FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests (No 6) [2020] FCA 1199

ORDERS

FRIENDS OF LEADBEATER'S POSSUM INC Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 21 August 2020 |

OTHER MATTERS:

In these orders:

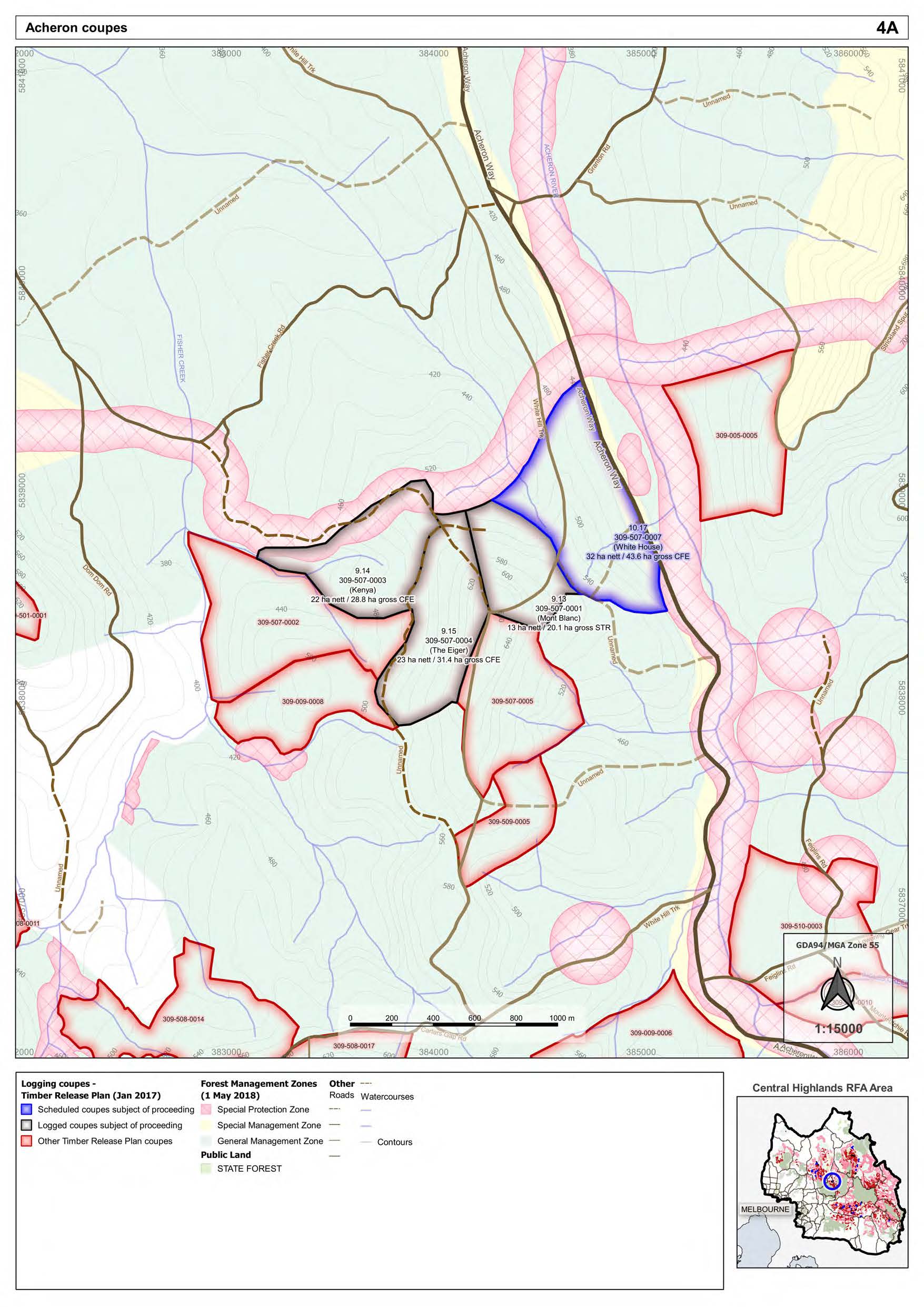

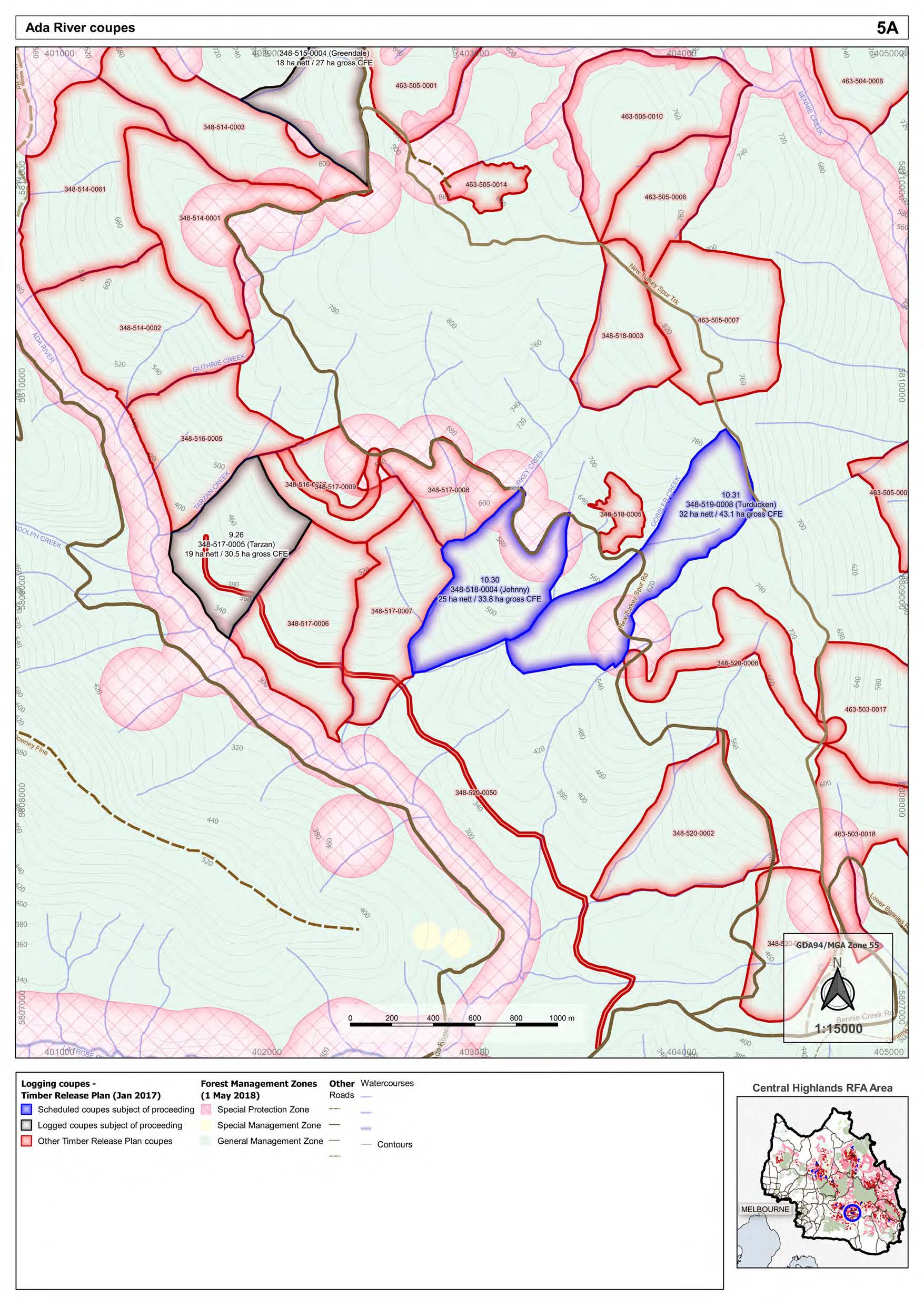

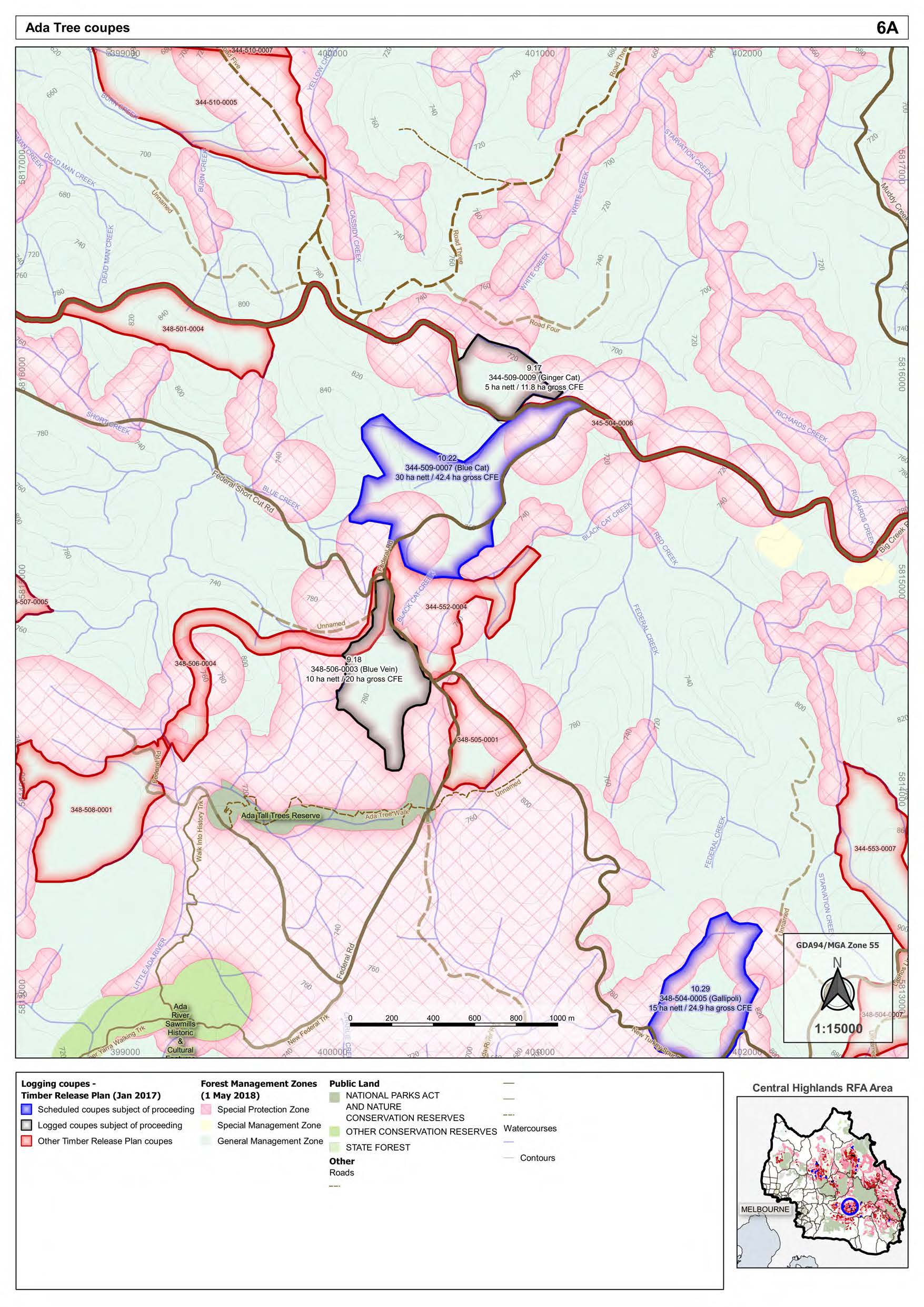

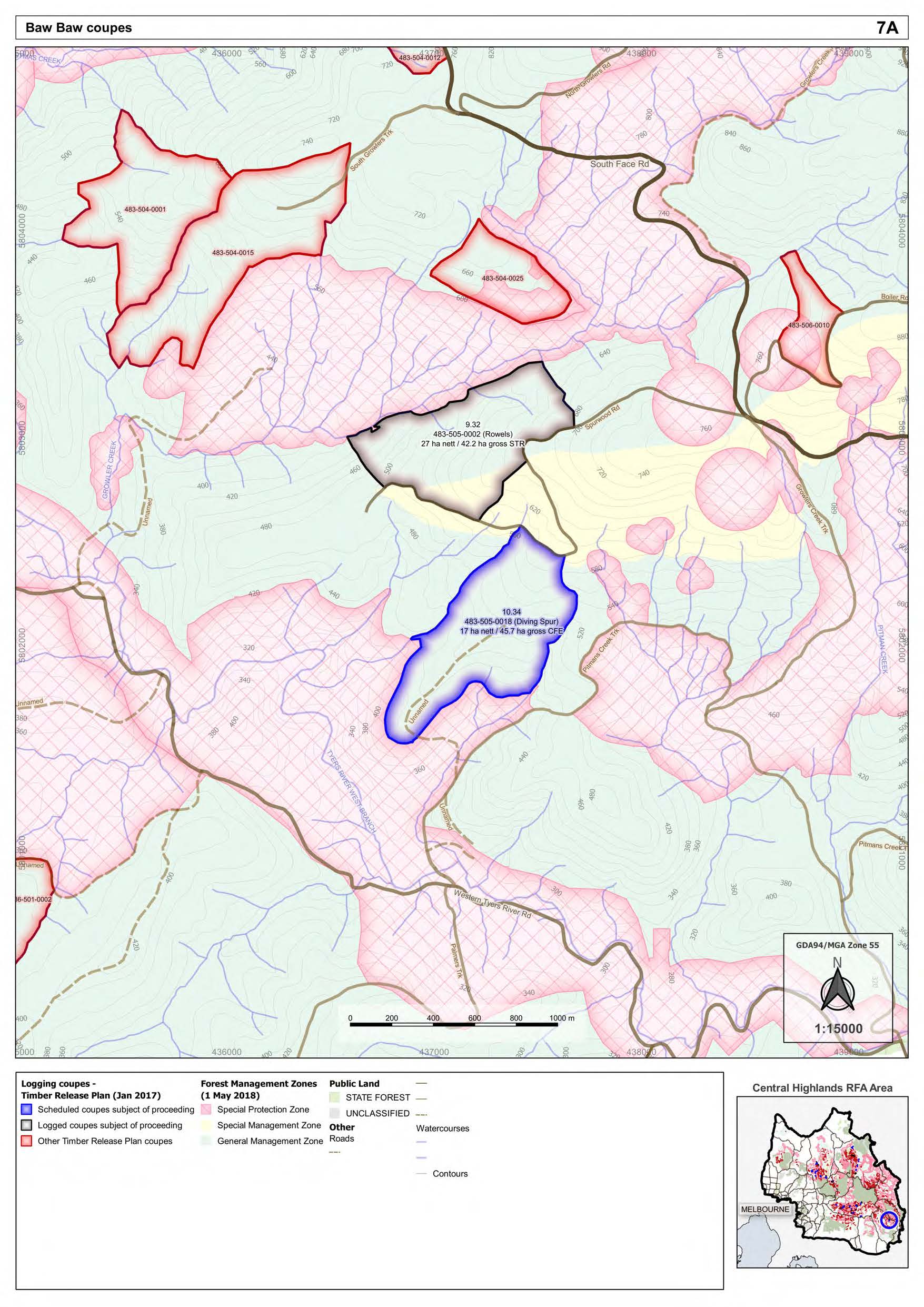

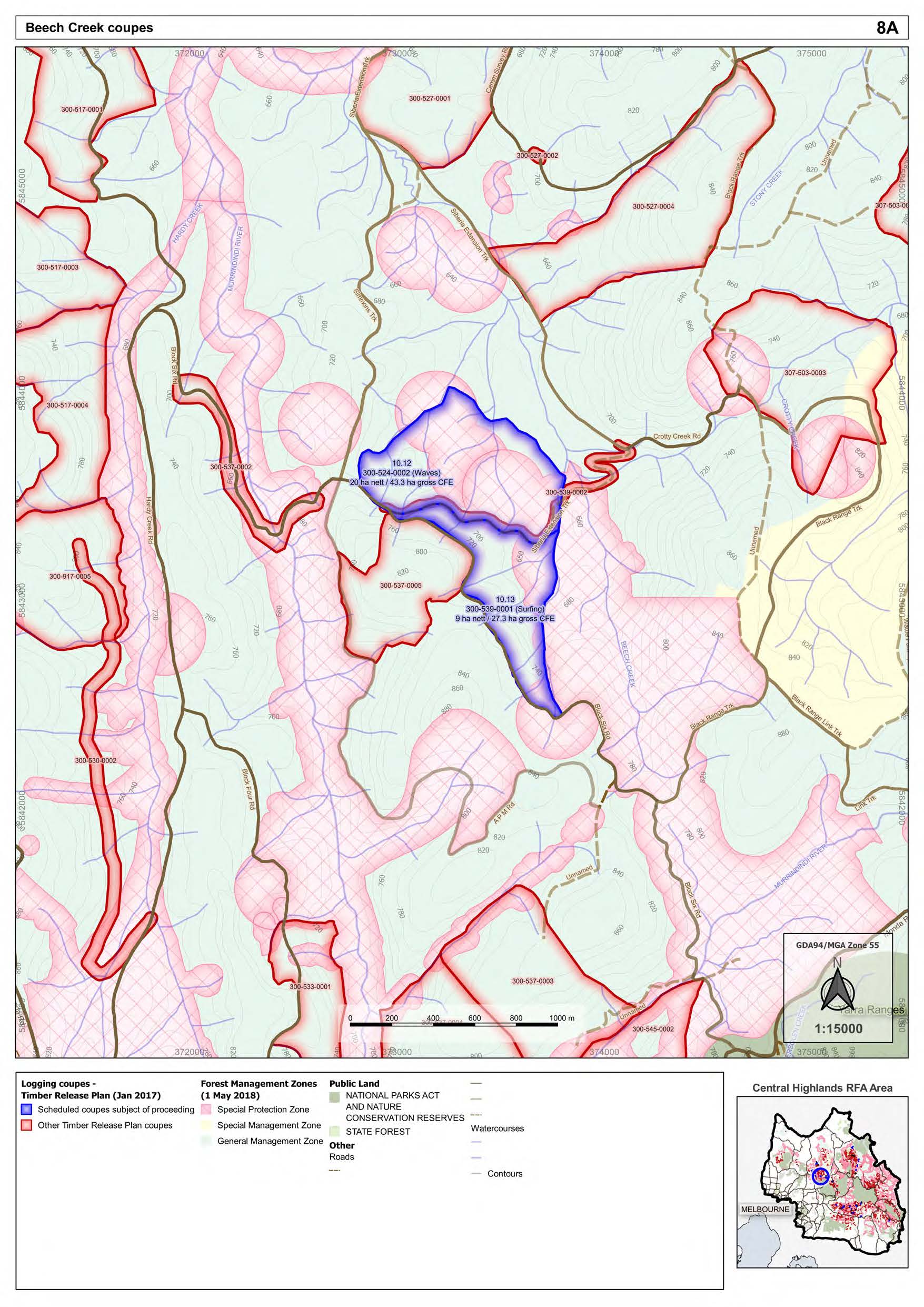

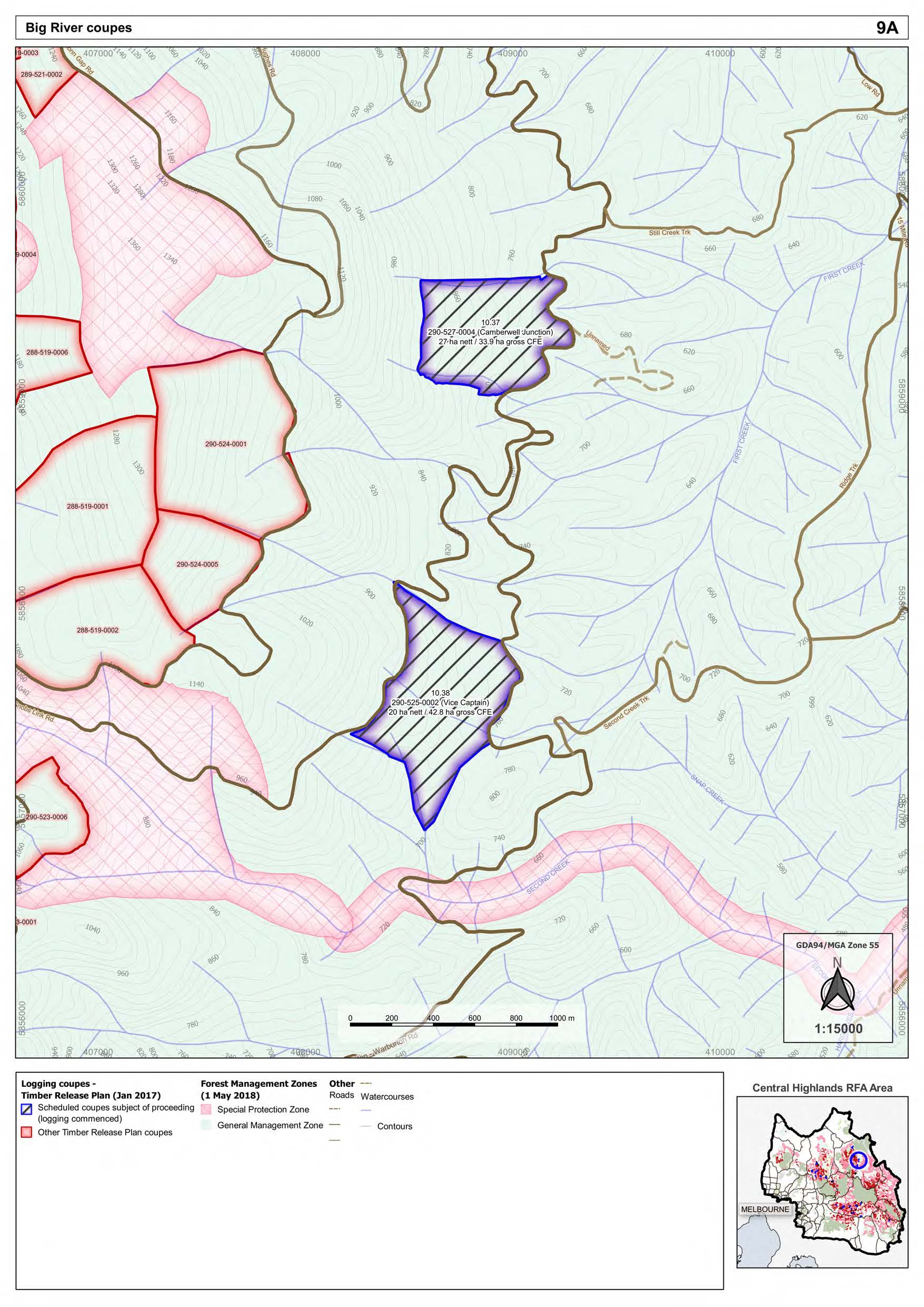

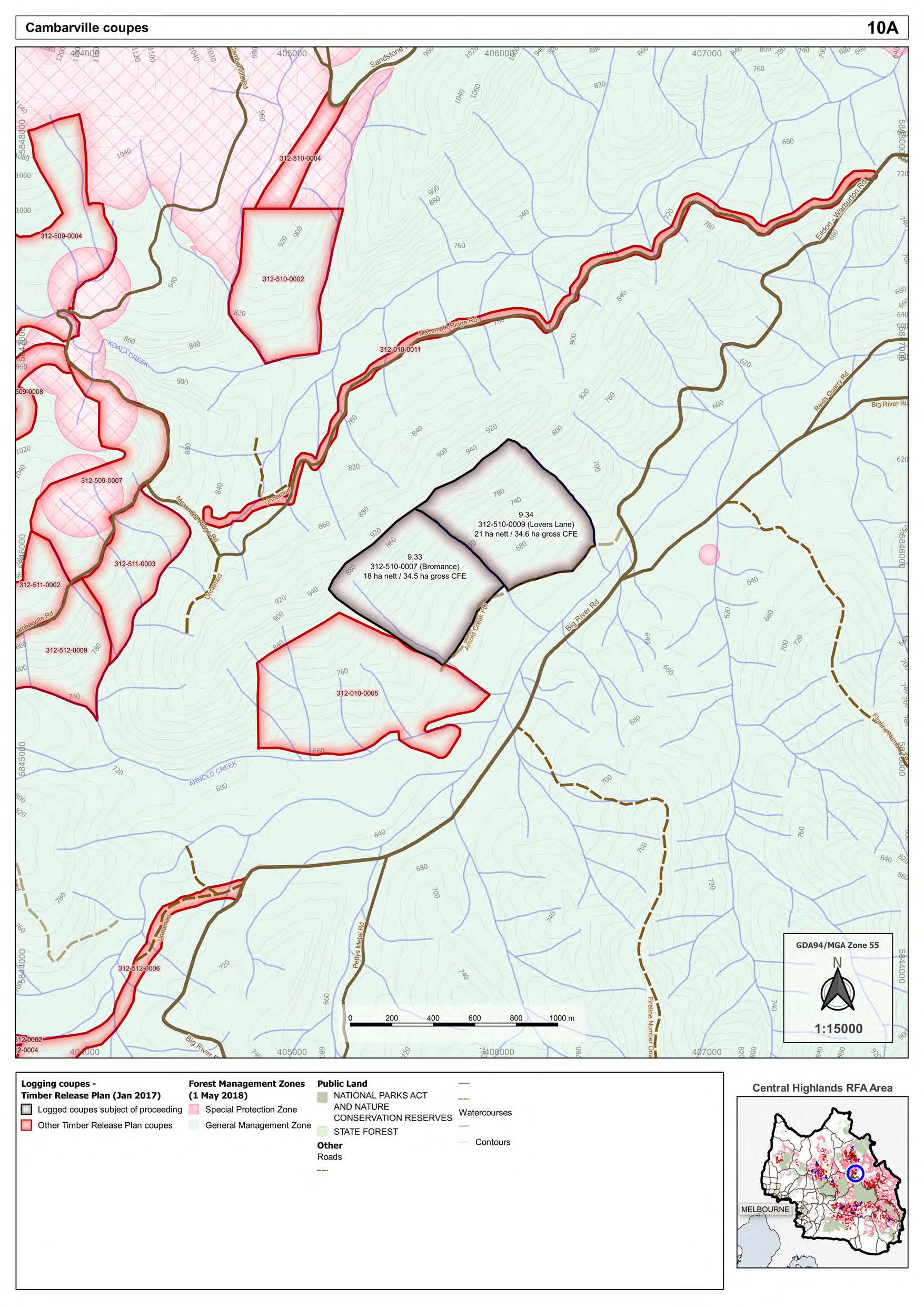

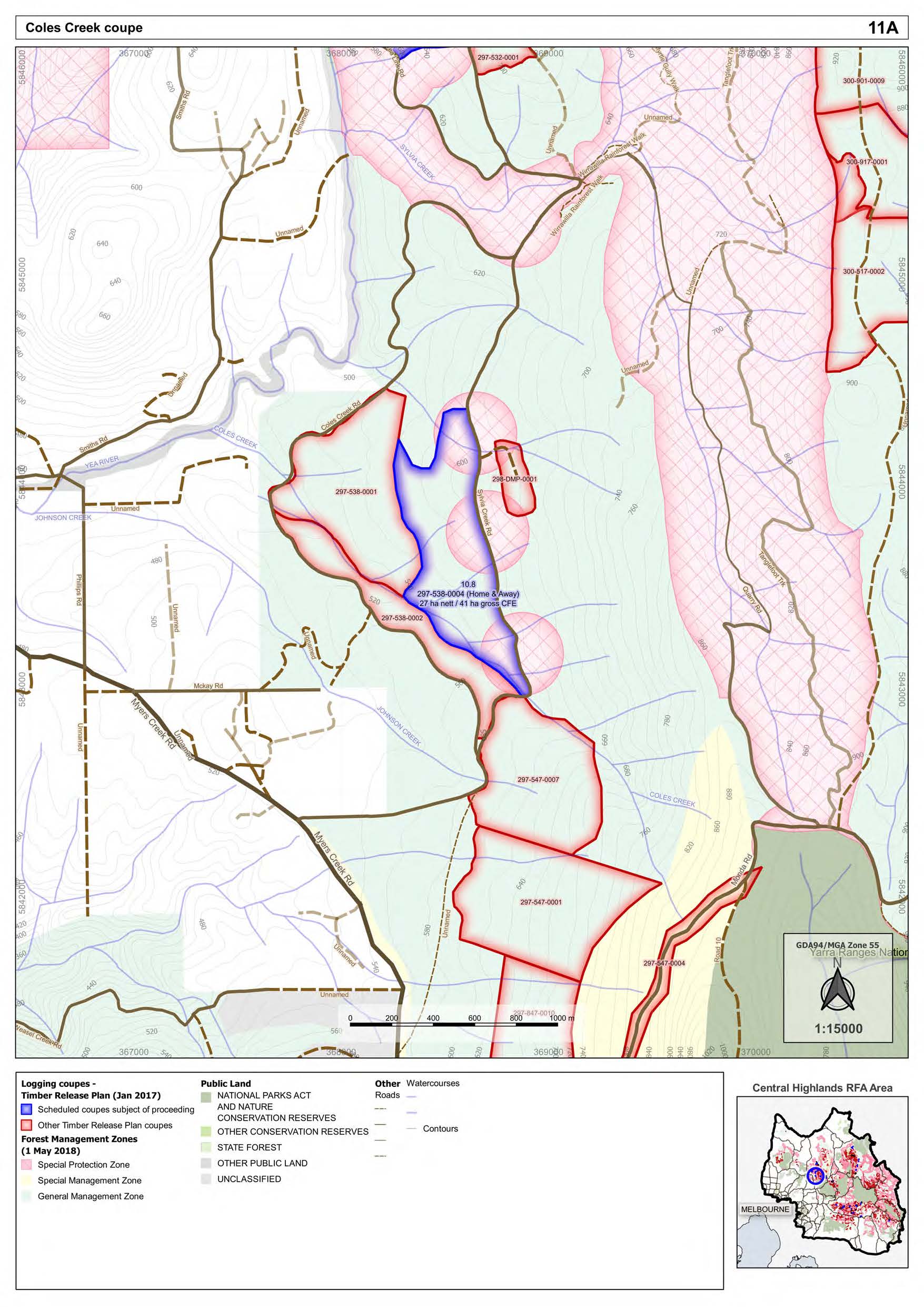

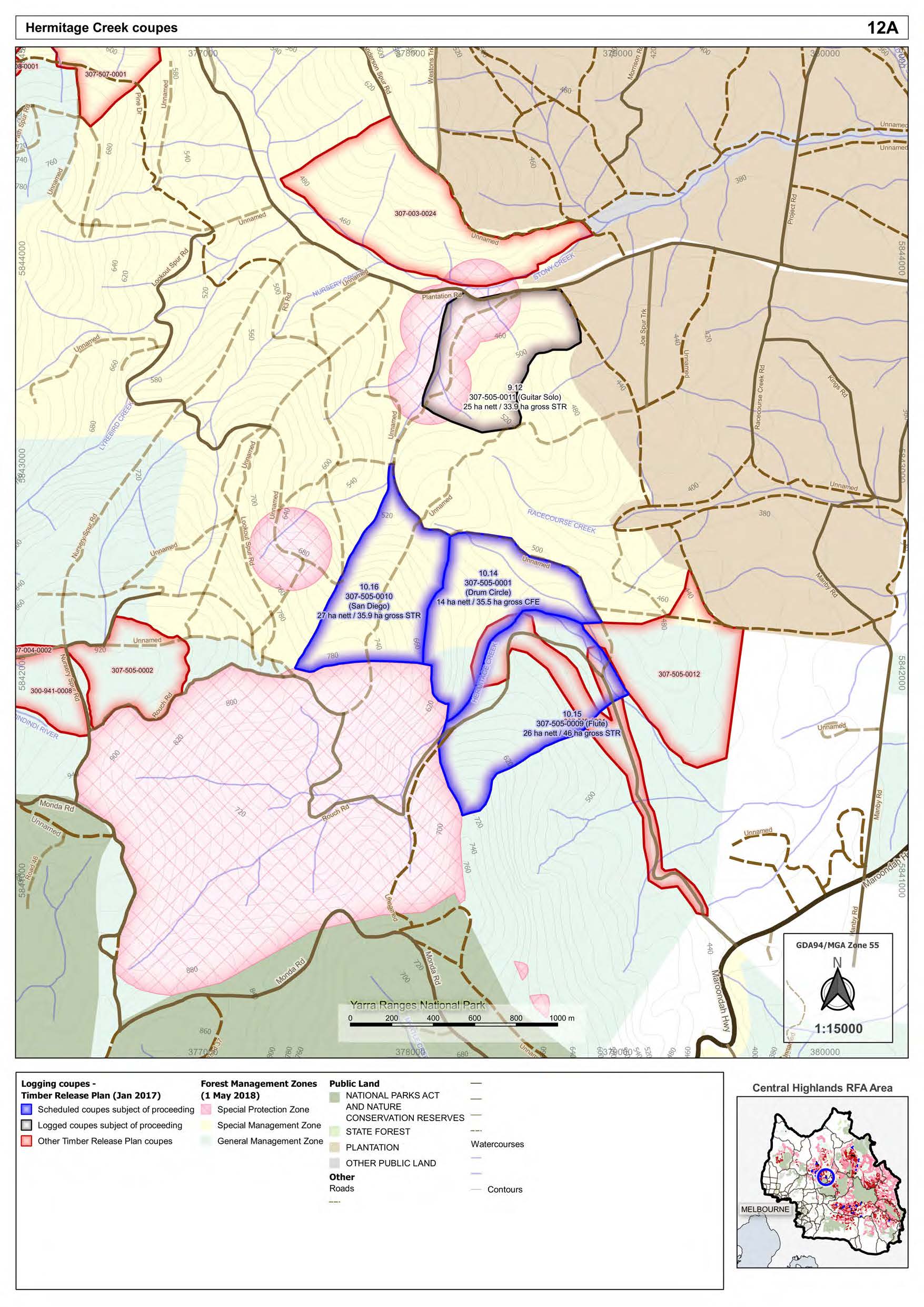

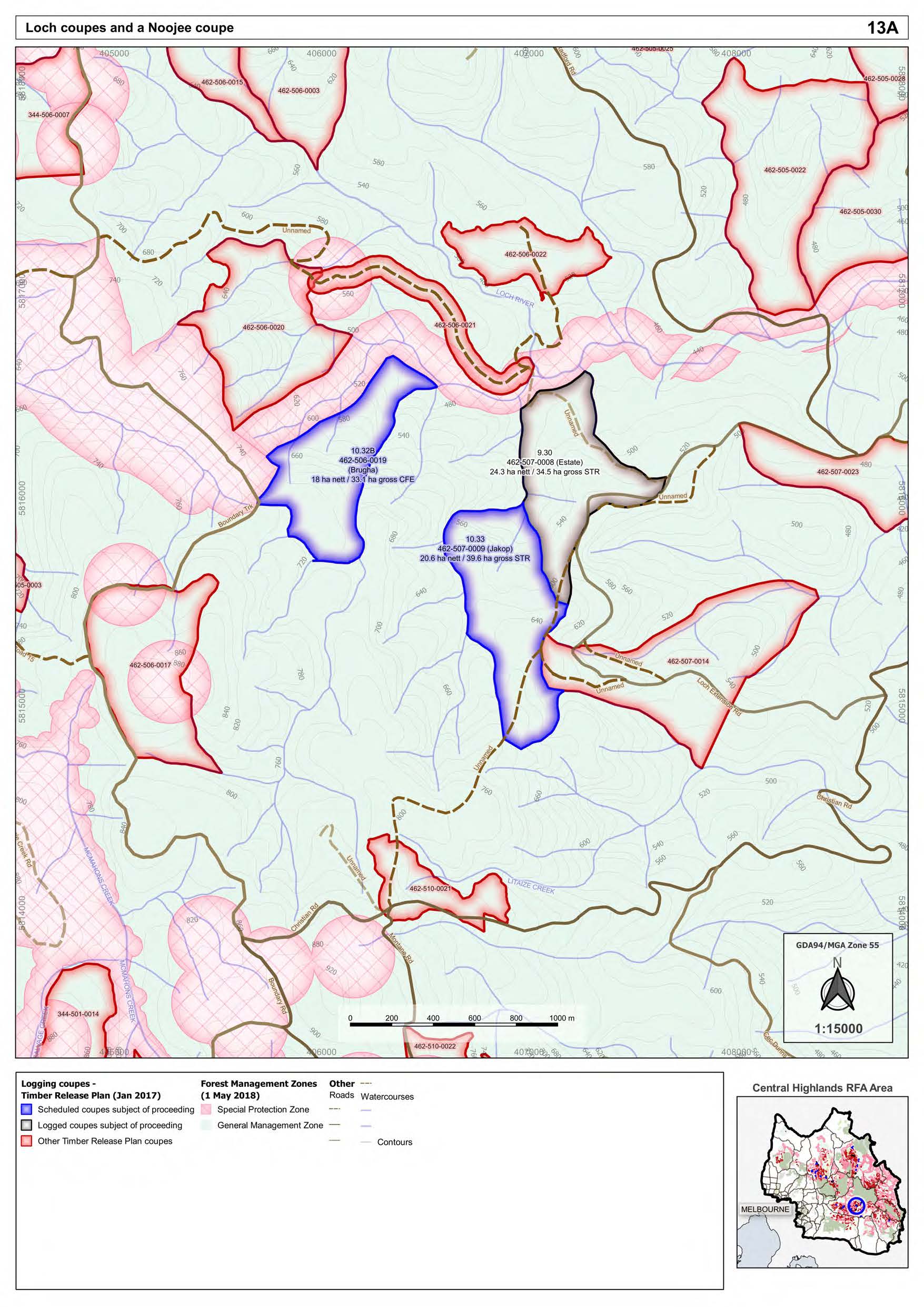

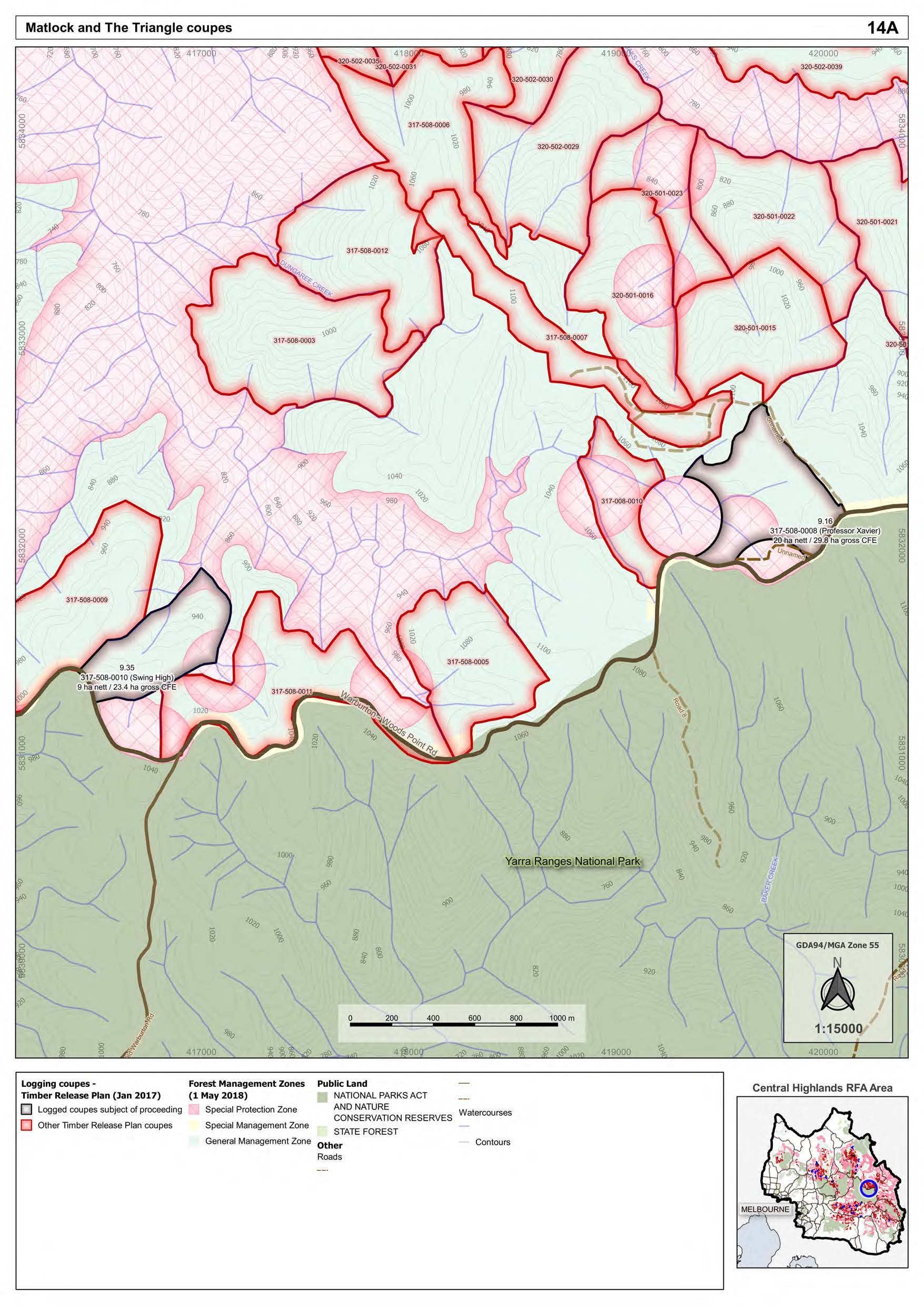

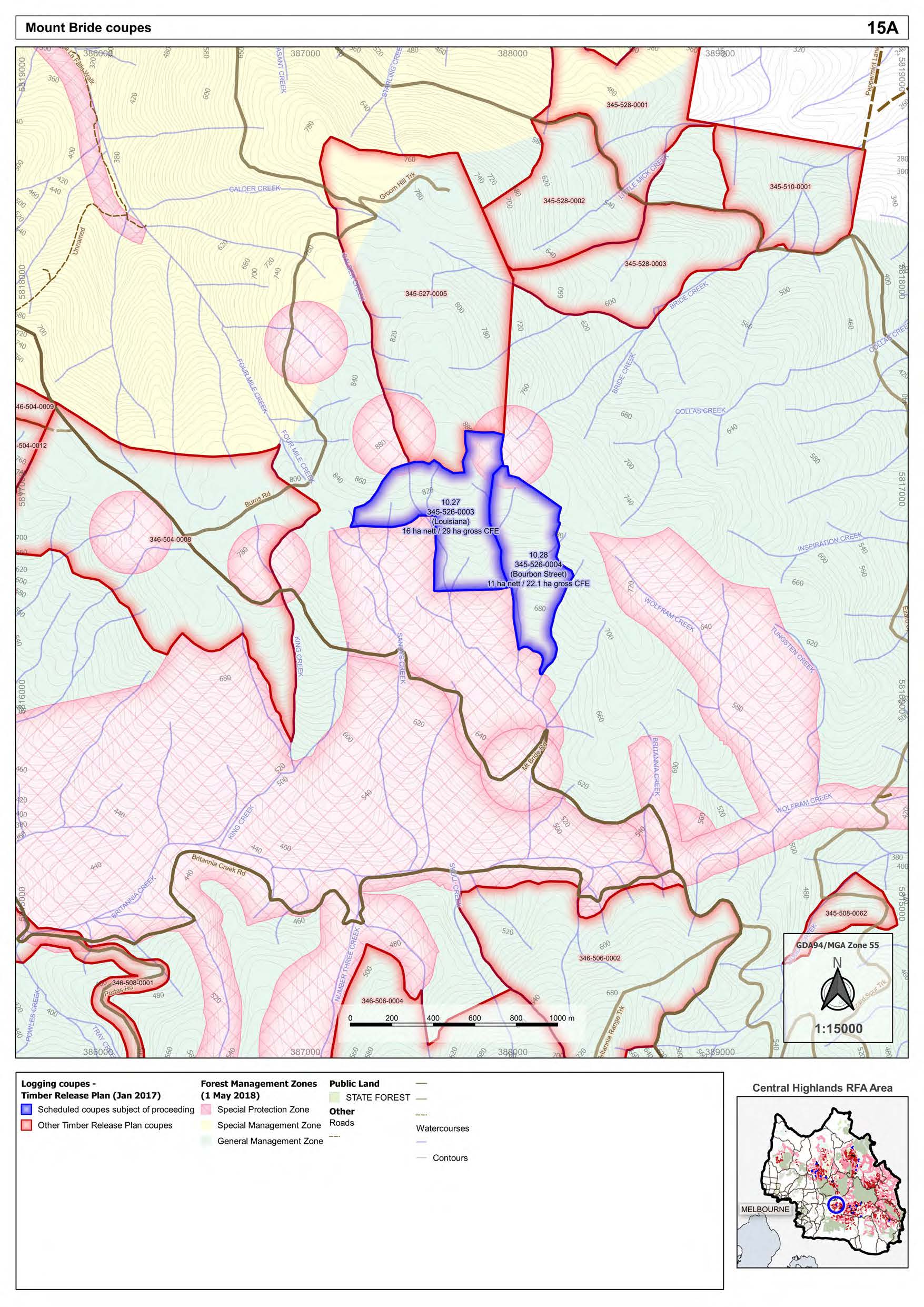

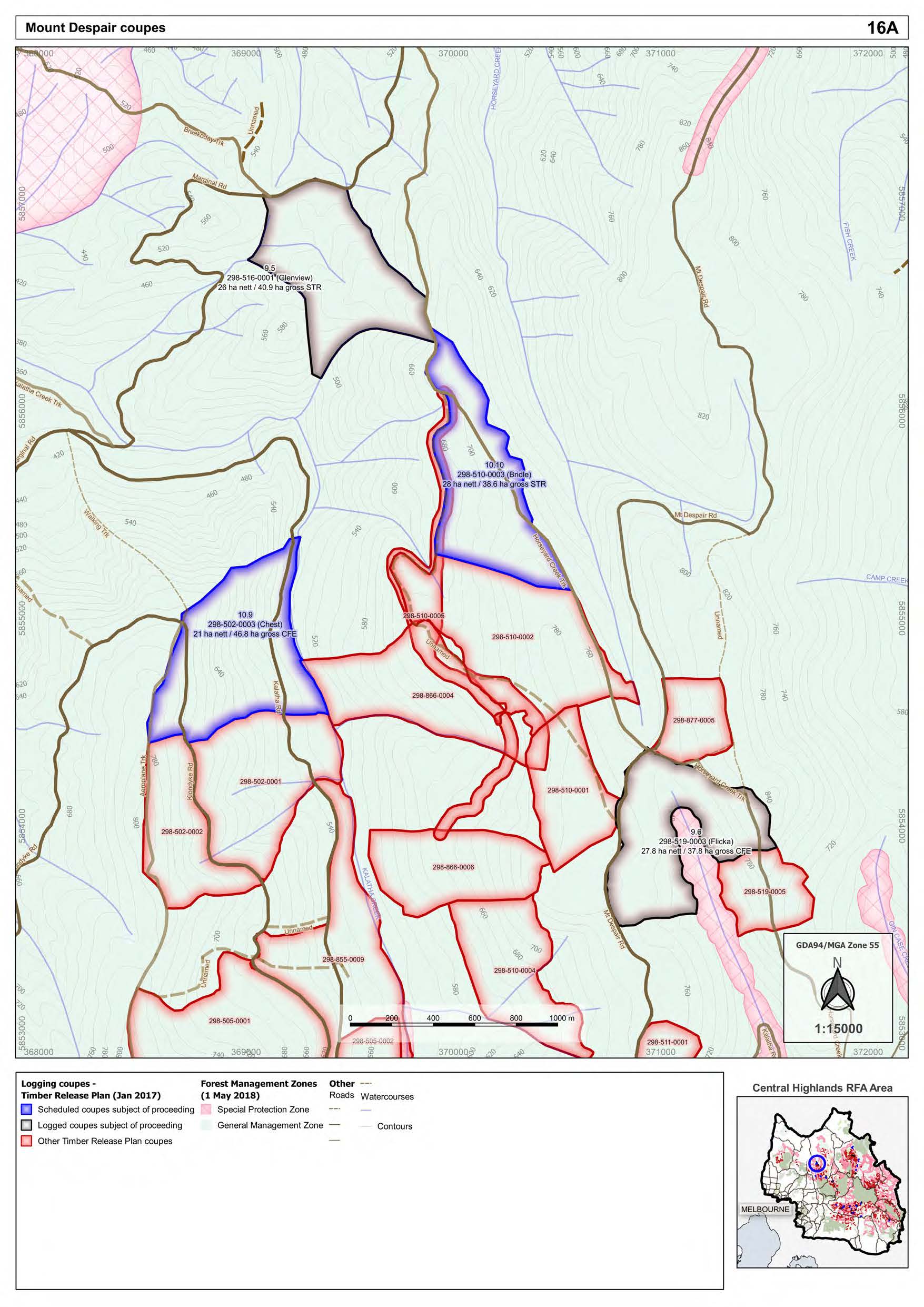

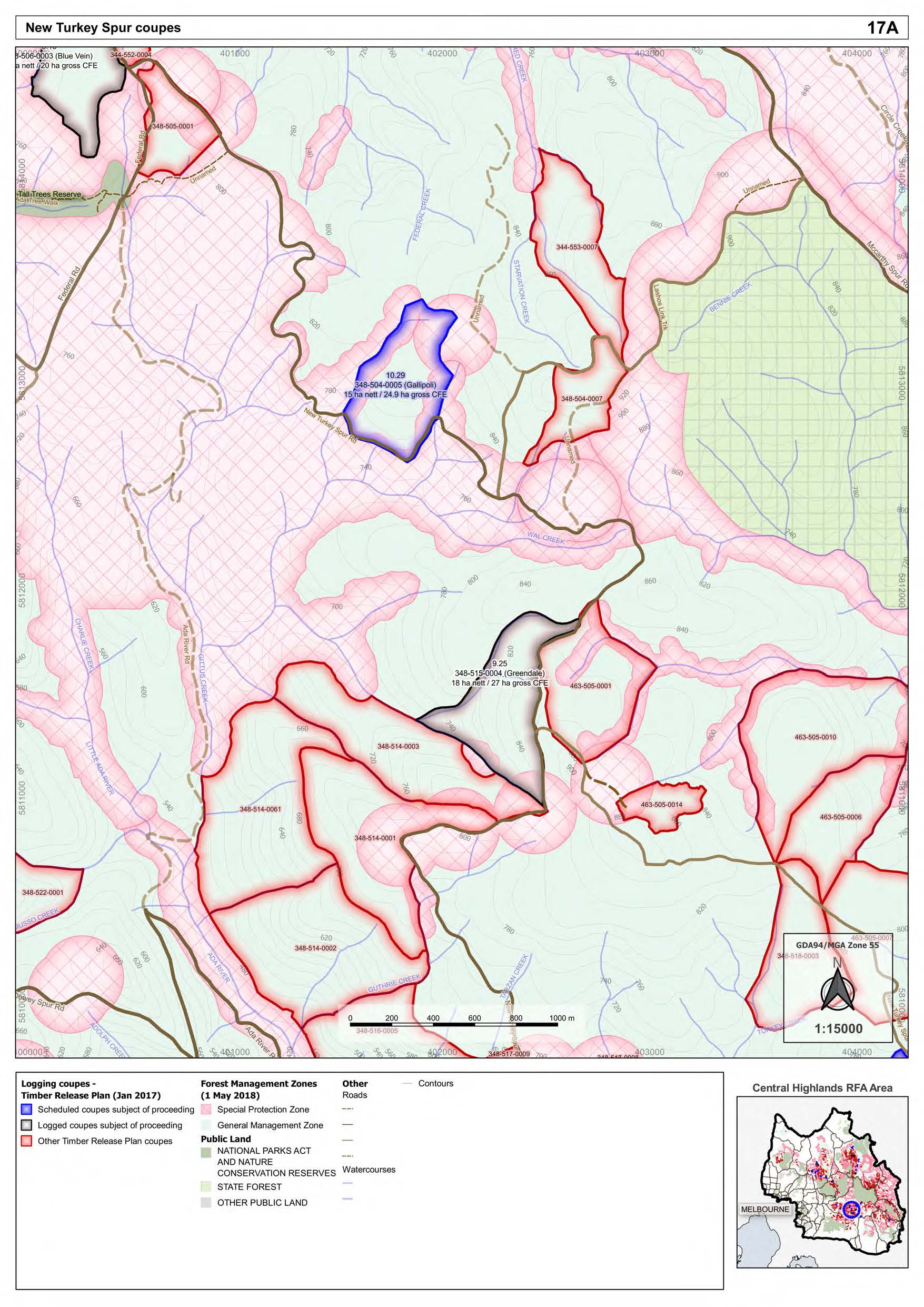

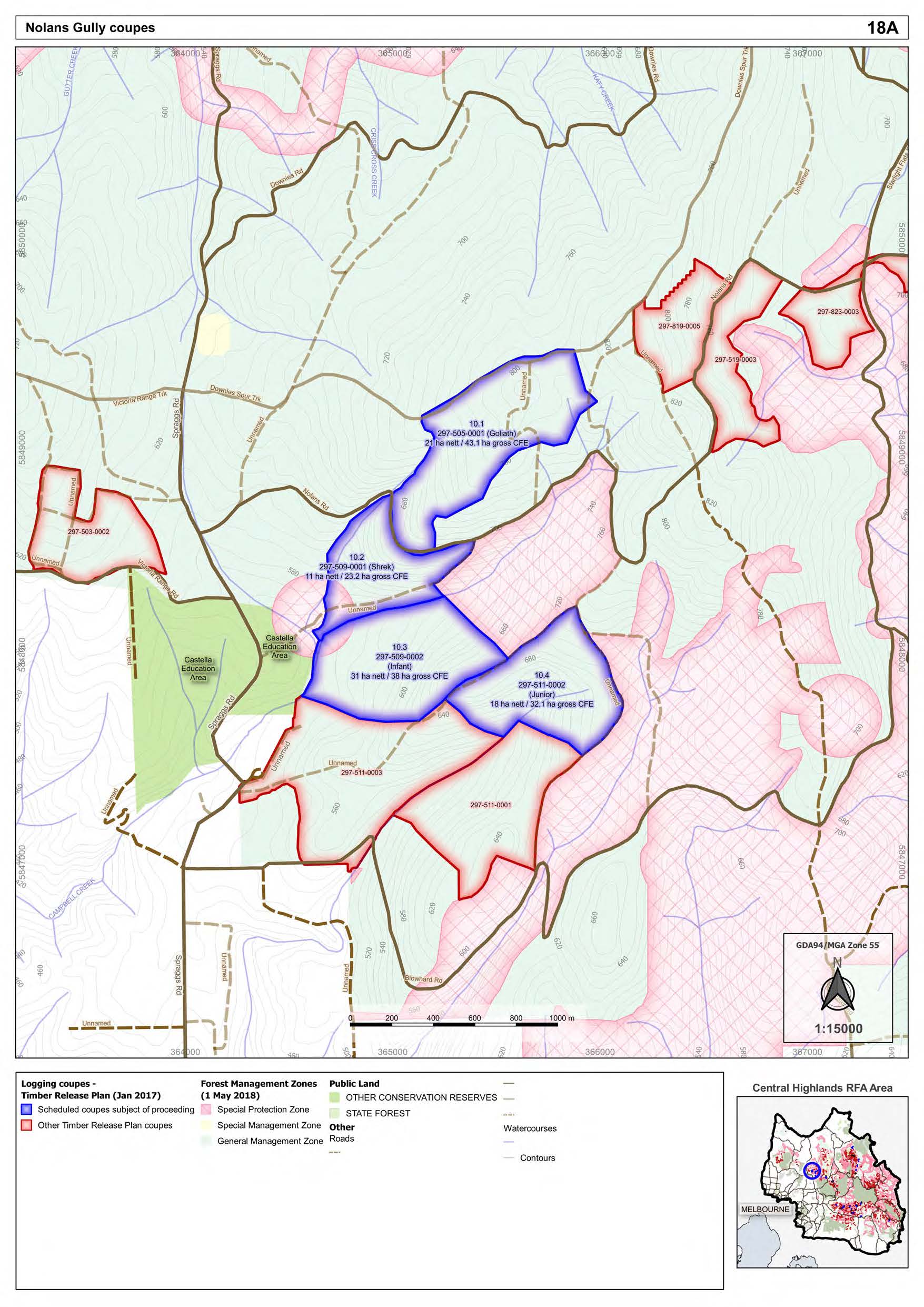

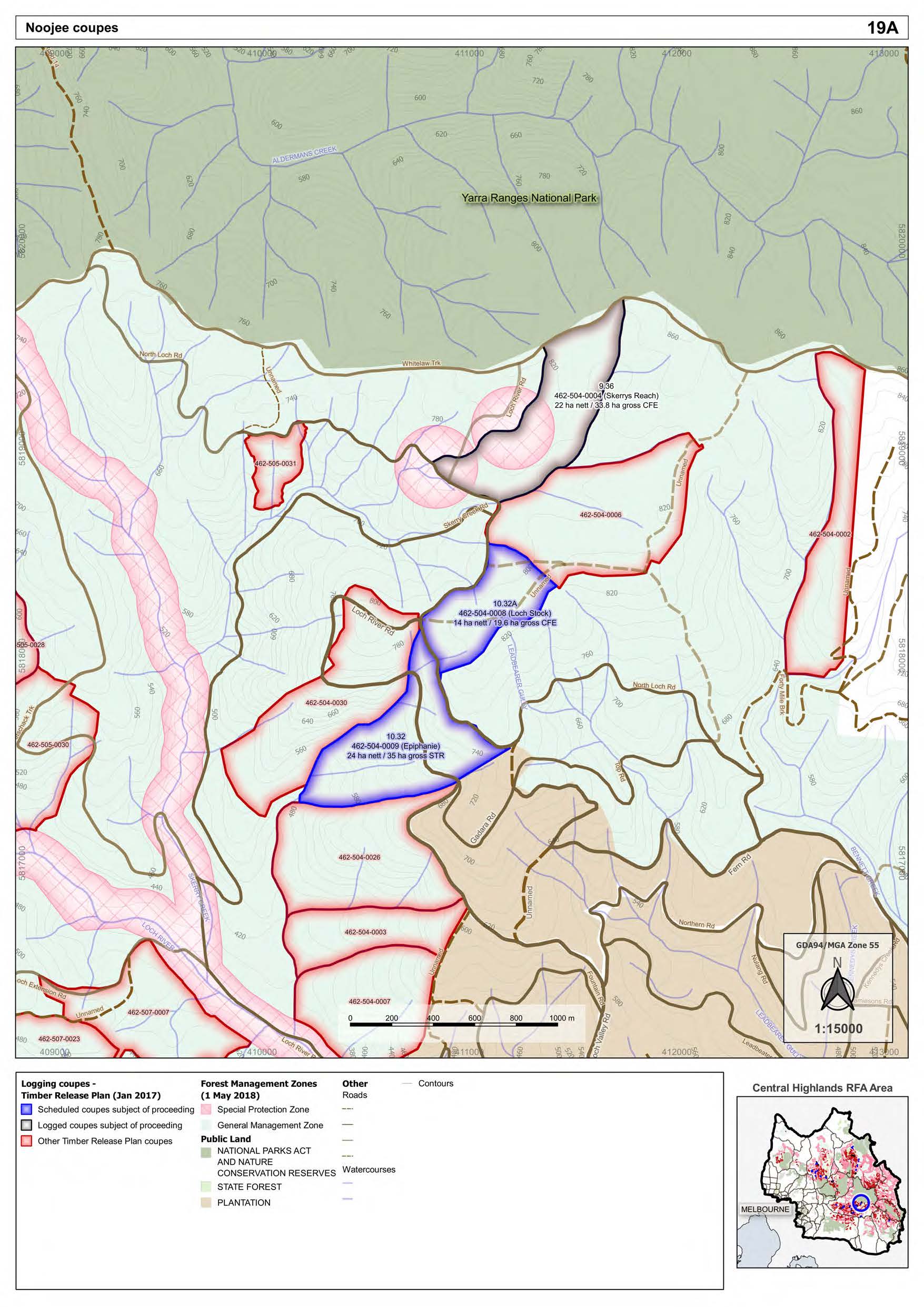

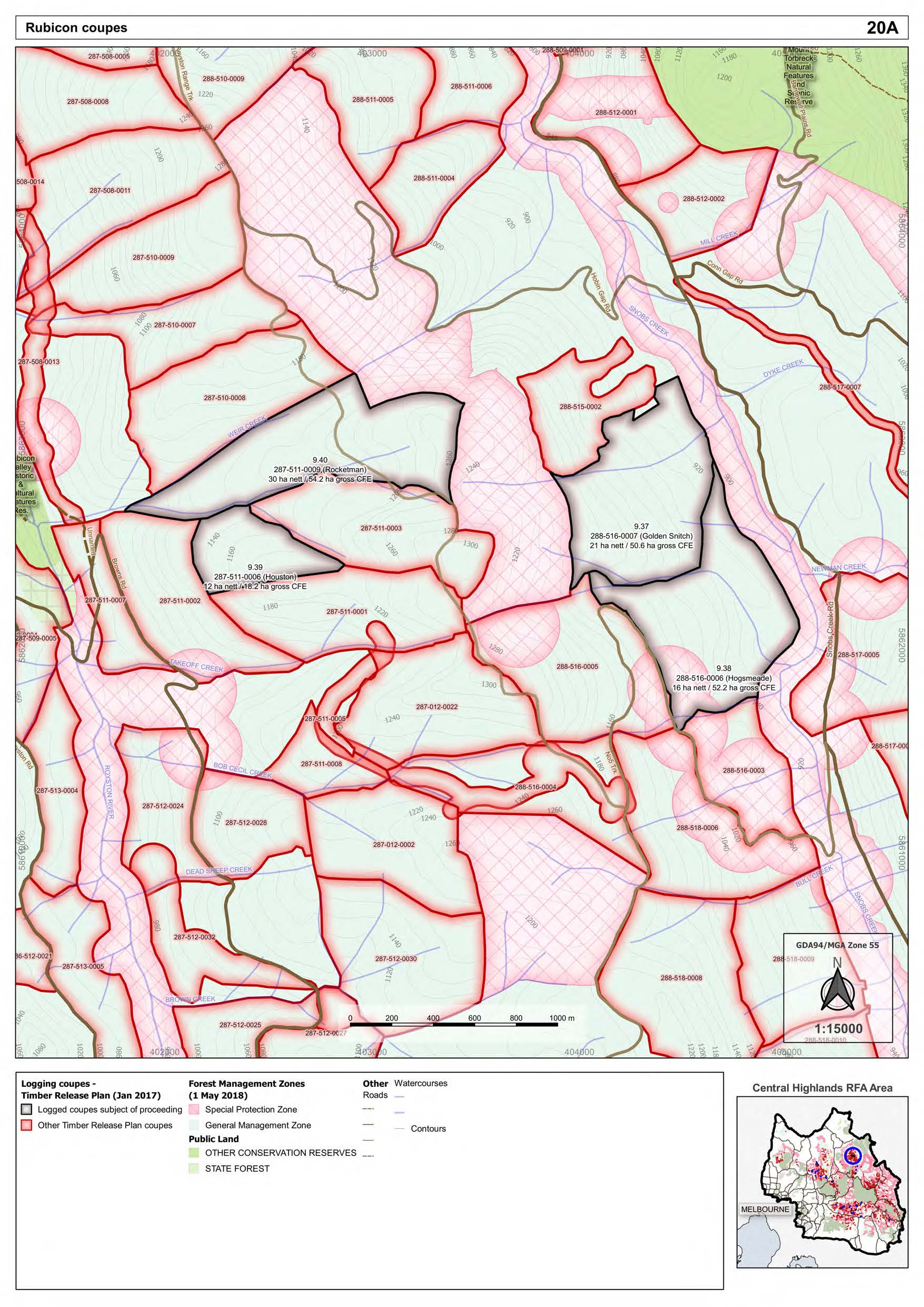

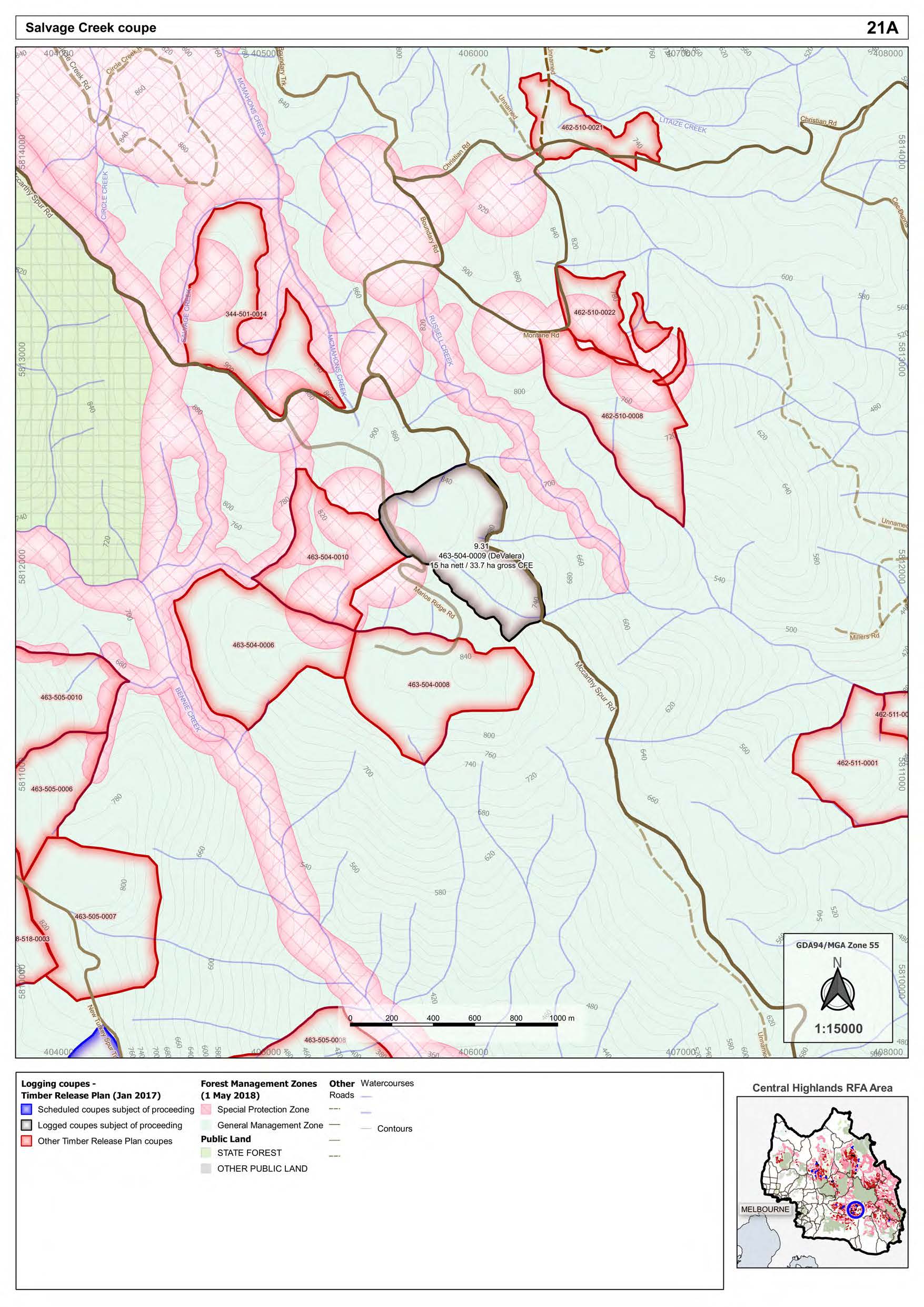

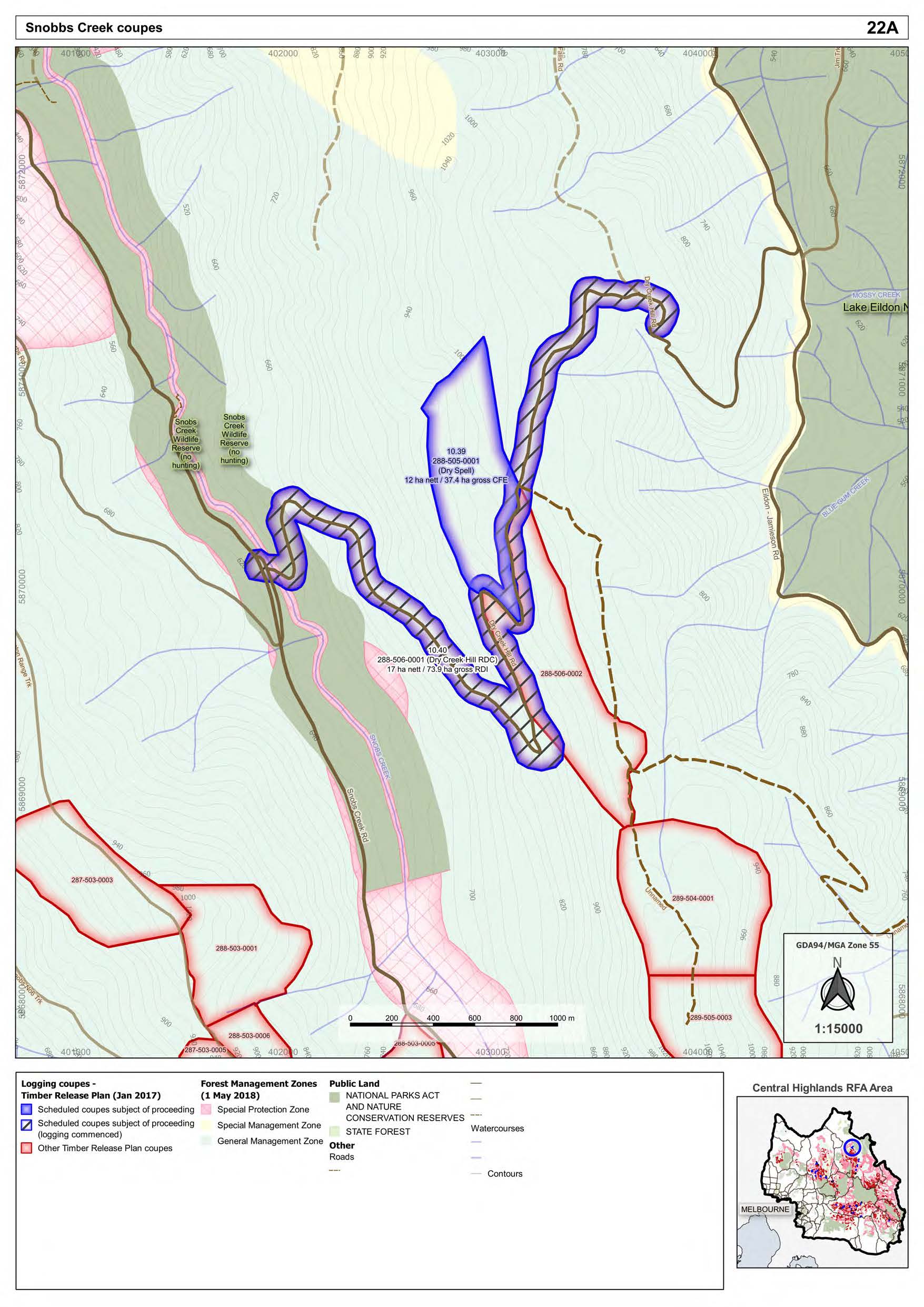

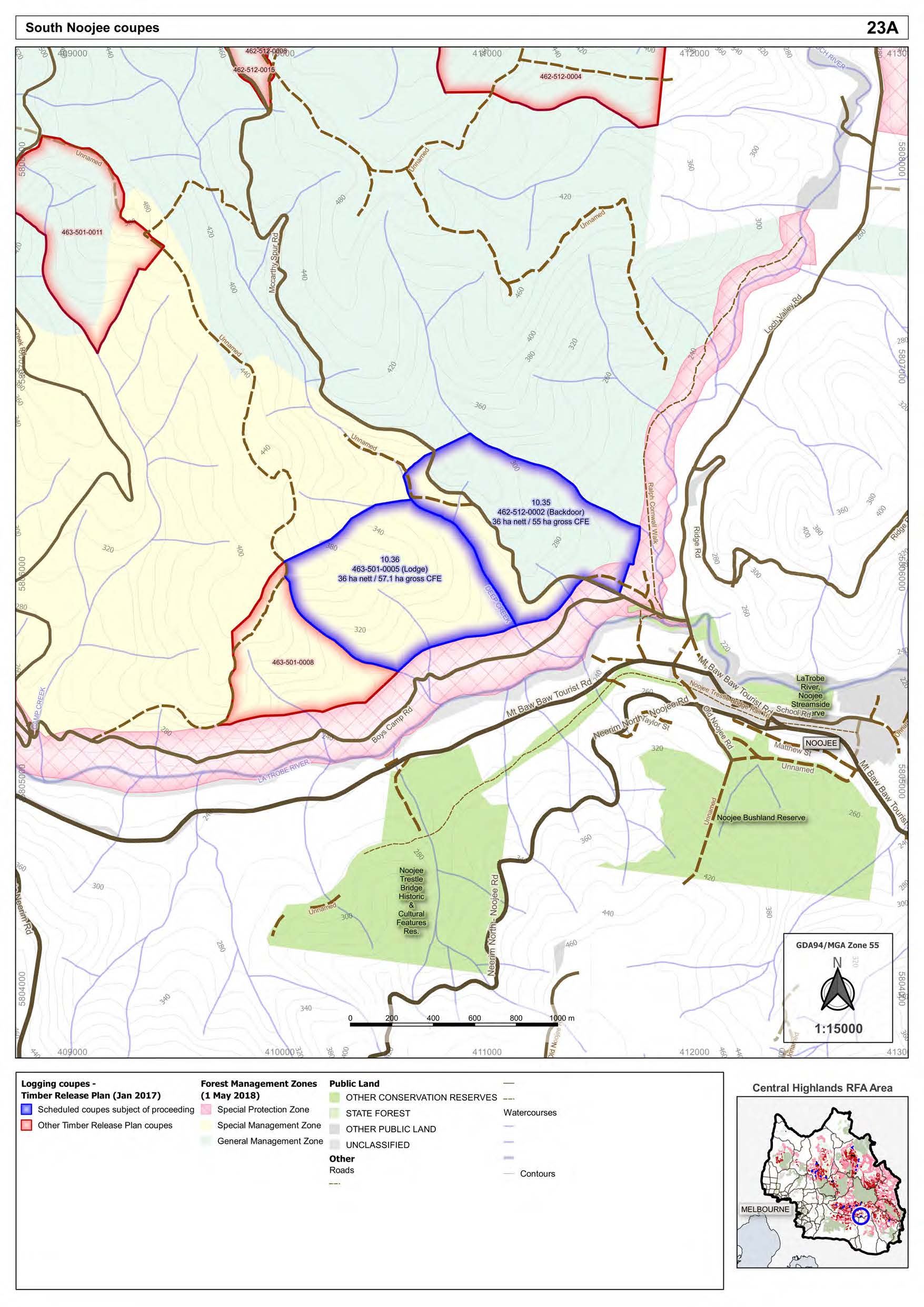

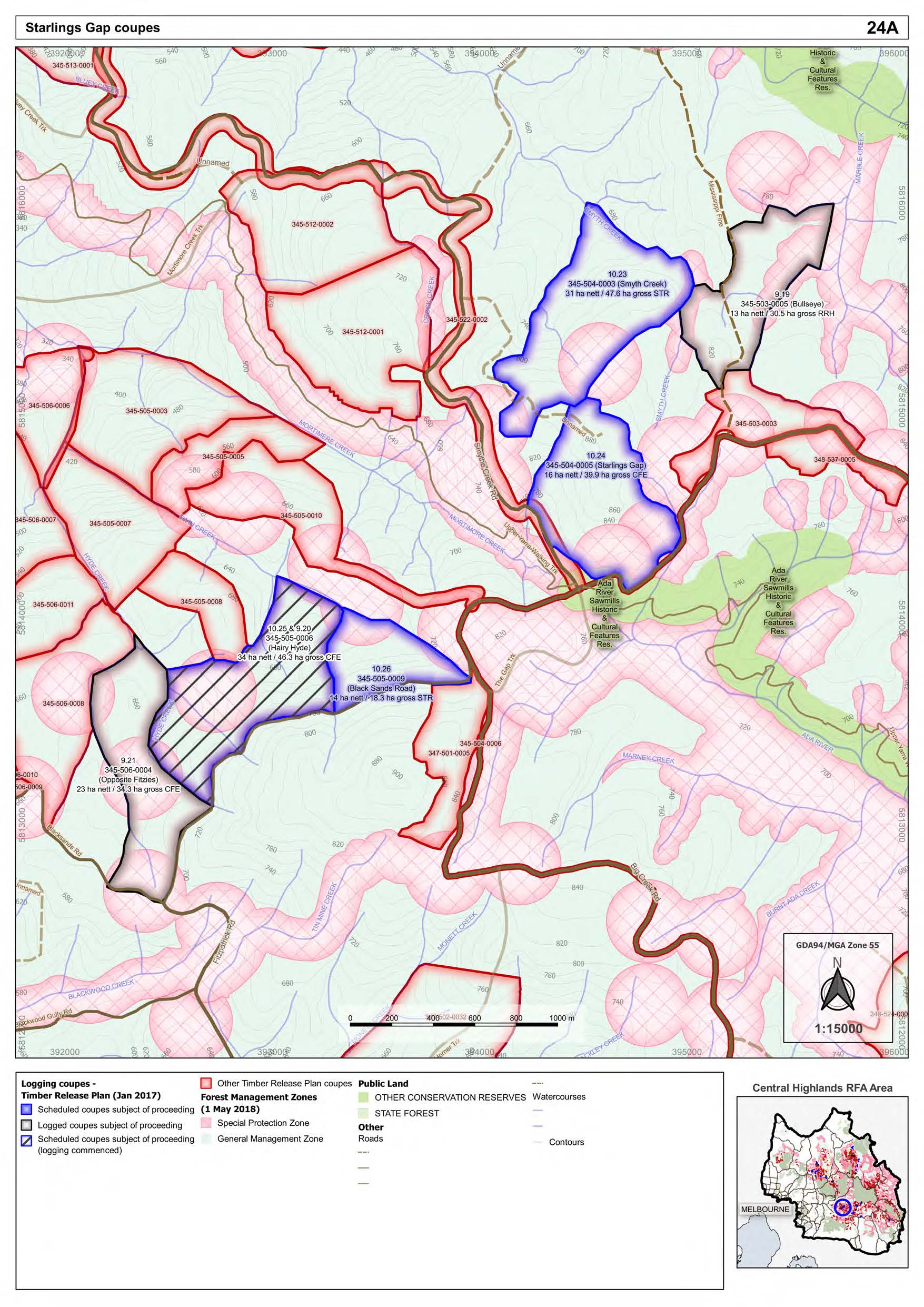

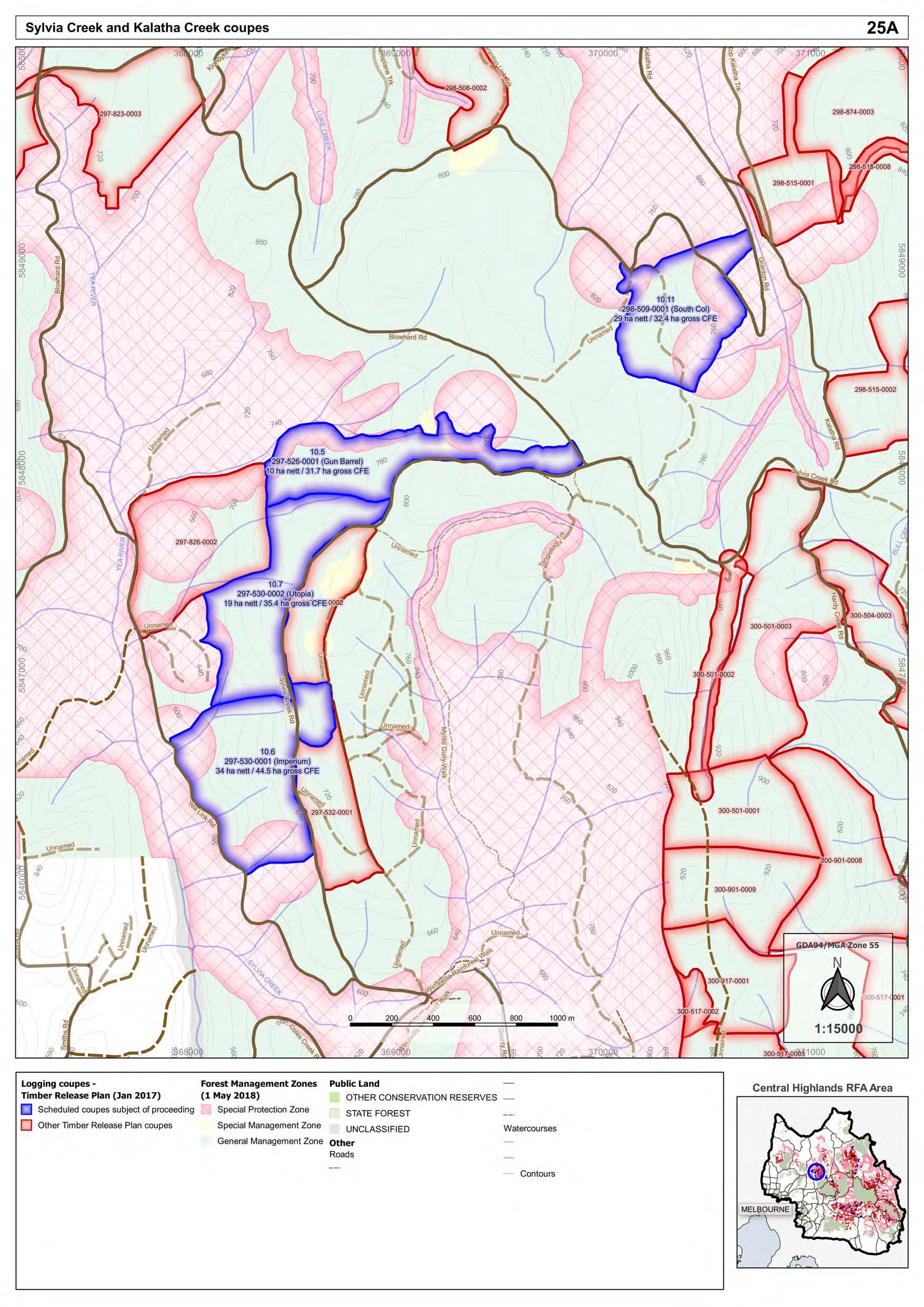

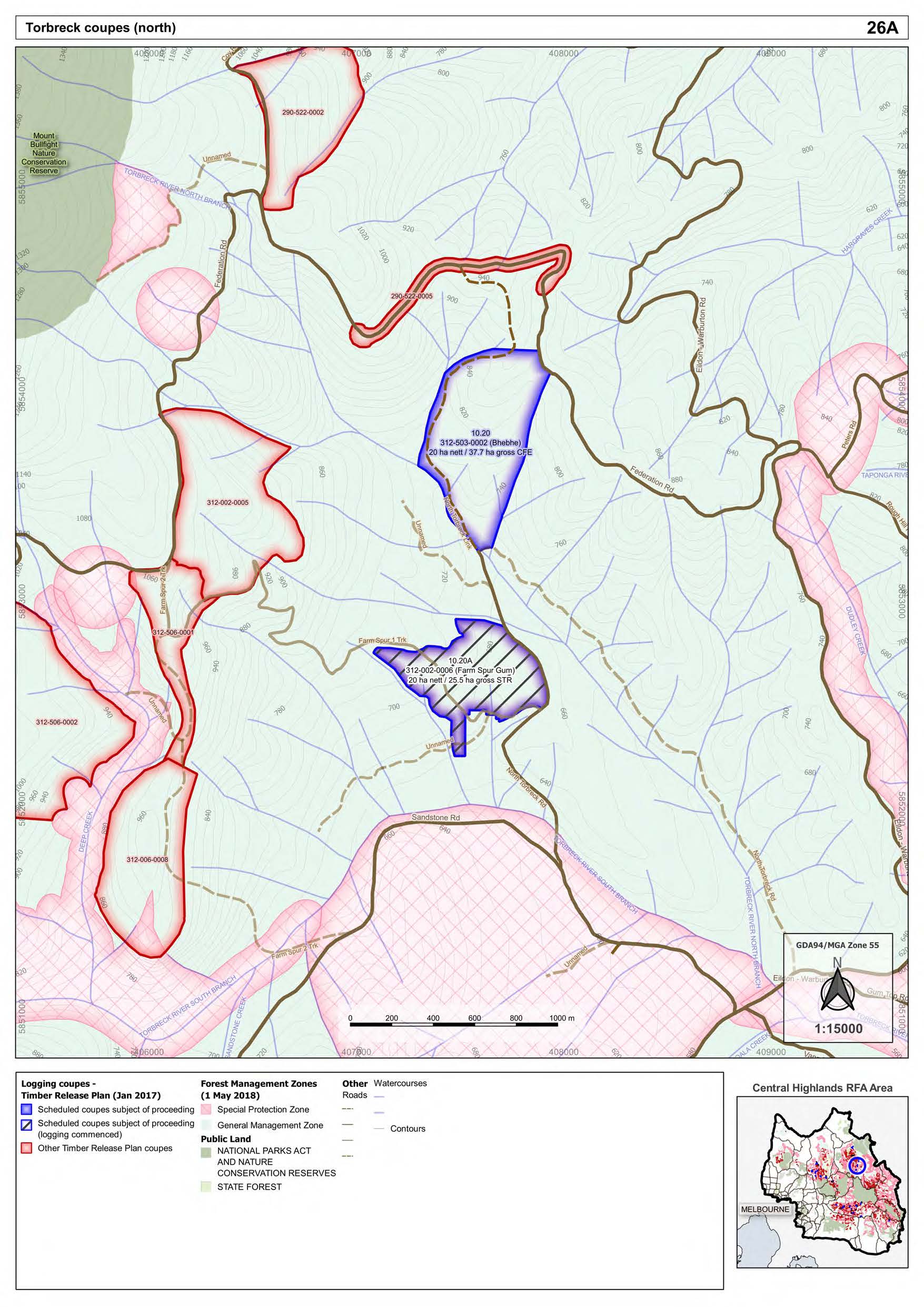

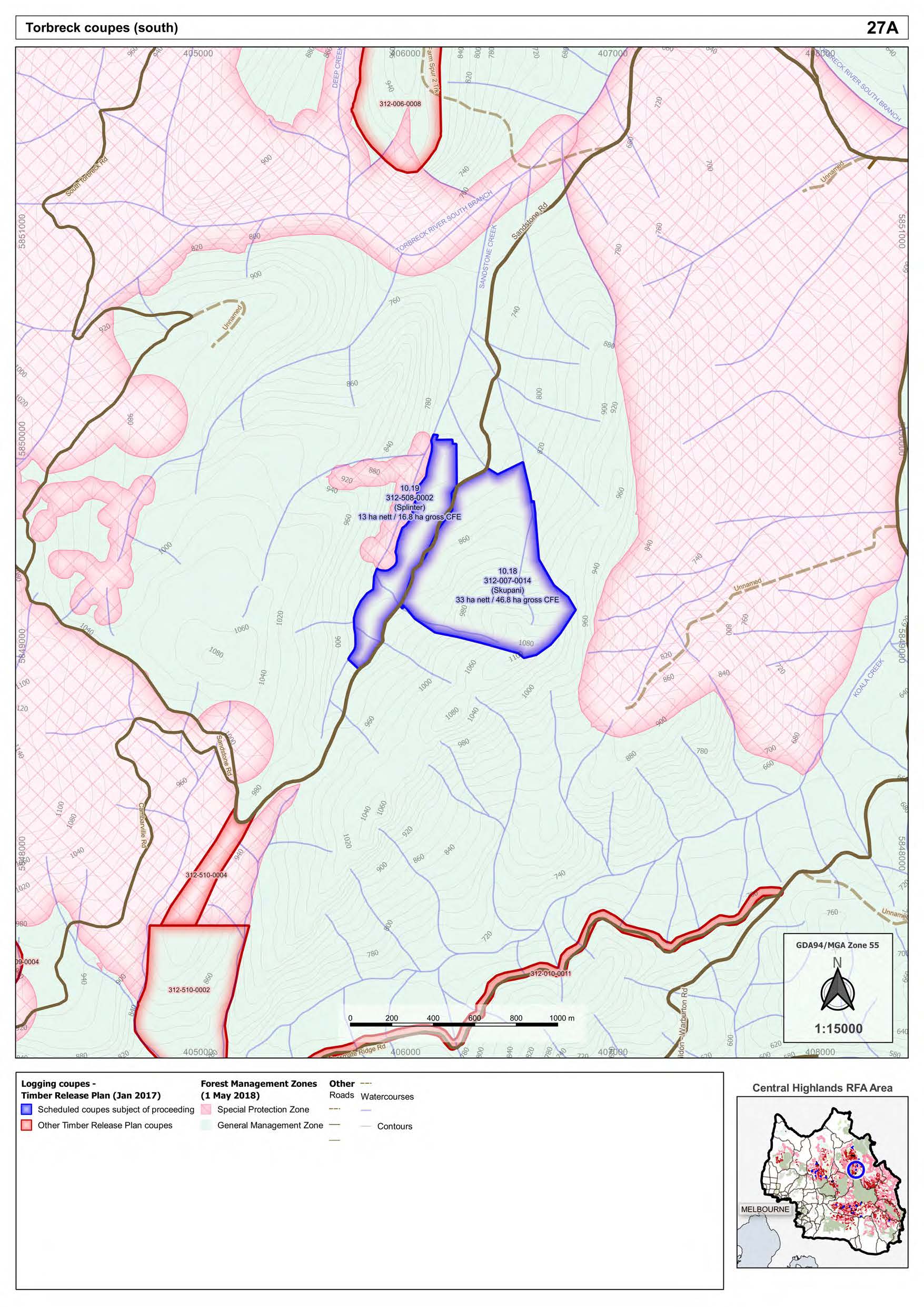

“The 66 impugned coupes” means the coupes listed in Table 14 of the Reasons for Judgment and replicated in the Schedule, as mapped in the Attachments.

“The Act” means the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth).

“The Attachments” means the maps included as Attachments to these orders.

“The Code” means the Code of Practice for Timber Production 2014 (Vic).

“Forestry operation” has the definition in the Central Highlands RFA dated 27 March 1998 excluding sub-paragraphs (a) and (b).

“Logged Coupes” means the coupes recorded as logged, including coupe 345-505-0006 (Hairy Hyde), in the “Logging Status” column in the Schedule, as those coupes are mapped in the Attachments.

“Logged Leadbeater’s Coupes” means the coupes recorded as logged, including coupe 345-505-0006 (Hairy Hyde), in the “Logging Status” column in the Schedule and recorded as “Yes” in the “LbP SI” column in the Schedule, as those coupes are mapped in the Attachments.

“Logged Glider Coupes” means the coupes recorded as logged, including coupe 345-505-0006 (Hairy Hyde), in the “Logging Status” column in the Schedule and recorded as “Yes” in the “GG SI” column in the Schedule, as those coupes are mapped in the Attachments.

“Management Standards” means the Management Standards and Procedures for timber harvesting operations in Victoria’s State forests 2014.

“Planning Standards” means the Planning Standards for timber harvesting operations in Victoria’s State forests 2014: Appendix 5 to the Management Standards and Procedures for timber harvesting operations in Victoria’s State forests 2014.

“Reasons for Judgment” means Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests (No 4) [2020] FCA 704.

“The Schedule” means the Schedule to these orders.

“Scheduled Coupes” means the coupes listed as scheduled in the “Logging Status” column in the Schedule, including coupe 345-505-0006 (Hairy Hyde), as those coupes are mapped in the Attachments.

Orders 10 to 12 refer to the coupes the subject of the proceeding as belonging to various “Coupe Groups”. The name, number and Coupe Group of each of the coupes comprising each Coupe Group are identified in the Schedule. The locations of all the coupes in each Coupe Group are mapped in the Attachments.

Orders 8 to 15 refer to forestry operations having a significant impact on the Greater Glider and/or the Leadbeater’s Possum. The coupes in which those forestry operations had a significant impact on the Greater Glider, and the coupes in which those forestry operations had a significant impact on the Leadbeater’s Possum, are recorded in the relevant column in the Schedule, as those coupes are mapped in the Attachments.

All coupe numbers in these orders refer to those coupes as mapped in the Attachments.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

Declarations that forestry operations not covered by exemption

1. In undertaking a forestry operation in each of the Logged Glider Coupes, including the planning and preparatory phases for that forestry operation, VicForests did not comply with cl 2.2.2.2 of the Code, and accordingly, the exemption in s 38(1) of the Act did not apply to those forestry operations.

2. VicForests is likely to undertake a forestry operation in each of the Scheduled Coupes, including the planning and preparatory phases for that forestry operation, in a manner that will not comply with cl 2.2.2.2 of the Code, and accordingly, the exemption in s 38(1) of the Act will not apply to those forestry operations.

3. In undertaking a forestry operation in coupe 462-504-0004 (Skerry’s Reach), including the planning and preparatory phases for that forestry operation, VicForests did not comply with cl 2.2.2.4 of the Code, cl 4.3.1.1 and Appendix 3 Table 14 of the Management Standards in respect of mature Tree Geebung, and accordingly, the exemption in s 38(1) of the Act did not apply to those forestry operations.

4. In undertaking a forestry operation in coupe 348-506-0003 (Blue Vein), including the planning and preparatory phases for that forestry operation, VicForests did not comply with cl 2.2.2.4 of the Code, cl 2.1.1.3, cl 4.2.1.1 and Table 13 of the Management Standards and Table 4 of the Planning Standards, in respect of Leadbeater’s Possum Zone 1A habitat, and accordingly, the exemption in s 38(1) of the Act did not apply to those forestry operations.

5. In undertaking a forestry operation in coupe 345-505-0006 (Hairy Hyde), including the planning and preparatory phases for that forestry operation, VicForests did not comply with cl 2.2.2.4 of the Code, cl 2.1.1.3, cl 4.2.1.1 and Table 13 of the Management Standards and Table 4 of the Planning Standards, in respect of a Leadbeater’s Possum colony, and accordingly, the exemption in s 38(1) of the Act did not apply to those forestry operations.

6. In undertaking forestry operations in coupes 309-507-0001 (Mont Blanc), 309-507-0003 (Kenya), 307-507-0004 (The Eiger), 344-509-0009 (Ginger Cat), 290-527-0004 (Camberwell Junction), 307-505-0011 (Guitar Solo), 462-507-0008 (Estate), 298-516-0001 (Glenview), 298-519-0003 (Flicka), 348-515-0004 (Greendale), 462-504-0004 (Skerry’s Reach), 463-504-0009 (De Valera), 345-503-0005 (Bullseye), 345-506-0004 (Opposite Fitzies), 317-508-0008 (Professor Xavier), including the planning and preparatory phases for those forestry operations, VicForests did not comply with cl 2.5.1.1 of the Code and cl 5.3.1.5 of the Management Standards, in respect of screening timber harvesting operations from view, and accordingly, the exemption in s 38(1) of the Act did not apply to those forestry operations.

7. In undertaking forestry operations in coupes 344-509-0009 (Ginger Cat), 348-515-0004 (Greendale), 288-516-0007 (Golden Snitch), 288-516-0006 (Hogsmeade), 287-511-0006 (Houston), 287-511-0009 (Rocketman), 463-504-0009 (De Valera), 317-508-0008 (Professor Xavier), including the planning and preparatory phases for those forestry operations, VicForests did not comply with cl 2.2.2.1 of the Code and cl 4.1.4.4 of the Management Standards, in respect of gaps between retained vegetation, and accordingly, the exemption in s 38(1) of the Act did not apply to those forestry operations.

Declarations that VicForests contravened s 18 in each of the coupes

8. In undertaking a forestry operation in each of the Logged Coupes, including the planning and preparatory phases for that forestry operation, VicForests took an action that is likely to have had a significant impact on:

(a) the Greater Glider, a listed threatened species included in the vulnerable category, contravening s 18(4)(a) of the Act; and/or

(b) the Leadbeater’s Possum, a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category, contravening s 18(2)(a) of the Act.

9. In proposing to undertake a forestry operation, including the planning and preparatory phases for that forestry operation, in each of the Scheduled Coupes, VicForests is proposing to take an action that is likely to have a significant impact on:

(a) the Greater Glider, a listed threatened species included in the vulnerable category, contravening s 18(4)(b) of the Act; and/or

(b) the Leadbeater’s Possum, a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category, contravening s 18(2)(b) of the Act.

Declarations that VicForests contravened s 18 in each of the Coupe Groups

10. In undertaking the series of forestry operations in each of the Cambarville, Matlock, Rubicon Coupe Groups, including the planning and preparatory phases for those forestry operations, VicForests took an action that is likely to have had a significant impact on:

(a) the Greater Glider, a listed threatened species included in the vulnerable category, contravening s 18(4)(a) of the Act; and/or

(b) the Leadbeater’s Possum, a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category, contravening s 18(2)(a) of the Act.

11. In proposing to undertake the series of forestry operations in each of the Beech Creek, Mount Bride, Nolan’s Gully, Snobbs Creek, South Noojee, Sylvia Creek, Torbreck River Coupe Groups, including the planning and preparatory phases for those forestry operations, VicForests is proposing to take an action that is likely to have a significant impact on:

(a) the Greater Glider, a listed threatened species included in the vulnerable category, contravening s 18(4)(a) of the Act; and/or

(b) the Leadbeater’s Possum, a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category, contravening s 18(2)(a) of the Act.

12. In undertaking the series of forestry operations in the Acheron, Ada River, Ada Tree, Baw Baw, Big River, Hermitage Creek, Loch, Mount Despair, New Turkey Spur, Noojee, Starlings Gap Coupe Groups, including the planning and preparatory phases for those forestry operations, VicForests has been taking and proposes to continue taking an action that is likely to have had, and is likely to have, a significant impact on:

(a) the Greater Glider, a listed threatened species included in the vulnerable category, contravening s 18(4)(a) of the Act; and/or

(b) the Leadbeater’s Possum, a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category, contravening s 18(2)(a) of the Act.

Declarations that VicForests contravened s 18 in the Logged Coupes as a whole

13. In undertaking forestry operations in all of the Logged Coupes, including the planning and preparatory phases for those forestry operations, VicForests has taken an action that is likely to have had a significant impact on:

(a) the Greater Glider, a listed threatened species included in the vulnerable category, contravening s 18(4)(a) of the Act; and/or

(b) the Leadbeater’s Possum, a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category, contravening s 18(2)(a) of the Act.

Declarations that VicForests contravened s 18 in the Scheduled Coupes as a whole

14. In proposing to undertake forestry operations in all of the Scheduled Coupes, including the planning and preparatory phases for those forestry operations, VicForests is proposing to take an action that is likely to have a significant impact on:

(a) the Greater Glider, a listed threatened species included in the vulnerable category, which would constitute a contravention of s 18(4)(b) of the Act; and/or

(b) the Leadbeater’s Possum, a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category, which would constitute a contravention of s 18(2)(b) of the Act.

Declaration that VicForests contravened s 18 in the Logged and Scheduled Coupes as a whole

15. In undertaking the series of forestry operations in the 66 impugned coupes, including the planning and preparatory phases for those forestry operations, VicForests has been taking and proposes to continue taking an action that is likely to have had, and is likely to have, a significant impact on:

(a) the Greater Glider, a listed threatened species included in the vulnerable category, contravening s 18(4)(b) of the Act; and/or

(b) the Leadbeater’s Possum, a listed threatened species included in the critically endangered category, contravening s 18(2)(b) of the Act.

Injunctions

16. Subject to order 17 below, and on the basis of orders 9, 11, 12, 14 and 15, pursuant to s 475(2) of the Act, VicForests whether by itself, its agents, its contractors or howsoever otherwise is restrained from conducting forestry operations in the Scheduled Coupes.

17. Nothing in order 16 above prevents VicForests from planning forestry operations in the Scheduled Coupes for the purpose of participating in any process under the Act which provides for Pt 3 of the Act being rendered inapplicable to forestry operations in the Scheduled Coupes.

18. Subject to order 19 below, and on the basis of orders 8, 10, 12, 13 and 15, pursuant to s 475(2) of the Act, VicForests whether by itself, its agents, its contractors or howsoever otherwise is restrained from conducting any further forestry operations in the Logged Coupes.

19. Nothing in order 18 above prevents VicForests from conducting regeneration activities other than burning for the purpose of compliance with Pt 2.6.1 of the Code within only that part of each of the Logged Coupes that is in fact already harvested.

Costs

20. Each party bear its own costs of the separate question hearing.

21. The respondent pay the applicant’s costs of the proceeding, other than the costs of the separate question hearing, to be fixed by way of lump sum.

22. In the absence of any agreement between the parties within 28 days of these orders, the question of an appropriate lump sum pursuant to order 21 above be referred to a Registrar for determination.

Discharge of interlocutory injunctions

23. The injunctions issued pursuant to paragraphs 1 and 2 of the orders made on 10 May 2018 be discharged.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SCHEDULE

Coupe Group | Coupe Number | Coupe Name | Logging Status | Reason s 38 exemption lost | GG SI | LbP SI |

Acheron | 309-507-0001 | Mont Blanc | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to screen | Yes | No |

Acheron | 309-507-0003 | Kenya | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to screen | Yes | No |

Acheron | 307-507-0004 | The Eiger | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to screen | Yes | No |

Acheron | 309-507-0007 | White House | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Ada River | 348-517-0005 | Tarzan | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Ada River | 348-518-0004 | Johnny | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Ada River | 348-519-0008 | Turducken | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Ada Tree | 344-509-0009 | Ginger Cat | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to screen Failure to keep gaps under 150 m | Yes | Yes |

Ada Tree | 348-506-0003 | Blue Vein | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to protect Zone 1A habitat | Yes | Yes |

Ada Tree | 344-509-0007 | Blue Cat | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Baw Baw | 483-505-0002 | Rowels | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Baw Baw | 483-505-0018 | Diving Spur | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Beech Creek | 300-524-0002 | Waves | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Beech Creek | 300-539-0001 | Surfing | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Big River | 290-527-0004 | Camberwell Junction | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to screen | Yes | No |

Big River | 290-525-0002 | Vice Captain | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Cambarville | 312-510-0007 | Bromance | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Cambarville | 312-510-0009 | Lovers Lane | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Coles Creek | 297-538-0004 | Home & Away | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Hermitage Creek | 307-505-0011 | Guitar Solo | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to screen | Yes | Yes |

Hermitage Creek | 307-505-0001 | Drum Circle | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Hermitage Creek | 307-505-0009 | Flute | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Hermitage Creek | 307-505-0010 | San Diego | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Kalatha Creek | 298-509-0001 | South Col | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Loch | 462-507-0008 | Estate | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to screen | Yes | No |

Loch | 462-506-0019 | Brugha | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Loch | 462-507-0009 | Jakop | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Matlock | 317-508-0010 | Swing High | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Mount Bride | 345-526-0003 | Louisiana | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Mount Bride | 345-526-0004 | Bourbon Street | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Mount Despair | 298-516-0001 | Glenview | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to screen | Yes | No |

Mount Despair | 298-519-0003 | Flicka | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to screen | Yes | No |

Mount Despair | 298-502-0003 | Chest | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Mount Despair | 298-510-0003 | Bridle | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

New Turkey Spur | 348-515-0004 | Greendale | Logged | Failure to screen Failure to keep gaps under 150 m | No | Yes |

New Turkey Spur | 348-504-0005 | Gallipoli | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Nolans Gully | 297-505-0001 | Goliath | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Nolans Gully | 297-509-0001 | Shrek | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Nolans Gully | 297-509-0002 | Infant | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Nolans Gully | 297-511-0002 | Junior | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Noojee | 462-504-0004 | Skerry’s Reach | Logged | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to protect mature Tree Geebung Failure to screen | Yes | Yes |

Noojee | 462-504-0009 | Epiphanie | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Noojee | 462-504-0008 | Loch Stock | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Rubicon | 288-516-0007 | Golden Snitch | Logged | Failure to keep gaps under 150 m | No | Yes |

Rubicon | 288-516-0006 | Hogsmeade | Logged | Failure to keep gaps under 150 m | No | Yes |

Rubicon | 287-511-0006 | Houston | Logged | Failure to keep gaps under 150 m | No | Yes |

Rubicon | 287-511-0009 | Rocketman | Logged | Failure to keep gaps under 150 m | No | Yes |

Salvage Creek | 463-504-0009 | De Valera | Logged | Failure to screen Failure to keep gaps under 150 m | No | Yes |

Snobbs Creek | 288-505-0001 | Dry Spell | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Snobbs Creek | 288-506-0001 | Dry Creek Hill | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

South Noojee | 462-512-0002 | Backdoor | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

South Noojee | 463-501-0005 | Lodge | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Starlings Gap | 345-503-0005 | Bullseye | Logged | Failure to screen | No | Yes |

Starlings Gap | 345-505-0006 | Hairy Hyde | Part logged, part scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) Failure to identify Leadbeater’s Possum colony | Yes | Yes |

Starlings Gap | 345-506-0004 | Opposite Fitzies | Logged | Failure to screen | No | Yes |

Starlings Gap | 345-504-0003 | Smyth Creek | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Starlings Gap | 345-504-0005 | Starlings Gap | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Starlings Gap | 345-505-0009 | Blacksands Road | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Sylvia Creek | 297-526-0001 | Gun Barrel | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Sylvia Creek | 297-530-0001 | Imperium | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

Sylvia Creek | 297-530-0002 | Utopia | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | Yes |

The Triangle | 317-508-0008 | Professor Xavier | Logged | Failure to screen Failure to keep gaps under 150 m | No | Yes |

Torbreck River | 312-007-0014 | Skupani | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Torbreck River | 312-508-0002 | Splinter | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Torbreck River | 312-503-0002 | Bhebe | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

Torbreck River | 312-002-0006 | Farm Spur Gum | Scheduled | Clause 2.2.2.2 (PP) | Yes | No |

ATTACHMENTS

MORTIMER J:

Introduction

1 On 27 May 2020, I delivered judgment on the applicant’s application in this proceeding: Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests (No 4) [2020] FCA 704 (liability reasons). On the same day, I made orders requiring the parties to provide proposed minutes of orders reflecting the reasons for judgment. In these reasons, I adopt abbreviations used in the liability reasons.

2 The applicant and VicForests filed competing proposed minutes of orders on 26 June 2020, together with submissions in support. No additional evidence was filed by either party. The matter was listed for an oral hearing on 8 July 2020. At the beginning of the hearing, counsel for the applicant stated that there had been “a slight change in position … about a source of power” for the orders it sought. In fact, the change was significant, and related to the construction and operation of s 475(3) of the EPBC Act. The argument ran for half a day on the parties’ original positions, which by and large remained relevant. However, as the change had not been raised with VicForests before the hearing, and as, in addition, some minor amendments to the proposed minutes of orders that had been filed were identified during the hearing, I ordered the parties to file and serve final proposed orders and further submissions.

3 By 22 July 2020, the parties had agreed on a form of declaratory relief, but remained in disagreement about the form of injunctive relief, the question of additional relief, and costs. The differences between the parties’ positions raised important questions relating to the Court’s power to issue certain kinds of relief. There were also some minor but important matters I sought to raise with the parties about the proposed form of declaratory relief. Accordingly, I considered that the matter should be listed for a further oral hearing. That hearing was held on 31 July 2020.

4 Yet again the applicant produced new information at the last moment: on this occasion, a table setting out the underlying details supporting its submissions about which coupes ought to be identified in the mitigation orders it proposed, and how the area of those coupes identified would offset the damage done by the s 18 contraventions in the Logged Coupes. This necessitated VicForests being given an opportunity to respond in writing, after the hearing. As I explain below, during the course of the hearing VicForests also proffered an undertaking in relation to the Logged Coupes, and I gave counsel for VicForests an opportunity to confer and provide the terms of the proposed undertaking after a reasonable opportunity to consider the terms and obtain instructions. The applicant then sought an opportunity to respond in short submissions about any undertaking proffered. Directions were made to provide for these steps, which resulted in a short further delay before orders could be pronounced in the proceeding.

Proposed declaratory relief

5 There was little substantive debate between the parties about the declarations which should be made. I am satisfied the declaratory relief is appropriate to be granted. Each of the declarations is based on the Court’s findings in relation to the loss of the exemption in s 38(1), and in relation to the contraventions of s 18 of the EPBC Act. I agree with the applicant’s submission that it is appropriate to attach maps of the impugned coupes to the orders, to avoid any uncertainty as to the effect of the orders that may arise if the names or numbers of the coupes change. VicForests did not oppose this occurring. At the second hearing, the Court raised with the parties some relatively minor but important proposed changes to the declaratory relief and both parties accepted the proposed changes were appropriate.

Prohibitory injunctive relief

6 The applicant sought two alternative forms of prohibitory injunctive relief, which it referred to as the “prohibitory injunction” and the “alternative prohibitory injunction”. VicForests opposed the prohibitory injunction but, with some amendments, agreed with the form of the alternative prohibitory injunction.

7 The parties’ competing sets of orders were as follows.

8 The applicant’s proposed prohibitory injunction was:

16. Subject to order 17 below, and on the basis of orders 1 to 15, pursuant to s 475(2) of the Act, VicForests whether by itself, its agents, its contractors or howsoever otherwise is restrained from conducting forestry operations in the 66 impugned coupes.

17. Nothing in order 16 above prevents VicForests from:

a. conducting regeneration activities other than burning for the purpose of compliance with part 2.6.1 of the Code within only that part of each of the Logged Coupes that is in fact already harvested;

b. planning forestry operations in the 66 impugned coupes for the purpose of participating in any process under the Act which provides for Part 3 being rendered inapplicable to forestry operations in the 66 impugned coupes.

9 The applicant’s proposed alternative prohibitory injunction (with the respondent’s proposed amendments in mark-up) was:

18. Subject to order 19 below, and on the basis of orders 9, 11 and 14, pursuant to s 475(2) of the Act, VicForests whether by itself, its agents, its contractors or howsoever otherwise is restrained from conducting forestry operations in the Scheduled Coupes, unless Part 3 of the Act is rendered inapplicable to those forestry operations for whatever reason.

19. Nothing in order 18 above prevents VicForests from planning forestry operations in the Scheduled Coupes for the purpose of participating in any process under the Act which provides for Part 3 being rendered inapplicable to forestry operations in the Scheduled Coupes for whatever reason.

10 The main difference between the proposed prohibitory injunction and the proposed alternative prohibitory injunction is that the former applies to all 66 impugned coupes the subject of the liability reasons – that is, both the Logged Coupes and the Scheduled Coupes – while the latter applies only to the Scheduled Coupes.

11 The effect of VicForests’ proposed changes to the form of the applicant’s alternative prohibitory injunction is that the injunction is conditional, although the form of the condition has changed from the form first proposed by VicForests.

Use of the term “forestry operations”

12 The parties initially disagreed about whether the injunctions should refer to “forestry operations”, a term used in the EPBC Act, or “timber harvesting operations”, a term used in State legislation. After the first hearing on orders, at which I indicated that it may be preferable to use the statutory term which had been in issue in this proceeding, both parties proposed the injunctive relief should employ the term “forestry operations”.

13 Although that is now a joint proposal, I consider it is appropriate to indicate why I expressed concerns about how VicForests’ conduct should be identified in the orders. While this proceeding involved consideration of the “substitute regime” accredited by the CH RFA for the purposes of the RFA Act and the EPBC Act, and therefore involved consideration of State legislation, including the SFT Act, the cause of action always remained framed around the EPBC Act, and principally s 18 and s 38 of that Act. At the centre of this proceeding therefore was the conduct of “RFA forestry operations”, being the statutory phrase in the EPBC Act and the RFA Act. It is appropriate to reflect the centrality of the term “forestry operations” in the relief granted by the Court.

14 The term “RFA forestry operation” or “RFA forestry operations” is defined in s 38(2), by reference to the definition in the RFA Act, which, by s 4 of the RFA Act, in turn picks up the definitions in each RFA. By that circuitous route, a meaning for the term “RFA forestry operation”, and then “forestry operation”, is arrived at. I addressed the significance, or lack of significance, of the use of the singular and plural in the liability reasons at [749]-[759].

15 The CH RFA defines forestry operations as follows:

“Forestry Operations” means

(a) the planting of trees; or

(b) the managing of trees before they are harvested; or

(c) the harvesting of Forest Products

for commercial purposes and includes any related land clearing, land preparation and regeneration (including burning), and transport operations

16 In the liability reasons at [714]-[745] I set out my findings, and the reasons for my findings, about what were the “forestry operations” to which the applicant’s pleaded allegations were directed. At [716]-[721], I explained why I considered the applicant’s pleaded case was confined to forestry operations which fell within the third limb of the definition, and also why that third limb was not to be construed narrowly, and was to be seen as including planning necessary to harvest timber products.

17 Neither party suggested the descriptor “RFA” added anything of substance to the term “forestry operations” in terms of the relief to be granted, likely because there was no dispute that all the impugned forestry operations occurred in the CH RFA region and were for that reason “RFA forestry operations”. The parties did not propose that the orders should use the descriptor “RFA”, and accordingly I have not added the descriptor. I take that matter to be understood, in the context of s 38(1) and (2) of the EPBC Act and s 4 of the RFA Act.

18 It is on that basis that the parties have proposed terms of injunctive relief which reflect those findings. I accept that is appropriate.

Whether prohibitory injunctive relief should extend to the Logged Coupes

The parties’ submissions

19 As I have noted, VicForests conceded that, to give effect to the liability reasons, prohibitory injunctive relief should issue in relation to the Scheduled Coupes. Consequently, the parties’ submissions focused on whether such relief should extend to the Logged Coupes, in circumstances where those coupes, or parts of each of them, have already been harvested.

20 In terms of the power of the Court to grant prohibitory injunctive relief, the relevant provision, identified in the proposed orders, is s 475(2) of the EPBC Act, which provides:

If a person has engaged, is engaging or is proposing to engage in conduct constituting an offence or other contravention of this Act or the regulations, the Court may grant an injunction restraining the person from engaging in the conduct.

21 The applicant submits that it is necessary to read this with s 479(1), which provides:

The Federal Court may grant an injunction restraining a person from engaging in conduct:

(a) whether or not it appears to the Court that the person intends to engage again, or to continue to engage, in conduct of that kind; and

(b) whether or not the person has previously engaged in conduct of that kind; and

(c) whether or not there is a significant risk of injury or damage to human beings or the environment if the person engages, or continues to engage, in conduct of that kind.

22 The applicant relies on the judgment of Black CJ and Finkelstein J in Humane Society International Inc v Kyodo Senpaku Kaisha Ltd [2006] FCAFC 116; 154 FCR 425 at [18], where their Honours stated that s 475 “authorises the grant of what has been called a public interest injunction”. Relying on that case, the applicant submits that the Court has power to grant an injunction “to mark the disapproval of the Court of the conduct which the Parliament has proscribed, or to discourage others from acting in a similar way”. In this sense, the applicant submits, such an injunction may be “entirely educative” – in other words, it does not matter that “there may be no further conduct left to restrain”.

23 The applicant’s submissions on why the Court should issue the proposed prohibitory injunction flowed from its submissions on the Court’s power to do so. In short, the applicant submitted the order “would mark the Court’s disapproval of [VicForests’] unlawful conduct, discourage VicForests and others from acting in a similar way, and reinforce the message that the restrained behavior is unacceptable”. In addition, the applicant submitted that while the evidence at trial suggests VicForests does not presently have plans to harvest the “retained forest” in the Logged Coupes (in substance the difference between the gross area of the coupes and the nett harvested area), the Court can have no confidence that it will not do so in the future.

24 It is the case that in the Logged Coupes, the difference between the gross and nett areas of some coupes is sometimes considerable (eg coupe 483-505-0002 (Rowels): 7.78 ha nett, 42.25 ha gross; coupe 345-506-0004 (Opposite Fitzies): 6.06 ha nett, 34.30 ha gross). In other cases, the differences are quite small (eg coupe 307-507-0004 (The Eiger): 28.78 ha nett, 31.38 ha gross; coupe 287-511-0006 (Houston): 16.15 ha nett, 18.23 ha gross). In some cases (such as Logged Coupe 307-505-0011 (Guitar Solo)), a considerable portion of the retained area in the coupe falls within Leadbeater’s Possum SPZs, which may not be permanent because of the relatively limited time in which particular forest may be suitable for Leadbeater’s Possum to feed and nest in: see liability reasons at [1130].

25 In response, VicForests made three points. First, it submitted that the applicant did not seek injunctive relief over the Logged Coupes as part of its pleaded case. Second, it submitted that discretionary considerations weigh against the grant of an injunction over the Logged Coupes. Third, it submitted that the prohibitory injunction is not aimed at preventing any significant impact on the Greater Glider and Leadbeater’s Possum but is “intended to provide a springboard to enable it to seek mitigation orders under s 475(3)”.

26 With respect to discretionary considerations, quoting the Humane Society case at [21], VicForests submits that, although the applicant seeks a statutory injunction, that “does not … mean that the traditional requirements are irrelevant”, and the lack of evidence that VicForests intends to harvest further in the Logged Coupes is a powerful consideration against the grant of injunctive relief over those coupes. VicForests also submits that no public purpose is served by an “educative” prohibitory injunction because, in contrast to other circumstances where such an approach might be taken (such as consumer law cases), there is no “market place in which non-parties [can] be educated”.

Resolution

27 The Full Court has held, in the Humane Society case, that s 475(2) and (4) as statutory injunctions confer power exercisable in a wider range of circumstances, and for a wider range of purposes, than the power available under equitable principles. The terms of s 479 confirm this. At [18]-[24], the majority of the Full Court (Black CJ and Finkelstein J) said:

18 There is another way of considering the question of futility. The injunctive relief that the appellant seeks is relief by way of statutory injunction under s 475 of the EPBC Act. That section authorises the grant of what has been called a public interest injunction: see ICI Australia Operations Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1992) 38 FCR 248 at 256. Section 475 and the related provisions in Div 14 of Pt 17 of the EPBC Act have their counterpart in s 80 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (the TP Act) upon which they appear to have been largely modelled.

19 Parliament has determined that it is in the public interest that the enforcement provisions of the EPBC Act should be unusually comprehensive in scope. Section 475 of the EPBC Act and its related provisions form part of a much larger enforcement scheme contained in the 21 divisions of Pt 17. The provisions include the conferral of powers of seizure and forfeiture, powers to board and detain vessels and authority to continue a pursuit on the high seas.

20 It is an important and distinctive feature of Div 14 of Pt 17 of the EPBC Act that, like s 80(4) of the TP Act, the Federal Court is expressly empowered to grant an injunction restraining a person from engaging in conduct whether or not it appears to the Court that the person intends to engage again in conduct of that kind and, even, whether or not there is a significant risk of injury or damage to the environment if the person engages or continues to engage in conduct of that kind: see s 479(1)(a) and (c).

21 The public interest character of the injunction that may be granted under s 475 of the EPBC Act is also emphasised by other elements in Div 14 of Pt 17. Thus, as we have noted, standing is conferred upon “an interested person” to apply to the Court for an injunction. Likewise, the traditional requirement that an applicant for an interim injunction give an undertaking as to damages as a condition of the grant is negated. Indeed, s 478 provides, expressly, that the Federal Court is not to require such an undertaking. These modifications to the traditional requirements for the grant of injunctions have the evident object of assisting in the enforcement, in the public interest, of the EPBC Act. This does not of course mean that the traditional requirements are irrelevant: see ICI Australia Operations Pty Ltd at 256-257.

22 Although “deterrence” is more commonly used in the vocabulary of the law than “education”, the two ideas are closely connected and must surely overlap in areas where a statute aims to regulate conduct. Thus, there being a “matter” (see [28]), the grant of a statutory public interest injunction to mark the disapproval of the Court of conduct which the Parliament has proscribed, or to discourage others from acting in a similar way, can be seen as also having an educative element. For that reason alone the grant of such an injunction may be seen, here, as potentially advancing the regulatory objects of the EPBC Act. Indeed, some of those objects are expressed directly in the language of “promotion”, including the object provided for by s 3(1)(c), namely to promote the conservation of biodiversity, which is an object that the legislation links to the establishment of an Australian Whale Sanctuary “to ensure the conservation of whales and other cetaceans”: s 3(2)(e)(ii).

23 Consistently with this view it has been said in relation to s 80(4) of the TP Act that whilst the Court should not grant an injunction unless it is likely to serve some purpose, it may be that in a particular case an injunction will be of benefit to the public by marking out the Court’s view of the seriousness of a respondent’s conduct: see Hughes v Western Australian Cricket Assn (Inc) [1986] ATPR 48,134 (40-748) at 48,135 and Trade Practices Commission v Mobil Oil Australia Ltd (1984) 4 FCR 296 at 300.

24 Similarly, it has been said, again in the context of s 80 of the TP Act, that the purpose of an appropriately drafted injunction may be merely to reinforce to the marketplace that the restrained behaviour is unacceptable: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v 4WD Systems Pty Ltd (2003) 200 ALR 491 (ACCC v 4WD Systems) at [217]. That is to say, a public interest injunction may have a purpose that is entirely educative. In ACCC v 4WD Systems, the enjoined behaviour had ceased and there was little likelihood of repetition and yet it was considered appropriate to grant an injunction.

28 There is nothing in those passages which requires the Court in the present case to grant the prohibitory inunctions sought by the applicant. Each case turns on its own facts, and the evidence available to the Court. However those passages amply demonstrate the width of the power available. Further, as the applicant submitted, the legislative scheme of the EPBC Act in this part (Pt 17 – Enforcement) is that injunctions will be the principal available remedy, and declaratory relief is available only by reason of s 23 of the Federal Court Act, read with s 480 of the EPBC Act.

29 Of course, one likely explanation for the scheme’s focus on injunctions is that a further part of the legislative scheme in Pt 9 contemplates that approval to take an action in the future might be sought, notwithstanding a Court has restrained the action because of a contravention of Pt 3. However another explanation, in my opinion compelling, is that the scheme has as one of its principal objects and purposes the prevention of damage to the environment, especially the avoidance of significant impact, and adverse impacts (the term used in Pt 9 – see eg s 75(2)) on matters of national environmental significance. Remedies that regulate conduct, in the environment, are a primary tool in achieving such objects and purposes.

30 In my opinion, the effect of granting an injunction over the Logged Coupes is capable of falling squarely within the principles outlined in the Humane Society case. RFAs, and the way they are treated under the EPBC Act, operate at a national level. There are other agencies (and also individuals or corporations) which conduct forestry operations in RFA regions around the country. Further, although it was not the applicant’s case in this proceeding, in principle I see no reason why logging contractors are not also capable of being subject to the provisions of Pt 3, read with s 38(1). The grant of an injunction relating to past conduct, whether or not the conduct is likely to be repeated in the near future in the Logged Coupes, and whether or not any future conduct would pose a significant risk of damage to the environment (see s 479(1)), would indeed mark the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct of VicForests. It would send a message to others who conduct forestry operations in RFA regions that they must adhere, on the ground and in the forest, in a real and not a theoretical way, to the suite of standards and actions which have been agreed to be necessary for the protection and recovery of threatened species that rely on those forests for their habitat and sustenance. It would make it clear that native forest, harvested other than in compliance with the substitute regime approved by the CH RFA, is now to be left to regrow, on the basis that at some time in the future (although many decades away) it might again perform the habitat function it was obviously performing for these two threatened species before it was logged.

31 Further, as I have explained, there are still some areas of forest left in some of the coupes. It may have been left for a number of reasons – the slopes were too steep to harvest, the forest formed part of an SPZ which was required to be created after a Leadbeater’s Possum detection, there were streams around which buffers had to be created, and so forth. Under the Code and the Management Standards there may be many reasons for certain areas not to be harvested, some conservation related, some forestry related. It is also the case that some of the 66 impugned coupes abut intact forest and therefore are capable of providing a greater contiguous area of forest for the two species, in a region which is very much a patchwork of logged, unlogged and re-growing forest. For example: Scheduled Coupes 307-505-0010 (San Diego), 307-505-0001 (Drum Circle) and 307-505-0009 (Flute) abut an SPZ, which in turn abuts the Yarra Ranges National Park; and Logged Coupes 462-504-0004 (Skerry’s Reach), 317-508-0010 (Swing High) and 317-508-0008 (Professor Xavier) themselves abut the Yarra Ranges National Park.

32 As I found in the liability reasons, the stability or permanence of this retained habitat in the Logged Coupes was unclear on the evidence. Certainly Dr Smith did not consider it was likely to be permanent, or stable, protection for that forest and habitat. At [932]-[934], I found:

Dr Smith also highlights the lack of utility in the Interim Greater Glider Strategy, in his first report, saying it will have “negligible ameliorative benefit for protecting and preventing the decline in numbers of Greater Gliders in timber production forests”. Leaving aside the inadequate underlying habitat model, which I discuss below, Dr Smith’s reasons for this opinion include the incompatibility of measures such as those contained in the Interim Greater Glider Strategy with planned logging rotations:

It does nothing to prevent or ameliorate the impacts of short harvesting rotations that do not allow forest to reach [an] old growth state. Under current clearfell regimes on short harvesting rotations neither the Interim Greater Glider Strategy nor the Regrowth Retention Harvesting System are likely to have any benefit to Greater Gliders. There is no point in improving habitat tree protection for Greater Gliders if you cut the forests on rotations too short for re-occupation, and if habitat trees are so poorly selected and protected that none will survive to a second cutting cycle.

I accept this opinion and consider it important. “Retained” does not mean “retained forever” or until natural senescence. In fact, “retained habitat” is defined in the Interim Greater Glider Strategy as “any intact forest unlikely to be harvest within the next 20 years”. Thus, “retained” simply means retained and set aside from the current harvesting schedule. So much is also apparent from VicForests’ Regrowth Retention Harvesting Instruction, which is in evidence, and which states that retained patches in coupes are to be retained “for at least one rotation”, implying they could be harvested on the second rotation. That is also the understanding of the rotations expressed by Dr Smith in his first report at p 49:

If coupes are harvested on short rotations retained habitat trees are of no benefit to Greater Gliders because the habitat will be removed before the hollows will be removed before the hollows can be re-occupied.

What occurs to the habitat of the Greater Glider because of the logging rotation cycle and harvesting choices to be made in the foreseeable future is something which VicForests’ management options do not grapple with. Again, in a sense, this illustrates the gap between having a policy document and ensuring it will work “on the ground”, in the forest. Dr Smith makes this point clearly, with respect.

33 Dr Smith also gave this opinion, during cross-examination:

Do you consider that, in assessing the threat that logging might pose to the scheduled coupes or the impact that any logging in the scheduled coupes might have on the greater glider – that it is relevant, to have regard to those percentages vis-à-vis the scheduled coupes?---I believe it’s relevant to have regard to the difference between the gross area and the net area, provided you have an understanding that this difference is going to be permanent through time, and I don’t have that understanding. This may be the difference between the gross area and the net area at the present time, but subject to future logging, that difference may diminish.

(Emphasis added.)

34 And at [1130]-[1131]:

Another example of the impact of logging rotations and reserves with a specific purpose is the evidence Dr Smith gave about some of the additional coupes. He was asked about Pieces of Eight, one of the additional coupes. This was the question and his answer:

But you will see that, although the growth area harvested – to be harvested was 33.71 hectares, the actual harvested area was 14.03 hectares. That does demonstrate, doesn’t it, that a significantly smaller amount of area might be harvested despite what appears in the TRP?---Yes, I agree in the short term, but I don’t know how long these areas will remain protected before – as SPZs. They may be logged in the future, particularly if they’re Leadbeater’s possum reserves because in 20 years time, they’re likely to be unsuitable for Leadbeater’s possum and anyone resurveying these sites would conclude they’re not there and – and say they’re available for logging.

Dr Smith makes an important point. That is why looking at maps with multiple SPZs does not tell the full story about the impact of forestry operations on species such as the Greater Glider. What is currently reserved from logging may not stay that way.

35 It was not clear on the evidence specifically what VicForests intends to do in the Logged Coupes in the future, including in relation to the retained habitat.

36 Therefore, on the findings made at trial, and based on Dr Smith’s opinion (which I accepted in the liability reasons), there is an evidentiary basis for the Court to grant injunctive relief over the Logged Coupes, to protect what habitat remains, to ensure there is no further damage (eg from burning, as to which see below), as well as to “send a message” that those who engage in conduct which contravenes the prohibitions in s 18 will be subject to orders regulating their ongoing conduct, including in areas that have already been damaged.

The “carve out” order, and its extent

37 There are two limbs to the proposed separate order: one is only necessary if there is a prohibitory injunction over the Logged Coupes; the other goes to conduct in connection with seeking an approval under Pt 9 of the EPBC Act.

The first limb

38 As I have noted, the first limb would permit

conducting regeneration activities other than burning for the purpose of compliance with part 2.6.1 of the Code within only that part of each of the Logged Coupes that is in fact already harvested

39 Part 2.6.1 of the Code provides:

2.6.1 Regeneration

Operational Goals

Harvested areas of native forest are successfully regenerated.

The natural floristic composition and representative gene pools are maintained when regenerating native forests by using appropriate seed sources and mixes of dominant overstorey species.

Mandatory Actions

2.6.1.1 Planning and management of timber harvesting operations must comply with relevant regeneration measures specified within the Management Standards and Procedures.

2.6.1.2 State forest available for timber harvesting operations must not be cleared to provide land for the establishment of plantations.

2.6.1.3 Action must be taken by the managing authority to ensure the successful regeneration of a harvested coupe, except where:

i. the land is to be used for an approved purpose for which native vegetation is not compatible (for example services, public infrastructure and structures); or

ii. timber has been harvested by thinning; or

iii. the naturally occurring regrowth is assessed as sufficient.

2.6.1.4 Following timber harvesting operations, State forest must be regenerated with overstorey species native to the area, wherever possible using the same provenances, or if not available, from an ecologically similar locality.

2.6.1.5 Regeneration must aim to achieve the approximate canopy floristics that were common to the coupe prior to harvesting, if known.

2.6.1.6 Silvicultural methods for regeneration must suit the ecological requirements of the forest type, taking into consideration the requirements of sensitive understorey species and local conditions.

2.6.1.7 Harvested coupes must be regenerated as soon as practical, including follow up or remedial action in the event of regeneration failure.

2.6.1.8 All practical measures must be taken to protect areas excluded from harvesting from the impacts of burns and other regeneration activities.

2.6.1.9 Where mechanical disturbance is used, it must be undertaken with due consideration of erosion risks and the proximity of waterways (refer to Section 2.2).

40 The proposed first limb excludes burning from the regeneration activities undertaken for the purpose of compliance with the Code. While Pt 2.6 of the Code does not expressly require burning as part of regeneration activities, the evidence at trial suggested burning (with various levels of intensity) was a regular feature of regeneration activities performed by VicForests. In support of this exclusion, the applicant submits that regeneration burning adversely affects the Greater Glider and Leadbeater’s Possum. I accept this is amply supported by the evidence in this proceeding. For example, in respect of the Greater Glider, Dr Smith’s evidence at [558] of the liability reasons, which I accepted, was:

habitat trees are not protected from post logging burning and many are so seriously damaged by fire that they are likely to fall before they are of use to Greater Gliders and other hollow using fauna (see Appendix 1).

41 And as I observed at [75], the effect of post-logging burning on the Leadbeater’s Possum and its habitat is recognised in the 2015 Conservation Advice.

42 In its response to VicForests’ proposed undertaking, but in my opinion relevantly also to the appropriateness of an injunction over the Logged Coupes, the applicant submitted:

These coupes were logged prior to 2017 so have already had at least three years of natural regeneration. VicForests’ own Harvesting and Regeneration Systems 16 August 2019 states that VicForests must minimise the use and intensity of controlled fire for regeneration (cl 3.2.3). VicForests has not adduced any evidence that indicates that burning of the kind specified is necessary in those coupes.

43 I accept that submission. There has been nothing preventing either party adducing further evidence in relation to the terms of relief, but neither party has chosen to do so. Precisely how and why any of the Logged Coupes might, in a period after these orders, require further burning, was not the subject of any evidence from VicForests. It is not immediately apparent why further burning after three years’ regeneration would be necessary. In the absence of any evidence on this matter from VicForests, and in the light of evidence at trial about the likely threats to the habitat of the two species posed by post-harvest burning, I consider the more appropriate course is to exclude burning from the regeneration activities which can be carried out.

44 The applicant also submitted:

The evidence about regeneration activities is that while most of the Logged Coupes have had regeneration treatment, five have not (Estate, Blue Vein, Hairy Hyde, Swing High, Opposite Fitzies): Second Paul CB 3.4 at [160(g)-(h)] and 3.4.34.

45 VicForests did not expressly respond to this submission, although the terms of its undertaking (see below) suggest it wishes to conduct further regeneration activities in a broader range of Logged Coupes. Again, no evidence was adduced, or submission made, by VicForests to explain the selection of coupes in its proposed undertaking.

46 In practical terms then, although the applicant proposed and I am prepared to accept that the injunction over the Logged Coupes should be qualified by a “carve out” order relating to regeneration activities other than burning, it is not possible for the Court to be satisfied on the balance of probabilities about whether there are different activities required in each coupe, and if so what those activities are. Accordingly, I consider it is appropriate for the Court’s orders generally to permit regeneration activities in the Logged Coupes in compliance with the Code and Management Standards, proscribing only burning. In addition, coupe 345-505-0006 (Hairy Hyde) is only partially harvested, and the unharvested part is covered by the injunction over the Scheduled Coupes.

The second limb

47 As to the second limb, while I have some concerns which mirror the concerns I identify below about making the injunction conditional (that is, the matter is presently hypothetical) I accept the clarity of the way in which VicForests is bound to act by reason of the injunction is improved by having an order which expressly provides that nothing in the prohibitory injunction over the Scheduled Coupes prevents VicForests planning forestry operations in the Scheduled Coupes for the purpose of participating in any process under the Act which provides for Pt 3 being rendered inapplicable to forestry operations in the Scheduled Coupes.

48 I do not agree the clarification needs to extend to the Logged Coupes. VicForests was prepared to proffer an undertaking not to conduct forestry operations in those coupes. That was a substantive change from the position which appeared on the evidence at trial. The fact of the undertaking implies it is able to avoid conducting, or does not need to conduct, any further forestry operations in those coupes. There is no reason to permit it to undertake planning for any further forestry operations, since the principal forestry operations in those coupes are concluded. If VicForests changes its position again about this matter, it can apply to the Court for a variation to the orders.

Whether the prohibitory injunction over the Scheduled Coupes should be “conditional”

49 The parties appeared to proceed on the basis that the prohibitory injunctive relief should either be subject to a “carve out” (the applicant’s position) or should be conditional (VicForests’ position). I have explained why I find it appropriate to include a carve out, and what the terms of that carve out should be. It remains necessary to explain why I do not consider the injunctions over the Scheduled Coupes should be conditional.

50 I accept that Allsop J, as the trial Judge in the Humane Society case (Humane Society International Inc v Kyodo Senpaku Kaisha Ltd [2008] FCA 3; 165 FCR 510), and Branson J as the trial Judge in Booth v Bosworth [2001] FCA 1453; 114 FCR 39, both framed the prohibitory injunctions in those cases in a conditional way.

51 In the Humane Society case the orders were:

[T]he respondent be restrained from killing, injuring, taking or interfering with any Antarctic minke whale (Balaenoptera bonaerensis), fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) or humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in the Australian Whale Sanctuary, or treating or possessing any such whale killed or taken in the Australian Whale Sanctuary, unless permitted or authorised under sections 231, 232 or 238 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth).

(Emphasis added.)

52 In the Humane Society case at first instance, on appeal and on remitter, the respondent did not appear and took no part in the proceeding. The respondent being a Japanese corporation, the attitude of the Government of Japan to whaling also formed part of the context. On remitter, having found (at [39]) that “a significant number of the whales were taken inside the Australian Whale Sanctuary”, and that no permit had been issued to the respondent under the EPBC Act authorising those acts, Allsop J found (at [40]):

[T[he applicant has established on the balance of probabilities that the fleet has engaged in conduct that contravenes ss 229, 229A, 229B, 229C, 229D and 230 of the EPBC Act, and intends to continue doing so in the future under the JARPA II regime.

53 However, his Honour did not address in his reasons for judgment why the injunction was made conditional.

54 In Booth, the final orders, recorded in a subsequent judgment on costs (Booth v Bosworth [2001] FCA 1718) were:

The Respondents be restrained and an injunction be granted to restrain the Respondents, whether by themselves or by their servants or agents or otherwise howsoever, from causing, procuring or allowing the death of or infliction of actual bodily harm to Spectacled Flying Foxes (Pteropus conspicillatus) by the connection or supply of electrical current to any electric grid erected on the Respondents’ farming property situated at Lots 107 and 108, Crown Plan CWL652, Parish of Meunga, County of Cardwell, in the State of Queensland unless such action is the subject of an approval by the Minister of the kind mentioned in s 12(2)(a) and granted pursuant to Part 9 of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth).

(Emphasis added.)

55 At [120] of the liability reasons, Branson J explained why her Honour considered the injunction should be conditional:

Moreover, I take the view that the injunction to be granted should be a conditional one. The action of the respondents in operating the Grid in a manner which leads to the death of large numbers of Spectacled Flying Foxes constitutes a contravention of the Act only while there is no approval of the taking of the action by the respondents in operation under Pt 9 of the Act (par 12(2)(a) of the Act). The respondents are presumably free to seek such an approval at any time. For this reason I also consider it inappropriate on the evidence before the Court to make an order requiring the respondents to dismantle the Grid.

56 I accept that orders framed in this way, or the way proposed by VicForests, expressly recognise the operation of other parts of the EPBC Act. However, in my opinion there are at least two reasons which justify not making the prohibitory injunction over the Scheduled Coupes a conditional one.

57 First, despite having the opportunity to do, VicForests adduced no evidence that it intended to apply for approval under Pt 9, whether under s 75 or s 158, despite VicForests having expressly drawn attention to the entitlement under s 158 in its first proposed form of orders. I accept in the Humane Society case there was no such evidence, but in that proceeding the respondent did not participate in the proceeding, and did not recognise the Court’s jurisdiction over it.

58 In Booth, while the report of the case does not disclose whether there was any direct evidence about an intention to seek approval, at [20] Branson J found:

The respondents in their amended defence assert that the first respondent holds a permit issued pursuant to s 112 of the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Qld) to take 500 Spectacled Flying Foxes during the period 24 November 2000 to 23 January 200 1 and that the respondents are thereby entitled to utilise the Grid. It was not, however, ultimately contended by the respondents that s 12(1) of the Act did not apply to their actions in operating the Grid.

59 That is, the evidence established the respondent had sought the permission it considered it needed to seek. No doubt her Honour inferred the respondent might well seek EPBC Act approval once it had been declared its conduct was otherwise in contravention of the EPBC Act. That is no doubt why the taking down of the Grid was opposed.

60 In Booth, the only action that the respondent was undertaking was the operation of a single Grid, which killed the flying foxes. That is quite unlike the circumstances in this proceeding. As the liability reasons explain, VicForests has a wide and ambulatory choice about the areas of forest it chooses to harvest. Not only is it not restricted to the Scheduled Coupes, it is not restricted to the CH RFA region. The allocation orders made by the State of Victoria allocate timber to VicForests across the State, in many different native forests. Indeed, there was evidence given by Mr Paul during the trial that, upon the making of interlocutory injunctions in this proceeding over certain coupes, VicForests chose also not to undertake forestry operations in other impugned coupes not subject to the injunctions, and chose to focus its harvesting activities elsewhere.

61 Thus there are a number of possibilities open to VicForests. On a cost and resource basis, it may choose to focus its harvesting activities elsewhere in the short, medium or longer term. Alternatively, it may consider the expert evidence adduced in this proceeding, and the Court’s findings, and voluntarily determine that the Scheduled Coupes should not be harvested because of their habitat value to the Greater Glider and the Leadbeater’s Possum. DELWP may have a role in such consideration and decision-making. VicForests may decide to pursue forestry operations in only a portion of the Scheduled Coupes. It may decide to apply for approval under Pt 9 on a coupe-by-coupe basis. It may decide not to apply for any approval under Pt 9 until it has exhausted its appeal options. The Court has no evidence which course might be chosen, but all these options are possible. And there may well be more.

62 In those circumstances, whether VicForests will seek approval under Pt 9 to undertake forestry operations in some or all of the Scheduled Coupes is no more than a hypothetical possibility. The Court should not include hypothetical possibilities in its injunctive orders. The scheme of the EPBC Act is what it is: given the “carve out” order, the terms of the Court’s injunctive orders do not remove or affect VicForests’ entitlement to make such an application, if it chooses to do so, over all or some of the Scheduled Coupes.

63 Second, including a condition – whichever of the formulations suggested during the hearing is chosen – introduces uncertainty into the operation of the injunction which I consider in the context of this particular proceeding is undesirable, and not appropriate.

64 It is important that injunctions be as clear as possible, for a contravention of an injunction may expose a party to the prospect of prosecution for contempt: Crescent Funds Management (Aust) Ltd v Crescent Capital Partners Management Ltd [2017] FCAFC 2; 118 ACSR 458 at [166], citing Melway Publishing Pty Ltd v Robert Hicks Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 13; 205 CLR 1 at [60]. As Lord Nicholls said in Attorney General v Punch Ltd [2002] UKHL 50; [2003] 1 AC 1046 at [35]:

A person should not be put at risk of being in contempt of court by an ambiguous prohibition, or a prohibition the scope of which is obviously open to dispute.

65 I note that, in this case, it is the party subject to the injunction that seeks a potentially ambiguous prohibition. In the circumstances, I do not consider that affects the matter.

66 Whether the condition is expressed as “unless Pt 3 of the Act is rendered inapplicable to those forestry operations for whatever reason”, or otherwise, in my opinion there will almost inevitably be further dispute between the parties about when that condition crystallises. The parties in this proceeding agree on very little. One wishes to harvest the native forest in the CH RFA region; the other wishes to stop that forest being harvested where it adversely affects the two threatened species. I consider it is more likely than not that if VicForests seeks approval under Pt 9, and is granted approval, there will be legal challenges to the grant of any such approval. I consider it is likely the parties will not agree on what is meant by “is rendered inapplicable”, or when an approval removes the effect of the injunction. There is likely to be the need for further argument about that matter – perhaps new proceedings. The factual basis may remain uncertain, or it may change – for example if a challenge is successful, then overturned on appeal. All these variables make for an uncertain operation of the injunction.

67 The better approach in my opinion, in the context of this particular proceeding, is for VicForests to apply to the Court to have the injunction discharged. That application can be made on proper material, on an expressed factual basis, and the Court will then be in a position to make a clear determination. Of course, if approval has been granted under Pt 9 and that approval has not been impugned in any proceeding, or has been unsuccessfully impugned, it is difficult to see how any party could resist an application to discharge the injunction, and it is difficult to see how the injunction would not be discharged. That need not be a resource- or cost-intensive process, in contrast to arguing about what the terms of an existing injunction mean.

68 Section 477 of the EPBC Act expressly contemplates such a scenario:

On application, the Federal Court may discharge or vary an injunction.

69 Where the variation is sought on the basis that the conduct prohibited is subsequently authorised, this reflects the position at general law. As King CJ said in Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation v Perry (No 2) (1988) 53 SASR 538 at 558:

I have no doubts as to the power of the court to dissolve a permanent injunction where Parliament expressly authorises that which the party is prohibited by the injunction from doing.

70 See also QDSV Holdings Pty Ltd v Trade Practices Commission (1995) 59 FCR 301 at 315.

The proposed undertaking

71 During the second hearing, and during submissions about the proposed prohibitory injunction over the Logged Coupes, senior counsel for VicForests informed the Court that he had instructions to proffer an undertaking that VicForests would not conduct forestry operations in the Logged Coupes. This, it was contended, obviated the need for any prohibitory injunction over the Logged Coupes.

72 The undertaking was filed on 5 August 2020 in the following terms:

VicForests undertakes that:

(a) it will not, whether by itself, its servants, agents, contractors or howsoever otherwise, conduct Forestry Operations in the Logged Coupes, including the planning and preparatory phases of such conduct, save for regeneration in the following coupes to be conducted in accordance with section 2.6 of the Code:

Glenview [298-516-0001];

Flicka [298-519-0003];

Mont Blanc [309-507-0001];

Kenya [309-507-0003];

The Eiger [309-507-0004];

Blue Vein [348-506-0003];

Tarzan [348-517-0005];

Estate [462-507-0008];

Rowels [483-505-0002];

Bromance [312-510-0007];

Lovers Lane [312-510-0009];

Swing High [317-508-0010];

Camberwell Junction [290-527-0004]; and

(b) the regeneration undertaken in accordance with subparagraph (a) above will not include burning save for the burning of ‘rough heaps’ that are generated through the process of mechanical seed bed preparation (rough heaping) and are to be interspersed throughout the harvest area of the coupe.

73 In proffering this undertaking, VicForests explained that it

should not be taken as conceding that there is any legal basis justifying any prohibitory injunction being granted in relation to the Logged Coupes or that the undertaking in any way affects its rights of appeal.

74 The applicant submits that an undertaking fails to reflect the gravity and seriousness of VicForests’ unlawful conduct, and to mark the Court’s disapproval of that conduct, in the same way than an injunction over the Logged Coupes would. The applicant also criticises the form of this particular undertaking on the ground that it is too vague (for example, it does not specify that burning of rough heaps should be low intensity) and if conditions were added to avoid this vagueness, and to avoid further significant impact on the two threatened species, the undertaking would be “less succinct, less certain, more complex, and more contentious”. In the alternative, the applicant submits that paragraph (b) of the proposed undertaking should end after “will not include burning”. The applicant points out that VicForests has not adduced any evidence that burning of rough heaps, in particular, is necessary in the coupes specified in paragraph (a) of the proposed undertaking.

75 I find that the undertaking is insufficient, and has some ambiguities about it. The latter is of concern because, as Simpson JA stated in LCM Litigation Fund Pty Ltd v Coope [2017] NSWCA 200 at [23], for an undertaking to be truly operative in the sense that its breach may result in a finding of contempt, “the terms … must be clear, unambiguous and capable of compliance”.

76 VicForests adduced no evidence about what burning of “rough heaps” was, let alone why it was necessary. Nor did it direct the Court to any evidence at trial on this matter. A search of the evidence at trial disclosed no references which would assist the Court to understand the function or process of “rough heaping” in any meaningful way. The Court cannot simply speculate about those matters. There is no evidentiary basis about the circumstances in which such burning would be carried out, including at what time of year, and how bushfire risks would be avoided.

77 Next, as I have found above, there is no evidence as to why the particular coupes identified in the undertaking have been identified and singled out for regeneration activities. Nor is there any explanation or evidence about which regeneration activities will be conducted in the coupes specified.

78 Accordingly, I am not satisfied the undertaking is sufficiently unambiguous. While it might be said the regeneration activities “carve out” to the injunction over the Logged Coupes suffers from the same difficulties, it is not restricted to specified Logged Coupes, and therefore relies only on what the Code authorises, or does not authorise.

79 Further, the undertaking was proffered very late. The Court’s reasons were published on 27 May 2020. The parties filed competing proposed minutes of orders on 26 June 2020. No undertaking was proffered at that stage. The matter was listed for an oral hearing on 8 July 2020. No undertaking was proffered then, nor in VicForests’ second set of written submissions on the appropriate orders. It was proffered during the course of the second hearing, and with no explanation as to why it was being proffered, nor why it was being proffered at that point in time.

80 One inference which is available is that it was proffered to avoid an injunction over the Logged Coupes, which on VicForests’ own arguments was the necessary precondition to the mitigation orders being available under s 475(3). That is, an available inference is that it was proffered in order to deny the applicant, at least on VicForests’ arguments, access to the power in s 475(3). I am not suggesting that is an improper forensic purpose, but it seems to me – in the absence of any positive explanation by VicForests or even by counsel on instructions – to be a possible explanation.

81 Of course, I assume that, having been given the opportunity to reflect on the undertaking, formulate it, and proffer it formally, VicForests intends to abide by it. However, as I have found, its content – as to the specific coupes – is not explained by any evidence. The fact that it was proffered so late, and in my opinion for a forensic purpose, means I do not consider it can be equated with the educative effect of an injunction.

82 By accepting a late proffered undertaking the Court also does not have the same opportunity to plainly mark its disapproval of the past conduct of VicForests in the Logged Coupes, in particular VicForests’ failure to adhere to the precautionary principle in the conduct of its forestry operations in the Logged Glider Coupes, and its failure to appreciate and recognise that its actions in all 66 impugned coupes were likely to have had, and were likely to have in the future, a significant impact on the Greater Glider and Leadbeater’s Possum.

83 This is a case where at no stage in its evidence or submissions did VicForests make any concession whatsoever about the level of impact of its forestry operations on these two species. In particular I refer again to my findings at [1015] of the liability reasons:

The attitude demonstrated by VicForests, through Mr Paul as its institutional witness, indicates a reluctance to accept basic and well-established general propositions about the role of forestry operations as a threat to hollow-dependent species such as the Greater Glider. This conduct confirms that any policy statements which have emerged indicating a voluntary change to its timber harvesting practices are driven by commercial motivations, rather than any acceptance of the repeated expert opinion (including in official documents issued under the EPBC Act) about the threats posed by timber harvesting. There is little evidence of sustained change on the ground. And VicForests’ reluctance in this proceeding to accept the obvious illustrates its defensive attitude and its apparent desire to protect the existing range and nature of its timber harvesting activities as much as possible. The Court does not accept it is likely that, on the ground, VicForests will in fact change the way it carries out its forestry operations so that the Greater Glider secures improved protection from forestry operations and its population decline is not only arrested but begins to be reversed. As I have noted, the expert evidence of both Dr Smith and Professor Woinarski is clear that recovery to sustainable and non-threatened levels is part of the conservation of any species.

84 Prior to this finding I had explained how VicForests, through Mr Paul, would not accept the most basic of propositions about the threats to each of the species, and the role of forestry operations as a major threat to them, and to their recovery. That is notwithstanding the unanimous views in the independent, objective, expert Conservation Advices to the responsible federal Minister, on which the species’ listings were based, and which I explained in detail in the liability reasons.

85 The attitude of VicForests in this proceeding was in the face of matters such as those I set out at [103] of the liability reasons (amongst other places):

This Court is not determining in this proceeding whether timber harvesting should cease in the CH RFA region in which the Logged Coupes and Scheduled Coupes are located. Its task is narrower than that. However, I consider it to be a factor of some weight that the expert committee established under the EPBC Act recommended, for the conservation and recovery of the Leadbeater’s Possum, a total cessation of timber harvesting in the Montane Ash forests of the region. The severity of that recommendation indicates the severity of the situation facing the Leadbeater’s Possum as a species.

86 These are circumstances which would be inadequately addressed by the Court accepting an undertaking proffered at one minute to midnight. These are circumstances which call for the Court to mark its disapproval of VicForests’ conduct in the past in the Logged Coupes through the grant of an injunction, to make clear that those contraventions should not have occurred.

Conclusion on the prohibitory injunction over the Logged Coupes

87 Accordingly, there will be separate injunctions over both the Scheduled Coupes and the Logged Coupes. I have decided that order 16 should be expressed to be made on the basis of orders 12 and 15, in addition to orders 9, 11 and 14, being the orders referred to in the parties’ proposed order. This is because the declarations in orders 12 and 15 concern the Scheduled Coupes (the subject of order 16) as well as the Logged Coupes. There will be tailored “carve outs” for each injunction, the “carve out” for the Logged Coupes being narrower.