FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Sony Interactive Entertainment Network Europe Limited [2020] FCA 787

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | SONY INTERACTIVE ENTERTAINMENT NETWORK EUROPE LIMITED First Respondent SONY INTERACTIVE ENTERTAINMENT EUROPE LIMITED Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Subject to further order, pursuant to s. 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth.), and on the ground that the order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, the information contained in the Confidential Annexure to the Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions not be published or otherwise disclosed to any person other than the parties or their external legal representatives.

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

Terms of Service Representation

2. Between October 2017 and May 2019, in circumstances where ss. 54 to 56 of the Australian Consumer Law (A.C.L.) provide consumer guarantees as to acceptable quality, the fitness of goods for disclosed purposes and the correspondence between goods and their description, Sony Interactive Entertainment Network Europe Limited (SIENE):

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s. 18 of the A.C.L.; and/or

(b) made false or misleading representations regarding the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy in contravention of s. 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L.,

in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply, possible supply and/or promotion of digital games to Australian consumers, by impliedly representing, in the following clause of its Terms of Service, that users do not have guarantees as to the quality, functionality, completeness, accuracy or performance of purchased digital games:

“Clause 19 – Your Rights and Our Liability

We do not exclude or limit our liability for:

…

(iii) any liability that cannot be excluded or limited under applicable law.

Other than as set out in this section 19, we are not responsible or liable in contract, tort, including negligence, or otherwise, for, nor do we give warranty or representation in relation to:

(i) the quality, functionality, availability, completeness, accuracy or performance of the PSN or its Products”.

Communications when adding funds to the PSN wallet

3. Between September 2017 and September 2019, SIENE, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply and/or possible supply of digital games to Australian consumers:

(a) engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s. 18 of the A.C.L.; and/or

(b) made false or misleading representations regarding the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy in contravention of s. 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L.,

by representing to Australian consumers (by messages and emails in connection with a purchase) that users could not obtain a refund of funds added to the PSN wallet, when in fact consumers are entitled to a refund if the purchased game has a major failure (or a non-major failure which is not rectified in a reasonable period of time) under ss. 54, 55, 56, 259(2)-(3) and 263 of the A.C.L.

PlayStation Support Centre Representations

4. In September and October 2017, SIENE (through its call centre agents), in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply of a particular digital game to User JA, engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, and made false or misleading representations concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any right or remedy User JA may have had, by representing that even if a game had a major failure or some other failure to comply with a guarantee that could not be, or had not been, remedied, SIENE was not required to refund User JA unless User JA obtained authorisation from the publisher (or developer) of the game for the refund to be made, when in fact ss. 259 and 263 of the A.C.L. confer rights on consumers to obtain redress directly from suppliers of goods, in contravention of ss. 18 and 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L.

5. Between October 2017 and November 2017, SIENE (through its call centre agents), in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply of particular digital games to each of Users BM, HP, JA and JS, engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive, and made false or misleading representations to each concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any right or remedy they may have had, by representing that, even if a game had a major failure or some other failure to comply with a guarantee that could not be, or had not been, remedied, SIENE was not required to refund the user more than 14 days after purchase or if the game had been downloaded, when in fact there is no such limit on consumers’ rights to obtain redress from suppliers of goods under ss. 259 and 263 of the A.C.L., in contravention of ss. 18 and 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L.

6. On 30 October 2017, SIENE (through its call centre agents), in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply of a particular digital game to User CK engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, and made false or misleading representations to User CK concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any right or remedy User CK may have had, by representing that even if a game had a major failure or some other failure to comply with a guarantee that could not be, or had not been, remedied, SIENE was not required to refund User CK in a currency or form that was useable outside the PSN, but could make any refund by crediting User CK’s PSN wallet, when in fact consumers are entitled to a refund in the form of “money” if the purchased game has a major failure (or a non-major failure which is not rectified in a reasonable period of time) under ss. 54, 55, 56, 259(2)-(3) and 263 of the A.C.L., in contravention of ss. 18 and 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L.

THE COURT FURTHER ORDERS THAT:

Pecuniary penalties

7. Pursuant to s. 224 of the A.C.L., SIENE pay to the Commonwealth, within 30 days of the date of order, pecuniary penalties of:

(a) AUD$2,000,000 in respect of the contravention of s. 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L. identified in paragraph 2 of this Order;

(b) AUD$1,000,000 in respect of the contravention of s. 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L. identified in paragraph 3 of this Order;

(c) AUD$150,000 in respect of the contraventions of s. 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L. identified in paragraph 4 of this Order;

(d) AUD$200,000 in respect of the contraventions of s. 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L. identified in paragraph 5 of this Order; and

(e) AUD$150,000 in respect of the contraventions of s. 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L. identified in paragraph 6 of this Order.

Disclosure orders

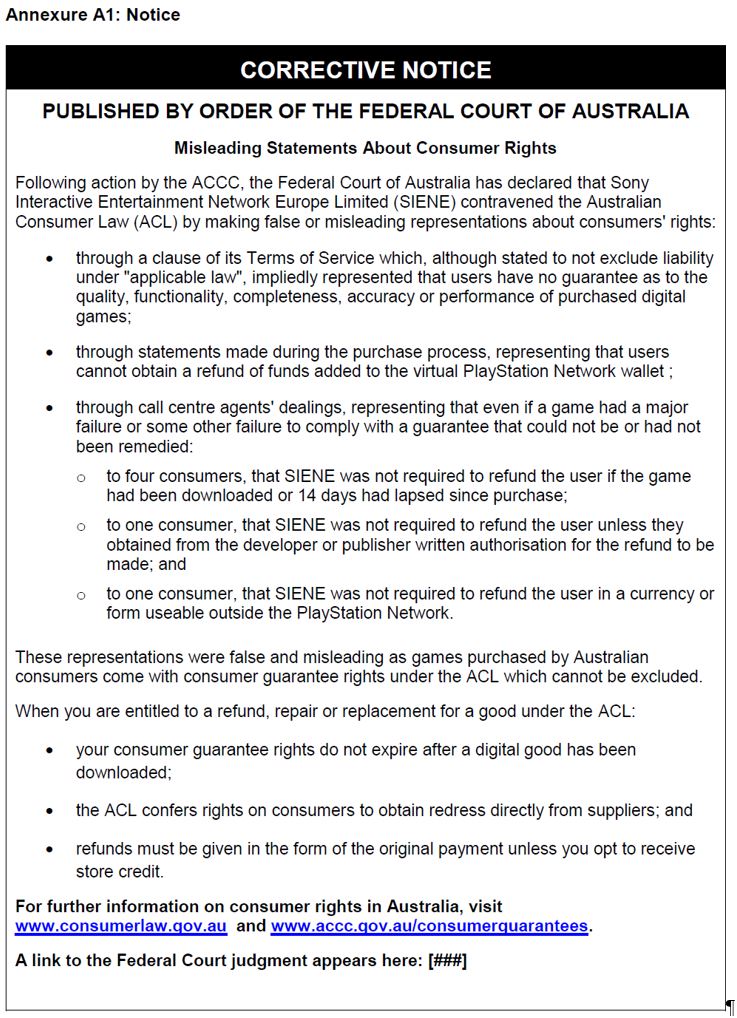

8. Pursuant to s. 247 of the A.C.L., SIENE, at its own expense and within 21 days of the date of this Order and for a period of 120 days, will publish on the Sony PlayStation Website www.playstation.com/en-au/ (Website) a notice in the terms set out in Annexure A1 (Notice), and ensure that the Notice complies with the following specifications:

(a) the Notice is viewable by clicking a hyperlink located on the Website;

(b) the hyperlink referred to in the previous sub-paragraph is located in the top third of the Website and is not obscured, blocked or interfered with by any operation of the Website;

(c) the hyperlink:

(i) contains the words:

“Corrective Notice Ordered by Federal Court of Australia About Consumer Rights – Click Here” in upper case 14 point, bold, black, Times New Roman font on a white background, centred and in a bordered box;

(ii) the bordered box and its contents, including the white space, is to operate in the form of a one-click hyperlink to the said Notice; and

(iii) the border must be black;

(d) the Notice must occupy the entire webpage that is accessed via the hyperlink;

(e) the Notice must not be displayed as a “pop up” or “pop under” window; and

(f) the Notice must be crawlable (i.e. its contents may be indexed by a search engine).

Other orders

9. A copy of the reasons for judgment, with the seal of the Court affixed thereon, and a sealed copy of the final orders in these proceedings be retained on the Court file for the purposes of s. 137H of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth.).

10. SIENE pay the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding in the sum of AUD$100,000.

11. The proceeding be otherwise dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

STEWARD J.:

1 In the period between 1 September 2017 and 23 May 2019 (the “Relevant Period”), Sony Interactive Entertainment Network Europe Limited (“SIENE”) – a subsidiary of Sony Interactive Entertainment Europe Limited (“SIEE”) – operated the PlayStation Network (“PSN”) and PlayStation Store for a number of jurisdictions, including Australia, New Zealand, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Russia and parts of Asia (the “SIENE Territory”). The PSN was, and continues to be, an online entertainment service. During the Relevant Period, the PSN allowed PSN account holders to interact online with other PSN account holders, and provided those account holders with access to a range of digital products and services, including the ability to purchase digital games from the PlayStation Store. The PlayStation Store was, and continues to be, on the PSN. During the Relevant Period, it could be accessed online. PSN account holders could purchase and download games via the PlayStation Store to play on the PlayStation console.

2 SIENE admits that it engaged in conduct that contravened ss. 18 and 29(1)(m) of the Australian Consumer Law (“A.C.L.”), as set out in Sch. 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth.). In broad terms, SIENE admits that:

(a) between October 2017 and May 2019, in circumstances where ss. 54 to 56 of the A.C.L. provide consumer guarantees as to acceptable quality, the fitness of goods for disclosed purposes and the correspondence between goods and their description, it impliedly represented in its Terms of Service and User Agreement (the “Terms of Service”) that PSN users do not have guarantees as to the quality, functionality, completeness, accuracy or performance of purchased digital games;

(b) between September 2017 and September 2019, it represented to Australian consumers (by messages and emails in connection with a purchase) that PSN users could not obtain a refund of funds added to an online wallet on the PSN (called the “PSN wallet”), when in fact consumers are entitled to a refund if the purchased game has a major failure (or a non-major failure which is not rectified within a reasonable period of time) under ss. 54, 55, 56, 259(2), 259(3) and 263 of the A.C.L.; and

(c) between September and November 2017, it made various representations (through its call centre agents) respecting SIENE’s requirement to refund users which were contrary to the terms of the A.C.L. when responding to five PSN user complaints.

3 Consequently, the applicant (the “A.C.C.C.”), SIENE and SIEE filed with the Court:

(a) a Statement of Agreed Facts and Admissions (the “SoAFA”) setting out facts agreed between the parties and admissions made by SIENE and SIEE pursuant to s. 191(3)(a) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth.);

(b) joint submissions on relief; and

(c) proposed consent orders, setting out the relief (including as to penalty) which the parties contend to be appropriate and which they request be ordered in this proceeding.

4 The principal components of the relief proposed in respect of SIENE are:

(a) declarations pursuant to s. 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth.) that SIENE contravened ss. 18 and 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L.;

(b) an order that SIENE pay to the Commonwealth a pecuniary penalty in the amount of AUD$3.5 million pursuant to s. 224 of the A.C.L.;

(c) a disclosure order pursuant to s. 247 of the A.C.L.; and

(d) an order that SIENE pay the A.C.C.C.’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding in the sum of AUD$100,000.

5 The parties otherwise request that the proceeding be dismissed.

6 For the reasons which follow, I consider that it is appropriate to make the declarations and orders proposed by the parties.

Applicable Legislation

7 Section 18 of the A.C.L. relevantly provides:

Misleading or deceptive conduct

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

…

8 Section 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L. provides:

False or misleading representations about goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services or in connection with the promotion by any means of the supply or use of goods or services:

…

(m) make a false or misleading representation concerning the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy (including a guarantee under Division 1 of Part 3‑2); or

…

9 Section 54 of the A.C.L. relevantly provides:

Guarantee as to acceptable quality

(1) If:

(a) a person supplies, in trade or commerce, goods to a consumer; and

(b) the supply does not occur by way of sale by auction;

there is a guarantee that the goods are of acceptable quality.

(2) Goods are of acceptable quality if they are as:

(a) fit for all the purposes for which goods of that kind are commonly supplied; and

(b) acceptable in appearance and finish; and

(c) free from defects; and

(d) safe; and

(e) durable;

as a reasonable consumer fully acquainted with the state and condition of the goods (including any hidden defects of the goods), would regard as acceptable having regard to the matters in subsection (3).

(3) The matters for the purposes of subsection (2) are:

(a) the nature of the goods; and

(b) the price of the goods (if relevant); and

(c) any statements made about the goods on any packaging or label on the goods; and

(d) any representation made about the goods by the supplier or manufacturer of the goods; and

(e) any other relevant circumstances relating to the supply of the goods.

…

10 Section 55 of the A.C.L. provides:

Guarantee as to fitness for any disclosed purpose etc.

(1) If:

(a) a person (the supplier) supplies, in trade or commerce, goods to a consumer; and

(b) the supply does not occur by way of sale by auction;

there is a guarantee that the goods are reasonably fit for any disclosed purpose, and for any purpose for which the supplier represents that they are reasonably fit.

(2) A disclosed purpose is a particular purpose (whether or not that purpose is a purpose for which the goods are commonly supplied) for which the goods are being acquired by the consumer and that:

(a) the consumer makes known, expressly or by implication, to:

(i) the supplier; or

(ii) a person by whom any prior negotiations or arrangements in relation to the acquisition of the goods were conducted or made; or

(b) the consumer makes known to the manufacturer of the goods either directly or through the supplier or the person referred to in paragraph (a)(ii).

(3) This section does not apply if the circumstances show that the consumer did not rely on, or that it was unreasonable for the consumer to rely on, the skill or judgment of the supplier, the person referred to in subsection (2)(a)(ii) or the manufacturer, as the case may be.

11 Section 56 of the A.C.L. relevantly provides:

Guarantee relating to the supply of goods by description

(1) If:

(a) a person supplies, in trade or commerce, goods by description to a consumer; and

(b) the supply does not occur by way of sale by auction;

there is a guarantee that the goods correspond with the description.

(2) A supply of goods is not prevented from being a supply by description only because, having been exposed for sale or hire, they are selected by the consumer.

…

12 Section 259 of the A.C.L. relevantly provides:

Action against suppliers of goods

(1) A consumer may take action under this section if:

(a) a person (the supplier) supplies, in trade or commerce, goods to the consumer; and

(b) a guarantee that applies to the supply under Subdivision A of Division 1 of Part 3‑2 (other than sections 58 and 59(1)) is not complied with.

(2) If the failure to comply with the guarantee can be remedied and is not a major failure:

(a) the consumer may require the supplier to remedy the failure within a reasonable time; or

(b) if such a requirement is made of the supplier but the supplier refuses or fails to comply with the requirement, or fails to comply with the requirement within a reasonable time—the consumer may:

(i) otherwise have the failure remedied and, by action against the supplier, recover all reasonable costs incurred by the consumer in having the failure so remedied; or

(ii) subject to section 262, notify the supplier that the consumer rejects the goods and of the ground or grounds for the rejection.

(3) If the failure to comply with the guarantee cannot be remedied or is a major failure, the consumer may:

(a) subject to section 262, notify the supplier that the consumer rejects the goods and of the ground or grounds for the rejection; or

(b) by action against the supplier, recover compensation for any reduction in the value of the goods below the price paid or payable by the consumer for the goods.

…

13 Section 263 of the A.C.L. provides:

Consequences of rejecting goods

(1) This section applies if, under section 259, a consumer notifies a supplier of goods that the consumer rejects the goods.

(2) The consumer must return the goods to the supplier unless:

(a) the goods have already been returned to, or retrieved by, the supplier; or

(b) the goods cannot be returned, removed or transported without significant cost to the consumer because of:

(i) the nature of the failure to comply with the guarantee to which the rejection relates; or

(ii) the size or height, or method of attachment, of the goods.

(3) If subsection (2)(b) applies, the supplier must, within a reasonable time, collect the goods at the supplier’s expense.

(4) The supplier must, in accordance with an election made by the consumer:

(a) refund:

(i) any money paid by the consumer for the goods; and

(ii) an amount that is equal to the value of any other consideration provided by the consumer for the goods; or

(b) replace the rejected goods with goods of the same type, and of similar value, if such goods are reasonably available to the supplier.

(5) The supplier cannot satisfy subsection (4)(a) by permitting the consumer to acquire goods from the supplier.

(6) If the property in the rejected goods had passed to the consumer before the rejection was notified, the property in those goods revests in the supplier on the notification of the rejection.

Applicable Principles – Misleading or Deceptive Conduct

14 The parties helpfully set out the following well settled principles in the joint submissions, which I gratefully adopt:

Conduct is misleading or deceptive if it has a tendency to lead into error: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 C.L.R. 640 at 651 [39].

Whether conduct is misleading or deceptive is a question of fact to be resolved by a consideration of the whole of the impugned conduct in the circumstances in which it occurred: Butcher v. Lachlan Elder Realty Pty Ltd (2004) 218 C.L.R. 592 at 625 [109] per McHugh J.; Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v. Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 C.L.R. 191 at 199.

Conduct may be directed at individuals or at a class: Butcher at 604 [36] per Gleeson C.J., Hayne and Heydon JJ.

Where conduct is directed at specific individuals, such conduct must be characterised in the context of their specific relations, including what matters of fact each knew, or may be taken to have known, about each other from their dealings and conversations: see Butcher at 604-605 [37], 605 [40] per Gleeson C.J., Hayne and Heydon JJ.; Campbell v. Backoffice Investments Pty Ltd (2009) 238 C.L.R. 304 at 319-320 [27] per French C.J.

Conduct may also be directed at a class of persons, in which case its character as misleading or deceptive must be considered by reference to ordinary or reasonable members of that class, which may include persons that may or may not be intelligent and may or may not be well educated: see generally Butcher at 604 [36]-[37] per Gleeson C.J., Hayne and Heydon JJ.; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 634; (2014) 317 A.L.R. 73 at [43] per Allsop C.J.; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. We Buy Houses Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 915 at [60] per Gleeson J. Extreme or fanciful reactions to conduct are not to be attributed to ordinary and reasonable members of the class: Campomar Sociedad Limitada v. Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 C.L.R. 45 at 86-87 [105].

A statement may be misleading even if it is literally true, or capable of multiple interpretations, so long as one reasonable interpretation would lead an ordinary member of the class into error: Tobacco Institute of Australia Ltd v. Australian Federation of Consumer Organisations Inc (1992) 38 F.C.R. 1 at 50; National Exchange Pty Ltd v. Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2004] FCAFC 90; (2004) 49 A.C.S.R. 369 at [24], [49].

Whether conduct is misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, is objective, and it is not necessary to show that any one person was actually misled: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Valve Corporation (No 3) [2016] FCA 196; (2016) 337 A.L.R. 647 at [223]-[228] per Edelman J.; Campbell at 319-320 [25]-[29] per French C.J.

Factual background

15 The following factual summary is drawn from the SoAFA prepared by the parties. Unless otherwise stated, the facts below relate to the Relevant Period.

Games developers and publishers

16 As aforementioned, PSN account holders could purchase and download games via the PlayStation Store which was on the PSN. Games were developed by entities commonly referred to as “developers”. Developers typically supplied their games to entities commonly referred to as “publishers”. Game publishers who wanted their games to be sold digitally online supplied their games to online retailers like SIENE, which then supplied the games to consumers (in SIENE’s case, via the PlayStation Store).

17 Most of the games available for purchase and download from the PlayStation Store were developed and published by third parties unrelated to SIENE or SIEE.

Terms of Service

18 In order to access the PSN and PlayStation Store, users had to create a PSN account. To create a PSN account, users had to click an image on her or his screen during the process indicating that they agreed to SIENE’s Terms of Service, thus entering into an agreement with SIENE. These Terms of Service applied to games purchased through the PlayStation Store.

19 The Terms of Service were available to be viewed and downloaded by Australian users from the PlayStation Australia website: www.playstation.com/en-au.

The PSN wallet

20 The PSN wallet was an online wallet containing virtual funds that could be used to purchase items in the PlayStation Store. The PSN wallet could be pre-loaded with funds using a credit card, a debit card, PayPal or a voucher code.

21 The PSN wallet was not a bank account. Funds in the PSN wallet had no value outside the PSN, could only be used to buy products sold by SIENE, were not redeemable for cash, were not a user’s personal property and could not be transferred to other PlayStation users.

The purchase flow process – online checkout and payment

22 In order to purchase a game from the PlayStation Store, PSN users had to select the game from the PlayStation Store and add it to their cart. The PSN user then had to view their cart and click an applicable image on her or his screen to proceed to the checkout. Once in the checkout, the user had to confirm their purchase to complete the transaction.

23 From at least 1 September 2017 until 17 September 2019, purchases in the PlayStation Store could only be made by debiting funds from the user’s PSN wallet.

24 If the PSN wallet had insufficient funds to complete a purchase, and the user did not pay with a PlayStation voucher code, then the purchase was completed by the user topping up their PSN wallet using their nominated credit card, debit card or PayPal account. After doing so, the balance of the purchase price was then able to be, and was, debited from the PSN wallet in order to complete the purchase.

The PlayStation Support Centre

25 The PlayStation Support Centre was operated on behalf of SIENE by a third party service provider. The PlayStation Support Centre was responsible for providing customer support services to Australian PSN users as well as other users in the SIENE Territory.

26 Australian PSN users who encountered difficulties with downloading or playing a game purchased from the PlayStation Store could fill out an online form on the PlayStation Australia website to seek assistance or a refund, email PlayStation at support@playstation.com.au, and/or call the PlayStation Support Centre. PlayStation Support Centre representatives who serviced Australian customers were located in Scotland. Interactions between the PlayStation Support Centre and PSN users in Australia took place over the phone and/or by email.

SIEE and SIENE’s management and culture

27 During the Relevant Period, senior staff within the relevant business area of SIEE, whose duties included aspects of the SIENE business, were responsible for:

(a) approving the Terms of Service that were displayed on the PlayStation Australia website: www.playstation.com/en-au;

(b) approving statements that were displayed to Australian consumers during the online checkout process described above at [22];

(c) approving statements that were displayed to Australian consumers in automated emails sent on behalf of SIENE to PSN account holders;

(d) approving scripts, manuals, instructions, policies and training provided to PlayStation Support Centre staff in relation to their dealings with Australian consumers and overseeing employees’ compliance with such material;

(e) approving the content available on the PlayStation Australia website, www.playstation.com/en-au, which displayed the Terms of Service; and

(f) providing oversight of the PlayStation Support Centre staff.

28 During the Relevant Period, SIEE and SIENE did not draft or approve any training materials or scripts, manuals, instructions or policies specifically about or related to Australian consumer law and the A.C.L.

29 SIENE had in place:

(a) a Cancellation Policy, which, prior to April 2019, stated: “[d]igital content that you have started downloading, streaming and in-game consumables that have been delivered, are not eligible for a refund unless the content is faulty”. The Cancellation Policy was available on a separate page to the Terms of Service; and

(b) instructions for PlayStation Support Centre staff to guide their dealings with customers including instructions relating to referrals to publishers and developers and responding to refund requests where customers were not happy with the quality of their game.

30 The aforementioned instructions relevantly provided:

When to refer Players to publishers

…

You must not refer to publishers for:

• Refund requests. (Note that if the Player is requesting a refund because of content missing in game … SIE can investigate further and contact the publisher directly to check this).

• PlayStation Store related issues (wrong pricing, inaccurate description, items missing from the store etc.)

• Download Issues (download button missing from the store etc.)

If further investigation is required, escalate to CC – PlayStation Network queue

Please remember, you should never refer Player to a developer!

…

4.4.1 – Can I get a refund because I’m not happy with the quality of the game I purchased?

In this case, the content has been downloaded, is available to use on your console and cannot be removed, even after refunding. As the content cannot be ‘returned’, we cannot consider a refund of the purchase.

We have a published Store Cancellation Policy to set a clear expectation for our consumers. If you change your mind about a purchase made from the PlayStation Store, you can request a refund to your PSN wallet within 14 days from the date of transaction, provided you have not started downloading or streaming your purchase.

As there is no actual fault with the content we cannot consider a refund of the purchase.

Many games have free demo versions which can be downloaded first to enable you to check the quality of the game. There are also a large number of specialist press reviews and gaming websites/forums to consult in order to judge the quality of the content before purchase.

The admitted contraventions

Terms of Service Representation

31 As previously mentioned, consumers had to agree to the Terms of Service when creating an Australian PSN account. The Terms of Service were also made generally accessible on the PlayStation Australia website. The Terms of Service applied to all goods purchased via the PlayStation Store.

32 Between 1 October 2017 and 23 May 2019, the Terms of Service relevantly contained the following clause:

Clause 19 – Your Rights and Our Liability

We do not exclude or limit our liability for:

…

(iii) any liability that cannot be excluded or limited under applicable law.

Other than as set out in this section 19, we are not responsible or liable in contract, tort, including negligence, or otherwise, for, nor do we give warranty or representation in relation to:

(i) the quality, functionality, availability, completeness, accuracy or performance of the PSN or its Products;

…

33 SIENE admits that notwithstanding the qualifying words at the start of this clause and the terms of the Cancellation Policy which provided for refunds to be given for faulty digital games purchased through the PlayStation Store, it impliedly represented to Australian consumers that PSN users did not have guarantees as to the quality, functionality, completeness, accuracy or performance of purchased digital games (the “Terms of Service Representation”). The implied representation was in conflict with ss. 54 to 56 of the A.C.L., which provide consumer guarantees as to acceptable quality, the fitness of goods for disclosed purposes and the correspondence between goods and their description.

34 SIENE admits that the Terms of Service Representation was made in trade or commerce.

35 SIENE admits that by reason of the foregoing, it:

(a) had engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s. 18 of the A.C.L.; and

(b) had made false or misleading representations regarding the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy in contravention of s. 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L.

36 The exact number of views the Terms of Service received from 1 October 2017 to 23 May 2019 is unknown.

Representations when adding funds to the PSN wallet

Statement via purchase flow process

37 Between 1 September 2017 and 17 September 2019, when a PSN user sought to purchase a game from the PlayStation Store but had insufficient funds in their PSN wallet to do so, the following statement would appear on the “confirmation of purchase” page during the purchase flow process described above at [22]:

Funds will be added to your wallet from your [payment method], and then used to fund any product purchase made in this transaction. Funds added to the wallet are non-refundable.

(the “Wallet Statement on the Confirmation of Purchase Page”).

38 The exact number of times this statement was made is unknown.

Statement via email correspondence

39 When an Australian PSN user topped up their PSN wallet and purchased a game in the circumstances described at [23]-[24] above, consumers would receive an email confirming that funds had been added to their PSN wallet (the “Top Up Confirmation Email”).

40 Between at least 1 September 2017 and at least 17 September 2019, the Top Up Confirmation Email contained the following statement:

At the time of making your purchase of wallet funds, you asked us to provide you with immediate access to the funds and confirmed your understanding that this means you will not have a “cooling off period” and cannot cancel your purchase of wallet funds or get a refund.

41 The exact number of times this statement in the Top Up Confirmation Email was made to consumers during the Relevant Period is unknown. However, between November 2018 and May 2019, the Top Up Confirmation Email was sent to Australian consumers on 8,903,856 occasions.

42 SIENE admits that, between at least 1 September 2017 and at least 17 September 2019, the Wallet Statement on the Confirmation of Purchase Page and Top Up Confirmation Email represented to Australian consumers that PSN users could not obtain a refund of funds added to the PSN wallet (the “Wallet Representation”). In fact, consumers were entitled to a refund if the purchased game had a major failure or a non-major failure which is not rectified in a reasonable period of time under ss. 54, 55, 56, 259(2), 259(3) and 263 of the A.C.L.

43 SIENE admits that the Wallet Representation was made in trade or commerce.

44 SIENE admits that by reason of the foregoing, it:

(a) had engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s. 18 of the A.C.L.; and

(b) had made false or misleading representations regarding the existence, exclusion or effect of any condition, warranty, guarantee, right or remedy in contravention of s. 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L.

PlayStation Support Centre Representations

45 As already mentioned, during the Relevant Period, Australian PSN account holders who encountered difficulties with downloading or playing a game purchased from the PlayStation Store could contact the PlayStation Support Centre. Dealings between the PlayStation Support Centre and five individual consumers (each of whom resided in Australia and held an Australian PSN account) were outlined in detail in “Attachment H” to the SoAFA. For present purposes, it is unnecessary for me to descend to that level of detail.

46 SIENE admits that the PlayStation Support Centre staff who dealt with those individual consumers were acting on its behalf. SIENE also admits that, through its call centre agents:

(a) during dealings with one user (“User JA”) in September and October 2017, it represented that even if a game had a major failure or some other failure to comply with a guarantee that could not be, or had not been remedied, SIENE was not required to refund User JA unless he obtained authorisation from the publisher or developer of the game for the refund to be made (the “Referral to Publisher Representation”), notwithstanding that ss. 259 and 263 of the A.C.L. conferred (and continues to confer) rights on consumers to obtain redress directly from suppliers of goods;

(b) during dealings with four users (“User BM”, “User HP”, “User JA” and “User JS”) between October and November 2017, it represented that even if a game had a major failure or some other failure to comply with a guarantee that could not be, or had not been, remedied, SIENE was not required to refund the user more than 14 days after purchase or if (prior to that 14-day mark) the game had been downloaded (the “No Obligation to Refund Representation”), notwithstanding that there were (and are) no such limits on consumers’ rights to obtain redress from suppliers of goods under ss. 259 and 263 of the A.C.L.; and

(c) during dealings with one user (“User CK”) on 30 October 2017, it represented that even if a game had a major failure or some other failure to comply with a guarantee that could not be, or had not been, remedied, SIENE was not required to refund User CK in a currency or form that was useable outside the PSN, but could make any refund by crediting User CK’s PSN wallet (the “Refund to Wallet Representation”), notwithstanding that consumers were (and are) entitled to a refund in the form of “money” if the purchased game has a major failure (or a non-major failure which is not rectified in a reasonable period of time) under ss. 54, 55, 56, 259(2), 259(3) and 263 of the A.C.L.

47 SIENE admits that the Referral to Publisher Representation, No Obligation to Refund Representation and Refund to Wallet Representation (collectively called the “PlayStation Support Centre Representations”) were made in trade or commerce.

48 SIENE admits that by reason of the foregoing, it:

(a) had engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of s. 18 of the A.C.L.; and

(b) had made false or misleading representations regarding the existence, exclusion or effect of any right or remedy in contravention of s. 29(1)(m) of the A.C.L.

Declaratory relief

49 The Court has a wide discretionary power to make declarations pursuant to s. 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act: Forster v. Jododex Australia Pty Ltd (1972) 127 C.L.R. 421 at 437-438. In Ainsworth v. Criminal Justice Commission (1992) 175 C.L.R. 564 at 582, Mason C.J., Dawson, Toohey and Gaudron JJ. said that declarations:

… must be directed to the determination of legal controversies and not to answering abstract or hypothetical questions. The person seeking relief must have “a real interest” and relief will not be granted if the question “is purely hypothetical”, if relief is “claimed in relation to circumstances that [have] not occurred and might never happen” or if “the Court’s declaration will produce no foreseeable consequences for the parties”.

(Footnotes omitted.)

50 The parties submit that each of these requirements is satisfied in the present case because:

(a) the proposed declaration determines what was a live controversy between the parties – whether SIENE contravened the A.C.L. – and the matters in issue have been identified and particularised by the parties with precision;

(b) the A.C.C.C., as a public regulator under the A.C.L., has a genuine interest in seeking the declaratory relief;

(c) it cannot be said that a declaration would have no consequences. In particular, declaratory relief serves in this case to:

(i) record the Court’s disapproval of the contravening conduct;

(ii) vindicate the A.C.C.C.’s claim that SIENE contravened the A.C.L.;

(iii) assist the A.C.C.C. to carry out the duties conferred upon it by the Competition and Consumer Act, including the A.C.L.;

(iv) inform the public of SIENE’s contravening conduct; and

(v) deter other corporations from contravening the A.C.L.;

(d) SIENE is a proper contradictor because it is the subject of the declarations and therefore has an interest in opposing the making of them; and

(e) there is also a “considerable public interest” in corporations observing the requirements of the A.C.L., which warrants the grant of declaratory relief when the A.C.L. is breached.

51 The parties further submit that:

(a) it is common for this Court to grant declaratory relief in cases brought by the A.C.C.C., including where the respondent consents to declaratory relief: see, for example, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Ford Motor Company of Australia Ltd [2018] FCA 703; (2018) 360 A.L.R. 124 at [30]-[33] per Middleton J.; and

(b) the form of the proposed declarations is appropriate, in that it contains sufficient indication of how and why the relevant conduct is a contravention of the A.C.L.

52 In view of the above, and given that the parties are in agreement about this form of relief, I will accept that the threshold requirements for making a declaration have been met. Hence, the declarations sought by the parties should be made.

Penalties

Principles respecting agreed penalties

53 The parties have agreed, amongst other things, upon a pecuniary penalty of AUD$3.5 million by way of resolution of the proceeding. This figure comprises a penalty of:

(a) AUD$2 million for the Terms of Service Representation;

(b) AUD$1 million for the Wallet Representation;

(c) AUD$150,000 for the Referral to Publisher Representation;

(d) AUD$200,000 for the No Obligation to Refund Representation; and

(e) AUD$150,000 for the Refund to Wallet Representation.

54 The Court of course is not bound to give effect to the agreed pecuniary penalty; it is the responsibility of the Court to determine the appropriate pecuniary penalty under s. 224 of the A.C.L. on the facts before it: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft [2019] FCA 2166 at [164]-[165] per Foster J.; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Bupa Aged Care Australia Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 602 at [15] per Mortimer J.

55 Having said that, in Commonwealth v. Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate (2015) 258 C.L.R. 482, the High Court reaffirmed the public interest in parties resolving civil penalty matters with regulators such as the A.C.C.C. In that respect, French C.J., Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ. said the following at 507 [57]-[58]:

… in civil proceedings there is generally very considerable scope for the parties to agree on the facts and upon consequences. There is also very considerable scope for them to agree upon the appropriate remedy and for the court to be persuaded that it is an appropriate remedy. … [I]t is entirely consistent with the nature of civil proceedings for a court to make orders by consent and to approve a compromise of proceedings on terms proposed by the parties, provided the court is persuaded that what is proposed is appropriate.

… Subject to the court being sufficiently persuaded of the accuracy of the parties’ agreement as to facts and consequences, and that the penalty which the parties propose is an appropriate remedy in the circumstances thus revealed, it is consistent with principle and … highly desirable in practice for the court to accept the parties’ proposal and therefore impose the proposed penalty.

(Emphasis in original.)

56 The parties submit that once the Court is satisfied that it has the power to make the orders and the orders are appropriate, it should exercise restraint in scrutinising proposed settlements. That is particularly so in circumstances, such as the present, where the consenting parties are legally represented and able to understand and evaluate the desirability of the settlement.

57 Acknowledging that the agreed penalty is most likely the product of “compromise and pragmatism”, to borrow the language of Wigney J. in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited [2016] FCA 1516; (2016) 118 A.C.S.R. 124 at [104], I now turn to consider: first, the factors relevant to the assessment of penalty; and, secondly, whether the agreed penalty is an appropriate penalty having regard to all relevant matters.

Factors to be taken into account in assessing the quantum of the pecuniary penalty

Section 224 of the A.C.L. and other relevant penalty factors

58 Pursuant to s. 224(1)(a)(ii) of the A.C.L., the Court may impose a pecuniary penalty on a person who has contravened a provision of Pt. 3-1 of the A.C.L. (including s. 29) in respect of “each act or omission” as the Court determines to be appropriate. Contraventions of s. 18 of the A.C.L. are not subject to a pecuniary penalty.

59 Pursuant to s. 224(2) of the A.C.L., in determining the appropriate pecuniary penalty, the Court must have regard to, but is not confined to, the following mandatory relevant considerations:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part [5-2] to have engaged in any similar conduct.

60 Additional matters relevant to the assessment of penalty include the factors listed by French J. (as his Honour then was) in Trade Practices Commission v. CSR Ltd [1990] FCA 762; [1991] A.T.P.R. ¶41-076 at 52,152-52,153:

…

4. The size of the contravening company.

5. The degree of power it has, as evidenced by its market share and ease of entry into the market.

6. The deliberateness of the contravention and the period over which it extended.

7. Whether the contravention arose out of the conduct of senior management or at a lower level.

8. Whether the company has a corporate culture conducive to compliance with the Act, as evidenced by educational programs and disciplinary or other corrective measures in response to an acknowledged contravention.

9. Whether the company has shown a disposition to co-operate with the authorities responsible for the enforcement of the Act in relation to the contravention.

Deterrence

61 It is well established that deterrence (both general and specific) is the “primary objective for the imposition of civil penalties”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Cement Australia Pty Ltd (2017) 258 F.C.R. 312 at 442 [385] per Middleton, Beach and Moshinsky JJ. The penalty must be set at a sufficiently high level to “deter repetition by the contravener and by others who might be tempted to contravene”: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v. Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (2018) 262 C.L.R. 157 at 185 [87] per Keane, Nettle and Gordon JJ. It is important, however, that a penalty must not be so high as to be oppressive: NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 F.C.R. 285 at 293 per Burchett and Kiefel JJ. (as her Honour then was).

Maximum penalty

62 In arriving at a particular penalty figure, “regard must ordinarily be had to the maximum penalty”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; (2016) 340 A.L.R. 25 at [154]. In Markarian v. The Queen (2005) 228 C.L.R. 357, the High Court considered the relevance of maximum penalties in the context of criminal sentencing. Relevantly, Gleeson C.J., Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ. stated at 372 [31]:

… careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick.

63 This explanation has been said to apply with equal force to the assessment of pecuniary penalties under s. 224 of the A.C.L.: Reckitt Benckiser at [155] and the authorities therein cited.

64 As at October 2017, the maximum penalty for a contravention of s. 29 of the A.C.L. was AUD$1.1 million: s. 224(3), item 2. Commencing 1 September 2018, a new regime for determining the maximum penalty came into force, as introduced into the A.C.L. by the Treasury Laws Amendment (2018 Measures No. 3) Act 2018 (Cth.). From that date onwards, the maximum penalty for a contravention of s. 29, as provided for in s. 224(3) (item 2) and s. 224(3A), is the greater of:

(a) AUD$10,000,000;

(b) if the court can determine the value of the benefit that the body corporate, and any body corporate related to the body corporate, have obtained directly or indirectly and that is reasonably attributable to the act or omission—3 times the value of that benefit;

(c) if the court cannot determine the value of that benefit—10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate during the 12-month period ending at the end of the month in which the act or omission occurred or started to occur.

65 It bears mentioning this change in the method for calculating the maximum penalty as some of SIENE’s contravening conduct (in particular, the Terms of Service Representation and the representations made when adding funds to the PSN wallet) occurred before 1 September 2018 and some of it occurred afterwards.

Course of conduct principle

66 The A.C.L. does not contain any express limitation requiring a course of conduct potentially involving multiple contravening acts to be treated as a single contravention: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Limited [2015] FCA 330; (2015) 327 A.L.R. 540 at [16] per Allsop C.J. There may, however, be instances where it is appropriate to regard multiple contravening acts as a single course of conduct and to fix a penalty accordingly. The “course of conduct” principle recognises that “where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences for which an offender has been charged, care must be taken to ensure that the offender is not punished twice for what is essentially the same criminality” (emphasis in original): Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union v. Cahill [2010] FCAFC 39; (2010) 194 I.R. 461 at [39] per Middleton and Gordon JJ. An application of that principle, however, does not limit the maximum penalty for the course of conduct as a whole to the maximum penalty for a single contravention: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Yazaki Corporation (2018) 262 F.C.R. 243 at 294 [227], 295 [229]-[232] per Allsop C.J., Middleton and Robertson JJ.

Totality principle

67 Where multiple penalties are to be imposed upon a particular wrongdoer, the “totality principle” ought also be considered. The “totality principle” dictates that the total penalty for related offences ought not exceed what is proper for the entire contravening conduct involved: Trade Practices Commission v. TNT Australia Pty Ltd [1995] A.T.P.R. ¶41-375 at 40,169. It operates as a “final check” to ensure that the penalties to be imposed on a wrongdoer, considered as a whole, are “just and appropriate”: Clean Energy Regulator v. MT Solar Pty Ltd [2013] FCA 205 at [80]-[83] per Foster J. and the authorities therein cited; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. EnergyAustralia Pty Ltd (2014) 234 F.C.R. 343 at 358 [100]-[102] per Middleton J. and the authorities therein cited.

Relevance of quantum of penalties in earlier cases

68 It is well established that “other things being equal, corporations guilty of similar contraventions should incur similar penalties”: NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd at 295 per Burchett and Kiefel JJ. (as her Honour then was). However, as Middelton J. observed in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Telstra Corporation Ltd (2010) 188 F.C.R. 238 at 275 [215]:

It is apparent that there are many difficulties in simply referring to penalties previously imposed for contraventions of legislation in widely differing circumstances or in circumstances where some of the factors are similar but others dissimilar to those of the present proceeding. In each case, the Court must take into account the deterrent effect of the penalty and the fact that the penalties “should reflect the will of Parliament that the commercial standards laid down in the Act must be observed but not be so high as to be oppressive”: see Trade Practices Commission v Stihl Chain Saws (Aust) Pty Ltd [1978] ATPR 40-091 at 17,896.

69 Indeed the parties acknowledged that “things are rarely equal in A.C.L. cases and comparison may be difficult and of limited utility”.

The appropriateness of the penalty

70 I now turn to an application of the foregoing penalty factors to the contravening conduct in this proceeding – namely, the Terms of Service Representation, the Wallet Representation, the Referral to Publisher Representation, the No Obligation to Refund Representation and the Refund to Wallet Representation.

Course of conduct

Terms of Service Representation

71 As to the Terms of Service Representation, the parties agreed, and I accept, that the instances in which SIENE made the representation constitute a single course of conduct. In each case the representation arose from the same matter, namely the wording of cl. 19 of the Terms of Service.

Wallet Representation

72 As to the Wallet Representation, the parties agreed that the instances in which SIENE made the Wallet Representation constitute either:

(a) a single course of conduct because the Wallet Statement on the Confirmation of Purchase Page and the statement in the Top Up Confirmation Email were made in the same context (namely, when funds were added to the PSN wallet); or

(b) two courses of conduct being the Wallet Statement on the Confirmation of Purchase Page and the statement in the Top Up Confirmation Email considered separately.

The parties agreed, and I accept, that nothing turns on this issue for the purposes of assessing penalty in this case as in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Valve Corporation (No 7) [2016] FCA 1553 at [17]-[18] per Edelman J.

PlayStation Support Centre Representations

73 As to the Referral to Publisher Representation and the Refund to Wallet Representation, the parties agreed, and I accept, that the Court can treat:

(a) the three Referral to Publisher Representations made to User JA as one course of conduct; and

(b) the three Refund to Wallet Representations made to User CK as one course of conduct,

on the basis that the groups of representations were made in the course of dealings with the same user about the same game with which they reported difficulties.

74 As to the No Obligation to Refund Representation, it was made to:

(a) User JA four times;

(b) User BM three times;

(c) User HP three times; and

(d) User JS five times.

In view of the approach taken immediately above at [73], one possibility would be for the Court to treat these as four courses of conduct. However, the parties agreed, and I accept, that it would be more appropriate for the Court to treat them as a single course of conduct, in a similar way to the approach adopted by Lee J. in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Apple Pty Ltd (No 4) [2018] FCA 953 at [41]. The parties submit, and I accept, that the No Obligation to Refund Representations reflect similar interactions with individual consumers, including in each case a reference to cancellation of refund policies, and the same representation.

75 The parties submit, and I accept, that a larger penalty is appropriate for the No Obligation to Refund Representations compared to the other PlayStation Support Centre Representations. This is because it affected a greater number of PSN users and was made on more occasions.

Nature, extent and duration of the conduct, and the circumstances in which the conduct took place

Terms of Service Representation

76 The Terms of Service, which conveyed the Terms of Service Representation, were displayed for a period of at least 18 months (from at least 1 October 2017 to 23 May 2019). About 1.9 million Australian PSN accounts were created during that period, and each of those persons was required to agree to the Terms of Service. There is, however, no evidence of the number of times that the Terms of Service were actually viewed by Australian users while creating their PSN accounts. To the extent that electronic clicks on some links were recorded, the parties noted that between 1 October 2017 and 30 September 2019, the Terms of Service link (which directed users to a URL containing the Terms of Service) on:

(a) the webpage on www.playstation.com/en-au/legal/ was electronically clicked 116 times; and

(b) the webpage on www.playstation.com/en-au/legal/psnterms/ was electronically clicked 1,693 times.

Wallet Representation

77 The Wallet Representation was made over a period of at least two years (from at least 1 September 2017 until at least 17 September 2019). I am willing to infer that the representation was made on many millions of occasions: the Top Up Confirmation Email was sent on 8,903,856 occasions between November 2018 to May 2019 alone.

PlayStation Support Centre Representations

78 The PlayStation Support Centre Representations were made in dealings between call centre staff and five consumers who were experiencing problems with games they had purchased. The A.C.C.C. does not allege, and SIENE does not admit, that any of these games were faulty or otherwise failed to comply with any consumer guarantee under the A.C.L.

79 Each of the five consumers indicated some level of awareness of their A.C.L. rights in their interactions with the PlayStation Support Centre. By way of illustration, User BM stated in an email that PlayStation Support were putting up “as many roadblocks” as possible to stop him from obtaining a refund, in violation of his consumer law rights and advised that he would be contacting the A.C.C.C. In a similar vein, User HP stated in an email to PlayStation Support that it was against the law for businesses not to give refunds and noted that if her refund request was refused, she would raise the issue with the A.C.C.C. Such awareness, however, does not prevent the conduct of SIENE (through its call centre agents) from being misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive; put simply, it is not necessary for a person in fact to be misled to contravene s. 18 of the A.C.L.

80 In addition, the parties highlighted that:

(a) instructions were provided to PlayStation Support Centre staff in the policy “Publisher & Developers – When to refer”, including to refer customers to publishers for in-game issues (for example where the customer was stuck on a level in the game or experienced issues connecting to the game servers), but PlayStation Support Centre staff were also instructed not to refer customers to publishers for, amongst other things, refund requests and never to refer customers to a developer; and

(b) the No Obligation to Refund Representation was inconsistent with the express terms of SIENE’s Cancellation Policy overall, which did not limit the availability of refunds for faulty games, but staff referred to the Cancellation Policy and its limitation on refunds after download or 14 days after purchase without necessarily or always referring to the right to refunds for faulty games.

81 It follows that the Referral to Publisher Representation and the No Obligation to Refund Representation (but not the Refund to Wallet Representation) were inconsistent with SIENE’s policies or instructions provided to PlayStation Support Centre staff.

Amount of loss caused

Terms of Service Representation

82 There is no evidence before the Court that the Terms of Service Representation caused any pecuniary loss. However, the contravening conduct did erect an impediment to consumers relying upon their statutory rights. This had the potential to cause loss and damage in the form of users not relying on their statutory rights, in circumstances where they may have been entitled to a refund or other form of redress under the A.C.L.

83 The A.C.C.C. does not allege, and SIENE does not admit, that any game supplied to an Australian user from the PlayStation Store was in fact faulty or otherwise failed to comply with any consumer guarantee under the A.C.L.

84 The parties submit, and I accept, that absence of evidence of actual pecuniary loss diminishes the weight that might otherwise be placed on this factor in favour of a significant penalty. Nevertheless, the potential for the Terms of Service to dissuade or discourage users from seeking to enforce their consumer rights constitutes a form of potential harm to which I may have regard.

Wallet Representation

85 Similarly, there is no evidence before the Court that the Wallet Representation caused any pecuniary loss. I repeat my comments at [82] above.

PlayStation Support Centre Representations

86 The A.C.C.C. does not allege, and SIENE does not admit, that the games purchased by the aforementioned five users were faulty or that SIENE otherwise failed to comply with any consumer guarantee under the A.C.L.

87 The Court was told that:

(a) Users CK and BM did not suffer any pecuniary loss: User CK was ultimately given a refund in the form of money; and User BM received a refund to his PSN wallet. These outcomes were secured by Users CK and BM only after engaging in extended correspondence with PlayStation Support Centre staff;

(b) Users JA, JS and HP did not receive refunds. User JS continued to play the game he purchased after he considered the issues he experienced in his game were no longer occurring; and

(c) SIENE made a minor financial gain from the supplies the subject of the relevant dealings, in that SIENE was paid for games that some users said they could not use and for which they did not receive a refund (Users JA, JS and HP).

88 In sum, the fact that the contravening conduct caused relatively minor pecuniary loss or damage is a mitigating factor.

Size of contravener

89 SIENE is a substantial company. It entered into 25.64 million transactions with Australian PSN users via the PlayStation Store between 1 September 2017 and 30 May 2019, and it had a substantial operating revenue as illustrated in the table below:

Annual operating revenue of SIENE April 2017 to March 2019

FY17 (1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018) | |

Operating revenue | EUR$3.2 billion |

FY18 (1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019) | |

Operating revenue | EUR$4.3 billion |

I note that the operating revenue figures include intragroup transactions with other SIEE group companies and is not confined to revenue or profit derived from Australia.

90 Further evidence respecting SIENE’s financial position is set out in a Confidential Annexure to the SoAFA.

91 In view of the above, and the financial information in the Confidential Annexure, it can be readily inferred that SIENE has the capacity to pay a significant penalty. However, the parties submit, and I accept, that SIENE’s size alone does not justify a higher penalty than would otherwise be imposed; although, it is relevant to goals of specific and general deterrence.

Deliberateness

92 The parties agree, and I accept, that there is no evidence that SIENE’s various contraventions were the product of deliberate attempts to contravene the A.C.L.

Involvement of senior employees or management

Terms of Service Representation and Wallet Representation

93 Senior staff with appropriate seniority within the relevant business area of SIEE, whose duties included aspects of the SIENE business, were responsible for approving:

(a) the Terms of Service; and

(b) the statements in both the messages that were displayed and the emails that were sent when adding funds to the PSN wallet.

94 As the parties submit, the involvement of senior employees, rather than the contraventions arising from the conduct of low level agents, is relevant to specific and general deterrence.

PlayStation Support Centre Representations

95 The PlayStation Support Centre Representations were made by call centre staff who were not senior employees or management of SIENE.

Culture of compliance

96 SIENE’s operations extended across a number of jurisdictions, and it had in place a number of general policies and guidelines relating to consumer interactions. It did not, however, have any compliance materials specifically related to Australian consumer law, and the general policies and guidelines did not deal specifically with the A.C.L.

Co-operation and corrective measures

97 I acknowledge that SIENE has co-operated with the A.C.C.C. in providing information and documents voluntarily, initiating settlement discussions and ultimately resolving this proceeding before any trial date had been set. SIENE is entitled to credit for having co-operated with the A.C.C.C. and for having admitted to contravening the A.C.L., thereby saving the A.C.C.C., the Court and the community at large the cost and burden of a trial.

98 Additionally, I note that:

(a) in December 2019 (and after the proceeding commenced in May 2019), SIENE amended the Terms of Service. The parties submit, and I agree, that this mitigates the penalty to be imposed to a degree;

(b) from 17 September 2019, the Wallet Statement on the Confirmation of Purchase Page ceased being made. The statement on the Top Up Confirmation Email is no longer made; and

(c) on May 2019, further instructions were provided to PlayStation Support Centre staff in relation to what they should do when a user quotes a law “to make a point about their objections”. Those instructions state that if a user quotes a law to make a point about their objection, the PlayStation Support Centre staff should say “I can’t comment on the law but we will investigate your concern in that regard and in the meantime, let’s see if we can solve the problem / get you playing again” and further escalate the incident internally for legal support or guidance.

Previous contravention

99 SIENE has not previously contravened the A.C.L. or its predecessor, the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth.). The parties submit, and I agree, that this is a significant mitigating factor.

Maximum penalty

100 The Terms of Service Representation and Wallet Representation were made before and after the change to the penalty regime from 1 September 2018. In that respect, before 1 September 2018, the maximum penalty for a single contravention was AUD$1.1 million. After 1 September 2018, the relevant provisions are found in s. 224(3) and (3A) of the A.C.L. The parties agreed that the benefit obtained by SIENE from the contraventions cannot be determined and thus:

… the maximum penalty for conduct after 1 September 2018 is the greater of $10,000,000 or 10% of the annual turnover of the body corporate during the 12-month period ending at the end of the month in which the act or omission occurred or started to occur. In this respect, based on Australian revenue figures for SIENE and Sony Interactive Entertainment Australia Pty Ltd, one of its related body corporates incorporated in Australia[,] the relevant maximum penalty as at September 2018 would be at least $63.9 million. The figure would be larger if consideration was given to all related bodies corporate.

101 The parties submit, and I accept, that:

(a) it is not possible, nor would it be meaningful or helpful, to seek to calculate the precise notional maximum penalty that might apply to this course of conduct on either side of the change in statutory regime, except to observe that, on both, it would be millions of dollars; and

(b) the goal remains to impose an appropriate penalty having regard to all of the circumstances of the case. One such circumstance is that the Terms of Service Representation and Wallet Representation were initially made at a time when the maximum penalty was AUD$1.1 million and thereafter at a time when the maximum penalty regime differed.

102 In contrast, the PlayStation Support Centre Representations were all made at a time when the maximum penalty was AUD$1.1 million. As adverted to earlier, 21 misrepresentations were made in total, each being a separate contravention, but some of which may be considered as part of a single course of conduct.

Deterrence

103 The parties submit that in light of the above factors, the agreed penalty sums of:

(a) AUD$2 million for the Terms of Service Representation;

(b) AUD$1 million for the Wallet Representation;

(c) AUD$150,000 for the Referral to Publisher Representation;

(d) AUD$200,000 for the No Obligation to Refund Representation; and

(e) AUD$150,000 penalty for the Refund to Wallet Representation,

are necessary and appropriate amounts in order to achieve the statutory objects of specific and general deterrence. I agree.

104 It is clear that SIENE is a large enterprise with vast resources. Realistically speaking, a penalty in the sum of AUD$3.5 million is highly unlikely to have a significant impact on SIENE’s overall financial position. But that is not to the point. The question is whether the size of the pecuniary penalty would operate as an effective deterrent. The penalty must be substantial in order to be meaningful given SIENE’s resources, but must not be so high as to be oppressive. In my view, the amount of the proposed penalty is in each case sufficiently high to have a deterrent quality. Further, the penalties have been set at a level which acknowledges the factors which support a lower penalty than might otherwise be imposed. In particular, SIENE co-operated in resolving this proceeding; it has since amended the Terms of Service; it ceased to make the Wallet Statement on the Confirmation of Purchase Page and changed the Top Up Confirmation Email prior to resolution of the proceeding; and it provided updated instructions to PlayStation Support Centre staff.

105 The parties submit, and I agree, that, in all of the circumstances, the penalty amounts which have been agreed carry a sufficient “sting” such that SIENE will take appropriate steps to avoid a repetition of the contravening conduct.

106 I am also satisfied that the penalty amounts proposed make it clear to other corporations dealing in digital goods that it is not acceptable to contravene the A.C.L. I consider they are of sufficient magnitude to deter others in the industry who may be disposed to engage in similar prohibited conduct.

Penalties in earlier cases

107 Finally, I note that the penalties imposed in earlier cases did not assist in calibrating the penalty figures in the present case. The parties themselves recognised the limited utility of drawing comparisons where cases are not factually aligned.

Conclusion on appropriate penalty

108 Taking into account the foregoing factors relevant to fixing a penalty, as well as applying the totality principle, I am satisfied that the proposed penalties are appropriate for the admitted contraventions. They shall be imposed accordingly.

Disclosure orders

109 The parties submit that the Court should make an “adverse publicity order” under s. 247(1)(a) of the A.C.L. Section 247(2) provides:

An adverse publicity order in relation to a person is an order that requires the person:

(a) to disclose, in the way and to the persons specified in the order, such information as is so specified, being information that the person has possession of or access to; and

(b) to publish, at the person’s expense and in the way specified in the order, an advertisement in the terms specified in, or determined in accordance with, the order.

110 The proposed notice is to be published on the PlayStation Australia website. It outlines SIENE’s contravening conduct and informs users of their rights under the A.C.L. I am satisfied that the proposed notice serves the purpose of protecting the public interest in “dispelling incorrect or false impressions created by contravening conduct, alert the consumer to the fact of contravening conduct, aid the enforcement of primary orders and prevent repetition of contravening conduct”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. amaysim Energy Pty Ltd (trading as Click Energy) [2019] FCA 430 at [48] per Middleton J. It is therefore appropriate that I make the adverse publicity order as agreed by the parties.

Costs

111 SIENE has agreed to pay the A.C.C.C.’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding in the sum of $100,000. That order will be made.

Application for suppression or non-publication order

112 Finally, I note that SIENE and SIEE seek an order pursuant to s. 37AF(1) of the Federal Court of Australia Act, on the ground that it is necessary to prevent prejudice to the proper administration of justice, that until further order the information contained in the Confidential Annexure to the SoAFA not be published or otherwise disclosed to any person other than the parties or their external legal representatives. The A.C.C.C. neither consents to nor opposes the order sought.

113 The respondents’ interlocutory application was supported by an affidavit of Ms. Marian Toole, Vice President, Legal and Business Affairs of SIEE and Secretary of SIEE and SIENE. In short, she deposed that the information contained in the Confidential Annexure is “confidential and commercially and completely sensitive” to SIENE and its related body corporate, Sony Interactive Entertainment Australia Limited (“SIE Australia”). The information contained in the Confidential Annexure comprises: the number of Australian PSN accounts, the number of transactions SIENE entered into with Australian PSN users via the PlayStation Store; and financial information concerning SIENE and SIE Australia. None of this information is publicly available.

114 SIENE and SIEE submit that the proposed order is necessary to prevent prejudice to the administration of justice because the information in question is confidential and commercially sensitive and, if disclosed, it could be used by competitors and suppliers of SIENE and SIE Australia, to their commercial advantage and to the detriment of SIENE and SIE Australia. They cite in support of their position the decisions of Motorola Solutions, Inc. v. Hytera Communications Corporation Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCA 17 per Perram J. and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v. Ultra Tune Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 12 per Bromwich J. In the latter case, Bromwich J. granted a suppression order to protect Ultra Tune’s confidential financial information, comprising profit and loss statements and balance sheets which were produced to the A.C.C.C. under compulsion. Relevantly, his Honour was satisfied (at [385]) that the order was:

… necessary in the interests of justice, including encouraging full compliance in future by both Ultra Tune and by other persons with notices requiring such material to be produced under compulsion to a regulator.

Relying on the foregoing, SIENE and SIEE submit that the proposed order would encourage respondents to regulatory proceedings to disclose confidential and sensitive information voluntarily in the course of settlement negotiations, and would thereby encourage the early and efficient resolution of proceedings.

115 I am satisfied on the basis of the evidence and the submissions advanced by SIENE and SIEE that the order they seek is appropriate and should therefore be made.

Conclusion

116 I wish to commend the parties for their high degree of mutual co-operation and commitment to resolving this proceeding efficiently. In that respect, as previously mentioned, SIENE voluntarily disclosed a large volume of information to the A.C.C.C. and initiated settlement discussions with the A.C.C.C. in relation to the mediation of this matter. As a result of the mediation, SIENE and the A.C.C.C. were able to reach agreement on all categories of contraventions, and the proposed declaratory relief in relation to those contraventions, for consideration by the Court. Their joint efforts have obviated the need for a full trial which undoubtedly would have demanded significant resources.

117 I shall make the orders as proposed by the parties.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and seventeen (117) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Steward. |

Associate: