Federal Court of Australia

Roohizadegan v TechnologyOne Limited (No 2) [2020] FCA 1407

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent ADRIAN DI MARCO Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 2 October 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Applicant’s application made pursuant to the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (the Fair Work Act) be upheld.

2. Pursuant to s 546 of the Fair Work Act:

(a) the First Respondent pay a penalty of $40,000.00; and

(b) the Second Respondent pay a penalty of $7,000.00.

3. Pursuant to s 546(3)(c) of the Fair Work Act, the penalties imposed pursuant to Order 2 be paid to the Applicant.

4. Subject to Order 9 in respect of pre-judgment interest to be awarded thereon, pursuant to s 545 of the Fair Work Act the First Respondent pay to the Applicant the sum of $756,410.00 as compensation in respect of his forgone share options.

5. Pursuant to s 545 of the Fair Work Act, the First Respondent pay to the Applicant the sum of $2,825,000.00 as compensation for his future economic loss.

6. Pursuant to s 545 of the Fair Work Act, the First Respondent pay to the Applicant the sum of $10,000.00 as compensation analogous to general damages.

7. In respect of the Applicant’s associated claim in contract against the First Respondent there be judgment for the Applicant.

8. Subject to Order 9 in respect of pre-judgment interest to be awarded thereon, the Applicant be awarded damages for breach of contract in the sum of $1,590,000.00.

9. The parties are to confer with the aim of providing the Court with agreed proposed orders as to what, if any, amounts should be awarded by way of pre-judgment interest additional to the compensation and damages awarded pursuant to Orders 4 and 8, no later than 14 days from the date of publication of these reasons.

10. If proposed orders cannot be agreed pursuant to Order 9, the parties are to provide the Court with their separate proposed orders and may file any written submissions (of no more than 2 pages) on which they would wish to rely with respect to those proposals, no later than 21 days from the date of publication of these reasons.

11. Subject to Orders 12-14, there be no order as to costs.

12. If a party seeks an order for costs, that party shall file and serve written submissions (of no more than 5 pages) within 14 days of the publication of these reasons.

13. If submissions are filed pursuant to Order 12, the party seeking an alternative order shall file and serve any responsive submissions (of no more than 5 pages) within 28 days of the publication of these reasons.

14. Any application for such orders in respect of costs to be determined on the papers.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

KERR J:

[1] | |

[6] | |

Mr Roohizadegan suffers personal crisis and ongoing Depression | [24] |

TechnologyOne remains unaware of the extent of Mr Roohizadegan’s distress | [32] |

[40] | |

[46] | |

[63] | |

[82] | |

[83] | |

[86] | |

[86] | |

[93] | |

[156] | |

[157] | |

[158] | |

[188] | |

[201] | |

[202] | |

[203] | |

[267] | |

[297] | |

[298] | |

[299] | |

[332] | |

[351] | |

[352] | |

[353] | |

[376] | |

[384] | |

[384] | |

[386] | |

[390] | |

[420] | |

[426] | |

[433] | |

[437] | |

[440] | |

[452] | |

[461] | |

[467] | |

[474] | |

[478] | |

[478] | |

[503] | |

[523] | |

[537] | |

[548] | |

[573] | |

[585] | |

[597] | |

[615] | |

[641] | |

[695] | |

[746] | |

[750] | |

[816] | |

[816] | |

[827] | |

[844] | |

[858] | |

[873] | |

[876] | |

[898] | |

[913] | |

[967] | |

[1007] | |

[1010] | |

Compensation for loss and other orders pursuant to s 545 of the Fair Work Act | [1021] |

[1023] | |

[1026] | |

[1033] | |

[1034] | |

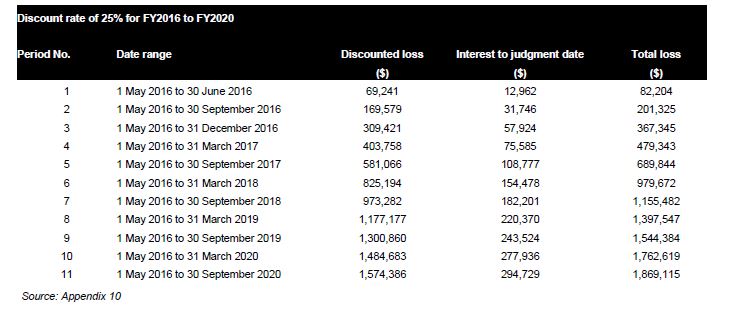

[1065] | |

[1076] | |

[1077] | |

[1113] |

1 The First Respondent, TechnologyOne Limited (TechnologyOne), is a publicly listed enterprise software company. At all times material to these proceedings Mr Adrian Di Marco, the Second Respondent, was Executive Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of TechnologyOne.

2 This case concerns proceedings brought by the Applicant Mr Benham Roohizadegan, a former senior employee of TechnologyOne, against the company and Mr Di Marco. Mr Roohizadegan seeks compensation and penalties arising out of what he alleges was his summary dismissal on 18 May 2016. He claims that his dismissal was for a reason that is, or reasons that are, prohibited by s 340(1) and/or s 351 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (Fair Work Act).

3 TechnologyOne denies that Mr Roohizadegan was dismissed for the reason, or for any reasons including, that he had exercised a workplace right as is protected by those provisions of the Fair Work Act. It says that Mr Di Marco alone made the decision to terminate his employment. It pleads that Mr Di Marco dismissed Mr Roohizadegan solely for the lawful and valid reasons of which he gave evidence in these proceedings.

4 Assuming the Court finds the First Respondent liable for breaches of the Fair Work Act in respect of Mr Roohizadegan’s termination (which is denied), Mr Di Marco does not dispute his accessorial involvement in that regard.

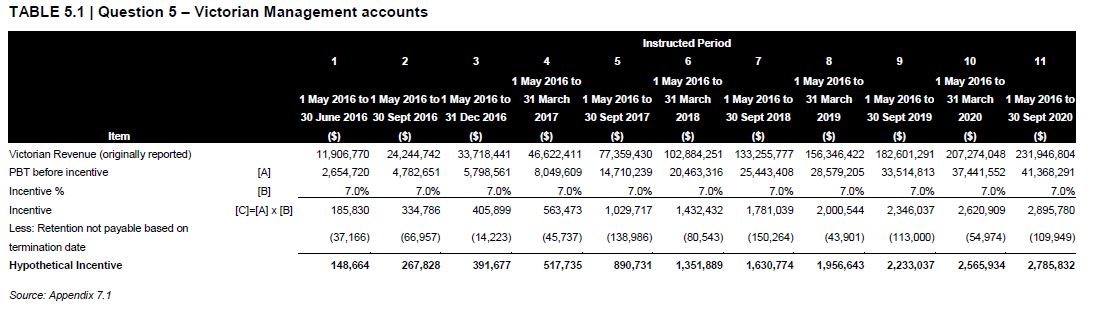

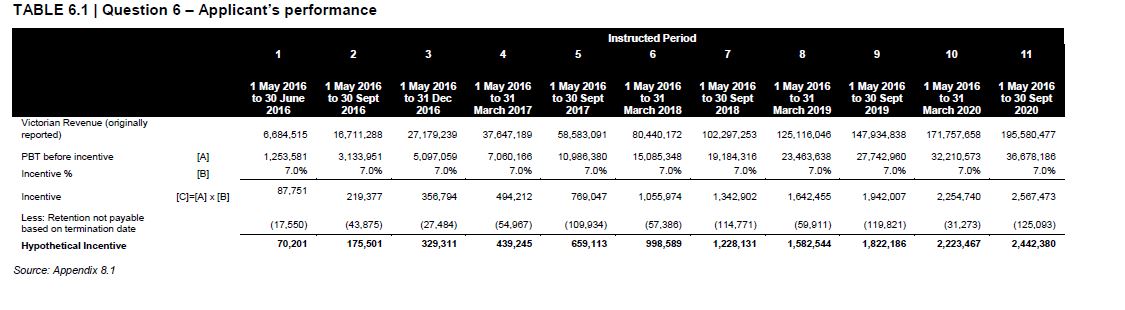

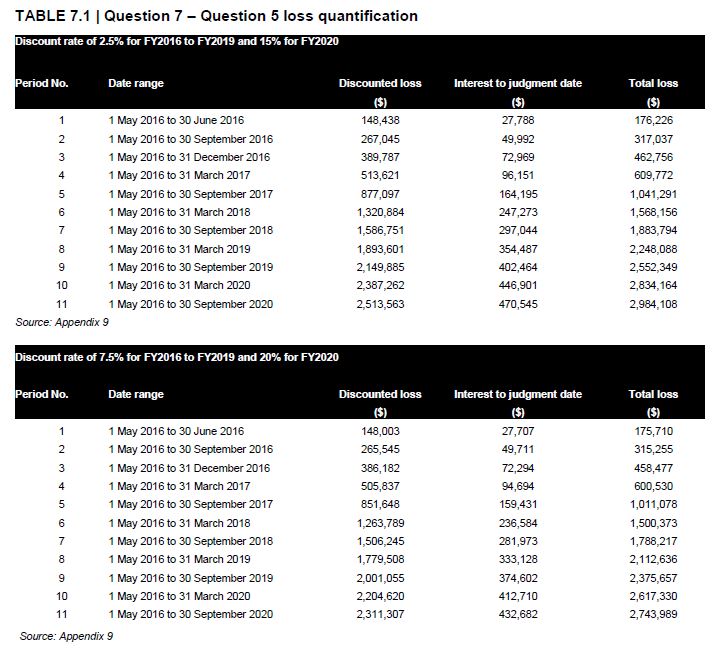

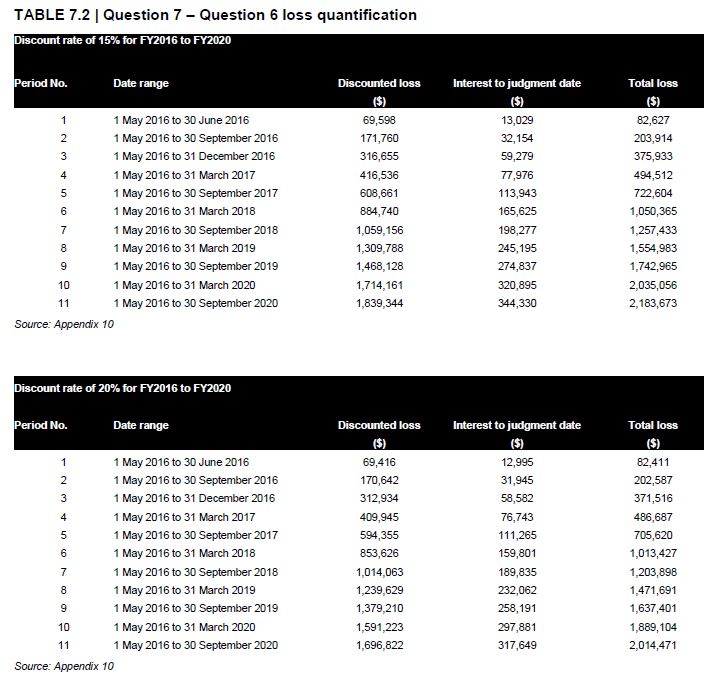

5 Additionally, Mr Roohizadegan seeks damages for breach of contract by TechnologyOne in respect of its alleged non-payment of part of the incentives due to him since 26 November 2009 as a percentage of the Profit Before Tax performance of TechnologyOne’s “Business Unit 03 –Victoria - Service Delivery”. TechnologyOne denies that he is owed any such outstanding payments.

History and background findings: things start well

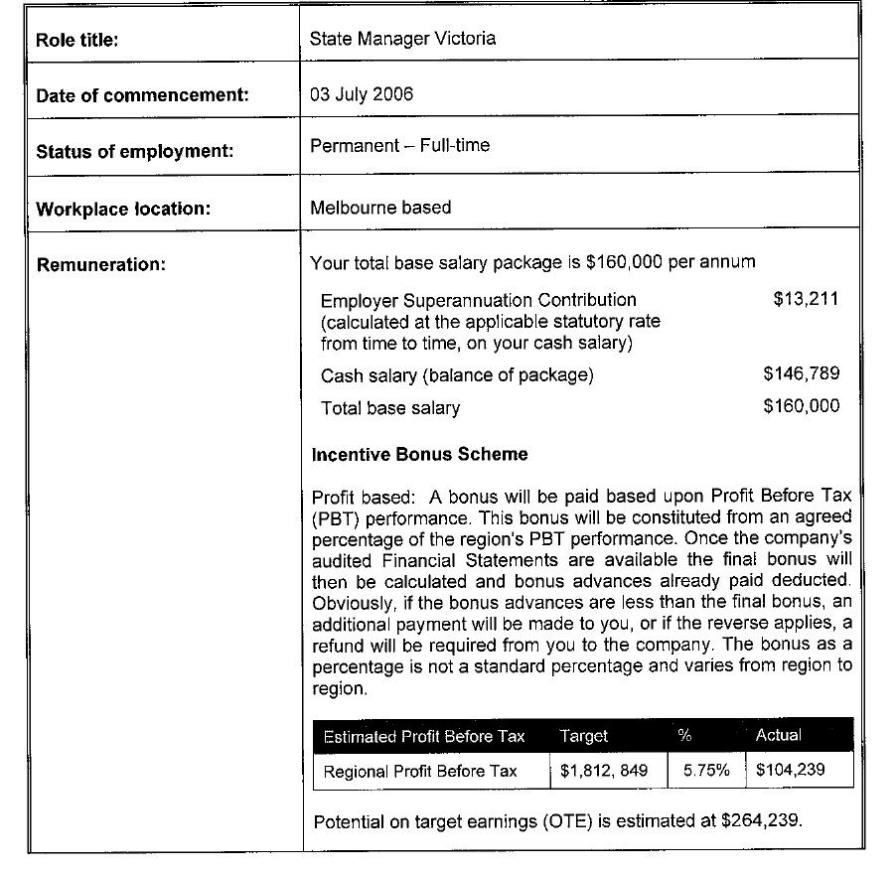

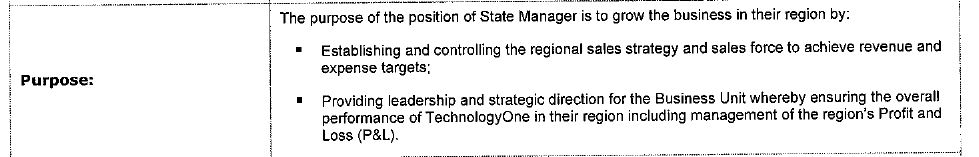

6 Mr Roohizadegan commenced employment with TechnologyOne as State Manager for Victoria on 3 July 2006.

7 When Mr Roohizadegan joined TechnologyOne, it was then a relatively smaller company. It had only a modest footprint in Victoria. However, under Mr Di Marco’s leadership it was setting ambitious growth targets. Mr Di Marco’s evidence is that, together with his former direct report Roger Phare, Mr Roohizadegan had built the Victorian region “from very small to very large” (T519, line 29).

8 Mr Di Marco’s evidence is that in 2006 TechnologyOne had 377 employees, its annual revenue for the 2005/06 financial year (which I interpolate from the evidence before me then ended on 30 June 2006 but was later changed to end, for TechnologyOne’s accounting purposes, on 30 September 2006) was $66.485 million, and licence fees were $17.150 million. By 2016, TechnologyOne had grown significantly. It had about 1000 employees, its annual revenue for the 2015/16 financial year (ending 30 September 2016) was $249 million, and licence fees were $56 million.

9 During his pre-employment interview Mr Di Marco told Mr Roohizadegan that if he was successful during his time at TechnologyOne, he “would make a lot of money”. That proved to be an accurate prediction.

10 Mr Roohizadegan’s gross income increased from $208,932.00 in the 2006/07 financial year to $845,128.00 in the 2015/16 financial year. Most of that increase was attributable to incentive payments; Mr Roohizadegan’s base salary increased only from $165,000.00 to $192,000.00 (see as submitted for by Mr Roohizadegan’s counsel at [888] below) during the same period.

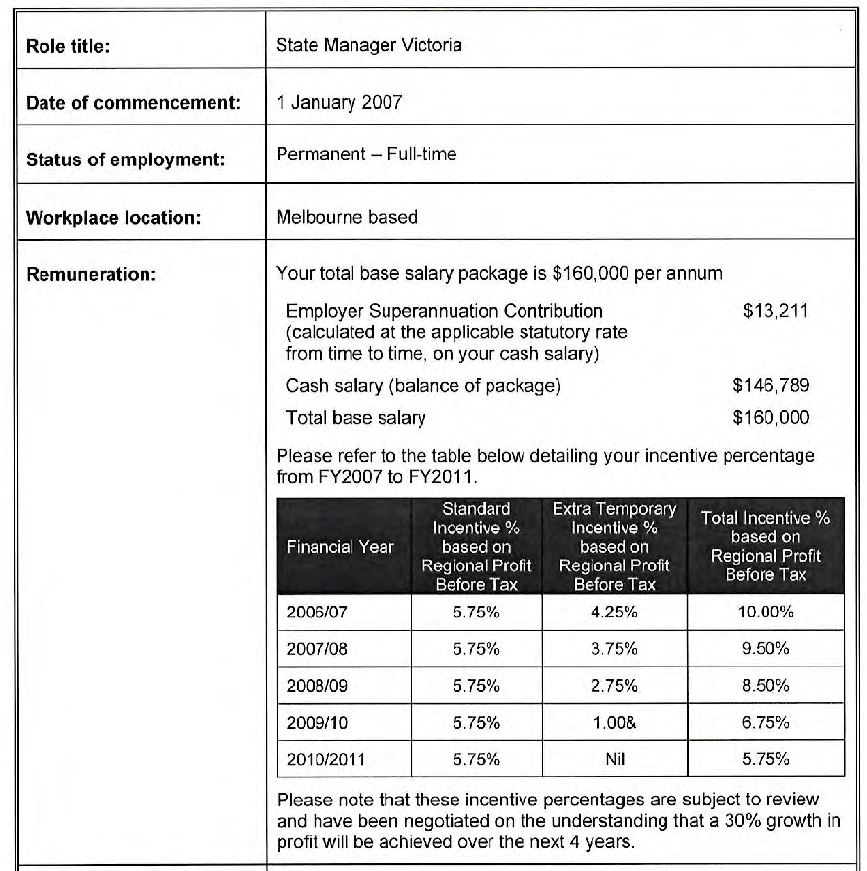

11 Mr Roohizadegan’s initial employment agreement (dated 3 July 2006) provided that he was to be paid a base salary and a bonus or “incentive” based upon the Profit Before Tax (PBT) performance of the Victorian “region”.

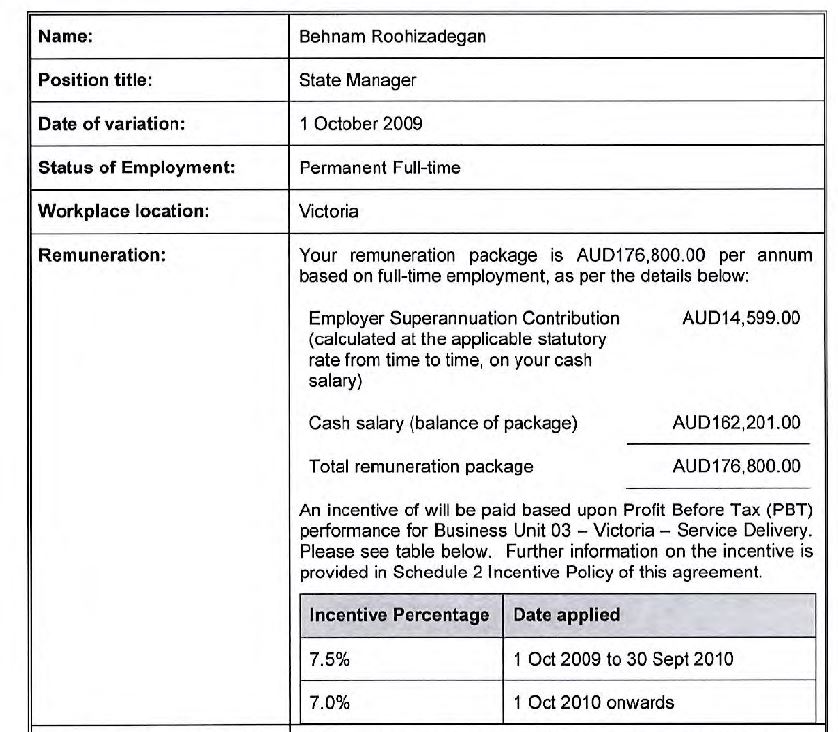

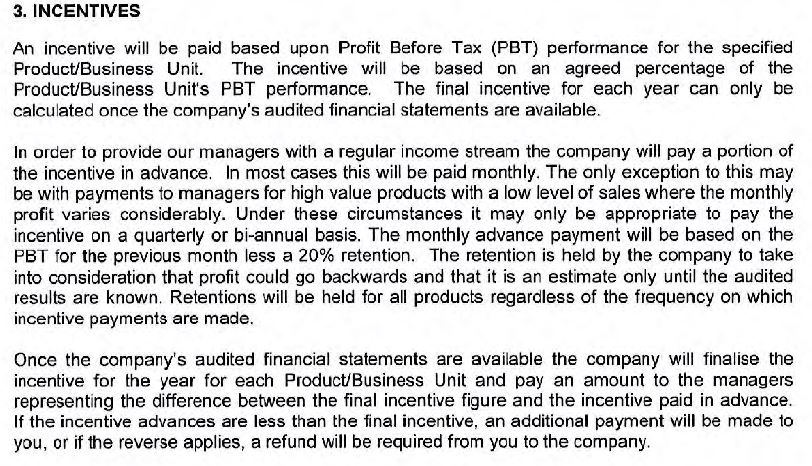

12 It is uncontentious that TechnologyOne operated for some purposes as if it were divided into semi-autonomous components. Each component (however described) reported to the company’s head office, located in Brisbane. It is similarly uncontentious that Mr Roohizadegan was appointed to be responsible for the management of the Victorian region.

13 Mr Roohizadegan’s employment contract was first varied on 7 March 2007. The terms of his employment were subsequently substituted for by a written agreement dated 26 November 2009. That agreement specified that, in addition to his base salary, Mr Roohizadegan was to be paid an incentive based on “PBT performance for Business Unit 03 – Victoria – Service Delivery”. The percentage specified was 7.5% from 1 October 2009 to 30 September 2010 and 7% thereafter.

14 It is uncontentious that in the 26 November 2009 agreement Mr Roohizadegan’s title, “State Manager”, remained the same. The Respondents however submit that, inter-alia, the change to the name “Business Unit 03 – Victoria – Service Delivery” to describe the component of TechnologyOne in respect of which PBT was to be measured for the purpose of calculating his incentives is of significance. Mr Roohizadegan takes issue with that proposition. He says that he remained (as he had always been) entitled to be paid an incentive based on his agreed share of PBT for all sales TechnologyOne made in the geographical region of Victoria.

15 There were further variations to Mr Roohizadegan’s employment agreement, dated 12 December 2014 and 13 November 2015 respectively. It is however common ground that those variations have no bearing upon the disposition of this matter.

16 According to Mr Roohizadegan, the total revenue for the Victorian region of TechnologyOne grew from approximately $8.4 million for the 2005/06 financial year to approximately $46.9 million for the 2014/15 financial year (Ex A30, CB132). That evidence is not in dispute.

17 Mr Roohizadegan received the TechnologyOne Chairman’s Award in 2010, 2012, 2013 and 2014. His uncontested evidence was that each year that award is given to only four to six of TechnologyOne’s approximately 800 to 1,000 employees.

18 It is thus undisputed that for the greatest part of his service, Mr Roohizadegan’s employment was of significant mutual financial benefit to both him and TechnologyOne. I take it to be in recognition of that mutuality that Mr Roohizadegan was granted share options in the First Respondent in 2013, 2014 and 2015 in addition to his contracted remuneration. Such a benefit was not granted to any other State Manager.

19 Mr Di Marco and the First Respondent acknowledge that until the circumstances that had led him to dismiss Mr Roohizadegan arose, Mr Di Marco had viewed him as a “real hunter”. Mr Di Marco accepts that Mr Roohizadegan had brought in some big deals for TechnologyOne. In his evidence-in-chief Mr Di Marco described Mr Roohizadegan as having been “really hardworking”, committed and loyal to the business (T519, lines 30-32).

20 Mr Di Marco qualified that laudatory description in his oral evidence by observing that from 2014, he had begun to question whether Mr Roohizadegan might be the right person to take the business forward.

21 Nonetheless, Mr Di Marco gave oral evidence that until the events which led to him to terminate Mr Roohizadegan’s employment occurred in 2016 he had remained confident that if Mr Roohizadegan had support from, and was mentored by, his direct report (TechnologyOne’s National Operating Officer for sales) “we could make that work” (T519, lines 29-39).

22 He had thought bringing in a new National Operating Officer would ensure success in that regard (T520):

It would assist Behnam. Someone who could mentor Behnam, who could bring the disciplines and help Behnam with those disciplines, and also help … structure Victoria for the next stage of growth, so to bring someone in to help him and to help the other regions, and I was confident that combining that with the other good things that Behnam did, because he was very hard working, very committed, very loyal and a good hunter, you know, that we could make this work, and so I was very positive at that point through 2015, 14-15, that this could work.

23 I note that there is one significant qualification I ought to record with respect to these introductory observations. At paragraph [11] of Mr Di Marco’s affidavit (Ex R31) he deposes that “over time” he had become aware that others saw Mr Roohizadegan differently. He deposes that as early as December 2007 he had received a complaint from a long serving employee, Mr Bernard Morris, about Mr Roohizadegan. I return to that specific evidence later in these reasons in regard to my findings as to Mr Di Marco’s credibility.

Mr Roohizadegan suffers personal crisis and ongoing Depression

24 On the surface, things were thus going very well at work for Mr Roohizadegan. However, it is uncontentious that from late 2010 he had come to grapple with a self-perceived burden of guilt.

25 In September 2010, Mr Roohizadegan’s then 14 year old daughter became ill (T159). He did not go to the hospital with her at that time. He had thought it vital to finalise an important deal on behalf of TechnologyOne before the end of the company’s financial year (T163). It is not in contest that as a result of that decision Mr Roohizadegan experienced extreme feelings of guilt about his then lack of involvement in his daughter’s care.

26 It is uncontentious that Mr Roohizadegan’s daughter was hospitalised for full time care in late 2010 after she had been diagnosed with Kawasaki disease (T162). She had required open-heart surgery in January 2011 (T161).

27 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that outside of the work environment, his feelings of guilt had a significant impact on his family and his personal life. Mr Roohizadegan escaped his pain in work.

28 Mr Roohizadegan identified his feelings of guilt as stemming from his inappropriately having prioritised his work for TechnologyOne over his daughter’s life and health. It is therefore perhaps cruelly ironic that Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that in order to avoid that distress, work became the one safe place where he could “escape”. He therefore increased his already long working hours (T163).

29 Outside of work however, Mr Roohizadegan could not escape his grief. He became emotionally closed off from his wife. Predictably, that gave rise to tensions within their marriage. Mr Roohizadegan gave evidence, which I accept, that at various times the marital relationship had been on the verge of breaking down. Mr Roohizadegan also experienced repeated thoughts of suicide. On at least one occasion he had taken steps, ultimately not implemented, directed towards that end.

30 The Respondents’ counsel Dr Spry’s cross-examination of Mr Roohizadegan proceeded on the premise that his having suffered feelings of guilt after his daughter had become ill was not in dispute.

31 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that he had told Mr Di Marco about his daughter’s grave illness shortly after becoming aware of its seriousness. However, he had he kept silent about his own suffering.

TechnologyOne remains unaware of the extent of Mr Roohizadegan’s distress

32 I proceed on the basis that beyond confirming to his work colleagues from time to time that he remained concerned about his daughter’s health, Mr Roohizadegan was careful not to reveal to anyone at TechnologyOne the depth of his private turmoil. Being able to focus on the practical problems of work without anyone at TechnologyOne knowing about his damaged condition allowed him to hide in his safe place, numb to his grief and pain.

33 There is no evidence at all to suggest that Mr Di Marco, or anyone else at TechnologyOne, at any time in the years that followed had the least inkling that Mr Roohizadegan was suffering from or had suffered a psychiatric illness (being a depressive disorder, as was the conclusion of the experts who gave evidence in this trial) until after he had been summarily dismissed. The Court has no reason to doubt the evidence that Mr Di Marco gave in describing what occurred after the meeting at which Mr Roohizadegan’s employment was terminated:

Dr Spry: Did he come back, or did he just leave?

Mr Di Marco: He talked to Kathy on the way out, and then he left, so I was very surprised with the whole way the meeting had gone. It was not what I expected. Kathy then talked to me. She said that he had made some concerning comments, something about jumping off a bridge. I didn’t believe it, you know. I was not aware of any mental health issues that Behnam had. They had never been raised. I didn’t know about that, so, to me, I couldn’t see why he would jump off a bridge. I mean, he’s paid $1 million a year, you know. He’s paid to deliver and perform. If you don’t, you leave, and we separated as nicely as possible. Why would you do that? So I didn’t believe it, but I said to Kathy, “Still, you need to follow up and you need to make sure he’s fine, just in case, and keep me informed.” And that was basically it.

34 Mr Chung, who at the time had been TechnologyOne’s Chief Operating Officer and had known Mr Roohizadegan for several years prior to his dismissal, gave evidence under cross-examination that when he had been told that Mr Roohizadegan had spoken of suicide after being dismissed his immediate reaction had been that Mr Roohizadegan was trying it on. I reject that that was a cruel observation. Rather, while perhaps bluntly expressed, that was simply what Mr Chung thought to be the most plausible explanation for Mr Roohizadegan’s statement. In common with everyone else with whom Mr Roohizadegan had worked at TechnologyOne, Mr Chung had been given no reason to suspect that Mr Roohizadegan did not enjoy robust mental health. It is only in retrospect that it seems so.

35 Sustaining his workplace as a place of safety where he could escape his otherwise incapacitating depression required Mr Roohizadegan not only to hide any symptoms of overt distress from his employer, but also to remain highly functioning in a demanding role. I am satisfied that to a very significant degree Mr Roohizadegan accomplished both of those objects.

36 I accept however that it is implausible that Mr Roohizadegan could have been capable of hermetically sealing off his work-life from the impact of his distress. Dr White, a psychiatrist, examined Mr Roohizadegan on 4 November 2015 in connection with other legal proceedings that he and his daughter were then bringing in which each had claimed damages on the basis that certain medical practitioners who were alleged to have misdiagnosed her had been negligent. Dr White recorded Mr Roohizadegan telling him:

They [TechnologyOne] don’t know about my suicidal tendencies but I’ve been told in the past four years that I could have done better. I haven’t been performance managed yet but I have to work longer hours because I get absolutely distracted about my daughter. I’m not efficient. Severe concentration problems. I forget things and I send the wrong emails to people, repeatedly getting into trouble with my boss because I misjudge situations.

37 Although Dr White’s note appears from its dating to have been made from memory a few days after his in person consultation, I accept that Mr Roohizadegan expressed himself to Dr White substantially to that effect.

38 However, two things are to be observed about what Mr Roohizadegan reported to Dr White. First, to the extent that Mr Roohizadegan told Dr White that he had suffered a deficit in concentration there is unchallenged evidence that he had adopted adaptive strategies in that regard such as working longer hours and making notes. As I have earlier noted, those strategies were demonstrably successful in achieving their object of compensating for those deficits: at least insofar as Mr Roohizadegan continued to be regarded as an outstanding performer (see below at [40]-[45]). It was for that reason that his work colleagues never recognised him to have suffered a psychiatric illness or injury.

39 Second, while it can be accepted that Mr Roohizadegan told Dr White about his getting into trouble with his then boss (being Mr Martin Harwood) Mr Roohizadegan was then unaware of certain matters as have emerged in this proceeding. The evidence that has emerged as to Mr Harwood’s conduct and motivations suggests there may be an alternative explanation for Mr Roohizadegan having found himself “in trouble” with his boss: see below at [302]-[331].

Mr Roohizadegan’s performance at work does not materially decline notwithstanding his (later diagnosed) depressive disorder

40 I do not understand the Respondents to ask the Court to find that Mr Roohizadegan’s long established, and only later diagnosed, depressive disorder caused a material decline in his performance at work. In any event, I am satisfied that it did not.

41 It is uncontentious that Mr Roohizadegan’s condition first manifested itself in late 2010, after his daughter had become ill.

42 Mr Roohizadegan’s receipt of the TechnologyOne Chairman’s Award in each of 2012, 2013 and 2014 is entirely inconsistent with his work performance having fallen off. It is equally inconsistent with Mr Roohizadegan having been granted share options in 2013 and early 2015, after he had complained to Mr Di Marco that his performance should entitle him to an equity interest in the company. Mr Roohizadegan was not the passive recipient of TechnologyOne’s general largess. He was always astute to ensure that his contribution to the success of TechnologyOne be acknowledged in hard economic terms. Indeed, in his evidence-in-chief Mr Di Marco describes Mr Roohizadegan as having been a constant complainer:

Behnam complained from the day he started at TechnologyOne. He complained from day one that the salary that we had offered him and that he had agreed was not enough and I had to change it. He complained about options. He complained about staff. He complained so much. You will see it through all the papers, and the last three or four months … I couldn’t care less about a complaint. All I cared about is his ability to perform, number 1, and number 2, that his behaviours were acceptable. But his complaints were totally irrelevant to the whole thing. And if Behnam had been the right person, he would still be there.

43 As Mr Di Marco’s evidence implies, I am entitled to be satisfied that had Mr Roohizadegan not been a strong performer he would have been given very short shrift. Instead, I infer that Mr Di Marco yielded to Mr Roohizadegan’s demands for additional financial rewards because he was a strong performer whose services he wished to retain.

44 The evidence also is clear that Mr Di Marco put up with Mr Roohizadegan’s practice of bypassing his direct reports to raise any concerns he had that touched on the success of the Victorian region directly with him. Mr Di Marco’s affidavit evidence on this point was as follows:

Behnam never reported directly to me, but always to one of the managers referred to in the paragraph above. Notwithstanding this, Behnam frequently emailed me about a range of issues, and when he was in Brisbane, he would often ask to speak with me. I would agree to see Behnam when he was in Brisbane as I thought he was working hard to grow TechnologyOne's business in Victoria. Behnam escalated lots of things to me, more than any other State Manager. I did not encourage him to do this, and as time went by, it became a major concern to me how often he was escalating matters to me which should have been discussed and addressed with his manager. (Ex R31, [10]).

45 I discount Mr Di Marco’s evidence to the extent that it might suggest that he had sought to counsel Mr Roohizadegan not to raise matters directly with him. Mr Di Marco accepted that Mr Roohizadegan had expressed appreciation of his willingness to meet him one on one whenever he came to Brisbane (T613, lines 3-4). There is no evidence before me as would entitle me to find that Mr Di Marco ever disabused Mr Roohizadegan of his understanding that his conduct in escalating his concerns was appropriate. I conclude that Mr Di Marco’s willingness to have routinely allowed Mr Roohizadegan direct access to him was because he had accepted that Mr Roohizadegan was, and remained until his dismissal, significantly responsible for TechnologyOne’s sales growth and increased profits in Victoria: a large and important part of its national market.

The core of Mr Roohizadegan’s dismissal case

46 Putting aside Mr Roohizadegan’s contractual claim, this proceeding thus turns on why, notwithstanding their prior mutually beneficial history, in 2016 TechnologyOne decided to terminate Mr Roohizadegan’s employment. In closing submissions his senior counsel, Mr Tracey (junior counsel being Mr Minson), abandoned reliance on Mr Roohizadegan’s pleadings insofar as they assert breaches of the Fair Work Act by TechnologyOne unrelated to Mr Roohizadegan’s dismissal (T1214, lines 26-31, 39-47).

47 Mr Roohizadegan’s case therefore is confined to the claim that he was dismissed for the following prohibited reasons, contrary to s 340 of the Fair Work Act:

• Seven instances of his exercising his workplace rights by making complaints in relation to his employment: in particular, complaints as to his having been bullied;

• His proposed exercise of his right to bring legal proceedings under a workplace law;

• His proposed exercise of a safety net contractual entitlement; and

• His having a safety net contractual entitlement.

48 I note in that regard that in closing submissions Mr Tracey also indicated that the Applicant did not press pleaded claims that he had been dismissed for other reasons (being his taking sick leave; being temporarily absent from work; and having a mental disability) (T1217, lines 15-39).

49 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that as a result of his dismissal he suffered a profound mental breakdown. Whether his dismissal caused that breakdown, or whether it was merely a manifestation of his earlier depressive disorder from which he had continued to suffer after his daughter’s illness, is the subject of contested expert evidence to be discussed later. It is however not in dispute that after he was dismissed Mr Roohizadegan became, and remains, incapable of ever working again.

50 The relevant statutory provisions upon which Mr Roohizadegan’s claims are based are those provided for in ss 340 and 341 of the Fair Work Act as follows:

340 Protection

(1) A person must not take adverse action against another person:

(a) because the other person:

(i) has a workplace right; or

(ii) has, or has not, exercised a workplace right; or

(iii) proposes or proposes not to, or has at any time proposed or proposed not to, exercise a workplace right; or

(b) to prevent the exercise of a workplace right by the other person.

Note: This subsection is a civil remedy provision (see Part 4-1).

(2) A person must not take adverse action against another person (the second person) because a third person has exercised, or proposes or has at any time proposed to exercise, a workplace right for the second person’s benefit, or for the benefit of a class of persons to which the second person belongs.

341 Meaning of workplace right

(1) A person has a workplace right if the person:

(a) is entitled to the benefit of, or has a role or responsibility under, a workplace law, workplace instrument or order made by an industrial body; or

(b) is able to initiate, or participate in, a process or proceedings under a workplace law or workplace instrument; or

(c) is able to make a complaint or inquiry:

(i) to a person or body having the capacity under a workplace law to seek compliance with that law or a workplace instrument; or

(ii) if the person is an employee—in relation to his or her employment.

51 Insofar as there are multiple reasons for the taking of adverse action, s 360 provides:

360 Multiple reasons for action

For the purposes of this Part, a person takes action for a particular reason if the reasons for the action include that reason.

52 In his Further Amended Statement of Claim Mr Roohizadegan pleads that he made seven complaints in relation to his employment, and that these were individually or severally the reason for his dismissal or were included as a reason for that action. Mr Tracey submits that Mr Roohizadegan was able make those complaints “in relation to his employment” pursuant to TechnologyOne’s “Open Door Policy” (Ex A32, CB 3553-33554) and its “Workplace Bullying Policy” (Ex A80).

53 Assuming the Court finds that Mr Roohizadegan did make those complaints, I do not take Dr Spry to submit that he was not “able” to make them “in relation to his…employment”.

54 That concession is appropriate. I will be brief in explaining why I accept that to be the case, because I do not take the conclusion to be in issue.

55 Mr Roohizadegan’s contract of employment referred to TechnologyOne’s policies and procedures as setting out the company’s expectations of how its employees were to conduct themselves. Clause 13 of his contract relevantly provided as follows:

13.1 To help our business operate lawfully, safely and efficiently, we have policies and procedures, which set out how all employees are to conduct themselves and processes, which are to be followed. You will be expected to follow these policies and procedures current at the time. Our company wide policies and procedures can be accessed on our intranet. It is incumbent on you to be familiar with all our policies and procedures. Serious breaches of our policies and procedures current at the time could result in termination of your employment.

13.2 To meet the changing environment in which we operate, it will be necessary to change these policies and procedures from time to time. You will be given notice of the changes and will be required to follow the change policies and procedures.

56 I am satisfied that TechnologyOne’s “Open Door Policy” and its “Workplace Bullying Policy” (as are in evidence as exhibits A32 and A80) are not disputed to have been applicable at the relevant time. They provide an explicit basis for the Court to be satisfied that Mr Roohizadegan was “able to make a complaint” as he claims he did, inter-alia, about his having been bullied in relation to his employment.

57 Having regard to the terms of Mr Roohizadegan’s contract and those policies, I am satisfied Mr Roohizadegan had the entitlement upon which he relies. My conclusion in that regard is consistent with the reasoning of Dodds-Streeton J in Shea v TRUenergy Pty Ltd (No 6) [2014] FCA 271 at [640].

58 I am satisfied for those reasons that Mr Roohizadegan possessed and was capable of exercising a relevant “workplace right”.

59 He was accordingly protected by s 341(1)(c)(ii) against adverse action being taken against him for the reason that he had made a complaint in relation to his employment.

60 The same applies with respect to any complaint Mr Roohizadegan made in good faith regarding his contractual entitlements. In that regard I respectfully adopt the reasoning of Rangiah and Charlesworth JJ in PIA Mortgage Services Pty Ltd v King [2020] FCAFC 15 at [19]-[20]:

Under the general law, an employee has a right to sue his or her employer for an alleged breach of the contract of employment. A suit may be regarded as the ultimate form of complaint. Accordingly, in our opinion, an employee is “able to make a complaint” about his or her employer’s alleged breach of the contract of employment. That ability is “underpinned by” (to use Dodds-Streeton J’s expression in Shea) the right to sue, and extends to making a verbal or written complaint to the employer about an alleged breach of the contract.

Further, an employee who alleges that his or her employer has contravened a statutory provision relating to the employment is “able to make a complaint” within s 341(1)(c)(ii) of the FW Act. That right or entitlement derives from the statutory provision alleged to have been contravened. The ability encompasses making a complaint to the employer or an appropriate authority about the alleged contravention, whether or not the statute directly provides a right to sue or make a complaint.

61 Again, I do not apprehend the Respondents to take issue with that proposition.

62 I further take the Respondents to accept that, to the extent that Mr Roohizadegan did exercise a workplace right by complaining inter-alia about his being bullied by one or more other employees of TechnologyOne or about his safety net contractual entitlements, the presumption provided for by s 361(1) of the FWA applies in these proceedings. In any event, for the reasons that follow I so find.

The statutory presumption and the Respondents’ case

63 The terms of s 361 of the Fair Work act are as follows:

361 Reason for action to be presumed unless proved otherwise

(1) If:

(a) in an application in relation to a contravention of this Part, it is alleged that a person took, or is taking, action for a particular reason or with a particular intent; and

(b) taking that action for that reason or with that intent would constitute a contravention of this Part;

it is presumed that the action was, or is being, taken for that reason or with that intent, unless the person proves otherwise.

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply in relation to orders for an interim injunction.

64 In Board of Bendigo Regional Institute of Technical and Further Education v Barclay [2012] HCA 32; 248 CLR 500 (Barclay) at [50] French CJ and Crennan J - while acknowledging that Mason J’s remarks had been directed to an earlier expression of the statutory presumption - adopted as applicable to its current expression his Honour’s observation in General Motors-Holden's Pty Ltd v Bowling (1976) 51 ALJR 235 at 241; 12 ALR 605 (Bowling) at 617 that:

the plain purpose of the provision [is to throw] on to the defendant the onus of proving that which lies peculiarly within his own knowledge.

65 That understanding of the purpose of the provision has been repeatedly reaffirmed: see, for example, Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v CoreStaff WA Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 893 per Banks-Smith J at [12].

66 In respect of the pleaded allegation that Mr Roohizadegan was dismissed for the reason that, or reasons including that, he had exercised his workplace rights, TechnologyOne thus has the burden of displacing the statutory presumption provided for by s 361(1): assuming the Court finds that he did make the complaints he alleges to persons with authority to address those complaints within TechnologyOne.

67 The Respondents’ case is that Mr Di Marco was the sole decision-maker with respect to Mr Roohizadegan’s dismissal.

68 The Respondents do not suggest that Mr Roohizadegan’s dismissal was not relevantly the taking of “adverse action”. They simply contend that Mr Roohizadegan’s dismissal was for different reasons to those alleged by Mr Roohizadegan. It had nothing to do with his having exercised any workplace right.

69 If “adverse action” is taken as a result of a decision that has been made by an individual within a corporation, the identification of the reasons for the corporation taking the adverse action requires an inquiry focussed on the actual mental processes of the relevant individual who made that decision: Barclay at [140] (Heydon J); Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v BHP Coal Pty Ltd [2014] HCA 41; 253 CLR 243 (BHP Coal) at [7] (French CJ and Kiefel J), [85] (Gageler J).

70 Barclay establishes that an employer will not be liable for a breach of the Fair Work Act simply because he or she has dismissed an employee in awareness that that employee has exercised a protected workplace right. An employer contravenes the Fair Work Act, and liability is imposed, only if their employee’s exercise of that right was the reason or part of the reason for their having taken that adverse action. A court is therefore required to make findings regarding the decision maker’s actual reasons. What those reasons are is to be determined from all of the facts established in the proceeding, and inferences properly drawn from them.

71 Section 361 however requires the Court to conclude that the reason the employee has alleged was his or her employer’s reason for taking adverse action against him or her was in fact the reason for that action, unless the employer can establish that the adverse action was not taken for that alleged prohibited reason. Proof in that regard is on the balance of probabilities: Barclay at [56] per French CJ and Crennan J, citing Gibbs J in Bowling at 239.

72 In State of Victoria (Office of Public Prosecution) v Grant [2014] FCAFC 184; 246 IR 441 at [32], Tracey and Buchanan JJ summarised (in terms which I respectfully adopt) the following propositions as having been established by Barclay:

• The question is one of fact. It is: “Why was the adverse action taken?”

• That question is to be answered having regard to all the facts established in the proceeding.

• The Court is concerned to determine the actual reason or reasons which motivated the decision-maker. The Court is not required to determine whether some proscribed reason had subconsciously influenced the decision-maker. Nor should such an enquiry be made.

• It will be “extremely difficult to displace the statutory presumption in s 361 if no direct testimony is given by the decision-maker acting on behalf of the employer.”

• Even if the decision-maker gives evidence that he or she acted solely for non-proscribed reasons other evidence (including contradictory evidence given by the decision-maker) may render such assertions unreliable.

• If, however, the decision-maker’s testimony is accepted as reliable it will be capable of discharging the burden imposed on the employer by s 361.

73 In BHP Coal at [93] Gageler J held that to escape liability, having regard to the presumption, an employer must “prove that the act or omission having the character of a protected industrial activity [as was relevant in that instance] played no operative part in its decision”.

74 However, in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Hall [2018] FCAFC 83; 261 FCR 347 a Full Court of this Court held at [100]:

The orthodox approach to dealing with allegations of adverse action said to be engaged in “because” of a particular circumstance requires the party making such an allegation to establish the existence of the circumstance as an objective fact. If an applicant, on the whole of the evidence, establishes, to the Briginshaw standard, that the elements of a particular contravention (other than the reasons for the respondent taking action) exist and if the respondent wishes to avoid an adverse finding in respect of the alleged contravention the respondent will bear the onus to establish, on the balance of probabilities, that he or she had not acted for any proscribed reason. As has already been noted above … s 360 contemplates that there might be multiple reasons for a respondent taking action to the prejudice of the applicant. A reason will not be proscribed unless it is “a substantial and operative factor” in the respondents' reasons for taking the adverse action (citing Barclay at [62] (French CJ and Crennan J) and [104] (Gummow and Hayne JJ)).

(Citations omitted except where expressly set out).

75 Although I remain challenged to understand how the conclusion stated in the final sentence of that passage can be reconciled with the operation of the statutory presumption, my failure in that regard is of no consequence; the outcome that the Full Court reached, which their Honours expressed as being required by Barclay, is binding on me. I thus proceed on the basis that if the Respondents establish on the balance of probabilities that Mr Roohizadegan’s pleaded instances of exercising his workplace rights (assuming the Court finds they were made) were not individually or collectively a “substantial and operative” reason for his termination then even if those pleaded instances were a factor or factors in his employer’s decision to dismiss him Mr Roohizadegan will fail to make good his case that he was terminated from his employment for a prohibited reason.

76 In the present case, the Respondents submit that the evidence entitles the Court to conclude that Mr Di Marco was the sole decision maker responsible for Mr Roohizadegan’s termination. On their behalf Dr Spry submits that the Court should accept Mr Di Marco’s evidence that he dismissed Mr Roohizadegan exclusively for the following reasons:

(1) The licence fees in the Victorian region (for which Mr Roohizadegan was responsible) were not growing;

(2) Concerns had been raised by Mr Roohizadegan’s team, which was a “team in crisis”; and

(3) Mr Roohizadegan had been unable to work well with three different managers within a two-year period (T594-596).

77 Dr Spry submits that the Court should accept Mr Di Marco’s evidence that none of the complaints as the Court might find Mr Roohizadegan to have made, whether about bullying or his contractual entitlements, played any part in TechnologyOne’s decision to dismiss him.

78 For reasons that I will later explain I accept the Respondents’ submission that Mr Di Marco was, ultimately, the sole decision maker in respect of Mr Roohizadegan’s dismissal.

79 However, for the reasons I further give I reject the proposition that I am entitled to conclude on the balance of probabilities that his termination was not for the reasons he alleges or did not include those reasons.

80 More specifically I am unpersuaded the Respondents prove, on the balance of probabilities, that Mr Roohizadegan’s complaints about having been bullied, inter-alia by his two most recent direct reports, Mr Martin Harwood and Mr Stuart MacDonald, were not a substantial and operative reason for Mr Di Marco’s decision to terminate Mr Roohizadegan’s employment.

81 Accordingly I have concluded that Mr Roohizadegan is entitled to rely on the presumption provided for by s 361 of the Fair Work Act.

82 Before turning to my reasons for reaching those conclusions, I should identify the key dramatis personae and their roles at TechnologyOne during the period material to these proceedings. Doing so will allow reference to be made to those individuals in these reasons without extensive explication:

Mr Benham Roohizadegan | The Applicant, employed from 3 July 2006 as State Manager for Victoria and later as Regional General Manager (incorporating Tasmania) from February 2015 until 18 May 2016, based in Melbourne. |

Mr Adrian Di Marco | The Second Respondent, Executive Chairman and Chief Executive Officer at TechnologyOne, based in Brisbane. Mr Di Marco stood down from the role of CEO on 23 May 2017. |

Mr Boris Ivancic | Employed at TechnologyOne as Regional Sales Manager for the Victorian Region from February 2016 to January 2017. Appointed in a caretaker role as Regional Manager reporting to Mr MacDonald after Mr Roohizadegan’s termination. |

Mr Lee Thompson | Employed as Operating Officer, Sales and Marketing at TechnologyOne from January 2014 to October 2014. Mr Roohizadegan’s direct report for that period. |

Mr Martin Harwood | Employed as Operating Officer, Sales and Marketing at TechnologyOne from late 2014 to 11 April 2016. Mr Roohizadegan’s direct report for that period. For a period thereafter he shares responsibility for that role with Mr Stuart MacDonald. |

Mr Stuart MacDonald | Employed as Operating Officer, Sales and Marketing at TechnologyOne from 11 April 2016 to 23 May 2017. Mr Roohizadegan’s direct report, until the latter is summarily dismissed by TechnologyOne. |

Ms Rebecca Gibbons | Employed at TechnologyOne from August 2011 to May 2017 as HR Business Partner responsible for sales, marketing, corporate services, products and solutions. |

Ms Kathryn Carr | Employed at TechnologyOne, initially as HR specialist from 16 May 2011 and then in the role of HR Director in the two years prior to her resignation on 31 March 2017. |

Mr Edward Chung | Employed at TechnologyOne as Chief Operating Officer from February 2016 to 22 May 2017, and for 16 months prior to that as Operating Officer Products and Solutions, and prior to this appointment Operating Officer Corporate Services and Chief Financial Officer. Currently employed by TechnologyOne as its Chief Executive Officer. Appointed to that role on 23 May 2017, replacing Mr Di Marco. |

Mr Richard Metcalfe | Employed at TechnologyOne for approximately nine years as State Manager, Sales and Marketing for Tasmania. Appointed by Mr Harwood on 16 March 2015 also to serve as Regional Sales Manager for Victoria. His appointment in that respect is terminated on 8 February 2016. |

Mr Peter Sutching | Employed at TechnologyOne as Products and Local Government General Manager: a position of equivalent seniority within TechnologyOne to that of Mr Roohizadegan. |

83 To allow the Court to focus its reasons on the core issues in dispute without the need for prolix background, I will now set out a chronology of events. In the majority of instances there is no significant dispute as between the parties that the events recorded in this chronology occurred. Subject to further explication in these reasons and to the qualification below, what is stated in the chronology serves as the Court’s findings.

84 Where the chronology refers to an event in dispute as between the parties, it is qualified by being identified as a “claim”. The matters so identified are not findings. They are recorded so that the events in dispute, to be the subject of later discussion, can be placed within their historical context.

85 The chronology also identifies in bold text when the bullying complaints on which Mr Roohizadegan relies as the relevant exercise of his workplace rights are alleged to have occurred. It similarly identifies in bold text the occasion when, on the Respondents’ case as advanced, Mr Di Marco made his decision to terminate Mr Roohizadegan’s employment.

The evidence and the credit of the principal witnesses

86 The parties agreed, and the Court ordered, that evidence concerning a number of critical matters (such as what transpired between Mr Roohizadegan and other relevant persons during the events he alleges were bullying) would be given viva voce. The trial was conducted on that basis. Having regard to that agreement, the paragraphs relating to the content of such conversations and events as were contained in the affidavits otherwise relied on by the parties were not read. The most critical evidence of the principal witnesses was thus given orally.

87 While adducing evidence viva voce may be accepted to have advantages over the giving of evidence by way of affidavit where the credit and reliability of recall must be assessed, it too has risks and weaknesses. It is in the nature of a trial, particularly one conducted some years after the events in dispute occurred, that a witness’s memory can - and, as judicial experience shows, not infrequently does - prove fallible. A court should therefore be cautious of attributing dishonesty to a witness who gives evidence which is not accepted.

88 Entirely without guile, a witness may confidently recall what they said, saw or did at the time of an event in terms that cannot be true. A belief that they must have acted or spoken in a particular way can become their actual, but false, recall. Further, because human memory is not as reliable as we would wish, this risk of firm but reconstructed memory increases as time passes. Contemporaneous written records, to the extent they exist, therefore generally provide a more solid basis for judicial fact-finding than human memory.

89 In this proceeding a number of important events were the subject of email exchanges or referred to in contemporaneous documents. Where the providence of such a document is not in dispute I have proceeded on the basis that - save where good reasons have been advanced for reaching a different conclusion - the Court should prefer what a contemporaneous document reveals, and any inferences open to be drawn on that basis, over the contrary present recall of a witness.

90 That acknowledged, there are a number of critical alleged events and conversations upon which this case potentially turns which were entirely undocumented. In such instances the Court cannot avoid basing its findings on contested evidence given by witnesses as to what was, or was not, said or done in particular circumstances: having regard to the inherent or contextual plausibility or implausibility of the evidence they gave, and the Court’s assessment of their credit.

91 Counsel representing the parties helpfully provided detailed written submissions with respect to the credit findings they respectively submitted the Court is entitled to, and should, make with respect to a number of witnesses who gave evidence in this proceeding.

92 It is convenient at this point first to address the evidence given by four of the most critical witnesses in this proceeding, and the parties’ respective submissions as to their credit. I proceed on that basis because in most regards, the remaining evidence is of more marginal relevance. That is because much of the evidence given by the other witnesses in this trial throws little or no light on the critical question of what was or were Mr Di Marco’s reason or reasons for his decision to dismiss Mr Roohizadegan. Moreover having regard to the principles governing the construction of contracts that bind this Court, little of that evidence is dispositive or even relevant in regard to Mr Roohizadegan’s claim in contract.

93 Mr Roohizadegan gives evidence that in 2006, in the course of pre-contractual discussions between himself and Mr Di Marco, he had been assiduous to seek and obtain confirmation that the incentive bonus provided for in the contract he ultimately signed was to apply to his benefit in respect of all revenue generated by TechnologyOne in the Victorian region without exception. In cross-examination, Mr Roohizadegan explained that he had sought that assurance because he had left his previous job after a dispute between himself and his former employer in respect of the scope of such a clause. He had not wanted any such problems to arise in his new role (T262, lines 1-8).

94 His contract, into which he had entered on 3 July 2006 after those discussions, provided that his remuneration was to include a base salary package plus an incentive bonus “based upon Profit Before Tax (PBT) performance” to be “constituted from an agreed percentage of the Region’s PBT performance”.

95 It is uncontentious that that contract was varied on 7 March 2007 by an agreement which set a schedule of revised “agreed percentages” upon which his incentive bonus was to be based for particular periods into the future.

96 By a further agreement dated 26 November 2009, Mr Roohizadegan’s contract of employment was varied for a second time. As varied, it refers to his being entitled to an incentive based on “Profit Before Tax (PBT) performance for Business Unit 03 – Victoria – Service Delivery”. The variation increase the rate of that incentive (7.5% from 1 October 2009 to 30 September 2010 and then 7% from 1 October 2010 onwards) above that which would have applied under the existing contract. The terms (but not the construction) of the contract as varied are not in dispute.

97 Mr Roohizadegan gave evidence that from the outset of his employment with TechnologyOne, some TechnologyOne products sold in Victoria that had been directly marketed or serviced from Brisbane had been included as part of his PBT performance. In respect of those sales, he had routinely received incentive payments.

98 However, his evidence is that he had also been contractually entitled to – but did not receive – incentive payments in respect of his PBT performance revenue from certain other TechnologyOne products sold in Victoria: principally Student Management Services (SMS) but later also “Plus Services”, and certain financially less significant transactions involving Victorian Legal Aid and Victorian Red Cross. He pleads that he is therefore entitled to damages for breach of his contract.

99 Mr Roohizadegan gave evidence that he had complained regularly to TechnologyOne, both before and after the variation to his contract on 26 November 2009, about not being paid incentives due to him in respect of such sales. His evidence was that he first raised that subject with Mr Di Marco during a discussion with Mr Harwood, Mr Phare, and Mr Di Marco that took place at the Gold Coast around 9 November 2009 (Ex A6, CB141-CB143).

100 It is uncontentious that on 8 April 2011, Mr Pye sent an email to Mr Roohizadegan to explain TechnologyOne’s commission policy. I infer that this was in response to a complaint or complaints that Mr Roohizadegan gave evidence of having made, concerning what he asserted to be the partial non-payment of the incentives to which he was entitled. Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that he made a contemporaneous handwritten note on a printed copy of Mr Pye’s email: “Where is SMS?! Regional P&L?? told to wait … Year End!” (Ex A37, CB1173).

101 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that notwithstanding his complaints in that regard, he worked assiduously in TechnologyOne’s interests from when he was first employed. He had built the Victorian region up from small beginnings to one where his incentives were calculable on profit and loss before tax of approximately $45 million.

102 I have set out above at [24]-[45] the substance of Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence as to his distress from September 2010 onwards after his daughter became ill with Kawasaki disease. I need not repeat that discussion. It is sufficient that I restate that, for the reasons I gave, I accept that Mr Roohizadegan found refuge in his work and that by reason of the compensation mechanisms he adopted his work performance was not materially adversely affected by his private suffering.

103 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that Mr Di Marco always encouraged him to run the Victorian region as if it were his own business. He was never denied direct access to Mr Di Marco. He had understood that Mr Di Marco thought well of him. He was the recipient of the Chairman’s Award in each of 2012, 2013 and 2014. That was an award made by Mr Di Marco and given to only a small number of TechnologyOne’s highest performing staff. His evidence is that having regard to his success in building TechnologyOne’s business, he pressed Mr Di Marco for additional financial recognition by way of giving him an equity interest in the company. Mr Di Marco had authorised that to happen. He had been granted share options in TechnologyOne in both 2013 and 2015.

104 His evidence is that although he personally played a significant part in making sales and building the business of TechnologyOne in Victoria, his role was not confined to securing new sales. Consistently with his contract, he had been responsible for the profitable management of the whole of the operations of TechnologyOne in Victoria.

105 His evidence is that in February 2015 he was promoted by TechnologyOne from the position of State Manager for Victoria to the position of Regional General Manager. His promotion to that position is not in dispute, although the Respondents submit that that was simply an aspect of a reorganisation within TechnologyOne in which State Managers in all of the more economically significant regions such as Victoria and New South Wales were given additional responsibilities.

106 His evidence is that he worked well and constructively with his first two direct reports, Mr Phare and Mr Thompson. He accepted there had been some initial tension when Mr Thompson replaced Mr Phare. However, his evidence was that he had accepted Mr Thompson’s mentoring. They had thereafter worked extremely well together.

107 His evidence is that he encountered significant difficulties only after Mr Harwood replaced Mr Thompson as TechnologyOne’s Operating Officer for Sales and Marketing. Those difficulties stemmed from his objections to Mr Harwood making unilateral decisions affecting his management of the Victorian region.

108 I note however that Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that even before he had become his direct report, Mr Harwood had to a limited extent intruded into his management of his region. His evidence is that in 2012 Mr Harwood had interfered in that way by intervening to prevent the termination of an under-performing employee. Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that Mr Di Marco became angry with Mr Harwood when Mr Roohizadegan complained to him about that interference (T169, lines 10-22).

109 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that in March 2015, after Mr Harwood had become his direct manager, Mr Harwood had appointed Mr Metcalfe to the position of Regional Sales Manager for Victoria: ostensibly to assist him to manage his increased responsibilities in the position of Regional General Manager. However, he had done so without consulting him. Mr Roohizadegan had complained to Mr Harwood that Mr Metcalfe was unsuitable for that position.

110 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that at around the same time (in June 2015), Mr Harwood moved to terminate the employment of one of his sales team: Mr Con Tsalkos (Ex A6, CB154-5). He had opposed that decision, his prior understanding having been that Mr Tsalkos was to be placed on a performance management plan and given a chance to improve. He gave evidence that the same had occurred in respect of another employee, Mark Loler (T320).

111 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that he sent an email to Mr Metcalfe, cc’ing Mr Di Marco, questioning why he and Mr Harwood had made the decision to terminate Mr Tsalkos on particular terms. He complained in his email that the decision to dismiss them had been taken without his involvement. He complained that he “cannot run [his] region in parallel with a fifth column” (Ex R12, CB4274-4275).

112 It is uncontentious that Mr Di Marco told Mr Roohizadegan and Mr Harwood to “sort it out, as this is escalating needlessly” and that “mistakes happen” (Ex R12, CB4266).

113 On 26 June 2015 Mr Di Marco informed Mr Roohizadegan and Mr Harwood that he had “recruiters telling [him] they will not put good sales staff to us in Victoria”. Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that he understood Mr Di Marco to have associated that difficulty with Mr Harwood having recently terminated Mr Tsalkos and Mr Loler (T321). In an email, Mr Di Marco instructed Mr Harwood and Mr Roohizadegan “the revolving door has to stop”. He told Mr Harwood that he was holding him accountable in that regard (Ex R13, CB4304).

114 It was in that context that Mr Roohizadegan then gave evidence that when Mr Harwood sent him an email on 12 January 2016 stating that “Victoria cannot go backwards for a fourth year in a row”, he had rejected that assertion in a long email which he had copied to Mr Di Marco (Ex R33). Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that he felt offended by Mr Harwood’s accusation (T304, lines 14-26). His evidence is that Mr Harwood was factually wrong to have claimed that the Victorian region had gone backwards (even if that statement were understood as applying only to new licence fees) for the past three years. He arranged to meet Mr Di Marco on 3 February 2016 to correct the record, and to complain about Mr Harwood undermining him.

115 He gave evidence that when Mr Harwood learned that he had arranged to meet Mr Di Marco, Mr Harwood demanded he cancel the meeting. Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that Mr Harwood had threatened that “one of us has to go” when Mr Roohizadegan rejected his repeated demands to do so (T172-173).

116 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that he made a handwritten contemporaneous note of those events in his diary. His note is in evidence as Ex A11 (CB4932). It reads as follows:

Monday 1 February 2016

Martin [Harwood] called whilst having lunch with Darryl

Said that he has just had a meeting with Adrian [Di Marco]

Why I am seeing Adrian this Wednesday and it is very serious so I need to tell him why and Martin wants me to call him later on

6:10pm Melbourne time – Martin called and I called Martin back, he was very very angry, why I am seeing Adrian, he is his boss and not my boss, I said Adrian is my boss too. I said Martin you expect me to advise big numbers but you do not support me and make decisions for my region, how do you expect me be accountable! etc

Tuesday 2 February 2016

Martin called me again @ 12pm today

He’s not happy with me, seeing Adrian etc.

I didn’t follow his instructions, I told him to give me an example of when

He said I lectured him on ‘how he can help me’ last night and he has been thinking last night

One of us has to go!

I said I am not going anywhere

Martin said that he is going to prepare a list for Adrian & tomorrow we see how things pan out! Martin has seen my e-mails to Adrian, and he is going to scrutinise me closely if I stay.

* Martin again called, left a message, I called back & he said we must make an offer to Boris [Ivancic], new Sales Manager today, I said this is the issue where everything started as I don’t agree to give him a guaranteed commission.

Martin said he is going to make a list of everything that I am going to complain to Adrian about and one of us has to go!

(Spelling and grammar as in original handwritten entry).

117 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that when he and Mr Di Marco met on 3 February 2016 he complained to Mr Di Marco about Mr Harwood having undermined him in his role, bullied him and having made decisions behind his back. He also told him that Mr Harwood had threatened him that if he did not cancel his meeting, one of them would have to go (T176, line 41-T177, line 14; T361, lines 5-14).

118 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that after he made Mr Di Marco aware of Mr Harwood’s conduct Mr Di Marco had said to him “I’m not having any of this from Martin. I’m going to get him”. He had left his office to do so. Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that just before Mr Di Marco went to fetch Mr Harwood Mr Di Marco had asked him not to “tell [Mr Harwood] in front of me that he has said to you ‘one of us has to go’”.

119 His evidence is that Mr Di Marco had returned a few minutes later with Mr Harwood. He told the Court that Mr Harwood “didn’t seem to be happy” (T177, line 30).

120 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that Mr Di Marco then had “said to both of us, ‘I think the world of both of you. I like you both. What is the issue?’”, to which he had responded by saying to Mr Di Marco “I like to recruit my own sales manager. I like to have my resources. I like not to be undermined. I like decisions not being made behind my back”.

121 His evidence is that he had told Mr Di Marco about Mr Harwood having vetoed Mr Pantano, who had been his first choice for the position of Regional Sales Manager. Their discussion had then turned to whether Mr Ivancic (who both Mr Di Marco and Mr Harwood agreed was suitable to be appointed), should be guaranteed a commission or not.

122 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that in the course of opposing offering Mr Ivancic a guaranteed commission for six months, he took the opportunity to raise with Mr Harwood and Mr Di Marco his own unpaid incentives for SMS by TechnologyOne to TAFE and universities in Victoria as were contractually due to him (T179, lines 20-37; T361, lines 15-23).

123 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is to the effect that Mr Di Marco agreed with Mr Harwood that Mr Ivancic should be offered a guaranteed commission. Mr Roohizadegan gave the following evidence as to the events that then transpired (T180-181):

Mr Roohizadegan: I said to – to Mr Di Marco and Mr Harwood. I said, “Okay. We go with Boris. We give him six months guaranteed commission. But if things doesn’t work out for my region, please do not hold me accountable for your decision.” And then Mr Harwood said “Behnam –” I – I remember he put his finger at me, “Behnam”, like this – “Behnam, you are responsible for Victoria. I hold you accountable, even though we are making decisions for you to have Boris or someone else as your sales manager.” And he raised his voice, similar to the way I tried to explain, your Honour, with a finger at me like this. And Mr Di Marco got a bit upset. I could see that. And then Mr Di Marco turned to Martin and said, “Martin, get out of my house. Martin, get out of my office now. I want to have another five minutes with Behnam alone.”

Mr Tracey: And what happened next?

Mr Roohizadegan: And then when Martin was leaving the office, his face was very red. He just gave me a look as he was leaving the office, and then Mr Di Marco turned to me, he said, “Buddy, I know how good you are. You do good work for me. You escalate things to me. I love the way you do things. Continue as you are, but I want you to know that I had to show that I’m on the side of Martin too because I need him as well as I need you”, some words to that effect. “Continue the way you are.” I asked him – at the end of that conversation, I asked him – because by that time I was just thinking, “Am I doing something wrong?” And – and I asked Mr Di Marco “Adrian –” I had a good relationship with Adrian, and I said, “Adrian, do I need to change anything?” And he said, “Not at all. Continue as you are. I’m happy you bring your prospects and your executives to Brisbane to see me. Continue as you are and carry on as you are.” And – and then I said to him before I left “So we – we had –” he asked me about my daughter, by the way, as well, around that time, “How is your daughter?” I said, “Well, it’s difficult, but I’ve focused my work on my – I’ve focused my life on my work.” And then – and before I left the room, I – I actually thanked Adrian. I said “Adrian, I would like to thank you that – and I appreciate –” I said, “I appreciate you take the time to see me one-on-one whenever I come to – whenever I come to – to Brisbane.” And then he turned back to me and he said, “Behnam, I am the one who should be thanking you. I’m the one who should be thanking you.” And I felt a bit embarrassed because this is the chairman of the company, and he – he – he said to me, “I’m the one who should be thanking you.” And I – I – I remember when I came back from the Brisbane trip I asked my wife, I said, “Why he’s thanking me?” I didn’t get it. And my wife said, “He’s effectively telling you that he appreciates that you tell him things, your – your transparency”, because I – I felt – when he said, “I’m the one – I should be thanking you”, I felt embarrassed. You know, I just – I just can’t explain the feeling I felt.

Mr Tracey: Okay. So that meeting between you and Mr Di Marco then ends?

Mr Roohizadegan: Yes, he said something else as well. I’m sorry, I just remembered. He – he said, “Behnam, go and build a relationship with Martin.”

His Honour: Sorry, he said?

Mr Roohizadegan: He – Adrian said to me, “Go and build a relationship with Martin.”

Mr Tracey: Okay?

Mr Roohizadegan: And I said, “I don’t have any issues with Martin.”

124 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that there had been no opportunity for him to “go and build a relationship” with Mr Harwood. His evidence is that later the same day, Mr Harwood had spoken to him using words to the effect that Mr Roohizadegan might have won a battle, but that he would win the war. Mr Harwood told Mr Roohizadegan he was going to “scrutinise” him until he left TechnologyOne (T182, line 35- T183, line 6).

125 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that he was subsequently informed that Mr MacDonald would replace Mr Harwood from 11 April 2016 in the position of Operating Officer for Sales and Marketing. In that capacity, he would become Mr Roohizadegan’s new direct report. Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence however is that he was advised that Mr Harwood was to remain jointly responsible in that position for an overlap period. That this was so does not appear to be contentious (T539, line 23).

126 It is also not in dispute that Ms Gibbons, a junior member of TechnologyOne’s HR team, visited Melbourne on 20 April 2016. Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that he complained to her, inter-alia, of his having been bullied by Mr Sutching. He also complained that Mr Harwood and Mr MacDonald were preventing him from doing his job. He told Ms Gibbons that he believed Mr MacDonald had made a decision to direct him not to attend TechnologyOne’s presentation to the Bass Shire Council on the recommendation of Mr Sutching.

127 Mr Roohizadegan gave evidence that he had asked Ms Gibbons whether what had happened to him amounted to bullying, and that she had told him that it did. (T183, line 34 – T184, line 29). It is uncontentious that Ms Gibbons later sent Mr Roohizadegan an email attaching a link to TechnologyOne’s bullying policy.

128 A version of Mr Roohizadegan’s alleged complaints, specifically referring to his considering legal action against Mr Sutching for bullying, was included in Ms Gibbons’ email to Ms Carr of 24 April 2016. It is uncontentious that Ms Carr later sent a copy of Ms Gibbons’ email to Mr Di Marco and the members of TechnologyOne’s executive.

129 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that at 9.15pm on 25 April 2016 he then sent an email to Mr MacDonald querying why he had instructed him (in a phone conference in which Mr Harwood had also participated) not to attend a meeting with Melbourne University (Ex R21, CB5676). In his email Mr Roohizadegan referred to his being bullied by Mr Sutching and Ms Phillips. He asked Mr MacDonald, in view of what he asserted to be his exclusion from the running of the region, “I need to understand what my job is please.”

130 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that later the same evening he had sent an email to Mr Di Marco to complain that Mr MacDonald was stopping him doing his job, decisions were being made behind his back and that he was being prevented from seeing customers and prospects (Ex R21, CB5674).

131 His evidence is that the next morning (26 April 2016) Mr Di Marco replied to his email saying “leave it with me to talk with Stuart [MacDonald]” (Ex A77, CB5656).

132 Mr Roohizadegan then gave evidence that during a phone conference in which he and Mr Ivancic jointly participated with Mr MacDonald on 9 May 2016, they gave an updated forecast of significantly increased sales for the Victorian region in respect of the current financial year (as noted above, I interpolate that it is uncontentious that TechnologyOne operated on a financial year ending 30 September). His evidence is that Mr MacDonald became angry after hearing that news. His evidence is that Mr MacDonald swore at them and told them: “You fucking two, get your forecasts together” (T196). Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that the revised sales forecasts he and Mr Ivancic provided to Mr MacDonald on 9 May 2016 had made TechnologyOne aware that it was in prospect that the Victorian region would increase its revenue in the 2016 financial year.

133 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that on 12 May 2016 he attended a routine meeting of TechnologyOne’s State Managers in Brisbane. His evidence is that during the morning session of that meeting he had been contacted on his mobile phone by Mr Nikoletatos of La Trobe University. Mr Nikoletatos told him that La Trobe had issues with the deal Mr Roohizadegan had understood was close to settling. Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that they arranged to speak later that day at a more convenient time.

134 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that he then asked Mr MacDonald to participate in that postponed call. Mr MacDonald had rebuffed him stating “Screw, you, Benham, I’ve seen your email”. Mr Roohizadegan gave evidence that at the time, he did not know to what email Mr MacDonald was referring (T204). Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence was that in view of Mr MacDonald’s response, he had arranged for Mr Paul James to be present when he returned the call from La Trobe as a “silent listener” telling him he was “scared or frightened if something goes wrong with Latrobe University, Stuart MacDonald is going to blame me for it” (T206). When he and Mr Nikoletatos spoke later in the day Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that Mr Nikoletatos had told him that La Trobe wanted a $7m reduction in the contract price Mr Roohizadegan had earlier negotiated.

135 His evidence is that he had told Mr Nikoletatos that he had no authority to make any concessions, and that in any event a reduction of $7m was impossible. Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is he had asked Mr Nikoletatos what La Trobe’s bottom line was and that, in response, Mr Nikoletatos had told him that a $1m reduction was the minimum La Trobe would accept. He had told Mr Nikoletatos that he had no authority to accept such a reduction but would convey his message to Mr Di Marco and the TechnologyOne executive.

136 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that he immediately communicated La Trobe’s demand for a $1m reduction to the members of TechnologyOne’s Executive Team by email.

137 His evidence is that after he did so, Mr MacDonald demanded to see him. Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that when they met Mr MacDonald claimed that he had told Mr Roohizadegan not to negotiate with La Trobe. His evidence is that he denied being given any such instruction. He also sought to clarify he had not negotiated anything. He was simply conveying La Trobe’s altered position.

138 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that during that discussion Mr MacDonald abused, bullied, and swore at him. His evidence is that he made a file note later the same day in which he recorded the events that had happened (T214). His file note (Ex A21, CB6346-6348) is as follows:

Angilika called me on my mobile, asking if I had left. I said I was downstairs and she said Stuart [MacDonald] wants to see me. I said okay and went upstairs. Stuart took me to Gareth Pie office and said he wanted Gareth to be a witness and started shouting at me with very loud voice “Should I tell you to negotiate with LaTrobe University or not?” “Why did you offer them $1m discount?” You cannot do that Benham. I said I didn’t negotiate, the customer wanted $7m discount and I said we had provided BAFO etc, but as the customer insisted (Peter), I said $7m will not be approved by TechnologyOne. What does he want his bottom line discount and Peter said $1m and this is what I have communicated at no time did I say that I have the authority to give $1m discount and I hope to take that to my Executive and Adrian.

Stuart said he didn’t accept that and that was negotiation. I said I didn’t agree to it. Stuart then shouted that you F… Benham you don’t understand I replied English is not my first language and I have not agreed to anything with the customer, and Stuart does not have a right to use bad language on me and shout at me. Stuart replied that he can use any language and swearing that he wants, and he can say and do anything that he likes and I cannot do anything about it. I replied no he could not swear, and abuse me and use bullying tactics on me and I said if there was nothing else.

I was going to leave Gareth [Pye’s] office to which Gareth & Stuart said fine and I went to Edward [Chung’s] office and told Edward about what had happened in Gareth office & Stuart swearing at me, etc. Edward said my email a bout La Trobe was good, he didn’t see anything wrong with it and seemed very surprised that Stuart had acted that way towards me.

I came out still shaken, bewildered and very upset downstairs to meet with Boris [Ivancic], Steve, Jerry and Mark … David Van De .. Boris and I caught a taxi to the airport.

139 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that he flew home to Melbourne that evening in a state of distress.

140 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that the following morning (13 May 2016) he sent emails to Mr Di Marco and Mr Chung to complain about having been bullied by Mr MacDonald. His evidence is that Di Marco responded immediately stating that such behaviour was unacceptable (Ex A30, CB6411-6427). Mr Di Marco had followed up that email with a personal phone call to Mr Roohizadegan.

141 His evidence is that Mr Di Marco sent an email to him (copied to Mr Chung and Ms Carr) later the same day to inform him that Mr MacDonald had been counselled. He advised Mr Roohizadegan to relax and enjoy the weekend. In concluding his email Mr Di Macro said he hoped that everyone would “start afresh” on Monday (Ex A24, CB6431).

142 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence was that he was further aggravated in that Mr Di Marco had not required Mr MacDonald to apologise.

143 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that on 15 May 2016 he sent a second email to Mr Di Marco to complain about MacDonald’s behaviour. He told Mr Di Marco that he had “completely fallen apart” as a result of his having been bullied. He attached a medical certificate that he had obtained to his email. The certificate stated that he was unfit for work. He asked Mr Di Marco what “disciplinary action” he proposed to take (Ex R26, CB6665-6667).

144 His evidence is that Di Marco responded by sending him an email to advise him that Ms Carr would be investigating his complaint about Mr MacDonald.

145 Mr Di Marco suggested that in the meantime both Mr Roohizadegan and Mr MacDonald should go back to work and resume their relationship (Ex R26, CB6664).

146 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that in the morning of 16 May 2016 he received an electronic diary invitation to attend a meeting in Brisbane with Mr Di Marco on 18 May 2016 at 10:30am. The other attendees invited included Mr MacDonald (Ex A6, CB178-177; Ex R30, CB6669-6670). Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that shortly after he received that invitation, Mr Di Marco sent him an email stating “I have allocated 5 hours for our meeting Wed so we are not rushed. If it finishes earlier that’s okay” (Ex R38, CB6670).

147 His evidence is that he had responded to Mr Di Marco to the effect that he was still unwell but that if Mr Di Marco really wanted him to attend such a meeting he would do so: notwithstanding that he was unwell.

148 Mr Roohizadegan’s evidence is that Ms Carr rang him the same day (16 May 2016). He explained he still was unwell but nonetheless provided her with a brief account of the events that had transpired.

149 His evidence is that on the faith of his understanding that Mr Di Marco had set aside five hours to review those events, Mr Roohizadegan flew to Brisbane to participate in the meeting that Mr Di Marco had asked him to make himself available to attend.