FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Kogan Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1004

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days the parties file a draft minute of proposed orders for timetabling a hearing as to penalties.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

DAVIES J:

INTRODUCTION

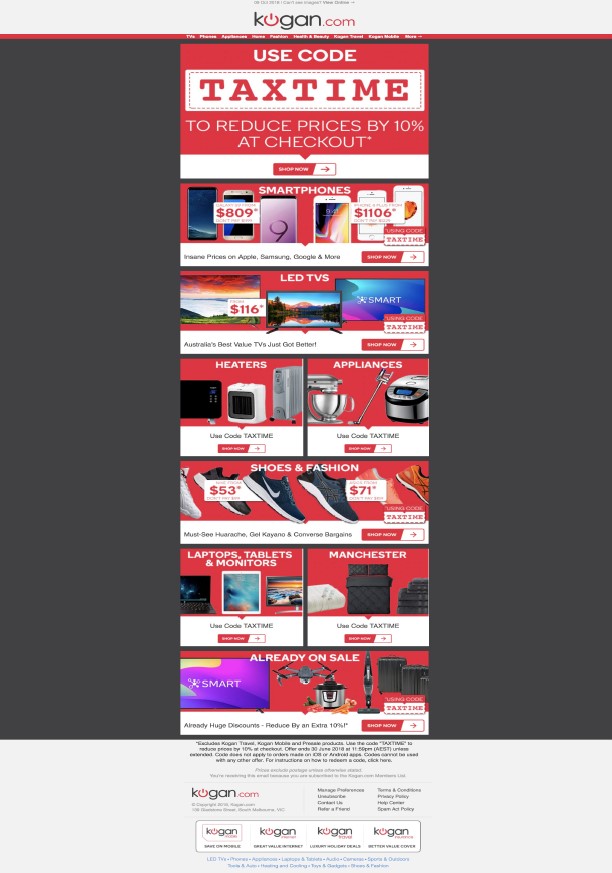

1 The respondent (Kogan) is an online retailer, conducting business in Australia. It offers goods for sale to Australian consumers through the website located at the URL www.kogan.com/au/ (website or Kogan website) and other online channels. From 27 to 30 June 2018, Kogan conducted a sales promotion in respect of 78,111 products on the website, offering a 10% reduction on prices for consumers who purchased those products and entered the promotional code “TAXTIME” at checkout (Tax Time Promotion). The entry of the code at checkout had the effect of reducing the price in the consumer’s cart in respect of items to which the Tax Time Promotion applied.

2 Kogan advertised the Tax Time Promotion to consumers in the following ways:

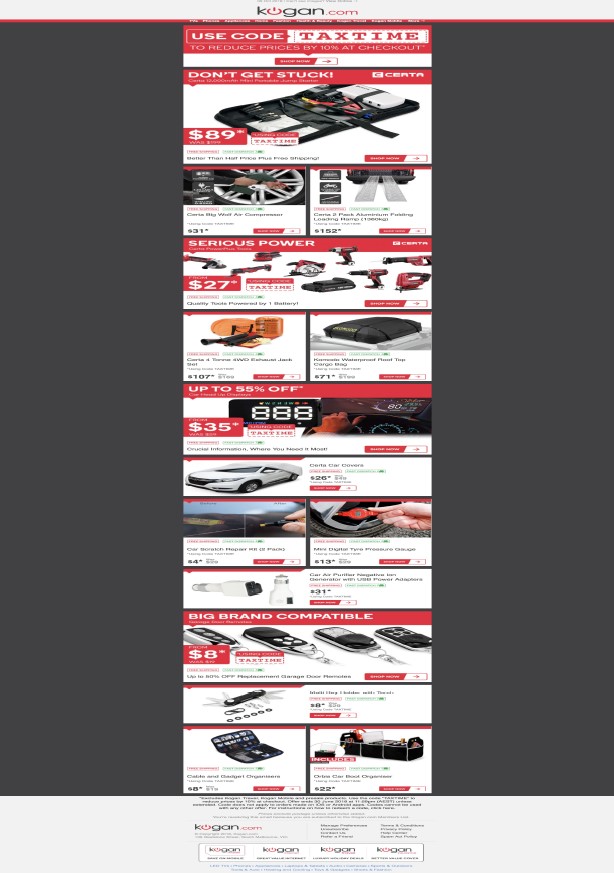

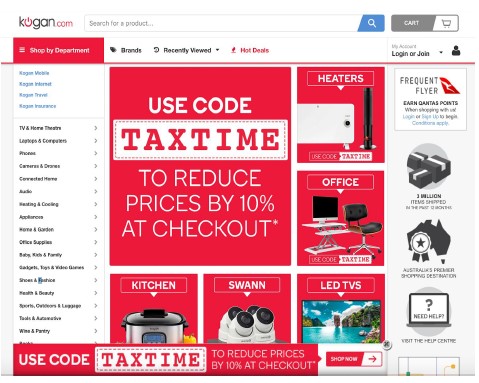

(a) by displaying banners on the website containing the statement “Use code TAXTIME to reduce prices by 10% at checkout”;

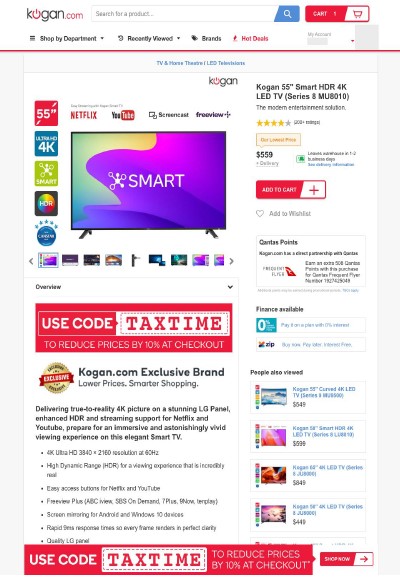

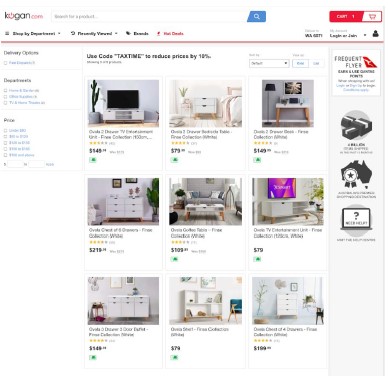

(b) by including the statement “Use code TAXTIME to reduce prices by 10% at checkout” on its homepage and on the individual product detail pages of the website;

(c) by sending electronic direct marketing (eDM) messages via email to consumers who had agreed to receive marketing communications (subscribing consumers) containing the statement “Use code TAXTIME to reduce prices by 10% at checkout” and, in some, also including the statements “48 hours left!” or “Ends midnight”; and

(d) by sending SMS messages to subscribing consumers containing the statement “[Name], use code TAXTIME to reduce almost all Kogan.com prices by 10% at checkout. Shop now [link] T&Cs Apply”.

3 The applicant (ACCC) alleged that the statements contained in the website banners, SMS and eDM communications represented to consumers that:

(a) if consumers purchased products during the Tax Time Promotion and used the code “TAXTIME” at checkout, they would receive a 10% discount off the price at which these products were available for sale for a reasonable period before the Tax Time Promotion (10% Discount Representation); and

(b) consumers had a limited opportunity, if they purchased products during the Tax Time Promotion and used the code “TAXTIME” at checkout, to receive a 10% discount off the price at which these products would be available for sale for a reasonable period after the Tax Time Promotion (Limited Time Discount Representation).

4 The ACCC alleged that these representations were false or misleading in relation to 621 of the products to which the Tax Time Promotion applied (affected products) and that Kogan thereby engaged in misleading conduct in contravention of ss 18 and 29(1)(i) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) at Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the Act). The allegations are denied by Kogan.

5 The primary issues in dispute are:

(a) whether by making the promotional statements in connection with the Tax Time Promotion Kogan conveyed to the reasonable consumer the representations alleged by the ACCC; and

(b) if the alleged representations were made, whether they were false or misleading in the circumstances.

RELEVANT LEGAL PRINCIPLES

6 Section 18(1) of the ACL provides as follows:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

7 Section 29(1)(i) of the ACL relevantly provides as follows:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services… make a false or misleading representation with respect to the price of goods or services.

8 The terms “misleading or deceptive” and “mislead or deceive” in s 18(1) of the ACL and the term “false or misleading” used in s 29(1) of the ACL have the same meaning: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Dukemaster Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 682 at [14]–[15] (in relation to cognate provisions in the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)).

9 The parties were not in dispute that the impugned conduct occurred in trade or commerce and the conduct was in connection with the supply of goods. The parties were also not in dispute that the Court must assess the relevant conduct by reference to the class of persons to whom the alleged representations were directed and that task involves the following steps.

10 First, it is necessary to identify the relevant section of the public at which the conduct was directed: Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Limited [2000] HCA 12; 202 CLR 45 (Campomar) at 84–5 [101]–[102].

11 Secondly, it is necessary to consider who comes within that target audience: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd [1982] HCA 44; 149 CLR 191 (Puxu) at 199 per Gibbs CJ.

12 Thirdly, the Court considers the natural and ordinary meaning conveyed by the representations by applying an objective test of what the ordinary or reasonable consumers in the class would have understood as the meaning in light of the relevant contextual facts and circumstances: Puxu at 199 per Gibbs CJ; Campomar at 85–7 [103]–[105]. This will, or may, include consideration of the type of market, the manner in which the goods are sold, and habits and characteristics of purchasers in such a market: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited [2014] FCA 634; 317 ALR 73 (Coles) at 81 [41], citing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; 250 CLR 640 (TPG) at 656 [52] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ; and Puxu at 199 per Gibbs CJ. In advertising material, where simple phrases and notions may evoke attractive notions without precise meaning, context and the “dominant message” are important: Coles at 83 [47], citing TPG at 653–4 [45] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ.

13 Fourthly, whether conduct is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive is to be tested by whether a hypothetical ordinary or reasonable member of the target audience is likely to be misled or deceived, excluding reactions that are extreme or fanciful: Campomar at 85–7 [103]–[105]. The issue is not whether the impugned conduct simply causes confusion or wonderment: Taco Company of Australia Inc v Taco Bell Pty Ltd [1982] FCA 136; 42 ALR 177 (Taco Bell) at 201 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ, cited with approval in Campomar at 87 [106]. Conduct is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive if it has the tendency to lead into error, requiring a causal link between the conduct and the error on the part of the person to whom the conduct is directed. The law is not intended to protect people who fail to take reasonable care to protect their own interests: TPG at 651–2 [39] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ. Further, there is no need to demonstrate any intention to mislead or deceive – conduct may be misleading and deceptive even where a person acts reasonably and honestly: Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2013] HCA 1; 249 CLR 435 (Google) at 443–4 [9] per French CJ, Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

14 Fifthly, whether the hypothetical member of the target audience is likely to be misled or deceived may involve questions as to the knowledge properly to be attributed to the members of the target audience: TPG at 656 [53] per French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ; Campomar at 85 [102]–[103]. It is also necessary to isolate by some criterion a hypothetical representative member of the class: Campomar at 85 [103].

15 Sixthly, within the target audience, the inquiry is whether a “not insignificant” portion of the people within the class have been misled or deceived or are likely to have been misled or deceived by the relevant conduct, whether in fact or by inference: Bodum v DKSH Australia Pty Limited [2011] FCAFC 98; 280 ALR 639 (Bodum) at 680–2 [205]–[210] per Greenwood J (Tracey J agreeing); cf National Exchange Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2004] FCAFC 90; 49 ASCR 369 at 375 [23] per Dowsett J; 384 [70]–[71] per Jacobson and Bennett JJ (where their Honours opined that the enquiry as to whether a “significant proportion” of the target audience is likely to have been misled or deceived was effectively another way of stating the test of whether the hypothetical ordinary or reasonable member of the target audience was likely to have been misled or deceived).

16 Seventhly, evidence that someone was actually misled or deceived by an advertisement is not required: Taco Bell at 199 per Deane and Fitzgerald JJ. In circumstances where the advertisements were directed to the public at large the absence of such evidence is not of great significance: Coles at 82 [45]. Correlatively, evidence that a person has been misled by an advertisement is not conclusive that its publication constitutes misleading or deceptive conduct.

17 The ACCC has the onus of proof on the balance of probabilities: s 140 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) (Evidence Act). By that section, in deciding whether it is satisfied that the case has been proved to that standard, the Court is to take into account the nature of the cause of action or defence, the nature of the subject matter of the proceeding and the gravity of the matters alleged. As the contravention of s 29 of the ACL may expose Kogan to the imposition of a civil penalty, it is relevant to take that matter into account and a very high level of satisfaction should be reached before finding the contraventions proven: Briginshaw v Briginshaw [1938] HCA 34; 60 CLR 336 (Briginshaw).

THE ACCC’S CASE

18 The allegation of false and misleading representations was limited to the 621 affected products. Those products were selected because they met the following criteria:

(a) the price of each product increased on 26 June 2018, in many cases by at least 10%;

(b) the price remained generally stable during the Tax Time Promotion period (ie 27 to 30 June 2018); and

(c) the price decreased on 2 July 2018, in many cases by at least 10%.

19 The ACCC alleged that representations conveyed by the promotional statements in connection with the Tax Time Promotion were false and misleading in relation to the affected products because:

(a) contrary to the 10% Discount Representation, a consumer who purchased an affected product using the code TAXTIME did not receive a 10% discount off the price at which that product was available for sale for a reasonable time before the Tax Time Promotion due to the price increase the day before the Tax Time Promotion commenced (other than in respect of 22 of the products whose prices were reduced for one day on 28 June 2018 to an amount equal to or less than the price before the increase on 26 June 2020); and

(b) contrary to the Limited Time Discount Representation, a consumer who purchased an affected product using the code TAXTIME did not receive a 10% discount off the price at which that product was available for sale for a reasonable time after the Tax Time Promotion due to the price decrease of the products two days after the Tax Time Promotion (other than in respect of 25 of the products whose prices were reduced for one day on 28 June 2018 to an amount equal to or less than the price after the price decrease on 2 July 2020).

20 The ACCC’s case also was that price adjustments immediately before and after the Tax Time Promotion were deliberate and occurred in circumstances where the prices of most of the affected products otherwise remained unchanged for a reasonable period before and after the Tax Time Promotion. The ACCC did not specify what constituted a “a reasonable period”, arguing that the period would vary depending on the product and its pricing history and so eschewed a temporal duration, save to contend that the period for which the prices of those products remained generally stable in the two-week period before and after the Tax Time Promotion was a reasonable period.

KOGAN’S CASE

21 Kogan did not deny that it increased the prices of the affected products immediately before the Tax Time Promotion, nor did it deny that it decreased the prices of the affected products soon after the Tax Time Promotion, but it did deny that by making the promotional statements in connection with the Tax Time Promotion, it represented to consumers that, by using the TAXTIME code, they would obtain a 10% “discount” off prices that had been available for a “reasonable period” prior to or after the Tax Time Promotion. Kogan contended that the Tax Time Promotion was a coupon code promotion which enabled consumers to obtain 10% off the price stated on its website at checkout by entering the specific coupon code “TAXTIME” after the consumer had added the product to their “shopping cart” and prior to payment. Consistent with that fact, it was said, Kogan advertised to consumers that they could “use the code TAXTIME to reduce prices by 10% at checkout”. It was contended that the price payable “at checkout” could only have been, and was understood by ordinary and reasonable consumers of the target audience to be, the current advertised price for the product. The ordinary and reasonable members of the target audience, it was submitted, would not have understood the promotional statements to convey an express or implied comparison with any previous or future prices for the relevant products, and the promotional statements were not false or misleading because all consumers who used the code at checkout in fact paid 10% less than the products’ advertised prices. Consumers who did not use the code paid the full advertised prices.

22 It was further contended that the ACCC ran a case at trial that went beyond its pleaded case of misleading and deceptive conduct based on the alleged representations. Kogan submitted that the ACCC’s claim as to the reasons why Kogan adjusted the prices of the 621 affected products immediately before and after the Tax Time Promotion was not part of, nor relevant to, the ACCC’s pleaded case, as were other matters upon which Kogan’s witnesses were cross-examined and submissions were made by the ACCC.

23 Kogan alternatively contended that even if the representations were made, the ACCC had not demonstrated to the standard required by s 140 of the Evidence Act that the representations were false or misleading because:

(a) the representations were made in respect of 78,111 products, of which the 621 affected products comprised only 0.8%, and even if the alleged representations were made (which was denied), the representations were correct in respect of 99.2% of products to which the Tax Time Promotion applied and therefore cannot properly be characterised as false or misleading or likely to mislead or deceive consumers;

(b) the ACCC’s case, which was based on an increase in the price of the affected products on 26 June 2018, a decrease in the price of the affected products on 2 July 2018 and the allegation that “most” of the affected products remained unchanged in the “reasonable period” before and after the promotion, lacked clarity and cogency;

(c) the evidence did not demonstrate that the prices of most of the affected products remained unchanged before and after the Tax Time Promotion; and

(d) the two-week “reasonable period” before and after the Tax Time Promotion for comparing the price of the affected products with the price during the promotion was chosen arbitrarily and unsupported by evidence as to what would constitute a reasonable period for a price comparison. In any event, it was submitted, there was evidence that the price of the affected products with the coupon code reduction during the promotion was a real discount to the price of the products previously sold on the Kogan website, being the evidence which showed that in the six months prior to the Tax Time Promotion, 56% of the sales of the 621 affected products made on the Kogan website prior to the Tax Time Promotion were sold at prices that were higher or the same as the non-discounted prices on 28 June 2018.

EVIDENCE AND WITNESSES

24 The ACCC relied on the information and documents produced by Kogan in response to notices issued by the ACCC under s 155 of the Act (s 155 notices) and pursuant to the Court’s discovery orders.

25 Kogan led evidence from David Shafer, an executive director of Kogan, and Lloyd Chee, Kogan’s Director of Import – Global Brands. Mr Shafer is responsible for, and has direct oversight over, relevantly, Kogan’s marketing, including the development and execution of marketing campaigns and promotional offers regularly conducted by Kogan. Mr Chee has responsibility for the monitoring and setting of the prices of products (including Apple and Samsung branded products) that Kogan ships from overseas and sells through its retail trading channels in Australia, including on Kogan's website. Mr Shafer’s affidavits affirmed on 10 October 2019 (first affidavit) and 11 March 2020 (fourth affidavit) and Mr Chee’s affidavit affirmed on 17 March 2020 were admitted as evidence in the proceeding. Both witnesses were cross-examined.

26 The ACCC was highly critical of Mr Shafer’s evidence, contending that some of his evidence lacked credibility and other parts did not rise above broad sweeping assertions, which were neither established in fact nor specific to Kogan’s conduct during the Tax Time Promotion. The ACCC further submitted that his evidence, even if accepted, did not support the inference for which Kogan contends, namely that ordinary and reasonable consumers would not have understood the promotional statements to convey any representation about past or future prices. Kogan, on the other hand, argued that the ACCC failed to comply with the rule in Browne v Dunn (1893) 6 R 67 (Browne v Dunn) in the cross-examination of Mr Shafer and it was not open to the ACCC to impugn the evidence he gave. Kogan also submitted that the evidence that the ACCC seeks to impugn was on issues that were irrelevant to the ACCC’s pleaded case and, if the evidence be relevant, Mr Shafer’s evidence was, in any event, supported by uncontroversial documentary evidence.

27 There were various inconsistencies in Mr Shafer’s evidence and if it were necessary to make findings of fact on controversial aspects of his evidence, the inconsistencies would bear upon the reliability and weight to be given to his evidence. However, ultimately, this case does not turn upon credit issues and despite the evidentiary controversies, the underlying facts regarding the operation of the Kogan website and the Tax Time Promotion were essentially not in dispute.

KOGAN

28 Kogan is an online retailer, trading primarily through four channels – the Kogan website, the Dicksmith.com.au website, the Dicksmith eBay store and the Kogan eBay store. The products it offers for sale through these channels are mostly third-party branded products which are sourced by Kogan from domestic and overseas third-party distributors, as well as a smaller number of products manufactured for Kogan by third parties and branded products it purchases directly from brand owners (or an official licensed distributor).

29 Kogan sets the prices of the products it sells on the Kogan website. Mr Shafer deposed that the prices change frequently, sometimes on a daily basis. The variability is caused by various factors such as product type, supply availability, wholesale costs, inventory levels, age of inventory, consumer demand and foreign exchange rates. Another factor is competitor pricing, as many of the products sold on the Kogan website are also sold by other major online retailers, such as eBay, Harvey Norman, Amazon, Groupon, Alibaba and JB Hi Fi. Mr Shafer deposed that Kogan has an aggressive price discounting strategy and constantly conducts price-based promotions for its products. Such promotions include price comparison sales, where the price charged for a product is compared with another price – typically, one of Kogan’s previous prices (eg, “was $100 / now $70”), a competitor’s price or the recommended retail price (RRP) – and discount/coupon code promotions, which offer a discount off, or reduction from, the listed price on Kogan’s website when a specific coupon code is applied at checkout.

TAX TIME PROMOTION

30 The Tax Time Promotion was a discount/coupon code promotion which applied to 78,111 products listed on the Kogan website. It enabled consumers to obtain a specified reduction of 10% off the price stated on Kogan’s website at checkout by entering the coupon code TAXTIME after the consumer had added the product to their shopping cart and prior to payment.

31 From 27 to 30 June 2018, Kogan advertised the Tax Time Promotion both on the homepage and on the individual product pages of the website. On the website homepage, and on each individual product page, the words “Use Code TAXTIME to reduce prices by 10% at checkout” were displayed prominently, in capital letters, in large white print on a red background, except for the word “TAXTIME” which was in a different and larger font, in red print on a white background. On the website homepage, the words were displayed prominently in the top middle of the page and the overall size of the banner was about four times as large as the surrounding images. On each individual product page, the words were displayed prominently in rectangular banners under the product image and at the bottom of the webpage. On the “list view” pages the words were displayed at the top of the page, in plain black print on a white background, with the word “TAXTIME” in capital letters. Examples are attached to these reasons in Annexure “A”. During the Tax Time Promotion, the website received 631,743 unique visitors.

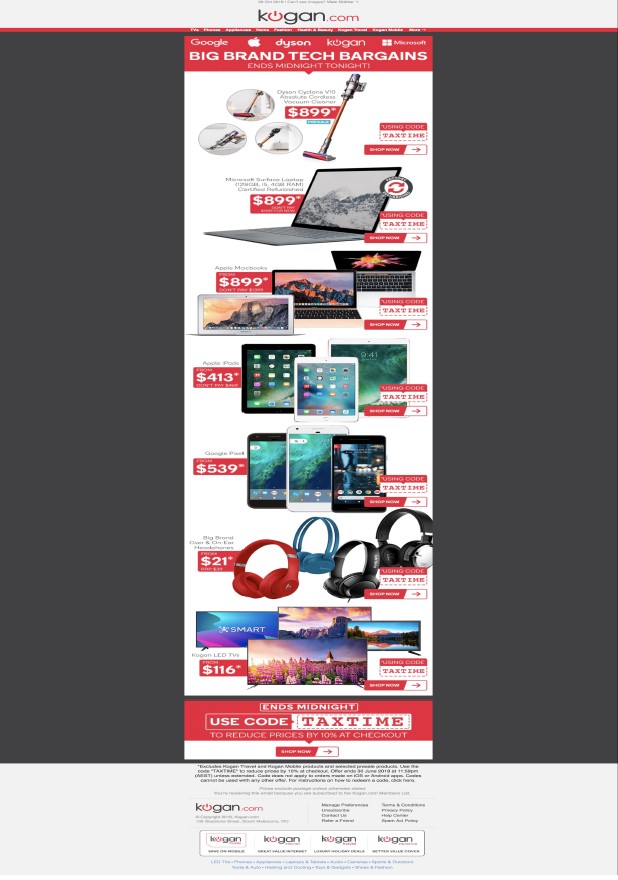

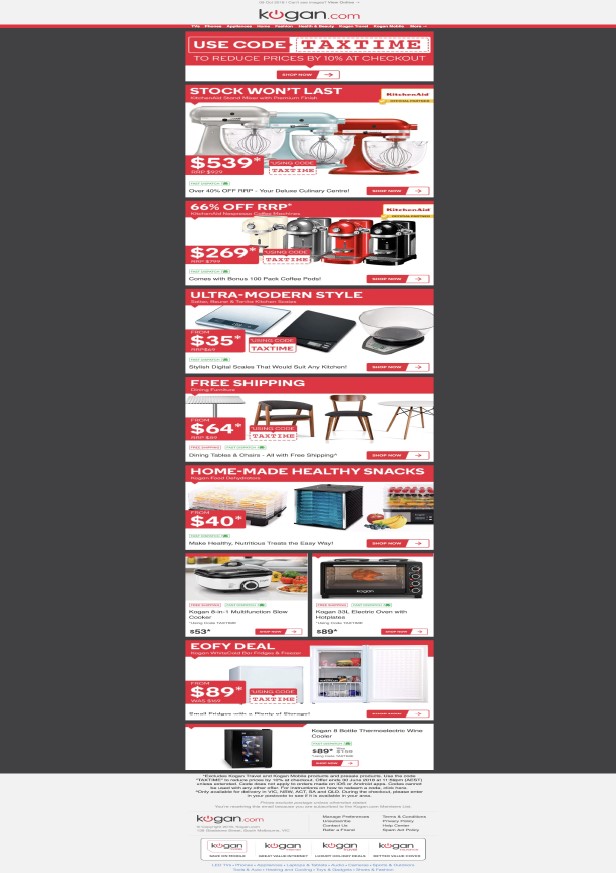

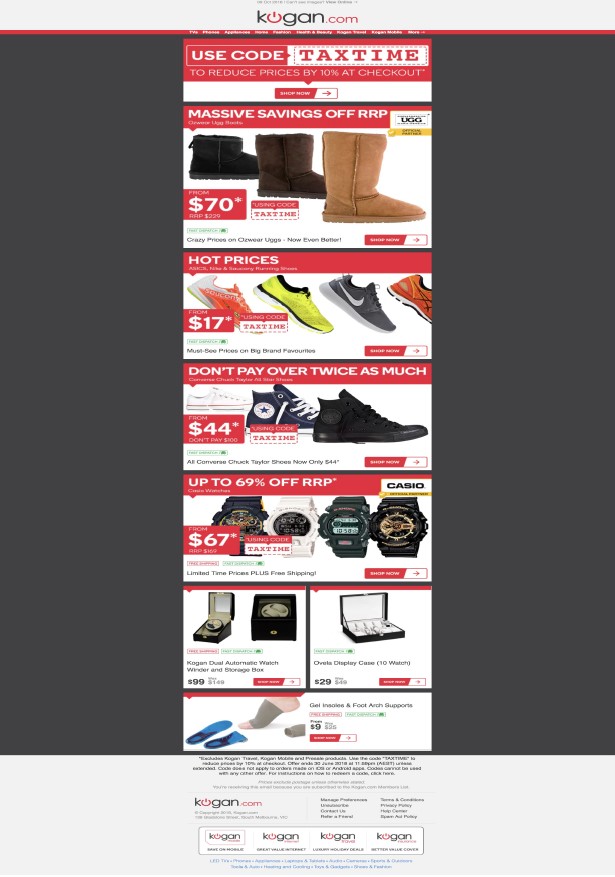

32 From 27 to 30 June 2018, Kogan also sent 25,696,963 eDM messages (being 12 separate eDM messages or between two and four eDM messages per day) to approximately 10,136,450 subscribing consumers. In the eDM messages, the words “Use Code TAXTIME to reduce prices by 10% at checkout” were also displayed prominently, in a similar way as the website. The words were displayed in all but two cases at the top of the message; in the other two messages the words were displayed at the bottom or middle of the message. Four of the eDM messages also included the words “ends midnight” or “48 hours left!” in capital letters, in two cases in a similar size and style print with a white border, and in the other cases in black print on a white background. All of the eDM messages included images of products offered for sale, almost all of which displayed the price of the product with the 10% Tax Time Promotion price reduction; that is, the product image displayed a price, accompanied by an asterisk, alongside the words “*using code TAXTIME”. The displayed products and prices included comparisons between those prices and other prices, including previous prices (“was/now”), RRP, and “don’t pay” prices. The eDM messages also included statements such as:

(a) under the heading “already on sale”, the words “already huge discounts – reduce by an extra 10%!”;

(b) “#frugalfriday – 48 hours left!” at the top of the page; and

(c) “Big Brand Tech Bargains Ends Midnight Tonight!” at the top of the page, with the words “Use code TAXTIME to reduce prices by 10% at checkout” and the words “ends midnight” at the bottom of the page.

33 Examples are attached to these reasons marked “B”. Of the 25,696,963 eDM messages sent to consumers during the Tax Time Promotion, a total of 3,367,910 were opened by consumers, and there were 249,106 clicks from the eDM messages directly to the website.

34 As well, on 27 June 2018, Kogan sent 930,142 SMS messages to subscribing consumers. The SMS messages included the recipient’s name and then stated, relevantly “use code TAXTIME to reduce almost all Kogan.com prices by 10% at checkout. Shop now [link] T&Cs Apply”. Consumers who clicked on the link in the message were taken to the website. Of the 930,142 consumers who received the SMS messages, there were 9,386 clicks directly to the website.

35 In his first affidavit, Mr Shafer deposed to another SMS communication being sent to subscribing consumers, stating “Use code TAXTIME to reduce prices by 10% at checkout”. That evidence was inconsistent with information which Kogan’s solicitors provided to the ACCC in response to a s 155 notice. At the hearing, Mr Shafer corrected that evidence in chief, stating that he could not recall whether that SMS was sent or if it was sent, to how many consumers it was sent. When asked questions about this in cross-examination, Mr Shafer could not recall or explain how the evidence came to be in his affidavit. He subsequently confirmed that no such SMS was sent. The ACCC submitted that the inconsistency in evidence and Mr Shafer’s explanation of it went to his credibility as a witness and the reliability of the evidence on behalf of Kogan in relation to the explanation for the price adjustments after the Tax Time Promotion. If it were necessary to make findings on credit, there may be some force in this submission, but on the view that I have taken of the matter, issues of credit are not material to the matters requiring determination in this proceeding.

CHECK-OUT PROCESS

36 Mr Shafer deposed that Kogan does not keep records of how the Kogan website looks at any given point in time in the past and for the purposes of the proceeding, the website was recreated to provide a representation of the checkout process on the website. Mr Shafer identified seven steps.

(a) step 1 is the Kogan website home page and when a consumer clicked the Tax Time banner, they were navigated to the “list view” page;

(b) step 2 shows the products within the list view section of the Kogan website. In the list view page, consumers could browse products. When the consumer found a product they were interested in, they could click on the image or product title to go to the product detail page and view more information about that product;

(c) step 3 was the specific product detail page, on which the consumer could see more specific information about a product, including the description, more images, the price and delivery details. This page also advertised the Tax Time Promotion banner for products subject to the Tax Time Promotion. When a consumer was ready to purchase they clicked “add to cart”;

(d) step 4 is that after the consumer clicked “add to cart” they landed on the shopping cart page. This page displayed all the products that the consumer had added to their cart. It is at this stage where a consumer could apply a discount code such as the “TAXTIME” code to their order. To do so they had to enter the code and then click the “Add discount” button to apply it to their order. A discount code box would only be displayed on this page if a product in the cart was eligible for the discount code;

(e) step 5 is the application of the code. After a consumer successfully entered a valid discount code, the code was accepted and the price of the product and total was updated. When a consumer hovered over “your total savings” heading, a tooltip appeared explaining the description of the savings. To proceed, the consumer clicked the “checkout” button;

(f) step 6 is the final view before making payment at a checkout. After clicking “checkout” the consumer was prompted to enter their name, email address, telephone number and delivery address for their order. The consumer was then presented with payment options to complete their purchase. After entering payment details the consumer clicked “confirm and pay” to complete the order; and

(g) step 7 is the confirmation of the order page where the consumer was given details about their completed order.

PRICE ADJUSTMENTS TO THE AFFECTED PRODUCTS

37 Mr Shafer’s evidence also addressed why the prices of the affected products were increased immediately before the Tax Time Promotion and then decreased immediately after the Tax Time Promotion.

38 In his first affidavit Mr Shafer deposed that the Tax Time Promotion was timed to coincide with a sales promotion on the Dick Smith eBay store offering 20% off the current advertised price for products from 27 to 30 June 2018 (eBay promotion). The discount was co-funded by Kogan as to 8% and eBay as to 12%.

39 Clause 17 of the agreement entered into between Kogan and eBay governing the conduct of the eBay promotion provided that:

During the Offer Period [Kogan] must maintain price parity between items listed on [Kogan’s] own website(s) (www.kogan.com.au and www.dicksmith.com.au) and any of [Kogan’s] items listed on www.ebay.com.au.

The “Offer Period” was defined as 10:00 am AEST on 27 June 2018 to 23:59 pm on 30 June 2018.

40 Mr Shafer deposed that Kogan’s products are typically priced at a premium on the Dick Smith eBay store as compared to the price for the same product on the Kogan website because eBay charges Kogan a “final value fee” to list its products on the Dick Smith eBay store, calculated as a percentage of the sale amount (generally around 10%). By reason of the price parity requirement, Kogan increased the prices of products on the Kogan website on 26 June 2018 so that those prices were the same as the higher prices charged for those products on the Dick Smith eBay store. In his first affidavit Mr Shafer initially stated that Kogan was “required” by the price parity requirement to increase the prices on the Kogan website. At the hearing, he amended that evidence to state that it was a “business requirement”, explaining that if Kogan reduced the prices on the eBay website to match the lower prices on the Kogan website in order to comply with the price parity requirement, Kogan would be selling those products at substantially below cost (taking account of the final value fee charged by eBay). Mr Shafer explained that the Tax Time Promotion was offered to avoid disadvantaging consumers in respect of the price increases on those products. He stated that Kogan preferred customers to purchase on its own website because it was more profitable and because it gives Kogan permission to send those consumers further marketing material. Mr Shafer also provided an explanation for the price decreases after the Tax Time Promotion but resiled from that evidence just before trial. In his fourth affidavit filed on the eve of the trial, Mr Shafer gave a different explanation for the price decreases in respect of the affected products. He deposed that the decreases in the prices of those products after the Tax Time Promotion were not due to the eBay price parity agreement coming to an end, but because Kogan decided to bear the cost of the GST (in the short term) which became payable under changes to the GST law as from 1 July 2018 on products which previously were not subject to GST, and because “there was a retail price reduction at some point during the two-week period following the Tax Time Promotion separately to the GST Strategy”. Mr Shafer further deposed that of the 621 affected products, four had price increases that were unrelated to the eBay price parity agreement. In respect of each of those four products, it was originally intended that the product would be listed on eBay and included in the concurrent eBay promotion. Kogan increased the price of those products on the Kogan website on that basis, however a decision was made not to list the products on eBay due to technical issues that occurred in the automation of product listings on eBay.

41 Mr Chee also gave evidence regarding the reason for the price decrease following the Tax Time Promotion. According to Mr Chee (who also swore his affidavit on the eve of the trial), Kogan decided on 2 July 2018 to reduce the GST-inclusive prices paid by consumers on products within his division (being the Global Brands division, which includes Apple and Samsung products). This was described by Mr Chee as a “re-pricing promotion” and Mr Chee’s evidence was that the purpose was to counter consumer expectations that prices for Kogan’s products would be going up because of the new GST laws and also to enable Kogan to compete on prices with several of its competitors based overseas. Kogan implemented this “GST strategy” in respect of all products in the Global Brands division, not just those products which became subject to GST for the first time as from 1 July 2018.

42 The ACCC contended that the “GST strategy” explanation was unconvincing, and it is open to the Court to infer that it was recently invented by Kogan to seek to justify its deliberate conduct in reducing prices immediately after the Tax Time Promotion, given that the explanation had not been put forward before, was inconsistent with the explanation previously given by Kogan to the ACCC in response to a s 155 notice – namely that at the end of the eBay promotional period, the price parity requirement no longer applied and Kogan adjusted its prices accordingly – and because Mr Shafer’s account of the GST strategy was vague, did not explain the price decrease on 2 July 2018 and was not aligned with Mr Chee’s account of the “re-pricing promotion”. It was submitted that it is highly unlikely that a director of Kogan, responsible for its corporate strategy and marketing, would only remember the “GST strategy” was relevant to Kogan’s pricing the day before the trial. The ACCC also urged the Court to be sceptical of Mr Shafer’s evidence in cross-examination that he explained the GST changes to his lawyers during the ACCC investigation and it was “self-evident” that the change in GST laws would affect the prices of those products. It was submitted that the Court should reject “the belated attempt” to justify Kogan’s conduct as reasonable or benign by reference to the GST strategy. It was further submitted that the inconsistent explanations for the price changes of the affected products affected the credibility of Mr Shafer’s evidence and the weight that should be given to his evidence.

43 It was argued for Kogan that it was not open to the ACCC to submit that the “GST strategy” was a recent invention as it was not put to Mr Shafer and the failure to put it to him infringed the rule in Browne v Dunn. It was further submitted that a finding was not required, in any event, as the reason for the decrease in the prices of the affected products was not an issue in this proceeding.

44 The rule in Browne v Dunn generally requires cross-examining counsel to put implications to a witness which counsel proposes to submit can be drawn from the evidence so that the witness has the opportunity to respond. In Allied Pastoral Holdings Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation [1983] 1 NSWLR 1, Hunt J described the rule in Browne v Dunn as follows (at 16):

It has in my experience always been a rule of professional practice that, unless notice has already clearly been given of the cross-examiner’s intention to rely upon such matters, it is necessary to put to an opponent’s witness in cross-examination the nature of the case upon which it is proposed to rely in contradiction of his evidence, particularly where that case relies upon inferences to be drawn from other evidence in the proceedings. Such a rule of practice is necessary both to give the witness the opportunity to deal with that other evidence, or the inferences to be drawn from it, and to allow the other party the opportunity to call evidence either to corroborate that explanation or to contradict the inference sought to be drawn.

The rule is an aspect of the principle that a trial must be conducted fairly, and where notice has been given that a witness’s account may be subject to challenge, the rule does not apply. Notice that the witness’s version of events may be subject to challenge may come from the pleadings or otherwise from the manner in which the case is conducted.

45 Such notice was given by the ACCC when it objected to the admission of the new evidence on the basis that it would want to test the new evidence but was not able to do so because it was not the case that the ACCC had come to meet. Such notice was sufficiently adequate. Further, although not directly put to Mr Shafer in cross-examination that the new evidence was a recent invention, it was put to Mr Shafer that the GST strategy explanation had not previously been put forward as the reason for the decrease in price on 2 July 2018 (as to which Mr Shafer eventually conceded that his fourth affidavit “could be the first express explanation of that fact”) and that the GST strategy did not explain the decrease in price on 2 July 2018 (as to which Mr Shafer disagreed). I am satisfied that Kogan and Mr Shafer were on notice that the ACCC may seek to challenge the account given by Mr Shafer in his fourth affidavit and Mr Shafer had the opportunity in cross-examination both to address the assertion that the GST strategy was put forward for the first time in the fourth affidavit and also the ACCC’s proposition that the GST strategy did not explain the decrease in price on 2 July 2018. Accordingly, I reject Kogan’s submission that it was not open to the ACCC to submit that the GST strategy was a recent invention. The criticism I would make of Mr Shafer’s fourth affidavit is that the change in his evidence just prior to trial called for an explanation which he did not provide, leaving the evidence in an unsatisfactory state and giving rise to the claim of recent invention being made.

46 However, I accept Kogan’s submission that a finding as to the reason for the price decrease is not required because, as the ACCC correctly acknowledged, the reasons Kogan decided to increase and decrease the prices of the affected products before and after the Tax Time Promotion are not an element of the alleged contravening conduct. The ACCC’s case is based on the mere fact of such increase and decrease in price and, as the ACCC stated in its written closing submissions, Kogan’s precise reasons for those decisions are “of no consequence to the ACCC’s case; nor do those reasons advance Kogan’s case”. Furthermore, as these reasons later demonstrate, the issues in this case do not turn on credit findings and the criticisms of Mr Shafer’s evidence advanced by the ACCC do not have any significant bearing upon the determination of the matters that are in issue.

47 If it were necessary to make such a finding, I would reject the ACCC’s claim of recent invention, as the second updated exhibit DS-1, annexed to Mr Shafer’s fourth affidavit as DS-27, provides some evidentiary foundation that none of the affected products which became subject to the new GST laws had their GST-inclusive prices increased on 1 July 2018. The third updated exhibit DS-1, annexed to Mr Shafer’s fourth affidavit as DS-28, also provides some evidentiary foundation for the factual finding which Kogan urged, namely that the price decreases of the affected products on 2 July 2018 were not due to the requirement for price parity with eBay coming to an end but rather were due to another promotion conducted by Kogan. Mr Chee’s evidence about the “re-pricing” promotion which commenced on 2 July 2018 is also consistent with DS-1. That said, the evidence does not support a finding that the price decreases of the affected products were due to the GST strategy. First, it appeared from the evidence that Kogan absorbed the GST which became payable on products subject to the new GST laws by not putting up the retail prices – that is, the price that consumers ultimately paid – of those products on 1 July 2018. Secondly, Mr Shafer gave evidence that the GST strategy was separate to the re-pricing promotion, although, contrary to his affidavit evidence, in cross-examination Mr Shafer did not accept that the GST strategy did not explain the retail price reductions on 2 July 2018. Thirdly and consistently, Mr Chee gave evidence that it was his belief that the products shown in the third updated exhibit DS-1 marked in red (which became subject to the new GST laws) did not have their prices put up on 1 July 2018 and all of the products in the third and the fourth updated exhibit DS-1 had their prices decreased on 2 July 2018 in accordance with the re-pricing promotion.

THE RELEVANT CLASS

48 There was no dispute about the relevant class of consumers, which the ACCC identified as prospective purchasers of the products offered for sale on the Kogan website and the consumers who had agreed to, and did, receive marketing communications from Kogan (target audience). Kogan also relied on evidence from Mr Shafer to impute to the ordinary and reasonable members of the target audience the following attributes and knowledge:

(a) past experience with the Kogan website;

(b) familiarity with internet shopping and the features of internet shopping displayed on the Kogan website of a “shopping cart”, a “checkout”, and “coupon codes”;

(c) familiarity with coupon code promotions and price comparison promotions and an understanding of the key difference between the two types of promotions, being that:

(i) coupon code promotions offer a reduction in the price of the product at checkout and operate by entering a coupon code in the checkout process; and

(ii) price comparison promotions offer a price reduction before the checkout and operate by comparing the currently available price of a product with another price – eg “was/now”, “don’t pay”, “beat the price rise” or the RRP;

(d) awareness that Kogan ran both types of promotions constantly and awareness that the promotions frequently overlapped;

(e) knowledge that the prices on the Kogan website are displayed next to the products before checkout and are subject to regular change; and

(f) some knowledge of the comparative prices in the market for the particular products they are interested in buying, though they may not necessarily be price sensitive.

49 The ACCC submitted that there was no basis on the evidence to impute such characteristics to all members of the target audience, and that Kogan had overstated the experience and knowledge that the relevant class of consumers would have in respect of Kogan’s particular website and processes. The ACCC argued that the relevant class could be expected to include consumers who were not repeat, let alone frequent, purchasers from the Kogan website and who had never purchased a product from Kogan. It was, however, not disputed by the ACCC that:

(a) some members of the target audience would have knowledge of, and experience using, the Kogan website;

(b) most members of the target audience would have experience purchasing consumer goods online and many would be familiar with internet shopping, shopping carts and checkouts generally;

(c) the target audience may have some experience with two-price comparison advertising and discount or coupon codes generally; and

(d) some members of the target audience may have been aware of comparative prices for particular products.

50 I accept the ACCC’s submissions. Mr Shafer gave evidence that of the customers who transacted on the Kogan website during the Tax Time Promotion to acquire an affected product:

(a) 29% had previously purchased products three or more times from the Kogan website;

(b) 12% had previously purchased products twice from the Kogan website;

(c) 20% had previously purchased products once from the Kogan website; and

(d) 39% had not previously purchased products from the Kogan website.

51 First, whilst on that evidence a majority of purchasers of the affected products were repeat customers to the Kogan website, a significant minority portion of the purchases made on Kogan’s website for the time period 27 to 30 June 2018 were by people who had not previously purchased a product on the Kogan website. Secondly, Mr Shafer’s evidence was that consumers can subscribe to receive the eDMs and SMS without having purchased a product from the Kogan website. Thirdly, the evidence was that a significant proportion of unique visits to the Kogan website during the Tax Time Promotion came other than from “clicks” on Kogan’s promotional communications. It is thus reasonable to infer that some members of the target audience would not have experience using the Kogan website and the relevant class, thus, should include members who were not familiar with the Kogan website, or familiar with Kogan’s promotions, and were not aware that Kogan’s prices frequently changed.

WERE THE REPRESENTATIONS MADE?

52 There was no dispute that the ordinary or reasonable member of the relevant class would have understood the words used in the promotional statements to mean a 10% reduction in price, or discount, if they used the Tax Time Promotion code. The dispute is over what the reasonable and ordinary member of the relevant class would have understood the relevant “price” to be: that is, whether consumers would have understood it to be the price at which the product was, or would be, available for sale for a reasonable period before or after the Tax Time Promotion (as the ACCC contended) or the then current listed price (as Kogan contended).

The ACCC’s submissions

53 The ACCC’s case was that the promotional statements, considered in the context in which those statements were made, impliedly conveyed the two representations alleged by the ACCC. The ACCC contended as follows.

54 First, the Tax Time Promotion was time-specific and time-limited, from which members of the relevant class would have understood there was a genuine 10% discount and a limited opportunity to obtain it:

(a) the words “Tax Time” were displayed prominently and as part of a recognisable theme advertised in the three days leading up to the end of the financial year (which, it was said, is a time synonymous with sales and discounts);

(b) the eDMs stated expressly that the Tax Time Promotion offer ended immediately before midnight on 30 June 2018, and included statements in capital letters emphasising “EOFY”, and “beat the price rise!” and other statements emphasising the time-related nature of the offer, such as “ends midnight tonight!”, “ends midnight!” and “48 hours left!”; and

(c) the subject lines and messages of the emails with the eDMs sent to consumers were said further to contextualise and emphasise the nature of the sale, the immediacy of the timing and urging consumers to act quickly, such as “48HRS Left of EOFY!”, “EOFY TV Madness! Reduce Prices by 10% using TAXTIME!*” and “Not long left - ends June 30”. Although only drafts of those emails were in evidence, Mr Shafer agreed in cross-examination that it was likely that the emails were sent with subject lines the same as those in the draft emails, save for the deletion of internal wording such as “forward proof launch” in the subject line.

55 Secondly, the Tax Time Promotion overlapped with advertising for Kogan’s “End of Financial Year” (EOFY) sale, from which consumers were likely to conclude that advertised prices would not increase before 1 July 2018 – that is, the price from which the consumer would obtain the discount was the price at which the product was advertised for sale during the EOFY sale, and consumers had a limited opportunity to obtain a genuine discount compared with the price at which the products would be available for sale after the financial year. In support, the ACCC emphasised that:

(a) the EOFY sale was advertised with an express representation that it lasted until 30 June;

(b) Kogan advertised that sale by way of eDM messages, in some cases in a similar getup to the Tax Time Promotion statements, using words relating to the EOFY and, in some cases, “tax time”;

(c) about 27 of the affected products were included in the EOFY sale and advertised at a particular price to last until 30 June. Those products were advertised under headings including “EOFY SALE ONLY UNTIL 30 JUNE”, “Top 10 EOFY deals”, “Blockbuster EOFY deals” and “the Best of the Big Brands: the hottest deals of EOFY”.

56 The EOFY sale was advertised from at least mid-June 2018. In cross-examination, Mr Shafer gave evidence that it was his belief from the form of the advertising of the EOFY sale that the prices of the products in the EOFY sale would have remained stable throughout the duration of the sale until 30 June 2018 and he accepted that consumers who saw the EOFY sale promotion would have expected the prices of products within that sale to remain the same until the end of the sale. Mr Shafer did not admit that any of the affected products were included in the EOFY sale, but he accepted that consumers may interpret some of the eDMs that contained a banner advertising the EOFY sale as including any affected products that were advertised in the same eDM.

57 Thirdly, like Kogan’s usual advertising, the Tax Time Promotion advertisements explicitly and implicitly compared prices of products to which the Tax Time Promotion discount applied with other prices, including for products that were already on sale (in the context of the ongoing EOFY sale), from which consumers were likely to conclude that the price which would be discounted using the Tax Time Promotion code was the price at which the product had been available for sale before the Tax Time Promotion. In support, it was said that:

(a) the Tax Time Promotion advertisements included prominent two-price comparisons in conjunction with the statement “using code TAXTIME”, comparing advertised prices with: “was” prices (such as jump starter “$89* was $199” next to the words “*using code TAXTIME”); RRP (such as KitchenAid Mix Masters “$539* RRP $929”, coffee machines “66% off RRP*” and “ultra modern kitchen scales from $35* RRP $69” next to the words “*using code TAXTIME”); and “don’t pay” prices (such as “Galaxy S9 from $809* don’t pay $1199” and “iPhone 8 Plus from $1106* don’t pay $1229” in conjunction with the statement “*using code TAXTIME”);

(b) the Tax Time Promotion advertisements also included statements such as “already on sale” and “Already Huge Discounts – Reduce By an Extra 10%!*”, and statements such as “EOFY deals” in conjunction with the price of the product “using code TAXTIME” and “beat the price rise” in conjunction with the price of various products “using code TAXTIME”. In cross-examination, Mr Shafer’s evidence was that “beat the price rise” meant the product would increase in price to the price with which the comparison was made (in the example on which he was cross-examined, the advertised office chair would increase from $170 – using the code TAXTIME – to $279 at some future date);

(c) the evidence showed that the prices at which products were advertised in the Tax Time Promotion eDMs were the prices with the Tax Time Promotion discount already applied (that is, the asterisk on the price was intended to refer to the words “using code TAXTIME”). By way of example, in the first eDM sent on 27 June 2018, Kogan advertised “iPhone 8 Plus from $1106* don’t pay $1229” in conjunction with the statement “*using code TAXTIME”. Annexure 3 to the ACCC’s concise statement (Annexure 3) (being a schedule prepared by the ACCC from data provided to it by Kogan pursuant to the s 155 notices containing pricing information for the affected products, including prices of those products before the increase on 26 June 2018 and after the decrease on 2 July 2018) showed that the price of the iPhone 8 Plus 64GB with the Tax Time Promotion discount applied was $1106 (in other words, the advertised price in the 27 June 2018 eDM was 10% off the then current listed price). Another example put forward was Kogan’s advertisement on 30 June 2018 of products including “Dyson Cyclone V10 Absolute Cordless Vacuum Cleaner $899*”, “Apple iPad from $413* don’t pay $469” and “Google Pixel from $539*” in conjunction with the statements “*using code TAXTIME”. Annexure 3 again showed that the then current listed prices of those products were the prices with the Tax Time Promotion discount code applied.

58 In cross-examination, Mr Shafer confirmed that wherever the eDMs used the words “using code TAXTIME”, the advertised price was the price after the application of the Tax Time Promotion discount code.

59 The ACCC also relied on consumer complaints about the prices during the Tax Time Promotion compared with the prices before, and in some cases after, the Tax Time Promotion, as evidence that ordinary and reasonable consumers understood the promotional statements to convey the alleged representations:

(a) a consumer who stated “putting your prices up by 10% to accommodate the ‘generous’ 10% off TAXTIME code. And you assume nobody would notice?”;

(b) a consumer who had identified the price advertised by Kogan for an iPad, went to the website to add the discount code TAXTIME “and the price jumped up”;

(c) a consumer who had identified the price advertised by Kogan for a LG V30+ phone “for at least the last 6 weeks”, noting they had been “regularly monitoring the phone”, and after receiving the Tax Time Promotion “offering a 10% discount at checkout”, logged back in to take advantage of that offer, and noticed that the sale price of the phone “has now increased, coincidentally, by almost exactly 10%”;

(d) a consumer who had identified the recent price of AirPods, then saw the price had increased and Kogan had a “‘10%’ off everything sale”, which the consumer described as “false advertising and unfair”;

(e) a consumer who had looked at the price of an iPhone X earlier in the week, then looked back again after seeing the Tax Time Promotion and realised “prices have conveniently been raised by 10%”;

(f) a consumer who had received an email from Kogan saying they had “a 10% discount on things like smart phones” but when the consumer looked at “getting 10% off the iPhone X” it seemed to the consumer that Kogan had raised its prices;

(g) a consumer who was going to purchase an Apple TV 4K, who noticed Kogan had “put the price back up” and stated that applying the 10% TAXTIME code discount “just brings it down to the same price it was basically so the taxtime code is just a gimmick on that particular product”;

(h) a consumer who received a “‘taxtime’ discount code” and looked at phones the consumer had been considering buying, noting the price a few days earlier and that “the exact same time the ‘sale’ was started” the price increased “to offset the discount”;

(i) a consumer, who had been researching prices of iPhones for over a month and had identified that the price of a particular phone had been stable, had received a Tax Time Promotion email from Kogan, and described the price as having increased, so with 10% off was “virtually exactly the same price – so there are NO taxtime savings”, stating “[t]hese false inflated sale prices are misleading and very annoying”. After the promotion, the consumer noted that the price of the iPhone had returned to the price observed before the promotion, repeating that “there was never a sale – just inflated prices to make people believe they would receive a 10% discount”;

(j) a consumer who received an eDM message about the Tax Time Promotion advertising a Samsung Galaxy S9 phone at $809 after TAXTIME discount, and noted that when he looked at the price on the website the next day, the price of the phone on the website was $900; the consumer also noted the phone was advertised at $899 on News.com.au with a direct link to the website where the price was “magically $999”;

(k) a consumer who received the TAXTIME “code promo” and decided to order a television and laptop, went to the website to order and found the prices had increased from the prices previously identified by the consumer, and noted that “[i]f you apply the 10% off the price on the TV is the same and the laptop has infact [sic] gone up in price”;

(l) a consumer who wanted to place an order for a Samsung Galaxy S9 but discovered the price “is much more than what it was a week ago” asking “[h]ow can price incraese [sic] if it is on promotion” and noting the phone had been promoted at a price of $899 with TAXTIME discount but when the consumer clicked on it the price changed to $999, which was higher than the price before the promotion, stating “in other words you are basically fooling people like us with this discount code”;

(m) a consumer who had been looking at a product two days earlier, noted the price, saw the Tax Time Promotion, and stated Kogan had increased the price for the product “effectively only saving $4”. The consumer noted this was “misleading consumers on the actual saving when you increase your price on products just before the 10% promotion deal”. After the promotion, the consumer noticed that the price had returned to the price noted before the promotion and described Kogan’s actions as “illegal and misleading”; and

(n) a consumer who complained that Kogan had increased the price of a Samsung Galaxy phone and noticed Kogan was also offering the TAXTIME discount and asked if Kogan “put…product prices up just before tax time then offer the discount to make it appear a good deal when in fact it is actually more expensive overall”.

60 Save for the complaints identified in pars (a), (i) and (k) above, the other complaints were about specified affected products. At least two of the affected products about which consumers complained were identified by the ACCC as products that also had been advertised at specific prices as part of Kogan’s EOFY sale. The ACCC submitted that it can be inferred from the content of those complaints that:

(a) the consumers were subscribed to receive Kogan’s eDM messages or SMS messages or had visited Kogan’s website: for instance, stating they had been regularly monitoring Kogan’s prices, had looked at prices in the week or days before the Tax Time Promotion, and had received Kogan’s marketing materials;

(b) the consumers were aware of the price at which the products were available for sale before the Tax Time Promotion and understood the statements to mean that they would receive 10% off that price (if they used the Tax Time Promotion code to purchase a product), but came to appreciate the true position upon visiting the Kogan website before purchasing the product. For instance, the complaints included statements such as: “putting your prices up by 10%”; “the price jumped up”; the price “has now increased, coincidentally, by almost 10%”; “prices have conveniently been raised by 10%”; Kogan “put the price back up… that just brings it down to the same price”; the price increased “to offset the discount”; the price with the code was “virtually exactly the same price – so there are NO taxtime savings”; “false inflated sale prices”; “if you apply the 10% off the price… is the same”; “how can price incraese [sic] if it is on promotion”; “misleading consumers on the actual saving when you increase your price on products just before the 10% promotion deal”; and putting “product prices up just before tax time then offer the discount to make it appear a good deal when in fact it is actually more expensive overall”;

(c) in some instances, consumers understood the promotional statements to mean they would receive a discount from the price at which the product had been available for sale before the Tax Time Promotion because it was specifically advertised as part of an EOFY sale and/or as on sale until 30 June; in other cases that understanding arose because consumers had observed ongoing stability in the prices or had observed the price advertised in the days or week before the Tax Time Promotion and asked that the discount be applied to the previously observed price; and

(d) consumers who noted the price had decreased after the Tax Time Promotion considered Kogan’s conduct had eroded the genuineness of the “sale”: for instance, two complaints noted that Kogan had reduced the price after the Tax Time Promotion to the same price as before the Tax Time Promotion and made comments including “there was never a sale – just inflated prices to make people believe they would receive a 10% discount” and described Kogan’s actions as “misleading”.

Kogan’s submissions

61 Kogan argued that the ACCC’s case had several “fatal” problems as follows.

62 First, the alleged representations were not clear and unambiguous. In particular, as to what constitutes a “reasonable period” and as to what was the “price at which these products were available for sale” in the reasonable period before and after the promotion – that is, whether it was the average price, medium price, lowest price, highest price or some other price, and in circumstances where the hypothetical ordinary and reasonable consumer would know that Kogan’s prices changed regularly and were not stable. Nonetheless, it was submitted, the alleged representations applied to all of the products which were part of the Tax Time Promotion, not just the affected products in issue, and the ACCC invited the Court to infer that the hypothetical ordinary and reasonable member of the target audience would identify an imprecise and different “reasonable period” covering each of the 78,111 products on the Kogan website that were subject to the promotion. It was submitted that the proposition that the hypothetical ordinary and reasonable member of the target audience would draw the representation of the discount coming off some unidentified, amorphous price in a reasonable period before or after the Tax Time Promotion was “fanciful”. It was also submitted that it was impossible on the evidence, as the ACCC was contending for a different reasonable period of price stability for each product and had only adduced the pricing history for approximately 4,408 products.

63 Secondly, in circumstances where the ACCC’s case was apparently an “implied comparison” case, Kogan submitted that the ACCC must identify the relevant comparator conveyed by the relevant statements to the hypothetical ordinary and reasonable member of the target audience. The pleaded comparator was the “price at which these products were [and would be] available for sale” during the “reasonable period” before and after the promotion. It was said that the ACCC failed in this regard because its alleged comparator was vague, imprecise and not supported by evidence as to the prices of the products on the Kogan website that were subject to the Tax Time Promotion. It was submitted that all of the price comparison cases concern express and identifiable price comparison prices and, in light of s 140(2) of the Evidence Act and the Briginshaw standard, the comparator must be identified with much more precision than how the ACCC had identified it in this case. It was also submitted that it is important to bear in mind that the ACCC had not brought a non-disclosure case alleging that Kogan misled consumers by not telling consumers about the price increases or price decreases with respect to the affected products. It was further submitted that the evidence also demonstrated that the prices of products on the Kogan website were not constant in the vast majority of cases in the two weeks either side of the Tax Time Promotion. Kogan submitted that in effect, the ACCC was running a “was/now” price comparison case without the “was” price.

64 Thirdly, contrary to the ACCC’s case, the ordinary and reasonable members of the target audience would not have understood the Tax Time Promotion as a price comparison promotion. Rather, the words “use code TAXTIME to reduce prices by 10% at checkout” and the words “use code TAXTIME to reduce almost all Kogan.com prices by 10% at checkout” in the advertisements for the Tax Time Promotion conveyed a coupon code promotion, which, as the hypothetical ordinary and reasonable consumer understood, was different in character to a price comparison promotion. A price comparison promotion involves the reduction in the listed price pre-checkout by reference to some other price, whereas the coupon code promotion works by giving a discount off the listed price at checkout.

65 Fourthly, alleged “reasonable period” representations were rejected in Australian Competition Consumer Commission v Woolworths Limited [2019] FCA 1039 (Woolworths) and Specsavers Pty Ltd v The Optical Superstore Pty Ltd [2009] FCA 692 (Specsavers).

66 Fifthly, the ordinary and reasonable members of the target audience would not have construed the statements relied on by the ACCC as conveying the alleged comparator (the “price at which these products were available for sale for a reasonable period” before and after the Tax Time Promotion) in circumstances where, not only is the concept vague and amorphous, but they would know that:

(a) Kogan runs regular promotions;

(b) prices on the Kogan website are subject to regular change; and

(c) the Tax Time Promotion involved a coupon “code”, which meant that a reduction would be applied at “checkout” from the price stated on the Kogan website.

67 Sixthly, Kogan argued that the ACCC’s case was not supported by the text of the communications. By way of illustration, Kogan pointed to the ACCC’s submission that the 10% Discount Representation, which included the notion that consumers would receive a 10% discount off the price at which the products were available for sale “a reasonable period before the promotion”, arose from the actual words used “to reduce prices” and the “general thrust” and dominant message of a price reduction or discount code promotion. However, the relevant communications said the “code” could be used to reduce prices by 10% “at checkout”. The words “code” and “reduce price… at checkout” were clearly identifiable to the hypothetical ordinary and reasonable member of the target audience as a reduction from the prices stated on the Kogan website next to the products prior to checkout (i.e. by the application of the “TAXTIME” coupon code at checkout). Unlike many other cases, here the words on which the Kogan relied (i.e. “at checkout”) were prominent. It was submitted that the ACCC’s case suffered from the vice identified by Gibbs CJ in Puxu (at 199): it “would be wrong to select some words … which, alone, would be likely to mislead if those words … when viewed in their context, were not capable of misleading … where the conduct complained of consists of words it would not be right to select some words only and to ignore others which provided the context which gave meaning to the particular words”.

68 Seventhly, Kogan contended that the alleged representations were extreme. On the ACCC’s case, the following scenarios, it was submitted, would be contrary to the alleged implied representations:

(a) if the price of any one of the 78,111 products which were subject to the promotion during the relevant period was greater by any amount than the price available a “reasonable period” before the promotion; and

(b) if the price of any one of the 78,111 products which were subject to the promotion during the relevant period was less by any amount than the price available a “reasonable period” after the promotion.

69 It was submitted that no ordinary and reasonable consumer would construe the relevant communications in that way, especially in the context of their knowledge that Kogan continually runs promotions and the prices on the Kogan website are subject to regular change. It was submitted that the impugned conduct (the alleged implied representations applying to the 78,111 products in the Tax Time Promotion) and the character of that conduct (as allegedly misleading in relation to the 621 affected products) should not be conflated.

70 Finally, it was submitted, the alleged implied representations failed to grapple with a relevant contextual matter, namely the end of the financial year and changes to GST legislation that occurred on 1 July 2018. The ordinary and reasonable members of the target audience would have expected prices on the Kogan website to be changing at that time of year, particularly when they were receiving from Kogan at that time various other promotions relating to the end of the financial year.

Consideration

71 In this case, context is of importance in evaluating whether the alleged representations were impliedly made because the imputations alleged by the ACCC do not arise on the express terms of the language used, if considered by reference to the language alone and without regard to context. However, when assessed in context, in my view the ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class would have understood the promotional statements to convey the representations alleged.

72 First, the eDMs advertised the Tax Time Promotion together with other promotions that Kogan was conducting at the time, including the EOFY sale, which was a two-price comparison sale. Examples of the eDMs are at Annexure “B”. Looking at the eDMs as a whole, the dominant message conveyed was a reduction or discount on the prices of the products offered for sale from the prices at which those products had previously been offered or would be offered for sale in the future. That dominant message was conveyed by the combination of the following in the layout of the eDMs:

(a) the feature of the advertisements was the display of the TAXTIME banner in a prominent position either at the top or at the bottom of the page;

(b) the Tax Time Promotion was also offered concurrently with the EOFY sale, which was a two-price comparison promotion and advertised under headings such as “EOFY deals”, “EOFY SALE ONLY UNTIL JUNE 30”, “Top 10 EOFY deals”, “Blockbuster EOFY deals” and “the Best of the Big Brands: the hottest deals of EOFY”;

(c) the promotional statements – “use code TAXTIME to reduce prices by 10% at checkout” – appeared in the same context as the promotion of two-price comparative pricing for products, e.g. “was/now”, “price/RRP”, “now/beat the price rise” and statements such as “ALREADY ON SALE”, “Already Huge Discounts – Reduce By an Extra 10%!*”;

(d) in some instances, the two-price comparisons appeared in conjunction with the statement “*using code TAXTIME”; and

(e) as well, the advertised prices for products to which the Tax Time Promotion applied were asterisked, identifying that the price was intended to refer to the discounted price.

73 The eDMs and SMSs sent to subscribing consumers enabled the consumer to click directly through to the website. The eDMs also explicitly and implicitly compared prices to which the Tax Time Promotion discount applied with other prices, from which the ordinary and reasonable member of the relevant consumer class was likely to conclude that the price which would be discounted using the Tax Time Promotion code was the price at which the product had been available for sale before the promotion or would be available for sale after the promotion. As stated, the eDM messages also included statements such as:

(a) under the heading “ALREADY ON SALE”, the words “Already Huge Discounts – Reduce By an Extra 10%!*”;

(b) “#frugalfriday – 48 hours left!” at the top of the page; and

(c) “Big Brand Tech Bargains Ends Midnight Tonight!” at the top of the page, with the words “Use Code TAXTIME to reduce prices by 10% at checkout” and the words “ends midnight” at the bottom of the page.

74 Secondly, Mr Shafer’s evidence was that the discount/coupon code form of promotion does not make a comparison against any previous or future price for the product or any competitor price for the product. But the advertised prices of products to which the Tax Time Promotion applied implicitly conveyed a two-price comparison because the advertised prices were the prices with the Tax Time Promotion discount of 10% already applied, with an asterisk noting “using code TAXTIME”. In some cases, the comparison was explicit. For example, an advertisement for smartphones showed the Galaxy S9 phone with the price $809* “don’t pay $1199” and the iPhone 8 plus “from $1106*” “don’t pay $1229”, both appearing beside the words “*using code TAXTIME”.

75 Thirdly, the Tax Time Promotion was a themed promotion that was time-specific and time-limited, from which consumers would have understood that there was a limited opportunity to obtain the reduced price.

76 Fourthly, some of the products advertised as part of the EOFY sale included products to which the Tax Time Promotion was shown also to apply. For example, the advertisement for small fridges showed:

77 I accept the ACCC’s submissions that the advertisements for the Tax Time Promotion, considered in context, blurred what Kogan described as the “key difference” between coupon codes and two-price comparisons, being that a coupon code “operates at the checkout after the price identified on the website, whereas the price comparison promotion offers a reduction before the checkout”. Further, although the ACCC did not dispute that the ordinary and reasonable member of the relevant class of consumers may have had some experience with two-price comparison advertising and/or discount or coupon codes generally, Kogan did not adduce evidence of any other coupon code promotions it offered or give any examples of such promotions, aside from evidence about how the Tax Time Promotion operated. In other words, it cannot be taken from the form of the advertising of the Tax Time Promotion that the ordinary and reasonable consumer would have understood that the discount at checkout was not a discount on either the price at which the product was offered for sale by Kogan before the promotion commenced or the price at which the product would be offered for sale after the promotion had concluded. Rather, in my view, the ordinary and reasonable consumer in the relevant class would be likely to have understood that the Tax Time promotion offered a 10% discount at checkout on past prices or future prices for the products to which the coupon code could be applied.

78 There was evidence given by Mr Shafer about the variability of Kogan’s prices, the frequency with which those prices changed and the reasons for the variability. Even if the ordinary and reasonable consumer in the relevant class understood that prices regularly changed on Kogan’s website, such knowledge does not gainsay the implication of the representations alleged.

79 There was also evidence given by Mr Shafer that coupon code promotions were “commonly used” by other major retailers in or around June 2018, including eBay, Amazon and Alibaba and that Australian consumers could find out from websites such as OzBargain, Cuponation Australia and Finder – Coupon Code finder what discount code promotions or other deals were on offer from the various online retailers, and in this way were able to compare the offers. Mr Shafer deposed that consumers were also able to compare prices for various products sold by Kogan and its competitors on dedicated price comparison websites such as GetPrice and Google Shopping, though as Mr Shafer agreed in cross-examination, these websites would not enable a consumer to track changes in a retailer’s prices over a period of time. The ACCC made submissions as to why the Court should give little weight to this evidence but it is unnecessary to address those submissions. Even if consumers understood how discount codes worked generally and could or did compare the coupon code promotions on offer at any one time, it does not follow that consumers would not have understood the promotional statements to convey the representations alleged.

80 Further, contrary to Kogan’s submission, the recreation of the checkout process did not make it clear that the Tax Time Promotion code “operated separately and in addition to any discount offered by Kogan relative to past prices for the specific product” in that the prices at steps 2, 3, 4 and 5 outlined above at [36] displayed “was/now” or strike-through prices where, if the Tax Time Promotion code was applied at step 4, then at step 5 the “was” stayed the same but the “now” price was reduced by a further 10%. Also at steps 4 and 5, the website displayed the words “your total savings in this order” with a dollar amount, described if the consumer hovered their cursor over the icon, as “[t]he total savings is the sum of all the savings on, and discounts that have been applied to, the items in your order”. If the Tax Time Promotion code was applied at step 4, the total savings displayed at step 5 would increase, but the savings from the Tax Time Promotion code were not identified separately. Further, step 4 required consumers both to enter the discount code and click the button “add discount” to obtain the Tax Time Promotion discount, which would take the consumer to step 5. If a consumer entered the code and then clicked “checkout” without also clicking “add discount”, the code would not be applied and the consumer would be taken straight to step 6. Step 6 (the checkout page) did not display the “was” amount, the savings or whether any discount codes had been applied. Mr Shafer in cross-examination stated that the customer “might” also have seen the price reduction from the Tax Time Promotion at step 6 (and the recreation might have missed that feature), but he agreed he couldn’t be confident about that. It is also reasonable to infer from Kogan’s evidence that 48% of all sales orders during the Tax Time Promotion were made without the discount code that consumers may have been confused about how the discount code applied, in that consumers may have expected that the discount had already been applied to the products prior to checkout because the advertised price in the eDMs included the “TAXTIME” discount already applied, and thus may not have understood they were required to add the coupon code at checkout. As stated, whilst consumers in the relevant class may have had some experience with two-price comparison advertising and coupon code promotions generally, the distinction between the two forms of promotion was blurred in the Tax Time Promotion because the advertisements for the Tax Time Promotion, which was a discount code promotion, used two-price comparisons including “was/now” pricing and “don’t pay” price comparisons in conjunction with the statement “using code TAXTIME”.