FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

In-N-Out Burgers, Inc v Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 193

ORDERS

Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent BENJAMIN MARK KAGAN Second Respondent ANDREW SALIBA Third Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Pursuant to s 37AF of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) and on the grounds set out in s 37AG(1)(a), disclosure, by way of publication or otherwise, of:

(a) the dollar figure amounts contained in Tabs 1 and 2 of Confidential Exhibit DW-2 to the affidavit of Denny Warnick affirmed 16 July 2018;

(b) Confidential Exhibit VS-4 to the affidavit of Valerie Sarigumba affirmed 17 September 2019; and

(c) the information highlighted in green in the applicant’s submissions in support of its request for suppression orders dated 18 September 2019, (Confidential Material),

is restricted to persons to whom the applicant permits access and who have provided a confidentiality undertaking in the form agreed by the parties.

2. Order 1 shall operate until 4 pm on 26 February 2025 or further order.

3. The parties have liberty to apply to the Court to extend the date referred to in order 2, provided that any such application is filed with the Court at least one month before the time expires.

4. The matter be listed for further case management on a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

KATZMANN J:

1 What is the line between inspiration and appropriation? That is the question at the heart of the dispute in the present case.

2 Since 2016 the second and third respondents, Benjamin Kagan and Andrew Saliba, and later the first respondent, Hashtag Burgers Pty Ltd (“Hashtag Burgers”) have operated a growing number of burger restaurants in Australia under the name “Down-N-Out” or a variant thereof (“DNO” or “the DNO marks”).

3 The applicant is an American corporation. For many years it has owned and operated a growing number of burger restaurants in the United States and has periodically showcased its business in several other countries, including Australia, by staging “pop-up” events. It also owns a number of registered trade marks used in connection with the business including a number which include the name “In-N-Out” (“the INO marks”).

4 The applicant claims that the DNO marks are deceptively similar to the INO marks. Indeed, the applicant contends that they were adopted by the respondents for this very reason. Based on those premises, it claims that the respondents have infringed their registered trade marks, committed the tort of passing-off, and engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct in contravention of the Australian Consumer Law (“ACL”). It sought damages, including additional, aggravated and exemplary damages, as well as declaratory and injunctive relief.

5 On 12 December 2017 an order was made for the separate determination of all issues except for the quantum of any pecuniary relief. But on the last day of the hearing the applicant abandoned its claim for aggravated damages and did not press its claims for additional or exemplary damages. Furthermore, notwithstanding the terms of the separate question order, the applicant made no submissions on the other forms of relief it sought in its originating application. It simply asked the Court to make findings of liability and submitted that it would be “most convenient” to address the final form of declaratory and injunctive relief in the light of the Court’s findings. The applicant was silent about the other forms of non-pecuniary relief.

6 Consequently, this judgment is only concerned with liability.

The evidence

7 Evidence in support of the application was given by Denny Warnick, Anna Elizabeth Harley, Sanil Khatri, Felipe Sandrini Pereira, and Elisabeth Jane White. With the exception of Mr Warnick, each of these witnesses is a solicitor employed by Baker McKenzie, the lawyers for the applicant. Mr Warnick is the applicant’s Vice-President of Operations.

8 No evidence was offered by Mr Kagan or Mr Saliba. The only witnesses for the respondents were Danielle Gleeson, a solicitor in the firm of Yates Beaggi Lawyers, which represented the respondents at the trial, and Andrelise Latreille, one of the firm’s legal secretaries. Ms Gleeson’s evidence was directed to the use by other fast-food businesses in Australia of the same or similar colours to those used by the parties to the present proceeding. Ms Latreille deposed about visiting the respondents’ restaurants on 24 June 2019 and what she saw at each venue.

The facts

9 Most of the facts were either admitted or not in dispute.

The applicant’s business

10 The In-N-Out Burger business was founded in Baldwin Park, California, in 1948. It was incorporated in California on 1 March 1963. The applicant is, and always has been, a family-owned private company. It has a chain of permanent restaurants which extends throughout California, Arizona, Oregon, Nevada, Texas, and Utah. As at May 2016 there were over 300 such restaurants. It continues to expand at a rate of 15 to 20 restaurants a year. Many of the restaurants are situated on major thoroughfares that are subject to high motor vehicle and/or foot traffic, including, for example, on Dean Martin Drive in Las Vegas (since July 1993), and in high profile tourist areas such as Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood (since December 1994), South Sepulveda Boulevard in Westchester within a mile of Los Angeles International Airport (“LAX”) (since January 1997), and on Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco (since September 2001). Many foreign tourists visit these restaurants. The applicant’s customers also include international visitors and flight crews In-N-Out Burger is commonly referred to merely as In-N-Out. In-N-Out restaurants are also situated near universities with international students, such as the In-N-Out restaurant in Austin, Texas, which is adjacent to the University of Texas.

11 The applicant is the registered owner of six Australian trade marks. Three are composite or stylised marks and three are word marks. The three word marks are IN-N-OUT BURGER, ANIMAL STYLE, and PROTEIN STYLE. Notwithstanding some evidence that might suggest otherwise, it is no part of the applicant’s claim that the latter two marks have been infringed. In these circumstances, it is only necessary to record the details of the registration of the first.

12 The applicant’s submissions incorporate a table setting out the relevant information which is reproduced below.

Reg. no. | Trade mark | Priority date | Goods and services | |

1. | 563986 |

| 23 September 1991 | Class 30: All products in class 30 including, hamburger sandwiches and cheeseburger sandwiches, hot coffee for consumption on or off the premises |

2. | 563987 |

| 23 September 1991 | Class 42: Restaurant services and carry-out restaurant services |

3. | 1190205 |

| 31 July 2007 | Class 29: Milk and french fried potatoes for consumption Class 30: Coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar, rice, tapioca, sago, artificial coffee; flour and preparations made from cereals, bread, pastry and confectionery, ices; honey, treacle; yeast, baking-powder; salt, mustard; vinegar, sauces (condiments); spices; ice; sandwiches, hamburger sandwiches and cheeseburger sandwiches; beverages included in this class; hot coffee for consumption on or off the premises Class 43: Restaurant services and carry-out restaurant services |

4. | 1345820 | IN-N-OUT BURGER | 16 February 2010 | Class 29: Meat, meat patties, burgers; french fried potatoes, potato chips; milk, milk shakes; spreads in this class; poultry; dairy desserts; preparations for sandwiches; potato products; prepared meals in this class, snack foods in this class Class 30: Coffee, tea, cocoa, sugar, rice, tapioca, sago, artificial coffee; flour and preparations made from cereals, bread, pastry and confectionery, ices; honey, treacle; yeast, baking-powder; salt, mustard; vinegar, sauces (condiments); spices; ice; chocolate beverages; ice cream; pepper; spreads in this class; bread, buns; burgers contained in bread rolls; hamburger sandwiches and cheeseburger sandwiches; sandwiches; prepared meals in this class; snack foods in this class; beverages in this class; filled rolls Class 43: Services for providing food and drink restaurant services and carry-out restaurant catering services, mobile catering services. |

13 This is the composite mark featuring a commonly deployed red and yellow colour scheme (“the In-N-Out logo”):

14 The applicant has never licensed or authorised the respondents to use any element of its In-N-Out branding in relation to their business activities or otherwise.

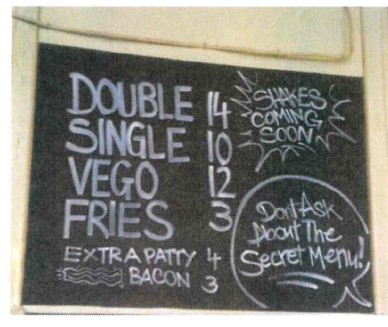

15 The applicant’s restaurants serve a basic menu consisting of three burgers, the “Double-Double” cheeseburger and hamburger, French fries, drinks, and “secret menu” variations to basic menu food items, such as “double meat”, “3x3”, “grilled cheese”, “protein style”, “animal style”, “4x4”, “flying Dutchman” and “Neapolitan shake”. The so-called “secret menu”, paradoxically often marketed as the “not-so-secret menu”, has been offered by all the applicant’s restaurants since at least the early 1960s and has been promoted on the applicant’s website since at least 2005.

16 The applicant has used and promoted its business by reference to a number of key branding elements. They include the names and trade marks IN-N-OUT and IN-N-OUT BURGER, both of which have been used since the inception of the business in 1948 and, since at least 1967, the In-N-Out logo and combinations of the above. These branding elements have been used prominently in advertising and promotion of the applicant’s goods and services across the world.

17 The In-N-Out logo is prominently displayed on signposts located in the vicinity of many of the applicant’s restaurants. Some signs featuring the logo are attached to poles and stand at heights of up to 80 feet (approximately 24 metres) from the ground. These signs are positioned so that they are visible from motorways and are illuminated in the evenings and when visibility is reduced due to poor weather. The exterior signpost to the In-N-Out restaurant near LAX can be seen from planes as they land at the airport. Since 1948, all In-N-Out restaurants have displayed the In-N-Out logo outside the buildings. These signs measure at least 6.3 x 9.7 feet (1.9 x 2.9 metres). The In-N-Out logo has also featured on signs used since 1948 to direct customers to the drive-through at the restaurants and on the menu board adjacent to the two-way speakers. Elements of the In-N-Out branding are displayed inside the applicant’s restaurants on menu boards, posters, and other point of sale materials, including the wrapping used for burgers and the paper trays on which the food is served at the restaurants.

18 Alcohol is not sold at any of the applicant’s US restaurants but customers are permitted to bring alcohol into at least some of them.

19 In about 1988, the applicant introduced “Cookout Trailers” to the market. Since then, these mobile versions of the In-N-Out restaurants have been used for corporate fundraisers, charitable events, picnics, parties, reunions, and other events. They have been operated and staffed by employees of the applicant and have prominently displayed the In-N-Out logo. Every year since 2008, the Cookout Trailers have been hired to provide food at Vanity Fair’s annual Oscars after-party held in conjunction with the Academy Award ceremonies in Hollywood.

20 The applicant’s marketing strategy includes radio, television and local store marketing, and print advertising. Since about August 1973, the applicant has also advertised on billboards displayed alongside motorways and other roads and in bus shelters. Since 1985, the applicant has distributed bumper stickers and car decals featuring the In-N-Out logo. In-N-Out is also promoted by word of mouth.

21 The applicant operates three company stores and an online store from which merchandise carrying the In-N-Out branding is available for sale. The company stores were established to meet the demand for souvenirs and collectibles carrying the branding. One store is located in Baldwin Park, California and two in Las Vegas, one on Dean Martin Drive and the other on south Las Vegas Boulevard. But the evidence does not indicate when the company stores were opened.

22 The applicant launched its own website in about June 1999. The online store was established in May 2004. Members of the public from throughout the world, including Australia, can purchase merchandise through the online store. This merchandise includes T-shirts, caps, jackets, key-rings, and similar accessories. In 2013 there were 37,631 visitors to the website from Australia. In 2014 there were 50,108. In 2015 it climbed to 61,988. In 2016 it rose even further to 78,098.

23 Since about 2011, the applicant has also been active on social media. It has operated and maintained a Facebook page, an Instagram page, and a Twitter account. The domain names of all these accounts include the word “innout”.

24 The applicant has what Mr Warnick described as “a significant and competitive presence in the US chain restaurant industry” and its revenue in each financial year from 2011 to 2017 has also been significant.

25 The applicant regularly hosts pop-up restaurant events outside the United States where consumers are exposed to the applicant’s goods and services and the In-N-Out branding. Mr Warnick described these events in his affidavit:

Each pop up restaurant event is for a limited period of time, on a single day, at a location that is advertised a day or two before the event, including on social media. The events are carefully managed to ensure consumers have the same high quality food and friendly service at each location. These events are very popular and tend to attract social media interest from members of the public, including previous ln-N-Out customers who have visited the US, as well as new customers who may never have been to an ln-N-Out restaurant in the US. At each pop up event, ln-N-Out sells food and merchandise.

26 Alcohol is not sold by the applicant at any of these events.

27 The applicant has hosted eight such events in several locations in Australia over the last seven years. The first was at Kings Cross in Sydney on 24 January 2012, the second in Darlinghurst, Sydney, on 20 January 2013, the third in the Melbourne CBD on 5 November 2014, the fourth in Parramatta, Sydney, on 14 January 2015, the fifth in Surry Hills, Sydney, on 20 January 2016, the sixth in Darlinghurst on 18 January 2017, the seventh in Northbridge, Perth, on 16 January 2018, and the eighth in Windsor, Melbourne, on 6 March 2018. These events have been very popular. Despite the limited advertising before they took place, there were often long queues to get into the restaurants and burgers were nearly or completely sold out within the first or second hour of opening.

28 At the pop-up events the applicant sold burgers, associated food and drinks, and In-N-Out branded T-shirts, and the applicant’s trade marks and branding were on display. Mr Warnick gave evidence that “up to” 300 burgers were sold at each such event. Records exhibited to his affidavit show that at the Surry Hills pop-up in January 2016, 238 burgers, 187 servings of chips, 291 drinks, and 192 T-shirts were sold. By January the following year the numbers had increased significantly. For example, 400 burgers and 420 T-shirts were sold at the Darlinghurst pop-up. Figures for sales in 2018 were not in evidence.

29 I will deal with the contentious question of the applicant’s reputation later in these reasons when it arises for consideration.

The respondents’ conduct

30 In June 2015, following the fourth In-N-Out pop-up event in Parramatta in January that year, Messrs Kagan and Saliba held a “Funk N Burgers” pop-up burger event at the Lord Gladstone Hotel in Chippendale, Sydney.

31 The Facebook promotion for this event announced:

This time on the menu we have the legendary In’N’Ou … I mean the Down’N’Out burger served up ANIMAL STYLE for all you fatties. Go single or double‑double that sexy MOFO.

32 On 10 June 2015 Messrs Kagan and Saliba worked with a graphic designer, John Paine, to prepare a flyer and logo for the event.

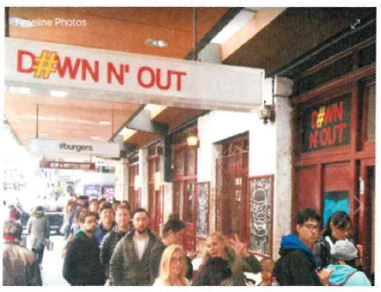

33 Mr Saliba asked Mr Paine to make “a funk n burgers sign like in n out burger” and emailed him a copy of the In-N-Out logo:

34 Mr Paine produced the following logo:

35 Mr Paine also produced the following flyer:

36 On 31 January 2016 Messrs Kagan and Saliba hosted another pop-up event advertised on Facebook as “FUNK‑N‑BURGERS: DOWN‑N‑OUT (IN‑N-OUT TRIBUTE) ~FREE PARTY”. The promotion stated (without alteration):

WE ARE BACK FOR 2016!! To kick of[f] the new year we are bringing back the MOST POPULAR burger from last year … the In-N-Ou..*cough* I mean … Down-N-Out Burger – served ANIMAL STYLE for all you fatty boombas!

And if that wasn’t enough, every burger will be accompanied by ANIMAL STYLE fries with liquid cheese! Hrrrrrggggggggg…

Still not satisfied? DOUBLE-DOUBLE that sucka and turn your meal into a heart attack on a plate.

37 Sometime before 5 May 2016, Messrs Kagan and Saliba decided to open their first pop-up and call it DOWN-N-OUT. They again enlisted Mr Paine’s help with the design features. On 9 May 2016 Mr Saliba contacted Mr Paine, using the pseudonym “Mr Seaman”, attaching copies of three logos which the exchange indicates he designed himself (“the Saliba logos”):

38 The font is different from that used in the INO marks, but the difference is unlikely to register with the viewer without a side-by-side comparison. The colours, however, were identical.

39 On about 13 May 2016 Messrs Kagan and Saliba hired a second designer, Olivia Tucker of Tablou Collective, to assist in the design and fit-out of the pop-up restaurant. Mr Kagan supplied her with copies of the Saliba logos.

40 On 25 May 2016 Mr Paine, who was designing the colour scheme for the Down-N-Out placemats and posters told Mr Kagan that he would use yellow so that “it matches In and Out branding”. Mr Kagan said that was “cool”. Although he flirted with the idea of playing with the colours to give them “that muted newspaper fade”, the idea was not taken any further, at least at that stage.

41 The same month the Down-N-Out Facebook page was launched. The initial cover photograph featured the following logo:

42 On 30 and 31 May 2016 Mr Kagan sent a media release to a number of organisations including Pedestrian Group TV and Timeout Magazine. It was entitled “Sydney’s Answer to In-N-Out Burgers Has Finally Arrived!” It read:

SYDNEY'S ANSWER TO IN-N-OUT BURGERS HAS FINALLY ARRIVED!

Hashtag Burgers, the masterminds behind BURGAPALOOZA, are teaming up with the former Head Chef of Mr. Crackles to bring In-N-Out inspired burgers to Sydney's CBD for ONE WHOLE MONTH.

Launching Wednesday June 7th, the cheekily named DOWN-N-OUT will be popping up at the SIR JOHN YOUNG HOTEL on the corner of George and Liverpool Street, in the heart of the CBD.

The menu will be kept simple, similar to the original In-N-Out, with the addition of a vegetarian option. Of course there will be shakes and a plethora of secret menu hacks such as Animal Style and Protein Style. These will be leaked to the public as the pop-up continues.

In true Hashtag Burgers style, this won't simply be a food offering.

There are a few surprises planned for this pop-up and the Sir John Young Hotel is in the process of being redecorated – the details of which are being kept secret however you can find some hints on the DOWN-N-OUT Facebook page.

Hashtag Burgers will be partnering with Murrays Brewery to bring a craft beer pairing for the meal. They will be launching with Murrays’ famous Angry Man Pale Ale on tap.

This pop-up is the first in a series of plans by the Sir John Young Hotel to reboot its look and to revitalize the area which has been damaged by the lockouts. They plan to renovate the bar in the near future.

Down-N-Out will be launching at the SIR JOHN YOUNG HOTEL on the corner of George and Liverpool street on June 7th until the 6th of July.

Follow the DOWN-N-OUT Facebook page for more information[.]

43 On 4 June 2016 the following image was posted on the Tablou Instagram page:

44 Alongside the image the following announcement was made:

We’re teaming up with the @hashtag_burgers boys over this rainy weekend to bring In-N-Out down under …

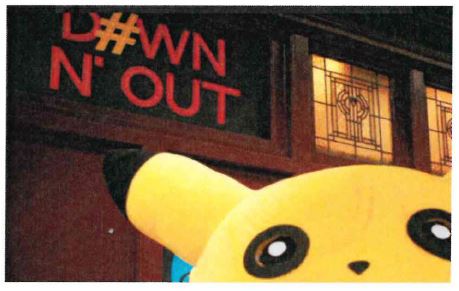

45 Using the account @hashtag_burgers, Mr Kagan or Mr Saliba (or both) replied with these emojis: .

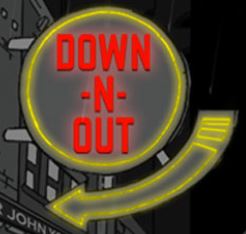

46 On about 7 June 2016, within six months of the applicant’s Surry Hills pop-up, Messrs Kagan and Saliba opened their “cheekily-named” pop-up burger restaurant. The following sign (“original DNO logo”) was displayed at various locations, including above the entrance to the restaurant and on the wall above the open kitchen:

47 At some point in time that month, the following neon sign appeared outside the entrance:

48 Inside the restaurant, a blackboard menu was on display:

49 On 8 June 2016, Mr Khatri attended the restaurant and took some photographs. He also inquired about the “Secret Menu” and was told that it was “an Animal Style or Tiger Style burger or fries, or a Protein Style burger”. When he was asked what Tiger Style was, he received the answer “just Animal Style”.

50 On 17 June 2016, the applicant wrote to Messrs Kagan and Saliba, politely requesting them to stop using its trade marks, ANIMAL STYLE and PROTEIN STYLE, and to select a different name and logo which sufficiently distinguished their business from the applicant’s so as to avoid confusion. The letter, which was signed by its Associate General Counsel, Valerie Sarigumba, was in the following terms:

We at In-N-Out Burger have heard from numerous international customers regarding your “Down-N-Out” tribute to In-N-Out Burger in Sydney. We were flattered to hear that you have admired our food and one-day events in Australia such that you decided to conduct a similar event. We also appreciate those who know what it means to have a good burger.

Nonetheless, the Down-N-Out event significantly trades off our well-known and valuable brand. For example, we note that as part of the event you have used the names ANIMAL STYLE and PROTEN STYLE, which are our registered trade marks, and adopting the name “Down-N-Out” displayed with a yellow arrow sounds and looks very similar to In-N-Out’s name and logo.

This may lead to some confusion amongst the Australian pubic that the In-N-Out is associated with the event (as reflected in some media reports to date). Even if you had the best of intentions, we still hope to avoid any such issues.

We therefore request that you do not use the above-mentioned trade marks. We also request that you select a different name for the remainder of this event and all of your future events that does not adopt In-N-Out’s name and logo.

51 Mr Kagan replied by email on 24 June 2016. He said they knew that “ANIMAL STYLE” and “PROTEIN STYLE” were “trademarked terms” and denied that they had ever been used for their menu items. He insisted that they were not trying to deceive customers or “rip-off” the In-N-Out brand. He advised that he and Mr Saliba intended to keep the name Down-N-Out, saying that they had legal advice that it did not infringe the In-N-Out “trade mark (sic)”. He asserted that:

This expression has its own separate and distinct meaning in the English language which is unlikely to conflict with the meaning of “In-N-Out”. Further, the word Down also relates to “Down Under” which relates to the fact that we are an Australian business.

52 On the other hand, Mr Kagan said that he understood the applicant’s concerns about the logo. He advised that, “as a temporary measure”, that is, until they could get new signs, they had covered up the arrows.

53 From then on a number of variations to the original logo started to appear.

54 A photograph of the DOWN-N-OUT sign on 24 June 2016, which Mr Saliba posted on his personal Facebook page, shows that the arrows had been obscured and that the word “censored” appears in upper case letters above and below the DOWN-N-OUT name where the arrow formerly appeared. In response to a query “What’s the deal with censored?”, Mr Kagan posted a photograph of part of Mr Sarigumba’s letter, advising that he had received the letter “the other day”. Mr Saliba replied that he was going to get the letter framed and put it on the wall at Down-N-Out.

55 On 29 June 2016 this variation of the original DNO logo appeared on the Down-N-Out Instagram page:

56 On 6 July 2016 two variations of the logo were posted on the Down-N-Out Facebook page:

57 On 6 and 7 July 2016 Mr Kagan (using the alias “Professor X”) advised Mr Paine of “some legal issues” and told him that “the main thing would be to change the sign and the arrow etc. but we might as well change the whole thing”. Mr Kagan informed Mr Paine that:

Need to differentiate ourselves ASAP before we get sued lol.

58 Mr Saliba (under the alias “Mr Seaman”) told Mr Paine that the yellow arrow “definitely needs to go”.

59 He then proposed a series of Down-N-Out logos using the same font and the same shade of red used in the In-N-Out device mark. In response to a question apparently from Mr Paine about the problem the applicant had with “the previous images”, Mr Kagan responded:

To put it as simply as possible – each element on its own isn’t infringing on anything. But everything together is enough to fool the stupider people in society into thinking that we ARE In-N-Out

Secret menu, menu ingredients, logo, name etc.

…

Hehe — all a bit of fun really. We are now Sydney’s most controversial burger restaurant.

60 Although Mr Kagan had told the applicant that he understood its concerns about the original Down-N-Out logo, on 7 July 2016 Mr Kagan sent Ms Tucker a group of photographs featuring the original logo accompanied by the following text:

The fukd thing is we can[’t] post most of them anymore because of the In N Out issues lol. You guys can though

61 On 13 July 2016, the hyphens were removed from the signs at the Sir John Young Hotel and photographs showing the signs without the hyphens were posted on Instagram and the DNO Facebook page.

62 By late August 2016, new signs were installed. They differed from the earlier signs in the following respects. They included neither arrows nor hyphens and the “O” in “DOWN” was replaced by a hashtag. The following images were taken from Facebook posts on 30 August and 4 September 2016 respectively:

63 Since the exchange of correspondence with Ms Sarigumba, the respondents’ business has grown significantly. The respondents admitted in their defence that between October and December 2016 Messrs Kagan and Saliba operated, on a pop-up basis, a restaurant in High Street, Penrith called “Down N’ Out West” and that since around January 2017 Mr Kagan has operated the burger restaurants at the Sir John Young Hotel (the “CBD restaurant”). The respondents also admitted in their defence that, in September 2017, a month before this proceeding was instituted, Hashtag Burgers opened a restaurant in Blaxland Road Ryde, operated by Mr Kagan. At some stage the CBD restaurant at the Sir John Young Hotel closed and reopened at another site in Liverpool Street. In April 2018 a Down N’ Out pop-up restaurant appeared in the Gold Coast during the Commonwealth Games. In May 2018 a restaurant opened in Keira Street, Wollongong. And on 14 February 2019 a restaurant was opened in Willoughby Road, Crows Nest.

64 Burgers and fries were sold at all of these restaurants and presumably continue to be sold. Orders could also be placed online through Foodora and Menulog.

65 The Down-N-Out restaurants, food and beverages are promoted on several online and social media accounts: a website with the domain name <downnout.com.au>; an Instagram page (https://www.instagram.com/downnout/) and five Facebook pages, four featuring the word “downnout” in the web address.

66 Annexure A to these reasons is a table showing the DNO marks and logos used at various times in relation to the restaurants and to the food and beverages offered for sale at those restaurants.

67 The applicant has not licensed or authorised the respondents to use any of them.

The trade mark infringement claim

In what circumstances is a registered trade mark infringed?

68 Section 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (“TM Act”) defines the circumstances which constitute an infringement of a registered trade mark. It relevantly provides that:

(1) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

(2) A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to the trade mark in relation to:

(a) goods of the same description as that of goods (registered goods) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; or

(b) services that are closely related to registered goods; or

(c) services of the same description as that of services (registered services) in respect of which the trade mark is registered; or

(d) goods that are closely related to registered services.

However, the person is not taken to have infringed the trade mark if the person establishes that using the sign as the person did is not likely to deceive or cause confusion.

69 “Trade mark” is “a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person”: TM Act, s 17. “Sign” is broadly defined in s 6 to include “the following or any combination of the following”: “any letter, word, name, signature, numeral, device, brand, heading, label, ticket, aspect of packaging, shape, colour, sound or scent”.

70 A sign is used as a trade mark if it is used as a badge of origin, to denote a connection in the course of trade between the goods or services in question and the person who applied the mark to those goods or services: see E & J Gallo Winery v Lion Nathan Australia Pty Ltd (2010) 241 CLR 144 at [43], citing Coca-Cola Company v All-Fect Distributors Ltd (1999) 96 FCR 107 (FC) at [19].

71 “[U]se of a trade mark in relation to goods” is “use of the trade mark upon, or in physical or other relation to, the goods” and “use of a trade mark in relation to services” is “use of the trade mark in physical or other relation to the services”: TM Act, ss 7(4) and (5). For the purposes of the Act, any aural representation of a trade mark is a use of the trade mark if the trade mark consists of, or any combination of, a letter, word, name or numeral: TM Act, s 7(2).

72 For the purposes of the Act, one trade mark is taken to be deceptively similar to another if it so nearly resembles that other mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion: TM Act, s 10.

73 The relevant principles were not in dispute.

74 First, in a case such as this, to deceive means to mislead into thinking that the applicant is the source of the goods or services carrying the mark of the respondent or respondents and confusion refers to a state of wonder as to whether that might be so: see All-Fect at [39]. But the likelihood of deception or confusion need not be confined to the source of the goods or services. It might arise, for example, from a mistaken belief that, or confusion as to whether, the alleged infringer is “in some way allied” with the owner of the registered trade mark: see, for example, Shell Co of Australia Ltd v Esso Standard Oil (Australia) Ltd (1963) 109 CLR 407 at 416–8 (Windeyer J).

75 Second, “likely” does not mean more probable than not or even probable. The threshold for confusion is not high: Australia Postal Corporation v Digital Post [2013] FCAFC 153; (2013) 308 ALR 1 at [70]. It is enough if the applicant proves that there is “a real risk” or “a real, tangible danger” that a number of persons will be caused to wonder or have a reasonable doubt about the matter: Registrar of Trade Marks v Woolworths Ltd (1999) 93 FCR 365 at [50] (French J) citing Southern Cross Refrigeration Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd (1954) 91 CLR 592 at 594–5 (Kitto J); Crazy Ron’s Communications Pty Ltd v Mobileworld Communications Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 196; (2004) 209 ALR 1; 61 IPR 212 at [76].

76 Third, the marks are not to be compared side by side. Rather, the comparison is between the impression made by the applicant’s registered marks based on the putative recollections of people of ordinary intelligence and memory and the impression they would have on seeing the respondents’ marks: Shell at 414–415 (Windeyer J): Australian Woollen Mills Limited v FS Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 658 (Dixon and McTiernan JJ). The basis of any mistaken belief or confusion is the impression or recollection carried away and retained: Australian Woollen Mills at 658. Consequently, allowance must be made for imperfect recollection (Crazy Ron’s at [77]) and fleeting or momentary confusion may be disregarded. In considering whether there is a likelihood of deception, what matters is not the reaction of the person whose knowledge of the two marks and the goods sold under them enables her or him to distinguish between them, but that of the person who lacks that knowledge: Berlei Hestia Industries Ltd v Bali Co Inc (1973) 129 CLR 353 at 362 (Mason J).

77 Fourth, although “[e]xceptional carelessness or stupidity may be disregarded”, potential purchasers of goods and services, particularly in the fast food industry, “are not to be credited with high perception or habitual caution”: Woolworths at [49].

78 Fifth, the TM Act is not merely concerned with the prospect of deception or confusion brought about by visual similarities. Where the mark is or by reason of its nature likely to be the subject of a verbal description by which consumers express their desire to acquire the goods or services, similarities of sound and meaning can be important: Australian Woollen Mills at 658.

79 Sixth, the marks must be compared in their entirety or, as Yates J put it in Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 (No 2) Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 1380; (2010) 275 ALR 526; 89 IPR 457 at [100], “as a whole” (Yates J). Furthermore, where a mark consists of a number of elements, the elements must be considered in their context. Context includes “the size, prominence and stylisation of words and device elements used in the mark and their relationship to each other”: Optical 88 at [100]. That said, where a word or words is an essential feature of a registered mark, the incorporation of that word or words in the mark or marks of a rival trader may cause confusion for consumers with an imperfect recollection of the registered mark: de Cordova v Vick Chemical Company (1951) 68 RPC 103 at 105–6; Crazy Ron’s at [79]. In de Cordova, for example, the Privy Council held that the use by the appellant of the trade name “Karsote Vapour Rub” with respect to an ointment infringed the respondents’ registered marks. The first of the registered marks consisted of the phrase “Vicks VapoRub Salve” and a triangle with the words “Vicks Chemical Company” printed on the sides along with other words underneath the triangle. The second registered mark was the word mark “VapoRub”. The Privy Council considered that the word “VapoRub” was an essential feature of the first mark and that the words “vapour rub” so closely resembled that word as to be likely to deceive. Lord Radcliffe, who delivered the judgment, observed at 105–6:

They have not used the mark itself on the goods that they have sold, but a mark is infringed by another trader if, even without using the whole of it upon or in connection with his goods, he uses one or more of its essential features. The identification of an essential feature depends partly on the court’s own judgment and partly on the burden of the evidence that is placed before it. A trade mark is undoubtedly a visual device; but it is well-established law that the ascertainment of an essential feature is not to be by ocular test alone. Since words can form part, or indeed the whole, of a mark, it is impossible to exclude consideration of the sound or significance of those words. Thus it has long been accepted that, if a word forming part of a mark has come in trade to be used to identify the goods of the owner of the mark, it is an infringement of the mark itself to use that word as the mark or part of the mark of another trader, for confusion is likely to result ... The likelihood of confusion or deception in such cases is not disproved by placing the two marks side by side and demonstrating how small is the chance of error in any customer who places his order for goods with both the marks clearly before him, for orders are not placed, or are often not placed, under such conditions. It is more useful to observe that in most persons the eye is not an accurate recorder of visual detail, and that marks are remembered rather by general impressions or by some significant detail than by any photographic recollection of the whole.

80 Seventh, all the surrounding circumstances must be taken into account, including the circumstances in which the marks have been or will be used, the goods or services to which the marks have been or will be applied, and the nature and kind of customer likely to acquire them: Cooper Engineering Company Pty Ltd v Sigmund Pumps Ltd (1952) 86 CLR 536 at 538 (Dixon, Williams and Kitto JJ); Southern Cross at 594; Woolworths at [50]. This last circumstance brings into consideration whether the purchaser is likely to be discerning, in a hurry to buy, or attentive to detail. The relevant circumstances also include how the goods and/or services will be sold and promoted: Anheuser-Busch Inc v Budějovický Budvar [2002] FCA 390; (2002) 56 IPR 182 (“Budweiser”) at [237] (Allsop J). In contradistinction to an action for passing-off or for misleading or deceptive conduct contrary to the ACL, however, questions of dissimilarity by reason of get-up or aspects of packaging are irrelevant: Aldi Stores Ltd Partnership v Frito-Lay Trading Co GmBH [2001] FCA 1874; (2011) 190 ALR 185; 54 IPR 344 (“Aldi v Frito-Lay”) at [155] (Lindgren J). The user of a deceptive or confusing mark cannot escape a finding of infringement by pointing to something outside the mark itself to show that it has distinguished its goods from those of the registered owner: Saville Perfumery Ltd v June Perfect Ltd (1941) 58 RPC 147 at 16 (Greene MR).

81 Eighth, the question of deceptive similarity must be considered against the “background of the usages in the particular trade”: Shell at 401; Woolworths at [50].

82 Ninth, the question “depends on a combination of visual impression and judicial estimation of the effect likely to be produced in the course of the ordinary conduct of affairs”; accordingly, it is “a question never susceptible of much discussion”: Australian Woollen Mills at 659 (Dixon and McTiernan JJ).

83 Tenth, with the possible exception of a notorious or ubiquitous mark of long-standing, any reputation which may exist in relation to the registered marks is irrelevant: CA Henschke & Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 1539; (2000) 52 IPR 42 at [45]–[52] (FC); Optical 88 at [96]. The same test of deceptive similarity applies to newly registered, previously unknown, and well-known marks: Optical 88 at [96]. In the present case, neither side contended that the applicant’s registered marks were notorious or ubiquitous so as to fall within the exception.

84 Eleventh, it is not necessary to prove that the alleged infringer intended to deceive or cause confusion. Section 10 is not concerned with the purpose or object of the alleged infringer but with the effect of the impugned mark or marks on prospective purchasers: All-Fect at [39]. That said, for the reasons discussed below, evidence of intention is certainly not irrelevant.

The nature and extent of the dispute

85 The applicant claims that the use of each of the names and trade marks DOWN-N-OUT, DOWN N’ OUT, and DOWN N OUT, the domain name “downnout”, and the DOWN N’ OUT logos infringes its registered marks.

86 There is no dispute that the respondents used the signs in question as trade marks in relation to goods and services in respect of which the INO marks were registered. Although the applicant pleaded that they were substantially identical or deceptively similar, it did not press the allegation that they were substantially identical. The issue is whether any of the respondents’ impugned trade marks are deceptively similar to the applicants’ registered trade marks.

Are any of the respondents’ impugned trade marks deceptively similar to the applicants’ registered trade marks?

87 It was common ground that “In-N-Out” is the essential feature of all the INO marks. The evidence showed that the applicant’s restaurants are commonly referred to by that name. Since each of the INO marks either consists of, or includes as its essential feature, the name “In-N-Out”, it was common ground that, if the name Down-N-Out, in whatever form it appears or has appeared in the various DNO marks, is deceptively similar to the name In-N-Out, then the applicant succeeds in its claim with respect to all the DNO marks. That was so, despite the fact that all the applicant’s registered marks included the word “burger” and none of the respondents’ marks did. No doubt that was because “burger” is a “mere descriptive element” and is not apt to distinguish the relevant goods or services from those offered by other traders: Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd (2007) 251 FCR 379 at [52].

88 Although the hyphens were removed after they received Ms Sarigumba’s cease and desist letter and an apostrophe inserted after the N, the respondents did not argue that these changes were of any moment. Nor could they reasonably do so. Any such argument would have been untenable. The changes did not affect the sound of the marks or materially alter their appearance. Indeed, as altered, they are substantially identical in appearance to the original DOWN-N-OUT word mark. It is highly unlikely that a person with an imperfect recollection of the applicant’s marks would recall that the applicant’s signs used hyphens or that the apostrophe after the “N” incorporated by the respondents in their signs was missing from the applicant’s. As the applicant put it, the changes effected distinctions without a difference. The respondents submitted that the substitution of the hashtag for the O in DOWN provided “a material point of distinction” from the registered marks and a connection with the first respondent, Hashtag Burgers. I cannot accept the submission and in closing argument the respondents’ counsel all but conceded the point. Speaking only of the question of visual similarity, he said:

And so it – the question, and the difficult – the difficulty that it poses for your Honour is whether or not your Honour could find, for example, that “Down” with an O is deceptively similar but “Down” with a hashtag is not. I must say, I struggle to see that that would – that your Honour could fall into that – right onto that juncture in full candour.

89 The natural way to pronounce D#WN N’ OUT is “down n’ out”. Indeed, the unchallenged evidence is that, after the hashtag was substituted for the O, Mr Pereira’s telephone call to D#wn N’ Out Top Ryde in July 2018 was answered with the words “Down N Out Ryde …”. If there is a real danger that the use of DOWN-N-OUT to refer to the respondents’ goods and/or services would cause confusion, then it is unarguable that D#WN N’ OUT would, too.

90 The respondents contended that the DNO word marks are not deceptively similar to the applicants’ registered marks for a number of reasons.

91 First, they submitted that they do not convey the same idea or impression. They argued that the impression conveyed by the phrase “down n’ out” is “one of pitiable hardship”. They pointed to the dictionary definitions of “down-and-out” as “a person, usually of disreputable appearance, without friends, money, or prospects” (Macquarie Dictionary online) and “a person completely without resources or means of livelihood, a vagrant a tramp” (Shorter English Oxford Dictionary). They argued that this idea is reinforced by other aspects of the branding of the DNO restaurants. As I observed above, however, such matters cannot be taken into account for the purposes of the infringement claim.

92 The respondents submitted that the idea or impression conveyed by the registered marks is very different. “In and out”, they said, connotes rapid inward and outward movement (Oxford English Dictionary online) or participating in a particular job or investment etc. for a short time and then getting out (Collins Dictionary). They argued that this idea is reinforced by the nature of the goods and services to which the registered marks are to be applied (fast-food restaurants) as well as the arrow in the registered composite mark.

93 Second, the respondents submitted that the marks incorporate important visual differences. They argued that the presence of the word “DOWN” is a sharp point of distinction: “Down” looks nothing like “In”. They noted that the arrow in the registered composite mark is missing from the DNO word marks. They contended that the use of the hashtag since at least 30 August 2016 is also a significant point of distinction. Not only is it missing from the applicant’s mark, they contended that it “requires the viewer to pause and interpret” the sign. Moreover, they submitted, it provides a connection with Hashtag Burgers.

94 Nor, the respondents submitted, do the respective marks sound alike. The respondents argued that, it was well-established that in conducting the necessary comparison, “due weight and significance” should attach to the first part of the mark.

95 Third, the respondents submitted that the essential features of the competing marks are different. They argued that the essential feature of the IN-N-OUT BURGER word mark is the phrase “In N Out”, not the “N-Out” or the use of hyphens.

96 Fourth, the respondents observed that no witnesses were called to give evidence that they were confused as a result of the use of the marks in relation to the respondents’ goods and services, although the DNO marks have been used throughout metropolitan Sydney for approximately three years.

97 For the same reasons, the respondents submitted that the DNO domain name was not deceptively similar to any of the applicant’s registered marks.

98 The respondents made the same points about their logos, arguing that the essential and dominant feature of each of them was the phrase “DOWN N OUT” or ‘D#WN N OUT”. They also submitted that the current DNO logo bears no resemblance to the registered IN-N-OUT logo because “it consists of different words and adopts a fundamentally different font, colour scheme and stylisation”.

99 Two questions arise for consideration. First, is there a resemblance between the competing marks? Second, if so, is the resemblance so close as to be likely to cause confusion, if not deception?

100 The respondents’ submissions as to the allegedly material visual differences between the respective marks would be powerful if the applicant were pressing its original claim that the marks were substantially identical. They are much less persuasive, however, with respect to the applicant’s claim that the respective marks are deceptively similar. There is no doubt that on a side by side comparison there are several points of distinction. But that is immaterial. Here, what counts is the impression the impugned mark would have on consumers of ordinary intelligence with an imperfect recollection of the registered marks.

101 There is undoubtedly a visual resemblance between the competing word marks. For a start, they all finish with “N” followed by “OUT”. In addition, they all appear in sans serif fonts. The later adoption of a different colour scheme is immaterial since the applicant’s marks are registered without limitations as to colour and therefore are taken to be registered for all colours: TM Act, s 70. The respondents conceded that “N-Out” is an important component of the IN-N-OUT marks and that IN-N-OUT would be nothing without the “N-Out”. The respondents also conceded that the fact that it appears in the applicant’s marks provides some visual similarity between the competing marks. For the same reason there is also some aural similarity.

102 I referred earlier to the respondents’ submission that weight and significance is to be given to the first syllable of a mark. This submission was supported by the following four authorities.

103 In Re London Lubricants (1920) Ltd’s Application (1925) 42 RPC 264 at 279 Sargant LJ observed that English speakers tend to slur the endings of words so that the first part of a word is accentuated. His Lordship concluded that, as a rule, the first syllable of any word is by “far the most important for the purpose of distinction”.

104 In Johnson & Johnson v Kalnin (1993) 114 ALR 215; (1993) 26 IPR 43, which concerned the marks “band-aid” and “band>>it”, Gummow J noted at 221 that the marks consisted of “the same first, and dominant, primary syllable”. His Honour acknowledged that the second syllable was not identical, but he said that the evidence suggested that “in Australian spoken English the final consonant tends not to be precisely articulated”.

105 In Conde Nast Publications Pty Ltd v Taylor (1998) 41 IPR 505 at 511, which concerned the marks VOGUE and EUROVOGUE, Burchett J referred with apparent approval to the remarks in Re London Lubricants and Johnson & Johnson v Kalnin. His Honour observed, however, that at times “a degree of dissonance between marks in sound and (speaking figuratively) in appearance may be balanced by an identity or close similarity in what has been called the idea of the mark”.

106 The final reference was to Aldi v Frito-Lay where, at [160], Lindgren J cited Conde Nast.

107 English speakers might well emphasise the first syllable of a word in ordinary conversation. But this is not universally so. As the learned authors of Shanahan’s Australian Law of Trade Marks & Passing Off (Thomson Reuters, 6th ed, 2016) point out at [30.1550], there will be cases where the emphasis is placed on another syllable or where the latter part of the word is the more unusual and distinctive. Several examples are cited there, including Upjohn Co v Schering AG (1994) 29 IPR 434 in which the suffix “velle” was found to be the essential element of the trade mark PROVELLE, and PROVELLE and NUVELLE were consequently considered to be deceptively similar. In that case, the delegate of the Registrar of Trade Marks was impressed by the similarity in the structure of the two words, found that they were built on a distinctive element (the same suffix) and that it was likely that buyers would assume a common origin. Further, despite the dissimilarity of the first syllables of COLGATE and TRINGATE, in Colgate-Palmolive Ltd v Pattron [1978] RPC 635 the Privy Council was persuaded that TRINGATE when used in connection with toothpaste was deceptively similar to the COLGATE mark. In Vivo International Corporation Pty Ltd v TiVo Inc [2012] FCAFC 159; (2012) 294 ALR 661; 99 IPR 1 the Full Court upheld the finding of the primary judge (Dodds-Streeton J) that VIVO was deceptively similar to the TIVO mark when used in relation to similar or closely related goods or services, amongst other things, because of “the very considerable aural similarity between the marks”, notwithstanding that her Honour accepted that the words were pronounced differently. In Berlei Hestia the High Court considered that the marks BALI- BRA and BERLEI were deceptively similar solely because of their phonetic similarity.

108 In any case, the “in” in IN-N-OUT BURGER is not a syllable, it is part of a phrase or expression. It is unlikely to attract any greater emphasis than “out”.

109 In my view, N-OUT is a distinctive and significant feature and an essential ingredient of all of the INO marks, just as “& GLORY” was an essential or distinguishing feature of the mark SOAP & GLORY in Soap & Glory Ltd v Boi Trading Co Ltd (2014) 107 IPR 574 at [33].

110 I accept that “down and out” and “in and out” can have different meanings. But meanings can change according to context. I also accept that, when spoken and when the present context is ignored, “Down-N-Out”, “Down N Out”, and “D#wn N Out” convey the same impression or idea as “down and out”. Focussing on the idea or impression created by the DNO marks, however, is apt to distract attention from the real question, namely, whether people with imperfect recollections of the applicants’ marks might be confused or deceived when coming across the respondents’ marks. What matters is the idea or impression carried away from seeing or hearing the applicant’s (registered) marks having regard to the surrounding circumstances. The idea or impression created by the registered marks is of fast-food, particularly burgers, and fast service. The respondents’ marks are being used with respect to the same kind of goods and services. The sort of deconstruction, if not reconstruction, in which the respondents engaged, albeit understandably, is an exercise the ordinary consumer is unlikely to undertake. A person seeing or hearing the registered marks might not be particularly struck by the “In”. After all, “in”, “out”, and “down” are all directional terms. As the applicant submitted, in the context in which they are used, at least some people may well understand DOWN-N-OUT (with or without the hyphens) to convey a similar idea to IN-N-OUT since “down” does not only mean “from higher to lower” but also means “into ... a lower position ...” (Macquarie Dictionary (4th ed, 2005)), as in “down the stairs and into the bar”, consistent with the location of the first DOWN-N-OUT pop up.

111 Although, when compared side by side, there are obvious differences in the design of the arrow in each of the respondents’ logo marks, the fact that they feature an arrow, a prominent feature of the applicant’s device marks, is an additional point of similarity. As the applicant submitted, it reinforces “the common directional idea”. Indeed, the respondents submitted, in effect, that the purpose of the arrows used in the respondents’ logos was to indicate the direction into a restaurant. It is likely that at least some people with an imperfect recollection of the INO marks would not be able to identify the differences in the arrows used by the respective businesses.

112 Does this mean that there is a real risk that a number of persons might be caused to wonder whether the applicant is the source of the respondents’ DNO goods and/or services or whether the respondents are in some way allied to, or associated with, the applicant?

113 In order to answer this question it is first necessary to examine two pieces of evidence.

114 The first is the evidence upon which the applicant relied to establish actual confusion, if not deception. That evidence was conveniently collected in a table annexed to the applicant’s closing submissions and reproduced below. Although the table was said to contain examples only, no other examples were drawn to my attention. If there were more, it is reasonable to assume that these were the best of them. Despite the heading given to this annexure, the first post appears to be taken from the Tablou Instagram account and not from a social media account operated by any of the respondents.

Annexure G – Schedule of examples on Down N' Out’s Social Media Pages that associate or confuse Down N' Out with In-N-Out

Nature of document | Date | Comment | Court book reference |

Instagram post | 5 June 2016 | Heyitsjulian: “what?! In n out?!? Huh?!”

Heyitsjulian: “don’t play with my heart like that!! So confused” | Annexure A-27 to Harley affidavit at p194 |

Instagram post | 27 June 2016 | “…is this the in and out burger place???” | Cbv2.p755 |

Instagram post | 2 July 2016 | “… is this the same people as in n out??”: | Cbv2.p789 |

Facebook post | In or about April 2017 | “… in out of aus” | Cbv2.p792 |

Facebook post | In or about December 2016 | “the Aussie in n out burger” | Cbv2.p756 |

Instagram post | 7 June 2016 |

| Cbv2.p787 |

115 Evidence of actual confusion can be very persuasive. But it is always necessary to evaluate the quality of the evidence “by reference to its internal features”, together with the other evidence and the court’s own knowledge of human affairs: Vivo at [137] (Nicholas J). In the absence of evidence of context and without being able to identify the people who posted the remarks, it is difficult to put a great deal of weight on any of this evidence. None of the authors of the posts gave evidence. It is impossible to know what factors they took into account. While all but the last of these posts suggest some confusion, it is conceivable, I suppose, as the respondents submitted, that this was the work of people “just joking around on social media”. In any case, even if they are genuine instances of confusion, when regard is had to the total number of comments across the respondents’ social media platforms and the period during which the DNO marks have been in use, they are few and far between.

116 Be that as it may, in order to establish the likelihood of deception or confusion, it is not necessary to adduce evidence that anyone was in fact deceived or confused. The test is an objective one. As Lord Devlin observed in Parker-Knoll Ltd v Knoll International Ltd [1962] RPC 265 at 291 in a passage cited with approval by the Privy Council in Colgate-Palmolive at 665:

[W]hat the judge has to decide in a passing off case is whether the public at large is likely to be deceived. What would the effect of the representation be upon the reasonable prospective purchaser? Instances of actual deception may be useful as examples, and evidence of persons experienced in the ways of purchasers of a particular class of goods will assist the judge. But his (sic) decision does not depend solely or even primarily on the evaluation of such evidence. The court must in the end trust to its own perception into the mind of the reasonable man …

117 Colgate-Palmolive was both a passing-off and a trade mark infringement case, but these remarks were not cited only in connection with the passing-off suit. In Colgate-Palmolive no evidence of confusion was admitted at the trial, yet neither the Court of Appeal nor the Privy Council had any difficulty in concluding that the mark TRINGATE used in connection with a brand of toothpaste was deceptively similar to COLGATE.

118 Moreover, the evidence of the social media posts does have some probative value. On the face of things it raises the possibility that some people did wonder about the relationship between IN-N-OUT BURGER and DOWN-N-OUT, including after the arrows and hyphens were removed and the hashtag inserted. Importantly, neither Mr Kagan nor Mr Saliba saw fit to answer the questions raised by the posts or dispel the possibility of confusion, let alone take steps to remove them. It is reasonable to infer that they were happy to leave the question hanging.

119 That brings me to the second piece of evidence: the evidence of the respondents’ intentions.

120 Apart from the likelihood of deception or confusion, the only real factual dispute concerned the respondents’ intentions. As I said earlier, although the owner of a registered trade mark is not obliged to prove intention in order to establish a case of infringement, the alleged infringer’s intentions are not irrelevant. An inference may be drawn from evidence disclosing an intention to deceive or confuse, that deception or confusion is likely to occur. As Dixon and McTiernan JJ explained in Australian Woollen Mills at 657:

The rule that if a mark or get-up for goods is adopted for the purpose of appropriating part of the trade or reputation of a rival, it should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to deceive or confuse, no doubt, is as just in principle as it is wholesome in tendency. In a question how possible or prospective buyers will be impressed by a given picture, word or appearance, the instinct and judgment of traders is not to be lightly rejected, and when a dishonest trader fashions an implement or weapon for the purpose of misleading potential customers he at least provides a reliable and expert opinion on the question whether what he has done is in fact likely to deceive.

121 The rule is not restricted to cases of “deliberate” dishonesty; it is enough that the allegedly infringing trader borrows aspects of the other trader’s mark: Homart Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Careline Australia Pty Ltd (2018) 264 FCR 422 (FC) at [97] (per curiam).

122 An imitation of another person’s product, however, does not necessarily signify an intention to deceive consumers: Campomar Sociedad, Limitada v Nike International Ltd (2000) 202 CLR 45 at [33]. Furthermore, as Burley J observed in Homart Pharmaceuticals Pty Ltd v Careline Australia Pty Ltd [2017] FCA 403; (2017) 349 ALR 598; 126 IPR 498 at [34], in a passage cited with approval by the Full Court on the appeal (Homart at [14]), albeit in the context of a misleading or deceptive conduct claim, “the role of intention should not be overstated”. It all depends on the circumstances. In some circumstances, proof of an intention to mislead may readily lead to an inference of the likelihood of deception, in others it may lead nowhere, the intention may simply miscarry: Windsor Smith Pty Ltd v Dr Martens Australia Pty Ltd [2000] FCA 756; (2000) 49 IPR 286 at [33] (Sundberg, Emmett and Hely JJ).

123 The applicant submitted that the inescapable inference is that the Down-N-Out name and logos were deliberately chosen in order to obtain the benefit of market recognition of the In-N-Out name, trade marks, and branding. The respondents’ position was that they were merely inspired by the applicant, indeed their counsel submitted that it was “plain as a pikestaff that [they] were inspired by In-N-Out”.

124 The evidence establishes that it was no coincidence that Messrs Kagan and Saliba settled on the name DOWN-N-OUT. The respondents’ own media release referred to the adoption of the name as “cheeky”, thereby owning up to their impudence. In closing argument, the respondents accepted that the “N-Out” was taken from the applicant’s trade name IN-N-OUT BURGER. They adopted the DOWN-N-OUT name, not to paint a picture of a person down on his luck, but to remind consumers of IN-N-OUT BURGER. On the face of the evidence, Messrs Kagan and Saliba chose the name DOWN-N-OUT because of its resemblance to IN-N-OUT. Why would they do that unless they believed that they would derive a commercial benefit from doing so?

125 In their June 2015 Facebook promotion for the “Funk N Burgers” pop-up, Messrs Kagan and Saliba described the IN-N-OUT burger as “legendary”. Mr Kagan attended the applicant’s pop-up event in January 2016, observed the length of the queue, and noted that the burgers sold out “before even opening”. Mr Saliba was in possession of a colour copy of the registered In-N-Out logo. So, too, was Mr Paine because Mr Saliba had sent it to him, asking him to make “a funk n burgers sign like in n out burger”. It was soon after this that Messrs Kagan and Saliba adopted the name DOWN-N-OUT for their new pop-up and created and adopted logos combining DOWN-N-OUT with a bent yellow arrow, knowing that the applicant’s registered logo mark used a bent yellow arrow, too.

126 Messrs Kagan and Saliba issued a media release which featured IN-N-OUT, not DOWN-N-OUT, in the title. The media release also referred to a “simple” menu “similar to the original”, together with “secret menu hacks” such as In-N’Out’s “Animal Style” and “Protein Style”. The media release made no reference to what the respondents submitted was the idea or impression given by the name DOWN-N-OUT as something disreputable or pitiable. Further, as the applicant submitted, if this were the message they were intending to convey, why choose DOWN-N-OUT rather than “down and out”?

127 Mr Kagan and/or Mr Saliba endorsed Ms Tucker’s Instagram post in which she declared that she was teaming up with Messrs Kagan and Saliba to “bring In-N-Out down under”.

128 When the first DOWN-N-OUT pop-up opened, “it broadly adopted the theme and style of an IN-N-OUT pop-up”, as the applicant put it, in that it was held inside a bar, offering a simple menu with three burgers and a “secret menu”. The so-called secret menu featured items the names of which, to the knowledge of Mr Kagan and Mr Saliba, were registered trade marks of the applicant. The use by Messrs Kagan and Saliba of these names, together with the reference to the “secret menu” when the applicant’s “secret menu” also offered burgers in ”Animal Style” and “Protein Style”, is likely to have fostered confusion. Having regard to the history and in the absence of evidence to the contrary, it is reasonable to infer that in all probability that was their intention.

129 There is no evidence that Messrs Kagan and Saliba took any steps to dispel the possibility of confusion before they were served with the applicant’s cease and desist letter. They did not reply to the queries or comments posted on their Facebook and Instagram pages. They did not remove the posts. Moreover, their endorsement of the Tablou post (that they were bringing In-N-Out down under), indicates that they were actively encouraging it.

130 The first promotional use of the name DOWN-N-OUT was to advertise the Funk N Burgers event on Facebook on 28 June 2015. That referenced IN-N-OUT BURGER. Unlike the Funk N Burgers event, however, the DOWN-N-OUT pop-up and its successors were not promoted as “tributes” to IN-N-OUT BURGER. The use of “N-OUT”, the choice of font, and the selection of the particular shade of red for the DOWN-N-OUT name were plainly designed to reflect the applicant’s branding. So, too, was the use of the yellow arrow, as Mr Kagan all but conceded in his reply to the applicant’s cease and desist letter. It will be recalled that the colour and particular shade of yellow were chosen by Mr Paine to match the applicant’s branding, a decision approved by Mr Kagan and, by inference Mr Saliba, too. As I have already mentioned, the respondents accepted during closing argument that the “-N-Out” in DOWN-N-OUT was taken from the trade name IN-N-OUT, the essential feature of all the INO marks.

131 Without explanation, neither Mr Kagan nor Mr Saliba gave evidence, although they were both present in the courtroom during the trial. Any inference favourable to the applicant for which there is a foundation in the evidence can more confidently be drawn when a person presumably able to put the true complexion on the facts relied on for the inference has not been called by the respondent and no sufficient explanation is given for his absence: Jones v Dunkel (1959) 101 CLR 298 at 308 (Kitto J); see also at 312 (Menzies J), 320–321 (Windeyer J). Where, as here, the only persons who could give direct evidence on the question of the respondents’ intentions “preferred the well of the court to the witness box”, the Court is entitled to be bold: The Insurance Commissioner v Joyce (1948) 77 CLR 39 at 49 (Rich J); also SS Pharmaceutical Co Ltd v Qantas Airways Ltd [1991] 1 Lloyds Rep 288 at 293 (Gleeson CJ and Handley JA).

132 The respondents submitted that the applicant’s evidence did not rise high enough to enable such an inference to be drawn or to warrant an explanation from the respondents. I disagree. The inference is open from the evidence tendered by the applicant that the respondents adopted aspects of the applicant’s registered marks in order to capitalise on its reputation. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, that is the inference that should be drawn. If this were not their intention, why choose DOWN-N-OUT? Why not stick with FUNK‑N‑BURGERS? In these circumstances, the choice of DOWN-N-OUT should be presumed to be fitted for the purpose and therefore likely to confuse, if not deceive, consumers.

133 It is true that the media release made it clear that down-n-out was an innovation of Hashtag Burgers, which I infer was at this point a business name used by Mr Kagan and Mr Saliba, and described the DOWN-N-OUT pop-up as “Sydney’s answer to In-N-Out burgers”. On balance, however, in the absence of evidence from Mr Kagan and Mr Saliba, the representations in the media release are not sufficient to dispel the inference or rebut the presumption that they intended at least to cause confusion. The similarities in the menus offered by the parties and their stated intention to use “Animal Style” and “Protein Style”, although they admittedly knew they were the applicants’ trade marks, support that conclusion.

134 Of course, the seriousness of the allegation made by the applicant necessarily affects the answer to the question of whether the issue has been proved to the requisite standard: Evidence Act 1995 (Cth), s 140(2); see Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 at 362. But for two pieces of evidence, I would not have been disposed to conclude that Messrs Kagan and Saliba were being dishonest in their decision to appropriate aspects of the applicant’s marks. Over-exuberant, perhaps foolhardy, might have been more accurate.

135 The first piece of evidence is the emphatic denial by Mr Kagan in his reply to the letter of demand that they had ever used the terms “Animal Style” and “Protein Style” for their menu items. The denial is inconsistent with both the statements made to Mr Khatri and the unequivocal representation made in the respondents’ media release that:

Of course there will be shakes and a plethora of secret menu hacks such as Animal Style and Protein Style.

136 In the absence of any evidence from Mr Kagan or Mr Saliba explaining the inconsistency, I have come to the conclusion that Mr Kagan’s denial was not only false but knowingly false. This false representation lends weight to the inference that that the respondents adopted the name “Down-N-Out” for their burger business, and for some time also used a yellow arrow in their logo, for the purpose of appropriating part of the applicant’s reputation and, potentially, its trade.

137 I therefore find that the respondents sought to attract potential customers by having them wonder whether DOWN-N-OUT was, indeed, IN-N-OUT BURGER, perhaps a down-market or down-under version, or, at least, that the two were connected or allied in some way. That was what was cheeky about its choice of name.

138 This question was defined in the agreed statement of issues as “which, if any, of the respondents’ trade marks/logos were adopted for the deliberate purpose of appropriating the trade marks/branding or reputation of the applicant”. Since all the respondents’ marks and the domain name included the phrase “Down N Out”, and it was not just the arrow but also the name that was adopted for this purpose, the answer must be all of them. As the applicant submitted, the incremental changes made by the respondents were not changes of substance. They do not affect in any way the sound of the name and it was the name that built the link between IN-N-OUT BURGER and DOWN-N-OUT.

139 The second piece of evidence is about the respondents’ lack of compliance with their discovery obligations.

140 An order was made by consent on 29 March 2019 for the respondents to give verified discovery by 10 April 2019. The order required verified discovery of documents evidencing or recording:

(a) The creation, selection or adoption of, or the reason(s) why the Respondents created, selected or adopted, any of the Down-N-Out names and logos.

(b) Any knowledge of one or more of the Respondents prior to 17 June 2016, or any investigation or research conducted by or on behalf of one or more of the Respondents prior to 17 June 2016 (including all investigation and research results, and any information received by the Respondents) in respect of In-N-Out, In-N-Out's pop ups, restaurants, menu, branding or logos.

(c) Any instructions, briefs, plans or proposals that concern the design or adoption of the name, logos, branding, fit out, menu, concept or aesthetic of any of the Down-N-Out pop ups or restaurants and reference In-N-Out, In-N-Out’s pop ups, restaurants, menu, branding or logos in any way.

(d) Any communications prior to the commencement of the proceedings, by or on behalf of any of the Respondents, with media publishers, journalists, bloggers, promoters, or customers regarding any of the Down-N-Out pop ups or restaurants or In-N-Out in any way.

141 A verified list of documents was emailed to the applicant’s solicitors on 24 April 2019, two weeks after the expiry of the time fixed by the order. The documents appearing in the list were emailed to the applicant’s solicitors on 29 April 2019.

142 On 15 May 2019 Baker McKenzie wrote to Yates Beaggi Lawyers expressing concern about the paucity of documents that were produced and requested that the respondents provide a description of the steps taken to conduct “a good faith proportionate search to locate discoverable documents, including details of what records were searched, any search criteria or terms which were used, and what databases were searched”. Ms Gleeson replied by email on 22 May 2019 that:

We are instructed that our clients searched all Facebook messages, emails and SMS messages between Ben Kagan and Andrew Saliba, and graphic designers, interior designers and media contacts for any mention of ln-N-Out or any reference to the design and branding process and development, in order to locate the discoverable documents.

Our clients also looked through all Facebook, emails and SMS messages and emails in the months leading up to the Sir John Young pop-up restaurant, to locate the discoverable documents.

143 If the instructions given to Yates Beaggi Lawyers were as Ms Gleeson represented, and there is no reason to think they were not, then Ms Gleeson was either misled or the search conducted by Messrs Kagan and Saliba was manifestly inadequate.

144 On 5 June 2016 a subpoena was issued at Baker McKenzie’s behest to Olivia Tucker, trading as Tablou. The subpoena sought the production of documents that should have been discovered and which would have been discovered if the representation by Ms Gleeson were correct. They were documents created during 2016 that evidence or record any instructions given to one of the respondents’ graphic designers concerning the design of any Down-N-Out names and logos or any Down-N-Out pop-up restaurant; any concepts, plans, or proposals she created in response to those instructions; and the creation, selection or adoption of the Down-N-Out names and logos.

145 The following day Baker McKenzie wrote again to Yates Beaggi Lawyers. They stated that the applicant had serious concerns about “the adequacy and completeness” of the discovery. They pointed out that the discovery appeared to be limited to communications rather than documents and, notwithstanding what they apparently told their lawyers, that the respondents had apparently failed to search and discover documents that might have been created and stored on other platforms, such as Instagram, WhatsApp, and, apart from Facebook messages, Facebook. They listed a number of documents which appeared on the Instagram and Facebook accounts of Mr Kagan and Mr Saliba, which had not been discovered, and sought an explanation as to why they were not discovered. They also attached images of the documents. Those documents were:

(a) an image appearing on Mr Kagan's Instagram account (@hashtag_hustler) dated 20 January 2016, showing a queue at our client's pop up restaurant at Dead Ringer in Sydney on 20 January 2016. The Instagram post by Mr Kagan tags our client's lnstagram account, by its handle @innout (lnstagram Post).

(b) an image and Face book post dated 5 January 2017 from Mr Saliba's Facebook page showing food from an In-N-Out restaurant and the hashtags “#overrated” and “dno41yf” (January 2017 Facebook Post); and

(c) a Facebook post dated 11 November 20I7 from Mr Saliba's Facebook page with a photo in which Mr Kagan is wearing one of our client's IN-N-OUT T-Shirts (November 2017 Facebook Post).

146 Baker McKenzie also noted that the respondents had not discovered any documents relating to the creation of the Down-N-Out name and logo in the form in which it was first used at the Sir John Young Hotel. They pointed out that documents produced by Ms Tucker on subpoena indicate that on 13 May 2016 Mr Kagan possessed documents evidencing or recording the Down-N-Out name and logo. They requested that Yates Beaggi Lawyers conduct a thorough investigation and asked for confirmation of certain matters. They foreshadowed, amongst other things requiring the respondents to attend court to be cross-examined on the issue of whether or not they complied with their discovery obligations.

147 Ms Gleeson sent back a fiery response on 12 June 2019, repudiating Baker McKenzie’s various contentions. A supplementary list of documents was sent at the same time. Only one document was on that list. It appears to be the first of the three documents mentioned in the Baker McKenzie letter.

148 Ms Gleeson’s apparent indignation was unjustifiable.

149 On 26 June 2019, just five days before the hearing was due to start, the respondents filed a second supplementary list and produced a further document. That document contained Facebook messages between Messrs Kagan, Saliba, and Paine. Included in the document were messages relating to the Funk-N-Burgers pop-up event in 2015. In one of them Mr Saliba asked for “a funk n burgers sign like in n out burger” and sent Mr Paine an image of the in-n-out device mark with the registration symbol ® clearly visible. The same day a subpoena was issued to Mr Paine requiring him to produce the same classes of documents that were sought in the subpoena to Ms Tucker.

150 At the hearing the applicants tendered a number of documents which should have been, but were not, discovered on 24 April 2019. They were either discovered in response to the letters of complaint from Baker McKenzie or produced to the Court on subpoena by third parties. Those documents and their sources are listed below: