FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

McKellar on behalf of the Wongkumara People v State of Queensland [2020] FCA 1394

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The interlocutory application dated 15 November 2018 be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MURPHY J:

INTRODUCTION

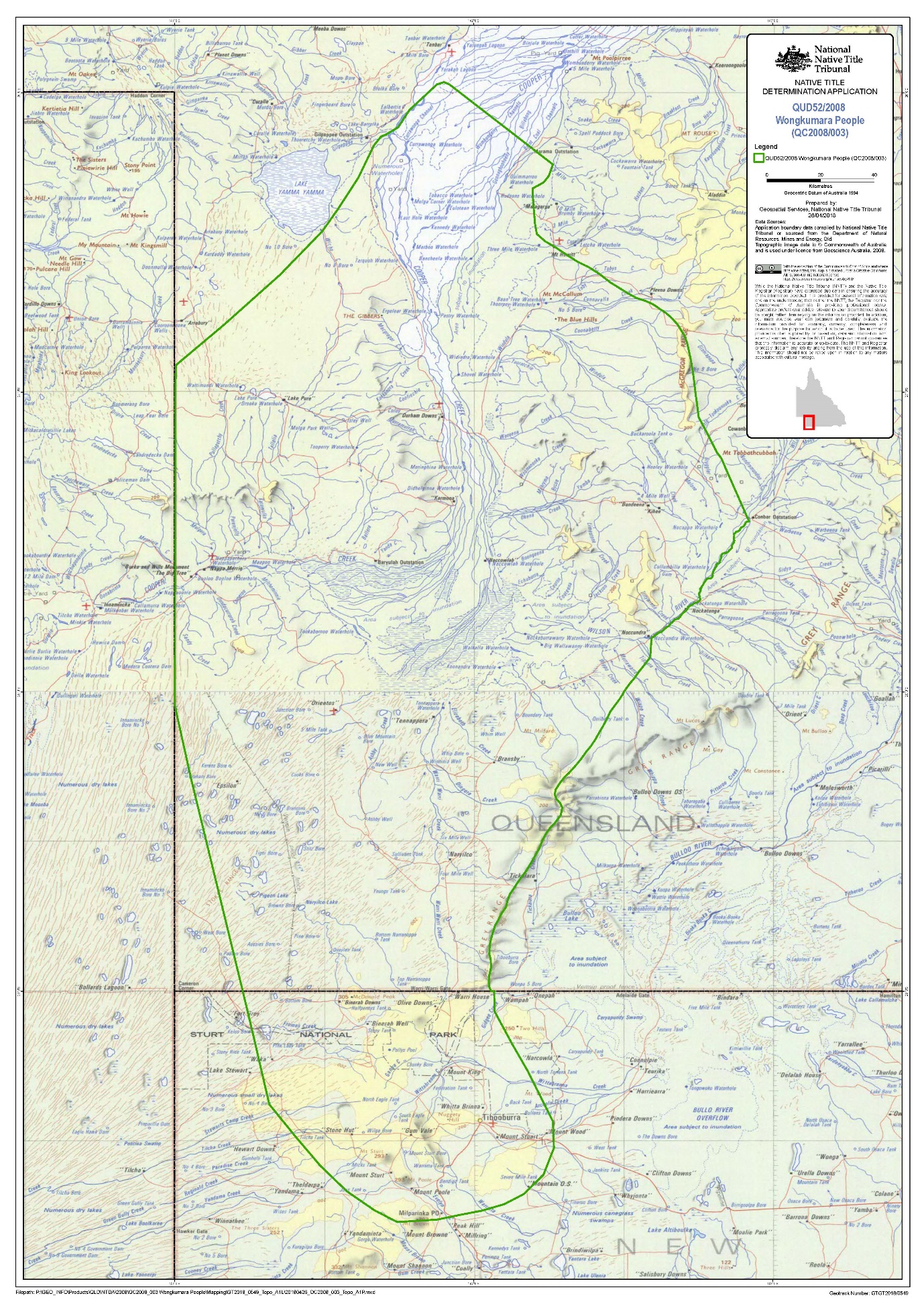

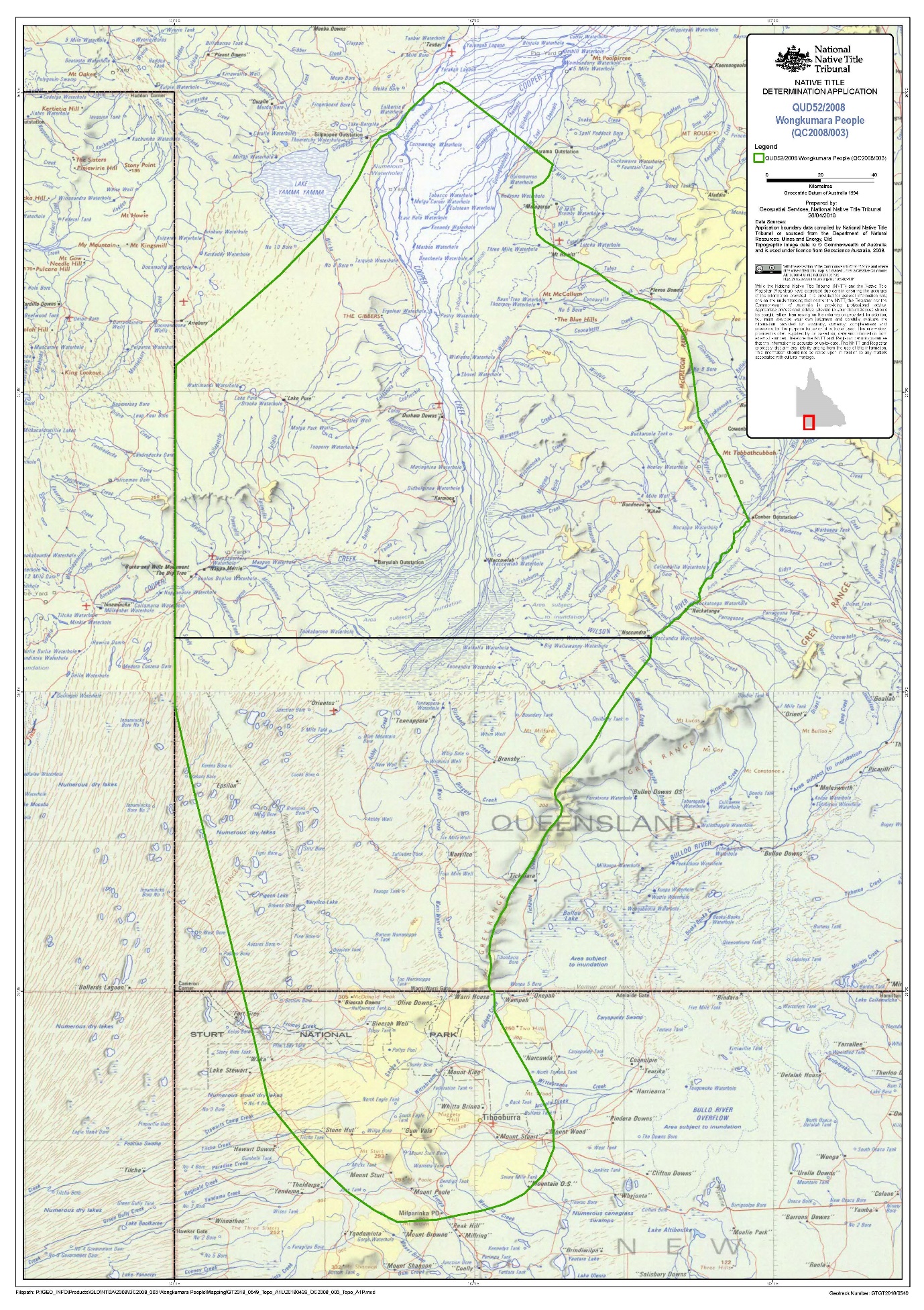

1 Before the Court is an interlocutory application by Coral Ann King in which she seeks an order to be joined as a respondent to this proceeding pursuant to s 84(5) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (the NTA). The substantive proceeding is an application for a native title determination brought by Clancy John McKellar and others on behalf of a native title claim group described as the Wongkumara People, comprising the descendants of one or more of 15 apical ancestors named in the second amended application (the Wongkumara application). On behalf of the claim group the Wongkumara applicants claim to have native title rights and interests in relation to a large area in the south-west corner of Queensland and the north-west corner of New South Wales, as shown in the map which is Schedule “A” to these reasons (the Wongkumara claim area).

2 In the joinder application Mrs King claims that through descent from her grandmother Toney (or Tonie) Booth, a Kungardutyi woman she (and other members of a group which I will describe as “the Booth family”) has acquired native title rights and interests in relation to the northern half of the Wongkumara claim area. The apical ancestors relied on in the Wongkumara application do not include Toney Booth.

3 For the reasons I explain it is not in the interests of justice to allow the joinder application. First, that is because different members of the Booth family have been parties in three proceedings in which they have claimed that through descent from Toney they have acquired native title rights and interests in relation to the Wongkumara claim area, each time unsuccessfully. Mrs King was not a party in the first two of those proceedings, but she was represented in them by her cousin Geoffrey Booth, and she was an active participant including by giving evidence in support of the claimed native title rights and interests:

(a) in the first proceeding Mrs King’s cousins, Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher, were respondents to a native title determination application brought on behalf of the Boonthamurra People in relation to the Boonthamurra claim area, which abuts the Wongkumara claim area. They claimed that through descent from Toney and another Aboriginal woman, Clara, they had traditional rights and interests in relation to areas which overlapped both those claim areas. The Court did not accept that they had acquired such rights and interests through Clara or Toney. In relation to the claim based in descent from Toney, the Court found that Kungardutyi country is well remote from the Boonthamurra claim, and in north-western New South Wales. That is also far from the area in which, in the joinder application, Mrs King claims to have traditional rights and interests through descent from Toney: see Wallace on behalf of the Boonthamurra People v State of Queensland [2014] FCA 901; (2014) 313 ALR 138 (Mansfield J);

(b) in the second proceeding Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher were respondents to the Wongkumara application from 2008. They claimed that through descent from Clara, her son Frank Booth, and Toney they had acquired native title rights and interests in relation to the Wongkumara claim area. In 2016 they withdrew when the Wongkumara applicants brought an interlocutory application seeking their removal; and

(c) in the third proceeding Mrs King, Geoffrey Booth and two others were applicants in a native title determination application brought on behalf of a claim group described as the Kungardutyi Punthamara People, in which they claimed that through descent from Clara and Toney, amongst others, they had acquired native title rights and interests in relation to the Wongkumara claim area. The Court dismissed the application on grounds including that it was an abuse of process having regard to the findings in Wallace, and because it had no reasonable prospects of success: see Booth on behalf of the Kungardutyi Punthamara People v State of Queensland [2017] FCA 638 (Jagot J).

4 To allow the joinder application would be to permit Mrs King to ignore the judgment in Booth and to avoid the findings in Wallace and in Booth. It would allow her to claim, in effect for the fourth time, that descent from Toney founds native title rights and interests in relation to the Wongkumara claim area. As a party in Booth it was open to Mrs King to appeal if she considered that decision to be wrong and she did not do so. Instead through the joinder application she now seeks to make the same claim in relation to a subset of the same claim area as in Booth based on the same apical ancestor, notwithstanding the judgments in Booth and Wallace. The bringing of similar claims in successive proceedings in this way amounts to an abuse of process. It is not in the interests of justice to allow the joinder application so that Mrs King can again litigate a claim to have native title rights and interests in relation to the Wongkumara claim area through descent from Toney.

5 Mrs King denies that her application is an abuse of process based, in summary, on contentions that: (a) she is not bound by the findings in Wallace as that decision concerned the Boonthamurra rather than the Wongkumara claim area and she was not a party; (b) the decision in Booth in which she was a party was based on the findings in Wallace; and (c) the findings in Wallace and Booth can now be shown to be unreliable as Mrs King has obtained “fresh evidence” which is sufficient to show that the findings in Wallace and Booth are unreliable. The material Mrs King asserts to be fresh evidence is primarily a statutory declaration made on 17 December 2017 by Dr Luise Hercus AM, an expert linguist in relation to Aboriginal languages, who has since passed away (the Hercus Declaration).

6 In my view Mrs King failed to confront the fact that she was a party in the Booth proceeding, and if she considered it to be wrongly decided the appropriate course for her to take was to appeal, not to wait a year and a half and then commence essentially the same claim differently cloaked. In effect, the joinder application invites a single judge to revisit findings made by other judges of the same Court on the basis of so-called fresh evidence. I am not persuaded that is permissible, and if it is permissible I am not persuaded it is appropriate in the circumstances of the present case. That is particularly so when the Hercus Declaration is not in any real sense “fresh”. It is a reinterpretation by Dr Hercus in 2017 of historical records and her earlier research, which material was available at the time the Wallace and Booth proceedings were decided. Nor, for the reasons I explain does the Hercus Declaration have the significance which Mrs King seeks to give it.

7 Second, even if, contrary to my view, it be accepted that the joinder application is not an abuse of process, I consider it nevertheless appropriate to refuse joinder because of the prejudice which will be suffered by Wongkumara applicants and Queensland South Native Title Services Ltd (QSNTS). The Wongkumara application was filed in March 2008 and the joinder application was not made until 10½ years later, in November 2018. The parties to the Wongkumara application have already suffered significant cost and delay through the earlier proceedings by members of the Booth family, through being respondents to the Wongkumara application and then withdrawing when challenged and also through the Booth proceeding. QSNTS was also a party to the Wallace proceeding. No hearing date has been fixed but all of the applicants’ expert evidence has been filed, and the parties are likely to incur significant further costs and delay if the applicants’ experts are required to prepare further reports to address the expert evidence upon which Mrs King now seeks to rely.

8 I accept that Mrs King is likely to be prejudiced if the joinder application is refused. I have given considerable weight to the statutory intention of having all parties whose interests may be affected before the Court at the one time to be dealt with by the one determination. But the prejudice Mrs King is likely to suffer must be seen in the context of the substantial delay in bringing the joinder application and that she and other members of the Booth family took up three earlier opportunities to assert any traditional rights and interests they claimed to have in relation to the Wongkumara claim area through descent from Toney, and each time they were unsuccessful. In my view it would be contrary to the interests of justice to allow the joinder application so that Mrs King can once more advance such a claim and vex the Wongkumara applicants and QSNTS with further inconvenience, cost and delay.

9 I have made orders to dismiss the joinder application, and have invited the parties to make submissions on the question of costs.

THE EVIDENCE

10 Mrs King relied upon the following material:

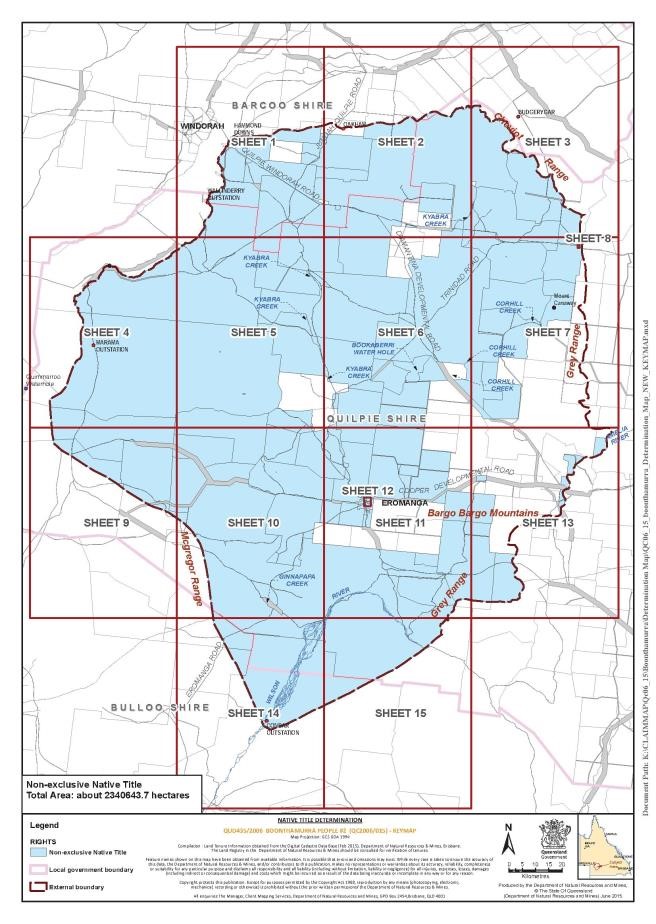

(a) four affidavits of Mrs King sworn 15 November 2018, 17 October 2019, 21 October 2019 and 30 November 2019;

(b) an affidavit of Stancy Veronica Booth sworn 28 November 2019;

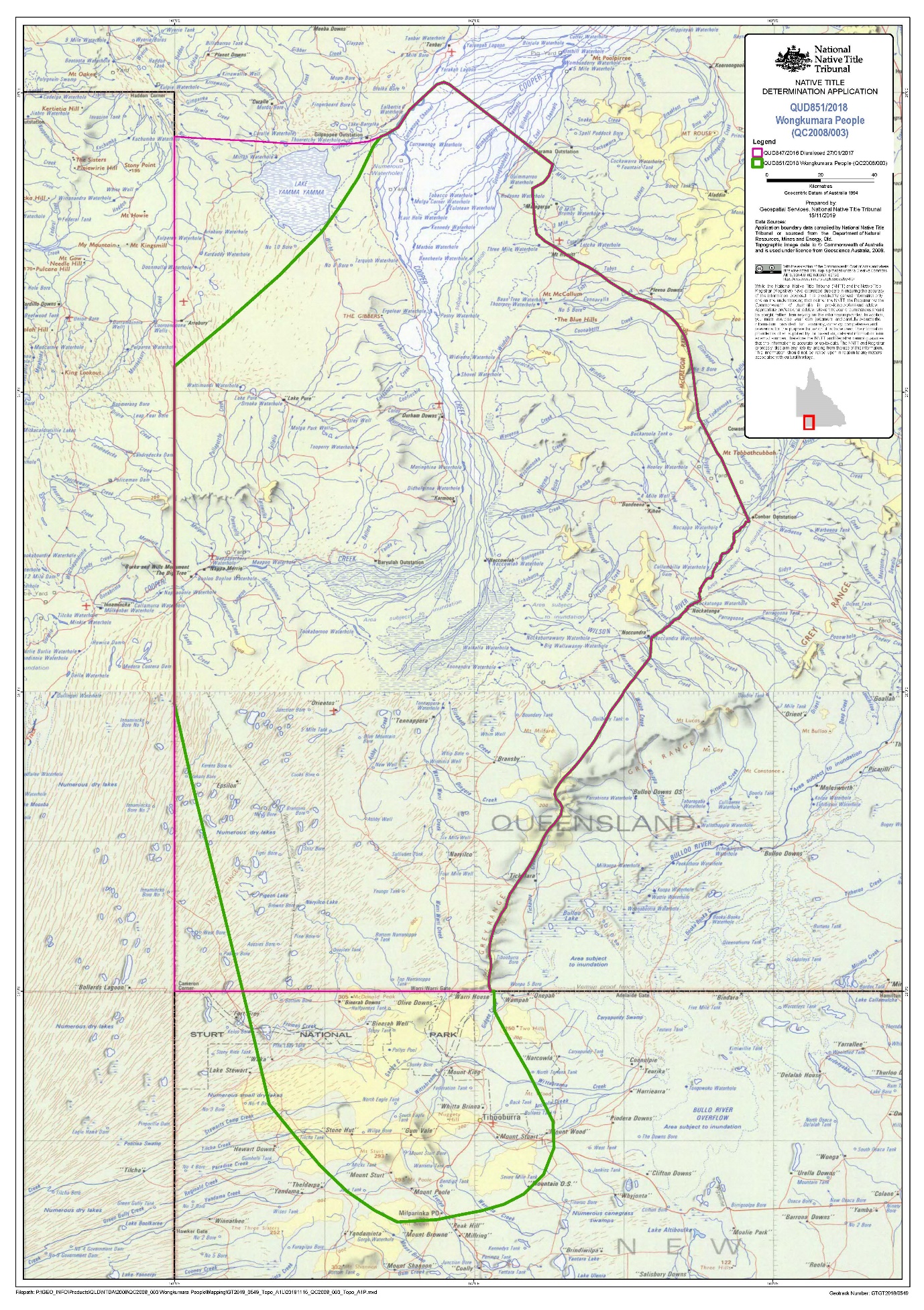

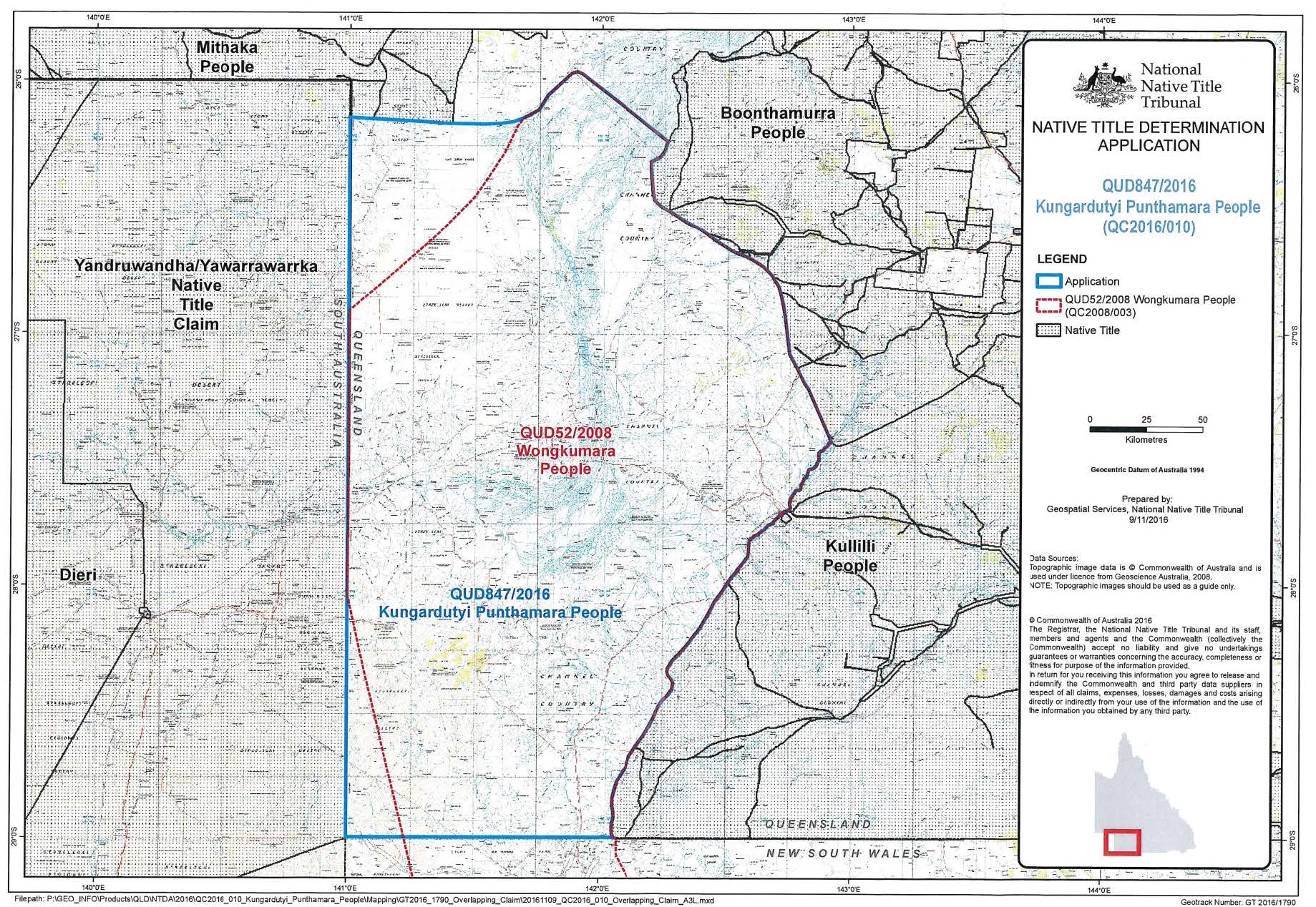

(c) two affidavits of Dr Fiona Powell, anthropologist, affirmed 29 August 2019 and 30 November 2019 respectively;

(d) a map of the Wongkumara claim area marked by counsel for Mrs King to show the part of the Wongkumara claim area in relation to which Mrs King asserts native title rights and interests, being exhibit “CK1”;

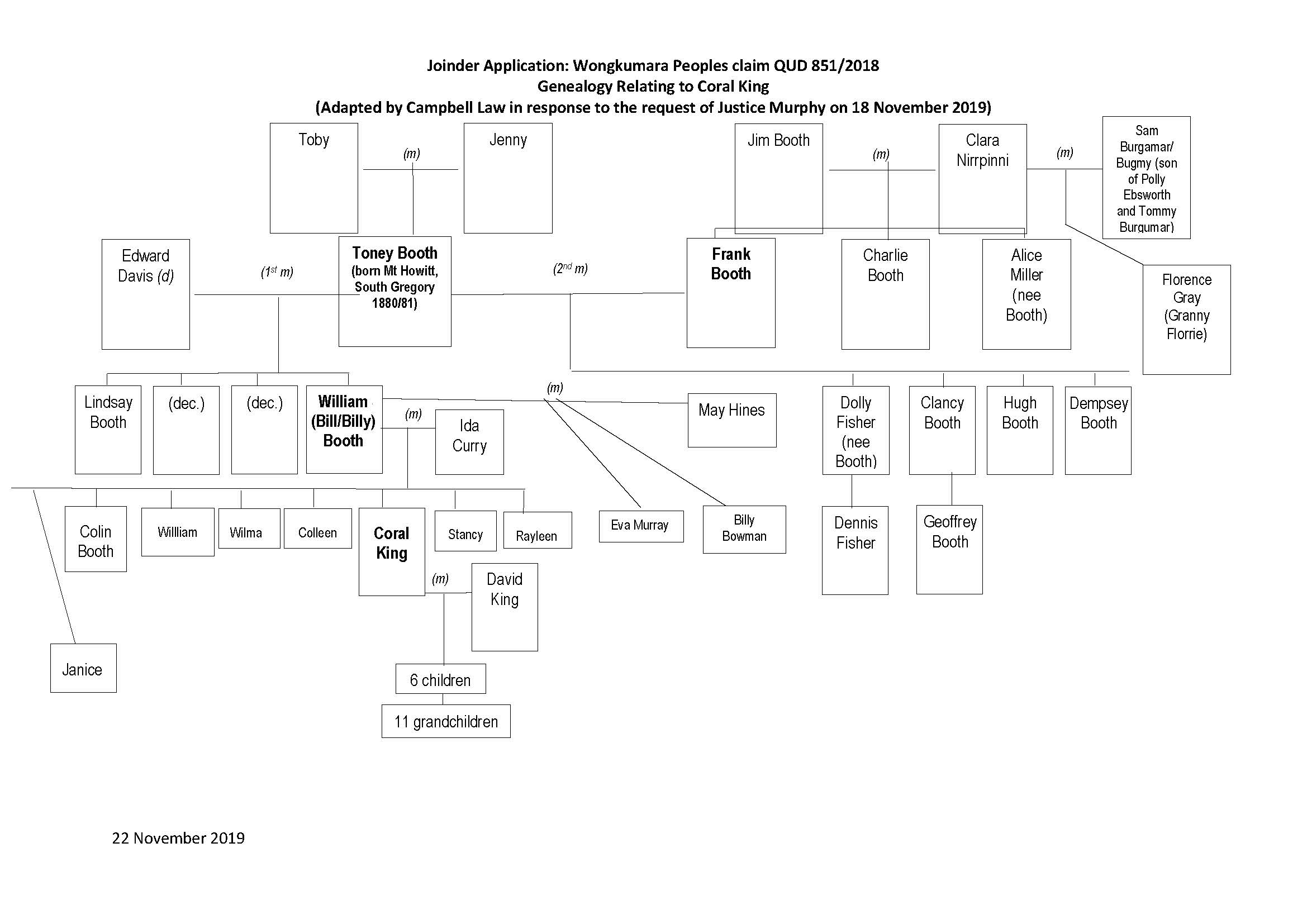

(e) a genealogical chart or family tree, agreed by Mrs King’s solicitors, Campbell Law, showing the descent of Mrs King and her family group from Toney Booth (which is Schedule “B” to these reasons).

11 The Wongkumara applicants relied upon the following material:

(a) an affidavit of Eduard Salomon Neumann, the solicitor for the applicants, affirmed 27 September 2019, which annexes numerous court documents, affidavits, anthropological reports and maps from the Booth and Wallace proceedings; and

(b) an affidavit of Timothy Wishart the Principal Legal Officer of QSNTS affirmed 27 November 2018, which annexes the transcript of the hearing in Wallace.

12 QSNTS, the eighth respondent, also relied on the affidavit of Timothy Wishart, its Principal Legal Officer, referred to above.

13 The evidence shows numerous variants of the spelling of the names of the relevant Aboriginal societies and languages. For example, some of the evidence and historical records refer to the Boonthamara People by names including Punthamara, Bunthamara and Bundhamara, the Wongkumara people by names including Wangkumara and Wannggumara, and Kungardutyi People by names including Kungardutji, Kungaddhutji and Gungagudji. Nothing turns on which of the spelling variants is used.

THE PRINCIPLES RELEVANT TO JOINDER

14 Section 84(5) of the NTA provides as follows:

The Federal Court may at any time join any person as a party to the proceedings, if the Court is satisfied that the person’s interests may be affected by a determination in the proceedings and it is in the interests of justice to do so.

15 There is no dispute between the parties as to the principles to be applied in a joinder application under s 84(5). The joinder applicant must satisfy the following three requirements:

(a) that the joinder applicant has an interest in the relevant claim area for the purpose of s 84(5) of the NTA. Such an interest “need not be proprietary, or even legal or equitable. But the interest must be ‘genuine’, not indirect, remote, or ‘lacking substance’; and it must be capable of clear definition: Far West Coast Native Title Claim v State of South Australia (No 5) [2013] FCA 717 at [28] (Mansfield J); Chippendale on behalf of the Wuthathi People #2 v State of Queensland [2012] FCA 310, [14]-[16] (Greenwood J). It is uncontentious that native title rights and interests are an interest capable of satisfying the requirements of s 84(5): Far West Coast at [30];

(b) that the identified interest in the relevant claim area may be affected by a determination of native title in the proceeding; and

(c) that it is in the interests of justice for the joinder applicant to be joined as a party.

If the Court is satisfied of those matters there is no residual discretion to exercise: Far West Coast at [26]-[27]; Blucher on behalf of the Gaangalu Nation People v State of Queensland [2018] FCA 1369 at [18] (Rangiah J).

16 In Blucher at [21], Rangiah J summarised some of the principles relevant to joinder of persons asserting competing native title rights and interests as follows:

(1) The interests of persons who claim to hold native title rights and interests in relation to the land or waters the subject of a proceeding may be sufficient interests.

(2) A member of another native title group cannot be joined as a respondent for the purpose of acting as a representative to assert native title rights on behalf of the other group. That is because the combined effect of ss 13, 61, 213 and 225 is that an application for a determination of native title can only be made by a duly authorised applicant using the procedures in Pt 3 of the NTA.

(3) A member of another native title group may be joined as a respondent for the purpose of “defensively asserting” native title rights and interests. Such a person is only permitted to pursue a personal claim to such rights and interests: that is, to protect them from erosion, dilution or discount.

[See Munn v State of Queensland [2002] FCA 486 at [8]; Kokatha Native Title Claim v South Australia (2005) 143 FCR 544 at [22], [24]–[25]; Worimi Local Aboriginal Land Council v Minister for Lands (NSW) (2007) 164 FCR 181 at [10]–[11], [26]; Commonwealth v Clifton (2007) 164 FCR 355 at [48], [57]–[58] and [61]; Moses v Western Australia (2007) 160 FCR 148 at [18]; Holborow v State of Western Australia [2009] FCA 1200 at [4]–[5]; Bonner on behalf of the Jagera People #2 v State of Queensland [2011] FCA 321 at [15]–[21]; Lander v State of South Australia [2016] FCA 307 at [73]; A.D. (deceased) on behalf of the Mirning People v State of Western Australia (No 2) [2013] FCA 1000 at [56]–[57]; Isaacs on behalf of the Turrbal People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2011] FCA 942 at [18]–[19].]

17 An applicant for joinder need only demonstrate the existence of the interest he or she relies upon for joinder on a prima facie basis: Wakka Wakka People #2 v State of Queensland [2005] FCA 1578 at [6] (Kiefel J as her Honour then was); Isaacs on behalf of the Turrbal People v State of Queensland (No 2) [2011] FCA 942 at [8] (Reeves J).

18 In Gamogab v Akiba (2007) FCAFC 74; (2007) 159 FCR 578 at [56]-[64] Gyles J, with whom Sundberg J agreed, said that:

(a) it is relevant that the joinder applicant could have been joined as a party to the proceeding as of right if he or she had applied in time. This indicates that the principal issue which arises under s 84(5) is to assess the prejudice occasioned to the other parties and the Court by the delay in applying to be joined (at [59]);

(b) it would be odd in this day and age if delay in applying, in itself, were to radically prejudice a potential party (at [59]);

(c) it is fundamental that an order which directly affects a third person’s rights or liabilities should not be made unless the person is joined as a party (at [60]);

(d) considerable weight should be given to the statutory intention of having all parties whose interests may be affected before the Court at the one time to be dealt with by the one determination (at [64]); and

(e) if necessary, conditions may be imposed upon a joinder) (at [63]).

THE BOOTH FAMILY

19 Mrs King’s first affidavit sets out her relevant family history which is consistent with the family tree confirmed by her solicitors during the hearing (Schedule “B”). Dr Powell’s genealogical research confirmed Mrs King’s evidence in this regard. Mrs King said that:

(a) she is the descendant of an Aboriginal woman named Toney (or Tonie) Booth of the Kungardutyi tribe, the daughter of Toby and Jenny, born in 1880 or 1881 at Mount Howitt Station;

(b) Toney was married twice and had eight children. First, she was legally married to a non-indigenous man, Edward Davis, on 28 October 1905, and they had four children, two of whom died at a young age. The two surviving children were Lindsay Davis born on 23 January 1912 at Kihee station, and William (Bill) Davis, born on 20 August 1914 at Noccundra. William (known universally as Bill) is Mrs King’s father;

(c) following the death of Edward Davis on 2 October 1915, Toney entered into a tribal marriage with Frank Booth, at Eromanga in about 1916. Frank Booth was the son of a non-indigenous man, Jim Booth, and an Aboriginal woman, Clara;

(d) following her marriage to Frank Booth, Toney’s sons from her previous marriage, Lindsay and Bill, took on the surname Booth. Frank Booth and Toney had four children together, Dolly Fisher (nee Booth) (born 1917 at Nockatunga Station), Clancy Booth (born 1921 at Nockatunga Station), Hughie Booth (born 1922 at Nockatunga Station) and Dempsey Booth (born 1924 at Thargomindah);

(e) Bill Booth married Ida Curry and Mrs King is the seventh child of that marriage, born on 15 July 1950 at Woorabinda Aboriginal Settlement; and

(f) Clancy Booth is the father of Geoffrey Booth, and Dolly Fisher (nee Booth) is the mother of Dennis Fisher. Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher are thus grandchildren of Frank Booth and Toney and cousins of Mrs King.

As I have said I describe the relevant descendants of Clara, her son Frank Booth and his wife Toney as “the Booth family”.

THE RELEVANT GEOGRAPHY

20 The south-western section of Queensland has been the subject of numerous competing claims for the recognition of native title rights and interests.

21 As shown in Schedule “A”, the Wongkumara application covers an area in south-west Queensland and north-west NSW, stretching above Mount Howitt, Queensland to the north, in the south to Milparinka Post Office, in the west to the border between Queensland and South Australia and to the Wilson River, Conbar outstation and Nockatunga to the east.

22 To the south-east the Wongkumara claim area is abutted by an area the subject of a native title determination made on 2 July 2014 in favour of the Kullilli People (the Kullilli area): see Smith on behalf of the Kullilli People v State of Queensland [2014] FCA 691.

23 To the north-east the Wongkumara claim area is abutted by an area the subject of a native title determination made on 25 June 2015 in favour of the Boonthamurra People (the Boonthamurra area): see Wallace on behalf of the Boonthamurra People v State of Queensland [2015] FCA 600. Schedule “C” to these reasons is a map of the Boonthamurra area.

24 To the west the Wongkumara claim area is abutted by an area the subject of a native title determination made on 16 December 2015 in favour of the Yandruwandha and Yawarrawarrka People (the Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka area): Nicholls v State of South Australia [2015] FCA 1407.

25 In the Booth proceeding Mrs King, Geoffrey Booth and two others, as applicants, on behalf of a claim group described as the Kungardutyi Punthamara People claimed to have native title rights and interests in relation to an area overlapping the entirety of the Wongkumara claim area above the Queensland/New South Wales border, based on descent from Clara, Toney and other apical ancestors as shown in Schedule “D” to these reasons (the Kungardutyi Punthamara claim area).

26 In the joinder application Mrs King claims to have native title rights and interests based on descent from Toney in relation to the northern half of the Wongkumara claim area, above a line drawn west from Noccundra to the Queensland/South Australian border (the joinder claim area), as shown in Schedule “E” to these reasons which is consistent with exhibit “CK-1”.

27 Schedule “F” to these reasons is a map showing the relationship of the Wongkumara claim area to the areas covered by native title determinations made in favour of the Kullilli, Boonthamurra and Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka Peoples, and overlaid with the Kungardutyi Punthamara claim area.

THE EARLIER CLAIMS BY THE BOOTH FAMILY AND THEIR RESOLUTION

28 Different members of the Booth Family have in five previous proceedings asserted native title rights and interests in relation to the Wongkumara claim area, each time unsuccessfully. Those applications were as follows.

The native title determination application by Clancy Booth

29 On 14 April 1998 Clancy Booth, Geoffrey Booth’s father, commenced a native title determination application on behalf of the Bunthamara People (QUD61871/1998). Paul Hoolihan, the solicitor for Clancy Booth at the time and subsequently also the solicitor for Geoffrey Booth, made an affidavit dated 31 October 2012 in the Wallace proceeding, which is annexed to Mr Neumann’s affidavit in the present application. The affidavit annexes several maps which show that he claimed to have native title rights and interests in relation to a substantial part of the Wongkumara claim area, including the Wilson River area and around Mount Howitt. In Wallace (at [57]), Mansfield J described the area Clancy Booth claimed as follows:

The map markings of the area of country identified by Clancy Booth, with the assistance of another Aboriginal person, extended generally in an oval shape from the western side of the Wilson River to an area roughly near the South Australian/Queensland border including Arrabury Station, and a little north to the lower part of the present claim area. That area covers much of the Wongkumara People claim area, and only the small lower section of the present [Boonthamurra] claim area.

30 Clancy Booth discontinued that application on 14 December 1999.

The native title determination application by Geoffrey Booth

31 On 8 April 2002 Geoffrey Booth filed a native title determination application on behalf of the Bunthamarra People (QUD6014/2002). On 9 May 2003 that claim was dismissed on the basis that it was not properly authorised: see Booth v State of Queensland (2003) FCA 418.

Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher as respondents in the Wallace proceeding

32 In 2006 Mark Wallace and Barbara Olsen, as applicants, commenced a native title determination application on behalf of a native title claim group described as the Boonthamurra People (QUD435/2006) in which they claimed to have native title rights and interests in relation to the Boonthamurra claim area (Schedule “C”) by reason of (as amended) their descent from 24 named apical ancestors.

33 In February 2008, Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher became respondents to the Wallace proceeding. They filed “Particulars of Interest” and a Statement of Agreed Facts and Evidence (as annexed to Mr Neumann’s affidavit) that show that they claimed to have acquired native title rights and interests both in the Boonthamurra claim area and extending substantially beyond it into the Wongkumara claim area, through descent from Clara, Frank Booth and Toney. They described themselves both as Bundamurra People and Kungardutji People and said that those two Peoples shared the same language, had many of the same ceremonies, but had different traditional country. They described themselves as the “Booth family respondents”.

34 The Court made orders for the determination of separate questions to resolve the parties’ competing claims to hold native title rights and interests in relation to the Boonthamurra claim area. Those questions required the Court, amongst other things, to determine whether the Booth family respondents had native title rights and interests, through descent from Clara and Toney, in areas within the Boonthamurra claim area abutting the Wongkumara claim area.

35 The relevant separate questions, and the answers to those questions decided by Mansfield J in Wallace, were as follows (at [6] and [109]):

(1) Were the deceased persons known as Clara and her son Frank Booth Boonthamurra persons?

No.

(2) Did the geographical area with which Clara and her son Frank Booth were traditionally associated extend into the claim area of this claim, and if so to what extent?

On the basis that the expression “traditionally associated” conveys that those persons held under the traditional laws and customs of a relevant native title claim group native title rights and interests in the claim area of this claim:

No.

(3) If so, is it reasonably arguable that Clara and her son Frank Booth acquired native title rights and interests in any part of the Boonthamurra claim area on the basis of that descent, other than as members of the claim group?

Not necessary to answer.

(4) Were the deceased persons known as Toby and/or Jenny, and their daughter, Toney:

(a) Boonthamurra persons;

No.

(b) Kungardutyi persons?

Not necessary to answer (see answer to question (5).

(5) Did the geographical area with which Toby and/or Jenny, and their daughter Toney were traditionally associated extend into the claim area of this claim and if so to what extent?

On the basis that the expression “traditionally associated” conveys that those persons held under the traditional laws and customs of a relevant native title claim group native title rights and interests in the claim area of this claim:

No.

(6) If so, is it reasonably arguable that persons who are descended from Toney acquired native title rights and interests in any part of the Boonthamurra claim area on the basis of that dissent, other than as members of the claim group?

Not necessary to answer.

36 In the hearing to determine the separate questions the Booth family respondents relied on evidence from various members of the Booth family, including Mrs King. His Honour noted their evidence as follows:

(a) Mrs King said that Boonthamurra was her chosen tribe but that “we referred to ourselves as the ‘Wilson River Clan’ “, being people who lived around the Nockatunga and Noccundra area, which was the area where her father, Bill Booth, and his tribe lived (at [68]).

(b) Ivy Booth, Clancy Booth’s wife (and Geoffrey Booth’s mother) said that Clancy always told her that he was Punthamara and that his country was the Wilson River area (at [67]);

(c) Geoffrey Booth said he was told by his father, Clancy Booth, that Frank Booth, his grandfather, was from Noccundra and Nockatunga. He said that around “that way” was Frank Booth’s country and that Nockatunga was “the main feature and central to his country” (at [65]). He testified that Frank Booth was a Boonthamurra man, and that Clancy Booth was from Nockatunga and that his tribe was the Boonthamurra/Wilson River tribe. Mansfield J said that it was in the evidence of Geoffrey Booth and Ivy Booth that the focus on the Wilson River area emerged, noting that the Wilson River area was largely to the south of the Boonthamurra claim area (at [67]);

(d) in relation to Toney, Geoffrey Booth said that she was a Kungadutyi woman who came from “around Eromanga” and that was her country (at [65]). He did not claim to be Kungardutyi as he was following his father’s line, but he had revised his position to also claim to be Boonthamurra through Toney. He said Toney chose Boonthamurra for Clancy Booth and that Clancy Booth made a conscious decision to not identify as Kungardutji “in order to keep the family together”, though Clancy Booth also told his son “a lot about Kungadutji laws and customs” (at [65]). He claimed that the country associated with Toney’s birthplace at Mount Howitt extended westward from there (at [108]); and

(e) Dennis Fisher gave evidence that his mother, Dolly Fisher (nee Booth), was Boonthamurra and she told him that was her tribe. She died when he was very young. That differed from what he said in his affidavit of 11 November 2008 in which he stated that he learned he was Boonthamurra from his cousin Tom when he was an adult. He lived over the road from Frank Booth for seven years in the 1960s and Frank Booth claimed him for his group, but he said he did not learn anything from Frank Booth. That differed from his affidavit of November 2008, where he said he learnt about their family and their history from Geoffrey Booth, which he did not elaborate upon during the hearing (at [69]). Mansfield J did not consider his evidence advanced the claim of the Booth family respondents to be of the Boonthamurra People.

As his Honour noted, the townships of Nockatunga and Noccundra are more or less on the boundary of the Wongkumara and Kullilli claim areas (at [19]), and the Wilson River area overlaps the Boonthamurra, Wongkumara and Kullilli claim areas (at [47]).

37 In relation to the claim based in descent from Clara, Mansfield J concluded on the evidence that Clara was a Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka woman, not Boonthamurra, and that it followed that Frank Booth and his lineal descendants including Clancy Booth and the Booth/Fisher families are not Boonthamurra persons through Clara, with native title rights and interests in relation to the Boonthamurra claim area (at [86]-[87], [89], [95]-[96] and [98]).

38 In relation to the claim based in descent from Toney, Mansfield J accepted that in 1938, Norman Tindale, an Australian anthropologist and archaeologist, who spent many years of his professional life mapping tribal areas of Aboriginal people and undertaking genealogies of the Aboriginal population in parts of Australia, identified Toney as of the Kungardutyi tribe and “of Mount Howitt”. His Honour found that Toney was a Kungardutyi woman born in about 1876-1880 at Mount Howitt Station (at [101], [105]). Mount Howitt Station is roughly on the boundary of the Boonthamurra and Wongkumara claim areas.

39 The question remained though as to whether Toney’s country, Kungardutyi country, was part of the Boonthamurra claim area (at [105]).

40 To decide that question the Court had before it:

(a) the evidence of Barbara Bond and Mark Wallace who denied that the Booth family were Boonthamurra (at [71]-[72]), the evidence given by the four members of the Booth family summarised above, together with the evidence of Mr Hoolihan as to what Clancy Booth had told him (at [56]-[63]), and some letters in which Clancy Booth described himself as a Kullilli elder rather than Boonthamurra (at [59]-[60]);

(b) a substantial body of expert anthropological evidence, including a joint report by a conclave of experts comprising Professor Trigger, Dr Andrew Sneddon, Dr Fiona Powell and Inge Riebe. Professor Trigger, Dr Sneddon, Dr Powell and Michael Southon, who conducted the primary research for the Wallace applicants, also gave concurrent evidence in the hearing.

41 His Honour gave careful consideration to the lay and expert evidence, giving particular attention to the evidence of Dr Powell (at [77]-[83]). In relation to Dr Powell’s evidence his Honour said (at [83]):

Most importantly, the crucial part of Dr Powell’s reasoning was to tie the term Kungadutji to a language or language land holding group with country that was occupied by Punthamara and/or Wongkumara People. She expressed the view that Kungadutji was the name of the language distinguished by others as “Punthamara” and/or “Wankumara” and that each of Kungadutji, “Punthamara” and “Wankumara” were socio-territorial identities associated with the region including Mt Howitt and the Wilson River region. Dr Powell’s view was that, over time, Kungadutji in that way stopped being used and thus, when Frank Booth identified himself as Kungadutji to Tindale, he was also in effect identifying himself as Punthamara (spelling variant of Boonthamurra). There are obviously several steps in that process of reasoning: the location of Kungadutji language use and its country; the use of that term by Frank Booth as indicating his country; and the step of equating Kungadutji country with Boonthamurra country for the purpose of tying Frank Booth to the present claim area. As noted above, there is an alternative use of the term Kungadutji – to describe an initiated man. So much was not in dispute. The step of taking its use by Frank Booth, as the informant to Tindale, as indicating that it describes his country rather than his initiated status is tied to the probability or otherwise that it describes his country around or in relation to the present claim area.

42 Mansfield J did not accept Dr Powell’s view that Kungardutyi country was in the Boonthamurra claim area. His Honour said (at [84]):

I think the strong preponderance of the evidence is that the Kungadutji People, as a language group holding interests in country, hold their interest quite remotely from the present claim area. Tindale’s journal records an interview with George Dutton describing the Kungadutji group as occupying the “upper Buloo River” area. Dr Breen’s interviews with George McDermott and King Miller in the 1960s record it as the area of Naryilco to Tibooburra. Dr Hercus and others in their study of Aboriginal Cultural Association with Mutawintji National Park entitled “Mutawintji”, prepared for the Registrar, Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 (NSW), say much the same thing. Their report at para 4.4 says:

All the evidence places Kungardutji in the area immediately east and north-east of Tibooburra and around the southern parts of the swampy areas around Lake Bulloo.

They refer to other earlier sources to support that. That area is, of course, in the north-western part of New South Wales.

43 Nor did his Honour consider that the “critical step” in Dr Powell’s reasoning – to tie the term Kungadutyi “to a language or language land holding group with country that was occupied by Punthamara and/or Wongkumara People” - was warranted on the evidence. His Honour further considered that another step in Dr Powell’s reasoning – namely that Kungardutyi is “a tribal ascription rather than a general description of status as an initiated person” - was also not warranted on the evidence (at [86]).

44 His Honour concluded (at [106]) as follows:

In my view, on the evidence, the views of Professor Trigger, Dr Sneddon and Mr Southon, based partly on Dr Hercus’ analysis, that Kungadutji was more likely to be further south than the Boonthamurra claim area are more probably correct. I have discussed above the reason why I conclude that the Kungadutji People as a language group is an area well remote from the present claim area.

(Emphasis added)

That reiterated the view his Honour had expressed (at [84]). That finding placed Kungardutyi country well away from the Wongkumara claim area in relation to which Mrs King now claims, through the joinder application, to have acquired native title rights and interests through descent from Toney (as shown in Schedule “E”).

45 His Honour found (at [107]) that there was “no evidence” which could support a finding that by her parentage Toney acquired native title rights and interests in the Boonthamurra claim area.

46 On the basis of those findings Mansfield J answered the separate questions as set out above; finding that Clara and her son Frank Booth, and Toney, did not have native title rights or interests in geographical areas which extended into the Boonthamurra claim area (at [110]). Thus their descendants, the Booth/Fisher families, could not have acquired native title rights and interests in that area through descent from them. His Honour ordered the removal of Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher as respondents to the Wallace proceeding.

Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher as respondents in the Wongkumara application

47 In March 2008 Noelene Edwards and others commenced the Wongkumara application (QUD52/2008) on behalf of a native title claim group described as the Wongkumara People, in which they claimed to have native title rights and interests in relation to the Wongkumara claim area (Schedule “A”) through descent from one or more of 15 named apical ancestors. The application does not name Clara, Toney and Frank Booth as apical ancestors.

48 In November 2008 Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher became respondents to the Wongkumara application. They claimed to have native title rights or interests in relation to part of the Wongkumara claim area based on their descent from Clara, Frank Booth and Toney. To identify the area in relation to which they claimed to have traditional rights and interests they relied on maps contained in the affidavit by Mr Hoolihan. The maps that they relied upon show that they claimed to have native title rights and interests in relation to a substantial part of the Wongkumara claim area, including the Wilson River area and around Mount Howitt.

49 Mrs King filed an affidavit in support of that claim, which was in essentially the same form as her affidavit in the Wallace proceeding. She again claimed to have acquired traditional rights and interests in the Wilson River area, around Nockatunga. Geoffrey Booth filed an affidavit in which he said that the area around Nockatunga was in the southern part of the country in relation to which he claimed native title rights and interests, and he described that area as “part of our country that we associate with Granny Tony’s people and which we call Kungardutji country”.

50 In February 2016 the Wongkumara applicants filed an interlocutory application seeking the removal of Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher as respondents. The application was listed for hearing on 8 March 2016. On 3 March 2016 Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher withdrew as respondents.

As applicants in the Booth proceeding

51 Eight months later, on 4 November 2016, Geoffrey Booth, Mrs King, Stewart Williams and Veronica Booth, as applicants, commenced a native title determination application on behalf of a native title claim group described as the Kungardutyi Punthamara People, in which they claimed to have acquired native title rights and interests in relation to an area which overlapped the entirety of the Wongkumara claim area north of the Queensland/NSW border (Schedule “D”), based on their descent from Toby and Jenny (Toney’s parents ), Alex and Maggie (Clara’s parents), Nancy (the mother of Rosie Williams) and Davey and Betty (the parents of Durham Bob).

52 In Booth, handed down on 9 June 2017, Jagot J dismissed the proceeding on three grounds: (a) because the application was not properly authorised; (b) because it was an abuse of process; and (c) because it had no reasonable prospect of success within the meaning of s 31A(2) of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the FCA).

53 In relation to the abuse of process issue Jagot J noted that:

(a) Clancy Booth had made a native title determination application in relation to the Wongkumara claim area in 1998, which was discontinued (at [46]);

(b) Geoffrey Booth had made a native title determination application in relation to the same area in 2002, which was dismissed (at [47]);

(c) in Wallace the Court found that Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher did not have native title rights or interests in the Boonthamurra claim area, which area abutted the Wongkumara claim area, by reason of their descent from either Clara or Toney (at [48]);

(d) Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher were previously respondents to the Wongkumara application and then withdrew when challenged by the Wongkumara applicants (at [61]); and

(e) the Booth proceeding concerned an area overlapping the entirety of the Wongkumara claim area above the Queensland/New South Wales border (at [62]).

54 Her Honour noted that the Booth applicants claimed to have native title rights and interests in the Wongkumara claim area based on their descent from Clara (who was an apical ancestor for the Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka native tile determination) and/or Toney, being the same apical ancestors that were the subject of the separate questions in Wallace, except for Stewart Williams who claimed descent from Nancy (his grandmother) and Clancy Booth (his grandfather). Her Honour said that nothing was shown in relation to Nancy’s lineage other than to say that she was a relative of Frank Booth (at [62]). On the basis that Stewart Williams is the grandson of Clancy Booth I note that he is a descendant of both Clara and Toney.

55 Her Honour said that in Wallace Mansfield J concluded:

(a) (at (45]-[49]) that the Booth family respondents’ claim to have native title rights and interests by reason of their descent from Clara or Toney was not limited to the Boonthamurra claim area but extended into the Wilson River area which was on the border of the Boonthamurra, Wongkumara and Kullilli claim areas: Booth at [51];

(b) (at [86]-[87] and [98]) that Clara was Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka rather than Boonthamurra, and therefore Frank Booth and his lineal descendants were not Boonthamurra people with traditional rights and interests in the Boonthamurra claim area through Clara: Booth at [56]; and

(c) (at [84], [100] and [105]-107]) that Kungardutyi People, “as a language group holding interests in country”, held their interests in an area to the south and “well remote” from the Boonthamurra claim area, being an area in north-western New South Wales: Booth at [57].

56 In Booth Jagot J did not accept the contention of Mrs King and Geoffrey Booth that in Wallace Mansfield J did not determine the status of apical ancestors outside of the Boonthamurra claim area (at [64]). In relation to the claim based on descent from Clara her Honour said that Mansfield J’s finding that Clara was not Boonthamurra, and was instead Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka was an essential fact underpinning the decision that Clara and thus her descendants could not have traditional rights and interests in the Boonthamurra claim area. It was also consistent with the subsequent decision in Nicholls that Clara is an apical ancestor for the native title determination made in favour of Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka People.

57 In relation to the claim based on descent from Toney, her Honour said that Mansfield J’s finding that Kungardutyi country was far to the south of the Boonthamurra claim area, and in north-western New South Wales underpinned his Honour’s conclusion that descent from Toney could not found traditional rights and interests in the Boonthamurra claim area (at [66]).

58 Her Honour concluded (at [67]-[68]):

Accordingly, to remove Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher as respondents to the Boonthamurra proceeding, Mansfield J had to be satisfied that neither descent from Clara nor Toney gave Geoffrey Booth rights and interests in the Boonthamurra claim area. To reach the conclusion that Geoffrey Booth had no such rights and interests and thus was not a proper party to the Boonthamurra proceeding it was necessary for Mansfield J to find, as he did, that Clara was Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka whose country was to the west of Boonthamurra country and Tonie was Kungardutyi whose country was remote from Boonthamurra country, being in north-western New South Wales. But for these findings, including that the location of Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka and Kungardutyi country was nowhere near Boonthamurra country, there would have been no factual foundation for his Honour to have ordered removal of Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher as parties from the Boonthamurra proceeding. These findings are inconsistent with Clara or Tonie being the source of any traditional rights and interests in the Wongkumara claim area to the immediate south of and abutting the Boonthamurra claim area.

Despite this, in the Kungardutyi Punthamara application there is a single claim area which is to the immediate south-west of Boonthamurra country, overlapping the Wongkumara claim area, with traditional rights and interests said to be sourced from descent from Clara and Tonie.

59 Her Honour considered the Booth proceeding to be an abuse of process because it sought to re-litigate the issue as to whether Clara was a Boonthamurra person by re-branding the relevant Aboriginal society from Boonthamurra to Kungardutyi Punthamara. Her Honour said that was vexatious and oppressive to QSNTS, which was party in Wallace and in the Wongkumara application, and also to the Wongkumara applicants. Her Honour considered it would also bring the administration of justice into disrepute because the identity of Clara as a Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka person was essential to the orders removing Geoffrey Booth as a party and to the native title determination in Nicholls (at [65]).

60 Her Honour also found the Booth proceeding to be inconsistent with the way Geoffrey Booth put the case in Wallace in a number of respects. Her Honour said that in Wallace Geoffrey Booth gave evidence that the lands of Kungardutyi people were separate from those of Boonthamurra, and that Kungardutyi country was to the north-west of Boonthamurra land whereas Wongkumara land was to the south of Boonthamurra land. Ultimately he contended that Toney was Kungardutyi but on the basis that “Kungardutyi was a part of the Boonthamurra and Wongkumara identity so as to found rights and interests, via Tonie in the Boonthamurra claim area” (at [66]) Mansfield J rejected that contention on the basis that Toney was Kungardutyi but that Kungardutyi country was far to the south of Boonthamurra country, in north-western New South Wales, which finding underpinned his Honour’s conclusion that descent from Toney could not found traditional rights and interests in the Boonthamurra claim area.

61 Her Honour held (at [69]-[71]):

[69] As QSNTS put it, Geoffrey Booth as a representative of the Booth family conducted the Wallace litigation on one basis and, having failed, now seeks to conduct litigation for the Kungardutyi Punthamara People on an inconsistent basis. The combining of the formerly separate alleged identities of Kungardutyi and Boonthamurra creates a new society, never identified in Wallace, said to have rights and interests in relation to a new area of land, the effect of which is to eradicate the land to the immediate south of the Boonthamurra land which was recognised by Geoffrey Booth as Wongkumara country. This too is an abuse of process as it is oppressive of QSNTS and the Wongkumara applicants. In Wallace at [48] Mansfield J said that:

…the general south-west area of Queensland has been the subject of extensive claims made over a long period of time. All of those claims (other than the ones presently on foot) have either been dismissed or discontinued. If there is to be another claim, it should have been brought earlier and in a timely manner.

[70] Yet having failed in Wallace, Clara having been determined to be not Boonthamurra but Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka and an apical ancestor of the Yandruwandha/Yawarrawarrka native title claim group whose land is to the west, and Tonie having been determined not to be Boonthamurra but Kungardutyi whose land was to the south of and remote from the Boonthamurra land (that is, land in the north-western part of New South Wales), the Kungardutyi Punthamara applicants made a claim in November 2016 over the same claim area as the Wongkumara applicants (the Wongkumara applicants claim having been on foot since 2008), being land immediately to the south of the Boonthamurra land. This also involves both oppression to QSNTS and the Wongkumara applicants and, if permitted, would bring the administration of justice into disrepute.

[71] Moreover, Geoffrey Booth was a party to the Wongkumara application and asserted interests in the Wongkumara claim area since 2008. When the Wongkumara applicants filed an interlocutory application in February 2016 seeking to challenge the existence of those interests in the Wongkumara claim area Geoffrey Booth withdrew as a party from the Wongkumara proceeding. Subsequently, the Kungardutyi Punthamara application was filed claiming rights and interests in the same area. As the Wongkumara applicants submitted, if it is the contention of the Booth family (and the Williams family) that apical ancestors have been omitted from the Wongkumara application then the proper way for that question to have been determined was as an issue in the Wongkumara proceeding. The making of an overlapping claim on behalf of a sub-set of a society, some eight years after the Wongkumara application was filed, is not a permissible way to resolve this issue. Geoffrey Booth had this opportunity to resolve his interests in the Wongkumara claim area in 2016 but declined to take that opportunity by withdrawing as a party from the Wongkumara proceeding before the Wongkumara applicants’ interlocutory application to determine this issue was heard. For Geoffrey Booth now to be an applicant in the Kungardutyi Punthamara application involves oppression of QSNTS and the Wongkumara applicants which also would bring the administration of justice into disrepute.

62 Her Honour said (at [74]) that exercising “a broad merits-based judgment” it was apparent that the actions taken by Geoffrey Booth in the past had been by him as a representative of the Booth family generally.

63 Her Honour then turned to consider whether the Booth proceeding had a reasonable prospect of success pursuant to s 31A(2) of the FCA, and cited (at [77]) the principles set out by the High Court in Spencer v Commonwealth of Australia [2010] HCA 28; (2010) 241 CLR 118 at [17], [22], [24], [25] and [60].

64 Her Honour found (at [78]) that the application has no reasonable prospects of success because:

(a) it was not properly authorised, as a matter of law, and it was not in the interests of justice for the proceeding to be heard despite the lack of proper authorisation; and

(b) it involved an abuse of process which ought not be permitted.

65 Her Honour concluded that the factual circumstances which made the proceeding an abuse of process also meant that, independently from that doctrine, the proceeding had no reasonable prospects of success (at [79]-[80]), including because:

(a) all of the available material indicates that the Kungardutyi Punthamara People are a sub-set of a broader regional society which did not vest in sub-groups any rights or interests in particular areas of land;

(b) it is also not apparent how descent from Clara or from Toney could give traditional rights and interests in the Wongkumara claim area given the findings in Wallace, the determination in Nicholls and the lack of any fresh evidence in support of the Kungardutyi Punthamara application. The evidence in support of the Booth proceeding appeared to be a mere selection of evidence from that relied upon by Geoffrey Booth in Wallace, with references to Boonthamurra rebranded to be references to Punthamara Kungardutyi.

On this basis as well her Honour concluded that the application should be summarily dismissed.

THE EVIDENCE IN SUPPORT OF THE JOINDER APPLICATION

Mrs King’s evidence

66 Mrs King adduced a series of historical records to establish that Toney was a Kungardutyi woman, the identity of Toney’s children, that she was born at Mount Howitt in 1876-1880, and that she and Frank Booth had lived at Noccundra and Nockatunga until they were removed to Barambah Aboriginal Settlement in 1930. It is unnecessary to detail these records because it is accepted by the Wongkumara applicants that: (a) there is evidence to suggest that Toney was born at Mount Howitt Station in 1880/1881; (b) in 1938 the researchers Norman Tindale and Joseph Birdsell had recorded information from Aboriginal persons then living at Woorabinda and Brewarrina Aboriginal Settlements (the Tindale records) in which Toney was identified as Kungardutyi; and (c) Mrs King is a descendant of Toney.

67 In summary, Mrs King deposed that:

(a) she was told by her father, Bill Booth, that his mother Toney and her people came from the Wilson River-Cooper Creek region of south-west Queensland, which area was their homeland;

(b) she was told that her country was the same as Granny Toney’s country and Granny Clara’s country which includes Mount Howitt, Nockatunga and the Wilson River-Cooper Creek area;

(c) she grew up hearing her father and other relations speak Punthamara, and was told this was her family’s language because it was their ancestor’s language. She now understands that her family’s language is alternatively known as Punthamara, Wangkumara or Kungardutyi, which language belongs in the Wilson River-Cooper Creek region, which her father told her was Toney’s country; and

(d) although she lives away from the Wilson River-Cooper Creek region she has a continuing connection with it and has sought to “keep in touch” with the country and to uphold traditional laws and customs.

68 Mrs King described her role in the Booth family’s earlier claims to have native title rights and interests in the areas outlined above as follows:

(a) she supported Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher as respondents in the Wallace proceeding because the Boonthamurra claim covered part of the country which she understood was her country. She was “astonished” by the decision in Wallace to the effect that Toney’s country was in north-west NSW, as that was fundamentally different to what she had always been told by her father, uncles and aunts;

(b) she knew that the Wongkumara claim went over Toney’s country and so, together with Geoffrey Booth and others, she commenced the Booth proceeding in order to protect their native title rights and interests. She understood that the Court dismissed the Booth proceeding because of the decision in Wallace and other reasons; and

(c) in 2018 she became aware of new evidence in the Hercus Declaration. Although that evidence did not change anything for her because she always believed where her country’s boundaries were, the new evidence came from an expert and confirmed her previously stated position.

Stancey Booth’s evidence

69 Mrs King’s sister, Stancey Booth, confirmed the family history as stated by Mrs King. She described herself as a member of the Kungardutyi Punthamara People through descent from her grandmother Toney and her father Bill Booth. She said that her family belongs to the Wilson River-Cooper Creek region of south-west Queensland and that when she was growing up her father “would always talk about Nockatunga” and say that “his country was west of the Grey Range”.

The Hercus Declaration

70 Mrs King annexed the Hercus Declaration, made 15 December 2017, to her first affidavit. It is significant to her argument and therefore appropriate to set it out in some detail. Dr Hercus stated:

(a) it is important to note that historical records from the time record that ‘Kungardutyi’ is not a tribal name. It is simply a noun meaning that these people have been initiated through the rites of circumcision, as all of the Wilson River men, Wangkumara and Punthamara, were. But the practice was not restricted to those tribes and it had been gradually spreading eastward in the 19th century (at [1]-[3] of the Hercus Declaration);

(b) a draft map made by Tindale in 1938 and a later map he made in 1974 show the circumcision line; being the line where the easterly movement stopped and the whole system broke down when Europeans took the land. The Hercus Declaration reproduced a portion of those two maps. Dr Hercus said that those maps show that the country that Tindale labelled ‘Kungardutyi’ is to the west of Mount Howitt and a long way from north-western NSW. Tindale associated the term ‘Kungardutyi’ with an area he described in 1974 as “Cooper Creek north of Durham Downs; east to Mount Howitt and Kyabra Creek, northwest to near Lake Yamma Yamma” (at [11]).

(c) the people who would have been most anxious to stress that they practice circumcision were those who lived in close proximity to those who did not. Some people who lived in an area of far north-western NSW were mentioned as ‘Kungardutyi’, presumably to reinforce the fact that they were circumcised. That is why information about that group was included in a report titled “Mutawintji Aboriginal Cultural Association with Mutawintji National Park” (the Mutawintji report) prepared by Dr Jeremy Beckett, Dr Sarah Martin and Dr Hercus (at [6]).

(d) “[t]he available evidence indicates that the use of the term ‘Kungardutyi’ by or for Wangkumara-Punthamara speakers as an alternative term for their identity or their language was probably a widespread practice and was not confined to one specific local group of speakers. This means that there is no reason that Wangkumara-Punthamara speakers should not call themselves also or be identified by others as ‘Kungardutyi the circumcised ones’ in other parts of the country associated with these speakers”. That is what happened in 1938 when Tindale interviewed Frank Booth (at [10]);

(e) it was likely that Tindale was “not aware that the term ‘Kungardutyi’ is a ‘shifter’term and that in particular contexts, was widely used in former times to distinguish the circumcised from the non-circumcised or as an alternative name for a particular language associated with south-west Queensland or for speakers of this language.” (at [11]); and

(f) that her post-Mutawintji research confirmed that “the use of the terms Punthamara or Wangkumara or Kungardutyi is context-dependent, and that, with respect to distinguishing a particular south-west Queensland Aboriginal language or a language-named identity, the terms Wangkumara and Punthamara are not mutually exclusive (at [12]);

71 Dr Hercus concluded as follows (at [13]-(14]):

The records made by Norman Tindale and Joseph Birdsell in 1938 pertain to a Kungardutyi group whose members include the family of Frank Booth and his wife Tonie. This is the Kungardutyi group that Tindale locates within the Wilson River-Cooper Creek region on the maps referred to above. It is clear from the Tindale records that this location is based on information supplied by Frank Booth and Tindale’s analysis of the written records that were available to him for his consideration. When these records are considered in conjunction with other records, in particular the linguistic records (Gavan Breen’s work with Frank Booth and Frank Booth sister Alice Millar, Nils Holmer’s work with Frank Booth’s sister Florrie Gray and Janet Matthews’ work with Frank Booth’s son, Bill Booth), it is clear that this particular Kungardutyi group spoke a language that was identified by most of the speakers as ‘Punthamara’ and by some as ‘Wangkumara’ or ‘Kungardutyi’. That is the language known today as ‘Wangkumara-Punthamara’ or ‘the Wilson River language’, speakers of which include members of the Booth family, members of the Ebsworth family and others, who have associations with south-west Queensland and north-west New South Wales.

Some of my findings of my post Mutawintji research are set out in my article “Language and Groupings of Wangkumara and Punthamara People”. In this article I refer to Kungardutyi 1 and Kungardutyi 2. Those are clearly not the same group: Kungardutyi 1 is a group in the Cooper-Kyabra region and Kungardutyi 2 is a group located in north-west NSW group mentioned in the Mutawintji article. The Tindale records about Kungardutyi indicates that my article needs to be revised to include a Kungardutyi 3 group.

(Emphasis added.)

Dr Powell’s evidence

72 Dr Powell is an expert anthropologist engaged by Mrs King. She has had a long involvement in proceedings in which the Booth family have claimed to have native title rights and interests in the relevant areas. During work she undertook in 2000-2004 in relation to the Wongkumara application she compiled some information about Mrs King’s antecedents and related persons. Then, from 2008 she conducted further research in relation to Mrs King’s antecedents and related persons, including by reviewing two reports prepared in 2010 and 2011 by Michael Southon for the Boonthamurra application. Dr Powell affirmed two affidavits in the joinder application in which she lists and annexes her earlier relevant reports.

73 By reference to various historical records Dr Powell said that Toney was born at Mount Howitt in 1876 or 1880 of two Aboriginal parents named Toby and Jenny. She said that her genealogical research confirmed the family history provided by Mrs King including that Mrs King is descended from Toney. That evidence is uncontentious.

74 Dr Powell considered it significant that Toney was born at Mount Howitt Station because: (a) it located Toney and her parents in that area in the period 1876-1880 which is shortly after the establishment of effective sovereignty of the State of Queensland in the region; (b) it established that Toney’s parents were born in the pre-sovereignty era; (c) it showed that Toney was born more probably than not within or near the region that Mrs King and other descendants said they were told was her parent’s country; and (d) Mount Howitt is associated in archival records dating from 1880 with the Koonandahburry (or Kurnandaburi) tribe whose language Dr Breen, an expert linguist, said in a 2015 report titled “Report on behalf of the Wongkumara Claimants” was “that of the Wilson River”.

75 Dr Powell also relied on historical records which in her opinion show that Toney had a long association with the Wilson River-Cooper Creek region, being:

(a) a 1905 letter by Mr Davis which described Toney as a “native of Mount Howitt”, and the Register of Permits for the Employment of Aboriginals kept by the Protector of Aboriginals, Nocundra for 1919 which recorded her as “a native of Nockatunga”. Mount Howitt and Nockatunga are pastoral properties located within the Wilson River-Cooper Creek region and both are located in the northern part of the Wongkumara claim area;

(b) the same Register of Permits for the Employment of Aboriginals recorded Toney as one of only six Aboriginal persons out of 38 Aboriginal persons registered as employed under a permit at Nockatunga Station who are recorded as being ‘native’ to that station rather than elsewhere.

(c) Toney’s marriage certificate and the birth and death certificates of her children from her unions with Edward Davis and Frank Booth which show that during her lifetime she lived at Mount Howitt, Nappa Merrie, Kihee, Noccundra and Nockatunga.

Dr Powell considered the records indicated that Toney had a lifelong association with the Wilson River-Cooper Creek region, notwithstanding that she was forcibly removed from the area in 1930.

76 Dr Powell relied on historical records in relation to Toney, Frank Booth and Bill Booth (Mrs King’s father) which in her opinion associated them with ‘Kungardutyi’ and ‘Punthamara’. She said that in 1938 Tindale recorded Toney as Kungardutyi, her son, Bill Booth (then 27 years old ) as Kungardutyi, and her husband Frank Booth as Kungardutyi. Dr Breen recorded Frank Booth as a Bundhamara (Punthamara) speaker. Frank Booth told Dr Breen that Bundhamara and languages named Wannggumara (Wangkumara) and Gungagudji (Kungardutyi) were “the same”. In Dr Powell’s opinion whether the term ‘Kungardutyi’ or ‘Punthamara’ is used is context-dependent, and her research also located records that associate ‘Kungardutyi’ with ‘Wangkumara’.

77 On the basis of her research Dr Powell said that Frank Booth and his family spoke Punthamara, his sister Alice Miller spoke Wangkumara, Frank Booth learned Punthamara at Durham Downs and “spoke it in the Wangkumara way”, Frank Booth’s younger sister Florrie Gray spoke Punthamara, Clancy Booth (Bill Booth’s brother) identified as Punthamara, and Jack O’Lantern who was the adopted son of Frank Booth spoke Wangkumara.

78 Dr Powell considered Punthamara had the broadest distribution of the three language names Kungardutyi, Punthamara and Wangkumara. In her opinion Punthamara or one of its accepted variants is associated in archival records with places within the northern part of the Wongkumara claim area, including Wilson River, Cooper, Mount Howitt, Cooper Creek south of Mount Howitt, Nockatunga, Conbar, Innamincka, Chaselton, Oontoo, Tinapera, Durham Downs, and Naryilco, and also beyond the Wongkumara claim area. She said that in some records or research (for example Tindale 1940, 1974) those three names are used to identify territorial groups or tribes. In others as summarised by Dr Breen in 2015 they are names for languages as well as for Aboriginal tribes or groups.

79 Dr Powell considered the Hercus Declaration to be significant in that it contains fresh information about Dr Hercus’ research and insight into the historical records about the term Kungardutyi with special reference to the Kungardutyi that Tindale associated with the Mount Howitt-Cooper Creek area. She also regarded the Hercus Declaration as significant because it refers to research that Dr Hercus undertook in 1999 when she interviewed Clancy Booth and other members of the Booth family, which research was not available or considered by the experts in Wallace.

80 She noted that the Hercus Declaration said that:

(a) in 1938 Tindale identified the family of Frank Booth and Toney as Kungardutyi and located them in the Wilson River-Cooper Creek region;

(b) “the country that Tindale actually labelled as Kungardutji on his 1974 map is to the west of Mount Howitt and a long way from north-west NSW;

(c) Dr Breen recorded from Frank Booth, George McDermott and Alice Miller that Kungardutji was the name of a language that was the same or almost the same as the language that he called the “Wilson River language”, which Dr Hercus called the Wangkumara-Punthamara language; and that Dr Breen mentioned that a 1965 recording of ‘Kungkatutyi from Bob Parker was in a language that was identical or almost identical to Wangkumara and Punthamara; and

(d) that the use of the term ‘Kungardutji’ by or for Wangkumara-Punthamara speakers as an alternative term for their identity or their language was probably a widespread practice and was not confined to one specific local group of speakers. There was no reason why Wangkumara-Punthamara speakers should not call themselves also or be identified by others as ‘Kungardutyi the circumcised ones’ in other parts of country associated with these speakers.

81 Dr Powell said that the Kungardutyi 3 group to which Dr Hercus referred is the group that Tindale represented in the maps set out in the Hercus Declaration, which drew on information provided at the time by Frank Booth and members of his family. In her opinion, Dr Hercus clearly regarded the Kungardutyi 3 group as a valid group, whose members included the family of Frank Booth, who Dr Hercus knew from her own research identified as Punthamara and who were speakers of a language that she identified as Wangkumara-Punthamara’. This group was not the same as the Kungardutyi 1 and Kungardutyi 2 groups earlier identified by Dr Hercus. In Dr Powell’s view the Kungardutyi 3 group includes Frank Booth and others who were interviewed by Tindale in 1938, and whose descendants were interviewed by Dr Hercus in 1999 who were recorded as identifying as Punthamara, which is the language Dr Hercus identified as the Wilson River Wangkumara-Punthamara language.

82 In Dr Powell’s opinion a “substantial portion” of the area that Dr Hercus associated with the Kungardutyi 3 group falls within the northern part of the Wongkumara claim area and includes the areas around Mount Howitt and the Wilson River-Cooper Creek area.

83 Dr Powell did not though agree with Dr Hercus’ statement that Kungardutyi is not a “tribal name” and is “simply a noun meaning that these people have been through the rights of circumcision, as all the Wilson River people were.” She accepted that the term “Kungardutyi” has the meaning “circumcised” but found evidence that the term is not confined to a named area and people located in northern New South Wales, as suggested in the Mutawintji report. In her opinion Kungardutyi is the name for a language or group or groupings associated with places or areas in Queensland, including places or areas that are within the Wongkumara claim area, as well as for a social category meaning “circumcised”.

84 Dr Powell was, as I have said, an expert witness for the Booth family in Wallace and she also undertook research for them when Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher were respondents to the Wongkumara application. She made it clear that she considers the decisions in Wallace and Booth to be wrong, including by stating that the Hercus Declaration has “implications for” those decisions, and that those decisions did not “properly consider” Toney’s location in south-west Queensland and her association with Kungardutyi.

CONSIDERATION

85 It is common ground that in order to succeed in the application Mrs King must satisfy the following three elements of s 84(5) of the NTA, being that:

(a) she has an interest in the Wongkumara claim area for the purpose of the NTA. It is uncontentious that native title rights and interests are capable of satisfying that requirement;

(b) the interest she holds may be affected by a determination of native title in the Wongkumara application; and

(c) it is in the interests of justice for her to be joined as a party.

Mrs King need only demonstrate a prima facie case for the existence of the native title rights or interests she asserts.

86 The joinder application is defensive in that, if Mrs King is joined as a respondent she cannot herself seek a determination of native title. She can though protect her claimed native title rights and interests from erosion, dilution or discount as a result of a native title determination made in favour of the Wongkumara People. Contrary to QSNTS’ submissions, little turns on the defensive nature of the joinder application. It is open to a non-applicant claimant to be joined as a party to a native title determination application to rely defensively on claimed native title rights or interests to oppose or to qualify an applicant’s claims: Kokatha People v State of South Australia [2007] FCA 1057 at [50] (Finn J); Blucher at [21].

Whether Mrs King made out a prima facie case

87 Mrs King contends that she put on sufficient evidence to demonstrate that she has a prima facie case that she has native title rights and interests in the Wongkumara claim area, which interests may be affected by a determination of native title in the proceeding.

88 I summarised the evidence of Mrs King and her sister in the joinder application (at [67]-[70]), the Hercus Declaration (at [71]-[72]) and the evidence of Dr Powell (at [73]-[85]), and it is unnecessary to reiterate that.

89 The Wongkumara applicants and QSNTS deny that Mrs King made out an arguable case. They submitted that the evidence does not provide a factual basis sufficient to support the native title rights and interests Mrs King claims to have in the Wongkumara claim area, which interests may be affected by a determination of the Wongkumara application, even on a prima facie basis. In particular, QSNTS noted that Mrs King’s claim to have native title rights or interests is based in descent from one apical ancestor, Toney, a Kungardutyi person, and argued there is no evidence of any Kungardutyi society. It relied on the evidence of Geoffrey Booth in the Wallace proceeding where he appeared to concede that he did not know of any Kungardutyi person other than Toney (at T152). QSNTS said that if there is no Kungardutyi society with rights or interests in land than Mrs King cannot have such native title rights or interests. QSNTS also noted Mansfield J’s finding in Wallace (at [85]-[86]) that Dr Powell’s reasoning that Kungardutyi is a tribal ascription rather than a general description of status as an initiated person was not warranted on the evidence. That contention also fits with the finding in Booth that the available evidence indicates that the Kungardutyi Punthamara People are a sub-set of a broader regional society which did not vest in sub-groups any rights or interests in particular areas of land (at [79]).

90 The submissions made by QSNTS in this regard have some force, but establishing a prima facie case is not a high bar. If not for the findings in Wallace and Booth I would be satisfied that the evidence is sufficient to show that Mrs King has made out an arguable case, but the question as to whether Mrs King has done so is bound up in the issue as to the effect of the findings made in Wallace and Booth. It is convenient to proceed on the assumption that Mrs King has established a prima facie case and turn to deal with the parties’ submissions in relation to the effect of the judgments in Wallace and Booth.

The abuse of process issue

91 The Wongkumara applicants and QSNTS contended that the joinder application involves an attempt to re-litigate issues previously decided by the Court in Wallace and Booth, and amounts to an abuse of process.

Mrs King’s submissions

92 Mrs King denied that the joinder application is an attempt to re-litigate the claims to native title rights and interests made by herself and/or other members of her family which were previously rejected by the Court and denied that it is an abuse of process. She contended that:

(a) although in Wallace she provided an affidavit and gave evidence in support of the claim made by her cousins Geoffrey Booth and Dennis Fisher, she was not a party to that case;

(b) in Wallace she gave evidence that she has native title rights and interests in relation to the Wilson River area, including the country around Nockatunga and Noccundra, which area largely fell outside the Boonthamurra claim area. The decision in Wallace related to the Boonthamurra claim and did not concern the Wongkumara claim area which is the subject of the joinder application;

(c) the findings in Wallace were based in the lay evidence and expert evidence before the Court, which was (and could only be) the expert evidence available at that time;

(d) in the joinder application she has adduced fresh evidence through the Hercus Declaration and from Dr Powell in regard to the relationship between Kungardutyi and Punthamara People and the geographical location of Kungardutyi country. On the basis of the fresh evidence the findings in Wallace and Booth are unreliable and should not be adopted, citing Fulton v Northern Territory of Australia [2016] FCA 1236 at [46] (White J).

(e) the findings in Booth that the Kungardutyi Punthamara native title determination application was an abuse of process and had no reasonable prospect of success, were based on the findings in Wallace (which the Court should treat as unreliable); and

(f) through the joinder application she now seeks to protect her native title rights and interests from erosion, dilution or discount by opposing a determination of native title in favour of the Wongkumara People.

93 Mrs King also put on post hearing submissions in which she contended that:

(a) if Geoffrey Booth acted as her privy in interest in the Wallace litigation he represented the Booth family in relation to “the claim the subject of that proceeding, but not with respect to their individual claims”, citing Timbercorp Finance Pty Ltd v Collins and Tomes [2016] HCA 44; (2016) 259 CLR 212 (French CJ, Kiefel, Keane and Nettle JJ at [49], [50], [53];

(b) Mrs King had limited control of the Wallace proceeding and in such circumstances it would be unjust to bind her to his actions, citing Timbercorp at [54]; Tomlinson v Ramsey Food Processing Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 28; (2015) 256 CLR 507 at [39] (French CJ, Bell, Gageler and Keane JJ);

(c) the decision in Wallace decided separate questions which determined the Boonthamurra native title determination application, between the parties to that litigation: Tomlinson at [20]; and

(d) Mrs King is not seeking to re-litigate the subject matter of the Wallace litigation. Although that judgment concerned her apical ancestor, Toney, the decision was about a claim area which is not part of the Wongkumara application.

94 Mrs King contended that, although she is a member of the Booth family, the Court should approach the joinder application independently of the past activities of Geoffrey Booth, including that she should not be disadvantaged because Geoffrey Booth withdrew from being a respondent to the Wongkumara application when challenged by the Wongkumara applicants.

95 She noted that s 86 of the NTA permits the Court to receive into evidence the transcript of evidence in another proceeding and to draw any conclusion of fact from that transcript that it thinks proper; and to adopt the judgment of the Court in another proceeding. She argued, and it is uncontentious, that while s 86 permits the Court to adopt the findings from another proceeding, it does not bind the Court to do so.

96 Mrs King relied on the decision in Murray on behalf of the Yilka Native Title Claimants v State of Western Australia (No 5) [2016] FCA 752 (McKerracher J) in which all of the parties relied to some extent on the evidence and/or reasons in the judgment of Lindgren J in Harrington-Smith on behalf of the Wongatha People v Western Australia (No 9) (2007) 238 ALR 1. In Yilka the State contended that the Court should adopt the findings in Wongatha, that it contained findings on important issues which were fatal to any finding in favour of the Cosmo applicant group or its successor the Yilka applicant (at [2279]), and that even if the Yilka applicant’s case was distinguishable from the case advanced in the Wongatha proceedings, the Yilka claim was an abuse of process as it presented issues fundamentally akin to the issues in the Wongatha claim and/or issues which were open to be raised, and ought to have been raised, in the Wongatha proceeding, relying on Walton v Gardiner (1993) 177 CLR 378 at 393 (Mason CJ, Deane and Dawson JJ): Yilka at [2236].

97 Mrs King noted that McKerracher J declined to adopt the findings in Wongatha. His Honour said (at [297]-[298]):