FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Boomerang Investments Pty Ltd v Padgett (Liability) [2020] FCA 535

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties bring in short minutes of order to give effect to these reasons within 14 days.

2. The matter be listed for a case management hearing on Friday 8 May 2020 at 9.30 am.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

PERRAM J:

1 This case concerns three songs, ‘Love is in the Air’ (‘Love’), ‘Warm in the Winter’ (‘Warm’) and an adaptation of Warm called ‘France is in the Air’ (‘France’), which was made for the airline Société Air France, SA (‘Air France’) for the purposes of a marketing campaign. The first two songs both include the lyric ‘love is in the air’ (or perhaps ‘love’s in the air’) arguably to the same melody. The third song, France, is similar to, although shorter than, Warm but with the lyric ‘love is in the air’ replaced with ‘France is in the air’.

2 Love was composed by Mr Johannes van den Berg (who is often called, as I will call him, Mr Vanda) and the late Mr George Young in Sydney in 1977. As I explain later, the musical work comprises both the instrumental music and the sung sound of the lyrics. The lyrics also comprise a separate literary work. A distinct copyright subsists in each: Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) (‘Copyright Act’) s 31(1).

3 The original publisher of Love in September 1977 was J Albert & Sons Pty Limited (‘Alberts’). That company was at that time controlled by the Albert family who have been music publishers in Sydney since the 1890s.

4 In 2016 the Albert family sold their music publishing business to a German multinational, Bertelsmann Music Group (‘BMG’), but decided to retain for the family the back catalogue in relation to a number of Australian pop songs including Love. On 30 August 2016, prior to it being sold to BMG, one of Alberts’ final acts whilst still under control of the family was therefore to assign to an entity controlled by them the copyright in, inter alia, Love. That entity was Boomerang Investments Pty Ltd (‘Boomerang’).

5 It will be necessary to identify the Applicants more precisely in due course for there is a dispute as to which of them owns which aspects of the copyright in Love, but for now it is convenient to refer to them globally as ‘the Applicants’ and thereby to denote the owners of that copyright.

6 In Australia, Love is a famous song not only from its original release in 1977 when the recording by Mr John Paul Young went to the top of the charts, but also because its fortunes (and those of Messrs Vanda and Young) were somewhat revived in 1992 by the release of the Baz Luhrmann film Strictly Ballroom, the soundtrack for which heavily featured Love. The Albert family was involved in the production of that film.

7 Warm was composed by the instrumentalist Mr John Padgett and the vocalist Ms Lori Monahan in Portland, Oregon, sometime between 2005 and 2011. Mr Padgett and Ms Monahan together constitute the duo known as ‘Glass Candy’. Mr Padgett is the owner of a Californian company called Italians Do It Better, Inc (‘IDIB’) which appears to be Mr Padgett’s personal publishing company. IDIB subsequently licensed the copyright in Warm to a US publisher, Kobalt Music Services America, Inc (‘Kobalt US’), which then licenced the Australian copyright in, inter alia, Warm to an Australian music publisher in the same group of companies, Kobalt Music Publishing Australia Pty Limited (‘Kobalt Australia’ or simply ‘Kobalt’).

8 France is an adaptation of Warm which was made by Glass Candy for the Fourth Respondent, Air France, for use in the airline’s international marketing campaign ‘France is in the Air’, which took place between March 2015 and March 2018. A number of short cinematographic films in which France has been synchronised as the soundtrack were created by Air France’s advertising agency, EURO RSCG BETC (‘BETC’).

9 The Applicants allege numerous acts of copyright infringement which hinge on their allegation that Warm contains a reproduction of a substantial part of Love in two ways. First, the Applicants focus on the music in Love corresponding to the phrase ‘love is in the air’. This line is sung to a series of five notes, and as the song progresses it returns repeatedly to the line ‘love is in the air’. On each occasion the line is sung in one of three slightly different variations. It is also the title of the song. The Applicants submit that it is the song’s central feature. The Applicants then submit that the line ‘love is in the air’ to the same melody appears in Warm on four occasions, and that the same melodic line with the lyric ‘France is in the air’ appears in France. They say that Glass Candy copied it from Love. The Respondents submitted that the lyrics as they appeared in Warm and France were, in fact, their contracted equivalents ‘love’s in the air’ and ‘France’s in the air’. I do not regard the aural differences between these as significant.

10 The second way the case is put is that a somewhat longer portion of Love, consisting of the following couplet and accompanying melody, has been copied by Glass Candy in Warm:

Love is in the air, everywhere I look around Love is in the air, every sight and every sound

11 The Applicants say that this part of Love has been copied by Glass Candy in this part of Warm:

Love’s in the air, whoa-oh Love’s the air, yeah

12 The Applicants also say that this part of Love has been copied in France:

France’s in the air, whoa-oh France’s in the air, yeah

13 Glass Candy denies that they copied either portion of Love. In any event, they say the sections in Love on the one hand and in Warm and France on the other are not objectively similar and, even if they were, neither section of Love is sufficiently original to warrant copyright protection.

The way the case has been pleaded

14 As will be seen, Warm was first commercially recorded in September 2011. The Applicants do not allege that Glass Candy’s initial recording of Warm was an infringement of the copyright in Love. This may be contrasted with EMI Songs Australia Pty Ltd v Larrikin Music Publishing Pty Ltd [2011] FCAFC 47; 191 FCR 444 (‘EMI’). In that case, the owner of the copyright in ‘Kookaburra Sits in the Old Gum Tree’ sued the persons responsible for the first recording of ‘Down Under’ in 1979. The applicants sought a portion of the royalty income that had been earned by Men at Work and their publisher EMI, but they did not claim that the sale of each record or cassette was an infringement of the copyright. They relied on only one breach of copyright—the initial recording—and characterised all the later sales activity as a matter going merely to quantification rather than separate legal wrongs.

15 In this case, the Applicants have taken a different course and allege that the copyright in Love was infringed each time Warm was made available for streaming or downloading on a number of online music platforms (specifically, iTunes, Spotify, Apple Music, Google Play and SoundCloud) and on two websites operated by IDIB, being the domain names italiansdoitbetter.com and italiansdoitbetter.bigcartel.com, which I refer to as the ‘IDIB website’ and the ‘Big Cartel website’ respectively.

16 It is not at once clear (nor is it necessary to consider) why it is that the Applicants have not brought a suit concerning the creative act of making the original recording of Warm in September 2011. Such a suit would, by operation of the Copyright (International Protection) Regulations 1969 (Cth) reg 4(3) and the Copyright Law of the United States 17 USC §104(b)(2), probably have had to have been brought in the United States and under United States copyright law. This might have been enough of a basis for the Applicants to have avoided such an option. It might also have been seen as an unattractive strategic decision on the basis of Glass Candy’s Seventh Amendment entitlement to demand a jury trial, given that it would have been a copyright infringement suit involving more than US$20 sought in damages: Feltner v Columbia Pictures Television Inc 523 US 340 (1998). All this, however, is speculation.

17 The right to stream Love and the right to permit copies of it to be downloaded over the internet are rights which are comprised in the copyright in Love, respectively, as parts of the right to reproduce Love in a material form (Copyright Act s 31(1)(a)(i)) and as part of the right to communicate Love to the public: s 31(1)(a)(iv). It is an infringement of a copyright to do an act comprised within it without the licence of the owner of that right: s 36(1). A reference to the doing of an act in relation to a work in s 36(1) includes, by s 14, a reference to the doing of an act in relation to a substantial part of the work. The allegation therefore is that because Warm contains a reproduction of a substantial part of Love, making Warm available for streaming and downloading infringes the copyright in Love.

18 The Applicants do not sue the online music platforms for permitting the streaming and downloading of Warm by their customers. They do not do so because such a case would fail. The reason for this is that each of the online platforms not only provides Warm to the music listening public but also Love and they do so, as it happens, with the express permission of the relevant Applicants. To the extent that the Applicants succeed in demonstrating that Warm has taken parts of Love, this cannot matter from the online music platforms’ perspective since they already have the right to stream Love. That right includes, by s 14, the right to stream a substantial part of Love. Ordinarily that might be thought to cover a situation such as where the streaming of Love might be terminated half way through the song. But because the Applicants’ case theory is that Warm contains a substantial part of Love, the permission from the Applicants to stream and make available for downloading Love therefore immunises the online platforms against any allegation of an infringement arising from their activities with Warm. This is so because it is not an infringement of the copyright in Love to do something which the Applicants have already authorised. To put it in a way which will offend purists but hopefully illustrate the problem at hand, proving that selling Warm to the public is really the same as selling a little bit of Love is pointless against a vendor who has the right to sell both.

19 The allegation that the Applicants make against Glass Candy is that the band itself made Warm available in Australia via these platforms (and that streaming and downloading in Australia occurred), or alternatively, that Glass Candy authorised the platforms to distribute their song in Australia. As to this alternative way of putting the case, it is useful to observe that by s 36(1), it is an infringement of a copyright to authorise another person to do something which itself is an infringement.

20 In addition to the allegations concerning the well-known platforms the Applicants also allege that Mr Padgett’s entity IDIB infringed their rights by allowing customers to download copies of Warm in Australia from two websites. The first of these in time was the Big Cartel website, which is a generic service which permits artists to set up their own online store, and the second (and current) site is the IDIB website, which is operated by IDIB itself. In both cases, IDIB is responsible for the content. Unlike the other platforms, IDIB does not have the permission of the Applicants to stream Love or make it available for downloading so the problem described above does not arise.

21 As explained above, a number of short films were produced by BETC, the advertising agency engaged by Air France, to which France was set as the soundtrack. These vignettes have been made available for streaming (but not for downloading) by Air France on its YouTube Channel. Air France admits that they have been viewed by Australian internet users and although Glass Candy submits that this has not been proved against them I am inclined to regard Air France’s admissions about its own conduct as reliable. The Applicants allege that this is an infringement of the copyright in Love. As in the case of the streaming and downloading of Warm from the online music platforms, YouTube has permission from the Applicants to stream Love.

22 Air France does not have any scheduled services which operate to or from Australia although it is involved in code share arrangements as part of the SkyTeam alliance. Consequently, the Applicants do not allege that Air France has played France in Australian airspace as part of its in-flight entertainment. Air France does not have a physical ticketing office in Australia but it is possible to ring Air France in Australia on a toll-free number, 1300 390 190, to purchase a ticket. Those who call this number and have the misfortune not to have their inquiry immediately handled are placed on hold and, whilst there, music is played to them to make the wait more pleasant. That music includes France. The Applicants allege that this use by Air France also infringes the copyright in Love.

The parties to this litigation

23 The Applicants fall into three classes: first, Mr Vanda and the estate of the late Mr George Young. They do not assert ownership of the copyright in Love which they long ago assigned to their publisher, Alberts, and they do not therefore complain that Warm or France infringes their copyright. But they do claim that France has infringed their moral rights in Love (a term of art in the copyright field which I explain later in these reasons but which, briefly, entitles authors of works to be recognised as such and not to have their works shabbily treated); secondly, Boomerang, which is the successor in title to the original publisher of the song, Alberts, and which claims therefore to be the owner of the Australian copyright in Love; and, thirdly, two collecting societies, the Australasian Performing Right Association Ltd (‘APRA’) and the Australasian Mechanical Copyright Owners Society Ltd (‘AMCOS’).

24 APRA, generally speaking, collects royalties on behalf of the owners of the copyright in music where that music is communicated to the public. It usually operates by providing blanket licences to persons whose businesses involve the communication of musical works to the public such as, for example, radio and television stations and online streaming services such as Spotify. For practical reasons, most artists enter into arrangements with APRA to collect royalties on their behalf. These arrangements usually include the artist assigning the copyright to APRA. Sometimes, where an artist already has a music publisher, the copyright will already have been assigned by the artist to the publisher and it is the publisher in such cases which deals with APRA. As will be seen, it is the former which has happened in this case.

25 The second collecting society, AMCOS, is a similar body but it provides blanket licences to persons who, as part of their business, need to make copies of musical works such as persons making a film or television commercial in which a musical work accompanies the images (so-called ‘synchronisation’ of the music with the film) or services which permit copies of a musical work to be downloaded over the internet, such as iTunes. As with APRA, most artists enter into arrangements with AMCOS to licence these uses and AMCOS then collects royalties on their behalf. Unlike arrangements with APRA, arrangements with AMCOS do not involve an assignment of the artist’s copyright to AMCOS but merely the grant to it of an exclusive licence. Again, sometimes the artist will deal directly with AMCOS and sometimes the artist’s publisher will.

26 Both Love and Warm are subject to blanket licences granted by APRA and AMCOS. The collecting societies have been joined as the Fourth and Fifth Applicants to the proceeding as a tactical response to a submission made by the Respondents that Boomerang has no title to sue for infringement because the relevant rights holders in Love are APRA and AMCOS. As will be seen, the issues involving APRA and AMCOS are complex.

27 This cluster of five Applicants has sued four respondents. The First and Second Respondents are the two current members of Glass Candy, Mr Padgett and Ms Monahan. The Third Respondent is Kobalt. Kobalt is the publisher of Warm in Australia, although, as will be seen, that is the beginning of the inquiry rather than its end. It is said to have authorised the streaming and downloading of Warm in Australia. The Fourth Respondent is Air France.

28 For the reasons which follow, I conclude on the copyright case that:

(1) the music and the sound of the accompanying lyric ‘love is in the air’ (or perhaps ‘love’s in the air’) in Warm is objectively similar to the same melody and lyric in Love;

(2) Glass Candy consciously copied that portion of the musical work in Love;

(3) the part taken from Love is original for the purposes of assessing substantiality; and

(4) the part taken is a substantial part of Love from a qualitative perspective, such that the taking by Glass Candy of this portion was the taking of a substantial part of the musical work in Love within the meaning of s 14 of the Copyright Act.

29 On the other hand, I do not find that:

(1) the longer musical couplet in Love has been reproduced in Warm, as they are not objectively similar; or

(2) there has been infringement of the literary work comprised in the lyrics of Love, as the portion alleged to have been copied is not original.

30 However, and leaving to one side the position of the IDIB and Big Cartel websites, I conclude that the Applicants’ case against Glass Candy insofar as it involves streaming or downloading from digital platforms such as Spotify or YouTube must fail. The Applicants’ case that Glass Candy themselves are responsible for the streaming and downloading from these websites fails as those sites are operated by their owners and not by Glass Candy. The Applicants’ case that Glass Candy is liable for secondary infringement on the basis that it authorised the platforms to stream and download Warm also fails. Those platforms were authorised by APRA and AMCOS to stream and make available for download Love as well as Warm. Since the platforms cannot be liable for infringement, Glass Candy cannot be liable for authorising them to do what the Applicants had already authorised them to do. There can be no secondary infringement (authorisation) without primary infringement (making available for streaming or downloading).

31 The only relevant activity on the IDIB and Big Cartel websites was some limited acts of downloading. Glass Candy authorised those downloads because Mr Padgett and Ms Monahan knew that Mr Padgett was making Glass Candy songs available for download from the IDIB website (and before that the Big Cartel website). The owner of the right to authorise the downloading of Love is Boomerang and AMCOS holds an exclusive licence of the same right. Both may sue Glass Candy for facilitating the download of Warm from the IDIB and Big Cartel websites because neither IDIB nor Mr Padgett had permission from Boomerang (or its predecessor in title) or AMCOS to permit users to download Love and because Warm infringes Love. The Applicants’ case against Glass Candy in relation to the downloading and streaming of Warm from the other digital platforms otherwise fails. The attempt to make Kobalt liable for Glass Candy’s actions also fails for the additional reason that the collection of Australian royalties from Warm by Kobalt is not sufficient to make it liable for secondary infringement and Kobalt is not the owner or licensee of the relevant rights.

32 In relation to France, the melody and lyric ‘France is in the air’ are substantially identical to the same line in Love and were copied by Air France from Love. In any event, it is clear that Warm was copied from Love and France was copied from Warm. For the same reasons as in relation to Warm I conclude that the part copied was a substantial part of Love. The case against Air France in relation to the streaming of France as part of its commercials on YouTube fails as YouTube held an APRA licence which authorised it to stream Love (and hence the substantial part of Love which was copied in France). The case in relation to the hold music, however, succeeds. The only party entitled to sue Air France in relation to that, however, is APRA and Boomerang lacks title.

33 The claim by Mr Vanda and the estate of Mr Young against Glass Candy and Air France for infringement of their moral rights is to be dismissed.

34 Boomerang and AMCOS are entitled to an injunction restraining Glass Candy from permitting the downloading of Warm from the IDIB website. AMCOS does not claim damages, however, but Boomerang does and it is entitled to damages or an account of profits for the 13 downloads of Warm which took place from the IDIB and Big Cartel websites. The copying was flagrant and Boomerang is entitled to be heard on additional damages. APRA is entitled to an injunction restraining Air France from using Warm as its telephone hold music but nothing else. APRA does not claim damages in that regard and although Boomerang does claim damages in relation to France it has no title to sue. Mr Vanda and the executor of the estate of the late Mr Young are not entitled to damages in relation to their moral rights claim against Glass Candy.

35 There will need to be a further hearing to assess damages. I will hear the parties on costs.

36 The Applicants relied upon the evidence of three witnesses.

37 Mr Vanda swore an affidavit dated 14 September 2018 and a supplementary affidavit dated 30 January 2019 on the eve of the trial. He was cross-examined on the first day of trial, Monday 4 March 2019. Mr Vanda, together with the late Mr Young, are the composers of Love and a large number of other well-known pop songs. He and Mr Young formed The Easybeats in 1964 whilst residing at the Villawood Migrant Hostel, after Mr Vanda emigrated from The Netherlands to Australia the previous year. He gave evidence of the history of The Easybeats including the band’s runaway hits, ‘She’s So Fine’ and ‘Friday On My Mind’, the band’s sojourn in the United Kingdom in the 1970s, and its subsequent breakdown there. He also explained the role of their publisher, Alberts, and its record label Boomerang in the pop music industry generally. Mr Vanda gave evidence of how he and Mr Young had composed Love, the role of Mr John Paul Young who performed the original recording, and the role of Alberts in the song’s promotion and distribution. He told the Court of his longstanding membership of the collecting society APRA and gave evidence about the licensing of Love. It was, in his opinion, the most valuable song that he and Mr Young had written and he was clear that although they were happy for the song to be licensed by their publisher, Alberts, to third parties, they never once agreed to a change in its lyrics. He was shocked when he first heard Warm and France and he reported that the late Mr Young had also been shocked, indeed shocked enough to swear.

38 Mr Albert swore an affidavit dated 17 September 2018. A second affidavit of Mr Albert, sworn 1 April 2019, was also read. Mr Albert is a Director and the Chief Executive Officer of the Albert Group of Companies which includes Boomerang. He explained the history of the Albert family in music publishing in Australia which commenced in 1894 with the work of his great-great-grandfather, Jacques Albert, and his son, Michel Francois (Frank) Albert. He explained the role of the Boomerang trade mark in the various Alberts businesses, the setting up of the Boomerang sound recording studio on King Street in Sydney and the construction by Frank Albert of Boomerang House in Elizabeth Bay in Sydney. His evidence was that his family had worked with Mr Vanda and the late Mr Young for over 50 years. His uncle, the late Mr Ted Albert, had been instrumental in setting up Albert Productions in 1964, an entity which had been focussed on signing up and producing Australian artists. It was Mr Albert’s view that Mr Vanda, the late Mr Young and his family members Malcolm and Angus Young, together with Bon Scott, are the most successful Australian songwriters of all time.

39 Mr Albert also explained the process by which Alberts was sold to BMG in 2016 and the decision that the family would retain, through Boomerang, the Vanda and Young back catalogue including Love. He gave evidence about the licensing of Love including for very many covers by well-known artists as disparate as Tom Jones and Richard Clayderman, its significant commercial success and its place in various charts around the world. He also gave evidence about Strictly Ballroom, his uncle’s decision to invest heavily in that film and the use of Love as part of its soundtrack. He also gave brief evidence about the roles of APRA and AMCOS and, like Mr Vanda, he reported statements by the late Mr Young consistent with considerable anger on his part about the Air France campaign. Mr Albert was called on Tuesday 5 March 2019 and cross-examined that day.

40 Dr Vines is a musicologist and composer. He holds a number of degrees in music and composition including a doctorate in composition from Harvard University and a bachelor of music from the University of Sydney for which he was awarded the university medal. He has received a large number of awards and prizes and principally practices in musical and compositional education. Dr Vines affirmed an affidavit on 17 September 2018 attached to which were attached to two expert reports dated 21 September 2016 and 17 September 2018 (‘Vines 1’ and ‘Vines 2’ respectively). He swore a subsequent affidavit on 30 January 2019 to which he attached another expert report (‘Vines 3’) of that same date. At trial, the Applicant did not rely upon Vines 1.

41 In Vines 2 and Vines 3, Dr Vines gave evidence about the extent and nature of the similarities between Love, Warm and France. He also joined in the preparation of a joint expert report with Dr Andrew Ford, the expert musicologist called by Kobalt (‘the Joint Report’). The Joint Report set out the matters upon which they were able to agree and those upon which they disagreed together with a brief explanation of the nature of their disagreement. Dr Vines and Dr Ford were called to give their evidence together so that they could respond to each other’s evidence in real time. This concurrent session took place on the fourth day of the trial, Thursday 7 March 2019.

42 Glass Candy relied upon the evidence of three witnesses.

43 Mr Padgett swore an affidavit dated 19 November 2018. He gave evidence about his background as a composer, the formation of Glass Candy and his collaboration with Ms Monahan. Mr Padgett’s stage name is ‘Johnny Jewel’ (and occasionally ‘John David V’). He gave detailed evidence about how Warm was composed between 2005 and 2011. His evidence was that he had not heard Love prior to September 2011 and could not therefore have copied it when he composed Warm. He also gave evidence about the commercial launch of Warm in September 2011 on iTunes and the website of his music publishing business IDIB, on which he made the song available for downloading. His evidence is centrally important to the resolution of the case. If his account of the manner in which Warm was composed is accepted then the Respondents will succeed. He was cross-examined at length on the second and third days of the trial, Tuesday 5 and Wednesday 6 March 2019. I deal with his evidence about the manner in which the song was composed in more detail below.

44 Ms Monahan swore an affidavit dated 21 November 2018. She is a vocalist and lyricist based in Altadena, Los Angeles County, California. Her stage name is ‘Ida No’, and together with Mr Padgett they form Glass Candy. Ms Monahan gave evidence about the circumstances of her collaboration with Mr Padgett to create Warm. It was Ms Monahan who wrote and sang the lyrics. She also gave evidence about the creation of a French version of Warm for Air France. Ms Monahan gave her evidence on the third day of the trial, Wednesday 6 March 2019.

45 Mr Williams is the solicitor for Glass Candy in this proceeding. He swore an affidavit on 21 November 2018 which was received in evidence. He gave evidence about the US charts from 1977-1978 and what certain copyright registration and other internet searches revealed in relation to Love. Mr Williams was not required for cross-examination and did not testify at the trial.

46 Kobalt relied upon the evidence of three witnesses.

47 Mr Moor is the Managing Director of Kobalt Australia and a related entity, Kobalt Music Services Australia Pty Ltd. He affirmed an affidavit dated 1 November 2018. Mr Moor explained that Kobalt Australia is part of a multinational group which is a rights management and publishing group. Kobalt Australia licensed Warm from another member of the group, Kobalt US, on terms which permit it to commercialise and collect income on that song in Australia. Mr Moor gave evidence about the contractual mechanics of that licensing arrangement, the role of the collecting societies APRA and AMCOS, and of the circumstances in which he became aware of the dispute about the similarities between Love, Warm and France. He also explained what had been happening with the royalties due on Warm since Kobalt Australia was notified of the dispute. Mr Moor gave his evidence on the fourth day of the trial, Thursday 7 March 2019.

48 Mr Tonkin is Kobalt’s solicitor. He affirmed an affidavit on 2 November 2018 which was received in evidence. His evidence was largely of a formal nature and consisted of various searches about the appearance of the phrase ‘love is in the air’ in music, literature and marketing which he either made or caused to be made within his office. He was not required for cross-examination and did not testify at the trial.

49 Dr Ford is a composer, writer and broadcaster with a significant academic and practical background in musicology. Amongst other achievements, he has been the Poynter Fellow and Visiting Composer at Yale University and a guest lecturer at the Juilliard School in New York, and was in 2018 the HC Coombs Creative Arts Fellow at the Australian National University. He swore an affidavit on 2 November 2018 to which were attached two expert reports of 3 May 2018 and 2 November 2018 (‘Ford 1’ and ‘Ford 2’ respectively). His evidence related to the similarities and differences between Love, Warm and France. As mentioned above, he prepared a joint report with Dr Vines and gave his evidence concurrently with Dr Vines on the fourth day of the trial, Thursday 7 March 2019.

50 Air France relied on the evidence of four witnesses.

51 Madame Castelli is the Chief Legal Officer (Distribution-Intellectual Property-Transport) of Air France. She swore an affidavit on 15 November 2018. Mme Castelli was not available for cross-examination but the parties agreed that certain parts of her affidavit could still be read. Largely these parts related to her identification of formal documentation and correspondence about the dispute. She also gave evidence that Air France did not conduct any legal due diligence on the creative content of the Air France television commercial created by BETC.

52 Madame Du Plessis is the Managing Director of BETC. She swore an affidavit on 4 December 2018. She gave evidence about the relationship between BETC and Air France, the latter’s decision to launch a new global advertising campaign in 2013, the work which BETC did on that campaign, the creation of the campaign including its signature ‘France is in the Air’, and the decision to change the lyric in Warm from ‘love is in the air’ to ‘France is in the air’. Mme Du Plessis gave her evidence on the seventh day of the trial, Friday 5 April 2019.

53 Madame Fontaine is the Director of Communications at the City of Paris but at the times relevant to this litigation she was the Advertising Director at Air France. She swore an affidavit on 16 November 2018 which was received in evidence. She gave evidence about Air France’s operations in Australia, the decision by Air France in 2013 to launch a new global advertising campaign and the decision to choose the signature ‘France is in the Air’. She also gave evidence about her dealings with BETC on the development of the campaign and its various constituent elements. Mme Fontaine testified on the seventh day of the trial, Friday 5 April 2019.

54 Monsieur Caurret is the Music Creative Director at BETC. He swore an affidavit on 15 November 2018. He gave evidence about the work he did for Air France for a new advertising campaign in 2013. M Caurret was responsible for the music used in the campaign and it was M Caurret who chose to use a modified version of Warm in that campaign with the lyric changed to ‘France is in the air’. He gave his evidence on the seventh day of the trial, Friday 5 April 2019.

55 Many of the affidavits were accompanied by exhibits. The affidavits and those exhibits were incorporated into a Court Book which I received on the first day of the trial as Exhibit 1. As a matter of formality the affidavits were read and the tender of them in the Court Book did not result in them being received as documents but was done for the sake of convenience. The exhibits to the affidavits were not separately tendered apart from their tender as part of Exhibit 1. Objections, where upheld, were marked on the Court Book which was maintained electronically.

56 In addition to Exhibit 1 there were ten other exhibits which were separately tendered during the course of the trial. The most significant of these was the Applicants’ updated tender bundle which was Exhibit 4 and Glass Candy’s tender bundle which was Exhibit 6. I have also made a copy of a notice to produce provided to the parties on my request Exhibit 12, to which point see below at [348].

57 The evidence was taken over seven days between Monday 4 March 2019 and Friday 5 April 2019. Closing submissions were made on Friday 12 April 2019. The parties then progressively delivered some 416 pages of written submissions and related documents titled as follows:

Applicants’ consolidated outline of closing submissions filed 26 April 2019 (85 pages);

Applicants’ supplementary closing submissions filed 18 April 2019 (7 pages);

Applicants’ chronology provided on 12 April 2019 (8 pages);

Glass Candy’s consolidated closing submissions filed 1 May 2019 (111 pages);

Glass Candy’s chronology filed 1 May 2019 (8 pages);

Glass Candy’s musical elements annotation filed 1 May 2019 (8 pages);

Kobalt’s outline of closing submissions filed 11 April 2019 (65 pages);

Kobalt’s supplementary closing submissions filed 26 April 2019 (5 pages);

Air France’s outline of closing submissions filed16 April 2019 (44 pages);

Air France’s supplementary closing submissions filed 26 April 2019 (7 pages); and

Applicants’ submissions in reply dated 13 May 2019 (36 pages)

58 On 12 June 2019, Glass Candy sought leave to file submissions in rejoinder to Boomerang’s submissions in reply and on 14 June 2019 Kobalt sought leave to do the same. Those submissions were as follows:

Glass Candy’s outline of submissions in rejoinder dated 26 June 2019 (12 pages),

Glass Candy’s response to the Applicants’ chronology dated 26 June 2019 (10 pages); and

Kobalt’s outline of submissions in rejoinder dated 19 June 2019 (8 pages).

59 Boomerang’s position is that Glass Candy and Kobalt should not be permitted to rely upon the submissions. It prepared a two-page written submission about these written submissions entitled ‘Applicants’ note on First to Third Respondents’ applications for leave to reopen’ dated 26 April 2019.

60 On 26 June 2019 a further hearing took place to determine whether the rejoinder submissions should be received. At the hearing I indicated that I would decide these procedural issues whilst I was considering the substance of the matter and would, if necessary, call for further submissions from Boomerang in the event that the outcome of the debate was that Glass Candy and Kobalt were entitled to file the rejoinder submissions. My conclusion on that debate is at the conclusion of these reasons at [412]ff.

61 I reserved judgment in this matter on 26 June 2019 at the conclusion of the hearing on the subject of rejoinder.

WARM AND THE MUSICAL WORK IN LOVE

62 The copyright in the lyrics is separate from the copyright in the musical work in Love. I begin with the musical work and then deal with the literary work in the lyrics subsequently.

63 As Emmett J explained in EMI, exactly what constitutes a ‘musical work’ is an ‘abstract concept’, and though it may be ‘evidenced by a noted musical score or a sound recording’, neither of these is the work itself: at 448 [10]. In Sawkins v Hyperion Records Ltd (2005) 64 IPR 627, Mummery LJ observed at 638 [53] that in the absence of a statutory definition, ‘ordinary usage assists’, and that ‘the essence of music is combining sounds for listening to’, adding wistfully that ‘[m]usic is not the same as mere noise’. The absence of a statutory definition is particularly relevant when it comes to considering the relationship (if any) between the sound of the lyrics as sung (the lyrics, of course, being a separate copyright work) and the instrumental portions of a musical work.

64 In EMI at 459-460 [66], Emmett J explained the correct approach in a case of alleged infringement of copyright in a musical work: see also 491 [187] per Jagot J (Nicholas J agreeing at 506 [254]). The first step is to identify the work in which copyright subsists. There must be an original musical work and it must have the necessary connection with Australia. The second step is to identify the part of the allegedly infringing work which is said to have been reproduced from the copyright work. For reproduction to be proved there must be sufficient objective similarity between the two works and there must be a causal link between them (i.e. taking, copying or reproducing). The third step is to determine whether the part taken constitutes a substantial part of the copyright work. This is primarily a qualitative matter; ‘[t]he question is whether the alleged infringement reproduces that which made the copyright work an original musical work’: at 460 [66]. That is, it ‘depends much more on the quality than on the quantity’ said to have been taken: at 457 [52].

First step: Identification of the work in suit

65 The Applicants rely upon the musical work constituted by the song Love. However, the parties disagreed at length over what, exactly, constitutes the musical work, namely whether or to what extent the lyrics, whilst their own separate literary work, may be taken into account as part of the musical work when sung.

66 Although the words constituting the lyrics form a separate literary work, I consider that the sound of those words being sung is part of the musical work. Words may have two relevant functions for present purposes. They are instructions on what sounds to say but they are also bearers of meaning. Thus the word ‘love’ is an instruction to make the sound denoted by the phonetic symbol ‘lʌv’. This is a very complicated manoeuvre only able to be mastered by years of practice. It involves putting one’s tongue just behind the front teeth touching the front of the palette and, whilst sounding with one’s voice box, moving the tongue smoothly into the middle of the mouth not contacting any other part of the mouth whilst simultaneously moving the front teeth lightly on to the middle of the bottom lip; there is also a slight unsounded exhalation once the teeth make contact with the lip. It is not for beginners.

67 But the word ‘love’ is also a symbol which denotes a range of abstract concepts relating to affection between people. Thus ‘lʌv’ is both a complex performance of human anatomy and a sound which bears symbolic meaning to a human listener. Although the musician who is a vocalist is not altogether deaf to the meaning of the words of a song their direct interest is in the former use of a word and not the latter. Indeed, often people are made to sing in languages they could not possibly speak (‘Frère Jacques / Frère Jacques / Dormez-vous? / Dormez-vous?’). This is because the human voice is, quite apart from being a device for communicating information by means of symbols conveyed phonically, also a musical instrument.

68 Like most musical instruments the voice is capable of playing various pitches to various rhythms and, like most musical instruments, it is also capable of different forms of articulation. Thus just as a violin may be played pizzicato or by bowing so too may the human voice be projected from the mouth in a large of variety of phonetic structures. The voice may be pitched (‘m’ sounds, for example) or unpitched (‘t’ sounds); the mouth may be bounded in some way to produce consonant sounds or unbounded so as to produce vowels. Different consonant sounds may be made in different parts of the mouth: guttural sounds at the back of the throat (‘g’), labial sounds on the lips (‘m’) and dental sounds (‘t’) using the teeth and the tongue. More than one sound may be rolled together (as in ‘gr’). The options are very many.

69 Viewed as instructions to the singer on what sounds to make with the mouth, the words of a song could not, in my view, more obviously be part of a musical work. In answering the questions posed by the Full Court in EMI it would seem to me to be surreal to ask about the various qualities of the musical work constituted by a song whilst insisting that one must put the activities of the instrument which is the human voice entirely from one’s mind and consider the song only as a non-human instrumental episode. For example, the lyrics of Love may be written out as these non-literary phonetic instructions:

lʌv ɪz ɪn ði eə, ˈɛvri weər aɪ lʊk əˈraʊnd

lʌv ɪz ði eə, ˈɛvri saɪt ænd ˈɛvri saʊnd

70 I have no doubt that this runic utterance is part of the musical work comprised in Love. Combined with the rhythm and melody of the vocal line (typically illustrated for the singer on staves beneath which the lyrics are written with generous use of hyphens to show how the syllables are strung together) this tells the musician what to do with his or her mouth as a musical instrument. That some people are better at this than others is why there is such a thing as a famous singer.

71 The symbols by which these mouth articulation instructions are usually conveyed are words in one sense (cf ‘have you learnt the words to this song?’) but they are also words in the sense of having the purpose of conveying meaning (cf ‘the words of this song are quite profound’). This distinction is not at once obvious but neither is it especially difficult to grasp once it is pointed out. It underpins, for example, the phenomenon of mondegreens in which the listener mishears the lyrics of a song and spends much of their life wondering why Olive, the other reindeer, always laughed at Rudolph and called him names. Thus one may accept entirely, as I do, that the above set of phonetic instructions when read aloud is a short Montaignian contemplation on the ubiquitous nature of love and its presence in everything that one can see and hear. But that does not deny their simultaneous quality as quite a catchy pop song, and the average soul jiving around the disco floor to Love in flares would hardly have given that meditation a moment’s thought.

72 I would accept, therefore, that it in assessing the qualities of the musical work one should put from one’s mind the qualities of the words qua literary work but excluding the instrumentation for the human voice seems entirely unsound. Given that a song tends to be a melody with words, ordinary members of the public might be surprised to hear that copyright litigation about songs was being conducted under a jurisprudence which denied that this was the case.

73 The root of the parties’ disagreement over this issue was that it is not subject to any authority in Australia which binds the Court one way or the other. The fact that there is a separate copyright in the music and the lyrics is, of course, accepted: Telstra Corporation Ltd v Australasian Performing Right Association Ltd [1997] HCA 41; 191 CLR 140 (‘Telstra v APRA’). But the present question takes as its point of departure that distinction and I do not see that that decision throws any light on the current question. Decisions in the United Kingdom after 1988 are also of no use since s 3(1) of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 (UK) specifically provides that a musical work does not include ‘any words or action intended to be sung, spoken or performed with the music’. Such a carve-out does not appear in the Copyright Act. I have not derived benefit from the Applicants’ or Glass Candy’s submissions about the construction of the Copyright Act on this issue or its history.

74 The distinction I have drawn between words as meaning and sung lyrics as part of the music was accepted in Williamson Music Ltd v Pearson Partnership [1987] FSR 97 at [109] by Judge Baker QC:

I should here say something about my understanding of the relationship between the words and the music. It is, I think, misleading to think of them in mutually exclusive compartments. The words by themselves are or may be the subject of literary copyright. But those same words when sung are to me part of the music. After all one gets enjoyment from hearing a song sung in a language with which one is totally unfamiliar. The enjoyment could well be diminished if the vocal line were replaced by another instrument, e.g., the piano or a flute …

75 However, that statement did not attract universal acceptance. Blackburne J in Hayes v Phonogram Limited [2002] EWHC 2062 (Ch) took Judge Baker QC to have meant that the human voice can constitute part of the overall orchestration of a musical work but cautioned that:

… one must beware of confusing the way in which the work is performed with the work itself. In the case of a song where the words take the form of rap lyrics, the fact that the performer expresses the lyrics in a particular manner, giving emphasis to their rhythmic or alliterative qualities in some distinctive manner, does not mean that the words become part of the musical work. Equally, the fact that the musical component of a song reflects the meaning and mood conveyed by the words of the song does not mean that the words somehow become a part of the musical work.

76 That caution is important. The question which arises here is not whether Ms Monahan singing ‘love is in the air’ in Warm is objectively similar to Mr John Paul Young singing ‘love is in the air’ in Love. It is whether the portion of Warm including the sung lyric as part of the orchestration is objectively similar to the corresponding portion in Love. In that analysis the identity of the singer is unimportant. Thus, the actual recordings of Warm and Love are sound recordings in which a separate copyright inheres under Pt IV of the Copyright Act (and with which this case is not concerned). No doubt, some changes in the lyrics to a song can be made without the song losing its essential nature. As Kobalt correctly pointed out, a musical work can be represented in other works such as foreign language covers. But to accept that is not to accept the much larger proposition that follows that a musical work which is a song does not include its sung lyrics.

77 In identifying the work in suit, therefore, I propose to take into account as part of the musical work the instrumentation including sung lyrics. But I will not include in that analysis the performance of the works which must remain separate from the works themselves. Returning to the musical work in suit, that work is Love. Love was composed in 1977 by Mr Vanda and the late Mr Young who, at that time, recorded the backing track and instrumentals. In 1978 they recorded a copy of the song with the lyrics sung by the singer, Mr John Paul Young. At the beginning of the recording session the lyrics were not quite complete and Mr Young was told to sing ‘whoa, whoa, whoa’ for the incomplete section. As it happened, this sounded quite good and a decision to maintain it in the final recording was made. In their submissions, the version the Applicants relied upon was referred to as the ‘master recording’ and was Exhibit DRA-1 in the Court Book (being a USB stick).

Second step: Identification of the portions of Warm said to have been taken from Love

78 Having identified the work in suit, one must identify in the work which is alleged to infringe the part taken, derived or copied from Love. The evidence included several copies of a recording of Warm including an audio recording and a music video. The infringements relied upon included the streaming and downloading of a recording Warm from various online music platforms as well as a small number of downloads from Mr Padgett’s former Big Cartel website and IDIB’s current website. Mr Padgett gave evidence that the commercial recording of Warm was first uploaded to iTunes in September 2011 (the ‘September 2011 Commercial Recording’) and the music video featuring the same soundtrack was uploaded to YouTube in November 2011. There was no direct evidence that the recordings of Warm available from Spotify, Google Play and Apple Music were, in fact, the September 2011 Commercial Recording but no party submitted that they differed and I will proceed on the basis that they are the same. The September 2011 Commercial Recording of Warm was provided to Dr Vines and Dr Ford along with a copy of the master recording of Love and it was those two competing versions to which they confined their analysis.

79 Next, as explained in EMI at 459 [66], there are then two questions to be answered about the allegedly infringing work: are the impugned portions of Warm objectively similar to their equivalent portions in Love, and is there a causal connection between those parts and Love (the causal connection in this case being said to consist of conscious or subconscious copying)?

80 Here the Applicants pursued two cases, the first of which was that the sung lyric ‘love is in the air’ and its accompanying music in Warm was objectively similar to the line ‘love is in the air’ and its accompanying music in Love. That line, which first appears at Bar 5 on the score, appears fourteen times throughout Love, being twice in each of the four verses and three choruses. As I shortly explain, it appears in three slightly different variants which were referred to by Dr Vines as ‘H1’, ‘H2’ and ‘H3’. Dr Ford referred to it in all of its forms as the ‘musical phrase’.

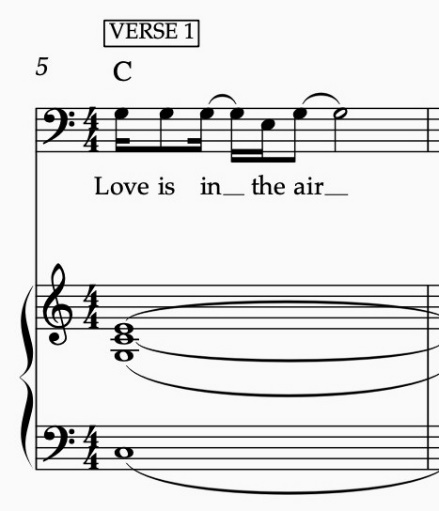

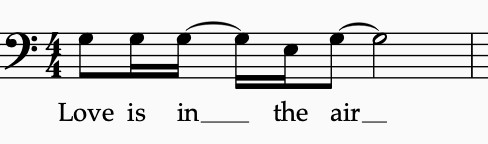

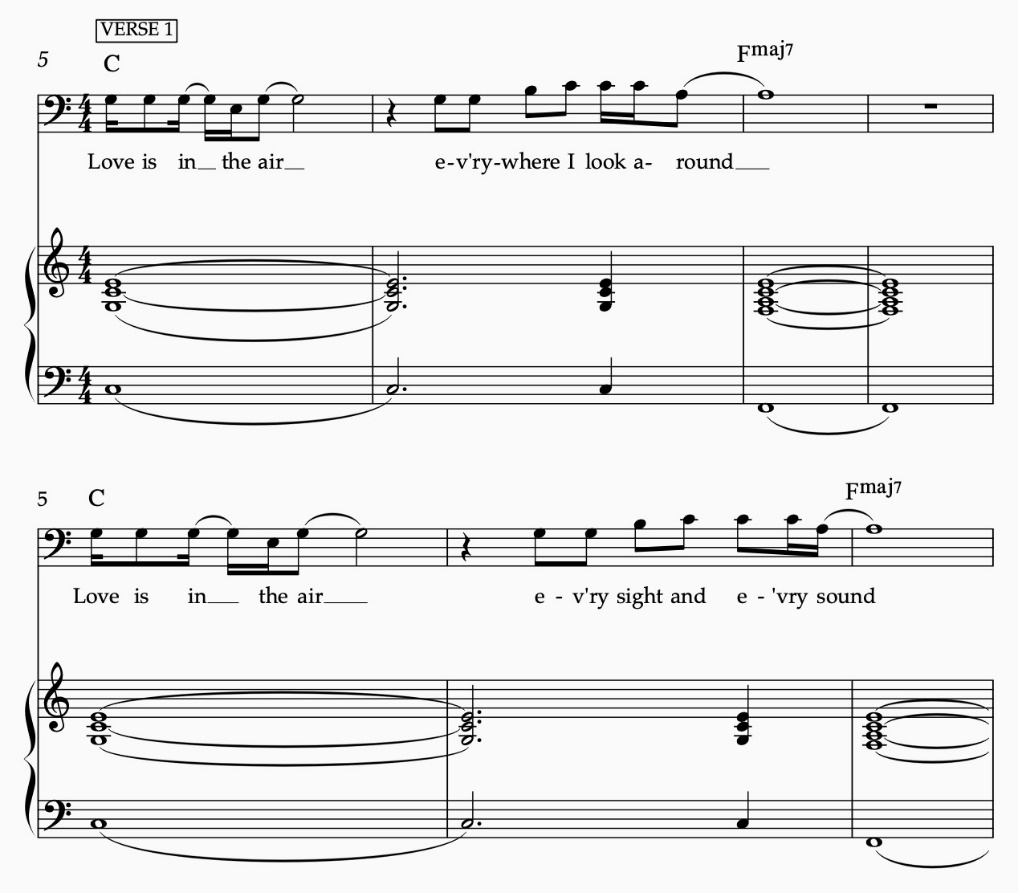

81 The four verses in Love are functionally equivalent and the first verse is sufficient to understand the issues which arise:

Love is in the air, everywhere I look around Love is in the air, every sight and every sound And I don’t know if I’m bein’ foolish Don’t know if I’m bein’ wise But it’s something that I must believe in And it’s there when I look in your eyes

82 The score for the first two lines is as follows:

83 Although the musical work is distinct from the sheet music and any performance of that sheet music, nevertheless it is useful to hear what they sound like. A link to an audio file of the first two lines is here.

84 The second verse is similar to the first and need not be set out. Whereas in the first verse love was ubiquitous and present in all sights and sounds, now it is to be found in the whisper of trees and the thunder of the seas, as it so often is. As in the first verse, the speaker then lingers on some personal doubts before finding certainty in the object of his affections. I make these remarks just to explain the structure of the song. Because the meaning of the lyrics is irrelevant to an assessment of the qualities of the musical work it must be kept firmly in mind that these textual observations must not inform that assessment.

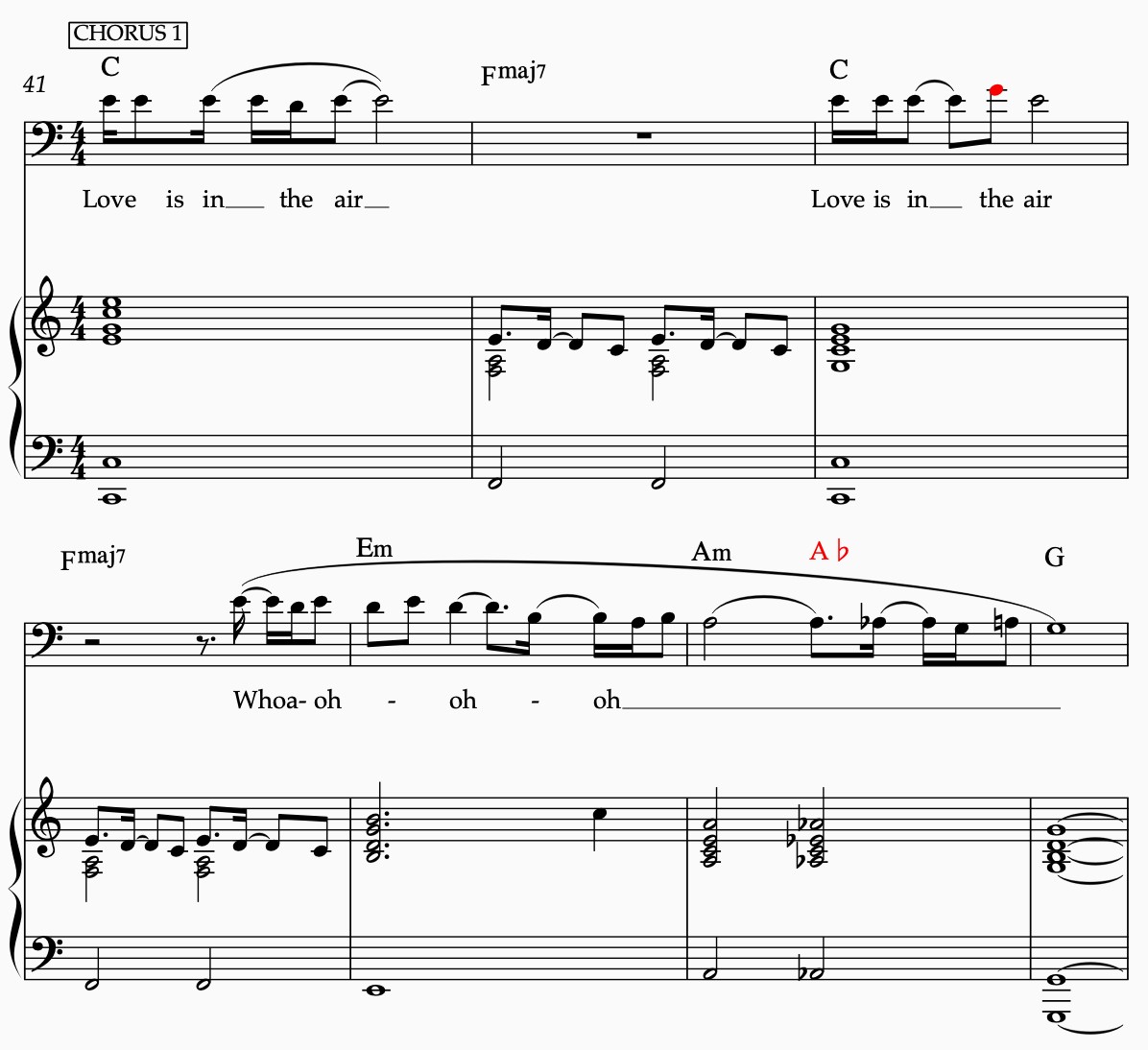

85 The second verse is then followed by an uplifting chorus in which the phrase again appears:

Love is in the air Love is in the air Whoa, oh, oh, oh

86 The score for this chorus is as follows:

87 An audio file of the chorus is here.

88 Dr Vines and Dr Ford agreed that the last line of the chorus is known as a melisma, that is, an example of a single syllable sung over several notes.

89 After this first iteration of the chorus, there is then sung a third verse which also begins with a repetition of the line ‘love is in the air’ in the first of its two lines. The third verse gives way immediately to the fourth and final verse of the song which repeats the line in the same way as each of the first through third verses. After the fourth verse the chorus is then repeated twice although on the second occurrence the melisma is truncated somewhat and an ‘ooh’ and ‘oh’ omitted.

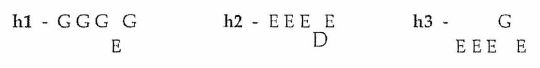

90 It will be seen (and heard) that the line ‘love is in the air’ appears in Love in three slightly different ways: first, in the first two lines of each of the four verses (H1); secondly, as the first line of the choruses (H2); and, thirdly, as the second line of the choruses (except for the last slightly truncated choral iteration) (H3). These three variants are not identical though they are, as Dr Vines put it, ‘connected aurally’.

91 Each of H1, H2 and H3 are underpinned by the tonic chord, C major, but the pitches of the vocal line are slightly different. Dr Vines’ transcription of the pitch classes and contours of the variants was as follows:

92 One of the central features of the vocal line in H1 is the minor third drop which occurs on the fourth note of the bar, being the note to which ‘the’ is sung. That interval is different in H2 and H3, though it remains constant that all words except for ‘the’ are sung to the one note. In H2, it is a tone drop, and in H3, it is a minor third rise.

93 The Applicants submit that parts of Warm are objectively similar to H1, H2 and H3. Warm is structured into four blocks. The line ‘love is in the air’ appears only in the first two blocks, the lyrics of which are as follows:

Block 1 Love’s in the air, whoa-oh Love’s in the air, yeah We’re warm in the winter Sunny on the inside We’re warm in the winter Sunny on the inside. Woo!

Block 2 Love’s in the air, whoa-oh Love’s in the air, yeah I’m crazy like a monkey, ee, ee, oo, oo! Happy like a new year, ee yeah yeah, woo hoo! I’m crazy like a monkey, ee, ee, oo, oo! Happy like a new year, yeah, yeah, woo hoo!

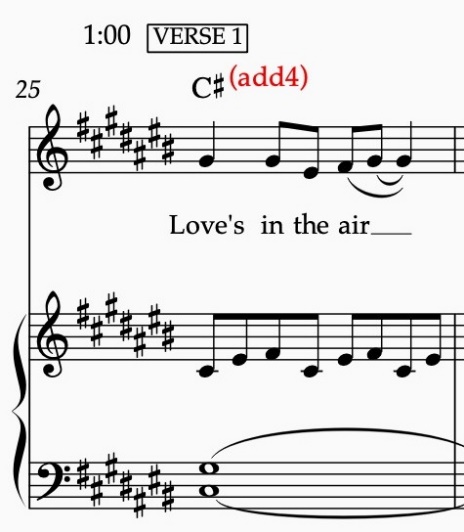

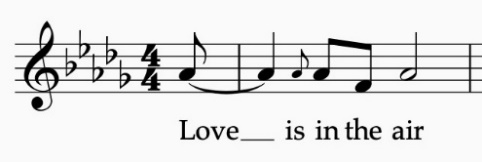

94 As it is relevant to an issue later about the composition of the lyrics, it might be noted for now that each of lines 3-6 in Block 2 is a cliché. A score of the first two lines of these two blocks is thus:

95 An audio file of the first two lines of Blocks 1 and 2 is here.

96 In the September 2011 Commercial Recording of Warm the sung line ‘love is in the air’ appears at about 1:00-1:02, 1:07-1:09, 2:00-2:02 and 2:08-2:10.

97 Is the sung line ‘love is in the air’ in Warm objectively similar to H1, H2 and H3? This question is not to be determined by a ‘note-for-note comparison’, and depends ‘in large degree upon the aural perception of the judge’: Francis Day & Hunter Ltd v Bron [1963] Ch 587 at 608 and 618; see also EMI at 475 [121(5)]. This analysis requires me to put myself in the shoes of the ‘ordinary, reasonably experienced listener’: EMI at 497 [209]. It is not clear (though not strictly necessary to answer in the present circumstances) whether that hypothetical person refers to an ordinary, reasonably experienced listener of death disco, regular disco, fem pop or all of the above. Nor does the requirement that I position myself as the ordinary, reasonably experienced listener necessitate pretending that my Associate and I have not been subjected to repeated and seemingly interminable renditions of the three works the subject of this proceeding, or that I have not been assisted by expert evidence (EMI at 466 [86]):

Sensitised though the primary judge may have been to the similarity, it is not erroneous to direct oneself to the relevant parts of the works, to listen to the works a number of times, and to accept the assistance of the views of experts, in determining the question of objective similarity …

98 I turn first to a comparison between H1 and the corresponding phrase in Warm. Whilst recourse to a score of both phrases is not determinative, it is nonetheless instructive. Dr Ford’s transcriptions of H1 and the impugned phrase in Warm are thus (Love being on the left, and Warm on the right):

|

|

99 For completeness, I note that Dr Vines’ transcription of the vocal line in H1 and Warm were slightly different, but the differences merely highlight the limitations of a comparison of the scores of two musical works for the purposes of assessing objective similarity. That is particularly so when dealing with pop or disco music, as compared to (say) a Baroque étude, because rhythmic precision (at least for the voice) is less important. Dr Vines’ transcriptions of H1 and the impugned phrase are thus (again, Love being on the left, and Warm on the right):

|

|

100 There are, one may accept, differences between them but I do not believe that these are significant. I do accept that the rhythmic underpinning of constant semiquavers in each work is caused by different instruments or synthesised sounds. In the same sense I accept that Love has a moving bass line whereas Warm does not. It was not to the point, as Dr Ford suggested, that a listener would be able to recognise Love even before the entry of the tambourine due to the bass line as the opening of Love is not alleged to have been taken. I also accept that Warm and Love are in very different styles. But the fact that in Love the line forms part of a song which is in the 1970s disco genre and that Warm has been described as a species of ‘death disco’ does not mean that the single line ‘love is in the air’ in both songs is not objectively similar. For example, the bass note progression from the air in Bach’s Orchestral Suite No 3 (BWV 1068) is clearly discernible in the organ line in Procul Harum’s ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’ and that conclusion is not slightly dented by the stylistic gulf between the two works. Nor did such a difference in genre prevent the outcome in EMI.

101 However, the differences between H1 on the one hand and H2 and H3 on the other prevent a similar conclusion about those iterations of ‘love is in the air’ and accompanying music. The ordinary, reasonably experienced listener would hear that their contours are distinct. Having regard to the factors considered appropriate for comparison in EMI, the similarities between H2 and H3 and the corresponding part of Warm could not be described by that hypothetical listener as ‘definite’ or ‘considerable’: at 456 [50]. Consequently, I conclude that the sung line ‘love is in the air’ and its accompanying music in Warm is objectively similar to H1, but not H2 and H3.

102 My conclusion in this regard is supported by the evidence of Dr Vines and Dr Ford who agreed that ‘the pitch and rhythmic content of the opening vocal phrase is notably similar’ between Love and Warm and that ‘there is a basic aural connection between this phrase and the corresponding phrases in Warm’. Glass Candy sought to limit that agreement to similarity between the vocal parts only, and not the music underlying them, on the basis of a clarification made by Dr Ford at the hearing. However, the experts separately agreed that the rhythmic profile of that bar was the same, and that each vocal part was sung atop a tonic chord.

103 Glass Candy also sought to diminish the similarity between the vocal lines on the basis of a potential glissando (that is, a vocal slide) between the notes on which ‘the’ and ‘air’ were sung in Warm, whereas the minor third drop and upward return on ‘the’ and ‘air’ in Love was more precise. As the excerpts above show, the ‘slide’ was represented in Dr Vines’ transcription as an appoggiatura, and in Dr Ford’s transcription as the E returning to the E# to the G# via an F# quaver). To the ordinary, reasonably experienced listener, however, that is of little import. As Glass Candy submitted:

… it is common ground that the vocal lines of both … comprise five notes, the first two or three notes … being in same pitch, the next note dropping down in pitch by a minor third, and the next note returning up in pitch by a minor third.

104 I accept the experts’ evidence, too, that the metre of both songs is the same (common time, or 4/4), both share a composite rhythm of constant semiquavers, both have a similar tempo in terms of beats per minute and that the two works are in keys which differ by only a semitone (Love in C major and Warm either in C# major or its enharmonic equivalent, D♭ major). I agree with Dr Ford that the similarities in metre, rhythmic structure and tempo probably do not take one very far in the case of music of the present kind as it a common feature of a lot of modern dance-style music. It is hard, when all is said and done, to dance to 5/4 as the self-referentially entitled theme from Mission Impossible shows. I find that the sung line ‘love is in the air’ in Warm is objectively similar to H1.

105 The Applicant’s second case on objective similarity concerns the sung couplet in Love:

Love is in the air, everywhere I look around Love is in the air, every sight and every sound

106 It is said that this part has been taken and reproduced in Warm as follows:

Love’s in the air, whoa-oh Love’s in the air, yeah

107 In the September 2011 Commercial Recording of Warm this section is about 12 seconds long and appears at 1:00-1:12 and 2:00-2:13. I have laid out the relevant portions of the scores above at [82] and [94].

108 There is no substitute for listening to these competing parts. An audio file of the relevant portion of Love is here and of Warm is here.

109 I do not accept that, beyond the line ‘love is in the air’, these portions are objectively similar. The melody to which Love’s ‘everywhere I look around’ is sung is quite different to Warm’s melismatic rendering of ‘whoa-oh-oh’ and the same is true as between Love’s ‘every sight and every sound’ and Warm’s lengthy ‘yeah’. They just do not sound the same to me. I accept, as Dr Vines and Dr Ford agreed, that there are similarities in tempo, rhythm, the contour of the phrasal structure, chord progression and the harmonic rate of change but to the comparatively untrained ear of the ordinary, reasonably experienced listener, they sound entirely different. I find that they are not objectively similar.

110 This requires consideration of the detailed evidence surrounding the composition of Warm. The broad thrust of that evidence is clear. Glass Candy say that they had never heard of Love until just before Warm’s commercial release in 2011 which was well after they had written it. Consequently, they certainly had not copied it or any part of it in Warm. The Applicants’ primary case, by contrast, is that the evidence that Mr Padgett and Ms Monahan have given as to how they came up with Warm is false. Their secondary case is that Glass Candy is mistaken and that Love, in effect, was sufficiently known to them that, even if they did not do it deliberately, they had subconsciously taken from Love in composing Warm.

111 Mr Padgett is a self-taught musician. He has had no formal musical training and he cannot read sheet music or write a musical score. His evidence was that he was born in 1974 in Houston, Texas, to parents who were ordained ministers of the Southern Baptist Church. Consequently, whilst he listened to gospel music and Christmas carols he did not get to listen to pop music until his teenage years when he began to frequent independent record stores looking for experimental vinyl records. He says his tastes in music lie on the periphery and he told the Court that he was interested in the recordings of modern composers like John Cage. His interest in experimental music continued in the early 1990s but he then became involved in skateboarding which led him into ‘non-mainstream punk rock’, pop art such as Andy Warhol and his association with The Velvet Underground. He described his work as ‘usually highly experimental’.

112 He explained his method of composition this way: he usually records the songs he plays on an electric keyboard or piano and later adds other sounds such as electronic hand-claps, drum lines or vocals. However, he is clear that he never writes the lyrics for Glass Candy—that is done by Ms Monahan. He has performed with a number of bands including Glass Candy, the Chromatics, Desire and Symmetry. All of these bands have been signed to his publishing company, IDIB. His music has been commercially successful and has been released as vinyl records, CDs and in digital formats such as are available from platforms such as iTunes and Spotify.

113 Mr Padgett says that he composed the music for Warm over a six year period between 2005 and 2011 as part of an iterative process involving multiple recordings. It is therefore necessary to trace that chronology.

114 Mr Padgett says that he composed the first musical elements of Warm in 2005 whilst working on a song then entitled ‘I Always Say Yes’. He says that he made multitrack recordings of this music on to 16-track tape. Three different versions were made but two of these have been lost as they have been overwritten. The surviving version did not make its way into evidence, however. Instead, Mr Padgett produced extracts from his notebook which explained each track.

115 According to the notes, one of the tracks on the tapes was a vocal recording of Ms Monahan singing ‘I Always Say Yes’ to the music of what he now says was the proto-version of Warm. This is why the notebook records his early work on the song under the title ‘I Always Say Yes’. These lyrics were eventually used for a different song entitled ‘I Always Say Yes’ which was released on a 12” vinyl record in 2007 and is an entirely different song.

116 Mr Padgett’s notes state that the taped recordings were made on 7 July 2005. On 8 July 2005 he burned a live copy of the musical elements of what was then called ‘I Always Say Yes’ but which, according to Mr Padgett, would go on to become Warm as Track 6 on a CD entitled the ‘Pink CD’. Perhaps confusingly, Track 6 has the working title ‘I Always Say Yes’. The date of this recording is known because the Pink CD bears that date on it.

117 A link to Track 6 of the Pink CD is here. The recording is 7:26 in duration. I will refer to it as the ‘2005 Recording’.

118 I do not accept Mr Padgett’s evidence that the 2005 Recording is a precursor to Warm. As a matter of overall impression this track has nothing to do with Warm.

119 Detailed analysis of it leads to the same conclusion. To begin with, the chord progression in the 2005 Recording consists of the triads I-VI-IV whereas the chord progression of Warm is most commonly I-IV with the occasional interjection of VI. Mr Padgett initially said during cross-examination that the chord progression of the two tunes was the same but eventually accepted that they were not:

So it’s not the same chord progression at all is it?---Not technically, no.

120 Not technically, not at all. Glass Candy’s eventual submission was that both tunes used the same three chords, I, IV and VI, which feature in ‘doo wop’. But doo wop is a chord progression and what matters in it is not only the identity of the chords but the order in which they appear. Also missing altogether from a typical doo wop progression in either work is the dominant (V) chord. The ‘doo wop’ language is of little use. Nor do I accept that the melody of the 2005 Recording is the same as in Warm or even remotely reminiscent of the melody in Warm. Initially Mr Padgett said that the melody was the same and what differed between the two tunes was the ‘sonic choices’. Although Mr Padgett thought the melodies were the same, to listen to the 2005 Recording is to hear that they are not at all the same. I reject this aspect of Mr Padgett’s evidence. Eventually Mr Padgett also accepted that the tempo and the rate of harmonic change were different to which one might as well add that they are in a different key (although for myself I would rate that of less importance).

121 Glass Candy submitted that the 2005 Recording had in common with Warm the following: chirping synthesizer melody played on three notes, the same three doo wop chords, hand clapping, the use of a melisma, the use of the spoken word, a glissando, a falsetto, a minor third drop happening in an entirely different part of the instrumentation, and common instrumentation in the form of a synthesizer and Ms Monahan’s vocals. I accept the chirpy synthesizer on the three notes and the three doo wop chords (although not in the same order). Whilst I accept Ms Monahan’s voice appears in the recording I have been unable to detect a falsetto or a glissando but the fault is probably mine. Even so, this does not alter my conclusion that Warm is not in any way related to the 2005 Recording. Vast swathes of pop music have features of this kind and although it is perhaps not quite as lame as the submission that the 2005 Recording and Warm have in common the fact that they are both songs, these points do not lie very far to the south of such a submission.

122 This conclusion is also inconsistent with statements made by Mr Padgett prior to the commencement of this litigation. When the September 2011 Commercial Recording of Warm was released, Mr Padgett wrote the accompanying sleeve for the CD and vinyl record release. That sleeve said that the song ‘was written and recorded between May 2008 and August 2011 in Portland and Montreal’. The same statement was also provided to an online publication, Discogs. Further, in an email dated 3 March 2015 Mr Padgett said that the song was ‘written and recorded in Montreal during the coldest winter of my life.’ Under cross-examination he agreed that this was a reference to the winter of 2008-2009. I reject the submission made on Glass Candy’s behalf I should downplay the importance of this contemporaneous material on the basis that Mr Padgett’s promotional materials exhibited a certain degree of ‘artistic licence’.

123 I find Mr Padgett’s evidence about the 2005 Recording to be implausible. It has nothing to do with Warm and Mr Padgett’s own statements are inconsistent with what he put on the sleeve of the CD of Warm. I reject his evidence about this and find that the 2005 Recording is not a precursor to Warm. I do not find that the 2005 Recording was made up. Instead, I find that it was produced by Mr Padgett in 2005 but that it has nothing to do with Warm and that Mr Padgett’s evidence that it forms an integer in the creative process leading to Warm is false. However, as I explain later in these reasons, the fact that I have found the earliest evidence of the sung line ‘love is in the air’ to have been from between May 2008 and May 2009 means that the correctness of this conclusion does not matter.

Glass Candy’s familiarity with Love

124 There is some debate about the timing of the next step in Glass Candy’s creation of Warm. The background to that debate is the need to be able to identify when Mr Padgett first heard Love and in what circumstances. Mr Padgett’s evidence at §80 was that he had not heard Love until an evening at a Portland club called Rotture shortly before the release of the September 2011 Commercial Recording and, importantly, after he had completed work on its vocal melody. However, an email and article about Glass Candy suggest that Mr Padgett had heard Love by 2007. Mr Padgett denied that this was the effect of these materials and it is therefore necessary to assess the matter.

125 On 16 January 2008 Mr Padgett sent an email to a Mr Byrne. As will be seen, Mr Byrne was the author of an article entitled ‘Glass Candy: Mystical Death Disco’ which was published online in a publication known as XLR8R. This article was a piece on Glass Candy which was written in a playful and relaxed manner, referred to them by their stage names Johnny Jewel and Ida No, and was intended to convey that it was the result of an interview with them. For example, at one point it says this:

Straining across the couch to grab a silver-blue Christmas tree bulb, Johnny explains, “The songs are like this; the songs are made from the reach.” And the reaching is endless – the two estimate that’ve only met perfectly in the middle of the songwriting process less than 10 times (in over 10 years).

126 At the end of the article there is a section headed ‘Ida’s Tape for Johnny’ which is a list of songs for Mr Padgett ostensibly crafted by Ms Monahan, each of which is accompanied by a jocular remark about the significance of the song for Mr Padgett. Thus:

Diana Ross “Do You Know Where You’re Going To”

Do we know where we’re going to? Hell is not an actual place that force outside yourself sends you to – it’s a state of mind. We learned this together. I’m so glad everyday we decide to keep smiling, no matter what life is showing us.

127 Following this list there then appears a similar list of songs headed ‘Johnny’s Tape for Ida’. The significance of Mr Padgett’s email to Mr Byrne of 16 January 2008 is that it contains both of these lists. The reference in the interview to Mr Padgett grabbing a silver-blue Christmas tree bauble suggests to me that Mr Byrne’s interview was conducted in the preceding December in 2007. In the email, one of the songs on Johnny’s Tape for Ida is entitled ‘“LOVE IS IN THE AIR” > MIKE SIMONETTI’S WHITE LABEL VERSION’.

128 As the article itself explained, at this time Mr Padgett ran IDIB with Mr Mike Simonetti. Mr Byrne did not publish his article until 11 March 2008. When it was published the two lists were identical to those in Mr Padgett’s email except that instead of saying ‘“Love is in the Air” (Mike Simonetti’s White Label Version)’ it now read ‘John Paul Young “Love is in the Air” (Mike Simonetti’s White Label Version)’. Mr Padgett denied that he had told Mr Byrne that what he had in mind was the John Paul Young performance of Love. His evidence was that Mr Byrne must have added that information himself or that it had been added by an editor somewhere between the email on 16 January 2008 and the publication of the article on 11 March 2008. Mr Padgett had to say this to maintain the apparent truthfulness of his clear evidence that he had not heard of Love until 2011.

129 His explanation raises the question of why he had referred to ‘Love is in the Air’ as a song on Johnny’s Tape for Ida when he did not know Love. His explanation was that he had picked up the song title ‘Love is in the Air’ from a blog on the IDIB website dated 2 January 2008 which, so Mr Padgett said, had been written by Mr Simonetti. This piece was a report of Mr Simonetti’s performance as a DJ at a New Year’s Eve party at the end of 2007 at Rubulad, an underground club in Brooklyn (which, I am informed, has since permanently closed). The relevant portion is as follows:

A HAPPY NEW YEAR MIX FOR YOU

Happy New Year from the Italians crew. all reports from San Francisco were that the Glass Candy New Years Eve blowout was indeed a blowout and it was full of New Years madness. Wish i was there.

But I had my thing at Rubulad and it was pretty crazy. Also apologies for those of you who came out late to see me and left when the cops came. After they left we started up and went well into the late morning. Next time I play Rubulad I’ll put you on the list and buy you a drink, so email me (you know who you all are).

ps: the midnight NYE tune was “Love is in the Air”…

Anyway, to celebrate the arrival of 2008, we offer you a mix by our own Qlint, who happens to be in TIEDYE. Our pal Pilcoski of Dirty Edits fame posted it on his blog and we are sending you to his website to grab it. Its a zshare file so you can stream it live or download it. The mix is pretty great. Look out for the third track, which is a Tiedye edit of Tom Petty “Dont Come Around Here No More”. Its an Italians favorite!

(Errors in original.)

130 The hypothesis Mr Padgett’s evidence requires one to embrace is that he included ‘Love is in the Air’ on Johnny’s Tape for Ida not ever having heard the song and not knowing to what it was a reference. Why would he do this? Mr Padgett’s evidence was that Mr Simonetti’s blog had omitted the identity of the performer of ‘Love is in the Air’ quite deliberately. Here the thinking was that DJs like to play music the origins of which are unclear to their audience. In that endeavour it was important for Mr Simonetti not to let on that ‘Love is in Air’ had been performed by John Paul Young as the mystery of its actual origins gave him a competitive edge over other DJs. Viewed in this way, the fact that Mr Simonetti had let on that the piece was called ‘Love is in the Air’ but had not gone so far as to disclose the identity of the performer was, Mr Padgett thought, ‘a wink, like a coded sort of Easter Egg’. That evidence is consistent with the ellipsis in the blog ‘ps: the midnight NYE tune was “Love is in the Air”…’

131 The competitive edge explanation and Mr Padgett’s evidence that it was a ‘wink’ or an ‘Easter Egg’ are not, however, consistent. There are two problems. First, if keeping the origin of tracks really was a question of competitive edge in the DJ market, it would not be profit-maximising to disclose, even by way of hint, those origins. Secondly, in 2008 it was a trivial matter for a person to look up ‘Love is in the Air’ on Google and immediately to see that it was performed by John Paul Young.

132 Mr Padgett’s evidence that it was a ‘wink’ or ‘coded sort of Easter egg’ makes a little more sense to me. On that view, Mr Simonetti was playing a game with his audience. I should say for completeness that Mr Padgett accepted under cross-examination that he now knew that Mr Simonetti had been playing the John Paul Young performance of Love but he testified that he found this out only subsequently to the creation of Warm.

133 In any event, accepting either of those explanations for Mr Simonetti’s decision not to include the name of John Paul Young in the blog does not throw any light on why Mr Padgett would himself decide to include in his list the name of a song he had not heard and did not know on Johnny’s Tape for Ida. There were several other songs mentioned in Mr Simonetti’s blog. Indeed, at the end of the blog he proffered for the reader a tape mix of 14 songs as follows:

TRACK LISTING FOR YOU:

1. Fabio Frizzi & Giorgio Cascio – Zombie Attack