FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

State of Escape Accessories Pty Limited v Schwartz [2020] FCA 1606

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days the parties provide by email to the Chambers of Justice Davies a draft form of order giving effect to these reasons and timetabling the hearing of the question of relief.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

DAVIES J:

INTRODUCTION

1 The applicant (State of Escape) is the assignee of any copyright subsisting in a perforated neoprene tote bag (the Escape Bag) designed by one of its directors, Brigitte MacGowan (Ms MacGowan). State of Escape alleges that copyright subsists in the Escape Bag as a “work of artistic craftsmanship” (s 10(1), definition of “artistic work” para (c), and s 32 of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (Copyright Act)) and that tote bags made of perforated neoprene imported and sold by the second respondent (Chuchka) in Australia (the Chuchka bags) have infringed that copyright: ss 36(1), 37 and 38 of the Copyright Act. State of Escape has also alleged that Chuchka engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct in contravention of ss 18 and 29(1)(a) of the Australian Consumer Law, contained in sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL), and engaged in the tort of in passing off. The second respondent (Ms Schwartz) is the sole director of Chuchka and State of Escape has alleged that Ms Schwartz is a joint tortfeasor with Chuchka in respect of the alleged infringements of copyright and acts of passing off, and accessorily liable in respect of Chuchka’s alleged contraventions of the ACL. The allegations have been denied by the respondents. The trial proceeded on liability only, with the question of relief to be determined at a later stage, depending on the outcome of the liability hearing.

WITNESSES

2 State of Escape’s lay witnesses were Ms MacGowan, Desley Maidment (Ms Maidment) and Alannah Gilchrist (Ms Gilchrist). Ms MacGowan was the designer and creator of the Escape Bag and is a co-founder and director of State of Escape. Ms Maidment is the other co-founder and director of State of Escape. Both were required for cross-examination. Ms Gilchrist is a legal assistant at Mills Oakley, the solicitors for State of Escape, who made a trap purchase of a Chuchka bag via the David Jones website. She was not required for cross-examination.

3 The respondents’ lay witnesses were Ms Schwartz and her husband, Marc Schwartz (Mr Schwartz). Ms Schwartz established the Chuchka business as a sole trader in early 2015 and incorporated Chuchka in June 2016. Ms Schwartz is the sole director of Chuchka and has the day-to-day running of the business. Mr Schwartz is the company secretary of Chuchka and assists Ms Schwartz with business decisions, accounting work and investigating business opportunities. Ms Schwartz also consults him about new designs. Both of them were required for cross-examination and the Court was urged by State of Escape to make adverse credit findings against each of them.

4 Both parties also relied on expert evidence. State of Escape’s expert was Claire Beale (Ms Beale). Ms Beale is an executive director of Designs Tasmania, a design gallery and cultural institution located in Launceston. She is also the past national president, chairperson of the board of directors and chairperson of the national advisory council of the Design Institute of Australia. She has tertiary qualifications in textile design from RMIT University, as well as a Bachelor’s degree in Arts (Honours) – Fine Art, from the University of Melbourne. She lectured at RMIT University’s School of Fashion and Textiles from about 2008 until January 2019. The respondents’ expert was Andrew Smith (Mr Smith). Mr Smith is an expert in the design, development and manufacture of handbags and accessories with more than 30 years’ experience. For more than a decade, Mr Smith taught the bag making 1: clutch bag; bag making 2: tote bag; and bag making 3: gusseted handbag courses at RMIT University.

THE ESCAPE BAG

5 State of Escape relied alternatively on two forms of the Escape Bag:

(a) a bag that Ms MacGowan handcrafted in early November 2013 which she considered to be her final work;

(b) alternatively the first of eight bags she handcrafted in December 2013 in order to meet State of Escape’s first order from a fashion boutique called Coconut in Noosa, Queensland.

6 Photographs of these bags are Annexure 1.

7 The Escape Bag is a soft, oversized tote bag. The key features of the Escape Bag are said by State of Escape to be:

(a) its composition from perforated neoprene fabric;

(b) its distinctive silhouette and shape (dimensions: approx. width 38cm x height 30cm x depth 24cm); and

(c) sailing rope (or rope of that appearance) as handles to wrap around the body and base of the bag.

8 These key features are said to give the Escape Bag “its overall distinctive personality”.

9 Further key features are said to include:

(a) an internal, detachable pouch made of perforated neoprene (dimensions: approx. width 16cm x height 12cm) rather than a stitched in pocket; and

(b) press studs at either end of the bag.

10 Other aspects of the bag also said to be important are:

(a) hand punched holes where the rope goes in;

(b) heat seal tape finish on the top lip of the bag;

(c) the following finishes on the inside of the bag:

(i) heat seal tape to reinforce re-entry points of rope handles (and press point of snaps) in combination with overlocked stitching;

(ii) heat shrink black tubing to protect ends of rope; and

(iii) heat shrink tubing finishing the rope which is attached to the pouch;

(d) the depth, which is 24cm (by the width of the gusset) and therefore quite wide, which has “obvious visual consequences”;

(e) the fact that there is no lining or base in the bag; and

(f) the interior seams involve no cuts through any of the holes in the perforated material.

THE ALLEGED INFRINGING CHUCHKA BAGS

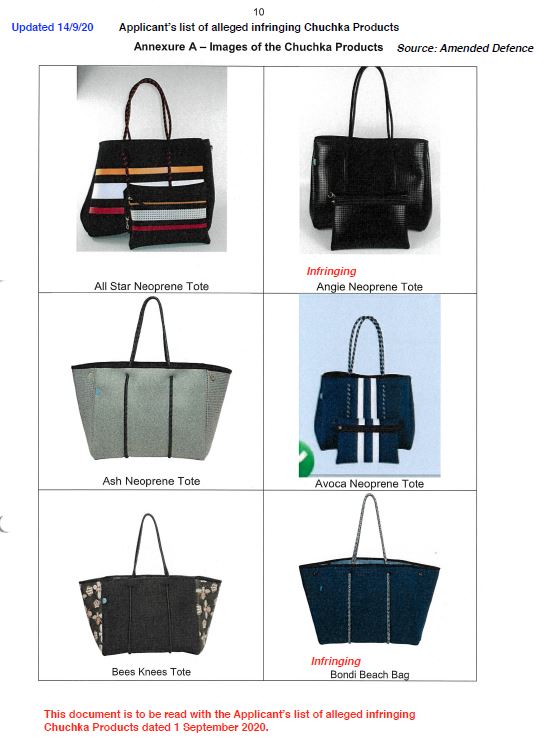

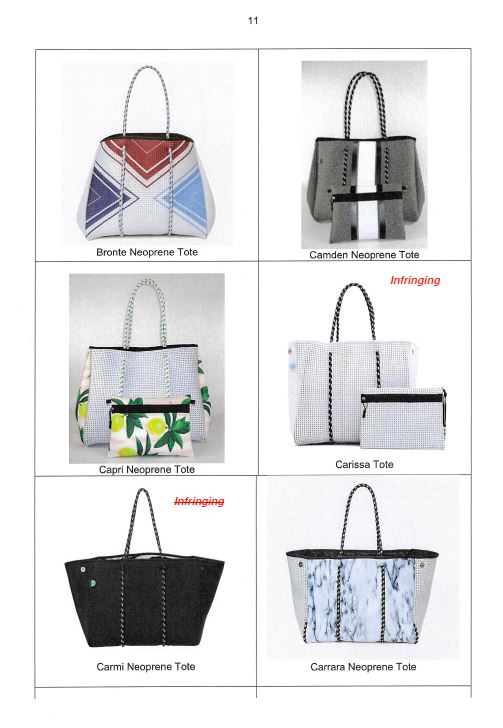

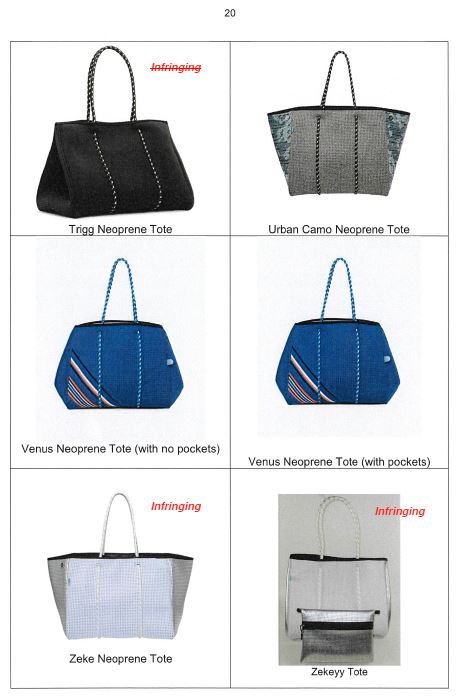

11 State of Escape has alleged infringement of copyright in respect of 34 neoprene tote bags with rope handles sold by Ms Schwartz and Chuchka. Photographs of the alleged infringing Chuchka bags are Annexure 2.

COPYRIGHT CASE

Legal framework for the copyright case

12 Section 32 of the Copyright Act provides that copyright subsists, relevantly, in an “artistic work”, if it is original and the author of the work was a “qualified person” within the meaning of s 32(4) at the time the work was made. Neither proviso is in issue. In issue in this case is whether the Escape Bag is “an artistic work”. Section 10(1) defines “artistic work” to mean, relevantly, “a work of artistic craftsmanship”. The expression “work of artistic craftsmanship” does not have a statutory meaning but its meaning in the context of the Copyright Act is the subject of the case law considered later in these reasons. It is sufficient at this juncture to identify that to be a “work of artistic craftsmanship”, the work must have an “artistic quality”: Burge v Swarbrick [2007] HCA 17; 232 CLR 336 (Burge) at 354–6 [46]–[49].

13 If the Escape Bag is a work of artistic craftsmanship, State of Escape, as the owner of such copyright, has the exclusive right, relevantly, to reproduce that work in a material form: s 31(1)(b) of the Copyright Act. The effect of s 14(1)(a) of the Copyright Act is that the exclusive right to reproduce the work “in a material form” is to be read as including reproduction of “a substantial part of the work”. In IceTV Pty Limited v Nine Network Australia Pty Limited [2009] HCA 14; 239 CLR 458 (IceTV) the High Court made clear that in order to infringe, a substantial part of the expression of the copyright work in a qualitative sense must be taken: IceTV at 473 [30] per French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ, 512 [170] per Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ.

14 State of Escape has alleged infringement by the respondents of its copyright in the Escape Bag pursuant to ss 36, 37 and 38 of the Copyright Act.

15 Section 36(1) provides:

Subject to this Act, the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia, or authorizes the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright.

16 In the case of an artistic work, the acts comprised in the copyright are found in s 31(1)(b) of the Copyright Act:

For the purposes of this Act, unless the contrary intention appears, copyright, in relation to a work, is the exclusive right:

…

(b) in the case of an artistic work, to do all or any of the following acts:

(i) to reproduce the work in a material form;

(ii) to publish the work;

(iii) to communicate the work to the public;

…

17 By s 37(1), the copyright in an artistic work is infringed by a person who, without the licence of the owner of the copyright, imports an article into Australia for the purpose of:

(a) selling, letting for hire, or by way of trade offering or exposing for sale or hire, the article;

(b) distributing the article:

(i) for the purpose of trade; or

(ii) for any other purpose to an extent that will affect prejudicially the owner of the copyright; or

(c) by way of trade exhibiting the article in public;

if the importer knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the making of the article would, if the article had been made in Australia by the importer, have constituted an infringement of the copyright.

18 By s 38(1) of the Copyright Act, the copyright in an artistic work is infringed by a person who, in Australia, and without the licence of the owner of the copyright:

(a) sells, lets for hire, or by way of trade offers or exposes for sale or hire, an article; or

(b) by way of trade exhibits an article in public;

if the person knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the making of the article constituted an infringement of the copyright or, in the case of an imported article, would, if the article had been made in Australia by the importer, have constituted such an infringement.

19 Both ss 37 and 38 require, in respect of imported articles, that the alleged infringer “knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the making of the article would… have constituted an infringement of the copyright” if it had been made in Australia.

20 If, contrary to the respondents’ case, infringement is established, the respondents rely on the defence of “innocent infringement” under s 115(3) of the Copyright Act to resist an award of damages. Section 115(3) provides as follows:

Where, in an action for infringement of copyright, it is established that an infringement was committed but it is also established that, at the time of the infringement, the defendant was not aware, and had no reasonable grounds for suspecting, that the act constituting the infringement was an infringement of the copyright, the plaintiff is not entitled under this section to any damages against the defendant in respect of the infringement, but is entitled to an account of profits in respect of the infringement whether any other relief is granted under this section or not.

21 Conversely, if infringement is established, State of Escape relies on s 115(4) of the Copyright Act to make a claim for additional damages against the respondents. Section 115(4) provides:

Where, in an action under this section:

(a) an infringement of copyright is established; and

(b) the court is satisfied that it is proper to do so, having regard to:

(i) the flagrancy of the infringement; and

(ia) the need to deter similar infringements of copyright; and

(ib) the conduct of the defendant after the act constituting the infringement or, if relevant, after the defendant was informed that the defendant had allegedly infringed the plaintiff's copyright; and

(ii) whether the infringement involved the conversion of a work or other subject-matter from hardcopy or analog form into a digital or other electronic machine-readable form; and

(iii) any benefit shown to have accrued to the defendant by reason of the infringement; and

(iv) all other relevant matters;

the court may, in assessing damages for the infringement, award such additional damages as it considers appropriate in the circumstances.

Issues on the copyright claims

22 The issues identified by State of Escape for determination on the copyright case are as follows:

(a) Does copyright subsist in the Escape Bag as a work of artistic craftsmanship?

(b) Have the respondents infringed State of Escape’s copyright in the Escape Bag?

(i) Do the Chuchka Bags constitute a reproduction of a substantial part of the Escape Bag within the meaning of s 36 of the Copyright Act?

(ii) If so, were the Chuchka Bags imported into Australia or sold in Australia with the knowledge required by ss 37 or 38 of the Copyright Act?

(c) If so, have the respondents established the requirements of section 115(3) of the Copyright Act so as to be entitled to an “innocence” defence?

(d) Is Ms Schwartz personally liable for Chuchka’s copyright infringements as a joint tortfeasor?

(e) Was the conduct of the respondents such as to attract an award of additional damages under s 115(4) of the Copyright Act?

State of Escape and the Escape Bag

23 Although Ms MacGowan and Ms Maidment were cross-examined in some detail, their evidence was largely unchallenged.

24 The commercial venture that became State of Escape was conceived by Ms MacGowan and Ms Maidment in late 2012. The product line developed embryonically from an initial product vision of a signature line of multi-purpose string, neoprene, mesh and net bags.

25 In mid-2013, Ms MacGowan came across perforated neoprene, which she considered had the “potential… to create an amazing looking bag” as it was a lot lighter than non-perforated neoprene and “aesthetically beautiful”. In July 2013, Ms MacGowan decided to use perforated neoprene to create a tote bag she could take on a forthcoming family holiday. She sketched designs and made many different size options just of the compartment element of the bag until she was happy with the proportions. Next she designed a structure and framework to support the compartment. She deposed:

Due to the soft nature of the fabric this structure was fundamental to the success of the bag… I wanted to avoid traditional handles like leather and webbing as they did not feel in the same design aesthetic as the neoprene. So I tried sailing rope. Sailing rope is hard wearing and non-stretch. This allowed me to create a framework that when sewn around the entire girth of the bag allowed me to carry heavy loads without compromising the fabric. I could not work out how to sew the rope onto the fabric, and so glued it on with a craft gun.

26 Ms MacGowan completed the bag in time to take on holiday. She was very happy with it and considered the form of the bag to be aesthetically appealing. That bag exhibited the basic concept and structure of what became, ultimately, the Escape Bag.

27 Ms MacGowan still had design aspects to resolve:

(a) how to sew the rope to the fabric rather than fixing it with a glue gun;

(b) with the rope handles on the outside of the bag, if one handle was to drop with a load inside, the pressure on the area where the rope was joined to the fabric would be immediately compromised, causing it to rip;

(c) the raw cut neoprene edges around the top would fray;

(d) the pressure points under the press snaps and entry points of the rope handles needed reinforcing so as not to damage the fabric;

(e) the rope had no real fixing point at the bottom;

(f) the four bottom corners were left exposed, resulting in a potential for the fabric to be damaged;

(g) there was no small pocket for valuables; and

(h) how to make the inside seams look as finished as the rest of the bag.

28 Ms MacGowan deposed:

The bag did not have any lining. I did not want it to have any embellishments. I did not want anything disguising something that was not beautiful. I wanted the whole thing to be beautifully created. I hand cut all the patterns. I wanted the inside to be as beautiful as the outside. I wanted to challenge ingrained ideas that a bag had to be a certain way. My focus was, ‘This is what it is’. I did not want the bag to be like something else. Everything in the design had to be there for a reason. For instance, there was a risk that binding could ruin the curve of the bag. I ended up putting binding on the top edge because I was concerned it would fray. There were a lot of things that I felt strongly about.

29 Ms MacGowan deposed that it was also important to her that the bag be useful – she “wanted the bag both to look beautiful and to be practical”.

30 Ms MacGowan made “at least” 15 samples, or prototypes, over the next few months. Her evidence was that “there was a lot of testing of components” and she “engaged in a lot of sewing, unpicking and recutting to get things right”. Her view was that this “was necessary in order to produce an item unique in its simplicity and originality”.

31 During this period, Ms MacGowan was also investigating sailing rope as she “felt it very incongruous to use traditional materials… on [neoprene]”. Her evidence was that she chose sailing rope “for its beauty”, “its structural quality, which was something that was also very, very important”, “the longevity” of sailing rope, “the feel of it in hand” and “the look of it”, adding:

It really complemented the neoprene beautifully. And also it was very important that I had to find rope that matched back with the fabric beautifully because it was really about creating an impression of the whole than the individual parts. So that was also very, very important.

32 Over the course of August to October 2013, Ms MacGowan resolved the design issues. She described “the creative design process” as follows.

33 How to sew the rope to the fabric rather than fixing it with a glue gun –

Eventually Ms MacGowan worked out a way to use her domestic sewing machine to sew on the rope but still keep the roundness of the rope on the bag so that it sat upright. She did this by lifting up the foot on her sewing machine.

34 How to stop the fabric from ripping at the pressure point where the rope is joined to the fabric at the top of the bag –

Ms MacGowan’s ideas to resolve this issue included:

(a) adding rope loops to the bag;

(b) reinforcing the vulnerable area of the fabric with a thicker plastic material;

(c) using knots at the entry hole of the rope; and

(d) eyelets at the entry hole.

The ultimate solution was “simple hand punched holes that snugly fitted the rope and were made exactly three perforated holes down” and reinforced on the inside. She described this solution as “clean and simple” and one which “did not detract from the clean lines”.

35 The raw cut neoprene edges around the top would fray –

Ms MacGowan deposed that to use a traditional binding she would have had to sew it on to the neoprene, which she thought would ruin the clean lines and not be aesthetically pleasing. She looked at a type of sailing tape (used to fix tears in sails) and many other “non-traditional” options. She ended up finding a “heat-seal” tape that could be ironed on and which kept the “clean and streamlined” aesthetic of the bag. The use of heat seal tape was a solution suggested to her by a woman named Lesley from Aquasea, a wetsuit repair company. Ms MacGowan explained in cross-examination:

…I had approached Lesley from Aquasea to see if she could make my bags, because I couldn’t get a conventional maker to make them, and I thought, well, someone who works with neoprene, maybe they can make my bag for me because they understand the fabrication, whereas traditional makers didn’t. So please understand that that in context of the overall design development… it was just one possible solution that I went on to explore. But no one had ever used heat seal tape. If it was used as a flat application to repair seams and splits in wetsuits. It hadn’t been used on a round lip on a bag. So it… then had to go another process of how do we apply that, how do we get this to work.

Ms MacGowan referred to this solution as a very “non-commercial” option because it was “incredibly time consuming and fiddly”. However, “it worked with the design”.

36 The pressure points under the press studs and entry points of the rope handles needed reinforcing as to not damage the fabric –

Ms MacGowan deposed that the heat seal tape also provided a solution for the pressure points under the press snaps and the re-entry points of the rope handles. As with the heat seal tape around the lip of the bag, these also had to be ironed on by hand.

37 The rope had no real fixing point on the bottom of the bag –

Ms MacGowan deposed that this proved difficult as there was no “off the shelf” solution. After research, she discovered a glue lined heat shrink black tubing that electricians use to protect exposed electrical cables. She explained that her logic was that if the specification of this product was sufficient to protect electrical cabling it would be suitable for joining the two ends of rope. It also provided her with a solution to finish the ends of the corner ropes that entered back into the bag and also for the application of the hook used to attach the interior detachable pouch to an internal rope.

38 The four bottom corners were left exposed resulting in the potential for the fabric to be damaged –

Ms MacGowan deposed that the rope provided the perfect solution for this, but the problem was how to attach it. She deposed that traditionally that would be done with a piping that could be easily sewn into the seam, but this was not possible with a round rope. Ms MacGowan deposed that she had a lot of problems getting the rope to sit in the corners but “perseverance paid off”. She deposed that the rope also frays very easily, so she had to retract it back into the bag approximately 6cm up from the base so it could be neatly finished.

39 There was no pocket for valuables –

Ms MacGowan did not want to sew a pocket directly onto the fabric for aesthetic reasons “because you would have been able to see that on the outside which would have ruined the visual look”, so she had to find a way to attach a separate pouch to the inside of the bag. This solution came with the rope corners and the re-entry point back into the bag. By making this section of the rope longer she could attach a hook to secure a pouch.

40 How to make the inside seams as finished as the rest of the bag –

Ms MacGowan deposed that, being a large open bag, the inside finish was just as important to her as the outside finish. She did not want to have lining inside the bag because she “wanted the fabric to speak for itself and be true to… its qualities”. Following on from her design principles to keep everything as simple and true to form as possible without unnecessary elements, she considered that the best way to make the seams “beautifully finished” was to cut very accurately between the lines of the perforations (which were 5mm apart) to form a “beautiful straight edge”. She deposed that traditionally you would bulk cut patterns and cut through the lines of holes, if necessary, and then just sew binding tape over the seams to neaten it up. However, in her endeavour to be as simple and beautiful as possible this was not a solution she was willing to consider. She deposed that every single pattern piece of each Escape Bag is hand cut with a rolling knife and ruler which has to be adjusted constantly in the cutting process to allow for the fact the holes are not straight due to the stretchy nature of the fabric. She deposed that, once again, this was a very design driven and “non-commercial” approach to the making of a bag. Whilst this approach was time consuming, Ms MacGowan deposed that it was fundamental to how she wanted the bag to look.

41 In early November 2013, she was very close to the final design of the Escape Bag and had prepared two final versions. The only difference between then was that one had eyelets and one did not. She decided not to proceed with the version that contained eyelets as she “had formed the view that eyelets did not make the bag look as elevated”.

42 Her evidence was that by 8 November 2013 she felt she had “nailed it” and was satisfied that this was the final product. She prepared specifications setting out the design and construction of the bag to help source an appropriate manufacturer.

43 There was no branding on the bag at this stage, but in December 2013, Ms MacGowan made three bags – one yellow, one blue and one coral – with branding.

44 In the meantime, Ms MacGowan and Ms Maidment had started to investigate manufacturers for the bag. They first contacted a Chinese manufacturer who produced a sample from the specifications they gave, but told them the sample was not workable in bulk production. A second sample produced by the manufacturer was, in Ms MacGowan’s view, “not up to scratch”. They then took a sample to a manufacturer in Surry Hills NSW who, according to Ms MacGowan, told them it was not possible to make the bag. Ms MacGowan’s evidence was that she learnt from this discussion that specific tooling was needed to make the bag on a volume basis, particularly to sew through the rope. Another manufacturer Ms MacGowan approached in November 2013 told her he did not have the machinery or expertise to make the bag. Ms MacGowan deposed that the feedback she received from potential manufacturers when they refused to make the bags related to her quality requirements, which impacted their ability to achieve the efficiencies necessary to make the bags to scale. Some of the issues were, according to Ms MacGowan:

(a) cutting the patterns near the holes of the perforated neoprene, which must be done by hand. Potential manufacturers were not prepared to do it by hand, or they covered the holes with something such as binding, or they would just not bother to cut them properly;

(b) the binding of the heat seal on the top of the bag, which needed to be hot enough to melt the glue and permit the fabric to stick, but not so hot as to destroy it by burning; and

(c) to sew the rope handles required a special tooling on the sewing machine.

45 Ultimately, Southern Cross Leathergoods (based in NSW) (Southern Cross) agreed to manufacture the bag.

46 The first order for the Escape Bag was in December 2013. The order came about after Ms Maidment happened to walk into the retail store “Coconut” in Noosa with a coral sample bag which caught the attention of the store manager. Over the Christmas/New Year period Ms MacGowan made eight bags (the Coconut bags) in three different colours – coral, neon yellow and electric blue – to fill the order.

47 The differences between the November 2013 bag specification, as sent to potential manufacturers, and the Coconut bags were:

(a) as to the November 2013 version of the bag, all elements were resolved except for:

(i) heat shrinkable tubing was not yet present on the bag;

(ii) the design of internal pouch was different; and

(iii) there was no branding.

(b) as to the Coconut bags, all outstanding design elements were by then resolved such that:

(i) the bags had heat shrinkable tubing;

(ii) the design of the internal pouch had altered; and

(iii) the bags had branding.

48 The bags which were from then on produced by Southern Cross were to the same specifications as the Coconut Bags.

49 The Escape Bag has been a highly successful product for State of Escape, which State of Escape sells both online and through various stockists, domestically and internationally.

50 Southern Cross was initially the only manufacturer prepared to manufacture the Escape Bags. The evidence was that it took almost four months for Southern Cross to come up with an acceptable sample. In an email dated 19 March 2014, Southern Cross said that if the final sample it had provided was unacceptable, it could not continue:

The demands and expectations are just too high – we need to work at a certain speed and we also have other customers who require products.

Essentially, there is no economy of scale with your product. We are required to make each and every product with the ultimate care, using a ruler at every stage to ensure absolute accuracy down to the millimetre.

Perhaps the best way is to make them as you were at home with meticulous care. You can do this but we unfortunately cannot.

51 Shortly after this, Southern Cross was selected as State of Escape’s manufacturer. The first production run by Southern Cross was completed on about 25 March 2014. By late March 2014, State of Escape had launched its online store and had also sold 36 bags to a fashion boutique called Bassike. The taglines for the launch of the State of Escape brand were “Beauty in utility” and “Form meets function”.

52 By September 2014, Southern Cross was struggling to keep up with demand and State of Escape approached another supplier, Ray from Bush Leather, to see if he could assist. Ms MacGowan informed him that:

Ideally we are looking to keep our manufacturing in Australia but we are struggling to keep up with the demand and need help in the preparation of the bags for making. Each bag is individually cut (due to the perforations) and finished with an iron on heat seal tape. We are looking to find someone to help us with this?

53 Ray declined, advising Ms MacGowan that “the degree of handwork and precision required to make these [bags was] not within our scope”.

54 In March 2016, Southern Cross increased manufacture from 40–50 bags per day to 60–70 bags per day.

Chuchka and the Chuchka bags

55 Chuchka carries on business in Australia selling a range of Chuchka branded accessories, including perforated neoprene tote bags. Ms Schwartz established the business under the business name “Chuchka” in early 2015 and, on 21 June 2016, had the business incorporated.

56 Ms Schwartz sources products for the Chuchka brand principally through the Alibaba website, a China-based website that connects manufacturers, suppliers, exporters and importers. Chuchka’s first product line was beach towels. During the 2015/16 summer period, Ms Schwartz added neoprene bags to Chuchka’s product range. Ms Schwartz’s evidence was that she thought stylish beach bags would sell well with the beach towels and she wanted to use neoprene for the beach bags because her research indicated it was “on trend” for apparel and accessories and she thought neoprene suited the practical/beach/outdoor feeling she was trying to achieve. She had also noticed people walking around in Sydney with neoprene bags. In cross-examination, Ms Schwartz said she could not remember whether the bags she saw had been made of perforated neoprene or had handles made from sailing rope, nor could she remember any of the brands nor recall asking anyone carrying a neoprene bag what brand it was.

57 Evidence was given by Ms Schwartz that she did some general internet searching of neoprene bags in October 2015. Those searches came up with a number of bags using neoprene as the main fabric, including tote bags, but, on her evidence, she did not come across the Escape Bag during her preliminary investigations and could not recall if she was aware of the State of Escape brand at the time. She deposed that if she was aware of the brand at the time, it did not cross her mind during those investigations. For reasons given later, I reject that evidence.

58 Ms Schwartz searched the Alibaba website for suppliers of neoprene beach bags. She deposed that prior to commencing her search on Alibaba she did not have any particular style or shape in mind for the bag, other than a bag made of neoprene and which was big enough to be useful as a beach bag or carry all bag, but she did want to be able to customise the bags by using multiple colours, metallic finishes and printing directly onto the fabric. She also wanted to include the Chuchka trade mark on the bag. She deposed that the search results came up with at least ten manufacturers and suppliers of neoprene beach bags and she used the Alibaba message service to enquire about the different tote bag styles and designs which a number of those manufacturers and suppliers offered. She sent those messages on 2 November 2015. The manufacturers she contacted included Crystal Xu from Wuxi Happy Sport Co Ltd (Happy Sport). She sent two messages to Happy Sport. The first was sent at 10.23 pm enquiring about the price for “neoprene beach bag” with an order for 2000 bags. The second was sent at 10.24 pm asking for the price for “perforated neoprene bag” with an order for 2000 bags. The messages showed the bags she was enquiring about.

59 Ms Schwartz gave the following evidence concerning the 10.24 pm email. She deposed that during the searching on Alibaba she did not recall seeing any bags that incorporated neoprene and sailing rope. However, she did recall finding a yellow perforated neoprene bag with the name “perforated neoprene bag”. She deposed that this bag was different to the others she enquired about because it was described as perforated. She was interested in the yellow neoprene bag as she believed it had an aesthetic in terms of both colour and style that appealed to her and she thought it would sit well with the Chuchka brand. She deposed that it seemed more modern than some of the other bags she had seen on Alibaba. She deposed she messaged the supplier about this bag, also using the Alibaba messaging system. Her evidence was that when she sent that message she was not aware that the supplier of this bag was also Happy Sport. She became aware of this when Happy Sport replied to her message.

60 On 3 November 2015:

(a) at 12:50, Happy Sport responded with a price for 2000 bags. Ms Schwartz then sought their email address because she wanted to email with some more questions.

(b) at 1.40 pm, Ms Schwartz sent an email to Fortune Bags (one of the other suppliers she had located on Alibaba) asking if they could do perforated neoprene “like this” (providing an image of a swatch of perforated neoprene). She also enquired as to options for the handle – “maybe a rope style?” – and whether they offered a small neoprene wallet/money case;

(c) at 2.47 pm, Happy Sport emailed Ms Schwartz asking whether the quote they had sent through the Alibaba message system had been received and advising they could be contacted if there were any further questions;

(d) at 2.56 pm, Ms Schwartz sent a return email to Happy Sport with follow up questions. She asked whether they “produce[d] the photo” of the yellow perforated neoprene handbag on their website and whether they could do perforated neoprene. She also asked whether, “for a bag like the yellow one”, there was another option for the handle as she did not want to “copy the same as them”, whether it was possible to do two colours and for them to send her a photo of a logo/company name on a rubber tag “[Happy Sport] have done”;

(e) at 5:46 pm, in response to a query that Ms Schwartz sent to another supplier on Alibaba on 2 November 2015, Will Zhang of Vshowbags Co emailed Ms Schwartz pictures of “different neoprene bags we’re running”. The images included an image which appears to be identical to the Escape Bag (including with branding) and the yellow perforated neoprene handbag promoted by Happy Sport on its website. Ms Schwartz’s evidence was that this email went to her junk email folder and she only found it after she had progressed discussions with Happy Sport and she had no further correspondence with Vshowbags Co;

(f) at 6.11 pm, Happy Sport informed Ms Schwartz by email that they could produce the yellow neoprene hand bag on their website, they had 32 regular colours and could also print an image on the neoprene;

(g) at 6.45 pm, Ms Schwartz asked for pictures of all styles of neoprene bags, and again asked whether there was another option for the handle as she “[didn’t] want the same rope as they have”. She also wanted to know whether they could do the rope in all different colours;

(h) at 6.48 pm, Happy Sport responded with pictures of other neoprene bag styles and wallets, advised that the handle could be made of neoprene and confirmed that Happy Sport could do two different colours on the bag;

(i) at 7.43 pm, Ms Schwartz emailed Happy Sport images of two mock-ups with the question, “Could we do something like these?”;

(j) at 9.11pm, Happy Sport confirmed that Ms Schwartz’s mock-up design was something they could do, and asked some follow up questions about the image printing and whether the full bag would be perforated neoprene;

(k) at 9.20 pm, Ms Schwartz confirmed that the printed image should be on the front and back, and the sides and inside should be perforated. She also asked for the usual dimensions of the bag and advised that she would like the rope handle to be longer;

(l) at 10.24 pm, Ms Schwartz sent an email to another supplier requesting whether they could do perforated neoprene, providing an image of the same swatch as that sent to Fortune Bags.

61 For the two mock-ups that she sent to Happy Sport at 7.43 pm, Ms Schwartz used images of neoprene bags on Happy Sport’s Alibaba website which she downloaded onto her computer and digitally adjusted. She gave the following evidence at [48] of her second affidavit:

(a) First, I used images of two different coloured bags (one grey bag and one black bag) that I had down loaded and saved from the HappySport site on Alibaba. I then superimposed them digitally. I then cropped out the interior section of the grey bag (that is the inside section of the bag) so that the black was visible on the interior section of the bag and the grey bag was visible on the exterior section of the bag (i.e. on the outside of the bag). I also found white and black marble patterns from Shutterstock online and overlaid the white marble pattern on the front of the bag image I had mocked up. The result is shown in the following image:

(b) Secondly, I followed the same process with a white and a red/black bag. I superimposed the white and red/black bag. I cropped out the interior section of the white bag so that the black/red bag was visible on the interior section of the bag and the white bag was visible on the exterior section of the bag. I then overlaid the black marble on the front of the bag image I had mocked up. The result is shown in the following image:

62 Her evidence was that she assumed that the bags featured on Happy Sport’s Alibaba website were bags that Happy Sport had already made and had actually produced themselves for customers. In fact, the images were of Escape Bags, which the respondents concede.

63 On 4 November 2015:

(a) at 1.11 am, Happy Sport sent an email with the usual dimensions of the neoprene bag – “35(l)*29(h)*15(w)cm” – and advised that the rope handle could be longer;

(b) at 6.34 am, Ms Schwartz emailed Happy Sport with some further queries;

(c) at 2.14 pm, Ms Schwartz advised Happy Sport of the dimensions that she wanted – “35(l)*29(h)*25(w) cm” – increasing the depth by 10 cm, asked about the size of the rope, whether the bag would have “[p]ress studs at the end to compress [the] bag like [the] picture attached”, and also requested a “small neoprene pouch”, dimensions “W 16cm x H 13cm. like attached picture”. The file names of the two attachments were “SOE bag” and “SOE pouch”;

(d) at 9.02 pm, Ms Schwartz provided instructions to Happy Sport for the order.

64 Ms Schwartz’s instructions to Happy Sport included:

(a) an increase of the depth of the standard dimensions by 10 cm to 25 cm (being only 1 cm greater than that of the Escape Bag). The dimensions were otherwise approximate to those of the Escape Bag;

(b) a black rope handle with white dot;

(c) press studs; and

(d) a pouch with dimensions almost identical to the pouch included in the Escape Bag.

65 The images of the “SOE bag” and the “SOE pouch” which Ms Schwartz emailed Happy Sport at 2.14 pm were other images that Ms Schwartz had saved from the Happy Sport page on the Alibaba website. Ms Schwartz deposed:

On about 4 November 2015, I also sent to Ms Xu some other images that I had saved from the HappySport Alibaba site. I sent these images to Crystal because I liked some of the features of these bags (the press studs and the small pouch) and I wanted to incorporate them into the bag HappySport was going to make for me. These images were called “SOE bag” and “SOE pouch”. When I saved the images, I saved them with the automatic name given to the image when they were down loaded to my computer. At the time, “SOE” did not mean anything in particular to me. I am aware that the image in the file entitled “SOE pouch” incorporates the branding “State of Escape”. I was aware at the time I saved that image that it had a brand on it. However, at that time, the brand “State of Escape” did not mean anything in particular to me. I assumed that HappySport made this bag for the company that appeared on the label and did not give it any more thought.

66 The “SOE bag” and the “SOE pouch” were images of an Escape Bag and the internal pouch sold with the Escape Bag, which the respondents have also conceded. In cross-examination, Ms Schwartz agreed that she knew at the time that the bag and pouch had the brand name State of Escape on them but she maintained her evidence that the brand “State of Escape” did not mean anything in particular to her at the time. I reject that evidence.

67 State of Escape’s business records conclusively established the online purchase on 30 October 2015 of a State of Escape grey perforated neoprene cross-body bag by a customer identified as “Stefanie Schwartz” who used a credit card with the cardholder name “Stefanie Schwartz” to pay for the purchase. Ms and Mr Schwartz’s residential address was given as the billing and shipping address as well as Ms Schwartz’s email address. Also in evidence was a delivery docket recording that at 8.34 am on 2 November 2015, StarTrack delivered the bag which was the subject of the order to the address noted on the sales receipt and a person who identified herself by signature as “S Schwartz” signed for the delivery.

68 The circumstance of this purchase was the subject of Mr Schwartz’s evidence. His affidavit evidence was that he had a meeting in Paddington, NSW on 30 October 2015 and as he walked back to his car he visited the Bassike store located on Glenmore Road, Paddington. He was looking for a present for his sister as it was soon to be her birthday and he thought she would appreciate a personal, fashionable gift. He deposed that his decision to walk into the Bassike store was spontaneous and he had not planned to go there, but only decided to go into the store as he walked past it. When he visited the store, he saw a number of clothes and bags on display for sale. One of those bags was a cross-body bag of perforated neoprene. He deposed he did not take much notice of the fabric at the time but thought the style was something his sister would like and he thought the look of the bag would suit her. He chose the grey colour because it was neutral. He deposed that he did not give the purchase a great deal of thought beyond the selection of style and colour and was in and out of the store in about 10 minutes. He further deposed that after picking out the bag he approached the counter in the store to purchase the bag. As he was in the process of paying for the bag, the sales assistant asked him for an email address to send an electronic copy of the receipt. He provided the email address of his wife because he wanted the receipt but did not want to deal with the “spam” email that usually comes with joining a marketing list. He deposed that he also thought that his wife might appreciate receiving marketing material about fashion more than he would. The email sent to Ms Schwartz’s email address, which was annexed to Mr Schwartz’s first affidavit, was entitled “Order confirmation for order #2554”. He deposed that he did not know why the email was titled “Order confirmation” when he actually purchased the bag in the Bassike store. He also deposed that he did not know why the email stated that the bag was to be delivered to the shipping address given in the email because he walked out of the store with the bag after purchasing it. He did not recall giving the store his address. Further, he did not know why the receipt was from State of Escape rather than from the Bassike store where he bought the bag. He deposed that soon after purchasing the bag he gave it to his sister for her birthday, and he did not take the bag home nor show it to his wife prior to giving it to his sister.

69 Ms Schwartz gave corroborating evidence. Her account that she was aware from a conversation she had with her husband after she received the first letter of demand from State of Escape in December 2016 that he had purchased a cross-body bag from a Bassike store on 30 October 2015 which was branded “State of Escape”. She deposed that her husband told her that the assistant at the store requested an email address for the purchase and he gave the store assistant her email address. She deposed that although an invoice was sent to her email address, she did not open the email on the date it was received and did not recall opening the email or seeing the invoice until after she received the first letter of demand from State of Escape. She also deposed she did not know why the sender of the invoice was State of Escape, rather than Bassike. She deposed that she did not see the bag her husband gave his sister before he gave it to her, she was not present when her husband gave the bag to his sister and she did not know exactly when he gave it to her. She deposed she only found the email from State of Escape in the weeks after she received the first letter of demand when she searched her email account for “State of Escape”.

70 In response to that evidence, Ms Maidment swore an affidavit in which she produced the relevant State of Escape business records evidencing the purchase of the bag online by Ms Schwartz and the acceptance of delivery by Ms Schwartz.

71 Mr Schwartz then filed a second affidavit by way of response to that evidence. In that affidavit he acknowledged that the documents exhibited to Ms Maidment’s affidavit were inconsistent with his recollection of how he purchased the State of Escape cross-body bag. He deposed that when he made his first affidavit the events he described were as best as he could recall them but accepted his recollection of those events “appears to have been incorrect” and “that the bag appears to have been purchased online”. In cross-examination Mr Schwartz maintained that he had a “very vivid recollection of going into [the Bassike] store”, and that his evidence about having a meeting in Paddington, going into the store and choosing the bag in the store was correct, but when pressed he agreed his recollection was “partly wrong”, in that “the purchase part was incorrect”. He proffered that “it would appear from the evidence that [he] had bought [the bag] subsequently online”. That answer was purely speculative and I do not accept it as a reliable account.

72 Ms Schwartz also filed an affidavit in response to Ms Maidment’s evidence. She deposed that she did not recall purchasing a bag from the State of Escape website nor signing for the parcel which was delivered on 2 November 2015, nor did she recall opening a parcel containing a State of Escape cross-body grey bag. Her evidence was that “[i]ndeed, [she did] not recall ever having or using such a bag”. She accepted that her recollection appeared to have been incorrect but it “remain[ed] the case that [she did] not have any recollection of purchasing a bag from the State of Escape website”. In cross-examination she was more emphatic in her evidence. She denied that: (1) she purchased the cross-body bag; (2) she was aware of the State of Escape brand at the time; (3) knew of the features of the Escape Bag as a result of visiting the State of Escape online store; and (4) she had visited the State of Escape website and looked at the bags depicted including the Escape Bag before placing her order with Happy Sport.

73 Mr Schwartz’s account of the purchase of the State of Escape cross-body bag was clearly discredited but I am prepared to find that his account was the result of faulty recollection rather than deliberate untruthfulness. However, I am not prepared to accept that it was Mr Schwartz who purchased the bag online. First of all, his evidence cannot be accepted as reliable having regard to his patently faulty memory. Secondly, there is no objective evidence to support his claim that he purchased the bag. Although Ms Schwartz maintained she had no recollection of ordering the bag, her lack of recollection is also not a reliable basis on which to find that she did not do so. To the contrary, it is reasonable to infer from the fact that the order confirmation was directed to Ms Schwartz, that her credit card was used to pay for the purchase and that she signed for the parcel, that it was Ms Schwartz who ordered the cross-body bag online from the State of Escape website. Moreover, the timing of the purchase, together with the steps Ms Schwartz then took that led to the order she placed with Happy Sport, tell against the creditworthiness of Ms Schwartz’s denials. The course of events is consistent with Ms Schwartz having knowledge of the State of Escape brand and its range of perforated neoprene bags at the time she fixed upon the design and specifications for the Chuchka bags to be made by Happy Sport. I find it improbable that Ms Schwartz had not visited the State of Escape website beforehand and was not then aware of the features of the Escape Bag and I also find it improbable that the brand did not particularly mean anything to her at that time. However, I am prepared to find that her account was also the result of faulty recollection rather than deliberate untruthfulness, given her husband’s evidence about the version of the events. Cross-examination did not disclose a proper basis for concluding that Mr and Ms Schwartz colluded in manufacturing the accounts they gave.

74 On about 18 November 2015, Ms Schwartz gave Happy Sport further production instructions and requested that it commence production. In about December 2015, Ms Schwartz imported the products and the Chuchka bags went into the Australian market. Since the initial order, Ms Schwartz has introduced features and changes to the Chuchka bags, which have included matters such as the way in which the pouch is attached to the tote bag, the addition of an internal lining in the bag, and the use of non-perforated as well as perforated neoprene. The respondents have accepted that each of the subsequent neoprene tote bags sold by Chuchka have been based on the initial Chuchka bags.

75 Ms Maidment’s evidence was that at some time prior to 2 December 2016 she became aware that Chuchka was selling a bag called “Luxe Neoprene Tote”, which was the same name and had similar colouring to one of the Escape Bag styles. A letter of demand was sent to the respondents on 7 December 2016 alleging copyright infringement, misleading and deceptive conduct and passing off. A second letter of demand was sent on 25 January 2018 when it was noticed that Chuchka had introduced a white perforated neoprene bag with blended sailing style rope. The evidence did not disclose whether responses were received to these letters of demand but it was not in dispute that Chuchka has continued to import and sell the Chuchka bags.

Is the Escape Bag a work of artistic craftsmanship?

76 The meaning of the expression “work of artistic craftsmanship” in the context of ss 10(1) and 77 of the Copyright Act was considered by the High Court in Burge. Section 77 has relevance because it provides a statutory context for the purpose and scope of the term “artistic craftsmanship”. Section 77 appears in div 8 of the Copyright Act, which provides a scheme that governs the interaction between copyright in artistic works and registered designs under the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) (Designs Act). In brief terms, the effect relevantly of s 77 is to extinguish copyright protection for an artistic work, except if it is a work of artistic craftsmanship, where a “corresponding design” of the work has been applied industrially with the licence of the copyright owner. Section 77 expressly does not apply to a work of artistic craftsmanship: s 77(1)(a). Such works have copyright protection, notwithstanding that the design which corresponds to that work has been embodied in a product. As explained in Burge, the legislative policy is to encourage design registration and to limit or remove copyright protection for artistic works which are applied to industrial products: Burge at 343 [10] and 351–3 [35]–[44]. Works of artistic craftsmanship are singled out because it was considered by Parliament that those works are more appropriately protected under the Copyright Act: Explanatory Memorandum to the Copyright Amendment Bill 1988 (Cth) at [24]; Burge at 352-3 [42]. Whereas under the Designs Act the maximum term of a registered design is 10 years (s 46(1)(b) of the Designs Act), copyright in a work of artistic craftsmanship generally subsists for the life of the author plus 70 years: s 33(2) of the Copyright Act. In Coogi Australia Pty Ltd v Hysport International Pty Ltd (1998) 86 FCR 154, in a passage cited with approval in Burge at 353 [43] and 356 [50], Drummond J observed at 168:

What may justify the special status conferred on works of artistic craftsmanship by ss 74-77 is recognition that the real artistic quality that is an essential feature of such works and the desirability of encouraging real artistic effort directed to industrial design is sufficient to warrant the greater protection and the accompanying stifling effect on manufacturing development that long copyright gives, in contrast to relatively short design-protection.

Thus, by the operation of ss 32(1) and 77 of the Copyright Act, if the Court finds the Escape Bag is a work of artistic craftsmanship then copyright will subsist. If not, State of Escape has no protection under the Copyright Act.

Principles – Burge

77 The parties were not in dispute on the guiding principles to apply in determining whether the Escape Bag is a “work of artistic craftsmanship”. Those principles were settled by the High Court’s decision in Burge and may be distilled as follows:

(a) the phrase “a work of artistic craftsmanship” is a composite phrase to be construed as a whole: Burge at 357 [56], 360 [66]. It is not permissible to inquire separately into whether a work is: (a) artistic; and (b) the manifestation of craftsmanship;

(b) in order to qualify as a work of artistic craftsmanship under the Copyright Act, the work must have a “real or substantial artistic element”: Burge at 356 [52];

(c) “artistic craftsmanship” does not mean “artistic handicraft”: Burge at 358 [59];

(d) a prototype may be a work of artistic craftsmanship “even though it was to serve the purpose of reproduction and then be discarded”: Burge at 359 [60];

(e) the requirements for “craftsmanship” and “artistic” are not incompatible with machine production: Burge at 358–9 [59]–[60];

(f) whilst there is a distinction between fine arts and useful or applied arts, when dealing with artistic craftsmanship there is no antithesis between utility and beauty or between function and art: Burge at 359 [61];

(g) a work of craftsmanship, even though it cannot be confined to handicraft, “at least presupposes special training, skill and knowledge for its production… ‘Craftsmanship’… implies a manifestation of pride and sound workmanship – a rejection of the shoddy, the meretricious, the facile”: Burge at 359 [61], citing George Hensher Ltd v Restawile Upholstery (Lancs) Ltd [1976] AC 64 (Hensher) at 91 per Lord Simon;

(h) although the matter is to be determined objectively, evidence from the creator of the work of his or her aspirations or intentions when designing and constructing the work is admissible, but it is neither determinative nor necessary: Burge at 360 [63]–[65]. In determining whether the creator intended to, and did, create a work possessing the requisite aesthetic quality and requisite degree of craftsmanship, the Court should weigh the creator’s evidence together with any expert evidence: Burge at 360 [64] and [65]; and

(i) in considering whether a work is one of “artistic craftsmanship”, the beauty or aesthetic appeal of the work is not determinative. The Court must also weigh in the balance the extent to which functional considerations have dictated the artistic expression in the form of the work: Burge at 364 [83]–[84].

78 At 364 [83] the Court in Burge stated:

It may be impossible, and certainly would be unwise, to attempt any exhaustive and fully predictive identification of what can and cannot amount to “a work of artistic craftsmanship” within the meaning of the Copyright Act as it stood after the 1989 Act. However, determining whether a work is “a work of artistic craftsmanship” does not turn on assessing the beauty or aesthetic appeal of work or on assessing any harmony between its visual appeal and its utility. The determination turns on assessing the extent to which the particular work’s artistic expression, in its form, is unconstrained by functional considerations.

As the Court observed, the more that functional considerations dictate the form of expression of the work, the less the scope for real or substantial artistic expression.

79 The facts of Burge were that Swarbrick was a naval architect who designed a yacht. In the course of doing so, he created a full scale model of the hull and deck (Plug) of what became the finished yacht, and mouldings of the hull and deck. The mouldings were exact, although inverted, copies of the Plug. In issue was whether the Plug and the hull and deck mouldings were works of artistic craftsmanship. It was held that they were not. The Court emphasised that determining whether a work is “a work of artistic craftsmanship” does not turn on assessing the beauty or aesthetic appeal of work or on assessing any harmony between its visual appeal and its utility, but rather “turns on assessing the extent to which the particular work’s artistic expression, in its form, is unconstrained by functional considerations”: Burge at 364 [83]. The Court accepted that the Plug was a work of craftsmanship but found that the work of Mr Swarbrick in designing the Plug was not that of an artist craftsman. The Court reasoned at 362 [73]:

Taken as a whole and considered objectively, the evidence, at best, shows that matters of visual and aesthetic appeal were but one of a range of considerations in the design of the Plug. Matters of visual and aesthetic appeal necessarily were subordinated to achievement of the purely functional aspects required for a successfully marketed “sports boat” and thus for the commercial objective in view.

As the Court observed at 364 [84], the more substantial the requirements in a design brief to satisfy utilitarian considerations of the kind indicated with the design of the yacht, the less the scope for that encouragement of “real or substantial artistic effort”.

80 The High Court adopted the approach of Lord Simon in Hensher. In issue in Hensher was whether a prototype chair of “a commercially bold and original design, though not calculated to appeal to fastidious taste” was a work of artistic craftsmanship within the meaning of the Copyright Act 1956 (UK). Lord Simon agreed with the Court of Appeal that mere originality in points of design aimed at appealing to the eye as commercial selling points was not sufficient to make the work a work of artistic craftsmanship. As Lord Simon explained, the issue was whether the work was a work of artistic craftsmanship, not an artistic work of craftsmanship. In passages cited by the High Court in Burge at 359 [61], Lord Simon said at 91:

A work of craftsmanship, even though it cannot be confined to handicraft, at least presupposes special training, skill and knowledge for its production… “Craftsmanship”, particularly when considered in its historical context, implies a manifestation of pride in sound workmanship—a rejection of the shoddy, the meretricious, the facile.

And at 93:

Even more important, the whole antithesis between utility and beauty, between function and art, is a false one—especially in the context of the Arts and Crafts movement. “I never begin to be satisfied,” said Philip Webb, one of the founders, “until my work looks commonplace.” Lethaby’s object, declared towards the end, was “to create an efficiency style.” Artistic form should, they all held, be an emanation of regard for materials on the one hand and for function on the other.

Lord Simon concluded that the chairs were “perfectly ordinary pieces of furniture”. Lord Simon considered it would be “an entire misuse of language to describe them or their prototypes as works of artistic craftsmanship”, stating that the “novelty” and “distinct individuality” of the chairs “at the most… established originality in points of design aimed at appealing to the eye as commercial selling points” but did not make the chair or its prototype a work of artistic craftsmanship.

Ms MacGowan’s evidence

81 Ms MacGowan’s evidence was that she designed, sketched and “creatively problem solved” every design aspect of the Escape Bag. Her design philosophy focussed on “simplicity, beauty and originality”. To her, this was the “pinnacle of design excellence”. She deposed that when creating the Escape Bag:

The aesthetic considerations which dominated were simplicity, beauty and originality. My aim was to create something free of embellishments, that was so pure in its form, structure and makeup that it embodied beauty in simplicity. It had to be unique.

82 She considers that what distinguishes the bag from simply being a utilitarian article is “the well-considered and resolved design aesthetics of the bag”. In her view:

It is beautiful, stylish and comment-worthy. The Escape Bag becomes part of the way a person can express individual fashion style, coordinating with one’s clothes and becoming part of one’s ‘look’. Purely utilitarian to me is a green Coles bag.

83 Ms MacGowan gave evidence that she regards the fundamental elements of the Escape Bag to be as follows:

(a) perorated neoprene;

(b) sailing rope (or rope of that appearance); and

(c) the shape and product dimensions “resulting in its distinctive silhouette”.

84 She stated that:

The overall appearance of the bag as an object was fundamentally the most important thing.

85 She also considers the press studs to be an important visual feature – in cross-examination she stated that there were so few elements of the bag that “every feature has… a significant look”.

86 Ms MacGowan further deposed that she “feel[s] deeply passionate about what [she] created. It was a labour of love [and her] ultimate design challenge”. Her view is that what she created “had never been seen before”.

Expert evidence

87 Both experts agreed that the Escape Bag displays quality of the workmanship. They also agreed that the neoprene fabric used in combination with the rope handles represented a departure from bags known as at November 2013. However, whereas Ms Beale referred to the Escape Bag as “unique”, Mr Smith was of the view that “combining 2 or more features that have been in common use over many years [was] an evolution in styling rather than a completely new design”. In cross-examination, Ms Beale accepted that the uniqueness to which she referred arises from the choice or “design decision” to use perforated neoprene and sailing rope, rather than in any contribution to the creation of those underlying materials.

88 Ms Beale, whose professional qualifications are in design, gave evidence that a designer uses their technical knowledge and understanding as well as aesthetics to come up with design solutions, and that the design of the Escape Bag is not only functional but assessed holistically the bag:

… has clever design elements that make it distinctive, such as the way in which the form makes the bag self-supporting – the bag sits squarely when the studs are open – which means that you are able to see and access the contents easily. Also, when the studs are closed, the overall form of the bag takes on a softly curved organic form.

89 In cross-examination, Ms Beale explained that what she meant by the term “organic” was something less geometric in form, so that the appearance of the bag changes quite substantially from when the press studs are undone, when it sits like a square bag or carry all bag.

90 Ms Beale was of the view that there was an exercise of skill on the part of the designer in the end to end creation process of the Escape Bag. She opined that it was obvious to her that an iterative design process had been employed and the stages of development – problem solving the overall shape and form, “particularly how they resolved the handles” – showed “an informed and observant approach”. She also opined that a “strong understanding of materials [was] demonstrated” –

the designer has intentionally selected specific materials and used their knowledge of their unique performance characteristics to assist in resolving the design.

Those materials included the sailing rope which, according to Ms Beale, was “only an aesthetic choice” and did not perform a function in itself.

91 Ms Beale expressed the opinion that the designer had used trained technical skills to work through different ideas, “refining and building upon previous samples to resolve specific issues, and then considering how this impacts the overall product”. She considered that it would be unusual for a person untrained in the design principles to follow this process.

92 When asked about the aesthetic qualities of the bag, Mr Beale stated:

Pleasing to the eye, this is a simple and elegant* neoprene tote. [Note: *elegant is used to not only describe aesthetics, but also the way in which this neatly solves the design problem – efficient, simple, no unnecessary materials or details to detract from the overall look, function or intent of the object].

The bag’s simplicity of form lies in a well-balanced silhouette, combined with a restrained use of materials (limited to the essential elements of neoprene, sailing rope, slimline press studs and other hardware)… This bag has clever design elements that make it distinctive, such as the way in which the form makes the bag self-supporting – the bag sits squarely when the studs are open – which means that you are able to see and access the contents easily. Also when the studs are closed, the overall form of the bag takes on a softly curved organic form.

93 Ms Beale also opined that overall ratios of the bag were “very well handled from an aesthetic and technical sense”, stating that:

When you are designing a bag, if the surface area or size of the base of the bag is narrower than the height of the bag (within a certain scale) then the base is not as stable – for the State of Escape bag, the base being the same size as the front panel means that it is able to support the structure – and if it were any narrower, the bag would not stand up.

94 Ms Beale regarded the key elements of the bag to be:

(a) its simple form:

… a rectangular shape that is self-supporting, but can also be closed through the use of two slim-profile press studs. When closed, the bag has a softened, sculptural and organic form.

(b) the sailing rope handles and trims:

… they are both functional and also decorative, making the bag have a distinctive look that is easily recognisable.

(c) the fact that the rope handles of the bag are stitched to the panels and base and then go through the panel to the inside of the bag to form handles;

(d) the use of high quality materials:

… a high grade neoprene, sailing rope, hardware and trims.

(e) the fact that the colour has been carefully considered in terms of the neoprene and rope combinations –

… harmonious colours to make the overall look of the bag consistent, rather than a bright contrast that would draw attention.

… it appears to me that time and energy has been spent in colour selection of each element so that the use of colour is harmonious. This gives an overall, sophisticated impression because nothing stands out. The colours are well selected, so that the overall effect is ‘balanced’.

95 In cross-examination, when asked about colour, Ms Beale said that colour related back to the overall look and impression of the bag being consistent – “all of the elements in the bag are harmonious”.

96 Mr Smith, who has had more than 30 years’ experience (both in Australia and internationally) in the design, development and manufacture of handbags and other accessories such as briefcases, wallets and belts, opined that there is an interplay between the functionality of a handbag and the design or styling choices. He gave two examples to illustrate this point. First, if the handles of a bag were placed inappropriately – either too close to the centre of the bag or too close to the extremities of the bag – the bag may sag or droop, making it awkward to carry. Secondly, the purpose of a bag might dictate the range of fabrics that can viably be used.

97 Mr Smith identified the following as functional considerations that informed the design of a tote bag:

(a) a durable base and sides with an opening at the top;

(b) comfortable handles positioned in a way that supports the structure of the bag and helps it to retain its form when in use;

(c) the size of the handles;

(d) material selection – for instance, synthetic materials have a tendency to fray and where such fabrics are used, the functional need to avoid the fabric fraying may dictate some design or style choices, such as the need to bind the edges of the fabric to prevent fraying; and

(e) the inclusion of pockets or removable pouches.

98 Mr Smith opined that the Escape Bag incorporates elements of conventional tote bags and conventional carry all bags. By way of explanation, he identified:

(a) the proportions, stating:

… there is nothing unique about the external shape of the bag... the State of Escape Bag reflects the design of conventional tote and carry all bags… I do not regard the dimensions of the State of Escape Bag as unusual – I have seen many bags with similar dimensions. It is a fairly common “east-west” design, which means it is wider than it is tall –

(b) the construction – saying that, like a conventional carry all bag, the Escape Bag has three elements (excluding the handles and detachable pouch), being a single piece which forms the front, base and back and two separate side pieces (gussets); and

(c) the stitching – saying that the bag has been stitched together in a conventional manner.

99 Mr Smith also made the following observations about the Escape Bag:

(a) Mr Smith considered there was nothing unique about the use of the press studs to “pinch” in the sides. His opinion was that the size and shape of the bag and use of press studs involved both functional considerations and design choices, though he agreed in cross-examination that the overall shape of the body of the bag is a design choice;

(b) the choice of neoprene as a fabric was primarily a design choice;

(c) the handles are clearly functional, but the use of sailing rope is a matter of design choice with an added functional quality that the rope is a strong material that is unlikely to stretch or break. In cross-examination Mr Smith agreed he had not seen sailing rope of the kind used in the Escape Bag on bags before;

(d) the use of rope passing under the body of the bag has both a functional and design purpose – in terms of design, the decision to have the handles pass under the body of the bag is aesthetic and does not seem to serve a significant structural purpose; in terms of functionality, the rope helps to protect the bottom of the bag and assist to limit wear and tear to the neoprene fabric. Small “feet” on the bottom of a bag play a similar role. The rope handles entering the body of the bag near the top lip is “mainly” a design feature;

(e) the detachable neoprene pouch has a functional role but the choice of neoprene for the pouch and sailing rope to attach the pouch to the bag are design choices;

(f) the use of rubber binding around the rope joins/ends is primarily a functional feature though the particular type of binding has a design aspect in that it works in with the overall look of the bag and provides a very neat finish;

(g) the heat seal binding around the top lip of the bag has two functions – it prevents the fabric from fraying and has a design function in that it gives a sharp edge to the bag and makes it look finished. Mr Smith commented that he had not seen that method of binding before;

(h) the use of the same binding around the point where the rope handles pass through the bag is a design choice in that it creates a neat finish around this area of the bag, but Mr Smith considered it also has an important functional purpose in that it prevents the fabric from fraying and tearing and also covers over some heavy stitching which strengthens this area of the bag and makes it more durable;

(i) the internal seams are “quite wide” (about 10mm) which means that the fabric gapes around the seam and creases around the corners. Mr Smith commented that if he was making the Escape Bag he would have a seam allowance of no more than 6mm to address this. In cross-examination he accepted that Ms MacGowan had chosen this aesthetic alternative; and

(j) Mr Smith accepted in cross-examination that cutting the material so as to avoid cutting through any of the perforated holes would be something requiring a good deal of care.

100 Mr Smith also gave evidence that he did not think that the process of designing the Escape Bag was likely to have involved any special training, skill or knowledge beyond the standard skill set of a person who has “quite basic” training and experience in handbag making. He opined:

The overall design of the State of Escape Bag (external shape, dimensions) itself is straight-forward, adopting… well-known elements of conventional tote bags and carry all bags.

…

I consider the bag itself to be very basic. It is a standard construction and size… In my view, the State of Escape Bag could be made easily by a person who has quite basic training and experience in handbag making.

101 Mr Smith also opined that the manufacturing techniques used to make the Escape Bag were largely standard techniques that he had seen used over many decades in the design and manufacture of handbags. His evidence was that there were some elements of the manufacture of the bag that were not personally familiar to him, being: the stitching of the sailing rope to the bag; the technique used to apply a rubber seal to the rope ends/joins; and the binding tape used around the lip of the bag and the entry point of the handles into the bag. In his view, these were examples of manufacturing solutions that are developed from time to time to meet the needs of a particular design and, in his experience, such solutions are usually arrived at through a process of research and trial and error.

102 Mr Smith was of the view that Ms MacGowan was “engrossed” in the making of her bag, wanting every detail to be perfect. He did not consider this practical for commercial production, unless it was for a high end bag (for example, a bag costing $2000). He considered her requirements to be “excessively pedantic”. It was submitted for State of Escape that this evidence drew into sharp focus the difference between Ms MacGowan’s quest for quality, simplicity and beauty and Mr Smith’s pragmatic concern to employ production techniques that were economically driven. In cross-examination, Mr Smith did agree that the overall aesthetic of the bag was one that was free of embellishments that might detract from the purity of the overall look. He was not prepared to say the bag was beautiful, because he did not find it beautiful, adding:

…but some people may, but it’s simple, elegant, and distinctive, yes, I agree.

103 In answer to the question whether the Escape Bag has any feature that represents a departure from carry all bags or tote bags Mr Smith had seen previously, his answer was:

In my opinion, the State of Escape Bag has a strong nautical / beach look. In itself, I do not regard this as an original idea… I have seen many bags which demonstrate a similar theme over my professional life. The two main features of the State of Escape Bag which create this look at [sic] the use of neoprene and sailing rope. These are strong design choices. However, in my view, neither of them is, in itself, new. Neoprene has been used extensively for items such as bags and laptop covers, particularly where protection from impact is an important factor. Similarly, rope handles have been used as a design choice on handbags in the past.

There are some features of the State of Escape Bag which… are unfamiliar to me as finishes for a handbag. They are: stitching the sailing rope to the bag, the technique used to apply a rubber seal to the rope ends / joins and the binding tape used around the lip of the bag and around the entry point of the handles into the bag.

104 Mr Smith concluded that the bag is “a very basic bag”, which he does not view as “original or unique”, and which is “largely made using quite basic techniques”. In his view, the differences between the Escape Bag and other bags that came before it are “minor and are no different to the incremental changes [he had] seen in handbag design over the years”. Whilst he agreed with Ms Beale that the rope and neoprene were “somewhat unusual” primary materials, he also stated that he had seen both rope and neoprene on bags previously. In his view, the shape of the bag was “standard”.

105 The experts prepared a joint expert report in which they agreed on the following matters, amongst others:

(a) the Escape Bag is in the style of a carry all bag;