FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Wells Fargo Trust Company, National Association (trustee) v VB Leaseco Pty Ltd (administrators appointed) [2020] FCA 1269

File number: | NSD 714 of 2020 |

Judgment of: | MIDDLETON J |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords:

| STATUTES – interpretation – statute implementing treaty – International Interests in Mobile Equipment (Cape Town Convention) Act 2013 (Cth) – Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment – Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Aircraft Equipment, Art XI – Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Arts 31, 32 STATUTES – meaning of “give possession of the aircraft object to the creditor” in the context of Art XI of Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Aircraft Equipment – whether “give possession” requires delivery of certain aircraft objects to the applicants in the United States or whether it entails making the aircraft objects available to the applicants – proper interpretation requires delivery of the relevant aircraft objects to the applicants in the United States CORPORATIONS – whether the administrators failed, for the purposes of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), to disclaim the applicants’ property and should be personally liable for post-appointment amounts payable under relevant lease agreements pursuant to s 443B of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) CORPORATIONS – notice under s 443B given by respondents did not discharge respondents’ obligation to “give possession” – notice could not satisfy the requirements of s 443B(3) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) or have the effect of relieving administrators of their obligations under s 443B(2) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) CORPORATIONS – whether administrators should be relieved of certain liability – administrators acted reasonably concerning providing assistance to the applicants to recover aircraft objects –s 443B notice of no effect upon the basis that the notice did not fulfil the obligations under Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Aircraft Equipment – administrators relieved of liability from the period 16 June 2020 to 20 October 2020 under s 443B(8) and s 447A of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) |

Legislation: | Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth), s 15AB Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), ss 440D, 440B(2), 443B, 447A Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment, Arts 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 13, 24 Convention on the International Recognition of Rights in Aircraft Declarations Lodged by Australia under the Aircraft Protocol at the Time of the Deposit of its Instrument of Accession International Interests in Mobile Equipment (Cape Town Convention) Act 2013 (Cth) Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (Cth), s 12 Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Aircraft Equipment, Arts I, IX, XI (Alternative A) United States Bankruptcy Code, s 1110 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Arts 31, 32 |

Cases cited: | Applicant A v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs (1997) 190 CLR 225 Barzideh v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs (1996) 69 FCR 417 Commonwealth v Tasmania (1983) 158 CLR 1 James Buchanan & Co Ltd v Babco Forwarding & Shipping(UK) Ltd [1978] AC 141 In Re Republic Airways Holding Inc, 547 BR 578 (2016) K (A Child), Re [2013] EWCA Civ 895 Melhelm Pty Ltd, Re Boka Beverages Pty Ltd (In Liq) v Boka Beverages Pty Ltd (In Liq) (No 2) [2019] FCA 1809 Nardell Coal Corp (in liq) v Hunter Valley Coal Processing Pty Ltd (2003) 46 ACSR 467 Pilkington (Australia) Ltd v Minister for Justice and Customs (2002) 127 FCR 92 Povey v Qantas Airways Ltd (2005) 223 CLR 189 Shipping Corporation of India v Gamlen Chemical Co A/Asia Pty Ltd (1980) 147 CLR 142 Silvia & Anor v Brodyn Pty Limited [2007] NSWCA 55 Strawbridge, in the matter of Virgin Australia Holdings Ltd (administrators appointed) [2020] FCA 571 Strawbridge, in the matter of Virgin Australia Holdings Ltd (administrators appointed) (No 2) [2020] FCA 717 Strawbridge, in the matter of Virgin Australia Holdings Ltd (administrators appointed) (No 3) [2020] FCA 726 Strawbridge, in the matter of Virgin Australia Holdings Ltd (administrators appointed) (No 4) [2020] FCA 927 Strawbridge, in the matter of Virgin Australia Holdings Ltd (administrators appointed) (No 5) [2020] FCA 986 Strawbridge, in the matter of Virgin Australia Holdings Ltd (administrators appointed) (No 6) [2020] FCA 1172 Strawbridge, in the matter of Virgin Australia Holdings Ltd (administrators appointed) (No 7) [2020] FCA 1182 Anthea Roberts, ‘Comparative International Law? The role of national courts in creating and enforcing international law’ (2011) 6(1) International Comparative Law Quarterly 57 Brian F Havel and Gabriel S Sanchez, The Principles and Practice of International Aviation Law (Cambridge University Press, 2014) Donald Gray, Dean Gerber and Jeffrey Wool, ‘The Cape Town Convention and aircraft protocol’s substantive insolvency regime: A case study of Alternative A’ (2016) 5(1) Cape Town Convention Journal 115 Dr Sanam Saidova, ‘The Cape Town Convention: Repossession and Sale of Charged Aircraft Objects in a Commercially Reasonable Manner’ (2013) Lloyd’s Maritime and Commercial Law Quarterly 180 Michael White, Australian Maritime Law (Federation Press, 3rd ed, 2014) Professor John F Wilson, Carriage of Goods by Sea (Pearson, 7th ed, 2010) Professor Sir Roy Goode CBE, QC, Official Commentary on the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment and Protocol thereto on Matters Specific to Aircraft Equipment (4th ed, May 2019) Professor Stephen Girvin, Carriage of Goods By Sea (Oxford University Press, 2nd ed, 2007) |

Division: | General Division |

Registry: | New South Wales |

National Practice Area: | Commercial and Corporations |

Sub-area: | Corporations and Corporate Insolvency |

Number of paragraphs: | |

Date of last submissions: | 25 August 2020 |

Solicitor for the Applicants: | Norton Rose Fulbright |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Dr R C A Higgins SC with Mr R Yezerski and Ms K Lindeman |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Clayton Utz |

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 89, “Applicant’s” has been replaced with “Applicants’” | |

7 September 2020 | In paragraph 153, “Art IX(2)” has been replaced with “Art XI(2)” |

7 September 2020 | In paragraph 180, “s 44B(8)” has been replaced with “s 443B(8)” |

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The First Applicant holds (for the benefit of the Second Applicant) an “international interest” in the “aircraft objects” identified in Schedule 2 of these Orders pursuant to Articles 2 and 7 of the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment done at Cape Town on 16 November 2001 (the ‘Cape Town Convention’).

2. The Notice dated 16 June 2020 given by the Third Respondent to the Second Applicant did not discharge the First or Third Respondent’s obligation, under Art XI of the Protocol to the Cape Town Convention on matters specific to Aircraft Equipment, to “give possession” of the “aircraft objects” identified in Schedule 2 of these Orders.

3. The Notice dated 16 June 2020 given by the Third Respondent to the Second Applicant did not satisfy the requirements of section 443B(3) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the ‘Corporations Act’), and did not (pursuant to section 443B(4)) have the effect of relieving the Third Respondent of their obligations under section 443B(2) of the Corporations Act in respect of the property identified in Schedule 2 of these Orders.

4. Any expenses incurred by the Respondents or Virgin Tech Pty Limited (Administrators Appointed) (‘Virgin Tech’) in complying with Orders 5 to 8 of these Orders are:

(a) expenses properly incurred by the Third Respondent in carrying on the businesses of the First, Second and Fourth Respondents and Virgin Tech within the meaning of section 556(1)(a) of the Corporations Act;

(b) debts or liabilities for which section 443D(aa) entitles the Third Respondent to be indemnified within the meaning of section 556(1)(c) of the Corporations Act from the assets of the First, Second and Fourth Respondents and Virgin Tech; and

(c) debts or liabilities for which s 443D(aa) entitles the Third Respondent to be similarly indemnified within the meaning of s 556(1)(c) of the Corporations Act.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

5. The Respondents or any of them “give possession” of the “aircraft objects” identified in Schedule 2 of these Orders, by delivering up, or causing to be delivered up, the “aircraft objects” to the Applicants in the manner set out in Schedule 3 of these Orders, at 4700 Lyons Technology Parkway, Coconut Creek, Florida, 33073, United States of America.

6. Subject to any further order, the time by which the Respondents are to carry out the steps required by Order 5 of these Orders to deliver up the “aircraft objects” is, using their best endeavours, as soon as possible but on or before 15 October 2020. The Applicants will provide such assistance as is reasonably necessary in relation to the Respondents’ obligations under these Orders, including taking any step that is reasonably required to give effect to those obligations of the Respondents.

7. Unless and until the Respondents, or any of them, “give possession” in accordance with Order 5, or until further order of the Court, the Respondents are to preserve the aircraft objects in Schedule 2 of these Orders by:

(a) maintaining the Engines identified in Schedule 2 of these Orders;

(b) maintaining insurance cover over the aircraft objects identified in Schedule 2 of these Orders;

to the same or greater extent as was maintained at the date of appointment of the Third Respondent as administrators.

8. The Third Respondent do all such things as are necessary and within its power, using best endeavours, to cause the First, Second, and Fourth Respondent to carry out the Orders of this Court in respect of the completion and transmittal of the records described at Schedule 2, paragraph 7 of these Orders.

9. Pursuant to section 443B(8) and section 447A(1) of the Corporations Act, the Third Respondent be excused and relieved of personal liability to pay rent or other amounts payable under any agreement in respect of the Applicants’ aircraft objects that would otherwise have been payable by the Third Respondent pursuant to section 443B(2) from the period commencing 16 June 2020 up to and including the date in Order 6 of these Orders.

10. To the extent that the Applicants require leave of the Court pursuant to section 440D or section 440B(2) of the Corporations Act to begin and proceed with the Originating Application filed on 30 June 2020 against the First and Second Respondents and as amended by the Amended Originating Process on 28 July 2020 against the Fourth Respondent, leave is granted nunc pro tunc from those dates.

11. Liberty to the parties to apply to Justice Middleton in respect of these Orders, including but not limited to liberty to make an application for extensions of time, alteration to the manner and extent of delivery up as required by Order 5 of these Orders, and for any other variation amendment or addition to these Orders that may be required before, during or after the process of delivery up.

12. The First, Second and Fourth Respondents to pay the Applicants’ costs as agreed or assessed as costs in the administrations of the First, Second and Fourth Respondents.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Schedule 2

NOTE: In this Schedule 2, Appendix A and Appendix B are references to Appendix A in the Court Book at pages 15 to 39 (inclusive) and to Appendix B in the Court Book at pages 40 to 99 (inclusive).

Schedule of “aircraft objects”

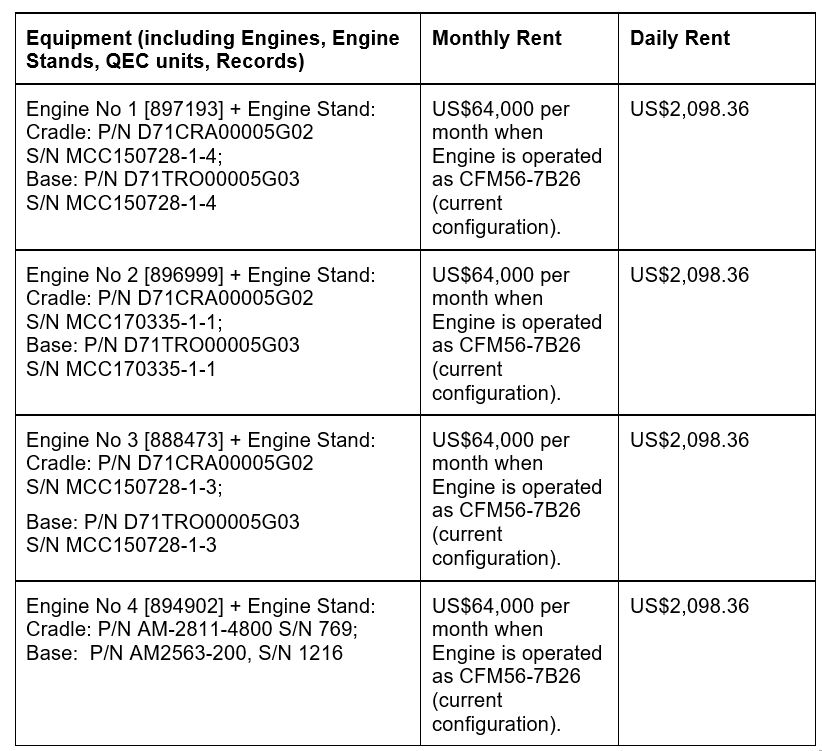

Engines

(1) CFM International Engine, Model CFM56-7B24 with engine serial number 888473.

(2) CFM International Engine, Model CFM56-7B24 with engine serial number 897193.

(3) CFM International Engine, Model CFM56-7B24 with engine serial number 896999.

(4) CFM International Engine, Model CFM56-7B24 with engine serial number 894902.

Accessories, parts, and equipment

(5) Engine stands:

(a) (for Engine 888473) with serial numbers:

(i) Cradle: P/N D71CRA00005G02, S/N MCC150728-1-3;

(ii) Base: P/N D71TRO00005G03, S/N MCC150728-1-3;

(b) (for Engine 897193) with serial numbers:

(i) Cradle: P/N D71CRA00005G02, S/N MCC150728-1-4;

(ii) Base: P/N D71TRO00005G03, S/N MCC150728-1-4;

(c) (for Engine 896999) with serial numbers:

(i) Cradle: P/N D71CRA00005G02, S/N MCC170335-1-1;

(ii) Base: P/N D71TRO00005G03, S/N MCC170335-1-1; and

(d) (for Engine 894902) with serial numbers:

(i) Cradle: P/N AM-2811-4800, S/N 769;

(ii) Base: P/N AM2563-200, S/N 1216.

(6) Quick engine change (QEC) units and accessories:

(a) (for Engine 888473) – as specified in Appendix A;

(b) (for Engine 897193) – as specified in Appendix A;

(c) (for Engine 896999) – as specified in Appendix A; and

(d) (for Engine 894902) – as specified in Appendix A.

Data, manuals, and records

(7) The following records in respect of each of the Engines:

(a) Historical Operator Records:

(i) Authorized Release Certificates and Installation Work Orders for any engine parts which are replaced on or before the date that the Engines are removed and prepared for transportation by road in accordance with paragraph 4 of Schedule 3 (in the form required under clause 18.3(g) of the General Terms of Agreement applicable to any Engine Lease (GTA)); and

(ii) Any records created, made or otherwise arising from the ferry flights or engine removal contemplated in Schedule 3 of these Orders (of the kind and in the form required under clause 7 of the GTA);

(b) End of Lease Operator Records/Status Statements:

(i) History Statement for each of the Engines in the form specified in Appendix B;

(ii) Non-Incident Statement for each of the Engines in the form specified in Appendix B;

(iii) In respect any ferry flight referred to in Schedule 3:

(A) Non Incident Statement exclusive to that ferry flight that identifies the engine Time and Cycles at removal in the form required under Exhibit E of the GTA;

(B) Aircraft journey logs that identify flight hours and cycles accumulated for that ferry flight in accordance with item F in Exhibit F of the GTA or in a form similar to Exhibit D of the GTA and amended to reflect the ferry flight;

(iv) Combination Statement for each of the Engines in the form specified in Appendix B;

(v) Life Limited Parts Status Statement for each of the Engines in the form specified in Appendix B;

(vi) Airworthiness Directive Status Statement for each of the Engines in the form specified in Appendix B;

(vii) Approved Maintenance Organization (AMO) Statement for each Engine in the form specified in Appendix B;

(viii) Commercial Traceability Statement to be completed by head lessee in the form specified in Appendix B;

(ix) Documentation pertaining to any engine removal carried out in accordance with Schedule 3 including but not limited to:

(A) Engine removal work Order in a form similar to item 9 of Exhibit D of the GTA; and

(B) Long term preservation work order and tag in accordance with items P and Q in Exhibit F of the GTA.

(c) Lease Inspection Records:

(i) OEM EHM redelivery report as referred to in clause 6(b)(i) of the GTA;

(ii) Borescope Report as referred to in clauses 18.1(c) and 18.2(c) of the GTA;

(iii) Borescope Video as referred to in clauses 18.1(c) and 18.2(c) of the GTA;

(iv) C Check / MPD Tasks sign off as referred to in clauses 18.1(c) and 18.2(c) of the GTA;

(v) Preservation tag as referred to in Exhibit F, clause q of the GTA;

(vi) Dual Release Certificate being a United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Form 337 and one of:

(A) a completed FAA Form 8130-3 (marked approved for Return to Service in accordance with part 43.9 of Title 14 of the US Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) and Release to Service in accordance with European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) regulation Part 145.A.50); or

(B) an EASA Form One (marked approved for Release to Service in accordance with EASA Part 145.A.50 and Return to Service in accordance with 14 CFR 43.9).

Definition of Engine Lease

(8) In this Schedule 2, a reference to an Engine Lease is a reference to any or all of, as the case may be, the lease agreements between the First Applicant and the First Respondent, the engine lease support agreement between the Second Applicant and the First Respondent, and the sub-lease agreements between the First Respondent and the Second Respondent described in paragraph 5 of Schedule 3 of these Orders.

Schedule 3

(1) Unless the parties otherwise agree in writing, consistent with the applicable engine manufacturer’s procedures for removal and the terms of the Engine Leases, the Respondents and where required, using Virgin Tech, to cause the Engines, Engine Stands and QECs to be transported to the Applicants according to the following steps as soon as possible using best endeavours but on or before 15 October 2020:

Ferry flight of Engine 894902 from Adelaide to Melbourne

(a) the Respondents to obtain from CASA the necessary regulatory approvals to carry out the terms of these Orders, including an extension of the Virgin Tech CASA approval to permit removal of the Engines at the facility operated by Delta Air Lines, Inc. (Delta) at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport at Atlanta, Georgia, United States (Delta Facility);

(b) the Respondents to cause aircraft VH-VUT to which is attached Engine 894902 to be transported from Adelaide to the Respondents’ and Virgin Tech’s Melbourne airport facility;

(c) the Respondents to cause to be created the End of Lease Operator Records/Status Statements described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(b)(iii) and to transmit them to the Applicants via email or via online data room;

Ferry Flight of Engine 894902 and Engine 896999 from Melbourne to Atlanta, USA

(d) at the Respondents’ and Virgin Tech’s Melbourne airport facility, the Respondents to cause Engine 896999 currently attached to VH-VOT to be removed and placed on VH-VUT;

(e) the Respondents to cause to be created the End of Lease Operator Records/Status Statements described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(b)(ix) in respect of Engine 896999 and to transmit them to the Applicants via email or via online data room; and

(f) the Respondents to cause VH-VUT to be flown (with Engine 894902 and Engine 896999 installed) to the Delta Facility;

(g) in the alternative to (d), (e) and (f) the Respondents to:

(i) at the Respondents’ and Virgin Tech’s Melbourne airport facility:

(A) cause Engine 896999 currently attached to aircraft with registration VH-VOT to be removed and placed on the Engine Stand specified at paragraph 5(c) of Schedule 2;

(B) cause Engine 894902 currently attached to aircraft with registration VH-VUT to be removed and placed on the Engine Stand specified at paragraph 5(d) of Schedule 2;

(C) cause to be created the End of Lease Operator Records/Status Statements described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(b)(ix) in respect of Engine 896999 and Engine 894902 to transmit them to the Applicants via email or via online data room;

(ii) cause Engine 896999 and Engine 894902 to be prepared for air freight transportation in accordance with paragraph 4 of this Schedule;

(iii) consistent with the applicable engine manufacturer’s procedures for air freight transportation and the terms of the Engine Leases, transport by air freight Engine 896999 and Engine 894902 to the Delta Facility.

Inspection, removal and road transportation of Engine 894902 and Engine 896999 from Atlanta, USA to Florida, USA

(h) the Respondents to cause, while Engine 894902 and Engine 896999 remain installed on airframe with registration VH-VUT, the inspections, checks and other steps necessary to enable the Respondents or Delta, as the case may be, to create, prepare or complete:

(i) End of Lease Operator Records/Status Statements described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(b)

(ii) Lease Inspection Records described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(c);

(i) the Respondents to cause:

(i) Engine 894902 and Engine 896999 to be removed from airframe with registration VH-VUT by Delta at the Delta Facility;

(ii) Engine 894902 and Engine 896999 to be placed into Engine Stands specified in paragraphs 5(a) and (b) of Schedule 2 currently located at the Delta Facility;

(iii) the QECs described at Schedule 2, paragraphs 6(c) and (d) of these Orders to be removed from Engine 894902 and Engine 896999 respectively;

(iv) Engine 894902 and Engine 896999 to be prepared in readiness for transportation in accordance with paragraph 4 of this Schedule 3;

(v) all End of Lease Operator Records/Status Statements described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(b) and Lease Inspection Records described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(c) in respect of Engine 894902 and Engine 896999 to be transmitted the Applicants via email or via online data room; and

(vi) Engine 894902 and Engine 896999 and the QECs described at Schedule 2, paragraphs 6(c) and (d) of these Orders to be transported by road using trucks equipped with air ride or air cushion tractors and trailers to the Applicants to their at facility at 4700 Lyons Technology Parkway, Coconut Creek, Florida, 33073, United States of America (Coconut Creek Facility).

Ferry Flight of Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 from Melbourne to Atlanta, USA

(j) using the Respondents’ and Virgin Tech’s Melbourne airport facility, the Respondents to cause Engine 888473 (currently installed on airframe with registration VH-VOY) and Engine 897193 (currently installed on airframe with registration VH-VUA) to be removed from airframes on which they are respectively installed and installed on airframe with registration VH-VUT;

(k) the Respondents to cause to be created the End of Lease Operator Records/Status Statements described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(b)(ix) in respect of Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 and to transmit them to the Applicants via email or via online data room;

(l) the Respondents to cause VH-VUT to be flown (with Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 installed) to the Delta Facility;

(m) in the alternative to (j), (k) and (l) the Respondents to:

(i) at the Respondents’ and Virgin Tech’s Melbourne airport facility:

(A) cause Engine 888473 currently attached to aircraft with registration VH-VOY to be removed and placed on an Engine Stand of the same make, model, condition and quality of the Initial Stands and which otherwise comply with the applicable engine manufacturer’s procedures for storage and transport of the Engines (Temporary Transportation Engine Stand);

(B) cause Engine 897193 currently attached to aircraft with registration VH-VUA to be removed and placed on a Temporary Transportation Engine Stand;

(C) cause to be created the End of Lease Operator Records/Status Statements described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(b)(ix) in respect of Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 to transmit them to the Applicants via email or via online data room;

(ii) cause Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 to be prepared for air freight transportation in accordance with paragraph 4 of this Schedule;

(iii) consistent with the applicable engine manufacturer’s procedures for air freight transportation and the terms of the Engine Leases, transport by air freight Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 to the Delta Facility.

Inspection, removal and road transportation of Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 from Atlanta, USA to Florida, USA

(n) the Respondents to cause, while Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 remain installed on airframe with registration VH-VUT, the inspections, checks and other steps necessary to enable the Respondents or Delta, as the case may be, to create, prepare or complete:

(i) End of Lease Operator Records/Status Statements described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(b)

(ii) Lease Inspection Records described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(c);

(o) the Respondents to cause:

(i) Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 to be removed from airframe with registration VH-VUT by Delta at the Delta Facility;

(ii) Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 to be placed into Engine Stands specified in paragraphs 5(c) and (d) of Schedule 2 currently located at the Virgin Tech’s Melbourne airport facility or alternatively:

(A) in lieu of using the Engine stands specified at paragraphs 5(c) and (d) of Schedule 2 (Initial Stands), the Respondents may substitute those stands with equivalent engine stands approved by the Applicants (acting reasonably) (Replacement Stands) after which time ownership and title to the Initial Stands will pass to Virgin and the Replacement Stands will pass to the Applicants;

(B) in respect of the preceding paragraph (A), the Applicants agree that they will not unreasonably withhold consent to the use substitute stands provided that those stands are of the same make, model, condition and quality of the Initial Stands and which otherwise comply with the applicable engine manufacturer’s procedures for storage and transport of the Engines.

(iii) the QECs described at Schedule 2, paragraphs 6(a) and (b) of these Orders to be removed from Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 respectively;

(iv) Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 to be prepared in readiness for transportation in accordance with paragraph 4 of this Schedule 3;

(v) all End of Lease Operator Records/Status Statements described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(b) and Lease Inspection Records described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(c) in respect of Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 are to be transmitted to the Applicants via email or via online data room; and

(vi) Engine 888473 and Engine 897193 and the QECs described at Schedule 2, paragraphs 6(a) and (b) to be transported by road using trucks equipped with air ride or air cushion tractors and trailers to the Applicants to their Coconut Creek Facility.

Applicants’ participation

(2) The steps to be taken by the Respondents under the previous paragraph involving:

(a) removal of Engines or QECs;

(b) placing of Engines on Engine Stands;

(c) inspections, checks or other steps necessary to produce End of Lease Operator Records/Status Statements described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(b) and Lease Inspection Records described in Schedule 2, paragraph 7(c); or

(d) preparation of Engines or QECs in readiness for road transport

are to be taken in the presence of the Applicants’ nominated representative and, so far as reasonable and consistent with the applicable engine manufacturer’s procedures for removal and the terms of the Engine Leases, will use their best endeavours to cause those steps to be carried out in accordance with the directions of the Applicants’ nominated representative.

(3) At the time of removal of Engines or QECs, the Respondents’ will give the Applicants’ nominated representative sufficient access to the Engines and components in order to undertake an inventory of the parts belonging to the Applicants.

Preparation of Engines in readiness for road transportation

(4) Where it is specified in these Orders that the Respondents shall cause the Engines prepared in readiness for transportation, they shall cause to occur, for each Engine, consistent with the applicable engine manufacturer’s procedures for removal and the terms of the Engine Leases:

(a) capping and plugging all openings of the Engine;

(b) preserving the Engine for long-term preservation and storage for a minimum of 365 days in accordance with the applicable manufacturer’s procedures for the Engine;

(c) completely sealing the Engine in a Moisture Vapour Proof (MVP) Bag provided by the Applicants or with heavy gauge vinyl plastic if the Applicants do not provide an MVP Bag;

(d) otherwise preparing the Engine for shipment and, if applicable, the shipment of the Engine, in accordance with the manufacturer’s specifications and recommendations.

Definition of Engine Lease

(5) In this Schedule 3, a reference to an Engine Lease is a reference to any or all of, as the case may be, the lease agreements between the First Applicant and the First Respondent, the engine lease support agreement between the Second Applicant and the First Respondent, and the sub-lease agreements between the First Respondent and the Second Respondent as follows:

(a) Engine Lease Support Agreement dated 24 May 2019 between the Second Applicant and the First Respondent;

(b) General Terms Engine Lease Agreement dated 24 May 2019 between the First Applicant and the First Respondent;

(c) Aircraft Engine Lease Agreement in respect of Engine 897193 dated 24 May 2019 between the First Applicant and the First Respondent;

(d) Engine Sublease Agreement in respect of Engine 897193 dated 24 May 2019 between the First Respondent and the Second Respondent;

(e) Aircraft Engine Lease Agreement in respect of Engine 896999 dated 14 June 2019 between the First Applicant and the First Respondent;

(f) Engine Sublease Agreement in respect of Engine 896999 dated 14 June 2019 between the First Respondent and the Second Respondent;

(g) Aircraft Engine Lease Agreement in respect of Engine 888473 dated 28 August 2019 between the First Applicant and the First Respondent;

(h) Engine Sublease Agreement in respect of Engine 888473 dated 28 August 2019 between the First Respondent and the Second Respondent; and

(i) Aircraft Engine Lease Agreement in respect of Engine 894902 dated 13 September 2019 between the First Applicant and the First Respondent; and

(j) Engine Sublease Agreement in respect of Engine 894902 dated 13 September 2019 between the First Respondent and the Second Respondent.

MIDDLETON J:

INTRODUCTION

Background

1 The First and Second Applicants (the ‘Applicants’) are respectively the legal and beneficial owners of four aircraft jet engines. The aircraft engines (and associated stands, equipment, and records) were leased to the First Respondent (‘VB’) who in turn subleased them to the Second Respondent, Virgin Australia Airlines Pty Limited (‘VAA’), together referred to as ‘Virgin’ in these reasons.

2 The First Applicant (‘Wells Fargo’) as lessor (holding its interest beneficially for the Second Applicant (‘Willis’)) holds an “international interest” (by reference to Art 2(2)(c)) of the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment (the ‘Convention’). Wells Fargo is afforded certain rights, privileges, and immunities by the Convention, and the Protocol to the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment on Matters Specific to Aircraft Equipment (the ‘Aircraft Protocol’). The Convention and Aircraft Protocol have the force of law as part of the law of the Commonwealth, so far as they relate to Australia, effective on 1 September 2015 upon the commencement of the International Interests in Mobile Equipment (Cape Town Convention) Act 2013 (Cth) (the ‘CTC Act’).

3 Both the Convention and Aircraft Protocol prevail over any law of the Commonwealth and over any law of a State or Territory, to the extent of any inconsistency (CTC Act, s 8).

4 Australia has declared that it will apply Art XI, Alternative A of the Aircraft Protocol in its entirety to all types of insolvency proceedings, and that the waiting period for the purposes of Art XI(2) shall be 60 calendar days: see Declarations Lodged by Australia under the Aircraft Protocol at the Time of the Deposit of its Instrument of Accession.

5 Article XI(2) of the Aircraft Protocol provides that upon the occurrence of an “insolvency-related event”, the insolvency administrator or the debtor “shall … give possession of the aircraft object to the creditor”. This is subject to Art XI(7) (to which I will come).

6 It is not in dispute between the parties that an insolvency-related event occurred at the time of the appointment of the Third Respondent (the ‘Administrators’) to the Virgin Australia airline group of companies, including VB and VAA. The primary question for this Court is whether the Administrators (or VB as the debtor) have complied with their obligation to “give possession” to the Applicants (ie Wells Fargo and Willis) of the engines and associated stands, equipment and records (collectively, the ‘aircraft objects’).

7 The Applicants’ case is that the Administrators (or VB) are required to give possession as a positive act of delivery in the United States in accordance with certain lease agreements, and not simply giving the Applicants the opportunity to take possession of the aircraft objects in Australia.

Summary of conclusion reached

8 I have reached the conclusion, for the reasons developed below, that the requirement under the Aircraft Protocol involves the delivery up (effectively in accordance with the contractual regime under the lease agreement for redelivery) to the Applicants in the United States. The Administrators cannot rely upon any lesser requirement found in the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (the ‘Corporations Act’), if for no other reason than because the Convention and Aircraft Protocol prevail over the Corporations Act to the extent of any inconsistency.

9 The Court has adopted a construction of the Convention and the Aircraft Protocol that is in accordance with the relevant text, and the object and purpose of the Convention and Aircraft Protocol. In my view, to interpret the relevant words, namely “shall … give possession of the aircraft object to the creditor”, as requiring redelivery in the manner ordered in these proceedings, which is effectively in accordance with the terms of the lease agreements, is consistent with the ordinary meaning of the phrase, the contractual bargain reached between the parties, the context in which the phrase is found in the Convention and Aircraft Protocol, and their object and purpose.

10 The construction adopted by the Court provides an efficient model for the return of the aircraft objects, and affords security (in the event of an insolvency-related event) against mobile assets, which are purposes envisioned by the Convention and Aircraft Protocol, and the Commonwealth Parliament when the Parliament wholly adopted their terms into the domestic law of Australia. The advantages of the Convention and Aircraft Protocol are predictability and enforceability, as well as reducing the risks for creditors (and consequently the borrowing costs of debtors) through the resulting improved legal certainty. By their nature, aircraft engines have no fixed location, and different legal systems have different approaches to such matters like securities and repossession remedies. The Convention and Aircraft Protocol were intended to ensure that interests (in, for example, aircraft engines) were “recognised and protected universally”, as indicated in the preamble to the Convention.

11 The second and separate issue raised in the Amended Originating Application (to which document I will come) is whether the Administrators failed, for the purposes of the Corporations Act, to disclaim the Applicants’ property by their 16 June 2020 s 443B(3) Notice and should be personally liable for post-appointment rent or other amounts payable by Virgin under the relevant lease agreements pursuant to s 443B of the Corporations Act.

THE AMENDED ORIGINATING APPLICATION OF THE APPLICANTS

12 The Applicants’ Amended Originating Application dated 26 July 2020 (Amended Originating Application) sought the following substantive relief, which it is convenient to set out here (omitting the inclusion of Schedule 2 and Schedule 3 and Annexures referred to therein):

… [T]he Applicants claim:

Declaration of international interest

1 A declaration that the First Applicant holds (for the benefit of the Second Applicant) an “international interest” in the “aircraft objects” identified in Schedule 2 [of the Amended Originating Application] pursuant to Article[s] 2 and 7 of the [Aircraft Protocol].

Declaration of failure to comply with Article XI of the Cape Town Aircraft Protocol

2 A declaration that the Notice dated 16 June 2020 given by the Third Respondent to the Second Applicant did not discharge the First or Third Respondent’s obligation under Article XI of the [Aircraft Protocol] to “give possession” of the “aircraft objects” identified in Schedule 2.

Delivery up of aircraft objects

3 An order that the Respondents or any of them “give possession” of the “aircraft objects” identified in Schedule 2, by delivering up, or causing to be delivered up the “aircraft objects” to the Applicants in the manner set out in Schedule 3 at Coconut Creek, Florida, United States of America by no later than 31 July 2020.

4 An order that unless and until the Respondents, or any of them “give possession” in accordance with prayer 3, or until further order of the Court, the Respondents are to preserve the aircraft objects in Schedule 2 by:

(a) maintaining the Engines identified in Schedule 2 in accordance with paragraph 1 of Schedule 3;

(b) maintaining insurance cover over the aircraft objects identified in Schedule 2 to the same or greater extent as was maintained at the date of appointment of the Third Respondent as administrators.

4A An order that the First, Second, and Fourth Respondents take all steps necessary to cause to be completed, and ‘give possession’ of, all records and information set out in Schedule 2, paragraph 7 of this Amended Originating Process.

4B An order that the Third Respondent do all such things as are necessary and within its power to cause the First, Second, and Fourth Respondents to carry out the Orders of this Court in respect of the completion and transmittal of the records described at Schedule 2, paragraph 7 of this Amended Originating Process.

Rent or other amounts payable under section 443B of the Corporations Act

5 A declaration that the Notice dated 16 June 2020 given by the Third Respondent to the Second Applicant did not satisfy the requirements of section 443B(3) of the [Corporations Act], and did not (pursuant to section 443B(4)) have the effect of relieving the Third Respondent of their obligations under section 443B(2) of the Corporations Act in respect of the property identified in Schedule 2.

6 An order that the Third Respondent pay rent or other amounts payable pursuant to section 443B(2) of the Corporations Act in respect of the property identified in Schedule 2 from 16 June 2020 until the date of this order.

13 I should indicate that, as these proceedings progressed, and once the Court indicated it was proposing to make the declarations and orders sought by the Applicants and had adopted their construction of the Aircraft Protocol, alterations were made to Schedule 2 and 3 of the proposed orders through a process of discussion between the parties as to the most effective and least costly method of giving possession of the aircraft objects.

THE AMENDED INTERLOCUTORY PROCESS OF THE RESPONDENTS

14 The Amended Interlocutory Process of the Respondents dated 5 August 2020 sought the remaining following substantive relief, which it is convenient to set out here:

1. An order pursuant to section 443B(8) or section 447A(1) of the Corporations Act that the Third [Respondent] be excused from liability in respect of the property identified in Schedule 2 to the [Applicants’] Originating Process.

2. …

3. …

4. …

5. A declaration, or alternatively, a direction pursuant to section 90-15 of the [Insolvency Practices Schedule (Corporations) (IPSC)], that, to the extent that any of the First [Respondent], Second [Respondent] and Fourth [Respondent] are ordered to:

a. “give possession” of the “aircraft objects” in the manner sought in paragraph 3 of Amended Originating Application filed by the [Applicants] on 28 July 2020 ([Applicants’] Originating Application) or such other manner as the Court determines;

b. maintain the “aircraft objects” in the manner sought in paragraph 4 of the [Applicants’] Originating Application or such other manner as the Court determines;

c. take all steps necessary to cause to be completed, and “give possession” of, records and information in the manner sought in paragraph 4A of the [Applicants’] Originating Application or such other manner as the Court determines;

the expenses of complying with those orders are:

d. expenses properly incurred by the Third Respondent in carrying on the company’s business within the meaning of s 556(1)(a) of the Corporations Act; or, alternatively,

e. debts or liabilities for which s 443D(aa) entitles the Third Respondent to be indemnified within the meaning of s 556(1)(c) of the Corporations Act. (Bold text in the original.)

THE POSITION OF THE RESPONDENTS

15 Contrary to the conclusion reached by the Court, the Respondents took the following overall position.

16 The Respondents submitted that the phrase “give possession of the aircraft object to the creditor” in Art XI(2) of the Aircraft Protocol should be construed to mean “make available the aircraft object to the creditor”. The Respondents submitted that what is involved in making aircraft objects available to a creditor/lessor will depend on the circumstances, and that the Court need not reach any generalised conclusion as to what is required of an insolvency administrator or debtor in order to satisfy their obligation to “give possession” under Art XI(2) of the Aircraft Protocol. The Respondents submitted that all that need be determined was whether the obligation—which the Respondents say consists of an obligation to make aircraft objects available to a creditor/lessor—has been satisfied on the facts before the Court.

17 The Respondents submitted that, in relation to prayers for relief 2 to 4 and 4A and 4B in the Amended Originating Application, the Applicants’ proposed construction of Art XI(2) of the Aircraft Protocol should be rejected. The Respondents submitted that the Court should conclude that the Respondents have complied with their obligation to “give possession” by reason of the steps they contend need to be taken to make the aircraft objects available to the Applicants.

18 As to prayers 5 and 6, the Respondents submitted that the Court should find that the s 443B(3) Notice dated 16 June 2020 satisfied the requirements of s 443B(3) of the Corporations Act, and therefore precluded any personal liability for rent or other amounts under s 443B(2) of the Corporations Act from arising with respect to the aircraft objects. It was then submitted that if the Court found that the s 443B(3) Notice was defective, it should nonetheless order that the Administrators be excused from any liability in respect of the aircraft objects from 16 June 2020 by way of an order pursuant to s 443B(8) or s 447A(1) of the Corporations Act.

FACTUAL AND PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

19 It is useful to set out in more detail the factual and procedural background to the dispute, which is not in contention. The parties also provided a Statement of Agreed Facts dated 30 July 2020 (Statement of Agreed Facts), which is Annexure A to these reasons.

The Applicants’ “international interest” in aircraft objects

20 Wells Fargo is the legal owner of certain aircraft objects, as trustee for a trust described as the “Willis Engine Structured Trust III”.

21 The Applicants agreed to lease to VB certain engines and equipment pursuant to lease arrangements detailed in the affidavit of Mr Dean Poulakidas sworn 29 June 2020 (Poulakidas Affidavit) filed on behalf of the Applicants. The Applicants also agreed to provide to VB lease support services in respect of these arrangements.

22 VB sub-leased these engines and equipment to VAA.

23 The Administrators were appointed as voluntary administrators to the Virgin Australia airline group of companies, including VB and VAA, on 20 April 2020.

24 The lease arrangements are detailed in the Poulakidas Affidavit and relevantly provide for the demise and delivery of the following (defined as the ‘Equipment’):

(1) four CFM International aircraft engines, model CFM-56-7B24, with engine serial numbers 888473, 897193, 896999 and 894902 (each an ‘Engine’ or, collectively, ‘Engines’), which have at least 24,000 pounds of thrust and are used on Boeing 737 aircraft;

(2) an engine stand for each Engine (‘Engine Stand’). The Engine Stands are essential for transportation in accordance with the manufacturer’s guideline when the engines are not attached to an airframe;

(3) a quick engine change (‘QEC’) unit for each Engine (which are components attached to the external part of an engine and are required to make the Engine operable); and

(4) Engine records relating to the use and airworthiness of the Engines (comprising historical records, records generated by VB and VAA during the term of the lease, and records to be provided on return of the engine) (‘Records’).

25 The agreed value of the Equipment totals US$40,000,000.

26 The Equipment comes within the definition of “aircraft objects” and “aircraft engines” for the purposes of Art I paragraphs 2(b) and (c) of the Aircraft Protocol. Article I(2)(c) defines “aircraft engines” as including “all modules and other installed, incorporated or attached accessories, parts and equipment and all data, manuals and records relating thereto”.

Security Interests over Engines

27 Wells Fargo has a security interest as that term is defined in s 12 of the Personal Property Securities Act 2009 (Cth) over each of the Engines pursuant to the following lease documents (registered on the Personal Property Securities Register (‘PPSR’) with the PPSR registration numbers listed below):

(1) Engine 897193 Lease (registered on the PPSR with PPSR numbers: 201905290067617, 201905290067629 and 201905290067638);

(2) Engine 896999 Lease (registered on the PPSR with PPSR numbers: 201906260103349, 201906260103401, 201906260103673, 201906260103591, 201906260103768 and 201906260103845);

(3) Engine 888473 Lease (registered on the PPSR with PPSR numbers: 201909120024204, 201909120024215 and 201909120024227); and

(4) Engine 894902 Lease (registered on the PPSR with PPSR numbers: 201910160000574, 201910160000588 and 201910160000590).

28 During the course of the administration of the Virgin Group, the Administrators sought (and were granted) orders from this Court including orders:

(1) extending the time limit imposed in s 443B(2) of the Corporations Act for the Administrators to decide whether to exercise Virgin’s rights in relation to leased property (ie including the rights of VB and VAA in respect of the Equipment), which time ultimately expired on 16 June 2020; and

(2) relieving the Administrators from personal liability that would otherwise arise under ss 443A and 443B of the Corporations Act in respect of any property leased, used or occupied by any member of the Virgin Group, up to 16 June 2020.

Administrators’ standstill proposal and disclaimer

29 Since 1 May 2020, the Administrators and Willis have been in communication in respect of the continued use and return of the Engines and Equipment leased by the Applicants to VB (and sub-leased to VAA by VB).

30 On 1 May 2020, the Administrators proposed that Willis agree to a “standstill” of its rights (this was proposed in a document styled “Aircraft Protocol”, which is separate from the defined term Aircraft Protocol used in this judgment). This standstill agreement was to the effect that Willis would agree not to enforce its rights for a period to be agreed by the parties (‘Standstill Agreement’).

31 On 30 May 2020 and again on 2 June 2020, Willis informed the Administrators that it would not agree to the terms of the proposed Standstill Agreement and sought expressly in writing the return of the Engines.

32 On 9 June 2020, the Administrators foreshadowed that by 16 June 2020 they proposed to issue a notice pursuant to s 443B(3) of the Corporations Act, and stated that the “issue of a s 443B(3) notice does not result in the redelivery of the engines pursuant to the redelivery provisions of the aircraft leases. After the notice is issued, you [ie Willis] will have to recover possession of the Engines at your own cost on an “as is, where is” basis…”.

33 On 10 June 2020, Willis sought the return of its Engines and stated that it expected the Administrators to comply with its obligations under the Convention and the delivery obligations prescribed by the terms of the leases.

34 On 16 June 2020, by letter from its solicitors, Willis wrote to the solicitors for the Administrators, insisting that the Administrators comply with their obligations under Art XI of the Aircraft Protocol to “give possession” of the Engines and Equipment.

35 On the same day the Administrators issued a notice to Willis purportedly in accordance with s 443B(3) of the Corporations Act disclaiming the Engines, and stating among other things:

(1) “the Administrators are unable to comply with all the return terms of the lease agreement that Virgin has with you [ie Willis]”;

(2) the Administrators proposed to pay for insurance “in the interest of maintaining the existing insurance protection for the engines during the period until you have taken possession or control of the engines and in any event no later than 14 days from this notice [ie, until 30 June 2020]”;

(3) Willis “will have all risk in the engines when you [ie Willis] have taken possession or control of the engines and in [any] event no later than 14 days from this notice [ie until 30 June 2020]”; and

(4) the engines were “on the wing of” four separate aircraft, three of which were in Melbourne, and one of which was in Adelaide.

36 This 16 June 2020 s 443B(3) Notice identified that:

(1) Engine 896999, Engine 897193, and Engine 888473 were each “on the wing” of three different Virgin aircraft at Melbourne Airport;

(2) Engine 894902 was “on the wing” of a different Virgin aircraft at Adelaide Airport.

The 16 June 2020 Notice identified nothing else of the Applicants’ Equipment.

37 On 16 June 2020, Willis provided the Administrators with details of the serial numbers of the Engines, Engine Stands, and the type of QEC kits provided to Virgin at the time of lease.

38 On 18 June 2020, Ian Boulton of the Administrators’ firm sent an email to Garry Failler and Steve Chirico of the Applicants identifying the locations of the Engine Stands.

39 The email identified differences in relation to the location of two of the Engines:

(1) Engine 897193 was in Adelaide on VH-VUT (not in Melbourne on VH-VUA as previously identified);

(2) Engine 894902 was in Melbourne on VH-VUA (not in Adelaide on VH-VUT as previously identified).

40 This 18 June 2020 email identified for the first time the whereabouts of the Engine Stands. Although the email did not identify serial numbers, it suggested that two of the Willis Engine Stands were in Melbourne, and two were located at “Delta, Atlanta”. No mention was made of the QECs (or an inventory of components), nor the Records.

41 On 19 June 2020, Willis sought clarification to determine if Willis was authorised to remove the Engines from the aircraft owned by third parties.

42 On 19 June 2020, the Administrators advised that Willis would be required to engage either Virgin technicians or other Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) approved engineers at Willis’s expense to remove the Engines. It was stated that the “limitations of the Adelaide facilities” would “require the ferrying of VH-VUT to another location” at Willis’s cost.

43 By letter dated 22 June 2020, the Respondents informed Willis (through their respective solicitors) that the “records, QEC units and engine stands (collectively, Ancillary Property), is all property that is directly associated with the Engines and necessary to operate, store, and transport them”, but indicated that this “Ancillary Property” had “no, or minimal, use or value independently of Engines”.

44 In respect of the Convention and Aircraft Protocol obligations, the 22 June 2020 letter clarified the Respondents’ position. It stated that the Aircraft Protocol does not give rise to any more onerous obligation on an “insolvency administrator” than simply giving an owner or lessor the opportunity to take possession of the relevant property.

45 On 8 July 2020, the Respondents provided the Applicants with access to an online “data room” containing “Operator Records”.

46 On and from 8 July 2020, the vast majority of the “Historical Operator Records” were provided by the Respondents to the Applicants.

47 Those records that have been provided are described as “Closed” in the “Records Open Items List” (referred to as the ‘ROIL’) for the Engines, which is a document that identifies the status of records provided by the Respondents as at 17 July 2020 in respect of the Engines, but was updated as these proceedings progressed.

48 At the time of the preparation of the Statement of Agreed Facts, the Respondents had not provided to the Applicants any of the “End of Lease Operator Records”. At the time of the preparation of the Statement of Agreed Facts, the Respondents had also not provided any of the “Lease Inspection Records from Engine Shop”.

49 By the time of the receipt of the final submissions to this Court, existing documents were provided by the Respondents to the Applicants and alternative arrangements may have become necessary for the removal of the aircraft engines, although, as Schedule 3 of the Orders indicate, further documentation needs to be delivered by the Respondents to the Applicants.

JURIDICTION OF THE COURT

50 Hence a dispute has arisen between the parties, and applications have been made to this Court for declarations and orders as identified above.

51 The Amended Originating Application in part seeks relief under the Convention and Aircraft Protocol. However, the Applicants’ cause of action arises under the CTC Act as the source of law: see Povey v Qantas Airways Ltd (2005) 223 CLR 189 (‘Povey’), at [12] (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ) and [59] (McHugh J).

52 These is no dispute as to the jurisdiction of this Court to consider and determine the relief sought by the parties.

53 There is also no dispute that the jurisdictional preconditions to enlivening the Convention and Aircraft Protocol are satisfied in the present proceedings because:

(1) the “international interest” in Art 2(2)(c) and Art 7 of the Convention is established by each engine lease (incorporating the terms of the “General Terms of Agreement applicable to any Engine Lease” (GTA)), which establishes Wells Fargo as the lessor of various “aircraft engines” as referred to in Art 2(3)(a);

(2) the aircraft engines are of the thrust required by Art I(2)(b) of the Aircraft Protocol, and are defined to include the “modules and other installed, incorporated or attached accessories, parts and equipment and all data, manuals and records relating thereto”;

(3) the Engines and Equipment are therefore each “aircraft objects” for the purpose of Art I(2)(c) of the Aircraft Protocol;

(4) the priority search certificates in evidence are prima facie proof of the interests in favour of Wells Fargo in each Engine: see Art 24 of the Convention;

(5) an “insolvency-related event” occurred within the meaning of Art I(2)(m) of the Aircraft Protocol, by reason of the commencement of “insolvency proceedings” (the latter term is defined in Art 1(l) of the Convention), when the Administrators were appointed to Virgin, on 20 April 2020.

THE CONVENTION AND AIRCRAFT PROTOCOL

Introduction

54 Whereas here Commonwealth legislation has wholly enacted the terms of the Convention and Aircraft Protocol it is necessary to interpret the words of the Convention and the Aircraft Protocol themselves in accordance with the principles of international law that govern the interpretation of treaties.

55 Given that the central issue relates to the proper construction of the Convention and Aircraft Protocol, it is convenient to set out in brief terms the principles governing the construction of the Convention and Aircraft Protocol.

56 Article 5(1) of the Convention provides that, in construing the Convention, regard is to be had to “its purposes as set forth in the preamble, to its international character and the need to promote uniformity and predictability in its application.” Article 5(2) provides that questions concerning matters governed by the Convention which are not expressly settled in the Convention itself are to be settled “in conformity with the general principles on which it is based or, in the absence of such principles, in conformity with the applicable law”. Article 6 further provides that, while the Convention and Aircraft Protocol “shall be read and interpreted together as a single instrument” (Convention, Art 6(1)), to the “extent of any inconsistency between [the] Convention and the Protocol, the Protocol shall prevail” (Convention, Art 6(2)).

57 The proper construction of the Convention and Aircraft Protocol is also governed by Arts 31 and 32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, done at Vienna on 23 May 1969 (the ‘Vienna Convention’). As McHugh J observed in Povey at [60] (when his Honour was considering Art 17 of the ‘Warsaw Convention’, being the Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules Relating to International Carriage by Air), “an Australian court should apply the rules of interpretation of international treaties that the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties has codified” (citations omitted).

58 Article 31(1) of the Vienna Convention requires that a treaty be interpreted “in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in light of its object and purpose”. As McHugh J also observed in Applicant A v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs (1997) 190 CLR 225 (‘Applicant A’) at 252-253 (footnotes omitted), Art 31(1):

contains three separate but related principles. First, an interpretation must be in good faith, which flows directly from the rule pacta sunt servanda. Second, the ordinary meaning of the words of the treaty are presumed to be the authentic representation of the parties’ intentions. This principle has been described as the ‘very essence’ of a textual approach to treaty interpretation. Third, the ordinary meaning of the words are not to be determined in a vacuum removed from the context of the treaty or its object or purpose.

59 His Honour, after considering the authorities, stated, at 254, that “[p]rimacy is to be given to the written text of the Convention but the context, object and purpose of the treaty must also be considered”.

60 Chief Justice Brennan agreed with McHugh J’s explanation of the operation of Art 31 and commented as follows (at 230-1):

If a statute transposes the text of a treaty or a provision of a treaty into the statute so as to enact it as part of domestic law, the prima facie legislative intention is that the transposed text should bear the same meaning in the domestic statute as it bears in the treaty. To give it that meaning, the rules applicable to the interpretation of treaties must be applied to the transposed text and the rules generally applicable to the interpretation of domestic statutes give way.

In interpreting a treaty, it is erroneous to adopt a rigid priority in the application of interpretative rules. The political processes by which a treaty is negotiated to a conclusion preclude such an approach. Rather, for the reasons given by McHugh J, it is necessary to adopt an holistic but ordered approach. The holistic approach to interpretation may require a consideration of both the text and the object and purpose of the treaty in order to ascertain its true meaning. Although the text of a treaty may itself reveal its object and purpose or at least assist in ascertaining its object and purpose, assistance may also be obtained from extrinsic sources. The form in which a treaty is drafted, the subject to which it relates, the mischief that it addresses, the history of its negotiation and comparison with earlier or amending instruments relating to the same subject may warrant consideration in arriving at the true interpretation of its text. (Citations omitted.)

61 Justice Dawson (at 240) provided an interpretation of Art 31 that was consistent with that of Brennan CJ and McHugh J, and Gummow J (at 277) agreed with McHugh J’s view of the operation of Art 31.

62 In Pilkington (Australia) Ltd v Minister for Justice and Customs (2002) 127 FCR 92 (‘Pilkington’), at [25]–[28], the Full Court of the Federal Court (Mansfield, Conti and Allsop JJ as Allsop J then was) set out the applicable principles of statutory construction in the context of a legislative scheme that gave effect to an international agreement and the rationale for the approach adopted. The Full Court said:

… To the extent that the Parliament has passed … legislation dealing with the subject matter of [an international] [a]greement, that legislation will be interpreted and applied, as far as its language permits, so that it is in conformity, and not in conflict, with Australia’s international obligations. Where a statute is ambiguous (the conception of ambiguity not being viewed narrowly) the court should favour a construction consistent with the international instrument and the obligations which it imposes over another construction …

The ascertainment of the meaning of, and obligations within, an international instrument … is to be ascertained by giving primacy to the text of the international instrument, but also by considering the context, objects and purposes of the instrument … The manner of interpreting the international instrument is one which is more liberal than that ordinarily adopted by a court construing exclusively domestic legislation; it is undertaken in a manner unconstrained by technical local rules or precedent, but on broad principles of general acceptation … The reasons for this approach were described by Lord Diplock in Fothergill v Monarch Airlines Ltd [1981] AC 251 at 281–2, as follows:

The language of that Convention that has been adopted at the international conference to express the common intention of the majority of the states represented there is meant to be understood in the same sense by the courts of all those states which ratify or accede to the Convention. Their national styles of legislative draftsmanship will vary considerably as between one another. So will the approach of their judiciaries to the interpretation of written laws and to the extent to which recourse may be had to travaux préparatoires, doctrine and jurisprudence as extraneous aids to the interpretation of the legislative text.

The language of an international convention has not been chosen by an English parliamentary draftsman. It is neither couched in the conventional English legislative idiom nor designed to be construed exclusively by English judges. It is addressed to a much wider and more varied judicial audience than is an Act of Parliament that deals with purely domestic law. It should be interpreted, as Lord Wilberforce put it, in James Buchanan & Co Ltd v Babco Forwarding & Shipping(UK) Ltd [1978] AC 141 at 152, ‘unconstrained by technical rules of English law, or by English legal precedent, but on broad principles of general acceptation’.

The need for a broad or liberal construction is reinforced by the matters which can be taken into account under Art 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties … in accordance with which Australian courts interpret treaties. (Citations omitted.)

63 The decisions of domestic courts with respect to the interpretation of the Convention and the Aircraft Protocol may have some relevance to the proper construction of those instruments: see Anthea Roberts, ‘Comparative International Law? The role of national courts in creating and enforcing international law’ (2011) 6(1) International Comparative Law Quarterly 57, 58-61 (eg “[a]cademics, practitioners and international and national courts frequently identify and interpret international law by engaging in a comparative analysis of how domestic courts have approached the issue”). However, a court should be careful in having any regard to a domestic decision when construing the Convention and Aircraft Protocol. The observation of Lord Wilberforce in James Buchanan & Co Ltd v Babco Forwarding & Shipping(UK) Ltd [1978] AC 141 at 152, referred to by the Full Court in Pilkington and set out above, has been approved by the High Court of Australia: see Shipping Corporation of India v Gamlen Chemical Co A/Asia Pty Ltd (1980) 147 CLR 142, 159 (Mason and Wilson JJ); Povey at 202 (Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ); Applicant A at 240 (Dawson J); see also the decision of Hill J in Barzideh v Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs (1996) 69 FCR 417, 425.

64 The need to disregard domestic legal precedent in construing a treaty reflects the fact that the construction of a treaty “must be uniform throughout the courts of the Member States. It cannot be dominated by a domestic law approach in cases brought under the domestic jurisdiction, whether it be statutory or inherent”: K (A Child), Re [2013] EWCA Civ 895 at [19] (Thorpe LJ; Tomlinson and Brigss LJJ agreeing).

65 For instance, at various points, the Convention and Aircraft Protocol refer to the debtor’s holding of an object as “possession”. The word “possession” must be given a meaning not necessarily constrained by English or Australian legal precedent. In civil law systems, the concept of possession seems to require a combination of factual possession of an object and an intention to hold it as owner, so that an equipment lessee is not a possessor but a “detainer” (détenteur) whose rights are in essence contractual rather than proprietary. The word “possession” will need to be construed as covering both possession in the common law sense and détention in the civil law sense. No issue in these proceedings was raised by the parties as to the interpretation of the word “possession”.

66 Returning then to the Vienna Convention, Art 31(2) sets out what constitutes “context” for the purpose of the interpretation of a treaty; namely, in addition to “the text, including its preamble and annexes”, any “agreement relating to the treaty which was made between all the parties in connection with the conclusion of the treaty” and “any instrument which was made by one or more parties in connection with the conclusion of the treaty and accepted by the other parties as an instrument related to the treaty”. No agreement or instrument of a kind described in Art 31(2) has been identified by the parties as being relevant to the construction exercise before the Court.

67 Article 31(3) requires that certain further matters shall be “taken into account, together with the context”, namely any “subsequent agreement between the parties regarding the interpretation of the treaty or the application of its provisions”, “any subsequent practice in the application of the treaty which establishes the agreement of the parties regarding its interpretation”, and “any relevant rules of international law applicable in the relations between the parties”. No agreement, practice or rules have been identified that would be required to be taken into account by this Court in construing Art XI(2) of the Aircraft Protocol, by reason of Art 31(3) of the Vienna Convention.

68 Article 32 addresses the extent to which recourse may be had to “supplementary means of interpretation” in construing a treaty. Two aspects of this Article should be noted. First, unlike Art 31, Art 32 is in permissive terms: “[r]ecourse may be had to supplementary means of interpretation”. Secondly, Art 32 is conditional; recourse may only be had to supplementary means of interpretation in certain circumstances, namely (a) “in order to confirm the meaning resulting from the application of article 31”; or (b) in circumstances where the interpretation according to Art 31 “leaves the meaning ambiguous or obscure” or “leads to a result which is manifestly absurd or unreasonable”. A court must be satisfied of either (a) or (b) before having regard to “supplementary means of interpretation”. Thus, Art 32 grants conditional permission to consider materials beyond the primary materials required to be considered under Art 31 when construing a treaty.

69 I should just mention that ambiguity (and obscurity) may arise because the intention of the rule maker is doubtful for any number of reasons, not just because of some grammatical or lexical ambiguity. Whilst some focus in these proceedings has been on the words “give possession”, any ambiguity that may arise from the use of the verb “give” is dispelled when that verb is considered in the context in which it appears, and more significantly once it is realised that the giving of possession is to be in accordance with the requirements of the lease agreements. As the parties recognised, the Court’s task is to determine the content of the obligation under Art XI(2) of the Aircraft Protocol, which involves more than an interpretation of the phrase “gives possession” in isolation divorced from its context.

70 I do not need to dwell on the extent to which I can have reference to supplementary materials, or supplementary means of interpretation, even if I did so only for the purpose of background information. Whilst I have been referred to a number of supplementary means of interpreting the Convention and Aircraft Protocol (to which I will return) –– including reference to domestic case law and the travaux préparatoires –– I consider these materials are of no real assistance in the task the Court needs to undertake. In my view, the text provides the complete answer to the correct interpretation of the relevant Articles of the Aircraft Protocol as to be applied to the facts before the Court. This is not to say that the meaning of the phrase “shall … give possession of the aircraft object to the creditor” is to be determined without regard to the context of the Convention and Aircraft Protocol, and their objects or purpose.

71 The approach taken to the use of supplementary materials as a means of interpretation in Commonwealth v Tasmania (1983) 158 CLR 1 (ie the Tasmanian Dam case) is instructive, although arising in a different context. One of the issues in that case was whether the World Heritage Convention, to which Australia was a party, imposed legal obligations on Australia to protect the Western Tasmania Wilderness National Parks from damage. Although the Vienna Convention, to which Australia was also a party, was not in force when the World Heritage Convention entered into force in 1972, both Gibbs CJ (at 93) and Brennan J (as his Honour then was) (at 222) considered that its interpretation was governed by the principles set out in Arts 31 and 32 of the Vienna Convention (which did “no more than indorse or confirm the existing practice” (Gibbs CJ at 93) and “codif[ied] existing customary law and furnish[ed] presumptive evidence of emergent rules of general international law”, ensuring it was “appropriate to refer to the Vienna Convention though it had not entered into force” at the relevant time (Brennan J at 222)).

72 On this basis, reference was made to the travaux préparatoires of the World Heritage Convention. Chief Justice Gibbs concluded (at 96) that the travaux préparatoires “confirm the meaning which the words of the Convention themselves reveal”. Justice Wilson reached a similar conclusion (at 191–2), while Dawson J merely referred (at 307–8) to some of the travaux préparatoires as background. Justice Mason (as he then was) did not find the travaux préparatoires “to be of assistance” (at 134) (noting that it did not “contain anything that [was] sufficiently definite to displace the natural construction of the language of the Convention”), while Brennan J (as he then was) refused to refer to them, stating (at 223):

We were invited to refer to travaux preparatoires of the Convention in order to perceive the attenuation of obligatory language from the first draft of the Convention to its final text. In my view that invitation should be rejected. It accords with the Vienna Convention and with the consistent practice of the International Court of Justice and, earlier, of the Permanent Court of International Justice, generally to decline reference to travaux preparatoires, for ‘there is no occasion to resort to preparatory work if the text of a convention is sufficiently clear in itself’ (citing Conditions of Admission of a State to Membership in the United Nations [1948] ICJR 56 at 63).

73 I find myself in a similar position to these Justices of the High Court referred to above in so far as there is a need to consider and take into account the supplementary materials referred to by the parties: those supplementary materials either confirm the ordinary meaning of the text, or in any event, are materials that I could refuse to resort to as not being of assistance, or because the text of the Convention and the Aircraft Protocol is sufficiently clear.

74 Nevertheless, I will refer to the supplementary materials later, but will now concentrate upon the text of the Aircraft Protocol.

Text of the Aircraft Protocol and the Convention

75 At the outset it is important to note that the Aircraft Protocol is just one of a number of protocols introduced, including others dealing with railway and space objects, although these are not in force. Each protocol (and the Aircraft Protocol) provide remedies tailored to the specific types of mobile equipment and are exercisable by all creditors to the case of the debtor’s default or insolvency.

76 Then it is important to note that the Convention in Chapter III deals generally with “Default remedies”, the meaning of default defined in Art 11 of the Convention. These are general remedies, not relating to insolvency. In the context of these remedies, it is clear that an available remedy is to “take possession or control” of any object (see eg Arts 8 and 10 of the Convention).

77 Then the Aircraft Protocol sets out specific Articles dealing with aircraft objects in Chapter II, including a specific Article (Art XI) dealing with remedies on insolvency. It is necessary not to conflate the requirements and the nature and content of the remedies available generally and these available in the context of insolvency.

78 It is to be observed that the remedies provided to a chargee (Art 8 of the Convention) and in relation to relief pending final determination (Art 13 of the Convention) (namely the remedies of the secured creditor) are to be exercised in a commercially reasonable manner (see Art 8(3) of the Convention). However, in relation to the Aircraft Protocol, all remedies given by the Convention and Aircraft Protocol should be exercised in accordance with this requirement, which is deemed to be in conformity with the underlying agreement unless a relevant provision is manifestly unreasonable (see Art IX(3) of the Aircraft Protocol). This provision is mandatory and cannot be derogated from by the parties (see Art IV(3) of the Aircraft Protocol).

79 Article IX – titled “Modification of default remedies provisions” – of the Aircraft Protocol (found in Chapter II headed “Default remedies, priorities and assignments”) provides in paragraph 3:

Article 8(3) of the Convention shall not apply to aircraft objects. Any remedy given by the Convention in relation to an aircraft object shall be exercised in a commercially reasonable manner. A remedy shall be deemed to be exercised in a commercially reasonable manner where it is exercised in conformity with a provision of the agreement except where such a provision is manifestly unreasonable.

80 Article XI – titled “Remedies on insolvency” – of the Aircraft Protocol (to the extent acceded to by Australia in adopting “Alternative A”) is (as far as relevant) in the following form:

Article XI — Remedies on insolvency

1. This Article applies only where a Contracting State that is the primary insolvency jurisdiction has made a declaration pursuant to Article XXX(3).

Alternative A

2. Upon the occurrence of an insolvency-related event, the insolvency administrator or the debtor, as applicable, shall, subject to paragraph 7, give possession of the aircraft object to the creditor no later than the earlier of:

(a) the end of the waiting period; and

(b) the date on which the creditor would be entitled to possession of the aircraft object if this Article did not apply.

3. For the purposes of this Article, the “waiting period” shall be the period specified in a declaration of the Contracting State which is the primary insolvency jurisdiction.

4. References in this Article to the “insolvency administrator” shall be to that person in its official, not in its personal, capacity.

5. Unless and until the creditor is given the opportunity to take possession under paragraph 2:

(a) the insolvency administrator or the debtor, as applicable, shall preserve the aircraft object and maintain it and its value in accordance with the agreement; and

(b) the creditor shall be entitled to apply for any other forms of interim relief available under the applicable law.

6. Sub-paragraph (a) of the preceding paragraph shall not preclude the use of the aircraft object under arrangements designed to preserve the aircraft object and maintain it and its value.

7. The insolvency administrator or the debtor, as applicable, may retain possession of the aircraft object where, by the time specified in paragraph 2, it has cured all defaults other than a default constituted by the opening of insolvency proceedings and has agreed to perform all future obligations under the agreement. A second waiting period shall not apply in respect of a default in the performance of such future obligations.

8. …

9. No exercise of remedies permitted by the Convention or this Protocol may be prevented or delayed after the date specified in paragraph 2.

10. No obligations of the debtor under the agreement may be modified without the consent of the creditor.