FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

ALDI Foods Pty Limited as General Partner of ALDI Stores (a Ltd Partnership) v Transport Workers’ Union of Australia [2020] FCA 269

ORDERS

ALDI FOODS PTY LIMITED AS GENERAL PARTNER OF ALDI STORES (A LIMITED PARTNERSHIP) Applicant | ||

AND: | TRANSPORT WORKERS' UNION OF AUSTRALIA Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding is dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

FLICK J:

1 The Transport Workers’ Union of Australia (the “Union”) have long campaigned for action in respect to its concerns about safety and fairness in the road transport industry.

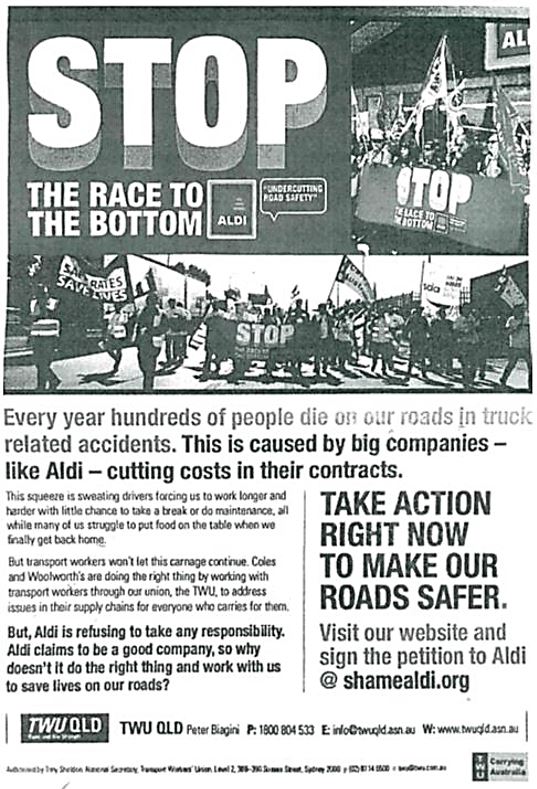

2 The Applicant in the present proceeding, ALDI Foods Pty Limited as General Partner of ALDI stores (a Limited Partnership) (“ALDI”), seems to have attracted the attention of the Union. Simply by way of example, ALDI contends that a pamphlet was distributed by the Union at an ALDI store in the Churchill Centre Mall in Adelaide in June 2017 titled “C’mon ALDI. Do the Right Thing”. By way of further example, in August 2017 the Union issued a media release titled “Enough is Enough: truckies protest Aldi’s squeeze”.

3 Prompted by such action on the part of the Union, in August 2017 ALDI filed in this Court an Originating Application. Amendments followed and at the outset of the hearing commencing in April 2019, ALDI relied upon an Amended Originating Application and an Amended Statement of Claim filed in December 2017. A Defence was filed by the Union in January 2018 and ALDI filed its Reply in February 2018. Leave was then sought and granted in the course of the hearing in May 2019 to file a Further Amended Statement of Claim. When the hearing resumed in October 2019, ALDI sought leave to file a Second Further Amended Statement of Claim that included a reference to s 6(3) of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (“Competition and Consumer Act”). The Union opposed the grant of such leave. A ruling on whether such leave was to be granted was deferred.

4 Attempts to resolve the present dispute between the parties, regrettably, proved unsuccessful.

THE STATUTORY PROVISIONS & THE COMMON LAW TORTS

5 In its Further Amended Statement of Claim, ALDI sought relief founded upon (inter alia) claims that the conduct on the part of the Union constituted breaches of:

section 45D(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act;

section 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act; and

section 31 of the Australian Consumer Law.

ALDI also contended that the Union had committed the common law torts of:

nuisance;

trespass; and

injurious falsehood.

The claims for relief were primarily confined to declaratory and injunctive relief. The claim for damages included a claim for aggravated damages.

6 In its written Outline of Submissions dated 23 October 2019, all claims for relief were abandoned other than those founded upon:

contraventions of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law; and

the tort of injurious falsehood.

7 In respect to the claim under s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, the two principal conclusions that have been reached are that:

the Union is not a trading corporation; and

statements made by the Union were not made in trade or commerce.

To the extent that reliance was sought to be placed upon the extended operation of the Act as to conduct involving “the use of postal, telegraphic or telephonic services”, it has been concluded that:

reliance upon the extended operation of the Act should have been expressly pleaded, but ALDI otherwise did enough to alert the Union that it intended to invoke the extended operation of s 18; and

if this conclusion is erroneous, leave to amend should, in any event, be granted to place reliance upon that provision.

Although it has proved unnecessary to resolve whether any of the representations as pleaded were false or misleading or likely to mislead or deceive for the purposes of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, it would have been concluded that:

all representations – other than the 2nd representation – were at least “likely to mislead…”.

In respect to the claim for injurious falsehood, the claim fails either because:

ALDI has not made out that the statements relied upon were malicious; and/or

ALDI concedes that it has suffered no actual loss or damage by reason of the making of either statement.

8 It has thus been concluded that both causes of action fail and that the proceeding should be dismissed.

The Australian Consumer Law – trading corporations

9 Section 18 is found within Chapter 2 of the Australian Consumer Law. Section 131 of the Competition and Consumer Act provides in respect to (inter alia) s 18 that it “applies as a law of the Commonwealth to the conduct of corporations…”. Section 4(1) of the Competition and Consumer Act, in turn, defines a “corporation” as, relevantly, a body corporate that is “a trading corporation formed within the limits of Australia…”. Section 6(3) provides for an “extended operation” of a number of provisions, including s 18 and provides, in relevant part, as follows:

In addition to the effect that this Act … has as provided by another subsection of this section, the provisions of Parts 2-1, 2-2 … of the Australian Consumer Law have, by force of this subsection, the effect they would have if:

(a) those provisions (other than section 33 and 155 of the Australian Consumer Law) were, by express provision, confined in their operation to engaging in conduct to the extent to which the conduct involves the use of postal, telegraphic or telephonic services or takes place in a radio or television broadcast; and

(b) a reference in the provisions of Part XI to a corporation included a reference to a person not being a corporation.

The expression “telephonic services” is not defined but has the same meaning as the same phrase in s 51(v) of the Constitution: Seafolly Pty Ltd v Madden [2012] FCA 1346 at [78], (2012) 297 ALR 337 at 359 per Tracey J (on appeal: Madden v Seafolly Pty Ltd (No 2) [2014] FCAFC 49). The phrase includes the use of the internet: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Jutsen (No 3) [2011] FCA 1352 at [100], (2011) 206 FCR 264 at 287 per Nicholas J; Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Homeopathy Plus! Australia Pty Ltd [2014] FCA 1412 at [111], (2014) 146 ALD 278 at 303 per Perry J.

10 The phrase “trading corporation” is not a term of art: R v The Judges of the Federal Court of Australia; Ex parte Western Australian National Football League (1979) 143 CLR 190 at 219 per Stephen J and at 233 per Mason J (“The Judges of the Federal Court”). Mason J concluded that a “trading corporation” is “[e]ssentially … a description or label given to a corporation when its trading activities form a sufficiently significant proportion of its overall activities as to merit its description as a trading corporation”: (1978) 143 CLR at 233. His Honour went on to observe that whether the “trading activities of a particular corporation are sufficient to warrant its being characterized as a trading corporation is very much a question of fact and degree”: (1978) 143 CLR at 234. Incorporated football clubs were there held to be trading corporations. Although their central activity was the promotion of Australian Rules Football, they nevertheless also carried on essentially commercial activities. “Trading” remained a “substantial corporate activity”. Barwick CJ relevantly concluded (at 208):

I remain of the firm conviction that for constitutional purposes a corporation formed within the limits of Australia will satisfy the description “trading corporation” if trading is a substantial corporate activity. Its activities rather than the purpose of its incorporation will designate its relevant character. But so to say assumes that such trading activities are within its corporate powers, actual or imputed. It is the corporation which satisfies the description which is the subject matter of the power. Thus its corporate capacity or incapacity cannot be ignored. But once it is found that trading is a substantial and not a merely peripheral activity not forbidden by the organic rules of the corporation, the conclusion that the corporation is a trading corporation is open.

In rejecting an argument that they were merely conducting a sport and therefore could not be regarded as being in trade, Barwick CJ further concluded (at 211):

In my opinion, the presentation of a football match as a commercial venture for profit to the promoting body is an activity of trade. …

Here, however, the commercial activity of the Club is not limited to the promotion of football matches. A diverse range of advertising rights, television rights and sundry other rights are sold in connexion with the presentation of the matches. The detail of these activities may be read in the reasons for judgment of other Justices. Further, large sums are at times demanded by the Club for the release of players by clearance to play with other clubs: in general, no part of these moneys is paid to the player concerned.

These activities, essentially commercial in nature, emphasize the trading quality of the manner in which the Club and the League promote Australian Rules Football.

Justice Mason similarly observed (at 235):

The prosecutors' case is that the trading activities of the two Leagues are incidental to their main objects which are the promotion and encouragement of the sport as a recreation. This to my mind is an inversion of the true position. To me it seems that the sport is promoted and encouraged as a means of ensuring the receipt of the large financial returns which are associated with it. The financial revenue of the Leagues is so great and the commercial means by which it is achieved so varied that I have no hesitation in concluding that trading constitutes their principal activity. In saying this I treat all their activities which I have listed and which produce revenue as trading activities. I do not limit the concept of trading to buying and selling at a profit; it extends to business activities carried on with a view to earning revenue.

Justice Jacobs agreed with Mason J. Justice Murphy (at 239) concluded that “[a] trading corporation may also be a sporting, religious or governmental body”. His Honour there went on to say that “[a]s long as the trading is not insubstantial, the fact that trading is incidental to other activities does not prevent it being a trading corporation”.

The Australian Consumer Law – misleading or deceptive conduct

11 Section 18(1) of the Australian Consumer Law provides as follows:

A person must not, in trade or commerce, engage in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive.

12 Section 18 of the current Australian Consumer Law may be most immediately traced back to ss 52 and 53 of the now-repealed Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth) (“Trade Practices Act”). Sections 52 and 53 were found within Pt V of the Trade Practices Act, headed “Consumer protection”. Section 52 was directed to misleading or deceptive conduct; s 53 was directed to false or misleading representations. They were “provisions designed to protect members of the public who [were] consumers of goods and services from unfair trading practices”: Mark Foys Pty Ltd v TVSN (Pacific) Ltd [2000] FCA 1626 at [38], (2000) 104 FCR 61 at 72 per Beaumont, Tamberlin and Emmett JJ (citing Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 (“Hornsby Building Information Centre”)). They were not provisions specifically designed to protect traders, although the operation of those provisions may incidentally have that effect. As stated by Barwick CJ, with whom Aickin J agreed, in Hornsby Building Information Centre (at 220):

Section 52 is concerned with conduct which is deceptive of members of the public in their capacity as consumers of goods or services: it is not concerned merely with the protection of the reputation or goodwill of competitors in trade or commerce.

13 For the purposes of s 52, conduct was held to be “misleading or deceptive” if it induced or was capable of inducing error: Parkdale Custom Built Furniture Pty Ltd v Puxu Pty Ltd (1982) 149 CLR 191 at 198. Gibbs CJ there further observed that “[t]he words ‘likely to mislead or deceive’ … add little to the section; at most they make it clear that it is unnecessary to prove that the conduct in question actually deceived or misled anyone”. In summarising some of the matters to be established and the manner in which those matters could be proved, Wilcox, Heerey and RD Nicholson JJ in Domain Names Australia Pty Ltd v .au Domain Administration Ltd [2004] FCAFC 247, (2004) 139 FCR 215 at 220 observed in relevant part:

[17] It has long been established that:

• When the question is whether conduct has been likely to mislead or deceive it is unnecessary to prove anyone was actually misled or deceived …

• Evidence of actual misleading or deception is admissible, and may be persuasive, but is not essential …

• The test is objective and the Court must determine the question for itself …

• Conduct is likely to mislead or deceive if that is a real or not remote possibility, regardless of whether it is less or more than 50% …

[18] The likelihood of recipients of a representation being misled or deceived is not a matter to be proved by evidence (testimony, documents or things), or by judicial notice or its statutory equivalent … The existence or otherwise of such a likelihood is a jury question for the trier of fact …

(citations omitted)

It is not necessary to prove an intention to mislead or deceive, but proof of such an intention “may be used to support an inference that the intent was effectuated”: cf. Interlego AG v Croner Trading Pty Ltd (1992) 39 FCR 348 at 394 per Gummow J.

14 A statement may be misleading or deceptive notwithstanding the fact that it is literally true: Hornsby Building Information Centre (1978) 140 CLR at 227 per Stephen J. There in question was whether the Australian Industrial Court was correct in granting the Sydney Building Information Centre an interim injunction restraining Hornsby Building Information Centre from using any name including the words “building information centre”. In reversing the decision of the Industrial Court, Stephen J (with whom Jacobs J agreed) relevantly observed:

… No doubt the meaning of the statutory prohibition which s. 52(1) enunciates must be gained from the terms of the sub-section itself; but nothing in those terms suggests that a statement made which is literally true, i.e. that the centre at Hornsby is conducted by Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty. Ltd. may not at the same time be misleading and deceptive. It clearly may be. To announce an opera as one in which a named and famous prima donna will appear and then to produce an unknown young lady bearing by chance that name will clearly be to mislead and deceive. The announcement would be literally true, but none the less deceptive, and this because it conveyed to others something more than the literal meaning which the words spelled out.

His Honour continued (at 228):

… If the consequence is deception, that suffices to make the conduct deceptive. Section 52(1) creates no offence, it only prescribes a course of conduct deviation from which may result in an order of the court, made under s. 80 of the Act, forbidding further deviation in the future. The section should be understood as meaning precisely what it says and as involving no questions of intent upon the part of the corporation whose conduct is in question.

When, as in s. 52(1), the focus is upon the misleading of others rather than upon the injury to a competitor, it becomes of particular importance to identify the respect in which there is said to be any misleading or deception. The particular feature of the Hornsby Centre's conduct of which the Sydney Centre complains as being misleading and deceptive is not simply the use of its corporate name, so similar in part to its own name, but rather that by that use others are led to believe that the Hornsby Centre is a branch of, or is otherwise associated with, the Sydney Centre.

15 These statements of general principle made in relation to the former s 52 of the Trade Practice Act apply equally to the manner in which the current s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law applies.

16 Within the more specific context of industrial law, it may be doubted whether s 52 – or s 18 as it now is – applies to conduct pursued in an existing employment relationship: cf. Westpac Banking Corporation v Wittenberg [2016] FCAFC 33, (2016) 242 FCR 505 at 538-539. Buchanan J there observed:

[181] Section 52 of the TP Act does not refer, in terms, to conduct in an employment relationship either. Its operation does depend on a connection with trade and commerce.

…

[186] … In my respectful view, it is clear from the earlier part of the judgment that matters arising within an existing employment relationship are unlikely to meet the requirements for the engagement of s 52.

Justice White did not express a concluded view: [2016] FCAFC 33 at [346]-[347], (2016) 242 FCR at 565. See also: Australian Education Union v Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology [2018] FCA 1985 at [49] to [51] per Wheelahan J.

Sections 18 – in trade or commerce

17 Section 18 requires that the impugned conduct engaged in be in “in trade or commerce”.

18 The terms “trade” and “commerce” are also not terms of art but are words “of common knowledge of the widest import”: Concrete Constructions (NSW) Pty Ltd v Nelson (1990) 169 CLR 594 at 602 (“Concrete Constructions”). When considering s 52 of the Trade Practices Act , Mason CJ, Deane, Dawson and Gaudron JJ there observed:

It is well established that the words “trade” and “commerce”, when used in the context of s. 51(i) of the Constitution, are not terms of art but are terms of common knowledge of the widest import. The same may be said of those words as used in s. 52(1) of the Act. Indeed, in the light of the provisions of s. 6(2) of the Act which give an extended operation to s. 52 and which clearly use the words “trade” and “commerce” in the sense which the words bear in s. 51(i) of the Constitution, it would be difficult to maintain that those words were used in s. 52 with some different meaning. The real problem involved in the construction of s. 52 of the Act does not, however, spring from the use of the words “trade or commerce”. It arises from the requirement that the conduct to which the section refers be “in” trade or commerce ...

Their Honours there went on as follows, to state that the phrase could have either of two potential meanings at 602-603:

The phrase “in trade or commerce” in s. 52 has a restrictive operation. It qualifies the prohibition against engaging in conduct of the specified kind. As a matter of language, a prohibition against engaging in conduct “in trade or commerce” can be construed as encompassing conduct in the course of the myriad of activities which are not, of their nature, of a trading or commercial character but which are undertaken in the course of, or as incidental to, the carrying on of an overall trading or commercial business. If the words “in trade or commerce” in s. 52 are construed in that sense, the provisions of the section would extend, for example, to a case where the misleading or deceptive conduct was a failure by a driver to give the correct handsignal when driving a truck in the course of a corporation’s haulage business.... Alternatively, the reference to conduct “in trade or commerce” in s. 52 can be construed as referring only to conduct which is itself an aspect or element of activities or transactions which, of their nature, bear a trading or commercial character. So construed, to borrow and adapt words used by Dixon J. in a different context in Bank of N.S.W v. The Commonwealth [(1948) 76 CLR 1 at 381], the words “in trade or commerce” refer to “the central conception” of trade or commerce and not to the “immense field of activities” in which corporations may engage in the course of, or for the purposes of, carrying on some overall trading or commercial business.

Their Honours resolved as follows this choice in favour of the narrower construction at 603-604:

As a matter of mere language, the arguments favouring and militating against these alternative constructions of s. 52 are fairly evenly balanced. The scope of the prohibition imposed by s. 52 is, however, governed not only by “the terms in which it is created” but by “the context in which it is found” … In that regard, it is of particular significance that the words “trade” and “commerce” have “about them a chameleon-like hue, readily adapting themselves to their surroundings” … Section 52(2) precludes limiting the scope of s. 52(1) by implication drawn from the contents of other provisions of Pt V. Nonetheless, when the section is read in the context provided by other features of the Act, which is “An Act relating to certain Trade Practices”, the narrower (i.e. the second) of the alternative constructions of the requirement “in trade or commerce” is the preferable one. Indeed, in the context of Pt V of the Act with its heading “Consumer Protection”, it is plain that s. 52 was not intended to extend to all conduct, regardless of its nature, in which a corporation might engage in the course of, or for the purposes of, its overall trading or commercial business. Put differently, the section was not intended to impose, by a side-wind, an overlay of Commonwealth law upon every field of legislative control into which a corporation might stray for the purposes of, or in connection with, carrying on its trading or commercial activities. What the section is concerned with is the conduct of a corporation towards persons, be they consumers or not, with whom it (or those whose interests it represents or is seeking to promote) has or may have dealings in the course of those activities or transactions which, of their nature, bear a trading or commercial character.

Justice Toohey there also concluded at 614:

… the preposition “in” clearly operates by way of limitation. The question is not whether the conduct engaged in was in connexion with trade or commerce or in relation to trade or commerce. It must have been in trade or commerce. While there are dangers in seeking for the meaning of an expression through the substitution of another, the phrase “as part of trade or commerce” does, I think, come close to what is intended.

19 The same approach to the construction of s 52 remains apposite to the construction of the like phrase in s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law: Murphy v Victoria [2014] VSCA 238 at [88]-[92], (2014) 289 FLR 337 at 366-368 per Nettle AP, Santamaria and Beach JJA. The conclusions expressed in Concrete Constructions as to the “restrictive operation” of s 52 have been endorsed by Judges of this Court in a variety of different legal contexts: e.g., Zaghloul v Woodside Energy Ltd (No 7) [2019] FCA 818 at [116] to [118] per McKerracher J.

Industrial campaigns

20 The making of statements having an overtly political or industrial message are “likely to fall outside” the phrase “trade or commerce”: National Roads and Motorists’ Association Limited v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union [2019] FCA 1491 at [134] per Griffiths J (“NMRA v CFMMEU”). In that case the NRMA were contending that statements that had been made by the Union amounted to a number of contraventions, including a contention that the statements were misleading or deceptive. The industrial dispute which gave rise to the litigation related to the wages and conditions of employees of the My Fast Ferry business. It was in that context that his Honour concluded (without alteration):

[135] It was properly acknowledged by Mr Cobden SC that there is no precedent which establishes that the conduct of a trade union or its members in campaigning for improved wages or conditions of employment constitutes conduct “in trade or commerce”. Conduct in the course of an existing employment relationship is unlikely to constitute conduct “in trade or commerce” even where it is the conduct of the parties to the relationship itself (see, for example, Westpac Banking Corporation v Wittenberg [2016] FCAFC 33; 242 FCR 505). Similarly, I consider that statements by an employer to its employees in the context of a proposed enterprise agreement will not generally constitute conduct “in trade or commerce”. By analogy, representations made by a trade union in the context of an industrial campaign in relation to the existing conditions of employment of employees will generally fall outside conduct that is “in trade or commerce”.

[136] Another important matter to bear in mind is that the enquiry must remain focussed on the particular conduct which is said to be misleading or deceptive. As Hayne J observed in Google Inc v Australian Competition and Consumer Commissioner [2013] HCA 1; 249 CLR 435 at [89] (emphasis in original):

Section 52 and the identification of the impugned conduct

The generality with which s 52 was expressed should not obscure one fundamental point. The section prohibited engaging in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive. It is, therefore, always necessary to begin consideration of the application of the section by identifying the conduct that is said to meet the statutory description “misleading or deceptive or ... likely to mislead or deceive”. The first question for consideration is always: “What did the alleged contravener do (or not do)?” It is only after identifying the conduct that is impugned that one can go on to consider separately whether that conduct is misleading or deceptive or likely to be so.

[137] In the present case, the impugned conduct is the conduct identified by the NRMA as giving rise to the representations which it says are misleading or deceptive …

[138] The conduct and representations the subject of complaint by the NRMA are, on their face and in their proper context, part of an industrial and incidental political campaign (noting the role of the NSW Government … and the correspondence which was in evidence between the MUA and the NSW Government concerning the dispute) aimed at securing permanent employment, achieving wage outcomes consistent with industry rates and recouping underpayments for employees. The conduct complained of has no trading or commercial character and is not directed at any person with whom the MUA has, or potentially has, any trading or commercial relationship.

[139] The substance and content of the communications subject of the proceedings are overtly industrial and/or political in substance and purpose. The communications or publications all directly concern the MUA’s views as to the fairness of the wages or conditions of employment of employees working on the My Fast Ferry service, including whether the rates of pay are adequate and the insecure nature of the employment. For example, each of the Pamphlets contains the following words encapsulating the campaign:

NRMA AND MANLY FAST FERRY

Its time to negotiate a fair deal with your workers.

Don’t let wages sink to the bottom of Sydney Harbour.

[140] The MUA is not a commercial business and is not engaged in trading activities in representing its members. The Rules of the CFMMEU set out the objects of the union which concentrate on regulating and protecting the wages and conditions of members, regulating the relations between members and employers and fostering the best interests of members.

[141] It is not sufficient that some or even most of the communications relate to or concern the business of the NRMA or Noorton. The conduct must itself be undertaken in trade or commerce and have a trading or commercial character.

(emphasis in original)

21 His Honour at para [133] also cited with approval the following observations of Finn J in Village Building Co Ltd v Canberra International Airport Pty Ltd [2004] FCA 133, (2004) 134 FCR 422 at 438-439 (“Canberra International Airport”):

[61] The representations in question were all made in the context of a planning application having been made to rezone Tralee — an application which CIA openly and repeatedly opposed. Its opposition was consistent with its own business interests and took the form of community consultation and representation for the purpose of informing and influencing public, political and governmental opinion. By virtue of the provisions of the Airports Act (and especially s 71), CIA had a necessary and ongoing interest in aircraft noise and its incidence. It sought to engage community interest not only in the subject of noise exposure as a matter of public concern but also in its specific opposition to the Tralee development. In both respects it was engaging in what properly should be described as political activity, but especially so in relation to the latter. The rezoning application highlighted both conflicting private interests and conflicting public interests. Those conflicts could only be resolved by governmental action. In seeking, directly or indirectly, to contrive or influence outcomes by representations made in public debate, or in the processes of informing the public, CIA was engaging in activities of a political, not of a commercial or trading, character. And this was not the less so because its activities were informed by a degree of self-interest. Altruism is often a stranger to political action.

These observations were made in the context where the Village Building Company had alleged that Civil International Airports had contravened s 52 of the former Trade Practices Act in respect to representations made as to noise forecasts or projected flight-paths. Finn J dismissed the proceeding. That conclusion was reached notwithstanding the commercial interests being pursued by Civil International Airports to protect its business. His Honour thus immediately continued on to further conclude:

[62] It is notable that the impugned representations were not made in circumstances in which it could properly be said that CIA was promoting, directly or indirectly, the services provided by the airport. It was, nonetheless, acting to protect its business. As I earlier indicated, action so taken is not for that reason alone in trade or commerce. It would be surprising if the legislature had intended the contrary to be the case in the Trade Practices Act. Corporations engage directly and indirectly in public and political debate on a myriad of matters that do or might impact actually or prospectively on their own interests. While all such debate will not be beyond the reach of s 52 of the Trade Practices Act: …; much will be as it will not be directed at consumers (actual or potential), or will not be an incident of an activity which bears a trading or commercial character.

[63] What Village is seeking to do in this proceeding is to have imposed on CIA “by a side-wind”: …; a form of legislative control in circumstances in which s 52 has no role to play. One may desire conduct in public and political debate to be not misleading or deceptive. Section 52 is not designed to secure that state of affairs. In saying this I express no view on whether or not CIA’s conduct was misleading or deceptive.

[64] I find that the conduct impugned in … the Further Amended Statement of Claim was not engaged in trade or commerce.

See also: Roo Roofing Pty Ltd v Commonwealth of Australia [2019] VSC 331 at [633] to [634] per Dixon J.

22 Concurrence is expressed with the views expressed by Griffiths J in NMRA v CFMMEU and by Finn J in Canberra International Airport.

Injurious falsehood

23 The tort of “injurious falsehood”, it has been said, has “undergone various changes of name” from “slander of title” through to “slander of goods”: Law of Torts at para [23.2] (5th ed., 2013).

24 In Palmer Bruyn & Parker Pty Limited v Parsons [2001] HCA 69, (2001) 208 CLR 388 at 404 (“Palmer Bruyn & Parker v Parsons”) Gummow J summarised the elements of the tort as follows:

[52] The elements of the action for injurious falsehood usually are expressed in terms which derive from Bowen LJ’s judgment in Ratcliffe v Evans [[1892] 2 QB 524 at 527-528] … Thus, generally, it is said that an action for injurious falsehood has four elements…: (1) a false statement of or concerning the plaintiff’s goods or business; (2) publication of that statement by the defendant to a third person; (3) malice on the part of the defendant; and (4) proof by the plaintiff of actual damage (which may include a general loss of business) suffered as a result of the statement.

This summary has been subsequently endorsed: e.g., Murdoch University v Gooding [2018] WASC 372 at [37] per Quinlan CJ; Ferguson v State of South Australia [2018] SASC 90 at [28] per Stanley J; Capilano Honey Limited v Mulvany [2018] VSC 672 at [68] per Dixon J; NMRA v CFMMEU [2019] FCA 1491 at [65] per Griffiths J; Giles v Jeffrey [2019] VSC 562 at [166] per Daly AsJ. See also: Heydon, Economic Torts at 81-86 (2nd ed., 1978).

25 When considering the appropriateness of injunctive relief to restrain a threatened injurious falsehood, McCallum J (as her Honour then was) in Neville Mahon v Mach 1 Financial Services Pty Ltd [2012] NSWSC 651 at [15] to [22], (2012) 96 IPR 547 at 549-550 (“Mahon v Mach 1”), granted a final injunction in circumstances where there was no proof of actual damage, but “on the strength of the probability that loss would occur if the injunction were not granted”. Her Honour there also referred to AMI Australia Holdings Pty Ltd v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Ltd [2010] NSWSC 1395, where Brereton J (as his Honour then was) found that “[t]he requirement for ‘actual damage’ does not, however, preclude the grant of injunctive relief to restrain a threatened publication, in which circumstance it will suffice to establish a reasonable probability, as opposed to the actual incurring, of such damage”.

THE BACKGROUND FACTS

26 The conduct engaged in by the Union, being conduct said to be directed to promote safety in road transport, is to be understood by reference to (inter alia):

the manner in which ALDI sought to establish itself in the Australian market through efficiencies;

the contracts pursuant to which goods were delivered by road; and

the policies implemented by ALDI in an attempt to ensure compliance by its drivers with all legal requirements and to ensure compliance with health and safety standards.

Competitive advantage through efficiency

27 ALDI projects itself as a retail store with a highly efficient competitive pricing strategy.

28 One publication by ALDI which was accepted by the Managing Director Corporate Logistics Services of ALDI, Mr Damien Scheidel, as an accurate statement of this strategy, starts with the statement that the “food retail industry is a highly competitive market” and continues as follows:

Since opening its first store in 1913, Aldi has established itself as a reputable retailer operating international markets including Germany, Australia and the U.S. Aldi has over 7,000 stores worldwide. What distinguishes Aldi from its competitors is its competitive pricing strategy without reducing the quality of its products. In fact, in some cases Aldi’s products are 30% cheaper than those offered by its competitors. Aldi can do this because the business operates so efficiently. Efficiency is the relationship between inputs and corresponding outputs. For Aldi operating efficiently involves reducing costs in all areas of the business. Some of the key areas where Aldi is able to minimise costs are by saving time, space, effort and energy. Aldi’s approach to doing this is to run its business around the principles of lean thinking.

Aldi has a no-nonsense approach to running its business. Whereas other food retailers have elaborate displays, additional services and promotions that draw customers into the business, Aldi’s core purpose is to ‘provide value and quality to our customers by being fair and efficient in all we do’. Everything Aldi does is focused around giving its customers value for money.

Through being efficient and cutting costs Aldi can then invest profits back into the business. They can then be used to further meet its business objectives for growth. Efficiency is not something that is achieved overnight. Lean thinking is a continuous process that constantly enables Aldi to improve the way in which it meets its business objectives. This enables Aldi to develop an ambitious investment programme to develop new properties and suppliers as well as to provide benefits for employees.

(emphasis in original)

That publication also goes on to outline ALDI’s “lean production”, which it describes as “simply … getting more for less”. The concept of “lean production” is said to be “based on a number of efficiency concepts”, including “[j]ust in time production” whereby “materials are received just as they are needed, eliminating the need to maintain large stock levels…”. The publication later expands upon this concept as follows:

JIT

Aldi uses a just-in-time approach to store management by only holding the stock that it needs. Stock is expensive. The company therefore only buys the stock required at any given time. When stock levels are reduced an organisations working capital is improved. In other words, Aldi is not tying up too much investment in stock that is then going to be held for a long period of time before it is sold to generate income. It also means Aldi does not pay for large warehouses to store stock or pay for additional staff to monitor warehouse stock.

From the moment stock arrives at an Aldi store everything is focused on reducing the cost of holding and managing the stock. For example, products are delivered in display ready cases. Once the top of the case is removed it can simply be lifted onto a shelf for display to customers. Units of 12, 24 or more can be handled easily and quickly merchandised. It means that individual units are not picked and lined up on shelves. In fact some products are sold in store from a pallet. This is a platform for large loads that can be brought mechanically into a store. This is an efficient way of getting a large volume of products into the shop very quickly.

(emphasis in original and without alteration)

29 ALDI is also, self-evidently, in competition with other retailers including Coles and Woolworths. One way in which ALDI seeks to address this competition was outlined as follows in an article published in the Australian Financial Review on 15 May 2017:

Aldi keeps pressure on Coles, Woolworths by cutting prices

German retailing giant Aldi is keeping up pressure on Coles and Woolworths by investing more than $75 million in cutting grocery prices as it pushes for another year of double-digit sales growth.

Aldi Australia chief executive Tom Daunt said the discount supermarket chain would “always” remain the price leader, despite strong competition from Australia’s supermarket chains.

“The fact is looking at any objective data Aldi always has been and always will remain the price leader,” Mr Daunt said. “This is our core competitive advantage and that is something we can’t give up.”

Woolworths has invested $1 billion into price and services in 18 months, while Coles ploughed $50 million into lower prices for groceries in the December quarter and is likely to repeat in the June quarter.

Mr Daunt said Aldi in the first quarter of the year has continued to reduce prices and on an annualised cost has spent $75 million reducing grocery prices.

Aldi’s trucking contracts

30 ALDI has a standard contract it employs when securing the delivery of products to its Distribution Centres.

31 In addition to the terms as to product requirement and packaging, its terms also address delivery requirements.

32 Clause 9 provides in part as follows:

Delivery

9. The Supplier shall deliver the Products to ALDI stores or its representatives on the date specified (and on such other dates as ALDI stores may from time to time notify) and to the place specified in the relevant Product Contract and/or Purchase Order (or such other place as shall from time to time be notified by ALDI Stores), in accordance with the relevant Delivery Guidelines specified by ALDI Stores in respect of the relevant Products, …

That clause goes on to state that “[t]ime is of the essence in relation to delivery of any Product…”.

33 Clause 11 also addresses in the following terms the rights reserved by ALDI to reject products:

ALDI Store’s right to reject Products and other rights and remedies

11. If all Products ordered are not or will not be delivered in accordance with clause 9 and the relevant part of the Delivery Guidelines specified by ALDI Stores to apply to the relevant Products, or the Supplier advises ALDI Stores that it is not or will not be able to perform all or any of its obligations under these Terms, or ALDI Stores believes on reasonable grounds that there will be a delay in delivery, a failure to comply with any Specification, a failure to comply with applicable laws or any other failure to comply with all or any of the Supplier’s obligations under these Terms, then in addition to and without limiting any other rights or remedies of ALDI Stores, including any right to claim for damages for breach of this clause (including under the indemnity in clause 26), ALDI Stores shall be entitled to:

(a) reject Products delivered late and immediately cancel an order and terminate the contract in respect of Products undelivered;

(b) immediately cancel the entire order for the Products and contract for such Products in which case ALDI Stores has no obligation to accept delivery of or pay for the Products whose order has been cancelled and may require the Supplier to collect any Products forming part of the order which have already been received, at the Supplier’s risk and expense, and shall be entitled to a refund for any such Products already paid; and/or

(c) purchase alternative supplies of the Products, and the Supplier will be liable for any additional costs incurred by ALDI Stores in respect of such alternative supplies.

34 The “Delivery Guidelines” referred to in cl 9 go on to provide as follows for delivery in accordance with 10 minute time slots:

Delivery Times

Delivery times and arrangements are set out in APPENDIX 1.

Note: ALDI Stores reserves the right to change delivery windows and specify delivery slots, subject to advance notification to Suppliers, and taking into account the requirements of the Heavy Vehicle Driver Fatigue Legislation.

• Vehicles that arrive more than 10 minutes past the start of the nominated delivery slot may not be received. A new delivery slot may be provided (at the discretion of ALDI Stores).

Appendix 1 further addresses the requirement for delivery in accordance with pre-determined time-slots as follows:

Note:

• Suppliers must contact ALDI Stores and arrange a delivery slot in advance of delivery for all Products, including Special Buys (no more than two weeks prior to the Scheduled delivery date). The relevant Purchase Order / Product Contract will contain the contact details for each regional Goods In department to allow the booking of delivery slots.

• In certain circumstances it is possible there are not time slots available for the due day of delivery for a PO. If it is practical to book the delivery on the next available day this should be done. If there is a reason the delivery should arrive on a date which there is no available slots there is an option ‘Request Date only’ within the C3 program. The use of this option will send a request through to ALDI to determine if an additional slot can be made available. ALDI can accept or reject the request and an email advising the outcome will be sent.

• Drivers must arrive no later than 10 minutes after the start of the nominated delivery slot. Trucks must be unloaded and removed from the port door by the close of the delivery slot.

• It is a condition of the supply contract that the Supplier observes the Heavy Vehicle Driver Fatigue Legislation in selecting a suitable delivery slot, and ensures that delivery drivers have sufficient time to drive required distances and take required rest breaks.

• Suppliers must notify ALDI Stores if drivers are delayed and will not arrive in time to complete unloading by close of the delivery slot. A new delivery slot will be arranged, to minimise delays to delivery drivers.

• Without prior arrangements, delivery slots must be adhered to.

• ALDI Stores reserves the right to change delivery windows and specify delivery slots, subject to advance notification to Suppliers, and taking into account the requirements of the Heavy Vehicle Driver Fatigue Legislation.

Aldi’s transport policies – its employees

35 ALDI takes some steps to ensure that the drivers it employs comply with all legal requirements and comply with health and safety standards.

36 As to the former, reference may be made to cl 9 of the above “Delivery Guidelines” and the “Note” to Appendix 1. Further reference may also be made to ALDI’s Employee Handbook current as at 2017, which provided in part as follows:

TRANSPORT OPERATOR LEGAL REQUIREMENTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES**

Transport Operators must comply with all applicable laws and regulations related to driving. Failure to observe applicable laws and regulations could lead to disciplinary action up to and including summary dismissal. Transport Operators responsibilities include, but are not limited to:

a. Adherence to the driving hour’s regulations (time spent driving and working).

b. Required rest breaks are taken.

c. Driving hours are recorded as required.

d. The vehicle does not exceed mass limits.

e. The vehicle and load do not exceed dimension limits.

f. The load is appropriately restrained.

g. Speed limits are not exceeded.

h. Seatbelts are worn as required by law.

i. The capacity for driving and working is no affected by alcohol or other drugs.

j. Equipment required to be fitted to the vehicle is not tampered with.

37 In addition, ALDI also has a General Transport Policy which applies not only to its own employees but also the “external transport operators”. Part of that Policy addresses fitness for duty and requires (inter alia) the provision of certificates showing that drivers “are fit to drive a heavy vehicle issued by a medical practitioner according to the Assessing Fitness to Drive by Austroads…”. For those drivers under 49 years of age, such certificates are required once every three years; for those aged 50 or over, such certificates are to be provided annually. Annexed to the Policy is a “list of sample fitness for duty questions”, which drivers are “expected to reference … on a daily basis…”.

38 ALDI also has a Napping Policy For Transport Operators. That Policy states in part as follows:

ALDI STORES

NAPPING POLICY FOR TRANSPORT OPERATORS

This Policy is to be read in conjunction with the ALDI Stores Fitness For Work Policy.

The National Transport Commission has confirmed that driver fatigue is a major cause of crashes involving heavy vehicle drivers. Napping is an effective tool to help drivers manage fatigue in the short-term and to maintain alertness. This policy has been developed to ensure safe working practices, employee health and compliance with ALDI’s and our employee’s obligations under occupation health and safety and driver fatigue management legislation.

Impact of Fatigue

Fatigued drivers experience slowed reaction times, reduced attention, memory lapses, lack of awareness, mood changes and a lack of judgment.

…

That Policy goes on to state the causes of fatigue and “fatigue indicators”. It then immediately thereafter goes on to state that “ALDI may require Transport operators to work for up to 14 hours in a shift”. ALDI also has a Transport Responsibilities policy which addresses Fatigue Management System which incorporates (inter alia) provision for an “internal review”.

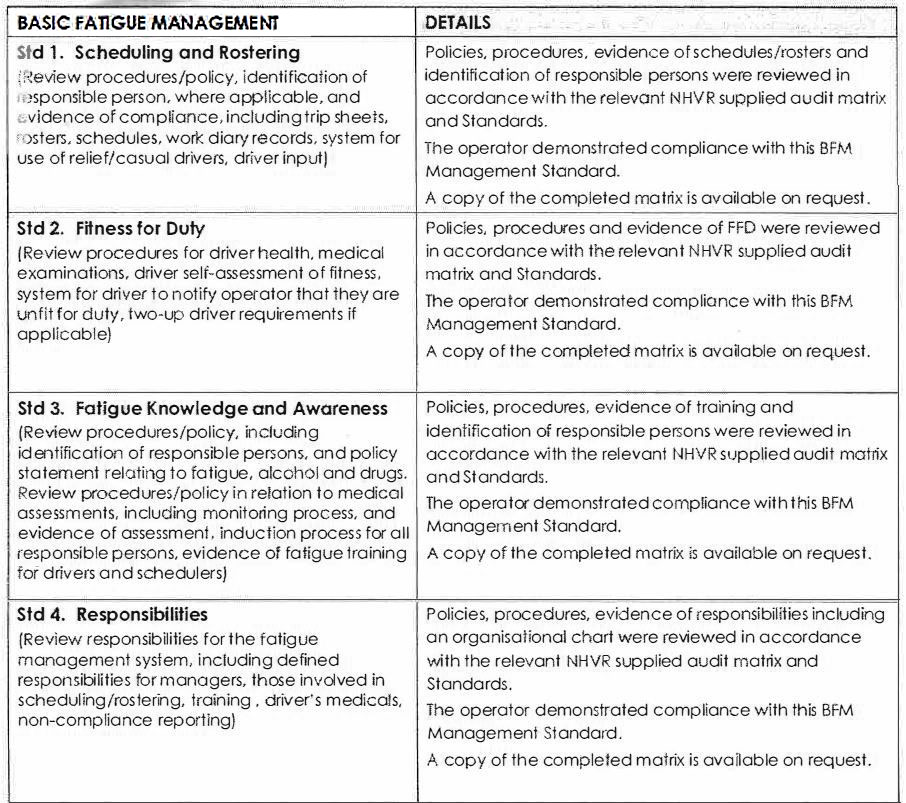

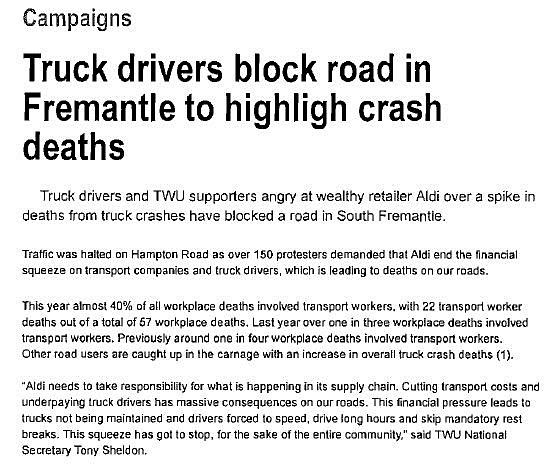

39 ALDI also participates in the National Heavy Vehicle Accreditation Scheme which regulates vehicle maintenance programs. External audits are carried out by authorised auditors and accreditation is for a three year period. The external audit carried out in 2016, and hence current during the 2017 period of present relevance, provides as follows in respect to fatigue management:

THE STATEMENTS & CONDUCT RELIED UPON

40 The Further Amended Statement of Claim makes reference to:

a series of media releases, pamphlets, flyers, a newspaper article and a television interview extending over the period from May 2017 through to November 2017; and

a series of protest actions at a number of ALDI stores and an ALDI distribution centre, being actions conducted at the Churchill Centre Mall in Adelaide on 15 June 2017; the Regency Park Distribution Centre in South Australia on 16 August 2017; and the Mount Druitt ALDI store on 24 August 2017.

Although the particular statements and conduct necessarily have to be considered by reference to the pleadings founded upon this conduct, each should be at least outlined at the outset.

The media releases, etc

41 The conduct said to contain misleading or deceptive statements, or conduct which was likely to mislead or deceive, was contained within a number of media releases, pamphlets and interviews issued by the Union.

42 These statements were said by Senior Counsel for ALDI to be included within the following:

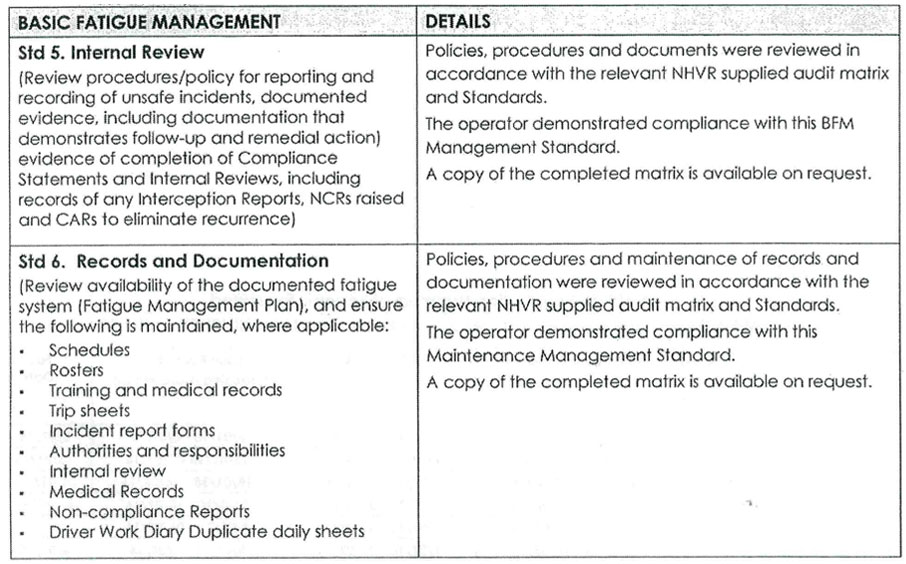

a media release on 16 May 2017 in which it was stated that “[t]ruck drivers and TWU supporters angry at wealthy retailer Aldi over a spike in deaths from truck crashes have blocked a road in South Freemantle”. The media release went on to state that “[t]raffic was halted on Hampton Road as over 150 protesters demanded that Aldi end the financial squeeze on transport companies and truck drivers, which is leading to deaths on our roads…”;

a flyer of an unknown date “found in the store by employees” titled “C’Mon Aldi. Do The Right Thing”. The flyer states that “Multi national corporations at the top of the supply chain, like Aldi, put pressure onto trucking companies and owner drivers to fulfil unsafe deadlines”. The flyer goes on to state “What can be done: Aldi needs to engage with transport workers through the TWU and take responsibility for its supply chain to ensure transport workers are not being unfairly pressured and are being properly compensated…”;

a flyer distributed at Regency Park on 16 August 2017 titled “Stop The Race To The Bottom”. The flyer goes on to state that “Multi national corporations at the top of the supply chain, like Aldi, put pressure onto trucking companies and owner drivers to fulfil unsafe deadlines”. The flyer goes on to further state: “What can be done: Aldi needs to engage with transport workers through the TWU and take responsibility for its supply chain to ensure transport workers are not being unfairly pressured and are being properly compensated…”;

a media release dated 16 August 2017 titled “Enough is enough: truckies protest Aldi’s squeeze”. The media release addresses a protest at the Regent Park store held “to ensure [that] Aldi heard their demands for a safer industry”. The text of the release states (inter alia) that “Aldi is refusing our requests to sit down and talk about the pressure they are putting transport operators and truck drivers under. They are refusing to accept that this pressure is leading to horrific deaths and injuries on our roads”. The release goes on to state that “[t]ransport workers in Aldi’s supply chain are constantly faced with pressure from above, leading to trucks not being maintained, drivers forced to speed, drive long hours and skip mandatory rest breaks ... Aldi last year attempted to pay truck drivers less than their already woefully low rate by misclassifying them in an Enterprise Agreement which, fortunately, the Federal Court struck down”;

an entry on a Facebook page dated 16 August 2017 which repeats the title “Enough is enough: Aldi needs to stop the squeeze… Truck drivers in SA today delivered a strong message to Aldi: stop the pressure on transport companies and drivers that is killing people…”;

a media release dated 24 August 2017 in which it stated that “[o]ver 500 truck drivers and their supporters have protested at an Aldi supermarket at Mt Druitt, Sydney, angry at the wealthy retailer’s refusal to ensure safety in its transport supply chain”. It goes on to state that “[t]he protest follows a Federal Court rejection on Wednesday of Aldi’s bid for an injunction to stop drivers protesting its poor safety practices and stopping them from revealing information about rates and conditions in its supply chain… Aldi must face up to the role they play in creating pressure on transport. Wealthy retailers through their low cost contracts are forcing transport companies and drivers to not maintain vehicles, drive long hours, speed and skip mandatory rest breaks. This pressure is killing people on our roads and leaving families and communities devastated…”;

a media release on 29 August 2017 in which it is stated that the Union has accused ALDI of (without alteration) “attacking free speech by pursing a Federal Court case to stop drivers from protesting over its unsafe practices and to restrict the union from publishing information on the rates and conditions of any transport workers in its supply chain…”. The media release goes on to state that “Aldi is trying to use bullying tactics to silence truck drivers and their supporters in highlighting the problems with safety in the Aldi supply chain…”. The statement went on to recount (without alteration) that “Aldi is separately appealing a Federal Court decision which struck down a bogus enterprise agreement voted on just two members of staff. The agreement denied minimum award rates and classified drivers of large trucks as store workers”;

a flyer left in a trolley after a protest held on 13 October 2017 at ALDI’s Kilburn store. The flyer is again headed “Stop the race to the bottom”. It goes on to state: “Every year hundreds of people die on our roads in truck related accidents. This is caused by big companies – like Aldi – cutting costs in their contracts. This squeeze is sweating drivers forcing us to work longer and harder with little chance to take a break or do maintenance … But transport workers won’t let this carnage continue. Coles and Woolworth’s are doing the right thing by working with transport workers through our union, the TWU, to address issues in their supply chains for everyone who carries for them”;

a flyer distributed at a protest at the ALDI Toombul store on 13 October 2017 again headed “Stop The Race To The Bottom” and again repeating the statement that “Every year hundreds of people die on our roads in truck related accidents. This is caused by big companies – like Aldi – cutting costs in their contracts”;

a flyer distributed at a protest at the ALDI Parramatta store and again headed “Stop The Race To The Bottom”. The flyer goes on to state that “Every year hundreds of people die on our roads in truck related accidents. This is caused by big companies – like Aldi – cutting costs in their contracts”;

an article in the Hobart Mercury (“Mercury”) published on 6 November 2017 stating (inter alia) that “protests were held only after the Federal Court rejected Aldi’s application for an injunction to force drivers from publicly highlighting its poor safety practices”. The article went on to state that “[i]t is appalling that this multinational’s solution to its own flawed attitude to safety was not to clean up the mess, but ask an Australian court to gag hardworking Australians from speaking out. Thankfully that failed”. The article went on to refer to ALDI appealing “a separate Federal Court decision which struck down a bogus enterprise agreement voted on by just two members of staff. The agreement denied minimum award rates and classified drivers of large trucks as store workers…”. That article was written by the secretary of the Victorian and Tasmanian Branch of the Union, Mr John Berger;

another a flyer distributed by protesters on 15 November 2017 at the Carrington store containing a statement that “hundreds of people die on our roads in truck related accidents” caused by “big companies – like Aldi – cutting costs in their contracts” such that “this squeeze is sweating drivers forcing us to work longer and harder with little chance to take a break or do maintenance…”;

a radio interview that took place on 28 February 2018 on 2GB, where Mr Tony Sheldon of the Union was interviewed by Mr Steve Price. In that interview, Mr Sheldon stated that “what’s particularly appalling is that ALDI does have a bad record… and they’re refusing to try to work out solutions”. He referred to ALDI’s direct hire drivers providing “sworn written statements… about excessive hours” and “when complaints are made about fatigue [drivers] are just told to go faster…”. He suggested that ALDI “squeeze[s] so much on price” and that direct hire operations contract companies “unwittingly but also unfortunately… are breaching fatigue hours, not training drivers properly… breaching very fundamental laws within Australia.”. Mr Sheldon stated that “ALDI’s certainly at the top of the list on not trying to deal with problems in their supply chain”. Towards the end of that interview, he went on to threaten “[w]e’re not going to stop. We’re going to keep pushing and I only see this escalating to more action against ALDI until they turn around and say Australian lives count”; and

a television interview on Channel 9 given by Mr Tony Sheldon on 15 November 2017, where he stated that “… we have trucks out there and drivers that are literally time bombs waiting to go off because of the pressure from ALDI” and that “ALDI is refusing whilst they are seeing people being slaughtered in our industry and they are doing nothing about it”.

Each of these publications were annexed to an affidavit affirmed by Mr Viktor Jakupec dated 8 May 2018, the Managing Director of ALDI’s Regency Park Region.

43 In addition, there was also the following publication annexed to another affidavit of Mr Jakupec, namely:

a media release dated 13 October 2017 headed “TWU protests ALDI’s cut-rate contracts putting motorists at risk”. The media release goes on to state: “[g]lobal supermarket giant Aldi is successful because it undercuts the competition. But the cheap groceries would not be possible without Aldi’s low-cost wages… It is the hidden shame of the supermarket wars that truck drivers down Aldi’s supply chain are forced to neglect vehicle maintenance, drive longer than recommended hours, break speed and other road rules and skip mandatory meal breaks… just to make ends meet”.

16 May 2017

44 More needs to be said about the 16 May 2017 publication.

45 On 19 April 2017, Ms McMillan forwarded the following e-mail to Mr Tom Daunt at ALDI (without alteration):

I am writing as the Chief of Campaigns The Transport Workers Union of Australia. We are currently looking to meet with Tom Daunt, or an appropriate person from the transport of logistics team at Aldi Australia. As a Union we think it is important to meet with all of the key stakeholders in the transport industry and discuss where we have common or overlapping interests. A large proportion of our members work in the retail supply chain and based on Aldi’s recent and ongoing expansion plans, we think there would be some benefit in us meeting.

Can you please contact me either at xxxxx.xxxxxxxx@xxx.com.au or on xxxx xxxxxx to discuss a possible meeting and whom it would be appropriate to meet with.

(contact details omitted)

46 ALDI responded on 10 May 2017. The Corporate Logistics Director of ALDI, Mr Adam Maher, wrote on that date to Mr Sheldon as follows:

…I have been provided with your letter to Tom Daunt, the Chief Executive Officer of ALDI Stores, which was received on 9 May 2017.

ALDI takes extremely seriously its responsibilities to ensure the safety of all participants in the supply chain. We participate in the National Heavy Vehicle Accreditation Scheme and our maintenance and fatigue management programs for our fleet and drivers operate in accordance with this Scheme. Arrangements with our suppliers also reflect ALDI’s high expectations in relation to safety.

As Corporate Logistics Director, I have responsibility for ensuring ALDI’s obligations under chain of responsibility and safety legislation are met. I have checked within the organisation and regret to advise that I could find no earlier record of any contact from the TWU about arranging a meeting.

I am available to meet representatives from the TWU to discuss your goals for the transport sector and for you to outline the TWU Safe Rates campaign. My colleague Tim Heron will also attend.

I have forwarded a copy of this letter to Emily McMillan, Chief of Campaigns with my contact details so that a meeting may be arranged at a mutually convenient time.

There was some question as to whether Ms McMillan’s email had been forwarded to the correct address and no “letter to Tom Daunt” was in evidence. But such matters can be left to one side. The Union had sought a meeting and ALDI had responded.

47 This exchange of communications was taking place against the factual backdrop of the Union proceeding to organise the events that took place at ALDI’s Fremantle store on 16 May 2017. A continuation of steps to organise those events, whilst at the same time seeking to organise a meeting with ALDI, was perhaps an understandable course. A request for a meeting had been made, and whilst those steps were continuing, the response of ALDI was unknown. But once ALDI had responded and expressed its agreement to the holding of a meeting, questions arose as to why the Union persisted in its conduct at the Fremantle store.

48 In respect to the events on 16 May 2017, the Union (in addition to the media release on that date) also caused to be distributed a flyer which stated in part as follows:

49 Also on 16 May 2017, Ms Carr, Director of Legal at the Union, wrote to Mr Maher. In part that letter was as follows:

…Thank you for your response. We will be in contact in due course to set up a meeting. Prior to meeting, however, please urgently address in writing the following aspects of your letter of 10 May, which raise serious concerns.

First, regarding prior contact from the TWU. You would no doubt be aware that across the country the TWU has made known at a store and local management level a number of serious matters including: ongoing concerns regarding the lack of integrity of Enterprise Agreement negotiations and approval processes; loading and unloading processes and entry and egress dangers at sites including dangers to the general public arising from the practice of backing into docks; and long hours of work and inadequate remuneration and related conditions for drivers not only those directly engaged by ALDI but those within ALDI’s supply chain, especially in the in-bound freight sector. We are concerned that such matters, which have been emphasised over several years, do not appear to be acknowledged in your correspondence. In fact, your correspondence reads like an attempt to ‘cover your tracks’ in this regard. Additionally, we also placed two calls through to both Ms Diana Chiong and your Head Office in the last month ahead of sending this letter in attempt to again reach out to your organisation to address issues.

Of equal concern in your correspondence is an apparent total reliance on flawed and inadequate regulation/voluntary schemes as a seemingly complete response to issues raised in the TWU correspondence. The NHVR accreditation scheme should not be the central response of any companies engaged in transport promoting its standards. In fact, the focus of ALDI on this scheme is a serious concern. The scheme was applied and similarly promoted by the companies whose trucks fleets have been found by road authorities to be systematically below standard, including fleets in NSW that have been grounded and later found to have numerous deficiencies. A case in point was the tragic fatality in Mona Vale where a tanker crash resulted in the incineration of two Australian road users.

…

(without alteration)

50 ALDI took time to consider its response. On 29 May 2017, Mr Maher wrote to Ms Carr at the Union as follows:

…

I refer to your letter dated 16 May 2017 concerning ALDI’s response to your invitation to meet with the TWU to discuss issues relating to the Transport Supply Chain.

Your original requests for a meeting (undated but received on 9 May 2017) noted that the TWU had recently contacted ALDI to attempt to arrange a meeting, however you did not receive a response.

We note in our letter of 10 May 2017 that no record of previous contact to arrange a meeting could be found. As stated in that letter, ALDI takes seriously its responsibilities to ensure the safety of participants in the supply chain, and we wished to indicate as a matter of courtesy that previous contact from the TWU had not been recorded, rather than simply being ignored.

ALDI also takes seriously misleading and deceptive information intended to detract from its corporate reputation. ALDI has always, in transport as in all other areas, operated safety and reasonably. ALDI provides superior terms and conditions of employment for our own Transport Operators as part of enterprise agreements which are negotiated with our employees and their bargaining representatives. ALDI also operates within the supply chain to ensure the safe operation of all participants.

As advised in our letter of 10 May, we were willing to meet with you to discuss, as your original invitation stated, your goals for the transport sector, the needs of your members and ALDI and to attempt to seek out shared interest and opportunities.

Your letter dated 16 May, the TWU actions in blockading an ALDI site in Fremantle and the associated press release issued by the TWU on 16 May, with the implication that ALDI is responsible for a ‘spike in deaths from road crashes’, has led us to question the sincerity with which such a meeting has been sought.

In this context, we do not consider a meeting to be appropriate at this time. Should you wish to provide details in writing of any specific safety concerns you may have about ALDI’s operations, please provide them via email to xxxx.xxxxxxx@xxxx.xxx.xx in order that they may be investigated and addressed.

In the meantime we respectfully suggest you refrain from your apparent attempt to tarnish ALDI’s reputation for excellence. ALDI will defend itself.

…

(contact details omitted)

Given the sequence of events, especially the offer made by ALDI on 10 May 2017 and the demonstration at the Freemantle site on 16 May 2017, ALDI’s response was understandable.

51 It is concluded that:

the offer made by ALDI on 10 May 2017 was an offer genuinely made to meet with the Union to discuss its concerns;

it would have been comparatively easy for the Union to cancel the demonstration on 16 May 2017, had it wished to do so;

the demonstration at the Freemantle store on 16 May 2017 was an event that had been planned and was going to go ahead irrespective of whatever response was provided by ALDI;

the flyer distributed at about the same time as the demonstration on 16 May 2017 was seriously misleading (or, at the very least, “likely to mislead”) in a number of respects, including the association of ALDI with “a spike in road deaths”;

the misleading association of ALDI with a “spike in road deaths” was not an inadvertent statement but one intentionally made by the Union; and

the purpose of the demonstration, it is concluded, was to “put a shot across the bows” of ALDI and put pressure on it to negotiate with or to discuss issues with the Union.

The conduct pursued by the Union was deliberate and intentional. The Union proceeded throughout April and May 2017 with an absence of good faith.

52 So much flows primarily from the sequence of events and the evidence of Ms Emily McMillan, the Chief of Campaigns for the Union. When questioned at the outset of her cross-examination as to the purpose behind the Freemantle incident, the following exchange occurred:

The whole point of that very first display at Aldi’s Fremantle store was to bring power to bear on Aldi to have them bend to your wishes, was it not?––No. I would say that’s not a particularly accurate way again of describing what happened.

What was the point, then?––The point was to raise awareness to our attempts to communicate with Aldi, to raise awareness about Aldi’s responsibility as a substantial client in road transport, to communicate to ask them to be part of an industry solution, but basically it was about gaining attention to what we were describing as going on both more broadly in road transport in some aspects, and also what we understood was happening in the Aldi supply chain as well.

53 Although it may not have been “a particularly accurate way” of describing the purpose, the answer given has to be considered in the light of her further evidence as to the two issues she wished to pursue with ALDI at the meeting that they were trying to arrange, namely:

to establish a “mature relationship” with ALDI, that company being a comparatively new entrant into the supermarket industry after Woolworths and Coles; and

to raise “specific issues”.

As explained by Ms McMillan:

… Of course, in the course of those discussions, we also talk through concerns that we may have, examples that we may have, ways to communicate that in an effective way – so, really, systems around how that’s communicated as well. So that approach early on was very much an introduction to say, “We want to talk more broadly about the industry, your role in the industry, and then also around specific issues as well.”

But these two issues were never identified by the Union in its correspondence with ALDI when seeking a meeting. It may have been prudent to do so – to put ALDI on notice as to the purpose of the meeting and what was sought to be achieved.

54 The purpose behind the events at Freemantle were inextricably intertwined with the meeting which was being sought. When cross-examined as to the ability to call off the demonstration if ALDI was agreeable to a meeting being held, it was suggested that it was “somewhat disingenuous” to be planning the demonstration whilst at the same time seeking a meeting. That exchange was as follows:

You would agree with me, it would be somewhat disingenuous to be planning something like that at the time a letter like this was going …

…

THE WITNESS: No, because these actions are very easy to cancel.

MR HATCHER: But this is attempting to set up a cooperative, mature … ?––Yes.

… relationship?––Yes. And we genuinely, as I said, hoped that it would result in really helpful, positive, constructive discussions, and still do. By that point, we had emailed. I had made two phone calls. We had written a letter. I also understood, from other unions’ dealings, both nationally and internationally, that we were unlikely to get a response, but we certainly wanted to make all attempts to try and engage with Aldi. But in the thinking that if we didn’t get a response, or we got one that wasn’t going to engage with us genuinely, then we were looking to prepare just a small, sharp action.

I see. But it was your intention that if you did receive a positive response, you would cancel that action?––If we got a genuine one, it would be simple to cancel that action. It’s a lot easier to cancel an action than it is to do an action.

It would have been easy to have called off the demonstration at Freemantle given the response of ALDI. But the demonstration went ahead. It was, indeed, “disingenuous” on the part of the Union to engage in the correspondence whilst at the same time planning the demonstration. It is concluded that the intention of the Union was to go ahead with the demonstration irrespective of whatever response had been provided by ALDI.

The Churchill Centre Mall in Adelaide – 15 June 2017

55 On 15 June 2017, approximately nine people entered the Churchill Central Mall in Adelaide. Within that centre was an ALDI store.

56 About five of the people were wearing clothing with a TWU logo and about four of these people entered the ALDI store. They distributed pamphlets titled “C’mon ALDI, Do the right thing”. These pamphlets were also distributed to people entering and leaving the ALDI store.

57 Some of these pamphlets were left amongst the stock in the ALDI store.

The Regency Park Distribution Centre – 16 August 2017

58 According to Mr Jonathan Aldridge, a Logistics Manager for ALDI, one ALDI truck left the Regency Park Distribution Centre at 12.29pm. Shortly thereafter, a black utility vehicle with a trailer attached was positioned across the driveway which was used by trucks to enter and leave those premises. Another ALDI truck which sought to leave the premises at 12.41pm was blocked from doing so. The driver of that truck reversed away from that exit and exited the premises by means of a driveway generally only available in case of fire. Before it could do so a number of bollards had to be removed. The truck exited the premises at approximately 12.46pm. The exit was delayed about 15 to 20 minutes.

59 A third truck also sought to exit the premises via the driveway normally used as a fire exit. It was prevented from doing so by protesters. The police were called and the third truck exited the premises at approximately 1.05pm.

60 The two trucks whose exit had been blocked were nevertheless “able to make the deliveries within the expected window at the store”.

61 Although the time of the delay in exit for the second and third trucks may have been slight, Mr Aldridge maintained that “there is a significant impact on our delivery schedules, even if only 1 truck is delayed”.

62 Those participating in the demonstration also placed under the windscreens of cars parked in the ALDI carpark a “flyer” which bore the TWU logo and was headed “Stop the Race to the Bottom”.

Mount Druitt – 24 August 2017

63 Again, in very summary form, the evidence as to the events that took place on 24 August 2017 was relatively uncontroversial.

64 On that day Mr Robert Eichfeld, a Store Operations Director for ALDI, was informed by the Area Manager (Ms Cornelia Maier) at about 12.00pm that there was a demonstration in the car park outside the Mt Druitt store. They were equipped with posters, flags, drums and banners with the TWU logo. Ms Maier advised Mr Eichfeld that the protest was “hindering customers entering and leaving the store and entering and leaving the car park”. Store management asked the protesters to leave but they refused. The police were called. But the protesters left at about 12.15pm before the police arrived.

65 In a media statement released by the Union on 24 August 2017, it was reported that over 500 truck drivers and their supporters had protested at the Mt Druitt store. The events on 24 August 2017 were reported by Channel 9 news, Channel 7 news, SBS World News Australia, NBN Gold Coast and the Daily Telegraph.

66 Mr Eichfeld caused to be undertaken a review as to what impact, if any, the protest had on sales. According to that review, average hourly sales between 12.00pm and 1.00pm were normally $7,153.35. On 24 August 2017, the hourly sales were $6,267.05.

MISLEADING OR DECEPTIVE CONDUCT – AS PLEADED

67 In its Further Amended Statement of Claim, ALDI relied upon eight “representations” which were said to fall within s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law.

The representations as pleaded

68 The Further Amended Statement of Claim pleads eight “representations” which were said to contravene ss 18 and/or 31 of the Australian Consumer Law, namely that ALDI:

“is responsible for road deaths” (the 1st representation);

“is responsible for cutting transport costs and underpaying truck drivers” (the 2nd representation);

“places pressure on its supply chain leading to trucks not being maintained” (the 3rd representation);

“attempted to pay truck drivers less by misclassifying them in an enterprise agreement which was struck down by the Federal Court” (the 4th representation);

“puts pressure on trucking companies and owner drivers to fulfil unsafe deadlines” (the 5th representation);

“undercuts road safety” (the 6th representation);

“maintained these proceedings for the purpose of inhibiting free speech by truck drivers” (the 7th representation); and

“places pressure on its supply chain which results in drivers engaging in unsafe practices such as speeding, driving long hours skipping mandatory test breaks” (the 8th representation).

69 Each of these representations is said to give rise to a separate cause of action and separate contraventions of ss 18 and/or 31 of the Australian Consumer Law.

70 There is a considerable overlap in the Particulars provided in respect to each of the pleaded representations. One or other of the media releases and the like are relied upon in support of different representations. The following Table correlates the representations pleaded and the Particulars relied upon:

Representation | Particulars |

1st representation – “Aldi is responsible for road deaths” | The TWU media releases dated 16 May and 16 August 2017 The TWU Facebook page 16 August 2017 |

2nd representation – “Aldi is responsible for cutting transport costs and underpaying truck drivers” | The TWU media release dated 16 May 2017 The TWU flyer at the Toombul store on 13 October 2017 The events at the Toombul store The events at the ALDI store in Tingalpa, Queensland on 15 November 2017 The Sheldon interview |

3rd representation – “ALDI places pressure on its supply chain leading to trucks not being maintained” | The TWU media release dated 16 May 2017 The TWU media release dated 16 August 2017 The TWU media release dated 13 October 2017 The Mercury article The Sheldon interview |