FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests (No 4) [2020] FCA 704

Table of Corrections | |

In paragraph 752, the word "not" has been added before "a substantive provision". |

ORDERS

FRIENDS OF LEADBEATER’S POSSUM INC Applicant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 27 May 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. On or before 4 pm on 10 June 2020, the parties file any agreed proposed minutes of orders, including the proposed form of declaratory relief, reflecting the Court’s reasons for judgment.

2. In the absence of agreement, on or before 4 pm on 17 June 2020, the parties each file proposed minutes of orders, including the proposed form of declaratory relief, reflecting the Court’s reasons for judgment, together with submissions limited to 5 pages in support of the proposed minutes of orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

Table of contents

MORTIMER J:

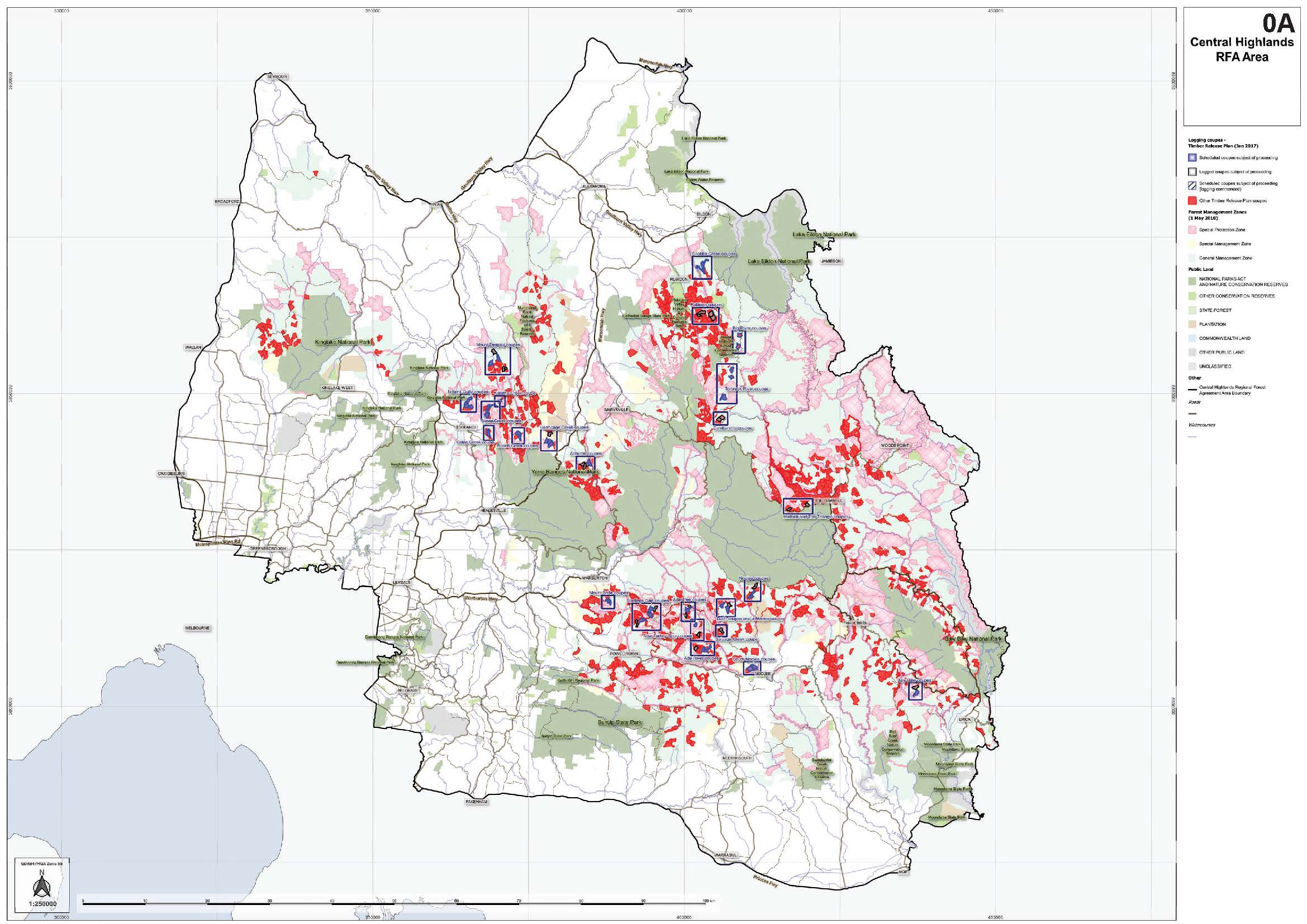

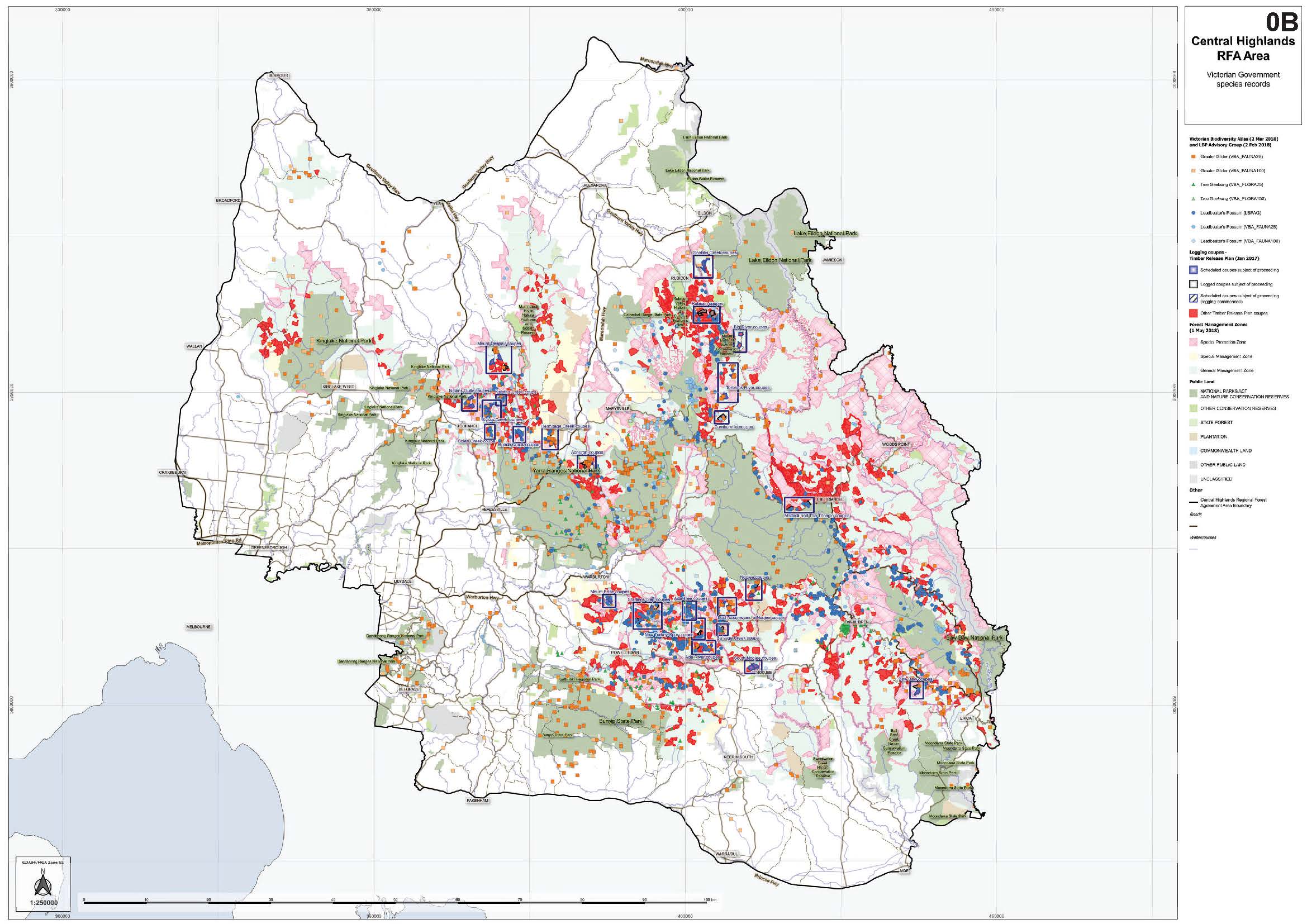

1 This proceeding concerns forestry operations in 66 specified native forest coupes in the Central Highlands region of Victoria and the effect of those forestry operations on two native fauna species, the Greater Glider and the Leadbeater’s Possum. Both are listed as threatened species under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth). The Greater Glider is listed as “vulnerable”, and the Leadbeater’s Possum is listed as “critically endangered”. Some of the 66 coupes have already been logged, and some have not. Thus, the proceeding concerns both past and proposed forestry operations.

2 The case has been brought by Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc, an environmental group, against VicForests, a Victorian statutory agency whose purpose is the management and sale of timber resources in Victorian State forests on a commercial basis. The native forest in question is included within the region covered by the Central Highlands Regional Forest Agreement (CH RFA), an intergovernmental agreement between the Commonwealth and the State of Victoria. The term “coupe” is a forestry term, referring to areas or patches of forest in which logging occurs.

3 The proceeding raises complex issues of law and fact about the operation of the EPBC Act on VicForests’ impugned forestry operations in those 66 coupes. It has already been the subject of two published decisions, the first of which in particular establishes the framework for the issues to be determined in these reasons: see Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests [2018] FCA 178; 260 FCR 1 and Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests (No 3) [2018] FCA 652; 231 LGERA 75. I shall refer to those two judgments as the “Separate Question reasons” and the “Injunction reasons” respectively. I also published reasons for judgment determining the form of answer to the separate question and addressing other matters relating to an amended statement of claim filed by the applicant in Friends of Leadbeater’s Possum Inc v VicForests (No 2) [2018] FCA 532. I will refer to that judgment as the “Relief reasons”. It will be necessary to refer to aspects of those three sets of reasons in this judgment, but it should be taken that I have generally adopted the reasoning I set out in those decisions in this judgment. In particular, my reasoning about the legislative scheme of the EPBC Act, and the way forestry operations as “actions” are dealt with in that Act, is set out in the Separate Question reasons at [123]-[135], [170], [195(a)], [197]-[198] and [223]-[226]. The core provisions of the EPBC Act are also set out in those reasons at [64]-[76].

4 Further, my reasoning on how the exemption conferred by s 38(1) might be lost can be found at [193]-[272] of the Separate Question reasons. While those findings may need to be developed somewhat, and applied to the evidence, the basic approach I have taken is set out in those passages.

5 These present reasons reflect the Court’s comfortable persuasion, on the balance of probabilities, that the applicant has made out its pleaded case. That pleaded case centres on allegations about the adverse impacts on the Greater Glider as a species and Leadbeater’s Possum as a species from VicForests’ past and proposed forestry operations in the 66 impugned coupes. The applicant’s pleaded case divides the 66 impugned coupes into a number of subsets, depending on whether they have been logged or are proposed to be logged, and depending on which coupes provide habitat for, and are used or occupied by, each of the two species. Thus, these reasons refer to the “Logged Coupes” (see [151] below); the “Scheduled Coupes” (see [152] below); the “Logged Glider Coupes”, the “Logged Leadbeater’s Possum Coupes” and the “Scheduled Leadbeater’s Possum coupes” (see [158] below).

6 In summary, the principal findings of the Court are as follows:

(a) I have accepted VicForests’ submission that the applicant’s case as put in closing submissions is wider than its pleaded case. Accordingly, the Court confined itself to the applicant’s pleaded case.

(b) In undertaking forestry operations in the Logged Glider Coupes, VicForests did not apply the precautionary principle to the conservation of biodiversity values in those coupes, as it was required to do by cl 2.2.2.2 of the Code of Practice for Timber Production 2014. Specifically, on the applicant’s case, VicForests did not apply the precautionary principle to the conservation of the Greater Glider as a threatened species present in, and using, the forest in those coupes. Accordingly, in relation to the forestry operations undertaken by VicForests in the Logged Glider Coupes, its conduct was not covered by the exemption in s 38(1) of the EPBC Act.

(c) Where made out, the miscellaneous breaches of the Code alleged by the applicant result in the loss of the exemption under s 38(1) in respect of forestry operations undertaken in the coupes in which the breaches occurred.

(d) In undertaking forestry operations in the Scheduled Coupes, VicForests is not likely to apply the precautionary principle to the conservation of biodiversity values in those coupes, as it is required to do by cl 2.2.2.2 of the Code. Specifically, on the applicant’s case, VicForests is not likely to apply the precautionary principle to the conservation of the Greater Glider as a threatened species present in, and using, the forest in those coupes. Accordingly, in relation to any forestry operations proposed to be undertaken by VicForests in the Scheduled Coupes, its conduct will not be covered by the exemption in s 38(1) of the EPBC Act.

(e) The result of the Court’s findings on (b), (c) and (d) means that none of the 66 impugned coupes are subject to the s 38(1) exemption.

(f) The findings in (b) to (d) do not result in only a qualified loss of the s 38(1) exemption, restricted to the impact of the forestry operations on the Greater Glider.

(g) For the purposes of s 18 of the EPBC Act, each forestry operation in each of the 66 impugned coupes is an action; each series of forestry operations in each coupe group (see [155] and [162] below) is an action; the forestry operations undertaken in the Logged Coupes are, collectively, an action; the forestry operations proposed to be undertaken in the Scheduled Coupes are, collectively, an action; and the forestry operations in all of the 66 coupes are, collectively, an action.

(h) In relation to each of the actions identified in (g), VicForests’ conduct of forestry operations is likely to have had, or is likely to have, a significant impact on the Greater Glider as a species and/or the Leadbeater’s Possum as a species. Accordingly, s 18 has been contravened and/or is engaged, depending on whether the action has been undertaken, or is proposed to be undertaken.

(i) The evidence provides sufficient certainty for the findings in (g) and (h) to be made, on the balance of probabilities. It will be a matter for further argument if, and how, those findings can and should be translated into injunctive relief in respect of the Scheduled Coupes.

(j) The consequence of these findings is that declaratory relief should be granted. The form of that declaratory relief will be determined after the parties have had an opportunity to consider the Court’s reasons and have attempted to agree on the form of declaratory relief or have made submissions about the appropriate form.

(k) In relation to the Logged Coupes (that is, the Logged Glider Coupes and the other Logged Coupes), relief of the kind set out in s 475(3) of the EPBC Act may also be available, subject to the Court hearing the parties’ further submissions, based on the findings the Court has made.

7 It is appropriate to make four general observations at the start of these reasons.

8 First, what the evidence in this proceeding has demonstrated is that the protection and conservation of biodiversity values – in this case relevantly the two listed threatened species in issue – is essentially a practical matter. Although policies and planning are important precursors and elements in protection and conservation, what happens on the ground in the native forest which supports and encompasses those values is how protection and conservation are achieved. Relevantly to the issues in this proceeding (rather than the wider biodiversity values protected by other aspects of the EPBC Act), understanding a native forest as a living, changing, finely balanced and often vulnerable ecosystem, and understanding the way in which all flora and fauna species in fact (rather than theory) use and depend on that native forest, are what best informs protection and conservation of, and the avoidance of adverse impacts on, those species. The evidence demonstrates the need for this approach is acute when dealing with listed threatened species.

9 Second, it was a repeated theme of VicForests’ submissions that the applicant’s case and arguments invite the Court to intrude into spheres of decision-making which are properly seen as reposed in the legislature or the executive. For example, VicForests contended (at [12] of its closing written submissions) the applicant’s case was not “essentially one of factual questions about the threat posed by the impact of forestry operations on Greater Glider and Leadbeater’s Possum” at some general level, but that it primarily concerned legal questions about the construction of the Code and the EPBC Act “as applied to factual matters”. In other words, that the Court was not examining what were the appropriate protections, at a policy level, for each of the species, but what the specified protections were, and whether they had been observed by VicForests. Another example is at [230] of its closing written submissions, where VicForests contended the Victorian legislature and the executive “have struck a balance between conservation measures and those that relate to the commercial use and exploitation of forest resources in State forests”, and that where there were “value judgments” to be made about that balance, those judgments were the “province of the legislature or the executive rather than the judiciary”. The Court’s role does not, VicForests submitted, extend to “the substitution of the court’s view of a more reasonable balance for that which was struck by the legislature or the executive”. These submissions were primarily made in the context of the approach VicForests contended should be taken to the obligation imposed by cl 2.2.2.2 of the Code.

10 It is not unusual for a respondent in the position of VicForests to make submissions that seek to confine the Court’s role as narrowly as possible, especially in a public interest case, involving contested issues of fact as well as law, and with significant consequences for a respondent in the performance of its functions and duties. Likewise, it is not unusual for an applicant in a public interest case to encourage the Court to take an expansive view of what matters need to be determined.

11 The Court’s function is to determine, on the evidence, whether the applicant has proven, on the facts and on the law as applied to those facts, its allegations against VicForests in respect of its forestry operations in the Logged Coupes and the Scheduled Coupes. Contrary to VicForests’ submissions, there is a significant factual aspect to the applicant’s allegations, which as a trial court, the Court must decide. It necessarily involves examining the competing evidence (including expert opinion evidence) about topics which are the product of wider policies and practices, and factual topics of more general application. In performing its task, the Court acts on the evidence before it, taking account of the submissions made. In this case, both the evidence and argument adduced by both parties travelled well outside evidence about these 66 coupes, as it needed to. Where the legal and statutory framework which the Court must consider, by reason of the parties’ respective cases, includes matters of degree, or has some qualitative or evaluative element, the determination of those matters is part of the exercise of judicial power, and not outside it.

12 Third, and not unconnected to the second matter, the evidence revealed that VicForests is required to operate under demands and constraints which pose something of an inherent contradiction. On the one hand, it is required to conduct forestry operations in Victoria’s native forest, rather than only in plantations. That native forest is identified as an available timber resource, indeed a principal available timber resource in Victoria, for VicForests to perform its commercial forestry function, as conferred by statute. On the other hand, VicForests is required by law to conduct those forestry operations in a way which avoids and mitigates adverse impacts on a wide range of biodiversity values, a range that is much wider than listed threatened flora and fauna species, but includes them. As I explain later in these reasons and as both VicForests and various reviewing bodies have recognised, for listed threatened species which are highly dependent on the very native forest which is to be subject to forestry operations, and for whom recovery out of the status of being a threatened species is expressed to be an objective, the avoidance of adverse impacts in a real world sense (rather than just an aspiration) inevitably involves compromising available commercial timber resources. Hence the conflict, which may explain (but not necessarily justify) why the actual conduct of forestry operations on the ground often cannot meet the conservation and protection obligations imposed by law.

13 Fourth, and no less importantly than the other general matters, all counsel, their instructing solicitors and their clients invested enormous amounts of time and resources in the conduct of this proceeding and did so with commendable efficiency and cooperation, including coping with the Court’s management of this proceeding as a digital trial, conducted only with the resources of the parties and the Court and no external provider. The Court is grateful to them all.

14 This proceeding was commenced by way of an originating application and statement of claim filed on 13 November 2017. On 17 November 2017, the Court made orders stating a separate question for hearing and determination, with the agreement of the parties. Prior to the hearing of the separate question, the Court issued rulings regarding the filing of an agreed statement of facts (on 1 December 2017) and the granting of leave to the State of Victoria and the Commonwealth to intervene (on 29 November 2017). The Separate Question reasons were delivered on 2 March 2018.

15 On 20 April 2018, the Court delivered the Relief reasons, which, as I have already noted, stated the answer to the separate question and addressed matters relating to the amended statement of claim filed by the applicant on 29 March 2018 (which amendments were generally summarised in those reasons at [30]-[33]). The amended statement of claim removed all references to cl 36 of the CH RFA, flowing from the Separate Question reasons, and instead put forward arguments relying on breaches of the Code. The Court concluded the operation of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) permitted the applicant to take this course.

16 On 23 April 2018, the applicant filed an application for an interlocutory injunction. Previous undertakings given by VicForests in relation to its timber harvesting operations pending the hearing and determination of the separate question had come to an end when the Court made its separate question orders on 20 April 2018. The Injunction reasons were delivered on 10 May 2018. On that date, the Court ordered that until the hearing and determination of the proceeding or further order, VicForests, whether by itself, its servants, agents, contractors or howsoever otherwise, be restrained from conducting forestry operations, felling, removing or damaging any trees or other substantial vegetation or widening the existing road line in certain specified coupes.

17 At the hearing of the injunction application, the proceeding was listed for trial commencing on 25 February 2019. On 11 February 2019, pursuant to leave granted by the Court on 7 February 2019, VicForests filed an affidavit of Mr William Edward Paul, which addressed “recent developments concerning VicForests’ silvicultural policies and practices” (at [5(a)]). At a case management hearing on 14 February 2019, both parties submitted that, as a result of the matters contained in Mr Paul’s affidavit, the trial dates should be vacated and the matter relisted for trial at a later date which could accommodate the developments to which Mr Paul’s affidavit adverted.

18 On 18 February 2019, the Court ordered, amongst other matters, that the trial be relisted to commence on 3 June 2019, and that the parties file proposed orders concerning the conduct of a joint experts’ conference and preparation of a joint report. The Court made further timetabling orders following a case management hearing on 25 February 2019, including orders for discovery of specified categories of documents by VicForests and the referral of other requests for discovery made by the applicant to Judicial Registrar Ryan for mediation and determination. Judicial Registrar Ryan conducted a mediation with the parties on 18 March 2019, following which he made orders for discovery of certain categories of documents and referred any outstanding discovery disputes back to the Court for hearing at a case management hearing on 16 April 2019. Following the filing of written submissions by the parties, the dispute concerning three remaining categories of discovery was determined by the Court in a ruling dated 17 May 2019.

19 On 22 March 2019, the Court made orders, with the agreement of the parties, in relation to the conduct of a joint experts’ conference and preparation of a joint report. The conference was scheduled to take place on 3 May 2019, facilitated by two Judicial Registrars. The parties were ordered to file an agreed list of questions for the experts (or separate proposed lists of questions) by 15 April 2019. Following further discussion with the parties at a case management hearing on 16 April 2019, and in written correspondence, it became apparent that the conference would be of little utility due to the divergence in the parties’ proposals regarding the approach to the conference. On 17 April 2019, the Court informed the parties that the joint experts’ conference and joint report orders would be vacated and the parties’ experts would be examined, cross-examined and re-examined at trial in the usual way. Although the Court left open the possibility of conducting a joint experts’ conference after the commencement of the trial, and VicForests again raised the possibility of a joint conference in its opening written submissions filed prior to trial, it did not eventuate. There remained no utility, in the Court’s opinion, in considerable resources and expense being applied to such a process, in light of the parties’ differing approaches to the proposed conference during case management and their considerably divergent approaches to how the experts should be asked to consider the complex factual issues in the proceeding.

20 Late in the afternoon of the Friday before the trial was scheduled to commence, the Court was notified of some proposed further amendments to the applicant’s claim. The amendments, which were foreshadowed at [172] and [174] of the applicant’s opening written submissions, narrowed the case to be put and added an additional ground of relief. They were the subject of consent from VicForests. The Court granted leave to the applicant to file and serve a third further amended statement of claim and amended originating application. Those documents were filed on 3 June 2019. As a result of those amendments the applicant:

(a) withdrew its allegations that forestry operations have had, are having, or are likely to have a significant impact on the Leadbeater’s Possum in the Ada River logged coupe 9.26 (Tarzan), Baw Baw logged coupe 9.32 (Rowels), Hermitage Creek scheduled coupes 10.14-10.16 (Drum Circle, Flute, San Diego) and the Torbreck River scheduled coupes 10.18-10.20 (Skupani, Splinter and Bhebe); and

(b) sought a declaration of right pursuant to s 21 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) that VicForests has breached s 18(2) of the EPBC Act by reason of its forestry operations in the “Logged Leadbeater’s Possum Coupes” and has breached s 18(4) of the EPBC Act by reason of its forestry operations in the “Logged Glider Coupes” (as those terms are defined in the third further amended statement of claim).

21 During the trial, the Court and the parties undertook an inspection or view of ten coupes in the Central Highlands pursuant to s 53 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth). The coupes inspected were Castella Quarry, Goliath, Shrek, Guitar Solo, Flute, Kenya, The Eiger, Mont Blanc, Hairy Hyde and Greendale, being a mix of Logged Coupes and Scheduled Coupes. Castella Quarry is not one of the 66 impugned coupes in the proceeding but was visited as an example of a coupe in which VicForests’ new silvicultural systems were being implemented. The Court expresses its gratitude to the parties for facilitating that inspection and in particular to the VicForests staff who assisted on the day.

22 While there was a significant dispute between the parties about the effects of VicForests’ forestry operations on the two species, there was also a dispute between the parties about how perilous the circumstances of the Greater Glider are, as a species. There appeared to be less debate about the perils facing the Leadbeater’s Possum. In relation to that species, the area of debate in assessing the impact of VicForests’ impugned forestry operations was about whether the measures in place were effective enough to avoid a conclusion of significant impact and whether VicForests adhered to them.

23 Unsurprisingly, each of the parties relied on the opinions given by their respective experts as the basis for the Court’s fact-finding about the species. As I explain later in these reasons, I accept and prefer the opinion evidence of the applicant’s species experts, Dr Smith and Professor Woinarski, and where the evidence of VicForests’ experts such as Dr Davey or Professor Baker conflicts with the applicant’s species experts, I prefer the evidence of the applicant’s species experts. Both Dr Smith and Professor Woinarski gave detailed evidence in their reports about each of the Greater Glider and the Leadbeater’s Possum. In terms of the characteristics of the species and their habitats, some of the significant differences of opinion between the applicant’s species experts and Dr Davey were their opinions about:

(a) the estimates of Greater Glider populations and their rates of decline;

(b) how Greater Gliders might use logged forest, including retained habitat trees;

(c) the effectiveness of the Comprehensive, Adequate and Representative (CAR) reserve system and existing management prescriptions; and

(d) the movement patterns of the Leadbeater’s Possum.

24 I rely on the expert evidence to some extent in setting out my general findings about each of the species; however, the principal sources I have relied upon are the Conservation Advices for each species.

25 I have placed significant weight in my fact-finding in this proceeding on the Conservation Advices. I consider that in the context of a proceeding under the EPBC Act, it is appropriate to do so. They are the mandatory and foundational documents describing each threatened species, its characteristics and habitat, and the threats posed to it. A Conservation Advice must be prepared for each listed threatened species: s 266B(1). The Conservation Advice must include a statement setting out the grounds on which the species is eligible to be included in the category in which it is listed and the main factors that are the cause of it being so eligible: s 266B(2)(a). Relevantly, it must also include “information about what could appropriately be done to stop the decline of, or support the recovery of, the species”: s 266B(2)(b)(i).

26 This document contains the formal recognition, for the purposes of the EPBC Act, of why the listed threatened species has been determined to need protection and what measures need to be taken to ensure its conservation and recovery.

27 The Conservation Advice for each species is issued by the Threatened Species Scientific Committee. The Threatened Species Scientific Committee is established pursuant to s 502 of the EPBC Act and is referred to in the Act as the “Scientific Committee”: see the definition of “Scientific Committee” in s 528. Amongst other functions, it has the function of advising the responsible Minister on the amendment and updating of the lists of threatened species for which s 178 and s 179 of the EPBC Act provide: s 503(b). It is an expert committee whose members are appointed by the responsible Minister: s 502.

28 The Conservation Advice for the Greater Glider states that it is based on “‘The Action Plan for Australian Mammals 2012’ (Woinarski et al., 2014)”. One of the authors of that publication is Professor Woinarski, the applicant’s Leadbeater’s Possum species expert. The fact that the Scientific Committee is prepared, for the purposes of performing its functions under the EPBC Act, to rely on a publication of which Professor Woinarski is an author confirms to me that Professor Woinarski’s opinions, where otherwise rational and having a scientific basis, as I find they are and do, should be given substantial weight.

29 The taxonomy of the Greater Glider species is accepted to be Petauroides Volans. It is the only species in the genus, with two recognised sub-species: P. v. minor (found in north-eastern Queensland) and P. v. volans (found in south-eastern Australia). The Greater Gliders which are the subject of this proceeding are the second sub-species.

30 The Greater Glider was listed in the vulnerable category under the EPBC Act effective 5 May 2016 and in the Threatened List under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Vic) effective 14 June 2017.

31 The Greater Glider is the largest gliding possum in Australia. It is a member of the nocturnal and arboreal leaf eating Ringtail Possum family (Pseudocheiridae). Being an arboreal mammal, it rarely travels along the ground. Its head and body length can reach 46 cm. Its thick fur increases its apparent size. It has an especially prominent, long furry tail measuring 45-60 cm. Sexual maturity is reached in the second year, and females give birth to a single young from March to June. The longevity of the Greater Glider has been estimated at 15 years, so generation length is likely to be 7-8 years. The Conservation Advice states:

The relatively low reproductive rate (Henry 1984) may render small isolated populations in small remnants prone to extinction (van der Ree 2004; Pope et al., 2005).

32 It is a nocturnal marsupial, largely restricted to eucalypt forests and woodlands. In the CH RFA region its habitat is the Mixed Species and Ash forests, which serve as both a source of food and a source of denning and resting. Dr Smith gave evidence that:

The Central Highlands is an area of exceptional site quality that is likely to sustain higher than average densities of the Greater Gliders because of its high rainfall, low temperatures and high eucalyptus growth rates.

33 Its preference for a diversity of eucalypt species is due to the seasonal variation in its preferred tree species. Its diet mostly comprises eucalypt leaves, and occasionally flowers. The Conservation Advice states:

It is typically found in highest abundance in taller, montane, moist eucalypt forests with relatively old trees and abundant hollows.

34 During the day it shelters in tree hollows, with a particular selection for large hollows in large, old trees. As to the significance of these hollows, in re-examination, Professor Woinarski gave the following evidence, which is relevant to my findings about both the Greater Glider and the Leadbeater’s Possum:

So it’s in almost all parts of Australia, hollows – there’s no – unlike in North America where woodpeckers make hollows for many other trees – for many other hollow-dependant species, there are no fauna species that make hollows in Australia. But it depends upon the rot and decay and the senility of the trees themselves for the hollows to form. The exception is, of course, termites, but we won’t go there. There aren’t so many termites in these forests. So it’s a – it’s a finite resource, and it’s eagerly used. There’s about 30 per cent Australian vertebrates species depend upon hollows. So it’s a really large component of the forest fauna is totally dependent on naturally occurring hollows. Naturally occurring hollows occur, as we’ve talking about previously, sort of they – they become established after 100 years or so, so it’s a really slow process. And there’s much more likelihood of the hollow in any forest to be declining than increasing, simply because of that age – that age disturbance factor. There’s a range – we know Greater Gliders, Sugar Gliders, Squirrel Gliders, a whole lot of owls, Pardalotes, kookaburras, cockatoos, parrots, all of those species are dependent upon hollows in this mountain ash environment, and will compete aggressively with other species for those hollows where they overlap. Leadbeater’s Possums, probably there’s a range of bird species which may compete with them for hollows. So cockatoos, rosellas and the like, for example, could aggressively kick them out. Also, there’s also competition within Leadbeater’s Possum families or – or neighbouring groups for hollow availability as well. So if a suitable den tree for Leadbeater’s Possum colony A and Leadbeater’s Possum colony B is running out of den trees, then it will – they will fight over that availability.

35 The Conservation Advice states:

In Grafton/Casino, Urbenville and the Urunga/Coffs Harbour Forestry Management Areas (FMAs) in northern New South Wales (NSW), the abundance of greater gliders on survey sites was significantly greater on sites with a higher abundance of tree hollows …

36 The expert evidence about the optimal number and placement of suitable tree hollows per hectare for the Greater Glider, and the significance of these needs in assessing the impact of forestry operations, are matters I will address when dealing with the precautionary principle and with significant impact. However, as one of VicForests’ witnesses, Mr Timothy McBride, noted in correspondence included in his affidavit affirmed on 15 October 2018 (at [23]), the hollows needed for the Greater Glider have to be fairly large, because of the size of the (mature) animal.

37 Home ranges for the Greater Glider are, according to the Conservation Advice, “typically relatively small”, around 1-4 ha. Males visit around 22 trees per night and females around 14: Tyndale-Biscoe H, Life of Marsupials (CSIRO Publishing, 2005) p 240. Home ranges can be larger in lower productivity forests and more open woodlands; they are larger for males than for females. Male home ranges are largely non-overlapping. Despite having small home ranges, the Greater Glider has a “low dispersal ability”, making it sensitive to habitat fragmentation. The Conservation Advice states that Greater Gliders:

have relatively low persistence in small forest fragments, and disperse poorly across vegetation that is not native forest. Modelling suggests that they require native forest patches of at least 160 km² to maintain viable populations (Eyre 2002). Kavanagh & Webb (1989) found no significant movement of greater gliders into unlogged reserves from surrounding logged areas.

38 The Conservation Advice also states:

Kavanagh & Webb (1989) found no significant movement of greater gliders into unlogged reserves from surrounding logged areas.

39 The Greater Glider is restricted to eastern Australia, but occurs from the Windsor Tableland in north Queensland through to central Victoria, at elevations ranging from sea level to 1200 m above sea level. Dr Davey stated that the population in the Central Highlands region is at the limits of the species’ distributional range. Similarly, when discussing Greater Glider populations most likely to be of key importance to the species’ long-term survival and recovery, Dr Smith acknowledged that populations at the limits of the species’ geographic ranges are important populations. I find that is an important fact in assessing the impact of forestry operations on the species.

40 As to distribution, the Conservation Advice states:

The broad extent of occurrence is unlikely to have changed appreciably since European settlement (van der Ree et al., 2004). However, the area of occupancy has decreased substantially mostly due to land clearing. This area is probably continuing to decline due to further clearing, fragmentation impacts, fire and some forestry activities. Kearney et al. (2010) predicted a “stark” and “dire” decline (“almost complete loss”) for the northern subspecies P. v. minor if there is a 3° C temperature increase.

41 I return to the last point made in this extract at several sections in these reasons: it is well accepted on the scientific evidence, and in the expert opinion, that there are large and presently unaddressed risks to species such as the Greater Glider from climate change and the warming of the environments in which they live.

42 As a species, the Greater Glider is considered to be “particularly sensitive” to forest clearance and to intensive logging, although the Conservation Advice qualifies this statement by stating that “responses vary according to landscape context and the extent of tree removal and retention”.

43 The species is also described in the Conservation Advice as “sensitive to wildfire” and “slow to recover following major disturbance”. The Conservation Advice states:

In the Urbenville FMA of northern NSW, the abundance of greater gliders on survey sites was significantly greater in forests that were infrequently burnt (Andrews et al., 1994).

44 The criterion which the Greater Glider met, and which was identified as justifying its listing in the vulnerable category as a threatened species under the EPBC Act, was Criterion 1, titled “Population size reduction (reduction in total numbers)”. Under this criterion, the Greater Glider was assessed by the Scientific Committee as experiencing:

(a) a population reduction observed, estimated, inferred or suspected in the past where the causes of the reduction may not have ceased or may not be understood or may not be reversible, based on an index of abundance appropriate to the Greater Glider, and a decline in area of occupancy, extent of occurrence and/or quality of habitat (Criterion 1 A2(b) and (c));

(b) a population reduction, projected or suspected to be met in the future (up to a maximum of 100 years), based on an index of abundance appropriate to the Greater Glider, and a decline in area of occupancy, extent of occurrence and/or quality of habitat (Criterion 1 A3(b) and (c)); and

(c) an observed, estimated, inferred, projected or suspected population reduction where the time period must include both the past and the future (up to a maximum of 100 years in the future), and where the causes of reduction may not have ceased or may not be understood or may not be reversible, based on an index of abundance appropriate to the Greater Glider, and a decline in area of occupancy, extent of occurrence and/or quality of habitat (Criterion 1 A4(b) and (c)).

45 The listing of the Greater Glider in the Vulnerable category by reference to Criterion 1 A2(b) and (c), A3(b) and (c) and A4(b) and (c) meant that the Greater Glider was assessed to be vulnerable to a reduction in population of more than 30%.

46 The Greater Glider was assessed by the Scientific Committee as not meeting listing Criteria 2, 3, 4 or 5: namely, geographic distribution as indicators for either extent of occurrence and/or area of occupancy, population size and decline, number of mature individuals or quantitative analysis indicating a probability of extinction in the wild.

47 In its closing submissions (at [310]-[322]), VicForests seeks to make something of the fact the Greater Glider’s EPBC Act listing was only under Criterion 1. The underlying theme appeared to be that the situation facing the Greater Glider was not the worst of the worst, and not – for example – as critical as that facing the Leadbeater’s Possum. I do not consider such a comparative approach assists the task the Court must perform. The fact is that the Greater Glider is a listed threatened species, and while it will be relevant in assessing both compliance with cl 2.2.2.2 of the Code and the issue of significant impact to bear in mind that the justification for its listing was its rate of population decline, there is no basis in the evidence or in the scheme of the EPBC Act for the Court to confine itself to any exact correlation between identified impacts or threats and the precise reason for the listing of the species. In relation to s 18, the question the statute relevantly asks is whether there is or will be a likely significant impact on a listed threatened species because of the actual or proposed conduct (here, of VicForests in its impugned forestry operations). In relation to cl 2.2.2.2 – as I explain below – the compliance question the Code asks of VicForests in its forestry operations is whether it has applied the precautionary principle to the conservation of the Greater Glider as a species (being a “biodiversity value”). The question is not as narrow as whether VicForests will, in its forestry operations, fail to apply the precautionary principle to conduct which may affect only the rate of population decline of the Greater Glider. An obvious reason for this is that threats to a listed species may increase or decrease over time, and they may alter in their significance because of particular events, such as climate change or wildfire. There is nothing static in assessing the nature of any threats and the range of impacts, and the scheme of the EPBC Act does not assume there is.

48 The Conservation Advice states that there “is no reliable estimate of population size” for the Greater Glider, by reference to a 2008 study which described the Greater Glider population as having a “presumed large population” and being “locally common”. In oral evidence Dr Smith appeared to disagree with this aspect of the Conservation Advice, saying that in 2008 not much was known about the Greater Glider population.

49 The Conservation Advice states that the estimate of the Greater Glider population across its range is in excess of 100,000 mature individuals. In oral evidence, Dr Smith considered this to be a reasonable estimate. To qualify under Criterion 4, relating to numbers of mature individuals, a species must have less than 1000 mature individuals to be characterised as “vulnerable”.

50 I note that Criterion 5 – the quantitative analysis of the probability of extinction in the wild – was not met in respect of the Greater Glider, but not because of any reliable estimate of the probability. Rather, the Conservation Advice indicates this criterion was not met (referring to the work of Professor Woinarski and others) because no population viability analysis had been conducted across the Greater Glider population as a whole, although some local analysis had been carried out.

51 In the section of the Conservation Advice explaining why the Greater Glider met the first criterion for listing, the Conservation Advice makes the following points relevant to the issues in this proceeding (with abbreviated citations as reproduced in the Conservation Advice):

(a) Despite the absence of robust estimates of total population size or population trends across the species’ total distribution, declines in numbers, occupancy rates and extent of habitat have been recorded at many sites, from which a total rate of decline can be inferred.

(b) The most comprehensive monitoring program for Greater Gliders is in the Central Highlands of Victoria, the region with which this proceeding is concerned.

(c) The Central Highlands region has been monitored annually since 1997.

(d) Over the period 1997-2010, the monitoring showed a population decline of an average of 8.8% per year.

(e) If that rate is extrapolated over the 22-year period relevant to this assessment, the rate of decline is 87% (citing a study by Lindenmayer et al., 2011).

(f) Higher rates of decline were recorded in forests subject to logging than in conservation reserves.

(g) Declines were also associated with major bushfires and lower than average rainfall.

(h) The Conservation Advice quotes a finding from a study conducted by Lumsden and others (2013 p 3) that a “striking result from these surveys was the scarcity of the Greater Glider which was, until recently, common across the Central Highlands”.

(i) Major bushfires in 2003, 2006-2007 and 2009 burnt much of the Greater Glider’s range in Victoria, and further fragmented its distribution.

(j) Reoccupation of burnt sites in subsequent years is likely to be a slow process due to the small home ranges (1-2 ha) of the species and its limited dispersal capabilities.

(k) Any reoccupation also depends on there not being further significant fires in the interim (citing Vic SAC 2015).

(l) Since the 2009 fires, which burnt the Kinglake East Bushland Reserve and nearby areas, spotlighting records of Greater Gliders in these areas have significantly declined.

(m) Preliminary results of an occupancy survey in 2015 suggest low occupancy rates in three of four survey areas in Victoria. Approximately 50% of the individual transects in this study incorporated sites of known previous occupancy by Greater Gliders based on systematic surveys in the 1990s.

(n) Other evidence supports a decline in East Gippsland. In the Mount Alfred State Forest, roadside spotlighting on the same route over a 30-year period was used to record frequent sightings (10-15 animals on each occasion), but only a single Greater Glider was sighted in the 18 months leading up to November 2015.

(o) There is evidence of some declines in occupancy in unburnt sites in the same parts of Victoria (and also at Booderee National Park in New South Wales), which the Conservation Advice took to suggest that factors other than fire are involved in the species’ decline. It nominated a lack of suitable browse due to water stress as a likely contributing factor, as central Victoria was significantly hotter and drier than normal during 2001-2009.

52 For many of its findings in relation to Criterion 1, the Conservation Advice relied on the work of Dr Lumsden in Victoria. The evidence suggests Dr Lumsden worked at the Arthur Rylah Institute in Victoria, an institute which on the evidence collaborates with the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) on many conservation-related projects. There is no evidence why VicForests, which also appears to have drawn on the work of the Arthur Rylah Institute from time to time, did not call Dr Lumsden. I note that Dr Smith’s opinion is that Dr Lumsden’s survey data is accurate, although her occupancy model is not.

53 After having noted the less comprehensive monitoring of Greater Glider populations which had been undertaken in New South Wales and Queensland, the Conservation Advice concluded that:

There is little other published information on population trends over the period relevant to this assessment (around 22 years), and the above sites are not necessarily representative of trends across the species’ range. However, they provide sufficient evidence to infer that the overall rate of population decline exceeds 30 percent over a 22 year (three generation) period (Woinarski et al., 2014), and indeed may far exceed 30 percent. The population of the greater glider is declining due to habitat loss, fragmentation, extensive fire and some forestry practices, and this decline is likely to be exacerbated by climate change (Kearney et al., 2010). The species is particularly susceptible to threats because of its slow life history characteristics, specialist requirements for large tree hollows (and hence mature forests), and relatively specialised dietary requirements (Woinarski et al., 2014).

The Committee considers that the species has undergone a substantial reduction in numbers over three generation lengths (22 years for this assessment), equivalent to at least 30 percent and the reduction has not ceased, the cause has not ceased and is not understood. Therefore, the species has been demonstrated to have met the relevant elements of Criterion 1 to make it eligible for listing as Vulnerable.

(Emphasis added.)

54 I note here the Scientific Committee’s clear opinion that the cause for substantial population reduction is “not understood”. Whatever legal approach is adopted, that clear opinion has considerable relevance for the obligation imposed on VicForests to apply the precautionary principle in its timber harvesting operations.

Threats to the sustainability and recovery of the Greater Glider as a species

55 The question of threats to the sustainability and recovery of the Greater Glider as a species occupied a great deal of the evidence, including the expert evidence, and I return to this topic at several points in these reasons. What I set out in this section is what might be described as the foundational points, without some of the nuances and detail, which may be important to the resolution of the issues in the proceeding, but about which more detailed findings will be made later in these reasons. As I have noted, the source of these facts, which I accept and adopt, is the Conservation Advice, which is of significant weight in my fact-finding.

56 The Conservation Advice identifies a number of key threats to the Greater Glider, as a species. It is appropriate to set out the table contained in the Conservation Advice in its entirety. Of particular importance for the issues in this proceeding is what is said about habitat loss, fire, climate change, and hyper-predation. The Scientific Committee’s summary of the “[c]umulative effects of clearing and logging activities, current burning regimes and the impacts of climate change [which] are a major threat to large hollow-bearing trees on which the species relies” is set out in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Extract from Greater Glider Conservation Advice

Threat factor | Consequence rating | Extent over which threat may operate | Evidence base |

Habitat loss (through clearing, clearfell logging and the destruction of senescent trees due to prescribed burning) and fragmentation | Catastrophic | Moderate-large | The species is absent from cleared areas, and has little dispersal ability to move between fragments through cleared areas; low reproductive output and susceptibility to disturbance ensures low viability in small remnants. Roadside clearing in state forests have destroyed many hollow-bearing trees previously left on the perimeter of logging coupes (Gippsland Environment Group pers. comm., 2015). |

Too intense or frequent fires | Severe | Large | Population loss or declines documented in and after high intensity fires (Lindenmayer et al., 2013). |

Timber production | Severe | Moderate | Prime habitat coincides largely with areas suitable for logging; the species is highly dependent on forest connectivity and large mature trees. Glider populations could be maintained post-logging if 40% of the original tree basal area is left (Kavanagh 2000); logging in East Gippsland is significantly above this threshold (Smith 2010; Gaborov pers. comm., 2015). There is a progressive decline in numbers of hollow-bearing trees in production forests as logging rotations become shorter and as dead stags collapse (Ross 1999; Ball et al., 1999; Lindenmayer et al., 2011). The species occurs in many conservation reserves across its range. In NSW, 83% of the public forested lands (that lie within the Integrated Forestry Operations Approval regions) that coincide with the distribution of the greater glider are protected in formal or informal reserves (Slade & Law, in press). However, the fraction of protected areas is likely to be [lower] in Queensland and Victoria. |

Climate change | Severe | Large (future threat) | Biophysical modelling indicates a severe range contraction for the northern subspecies (Kearney et al., 2010). Occupancy modelling indicates that the degree of site occupancy is associated with vegetation lushness and terrain wetness (Lumsden et al., 2013). Water stress affects growth in forest eucalypts (Matusick at al., 2013) and the availability of browse, and higher temperatures may cause heat stress and mortality (Vic SAC 2015). |

Barbed wire fencing (entanglement) | Minor | Minor | There are occasional losses of individuals. |

Hyper-predation by owls | Severe | Local | The greater glider forms a significant part of the powerful owl’s diet (Bilney et al., 2006). Powerful owl numbers have increased greatly in the Blue Mountains since 1990 and have been recorded at many sites with greater gliders (Smith pers. comm., 2015). Reduction in the stand density of hollow-bearing trees could increase predation threat whilst the species is moving between hollows. Since the widespread decline of terrestrial species, the greater glider has become a significant part of the sooty owl’s diet – increasing from 2% of its diet at pre-European settlement to 21% (Bilney et al., 2010). The greater glider has significantly declined or become locally extinct in some intact forest, possibly due to owl predation (Lindenmayer et al., 2011; Lumsden et al., 2013; Rickards pers. comm., 2015). At Boodoree National Park, the increase in large forest owls coincided with a reduction in foxes, which may have reduced competition for prey with the powerful owl and sooty owl (Lindenmayer et al., 2011). |

Competition from sulphur-crested cockatoos | Minor-moderate | Local | Numbers of cockatoos in the Blue Mountains have increased significantly since 1990. They are likely to be competing with greater gliders for hollows and have been observed taking over nesting hollows of powerful owls (Smith pers. comm., 2015). |

Phytophthora root fungus | Minor | Large | The fungus is known to impact on the health of eucalypts. |

57 The applicant submits at [464] of its closing submissions, and I accept:

The rating of ‘catastrophic’ is drawn from the action plan for Australian mammals 2012 (CB 12.60 p256) which describes the “Threat factor” of “Habitat loss (through clearing) and fragmentation” as having a catastrophic consequence rating. The source of this descriptor is the article titled “Action plan for Australian mammals 2012” authored by Woinarski (et al.) which sets out at Table 1.3 the definition of catastrophic, being “likely to cause complete population loss, where operating” (CB 11.4 pdf p 22-23).

58 Although VicForests in its evidence and submissions sought to downplay both the threatened status of the Greater Glider and the role of timber harvesting in its threatened status, and although for many aspects of its submissions VicForests urged the Court to focus on State-based regulatory mechanisms and State-based instruments, some of the clearest statements about the role of timber harvesting in threats to the Greater Glider come from a Victorian document. The final recommendation for the nomination of the Greater Glider for listing as a threatened species under Victoria’s FFG Act in March 2017 states (with my emphasis):

While the Greater Glider is “well represented in a number of conservation reserves” (Menkhorst 1995), the bulk of its distribution remains in forest available for timber harvesting. Wood production practices are known to substantially deplete Greater Glider populations and gliders usually die if all or most of their home range is intensively logged or cleared (Menkhorst op. cit.). Unless they are linked as part of an interconnecting network of reserves, local populations risk extinction through catastrophe or by loss of genetic vigour through inbreeding. Again Menkhorst (1995) notes that agricultural development has already isolated populations in the Wombat Forest, Gippsland Highlands and Gelliondale Forest and in smaller areas on the fringes of the Eastern Highlands. McKay (1988) notes that conservation of the species “is utterly dependent on sympathetic forest management which retains buffer strips of old forest between coupes and preserves old ‘habitat trees’ and their potential successors in small unlogged areas.”

59 The statement that the “bulk” of the distribution of the Greater Glider in Victoria remains in forest available for timber harvesting (and not in conservation reserves) substantially contradicts one of the underlying premises of Dr Davey’s evidence, and of VicForests’ contentions. This document represents the formal, official reasons for listing of the Greater Glider as a threatened taxon under the Victorian regulatory scheme of which VicForests made much in this proceeding. This, like other documents on which VicForests relied, is a judgment made by the executive. The authority and accuracy of what is stated in it should be accepted.

60 Returning to the Conservation Advice, in terms of conservation actions which should be taken, the Scientific Committee recommended to the Minister that, as “primary conservation actions”, the following should occur:

1. Reduce the frequency and intensity of prescribed burns.

2. Identify appropriate levels of patch retention, habitat tree retention, and logging rotation in hardwood production.

3. Protect and retain hollow-bearing trees, suitable habitat and habitat connectivity.

61 All three of those recommendations have a direct connection to forestry operations. The Conservation Advice goes on to make the following specific recommendations about the conduct of forestry operations in Victoria:

In production forests some logging prescriptions have been imposed to reduce impacts upon this species, however these are not adequate to ensure its recovery.

In Victoria, logging of areas where greater gliders occur in densities of greater than two per hectare, or greater than 15 per hour of spotlighting, require a 100 ha special protection zone (Vic DNRE1995). However, this threshold is quite high given that density estimates in Victoria range from 0.6 to 2.8 individuals per hectare (Henry 1984; van der Ree et al., 2004), and mature tree densities are declining meaning a lower probability that gliders will occur at higher densities (Gaborov pers. comm., 2015). This management requirement may therefore not adequately protect existing habitat and greater glider populations.

62 The Conservation Advice then sets out further tables summarising the management actions required to advance the conservation and protection of the Greater Glider. Again, these tables should be set out in their entirety.

Table 2: Recommended management actions

Theme | Specific actions | Priority |

Active mitigation of threats | Reduce the frequency and intensity of prescribed burns. | High |

Constrain impacts of hardwood production through appropriate levels of patch and hollow-bearing tree retention, appropriate rotation cycles, and retention of wildlife corridors between patches. | High | |

Constrain clearing in forests with significant subpopulations, to retain hollow-bearing trees and suitable habitat. | High | |

Avoid fragmentation and habitat loss due to development and upgrades of transport corridors. | High | |

Restore connectivity to fragmented populations. | Medium | |

Captive breeding | N/a | |

Quarantining isolated populations | N/a | |

Translocation | Reintroduce individuals to re-establish populations at suitable sites. | Low |

Community engagement | Develop conservation covenants on lands with high value for this species. | Low |

Table 3: Survey and monitoring priorities

Theme | Specific actions | Priority |

Survey to better define distribution and abundance | Assess population size (or relative abundance) and viability of populations across the species’ range, using standardised and repeatable methodology. | Low |

Determine the distribution and abundance in relation to forest vegetation class, age class, and amount of old growth forest in the landscape to understand the pattern of occurrence. | Medium | |

Establish or enhance monitoring program | From existing monitoring projects, design an integrated monitoring program across major subpopulations, linked to the assessment of management effectiveness. | High |

Monitor the abundance and size structure of critical habitat tree species, and their responses to management including before and after prescribed burns, and before and after logging. | High | |

Continue to model impacts of wildfire and logging on population viability. | Medium | |

Monitor the incidence of wildfire within the species’ range. | Medium |

Table 4: Information and research priorities

Theme | Specific actions | Priority |

Assess relative impacts of threats | Assess the impacts of a range of possible fire regimes on the species. | Medium-high |

Assess the impacts of ongoing habitat fragmentation (e.g. through peri-urban expansion, coal seam gas mining activities, road networks). | Medium | |

Investigate the potential causes of recent declines, including cumulative impacts and impacts of owl predation. | Medium | |

Assess relative effectiveness of threat mitigation options | Assess the impacts of fire management (prescribed burning programs) on habitat, hollow availability, preferred tree species, and glider population size. | High |

Assess responses to habitat re-connections (e.g. rope ladder crossings over transport corridors). | Medium | |

Continue to assess and monitor the species’ responses to logging regulations and conditions. | Medium | |

Investigate the practicality of supplementing hollow availability with artificial hollows. | Low-medium | |

Resolve taxonomic uncertainties | Assess the extent of genetic variation and exchange between subpopulations. | Low |

Review taxonomic status. | Low | |

Assess habitat requirements | Investigate the numbers, densities and types of hollow-bearing trees that must be retained to ensure viable populations. | High |

Assess diet, life history | N/a |

63 The following matters are of particular importance to my findings:

(a) the recommendations for the active mitigation of threats and their specification as being of “high priority”;

(b) the recognition by the Scientific Committee that more survey work was needed to “better define distribution and abundance” of the Greater Glider, and (I infer) therefore that there remained scientific uncertainty about those issues;

(c) that there was a “medium to high” need to assess the impacts of a range of possible fire regimes on the species, again (I infer) indicating scientific uncertainty about this question;

(d) the need – identified in the low-medium, medium and high priority range on matters relevant to forestry operations – to “assess relative effectiveness of threat mitigation options”. This is a matter to which I return later in these reasons, however I note here that, aside from the adverse opinion of Dr Smith and Professor Woinarski, there is little, if any, scientific evidence in this proceeding about the effectiveness of the prescriptions and other mitigations for which the policies of VicForests provide. As I explain later in these reasons, in the absence of any scientific evidence (by way of studies and monitoring) that existing prescriptions and mitigations are effective in reducing the population decline of the Greater Glider and assisting its recovery, I find the need, in forests where the Greater Glider may be present, for a complete application of the precautionary principle in VicForests’ forestry operations is imperative. The absence of such studies was a point repeatedly made by Dr Smith and Professor Woinarski. I also find the likely impact of forestry operations in forests where the Greater Glider may be present is significant.

64 Finally, the Scientific Committee made the following recommendation in the Conservation Advice:

The Committee recommends that there should be a recovery plan for this species.

65 Recovery Plans can be made pursuant to an exercise of a discretionary power conferred on the responsible Minister by s 269AA of the EPBC Act. No Recovery Plan has been issued for the Greater Glider; however, a document entitled “Draft National Recovery Plan for the greater glider (Petauroides volans)” was in evidence. That document is dated October 2016. The promulgation of a Recovery Plan under the EPBC Act seems to have stalled since 2016.

66 The Greater Glider Conservation Advice was approved by a delegate of the Minister on 25 May 2016. Its content should be taken to have been known to VicForests from a reasonable time after that date. In respect of the Logged Coupes, the table at [161] of Mr Paul’s second affidavit affirmed on 15 October 2018 indicates that in 17 of those coupes, harvesting commenced and completed on dates after 25 May 2016. In five coupes, harvesting operations were commenced prior to 25 May 2016 but completed after that date. In respect of the Camberwell Junction coupe, Mr Paul indicates at [178] of his second affidavit that harvesting was completed on 24 April 2018.

Dr Smith’s description of the Greater Glider

67 From Dr Smith’s first report (dated 7 January 2019), I consider the following additional characteristics of the Greater Glider and its habitat are important to note specifically.

68 Dr Smith explains why a single Greater Glider needs access to more than one suitable tree hollow:

Greater Gliders are predominantly solitary and each individual may occupy many different nest trees (habitat trees or trees with suitable hollows) within its home range which are about 1-3 hectares in size in the more productive forests (Kehl and Boorsboom 1984, Smith et al 2007). Nest sites may be changed frequently with individual gliders reported to use up to 18 den trees within their home ranges (Kehl and Boorsboom 1984, Comport et al 1996, Smith et al 2007). Frequent nest tree changes may be necessary for [temperature] control, avoidance of parasites and to reduce predation by Powerful Owls, Sooty Owls and Spotted Tail Quolls. Greater Gliders are an important (keystone) food resource for these large predators.

69 Dr Smith goes on to expand on the relationship between the Greater Glider and species which prey on it:

The Spotted-tail Quoll, which is listed as endangered under the EPBC Act in south eastern Australia, is particularly dependent on Greater Gliders which it hunts by climbing trees and removing them from tree hollows (Belcher et al 2007). The importance of Greater Gliders to the Spotted-tail Quoll is such that timber harvesting regimes that reduce Greater Glider numbers is recognized as a key threat to this species (Belcher et al 2007).

Powerful Owls (Ninox strenua) have been associated with catastrophic (90%) population declines in local Greater Glider populations (Kavanagh 1988). Powerful Owls may consume approximately 80-250 large mammal prey like Greater Gliders every year within their home ranges which are about 300-350 hectares for breeding females (Higgins 1999). At this rate if [Powerful] Owls fed solely on Greater Gliders they would remove one Greater Glider in every two hectares within their home range each year. This rate of predation exceeds the population growth rate of the Greater Glider in many forests.

70 The issue of predation of Greater Gliders by other species, in particular Powerful Owls, as Dr Smith highlights, has considerable relevance to the operation of the precautionary principle in VicForests’ forestry operations, and to the question of significant impact under s 18.

71 As to the nature of the preferred habitat of the Greater Glider – an issue also of key relevance for the precautionary principle question and for s 18 – Dr Smith states:

The Greater Glider has generally been found to prefer tall more productive “old growth” eucalyptus forests with an overstorey of large old trees that provide hollows suitable for nesting and a high basal area of large trees (> 40 cm diameter) suitable for movement by gliding. These forests may be referred to as “old growth” because it takes 120 -300+ years for trees to become old enough to develop hollows and it takes about 40-80 years for trees to reach a diameter of about 40 cm. (Ambrose 1982).

72 Dr Smith explained that because the Greater Glider is such a large possum, the trees between which it glides have to be sufficiently robust to take its weight, and the force applied when it lands on the trees.

73 There follows a detailed description of the kind of tree species favoured by the Greater Glider, and the characteristics of such forest. Although lengthy, it is important to set this part of Dr Smith’s report out, as the characteristics of the forests in which the Greater Glider is found is central to both the precautionary principle issue and the s 18 issue:

In the Central Highlands the Greater Glider habitat is found in the following three broad forests types:

a) uniform aged old growth Ash forests that have not been intensively burnt for more than 120 years,

b) uneven-aged Ash forests with an overstorey of scattered old trees with hollows and an understorey of advanced regrowth or mature forest (> 40 years of age) that developed after infrequent low intensity wildfire; and

c) uneven aged old growth Mixed Species (Stringybark) forests with an overstorey of scattered or abundant old trees with hollows and an understorey of trees of different sizes including abundant trees > 40 cm diameter.

Ash forest refers to tall open wet forests dominated by Mountain Ash (Eucalyptus regnans), Alpine Ash (E. delegatensis) and/or Shining Gum (E. nitens). They generally occur at high elevations in cooler, wetter more productive environments. Ash forests give way to Mixed Species forests at lower elevations. Mixed Species forests are commonly dominated by Messmate Stringybark (E. obliqua), Mountain Grey Gum (E. cypellocarpa) and other species of Stringybarks, Peppermints and Gums. Mixed Species forests extend to low elevations and are sometimes referred to as foothill forests. Trees in Mixed Species forests are much more likely to survive wildfires than trees in Ash forests and hence are typically found in uneven-aged stands (Victorian Environment Assessment Council 2017).

In Ash forests of the Central Highlands old growth commonly occurs in uniform aged stands regenerating after a single past intense wildfire disturbance or as uneven-aged stands with two or more distinct age classes of trees that regenerated after separate less intense fires. Ash old growth appears to be most prevalent in gullies, riparian zones and sheltered aspects that have been protected from intense fire for long periods of time (>120 years). In contrast, Mixed Species forests of the Central Highlands (and elsewhere in Victoria VEAC 2017) naturally occur as uneven-aged old growth because the dominant tree species are generally not killed by intense wildfire, recover rapidly by re-sprouting (coppice) and do not require fire for regeneration (Florence 1996, Lutze et al 2004,). Consequently, large old trees with hollows are common and persistent after wildfire in Mixed Species forests. Because the dominant trees species in Mixed Species forests (Stringybarks) are also generally shade tolerant (Florence 1996) they can regenerate under an existing tree canopies and do not require post logging burning or wildfire for regeneration.

…

The Greater Glider is not present in all old growth eucalyptus forests throughout its range. It is scarce or absent from old growth [eucalyptus] forests in hot and/or dry environments, in forests that are frequently burnt or have been intensively logged and in some parts of forests that have been subject to intensive owl predation. Physiologically the Greater Glider is unable to cool itself effectively at high temperatures (> about 20c) (Rubsamen et al 1984) which explains its restriction to cool, wet forests at higher elevations, especially in the tropics and sub-tropics.

The habitat requirements of the Greater Glider may be more specifically summarized as:

1. scattered emergent (> 1/ha) to abundant (> 12/ha) large diameter living and dead trees with hollows suitable for nesting;

2. a tall open forest structure with an abundance of large tree stems (> 25 /ha) in the mature size class (40 - 80 cm diameter at breast height (dbh) and a scarcity of dense young regrowth in the understorey, to provide an open structure suitable for movement by gliding;

3. low maximum mean monthly temperatures that do not exceed about 20 degrees C and moderate to high rainfall (>[about] 400 mm /annum);

4. infrequent disturbance by fire, >10 year intervals in Mixed Species eucalyptus forest and > 40 - 120+ year intervals in wet Eucalyptus forests;

5. no recent history of high intensity logging (clearfelling) or timber harvesting that has removed more than about 33% (wet forests) to 15% (dry forests) of the natural tree basal area (Dunning and Smith 1985, Howarth 1989, Kavanagh 2000, Eyre 2006).

6. no recent history of intensive Owl Predation.

74 As the Conservation Advice also notes, Dr Smith’s opinion is that the Greater Glider has low annual fecundity, and at best (fecundity sitting at about 0.5-0.9 young per female per year) raises a single young each year. It has a short reproductive lifespan (likely less than 10 years). Dr Smith’s opinion is that the low fecundity of the Greater Glider “makes it especially vulnerable to predation, and slow to recover after disturbance events such as clear-felling and intense wildfire”.

75 Having reviewed a number of surveys of Greater Gliders conducted in the Central Highlands (noted by the Conservation Advice to be the most comprehensive), Dr Smith identifies the population decline of the Greater Glider and its causes, in his opinion (which I accept):

Together these surveys suggest that Greater Glider numbers in the Central Highlands increased from moderate levels (32%) in 1983 to a peak of up to 60% in 1996 and then declined reaching a low of 10-16% of sites. This rate of decline (more than 50% reduction in 13 years) is consistent with the requirements for listing of the Greater Glider as vulnerable under the EPBC Act.

The pattern of decline is broadly consistent with what we know about changes in the geographic extent of potential Greater Glider habitat in the Central Highlands. It is consistent with an initial increase in the structural suitability of 1939 regrowth Ash Forest for Greater Gliders as these forests increased in age (from 44- 79 years of age), followed by a steady decrease in the overall extent of habitat caused by a combination of:

a) ongoing clearfelling and post logging burning of 1939 regrowth and uneven-aged ash regrowth and particularly the loss of scattered living old growth trees with hollows during logging and post logging burning operations;

b) ongoing natural decay and collapse of dead trees with hollows in 1939 regrowth Ash Forests (Smith 1982, Smith and [Lindenmayer] 1988, [Lindenmayer] et al 1990),

c) ongoing clearfelling of old growth Mixed Species forests (largely found to be incorrectly mapped as 1939 regrowth by VicForests in this study);

d) extensive wildfires in Ash Forests and Mixed Species forests in 2009;

e) increased isolation and fragmentation of remnant habitat caused by excessive logging of old growth Ash and Mixed Species forests remnants in gullies and riparian zones and failure to maintain substantive corridor links between remnant old growth and uneven-aged habitats; and

f) potential loss of habitat in the hotter and drier patches of Mixed Species and Ash Forest at lower elevations and on exposed aspects due to hotter and drier conditions than normal over recent years (Lumsden et al 2013).

76 A recurring theme in the evidence of both Dr Smith and Professor Woinarski, on which I have placed some weight, is the critical role played by the 1939 regrowth Ash forest in the habitat needs of both the Greater Glider and Leadbeater’s Possum in the CH RFA region. It is the 1939 regrowth which is also one of the targets of VicForests’ forestry operations.

77 Finally, I note some further evidence from Tyndale-Biscoe’s Life of Marsupials, which was a principal source relied on by Mr McBride for information about the characteristics of the Greater Glider. The author compares the Greater Glider to the Koala, in terms of its focus on eucalyptus foliage as a diet, and states (at p 240):

Greater gliders are at about the minimum size for an animal subsisting exclusively on Eucalyptus leaves and it is clear from the analysis of their energetics that they are only able to live on this diet by leading a slow life.

…

For a species living so close to the limits of sustainability the nutritional quality of the food, both its energy content and nitrogen content, are critical to survival.

78 As to breeding patterns, the author states:

They generally live alone except during the brief highly synchronised breeding season in April-June when the single young is born. Young lost prematurely are not replaced and there is no second peak of breeding because the males are no longer producing sperm (see Chapter 2).

…

More interestingly, the number of females with pouch young is about the same as the number of adult males, so that there is a pool of non-breeding females. This is because gliders form monogamous pairs (Henry 1984, Kehl and Borsboom 1984). In both studies the home ranges of adult females did not overlap in the forest but those of males were larger and overlapped the home range of one or two females, depending on the quality of the forest.

79 This text contains some important observations, including observations derived from a study of the effects of forestry operations on the Greater Glider in New South Wales, which are material to the findings I make about the application of the precautionary principle to the Greater Glider and to the question of significant impact. I extract those passages of the text later in these reasons. In substance, the text paints a gloomy picture of the capacity of the Greater Glider to survive forestry operations even in the short to medium term, if they are not killed by the logging event itself. It paints an equally gloomy picture of the capacity of the Greater Glider to move to unlogged forest, or to recolonise logged forest. I reiterate this was a key source of Mr McBride’s information about the Greater Glider.

80 The Leadbeater’s Possum was initially listed as a threatened species under the EPBC Act in the endangered category, but was transferred to the critically endangered category, effective from 2 May 2015. There was less debate about the characteristics and habitat needs of the Leadbeater’s Possum. As well as the 2015 Conservation Advice for this species, setting out the justifications for its listing as critically endangered, there is an Action Statement published in 2014 by the then Victorian Department of Environment and Primary Industries. The Action Statement was made pursuant to s 19 of the FFG Act.

81 There is no current Recovery Plan under the EPBC Act for the Leadbeater’s Possum, although there is a draft, dating from 2016, of which Professor Woinarski was one of the co-authors. There was an earlier Recovery Plan, which is now out of date. On 22 June 2019, shortly after this trial was completed, a new Conservation Advice for the Leadbeater’s Possum was issued. The parties and witnesses mostly relied on the 2015 Conservation Advice and I have done the same. However it is worth noting from the 2019 Conservation Advice, which was in evidence, that:

(a) like the 2015 Conservation Advice, the 2019 Conservation Advice lists the Leadbeater’s Possum as critically endangered, although under a different criterion: namely, Criterion 1 A4(b) (“An observed, estimated, inferred, projected or suspected population reduction where the time period must include both the past and the future (up to a max. of 100 years in future), and where the causes of reduction may have ceased OR may not be understood OR may not be reversible” based on “an index of abundance appropriate to the taxon”);

(b) the 2019 Conservation Advice lists the Leadbeater’s Possum as endangered under criteria not relied upon in the 2015 Conservation Advice: namely, Criteria 1 A2(a) and A2(b) (“Population reduction observed, estimated, inferred or suspected in the past where the causes of the reduction may not have ceased OR may not be understood OR may not be reversible” based on “direct observation” and “an index of abundance appropriate to the taxon”) and A3(b) (“Population reduction, projected or suspected to be met in the future (up to a maximum of 100 years) based on “an index of abundance appropriate to the taxon”); and

(c) the 2019 Conservation Advice notes that, although, as a result of extensive work that has been undertaken “most notably by scientists from the Arthur Rylah Institute, as well as community groups and the logging industry”, large numbers of additional Leadbeater’s Possum colonies have been identified, reliable population estimates still cannot be generated from the data.