Federal Court of Australia

Manolo Blahnik Worldwide Limited v Estro Concept Pty Limited [2020] FCA 1561

File number: | NSD 609 of 2020 |

Judgment of: | MARKOVIC J |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords: | PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE – application for preliminary discovery pursuant to r 7.22 and r 7.23 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) – whether prospective applicant has sufficient information to decide whether to commence a proceeding against prospective respondent – application allowed |

Legislation: | Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), Sch 2, ss 18, 29 Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth), s 120 Federal Court Rules 1979 (Cth), r O 15A r 6 (repealed) Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), rr 7.22, 7.23 |

Cases cited: | BCI Media Group Pty Ltd v Corelogic Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1556 Bonham v Iluka Resources Ltd (2017) 252 FCR 58 Dallas Buyers Club LLC v iiNet Ltd (2015) 245 FCR 129 E D Oates Pty Ltd v Edgar Edmondson Imports [2012] FCA 607 Hooper v Kirella Pty Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 1 McFarlane as Trustee for the S McFarlane Superannuation Fund v IOOF Holdings Limited [2018] FCA 692 ObjectiVision Pty Ltd v Visionsearch Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1087 Optiver Australia Pty Ltd v Tibra Trading Pty Ltd (2008) 169 FCR 435 Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals v Samsung Bioepis AU Pty Ltd (2017) 257 FCR 62 Quanta Software International Pty Ltd v Computer Management Services Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 969; (2000) 175 ALR 536 Siemens Industry Software Inc v Telstra Corporation Limited [2020] FCA 901 |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Intellectual Property |

Sub-area: | Trade Marks |

Number of paragraphs: | 95 |

Solicitor for the Prospective Applicant: | DLA Piper Australia |

Counsel for the Prospective Respondent: | Mr A D B Fox |

Solicitor for the Prospective Respondent: | ClarkeKann Lawyers |

ORDERS

MANOLO BLAHNIK WORLDWIDE LIMITED Prospective Applicant | ||

AND: | ESTRO CONCEPT PTY LIMITED ACN 169 608 548 Prospective Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to r 7.23 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Rules), the prospective respondent is to give discovery to the prospective applicant of documents that refer to, relate to or record:

(a) in respect of each of the Goods supplied to the prospective respondent by Codimark Projects Pty Ltd (Supplier) (Goods Received):

(i) the style, colour-way and size (including but not limited to photographs) of the Goods Received;

(ii) the quantity of the Goods Received; and

(iii) the unit price that the prospective respondent has paid, or is required to pay, to the Supplier for the Goods Received; and

(b) in respect of each of the Goods that the prospective respondent has sold to its customers (Goods Sold):

(i) the style, colour-way and size (including but not limited to photographs) of the Goods Sold;

(ii) the quantity of the Goods Sold; and

(iii) the unit price that each of the prospective respondent’s customers have paid for the Goods Sold.

2. For the purposes of Order 1, the term “Goods” shall mean:

(a) the Disputed Products as defined in paragraph 16 of the affidavit of Natalie Lauren Caton sworn on 1 June 2020 and filed in this proceeding by the prospective applicant; or

(b) goods, including but not limited to shoes, that bear the name, mark or brand “MANOLO”, “BLAHNIK” or “MANOLO BLAHNIK”.

3. The parties are to agree on the dates for the filing and service of a list of documents in accordance with r 7.25 of the Rules and the manner of inspection of the discovered documents. If the parties cannot agree on either of those matters, liberty is given to any party to relist the proceeding on three days’ notice for further orders.

4. Within 14 days of the date of these Orders, the prospective applicant is to file and serve any submissions, not exceeding three pages in length, in relation to the question of the costs of the provision of the discovery the subject of Order 1 and of this application.

5. Within 28 days of the date of these Orders, the prospective respondent is to file and serve its submissions, not exceeding three pages in length, in relation to the question of the costs of the provision of the discovery the subject of Order 1 and of this application.

6. Unless a party requests that there be an oral hearing, the question of costs of the provision of the discovery the subject of Order 1 and of this application will be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC J:

1 Manolo Blahnik Worldwide Limited (Manolo Blahnik), the prospective applicant, is a wholly owned subsidiary of Blahnik Group Limited (BGL) and a related entity of Manolo Blahnik International Limited (MBIL). BGL and its subsidiaries (BGL Group), including Manolo Blahnik, manufacture, distribute and sell luxury shoes and accessories bearing the “MANOLO BLAHNIK” name and brand, which are sold in over 65 countries including Australia.

2 Manolo Blahnik is the owner of eight Australian registered word trade marks for “MANOLO”, “BLAHNIK” and “MANOLO BLAHNIK” in various classes of goods and services including print matter, cardboard, paper, plastic and cardboard boxes (class 16), bags and accessories (class 18), footwear (class 25), retail services (class 35) and wholesale services (class 42) (MB Trade Marks).

3 Estro Concept Pty Limited (Estro), the prospective respondent, runs two retail stores described as luxury designer outlets offering a wide selection of competitively priced fashion apparel, items and accessories from Europe’s most prestigious designers. The brands stocked by Estro in its stores include Moschino, Valentino, Prada, Fendi, Gucci, Versace, Armani, Kenzo, Max Mara, Lanvin, Giuseppe Zanotti, Dolce & Gabbana, Miu Miu and Givenchy. Estro has also stocked and offered for sale in its stores Manolo Blahnik products.

4 As will become apparent from the evidence relied on by it, Manolo Blahnik believes that Estro has sold counterfeit “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded shoes and that it may have a right to obtain the relief set out at [31] below from Estro or its supplier of those goods. However, in order to determine whether it should commence a proceeding to obtain that relief Manolo Blahnik now seeks an order under r 7.22 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (Rules) for the examination of the proper officer of Estro and that Estro give discovery of documents which refer to, relate to or record the identity and contact information of its suppliers of the goods sold by it bearing any of the MB Trade Marks or the “MANOLO”, “BLAHNIK” and “MANOLO BLAHNIK” name or brand, and an order that Estro give discovery under r 7.23 of the Rules of documents that refer to, relate to or record:

(a) the relationship (contractual or otherwise) between the Prospective Respondent and each of its Suppliers;

(b) in respect of each of the Goods supplied to the Prospective Respondent by any of its Suppliers (Goods Received):

(i) the style, colour-way and size (including but not limited to photographs) of the Goods Received;

(ii) the quantity of the Goods Received;

(iii) the unit price that the Prospective Respondent has paid, or is required to pay, to each of its Suppliers for the Goods Received;

(c) in respect of each of the Goods that the Prospective Respondent has sold to its customers (Goods Sold):

(i) the style, colour-way and size (including but not limited to photographs) of the Goods Sold;

(ii) the quantity of the Goods Sold;

(iii) the unit price that each of the Prospective Respondent’s customers have paid for the Goods Sold;

(d) in respect of each of the Goods Received that the Prospective Respondent has in its possession, custody or control (Possessed Goods):

(i) the style, colour-way and size (including but not limited to photographs) of the Possessed Goods;

(ii) the quantity of the Possessed Goods;

(e) in respect of each of the Goods Received that the Prospective Respondent has returned to any of its Suppliers (Returned Goods):

(i) the style, colour-way and size (including but not limited to photographs) of the Returned Goods;

(ii) the quantity of the Returned Goods.

The evidence

“MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded products in Australia

5 Since 1997 products sold by reference to the “MANOLO BLAHNIK” name and brand have been available for sale in Australia. Between 1997 and 2016 sales of “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded products were made by a Hong Kong based distributor either directly or via third parties to a number of Australian retailers including Myer and David Jones. Since 2016 “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded products have been made available by MBIL directly to wholesale partners and/or distributors in Australia, rather than via the Hong Kong based distributor, and are currently available to Australian consumers either:

(1) directly from Manolo Blahnik’s online store at www.manoloblahnik.com/au/; or

(2) from Harrolds, a Sydney based retailer, which is the only retailer presently authorised by Manolo Blahnik to sell its products in Australia.

Protection of the “MANOLO BLAHNIK” brand

6 Given the value of the “MANOLO BLAHNIK” brand to the BGL Group, enforcement of intellectual property rights against infringing use by unauthorised third parties and combatting the sale of counterfeit “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded products are key worldwide priorities. As part of its enforcement efforts, the BGL Group, including Manolo Blahnik, is focused on pursuing actions against retailers and their suppliers to the extent they can ascertain the identity of those suppliers, which can often prove to be difficult.

7 In order to assist Manolo Blahnik to ascertain whether products sold to consumers are genuine or counterfeit, the authorised manufacturers of “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded products apply certain indicators of authenticity to the products and, in particular, the shoes. Those indicators include the use of one matte colour and dots on the soles of all shoes manufactured after 2013, with the number of dots varying depending on the style of the shoe.

Estro

8 In the early 1980s Gennaro Autore founded the SoloModa Luxury Brands Outlet Model to bring a new designer store concept to the Australian consumer. In 2016 that concept was sold to Estro and Mr Autore continues to work for Estro on a consultancy basis. In that capacity Mr Autore provides strategic direction across all aspects of business development, marketing and operations. Accordingly, Mr Autore says that he has a significant understanding of Estro’s business.

9 Mr Autore’s evidence is that, since its commencement, Estro has been a reputable business that buys and sells genuine products, not counterfeits. As at 9 July 2020 it ran two stores: one located at Pitt Street, Sydney (Estro Pitt Street) and the other located at Birkenhead Point Shopping Centre, Drummoyne. It previously operated two other retails stores at 19 Roseby Street, Drummoyne (Estro Drummoyne) and at 106 King Street, Sydney (Estro King Street).

10 As at 9 July 2020 all “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded products offered for sale by Estro in its stores were obtained from its supplier, Codimark Projects Pty Ltd (Supplier), from whom since about June or July 2019 Estro has sourced a variety of products under various brands.

Manolo Blahnik becomes aware of sale of its products by Estro

11 On 26 July 2019 Manolo Blahnik’s online customer services portal received an email from a person, who I will refer to as Ivy in these reasons, in relation to a pair of shoes which had been purchased from Estro Drummoyne. That email included:

I bought a pair of your heels in ESTRO Sydney today. When I got home and check my shoes, I noticed the bottom of the heels look kind of weird, like the left one and the right one doesn’t have the same soles (eg: the brand name and descriptions are located at spot on each shoe. Are they supposed to be on the same area?)

They just not look like genuine to me as they are luxury and supposed to have the same standard for each shoe even though they are handmade.

Can you please check the photos and let me know if they are genuine or not. If they are fake, I can return to the shop as soon as possible:(

I’m looking forward to your reply

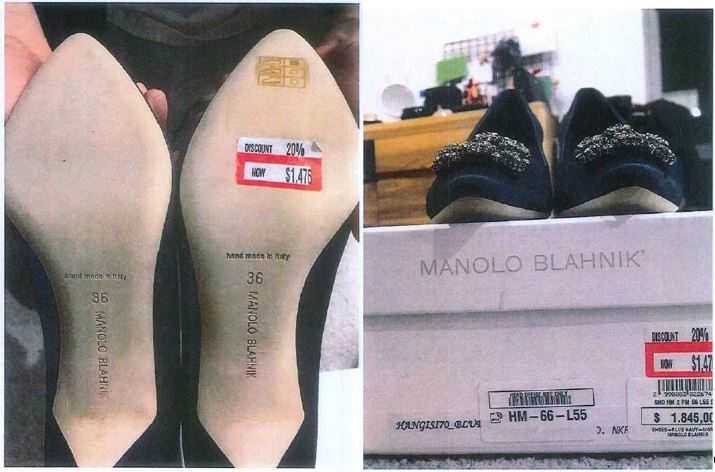

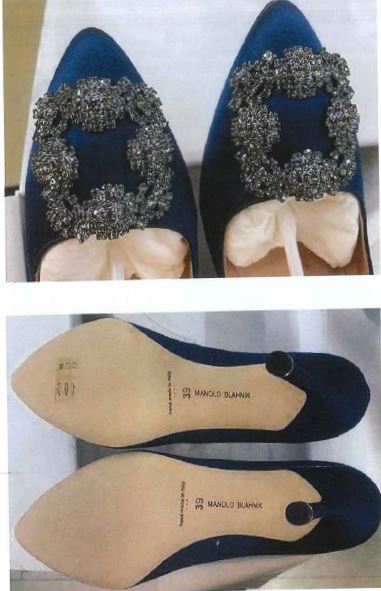

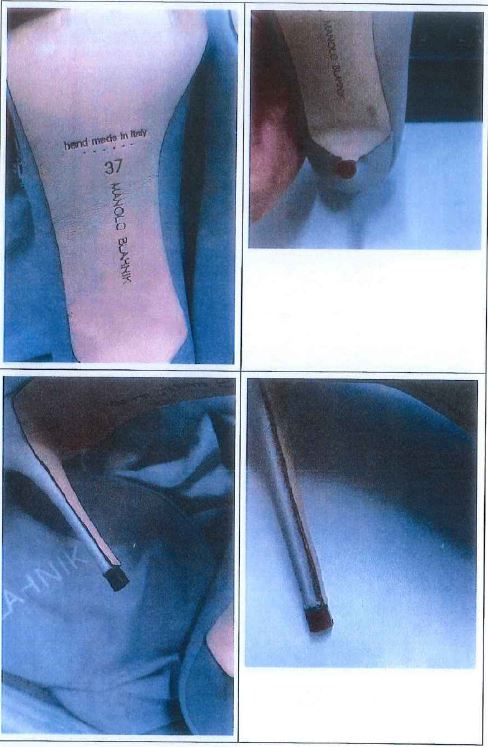

The photographs referred to by Ivy in her email were as follows:

The photographs depict the “Hangisi” shoe, a particular style of “MANOLO BLAHNIK” high heeled shoe.

12 On 26 July 2019 Natasha from Manolo Blahnik Customer Service responded to Ivy:

Thank you for sending this though.

Can you please let us know exactly where you have purchased these?

Unfortunately we are unable to confirm the authenticity of sites and/or shoes.

Please note that all of our authorised re-sellers are listed on our website here

https://www.manoloblahnik.com/gb/boutiques

Additionally, you can find a list of our official online stockists below

www.manoloblahnik.com

www.farfetch.com

www.saksfifthavenue.com

www.barneys.com

www.neimanmarcus.com

http://shop.nordstrom.com/

www.bergdorfgoodman.com

www.marissacollections.com/

http://josephsstores.com/

http://footcandyshoes.com/

www.luisaviaroma.com

www.savannahs.com

www.brownsfashion.com

www.fwrd.com

Please note that anything not listed here is not authorised by us and therefore we cannot guarantee its authenticity.

If you need any further information please let me know.

13 By email dated 26 July 2019 Ivy responded to the email referred to in the preceding paragraph noting that she had “bought these pump at ESTRO, Sydney” and stating:

I’m just wondering if the pumps look authentic from the photos? Like do your pumps always have different soles for the same shoes? And I also noticed other authentic MB pumps’s soles all have little dots, but mine one has none, is that normal?

14 Later that day Natasha from Manolo Blahnik Customer Service sent Ivy two further emails. In her first email Natasha informed Ivy that she could not confirm authenticity and provided some further information. In her second email timed at 5.25 pm, among other things, Natasha wrote:

I have just spoken to our legal department about your shoes purchased at Estro in Sydney.

They may be in touch to discuss this further next week, if that’s OK with you.

It would be great if you could send through your receipt or invoice for the shoes.

Additionally, they have asked that you not return the shoes just yet until they obtain some further Information.

This would be of great assistance to us.

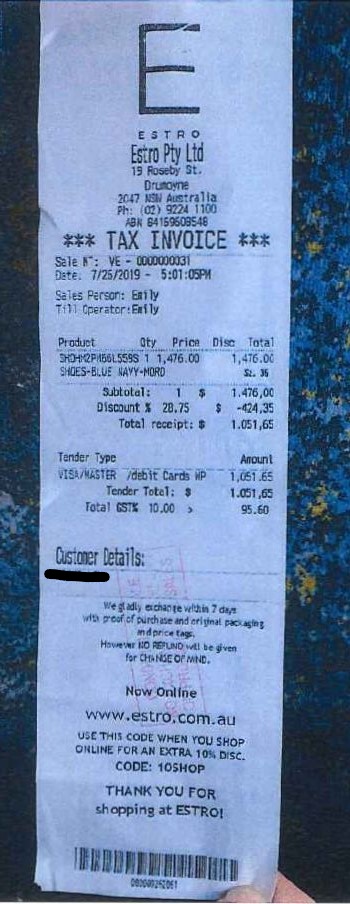

15 By email dated 27 July 2019 Ivy provided a copy of her receipt to Natasha from Manolo Blahnik Customer Service which was as follows:

The receipt relevantly states:

(1) in the header, “Estro Pty Ltd” and “19 Roseby St. Drummoyne”;

(2) under “Product”, “SHOHM2PM66L559S SHOES-BLUE NAVY-MORD Sz. 35”;

(3) under “Qty”, “1”; and

(4) under “Price” and “Total”, “$1,476.00” (but a “Discount” of “$424.35” has been applied).

16 On 1 August 2019 Jack Randles, senior legal counsel for Manolo Blahnik based at its main office in London, England with day to day responsibility for all intellectual property and commercial matters, including enforcement proceedings, sent an email to Ivy which included:

I received your details from our customer service team.

I work in the legal team at Manolo Blahnik and am responsible for anti-counterfeiting and intellectual property.

Would it be possible for us to have a quick call to discuss your purchase from Estro? I would like to discuss a proposal with you and will follow up with a detailed summary by email. I appreciate the time difference will be a challenge but if you can let me know some times and dates that are convenient for you (and a number to reach you on) I can give you a call.

For now, we ask that you keep this confidential and do not make contact with Estro or tell anyone about this. We need to be able to investigate this quietly and take action without drawing any suspicion or alerting Estro/others.

Thank you for bringing this to our attention and I look forward to speaking with you.

17 By email also dated 1 August 2019 Ivy responded to Mr Randles’ email noting, among other things:

I have just asked some professional people to check my shoes and they said the pumps I bought were genuine. I believe Estro is selling “imperfect” genuine products with a discount, thus the imperfect soles look reasonable to me now. ;')

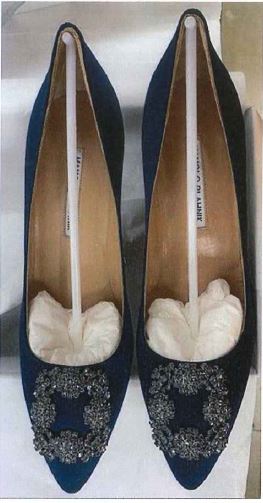

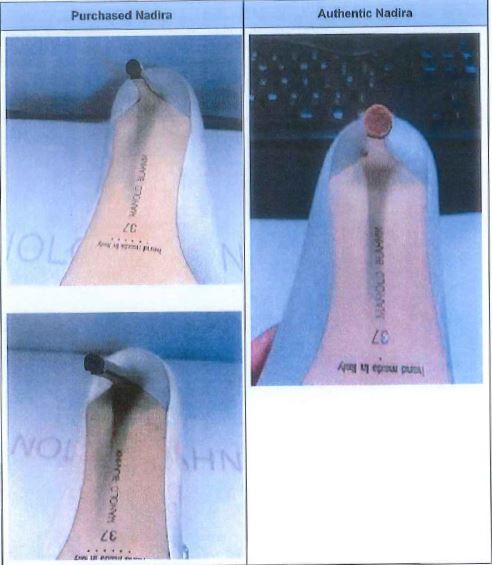

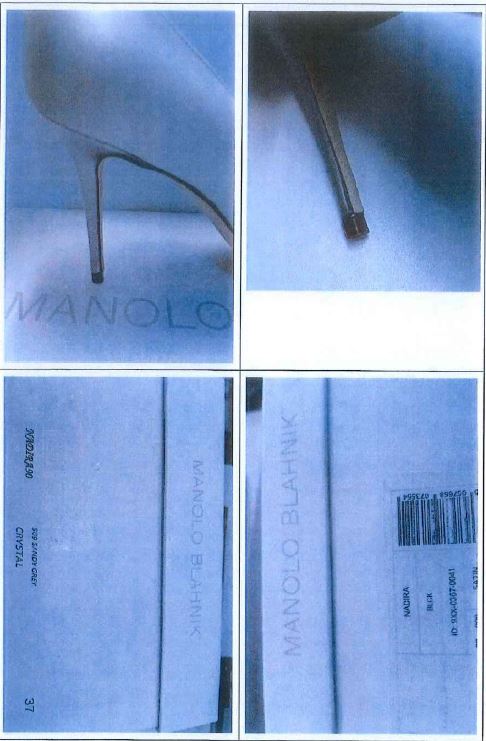

18 Natalie Lauren Caton, a partner of DLA Piper Australia, the solicitors for Manolo Blahnik, has been instructed that the Hangisi shoe, like all of Manolo Blahnik’s products, bears the “MANOLO BLAHNIK” trade mark on the inner sole of the shoe as well as on the shoe box packaging and outer sole. Upon inspecting the photographs of the Hangisi shoe purchased by Ivy (Purchased Hangisi Shoe) Mr Randles identified that the authenticity indicators did not match those of Manolo Blahnik’s Hangisi shoe (referred to as an Authentic Hangisi Shoe) as depicted below:

19 Ms Caton is instructed that, in particular, Mr Randles identified differences in the quality and finish of certain aspects of the Purchased Hangisi Shoe compared to an Authentic Hangisi Shoe including:

(1) inconsistency in the soles such as differences in colour and finish;

(2) incorrect font and labels on the packaging in that the labels on the box for the Purchased Hangisi Shoe uses a font that Manolo Blahnik does not use on its packaging; and

(3) the lack of dots on the sole of the Purchased Hangisi Shoe, which does not match the number of dots associated with an Authentic Hangisi Shoe.

20 Ms Caton is instructed that, based on his inspection, Mr Randles ascertained that the Purchased Hangisi Shoe is not an Authentic Hangisi Shoe.

Other shoe purchases from Estro

21 On about 1 August 2019 Mr Randles purchased a “Nadira” shoe, which is another style of “MANOLO BLAHNIK” high heeled shoe, from Estro’s online store. On 4 August 2019 Estro cancelled Mr Randles’ order “due to unforeseen circumstances” because the shoes had “some crystal missing”.

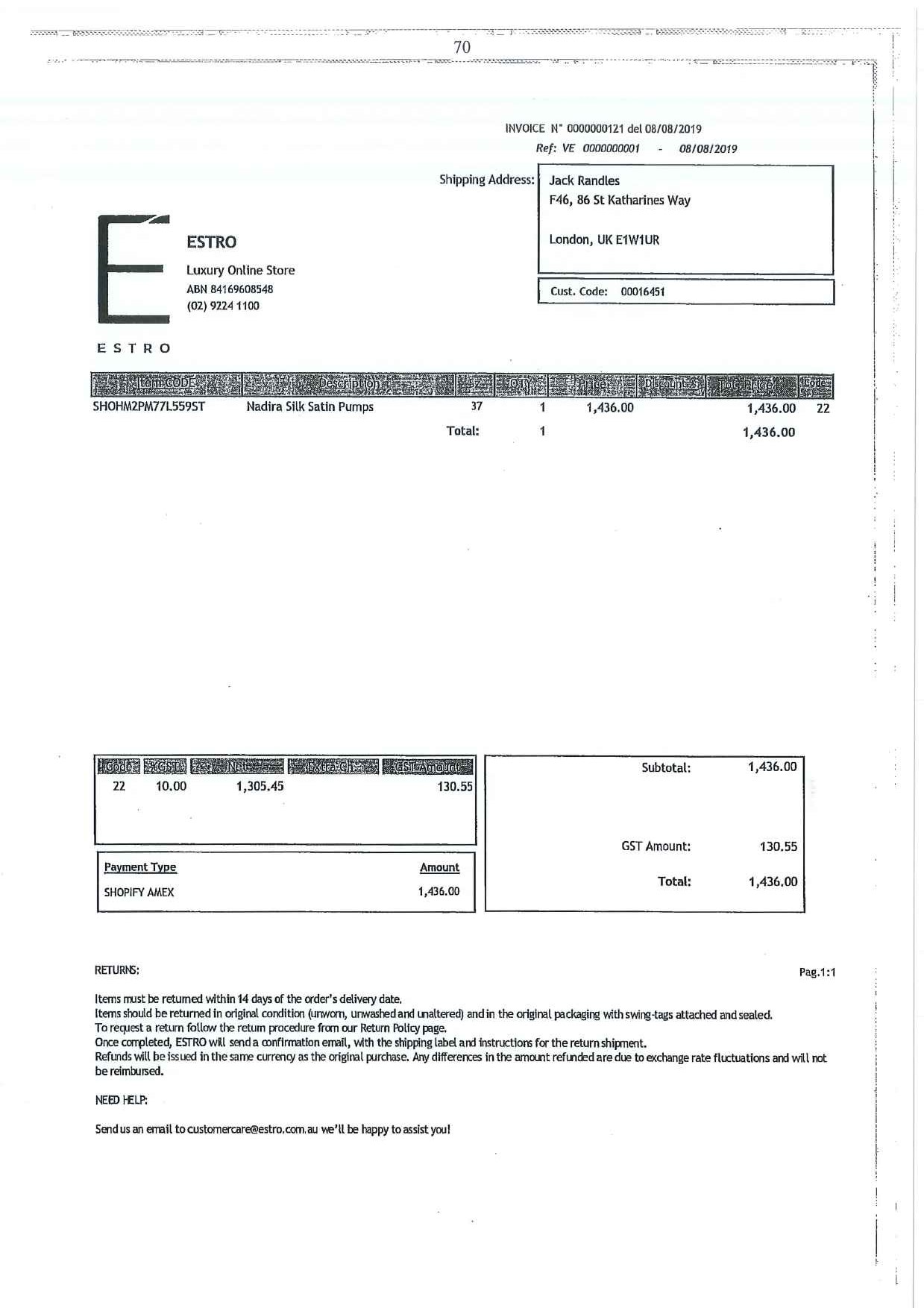

22 On about 7 August 2019 Mr Randles purchased another Nadira shoe from Estro’s online store, which he received on 21 August 2019. A copy of Mr Randles’ invoice appears below:

The invoice relevantly states:

(1) under “Item CODE”, “SHOHM2PM77L559ST”;

(2) under “Description”, “Nadira Silk Satin Pumps”;

(3) under “Sz”, “37”;

(4) under “QTY”, “1”;

(5) under “Price” and “Tot Price”, “1,436.00”; and

(6) under “Code”, “22”.

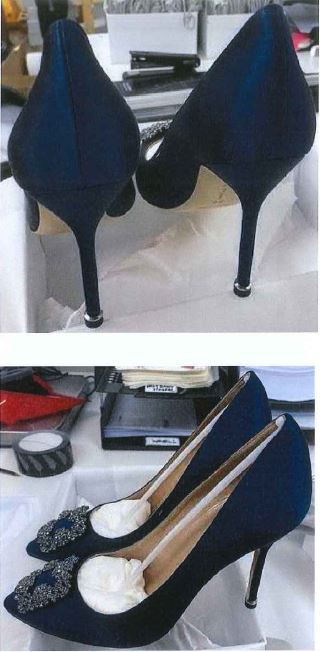

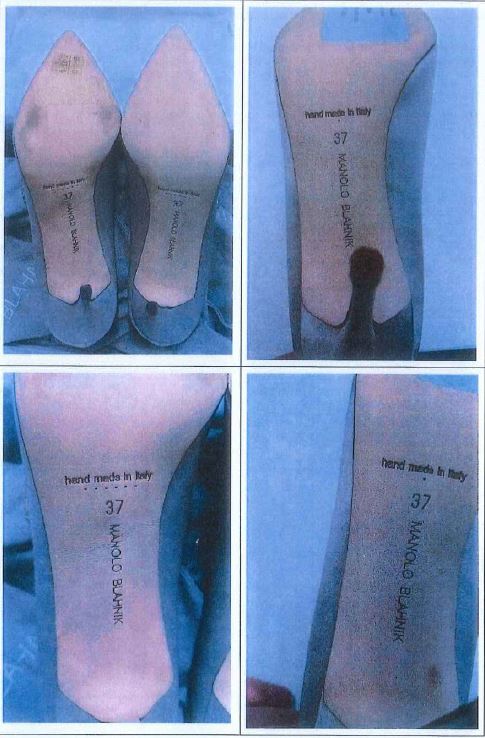

23 Ms Caton is instructed that the Nadira shoe bears the “MANOLO BLAHNIK” trade mark on the inner sole of the shoe as well as on the shoe box packaging and outer sole. Appearing below are photographs of the Nadira shoe purchased by Mr Randles (Purchased Nadira Shoe) on the left hand side and Manolo Blahnik’s Nadira shoe (referred to as an Authentic Nadira Shoe) on the right hand side:

24 Ms Caton is instructed that, upon inspection of the Purchased Nadira Shoe, Mr Randles identified that the authenticity indicators did not match those of an Authentic Nadira Shoe and that there were differences in the quality and finish of certain aspects of the Purchased Nadira Shoe when compared to an Authentic Nadira Shoe including:

(1) the shape, size and style of the heel tips, which should appear more rounded, match the edge of the shoe sole, be natural in colour as opposed to black and contain a metal ring;

(2) the presence of only one layer of stitching on the back of the shoe, which should contain two horizontal layers of stitching;

(3) inconsistency in the shoe soles, including differences in colour and finish;

(4) incorrect font and labels on the packaging. In particular, the labels on the box for the Purchased Nadira Shoe was in a font that Manolo Blahnik does not use on its packaging;

(5) visible bumps in the satin on the side of the Purchased Nadira Shoe, which should not be present; and

(6) the number of dots on the sole on the Purchased Nadira Shoe do not match the number of dots associated with an Authentic Nadira Shoe.

25 Ms Caton is instructed that, based on his inspection, Mr Randles ascertained that the Purchased Nadira Shoe is not an Authentic Nadira Shoe.

Visits to Estro’s online store and other stores

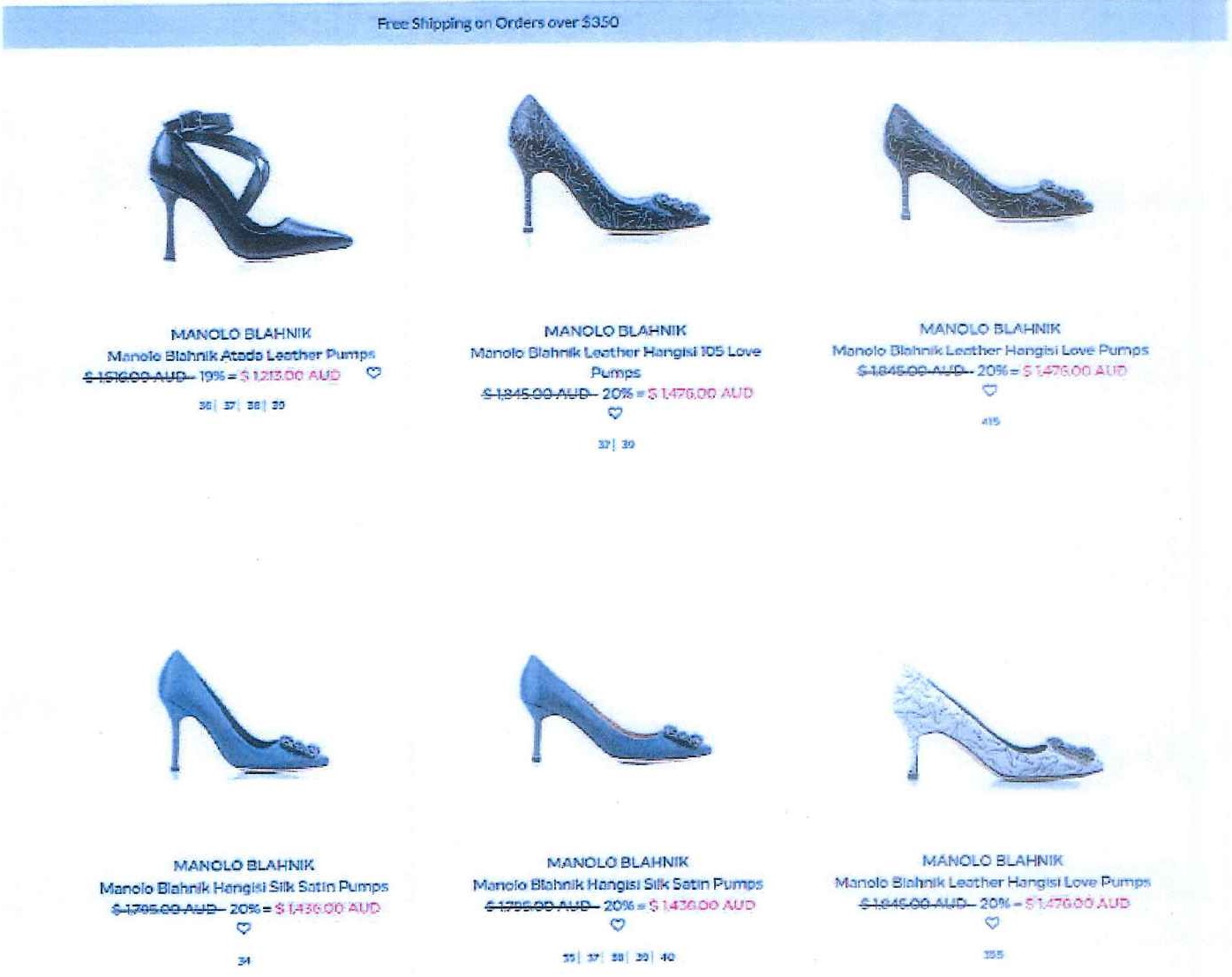

26 On or about 30 September 2019 Jessie Buchan, a senior associate in the employ of Manolo Blahnik’s solicitors, accessed Estro’s online store which, as described by Ms Caton, advertised “numerous ‘MANOLO BLAHNIK’ shoes for sale at a discounted price (stated to be 20% off the ordinary Online Store price)” (referred to as the Disputed Products), including the Nadira shoe. At the time Ms Buchan took images of the Disputed Products listed there for sale. There were four pages of such products. By way of example it is sufficient to reproduce one page which appears as follows:

The image shows that the “MANOLO BLAHNIK” brand, style, price and sizes available were displayed below each product.

27 On 18 October 2019 Annie George, a paralegal in the employ of Manolo Blahnik’s solicitors, attended Estro Pitt Street and Estro King Street and took photographs of the Disputed Products displayed for sale at those stores. Ms George visited those stores again the following day, 19 October 2019, and informed Ms Caton that she had observed that each store had removed all Disputed Products from display.

Correspondence between Manolo Blahnik and Estro

28 Between 30 September 2019 and 6 December 2019 the solicitors for Manolo Blahnik, DLA Piper, and the solicitors for Estro, ClarkeKann, exchanged correspondence in relation to the sale by Estro of the Disputed Products including, for a part of that time, on a without prejudice basis. It is not necessary to set out that correspondence in detail save to note that:

(1) on 30 September 2019 DLA Piper, on behalf of MBIL, wrote to Estro (September 2019 Letter). That letter included:

Your Conduct

It has come to our client’s attention that your company has reproduced, imported, sold, and/or offered for sale, or otherwise dealt with in Australia, goods to which the MBIL Trade Marks (or substantially identically or deceptively similar marks) have been applied without our client’s consent.

Specifically, having inspected the Disputed Products available for sale on www.estro.com.au, and following an email from an Australian purchaser of these products, there are some highly confidential, specific indicators of authenticity (of necessity known only to MBIL and authorised manufacturers) that are not present on some of the Disputed Products. In other instances, these specific indicators are incorrect for the specific style of shoe. On that basis, our client is of the view that the Disputed Products are not genuine Manolo Blahnik shoes and are, therefore, counterfeit goods.

Trade Mark Infringement

The Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) provides that a person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

The Disputed Products bear trade marks that are substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the MBTL Trade Maries. In addition, the Disputed Products are the same as, similar to, or closely related to the goods and services covered by the MBIL Trade Marks. Our client has not authorised the use of the MBJL Trade Marks in relation to the Disputed Products.

Furthermore, the false application of a substantially identical trade mark to goods being dealt with or provided in the course of sale in Australia, without authorisation of the registered trade mark owner, is a criminal offence.

In the circumstances, you have infringed our clients [sic] registered trade mark rights.

Australian Consumer Law

Section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), set out in Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), provides that:

…

Sections 29(l)(a) and (h) of the ACL also provide:

…

In the circumstances, your conduct has the potential to convey representations in trade or commerce that:

1. your company is affiliated with, approved by, or trading as an authorised distributor of MBIL, when it is not; and

2. purchasers of the Disputed Products are purchasing genuine MBIL products, when they are not; and

3. purchasers of the Disputed Products are to expect the same standard and quality as genuine MBIL products, when they do not. To this end, we are instructed that our client has already received at least one enquiry from an Australian purchaser of the Disputed Products querying whether such products are genuine.

In the circumstances, each of these representations are untrue and misleading and in breach of the cited provisions of the ACL.

Passing off

In Australia, an action for passing off can be made when:

…

As mentioned, MBIL enjoys substantial market reputation in respect of the MBIL Trade Maries and brand in Australia, such that consumers associate the MBIL Trade Marks exclusively with the MBIL group and with Mr Blahnik. Your company’s conduct is extremely concerning to our client, particularly in view of the fact that the standard and quality of the product sold by you is not of the same standard and quality of that sold by our client. This has caused, and continues to cause, damage to our client.

Given the extent of our client’s reputation in Australia and your actions, our client must assume that your conduct is designed to exploit our client’s reputation and goodwill in the Australian market.

(2) DLA Piper’s letter to ClarkeKann dated 25 November 2019 included the following:

8. We request that you provide, by 4 pm on 29 November 2019 the following information …:

a. the identity, contact information and address of the Suppliers of the Disputed Products;

b. the total quantity of the Disputed Products your client has received from the Suppliers as at the date of this letter;

c. the price your client has paid, or is required to pay, Suppliers for the Disputed Products;

d. the quantity of the Disputed Products sold by your client as at the date of this letter;

e. the selling price(s) for the Disputed Products; and

f. your client’s estimate of the quantity of the unsold stock of the Disputed Products in its possession as at the date of this letter.

9. For each of the above paragraphs b through to f above (inclusive), our client requires a breakdown of the Disputed Products by size, colour-way, style and prices by unit.

10. If the above information is not forthcoming by the date requested, our client has instructed us to make an application before the Federal Court seeking orders for preliminary discovery of the information requested above.

(3) by email dated 2 December 2019 ClarkeKann responded to DLA Piper’s letter dated 25 November 2019 in the following terms:

We refer to your letter dated 25 November 2019.

In light of the investigations outlined in your letters to our client and us, please inform us why your client says that it does not have sufficient information available to decide whether or not to commence proceedings.

Please inform us of the reasonable inquiries that your client has made to date to obtain the information requested of our client.

Please also inform us whether pursuant to rule 7.29 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) your client will be giving security for, and paying, our client’s costs and expenses in respect of giving information, discovery and/or production.

We require a response to this email so we may take instructions.

We will rely on this correspondence and prior correspondence in seeking our client’s wasted costs should your client unnecessarily file an application for preliminary discovery as foreshadowed.

Our client reserves all of its rights.

We await your reply.

(4) on 6 December 2019 DLA Piper again wrote to ClarkeKann noting, among other things, that:

Thank you for your email dated 2 December 2019 (Email).

Request in your Email

The matters sought in your Email are matters for our client to address in any forthcoming preliminary discovery application, not in pre-litigation correspondence. ·

In any event, it should be obvious to your client that it is the only party who our client knows has the information, and may indeed be the only party (other than your client’s supplier) who is privy to the information.

In circumstances where the information sought from your client is:

1. the name of your client’s supplier; and

2. details of the Dispute Products that your client has received from its supplier,

there are no other sensible, or reasonable, steps that our client could take to obtain the information.

We have asked your client reasonably and on numerous occasions for this information, and are disappointed that your Email demonstrates yet another refusal by your client to provide the information; noting that the information is entirely within your client’s knowledge and readily available to it.

(5) neither DLA Piper nor Manolo Blahnik have received any response to DLA Piper’s letter dated 6 December 2019.

Subsequent events

29 Ms Caton is instructed that, since the beginning of 2020, Manolo Blahnik has been dealing with significant disruptions to its business, in particular the diversion of considerable administrative resources to address issues associated with its manufacturing activities in Italy, its own retail stores and its retail and wholesale partners in various countries due to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. This has led to this proceeding being commenced later than it had anticipated.

30 On 29 May 2020 Ms Caton accessed Estro’s online store and, upon accessing the “view all” tab in the “women” section of “shoes” and performing the searches “Manolo” and “Manolo Blahnik” using the site’s search function, could not find any of the Disputed Products displayed on the site.

Manolo Blahnik’s belief about a right to obtain relief

31 Ms Caton is instructed by Manolo Blahnik that it believes that it may have a right to obtain relief from Estro and its supplier for:

(1) infringement of its trade marks pursuant to s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) in that:

(a) the Disputed Products offered for sale by Estro bear trade marks that are substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the MB Trade Marks;

(b) those products are the same as, similar to, or closely related to the goods and services covered by the MB Trade Marks; and

(c) Manolo Blahnik has not authorised Estro to use the MB Trade Marks in relation to those products;

(2) breach of s 18 or s 29 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth), in circumstances where promoting and selling the Disputed Products has the potential to convey representations in trade or commerce that Estro or its supplier is affiliated with, approved by, or trading as an authorised distributor of “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded shoes, and that purchasers of those products are purchasing genuine “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded shoes and are to expect the same standard and quality as genuine “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded shoes; and

(3) passing off for the reasons set out in the September 2019 Letter (see [28(1)] above).

32 Ms Caton is also instructed that although Manolo Blahnik may have a right to obtain relief against Estro as set out in the preceding paragraph:

(1) due to the limited information available to it, Manolo Blahnik is not aware if the relationship between Estro and its supplier is such that Estro may have an available defence which would militate against Manolo Blahnik deciding to pursue a claim for relief against it;

(2) it has limited information as to the style, colour-way and size of the goods offered for sale by Estro;

(3) it is not aware of whether Estro was supplied with or sold goods other than the Disputed Products that bear the MB Trade Marks or the “MANOLO”, “BLAHNIK” or “MANOLO BLAHNIK” name or brand;

(4) Estro did not accede to the requests made by Manolo Blahnik for delivery up of the goods in its possession. Information in relation to the style, colour-way and size of the goods would likely assist Manolo Blahnik in verifying such goods are not authentic “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded shoes and, therefore, in deciding whether to start a proceeding against Estro in respect of any such goods; and

(5) it does not know the quantity of goods Estro still holds in its possession or the quantity or price of goods sold by Estro. That information is relevant to deciding whether to commence a proceeding seeking injunctive relief, damages or both and is necessary to consider whether the volume and sales of the goods warrant expending significant cost and effort in pursuing a proceeding against Estro for such relief.

Estro’s estimates of the Disputed Products

33 For the purpose of this proceeding, Mr Autore endeavoured to determine the precise number of “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded products obtained by Estro from, and eventually returned to, the Supplier i.e. the number of Disputed Products. However, based on Estro’s records, only an estimate or approximate number could be calculated. In that regard Mr Autore gives the following evidence:

(1) Estro received approximately 85 pairs of the Disputed Products from the Supplier, of which 31 pairs were purchased by it and the rest received on consignment;

(2) Estro offered for sale and/or sold the Disputed Products for prices in the range of $1,100 to $1,500 per pair; and

(3) Mr Autore estimates the total profit made by Estro from sale of the Disputed Products is less than approximately $6,000.

34 At all times Mr Autore believed that the Disputed Products were genuine and says that Estro neither received nor offered for sale any other “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded products in its stores or otherwise. On or about 19 October 2019 Estro stopped selling the Disputed Products. On or about 21 October 2019 all of the unsold Disputed Products, comprising approximately 40 to 50 pairs of shoes, were returned to the Supplier.

35 Around Christmas 2019, for a period of approximately four weeks, Estro granted the Supplier a licence to occupy a designated portion of Estro Drummoyne. According to Mr Autore, the Supplier’s retail activities in that portion of Estro Drummoyne were entirely independent of Estro’s retail activities with, for example, the Supplier using its own EFTPOS facilities for the sale of its products. Mr Autore is not aware if any of the products sold by the Supplier during this time at Estro Drummoyne consisted of any “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded shoes but considers that Estro had no responsibility for the sale of the Supplier’s products at that time.

Legal framework and principles

36 Manolo Blahnik seeks orders for discovery under r 7.22 and r 7.23 of the Rules.

37 Rule 7.22 of the Rules relevantly provides:

(1) A prospective applicant may apply to the Court for an order under subrule (2) if the prospective applicant satisfies the Court that:

(a) there may be a right for the prospective applicant to obtain relief against a prospective respondent; and

(b) the prospective applicant is unable to ascertain the description of the prospective respondent; and

(c) another person (the other person):

(i) knows or is likely to know the prospective respondent’s description; or

(ii) has, or is likely to have, or has had, or is likely to have had, control of a document that would help ascertain the prospective respondent’s description.

(2) If the Court is satisfied of the matters mentioned in subrule (1), the Court may order the other person:

(a) to attend before the Court to be examined orally only about the prospective respondent’s description; and

(b) to produce to the Court at that examination any document or thing in the person’s control relating to the prospective respondent’s description; and

(c) to give discovery to the prospective applicant of all documents that are or have been in the person’s control relating to the prospective respondent’s description.

…

38 Rule 7.23 of the Rules provides:

(1) A prospective applicant may apply to the Court for an order under subrule (2) if the prospective applicant:

(a) reasonably believes that he or she may have the right to obtain relief in the Court from a prospective respondent whose description has been ascertained; and

(b) after making reasonable inquiries, does not have sufficient information to decide whether to start a proceeding in the Court to obtain that relief; and

(c) reasonably believes that:

(i) the prospective respondent has or is likely to have or has had or is likely to have had in the prospective respondent’s control documents directly relevant to the question whether the prospective applicant has a right to obtain the relief; and

(ii) inspection of the documents by the prospective applicant would assist in making the decision.

(2) If the Court is satisfied about matters mentioned in subrule (1), the Court may order the prospective respondent to give discovery to the prospective applicant of the documents of the kind mentioned in subparagraph (1)(c)(i).

39 The terms “prospective applicant” and “prospective respondent” are defined in r 7.21 of the Rules to mean:

prospective applicant means a person who reasonably believes that there may be a right for the person to obtain relief against another person who is not presently a party to a proceeding in the Court.

prospective respondent means a person, not presently a party to a proceeding in the Court, against whom a prospective applicant reasonably believes the prospective applicant may have a right to obtain relief.

40 There was no dispute between the parties about the applicable principles.

Rule 7.22 of the Rules

41 To meet the requirements of r 7.22 of the Rules it is necessary for a prospective applicant to satisfy the Court that: it may have a right to obtain relief against a prospective respondent, in this case, the Supplier; it cannot identify the prospective respondent, that is, the Supplier; and another person, in this case, Estro, knows or is likely to know the identity of that prospective respondent or have a document which reveals that identity. Further, given the definition of “prospective applicant” in r 7.21 of the Rules, a prospective applicant must hold a belief that there may be a right to obtain relief against another party who is not presently a party to a proceeding in this Court and that belief must be reasonable: see Dallas Buyers Club LLC v iiNet Ltd (2015) 245 FCR 129 at [52].

42 A prospective applicant is not required to demonstrate the existence of a prima facie case. However, r 7.22 of the Rules is not to be used in favour of a person who intends to commence merely speculative proceedings: see Siemens Industry Software Inc v Telstra Corporation Limited [2020] FCA 901 (Siemens) at [20], citing Hooper v Kirella Pty Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 1 (Hooper) at [33].

43 Whilst r 7.22 of the Rules does not contain any express requirement that a prospective applicant has made reasonable inquiries, that has been taken to be an implicit requirement: see Siemens at [27].

Rule 7.23 of the Rules

44 In order to obtain an order under r 7.23 of the Rules, a prospective applicant must satisfy three requirements.

45 First, a prospective applicant must demonstrate that he, she or it may have the right to obtain relief from a prospective respondent who has been identified. In that regard, a prospective applicant is required to demonstrate only a reasonable belief that it may have the right to obtain relief and is not required to make out a prima facie case: see Bonham v Iluka Resources Ltd (2017) 252 FCR 58 at [90].

46 In Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals v Samsung Bioepis AU Pty Ltd (2017) 257 FCR 62 (Pfizer) Allsop CJ observed at [2] that applications under r 7.23 of the Rules are “summary applications not mini-trials”. At [8] his Honour said:

… The foundation of the application in r 7.23(1)(a) is that an applicant (a person or a corporation) reasonably believes that he, she or it may have a right to relief. The belief therefore must be reasonable (expressed in the active voice that someone reasonably believes) and it is about something that may be the case, not is the case. It is unhelpful and likely to mislead to use different words such as “suspicion” or “speculation” to re-express the rule. For instance, it is unhelpful to discuss the theoretical difference between “reasonably believing that one may have a right to relief” and “suspecting that one does have a right to relief” or “suspecting that one may have a right to relief” or “speculating” in these respects. The use of such (different) words and phrases, with subtleties of differences of imprecise meaning, and not found within the rule itself is likely to lead to the proliferation of evidence and of argument, to confusion and to error. One must keep the words of the rule firmly in mind in examining the material that exists in order to come to an evaluation as to whether the relevant person reasonably believes that he or she may have a right to relief. That evaluation may well be one about which reasonable minds may differ.

(Original emphasis.)

47 Similarly, at [108] Perram J (with whom Allsop CJ generally agreed) said:

As I have noted already, it is not the requirement of this rule that there be a reasonable belief that there is a right to obtain relief. This is an important qualification and it colours necessarily the analysis involved in assessing the reasonableness of the belief. FCR 7.23(1) is not about giving preliminary discovery to those who believe they do have a case. Its wording unequivocally shows that it is about those who do not know that they have a case but believe that they may. In terms, it authorises what traditionally have been referred to as fishing expeditions; that is to say, evidentiary adventures in which the goal is not to find proof of a case already known to exist, but instead to ascertain whether a case exists at all.

(Original emphasis.)

48 At [120]-[121] his Honour said:

120 The following propositions about preliminary discovery applications should be accepted:

(i) the prospective applicant must prove that it has a belief that it may (not does) have a right to relief;

(ii) it must demonstrate that the belief is reasonable, either by reference to material known to the person holding the belief or by other material subsequently placed before the Court;

(iii) the person deposing to the belief need not give evidence of the belief a second time to the extent that additional material is placed before the Court on the issue of the reasonableness of the belief. That belief may be inferred;

(iv) the question of whether the belief is reasonable requires one to ask whether a person apprised of all of the material before the person holding the belief (or subsequently the Court) could reasonably believe that they may have a right to obtain relief; and

(v) it is useful to ask whether the material inclines the mind to that proposition but very important to keep at the forefront of the inclining mind the subjunctive nature of the proposition. One may believe that a person may have a case on certain material without one’s mind being in any way inclined to the notion that they do have such a case.

121 In practice, to defeat a claim for preliminary discovery it will be necessary either to show that the subjectively held belief does not exist or, if it does, that there is no reasonable basis for thinking that there may be (not is) such a case. Showing that some aspect of the material on which the belief is based is contestable, or even arguably wrong, will rarely come close to making good such a contention. Many views may be held with which one disagrees, perhaps even strongly, but this does not make such a view one which is necessarily unreasonably held. Nor will it be an answer to an application for preliminary discovery to say that the belief relied upon may involve a degree of speculation. Where the language of FCR 7.23 relates to a belief that a claim may exist, a degree of speculation is unavoidable. The question is not whether the belief involves some degree of speculation (how could it not?); it is whether the belief resulting from that speculation is a reasonable one. Debate on an application will rarely be advanced, therefore, by observing that speculation is involved.

(Original emphasis.)

49 At [123]-[125] Perram J continued:

123 … Ultimately, a degree of speculation on a preliminary discovery application is an inevitable consequence of the nature of the application itself. However, the concept of speculation operates on a broad spectrum. There will, obviously enough, be cases where the prospective applicant’s claims are so speculative as to warrant the dismissal of the preliminary discovery application. But what must be shown by the prospective respondent to defeat the application in such cases is not the existence of speculative reasoning on the part of the prospective applicant, but rather that the applicant’s belief that there may be a right to obtain relief in the circumstances is not a belief reasonably held.

124 There are three further observations I would make in the present context. First, many, if not most, preliminary discovery applications will rest on case architecture which is circumstantial in nature. In assessing such cases it is to be kept in mind that it is not to be asked whether each integer of the circumstances may prove the case. Rather, it is to be asked whether they do when taken together: Palmer v Dolman [2005] NSWCA 361 at [41].

125 Secondly, it may prove practically difficult to disprove a reasonable belief that a case may exist by seeking to demonstrate that the internal legal mechanics of the suspected case are faulty or contestable. In many cases this will have little impact on the question of whether the belief that a case may exist is reasonably held. More likely fruitful will be arguments to the effect that no reasonable person apprised of what the prospective applicant puts before the Court would think that a right to obtain relief might exist. Couched in those terms the difficulty confronting a prospective respondent on a preliminary discovery application may be clearer.

50 Secondly, a prospective applicant must show that, after making reasonable inquiries, he, she or it does not have sufficient information to decide whether to start a proceeding to obtain the identified relief. In that regard, a prospective applicant is not required to exhaust all possible avenues of inquiry but is required “to make those inquiries that are reasonable in the circumstances”: see E D Oates Pty Ltd v Edgar Edmondson Imports [2012] FCA 607 (E D Oates) at [24].

51 In Optiver Australia Pty Ltd v Tibra Trading Pty Ltd (2008) 169 FCR 435 (Optiver) at [36] a Full Court of this Court (Heerey, Gyles and Middleton JJ) relevantly said:

The concept of a “bare pleadable case” is not only a gloss on the text of the rule but is fundamentally inconsistent with its purpose. The policy behind the rule is that even where there is a reasonable cause to believe that a person may have a right to relief, nevertheless that person may need information to know whether the cost and risk of litigation is worthwhile. As Hely J pointed out in St George Bank Ltd v Rabo Australia Ltd (2004) 211 ALR 147 at [26], the question does not concern the right to relief but rather “whether to commence proceedings”. Inspection of documents in the possession of the proposed defendant may enable a properly informed decision to be made whether to commence a proceeding to obtain the relief. The “bare pleadable case” approach diverts attention from the true purpose of the rule. A person may have a pleadable case, but still not sufficient information upon which to decide whether to embark upon litigation. We are satisfied that his Honour asked himself the wrong question on this ground and that his conclusion cannot stand. There is ample material upon which this Court can consider the ground for itself.

52 The question of whether a prospective applicant can seek discovery of documents going to quantum was considered by Sackville J in Quanta Software International Pty Ltd v Computer Management Services Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 969; (2000) 175 ALR 536 (Quanta) at [33]-[34] in the context of an application pursuant to O 15A r 6(b) of the Federal Court Rules 1979 (Cth), the predecessor to r 7.23 of the Rules which was in substantially the same terms. His Honour said:

33 In any event, I would not accept the proposition that documents relating only to quantum are necessarily irrelevant in determining whether an applicant has satisfied O 15A r 6(b). As Lindgren J observed in Alphapharm Pty Ltd v Eli Lilly Australia Pty Ltd at p 24, r 6(b) invokes a notion of “reasonable sufficiency”. The question posed by the subrule is not whether an applicant has sufficient information to enable it to decide if a cause of action is available against the prospective respondent. The question is whether the applicant has sufficient information to enable a decision to be made whether to commence a proceeding in the court to obtain relief from an ascertained person. The extent to which copyright has been infringed, for example, may be highly material to a decision to commence a proceeding in respect of infringement of copyright. A trivial claim may not be worth pursuing and might prove to be a waste of the time and resources not only of the applicant but of the court.

34 None of this is intended to imply that FCR O 15A r 6 can be used as a matter of course to obtain preliminary discovery of documents relevant to the quantum of a particular claim. Each case must depend on its own circumstances. There may be cases, however, in which an applicant, after making the reasonable inquiries, has insufficient information relating to quantum to enable it to make a decision whether to commence a proceeding in the Court. In such instances the requirements of O 15A r 6(b) may well be satisfied.

(Original emphasis.) (Citation omitted.)

53 Recently, in BCI Media Group Pty Ltd v Corelogic Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1556 (BCI Media) Charlesworth J considered the same question in the context of r 7.23(2) of the Rules, namely whether that rule authorises the Court to make an order for preliminary discovery of documents relevant only to quantum of the monetary remedies in the prospective proceeding. In that case the prospective applicant, BCI Media Group Pty Ltd (BCI), the owner of copyright, asserted that the prospective respondents had downloaded the copyrighted material from its database and that it may have a right of action against the prospective respondents for infringement of its copyright, breach of contract and misuse of confidential information. BCI sought preliminary discovery pursuant to r 7.23 of the Rules in eight categories.

54 As recorded by her Honour at [35] the prospective respondents did not dispute that the requirements of r 7.23(1)(a) were fulfilled, although there was an issue as to how far their concession went. However, the prospective respondents submitted that BCI’s evidence supported an inference that BCI believes that it does have claims against the prospective respondents, not that it may have such claims and, accordingly, that BCI already had sufficient information to decide whether to start a proceeding. In those circumstances, the prospective respondents submitted that the Court could not be satisfied that the criterion in r 7.23(1)(b) had been met. They contended that BCI was using r 7.23 to assess its prospects of success and quantum, or otherwise to assess the costs and risks of its intended litigation which is not a permissible purpose for a preliminary discovery order.

55 In considering this issue at [38] Charlesworth J first made some general observations about r 7.23 including, in relation to subpara (1)(b), that it “requires an objective assessment to be made as to whether or not the prospective applicant has sufficient information ‘to decide whether to start a proceeding in the Court to obtain’ the relief”. Thereafter, her Honour referred to the decisions in Quanta, Optiver and Hooper and noted at [46] that authorities decided after the repeal of O 15A r 6 and the introduction of r 7.23 contain statements which support the positon contended for by BCI that documents going solely to quantum may be the subject of an order under r 7.23(2) of the Rules. Her Honour referred in particular to ObjectiVision Pty Ltd v Visionsearch Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1087 (ObjectiVision) at [30] and E D Oates at [26]. Her Honour rejected a submission that the Full Court in Pfizer had disapproved of the statements of principle in Quanta, Optiver or ObjectiVision or in any other earlier case to which her Honour had referred: see at [51], [57].

56 Justice Charlesworth then turned to consider the text of r 7.23 noting at [60] that there was “some force in the submission that r 7.23 does not include a power to compel the disclosure of every species of document that might assist a prospective applicant to decide whether to start a proceeding”. At [61]-[68] her Honour set out her preliminary observations on the issue by reference to two classes of information: the first being information which is “directly relevant to the question of whether the prospective applicant has the right to obtain the particular relief forming the subject matter of the reasonable belief mentioned in subpara (1)(a)”; and the second being information “which is not directly relevant to the existence of that right, but which may otherwise assist the prospective applicant to make a prudent commercial assessment as to whether the cost and risk of the contemplated litigation would be worthwhile”. At [66] her Honour concluded that both classes of information were capable of informing the question of whether the costs and risk of the litigation are worthwhile and thus are within the text of r 7.23(1)(b) as construed by the Full Court in Optiver and the other decisions referred to by her Honour. At [67]-[69] her Honour said:

67 It is accepted that the rule “should be given the fullest scope its language will reasonably allow”: Optiver at [43]. However, I consider subpara (1)(c)(i) to be worded in a way that permits of only one meaning. It is concerned with information contained in documents “directly relevant to the question whether the prospective applicant has a right to obtain the relief”. It is not concerned with a wider class of document that might assist the prospective applicant in making an assessment as the likely quantum of damages or the costs to be expended in obtaining it.

68 Critically, the power of this Court to make an order under r 7.23(2) is expressly confined to documents of the kind mentioned in subpara (1)(c)(i). It does not pick up all documents that might fill the gap in information of the kind that subpara (1)(b) is concerned with. On that construction it would follow that the Court is not empowered to make an order for the discovery of the documents that do not contain any information that is directly relevant to establishing the prospective applicant’s right. It may be that documents ordered to be produced under r 7.23(2) incidentally contain information that is not directly relevant in the requisite sense but that otherwise inform the decision as to whether or not to commence a suit. In my view discovery of that material is not the purpose of the rule.

69 My analysis is inconsistent with Sackville J’s reasoning in Quanta concerning documents going only to quantum. His Honour’s reasoning has not been overruled or disapproved in any of the authorities to which the parties referred. The circumstance that Quanta was decided under the old rule does not provide a sufficient basis to distinguish it. The relevant textual components of the old rule remain intact in r 7.23. The reasoning in Quanta has been applied in at least one case decided under r 7.23 and otherwise referred to with approval since the rule was enacted. The reasoning is not plainly wrong and it is appropriate that I follow it: Farah Constructions Pty Ltd v Say-Dee Pty Ltd (2007) 230 CLR 89 at [135].

57 Thirdly, a prospective applicant must reasonably believe that a prospective respondent has or is likely to have in his, her or its control documents that are directly relevant to the question whether it has a right to obtain relief against the prospective respondent and inspection of which would assist in making that decision. The measure of preliminary discovery to be ordered is the extent to which that information is necessary to overcome the insufficiency of information already possessed by a prospective applicant after it has made all reasonable inquiries to enable it to make a decision as to whether to commence a proceeding: see McFarlane as Trustee for the S McFarlane Superannuation Fund v IOOF Holdings Limited [2018] FCA 692 at [68] and the cases cited therein.

58 Once the Court is satisfied of the matters in r 7.23(1), it retains a discretion as to whether it will order discovery by the prospective respondent of documents of the kind set out in r 7.23(1)(c)(i): see r 7.23(2) of the Rules.

Consideration

Relief sought under r 7.22 of the Rules

59 Manolo Blahnik seeks an order pursuant to r 7.22 of the Rules that Estro by its proper officer attend before the Court for examination about the description of all persons or entities that have supplied it with, in effect, the Disputed Products or other goods bearing the MB Trade Marks or the “MANOLO”, “BLAHNIK” or “MANOLO BLAHNIK” name or brand and that it produce documents which refer to, relate to or record the identity and contact information of those entities.

60 This order is sought despite Mr Autore now providing the identity of the Supplier.

61 Manolo Blahnik submits that the information about the identity of the Supplier is given by someone who is a consultant and not Estro’s proper officer who it says would be its sole director, secretary and shareholder as disclosed in a search of Estro obtained from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission in evidence before me, Niral Patel. Estro submits that there are other reasons why I would not accept Mr Autore’s evidence (see [80] below), that he has not been frank with the Court and that the only way that Manolo Blahnik will truly know the identity of Estro’s supplier(s) is by seeing documents which identify its or their name(s) and to have Estro’s proper officer examined on that issue.

62 Mr Autore has a relatively detailed knowledge of Estro’s business and has disclosed the name of the Supplier. Manolo Blahnik accepts the evidence of the identity of the Supplier but submits that, even if it had made inquiries of the Supplier, it may only be one of a number of sources from whom Estro received the Disputed Products. While there may be other aspects of his evidence that are not satisfactory (as described at [82] below), I would not reject the whole of Mr Autore’s evidence. In particular, I am not persuaded that there is any proper basis to reject his evidence in relation to the identity of the Supplier. There is simply no evidence that there is more than one supplier. In that regard, Manolo Blahnik has not tested the evidence provided by Mr Autore as to the identity of the Supplier by, for example, attempting to contact the Supplier.

63 In short, given the disclosure of the identity of the Supplier, and notwithstanding the lack of precision in other aspects of Mr Autore’s evidence, it cannot be said that Manolo Blahnik is unable to ascertain the identity of the supplier of the Disputed Products. Accordingly, I am not satisfied that the order sought by Manolo Blahnik pursuant to r 7.22 of the Rules should be made.

Relief sought under r 7.23 of the Rules

64 Manolo Blahnik seeks an order pursuant to r 7.23 of the Rules that Estro give discovery of five categories of documents that relate to the relationship between Estro and its supplier and the extent of the “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded stock held and sales of such goods made by Estro (see [4] above).

65 Estro makes two principal submissions in relation to the order sought by Manolo Blahnik under r 7.23 of the Rules.

66 First, Estro submits, based on the September 2019 Letter (see [28(1)] above) and some of the evidence relied on in support of this application, for example, the conclusions drawn by Mr Randles that the Purchased Hangisi Shoe and the Purchased Nadira Shoe were not authentic Manolo Blahnik products (see [18]-[20] and [23]-[25] above), that Manolo Blahnik cannot utilise r 7.23 of the Rules. Estro submits that this is because Manolo Blahnik has already formed the view that it has available causes of action against Estro.

67 Secondly, Estro submits that, to the extent Manolo Blahnik seeks preliminary discovery against Estro in order to form a view about whether to bring a proceeding against the Supplier, r 7.23 of the Rules provides only for documents to be produced by a prospective respondent in relation to relief sought against that person or entity.

68 In order to obtain the relief sought by it under r 7.23 of the Rules, Manolo Blahnik must satisfy each of the three requirements set out in r 7.23(1). That is, that it has a reasonable belief that it may have a right to obtain relief from Estro; that, after making reasonable inquiries, it does not have sufficient information to start a proceeding to obtain that relief; and that it reasonably believes Estro has or is likely to have in its control documents which are directly relevant to the question whether Manolo Blahnik has a right to obtain relief and inspection of which would assist in making that decision.

69 The issue raised in relation to the first requirement of r 7.23(1) is not, as is usually the case, that Manolo Blahnik’s belief that it may have a right to obtain relief is not reasonably held, but rather that its belief has gone beyond the realm of speculation and is so firmly held that it does not require any further assistance by way of preliminary discovery to assist it in making a decision as to whether to commence a proceeding for the identified relief.

70 True it is that the evidence relied on by Manolo Blahnik establishes that it has formed the view that the Purchased Hangisi Shoe and the Purchased Nadira Shoe are counterfeit and that the September 2019 Letter is written in emphatic terms. Manolo Blahnik submits that the September 2019 Letter was, in effect, a letter of demand and that it was written having regard to the requirement for parties to comply with the Civil Dispute Resolution Act 2011 (Cth) prior to commencing any proceeding. The September 2019 Letter commenced the dialogue with Estro. At its conclusion MBIL, on whose behalf the letter was written, made a number of demands of Estro including that it provide the following information:

(1) the identity, contact information of the supplier(s) and/or manufacturers of the Disputed Products;

(2) the quantity of the Disputed Products received and the price paid for the Disputed Products;

(3) the quantity of the Disputed Products sold and the selling price(s) for the Disputed Products; and

(4) the quantity of the unsold stock of the Disputed Products held by it.

71 Given the circumstances in which the September 2019 Letter was written and what MBIL had hoped to achieve by it, its tone is hardly surprising.

72 However, in my opinion, neither the concluded view about the authenticity of the Purchased Hangisi Shoe and the Purchased Nadira Shoe nor the September 2019 Letter put relief under r 7.23 of the Rules out of Manolo Blahnik’s reach.

73 First, I would not conclude based only on those matters that Manolo Blahnik had reached the state of satisfaction attributed to it by Estro. There is also less emphatic evidence given by Ms Caton who deposes in her affidavit that Manolo Blahnik believes that it may have a right to obtain relief against Estro and its supplier as outlined in the September 2019 Letter.

74 Secondly, as Manolo Blahnik submits, other than in the case of the Purchased Hangisi Shoe and the Purchased Nadira Shoe, it has only had access to Estro’s online store and been able to view some of the Disputed Products offered for sale on a visit by a paralegal in the employ of its solicitors to two of Estro’s stores. Thus, it does not know if any of the other shoes offered for sale are, for example, “grey market goods”, which I understand to be goods purchased from an authorised retailer and offered for re-sale, or whether they are genuine Manolo Blahnik products or not.

75 Thirdly, as Estro conceded, documents going to the question of the extent or quantum of damages can be obtained on an application under r 7.23 of the Rules. As recognised by the Full Court in Optiver and the other authorities referred to above (see [51]-[56] above), even where a prospective applicant has a reasonable belief that it may have a right to relief, it may need information in order to assess whether the cost and risk of bringing a proceeding is worthwhile.

76 As to the second requirement of r 7.23(1) of the Rules, Manolo Blahnik must establish that, after making reasonable inquiries, it does not have sufficient information to decide whether to start a proceeding to obtain the identified relief.

77 There is no suggestion on the part of Estro that Manolo Blahnik has not made reasonable inquiries. As the evidence demonstrates, Manolo Blahnik requested Estro to provide information substantially in the categories it now seeks pursuant to r 7.23 of the Rules on two occasions: first, in the September 2019 Letter (see [28(1)] above); and then by a letter dated 25 November 2019 (see [28(2)] above). At least up until the commencement of this proceeding, no such information was forthcoming from Estro, being the only party which could have provided Manolo Blahnik with the information it seeks.

78 The issue that arises is whether Manolo Blahnik has “sufficient information” to decide whether to start a proceeding against Estro in relation to the identified relief. I am satisfied that it does not. This is particularly so in relation to documents going to quantum which, as I have already observed and as is confirmed on the current state of the authorities, are documents that are relevant to such a decision.

79 In addition, and in contrast to the position contended for in BCI Media (see [54] above), Manolo Blahnik also says that the documents sought by way of preliminary discovery are relevant to identifying the extent of any alleged infringing conduct. This is because the provision of documents identifying a description of the Disputed Products sold by Estro, including style, colour-way and size, will assist in identifying whether the goods are counterfeit or may have been sourced via parallel importing.

80 Estro submits that, having regard to the evidence given by Mr Autore since the commencement of this proceeding, the order sought pursuant to r 7.23 of the Rules is not warranted. In other words, as I understand Estro’s submission, it is that, to the extent Estro has the information sought, it has been provided by Mr Autore.

81 Mr Autore’s evidence is summarised at [8]-[10] and [33]-[35] above. Manolo Blahnik submits that I would not accept Mr Autore’s evidence given its lack of detail and particularity and what it described as inconsistencies between his evidence and “what is a matter of common sense” that arises from the documents. It contends that it is implausible that Estro did not maintain or keep records of the actual number of shoes returned to the Supplier and that it is implausible for, on the one hand, Mr Autore to give evidence about the Supplier conducting independent activities in one of Estro’s stores and, on the other, not to know what that independent entity was in fact selling at the time. Manolo Blahnik says that is particularly so in circumstances where, in light of the issues raised by it, Estro stopped selling “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded shoes and returned its stock of those shoes to the Supplier some six weeks prior to the Supplier conducting independent activities in one of Estro’s stores.

82 In my opinion, Mr Autore’s evidence is not a complete answer to Manolo Blahnik’s application pursuant to r 7.23 of the Rules. While Mr Autore has provided some evidence about the number of the Disputed Products Estro received from the Supplier and their sale price range, he has not provided the specific information sought by Manolo Blahnik. Mr Autore says that, for the purposes of his affidavit, he has “endeavoured to determine the precise number” of “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded products that were obtained from and then returned to the Supplier and that, based on Estro’s records, the best he can ascertain is an approximate number.

83 However, the evidence before me establishes that Estro runs a number of retail stores (up to four at one point in the recent past), provides its customers with detailed invoices showing size, colour, style and price of products sold and operates a website which depicts products for sale, their sale price and the size range available. In those circumstances, while I accept that Mr Autore has done his best to provide an estimate of the Disputed Products that Estro had in its possession, of the numbers sold and returned and the price range for those products, I do not accept that more precise information is not available. By way of illustration, I note that Mr Autore’s evidence is that the best he can provide, based on Estro’s records, is the approximate number of the Disputed Products that were obtained from and returned to the Supplier. However, Mr Autore then goes on to provide a precise number of Disputed Products that Estro purchased from the Supplier as opposed to receipt on consignment. He then provides only scant information about sale price and profit made without disclosing the cost price for the goods received, whether by purchase or on consignment from the Supplier.

84 The third requirement of r 7.23(1) of the Rules concerns Manolo Blahnik’s belief that Estro has or is likely to have had in its control documents directly relevant to the question whether it has the right to obtain the relief and that inspection of those documents would assist it in making the decision about whether to start a proceeding. Manolo Blahnik must identify the issues in relation to which the documents are likely to be directly relevant and in relation to which there is an insufficiency of information. The extent of preliminary discovery is limited to the information reasonably necessary to overcome the insufficiency of information already in Manolo Blahnik’s possession, having made all reasonable inquiries to enable it to make a decision about whether to commence a proceeding (see [50] above).

85 Relevantly, as Estro submits, r 7.23 concerns the provision of preliminary discovery by a prospective respondent in relation to a prospective applicant’s consideration of whether to commence a proceeding for the relief it believes it may have a right to obtain from the prospective respondent, that is Estro, and not any third party, in this case, the Supplier.

86 As observed at [10] above, Estro has identified the Supplier. In those circumstances it is not clear, and Manolo Blahnik has not specified, how documents relating to Estro’s relationship with the Supplier are relevant to the decision whether to commence a proceeding against Estro. Similarly, it is not clear how the style, colour-way, size and quantity of the Disputed Products returned to the Supplier could be relevant to a decision whether to commence a proceeding against Estro.

87 There is also evidence that the Disputed Products which had not been sold were returned to the Supplier on or about 21 October 2019. This seems to be borne out by the evidence relied on by Manolo Blahnik that, as at 19 October 2019, there were no Disputed Products on display at Estro King Street and Estro Pitt Street and, as at May 2020, Estro’s website did not display any “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded products. In those circumstances, categories seeking documents in relation to Disputed Products that remain in Estro’s possession, custody or control could not be directly relevant to the decision whether to commence a proceeding against Estro.

88 That said, I am satisfied that, insofar as Manolo Blahnik seeks documents going to the quantity, style and price of goods received from the Supplier and then sold, they are relevant to Manolo Blahnik’s consideration of whether it should commence a proceeding for the relief it believes it may have against Estro.

89 Once it is satisfied of the matters set out in r 7.23(1) of the Rules, the Court has a discretion as to whether it will order a prospective respondent to give discovery to a prospective applicant: see r 7.23(2) of the Rules. I am satisfied that I should make an order in Manolo Blahnik’s favour requiring Estro to give discovery of documents in the nature of those described in the preceding paragraph as sought by Manolo Blahnik. Manolo Blahnik has satisfied the requirements of r 7.23(1) of the Rules and there is no reason why I would exercise my discretion not to make an order. On the contrary, Manolo Blahnik has taken steps over a relatively lengthy period to obtain voluntarily the information it now seeks by way of this application. While some information was provided, albeit after the commencement of this proceeding, that information is not sufficient to enable it to make a decision about whether to commence a proceeding. The information provided is imprecise and in the form of an estimate including as to profits made, which appear to be modest. In the circumstances of this case, Manolo Blahnik is entitled to seek and obtain more information before making its decision.

Application to cross-examine

90 Finally, I address the application made by Manolo Blahnik to cross-examine Mr Autore. That application was opposed by Estro. After hearing from the parties, I refused leave to cross-examine Mr Autore because, in summary, I was not satisfied that I would be assisted by it.

91 Manolo Blahnik submitted that a key element of Estro’s response to its application is the acceptance of Mr Autore’s evidence, not only in respect of the name of the supplier of the “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded shoes to Estro but also in relation to evidence Mr Autore provides about the quantity and nature of the goods supplied and sold. Manolo Blahnik submitted that it may, ultimately, after cross-examination, submit that Mr Autore’s evidence is not to be accepted. In other words, Manolo Blahnik wished to attack Mr Autore’s credit as there are, in its view, serious questions as to whether Mr Autore has been frank in his evidence.

92 On an application made under r 7.22 or r 7.23 of the Rules for preliminary discovery, a prospective applicant must establish the matters set out in those rules as explained at [41]-[58] above. An attack on the credit of a witness relied on by a prospective respondent in the way envisaged by Manolo Blahnik would not, in my opinion, have assisted me in the determination of those matters, particularly having regard to the narrow basis on which this application was opposed by Estro. As I have already observed, applications of this kind are “summary applications not mini-trials”: Pfizer at [2].

93 To the extent that Manolo Blahnik wished to put in doubt estimates provided by Mr Autore in relation to quantities of “MANOLO BLAHNIK” branded products received or sold by it, it remained open to Manolo Blahnik to refer me to the competing evidence that it submitted was available and to make appropriate submissions. To that end, there was nothing in the evidence relied on by Manolo Blahnik that, on its face, undermined the estimates provided by Mr Autore and which might be put to him. To the extent that Manolo Blahnik wished to submit that Mr Autore’s evidence was lacking in detail, that was a matter that could be put by way of submission based on the evidence and did not, in my opinion, require cross-examination.

Conclusion

94 I will make orders in accordance with these reasons.

95 The parties agreed that I should reserve on the question of costs, which I understood to be both in relation to the costs of the provision of the discovery by Estro pursuant to r 7.23 of the Rules and the costs of the proceeding. Accordingly, I will also make orders requiring the parties to provide submissions on those questions. Unless either party indicates to the contrary, those questions will be determined on the papers.

I certify that the preceding ninety-five (95) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justice Markovic. |