FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd (No 2) [2020] FCA 724

File number: | NSD 2145 of 2017 |

Judge: | BROMWICH J |

Date of judgment: | |

Catchwords: | CONSUMER LAW – where parties agreed on the penalty and declarations to be made following admitted contraventions of ss 18, 29(1) and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law – where the respondents had conveyed by implied representation that there were material differences between two products, Osteo Gel and Emulgel, when in fact they were the same – held: agreed form of declaration and penalty of $4.5 million approved COSTS – where the respondents had admitted some contraventions prior to the liability hearing and denied others – where the disputed contraventions were not made out – held: the respondents pay the applicant’s costs of the proceeding up to and including the date admissions were made – the applicant pay the respondents’ costs of the proceeding from the date after admissions were made up to and including the date of the liability judgment – the respondents pay costs thereafter |

Legislation: | Australian Consumer Law (contained in Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth)) ss 18, 29(1), 29(1)(g), 33, 224(4) Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) s 76(3) Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) s 191 |

Cases cited: | Ainsworth v Criminal Justice Commission (1992) 175 CLR 564 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; 327 ALR 540 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCA 205 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v MSY Technology Pty Ltd [2012] FCAFC 56; 201 FCR 378 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 4) [2015] FCA 1408 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 7) [2016] FCA 424; 343 ALR 327 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25 Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; 262 FCR 243 Coffs Ex-Services Memorial & Sporting Club Ltd v Coffs Harbour Catholic Recreation & Sporting Club Ltd [2010] NSWSC 605 Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482 Edutainments Pty Ltd v JMC Pty Ltd [2003] FCA 1253 Forster v Jododex Australia Pty Limited (1972) 127 CLR 421 GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Investments (Ireland) (No 2) Ltd v Generic Partners Pty Ltd (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 100 Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; 54 ACSR 395 NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; 71 FCR 285 Paciocco v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCAFC 146; 253 FCR 403 Parker v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2019] FCAFC 56; 365 ALR 402 Ruddock v Vadarlis (No 2) [2001] FCA 1865; 115 FCR 229 Russian Commercial and Industrial Bank v British Bank for Foreign Trade Ltd [1921] 2 AC 438 |

Registry: | New South Wales |

Division: | General Division |

National Practice Area: | |

Sub-area: | Regulator and Consumer Protection |

Category: | Catchwords |

Number of paragraphs: | |

Solicitor for the Applicant: | Webb Henderson |

Counsel for the Respondents: | Mr R Cobden SC with Mr H Bevan |

Solicitor for the Respondents: | Bird & Bird |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | GLAXOSMITHKLINE CONSUMER HEALTHCARE AUSTRALIA PTY LTD First Respondent NOVARTIS CONSUMER HEALTH AUSTRALASIA PTY LTD Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

1. The First Respondent, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd (GSK), in marketing and selling Voltaren Osteo Gel (Osteo Gel):

(a) in the form of packaging shown at page 2 of Schedule D to the Statement of Agreed Facts filed 20 September 2019 (SOAF); and

(b) in the context of marketing and selling Voltaren Emulgel (Emulgel) in the forms of packaging shown at Schedule C to the SOAF;

has, in trade or commerce, from 9 March 2016 to at least 28 February 2017:

(c) engaged in conduct which was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, in contravention of section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) which is Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA);

(d) in connection with the supply, the possible supply or the promotion of the supply of the products Osteo Gel and Emulgel, made false or misleading representations with respect to the performance characteristics, uses and/or benefits of Osteo Gel in contravention of section 29(1)(g) of the ACL; and

(e) engaged in conduct that was liable to mislead the public as to the nature, the characteristics and/or the suitability for their purpose of the product Osteo Gel within the meaning of section 33 of the ACL,

by representing that Osteo Gel:

(f) was specifically formulated to treat local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers;

(g) solely or specifically treated local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers; and

(h) was more effective than Emulgel at treating local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers;

(together, the Osteo Gel Representations), in circumstances where:

(i) Osteo Gel contained the same active ingredient, had the same Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) approved indications and was of identical formulation to Emulgel;

(j) Osteo Gel had efficacy, and was equally effective as Emulgel, in the local symptomatic treatment of musculoskeletal inflammatory conditions, including acute soft tissue injuries (including sprains, strains, tendinitis and sports injuries) and soft tissue rheumatism (including tendinitis and bursitis);

(k) Emulgel was equally effective as Osteo Gel at treating local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers,

(together, the Osteo Gel Properties).

2. The Second Respondent, Novartis Consumer Health Australasia Pty Ltd (now known as VOG AU Pty Ltd) (Novartis), in marketing and selling Osteo Gel:

(a) in the form of packaging shown at Schedule D to the SOAF; and

(b) in the context of marketing and selling Emulgel in the forms of packaging shown at Schedule B and page 1 of Schedule C to the SOAF;

has, in trade or commerce, from 1 January 2012 to 31 May 2016, engaged in conduct in contravention of:

(d) section 29(1)(g) of the ACL, with respect to the performance characteristics, uses and/or benefits of Osteo Gel; and

(e) section 33 of the ACL, with respect to the nature, the characteristics and/or the suitability for their purpose of Osteo Gel,

by making the Osteo Gel Representations in circumstances where Osteo Gel had the Osteo Gel Properties.

3. GSK, in promoting Osteo Gel and Emulgel on the website www.voltaren.com.au (Voltaren Website) during the period June 2015 to on or around 24 November 2017 and, in publishing or causing to be published:

(a) during the period from June 2015 to on or around 26 February 2016:

(i) a page with the heading “Product Comparison”;

(ii) a page with the heading “Choose how to manage your pain”;

(iii) a page with the heading “Voltaren Osteo Gel”; and

(iv) a page with the heading “Voltaren Emulgel”;

copies of which are set out at Schedule I to the SOAF;

(b) during the period from on or around 26 February 2016 to around early July 2017:

(i) a page with the heading “Products”;

(ii) a page with the heading “Voltaren Osteo Gel” and

(iii) a page with the heading “Voltaren Emulgel”;

copies of which are set out at Schedule J to the SOAF;

(c) during the period from on or around 10 July 2017 to on or around August or September 2017:

(i) a page with the heading “Explore our products” including a section with the heading “Compare our products”;

(ii) a page with the heading “Voltaren Osteo Gel”; and

(iii) a page with the heading “Voltaren Emulgel”;

copies of which are set out at Schedule K to the SOAF;

(d) during the period from around August or September 2017 to on or around 24 November 2017:

(i) a page with the heading “Explore our products” including a section with the heading “Compare our products”;

(ii) a page with the heading “Voltaren Osteo Gel”; and

(iii) a page with the heading “Voltaren Emulgel”;

copies of which are set out at Schedule L to the SOAF,

has, in trade or commerce, engaged in conduct in contravention of:

(e) section 18 of the ACL;

(f) section 29(1)(g) of the ACL, with respect to the performance characteristics, uses and/or benefits of Osteo Gel; and

(g) section 33 of the ACL, with respect to the nature, the characteristics and/or the suitability for their purpose of Osteo Gel,

by making the Osteo Gel Representations in circumstances where Osteo Gel had the Osteo Gel Properties.

4. Novartis, in promoting Osteo Gel on the website myjointhealth.com.au (MyJointHealth Website) during the period from January 2012 to 8 March 2016, and, in publishing or causing to be published a page with the heading “About Voltaren Osteo Gel”, a copy of which is set out at Schedule H to the SOAF, has, in trade or commerce, engaged in conduct in contravention of:

(a) section 18 of the ACL;

(b) section 29(1)(g) of the ACL, with respect to the performance characteristics, uses and/or benefits of Osteo Gel; and

(c) section 33 of the ACL, with respect to the nature, the characteristics and/or the suitability for their purpose of Osteo Gel,

by making the Osteo Gel Representations in circumstances where Osteo Gel had the Osteo Gel Properties.

5. Novartis, in promoting Osteo Gel and Emulgel on the Voltaren Website during the period 1 January 2014 to 31 May 2016, and, in publishing or causing to be published:

(a) during the period 1 January 2014 to on or around 26 February 2016:

(i) a page with the heading “Product Comparison”;

(ii) a page with the heading “Choose how to manage your pain”;

(iii) a page with the heading “Voltaren Osteo Gel”; and

(iv) a page with the heading “Voltaren Emulgel”;

copies of which are set out at Schedule I to the SOAF;

(b) during the period from on or around 26 February 2016 to 31 May 2016:

(i) a page with the heading “Products”;

(ii) a page with the heading “Voltaren Osteo Gel”; and

(iii) a page with the heading “Voltaren Emulgel”;

copies of which are set out at Schedule J to the SOAF, has, in trade or commerce, engaged in conduct in contravention of:

(c) section 18 of the ACL;

(d) section 29(1)(g) of the ACL, with respect to the performance characteristics, uses and/or benefits of Osteo Gel; and

(e) section 33 of the ACL, with respect to the nature, the characteristics and/or the suitability for their purpose of Osteo Gel;

6. by making the Osteo Gel Representations in circumstances where Osteo Gel had the Osteo Gel Properties.

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

7. GSK pay the Commonwealth of Australia, within 30 days of the date of this order, a pecuniary penalty pursuant to s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law in respect of the contraventions declared in paragraphs 1 and 3 of these orders in the sum of $1,500,000.

8. Novartis pay the Commonwealth of Australia, within 30 days of the date of this order, a pecuniary penalty pursuant to s 224 of the Australian Consumer Law in respect of the contraventions declared in paragraphs 2, 4 and 5 of these orders in the sum of $3,000,000.

9. The relief otherwise sought by the Applicant in the Originating Application filed 5 December 2017 in paragraphs 1 with respect to the packaging in Annexure D to the Originating Application, 5 to 6 and 9 to 11 be dismissed.

Costs

10. The respondents pay the applicant’s costs of the proceeding up to and including 27 February 2018.

11. The applicant pay the respondents’ costs of the proceeding from 28 February 2018 up to and including 17 May 2019, excluding the costs associated with obtaining or preparing any evidentiary material that was not adduced or admitted into evidence, as agreed or determined by a registrar.

12. The respondents pay the applicant’s costs of the proceeding from 18 May 2019 up to and including 4 May 2020, excluding costs associated with the costs dispute.

13. Each party pay their own costs of the costs dispute.

14. The parties have leave to furnish, within 14 days or such further time as may be allowed, draft agreed or competing orders for the making of a lump sum costs determination by a registrar of the costs orders above, to produce a net sum payable.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BROMWICH J:

INTRODUCTION

1 The applicant, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC):

(1) succeeded in a proceeding brought against the two respondents, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd (GSK) and Novartis Consumer Healthcare Australasia Pty Ltd, now known as VOG AU Pty Ltd, to the extent that contraventions of ss 18, 29(1) and 33 of the Australian Consumer Law were admitted prior to the trial for the period up to March 2017; but

(2) failed, in a finely balanced decision, in relation to similar contested alleged contraventions for the period from March 2017, when the representations changed: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Australia Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 676; 371 ALR 396 (Liability Judgment or LJ).

2 The parties have reached an agreed position on the declarations and orders that should be made, including that an overall penalty of $4.5 million should be imposed in relation to the admitted contraventions. They dispute the costs orders that should be made. These are the reasons addressing both the agreed and competing positions and for the orders and declarations made.

DECLARATIONS AND PENALTIES

The nature of the representations

3 The respondents were involved in marketing and selling, as two different products, a single formulation of an over-the-counter skin gel in a tube used to treat pain and inflammation. Both products were sold under the primary brand name of Voltaren, one with the sub-brand name Emulgel and the other the sub-brand name Osteo Gel. This proceeding does not concern other Voltaren products. In particular, it does not concern a version of Osteo Gel which has a different formulation to Emulgel.

4 Emulgel was, and still is, marketed to be used for the temporary relief of local pain and inflammation. Osteo Gel was, for a more limited time, marketed to be used for the relief of osteoarthritis symptoms. The following list of features identifies the points at which the products as marketed were the same or different:

(1) both had as their active ingredient diclofenac diethylammonium, at an identical dose level of 11.6 milligrams per gram, also described as having a 1% active ingredient formulation;

(2) neither had any ingredient that the other did not, so the contents were the same;

(3) there were some differences in the range of available tube sizes;

(4) Osteo Gel had a higher recommended retail price per gram in the same or similar sized tubes;

(5) the cap on Osteo Gel was different, being designed to be easier to open, and therefore easier for a person with osteoarthritis in the hands to open;

(6) the use instructions on the Emulgel packaging were directed to general use for up to two weeks at a time;

(7) the use instructions on the Osteo Gel packaging were directed to the treatment of osteoarthritis for up to three weeks at a time;

(8) at an earlier time, Emulgel packaging contained both sets of instructions; and

(9) the respondents made different claims about Emulgel and Osteo Gel on packaging and via two different websites, reflective of the different types of condition which the same gel could be used to treat.

5 The ACCC alleged that the claims made conveyed to consumers the impression that there were material differences between Emulgel and Osteo Gel, and their use, when in fact they were the same, contrary to ss 18, 29(1)(g) or 33 of the Australian Consumer Law, which is to be found in Sch 2 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). The ACCC contended that it was not made sufficiently clear that there was no difference at all between the gel in the two products. That contention was not disputed in the period up to March 2017, but was disputed for the period from March 2017, when changes were made to the packaging of Osteo Gel, until the sale of Osteo Gel was discontinued in May 2018.

6 The admitted contravening implied representations, accepted to be false and misleading, are described in the joint submissions on penalty as being to the effect that Osteo Gel was “specifically formulated to treat, solely or specifically treated, and was more effective than Emulgel in treating, local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis, when the products were in fact identically formulated and equally effective in treating this condition”. I am satisfied that this accurately and succinctly captures the nature of the contraventions admitted to.

7 Before turning to the assessment of the agreed position on declarations and penalties, and the disputed position on costs, it is convenient to again reproduce the packaging contained in the Liability Judgment and the conclusions reached. The figures begin with the Emulgel packaging for history and context, and are followed by the admitted contravening Osteo Gel packaging, and then the Osteo Gel packaging that was found not to be contravening.

1 January 2012 to about late November or December 2014 – Novartis’ Emulgel packaging (specific reference to osteoarthritis)

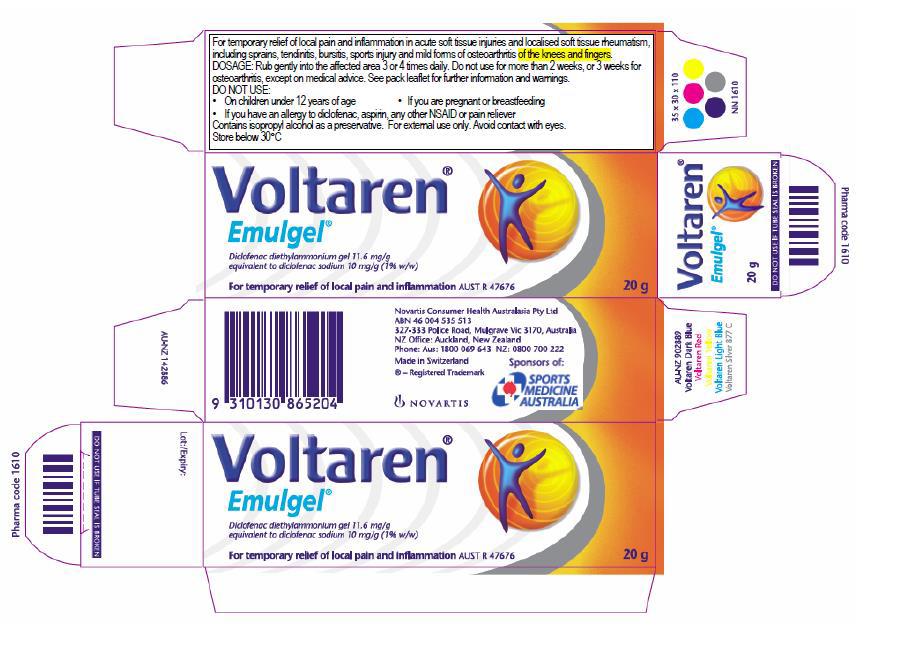

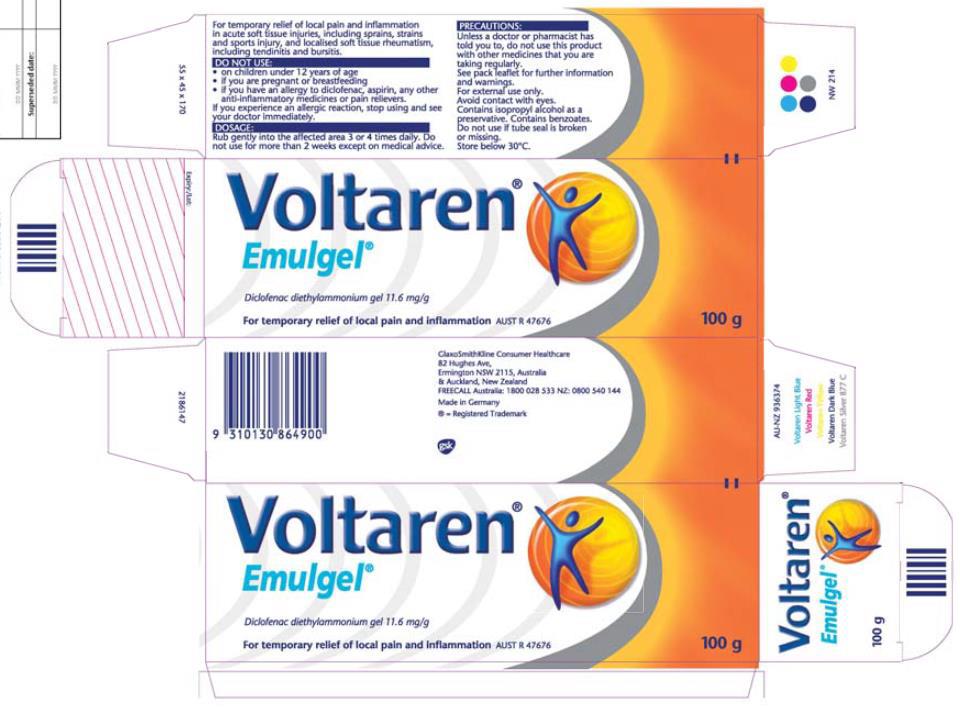

Late November or December 2014 until mid-May 2016 – Novartis’ Emulgel packaging (no reference to osteoarthritis and usage periods)

3 May 2016 to 28 February 2017 – GSK’s Emulgel packaging (no reference to osteoarthritis and usage periods)

1 January 2012 to mid to late November 2014 – Novartis’ Osteo Gel packaging (no reference to Emulgel): contraventions admitted

March 2016 to March 2017 – GSK’s Osteo Gel packaging (minor changes to Novartis’ packaging below; no reference to Emulgel): contraventions admitted

6 March 2017 to 31 May 2018 – GSK’s Osteo Gel packaging (specific reference to Emulgel): contraventions denied and not established

8 The Liability Judgment contains the following summary in relation to the admitted Osteo Gel packaging contraventions:

[80] The admitted contraventions may be seen to have turned on the interplay of a number of factors. Non-exhaustively, they include the uninterrupted flow from the name to the contiguous claim in white text on a blue background as to the use for treating osteoarthritis. That name and that claim were mutually reinforcing, further reinforced by appearing side by side with Emulgel packaging which had a more general use claim. While both products listed the same active ingredient, this was subordinate to the main effect. The dominant message and thus overall effect was of a product that was, to repeat the ACCC’s summary description, specifically formulated to treat, and solely or specifically treats, local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers, and is more effective than Emulgel at treating those conditions. It is not necessary to go further and refer to other features that reinforced this proscribed impression, although it may be seen that the increase in price for the same or similar sized tubes would reinforce, rather than create, that effect.

9 The Liability Judgment also contains the following conclusions, which summarise why the ACCC’s case did not succeed after the Osteo Gel packaging was changed in March 2017:

[85] The risk or possibility of a misleading impression being conveyed by reason of any special susceptibility in the relevant consumer class needs to be balanced against the assistance given to such a consumer, be that an osteoarthritis sufferer, or someone seeking a treatment product for such a sufferer, in readily finding a product that will treat that condition, without having to look to small print, and potentially a list of other irrelevant conditions. That is, the marketing of a product for use in treating a specific condition, even if it is the same underlying product used to treat other conditions, can be beneficial in some circumstances.

[86] An average, sensible consumer with osteoarthritis, or considering buying a treatment product for such a person, might have stopped and wondered. They might have questioned what the difference was between Emulgel and Osteo Gel. Upon reading the additional words on the Osteo Gel packaging, which were, only just, sufficiently clear and prominent, they most likely would have realised that the gel in each was the same, or at least that there was no material difference between the formula for Emulgel and the formula for Osteo Gel. They would have had clear information that Osteo Gel did treat osteoarthritis, a claim that was not made for Emulgel. They would have had the treatment duration information for osteoarthritis, with a longer maximum period of use; and they would have been aware that the cap would be easier to open (especially, but not only, for those with osteoarthritis in their hands).

[87] On a reasonably finely balanced basis, I am unable to conclude that the overall impression created by the revised packaging is that of a product that has been specifically formulated for treating osteoarthritis, or that solely or specifically treats osteoarthritis, or that is more effective than Emulgel in treating osteoarthritis, as opposed to a product that is suitable for use in treating osteoarthritis. By the narrowest of margins, the disputed contraventions have not been established.

Principles in relation to agreed penalties

10 This Court may make orders in accordance with an agreement between the parties as to a specific penalty, or within a range of penalties, if satisfied that it is appropriate in all the circumstances to do so: Minister for Industry, Tourism and Resources v Mobil Oil Australia Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 72; 54 ACSR 395 at [51], endorsing and applying the Full Court decision in NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [1996] FCA 1134; 71 FCR 285. Both Mobil Oil and NW Frozen Foods were approved by the High Court in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46; 258 CLR 482.

11 The Full Court in Mobil Oil summarised the principles to emerge from NW Frozen Foods in relation to a proposed agreed penalty as follows in the balance of [51]:

(i) It is the responsibility of the Court to determine the appropriate penalty to be imposed under s 76 of the [Trade Practices] Act in respect of a contravention of the [Trade Practices] Act.

(ii) Determining the quantum of a penalty is not an exact science. Within a permissible range, the courts have acknowledged that a particular figure cannot necessarily be said to be more appropriate than another.

(iii) There is a public interest in promoting settlement of litigation, particularly where it is likely to be lengthy. Accordingly, when the regulator and contravener have reached agreement, they may present to the Court a statement of facts and opinions as to the effect of those facts, together with joint submissions as to the appropriate penalty to be imposed.

(iv) The view of the regulator, as a specialist body, is a relevant, but not determinative consideration on the question of penalty. In particular, the views of the regulator on matters within its expertise (such as the ACCC’s views as to the deterrent effect of a proposed penalty in a given market) will usually be given greater weight than its views on more “subjective” matters.

(v) In determining whether the proposed penalty is appropriate, the Court examines all the circumstances of the case. Where the parties have put forward an agreed statement of facts, the Court may act on that statement if it is appropriate to do so.

(vi) Where the parties have jointly proposed a penalty, it will not be useful to investigate whether the Court would have arrived at that precise figure in the absence of agreement. The question is whether that figure is, in the Court’s view, appropriate in the circumstances of the case. In answering that question, the Court will not reject the agreed figure simply because it would have been disposed to select some other figure. It will be appropriate if within the permissible range.

12 The High Court plurality in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate summarised (at [31]) the observations in Mobil Oil that there is little advantage in limiting parties to an agreed range rather than an agreed figure and that a better way of reinforcing the court’s responsibility to determine an appropriate penalty was to scrutinise the material presented carefully and be satisfied that it was sufficient to determine whether the agreed penalty was appropriate. This approach is sufficient to remove any realistic danger of the court being perceived as a mere “rubber stamp” in relation to the penalty agreed upon. Their Honours then (at [32]) summarised five observations made in Mobile Oil as follows (omitting footnotes):

(1) As noted in Allied Mills and NW Frozen Foods, the rationale for giving weight to a joint submission on penalty rests on the saving in resources for the regulator and the court, the likelihood that a negotiated resolution will include measures designed to promote competition and the ability of the regulator to use the savings to increase the likelihood of other contraveners being detected and brought before the courts.

(2) NW Frozen Foods does not mean that a court must commence its reasoning with the penalty proposed by the parties and then limit itself to a consideration of whether the penalty proposed is within the range of permissible penalties. That is one option, but another is to begin with an independent assessment of the appropriate range of penalties and then compare it with the proposed penalty.

(3) The decision in NW Frozen Foods represented a correct application of the approach enunciated by Sheppard J in Allied Mills. As Sheppard J stated, the court is not bound by the figure suggested by the parties. Rather, the court has to satisfy itself that the submitted penalty is appropriate while acknowledging that, uninformed by the agreed penalty submission, the court might have selected a slightly different figure. That approach is correct in principle and it has been cited with approval by the High Court of New Zealand in Commerce Commission v New Zealand Milk Corporation Ltd.

(4) The decision in NW Frozen Foods is consistent with the imperative recognised in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Ithaca Ice Works Pty Ltd that the regulator should explain to the court the process of reasoning that justifies a discounted penalty.

(5) The decision in NW Frozen Foods allows for the following possibilities:

(a) if the court is not satisfied that the evidence or information offered in support of an agreed penalty submission is adequate, it may require the provision of additional evidence, information or verification and, if that is not forthcoming, may decline to accept the agreed penalty;

(b) if the absence of a contradictor inhibits the court in the performance of its task of imposing an appropriate penalty, the court may seek the assistance of an amicus curiae or an individual or body prepared to act as an intervener;

(c) if the court is not prepared to impose the penalty proposed by the parties, it may be appropriate to allow the parties to withdraw their consent and for the matter to proceed on a contested basis.

13 The approach of the Full Court in Mobil Oil and NW Frozen Foods was then endorsed by the plurality at [47] and [48].

Proof of the facts for penalty and declaration purposes

14 The Liability Judgment was principally concerned with the dispute as to alleged contraventions that were not ultimately established. The admitted contraventions always needed to be considered in greater detail when it came to penalty. The statement of agreed facts relied upon by the parties is formally made under s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). Evidence cannot be adduced to qualify or contradict the agreed facts without the leave of the Court. The agreed facts do not require letter and verse reproduction, especially as to formal matters. As the parties jointly submit, the Court may rely upon those agreed facts to pronounce judgment and make orders. Somewhat inconsistently with the binding nature of the agreed facts, the parties also rely upon a filed joint tender bundle. However, the parties confirmed at the penalty hearing that those additional documents are not intended to be more than an aid in understanding the facts and submissions that have been agreed upon. In the greater part, it has not been necessary to descend into any greater factual detail in these reasons than is summarised in the joint submissions, although both the agreed facts, some of the annexures and some of the documents in the tender bundle have been examined to ensure that the point being made has been properly understood.

Overview of the contraventions

15 GSK and its predecessor companies have being operating in Australia since 1886. GSK was incorporated in 2014 and commenced trading in 2015, being ultimately owned by GlaxoSmithKline PLC, a company registered in the United Kingdom (GSK PLC) via an intermediate subsidiary, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare (Overseas) Ltd (GSK Overseas), a company also registered in the United Kingdom. Novartis was incorporated much earlier in 1961, and was formerly ultimately owned by Novartis AG, until 22 March 2015 when it came into the GSK PLC fold. Novartis ceased trading on 31 May 2016, does not currently trade, and is also ultimately owned by GSK PLC via GSK Overseas.

16 As relevant to the admitted contraventions over five years and two months between 1 January 2012 and 28 February 2017, Osteo Gel and Emulgel were supplied by the respondents over four identified consecutive periods:

(1) a three-year-and-two-month Novartis Period from 1 January 2012 to 2 March 2015, during which Novartis supplied Osteo Gel and Emulgel;

(2) a 12-month Joint Venture Period from 3 March 2015 until 8 March 2016, when the consumer divisions of GSK and Novartis were combined;

(3) a less-than-three-month Transition Period from 9 March 2016 to 31 May 2016, when GSK supplied Osteo Gel and Emulgel on behalf of Novartis as a transitional measure, and all revenue from the sale of Osteo Gel and Emulgel went to Novartis; and

(4) a nine-month GSK Period from 1 June 2016 to 28 February 2017 when GSK supplied Osteo Gel and Emulgel on its own behalf, until the packaging of Osteo Gel was changed so that it was no longer contravening.

17 It is convenient to reproduce the balance of the part of joint submissions where the parties address the background to the admitted contraventions (omitting the footnotes which identify the part of the agreed facts and Liability Judgment by which those facts are established):

[10] The change to the Emulgel packaging in late 2014 removed directions for use relating to osteoarthritis conditions and usage periods. That is, whereas the packaging had previously specified that, in addition to the treatment of “local pain and inflammation in acute soft tissue injuries” for a period of 2 weeks, Emulgel was also suitable for use for the temporary relief of mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers and warned not to use (except on medical advice) for more than 3 weeks for osteoarthritis, the altered packaging of Emulgel removed all references to the treatment of osteoarthritis. The alteration to the Emulgel packaging to confine the stated [Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA)]-approved indications was not itself unlawful conduct.

[11] Emulgel and Osteo Gel were typically displayed for sale next to or in close proximity to each other in retail stores. This proximity had the effect of inviting a comparison that contributed to the misleading impression, by suggesting a difference that did not really exist. The respondents did not control the way the products were displayed to consumers by retailers. The placement of Osteo Gel and Emulgel in retail stores largely took place in accordance with planograms furnished by the respondents.

[12] There was a price premium for Osteo Gel compared to Emulgel based on the recommended retail prices (RRP) for those products in their respective packaging sizes. A direct comparison is possible with respect to certain periods of the 150g pack of Osteo Gel and Emulgel, which reflected:

(a) an 11.5% premium in the period 1 July 2015 to 31 May 2016 and 1 January 2017 to 28 February 2017; and

(b) a 16% premium in the period 1 June 2016 to 31 December 2016.

[13] The acquisition costs to GSK of the Osteo Gel product do not include costs incurred after that point (such as freight, storage, transport and distribution, or advertising costs).

[14] During the period from January 2014 to 24 November 2017, Novartis (from January 2014 to 31 May 2016), and later GSK (from 26 February 2016 to 24 November 2017), promoted Osteo Gel and Emulgel on the website displayed at the URL voltaren.com.au (Voltaren Website). The content displayed on the Voltaren Website varied during this period. There is no evidence before the Court indicating that the websites were not displayed in the forms shown in the [agreed facts], or were displayed in a substantially different form, at any point in the relevant period.

[15] Novartis also promoted Osteo Gel on a second website, at the URL myjointhealth.com.au, relevantly from January 2012 to 8 March 2016 (MyJointHealth Website). As at June 2014, the MyJointHealth Website was displayed in the form shown in Schedule H to the [agreed facts].

[16] The Representations were made by:

(a) Novartis, on the Original Packaging during the Novartis Period, the Joint Venture Period and the Transition Period, on the MyJointHealth Website relevantly from January 2012 to 8 March 2016, and on the Voltaren Website from January 2014 to 31 May 2016; and

(b) GSK on behalf of Novartis in the Transition Period under the Joint Venture, on the Original Packaging;

(c) GSK, on the Original Packaging during the GSK Period and on the Voltaren Website from 26 February 2016 to 24 November 2017.

18 Contraventions of this kind over such a long period of time by major corporations would ordinarily call for a significant penalty, calling for careful consideration of the adequacy of the penalty that the parties have agreed upon.

The relevant considerations on penalty in this case

19 Section 224(2) of the Australian Consumer Law mandates that, in determining the appropriate penalty, the Court must have regard to “all relevant matters”, including:

(a) the nature and extent of the act or omission and of any loss or damage suffered as a result of the act or omission; and

(b) the circumstances in which the act or omission took place; and

(c) whether the person has previously been found by a court in proceedings under Chapter 4 or this Part to have engaged in any similar conduct.

20 While this adds little or nothing to what would ordinarily be taken into account in any event, it reinforces the importance of determining the objective seriousness of the contraventions and their surrounding circumstances, and the importance of any prior contraventions. The following builds upon and develops that baseline.

21 The High Court in Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate confirmed (at [55]) that the principal purpose in the imposition of a civil penalty, and thus in assessing the appropriateness of an agreed penalty, is the capacity to deter so as to promote the public interest in compliance. The targets of such deterrence are both the contraveners before the Court and any other would-be contraveners, with this dichotomous targeting often described as specific and general deterrence. The principle is so well understood and so often applied that it requires no further elaboration.

22 In pursuit of the overall objective of deterrence, the penalty imposed must not be so low as to be no more than the cost of doing business, nor so high as to be disproportionate to the particular contraventions in question. The means by which that is to be assessed varies from case to case. The factors that have been addressed by the parties in their joint submissions are detailed and comprehensive. What follows contains some degree of elaboration on those joint submissions.

23 On the topic of general deterrence, the parties jointly submit, and I accept, that the penalty to be imposed in this case needs to send a strong message to the pharmaceutical industry. That is especially so as this is the second case, in relatively recent times, brought by the ACCC involving identically formulated products being marketed by a pharmaceutical company in a way that conveyed that they were different, rather than the same, for use for different ailments. This conduct in both cases contravened important consumer protection provisions proscribing such misleading, deceptive, and false representations.

24 The first such case was the Nurofen case¸ manifested by the following first instance and appeal judgments:

(1) the Nurofen liability judgment, in which Edelman J found Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd liable, following an eleventh hour capitulation: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 4) [2015] FCA 1408;

(2) the Nurofen penalty judgment, in which Edelman J imposed a penalty of $1.7 million: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd (No 7) [2016] FCA 424; 343 ALR 327, decided on 29 April 2016; and

(3) the Nurofen appeal judgment, by which error was found as to findings concerning key parts of Reckitt Benckiser’s conduct and the penalty was substantially increased to $6 million: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Reckitt Benckiser (Australia) Pty Ltd [2016] FCAFC 181; 340 ALR 25.

25 There are some material differences between this case and the Nurofen case, detailed further below, which make the latter considerably more serious. Importantly, the penalty able to be imposed by the Full Court was inhibited by the ACCC seeking a penalty range at first instance that can fairly be regarded as modest to the point of being arguably inadequate (see [178] and [179] of the Nurofen appeal judgment). Neither the ACCC nor the Court is bound by any prior penalty decision as though it was a precedent rather than merely a comparator or yardstick, let alone when forensic choices of that kind are not repeated.

26 On the topic of specific deterrence, the parties jointly submit, and I accept, that a suitable penalty is necessary to deter GSK, as the only respondent still trading, from engaging in similar conduct in future in relation to packaging, marketing and promotional activities. They note that GSK sells a range of other over-the-counter pharmaceutical products, such as Panadol, Sensodyne and Nicabate. Moreover, GSK’s contravening conduct continued for a substantial period of time even after it became aware of the liability decision in the Nurofen case on 11 December 2015. However, the parties submit, and I accept, that the seriousness of these matters should be viewed in light of the largely mitigating steps taken by GSK subsequent to the handing down of the Nurofen case liability decision. That includes in particular:

(1) In late 2015, after the Nurofen case liability decision, GSK commenced assessing its entire product range, following which it made changes to some products and deleted others;

(2) The process to change the Osteo Gel packaging started early in March 2016 and was in progress by 28 June 2016 when the ACCC first raised its concerns. GSK responded on 27 July 2016 by notifying the ACCC of its proposed changes to the packaging that were then approved by the TGA in July 2016. Revised (non-contravening) Osteo Gel packaging was expedited into the market by airlift and released from 1 March 2017;

(3) While the Voltaren Website continued for a further nine months after the supply of Osteo Gel in the original packaging to retailers stopped, GSK’s head of legal and company secretary, Ms Navaneetha Dilipumakanth deposes by affidavit that she approved changes made to the website in July 2017 in error. That error included overlooking a particularly egregious contravening table titled “compare our products”, which emphasised the misleading, deceptive and false representations upon which the ACCC’s case was based. That assertion of error is not challenged and I accept that explanation. It is a sound reason, if not a very compelling excuse. This places that aspect of the continued contravening conduct in a category approaching the mitigating “innocent” category identified in the Nurofen appeal judgment at [131];

(4) GSK decided in October 2017 to cease the supply of the product in the revised packaging in May 2018. This packaging was found not to be contravening by the Liability Judgment. Thus GSK went further than it was legally required to by removing Osteo Gel from sale in the revised packaging. GSK asks that the cost of withdrawing both the infringing and non-infringing product be taken into account. However, I do not consider that this is sound for the following reasons:

(a) In relation to the infringing product, the act of withdrawing it from sale is to be taken into account on the mitigation side of the ledger, because it has bearing on the need for deterrence. Had that not been done, the contravening conduct would have continued and the penalty would have arguably needed to be even higher, both in terms of the conduct itself, and in terms of the greater need for specific deterrence. But the cost of doing so is not mitigating, because that is the product of undoing what should not have been done in the first place.

(b) In relation to the non-infringing product, the act of withdrawing it from sale may again be taken into account on the issue of the need for specific deterrence, because it indicates that GSK was prepared to err on the safe side. It demonstrates active compliance processes and increasing the comfort in concluding that the risk of recurrent contravening conduct is thereby reduced. However, the cost of doing so is not mitigating, because it is not the product in relation to which the penalty is being imposed;

(5) GSK made full formal admissions in relation to the original Osteo Gel packaging on 27 February 2018, following commencement of the proceedings on 5 December 2017 (the continued denial of the contraventions alleged in relation to the revised Osteo Gel packaging was vindicated by the Liability Judgment);

(6) GSK took steps to improve its processes for compliance; and

(7) GSK, by Ms Dilipumakanth’s affidavit, expressly acknowledges and apologises that its past conduct has fallen short of the standards expected of it under the Australian Consumer Law. That is a candid and appropriate admission and amounts to the right kind of sorry – sorry for engaging in the conduct, not just sorry for being caught out.

27 I consider that each of the above aspects are noteworthy and as dealt with above stand to the credit of GSK, to be weighed in the balance in considering the adequacy of the penalty that has been agreed between the parties.

28 The parties point out that Novartis has not generated any sales revenue since 31 May 2016 when it ceased to trade. They submit that while the current trading state of Novartis does not prevent a significant penalty being awarded against it in aid of general deterrence, specific deterrence is unlikely to be a material consideration. If a contrary view is formed by the Court in relation to specific deterrence, the parties agree that Novatis should garner the benefit of the factors listed at [26] above as a company now in the GSK group. I accept that there is no meaningful role for specific deterrence in relation to Novartis, especially as that objective has direct work to do in relation to GSK as a substantial ongoing trading concern in Australia.

29 On the topic of the number of contraventions, the parties acknowledge that a vast number of contraventions took place in the five-year-and-two-month period from 1 January 2012 to 28 February 2017. That is because a contravening misleading representation took place not just each time a tube of Osteo Gel was sold, but each time one was examined on a retail display, or information of a like kind was viewed on one of the websites. In the period from 1 July 2011 to 28 February 2017 prior to the change to the (non-contravening) revised packing in March 2017 (noting that this period includes five months in which the limitation period of six years prior to the commencement of this proceeding on 5 December 2017 had expired), 1.4 million units of Osteo Gel were sold.

30 At a minimum, therefore, 1.4 million contraventions took place, with a theoretical maximum penalty at the time of each contravention of $1.1 million, even without regard to other consumers who also saw the packaging and without taking into account website visits. The maximum penalty is therefore to be so large as to be meaningless when it comes to penalty assessment: see the Nurofen appeal judgment at [157]. As in the Nurofen case, when there is no practical upper limit, the better focus is on the substance of what took place. The parties jointly submit, and I accept, that in this case the appropriate focus is on:

(1) which of the contraventions relate to the same conduct;

(2) whether there were courses of conduct, and if so, how many;

(3) comparative penalties; and

(4) to the extent it is needed, totality.

31 As to the question of the same or different conduct, s 224(4) of the Australian Consumer Law provides that if conduct constitutes a contravention of two or more provisions set out in s 224(1)(a), while a proceeding may be instituted in relation to each such provision, the respondent is not liable to more than one pecuniary penalty for each provision covering the same conduct. This constraint has been held to apply only to conduct which is truly the same, not merely similar or repeated, so as to be different from the course of conduct principle: see Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Yazaki Corporation [2018] FCAFC 73; 262 FCR 243 at [217]-[224] (concerning s 76(3) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) dealing with contraventions of Pt IV, which is relevantly equivalent to s 224(1)(a)), and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jetstar Airways Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCA 205 at [13]-[17]. The parties submit, and I accept, that each time the contravening representations were conveyed by the packaging or websites, multiple provisions were contravened, but each resulted from the same conduct by the repeated conveying of those same representations.

32 As to the course of conduct principle, the parties acknowledge that separate contraventions from separate acts ordinarily attract separate penalties, but jointly submit that where those acts are inextricably interrelated they may properly be grouped as a single course of conduct, so as to avoid double punishment for overlapping conduct, citing Yazaki at [234]. I accept that this is an appropriate approach. Applying that analytical tool for assessing the contraventions in this case, but not dominating the exercise of discretion so as to impose a limit that s 224 does not authorise, I have had regard to the joint submissions by the parties on this topic. Those submissions suggest five possible courses of conduct as follows:

(1) the contraventions by Novartis can be classified as involving three courses of conduct, being the contravening representations made on:

(a) the Osteo Gel packaging;

(b) the MyJointHealth Website; and

(c) the Voltaren Website; and

(2) GSK’s contraventions can be classified as involving two courses of conduct, being the contravening representations made on:

(a) the packaging; and

(b) the Voltaren Website.

33 The respondents separately contend, as a possible alternative, only three courses of conduct, being:

(1) the contravening representations on the packaging;

(2) the contravening representations made on the Voltaren Website; and

(3) the contravening representations made on the MyJointHealth Website,

each carried on in succession by Novartis and then by GSK.

34 The parties jointly emphasise that this grouping is not to downplay the wrongdoing by the respondents, nor to convert the many contraventions into only three or five contraventions, nor to limit the maximum penalty. Rather, they submit, it remains critical to ensure that the penalties imposed are of sufficient deterrent value having regard to what took place, noting the observations in the Nurofen appeal judgment at [139]-[145] and also at [157]. On this argument, as expressly put, the proposed penalty is said to be consonant with either three or five courses of conduct, properly reflecting the seriousness of the contraventions.

35 In my view, the better way to view the conduct for penalty purposes is by reference to the three courses of conduct suggested in the alternative by the respondents. On the one hand, it reduces the number of courses of conduct, but on the other it increases the seriousness of each such course of conduct as to duration, persistence and adverse effect on consumers. It also reflects the reality that the specific corporate entity assigned to sell Osteo Gel in contravening packaging at a particular point in time was of no great importance from a consumer perspective. That reflected organisational arrangements put in place at different points in time, rather than any substantive difference from a market place perspective, a view that may now more readily be taken given that the two respondents are ultimately owned by the same entity. This is an exercise in characterisation to aid in assessment of the penalties jointly proposed.

36 Over more than half a decade, this group of companies sought to maximise their sales and thereby profits by artificially boosting the breadth of its product range in three different ways in packaging and online, thereby representing to consumers that there were two different products for two different conditions, when the truth was that there was differential use of the same product. As the Liability Judgment demonstrates, the contravening conduct could have been avoided by making it clear that the active ingredient was the same in the two products marketed for different uses and indeed generally different users.

37 As to comparative penalties, the parties jointly point to the Nurofen case and rely upon the consideration of that case in the Liability Judgment at [39]-[43], [47] and [64(1) and (3)]. The substance of that comparison was that the contravening conduct in the Nurofen case, while over a very similar duration overall when the present case is taken as three contiguous courses of conduct by the two respondents, was more serious because the contravening representations were overt, not implied, and had added adverse features such as only being admitted to at the eleventh hour. The respondents furnished a helpful table comparing a number of the key features in this case with comparable features in the Nurofen case. The valid points made, with some embellishment by me, include:

(1) in the Nurofen case, there was no difference whatsoever between the five products, four of which were marketed as the contravening “specific pain” representations (asserting that each product was targeting four different types of pain, when no such targeting was even possible, beyond the contravening aspect of the outer packaging of those four products, whereas there was at least the material difference of the easy-to-open cap for Osteo Gel;

(2) in the Nurofen case, the four contravening products sold for double the standard Nurofen, whereas the markup for Osteo Gel was about 11.5% to 16%;

(3) consumers were much more likely to be misled by the overtly and expressly false representations in the Nurofen case, compared to the implied representations about Osteo Gel;

(4) consumers were at a greater risk of double-dosing in the Nurofen case by using the same product, labelled differently, to treat more than one pain condition at the same time;

(5) 5.9 million units of the four contravening products were sold in the Nurofen case with revenue of about $45 million, compared to 1.4 million units of Osteo Gel with a combined revenue of about $20 million (some $6.5 million in the case of GSK and $13.5 million in the case of Novartis), as detailed below;

(6) the likely loss to consumers in the Nurofen case was in the order of $26.25 million, much more than for Osteo Gel, with at least some of the sales in the latter case reasonably attributable to the real difference of the easy-to-open cap – there is nothing inherently misleading in charging more for a product that has an identified difference, even if it is not as to the active ingredient;

(7) the admissions were made at a much earlier stage in relation to Osteo Gel, compared to the 11th hour admissions, on the eve of the trial, in the Nurofen case; and

(8) numerous events put Reckitt Benckiser on notice of the problem:

(a) it had been given the Choice Magazine “Shonky Award” in 2010 for its false representations in relation to the four contravening products;

(b) complaints were made to the TGA in 2012 which in substance were upheld in June 2013;

(c) in April 2013, the ABC’s “The Checkout” consumer program featured a segment criticising this conduct; and

(d) on 11 April 2014, the Secretary of the Department of Health (Cth) ordered Reckitt Benckiser to withdraw the specific pain representations, resulting in webpages being withdrawn a month later;

but Reckitt Benckiser continued to market the four contravening products without any material change, whereas GSK commenced changing its packaging, continuing the sale of the contravening product for the lesser period of 14 months.

38 The increased penalty imposed by the Full Court in the Nurofen case of $6 million was held to be at the bottom end of the appropriate range. That range was limited by the upper end of the penalty range that the ACCC had sought before the trial judge: see the Nurofen appeal judgment at [178]. It suffices to say for present purposes that Reckitt Benckiser in the Nurofen case ended up being fortunate that it was dealt with at the tail end of a period of relative penalty leniency for this sort of conduct both by this Court and on the approach then taken by the ACCC. The penalty imposed in that case would probably be considerably greater if it came before this Court now. The Nurofen case does not represent any yardstick constraint on the appropriate penalty in this case in those circumstances.

39 On the topic of the nature and extent of the respondents’ conduct, the parties jointly point to the following features of the contravening conduct drawn from the evidence and certain of the findings in the Liability Judgment:

(1) the conduct occurred over a significant period of five years and two months as detailed above;

(2) it affected a large number of consumers, with the sales well in excess of one million units of Osteo Gel during the contravening period;

(3) as was found in the Liability Judgment as to differential marketing of the same product to different consumers for different conditions:

[73] It was legitimate for GSK to market a general product and a specialist product, each containing the same gel. Generally older consumers, suffering from a condition that is at least uncomfortable, and may also be distressing and even debilitating, are not compelled by the consumer protection provisions that the ACCC relies upon to have presented to them a shopping list of conditions that are mostly irrelevant to them in order to find out if a given product will address their specific need.

(4) however, as was also found in the Liability Judgment when characterising the contravening conduct:

[79] Osteo Gel is plainly being encouraged for use with osteoarthritis. That encouragement is enhanced by also having a cap that is easy to open. If the prospective buyer wants to go further in the comparison exercise, the back of each package discloses a differential maximum duration of use. But the use of the name “Osteo Gel”, so clearly connected with such a well-known condition as osteoarthritis, carried with it the risk that it would convey not just the permitted impression, but also a proscribed impression. The respondents took that risk with the initial marketing of Osteo Gel, and crossed the line. That crossing of the line has been admitted.

[80] The admitted contraventions may be seen to have turned on the interplay of a number of factors. Non-exhaustively, they include the uninterrupted flow from the name to the contiguous claim in white text on a blue background as to the use for treating osteoarthritis. That name and that claim were mutually reinforcing, further reinforced by appearing side by side with Emulgel packaging which had a more general use claim. While both products listed the same active ingredient, this was subordinate to the main effect. The dominant message and thus overall effect was of a product that was, to repeat the ACCC’s summary description, specifically formulated to treat, and solely or specifically treats, local pain and inflammation associated with mild forms of osteoarthritis of the knees and fingers, and is more effective than Emulgel at treating those conditions. It is not necessary to go further and refer to other features that reinforced this proscribed impression, although it may be seen that the increase in price for the same or similar sized tubes would reinforce, rather than create, that effect.

…

[82] … the proximity of packages of Osteo Gel to packages of Emulgel had the effect of inviting a comparison that contributed to the misleading impression, suggesting a difference that did not really exist. …

(5) Novartis launched Osteo Gel as an additional and new product, that was distinct from Emulgel, to increase market share without “cannibalising” sales of Emulgel by alienating purchasers of Emulgel, as demonstrated by its internal communications and media briefings;

(6) Novartis’ aim was:

(a) to attract the custom of osteoarthritis sufferers who were typically an older demographic (typically 55 years or older) than Emulgel consumers; and

(b) to attract the custom of consumers who were purchasing heat and herbal treatments for the alleviation of pain associated with osteoarthritis,

in circumstances where the easy-to-open cap delivered a benefit for those consumers which was not available on Voltaren Emulgel;

(7) to achieve that objective, Novartis developed and implemented a considered and deliberate marketing strategy:

(a) targeting osteoarthritis pain sufferers as potential purchasers of Osteo Gel, including the easy-to-open cap that was not available on other products (including Emulgel) that provided a benefit to potential purchasers suffering mild to moderate osteoarthritis of the fingers; and

(b) targeting (somewhat) younger audiences as potential purchasers of Emulgel;

(8) the consumers described in the Liability Judgment at [73] reproduced above as generally “older consumers, suffering from a condition that is at least uncomfortable, and may also be distressing and even debilitating” were profiled as often trialling alternative products, and likely to have been willing to pay a higher price for products specifically formulated to treat the local pain and inflammation associated with their osteoarthritis – the ACCC submits, and I accept, that as such they were more vulnerable than consumers without those or like characteristics;

(9) Novartis, and later GSK, sought to achieve a legitimate commercial advantage by marketing Osteo Gel as a separate and “new” treatment to attract the target consumers, without alienating Emulgel customers who are younger and did not want to be associated with osteoarthritis;

(10) the contravening conduct here was in the nature of implied misrepresentations brought about by differential marketing that was not sufficiently careful, as opposed to flagrant deception: Liability Judgment at [76];

(11) Osteo Gel and Emulgel were sold as over-the-counter pain relief products in retail outlets throughout Australia, including during the period 4 June 2015 to 28 February 2017 in some 5,678 pharmacies and over 4,100 major grocery stores including Coles, Woolworths and Metcash grocery stores, making the conduct widespread during the contravening period; and

(12) the impression created by the Osteo Gel packaging, especially when displayed next to or near Emulgel, and taken in the context of the respondents’ promotional materials and strategies, meant that some ordinary consumers, perhaps many, would have been misled, but others would not: Liability Judgment at [64(3)] – to which I would add the observation that this may be seen often to be an inherent feature and risk with implied representations where some consumers will detect the implication, while others will not.

40 On the topic of loss or damage suffered as a result of the contravening conduct, the parties jointly submit that it is likely that the contravening conduct caused loss to consumers and harm to the respondents’ competitors. Consumers who purchased Osteo Gel are likely (according to the ACCC) or plausibly (according to the respondents) to have included those who:

(1) purchased Osteo Gel without realising it had the identical contents to Emulgel, which they may otherwise have elected to purchase at a lower price;

(2) purchased both Osteo Gel and Emulgel under the misapprehension that Osteo Gel specifically treated osteoarthritis, and Emulgel was for generic use;

(3) purchased Osteo Gel under the misapprehension that it specifically treated osteoarthritis, and may otherwise have elected to purchase a competitor product; or

(4) purchased Osteo Gel knowing that it was in fact identical in treatment benefit to Emulgel, and the only difference between the two products was that Osteo Gel included an easy-to-open cap.

I am content to treat each of the above as a likely outcome, but for an unknown and unknowable proportion of consumers, simply because each is a readily available conclusion for at least some ordinary consumers to reach, with (2) being probably the least likely.

41 The possible losses in the first three categories listed above would arise as soon as Osteo Gel was purchased in error, with the financial loss to consumers to be measured by:

(1) the difference in price between Osteo Gel and Emulgel for (1) above;

(2) the entire price of Osteo Gel for (2) above; and

(3) the difference in price between Osteo Gel and a competitor product for (3) above.

42 The financial loss to consumers is difficult to quantify with a great degree of accuracy, and could be calculated using a number of different methodologies. A sample calculation made using the price differential between 150 g tubes of Emulgel and Osteo Gel reveals a financial loss to consumers, assuming substitution, in the order of $2.4 million. This, however, is more a measure of potential loss, than proven actual loss. The main point is that the losses to consumers could well have been in the millions of dollars. At the very least that was the risk to which consumers were collectively exposed by the contravening conduct.

43 The parties also point to:

(1) non-financial loss by consumers being deprived of the opportunity to make properly informed purchasing decisions and exercising a different purchasing choice, citing Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Coles Supermarkets Australia Pty Ltd [2015] FCA 330; 327 ALR 540 at [57] and the Nurofen appeal judgment at [114]; and

(2) the possible but unquantifiable loss of sales by the respondents’ competitors. However, the respondents submit there was only a low likelihood of consumers purchasing a competitor’s products because the widely available competitor products were topical rubs (heat and ice) which mask pain and do not treat inflammation. There were only a small number of truly competitive generic forms which treat inflammation. This submission is supported by unchallenged affidavit evidence from Mr James Robert Ellery Meins, a marketing manager at GSK, and accepted for the purposes of this penalty determination.

44 As was pointed out in the Nurofen appeal judgment at [131], if as here, “a contravention does not involve any state of mind then it is for the party asserting any particular state of mind (be it a deliberate flouting of the law, recklessness, wilful blindness, ‘courting the risk’, negligence, or innocence or any other characterisation of state of mind) to prove its assertion”. With that in mind, I turn to the parties’ joint submissions on how the Court should characterise the respondents’ state of mind in relation to the contravening conduct. They jointly point to the following features:

(1) Novartis launched Osteo Gel as a “new” product for mild to moderate osteoarthritis in the knees and fingers, yet was fully aware that the gel was not new because it was identical to its existing Emulgel product, and the only distinguishing feature was the easy-to-open cap;

(2) the launch of Osteo Gel was done as part of a considered and deliberate commercial strategy to market Emulgel and Osteo Gel in respect of the treatment benefits that would be attractive to two separate target markets:

(a) muscle and joint pain for Emulgel; and

(b) osteoarthritis pain of the knees and fingers for Osteo Gel;

(3) while such a strategy is not inherently unlawful, it was pursued in circumstances where the contravening representations were misleading and false, and liable to mislead consumers, with respect to the benefit to be gained from purchasing Osteo Gel as opposed to Emulgel;

(4) GSK continued to implement that strategy after acquiring the Voltaren portfolio in about March 2016;

(5) GSK was on notice of the risks of misleading consumers through the marketing of the same medication as different products treating different conditions once it became aware of the liability decision in the Nurofen case in around December 2015, yet continued to supply Osteo Gel in the contravening original packaging for another 14 months;

(6) it was GSK’s responsibility to take appropriate steps to assess its own marketing strategies and ensure compliance with the Australian Consumer Law;

(7) GSK began taking those steps from December 2015 with a product range review, to which I add the observation that this and the actions taken up to the point of the revised packaging being introduced were too leisurely, accepting that short of withdrawing the product from sale altogether without a replacement, to the detriment of consumers who benefited from knowing that it was appropriate for their condition, this was always likely to have taken some time;

(8) GSK continued to supply Osteo Gel in the contravening packaging while developing changes to the packaging from March 2016, obtaining TGA approval for the non-contravening revised packaging in July 2016 and, once approved and ready for shipment, expediting the delivery of product in that revised packaging, and releasing it to the Australian market from 1 March 2017;

(9) Osteo Gel stock in the contravening packaging continued to be available for sale in grocery stores and pharmacies after this date until sold;

(10) GSK’s website conduct continued for a further nine months after it stopped supplying the products to retailers; and

(11) GSK also made changes to the Voltaren Website in July 2017, including to introduce a table titled “compare our products”, albeit as already noted due to a mistake.

45 A fair way to characterise the relevant state of mind is negligent up to very soon after the publishing of the Nurofen liability judgment on 11 December 2015 (that is, October 2010 to mid-December 2015 for Novartis’ Osteo Gel packaging, with contraventions admitted from 1 January 2012), and thereafter knowingly courting the risk (from mid-December 2015 to March 2016 in relation to the Novartis’ Osteo Gel packaging, and from March 2016 to March 2017 for the GSK Osteo Gel packaging), both an important aggravating step up from a state of mind of innocence or no established state of mind. The representations, albeit implied, were the product of a deliberate, and insufficiently careful, marketing strategy to sell the same product to two separate, but not entirely mutually exclusive, markets. Those lesser states of mind than intentional conduct are generally appropriate for implied contravening representations, although those too may be shown to be intentional. The lesson to be learnt is to tread carefully in such circumstances, because of the inherent risks involved; lack of care may even support an inference that an implied contravening representation was intentional in some cases.

46 The respondents’ conduct was authorised at a high managerial level in both companies. Their marketing strategies for the Voltaren brand, including in particular Osteo Gel, were developed at a high level by a global team, with local divisions and business units in each company that were responsible for the advertising and promotion of Osteo Gel and Emulgel, headed by persons in senior positions. In particular, directors and senior managers (within the meaning of s 9 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)) were responsible for overseeing and approving the advertising and promotion of Osteo Gel and Emulgel, including the Voltaren Website, MyJointHealth Website and the development and release of the product packaging. Moreover, a number of the changes in packaging for both Emulgel and Osteo Gel were authorised by very senior managers, including the head of legal and company secretary for GSK.

47 Based on long-standing authority of this Court, both at first instance and on appeal, the parties jointly submit, and I accept, that it is appropriate to have regard to the size of the respondents and their financial position. GSK was and is a large and profitable company, with a total turnover for Australia of almost $933 million in the period from 2 March 2015 to 31 December 2017. While Novartis ceased trading on 31 May 2016, during the period from 1 July 2011 to 31 May 2016 its turnover for Australia and New Zealand was almost $311 million.

48 The parties diverge on the relevance of the size, revenue and gross profits of the parent companies of the respondents. The respondents submit that it is they, and not their owners, who are the contraveners, their parent companies had no involvement in the contraventions, and there is no issue of their capacity as subsidiary companies to pay the penalty, operating a substantial business in their own right. The parties jointly submit that this is a matter of emphasis and neither position would alter the agreement on the quantum of the penalty agreed upon.

49 The relevant and undisputed statistics on these positions are:

(1) the respondents are both now wholly owned subsidiaries of GSK PLC, the ninth largest pharmaceutical company in the world in 2017, based in the United Kingdom;

(2) prior to the joint venture, Novartis was a wholly owned subsidiary of Novartis AG, another company operating internationally;

(3) encompassing the period of the contraventions by GSK, from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2017, GSK PLC’s total annual turnover was almost £82 billion with a gross profit of over £53.5 billion; and

(4) encompassing the period of the contraventions by Novartis, from 1 January 2012 to 31 May 2016, Novartis AG had a total turnover of over USD270 billion and a gross profit of some USD179 billion.

50 In my view, those background statistics have limited weight, but are not irrelevant. It would be artificial not to at least have cognisance of the ownership and ultimate control of the respondents. The conduct of the respondents does reflect poorly on their ultimate parent companies, now just GSK PLC. The subsidiaries bear the name of the parents (or did previously in the case of Novartis), and to that extent there is some general deterrence, and even almost specific deterrence, by reason of the adverse impact on their reputation. On the other side of the ledger, the scale of both the revenue and gross profits in Australia are put in a context in which the deterrent value of the penalty can be seen to be diminished somewhat insofar as that the parent companies, now just GSK PLC, might be in danger of not taking this very seriously. I therefore take the statistics above into account, and note that the time may come when this may need to have a greater role in the assessment of penalty at least in relation to deterrence of a parent to encourage compliance by a subsidiary.

51 The parties jointly point to both respondents’ earnings and profits from the sale of Osteo Gel in Australia, using slightly different time periods for the earnings and profits:

(1) Novartis earned gross revenue in the period 1 July 2011 to 31 May 2016 (again, noting that the first five months of this period is outside the limitation period) of almost $13.5 million, with gross profits in the contravening period from 1 January 2012 to 31 May 2016 of about $6.9 million;

(2) GSK earned gross revenue in the period 1 June 2016 to 24 November 2017 of almost $6.5 million, with gross profits in the contravening period from 1 June 2016 to 28 February 2017 of about $1.14 million.

52 The parties are undoubtedly correct in jointly submitting that the precise impact the contravening conduct had on Osteo Gel sales cannot be quantified. While many consumers would have purchased Osteo Gel under the shadow of the contravening impression conveyed and admitted to, others would not have been misled in any way (as careful scrutiny of the identical active ingredients in Osteo Gel and Emulgel would have revealed), and may well have been prepared simply to pay more for the benefit of ease of use with the easy-to-open cap. I would add that for perhaps a small number or proportion of consumers, a clear indication that Osteo Gel was suitable for treatment of osteoarthritis, with instructions tailored to that use, might have made the marginal extra cost worthwhile. Put simply, the proportions are impossible to know, but at least a significant majority would most likely have been misled or deceived; they were entitled not to be.

53 As to contravening history, neither GSK, nor Novartis have previously been found to have engaged in similar conduct or other contraventions of the Australian Consumer Law.

54 An important factor to take into account is whether a contravening company had an effective compliance regime, not just one that looks good on paper. This may lessen the need for specific deterrence, as is recognised in the joint submissions. The evidence is silent on this precise topic. However, GSK has filed two affidavits from Ms Dilipumakanth, including annexed documents. That evidence concerns GSK’s competition law training programs, as reviewed and updated. Since August 2014, specific training has been provided to staff in relation to misleading or deceptive conduct, including a presentation by external lawyers to the sales and marketing teams in relation to issues in the Nurofen case. GSK has also made changes to its approval processes since July 2017 to prevent the type of mistake that Ms Dilipumakanth described concerning the website and the comparison table, referred to above at [26(3)].

55 Following, and presumably as a result of, the Nurofen case, GSK took a number of steps to improve its compliance, as follows, all of which go to the risk of conduct of this kind being repeated, and thereby the need, or reduced need, for a stiffer penalty to enhance specific deterrence. Some of those steps are set out in [26] above, such as the product review that commenced after the Nurofen liability judgment was delivered on 11 December 2015, and the revised packaging being in progress by the time the ACCC raised concerns in late June 2016. Others are summarised as follows in the joint submissions (omitting footnotes and ordinal numbers):

• on 5 August 2016, GSK implemented a global policy setting out guiding principles in respect of the pricing, naming and packaging of same or similar products;

• following commencement of these proceedings, Ms Dilipumakanth has been involved in “Portfolio Management Review” meetings, which are conducted for the purpose of considering whether or not certain products should be brought to market in Australia, including legal and regulatory considerations;

• same or similar products are considered by a Risk Management and Compliance Board. Where an issue of this nature is identified by a business unit leader, it is expected to be escalated to the Risk Management and Compliance Board; and

• in January 2020, GSK introduced a new system for consumer-facing materials, which involves the same approval process already in use by GSK.

56 The parties jointly submit, and I accept, that within two months after the commencement of this proceeding, and against the background of the Nurofen case, the respondents made full admissions as to the contravening packaging.