FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Employsure Pty Ltd

[2020] FCA 1409

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | EMPLOYSURE PTY LTD ACN 145 676 026 Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The amended originating application be dismissed.

2. Within 21 days hereof, the parties are to seek to agree costs. If they are unable to reach such an agreement, within that time each should file and serve an outline of submissions on costs not exceeding three pages in length. Unless either of the parties can demonstrate the need for a further oral hearing, the issue of costs will be determined on the papers and without a further oral hearing.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[8] | |

[11] | |

(b) Use of keywords and design of Google Ads liable to mislead | [21] |

[23] | |

[25] | |

[41] | |

[44] | |

PART B: AGREED FACTS RELATING TO THE OPERATION OF THE GOOGLE SEARCH ENGINE | [45] |

[46] | |

[51] | |

[53] | |

(ii) The evidence of some small business owners and their dealings with Employsure | [58] |

[59] | |

[89] | |

[122] | |

[154] | |

[155] | |

[208] | |

[232] | |

[233] | |

[233] | |

(i) Section 18 of the ACL | [236] |

[245] | |

[250] | |

[251] | |

[260] | |

[263] | |

[266] | |

[273] | |

[283] | |

[283] | |

(b) Conclusions concerning use of keywords and design of Google Ads | [288] |

[303] | |

[303] | |

[304] | |

[305] | |

[306] | |

[310] | |

[314] | |

[321] | |

[321] | |

[323] | |

[333] | |

[345] | |

[351] | |

[353] | |

[371] | |

[372] | |

[388] | |

[411] | |

[425] | |

[425] | |

[427] | |

[428] | |

[434] | |

[434] | |

[436] | |

[444] | |

[446] | |

[446] | |

[450] | |

[454] | |

[456] | |

[456] | |

[459] | |

[463] | |

[465] | |

[466] | |

ANNEXURE A: AGREED FACTS RELATING TO OPERATION OF THE GOOGLE SEARCH ENGINE |

GRIFFITHS J:

PART A: INTRODUCTION AND THE ACCC’S CLAIMS SUMMARISED

1 Employsure Pty Ltd is a specialist workplace relations consultancy. It advises employers and business owners regarding the requirements of workplace relations and work health and safety legislation. Employsure operates nationally and, during the period in respect of which the claims of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) relate, it provided products and services to over 20,000 employers across the nation. Those services included reviewing client documentation relating to workplace relations and work health and safety compliance, providing an advice helpline which was available at all times and representing clients in courts and tribunals if they became involved in formal proceedings.

2 Employsure’s business model applies by way of a subscription as opposed to a fee for service model. Under the subscription model, Employsure’s clients pay a fixed fee and they are then entitled to access Employsure’s products and services as required. The subscription fee is not affected by the volume of work which a particular client requires from Employsure.

3 The majority of Employsure’s client base are small business owners who employ staff, although Employsure also has several large clients.

4 Employsure offers on-site consultancy services as required, including staff training, management of disciplinary processes and risk reviews, as well as an initial review of a client’s work health and safety practices (which Employsure calls a “Safe Check Review”) and a review of a client’s workplace relations practices (which Employsure calls a “Wage Check and Contract Check”). These particular services are generally offered by Employsure to its clients on payment of an additional fee, although sometimes they may be provided gratuitously as part of the negotiations of the total subscription fee.

5 It is appropriate to say something briefly about how Employsure provides its products and services. Where a prospective client or interested person telephones Employsure, the calls are received by Employsure’s business sales consultants (BSCs). Sometimes these calls involve BSCs providing free advice to the caller. If a caller is, or may be, interested in acquiring Employsure’s services, there is a procedure whereby the BSC offers to arrange a face-to-face meeting with one of Employsure’s business development managers (BDMs). Where that opportunity is taken up, the BDM normally provides the person with additional advice, as well as explaining Employsure’s services and providing an obligation free quote. As will emerge, some clients enter into a formal agreement with Employsure at this initial meeting or shortly thereafter.

6 The ACCC raises five separate causes of action against Employsure, all of which relate to the manner in which Employsure has promoted its products and services to the public and, in particular to people who search online for employment related advice. Those five causes of action are as follows:

(a) The making of what are described as Government Affiliation Representations by way of seven Google Ads which the ACCC claims conveyed representations that Employsure was, or was affiliated with, and/or was endorsed by, a government agency.

(b) The use by Employsure of keywords and design of Google Ads which was said to involve misleading or deceptive conduct in circumstances where Employsure:

(i) researched the terms used by persons visiting the official websites of government agencies such as the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) and the Fair Work Commission (FWC);

(ii) used terms in its Google Ads campaigns knowing that the keywords it chose reflected the search terms used by consumers in accessing online the FWO and FWC websites; and

(iii) designed its Google Ads in a fashion whereby the headline repeated or incorporated those keywords, sometimes being the names of government organisations, such as FWO, together with a URL, such as “fairworkhelp.com.au”.

(c) In the period January 2016 to 30 November 2018, in 16 of its Google Ads and three of its landing pages websites, Employsure prominently advertised its “free advice” telephone helpline, which represented that Employsure provided a free advice service and also represented that the provision of free advice was Employsure’s primary function, which the ACCC alleges also involved misleading or deceptive conduct.

(d) Employsure engaged in unconscionable conduct, contrary to s 21 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) with respect to its dealings with three small businesses. The unconscionable conduct was said to relate to Employsure’s conduct in entangling those businesses in its “marketing web”.

(e) Certain clauses in Employsure’s standard form small business contract were unfair contract terms in contravention of ss 23 and 24 of the ACL.

7 It is desirable to say something more about each of those five causes of action. The relevant legal principles will be discussed later in these reasons for judgment.

8 The ACCC alleges that in seven Google Ads, which appeared over the period from 10 August 2016 to 30 November 2018, Employsure represented that it was, or was affiliated with, or endorsed by, a government agency contrary to the fact (Government Affiliation Representations). The ACCC alleged that the representations were made through Employsure’s use of Google Ads services, which resulted in consumers who used search words, such as “fair work ombudsman” and “fair work commission” and other associated keywords, accessing Employsure’s Google Ads. It claimed that those advertisements conveyed an association with a government agency, contrary to the fact, because Employsure is a private company which has no affiliation with, or endorsement by, any government agency. The Google Ads appeared on webpages which were accessed by a computer, smartphone or other internet capable device (such as a tablet).

9 The ACCC alleges that Employsure:

(a) engaged in conduct which was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s 18(1) of the ACL; and

(b) made false or misleading representations that its services:

(i) are of a particular standard or quality in contravention of s 29(1)(b) of the ACL; and

(ii) had government sponsorship or approval in contravention of s 29(1)(h) of the ACL.

10 It should be noted at the outset that there was some inconsistency in the ACCC’s presentation of this particular claim. In both its written and oral submissions the ACCC referred to the Government Affiliation Representation (i.e. as if there was only one such representation). In contrast, in the amended concise statement the ACCC referred repeatedly to the “Government Affiliation Representations” (see e.g. [5] and [13]). Given the fact that the ACCC claimed that Employsure represented that it was, or was affiliated with, or endorsed by, a government agency, which presents three alternative possibilities, it is more accurate to refer to the Government Affiliation Representations, which I will adopt for the remainder of these reasons for judgment.

11 It is well to set out the seven Google Ads which are the subject of the ACCC’s claims concerning the “Government Affiliation Representations”.

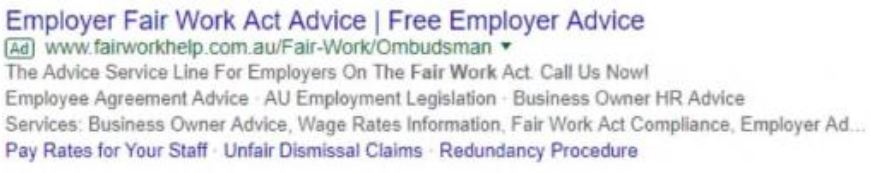

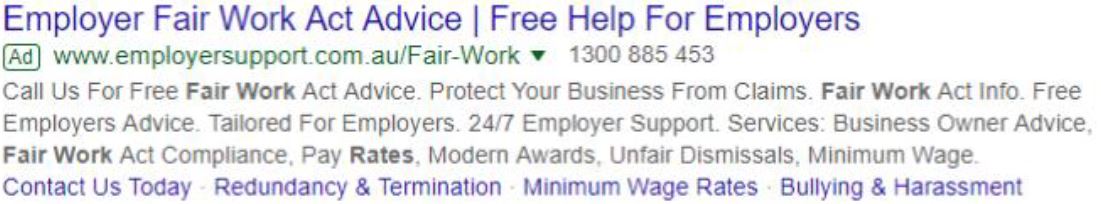

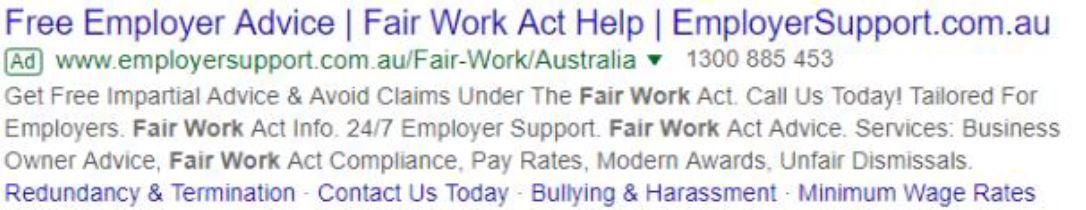

12 The first Google Ad, which was published during the period 27 August 2016 to 12 April 2018 when a Google searcher inserted the search words “fair work ombudsman”, was as follows (as revealed by a Google search conducted on 3 November 2017):

13 The second Google Ad, which was published during the period 10 August 2016 to 23 April 2018 when a Google searcher entered the search words “fair work australia”, was as follows (as revealed by a Google search conducted on 3 November 2017):

14 The third Google Ad, which was published during the period was published during the period 1 February 2017 to 30 April 2018 when a Google searcher inserted the search words “fair work commission” was as follows (as revealed by a Google search conducted on 3 November 2017):

15 The fourth Google Ad, which was published during the period 31 August 2017 to 31 August 2018 when a Google searcher inserted the search words “fair work ombudsman” was as follows (as revealed by a Google search conducted on 30 November 2017):

16 The fifth Google Ad, which was published during the period 2 January 2017 to 9 August 2018 when a Google searcher inserted the search words “australia government fair work” was as follows (as revealed by a search conducted on 30 November 2017):

17 The sixth Google Ad, which was published during the period 2 January 2017 to 9 April 2018 when a Google searcher inserted the search words “australia fair pay” was as follows (as revealed by a search conducted on 30 November 2017):

18 The seventh Google Ad, which was published during the period 9 April 2018 to 30 November 2018 when a Google searcher inserted the search words “fair work ombudsman” was as follows (as revealed by a search conducted on 16 April 2018):

19 The ACCC contended that the Government Affiliation Representations are conveyed by the headline and other words and phrases in the Google Ads and the URLs. Those phrases included “Fair Work Ombudsman” (FWO), “Fair Work Australia” or “Fair Work Commission” (FWC), which are major government agencies dealing with workplace relations. It contended that, by using those words in the Google Ads, the advertisements took on an “official” or “authoritative air”. The ACCC emphasised that the term Employsure did not appear in the advertisements. The ACCC contended that the Government Affiliation Representations were further conveyed by:

(a) the URL www.fairworkhelp.com.au/Fair-Work/Australia being displayed in the first six of the seven Google Ads immediately under the headline;

(b) the references to “free” advice, which appeared in all seven Google Ads, and to which particular emphasis was given in the first four ads by being expressed as “Free 24/7 Employer Advice”; and

(c) referring to its helpline as “the” advice service (or “the” free advice service) with the definitive article being used to reinforce the association of the service, or its resemblance, to the FWO helpline.

20 Finally, the ACCC relied upon the context in which the relevant representations were made. In particular, it emphasised that the seven Google Ads appeared following an internet search for the terms “fair work ombudsman” (Google Ads 1, 4 and 7), “fair work australia” (Google Ad 2), “fair work commission” (Google Ad 3), “australian government fair work” (Google Ad 5) and “australia fair pay” (Google Ad 6). It emphasised that Employsure knew that those search terms were commonly used by consumers searching for the FWO or the FWC. Another matter of context relied upon by the ACCC was the fact that several of the Google Ads (1, 3, 4, 5 and 6) displayed a phone number which allowed Google searchers to call simply by linking through to Employsure.

(b) Use of keywords and design of Google Ads liable to mislead

21 The ACCC claimed that, from February 2017 to 30 November 2018, Employsure sought and obtained information about the search terms most frequently used by consumers searching for the FWO websites and then used those keywords as part of the design of its Google Ads campaigns. It contended that the selection and use of those keywords (which were known to be associated with key government websites) in the design of the Google Ads campaigns was liable to mislead the public about the nature and characteristics of the services provided by Employsure. The ACCC contended that Employsure’s conduct contravened both ss 18 and 34 of the ACL. Section 18 is set out at [233] below. Section 34 provided:

34 Misleading conduct as to the nature etc. of services

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics, the suitability for their purpose or the quantity of any services.

Note: A pecuniary penalty may be imposed for a contravention of this section.

22 It may be noted that, in contrast with the terms of ss 18 and 29, a contravention of s 34 relates to conduct “that is liable to mislead the public”. As Gleeson J pointed out in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v We Buy Houses Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 915 at [73] “there will be a sufficient approach to the public if first, the approach is general and at random and secondly, the number of people are approached is sufficiently large…”. It is also established that the phrase “liable to mislead” is a narrower concept (see Trade Practices Commission v J & R Enterprises Pty Ltd [1991] FCA 23; 99 ALR 325). The notion of “liable to mislead” requires an actual probability that the relevant consumer class will be misled (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; 317 ALR 73 at [44] per Allsop CJ). Finally, it should be noted that s 34 is a civil penalty provision.

23 The ACCC claimed that in 16 of Employsure’s Google Ads, which appeared on three different websites (i.e. www.fairworkhelp.com.au, www.employersupport.com.au and www.employerline.com.au) over different periods of time from January 2016 to November 2018, Employsure prominently advertised “free advice” (Google Free Advice Ads). Those words usually appeared in the headline, together with a telephone number. The ACCC contended that this conduct contravened ss 18, 29(1)(b) and 34 of the ACL. It contended that the relevant Google Ads:

(a) represented that consumers could call the displayed telephone number to receive free advice during the call; and

(b) the primary function of that advice was to provide free advice.

24 The ACCC contended that this was false and misleading, and liable to mislead the public, because the primary purpose of the free advice hotline was to generate leads for Employsure’s paid services.

The 16 Google Free Advice Ads

25 The 16 Google Free Advice Ads the subject of these claims are as follows. The first is the same as the first Google Ad set out at [12] above.

26 The second Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

27 The third Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

28 The fourth Ad is the same as the second Google Ad set out at [13] above.

29 The fifth Ad is the third Google Ad which is set out at [14] above.

30 The sixth Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

31 The seventh Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

32 The eighth Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

33 The ninth Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

34 The tenth Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

35 The eleventh Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

36 The twelfth Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

37 The thirteenth Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

38 The fourteenth Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

39 The fifteenth Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

40 The sixteenth Ad is not included in the seven Google Ads. It is as follows:

41 The ACCC claimed that Employsure engaged in unconscionable conduct, contrary to s 21 of the ACL, in its dealings with the following three small businesses: Blue Print Painting (BPP), Active Community OOSH (ACO) and The Dutch Butcher (TDB). The relevant conduct occurred between August 2015 and June 2017.

42 The matters relied upon by the ACCC as constituting unconscionable conduct included the following. Representatives of the three small businesses conducted Google searches looking for contact details for the FWO or another similar regulatory agency to obtain advice in relation to an employment related issue concerning them. Each of the representatives made a search associated with a keyword used by Employsure in its Google Ad ads campaigns. The Google Ads included links to one of Employsure’s websites and a phone number that connected to Employsure’s inbound call centre was displayed either on the Google Ad or the Employsure website to which it was linked. The representatives called the promoted telephone number in the mistaken belief that they were calling a government agency. They were then caught up in the sales process involving BSCs and BDMs.

43 The following particular matters (in one or more dealings with the three small businesses) were also relied upon by the ACCC:

(a) The Employsure BSC answered the call with “fair work help” and did not disclose that they were from Employsure.

(b) The BSC referred to Employsure or the BDM as a third party whom they were recommending.

(c) The BSC did not provide advice, but used responses to obtain information about the particular small business which was then used to emphasise the risks the business faced in relation to employment issues, with the aim of securing a face-to-face meeting between an Employsure BDM and the particular business.

(d) The BDM did not provide advice in the initial face-to-face meeting with the relevant small businesses, rather he or she promoted Employsure’s commercial services and used various sales techniques to induce the small business owner to enter into a standard form agreement with Employsure during the course of the initial meeting.

(e) Individual consumers were not provided with an opportunity to read and/or understand the terms of Employsure’s standard form contract. The key terms of the contract were not disclosed to the consumer, including the fact that there was no cooling off period, no early termination provision, that the contract automatically renewed and the full amount became immediately payable if a payment was missed. A copy of the contract was not left with the consumer upon execution notwithstanding the significant fees payable under the contract, depending upon its duration.

(f) Neither the BSC nor the BDM made it clear that they were not from, nor had the particular small business been referred to them by, the government, including not correcting the individual representatives when it became evident that they mistakenly believed that to be the case.

(g) Employsure relied upon the no early termination clause and made it difficult for the three relevant small businesses to terminate their contracts, despite the circumstances in which the contracts had been entered into.

44 The ACCC claimed that, contrary to ss 23 and 24 of the ACL, Employsure included unfair contract terms in three versions of its standard form contract in the period from 12 November 2016 to October 2018. The terms related to the clauses of those contracts concerning no provision for early termination, unilateral price increases on automatic renewal and a penalty provision.

PART B: AGREED FACTS RELATING TO THE OPERATION OF THE GOOGLE SEARCH ENGINE

45 The parties were able to agree many facts relating to the operation of the Google search engine. Although the statement of agreed facts is lengthy, it is desirable to set it out in full (save for the single footnote and annexures) given the central significance of Google advertising in this proceeding. The statement of agreed facts is Annexure A to these reasons for judgment.

46 The parties tendered a large volume of documentary evidence.

47 The ACCC led evidence from several witnesses, including representatives of the three small businesses who had dealings with Employsure, which dealings underpinned the ACCC’s claims of unconscionability and unfair contract terms.

48 Although Employsure filed affidavits from six witnesses, including several of its employees whose conduct lies at the heart of the ACCC’s claims, Employsure ultimately called only two witnesses. The first was Employsure’s chief executive officer, Mr Edmund Mallett. The other was Employsure’s finance director, Mr Steven Nicholson, who affirmed two affidavits.

49 The ACCC contended that the principle in Jones v Dunkel [1959] HCA 8; 101 CLR 298 is triggered by Employsure’s failure to call the employees referred to at the beginning of [48] above.

50 I will now summarise the parties’ evidence and state my relevant findings of fact.

51 The ACCC’s witnesses were in two broad categories. The first category broadly relates to evidence which describes the steps taken to access copies of the Google Ads and other materials which are the subject of the ACCC’s claims. The ACCC also called a FWO employee, who described the services provided by that government agency.

52 The second category comprises witnesses involved in the three small business operations who had dealings with Employsure.

53 Evidence was given by Mr Mark McCarthy, an ACCC senior investigation officer, as to how he “captured” various screenshots linked to Employsure’s marketing. Mr McCarthy’s evidence was uncontroversial and he was not required for cross-examination. I accept his evidence in its entirety.

54 Similar evidence was given by Mr Sam Spirou, another ACCC senior investigator. Again, his evidence was uncontroversial and he was not required for cross-examination. I accept his evidence in its entirety.

55 Similar evidence was given by another ACCC senior investigation officer, Ms Rachel Waye. Ms Waye described the steps she took to capture still images of search engine results and website screen captures. Her evidence was also uncontroversial and she was not required for cross-examination. I accept her evidence in its entirety.

56 The ACCC also relied upon an affidavit dated 26 April 2019 sworn by Ms Antonia Parkes, who works in the office of the FWO. Ms Parkes described how the FWO commenced operating the Fair Work Infoline when the FWO began in 2009. This Infoline is accessed by dialling 13 13 94. Ms Parkes described the purpose of the Fair Work Infoline as to provide practical workplace relations advice to assist both employees and employers to comply with their workplace relations obligations. The Fair Work Infoline is funded by the federal government and provides free advice and assistance on matters such as minimum wages, termination of employment, entitlements and managing performance.

57 Ms Parkes described how in December 2013 the FWO launched a Small Business Helpline as an aspect of the Fair Work Infoline. It too is federally funded and provides free advice and assistance on matters such as wages, conditions of employment and termination of employment. I accept Ms Parkes’ evidence.

(ii) The evidence of some small business owners and their dealings with Employsure

58 It is convenient to summarise this evidence by reference to the three relevant small businesses.

59 Ms Kerri-Ann Richardson was called as a witness by the ACCC. Like all the witnesses who were called to give evidence in the proceeding, Ms Richardson gave her evidence by video link. From 2013 to 2018, Ms Richardson was the owner of The Trustee for GKC Family Trust, trading as BPP, which ceased business in May 2018. Ms Richardson’s evidence in chief may be summarised as follows. BPP, which Ms Richardson established together with her husband in August 2013, operated a domestic and commercial painting business. At the relevant times, it had five employees. Ms Richardson had responsibility for staff payments, accounts and other administrative responsibilities.

60 Prior to August 2015, Ms Richardson had called the FWO and the Department of Fair Trading on several occasions to inquire about pay rates or loadings. She estimated that she called those agencies approximately three times a year. She said that whenever she needed to call the FWO, she used Google to find a telephone number.

61 Around 13 August 2015, Ms Richardson performed a Google search. She wanted to obtain information from the FWO regarding overtime payments. She had not heard of the business called Employsure and she did not use the word “Employsure” in her Google search. Under cross-examination Ms Richardson acknowledged that she could not recall the precise words she used in her Google search. They may have been any of “Fair Work Ombudsman”, “Department of Fair Trading”, “Fair Work” or “award wages”. She said that upon entering her Google search she either saw a phone number in the Google search results or found the phone number by clicking on one of the first search results displayed.

62 In preparing her affidavit, Ms Richardson listened to an audio recording of the approximately 15 minute conversation she had with a man called Ross. She reiterated that she thought she was speaking to someone at the FWO and did not appreciate that she had actually called Employsure.

63 The Employsure representative answered her call by saying “Fair Work help, Ross speaking”. At no time during the conversation did Ross tell her that he worked for Employsure.

64 Ms Richardson asked Ross for advice regarding overtime payments, to which he replied by asking whether she had any agreements with her staff. When she said she did not, she recalled that “it made me feel as if I was doing something wrong that I wasn’t aware of – and that there was something I had to do”. She thought she was speaking to someone from the government who was telling her that that was something she needed or had to do.

65 After Ross told Ms Richardson that he could organise a face-to-face with a meeting with a consultant from Employsure, Ms Richardson said that she asked him to email her Employsure’s details. Under cross-examination, Ms Richardson said that by the end of her telephone conversation with Ross she understood Ross to be describing a consultancy endorsed by the FWO. In her affidavit, Ms Richardson deposed that she understood Ross to be describing a consultancy which worked with the FWO to educate business owners on what their requirements were. She also understood that the initial information session described by Ross would be free, because no fee was discussed. Under cross-examination, Ms Richardson said that she understood that the consultancy would work side by side with BPP in a similar manner to that which an accountant would work with a company.

66 When Ross told her that “they actually give us access to their diary, and their calendars”, she thought that Ross was describing something like a sub-branch of, or a consultancy which worked with, the FWO.

67 Ms Richardson then described the meeting she had at her home on 20 August 2015 with Ms Roxanne Miners, who was a consultant with Employsure. The meeting took about an hour and a half and that Ms Miners did not provide her with any hardcopy documents.

68 Early in their meeting, Ms Miners said that she was not from the FWO but said something along the lines of “we work in conjunction” with them. This caused Ms Richardson to understand that Employsure worked together with FWO to help small businesses. In cross-examination, Ms Richardson was closely questioned about that evidence and the accuracy of her claim that Ms Miners only told Ms Richardson that she “did not work for” the FWO and did not inform her that Employsure was “not affiliated” with the FWO. That evidence was inconsistent with what she told another representative of Employsure in 2016. She told him (Mr Keenan) that Ms Miners told her that she was “not affiliated with them”. I prefer this evidence, which is confirmed by a contemporaneous recording of the telephone conversation with Mr Keenan.

69 Ms Richardson gave detailed evidence of the need for BPP to obtain assistance because they were tendering for a big contract in the Northern Territory and would need to employ additional painters. In her affidavit, Ms Richardson described the advice which she received from Ms Miners, including various case studies used by Ms Miners to market Employsure’s various services. Ms Richardson was closely cross-examined on her recollection of the details of those case studies. She ultimately acknowledged that, with the passage of time, it was possible that that she could not accurately recall the specifics of the examples given by Ms Miners.

70 Ms Richardson deposed that when she told Ms Miners that she would contact FWO or the Department of Fair Trading (as it used to be called according to her) to raise employee matters, Ms Miners responded by saying that if she continued to do that “that could trigger an audit, in which case they’ll come out”. Ms Richardson remembered this phrase because it made her feel quite worried and that this was one of the main reasons why she felt that BPP should sign up with Employsure’s services. At this stage, she still understood that the number she had called to check the pay rates was the phone number for the FWO.

71 Ms Richardson said that, because of things she was told by Ms Miners, she felt like she was doing the wrong thing as an employer by not having policies and procedures and contracts in place as advised by Ms Miners. She was concerned because she thought that Ms Miners was a representative of a company who worked with the FWO.

72 Ms Richardson described what Ms Miners told her about Employsure’s contract to provide services: that it would be for three years and would include services such as company policies and procedures, template employee contracts, insurance and the 24/7 helpline. Ms Miners told her the price for Employsure’s services. Ms Richardson first thought it was $3,000 in total. Ms Miners then confirmed that the fee was $3,000 for each year of the three year contract. Ms Richardson agreed to the contract because she thought that BPP needed it. A major reason for this belief was that she thought that Employsure worked with the government and that the FWO might audit the business if she did not sign up.

73 Ms Richardson then described how she used her finger to place her signature electronically on Ms Miners’ iPad, which had a blank screen. Ms Richardson did not read the contract, either in hardcopy form or on the iPad, before placing her signature electronically on the iPad. Under cross-examination, she acknowledged that she knew she was signing a contract which was legally binding.

74 Ms Richardson deposed that the first time she saw a copy of the contract was the following day, after Ms Miners emailed it to her at Ms Richardson’s request. Ms Richardson said that Ms Miners never told her that there were shorter contract options available. Ms Richardson believed that a shorter contract would have been an attractive option for BPP given the nature of its business and the financial difficulties it faced.

75 Ms Richardson then gave evidence of the discussion she had with her husband after she signed the contract. Her husband raised concerns, after which she felt physically sick and stupid. She was unable to sleep that night. Ms Richardson subsequently contacted Ms Miners and asked her whether there was a cooling off period because she was not feeling confident and “my husband has some questions he wants to talk more about it”. Ms Miners told her that there was no cooling off period because it was a business to business contract.

76 Ms Richardson then described how she subsequently received two separate copies of the contract on two separate email addresses. She reviewed one copy and made handwritten comments on it. Those handwritten comments included that “Roxanne verbally read the contract to me then passed me an ipad with only the signing screen available” and that the “further terms were NOT read out to me”. Under cross-examination, Ms Richardson acknowledged that she had no recollection of which parts of the contract were read out to her by Ms Miners, but she stood by her handwritten note which was made shortly after her meeting with Ms Miners.

77 Ms Richardson described her subsequent conversations with various Employsure representatives, including one conversation with Mr Mark Callaghan on 24 August 2015 (i.e. four days after her meeting with Ms Miners) regarding a compliance review teleconference. She deposed that she told him that she was happy to go ahead with that review. She added in her affidavit that she did this because she was aware at the time that she couldn’t cancel the contract and there was no cooling off period.

78 Ms Richardson described a conversation she had later on 24 August 2015 with another Employsure representative, Ms Carole-Anne Byrne. Ms Richardson deposed that in preparing her affidavit she had listened to the audio recording of that telephone conversation. The recording confirms that after Ms Byrne enquired whether there was anything she wished to discuss regarding the initial meeting with Ms Miners, Ms Richardson said (in part):

Yes, sure. Look, every – everything was fine. I’ve booked in to go ahead with the policy. What my concerns were, was that after I had the discussions with Roxanne and she left and my husband came home, and I was talking to him and telling him the different things that she had told me, and he was a little bit concerned in regard to the validity of things that she had said.

79 When Ms Byrne raised whether she wanted to continue with Employsure, Ms Richardson replied by saying:

Yes, yes, all right. Well, I know that we are going to be growing, because we’re going to be advertising for more staff very shortly. And, you know, so we’ve sort of had a – I’ve had a look at – it’s really hard for an employee to get information off the internet or from the Fair Work Ombudsman or whatever to actually know what we have to do, you know, what our responsibilities are. So that is the reason why I’m going to go ahead with it.

…

Yes, yes. No, I’m happy to go ahead with it, and – yes, we will just move forward from here.

80 Ms Richardson said she agreed to go ahead because she believed that she had no choice and that she still believed at this stage that Employsure was a “trustworthy authority associated with the Government”.

81 Under cross-examination, Ms Richardson confirmed that when she talked to Ms Byrne on 24 August 2015, she had read all the terms and conditions of the contract with Employsure (including the further terms). She also confirmed that she understood that Ms Byrne made it clear to her that she was willing to “engage” with her if she wasn’t happy to continue with the contract. Furthermore, she confirmed that, after looking at the contract closely over the weekend and discussing it with her husband, she was happy to proceed with the contract. In particular, although Ms Richardson said that she was initially concerned about the automatic renewal clause, her concerns were met when it was explained to her that she could give notice not to renew at any time. Ms Richardson declined Ms Byrne’s invitation to take a few more days if she wished to consider her position and, instead, elected to proceed with the contract.

82 Ms Richardson gave evidence regarding the compliance review teleconference held with an Employsure representative on 28 August 2015, as well as other advice and services BPP obtained from Employsure.

83 In July 2016, Ms Richardson did some Google searches about Employsure. She did so because of her dissatisfaction with the response she had received from Employsure concerning a prospective employee from New Zealand and she was told that she needed to get the information elsewhere. The Google searches revealed reviews of other people’s experiences with Employsure. Ms Richardson deposed that, based upon those reviews, she understood for the first time that Employsure was not associated with the FWO. On that day, she made a complaint with the ACCC through its website about Employsure. In part, her online complaint was that the “further terms were not read out” and she was not given a copy of the policy before signing.

84 Ms Richardson gave evidence of her attempts to terminate the contract with Employsure in August-September 2016. BPP continued to pay Employsure’s fees under the contract until 19 April 2018. BPP ceased business the following month.

85 Subject to the following significant qualifications which are based upon the cross-examination of Ms Richardson, I generally accept her evidence as summarised above.

86 First, as previously stated, I do not accept Ms Richardson’s claim that Ms Miners only told her in their meeting on 20 August 2015 that she “did not work for” the FWO. I prefer the accuracy of the audio recording of Ms Richardson’s conversation with Mr Keenan in 2016, when she told him that Ms Miners had said that she was “not affiliated” with the Department of Fair Trading (which Ms Richardson used interchangeably with the FWO).

87 Secondly, whether or not Ms Richardson continued to believe that Employsure had some association with the FWO, the evidence is clear that Ms Richardson made a considered decision, after closely reading the contract she had signed, to continue with that contract, as is made clear by the terms of her conversation with Ms Byrne on 24 August 2015. Not only did Ms Richardson decline Ms Byrne’s offer to take a few more days to consider her position, but it is also evident that, within Employsure, Mr Nicholson had given his formal approval for the contract with BPP to be cancelled and without any charge to BPP.

88 Thirdly, perhaps unsurprisingly given the passage of time since Ms Richardson met with Ms Miners, her recollection of some of the details of that meeting was not sound, as she frankly acknowledged in her cross-examination. I do not accept these aspects of Ms Richardson’s evidence unless they are confirmed by contemporaneous documentary evidence.

89 ACO conducted a before and after school care business. Its director is Ms Heather Martindale, who gave evidence for the ACCC. She provided two affidavits.

90 Ms Jenny Fahy was the next senior member of staff at ACO. Ms Fahy was also called as a witness by the ACCC.

91 ACO is a small business which currently employs about nine staff members, being two permanent staff and about seven casual staff. When ACO dealt with Employsure in 2016, there were four permanent part-time staff and about three to five casual staff.

92 Ms Martindale described how, after she first set up ACO in 2012, she sought assistance from the Fair Work office in Newcastle about industrial relations matters, including pay rates. She went to the Newcastle Fair Work office two or three times after her initial visits in 2012.

93 Ms Martindale deposed that in late January 2016, she wanted some advice from the FWO about paying staff. Because she did not have time to drive to Newcastle, Ms Martindale did a Google search for the terms “Fair Work Ombudsman” to find the telephone number to call. Although Ms Martindale said that when she made this call she had never heard of Employsure, she accepted that there was an accurate Employsure business record which detailed a phone call it had received from her in 2013. Thus her contact in January 2016 was not the first time she had approached Employsure.

94 Ms Martindale described how she clicked on a phone number which was displayed in the Google search result, believing that it was the number for FWO. The transcript of the audio recording of the phone call with a representative of Employsure, Ben, records him answering Ms Martindale’s call by saying:

Fair Work Help, Ben speaking.

95 Ms Martindale said that when she heard these words, she thought she was speaking to Fair Work because she believed that she had called their number.

96 After giving Ben her personal name and the ACO business name, Ms Martindale said that she was not surprised that her business was recognised by Ben because she assumed that Fair Work kept records of their past contact. She told Ben that she had “been in a few times over the years with a few things” and that she liked to get things right. She deposed that she said these things because she thought she had called Fair Work and she was referring to her previous attendances at that agency’s Newcastle office.

97 When Ms Martindale told Ben about the information she was seeking, Ben asked her whether she had a staff handbook and whether there was a bullying and harassment policy. In confirming that she had both these things, Ms Martindale said that she thought Ben was asking her about these matters acting in his capacity as an officer of the FWO’s office and that she felt obliged to answer. She said that if she had known that Ben was from a private company, she would not have answered his questions.

98 The audio recording captures Ben telling Ms Martindale:

Well, look, if – if you like, I’ve got something I can suggest for you, if you want a bit of peace of mind… Just check over your bullying and harassment policy and that side of things… We do something on this line here with one of our sponsors, a private company called Employsure… I don’t know if you’ve ever come across them before or not.

99 Ms Martindale deposed that when reference was made to Employsure being a “sponsor”, she thought that this meant that Employsure was part of Fair Work and was part of the government. It should be noted that the ACCC did not contend that Ben’s reference to Employsure being “one of our sponsors” was itself a misleading or deceptive representation. The ACCC’s case relating to the concept of sponsorship was directed to two separate complaints, being the claim summarised in [9(b)(ii)] above with respect to the seven Google Ads and in its claims concerning unconscionable conduct summarised at [41]-[43] above.

100 After Ben offered a free consultation and review with a field consultant, arrangements were made for an Employsure consultant, Ms Cassy Bailey, to come to Ms Martindale’s home. Ben never told Ms Martindale at any point that he was employed by Employsure.

101 When Ms Martindale sought subsequently to confirm an appointment with Ms Bailey (which had to be rescheduled), she said that her telephone call was answered by a man called Daniel who said “Welcome to Fair Work Help, my name’s Daniel”.

102 Ms Martindale then gave detailed evidence of the meeting with Ms Bailey at Ms Martindale’s home on 1 February 2016. Ms Fahy also attended the meeting. Ms Bailey told them about Employsure’s services, which included a complimentary review of ACO’s policies, the ability to call Employsure 24/7 with queries, that the contract was for one, two or three year periods, that it was cheaper to sign up for three years and that the fees for a one year contract worked out at about $40.00 a month.

103 Ms Martindale said that Ms Bailey was keen to sign ACO up for three years and she told Ms Martindale that they could offer a cheaper rate for that period. Ms Martindale told her, however, that they could only sign up for one year. Ms Bailey said that she could do a special deal and she wrote a price down on a piece of paper. Although Ms Martindale couldn’t recall the exact amount, she understood that it worked out at around $40.00 a month. Ms Martindale said that Ms Bailey did not tell her that the total contract price would be $3,854.

104 Ms Martindale explained how she rationalised that a fee of $40.00 a month to Employsure was approximate to the cost of her internet charges and storage shed rental. She was looking at that time to acquiring a second storage lock-up for ACO’s business equipment and that Ms Fahy said to her that that money could be spent on the Employsure contract instead. As will emerge, Ms Martindale was closely cross-examined on this evidence.

105 Ms Martindale also gave evidence of her signing a blank screen on Ms Bailey’s iPad or tablet. She said that this was the first time she had ever signed an iPad or tablet and she believed that she would have to actually sign a formal hardcopy of the contract later. Ms Martindale had no recollection of signing a direct debit form during her meeting with Ms Bailey.

106 Ms Martindale subsequently received a copy of the one year contract, which required a payment of $3,854 excluding GST. She said that if she had known that the contract was for that amount, she would never have agreed to it.

107 When Ms Martindale complained to Ms Bailey that she did not want to continue with Employsure’s services, she was told for the first time that there was no cooling off period.

108 Ms Martindale gave detailed evidence of her subsequent dealings with various Employsure representatives regarding the contract and the services which Employsure provided to ACO, including her attempts to terminate the contract. Ms Martindale’s contract was ultimately cancelled in November 2016 after she paid an early termination fee of $352.96.

109 Ms Martindale was closely cross-examined. I found her to be an honest and responsive witness and I generally accept her evidence, subject to the following important qualifications which reflect the fact that, as Ms Martindale herself candidly acknowledged, her recollection of the details of some events was poor. Moreover, at times her evidence was confusing.

110 Although it is plain that there was some discussion at the meeting on 1 February 2016 regarding the cost of the contract, Ms Martindale’s recollection of the details was poor. Ms Martindale said that Ms Bailey wrote down on a notepad the cost for a two or three year contract and that after Ms Martindale said that she could only enter into a one year contract, Ms Bailey wrote down a new figure and passed it to Ms Martindale for her approval. Ms Martindale acknowledged, however, that she could not remember the precise figures provided by Ms Bailey. For the following reasons, as well as those given at [361] to [365] below, I believe that Ms Martindale was mistaken when she said that Ms Bailey told her that the cost of the contract would be $40.00 per month. As will also shortly emerge, I do not accept Ms Fahy’s evidence that Ms Bailey told them that the cost of the contract would be $40.00 per month.

111 Ms Martindale’s evidence concerning the issue of contract fees was not consistent. An audio recording of Ms Martindale’s conversation with an Employsure representative on 8 March 2016 captures her saying that she understood the cost of the contract would be “about $50.00 a week – a month, you know. So I thought two something, like $200 a year just to having someone to phone up and just get the rates for wages and things like that”.

112 Ms Martindale is recorded as subsequently telling an Employsure representative in a telephone call on 17 March 2016 that the cost of the ACO storage shed was $40.00 a week. In her evidence, Ms Martindale said that she meant to say $40.00 a month but that she’d got her months and weeks “muddled up”.

113 At [101]-[102] of her first affidavit, Ms Martindale said that she thought that the first direct debit ACO paid to Employsure in the amount of $353.00 was the total contract sum for a year’s worth of services. If so, this would work out at around $29.00 a month. Ms Martindale said that she later found out that the contract cost was $40.00 per week, when the figure was in fact $74.11 per week. When it was put to Ms Martindale in cross-examination that it was possible that she had got some of her numbers wrong, she candidly responded by saying “I don’t know”.

114 It should also be noted that after the meeting with Ms Bailey on 1 February 2016, Employsure forwarded to ACO a copy of the contract by email on three separate occasions (3, 17 and 24 February 2016), all of which clearly disclosed the contract price. On 8 February 2016, a separate email was sent to ACO with a statement detailing the amounts to be debited from ACO’s account.

115 As mentioned, Ms Fahy was also called as a witness by the ACCC. Ms Fahy swore two affidavits. I accept Employsure’s submission that Ms Fahy “presented as a formidable character who was capable of protecting ACO’s interests”.

116 Ms Fahy described the meeting with Ms Bailey at Ms Martindale’s home on 1 February 2016. She described the services which Ms Bailey said Employsure could provide to ACO. Ms Fahy said that Ms Bailey told them that the cost of the services was around $40.00 a month. Ms Fahy said that, at the end of the meeting, Ms Bailey said that she needed Ms Martindale to sign the iPad because she needed “to show that I have been here and explained to you what we do, and that you are happy with what I’ve explained to you”. Ms Fahy saw Ms Martindale sign the iPad with her finger.

117 Ms Fahy described her subsequent dealings with various representatives of Employsure, including calling Employsure’s advice line on 1 February 2016 with a query regarding a pregnant staff member who was employed by ACO on a casual basis, as well as calling the next day with a query about a traineeship pay rate.

118 Ms Fahy was cross-examined. As a result of that cross-examination, I would make some qualifications to my otherwise general acceptance of her evidence. Those qualifications are as follows. First, as to Ms Fahy’s claim that she and Ms Martindale were told by Ms Bailey that the cost of Employsure’s services was around $40.00 a month, I do not accept that evidence (see [110]-[112] above and [366]-[369] below).

119 Secondly, I do not accept Ms Fahy’s evidence that she did not appreciate at the 1 February 2016 meeting that Ms Martindale was entering into a contract when she signed Ms Bailey’s iPad. This is inconsistent with what Ms Fahy recorded in the ACO diary that day where she stated that ACO had “[j]oined up with employsure for all fair work, legal advice & policies help”. On that same day, Ms Fahy spoke to Employsure and is recorded as saying “look, we signed up this afternoon, or around lunchtime, and we were talking to Cassy”.

120 The ACCC also called Ms Linda Green as a witness in the case against Employsure relating to ACO. Ms Green provided accounting services to ACO. She gave evidence that she advised Ms Martindale in January 2016 to contact the FWO regarding the pay rates of two trainees who were about to start work with ACO. Ms Green stated that, in late January or early February 2016, Ms Martindale informed her by telephone that she had “Fair Work coming out to visit”. Ms Martindale subsequently informed her that the meeting had gone well. There is no need to summarise the other parts of Ms Green’s evidence because they were not relied upon.

121 Ms Green was not required for cross-examination. I accept her evidence.

122 TDB is a small café in Perth, which was bought by Mr Johannes Ottes in May 1980. In 2017, the café had about 8-12 employees, including Mr Ottes’ daughter, Kim Ottes, who at that time was the General Manager of the business. Both Mr Ottes and Ms Ottes were called as witnesses by the ACCC, and both were cross-examined. The ACCC filed an affidavit by Mr Henry Koldenhoven, who provided accounting services to TDB for 25 years. Ultimately, however, the ACCC did not read Mr Koldenhoven’s affidavit so nothing more needs to be said about it.

123 In her affidavit, Ms Ottes said that she managed the daily running of the business along with her father. She said that her father relied on her to help with any technical aspects of running the business, including attending to such matters as getting a large commercial printer or computers fixed. Both Ms Ottes and her father each had a computer in the office, as did their bookkeeper.

124 Annexed to Ms Ottes’ affidavit were several transcripts of audio recordings of conversations she had with Employsure representatives, the accuracy of which was not disputed.

125 Ms Ottes gave evidence of some problems the business was experiencing in 2017 with one of its employees. Mr Ottes told her that he had contacted Fair Work about the matter, that there was to be a meeting with Fair Work at the shop and that they would “sort our issue out”. Ms Ottes described a meeting she and her father had at the shop with Mr Greg Langton, whom she believed was from Fair Work. In her affidavit, Ms Ottes said, as best she could recall, Mr Langton mentioned that he was from Employsure but she assumed that this was a division of Fair Work. Under cross-examination, when it was put to Ms Ottes that, once he had sat down at the meeting, Mr Langton told them that he was from Employsure, she responded “Correct”. When it was also put to her that he told them that Employsure was a private company, Ms Ottes said “I can’t quite remember”. Ms Ottes also gave evidence in cross-examination that Mr Langton never told them that he was from the FWO or from Fair Work.

126 Ms Ottes candidly acknowledged that while she participated in the meeting along with her father and Mr Langton, she was often distracted because she had to keep an eye on what was happening in the café. Ms Ottes had no detailed recollection about the advice Mr Langton gave as to the particular employee, but she recalled that he talked about other services which Employsure could provide, particularly if the business had issues with other employees.

127 Ms Ottes recalled that Mr Langton talked very quickly and that she found it “really hard to keep up”. She added that, towards the end of the meeting, “he was pushing all of this stuff on us to sign” and that he mentioned Employsure’s fees. She recalled Mr Langton handing a tablet, like an iPad, to her father, and asking him to sign on it.

128 Ms Ottes said that when she recently reviewed a copy of the contract dated 30 June 2017, she saw that the contract was for workplace relations services for three years for a total fee of $19,471.92, excluding GST.

129 Ms Ottes gave evidence of her dealings with Employsure, including arranging for a compliance review and a separate work health and safety check. As to the latter, Ms Ottes recalled that her father and she met with a woman from Employsure about work health and safety. She did not remember the specific content of the discussion but had a vague recollection that a further contract was signed at that meeting.

130 Ms Ottes also described her participation in the compliance review with an Employsure representative, Ms Melissa George.

131 Ms Ottes said that at some point the business’s bookkeeper told Ms Ottes and her father the total figure of the contracts with Employsure. She “got a fright” because the figure was about $19,000. She considered this to be a big sum, particularly because the business had been struggling financially. Ms Ottes asked her father how he had got in touch with Employsure. She said that around this time she had real doubts and concerns about whether he had ever been in contact with Fair Work or the government. Her father responded to her question as to how he found Fair Work’s telephone number by saying that it was “just off their website”. Mr Ottes told her that he had Googled “Fair Work” and then clicked on a link. He demonstrated this to her on his computer. She saw her father type in something like “Fair Work” into Google and she saw a link that had been previously clicked on because it was coloured in purple.

132 Ms Ottes gave evidence of her dealings with Employsure in October 2017, when attempts were made to cancel the contracts the business had with Employsure. Ms Ottes said that, having left the business, she did not know how things ended up with Employsure and that it was mainly her father and Mr Koldenhoven who were involved with Employsure after she left.

133 Ms Ottes said that overall she had “a bad feeling towards Employsure”, particularly because she considered that the business did not need Employsure’s services on a regular basis and she added that the emailed newsletters TDB received from Employsure “were just forwarded straight to my junk inbox and were not very helpful for us”.

134 I found Ms Ottes to be an honest and responsive witness and I generally accept her evidence, which largely reflected her subjective state of mind while noting that she frequently acknowledged that she did not have a good or clear recollection of many matters, including the meeting with Mr Langton. This may be because, as she said, during the course of the meeting she was distracted by managing the business.

135 Mr Ottes, who is now 81 years old, swore an affidavit and was cross-examined. Mr Ottes owned the TDB and ran a successful business there for almost 40 years. Several transcripts of audio recordings of conversations he had with Employsure representatives were attached to his affidavit. The accuracy of those transcripts was not disputed.

136 Mr Ottes said that during the period he had dealings with Employsure in 2017, TDB had about eight employees. He described some difficulties he was having with one of those employees in mid-June 2017. He decided he needed to get some advice so he decided to call the government for help. He said he remembered wanting to call Fair Work or Worksafe, which meant the same thing to him. As best he could recall, Mr Ottes said that he used his computer in the office above the café to Google “fair work” or “work safe” and that he rang the number which appeared on the screen. He said he recalled seeing something about “free advice”. He confirmed that when he made the call, he both intended to call, and believed that in fact he was calling, a government organisation for free advice. He had never previously heard of Employsure and he said that he did not use the term “Employsure” in his Google search. His call was answered by a recorded message which said “Welcome to Employsure Fair Work Help. This advice line has been specifically designed to assist employers and business owners…”.

137 Having relistened to the recording, Mr Ottes acknowledged that he could hear Employsure’s name mentioned but he said this would not have meant anything to him at the time because there were “so many sections within government organisations, and I do not know what they are all called”.

138 Mr Ottes then addressed various aspects of the transcript of the telephone conversation he had with an Employsure representative called “Nate”. He told Nate about the problems he was having with the particular employee. Nate told him that they had to be careful because the employee might be mentally unstable and sue TDB. Mr Ottes deposed that he was concerned that the business could be in trouble, even though he thought that they had done nothing wrong, and that the matter might cost a lot of money. He said that because of what Nate said, his impression was that “I could be up for a lot of money and that this issue I was having was my employee could go further”.

139 Mr Ottes said that, at this time, he didn’t understand that Employsure was a private company, even though he acknowledged that Nate told him that fact during the course of their conversation. Even after Nate arranged for Mr Greg Langton to meet with Mr Ottes to discuss the situation, Mr Ottes said that he still thought he was dealing with someone who was either part of the government or recommended by the government.

140 Mr Ottes was cross-examined on this and other parts of his evidence. The transcript of Mr Ottes’ telephone conversation with Employsure records Nate as saying that he was “from a private company” and that the business was “actually called Employsure”. Mr Ottes was told that Employsure was “the largest workplace relations consultancy in Australia” and he was given a broad description of the services it provided. He was also told that while the initial advice would be free, Employsure could provide an obligation-free quote to offer further assistance.

141 Mr Ottes then gave evidence of the meeting held at the café on 30 June 2017, which was attended by Mr Langton from Employsure, Mr Ottes and his daughter. Mr Ottes reiterated that he thought Mr Langton was from the government or from a body recommended by the government. Mr Ottes recalled Mr Langton saying that it could cost around $80,000 in legal fees if we ever “stepped out of line” and were sued. He recalled Mr Langton saying that under a contract with Employsure the business would be “covered by their lawyers” and that there was no need to worry because “they would take care of everything for us”.

142 Mr Ottes said that Mr Langton spoke very quickly and sounded very professional and convincing but that the more he talked Mr Ottes became more frightened.

143 Mr Ottes was not sure if he was shown a copy of the contract at the meeting or had its terms explained to him. He had no recollection of reading the contract at the meeting. He said that he was worried that he could be in a lot of trouble if he didn’t sign it. So he signed, for fear that he would not otherwise be protected. He recalled that he chose a three year contract from the three options that were available but that he did “not think this through at the time”. He said that he now realised that, given the history of the business, he didn’t need the ongoing services of Employsure and simply needed to get advice on the particular employee. Mr Ottes had no recollection of Mr Langton explaining to him the total cost of the contract.

144 Under cross-examination, Mr Ottes had an incomplete recollection of what he and his daughter were told by Mr Langton. He could not remember whether the contract terms were read to him by Mr Langton or whether he read them himself, but he did not deny that one or other of those things occurred.

145 Mr Ottes acknowledged that he signed something on Mr Langton’s iPad. He had no recollection of getting a hard copy of the contract at that time, however, he acknowledged that he was sent an electronic copy by email later that day, together with a copy of an insurance policy.

146 Mr Ottes gave evidence of his response when he read the contract, highlighting terms contained therein which he said he had not previously appreciated, including that there was no provision for early termination, that the contract would automatically renew for the same period unless notice was given and that failure to adhere to the payment schedule would result in the total balance outstanding becoming payable immediately in full.

147 Mr Ottes described the meeting he had on 13 July 2017 with another Employsure representative, Ms Barbara Channing. He assumed that he was still dealing with the government because he believed they were the ones he originally rang. Although Mr Ottes had no specific recollection of signing another contract with Employsure, he did not dispute that in fact he did sign a three year contract with Employsure for workplace health and safety services for a total of $9,207.08.

148 Under cross-examination, it was evident that Mr Ottes did not have a full recollection of the meeting with Ms Channing. Mr Ottes could not remember signing the further contract but he accepted that he had.

149 Mr Ottes said he didn’t realise at the time how much the two contracts would cost the business. He had no recollection of anyone from Employsure explaining to him exactly what he was signing up for and how much it would cost.

150 Mr Ottes described how he attempted to cancel his contracts with Employsure and how he discussed how that should be done with both his bookkeeper and Mr Koldenhoven, who handled it on his behalf.

151 Mr Ottes said that he could “vaguely recall” his bookkeeper contacting the FWO and that a teleconference was arranged for 13 September 2017. He acknowledged, however, that he had no recollection of meeting with the FWO on that day. Mr Ottes made reference to an email exchange between the FWO and his bookkeeper.

152 Finally, Mr Ottes said that he felt that the whole experience with Employsure was “a big disappointment and an absolute waste of time and money”. He explained that, upon reflection, all he needed was advice about the one particular employee but that he was worried that if he didn’t have Employsure involved “something drastic would happen and I was worried about expensive lawyers’ fees if something went wrong”. He emphasised that he wanted to deal with the government and that he had never heard of Employsure before.

153 I found Mr Ottes to be an honest and responsive witness, however, as he himself repeatedly acknowledged, he did not have a good recollection of all his dealings with Employsure. For that reason, I would not base a finding of fact on Mr Ottes’ personal recollection unless it was supported by contemporaneous documentary material or other evidence.

154 As previously mentioned, Employsure called Mr Mallett and Mr Nicholson as witnesses. Both were subjected to lengthy cross-examinations. Employsure did not read the affidavits filed by it of several Employsure representatives who had had dealings with BPP, ACO and TDB (namely, Ms Bailey, Ms Miners, Mr Langton and Ms Channing).

155 Mr Mallett is the managing director of Employsure and has held that position since its incorporation in September 2010. Previously, Mr Mallett was a barrister based in London who specialised in employment law. He studied law at Cambridge University and obtained an LLM from Duke University in the United States. He practised at the London Bar from 2004 to 2010, when he moved to Australia with his Australian wife. He saw an opportunity to develop a business model here based upon that operated by Peninsula Business Services Limited (Peninsula) in the United Kingdom, the features of which involve providing clients with the following four services:

(a) a review of the client’s current documentation, including employment contracts, workplace policies and manuals, and the preparation of any new documentation required;

(b) advice which is available at all times all year round;

(c) representation in courts and tribunals; and

(d) an insurance policy which provides an indemnity against the costs associated with any court or tribunal proceedings with no excess payable by the client.

156 This business model was adopted by Employsure, which started offering the four services in April 2014 and after Peninsula agreed to invest in Employsure two years earlier.

157 Although Employsure’s model expanded into a much larger scale, it did not record a profit until the financial year 2014-2015. As at 30 May 2019, Employsure had approximately 20,500 clients, which included both large employers (i.e. with more than 20 employees) and many small to medium sized enterprises (SMEs). It had over 600 employees in various roles. As at 30 May 2019, 13 percent of Employsure’s clients were large employers.

158 In April 2016, Employsure expanded its operations to New Zealand, where it had over 4,000 clients and almost 200 employees in mid-2019.

159 Mr Mallett emphasised that Employsure’s services are designed specifically for employers and that the advice it provided to clients was independent from the dispute resolution and investigation functions of the FWO and FWC.

160 Initially, Employsure offered only its employment relations services, but in around March 2014 it expanded to offer its workplace health and safety (WHS) services.

161 Mr Mallett described how in 2013, Employsure began offering three different standard services to its clients. The “Tier 1” service is Employsure’s basic service for businesses with less than five employees and where the review of the client’s business is typically done over the telephone rather than fact-to-face. The “Tier 2” service is Employsure’s original standard service, which included face-to-face meetings with clients. The “Tier 3” service is an enhanced offering which includes all elements of the Tier 2 service, plus additional on-site consultancy services (such as staff training, internal management of disciplinary processes and risk reviews). In addition to these standard services, Employsure also offers an “add-on” service called “Safe Check”, for which clients are typically charged $500 but may sometimes be offered free of charge as part of a contract price negotiation. Safe Check was introduced in around 2015.

162 Mr Mallett described what was involved in Employsure providing services such as the initial compliance review, an employment relations review and the WHS services. He described what was involved in preparing a corrective action plan following an assessment of a client’s documentation, as well as the “implementation meeting” which Employsure consultants conducted with a client after providing a corrective action plan. Mr Mallett annexed to his affidavit copies of the corrective action plans and related documents provided to both TDB and BPP.

163 Mr Mallett described how all of Employsure’s clients had access to Employsure’s ongoing advice service at all times during the duration of their contract. He emphasised that the advice service was not limited in any way by call time, length or volume of calls. He described how the telephone advice service operated 24 hours a day. He gave examples of the type of requests Employsure received over the advice service, either by telephone or email. Mr Mallett estimated that Employsure had one advisor to every 250 clients and that during the 12 months from 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019, Employsure’s advisors sent and received a total of approximately 300,000 emails with clients who requested advice. During the same period, approximately 220,000 telephones calls were received from clients seeking advice and approximately 94,000 calls were made by Employsure advisors to clients concerning requests for advice.

164 Mr Mallett gave a detailed description in relation to its clients (who are all employers) in relation to workplace claims by employees. This included claims made in regulatory bodies such as the FWO, the Australian Human Rights Commission, SafeWork NSW and Work Safe Victoria. Employsure also provided representation in courts and tribunals. Prior to mid-2018, Employsure’s legal representation services in courts and tribunals were provided through Sparke Helmore lawyers but subsequently such representation occurred through Employsure’s internal law firm, Employsure Law. Outsourcing claims only occurs if the matter is beyond Employsure Law’s resources or expertise.

165 Mr Mallett described how from around August 2012 until March 2019, Employsure’s clients had an option of taking out insurance policies which were underwritten by QBE Insurance Group Limited. One kind of policy related to the employment relations service while the other was for Employsure’s WHS clients. The insurance policies covered clients’ legal expenses.

166 Mr Mallett gave detailed evidence regarding Employsure’s online marketing practices. He described Employsure’s objective in using online marketing as “to find SMEs, or other businesses, who might have use for Employsure’s services, and ultimately to form a relationship with those employers to see if they want to become clients”. He described the marketing practices known as search engine optimisation (SEO) and search engine marketing (SEM). SEO is the marketing practice by which websites are sought to be “optimised” to respond “organically” to search engine enquiries, such that when a consumer searches for a term a website is returned as high as possible in the search results (below the advertisements). SEM involves bidding on search terms, known as “keywords”, with a view to Google accepting a bid and an advertisement appearing in response to a particular search. The presentation of an advertisement in response to a given search is determined by Google’s proprietary algorithms, which undertake an almost instantaneous calculation of the maximum amount an advertiser is willing to pay to present an advertisement, multiplied by a “Quality Score”. The presentation of advertisements did not depend only on the amount paid by the advertiser, but also on the quality of the advertisement as assessed by Google. Advertisements with the highest “Ad Rank” as assessed by Google are presented above Google’s organic search results. In his oral evidence in cross-examination, Mr Mallett explained that by using the words “fair work” in the URL in Employsure’s Google Ads, the cost of the advertisements was reduced because it increases the “Quality Score”. Mr Mallett explained that Employsure used the term “fair work” in its URL so as to reduce the cost of its advertising with Google. I accept that evidence.

167 Mr Mallett gave detailed evidence as to the three constituent parts of Employsure’s SEM strategy, namely its keyword strategy, its Ad Copy strategy and its landing page strategy. The keyword strategy involved Employsure selecting a series of keywords which it believed prospective clients might search for. Many of those keywords included the phrase “fair work” because such terms are likely to be relevant to employers who may be prospective clients for Employsure. Mr Mallett also emphasised that the words “fair work” are part of the name of two relevant regulatory bodies operating in the employment relations area, namely the FWC and FWO. The words “Fair Work” also appear in the name of the primary legislation. Mr Mallett deposed that the purpose of Employsure bidding on the search terms, including the words “fair work”, is to seek to present Employsure’s advertisements to internet users who might wish to use Employsure’s services and that there was no purpose of conveying any organisational association with, or endorsement from, either the FWC or FWO.

168 Mr Mallett described how Employsure used negative keywords so as to prevent Employsure’s advertisements appearing in response to a search. Employsure currently uses 60,000 negative keywords, such as “fair work employee”, which are intended to exclude employees accessing Employsure for information about fair work.

169 Mr Mallett pointed out that part of Employsure’s keyword strategy was the price that Employsure was willing to pay for each click. Employsure limits price per click by budgeting through Google’s advertising platform. If the price per click budget is set too low, Employsure’s advertisements would not be preferentially placed. If the price per click budget is set too high, Google may accept the higher bid unnecessarily or SEM could otherwise become too expensive as a way of finding new clients. For these reasons, Mr Mallett said that Employsure closely monitors the price per click to ensure that it is budgeting optimally. Finally, he said that Employsure’s keyword strategy is designed to have its advertisements only being presented to employers who require advice, or who may be prospective clients of Employsure.

170 Mr Mallett’s description of Employsure’s Ad Copy strategy involved three elements, namely the headline, the display URL and the description. Google Ads are distinguished from organic search results by the term “Ad” appearing in the box just below the headline, although this may vary if a mobile device was being used. Some Employsure Google Ads also included the phone numbers that could be dialled without clicking through to a website or landing page.

171 Mr Mallett said that Employsure had two objectives in its Ad Copy drafting. First, to exclude searchers who were not employers or prospective clients (particularly employees). Thus Employsure’s advertisements clearly stated that the services were for employers only. Despite this, many employees still click on Employsure advertisements, which take them to an Employsure website and this has the consequence of generating a payment to Google from Employsure.

172 Secondly, Mr Mallett stated that Employsure seeks to attract potential clients to its website or landing pages by advertising a free advice service. He said that this is intended to help the potential client with the problem that has led the person to the search engine in the first place.

173 Mr Mallett described how during the relevant period Employsure used not only its own website but also the following landing pages – fairworkhelp.com.au, employersupport.com.au and employerline.com.au. These landing pages are websites with different domain names. Their main benefit, according to Mr Mallett, is that they offer a simple “call to action” for an employer to call Employsure and request advice, as opposed to navigating Employsure’s more complex main website (www.employsure.com.au).