FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Urban Alley Brewery Pty Ltd v La Sirène Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 82

ORDERS

Applicant / Cross-Respondent | ||

AND: | Respondent / Cross-Claimant | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 7 february 2020 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties file, within 14 days, draft short minutes containing an agreed form of orders reflecting the reasons for decision of the Court (including as to the costs of the proceeding) or, in the absence of agreement, the parties file competing draft short minutes containing the orders proposed by each party and accompanying submissions in support of no more than 3 pages in length.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

O’BRYAN J:

A. Introduction

1 The parties are in dispute with respect to marks used in connection with the supply of their craft beer products. Nowadays, the expression “craft beer” is a commonly used description for beer products produced by smaller breweries. Such breweries are often referred to as “microbreweries” and craft beers are also referred to as “boutique” beers. The description “craft beer” is used to distinguish beer products produced in smaller breweries from beer products produced by the large multinational brewing companies, which might be referred to as “traditional” or “mainstream” beer products. Brewers of craft beers seek to differentiate their products from traditional beers by highlighting the flavours of the ingredients, the story behind the beer and brewery and the techniques involved in production. Since 2011, the craft beer segment of the beer market has had its own national industry association, originally called the Craft Beer Industry Association but now called the Independent Brewers Association. The association defines a craft brewer as a brewer that produces less than 40 million litres of beer per year.

2 Writing in The Australian newspaper for the weekend of 4-5 November 2017, Peter Lalor commenced his article on the “Top 20” beers for that year with the observation that: “The craft beer market’s relentless expansion continues apace. Barely a day goes by without a fistful of new brews landing on the shelves of good bottle shops; barely a month passes without another brewery opening its doors.” Perhaps indicating that more flavoursome beers are not the preserve of newly released craft beers, Mr Lalor includes Coopers Sparkling Ale, made by Coopers Brewery, in his list, describing it as:

Old Red, as faithful and consistent as the family labrador, for decades was an anachronism as the world was obsessed with lagers. But eventually things come full circle - think beards and pickling - and ales are popular again. This brew is as iconic as Vegemite and the baggy green. Unfiltered, fruity and honest, Sparkling is craft’s granddaddy.

3 The applicant, Urban Alley Brewery Pty Ltd (Urban Alley), produces and distributes a craft beer product in bottles and cans from its “brewpub” located in the Docklands area of Melbourne. Although not the subject of specific evidence, I understand the expression “brewpub” to refer to a microbrewery which also operates as a pub, enabling patrons to drink the craft beer that is manufactured on the premises. Urban Alley is the owner of the registered trade mark “URBAN ALE” in class 32 for beer (to which I will refer as the Urban Ale mark). The Urban Ale mark has a priority date of 14 June 2016.

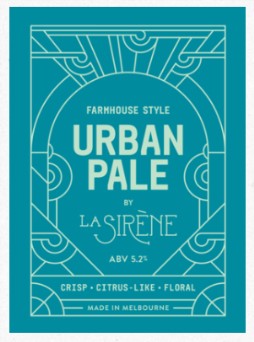

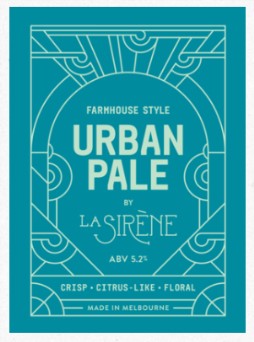

4 The respondent, La Sirène Pty Ltd (La Sirène), is also a producer and distributor of various craft beer products from its brewery located in the suburb of Alphington in Melbourne. In about October 2016, La Sirène began manufacturing, marketing, offering for sale and selling a beer product under a name that incorporated, in large lettering, the words “URBAN PALE”. A representation of the label for La Sirène’s Urban Pale product is shown below:

5 On 28 February 2018, Urban Alley commenced this proceeding claiming that the use of the Urban Pale name by La Sirène constitutes:

(a) an infringement of the Urban Ale mark in breach of s 120 of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (TMA);

(b) misleading and deceptive conduct in breach of ss 18 and 29 of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) as found in Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth); and

(c) the tort of passing off.

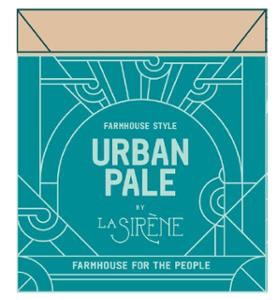

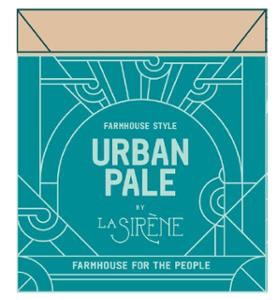

6 On 24 October 2018, and after the commencement of this proceeding, La Sirène filed a trade mark application for “FARMHOUSE STYLE URBAN PALE BY LA SIRÈNE” in class 32 in relation to beer (the La Sirène word mark). On 26 October 2018, La Sirène filed a further trade mark application in class 32 in relation to beer for the following trade mark (the La Sirène label mark):

7 The La Sirène label mark is in the same form as the label that has appeared on the La Sirène Urban Pale product since its launch in October 2016. The marks were registered on 4 June 2019.

8 The trade mark infringement claims made by Urban Alley in this proceeding have given rise to a series of competing claims between the parties.

9 First, La Sirène seeks orders for the cancellation of the Urban Ale mark under s 88(1)(a) of the TMA on the following three bases:

(a) under s 41 of the TMA on the basis that the mark is not capable of distinguishing Urban Alley’s goods (in respect of which the trade mark is registered) from the goods of other persons;

(b) under s 44 of the TMA on the basis that the mark is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the prior registered mark “URBAN BREWING COMPANY”; and

(c) under s 58 of the TMA on the basis that Urban Alley is not the owner of the mark (based on the registration of the prior mark Urban Brewing Company).

10 Second, La Sirène defends the infringement claims on the following four bases:

(a) under s 120 of the TMA on the basis that it has not used the name Urban Pale as a trade mark;

(b) under s 122(1)(b)(i) of the TMA on the basis that it has used the name Urban Pale in good faith to indicate the kind, quality, geographical origin, or some other characteristic, of its beer product;

(c) under s 124 of the TMA on the basis that it has used an unregistered trade mark, being the word “urban”, continuously in the course of trade in relation to craft beer products from before the priority date; and

(d) under s 122(1)(e) of the TMA on the basis that it has exercised its right to the La Sirène word and label marks in the period since the date of registration of those marks.

11 Third, to counter La Sirène’s reliance on s 122(1)(e), Urban Alley seeks the cancellation of the La Sirène word and label marks under s 88(1) of the TMA on the following bases:

(a) under s 44 of the TMA on the basis that the La Sirène marks are substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the Urban Ale mark;

(b) under s 42(b) of the TMA on the basis that the use of the La Sirène marks would be contrary to law because such use constitutes misleading and deceptive conduct in breach of ss 18 and 29 of the ACL and the tort of passing off;

(c) under s 60 of the TMA on the basis that, before the priority date of the La Sirène marks, the Urban Ale mark had acquired a reputation in Australia and, because of that reputation, use of the La Sirène marks would be likely to deceive or cause confusion; and

(d) under s 88(2)(c) of the TMA, on the basis that, as at the filing date of the claim (being 11 June 2019), the use of the La Sirène marks is likely to deceive or cause confusion.

12 Fourth, La Sirène makes a claim under s 129 of the TMA alleging that Urban Alley has no grounds for bringing an action against it for infringement of Urban Alley’s trade mark.

13 Urban Alley’s claims based on ss 18 and 29 of the ACL and the tort of passing off stand apart from the competing trade mark claims of the parties, but are based on the same underlying facts.

14 The evidence on behalf of Urban Alley was principally given by its director and chief executive officer, Mr Ze’ev Meltzer. The evidence on behalf of La Sirène was principally given by its director, Ms Eva Nikias. La Sirène also adduced evidence from Mr Matthew Kirkegaard, who is a freelance beer writer, commentator, educator and consultant focussed on the craft beer industry. Each of those witnesses was cross-examined. In the end, there were no contested issues of primary fact. The contested issues of fact largely involved the characterisation of the primary facts. A central issue is the ordinary signification of the words “urban” and “ale” when used in connection with beer and whether the Urban Ale mark was capable of distinguishing the craft beer product sold by Urban Alley.

B. The factual background

B.1 Urban Alley’s business

15 In 2015, Mr Meltzer began taking steps to establish a beer brewing business, which he planned to operate in the Melbourne central business district. Throughout late 2015 and early 2016, Mr Meltzer took preliminary steps to establish the business, including creating a recipe for the beer and identifying possible brand names for the beer. Mr Meltzer’s initial idea was to name the brewing company after a prominent Melbourne street and he came up with the name Swanston Street Brewing Co Pty Ltd. He incorporated that company on 13 November 2015. A short time later, on 1 March 2016, he changed the company’s name to Collins Street Brewing Co Pty Ltd (CSBC) because at that time he was working in Collins Street.

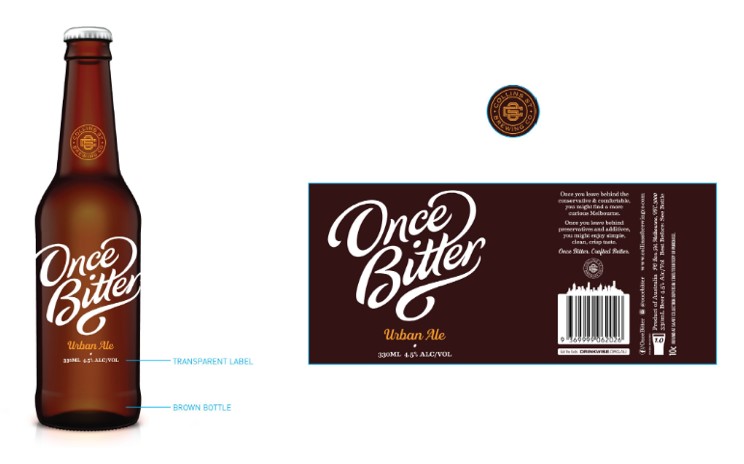

16 On 17 November 2015, CSBC filed a trade mark application for the word mark “ONCE BITTER” in class 32 for beer. The mark was entered on the Register of Trade Marks on 17 May 2017 with a priority date of 17 November 2015. Mr Meltzer initially envisaged that the Once Bitter trade mark would serve as a parent brand name to be used in conjunction with other product specific brand names. It was his intention to create a range of new beers as a sub-brand to the Once Bitter brand.

17 Mr Meltzer gave evidence that, in early 2016, he conceived the name “Urban Ale” as a possible brand name for the beer to be sold by CSBC. At the time, he decided that he did not want to use a generic beer descriptor on the beer label such as Pale Ale or Golden Ale, but he wanted to create a new style of beer and a segment of the market that the business could own.

18 By early 2016, Mr Meltzer had developed the business to the point where he had a recipe for the beer to be sold and he had settled on the brand names “Urban Ale” and “Once Bitter”. Since he had not constructed a brewery of his own, he engaged a contract brewer, Southern Bay Brewing Company, to brew the beer.

19 In May 2016, CSBC launched its first beer product under the names “Once Bitter” and “Urban Ale”. The product was sold in 330ml bottles in packs of 4 or 24 and in kegs (50 litres) supplied to hotels and pubs in Melbourne. Initially, the product was sold through pubs, bars and independent bottle shops. The bottles bore the labelling depicted below:

20 The packaging of the 4 and 24 packs of the bottles was as follows:

|

|

21 It can be seen that the most prominent label on the product and its packaging was Once Bitter and the Urban Ale label was depicted in a subsidiary manner in a contrasting font. For that reason, and to distinguish the product from a subsequent version which had different packaging, I will refer to this product as the Once Bitter product.

22 From about May 2016, coinciding with the launch of the Once Bitter product, CSBC disseminated promotional material relating to the Once Bitter product, which included table talkers for display on the tables and bars at the Network Public Bar located at Southern Cross Station, Melbourne, and decals for use on beer taps in bars and pubs. In May 2017, CSBC disseminated further decals. That material took materially the same form as the labelling and packaging of the Once Bitter product, with the dominant label being Once Bitter and the subsidiary label being Urban Ale.

23 On 14 June 2016, CSBC filed a trade mark application for the word mark “URBAN ALE” in class 32 for beer. That mark was entered on the Register of Trade Marks on 11 January 2017 with a priority date of 14 June 2016.

24 On 25 June 2016, the Once Bitter product was listed on Untappd under the style category of “Golden Ale”. Untappd is a mobile phone application that allows its users to check beer ratings and post and share their beer ratings. It has 8 million registered users. The listing contained no reference to the label Urban Ale.

25 On 14 July 2016, CSBC filed a trade mark application for the word mark “ONCE BITTER” in the fancy lettering depicted above in class 32 for beer. That mark was entered on the Register of Trade Marks on 11 January 2017 with a priority date of 14 July 2016.

26 On 8 September 2016, CSBC issued a press release with the subject heading “Once Bitter, Melbourne’s Brand New Craft Beer”. The covering email introduced the brand as Once Bitter and the brewery was introduced as Collins St Brewery and prominently displayed the Once Bitter label in fancy letters. The press release commenced with the heading “ONCE BITTER LAUNCHES INTO THE AUSTRALIAN CRAFT BEER MARKET” and the beer product was referred to as Once Bitter throughout the press release. There were two references to Urban Ale in the press release. The first was in the following sentence:

The signature Urban Ale sits somewhere between a classic Australian golden ale and a Belgian blonde, with pleasant tropical notes but a crisp, clean finish. This is a premium beer for the people and is described as a 'celebration of our great city, a tribute to the laneway culture and a blend of the old and the new'.

27 The second reference appeared at the end of the press release in an information section as follows:

Name: Once Bitter

Style: Urban Ale (Somewhere between an Aussie Golden Ale and Belgian Blonde)

ABV: 4-5%

Hops: Motueka, Galaxy, Southern Cross, Citra, Cascade and a secret dry hop!

Malt: Wheat, Pilsner and Vienna

Yeast: American ale yeast

28 It is apparent that, in the press release, the words Urban Ale were used to describe the style or flavour of the product. That use is consistent with Mr Meltzer’s evidence that he wanted to create a new style of beer and a segment of the craft beer market that the business could own. Mr Meltzer also gave evidence that, over the years, he has been questioned by numerous buyers and consumers about the kind of beer offered by reference to “Urban Ale”, and he has explained that Urban Ale is a new style of beer that is a cross between a classic Australian Golden Ale and a Belgian Blonde.

29 On 16 September 2016, a publication called “We Know Melbourne” published an online article titled “Interview: Ze’ve Meltzer of Once Bitter”. In the article, the Once Bitter product is predominantly referred to as Once Bitter, although in one paragraph it is referred to as Urban Ale.

30 On 20 September 2016, The Age newspaper featured the Once Bitter product in the article titled “10 fresh Australian beers to drink this spring” in the Good Food Guide. In the article, the product was identified as Once Bitter and the brewer was identified as Collins Street Brewing Co. The article commences with the statement that “The media release for this Melbourne “urban ale” (which seems to be a cross between a Belgian blonde and Australian golden ale) says it’s a celebration of our great city…”. Again, the name Urban Ale is understood as a description of the style or flavour of the product.

31 On 16 November 2016, CSBC registered the domain name “www.oncebitter.com.au”. The website featured a large depiction of the brand, Once Bitter, above a depiction of the product bearing no reference to Urban Ale at all. After various passages of text elaborating on the Once Bitter brand, the only reference to Urban Ale was towards the bottom of the website, in answer to the question “What does it taste like?”, with the answer stating: “Our signature Once Bitter Urban Ale sits somewhere between a classic Australian golden ale and a Belgian blonde, with pleasant tropical notes but a crisp, clean finish”. On the last page of the website, next to an image of the Once Bitter product, the following words appear: “A CELEBRATION OF OUR GREAT CITY, A TRIBUTE TO THE LANEWAY CULTURE AND A BLEND OF THE OLD AND THE NEW”. These features of the webpage remain in the same form today.

32 On 27 December 2016, a publication called “The Crafty Pint” published an interview with Mr Meltzer titled “WHO BREWS ONCE BITTER?” The Crafty Pint is an Australian beer news website. It is an online magazine and resource for people interested in craft beer in Australia. Throughout the interview, the Once Bitter product was referred to as Once Bitter, save in one part of the interview in which Mr Meltzer explained that his intention was to bring out a variety of beers under the Once Bitter banner, stating: “I'm also keen to explore a secondary range of beers that will be limited releases under a separate name. They’ll be challenging, varied in style, and offer up something at the other end of the scale from our Urban Ale. In ten years’ time, I hope there’ll be plenty of them.”

33 By mid-2017, Mr Meltzer decided to build his own brewery, which he initially wanted to locate on Collins Street since he had named his company “Collins Street Brewing Co”. However, after making some initial enquiries, Mr Meltzer determined that it would not be feasible to operate a brewery at a location on Collins Street and instead decided to build a brewery and bar in the Docklands area of Melbourne. Mr Meltzer decided to transfer the assets of CSBC to the applicant company, which was then named Laneway Brewery Pty Ltd (Laneway Brewery), and to trade under the name “Urban Alley Brewery”. He also decided to stop using the “Once Bitter” brand name as he was of the view that, by incorporating the word “bitter” into the label, consumers might think that the beer had an accentuated bitter taste, which it did not. Mr Meltzer deposed that he also wished to further emphasise the Urban Ale mark on the urban ale products.

34 From November 2017, the business produced and distributed to bars and pubs that stocked its products 1,000 coasters featuring the Urban Ale mark (and without the Once Bitter mark).

35 On 21 December 2017, Laneway Brewery purchased the business of CSBC. Under a deed of assignment entered into on that date, CSBC assigned to Laneway Brewery:

(a) any and all past, present and future rights, title and interest in and to the intellectual property owned by CSBC together with the associated goodwill (if any) throughout the world; and

(b) all rights to bring, make, oppose, defend or appeal claims, proceedings or actions and obtain relief including but not limited to injunctive relief and pecuniary relief (and to retain any amounts recovered) in respect of any cause of action arising from CSBC's intellectual property whether occurring before, on or after 21 December 2017.

36 On 28 February 2018, Laneway Brewery added a product listing to Untappd called “Urban Ale”, under the style category of “pale ale”.

37 On 15 March 2018, Laneway Brewery registered the domain name “urbanalley.com.au”. The website features the prominent statement “SUSTAINABLY CRAFTED IN THE HEART OF MELBOURNE”.

38 On 30 April 2018, Laneway Brewery changed its name to Urban Alley Brewery Pty Ltd.

39 From May 2018, Urban Alley launched its new beer product under the dominant label Urban Ale (to which I will refer as the Urban Ale product to differentiate it from the product sold under the dominant Once Bitter label) and began to phase out supply of the Once Bitter product. Mr Meltzer was unable to say how long it took to phase out existing supplies of the Once Bitter product, although he accepted it took some months in certain cases. From about June 2018, the Urban Ale product was sold in 375ml cans (either in packs of 6 or cases of 24) as well as bottles.

40 The bottles bore the labelling shown below:

41 The cans bore the labelling shown below (shown in a 6 pack):

42 The case of 24 cans bore the labelling shown below:

43 From May 2018, Urban Alley has been distributing to customers t-shirts and clothing patches featuring the Urban Ale mark as depicted on the products shown above. Urban Alley distributed 50 t-shirts and 50 clothing patches for bar staff to wear at The South Melbourne Mussel & Jazz Festival in 2018. Urban Alley has also distributed t-shirts featuring the Urban Ale mark to bars and pubs throughout Victoria that stock the Urban Ale products.

44 On 27 July 2018, Australian Brews News published an online article titled “Production to begin at Urban Alley Brewery”, which described the brewhouse then being constructed by Urban Alley in the Docklands suburb of Melbourne. The article stated that Urban Alley had been brewing its “Urban Pale Ale” at Southern Bay and Hawkers Brewery since May 2016. Australian Brews News publishes online content relating to beer, brewing, beer history and breweries. Australian Brews News' daily news digest has a subscriber list of over 2750 people, primarily people involved in the brewing industry, and its website receives in excess of 600,000 unique visits a year.

45 On 6 March 2018, Urban Alley filed trade mark applications for “URBAN ALLEY BREWERY”, “URBAN LAGER”, “URBAN IPA”, “URBAN DARK”, “URBAN APA” AND “URBAN PILSNER” in class 32 for beer. Each of those applications has been opposed by La Sirène, but the applications and the marks are not the subject of the present proceeding.

46 In September 2018, Urban Alley launched its “brewpub” in the Docklands region of Melbourne. The Urban Alley business currently has 7 employees, including Mr Meltzer.

47 From September 2018, Urban Alley has developed and used a bar and tasting station which features the Urban Ale mark. The bar and tasting station has been used at various retail outlets including at Liquorland stores for tastings and at events and beer festivals. Urban Alley has also provided further decals for use on beer taps in bars and pubs with the Urban Ale mark.

48 After December 2018 (the evidence does not reveal when, but by at least June 2019), Urban Alley changed the label of its Urban Ale product to the form depicted below:

49 Urban Alley adduced in evidence some financial data concerning the volume of products sold by it and the revenue earned, and marketing expenditure incurred, in the period from May 2016 until August 2018. Urban Alley sought an order from the Court to keep the data confidential. However, in circumstances where Urban Alley has made claims under ss 18 and 29 of the ACL and in passing off, it is necessary to refer to the data at least in general terms for the purposes of this decision. The data does not differentiate between the Once Bitter and Urban Ale products, but the volume data is provided in monthly figures which provides some indication of the sales of each product by reason of the fact that the Urban Ale product was launched and the Once Bitter product was phased out from May 2018. I have extracted the following figures from the data provided:

May to June 2016 | July to October 2016 | FY2017 | FY2018 | July to August 2018 | |

Volume of kegs (50 litres) sold | 51 | 237 | 1,310 | 2,444 | 472 |

Volume of bottles (case of 24) sold | 26 | 157 | 430 | 307 | 99 |

Volume of cans (case of 24) sold | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 869 |

Total revenue | $10,954 | na | $247,920 | $520,514 | $119,730 |

Marketing expenditure | $2,142 | na | $74,757 | $77,531 | na |

50 Overall, the sales of the Once Bitter and Urban Ale products, and the marketing expenditure, have been modest. This is particularly so in the period to October 2016 when La Sirène launched the Urban Pale product.

B.2 La Sirène’s Business

51 In December 2007, Ms Eva Nikias, together with her husband, Mr Costa Nikias, incorporated a company under the name Ensticto Pty Ltd (now called Beverage & Brewing Group Pty Ltd) through which they established a business of setting up microbreweries for third parties in Australia and Asia. From 2009 to 2017, the business expanded to offer courses, run by Costa Nikias, for people looking to establish their own microbrewery.

52 In January 2010, the Nikias founded their own brewing business, La Sirène Brewing (La Sirène), through their company Beverage & Brewing Group Pty Ltd.

53 On 14 January 2011, Beverage & Brewing Group Pty Ltd filed a trade mark application for the word mark “LA SIRÈNE” in class 32 for beer (to which I will refer as the La Sirène mark). The La Sirène mark was entered on the Register of Trade Marks on 10 November 2011 with a priority date of 14 January 2011.

54 On 25 July 2012, Beverage & Brewing Group Pty Ltd incorporated the respondent company, La Sirène Pty Ltd, as its wholly owned subsidiary, to conduct the brewing business. La Sirène Pty Ltd licenses the La Sirène mark from Beverage & Brewing Group Pty Ltd.

55 La Sirène brews farmhouse-style ales, also known as “saisons” (French for “seasons”). The Wikipedia entry for “farmhouse ale” (to which no objection was taken) provides the following description:

Farmhouse ale is an ancient European tradition where farmers brewed beer for consumption on the farm from their own grain, hops and yeast. Most farmers would brew for Christmas and/or harvest time, but in areas where they had enough grain farmers would use beer as the every-day drink. This was in a time when it was safer to drink beer than water. Farmhouse ale has enormous variation in the ingredients and brewing process used, both of which follow ancient local traditions.

56 La Sirène’s brewery is located in Alphington, an inner suburb of Melbourne. Proximity to the Darebin Parklands is important to the business, because of the availability of local indigenous yeast and bacteria that is incorporated into the farmhouse ales produced by La Sirène.

57 Since December 2011, La Sirène has produced a significant number of products, including saisons, sour ales, witbiers, dark ales, fruit beers and Belgian ales. Each of these products has been sold with labels that incorporate the La Sirène mark together with the name of the product that describes the type and style of beer such as Saison, Wild Saison, Farmhouse Red, Belgian Sour, Witbier and Praline (to name a few).

58 La Sirène has won 23 national and international awards for its beers, including winning Champion French and Belgian Category Gold at the Australian Craft Beer Awards 2014, the “People’s Choice Award” at the Great Australasian Beer Spectacular in 2014 and silver medals at both the International Beer Cup in Japan in 2015 and the International Beer Challenge in the UK in 2018.

59 In 2012, Costa Nikias began working on the creation of a pale ale with the aim of targeting a wider audience as well as offering an “everyday” La Sirène pale ale to existing customers. However, the first pilot brews of the pale ale product were not undertaken until 2015 and early 2016.

60 In January 2015, a journalist at The Australian newspaper, Max Allen, visited the La Sirène brewery and met with the Nikias. In an article published on 31 January 2015 in The Australian, Mr Allen wrote:

The brewery’s location is about as far from a French farmhouse as it's possible to imagine: the fermenting tanks and cool store and barrel room are located on an old urban industrial park ... [b]ut what’s inside La Sirène’s art nouveau labelled bottles is anything but industrial: these are seriously exciting, complex, in some cases groundbreaking, artisan beers of the very highest quality.

61 On 8 December 2015, another article featuring Costa Nikias was published in Ale of A Time titled “The Nation of Unconventional Fermentation”. Ale of a Time is a craft beer focussed Australian beer blog and beer pod cast with approximately 3,100 followers on Twitter. The article included the following quote from Costa Nikias:

I think we are lucky because being in an urban area, 9kms from the city, you wouldn't think there is a huge amount of opportunity to harvest indigenous yeast and bacteria. I think the opposite, I think in urban areas you've got more diversity and where our brewery is located, we are bordered by a creek, and bordered on the other side by a national park, so our brewery is directly exposed to this amazing diversity of microflora.

62 It was around this time (December 2015) that the Nikias began referring to La Sirène more regularly as an “Urban Farmhouse”. An email dated 10 December 2015 from Costa Nikias sent to a potential US distributor refers to La Sirène as an “urban farmhouse”. On 25 January 2016, The Crafty Pint published an article on La Sirène’s Wild Tripelle product and referred to La Sirène’s aim to “spontaneously ferment several thousand litres of wort using the native yeasts and bacteria that exist in the nearby Darebin Creek and Parklands, thus creating an ‘urban farmhouse’ ale”.

63 Between late 2015 and early 2016, the Nikias decided to pursue the “Urban Farmhouse” concept more formally because they considered that that particular combination of words aptly described the interplay between what they were doing (creating “farmhouse style” beers) and where they were doing it (in an “urban” location). On 15 February 2016, La Sirène registered the business name “Urban Farmhouse Brewing Co” with ASIC and also registered the domain names “www.urbanfarmhousebrewing.com.au” and “www.urbanfarmhousebrewing.com”.

64 On 21 February 2016, Costa Nikias created a document on his computer titled “Urban Farmhouse Brewing Co. Concept” which described a range of beer products the Nikias had been discussing, including two products under the names “urban ale” and “urban wit”. The name “urban ale” also appeared in a recipe for the pale ale being created by La Sirène in a document which bears the date February 2016 and which was last modified on 25 April 2016.

65 Prior to departing on a family holiday on 25 February 2016, Eva Nikias conducted a number of internet searches of the word “urban” in connection with beer in Australia. Those searches included searches using the Google search engine and searches on the Untappd website. The searches returned a large number of results for other beer names and breweries containing the word “urban” in conjunction with other words but no results in Australia for the names “urban ale” or “urban pale”.

66 At about this time, Eva Nikias also ran searches of the Australian Trade Mark Register for trade mark applications and registrations containing the word “urban” in connection with beer. This was because the Nikias were contemplating registering the name Urban Farmhouse Brewing Co as a trade mark. Eva Nikias gave evidence that she did not print out the results of those searches, but recalled that the results showed several trade marks on the Register containing the word “urban”, including:

(a) five trade mark applications containing the words “Passionate Urban Brewers Hahn Brewers ESTO 1987” in the name of Lion-Beer, Spirits & Wine Pty Ltd; and

(b) one trade mark consisting of the words “Urban Crusader” in the name of Liquorland (Australia) Pty Ltd.

67 On 13 April 2016, Eva Nikias filed a trade mark application for the word mark “URBAN FARMHOUSE BREWING CO” in class 32 for beer (to which I will refer as the Urban Farmhouse mark). The Urban Farmhouse mark was entered on the Register of Trade Marks on 2 March 2017 with a priority date of 13 April 2016.

68 As mentioned above, the first pilot brews of La Sirène’s proposed pale ale product were undertaken in 2015 and early 2016. It is common ground that “pale ale” is a well-recognised description of a style or flavour of beer. Eva Nikias gave evidence that, in creating a farmhouse style pale ale, she and her husband wanted to contribute to the diversity of pale ales which constitute the majority of the craft beer market in Australia. Since they operated a brewery that identified itself as an “urban farmhouse” brewery, the Nikias decided to name the pale ale “Farmhouse Style Urban Pale by La Sirène” because they considered that the name succinctly described the key elements of the product, which included: the style (farmhouse); the location of its production (urban); and its colour and type (pale ale). The precise timing of that decision was not clear from the evidence. Eva Nikias could not recall when the decision was made.

69 During 2016, the Nikias made the decision to package their pale ale product in a can rather than a bottle. In late June 2016, work began with the can designer engaged by La Sirène on the labelling for the can. On 12 October 2016, La Sirène’s new pale ale product was listed on Untapped under the style category of “Pale Ale – Belgian” and was referred to in the listing by the name “Urban Pale”. The first commercial batch of La Sirène’s Urban Pale product was brewed in September 2016 and canned on 25 and 26 October 2016. The product was formally launched on 27 October 2016. The press release accompanying the launch stated that “The Urban Pale is a hop-driven juicy Farmhouse Pale Ale made in our Urban Farmhouse Brewery” and contained an image of the product as shown below:

70 It is apparent from the above picture that the words “Urban Pale” dominate the label, being in a larger and more prominent font compared with the other words that appear on the label.

71 On 31 October 2016, Australian Brews News published an article about the La Sirène Urban Pale product, in which the product was consistently referred to by the name “Urban Pale”, while also identifying the brewer as La Sirène.

72 Eva Nikias gave evidence that, at the time that La Sirène launched its Urban Pale product, she had not heard of Urban Alley’s Once Bitter product (which, as described above, included the name Urban Ale on the label). There is no evidence to the contrary and I accept that evidence. For the same reason, I also accept Eva Nikias’ evidence that La Sirène chose to use the word “urban” in the name of its product because it described the location of the production of the beer (in an urban area).

73 On 4 November 2016, La Sirène filed a trade mark application for “URBAN PALE” in class 32 for beer. Eva Nikias gave evidence that La Sirène chose not to proceed with the application because there were a considerable number of third parties already using the word “urban” in relation to beer and related goods and services, and the word “pale” is a shorthand description of a very popular style of beer, being pale ale, as well as a key descriptor of the colour and appearance of a wide range of beers. I accept that evidence.

74 The evidence shows that, on its website and its Instagram account, La Sirène has commonly referred to the Urban Pale product as “Urban Pale” or “La Sirène Urban Pale” and not the lengthier name “Farmhouse Style Urban Pale by La Sirène”.

75 In an article published in The Weekend Australian on the weekend of 4-5 November 2017 (referred to earlier), Peter Lalor named La Sirène’s Urban Pale product as the “Best Beer 2017”. In the article, Mr Lalor described the product as “My favourite drop from 2017”, and “Definitely the best new beer of the year. La Sirène is an elite Melbourne outfit that specialises in the sour to saison range.”

76 As noted earlier, on 24 October 2018, and after the commencement of this proceeding, La Sirène filed a trade mark application for the La Sirène word mark (Farmhouse Style Urban Pale by La Sirène) and, on 26 October 2018, La Sirène filed a further trade mark application for the La Sirène label mark (which is in the same form as the can packaging). The trade marks were subsequently registered.

77 No evidence was adduced concerning the volume of sales of the Urban Pale product since its launch, or revenue earned.

B.3 Use of the word "urban" in connection with beer

78 The evidence shows that the word “urban” has been used in connection with breweries and beer products for a considerable period of time, both in Australia and in other countries. La Sirène relies on this evidence to establish the common usage and meaning of the word “urban” in connection with beer in Australia. A significant part of the evidence concerned usage in other countries, which I consider has little if any relevance to the issues in this proceeding. The evidence which I regard as relevant, and which is referred to below, concerns usage in Australia as well as usage in publications such as Time magazine which, while produced overseas, have a recognised readership in Australia.

79 It is a well-known fact that many traditional or mainstream brewers are located in urban areas. In Melbourne, for example, where both the parties to this proceeding are based, Carlton & United Breweries has a major brewing facility in the inner city suburb of Abbotsford. Nevertheless, the evidence shows that, in recent times, the word “urban” has been used by beer writers and brewers as signifying a connection with the craft beer industry. The usage appears intended to convey not merely a generic city location, but a laudatory epithet to refer to craft beer made in an inner city location and indicating that the brewer or the beer is “fashionable”, “trendy” or “cool”.

80 Broadsheet is an Australian online city guide founded in 2009. The site covers news related to food and drink, fashion and shopping, art and design, and entertainment. It also has a directory of cafes, restaurants, bars and shops which contains imagery and short descriptions of each venue. There are separate versions of the site for Melbourne and Sydney. In an article published on Broadsheet on 20 October 2010 and titled “Band of Brewer”, Hilary McNevin discussed craft beer culture in Melbourne and brewers building their own breweries around the city. The article contained the following quote from Renee Mathie, founder and director of BeerMasons, an online craft beer appreciation society:

Being close to the disposable income and dwellers of a large city reduces some major overheads and increases your opportunity to sell directly to a local market while building a wider distribution chain. Beer has historically been an urban product, a working-class drink, produced in working-class suburbs, whereas wine was a product of the countryside and the landed gentry.

81 In November 2010, Mountain Goat Beer’s Hightail Ale made the list of Peter Lalor’s Top 20 Beers of 2010 published in The Weekend Australian. The listing for the ale was accompanied by the following description:

About a decade back, word filtered out about a cult in inner city Melbourne devoted to mountain goat. It wasn't as bad as it sounds. Cam and Dave hooked the locals and have slowly spread the word of their crafted and very popular urban brews.

82 In an accompanying article called “Cheers All Round – James Halliday’s Top 100 Wines” published that same weekend, Peter Lalor made further reference to the “inner-urban market” for craft beers.

83 An article published in Time magazine in America on 9 December 2014, titled “Craft Beer Officially Isn't Cool Anymore Because Delta Will Begin Selling It On Flights", satirically posed the question “[h]as craft beer - the sweet, sweet nectar of urban hipsters trying to impress their friends who are in town for the weekend - officially Jumped the Shark?”

84 On 1 April 2015, Kylie Fleming published an article titled “Golden age of dining is upon us” in The City Messenger which is an Adelaide newspaper focussing on local news and sport published by News Corp Australia. Amongst “Kylie's Food Predictions” for Adelaide were “more specialty coffee, craft beers and urban breweries (such as Lady Burra in Currie St in April/May)”.

85 On 27 March 2015, Australian Brews News republished an article appearing on the website of Stone & Wood Brewing Co. which referred to porter being the “original urban ale”:

Porter is the original urban ale, getting its name from the 1700’s equivalent of white delivery van drivers who loaded and unloaded the ships, moving goods around the city. Its silky charms made this dark brew the pint for the people.

86 On 4 January 2016, Hospitality Magazine published an article titled “Urban dwellers increasingly choosing craft over regular beer: Clipp” which summarised analysis drawn from beer purchase data compiled by mobile payment app Clipp. Hospitality Magazine is a source of news and industry insights for Australia’s food service businesses. The article stated:

Australian urban dwellers are choosing craft beer over regular beer new data compiled by mobile payment app Clipp has revealed.

…

The data revealed that urban areas led the craft beer charge with craft beer accounting for 45 per cent of all purchases nationally, with regular beer coming in second at 40 per cent. Melbourne had the highest percentage of craft beer purchases (55 per cent) against just 34 per cent of regular beer purchases.

…

“With the variety of beers on offer at Australian establishments, urban beer lovers now regard beer as an experience - much like they do wine and coffee. People seek to be more adventurous and it's common now to be offered ‘beer tastings’ at pubs to enable you to choose your preferred beer,” says Greg Taylor, CEO and co-founder of Clipp.

87 On 24 February 2017, Renata Gortan published an article in the Sydney newspaper The Daily Telegraph titled “Sydney's newest urban brewer taps into our love of a good, local beer”. The article refers to the fact that “Australians love their beer and their urban breweries”; that “[Endeavour Vintage Beer Co] is the latest to hit Sydney’s booming urban brewery scene”; and referred to “Sydney's urban brewery pioneer Young Henry’s at Newtown ...”.

88 On 29 August 2017, Anna Webster published an article in Broadsheet titled “A New Brewery for Burnley” with the subtitle “Romulus & Remus to close and reopen as an urban brewery serving everything from Australian summer ales to barrel-aged Russian imperial stouts” and reported that “Italian restaurant Romulus & Remus will close to make way for a new urban brewery, Burnley Brewing, which will open in November.”

89 On 24 April 2018, Matthew Kirkegaard (an expert witness in this proceeding) published an article in the Brisbane newspaper The Courier Mail titled “Beer booming in our ageing tourism scene” which observed:

An interesting aspect of the brewing industry is that breweries are largely city-based which makes it such an ideal urban tourism drawcard. Wine tends to be made where the grapes are grown, but the transportability of beer’s ingredients means a vibrant small brewing culture can be cultivated anywhere, as has happened in Brisbane.

90 On 7 November 2018, Jaydn O’Neil published an article in Broadsheet titled “Beer Fest 2018 Is Coming to Esplanade Park This Weekend” which described attending brewers Nowhereman and Otherside Brewing as “urban breweries”.

91 On 6 December 2018, Visit Victoria (the primary tourism and events company for the State of Victoria), published the article “Melbourne’s urban producers” which, under the heading “Urban Drinks Producers”, included the following information about urban breweries:

Urban Breweries

Craft & Co, Colonial Brewing, Thunder Road Brewery, Temple Brewing, Two Birds, Clifton Hill Brewpub, Mountain Goat, Stomping Ground, 3 Ravens, Tall Boy and Moose, Westside Ale Works, MoonDog, Hop Nation, Burnley Brewing, Hawkers, La Sirène - this is unlikely to be the exhaustive list of an inner-city brewery scene which just keeps growing. The pure range of styles from IPA to NEIPA to sours, pale ales, lagers, saison, wheat beer, porter, red ale, amber ale, golden ale and more, plus the fresh taste straight from the keg will keep hop lovers happy in Melbourne.

92 The evidence shows that a number of brewers and beer suppliers have chosen to use the word “urban” in the name of their beer products. The usage is not confined to craft beer producers.

93 Tiny Rebel is a brewery located in Newport, South Wales, in the United Kingdom. It has produced a number of beers containing the word “urban” in their name, specifically:

(a) Tiny Rebel Urban IPA (listed on Untappd on 7 February 2012);

(b) Tiny Rebel Belgian Urban IPA (listed on Untappd on 12 November 2013);

(c) Tiny Rebel Urban Pils (listed on Untappd on 3 May 2013); and

(d) Tiny Rebel Urban Bourbon (listed on Untappd on 28 August 2015).

94 The evidence showed that Tiny Rebel products, including its Urban IPA and Urban Belgian IPA products, have been available in Australia since at least February 2014.

95 On March 2014, Goose Island released a product called “312 Urban Pale Ale”. Goose Island was established in Chicago in 1988 as craft brewery and was acquired by Anheuser-Busch in 2011. The number “312” in the label refers to the Chicago telephone code and “urban” refers to the ale’s inner-city industrial origins of Chicago. While the evidence indicated that Goose Island products have been sold in Australia, there was no evidence that that included the 312 Urban Pale Ale product.

96 Liquorland (Australia) Pty Ltd is the owner of an Australian Trade Mark “URBAN CRUSADER” in relation to beer and other beverages in class 32 with a priority date of 16 July 2015. A lager sold under and by reference to the “URBAN CRUSADER” trade mark was listed on Untappd on 26 February 2016.

97 Lion-Beer, Spirits & Wine Pty Ltd filed a number of Australian trade mark applications for its famous HAHN beer brand using the tagline “PASSIONATE URBAN BREWERS” on 14 and 21 August 2015 in relation to beer and other goods in class 32. Those trade marks have been registered. However, the evidence did not establish how the mark had been used (if at all) in connection with Hahn beer.

98 Urban Purveyor Group Pty Ltd is the owner of the following Australian trade marks containing the word “urban”:

(a) URBAN BREWING COMPANY in classes 31, 32 and 40 in respect of, amongst other things, beer and the brewing of beer with a priority date of 24 March 2016; and

(b) URBAN CRAFT BREWING COMPANY in classes 32, 33, 40, 41 and 43 in respect of, amongst other things, beer and the brewing of beer with a priority date of 5 July 2016.

99 The evidence concerning the activities of the Urban Purveyor Group was limited, but its webpage indicates that it was part of the “Rockpool Dining Group” and offered a range of craft beers (none of which included the word “urban” in their names).

100 Hopworks Urban Brewery was founded in 2007 in Portland, Oregon in the United States of America and a number of its beer products are available in Australia. At the Australian International Beer Awards hosted by The Royal Agricultural Society of Victoria Limited at the Melbourne Showgrounds in May 2016, Hopworks Urban Brewery received a number of medals for its products. A number of its products are listed on Untappd.

101 Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. is a large brewer based in California in the United States of America. Its products have been available in Australia since around 2010. Sierra Nevada has produced at least one beer containing the word “urban” in its name, being the Sierra Nevada Urban Trail Happy Pale Ale. That product was listed on Untappd on 9 September 2016.

102 The evidence showed that there are also a number of beer tour providers in Australia who use the word “urban” in connection with their beer tours, including Urban Beer Tour, Urban Beer Odyssey and Melbourne Urban Beer Tour. There are also a number of restaurants and bars in Australia, with a focus on beer, that use the word “urban” as part of their name, including:

(a) the Riverland Urban Beer Garden located at Federation Wharf in Melbourne (which has been operating under that name since at least 4 October 2015); and

(b) the Hopscotch Urban Beer Bar located at Southbank in Melbourne (which has been operating under that name since at least 30 September 2016).

103 A Facebook page of the Riverland Urban Beer Garden dated 21 January 2016 promoted a meal of barbecue prawns paired with wine or “anything from our urban beer list”.

104 Urban Alley also adduced evidence from the Australian Register of Trade Marks of marks which are registered in class 32 and related classes and which contain the word “urban” as the first word in the trade mark followed by a word which describes the goods claimed. Urban Alley relied on the fact that these trade marks proceeded to acceptance and registration without a distinctiveness objection being raised. Those trade marks included (in respect of class 32): Urban Detox, Urban Remedy, Urban Guru, Urban Fruit, Urban Crusader, Urban Beverage Imports, Urban Casual Dining Company, Urban Brewing Company, Urban Farmhouse Brewing Co, Urban Craft Brewing Company, 312 Urban Wheat, Urban Cellars, Urban Fatigue And Urban Aloe. Numerous other trade marks were registered in other classes which contained the word “urban” as the first word of the mark. No evidence was adduced about the use of those marks in relation to the products in respect of which they were registered, save for the mark registered by La Sirène (Urban Farmhouse Brewing Co). In my view, the fact that numerous trade marks containing the word “urban” as the first word of the mark have been registered in respect of beer and other drinks products has little if any bearing on the question whether the Urban Ale mark is entitled to registration in respect of beer products.

B.4 Opinions of Mr Kirkegaard

105 As noted earlier, La Sirène also adduced evidence from Mr Matthew Kirkegaard, who is a freelance beer writer, commentator, educator and consultant focussed on the craft beer industry. Mr Kirkegaard started writing about beer (and, in particular, craft beer) on a freelance basis about fourteen years ago and, in the last 10 years, has published articles about craft beer in the following publications:

(a) the Virgin In-flight Magazine (periodically between about 2005 and 2013);

(b) Australian Beer and Brewer, which is a quarterly trade and consumer magazine relating to beer and cider (between about 2007 and 2010);

(c) Drinkstrade, which is a bi-monthly trade magazine for the liquor industry (between about 2010 and 2015);

(d) Beers of the World, which was formerly an English beer magazine (in 2008);

(e) All About Beer, which is an American beer magazine (between about 2008 and 2011);

(f) the Courier Mail newspaper, which is a daily newspaper distributed in Queensland and published by News Limited (since about 2010);

(g) various lifestyle magazines such as Lexus Magazine, a glossy lifestyle magazine distributed to Lexus owners (from time to time);

(h) James Halliday’s Wine Companion, which is a wine industry magazine that also covers other aspects of the drinks trade;

(i) The Broadsheet, an online consumer-focused publication that covers food, drink and lifestyle; and

(j) ABC Online, which is the online news and opinion service of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

106 Mr Kirkegaard also founded Australian Brews News in about 2010.

107 Mr Kirkegaard was the inaugural winner of the Australian Beer Writer of the Year award at the 2014 Australian International Beer Awards. In 2017, Mr Kirkegaard was presented with a special achievement award at “The Beeries”, a Queensland beer industry-based awards event, in recognition of his services to the craft beer industry.

108 Mr Kirkegaard gave evidence about the meaning of the word “urban” as used in the context of the beer market in Australia. Mr Kirkegaard expressed the opinions that:

…in the context of beer in Australia, “URBAN” does not have any particular significance in terms of beer style or flavour characteristics. It is a very generic term used to describe the location of a brewery or its target audience.

…

As a writer, it would be difficult to communicate the aesthetic of an inner-city brewery or describe the inner-city beer movement without using the word “URBAN”.

…

…“URBAN” is a generic term that brewers use to describe their location or ground their beer marketing as being relevant to an inner-city consumer.

109 Mr Kirkegaard expressed the opinion that craft beer began and gained popularity in inner city or urban areas, stating that “Whether consumers are identified as ‘urban hipsters’, ‘urban professionals’ or another term, craft beer really gained acceptance as an urban beverage and the styling and culture around it has generally reflected this fact.”

110 Mr Kirkegaard expressed the view that the label “Urban Ale” used by Urban Alley does not communicate anything to consumers in terms of what they could expect from the taste of the product. That is because the word “urban” is not a beer style recognised by the market and the word “ale” is a description of the process used to make the beer. In respect of the word “ale”, Mr Kirkegaard explained that the two major classifications of beer are ales and lagers. As a general rule, “ales” are beers that have been fermented at relatively warm temperatures for short periods of time with top-fermenting yeasts whereas “lagers” are cold fermented for longer periods of time with bottom-fermenting yeasts.

B.5 Evidence of confusion between the parties’ products

111 No evidence was adduced by Urban Alley as to possible confusion between its Once Bitter product and La Sirène’s Urban Pale product. The only evidence adduced as to possible confusion between the Urban Ale and Urban Pale products was given by Mr Matthew Powell who was employed as the off premises sales representative for Urban Alley since about March 2019. In his role, Mr Powell visits retailers of beer to promote the beers manufactured and sold by Urban Alley.

112 Mr Powell gave evidence that Dan Murphy’s commenced selling the Urban Ale product in about 50 of its stores from the end of May 2019. Dan Murphy’s is owned by the Woolworths Group and is the largest retailer of alcohol products in Australia with over 220 retail outlets Australia wide. On 5 June 2019, Mr Powell accessed the Dan Murphy’s website and searched on the words “urban ale”. The results showed the Urban Ale product and the La Sirène Urban Pale product.

113 I do not consider that the foregoing evidence is probative of the risk of confusion between the parties’ products. It is common for an internet search to produce results based on similar but not identical search terms. The search results depicted each of the parties’ products and the question of confusion needs to be considered by reference to the labelling and promotion of the competing products.

114 Mr Powell also gave evidence that on 3 June 2019 he visited the Dan Murphy’s retail store located at 567 Bridge Road, Richmond (a suburb of Melbourne) to determine the shape and size of shelf talkers that could be displayed for the Urban Ale product. A shelf talker is a label which allows brands to provide marketing information to potential customers. After locating the Urban Ale product in the store, Mr Powell observed that the beer brand and price ticket used under the product listed the La Sirène Urban Pale product and the price for that product (which was more expensive than for Urban Ale). Mr Powell looked around for the La Sirène Urban Pale product in the same aisle but was unable to locate it, concluding that it was not merchandised in the same area or on the same shelf as the Urban Ale product. Mr Powell then spoke to a member of Dan Murphy’s staff and asked him to correct the store labelling.

115 Again, I do not consider that the foregoing evidence is probative of the risk of confusion between the parties’ products. It merely establishes that someone in Dan Murphy’s pinned the incorrect store labelling to the shelf where the Urban Pale product was displayed. The reason for the error is not known. It may have been due to confusion between the names of the products, but equally it could have been due to a lack of care or clumsiness in picking up the wrong label. It is also a single instance of such an error.

C. Cancellation of the Urban Ale mark

116 By its cross-claim, La Sirène seeks orders for the cancellation of the Urban Ale mark under s 88(1)(a) of the TMA. That section provides that, subject to ss 88(2) and 89, the Court may order that the Register be rectified by cancelling the registration. Relevantly, s 88(2)(a) provides that an application may be made on any of the grounds on which registration of the trade mark could have been opposed under the TMA. La Sirène relies on the following three grounds of opposition:

(a) under s 41 of the TMA, on the basis that the mark is not capable of distinguishing Urban Alley’s goods (in respect of which the trade mark is registered) from the goods of other persons;

(b) under s 44 of the TMA, on the basis that the mark is substantially identical with or deceptively similar to the prior registered mark “URBAN BREWING COMPANY”; and

(c) under s 58 of the TMA, on the basis that Urban Alley is not the owner of the mark (based on the registration of the prior mark Urban Brewing Company).

117 It is convenient to consider each of these grounds in turn.

C.1 Opposition under s 41

Relevant principles

118 Section 41 of the TMA was amended by the Intellectual Property Laws Amendment (Raising the Bar) Act 2012 (Cth) with effect from 15 April 2013. As stated in the relevant Explanatory Memorandum (at pages 145-146), the amendments were intended to clarify that the presumption of registrability, as provided for in s 33, applies to s 41. Otherwise, though, the principal concepts in s 41 are unchanged. The amended form of s 41 provides as follows:

(1) An application for the registration of a trade mark must be rejected if the trade mark is not capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is sought to be registered (the designated goods or services) from the goods or services of other persons.

Note: For goods of a person and services of a person see section 6.

(2) A trade mark is taken not to be capable of distinguishing the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons only if either subsection (3) or (4) applies to the trade mark.

(3) This subsection applies to a trade mark if:

(a) the trade mark is not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons; and

(b) the applicant has not used the trade mark before the filing date in respect of the application to such an extent that the trade mark does in fact distinguish the designated goods or services as being those of the applicant.

(4) This subsection applies to a trade mark if:

(a) the trade mark is, to some extent, but not sufficiently, inherently adapted to distinguish the designated goods or services from the goods or services of other persons; and

(b) the trade mark does not and will not distinguish the designated goods or services as being those of the applicant having regard to the combined effect of the following:

(i) the extent to which the trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish the goods or services from the goods or services of other persons;

(ii) the use, or intended use, of the trade mark by the applicant;

(iii) any other circumstances.

Note 1: Trade marks that are not inherently adapted to distinguish goods or services are mostly trade marks that consist wholly of a sign that is ordinarily used to indicate:

(a) the kind, quality, quantity, intended purpose, value, geographical origin, or some other characteristic, of goods or services; or

(b) the time of production of goods or of the rendering of services.

Note 2: For goods of a person and services of a person see section 6.

Note 3: Use of a trade mark by a predecessor in title of an applicant and an authorised use of a trade mark by another person are each taken to be use of the trade mark by the applicant (see subsections (5) and 7(3) and section 8).

(5) For the purposes of this section, the use of a trade mark by a predecessor in title of an applicant for the registration of the trade mark is taken to be a use of the trade mark by the applicant.

Note 1: For applicant and predecessor in title see section 6.

Note 2: If a predecessor in title had authorised another person to use the trade mark, any authorised use of the trade mark by the other person is taken to be a use of the trade mark by the predecessor in title (see subsection 7(3) and section 8).

119 The meaning of the phrase “inherently adapted to distinguish” in subsections (3) and (4) was recently considered by the High Court in Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd v Modena Trading Pty Ltd (2014) 254 CLR 337 (Cantarella). The majority endorsed the test formulated by Lord Parker in Registrar of Trade Marks v W & G Du Cros Ltd [1913] AC 624 (Du Cros) at 635 under earlier UK legislation, whether other traders are likely, in the ordinary course of their business and without improper motive, to desire to use the same mark, or some mark nearly resembling it, upon or in connection with their own goods. The majority observed that that test had been long applied in Australia, including by Kitto J in Clark Equipment Co v Registrar of Trade Marks (1964) 111 CLR 511 (Clark Equipment) (at 514) and F.H. Faulding & Co Ltd v Imperial Chemical Industries of Australia and New Zealand Ltd (1965) 112 CLR 537 (F.H. Faulding) (at 555) and by Gibbs J in Burger King Corporation v Registrar of Trade Marks (1973) 128 CLR 417, stating (at [44]):

The requirement that a proposed trade mark be examined from the point of view of the possible impairment of the rights of honest traders to do that which, apart from the grant of a monopoly, would be their natural mode of conducting business (Lord Parker), and from the wider point of view of the public (Hamilton LJ), has been applied to words proposed as trade marks for at least a century, irrespective of whether the words are English or foreign. The requirement has been adopted in numerous decisions of this Court dealing with words as trade marks under the 1905 Act and the 1955 Act. Those decisions show that assessing the distinctiveness of a word commonly calls for an inquiry into the word’s ordinary signification and whether or not it has acquired a secondary meaning.

120 The reference to a word’s “ordinary signification” reflects the statement of Kitto J in Clark Equipment (at 514) that whether a trade mark consisting of a word is “adapted to distinguish” certain goods is to be tested:

…by reference to the likelihood that other persons, trading in goods of the relevant kind and being actuated only by proper motives – in the exercise, that is to say, of the common right of the public to make honest use of words forming part of the common heritage, for the sake of the signification which they ordinarily possess – will think of the word and want to use it in connection with similar goods in any manner which would infringe a registered trade mark granted in respect of it.

121 The majority in Cantarella summarised the applicable principle in the following terms (at [59] and [71]):

It is the “ordinary signification” of the word, in Australia, to persons who will purchase, consume or trade in the goods which permits a conclusion to be drawn as to whether the word contains a “direct reference” to the relevant goods (prima facie not registrable) or makes a “covert and skilful allusion” to the relevant goods (prima facie registrable). When the “other traders” test from Du Cros is applied to a word (other than a geographical name or a surname), the test refers to the legitimate desire of other traders to use a word which is directly descriptive in respect of the same or similar goods. The test does not encompass the desire of other traders to use words which in relation to the goods are allusive or metaphorical. In relation to a word mark, English or foreign, “inherent adaption to distinguish” requires examination of the word itself, in the context of its proposed application to particular goods in Australia.

…

As shown by the authorities in this court, the consideration of the “ordinary signification” of any word or words (English or foreign) which constitute a trade mark is crucial, whether (as here) a trade mark consisting of such a word or words is alleged not to be registrable because it is not an invented word and it has “direct” reference to the character and quality of goods, or because it is a laudatory epithet or a geographical name, or because it is a surname, or because it has lost its distinctiveness, or because it never had the requisite distinctiveness to start with…

122 As observed by Lockhart J in Oxford University Press v Registrar of Trade Marks (1990) 24 FCR 1 (Oxford University Press) at 8, the “other traders” test from Du Cros reflects the underlying policy objective of s 41 that no person should be able to monopolise a word or phrase and thereby impose an unreasonable restraint upon other traders who may legitimately wish to use that name in relation to their own goods.

123 In Apple Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (2014) 227 FCR 511 (Apple), a decision handed down on the same day as Cantarella, Yates J explained (at [11]):

What does it mean to say that a trade mark is inherently adapted to distinguish the goods or services of one person from the goods or services of another? The notion of inherent adaptation is one that concerns the intrinsic qualities of the mark itself, divorced from the effects or likely effects of registration. Where the mark consists solely of words, attention is directed to whether those words are taken from the common stock of language and, if so, the degree to which those words are, in their ordinary use, descriptive of the goods or services for which registration is sought, and would be used for that purpose by others seeking to supply or provide, without improper motive, such goods or services in the course of trade.

124 The foregoing statement by Yates J has been endorsed by Allsop CJ and Perram J in the Full Court decision of Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd (2018) 261 FCR 301 (Aldi Foods) (per Allsop CJ at [13] and Perram J at [126]) and by Burley J in Bohemia Crystal Pty Ltd v Host Corporation Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 235 (Bohemia Crystal) at [93]; 354 ALR 353; 129 IPR 482.

125 While every case turns on its own facts, examples of trade marks found to have no inherent adaption to distinguish include ROHOE for rotary hoes (Howard Auto-Cultivators Ltd v Webb Industries Pty Ltd (1946) 72 CLR 175), BARRIER for skin cream (F. H. Faulding), MICHIGAN for excavating goods (Clark Equipment), OXFORD for printed publications (Oxford University Press), OREGON for chainsaw accessories (Blount Inc v Registrar of Trade Marks (1998) 83 FCR 50), COLORADO for shoes, bags, wallets, purses and backpacks (Colorado Group Ltd v Strandbags Group Pty Ltd (2007) 164 FCR 506 (Colorado)), PERSIAN FETTA for cheese (Yarra Valley Dairy Pty Ltd v Lemnos Foods Pty Ltd (2010) 191 FCR 297), APP STORE for retail store services for computer software provided by the internet (Apple), MOROCCANOIL for hair care products (Aldi Foods) and BOHEMIA for glassware (Bohemia Crystal).

La Sirène’s submissions

126 La Sirène places primary reliance on s 41(3), submitting that the Urban Ale mark is not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish Urban Alley’s beer from rival producers and Urban Alley did not use the Urban Ale mark before the filing date to such an extent that the mark does in fact distinguish the Urban Ale product as being that of Urban Alley.

127 La Sirène submitted that the ordinary signification of the words “urban ale” is to describe an ale made in an urban area or intended for consumption by an urban audience. It says that the word “urban” is an ordinary, common word which means “of or in or relating to cities or towns”. La Sirène says that the evidence shows that the ordinary signification of the word “urban” when used in connection with beer is as a laudatory epithet to describe inner-city craft breweries, their beers and their target market; it conveys that the product is “cool” or “trendy”. In the context of beer, the word has a tangible meaning and has promotional attraction. The word “ale” describes one of the two principal classifications of beer, being beer that has been fermented at relatively warm temperatures for short periods of time with top-fermenting yeasts. As such, La Sirène submitted that the words “urban ale” are not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish the beer produced by Urban Alley from beer produced by any other brewer. They are words that any other brewer might choose to use without improper motive; that is, for their ordinary signification. The fact that La Sirène chose to use the words “Urban Pale” within the name of its beer product, without improper motive, is an illustration of the very point.

128 La Sirène further submitted that the combination of the words “urban” and “ale” does not result in the trade mark being inherently adapted to distinguish the goods. Both words, when used in connection with beer, are wholly descriptive.

129 La Sirène submitted that Urban Alley had not used the Urban Ale mark before the filing date of 14 June 2016 to such an extent that the mark did in fact distinguish its beer. La Sirène relies on the following matters. First, Urban Alley had only used the Urban Ale mark for two weeks prior to the filing date and, in that period, Urban Alley made minimal sales of its Once Bitter product. Secondly, during those two weeks, La Sirène submitted that the Urban Ale mark was not used by Urban Alley as a trade mark. Rather, the label “Once Bitter” served to distinguish the commercial source of the product, whereas “Urban Ale” described the style of the product. Thirdly, La Sirène submitted that the prior and ongoing use of the word “urban” at that time by many others in relation to beer prevented the Urban Ale mark from becoming distinctive of Urban Alley in that short period.

Urban Alley’s submissions

130 Urban Alley submitted that the Urban Ale mark is sufficiently inherently adapted to distinguish its beer products without the need for any consideration of the use of the mark under ss 41(3) or 41(4). Alternatively, Urban Alley relies on s 41(4) and submitted that, even if the Urban Ale mark is only to some extent, but not sufficiently, inherently adapted to distinguish Urban Alley’s beer products from those of other traders, the combined effect of the extent to which the Urban Ale mark is inherently adapted to so distinguish Urban Alley’s beer products and Urban Alley’s use and intended use of the mark are such that the mark does and/or will in the future distinguish Urban Alley’s beer products. Urban Alley does not rely on s 41(3), accepting that the extent of its use of the Urban Ale mark prior to the filing date was minimal.

131 Urban Alley accepts that the word “urban” is an ordinary, common word (rather than a made-up word) and has a meaning (namely “of or in or relating to cities or towns”) that may be used in a descriptive sense. Urban Alley also accepts that the word “ale” has a descriptive meaning (being a type of beer). Urban Alley concedes, and indeed embraces, the fact that the combination of words “urban ale” does not convey any significance in terms of style or flavour characteristics of beer.

132 Urban Alley’s principal argument is that the words “urban ale”, when used in combination, do not convey any meaning or idea that is sufficiently tangible to anyone in Australia concerned with beer products as to be words having a direct reference to the character or quality of the goods. Urban Alley argued that the words “urban ale” are capable of distinguishing the particular beer sold by Urban Alley because, in the context of beer, they have an allusive or metaphorical meaning of being cool, trendy and perhaps industrial or grungy.

133 Urban Alley submitted that that conclusion is supported by the evidence that many trade marks have been registered in class 32 and related classes which have the word “urban” as the first word of the trade mark. It argued that the presence of various other marks on the Register of Trade Marks that comprise the word “urban” together with another descriptive word or words reinforces the inherent adaptability of the Urban Ale mark to distinguish Urban Alley’s beer products. It further argued that neither Urban Alley nor any other trader is entitled to a monopoly over the word “urban” in respect of beer products; rather, Urban Alley claims only a monopoly over the Urban Ale mark and marks that are substantially identical or deceptively similar to the Urban Ale mark in respect of beer products.

Consideration

134 In my view, the submissions of La Sirène should be accepted and those of Urban Alley should be rejected. In particular, I find that the Urban Ale mark is not to any extent inherently adapted to distinguish Urban Alley’s beer products from those of other beer producers.

135 To a considerable extent, the parties are in agreement as to the ordinary signification of the word “urban” when used in connection with beer and breweries. They agree, and I find, that at one level the word conveys its ordinary meaning that the beer is brewed in a city as opposed to a country location. They also generally agree, and I find, that on another level the word has become associated with craft beer products and breweries, referring to the fact that the beer is produced in an inner city location which is regarded within a certain segment of the market as being “cool” or “trendy” and attractive for that reason. They also agree that the combination of words “urban ale” does not convey any significance in terms of style or flavour characteristics of beer.

136 The evidence shows that many journalists writing about beer in Australia have used the word “urban” in a laudatory manner to describe inner city craft breweries. The articles were directed to beer producers and consumers. In my view, they are evidence of the common usage of the word “urban” by those who have an interest in beer whether as producers or consumers. The evidence includes many articles published before the filing date for the Urban Ale mark on 14 June 2016, including articles appearing in Broadsheet, The Australian newspaper, the City Messenger, Australian Brews News and Hospitality Magazine. While other articles appeared after the filing date of the mark, including articles in the Daily Telegraph and the Courier Mail, in my view those articles are consistent with the earlier usage of the word “urban” and therefore reinforce the ordinary signification of the word as at the filing date.

137 The evidence also shows that a number of businesses associated with beer, whether brewers or vendors, had adopted or used the word “urban” as part of their product or business name in Australia. Prior to the filing date for the Urban Ale mark, the evidence included the use in Australia of the names Tiny Rebel Urban IPA and Urban Belgian IPA (available in Australia since February 2014), Urban Crusader lager (a Liquorland product listed on Untappd from February 2016), Urban Brewing Company (registered as a trade mark in classes 31, 32 and 40 with a priority date of 24 March 2016), Hopworks Urban Brewery (which exhibited its beer products at the Australian International Beer Awards hosted by The Royal Agricultural Society of Victoria Limited at the Melbourne Showgrounds in May 2016 and received a number of awards), and the Riverland Urban Beer Garden (which has been operating under that name since at least 4 October 2015).

138 Shortly after the filing date of the Urban Ale mark, La Sirène began using the word “urban” as part of the name of its beer product called “Farmhouse Style Urban Pale by La Sirène”. As noted earlier, I accept the evidence of Eva Nikias that La Sirène was unaware of the Urban Ale mark or product at the time it chose to adopt the words “urban pale” as part of the name of its product, and that La Sirène chose to use the word “urban” in the name of its product because it described the location of the production of its beer (in an urban area). I accept La Sirène’s submission that its adoption of the word “urban” in its name affords evidence of a rival trader seeking to use the word without improper motive; that is, for its ordinary signification.

139 The evidence supports the opinions expressed by Mr Kirkegaard. In my view, Mr Kirkegaard’s experience as a beer industry writer qualifies him to express an opinion on the common usage and meaning of the word “urban” in connection with beer products and breweries. I accept Mr Kirkegaard’s opinions that the word “urban” does not have any particular significance in terms of beer style or flavour characteristics; that it is a very generic term used to describe the location of a brewery or its target audience; that it communicates the aesthetic of an inner-city brewery or describes the inner-city beer movement; and that it is a generic term that brewers use to describe their location or ground their beer marketing as being relevant to an inner-city consumer.

140 As already noted, both parties agree that the words “urban ale” do not have significance in terms of the style or flavour of the beer beyond what is ordinarily conveyed by the word “ale”. This is despite Mr Meltzer’s evidence that he adopted the name “Urban Ale” with the intent of creating a new style or flavour of beer and that, in Urban Alley’s press release and on its website and in interviews given by Mr Meltzer following the launch of the Urban Ale product, Urban Ale is described as a new style of beer that is a cross between a classic Australian golden ale and a Belgian blonde. Despite those efforts, the words have not taken on that signification. Rather, the words signify a craft beer brewed in an inner-city location. The evidence shows that Urban Alley, and its predecessor, has consistently promoted itself as a craft brewery in an inner-city location: it has adopted a corporate and business name that implies an inner city location (Swanston Street Brewing Co, Collins Street Brewing Co, Laneway Brewery and Urban Alley Brewery); the Once Bitter website promoted the inner-city location of the Once Bitter product (describing the product as “A celebration of our great city, a tribute to the laneway culture and a blend of the old and the new”); and the more recent Urban Alley website also promoted Urban Alley as a craft brewery in inner-city Melbourne (stating prominently “Sustainably crafted in the heart of Melbourne”).