FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Securities and Investments Commission v National Australia Bank Limited [2020] FCA 1494

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | NATIONAL AUSTRALIA BANK LIMITED (ACN 004 044 937) Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. On or by 26 October 2020, the parties provide to the Associate to Justice Lee an agreed minute of order to reflect these reasons or, failing agreement, the proposed orders the party contends reflect the reasons.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

LEE J:

[1] | |

[10] | |

[10] | |

[30] | |

[39] | |

[39] | |

[40] | |

[48] | |

III The circumstances in which the Admitted Contraventions took place | [50] |

[52] | |

[54] | |

[58] | |

[61] | |

[62] | |

[62] | |

[63] | |

[65] | |

[67] | |

XI Whether NAB is likely to engage in further contraventions | [68] |

[69] | |

[83] | |

[87] | |

[88] | |

[89] | |

[91] | |

[95] | |

[97] | |

[98] | |

E.1 Section 47(1)(a) – General conduct obligations of licensees | [99] |

[102] | |

[107] | |

[107] | |

[114] | |

[115] | |

[118] | |

[123] | |

[124] | |

[136] | |

VI A pecuniary penalty that the Court considers is appropriate | [141] |

[146] | |

[148] | |

[153] | |

[163] | |

OVERVIEW AND A PRELIMINARY OBSERVATION

1 A large retail bank put in place a programme whereby unlicensed “Introducers” would “spot” prospective customers and “refer” them to bankers; if the bank then advanced a loan, the Introducers were rewarded by a payment – the bigger the loan, the bigger the reward. There were no uniform processes for selection of the Introducers, no requirement that they have any particular training and no minimum level of due diligence; there was also no relevant formal training for “frontline” bankers, including as to the nature of the information the Introducer could lawfully provide. The programme at times resulted in the bank receiving information and documents about customers from financially interested third parties. At any one time there were hundreds to thousands of these untrained Introducers.

2 What could possibly go wrong?

3 The programme to which I refer was the “spot and refer” programme (programme) operated by National Australian Bank Limited (NAB). It generated a very large number of loans worth thousands of millions of dollars. NAB profited handsomely from the loans generated. It operated from at least 2000, lasting for around 19 years until it was, to use the NAB’s euphemistic term, “retired”.

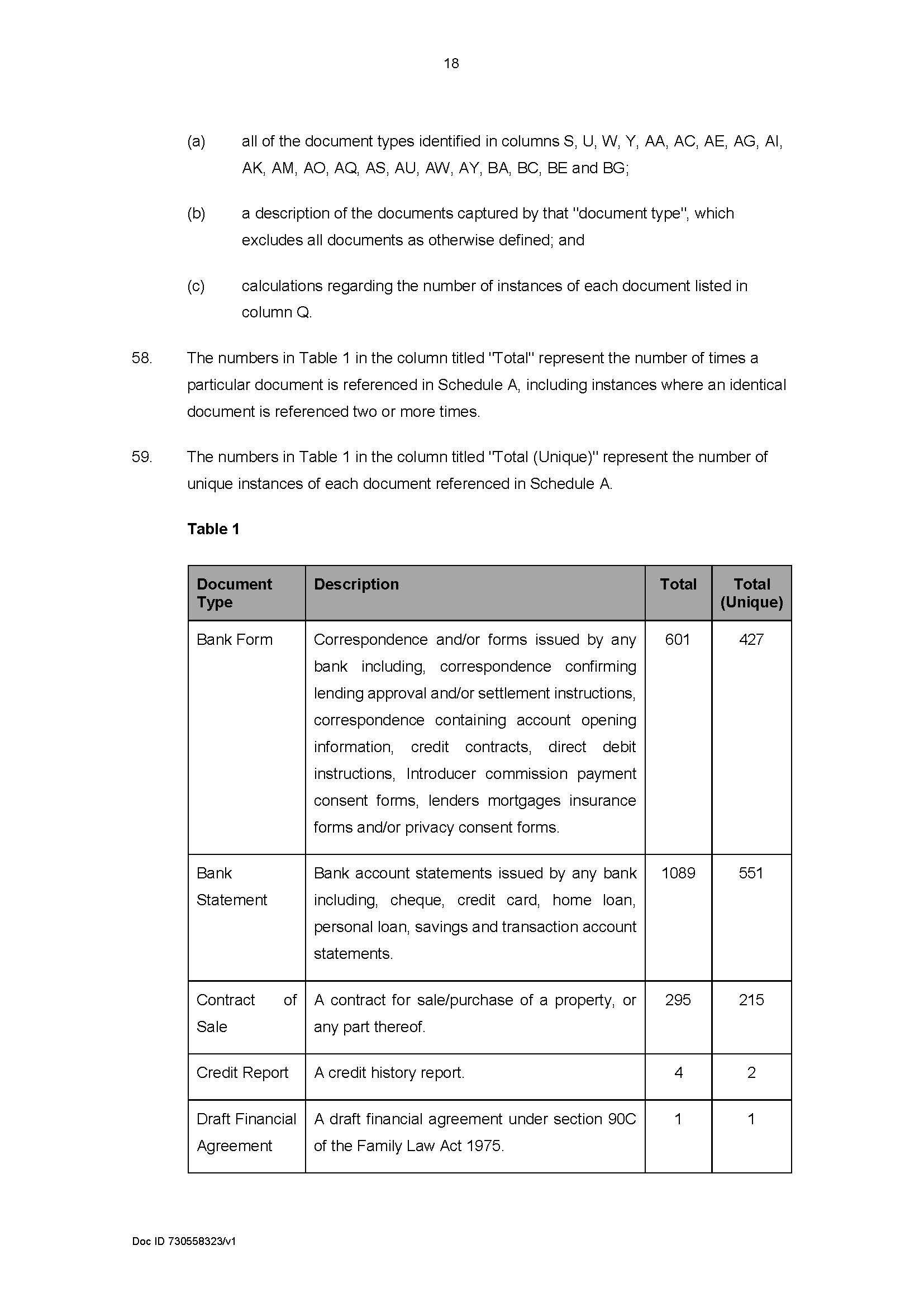

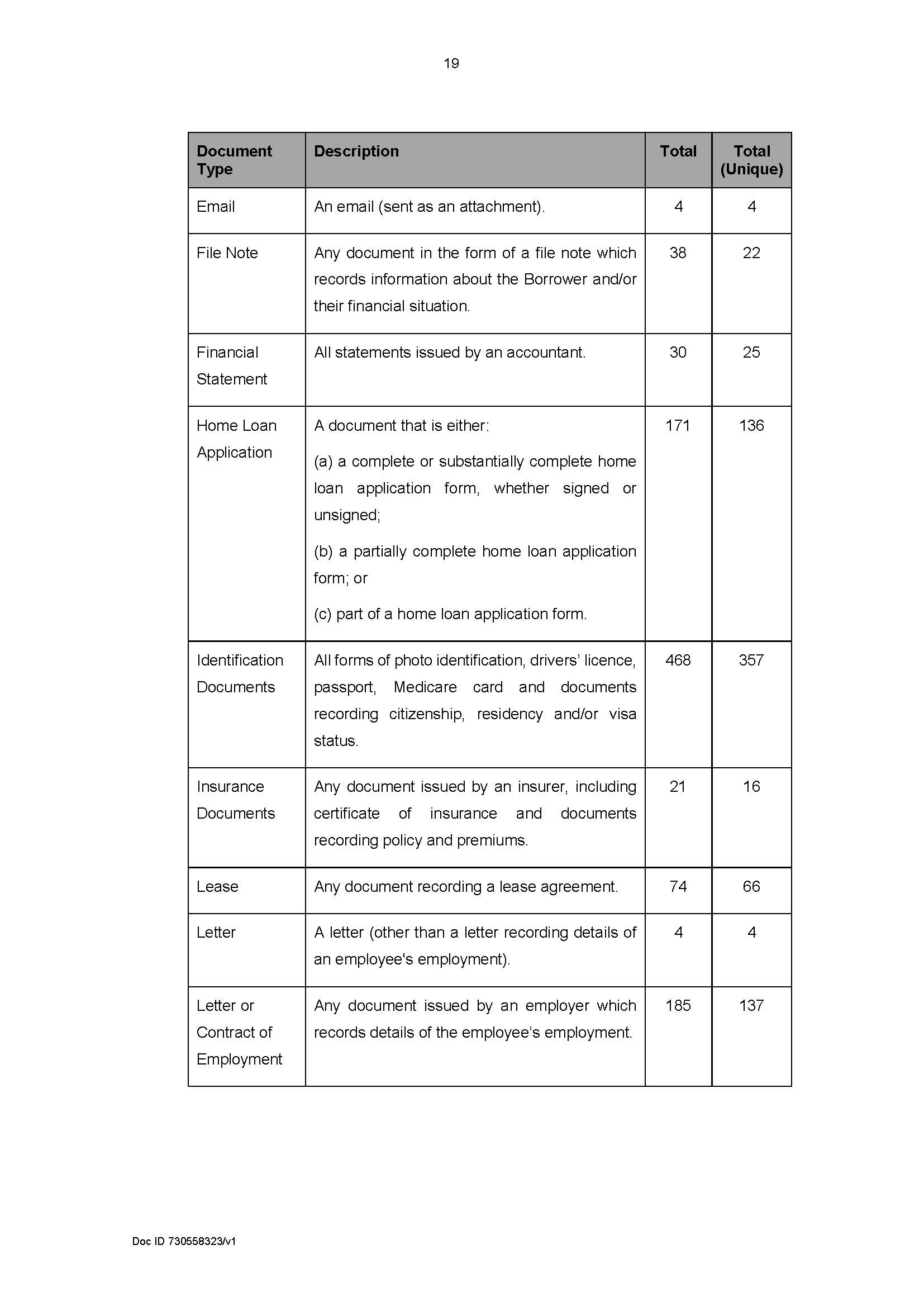

4 At the outset, it is worth noting that this regulatory proceeding was filed relatively soon after the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry tabled its final report in February 2019. Since the Royal Commission, but prior to the hearing of this proceeding, Parliament enhanced the powers of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) including by increasing the size and scope of available penalties by the introduction of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Strengthening Corporate and Financial Sector Penalties) Act 2019 (Cth). Even though these higher penalties do not apply in the present case, at least at the time they were introduced, they reflected a shift in Parliament’s attitude to the conduct to which they relate, including conduct under the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009 (Cth) (National Credit Act). This is made clear in the Second Reading Speech to the Bill introducing that legislation, which recognised it as “an essential part of rebuilding community trust in the financial services industry” because “some financial institutions have engaged in conduct that falls well short of community expectations”.

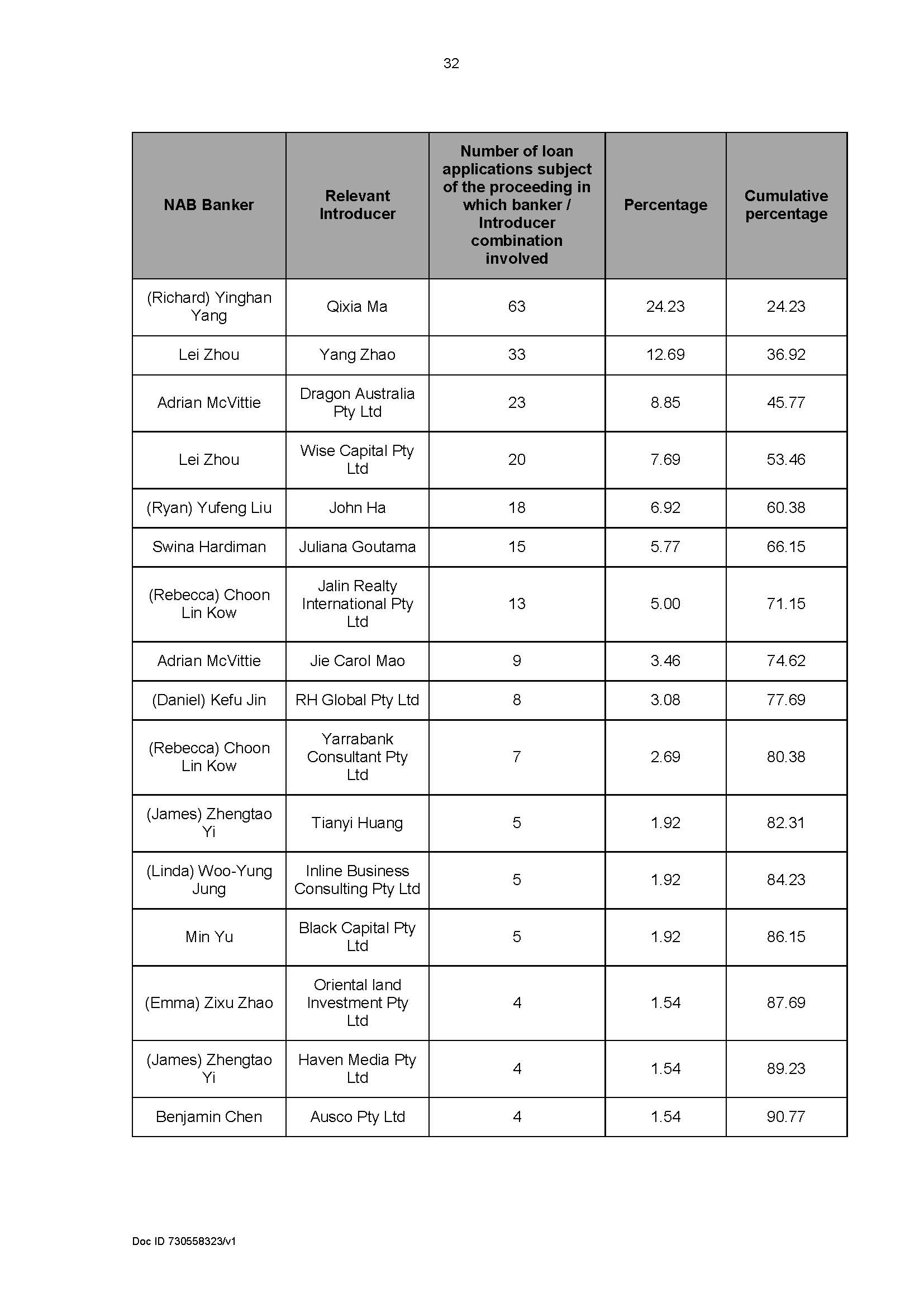

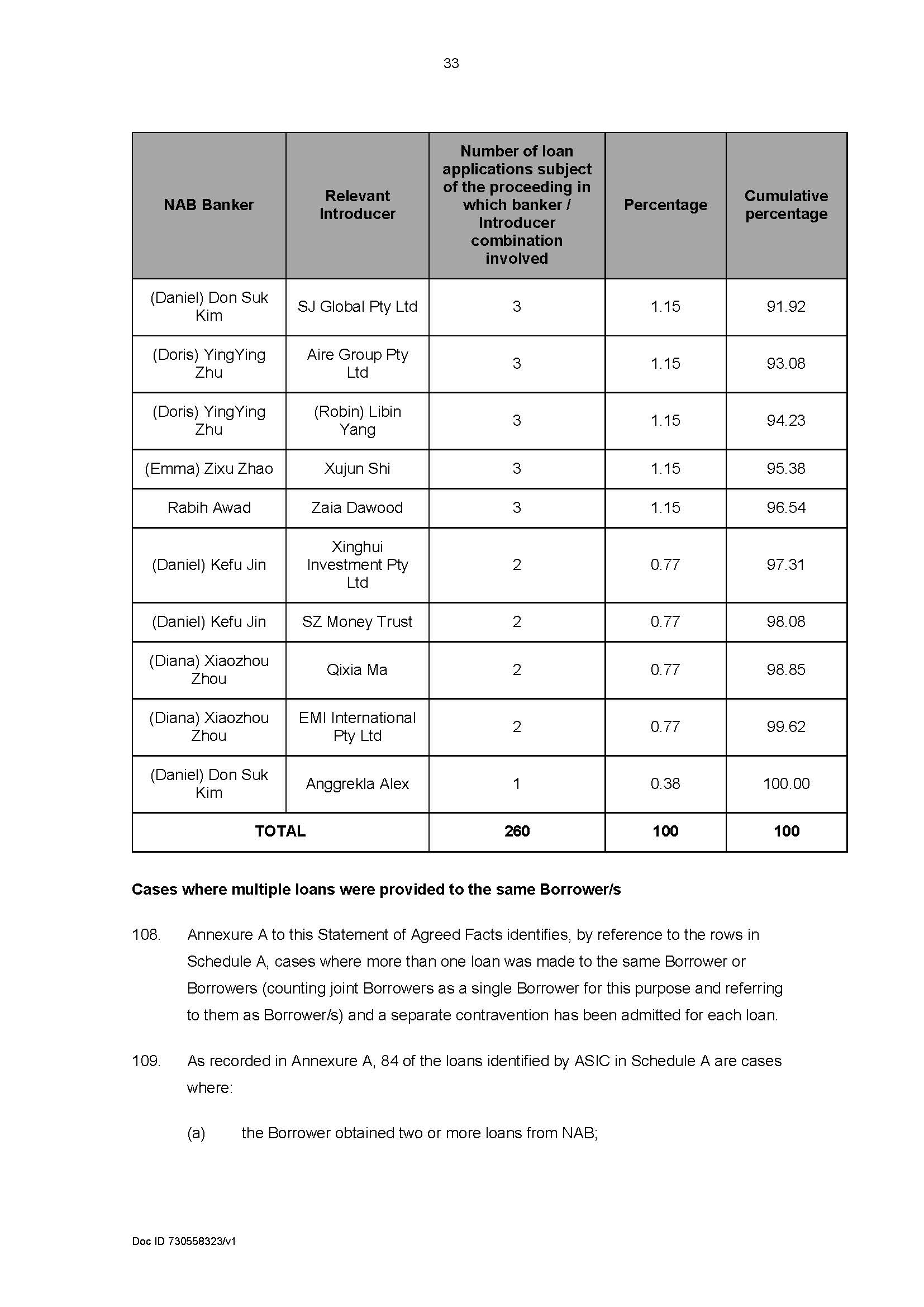

5 Prior to proceeding further, I consider it necessary to make a further preliminary but more specific observation: while during the period relevant to this case (23 August 2013 to 29 July 2016 (Relevant Period)) there were thousands of Introducers registered with NAB, this proceeding only concerns conduct engaged in by 25 of them. Further, as noted above, the programme operated as long ago as 2000 (although initially, of course, in the context of a quite different regulatory regime).

6 Although NAB has admitted that it engaged in conduct amounting to 260 contraventions of s 31 of the National Credit Act, which also involved 260 contraventions of s 47(1)(d) and at least one contravention of s 47(1)(a) of that Act, there is a high degree of artificiality in proceeding on the basis that I have been presented with anything like a full picture of what actually occurred in relation to the programme. This results from deliberate regulatory and forensic choices made by ASIC. It is not for me to gainsay these decisions of ASIC. It evidently has competing and heavy demands upon its finite resources. What became evident during the course of the hearing, however, is the very limited independent investigation as to the true scope of what has occurred during the Relevant Period and the significant reliance by ASIC on the internal work done by NAB in its investigations (by its officers or by a professional services firm it had engaged) as to where the problems were located within NAB and what went wrong.

7 I must deal with the evidence adduced and put out of my mind speculation. I will fix penalties and make other orders on the basis of the issues as presented by the parties and what has been proved. But having said that, I have a nagging feeling of disquiet that the true picture of the extent of the problems with the programme has not been revealed because there was not a real regulatory desire to pursue a thorough investigation as to what in truth occurred.

8 It is both unnecessary and unsafe for me to speculate as to why these regulatory and forensic decisions have been made, including any attempt to prove actual harm to individual customers, but their consequence is to require me to fix penalties in circumstances where my understanding of the true scope of what occurred in relation to the general operation of the programme during the Relevant Period (let alone at earlier times to the extent it reflects on conduct during the Relevant Period) is incomplete.

9 I will address the matters that fall for consideration by reason of these breaches and contraventions of the National Credit Act under the following headings:

A – Enforcement action by ASIC

B – Agreed factual background

C – Statutory framework

D – Relevant statutory provisions

E – Contested legal issues

F – Relief

G – Orders

10 Set out below is a brief overview of events leading up to the enforcement proceedings commenced by ASIC which are agreed between the parties, as set out in the Statement of Agreed Facts (SOAF) at Appendix A to this judgment. I adopt the abbreviations used in the SOAF in this judgment and make findings in accordance with that document.

11 On 14 September 2015 and 15 October 2015, NAB received anonymous whistle-blower reports of possible misconduct by branch managers and bankers within branches in the Greater Western Sydney region (GWS) involving the programme: SOAF [133].

12 Between October 2015 and January 2019, NAB conducted its own internal investigations into the conduct identified in the whistle blower reports, concentrating on the GWS region: SOAF [134]–[164]; [190]–[204]. I will refer to this as “Stage 1” of NAB’s review. As part of this stage, NAB undertook various reviews and investigations including establishing a Task Force into the programme and an internal audit: SOAF [245].

13 On 11 December 2015, NAB engaged KPMG to undertake an investigation into the conduct identified and to report on its findings to NAB: SOAF [137], [245].

14 Stage 1 identified the following “persons of interest”: 13 bankers and 8 Introducers from the initial GWS Investigation (SOAF [136]); and 13 additional bankers and 33 additional Introducers identified by KPMG (SOAF [138]), bringing the total to 26 bankers and 41 Introducers.

15 On 21 December 2015, NAB first wrote to ASIC reporting its findings of banker fraud and “potential control breakdowns” in the programme in the GWS area, involving the loan origination and application process and income verification procedures for both personal loans and home loans. This was a voluntary communication: SOAF [233].

16 On 20 January 2016, NAB’s Significant Event Review Panel (SERP) received an internal report advising it that the issues with the programme were not isolated to GWS: SOAF [148]. At all material times the SERP had responsibility for determining whether there existed a significant breach or likely breach that NAB was required to report to ASIC pursuant to NAB’s obligations as a financial services licensee under s 912D of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth): SOAF [148]–[149].

17 On 3 February 2016, ASIC was first officially notified by NAB of relevant breaches of the National Credit Act in a breach report titled “National Australia Bank Limited: Banker Investigation: Western Sydney”. Its stated purpose was to update ASIC on the matter of banker investigations in the GWS area: SOAF [191(d)].

18 On 26 February 2016, ASIC commenced an enforcement investigation into the matters the subject of the GWS Investigation: SOAF [200(a)]. ASIC notified NAB that it had opened an investigation on 1 March 2016: SOAF [196(d)].

19 In the 2016 financial year, NAB undertook an expanded review into conduct beyond the GWS region. This was “Stage 2” of NAB’s review. In July 2016, a project investigating systemic factors contributing to the misconduct identified in the Stage 2 review also commenced: SOAF [158].

20 Stage 2 identified the following persons of interest: 44 additional retail bankers, selected primarily on the basis that they had the highest Introducer commissions. These individuals were located in New South Wales, the Australian Capital Territory and Victoria. The review focussed upon a review of six months of emails from those individuals from 1 December 2015 to 31 May 2016: SOAF [153]. 72 associated Introducers were also identified for review; and 91 business bankers from NAB’s Business and Private Banking division were also selected by applying a range of criteria including a sample of bankers who had received high incentive payments in connexion with loans referred by Introducers or who were associated with Introducers who had received high commission payments: SOAF [155]. This brought the number of individuals under investigation to 161 bankers and 113 Introducers.

21 On 31 August 2016, NAB sent a second breach report to ASIC reporting the results of additional reviews by NAB in other channels and regions: SOAF [193(c)]. This led to NAB expanding its review beyond only the GWS area into different regions and different business channels.

22 In or around October 2016, a new project was established to streamline the separate projects undertaken in Stages 1 and 2 and to review them under a single governance structure, given identified similarities in conduct identified: SOAF [164]. This was “Stage 3” of the review and it considered those persons of interest already identified.

23 On 21 December 2016, the SERP met and considered whether the findings of its expanded review constituted a continuance of the event breach reported to ASIC in August 2016, or whether another breach report was required. It was determined that a status update to ASIC would be sufficient.

24 Accordingly, in January 2017, NAB notified ASIC of the initial findings of the expanded Stage 3 review.

25 In or about February 2017, NAB commenced designing a remediation scheme in respect of the misconduct relating to Introducers. At a meeting with ASIC in July 2017, NAB committed to providing ASIC with a copy of the draft remediation scheme document that NAB was preparing, and it did so on 16 August 2017. ASIC and NAB met again on or about 13 November 2017, prior to NAB commencing customer contact pursuant to the proposed remediation scheme: SOAF [209]–[211].

26 The final remediation scheme involved (SOAF [213]) consideration of 60 employees who were suspected of having potentially breached one or more of NAB’s internal policies or procedures, selected from the NAB Bankers identified during Stage 1 and Stage 2, of which 44 were found to have engaged in misconduct deemed sufficiently serious to warrant the application of a “red compliance gate” or dismissal of employment. The review of all secured files of the 60 employees of interest and the determination of whether each loan reviewed required further consideration and, ultimately, whether remediation in respect of that loan was required.

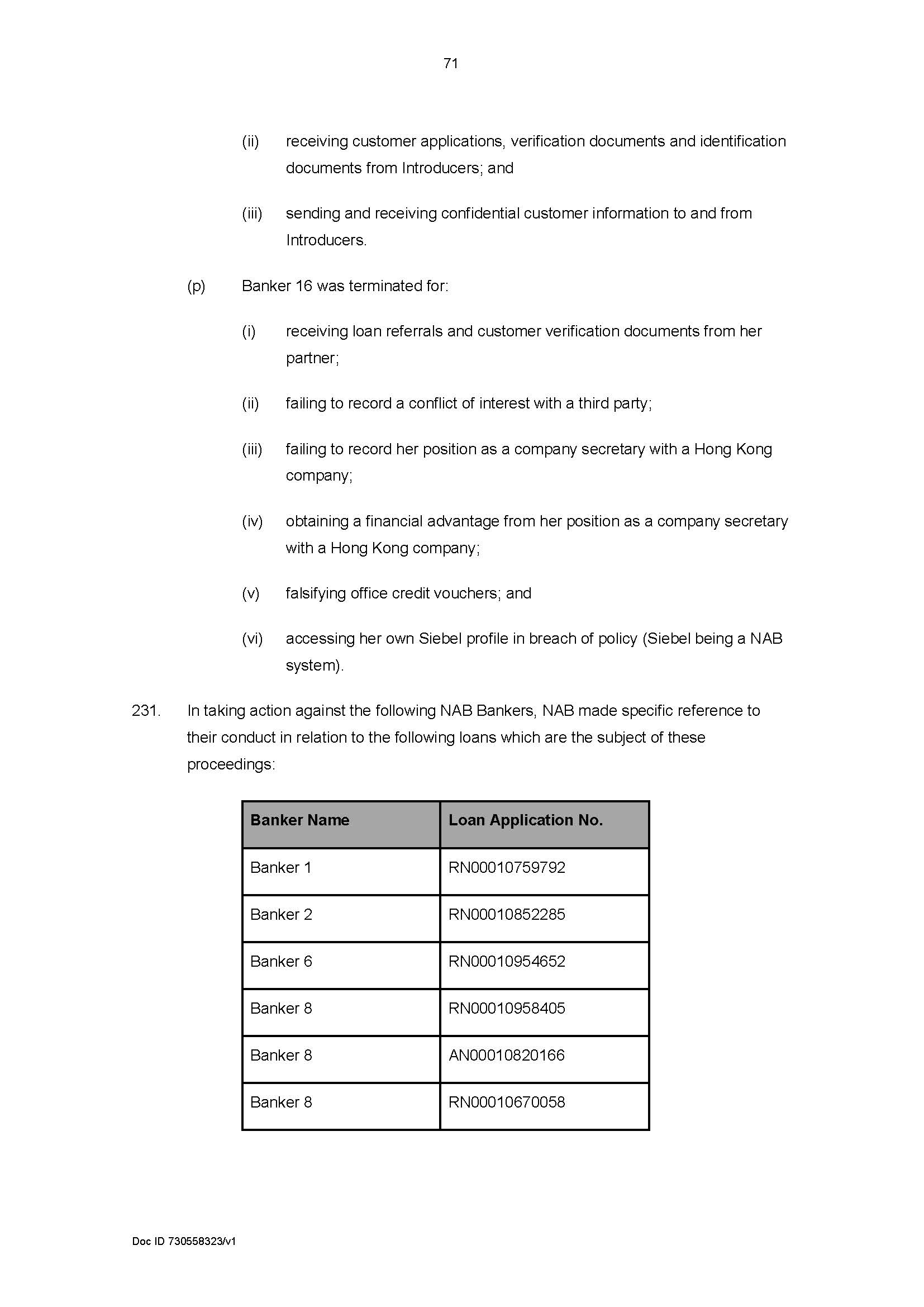

27 In July 2018, separately from this proceeding, ASIC banned Mr Awad (who is one of the 16 bankers identified in the present proceeding, set out in Schedule C to the SOAF (NAB Bankers)) from engaging in credit activities and providing financial services for a period of seven years in relation to the admitted conduct. Mr Awad was found to have given NAB false payslips, letters of employment, and entered false referrer contact details in NAB’s lending systems in multiple home loan applications. A majority of the false documentation Mr Awad submitted to NAB was provided to him by a real estate agent who was previously registered as an Introducer (and is one of the 25 Introducers identified in the present proceeding (Relevant Introducers)): SOAF [232].

28 Between 16 January 2018 and 6 September 2019, NAB provided ASIC with bi-monthly reports regarding its remediation scheme arising out of its investigations: SOAF [220].

29 From time to time between November 2017 and September 2019, there was communication between ASIC and NAB about the remediation scheme. NAB provided such information as was sought by ASIC and accepted recommendations made by ASIC, including as to the scope of KPMG’s independent quality assurance review. NAB also provided ASIC with copies of all of the reports prepared by KPMG in connexion with its assurance reviews: SOAF [22].

A.2 Commencement of this proceeding

30 It is against this backdrop, including the discussions in early 2017 by which ASIC appears to have accepted that NAB and its consultants should be allowed to proceed to devise its own remediation scheme, that ASIC apparently took the regulatory decision not to take steps to undertake its own expanded investigation.

31 In Australian Securities & Investments Commission v AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd (No 2) [2020] FCA 69, I noted (at [252]) that notwithstanding a large accounting firm would no doubt perform a role administering a remediation scheme conscientiously, it was “suboptimal” that the firm conducting the remediation scheme was selected by the contravenor “and not the Court” and said further:

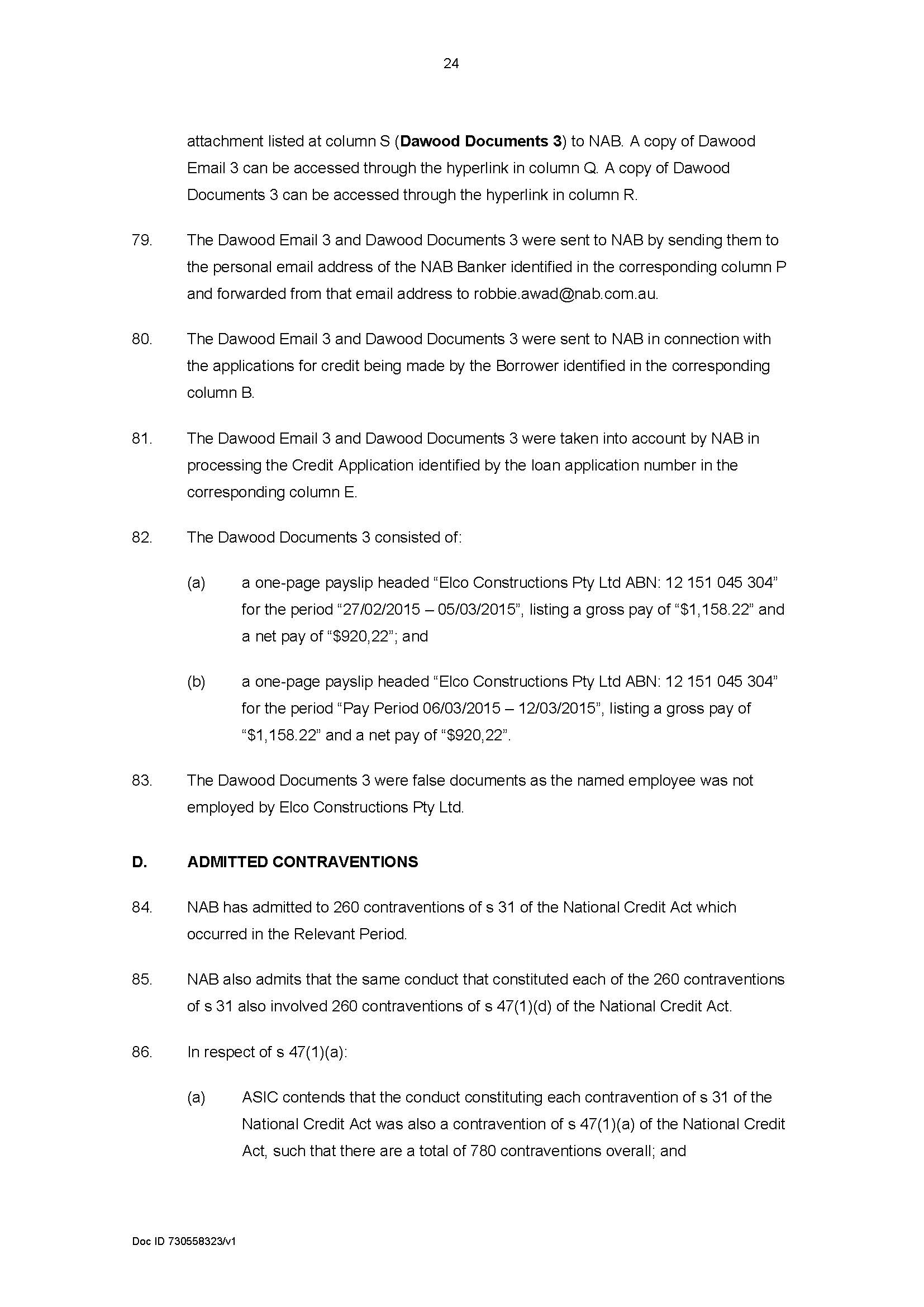

This raises an issue in regulatory proceedings of more general importance. In my experience of a number of these cases, it has been common, quite early in the investigatory or enforcement stage, for large institutions to select professional services firms to provide advisory, investigative and implementation services. These are often vast exercises and involve the professional services firm being paid very large fees. Speaking generally, no doubt some selections are made with the knowledge and encouragement of a regulator. It is easy to understand why this occurs and speed of remediation is highly desirable, but the difficulty is that when the matter comes to Court, the judge hearing the case (and determining what orders should be made) is presented with what amounts to a fait accompli: so many costs have been expended, and so much work has been done, that the Court cannot practically fasten upon a new approach run by wholly independent professionals selected by the Court.

32 Of course, in this case the issue is somewhat different to that in AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd (No 2) as ASIC does not seek any “forward-looking” orders or a Court-sanctioned remediation scheme. It is apparently satisfied with the scope of the programme devised and its operation. But it is worth noting that this has meant that the Court is not being asked to make compensatory orders because a regime of compensation has been designed, no doubt at very considerable expense, by the contravenor and a firm of accountants engaged by the contravenor.

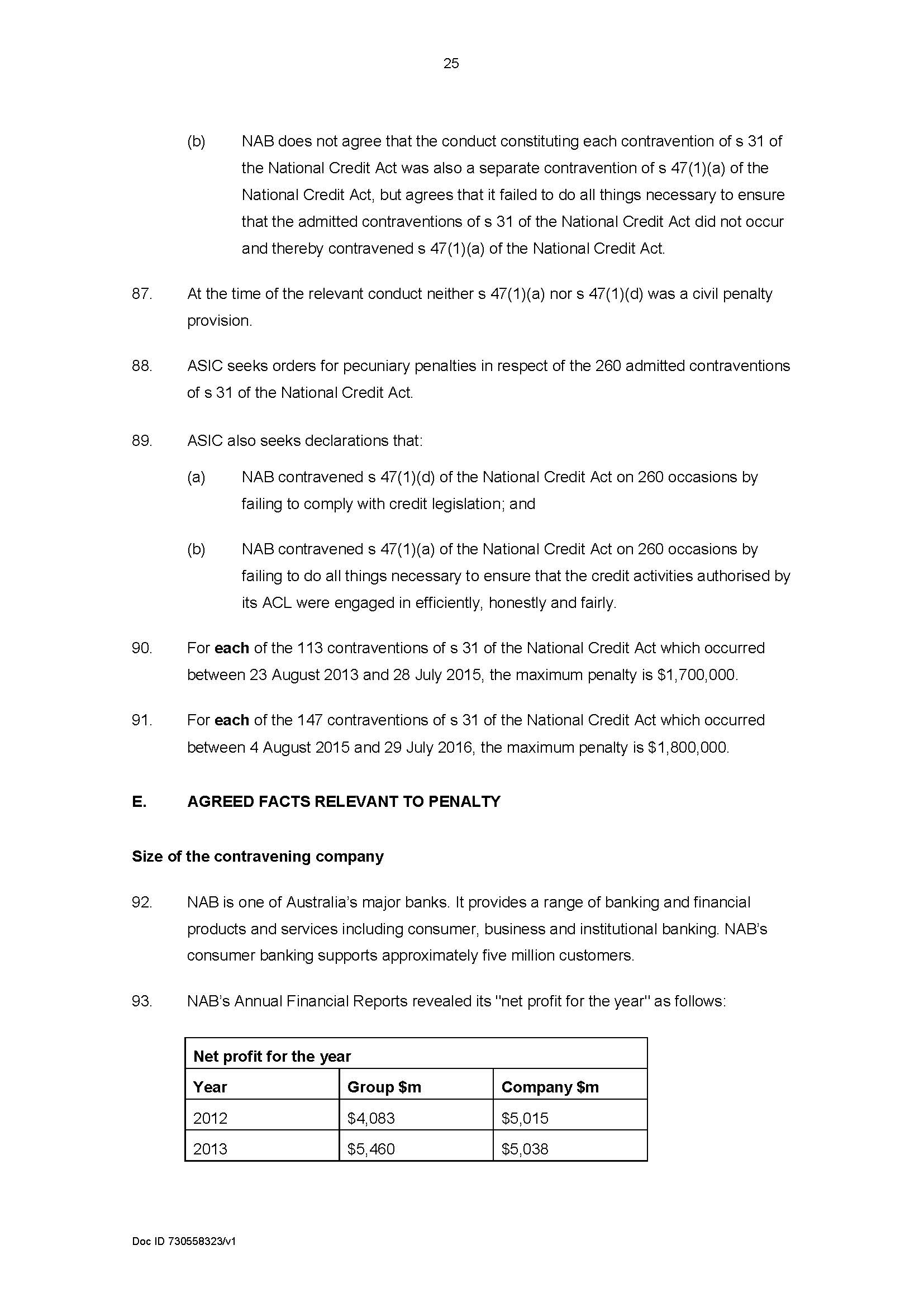

33 In any event, eventually, ASIC commenced proceedings against NAB by way of Originating Application and Concise Statement filed on 23 August 2019 seeking, in summary:

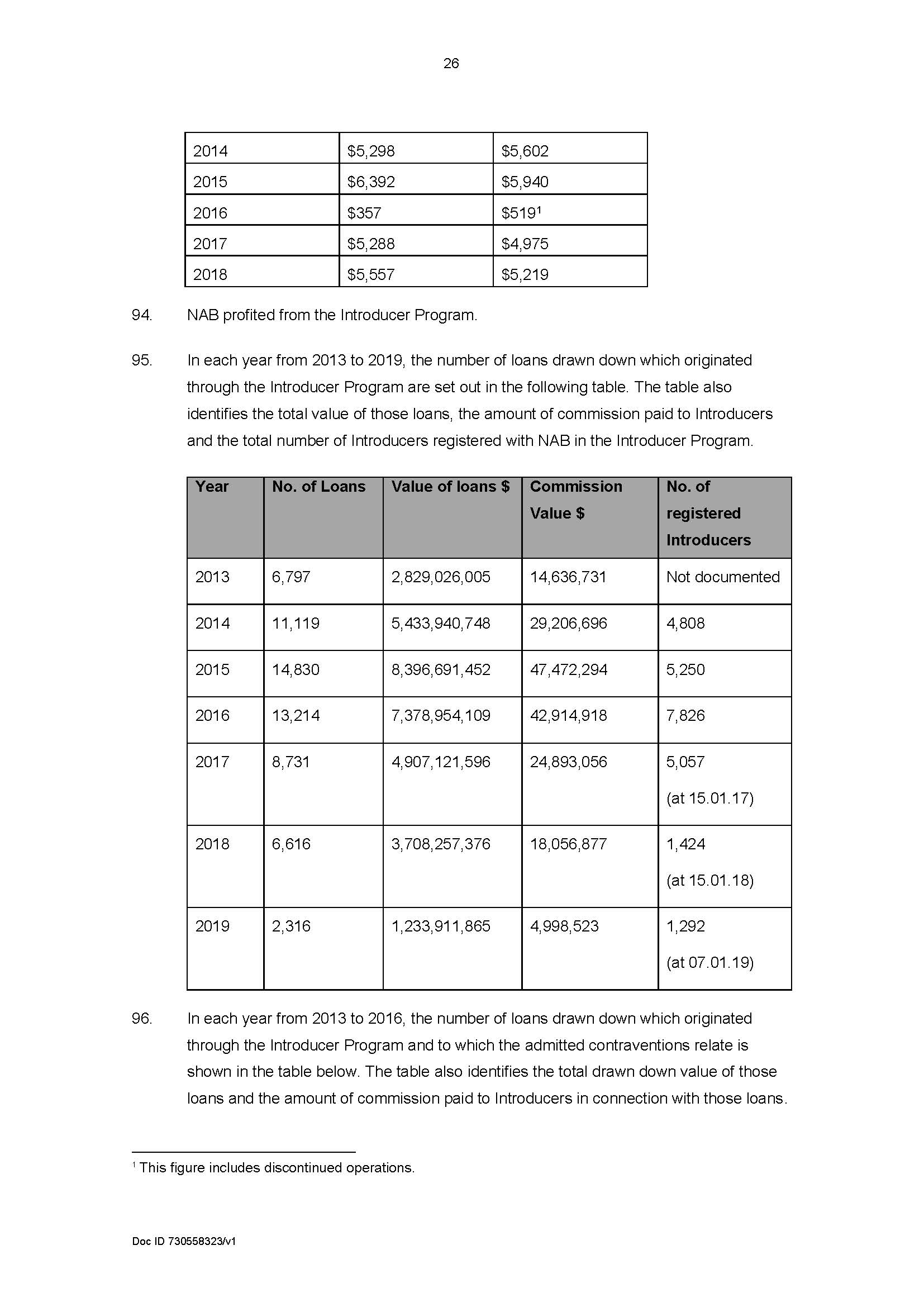

(1) pecuniary penalties in relation to alleged contraventions of s 31 of the National Credit Act in the Relevant Period relating to the involvement of unlicensed Introducers in Borrowers’ applications for residential mortgages from NAB contrary to s 29; and

(2) declarations of contravention in relation to alleged contraventions of s 31 of the National Credit Act, and declarations of contravention of s 47(1)(a) and (d) of that Act on the basis that the same conduct of NAB as constitutes the alleged contraventions of s 31 is also contrary to those provisions.

34 At the time the proceeding was commenced, ASIC identified 297 loans. ASIC did not press its allegations in respect of 37 of these loans.

35 ASIC’s investigation, such as it was, involved the issuing of notices to produce to NAB and the review of this material (apparently in excess of 20,000 emails and attachments), in addition to its review of the reports and other information provided by NAB in relation to the reported breaches. But ultimately, the contraventions all arise from NAB’s own self-reporting and ASIC’s subsequent investigation into this conduct was based on this self-reporting, as was accepted by Senior Counsel for ASIC (at T15).

36 In the end, admissions were made:

(1) that NAB engaged in 260 contraventions of s 31 of the National Credit Act which occurred in the Relevant Period;

(2) the same conduct that constituted each of the 260 contraventions of s 31 also involved 260 contraventions of s 47(1)(d) of the National Credit Act; and

(3) NAB failed to do all things necessary to ensure that the admitted contraventions did not occur and thereby contravened s 47(1)(a) of the National Credit Act.

(together, the Admitted Contraventions).

37 There remains some dispute about s 47(1)(a) of the National Credit Act. It is common ground that there was at least one contravention of s 47(1)(a). The dispute lies in whether there was just this one contravention or, as ASIC alleges, 260 contraventions. ASIC contends that the same conduct that constituted each of the 260 contraventions of s 31 also involved 260 contraventions of s 47(1)(a) of the National Credit Act. NAB disagrees, and says there was a single contravention of that provision in that it failed generally to do all things necessary to ensure that the Admitted Contraventions did not occur. For reasons I will explain, it is unnecessary for me to determine this aspect of the dispute.

38 Given these admissions, the proceeding was principally focused on a small number of factual disputes, the legal dispute described above and the amount of the penalty to be imposed and declarations made in respect of the Admitted Contraventions.

39 As noted above, details about how the programme worked, the role of the Introducers and bankers and NAB’s investigation of the misconduct and the actions it took, including as to remediation, are set out in my findings based on the agreement between the parties as reflected in the SOAF. Notwithstanding Annexure A sets out all relevant details, it is useful to provide a brief outline of important aspects of these findings below.

I The spot and refer programme

40 As noted above, the programme operated from at least 2000 including during the Relevant Period: SOAF [10]. Introducers would “spot” prospective customers and “refer” them to NAB Bankers with whom they had a relationship. An Introducer could be an individual or a company engaged in a business not ordinarily involving finance or lending. If NAB advanced a loan to a referred customer, Introducers were paid a commission: SOAF [11]. Critically, an Introducer did not hold an Australian Credit Licence (ACL).

41 The programme took advantage of an exception in the National Consumer Credit Protection Regulations 2010 (Cth) (National Credit Regulations) without which the National Credit Act would have prohibited an Introducer’s involvement completely: see ss 29, 31. By reason of r 25, Introducers who did not hold an ACL were permitted, only, to provide NAB with a prospective customer’s name and contact details and a short description of the purpose for which the customer sought credit. A policy to this effect applied at NAB during the Relevant Period: SOAF [12]–[13]. Agreements between NAB and each Introducer also included these stipulations.

42 The programme operated in one of two ways: either, an Introducer was “on-boarded” by an individual banker who then generally maintained a relationship with that Introducer; or an Introducer was on-boarded by a National Referral Partner (NRP), who aggregated referrals on behalf of a number of affiliated individual Introducers for a commission and maintained a single relationship with a particular banker: SOAF [14]–[15]. The commission paid to the Introducer, including the NRPs, was calculated as a percentage of the total of the loan: SOAF [14], [23]. As I have already explained, while during the Relevant Period there were thousands of Introducers registered with NAB (SOAF at [95]), of course, this proceeding only concerns conduct engaged in by as little as 25 of them.

43 As part of the programme, either the banker or the NRP was required, among other things, to record the Introducer’s details in NAB’s systems, perform on-boarding verifications, arrange for the Introducer to enter into an agreement with NAB, establish an “introducer number” used to identify lending as being referred by that Introducer and establish payment authorities for the Introducer: SOAF [15]–[20]. The Introducer was also required to make a number of disclosures to the customer and to obtain consent: SOAF [201].

44 Once the Introducer referred a customer to NAB, the assigned banker was required to deal directly with the customer in respect of all aspects of the loan application process in accordance with NAB’s lending policies (SOAF [20]), including an interview to assess the customer’s situation, needs and objectives: SOAF [100]. In respect of the 16 bankers (Bankers) who dealt with these 25 Introducers, this did not happen, or did not consistently happen as required. The facts surrounding the precise details of how, in respect of each of the Admitted Contraventions, this transpired are complex and lengthy and I do not propose to set them out here; they have been detailed in the SOAF (at [97]–[114]).

45 While there is some dispute between the parties about the particulars of certain of this conduct, the parties agree (SOAF [65]), and I accept, that each of the Relevant Introducers:

(1) dealt directly with the Borrower or the Borrower’s agent; and

(2) in the course of, as part of, or incidentally to:

(a) carrying on their Business; and

(b) the business carried on by NAB; and

(c) the business each Relevant Introducer conducted with NAB characterised by the payment of the Commission; and

(3) in each case, acted as an intermediary between NAB and the Borrower wholly or partly for the purpose of securing the provision of credit under a credit contract for the Borrower with NAB; and

(4) in some cases, also assisted the Borrower to either apply for a particular credit contract with NAB or an increase to the credit limit of a particular credit contract with NAB.

46 In the Relevant Period, the programme generated significant loan value, from which NAB profited. For example, in 2015, the value of loans drawn down exceeded $8.3 billion. In that year, there were 5,250 Introducers who were paid total commissions of $47,472,294: SOAF [94]–[95]. While only a small subsection of these loans is the subject of this proceeding, the programme was big business for NAB. Continuing with 2015 as an example, the Admitted Contraventions relate to 1.011% of the loans generated by the programme for that year, representing $105,120,700 in loan value in respect of which 1.176% of the commission described was paid: SOAF [96].

47 There appears to have been a focus on non-resident lending by Introducers and Bankers. The proportion of non-resident lending was 53% in April 2015 and 71% in April 2016: SOAF [104].

48 The Borrowers were exposed to the risk that Bankers would rely on information and documents provided by unlicensed Introducers rather than dealing directly with the Borrower, and would not make their own inquiries about the Borrower’s requirements and objectives in relation to the loan, and would not take reasonable steps to assess the veracity of information and documents put forward in support of loan applications to determine whether loans were unsuitable: SOAF [101]. This necessarily exposed the Borrowers to the risk that loans would be unsuitable or calculations as to serviceability would be incorrect and to the risk of wrongful conduct and fraud: SOAF [205]. The parties disagree about whether, and the extent to which, these risks eventuated: SOAF [102], [207].

49 In three cases, fraudulent payslips were provided by an Introducer. Here, the parties expressly agree (and I find) that the Borrowers were exposed to the risk that the loan would be unsuitable to them: SOAF [106]. All instances of the provision of fraudulent payslips were isolated to one Introducer. Details are set out in the SOAF (at [66]–[83], [208]).

III The circumstances in which the Admitted Contraventions took place

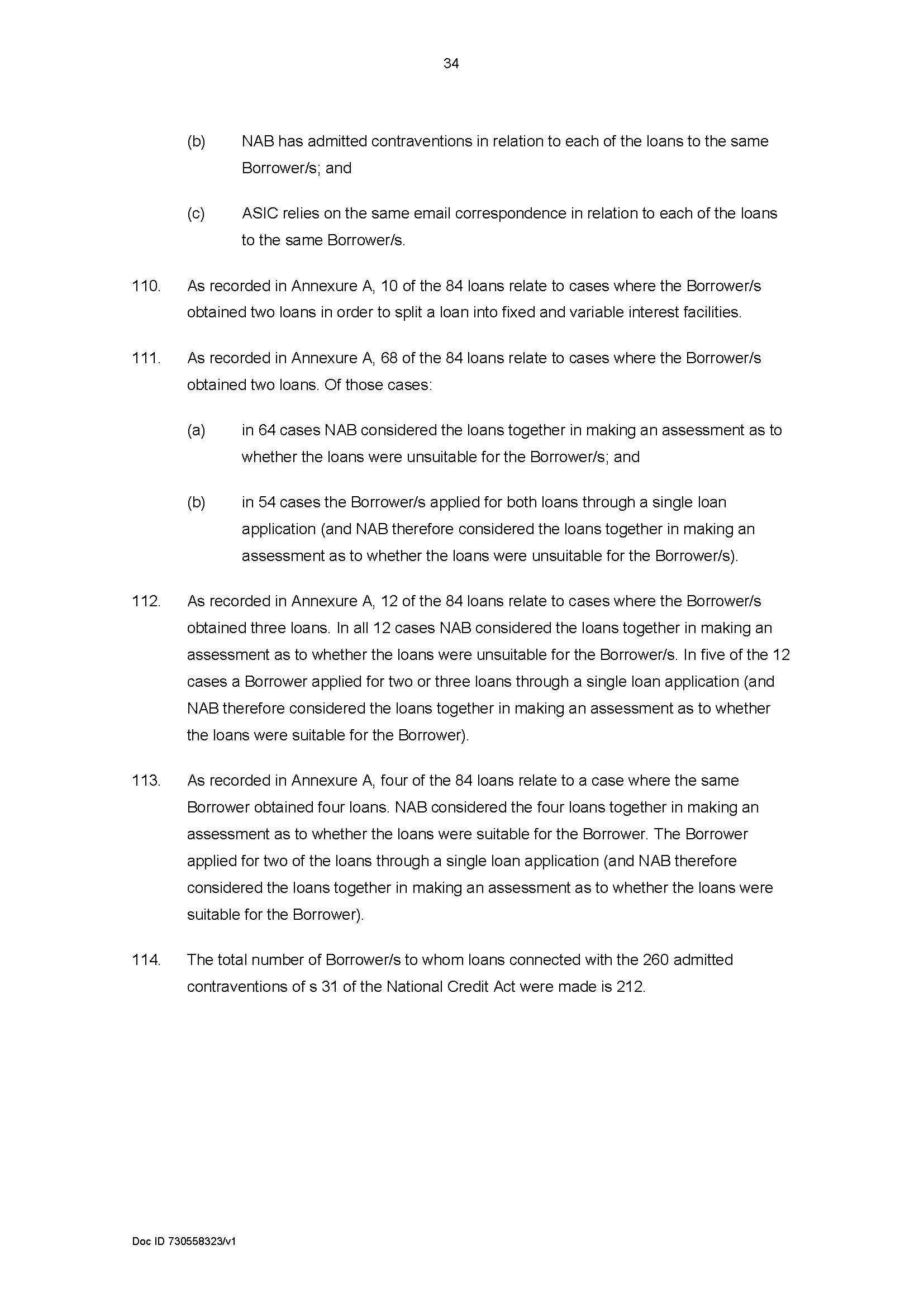

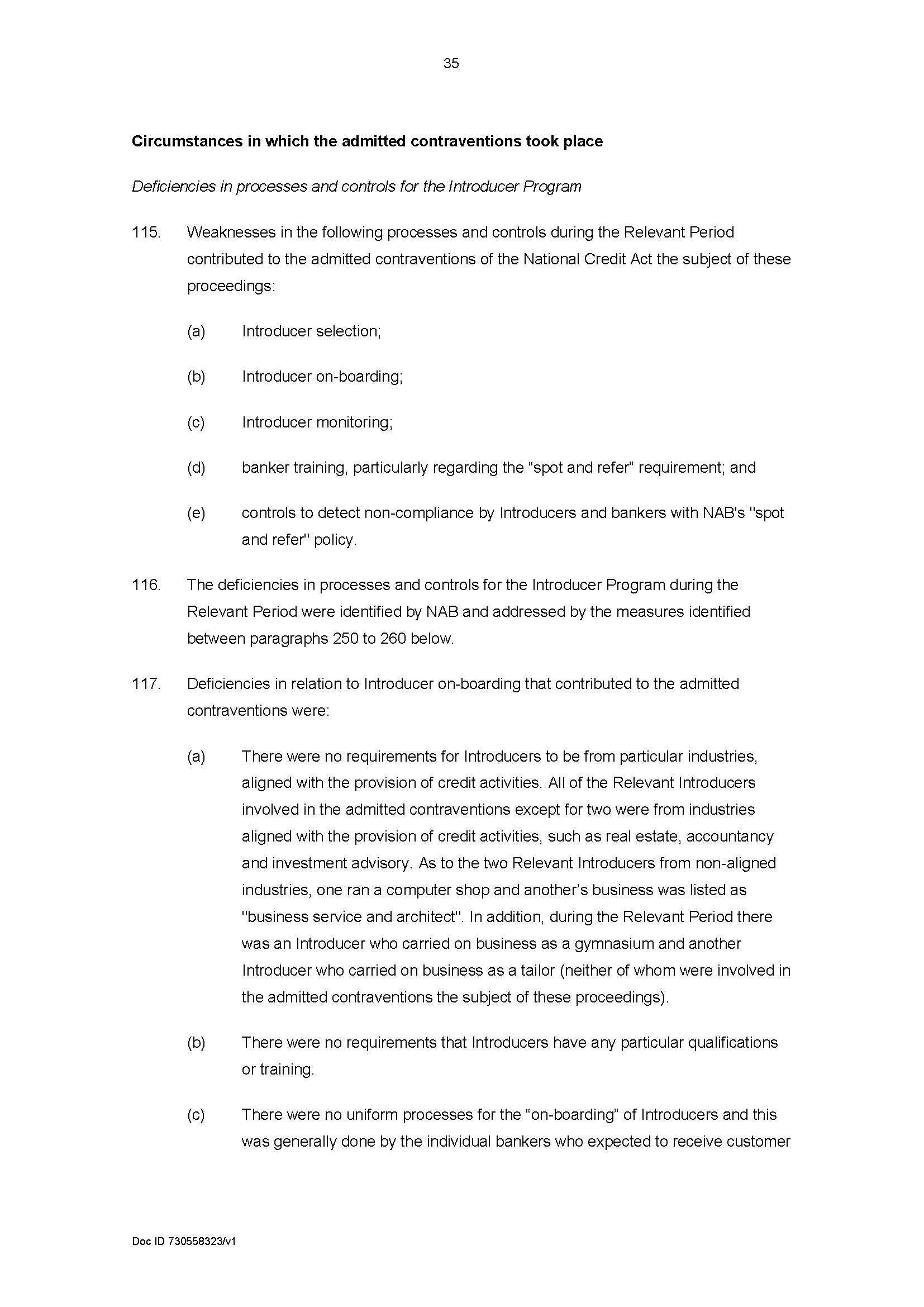

50 Weaknesses in the following processes and controls during the Relevant Period included:

(1) Introducer selection;

(2) Introducer on-boarding;

(3) Introducer monitoring;

(4) banker training, particularly regarding the “spot and refer” requirement; and

(5) controls to detect non-compliance by Introducers and bankers with NAB’s “spot and refer” policy: SOAF [115].

51 Details of each of these admitted deficiencies is set out in the SOAF (at [117]–[132]). Some I have already touched upon. In short, there were no requirements for Introducers to be from particular industries aligned with the provision of credit activities or to have any particular qualifications or training. There were no uniform processes for the “on-boarding” of Introducers and this was generally done by the individual bankers or the NRPs. There was no minimum level of due diligence required to be carried out by bankers and NRPs and no consequences for non-compliance. There was no formal training for frontline bankers regarding the programme including on what information the Introducer could provide. During the Relevant Period there was no single point of accountability for the programme across NAB. Investment in the systems and processes had not kept up with the growth of the programme, in that the last significant investment in the Introducer system had been made over 10 years prior to the discovery of the GWS conduct, notwithstanding the significant growth in the programme over that time. There were shortcomings in the controls used to ensure that NAB’s policies were followed and to detect conflicts of interest or fraud; there were database and information systems limitations; and inadequate monitoring and reporting of Introducer activity. Controls were not designed to identify instances of intentional misrepresentation of information effectively and consistently.

52 NAB’s internal audit revealed that there was a lack of ongoing due diligence to check if active Introducers had become undesirable and the Introducer termination process was not documented: SOAF [165]–[166].

53 In the end, of the 60 bankers NAB investigated for potential misconduct and policy non-compliance in relation to the programme, 44 were found to have engaged in misconduct that was deemed sufficiently serious as to warrant a so-called “Red Conduct Gate” (whatever that is supposed to mean). The most common reason for a “Red Conduct Gate” being applied was suspicion of fraud. Of those 44 bankers, 20 resigned or were terminated. NAB applied an “Amber Gate” to nine employees. All of the 16 Bankers involved in this proceeding either resigned, were terminated and/or received “Red Conduct Gates”: SOAF [227]–[232].

54 During the Relevant Period, NAB had an incentive programme, known as the Star Sales Incentives (SSI) scheme. Under the SSI scheme, branch bankers and mobile bankers were rewarded on the basis of the number of loans they sold. Branch Managers were rewarded based on the sales performance of those they managed. The same SSI was paid regardless of whether a loan was introduced to NAB through an Introducer or by another NAB employee. All Bankers the subject of this proceeding received SSI payments: SOAF [167]–[169].

55 Because of these financial incentives and inadequate controls, it was difficult for NAB to prevent and detect fraud from loan applications originating from the programme: SOAF [170]. NAB admits the possibility that “this increased the risk or incidence of unsuitable loans being made based on fraudulent or unverified information”, though as will be outlined below, there is some disagreement between the parties as to the extent to which this risk came home: SOAF [171]–[173].

56 NAB’s corporate culture and the effect of the SSI payments was the subject of internal investigation following the initial review of banker conduct at GWS and other identified misconduct: SOAF [174]–[183].

57 The contraventions were also a consequence of payments to Introducers, who received commissions for successful loan referrals. The total value of commissions received by the Relevant Introducers involved in this proceeding from the relevant 260 Credit Contracts was $929,403.67. The commissions ranged between $88.00 and $29,700.00 with an average of approximately $3,500.00. This provided an incentive to Introducers, which, as one would have thought was obvious from the outset, increased the risk of breaches of ss 29 and 31 of the National Credit Act.

58 Twenty-six of the Admitted Contraventions of s 31 of the National Credit Act were the result of conduct of NAB Bank Managers. Otherwise, the direct dealings with Relevant Introducers that constituted the Admitted Contraventions of s 31 of the National Credit Act were engaged in by NAB Bankers at lower levels: SOAF [187]–[189].

59 During the Relevant Period, reports made to, or reviewed by, a number of NAB senior executives identified concerns regarding the conduct of some bankers involved in the programme, and largely, but not exclusively, related to investigations into conduct in the GWS region. Some details of these reports, and the information which NAB senior executives and the Board Risk Committee received from time-to-time during the Relevant Period are set out in the SOAF (at [191]–[196]). This included a memorandum dated 7 June 2016, prepared by the Executive General Manager Retail and supported by the Group Executive Personal Banking that was submitted to the Group Risk Return Management Committee. The memorandum provided a summary of the high-level findings of three reviews into the Introducer channel, including a finding (at SOAF [192]) of:

[i]nconsistent and potentially ineffective application across the enterprise of … regulatory requirements, due to varying levels of understanding (ie. operating under NCCP Exemption to provide brief customer details - ‘Spot & Refer’).” The memorandum also indicated that the initial findings “show that the Introducer channel is a viable and commercially solid source of business for NAB and one that will be strengthened by the actions resulting from the risk reviews undertaken.”

60 After the Relevant Period, further updates about NAB’s various internal investigations were provided to these executives and the outcomes they generated: SOAF [197]–[204]. This included the Board being informed, on 7 September 2016, that NAB had breach reported to ASIC in relation to the NAB Banker/Introducer behaviour uncovered between December 2015 to May 2016. During this time, there were various interactions between the Board, the Board Risk Committee and the newly formed Board Audit Committee.

VII NAB cooperation with the authorities

61 NAB cooperated with ASIC. Details are in the SOAF (at [233]–[243]). Further, NAB admitted to the contraventions the subject of this proceeding at the earliest available opportunity: SOAF [243].

VIII Loss and damage caused by the contraventions

62 By reason of the Introducers providing one or more income verification documents to a NAB Banker in support of a loan application, Borrowers were exposed to the risk of wrongful conduct or fraud by the Introducer. Additionally, control breakdowns in relation to the programme increased the risk of loans being provided to Borrowers that were unsuitable for them, the provision of false documentation to support loan applications and the use of incorrect figures in loan serviceability assessments. These risks, if they eventuated, may have exposed Borrowers to hardship and default: SOAF [205]–[208].

Remediation and cooperation with ASIC

63 Certain details about NAB’s investigations and the remediation scheme were contained in the affidavit of James Joshua Stafford affirmed on 27 May 2020, which was read without objection at the hearing. Mr Stafford is the Head of Customer Resolutions at NAB. I accept his evidence.

64 NAB’s remediation efforts, and its cooperation with ASIC, are set out in detail of the SOAF (at [209]–[243]). It suffices to set out a brief summary:

(1) in or about February 2017, NAB commenced designing a remediation scheme in respect of NAB’s misconduct relating to Introducers; ASIC was informed about and had the opportunity to raise questions or concerns about NAB’s proposal;

(2) the remediation scheme initially involved 60 employees of interest who were suspected of having potentially breached one or more of NAB’s internal policies or procedures but that scope was later expanded somewhat; disciplinary action was taken against certain of these individuals where misconduct was identified;

(3) the loan files of these individuals were reviewed, and it was determined if any loss had been suffered by customers in relation to the loans; where possible, customers were contacted and offered the determined amount of compensation;

(4) KPMG was engaged, including to conduct what was described as an “independent” assurance review of the remediation scheme (although I consider that the use of the term independent in this context is somewhat apt to mislead; with no intended disrespect to those involved in this review, to my mind, as a general proposition, it unduly strains the language to describe a reviewer as “independent” when the reviewer is paid by the person he is reviewing); and

(5) ASIC asked or directed NAB to provide information about the remediation scheme from time-to-time.

IX Corrective measures and enhancements

65 In addition to the investigations into the programme, NAB also reviewed its processes and associated risks: SOAF [245]–[249]. NAB introduced various new controls. These were belatedly introduced between 2015 and around 2017 and included (adopting the jargon used) “tightening” the criteria for selection of Introducers, providing education and “upskilling” of retail sales “leaders” on Introducer policies, regulations, “engagement protocols” and monitoring. Most importantly, perhaps, was a change to the commission structure of the programme for the bankers which placed less emphasis on loan sales volume: SOAF [250]–[272].

66 NAB terminated agreements with certain Introducers, conducted interviews into their conduct and took other actions. By April 2017, NAB had terminated around 3,700 Introducers: SOAF [273]–[275]. It also took action against employees, including by dismissing a number of bankers and taking managerial action against others. A number of NAB employees resigned: SOAF [276]–[281].

67 As at 4 May 2020, NAB has not previously been found liable for any prior contraventions of the National Credit Act: SOAF [244].

XI Whether NAB is likely to engage in further contraventions

68 As noted above, effective 1 October 2019, NAB “retired” the programme, as it existed at the time of the Admitted Contraventions: SOAF [282]. Also on 1 October 2019, NAB replaced the programme with the “NAB Referral Program”, which operates in the same way as the revised programme, including having the same controls, except that NAB no longer pays commissions for successful referrals by Introducers: SOAF [284]–[285]. Details were contained in the affidavit of Thomas Mark Crowley affirmed 27 May 2020, which was read without objection at the hearing. Mr Crowley has the title “General Manager of Enablement” at NAB. I accept his evidence.

B.2 Disputed factual background

69 As noted above, the parties dispute the extent to which risks associated with the programme actually eventuated and the relevance of this fact: SOAF [102], [172], [207].

70 The issue of risk was canvased extensively in written submissions, though perhaps the lack of focus on it in oral submissions is indicative of its secondary nature to any penalty determination. That it is unlikely to affect the penalty was recognised by ASIC in its written submissions (at [100]), and was noted by NAB in its submissions (at [55]). This is because, for the purposes of this proceeding, customer harm only relevantly manifests in the form of exposure to a risk of harm as a result of the contraventions. Now, ASIC accepts that there is in fact no evidence before me about actual harm to Borrowers, though Senior Counsel urged that this was “only [part] of the picture” (T30). While proof of harm would likely have been an aggravating factor in determining the penalty imposed, it is not essential to establishing a contravention of s 31. To the extent that ASIC seeks to establish “manifestations” of these risks, this too is beyond the case ASIC actually ran.

71 Specifically, ASIC alleges (at [9] of its Concise Statement) that the contravening conduct “exposed the customers and NAB to the risks of wrongful conduct by the introducer, including possible fraud. It also exposed customers to a risk that loans would be advanced to them that were unsuitable” (emphasis added). I shall refer to these risks respectfully as “the wrongful conduct risk” and the “unsuitable loan risk”. It is the assessment of whether NAB’s conduct resulted in these risks arising that is of some relevance.

72 NAB accepted in its written submissions (at [47], [51]) that the Admitted Contraventions did give rise to certain risks (SOAF [100]–[101]), being the risks that: (a) NAB Bankers would, contrary to NAB policy, rely on information provided by the Introducer rather than dealing directly with the Borrower, without making their own inquiries about the Borrower's requirements and objectives in relation to the loan and without taking reasonable steps to assess the veracity of information and documents regarding the Borrower's financial situation put forward in support of loan applications to determine whether loans were unsuitable for that Borrower; and (b) that loans would therefore be made based on incorrect or fraudulent information.

73 NAB also accepts (at SOAF [50], [103], [106], [170]–[171], [205]–[207] and submissions at [51]) that there were:

(a) increases in risk and:

i. that in relation to 202 of the contraventions there was an increase in the risk of Borrowers being exposed to wrongful conduct or fraud because it is possible that Introducers were responsible for causing or encouraging the use of fraudulent documents (thought there is said to be no evidence of this in the cases the subject of this proceeding); if this did occur, it is “possible” the Introducer was incentivised to do so by the prospect of an Introducer fee;

ii. that its reward structure had inadequate controls in respect of the programme that made it more difficult for NAB to prevent and detect fraud from loan applications originating through the programme which may have increased the risk or incidence of unsuitable loans made based on fraudulent or unverified information; and

iii. the control breakdowns that occurred in relation to the programme increased the risk of loans being provided to Borrowers that were unsuitable, the provision of false documentation to support loan applications and the use of incorrect figures in loan serviceability assessments;

(b) manifestations of risk and:

i. insofar as Bankers received some documents from, or sent some documents to, Introducers in circumstances where they might otherwise have received those documents from, or sent them to, Borrowers directly, the relevant Banker did not deal directly with the Borrower in respect of the communication of those documents;

ii. that it is possible that, across the 260 contraventions, there were some instances where the Banker, contrary to policy, in fact relied on unverified information and failed to make direct contact with the customer or Borrower;

iii. the conduct in relation to 202 of the contraventions involved an Introducer providing one or more income verification documents to a Banker in support of a loan application, including payslips and rental appraisals and in these cases the Borrowers were exposed to the risk of wrongful conduct or fraud by the Introducer because payslips and rental appraisals are types of documents that can readily be falsified; and

iv. in the three cases where fraudulent payslips were presented, Borrowers were exposed to the possibility that the loans they sought would be unsuitable for them, in which case they might face difficulties in servicing the loans and therefore financial hardship.

74 I have been asked by ASIC to draw a number of inferences which are said to arise from NAB’s admissions. But as one approaches the task urged by ASIC, difficulties arise.

75 First, I wish to clarify the language used to describe the admitted risk exposure by NAB. NAB does not admit that the contravening conduct gave rise to risks that Borrowers were exposed to “wrongful conduct” risk generally; rather, it accepts this only in respect of certain types of risks and the increase or manifestation thereof. I have summarised these above. The admissions therefore relate to exposure to types of wrongful conduct risk, but not all wrongful conduct risks. The inferences ASIC seeks that I draw relate to “manifestations” of types of wrongful conduct risk not otherwise admitted to, being: (a) that at least on occasion, Bankers did not deal directly with customers in relation to the content of the documents exchanged with Introducers; and (b) that Bankers at least on occasion did not make their own independent inquiries, or take reasonable steps to verify information provided by Introducers. ASIC also says that this Court should find that the risk of Bankers not dealing directly with customers, for instance by face-to-face meetings, manifested in relation to some loans. As to the unsuitable loan risk, NAB accepts that the control breakdowns that occurred in relation to the programme increased the risk of loans being provided to Borrowers that were unsuitable for them, the risk that false documentation would be provided to support loan applications and the risk that incorrect figures would be used in loan serviceability assessments: SOAF [206]. This risk came home on three occasions. As a matter of logic, if the veracity of the information used to advance the loan cannot be assured, neither can the suitability of the resulting loan. This has the necessary consequence that Borrowers were exposed to the risk that loans would be advanced to them that were unsuitable. Therefore, and although NAB did not admit this directly, the admissions it did make nevertheless made out the unsuitable loan risk alleged. By reason of the contravening conduct, borrowers were exposed to the unsuitable loan risk.

76 The inferences that ASIC asks the Court to draw primarily relate to the wrongful conduct risk.

77 An inference is a tentative or final assent to the existence of a fact which the drawer of the inference bases on the existence of some other fact or facts. The quality of the facts established affect the inference which may be drawn; “[n]o greater cogency can be attributed to an inference based upon particular facts than the cogency that can be attributed to each of those facts”: Chamberlain v The Queen (No 2) (1984) 153 CLR 521 (at 599 per Brennan J), cited in Shepherd v The Queen (1990) 170 CLR 573 (at 583 per Dawson J). The inferences to be drawn must be established on the balance of probabilities: Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 140.

78 The strength of the evidence necessary to establish a fact or facts on the balance of probabilities or the “degree of satisfaction that is required in determining that that standard has been discharged” varies according to the considerations listed in s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth): see Qantas Airways Ltd v Gama [2008] FCAFC 69; (2008) 167 FCR 537 (at 571 [110] per French and Jacobson JJ); see also Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2007] FCAFC 132; (2007) 162 FCR 466 (at 480 [30] per Weinberg, Bennett and Rares JJ). Here, the inferences sought are not determinative of liability, and in all the circumstances, are unlikely to have any or any meaningful impact on penalty. However, the alleged contraventions are civil penalty provisions and hence are serious: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Limited (No 3) [2002] FCA 1294; [2002] ATPR 41-901 (at 45,414 [53] per Goldberg J).

79 NAB admits (at SOAF [103]) that Bankers “did not deal directly with the Borrower in respect of the communication of those documents” (emphasis added). ASIC seeks that the Court draw an inference that the Banker also did not deal directly with customers in relation to the content of the documents exchanged with Introducers. However, the fact that there was not direct communication about a document does not lead me to conclude that there was also no direct later communication about the document’s content. It seems entirely possible that in any particular case, the document’s content may have been dealt with by other means, for example, by way of telephone conversation not recorded in Schedule A. Given the way ASIC has run its case, despite suspicions I may have that the inference could be proved in a large number of cases, suspicion is not proof and it would be speculation to conclude that a Banker did not deal directly with customers in relation to the content of the documents exchanged with Introducers.

80 Similarly, ASIC seeks that the Court infer that NAB Bankers “did not make their own independent inquiries, or take reasonable steps to verify information provided by Introducers”. Again, I have not been provided with anything like a complete picture of the independent inquiries made by Bankers, or any particular banker. No Bankers or Introducers were called to give evidence and what I have before me are tables summarising the various loans, relevant parties and associated emails and attachments. There are around 4,309 documents which appear to be referenced in Schedules A, B and C. I have been referred to some of them briefly in Counsels’ submissions. From these, I cannot say, in any particular case, that on the balance of probabilities, I have a state of reasonable satisfaction that independent inquiries were not made whether by telephone or other means not recorded in these documents. I am also asked to draw this inference regarding reasonable steps not taken. What were the reasonable steps required to be taken? If it is face-to-face meetings with each Borrower, ASIC’s regulatory guidance during the Relevant Period included that a licensee can meet responsible lending obligations “using an online or face-to-face approach”. Proof that there was no face-to-face meeting cannot, in and of itself, establish unreasonableness.

81 As in AMP Financial Planning Ltd (No 2), given ASIC’s forensic decision to eschew adducing any direct evidence as to these matters, I am left looking through a glass darkly (at 81 [88]). Further, I also cannot say whether the involvement of the Introducer affected the integrity of the loan application and assessment process, or if the contravening conduct did or did not result in any actual unsuitable lending including whether any customers have suffered actual loss or damage. It may very well have done. I simply do not know.

82 Properly analysed, the inferences which ASIC seeks the Court to draw would not really have been about the consequences of the contravening conduct (in terms of customer harm) but would be evidence concerning separate alleged wrongdoing by the Bankers. This is not a case where it is alleged that any Banker, or NAB, breached the responsible lending requirements in the Act. NAB should not have to meet such a case by a side-wind. The decision by the regulator to run such a case on an opaque evidentiary foundation has deprived me (to use the words of Sir Owen Dixon) of the opportunity of feeling an actual persuasion of the absence of the relevant communications (Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 361) or, to put it another way, has prevented me forming a state of “reasonable satisfaction” on the preponderance of probabilities such as to sustain the relevant issue as ASIC submits: Axon v Axon (1937) 59 CLR 395 (at 403).

83 The National Credit Act was enacted to introduce a comprehensive licensing regime for engaging in a “credit activity”. Under this regime, those wishing to engage in a “credit activity” are required to apply for, be issued with, and hold, an ACL. The National Credit Act imposes entry standards for licensing and, once an ACL is granted, licensees must meet ongoing standards of conduct. ASIC has the power to suspend or cancel an ACL, or to ban individuals from engaging in a “credit activity”. The key aims of the licensing regime are to regulate credit industry participants and enhance consumer protection.

84 Section 27 provides a guide to Part 2-1 of the National Credit Act which makes this clear, comprising Division 2 – Engaging in credit activities without a licence (containing s 29) and Division 3 – Other prohibitions relating to the requirement to be licenced (containing s 31):

This Part is about the licensing of persons to engage in credit activities. In general, a person cannot engage in a credit activity if the person does not hold an Australian credit licence.

Division 2 prohibits a person from engaging in credit activities without an Australian credit licence. However, the prohibition does not apply to employees and directors of licensees or related bodies corporate of licensees, or to credit representatives of licensees.

Division 3 deals with other prohibitions relating to the requirement to be licensed and to credit activities. These prohibitions relate to holding out and advertising, conducting business with unlicensed persons, and charging fees for unlicensed conduct.

85 The National Credit Act also introduced industry-wide responsible lending conduct requirements for licensees. Those requirements aim to protect consumers (both from conduct of lenders and from consumers making poor borrowing decisions) by imposing standards of behaviour on licensees prior to and when entering into a credit contract. The conduct requirements apply only to persons who are licensed under the National Credit Act (that is, holders of an ACL). Relevantly, licensees are required to test the suitability of the proposed credit contract and assess the consumer’s ability to meet their financial obligations under the proposed credit contract. To do so requires direct dealings between the lender and the putative borrower, hence the prohibition on an unlicensed intermediary.

86 Compliance with responsible lending conduct requirements is achieved by ASIC’s ability to impose sanctions on licensees should they fall short of their obligations.

D RELEVANT STATUTORY PROVISIONS

87 I will now set out the relevant statutory provisions which exist within the framework above. Again, much has been agreed between the parties as to the application and interpretation to be given to these provisions, though that agreement is not total.

D.1 Section 29 of the National Credit Act

88 By s 29, the National Credit Act required NAB to hold a licence to conduct its credit activities including its retail mortgage business:

29 Prohibition on engaging in credit activities without a licence

Prohibition on engaging in credit activities without a licence

(1) A person must not engage in a credit activity if the person does not hold a licence authorising the person to engage in the credit activity.

Civil penalty: 2,000 penalty units.

Offence

(2) A person commits an offence if:

(a) the person is subject to a requirement under subsection (1); and

(b) the person engages in conduct; and

(c) the conduct contravenes the requirement.

Criminal penalty: 200 penalty units, or 2 years imprisonment, or both.

D.2 Section 31 of the National Credit Act

89 NAB, by s 31, was prohibited from conducting business with an unlicensed person:

31 Prohibition on conducting business with unlicensed persons

Prohibition on conducting business with unlicensed persons

(1) A licensee must not:

(a) engage in a credit activity; and

(b) in the course of engaging in that credit activity, conduct business with another person who is engaging in a credit activity;

if, by engaging in the credit activity, the other person contravenes section 29 (which deals with the requirement to be licensed).

Civil penalty: 2,000 penalty units.

90 By s 31, the National Credit Act seeks to ensure that the overall objectives of the credit regime are not frustrated by licensees engaging with unlicensed persons to subvert its intent. In the present case, the relevant “credit activity” engaged in by each Introducer (the unlicensed person) in relation to each of the 260 occasions was providing “credit assistance” or acting as an “intermediary”.

D.3 Other relevant provisions of the National Credit Act

91 During the Relevant Period, “credit activity” was defined in s 6 of the National Credit Act. Relevantly, a person engages in a “credit activity” in relation to a “credit contract” if:

(1) the person is a “credit provider” under a “credit contract”; or

(2) the person carries on a business of providing credit, being credit the provision of which the National Credit Code applies; or

(3) the person performs the obligations, or exercises the rights, of a “credit provider” in relation to a “credit contract” or proposed credit contract.

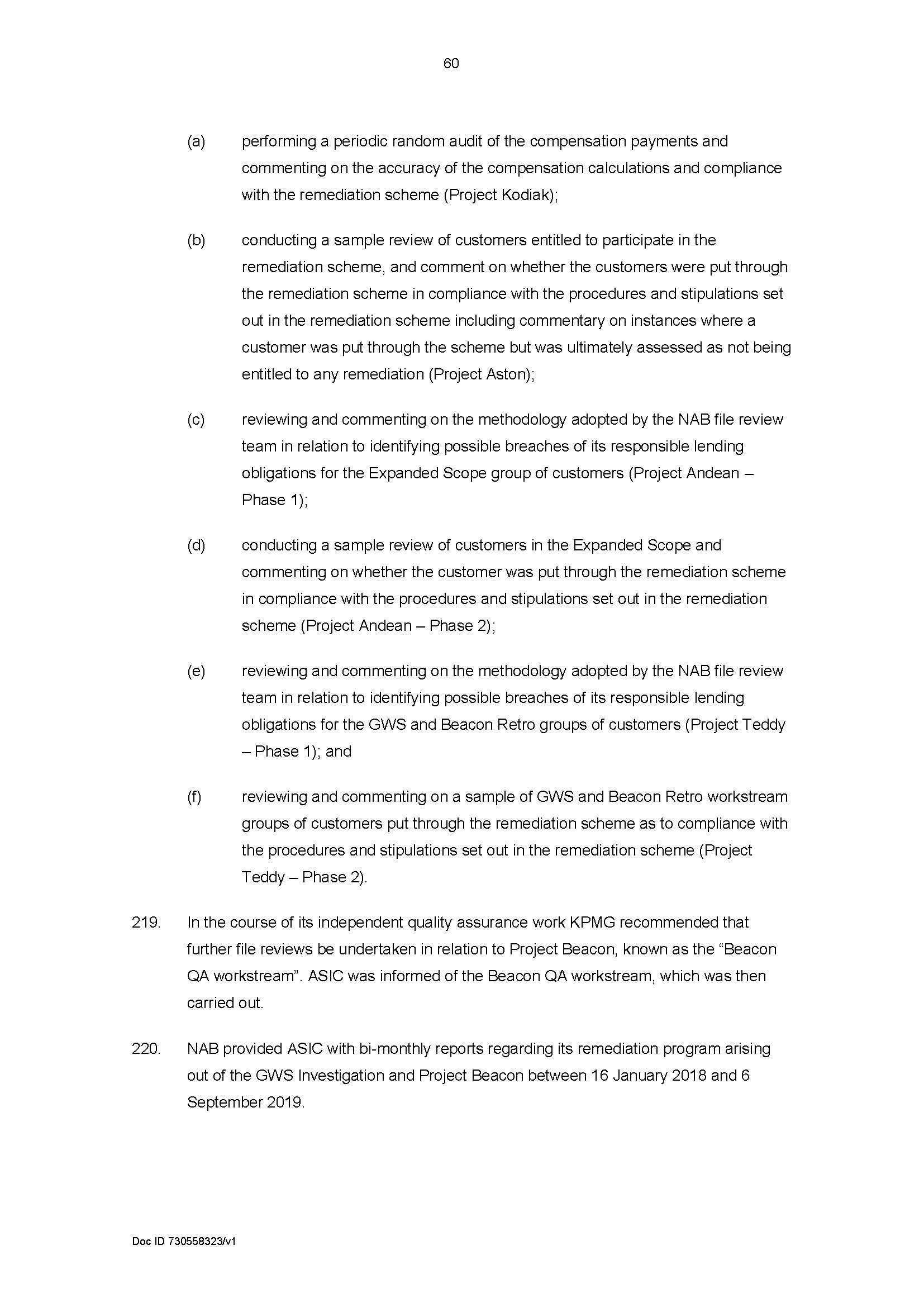

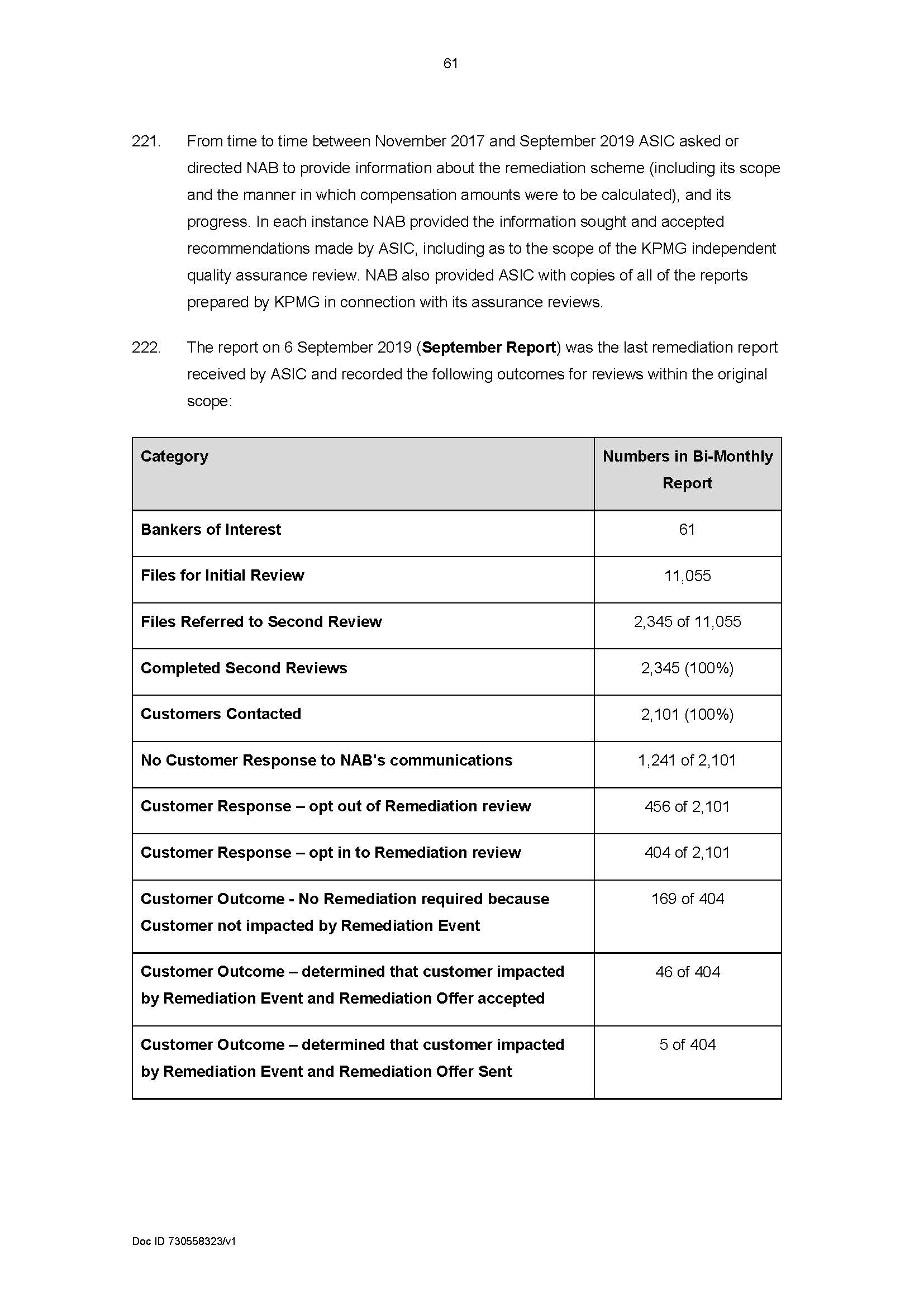

92 A person also engages in a “credit activity” if the person provides a “credit service”. “Credit services” are in turn defined in s 7 to mean: (a) providing “credit assistance” to a consumer; or (b) acting as an “intermediary”.

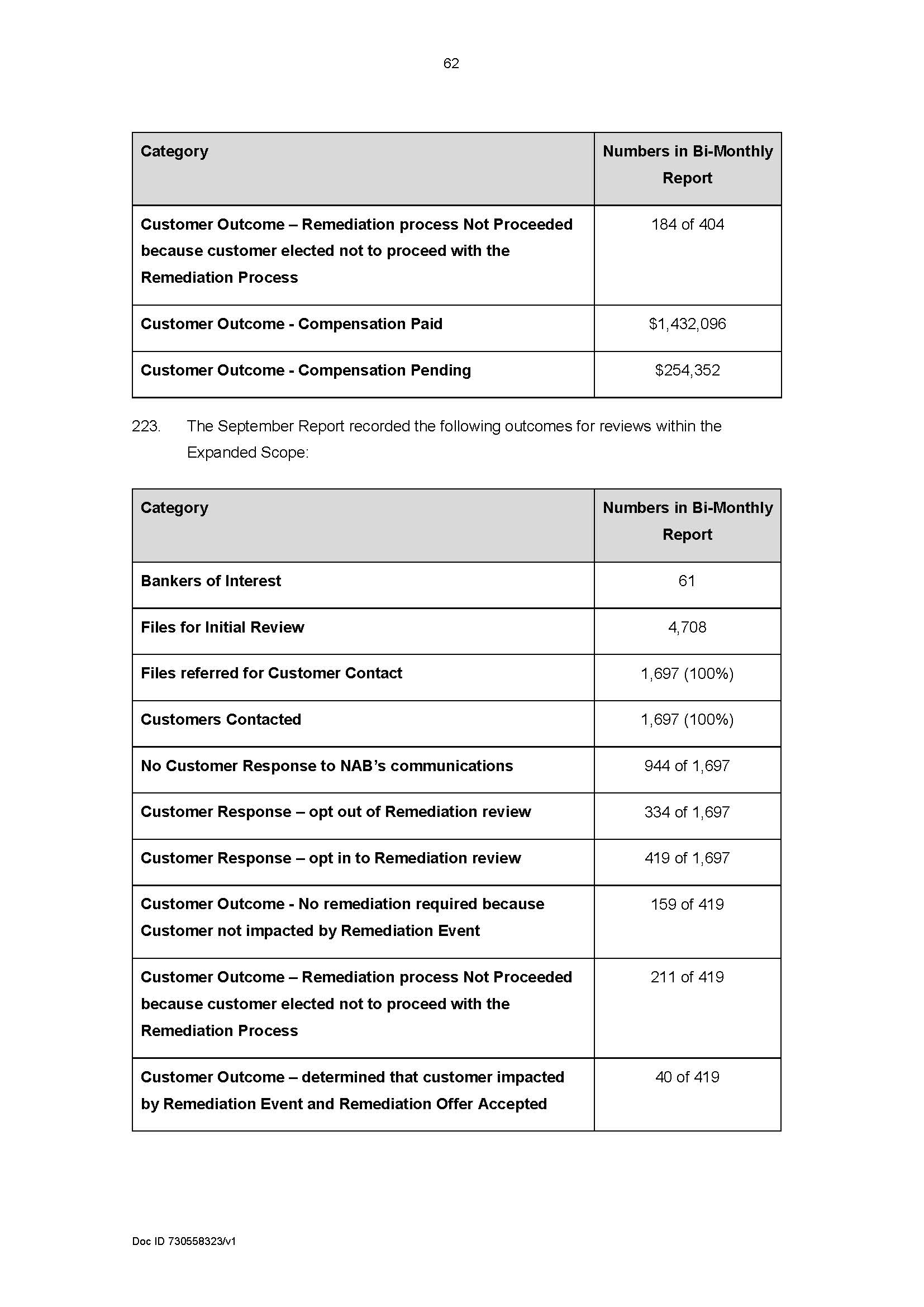

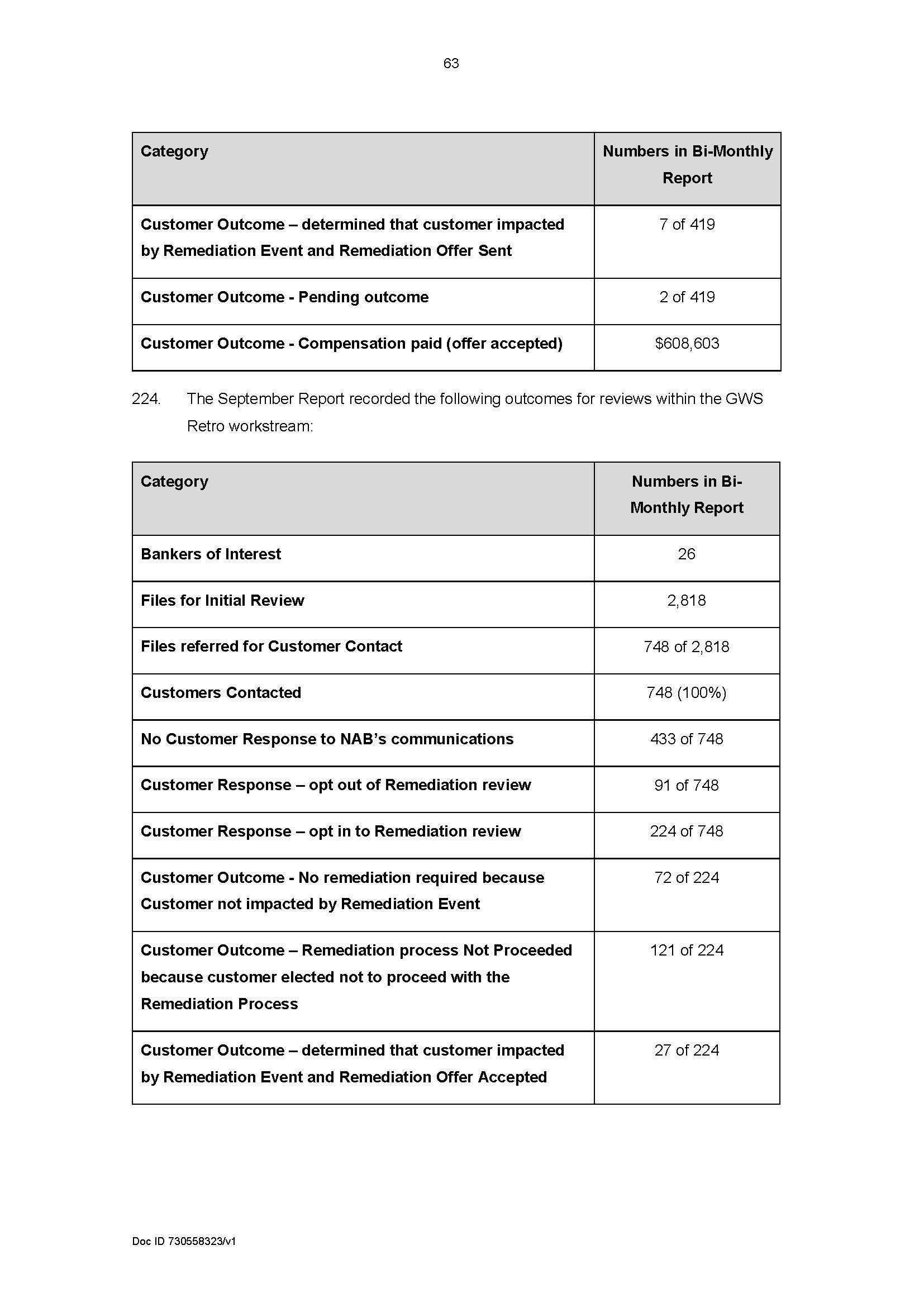

93 Section 8 of the National Credit Act defines the meaning of “credit assistance” in the following terms:

A person provides credit assistance to a consumer if, by dealing directly with the consumer or the consumer’s agent in the course of, as part of, or incidentally to, a business carried on in this jurisdiction by the person or another person, the person:

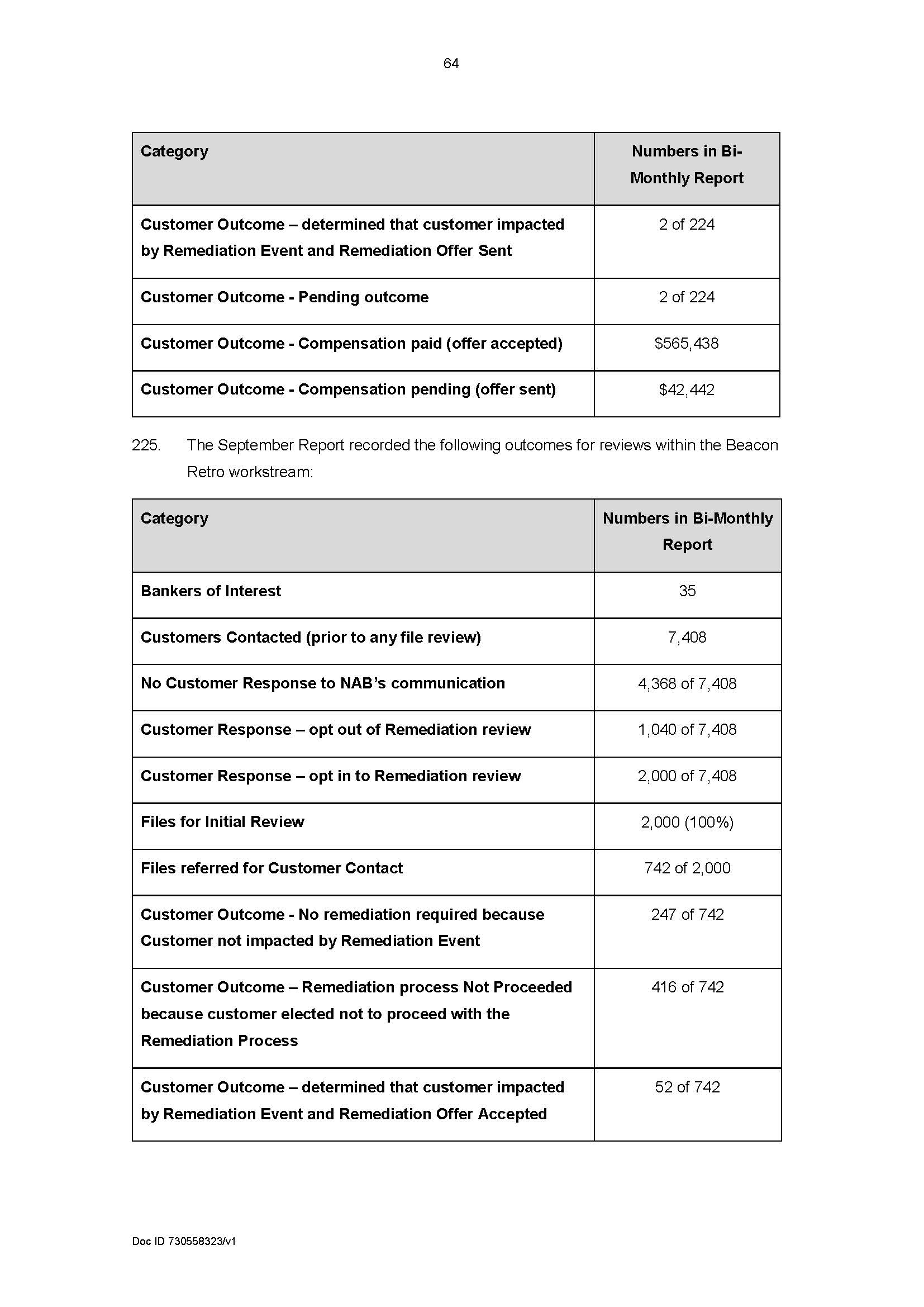

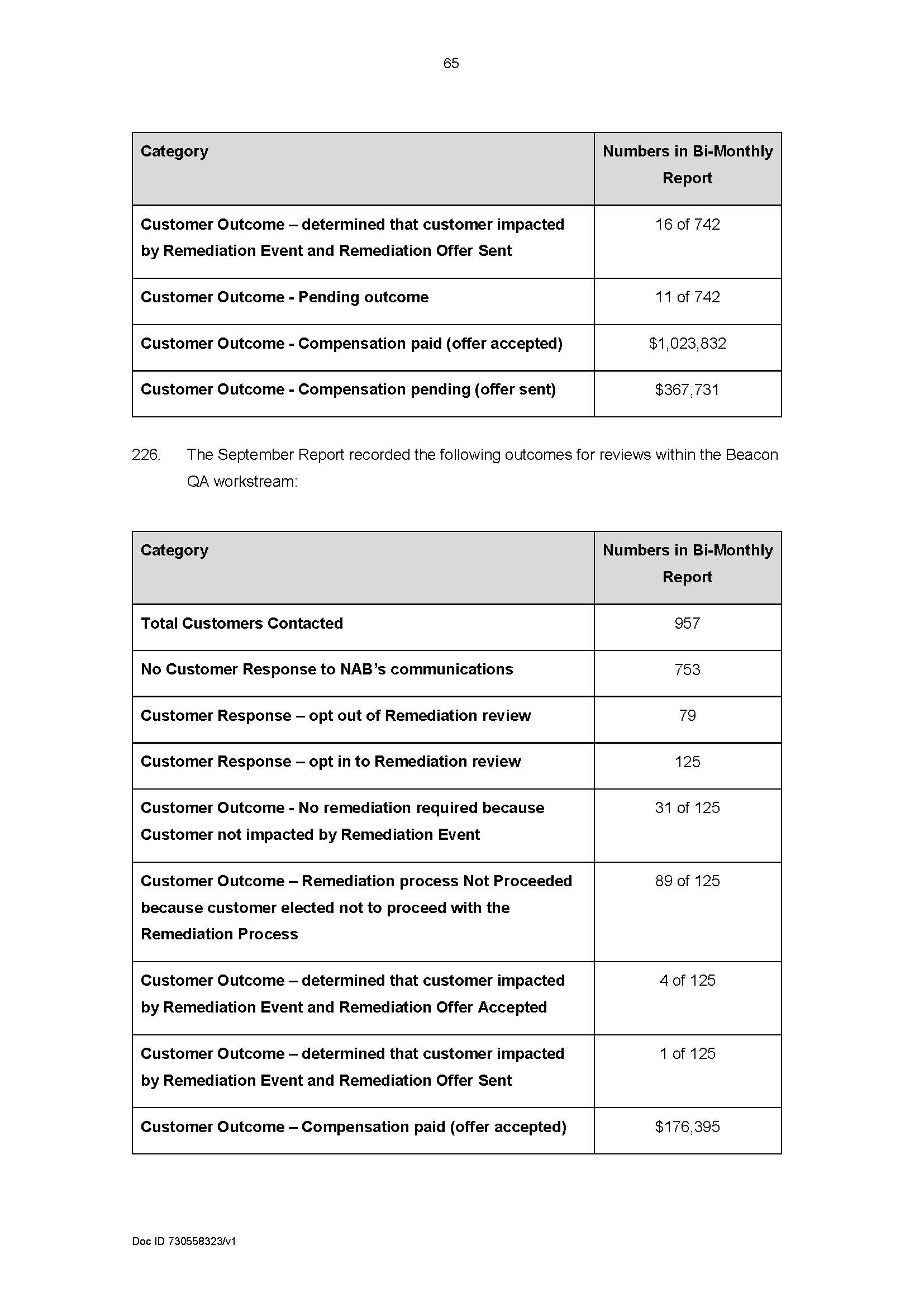

(a) suggests that the consumer apply for a particular credit contract with a particular credit provider; or

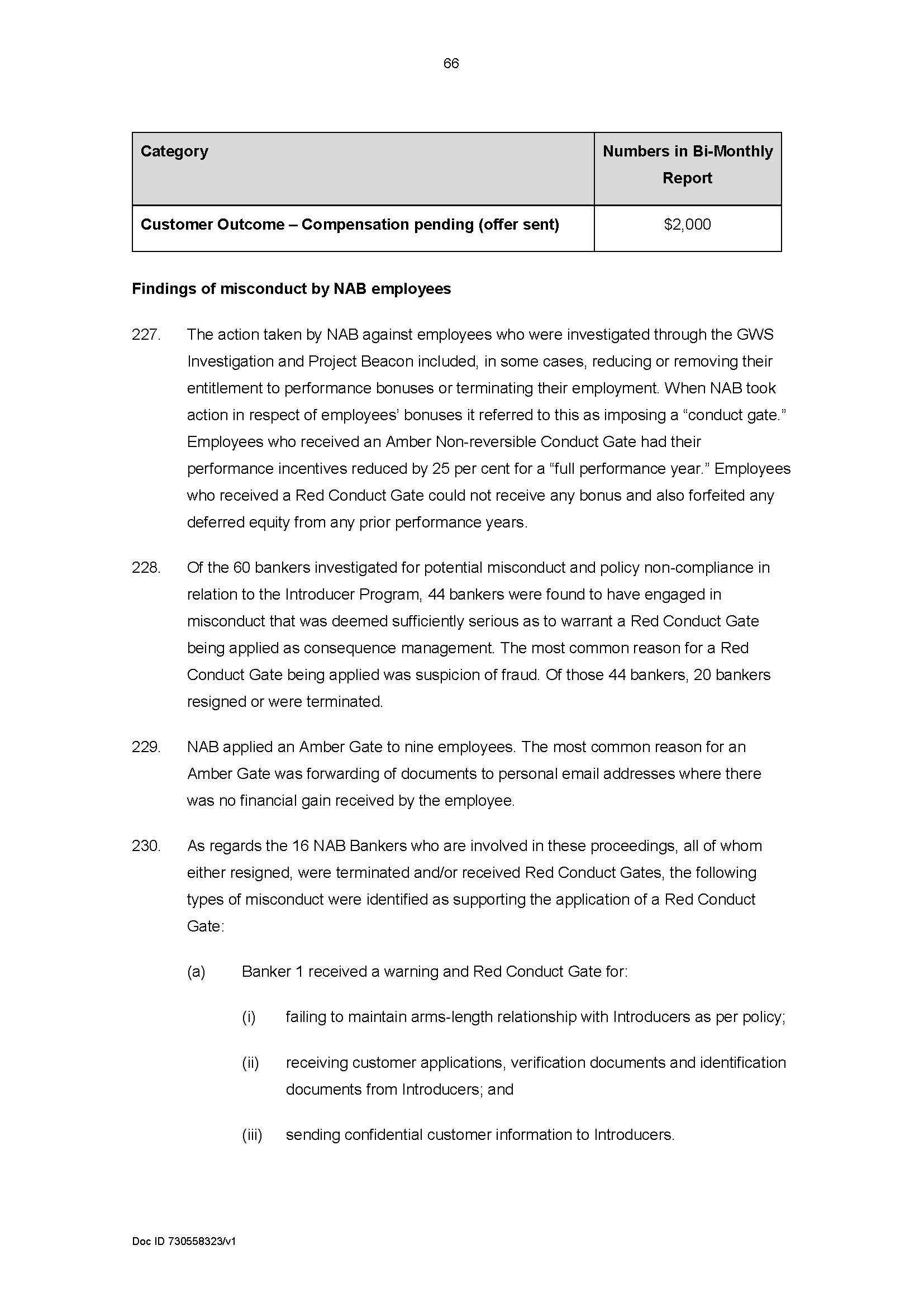

…

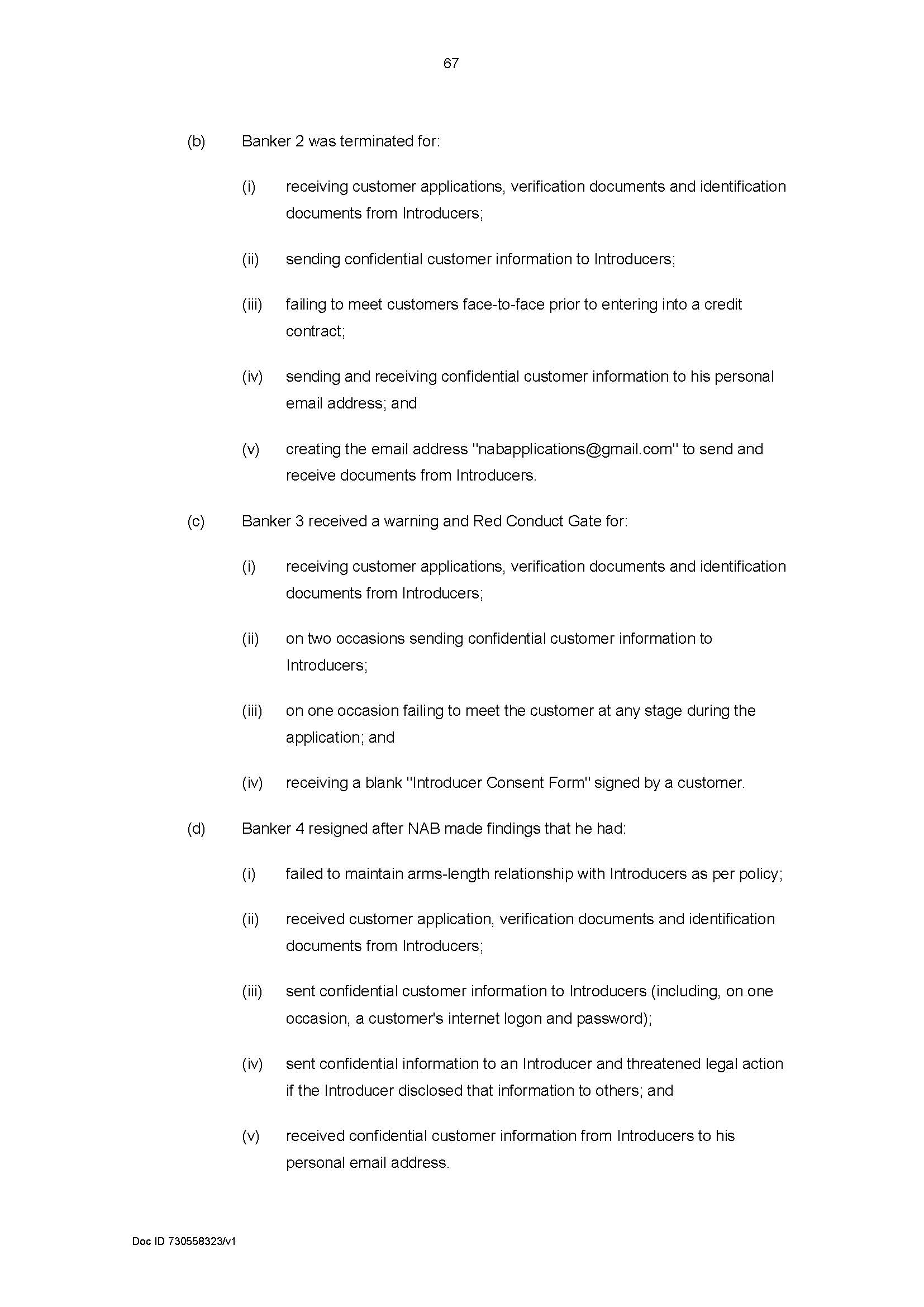

(d) assists the consumer to apply for a particular credit contract with a particular credit provider; or

…

It does not matter whether the person does so on the person’s own behalf or on behalf of another person.

94 Section 9 of the National Credit Act defines the meaning of “acts as an intermediary” in the following terms:

A person acts as an intermediary if, in the course of, as part of, or incidentally to, a business carried on in this jurisdiction by the person or another person, the person:

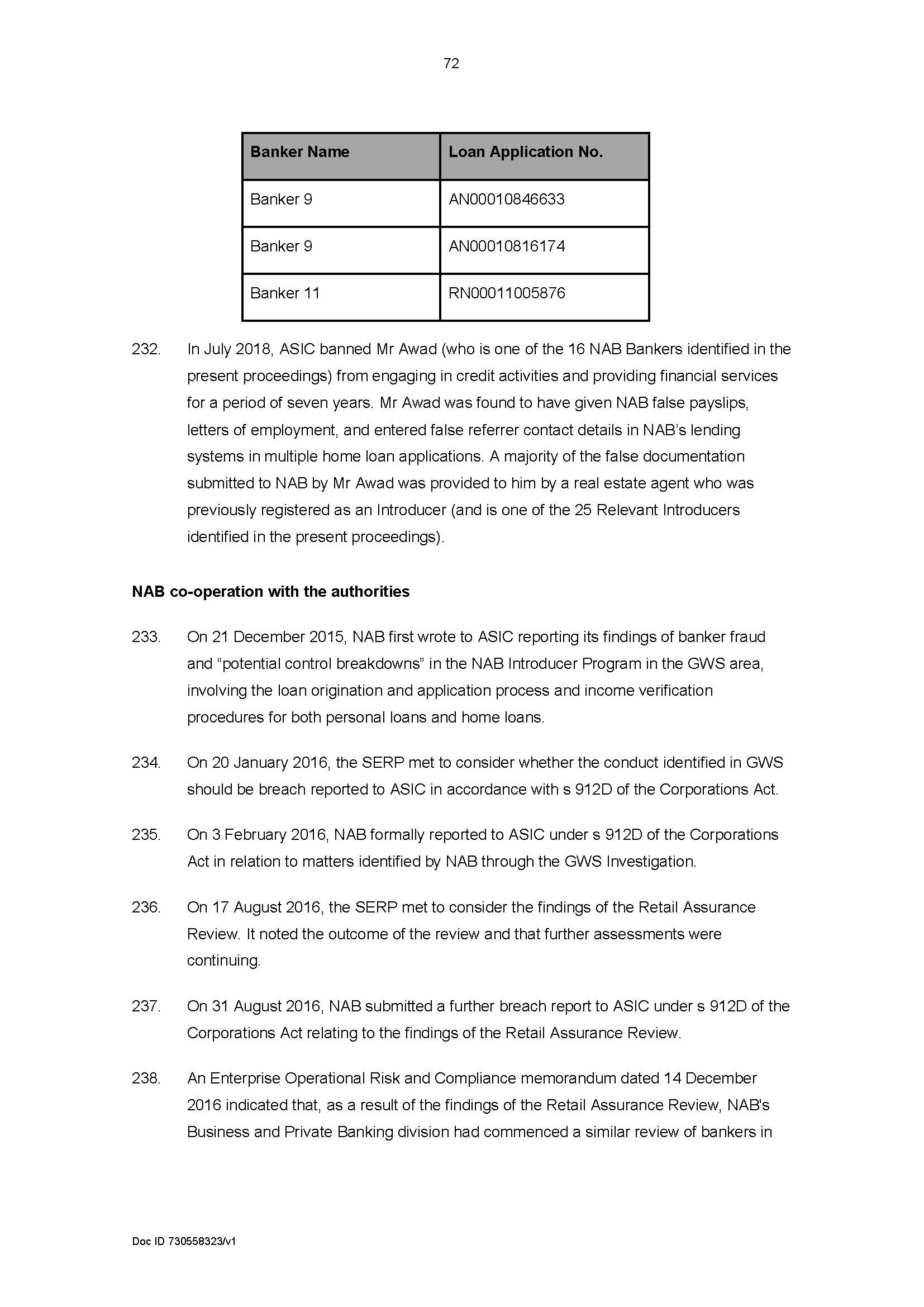

(a) acts as an intermediary (whether directly or indirectly) between a credit provider and a consumer wholly or partly for the purposes of securing a provision of credit for the consumer under a credit contract for the consumer with the credit provider; or

(b) acts as an intermediary (whether directly or indirectly) between a lessor and a consumer wholly or partly for the purposes of securing a consumer lease for the consumer with the lessor.

It does not matter whether the person does so on the person’s own behalf or on behalf of another person.

D.4 Section 47 of the National Credit Act

95 Section 47(1)(a) and (d) sets out general obligations for those who hold an ACL. These subsections are in the following terms:

47 General conduct obligations of licensees

General conduct obligations

(1) A licensee must:

(a) do all things necessary to ensure that the credit activities authorised by the licence are engaged in efficiently, honestly and fairly; and

…

(d) comply with the credit legislation.

96 Section 47 did not attract a civil penalty during the Relevant Period.

D.5 The National Credit Regulations

97 Regulation 25 of the National Credit Regulations exempts certain activities from the requirement to be licensed. Relevantly, r 25(5) provides:

25 Activities exempt from requiring a licence

…

(5) A credit activity is exempted if:

(a) a person (the referrer) engages in a credit activity on or after 1 October 2010 under an agreement with the licensee or registered person or a representative of the licensee or registered person; and

(b) the agreement:

(i) specifies the conduct in which the referrer can engage as conduct to which the exemption applies; and

(ii) is:

(A) in writing only; or

(B) based on an offer made in writing by the licensee, registered person or representative that has been accepted by the referrer; and

(c) the activity consists only of:

(i) the referrer informing another person (the consumer) that the licensee or registered person, or a representative of the licensee or registered person, is able to provide a particular credit activity or a class of credit activities; and

(ii) the referrer giving to the licensee, registered person or representative the consumer’s name and contact details within 5 business days after informing the consumer; and

(iii) the referrer giving to the licensee, registered person or representative a short description of the purpose for which the consumer may want a provision of credit or a consumer lease (if the referrer knows the purpose); and

(d) the referrer is not banned from engaging in the credit activity under:

(i) a law of a State or Territory; or

(ii) Part 2‑4 of the Act; and

(e) at the time the activity is engaged in, the referrer discloses to the consumer:

(i) any benefits, including commission, that the referrer, or an associate of the referrer, may receive in respect of the activity; and

(ii) any benefits, including commission, that the referrer, or an associate of the referrer, may receive that are attributable to the activity; and

(f) the referrer has not required the consumer to pay a fee to any person in relation to the referrer giving to the licensee, registered person or representative the consumer’s name; and

(g) the consumer has consented to the referrer giving to the licensee, registered person or representative the consumer’s name; and

(h) the referrer engages in the activity as a matter incidental to the carrying on of a business that is not principally making contact with persons for the purpose of giving their names or other details to another person; and

(i) the referrer does not conduct a business as part of which the referrer contacts persons face‑to‑face from non‑standard business premises.

98 As noted above, the principal contested legal issue concerns s 47(1)(a) and the number of times it was contravened by NAB. It is not disputed that it was contravened at least once. There is also a minor dispute about the meaning to be given to the term “particular credit contract” in s 8 of the National Credit Act. I deal with each below.

E.1 Section 47(1)(a) – General conduct obligations of licensees

99 ASIC contends that the conduct in relation to each of the 260 loans was a contravention of both s 47(1)(d), which is not disputed, and s 47(1)(a) of the National Credit Act, which is disputed. As to the latter, it is argued that there must be 260 contraventions when, by NAB’s own policies and the terms of the Introducer Agreements, NAB failed to do all things necessary to ensure that the credit activities authorised by its ACL were engaged in “efficiently, honestly and fairly” in respect of each loan application. In taking this position, ASIC rejects NAB’s assertion that there was instead a single, system wide failure constituting a single contravention of s 47(1)(a).

100 In support of its view, ASIC says that the requirement in s 47(1)(a) of the National Credit Act is analogous to that in s 912A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), which has received prior judicial consideration including recently in the decision in Australian Securities and Investments Commission v AGM Markets Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2020] FCA 208; (2020) 143 ACSR 140 (at 229–32 [505]–[528] per Beach J) and Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Westpac Securities Administration Ltd [2019] FCAFC 187; (2019) 373 ALR 455 (per Allsop CJ, Jagot and O’Bryan JJ).

101 As I will come to discuss below when considering whether to make the declarations urged by ASIC, I do not find it necessary to determine this issue. I accept NAB’s admission that it has contravened s 47(1)(a) once because NAB failed to do all things necessary to ensure that the Admitted Contraventions did not occur: SOAF [4(d)]. I make no finding as to whether it also contravened s 47(1)(a) on 259 additional occasions. As matter of discretion, I will leave the question of whether the underlying conduct constituted one or many breaches of s 47(1)(a) of the National Credit Act to a future proceeding where something may turn on the determination of that matter and full submissions can be received – particularly as this is now a civil penalty provision. As it was not a civil penalty provision during the Relevant Period, nothing turns on it now. There is no impact on the penalty to be imposed.

E.2 Meaning of “particular credit contract”

102 This is a minor area of dispute and I will deal with it only briefly. The prohibition in s 31 of the National Credit Act prohibited NAB from engaging in a “credit activity” and, in the course of engaging in that “credit activity”, conducting business with another person who is engaging in a “credit activity” without a licence.

103 The issue arises as to whether, in the above context, certain of the 260 admitted instances of credit activity by a person who “acts as an intermediary” within the meaning of s 9 also involved the provision of “credit assistance” pursuant to s 8, which would also contravene s 31.

104 ASIC submits that, in addition to engaging in a credit activity under s 9, in some cases, Introducers also provided credit assistance within the meaning of s 8 (SOAF [65(d)]). It says, whether or not an Introducer was providing “credit assistance” turns in part on the interpretation given to the words “a particular credit contract” in s 8 of the National Credit Act. The degree of specificity which the word “particular” requires has not previously been the subject of judicial consideration. It is ASIC’s position that the word “particular” in that context should require no more than identification of the general type of credit contract (e.g. the type or perhaps purpose of the loan) rather than an individual product feature (such as, for example, a fixed rate home loan or a variable rate home loan; or a loan of a precise amount for a precise period with the consequence that a slightly larger or slightly smaller loan be treated as a different contract). Such an interpretation is said not to be inconsistent with any Regulatory Guide issued by ASIC.

105 Were the Court to find that the words “particular credit contract” required that the Introducer assist the Borrower to apply for a home loan with NAB, then it says there are 171 instances of such conduct on the admitted facts, relating to 113 of the 260 loans. Even if the Court were to take a narrower view, it submits that the number of contraventions under s 31 would not be affected. Each Introducer was engaging in a “credit activity” without a licence to do so, whether they were acting as an “intermediary” only or acting as an “intermediary” and providing “credit assistance” in the particular instance.

106 But the meaning to be given to “a particular credit contract” in s 8 is not an issue that needs to be addressed in this case since NAB admits that the Introducers either provided “credit assistance” within the meaning of s 8 or “act[ed] as an intermediary” within the meaning of s 9. It also challenges ASIC’s assertion that there would be 171 instances of such conduct on the admitted facts based on a review of Schedule A and suggests an inconsistency with ASIC’s Regulatory Guide 203 (at [RG.203.64]). Again, there is no impact on penalty because there would not be more contraventions, simply the same conduct breaching the provision by way of a slightly different path. However, although it does not matter, it seems to me the preferable interpretation is likely to be that suggested by ASIC, that the words “particular credit contract” in s 8 of the National Credit Act in the above context only require the identification of the general type of credit contract rather than an individual product feature. I agree with ASIC that it would be odd if a person could suggest that a customer apply for a home loan with NAB without engaging in a credit activity (as opposed to some more general statement), but if they used the words “fixed” or “variable” in their suggestion, the provision would be engaged.

107 By the Originating Application filed on 23 August 2019, ASIC seeks a vast array of declarations.

108 Section 166(1) of the National Credit Act provides that, within six years of a person contravening a civil penalty provision, ASIC may apply to this Court for a declaration that the person contravened the provision. By s 166(2), the Court must make the declaration if it is satisfied that the person has contravened the provision. Section 31 is a civil penalty provision hence I am required to make the declarations sought if I am satisfied that contravention has occurred. This is not in dispute and I am so satisfied.

109 But as noted above, ASIC also seeks declarations that NAB contravened s 47(1)(d) of the National Credit Act on 260 occasions by failing to comply with credit legislation; and s 47(1)(a) of the National Credit Act on 260 occasions by failing to do all things necessary to ensure that the credit activities authorised by its ACL were engaged in efficiently, honestly and fairly.

110 Of course, the Court has power to make declarations pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth). In AMP Financial Planning (No 2) I accepted (at 93 [143]) that pursuant to s 21 the Court has a general power to make a binding declaration of right even where no consequential relief is claimed: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australian Lending Centre Pty Ltd (No 3) [2012] FCA 43; (2012) 213 FCR 380 (at 441 [271] per Perram J). But, as I said there (at 93 [144]), that does not mean they should be thrown around like confetti. Discretion and utility is key: see eg, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Target Australia Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1326 (at [19] per Lee J). I must be satisfied that the making of each declaration is appropriate and utile: Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v De Martin & Gasparini Pty Limited (No 3) [2018] FCA 1395 (at [74] per Wigney J).

111 ASIC says that I should be so satisfied including because s 47(1)(a) and (d) are now civil penalty provisions and a declaration may be relevant to assessing any civil penalty sought against NAB in the future in respect of those provisions and any disciplinary sanctions under s 55 of the National Credit Act (suspension or cancellation of an ACL). ASIC also says that it has a real interest in obtaining declarations in respect of breaches of legislation over which it has a regulatory role: Commonwealth Bank of Australia (at [154] per Beach J). The declarations sought are said to both vindicate the regulator’s claim and assist the regulator carry out its duties: Westpac Banking Corporation (at [251] per Wigney J). Accordingly, and despite what I said in AMP Financial Planning (No 2), ASIC says there is utility given NAB itself is the holder of the ACL and engaged in the conduct comprising each breach of s 31.

112 I remain aporetic about making the “repetitive” declarations sought by the regulator. As with all discretionary remedies, if no good purpose will be served by granting it, it should be refused: see Dillon v RBS Group (Australia) Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 896; (2017) 252 FCR 150 (at 158 [39] per Lee J); Ainsworth v Criminal Justice Commission (1992) 175 CLR 564 (at 582 per Mason CJ, Dawson, Toohey and Gaudron JJ). As NAB submits, the declarations sought add nothing in the quelling of this controversy. In circumstances such as this, the cautions recalled in Ibeneweka v Egbuna [1964] 1 WLR 219 (at 224–5 per Viscount Radcliffe, Lord Guest and Lord Upjohn) become relevant: “declarations are not lightly to be granted. The power should be exercised ‘sparingly’, with ‘great care and jealousy’, with ‘extreme caution’, with ‘the utmost caution’”. Gibbs J in Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Limited (1972) 127 CLR 421 (at 438, with whom Walsh J agreed at 427, at 448 per Stephen J, at 450 per Mason J, and at 426 per McTiernan J), referring to Ibeneweka (at 225), said that “the undoubted truth” was “that the power to grant a declaration should be exercised with a proper sense of responsibility and a full realisation that judicial pronouncements ought not to be issued unless there are circumstances that call for their making.”

113 To accede to ASIC’s request in these circumstances would be to satisfy the “fetish”, as Gray J has described it, of certain regulators seeking, and the Court granting, declaratory relief simply because the Court finds that a contravention has occurred: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Francis [2004] FCA 487; (2004) 142 FCR 1 (at 36 [110]). There is simply no point. The declarations sought would have no impact on the penalty. Contrary to ASIC’s submission, it would also have no impact on any sanctions under s 55 of the National Credit Act because the relevant factor under that section is the contraventions themselves (s 55(1)(a)), not whether declarations have been made. Had it been relevant to any part of the National Credit Act, one would expect that a mandatory declaration, such as that found in s 166, would have been provided for – as is now the case. Rather, and as I said in AMP Financial Planning (No 2) (at [151]), the “reality is that both the Court’s disapproval of contravening conduct and clarification of the law is much more likely to emerge from a perusal of reasons than the bare terms of essentially repetitive declarations”.

114 The parties have agreed a number of facts relevant to the Court’s consideration of pecuniary penalties in the light of the Admitted Contraventions. These are set out in the SOAF (at [92]–[285]). The facts are complex and I do not propose to set out any summary of these facts beyond what I have already explained above.

I Section 167 of the National Credit Act

115 Section 167(1) of the National Credit Act provides that, within six years of a person contravening a civil penalty provision, ASIC may apply to this Court for an order that the person pay the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty. Section 167(2) provides that, if a declaration has been made under s 166 that the person has contravened the provision, the Court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty that the Court considers is appropriate.

116 Section 167 was in the following terms at the relevant time:

167 Court may order person to pay pecuniary penalty for contravening civil penalty provision

Application for order

(1) Within 6 years of a person contravening a civil penalty provision, ASIC may apply to the court for an order that the person pay the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty.

Court may order person to pay pecuniary penalty

(2) If a declaration has been made under section 166 that the person has contravened the provision, the court may order the person to pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty that the court considers is appropriate (but not more than the amount specified in subsection (3)).

Determining amount of pecuniary penalty

(3) The pecuniary penalty must not be more than:

(a) if the person is a natural person—the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the civil penalty provision; or

(b) if the person is a body corporate, a partnership or multiple trustees—5 times the maximum number of penalty units referred to in the civil penalty provision.

Note: This Act treats partnerships and multiple trustees as if they were persons (see sections 14 and 15).

Recovery of penalty as a debt

(4) The pecuniary penalty Application to s 31 may be recovered as a debt due to the Commonwealth.

117 The amount of the maximum pecuniary penalty changed during the Relevant Period. For each of the 113 contraventions of s 31, which occurred between 23 August 2013 and 28 July 2015, the maximum penalty is $1,700,000; for each of the 147 contraventions of s 31, which occurred between 4 August 2015 and 29 July 2016, the maximum penalty is $1,800,000. As ASIC pointed out, the theoretical maximum penalty for the 260 Admitted Contraventions is $456.7 million.

118 ASIC made detailed submissions about the principles applicable to determining an appropriate penalty under the National Credit Act. NAB did not disagree with this statement of applicable principles, although it made its own further submissions clarifying certain aspects.

119 The general thrust of ASIC’s submissions is that the 260 contraventions circumvent a fundamental tenet of the Australia’s financial licensing regime requiring that persons engaging in credit activities be licensed. They therefore represent serious breaches of the National Credit Act. In these circumstances, it is said, a penalty must be imposed that reflects the seriousness of this conduct, which has regard to the size of NAB, the period of time over which the contraventions occurred, the time taken to suspend lending through the programme and the lack of effective compliance monitoring at NAB, and to ensure that the objective of deterrence is achieved. ASIC pointed to several cases it says are relevant to the determination of the penalty to be imposed including Westpac Banking Corporation (at [255]–[272] per Wigney J), Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2018] FCA 155 (per Middleton J) and Commonwealth Bank of Australia (at [65]–[79] per Beach J). It emphasised the fundamental objective of a pecuniary penalty, which is deterrence: NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285; Westpac Banking Corporation (at [255] per Wigney J). And while the process of quantifying pecuniary penalties is an inexact science (AMP Financial Planning Pty Ltd (No 2) at [159] per Lee J), the question of what amount constitutes an appropriate penalty in all the circumstances is a question for the Court.