FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Siemens Industry Software Inc v Telstra Corporation Limited [2020] FCA 901

ORDERS

Prospective Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The prospective applicant have leave to file:

(a) the Affidavit of Jonathan Harris affirmed 19 May 2020; and

(b) the Confidential Affidavit of Saurabh Bose affirmed 11 March 2020 in Singapore (subject to the restrictions set out in Order 2, below).

2. Until further order and on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, pursuant to section 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth), publication or any other form of public disclosure of the following materials which are confidential to the applicant:

(a) Confidential Affidavit of Saurabh Bose affirmed 11 March 2020;

be prohibited other than to:

(i) the Court;

(ii) the legal representatives of the respondent (including solicitors, support and administrative staff, and Counsel); and

(iii) other persons with the prior written consent of the applicants, provided such persons have provided signed undertakings in accordance with the confidentiality regime agreed by the parties.

3. The respondent within 14 days give discovery to the prospective applicant of all documents that are in its control relating to the identity of the registered Telstra account holders for the IP addresses which were in use at the times indicated set out in the attached Schedule A, but need not discover any information or material the disclosure of which is not required or authorized because of the operation of section 280(1B) of the Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth).

4. The prospective applicant pays the respondent’s costs of compliance in respect of these Orders in the sum of $18.00 per IP address.

5. The prospective applicant:

(a) is not permitted to disclose to any third party the name and address of any Telstra account holder disclosed to the prospective applicant pursuant to Order 3, other than agents or representatives of the prospective applicant, who are to be notified of and are also bound by this Order;

(b) is permitted to use the information disclosed pursuant to Order 3 only for purposes relating to the recovery of compensation for infringement, including:

(i) seeking to identify the end-users who have installed the NX and Solid Edge software programs;

(ii) bringing proceeding against end-users for infringement of copyright in the NX and Solid Edge software programs; and

(iii) negotiating with end-users regarding their liability for such infringement.

THE COURT NOTES:

1. The undertaking given to the Court by the prospective applicant that:

(a) it will not pursue any action against any individual who has not made commercial use of any of the asserted software products;

(b) it will send to any prospective respondent identified as a result of the production of documents in accordance with these orders a letter in the form set out in the attached Schedule B.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SCHEDULE A

SCHEDULE B

OUR REF: GSH: [lnsert Details]

[Insert Date]

[Addresses]

[Insert Address for Addressee]

ALSO BY EMAIL: [Insert Email Address]

BY EXPRESS POST

Dear Sirs,

RE: SIEMENS INDUSTRY SOFTWARE INC - UNLICENSED INSTALLATION AND USE OF SOFTWARE

We act for Siemens Industry Software Inc. (Siemens).

Siemens is the owner of the copyright in the [name of product] including all its various versions, releases, upgrades and updates (collectively, the Software). As the owner of the copyright in the Software, Siemens has the exclusive right to, among other things, reproduce the Software and to authorise others to do the same.

As a result of obtaining an order under rule 7.22 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) for preliminary discovery from your ISP, Telstra Corporation Limited, our client has reason to believe that on the dates and times specified below you used the Software installed on the computers identified with the MAC addresses set out below.

MAC Address | IP Address | Date | Time |

You are not licensed to install or use the Software.

Section 36(1) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (Act) provides that the copyright in a literary work (such as a software program) is infringed where a person, without the licence of the owner, does or authorises the doing of an act comprised in the copyright.

Section 36(1A) of the Act provides that in determining whether or not a person has authorised the doing of any act comprised in the copyright in a work, without the licence of the owner of the copyright, the matters that must be taken into account include the following:-

1. the extent (if any) of the person's power to prevent the doing of the act concerned;

2. the nature of any relationship existing between the person and the person who did the act concerned; and

3. whether the person took any reasonable steps to prevent or avoid the doing of the act, including whether the person complied with any relevant industry codes of practice.

Section 115(2) of the Act entitles Siemens to recover damages or account of profit for unlicensed reproduction of its Software or the authorisation of such reproduction. Damages are often calculated on the basis of the licence fee lost by the owner of the copyright due to the unauthorised reproduction of the Software.

In addition, section 115(4) of the Act permits Siemens to obtain additional damages for breach of copyright having regard to the flagrancy of the infringement; the need to deter similar infringements; the conduct of the respondent after the act constituting the infringement; and any benefit shown to have accrued to the respondent (refer to section 115(4)(b) of the Act).

Where you had no reasonable basis for believing that the use of the Software was infringing, you may have a defence to a claim for damages and only be liable for an account of profit (refer to section 115(3) of the Act).

Siemens has invested substantial time, effort and resources in developing and manufacturing its Software, and will not hesitate to take all steps as may be necessary to protect its intellectual property rights, including bringing an action in Court for the appropriate orders, as necessary.

Siemens would however prefer to settle this matter amicably without resorting to legal proceedings.

We are instructed to request that you or your solicitor contact the writer by 5:00 pm on [insert date] agreeing to attend a settlement conference with our client's representative [insert details] in the week beginning [insert date] for the purpose of seeking a consensual resolution of this matter.

Any such resolution may include the following elements:-

1. appropriate financial compensation for past infringement;

2. the acquisition by you of all licences necessary to ensure that all copies of Siemens' software used by you or installed on computers in your possession or control are licensed; and

3. an undertaking by you to refrain from any unauthorised use or copying of Siemens' software in the future.

Please note that any attempt to erase copies of software already installed on computers can be detected. Such copies may be required as evidence in the event that proceedings are commenced.

Siemens reserves its rights to pursue financial compensation pending the outcome of the settlement conference proposed.

This letter is sent in accordance with section 4 of the Civil Dispute Resolution Act 2011 (Cth).

All our client's rights are reserved.

Yours faithfully

BURLEY J:

1. INTRODUCTION

1 The prospective applicant, Siemens Industry Software Inc, is engaged in the business of developing, publishing and distributing software. It seeks an order pursuant to r 7.22 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (FCR) requiring the respondent, Telstra Corporation Limited, to give discovery to Siemens of all documents that are in Telstra’s control relating to the identity of various registered Telstra account holders. Siemens is considering commencing proceedings against those registered account holders for infringement of s 36(1) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), but contends it does not have sufficient information to ascertain the identities of those account holders in order to seek relief.

2 At the first return date of the matter on 21 May 2020, counsel for Siemens, Mr Julian Zmood, sought that the matter be determined on the papers without an oral hearing. Siemens relies on a letter dated 18 May 2020 sent by Telstra to Siemens, which states that Telstra does not consent to or oppose the application, and would not appear on 21 May 2020. Telstra asked that the letter be provided to the Court. Based on that correspondence, I gave leave to Siemens to file written submissions in support of the application, which it has done. Telstra has filed no appearance in the proceedings. For the reasons set out below, I consider it appropriate to grant orders substantially in the form sought by Siemens.

3 Siemens relies on the evidence of Saurabh Bose, its Senior Director and Head of License Compliance in Asia Pacific/Australia and New Zealand. Mr Bose affirmed two affidavits on 11 March 2020, one that is open and has been filed and another that Siemens contends contains confidential information and in respect of which it seeks a suppression order pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (FCA Act). It also relies on affidavit sworn by Jonathan Harris, a paralegal in the employ of Harris & Company, solicitors for Siemens.

4 FCR r 7.22 provides:

Order for discovery to ascertain description of respondent

(1) A prospective applicant may apply to the Court for an order under subrule (2) if the prospective applicant satisfies the Court that:

(a) there may be a right for the prospective applicant to obtain relief against a prospective respondent; and

(b) the prospective applicant is unable to ascertain the description of the prospective respondent; and

(c) another person (the other person):

(i) knows or is likely to know the prospective respondent’s description; or

(ii) has, or is likely to have, or has had, or is likely to have had, control of a document that would help ascertain the prospective respondent’s description.

(2) If the Court is satisfied of the matters mentioned in subrule (1), the Court may order the other person:

(a) to attend before the Court to be examined orally only about the prospective respondent’s description; and

(b) to produce to the Court at that examination any document or thing in the person’s control relating to the prospective respondent’s description; and

(c) to give discovery to the prospective applicant of all documents that are or have been in the person’s control relating to the prospective respondent’s description.

…

5 To meet the requirements of FCR r 7.22 it is necessary for Siemens to satisfy the Court that it may have a right to obtain relief against a prospective respondent, that it cannot identify the prospective respondent and that Telstra knows or is likely to know the identity of that person or have a document which reveals it. In addition, the definition of ‘prospective applicant’ in FCR r 7.21 as a person who “reasonably believes that there may be a right for the person to obtain relief against another person who is not presently a party to a proceeding in the Court” means that Siemens must possess such a belief and that belief must be reasonable: Dallas Buyers Club LLC v iiNet Limited [2015] FCA 317; 245 FCR 129 at [52] (Perram J).

2. THE EVIDENCE

6 Siemens contends that it may have a right to obtain relief against 20 prospective respondents for infringement of copyright in certain computer software that it owns. Mr Bose explains in his affidavit evidence that Siemens is a subsidiary of Siemens AG, a substantial enterprise which generated €83 billion and net income of €6.1 billion in the financial year ending 30 September 2018. Siemens is incorporated in the United States of America and is a business unit of the Siemens Digital Industries Division of Siemens AG. Siemens engages in the development, publishing and distribution of software. Of present relevance is a suite of what it terms “high-end product lifecycle management software” (PLM software), which assists companies in the efficient management of the entire lifecycle of a product (from design through to manufacture, service and disposal). The PLM software is said to be extremely sophisticated. It is primarily used to model real-world products and test how these will perform under real-world conditions, without having to build them, thereby saving their users time and costs. As an illustration, the PLM software can be used to create a computerised model of a product, develop a physical product from the model, and put it to use, with little or no physical testing.

7 The parts of the PLM software relevant to the present application fall into two categories, being the NX software and the Solid Edge Software (collectively, the asserted software), including various versions, releases, upgrades and updates of this software. Siemens claims to own the copyright in this software.

8 Mr Bose provides details to support the claim to ownership. He states that the asserted software were first published in the USA after 1980 and that Siemens’ name appeared on it. He gives evidence that in the United States, Siemens has registered the copyright in at least 14 of the most recent versions of the NX software and 13 of the most recent versions of the Solid Edge Software, and exhibits each of these. He also deposes that the exterior packaging, computer media, manuals and related documents for all of the asserted software prominently display copyright notices that identify Siemens as the owner of the copyright. He exhibits non-exhaustive samples of discs which illustrate this point.

9 Mr Bose gives evidence that the asserted software is comprised of numerous modules that are individually licenced to end users. As examples of the pricing for the most commonly used individual modules (including the first year of maintenance support), he provides the amounts of $60,072.00, $12,569.00, and $41,602.00, and for the prices of what he terms representative bundles of some of the most commonly purchased modules of the asserted software, he provides the amounts of $337,514.45 (for the NX software) and $88,440.47 (for the Solid Edge software). It is apparent from the evidence that the asserted software is likely to be used for business purposes, and is of considerable commercial value.

10 In order to prevent and detect copyright infringement Siemens has developed and uses an “automatic reporting function” or ARF, which it has embedded in each of the asserted software products. It cannot be removed or “switched off” from the asserted software. The details of the operation of the ARF are set out in the confidential affidavit affirmed by Mr Bose. Having regard to the evidence given by Mr Bose, I am satisfied that it is appropriate for the information contained in the confidential affidavit to be the subject of a suppression order pursuant to s 37AF of the FCA Act.

11 The ARF is capable of identifying the computer on which unlicensed copies of the asserted software are used by collecting data related to the source of that use, when that computer is connected to the internet. The primary method of copyright infringement about which Siemens is concerned is where the alleged infringer uses versions of the asserted software that have been “cracked” or tampered with by a person or (more likely) a company who is licensed to use some, but not all of the asserted software. The cracking allows the infringer to have full access to all of the modules of the asserted software without having paid to licence them. In his confidential affidavit, Mr Bose describes how the ARF is able to inform Siemens that its software has been tampered with. The process results in the production of an ARF report that can be extracted by Siemens containing information about the unauthorised use. Sometimes the information generated in an ARF report is sufficient to identify the person responsible for cracking the software. On other occasions, the details are insufficient, and only a general company or email domain is given (such as “telstra.com.au”, or “outlook.com”) and the only unique identifier captured within the report is an IP address. If a static IP address has been assigned to a specific entity, rather than an internet service provider (ISP), then a search of the publicly available register of IP addresses will resolve to a particular entity that is likely to be the alleged infringer. If the IP address resolves to an ISP, then the alleged infringer is, according to Mr Bose, likely to be a subscriber of the ISP.

12 Mr Bose gives evidence as to how Telstra would be able to identify an alleged infringer for the purpose of the present application. He says that when an ISP provides its subscribers with access to the internet, the subscriber will provide personal and contact information for, amongst other things, identification and billing purposes. An ISP will also maintain user logs recording access to the internet by the subscriber, including the specific time and date when a particular IP address was used to access the internet.

13 Having regard to the content of the logs associated with a particular IP address, and the information obtained from an ARF report, the ISP will, Mr Bose contends, be able to identify the alleged infringer of the asserted software.

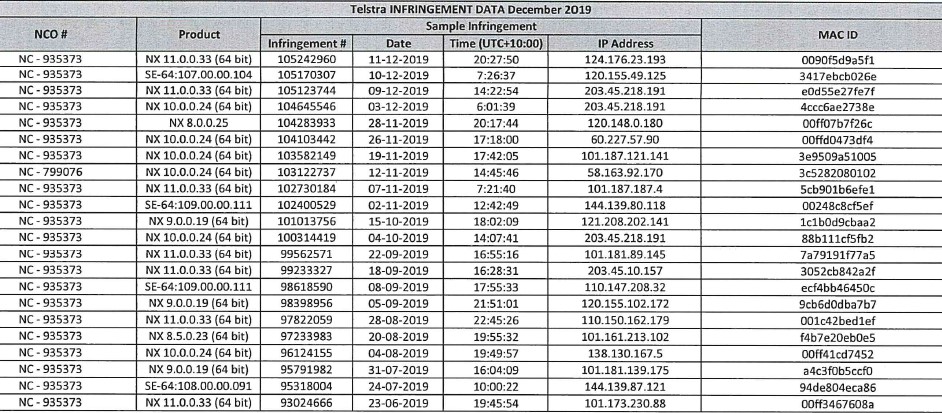

14 Mr Bose gives evidence that he has supervised the extraction of various ARF reports to identify the IP addresses and the corresponding dates and times in respect of which information in the present application is sought. In a document that he has prepared, he lists all the IP addresses of the users who have carried out what he contends to be the unlicensed use of any of the asserted software together with the corresponding date and time those instances occurred. He has identified 20 potential infringing users of the asserted software who are Telstra subscribers.

15 Mr Bose deposes that based on the data contained in the ARF reports, Siemens has good reason to believe that there have been multiple instances of unlicensed use of the asserted software and accordingly multiple instances of copyright infringement. However, the information available does not reveal any information that will enable Siemens to ascertain the identities of the alleged infringers. Without that information, he considers that it is impossible to pursue legal action.

16 Mr Bose refers to correspondence between Harris & Company and Telstra. In an email dated 6 January 2020, Telstra responded in brief terms to a request that information of the type to which I have referred be supplied:

Due to privacy reasons, a coercive instrument such as a court order will need to be served on Telstra in order for us to disclose customer information. [an address for service is then provided] ...Please be advised that our cost to perform a query [sic] on one IP address to produce any account information is $18.

17 Mr Bose states that Siemens intends only to seek relief under the Copyright Act against commercial organisations using the asserted software for commercial purposes and without licence. He offers an undertaking on behalf of Siemens that it will not pursue any action against any individual who has not made commercial use of any of the asserted software. He supplies a draft letter that Siemens would undertake to send to any alleged infringer.

3. CONSIDERATION

18 Section 36 of the Copyright Act provides:

Infringement by doing acts comprised in the copyright

(1) Subject to this Act, the copyright in a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work is infringed by a person who, not being the owner of the copyright, and without the licence of the owner of the copyright, does in Australia, or authorizes the doing in Australia of, any act comprised in the copyright.

(1A) In determining, for the purposes of subsection (1), whether or not a person has authorised the doing in Australia of any act comprised in the copyright in a work, without the licence of the owner of the copyright, the matters that must be taken into account include the following:

(a) the extent (if any) of the person’s power to prevent the doing of the act concerned;

(b) the nature of any relationship existing between the person and the person who did the act concerned;

(c) whether the person took any reasonable steps to prevent or avoid the doing of the act, including whether the person complied with any relevant industry codes of practice.

…

19 Siemens contends that it is the owner of copyright in the asserted software and that the Court should be satisfied that it may have a right to obtain relief against another person who is not presently a party to this proceeding. Siemens also contends that it reasonably believes that it has such a right.

20 Siemens is not required to demonstrate the existence of a prima facie case; however, FCR r 7.22 is not to be used in favour of a person who intends to commence merely speculative proceedings, and so a material factor in the exercise of the Court’s discretion is the prospect of Siemens succeeding in proceedings against the alleged infringers: Hooper v Kirella Pty Ltd [1999] FCA 1584; 96 FCR 1 (Wilcox, Sackville and Katz JJ) at [33] and the cases cited therein.

21 On the basis of the material before me I consider that this threshold has been met. I do not, by this finding, pre-judge the outcome of any proceedings that ultimately may be brought.

22 The evidence indicates that Siemens will be entitled to rely on relevant presumptions going to the ownership and subsistence of copyright in the asserted software on the basis of ss 126A(2) and 126B(2) of the Copyright Act, concerning labels and marks, and the presumptions of ownership contained in ss 126A(3) and 126B(3), concerning foreign certificates. In relation to the former, Siemens points to the exhibited examples of the packaging for the “NX 9” and “Solid Edge with synchronous technology 6” software programs, each bearing a label or mark stating the year of first publication or making by Siemens Product Lifecycle Management Software Inc as being 2013. Furthermore, Mr Bose deposes that the exterior packaging, computer media and manuals of the original versions of the software products published in 1980 prominently displayed copyright notices that identify Siemens as the owner of the copyright in the relevant works. In relation to the latter, Siemens is able to rely on the copyright certificates issued by the United States Copyright Office, which form the basis for a presumption that it was the owner of the asserted software at the particular date set out in each certificate. In this regard the certificates exhibited indicate that Siemens Product Lifestyle Management Software Inc, the name of Siemens prior to 21 October 2019, was the owner of copyright in versions NX 5 – 12 and Solid Edge with synchronous technology versions 1.0 to 9.

23 In relation to the alleged infringement, the ARF provides a logical basis upon which Siemens may consider it likely that when data is generated in an ARF report, a material reproduction of the asserted software has taken place without licence.

24 Having regard to the process described in the affidavit evidence, it does appear that a person responsible for cracking the software may be liable for infringement of copyright. Whilst it is true that Siemens has not provided details that might enable an assessment to be done of how much of the source code has been reproduced, it is reasonable to infer that the purpose of obtaining unauthorised access to otherwise secure (and unlicensed) portions of the asserted software is to enable a user to run those portions of the software without paying a licence fee for that access. A work is “reproduced” if there is a sufficient degree of objective similarity between the copyright work and the work said to infringe and there is “some causal connection” between the form of the allegedly infringing work and the form of the copyright work: SW Hart & Co Pty Ltd v Edwards Hot Water Systems [1985] HCA 59; 159 CLR 466 at 472 (Gibbs CJ, with whom Mason and Brennan JJ agreed). Each time that a portion or the entirety of the asserted software is loaded onto a computer hard drive, that software will be reproduced: see University of Sydney v ObjectiVision Pty Limited [2019] FCA 1625; 148 IPR 1 at [640] – [648] (Burley J).

25 In the circumstances outlined above, it would follow that by obtaining access to and then running the software, an alleged infringer makes an unauthorised reproduction of a substantial part (see s 14(1) of the Copyright Act) of the literary work represented by the object code in the asserted software.

26 It is apparent from the evidence that Siemens is unable to ascertain the description of the prospective respondents on the basis of the material currently available to it: FCR r 7.22(1)(b). The word ‘description’ is defined in the Dictionary to the FCR as follows:

(a) for a person who is an individual — the person’s name, residential or business address and occupation;

(b) for a person that is not an individual:

(i) the person’s name; and

(ii) the address of one of the following:

(A) the person’s registered office;

(B) the person’s principal office;

(C) the person’s principal place of business.

27 Mr Bose gives evidence of the attempts that Siemens has made to ascertain the description. It has deployed apparently sophisticated anti-piracy software to no avail. It has made enquiries to Telstra. Whilst FCR r 7.22 does not contain any express requirement that a prospective applicant have made reasonable enquiries, the authorities have taken that to be an implicit requirement: see John Bridgeman Limited v Dreamscape Networks FZ-LLC [2018] FCA 1279; 360 ALR 768 (Rangiah J) at [9]. I consider that requirement to have been satisfied.

28 For the reasons set out in Mr Bose’s evidence, I am also satisfied that another person, here Telstra, knows or is likely to know the prospective respondents’ description or is likely to have control of a document that would help to ascertain the prospective respondents’ description within FCR r 7.22(1)(c). In this regard “Document” in the FCR is defined as:

(a) any record of information mentioned in the definition of document in Part 1 of the Dictionary to the Evidence Act 1995; and

(b) any other material, data or information stored or recorded by mechanical or electronic means.

29 It appears from the evidence that Telstra is likely to have documents of the type in respect of which discovery is sought.

30 Finally, the grant of preliminary discovery is subject to the exercise of the Court’s discretion that it is appropriate. Siemens has been alert to various considerations that were taken into account in Dallas Buyers Club (at [73] – [91]), and in particular to privacy concerns that arise from the protections afforded to persons under s 276(1)(a)(iv) of the Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth) and Privacy Principle 6.1 of the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth), which limit the ability of Telstra to disclose personal particulars of other persons. Siemens draws attention to s 280(1)(b) and Privacy Principle 6.2(b) (respectively) of those Acts, which would permit Telstra to release such information if required to do so by the Court.

31 Nevertheless, to address concerns that any information received be used appropriately, Siemens proposes a form of orders that restricts the uses to which the information can be put, along the lines of the orders made in Dallas Buyers Club (see [83] – [87] and Dallas Buyers Club LLC v iiNet Limited (No 3) [2015] FCA 422; 327 ALR 695 (Perram J) at [22]), namely that the information be used only for the purpose of the recovery of compensation of infringement of copyright, including by: seeking to identify the end-users who have installed the asserted software; suing end-users for infringement of copyright in the asserted software; and negotiating with end-users regarding their liability for such infringement. Siemens has also offered an undertaking to the Court that it will not pursue any action against any individual who has not made commercial use of any of the asserted software products. The proposed form of orders and undertaking are, in my view, appropriate to address legitimate privacy concerns.

32 The Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Amendment (Data Retention) Act 2015 (Cth) (the Amendment Act) introduced Part 5-1A entitled “Data retention” into the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 (Cth). It includes various requirements that ISPs must keep certain personal information including names, addresses, and billing information for a prescribed minimum period: s 187C. Section 187BA imposes an obligation on the provider to ensure the confidentiality of the information stored. The Amendment Act also introduced s 280(1B) to the Telecommunications Act, which provides that information that is kept “solely for the purpose of complying with Part 5-1A” of the (Interception and Access) Act cannot be disclosed except in certain prescribed circumstances. Unlike the other privacy provisions to which I have referred, an order of the court in civil proceedings is not one of those circumstances, which is a reflection of the intention of the legislature to ensure that data available to litigants is neither increased nor reduced by the data retention obligations introduced in the Amendment Act: see the Revised Explanatory Memorandum to the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Amendment (Data Retention) Bill 2015 (Cth) at [165] – [169].

33 The orders proposed by Siemens do not address the data retention provisions introduced by the Amendment Act. For the avoidance of doubt, in my view it is appropriate that the order requiring preliminary discovery make clear that Telstra need not discover any information or material the disclosure of which is not required or authorized because of the operation of section 280(1B) of the Telecommunications Act. This was the approach adopted in All Trades Queensland Pty Ltd v Telstra Corporation Limited [2016] FCA 1603 (Dowsett J).

34 I will make orders accordingly.

I certify that the preceding thirty-four (34) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Burley. |

Associate:

Dated: 26 June 2020