieve sinus congestion. Other methods of treatment, such as those involving the inhalation of emitted vapours from the essential oil in order to relief sinus congestion, are not methods of treatment within the scope of claim 7.

66 Ultimately, the applicant accepted that the reference to claim 4 in claim 7 (and all other claims affected by the same error) should be understood as referring to claim 5 and that, if those claims were not open to that interpretation as a matter of construction, then these are obvious errors which should be corrected by way of a series of simple amendments. I will say more on this issue when considering the amendment application.

67 In circumstances where claims 6-9 refer to claim 4 rather than claim 5, each of those claims is invalid for lack of clarity. An error of this kind appearing in a claim cannot be disregarded or corrected on the basis that the skilled addressee would understand that an error had been made in the drafting of the claim: see Glaxosmithkline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd and Another v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (2018) 264 FCR 474 at [117]-[121], [126]-[130].

68 Claims 11, 12 and 13 contain another obvious error in that they refer to claim 8 rather than claim 10. Those claims are also invalid for lack of clarity. Once again, the lack of clarity arising out of the obvious error is easily corrected by an amendment substituting the reference to claim 8 in claims 11, 12 and 13 with a reference to claim 10.

69 There are other issues that arise in relation to claims 10, 11, 12 and 13.

70 Claim 10 refers to a method of treatment “wherein the essential oil is applied in a carrier”. Claims 11, 12 and 13 require that the carrier be “a vegetable oil”, “a lotion”, and “an ointment” respectively.

71 There was no expert evidence led by any of the parties aimed at elucidating the meaning of the words “applied in a carrier” in claim 10.

72 I have previously referred to statements appearing in the specification concerning the use of the essential oil in a carrier. The relevant paragraphs of the specification state:

The oil appears to have no strongly adverse reaction with the skin, although as with all essential oils, people with sensitive skin should be careful before they apply it at full strength, but it can readily be applied, diluted in a carrier oil, preferably a pure vegetable oil, a lotion which can be an aqueous suspension, or an ointment, which can often be a petroleum emulsifying ointment base.

Where the Kunzea ambigua oil is applied, either pure or in a carrier oil or a lotion, the oil seems to pass through the skin relatively quickly, so no doubt it has a molecular size to enable this to occur, although to date I have not studied the size of the molecule.

73 There are a couple of matters to note about these paragraphs in the specification which provide the basis for claims 10, 11, 12 and 13. The use of a carrier is discussed in the context of the desirability of directly applying the oil to the skin in a diluted form rather than at full strength. It is clear from what is said that the function of the carrier is to enable the oil to be topically applied at less than full strength. Importantly, there is no suggestion in the body of the specification that the carrier, whether it is a vegetable oil, a lotion, an ointment, or something else, may consist of a formulation including other ingredients that cannot be sensibly understood to act as a carrier for the oil. A good example of such an ingredient would be a colouring agent the function of which is to colour the formulation rather than to carry it.

Proposed amendments to the patent

74 It is useful at this point to identify the amendments that the applicant originally proposed to the patent. The proposed amendments, at least in the form they were propounded until the applicant’s closing submissions, are set out in the second amended originating application filed in Proceeding NSD 1267 of 2017. Orders to the same effect were also sought in each of the other proceedings brought by the applicant. The Commissioner of Patents was given notice of the application to amend the patent in accordance with Rule 34.41 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth).

75 If the amendments in the form first proposed by the applicant were made, claims 3-13 would read as follows:

3. The essential oil of claim 1 2 in which the oil is obtained from the distillation of the green matter of the shrub.

4. The essential oil of claim 2 3 wherein the distillation is by steam distillation.

5. A method of treatment in which the essential oil as claimed in any one of claims 1 to 4 is applied topically as a treatment to relieve pain, minimize bruising, or to assist in healing.

6. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 4 5 wherein the pain relieved is pain from muscle and tendon strain, impact trauma, gout, headaches and insect and other bites.

7. A method of treatment in which the use of the essential oil as claimed in claim 4 wherein the use of essential oil relieves sinus congestion.

8. A method of treatment in which the use of the essential oil as claimed in claim 4 wherein the essential oil limits the progress of cold sores, dries up dermatitis and aids in the healing of contusions.

9. A method of treatment in which the use of the essential oil as claimed in claim 4 wherein the essential oil assists in the treatment of rashes, skin irritations and acne.

10. A method as claimed in any of claims 4 to 7 5 to 9 and 19 to 26 wherein the essential oil is applied in a carrier.

11. A method as claimed in claim 8 10 wherein the carrier is a vegetable oil.

12. A method as claimed in claim 8 10 wherein the carrier is a lotion.

13. A method as claimed in claim 8 10 wherein the carrier is an ointment.

76 The applicant also sought to make amendments to the complete specification to include the following additional claims:

19. A method of treatment in which the essential oil as claimed in anyone of claims 1 to 4 is applied topically as a treatment to minimize bruising.

20. A method of treatment which the essential oil as claimed in anyone of claims 1 to 4 is applied topically as a treatment to assist in healing.

21. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 5 wherein the pain relieved is pain from impact trauma.

22. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 5 wherein the pain relieved is pain from gout.

23. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 5 wherein the pain relieved is pain from headaches.

24. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 5 wherein the pain relieved is pain from insect and other bites.

25. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 8 wherein the essential oil dries up dermatitis.

26. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 8 wherein the essential oil aids in the healing of contusions.

27. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 9 wherein the essential oil assists in the treatment of skin irritations.

28. A method of treatment as claimed in claim 9 wherein the essential oil assists in the treatment of acne.

77 The applicant stated in its opening submissions in relation to the proposed amendments:

18. Section 102 of the Patents Act applies in relation to the application to amend in the form it existed prior to the amendments effected by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth). The basis for the Proposed Amendments is set out in Mr Hood’s Statement of Grounds for Application to Amend Patent (the Grounds), and include that: (a) proposed amendments are to correct obvious mistakes in claim numbering in dependent claims (and as such s.102(3) provides so that s.102 is not operative); and (b) in respect of all proposed amendments, the proposed claims as amended are supported by the matter disclosed in the specification and in substance fall within the scope of the claims prior to amendment, and so are allowable under Patents Act: s.102.

(footnotes omitted)

78 I do not propose to say too much at this stage about the amendments originally proposed by the applicant to claims 7 to 13 except to note that, contrary to the submission made by the applicant, those amendments, if made, would have broadened the scope of the claims so that they encompassed methods of treatment that did not involve the topical application of the oil. In my view the submission that the proposed amendments to those claims were intended to correct an obvious error was only half true. While it is true that there is an obvious error in those claims, the applicant sought to correct it not by merely substituting a reference to claim 5 in place of claim 4, but by making other changes to the language of the claims that would have enlarged their scope.

79 In closing submissions the applicant did not press its original application to amend claims 3-13. But it did propose amendments to correct what were said to be obvious errors:

the reference in claim 3 to claim 1 which the applicant says should refer to claim 2;

the reference in claim 4 to claim 2 which the applicant says should refer to claim 3;

the reference in each of claims 6-9 to claim 4 which the applicant says should be a reference to claim 5;

the reference in claim 10 to claim 4-7 which the applicant says should be a reference to claims 5-9; and

the reference in each of claims 11-13 to claim 8 which the applicant says should be a reference to claim 10.

80 The following amendments were also proposed to claims 5, 14, 15 and 18 as consequential to any finding that claims 1-4 are invalid:

5. A method of treatment in which the essential oil as claimed in any one of claims 1 to 4an essential oil derived from the shrub Kunzea ambigua, obtained by steam distillation of the green matter of the shrub, is applied topically as a treatment to relieve pain, minimize bruising, or to assist in healing.

14. The essential oil of any one of claims 1 to 3An essential oil derived from the shrub Kunzea ambigua, obtained by steam distillation of the green matter of the shrub, wherein the oil is used as an insect repellent.

15. The essential oil of any one of claims 1 to 3An essential oil derived from the shrub Kunzea ambigua, obtained by steam distillation of the green matter of the shrub, wherein the oil is used as a rust inhibitor.

18. The use of the essential oil as claimed in any one of claims 1 to 4An essential oil derived from the shrub Kunzea ambigua, obtained by steam distillation of the green matter of the shrub, and substantially as hereinbefore described.

81 I note that the proposed amendment to claims 14-18 are problematical because they claim matter that is within the scope of the existing claim 4 which the applicant has accepted is invalid. I will say more about the proposed amendments later in these reasons.

82 The submissions made by Mr Fox on the issue of validity of the relevant claims were adopted by Mr Reuben on behalf of the respondents for whom he appeared.

83 The main focus of the validity attack was directed to the contention that the relevant claims were not to a manner of manufacture and did not involve an inventive step. It is important to recognise, at the outset, that there was no allegation that any of the claims was to an invention that was not useful. In particular, none of the respondents contended the claimed methods of using essential oil derived from plants of the Kunzea genus were not useful methods of treating the conditions referred to in the claims or that the invention, as claimed, did not fulfil any promise conveyed by the specification. It follows that the invalidity case is to be determined on the basis that the methods of treatment referred to in the relevant claims are useful in the treatment of those different conditions.

84 The respondents allege that claim 8 is invalid for lack of fair basis. They submitted there was no disclosure in the body of the specification of any method of treatment that “dries up dermatitis” and “aids in the healing of contusions”. A similar submission was made in relation to claim 9 which is to “[a] method of treatment as claimed in claim 4 [sic] wherein the essential oil assists in the treatment of rashes, skin irritations and acne”.

85 The test to be applied for the purpose of ascertaining whether a claim is fairly based on the matter described in the specification as required by s 40(3) of the Act (as it stood at the time the specification became open for public inspection) requires that the specification contain “a real and reasonably clear disclosure” of what is claimed: Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd (2004) 217 CLR 274 at [68]-[69]. I agree with the respondents that there is no real or reasonably clear disclosure of the method of treatment claimed in claim 8. Claim 8 is therefore invalid for lack of fair basis.

86 The same is not true of claim 9. The specification includes a statement that “[i]t has also had positive results in the treatment of rashes, skin irritations and acne”. In my opinion there is a real and reasonably clear disclosure of the use of the essential oil derived from Kunzea ambigua as a treatment for those three conditions. I do not think claim 9 is invalid for lack of fair basis.

87 For an invention to be patentable, it must meet the relevant requirements of the Act including s 18(1)(a) which requires that the invention, as claimed, be a manner of manufacture within the meaning of s 6 of the Statute of Monopolies 1624 21 Jac 1 c 3. Schedule 1 to the Act defines “invention” as “any manner of new manufacture the subject of letters patent and grant of privilege within section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, and includes an alleged invention”. This element of patentability was considered in National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (1959) 102 CLR 252 (“NRDC”) and, more recently, D'Arcy v Myriad Genetics Inc (2015) 258 CLR 334 (“Myriad”). According to NRDC, as explained in Myriad, for an invention to constitute a manner of manufacture in the relevant sense, it must first be “for a product made, or a process producing an outcome as a result of human action” and, secondly, it must have “economic utility”: see Myriad at [28] per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ. However, while these two characteristics are essential to the existence of a patentable invention, they will not always provide a sufficient criteria against which to determine whether an invention is a manner of manufacture. As their Honours also observed at [28]:

… When the invention falls within the existing concept of manner of manufacture, as it has been developed through cases, they will also ordinarily be sufficient. When a new class of claim involves a significant new application or extension of the concept of “manner of manufacture”, other factors including factors connected directly or indirectly to the purpose of the Act may assume importance …

Their Honours went on to identify at [28] a number of additional factors that may need to be considered when a new class of claim is in issue.

88 In their submissions the respondents did not suggest that the claims in suit in this case involve any new class of claim and did not make any submissions directed to the additional factors identified in Myriad at [28]. Rather, the focus of the respondents’ submissions was on the principle considered by the High Court in Commissioner of Patents v Microcell Limited (1959) 102 CLR 232 (“Microcell”) and the finding that what was claimed in that case was not patentable because (at 251):

We have in truth nothing but a claim for the use of a known material in the manufacture of known articles for the purpose of which its known properties make that material suitable. A claim for nothing more than that cannot be subject matter for a patent, and the position cannot be affected either by the fact that nobody thought of doing the thing before, or by the fact that, when somebody did think of doing it, it was found to be a good thing to do.

89 In that case the patent specification described an invention consisting of a self-propelled rocket projector comprising a tube of synthetic resinous material reinforced with mineral fibres. It was apparent on the face of the specification that the invention was said to reside in the use of such material in the construction of the self-repelled rocket projector. In the course of the High Court’s judgment in Microcell, reference was made to the “old and well-established principle that the mere discovery of a new use of a particular known product is not what is meant by invention … [and] that where by the alleged invention no new product is obtained, no new method of manufacture suggested nor an old one improved, the discovery cannot be protected by a grant of Letters’ Patent …”. Their Honours said at 250:

Here the specification does not on its face disclose more than a new use of a particular known product. To use Lord Buckmaster’s words, no new product is obtained, and there is no new method of manufacture suggested or an old one improved. Tubular self-propelled-rocket projectors were at the relevant time well-known articles of manufacture. Synthetic resinous plastics reinforced with mineral fibres, and in particular polyester plastics reinforced with glass or asbestos fibres, were well-known materials. These things are to be gathered from the specification itself, which contains no suggestion of novelty in relation to the article to be manufactured or the material to be used. It further appears from matter published in Australia as early as 1946 that the reinforced plastic materials referred to in the specification had been used in the manufacture of a wide variety of articles. The properties of those materials were known generally, and in particular it was well known that they possessed that combination of great strength and lightness wherein, according to the specification itself, lies their virtue for the purpose in hand. The matter published in 1946 refers to their “extraordinary strength in relation to weight” – they are “stronger for their weight than steel” – and to their high tensile strength – another quality which the specification regards as a virtue for the purpose in hand. It was well known too that they possessed high impact strength and high resistance to heat. In these circumstances we do not think it can be said, merely because it does not seem previously to have occurred to anyone to make a rocket projector out of reinforced plastic, that any inventive idea is disclosed by the specification.

90 Gageler and Nettle JJ referred to Microcell in Myriad. Their Honours said, in a passage that was relied on by the respondents in this case, at [129]-[131]:

[129] Admittedly, it has occasionally been doubted that there is any longer a threshold requirement of inventiveness as opposed to the specific requirements of inventive step and novelty for which s 18(1)(b) provides. It has also been suggested that it would be desirable to collapse the subject matter requirement into the specific inquiries of inventive step and novelty. The Advisory Council on Intellectual Property concluded that it would make sense for “questions of newness to be dealt with under the specific provisions for novelty and inventive step, rather than under the general umbrella of manner of new manufacture”.

[130] But for present purposes, the law on the point appears to be tolerably clear. In Commissioner of Patents v Microcell Ltd, the Full Court held that the subject matter of a claim as disclosed in the specification must possess a quality of inventiveness or, in other words, the use of ingenuity that adds to the sum of human knowledge. In NV Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken v Mirabella International Pty Ltd, the majority recognised that the quality of inventiveness must appear on the face of the specification. In Advanced Building Systems Pty Ltd v Ramset Fasteners (Aust) Pty Ltd (1998) 194 CLR 171 (Ramset), the majority held that whether claimed subject matter is an invention for the purposes of s 100(1)(d) of the Patents Act 1952 (Cth) is distinct from inquiries as to inventive step, obviousness and novelty under s 100(1)(e) and (g), and that the court below had erred in considering “inventive merit” in light of prior art for the purposes of s 100(1)(d). The majority distinguished Philips on the basis that it was decided under the Patents Act 1990 (Cth). But, at a later point in the judgment, the majority also acknowledged that, where the subject matter of a claim as disclosed in the specification is plainly not an invention, the claim should be dismissed.

[131] Notwithstanding that Microcell did not establish a discrete “threshold” test, each of those decisions is consistent with the requirement, essential to the concept of a “manner of manufacture”, that the subject matter of a claim have about it a quality of inventiveness which distinguishes it from a mere discovery or observation of a law of nature. That requirement is separate and distinct from the other requirements of inventive step and novelty. As Brennan, Deane and Toohey JJ stated in Philips, an alleged invention will:

“remain unsatisfied if it is apparent on the face of the relevant specification that the subject matter of the claim is, by reason of absence of the necessary quality of inventiveness, not a manner of new manufacture for the purposes of the Statute of Monopolies. That does not mean that the threshold requirement of ‘an alleged invention’ corresponds with or renders otiose the more specific requirements of novelty and inventive step (when compared with the prior art base) contained in s 18(1)(b). It simply means that, if it is apparent on the face of the specification that the quality of inventiveness necessary for there to be a proper subject of letters patent under the Statute of Monopolies is absent, one need go no further.”

(some footnotes omitted)

91 The particulars given by the respondents in support of their manner of manufacture case were as follows:

(a) The alleged invention, as claimed in each of claims 1 to 4 of the Patent, is not the proper subject matter for the grant of a patent, in that it is not an “artificially created state of affairs”:

(i) The essential oil claimed in each of claims 1 to 4 of the patent is naturally occurring.

(ii) The essential oil claimed in each of claims 1 to 4 of the patent is not “made”.

(b) Further, the alleged invention, as claimed in each of claims 1 to 4 of the Patent, is not the proper subject matter for the grant of a patent, in that what is claimed is “the use of a known material in the manufacture of known articles for the purpose which its known properties make that material suitable”: Commissioner of Patents v Microcell Ltd (1959) 102 CLR 232. That is, at the priority date of the Patent the processes of distillation and steam distillation were known processes by which essential oils could be, or were, derived from native Australian shrubs.

(c) As to claims 5 to 9, the alleged invention as claimed in each claim is not the proper subject matter for the grant of a patent as the use of the essential oil in the method of treatment (in each claim) claims a known use for a known material. It was known at the earliest priority date of the Patent that essential oils obtained from native Australian shrubs referred to in paragraphs [29] to [36] of the affidavit of Dr Philip Allan Clarke sworn 20 June 2018 had, amongst other potential uses and applications, medicinal and therapeutic applications, including those mentioned in the said claims. No patentable subject matter resides in an alleged invention which seeks to claim a monopoly over attributes or capabilities inherent in and to, and/or attributes or capabilities known to be inherent in and to, essential oils.

(d) Further or in the alternative to (a) and (c), no manner of manufacture resides in a purported invention to a mere discovery (if there be one) that an essential oil derived from an Australian native shrub, such as the kunzea ambigua, may be a product and/or used in a method of treatment involving medicinal or therapeutic applications such as those mentioned in the claims. Such a discovery (if there be one) is not an invention capable of being the proper subject matter of a standard patent and is not a manner of manufacture.

92 As I have mentioned, the applicant accepts that claims 1-4 are invalid on the basis that they lack novelty. In those circumstances it is unnecessary to determine whether those claims are also invalid on the ground that they are not to a manner of manufacture. However, there are a number of observations that I will make in relation to that issue.

93 The respondents submitted that Mr Hood was not the first to discover an essential oil derived from Kunzea ambigua because the authors of the Morrison Paper published in 1922 and the Dragar Thesis published in 1984 had already extracted essential oil from Kunzea ambigua in connection with their investigations of the species many years before Mr Hood first produced essential oil from Kunzea ambigua growing on his property.

94 The difficulty with that submission is that the specification itself does indicate that the essential oil derived from Kunzea ambigua was a known substance that had been previously extracted from the plant. On the contrary, the specification states that it is the object of the invention described to provide a new essential oil. There is in my view nothing in the specification to suggest to the person skilled in the art that the essential oil of Kunzea ambigua had been extracted from the plant before the Priority Date. It is not apparent on the face of the specification that the quality of inventiveness necessary for there to be a proper subject of letters patent is absent. The present case is therefore outside the ratio of the decision of the majority in NV Philips Gloeilampenfabrieken v Mirabella International Pty Ltd (1995) 183 CLR 655 (“Philips”) at 663-664 per Brennan, Deane and Toohey JJ.

95 However, in Philips the majority (Brennan, Deane and Toohey JJ) went on to express the opinion that the same conclusion would follow even if the lack of inventiveness was not apparent on the face of the specification. Their Honours said at 666-667:

Strictly speaking, it is unnecessary to answer the question whether a process which could not be a proper subject matter for a patent according to traditional principle, for the reason that it is merely a new use of a known product, can nonetheless be a “manner of manufacture within the meaning of section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies” for the purposes of s 18(1)(a). However, in view of the fact that the argument in this Court and the judgments in the Full Court were primarily directed to that question, it is appropriate that we indicate that we consider that the above construction of s 18(1)’s threshold requirement of “an invention” goes a long way towards answering it since it would border upon the irrational if a process which was in fact but a new use of an old substance could be a “patentable invention” under s 18 if, but only if, that fact were not disclosed by the specification. In the context of that construction of s 18(1)’s threshold requirement of an “invention”, the preferable conclusion is that the phrase “manner of manufacture within the meaning of section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies” in s 18(1)(a) should be understood as referring to a process which is a proper subject matter of letters patent according to traditional principle.

96 In Bristol-Myers Squibb Co v F H Faulding & Co Ltd (2000) 97 FCR 524 (“Faulding”) the Full Court treated the majority decision in Philips as authority for the proposition that if, on the basis of what was known, as revealed on the face of the specification, the invention was obvious or did not involve an inventive step, the threshold requirement of inventiveness imposed by s 18(1) of the Act would not be met. Black CJ and Lehane J said at [30]:

The majority of the High Court in Philips explicitly say that their observations about a case where want of the threshold requirement of inventiveness is not apparent on the face of the specification are not necessary to their decision. And, in discussing the commencement point (what is “known”) of the inquiry about inventiveness, their Honours refer only to the Microcell principle. In our view, in the light of the authorities to which we have referred, Philips stands for the proposition (as a matter of construction of the 1990 Act) that if, on the basis of what was known, as revealed on the face of the specification, the invention claimed was obvious or did not involve an inventive step – that is, would be obvious to the hypothetical non-inventive and unimaginative skilled worker in the field […] – then the threshold requirement of inventiveness is not met. Some elaboration, however, is required in relation to what the specification reveals as “known”. If a patent application, lodged in Australia, refers to information derived from a number of prior publications referred to in the specification or, generally, to matters which are known, in our view the Court – or the Commissioner – would ordinarily proceed upon the basis that the knowledge thus described is, in the language of s 7(2) of the 1990 Act, part of “the common general knowledge as it existed in the patent area”. In other words, what is disclosed in such terms may be taken as an admission to that effect. In substance, we think, that is what happened, both in Microcell and in Philips. If, however, the body of prior knowledge disclosed by the specification is insufficient to deprive what is claimed of the quality of inventiveness, then the only additional knowledge or information which will be taken into account is knowledge or information of a kind described in s 7(2) of the 1990 Act. That again, in our view, is consistent with the approach taken in Microcell. It is also, with respect, the only approach which does not, in practical terms, render s 18(1)(b)(ii) otiose. Of course, once that additional knowledge is taken into account, one is applying s 18(1)(b)(ii), not the opening words of s 18(1) – unless, perhaps, one might apply either, there being, in this respect, no difference between them.

The decision in Faulding is authority for the proposition that it is not enough to establish that an invention is not a manner of manufacture by showing that it lacks inventiveness unless the lack of inventiveness is apparent on the face of the specification. This is the approach followed in a number of subsequent Full Court decisions including Novozymes A/S v Danisco A/S (2013) 99 IPR 417 per Jessup J and AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2014) 226 FCR 324 (“AstraZeneca”) at [379]-[387] per Besanko, Foster, Nicholas and Yates JJ.

97 In Myriad, Gageler and Nettle JJ said at [126]-[128]:

[126] For a claimed invention to qualify as a manner of manufacture it must be something more than a mere discovery. The essence of invention inheres in its artificiality or distance from nature; and thus, whether a product amounts to an invention depends on the extent to which the product “individualise[s]” nature. As Professors Sherman and Bently wrote:

“What then was required in order to move from the realm of discovery to that of invention? The simple answer was that it was necessary to show that abstract principles had been reduced to practice, that Nature had been individualised or activated … While philosophical or abstract principles could not on their own be patented, their embodiment in a material or practical form could. In these circumstances it was clear that in law it was the artificial or created nature of the final product, its distance from Nature, which ensured that an object became an invention rather than a mere discovery.”

[127] The question then is whether the subject matter of the claim is sufficiently artificial, or in other words different from nature, to be regarded as patentable.

[128] Relevantly, the artificiality of a product may be perceived in a number of factors, including the labour required to create it and the physical differences between it and the raw natural material from which it is derived. Regardless, however, of the amount of labour involved or the differences between the product and the raw natural material from which it is derived, it is necessary that the inventive concept be seen to make a contribution to the essential difference between the product and nature.

(footnotes omitted)

98 In the present case each of claims 1-4 is to an essential oil derived from plant matter of the kind identified in the claims. These claims are to the essential oil so derived in whatever form the extracted oil takes. This is significant because, according to the evidence, the chemical composition of the plant will vary depending on growing conditions and this will in turn affect the composition of the essential oil derived from the plant. While the chemical composition of the oil extracted from different plants will vary, this is due to the way in which the plant responds to the conditions in which it is grown and the stage at which it is harvested. The composition of the essential oil will mirror what is found in the plant. Moreover, the usual method by which the essential oil is extracted from the plant (ie. steam distillation) is one of great antiquity. It was common ground that essential oil has been extracted from plants using this process for many hundreds (perhaps thousands) of years. In those circumstances, a question arises as to whether the essential oil the subject of each of claims 1-4 is (adopting the language used by Gageler and Nettle JJ in Myriad at [127]) sufficiently artificial or different from nature to be regarded as patentable.

99 Of course, as the applicant now concedes, an essential oil of the kind referred to in each of claims 1-4 had been extracted and described in the documents that form part of the prior art base before the Priority Date with the consequence that each of those claims is invalid for lack of novelty. It is therefore unnecessary for me to express any final conclusion with respect to the issue of manner of manufacture as it relates to claims 1-4. However, it seems to me that if the question posed by Gageler and Nettle JJ in Myriad at [127] is the right question to ask, it is strongly arguable that the difference between the raw oil extracted from the Kunzea ambigua shrub is insufficiently artificial or different from nature to qualify as patentable subject matter.

100 I now turn to the challenge to the validity of claims 5-9 each of which is to a method of treatment. It is clear that each of claims 6-9 mistakenly refer to claim 4 when they should refer to claim 5. For the purposes of addressing the validity issues I will proceed as if the reference in claims 6-9 to claim 4 was a reference to claim 5.

101 The respondents accepted that a method of treatment may be patentable subject matter. The correctness of that proposition was confirmed by the High Court in Apotex Pty Ltd v Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd (2013) 253 CLR 284 (“Apotex”). In that case the High Court rejected the submission that the subject matter of the claim in suit was “essentially non-economic” and therefore not to a manner of manufacture: see Apotex at [277] per Crennan and Kiefel JJ. Their Honours said at [283]:

[283] … a method claim in respect of a hitherto unknown therapeutic use of a (known) substance or compound satisfies the general principle laid down in the NRDC Case. Such a method belongs to a useful art, effects an artificially created improvement in something, and can have economic utility. The economic utility of novel products and novel methods and processes in the pharmaceutical industry is underscored by s 119A of the 1990 Act and by their strict regulation in the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 (Cth) (the TGA).

102 It is apparent from the particulars of invalidity which I have previously set out that claims 5-9 of the patent are said by the respondents not to be to a manner of manufacture not because they lack economic utility but because they are for the “known use of a known material”. The respondents rely on the principle discussed in Microcell to which I have previously made reference.

103 Dr Clark gave some evidence on a range of different plants in Australia from which essential oils may be derived. According to this evidence, there are roughly 20 to 50 different plant families in Australia from which essential oils may be derived. However, a large proportion of oils (approximately 70%) come from a small number of families (approximately 12 families). The main families of essential oil producing plants are the following:

(a) Myrtaceae;

(b) Rutaceae;

(c) Lamiaceae;

(d) Fabaceae;

(e) Poaceae;

(f) Santalaceae;

(g) Solanaceae.

104 Dr Clark also gave evidence that the genera of plants from Australia which were commonly and generally known by October 1996 for producing oils with therapeutic uses included:

(a) Eucalyptus/Corymbia – Myrtaceae family;

(b) Melaleuca (“tea tree”) – Myrtaceae family;

(c) Leptospermum (“tea tree”) – Myrtaceae family;

(d) Kunzea (“tea tree”) – Myrtaceae family;

(e) Backhousia – Myrtaceae family;

(f) Santalum (“sandalwood”) – Santalaceae family;

(g) Boronia – Rutaceae family;

(h) Prostranthera (“mint bush”) – Lamiceae family;

(i) Cymbopogon (“Lemongrass”) – Poaceae family;

(j) Callitris (“Australian pine”) – Cupressaceae family.

105 One of the most well-known Australian essential oils in October 1996 was tea tree oil. There are also tea tree oils from New Zealand (and other places), which were commonly and generally known in Australia in October 1996.

106 Whilst I accept Dr Clark’s evidence in relation to the different types of essential oils and their uses, I do not think it establishes that the essential oil derived from Kunzea ambigua had been used for therapeutic purposes before the Priority Date. It is true that Dr Clark’s evidence shows that Australian Aboriginal people have used native plants for therapeutic purposes for thousands of years, including to treat infections, skin problems, colds and nasal conditions. However, Dr Clark did not suggest that any of those treatments involved extracting the essential oil of the plants nor did he suggest that Kunzea ambigua had been used by them for therapeutic purposes.

107 In submissions it was accepted by Mr Fox, correctly in my view, that the evidence did not establish that the essential oil derived from Kunzea ambigua had been used for therapeutic purposes before the Priority Date. Even if it is correct to say that such an essential oil was a known material, it has not been shown that it had known properties that made it suitable for use in the treatment of any of the ailments referred to in the claims. It is true that a person skilled in the art, if he or she was to ascertain the chemical composition of oil derived from Kunzea ambigua, may infer that there were some chemical components in the oil that may be useful as a treatment for one or more of the ailments referred to in the method of treatment claims. But the evidence given by Dr Carson and some of the other witnesses called by the respondents to that effect was more in the nature of a conjecture, it being recognised that the essential oil would need to be tested to determine whether it was suitable for such a purpose.

108 In my view the evidence does not support a finding that any of the method of treatment claims was for a known use of a known material. In any event, as I have previously observed, there is nothing on the face of the specification to suggest that the essential oil derived from Kunzea ambigua was not new or that the methods of treatment that used such an oil lacked the quality of inventiveness necessary to support the grant of a valid patent.

109 The respondents submitted that what Mr Hood claims to have discovered is that Kunzea ambigua is suitable for a number of uses including as a treatment for various ailments. They then submitted that the methods of treatment defined by the claims, and which Mr Hood is said to have invented, were based on anecdotal evidence obtained from family and friends to whom Mr Hood supplied his essential oil before the Priority Date. It was submitted that any discovery made about the use of Kunzea ambigua oil as a method of treatment was therefore made not by Mr Hood but by his family and friends.