FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Axent Holdings Pty Ltd t/a Axent Global v Compusign Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1373

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. On or before 4:30 pm on 9 October 2020 the respondents/cross-claimants file and serve:

(a) a proposed minute of orders giving effect to these reasons for judgment; and

(b) written submissions on costs (not exceeding 7 pages).

2. On or before 4:30 pm on 23 October 2020 the applicant/cross-respondent file and serve written submissions (not exceeding 10 pages) in response to:

(a) the proposed minute of orders of the respondents/cross-claimants; and

(b) their written submissions on costs.

3. On or before 4:30 pm on 30 October 2020 the respondents/cross-claimants file and serve any submissions in reply to the written submissions of the applicant/cross-respondent (not exceeding 3 pages).

4. Unless determined otherwise, issues relating to the form of final orders or costs be determined on the papers, without oral hearing.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

KENNY J:

Introduction

1 This proceeding involves the construction, validity and, if valid, the alleged infringement of a patent titled “Changing Sign System” (Patent). The Patent is Australian Patent No. 2003252764. For the reasons stated hereafter, Axent has not made out its case of infringement by the respondents. The respondents established that the Patent was wholly invalid for lack of inventive step.

2 Axent Holdings Pty Ltd (trading as Axent Global) is the registered proprietor of the Patent. It is the applicant/cross-respondent in these proceedings. Axent is an electrical engineering company specialising in the design, manufacture, supply and support of LED-based visual communication systems, including electronic speed signs on Australian roads. Axent operates from a purpose-built facility in Clayton in metropolitan Melbourne.

3 Compusign Australia Pty Ltd and Compusign Systems Pty Ltd (together referred to as Compusign) also manufacture and install LED-based displays for the traffic control industry in Australia. In the proceedings, the two companies are the first and third respondents, and Compusign Australia is the first cross-claimant. Compusign Systems was incorporated on 15 January 2013 some years after the incorporation of Compusign Australia. Compusign, which has a factory in Victoria, also provides service and maintenance for Compusign products throughout Australia.

4 Hi-Lux Technical Services Pty Ltd, which is the second respondent and the second cross-claimant in the proceedings, provides a range of products to the traffic signal industry and government departments throughout Australia. Hi-Lux has a purpose-built office and manufacturing facility in Thomastown in metropolitan Melbourne.

5 In an originating application and statement of claim filed on 2 December 2016, Axent alleged that Compusign Australia and Hi-Lux had infringed all the claims of the Patent. Compusign Systems was joined as a respondent on 24 May 2017. Axent sought declaratory, injunctive and other relief, including damages or an account of profits.

6 In cross-claims filed on 14 February 2017, Compusign Australia and Hi-Lux alleged that all the claims of the Patent were invalid. Both respondents pleaded that the invention as claimed was not novel or fairly based on the matter described in the specification, and lacked inventive step. They pleaded non-compliance with s 40(3) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) in that the claims were not clear and succinct. Hi-Lux also alleged that the Patent was invalid on the ground that the invention as claimed had been secretly used by the patentee in Australia before the priority date of the claims. Only some of these grounds were, however, pursued at the hearing, and Axent denied that the Patent was invalid in any respect.

7 In its Amended Defence, Compusign admitted that: (1) between 22 April 2004 and July 2013, Compusign Australia had imported into Australia components for, and had manufactured, promoted, sold, supplied, repaired and replaced in Australia, variable speed limit signs for traffic control on roadways; (2) from July 2013, Compusign Systems had undertaken the same activities; and (3) it did not have any licence, authority or consent from Axent to supply these products. Compusign also alleged that, if the Patent were valid:

(1) any infringements before 2 December 2010 were statute-barred by virtue of s 120(4) of the Patents Act;

(2) by reason of the amendment of the complete specification of the Patent, by operation of s 115(1) of the Patents Act, no pecuniary relief is available for any alleged infringements of the Patent before the amendment (i.e, 22 August 2011);

(3) Compusign Australia was making or had taken definite steps to make a product as claimed, by reason of its use of the Compusign prototype before the priority date and, accordingly, pursuant to s 119 of the Patents Act, Compusign would not infringe the Patent;

(4) Compusign was not aware that the Patent existed before about 16 September 2016, when it received a letter of that date from Axent’s solicitors enclosing a copy of the Patent, with the result that any damages for infringement before that date ought to be refused under s 123 of the Patents Act;

(5) any exploitation of the Patent by Compusign was by, or authorised in writing by, an authority of a State for the services of that State, such that the exploitation was not an infringement of the Patent by reason of s 163 of the Patents Act;

(6) due to Axent’s non-payment of fees, the Patent ceased on 7 October 2015 and was not restored until 15 September 2016, with the effect that by operation of ss 223(10) and 143(a) of the Patents Act and reg 13.6(1) of the Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth), Axent was unable to bring infringement proceedings in respect of the period when the Patent had ceased.

8 In its Amended Defence, Hi-Lux admitted that: (1) in Australia, it had manufactured, sold and supplied, offered to sell and supply, and kept for those purposes, products that it described as variable speed limit signs (including versions with pre-programmed displays and that its customers programmed); and (2) it had no licence, authority or consent from Axent to supply these products.

9 In its Amended Defence, Hi-Lux relied on ss 119, 120(4), 143(a), 163 and ss 223(10) of the Patents Act, and reg 13.6(1) of the Patents Regulations with respect to Axent’s non-payment of fees. Besides this, its Amended Defence also included the following, at [18(c)-(e)]:

(c) It says that Axent has pleaded in the alternative that each of claims 1 to 28 is a product claim, and a method claim, and that the proper construction of each claim remains unclear …

(d) It says further that various integers of claims 1 to 28 are unclear, as detailed in its cross-claim; and

(e) It sets out in Annexure A to this defence a list of features that it admits that its Hi-Lux VSL Signs have.

10 In a Reply filed on 15 March 2017, Axent specifically denied that Compusign’s exploitation of the Patent was an exploitation by a State or an exploitation authorised in writing by a State for the services of the State, although it admitted that:

… VicRoads or the Roads Corporation of Victoria:-

a) was at all relevant times until 1 July 2010 a statutory corporation established under the Transport Act 1983 (Vic);

b) is and has been since 1 July 2010 a statutory corporation established under the Transport Integration Act 1983 (Vic); and

c) is and has at all relevant times been an authority of a State within the meaning of that phrase in section 163 of the Patents Act[.]

11 On 24 May 2017, the Court ordered that issues of liability be heard and determined separately from and in advance of issues of the quantum of any pecuniary relief. Only issues of liability therefore arose at the hearing, which was held on 23, 24, 26, 27 and 30 April 2018, 1 and 2 May 2018, and on 17 October 2018.

12 In an attempt to identify and resolve the parties’ ongoing difficulties with one another’s conduct of the litigation, the court made orders on 24 May 2017 for the filing of position statements, first on infringement and secondly on invalidity. Axent filed an amended position statement on infringement on 28 July 2017, while Compusign filed a position statement in response on infringement on 18 July 2017. Hi-Lux filed its position statement in response on infringement on 17 July 2017. The parties also exchanged position statements on invalidity.

13 Compusign’s responsive position statement on infringement clarified its position as follows:

4. From about 22 April 2004 and until about July 2013, [Compusign Australia] imported into Australia components for and manufactured, promoted, sold, supplied, repaired and replaced in whole or in part in Australia variable speed limit signs for traffic control on roadways (the Compusign Products).

5. From about July 2013, [Compusign Systems] has imported into Australia components for and manufactured, promoted, sold, supplied, repaired and replaced in whole or in part in Australia the Compusign Products.

6. The Compusign Products were so designed, made and/or supplied from time to time by the Compusign Parties for specific traffic works and projects in accordance with technical specifications of road authorities and other third parties. The products are made specifically for each such project in accordance with the technical requirements of that project.

…

23. As shown in the table in Annexure 1, the supply of the Compusign Products for the listed road projects occurred before 2 December 2010 (being six years before these proceedings were commenced). … [T]he Applicant asserts that supplies of signs for the Clem 7 project occurred in 2011 and 2012. However, contrary to that assertion, Compusign Australia supplied the Compusign Products in around March 2009 and not in 2011 or 2012.

24. Accordingly, any alleged infringements of the claims of the Patent by [Compusign Australia] before 2 December 2010 are statute-barred by operation of section 120(4) of the Act.

25. As Compusign Systems was not incorporated until January 2013 and did not commence selling Compusign Products until about July 2013, this time-bar only applies to alleged infringing exploitation of Compusign Products by Compusign Australia before 2 December 2010.

Annexure 1 set out the various projects for which Compusign had designed and supplied the relevant signage products.

14 The parties filed an agreed statement of issues on infringement (agreed infringement issues) and an agreed statement of issues on invalidity (agreed invalidity issues) on 17 April 2018. The agreed infringement issues listed some but not all the issues that were the subject of argument in submissions and at the hearing.

15 I note here that in the agreed infringement issues document, Axent also identified issues that it said had not previously been raised and that its evidence did not address, but it did not in substance renew this complaint at the hearing. Rather, Axent addressed the issues in dispute between the parties in opening and closing submissions. There was no apparent basis for any contention to the effect that Axent was unfairly prejudiced in doing so.

Overview of the patent

16 The Patent claimed an earliest priority date of 4 October 2002 (priority date), being the date on which a provisional application was filed. The application for the Patent was filed on 6 October 2003. The Patent was granted on 26 June 2008.

17 Save for any issues that may arise under s 138 of the Patents Act, issues of infringement and validity are to be determined under the Patents Act, in the form in which it existed on the date of application. This was prior to, among other Acts, the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) (Raising the Bar Act). So far as any issue under ss 22A and 138 of the Patents Act is concerned, these provisions apply in their form as at the date on which application is actually made for the revocation order: see AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 99; 226 FCR 324 at [182]-[184] (AstraZeneca FCAFC); Apotex Pty Ltd v Warner-Lambert Company LLC (No 2) [2016] FCA 1238; 122 IPR 17 at [7].

18 In 2009, after the Patent was granted, Axent applied to amend the specification, including some of the claims of the Patent. The Roads Corporation (a predecessor to VicRoads) unsuccessfully opposed the application. IP Australia granted Axent’s amendment application on 29 June 2011: see Roads Corporation v Axent Holdings Pty Ltd [2011] APO 43.

19 Axent did not pay the renewal fees for the Patent by 6 October 2015, as it was required to do. Nor did Axent pay these fees within the additional period of grace for which the Patents Regulations provide. The fees were treated as paid in September 2016. As will be seen below, the parties contested the duration of the period in which the Patent ceased to be registered for non-payment of fees.

The background to the invention

20 The invention the subject of the Patent is said to relate to a changing sign system for use as a variable speed limit sign on roadways. The specification explains:

Existing speed signs, which are typically static, have to be a black number on a white background with a red outer circle (annulus) using reflective material. (In accordance with Australian Standards, as incorporated herein by reference.) This style of sign is important and particularly the annulus. If speed sign structures were allowed to have varying forms, users of the roadways would not be able to identify the sign as a speed sign. … It is therefore imperative to retain speed signs within this narrow defined structure.

The applicant has recently developed new technology and manufactured and operated variable speed limit signs (VSLS) in Australia, which incorporate a flashing annulus to comply with the Australian Standards and the law in respect of a regulatory traffic device. The VSLS are electronic and typically incorporate the use of white light emitting diodes (LEDs) to form the number, red LEDs to form a plurality of outer rings which together form the annuls [sic] and a static black background.

VSLSs can be used alongside roadways or bridges … where there is a likelihood of a change in road condition, such as high wind or sun glare. Instead of a normal maximum safe speed indication of, say, 100 kilometres per hour a hazard lower maximum speed can apply. The VSLS would be switched to the lower maximum speed when a certain wind speed is detected or the sun happens to be at the most distracting level.

21 The specification emphasised the need for the driver of a vehicle on a roadway to be “not only aware of the lower determined speed limit but also aware that this is a lower limit due to a hazard so that the driver also drives with extra caution in case of the lower determined speed limit not being sufficiently low”. The specification noted possible solutions included “a second light such as a flashing amber hazard light where the flashing is caused by a rotating shield around the light such as often used on towing vehicles or used with blue and red lights on emergency vehicles”. Another possible solution “is to use variable message signs (VMS) to display speed related messages”. As to the first possible solution, the specification stated:

[T]he use of a second light increases the installation wiring and costs. Further there is the high likelihood of a misunderstanding by the driver since there is no shown connection between the two lights. This misunderstanding is increased since the two lights must be sufficiently spaced to be clearly seen separately and will need to be spaced sufficiently to avoid the glare of one blocking the other.

Regarding variable message signs, the specification stated:

This will need a much larger sign so that it can display a plurality of alphanumeric characters and must be programmed. Further it is necessary to scroll through a message and therefore must be repeated. The timing of the scroll might not be sufficient for all roadway users to read at the time they are passing the sign.

Further, the reading of the sign is a distraction to driving in a similar manner to the use of mobile telephones while driving, this distraction could be increasing the number of road accidents rather than the intention of the sign advising of hazards to decrease the number of road accidents. Still further, the costs of variable message signs can be ten times the costs of single image signs.

22 The specification advised that the object of the invention was:

.. to provide an improved variable speed limit sign, which fulfils the requirements of showing a lower maximum speed limit but also advising of the hazard while maintaining the restrictive requirements of being identifiable as a speed limit sign.

23 The specification described embodiments of the invention, which find expression in claims 1, 17 and 20. There is also an independent omnibus claim in claim 28.

24 In respect of the embodiments, the specification explained:

It is to be understood that one of the possible speed limit displays is a “blank” sign, indicating no fixed speed limit other than the maximum in the given jurisdiction.

In one aspect the annulus is formed by three to five outer rings of light emitting structures and the change of conditions is indicated by flashing some of those outer rings while always retaining one ring on to fulfil the criteria of being a speed display sign by always showing a number in a circle on a display panel. Generally the central numeric displaying area is formed by a plurality of white light emitting diodes while the annulus is formed by red light emitting diodes and the display panel forms a black background. Preferably, the display panel is included with a frame.

The criterion to which the control means responds can be an external sensor such as a wind sensor, light sensor or the like. In another form there can be a programmed time and speed limits such as usable at time-defined hazards such as schools or sunset. In a further embodiment, the criterion could be receipt of an external signal from a control centre such as a freeway control centre or the like. The response is then made according to the input criteria and selects one of at least two possible speed limits and varies part of one or more of the display panel, the central numeric displaying area or the annulus.

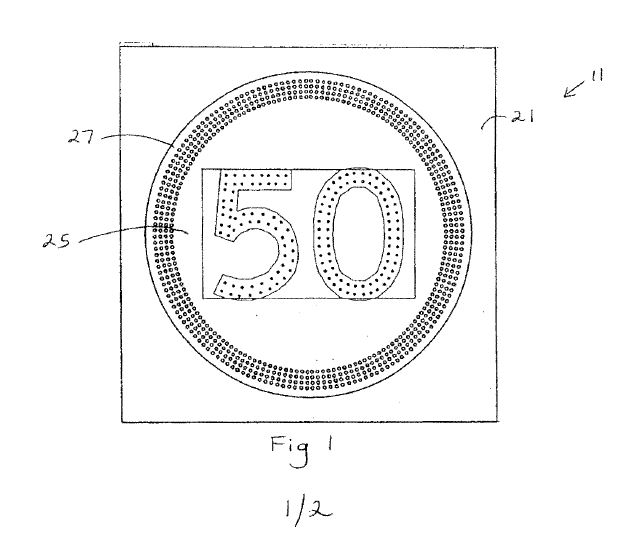

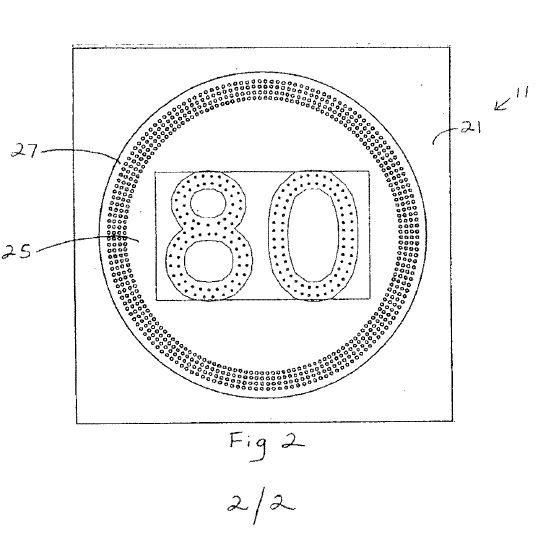

25 The embodiments were described in the specification by way of two drawings.

Figure 1 was said to be a diagrammatic view of a changing sign system in accordance with an embodiment of the invention in one state of display. Figure 2 was a diagrammatic view of a changing sign system in accordance with the embodiment of Figure 1 in a second state of display.

26 With reference to Figure 1 and Figure 2, the specification continued:

Referring to the drawings there is shown a changing sign system for use as variable speed limit sign (11) on roadways. The sign includes a frame having a front square display panel (21). A central numeric displaying area (25) is formed on the display panel (21) by a plurality of light emitting structures (29) which when activated can display a selected one of at least two possible speed limits.

An annulus (27) is formed by a plurality of outer circles on the display panel (21) around the central numeric displaying area (25) by a plurality of light emitting structures.

A control means (not shown) is included in the changing sign system (11) for selecting the selected one of at least two possible speed limits which is 80 kilometres per hour in Figure 1 and 50 kilometres per hour in Figure 2. This speed limit is changed according to an input criterion and varies in this embodiment the annulus (27).

The annulus (27) is formed by four outer rings of light emitting structures and the change of conditions is indicated by flashing some of those outer rings while always retaining one ring on to fulfil the criteria of being a speed display sign by always showing a number in a circle on a display panel.

The central numeric displaying area (25) is formed by a plurality of white light emitting diodes while the annulus (27) is formed by red light emitting diodes and the display panel (21) forms a black background.

The changing sign system (11) thereby fulfils the criteria of being a speed display sign by always showing a number in a circle on a display panel while being able to indicate a selected one of at least two possible speed limits and while simultaneously indicating a change of speed limits and therefore a change in conditions by the varying of part of one or more of the display panel, the central numeric displaying area or the annulus.

27 The specification further stated that:

The fabrication and supply of all components for the changing sign system of the invention shall be in accordance with all relevant Australian Standards or, in the absence of same, with appropriate international standards. All installation works, where necessary, shall conform to the relevant road authority specifications that are in force from time to time. Examples of such specifications include VicRoads specifications for installations in Victoria, Australia. The following related specifications and standard drawings are defined and incorporated herein by reference:

i. Manual of uniform traffic control devices, Part 2: Traffic control devices for general use AS 1742.2 and particularly Regulatory Sign R4-1

ii. Road Signs – Specifications AS 1743

iii. Degrees of Protection provided by enclosures for electrical equipment (IP code) AS 1939 and particularly IP55

iv. SAA Wiring Rules AS 3000

v. Colour Displays Section 2 and section 3.2.2 of AS 2144

vi. Electromagnetic Compatibility – Generic Emission Standard AS/NZS 4251

vii. Approval and test specification – Electric cables – Thermoplastic insulated for voltages up to and including 0.6/1kV AS 3147

viii. Approval and test specification – General requirements for electrical equipment AS 3100

ix. Retroreflective materials and devices for road traffic control purposes, Part 1: Retroreflective materials AS 1906.1

x. Road Rules – Victoria and particularly Rule 21

xi. VicRoads Guidelines “Variable Speed Limits on Freeways (Draft)

xii. VicRoads Traffic Engineering Manual, Volumes 1 and 2.

28 The specification described the materials from which the sign and support structure were to be constructed, including that the “display face”:

… consists of a red annulus on a black background with white numerals within the annulus. The numerals are centrally located within the red annulus. When displaying other than the normal speed i.e., 100 km/h the sign is capable of flashing part of the inner diameter of the red annulus.

An accompanying table set forth the approximate amount of the annulus capable of flashing by reference to the dimensions of the sign.

29 The specification further stated:

While the inner diameter of the annulus is flashing, the remaining portion of the outer diameter of the annulus shall remain on to retain the regulatory status of the sign. The flash rate of the annulus is fully programmable and preferably is between 50 and 60 cycles per minute. The off time is the same as the on time.

The required display technology is either fibre optic display matrix or light emitting diodes (LEDs). … The sign control system permits total flexibility in the selection of time functions such as blanking times. These times are selectable through the sign controller’s system configuration menu, available both locally and remotely.

30 Finally, apart from the claims, the specification affirmed that:

Although this invention has been described in its preferred forms with a certain degree of particularity, it is understood that the present disclosure of the preferred form has been made only by way of example and numerous changes in the details of construction and combination and arrangement of parts can be resorted to without departing from the spirit and scope of the invention.

It should be understood that the above is a description of the preferred embodiments of the invention but the disclosure of the invention is not limited to those embodiments. Clearly other variations that would be understood by people skilled in the art without any inventiveness are included within the scope of the invention.

The claims

31 As already noted, the three principal independent claims of the Patent are claims 1, 17 and 20. These claims are broadly similar in wording and structure, and describe an electronic variable speed limit sign, which has a plurality of lights forming the central speed limit numerals and the annulus rings around those numerals. The three principal independent claims also specify that there must be a variation of that display when a speed limit other than a “normal speed limit” is being displayed. Claim 2 is dependent on claim 1. As stated already, claim 28 was an independent omnibus claim.

32 Claims 3-16 are dependent on claims dependent on claim 1 or claims within this group, which themselves are dependent on claim 1. Claim 18 is dependent on claim 17. Claim 19 is dependent on claim 18. Claim 21 is dependent on claim 20. Claim 22 is dependent on claim 20 or 21. Claim 23 is dependent on claim 20 or other claims dependent on claim 20. Claims 24, 25 and 26 are dependent on claim 23, which is in turn dependent on claim 20 or on other claims dependent on claim 20. Claim 27 is expressed as a changing sign system according to any one of claims 20 to 26, in which the display system is included with a frame.

33 These twenty-four dependent claims describe a range of variations in the signs. For example:

claims 2, 3, 18, 19, 21 and 23: specify that the relevant variation of the display is to be a flashing of a portion of the annulus;

claims 4, 6 and 8: specify the proportion of the annulus thickness that is flashed;

claims 5, 7 and 24 to 26: specify the dimensions of the sign face;

claims 9 and 10: specify the frequency of the flashing;

claims 11 and 22: specify the colours of the display components, and the use of light emitting diodes;

claims 12 and 13: specify the use of an external sensor to provide an input to the control means;

claims 14 to 16: specify the nature of an external signal; and

claim 27: specifies the inclusion of a frame.

Overview of evidence

Axent’s evidence

34 Axent filed the following affidavits, which, save for successful objections, were admitted in evidence: the three affidavits with annexures of Geoffrey Francis Fontaine affirmed on 18 September 2017, 12 December 2017 and 19 April 2018; the four affidavits of Stephen Bean sworn on 11 October 2017, 1 December 2017, 28 February 2018 and 19 April 2018; the two affidavits of Peter Slavko Cestnik sworn on 18 September 2017 and 13 December 2017; the two affidavits of Michael Zammit sworn on 12 December 2017 and 19 April 2018; the three affidavits of Charles Leonidas sworn on 18 September 2017, 2 February 2018 and 12 April 2018; and the four affidavits of Sachin Prasad affirmed on 16 November 2017, 28 February 2018, 12 April 2018 and 25 April 2018. The respondents chose not to press their objections to Mr Leonidas’s affidavits of 2 February 2018 and 12 April 2018, “as a matter of expediency”. There was limited additional evidence in chief given at the hearing. Mr Fontaine, Mr Bean, Mr Cestnik, Mr Zammit, and Mr Prasad were cross-examined.

35 Issues concerning the admissibility of other evidence are discussed at the end of these reasons. These issues include the admissibility of a 3 November 2017 affidavit of Axent’s solicitor, Mr Leonidas, which Axent sought to tender during the hearing on 1 May 2018. The affidavit had originally been filed in support of an application by Axent for further and better discovery, and its tender at the hearing was subject to the respondents’ objection. As will be seen, Axent ultimately sought to tender annexures to the affidavit as in a list that it prepared. For the most part, these annexures comprised letters passing between the parties’ solicitors. A further issue arose in relation to the admissibility of a 30 April 2018 affidavit sworn by Mr Leonidas, which is also discussed below.

36 I also note that, on 30 April 2018, midway through the hearing, Axent tendered four affidavits of discovery that had been sworn by Mr Sozio, on behalf of Hi-Lux, on 25 September 2017, 11 October 2017, 4 December 2017, and 1 March 2018 respectively, without objection by the respondents. Nothing apparently turns on any of these four affidavits.

37 The following is a necessarily incomplete overview of the evidence in the proceedings, set out by reference to the principal witnesses.

Geoffrey Fontaine

38 Mr Fontaine, who was Axent’s managing director and sole director, claimed to be the inventor of the invention the subject of the Patent. His evidence was that, as at September 2017, he had been running companies supplying electronic signage for over 30 years, although he had no formal qualifications as an engineer. From 1998 until the establishment of Axent in March 2001, his “principal trading entity” was Symon Australia Pty Ltd.

39 Mr Fontaine’s evidence was (and I accept) that Symon Australia designed, engineered and supplied signage for various roads and railways in Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland. Symon Australia also supplied LED lighting for road signage. Mr Fontaine’s evidence was that the business of Symon Australia was transferred to Axent when Axent was established in March 2001. At its Clayton facility, Axent designs and constructs the signage and visual communication systems that it sells, including the variable speed limit signage system that is the subject of the Patent.

40 In his 18 September 2017 affidavit, Mr Fontaine explained, and I accept, that the market for speed sign systems in Australia included supply to government authorities, such as VicRoads, and non-government authorities. In relation to VicRoads, Mr Fontaine deposed, and I accept as consistent with the evidence of other witnesses, that:

… funding is often project based, for example, for the building or upgrading of a road or freeway, or for the installation of school zone signage throughout Victoria. For such projects VicRoads seeks competitive tenders. It also has preferred suppliers.

VicRoads prepares various specifications for the products and systems that it seeks to have supplied to it. …

VicRoads has internal processes for the approval of the products and systems supplied to it as well as for the approval of its suppliers themselves. It is possible for a supplier to obtain a type approval for their product or system, so that they can supply it on an ongoing basis without having to go through an individual approval for every tender or contract. The process of obtaining type approval involves submitting a range of technical documentation and often product testing also. If a type approval is not in place then the relevant documentation is usually a requirement of the tender or contract itself, including certification that the relevant VicRoads technical requirements are met.

41 Mr Fontaine acknowledged in cross-examination that he was aware in 2000-2001 that VicRoads had the type approval system to which he referred in this passage. He accepted that in order to supply a product to VicRoads it was “advantageous” to have a type approval for the product, and that there was generally a need to demonstrate that the product met the relevant VicRoads specifications in order to gain type approval. Mr Fontaine deposed that, in his experience, the supply of variable speed limit sign systems involved: (a) the initial manufacturer or supplier of the signage system; (b) a third party or parties (with whom that manufacturer contracts) supplying the system to an end user; and (c) end users (such as VicRoads) that own or manage the roads on which the signage system operates.

42 Mr Fontaine gave evidence that he had developed a variable speed limit sign using LED lights from around June 2000, and that this had involved the design and construction of a prototype sign from the “ground up”, beginning with the desired features and functions it needed to perform. This was, he said, a time-consuming process given the software and manufacturing conditions of the day. His evidence was that all the various components of the sign had to be located, obtained, made and tested in order to ensure the sign’s effectiveness and visibility. He deposed that:

Designing the layout and software, putting all the physical components together and connecting everything to the central processing unit (CPU) within the sign that controls the system and allows it to display differently depending on signals that the CPU receives was a very time-intensive process. The later part of the prototype’s development focused more intensively on software development, after the physical components had been decided upon.

There was, Mr Fontaine said, a large amount of experimentation around the width of the annulus, as well as around the positioning and brightness of the LEDs.

43 In cross-examination, Mr Fontaine accepted that Axent had supplied signs described as variable speed limit signs for the CityLink project, which went live prior to November 2001. He accepted that these were LED signs that could vary the displayed speed limit, and could be controlled by the front-end computer at the Transurban control centre. This worked in much the same way as a VicRoads control centre. He also accepted that there were communication protocols used to communicate between the signs.

44 Also in cross-examination, Mr Fontaine’s attention was drawn to the following statement in Axent’s November 2001 tender documents for the Western Ring Road project:

Our experience and history with signs has shown us that the advantages of using an aXent product are extremely valuable. For instance, our signs are capable of having synchronised dimming, flashing and display, purely based on our Citylink experience where we provided the same and far exceeded the presentation of the product to the motorist.

(Bold, italics in original)

As a consequence, he accepted that some of the signs supplied by Axent for the earlier CityLink project had a flashing feature, although he went on to express some uncertainty about this after an intervention by Ms Gatford, counsel for Axent. The result was the following exchange between counsel for the respondent, Mr Smith, and Mr Fontaine:

Mr Smith: Are you saying that you are certain now that the signs that you supplied for the CityLink project did not have a flashing feature?

Mr Fontaine: Which signs in particular are you referring to?

Mr Smith: The variable speed limit signs?

Mr Fontaine: I can’t recall.

Mr Smith: Okay. But do you agree that your recollection would have been – of those matters would have been better in November 2001 when you approved this document?

Mr Fontaine: I think that’s fair to say.

45 In later cross-examination, Mr Fontaine denied that Axent had a variable speed limit sign prior to June 2000. Mr Smith asked Mr Fontaine to explain this further:

Mr Fontaine: We’re software and electronic engineers. It’s – they’re not – they were completely different products, and you’re trying to make a correlation which doesn’t exist.

Mr Smith: How do you say that the signs you were developing from June 2000 differed precisely from the LED signs that you had supplied to the CityLink project that showed more than one speed?

Mr Fontaine: Different controller, different printed circuit boards, different LEDs, different software, different firmware. The … advancement is ongoing, even today were just prolific.

Subsequently, in re-examination, Mr Fontaine gave evidence that none of the signs supplied to the CityLink project had a partly flashing annulus.

46 I interpolate here that Mr Fontaine’s uncertainty about whether the variable speed limit signs Axent supplied for the CityLink project had a flashing feature does not detract from his prior acceptance that some of the signs Axent provided for that project had a flashing feature (which included the lane use signs and possibly the variable speed limit signs). Prior to Ms Gatford’s intervention, Mr Fontaine stated that the lane use signs provided for the CityLink project did flash, that he was unsure whether the variable speed limit signs provided for the project flashed, and that he could recall that some of the signs provided did have a flashing feature. Mr Fontaine’s acceptance that some signs had a flashing feature was prompted by the reference to Axent’s November 2001 tender documents, which indicated that Axent had signs with a flashing feature and demonstrated this by its provision of such signs to the CityLink project. After Ms Gatford’s intervention, Mr Fontaine’s statement that he could not recall whether the variable speed limit signs had a flashing feature repeated his previous answer. It did not extend to all the signs Axent provided for the CityLink project, nor to Axent’s capability to provide variable speed limit signs that had a flashing feature; and, as already indicated, Mr Fontaine subsequently accepted that his recollection of whether the variable speed limit signs had a flashing feature would have been better in November 2001 when he approved Axent’s tender documents. I found Mr Fontaine’s answers in this instance to be evasive and that, taken as a whole, it did not seem to me that Mr Fontaine’s evidence was entirely reliable, possibly because his recollection of pertinent matters had dimmed with the passage of time.

47 Mr Fontaine’s evidence was that at the time Axent’s variable speed limit sign in LEDs was being developed he was in contact with Mr Bean, then at VicRoads. Mr Fontaine’s evidence was that Mr Bean visited Axent’s premises on several occasions during this period and told Mr Fontaine that:

VicRoads [was] interested in upgrading their variable speed limit signs to full LED if a suitable product could be developed …

Mr Fontaine agreed in cross-examination that VicRoads had variable speed limit signs before June 2000, although these signs were fibre optic signs. He also agreed that his understanding at the time was that VicRoads required a flashing feature for the variable speed limit sign.

48 In around September 2000, so Mr Fontaine said (and I accept), Mr Bean representing VicRoads attended Axent’s premises, with another VicRoads employee (who he believed was Mr Priest) to view the prototype for Axent’s variable speed limit sign. Mr Fontaine said that Axent’s production manager, Mr Cestnik, was also at the meeting. Mr Fontaine’s evidence was that at the meeting they discussed the sign, the need for the sign to warn drivers that the speed was changing, and that there were various existing signage products with warning devices. Mr Fontaine’s evidence was (and again I accept) that he told Mr Bean (who corroborated his evidence) and Mr Priest that Axent’s signage could be programmed to warn the driver of the speed zone change by flashing some but not all of the rings of the annulus around the speed limit number. Mr Fontaine’s evidence was that Mr Cestnik then demonstrated the modified partly flashing annulus feature and said that in future this could be controlled through software. Mr Fontaine indicated that this modification did not take a long time when he said:

We had from – switches that were hardwired to the sign, and we could demonstrate a myriad of different display patterns at that time and see which one looked the best and was most effective.

I interpolate here that Mr Cestnik’s evidence was also broadly consistent with the evidence of Mr Fontaine at this point, although he could not recall whether the partly flashing annulus was demonstrated on that day or subsequently. It does not seem to me that anything turns on this difference.

49 According to Mr Fontaine, Mr Bean and his colleague said that they liked Axent’s solution, but that VicRoads would need to be satisfied that a speed sign with that proposed feature complied with the Road Rules, and that they wanted to be sure by checking with their legal team that the sign would be regulatory (i.e., that the displayed speed limit was enforceable). Mr Bean later contacted Mr Fontaine to say that VicRoads’ lawyers had advised that Axent’s proposed variable speed limit sign would be regulatory. Mr Fontaine’s evidence at this point is corroborated by Mr Bean. In cross-examination, in the context of the September 2000 meeting, Mr Fontaine was asked whether he was “seeking to have that product approved as an option for [the Western Ring Road] project”. Mr Fontaine answered “I had a desire to have it included, but I didn’t press the point”.

50 In March 2001 Mr Bean told Mr Fontaine that VicRoads would shortly be advertising for expressions of interest to tender for signage for the Western Ring Road in The Age newspaper. Mr Fontaine saw the advertisement and subsequently spoke with a VicRoads representative about the tender. In early April 2001, shortly after VicRoads had called for expressions of interest for the Western Ring Road Project, Mr Fontaine met with Mr Bean, showing him the prototype variable speed limit sign and demonstrating the brightness of the white LEDs in full sunlight. Around the same time, Mr Fontaine delivered a prototype variable speed limit sign to Mr Bean at the VicRoads office, although the prototypes at the time were not connected or fully operational and still had switches on the side. At a subsequent stage in the development of the sign, these switches were reprogrammed to allow part of the annulus to flash. Mr Fontaine said that he recalled that Axent had tested various flash rates on the prototypes to see what was the most effective flash rate prior to this reprogramming.

51 Mr Fontaine deposed that sometime shortly after his meeting with Mr Bean in March 2001, a VicRoads representative told him that Axent would need to comply with a VicRoads specification for the supply and installation of electronic variable speed restriction signs; that further testing would need to be done on Axent’s variable speed limit sign; and that the sign’s legend had to comply with the Australian Standard and the Road Rules in place at that time. About the same time Mr Fontaine was provided with the “VicRoads Specification for the supply and installation of electronic variable speed restriction signs TCS-037-2-2001” dated April 2001 (April 2001 specification). This specification did not refer to any portion of the annulus flashing or to any need to warn of a change in speed.

52 In September 2001, Mr Fontaine met with Mr Bean and another VicRoads representative to view a demonstration of Axent’s proposed variable speed limit sign with a partly flashing annulus. Mr Fontaine stated that he subsequently received the tender documents for Contract 5273 from VicRoads for a variable speed limit system on the Western Ring Road (the VicRoads Contract), which included the VicRoads specification No: TCS 037-5-2001. This specification, which I refer to hereafter as the September 2001 specification, contained a requirement, in section 4.6, that part of the inner diameter of the red annulus should be capable of flashing on and off. Mr Fontaine deposed that he had never before seen this requirement in a VicRoads specification and that he “had not been asked by VicRoads if they could include [his] invention in the 2001 specification before [he] received the tender documents”. I accept Mr Fontaine’s evidence in this regard, since it is consistent with Mr Bean’s evidence and the two relevant specifications.

53 In relation to the inclusion of the flashing red annulus requirement in the September 2001 specification, Mr Smith, for the respondents, and Mr Fontaine had the following exchange:

Mr Smith: And you knew at that time that there would be other tendering parties receiving the same specification?

Mr Fontaine: I believe two others were shortlisted.

Mr Smith: … And you made no complaint at that time to VicRoads about the specification of a partially flashing annulus in that specification?

Mr Fontaine: No.

…

Mr Smith: You’ve never asked VicRoads to remove that requirement from their specification?

Mr Fontaine: No.

…

Mr Smith: You knew that a document such as the one you just saw was not specific to a project?

Mr Fontaine: Correct.

Mr Smith: And it could form the basis of other companies’ applications for type approval, for example?

Mr Fontaine: Possibly.

Mr Smith: And at that time you didn’t consider, did you, that the partially flashing annulus was confidential to Axent?

Mr Fontaine: I did.

Mr Smith: In fact, you were happy that VicRoads had included it in their specification for the Western Ring Road project, weren’t you?

Mr Fontaine: I wasn’t unhappy.

54 In his 12 December 2017 affidavit, Mr Fontaine deposed that Axent and VicRoads entered into the VicRoads Contract on 21 February 2002. The contract was relevantly for Axent to supply a complete traffic management system for the Western Ring Road, including the supply to VicRoads of its variable speed limit signs, and the development and supply of a system linking the signage and other hardware such as speed cameras to the VicRoads traffic centre in metropolitan Melbourne. Mr Fontaine further deposed that the sign had been developed prior to Axent entering into the VicRoads Contract, and was used in public for the first time at the launch of the Western Ring Road Project by VicRoads, which “went live” in December 2002. This latter evidence was contested, and I return to it hereafter.

55 Mr Fontaine’s evidence was that by the time he came to supply Axent’s variable speed limit sign, Axent had undertaken substantial work to optimise the performance of the sign with a partially flashing annulus. This work was undertaken to address “the size, the neatness, clarity, power consumption”, and to optimise the circuit board. He affirmed that it was correct to say:

[A]lthough the outward appearance of the sign did not change the Axent VSLS became much more complex in its internal workings once the partly flashing annulus was included into it. The creation of a variable flashing annulus system required numerous hardware, firmware and control software changes that took significant time, resources and cost to implement, test and fine tune by experienced and qualified electrical engineers. It required complex circuit design and changes to the SY98012B PCB, dedicated software code in C and C++ and a full understanding of complex electronic componentry including driver chips, microprocessors, power switching, connectors and LED’s. The design work was intricate at that time in regard to uniformity, synchronisation, brightness control, variable flash rates on different rings, protocol changes, and much more difficult that [sic] if the equivalent task were undertaken today.

56 Mr Fontaine said in cross-examination that:

… the SY98012B, which I tendered a photo [sic] in my affidavit was … the size of two cigarette packets whereas a few years earlier, it would have been the size of two shoe boxes.

His evidence was that this not only made the sign more compact, it also reduced the manufacturing cost. He explained that the hardware improvements were improvements principally to the electronic printed circuit board (PCB) design, but included power supplies, cables, and connectors. It was, Mr Fontaine said:

…a whole host of things that go into a new product and new PCB design and microprocessors. They were evolving rapidly during that time.

….

LEDs were being refined and …. our job was to keep testing and trialling the product until we found a product that we believe was suitable for outdoor use.

Mr Fontaine’s evidence was that he believed these sorts of things (although not the LEDs selected) “came with the creation of the product and the software” and that the improvements that Axent developed such as the PCB design, and the software design, were confidential to Axent at the time.

57 Mr Fontaine deposed that he told VicRoads representatives about Axent’s patent application in 2003. His evidence in this regard was corroborated by an email that he sent to Mr Dean Zabrieszach of VicRoads in September 2003. Mr Fontaine said that some time later Mr Zabrieszach and others from VicRoads attended Axent’s manufacturing facility where Axent’s variable speed limit sign was shown to them and, according to Mr Fontaine, “we spoke about the patent”. When giving evidence about this matter in chief, Mr Fontaine added, self-servingly it seemed to me, “I didn’t think that there wasn’t anybody who didn’t know about the patent, to be honest, thereafter”. Mr Fontaine went on to say:

… I don’t think there would be one person within VicRoads over a period of a decade that didn’t know I had a patent either by way of telephone call, email, letter, tender submission, document, manual and general industry knowledge.

58 Mr Fontaine’s evidence was that Axent had successfully tendered for a number of other VicRoads contracts after the Western Ring Road Project, including Contract 5822 (for the supply of the signage in school zones throughout Victoria). He also said that Axent supplied its variable speed limit sign to other parties from 2003 onwards, although sales decreased from 2008 coincident with other suppliers releasing competing variable speed limit signs.

59 Mr Fontaine’s evidence was that he did not ask Mr Bean or anyone from VicRoads to sign a written confidentiality agreement before he showed the prototype to Mr Bean or anyone else at VicRoads. In his 18 September 2017 affidavit, he said that he had previously told Mr Bean that anything that he saw or was provided with in the way of an Axent sample or product was for VicRoads’ purposes only and was not to be talked about or shown outside VicRoads, including to any suppliers. In cross-examination he agreed, however, that he could not recall the date or topic of any such conversation. Instead Mr Fontaine said:

From the minute he [Mr Bean] walked in the front door, I didn’t want him to discuss any product or any VicRoads employee discuss any of my products to any other people in the industry.

60 In evidence in chief Mr Fontaine reiterated that during the 30-plus years he had worked with VicRoads “many documents, contracts, tenders were all provided on a confidentiality basis clearly marked on drawings”. He added that it was:

[c]learly understood mutually that when they come into my factory that we respect each other’s premises and effectively it was to some extent an unwritten understanding, over and above what was already in situ, that there was confidentiality every time they visited our premises or every time we emailed them drawings and the like.

61 In his 12 December 2017 affidavit, Mr Fontaine took issue with Mr Sozio’s evidence (outlined below) including with Mr Sozio’s evidence about the manufacture and supply of a variable speed limit sign with a partly flashing annulus before October 2002 and about Hi-Lux’s supply of a school zone sign on the Warburton Highway at Yarra Junction in 2002-2003. In the same affidavit, Mr Fontaine agreed with Mr Zammit about what Mr Sozio had referred to as “a fibre optic variable speed sign made by Hi-Lux” containing control boards marked as manufactured in 1998 recovered from Hi-Lux’s warehouse, although in cross-examination Mr Fontaine agreed that fibre optic speed limit signs had not been supplied in Victoria since well before 2014.

62 Also in his 12 December 2017 affidavit, Mr Fontaine contested some of the evidence of Mr Priest (discussed below) including Mr Priest’s account of the steps taken to commission the signs for the Western Ring Road Project. Mr Fontaine’s evidence was that Axent checked the functionality of each sign in Axent’s factory before the signs were installed, not after they were in place on the Western Ring Road. His evidence was that Axent had designed a program that simulated all of the signs as they were in the field, and that software was used to test the overall system. In his 19 April 2018 affidavit, Mr Fontaine deposed that he went to the opening of the Western Ring Road Project in December 2002. He referred to an email dated 20 November 2002, which was sent to him by Mr Petridis at VicRoads (who, according to the evidence was primarily responsible on VicRoads’ side for the Project) indicating that the system would go live the next day, 21 November 2002, although Mr Fontaine could not recall whether the system went live on 21 November 2002 or a little later.

63 In his 12 December 2017 affidavit. Mr Fontaine also contested parts of Mr Jan’s evidence, including that variable speed limits signs using LEDs were developed during the 1990s and that if the sign dimensions were minimised, there would be sufficient space in each corner for yellow flashing lights. Mr Fontaine also disagreed with Mr Jan and Mr Sozio concerning trials at the VicRoads Mulgrave facility, deposing that he had often visited the Mulgrave premises, with a clear view of the gantry, and that at no time did he see a peg board, a trial fibre optic speed sign, with or without multiple and variable flashing annuluses, or a 90 km/h sign.

Stephen Bean

64 Mr Bean had worked for VicRoads and its predecessors from 1981 until September 2017, most recently as the Manager of VicRoads Traffic and Incident Management. From the mid-1990s, Mr Bean was part of the VicRoads Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) Branch in charge of traffic signal controls, CCTV, electronic signage and other intelligent transport systems.

65 At the time he joined VicRoads, Mr Jan (who also gave evidence in the proceeding: see below) was the leader of ITS, a role which Mr Bean took over when Mr Jan left. While at ITS, Mr Bean also worked closely with suppliers, including Mr Fontaine and Mr Sozio (see below), although he did not recall working with anyone from Compusign. Mr Bean deposed that VicRoads had a modest research and development budget, and relied on its suppliers to develop and source innovative products for it. His evidence was that the ITS group was also relatively small within VicRoads, with the bulk of funding going to road and bridge construction.

66 Mr Bean gave evidence that, in his experience, although VicRoads occasionally held meetings with multiple suppliers if VicRoads wanted them all to be aware of an issue, VicRoads and its suppliers did not come together to discuss and share ideas for new products. Mr Bean’s evidence was that suppliers would approach him or his staff separately on a confidential basis, seeking information about whether VicRoads was interested in any of their proposed new initiatives. Although Mr Bean, as the ITS manager, did not sign confidentiality agreements with suppliers, he worked closely with them, on the basis that whatever they told him about their new products or innovations would not be disclosed by VicRoads to a third party, particularly not to other suppliers.

67 Mr Bean deposed that at the time he joined ITS in the mid-1990s electronic signage for speed signs was principally fibre optic signage and relatively rare. His evidence was that Hi-Lux supplied fibre optic signage to VicRoads at that time. Mr Bean’s evidence was that among the first of such signage installed by VicRoads was at a road crossing at a primary school in Yarra Glen “about 1999”. His evidence was that the Yarra Glen sign was memorable as it was the first time VicRoads had put a variable speed limit sign in front of a school. According to Mr Bean, the signs were manually operated by a crossing supervisor to display a 40 km/h speed limit. When the supervisor was not on duty, the signs were switched off or changed to display a 60 km/h speed limit. Mr Bean said that the red annulus on these signs did not flash, although they may have had a flashing yellow light. In cross-examination, he accepted that there may have been other examples of electric variable speed limit signs from this time, such “the flap-style sign”, and a prism-style sign on the West Gate Bridge, both of which were electronically controlled although they had physical sign plates.

68 In cross-examination, Mr Bean readily agreed that he was wrong when he had deposed in his 11 October 2017 affidavit that the Western Ring Road Project was the first time that variable speed limit LED signage was used on a Melbourne freeway. He agreed that such signage had been used in the Burnley Tunnel for the CityLink Project. He also agreed that a significant factor, so far as the Western Ring Road Project was concerned, was the fact that it was the first time that road speeds were programmed to change based on real time traffic flow data.

69 Mr Bean deposed that in the mid-1990s he met Mr Fontaine, who at that time was involved in supplying variable message signs and trip information systems to VicRoads (as indeed was its competitor, Hi-Lux). Mr Bean’s evidence was that Mr Fontaine was “a market leader in introducing LED signage”, which he said had considerable benefits so far as VicRoads was concerned, observing that VicRoads mandated the use of LEDs for all new traffic light installations from 1999 and began replacing existing traffic signals from that time.

70 Mr Bean deposed that, sometime in 2000, he spoke with Mr Fontaine about Mr Fontaine developing a LED variable speed limit sign. He accepted that at the time there was a recognised need for some conspicuity feature if the speed limit was to drop. His evidence was that the then common practice in road signage was to include a separate amber warning beacon as a warning device alerting a driver to a speed or condition change or both, and referred in this connection to the NSW Road Traffic Authority, whose practice was to include two flashing amber warning lights at the top of the display panel. Also at this time, Mr Bean was aware of the variable speed limit signs used in the tunnel as part of the CityLink project and he was aware that the Road Rules “had relatively recently been changed to allow for those … variable electronic speed limit signs”.

71 Throughout 2000 and 2001, Mr Bean visited Mr Fontaine’s factory perhaps once a month or two months, often with Mr Priest. Mr Bean deposed (and I accept) that, at two such meetings, he was shown a sample of the LED variable speed limit signs under development. This sign did not use flashing amber warning lights, but rather had a red annulus with numbers in white in the centre. Mr Bean’s evidence was that he and Mr Fontaine discussed how to avoid putting separate amber flashing lights on the sign and, although he could not recall the exact date, at one meeting, someone from Mr Fontaine’s side (he could not recall precisely who) put forward the solution of flashing part of the annulus. Mr Bean could not recall whether this was demonstrated by Mr Cestnik or Mr Fontaine. Mr Bean said that:

It had not occurred to me to do this. I recall being impressed by it. To the best of my knowledge at the time no one had done this before. I thought that it was a good solution and said so. To me at the time it seemed a simple and clean solution, but not an obvious one.

Mr Bean added in cross-examination:

… they actually showed me that they could flash the full annulus on, off, or they could flash one ring or two rings or three, so it appeared to be just programmable. They could do what they like … and that was new.

72 Mr Bean’s evidence was (and I accept) that he told Mr Fontaine he would need to check that such a sign complied with the Road Rules. He said that he was subsequently advised that such a device would be regulatory and that he communicated this to Mr Fontaine.

73 Mr Bean accepted that Mr Fontaine had emailed him on 21 June 2000 about the requirements for a variable speed limit sign with LEDs and that he had responded by email the same day setting out those requirements. Unsurprisingly, given the passage of time he had no recollection of the email exchange. Mr Bean stated that the draft specification for the supply of changeable fibre optic speed restriction signs that was an attachment to his email would have been used for the Yarra Glen Primary School. When taken to the reference in clause 6.3 of that specification to a variable flasher unit, Mr Bean said that this unit would have been used with other equipment to cause the display to flash in order to attract motorists’ attention.

74 Mr Bean was responsible for managing the tender process for the Western Ring Road Project. He accepted in cross-examination that he started to think about using the partially flashing annulus as a possible conspicuity feature for the signs for the Western Ring Road “closer to seeking expressions of interest”. He agreed that Mr Fontaine was not unhappy about having Axent’s variable speed limit sign included in the September 2001 specification and that Axent’s product continued to develop “through until April 2001 and through until September 2001 … with at least some form of encouragement from [him]”.

75 Mr Bean was clear that Mr Fontaine had proposed the flashing annulus solution to VicRoads before this feature was made a requirement in the September 2001 specification for the signage on the Western Ring Road Project. Mr Bean added that:

I do not recall specifically ask[ing] Geoff for permission to include the requirement of a partly flashing annulus in the VicRoads specification. As best as I recall I simply asked Stephen Purtill to include it without asking anyone else.

Mr Bean said in cross-examination that he “could see no reason why they wouldn’t” be happy with the inclusion of the product in the specification for use on the Western Ring Road Project and that he believed he acted reasonably in including it. He added:

Bear in mind, of course, that I assume that if one company can build a sign that can do this, then others could come along and say, “I can do that too.”

Mr Bean said that, after receiving expressions of interest for the Western Ring Road Project, VicRoads invited the shortlisted companies to tender and, in the course of so doing, sent them a bundle of documents including the September 2001 specification. Axent was awarded the tender based on its ability to meet the tender requirements and on price.

76 Mr Bean accepted in cross-examination that he viewed the prototype of Axent’s variable speed limit sign sometime around September 2001, to see whether it was going to work well for the specification for the project. Mr Bean conceded in cross-examination that shortly before the tender was to be issued he would have told Mr Fontaine that VicRoads was going to use the partially flashing annulus option for the specification for the project, although he could not recall precisely when he said this.

77 Mr Bean’s evidence was clear that the specification was not confined to the Western Ring Road Project but was a general specification for other applications requiring a variable speed limit sign. In cross-examination, Mr Bean agreed that any supplier would be required to incorporate the partly flashing annulus feature in future products where the specification applied.

78 Mr Bean’s evidence was that his involvement in the Western Ring Road Project substantially diminished after the tender was awarded and that he had limited involvement in the onsite testing of the signage prior to the “go live date” in late 2002. He deposed that:

The signage was installed before then, but, in line with standard practice, was covered and not visible to oncoming traffic.

… Throughout my time at VicRoads, however, I observed that VicRoads was always careful to take whatever steps are possible during acceptance testing of any newly installed signals or signage to ensure that road users do not see the new signs or become confused as to what signals or signage to obey and also to avoid any safety issues. For this reason new signage or traffic signals are, wherever possible, and particularly if in conflict with the existing signage or signals, turned away from being visible by drivers when being tested.

Mr Bean and Mr Priest agreed that Mr Petridis (who, so Mr Bean said, was still working for VicRoads in April 2018) was primarily responsible for the implementation of the Western Ring Road Project and would be the person within VicRoads most likely to know “exactly what happened during the commissioning”.

79 Mr Bean was unsure when he became aware of the Patent and said that it was well after the Western Ring Road Project had been completed.

80 Mr Bean deposed that, after the Western Ring Road Project, demand for the partly flashing annulus signage “became high on other freeways and also in strip shopping centres and school zones”. Mr Bean added that in 2003 VicRoads put out a tender for a state-wide school zone variable speed limits signage project (school zones project), for which Axent and Hi-Lux submitted tenders. By that time, Mr Bean said that Axent had demonstrated compliance with the VicRoads specification; it had a type approval for its variable speed limit LED sign; and it was successful in its tender. By the same time, Hi-Lux had not demonstrated compliance with the specification and did not have a type approval.

81 In cross-examination, Mr Bean clarified his affidavit evidence regarding a Hi-Lux variable speed limit product. He accepted that Mr Sozio, for Hi-Lux, submitted a variable speed limit sign to VicRoads on 22 October 2003 for VicRoads to look at, but he said at that point Mr Sozio did not have type approval for the product. Mr Bean also deposed that he had advised Hi-Lux that VicRoads would assess the fibre optic signage previously installed in Yarra Glen as part of the process. He deposed that although it was by then too late for Hi-Lux signage to be considered for the school zones project, type approval would mean that that signage could be considered for future tenders. At the time, type approval decisions were made by a committee within VicRoads, which would consider any ITS recommendation. Mr Bean explained that once type approval had been given, it was VicRoads’ practice to require all signage of that type supplied to it by that supplier to comply with the type approval. Mr Bean also said in cross-examination that type approval was generally but not necessarily referable to a VicRoads specification.

82 Mr Bean disputed the accuracy of Mr Sozio’s recollection that VicRoads required signs to have a partly flashing functionality in 1991. Mr Bean said that he had never seen a Hi-Lux variable speed limit sign with a partly flashing annulus in 2003 or earlier. Mr Bean deposed that VicRoads did not require the flashing of part of a speed sign until the September 2001 specification and that, until that time, separate amber flashing lights or other signage were used to warn of a speed change.

83 Regarding Mr Sozio’s evidence about Bastow Place, Mulgrave, Mr Bean said that at different times there was a variety of signage around VicRoads’ Mulgrave offices. He added that following the closure of the Bastow Place premises in 1995, there was another VicRoads facility in Mulgrave where traffic lights and other signs were tested. In response to Mr Jan’s affidavit evidence, Mr Bean said:

… I never saw a sign with a partly flashing annulus at any VicRoads facility before the time of my meetings at Geoff Fontaine’s premises …

… I never observed any testing or trialling of speed sign prototypes with a partly flashing annulus occurring at VicRoads while Barry [Jan] was working with me in the ITS Group. ... I joined the Group in 1995. At that time, I don’t recall that we had any electronic style speed signs at that time. When I joined, we set up the new test facility at South Eastern Freeway Mulgrave. I visited the premises on may [sic] occasions and would have been aware if we were testing an electronic speed zone sign. We weren’t.

…

… I agree that wind detectors operated in the Westgate Bridge at the time that Barry was at VicRoads. The signs on the bridge at that time were mechanical tri-signs. These signs were replaced with electronic signs after the success of the Western Ring Road project.

Mr Bean also deposed that he had never seen the gantry to which Mr Jan referred in his affidavit evidence (see below).

84 Mr Bean also disputed Mr Sozio’s description of the Yarra Glen variable speed signs, stating that these signs did not flash the rings as Mr Sozio described. He also said that he had never seen a sign in Bendigo with a flashing annulus such as Mr Sozio claimed to have seen. Mr Bean’s evidence was that:

… [A]t that time the signs that VicRoads was using in fibre optic were things like GIVE WAY TO PEDS signs, where the whole message might flash. The variable flasher unit is what would enable this.

His evidence was that the changeable fibre optic speed limit restriction signs also required a variable flasher unit.

85 Mr Bean deposed that a benefit of the invention involving a partly flashing annulus was as a warning to motorists “both of the presence of something that called for a change in speed … and the change in the speed limit itself”. A further benefit was, so he deposed, that it removed the need for flashing amber warning signals. He concluded that “this solution in the Patent is more compact, more elegant, cheaper and arguably more effective than anything that had been used by VicRoads or anyone else at the time”. In cross-examination, he conceded that he did not know what costs might be involved, and it was merely his opinion that the flashing annulus was more effective than another solution. He went on to say “the motorist needs to recognise there has been [a] change and I think [the partly flashing annulus is] effective in doing that”, whilst conceding that if motorists were used to seeing flashing yellow lights as indicating caution was needed, then this would also be effective.

86 Mr Bean also clarified in cross-examination that although VicRoads had a specification for variable speed limit signs from around September 2001, which was applicable to the Western Ring Road Project, it was not the case that VicRoads wanted other variable speed limit signs brought into compliance with that specification. Mr Bean said:

... [W]e didn’t want to change what people were doing. The specification at that time allowed for fibre optic signs as well.

87 In response to the affidavit evidence of Mr He and Mr Riquelme (see below), Mr Bean subsequently deposed that he was unaware of any variable speed limit sign prototype being developed by Compusign during the tender process for the Western Ring Road Project; that he did not recall going to Compusign’s premises to look at passenger information display signs in early 2002, although it was possible that he had done so; and that he did not recall seeing the letter annexed to Mr He’s 28 March 2018 affidavit and marked ZQH-4 (see below). Regarding this letter, Mr Bean deposed that he had seen an email sent to him by Mr Thurairatnam at Hi-Lux, which indicated that this letter had been forwarded to him on 8 January 2002. The letter proposed that VicRoads pay Compusign to adapt passenger information display technology for a variable speed limit sign that had pixel failure detection, LED driver circuitry not requiring resistors, and a sign controller. Mr Bean’s evidence was that he did not approve the project that the letter proposed and that, to his knowledge, the project did not receive VicRoads approval and did not proceed.

Peter Cestnik

88 Mr Cestnik was the General Manager of Axent at the time of the hearing. From 1998, he had worked for Symon Australia. From March 2001, he worked for Axent, including as Production Manager in 2001.

89 Mr Cestnik deposed that during 2000 and 2001 Symon Australia and then Axent were working to develop a variable speed limit sign using LED lighting, and that Mr Bean and other VicRoads personnel had visited Axent’s premises on a few occasions to discuss what Axent was doing. In particular he recalled that, with Mr Fontaine, he had demonstrated the prototype variable speed limit sign to Mr Bean in September 2000 and Mr Bean had said that he liked the size and neatness of how it was made. He also recalled that Mr Bean and Mr Fontaine had discussed the need to warn drivers of the change in speed, and that Mr Bean said “something like a separate warning light of some kind would need to be added for this purpose”.

90 Mr Cestnik deposed that he and Mr Fontaine discussed alternatives to a separate set of warning amber lights, and ultimately made a proposal to Mr Bean along the lines of “what about if we were to make it flash part of the annulus?”. Mr Cestnik said that Mr Bean indicated that he really liked this solution but that he would need to confirm that it met the requirements of the Road Rules. Mr Cestnik arranged for changes to the prototype sign so that the partly flashing annulus could be demonstrated.

91 In cross-examination, Mr Cestnik accepted that VicRoads was “[p]otentially” one of the contemplated customers for Axent’s variable speed limit sign, and that Axent might “[p]otentially” wish to know whether they would approve the product. Mr Cestnik said in evidence that he could not recall whether he was involved in any meetings with VicRoads in around April 2001 in relation to a prototype variable speed limit sign or any meetings with VicRoads in relation to the variable speed limit signs at any time before Axent tendered for the Western Ring Road Project.

92 In cross-examination, Mr Cestnik said that Symon Australia had developed variable speed limit signs in the late 1990s for the CityLink Project. He described them as “basic LED signs” and “the basic version of a variable speed limit sign”. His evidence was that these signs could display two different speeds using LED lighting, but did not have a flashing annulus or dimming features, and could not otherwise flash.

93 In respect of Mr Priest’s evidence about the commissioning process for Axent’s variable speed limit sign along the Western Ring Road, Mr Cestnik’s evidence was that he was present when night-time works were undertaken in late 2002. His evidence was that the testing was needed to set the appropriate night-time lighting levels in the signs, and not to test the flashing of the annulus components of the signs. In cross-examination, he said that the testing occurred on only one night, disagreeing with Mr Priest that the testing occurred over multiple nights (see below). Mr Cestnik’s evidence was that during the night of the testing Mr Zammit was in a “communications hut” and unable to see the sign faces and what was displayed. He agreed that the signs were uncovered on the night that testing occurred and insisted that the system was not yet live. His evidence was that VicRoads had previously approved the functionality and the operation of Axent’s variable speed limit sign in factory testing at the Axent factory prior to installation. He accepted that the control of the signs from the VicRoads control centre was a deliverable for the Project but said that this was not verified by VicRoads before practical completion.

Michael Zammit

94 At the time of the hearing, Mr Zammit was Axent’s production manager/project manager. He had been employed by Axent in this capacity since March 2001. Previously from 1994, he had worked for Symon Australia, initially as a software programmer and later as a design engineer, project engineer, service manager and technical specialist before taking up his current position. In particular, during 2001 and 2002, he was Axent’s project manager and production manager for various projects across Victoria and Australia.

95 Mr Zammit worked on the development and installation of the Axent system for the Western Ring Road Project. His evidence was that Axent’s task in relation to the Project was to implement a system to dynamically read information regarding traffic volumes, and feed that information into an algorithm, which would then calculate the required speeds in a dynamic mode of operation. That algorithm would then determine what the recommended speeds for traffic in the area were and then adjust the traffic flow accordingly.

96 Mr Zammit’s evidence was (and I accept) that the Western Ring Road Project involved the installation of approximately 80 of Axent’s variable speed limit signs on the Western Ring Road in late 2002. Mr Zammit said that these signs commenced operating in December 2002. In 2002, there were 15 groups of the Axent signs, linking back to a communications hut, which was in turn linked to the VicRoads traffic control centre at Camberwell (not Kew as Mr Priest deposed: see below). Mr Zammit said (and I accept having regard to all the evidence) that it was only later that the traffic control centre at Camberwell moved to Kew.

97 Mr Zammit was involved in the development, commissioning and testing of the traffic management system and Axent’s variable speed limit signs for the Western Ring Road, although Mr Petridis from VicRoads, with whom he dealt on a regular basis, was primarily responsible for the Project on VicRoads’ side. Mr Zammit’s evidence was (and I accept, noting that it was corroborated by others at Axent) that each of Axent’s signs was tested at Axent’s factory during and after manufacture and, when installed along the Western Ring Road, each was covered and/or turned away from oncoming traffic. The signs were not tested on site. Rather, Axent designed a program that simulated all the signs as they were in the field, and the software for the traffic management system itself was developed and tested using a simulator program. Mr Zammit’s evidence was the sign simulator software module simulated the operation, reporting and all display modes without having the signs installed in the field or operating in real time. His evidence was that he was not involved in any live testing where the system was controlled from either the traffic control centre at Camberwell or the traffic management centre at Kew, and that he had not observed any live testing via CCTV.