FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Registered Organisations Commissioner v Communications, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia [2020] FCA 96

ORDERS

REGISTERED ORGANISATIONS COMMISSIONER Applicant | ||

AND: | COMMUNICATIONS, ELECTRICAL, ELECTRONIC, ENERGY, INFORMATION, POSTAL, PLUMBING AND ALLIED SERVICES UNION OF AUSTRALIA Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties are to bring in Short Minutes of Orders to give effect to these reasons within fourteen (14) days.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

FLICK J:

1 The Applicant in the present proceeding is the Registered Organisations Commissioner (“the Commissioner”).

2 The Respondent is the Communications, Electrical, Electronic, Energy, Information, Postal, Plumbing and Allied Services Union of Australia (“the Union”). It has three Divisions, namely:

the Electrical, Energy and Services Division (the “EES Division”);

the Plumbing Division; and

the Communications Division.

These three Divisions consist of a total of 17 Divisional Branches. For the financial year ending in 2017 (and March 2018), the Union’s total income exceeded about $20.7 million and had a total net equity exceeding $170 million.

3 The Union is one of 106 federally registered organisations and represents approximately 2 million members nationally.

4 The Commissioner seeks declaratory relief and the imposition of penalties pursuant to s 306 of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009 (Cth) (the “Registered Organisations Act”) for a total of four contraventions of s 230(1) and 82 contraventions of s 233(2) of that Act. In summary form, the four contraventions of s 230(1)(b) and (c) relate to a failure to include in the annual List of Offices and Office Holders (the “Annual Return”) for 2015 and 2016 the office of Divisional Trustee in the Plumbing Division and the failure to include in those Lists the required information regarding the persons holding that office; the 82 contraventions of s 233(2) relate to the failure to notify of changes made to records within the prescribed period of 35 days.

5 The Union initially admitted all contraventions but contended that it should be relieved from any penalty by reason of s 315(2) of the Registered Organisations Act in respect to some or all of the admitted contraventions. In the alternative, in its written submissions filed in December 2018, the Union submitted that “either no or a very low pecuniary penalty should be imposed in respect of any remaining contraventions for which relief from penalty has been provided”. In March 2019, however, the Union filed an interlocutory application seeking leave pursuant to r 26.11 of the Federal Court Rules 2011 (Cth) (the “Federal Court Rules”) to withdraw its admission in respect to four contraventions. During the course of the hearing the Union withdrew its application for relief from liability pursuant to s 315(2).

6 Together with the Union’s National Office and the three Divisions and their Branches, the Union comprises 21 separate reporting units for the purposes of Div 2, Pt 3 of Ch 8 of the Registered Organisations Act. Given the large number of Divisional Branches within the Union there is a correspondingly large number of offices. The Annual Return 2018 – as at 31 December 2017 thus discloses in excess of 550 offices, comprising, at least:

National Council: 56

EES Division: 259

Plumbing Division: 86

Communications Division: 150

Notwithstanding the structure of the Union as a single Union comprising three Divisions, the National Secretary (Mr Allen Hicks) described it as essentially three separate Unions operating autonomously. Indeed, Mr Hicks further described the Branches as also operating autonomously. It is this dysfunctional structure of the Union which largely occasioned many of the contraventions.

7 In very summary form it has been concluded that:

the Union’s submission that “either no or a very low pecuniary penalty” should be imposed (with the Union initially submitting a penalty in the range from $25,000 to $75,000 and later a penalty of $90,360 (or less)) should be rejected;

leave to withdraw the admissions as to liability in respect to contraventions 66 to 69 should be granted;

contraventions 66 to 69 have been made out by the Commissioner; and

penalties should be imposed in the total sum of $445,000 payable to the Commonwealth.

THE REGISTERED ORGANISATIONS ACT

8 Section 5(1) of the Registered Organisations Act provides that it “is Parliament’s intention in enacting this Act to enhance relations within the workplaces between federal system employers and federal system employees and to reduce the adverse effects of industrial disputation”.

9 Section 5(2) provides that Parliament considers “that those relations will be enhanced and those adverse effects will be reduced, if associations of employers and employees are required to meet the standards set out in this Act in order to gain the rights and privileges accorded to associations under this Act and the Fair Work Act”.

10 Section 5(3) and (4) then provides as follows:

(3) The standards set out in this Act:

(a) ensure that employer and employee organisations registered under this Act are representative of and accountable to their members, and are able to operate effectively; and

(b) encourage members to participate in the affairs of organisations to which they belong; and

(c) encourage the efficient management of organisations and high standards of accountability of organisations to their members; and

(d) provide for the democratic functioning and control of organisations; and

(e) facilitate the registration of a diverse range of employer and employee organisations.

(4) It is also Parliament's intention in enacting this Act to assist employers and employees to promote and protect their economic and social interests through the formation of employer and employee organisations, by providing for the registration of those associations and according rights and privileges to them once registered.

11 The provisions of the Registered Organisation Act which assume present relevance are found within Ch 8 of that Act, a chapter which is headed “Records and accounts”. Within that Chapter, s 230 provides as follows:

Records to be kept and lodged by organisations

(1) An organisation must keep the following records:

(a) a register of its members, showing the name and postal address of each member and showing whether the member became a member under an agreement entered into under rules made under subsection 151(1);

(b) a list of the offices in the organisation and each branch of the organisation;

(c) a list of the names, postal addresses and occupations of the persons holding the offices;

(d) such other records as are prescribed.

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

(2) An organisation must:

(a) enter in the register of its members the name and postal address of each person who becomes a member, within 28 days after the person becomes a member;

(b) remove from that register the name and postal address of each person who ceases to be a member under section 171A, or under the rules of the organisation, within 28 days after the person ceases to be a member; and

(c) enter in that register any change in the particulars shown on the register, within 28 days after the matters necessitating the change become known to the organisation.

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

(note omitted)

12 Also within Ch 8, s 233 provides as follows:

Obligation to lodge information with the Commissioner

(1) An organisation must lodge with the Commissioner once in each year, at such time as is prescribed:

(a) a declaration signed by the secretary or other prescribed officer of the organisation certifying that the register of its members has, during the immediately preceding calendar year, been kept and maintained as required by paragraph 230(1)(a) and subsection 230(2); and

(b) a copy of the records required to be kept under paragraphs 230(1)(b), (c) and (d), certified by declaration by the secretary or other prescribed officer of the organisation to be a correct statement of the information contained in those records.

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

(2) An organisation must, within the prescribed period, lodge with the Commissioner notification of any change made to the records required to be kept under paragraphs 230(1)(b), (c) and (d), certified by declaration signed by the secretary or other prescribed officer of the organisation to be a correct statement of the changes made.

Civil penalty: 60 penalty units.

(3) A person must not, in a declaration for the purposes of this section, make a statement if the person knows, or is reckless as to whether, the statement is false or misleading.

Civil penalty: 100 penalty units.

13 Although ss 230 and 233 may properly be characterised as “record keeping provisions”, those provisions impose important and “significant” obligations upon a registered organisation: Registered Organisations Commissioner v Transport Workers’ Union of Australia [2018] FCA 32. Perram J when considering the need for deterrence there observed:

[79] … Because of the democratic principles underpinning the RO Act (see s 5 above), record keeping under this legislation is a significant matter ...

On appeal, in Transport Workers’ Union of Australia v Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 203, (2018) 363 ALR 464 at 489 (“Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 2)”), the Full Court (also when considering the need for deterrence in imposing penalties) similarly observed:

[130] The overwhelming sentencing factor in this case is general deterrence. As the objects set out in s 5 of the Registered Organisations Act make clear, registration confers rights, privileges and protections upon registered organisations. However, those advantages come with serious obligations, including obligations to keep accurate records about their membership. It is important that registered organisations should understand that those obligations must be complied with and that non-compliance will attract substantial penalties.

[131] Whilst ignorance of compliance may explain, it does not excuse. Registered organisations should have it made clear to them the importance of record-keeping of members. ...

14 When addressing the requirement to prepare and provide copies of a general purpose financial report as required by ss 253, 265 and 266 of the Registered Organisations Act, Barker J has similarly referred to the joint agreement of the parties that “the obligation to prepare reports required by the RO Act is an important matter in the administration of an organisation registered under the RO Act…”: Registered Organisations Commissioner v Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (No 2) [2018] FCA 2004 at [34] (“Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (No 2)”). His Honour agreed that this was “undoubtedly so” and went on to observe that “[u]nless the responsible officers of reporting units take the steps that they are expected to take to comply with the law, members and regulators alike risk being deprived of an effective means of understanding, detecting and responding to any issues that might arise in connection with the management of organisations”.

15 Chapter 10 of the Registered Organisations Act is headed “Civil penalties”. Within that Chapter, s 315 provides as follows:

Relief from liability for contravention of civil penalty provision

(1) In this section:

eligible proceedings:

(a) means proceedings for a contravention of a civil penalty provision; and

(b) does not include proceedings for an offence.

(2) If:

(a) eligible proceedings are brought against a person or organisation; and

(b) in the proceedings it appears to the Federal Court that the person or organisation has, or may have, contravened a civil penalty provision but that:

(i) the person or organisation has acted honestly; and

(ii) having regard to all the circumstances of the case, the person or organisation ought fairly to be excused for the contravention;

the Court may relieve the person or organisation either wholly or partly from a liability to which the person or organisation would otherwise be subject, or that might otherwise be imposed on the person or organisation, because of the contravention.

(3) If a person or organisation thinks that eligible proceedings will or may be begun against them, they may apply to the Federal Court for relief.

(4) On an application under subsection (3), the Court may grant relief under subsection (2) as if the eligible proceedings had been begun in the Court.

The power to impose penalties & the maximum penalty

16 The source of the statutory power for this Court to impose penalties is to be found in ss 305 and 306 of the Registered Organisations Act.

17 Section 305 provides that an application may be made to this Court for an order under s 306 “in respect of conduct in contravention of a civil penalty provision”. Section 306 provides that the Court may make an order imposing a penalty. In the case of a body corporate, the maximum penalty that may be imposed is “5 times the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision” (s 306(1)(a)) and, in any other case, the maximum penalty is “the pecuniary penalty specified for the civil penalty provision” (s 306(1)(b)).

18 Contraventions of ss 230 and 233(2) each attracted a penalty of 60 penalty units.

19 For those contraventions that occurred prior to 31 July 2015, the value of a penalty unit was $170, giving a total maximum of $10,200 per contravention. For contraventions after that date, the value of a penalty unit was $180, giving a maximum of $10,800 per contravention.

20 Pursuant to s 306(1)(a), the maximum penalty per contravention which could be imposed on the Union (as a body corporate) is $51,000 for those contraventions that occurred prior to 31 July 2015 and $54,000 for those contraventions that occurred after that date.

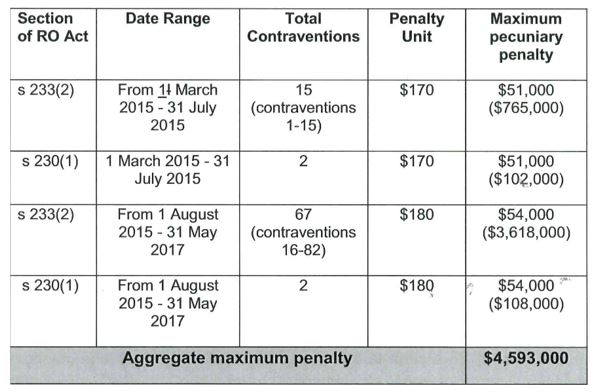

21 The maximum penalties that could potentially be applied in the present case, assuming that each of the contraventions pleaded by the Commissioner is made out and that each attracted its own individual penalty, has been calculated by the Commissioner as follows:

The Union accepted, in its written submissions, that the Commissioner “correctly identified the value of penalty units at the relevant times”.

22 The maximum penalty that can be imposed serves, it has been said, as a “yardstick” against which the assessment of penalties is generally to proceed: Markarian v The Queen [2005] HCA 25, (2005) 228 CLR 357 at 372 (“Markarian”). Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne and Callinan JJ there observed:

[30] Legislatures do not enact maximum available sentences as mere formalities. Judges need sentencing yardsticks. It is well accepted that the maximum sentence available may in some cases be a matter of great relevance. In their book Sentencing, Stockdale and Devlin observe that:

“A maximum sentence fixed by Parliament may have little relevance in a given case, either because it was fixed at a very high level in the last century … or because it has more recently been set at a high catch-all level … At other times the maximum may be highly relevant and sometimes may create real difficulties …

A change in a maximum sentence by Parliament will sometimes be helpful [where it is thought that the Parliament regarded the previous penalties as inadequate].”

[31] It follows that careful attention to maximum penalties will almost always be required, first because the legislature has legislated for them; secondly, because they invite comparison between the worst possible case and the case before the court at the time; and thirdly, because in that regard they do provide, taken and balanced with all of the other relevant factors, a yardstick…

(footnote omitted)

Their Honours there continued (at 372):

[31] … That having been said, in our opinion, it will rarely be, and was not appropriate for [the Judge below] to look first to a maximum penalty, and to proceed by making a proportional deduction from it. That was to use a prescribed maximum erroneously, as neither a yardstick, nor as a basis for comparison of this case with the worst possible case…

(footnote omitted)

Although these comments were made in the context of the criminal law and sentencing for drug offences, they have since been applied by this Court when assessing penalties under fair work legislation: e.g., Fair Work Ombudsman v Grouped Property Services Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCA 557 at [390] to [391] per Katzmann J (“Grouped Property Services Pty Ltd (No 2)”); Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 113 at [106], (2017) 254 FCR 68 at 90 per Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ (“ABCC v CFMEU”); Registered Organisations Commissioner v Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (No 2) [2018] FCA 2004 at [23] per Barker J.

The quantification of penalties – the principles to be applied

23 Although the maximum penalty prescribed by the Commonwealth Legislature for contravention of civil remedy provisions always serves as a useful “yardstick” against which the assessment of penalties is generally to proceed (cf. Markarian), the considerations to be taken into account when making the evaluative judgment as to what should be the appropriate penalty – or total penalty – to be imposed are well settled.

24 In Kelly v Fitzpatrick [2007] FCA 1080 at [14], (2007) 166 IR 14 at 18 to 19, Tracey J was called upon to quantify penalties for admitted contraventions of the Transport Workers Award 1998 and in doing so adopted the following as a “non-exhaustive range of considerations” to be taken into account:

the nature and extent of the conduct which led to the breaches;

the circumstances in which that conduct took place;

the nature and extent of any loss or damage sustained as a result of the breaches;

whether there had been similar previous conduct by the respondent;

whether the breaches were properly distinct or arose out of the one course of conduct;

the size of the business enterprise involved;

whether or not the breaches were deliberate;

whether senior management was involved in the breaches;

whether the party committing the breach had exhibited contrition;

whether the party committing the breach had taken corrective action;

whether the party committing the breach had cooperated with the enforcement authorities;

the need to ensure compliance with minimum standards by provision of an effective means for investigation and enforcement of employee entitlements; and

the need for specific and general deterrence.

25 Two of these considerations should be further expanded upon.

26 First, the “course of conduct” concept recognises that the legal and factual interrelationship between a series of contraventions may be such that the imposition of one or more penalties for each contravention would be to repeatedly punish the offender for the same conduct. The legal and factual interrelationship between a series of contraventions may be such that it is open to conclude that the multiple contraventions are but a single course of conduct and that the penalty to be imposed should reflect that interrelationship.

27 But caution must be exercised when considering and applying that phrase. The use of the phrase, it has been said, can be “problematic”: Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 203 at [84], (2018) 363 ALR at 479 per Allsop CJ, Collier and Rangiah JJ. Their Honours there went on to further observe that the “singular phrase should not be simplistically adopted to transform multiple contraventions into one contravention, or, necessarily impose one penalty by reference to one maximum amount”: [2018] FCAFC 203 at [85], (2018) 363 ALR at 479.

28 Absent statutory authority, separate contraventions of civil remedy provisions should generally each attract a separate penalty.

29 In an appropriate case, however, a single penalty can be imposed in respect to a single course of conduct comprising multiple contraventions: Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 203 at [90], (2018) 363 ALR at 481. But a finding that there is a single course of conduct does not imply a single contravention or a single maximum penalty. That, according to Allsop CJ, Collier and Rangiah JJ “is the danger of the phrase”: [2018] FCAFC 203 at [91], (2018) 363 ALR at 481.

30 In ABCC v CFMEU [2017] FCAFC 113, (2017) 254 FCR, Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ thus summarised the approach in relevant part as follows (at 91 to 92):

Course of conduct

[111] Like many of the principles that apply to the fixing of pecuniary penalties, the so-called course of conduct, or one-transaction, principle is derived from criminal law sentencing principles. …

[112] The principle, as applied in sentencing for criminal offences, was explained in the following terms by Owen JA in Royer v Western Australia (2009) 197 A Crim R 319 at [22]:

… At its heart, the one transaction principle recognises that, where there is an interrelationship between the legal and factual elements of two or more offences with which an offender has been charged, care needs to be taken so that the offender is not punished twice (or more often) for what is essentially the same criminality. The interrelationship may be legal, in the sense that it arises from the elements of the crimes. It may also be factual, because of a temporal or geographical link or the presence of other circumstances compelling the conclusion that the crimes arise out of substantially the same act, omission or occurrences.

[113] In the criminal sentencing context, the course of conduct is a tool of analysis that generally assists a sentencing judge in determining whether sentences of imprisonment for separate offences should be ordered to be served concurrently or consecutively. …

[114] The important point to emphasise is that the course of conduct principle, in the criminal context at least, does not operate to permit a sentencing judge to impose a single sentence in respect of multiple offences on the basis that the offences formed part of a course of conduct. Absent a statutory provision that provides otherwise, a sentencing judge is to impose a separate sentence, albeit with the option of concurrency, for each offence.

[115] The course of conduct principle has been applied in the civil pecuniary penalty context …

Their Honours went on to further observe (at 99-100):

[148] The important point to emphasise is that, contrary to the Commissioner’s submissions, neither the course of conduct principle nor the totality principle, properly considered and applied, permit, let alone require, the Court to impose a single penalty in respect of multiple contraventions of a pecuniary penalty provision. There is no doubt that, in an appropriate case involving multiple contraventions, the Court should consider whether the multiple contraventions arose from a course or separate courses of conduct. If the contraventions arose out of a course of conduct, the penalties imposed in relation to the contraventions should generally reflect that fact, otherwise there is a risk that the respondent will be doubly punished in respect of the relevant acts or omissions that make up the multiple contraventions. That is not to say that the Court can impose a single penalty in respect of each course of conduct. Likewise, there is no doubt that in an appropriate case involving multiple contraventions, the Court should, after fixing separate penalties for the contraventions, consider whether the aggregate penalty is excessive. If the aggregate is found to be excessive, the penalties should be adjusted so as to avoid that outcome. That is not to say that the Court can fix a single penalty for the multiple contraventions.

31 Their Honours there also addressed the “totality” principle, namely the need to ensure that the aggregate penalty is “just and appropriate”. The “totality” principle, their Honours there emphasised, stood separate and apart from the “course of conduct” principle. In doing so, their Honours observed in relevant part (at 92 to 94):

Totality

[116] The totality principle, like the course of conduct principle, has its origins in criminal sentencing. …

[117] The totality principle is sometimes confused or conflated with the course of conduct principle. That is perhaps not surprising because application of the totality principle may again result in a court adjusting what would otherwise have been consecutive or cumulative sentences to sentences that are wholly or partially concurrent. The proper approach, however, is to first consider the course of conduct principle and determine whether the sentences should be consecutive, or wholly or partly concurrent. Once that is done, the Court should then review the aggregate sentence to ensure that it is just and appropriate. That may require a further adjustment of the sentences: either by ordering further concurrency or, if appropriate, lowering the individual sentences below what would otherwise be appropriate.

[118] While, in the criminal sentencing context, the totality principle is generally applied in cases involving sentences of imprisonment, it has been held to apply to the fixing of fines. In the case of fines, the Court must fix a fine for each offence and then review the aggregate to ensure that it is just and appropriate. If the result of the aggregation of multiple fines is that the penalty is excessive, that may lead to the moderation of the fine imposed in respect of each offence. …

[119] Once again, the important point to emphasise is that, in the criminal sentencing context, application of the totality principle does not authorise or permit the sentencing court to impose a single sentence for multiple offences. That has been made clear in a number of cases. …

[120] Like the course of conduct principle, the totality principle has been picked up and applied in the context of civil pecuniary penalty proceedings: …

[121] It would also appear that in the civil penalty context the totality principle, often in conjunction with the course of conduct principle, has been relied on to support the imposition of a single pecuniary penalty for multiple contraventions. Consideration must now be given to whether that is permissible and appropriate, either pursuant to the course of conduct principle, the totality principle, or on some other basis.

(citations omitted)

32 The totality principle had previously been summarised by Goldberg J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Safeway Stores Pty Ltd (1997) 145 ALR 36 at 53 as follows:

The totality principle is designed to ensure that overall an appropriate sentence or penalty is appropriate and that the sum of the penalties imposed for several contraventions does not result in the total of the penalties exceeding what is proper having regard to the totality of the contravening conduct involved: McDonald v R (1994) 48 FCR 555; 120 ALR 629. But that does not mean that a court should commence by determining an overall penalty and then dividing it among the various contraventions. Rather the totality principle involves a final overall consideration of the sum of the penalties determined. In Mill v R (1988) 166 CLR 59; 83 ALR 1 the High Court accepted the following statement as correctly describing the totality principle:

The effect of the totality principle is to require a sentencer who has passed a series of sentences, each properly calculated in relation to the offence for which it is imposed and each properly made consecutive in accordance with the principles governing consecutive sentences, to review the aggregate sentence and consider whether the aggregate is “just and appropriate”. The principle has been stated many times in various forms: “when a number of offences are being dealt with and specific punishments in respect of them are being totted up to make a total, it is always necessary for the court to take a last look at the total just to see whether it looks wrong”; “when … cases of multiplicity of offences come before the court, the court must not content itself by doing the arithmetic and passing the sentence which the arithmetic produces. It must look at the totality of the criminal behaviour and ask itself what is the appropriate sentence for all the offences”.

See also: Grouped Property Services Pty Ltd (No 2) [2017] FCA 557 at [428] per Katzmann J.

33 The second consideration referred to by Tracey J in Kelly v Fitzpatrick which warrants further consideration is “the need for specific and general deterrence”. It is well-accepted, that a primary purpose in imposing any civil penalty is that of deterrence: Commonwealth v Director, Fair Work Building Industry Inspectorate [2015] HCA 46 at [55], (2015) 258 CLR 482 at 506 per French CJ, Kiefel, Bell, Nettle and Gordon JJ. See also: ABCC v CFMEU [2017] FCAFC 113 at [98] to [99], (2017) 254 FCR at 88 per Dowsett, Greenwood and Wigney JJ. The purpose of imposing a civil penalty is to promote the public interest in compliance.

34 The objective of a penalty acting as a deterrent focusses not only upon the objective of deterring the entity involved in a particular proceeding from again engaging in the same conduct (i.e., “specific deterrence”) but also upon deterring others from engaging in like conduct (i.e., “general deterrence”): Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (“Cardigan St Case”) [2018] FCA 957. Bromberg J there helpfully summarised this objective as follows:

[50] In relation to specific deterrence, it has been frequently observed that a pecuniary penalty for a contravention of the law must be fixed with a view to ensuring that the penalty is not to be regarded by the offender or others as an “acceptable cost of doing business”: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v TPG Internet Pty Ltd (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [66] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ); Singtel Optus Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2012] FCAFC 20 at [62]-[63] (Keane CJ, Finn and Gilmour JJ). On the other hand, general deterrence is directed at sending a message to a broader audience that contraventions of the kind under consideration are serious and not acceptable: Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Southcorp Ltd (No 2) (2003) 130 FCR 406 at [32] (Lindgren J).

An option not to be countenanced is that an offender may not “choose to break the law and simply pay the penalty”: Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union [2017] FCAFC 53, (2017) 249 FCR 458. Dowsett and Rares JJ there observed (at 481):

[100] In a liberal democracy, it is assumed that citizens, corporations and other organisations will comply with the law. Such compliance is not a matter of choice. The community does not accept that a citizen, corporation or other organisation may choose to break the law and simply pay the penalty. The courts certainly do not accept that proposition. Such acceptance would pose a serious threat to the rule of law upon which our society is based. It would undermine the authority of Parliament and could lead to the public perception that the judiciary is involved in a process which is pointless, if not ridiculous.

[101] The Parliament’s purpose in legislating to provide that particular proscribed conduct will attract a civil penalty was to deter persons, including but not limited to trade unions or corporations, from engaging or continuing to engage in such conduct. A civil penalty would lose its utility if the person on whom it was imposed simply treated it as a cost of continuing to carry on with the very conduct that had just been penalised.

THE CONTRAVENTIONS

35 The Commissioner seeks penalties in respect to contraventions of the Registered Organisations Act with respect to both:

section 230(1)(b) and (c); and

section 233(2).

Each section should be considered separately, as should the application for leave to withdraw the admissions in respect to contraventions 66 to 69 (as set forth in items 66 to 69 of Appendix A of the Statement of Claim) and whether those particular contraventions have been made out.

The four contraventions of s 230(1)(b) & (c)

36 Section 230 requires that certain “records” be “kept and lodged” by organisations. In the present proceeding, the Commissioner relies on four contraventions of s 230, namely a failure by the Union to include:

in the “2015 List of Offices and Office Holders” lodged with the Fair Work Commission, the office of “Divisional Trustee in the Plumbing Division”: s 230(1)(b);

in the “2015 List of Offices and Office Holders” lodged with the Fair Work Commission, the name, postal address and occupation of persons holding the office of “Divisional Trustee in the Plumbing Division”: s 230(1)(c);

in the “2016 List of Offices and Office Holders” lodged with the Fair Work Commission, the office of “Divisional Trustee in the Plumbing Division”: s 230(1)(b); and

in the “2016 List of Offices and Office Holders” lodged with the Fair Work Commission, the office of “Divisional Trustee in the Plumbing Division”: s 230(1)(c).

37 The Union, in its Amended Defence, admitted these contraventions.

The 82 pleaded contraventions of s 233(2)

38 Appendix A to the Statement of Claim filed by the Commissioner is a Table setting forth each of the 82 contraventions relied upon by the Commissioner and – subject to contraventions 66 to 69 and the corrections as to the dates upon which notifications were required to have been given – admitted by the Union. The Union in its written submissions (noting these submissions were filed prior to the interlocutory application seeking leave to withdraw the admissions with respect to contraventions 66 to 69) groups these contraventions in a somewhat similar manner but in a manner which seeks to group individual contraventions in what it perceives to be those arising out of the same event which occasioned the contravention.

39 Relying upon the groupings of contraventions relied upon by the Union, a summary broadly drawn from the Union’s written submissions (and not an exhaustive review of the evidence) is as follows:

Items | Nature of change leading to contravention | Person responsible | Delay (days) | Reasons |

1 - 4 | Four changes to office holders in Queensland; namely the resignation of Mr Towler from State Council; Appointment of Messrs Muller & Mills to State Council and Mr Taylor to Divisional Branch Executive | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Simpson | 16 | Notification of changes due 15 June 2015 but were not notified until 1 July 2015. Mr McKenzie, the current Assistant Divisional Branch Secretary, was “unable to determine why these changes were filed late” and was “unaware of … there being any intent for these changes not to be notified”. |

5 - 10 | Six changes in office holders in the Western Australian Divisional Branch | Mr Coffey (from the Victorian Divisional Branch) told Mr Bintley (the WA Divisional Branch Secretary) that the Victorian Divisional Branch would deal with the paperwork | 31 | Notification of changes due 15 June 2015 but were not notified until 16 July 2015. Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Bintley, forwarded to Mr Coffey in the Victorian Divisional Branch a Declaration of results of the 2015 Divisional Branch Quadrennial Elections. The Victorian Divisional Branch then being responsible for dealing with the “paperwork”. Mr Coffey thought the AEC provided a copy of the Declaration to the FWC and did not lodge notifications with the FWC. The National Office lodged the notifications. The Union submits that the failure to lodge the notifications in time was “mere oversight & not intentional”. |

11 - 15 | Five changes in office holders in the New South Wales Divisional Branch | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Broadley | 14 | Notification of changes due 2 July 2015 but were not notified until 16 July 2015. Current Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Samartzopoulous, states there is “…nothing to suggest that the delay was deliberate or intentional…” but that his impression of the then Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Broadly, was that “his focus as Divisional Branch Secretary was upon representing members in their workplaces at the expense of the union’s compliance obligations…” |

16 - 29 | Fourteen changes to office holders in the Victorian Divisional Branch as a result of the 2015 Branch Quadrennial elections | Chief Operations Officer | 31 | Notification of changes due 24 August 2015 but were not notified until 24 September 2015. The Chief Operations Officer had resigned in September 2015 and the Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Gray, “had omitted to allocate responsibility for this task to another staff member”. Mr Gray “was unaware at the time that the changes had not been notified”. |

30 - 37 | Eight changes to office holders in the South Australian and Northern Territory Divisional Branch | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Townsend Divisional Branch President, Mr Lorrain | varied | Contraventions 33-36 each had a due notification date of 5 September 2015. The remaining contraventions each had due notifications dates varying from 19 August to 3 October 2015. All contraventions were notified on 21 October 2015 Mr Townsend states he was “…a newly appointed Divisional Branch Secretary… it was unclear who was going to be responsible… as there was no established process …” |

38 - 40 | Three changes in office holders in the Victorian Divisional Branch due to a second-tier quadrennial election | Chief Operations Officer | 33 | Notification of changes due 29 October 2015 but were not notified until 1 December 2015. After the resignation in September 2015 of the former Chief Operations Officer, the Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Gray, had at the relevant time “not allocated the responsibility for the notification of changes to another member of staff…” |

41 - 42 | Two changes in office holders in the Western Australian Divisional Branch due to a second-tier quadrennial election | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr McLaughlin | 16 | Notification of changes due 11 November 2015 but were notified on 1 December 2015. Mr McLaughlin mistakenly believed AEC’s notification to the FWC discharged his own obligation. The branch received a letter from the FWC on 16 November 2015 about the reporting obligations but Mr McLaughlin does “not know why it took a further two weeks for the notice to be filed. I do not know of any improper reason for that two week delay”. |

43 | Mr Halloran replaces Mr O’Carroll as Assistant General Secretary, Plumbing Division, Victorian Branch | Industrial Officer, Mr Coffey | 110 | Notification of change due 21 August 2015 but was not notified until 9 December 2015. Mr Coffey did not think he had to notify the FWC because he thought AEC notified the FWC. Mr McCrudden brought the oversight to Mr Coffey’s attention in November 2015 and the FWC was notified in December 2015. |

44 - 46 | Three resignations from the South Australian State Council – Mr Smith in September 2015; Mr Mutton in December 2015 and Mr Buchanan in February 2016 | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Adley | Various delays; notice given in June 2016 for all three changes | Notification of each change due at various times in 2016 but notifications were not made until 22 June 2016. Mr Adley was “unaware of the requirement to notify changes in office holders within 35 days” and stated “I regret my mistake”. |

47 | Mr Bland resigns as the Victorian Divisional Branch President | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Ellery | 20 | Notification of change due 22 September 2016 but was not notified until 12 October 2016. Mr Ellery “believed notices of change … were only required where an office was filled ….” He further stated that “The delay…occurred at the Divisional Branch level due to my misunderstanding … It was in no way intentional. I regret the errors that I made”. |

48 | Ms Stubberfield resigns as Elected Divisional BCOM Member in the Victorian Branch | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Ellery | 21 | Notification of change due 18 October 2016 but was not notified until 8 November 2016. Mr Ellery believed notification only required when an office was filled. The “failure to notify… inadvertently occurred as a result of [his] misunderstanding…[he] regret[s] the errors that [he] made”. |

49 - 51 | Three changes to office holders in the Western Australian Branch | Ms Stewart Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr McLaughlin | 64 | Notification of changes due 7 September 2016 but were not notified until 10 November 2016. Ms Stewart had taken on responsibility for notifications but “was not provided any training…”. Mr McLaughlin accepts “this was a mistake and I should have provided that training” |

52 - 63 | The merger of the Communications Branch and Electrical Branch of the Union in Tasmania | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Gauld | 67 | Notification of changes were due 15 September 2016 but were not notified until 21 November 2016. This was Mr Gauld’s first branch merger. The process was complicated due to the loss of important administrative staff. Mr Gauld maintains that the “errors were no intentional, and were not dishonest.” He further maintained “I regret that these errors were made…” |

64 - 65 | Two changes in office holders in the New South Wales Divisional Branch | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Metcher | Various delays | Notification of changes were due on 9 September and 4 November 2016 respectively but were not notified until 5 December 2016. Current Divisional Secretary, Mr Murphy, explains that the period prior to Mr Metcher’s departure “was a personally difficult one … and that he was under significant pressure in relation to allegations of his personal conduct…” and that “nothing from the records…suggest that the non-compliance was deliberate”. |

66 - 69 | Four vacant positions in the South Australian Divisional Branch Committee of Management were purportedly abolished | Divisional Branch President, Mr Lorrain | 72 | Notification of changes due 26 October 2016 but were not notified until 6 January 2017. Mr Lorrain only became aware of the Divisional Branch’s obligation to notify of changes in office holders in December 2016. Further, Mr Lorrain states: “December was a very busy month and it took me some time to gather the appropriate documents. I was also on leave from 24 December 2016, returning 2 January 2017”.

|

70 | Resignation of a State Councillor in the New South Wales Branch | Unknown but usually the Operations Manager or Legal Officer in the Divisional Branch | 35 | Notification of change due 12 December 2016 but was not notified until 16 January 2017. The then Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Butler is “…unaware why this notice was not filed on time but it may have been due to [his] absence and not being there to follow the matter up…” |

71 | Change in office holder in the Victorian Divisional Branch in the EES Division | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Gray | 40 | Notification of change due 29 December 2016 but was not notified until 7 February 2017. According to Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Gray “at the time there was no process in place for notifying changes in office holder mid-term” and it was an “an oversight on [his] part” |

72 | Mr Betts resigns from four offices but notification is only given in respect to three offices – New South Wales Divisional Branch in the EES Division | Divisional Branch Secretary | 160 | Notification of change due 6 October 2016 but was not notified until 15 March 2017. Current Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr McKinley does not know “why this particular change was not notified”. Former Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Butler does “not believe that the omission was deliberate”.

|

73 | Mr Hancock resigned from the Divisional Branch Committee of Management of the Western Australian Branch of the Plumbing Division | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Bintley | 50 | Notification of change due 27 March 2017 but was not notified until 16 May 2017. Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Bintley “forgot to pass on the resignation in accordance with the new procedure. I mistakenly believed that I had notified the Victorian Divisional Branch when I had not. I do not know why I believed this. It was a genuine oversight…” |

74 - 76 | Messrs McCrudden, Kelly and Menzies elected as Divisional Trustees of the Plumbing Division | Industrial Officer, Mr Coffey | No notification lodged prior to proceeding commencing | Notification of changes due 21 August 2015 but no notification has been lodged prior the proceeding commencing. Mr Coffey “was under the mistaken belief that there was no distinction between the office of the Divisional Councillor and Divisional Trustee, as these offices were occupied by the same persons.” |

77 | Change in office holders as a result of the Queensland Branch’s quadrennial election, Mr Humphrey’s appointment to State Council was not included in the notification of changes provided | Assistant Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr McKenzie | No notification lodged prior to proceeding commencing | Notification of change due 11 September 2015 but no notification was lodged prior the proceeding commencing. Current Assistant Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr McKenzie, does “not know why [the notice] does not” include Mr Humphrey’s name. Mr McKenzie has “ been unable to determine the cause of the initial oversight” |

78 | Change in office holder as Mr Banting resigns from the Divisional Branch Committee of Management (Western Australia) | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr McVee | No notification lodged prior to proceeding commencing | Notification of change due 14 September 2015 but no notification was lodged prior the proceeding commencing. Ms Di Re received Mr Banting’s resignation but did not pass the email on to Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr McVee. Further, Mr McVee “believed that by writing to the FWC in the first instance, we had complied with our obligations in the process…” |

79 - 80 | Changes in office holders in in the South Australian EES Divisional Branch; Mr Harrison replaces Mr Borg as Vice President of the Divisional Branch and Mr Borg appointed as Divisional Branch Executive Member | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr Adley | No notification lodged prior to proceeding commencing | Notification of changes due 17 December 2015 but no notification was lodged prior the proceeding commencing. Mr Adley misread an email from Ms Moran and “formed the incorrect impression from the email that the Divisional Office was attending to the filing of the notices…” |

81 - 82 | Two changes in office holders; Messrs Thomas & Van Der Stelt elected to Divisional Branch Committee of Management (Western Australia) | Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr McVee | No notification lodged to proceeding commencing | Notification of changes due 23 May 2016 but no notification was lodged prior the proceeding commencing. At the time the Divisional Branch Secretary, Mr McVee, did not appreciate he was to separately notify the FWC. |

Mr Hicks, in his affidavit affirmed 10 July 2019, made statements to the effect that he “acted promptly upon being advised” of the change in office holders with respect to items 5 – 10, 11 15, 16 – 29, 38 – 40, 41 – 42, 49 – 51, 71 and 73 of Annexure A to the Statement of Claim.

40 The Union’s corrections as to the dates upon which notifications were required to be given, being corrections agreed to by the Commissioner, affected:

contravention 31 – the correction being that the notification date was 31 August 2015 and not 30 August 2015 (30 August 2015 being a Sunday);

contraventions 33 to 36 – the correction being that the notification date was 7 September 2015 and not 5 September 2015 (5 September 2015 being a Saturday); and

contravention 37 – the correction being that the notification date was 5 October 2015 and not 3 October 2015 (3 October 2015 being a Saturday).

But nothing of relevance to the assessment as to the penalties to be imposed turns upon these corrections.

41 If reference is made to the pleaded contraventions, what this summary exposes (and as submitted on behalf of the Commissioner) is that:

in nine instances there was no notification of changes made at all prior to the commencement of the present proceeding.

The summary, as contended by the Commissioner in its Reply, also exposes the fact that in at least:

5 instances, notification was between 100 and 255 days outside the prescribed period;

23 instances, notification was between 45 days and 99 days outside the prescribed period;

31 instances notification was between 30 and 44 days outside the prescribed period; and

14 instances, notification was between 14 and 30 days outside the prescribed period.

42 The summary also exposes the fact, again as submitted on behalf of the Commissioner, that the contraventions were wide-ranging and persistent in that the contraventions occurred:

over an extended period of time – from 2015 through to 2017.

The contraventions occurred across six States and one territory, namely:

Queensland (EES Division);

Victoria (EES and Communications Divisions);

Western Australia (EES, Communications and Plumbing Divisions);

South Australia (EES and Communications Divisions);

South Australia and Northern territory (Communications Division);

New South Wales (EES, Communications and Plumbing Divisions); and

Tasmania (Communications/EES Division).

Expressed differently, the contraventions occurred:

within all of the six Branches of the EES Division;

within a number of Branches of the Communications Division; and

within 2 out of 3 Branches of the Plumbing Division.

To this list of considerations is the further fact that the failures to notify:

extended to the most senior positions within the Branches, Divisions and the Union as a national body.

43 The impact upon this analysis of the withdrawal of the admissions as to contraventions 66 to 69 and the impact of the corrections to the dates upon which notifications were required to be given, may presently be placed to one side. On any view, the analysis exposes widespread contraventions over a considerable period of time.

The withdrawal of admissions

44 The Union’s application for the withdrawal of the admissions made in its Defence as first filed on 12 July 2018 required the grant of leave pursuant to r 26.11 of the Federal Court Rules.

45 That Rule provides as follows:

Withdrawal of defence etc

(1) A party may, at any time, withdraw a plea raised in the party's pleading by filing a notice of withdrawal, in accordance with Form 47.

(2) However, a party must not withdraw an admission or any other plea that benefits another party, in a defence or subsequent pleading unless:

(a) the other party consents; or

(b) the Court gives leave.

(3) The notice of withdrawal must:

(a) state the extent of the withdrawal; and

(b) if the withdrawal is by consent--be signed by each consenting party.

46 Rule 26.11(2) requires a party to specifically obtain the leave of the Court: cf. Forbes Engineering (Asia) Pte Limited v Forbes (No 3) [2007] FCA 1637 at [9] per Collier J. In granting leave, the Court has a “broad discretion”: Jeans v Commonwealth Bank of Australia Ltd [2003] FCAFC 309 at [18], (2003) 204 ALR 327 at 330 per Hill, Madgwick and Conti JJ.

47 The Commissioner neither consented to nor opposed the grant of leave pursuant to r 26.11 of the Federal Court Rules.

48 Notwithstanding the fact that the admission previously made in the Defence as first filed was a considered position then taken by the Union, it was concluded that leave to withdraw the admissions should be granted because:

there was an absence of prejudice to the Commissioner in granting leave; and

it was considered to be in the interests of the administration of justice that the Union be given an opportunity to advance submissions as to why the events in September 2016 did not constitute a contravention.

49 Leave pursuant to r 26.11(2) was granted during the course of the hearing and an Amended Defence, withdrawing those admissions in relation to items 66 to 69 of Annexure A to the Statement of Claim, was filed on 24 July 2019.

Contraventions 66 to 69 – the abolition of an office

50 Contraventions 66 to 69 centre upon action taken on 21 September 2016.

51 On that date the Divisional Branch Committee of Management in the SA/NT Communications Division Branch resolved “to abolish four of the vacant Branch Committee of Management Telecommunications & Information Technology Industry Section positions effective immediately”. Attempts to fill those four positions, the then Divisional Branch President (Mr Lorrain) maintained, had proved unsuccessful.

52 The Commissioner contends that notification of the abolition of those four positions should have been given by 26 October 2016. Notification was not in fact given until 6 January 2017.

53 So much was accepted by the Union in its Defence as first filed. The Union’s present position, and the position it can now pursue given the grant of leave to withdraw its admissions, is that there was no power to abolish these positions. The only express power conferred by the CEPU Communications Division Rules to abolish an office is that conferred by r 70 and that power, so the Union contends, is a power to abolish a “full time” position. And the four positions abolished, so the Union submits by reason of the identification of “full-time” positions in r 75, were not full-time. The Court, it is further submitted, should give to the rules of a union “a sensible practical construction” (cf. ResMed Ltd v Australian Manufacturing Workers’ Union (No 2) [2017] FCAFC 14 at [14], (2017) 249 FCR 408 at 413 per Siopis, Bromberg and Katzmann JJ) and should be reluctant to imply a power to abolish other positions, especially given the express conferral of power effected by r 70.

54 The preferred approach of the Commissioner was not to cavil with the difficulties inherent in implying a power to abolish non full-time positions in the face of an express power to abolish full-time positions but to contend that the Rules, “properly construed”, permitted of a power to abolish the positions the subject of the 21 September 2016 resolution.

55 Had it been necessary to do so, these competing submissions would in all likelihood have been resolved in favour of the Union.

56 But it is unnecessary to reach any concluded position. Even in the absence of any such power, and even assuming that the 21 September 2016 resolution was of no effect such that the four positions remained and were not abolished, it is nevertheless concluded that there remained a requirement imposed by s 233(2) of the Registered Organisations Act to lodge a notification of the purported change with (at that time) the Fair Work Commission.

57 Any construction of s 233(2) which confined the requirement to “lodge” with the Fair Work Commission (or the Commissioner) a notice of “any change” to the records to such changes as were within the power of a Union or a Division or Branch to make should be rejected principally by reason of:

the use of the term “any” and its juxtaposition with the term “change”. The natural and ordinary meaning of those terms and the phrase as a whole is such that the requirement to “lodge” with the Fair Work Commission or Commissioner attaches to any change in fact made and irrespective of whether or not the change was within or outside of the powers conferred by any relevant rule.

Any contrary construction of s 233(2) and a construction which would confine the operation of s 233(2) to such changes as are “validly” made, it is respectfully considered, would:

have the potential to defeat or at least frustrate a presumed legislative intent that, at the relevant times, the Fair Work Commission or Commissioner was to be the repository of changes in fact made to offices or office and for those records to be publicly available to those who seek to make inquiries as to what are the offices within a Union, Division or Branch and who are the persons who hold such positions – it may equally be of importance for a person making inquiries to determine what positions have in fact been created (or abolished) within a Union, Division or Branch as it is to know what are the positions for which any rule permits.

58 The extent to which persons may, in practice, seek access to such records is (with respect) not to the point, other than to underline the absence of any prejudice that has in fact resulted from the contraventions in issue. Mr Coffey, for example, maintained in his affidavit that during his time working for the Plumbing Division he could not recall “any instance where a member of any of the Divisional Branches has requested to see the list of office holders of the Divisional Branch…”.

59 It is no sufficient answer to that presumed legislative intent to contend that s 230 imposed a separate and discrete obligation upon an organisation “to keep” its own records and that a person seeking to make inquiries could just as easily seek to access the records of the organisation as opposed to accessing such information as is “lodged” with the Fair Work Commission or Commissioner pursuant to s 233(2). The statutory requirement imposed by s 233(2) and the presumed legislative intent of making such information as is “lodged” publicly available remains irrespective of whatever other means may equally be available to access the same information. The importance of “lodging” with the Fair Work Commission or Commissioner the information identified in s 233 is only further emphasised by:

section 349 of the Registered Organisation Act; and

regulation 20 of the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Regulations 2009 (Cth).

The construction urged upon the Court by the Union would also be potentially productive of mischief in that:

a person making an inquiry of the Union on (for example) 22 September 2016 as to the prospect of standing for election to one or other of the positions purportedly abolished would be inevitably confronted with the Union’s response that “there is no position” whereas on the Union’s current argument the position remained available.

The mischief can be further exposed by considering:

the same person accessing the records of the Fair Work Commission (for example between 22 September 2016 and prior to 6 January 2017) would have been led to believe that those positions still existed but if making an inquiry after 6 January 2017 would have been informed that the position by then had been abolished.

Such a state of potential mischief is best addressed by a construction of s 233(2) which promotes certainty – namely, the certainty of requiring there be “lodged” with the Fair Work Commission/Commissioner all such “changes”, whether they be later held by to be within or without power. A construction of s 233(2) which invites scrutiny going beyond the resolution abolishing those positions and into a construction of the rules and possible distinctions between resolutions which are a “nullity” or “void” or “invalid” (cf. Hossain v Minister for Immigration and Border Protection [2018] HCA 34 at [24], (2018) 92 ALJR 780 at 787 per Kiefel CJ, Gageler and Keane JJ) is to be rejected.

60 The consequence is that there remain 82 contraventions of s 233(2) which attract the imposition of a penalty and not 78 contraventions, as would have been the position had the Union’s current submissions in respect to contraventions 66 to 69 prevailed.

THE RESPONSIBILITY TO NOTIFY

61 Prior to changes introduced in 2016 and 2017, the position responsible for compliance with ss 230 and 233(2) of the Registered Organisations Act to keep and lodge information was not clearly identified in the rules of either the Union itself or its Divisions.

62 Throughout 2015 and 2016, the responsibility to lodge such information was poorly understood by the Union, its Divisions and its Branches. An increasing awareness, at least on the part of the Union’s National Secretary (Mr Allen Hicks), as to the reality of recurring contraventions and the prospect of penalties being imposed led to a move within the Union to remedy the situation.

63 In July 2016 a new rule was inserted into the Union’s National Rules. However, many of the substantive internal changes resulting from this new rule were, in fact, implemented in early 2017.

Pre-2016/2017 – An “ad hoc” system of reporting or “no system”

64 Throughout that period of time when most of the contraventions took place, the internal rules of the Union nevertheless contained provisions allocating responsibility for compliance with administrative and record keeping responsibilities.

65 Thus, by way of example, in the case of:

the Union, r 8.4.2.2 of the National Rules (as certified on 5 July 2016) provided that the National Secretary “shall prepare and forward records and returns to the Industrial Registrar in accordance with the Industrial Relations Act 1988” and r 8.5.2 provided that in his absence it was the Assistant National Secretary who was to “carry out the duties and assume the responsibilities of the National Secretary”. The National Secretary was (and remains) Mr Allen Hicks.

the EES Division, r 9.4.2.2 of the EES Divisional Rules (as certified on 30 June 2014) provided it was the Divisional Secretary who “shall prepare and forward all appropriate records and returns to the General Manager in accordance with the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009” and in their absence r 9.5.5 provided that it was the Assistant Divisional Secretary who was to assume those responsibilities. Rule r 33.1 provided that it is the duty of “every member to observe the rules of the Union and the Division and Branch”. The EES Divisional Secretary was Mr Allen Hicks.

the Communications Division, r 40(ii) of the Communications Divisional Rules (for example, as certified on 17 October 2014) provided that it was the Divisional Secretary who was “responsible for the overall administration of the Divisional Office …”. The Divisional Secretary was Mr Dan Dwyer until August 2015 and thereafter Mr Greg Rayner.

the Plumbing Division, r 30.3.1 Plumbing Divisional Rules (as published on 28 August 2015) provided that the General Secretary was to “keep and provide to the National Secretary … the Divisional records required to be kept by the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009”. In his absence, r 30.4.2 provided for the Assistant General Secretary to “carry out the duties of the General Secretary”. The General Secretary was Mr Earl Setches.

Messrs Hicks, McKenzie, Bintley, Coffey, Samartzopoulos, McCrudden, Gray, McVee, Townsend, McLaughlan, Adley, Ellery, Murphy and McKinley have each undertaken the ACTU’s union governance training.

66 But whatever the rules may have provided, it was accepted by Mr Hicks that prior to 2016/2017 the system or responsibility for reporting was variously described as “ad hoc”, or “no system” or “very light on”. In his evidence in chief he thus proffered the following account:

…His Honour wants to know prior to the implementation of rule 35, what obligations were provided under the rules in respect of reporting obligations in respect of each of the divisions and/or branches?––So the – there’s one particular rule in the CEPU, obviously, in the – the responsibility of the National Secretary and that’s to deal with the paperwork of the union and to – I think – I think the rule even still says now to the Industrial Registry under the – you know, the previous Act and that sort of stuff. The – where this information would be found is in the actual roles of the divisional secretaries and of the branch secretaries, so what their roles are, and that is under rule, and in those, it would talk about lodging the paperwork required, but again confined to the state or the territory that they’re responsible for. So I can’t tell you exactly what those – that – that says in the particular unless I go and grab the rule, but certainly, in the roles of the branch secretary and in the role of the divisional secretaries, there’s certain requirements but it – it – it was very – very light on, if I could say that, with any respect to reporting requirements other than general statements about submitting paperwork to industrial registries and the like.

All right. And how did it work in practice prior to rule 35?––So, again, it was a – an ad hoc-type arrangement where the Branch Secretary – and if I can just use Victoria, for example, if the Victorian Branch Secretary of the Electrical Division had an office holder change and it was a requirement upon him because it happened in Victoria to notify that change, but, again, there was no real system in place because some of the branches would contact Annette when she was working for the Electrical Division and ask her to do it. Others would do it themselves and I think that’s evidenced by the fact that there has been a whole range of – like, we did a lot through the National Office – the – the Divisional Office, I should say, but there was also a lot that was done from branches and from divisional offices, as well.

And what do you say about that system now, given all of the consequences?––Well, the system – the system needed significant – there was no system. There was an ad hoc process where the responsibility of those office holders to report is clearly – over – over a period of time was clearly shown to be deficient and we needed to fix it. And the only way I believe that we could fix it and fix it properly was to centralise the system, to have a rigorous process in place that ensured that there was reporting mechanisms and checks and balances and a capacity to go back to review those ...

That account is accepted. Whatever the rules of individual Divisions or Branches may have provided, the fact is that the pre-2016/2017 position within the Union as a whole was productive of an unacceptable level of non-compliance with reporting requirements.

Rule 35 – a centralised system of reporting

67 Without ignoring the unacceptable state of affairs prior to the 2016/2017 reforms, the Union as a whole – and Mr Hicks in particular – is to be given credit for implementing changes by the introduction of rule 35 of the National Rules and for further refining the new system of reporting to make it more effective. But for his intervention the total penalty to be imposed upon the Union would have been much greater.

68 In June 2016, the National Council of the Union voted in support of the introduction of a new rule – rule 35. That Rule (as at 5 July 2016) provided as follows:

35 – GOVERNANCE AND COMPLIANCE

35.1 Powers of the National Secretary

35.1.1 Notwithstanding anything in the rules of the Union, the National Council is empowered to authorise the National Secretary to take all steps necessary to ensure compliance by the CEPU in connection with the Reporting Obligations.

35.1.2 Without limitation to the power conferred by rule 35.1.1, the National Council is empowered to authorise the National Secretary to:

• direct any officer or employee of the CEPU, including of its branches, to provide any information or document within their possession or control necessary for the satisfaction of the Reporting Obligations;

• access any premises and review any databases held by the CEPU, including its branches, for the purpose of satisfying the Reporting Obligations; and

• require any officer or employee of the CEPU, including of its branches, to provide such assistance as is necessary for the satisfaction of the Reporting Obligations.

35.2 Auditing of membership data

35.2.1 Where a reporting unit is required to include membership numbers in any report prepared pursuant to the Reporting Obligations, the reporting unit shall obtain an audit report of these numbers.

35.2.1 Each reporting unit shall comply with the following conditions in obtaining an audit report of its membership numbers under rule 35.2.1:

(a) engage a registered company auditor; and

(b) request that the work performed in the audit be in accordance with Australian Accounting Standard 802 “The Audit Report on Financial Information Other than a General Purpose Financial Report” and Auditing Guidance Standard 1044 “Audit Reports on Information Provided Other than a Financial Report” or any successor to these standards.

35.2.3 The independent audit report shall include an audit certificate signed by the auditor detailing the financial and total membership of the reporting unit.

35.3 Governance Officer

35.3.1 The National Executive Officers shall appoint a Governance Officer. The Governance Officer shall be an employee of the Union, with the salary and on-costs met by the funds of the National Council.

35.3.2 The Governance Officer shall carry out such duties as the National Secretary may direct.

69 It is unclear whether this Rule was introduced in response to the concerns being raised by the Commissioner.

70 A Governance and Compliance Officer, Ms Annette Moran, commenced in January 2017 with the annual expenditure in employing Ms Moran being about $150,000. In her opinion, the reasons for the failures to comply with reporting obligations in the past have been “greatly improved” by the new regime implemented in 2017 which incorporates, for example:

a monthly reporting process;

an audit of all office holders;

monthly spot checks on office holders; and

procedures policy.

71 With reference to the “monthly spot checks”, Mr Hicks maintains that as “an added measure to ensure the compliance process adopted by the CEPU was robust”, he directed that “each month an administration officer, under the supervision of the Governance Officer, contacts at random 3 office holders from each Division to confirm” (inter alia) that the office holder continues to hold the office stated on the Officer’s Register.

72 These changes, Ms Moran maintains, have been further refined by:

implementing further checks built into the formal reporting system which follow up with questions regarding eligibility of officer holders to take office under the rules; and

the introduction of reminder emails.

73 Mr Hicks maintains that “[f]rom commencing to implement the new system in April 2017” he is only aware of a failure to “properly notify” on three occasions; and, since “the implementation of the complete series of reporting reforms in late 2017 there has only been a single instance of failing to report on time…”. That failure “arose from an administrative error which coincided with the Christmas office shutdown, resulting in the notice being lodged 6 days late”.

THE QUANTIFICATION OF PENALTIES

74 In assessing or quantifying the penalty or penalties to be imposed in respect to contraventions of legislation such as the Registered Organisation Act it is to be recognised, at the outset, that it is not an “exact science” but rather a process of “instinctive synthesis”: Australian Ophthalmic Supplies Pty Ltd v McAlary-Smith [2008] FCAFC 8 at [27] to [28], [55] and [78], (2008) 165 FCR 560 at 567 to 568 per Gray J, 572 and 577 per Graham J (“Australian Ophthalmic Supplies”); Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (No 2) [2018] FCA 2004 at [20] - [21] per Barker J.

75 With the maximum penalty being the upper limit of any penalty to be imposed, and recognising that the process of assessing or quantifying a penalty or penalties is not an “exact science”, the process is nevertheless neither arbitrary nor unguided by well-accepted principles. The considerations to be taken into account are those identified by Tracey J, albeit not exhaustively, in Kelly v Fitzpatrick.

76 In very summary form, and by reference to the generally accepted principles to be applied in respect to the quantification of the penalties to be imposed, it has been concluded that:

the maximum penalty which could be imposed in respect to each of the contraventions – and disregarding any consideration as to whether separate contraventions gave rise to a course or courses of conduct – is a sum of $4,593,000;

the Commissioner and the Union were correct in contending that the maximum penalty should not be imposed and not be imposed in disregard of such conclusions as may be reached as to which contraventions constituted a “course of conduct”;

although individual penalties should be assessed in respect to each contravention which has been made out, it is nevertheless been further concluded that the facts are such that there are:

13 separate “courses of conduct” in respect to the contraventions of s 233(2) and eighteen remaining contraventions of s 233(2); and

two courses of conduct in respect to the contraventions of s 230(1) – one course of conduct arising in respect to the 2015 contraventions and another in respect to the 2016 contraventions.

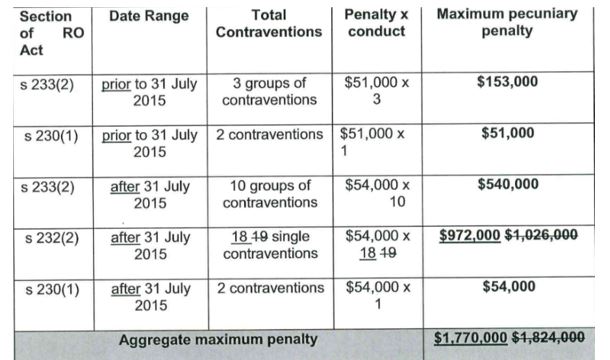

77 Given the acceptance of the case advanced on behalf of the Commissioner as to the manner in which the contraventions are to be characterised as separate “courses of conduct” and the number of contraventions that have been made out, it is understood that one of the calculations undertaken by the Commissioner calculated the maximum quantum of the penalties that could be imposed as follows:

Of this aggregate, the Commissioner contends that “a penalty at the lower end of the mid range is warranted”.

78 The Union initially contended that the “appropriate penalty is in a range between $25,000 and $75,000”. With reference to the table above, and expressed as a percentage, the aggregate penalty would therefore be in the range between about 1.5% and about 4.2% of the maximum. As the submission was initially advanced, there was a lack of precision as to the penalty proposed by the Commissioner to be imposed in respect to a particular contravention. In submissions filed after the hearing concluded, the Union revised this figure to $90,360 (or less). Nothing much turns on the difference, other than to expose the very fact that the process of imposing a penalty – or making submissions as to penalties – is not “an exact science” for either a party or the Court itself.

79 It has been concluded on the facts of the present case that an aggregate penalty of $445,000 should be imposed, that being about 25% of the maximum. At the outset of the hearing, a tentative view was expressed that a percentage of about 30% was under consideration. But that tentative expression, together with the tentative observation respect of whether contraventions 30 to 37 and 44 to 46 formed a “course of conduct”, were the subject of both further oral and written submissions.

80 The manner in which the aggregate penalty should be assessed, not surprisingly, was the subject of competing submissions – albeit within the confines of the principles expressed (inter alia) by Tracey J in Kelly v Fitzpatrick.

Other penalties that have been imposed

81 Other decisions of this Court have imposed penalties with respect to the requirements imposed by the Registered Organisations Act and what may loosely be described as “record keeping”.

82 In Registered Organisations Commissioner (No 2) [2018] FCAFC 203, (2019) 363 ALR, the Full Court considered penalties that had been imposed in respect to contraventions of ss 172(1) and 231(1) of the Registered Organisations Act. Section 231 addressed the requirement for an organisation to “keep a copy of its register of members … for the period of seven years”. The primary Judge had concluded that the penalties for the five contraventions of s 231(1) should be a little less than $75,000 and that the in excess of 20,000 contraventions of s 172 should attract a penalty of $200,000. In total, a penalty of $271,362.36 was imposed. The penalties in respect to the contraventions of s 231(1) represented 45% of the maximum penalty applicable at the relevant date. Before the Full Court, it was concluded in respect to the s 231(1) contraventions that:

four of the contraventions constituted a single course of conduct for which a “combined penalty of $48,000” was imposed; and

the remaining fifth contravention attracted a penalty of $20,000.

Those penalties, the Full Court observed (at para [139]), were “broadly in line with the approach of the primary Judge”.

83 In Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (No 2) [2018] FCA 2004 the first respondent there admitted nine contraventions of ss 253(1), 265(5) and 266(1) of the Registered Organisations Act. There had been a failure to prepare financial reports and to provide members with a copy of a complying report. Penalties were imposed on the first respondent in the aggregate of $29,250.

84 Although these cases reflect the quantum of penalty that the Courts there considered appropriate, it must necessarily be recognised that the quantum of penalty in any given case must depend upon the particular facts and circumstances there prevailing. As Gray J has observed, “[p]enalties are not a matter of precedent”: Australian Ophthalmic Supplies [2008] FCAFC 8 at [12], (2008) 165 FCR 560 at 564. A “hallmark of justice” nevertheless remains “equality before the law” and Courts should attempt to be “even handed”: NW Frozen Foods Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (1996) 71 FCR 285 at 295 per Burchett and Kiefel JJ.

85 Although it thus remains useful to use the quantum of penalties imposed in other cases as one of the means to attempt to achieve a degree of comparability in penalties, the facts and circumstances of an individual case must remain the yardstick against which penalties are assessed and imposed. To the extent that the Transport Workers’ Union (No 2) case nevertheless provides some guidance, the penalties imposed in respect to the s 231(1) contraventions provide a more useful yardstick rather than the s 172 contraventions which were there characterised as a single course of conduct.

A course or courses of conduct?