FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Sovereign Hydroseal Pty Ltd v Steynberg [2020] FCA 1084

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days of the date of these orders, the parties are to file either:

(a) An agreed minute of orders reflecting the outcome of these reasons, that the prospective applicants are entitled to the discovery orders they seek subject to the provision of security for the costs of compliance or a sufficient reduction in the scope of the orders; or

(b) Minutes of competing orders.

2. Within 14 days of the date of these orders, the parties are to file any submissions (not to exceed 3 pages) on the question of the costs of the application.

3. Unless the Court orders otherwise, the settling of the orders and the question of costs be determined on the papers.

MCKERRACHER J:

A PRELIMINARY DISCOVERY APPLICATION

1 Pursuant to r 7.23 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth), the prospective applicants seek an order for preliminary discovery of documents to be produced by the prospective respondent (Mr Steynberg), who is a former employee of the first prospective applicant (Sovereign).

2 Mr Steynberg strenuously opposes the application for a number of reasons.

3 Sovereign is the exclusive licensee of Australian Standard Patent No. 2012216392 for the invention entitled ‘Method and Composition for Sealing Passages’ (392 Patent). Triomviri Pty Ltd and Relborgn Pty Ltd, (the second and third prospective applicants) are the joint patentees of the 392 Patent. The prospective applicants are referred to collectively as ‘Sovereign’.

4 Sovereign seeks documents in five categories. It contends it requires production of these documents on the basis that it does not have sufficient information to decide whether to start a proceeding against Mr Steynberg in respect of causes of action for patent infringement, breach of confidence, breach of contract, and contempt.

5 For the following reasons, I consider that Sovereign is entitled to some of the discovery it seeks.

THE EVIDENCE

6 In support of its application, Sovereign relies upon the following affidavits:

(a) of Mr Deon Van Dyk filed 8 April 2020 (the Van Dyk affidavit), who is a director of the first and second prospective applicants;

(b) of Mr David Le Roux filed 8 April 2020, who is the general manager of Sovereign.

7 In response, Mr Steynberg has sworn two affidavits dated 18 May 2020 (the First Steynberg affidavit) and 21 June 2020 respectively.

8 Sovereign has not served any evidence in reply to Mr Steynberg’s affidavits. It objects to a statement in the First Steynberg affidavit that previous litigation between the parties almost ruined him financially and, in effect, that he anticipates compliance with the orders sought by Sovereign would have the same outcome. It is true that the evidence as to the previous experience is an unparticularised generalisation which cannot adequately be tested by Sovereign and therefore I treat the content as more in the nature of a submission. I treat the submission as being that compliance with the orders sought by Sovereign will inevitably occasion considerable and unwelcome expense to Mr Steynberg who is not in a particularly strong economic position, particularly during the current economic circumstances caused by the coronavirus pandemic. I accept that submission. I will take it into account in determining what, if any, orders are to be made.

RELEVANT PRINCIPLES

9 Rule 7.23 of the Rules provides:

7.23 Discovery from prospective respondent

(1) A prospective applicant may apply to the Court for an order under subrule (2) if the prospective applicant:

(a) reasonably believes that the prospective applicant may have the right to obtain relief in the Court from a prospective respondent whose description has been ascertained; and

(b) after making reasonable inquiries, does not have sufficient information to decide whether to start a proceeding in the Court to obtain that relief; and

(c) reasonably believes that:

(i) the prospective respondent has or is likely to have or has had or is likely to have had in the prospective respondent’s control documents directly relevant to the question whether the prospective applicant has a right to obtain the relief; and

(ii) inspection of the documents by the prospective applicant would assist in making the decision.

(2) If the Court is satisfied about matters mentioned in subrule (1), the Court may order the prospective respondent to give discovery to the prospective applicant of the documents of the kind mentioned in subparagraph (1)(c)(i).

10 All parties have cited extensively from the Full Court’s decision in Pfizer Ireland Pharmaceuticals v Samsung Bioepis Au Pty Ltd (2017) 257 FCR 62 per Allsop CJ, Perram, Nicholas JJ.

11 In Pfizer (at [4]), Allsop CJ described rule 7.23 as ‘a beneficial provision, the purpose of which is to enable a person who believes he, she or it may have a right to seek relief to obtain information to make a responsible decision as to whether to commence proceedings’. His Honour also said (at [8]):

It is important to approach the task with the fundamentals of the rule in mind. There have been a large number of cases now (both at first instance and Full Court) dealing with and explaining the relevant rule. Those authorities should not be utilised to form a complex matrix of sub-rules for the operation and application of a tolerably straightforward provision. Whilst there was no submission that any of these cases was wrongly decided, there does appear to have been a tendency to create an overly abstracted conceptualisation of refined states of mind which, if the words of the rule are not kept in mind, can lead in application to a misstatement of the essence of the rule, focused as it is upon what may be the position. The foundation of the application in r 7.23(1)(a) is that an applicant (a person or a corporation) reasonably believes that he, she or it may have a right to relief. The belief therefore must be reasonable (expressed in the active voice that someone reasonably believes) and it is about something that may be the case, not is the case. It is unhelpful and likely to mislead to use different words such as “suspicion” or “speculation” to re-express the rule. For instance, it is unhelpful to discuss the theoretical difference between “reasonably believing that one may have a right to relief” and “suspecting that one does have a right to relief” or “suspecting that one may have a right to relief” or “speculating” in these respects. The use of such (different) words and phrases, with subtleties of differences of imprecise meaning, and not found within the rule itself is likely to lead to the proliferation of evidence and of argument, to confusion and to error. One must keep the words of the rule firmly in mind in examining the material that exists in order to come to an evaluation as to whether the relevant person reasonably believes that he or she may have a right to relief. That evaluation may well be one about which reasonable minds may differ.

(Emphasis in original.)

12 Pfizer emphasised that a preliminary discovery application is not a mini-trial: (at [2] and [119]). As a beneficial provision, r 7.23 focuses on what may be the case, not on what is the case (Pfizer (at [8])), and to a certain extent authorises ‘fishing expeditions’ to allow an applicant to ascertain whether a case exists: Pfizer (at [108]-[109]).

13 As to the requirement that an applicant must show a ‘reasonable belief’ that it may have the right to obtain relief from a prospective respondent, and to show that the respondent may have documents directly relevant to that question, a belief will be reasonable if it is founded on considerations or views that are reasonably open, even if they are contested as incorrect by others: Pfizer (at [69]). A reasonable belief also arises where a person apprised of all the material before the Court could reasonably believe that they may, not do, have a right to obtain relief: Pfizer (at [8] and [120(i),(iv)-(v)]). A belief will not be likely to be reasonable if it is based on ‘considerations or views that are unreasonable, untenable, irrational or baseless’: Pfizer (at [69]). The question is not whether the belief involves a degree of speculation. It is whether the belief resulting from that speculation is a reasonable one: ‘Debate on an application will rarely be advanced, therefore, by observing that speculation is involved’: Pfizer (at [121] and [123]).

14 In practice, in order to defeat a claim for preliminary discovery it is necessary either to show that the subjectively held belief does not exist or, if it does, there is no reasonable basis for thinking that there may be (not is) such a case: Pfizer (at [121]).

15 In opposition to this application the main ground raised in considerable detail by Mr Steynberg is that there is no adequate foundation for a reasonable belief. In addition, any breach of any nature is firmly denied. For the reasons that follow, Sovereign is entitled to the relief it seeks subject to further consideration as to the scope of the discovery orders and the need for security for costs to be given. In reaching this conclusion, I rely solely on the evidence going to a possible claim for infringement of the 392 Patent.

BACKGROUND

16 The background to Sovereign’s present concerns is set out in some detail in the Van Dyk affidavit. Matters relied upon by Sovereign include the following:

17 Sovereign operates a waterproofing and water sealing business based in Perth. Its business involves repairing cracks, joints and voids in concrete structures and geological formations to eliminate water seeping through them. Sovereign’s services are provided throughout Australia.

18 Sovereign is the exclusive licensee of the 392 Patent for the invention titled ‘Method and Composition for Sealing Passages’. Triomviri and Relborgn are the joint patentees of the 392 Patent. Sovereign was also the exclusive licensee of Australian Patent No. 739427 for the invention titled ‘Method of sealing a fluid passage’ (Expired Patent). That patent expired on 6 June 2017, and was held by the same patentees as the 392 Patent.

19 Mr Steynberg was employed by Sovereign from 1 July 2008 to 19 June 2009, although there is a dispute both as to his functions and his personal knowledge in the field of water sealing. There may well be, as Mr Steynberg asserts, personal animosity which has given rise to different perceptions as to his role and knowledge. Sovereign says he was employed initially as a labourer and later as a logistics officer. It says he was trained on how to seal a passage in a body such as a geological formation with a seal composition, including delivering a mix of latex and additional components under pressure into the passage; the training is said to have provided insight into the types of equipment used for this process, and also details of the materials and compositions used. For the purposes of his work, Mr Steynberg had access to Sovereign’s business records including its main computer server where its confidential information (including client and data files) were stored. He also had a company ‘laptop’ computer and was able to access Sovereign’s main server remotely (with password access). Sovereign submits that its confidential information relates principally to the manner of its business operations which includes details of product specifications and formulations, methods and processes involving those products, customer records and customer information. Mr Steynberg does not deny those matters but makes the point that he was only employed for one year during that period.

20 Sovereign says that shortly after Mr Steynberg ceased employment with Sovereign on 19 June 2009, he established a business under the name ‘Sovereign Water Control Pty Ltd’ (SWC), of which he was a director. Sovereign asserts that SWC operated from its inception in competition with Sovereign. It says that after challenging SWC’s use of its intellectual property, the dispute was settled in September 2009 with the result being that ownership of SWC was transferred to Sovereign.

21 Mr Steynberg disputes this account. He says that SWC was set up as a joint venture company to expand Sovereign’s operations in Queensland and allow Mr Steynberg to be closer to his family. In the First Steynberg affidavit he deposes that ‘Sovereign changed its mind on the joint venture and made allegations. To resolve this, I sold SWC Ltd to them at a nominal value.’ Mr Steynberg strongly denies the allegation that SWC used Sovereign’s intellectual property or confidential information and says he entered into the settlement agreement without obtaining legal advice due to a lack of financial resources and a desire to put the matter behind him.

22 Almost two years later in April 2011, Mr Steynberg commenced trading through a new company known as ‘H2O Control Systems Pty Ltd’. By reason of the manner of conduct of the H2O business, Sovereign instituted proceedings for preliminary discovery in this Court. In response to the application, H2O consented to the provision of documents.

23 On 11 April 2013, proceedings were commenced by Sovereign, Triomviri and Relborgn for infringement of the Expired Patent, breach of confidence, breach of contract, and copyright infringement (the Earlier Proceeding). Shortly thereafter, the parties reached a negotiated settlement, and written terms of settlement were entered. On 24 June 2013, the Court made orders by consent which included orders restraining Mr Steynberg from infringing claims 1 and 2 of the Expired Patent and from using Sovereign’s confidential information. The nature of Sovereign’s confidential information was defined in the orders.

24 H2O was subsequently deregistered.

25 I cannot presently resolve what happened historically. But I make no finding (provisional or otherwise) as to the circumstances under which SWC commenced operation. It does not affect determination of this application.

26 I also make no finding about the Earlier Proceeding and in particular as to the question of whether or not Mr Steynberg committed any breach at all. I do however accept that Mr Steynberg’s employment history is relevant to showing that he had some opportunity to acquire relevant information. In the end, given that I have decided this application only on the possible infringement of the 392 Patent I have not needed to take that material into account other than in the most general sense by way of common background.

27 In late September 2019, Sovereign became aware that Mr Steynberg was operating a business called ‘H2O Seal’ pursuant to which a process was being used for sealing cracks and joints involving a ‘liquid rubbery substance’ injected by pumps. It says it was made aware of these facts through representations made by a potential customer of Sovereign to Mr Le Roux. The unnamed customer also indicated that Mr Steynberg is likely to have ‘Safety Data Sheets (SDS) and information about his products.’ On about 23 October 2019, Sovereign also obtained a ‘flyer’ for the H2O Seal business from the customer. I give no weight to this hearsay evidence even though it may be admissible. It adds very little to the relevant issues. Sovereign also undertook internet-based searches (which located a website for the H2O Seal business) as well as enquiries which confirmed the H2O Seal business was being operated by Mr Steynberg.

28 Mr Steynberg contends there are numerous persons operating in Australia who might use a process for sealing cracks and joints involving a ‘liquid rubbery substance’ injected by pumps. Although there is no evidence of this, I will assume it to be correct for present purposes. His point is that knowing that information could not possibly support a reasonable belief that Sovereign may be entitled to relief for patent infringement or otherwise. I will address this argument below.

29 Sovereign then engaged a private investigator to undertake enquiries about the H2O Seal business and to attempt to ascertain details of the process and materials that were being used by that business for sealing cracks and joints. The investigator was able to obtain some limited information from communications with Mr Steynberg that a product called ‘N-LICS’ was being used, and that H2O Seal used ‘a natural nanotechnology rubber grout injected under pressure into the voids sealing cracks and joints’. No other information was able to be obtained which might describe the method and composition used by the H2O Seal business.

30 Sovereign then wrote to Mr Steynberg requesting information, documents and samples from him regarding the methods and processes used by his H2O Seal business. As to compositions and formulations that were apparently being used by him as part of his H2O Seal business, Sovereign asked for technical information (such as chemical compositions) for products being referred to as ‘NOH2O’, ‘N-LICS’ and any rubber grout that was injected under pressure into cracks for the purpose of sealing. Mr Steynberg declined to provide the materials requested. I agree with Mr Steynberg’s complaint that the time given by Sovereign in a demand letter sent by email on a Saturday to produce this information by the following Tuesday was unreasonable (albeit that it had been preceded by a much earlier request).

31 In general terms, the thrust of Sovereign’s concern is that Mr Steynberg is using, as part of conducting a business by him personally under the name ‘H2O Seal’, at least one method of sealing cracks and joints that infringes the method claimed in the 392 Patent. Additionally, and related to that concern, Sovereign says that Mr Steynberg’s conduct contravenes contractual obligations given, and injunctive orders entered, as part of the resolution of the Earlier Proceeding, and involves conduct which contravenes equitable obligations of confidence. The main point of emphasis however was on the possible infringement of the 392 Patent.

32 Having regard to the nature of the (allegedly) infringing conduct, it is notoriously difficult for Sovereign to know the viability of any of the proposed causes of action absent production of the requested documents: see Pfizer (at [4]). Unless technical documents, such as data sheets and specifications are produced, Sovereign says the precise constituents of the products used by Mr Steynberg’s business for his sealing method(s) are not readily identifiable. It is claimed that documents of that kind would be likely to permit Sovereign to determine, in an efficient manner, whether any of the proposed causes of action might be available. Documents are also sought in relation to the extent of any potentially infringing conduct, such as invoices, ledgers and supply records regarding dealings with H2O Seal’s customers – a further relevant consideration as to whether a proceeding should be commenced: Quanta Software International Pty Ltd v Computer Management Services Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 969 per Sackville J (at [32]-[34]).

33 That Sovereign has made reasonable inquiries as best it can by undertaking searches (including internet searches) and by engaging a private investigator to ascertain information as to the methods and processes being used by Mr Steynberg’s H2O Seal business is not in dispute. Those inquiries have not elicited sufficient information to enable it to make a decision on whether to commence a proceeding against Mr Steynberg.

34 Sovereign has also approached Mr Steynberg directly. Mr Steynberg is the logical person to approach for the information and materials sought. There is no suggestion the information and materials could be obtained from any other source. Sovereign has requested production of documents from Mr Steynberg and he has refused. However as observed, the deadline for compliance with Sovereign’s request for information was unreasonably brief. That said, Mr Steynberg has not made any offer subsequently or before that demand to provide the information sought.

35 It is common ground that Mr Steynberg uses a ‘process’ and ‘materials’ for sealing cracks and joints. That is, Sovereign says, he is using a method which may infringe or contravene (at least) Sovereign’s patent rights. Mr Steynberg does not suggest in either of his affidavits that he is using proprietary methods of any other third party, but says he is using his ‘intellectual property.’ Sovereign contends that in these circumstances the inference can be drawn that Mr Steynberg may be using either a method the same as that of Sovereign, or is derived from Sovereign’s method, or has been developed by him.

36 Mr Steynberg does not suggest that he does not have materials that could be produced in response to the requested categories. His main objection is as to any basis for a reasonable belief on the evidence produced by Sovereign. In addition, Mr Steynberg says that Sovereign’s account of these events is misleading and is a deliberate attempt to cause him ‘as much financial damage as possible’ and is a personal vendetta against him. He says that it is implausible that he is in competition with Sovereign when his net profit for the year ending 30 June 2019 was only $31,233.00. It is also submitted that compliance with discovery orders in the Earlier Proceeding ‘financially ruined’ him. As noted above (at [8]), I have treated this only as a submission that the cost of compliance with any further discovery orders would impose unwelcome expense on Mr Steynberg..

37 Mr Van Dyk, in his capacity as a director of the first and second prospective applicants (Sovereign and Triomviri), gives evidence as to his subjective belief. Mr Van Dyk says that without the provision of the requested materials he is unable to determine whether Sovereign is able to bring an action against Mr Steynberg in respect of any of the potential claims.

38 Sovereign accepts that its belief involves a degree of speculation on its part, but says that is unsurprising in the present case (or in any case of preliminary discovery: see Pfizer (at [121]). It relies on the fact that Mr Steynberg is a former employee who had received training in respect of Sovereign’s methods and had access to its business information (including confidential information). Sovereign has already had to pursue Mr Steynberg in proceedings in respect of previous concerns it held that he may have been engaging in acts of patent infringement and/or breach of confidence. Despite assurances made by Mr Steynberg as part of the negotiated resolution of those earlier proceedings, which includes injunctive orders made against him (by consent), Sovereign now has renewed concerns in respect of Mr Steynberg’s conduct.

39 Having regard to all these circumstances and matters as a whole, Sovereign argues that its belief in its right to obtain relief is reasonable.

CONSIDERATION

40 Without conducting a mini-trial, it is necessary not to gloss over the evidence that Sovereign relies on to demonstrate that it holds the ‘reasonable belief’ required by r 7.23. This is especially so given the invasive and costly relief sought.

41 The first of the items of evidence that Sovereign relies upon ‘that it may have a right to obtain relief’ is set out by Mr Le Roux, the General Manager of Sovereign and relates to the anonymous information Sovereign received from a potential customer who had been in contact with Mr Steynberg. As I made clear to the parties during the hearing, and at [27] above, I give no weight to this hearsay evidence except to the extent that it demonstrates why Sovereign proceeded to make further enquiries into Mr Steynberg’s business activities. It is no more than a part of the narrative.

42 The second piece of evidence that the prospective applicants rely upon as the basis for holding a reasonable belief that Sovereign may have the right to obtain relief in the Court from Mr Steynberg is the evidence relating to the flyer obtained from the anonymous customer.

43 Mr Van Dyk says that the photographs on the flyer ‘show jobs that have been conducted by Sovereign using the Sovereign process and methods’. He goes on to express his concern that ‘if Mr Steynberg is using photographs of Sovereign’s method to promote his services, then he may also be using those methods himself’. Sovereign says these facts support its reasonable belief that it may have a right to obtain relief.

44 On this point, Mr Steynberg’s evidence is that:

(a) All of the photographs with the exception of three are freely available and can be used without breach of copyright;

(b) the remaining three photographs were taken by him in his personal capacity during his employment with Sovereign; and

(c) ‘None of the photographs reveal any confidential information of Sovereign’.

45 Mr Steynberg contends that the photographs in the flyer, whether taken alone or with other evidence, are ‘considerations or views that are unreasonable, untenable, irrational or baseless,’ and ‘it would be difficult to conclude that the applicant has a reasonable belief’ based on them: Pfizer (at [69]). As will be seen in the further discussion below, while there is force in this submission concerning the photographs, it is not the photographs in the flyer so much as the words used which may support Sovereign’s reasonable belief.

46 In addition, Sovereign relies on evidence contained in the private investigator’s report of a phone conversation and an email sent by Mr Steynberg, as well as statements made by him in recent correspondence with Sovereign’s solicitors and wording from his business website. By reference to the 392 Patent, Sovereign claims that this evidence indicates there is sufficient similarity in Mr Steynberg’s process and method to warrant a reasonable belief that Sovereign may be entitled to relief.

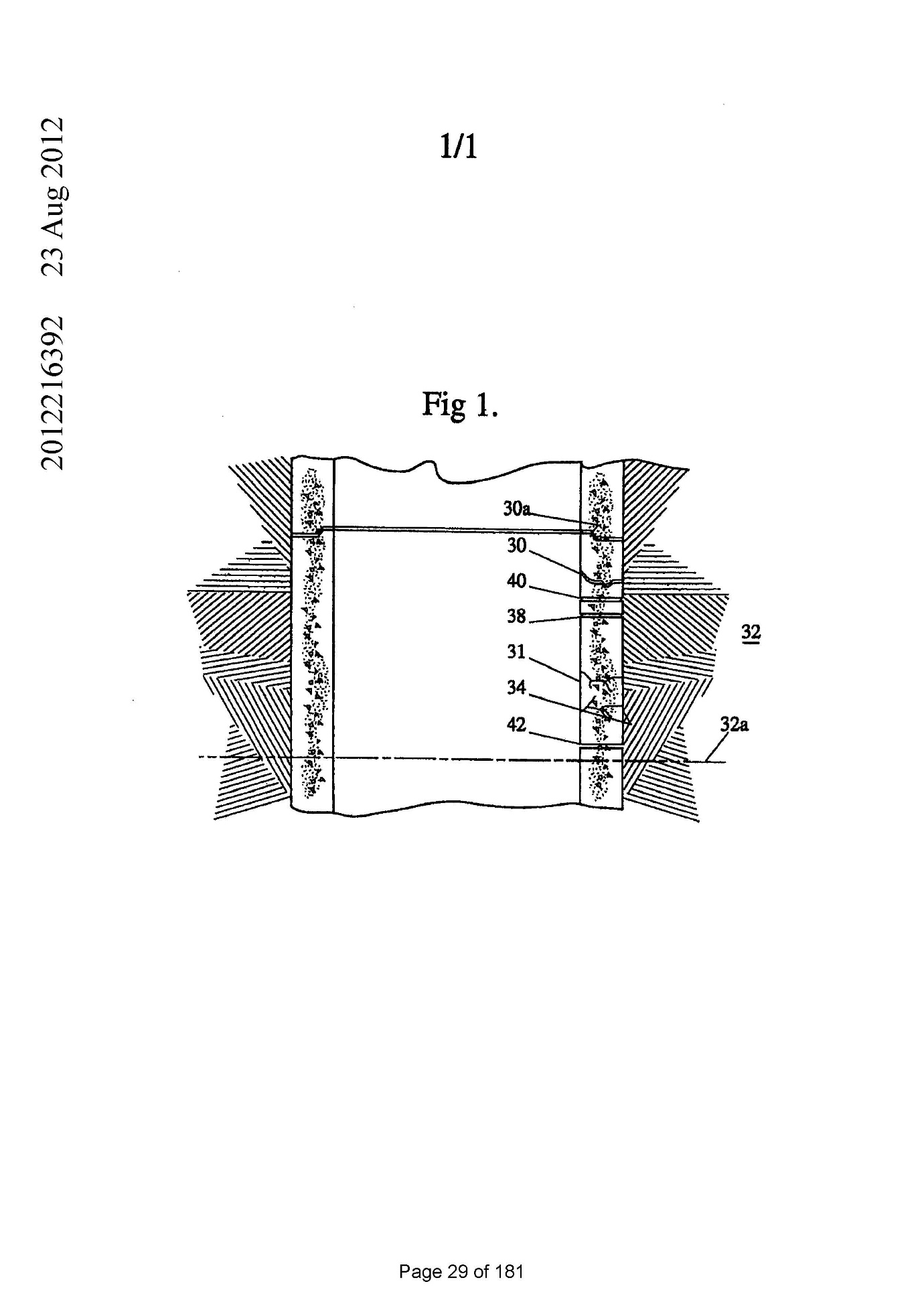

47 The 392 Patent is appended to these reasons as Annexure A.

48 It can be seen that under field of invention, the following appears:

The present invention relates to a method and composition for sealing passages.

49 Under background, at line 16 the following appears:

However, it has been found that the appropriate sealing of cracks may require injection of sealing composition at pressures from 1 bar up to 200 bar. At these pressures, pure and natural latex or natural rubber latex, being incapable of resisting hydrostatic pressures without setting is unsuitable.

50 Line 21 says:

Thus in these situations it appears that natural latex compositions or emulsions cannot be used.

51 Thus a hybrid product is used. Line 26:

It is the object of the present invention to provide a method and composition for sealing a passage in a body that enables employment of a latex-based composition.

52 There is an example of the sealing composition:

…the composition, or grout, as it may be known, may comprise of the following three elements –

53 There is specific reference to lauric acid. Sovereign now seeks the technical information that would give it an understanding about what precisely comprises the fluids that Mr Steynberg’s business is using. It is spelt out that:

The present invention has an advantage, the ability to employ latex-based sealing compositions and sealing agents and the capacity to pump such compositions at high pressure to seal leaks especially in geological formations.

And Claim 1 provides, after the sealing proposition, that:

... said composition is pumped into the said passage where it is set or coagulated to form a seal and wherein setting or coagulation of said composition is initiated once said composition is in situ within the passage to be sealed.

54 In summary, Patent 392 provides a method for sealing passages that overcomes the problems that arise when latex compounds are pumped under pressure by the addition of an additive such as lauric acid. Sovereign says that this is the very work that Mr Steynberg’s product is being utilised for.

55 To demonstrate this, Sovereign produces a document printed on 23 June 2011, taken from Mr Steynberg’s then company’s website showing a logo for ‘LICS 100 liquid injective containment system’. Underneath that is the paragraph starting:

Our proprietary LICS-100 is a natural based highly efficient, flexible and permanent impenetrable waterproofing barrier that can be injected.

(Emphasis added.)

56 Below that there is a heading saying:

What is LICS?

It is a blend of rubber emulsions, which have the ability to convert from liquid into a strong flexible and durable rubber-like three dimensional seal. This process can be described as coagulation.

Grouting is injection of a liquid-like substance into various narrows cavities… to fill them and consolidate into a solid mass at the same time affecting a water tight seal.

(Emphasis added.)

Coagulation is then described as ‘a complex process by which a liquid forms a solid’. The website goes on to state that ‘H2O Control Systems do not use any polyurethane in our applications.’

57 In the flyer for H2O Seal obtained by Sovereign there is the heading:

Specialists in sealing all types of water ingress. H2O is dedicated to the development and application of effective water and gas sealing technologies.

58 There is also reference to ‘under pressure’ similarly to the patent and ‘pressure injection grouting’. In a series of bullet points there is reference to ‘tailored emulsions for different environments’, which Sovereign says is also similar to the type of liquid that is the subject of the Patent.

59 The process itself seems similar to that described in Patent 392 as Mr Steynberg himself acknowledges, saying in fact that lots of people do it. What is not, however, revealed from these documents in the public domain is whether the same formula is being used for the injected grout.

60 Sovereign also relies on an email from Mr Steynberg produced in the investigator’s report in which he describes his process. He says:

…

Wed, Dec 11, 2019 at 11:08 PM

Hi Emma,

Thank you for the photos, the construction appears to be a besser block wall with the floor slab being poured after. If this is correct there would be a vertical cold joint between the block work and the floor slab. It also appears that water is penetrating through the brickwork mortar joints. Besser blocks can be notoriously difficult to seal. Assuming it is only the cold joint that is leaking the cost is $380 exc GST per linear meter with a 2 meter minimum. If the blocks also needs sealing it is sometimes better to get us in on a day rate of $1,800 exc GST, including 50 liters [sic] of N-LICS and $28.50 per liter [sic] after. This is a rough estimate from the photos, we will be able to give you a much more accurate indication after a site visit.

The joint gets drilled with a specialised diamond drill 14-18mm, that is significantly quieter than conventional hammer drills. A natural nanotechnology rubber grout gets injected under presure [sic] into the voids sealing the joints and cracks.

Yes we are working over the Christmas period and filling up fast, let me know if you have any other questions.

Thanks and kind Regards,

Micheal Steynberg

…

(Emphasis added.)

61 The email makes clear that N-LICS is a liquid but Mr Steynberg now appears to suggest in his first affidavit that it is not a liquid but a name he has given to his process for waterproofing. He says that N-LICS is an acronym for ‘Nano Liquid Injection Containment System’. The email describes the liquid as a rubber grout – which is injected under pressure into the voids sealing the joints and cracks. This description appears to correspond with the description of ‘LICS’ as a ‘blend of rubber emulsions’ from Mr Steynberg’s website in June 2011 which is set out above (at [56]).

62 Finally, Sovereign relies on a statement made by Mr Steynberg in a letter to its solicitors dated 26 February 2020 that, ‘I’m carrying on the same business of waterproofing and of sealing as I was carrying before the making of the Consent Order.’ Mr Van Dyk deposes to his belief that this statement raised ‘some prospect’ that Mr Steynberg is using the same ‘method, process and composition for sealing passages that he was at the time the Orders were made.’

63 The crux of Mr Steynberg’s opposition to this evidence and Sovereign’s contentions is that, whether taken together or alone, they are insufficient to ground a reasonable belief that Mr Steynberg may be using the same method, process or composition as Sovereign such that a potential patent infringement claim could arise.

64 Mr Steynberg says that a letter to him by Sovereign’s solicitors (‘Watermark’) dated 31 January 2020 shows that Sovereign has engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct. Watermark alleges:

From our client’s investigations, it appears that you are using very similar chemicals and methods as you previously used in your H2O Control Systems business. Our client’s investigations have revealed that you appear to be using NOH2O and/or N-LICS and/or an alternative rubber grout that is injected under pressure into cracks.

(Emphasis added.)

65 Mr Steynberg says the material filed by Sovereign in the present proceedings has not revealed that Mr Steynberg was or is using similar chemicals and/or methods as he did previously, nor is there any evidence that he was using NOH2O.

66 Mr Steynberg also makes the point in written submissions that a prospective applicant’s right to discovery under r 7.23 needs to be weighed against the rights of Mr Steynberg to his own intellectual property rights. I agree with this contention, however in the minute of orders provided by Sovereign just prior to the hearing, they have responded to this concern by proposing a relatively conventional confidentiality regime: see for example MMD Design and Consultancy Limited v Camco Engineering Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 1803 per O’Bryan J (at [57] and [61]) and SmithKline Beecham plc v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 271 per Finkelstein J (at [33]).

67 It is clear that the evidence obtained by Sovereign so far does not provide it with sufficient information to consider whether it is entitled to relief against Mr Steynberg. Although Mr Steynberg is correct that none of the evidence adduced proves that he is employing the same method and using the same chemical composition as Sovereign, there is no doubt that the processes being carried on by both parties appear on their face to be very similar.

68 It is not clear however, how more detailed information regarding the precise constituent elements of Mr Steynberg’s sealing composition could be obtained outside of the discovery orders sought. In my view Sovereign is entitled to test that composition.

69 As to the evidence from Mr Steynberg that he was not aware of the 392 Patent, that would not usually, taken alone, be an adequate response to an infringement allegation, nor would the fact that others are using the same process (if that indeed be the case though there is no evidence here). But more importantly for present purposes, a lack of awareness of the patent is no answer to Sovereign’s discovery orders which are directed principally at providing Sovereign with sufficient information to determine whether it could be entitled to commence proceedings.

70 Although I am of the view that Sovereign is entitled to the relief it seeks, I am concerned about the cost of compliance with the orders in the terms sought by Sovereign. They are quite expansive. Although no application has been made, my tentative view is that if Sovereign presses for orders of such width, it should give security for the costs of compliance.

71 Rule 7.29 of the Rules is in these terms:

7.29 Costs

A person against whom an order is sought or made under this Division may apply to the Court for an order that:

(a) the prospective applicant give security for the person’s costs and expenses including:

(i) the costs of giving discovery and production; and

(ii) the costs of complying with an order made under this Division; and

(b) the prospective applicant pay the person’s costs and expenses.

Note: Part 40 deals with costs and Division 40.2 deals with taxation of costs

(Emphasis added.)

CONCLUSION

72 For these reasons, I consider that Sovereign has made out its entitlement to relief principally in the form of the orders sought although the scope of the orders sought needs to be narrowed. Further, I consider at least tentatively, that it should provide security. I will allow the parties an opportunity to attempt to agree these terms and failing agreement I will fix them.

73 If the parties seek costs or wish to be heard on costs, they should file submissions not exceeding three pages within 14 days. Unless otherwise ordered, costs will be determined on the papers. One possibility is that the prospective applicants pay the prospective respondent’s costs of the application unless the prospective applicants commences proceedings within a certain period (see SmithKline Beecham at [32]) failing which costs be reserved to the proceeding.

I certify that the preceding seventy-three (73) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice McKerracher. |