FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Caffitaly System S.p.A v One Collective Group Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 803

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Claims 1, 2, 9, 16 and 17 of Australian Patent No. 2003200627 be revoked.

2. Claims 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 14 of Australian Patent No. 2010227121 be revoked.

3. Claims 34, 35 and 36 of Australian Patent No. 2008259388 be revoked.

4. The amended originating application be dismissed.

5. Within 14 days, the parties file and serve (by way of exchange) written submissions (limited to 3 pages in length) on the question of costs.

6. Within 21 days, the parties file and serve (by way of exchange) any written submissions in reply (limited to 2 pages in length) on the question of costs.

7. Upon the applicant, by its counsel, undertaking to the Court during the period of the stay:

A. to prosecute any appeal expeditiously;

B. forthwith to serve on the Commissioner of Patents copies of these orders pursuant to s 140 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) with a request that particulars of Orders 1, 2 and 3 (“the Revocation Orders”) be registered in accordance with s 187 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth); and

C. not to commence any proceeding (apart from any appeal) or make any threat to do so in respect of any alleged infringement of any one or more of the claims the subject of the Revocation Orders,

the Revocation Orders be stayed:

(a) initially for a period of 21 days from today; and

(b) if an appeal from any of the Revocation Orders is lodged within that period, until the final determination of that appeal or further order.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

[3] | |

[3] | |

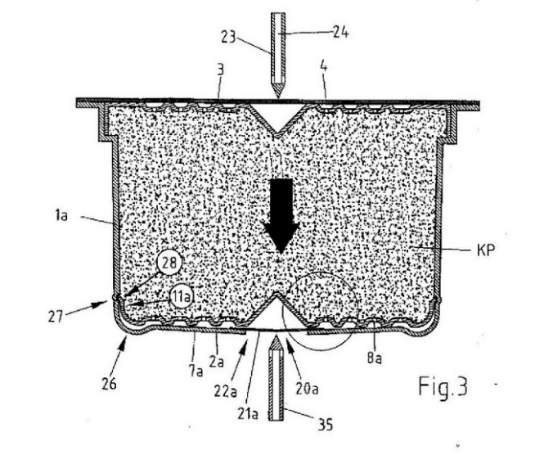

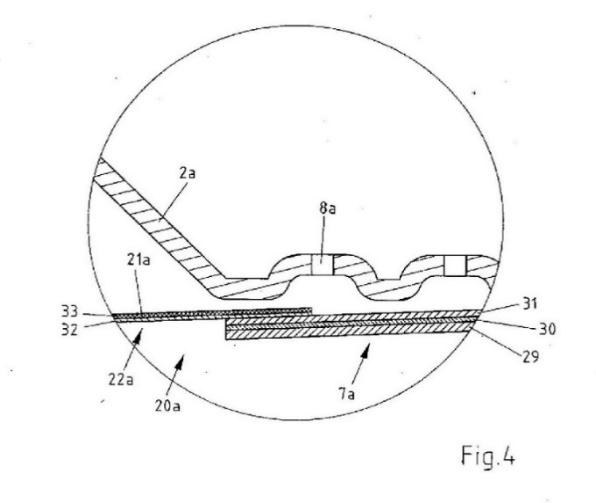

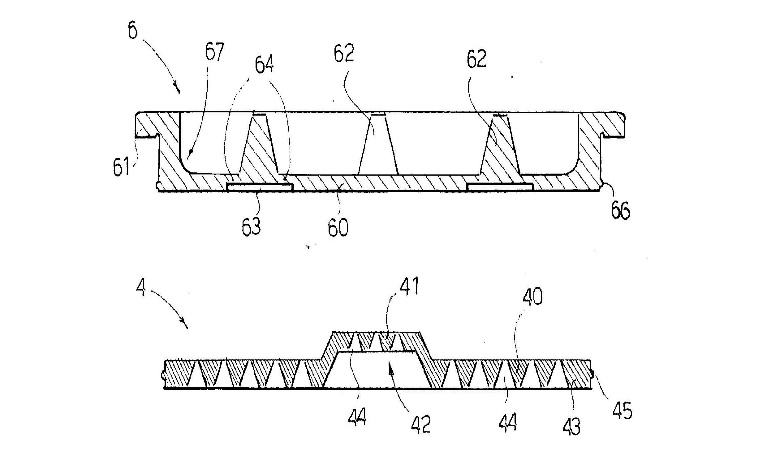

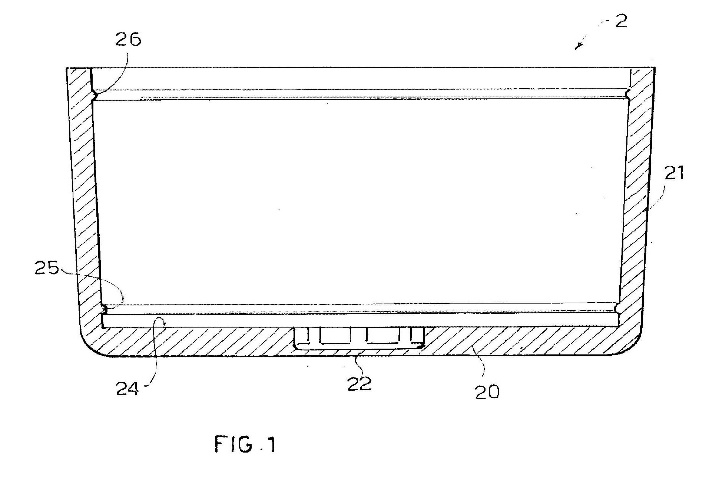

[13] | |

[14] | |

[14] | |

[27] | |

[28] | |

[47] | |

[54] | |

[137] | |

[137] | |

[145] | |

[163] | |

[166] | |

[221] | |

[221] | |

[229] | |

[238] | |

[265] | |

[297] |

NICHOLAS J:

1 In this proceeding the applicant claims injunctive and pecuniary relief against the three respondents for patent infringement. The applicant is the patentee of the three patents in suit, each of which relates to coffee capsule technology. The first respondent imports and sells coffee capsules that are alleged by the applicant to infringe one or more of the claims of the patents. The third respondent (“Ms Tink”) is the sole director and shareholder of the first respondent. The second respondent (“Mr Knox”) is her husband. Both are sued for authorisation and also for having induced or procured the first respondent’s infringements. Each of the respondents denies infringement. The first respondent also contends that each of the relevant claims is invalid and has brought a cross-claim seeking orders for their revocation.

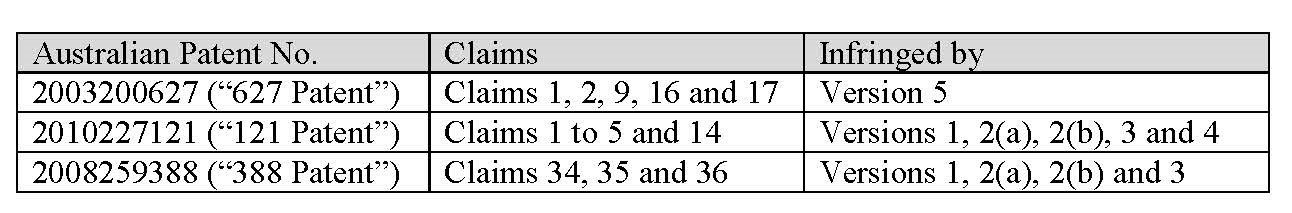

2 The proceeding is complicated by the number of patents in suit, the number of asserted claims, and the number of different coffee capsules that are alleged to infringe one or more of the applicant’s patents. Details of the three patents, the asserted claims, and the different versions of the first respondent’s coffee capsules that are alleged to infringe those claims are as follows:

3 The applicant called two expert witnesses, Mr William Hunter and Dr Frederick Davis.

4 Mr Hunter is a mechanical design engineer based in Australia with experience in packaging and product design. He provides consultancy services in the areas of engineering design and product development. In his first affidavit he gave evidence on his understanding of the integers within each claim in suit in the 388 patent and the 121 patent and described the nature of the inventions disclosed in both specifications. He also gave evidence directed to whether the integers of the asserted claims of the 388 patent and the 121 patent are present in the first respondent’s capsules. In his second affidavit, he gave evidence relevant to the sufficiency issue in relation to the 388 patent.

5 Dr Davis is an engineer based in Australia with experience in mechanical engineering. He has completed courses in plastic materials and manufacturing processes. He was not involved with coffee capsule design at any of the relevant priority dates. However, he has held various roles in a professional services firm that specialises in product design, development and contract manufacturing. He made two affidavits in the proceeding. In his first affidavit Dr Davis addressed the validity issues in relation to all of the patents. In his second affidavit he gave evidence directed to his understanding of the integers within each of the asserted claims of the 627 patent and whether those integers are present in the first respondent’s capsules.

6 The respondents called two expert witnesses, Mr Karl Winkler and Professor Gianluca D’Urso.

7 Mr Winkler is a mechanical engineer based in the United States with experience in consumer and commercial product development. From 2000 to 2003 he was employed as a Principal Engineer and Senior Product Development Engineer at Keurig Inc (“Keurig”). Keurig was a commercial coffee machine manufacturer and distributor. During his time at Keurig he was the principal engineer of the division which developed a single serve consumer coffee machine for use in the home. He made one affidavit in the proceeding in which he gave evidence relevant to the validity issues in relation to all three patents.

8 Professor D’Urso is a management engineer and Associate Professor in Technologies and Manufacturing Systems at the University of Bergamo, Italy. He has experience in mechanical and manufacturing engineering. He has consulted with Gruppo Gimoka s.r.l. (“Gimoka”) in relation to the design of its coffee capsules. Gimoka is the manufacturer of the first respondent’s coffee capsules. He made two affidavits and gave evidence relevant to the infringement issues in relation to all three patents. He also gave evidence on the issue of sufficiency in relation to the 388 patent.

9 The evidence given by the four witnesses to whom I have referred was given in a number of concurrent sessions and was the subject of three joint expert reports that were also admitted into evidence. Their evidence was admitted generally (ie. not the subject of any particular limitations) which means that although some of their evidence was given in relation to particular issues, it had sometimes broader relevance.

10 I formed a favourable impression of all four experts. However, I also formed the impression that Professor D’Urso and Mr Winkler were more familiar with the state of the art with respect to coffee machines at relevant times. I should also add that English is Professor D’Urso’s second language. This contributed to him taking what I would regard as an excessively literal interpretation of one particular aspect of one claim.

11 A considerable amount of the expert evidence related to experiments conducted by Mr Hunter that were relied on by the applicant in support of its infringement case. For reasons that I will later explain, I did not find the experimental evidence relied on by the applicant persuasive. My criticisms of the experimental evidence should not be taken as reflecting on Mr Hunter as a witness. I found much of his evidence helpful particularly in elucidating the relevant issues. I believe the difficulties associated with the experimental evidence are largely the result of difficulties with the way in which the relevant claims are drawn.

12 Evidence was also given for the respondents by Ms Susan Hantos, who is a patent attorney specialising in searching and analysing patent and other technical information. Her evidence related to patent searches she conducted relating to patent publications relied on by the respondents as s 7(3) information. Ms Hantos was not cross-examined.

13 There were three lay witnesses who were called and cross-examined. The first was Ms Tink. She was cross-examined at length in relation to matters that were relied upon by the applicant in support of a claim for additional damages and also the claim against her husband, Mr Knox. Mr Knox also gave evidence and he was also cross-examined at length on the same issues that were canvassed in the cross-examination of Ms Tink. There was also cross-examination of Ms Nicole Reynolds in relation to Mr Knox’s involvement in the first respondent’s business. Given that I have found that the asserted claims of each of the three patents is invalid, it is unnecessary to make any further reference to the evidence given by the lay witnesses in these reasons.

14 The 627 patent is entitled “Cartridge containing a single serving of a particulate substance for preparing a beverage”. It is common ground that the priority date of each of the asserted claims is 14 March 2002.

15 The specification begins with a general description of the invention. The specification states at page 1A, lines 1-9:

The present invention refers to a cartridge adapted to contain a single serving of a particulate substance, extractable by means of water for preparing a beverage, preferably an espresso coffee beverage, comprising an essentially cup- or bucket-shaped main body portion having a bottom portion and an open end opposite to the bottom portion, and a cover member adapted to be sealingly attached to the open end of the main body portion.

16 There follows a discussion of prior art cartridges and the manner in which they work. The specification states at page 1A, line 10 – page 2, line 13:

Such cartridges are well known in the art in a variety of different embodiments, whereby particularly [sic] cartridges containing a single serving of coffee powder for preparing an espresso coffee are in widespread use. One of the fundamental advantages of such cartridges may be seen in the fact that they are gas tight, thus keeping the ground coffee contained therein fresh over an extended period of time. For brewing the coffee powder received in the cartridge, predominantly semi-automatic espresso coffee machines are in use whereby the cartridge is inserted into a cartridge holder of the machine, with its cover facing downwards. Then, the cartridge holder is inserted manually into the coffee machine. The coffee machine is provided, in the region of the area where the cartridge holder is to be inserted into the machine, with a so-called brewing spike, i.e. a hollow piercing member comprising radial outlet openings for feeding the brewing water into the interior of the cartridge, once the bottom of the cartridge has been pierced upon insertion of the cartridge holder into the coffee machine. The bottom of the cartridge holder itself is provided with a plurality of projections located on a collecting tray. These projections penetrate the cover of the cartridge and provide a plurality of openings in the cover as soon as pressurized brewing water is fed into the cartridge and the cover thereof is pressed against the projections due to the hydraulic overpressure in the interior of the cartridge. During the subsequent brewing operation, the brewing water is fed into the interior of the cartridge through the brewing spike, with the result that it flows under pressure through the coffee powder in the cartridge, finally leaving the cartridge as coffee beverage through the openings in the cover. The freshly brewed coffee is collected in the collecting tray and flows through a beverage outlet out of the machine. A coffee machine comprising such a setup for the extraction of the coffee powder contained in a cartridge is disclosed, for instance, in the document EP 0,512,470.

17 There is then some discussion of certain disadvantages of the prior art. The specification continues at page 4, line 22 – page 5, line 10:

Embodiments of the invention provide a cartridge adapted to contain a single serving of a particulate substance, extractable by means of water for preparing a beverage, preferably an espresso coffee beverage, in which the brewing water flows through the extractable substance contained therein as uniformly as possible to thereby extract the substance as fully as possible.

Embodiments of the invention provide a cartridge adapted to contain a single serving of a particulate substance, extractable by means of water for preparing a beverage, preferably an espresso coffee beverage, in which the associated coffee machine can be kept as simple as possible, removing the need to provide the machine with means for distributing and/or collection [sic] the brewing water and the beverage, respectively, with regard to the cartridge.

Embodiments of the invention provide a cartridge adapted to contain a single serving of a particulate substance, extractable by means of water for preparing a beverage, preferably an espresso coffee beverage, in which the brewing water can flow through the cartridge from cover to bottom or vice versa, without the need to provide substantial structural modifications to the cartridge.

18 This is followed by the first of six consistory statements which states at page 5, lines 11-26:

According to a first aspect of the invention, there is provided a cartridge adapted to contain a single serving of a particulate substance, extractable by means of water for preparing a beverage, comprising an essentially cup- or bucket-shaped main body portion having a bottom portion and an open end opposite to said bottom portion, and a cover member adapted to be sealingly attached to the open end of the main body portion wherein at least one fluid director member having essentially disc-shaped configuration with a central longitudinal axis and a dimension essentially corresponding to the interior cross sectional dimension of the main body portion, the fluid director member adapted to be received in the interior of the main body portion whereby each fluid director member is provided with a plurality of openings and a plurality of embossings, each of the embossings having a raised portion, whereby a plurality of communicating fluid channels is created between the raised portions of the embossings.

19 The specification then states at page 5, lines 28 – page 6, line 3:

By providing at least one fluid director member of the kind explained herein above, for example, at the inlet side of the cartridge above the particular substance, a uniform distribution of the water fed into the cartridge for extracting the particulate substance can be ensured, independent of the number and the size of the inlet perforations.

20 Some preferred embodiments are then described. This is followed by further consistory statements describing the other four aspects of the invention.

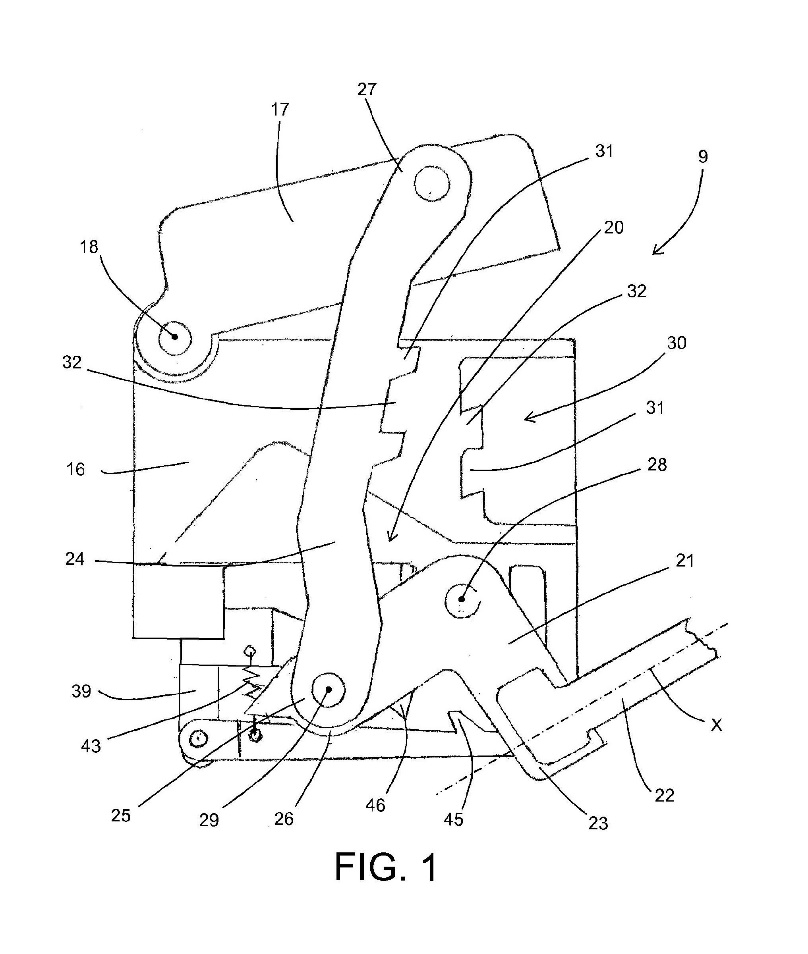

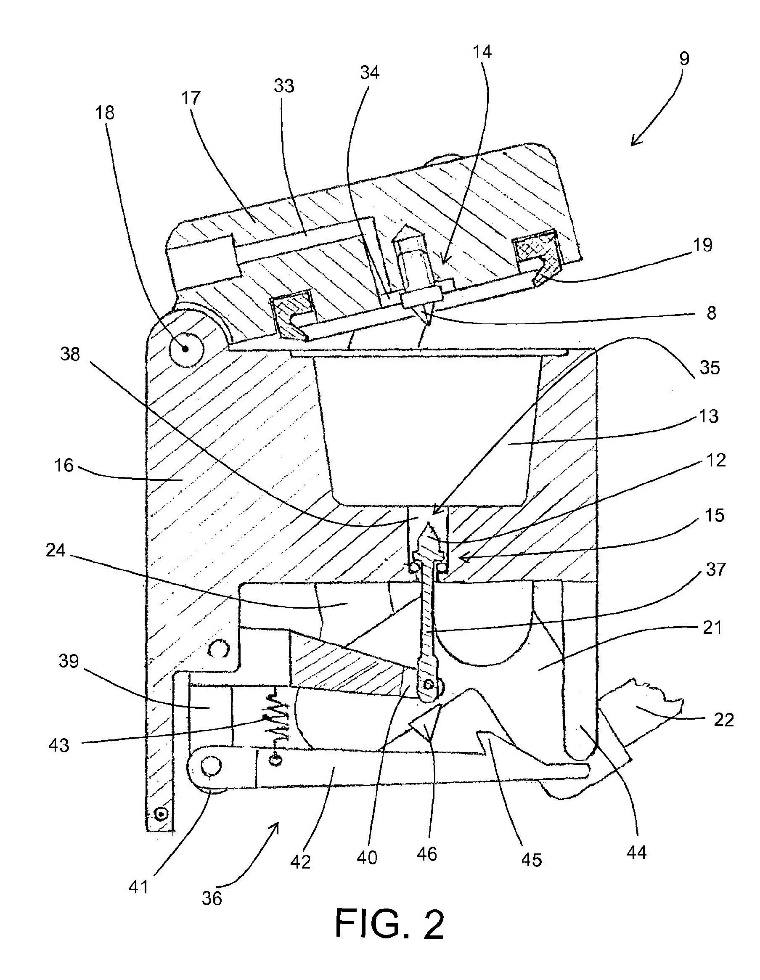

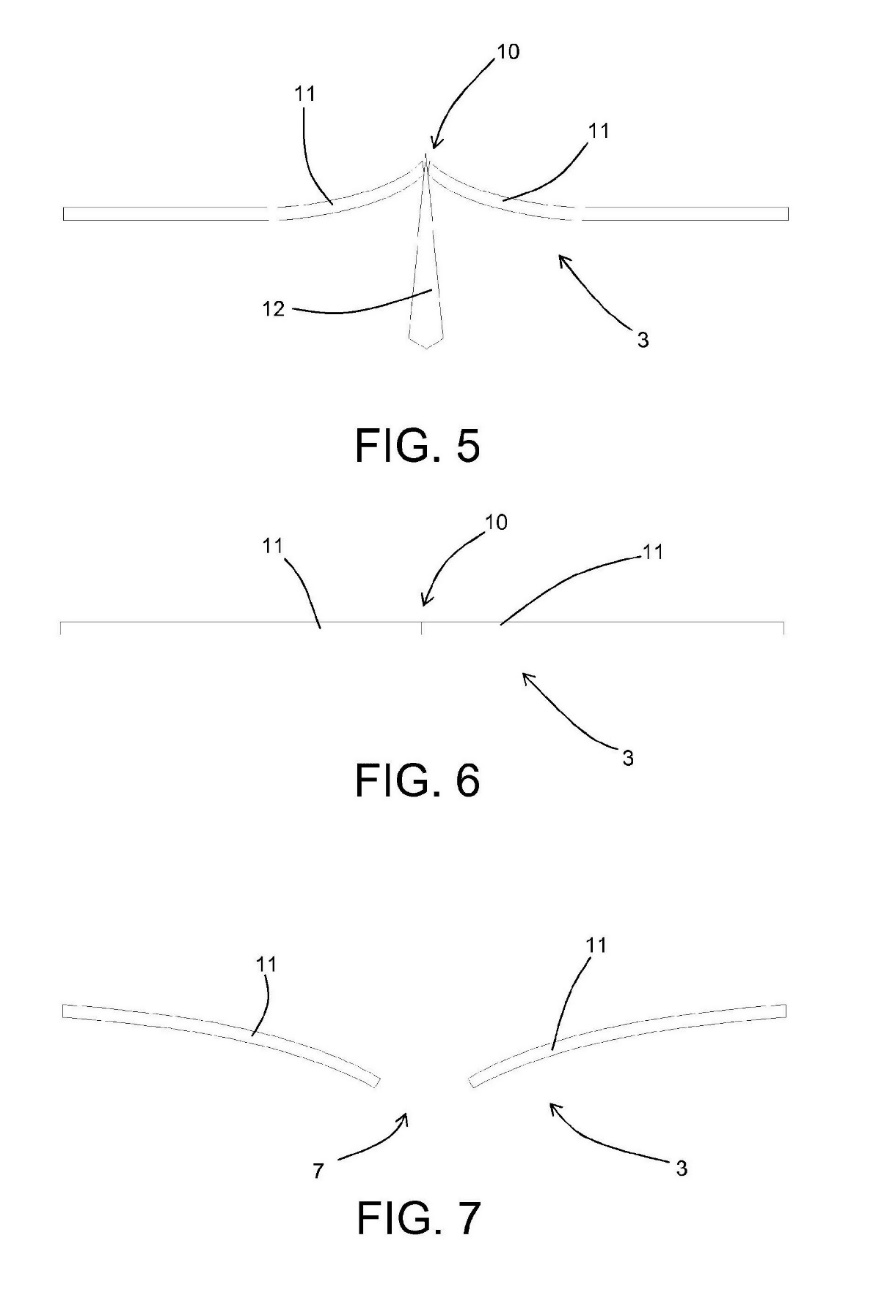

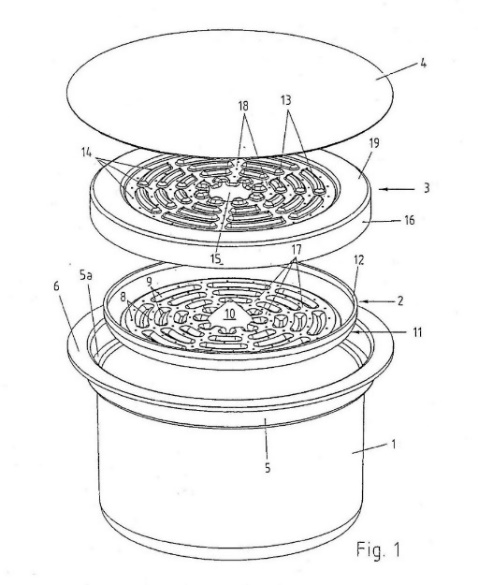

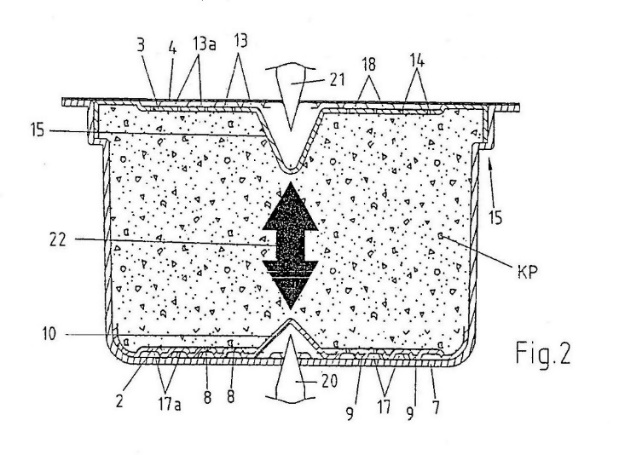

21 The specification includes a detailed description of the invention by reference to seven drawings. The most significant of these for present purposes are Figs 1 and 2 which are as follows:

|

|

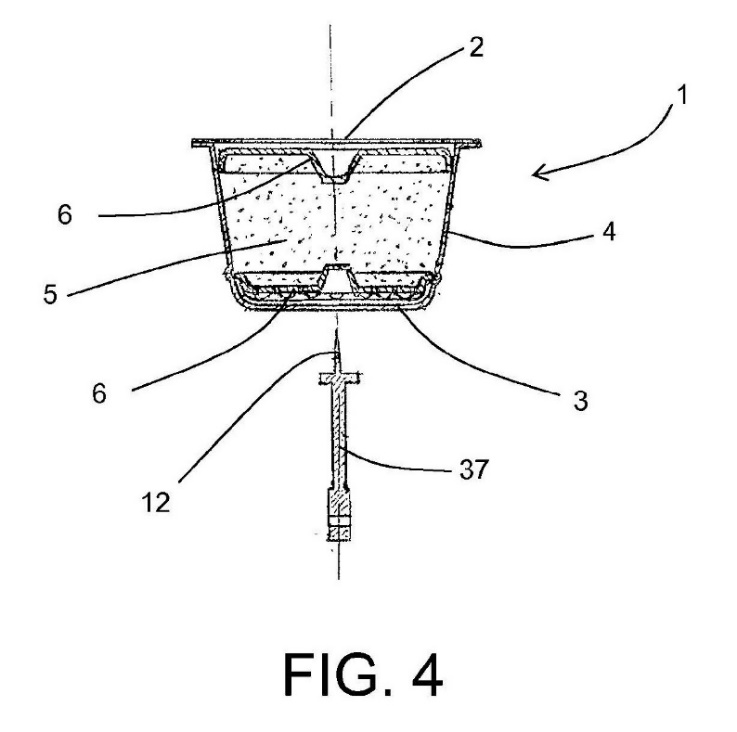

22 Figure 1 is an exploded view of a cartridge adapted to receive a single serving of a particulate substance used in the preparation of a beverage. Figure 2 shows a longitudinal sectional view of an assembled cartridge containing a single serve of coffee powder. The coffee powder is enclosed between the lower collection member (2) and the upper distribution member (3).

23 Figure 1 shows a cartridge with a main housing portion (1), a lower fluid collection member (2), an upper fluid distribution member (3) and a cover (4). Coffee powder is stored in the main housing portion (1) between the fluid collection member (2) and the fluid distribution member (3). The main housing portion (1) and the cover (4) consist of a gas-tight multi-layer composite foil material. The specification states at page 8, lines 18-21:

The fluid collection member 2 and the fluid distribution member 3 both are generally disc-shaped and are manufactured preferably by deep drawing.

24 The specification continues at page 9, lines 1-13:

The collection member 2 is provided with a plurality of embossings having the shape of annular segments; these embossings show as raised portions 9 protruding from the bottom surface of the lower collection member 2. Once the collection member 2 having been inserted into the main portion 1 of the cartridge, the raised portions 9 rest on the flat bottom surface of the main portion 1, with the result that a plurality of fluid channels 17 are created, running from the central longitudinal axis of the collection member 2 radially outwards and concentrically around the central longitudinal axis of the collection member 2. Beside the raised portions 9, i.e. in the region of the thus created fluid channels 17, the collection member 2 is provided with a plurality of openings 8.

25 The specification also states at page 9, line 21 – page 10, line 3:

As far as the design is concerned, the upper distribution member 3 is essentially a mirror image of the lower collection member 2. Again, the distribution member 3 comprises a plurality of embossings having the shape of annular segments; these embossings show as raised portions 13 protruding from the top surface of the upper distribution member 3. By means of these raised portions 13, a plurality of fluid channels 18 are created at the top surface of the upper distribution member 3, these fluid channels 18 running from the central longitudinal axis of the distribution member 3 radially outwards and concentrically around the central longitudinal axis of the distribution member 3. Beside the raised portions 18, i.e. in the region of the thus created fluid channels 18, the distribution member 3 is provided with a plurality of openings 14.

26 The specification also states at page 10, line 31 – page 11, line 6:

Moreover, it can be clearly seen that fluid channels 17 are created by the raised portions 9 of the lower collection member 2 resting on the bottom of the main cup- or bucket-shaped main portion 1 of the cartridge. Similarly, fluid channels 18 are created by the raised portions 9 of the upper distribution member 3 resting on the bottom surface of the cover 4 of the main portion 1 of the cartridge.

27 Claims 1, 2, 9, 16 and 17 are as follows:

1. A cartridge adapted to contain a single serving of a particulate substance, extractable by means of water, extractable by means of water for preparing a beverage comprising an essentially cup- or bucket-shaped main body portion having a bottom portion and an open end opposite to said bottom portion, and a cover member adapted to be sealingly attached to said open end of said main body portion, wherein there is provided at least one fluid director member having essentially disc-shaped configuration with a central longitudinal axis and a dimension essentially corresponding to the interior, cross sectional dimension of said main body portion, said fluid director member adapted to be received in the interior of said main body portion, whereby said fluid director member has a plurality of openings and a plurality of embossings, each of said embossings having a raised portion, whereby a plurality of communicating fluid channels is created between said raised portions of said embossings.

2. A cartridge containing a single serving of a particulate substance, extractable by means of water for preparing a beverage, comprising:

an essentially cup- or bucket-shaped main body portion having a bottom portion and an open end opposite to said bottom portion;

a cover member sealingly attached to said open end of said main body portion;

a fluid director member having essentially disc-shaped configuration with a central longitudinal axis and a dimension essentially corresponding to the interior cross sectional dimension of said main body portion;

said fluid director member having a plurality of openings and a plurality of embossings, each of said embossings having a raised portion, whereby a plurality of communicating fluid channels is created between said raised portions of said embossings, and;

said fluid director member located in the interior of said cartridge between said particulate substance and said bottom portion of said main body portion, thereby constituting a collection member for the water flowing through said particulate substance.

…

9. Cartridge according to any one of ·the claims 1, 2, 4 or 7, wherein said openings are located in said fluid channels created between said raised portions of said embossings.

…

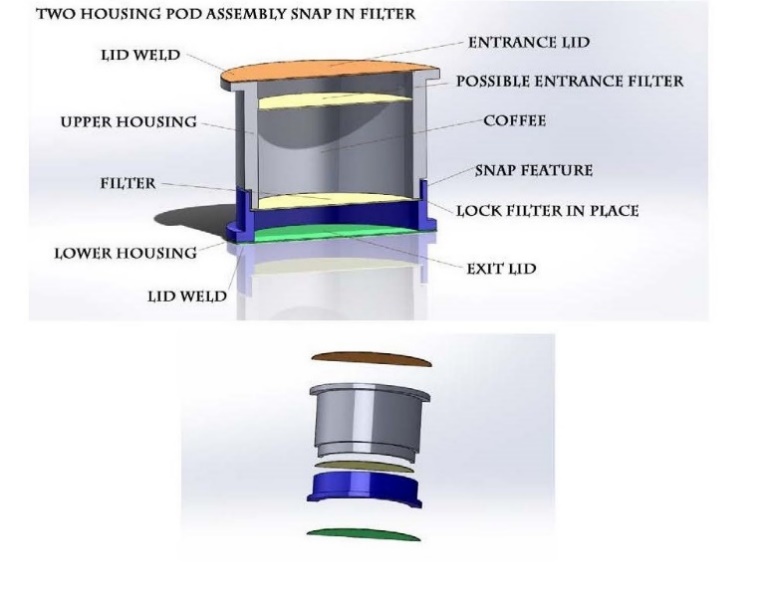

16. Cartridge according to claim 1 or 12, wherein said fluid director member is located in the interior of said cartridge with a certain distance from the bottom of said main body portion or from said cover member.

17. Cartridge according to any one of the claims 1, 2, 4 or 7, wherein said openings have a size that is less than the statistical mean value of the diameter of one particule of said particulate substance

28 There was no dispute between the parties as to the relevant principles of construction. These were summarised by the Full Court (Hill, Finn and Gyles JJ) in Jupiters Ltd and Ors v Neurizon Pty Ltd (2005) 222 ALR 155 at 168-169 [67]:

…

(i) the proper construction of a specification is a matter of law: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd v Dart Industries Inc (1988) 13 IPR 385 at 400;

(ii) a patent specification should be given a purposive, not a purely literal, construction: Flexible Steel Lacing Co v Beltreco Ltd (2000) 49 IPR 331; [2000] FCA 890 at [81] (Flexible Steel Lacing); and it is not to be read in the abstract but is to be construed in the light of the common general knowledge and the art before the priority date: Kimberley-Clark Australia Pty Ltd v Arico Trading International Pty Ltd (2001) 207 CLR 1; 177 ALR 460; 50 IPR 513; [2001] HCA 8 at [24];

(iii) the words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the normal person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to his or her own general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification: Décor Corporation Pty Ltd at 391;

(iv) while the claims are to be construed in the context of the specification as a whole, it is not legitimate to narrow or expand the boundaries of monopoly as fixed by the words of a claim by adding to those words glosses drawn from other parts of the specification, although terms in the claim which are unclear may be defined by reference to the body of the specification: Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [15]; Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel (1961) 106 CLR 588 at 610; Interlego AG v Toltoys Pty Ltd (1973) 130 CLR 461 at 478; the body of a specification cannot be used to change a clear claim for one subject matter into a claim for another and different subject matter: Electric & Musical Industries Ltd v Lissen Ltd [1938] 4 All ER 221 at 224–5; (1938) 56 RPC 23 at 39;

(v) experts can give evidence on the meaning which those skilled in the art would give to technical or scientific terms and phrases and on unusual or special meanings to be given by skilled addressees to words which might otherwise bear their ordinary meaning: Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd v Koukourou & Partners Pty Ltd (1994) 30 IPR 479 at 485–6 (Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd); the court is to place itself in the position of some person acquainted with the surrounding circumstances as to the state of the art and manufacture at the time (Kimberley-Clark v Arico at [24]); and

(vi) it is for the court, not for any witness however expert, to construe the specification; Sartas No 1 Pty Ltd at 485–6.

29 Plain language must be given its plain meaning, and clear words in a claim must not be given an unnatural meaning by imposing glosses drawn from the body of the specification. However, the context in which the relevant language is used is of crucial significance to the ascertainment of its meaning. When construing a patent specification the Court seeks to give the document a purposive construction by reading the document as it would be understood by a person skilled in the art and without engaging in overly meticulous verbal analysis. As Lord Hoffman said on the topic of purposive construction in Kirin-Amgen Inc and Others v Hoechst Marion Roussel Ltd and Others (2004) 64 IPR 444 at 454-455 [34]:

“Purposive construction” does not mean that one is extending or going beyond the definition of the technical matter for which the patentee seeks protection in the claims. The question is always what the person skilled in the art would have understood the patentee to be using the language of the claim to mean. And for this purpose, the language he has chosen is usually of critical importance. The conventions of word meaning and syntax enable us to express our meanings with great accuracy and subtlety and the skilled man will ordinarily assume that the patentee has chosen his language accordingly. As a number of judges have pointed out, the specification is a unilateral document in words of the patentee’s own choosing. Furthermore, the words will usually have been chosen upon skilled advice. The specification is not a document inter rusticos for which broad allowances must be made. On the other hand, it must be recognised that the patentee is trying to describe something which, at any rate in his opinion, is new; which has not existed before and of which there may be no generally accepted definition. There will be occasions upon which it will be obvious to the skilled man that the patentee must in some respect have departed from conventional use of language or included in his description of the invention some element which he did not mean to be essential. But one would not expect that to happen very often.

30 There is a danger that in seeking to give a claim a purposive construction, or in seeking to read it in context, an impermissible gloss might be imposed upon the language used based on material found in the body of the specification: see Sachtler GmbH & Co KG v RE Miller Pty Ltd (2005) 65 IPR 605 at 613-614 [42], Tramanco Pty Ltd v BPW Transpec Pty Ltd (2014) 105 IPR 18 at 48-49 [175]. Purposive construction does not justify departing from clear and unambiguous language used in the claim.

31 The principal issue of construction concerns the following words of claim 1 (referred to in the evidence variously as integers 1.5 and/or 1.6) and similar wording in claim 2:

… whereby said fluid director member has a plurality of openings and a plurality of embossings, each of said embossings having a raised portion, whereby a plurality of communicating fluid channels is created between said raised portions of said embossings.

32 There are two aspects to the construction issue. The first concerns the meaning of the term “embossings” which is not defined in the specification. The second concerns the meaning of the words “communicating fluid channels”. As the claim states, the cartridge includes a fluid director member that has a plurality of embossings, each of which has a raised portion, creating a plurality of communicating fluid channels between them.

33 The meaning of the term “embossings” and the words “communicating fluid channels” are closely related. This is because the claim requires that “a plurality of embossings, each … having a raised portion” create between those raised portions “a plurality of communicating fluid channels”. The function that is performed by the raised portions of the embossings is relevant to understanding what the word embossings means as used in the claim.

34 The respondents submitted that the term “embossings” has a technical meaning that refers to a type of manufacturing process that introduces a shape or geometry into a flat surface. In support of this submission they relied on evidence given by Professor D’Urso. He understood the term to refer to shapes produced using processes such as stamping, pressing and deep drawing which result in a raised area above the top plane of the material matched by a cavity on the lower plane. According to the respondents, the raised areas created through such processes are what are described as the “raised portions” in the claims.

35 The applicant submitted that the respondents’ interpretation of the word “embossings” is too narrow and does not reflect the wide meaning that the word “embossings” naturally bears. It submitted that the respondents’ interpretation is arrived at from an impermissible reading down of the wide language of the claim by reference to the preferred embodiments described in the specification.

36 The applicant relied on expert evidence given by Dr Davis to the effect that an “embossing” is a geometry of any shape that is raised off a surface. According to the applicant, Dr Davis’ understanding of the term embossing is consistent with the following definition of “emboss” in the Macquarie Dictionary (“Macquarie”) upon which the applicant also relied:

emboss / verb (t) 1. to raise or represent surface designs in relief. 2. to cause to bulge out; make protuberant; make umbonate. 3. to raise a design on a fabric by pressing. 4. to cover or ornament with bosses or studs.

In its submissions the applicant placed particular reliance on meanings 1, 2 and 4. The Macquarie does not include any definition of the word “embossing”.

37 The Oxford English Dictionary (“OED”) defines the verb “emboss”, the noun “embossing” and the adjective “embossed” as follows:

Emboss, v. 1. a. To cause to bulge or swell out, make convex or protuberant; to cover with protuberances…b. To emboss (out): to inflate (style), render tumid; to give exaggerated prominence to. c. To bulge, be convex. 2. a. To carve or mould in relief; to cause (figures, parts of a wrought surface) to stand out, project or protrude… b. To adorn with figures or other ornamentation in relief; to represent (a subject) in relief. (Sometimes with reference to embroidery.) Also of the figures, etc.: To stand out as an ornament upon. 3. To ornament with or as with bosses or studs. Hence, To adorn or decorate sumptuously.

Embossing, n. a. The action of emboss (verb). b. Embossed ornamentation; formerly in wider sense, swelling, protuberance.

Embossed, adj. 1. Carved or moulded in relief; ornamented with figures in relief; (of figures or ornament) raised, standing out in relief. 2. Covered with ornamental bosses or studs; richly or sumptuously decorated. 3. Humpbacked. 4. Bulging, convex, swollen, tumid. 5. Projecting in the centre like the boss of the shield.

38 Dr Davis drew some support for his understanding of the word “embossing” from the word “boss”, which is a term that is used in the field of engineering. According to the Macquarie, when used in relation to machinery, a “boss” is:

a. an enlarged, usually strengthened section of a shaft, wheel hub, etc. b. a raised circular pad on a machine part, which surrounds an attachment hole …

That meaning is narrower than the meaning given to the word by Dr Davis. In any event, the word with which I am directly concerned is “embossing” and there is nothing in either the OED or the Macquarie to indicate the two words have the same meaning.

39 The applicant also relied on the evidence of Mr Winkler in relation to the meaning of the word “embossing”. In his oral evidence Mr Winkler indicated that he agreed with Dr Davis’ understanding of the word embossing. I found that evidence difficult to reconcile with the statement made in his affidavit indicating that “embossing” refers to a particular type of geometry in which there is a raised area above the plane of the material which is matched by a cavity on the underside of the plane. The apparent inconsistency in Mr Winkler’s evidence was not taken up in cross-examination.

40 I did not find the evidence of Dr Davis or Mr Winkler in relation to the meaning of the word embossing of assistance. It seems to me that Dr Davis wrongly equated the word embossing with the word boss and gave insufficient attention to the context in which the word appears in the relevant claims when read in light of the specification as a whole. I think this is also true of the oral evidence to which I have referred given by Mr Winkler.

41 It seems to me that the word embossings is intended to convey more about the configuration of the shape and structure of the relevant integer than the applicant’s interpretation allows. In particular, in my view the word refers to the bulging or convex nature of the shape. Contrary to the applicant’s submission, it is not referring to a geometry of any shape that is raised off a surface. The meaning of the word embossings, when read in the context of the claims and the specification as a whole, has a more nuanced meaning.

42 The word “embossings” does not have a technical or special meaning in the sense discussed in the authorities. In particular, the evidence does not establish that it is a word that would ordinarily be used by a person skilled in the art to describe a feature of a coffee capsule. The word must be given an ordinary and natural meaning best suited to the context in which it is used in the specification as a whole. I think in context it is used to describe a surface of the fluid director member that has been “embossed”. This implies that the surface is bulging or convex. The words bulging and convex both feature in the OED definitions of emboss and embossed.

43 When regard is had to the detailed description of the preferred embodiments, it is clear that the raised portions (9, 13) of the embossings protrude from the top surface of the upper distribution member (3) and the bottom surface of the lower collection member (2). They are bulging and convex in shape. They create the fluid channels referred to in the claim.

44 Embossings, in the sense that word is used in the claims, may be stamped, pressed or deep drawn into the surface on which they reside. That is not to say that they must be made by any particular manufacturing process. Provided they exhibit the bulging and convex appearance that can be achieved using those processes, it does not matter how they are manufactured. There is no reason why the relevant effect might not be achieved by a process of injection moulding. It is the bulging and convex shape of the relevant feature in the finished componentry that will determine whether the requirement that there be a plurality of embossings is satisfied.

45 The next question that arises concerns the meaning of the words “communicating fluid channels”. Here the applicant again relied on the evidence of Dr Davis who it said suggested that a “communicating fluid channel” is a path or flow of fluid itself rather than a physical feature of the fluid director member. The evidence given by Dr Davis to which I was referred by the applicant in support of its submission does not say this. What it says is that the term “channels” does not necessarily require that there be a long or thin-shaped fluid passage. Rather, Dr Davis said that the fluid channels were created by “… raised solid geometries that act to create channels which divide beverage fluid flows …”.

46 The relevant words of the claim define a physical feature of the fluid director member. This requirement of the claim will be satisfied regardless of whether or not fluid is present. I accept the respondents’ submission that what is referred to is not an actual flow of liquid, but a shape or geometry that can contain and direct such a flow during use. It is the raised portions of the embossings that will contain and direct the flow of liquid when the coffee capsule is in use.

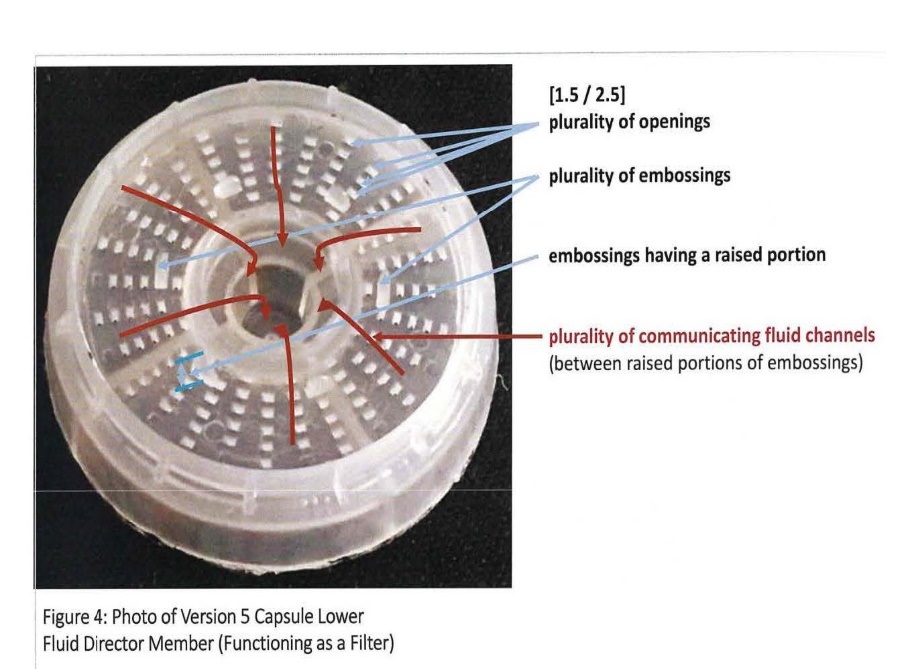

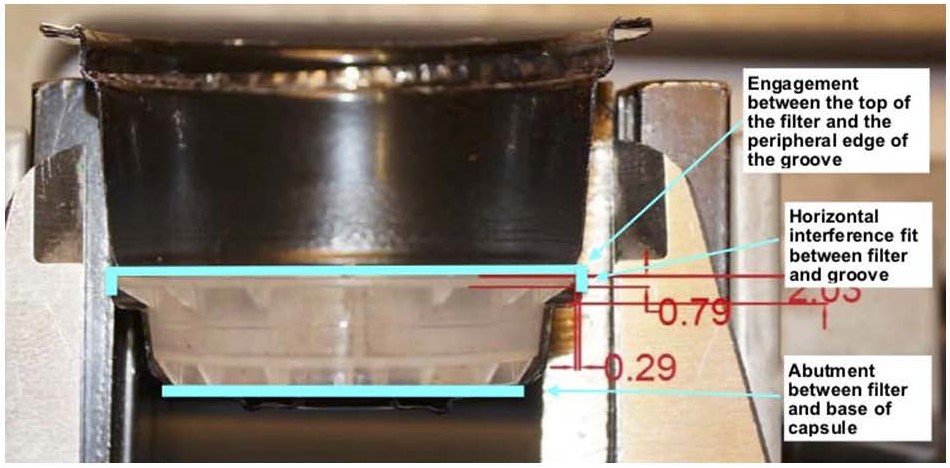

47 The applicant alleges that the first respondent’s version 5 coffee capsule includes a lower fluid director member that meets the requirements of claims 1, 2, 9, 16 and 17. Whether or not that is so depends on whether the version 5 capsule has “a plurality of embossings” and “a plurality of communicating fluid channels … created between [the] raised portions of said embossings”.

48 Dr Davis produced the following annotated photograph of the version 5 capsule fluid director member that indicates where each of the relevant integers is alleged by the applicant to be found:

49 Towards the centre of the fluid director member is what was described in the evidence as an inner castellated ring. In his oral evidence Dr Davis accepted that his annotated photograph depicted fluid flow over the top of the raised portions of the inner castellated ring. But he went on to state that he believed the way in which he had drawn the fluid flow in the photograph was in error. He said that the dominant flow would be in the “notches” by which I understood him to mean the “plurality of openings” shown in the photograph.

50 The applicant made clear in its closing submissions that it does not contend that the castellated ring, or the castellations themselves, are embossings within the meaning of the relevant claims. The applicant identified the six piercers or ribs on the underside of the fluid distribution member in the version 5 capsule as the plurality of embossings. It was submitted that these six piercers or ribs are:

… “embossings” as they are raised portions which stand the filter off the base of the capsule. They allow fluid to flow from the apertures and between the six ribs or piercers to the central region, where the flows merge, and to the exit holes, and thereby create a plurality of communicating fluid channels.

51 I think the words piercers or ribs accurately describe what the applicant called embossings. However, in my view these piercers or ribs do not constitute embossings within the meaning of the claims. They are not bulging or convex in shape and they do not control or direct fluid flow in any meaningful sense.

52 In his written evidence Dr Davis suggested that in the version 5 capsule the piercers or ribs create communicating fluid channels in which liquid will flow towards the centre of the fluid director member as depicted in his photograph. He later qualified this evidence as I have previously discussed. I am satisfied that the function of the piercers is not to create fluid channels or to direct fluid flow. That is not their purpose and that is not what they do when the version 5 capsule is in use. In his oral evidence Dr Davis accepted when pressed that the purpose of the piercers was to pierce and provide structural support and that they were not intended to create fluid channels.

53 In the result, I am not satisfied that the first respondent’s version 5 capsule includes a plurality of embossings with raised portions that create a plurality of communicating fluid channels. I am therefore not satisfied that the version 5 capsule infringes any of the asserted claims.

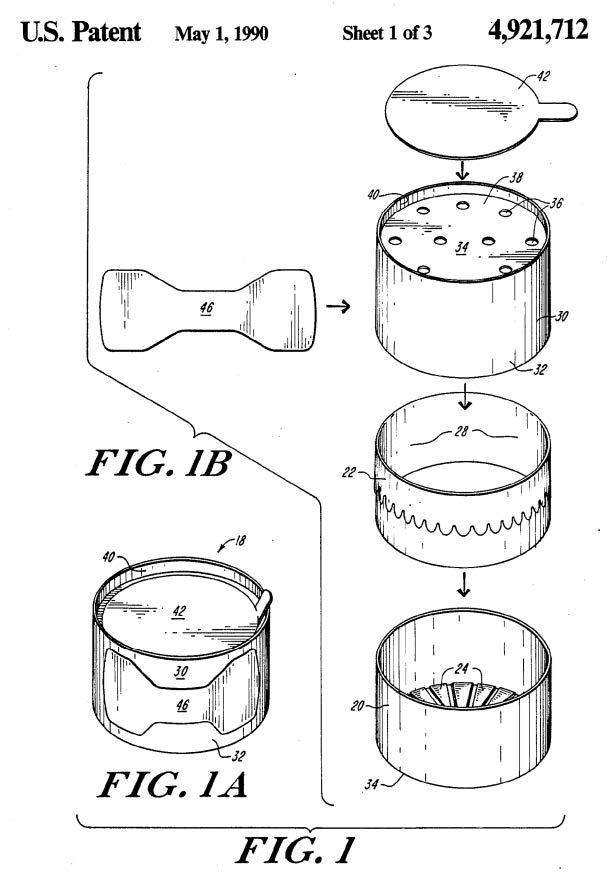

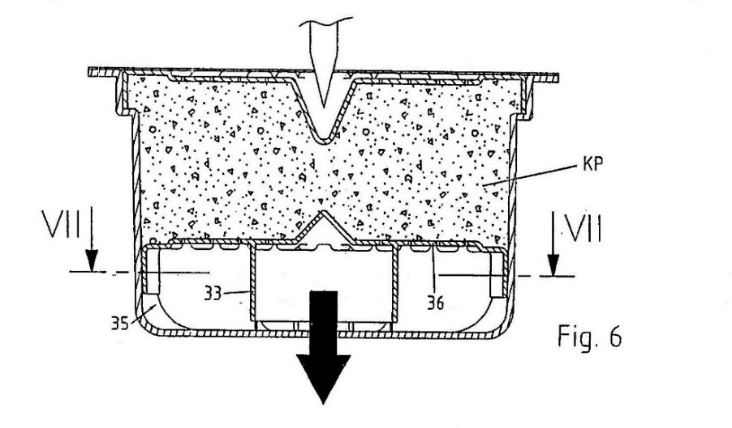

54 The respondents allege that claims 1, 2, 9 and 16 of the 627 patent are invalid for lack of novelty. They contend that each of those claims is anticipated by US patent 4,921,712 (“the 712 patent”). There is no issue as to the relevant legal principles, or the date of publication of the 712 patent. The question is whether the 712 patent provides a clear disclosure of the invention as claimed. In my opinion it does not.

55 The 712 patent includes a detailed description of a coffee brewing system comprising an automatic drip coffee brewing machine and a disposable coffee cartridge. The cartridge is made from a disposable material. It consists of a first cup, having an open first end and a substantially closed second end, a filter member that has an open end and a closed end, and a closure member having an open end and a substantially closed end. The closed end of the closure member includes a plurality of holes. A sealing sheet is provided at the top to keep the coffee fresh and to stop it from leaking out through the holes.

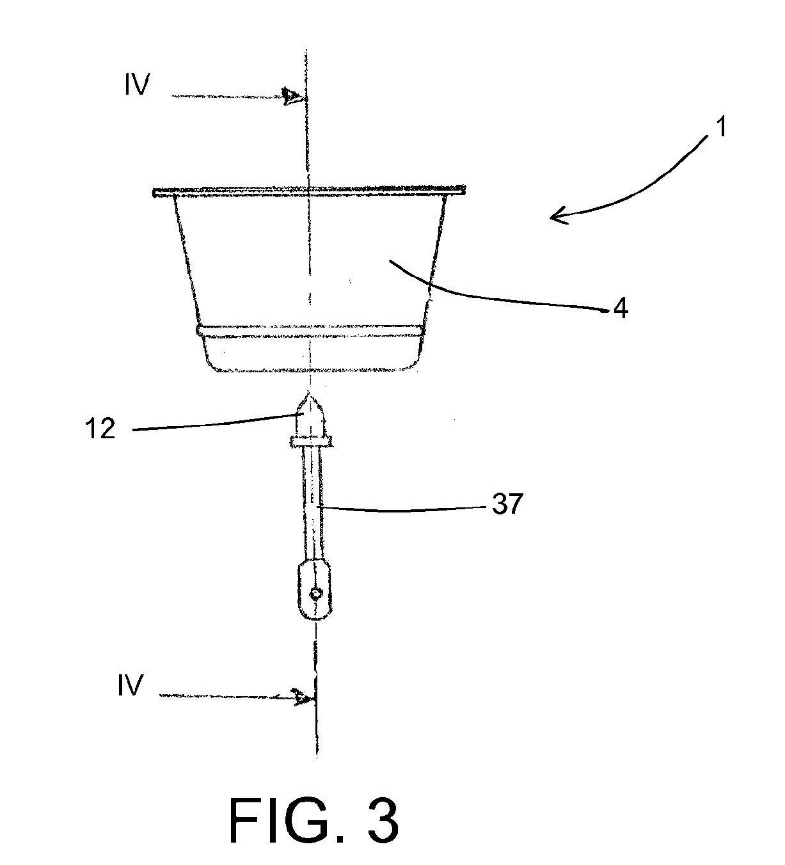

56 The coffee cartridge design is depicted in various drawings including Fig 1 which is as follows:

57 Figure 1A depicts an assembled coffee cartridge. Figure 1B shows an exploded view of the elements of the cartridge which consists of the following four parts: a lower cup (20), a filter element (22), an upper closure member (30) (also referred to as the upper closure cup or upper cup) and a sealing sheet (42). Coffee is stored in the filter element (22). The sealing sheet is adhesively sealed to the upper closure member (34).

58 When the capsule is ready to be used, the sealing sheet (42) is removed. The capsule is then inserted into the machine. Water drips from a water spout located above the capsule. The water drips through the holes (36) of the upper closure member (30), then through the filter element (22) and into the lower cup (20). The bottom of the lower cup includes exit ports (not shown in Fig 1) through which the brewed coffee flows from the lower cup into a serving cup or mug.

59 The critical question is whether the 712 patent clearly discloses a main body portion having a bottom portion and an open end opposite to said bottom portion, and a cover member adapted to be sealingly attached to the said open end of said main body portion as required by claim 1. The corresponding language of claim 2 is slightly but not materially different. Claims 9 and 16 are dependent on either claims 1 or 2.

60 The respondents submitted that the sealing sheet (42) and the upper closure member (30) together form a cover member which is adapted to be sealingly attached to the main body portion of the cartridge, being the lower cup (20). There are two difficulties with this submission.

61 The 712 patent clearly discloses a cover member (ie. the sealing sheet). However, the sealing sheet is not “adapted to be sealingly attached” to the main body portion of the cartridge. According to the respondents, the main body portion of the cartridge as shown in Fig 1 of the 712 patent is the lower cup (2). Assuming that to be correct, the sealing sheet disclosed in the 712 patent is not adapted to be sealingly attached to the lower cup. According to the 712 patent at column 4, lines 8-10:

The lower cup 20 is dimensioned slightly smaller in diameter than the upper cup, so that the upper closure cup can slip over it.

There is nothing in the description to suggest that the upper closure cup (or member) and the lower cup are adapted to be “sealingly attached” to each other.

62 The upper closure member (30) is not a “cover member”. Nor do I accept that the sealing sheet (42) and the upper closure member (30) shown in Fig 1 of the 712 patent together form a cover member. The purpose of the upper closure member is to receive and distribute water through the holes onto the coffee in the filter element. Mr Winkler was asked whether he contended that the upper closure member (30) shown in Fig 1 was a cover member. It is apparent from his answer that he did not consider that it was.

63 I am not satisfied that the 712 patent contains a clear disclosure of the invention defined by any of the relevant claims.

64 The respondents also allege that each of claims 1, 2, 9, 16 and 17 of the 627 patent is invalid for lack of inventive step.

65 Section 18(1)(b)(ii) of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) (“the Act”) provides that an invention is a patentable invention for the purposes of a standard patent if the invention, so far as claimed in any claim, involves an inventive step when compared with the prior art base as it existed before the priority date of that claim. At the relevant times subs 7(2) and (3) of the Act provided:

(2) For the purposes of this Act, an invention is to be taken to involve an inventive step when compared with the prior art base unless the invention would have been obvious to a person skilled in the relevant art in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed in the patent area before the priority date of the relevant claim, whether that knowledge is considered separately or together with the information mentioned in subsection (3).

(3) The information for the purposes of subsection (2) is:

(a) any single piece of prior art information; or

(b) a combination of any 2 or more pieces of prior art information;

being information that the skilled person mentioned in subsection (2) could, before the priority date of the relevant claim, be reasonably expected to have ascertained, understood, regarded as relevant and, in the case of information mentioned in paragraph (b), combined as mentioned in that paragraph.

66 As to the operation of subs 7(3) of the Act, see AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd (2015) 257 CLR 356 (“AstraZeneca”) at [18]-[19] per French CJ, at [68] per Kiefel J (as her Honour then was), at [111] and [115] per Gageler and Keane JJ.

67 The expression “patent area” is relevantly defined in Sch 1 to mean Australia. The expression “prior art information” is relevantly defined to mean information that is part of the prior art base for the purposes of subs 7(3) in relation to deciding whether an invention does or does not involve an inventive step. At the relevant times the expression “prior art base” was defined in para (a) of the definition as:

in relation to deciding whether an invention does or does not involve an inventive step or an innovative step:

(i) information in a document that is publicly available, whether in or out of the patent area; and

(ii) information made publicly available through doing an act, whether in or out of the patent area.

68 There is no dispute that the priority date of the relevant claims is 14 March 2002. Nor is there any dispute that the person skilled in the relevant art is an engineer working in the field of developing coffee machines and capsules as at the priority date or a team comprising an engineer with more general product development experience working with another person with knowledge in relation to coffee, coffee machines and capsules (such as a food technologist and/or a barista).

69 The respondents’ inventive step case was put on the basis of first, the common general knowledge as it existed in Australia at the priority date, and secondly, the common general knowledge together with the information disclosed in the 712 patent which was said to satisfy the requirements of s 7(3) of the Act.

70 Neither party made any detailed submissions in relation to the content of the common general knowledge. The focus of the respondents’ attention was on a hypothetical design task undertaken by Mr Winkler for the purposes of this proceeding that was said by the respondents to provide evidence that the claimed invention was obvious. The applicant also focused its attention on Mr Winkler’s hypothetical design task and the reasons why, according to the applicant, it did not provide any reliable evidence from which to conclude that the claimed invention did not involve an inventive step.

71 Each of the claims that is alleged to be invalid for lack of inventive step is to a combination. In Garford Pty Ltd v Dywidag Systems International Pty Ltd (2015) 110 IPR 30 (“Garford”) the Full Court said at 43 [54]-[55]:

[54] … the question to be addressed in relation to inventive step is directed to the combination. The combination will be taken to involve an inventive step unless it is established that it would be obvious to the notional person skilled in the art in light of the common general knowledge considered separately from, or together with, any available s 7(3) information. As Aickin J observed in 3M at CLR 293:

In the case of a combination patent the invention will lie in the selection of integers, a process which will necessarily involve rejection of other possible integers… It is the selection of the integers out, of perhaps many possibilities, which must be shown to be obvious.

[55] In Elconnex Pty Ltd v Gerard Industries Pty Ltd (1992) 25 IPR 173 (Elconnex FC) Lockhart J (with whom Sheppard and Wilcox JJ agreed) referred to this observation of Aickin J and added (at 184) that in the case of a combination “it is impermissible to determine inventiveness by a piecemeal examination integer by integer”.

72 As to whether a combination is obvious, it will often be appropriate to adopt a problem and solution analysis which involves asking whether the hypothetical person skilled in the relevant art, if faced with the same problem to which the invention is directed, would have taken as a matter of routine whatever steps might have led from the prior art to the invention, whether they be the steps of the inventor or not, if the person skilled in the art would be directly led as a matter of course to take such steps in the expectation that doing so might well produce a useful or better alternative to the prior art: Wellcome Foundation Ltd v VR Laboratories (Aust) Pty Ltd (1981) 148 CLR 262 at 286, Aktiebolaget Hässle v Alphapharm Pty Limited (2002) 212 CLR 411 (“Alphapharm”) at [50]-[53], Garford at 39-40 [41]-[43], Becton Dickinson Pty Ltd v B. Braun Melsungen AG [2018] FCA 1692 at [303]. Of course, in this context, prior art refers to information that formed part of the common general knowledge at the relevant priority date together with any other information to which regard may be had in accordance with s 7(3) of the Act.

73 The hypothetical person skilled in the art is assumed to possess the common general knowledge in the relevant field in so far as it is relevant to the subject matter of the patent in suit. This will include the background knowledge and experience available to all persons engaged in the relevant field within the patent area and includes publications to which they would refer as a matter of course: Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Company v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd (1980) 144 CLR 253 (“3M”) at 292 per Aickin J, ICI Chemicals & Polymers Ltd v Lubrizole Corporation Inc (1999) 45 IPR 577 at 599 [11] per Emmett J.

74 Although it is correct to say that the hypothetical person skilled in the art is assumed to lack any capacity for invention, it does not follow that this person is taken to be incapable of finding a solution to a known problem that does not require inventive ingenuity. As the Full Court in Garford observed at [44], “[t]he inventiveness required to sustain a patent for a claimed invention is quite small. A “scintilla” of inventiveness is all that is required …”. But there must still be “some difficulty overcome, some barrier crossed” per Lockhart J, RD Werner & Co Inc v Bailey Aluminium Products Pty Ltd (1989) 85 ALR 679 at 689, or some contribution to the art “beyond the skill of the calling” per Bowen CJ, Beaumont and Burchett JJ, Allsop Inc v Bintang Ltd (1989) 15 IPR 686 at 701. Both of these formulations were referred to with apparent approval by the High Court in Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd (No 2) (2007) 235 CLR 173 at 195-196 [52] per Gummow, Hayne, Callinan, Heydon and Crennan JJ.

75 Also relevant is the use that may be made of hindsight or ex post facto analysis in deciding whether an invention lacks an inventive step. Many inventions may seem obvious with the benefit of hindsight. An ex post facto analysis of an invention can be particularly unfair to the inventor of a new combination which involves selecting a number of known integers from a large range of possible alternatives: see the observations of Aickin J in 3M at 293-294.

76 It is necessary to make findings in relation to the common general knowledge as at the priority date. Mr Winkler gave evidence that the field of consumer and commercial product development engineering, including in respect of single serve coffee machines and capsules, was an international field as at the priority date. Mr Winkler also gave evidence as to the different type of machines that were well-known as at the priority date which was unchallenged and which I accept.

77 The following description of single serve coffee machines, traditional espresso machines, and drip coffee machines is based on Mr Winkler’s evidence and is consistent with statements appearing in the body of the specification which describe single serve coffee cartridges for preparing espresso coffee in a coffee machine as well-known and in widespread use.

78 A single serve coffee machine is a machine that utilises a capsule containing a predetermined amount of coffee grounds to make a standardised cup of coffee. The single serve coffee machine delivers an amount of water heated to a particular temperature under pressure into the capsule to extract certain flavours from the coffee grounds. The coffee beverage then passes through a filter and exits the machine into a receptacle for drinking.

79 In traditional espresso machines, a portafilter is utilised rather than a capsule. A portafilter has a handle and a filter basket for holding the coffee grounds. Coffee grounds are manually placed into the filter basket by the operator. The operator then uses a tamp to manually compact the coffee grounds in the filter basket. The portafilter is then attached to the espresso machine. The espresso machine then delivers heated water under pressure through the coffee grounds through a shower head mechanism. The shower head provides an even coverage of water over the coffee grounds to ensure that the coffee grounds are fully extracted. The coffee beverage then passes through the filter in the bottom of the filter basket and exits the machine into a receptacle for drinking. The operator then removes the portafilter from the espresso machine and removes the used coffee grounds. Espresso machines are generally considered to produce good quality espresso coffee. However, the manual handling of the coffee grounds can be messy and the process of preparing the coffee beverage can be time consuming.

80 Dr Davis agreed in his oral evidence with Mr Winkler’s explanation of the portafilter system. Dr Davis was shown a photograph of a traditional espresso machine portafilter which was admitted into evidence. He agreed that it showed three components of a portafilter. The three components are the exterior part of the portafilter with the handle and two cups (or baskets). He agreed that in use, either one of the two cups (one is larger than the other) is filled with compacted coffee and is then placed inside the main part of the portafilter with the handle.

81 In drip coffee machines, the coffee grounds are held in a large conical paper filter in a brewing basket. Heated water is then fed onto the coffee grounds through a shower head mechanism and the flavours of the coffee are extracted from the grounds. However, unlike in an espresso machine, the extraction does not occur under pressure. Drip coffee machines usually create between 8 to 12 cups of coffee at a time and, therefore, are not suitable for making a single serving of coffee.

82 Drip coffee is made by pouring hot water over the top of coffee grounds, which are held in a filter, and letting the water slowly pass through the coffee grounds and the filter by the force of gravity. In contrast, an espresso coffee is made by pressing hot water at a high pressure through compacted coffee grounds. Drip coffee has a different flavour profile to espresso coffee. Espresso coffee is generally made using darker roast coffee beans which give it a stronger flavour. Drip coffee is made with a lighter roast and has a lighter, more nuanced flavour. The grind profile of an espresso coffee is generally finer than for drip coffee. The finer particles allow for a more compacted coffee bed which increases the resistance of water passing through the coffee bed. This extracts soluble compounds from the coffee grinds, which have a different flavour profile from the coffee grinds used in drip coffee which are generally considered to be sharper and have a different mouth feel. In drip coffee, the heavier grind and larger particles facilitate the passage of the water through the coffee bed under the force of gravity alone.

83 Mr Winkler was asked by the solicitors for the respondents to describe the features that he would have adopted if he was developing a single serve espresso coffee capsule as at the priority date in light of information that he knew and regarded as well-known and generally accepted by engineers working in the field of developing single serve coffee machines and capsules as at that date. He said that he would have included a number of standard features in his design.

84 According to Mr Winkler’s evidence, as at the priority date, it was well-known and generally accepted by engineers working in the field of developing single serve coffee machines and capsules that single serve coffee capsules had at least the following features (“the standard features”):

(a) an enclosure for storing the coffee grounds;

(b) an entrance means for the water to enter the enclosure;

(c) an exit means for the water to exit the enclosure;

(d) at least one filter inside the enclosure between the coffee grounds and the exit means to prevent the coffee grounds from exiting the capsule with an open area beneath the filter for the water to flow and exit the enclosure; and

(e) a hermetical seal.

85 Dr Davis accepted that he had no experience in the design of coffee capsules as at 2002. With reference to the paragraph in Mr Winkler’s affidavit in which he identifies the standard features, Dr Davis was asked:

May we take it that if you had been asked to develop a coffee machine for use with … single serve coffee capsules at that time you would have familiarised yourself with the products on the market and become aware that these were the standard sorts of features of those capsules at that time.

Dr Davis’ response to this question was:

Yes. I agree I would have.

86 Although I can accept that (a), (b), (c) and (e) were standard features as at the priority date, I am not persuaded that there was any coffee capsule shown to be common general knowledge as at the priority date which included feature (d). The Keurig K-Cup included an open area below the filter but it was not shown to have been common general knowledge as at the priority date. Although I accept that the Nespresso capsule was likely to have been well-known as at the priority date, it did not include any open area below the filter.

87 Mr Winkler said that a cup shape is particularly relevant for an espresso coffee capsule because cup-shaped capsules replicate the shape of the portafilter of traditional espresso machines. He said that he would have made a capsule from materials which were able to withstand the pressures required to make an espresso coffee, were impermeable to oxygen, and would be capable of being hermetically sealed. He said that he would have also included an optional second filter between the coffee grounds and the entrance means to act like a shower head to evenly disperse the water across the coffee grounds. This second filter would replicate the shower head of a standard espresso machine.

88 In response to a request from the solicitors for the respondents, Mr Winkler produced three designs using those features on a design software program that he used as at the priority date. He said that the impetus for these designs was to, as much as possible, replicate the features of a portafilter from a traditional espresso machine in the coffee capsule.

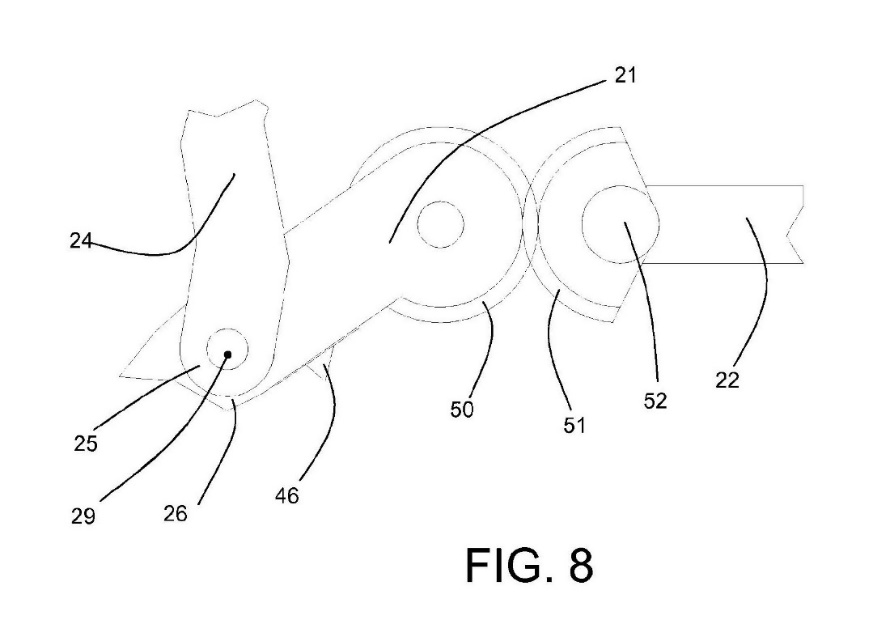

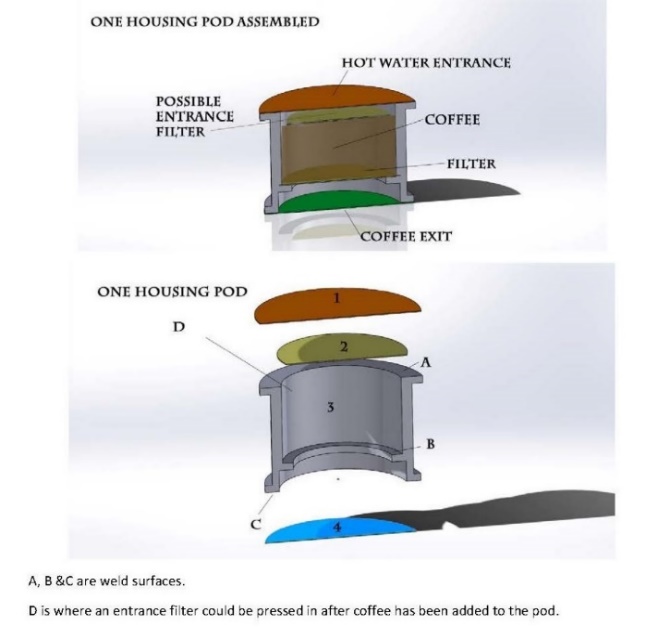

89 The first design (Fig 1) was a one piece pod housing design as follows:

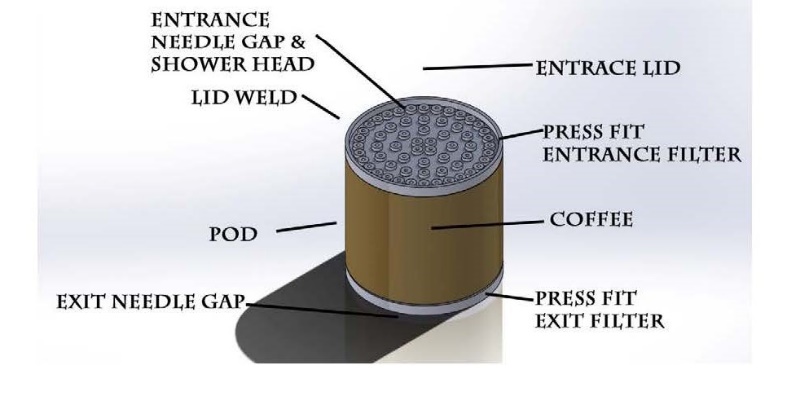

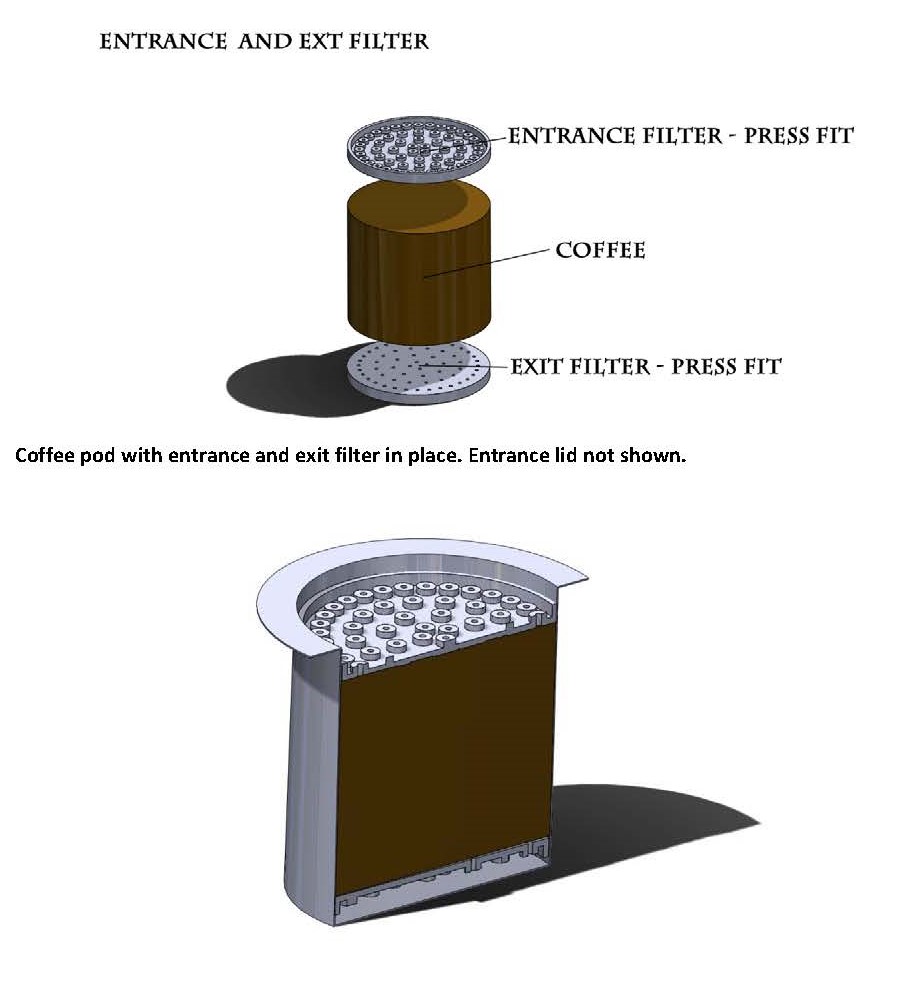

Figure 1

90 Both images are cross-sections of the cup-shaped coffee pod design by Mr Winkler. The exploded image shows an upper cover member (1), an upper filter (2), a main body (3) in which coffee is stored and a lower filter (4) which is welded to a lip at the bottom of the main body. The upper filter is described as a “possible entrance filter” which is not essential. The lower filter is essential. It is designed to prevent particulate exiting the main housing into the coffee cup.

91 Mr Winkler also produced what he referred to as a two piece pod housing design as follows:

Figure 2

92 In his second design (Fig 2) Mr Winkler used a two piece housing pod. The two pieces could be either welded or “snap fit” together with a filter made of woven polymer, an injection moulded filter or a plastic sheet material with filter holes punched or sliced into it. The two piece pod design also included provisions for the inclusion of an optional upper filter.

93 In his third design (Fig 3) Mr Winkler incorporated upper and lower exit filters as shown below:

Figure 3

94 There are a couple of points to note about the entrance and exit filter designs. The entrance filter resembles an inverted shower head with cylindrical bosses facing upwards. The exit filter is facing in the opposite direction so that the cylindrical bosses face downwards. The bosses on the exit filter create a space between the base of the filter and the exit lid. According to Mr Winkler’s description of his design, this allows the filter to stand off the bottom of the cartridge, allowing coffee to collect and pass to the exit.

95 Both filters were designed by Mr Winkler to be made of injection moulded material. But he said that a simple punched filter made of mylar, polyethylene or other food safe flexible plastic could also be used.

96 None of the asserted claims require that the cartridge include more than one filter. For present purposes, I think the presence of the upper filter in Mr Winkler’s design can be disregarded. It is apparent that Mr Winkler’s design has all of the features of the cartridges described in claims 1 and 2 subject to the requirement that the fluid director member (ie. the exit filter in his design) have “… a plurality of openings and plurality of embossings, each of said embossings have a raised portion, whereby a plurality of communicating fluid channels is created between said raised portions of said embossings”.

97 In his evidence Mr Winkler explained that the main difference between the three designs is the method by which the exit filter is attached. In the first design, the filter is welded to a preformed inner ring inside the capsule. Mr Winkler said that welding a filter in this manner was well-known prior to March 2002. However, he did not point to any specific examples where the filter was welded to a preformed inner ring inside the capsule (as opposed to the base of the capsule) in the prior art capsules described in the evidence.

98 In his second design, the filter is locked into place between the two housings. The filter is made of woven polymer, injection moulded material or plastic sheet material with a filter hole punched or sliced into it.

99 In the third design, the filter is press fit into the capsule and is spaced away from the bottom of the capsule by what he referred to as “stand offs” which form part of the filter. He said that this feature was known more broadly in product development engineering. According to Mr Winkler:

I considered that the third design (the Press-Fit Design) was superior to the others because it provides more versatility as to how to execute the design. The exterior housing for the capsule can be chosen without being limited by the filter material because the filter is press fit into the housing. By contrast, if the filter is welded to the interior of the housing, the housing would need to be made of a material which is compatible with the filter material. Further, if the filter was snapped between upper and lower segments of the capsule, the capsule might be susceptible to leakage, i.e. oxygen might permeate the capsule through leaks in the snapping mechanism.

100 The applicant made a number of criticisms of Mr Winkler’s evidence.

101 First, it was suggested that Mr Winkler’s design task was artificial in that it would be unusual for a product engineer to be requested to design a coffee cartridge without also being told exactly what type of machine it was to be used in. Whether that is true or not is neither here nor there. The patent specification does not describe the coffee machine in which the cartridge is to be used except in the most general terms. Mr Winkler has approached the design task in much the same way as the specification proceeds, that is to say, he has designed a cartridge for use in a single serve machine adapted to use such a cartridge.

102 Secondly, it was submitted that rather than attempting to design a cartridge for use in a single serve espresso coffee machine, Mr Winkler instead sought to design a cartridge that could be used in a portafilter in a traditional espresso machine. I do not think that is an accurate characterisation of his evidence. Mr Winkler agreed that he took the portafilter of a traditional espresso machine as his starting point and it provided the inspiration for his design. He was seeking to replicate some of the design characteristics of a traditional espresso machine in his cartridge design. Dr Davis agrees that if he was asked to develop a single serve espresso coffee cartridge then that would be a reasonable approach and “one of [his] approaches”.

103 Thirdly, it was submitted by the applicant that:

… the key difficulty with Mr Winkler’s design task is that there is no satisfactory explanation as to why the non-inventive worker would have included, as he did, (a) a filter element which is solid rather than fabric, and which also acts as a fluid collection member, by incorporating features which stand it off from the base of the capsule so that the beverage can flow beneath it; and (b) a similar solid filter element, constituting a distribution member, inserted at the top of the body of the capsule, when neither feature, or anything like them, existed at all in the prior art …

104 As to the first point, there is nothing in claims 1 or 2 that requires that the distribution member (the exit filter in Mr Winkler’s design) be made of any particular material. Mr Winkler said that the filter could be made from an injection moulded material or a simple food safe flexible plastic. Nor is there anything in claims 1 or 2 which requires that the fluid collection member incorporate features which stand it off from the base of the capsule. Although dependent claim 16 requires that the fluid member “… is located in the interior of the cartridge with a certain distance from the bottom of said main body portion or from said cover member” there is no requirement that the “raised portions” stand the filter member off the base of the capsule so that beverage may flow beneath it. That is no doubt a feature of a preferred embodiment (see page 9, lines 1-10 of the specification) but it is not a feature that is carried through into any of the asserted claims.

105 As to the second point, none of the asserted claims require that the cartridge include a filter at the top above the store of coffee. As I have mentioned, Mr Winkler’s designs included a “possible entrance filter”. The fact that he included an entrance filter is perhaps not surprising if he was trying to, as much as possible, replicate the features of a portafilter from a traditional espresso machine in a coffee capsule. It would seem logical to include in the design a shower head mechanism similar to that found in a traditional espresso machine. Mr Winkler stipulated that the upper filter in his design was optional only. It is not apparent to me why he decided to make this element of his design optional. Curiously, claims 1 and 2 also allow for the cartridge to have only one fluid director member (ie. a second fluid director member is optional).

106 Mr Winkler referred in his evidence to a number of coffee capsules that were, as at the priority date, relevant prior art. These were:

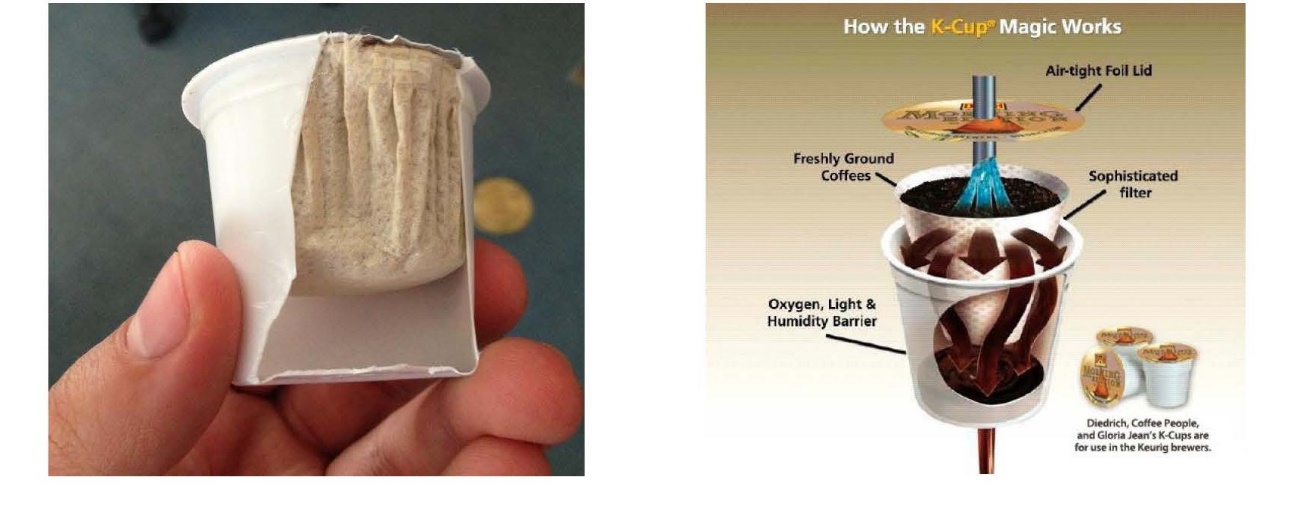

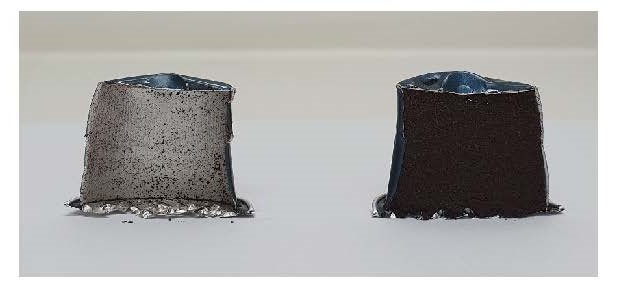

Keurig K-Cup. The K-Cup was a pour-over coffee machine capsule which had a paper polymer filter held within it. The filter was welded directly to the side wall of the pod. Entry and exit was via a cannula. The K-Cup as at 2001 is depicted in the images below (the exit cannula is not shown). The capsule and the Keurig B-100 machine were designed as a system.

Flavia by Mars. The Flavia pack was a foil sealed pack containing coffee with an enclosing made of flexible laminate. Entry was by an injector and nozzle. The filter was a satchel or bag and was contained inside the pack. Exit was by a weakened seal at the bottom, whereby the filter would drop down and liquid would pass through the filter and into the cup. The Flavia pack as at 2001 is shown in the images below.

Kenco Cappio. The Kenco Cappio was a rectangular plastic cartridge that looked similar to an eight-track tape. That cartridge is shown in the image below (save that the exit was not by a nozzle but some form of puncture). Entry was via a nozzle (indicated by the words “Water Flow”). There was a filter in the cartridge made of cloth. Exit was via some form of exit puncture at the location with the words “Freshly Brewed Coffee”.

Philips Senseo. The Senseo coffee pod was a soft satchel or bag containing coffee. The coffee was held between two disc-shaped filters made of paper polymer. Water entered through the filter on the top of the pod. Water exited through the underside of the pod into a collection means which had a decelerating feature. The coffee then went through a spout to an exit. The Senseo machine as at 2001 is shown in the images below.

Nespresso. The Nespresso capsule as at 2001 was a cup-shaped capsule containing coffee. Entry was via a canula that entered the pod. It did not have a solid filter inserted in the body of the capsule. The Nespresso machine had plates with pyramid-shaped geometries that pressed onto the lid of the capsule to create openings that allowed the coffee beverage to exit but retain the coffee grounds. The following image is indicative of a Nespresso capsule as at 2001, at least with respect to the exit means.

107 Mr Winkler’s evidence as to when the Nespresso system first entered the market is unclear. He said that he first inspected a Nespresso machine at a tradeshow in Chicago in 2001. However, the specification of the 627 patent describes at page 1A, line 10 – page 2, line 13 a system that is the same or very similar to the Nespresso system. Cartridges used in the system described are said to be “well known” in the art. In light of that statement and, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, I am satisfied that the Nespresso system as described by Mr Winkler was common general knowledge as at the priority date.

108 The Nespresso capsules were cup-shaped and made of aluminium. They did not contain a separate internal filter. Rather, once pierced by the machine, the cover of the capsule functioned as a filter through which brewed coffee could exit.

109 At this point it is useful to consider what the applicant says the inventive step is. Although it did not identify the inventive step in terms, it referred in its written submissions to a number of features which were said to distinguish the inventive cartridges described in the specification from the prior art. The following four features were identified by the applicant as distinguishing the cartridge described in the specification from the prior art:

(a) the use of a filter element at the bottom of the body of the capsule made of solid material rather than paper or fabric;

(b) the use of a filter element that acts as a fluid collection member by incorporating features which stand it off from the base of the cartridge so that the beverage can flow beneath it;

(c) a distribution member located at the top of the cartridge that simplifies the coffee machine by removing the need for a distribution mechanism in the machine, providing for a more uniform flow of liquid through the capsule;

(d) the ability to reverse the flow.

110 It is important to note that these are features of various preferred embodiments but are not requirements of claims 1 or 2. The question whether an invention involves an inventive step is to be answered by reference to the invention as claimed. None of the distinguishing features identified by the applicant are requirements of claims 1 and 2.

111 As to the use of a filter element which is solid rather than paper or fabric, this reflects an obvious design choice. If the filter is to be used in a pressurised system it would be both natural and logical to select a material capable of withstanding the pressure. There is nothing in Dr Davis’ evidence to suggest that the use of a filter made from a solid material (eg. aluminium or plastic) would be anything other than an obvious design choice. Mr Winkler said that a capsule used to make espresso coffee would need to be able to withstand the pressures used to make espresso coffee. Dr Davis disagreed because, in his opinion:

… many Australian mechanical engineers specialising in product design … would readily recognise both the capsule and the cavity of the coffee machine (in which the capsule is inserted into) must be able to withstand internal pressures in the capsule. In other words, the material used to manufacture the coffee capsule would not need to be able to withstand the pressure in question on a standalone basis as the cavity of the machine needs to provide support to assist the capsule in withstanding internal pressure.

112 While it may be accepted that both the machine and the capsule must be able to withstand the pressures within the system, and that the cartridge would not be required to withstand pressure on a “stand alone” basis, I did not understand Dr Davis to suggest that a product design engineer designing a coffee capsule for use in a pressurised system that was intended to be used to brew espresso coffee would be likely to opt for a capsule made of paper, fabric or some similar material in preference to something more rigid such as lightweight polypropylene or aluminium. But if that is what Dr Davis was suggesting then I prefer the evidence of Mr Winkler on this point.

113 I have already referred to criticisms made by the applicant of Mr Winkler’s design task. In my view Mr Winkler’s evidence as to how he would have gone about designing an espresso coffee cartridge was helpful and, generally speaking, persuasive. Dr Davis accepted that the approach taken by Mr Winkler was reasonable. He did not suggest that Mr Winkler’s approach would be unlikely to be followed by other persons skilled in the art who were seeking to design a new or improved espresso coffee cartridge. In my view, the design pathway followed by Mr Winkler (including its starting point) would have been obvious to a person skilled in the relevant art at the priority date and was one that would have directly led to an espresso coffee cartridge within claims 1 and 2 of the 627 patent subject only to the requirement that the fluid director member have a plurality of embossings (as I have interpreted that word) and fluid channels.

114 The applicant did not suggest that there was anything unusual about the shape or configuration of the embossings in the lower distribution member of the invention claimed in claims 1 and 2. That is hardly surprising in circumstances where the applicant has always contended that the word “embossing” refers to no more than the geometry of any shape that is raised off a surface. That said, it is still necessary to ask whether the shape or configuration of the embossings referred to in the claims, as I have construed them, might somehow involve an inventive step.

115 Whether or not the bosses on the underside of the exit filter in Mr Winkler’s third design (Fig 3) are embossings in the sense that word is used in the claim is doubtful. I would not describe their shape as bulging or convex. But on the issue of inventive step I do not regard that as a matter of any real significance. If similar shapes were to be created using well-known manufacturing techniques such as pressing or deep drawing, then they would be likely to exhibit the bulging or convex shapes that would also create fluid channels as described in the claims. The difference between what Mr Winkler produced and what is claimed seems to me to reflect small differences in detail that are of no importance to the inventive step analysis. The fact that Mr Winkler’s designs may not in all respects have met the exact requirements of the claims does not diminish the value of his evidence.

116 The applicant submitted that Mr Winkler’s evidence must be approached with some caution given that he is a highly experienced and inventive design engineer. The submission was, in effect, that he was not a good proxy for the hypothetical person skilled in the art who lacks any capacity for invention. I do not accept that submission. I found the evidence of Mr Winkler’s design task and his explanation for it helpful in understanding the way in which a person skilled in the art would be likely to go about designing a single serve coffee cartridge suitable for making espresso coffee in a pressurised coffee machine as at the priority date.

117 In my opinion the design of an espresso coffee cartridge for use in an espresso machine having the features of the combination defined by claims 1 and 2 would be obvious to a non-inventive product design engineer equipped with the common general knowledge at the priority date. It would not require inventive ingenuity or any contribution to the art that was “beyond the skill of the calling” to design a coffee cartridge within each of those claims as at the priority date: Allsop Inc v Bintang Ltd (1989) 15 IPR 686 at 701.

118 None of the dependent claims that are asserted against the respondents add any additional feature to the combination described in claims 1 or 2 that could render it inventive.

119 Claim 9 requires that the exit holes be located in the fluid channels created between the raised portions of the embossings. In circumstances where the function of the fluid channels is to direct brewed coffee out of the cartridge, there cannot be any inventive step arising out of the addition of this requirement. The use of exit holes and channels in the surface of the exit filter reflects a simple design choice that would be well within the capabilities of a non-inventive product design engineer who was tasked with designing aa single serve coffee cartridge suitable for making espresso coffee in a pressurised coffee machine as at the priority date.

120 Claim 16 imposes the additional requirement that the fluid director member be spaced a certain distance from the bottom of the main body portion of the cartridge or from the cover member. Incorporating some form of support (eg. a step in the interior of the main body of the cartridge) to enable the filter to stand off the base of the cartridge would, as Mr Winkler explained, be a means of enabling the beverage to flow out of the exit holes. Given the need for such a spacing, there is nothing inventive about the combination that includes this additional integer.