FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Quaker Chemical (Australasia) Pty Ltd v Fuchs Lubricants (Australasia) Pty Ltd (No 2) [2020] FCA 306

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Within 14 days of the date of these orders the parties file an agreed form of orders, including as to costs. Failing agreement, the parties file and serve competing forms of orders within 21 days of the date of these orders.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ROBERTSON J:

Introduction

1 These proceedings concern two Patents, the Standard Patent, Australian Patent No. 2012304245, entitled Method for Detecting Fluid Injection in a Patient, with a priority date of 2 September 2011, and the Innovation Patent, Australian Patent No. 2013100458 which in part is in similar terms. The Innovation Patent is a divisional of the Standard Patent claiming the same priority date, and was certified on 25 July 2013.

2 The Patents relate generally to a method for detecting high pressure fluid injection (HPFI or HPI) injuries. These injuries can occur where fluid is kept under high pressure in machinery, such as hydraulic machinery used in mines. For example, longwall systems are used to extract coal resources from underground. They utilise many very large hydraulic roof supports which operate under extremely high pressures, often 5000 psi and above, and require very large amounts of hydraulic fluid given their size, length of hosing and pressure requirements.

3 Fluid may escape from the machinery, for example, through a small crack in a tube carrying the fluid. When it escapes, it can emerge under high velocity, as a fine stream of liquid, which is capable of injecting itself into the body of a person. Injuries of that type can be difficult to detect, but can lead to severe health consequences.

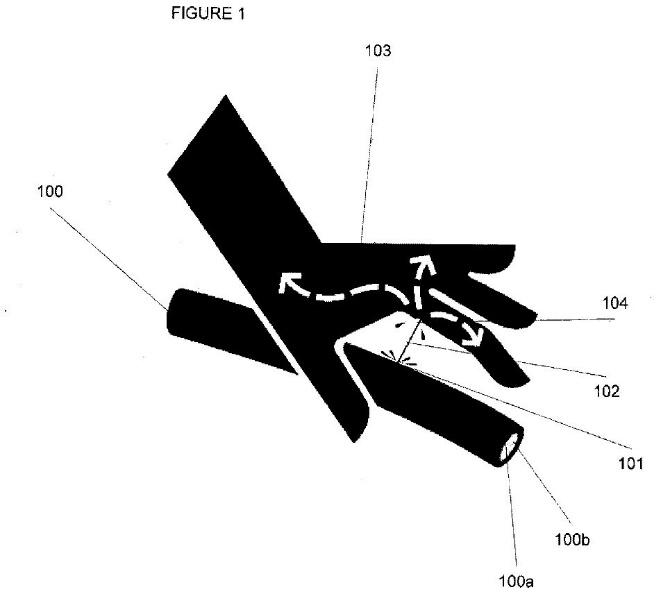

4 As explained under the heading “Preferred Embodiment of the Invention”, Figure 1 in each of the Patents shows a view of a fluid injection according to the invention:

…

Tubing 100 has pressurised fluid such as hydraulic fluid 100a flowing through it. The hydraulic fluid 100a has fluorescence 100b added to it. Tubing 100 includes a leak 101 that has resulted in a high pressure leak 102. In this instance a patient’s hand 103 is in the way of the stream and the hand 103 receives a fluid injection through injection point 104.

5 The Patents are directed to a method for detecting fluid injection in a patient, having certain specified steps. In broad outline, the method involves the inclusion in the machine fluid, such as the hydraulic fluid, of an additive, which is a dye that fluoresces. That dye will fluoresce in the presence of ultraviolet light, and the method involves the use of that property to detect fluid injection in a patient.

6 The parties appeared to be at one in saying that the nature of the invention was easily conveyed in a single sentence. “It is simply a method where fluorescent dye is added to the fluid in a hydraulic system and, if it is suspected that fluorescently-dyed fluid has been accidentally injected into a person, then a UV/blue light is shone on the site of the suspected injection, with fluorescence in or under the skin said to assist in indicating where the injection has occurred.”

7 The inventor recorded in the Patents is Mr Wayne Thompson. The original applicants for the Patents were two companies, Thommo’s Training and Assessment Systems Pty Ltd (TTAAS) and T&T Global Solutions Pty Ltd (T&T), of which Mr Thompson was a director.

8 Quaker Chemical (Australasia) Pty Ltd (Quaker) acquired the Patents from those companies in late 2014.

9 Fuchs Lubricants (Australasia) Pty Ltd (Fuchs), the respondent/cross-claimant, was a supplier of fluid products capable of being used in the claimed method. In particular, Fuchs supplied hydraulic fluid.

10 Two categories of hydraulic fluid supplied by Fuchs were water-based fluids, used in longwall machinery, and mineral oils, used in other hydraulic machinery.

11 Fuchs supplied water-based longwall fluids and concentrates under the “Solcenic” brand and mineral oil products under the “Renolin” brand.

12 TTAAS, and later Quaker, offered two “Oil-Glo” fluorescent dye additive products: Oil-Glo WB (water-based) (also called WD 802 or Oil-Glo 802) for use in longwall fluids, and Oil-Glo OB (oil-based) (also called Oil-Glo 33) in mineral oil systems. These two products were later renamed FluidSafe WB and FluidSafe OB. Quaker had earlier offered a water-based fluorescent dye additive product called “Quinto Glow”.

13 The essence of the case brought by Quaker was that Fuchs had infringed the Patents by supplying, or offering to supply, to certain of its customers, Solcenic and Renolin containing fluorescent dye, in circumstances where the dye or product was not acquired from the patentee. That is, the infringement case was concerned with the supply of Solcenic or Renolin products with a different dye included in particular cases that was not Oil-Glo or FluidSafe. The contention was that Fuchs had infringed the Patents by supplying products in circumstances where the use of those products by the persons to whom they were supplied would infringe the claimed method.

14 Quaker did not complain that the supply by Fuchs of Solcenic or Renolin products which included, or was later mixed by the customer with, Oil-Glo or FluidSafe sourced from the patentee was an infringement. It was accepted that the Oil-Glo or FluidSafe dye was supplied by TTAAS or Quaker on the basis that it could be used for that purpose, and that there was therefore an implied licence, or an authorisation, for that use. As I have said, Quaker contended that subsequently Fuchs sought to, and did, include in its products fluorescent dye additives not sourced from the patentee. It was that conduct that gave rise to the infringement claim. In particular, Quaker claimed, it was the supply by Fuchs to three customers, in specific instances, that involved an infringement by supply. Those customers were: first, from 2016 onwards, BHP Billiton Mitsubishi Alliance (BMA), which was the operator of a mine site at Broadmeadow; second, from 2015 onwards, Glencore, which was the operator of various mine sites, relevantly including Oaky North, Bulga, Ulan No. 3 and Ulan West; and third, from 2015 onwards, Yancoal, the operator of, relevantly, Moolarben and Ashton mine sites.

15 In terms of the legal principles, there were three ways in which the case for Quaker was put. The first relied on s 117 of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth). The second relied on the concept of authorisation under s 13 of the Act: infringement by authorising the act of another. The third relied on the law of joint tortfeasance in a similar way.

16 Fuchs cross-claimed against Quaker, and alleged that both Patents were invalid and liable to be revoked on the grounds of lack of clarity, insufficiency and failure to disclose best method, lack of utility, lack of novelty and secret use. It also alleged that the Standard Patent and Innovation Patent were invalid and liable to be revoked on the ground of lack of fair basis and lack of support, respectively.

17 2 September 2011 was the date of filing of the provisional specification. One significant date, besides the priority date of 2 September 2011, was 2 September 2010, being the date 12 months before the earliest priority date of the claims of the Standard Patent and the Innovation Patent. 2 September 2010 is relevant in considering the publication or use of the invention for the purpose of reasonable trial or experiment.

18 2 February 2012 was the date of filing of the complete specification for the Standard Patent. 2 February 2011 is therefore the date which is 12 months before the filing date of the complete specification for the Standard Patent. That date is relevant because there is an additional grace period provided under the Act and the Patents Regulations 1991 (Cth). In short, information made publicly available by publication or use of the invention by or with the consent of the inventor after that date is to be disregarded.

19 10 April 2013 was the date of filing of the complete specification for the innovation patent.

20 On 21 April 2017, Jagot J ordered that the issue of the quantum of any pecuniary relief be determined separately from, and subsequent to, the determination of all other issues in the proceeding. That leaves for determination the question of liability for additional damages, not the quantification of them, as part of the first hearing.

The witnesses

21 Quaker relied on affidavits of:

(a) Wayne Thompson affirmed on 22 May 2018 and 5 September 2018; Mr Thompson was cross-examined;

(b) Harold Kraus, General Manager and Business Director of Quaker, sworn on 22 May 2018 and 31 August 2018; Mr Kraus was cross-examined;

(c) Peter Gray, consulting engineer, who was called as an independent expert, affirmed on 20 December 2018; Dr Gray produced a joint report with Mr Russell Smith dated 4 February 2019 and gave oral evidence.

22 Fuchs relied on affidavits of:

(a) Craig Roberts, account manager, affirmed on 27 April 2018; Mr Roberts was cross-examined;

(b) Christopher Bate affirmed on 3 May 2018 and 7 March 2019; Mr Bate was cross-examined;

(c) Stuart Knight, Deputy Managing Director of Fuchs, affirmed on 4 May 2018, 17 August 2018 and 2 November 2018; Mr Knight was cross-examined;

(d) Katrina Crooks, solicitor, affirmed on 10 May 2018; Ms Crooks was not required for cross-examination;

(e) Russell Smith, longwall hydraulics consulting engineer, who was called as an independent expert, affirmed on 5 October 2018; as noted above Mr Smith produced a joint report dated 4 February 2019. He gave oral evidence.

The statutory provisions

23 Section 117 stated:

117 Infringement by supply of products

(1) If the use of a product by a person would infringe a patent, the supply of that product by one person to another is an infringement of the patent by the supplier unless the supplier is the patentee or licensee of the patent.

(2) A reference in subsection (1) to the use of a product by a person is a reference to:

(a) …; or

(b) if the product is not a staple commercial product—any use of the product, if the supplier had reason to believe that the person would put it to that use; or

(c) in any case—the use of the product in accordance with any instructions for the use of the product, or any inducement to use the product, given to the person by the supplier or contained in an advertisement published by or with the authority of the supplier.

24 The term “supply” was defined in Sch 1, the Dictionary, as follows:

supply includes:

(a) supply by way of sale, exchange, lease, hire or hire-purchase; and

(b) offer to supply (including supply by way of sale, exchange, lease, hire or hire-purchase).

25 Section 13 provided:

13 Exclusive rights given by patent

(1) Subject to this Act, a patent gives the patentee the exclusive rights, during the term of the patent, to exploit the invention and to authorise another person to exploit the invention.

(2) The exclusive rights are personal property and are capable of assignment and of devolution by law.

(3) A patent has effect throughout the patent area.

26 Section 18 provided:

Patentable inventions for the purposes of a standard patent

(1) Subject to subsection (2), an invention is a patentable invention for the purposes of a standard patent if the invention, so far as claimed in any claim:

(a) is a manner of manufacture within the meaning of section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies; and

(b) when compared with the prior art base as it existed before the priority date of that claim:

(i) is novel; and

(ii) involves an inventive step; and

(c) is useful; and

(d) was not secretly used in the patent area before the priority date of that claim by, or on behalf of, or with the authority of, the patentee or nominated person or the patentee’s or nominated person’s predecessor in title to the invention.

Patentable inventions for the purposes of an innovation patent

(1A) Subject to subsections (2) and (3), an invention is a patentable invention for the purposes of an innovation patent if the invention, so far as claimed in any claim:

(a) is a manner of manufacture within the meaning of section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies; and

(b) when compared with the prior art base as it existed before the priority date of that claim:

(i) is novel; and

(ii) involves an innovative step; and

(c) is useful; and

(d) was not secretly used in the patent area before the priority date of that claim by, or on behalf of, or with the authority of, the patentee or nominated person or the patentee’s or nominated person’s predecessor in title to the invention.

(2) Human beings, and the biological processes for their generation, are not patentable inventions.

Certain inventions not patentable inventions for the purposes of an innovation patent

(3) For the purposes of an innovation patent, plants and animals, and the biological processes for the generation of plants and animals, are not patentable inventions.

(4) Subsection (3) does not apply if the invention is a microbiological process or a product of such a process.

[Note: see also sections 7 and 9.]

27 Section 7 provided:

7 Novelty and inventive step

Novelty

(1) For the purposes of this Act, an invention is to be taken to be novel when compared with the prior art base unless it is not novel in the light of any one of the following kinds of information, each of which must be considered separately:

(a) prior art information (other than that mentioned in paragraph (c)) made publicly available in a single document or through doing a single act;

(b) prior art information (other than that mentioned in paragraph (c)) made publicly available in 2 or more related documents, or through doing 2 or more related acts, if the relationship between the documents or acts is such that a person skilled in the relevant art would treat them as a single source of that information;

(c) prior art information contained in a single specification of the kind mentioned in subparagraph (b)(ii) of the definition of prior art base in Schedule 1.

Inventive step

(2) For the purposes of this Act, an invention is to be taken to involve an inventive step when compared with the prior art base unless the invention would have been obvious to a person skilled in the relevant art in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed in the patent area before the priority date of the relevant claim, whether that knowledge is considered separately or together with the information mentioned in subsection (3).

(3) The information for the purposes of subsection (2) is:

(a) any single piece of prior art information; or

(b) a combination of any 2 or more pieces of prior art information;

being information that the skilled person mentioned in subsection (2) could, before the priority date of the relevant claim, be reasonably expected to have ascertained, understood, regarded as relevant and, in the case of information mentioned in paragraph (b), combined as mentioned in that paragraph.

Innovative step

(4) For the purposes of this Act, an invention is to be taken to involve an innovative step when compared with the prior art base unless the invention would, to a person skilled in the relevant art, in the light of the common general knowledge as it existed in the patent area before the priority date of the relevant claim, only vary from the kinds of information set out in subsection (5) in ways that make no substantial contribution to the working of the invention.

(5) For the purposes of subsection (4), the information is of the following kinds:

(a) prior art information made publicly available in a single document or through doing a single act;

(b) prior art information made publicly available in 2 or more related documents, or through doing 2 or more related acts, if the relationship between the documents or acts is such that a person skilled in the relevant art would treat them as a single source of that information.

(6) For the purposes of subsection (4), each kind of information set out in subsection (5) must be considered separately.

28 Section 9 provided:

For the purposes of this Act, the following acts are not to be taken to be secret use of an invention in the patent area:

(a) any use of the invention by or on behalf of, or with the authority of, the patentee or nominated person, or his or her predecessor in title to the invention, for the purpose of reasonable trial or experiment only;

(b) any use of the invention by or on behalf of, or with the authority of, the patentee or nominated person, or his or her predecessor in title to the invention, being use occurring solely in the course of a confidential disclosure of the invention by or on behalf of, or with the authority of, the patentee, nominated person, or predecessor in title;

(c) any other use of the invention by or on behalf of, or with the authority of, the patentee or nominated person, or his or her predecessor in title to the invention, for any purpose other than the purpose of trade or commerce;

(d) any use of the invention by or on behalf of the Commonwealth, a State, or a Territory where the patentee or nominated person, or his or her predecessor in title to the invention, has disclosed the invention, so far as claimed, to the Commonwealth, State or Territory.

29 The operation of ss 7 and 9 is affected by s 24, extracted at [37] below.

30 The new s 7A provided:

(1) For the purposes of this Act, an invention is taken not to be useful unless a specific, substantial and credible use for the invention (so far as claimed) is disclosed in the complete specification.

(2) The disclosure in the complete specification must be sufficient for that specific, substantial and credible use to be appreciated by a person skilled in the relevant art.

(3) Subsection (1) does not otherwise affect the meaning of the word useful in this Act.

31 The parties agreed that certain parts of the post-Raising the Bar version of the Act applied to the Innovation Patent, including the requirements of the new s 7A, in addition to s 18(1A)(c) of the Act.

32 The previous s 40 provided:

(1) A provisional specification must describe the invention.

(2) A complete specification must:

(a) describe the invention fully, including the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention; and

(b) where it relates to an application for a standard patent—end with a claim or claims defining the invention; and

(c) where it relates to an application for an innovation patent—end with at least one and no more than 5 claims defining the invention.

(3) The claim or claims must be clear and succinct and fairly based on the matter described in the specification.

(4) The claim or claims must relate to one invention only.

33 The new s 40 provided:

Requirements relating to provisional specifications

(1) A provisional specification must disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art.

Requirements relating to complete specifications

(2) A complete specification must:

(a) disclose the invention in a manner which is clear enough and complete enough for the invention to be performed by a person skilled in the relevant art; and

(aa) disclose the best method known to the applicant of performing the invention; and

(b) where it relates to an application for a standard patent—end with a claim or claims defining the invention; and

(c) where it relates to an application for an innovation patent—end with at least one and no more than 5 claims defining the invention.

(3) The claim or claims must be clear and succinct and supported by matter disclosed in the specification.

(3A) The claim or claims must not rely on references to descriptions or drawings unless absolutely necessary to define the invention.

(4) The claim or claims must relate to one invention only.

34 The parties agreed that the post-Raising the Bar versions of ss 40(2)(a) and (3) applied to the Innovation Patent.

35 Section 138 provided:

138 Revocation of patents in other circumstances

(1) Subject to subsection (1A), the Minister or any other person may apply to a prescribed court for an order revoking a patent.

(1A) A person cannot apply for an order in respect of an innovation patent unless the patent has been certified.

(2) At the hearing of the application, the respondent is entitled to begin and give evidence in support of the patent and, if the applicant gives evidence disputing the validity of the patent, the respondent is entitled to reply.

(3) After hearing the application, the court may, by order, revoke the patent, either wholly or so far as it relates to a claim, on one or more of the following grounds, but on no other ground:

(a) that the patentee is not entitled to the patent;

(b) that the invention is not a patentable invention;

(d) that the patent was obtained by fraud, false suggestion or misrepresentation;

(e) that an amendment of the patent request or the complete specification was made or obtained by fraud, false suggestion or misrepresentation;

(f) that the specification does not comply with subsection 40(2) or (3).

36 The pre-Raising the Bar versions of the Act and Patents Regulations apply to the disclosures relied upon, which occurred before 15 April 2013: See Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) s 3 and Sch 6 items 32, 33 and 133(4) (concerning the application of amendments to s 24) and the Intellectual Property Legislation Amendment (Raising the Bar) Regulation 2013 (No 1) (Cth) reg 4 and Sch 6 item 7 (substituting new regs 2.2 and 2.3), and reg 23.36(4) item 3 of the Patents Regulations (concerning the application of those amendments).

37 Section 24 provided:

24 Validity not affected by certain publication or use

(1) For the purpose of deciding whether an invention is novel or involves an inventive step or an innovative step, the person making the decision must disregard:

(a) any information made publicly available, through any publication or use of the invention in the prescribed circumstances, by or with the consent of the nominated person or patentee, or the predecessor in title of the nominated person or patentee; and

(b) any information made publicly available without the consent of the nominated person or patentee, through any publication or use of the invention by another person who derived the information from the nominated person or patentee or from the predecessor in title of the nominated person or patentee;

but only if a patent application for the invention is made within the prescribed period.

(2) …

38 Turning to the Patents Regulations, regs 2.2 and 2.3 relevantly provided:

2.2 Publication or use: prescribed circumstances

(1) …

(1A) For paragraph 24 (1) (a) of the Act, the circumstance that there was a publication or use of the invention within 12 months before the filing date of the complete application, is a prescribed circumstance.

(2) For paragraph 24 (1) (a) of the Act the following are also prescribed circumstances:

(a) …;

(b) …;

(c) … ; or

(d) the working in public of the invention within the period of 12 months before the priority date of a claim for the invention:

(i) for the purposes of reasonable trial; and

(ii) if, because of the nature of the invention, it is reasonably necessary for the working to be in public.

(3) …

(4) …

2.3 Publication or use: prescribed periods

(1A) For information of the kind referred to in paragraph 24 (1) (a) of the Act, if the applicant relies on the circumstance in subregulation 2.2 (1A), the prescribed period is the period of 12 months after the information was first made publicly available.

(1) For information of the kind referred to in paragraph 24 (1) (a) of the Act, if the applicant relies on a circumstance in subregulation 2.2 (2), the prescribed period is:

(a) in the case of a circumstance mentioned in paragraph 2.2 (2) (a) or (b):

(i) if the application claims priority from a basic application made within 6 months of the date of the first showing or use of the invention at a recognised exhibition — 12 months from the making of the basic application; and

(ii) in any other case — 6 months after the first showing or use of the invention at the exhibition; and

(b) in the case of the circumstance mentioned in paragraph 2.2 (2) (c):

(i) if the application claims priority from a basic application made within 6 months of the date of the first reading or publication referred to in that paragraph — 12 months from the making of the basic application; and

(ii) in any other case — 6 months after the first reading or publication; and

(c) in the case of the circumstance mentioned in paragraph 2.2 (2) (d) — 12 months from the start of the first public working of the invention referred to in that paragraph.

(2) For the purposes of subsection 24 (1) of the Act, in the case of information of the kind referred to in paragraph 24 (1) (b) of the Act, the prescribed period is 12 months from the day when the information referred to in that paragraph became publicly available.

(3) Subregulation (4) applies:

(a) if an application for a patent is a divisional application:

(i) under section 79B of the Act for an invention disclosed in the specification filed with a previous application for a standard patent (the original application); or

(ii) under section 79C of the Act for an invention disclosed in the specification filed in respect of an application for an innovation patent (the original application); and

(b) only to information disclosed in the divisional application that was disclosed in the original application.

(4) For determining the prescribed period for subsection 24 (1) of the Act, the filing date of the divisional application is taken to be the filing date of the original application.

39 The following grace periods were said by Quaker to be relevant:

(a) Pursuant to s 24(1)(a) of the Act and regs 2.2(1A) and 2.3(1A), any publication or use of the invention after 2 February 2011 by or with the consent of the patentee cannot be taken into account for the purposes of novelty (General Grace Period).

(b) Pursuant to s 24(1)(a) of the Act and regs 2.2(2)(d) and 2.3(c), any publication or use of the invention after 2 September 2010 by or with the consent of the patentee in the context of the working in public of the invention for the purposes of reasonable trial, where, having regard to the nature of the invention it was reasonably necessary for the working to be in public, cannot be taken into account for the purposes of novelty (Reasonable Trials Grace Period).

(c) Pursuant to s 24(1)(b) of the Act and reg 2.3(2), any publication or use of the invention after 2 September 2010 without the consent of the patentee by a person who derived the information from the patentee, cannot be taken into account for the purposes of novelty (Unauthorised Disclosures Grace Period).

The names of the products

40 The names and variations of the water-based longwall hydraulic fluid products were:

Fuchs Solcenic 3002 (concentrate, undyed)

Fuchs Solcenic 3002 (concentrate, dyed)

Fuchs Solcenic 2020 (concentrate, undyed)

Fuchs Solcenic 2020 D (concentrate, dyed)

Fuchs Solcenic 2020 4% Emulsion (pre-mixed emulsion, 96% water, undyed)

Fuchs Solcenic 2020 D 4% Emulsion (pre-mixed emulsion, 96% water, dyed)

Fuchs Solcenic GM20 (concentrate, undyed)

Fuchs Solcenic GM20 D (concentrate, dyed)

Fuchs Solcenic GM20 LD (concentrate, dyed)

Fuchs Solcenic GM20 3% (pre-mixed emulsion, 97% water, undyed)

Fuchs Solcenic GM20 D 3% Premix Emulsion (pre-mixed emulsion, 97% water, dyed)

Fuchs Solcenic GM20 D Plus 3% Premix Emulsion (pre-mixed emulsion, 97% water, dyed)

Fuchs Solcenic GM20 D Plus 3% Premix Emulsion (pre-mixed emulsion, 96% water, dyed)

Fuchs Solcenic 2B (concentrate, dyed)

Fuchs Solcenic 7 (concentrate, dyed)

Fuchs Solcenic 3C (concentrate, dyed)

Quaker Quintolubric 814

Quaker Quintolubric 818-02

41 The names of the mineral oil products were:

Fuchs Renolin B 68 [Renolin B 68 Plus when different base oil used] (undyed)

Fuchs Renolin B 68 [Renolin B 68 Plus when different base oil used] (MET) (dyed)

Fuchs Renolin B 68 [Renolin B 68 Plus when different base oil used] D (NG) (dyed)

Fuchs Renolin B 68 [Renolin B 68 Plus when different base oil used] D (dyed)

Fuchs Renolin B PLUS 68 LD (dyed)

42 The names of the fluorescent dye products were:

Quaker [previously TTAAS] Oil-Glo 33, also known as Oil-Glo OB, rebranded FluidSafe OB in early 2012 (oil-based fluorescent dye additive)

Quaker [previously TTAAS] WD 802, also known as Oil-Glo WB or Oil-Glo 802, rebranded FluidSafe WB in early 2012 (water-based fluorescent dye additive)

Quaker Quinto Glow (water-based fluorescent dye additive)

Fuchs [sourced from third party] Fluoresceine LT (water-based fluorescent dye additive)

Fuchs [sourced from third party] Uniqua W400X (water-based fluorescent dye additive)

Fuchs [sourced from third party] Uniglow F-4 HF (oil-based fluorescent dye additive)

The Patents

43 Under the heading “Field of the Invention” in the Standard Patent, the description states:

The present invention relates to the detection of fluid in the human body and in particular to the detection of hydraulic and fuel fluid within the human body. The invention has been developed primarily for use in detecting the presence of hydraulic and diesel fuel in the human body as a result (sic) accidental fluid injection and will be described hereinafter with reference to this application. However, it will be appreciated that the invention is not limited to this particular field of use.

44 Under the heading “Background of the Invention” is stated:

…

Hydraulic and diesel fuel systems machinery such as those in mining and other industrial areas, operate at very high pressures, often 207 bar (3000 psi) and above. Loose connections or defective hoses can cause a fine, high velocity stream of fluid. Testing has shown that even in systems pressurised to as little as 7 bar (100 psi), this fluid stream can penetrate human skin.

The injury sustained in a high pressure injection incident is usually worse than it will first appear. The injury is relatively rare and it may be that some medical practitioners or hospital services will not be alert to the severity of an injury of this type.

An accidental fluid injection beneath the skin may initially only produce a slight stinging sensation. The danger is that a victim will tend to ignore this, thinking that it will get better with time. This is not often the case and the fluid can cause serious tissue damage. Fluid injected directly into a blood vessel can spread rapidly through a victim’s circulatory system leaving the human body with little ability to purge these types of fluid.

A fluid injection injury can become very serious or even fatal if not dealt with promptly and properly. Typically the only treatment available is to surgically remove the fluid within a few hours of injection. The longer the delay in getting professional medical aid, the further the tissue damage can spread. If left untreated, the injury could result in disfigurement, amputation of the affected part or death of the victim.

Accidental fluid injections can be difficult to confirm. That is, victims may be covered by fluid externally however there may be uncertainty on whether any fluid has penetrated the victim’s skin. As discussed above any delay in treating a victim can cause sever (sic) harm and as such it would be advantageous if confirmation of fluid injection can be confirmed.

45 Under the heading “Summary of the Invention” it is said as to the first aspect:

It is an object of the present invention to overcome or ameliorate at least one of the disadvantages of the prior art, or to provide a useful alternative.

According to a first aspect of the invention there is provided a method for detecting fluid injection in a patient, the method including the steps of:

providing a fluid storage tank;

providing fluid for use in machinery and adding said fluid to the fluid storage tank; and

providing a fluorescent dye and adding the fluorescent dye to the fluid such that the fluid fluoresces in the presence of ultraviolet light.

Preferably the method includes the step of providing a fluorescent light to detect the presence of the fluid.

Preferably the light is a high intensity blue light.

Preferably the method includes the step of a possible fluid injection occurring in a patient.

Preferably the method includes the step of providing a dark room and examining the patient with the blue light in the dark room to determine whether possible fluid injection has occurred.

Preferably the method includes the step of washing the patient.

Preferably the method includes the step of washing the point of possible fluid injection on the patient.

Preferably the method includes the step of examining the patient with the blue light in the dark room to determine whether possible fluid injection has occurred after the step of washing the patient.

Preferably the method includes the step of determining whether or not fluid injection has occurred.

…

46 Under the heading “Preferred Embodiment of the Invention” it is said:

The preferred embodiment of the invention provides a method for detecting fluid injection in a patient following a possible fluid injection. The method including (sic) the step of providing a fluid storage tank in the form of equipment having a diesel or hydraulic tank. The appropriate fluid such as diesel or hydraulic fluid is added to the fluid storage tank. A fluorescent dye is then provided and adding (sic) to the fluid such that the fluid fluoresces in the presence of ultraviolet light. It would be understood that the fluorescent dye can be added to any suitable fluid and the scope of the invention is not limited to diesel and hydraulic fluid.

The preferred embodiment of the invention also provides a fluid reservoir, the fluid reservoir adapted to store hydraulic fluid and fluorescent dye such that the hydraulic fluid and the fluorescent dye mix in the fluid reservoir. The fluid reservoir is connected to and is in fluid communication with at least one hydraulic actuator and/or motor such that the flow of hydraulic fluid and the fluorescent dye such (sic) drives the actuator and/ore (sic) motor. As would be understood, the hydraulic system can be used to drive any number of motors, pumps and the like and many different types of machinery used in mining an (sic) in other applications. The fluid reservoir is connected to the (sic) at least one hydraulic actuator and/or motor by at least one of the following: a hydraulic tube; a hydraulic pipe; a hydraulic hose or the like such that a leak in the hydraulic tube, hydraulic pipe or hydraulic hose results in both hydraulic fluid and fluorescent dye leaking therefrom.

As would be understood, a broad spectrum of light could be used in embodiments of the invention and the invention is not limited to light of any particular wavelength or colour.

In the preferred embodiment the fluorescent dye used is sold under the brand name OILOil Glo (sic) and is manufactured by T&T Global Solutions Pty Ltd. As would be understood any other suitable fluorescent dye can be used and chosen according to the particular application and specifications required.

Following a suspected fluid injection, the method includes the step of providing a fluorescent light to detect the presence of the fluid on a patient. In the preferred embodiment the light is a high intensity blue light although it would be understood that any suitable ultra violet light could be used. That is, following a suspected fluid injection of a person as a result of a high pressure stream of fluid from hydraulic machinery, if the person has been injected, hydraulic fluid mixed with the fluorescent dye would be injected into the patient. As a result of this injection with both hydraulic fluid and the dye, the injection point along with the injected tissue can be found using the ultra violet light which causes the dye to fluoresce.

Once a suspected fluid injection occurs, the method includes the step of providing a dark room and examining the patient with the blue light in the dark room to determine whether possible fluid injection has occurred. After the initial examination, the method includes the step of washing the patient and particularly the point of possible fluid injection preferably with water and detergent.

After the step of washing the patient and the point of possible fluid injection, the method includes the step of re-examining the patient with the blue light in the dark room to determine whether possible fluid injection has occurred.

By following the steps of the preferred embodiment, it is possible to determine whether or not fluid injection has occurred in the patient.

…

47 The claims in the Standard Patent, claims 1 to 22, were as follows, claims 1 and 9 being the independent claims:

THE CLAIMS DEFINING THE INVENTION ARE AS FOLLOWS:

1. A method for detecting fluid injection in a patient, the method including the steps of:

providing a fluid storage tank;

providing fluid for use in machinery and adding said fluid to the fluid storage tank;

providing a fluorescent dye and adding the fluorescent dye to the fluid such that the fluid fluoresces in the presence of ultraviolet light; and

a possible fluid injection occurring in a patient.

2. A method according to claim 1 including the step of providing an ultraviolet light to detect the presence of the fluid.

3. A method according to claim 2 including the step of providing a dark room and examining the patient with the ultraviolet light in the dark room to determine whether possible fluid injection has occurred.

4. A method according to claim 3 including the step of washing the patient.

5. A method according to claim 4 including the step of washing the point of possible fluid injection on the patient.

6. A method according to claim 5 including the step of examining the patient with the ultraviolet light in the dark room to determine whether possible fluid injection has occurred after the step of washing the patient.

7. A method according to claim 6 including the step of determining whether or not fluid injection has occurred.

8. A method substantially as herein described with reference to the accompanying drawings.

9. A method of detecting an accidental hydraulic or fuel fluid injection in a patient having a possible fluid injection, the fluid having been added to a storage tank provided for use in machinery and a fluorescent dye having been added to the fluid such that the fluid fluoresces in the presence of UV light, the method including the steps of:

examining the patient by exposing the patient to UV light; and

determining the presence of fluorescence,

wherein fluorescence indicates a hydraulic fluid injection occurring in the patient.

10. A method according to claim 9, wherein the hydraulic fluid is water or oil or a combination of both water and oil.

11. A method according to claim 10, wherein the hydraulic fluid is a combination of water and oil.

12. A method according to claim 11, wherein the fuel is diesel or petrol.

13. A method according to any one of claims 9 to 12, wherein the step of examining the subject by exposing the patient to UV light occurs in a dark room.

14. A method according to any one of claims 9 to 13, wherein the method includes the step of washing the patient.

15. A method according to claim 14, wherein the step of washing the patient is at a site of possible fluid injection.

16. A method according to claim 15, wherein after washing the site of possible fluid injection, the method includes re-examining the subject by exposure to the UV light.

17. A method according to any one of claims 9 to 16, wherein the hydraulic fluid is used in machinery at a pressure of about 100psi to about 3000psi.

18. A method according to any one of claims 9 to 16, wherein the hydraulic fluid is used in machinery at a pressure of about 150psi to about 2000psi.

19. A method according to any one of claims 9 to 16, wherein the hydraulic fluid is used in machinery at a pressure of about 500psi to about 1500psi.

20. A method according to any one of claims 9 to 19, wherein the fluorescent dye is present in the fluid in at least about 0.0 1% (v/v).

21. A method according to any one of claims 9 to 20, wherein the fluorescent dye is present in the fluid in at least about 0.2% (v/v).

22. A method according to any one of claims 9 to 21, wherein a colouring dye is also added to the hydraulic fluid such that the hydraulic fluid changes colour.

48 By its cross-claim, as amended, Fuchs sought an order revoking claims 1 to 22 of the Standard Patent pursuant to s 138.

49 The claims in the Innovation Patent, claims 1 to 3, were:

THE CLAIMS DEFINING THE INVENTION ARE AS FOLLOWS:

1. A method for detecting fluid injection in a patient, the method including the steps of:

providing a fluid storage tank;

providing fluid for use in machinery and adding said fluid to the fluid storage tank;

providing a fluorescent dye and adding the fluorescent dye to the fluid such that the fluid fluoresces in the presence of ultraviolet light;

a possible fluid injection occurring in the patient; and

providing a high intensity blue ultraviolet light to detect the presence of the fluid.

2. A method according to claim 1 wherein the fluorescent dye has colour characteristics such that when the dye is mixed with an industrial fluid the fluid takes on the colour characteristics of the dye.

3. A method according to claim 2 wherein the industrial fluid is one or more of the following: hydraulic fluid; petrol; or diesel.

50 By its cross-claim, as amended, Fuchs sought pursuant to s 138 an order revoking claims 1 to 3 of the Innovation Patent.

Chronology of events

51 In mid-2009, Mr Thompson/TTAAS was contracted by Peabody Energy Australia to develop mechanical and hydraulic-based training for the mechanical trade staff at Peabody’s Metropolitan mine (Mechanical Training). Mr Thompson designed and manufactured for TTAAS a fluid injection simulator as part of the practical component of his Mechanical Training. This Mechanical Training was provided from around the end of 2009 or beginning of 2010 until around late 2010.

52 On 6 May 2010, a fitter working on a longwall was struck in the hand by high pressure fluid at Metropolitan.

53 In mid-2010, an HPFI task force was established by Peabody. Between 6 May 2010 and 30 July 2010 the taskforce visited Metropolitan.

54 Also in 2010, Mr Thompson and TTAAS were engaged to prepare and provide fluid injection awareness training at Metropolitan (HPFI Training).

55 On 3 September 2010, an electrician at Metropolitan was struck on the arm by pressurised fluid.

56 In mid to late September 2010 or in October 2010 Mr Thompson conceived of the claimed method.

57 In October or November 2010, Mr Thompson disclosed the use of Oil-Glo fluorescent dye in hydraulic fluids to facilitate detection of HPFI using a UV/blue light to Mr Andy Withers of Peabody and demonstrated detecting fluid injection with fluorescent dye using a simulator in the car park at Metropolitan. In November 2010, Mr Thompson conducted tests using pigskin and the simulator and took photographs and videos of these tests.

58 During November 2010, there was disclosure, via in person conversation, telephone and/or emails, by Mr Ken Risk of Peabody to Mr Craig Roberts of Fuchs, of the method of adding a chemical dye to the longwall fluid at Metropolitan so as to enable detection of fluid under a person’s skin in the case of a suspected HPFI.

59 In early December 2010, Mr Thompson conducted compatibility tests of Oil-Glo 33 on a Bobcat machine. On 16 December 2010, TTAAS submitted a risk assessment report for Oil-Glo 33 to be tested in Metropolitan’s machinery.

60 On 21 March 2011, there was a suspected fluid injection recurrence at Metropolitan. The incident report stated, under recommendations: “Implement the oil glow to high potential equipment when trial complete. (Trial currently on 6 shooter, Eimco and Shuttle Car)”.

61 On 23 March 2011, Metropolitan completed its risk assessment for, the introduction of “Oil Glo 802” into its longwall emulsion mix. Metropolitan completed the risk assessment tasks for Oil-Glo and responsibilities around protocols and training in April-May 2011.

62 On 31 March 2011, TTAAS provided to Metropolitan a tax invoice for the supply of “six 20 litre drums of solcenic – Premix each drum with 6.125 litres of Oil Glo 802”.

63 On 16 April 2011, Dr Sean Nicklin from Sydney Hospital emailed Mr Thompson suggesting that “some product testing of the fluid in deeper tissues” could be done using pigs trotters.

64 Early in May 2011, TTAAS provided HPFI training at Peabody’s North Goonyella mine.

65 Also in May 2011, Oil-Glo (WD802 or Oil-Glo 802) was added to Metropolitan longwall fluid. On 26 May 2011, a sample of Solcenic fluid containing Oil-Glo was taken by Fuchs from the longwall at Metropolitan for testing.

66 Between May and June 2011 various supplies were made by TTAAS of Oil-Glo and related products to North Goonyella and Metropolitan.

67 In July 2011, Oil-Glo 802 (WD 802) was added to North Goonyella longwall fluid.

68 Between 24 and 27 July 2011, the NSW Minerals Council Occupational Health & Safety Conference was attended by Mr Bate. Mr Peter Doyle of Peabody presented, referring to a strategy for detection and disclosing HPFI detection using fluorescent dye in hydraulic fluid and UV/blue light.

69 On 26 July 2011, Felix Radu of Quaker emailed Mr Thompson, referring to a discussion on the same date and requesting Mr Thompson’s availability “to discuss Oil Glow supply for Quaker longwall fluids”.

70 On 18 August 2011, Mr Thompson met with Dr Sean Nicklin.

71 On 26 October 2011, there was a suspected HPFI incident at North Goonyella. The first aid report recorded under “Initial Treatment” that the patient was “Examined with Blue light for fluid presence and or penetration” and “nil evidence found”, and under “Signs and Symptoms” there was “evidence of ‘Oil Glo’ on initial or subsequent examination with ‘Blue light’”.

72 On 23 December 2011, Mr Thompson was informed that an HPFI injury had occurred at North Goonyella with fluid that contained the fluorescent additive.

73 On 22 February 2012, an email from Mr Wayne Pearce of Fuchs recorded that Mr Thompson “would like to meet with Fuchs as site dosing is not his preferred option”, and had informed Mr Pearce that “Fuchs is the only oil company he has provided samples to and although other companies have requested samples at this stage he would prefer to work with us”.

74 On 13 March 2012, Mr Pearce emailed Fuchs global personnel outlining some “major concerns” relating to Fuchs’ business arising from the “Oil-Glo situation”.

75 On 26 April 2012, Mr Michaelson of Fuchs emailed Mr John Snape and Mr Peter Crossland of Xstrata (now Glencore) to enquire about Xstrata’s position with regard to the use of Oil-Glo for HPI mitigation.

76 Fuchs admitted that since 2012, it had supplied Solcenic longwall fluid products and Renolin hydraulic mineral oil products in Australia which contained fluorescent fluid additives. It contended that since August 2012 it had on occasion supplied hydraulic fluids mixed with FluidSafe dyes purchased from the patentee (TTAAS until the end of 2014 and Quaker thereafter) to customers in Australia in response to requests from customers for HPFI detection.

77 On 6 September 2012, Tahmoor Colliery (Xstrata) informed Fuchs that FluidSafe would be added to its hydraulic oil and requested information regarding estimated time and costs of the supply.

78 On 25 March 2013, Mr Knight sent an internal email to Fuchs stating that “We have been instructed by North Goonyella, Metropolitan and Wambo Mines (Peabody) to introduce a product called Fluidsafe into their Solcenic and Hydraulic oils” and that “[w]e recently had a request from Yancoal to put the oil based product in their hydraulic oil.”

79 On 28 March 2013, Mr Michaelson emailed Mr Knight and Wayne Hoiles of Fuchs in relation to requests received from Peabody, Donaldson, Tahmoor (Xstrata) and Ravensworth (Xstrata) for FluidSafe. Mr Michaelson expressed concern about liability if the dye did not work in its intended role in identifying the HPI.

80 On 6 August 2013, NRE No 1 (Gujarat NRE) requested that Fuchs work with Mr Thompson to “ensure that GM20 concentrate is provided with a suitable level of fluid dye to ensure that our emulsion always has the correct amount of dye”.

81 On 23 August 2013, Mr Michaelson noted an inquiry from Glencore concerning the potential use of dye added to its longwall fluids for leak detection and instructed Mr Pearce to contact Paul Littley in the UK to jointly provide information on a suitable dye and “the method of enhanced detection” and noting “I do not know if we can purchase the dye from Spectroline as Wayne Thompson may be the Australian agent but there must be products available elsewhere”. Mr Pearce emailed Mr Littley stating: “Glencore (Xstrata) have requested a Fluorescein dye in the Solcenic we provide to assist in leak detection. As it is only for leak detection (not HP detection) we can use any fluorescein dye, they do not want to use the FluidSafe product as it is too expensive. We worked out the concentration of dye in the Quaker product at the recent Chemist meeting so I am thinking we go with the same dose rate for this.”

82 On 28 August 2013, Mr Pearce emailed Mr Esdaile of Glencore regarding “[l]eak detection in longwall fluid”, stating “I phoned you yesterday and left a message regarding the plan to add a leak detection dye to our Solcenic products supplied to Xstrata. I would like to discuss this matter further with you either over the phone or if preferred I could come and meet you in person.”

83 On 30 August 2013, Mr Pearce emailed Mr Esdaile of Glencore regarding “Leak Detection – Longwall Fluids” stating, in part, “To summarise our conversation earlier this week”:

- Fuchs is able to supply longwall Fluids to Glencore sites with a fluorescent dye in them for the use of leak detection only (not HP injection detection).

Mr Esdaile responded stating “Thanks Wayne. Appreciate the follow up. I will be in touch.”

84 On 6 September 2013, Mr Graham Mackenzie of Oaky No 1 (Glencore) requested information from Fuchs in relation to dye additives for both HPFI injection detection and leak detection.

85 Mr Pearce responded:

There is a lot of information on this topic so I will attempt to provide you with the nuts and bolts.

HPI Detection: The dye currently being marketed for use in cases of high pressure injection (HPI) is branded as Fluidsafe WB, this product is supplied by a company called n AAS which is owned and managed by Wayne Thompson. Wayne has recently been granted a patent for the use of his product for HPI detection and it has been used for several years in coal mines in QLD and NSW with some success. The required concentration is quite high for a dye of this type and the product is rather expensive thus implementation of the dye has a significant financial cost.

Fuchs has tested it’s (sic) range of Solcenic products with the Fluidsafe WB dye at the recommended treat rate and have deemed that the dye has no impact on the key performance characteristics of the longwall fluid (seal compatibility, biostability, corrosion protection etc.). I have attached some information from TTAAS on the dye in question.

Leak detection: There are many dyes on the market that can be added to oil based and water based products to assist in leak detection using a blue light. Dyes used for leak detection are significantly lower in cost and require a much lower treat rate than the dye discussed above for HPI detection. Fuchs is able to add dyes to its range of products with full confidence that the performance of its product will not be affected.

It must be understood however that dyes added to products for leak detection shall not be used for HPI detection.

As mentioned on the phone I have had a similar request for information from Andrew Esdaile for XCN and provided him with information as requested.

86 On 24 October 2013, Mr Roberts sent an email to Mr Michaelson:

Justin Ryan indicated that he would like Fuchs to introduce a dye into Solcenic 2020 for their next longwall block in 2014. He mentioned we have had this discussion with Andrew (I’m assuming Andrew Esdale – Group Engineer) on this matter and raised concerns with the FluidSafe patent.

Fluidsafe is only used at a low concentration for leak detection and NOT for identifying fluid injection.

87 On the same date, Mr Pearce sent an email to Mr Roberts:

Please confirm whether they want dye for leak detection only or injection detection?

I have informed Andrew that we can add a dye for leak detection at no extra cost to the customer. The dye used in this scenario is not Fluidsafe.

If they want injection detection we will need to look at extra costs associated with this.

88 On 25 October 2013, Mr Thompson provided a copy of the certified Innovation Patent to Fuchs and stated “my legal advice with respect to leak detection and prior knowledge is captured in the certification.”

89 Also on 25 October 2013, Broadmeadow (BMA) asked Fuchs to provide a dye equivalent to Quinto Glow for HPFI detection. Mr Michaelson contacted Mr Thompson for him to send details of FluidSafe to Broadmeadow.

90 On 26 October 2013, Mr Michaelson responded to Mr Roberts’ email of 24 October 2013 stating “Gents we may have a legal problem with Wayne Thompson on this leak detection as he says his patent covers leak detection. So let’s take a breather and discuss before moving on Ulan.”

91 On 29 October 2013, Mr Michaelson stated in an email that “Presently there is a patent covering the use of dyes for leak detection but particularly HPI injuries.”

92 On 21 November 2013, Mr Jeff Daveson of Oaky No 1 (Glencore) emailed Mr Garry Cooper of Fuchs asking whether he had “heard of or have info/feedback/benefits on any mines using phosphorescent dye in LW emulsion”.

93 On 22 November 2013, representatives of Quaker Chemical Corporation (Quaker US) filed a Notice of Opposition to the grant of the Standard Patent.

94 Also on 22 November 2013, Mr Cooper replied to Mr Daveson in substantially the same terms as Mr Pearce’s email of 6 September 2013 to Mr Mackenzie of Oaky No 1.

95 On 20 January 2014, Mr Michaelson sent an email to Mr Knight stating that he had been informed by Mr Thompson that “he has been approached by Quaker Australia and US to discuss the purchase of his Patent and rights to the use of Fluid Safe for use in Longwall fluid in both regions.” Mr Michaelson further stated in his email:

The following mines use Fluid Safe WB in Australia Russel Vale NRE North Goonyella Metropolitan Austar Coal Mine Wambo Coal Ulan #3

Broadmeadow mine is pursing (sic) the Fluid Safe approach although this has waned in the recent past.

Xstrata at a high level has stopped Tahmoor adopting Fluid Safe but it has been introduced to Ulan #3 on the basis of leak detection

96 On 21 January 2014, Mr Cooper sent a response to Mr Daveson’s email of 21 November 2013 to Mr Kimber of Glencore in substantially the same terms as Mr Pearce’s email of 6 September 2013 to Mr Mackenzie of Oaky No 1.

97 On 23 January 2014, Mr Elliot of Fuchs sent an internal email to Mr Lingg and others stating:

We have used standard green fluorescein dye for a number of years in association with longwall fluid leak detection. In the USA, we received MSHA approve to add this dye to our Solcenic products in 1991.

Fluidsafe is an Australian company that sells a similar green florescent dye for detection of high pressure injection incidents with people.

Fluidsafe provides detection equipment (black light technology) and has conducted medical research that shows their dye to be detectable after injection to the body. Fluidsafe has applied for a patient (sic) to protect this technology, and they appear to be protected in the Australian market. Because this process is considered medical, it is not patentable in the UK and possibly other European markets.

Peabody Coal has driven the use of Fuildsafe (sic) dye in the emulsions being used in all of their longwall mines.

Fuchs Australia has used the Fluidsafe dye in all Solcenic sales to Peabody over the last couple of years.

In the USA, we are supplying Peabody with a Spectroline Blue UV dye for use with our Solcenic GM-20.

In their recent tender, Peabody requested this dye be used in their Twentymile mine (USA).

We have begun an emulsion high pressure injection study with Dr. Pittermann (Germany).

This testing so far has involved two different dyes; standard green florescent dye and the blue UV dye being used at Peabody’s Twentymile mine.

This test involves the injection of dyed emulsion into a live cow udder.

The preliminary results indicate that the blue dye is more difficult to detect due to fatty tissue also showing up as bluish.

The standard green is more easily detectable.

Our position on dye, is to find a comparable product to Fluidsafe and do the research in order to show similar performance.

It would appear to us that the market will lean towards the use of dyed longwall fluids if they can be marketed as a safety advantage.

The level of dye required to treat fluids for pressure injection is considered higher that (sic) what would be necessary for leak detection, on the order of six times as much. This amount of green dye makes the fluids look very intense in the working fluid. There have been incidents where the green dyed emulsion has been pumped to an outside holding pond which has created problems for some customers. Quaker had to remove their dye from some mines due to environmental issues being raised.

98 On 24 January 2014, Mr Knight emailed senior global Fuchs personnel in relation to Quaker’s proposed purchase of the FluidSafe business, stating:

The relationship between Quaker and Wayne Thompson has not been good as Quaker produced their own product ‘Quintoglo’ which Wayne believed breached patent.

Fuchs Australia have used Fluidsafe in Solcenic and hydraulic oil at Peabody sites. The Fluidsafe was purchased by Peabody and delivered to Fuchs where we blended it into Peabody product. This business was lost in a tender situation to Quaker and BP Castrol in September 2013.

Further to Georg’s comments

*This is a threat to our business however uptake has been slow with some organisations reticent to move to the use of dye in longwall fluid. There is pressure from Unions and the Mines Inspectorate to move in this direction given the product has been proven to be successful in identifying High Pressure Injection Injuries (HPI) on several occasions and also identifying where a HPI has not taken place

…

If a customer wants a dyed product for HPI detection we will play with a straight bat and inform them that the product is patented in Australia and we must buy the patented product. We will be open book on the dye.

99 On 2 April 2014, a Ulan No. 3 (Glencore) document titled “Toolbox Talk” stated:

To assist to reducing cost to the operation Fuch (sic) our oil supplier are introducing Fluorescenine LT dye into the hydraulic oil and solcenic fluid. This dye will assist in locating leaks.

…

• Similar to the dye used previously on the longwall (lower concentration), this dye CAN NOT be used for detecting fluid injections.

…

• There will be a change in the colour of the hydraulic fluid, from an orange/yellow to a crisp yellow

…

• When exposed to a blue light the oil will glow, helping to locate the leak.

100 On 21 May 2014, Mr Justin Ryan of Ulan No. 3 (Glencore) requested information on products from Fuchs that could be added to hydraulic oil to identify leaks. Mr Ryan stated in his email:

Andrew Esdaile when looking into fluid safe said that Fuchs have products that can be used for leak detection, we still have some fluid safe for the longwall (will be interested in products when this runs out), but I am looking at products for hydraulic oil. Does Fuchs have products that can be added to hydraulic oil to identify leaks?

101 On 22 May 2014, Mr Roberts forwarded the email from Mr Ryan of 21 May 2014 internally, stating: “This is back on the radar again and we were advised yesterday of concerns with HP injections for both hydraulic oil and Solcenic”. Mr Pearce responded stating:

Attached is my correspondence with Andrew Esdaile regarding fluorescent dye in Solcenic for leak detection only.

As for the hydraulic oil, the Fluidsafe when used at the correct level adds about [redacted] and we already have this product setup and supply several sites frequently. We can however source other dyes at lower concentrations to significantly reduce this cost however this would create further complexity in our range.

(Emphasis in original.)

102 On 27 May 2014, Mr Roberts sent Mr Michaelson a draft response to Mr Ryan for approval posing two options for hydraulic oil:

1. Hydraulic oil containing Fluid Safe OB which will incur an extra cost of [redacted] per litre

2. Hydraulic oil with dye under investigation

103 On the same day, Mr Michaelson forwarded Mr Roberts’ draft email to Mr Knight stating:

We are at a cross roads with dye in hydraulic and longwall fluids.

Ulan is asking can we supply a dye for leak detection in the longwall and mineral oil applications.

Ulan are presently using fluid safe on their longwall but want to explore other alternatives.

Initially this fellow introduced fluid safe based on leak detection not HPI.

Craig’s concern is that by not proceeding that this could provide an avenue for Quaker who has not been approached or approached Ulan.

This is a quandary given we have stayed close to Fluid Safe and Wayne Thompson and if we move in this direction that relationship will be irreparably damaged. Thompson believes he has patent coverage of leak detection.

The decision needs to be taken by a director.

Do we proceed and supply dyed longwall fluid and hydraulic oil using a standard dye which has no additional product cost impact or defer to the expensive fluid safe option.

104 Again on the same day, Mr Knight responded stating:

Where we are selling for HPI detection we need to us (sic) FluidSafe. For leak detection only Wayne’s patent cannot hold as other products have been around for many years. Therefore lower cost alternatives can be used for leak detection.

105 On 11 June 2014, Mr Roberts responded to Mr Ryan of Glencore’s email stating:

Fuchs are (sic) currently reviewing and conducting R&D along with QC testing with dyes for both mineral hydraulic oils and longwall fluids.

…

It should be clear at all stages that Fuchs makes no undertakings in relation to the use and monitoring of such products by Ulan Coal Mines and specifically and explicitly rules out any correlation of the use of such products for High pressure injection injuries detection.

106 Also on 11 June 2014, Mr Burns of Oaky Creek (Glencore) requested information from Fuchs on compatibility of FluidSafe with Solcenic 2020. Mr Michaelson responded to Mr Burns’ email stating that Fuchs had “previously supplied Solcenic 2020 with Fluid Safe WB blended into the final delivered product.”

107 On 13 June 2014, lawyers acting for TTAAS and T&T wrote to Whitehaven Coal Ltd, referring to the applications for the Standard Patent and Innovation Patent, and stating:

We hereby advise that the use of any product by you incorporating a fluorescent dye for detecting fluid injection when that product and system has not been supplied by our clients may render you liable to a claim for damages by our clients for the breach of our clients (sic) intellectual property rights.

108 On the same day, lawyers acting for TTAAS and T&T wrote to Anglo Coal Aus Ltd, stating:

Our client has information to indicate that your company amongst others may have been approached by Quaker Chemical seeking to sell you products which they claim incorporate a fluorescent dye which would allow you to detect high pressure fluid injection. It is our clients’ view that the method proposed by Quaker Chemical for detecting such injuries is in breach of our clients’ intellectual property rights as established under its patents.

109 On 16 July 2014, Mr Ryan of Glencore responded to Mr Roberts’ email stating:

As per our discussions Ulan would like to progress as soon as practical adding the leak detection dye (not for fluid injection) to our hydraulic oil and within 2 months for our solcenic.

Could you please provide the technical specs … and procedure for detection etc, so we can assess the level of risk control we will need to implement when we make this change.

110 On 18 July 2014, Mr Pearce sent an email to Glencore titled “Proposed Colour Change to Fuchs Hydraulic oil” which stated:

A couple of months ago we were approached by Ulan underground mine regarding the potential use of dyes in our hydraulic products to assist in leak detection.

The scope of this enquiry encompassed standard mineral oil based hydraulic oil (Renolin B PLUS range) and longwall Hydraulic fluid type HFA (Solcenic 2020).

In response to this request Fuchs proposes to make a modification to the dye that is used in our Renolin B PLUS range. This change will result in a slight change in the colour of the product from an orange/yellow to a crisp yellow as seen in figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Proposed colour vs Existing colour

The total dye concentration in the product is unchanged as this is a simple partial substitution of dye.

The additive pack and base stock in the product have not been altered and as such there is no impact on product performance.

Under the right light and conditions the product will fluoresce enough for leak detection.

Due to the fact that this improvement is cost neutral Fuchs is proposing to make this change across the entire Renolin B PLUS range.

…

I must stipulate that these proposed changes described above are in direct response to the enquiry raised by Ulan Underground for leak detection only.

Under no circumstances does the type of, or concentration of dye in these products make them suitable for HPI detection.

Fuchs is offering to supply products with fluorescing capabilities at no extra cost to Glencore, equipment used to detect the fluid and associated methods cannot be supplied by Fuchs at this stage.

111 On 21 July 2014, David Young of Glencore forward Mr Pearce’s email of 18 July 2014 to Mr Thompson, asking “Is this FluidSafe they are referring too (sic)?”

112 On 28 July 2014, Mr Pearce emailed Mr Thompson requesting that he “provide details as to whether or not the changes proposed by Fuchs is (sic) in breach of your patent.” Mr Thompson responded that “TTAAS’s and T&T’s lawyers had already been instructed (by me) to write to Fuchs setting out our position in relation to its conduct with respect to use of fluorescent additives.”

113 Prior to mid-2014, TTAAS and Fuchs had a working relationship and shared sensitive commercial information.

114 On 30 July 2014, TTAAS and T&T, through Silberstein & Associates, issued a letter of demand to Fuchs alleging patent infringement by supply.

115 Also on 30 July 2014, in response to the letter of demand, Mr Pearce made the following observations in internal Fuchs correspondence:

I have made comment against many of the points. Basically he has made many assumptions that are unfounded. He is trying to link it all to HPI injection which is not the intended use of our product and we have made this clear.

…

Just by scratching the surface it is clear to see that the use of fluorescent dyes for leak detection with a UV light is in the public domain and evidence is readily available. This opens the question why he is not hitting the dye suppliers in Australia?

The easier option is to roll over to TTAAS, this would prevent us from fulfilling the customer’s needs and potentially give opportunity to a competitor. We know that Quaker use a fluorescent dye in their LW fluids and as this was used prior to patent they would not be under the same restrictions that we are. This would give them a point of difference in the market.

Glencore do not support TTAAS at the higher level in the business and it does not look great for Fuchs if we do not stand our ground on an issue where we appear to be in the right. Andrew Esdaile and Garry Horner have both made comments about challenging Wayne Thompson due to the precarious nature of the patent and they are aware that Quaker have done just that. The Quaker challenge is much more contentious being that they introduced a dye for HPI injection.

I am no lawyer but all the conversations I have had internally at Fuchs and abroad (Martyn, Paul etc.) on this matter [redacted]. We have worked in good faith with Wayne Thompson and have supported the implementation of his product into the market, his product however has a purpose and the patent is titled as such “The Method for detecting Fluid Injection in a Patient”. His claims at present are all based on assumptions which I do not believe should prevent us from providing the best products and solutions to our customers possible.

116 On 8 August 2014 Fuchs, through Collison & Co, responded to letter of demand.

117 On 9 October 2014, in response to a request from Mr Russell of Fuchs in relation to an update on FluidSafe, Mr Pearce stated:

Regarding the patent; we continue to recommend and use Fluidsafe WB and Fluidsafe OB where the customer requires a dye specifically for the purpose of high pressure injection detection (HPID).

We have not and have no plans to challenge TTAAS on the validity of his patent in regards to HPID.

We did however challenge the patent validity in regards to fluorescein dyes used for leak detection and are quite comfortable that dyes added to fluids for this application are not covered by the scope of the patent.

…

… my concern with adding another dye is that without concrete test data we cannot be sure that the dye will remain adequately detectible for 24 hours in the human body. Remember that TTAAS claimed that special additives were added to stabilise the dye in the human body, we do not have any evidence to prove or disprove this claim and as we are dealing with a medical process I would be reluctant to assume that the Fluidsafe product is simply straight Fluorescein.

118 On 20 or 22 October 2014, Fuchs met with Broadmeadow (BMA) to discuss fluorescent dye for use in HPFI detection.

119 On 21 November 2014, Mr Pearce sent an internal Fuchs email which stated:

As the concept of changing the dye across the whole Renolin B PLUS hydraulic range seemed to come up against a significant amount of hurdles the decision has now been made to create a stand-alone product, ingeniously named Renolin B 68 LD.

As this will now be a Ulan No.3 specific product we do not need to keep the colour in line with the existing product and as such can remove the previous dye completely and increase the fluorescent dye up to the point where the product is cost neutral.

Please update the R&D brief for this project with the new target outcome, we aim to supply site at the beginning of 2015.

120 Also on 21 November 2014, Austar (Yancoal) provided Fuchs with FluidSafe WB to mix into their emulsion.

121 On 8 December 2014, Appin (BMA) requested information from Fuchs for fluorescent additive.

122 On 12 December 2014, TTAAS and T&T sold its FluidSafe business to Quaker, assigning to Quaker the patents in suit and any right to sue for prior infringement.

123 On 24 February 2015, a Ulan No. 3 document entitled “Change Management” for a change summarised as the “Introduction of dye to Fuchs Solcenic and hydraulic for leak detection” was approved by Mr Gavin Foster and Mr Ryan. The purpose of the change was said to be “A dye is being added to the solcenic and hydraulic fluid by the supply (sic) Fuch (sic), to aid in the dection (sic) of leaks.”

124 On 26 February 2015, Mr Ryan emailed Mr Roberts stating: “The change management is completed as per Grants (sic) Email, it was done both for solcenic and hydraulic oil. One of the action (sic) is to develop a procedure for using the product to detect a leak. What tools you need etc. Can you please provide details so I can put together?”

125 On 3 March 2015, Mr Roberts of Fuchs forwarded to Mr Ryan an email from Mr Pearce, with the subject line “[l]eak detection equipment” and body text as follows:

On the attached image you have the lamp cover for use underground, the torch for surface use and some yellow tinted safety glasses (any make will do).

The torch and glasses can be supplied in a kit with chargers for the torch. The lamp covers where purchased from Wayne Thompson. I have a couple that I can spare Ulan if required.

To detect leaks essentially shine the blue light in the direction of the equipment whilst wearing the glasses and look for the illuminated fluid.

126 On 24 March 2015, Mr Roberts’ weekly report noted in relation to Ulan West (Glencore): “Leak detection dye for Solcenic GM20 for next longwall block”.

127 On 13 May 2015, Mr Pearce emailed Mr Ben Withers and Mr Besley of Glencore stating, in part: “Fluorescein dye offered for leak detection only is a sodium salt of fluorescein. There is no specific data from the supplier however fluorescein dye is classified as biodegradable which indicates that it will rapidly biodegrade in the environment. The quantity used in the final emulsion supplied to site is <0.01% m/m (SDS attached).”

128 On 18 May 2015, Narrabri (Whitehaven Coal) requested pricing on Solcenic with HPFI dye. In an internal email to Robert Fryer of Fuchs about this request Mr Pearce stated: “Quaker supply a HPI dye for Narrabri, this gives them a significant cost advantage as we need to by (sic) the dye from them. I will confirm price of dye and get back to you.”

129 On 21 May 2015, Mr Roberts’ weekly report noted in relation to Ulan No. 3: “SWP for leak detection”.

130 In May 2015, a Fuchs document titled “Business Activity Report” addressed to Mr Pearce from Mr Roberts stated in relation to Ulan No. 3: “6. Leak detection procedure required ASAP.”

131 On 3 June 2015, Newlands (Glencore) requested information from Fuchs on “the UV dye that can be put into emulsion to assist with fluid injection detection.” Mr Pearce responded on 5 June 2015 stating that Fuchs “can supply the product with the dye that claims to assist with HPI” for an additional cost. Mr Pearce also said that “There is (sic) some question marks over this technology including, stability of the dye, maintaining adequate concentration of dye and training in the medical industry” and also that “Fuchs is able to supply a dye for leak detection free of charge in your Solcenic 2 B-W however we do not recommend the use of dye for HPI detection, our advice is always to seek professional medical attention for suspected HPI.”

132 Also on 5 June 2015, Whitehaven Coal requested pricing from Fuchs on longwall fluids with and without dye. Mr Pearce responded with pricing and stating “The dye matter is more complex. We can supply a dye for leak detection only free of charge however the cost of the dye required for HPI injection is extremely expensive and will add an extra [redacted] to the price.” (Emphasis in original.) Mr Pearce also referred to “some question marks over this HPI detection technology” in similar terms as in his other 5 June 2015 email.

133 On 16 June 2015, Ulan No. 3’s leak detection procedure was prepared.

134 On 24 June 2015, Mr Roberts’ weekly report noted in relation to Ulan No. 3: “leak detection products”.

135 On 6 July 2015, Mr Pearce sent an email to Mr Darren Stephens of Ashton (Yancoal) stating “With increased focus on cost savings and minimising leaks across the face we have incorporated a very small amount of fluorescent dye into our GM20 product.”

136 In August 2015, Fuchs commenced supplying Solcenic GM20 D to Ulan No. 3 (Glencore), to Bulga (Glencore) and to Ashton (Yancoal). The supply to Bulga (Glencore) was later described in December 2016 “Updated Sales Data” as having been initiated by “Leak detection promotion”.

137 On 4 August 2015, Kevin Meyer of Broadmeadow (BMA) requested information from Fuchs on “glow additive”. Mr Pearce replied that Fuchs could “provide a glow product for leak detection” and asked “Are you only wishing to use it for leak detection?” and further stated “FYI, I am on site next Thursday week for my routine visit.” Mr Meyer replied “Not so much leak detection but more in regard to high pressure fluid injection detection.” Mr Pearce responded stating:

To achieve the target concentration of 0.015% HPI dye in the emulsion at 2% operating concentration the dye must be supplied in the concentrate at 0.75%.

The dye itself is very expensive and at 0.75% will increase the cost of your longwall fluid from [redacted].

There are however some question marks over this technology including, stability of the dye, maintaining adequate concentration of dye and training in the medical industry.