Federal Court of Australia

Tayeh v Commonwealth of Australia, in the matter of 1st Fleet Pty Limited (In Liq) [2020] FCA 1323

NSD 1796 of 2019 | |

Judgment of: | JAGOT J |

Date of judgment: | 18 September 2020 |

Catchwords: | CORPORATIONS – application for declaration that resolutions passed by committee of inspection were valid – purported members of committee natural persons said to be representatives of creditors – whether appointment of representatives invalid – whether appointment of representatives a “procedural irregularity” under s 1322(2) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) – requirements for granting of relief under s 1322(6) – application dismissed |

Legislation: | Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) Fair Entitlements Guarantee Act 2012 (Cth) Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (Cth) Superannuation Guarantee Charge Act 1992 (Cth) Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) Long Service Leave Act 1955 (NSW) |

Cases cited: | Allen v Townsend [1977] FCA 10; (1977) 31 FLR 431 Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2005] NSWSC 417; (2005) 216 ALR Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2009] NSWSC 1229; (2009) 236 FLR 1 Barter v Maher (1972) 21 FLR 10 Brown v West [1990] HCA 7; (1990) 169 CLR 195 Chalet Nominees (1999) Pty Ltd v Murray [2012] WASC 147; (2012) 30 ACLC 12-017 City Pacific Ltd v Bacon (No 2) [2009] FCA 772; (2009) 178 FCR 81 Clark v Framingham Aboriginal Trust [2014] VSC 367 Cordiant Communications (Australia) Pty Ltd v The Communications Group Holdings Pty Ltd [2005] NSWSC 1005; (2005) 55 ACSR 185 Hall v Poolman [2007] NSWSC 1330; (2007) 215 FLR 243 Harris v Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority [1999] FCA 437; (1999) 162 ALR 651 James v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [1957] HCA 36; (1957) 97 CLR 23 Jones v Dunkel [1958] HCA 8; (1959) 101 CLR 298 Kalis Nominees Pty Ltd v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation (1995) 95 ATC 4519 Lockwood v the Commonwealth [1954] HCA 31; (1954) 90 CLR 177 Lynch v Hodges (1963) 4 FLR 348 McGovern v Ku-Ring-Gai Council [2008] NSWCA 209; (2008) 72 NSWLR 504 New South Wales Land and Housing Corporation v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2015] NSWSC 176 Newcrest Mining (WA) Ltd v Commonwealth [1997] HCA 38; (1997) 190 CLR 513 Onefone Australia Pty Ltd v One Tel Ltd [2008] NSWSC 1335; (2009) 69 ACSR 290 Onefone Australia Pty Ltd v One.Tel Ltd [2010] NSWSC 1120; (2010) 80 ACSR 11 Poliwka v Heven Holdings Pty Ltd (1992) 7 ACSR 85 Project Blue Sky Inc v Australian Broadcasting Authority [1998] HCA 28; (1998) 194 CLR 355 Re Chevron Furnishers Pty Ltd (in liq) [1994] 2 Qd R 475 Re Compaction Systems Pty Ltd [1976] 2 NSWLR 477 Re Great Southern Ltd (in liq), Ex parte Jones [2016] WASC 234; (2016) ACLC 16-032 Re Ryde Ex-Services Memorial & Community Club Limited [2015] NSWSC 226 Re Wave Capital Ltd [2003] FCA 969; (2007) 47 ACSR 418 Shearwood (Trustee), in the matter of Allied Resource Partners Pty Ltd v Allied Resource Partners Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1451 Sipad Holdings DDPO v Popovic [1995] FCA 890; (1995) 61 FCR 205 Williams v The Queen [1977] Tas SR (Pt 2) 135 Steuart v Oliver (No 2) (1971) 18 FLR 83 Sydney Appliances Pty Ltd (in liq) v Robert Bosch (Australia) Pty Ltd [2000] NSWSC 32; (2000) 33 ACSR 680 Weinstock v Beck [2013] HCA 14; (2013) 251 CLR 396 Whitehouse v Capital Radio Network Pty Ltd [2002] TASSC 78; (2002) 21 ACLC 17 Whitehouse v Capital Radio Network Pty Ltd [2004] TASSC 128; (2004) 13 Tas R 27 Williams v The Queen [1977] Tas SR (NC) 135 |

Number of paragraphs: | |

Date of last submissions: | 30 July 2020 |

Division: | General |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub Area: | Corporations and Corporate Insolvency |

Counsel for the Plaintiffs: | Mr S Golledge SC with Mr G Ng |

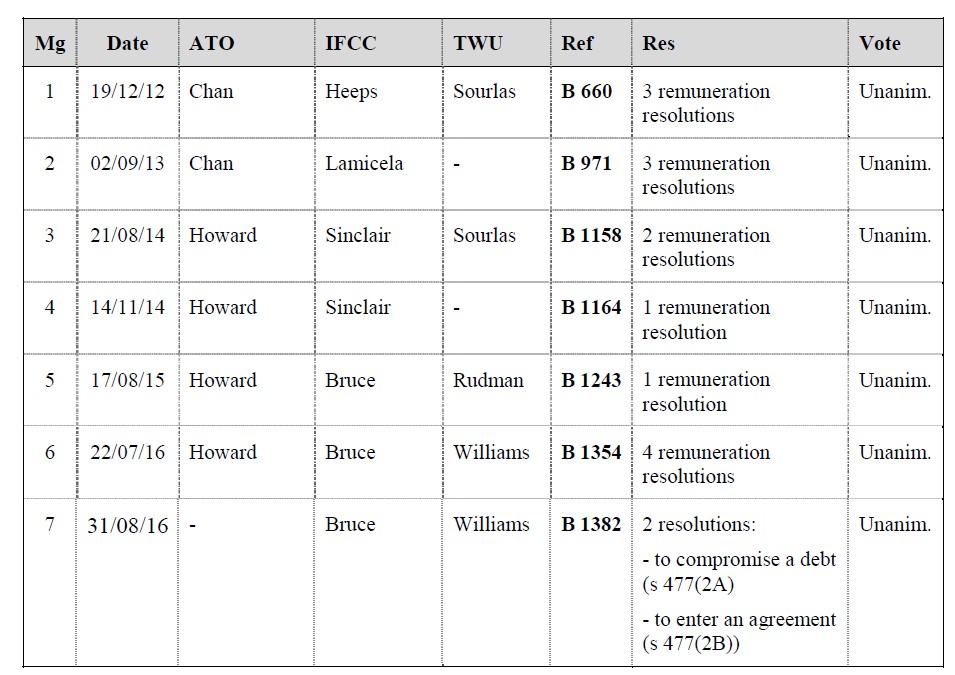

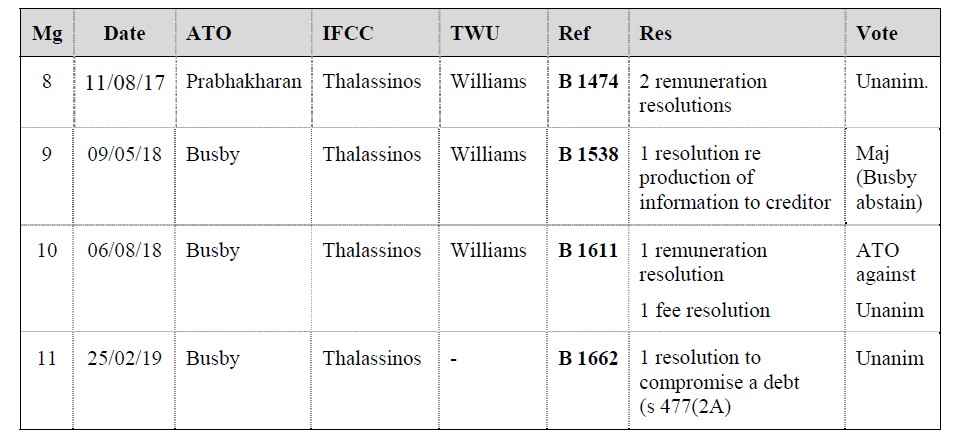

Solicitor for the Plaintiffs: | Somerset Ryckmans |

Solicitor for the Defendant: | Minter Ellison |

Counsel for the Intervener: | Dr Ruth Higgins SC with Mr T Rogan |

Solicitor for the Intervener: | Craddock Murray Neumann |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: | 18 SEPTEMBER 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Paragraphs 1 to 9 of the amended originating application be dismissed.

2. Within 14 days, the parties confer and file agreed or competing proposed orders for the resolution of all outstanding issues in this proceeding (including orders as to costs).

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JAGOT J:

THE PROCEEDING

1 The plaintiffs are the liquidators of a group of companies known as the 1st Fleet Group (the Group). The liquidators seek declarations to the effect that the appointment of persons to and the purported representation of those persons during meetings of the committee of inspection (COI) of the second to ninth plaintiffs are not invalid by reason of any procedural irregularities and that the resolutions passed by the committee of inspection are not invalid by reason of any such procedural irregularities (the process issue). In the alternative the liquidators seek a determination of the remuneration of the first plaintiff in the winding-up of the second to ninth plaintiffs (the quantum issue).

2 These reasons for judgment concern the process issue. The parties consented to the process issue being decided on the papers and without an oral hearing. On reviewing the material I considered that, in respect of some of the issues, I would be assisted by an oral hearing. It proved impossible to identify convenient dates for the oral hearing. In the circumstances I informed the parties that I proposed to decide the issues which I could decide without an oral hearing and to defer the balance for subsequent consideration if necessary. As discussed below it has not proved necessary to defer the consideration of any question relating to the process issue.

3 The amended originating process identifies the foundation of the application for relief as s 1322(4)(a) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the Act). That provision is to the effect that the Court may, on application by any interested person, make:

an order declaring that any act, matter or thing purporting to have been done, or any proceeding purporting to have been instituted or taken, under this Act or in relation to a corporation is not invalid by reason of any contravention of a provision of this Act or a provision of the constitution of a corporation.

4 By s 1322(6)(a)(i)-(iii) the Court must not make such an order unless it is satisfied that the act, matter or thing, or the proceeding, is essentially of a procedural nature, or that the person or persons concerned in or party to the contravention or failure acted honestly, or that it is just and equitable that the order be made, and in every case, that no substantial injustice has been or is likely to be caused to any person.

5 However, the liquidators’ primary position is that the declarations may be made on the basis of s 1322(2) of the Act. Section 1322(2) provides that a:

proceeding under this Act is not invalidated because of any procedural irregularity unless the Court is of the opinion that the irregularity has caused or may cause substantial injustice that cannot be remedied by any order of the Court and by order declares the proceeding to be invalid.

6 The declarations which are sought are as follows:

1 the resolution passed by the creditors of the second to ninth plaintiffs on 2 July 2012 appointing a COI and specifying the members of the COI for the purposes of section 548A of the Act (Resolution) is not invalid by reason of the resolution not being expressed to be made under section 548A of the Act.

2 the appointment of Michael Thomas Scott as a member of the COI is not invalid by reason of the Resolution referring to the appointment of Helen Sourlas representing the Transport Workers Union of Australia (TWU) and thus failing accurately to specify the persons who were to be members of the COI for the purposes of s 548A of the Act.

3 the representation of Michael Thomas Scott at meetings of the COI by Helen Sourlas, Alison Rudman and Herbert Williams (TWU employees) being employees of the TWU, is not invalid by reason of the TWU employees not having been appointed to represent Michael Thomas Scott under a proxy by instrument in accordance with Form 532 pursuant to regulation 5.6.29 of the Corporations Regulations 2001 (Cth) (Regulations).

4 neither the Resolution nor the constitution and appointment of the COI are invalid by reason of the Resolution failing to specify, for the purposes of s 548A(1)(d)(i) of the Act, the number of members of the COI to represent the creditors of the second to ninth plaintiffs.

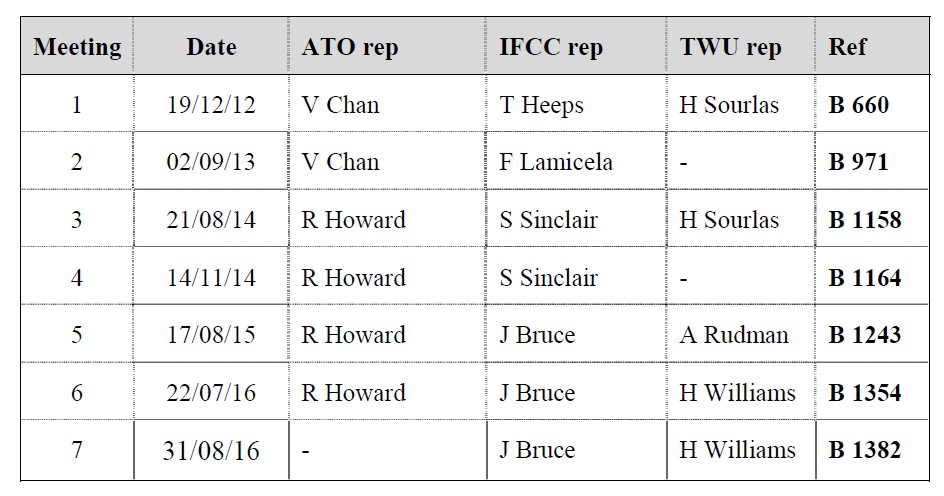

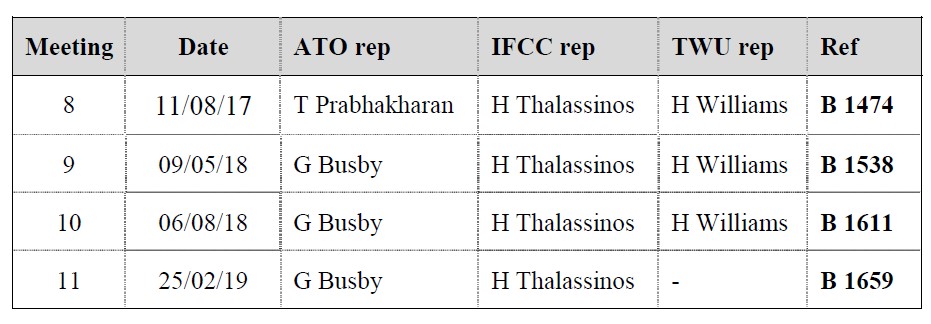

5 the acts, decisions and resolutions, in favour of which the TWU employees are recorded as having voted in the minutes of COI meetings dated 19 December 2012, 21 August 2014, 17 August 2015, 22 July 2016, 31 August 2016, 11 August 2017, 9 May 2018, 6 August 2018 and 25 February 2019 are not invalid by reason of:

a the TWU employees not having been appointed to represent Michael Thomas Scott under a proxy by instrument in accordance with Form 532 pursuant to regulation 5.6.29 of the Regulations; or

b the failure of the minutes to record that the TWU employees voted in favour of those acts, decisions and resolutions as the representatives of Michael Thomas Scott.

6 the appointment of AustralianSuper as a member of the COI is not invalid by reason of the Resolution referring to the appointment of Clara Lai as a representative of the Industry Fund Credit Control (IFCC) and thus failing accurately to specify the persons who were to be members of the COI for the purposes of s 548A of the Act.

7 the representation of AustralianSuper at meetings of the COI by Tani Heeps, Francesca Lamicela, Samantha Sinclair, Jayson Bruce and Helen Thalassionos (IFCC employees) being employees of the IFCC, is not invalid by reason of each individual IFCC employee not having been authorised in writing by AustralianSuper to represent AustralianSuper at meetings of the COI pursuant to s 549(4)(b) of the Act.

the acts, decisions and resolutions, in favour of which the IFCC employees are recorded as having voted in the minutes of COI meetings dated 19 December 2012, 2 September 2013, 21 August 2014, 14 November 2014, 17 August 2015, 22 July 2016, 31 August 2016, 11 August 2017, 9 May 2018, 6 August 2018 and 25 February 2019, are not invalid by reason of:

a each individual IFCC employee not having been authorised in writing by AustralianSuper to represent AustralianSuper at meetings of the COI pursuant to s 549(4)(b) of the Act; or

b the failure of the minutes to record that the IFCC employees voted in favour of those acts, decisions and resolutions as the representatives of AustralianSuper.

8 any act, matter or thing purportedly done by the first plaintiff, or by persons acting on the first plaintiff’s behalf, in reliance on resolutions passed by the COI are not invalid, by reason of the contraventions of the Act referred to in orders 1 to 8 above.

BACKGROUND

7 The following summary is taken from the submissions for the liquidators and the Commonwealth.

8 The 1st Fleet Group provided national transportation and related services.

9 The liquidators were first appointed as the voluntary administrators of each of the companies in the Group on 25 April 2012. They were subsequently appointed as the liquidators of each company in the Group and the company Transport Payroll Services Pty Ltd on 22 May 2012.

10 On 21 June 2012 the liquidators made a pooling determination in respect of the companies in the Group and Transport Payroll under s 571(1) of the Act. By s 574(1) of the Act the liquidators were required to convene a meeting of the creditors of each of the companies within five days for the purpose of allowing them to consider and approve the pooling determination. To that end the liquidators circulated a notice of meeting of creditors under s 574(2) of the Act for each company within the Group and Transport Payroll.

11 One of the agenda items on the notice was the appointment of a committee of inspection. Section 548A of the Act applied to a committee of inspection in respect of a pooled group. The section provided that:

(l) If:

(a) either:

(i) a pooling determination is in force in relation to a group of 2 or more companies; or

(ii) a pooling order is in force in relation to a group of 2 or more companies; and

(b) each company in the group is being wound up;

the liquidator or liquidators must, if requested by a creditor of a company in the group, convene a meeting, on a consolidated basis, of the creditors of the companies in the group for the purposes of determining:

(c) whether a committee of inspection should be appointed for the group; and

(d) if a committee of inspection is to be appointed:

(i) the number of members to represent the creditors of the companies in the group; and

(ii) the persons who are to be members of the committee representing the creditors of the companies in the group.

…

(3) A person is not eligible to be appointed as a member of a committee of inspection as a result of a determination under subsection (1) unless the person is an eligible unsecured creditor (within the meaning of Division 8) of a company in the group.

(4) A committee of inspection for a group of 2 or more companies is taken to be a committee of inspection for each company in the group.

12 Section 548 dealt with the establishment of a committee of inspection where no pooling determination was in place in equivalent terms to s 548A (but for the fact that under s 548A creditors of a number of companies are involved).

13 An eligible unsecured creditor is defined in s 579Q of the Act as a creditor whose debt or claim is unsecured and who is not a company in the group or is specified in the Regulations.

14 The minutes of a meeting on 2 July 2012 establish that the creditors of the second plaintiff approved the liquidators’ pooling determination. Thereafter a combined meeting of all the companies the subject of the pooling determination was convened at which time a resolution was passed as follows:

That the meeting appoint a committee of inspection and that the members of the committee of inspection formed in accordance with section 548 of the Corporations Act 2001 be:

1. Clara Lai representing IFCC

2. Kevin Smith representing ATO

3. Helen Sourlas representing TWU

and their appointment shall take place subject to them each satisfying the requirements of section 548 of the Corporations Act 2001.

15 The COI held 11 meetings between 19 December 2012 and 25 February 2019 at which it passed resolutions including resolutions authorising the liquidators to draw down remuneration of $5,654,228. As at 1 July 2019 the liquidators had drawn down $3,861,476 pursuant to the resolutions made by the COI.

16 Ms Lai did not attend any of the 11 meetings. Instead, the meetings were attended by various other employees of IFCC. Ms Sourlas attended two of the meetings and a further six were attended by other employees of the TWU. Mr Smith did not attend any of the meetings. Instead the meetings were attended by various other employees of the ATO.

17 The Commonwealth is an admitted creditor of two companies in the Group for advances of $9,444,014 made by it to those companies between 28 May 2012 and 24 October 2013 under the General Employee Entitlements and Redundancy Scheme (GEERS). GEERS was a scheme administered by the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations under which the Commonwealth advanced money to an insolvent company for the purpose of it paying certain outstanding employee entitlements to former staff. As a result of the advances the Commonwealth became entitled to prove in the winding up for the amount advanced, with the same priority as the employees would have had under s 560 of the Act.

18 The Deputy Commissioner of Taxation is a creditor of two companies in the Group for $9,545,784 for various unpaid tax liabilities including superannuation guarantee charges arising from the non-payment of superannuation contributions by those companies of which at least the superannuation guarantee charge component has been admitted.

19 The debts owing to the Commonwealth and the Deputy Commissioner include debts that must be paid in priority to other unsecured debts under s 556(1)(e) of the Act. The liquidators estimated that as at 31 July 2018 the debts within s 556(1)(e) of the Act amounted to $3,003,626 of which the claims of the Commonwealth and the Deputy Commissioner represent 98.2%. The liquidators paid a dividend of $2 million to s 556(1)(e) priority creditors on 6 September 2018. The liquidators’ most recent estimate is that the surplus available in the winding up will be sufficient to pay, on an optimistic basis, 82.04% of the remaining s 556(1)(e) priority debts (of $972,435), with nothing remaining for other unsecured creditors. As the Commonwealth put it, “the Commonwealth and the Deputy Commissioner have the overwhelming financial interest in the outcome of the winding up of the companies.”

20 On 24 August 2018 the Commonwealth notified the liquidators that it was concerned that the resolutions approving the liquidators’ remuneration may be invalid because the resolution appointing the COI may have been ineffective for three reasons:

(1) the resolution was made under s 548 of the Act (applying to a single company in liquidation) rather than under s 548A (applying to a pooled group);

(2) the resolution failed to satisfy s 548A(1)(d) by failing to determine the number of members of the COI; and

(3) the resolution purported to appoint persons who were ineligible for appointment.

21 In its written submissions opposing the grant of the declarations the Commonwealth identified five issues for determination as follows:

First, did the creditors appoint AusSuper and Mr Scott as members of the COI at the pooling meeting?

Second, if so, were AusSuper and Mr Scott eligible to be appointed to the COI?

Third, if so, did AusSuper and Mr Scott validly authorise the persons who attended the COI meetings to do so in their stead?

Fourth, if the answer to any of those questions is no, is the attendance at and participation in the COI meetings and, in particular, the making of the COI resolutions by those persons a procedural irregularity within the meaning of s 1322(2) of the Corporations Act, so that the COI resolutions are not invalidated because of the irregularity?

Fifth, if the answer to the fourth question is no, should the Court make an order under s 1322(4) of the Corporations Act declaring the COI resolutions to be not invalid by reason of them being made by persons who were not authorised to do so?

PROCEDURAL IRREGULARITY

22 Section 1322(1)(a) of the Act provides that “a reference to a proceeding under this Act is a reference to any proceeding whether a legal proceeding or not.”

23 In City Pacific Ltd v Bacon (No 2) [2009] FCA 772; (2009) 178 FCR 81 at [51] Dowsett J held that “the adoption of a resolution at a meeting is a proceeding for the purposes of s 1322(1) and (2).”

24 In Sipad Holdings DDPO v Popovic [1995] FCA 890; (1995) 61 FCR 205 at 219 Lehane J said that a procedural irregularity encompassed circumstances in which a person has attempted to do something which the Act permits, but has failed to do that thing effectively because of a procedural failure or omission, but does not encompass a circumstance where a person has tried to do something which the Act does not authorise.

25 Shearwood (Trustee), in the matter of Allied Resource Partners Pty Ltd v Allied Resource Partners Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 1451 at [160] applied the views of Palmer J in Cordiant Communications (Australia) Pty Ltd v The Communications Group Holdings Pty Ltd [2005] NSWSC 1005; (2005) 55 ACSR 185 at [103] that:

– what is a ‘procedural irregularity’ will be ascertained by first determining what is ‘the thing to be done’ which the procedure is to regulate;

– if there is an irregularity which changes the substance of ‘the thing to be done’, the irregularity will be substantive;

– if the irregularity merely departs from the prescribed manner in which the thing is to be done without changing the substance of the thing, the irregularity is procedural.

26 In Onefone Australia Pty Ltd v One.Tel Ltd [2010] NSWSC 1120; (2010) 80 ACSR 11 at [8] Barrett J referred to Cordiant with approval and said that the relevant distinction is:

between doing the ‘thing to be done’ in a way that departs from the prescribed way and doing something other than the ‘thing to be done’. The former involves procedural irregularity. The latter does not.

INCORRECT REFERENCE TO S 548

27 It will be apparent from the text of the resolution appointing the COI that the resolution refers to the COI being formed under s 548 of the Act. The reference to this section is in error. The relevant provision under which a COI may be formed for two or more companies subject to a pooling determination is s 548A.

28 The liquidators submitted that the reference to s 548 constitutes an “obvious error” and that the Court could construe the minutes of the resolution as referring to the correct provision, being s 548A: New South Wales Land and Housing Corporation v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2015] NSWSC 176 at [46]-[64].

29 Alternatively, the liquidators said that it is the case that “the validity of an administrative act is not necessarily impugned by there having been a mistake as to the source of power stated by the decision-maker as that upon which reliance was placed” (emphasis in original): Harris v Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority [1999] FCA 437; (1999) 162 ALR 651 at [14], relying on Brown v West [1990] HCA 7; (1990) 169 CLR 195, 203-4; Newcrest Mining (WA) Ltd v Commonwealth [1997] HCA 38; (1997) 190 CLR 513, 618. As was said by Fullagar J in Lockwood v the Commonwealth [1954] HCA 31; (1954) 90 CLR 177 at 184 “an act purporting to be done under one statutory power may be supported under another statutory power”. In the present case, the meeting was of a pooled group. The relevant power was s 548A and not s 548. In these circumstances the meeting should be taken to have intended to rely on s 548A, the available source of power to appoint a committee of inspection, and to have in fact invoked that available power.

30 If these submissions are not accepted, the liquidators submitted further that the defect in the resolution is a mere procedural irregularity. The thing to be done was the appointment of a committee of inspection and that was to be done under s 548A but the meeting departed from the way the thing was to be done by relying instead on s 548. The defect involved no alteration to the substance of the thing to be done. There is no evidence of any injustice let alone substantial injustice caused by the erroneous reference to s 548. Accordingly, the error is a procedural irregularity as provided for in s 1322(2) which does not invalidate the resolution of 2 July 2012.

31 No submissions to the contrary were put.

32 I accept the liquidators’ submissions about this issue. The resolution of 2 July 2012 is not invalid by reason of the erroneous reference to s 548 rather than s 548A of the Act as the relevant source of power.

NUMBER OF MEMBERS OF COI

33 It will be apparent from the text of the resolution appointing the COI that the resolution does not refer to the number of members to represent the creditors of the companies in the group.

34 The liquidators submitted that s 548A does not require the resolution to specify the number of members to represent the creditors of the companies in the group separately from specifying the members to represent the creditors of the companies in the group.

35 Alternatively, the liquidators submitted that if s 548A does require the number of members to represent the creditors of the companies in the group to be specified separately from specifying the members to represent the creditors of the companies in the group then the resolution satisfied that requirement because, in terms, it fixed the number of members as the three members specified.

36 In any event, the liquidators submitted that the failure to specify the number of members of the COI separately from the members of the COI is a procedural irregularity as provided for in s 1322(2) of the Act.

37 No submissions to the contrary were put.

38 I agree with the liquidators’ submission that s 548A(1)(d)(i) does not require the resolution appointing a COI to specify the number of members separately from specifying the members of the COI. In other words, specifying the members of the COI will also specify the number of those members as provided for in s 548A(1)(d)(i) of the Act. If this is incorrect, I would also accept the liquidators’ submission that this is a procedural irregularity which has not caused any injustice to any person. Either way, the fact that the resolution of 2 July 2012 does not specify that the COI shall consist of three members but instead specifies the members of the COI (who are three in number) does not have the effect of invalidating the resolution.

WHO WAS APPOINTED TO THE COI?

39 The terms of the resolution of 2 July 2012 are set out above. The liquidators contended that AustralianSuper and Michael Thomas Scott were intended to be appointed to the COI and the terms of the resolution as recorded in the minutes inaccurately reflect that intention by referring instead to Ms Lai representing IFCC and Ms Sourlas representing the TWU. The Commonwealth contended that the terms of the resolution as recorded in the minutes should be found to be accurate so that the persons appointed to the COI were Ms Lai and Ms Sourlas or IFCC and the TWU.

40 There is no dispute that neither Ms Lai nor IFCC were at any time an eligible unsecured creditor of any company within the Group as required by s 548A(3) of the Act for eligibility to be appointed as a member of the COI.

41 Further, there is no dispute that neither Ms Sourlas nor the TWU were at any time an eligible unsecured creditor of any company within the Group as required by s 548A(3) of the Act for eligibility to be appointed as a member of the COI.

Liquidators’ submissions

42 The liquidators noted that on or about 4 May 2012 two proofs of debt were lodged on behalf of AustralianSuper in respect of outstanding superannuation contributions for $2,271.90 and $39,570.93. These proofs of debt were accompanied by a letter dated 4 May 2012 from Industry Fund Credit Control stating that IFCC was the appointed credit manager for AustralianSuper.

43 The liquidators identified the evidence further explaining the relationship between AustralianSuper and IFCC in the following terms:

The relationship between AustralianSuper and IFCC is further explained in the evidence of Ms Mather. In 2006, AustralianSuper and Industry Funds Credit Control Pty Ltd (IFCC Pty Ltd) entered into an Arrears Collection Agreement (the 2006 Agreement), pursuant to which the latter was appointed as a “contributions arrears collection agent” for “the Fund known as the AustralianSuperfund”. Among the services IFCC Pty Ltd was obliged to provide under the 2006 Agreement were the following:

(a) Upon receipt of advice from the Trustee [AustralianSuper], such advice to be communicated by the Trustee or through the administrator of the Fund, that a participating Employer has failed to satisfactorily respond to a request for payment of outstanding contributions, IFCC shall use its best endeavours to obtain such participating Employers prompt and total payment of all outstanding contributions due to the Fund on behalf of the Employees.

…

(e) Subject to the prior approval of the Trustee, IFCC shall represent the Trustee or appoint a firm of solicitors to represent the Trustee at any legal or non-legal proceedings (eg prior to creditors’ meetings) in relation to an insolvent participating Employer and shall provide a quarterly report to the Trustee of the status of actions taken in respect of insolvent participating Employers. The Trustee appoints IFCC as attorney for the purpose of such representation and IFCC may subject to any direction of the Trustee act in the name of the Trustee for such purpose (cl 2).

On 1 July 2011, the business of IFCC Pty Ltd was transferred to Industry Fund Services Ltd (IFS), which appears to have continued trading under the IFCC name. The tenor of Ms Mather’s evidence is that while a copy of the agreement between IFCC Pty Ltd and IFS by which the 2006 Agreement was novated in favour of the latter cannot be located, AustralianSuper dealt with IFS as it did with IFCC Pty Ltd. This continued after 2016, when AustralianSuper and IFS entered into a new Arrears Collection Agreement (the 2016 Agreement) on terms not dissimilar from the 2006 Agreement. In particular, cl 2(e) contained an authorisation by AustralianSuper for IFS ‘to represent the Trustee or appoint a firm of solicitors to represent the Trustee at any legal or non-legal proceedings (eg prior to creditors’ meetings) in relation to an insolvent Employer’.

44 The liquidators noted also that a form dated 10 July 2012 states that “IFCC on behalf of AustralianSuper” appoints Ms Lai to be “the pool group’s representative as a member of the [COI]”.

45 According to the liquidators, there can be no real issue about the fact that IFCC (then IFS) were, throughout the winding up of the Group, authorised to act on behalf of AustralianSuper. In these circumstances the liquidators submitted that the resolution of 2 July 2012 contains a procedural irregularity as it refers to Ms Lai representing IFCC when, in fact, Ms Lai was an employee of IFCC who was representing AustralianSuper. In other words, it should be taken that the resolution of 2 July 2012 in fact appointed AustralianSuper to the COI but, by reason of a procedural irregularity, referred in error to Ms Lai representing IFCC.

46 As the liquidators put it:

What was important in terms of the validity of the Resolution was that AustralianSuper be identified appointed as the member. To that extent, the Resolution fell short of what was required. However, the evidence establishes that:

(a) AustralianSuper was entitled to be appointed to the COI;

(b) its intention was that Ms Lai would be its representative on the COI; and

(c) Ms Lai was named as the person who was in fact representing AustralianSuper at the meeting and had been specifically authorised to take a role in the proceedings of any COI and

(d) the will of the meeting was that Ms Lai as the representative of IFCC (the Recovery Agent of AustralianSuper) should be appointed.

The error in describing Ms Lai as the representative of the agent of the creditor (IFCC) as a member is a procedural irregularity. Given the nature of the enquiry posited by sn 1322(2), the conclusion to be drawn from the evidence is that, being in a position to seek appointment as a member of the COI and to nominate, in some appropriate manner, who would actually participate in the meetings of the COI, AustralianSuper and the meeting of creditors failed to make clear that was what was intended to be achieved. No injustice, let alone any substantial injustice can be seen to have flowed from any infelicity in the steps taken to achieve that result when it is clear that ‘if the I’s had been dotted and the T’s crossed’ the same result would have enured.

47 As to the appointment of Ms Sourlas representing the TWU, the liquidators said that Ms Sourlas had attended the meetings on 2 July 2012 as the proxy of one Michael Thomas Scott, a former employee and a creditor of 1st Fleet in respect of his entitlements. Mr Scott had signed a form purporting to appoint the TWU as his representative on the COI. In the liquidators’ submission:

In other words, it was Mr Scott, rather than Ms Sourlas or the TWU, who should have been identified as the creditor who was appointed to the committee although it would have been open to Mr Scott to appoint Ms Sourlas as his representative on the committee as it was his apparent intention that someone from the TWU would fill that role.

48 The liquidators contended that both AustralianSuper and Mr Scott were eligible unsecured creditors of one of the companies in the Group as at 2 July 2012. That issue will be separately considered. Assuming that to be so for present purposes, the liquidators submitted that the Court should be satisfied that it was the intention of AustralianSuper and Mr Scott to each appoint a proxy to be their representative on the COI and the form of the resolution of 2 July 2012 involves a procedural irregularity by not referring to Australian Super represented by Ms Lai and Mr Scott represented by a representative of the TWU. The liquidators submitted that:

The Resolution achieved the apparent and legitimate objectives of the creditors who had nominated as members of the committee and of the apparent intention of the meeting to endorse those persons in accordance with those objectives. That, in doing so, these errors occurred does not alter the substance and should not alter the effect of that which was done. Again, no evidence has been led and it is difficult to envisage any which would be available which would establish that any substantial injustice has been caused by any misdescription.

The Commonwealth’s submissions

49 The Commonwealth noted that the minutes of the first meeting of creditors of the companies in the Group on 7 May 2012 record that AustralianSuper was a creditor for $2,271.90 represented by Jo Prossimo and Mr Scott as a creditor for $1.00 represented by Ms Sourlas. The minutes of the second meeting of creditors held on 22 May 2019 record the resolution to wind up the companies and identify AustralianSuper as a creditor for $2,271.90 and $1.00, each of which was admitted to vote, and, as for the second amount, represented by Ms Lai and Mr Scott as a creditor for $1.00 for which he was not admitted to vote represented by Ms Sourlas. Transport Payroll was placed into liquidation on 22 May 2012 and the liquidators were appointed as its liquidators. As noted, the liquidators’ pooling determination for the 1st Fleet companies and Transport Payroll was made on 21 June 2012.

50 The minutes of the meeting of 2 July 2012 record six creditors as present. The names of the relevant creditors are said to be IFCC represented by Ms Lai and Employee Proxy represented by Ms Sourlas. The minutes record the resolution of the meeting to appoint a COI and its members as identified above.

51 According to the Commonwealth:

(1) the pooling meeting was properly convened and conducted;

(2) the minutes produced by the liquidators must be taken to have formed part of the books kept by them to record the proceedings at the pooling meeting as required by s 531 of the Act and reg 5.6.01 of the Regulations; and

(3) the minutes are prima facie evidence of the meeting and resolutions made at the meeting, being matters stated or recorded in the minutes: s 1305 of the Act; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2005] NSWSC 417; (2005) 216 ALR at [269]-[271]; Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Rich [2009] NSWSC 1229; (2009) 236 FLR 1 at [396]-[400].

52 The Commonwealth submitted that the liquidators have not explained why the minutes should not be accepted as an accurate record of the resolution of the meeting and that the liquidators suggest that it was the “intention” of the creditors attending the meeting to appoint AustralianSuper and Mr Scott as members of the COI, but that the form of the resolution did not reflect this intention. According to the Commonwealth this submission fails as:

(1) the intentions of creditors are ascertained objectively from the terms of the minutes and not subjectively or as a result of subsequent conduct;

(2) if subjective intentions are relevant at all it must be the subjective intentions of the persons who were present at the meeting; and

(3) the liquidators have not adduced any evidence from the six creditor representatives at the meeting on 2 July 2012.

53 In answer to the liquidators’ submissions about circumstances said to support the proposition that the six creditor representatives intended to appoint AustralianSuper to the COI the Commonwealth made the following submissions:

(1) as to the 4 May 2012 AustralianSuper proofs of debt identifying IFCC as its credit manager: these do not assist in determining what occurred at the pooling meeting two months later;

(2) as to the entitlement of AustralianSuper to be appointed: this does not assist in determining that AustralianSuper was in fact appointed or intended to be appointed to the COI. There were a large number of creditors eligible to be appointed to the COI;

(3) as to the asserted intention of AustralianSuper that Ms Lai be its representative on the COI: there is no evidence identified to support this submission. The authority form signed by Ms Lai on 7 June 2012 can only be evidence that if AustralianSuper was appointed to a committee of inspection then it appointed Ms Lai as its representative. But insofar as subjective intention might be relevant, it must be the intention of those creditors at the meeting of 2 July 2012 which is material, not the intention of creditors before and outside of that meeting;

(4) as to the fact that Ms Lai represented AustralianSuper at the pooling meeting under an authority dated 21 June 2012:

(a) it is doubtful the other creditors at the meeting on 2 July 2012 knew who Ms Lai was representing given that when she attended the second meeting of creditors she represented AustralianSuper, Care Superannuation, CBUS Superannuation, Host Plus, MTAA Superannuation Fund, REST Superannuation, Statewide Superannuation, TWU Super, and TWU Superannuation;

(b) the liquidators’ evidence does not disclose whether Ms Lai represented those other creditors at the meeting on 2 July 2012 or if she disclosed who she was representing other than IFCC; and

(c) it is an available inference that she continued to represent all nine superannuation funds so that there is even less reason to find that when the creditors appointed Ms Lai representing IFCC they intended to appoint AustralianSuper;

(5) as to the assertion that it was the will of the meeting that Ms Lai be appointed as representative of IFCC as recovery agent for AustralianSuper: the will of the meeting is evidenced by the minutes of the meeting and what they record and those minutes make no reference to IFCC as agent for AustralianSuper;

(6) as to the form dated 10 July 2012 which states that IFCC on behalf of Australian Super appoints Ms Lai to be the pool group’s representative as a member of the COI: the form is a bootstraps exercise completed by Ms Lai after the meeting on 2 July 2012 and does not evidence the intention of the creditors at that meeting.

54 In answer to the liquidators’ submissions about circumstances said to support the proposition that the six creditor representatives intended to appoint Mr Scott to the COI the Commonwealth submitted as follows:

(1) as to the fact that Mr Scott appointed Ms Sourlas of the TWU to be his proxy for the first and second meeting of creditors: Ms Sourlas attended the first and second meeting of creditors as the proxy for many employees of the companies and not just Mr Scott and Ms Sourlas was not permitted to vote as Mr Scott’s proxy at the second meeting of creditors;

(2) as to the assertion Mr Scott was an eligible unsecured creditor: if correct, that does not assist the Court in determining that the six creditor representatives at the meeting on 2 July 2012 intended to appoint Mr Scott to the COI. More importantly, the evidence indicates that neither the liquidators nor Ms Sourlas treated Mr Scott as a creditor as at 2 July 2012. As to the latter contention, the Commonwealth submitted that:

(a) Mr Tayeh deposes that he adopted his usual practice of reviewing proofs of debt prior to a meeting of creditors and not allowing a person to be admitted as a creditor without a proof of debt for the first and second meetings of creditors. He deposes that no proof of debt for Mr Scott can be located but surmises that it was lodged and has been displaced due to the duration of the liquidation. Mr Solomons gives evidence to similar effect;

(b) the Court may accept the evidence of Mr Tayeh and Mr Solomons concerning their practice of assessing creditors’ claims prior to creditors’ meetings, at least in respect of the first and second creditor meetings. However, it should reject their evidence that that assessment was dependent on the creditor having lodged a proof of debt. It should also reject their submission, based on those speculations, that Mr Scott did lodge a proof of debt and that it has been lost;

(c) at the first meeting, employees with no proofs of debt or where the employment company was disputed were admitted for $1, so that at that meeting the lodgment of a proof of debt was not a precondition to being admitted as a creditor. At the second meeting, all proofs received were admitted for the purpose of voting so that creditors who had not lodged a proof of debt were not treated as creditors and not admitted to vote;

(d) the attendance list for the first meeting includes many creditors represented by Ms Sourlas claiming to be a creditor for $1 and admitted to vote for $1, while all other creditors are shown for varying specific amounts. The Court should find that persons shown as claiming to be a creditor for $1 are persons who have been identified by the liquidators as a potential creditor but who had not lodged a proof of debt;

(e) the attendance list for the second meeting shows many creditors not claiming an amount (reflecting a failure to lodge a proof of debt) and being admitted to vote for $0 …. Mr Scott was admitted to vote for $0. The Court should find that Mr Tayeh had determined that Mr Scott was not a creditor and not admitted to vote;

(f) the attendance register of creditors at the pooling meeting on 2 July 2012 does not include a list of creditors or any assessment of their claims. It shows Ms Sourlas as representing “Employee Proxy’s” with no identification of the employees, the value of their debts or the amount admitted for voting; and

(g) the Court should infer that as at 2 July 2012 Mr Scott’s status as a creditor for the purpose of participation in the pooling meeting was that most recently determined by the liquidators, that he was not a creditor, as determined at the second meeting of creditors;

(3) as to the assertion that Ms Sourlas attended the meeting of 2 July 2012 as the proxy of Mr Scott: there is no evidence cited in support of that assertion. The liquidators have not produced a proxy form from Mr Scott to Ms Sourlas for the 2 July 2012 meeting. The Court “should find that Ms Sourlas did not act as Mr Scott’s proxy at the pooling meeting. At its highest, she acted as a representative of unidentified members of the TWU who had been accepted by the Liquidators as creditors of the pooled group. Mr Scott was not one of them”;

(4) as to the fact that Mr Scott signed a form purporting to appoint the TWU as his representative on the COI: the form is dated 30 July 2012, after the meeting on 2 July 2012. It does not assist in determining what occurred at the meeting; and

(5) as to the submission that “it was Mr Scott, rather than Mr Sourlas or the TWU, who should have been identified as the creditor who was appointed to the committee”: the submission exposes the problem as the issue is not who should have been appointed to the COI but who in fact was appointed. It appears that subsequent to 2 July 2012 someone discovered that neither Ms Sourlas nor the TWU were eligible to be members of the COI and tried to find a member of the TWU willing to fulfil that role and that on 30 July 2012 Mr Scott agreed to do so. As there is no evidence from the liquidators, Ms Sourlas or Mr Scott as to the circumstances of him signing the form on 30 July 2012 the precise facts concerning it remain a mystery.

Discussion

55 There are two critical facts which, in my view, undermine the liquidators’ contentions about the appointment of AustralianSuper and Mr Scott to the COI at the meeting on 2 July 2012.

56 First, as to AustralianSuper, I would infer from the evidence about the second meeting of creditors that at the meeting on 2 July 2012 Ms Lai was representing a multiplicity of superannuation entities of which AustralianSuper was but one. In these circumstances, it cannot be inferred that the intention of the creditor representatives was to appoint AustralianSuper, as opposed to one of the other superannuation entities, to the COI. The documents on which the liquidators relied as to Ms Lai’s authority from AustralianSuper do not assist in determining the intention of the creditor representatives at the meeting for the reasons given by the Commonwealth. It is the intention of those creditors which is relevant, but the evidence of their intention (such as it is) does not enable it to be inferred that they appointed AustralianSuper, specifically, to be a member of the COI (in distinction from any of the other superannuation entities represented by Ms Lai).

57 Second, as to Ms Sourlas, again, I would infer from the evidence that Ms Sourlas of the TWU was representing a multiplicity of employee creditors at the meeting on 2 July 2012. The evidence does not permit an inference to be drawn that she was appointed to the COI in her capacity as a representative of Mr Scott in particular, in distinction from any of the other employees that Mr Sourlas was representing.

58 For these reasons I consider that the resolution recorded in the minutes, construed in accordance with the objective circumstances as they existed up to the time of the meeting, means that Ms Lai representing IFCC as agent for any one or more of nine superannuation entities was appointed to the COI. Further, Ms Sourlas representing the TWU as agent for any one or more of multiple employees was appointed to the COI. The problem with the resolution is thus one of indeterminacy. It cannot be known who in fact IFCC or the TWU were representing for the purpose of their appointment. It may or may not be AustralianSuper for IFCC and may and may or may not be Mr Scott for the TWU.

59 The indeterminacy of the resolution does not constitute a mere procedural irregularity for the purposes of s 1322(2) of the Act. The thing to be done, the constitution of the COI, has not been done at all because there has been no determination of the number of members to represent the creditors (as the number is indeterminate) and no determination of the persons who are to be the members of the COI (as, apart from Mr Smith representing the ATO which would be construed to mean the Deputy Commissioner as the relevant creditor, the membership is indeterminate). Nor can it be said that the indeterminacy of the resolution is essentially of a procedural nature for the purposes of s 1322(6)(a)(i) of the Act for the same reasons. I will deal subsequently with the other criteria raised by s 1322(6)(a) (honesty or just and equitable for the order to be made).

60 I do not accept the submissions for the liquidators to the contrary.

61 The status of Mr Smith representing the ATO (the Deputy Commissioner) on the COI is not in issue. The liquidators’ submissions to the effect that the Commonwealth’s contentions would mean that Deputy Commissioner (the relevant creditor) had not been appointed to the COI do not assist the liquidators. It may be accepted that Mr Smith was not a creditor and that the “ATO” is not a legal entity capable of appointment to the COI. There was only one creditor, the Deputy Commissioner, who Mr Smith or the ATO could have been representing. As such, it is a straightforward exercise to construe the resolution as appointing the Deputy Commissioner to be a member of the COI on the basis that the reference to the ATO is a mere misnomer. The problem I have identified with the resolution otherwise is that the nominated agents were representing many more creditors than AustralianSuper and Mr Scott and, accordingly, it is not possible to know who was appointed to the COI, being a defect in substance as to the constitution of the COI and not some mere procedural irregularity.

62 It may be accepted that every attendee at the meeting (leaving aside the liquidators) was present in the capacity of proxy, as had been the case at the earlier meetings of the creditors. As I have said, however, the problem is that they were proxies for multiple putative creditors and it cannot be known from the terms of the resolution who the creditor was in fact being appointed to the COI. This problem is not answered by the submission that the persons voting at the 2 July 2012 meeting must have realised that they were not voting to appoint Ms Sourlas or the TWU or Ms Lai or IFCC to be on the COI. So much may be accepted. The problem comes with the liquidators’ next submission that, as to Ms Sourlas and the TWU, any reasonable person must have understood that what was being proposed was representation on the COI “of an employee of the 1st Fleet pooled Group”. It is not possible to appoint to a COI an unidentified employee from a number of creditor employees without specifying the identity of the employee.

63 The liquidators sought to address this indeterminacy of identity of the person appointed to the COI by submitting that they accepted that Mr Scott was not sufficiently identified in the resolution. The submission continued to the effect that as those in attendance at the meeting must have understood that Ms Sourlas was a representative of at least one employee of the Group, the insufficient identification of Mr Scott was a mere procedural irregularity within the meaning of s 1322(2) of the Act. The problem is that it is not possible to infer that the attendees at the meeting intended to appoint Mr Scott (or any other particular employee) to the COI. This is not a procedural irregularity as it concerns the substance of the constitution of the COI as required by s 548A(1)(d) of the Act.

64 The same reasoning, in my view, must apply to the appointment of Ms Lai as representative of IFCC given that Ms Lai and IFCC were the representatives of a number of superannuation entities. Subsequent authorisation documents cannot change the fact that no inference can be drawn on the evidence that at the 2 July 2012 meeting the attendees intended to appoint AustralianSuper (and not one of the other superannuation entities IFCC represented) to the COI. The liquidators’ submissions provide no cogent answer to this problem with the constitution of the COI. The liquidators’ submissions in fact expose the problem. As the liquidators put it:

a. at the first meeting of creditors on 7 May 2012, a resolution was passed appointing a committee of creditors … Among the persons appointed were “Jo Prossimo representing IFCC’ and ‘Kevin Smith representing ATO’;

b. on the list of persons present at that first meeting … Ms Prossimo was identified as the proxy of AustralianSuper, Care Super, Host Plus Superannuation, Retail Employees Superannuation Trust and TWU Super;

c. among the documents circulated prior to the second meeting of the creditors of 1st Fleet on 22 May 2012 was a report to creditors by the Liquidators … This document included, in Annexure H, a list of unsecured creditors, which tellingly did not include IFCC …;

d. at the second meeting, a resolution was passed appointing a committee of inspection for 1st Fleet, the members of which included ‘Jo Prossimo of IFCC’…;

e. on the list of persons present on 22 May 2012, both Ms Prossimo and Ms Lai were identified as the proxies, in respect of different debts, of Statewide Superannuation …;

f. aside from Ms Lai and Mr Tayeh, the proxies in attendance on 2 July 2012 were Ms Sourlas, Ms Smith representing the ATO and a Mr Beau Weigand representing an entity referred to as ‘ERA’ …; and

g. Ms Sourlas was present at both the first and second meetings of creditors, as was Mr Smith …. Moreover, ‘ERA’ was present at the first meeting, represented by one Darren Anderson.

65 The liquidators submitted, on this basis, that:

It follows then that the creditors present on 2 July 2012, or at least the majority of them, knew or can reasonably be taken to have known that IFCC was not a creditor of the 1st Fleet Pooled Group, but instead acted as a representative of the trustees of a number of superannuation funds, including AustraliaSuper, that in turn claimed to be creditors of one or more companies within the group. That being so, it may be inferred that in passing the Appointment Resolution, those present understood that the trustee of a superannuation fund was to be represented on the COI by Ms Lai or IFCC. Similarly there is no evidence that Ms Lai was being nominated to represent anyone on the Committee other than AustralianSuper. Again, the plaintiffs accept that the trustee in question was not sufficiently identified in the text of the Appointment Resolution. However, as was the case with Mr Scott, the failure to identify AustralianSuper did not result in the Appointment Resolution producing an outcome substantively different from what was contemplated at the meeting – put simply, the representation on the COI by IFCC of the trustee of a superannuation fund claiming to be a creditor of the 1st Fleet Pooled Group.

66 The submission breaks down, in my view, at the point that as at 2 July 2012 IFCC was representing multiple superannuation entities. It cannot be known which entity the creditors intended to appoint to the COI. The subsequent authority form of 10 July 2012 cannot assist in the drawing of an inference as to the actual appointment to the COI of any particular superannuation entity as at 2 July 2012.

ELIGIBILITY FOR APPOINTMENT

67 Given my conclusion above about the indeterminacy of the resolution of 2 July 2012 so that no COI was effectively constituted the eligibility for appointment of AustralianSuper and Mr Scott is a hypothetical issue only. I will deal with it in as abbreviated terms as possible.

AustralianSuper

Liquidators’ submissions

68 As to AustralianSuper:

(1) the superannuation funds collectively so known are governed by a Trust Deed initially dated 13 December 1985, and more recently consolidated, after a series of amendments, on 1 August 2000 (the Trust Deed);

(2) cll 1 and 2 contain a declaration of trust and cl 4 provides that the annexed schedules comprise part of the Trust Deed;

(3) under rule 4.1 of Sch 1 to the Trust Deed so long as the Trustee remains an approved trustee in accordance with, relevantly, the standards and requirements of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) (the SIS Act), what is referred to as “the Fund” is “a public offer fund and the Fund comprises all moneys, policies and other assets and investments held by the Trustee in accordance with this Deed”;

(4) rule 4.7 provides for the Accumulation Part of the Fund and the Defined Benefit Part of the Fund;

(5) rule 1.2 of Sch 1 to the Trust Deed defines “Standard Employer Sponsor” as having the same meaning as in s 16(2) of the SIS Act, which is an employer who makes contributions to a superannuation fund on behalf of an employee who is a member of the fund;

(6) rule 16.1 in Sch 1 provides for applications to become a Standard Employer Sponsor;

(7) rule 17.3 of Sch 1 provides that in the winding up of a Standard Employer Sponsor, no further contributions shall be made by the Standard Employer Sponsor except contributions that accrued before the date on which the resolution was passed or order made for its winding up; and

(8) the Accumulation Part of the Fund is dealt with in Sch 3 which provides for contributions by the Standard Employer Sponsor on behalf of members.

69 Further, according to the liquidators’ submissions, the evidence shows that the second plaintiff had applied to be a Standard Employer Sponsor in 2001 and 2008 and its status as such was terminated on 30 November 2016. Accordingly, as at 2 July 2012 AustralianSuper was a Standard Employer Sponsor and subject to the payment obligations in Sch 3 to the Trust Deed.

70 Further, to this, as at 2 July 2012 s 553AB of the Act provided that:

(1) In a winding up, the liquidator must determine that the whole of a debt by way of a superannuation contribution is not admissible to proof against the company if:

(a) a debt by way of superannuation guarantee charge …

(i) has been paid; or

(ii) is, or is to be, admissible to proof against the company; and

(b) the liquidator is satisfied that the superannuation guarantee charge or estimate liability is attributable to the whole of the first-mentioned debt.

(2) If the liquidator determines, under subsection (1), that the whole of a debt is not admissible to proof against the company, the whole of the debt is extinguished.

71 The Deputy Commissioner did not submit any proofs relating to the amounts owed by 1st Fleet by way of superannuation guarantee charge until 5 May 2016. The liquidators were thus not in a position to make a determination under s 553AB(1) until that date. The liquidators submitted that it follows that it cannot be said that as at 2 July 2012 any debt owed by 1st Fleet to Australian Super by way of superannuation contribution had been wholly extinguished. For this reason AustralianSuper was an eligible unsecured creditor of the 1st Fleet Pooled Group, and therefore was eligible to be appointed to the COI.

Commonwealth’s submissions

72 The Commonwealth submitted that no evidence had been adduced of 1st Fleet’s applications to become a Standard Employer Sponsor or to identify the members of the Fund who were 1st Fleet employees so it is not possible to determine whether the amounts claimed by AustralianSuper in its proofs of debt were required to be paid under Sch 3 to the Trust Deed.

73 The Commonwealth also submitted that unpaid superannuation contributions by an employer also give rise a superannuation guarantee charge payable by the employer to the Deputy Commissioner under the Superannuation Guarantee Charge Act 1992 (Cth) (SGC Act). As the Commonwealth put it:

A liquidator must determine that a debt by way of a superannuation contribution is not admissible to proof to the extent a debt by way of a superannuation guarantee charge that has been paid or is admissible is attributable to the superannuation contribution: s 553AB(1) and (3) [of the Corporations Act]. The determination extinguishes the superannuation contribution debt to that extent: s 553AB(2) and (4) [of the Corporations Act].

The Liquidators have not given evidence as to whether they have made a determination under s 553AB in respect of AusSuper’s proofs of debt, the effect of which would be to extinguish those debts (Mr Solomons’ evidence is confined to the position as at the date of the pooling meeting …). The Liquidators submit that they could not have done so prior to 5 May 2016, since that is the first date on which the Deputy Commissioner submitted proofs for debts owing by way of superannuation guarantee charge ….

That is incorrect. The Deputy Commissioner’s proof of debt lodged on 4 May 2012 included a claim for superannuation guarantee charge. To the extent that proof did not include a superannuation guarantee charge for all unpaid ‘compulsory’ superannuation contributions by 1st Fleet (whether to AusSuper or otherwise) then it was likely that the Deputy Commissioner would in due course make that assessment and submit an amended proof. The Liquidators would then be required to determine that AusSuper’s proofs were not admissible to the extent the Deputy Commissioner’s proof ‘overlapped’ with AusSuper’s, whereupon AusSuper would cease to be a creditor.

In fact, the Liquidators did make that determination at some time prior to 6 September 2019.

At that time they paid a priority dividend of $2 million under s 556(1)(e) to creditors owed wages, superannuation contributions and superannuation guarantee charge. The Liquidator’s statutory annual return for 2018-19 … shows that payment comprised:

(a) $603,760 paid to priority creditors for wages (of which $555,576 was paid to the Commonwealth in respect of its GEERS claim …)

(b) $1,396,240 paid to the ATO for superannuation.

They could only have done so had they determined to reject that the whole of the superannuation contribution debt the subject of AusSuper’s proof of debt under s 553AB, on the basis the superannuation guarantee charge the subject of the Deputy Commissioner’s proof of debt was, in part, attributable to that debt.

Thus, while AusSuper had been admitted as a creditor of the pooled group as at 2 July 2012 for the purposes of voting, it never had any prospect of having its proofs admitted by the Liquidators for the purpose of being paid a dividend, and thus had no real financial interest in the winding up of the pooled group.

Deputy Commissioner’s submissions

74 The Deputy Commissioner of Taxation was given leave to file submissions.

75 The Deputy Commissioner explained:

No statutory obligation to pay superannuation contributions in favour of an employee or a superannuation fund can arise. This is because pursuant to the …SGC Act… and the Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (Cth) (SGA Act), the employer is under no statutory obligation to pay ‘compulsory’ superannuation contributions. An employer may elect not to pay such contributions, and instead become indebted to the Commonwealth for the amount of the SGC.

…

An employee may have separate contractual entitlements over and above their entitlement to the ‘compulsory’ minimum contribution, and in principle there is no reason why—given effective contractual arrangements—a superannuation fund could not stand in for an employee as beneficiary of those contractual obligations.

(Emphasis in original).

76 The Deputy Commissioner said that while the liquidators submitted that AustralianSuper sought to prove on the basis of contractual obligations, the available evidence does not support an inference of any contractual obligation. The Deputy Commissioner noted:

Clause 3 of Schedule 3 to the Trust Deed provided that each ‘Standard Employer Sponsor shall, on behalf of Members, contribute to the Fund the amounts determined in accordance with Clause 4 of this Schedule 3’ … Clause 4 states that the required contributions shall be ‘the relevant amount that is stipulated in the application made by that Standard Employer Sponsor’

The available evidence may ground an inference that 1st Fleet Pty Ltd … did at some point in time make such an application … But the application of 1st Fleet contemplated by cl 4 of the Trust Deed itself is not in evidence, and there is no other available means by which the Court could be satisfied of the basis upon which 1st Fleet was required to pay contributions to AustralianSuper: including whether those contributions were limited to the ‘compulsory’ minimum contributions or included employer’s or employees’ additional contributions.

There does not therefore appear to be any basis upon which the Court could be satisfied that the companies in liquidation owed contractual obligations with respect to unpaid contributions to AustralianSuper … The Court would therefore assume that amounts owing by 1st Fleet to AustralianSuper represented the employer’s ‘compulsory’ minimum contributions.

(Emphasis in original).

77 This, said the Deputy Commissioner, means that s 553AB of the Act is relevant. In response to the liquidators’ submission that no determination could have been made under s 553AB until 6 May 2016 the Deputy Commissioner said:

That submission should not be accepted. Its factual basis is incorrect… the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation submitted a proof of debt on 4 May 2012 itemising an SGC payable by 1st Fleet. That proof of debt provided a basis for the liquidator to make the s 533AB determination prior to 2 July 2012. Accordingly, s 553AB applied, and the liquidator should have determined that AustralianSuper’s debt was not admissible to proof pursuant to s 553AB(1), with the consequence that AustralianSuper’s debt should have been extinguished pursuant to s 553AB(2).

78 The Deputy Commissioner made further detailed submissions about the operation of s 553AB. I explain below why I do not summarise those submissions.

Discussion

79 I do not consider it necessary or appropriate to record the detailed submissions about s 553AB as the issue is hypothetical. For one thing, I have decided above that AustralianSuper was not appointed to be a member of the COI. The resolution constituting the COI is indeterminate in the way I have explained above. For another, there is no evidence indicating that the liquidators did in fact make a determination for the purposes of s 553AB before 2 July 2012. It is the fact of a determination by a liquidator which has the effect of extinguishing the debt. Accordingly, the fact that the liquidators could have made a determination under s 553AB(1) before 2 July 2012 is immaterial. Further, the question of eligibility for appointment is to be determined as at the date of appointment. As at that date, if it were necessary to so decide, I would accept the liquidators’ submissions that AustralianSuper was at that time an eligible unsecured creditor of 1st Fleet for the reasons the liquidators have given. As the liquidators put it in their submissions in reply:

(1) the evidence unambiguously supports the conclusion that 1st Fleet was a Standard Employer Sponsor within the Accumulation Part of the Fund;

(2) AustralianSuper’s proofs of debt were accompanied by records identifying the amounts of superannuation contribution outstanding in respect of certain named individuals;

(3) the debts were admitted for voting purposes, and there was no appeal against that decision; and

(4) accordingly, in the absence of evidence showing that the individuals identified in the records provided by AustralianSuper were not in fact employees of 1st Fleet or that the amount of superannuation contribution were not in fact outstanding, the Court has no basis for finding otherwise than that AustralianSuper was a creditor of 1st Fleet as at 2 July 2012.

Mr Scott

Liquidators’ submissions

80 According to the liquidators their records indicate that at the time of his termination of employment by 1st Fleet Mr Scott was a creditor of the company for $33,955.04, a sum that included wages and annual leave, redundancy and long service leave entitlements. The liquidators submitted that while there was not a proof of debt of Mr Scott in the evidence, their evidence about how they conducted meetings of creditors should be accepted, making it more likely than not that a proof of debt had been lodged. The evidence also includes the fact that through his appointed proxy, Ms Sourlas, Mr Scott participated in the first and second meetings of the creditors on 7 and 22 May 2012 respectively. According to the liquidators there should be no doubt that as at 2 July 2012 Mr Scott was an eligible unsecured creditor within the meaning of s 579Q of the Act.

81 In response to the Commonwealth’s argument that Mr Scott ceased to be a creditor of the 1st Fleet Group on 3 August 2012 when a payment was made to him under GEERS, the liquidators noted the argument as follows:

Pursuant to s 4(2)(a)(iii) of the Long Service Leave Act 1955 (NSW) (LSL Act), a worker who has completed with an employer at least five years’ service, and whose services are terminated by the employer for any reason other than the worker’s serious and wilful misconduct, was entitled to long service leave in an amount corresponding to ‘a proportionate amount on the basis of 2 months for 10 years’ service.’ The first plaintiffs were appointed as voluntary administrators of 1st Fleet on 25 April 2012, whereupon, pursuant to s 443A of the Act, they became liable for debts they incurred, in the performance or exercise, or purported performance or exercise, of any of their functions as administrators for, amongst other things, services rendered or goods bought. The Commonwealth’s position appears to be that having regard to s 443A, in calculating the amount owed by 1st Fleet by way of Mr Scott’s long service leave entitlement, one should adopt 24 April 2012 as an end date for that calculation. The result is that Mr Scott is said to be owed $33.51 less by way of long service leave entitlements than asserted by the plaintiffs.

82 According to the liquidators, however:

(1) there is no evidence that Mr Scott ever rendered services to the first plaintiffs as administrators of 1st Fleet in the course of the exercise of their functions as administrators;

(2) Mr Scott’s employment with 1st Fleet was, on the Commonwealth’s own records, formally terminated on 2 May 2012 so that his claim against 1st Fleet for long service leave is to be calculated by reference to that date even if, which is not established, he may have some claim against the Administrators for that sum as well (though it is difficult to see how that could arise under the LSL Act); and

(3) in circumstances where a worker’s employment is terminated otherwise than by the worker’s death, and any long service leave to which worker is entitled has not been taken, then s 4(5)(a) of the LSL Act provided that “the worker shall ... be deemed to have entered upon the leave from the date of such termination and the employer shall forthwith pay to the worker in full the worker’s ordinary pay for the leave less any amount already paid to the worker in respect of that leave.”

83 As the liquidators put it:

In other words, the obligation to pay long service leave, which accrued up to the point of termination of Mr Scott’s employment, was imposed by statute on 1st Fleet, in circumstances where that same statute did not qualify this obligation by reference to the possibility that 1st Fleet might go into administration and that its administrators might thereafter be personally liable for debts they incurred in respect of services rendered.

84 The liquidators noted further that, in administering GEERS, the Commonwealth, on or about 19 July 2012, paid $166,324.32 to the liquidators for distribution to eight employees of 1st Fleet, including $33,921.53 for Mr Scott, which sum was paid to him on 3 August 2012. The liquidators referred to s 563B of the Act in these terms:

(l) If, in the winding up of a company, the liquidator pays an amount in respect of an admitted debt or claim, there is also payable to the debtor or claimant, as a debt payable in the winding up, interest, at the prescribed rate, on the amount of the payment in respect of the period starting on the relevant date and ending on the day on which the payment is made.

(2) Subject to subsection (3), payment of the interest is to be postponed until all other debts and claims in the winding up have been satisfied, other than subordinate claims (within the meaning of section 563A).

(3) If the admitted debt or claim is a debt to which section 554B applied, subsection (2) does not apply to postpone payment of so much of the interest as is attributable to the period starting at the relevant date and ending on the earlier of:

(a) the day on which the payment is made; and

(b) the future date, within the meaning of section 554B.

85 The liquidators also referred to reg 5.6.70A of the Regulations which provides that:

For section 563B of the Act, the prescribed rate of interest on the amount paid in respect of an admitted debt or claim for the period starting on the relevant date and ending on the day on which the payment is made is 8% a year.

86 Accordingly, the liquidators submitted that if Mr Scott’s entitlements were paid in full he was nevertheless owed interest for the period between the date on which the winding up of 1st Fleet is taken to have begun and the date on which he was paid by the liquidators.

87 The liquidators thus submitted that the better view is that Mr Scott was at July 2012 a creditor and remained as such for the amount of $33.51 in respect of interest on the debt owed to him as at July 2012.

88 In response to the Commonwealth’s submissions that a person is an eligible unsecured creditor only if a liquidator has admitted the debt of the creditor for voting purposes the liquidators submitted:

(1) the Commonwealth’s argument implies into the definition in s 579Q of the Act an additional criterion which is not prescribed;

(2) s 548A establishes the requirement for eligibility, which is status as a creditor. The Regulations do not establish the requirement for eligibility. It is fallacious to suggest that subordinate legislation may constrict the meaning of principal legislation as the Commonwealth proposes;

(3) the invitation to qualify the plain words of s 548A(3) by the introduction of a further condition for eligibility should not be accepted, particularly when the provision expressly adopts the definition of “eligible unsecured creditor” which appears in s 579Q, and there is no indication in the text of s 548A(3) that it did so with the addition of some further criteria as suggested by the Commonwealth;

(4) the Commonwealth offers no reason for its contention beyond a consequentialist argument that it would be inconvenient if a nominated person’s eligibility to act as a member of the COI could await definitive assessment until some later time;

(5) in any event, it is clear that Mr Scott had been admitted as a creditor at the first meeting … and was listed as one of the employee creditors in the s 439A report …; and

(6) the evidence of both of the liquidators is that they were of the view Mr Scott was a creditor and their evidence should be accepted.

Commonwealth’s submissions

89 The Commonwealth said that it accepted that Mr Scott was a creditor of 1st Fleet as at 2 July 2012. According to the Commonwealth, however, the issue is not whether Mr Scott was in fact a creditor at that time but rather is whether he had been admitted by the liquidators to be a creditor at that time. Relevantly, the Commonwealth submitted:

(1) a person is only eligible to be appointed to a committee of inspection under s 548A(3) of the Act if the person “is” an eligible unsecured creditor at the time of appointment;

(2) a determination to appoint a committee of inspection and its members is made at and by a meeting of creditors of the pooled group: s 548A(1);

(3) the meeting must be conducted in accordance with the Regulations: s 548A(2);

(4) a committee of inspection once appointed has power to meet at such times and places as its members determine: s 549(1);

(5) a committee of inspection is entitled to act by a majority of its members present at a meeting: s 549(3);

(6) regs 5.6.12 to 5.6.36A set out a comprehensive scheme for the conduct of a meeting of the creditors of a pooled group convened for the purpose of appointing a committee of inspection under s 548A(1);

(7) specifically, reg 5.6.23(1) provides a regime for identifying who is a creditor entitled to vote at the meeting, namely a creditor:

(a) whose debt or claim has been admitted wholly or in part by the liquidator; or

(b) who has lodged particulars of the debt or claim with the Chairperson or, if required, formal proof of the debt or claim; and

(8) the Chairman may admit or reject a proof of debt for the purposes of voting: reg 5.6.26(1).

90 On the basis of the above factors the Commonwealth contended that:

the Court should find that the persons who are eligible unsecured creditors within the meaning of s 548A(3) are limited to those unsecured creditors of a company in the pooled group, which are not themselves a company in the group (s 579Q), that the liquidators have admitted for the purposes of voting at the appointment meeting, in accordance with the regulations made under s 548A(2).

Were that not the case, so that a nominated person’s eligibility to act as a member of the committee of inspection could await definitive assessment until some later time, the scheme for appointing committees of inspection set out in Division 5 of Part 5.6 of the Act would be unworkable. Until what time? Determined by who?

91 The Commonwealth also submitted that:

a fundamental vice of the appointment resolution was its qualified form, namely that the appointments of the three nominated persons ‘shall take place subject to each of them satisfying the requirements of section 548 (sic, 548A)’. How were they to satisfy those requirements? Who was to determine whether they had done so? When was that to occur?

(Emphasis in original)

92 For the reasons set out above the Commonwealth contended that the Court should find that as at 2 July 2012 the liquidators had determined that Mr Scott was not a creditor and was not entitled to vote at creditors’ meetings, with the consequence that he was not an eligible unsecured creditor within the meaning of s 548A(3) of the Act.

Discussion

93 I do not accept the Commonwealth’s approach to the meaning of eligible unsecured creditor. The liquidators’ submissions to the contrary are persuasive. There is nothing in the text or context of s 579Q or s 548A which supports the implication of an additional requirement that a liquidator must first have admitted the debt of the creditor for voting purposes before the creditor may be taken to be an eligible unsecured creditor. In circumstances where the Commonwealth accepts that Mr Scott was a creditor of the 1st Fleet pooled Group as at 2 July 2012, I consider that Mr Scott was eligible to be appointed to the COI.

MR SCOTT’S CONTINUING STATUS