FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

The Good Living Company Pty Limited ATF the Warren Duncan Trust No 3 v Kingsmede Pty Ltd [2019] FCA 2170

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. Paragraph 1 of the originating application filed on 29 December 2017 is dismissed.

2. Grant leave to the parties to file and serve submissions, not exceeding two pages in length, on the question of costs of the proceeding by 31 January 2020.

3. If submissions are filed in accordance with Order 2 and neither of the parties requests that there be an oral hearing, the issue of costs of the proceeding will be determined on the papers.

4. If no submissions are filed in accordance with Order 2 the following order be made with effect from 31 January 2020:

(a) the applicants pay the respondents’ costs of the proceeding.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC J:

1 This proceeding arises out of the lease (Lease) of premises located at ground floor and mezzanine level, 25 Bligh St, Sydney (Premises) to Chop 1 Pty Ltd (in liquidation) (receivers and managers appointed) (Chop 1). A restaurant known as the “Chophouse” was operated from the Premises by Chop 1. The respondents, Kingsmede Pty Ltd (Kingsmede) and Pamiers Pty Ltd (Pamiers), are the landlords of the Premises.

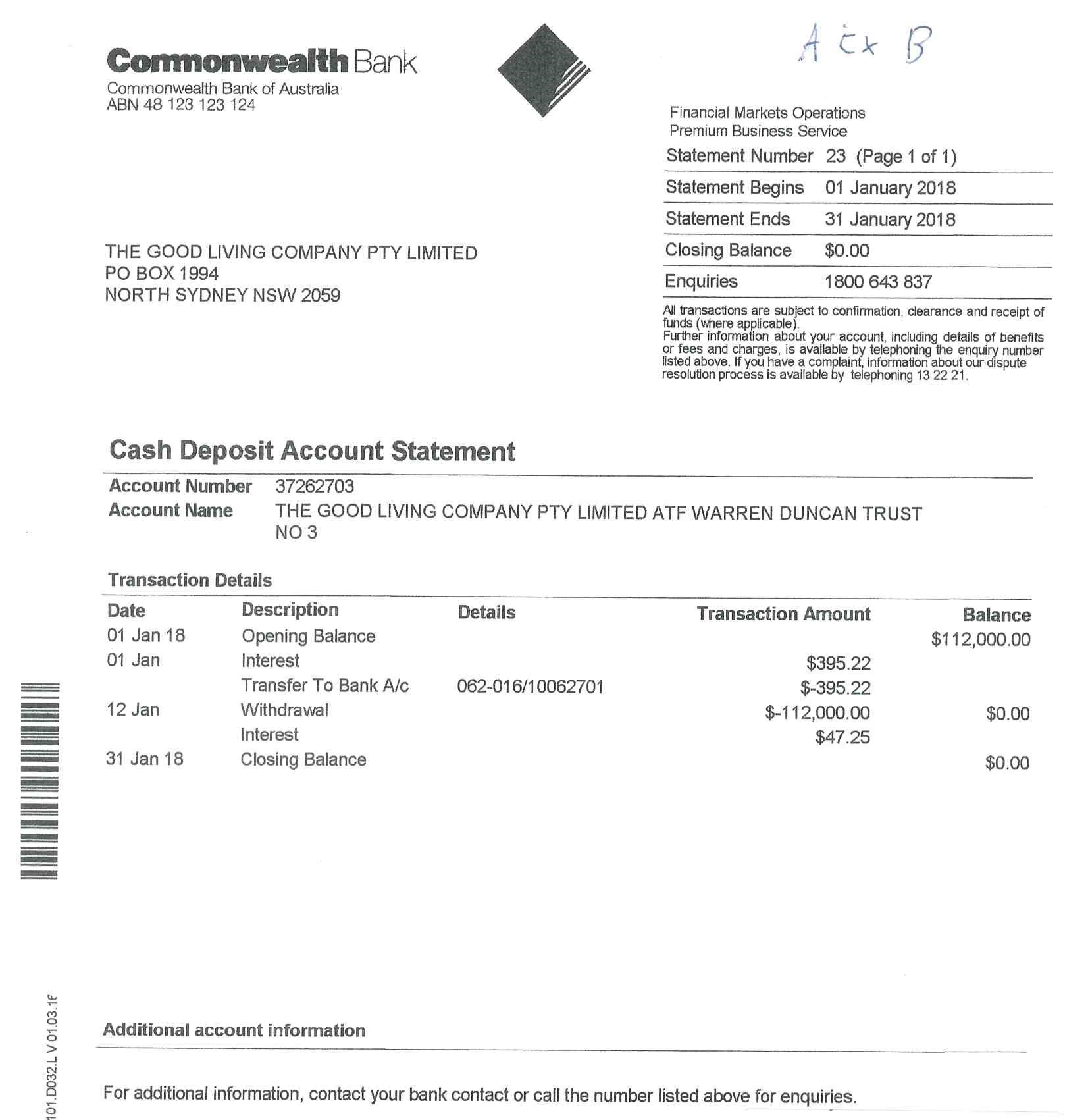

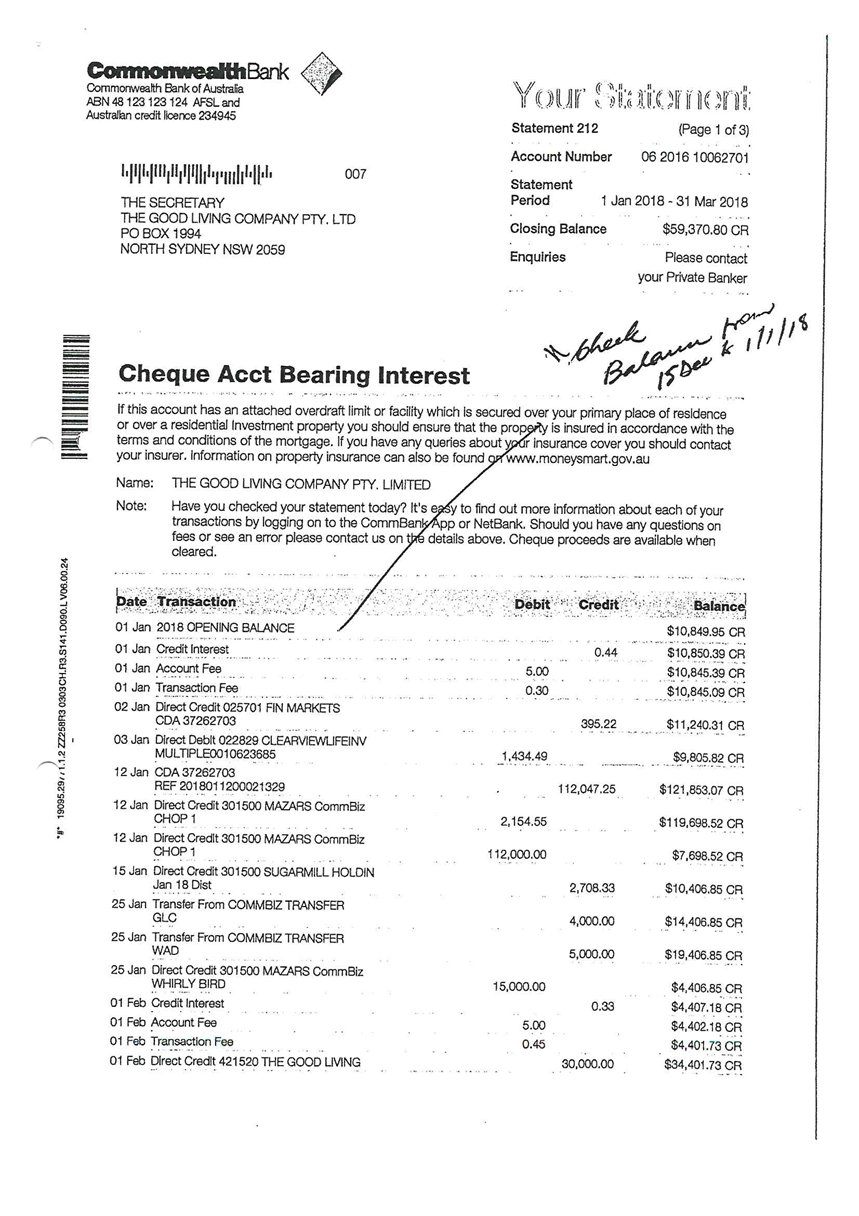

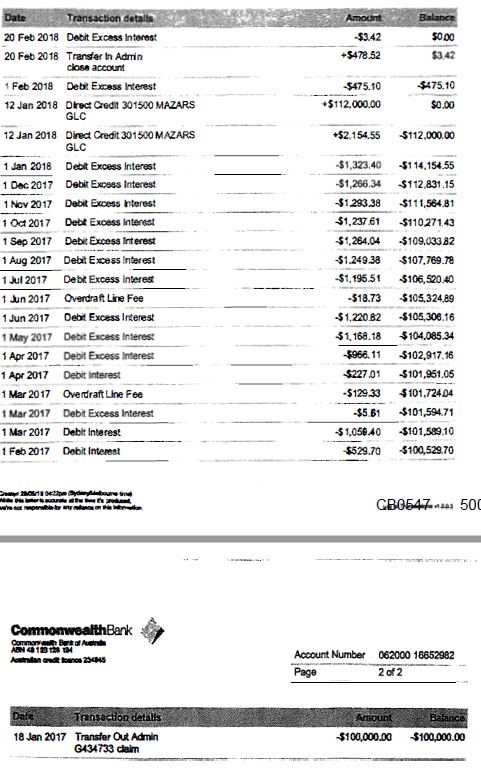

2 The applicants, The Good Living Company Pty Limited as trustee for the Warren Duncan Trust No 3 (TGLC) and Kimana Pty Ltd (Kimana), provided security for, among other things, a bank guarantee issued by the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) in support of the Lease. On 16 December 2016, in circumstances more fully described below, the respondents called on the bank guarantee.

3 The applicants allege that in calling on the bank guarantee the respondents engaged in unconscionable conduct within the meaning of ss 20 and 21 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL) as a result of which they have suffered loss and damage and the respondents have been unjustly enriched. The applicants claim damages pursuant to ss 236 and 237 of the ACL.

material before the court

4 Before turning to consider the facts I note that the parties provided the Court with a court book comprising some 3,000 pages. However, they ultimately tendered or sought to tender only some of that material. That was done in two stages: a number of documents were tendered during the course of the hearing; and following the conclusion of the hearing, together with post-hearing submissions going to particular issues, the parties provided lists of additional documents they sought to tender. Save for three documents, the admissibility of which was the subject of oral argument which I address below at [130]-[140], the documents included on those lists were admitted as exhibits.

facts

The Keystone Group of Companies

5 Warren Duncan is a director of each of TGLC and Kimana. He is also a chartered accountant and partner in the international accounting firm known as Mazars.

6 Mr Duncan and his family have been involved in the hospitality and hotel business for many years and were involved with each of the venues that became assets of Keystone Australia Holdings Pty Ltd (referred to as the Keystone Group) on 13 August 2014. Prior to that date the Keystone Group was an amalgamation of various entities and venues, all of which were controlled by Mr Duncan and his son, John Duncan.

7 On 13 August 2014 the Keystone Group acquired the Pacific Restaurant Group Limited (PRG) and, as a result, the control of Chop Brands Pty Limited and Chop 1, which became part of the Keystone Group. The funds used to acquire PRG and the assets of the Keystone Group were provided by PT Limited as security trustee for Corporate Capital Trustee Inc, KKR Mezzanine Partners ILP, KKR Mezzanine Partners Side by Side and Koi Structured Credit Pte Ltd (Senior Lenders).

8 By June 2016 the Keystone Group consisted of 42 companies, of which 17 companies (Operating Companies) each owned and operated a single venue being either a hotel, wine bar or restaurant.

9 Keystone Group Holdings Pty Limited (KGH) acted as the treasury company for the Keystone Group. John Duncan has been a director of KGH since 15 April 2011 and on 1 February 2012 Warren Duncan became a non-executive director of KGH.

10 TGLC was a secured creditor of Keystone (Australia) Pty Ltd (administrators appointed) (receivers and managers appointed) and other entities within the Keystone Group including Chop 1. TGLC had, for its benefit and the benefit of other parties (Noteholders), a general security agreement over the assets of each of the companies in the Keystone Group including Chop 1.

11 On 18 December 2015 TGLC entered into an inter-creditor deed with other secured creditors of the Keystone Group, one effect of which was to rank the security interest of the Senior Lenders ahead of that of TGLC and the Noteholders.

Kingsmede and Pamiers

12 Andrew Potter is the sole director and secretary of each of Kingsmede, Pamiers and Kingsmede Property Management Services Pty Ltd (KPMS), a wholly owned subsidiary of Kingsmede. Scott Somerton is the director of finance and operations at KPMS. Brent Mulligan is an employee of KPMS but holds the title “General Manager, Kingsmede”.

13 KPMS provides property management services to companies in the Kingsmede group of companies, including Kingsmede and Pamiers. Those services include organising leases and memoranda, dilapidation reports and make-good reports; collecting rent; corresponding with tenants and building managers; handling lease disputes; and the other day-to-day activities that a landlord needs to perform to manage a commercial property. There is no written management services agreement between KPMS and the respondents.

14 Mr Potter is away from Sydney for about six months every year. He is most involved in the respondents’ operations when he is in Sydney. Mr Potter guides the respondents’ business plans and growth strategies and provides Mr Somerton with instructions about the outcomes he would like the respondents to achieve.

15 As director finance and operations, Mr Somerton is responsible for the day-to-day operation of KPMS in the provision by it of property management services to the respondents and, in effect, responsible for the respondents’ day-to-day operations. According to Mr Potter, Mr Somerton is responsible for creating and implementing plans, policies and tactics to manage and resolve accounting, legal, insolvency and back-office issues, and if necessary, contesting any legal issues. This includes liaising with external accountants, lawyers and insolvency practitioners on behalf of the respondents as required. While not documented, Mr Potter has delegated the role of managing and resolving the respondents’ legal, accounting, insolvency and back-office issues to Mr Somerton.

16 Mr Somerton said that, in addition to his duties at KPMS, he contributes to growing the respondents’ business which includes formulating and implementing business plans and growth strategies.

17 Mr Mulligan is responsible for developing and implementing policies and plans to grow and manage the respondents’ investments. Mr Potter gives Mr Mulligan wide discretion to implement the policies and plans that he believes will achieve the best investment results for the respondents.

18 Mr Somerton, with other employees of KPMS, in particular Mr Mulligan, develops and implements methods to achieve Mr Potter’s business plans and growth strategies and to meet his desired outcomes. Mr Somerton said that he has wide discretion about how to do those things. While he defers questions of large capital expenditure to Mr Potter, he is otherwise authorised by Mr Potter to run and operate the respondents’ business and to manage its properties.

The Lease and the provision of the bank guarantee

19 On 1 March 2008 Kingsmede and Pamiers as landlord and Chop 1 as tenant entered into the Lease. Chop 1 owned and operated a restaurant called the Chophouse from the Premises (Chophouse Sydney). The Lease was for a term of 10 years commencing on 1 March 2008, with an option for a further 10 year term. The Lease relevantly provided:

(1) in cl 12.1 “Right of re-entry” that the following were events of default:

…

(e) the Tenant (being a company):

…

(iv) is placed under official management; or

(v) has a receiver or manager of any of its assets appointed; or

…

(2) in cl 12.4 “Landlord’s rights of damages” that:

In addition to the right of the Landlord to·re-enter the Premises after breach by the Tenant of this Lease, and any other rights and remedies of the Landlord, the Landlord may sue the Tenant for damages for loss of the benefits which performance of this Lease by the Tenant would have conferred on the Landlord.

(3) in cl 19 “Bank guarantee” that:

19.1 Issue of Bank Guarantee

On or before the signing of this Lease the Tenant must cause an unconditional bank guarantee in a form acceptable to the Landlord issued by an Australian bank (the bank guarantee) for the sum set out in Item 18 in favour of the Landlord to be provided to the Landlord to secure the performance by the Tenant of its obligations under this Lease. The bank guarantee must not specify any expiry date.

19.2 Entitlement on default

If an event of default occurs, the Landlord may, without Notice to the Tenant, call up the bank guarantee in whole or part. The amount claimable by the Landlord will include, without limitation the amount of any consequential loss, damage or expense incurred by the Landlord in respect to the event of default.

…

(4) in Item 18 of annexure A to the Lease, which set out a summary of particulars, for a bank guarantee in the sum of $75,000 to be provided.

20 On 22 October 2012 the Lease was amended by a variation of lease as a consequence of which item 18 of annexure A to the Lease was varied so that, relevantly, on and from 1 September 2012 a bank guarantee in the sum of $100,000 was to be provided.

21 On 24 December 2012 the CBA issued a bank guarantee in the sum of $100,000 in favour of the respondents (Chophouse Guarantee). This was prior to acquisition of Chop 1 by the Keystone Group. The Chophouse Guarantee was addressed to the respondents and was expressed to be security for the obligations of Chop 1, defined as the Customer. It was to continue until one of the following events occurred: the CBA received written notification from the respondents that it was no longer required, it was returned to the CBA; or upon payment by the CBA to the respondents of the whole of the guaranteed amount or such lesser amount as required by the respondents. Relevantly, it provided that:

Should the [respondents] notify the [CBA] in writing that it requires payment to be made to it of the whole or any part or parts of the Guaranteed Amount, it is unconditionally agreed that such payment will be made to the [respondents] forthwith without further reference to the Customer and notwithstanding any notice given by the Customer to the [CBA] not to pay same. The [CBA] reserves the right to require proof of identity of any person acting on behalf of the [respondents] and to confirm the authenticity of the written notification of the [respondents] before making payment to the [respondents].

Facility agreement with the CBA

22 On or about 8 August 2014 the Keystone Group entered into a facility agreement with the CBA for a sum of $8,050,000 (CBA Facility) which was subsequently amended by deed dated 3 October 2014.

23 On 3 October 2014, pursuant to the CBA Facility as amended, TGLC and Kimana executed guarantees of the obligations of each of the companies in the Keystone Group to the CBA. Kimana’s obligations to the CBA under the guarantee were secured by a real property mortgage dated 3 October 2014 granted by it over a rural property located in Murringo, NSW. The CBA provided bank guarantees in support of the leases executed by each of the Operating Companies, including, as set out at [21] above, Chop 1.

External administration of companies in the Keystone Group

24 From March 2016 the Keystone Group was involved in discussions with the Senior Lenders about the restructuring of its debt. On 28 June 2016 the Senior Lenders appointed Ryan Eagle and Morgan Kelly of Ferrier Hodgson as the joint and several receivers and managers of each of the companies in the Keystone Group, including Chop 1 (Receivers). On 14 May 2018 the Receivers retired as receivers and managers of Chop 1.

25 As the Senior Lenders did not have security over the leasehold interests of the Operating Companies, in the case of Chop 1 the Receivers were appointed over all of its assets other than its leasehold interest in the Premises.

26 Also on 28 June 2016:

(1) the directors of each of the companies in the Keystone Group appointed Kate Barnet, Hugh Armenis and Henry McKenna of Bentleys as joint and several voluntary administrators (Administrators) of each of the companies in the Keystone Group, including Chop 1; and

(2) the Receivers and Administrators entered into an agreement which provided, amongst other things, that the Receivers were responsible for the day-to-day operation of each “Keystone Company” which included Chop 1 and the process of selling or disposing of the property of, relevantly, Chop 1.

27 The convening period for Chop 1 was extended on at least two occasions and the voluntary administration of Chop 1 came to an end on 11 April 2017 when its creditors voted to appoint Ms Barnet and Mr Armenis as liquidators (Liquidators).

28 From the date of their appointment the Receivers traded the businesses owned by each of the Operating Companies, including Chop 1, and each Operating Company (except the owner of the Chophouse Perth) continued to occupy its respective premises until business sale agreements for its assets were exchanged. To assist them in running the businesses owned and operated by the Operating Companies, the Receivers engaged the executive directors and most of the managers of the various Keystone Group companies and retained most of the staff.

29 In about August 2016 the Receivers commenced a sale process for the businesses of the Keystone Group. Details of that process were not provided to or discussed with Mr Duncan. Mr Kelly, one of the Receivers, gave evidence about the sale process. He said that the Receivers’ capacity to recover the value in the businesses depended on the landlords of each property agreeing to assign the existing lease to a purchaser or agreeing to enter into a new lease with a purchaser.

30 During the sale process the directors of the companies in the Keystone Group submitted three proposals for a pooled deed of company arrangement and incorporated a company, K2 MBO Pty Ltd (K2MBO), which submitted a number of offers to acquire various combinations of venues.

The Receivers’ early dealings with the respondents and attempts to sell Chophouse Sydney

31 Initially, Mr Kelly and Ryan Spooner, a director at Ferrier Hodgson, dealt with Stephen Harrison and Mr Mulligan of Kingsmede, who Mr Kelly understood represented Kingsmede as landlord. They first met with Messrs Harrison and Mulligan in early July 2016, and during July and August 2016 negotiated variations to the Lease which the respondents required.

32 According to Mr Somerton, between around 29 June 2016 and 17 October 2016 Messrs Mulligan and Harrison worked with the Receivers to identify a replacement or new tenant for the Premises and during that time kept Mr Somerton informed about developments in the receivership.

33 On 29 August 2016 Mr Spooner attended a meeting with Messrs Mulligan and Harrison. Mr Kelly said that later that day he was notified by the CBA that it had received correspondence putting it on notice that the respondents intended to terminate the Lease.

34 On 30 August 2016 Henry Davis York (HDY), the solicitors for the respondents, wrote to the CBA informing it that Chop 1 was in breach of cl 12.1(e)(v) of the Lease because of the appointment of the Receivers and, relevantly, notifying the CBA of their clients’ intention to terminate the Lease effective from 7 September 2016.

35 On 31 August 2016 Mr Spooner sent an email to Mr Mulligan, copied to Messrs Kelly and Harrison, in which he thanked Mr Mulligan for his time earlier in the week and noted that “[o]n the basis that Kingsmede will remove the demolition clause in the [Lease] and offer an extended 5 year option” the Receivers were prepared to accept the terms offered. Mr Spooner then set out a summary of “the commercial terms for a variation of the [Lease]”. Mr Mulligan responded by email dated 2 September 2016 thanking Mr Spooner for the information and noting that they would “be taking it up with the owners Monday”.

36 On 6 September 2016:

(1) Mr Mulligan sent a further email to Messrs Spooner and Harrison, copied to Mr Kelly, in which he noted that he had left the matter with Mr Harrison to finalise;

(2) Tim Grosmann of CBRE Group, the Receivers’ appointed sales agents and advisers, informed Mr Kelly by email that he had spoken with Mr Harrison who had confirmed that they were “happy with the proposal and happy for CBRE to try to secure them a tenant through [its] sales process”. Mr Kelly understood the reference by Mr Grosmann to “our proposal” was a reference to the agreed terms set out in Mr Spooner’s email of 31 August 2016 and that the reference to “they” was a reference to the owners of Kingsmede; and

(3) Mr Spooner responded to Mr Grosmann’s email noting that he had had a similar discussion with Mr Harrison that evening.

37 Mr Kelly instructed the Receivers’ solicitors, Herbert Smith Freehills (HSF), to prepare documentation allowing for the variation and assignment of the Lease. HSF provided the documentation on 8 September 2016. The Receivers’ online data-room for the sales process, which had information for potential purchasers of the businesses of the Keystone Group, including the indicative terms on which landlords were willing to transfer their leases as part of the sale of the businesses conducted at each venue, was updated to reflect the terms agreed with the respondents.

38 On 27 September 2016 Mr Spooner provided Messrs Harrison, Mulligan and Kelly with a confidential update on the sales campaign for the Keystone Group portfolio.

39 By mid-October 2016 Mr Kelly had identified Dixon Hospitality Pty Limited (Dixon) as the preferred purchaser of seven of the 17 venues operated by the Keystone Group, including Chophouse Sydney.

40 On 17 October 2016:

(1) Messrs Somerton, Mulligan and Harrison met with Dixon and, among others, representatives of the Receivers; and

(2) Mr Spooner sent an email to Mr Harrison in which he thanked him for meeting with Dixon, noted that the Receivers were working on “transitioning the business under a licence to [Dixon]” and asked that Mr Harrison provide his “‘in principle’ consent by 19 October 2016 that [Dixon] is a suitable tenant and that Kingsmede would be prepared to assign the [Lease] including the variations as previously discussed”. A copy of the email was forwarded to Mr Somerton by Mr Mulligan.

41 As a result of the meeting referred to in the preceding paragraph, Mr Somerton understood that Dixon proposed to replace Chophouse Sydney with a “gastro pub”. Mr Somerton did not consider that Dixon’s proposal reflected the standing of the building or that it was in keeping with the quality and location of the Premises and believed that the proposed use of the Premises was inconsistent with the terms of the Lease. Mr Potter had informed Mr Somerton that he was not happy with Dixon as a tenant, that he wished to explore options for the respondents without the Receivers and that he would not agree to allow the Premises to be transformed from a high-end fine-dining restaurant into a “gastro pub”. For those reasons, Mr Somerton considered that Dixon was not a suitable tenant for the Premises

42 Mr Potter’s evidence was to the same effect. He said that in about mid-October he learnt from Mr Mulligan or Mr Somerton that the Receivers’ preferred new tenant was Dixon and that it proposed to set up a gastro pub in the Premises. Mr Potter described the building at 25 Bligh Street, Sydney, in which the Premises are located, as the respondents’ most important and valuable property and a significant high-rise tower in which over 95% of the rental income is generated from leasing the office space. Mr Potter said that the Premises, where Chophouse Sydney is located, is a very desirable site with outside seating which people entering the building must walk past. Mr Potter believed setting up a “gastro pub” in the Premises would make the office space less desirable, undermine the respondents’ ability to let the office space and put at risk 95% of the rental income generated by the building. He strongly opposed the idea and informed Mr Somerton accordingly.

43 At that point Mr Potter came to believe that the failure of Chop 1, the receivership and the future tenancy of the Premises would be contentious and could have legal implications. Mr Potter thus decided that Mr Somerton should manage all of the day-to-day issues connected with the receivership of Chop 1.

44 Upon becoming involved in the issues surrounding the receivership of Chop 1 and taking over the management of the relationship with the Receivers and the Administrators, Mr Somerton reviewed the records to acquaint himself with the dealings between the respondents and the Receivers. He became aware that the Receivers had continued to pay the rent, albeit not always on the first day of each month as required by the terms of the Lease.

Termination of the Lease

45 On 18 October 2016:

(1) HDY notified Chop 1, the Receivers and the Administrators that Chop 1 was in breach of the Lease by reason of the appointment of the Receivers and that the Lease was terminated effective 5 pm on 1 November 2016; and

(2) Mr Somerton notified the Receivers that all future correspondence should be directed to him and in a letter of the same date informed the Receivers that the terms of the proposed assignment to Dixon were “wholly unacceptable to the [respondents]” and set out the reasons why that was so, principally because of the nature of Dixon’s intended business at the Premises and the resulting change in use. The letter concluded:

The Receivers made it clear to us in the meeting yesterday that Dixon’s offer to take over seven of the operations of the Keystone Group, including Chop House, is by far the best offer received. Further, the Receivers advised that they do not expect a better offer to eventuate. As Dixon’s plan for the space is an unacceptable change of use, the Landlord has lost faith in the Receivers ability to finalise a sale acceptable to the Landlord. Accordingly, the Landlord has no option but to terminate the Lease (in accordance with its rights under clause 12.1 of the Lease) so that it may prospect for a suitable operator for the space.

Subsequent to the appointment of the Receivers, officers of the Landlord have impressed upon officers of the Receivers the importance of locating an operator compatible with the use of the premises. The importance of the operator’s offering cannot be overstated.

Mr Kelly cannot recall any conversations of the nature referred to by Mr Somerton in the final paragraph of his letter and does not recall such statements having been made by Mr Somerton or any other representatives of Kingsmede.

46 On 19 October 2016 Kingsmede informed the CBA, as a matter of courtesy, that on the preceding day it had notified Chop 1, its Receivers and Administrators of termination of the Lease effective at 5 pm on 1 November 2016.

47 Notwithstanding the termination of the Lease, the respondents continued to accept rent for the Premises from the Receivers and to demand and to be paid outgoings.

48 On 15 December 2016 the Lease was removed from the title of the Premises.

Subsequent steps to sell the Chophouse Sydney business

49 According to Mr Kelly, after 18 October 2016 Mr Somerton indicated that it was possible Kingsmede would accept Dixon as a tenant and that the respondents would prefer a 12-month bank guarantee. According to Mr Somerton, on or about 19 October 2016 he had a conversation with Mr Kelly to the following effect:

Mr Somerton: Dixon Hospitality wasn’t right for the Property. We’ve lost faith in the Receivers, Morgan. I don’t think you can find us the right tenant for the Property.

Mr Kelly: Stick with us, Scott. We want you to attend a second meeting. KKR really want you to reconsider accepting Dixon. If you don’t, we can cure the technical breach under the lease. We are paying rent, so there is no financial default. We require you to attend a second meeting.

Mr Somerton: Alright, we’ll attend.

50 On 20 October 2016 Mr Somerton and Mr Mulligan attended a meeting with, among others, representatives of Dixon and Mr Kelly. On 21 October 2016 Mr Kelly received a detailed list of queries about Dixon from Mr Somerton.

51 On 26 October 2016 Mr Somerton sent a letter to the Receivers in which he, in effect, rejected Dixon as a tenant for premises. In that letter, among other things, Mr Somerton said that “Dixon’s proposed operation of the Premises would be an unacceptable change in use that is inconsistent with the Lease” and that “Dixon’s proposed use would (amongst other things) significantly prejudice the [respondents’] ability to attract high-quality tenants to the Premises”.

52 On 26 October 2016, Mr Somerton received an email from Mr Kelly indicating that Bruce Solomon and Matt Moran may be interested in Chophouse Sydney and in entering into a lease for the Premises. Mr Somerton was aware of Messrs Solomon and Moran and their business, Solotel.

53 On 28 October 2016 Messrs Somerton and Mulligan met with, among others, Messrs Solomon, Spooner and Kelly. According to Mr Somerton, the purpose of the meeting was to discuss the possibility that a company within the Solotel group of companies would enter into a lease for the Premises and maintain Chophouse Sydney if the respondents agreed to a new lease. After that meeting, Mr Somerton was satisfied that Solotel would be a good tenant for the Premises as it would maintain Chophouse Sydney if the respondents agreed to a new lease.

54 On or about 31 October 2016 the Administrators and Receivers executed a sale agreement for the sale of six venues, not including Chophouse Sydney, to Dixon (Dixon Sale Agreement). Mr Duncan understood from the Administrators that the respondents had refused to assign the Lease to Dixon or to enter into a new lease with it. After the execution of the Dixon Sale Agreement, Mr Duncan was in regular contact with the Administrators and Receivers in relation to the sale of venues. That was for two reasons: first, he was concerned that all of the bank guarantees be returned; and secondly, because K2MBO had submitted an offer for some venues, including Chophouse Sydney.

55 By 30 November 2016 Mr Kelly understood that Kingsmede had agreed that Solotel would be an acceptable tenant for the Premises and that the terms of a proposed lease to companies within the Solotel group were more or less settled. According to Mr Somerton, between 28 October 2016 and 16 December 2016 JDK Legal, on behalf of the respondents, and Phoenix Legal, on behalf of Solotel, negotiated the terms of a lease pursuant to which two companies within the Solotel group of companies, Sol Bligh Pty Ltd and Mash Bligh Pty Ltd (Solotel Companies), would lease the Premises. By 1 December 2016 it seemed to Mr Somerton that it was likely, although not yet guaranteed, that the Solotel Companies would take a lease of the Premises.

56 On 1 December 2016 Mr Somerton sought a meeting with Mr Kelly. On 2 December 2016 Mr Somerton telephoned Mr Kelly and they had a conversation during which Mr Kelly recalls that Mr Somerton said words to the following effect:

Kingsmede would prefer to have Bruce Solomon as the tenant to move in now however Leon Fink has offered a $1 million cash incentive. This is not our preferred option because Leon Fink is not willing to take possession until after Christmas. If you were willing to pay $500,000 then you can have the premises. I understand that Bruce Solomon is paying $1.5 million so you walk away with $1 million and we keep $500,000 and Bruce Solomon can move in now. In my view the easiest way forward is for the Solotel sale to occur immediately however the $500,000 needs to be paid to Kingsmede immediately otherwise there will be no deal.

Mr Kelly took a note of his conversation with Mr Somerton which he immediately dictated after the discussion and had typed by a staff member, which includes a record of Mr Somerton’s comments set out above. In cross-examination Mr Kelly agreed that his conversation with Mr Somerton was so heated that he thought it was possible that one day it would result in litigation.

57 Although Mr Somerton did not give any evidence in his affidavit about his conversation with Mr Kelly on 2 December 2016, in cross-examination he:

(1) accepted that he said to Mr Kelly words to the effect that “Kingsmede would prefer to have Bruce Solomon as the tenant to move in now”, that “however, Leon Fink has offered a $1 million cash incentive” and “this is not our preferred option because Leon Fink is not willing to take possession until after Christmas”;

(2) accepted that he knew that as at 2 December 2016 the Receivers wanted the Solotel Companies to take possession before Christmas and assumed that they would be capable of doing so;

(3) said that he understood that Kingsmede had a critical role in the process because there was no possibility of Chophouse Sydney business being sold without a lease;

(4) accepted that he said words to the effect that “if you’re willing to pay $500,000 then Bruce Solomon can have the Premises” and “I understand that Bruce Solomon is paying $1.5 million”. By that latter statement Mr Somerton understood that the amount of $1.5 m was the purchase price for the Chophouse Sydney business from the Receivers and that he was asking that, of that amount, the Receivers take $1 m and Kingsmede be paid $500,000;

(5) said that the idea of the negotiation was that the respondents, specifically Mr Somerton, “had been highly inconvenienced by the receivership, and it was an arrangement whereby [the Receivers] could walk away, Solotel could be in place, and we could receive some level of compensation for what I felt was significant amount of time spent on this issue”;

(6) understood that the $500,000 to be paid to the respondents would have to be paid simultaneously with the business sale agreement for the Chophouse Sydney business and out of the purchase price;

(7) denied saying words to the effect that “unless Kingsmede is going to be paid there will be no deal” and giving an ultimatum. He said that he and Mr Kelly spoke about what would be most beneficial for both parties;

(8) accepted that Mr Kelly said words to the effect “you want us to pay $500,000 key money to you”, that he responded “yes, we are asking for a payment of $500,000” and that Mr Kelly had said that “key money” would be illegal. However, Mr Somerton said that he never responded to the term “key money” and that he did not know what key money was at the time but has subsequently come to understand the concept; and

(9) said that Mr Kelly became quite irate at that point, screamed that he had lost lots of money through Mr Somerton’s actions already and hung up the phone.

58 Mr Kelly recalls that on 2 December 2016 he had a further conversation with Mr Somerton in which Mr Somerton suggested that the $500,000 Kingsmede required could be considered compensation for its losses as a result of the receivership and the time and effort expended by the owners/respondents. Mr Somerton also recalls a subsequent conversation with Mr Kelly in which Mr Kelly indicated that the Receivers would be prepared to pay $500,000 as compensation.

59 In cross-examination Mr Somerton was asked to explain what he intended the $500,000 payment would cover. The following exchanges occurred with Mr Somerton:

Mr DeBuse: And was that in the context of you saying the $500,000 can be considered compensation for losses as a result of the receivership and the time and effort expended by the owners?

Mr Somerton: It was – I described it as widely as I could. It was compensation for expenses, losses, the time spent …

Mr DeBuse: And what that $500,000 was to cover everything that you could possibly think of that you had incurred under the lease by way of a loss, a damage or an expense?

Mr Somerton: No, that’s not the case. The 500,000 together with the settlement agreement together with any amounts that have been paid for rent and so forth. So it was – it was a package deal that included everything, including what was to come.

…

Her Honour: What do you mean by “that included everything”?

Mr Somerton: So releases under the agreement between the receivers and I were hard fought and very strongly negotiated and they were crucial to us agreeing.

Her Honour: But you say the $500,000 was partly in payment for the release?

Mr Somerton: Partly in payment for – it just encompassed everything. The time spent on the receivership, the agreements we had to put forward, a release form Chop 1 and the receivers, and the expenses and the loss.

60 Mr Somerton accepted that as at 2 December 2016 there had been no discussion about the Chophouse Guarantee and what was to occur in relation to it, and that there had been no threat to call on it as at that date.

61 In relation to the new lease being negotiated with the Solotel Companies, Mr Somerton gave the following evidence in cross-examination:

Mr DeBuse: Okay. You had, in negotiating the lease with Mr Soloman and Solotel, insisted on terms which resulted in a significantly increased rent from the rent that Chop 1 had been paying?

Mr Somerton: Yes.

Mr DeBuse: And the term, the initial term under the lease, was longer than the remaining – than the balance of the term under the Chop 1 lease?

Mr Somerton: Yes.

Mr DeBuse: And the amount of the bank guarantee that you were obtaining from Solotel in the event of the lease was $175,000, as opposed to the bank guarantee you held of $100,000?

Mr Somerton: I can’t recall the exact amount, but I think the bank guarantee was higher than that.

Mr DeBuse: You think it was higher than 175,000?

Mr Somerton: Yes.

Mr DeBuse: So there was an – at least in those ways, there was significant benefits in the proposed lease with Solotel to Kingsmede?

Mr Somerton: With the exception of time, yes. Those were more financially beneficial terms than the previous lease.

62 On 9 December 2016 Mr Duncan became aware that on 8 December 2016 Chop 1 as vendor had exchanged a contract for sale of Chophouse Sydney (Chophouse Sale Agreement). An email dated 9 December 2016 from John Duncan to, among others, Mr Duncan was in evidence before me. In that email, John Duncan informed the recipients that “Chophouse Sydney has exchanged last night to Solotel”. John Duncan’s email dated 9 December 2016 was a part of an email chain which included an earlier email dated 7 December 2016 from Mr Spooner in which he wrote:

Hi Ant

Further to Phil’s note below regarding the Chophouse Sydney venue, we confirm:

• Contracts are being exchanged on the venue today / tomorrow

• The landlord and purchaser have agreed the new lease agreement

• Completion is scheduled for 19 December 2016

• I am expecting a call from Solotel’s HR manager to discuss the employment of Keystone staff following exchange

• I was proposing to introduce you to Solotel’s HR lead for you to liaise with throughout the process.

Please let me know if this creates any issues.

I will give you a call once exchange occurs.

Mr Duncan could not recall seeing the earlier email dated 7 December 2016 which notified the scheduled completion date for the sale of Chophouse Sydney as 19 December 2016.

63 The Chophouse Sale Agreement provided for the sale of the business carried on at the Premises, ie Chophouse Sydney, to the Solotel Companies as Buyer. The other parties to the Chophouse Sale Agreement were Chop 1 and Chop Brands Pty Ltd (receivers and managers appointed) (administrators appointed) as Sellers, Keystone Group Holdings Pty Ltd (receivers and managers appointed) (administrators appointed), the Receivers and the Administrators. The Chophouse Sale Agreement included the following terms:

(1) in cl 1.1 “Definitions” the term “Bank Guarantee” is defined to mean:

the Bank Guarantee issued by [the CBA] in favour of [Kingsmede] and [Pamiers] for an amount of $100,000.00

(2) clause 2.1 “Conditions precedent” includes:

(a) Clauses 4.1 and 6 do not become binding on the parties and are of no force or effect unless and until:

…

(2) (grant of new lease) the ‘Lease Condition Precedent’;

…

(5) (Bank Guarantee) the ‘Bank Guarantees Condition Precedent’

have been satisfied or waived in accordance with clause 2.4.

…

(c) In this clause 2.1:

…

(2) ‘Lease Condition Precedent’ means the owner of the Property grants a new lease in respect of the Property to the Buyer on terms satisfactory to the Buyer (acting reasonably);

…

(5) ‘Bank Guarantee Condition Precedent’ means the lessor under the Property Lease has confirmed in writing to the relevant Seller (a copy of which confirmation has been provided to the Buyer) it will return the original of the Bank Guarantee held by (or on behalf of) the lessor under the Property Lease at Completion.

(3) clause 2.4(b) provided relevantly that the condition in cl 2.1(a)(5), which I will refer to as the Chophouse Guarantee Condition Precedent, is for the benefit of the Sellers and may only be waived by the Sellers in writing;

(4) clause 4.1 provided for the sale of the “Business Assets” on the “Completion Date” in consideration of the Buyer assuming the “Assumed Liabilities” and agreeing to pay the “Purchase Price”; and

(5) clause 6 concerned “Completion”.

64 There was no evidence that the Chophouse Sale Agreement was provided to Mr Somerton or any other employee of KPMS or the respondents. Mr Somerton’s evidence, which I accept, is that he had nothing to do with the Chophouse Sale Agreement and did not know about it at the time, by which I infer he was unaware of its terms.

The Chophouse Guarantee

65 Mr Somerton’s evidence was that he was still concerned that the lease between the respondents and the Solotel Companies would not proceed. While he did not identify when in time he held that belief, he said that it was “a real risk in [his] mind”. Mr Somerton said that from about 31 October 2016 the respondents and the Solotel Companies had had disagreements about the terms of the proposed new lease, particularly in relation to turnover rent.

66 In late November or early December 2016 Mr Somerton had conversations with Mr Potter about calling on the Chophouse Guarantee due to Chop 1’s default. Mr Somerton considered that Chop 1 had breached the Lease and that the respondents had incurred and were continuing to incur costs and expenses in connection with that breach and the receivership. Mr Somerton said that he discussed this with Mr Kelly when he learnt that the Receivers intended to have the Chophouse Guarantee returned as a condition of settlement on 19 December 2016.

67 Mr Potter recalled that at some point he had a conversation with Mr Somerton about the Chophouse Guarantee but does not recall the specific details of that conversation.

68 Mr Somerton believed that if the negotiations for the proposed new lease with the Solotel Companies failed the respondents would have large claims for costs and expenses against Chop 1 which could not be met by Chop 1, including:

(1) the loss of rental income as there would be no tenant for the Premises;

(2) the fit out of the Premises would be rendered useless without an operator for the restaurant;

(3) make-good costs for the Premises which the respondents may have to incur and the cost of fitting out the space for a new tenant;

(4) marketing and agent fees to obtain a new tenant;

(5) actual expenses comprising legal fees in connection with the breach of the Lease and the receivership and the time spent and invested over the preceding six months by officers and employees acting for the respondents; and

(6) potential liability and expense in the event that the Receivers might sue the respondents because they had somehow acted in a way that caused them loss or damage.

69 Mr Somerton was also concerned that the settlement between the respondents and the Receivers would not occur. On 13 December 2016 Mr Somerton received a draft of the proposed deed between the respondents and the Receivers which incorporated changes proposed by the Receivers, a number of which he did not agree with. Mr Somerton said that on 13 December 2016 he spoke with, among others, Messrs Solomon, Kelly and Spooner and informed them of his concerns and that on 13 and 15 December 2016 he exchanged emails with Messrs Kelly and Spooner.

70 Mr Somerton said that, having regard to the matters set out at [65]-[66] and [67]-[69] above, his reasons for calling on the Chophouse Guarantee on 16 December 2016 were:

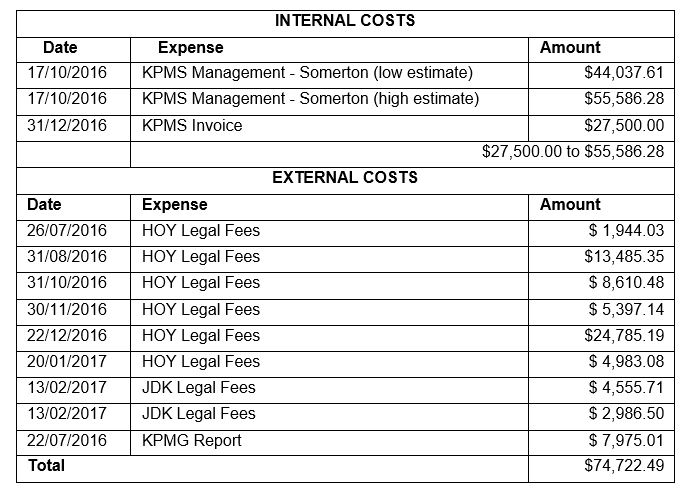

(1) the respondents already had claims on Chop 1 for external costs and “internal notional costs”. He did not know what the total value of those claims might be, but thought that the legal costs were already about $40,000 to $50,000 and that there would be more to come;

(2) he had a feel for how much time he and others at KPMS and Kingsmede had spent and were still spending on the receivership and it seemed that they were investing enormous time and energy to resolve a problem caused by Chop 1;

(3) there were growing costs that were unknown, since he could not predict with any accuracy the future costs or how much more time and energy KPMS and the respondents would have to continue to invest in the receivership to achieve a final outcome; and

(4) there was a real possibility that the respondents would lose around $40,000 per month if the proposed new lease fell away and Chop 1 left the premises, which could amount to hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost revenue.

71 Accordingly on 16 December 2016 Mr Somerton decided to cause the respondents to call on the Chophouse Guarantee by sending a letter to the CBA.

72 On 16 December 2016 Mr Potter signed a letter addressed to the CBA which had been prepared by Rachel Fisher, a former employee of Kingsmede who held the position of property manager. At the time Mr Potter understood that Mr Somerton had decided to have the respondents claim the Chophouse Guarantee in connection with the receivership of Chop 1, and that this letter was that call on the guarantee. The letter included:

With reference to the above bank undertaking dated the 24th of December 2012 in the sum of $100,000.00, copy of which I have enclosed, we would like to make a full claim for the total amount of the bank guarantee being $100,000.00 due to the tenant’s default.

As a result, kindly have the proceeds paid by cheque. Please be informed that I hereby authorise our Property Manager, Rachel Fisher, to pick up the cheque in exchange of the original bank guarantee at the CBA branch at 48 Martin Place, Sydney NSW 2000.

73 Between 16 December 2016 and 17 January 2017, when the CBA paid out the amount due under the Chophouse Guarantee (see [112] below), Mr Somerton had no contact with the CBA.

74 In cross-examination Mr Somerton:

(1) accepted that:

(a) as at 16 December 2016 the Receivers had paid rent, as he recalled, up to 19 December 2016;

(b) there was significant financial benefit to the respondents in completing and entering into the new lease with the Solotel Companies;

(c) on the sale of Chophouse Sydney the respondents would receive $500,000; and

(d) none of the matters set out at [70] above could have operated on his mind either as at 20 December 2016, the day after the deed of settlement and release had been signed by the Receivers and delivered with a cheque for $500,000 to HDY, or as at 17 January 2017, when the CBA paid out the Chophouse Guarantee;

(2) agreed that he knew that as at 12 December 2016 HDY had received a signed copy of the new lease from the Solotel Companies and that all he had to do was to have it signed by the respondents and there would be a binding agreement;

(3) said that at the time there was “risk floating around between all the parties” and that they “required all pieces of the puzzle to land” by which he meant the respondents’ deed of settlement with the Receivers, the new lease, which he accepted they had, and the Chophouse Sale Agreement;

(4) said that he was not aware of the arrangements sitting behind the Chophouse Guarantee but accepted that there was likely to be an arrangement for indemnification of the CBA;

(5) said it was not the case that he used the Chophouse Guarantee to obtain money to which he knew he, in a very short period of time, would not be entitled;

(6) was emphatic that he had serious concerns that the settlement between the respondents and the Receivers might not occur (see [69] above); and

(7) disagreed both that the only thing that could have possibly caused the transaction between the respondents and the Solotel Companies to not go ahead was the actions of Kingsmede and that there was no serious concern in his mind that the respondents and the Solotel Companies would not enter into the transaction documents.

75 Mr Somerton said that he called on the Chophouse Guarantee on 16 December 2016 because of the difficult relationship he had with the Receivers. He said that after the respondents terminated the Lease, the Receivers maintained that the Lease was still on foot and they could cure the technical default, so it was only after Mr Somerton went through the process of terminating the Lease and having it removed from the title of the Premises, which occurred on 15 December 2016, that he felt sufficiently comfortable that the Receivers could not rectify the breach and so he called on the Chophouse Guarantee. He denied that:

(1) he called on the Chophouse Guarantee on 16 December 2016 because there was nothing anybody could do about it at that point;

(2) his explanation for calling on the Chophouse Guarantee was one he had come to with the benefit of hindsight; and

(3) at the time he called on it he knew that the respondents were not going to suffer any expense, loss or damage.

76 According to Mr Somerton on or about 16 December 2016 he was told by HDY that the Receivers wanted to finalise the receivership and one of the things they wanted was the Chophouse Guarantee.

77 According to Mr Kelly on 16 December 2016 he had a telephone conversation with Mr Somerton during the course of which they had an exchange to the following effect:

Mr Kelly: Can we discuss the bank guarantee? It is an outstanding item.

Mr Somerton: We won’t return the bank guarantee. We will call on it when the sale settles. What made you think we would return the bank guarantee? It has always been our intention to draw down on it, and we have the right to.

A letter from the Receivers to the respondents dated 19 December 2016 (see [87] below) refers to a conversation between Messrs Somerton and Kelly on 16 December 2016 and an email from Mr Kelly to the Administrators dated 19 December 2016 (see [92] below) refers to a conversation which took place “late on Friday”. I am satisfied that late on 16 December 2016 Messrs Somerton and Kelly had a conversation in which Mr Kelly sought return of the Chophouse Guarantee and Mr Somerton informed Mr Kelly that it would not be returned.

78 Mr Somerton said that he informed the Receivers in a conversation with Mr Kelly on the morning of 19 December 2016 that the respondents had called on the Chophouse Guarantee. Given the matters set out in the preceding paragraph it is likely that this conversation took place late on 16 December 2016. Mr Somerton’s version of the conversation is to the following effect:

Mr Kelly: The directors want the Bank Guarantee back.

Mr Somerton: The Bank Guarantee has been claimed already. It’s ours. I can’t do anything about it now, it’s too late. If you want us to give $100k to the Directors, you need to make good the difference and tip on another $100k to our agreement. We need to get to that figure.

Mr Kelly: That’s nuts. I’m not doing that. You’ve already cost us millions of dollars.

Mr Somerton: Where do you want to go from here?

Mr Kelly does not recall having a conversation in the terms recorded above and does not recall Mr Somerton informing him that the Chophouse Guarantee had already been called on.

79 In cross-examination Mr Somerton gave evidence that the Chophouse Guarantee was never discussed with Mr Kelly and when the issue of its return came to light he told Mr Kelly that it had been called. He said that he had always assumed the Chophouse Guarantee was part of what he described as “the package deal” while Mr Kelly had assumed that it was not.

80 The arrangements that had been struck between the respondents and the Solotel Companies, the Receivers and the Solotel Companies and the respondents and the Receivers were interdependent. However, as at 16 December 2016 there was, on the evidence, no certainty one way or the other that all parts of the transaction would complete. Mr Somerton aptly described them as pieces of a puzzle. As at 16 December 2016 the puzzle was not complete. While the new lease had been signed by the Solotel Companies, the Chophouse Sale Agreement had been exchanged but not completed and the deed of settlement and release had not been finalised.

81 As at 16 December 2016 Mr Somerton had the concerns set out at [65]-[66] and [67]-[70] above. There was nothing in any of the evidence before me that displaced Mr Somerton’s evidence in that regard or that would cause me to conclude that Mr Somerton did not have those concerns at the time.

82 As set out at [79] above, Mr Somerton and the Receivers never discussed the Chophouse Guarantee prior to it being called on 16 December 2016. The evidence bears that out. It is also apparent that on 16 December 2016 Mr Somerton became aware that the Receivers sought the return of the Chophouse Guarantee. That was the first time Mr Somerton became aware that was so. That occurred in the conversation which took place on the evening of 16 December 2016 and thus, I infer, after Mr Potter had signed the letter addressed to the CBA and the call on the Chophouse Guarantee had been made. Mr Kelly cannot recall whether Mr Somerton informed him that the respondents had called on the Chophouse Guarantee at that time but does not deny that he did. That being so, I would accept that Mr Somerton did inform Mr Kelly of that fact. In any event, even on Mr Kelly’s version of his conversation with Mr Somerton on 16 December 2016, it is clear that the respondents’ and the Receivers’ respective positions on, and assumptions in relation to, the Chophouse Guarantee and what would happen to it were at odds, it being a matter which had simply not been a part of any discussion or negotiation between those parties.

The Deed of Release

83 The deed to be entered into reflecting the arrangement referred to at [58] above, called a deed of settlement and release (Deed of Release), was the subject of negotiation between the solicitors for the respondents, HDY, and the solicitors for the Receivers, HSF, over the period from about 8 to 19 December 2016.

84 On 16 December 2016 HDY provided an amended version of the Deed of Release to HSF and asked for confirmation that the Deed of Release was “now agreed”. By email sent at 8.35 pm that evening HSF confirmed that the Deed of Release was “now in agreed form” and that it could “be put into execution form of signing, with exchange at completion”.

85 Mr Kelly said that he agreed to enter into the Deed of Release with the respondents as he believed that it would result in the sale of Chophouse Sydney finally settling and, in accordance with the Chophouse Sale Agreement, assumed that the Chophouse Guarantee would be returned. Of course Mr Kelly could have only assumed that to be so until the evening of 16 December 2016. Mr Kelly also believed that once the Deed of Release had been signed the respondents would have experienced no losses and were receiving a replacement guarantee from the incoming party.

The events of 19 December 2016

86 A number of events took place on 19 December 2016, although the order in which they occurred is not clear.

87 Mr Kelly sent a letter to Kingsmede and Pamiers in which he referred to the Lease, the Chophouse Guarantee, the proposed sale of the business of Chop 1 to the Solotel Companies and his conversation with Mr Somerton on 16 December 2016 in which Mr Somerton had informed him that they intended “to make a call on the [Chophouse Guarantee] at or after completion of the Sale in the amount of $100,000”. Mr Kelly’s letter continued as follows:

As I have previously communicated to Mr Somerton, [Chop 1] disputes the [respondent’s] entitlement to call on the [Chophouse Guarantee]. I note that there are no rental arrears under the Lease and that the Lessor has to date failed to articulate any basis upon which it would be entitled to call on the [Chophouse Guarantee]. [Chop 1] will hold the [respondents] responsible for any loss suffered by [Chop 1] in connection with any improper call on the [Chophouse Guarantee].

We reserve all rights of [Chop 1], the Receivers and the Administrators in respect of the Lease, the [Chophouse Guarantee] and the Premises.

In cross-examination Mr Kelly accepted that at this time he was in a predicament: the Receivers had signed the Chophouse Sale Agreement which included as a condition precedent the return of the Chophouse Guarantee; and the respondents had informed him that they were not going to return the Chophouse Guarantee.

88 By email sent at 9.38 am HSF requested an execution copy of the Deed of Release and by email sent at 10.16 am that was provided by HDY together with a request that HSF confirm that completion would take place at 4.00 pm on that day.

89 By email sent at 10.33 am to Ron Zucker, the solicitor for the Solotel Companies, Mr Somerton confirmed that the lease was in a form acceptable to the respondents subject to:

1. settlement of the Business Sales Agreement between your clients and the Receivers; and

2. execution of the [Deed of Release] between the [respondents], the Receivers and Chop 1 Pty Ltd (administrators appointed) (receivers and managers appointed).

90 By email sent at 11.18 am, Mr Zucker sought “confirmation in more specific terms” from Mr Somerton. His email included:

Could you please confirm the following on behalf of the [respondents]:

1. You have received the attached executed lease, the Lessee’s disclosure statement, the original bank guarantee and evidence of current insurances.

2. These documents are satisfactory and meet the Lessor’s requirements in relation to the granting of the lease.

3. Provided:

a) settlement of the Business Sale Agreement between the Lessee and the Receivers occurs; and

b) the [Deed of Release] between the Landlord, the Receivers and Chop 1 Pty Ltd (administrators appointed) (receivers and managers appointed) is exchanged and you receive $550,000 pursuant to that deed,

the Lessor will accept the lease with a commencement date of 19 December 2016 and as soon as practicable, have it executed and registered.

91 By email sent at 11.25 am Mr Somerton provided the confirmation sought by the Solotel Companies.

92 At 11.51 am Mr Kelly sent an email to Mr McKenna, one of the Administrators, which included:

Just by way of update, in a discussion with the landlord of Chophouse Sydney late on Friday the landlord advised that they would not return the bank guarantee for Chophouse.

The bank guarantee for Chophouse is a property backed guarantee provided by CBA, with a limit of $100k. We have advised the landlord that they have no right to draw down on the guarantee because:

- There are no rental arrears, and no economic loss to the landlord

- There is a new tenant

- There is a replacement guarantee in place

The landlord has not advised us whether they are planning to draw down on the guarantee nor provided any reason or basis for doing so. HSF have written to the landlords solicitors confirming this position, and we will keep you informed as to how these discussions progress.

This development will not prevent settlement, as we have the ability to waive the CP in the sale agreement that provides for the return of the bank guarantee, and we have significant concerns that settlement is in fact not going to happen if there are further delays from today. It may be worth notifying Wendy Jacobs of this development and she may wish to correspond with the landlord directly.

In cross-examination Mr Kelly was asked why he included the statement in his email that “[t]he landlord has not advised us whether they are planning to draw down on the guarantee”. It was put to Mr Kelly that he did so because he did not want Mr Duncan to know that the landlords had stated unequivocally that they were going to call on the Chophouse Guarantee but Mr Kelly could not recall if that was so. He said that he did not recall his motivation for using those words, noted that he expressly said that the respondents were refusing to return the Chophouse Guarantee and surmised that he was hoping to negotiate with the respondents to encourage them not to drawdown on the Chophouse Guarantee. He said that he was not trying to conceal from anyone the fact that the Chophouse Guarantee was at risk. It is clear, even on Mr Kelly’s version of his conversation with Mr Somerton on the evening of 16 December 2016, that the Receivers knew at the very least that the respondents intended to call on the Chophouse Guarantee. However, I accept Mr Kelly’s evidence that his email to Mr McKenna was framed as it was because, at that stage he hoped, though his solicitors, to achieve a different outcome.

93 At 12.33 pm Leonard McCarthy, special counsel at K&L Gates, lawyers for the Administrators, sent an email to, among others, Stephen Mattiussi at Russells, at the time the lawyers for TGLC, (Administrators’ Email), which included:

In relation to Chophouse Sydney, completion of that sale is expected to occur today. The administrators have been informed by the receivers and managers this morning that the landlord it is not proposing to return the bank guarantee. The administrators together with the receivers and managers do not consider the landlord is able to do this because:

• There are no rental arrears, and no economic loss to the landlord.

• There is a new tenant.

• There is a replacement guarantee which will be provided by the new tenant.

The landlord has not advised whether it is planning to draw down on the guarantee nor provided any reason or basis for doing so. HSF, the solicitors for the receivers and managers, have written to the landlords solicitors confirming this position.

We are instructed to inform you of this development as we understand the bank guarantees generally have been issued at the request of one or more of the directors or entities associated with them and are secured by property in which the directors have, directly or indirectly, an interest. You therefore may wish to agitate the issue with the landlord directly at the same time as it is being agitated through the external administrations.

94 By email sent at 4.05 pm Mr Somerton informed Mr Zucker that they were “presently trying to resolve an issue with respect to execution of the [Deed of Release]” and that until it was resolved, the respondents were “unable to accept the lease with a commencement date of 19 December 2016”.

95 It seems that Mr Somerton had assumed that the execution of the Deed of Release and the proposed new lease could occur without Mr Potter. At some point on 19 December 2016 Mr Somerton was informed by the respondents’ lawyers that that was not possible. As Mr Potter was not available on 19 December 2016, an issue arose as to how to manage and co-ordinate the settlement going forward.

96 The proposed resolution of that issue which was discussed between the parties’ lawyers was for an escrow arrangement to be put in place. In that regard, by email sent at 4.12 pm HDY proposed that they would hold and not release the original signed counterparts of the Deed of Release signed by Chop 1 and the Receivers and the bank cheque for $550,000 (collectively, Receiver Documents) until they received the original signed counterparts of the Deed of Release and the proposed new lease from the respondents (Respondents’ Undertaking).

97 By email sent at 4.26 pm HDY informed HSF that the respondents would “confirm entry into the new lease upon provision of the Receiver Documents to HDY in accordance with the terms set forth in the undertaking below”. They requested that the Receivers’ lawyers confirm that they “agree to the below terms”.

98 By email sent at 4.58 pm HSF confirmed that the Receivers were “willing to proceed on the basis of the HDY undertaking set out below” and that in order to settle the transaction the Solotel Companies required confirmation from the respondents “that the new lease has been accepted by the [respondents] and will be signed and registered by the [respondents]”.

99 By email sent at 5.01 pm Mr Somerton confirmed to Mr Zucker “the position as set out in [Mr Zucker’s] email at 11:18AM today”.

100 By email sent at 5.35 pm HSF sought confirmation from the Solotel Companies that they were happy to proceed to completion on the basis of the Respondents’ Undertaking. Mr Zucker responded noting that the form of undertaking was of no consequence to the Solotel Companies. Rather, they required confirmation from the respondents that the lease had been accepted and would be registered.

101 The copy of the Deed of Release in evidence before me, signed by Chop 1 and Mr Kelly, was not dated. It includes the following terms:

(1) clause 2 titled “Payment” provided that:

(a) The Receivers will pay the Payment Amount to Kingsmede by bank cheque simultaneously on exchange of original executed counterparts.

(b) The parties acknowledge and agree that the Payment Amount represents a payment to compensate Kingsmede for the internal and external fees and expenses incurred by Kingsmede as a result of the Receivership.

(c) Payment of the Payment Amount is in full and final settlement of any Dispute.

(2) in cl 3 the provision of mutual releases by the Receivers on the one hand and Kingsmede on the other. The release provided by the Receivers, referred to as the “Releasor”, was in the following terms:

(a) The Releasor, to the extent it is able:

(i) jointly and severally releases Kingsmede and its Related Persons from any Claim which it has or may have in the future against Kingsmede or its Related Persons; and

(ii) irrevocably covenants with Kingsmede and its Related Persons jointly and severally not to make or bring any Claim against Kingsmede or its Related Persons in any jurisdiction,

in respect of or arising in whole or in part, either directly or indirectly, out of any Dispute, wherever and whenever arising, whether known or unknown at the time of execution of this deed, whether presently in contemplation of the parties or not and whether arising at common law, in equity, under statute or otherwise (collectively the Releasor or Released Matters).

In the Receivers’ counterpart the following was included in handwriting in cl 3(a) after the word “otherwise” and before the words in round brackets:

but not including any Dispute relating to the bank guarantee issued to Kingsmede in connection with the lease

(3) in cl 5 that the parties to the Deed of Release treat the existence and provisions of the deed and all information provided by any other party under the deed on a without prejudice basis in an attempt to settle or resolve any dispute as confidential information not to be disclosed except in the specified circumstances set out in cl 5(b).

102 Mr Duncan first became aware that the respondents would not return the Chophouse Guarantee on 19 December 2016. Mr Duncan cannot recall whether he became aware of this from Mr Kelly or via the Administrators’ Email (see [93] above).

Subsequent events

103 By letter dated 23 December 2016 HDY provided HSF with the original signed counterparts of the Deed of Release and a copy of the new lease for the Premises. Their letter included:

In accordance with the undertaking given on 19 December 2016, we are now irrevocably authorised to release the Receiver Documents held in escrow by Henry Davis York to Kingsmede Pty. Limited and Pamiers Pty. Ltd.

We note that our client does not accept the last minute (and without notice) hand written amendment to clause 3(a) of the Deed. The enclosed Deed and Lease are provided to you upon that basis.

104 For the purposes of the proceeding TGLC and Kimana provided a concession in the following terms:

That the [Deed of Release] in the form executed by the respondents was binding from at the latest 23 December 2016 on all of the parties to it (including [Chop 1]).

The effect of the concession is that for the purpose of resolving the issues in dispute between the parties, the Deed of Release signed by the respondents, without the handwritten amendment inserted by the Receivers, is the version of that document which TGLC and Kimana accept is binding on the parties to it.

105 Mr Somerton accepted that as at 23 December 2016 the respondents had received a cheque for $500,000, entered into a new lease on more advantageous terms with the Solotel Companies, received a new guarantee on behalf of the Solotel Companies for the new lease and no longer had to deal with the Receivers.

106 On 23 December 2016 Steven Mattiussi of Russells delivered a letter addressed to the respondents to Mr Somerton. In that letter Russells indicated that it acted for TGLC and “other related entities” of Chop 1. The letter included:

Our instructions are that:

l. the Former Lease has been terminated, and there are no rental arrears or other financial obligations owing to you by the Former Lessee;

2. a bank guarantee was issued in your favour by the Commonwealth Bank of Australia in connection with the Former Lease (the Bank Guarantee);

3. the Former Lessee (by way of its external controllers) has requested the return of the Bank Guarantee;

4. despite the request, you have not returned the Bank Guarantee;

5. to the contrary, on or about 16 December 2016, Mr Scott Somerton (on your behalf) informed Mr Morgan Kelly (one of the Former Lessee’s joint and several Receivers and Managers) that you intend to call on the Bank Guarantee;

6. Mr Kelly, on behalf of the Former Lessee, has (by way of letter to you dated 19 December 2016):

(a) disputed your entitlement to call on the Bank Guarantee;

(b) noted your ongoing failure to articulate any basis upon which you would be entitled to call on the Bank Guarantee;

(c) confirmed that the Former Lessee will hold you responsible for any loss suffered by the Former Lessee in connection with any improper call on the Bank Guarantee; and

(d) otherwise reserved all of the Former Lessor’s rights in respect of the Bank Guarantee and the Premises;

7. a new lease of the Premises has been executed in favour of Sol Bligh Limited and Mash Bligh Pty Ltd (the Current Lessee); and

8. the Current Lessee has provided a bank guarantee in your favour in connection with the new lease.

Please confirm, by COB today (23 December 2016), that the Bank Guarantee has been returned. Otherwise, we too are instructed to demand the immediate return of the Bank Guarantee.

If the Bank Guarantee has not or will not be returned, and in addition to the exposure you will have to the Former Lessee, our clients will also look to you for damages and loss that they too will suffer in connection with any improper call on the Bank Guarantee.

Mr Somerton said that it was only by reason of this letter that he first heard of TGLC.

107 At the time of delivery of the letter referred to in the preceding paragraph Mr Somerton had a conversation with Mr Mattiussi to the following effect:

Mr Mattiussi: I act for the directors of companies in the Keystone Group of Companies. I understand Kingsmede has claimed a bank guarantee in the Chop 1 receivership. The directors want it back.

Mr Somerton: The bank guarantee has already been claimed. We won’t be returning it.

Mr Mattiussi: I understand. The directors are very upset. Here’s a letter. Have a good Christmas.

108 Later on 23 December 2016 Mr Mattiussi sent an email to the solicitors for the Administrators and the solicitors for the Receivers which included:

Earlier today, we wrote to Kingsmede/Pamiers regarding the bank guarantee. A copy of our letter is also attached. On delivering the letter, I met briefly with Mr Somerton who indicated, amongst other things, that:

1. the bank guarantee was called upon 3 or 4 days ago; and

2. there is an agreement of some kind regarding the lease (to which the Receivers are a party) and, consistent with its terms, the landlord felt perfectly entitled to call on the bank guarantee.

Our clients are both surprised and disconcerted by these developments, particularly in light of the previous correspondence referred to above.

Please immediately provide a copy of the agreement referred to at 1 above so that we may take a coordinated approach to what, on its face, appears to be conduct by the landlord that is entirely inconsistent with the stance that both the Receivers and the Administrators have taken with respect to the bank guarantee.

109 By email dated 6 January 2017 K&L Gates informed Russells, among other things that:

As has been conveyed to you previously by both the administrators and the receivers and managers, it is a condition precedent to completion in the relevant BSA’s that the relevant landlord(s) agree to the return of the existing bank guarantee(s). That condition precedent is able to be waived by the Seller and was waived by he [sic] Seller, through the receivers and managers, in the case of Chophouse Sydney. This was because of a real apprehension the sale would be lost if the waiver was not given and completion did not occur on the day that it in fact did. We refer to our emails to Steven Mattiussi in that regard.

…

110 By letter dated 12 January 2017 HDY responded to Russells’ letter dated 23 December 2016. That response relevantly included:

Clause 12.1(e) of the Lease provides that it is an event of default if, amongst other things, the Tenant is placed under official management or has a receiver or manager of any of its assets appointed. In accordance with clause 12, if an event of default occurs, the Landlord has a contractual right to re-enter the Premises and determine the Lease. Clause 19.2 of the Lease provides that the Landlord may, without notice to the Tenant, call upon the bank guarantee in whole or in part if an event of default occurs.

The Lease was terminated by the Landlord effective 1 November 2016 pursuant to the Termination Letter, a copy of which is attached.

The Landlord called upon the bank guarantee in accordance with the terms of the Lease. The bank guarantee was claimed by the Landlord in advance of it entering into the deed of settlement and release between the Landlord, the Tenant and Morgan John Kelly and Ryan Reginald Eagle in their capacity as joint and several receivers and managers of the Tenant.

The Lease was terminated and the security was called upon as a result of the event of default. Accordingly, the Landlord will not return the bank guarantee nor will it account to the Tenant for any moneys received in accordance with its claim on the bank guarantee.

111 On 17 January 2017 Russells wrote to HDY seeking “full particulars of any alleged loss or damage suffered by [the respondents] in respect of the [Lease]” and requesting those solicitors to indicate how the respondents “intend to apply or account for any proceeds of the [Chophouse Guarantee]”.

112 Also on 17 January 2017 a bank cheque for $100,000 was drawn by the CBA in the names of Kingsmede and Pamiers and on 18 January 2017 a deposit of $100,000 was made into an account in the names of Kingsmede and Pamiers held with the National Australia Bank.

113 On or about 18 January 2017 Mr Duncan was informed by John Duncan that the CBA had paid out the Chophouse Guarantee. Mr Duncan understood that the CBA had paid $100,000 to the respondents.

114 By letter dated 20 January 2017 the CBA demanded payment of the amount paid out by it under the Chophouse Guarantee from Chop 1. Mr Duncan did not become aware of this demand until after commencement of this proceeding.

115 On 23 January 2017 HDY responded to Russells’ letter dated 17 January 2017 including that:

The Landlord has incurred significant costs as a direct result of the Tenant’s default under the Lease. The costs include but are not limited to, legal costs and management costs.

In no event will the Landlord account to your client for the moneys received in accordance with its claim on the bank guarantee as the Lease was terminated and the security was called upon in its entirety to compensate the Landlord for its loss due to the event of default.

What’s more, your client is The Good Living Company Pty Ltd and other (non-specified) related entities of the Tenant. As such, your client has absolutely no authority to demand the return of the bank guarantee on behalf of the Tenant nor does your client have any right to claim against the Landlord for any alleged damages or loss as your client has no connection with, or entitlement to, the bank guarantee.

Those solicitors refused to provide the Deed of Release and correspondence with the Receivers and their solicitors as requested by Russells on the basis that that document and the correspondence were governed by a confidentiality agreement.

116 By email dated 8 February 2017 Mr Mattiussi informed Mr Steele of HDY that:

We are instructed as follows in response to your letter dated 23 January 2017:

1. the administrators and receivers have previously advised that they do not consider that the landlord was able to validly call on the bank guarantee because:

(a) there were no rental arrears, and no economic loss to the landlord;

(b) there was a new tenant; and

(c) there was a replacement guarantee provided by the new tenant;

2. the solicitors for the receivers have previously written to you confirming the position referred to at 1 above;

3. notwithstanding 1 and 2 above, your recent oblique reference to “significant costs” remains entirely unsubstantiated; and

4. as each of the receivers and administrators will no doubt confirm for you, the bank guarantee was issued at the request of certain of our clients’ directors, and is secured by property in which our clients have an interest - accordingly, our clients have suffered loss as a direct consequence of the landlord’s conduct.

Unless the alleged “significant costs” can be substantiated (with supporting evidence) to our clients’ satisfaction, they will be left with no alternative but to commence proceedings against the landlord (and others) for the loss suffered as a direct consequence of your clients calling on the bank guarantee. Accordingly, whilst reserving all of our clients’ rights and without making any admissions, we are instructed to reiterate our previous request for full particulars of the alleged “significant costs” with all supporting material. Should you fail to answer this request, we will rely on this and previous correspondence on the question of the costs of court proceedings.

Finally, we are not aware that the receivers have any objection to the said deed of settlement and release being disclosed to us, subject to any reciprocal confidentiality regime that might be necessary; please let us know what obligations of confidentiality you require before that document can be provided.

117 On 15 February 2017 Mr Mattiussi sent a follow-up email to Mr Steele of HDY seeking a response to his email of 8 February 2017.

118 On 29 March 2017 Mr Duncan received an email from Ricardo Woelms, relationship executive CBA, in which Mr Woelms confirmed that there had been a claim on the Chophouse Guarantee. In his email Mr Woelms also informed Mr Duncan that:

As you know the Bank is obligated to make an immediate payment upon demand and has duly done so. In the absence of direct cash support the Bank has had to establish a loan account to make the necessary payment of $100,000.00.

If the loan account is not repaid in full the Bank will need to commence recovery action. Security consists of:

…

119 On 4 April 2017 Mr Mattiussi sent a further email to Mr Steele which included:

Our clients need to properly understand, with precision, the loss or damage your clients say they have suffered as a consequence of the event of default under the lease with Chop 1. However, despite all previous requests for information and documentation, our clients have not received any substantive information or documentation to support your clients’ position in calling on the relevant bank guarantee. Given the information and documentation vacuum - and whilst reserving all rights - our clients cannot begin to understand how any purported loss or damage might total $100,000.

Importantly, your clients’ conduct (in denying previous requests for information and documentation) must be considered in the context of the Receivers having repeatedly indicated and confirmed to us that all necessary payments under the lease with Chop 1 were made, that the new tenant took the premises on an ‘as is’ basis, and that the new lease was on better terms and included a guarantee (to replace the guarantee called upon by your clients to the detriment of our clients).