Federal Court of Australia

ASD17 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2020] FCA 1653

ORDERS

Appellant | ||

AND: | MINISTER FOR IMMIGRATION AND BORDER PROTECTION First Respondent IMMIGRATION ASSESSMENT AUTHORITY Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The oral application for leave to appeal in relation to grounds 4 and 6 be dismissed.

2. The Appellant is granted leave to amend his notice of appeal to raise ground 8.

3. The appeal be dismissed.

4. The Appellant pay the First Respondent’s costs of the appeal as taxed or assessed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

Introduction

1 This is an appeal from orders made by the Federal Circuit Court on 13 March 2019: ASD17 v Minister for Immigration [2019] FCCA 295. That Court dismissed with costs an application for judicial review of a decision made by the Immigration Assessment Authority (‘the Authority’) on 19 January 2017. The Authority had affirmed an earlier decision of a delegate of the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection (‘the Minister’) not to grant the Appellant a Safe Haven Enterprise visa (‘SHEV’). A SHEV is a species of protection visa. The effect of what has happened thus far is that the Appellant has been denied a SHEV. If the appeal succeeds, the Authority’s decision will be set aside and it will be required once more to conduct a review of the delegate’s decision under Pt 7AA of the Act. For the reasons which follow, the appeal will be dismissed with costs.

Preliminary matters

The Interpreter Issue

2 When the appeal was called on for hearing in this Court, the Appellant appeared unrepresented. An interpreter, fluent in Tamil, was present at the hearing. The Appellant raised with me the fact that the interpreter had a Tamil Nadu background which the interpreter confirmed. She told me that she was from Sri Lanka but had studied in Tamil Nadu as a consequence of which her Tamil had a Tamil Nadu flavour. Tamil Nadu is the southernmost state in India and lies across the Palk Strait from Sri Lanka. The official language of Tamil Nadu is Tamil and nearly 90% of the population speak Tamil. I accept the statement made by the interpreter that her Tamil has the flavour of a person from Tamil Nadu. She also informed me that Tamil as spoken in Sri Lanka and Tamil as spoken in Tamil Nadu differed in the sense that they were different dialects of the same language.

3 On this basis the Appellant sought an adjournment of the appeal to obtain an interpreter in Tamil who did not have a connection to Tamil Nadu. I declined that adjournment application. The interpreter was from Sri Lanka and was an interpreter in Tamil which both she and the Appellant spoke. I do not think that the fact that the interpreter had subsequently lived in Tamil Nadu and thereby obtained a Tamil Nadu flavour to her Tamil undermined the integrity of the appeal.

The timing of the Minister’s written submissions

4 The Appellant’s second complaint was that the Minister’s solicitors had only provided him with his written submissions on Tuesday 28 January 2020. The hearing in this Court took place on Monday 3 February 2020. This delay had meant, so he submitted, that he had not been able to obtain legal advice about the Minister’s submissions.

5 However, as the Minister correctly observed, the Appellant was himself obliged to serve his submissions upon the Minister by 20 January 2020 and had failed to do so or indeed to serve any submissions in chief by Tuesday 28 January 2020, three business days before the hearing. When the Appellant failed to serve any submissions, the Minister’s solicitors decided to serve his submissions notwithstanding that he had nothing to which to respond. I do not think that the Minister can be criticised for doing so. The Appellant cannot turn to his own advantage the consequences of his own procedural defaults.

Relevant facts

6 The Appellant is a Sri Lankan national of Tamil ethnicity. He arrived without a visa by boat in Australian waters on 20 September 2012 on a boat designated by authorities as ‘Gabi’. The vessel was intercepted and he was taken to Christmas Island where he disembarked, I assume, at Flying Fish Cove, the only declared port on Christmas Island at which unauthorised maritime arrivals may enter Australia: see DBB16 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] FCAFC 178; 260 FCR 447 at [69]-[78]. Since he did not have a visa he was placed in immigration detention in the Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centre.

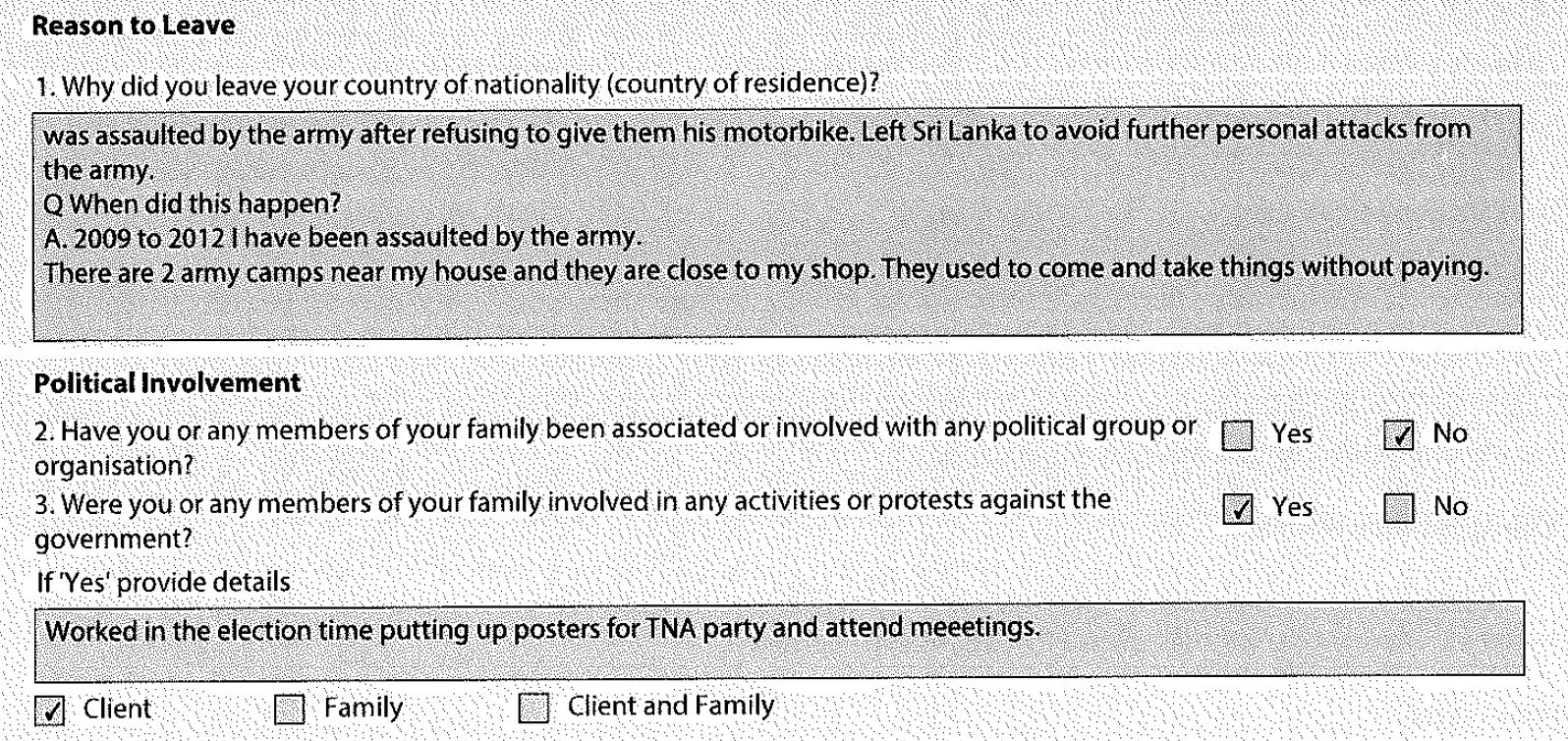

7 Some months later, on 8 January 2013, he attended an entry interview with a departmental official. During the interview he was asked whether he was involved in any political group or organisation and answered that he had not been but he did say he had been involved in putting up posters for the Tamil National Alliance (‘TNA’) during election time and had attended meetings of the TNA.

8 During that interview he did not expressly mention that whilst he had been in Sri Lanka, members of another political party, the Tamil Makkal Viduthalai Pulikal (‘TMVP’), had threatened to shoot him if he did not stop campaigning for the TNA. In answer to Question 7, however, he did indicate that two groups – the Karuna Group and the Pillayan Group – had been operating in the area where he lived. And in answer to Question 18 he did say that he feared he would be harmed by the same groups if he were repatriated to Sri Lanka. The Karuna Group and the Pillayan Group are schismatic factions within the TMVP. As will be seen, in its reasoning the Authority thought that it was material that the Appellant had failed to mention at the entry interview that he had been threatened by the TMVP. I am not so sure. However, this was not the point the Appellant pursued.

9 Since he had arrived by boat without a visa he was subject to a complex regulatory scheme which prohibited him from applying for a visa unless the Minister invited him to do so under s 46A(2) of the Migration Act 1958 (Cth) (‘the Act’). On 1 September 2015, the Minister invited him to apply for a SHEV and he did so on 28 September 2015. It is that application which is the underlying subject matter of the present appeal.

10 He was interviewed in relation to his SHEV application on 12 February 2016 at which time he provided a letter which purported to be from a Sri Lankan MP, Seenithamby Yoheswaran, dated 25 January 2013. The letter was in Tamil but was translated by the interpreter during the interview for the benefit of the delegate. The delegate recorded the crucial elements of the letter in his reasons for decision. The key points in the letter were the author’s confirmation that the Appellant was a supporter (cf a member) of the TNA; had been threatened by an unidentified group; kept a low profile; and, that his security was in danger. The delegate did not suggest that the letter was bogus.

11 The Appellant told the delegate that he had been threatened by members of the TMVP (which it accepted to an extent). These included in 2010 threats to shoot him. Ultimately, the delegate accepted that he had been a member of the TNA and that the threats by the TMVP had been made but not carried out. Ultimately, the delegate refused the SHEV application on 31 August 2016. The delegate did so principally on the basis that the Appellant did not have a substantial political profile and the situation in Sri Lanka was much improved for Tamils since the end of the civil war.

12 The matter was then automatically referred to the Authority which is obliged to conduct a review on the papers. In some limited circumstances it may invite the applicant to provide new information orally or in writing but in this case it did not.

13 The Authority found that the politician’s letter was not credible. It also thought that the Appellant had failed to mention at the entry interview the fact that someone from the TMVP had threatened to shoot him. As I have already hinted, this reasoning is questionable. It decided to give this omission some weight in its assessment (although it did not say how much). It also concluded that it was discreditable for the Appellant to rely on the letter. It then reasoned that he had not been a member of the TNA (as he claimed) and had never been threatened by the TMVP (as he claimed).

14 The Authority affirmed the delegate’s decision to refuse the application on 19 January 2017. Subsequent, judicial review proceedings in the Federal Circuit Court were unsuccessful.

The Appeal

15 On 3 April 2019 the Appellant filed a notice of appeal seeking to set aside the orders of the learned primary judge made on 13 March 2019. The notice contained seven grounds of appeal.

16 The first ground of appeal relates to the Authority’s use of a letter which the Appellant provided to the delegate at the interview he attended on 12 February 2016. As noted above, this letter was dated 25 January 2013 and was expressed to be from a TNA member of the Sri Lankan Parliament, Seenithamby Yoheswaran. At the SHEV interview, the letter of 25 January 2013 was translated by the interpreter who attended the interview to assist the Appellant. The delegate included a translation of the key parts of the letter in his decision. From that translation, it appeared that the letter was used to make good two points. These were that the Appellant was a supporter of the TNA and that he had been threatened by an unidentified group. The contents of the letter which the delegate had included in his reasons were as follows:

[The Applicant] is a supporter of the TNA and worked for the party in the past. He was threatened by an unidentified group and kept a low profile. His mother advised him that boats are leaving for Australia and his security is in danger. We would like to request Australia to provide protection for him.

17 On its review, the Authority did not obtain a translated version of the letter for the purpose of its deliberations but the Appellant submitted that it had nevertheless found itself able to dismiss the letter as not being credible. That the Authority did not obtain for itself a translation of the letter and that it thought the letter lacked credibility appears to be correct. At [10] in its reasons the Authority said that it considered ‘the politician’s letter is not a credible document’ and, further, that by providing such a non-credible document to support his claims the Appellant had undermined his own credibility: [10].

18 The Appellant submitted that it was difficult to understand how the Authority could have reached that conclusion if it did not have a translation of the letter before it. In terms of legal mechanics, his notice of appeal said that the Tribunal had acted in a legally unreasonable way under s 473DC of the Act by failing to obtain ‘new information’, that information being a translation of the letter. There was, on this view, no evident or intelligible justification for not obtaining a translation of the letter if the Authority was considering dismissing the letter as lacking credibility.

19 What the Authority said in full about this letter is at [10]:

At the SHEV interview, he provided an untranslated letter purportedly from a TNA politician dated 25 January 2013. The interpreter read the letter and advised the contents stated the applicant was a supporter of the TNA. He was threatened by an unidentified group. The applicant kept a low profile and came to Australia because his mother told him about boats leaving. At the SHEV interview, the applicant claimed he accompanied the author politician at some TNA functions. I consider the politician’s letter is not a credible document. It does not refer to the applicant being a member of the TNA or that he campaigned for Mr W. It is inconsistent too with the applicant’s claim he was threatened by supporters of the TMVP, not unknown persons. I consider the politician’s letter is not a credible document and I consider his providing such a non-credible document to support his claims undermines his credibility generally.

20 There may be some problems with this. Why did the Authority conclude the document was not credible? It cannot have been by reading its full terms which were not available to it. For example, the Authority does not say that it had inspected the Tamil original and concluded the letter lacked credibility because it appeared to be a bogus document. Instead, [10] sets out three reasons for concluding that the letter was not credible:

(1) The letter did not refer to the Appellant as a member of the TNA but only as a supporter;

(2) The letter did not refer to the Appellant campaigning for Mr W; and

(3) The letter was inconsistent with the Appellant’s claim that he had been threatened by the TMVP because it only said that he had been threatened by unknown persons.

21 Each of the points (1)-(3) could suggest the letter was inconsistent with the Appellant’s account. For example, it is true that the Appellant said he was a member of the TNA whereas the letter apparently says that he was a supporter.

22 Initially, I was somewhat persuaded by the proposition that there was a logical inconsistency between disbelieving the Appellant’s evidence that he was a member of the TNA and concluding that the letter lacked credibility because it said only that he was a supporter. Here the thinking is that having found that the Appellant was not a member of the TNA, the credibility of the letter would certainly be impacted if it had recorded the fact that he was. On that view, the letter would contain a statement which the Authority would have found to have been false. It is an easy step to reason from that proposition to a conclusion that the letter lacked credibility.

23 However, this is not what occurred. Where the Authority found that the Appellant was not a member of the TNA no strict conflict then existed because the letter does not say that the Appellant was a member, only that he was a supporter. Put another way, there is no direct conflict between the statement that the Appellant was not a member of the TNA and the statement that he was a supporter of the TNA. Both statements may be simultaneously true as a matter of logic. However, they need not be. It is also logically possible that the Appellant was not a member of the TNA (as he claimed) and was not a supporter of it either (as the letter suggested).

24 I do not think therefore that one can logically conclude from the fact the Appellant was not a member of the TNA that the statement in the letter that he was a supporter of the TNA is not credible. However, just because an argument is illogical does not mean it is wrong. Logic is concerned with the validity of the process of reasoning and not with the correctness of any conclusions drawn. Logical arguments may be untrue just as illogical arguments may be correct. For example, the argument that all judges have tails, I am a judge, therefore, I have a tail is impeccably logical but clearly false (or so I believe). The argument that all cats have tails, Oscar has a tail therefore Oscar is a cat is, on the other hand, entirely illogical. The premise does not exclude the possibility that there are creatures with tails which are not cats and the quality of having a tail therefore does not inevitably point to being a cat. This argument’s lack of logic, however, throws no light on the real world question of whether Oscar is in fact a cat. Concluding that Oscar is not a cat because the argument against his cathood is illogical is itself an example of the fallacy-fallacy ie the illogical conclusion that because the argument which leads to a proposition is illogical that the proposition is itself false. Logic and truth are different domains of discourse.

25 It is for that reason that it is generally accepted that a lapse in logic need not imply the presence of a jurisdictional error: Minister for Immigration and Citizenship v SZMDS [2010] HCA 16; 240 CLR 611 (‘SZMDS’) at 649 [130] per Crennan and Bell JJ.

26 It is true that it was not logical for the Authority to reason from the letter’s failure to refer to the fact that the Appellant was a member of the TNA to a conclusion that the letter itself lacked credibility. But, for the reasons I have just given, this does not entail that the letter was in fact credible and therefore that its contents were true. The ultimate use to which the Authority put the letter was for the purpose of disbelieving the Appellant. In my view, the failure of the letter to refer to the Appellant’s membership of the TNA could have supported a rejection of the Appellant’s evidence on the basis that it was not supported by the evidence he proffered. This therefore is a case where a lack of logic in the Authority’s reasoning by no means entails that the result it arrived at is one involving jurisdictional error. A logical or rational decision maker could have reached the same ultimate conclusion to reject the Appellant’s evidence.

27 Consequently, I do not accept that this want of logic in this case gives rise to a jurisdictional error. Similar reasoning applies to points (2) and (3) of the same argument. I invited further submissions on this issue following the hearing and the Appellant, now with the representation of counsel, then sought leave to raise this point by way of amendment. I would grant leave to amend to raise the proposed ground 8 but I would reject the ground.

28 In the Court below the argument run appears to have been markedly different and was to the effect that the Authority’s reasons for concluding that the document was not credible were not adequate, ie, one could not discern from them why the Authority had thought the letter lacked credibility. I agree with the Federal Circuit Court that the reasons are adequate in an administrative law sense. They are sufficient to disclose the difficulties identified above in [20].

29 The Appellant also submits that it was legally unreasonable for the Authority to conclude that the letter was not credible if it did not have a translation of it.

30 I do not accept that argument. The letter was translated at the hearing before the delegate by the interpreter who was present and details of the content were then set out in the delegate’s written reasons for refusing the SHEV application. The Authority therefore had access to a translation of the contents of the letter. There was no need for the Authority’s assessment of the letter’s credibility to coincide with that of the delegate: see ABT17 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2020] HCA 34 at [23] per Kiefel CJ, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ. The proposition that it was legally unreasonable for it not to obtain another translation is not viable. It is likely that this point was not raised below and that leave would have been required to pursue it. To the extent that leave is required in relation to ground 1 it is refused and the ground will be otherwise dismissed.

31 The second ground of appeal relates to the Authority’s reliance on the Appellant’s failure to mention at the entry interview the fact that he had been threatened by members of the TMVP (including with threats of shooting). The relevant portion of the Authority’s reasons is at [12]:

I note too at the entry interview, while the applicant claimed to be a supporter of the TNA, he made no claim he was threatened at gun point or threatened at all by supporters of the TMVP. I am mindful the entry interview was conducted shortly after the applicant arrived in Australia, that he was not represented during the entry interview and that the purpose of the entry interview is not to assess his claims. I still consider it reasonable to put weight on the applicant’s claims at the entry interview not including any reference to his being threatened by supporters of the TMVP.

32 The weight to be afforded to the Appellant’s omission to mention at his entry interview the fact that he had been threatened at gunpoint by members of the TMVP is a function of the questions he was asked at that interview. For example, if all that he was asked during the entry interview was where had he lived in Sri Lanka and the name of the vessel upon which he arrived, then an omission by him to inform the delegate that members of the TMVP had threatened to shoot him would be irrelevant. On the other hand, if he was asked why it was that he feared returning to Sri Lanka and failed to mention, at that time, his harassment at the hands of the TMVP this would be rationally capable of supporting an inference that the contention was a recent invention.

33 The decisions of this Court show that there is nothing wrong in principle with the Authority using, as part of its reasoning, an omission to mention a matter at an entry interview. To do so the Authority must conclude that the omission is relevant to its assessment of the protection claims. Its determination that the omission is relevant to its assessment of those claims is for it, not a judicial review court. Nevertheless, the determination is circumscribed by the need for it to be legally reasonable: see DWA17 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2019] FCAFC 160; 272 FCR 152 (‘DWA17’) at [38]-[39] per McKerracher, Banks-Smith and Jackson JJ; MZZJO v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2014] FCAFC 80, 239 FCR 436 at [56] per North, Bromberg and Mortimer JJ.

34 I would read [12] as proceeding on an unstated assumption that the omission was relevant to the Authority’s assessment of the Appellant’s protection claims. That assumption is reviewable on the grounds of legal unreasonableness: DWA17 at [39] citing Perry J in Paerau v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2014] FCAFC 28; 219 FCR 504 at [105].

35 Such a challenge will fail if the decision which the Authority has arrived at (on the question of relevance) is one which a rational decision maker could arrive at: SZMDS at 649 [135] per Crennan and Bell JJ; Fattah v Minister for Home Affairs [2019] FCAFC 31; 268 FCR 33 at [45] per Perram, Farrell and Thawley JJ. In this case, the relevance of the omission must be gauged by the questions which the Appellant was asked at the entry interview. In the present case, there are only five questions recorded in the entry interview template which could reasonably be seen as touching upon whether the Appellant had been threatened by members of the TMVP. These are Questions 1-3, 7 and 18. Those questions, the headings under which they appear and the Appellant’s answers to them are as follows:

36 Question 1 repays careful reading. There is a distinction between the reasons a person left their country of origin and the reasons they do not wish to return there. For example, often enough a person (including, as it happens, the present Appellant) may have departed their country of origin in contravention of that country’s internal law and may be concerned that they will face prosecution for their illegal departure if they are returned there. It would be absurd to suggest that a person left their country of origin because they were concerned that if they were returned there they would be prosecuted for leaving illegally.

37 Further, it is quite possible that a person may have been subject to persecution for several reasons and in disparate ways in their country of origin but that it was a particular incident which was the proximate cause of their immediate departure. For example, persecution of a particular religious minority may have been ongoing for some time in a particular village. There may have been petty attacks, property damage and verbal abuse but members of the religious minority in the village may have concluded that the unknown perils of relocation to elsewhere outweighed the ongoing daily difficulties of life in the village. But the appointment of a new, more bloodthirsty town commander with a reputation for increased violence may have caused some of them to have revisited this assessment. Confronted with this changed situation some may have then decided to flee.

38 A person in that circumstance who had fled the village, confronted at an entry interview by Question 1, would answer that they had left because of the appointment of the bloodthirsty commander. They would not include in that answer any reference to the various other slights they had suffered over the years in the village. Those slights were not why they left although they are included amongst the reasons why they would not want to return.

39 Once that is appreciated, it will be seen that Question 1 is asking about reasons for departure and not about reasons for not wanting to return. The question of whether an applicant is entitled to a protection visa turns on whether they have a well-founded fear of persecution if returned to their country of origin for a reason in the definition in the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Opened for signature 28 July 1951. 189 UNTS 137 (entered into force 22 April 1954), as amended by the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Opened for signature 31 January 1967. 606 UNTS 267 (entered into force 4 October 1967) (‘Convention’). Whilst it is very likely that fear of persecution for a Convention reason would lead a person to depart their country of origin, it is irrational to reason that an answer to Question 1 must exhaust the range of protection claims which a person might have. The sad reality is that the reason many people leave their country of origin relates to a single event which, against the backdrop of a long litany of persecutions, is the straw that breaks the camel’s back. The difficulty with using what is not said in answer to Question 1 is that it confuses the straw which broke the camel’s back with everything else the camel was carrying.

40 The situation is really no better in relation to Questions 2 and 3. So far as the Appellant is concerned neither of these could coherently be answered ‘Members of the TMVP threatened to shoot me’.

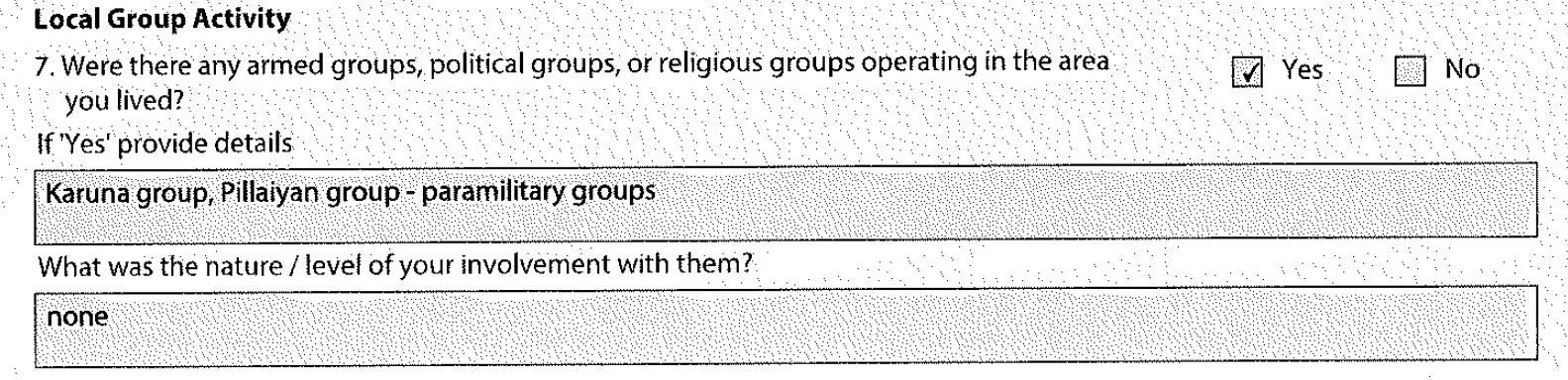

41 Question 7 is different. On the Appellant’s current account there was a political group operating in the area – the TMVP. As is discussed above while the Appellant’s recorded response to Question 7 did not explicitly mention the TMVP, it named the ‘Karuna group’ and the ‘Pillaiyan group’ [sic]. The Karuna group and the Pillayan group refer to factions within the TMVP and appear to have been used metonymically to refer to the TMVP itself. An example of this appears at [102] of the delegate’s reasons.

42 Having then referred to the TMVP in this manner, in the follow-up sub-question the Appellant answered that the ‘nature/level of involvement with them’ was ‘none’. Presumably, on the Authority’s use of the omission, the answer should have been that the ‘nature’ of his ‘involvement’ with the TMVP or the Karuna and Pillayan groups was that its members had threatened to shoot him.

43 So read, the idiom of Question 7 is a little odd. A quick glance at it might suggest that it is concerned with an applicant’s membership of political or armed groups. The sub-question, for example, which seeks to ascertain what ‘level’ of involvement an applicant had with the group is apt to encourage such a reading. On the other hand, the word ‘involvement’ may be susceptible to an interpretation which includes being on the receiving end of conduct. On balance, reading Question 7 as a whole, it seems that the Appellant could have answered Question 7 to the effect that the TMVP’s members were threatening him.

44 If the matter were for me, I would not read Question 7 that way. However, it can be read that way and since it can be read that way it is possible to say that it was relevant to the Authority’s assessment of his protection claims that at the entry interview he omitted mention of the fact that members of the TMVP had threatened to shoot him.

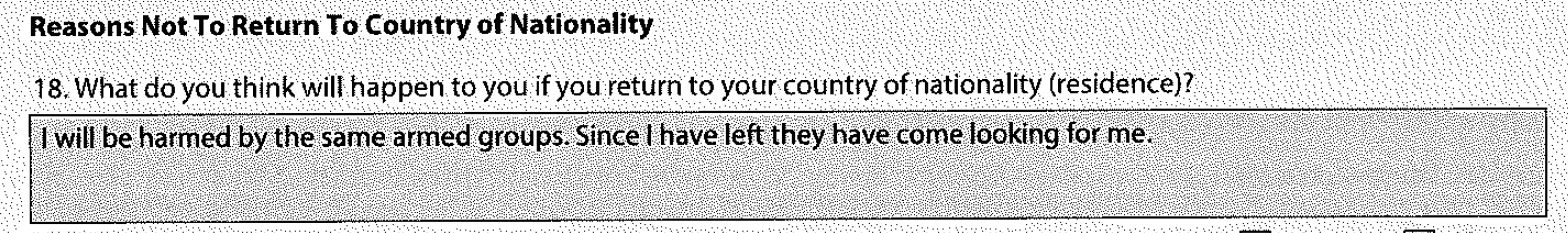

45 I note for completeness that in response to Question 18, the Appellant answered that he would be harmed by ‘the same armed groups’ and stated that since he left ‘they have come looking for me’. Again if the matter were for me, taking this response into account, I would not be inclined to draw an inference that the Appellant omitted any reference to past threats from the TMVP. However, the response to Question 18 does not explicitly refer to the TMVP (or any of its factions) nor to a previously articulated threat of harm.

46 Consequently, the Authority could reasonably have arrived at the conclusion that the omission was relevant to its inquiries. It follows that a rationality challenge to its treatment of the omission as being a matter to which it was inclined to give weight must fail.

47 The third ground of appeal was that the Authority had failed to consider the question of whether the Appellant’s father had a connection with the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (‘LTTE’). The Appellant’s father had disappeared in 1991 and it is clear that the Appellant contended that an aspect of his claim was that he would be suspected of being associated with the LTTE in part because of his father. The Authority rejected this at [22] where it concluded that ‘the Sri Lankan authorities do not suspect the applicant has any connection to the LTTE due to his father’s disappearance’. The Appellant’s point is that the Authority had failed to address whether his father had such a connection. The court below found that the Authority had implicitly rejected the contention that his father had an LTTE connection when it concluded that the Appellant himself was not suspected by Sri Lankan authorities. Although the Authority’s reasons are not entirely clear on this point, I am inclined to agree with this reading. As such there is nothing in this point.

48 The fourth ground was that the Authority had failed to take into account fresh information about the situation in Sri Lanka which had become available since the delegate’s decision on 31 August 2016. This was not a ground which was pursued before the Federal Circuit Court and the Appellant sought leave to raise it for the first time on appeal. The Appellant informed me, and this was reflected in the notice of appeal, that the new information was the return to power in Sri Lanka of former President Mahinda Rajapaksa and subsequently his brother, Gotabaya, who was elected President on 17 November 2019. The Appellant submitted that both had committed war crimes and human rights violations. In the Northern and Eastern provinces, where most Sri Lankan Tamils live, the Appellant said that new army camps had been established and that arrests had resumed. The President had appointed Kamal Gunaratne, as Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and the Appellant submitted that he too had been involved in the commission of war crimes. This had worsened the situation of Tamils in the area and this was exacerbated by the appointment of a fresh Commander of the Army, Shavendra Silva. The Appellant submitted that the current position of Tamils in Sri Lanka was extreme.

49 I propose to assume that the Appellant could have placed evidence to this effect before this Court. The difficulty is that in the somewhat convoluted way in which Pt 7AA operates, any such evidence would – by definition – have been material which was not before the delegate. Ordinarily, the Authority is to decide the review application on the papers based on the material which was before the delegate and any other material in the possession of the Secretary of the Department of Home Affairs that the Secretary considers relevant to the review: s 473DB (read with s 473CB). The Authority has a power to itself obtain new information (s 473DC(1)) but it is under no duty to exercise that power (s 473DC(2)). It nevertheless appears that in the course of its review it must not unreasonably fail to exercise that power: Plaintiff M174/2016 v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] HCA 16; 264 CLR 217 at 227 [21] per Gageler, Keane and Nettle JJ, 245 [86] per Gordon J and 249 [97] per Edelman J. Consequently, the particular circumstances of a review may require the Authority to consider whether to exercise the s 473DC power: Minister for Immigration and Border Protection v CRY16 [2017] FCAFC 210; 253 FCR 475 at [82] per Robertson, Murphy and Kerr JJ. In this case, however, there is nothing which indicates why it would have been unreasonable for the Authority not to consider whether to exercise the power in s 473DC(1).

50 If there had been something before the Authority which suggested that the situation had changed in Sri Lanka after the delegate’s decision this may have enlivened the principle. But there is no material which suggests that was the case. Although for the purposes of determining this ground, I am prepared to accept the Appellant’s submissions about the new situation in Sri Lanka, doing so does not demonstrate anything which would suggest that the Authority had acted unreasonably in not considering whether to exercise the power in s 473DC(1). This is particularly so where the various members of the Sri Lankan government named by the Appellant assumed these roles well after the Authority concluded its review on 19 January 2017.

51 Accordingly, this ground would fail if leave were granted to pursue it and I therefore decline to grant leave on the grounds of lack of utility.

52 The fifth ground involved a contention that the Authority had reached adverse conclusions about his credit without explaining how it did so and thereby denied him procedural fairness. This was not entirely clear from the way in which the ground was drafted but emerged during the Appellant’s oral submissions at T12.10. This ground cannot succeed. Section 473DA provides that Pt 7AA is taken to be an exhaustive statement of the requirements of the natural justice hearing rule in relation to Pt 7AA reviews. There is no provision in Pt 7AA which requires the Authority to give reasons for why it finds an applicant lacks credit. Consequently, this ground – as framed – cannot succeed. In any event, it is tolerably clear that the adverse credit finding flowed from the Authority’s view that it was discreditable of the Appellant to use a letter which was not credible [10] and because he gave inconsistent evidence about a threat made to him at gunpoint in 2012 [11].

53 The sixth ground was a contention that the Authority had erred in failing to respond to his contention that he feared significant harm in Sri Lankan prisons because he would be imprisoned on remand upon his return (on a charge of having departed Sri Lanka unlawfully). The difficulty with this contention is that the Authority did deal with this argument at [31]-[38] in these terms:

The applicant claims he will be harmed by the Sri Lankan authorities because he departed Sri Lanka illegally. He fears he will be jailed for a long time. As part of this claim, he made reference to his scars and the CID extorting his mother, claims which I found above not to be credible. I accept though that the applicant departed Sri Lanka without a passport when he came to Australia. For that reason, he has committed an offence under Immigrants and Emigrants Act (“IAEA”).

The DFAT reports indicate that returnees will be processed by the Department of Immigration and Emigration, (“DOIE”), the State Intelligence Service (“SIS”) and the CID based at the airport. DOIE officers check travel documents and identity information against the immigration database. SIS checks the returnee against intelligence databases. The CID verifies a person’s identity to determine whether the person has any outstanding criminal matters. I am satisfied on the credible information before me that the applicant has no identification concerns, or criminal or security records in Sri Lanka that would raise the concern of these authorities. I found above that I was not satisfied regarding the applicant’s claims he was a person of interest to the CID or the Sri Lankan authorities.

If the authorities suspect the applicant has departed Sri Lanka illegally, he may be charged under the IAEA. As part of this process, most returnees will have their fingerprints taken and be photographed. They will then be transported by police to the closest Magistrates Court at the first available opportunity after investigations are completed. The Court will then make a determination as to the next steps or each individual. Those arrested can remain in police custody at the CID Airport Office for up to 24 hours. In the event that a Magistrate is not available before this time, due to weekends or public holidays for example, those charged may be held at a nearby prison.

Penalties can include up to five years imprisonment and fines of up to SLR200,000. DFAT advises that in practice, penalties are applied on a discretionary basis and usually in the form of a fine. Advice from Sri Lanka’s Attorney General’s Department to DFAT is that no returnee who left Sri Lanka unlawfully as a simple passenger has been given a custodial sentence for their breach of IAEA. Fines are common, but the amounts vary depending on the circumstances of the case and are typically on the lower end.

On return to Sri Lanka, I find the applicant would likely be charged and fined under the IAEA and then released. In the event that the applicant elected to plead not guilty to the offence under the IAEA, he would either be granted bail on personal surety or a family member. The evidence before me is the applicant’s mother and wife are in Sri Lanka. There is no suggestion the applicant was anything other than an ordinary illegal departee from Sri Lanka. In that context, I find that he would not face any chance of imprisonment, but it is likely that he will be fined. On the evidence before me, I find the imposition of any fine, surety or guarantee would not of itself constitute serious harm. I have considered the possibility of a custodial sentence, but there is no country information before me that indicates that custodial sentences are being levelled against low profile illegal departees. In the context of a significant number of Sri Lankan nationals being returned to Sri Lanka, and the absence of any profile that would elevate the penalty the applicant would face, I find there is not a real chance that the applicant would face such a period of detention or imprisonment.

I note the country information indicates that while custodial sentences are not levelled against returnees, a person charged under the IAEA may, in some instances, be detained for several days pending an opportunity to appear before a Magistrate. I note the Australian courts have confirmed that whether a loss of liberty amounts to serious harm involves a qualitative judgment, involving the assessment of matters of fact and degree – including an evaluation of the nature and gravity of that loss of liberty. I have considered whether a detention of several days would constitute serious harm. While I accept that conditions in Sri Lankan prisons are poor due to a lack of resources, overcrowding and poor sanitation, I find that any questioning and detention the applicant may experience would be brief and would not constitute serious harm as inexhaustibly defined in the Act.

I am also satisfied that the provisions and penalties of the IAEA are laws of general application that apply to all Sri Lankans equally. The law is not discriminatory on its terms, nor is there country information before me that indicates that the law is applied in a discriminatory manner or that it is selectively enforced.

When considered singularly or cumulatively, I am also not satisfied that any processes or penalties that the applicant may face as person who left Sri Lanka illegally and returning to Sri Lanka would amount to serious harm. Accordingly, I am satisfied that any process or penalty the applicant may face on return to Sri Lanka because of his illegal departure would not constitute persecution for the purpose of the Act.

54 The ground cannot therefore succeed. This point was not raised in the court below and the Appellant therefore requires a grant of leave to pursue it. I would decline leave on the basis of lack of utility.

55 The seventh ground related to the procedural fairness of the trial. There is some reason to think that ground 7 may have been copied from the notice of appeal in some other matter. It twice refers to the trial judge as Judge Street which is not correct. It also refers to the trial judge as Judge Emmett which is correct although inconsistent with the assertion that the trial judge was Judge Street.

56 As set out in the notice of appeal ground 7 contained three elements. The first two related to the manner in which the Appellant submitted he had been treated as a litigant in person by the trial judge. I would reject both arguments. The trial judge set out in her reasons what she had explained to the Appellant about the procedure before the Federal Circuit Court. It was not suggested by the Appellant that her Honour’s account was factually incorrect. As an explanation to a litigant in person it was legally adequate. The trial judge explained the need for the Appellant to establish that the decision was not made according to law and to identify some error by the Authority going to its jurisdiction. Thus I do not accept that her Honour failed to take appropriate steps to ensure that the Appellant as an unrepresented litigant had sufficient information about the court’s practice and procedure (particular (a)) or that her Honour had failed to explain in plain terms that the Appellant was to identify why the Authority’s decision was not made lawfully or by a fair process (particular (b)).

57 The third element stands in a slightly different position. Not too far into the hearing before the trial judge, the Appellant dispensed with the services of the solicitor who had been representing him. Having done so he then applied for an adjournment which her Honour declined. Her Honour did so principally because it was the Appellant who dispensed with his own lawyer during the hearing and, in any event, she had had the benefit of the solicitor’s oral submissions on ground 1 and his written submissions on the other grounds. Her Honour also observed that the Appellant did not suggest that he had yet engaged a new lawyer to act for him so that a short adjournment only might be involved.

58 I do not see that there was any want of procedural fairness in the course her Honour took. The Appellant was afforded a fair opportunity to be heard. He did not have to terminate the services of his own lawyer during the hearing. Even when he did he had the benefit of the solicitor’s written submissions and an opportunity to present oral submissions. Any procedural disadvantage flowing to the Appellant came from his own actions.

59 In light of these conclusions the appropriate orders are as follows:

(1) The oral application for leave to appeal in relation to grounds 4 and 6 be dismissed.

(2) The Appellant is granted leave to amend his notice of appeal to raise ground 8.

(3) The appeal be dismissed.

(4) The Appellant pay the First Respondent’s costs of the appeal as taxed or agreed.

I certify that the preceding fifty-nine (59) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Perram. |