FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd v SARB Management Group Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 408

ORDERS

VEHICLE MONITORING SYSTEMS PTY LTD Appellant | ||

AND: | Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties provide short minutes of order to chambers as to the appropriate form of orders and costs, with any areas of disagreement marked up, by 27 April 2020.

2. In the event of disagreement, the matter be listed for a case management hearing at 9.30am on 15 May 2020.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

2. THE WITNESSES | [14] |

2.1 Introduction | [14] |

2.2 VMS | [15] |

2.3 SARB | [20] |

3. THE SARB APPLICATION | [23] |

3.1 The approach to be taken to the construction of the specification | [23] |

3.2 The specification | [26] |

3.3 The claims | [53] |

4. CLAIM CONSTRUCTION ISSUES | [54] |

4.1 ‘Operable to initiate a communication’ | [56] |

4.2 ‘Data items’ | [63] |

4.3 Processing of data items | [66] |

5. LACK OF INVENTIVE STEP: BACKGROUND | [73] |

5.1 Introduction | [73] |

5.2 The law of inventive step | [74] |

5.3 The parties’ approach to lack of inventive step | [97] |

5.4 Common general knowledge | [102] |

5.4.1 Introduction | [102] |

5.4.2 Overstay detection methods | [103] |

5.4.3 The POD system | [113] |

5.4.4 Electrical engineering common general knowledge | [138] |

6. LACK OF INVENTIVE STEP: THE PCT APPLICATION | [147] |

6.1 Background | [147] |

6.2 The contentions | [154] |

6.3 The expert evidence | [161] |

6.4 Disclosures of the PCT application | [186] |

6.5 Consideration of inventive step in the context of the PCT application | [195] |

6.6 The PCT application considered with the POD system prior art – s 7(3) | [215] |

6.6.1 Introduction | [215] |

6.6.2 The POD system prior art | [217] |

6.7 The Collins patent | [226] |

7. LACK OF ENTITLEMENT | [231] |

7.1 Introduction | [231] |

7.2 The law relating to entitlement | [235] |

7.3 The facts | [241] |

7.4 Consideration | [268] |

8. LACK OF SUFFICIENCY | [272] |

9. DISPOSITION | [274] |

BURLEY J:

1. INTRODUCTION

1 In Australia’s congested urban areas the competition for public parking spaces is intense. It is the responsibility of local councils to regulate it. For many years this has been done by imposing time and zone restrictions, such that vehicles may park for a limited duration, or not at all, in various zones. Monitoring vehicle non-compliance has been a time-consuming and costly exercise. Traditionally, council parking officers manually checked vehicles, marking tyres with chalk and issuing handwritten infringement notices in the event that they were in breach. The mid-2000s brought changes to the industry. One was introduced by the present appellant, Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd (VMS). It developed a system using in-ground sensors to detect changes in the earth’s magnetic field when a vehicle entered a parking space (or bay). A message could be sent wirelessly to a device carried by a parking officer who could then issue a ticket. The system was dubbed the Parking Overstay Detection System or the POD system by its inventor, Fraser Welch. It was the subject of patent applications and first trialled by the Maribyrnong City Council in Melbourne from 2005. Another was the use of handheld personal digital assistants (PDAs) for issuing tickets.

2 During the course of 2005 VMS sought to collaborate with the respondent, SARB Management Group Pty Ltd, to advance the POD system technology. SARB is the designer and distributor of PinForce, which was software popularly used for issuing parking infringement notices (or PINs) by council officers. It operated on generic handheld PDAs. Discussions between Sandy Del Papa from SARB and Mr Welch took place in 2005 and 2006 but no collaboration eventuated. Instead, SARB developed its own vehicle detection system which was also based on the use of a sensor to detect changes in the earth’s magnetic field when a vehicle enters a parking space.

3 Perhaps unsurprisingly, since then SARB and VMS have become antagonists, both in the marketplace and in this Court. VMS has sued SARB for patent infringement and opposed its patent applications. SARB in its turn, has opposed the grant to VMS of patent applications and contested the validity of VMS’s patents. The present case is the next round of disputation.

4 VMS opposes, pursuant to s 59 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth), the grant to SARB of Australian Patent Application No. 2013213708, which is entitled ‘Vehicle Detection’ (SARB application). The priority date of the SARB Application is 23 August 2007.

5 An opposition hearing (opposition proceedings) was conducted before a delegate of the Commissioner of Patents where VMS advanced three grounds: (a) that the SARB application lacks an inventive step; (b) that SARB is not entitled to the grant of the patent; and (c) that the claims do not comply with ss 40(2) and (3) of the Patents Act. The delegate rejected each of these grounds, but found that claims 25 – 28 of the SARB application should not proceed to grant because they contravene s 40(3A) of the Patents Act: Vehicle Monitoring Systems Pty Ltd v SARB Management Group Pty Ltd [2017] APO 63; 133 IPR 352 at [8], [100] – [103].

6 VMS now appeals from the delegate’s decision pursuant to s 60(4) of the Patents Act. Such an appeal is determined as a hearing de novo by the Court, being the first judicial consideration of this particular dispute between the parties: New England Biolabs Inc v F Hoffmann-La Roche AG [2004] FCAFC 213; 141 FCR 1 at [44] (Kiefel, Allsop JJ, as their Honours then were, and Crennan J).

7 This appeal, as before the delegate, is governed by the Patents Act as amended by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth). One consequence is that the Commissioner, and this Court, is to determine whether the grounds of opposition pressed have been established by VMS on the balance of probabilities: s 60(3A) of the Patents Act.

8 The parties co-operated to ensure that the many issues and sub-issues raised were corralled into a manageable form for which they are to be congratulated. In summary, the three grounds of opposition advanced by VMS in its Further Amended Notice of Appeal are as follows.

9 First, that claims 1 – 24 lack an inventive step in the light of the common general knowledge and each of the following sources of prior art information:

(1) International Patent Application No. WO2005/111963 filed by VMS in which Mr Welch is the named inventor (PCT application);

(2) an article published in June 2005 in the Australian National Parking Steering Group (ANPSG) Journal entitled ‘PODS – the Next Big Thing’ (PODS article);

(3) the slides of a presentation about the POD system given by Tom Gladwin at the ANPSG Perth Conference on 18 November 2005 (Gladwin PowerPoint);

(4) a presentation about the POD system given by Mr Welch at the ANPSG conference in November 2006 (Welch presentation); and

(5) Australian Patent No. 2006235864 owned by Meter Eye IP Limited published on 24 May 2007 (Collins patent).

10 In its closing submissions, VMS confined its obviousness case to the contention that the invention claimed lacks an inventive step having regard to the common general knowledge, in combination with: (a) the PCT application; or (b) the PCT application together with the PODS article, the Gladwin PowerPoint and/or the Welch presentation; or (c) the Collins patent. For the reasons set out below in section 6, I conclude that this ground has not been established.

11 Secondly, VMS contends that SARB is not entitled to be the person to whom the patent is granted because Mr Welch or alternatively Mr Welch and Mr Gladwin conceived of all or part of the invention disclosed in the SARB application and communicated it to Mr Del Papa, and in doing so sufficiently contributed to the invention so as to be inventors. In the alternative, VMS submits that Mr Welch and Mr Gladwin are entitled to joint inventorship with the currently named inventors. I have concluded in section 7.4 below that VMS has not established this ground. SARB has advanced a Notice of Contention in which it contends that Mr Welch and/or Mr Gladwin were necessarily excluded from being entitled to be named as inventors because Mr Welch publicly disclosed or consented to the disclosure of their alleged contribution to the inventive concept. However, in light of my findings it has not been necessary to address this point.

12 Thirdly, VMS contends that the invention claimed is not patentable because it does not disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art, in breach of s 40(2)(a) of the Patents Act. I have concluded in section 8 below that this ground has not been made out.

13 The delegate determined that claims 1 – 24 may proceed to grant, but that claims 25 – 28 should not. SARB has lodged no cross-appeal, nor advanced any contention to challenge the finding on claims 25 – 28, or otherwise to support the validity of those claims. Having regard to my findings, it appears that the appropriate orders are that the appeal be dismissed, that VMS pay the costs of the appeal, and that claims 1 – 24 of the SARB application proceed to grant. However, I have heard no submissions on the form orders and accordingly I will put in place a timetable for submissions to be made.

2. THE WITNESSES

2.1 Introduction

14 Most of the witnesses were cross-examined. Except where otherwise noted, I find that each did his best to assist the Court, and each was subject to the usual difficulties involved in cases such as the present in attempting to recall events that took place, and the knowledge that they had, many years in the past.

2.2 VMS

15 Mr Welch is the executive director of VMS. He established Focus International Pty Ltd in 1993 as a business involved in the design and manufacture of parking meters and paid parking ticket machines for local councils. A client of Focus in the late 1990s was the Maribyrnong City Council and Mr Gladwin was the Manager of Parking there. Following discussions with Mr Gladwin about how parking enforcement efficiency could be improved, Mr Welch began designing the POD system, and in December 2003 Mr Welch incorporated VMS for the purpose of developing and commercialising the POD system. VMS has subsequently obtained the grant of patents in relation to the technology so developed. Mr Welch gives evidence that during the course of 2005 and 2006 he had various oral and written exchanges with Mr Del Papa of SARB about commercial terms upon which the companies might work together, including the development of a ticketing system that integrated the POD system with SARB’s ticketing issuing software and PDAs. He also gives evidence about the ANPSG (an industry association for members of the parking enforcement industry) conferences in Perth in November 2005 and in Hobart in November 2006, where the Gladwin PowerPoint and Welch presentations were respectively given, as well as evidence about the collaboration between VMS and Schweers Informationstechnologie GmbH during and after the Hobart conference. VMS relies on: two affidavits sworn by Mr Welch in these proceedings; one affidavit sworn by on 14 April 2014 in proceedings between the same parties (VID 318 of 2012); and a statutory declaration in the opposition proceedings before the delegate. He was cross-examined.

16 Mr Gladwin was the Manager of Parking and Local Laws at Maribyrnong City Council between May 1996 and October 2011. Since January 2013 he has been the Local Laws Supervisor at Boroondara Council in the inner-eastern suburbs of Melbourne. He gives evidence about events relating to the development of the POD system with Mr Welch, the Gladwin PowerPoint and aspects of the POD system in operation. VMS relies on one affidavit sworn by Mr Gladwin in proceedings VID 318 of 2012 on 14 April 2014 and three affidavits sworn in these proceedings. He was cross-examined.

17 Larry Schneider is the Principal Technology Leader, Future Transport Infrastructure, at Australian Road Research Board Group Limited (ARRB), which is a provider of advisory and consultancy services to road agencies and public and private organisations including local councils and state governments. He has expertise in the methods and equipment that have been used in public parking compliance in Australia since before the priority date, and has over 32 years of experience in the parking industry in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce (University of Natal), a Bachelor of Arts (University of South Africa) and a Bachelor of Laws (University of Rhodesia). From 1992 until March 2003 he was an Executive Director of Wilson Parking Australia 1992 Pty Ltd, a parking services and equipment company. Since January 2004 he has provided advisory and consultancy services in parking management, operations, planning and technology for ARRB. In his 6 June 2018 affidavit he refers to the large number of projects that he has been involved in and speaks of technology trends in public parking. VMS relies upon three affidavits affirmed by Mr Schneider in these proceedings and a statutory declaration given by him in opposition proceedings brought by SARB against a patent application lodged by VMS. He was cross-examined.

18 Craig Ion has been employed by Maribyrnong City Council since 2005, first as a parking officer and now as the coordinator of parking, animal management and local laws. He gives evidence about the state of parking enforcement as at the priority date and his use of and interest in the POD system before that time. He affirmed two affidavits and was cross-examined.

19 Darrin James Wilson is an engineering consultant and contractor engaged in electronic design and manufacturing. He was awarded a Bachelor of Electronic Engineering from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in 1991. Mr Wilson was employed as a Design Engineer from 1993 until 2006 with Setec Pty Ltd, a designer and manufacturer of power solutions in the automotive, communications, medical, scientific and other, industries. From 2001 until 2006 Mr Wilson held the roles of Senior Design Engineer and Deputy Research and Development Manager with Setec and was responsible for managing the hardware design and software development for a power system monitor and controller for a telecommunications exchange. Between 2006 and 2008 Mr Wilson was the Technical Solutions Manager at Future Electronics, which sold electronic components. In this role he attended meetings with potential clients to discuss projects they were working on, provided technical information about the products available and in some cases provided technical and design solutions as well as componentry for their projects. Mr Wilson affirmed four affidavits, and participated in the preparation of a Joint Expert Report and the provision of concurrent evidence with Professor Evans during the course of which he was cross-examined.

2.3 SARB

20 Mr Del Papa is a project director at SARB and a named inventor in the SARB application. He was awarded a Bachelor of Science from the School of Mathematical and Information Sciences at La Trobe University in 1990 and has experience working as a software programmer and a software systems analyst. He joined SARB in about March 2000, initially as an e-Solutions Manager, and in 2003 he became a director of the company. He is currently responsible for managing the commercial aspects of the civic compliance arm of SARB’s business. Mr Del Papa gives evidence about the state of the art of parking enforcement systems as at the priority date, his role in the development of the invention and his response to the Welch and Gladwin evidence concerning inventorship. SARB relies on one affidavit affirmed by Mr Del Papa in these proceedings and a statutory declaration declared by him in the opposition proceedings. He was cross-examined.

21 Mark Alan Richardson has since March 2003 been the Manager of Ranger and Parking Services for North Sydney Council in Sydney. He worked as a patrol team leader for the NRMA from 1998 to 2003, and before that he spent about 19 years working for New South Wales State Rail. He holds a Bachelor of Management from the University of Newcastle. In 2004, 2007 and 2010 Mr Richardson sat on New South Wales government evaluation panels to determine which providers were to be included in the State Government Contract for electronic parking infringement management systems for the following three years. Mr Richardson gives evidence about the transition in New South Wales to the use of electronic parking infringement notices (or PINs), the methods of parking enforcement used prior to the priority date, the use of sensors in parking enforcement prior to that date, the current methods of parking enforcement and the role of ANPSG. He was cross-examined.

22 Jamie Scott Evans is a professor in the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering at the University of Melbourne and the Deputy Dean (Academic) in the Melbourne School of Engineering. In 1993 he was awarded a Bachelor of Science in Physics and in 1994 he was awarded a Bachelor of Engineering in Computer Engineering by the University of Newcastle. In 1998 he was awarded a PhD in Electrical Engineering by the University of Melbourne. During 1998 and 1999, as a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley, Professor Evans conducted research focussed on wireless networks and signal processing to optimise network performance. From June 1999 until July 2001 he was a lecturer at the University of Sydney and continued research into network systems. He was then appointed to various academic positions at the University of Melbourne between 2001 and 2012, before moving to Monash University, and then back to the University of Melbourne to his present position in February 2016. From 2003 until 2010 he conducted research and study into the fields of wireless networking and signal processing. Professor Evans gives evidence about wireless sensor networks and their function prior to priority date, his understanding of the SARB application and the prior art documents relied upon by VMS. He also responds to the written evidence of Mr Wilson. Professor Evans participated in the preparation of a Joint Expert Report with Mr Wilson, gave concurrent evidence with him, and was cross-examined.

3. THE SARB APPLICATION

3.1 The approach to be taken to the construction of the specification

23 Many leading authorities have set out the principles relevant to the construction of patents and patent applications and there was no dispute in the present case as to the general requirements imposed by those principles. The end point is that the words in a claim should be read through the eyes of the person skilled in the art in the context in which they appear. Words used in a specification are to be given the meaning which the person skilled in the art would attach to them, having regard to the common general knowledge and to what is disclosed in the body of the specification. The same applies to the words used in the claims. The construction of a specification, including the claims, is ultimately a matter for the Court. While the claims define the monopoly claimed in the words of the patentee’s choosing, the specification should be read as a whole. However, it is not permissible to read into a claim an additional integer or limitation to vary or qualify the claim by reference to the body of the specification. That said (and to the endless entertainment of patent lawyers), terms in claims which are unclear may be defined or clarified by reference to the body of the specification, such that language of claims that may have no positive meaning when read apart from the specification may become clear, and the invention sufficiently defined when read using the body of the specification as a dictionary of the jargon and ascertaining the nature of the invention. See generally: Welch Perrin & Co Pty Ltd v Worrel [1961] HCA 91; 106 CLR 588 at 610, 616; Kimberly-Clark Australia Pty Limited v Arico Trading International Pty Limited [2001] HCA 8; 207 CLR 1 at [15]; H Lundbeck A/S v Alphapharm Pty Ltd [2009] FCAFC 70; 177 FCR 151 (Bennett J, with whom Middleton J agreed) at [118] – [120].

24 In the present case the person skilled in the art is someone with a practical interest in devices used for the automated enforcement of vehicle parking compliance requirements. There is no dispute that such persons may consist of a team, or that in the present case the team will include: (a) an electrical or electronics engineer familiar with sensing devices, radio frequency communications and the communication of data; and (b) a person or persons with a practical interest in and, knowledge of, parking practices, equipment and technology. I refer to these persons collectively as the skilled team. Mr Wilson and Professor Evans, as engineers, fall within the first part of the team and one or more of Mr Richardson, Mr Schneider, Mr Gladwin and Mr Ion fall within the latter part.

25 When it comes to construing the SARB application and the prior art documents in the proceedings, their meaning is ascertained having regard to normal English grammar, syntax and meaning, albeit in a context involving some technical subject matter.

3.2 The specification

26 The specification describes the technical field of the invention as relating to vehicle parking compliance and in particular to the automated determination of notifiable parking events.

27 The ‘Background of the Invention’ describes vehicular parking as usually being subjected to rules and regulations such as absolute prohibitions in areas in which no parking is permitted, conditional prohibitions such as permit-only parking, and time-limited parking regulations, which may be free or metered or ticketed. It says that the enforcement of parking regulations can be costly and time-consuming for the private or public agencies responsible. It says (page 1 lines 21 – 34):

…Typical enforcement involves a parking inspector manually inspecting all of the restricted spaces periodically, regardless of whether vehicles are actually present. Further, to identify a violation in a free time-limited zone requires that the parking inspector inspect the violating car at least twice, once to establish a time of arrival of the car (for example by chalking the tire of the car), and a second time once the permitted time period for parking has elapsed. Even in paid metered zones, such manual enforcement is inefficient as the parking inspector may fail to note an expired meter or ticket before the violating car departs, reducing the deterrent to infringers and denying fines revenue to the relevant body. It has been estimated that only 1 in 25 parking violations are identified by manual enforcement. Enforcement is made even more difficult when the spaces are distributed over a large area, such as a city block or a large, multi-level parking garage. Manual enforcement is also unable to provide historical data of parking usage, and such data is becoming of increasing importance to the implementation of parking supply and regulation.

28 The ‘Summary of the Invention’ provides a series of statements setting out what the patentee contends is the invention. The first, which is a consistory statement for claim 1, says (page 2 lines 14 – 26):

According to a first aspect the present invention provides a vehicle detection unit comprising: a magnetic sensor able to sense variations in magnetic field and for outputting a sensor signal caused by occupancy of a vehicle space by a vehicle; a storage device carrying parameters which define notifiable vehicle space occupancy events; a processor operable to process the sensor signal to determine occupancy status of the vehicle space, and operable to compare the occupancy status of the vehicle space with the parameters in order to determine whether a notifiable event has occurred, and operable to initiate a communication from the vehicle detection unit to a supervisory device upon occurrence of a notifiable event, wherein the communication includes data items pertaining to the notifiable event and communicated in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software.

29 It is this aspect of the invention that attracts the most attention in the submissions of both parties. It will be seen that the vehicle detection unit (also referred to as a VDU) includes three operational elements, first a magnetic sensor, secondly a storage device and thirdly a processor. The sensor is suitable for detecting the presence of a vehicle in a parking bay, and the storage device has within it details of the permissible parking conditions. The processor checks the sensor signal against the permissible parking conditions and, if a notifiable event (such as a parking violation, an imminent parking violation or other event of interest such as a change in occupancy status) has occurred, the processor initiates a communication from the VDU to a ‘supervisory device’ that is located remotely to the VDU. The communication includes data items concerning the notifiable event which are communicated ‘in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software’.

30 The second aspect of the invention, which is a consistory statement for claim 11, is a method for vehicle detection involving the use of a VDU with the characteristics described in the first aspect.

31 The specification then states that the invention provides for the VDU to determine whether a notifiable event has occurred. It then describes some preferred embodiments. In one it is said that the VDU communicates wirelessly directly with a portable supervisory device, such as a PDA carried by an inspector, in an ad hoc manner at times when a notifiable event has occurred and when the portable supervisory device is in range. Such a network topology is referred to as a ‘transient middle tier’ (or TMT) which obviates the need for fixed communications infrastructure to connect each VDU with a head officer server, and that server to in turn communicate with a supervisory device. The fixed infrastructure is referred to in the specification as a ‘fixed middle tier’ (or FMT).

32 In further preferred embodiments, the VDU is said to be operable to provide information associated with the notifiable event to the supervisory device so that information may be pre-populated into the supervisory device without requiring manual entry of the information by the parking inspector.

33 The specification then says (emphasis added) (page 3 line 29 to page 4 line 2):

Preferably, a plurality of vehicle detection units in accordance with the first aspect of the present invention communicate with a single supervisory device such as a PDA carried by a parking inspector. The single supervisory device may thus be provided with real time reporting of the occupancy status of each of a plurality of parking spaces, including information such as the presence or absence of a vehicle in each location, a duration of occupancy of each vehicle present, a violation status of each vehicle present such as no violation, violation imminent and in violation. Notably, due to the ability of each vehicle detection unit to determine whether notifiable events are occurring, the supervisory device is not required to possess the substantial processing power needed to make such determinations for every such vehicle detection unit.

34 In preferred embodiments of the invention, the VDU is embedded in the roadway beneath the associated parking space. The sensor of the VDU is said to be preferably a magnetometer able to sense variations in magnetic field caused by the arrival or departure of a vehicle. In such embodiments the VDU is operable to receive updates (preferably wirelessly) to the parameters defining notifiable events, such as when the signage associated with the parking space is altered.

35 The third aspect of the invention described, which is a consistory statement for claim 20, is a method of issuing a PIN including the use of a portable device establishing a transient wireless connection with at least one VDU. A preferred form of this method is said to involve the automated pre-population of the data arising from the notifiable parking event into infringement issuing software of the portable device.

36 The fourth aspect of the invention described, which is a consistory statement for claim 21, is a system for detecting parking infringements, where a mobile supervisory device may be a portable digital device carried by a parking inspector or mounted on a vehicle, which preferably collates data from a plurality of VDUs for simultaneous display to a parking officer.

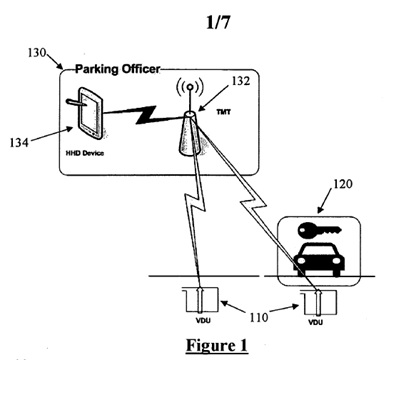

37 The specification then describes various preferred embodiments by reference to 8 drawings. Figure 1 (set out below) illustrates a network topology comprising a TMT, which is described in a glossary of terms as the conduit between a handheld device (HHD) and a VDU embedded in the ground containing a processor, a magnetic sensor and a communications module. Figure 2 (not shown) also illustrates a network topology but with a FMT as an alternative to a transient middle tier. It provides the conduit between the VDU and a ‘vehicle detection system internet gateway’ which is ‘fixed’ because it is permanently in place in the field. It may comprise wireless network nodes attached to a parking meter or light poles or the like.

38 The description of the TMT of figure 1 provides that each VDU 110 is battery-powered and embedded in the ground, and is able to detect the arrival and departure of a vehicle 120 by way of a three-axis magnetic sensor. This reads the magnetic field at sufficiently regular intervals to detect a magnetic field disturbance created by a vehicle travelling at 20 kilometres per hour or less. Each reading taken outside prescribed thresholds is passed to the ‘vehicle detection algorithm’ (VDA) for determination of the presence of a vehicle. The three-axis sensor takes readings in the X, Y and Z axes. The VDA is run in the firmware of the VDU 110. Upon the determination of the arrival of a vehicle 120 by the VDA, the VDU 110 determines when the vehicle violates parking restrictions. This is done by a ‘vehicle in violation algorithm’ (VIVA) which is run in the firmware of the VDU.

39 The steps next described in the specification were the subject of submissions and warrant quotation (emphasis added):

Upon determination of an actual or impending infringement, the VIVA initiates communications from the VDU 110 to the TMT 132, to alert the parking officer 120 of the infringement. This is effected by an RF [i.e. radio frequency] communications component of the VDU 110. The RF communications component of the VDU 110 “listens when required” for the broadcast beacon from the TMT 132, and organises communications.

Each VDU 110 has onboard memory storage to store Parking Events, enabling the VDU 110 to upload data for pre-population into the HHD 134 as required. Such data includes infringement data, parking event data, system health status, offence type (eg no standing), location details (physical), parking restrictions (eg signage), offence details such as arrival time and departure time, offence notes such as arrival time and time overstayed, and firmware details. Once the Parking Event data has been transferred, it is removed from the VDU 110. Further, the HHD 134 issues a confirmation message indicating that an infringement has been issued, which is received by the VDU 110 and causes the VDA to be reset.

As it is unlikely to be economic to replace the battery and/or VDU 110, each VDU 110 is configured to be highly power efficient on the basis that once the battery has been exhausted the life of the VDU will be over. One measure to provide for longevity is that each VDU 110 is operable to download updated firmware and firmware parameters (such as changed parking restrictions), as required.

40 The specification notes that while using the TMT described by reference to Figure 1 is preferable, the invention includes within its scope FMT topologies communicating with VDUs.

41 Figure 2 illustrates a system with a FMT topology and also a TMT. The specification explains that each VDU 110, is embedded about 2 centimetres below the surface of the parking space and can typically communicate with a TMT or FMT that is 20 metres away. It says (page 12 lines 19 – 24):

To conserve battery power, each VDU 110, 210 only attempts to detect the presence of the beacon signal of the TMT 132 and/or FMT 240 at times when communication is required, such occasions include when the VIVA indicates a vehicle is in violation, when the predefined Parking Event storage limits have been met, when the system is in a “maintenance required” state, and when listening for a routine maintenance request.

42 A VDA is set out in figure 4 (not shown). This may be updated remotely via a radio frequency link. Any object that creates a disturbance to the magnetic field far greater than that created by a vehicle (such as a powerful magnet within the vicinity of the sensor) is to be treated as an exception, as well as other circumstances likely to be recorded as false positives. The VDA operates in conjunction with the VIVA which operates on multiple time-based triggers to determine whether a parking violation has occurred.

43 The specification then describes some case examples relevant to the operation of the algorithms for detecting vehicles and parking violations.

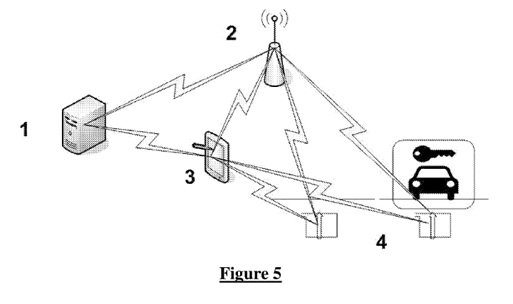

44 Figure 5 then illustrates a generalised network topology of a further embodiment of the invention as follows:

45 In figure 5, the back-end system 1 provides for configuration, processing and storing of data, in particular for the entry of street names and for the identification and recording of the location of each VDU. It also provides back-end processing of all PINs and stores all signage information to be able to determine if a vehicle has committed an offence. The middle tier 2 is between, and communicates with, the VDUs 4, which are located in the ground, and the back-end system 1 and/or the handheld device 3. The specification provides (emphasis added) (at page 19 lines 27 to page 20 line 2):

The hand held device (HHD) 3 is carried by a parking officer, and receives communications regarding the details of an infringement (or pending infringement) and is provided with “pre populated” details which are automatically passed into the PINS for processing by the officer. The data fields provided for automated pre-population include Offence Type, Offence Date and Time, Offence Location (e.g. Street No, Street Name, Suburb), Parking Bay Identifier, Vehicle Arrival Time, Vehicle Stay Duration. Location Information...Parking Sign Information... Parking Restriction and Officer Notes. Such communications could arrive from the back-end system 1, from a middle tier 2 separate to the HHD, or directly from the VDUs 4.

46 The meaning of ‘pre-population’ adopts some significance in the proceedings. It will be seen from the above passage that communications that arrive from the VDUs contain details of an infringement which are automatically ‘passed into the PINs for processing by the officer’. The data fields providing for such population include details of the offence, such as time and location.

47 The specification continues (at page 20 lines 5 – 11):

The Vehicle Detection Units (VDUs) 4 are placed into the ground beneath each vehicle parking space. The readings taken by a sensor of each unit are used by the vehicle detection algorithm (VDA) run by the VDU to determine the presence of a vehicle. Depending on the end architecture and design, each VDU 4 may be required to send a signal identifying itself, send a signal defining the magnetic field reading, send a signal defining the presence of a vehicle over the detector, send a signal defining the history of vehicle movements within the bay, and/or be able to download new firmware as required.

48 In the embodiment described by reference to figure 7 (not shown), the specification refers to an ‘intelligent’ VDU which stores each reading, taken over a period of time. It determines if a vehicle has infringed by referring to signage details of the bay stored by the VDU, such as date and time details, and for each uniquely designated period, the allowed length of stay, the start time and the end time. The specification states that an advantage of this VDU is that it is able to communicate to the listening device the fact that the vehicle is in violation ‘and is not required to continuously broadcast the “vehicle present” signal’.

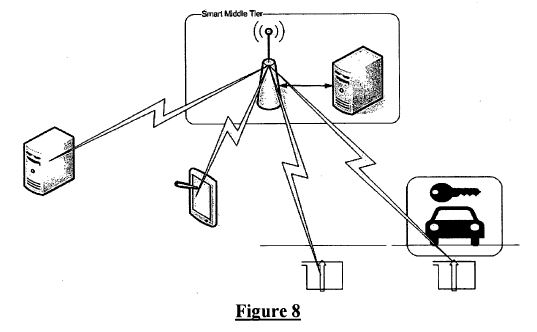

49 In a further embodiment, a ‘smart middle tier’ is responsible for determining if the vehicle in the bay is in violation of a parking requirement and will communicate that information to a HHD. The specification then describes a system architecture by reference to figure 8:

The description says:

In still further embodiments a smart middle tier (with smart VDUs) may be deployed. In this scenario the middle tier provides the sophisticated functionality of the backend head office system, including receiving signals from the VDUs and storing this data in its own database. The topology of this system is illustrated in Figure 8. This system would work as follows. The Smart VDUs behave as outlined above, the smart middle tier will receive signals from all VDU's that it is configured to receive data from. The smart middle tier is constantly broadcasting wake-up messages on the designated frequency to all VDU's that are within range. Once a VDU comes within range of the smart middle tier, it responds to the connect message back to the smart middle Tier. The smart middle tier then handshakes with the VDU and requests data indicating how long the vehicle has been above the VDU (0 mins for no vehicle present), the MAC address of the VDU, and the vehicle movement in the bay since the VDU last spoke to the smart middle tier.

50 The reference to a ‘handshake’ mechanism is to technology known to those skilled in the field of electrical engineering whereby a ‘wake-up’ message is sent out by a transceiver (here, in the TMT) and a remote unit (here, the VDU) responds.

51 The specification goes on to say:

The middle Tier would then subsequently be responsible for determining if the vehicle in that bay is in violation of parking, communicate to a HHD which bay has a vehicle over it, and pass street details and infringement details to the handheld device for issuing of a PIN. Advantages if the smart middle tier include that by using smart VDU's, a permanent connection to the smart middle tier is not required in order to detect the presence of a vehicle. Subsequently the infrastructure costs are reduced as it is not required to affix the middle tiers to infrastructure every 100 metres or so. Further, this topology does not require a 3rd party permanent wireless network to communicate to the hand held devices. This would be done in a piece meal [sic] basis, by the smart middle tier as violations are detected. Also, HHDs communicate via the middle tier (and not the VDU's), and a smaller set of communications is required for both the VDU and hand held. The handheld receives infringement data and the street details, and is not required to have this data stored and determine the bay details from its internal database. This topology also lowers battery requirements due to the VDU only communicating when the smart middle tier comes within range.

52 VMS emphasises in its submissions that in this embodiment it is the smart middle tier that determines if a vehicle has overstayed, not the VDU. The smart middle tier is mobile and may be carried by a parking officer in a HHD.

3.1 The claims

53 Claims 1 – 11 and 20 – 24 are reproduced below. It will be seen that claims 1, 11, 20 and 21 are independent claims. For convenience, integers have been added to claim 1:

1. A vehicle detection unit (VDU) comprising:

(1) a magnetic sensor able to sense variations in magnetic field and for outputting a sensor signal caused by occupancy of a vehicle space by a vehicle;

(2) a storage device carrying parameters which define notifiable vehicle space occupancy events;

(3) a processor (a) operable to process the sensor signal to determine occupancy status of the vehicle space, and (b) operable to compare the occupancy status of the vehicle space with the parameters in order to determine whether a notifiable event has occurred, and (c) operable to initiate a communication from the vehicle detection unit to a supervisory device upon occurrence of a notifiable event, wherein the communication includes (i) data items pertaining to the notifiable event and (ii) communicated in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software.

2. The vehicle detection unit of claim 1, wherein the communication is wireless and directly with a portable supervisory device.

3. The vehicle detection unit of claim 2 wherein the communication is established in an ad-hoc manner at times when a notifiable event has occurred and when the portable supervisory device is in range.

4. The vehicle detection unit of claim 1 or claim 2 wherein the communication is with a fixed supervisory device effecting a fixed middle tier.

5. The vehicle detection unit of any one of claims 1 to 4 wherein the information comprises at least one of: street name, parking bay number, vehicle occupancy duration, offence details, applicable regulations, applicable monetary fine, and historical usage data.

6. The vehicle detection unit of any one of claims 1 to 5 wherein the notifiable event comprises at least one of: occurrence of a parking violation, an imminent parking violation, a non-violating parking event of interest, and a change in occupancy status of the vehicle space.

7. The vehicle detection unit of any one of claims 1 to 6 and further configured to be embedded in the roadway beneath an associated vehicle space.

8. The vehicle detection unit of claim 1 wherein the sensor is a 3-axis magnetometer able to sense components of the magnetic field in x, y and z directions.

9. The vehicle detection unit of any one of claims 1 to 8 wherein the processor is configured to execute a vehicle detection algorithm to determine whether detected variations in the sensor signal are caused by a vehicle.

10. The vehicle detection unit of any one of claims 1 to 9 wherein the parameters are provided in firmware, and wherein the vehicle detection unit when deployed is operable to receive firmware updates to the parameters.

11. A method for vehicle detection by a vehicle detection unit, the method comprising: sensing variations in magnetic field caused by occupancy of a vehicle space by a vehicle, and outputting a sensor signal; retrieving from a storage device parameters which define notifiable vehicle space occupancy events; processing the sensor signal to determine occupancy status of the vehicle space, comparing the occupancy status of the vehicle space with the parameters in order to determine whether a notifiable event has occurred, and initiating a communication from the vehicle detection unit to a supervisory device upon occurrence of a notifiable event, wherein the communication includes data items pertaining to the notifiable event and communicated in a format suitable for pre-population into an infringement issuing device.

...

20. A method for issuing a parking infringement notice, the method comprising: a portable device establishing a transient wireless connection with at least one fixed vehicle detection unit (VDU); the portable device obtaining from the VDU via the wireless connection data arising from a notifiable parking event magnetically detected by the VDU; and the portable device pre-populating the data into infringement issuing software and generating a parking infringement notice using the pre-populated data obtained from the VDU.

21. A system for detecting vehicle parking infringements, the system comprising: a plurality of vehicle detection units (VDUs) each associated with a respective vehicle parking space and storing parameters defining notifiable vehicle space occupancy events, each VDU configured to sense variations in magnetic field caused by occupancy of the associated vehicle space and determine by reference to the parameters whether a notifiable event has occurred, and operable to communicate wirelessly including wirelessly transmitting data items pertaining to the notifiable event and communicated in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software; a mobile supervisory device configured to wirelessly communicate with each respective VDU when brought within range, to receive information from the VDU arising from a notifiable parking event detected by the VDU, to pre-populate received data items into infringement issuing software and to generate a parking infringement notice using the pre-populated data items obtained from the VDU.

22. The system of claim 21 wherein the mobile supervisory device is a portable digital device carried by a parking inspector.

23. The system of claim 21 wherein the mobile supervisory device is vehicle mounted.

24. The system of any one of claims 21 to 23 wherein the supervisory device collates data from a plurality of VDUs for simultaneous display to a parking officer.

4. CLAIM CONSTRUCTION ISSUES

54 It may be seen that the VDU of claim 1 is a combination of parts and functions that has: a magnetic sensor that must be able to output a sensor signal caused by the occupancy of a vehicle space by a vehicle (integer (1)); a storage device that contains the parameters defining notifiable occupancy events (such as the duration of permitted parking) (integer (2)); and a processor that is able to process the sensor signal, and compare the occupancy status of the vehicle space with the parameters provided by the storage device, to determine whether a notifiable event (such as a parking overstay) has occurred (integers (3)(a) and (b)). In addition, the processor must have the operability to initiate a communication from the VDU to a supervisory device, such as a HHD carried by a parking officer, when a notifiable event occurs (integer (3)(c)) and include within that communication data items relating to the notifiable event (integer (3)(c)(i)) ‘in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software’ (integer (3)(c)(ii)).

55 The construction of issues that arise in relation integer 3 involves addressing three interrelated questions raised by VMS: first, what is meant by the requirement that the processor is ‘operable to initiate’ communications to the supervisory device upon the occurrence of a notifiable event; secondly, the meaning conveyed in integer 3(c)(i) by the words ‘data items’; and thirdly, the level of processing required of data items once communicated to the infringement issuing software in integer 3(c)(ii). The following paragraphs should be read in conjunction with section 5.4.4 (electrical engineering common general knowledge) below.

4.1 ‘Operable to initiate a communication’

56 Claim 1 requires the VDU to include a processor ‘operable to initiate a communication’ from the VDU to a supervisory device ‘upon the occurrence of a notifiable event’. VMS contends that these words include that the VDU is operable (i.e. able) to initiate a communication upon receiving (and in response to) a ‘beacon’ (or wake-up signal) that is transmitted by a TMT or FMT. Although it is not completely clear from its submissions, it would appear SARB contends that claim requires that the VDU sends a response to a broadcast beacon message only upon the occurrence of a notifiable event. I prefer the construction advanced by VMS, for the following reasons.

57 First, the requirement of the claim is that the processor be ‘operable’ to initiate a communication upon the occurrence of a notifiable event. This means that the processor must be capable of so operating. To the extent that SARB contends that the language of the claim requires that the processor only be programmed to receive a broadcast beacon signal when a notifiable event has occurred, I reject that contention. It suffers the vice of adding a limitation into the claim that is not present – that is, inserting the word ‘only’ before ‘operable’. Claim 1 does not preclude a communication being initiated by the VDU at a time other than when a notifiable event has occurred.

58 In his written evidence Mr Evans contended otherwise, stating that the VDU ‘waits for the supervisory device to come into range and only initiates communication if there is a notifiable event’. He expanded on this in his oral evidence, stating that he considered the VDU initiates communications because it is ‘not even listening’ until it has a notifiable event to report. While I agree that the VDU does initiate communications in this context, I have rejected the suggestion that the VDU may only initiate communications with respect to notifiable events. I also reject the suggestion that the VDU is only ‘listening’ when it has a notifiable event to report on. That is not a feature of claim 1.

59 Secondly, the SARB application describes the VDU initiating a communication by listening for a beacon and, upon detecting such a signal, sending a communication in response. Thus at page 9 (line 30) it provides:

The communication between the TMT 132 and each VDU 110 is by way of an RF link. Due to the transient nature of the TMT 132 and the need to establish a new wireless connection each time it comes into range of a VDU in violation, the TMT 132 issues a broadcast beacon which can be picked up by any VDU 110 within range. If a given VDU 110 responds, the TMT 132 will then schedule communications with the VDU 110 so as to establish the new connection.

60 As the expert evidence indicates, the beacon contains data communicated by the TMT, to which the VDU is programmed to respond. In this embodiment, before the VDU will communicate with the supervisory device, it must first receive a broadcast beacon signal. However the ‘communication’ that is the subject of claim 1 is one which includes within it ‘data items pertaining to the notifiable event … in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software’. The data contained in the broadcast beacon signal is not the same data which makes up the ‘communication’ as defined in claim 1.

61 This construction also applies to claim 11. The ‘initiate’ requirement is not present in claims 20 and 21.

62 In the context of this aspect of claim 1, it is to be noted that the term ‘notifiable event’ is defined non-exclusively in the specification to include a parking violation, an imminent parking violation or ‘any non-violating parking event of interest such as a change in occupancy status’. Contrary to the suggestion made in the submissions by VMS, integer 3(c) is not to be understood to require the notification to the supervisory device of every potential notifiable event. In this regard it may be noted that dependent claim 6 is more prescriptive of notifiable events, and specifies that they will include at least one of a parking violation, an imminent parking violation or a change in the occupancy status of the parking bay. In this context I note that Professor Evans considers that a ‘key feature’ of the invention is that it minimises the amount of data that the parking inspector needs to enter manually in order to generate a PIN. This, he says, is achieved by communicating the information associated with a notifiable event in such a way that it can be pre-populated into the ticket-issuing device. Later in his written evidence he suggests that all information required to populate the fields in the infringement issuing software must be transmitted by the VDU. It will be apparent from the construction of the claim that I have adopted that this is not a requirement. In his oral evidence Professor Evans appeared to accept this view.

4.2 ‘Data items’

63 The second issue concerns the construction of integer (3)(c)(i). VMS submits that ‘operable to initiate a communication ... wherein the communication includes data items pertaining to the notifiable event’ means that all data items must be communicated in the requisite format suitable for pre-population into the infringement issuing software. SARB disputes this. In my view the construction proposed by VMS tends to overlook the plain language of the claim, which simply refers to ‘data items’ not ‘all data items’. As a matter of ordinary English, this means two or more such items. There is no technical reason why all items must be communicated in such a way. As Professor Evans explains, it could be just a sensor node ID and the duration the vehicle has been there that is communicated. Other information could be obtained by looking up the street address and suburb from a database on the supervisory device, and so it would not need to be sent by the VDU.

64 Furthermore, all information pertaining to the most relevant notifiable event – a vehicle overstay – could not be sent from a VDU, because the registration plate of the vehicle (probably the most important data item) could not be identified by the VDU, and would have to be populated in the infringement issuing software from another source (typically, manual entry by a parking officer).

65 Accordingly, the requirement of integer (3)(c)(i) is that two or more items pertaining to the notifiable event must be communicated in the requisite format for pre-population.

4.3 Processing of data items

66 The third issue concerns the meaning of the words ‘communicated in a format suitable for pre-population into infringement issuing software’ in integer (3)(c)(ii). There is no dispute that ‘pre-population’ means that data items pertaining to the notifiable event are transmitted directly into the infringement issuing software by the VDU without the need for a parking officer to take a step to do so. This approach satisfies an objective of the invention disclosed to save the parking officer time and effort.

67 VMS submits that this integer requires that the data communicated by the VDU to the supervisory device be able to be pre-populated into the data fields in the infringement issuing software without further data processing by the supervisory device. In that regard, the supervisory device should not, by the language of the claim, be required itself to process the infringement data generated and communicated by the VDU, because the work has already been done by the processor in the VDU. For instance, information generated by the VDU may include the time that a vehicle is detected arriving at a parking bay, or that a vehicle has contravened a parking requirement by overstaying. That will be recorded in a binary, computer-readable form. VMS submits that the language of integer (3)(c)(ii) contemplates that the information will be communicated from the VDU to the supervisory device in a form that can be introduced into the infringement issuing software without any translation (or ‘processing’) at the supervisory device. Accordingly, the binary computer-readable form of the data items must first be converted to a form suitable for pre-population communication to the supervisory device at the VDU, and then communicated. An example given in the evidence is where the VDU collects data as to the ‘offence date and time’ and initially records it as a 32 bit binary number in UNIX epoch format (which is the number of seconds since 1 January 1970 – for instance, 1,235,068 seconds). Infringement issuing software will use data fields in the hour/minutes and day/month/year format. VMS submits that the integer requires that the VDU communicate information in the latter format, without the supervisory device engaging in that processing. This type of processing is referred to below, depending on the context, as formatting.

68 SARB largely accepts this construction, but it submits that the language of claim 1 does not preclude additional necessary processing at the supervisory device. It accepts that where data is transmitted concerning a notifiable event from the VDU to the supervisory device, it must be in a format that is able to be placed directly into the infringement issuing software in a format that is human readable, any conversion from binary form to readable form having taken place in the VDU. However, it submits that this should not be taken to preclude some processing that is still required at the supervisory device that must always be done at the receiver end to return the data to its original form.

69 This qualification arises from the evidence of the experts as to the means by which data may be wirelessly sent and received. As noted in section 5.4.4. below, methods of wirelessly sending packets of data over standard protocols require the addition of headers and footers, and utilise cyclic redundancy checks. Data is processed in various ways in preparation for communications. For example, a ‘header’ may typically be added, such that the data transmitted does not look exactly the same, or is not in the same format, as the user wants to send. There will always be processing required at the receiver end to return the data to its original form (for instance by removing a header or conducting a cyclic redundancy check) so that the wirelessly transmitted packet of data can be received and organised.

70 In my view the requirement of integer (3)(c)(ii) is that the data communicated by the VDU to the supervisory device pertaining to a notifiable event must be able to be pre-populated into the data fields in the infringement issuing software without further conversion or calibration, as VMS submits. The integer requires that it is the VDU that performs that work, and that the supervisory device is relieved of the processing obligation for any items of data that are communicated by the VDU concerning a notifiable event. As the expert evidence explains, this involves a choice designed to save power at the supervisory device end (typically a HHD) and to impose the processing task on the in-ground VDU. An exception to this finding is necessary processing by the supervisory device of data packets sent by the VDU, such as the removal of headers, that must always be done at the receiver end to return the data to its original form. I do not consider that the language of the claim precludes processing of this nature. The fact that wireless communication is contemplated within the claim indicates that processing required as a necessary incident of such communication falls within the scope of the monopoly. Accordingly, I agree with the submission advanced by VMS, and also with the refinement or qualification added by SARB.

71 The parties agree that the limitation imposed by integer (3)(c)(ii) is present in all of the independent claims. However, VMS advances a submission that despite this agreement, the Court should independently consider and determine whether, despite slight differences in the wording, independent claims 11 and 20 include this limitation. It submits that the Court ‘stands in the shoes’ of the Commissioner in these appeal proceedings. Section 60(3) of the Patents Act provides that ‘the Commissioner may, in deciding a case, take into account any ground on which the grant of a standard patent may be opposed, whether relied upon by the opponent or not’. VMS submits that if the Court now does not consider that this integer is present in all of the claims, it should proceed to consider whether or not an additional ground for refusing the grant of the SARB application arises, such as a failure by the claims to define the invention under s 40(2) of the Patents Act.

72 In my view the limitation expressed in integer (3)(c)(ii) is present in all of the claims. However, were it not, I would not be disposed to take up the invitation advanced by VMS. The metaphor that the Court stands in the shoes of the Commissioner does not open the door for an unpleaded and unargued ground of opposition to be raised on appeal. An opponent in this Court stands as the party advancing the basis upon which a patent application should not proceed to grant. Absent such a party, or any opposition raised by the Commissioner, the patent application will in the ordinary course proceed to grant: see Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited v Alethia Biotherapeutics Inc. [2016] FCA 1540 at [5] and [6], and the cases cited therein. The present position is analogous.

5. LACK OF INVENTIVE STEP: BACKGROUND

1.1 Introduction

73 VMS contends that the invention claimed in claims 1 – 24 of the patent application is not patentable within the meaning of s 18(1)(b)(ii) of the Patents Act because it does not involve an inventive step when compared with the prior art base as required by s 7(2). It relies on the disclosure of the prior art information contained in each of the PCT application, the PODS article, the Gladwin PowerPoint, the Welch presentation and the Collins patent to supplement the common general knowledge available to the hypothetical skilled person for the purpose of assessing obviousness within s 7(2). In the sections below I first consider the relevant law. I then make findings as to the relevant common general knowledge, before turning to consider the case advanced by VMS, having regard to each of the pieces of prior art information relied upon.

5.1 The law of inventive step

74 Section 7(2) of the Patents Act provides:

For the purposes of this Act, an invention is to be taken to involve an inventive step when compared with the prior art base unless the invention would have been obvious to a person skilled in the relevant art in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed (whether in or out of the patent area) before the priority date of the relevant claim, whether that knowledge is considered separately or together with the information mentioned in subsection (3).

75 The ‘common general knowledge’ is information that forms the background knowledge and experience of, and which is available to, all in the trade, when considering the making of new products or the making of improvements in old products, and it must be treated as being used by an individual as a general body of knowledge: Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co v Beiersdorf (Australia) Ltd [1980] HCA 9; 144 CLR 253 at 292 (Aickin J).

76 The text of s 7(2) in effect deems that an invention claimed contains an inventive step, unless the party asserting its absence establishes that it does not contain such a step: AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2015] HCA 30; 257 CLR 356 at [18] (French CJ). Whether or not a claim lacks an inventive step involves a rich factual enquiry. At its heart lies a qualitative assessment of whether there is sufficient invention in a combination, or a thing claimed, to arrive at the conclusion that it is obvious: Lockwood Security Products Pty Ltd v Doric Products Pty Ltd (No 2) [2007] HCA 21; 235 CLR 173 at [124] and [126]. The question of determining whether a patent involves an inventive step is one of degree, and is often by no means easy, because ingenuity is relative, depending as it does on relevant states of common general knowledge. This difficulty is complicated by the need to consider, as here, s 7(3) information (to which I refer below), as well as the common general knowledge: Lockwood at [51].

77 In AstraZeneca, French CJ noted (at [15]) that relevant content was given to the term ‘obvious’ by Aickin J in Wellcome Foundation Ltd v VR Laboratories (Aust) Pty Ltd [1981] HCA 12; 148 CLR 262 at 286:

The test is whether the hypothetical addressee faced with the same problem would have taken as a matter of routine whatever steps might have led from the prior art to the invention, whether they be the steps of the inventor or not.

78 French CJ went on to explain (at [15], citations omitted and square brackets in the original):

The idea of steps taken "as a matter of routine" did not, as was pointed out in AB Hässle, include "a course of action which was complex and detailed, as well as laborious, with a good deal of trial and error, with dead ends and the retracing of steps". The question posed in AB Hässle was whether, in relation to a particular patent, putative experiments, leading from the relevant prior art base to the invention as claimed, are part of the inventive step claimed or are "of a routine character" to be tried "as a matter of course". That way of approaching the matter was said to have an affinity with the question posed by Graham J in Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation v Biorex Laboratories Ltd. The question, stripped of references specific to the case before Graham J, can be framed as follows:

"Would the notional research group at the relevant date, in all the circumstances, which include a knowledge of all the relevant prior art and of the facts of the nature and success of [the existing compound], directly be led as a matter of course to try [the claimed inventive step] in the expectation that it might well produce a useful alternative to or better drug than [the existing compound]?"

That question does not import, as a criterion of obviousness, that the inventive step claimed would be perceived by the hypothetical addressee as "worth a try" or "obvious to try". As was said in AB Hässle, the adoption of a criterion of validity expressed in those terms begs the question presented by the statute.

79 The approach proposed by Graham J in Olin Mathieson Chemical Corporation v Biorex Laboratories Ltd [1970] RPC 157 to which French CJ refers is often referred to as the ‘modified Cripps question’. As the Full Court noted in Generic Health Pty Ltd v Bayer Pharma Aktiengesellschaft [2014] FCAFC 73; 222 FCR 336 (Besanko, Middleton and Nicholas JJ) at [70] and [71], it not a question of universal application in the context of determining whether or not there is a lack of inventive step. That enquiry may be considered by reference to whether there was ‘some difficulty overcome, some barrier crossed’ or whether what is claimed is ‘beyond the skill of the calling’: Lockwood at [52], citing RD Werner & Co Inc v Bailey Aluminium Products Pty Ltd [1989] FCA 57; 25 FCR 565 at 574 (Lockhart J). It has often said that a ‘scintilla of invention’ can sustain a valid invention, although this proposition is somewhat circular, because the requirement of the qualitative assessment remains that the scintilla so identified must be inventive. In any event, it is to be noted that the component of inventiveness may be but a spark.

80 As noted above at [25], there is no dispute that the person whose knowledge and approach is relevant for the consideration of inventive step in the present case is a team comprised of a person who has a practical interest in and knowledge of parking practices, equipment and technology, and an electrical or electronics engineer familiar with sensing devices, radio frequency communications and the communication of data. However, it is recognised that the question of whether or not an invention lacks an inventive step is for the Court to determine: AstraZeneca at [43]. In this regard the notional person skilled in the art is not an avatar for expert witnesses whose testimony is accepted by the Court. It is a tool of analysis ‘which guides the Court in determining, by reference to expert and other evidence, whether an invention as claimed does not involve an inventive step’: AstraZeneca at [23].

81 Section 7(3) of the Patents Act provides:

The information for the purposes of subsection (2) is:

(a) any single piece of prior art information; or

(b) a combination of any 2 or more pieces of prior art information that the skilled person mentioned in subsection (2) could, before the priority date of the relevant claim, be reasonably expected to have combined.

82 The ‘prior art base’ is defined in Schedule 1, relevantly as follows:

"prior art base" means:

(a) in relation to deciding whether an invention does or does not involve an inventive step or an innovative step:

(i) information in a document that is publicly available, whether in or out of the patent area; and

(ii) information made publicly available through doing an act, whether in or out of the patent area.

83 The ‘prior art information’ is relevantly defined in Schedule 1 as follows:

(b) for the purposes of subsection 7(3) – information that is part of the prior art base in relation to deciding whether an invention does or does not involve an inventive step

84 As a matter of history, under the Patents Act 1952 (Cth) (now repealed), the question of whether or not an invention was obvious was determined having regard only to the common general knowledge. Documents not part of the common general knowledge were excluded from consideration: Minnesota Mining at 287 – 292. The enactment of subsections 7(2) and (3) in the present Patents Act opened the door for additional information to be considered. Several amendments have been made to these subsections since the Patents Act came into force. Only the current version and its immediate predecessor warrant attention at present.

85 Section 7(3)(a) enables any publicly available single item of prior art information to be added to the common general knowledge for the purpose of considering the application of s 7(2). Section 7(3)(b) facilitates the addition of a combination of two or more pieces of prior art information to supplement the common general knowledge, subject to the condition that the skilled person identified in s 7(2) could, before the priority date, be reasonably expected to have combined them.

86 These requirements represent a significant departure from the more rigorous requirements of s 7(3) as it existed before the Raising the Bar Act. The earlier provision stipulated that no prior art information could be added to the common general knowledge unless the skilled person could, before the priority date, be reasonably expected to ascertain, understand, regard as relevant and, in the case of a combination of any two or more pieces of prior art, combine them.

87 As French CJ observed in AstraZeneca at [18], prior art information which is publicly available in a single document is ‘ascertained’ if it is discovered or found out, and ‘understood’ means that, having discovered the information, the skilled person would have comprehended it or appreciated its meaning or import (see also Kiefel J (as her Honour then was) at [68], with whom Gageler and Keane JJ, and Nettle J agreed). His Honour considered that the ‘relevance requirement is a threshold criterion for consideration, by the court, of a prior art publication in conjunction with common general knowledge for the purpose of determining obviousness’ (at [22]). Keifel J noted at [68], citing Lockwood at [152], that the relevance requirement is directed to publicly available information, ‘which the skilled person could be expected to have regarded as relevant to solving a particular problem, or meeting a long-felt want or need’.

88 The current form of s 7(3) was introduced into the Patents Act under the Raising the Bar Act in 2012. Item 3 of the Explanatory Memorandum for the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Bill 2011 states that the new Act amends sub-s 7(3) to remove the requirement that prior art information, for the purposes of the enquiry under s 7(2), must be first ‘ascertained, understood and regarded as relevant’ by a skilled person in the art. It identifies three problems with the previous form of the subsection. First, information that was clearly relevant could be excluded on the basis that the skilled person would not have ‘ascertained’ the information. It explains that this exclusion of relevant information, which nowadays is readily available through the internet, undermines the principle that patents should not be granted for routine modifications of what was already publicly available. Secondly, that the requirements that prior art information be ‘understood’ and ‘regarded as relevant’ are implicit in the prior tests for inventive step, and those being included as threshold limitations on the prior art base complicated the provision unnecessarily, without having any substantial effect on the outcome of the inventive step enquiry. Thirdly, the then current restrictions were ‘out of alignment’ with the patent systems of Australia’s major trading partners.

89 The Explanatory Memorandum goes on to say (emphasis added):

Importantly, the changes are not intended to substantially change the operation of the existing tests for inventive step as applied to the prior art base or to permit hindsight analysis. While a skilled person is essentially deemed to be aware of and to have carefully read the publically available information, the inventive step tests are otherwise applied in the context of what the skilled person would have known and done before the priority date of the claims in question. The tests will therefore continue to take account of factors such as whether the skilled person would have understood and appreciated the relevance of the prior art to the problem the invention was seeking to solve and whether it would be considered a worthy starting point for further investigation or development.

It also remains the case that individual pieces of prior art information can only be combined where the skilled person would have been reasonably expected to have combined them.

90 There was some dispute between the parties as to the approach to be taken under s 7(3)(b) to the combination of the prior art information upon which VMS relies. VMS first submits that the test to determine whether or not information is ‘publicly available’ under s 7(3) is answered simply by considering whether it is accessible to the public. A document that is available for inspection, or a speech delivered, anywhere in the world (the example it gives is in the basement of an obscure Russian library) is nonetheless publicly available. Next, it submits that once it is established that the information is publicly available, s 7(3) proceeds on the footing that the hypothetical skilled team is aware of and has carefully read that information. Thirdly, it submits that no single or rigid test should govern whether the skilled team could reasonably be expected to combine pieces of prior art information. It will depend on the circumstances of each case.

91 In response, SARB emphasises that once the information identified in s 7(3) has been added to the common general knowledge, it is likely that the questions of whether they would be understood and regarded as relevant is folded into the factual enquiry in s 7(2). More particularly, SARB submits that in order to establish that two or more pieces of prior art could have reasonably been expected to be combined by the skilled person for the purposes of s 7(3)(b), it is still necessary for VMS to demonstrate that the skilled addressee would have understood the pieces of prior art and regarded them as relevant, despite the fact that these words were excised from s 7(3). Furthermore, it submits that in order to conclude that it is reasonable to combine pieces of prior art within s 7(3)(b), it is necessary to canvass how and why the skilled person or team could come to do so. If the skilled person or team would not realistically combine the prior art (for instance, due to the prior art not being widely communicated or recorded), then it is not reasonable to do so.

92 As set out above, ‘prior art information’ is information in the ‘prior art base’ being information in a document that is publicly available and also information made publicly available through doing an act. Insofar as the definition concerns ‘information’ contained in a ‘document’, it is difficult to see a meaningful distinction between the two. For the most part, information in a document will be that which is written in it. A document that contains information will necessarily need to be considered in its context. If a document is made publicly available, then one may assume that all of the information in it is available to be added to the common general knowledge for the purpose of consideration by the notional skilled person.

93 The identification of any information made publicly available through doing an act, such as information imparted by the public use or demonstration of a product, or by a lecture presented in public, will be determined by proving whether the act was public or not and what was disclosed. That can be particularly challenging when it comes to ephemeral acts. However, once the Court is satisfied that identified information has been made publicly available, then that information is deemed to be available to the hypothetical skilled person for the purpose of the enquiry under s 7(2). Further, once the Court determines what information has been made publicly available, s 7(3)(a) operates such that that information is assumed to be supplied to the notional skilled person within s 7(2), for the purpose of understanding how he or she (or, in the case of a notional team, they) would consider it. Then it must be determined whether, in the light of the common general knowledge, this additional information reveals an absence of inventive step.

94 In practical terms, one may expect a party to proffer in evidence the subject matter of the information that it contends is the prior art information and, in many cases, supply that to an expert on the basis that this is assumed to be such information. That is what VMS correctly did here.

95 In relation to s 7(3)(b), when considering the combination of two pieces of prior art information, the Court must first decide what two or more pieces of prior art information were publicly disclosed. It is that prior art information that the notional person skilled in the art is deemed by the subsection to possess. Secondly, the Court must consider whether the skilled person or team could reasonably be expected to combine the two or more pieces of prior art. That enquiry is not undertaken in a vacuum, but is to be considered in the context of the task that the skilled person or team is to ‘consider’ as required under s 7(2), which is in moving from the common general knowledge to solving a particular problem, or meeting a long-felt want or need: see, by analogy, Lockwood at [152]; AstraZeneca at [68].