Federal Court of Australia

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AGM Markets Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 4) [2020] FCA 1499

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The first defendant (AGM) pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $35 million in respect of the contraventions of ss 961K and 961L of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and ss 12CB and 12DB of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) referred to in paragraphs 2 to 6 of the orders made by the Court on 20 March 2020 modified on 23 April 2020 (the Declarations).

2. AGM pay to each client of AGM’s Alphatrade business who deposited money to the trading account held by that client with AGM an amount equal to the person’s Net Deposits, where Net Deposits means, for the purpose of these orders:

(a) the total amount that the client deposited to the client’s trading account (as defined in the plaintiff’s further amended points of claim); less

(b) any amounts withdrawn, or already refunded to the client, from the client’s trading account; less

(c) any amounts refunded to the client as a result of any arrangement or agreement; less

(d) any amounts which the client in fact receives pursuant to reg 7.8.03(6) of the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth),

as adjudicated by the liquidator in the normal process under the Corporations Act.

3. AGM pay one third of ASIC’s party / party costs of the proceeding, to be taxed in default of agreement.

4. The third defendant (OTM) pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $20 million in respect of the contraventions of s 961Q of the Corporations Act and ss 12CB and 12DB of the ASIC Act referred to in paragraphs 16 to 19 and 21 of the Declarations.

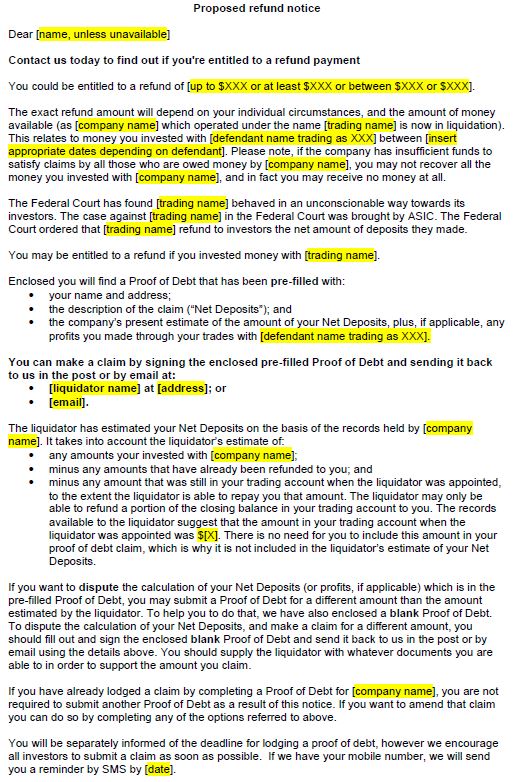

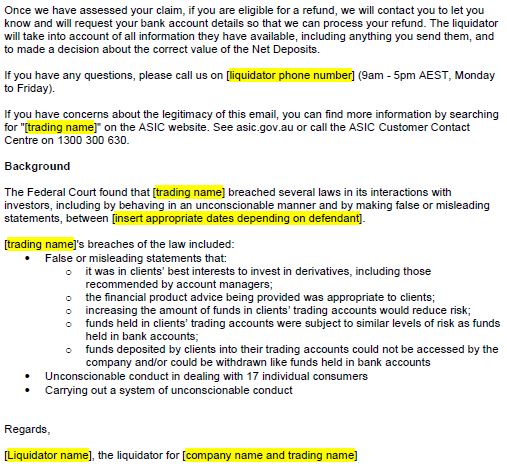

5. Within 28 days of the date of these orders, OTM send to each person who was a client of OTM in the period between September 2017 and April 2018:

(a) an email where OTM has an email address for the client; or

(b) a letter where OTM does not have an email address for the client, or if the client has requested all documentation be provided by ordinary post,

at its own expense, that:

(c) is sent separately to any other communication sent to creditors in the liquidation of OTM;

(d) has the subject line “OT Capital – refund payment potentially available”;

(e) has in the body of the email/letter, a colour copy of a notice in the form and in terms set out in in Annexure A to these orders (Refund Notice), that:

(i) appears in the body of the email/letter that the company sends to each client;

(ii) has a headline font of no less than 18 point, bold, black sans serif font on a white background;

(iii) has a body font of no less than 14 point, black, sans serif font on a white background;

(f) attaches or encloses two copies of a proof of debt in the form that appears at page 65 of Annexure MTG-3 to the unsworn affidavit of Mathew Terrance Gollant dated 29 September 2020, one of which is prepopulated with:

(i) the name and address of the client;

(ii) the particulars of the debt, so that they state:

A. the date on which these orders are made;

B. that the “Consideration” is the client’s “Net Deposits”, as defined in order 7 below; and

C. the “Amount” is equal to the liquidator’s present estimate of the relevant client’s Net Deposits, as defined in order 7 below, and of any profits made by the relevant client as a result of the client’s trading through OTM; and

(iii) a check in the box that indicates that the person completing the proof of debt is the creditor personally.

6. No earlier than 14 days, and no later than 28 days, from the date on which it sends the Refund Notice, OTM send at its own expense:

(a) to each person to whom it sent a Refund Notice by email and for whom OTM has an email address and/or mobile telephone number, an email and text message in the following terms:

Hi [name – if available]. You may be eligible for the OT refund payment scheme. You should have received a pre-filled form to sign by email on [date]. If you did not receive it, please call [liquidator’s phone number]. For further information about the scheme go to the ASIC website and search for “OT Capital”.

(b) to each person to whom it sent a Refund Notice by letter, a further letter in the following terms:

Hi [name – if available]. You may be eligible for the OT refund payment scheme. You should have received a pre-filled form in the post. If you did not receive it, please call [liquidator’s phone number]. For further information about the scheme go to the ASIC website and search for “OT Capital”.

7. OTM pay to each client of OTM who deposited money to the trading account held by that client with OTM an amount equal to the client’s Net Deposits where Net Deposits means for the purpose of these orders:

(a) the total amount that the client deposited to the client’s trading account (as defined in the plaintiff’s further amended points of claim); less

(b) any amounts withdrawn, or already refunded to the client, from the client’s trading account; less

(c) any amounts refunded to the client as a result of any arrangement or agreement; less

(d) any amounts which the client in fact receives pursuant to reg 7.8.03(6) of the Corporations Regulations,

as adjudicated by the liquidator in the normal process under the Corporations Act.

8. OTM pay one third of ASIC’s party / party costs of the proceeding, to be taxed in default of agreement.

9. The fifth defendant (Ozifin) pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $20 million in respect of the contraventions of s 961Q of the Corporations Act and ss 12CB and 12DB of the ASIC Act referred to in paragraphs 23 to 26 of the Declarations.

10. Within 28 days of the date of these orders, Ozifin send to each person who was a client of Ozifin in the period between September 2017 and April 2018:

(a) an email, where Ozifin has an email address for the client; or

(b) a letter where Ozifin does not have an email address for the client, or if the client has requested all documentation be provided by ordinary post,

at its own expense, that:

(c) is sent separately to any other communication sent to creditors in the liquidation of Ozifin;

(d) has the subject line “Trade Financial –refund payment potentially available”;

(e) has in the body of the email/letter, a colour copy of a notice in the form and in terms set out in the Refund Notice, that:

(i) appears in the body of the email that the company sends to each client;

(ii) has a headline font of no less than 18 point, bold, black sans serif font on a white background;

(iii) has a body font of no less than 14 point, black, sans serif font on a white background;

(f) has attached to it two copies of a proof of debt in the form that appears at page 142 of the Annexures to the affidavit of Richard Lawrence dated 29 June 2020, one of which is prepopulated with:

(i) the name and address of the client;

(ii) the particulars of the debt, so that they state:

A. the date on which these orders are made;

B. that the “Consideration” is the client’s “Net Deposits”, as defined in order 12 below; and

C. the “Amount” is equal to the liquidator’s present estimate of the relevant client’s Net Deposits, as defined in order 12 below, and of any profits made by the relevant client as a result of the client’s trading through Ozifin; and

(iii) a check in the circle that indicates that the person completing the proof of debt is the creditor.

11. No earlier than 14 days, and no later than 28 days, from the date on which it sends the Refund Notice, Ozifin send a text message to each person to whom it sent a Refund Notice, and for whom Ozifin has a mobile telephone number, in the following terms:

Hi [name – if available]. You may be eligible for the Ozifin refund payment scheme. You should have received a pre-filled form to sign by email on [date]. If you did not receive it, please call [liquidator’s phone number]. For further information about the scheme go to the ASIC website and search for “Ozifin”.

12. Ozifin pay to each client of Ozifin who deposited money to the trading account held by that client with Ozifin an amount equal to the client’s Net Deposits where Net Deposits means for the purpose of these orders:

(a) the total amount that the client deposited to the client’s trading account (as defined in the plaintiff’s further amended points of claim); less

(b) any amounts withdrawn, or already refunded to the client, from the client’s trading account; less

(c) any amounts refunded to the client as a result of any arrangement or agreement; less

(d) any amounts which the client in fact receives, pursuant to reg 7.8.03(6) of the Corporations Regulations,

as adjudicated by the liquidator in the normal process under the Corporations Act.

13. Ozifin pay one third of ASIC’s party / party costs of the proceeding, to be taxed in default of agreement.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Annexure A

REASONS FOR JUDGMENT

BEACH J:

1 This matter concerns the promotion of derivative instruments by the first defendant (AGM), the third defendant (OTM) and the fifth defendant (Ozifin), each of whom has now been placed in liquidation as a result directly or indirectly of my prior orders.

2 From the latter part of 2017 until the middle of 2018, each of the three defendants operated separate businesses in Australia that offered over-the-counter (OTC) derivative products being contracts for difference (CFDs) including margin foreign exchange contracts (FX contracts) to retail investors in Australia. The defendants provided retail investors with an online platform on which to invest in those products and also provided to them financial product advice by telephone and email. That advice was provided by account managers who were engaged on behalf of the defendants but based overseas. The account managers engaged on behalf of AGM were based in Israel. The account managers engaged on behalf of OTM were based in Cyprus and later the Philippines. And the account managers engaged on behalf of Ozifin were based in Cyprus.

3 Late last year I dealt with the trial on the issue of liability. I delivered judgment in February 2020. Subsequently, in March and April 2020 I made extensive declarations of contravention of various provisions of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 (Cth) concerning the conduct of the defendants that I found to have been established (see Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AGM Markets Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 3) (2020) 380 ALR 27; [2020] FCA 208); unless otherwise stipulated, the definitions in my principal reasons apply to the present reasons.

4 ASIC now seeks orders that each of AGM, OTM and Ozifin:

(a) pay to the Commonwealth pecuniary penalties pursuant to the applicable forms of s 1317G(1E) of the Corporations Act and s 12GBA(1)(a) of the ASIC Act; and

(b) pay refunds pursuant to the applicable forms of ss 12GNB and 12GNC of the ASIC Act to each client who has not received from the relevant defendant their net deposit, which I am defining to be the total amount deposited to the client’s trading account with AGM, OTM or Ozifin, less any amounts withdrawn by or already refunded to the client from their trading account, less any amounts refunded under separate arrangements and less any statutory funds received; I will explain that last concept later.

5 I should say now that the statutory preconditions to the making of pecuniary penalty orders have been satisfied. In relation to each particular financial services civil penalty provision in the Corporations Act, the only relevant statutory precondition is the making of a declaration of contravention under s 1317E. Relevantly to such a precondition, I have made declarations that the defendants contravened:

(a) in the case of AGM, ss 961K and 961L of the Corporations Act;

(b) in the case of OTM and Ozifin, s 961Q of the Corporations Act; and

(c) in the case of AGM, OTM and Ozifin, ss 12CB and 12DB of the ASIC Act, although such declarations are not preconditions to exercising my powers under the applicable form of s 12GBA.

6 Further, I declared that the conduct undertaken by OTM and Ozifin that constituted contraventions of ss 12CB and 12DB was conduct engaged in by them on behalf of AGM.

7 ASIC says that I should now fix pecuniary penalties totalling $100 million, being:

(a) $40 million for AGM;

(b) $30 million for OTM; and

(c) $30 million for Ozifin.

8 In addition, it says that I should make statutory redress orders requiring the defendants to refund their clients’ net deposits.

9 Now I will make statutory redress orders subject to discussing various aspects of how they are to interact with the applicable statutory insolvency regime concerning proofs of debt and priority questions. But as to fixing the quantum of the pecuniary penalties, in my view a total amount of $75 million more satisfactorily reflects the pattern of offending and meets the objective of general deterrence; I should say that the objective of specific deterrence is not of major importance in the present context given that AGM, OTM and Ozifin are now in liquidation.

10 Accordingly, I propose to order that:

(a) AGM pay a pecuniary penalty of $35 million;

(b) OTM pay a pecuniary penalty of $20 million; and

(c) Ozifin pay a pecuniary penalty of $20 million.

11 Such individual amounts better reflect the application of the totality principle to the relevant circumstances concerning each defendant and the relevant offending. Moreover, the aggregate sum of $75 million is a more proportionate numerical denunciation of the mendacity practised by the defendants on the unsophisticated and the unwary.

12 Before justifying in more detail why I propose to impose such penalties, it is useful to provide some general context concerning OTC derivatives.

SOME RELEVANT BACKGROUND

13 Retail OTC derivatives issuers in Australia offer various products, including margin FX contracts, binary options and CFDs. And the volume of trafficking in such products to retail investors is best reflected in considering the volume of money involved.

14 Under the ASIC Client Money Reporting Rules 2017 (Cth), the holder of an Australian financial services licence (AFSL) that holds reportable client money is required to comply with record-keeping, reconciliation and reporting requirements. Under Pt 2.2 of the Rules, a licensee is required to perform daily and monthly reconciliations of the amount of reportable client money that it is required to hold in a client money account against the amount of reportable client money it is actually holding in that account. A record of such reconciliations performed by the licensee is required to include:

(a) the total balance of reportable client money owed to the licensee’s clients;

(a) the total amount of reportable client money which is being held or has otherwise been permissibly withdrawn or invested by the licensee;

(b) an explanation of any difference between the amount of reportable client money owed to the licensee’s clients and the amount being held or otherwise permissibly withdrawn or invested by the licensee; and

(c) the total balance of the licensee’s client money account(s) in which it holds reportable client money and the total amount of money other than reportable client money the licensee holds in the account(s).

15 For the purposes of the present proceeding, ASIC has accessed monthly reconciliation records lodged through its regulatory portal. It has reviewed the records lodged by licensees which held retail derivatives client money and which had previously been identified as providing OTC derivatives services to retail clients. The monthly reconciliation records for the final business day in each month from December 2019 to May 2020 reveal the following:

Month | Total derivative client money | % change | Number of licensees | Number of licensees with $0 balance |

December 2019 | $2,069,715,173.65 | 66 | 4 | |

January 2020 | $2,194,323,151.59 | 5.68% | 65 | 3 |

February 2020 | $2,138,558,640.34 | -2.61% | 65 | 4 |

March 2020 | $2,163,950,480.08 | 1.17% | 65 | 4 |

April 2020 | $2,288,398,138.89 | 5.44% | 65 | 5 |

May 2020 | $2,342,570,836.35 | 2.31% | 64 | 4 |

16 One can see from these figures that the amount of client money invested in and at risk concerning OTC derivatives at the retail level is significant. Let me now make some more general observations.

17 As ASIC rightly explains it, binary options are OTC derivatives that allow clients to make “all-or-nothing” bets on the occurrence or non-occurrence of a specified event in a defined timeframe, for example, the price of gold increasing in 30 seconds. In other words, they are little more than gambling.

18 CFDs are leveraged OTC derivatives that allow clients to speculate on the change in the value of an underlying asset. As I explained in my principal reasons (at [22] and [23]):

A CFD is an agreement to exchange, at the closing of the contract, the difference between the opening and closing price of the underlying asset, multiplied by the number of units of that asset detailed in the contract. A CFD essentially allows a person to bet on whether the value of the underlying asset will increase or decrease over time. An FX contract is a form of CFD that allows a person to take a position on the change in value over time of one currency relative to another.

The precise terms of the contract that represents a CFD or FX contract are determined by the disclosure documents provided by the issuer of the product. Nevertheless, under both CFDs and FX contracts, investors are exposed to movements in the value of the underlying asset, without having to purchase the asset itself. CFDs and FX contracts are highly leveraged. They require the investor initially to pay only a fraction of the price of the value of the underlying asset or currency to open the position. The investor is exposed, however, to the total of the movement in the price of the underlying asset or currency. Whilst those products can thereby be used to magnify profits relative to the initial investment, they have a commensurate potential to magnify losses.

19 ASIC in various publications including its Consultation Paper No 322 titled “Product intervention: OTC binary options and CFDs” published in August 2019 has expressed the view that binary options and CFDs have resulted in significant financial losses to retail clients.

20 It has explained that in relation to binary options:

(a) most retail clients who trade binary options lose money;

(b) there is a negative expected return, resulting in significant market-wide financial losses;

(c) there is a high likelihood of cumulative losses; and

(d) the inherent structural design flaws are confusing and make them unsuitable as an investment or risk management product for retail clients.

21 Further, its investigations have revealed that in relation to CFDs:

(a) most retail clients who trade CFDs lose money;

(b) high leverage ratios carry inherent risk of significant losses, including losses which can exceed a retail client’s initial investment;

(c) fees and costs lack transparency, are magnified by leverage and can quickly and significantly deplete a retail client’s investment; and

(d) confusing and unclear pricing methodologies can lead to the sale to retail clients of CFDs that are misaligned with their needs, expectations and understanding.

22 If I may say so, the evidence adduced before me at the trial on liability provided ample evidence of these vices in CFDs and retail clients’ addiction for such products.

23 Further, these concerns about binary options and CFDs, and the significant detriment to retail clients resulting from these high-risk products, are not unique to the Australian market. Indeed various foreign regulators have implemented measures to prohibit or restrict the offer of binary options and CFDs.

24 In that regard, ASIC has recently suggested the possibility of making a market-wide product intervention order that prohibits the issue and distribution of OTC binary options to retail clients as they provide no meaningful investment or economic utility. Unlike other types of OTC derivatives or exchange traded products, binary options do not offer participation in the growth in value of the underlying asset. Further, the “all-or-nothing” payoff structure makes them unsuitable for risk management such as hedging.

25 Further, ASIC has recently suggested that it might make a market-wide product intervention order that imposes conditions on the issue and distribution of OTC CFDs to retail clients. Now no doubt it can be said that CFDs might serve legitimate investment and hedging purposes. But most retail clients lose money trading CFDs, often due to excessive leverage. The present case before me is a classic example of unsophisticated retail investors seeking such financial heroin hits. Further, unclear or confusing presentation of information to retail clients about the risks, pricing and costs of CFD trading can lead to the sale of CFDs that are misaligned with clients’ needs, expectations and understanding. In my case, that was the reality for the retail clients of the defendants rather than a bare possibility. Further, and importantly, none of the defendants’ clients were acquiring CFDs for hedging purposes. They were unsophisticated and ill-informed speculators.

26 ASIC has outlined the following conditions on the issue and distribution of CFDs to retail clients that it suggests could be included in a product intervention order (Table 5 of ASIC’s Consultation Paper No 322):

Condition | Requirement |

1. Leverage ratio limits | Minimum initial margin requirements on CFDs issued to retail clients are applied such that leverage ratios offered to retail clients do not exceed the following limits at the time of issue: • 20:1 for CFDs over currency pairs or gold; • 15:1 for CFDs over stock market indices; • 10:1 for CFDs over commodities (excluding gold); • 2:1 for CFDs over crypto-assets; and • 5:1 for CFDs over shares or other underlying assets. The leverage ratio limits take into account any leverage inherent in an underlying reference asset (e.g. a CFD on a futures contract, an option contract or a leveraged exchange traded fund). |

2. Margin close-out protection | The terms of a CFD offered to a retail client must provide that, if a retail client’s funds in their CFD trading account fall to less than 50% of the total initial margin required for all of their open CFD positions on that account, a CFD issuer must, as soon as market conditions allow, close out one or more open CFD positions held by the retail client. |

3. Negative balance protection | The terms of a CFD offered to a retail client must limit the retail client’s losses on CFD positions to the funds in that retail client’s CFD trading account. |

4. Prohibition on inducements | A person must not, in the course of carrying on a business, give or offer a gift, rebate, trading credit or reward to a retail client or a prospective retail client as an inducement to open or fund a CFD trading account or trade CFDs. However, the prohibition would not cover information services or educational or research tools. |

5. Risk warnings | A CFD issuer must provide a prominent risk warning to retail clients and prospective retail clients on all account opening forms, PDSs, any trading platforms maintained by the CFD issuer and websites relating to CFD trading which, at a minimum: • includes a warning on the complexity, risks and likelihood of losses; and • discloses the percentage of the CFD issuer’s retail clients’ CFD trading accounts that made a loss over a 12-month period. |

6. Real-time disclosure of total position size | A CFD issuer must provide real-time disclosure to a retail client, in any trading platforms maintained by the CFD issuer, of the retail client’s total position size in monetary terms for all open CFD positions for the retail client’s CFD trading account. |

7. Real-time disclosure of overnight funding costs | If a CFD issuer charges a retail client funding costs for holding open CFD positions overnight, the CFD issuer must clearly and prominently disclose, in any trading platforms maintained by the CFD issuer, applicable overnight funding costs to the retail client, both as an annualised rate of interest and as an estimated cost expressed in the currency denomination of the CFD. |

8. Transparent pricing and execution | A CFD issuer must maintain and make available on its website a CFD pricing methodology and a CFD execution policy. The CFD pricing methodology must explain how the CFD issuer determines its CFD prices, including: • how it uses independent and externally verifiable price sources; • how it applies any spread or mark-up; and • any circumstances under which its CFD prices will vary from the methodology. The CFD execution policy must explain how the CFD issuer deals with clients’ offers to trade CFDs and effects CFD trades. |

27 If I may say so, there is considerable merit in ASIC’s proposal, but of course these are policy matters outside my realm of influence. But what I can say is that if such measures had been in place, most of the egregious conduct and its consequences that was exposed in the present case would in all likelihood not have occurred.

28 Let me make one other interesting observation. A report of the International Organization of Securities Commissions published in December 2016 titled “Report on the IOSCO Survey on Retail OTC Leveraged Products” that was in evidence before me described considerable international variations in leverage levels. It said (at p 22):

Jurisdictions report a broad range of features associated with the sale and trading of the relevant products, including commonly high leverage levels offered to retail clients and the prevalent use of automatic close-outs.

In the United States, CFTC and NFA rules limit leverage on OTC leveraged forex products to 50:1 for major currency pairs (minimum 2% margin) and 20:1 for other currency pairs (minimum 5% margin). The US NFA can increase minimum margin levels based on market volatility, and has done so recently for certain currencies. The relevant firms commonly offer stop losses, and some claim to automatically liquidate customer positions having fallen below minimum margin levels.

The Mexican CNBV reports that foreign websites active in the relevant market sector and accessible to Mexican investors offer varying levels of leverage depending on the firm and the product. The CNBV has observed leverage as high as 500:1. Some of the websites also offer stop losses, margin calls and close-outs.

Foreign firms marketing the relevant products on-line in Brazil offer leverage ranging from 5:1 to 2000:1, according to the Brazilian CVM. Some offer stop-loss features.

In Australia common leverage levels offered range from 10:1 to 500:1 in the relevant products. The level offered depends on the firm and the particular product. Typically, the smaller entities offer the higher leverage levels. The more established, reputable firms tend to have varying leverage rates depending on the product and the client, according to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission. The majority of firms offer stop losses for an additional fee, although the type of mechanism varies: some firms will guarantee an execution at the next available price while others will guarantee a price. The majority of firms implement margin calls and offer the client the opportunity to top up the account, so that the close-out occurs only if the client does not meet the specified margin call in the specified timeframe.

29 So it would seem that Australian leverage levels have been comparable to Mexican practices, but shy of the Brazilian heights. In that context, ASIC’s regulatory proposal has considerable merit.

30 Why have I included the above discussion? As I said at the outset, in the present context general deterrence is the principal question for me in setting pecuniary penalties. But in the future, the pushing of these derivative instruments in their current form at the retail level is likely to be significantly curtailed by changes in the regulatory regime. That being the likelihood, the causative effect on general deterrence of a high penalty may not have or require as much potency if the causative effect on general deterrence is produced or strengthened by regulatory changes that are likely if not inevitable. It is this consideration and also the fact that the total quantum for the penalties of $75 million will more than notionally wipe out all profits made by the defendants that justifies the more proportionate sums that I intend to impose.

31 Further, it should not be lost sight of that in essence the operations of AGM, OTM and Ozifin were shut down some time ago as a result of the freezing orders that I made and a suite of other injunctions and court enforceable undertakings. And no doubt the direct and indirect consequences of such orders has now produced the liquidations of all three entities. Such a judicial response also has a general deterrence effect that I have taken into account. Further, the declarations that I have made also have a general deterrence effect. All of this is to say that the objective of general deterrence can be served by both penalty and non-penalty consequences.

32 And all of this now leads me to discuss the question of pecuniary penalties in more detail. I should begin with some principles.

PECUNIARY PENALTIES

33 The central purpose of a pecuniary penalty has the two dimensions of general deterrence and specific deterrence, although as I have said it is the former that is the focus in the present context. As I said in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Banking Corporation (No 3) (2018) 131 ACSR 585; [2018] FCA 1701 at [117] to [119]:

It is well established that deterrence is the primary objective for the imposition of civil penalties (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cement Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 159 at [385] per Middleton, Beach and Moshinsky JJ; see also Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia (2018) 128 ACSR 289 at [62]). In Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 CLR 482; 326 ALR 476; [2015] HCA 46 at [55], the High Court approved of French J’s observation in Trade Practices Commission v CSR Ltd [1991] ATPR 41-076 at 52,152:

The principal, and I think probably the only, object of the penalties imposed by s 76 is to attempt to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravenor and by others who might be tempted to contravene the Act.

In ASIC v CBA, I observed (at [62]) that the penalty:

must be fixed to ensure that the penalty is not to be regarded as an acceptable cost of doing business. As I have said, both specific and general deterrence are important. The need for specific deterrence is informed by the attitude of the contravener to the contraventions, both during the course of the contravening conduct and in the course of the proceedings. And the need for general deterrence is particularly important when imposing a penalty for a contravention which is difficult to detect.

The High Court considered civil penalty provisions in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2018) 351 ALR 190; [2018] HCA 3 (ABCC v CFMEU). Kiefel CJ referred to “the deterrent effect which is the very point of the penalty” and “the purpose for which the power is given” (at [44]). Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ reiterated (at [87]) that:

the principal consideration in the imposition of penalties for contravention of civil remedy provisions is deterrence, both specific and general; more particularly, the objective is to put a price on contravention that is sufficiently high to deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to contravene.

34 Now given that each of the defendants are being wound up, and in all likelihood are insolvent, any penalty fixed by me cannot be proved in the liquidation of those companies. Section 553B of the Corporations Act provides:

(1) Subject to subsection (2), penalties or fines imposed by a court in respect of an offence against a law are not admissible to proof against an insolvent company.

(2) An amount payable under a pecuniary penalty order, or an interstate pecuniary penalty order, within the meaning of the Proceeds of Crime Act 1987, is admissible to proof against an insolvent company.

35 But the fixing of a pecuniary penalty in such cases can be justified in circumstances where to do so will serve the purpose of general deterrence. I said in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Get Qualified Australia Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (No 3) [2017] FCA 1018 at [78] to [80]:

Penalties are not provable in a liquidation and it is most unlikely that GQA will pay any penalty that is imposed upon it. But in my view general deterrence considerations warrant making an order that GQA pay a significant pecuniary penalty. Now although it may not always be appropriate to order that a company in liquidation pay a pecuniary penalty, the Court should not be dissuaded from imposing a penalty on a company in liquidation if to do so will serve the purpose of deterring others from engaging in the same or similar conduct (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dataline.Net.Au Pty Ltd (2007) 161 FCR 513 (ACCC v Dataline.Net.Au); Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Chaste Corporation Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2005] FCA 1212; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Fila Sport Oceania Pty Ltd (administrators appointed) [2004] ATPR 41-983; [2004] FCA 376; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v SIP Australia Pty Ltd [2003] ATPR 41-937 (ACCC v SIP); [2003] FCA 336; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v The Vales Wine Company Pty Ltd [1996] ATPR 41-528; [1996] FCA 854).

In ACCC v Dataline.Net.Au, the Full Court said at [20]:

… a court may impose a penalty on a company in liquidation if to do so would clearly and unambiguously signify to, for example, companies or traders in a discrete industry that a penalty of a particular magnitude was appropriate (and was of a magnitude which might be imposed in the future) if others in the industry sector engaged in the same or similar conduct.

See also Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v EDirect Pty Ltd (in liq) (2012) 206 FCR 160; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Homeopathy Plus! Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2015] FCA 1090; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v South East Melbourne Cleaning Pty Ltd (in liq) (formerly known as Coverall Cleaning Concepts South East Melbourne Pty Ltd) (No 2) [2015] ATPR 42-492; [2015] FCA 257.

In ACCC v SIP Goldberg J said at [59]:

If general deterrence is to have any meaning, a company in liquidation which has contravened the Act must be ordered to pay an appropriate pecuniary penalty as a deterrent to others who might be tempted to engage in similar conduct.

36 Let me turn to the next question.

37 The maximum penalty for each contravention of:

(a) sections 12CB or 12DB of the ASIC Act is $2.1 million, being 10,000 penalty units (s 12GBA(3)), the value of each of which was $210 since 1 July 2017 up until 1 July 2020; and

(b) sections 961K, 961Q and 961L of the Corporations Act is $1 million (s 1317G(1F)(b)).

38 The number of contraventions in which the defendant has engaged and the theoretical maximum penalty for those contraventions are relevant considerations in determining the appropriate penalty.

39 In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Commonwealth Bank of Australia [2020] FCA 790 I said at [65]:

Now the process to be used in setting a civil penalty for contravention of statutory provisions is similar to that used in criminal sentencing. The maximum penalty must be given due attention because it has been legislated for, it invites comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the Court at the relevant time, and it provides a form of yardstick. But it may be an arid exercise in cases such as the present to engage in a mere arithmetical calculation multiplying the maximum penalty by the number of contraventions to get a theoretical maximum for all offending even if one could theoretically quantify that latter number (see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd (2015) 327 ALR 540 at [17], [18], [84] and [85] per Allsop CJ). But I do accept that some estimate of the number of contraventions is to be taken into account in getting some sense of the overall maximum. Now in the present case, I am theoretically considering orders of magnitude above a single contravention. But it is not productive to quantify this further. Moreover, it is not appropriate to quantify a theoretical maximum for the purpose of then ratcheting down, which is an impermissible exercise.

40 Where I have determined that the defendants have each engaged in a large number of contraventions, as I have here, it might not be productive to quantify the number of contraventions beyond saying that they are large in number (Get Qualified (No 3) at [32]). But it is instructive to take account of the theoretical maximums so that consideration can be given to the egregiousness of the conduct in question.

41 In the present case, I have made declarations that each of the defendants has engaged in thousands of separate contraventions of the Corporations Act and the ASIC Act that satisfy the statutory preconditions for the imposition of a pecuniary penalty. Putting to one side the contraventions of s 961L of the Corporations Act in which AGM engaged, the established contraventions arose for the most part from telephone conversations and emails between representatives of the defendants and identified clients of each defendant. Single statements or single phone calls gave rise in many instances to multiple contraventions that provide the basis for the imposition of a pecuniary penalty. In particular, each time a representative of a defendant made an advice statement (as defined in my principal reasons):

(a) in the case of AGM, for those advice statements made by people engaged by the third party account managers, Falcon and IBD, it contravened s 961K of the Corporations Act because the account manager did not comply with what I would describe as personal advice obligations to:

(i) act in the best interests of the relevant client as required by s 961B;

(ii) provide advice that was appropriate to the client as required by s 961G; and

(iii) give priority to the interests of the clients to whom those people provided advice as required by s 961J;

(b) in the case of OTM and Ozifin, for those advice statements made by people acting on their behalf, contravened s 961Q because the account managers did not comply with the personal advice obligations; and

(c) the defendant who had engaged that representative made what I have previously defined in my principal reasons as a best interests representation and an appropriate advice representation, in contravention of ss 12DB(1)(e) and 12DB(1)(h) of the ASIC Act, and a personal advice representation, in contravention of ss 12DB(1)(e), 12DB(1)(f) and 12DB(1)(h) (together, the implied representations).

42 Further, in this case I determined that what I have previously defined in my principal reasons as each of the investment representations, except the revenue representations, and the regulation representations (together, the express representations) made by each of the defendants contravened multiple parts of s 12DB(1).

43 Let me turn to another matter.

44 At the time of the contraventions in this case, s 12GBA(2) of the ASIC Act stated that in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty I must have regard to all relevant matters and set out certain mandatory considerations to which I must have regard in determining an appropriate pecuniary penalty for contraventions of ss 12CB and 12DB of the ASIC Act, namely:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission that constitutes the relevant contravention, and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission;

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person who has been determined to have engaged in the contravention has previously been found in proceedings under Div 2, Subdiv G of the ASIC Act to have engaged in similar conduct.

45 At the time of the contraventions in this case, there was no equivalent list of mandatory considerations for civil penalties fixed under the applicable version of s 1317G(1E) of the Corporations Act for contraventions of ss 961K, 961L or 961Q.

46 As to the non-mandatory factors, I said in Westpac (No 3) at [49] and [50]:

The fixing of a pecuniary penalty involves the identification and balancing of all the factors relevant to the contravention and the circumstances of the defendant, and the making of a value judgment as to what is the appropriate penalty in light of the purposes and objects of a pecuniary penalty that I have just explained. Relevant factors include the following:

(a) the extent to which the contravention was the result of deliberate or reckless conduct by the corporation, as opposed to negligence or carelessness;

(b) the number of contraventions, the length of the period over which the contraventions occurred, and whether the contraventions comprised isolated conduct or were systematic;

(c) the seniority of officers responsible for the contravention;

(d) the capacity of the defendant to pay, but only in the sense that whilst the size of a corporation does not of itself justify a higher penalty than might otherwise be imposed, it may be relevant in determining the size of the pecuniary penalty that would operate as an effective specific deterrent;

(e) the existence within the corporation of compliance systems, including provisions for and evidence of education and internal enforcement of such systems;

(f) remedial and disciplinary steps taken after the contravention and directed to putting in place a compliance system or improving existing systems and disciplining officers responsible for the contravention;

(g) whether the directors of the corporation were aware of the relevant facts and, if not, what processes were in place at the time or put in place after the contravention to ensure their awareness of such facts in the future;

(h) any change in the composition of the board or senior managers since the contravention;

(i) the degree of the corporation’s cooperation with the regulator, including any admission of an actual or attempted contravention;

(j) the impact or consequences of the contravention on the market or innocent third parties;

(k) the extent of any profit or benefit derived as a result of the contravention; and

(l) whether the corporation has been found to have engaged in similar conduct in the past.

Moreover and importantly, attention must be given to the maximum penalty for the contravention. But if contravening conduct is not so grave as to warrant the imposition of the maximum penalty, I am bound to consider where the facts of the particular conduct lie on the spectrum that extends from the least serious instances of the offence to the worst category.

47 Clearly, in considering and weighing all relevant factors I need to engage in intuitive synthesis, which requires a weighing together of all relevant factors, rather than an arithmetical algorithmic process that starts from some pre-determined figure and then makes incremental additions or subtractions for each factor according to a set of predetermined rules. And it is also important to note that intuitive synthesis conducted in criminal sentencing does not have the same boundaries and content as intuitive synthesis in the context that I am considering. In criminal sentencing, the synthesis involves not only the facts and circumstances of the offending, but also conflicting sentencing considerations such as retribution and rehabilitation, and differing sentencing options along a broader spectrum than the civil context from a donation to the poor box through to imprisonment.

48 Let me deal with another matter. Because discrete conduct on the part of the defendants gave rise to multiple contraventions, there are three further principles that are relevant to consider in the present context.

49 First, there is a statutory restriction in the applicable form of s 12GBA(4) that operates to preclude more than one pecuniary penalty being fixed under s 12GBA(1) if the same conduct contravenes two or more provisions of the relevant subdivisions of the ASIC Act. Accordingly, the conduct that gave rise to each of the implied representations and the express representations can be subject to only one pecuniary penalty under s 12GBA(1). I should note that there was at the time of the contraventions by the defendants no equivalent provision in the Corporations Act, but I will nevertheless adopt the same approach.

50 Second, where there is an interrelationship between the factual and legal elements of two or more contraventions, consideration may be given to whether it is appropriate to impose a single overall penalty for that course of conduct. Now as I said in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Murray Goulburn Co-Operative Co Limited [2018] FCA 1964 at [29]:

It is therefore necessary to say something on the “course of conduct” question. Separate contraventions arising from separate acts should ordinarily attract separate penalties. But a different principle may apply where separate acts, giving rise to separate contraventions, are so inextricably interwoven that they should be viewed as one multi-faceted ‘course of conduct’ such that a single penalty should be imposed for all contraventions. This provides one way of avoiding double-punishment for those parts of the legally distinct contraventions that involve overlap in wrongdoing; the other way is to apply the totality principle. But the question of whether multiple contraventions should be treated as being a single course of conduct is a factual inquiry to be made having regard to all of the circumstances. It is a ‘tool of analysis’ which can, but need not, be used in any given case. And its application and utility must be tailored to the circumstances (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Hillside (Australia New Media) Pty Ltd trading as Bet365 (No 2) [2016] FCA 698 at [25]). But to apply such an approach is not to downplay the wrongdoing. This does not convert the many separate contraventions into only one contravention, and nor does it constrain the available maximum penalty let alone necessarily constrain it to the maximum penalty for one contravention. And notwithstanding a grouping into a course(s) of conduct, one must ensure that any penalty imposed is of appropriate deterrent value, whether specific or general.

51 Third, the totality principle requires me to review the aggregate penalty to ensure that it is just and appropriate and not out of proportion to the contravening conduct considered as a whole. It involves a final consideration of the sum of the penalties determined by consideration of all the relevant factors, and requires me to make a final check of the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole. In cases where I consider that the cumulative total of the penalties to be imposed would be too high, I can alter the final penalties to ensure that they are just and appropriate and in proportion to the nature, quality and circumstances of the conduct involved.

52 Let me now turn to the application of these principles.

53 ASIC has sought to justify the fixing of a pecuniary penalty for:

(a) AGM of $40 million;

(b) OTM of $30 million; and

(c) Ozifin of $30 million.

54 But as I have indicated, in my view the penalty for AGM should be $35 million. And for OTM and Ozifin, they should separately pay a penalty of $20 million each. Let me explain my reasons.

55 Putting to one side AGM’s contravention of s 961L, the contravening conduct by each of the defendants that has enlivened my power to fix civil penalties arose out of the provision by the defendants’ representatives of unlicensed personal financial advice to identified clients in situations involving conflicts of interest, the making of various express or implied representations to identified clients that were false or misleading, and conduct that was intended to engender trust from clients and to advance the defendants’ purpose of having clients deposit additional funds and therefore to expose them to a greater risk of loss.

56 I determined that the conduct towards identified clients of the defendants was unconscionable, and that each of the defendants engaged in a system of conduct that was unconscionable.

57 In addition to those contraventions that enlivened my power to fix a civil penalty, I also determined that each of the defendants engaged in contraventions of at the time non-civil penalty provisions, including:

(a) the provision by each defendant of unlicensed financial services in contravention of s 911A, namely, the provision of personal financial advice;

(b) conduct that was misleading or deceptive in contravention of s 1041H of the Corporations Act and s 12DA of the ASIC Act, including by making the express representations, implied representations, revenue representations and location representations as referred to in my principal reasons;

(c) AGM’s failure to comply with its compliance obligations in s 912A(1); and

(d) AGM’s non-compliance with ss 991A and 946A, OTM’s non-compliance with s 916B(2A) and Ozifin’s non-compliance with s 923C.

58 As to the contraventions for which a pecuniary penalty can be imposed, I should observe the following:

(a) The s 12DB contraventions occurred when the representatives made statements to the relevant clients that were false or misleading, or provided personal financial advice to the identified clients carrying implied representations that were false or misleading.

(b) The s 12CB unconscionable conduct contraventions were directed towards the 21 clients identified in my declarations. Each constituted a separate contravention. Further, the nominal number of contraventions that arose from the unconscionable system of conduct in which each defendant engaged can be determined by ascertaining the number of clients of each defendant. I am prepared to infer that each of those clients was subject to the unconscionable system of conduct.

(c) The ss 961K and 961Q contraventions occurred on each occasion that the representatives made advice statements, which contravened the personal advice obligations.

(d) The s 961L contraventions arose from the failure by AGM to take reasonable steps to ensure that the people engaged by Falcon and IBD complied with the personal advice obligations. Those contraventions are distinct from the contraventions of s 961K. Whereas the contraventions of s 961L arose from AGM’s failure to take reasonable steps to ensure that its representatives complied with the personal advice obligations, s 961K allows me to look through the conduct of the representatives to impose liability on the licensee for engaging in a breach of those obligations.

59 Now ASIC provided me with a table setting out the number of instances and maximum penalties applicable to the contraventions the subject of my principal findings and declarations. No party took issue with its accuracy; for convenience it is a schedule to my reasons. But there are four matters that I should discuss at this point.

60 First, each advice statement constituted a contravention of s 12DB because the advice carried with it the implied best interests representation, appropriate advice representation and personal advice representation, each of which I determined was false or misleading. Further, in the case of the advice provided by Falcon or IBD, s 961K was contravened by AGM. Further, in the case of advice provided by OTM or Ozifin, s 961Q was contravened by OTM or Ozifin. This is because the providers of that advice failed to comply with the personal advice obligations.

61 The calculation of the number of unique instances that has been undertaken by ASIC and with which I agree ensures that particular conduct that constituted multiple contraventions of s 12DB has only been counted once. Further, the calculation has been done on the basis that on each occasion that an advice statement was made, there were contraventions of each of ss 961B, 961G and 961J, which has in each case been counted as a unique instance of conduct that contravened ss 961K or 961Q.

62 Second, and consistent with the approach adopted by me in Get Qualified (No 3), in assessing the appropriate penalties for the unconscionable systems of conduct in which each defendant engaged, I am not limited to imposing a penalty equivalent to the maximum penalty for one contravention of s 12CB. That is particularly so in a case such as the present. As I explained in my principal reasons, I was satisfied that the approach adopted by the account managers engaged by the three defendants was consistent across clients of all defendants. Further, the conduct of the account managers towards the 21 individual investors identified in my declarations was representative of the conduct towards all clients of the defendants. Moreover, it seemed to me that systems put in place were designed to identify and interact with investors in the way exemplified by the 21 specific instances of individual unconscionable conduct. Accordingly, I am satisfied that the conduct by each defendant that constituted the system of conduct determined to have been unconscionable was directed to each of the many thousands of clients of the defendants.

63 Third, AGM engaged in nine contraventions of s 961L. The number of contraventions has been appropriately calculated by multiplying the three groups of representatives who provided personal financial advice on AGM’s behalf, that is, those who were engaged by AGM, OTM and Ozifin, by the three personal advice obligations that those representatives contravened, namely, as contained in ss 961B, 961G and 961J.

64 Fourth and more generally, each of the defendants engaged in many thousands of individual instances of conduct that contravened the relevant statutory provisions. And the theoretical maximum penalty derived from that number of contraventions is enormous. So in the case of AGM, it is approximately $27 billion. In the case of OTM, it is approximately $13 billion. And in the case of Ozifin, it is approximately $13 billion. I have had regard to such theoretical maximums although there is an air of unreality to them given that they are at least two orders of magnitude above what I consider to be the realistic range for the penalties that I propose to impose.

65 Let me now say something about general deterrence although I have already touched on this.

66 Each of the civil penalty provisions that the defendants contravened was a provision intended for the protection of consumers of financial services generally, and consumers receiving financial product advice in particular. The advice provided and the representations made by the defendants concerned high risk and complex financial products.

67 Moreover, the conduct arose in circumstances where retail clients were exposed to the risk of losses that exceeded the amount that clients had deposited to their trading accounts.

68 Further, apart from a small number of clients whose positions AGM had hedged directly, the defendants each stood to generate revenue directly from any loss suffered by a client, putting the defendants in a direct conflict of interest with their clients.

69 Further, the risk that retail participants in the market for CFDs and margin FX contracts will be misled if similar conduct occurs in the future, the risk of those participants suffering significant losses, and the commensurate prospect of gain to the issuer of those products or their authorised representatives supports the imposition of a significant penalty to deter licensees and their representatives from engaging in the type of conduct exposed in the present case.

70 Further, the size of the market for retail OTC derivatives in Australia, and the risk of loss to clients exposed to the sort of conduct engaged in by the defendants that I found to be established, supports the fixing of a significant pecuniary penalty to advance the purpose of general deterrence. Since December 2019, there have been at least 60 holders of an AFSL who have been entitled to hold and have in fact held money on behalf of people who have invested in retail OTC derivatives. I have set out some details earlier in my reasons.

71 Further, in addition to the Australian market, providers of OTC derivatives offer comparable products to investors in various jurisdictions. Jurisdictions such as the UK and Europe have seen an increase in recent years of the number of providers of derivatives, as well as the number of retail investors for those products, and continued consumer complaints to regulatory authorities by those retail investors. And various regulatory agencies in those jurisdictions have taken enforcement action against some providers as the result of conduct or contraventions equivalent to that in which the present defendants have engaged. Further, since 2017 at least 16 of the AFSL holders who have offered retail OTC derivatives in Australia have been or are the subsidiary or associate of an offshore company that has been the subject of enforcement action in an overseas jurisdiction. Those 16 AFSL holders as at May 2020 held about $1.34 billion in retail client funds. What all these matters reveal is, first, the prevalence of such providers in overseas jurisdictions, second, conduct on the part of some of those providers that is equivalent to the conduct at issue in this proceeding and, third, links between those that carried out that conduct and AFSL holders. The quantum of the civil penalty to be fixed in the present proceeding should also be sufficient to deter overseas providers of OTC derivatives from engaging in equivalent conduct in this jurisdiction.

72 In summary, general deterrence is of paramount importance in the present case and all of the above considerations justify a high penalty. But where I differ from ASIC is that in my view total penalties of $75 million rather than $100 million adequately satisfy the objective of general deterrence.

73 In this regard, general deterrence is not just served by the quantum of the pecuniary penalties. It is also served by my declarations and also by the orders that I have previously made shutting down the defendants’ operations and ultimately resulting in the liquidation of each of the defendants. All of that has a general deterrence effect.

74 Further, as I discussed earlier in my reasons, the regulatory changes proposed are likely to result in a reduced risk of similar conduct being repeated in the future by other market participants or at least significantly ameliorate its scope or effect.

75 Further, on any view, the quantum of penalties to be set by me at $75 million well wipes out any profits made by the defendants.

76 Let me turn to another matter. The deliberateness of the conduct of each defendant supports imposing significant penalties. I should address four specific matters.

77 First, the purpose advanced by each of the defendants in their interactions with their clients was to have the clients increase the amount of money that they deposited to their trading accounts, to have the clients open multiple CFD or FX contract positions, and for the consequence of those steps to be that the clients lost the money they deposited. For example, the account managers engaged on behalf of OTM were instructed to “kill your customers”, which was a reference to the purpose of the defendants to encourage deposits and trades and ultimately for those clients to lose their funds. And in advancing such a purpose, the account managers engaged by or on behalf of the defendants explicitly sought to and did win the trust of vulnerable investors. And at least in the case of those account managers engaged on behalf of AGM and OTM, they were paid significant commissions based on the quantum of deposits that they were able to secure from clients. So, the account managers were incentivised to induce clients to expose themselves to increasing losses.

78 Second, the approach of each defendant to assessing the appropriateness of the services offered to their clients was inadequate, perhaps non-existent. Moreover, the failure by the defendants to apply the appropriate benchmarks to determine the appropriateness of the products for potential clients was a determinant in my conclusion that the conduct towards the identified investors was unconscionable.

79 Third, each of the defendants was aware from early in the relevant period that clients had raised concerns with the defendants in relation to their conduct. Further, at least AGM and OTM were aware that ASIC had concerns about certain aspects of OTM’s conduct from December 2017 in relation to representations on its website regarding the segregated nature of client funds and OTM being a regulated broker and the issuer of the securities. Further, all three defendants were aware of the breadth of ASIC’s concerns against each of them by February 2018 at the latest. Further, the defendants knew that the Australian Financial Complaints Authority, or its predecessor the Financial Ombudsman Service, had received complaints from their clients by:

(a) in the case of AGM, no later than 21 November 2017;

(b) in the case of OTM, no later than 8 January 2018; and

(c) in the case of Ozifin, no later than November 2017.

80 Fourth, the defendants were in a position of conflict of interest with their clients. Indeed, the purpose advanced by the defendants increased the prospects of losses to the clients and commensurate gains to the defendants.

81 Let me now deal with the question of the clients’ losses and the defendants’ gain.

82 As a result of the contravening conduct, clients of each of the three defendants lost significant amounts of money. And as a direct consequence, each of the three defendants earned significant profits.

83 Now ASIC has not received from the defendants or their liquidators a reconciliation of the total amounts lost by clients, or the profit earned by the defendants, in the period that they each were operating.

84 But it would seem on the figures available, which I am prepared to accept, that considering only those clients who suffered overall losses from their trading, their total trading losses were:

(a) in the case of AGM, approximately $1.21 million up to September 2018;

(b) in the case of OTM, approximately $19.64 million up to September 2018; and

(c) in the case of Ozifin, approximately $11.36 million in the period between October 2017 and January 2019.

85 Further, I am satisfied that such trading losses translated on the other side to revenue earned by the defendants.

86 Further, the share of the revenue received by each defendant is also to be adjusted by the commission arrangements between AGM and each of OTM and Ozifin set out in the corporate authorised representative (CAR) agreements that I discussed in my principal reasons. Under the OTM CAR agreement, AGM was entitled to a percentage of OTM investor losses varying on a marginal basis starting from 7% and decreasing incrementally to 5% based on the quantum of gross monthly client P&L. Given difficulties in ascertaining those monthly values, a range has been calculated, with 5% used at the bottom end of the range and 7% at the top end. Under the Ozifin CAR agreement, AGM was entitled to 7% of Ozifin investor losses.

87 Taking into account the percentage of revenue from clients of OTM and Ozifin to which AGM was entitled under the terms of the CAR agreements, AGM earned approximately $2.96 to $3.34 million up to September 2018, including commissions paid by Ozifin to AGM in respect of that period during the following months up to January 2019. Further, OTM earned approximately $18.30 to $18.68 million up to September 2018. And Ozifin earned approximately $10.56 million in the period between October 2017 and January 2019.

88 Further, in the case of Ozifin, its liquidators have provided an updated estimate of the total client losses of approximately $13.93 million for the period 15 February 2018 to 29 September 2019.

89 Let me make a more general point. I have determined that each of the defendants engaged in a system of conduct that was unconscionable, that the conduct by the defendants towards the 21 investors identified in my principal reasons was representative of that system of conduct, and that the system was designed to identify and interact with investors in the way exemplified by the specific instances. Accordingly, I am satisfied that the revenue earned by the defendants was the result of the unconscionable system employed by the defendants.

90 Further, in addition to the direct financial losses suffered by clients, which constituted revenue earned by the defendants, clients of those defendants suffered significant indirect financial losses caused by conduct of the defendants. Various clients were unable to meet existing financial obligations.

91 More generally, I am not in doubt that the penalties should provide sufficient sting, and to ensure that other participants in the OTC derivatives market do not look upon the pecuniary penalties fixed in this case simply as a cost of doing business. The penalties that I intend to impose significantly exceed the revenue earned by each of the defendants. Such a level serves the purpose of general deterrence.

92 Let me now deal with the factor concerning the conduct of senior management.

93 The sole director of AGM, Mr Yossef Ashkenazi, was responsible for the management of AGM, including having ultimate responsibility for the design and implementation of its compliance systems. In addition, Mr Ashkenazi was responsible for the training of the account managers engaged on behalf of the defendants. I am satisfied that the approach adopted by the account managers was consistent partly because Mr Ashkenazi was responsible for conducting their training.

94 Indeed, for the purposes of setting the appropriate penalty for AGM, it is relevant that the system of conduct in which each of the defendants engaged was consistent with the content of the training provided by Mr Ashkenazi. In the case of OTM and Ozifin the conduct that constituted the contraventions, except for Ozifin’s contraventions of s 923C(1)(c) by using the term “financial advisor”, was undertaken on behalf of AGM. Moreover the conduct was consistent with training provided by Mr Ashkenazi in his role as a director of AGM. So, AGM’s vicarious liability for the conduct of OTM and Ozifin did not arise simply from a passive relationship between the holder of an AFSL and its corporate authorised representatives.

95 Further, Mr Ashkenazi had overall responsibility for AGM’s compliance with its statutory and licence obligations. And the nine contraventions by AGM of its obligations under s 961L were contraventions that have enlivened my power to fix a pecuniary penalty against AGM, and represent a compliance failure by AGM. Further, Mr Ashkenazi’s ultimate responsibility for AGM’s compliance obligations as the holder of an AFSL, and his contribution to the contraventions by OTM and Ozifin in particular are aggravating factors.

96 Let me say something separate about OTM and Ozifin. During the period in which the contravening conduct occurred:

(a) the sole director of OTM was Mr Guy Stein; and

(b) the directors of Ozifin resident in Australia were Ms Hagar Lipa and Mr Amadom Nagash.

97 Now neither Mr Stein in relation to OTM nor Ms Lipa or Mr Nagash in relation to Ozifin played any meaningful role in the management of those companies. Instead, effective control of those companies during the relevant period was exercised by overseas interests. I infer that the system of conduct undertaken by OTM and Ozifin was implemented or sanctioned by the controlling minds of OTM and Ozifin, who were located overseas, whether or not that system was based at least in part on the training and other guidance provided by Mr Ashkenazi. In my view, the control exerted over the operations of OTM and Ozifin by overseas interests fortifies the need for pecuniary penalties to be fixed for OTM and Ozifin at a level that deters other participants in the OTC derivatives market, and that might be controlled by overseas interests, from engaging in such conduct.

98 Let me now deal with the defendants’ culture of non-compliance.

99 In my view, AGM disregarded its compliance obligations, particularly as the holder of an AFSL. In addition to the nine contraventions of s 961L, I have determined that AGM failed to comply with various compliance obligations that fell on it by reason of its being a holder of an AFSL. In particular, it failed to:

(a) do all those things necessary to ensure that the financial services covered by its AFSL were provided efficiently, honestly and fairly, in contravention of s 912A(1)(a);

(b) have in place adequate arrangements for the management of conflicts of interest that arise in relation to activities undertaken by it and its representation in the provision of the financial services as part of its financial services business, and those of its representatives, in contravention of s 912A(1)(aa);

(c) take reasonable steps to ensure that its representatives complied with the financial services laws, in contravention of s 912A(1)(ca);

(d) have available adequate resources to provide the financial services covered by its AFSL and to carry out supervisory arrangements, in contravention of s 912A(1)(d); and

(e) ensure that its representatives were adequately trained and were competent to provide financial services under its AFSL, in contravention of s 912A(1)(f).

100 There was a failure by Mr Ashkenazi, as the person charged with responsibility for AGM’s compliance with the financial services laws, to understand what was required of AGM and its representatives to discharge its obligations as the providers of financial advice to retail clients.

101 Now in my principal reasons I identified various matters that revealed numerous systemic deficiencies in the operations of AGM, OTM and Ozifin which separately or cumulatively well justified my finding of a breach by AGM of s 912A(1). But at the time they occurred, AGM’s various contraventions of s 912A(1) did not enliven my power to order it to pay a pecuniary penalty. Nevertheless, AGM’s systemic compliance deficiencies support the fixing of a significant penalty for the large number of unique instances of contravening conduct in which AGM engaged so as to deter other AFSL holders who deal in OTC derivatives from failing to meet their statutory obligations, including their obligations properly to supervise the conduct of their authorised representatives. Indeed, the protection that the consumers of financial services might expect from compliance with those obligations is particularly important in the market for OTC derivatives. Derivatives are complex instruments and risky investments.

102 Further, each of OTM and Ozifin were incorporated shortly before they commenced providing financial services in Australia. And as I have said, the directors of those companies exercised minimal, if any, control over the operation of those companies, which in and of itself represents a shortcoming in their culture of compliance. Moreover, there is no evidence that those controlling OTM or Ozifin exercised any independent judgment as to whether their conduct complied with the statutory requirements. And to the extent that there was any monitoring of the conduct of the account managers engaged on behalf of those companies, it was outsourced to AGM. But AGM’s monitoring was self-evidently inadequate. The failure by OTM and Ozifin to exercise any independent control over their account managers supports a significant pecuniary penalty.

103 Let me make a separate point. None of the defendants displayed any meaningful disposition to cooperate in the conduct of this proceeding until the start of the main trial late last year.

104 Finally, before I discuss the arithmetic I should say something on questions relating to duplication and also the course of conduct. I will deal with the totality question later.

105 First, although each of the statements made by the defendants that constituted an express or implied false or misleading representation by the defendants contravened various subsections of s 12DB(1), s 12GBA(4) operates to limit the liability of each defendant to one pecuniary penalty for each such statement.

106 Second, there are some common elements across the contraventions of:

(a) s 12DB(1) that resulted from the defendants making the:

(i) best interest representations; and

(ii) appropriate advice representations; and

(b) s 961K by AGM and s 961Q by OTM and Ozifin by reason of, respectively, the contraventions by the providers of that advice of:

(i) s 961B, in respect of acting in the best interest of the recipient of the advice; and

(ii) s 961G, in respect of providing advice that was appropriate to the client.

107 But there is no overlap in relation to the contravention of s 961J being the obligation to give priority to the client’s interests where there is a conflict. None of the representations established in this case included any representation that the providers of the advice had satisfied the obligations in s 961J, or any representation to a similar effect. Therefore, each contravention of ss 961K or 961Q by reason of the contravention of s 961J justifies a penalty.

108 I have set out earlier the principles concerning the course of conduct question. They have been applied in what follows.

109 What should be the quantum of the penalties in the present case?

110 ASIC says that the appropriate pecuniary penalties should be the following, putting to one side the totality question.

111 First, it says that there should be a penalty of $98.97 million for AGM, of which:

(a) $11.98 million relates to the 347 unique instances of conduct that constituted contravening representations, which were made to 15 separate clients;

(b) $6 million relates to the four individual instances of unconscionable conduct;

(c) $5 million relates to the unconscionable system of conduct or pattern of behaviour engaged in;

(d) $30.71 million relates to AGM’s liability for OTM’s conduct;

(e) $32.30 million relates to AGM’s liability for Ozifin’s conduct;

(f) $6.98 million relates to the 698 unique instances of conduct that constituted contraventions of s 961K; and

(g) $6 million relates to the breaches of s 961L.

112 Second, it says that there should be a penalty of $65 million for OTM, of which:

(a) $29.42 million relates to the 448 unique instances of conduct that constituted contravening representations, which were made to 15 separate clients;

(b) $12 million relates to the eight individual instances of unconscionable conduct;

(c) $20 million relates to the unconscionable system of conduct or pattern of behaviour engaged in; and

(d) $3.58 million relates to the 358 unique instances of conduct that constituted contraventions of s 961Q.

113 Third, it says that there should be a penalty of $72.52 million for Ozifin, of which:

(a) $31.09 million relates to the 693 unique instances of conduct that constituted contravening representations, which were made to 12 separate clients;

(b) $13.5 million relates to the nine individual instances of unconscionable conduct;

(c) $20 million relates to the unconscionable system of conduct or pattern of behaviour engaged in; and

(d) $7.93 million relates to the 793 unique instances of conduct that constituted contraventions of s 961Q.

114 Let me also record some other matters of detail upon which some of ASIC’s figures are based.

115 ASIC says that it is appropriate to fix a penalty of $2.1 million, being the maximum penalty available) for what I have described in my principal reasons as OTM’s Shark Tank representation. This representation was made on a public website to an unknown number of people. It purported to be a news article relating to a popular television show. It is evident that the bitcoin trader ad was designed to lure users into signing up with OTM, despite OTM not offering the product that was described in the purported news article. It is said that the presence within the article of false or misleading testimonials as to that non-existent product is an aggravating factor.

116 Further, ASIC says that it is appropriate to fix a penalty of $1.05 million, being half the maximum penalty available, for what I have described in my principal reasons as Ozifin’s analysis representation.