FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft [2019] FCA 2166

Table of Corrections | |

29 January 2020 | In paragraph 272, replace the third last word (“conducted”) with the word “conduct”. |

In the second sentence of paragraph 273, replace the word “various” where it appears before the words “serious deception” with the word “very”. |

ORDERS

AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | ||

AND: | First Respondent VOLKSWAGEN GROUP AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 093 117 876) Second Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

UPON the basis of the matters set out in the Statement of Agreed Facts dated 15 October 2019 (Ex C in the penalty hearing) (SOAF) and upon the basis of other material admitted into evidence at the penalty hearing and having considered the Joint Written Submissions of the parties dated 15 October 2019 and filed herein and the oral submissions made by the parties on 16 October 2019 and on 13 November 2019

THE COURT DECLARES THAT:

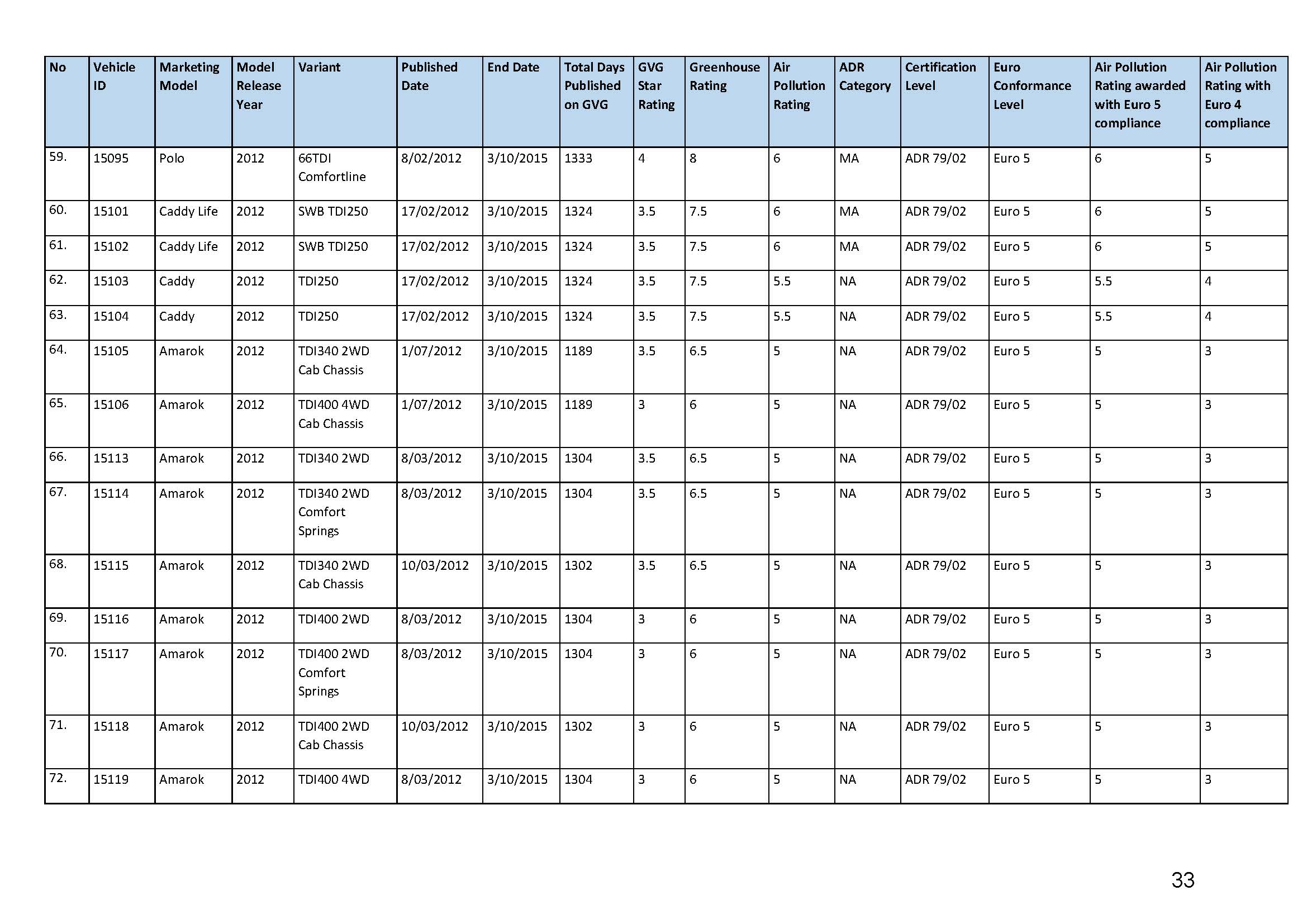

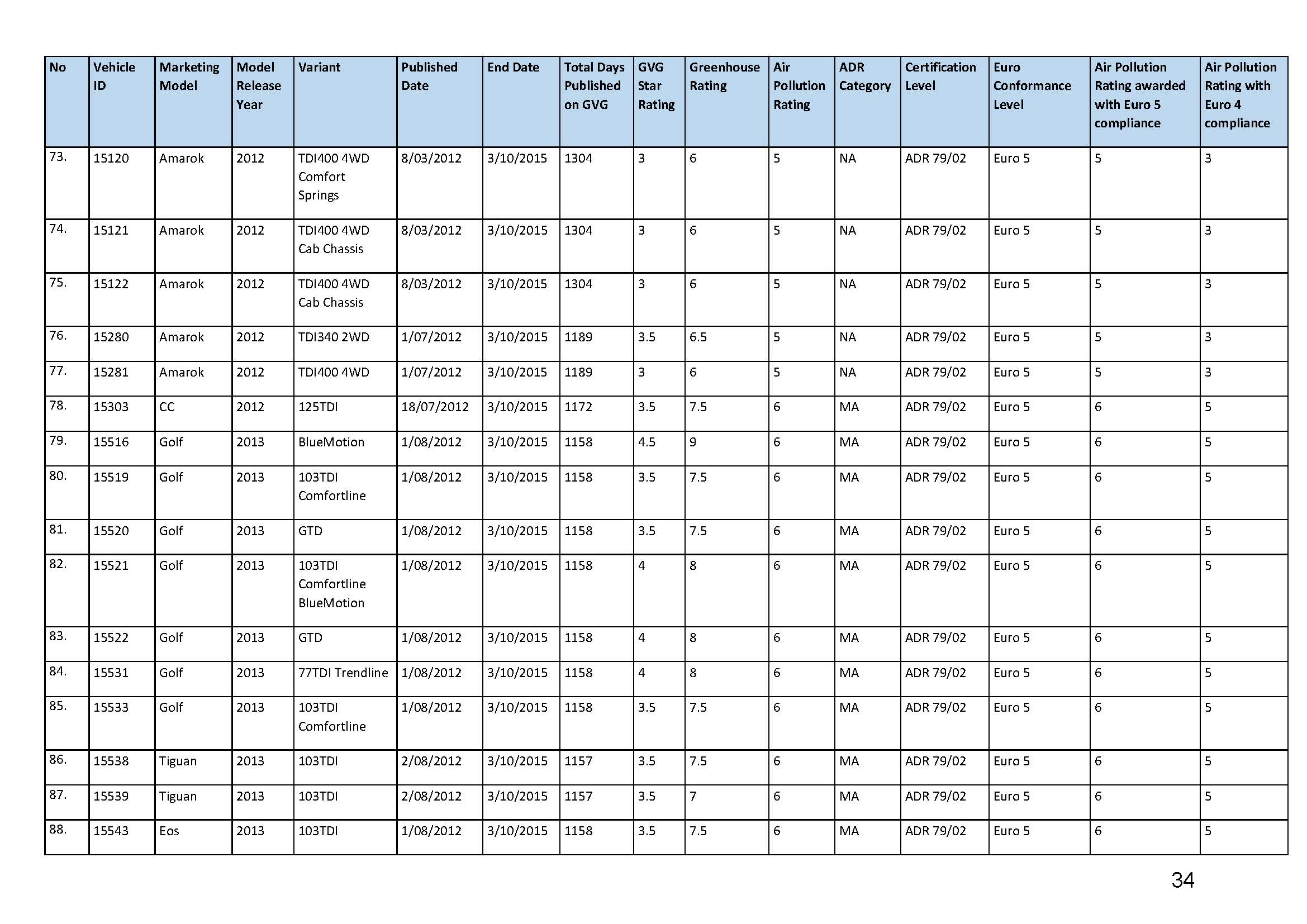

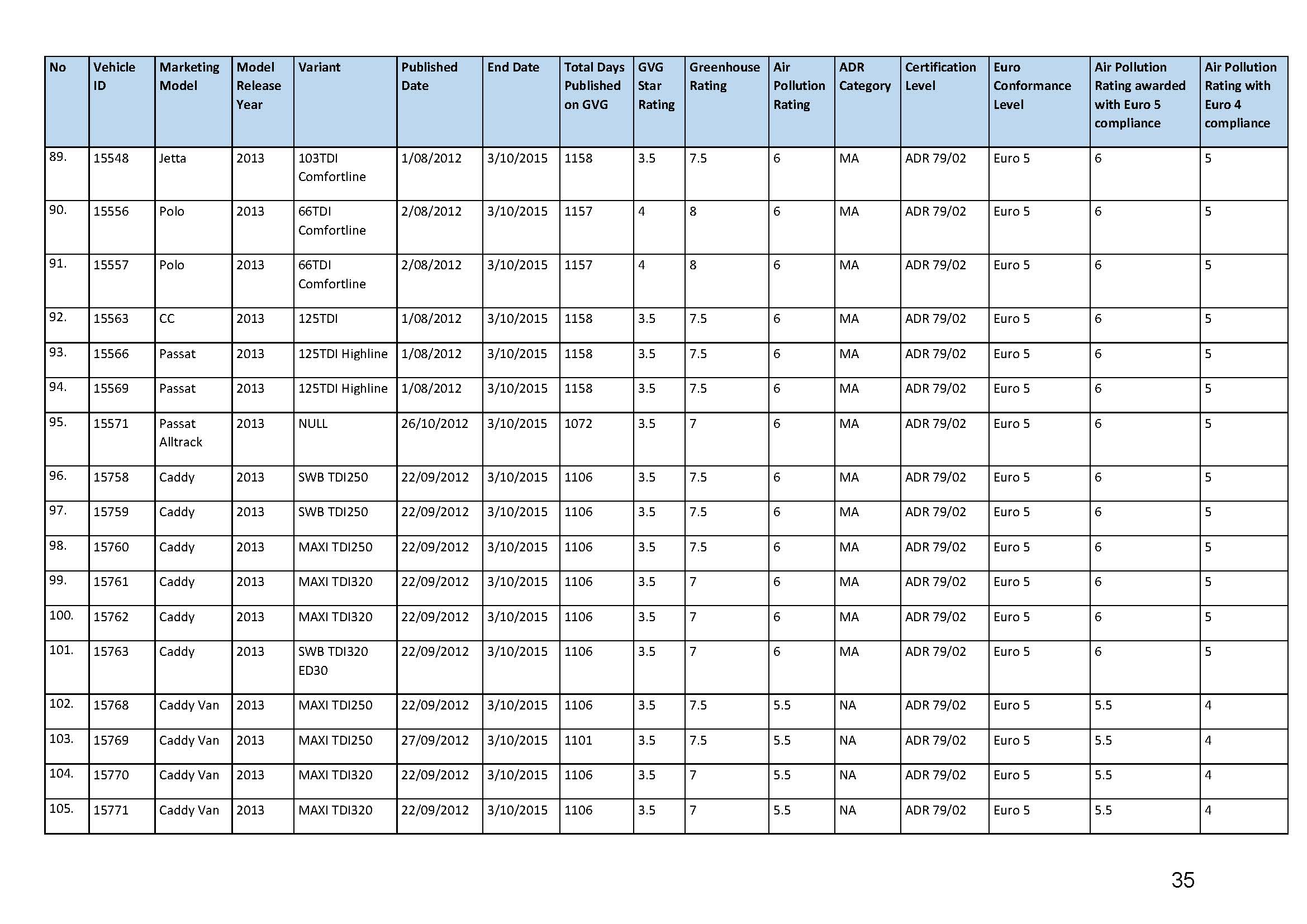

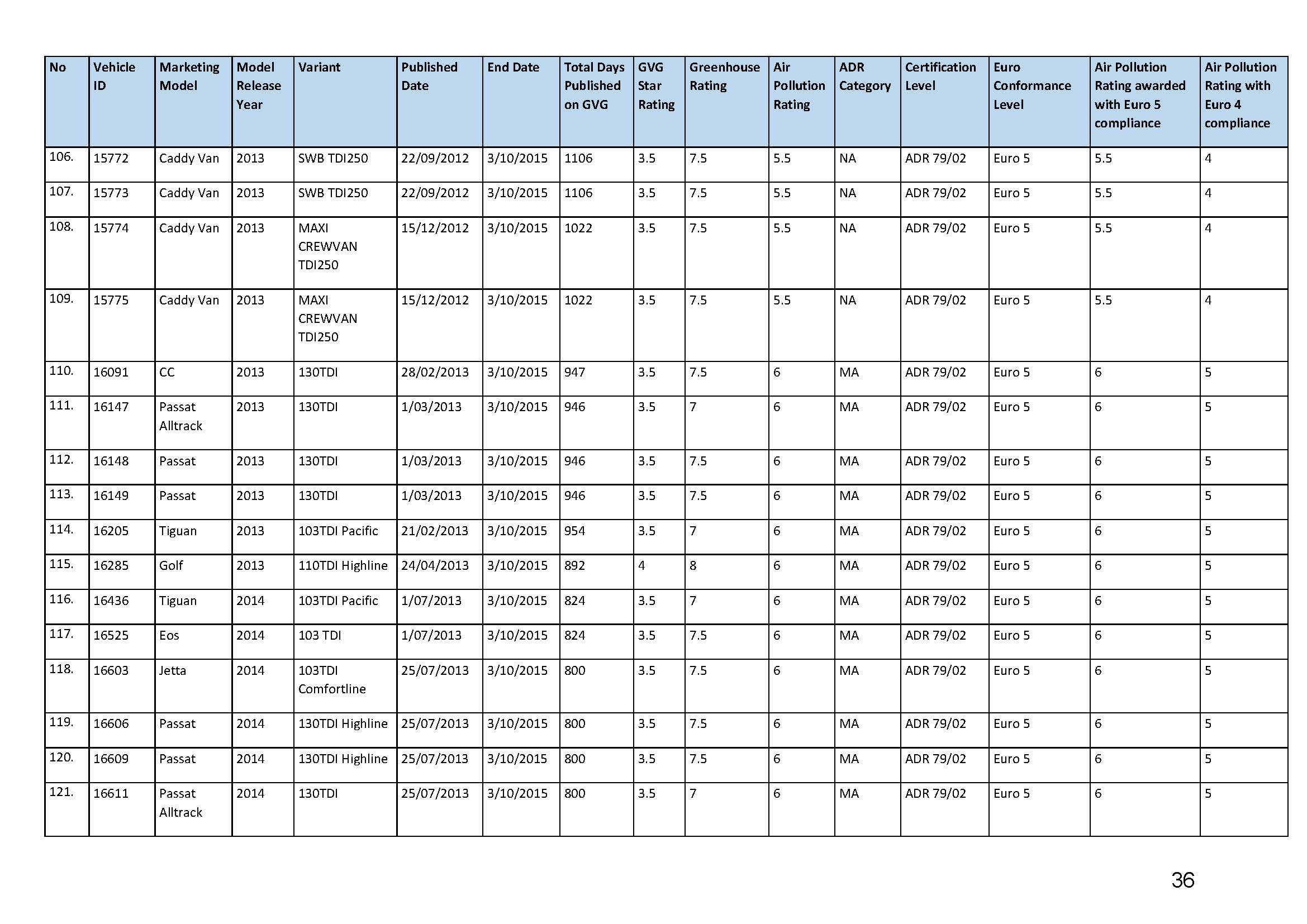

1. On 171 separate occasions in the period from 1 January 2011 to 3 October 2015 (Sales Period), in respect of 57,082 Volkswagen-branded motor vehicles more particularly described in Schedule 1 hereto (Relevant Vehicles), the first respondent (VWAG) submitted to the Delegate (delegate) of the Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development the documents more particularly described in Schedule 2 hereto (approval applications) in order to obtain approvals under s 10A of the Motor Vehicle Standards Act 1989 (Cth) (MVSA) so that motor vehicles covered by the said approvals might be lawfully imported into Australia and supplied for use as road vehicles in Australia.

2. On each of the 171 occasions referred to in Declaration 1 above, by submitting the approval applications to the delegate, in all the circumstances and in the regulatory context in which such submissions were made, VWAG impliedly represented to the delegate that each of the Relevant Vehicles would, when imported into Australia and when supplied in Australia, comply with Australian Design Rule 79 (which is delegated legislation under the MVSA) (ADR 79) as in force from time to time during the Sales Period.

3. VWAG was granted identification plate approvals in respect of all of the Relevant Vehicles upon the basis of the information provided by it in or with the approval applications submitted to the delegate.

4. Each of the implied representations specified in Declaration 2 above was false because, in the events which happened, the Relevant Vehicles did not comply with ADR 79 when imported into Australia and when supplied in Australia in that:

(a) Each of the Relevant Vehicles was fitted with the Two Mode software more particularly described in Schedule 3 hereto (the contravening software); and

(b) If the Relevant Vehicles had been subjected to a New European Drive Cycle (NEDC) Type 1 test while operating in Mode 2, thereby substantially replicating the mode that would have been activated when the vehicles were driven on the road, the Relevant Vehicles would have exceeded the NOx emission limits prescribed by ADR 79,

with the consequence that, on each of the 171 occasions referred to in Declarations 1 and 2 above, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods, namely, the Relevant Vehicles, VWAG made a false representation as to the composition, standard or grade of the vehicles the subject of the approval application in each case and thereby, on each such occasion, contravened s 29(1)(a) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth).

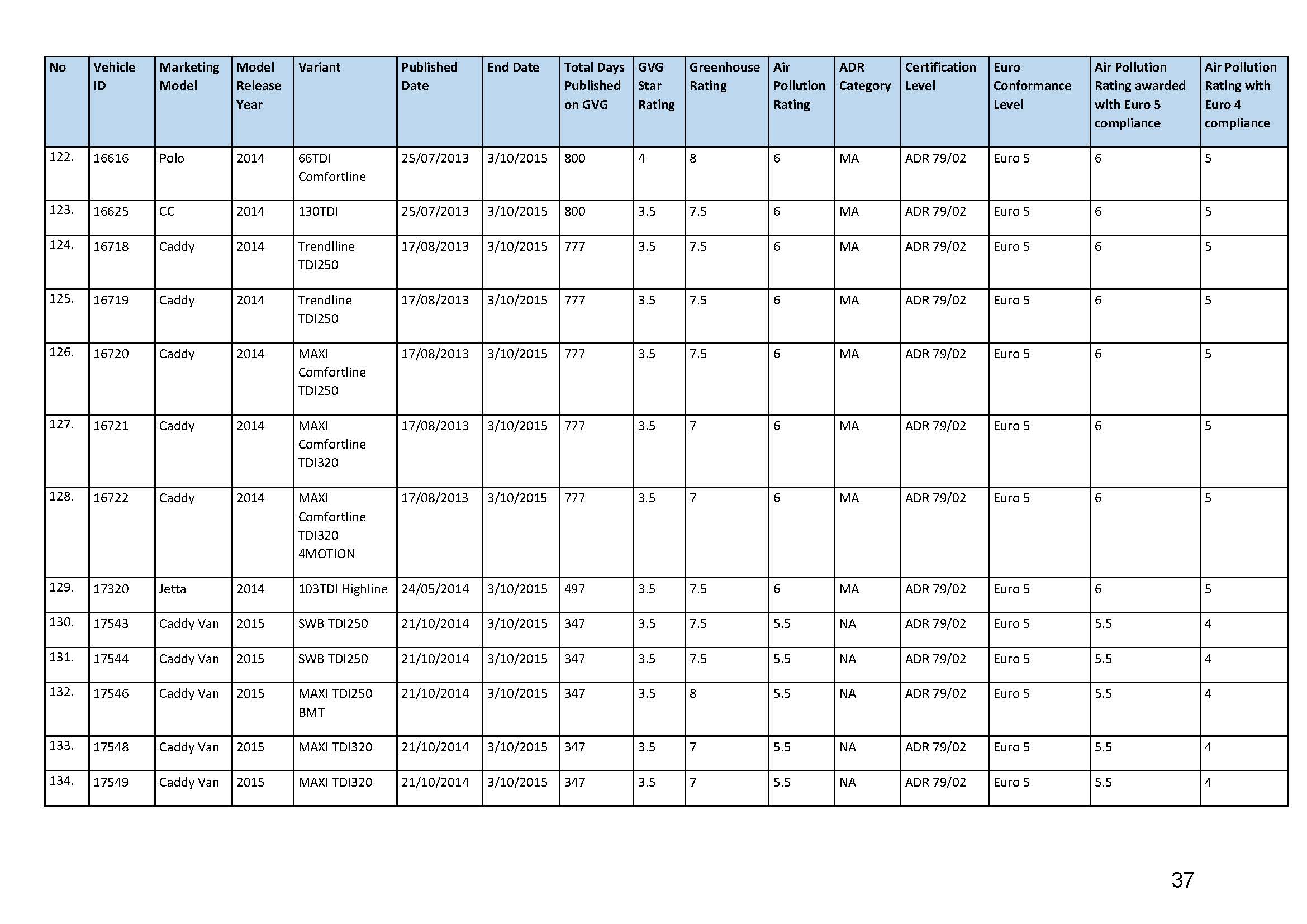

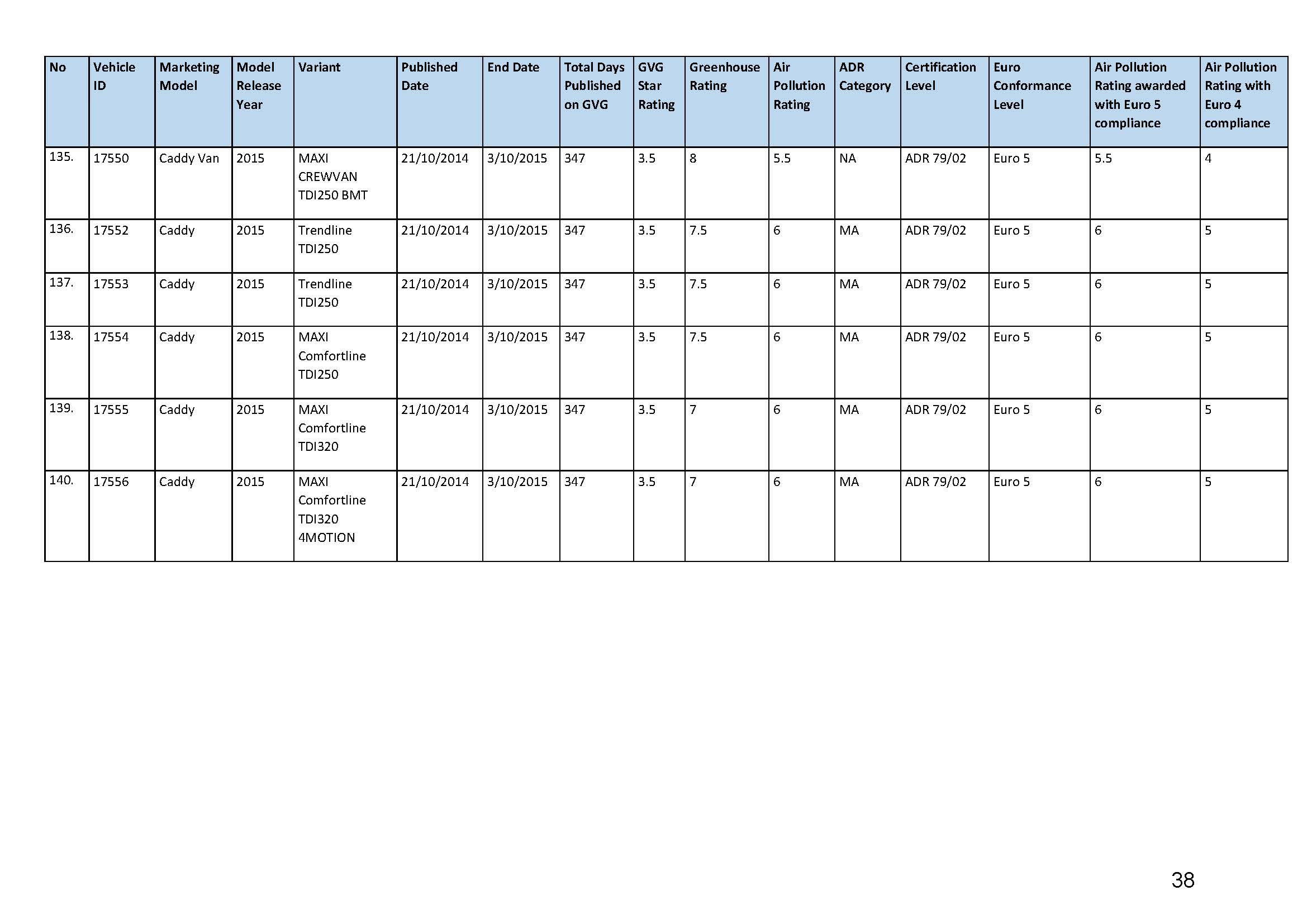

5. By making the applications specified in Schedule 4 hereto from time to time in the Sales Period through the online administration portal on the GVG Website administered by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (DIRD), VWAG falsely represented to DIRD on at least 162 occasions in respect of the Volkswagen-branded vehicles identified in Annexures 4 and 5 to the SOAF that the motor vehicles the subject of each such application complied with ADR 79 as in force at the relevant time when, in fact, those vehicles did not so comply because:

(a) The engine in each of the said vehicles was fitted with the contravening software; and

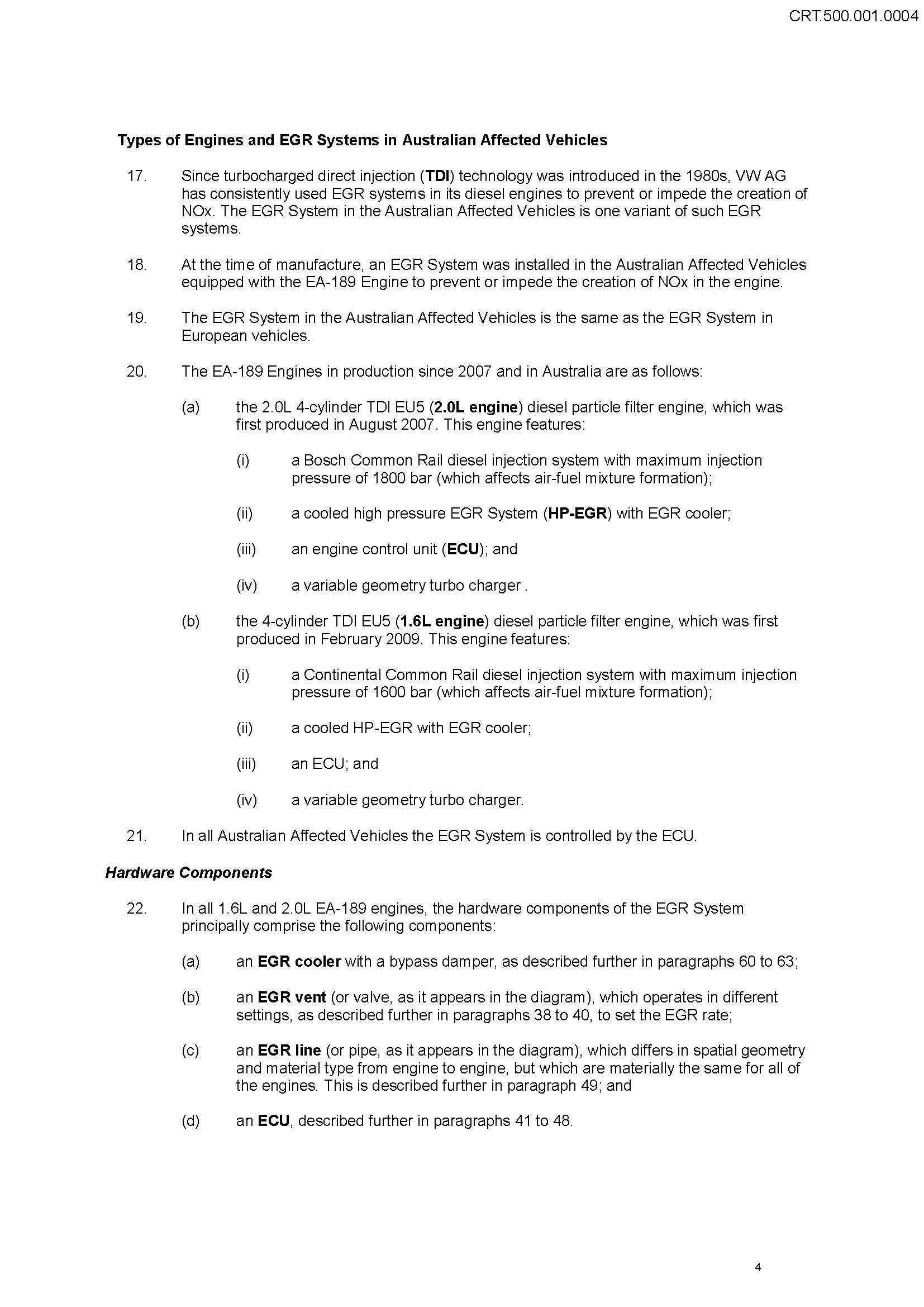

(b) If the said vehicles had been subjected to an NEDC Type 1 test while operating in Mode 2, thereby substantially replicating the mode that would have been activated when the vehicles were driven on the road, the said vehicles would have exceeded the NOx emission limits prescribed by ADR 79,

resulting in the said vehicles obtaining ratings on the GVG Website which they would not have obtained had the said false representations not been made with the consequence that, on each of the 162 occasions referred to above, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods, namely the Relevant Vehicles, or in connection with the promotion of the supply or use of the said goods, VWAG made a false representation as to the composition, standard or grade of the said vehicles the subject of the listing application in each case and thereby, on each such occasion, contravened s 29(1)(a) of the ACL.

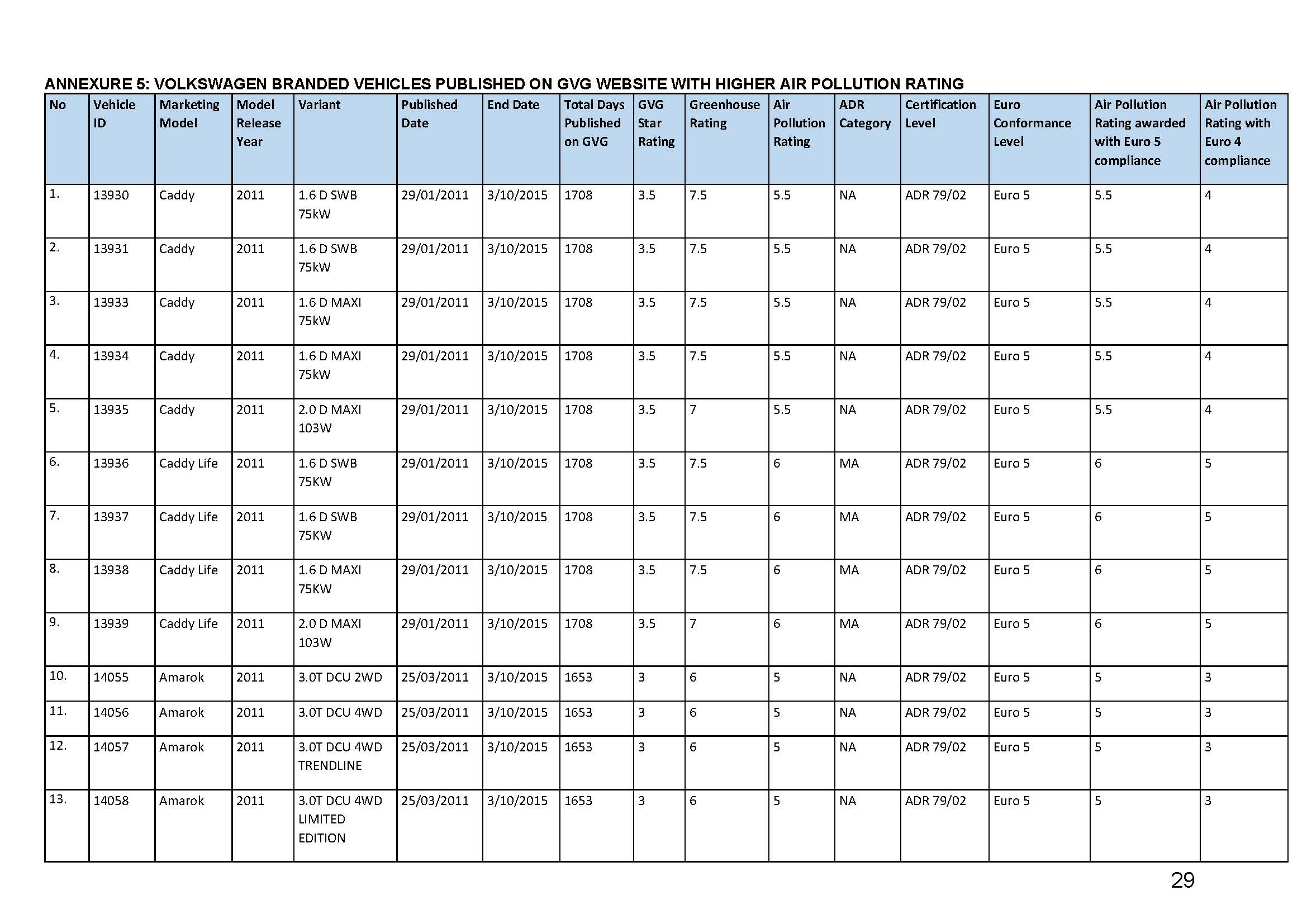

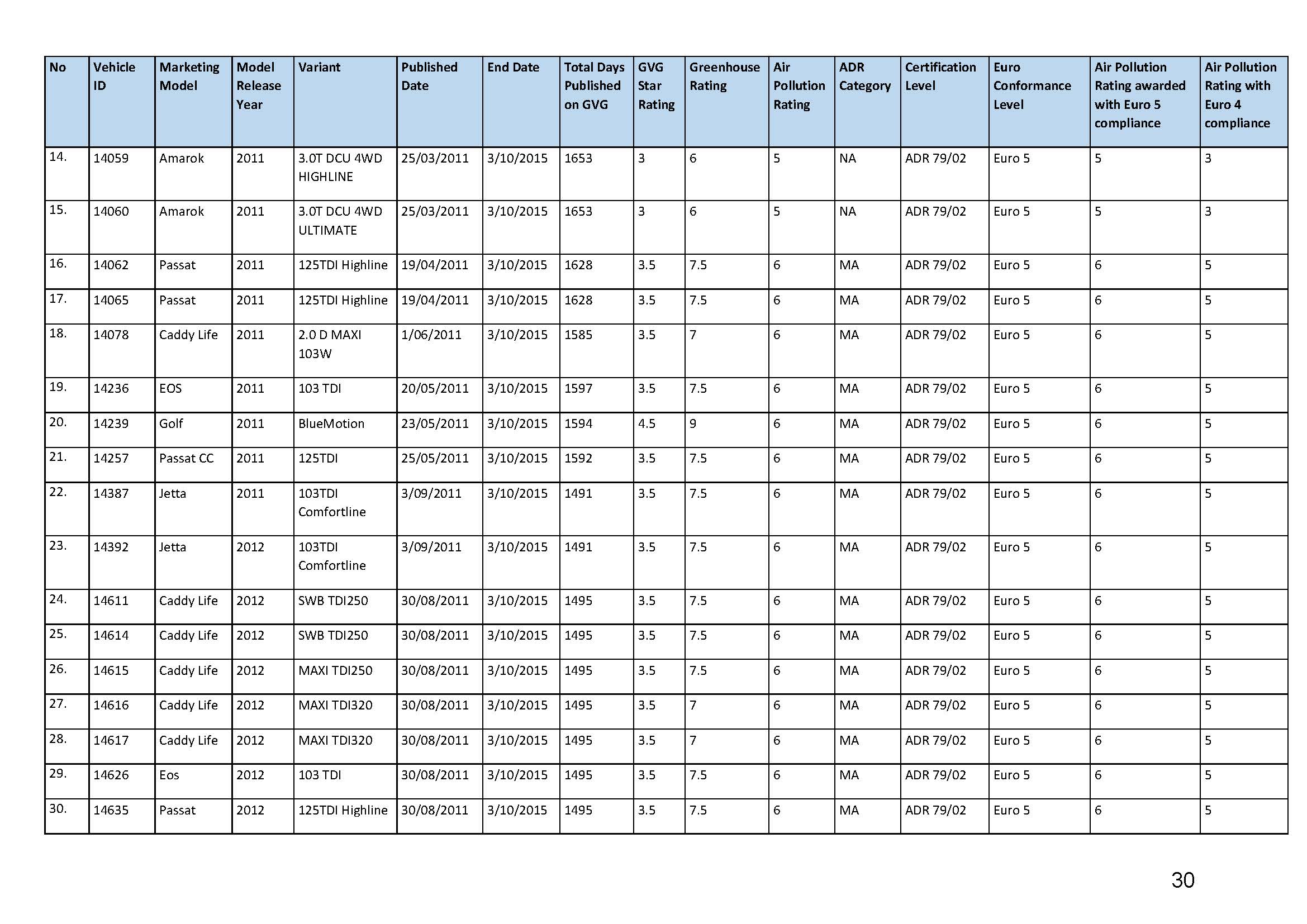

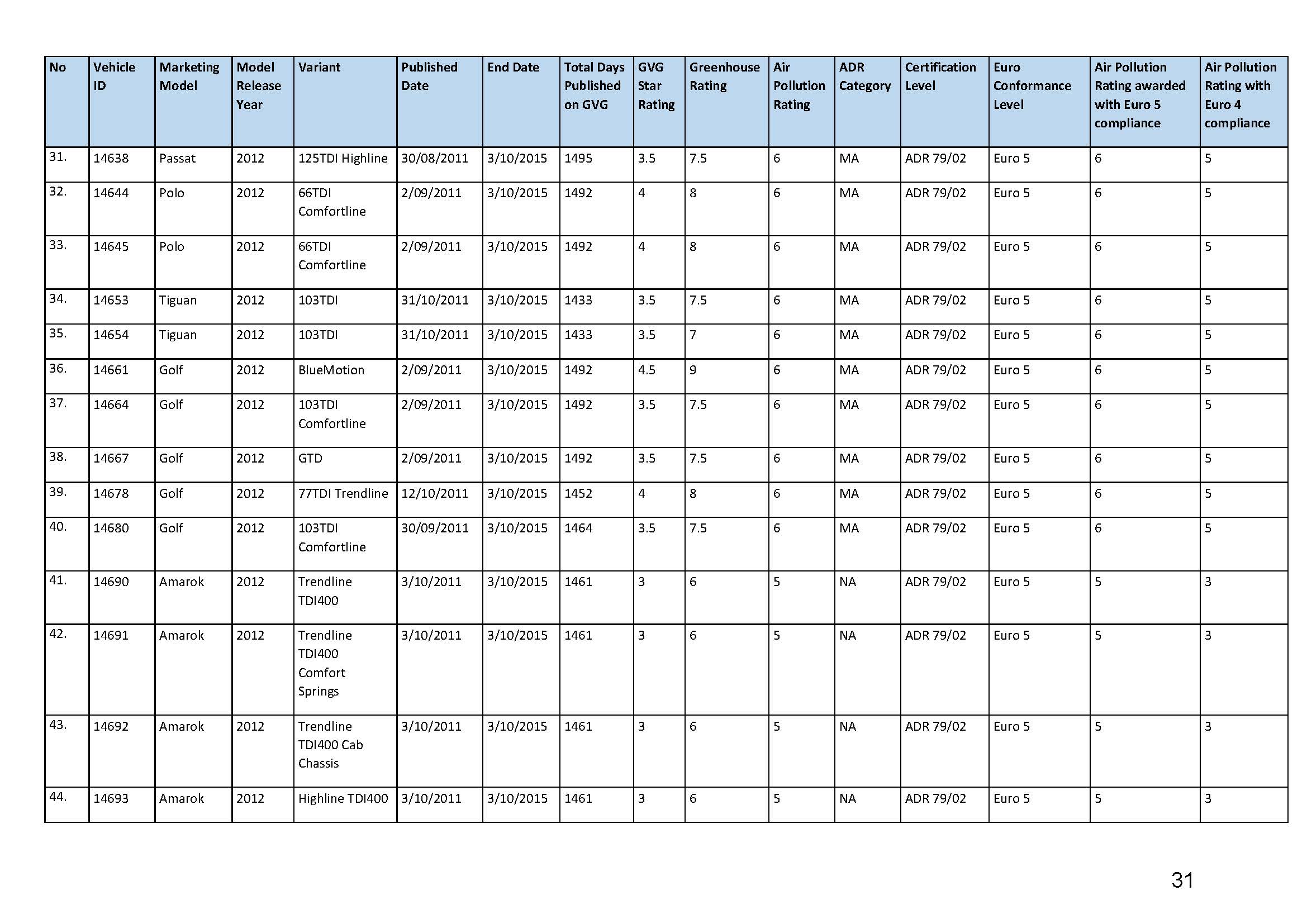

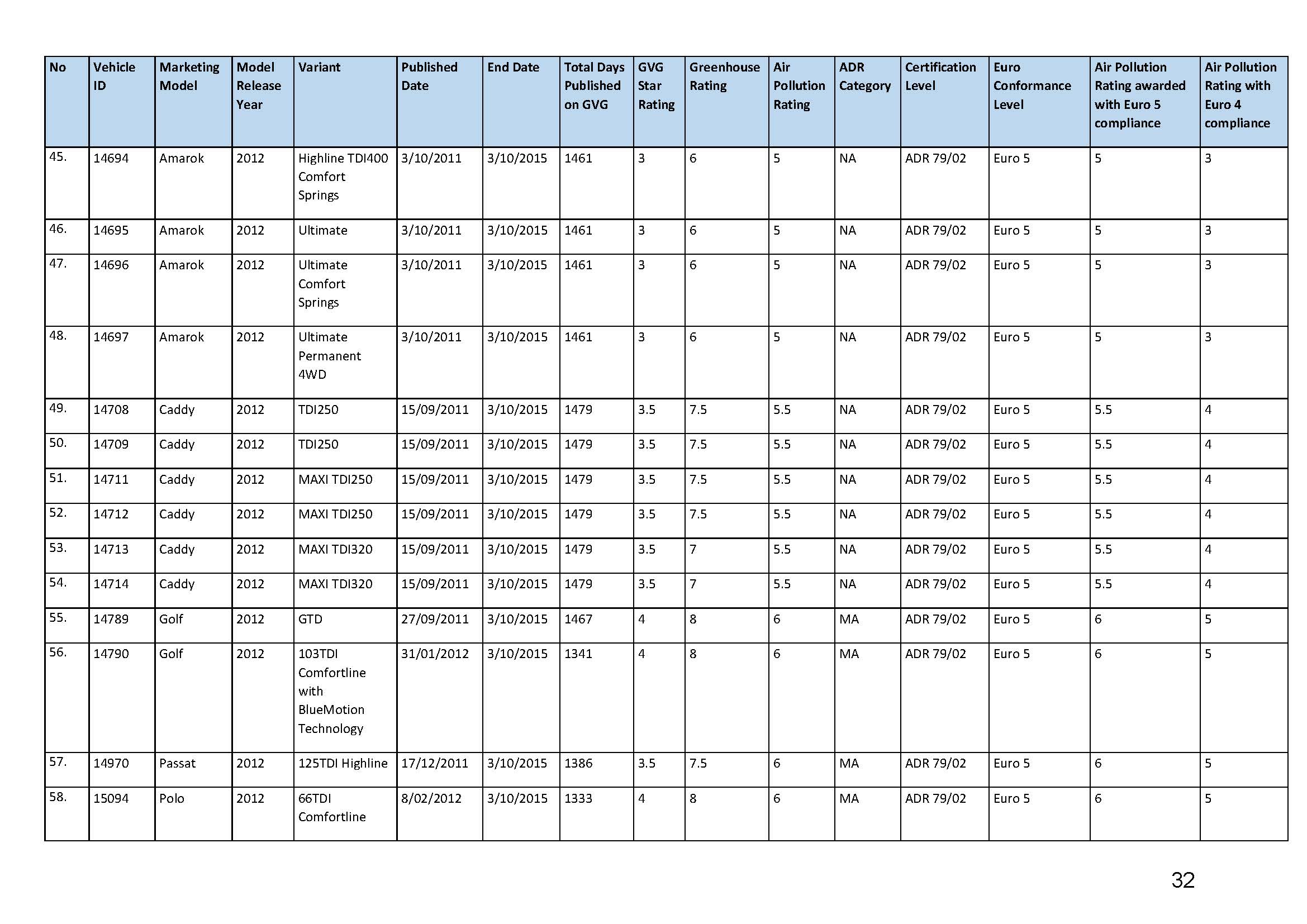

6. By making the additional applications specified in Schedule 5 hereto from time to time in the Sales Period, through the online administration portal on the GVG Website, VWAG falsely represented to DIRD on at least 140 occasions in respect of the Volkswagen-branded vehicles identified in Annexure 5 to the SOAF that the motor vehicles the subject of each such application complied with a later, more stringent version of ADR 79 than was applicable to the vehicles at the relevant time when, in fact, those vehicles did not so comply with that more stringent version because:

(a) The engine in each of the said vehicles was fitted with the contravening software; and

(b) If the said vehicles had been subjected to an NEDC Type 1 test while operating in Mode 2, thereby substantially replicating the mode that would have been activated when the vehicles were driven on the road, the said vehicles would have exceeded the NOx emission limits prescribed by ADR 79,

resulting in the said vehicles obtaining higher air pollution ratings on the GVG Website than they would have obtained had the said false representations not been made with the consequence that, on each of the 140 occasions referred to above, in trade or commerce, in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods, namely the Relevant Vehicles, or in connection with the promotion of the supply or use of the said goods, VWAG made a false representation as to the composition, standard or grade of the said vehicles the subject of the listing application in each case and thereby, on each such occasion, contravened s 29(1)(a) of the ACL.

AND THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

7. Pursuant to s 224(1) of the ACL, within twenty-eight (28) days of the making of this Order, VWAG pay to the Commonwealth of Australia a pecuniary penalty of $125,000,000 (One Hundred and Twenty-Five Million Dollars) in respect of the contraventions of the ACL declared at Declarations 4, 5 and 6 above.

8. Within twenty-eight (28) days of the making of this Order, VWAG pay the applicant’s costs of and incidental to this proceeding agreed in the amount of $4,000,000 (Four Million Dollars).

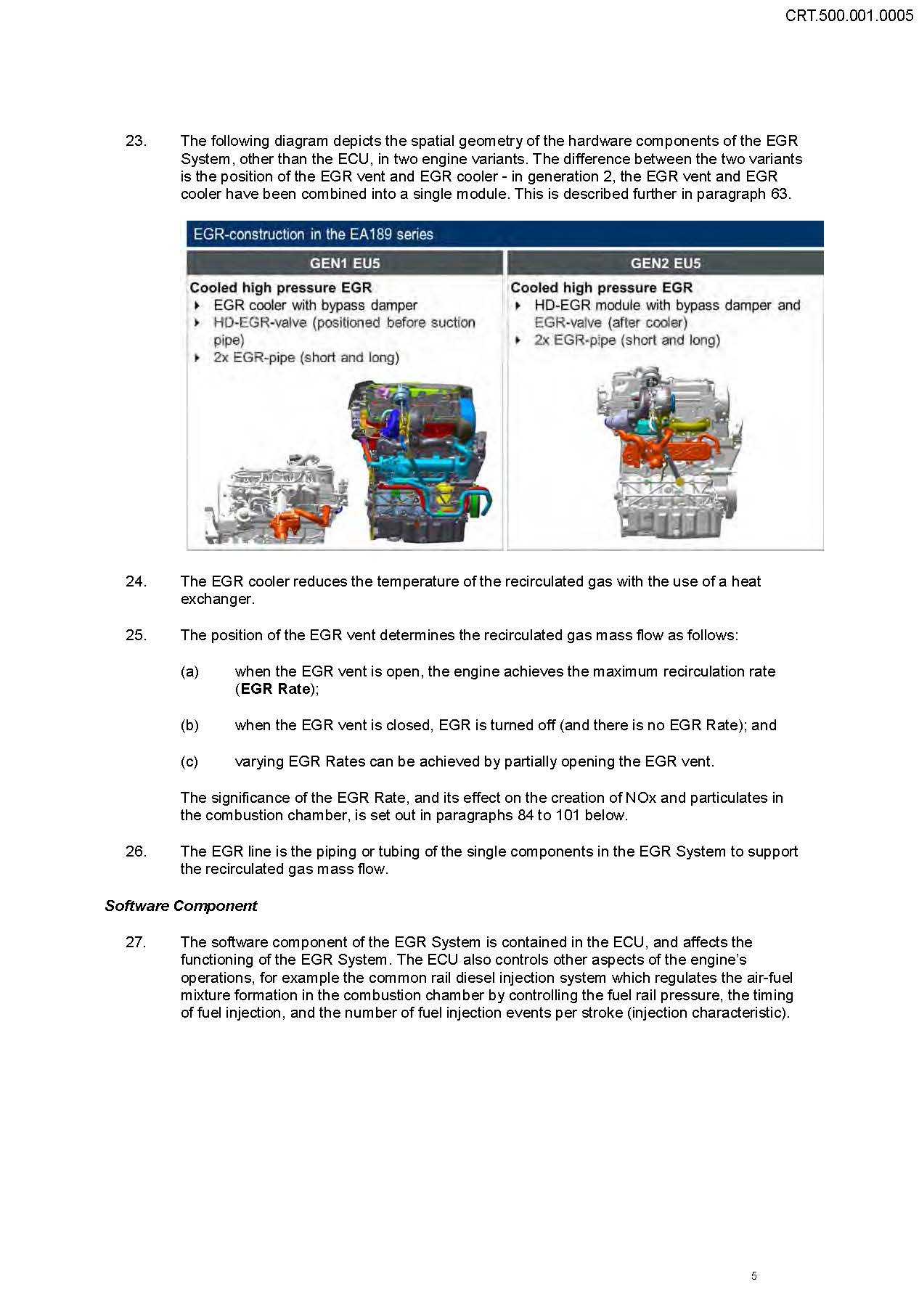

9. The remaining claims for relief made by the applicant in this proceeding (including all claims for relief made in any Interlocutory Applications which have not been determined as at the date hereof) be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

SCHEDULE 1

RELEVANT VOLKSWAGEN BRANDED VEHICLES

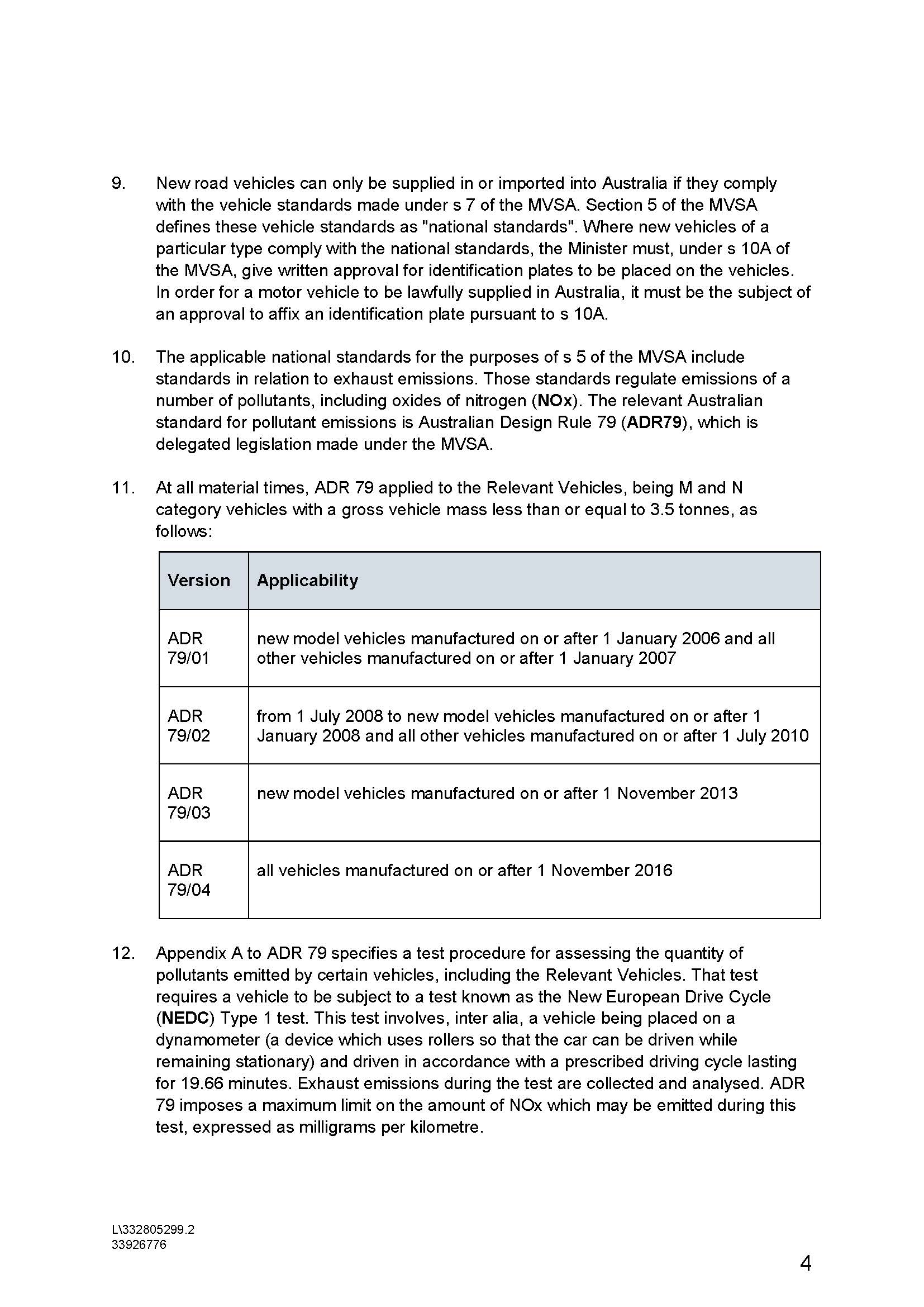

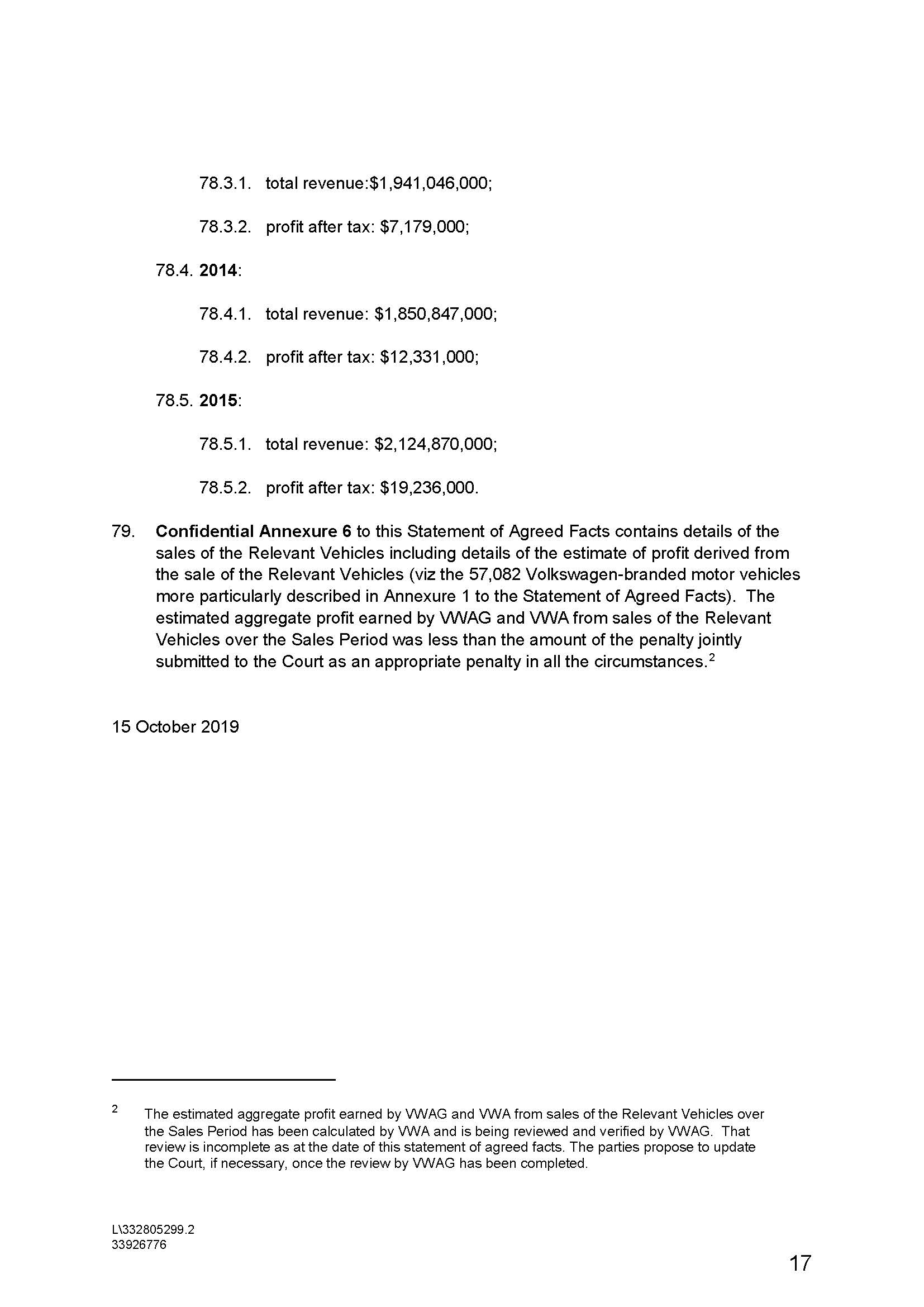

Model (type) | Years of manufacture | No of vehicles sold |

Amarok (2.0L) | 2010–2012 (Model Year (MY) 2011 – MY2012) | 8,694 |

Caddy, including the maxi Caddy (1.6L and 2.0L) | 2010–2015 (MY2010 – MY2016) | 8,558 |

CC (2.0L) | 2012–2015 (MY2012 – MY2016) | 1,241 |

Eos (2.0L) | 2008–2014 (MY2009 – MY2014) | 845 |

Golf (1.6L and 2.0L) | 2008–2012 (MY2009 – MY2013) | 11,539 |

Jetta (1.6L and 2.0L) | 2008–2015 (MY2009 – MY2016) | 2,527 |

Passat (2.0L) | 2008–2015 (MY2009 – MY2015) | 10,863 |

Passat CC (2.0L) | 2009–2012 (MY2009 – MY2012) | 804 |

Polo (1.6L) | 2010–2014 (MY2010 – MY2014) | 2,618 |

Tiguan (2.0L) | 2007–2015 (MY2008 – MY2016) | 9,393 |

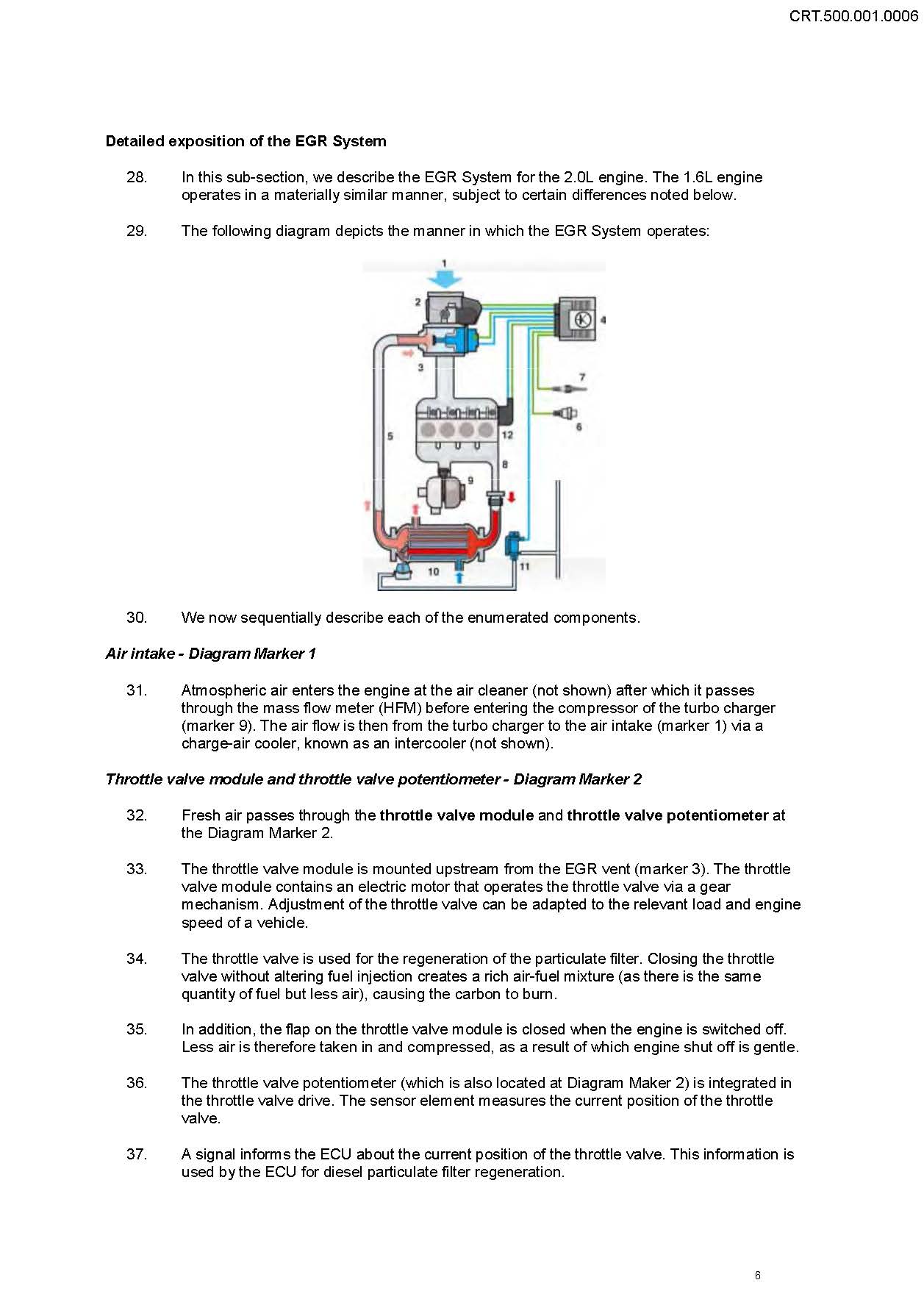

Total vehicles sold | 57,082 |

SCHEDULE 2

Documents submitted to the Delegate of the Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development in order to obtain approvals under s 10A of the Motor Vehicle Standards Act 1989 (Cth):

(i) Application for Compliance Approval Forms;

(ii) In some cases, Selection Test Fleet Forms; and

(iii) Summary of Evidence Forms.

SCHEDULE 3

The Two Mode Software

(a) The operation of the Two Mode Software is described in more detail in the Agreed Technical Document dated 17 February 2017 tendered and admitted into evidence in the Stage 1 hearing (CRT.500.001.0001). The text of the said Agreed Technical Document (excluding annexures and appendices) was admitted into evidence in the penalty hearing as Exhibit A.

(b) In summary, simplifying the description in that document:

(i) All of the Relevant Vehicles contained an exhaust gas recirculation system (EGR System).

(ii) In all Relevant Vehicles, the EGR System is controlled by the Engine Control Units (ECU).

(iii) All of the Relevant Vehicles contained software in their ECU which, subject to certain operating conditions, caused the EGR System to operate in one of two modes (Two Mode Software):

(A) Mode 1 was optimised for NOx and other pollutant emissions (primarily by specifying lower target air mass which would be expected to result in a higher Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR) Rate and compliance with applicable emissions limits).

(B) Mode 2 was the mode optimised for comfort including fuel economy, reliable regeneration of the particulate filter and noise, vibration and harshness (primarily by specifying a higher target air mass which would be expected to result in a lower EGR Rate), which would result in higher NOx emissions than in Mode 1.

(iv) The Two Mode Software caused Mode 1 to operate when the Relevant Vehicles were being driven after start-up according to the Type 1 emissions test (which used the NEDC), which is the primary legislated emissions test in Australia. At all other times, the Two Mode Software caused the Relevant Vehicles to operate in Mode 2.

SCHEDULE 4

Applications to have the Volkswagen-branded vehicles more particularly described in Annexures 4 and 5 to the SOAF included on the GVG Website.

SCHEDULE 5

Applications to have the vehicles more particularly described in Annexure 5 to the SOAF given a higher air pollution rating on the GVG Website.

ORDERS

NSD 322 of 2017 | ||

BETWEEN: | AUSTRALIAN COMPETITION AND CONSUMER COMMISSION Applicant | |

AND: | AUDI AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT First Respondent AUDI AUSTRALIA PTY LIMITED (ACN 077 092 776) Second Respondent VOLKSWAGEN AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT Third Respondent | |

JUDGE: | FOSTER J |

DATE OF ORDER: | 20 december 2019 |

BY CONSENT, THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The Originating Application be dismissed.

2. There be no orders as to the costs of this proceeding.

THE COURT NOTES THAT:

3. The above Consent Orders have been made at the request of all parties to this proceeding as part of the overall settlement reached among the parties to this proceeding and the parties to proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016 (two of whom, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission and Volkswagen Aktiengesellschaft, are parties to both this proceeding and proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016) and notwithstanding the fact that all of the diesel engines installed in the Audi-branded vehicles the subject of this proceeding were equipped with the Two Mode Software described in Schedule 3 to the Orders made this day in proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

[1] | |

THE HEARING OF THE JOINT SETTLEMENT APPLICATION | [34] |

VW’S EA189 DIESEL ENGINE AND THE RELEVANT EMISSIONS STANDARDS | [41] |

THE IDENTIFICATION PLATE SYSTEM IN AUSTRALIA | [72] |

THE ACCC’S PLEADED CASES | [75] |

THE ADMITTED CONTRAVENTIONS | [85] |

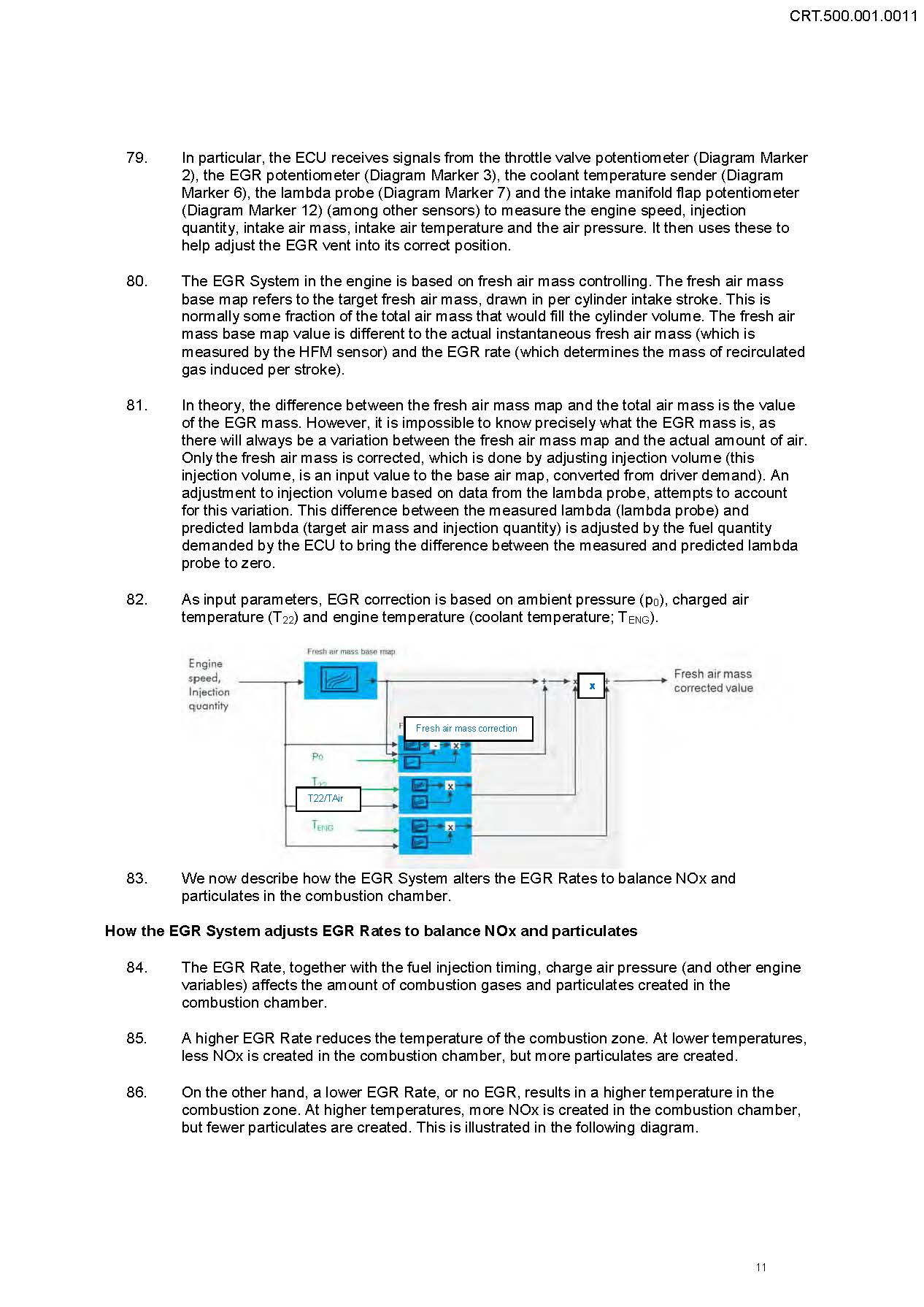

THE US PLEA AGREEMENT | [101] |

The Terms of the Plea Agreement | [103] |

The USSOF | [117] |

The US Plea Agreement and the Australian Position as Agreed in the SOAF | [133] |

CONSIDERATION (PECUNIARY PENALTY) | [138] |

The Relevant Legislative Provisions | [138] |

The Relevant Authorities | [147] |

The Correct Approach | [147] |

The Significance of the Amount of the Maximum Penalty | [197] |

Deterrence | [198] |

Instinctive Synthesis | [203] |

The Course of Conduct Principle | [206] |

The Totality Principle | [215] |

Parity | [217] |

Decision | [219] |

Some Preliminary Matters | [219] |

The Nature and Extent of the Act or Omission and any Loss or Damage Suffered as a Result of the Act or Omission (s 224(2)(a)) | [232] |

The Maximum Penalty | [239] |

The Remedial Technical Measures | [244] |

Harm to Public Health and the Environment | [248] |

Harm to the Public and Competitors | [251] |

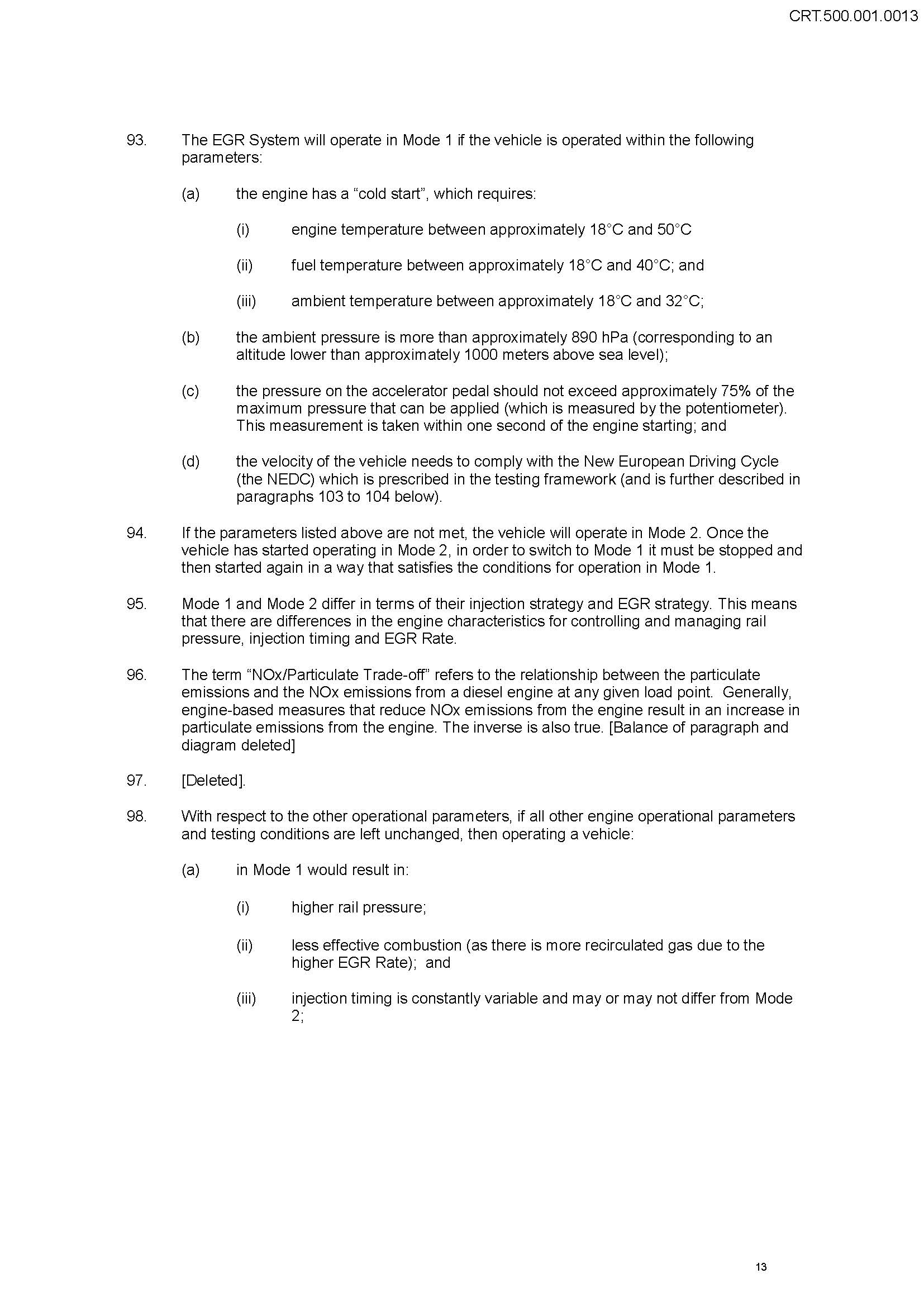

Compensation to Consumers | [253] |

The Circumstances in which the Act or Omission Took Place (s 224(2)(b) of the ACL) | [254] |

The Appropriate Penalty | [261] |

FOSTER J:

Introduction

1 There have been filed in the Court seven sets of proceedings which concern the global corporate scandal involving Volkswagen AG (VWAG), a German corporation which carries on a multinational business of designing, manufacturing and selling motor vehicles under the brands “Volkswagen”, “Audi” and “Skoda”, among others, and certain of its subsidiaries and affiliates, which has become known as “dieselgate” or “the VW global emissions scandal” or “the VW global emissions issue”. In these Reasons, I shall refer to that matter as “the emissions issue”. Approximately 10.7 million to 11.5 million vehicles were affected by the emissions issue worldwide, including almost 100,000 vehicles sold in Australia.

2 Although the litigation in this Court addresses most particularly the impact of the emissions issue on Australian consumers, it is necessary to pay some regard to events which took place outside Australia, especially in Europe and in the United States of America, in the period 2006–2015. The motor vehicles the subject of the Australian litigation were manufactured in the period 2007–2015.

3 The emissions issue was initially publicly revealed on 3 September 2015 when, according to a statement made on 8 October 2015 by Michael Horn, the then President and CEO of Volkswagen Group of America Inc (VW America) to a US Congressional Committee, representatives of VWAG disclosed at a meeting with representatives of the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that emissions software in certain four cylinder diesel engines manufactured by VWAG and its affiliates in the years 2009–2015 contained a “defeat device” in the form of hidden software which could recognise whether a vehicle was being operated in a test laboratory or on the road. The deployment of this software resulted in the motor vehicles fitted with the affected diesel engines emitting significantly higher levels of nitrogen oxides (NOx) when driven on the road than when tested in the laboratory. NOx is harmful to humans and to the environment. This is a generally accepted fact among scientists who work in the relevant fields and among many governmental authorities around the world charged with regulating emissions from motor vehicles. In many countries, including in Europe, the US and Australia, the emission of NOx into the atmosphere from motor vehicles is closely controlled.

4 Throughout the period 2006–2015, the installation of such a defeat device in vehicles to be sold in the US was prohibited under US law. That has remained the position at all times after 2015. By early September 2015, VWAG had acknowledged that it had installed a defeat device in the affected vehicles in the US and that, by so doing, it had broken US law.

5 On or about 7 October 2015, after suspending sales of affected vehicles in Australia, Volkswagen Group Australia Pty Ltd (VW Australia) announced that it had made available online a tool so that customers of VW and Skoda Auto a.s. (Skoda) who had purchased vehicles in Australia could check if their vehicles had been fitted with the affected diesel engines as part of VWAG’s action plan to respond to “the global emissions issue”. I infer that the reference to the “global emissions issue” in that announcement was a reference to the capacity of the software in the affected diesel engines to cause those engines to emit lower levels of NOx when being tested in the laboratory than would have been emitted when the same vehicles were driven on the road. No mention was made in that announcement that Audi-branded diesel vehicles were also affected by the emissions issue.

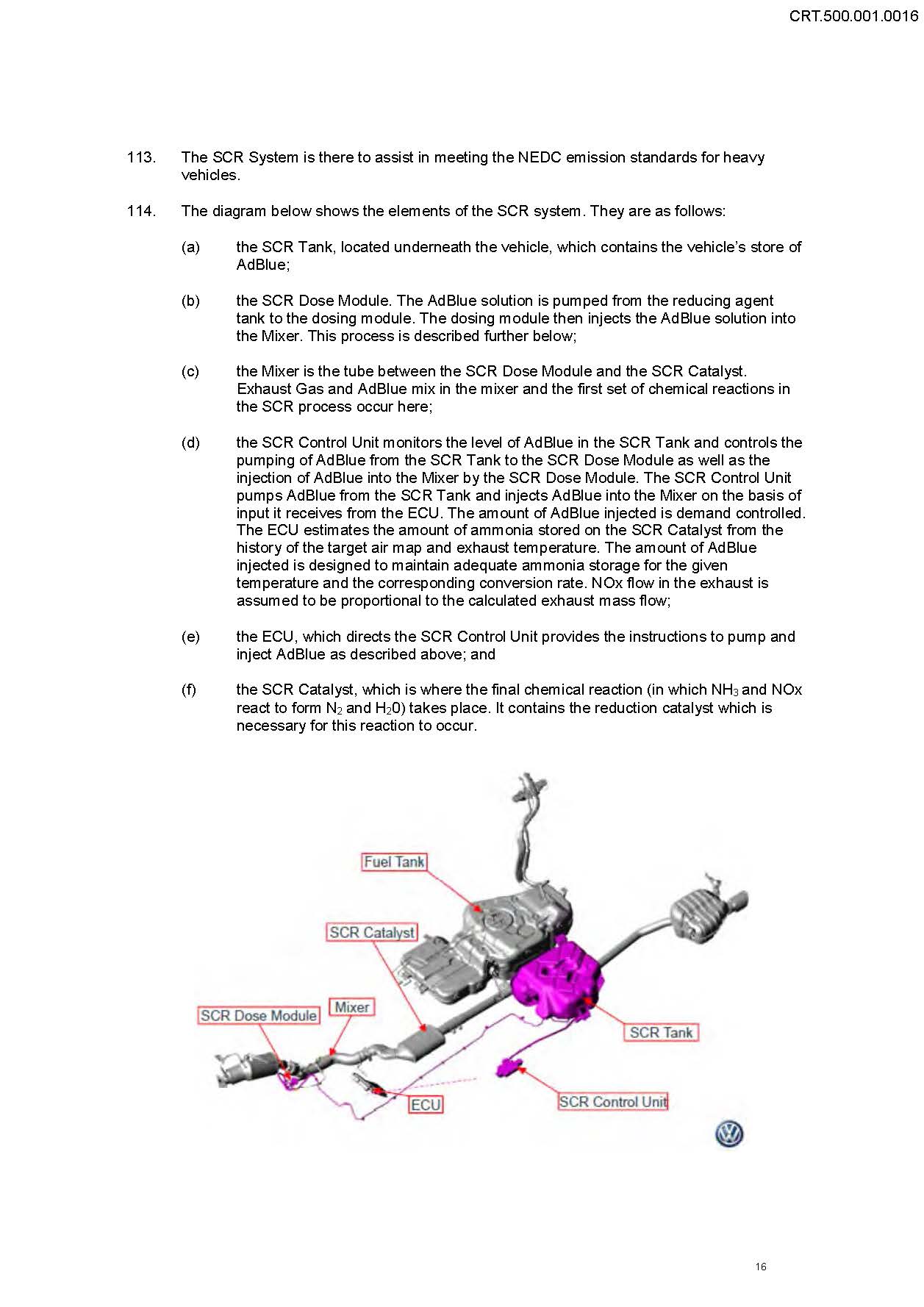

6 On 30 October 2015, Bannister Law, as solicitors on the record, commenced two class actions in this Court—Cantor v Audi Australia Pty Ltd (Audi Australia) (NSD 1307 of 2015) and Tolentino v VW Australia (NSD 1308 of 2015)—in which the applicant in each of those proceedings claimed relief in respect of the emissions issue.

7 On 20 November 2015, Maurice Blackburn, as solicitors on the record, commenced a class action in this Court—Dalton v VWAG and VW Australia (NSD 1459 of 2015). On 22 November 2015, Maurice Blackburn commenced two further class actions in this Court—Richardson v Audi AG, Audi Australia and VWAG (NSD 1472 of 2015) and Roe v Skoda, VW Australia and VWAG (NSD 1473 of 2015).

8 The claims made in the five class actions referred to at [6] and [7] above relate to approximately 100,000 motor vehicles. The five class actions cover Volkswagen, Audi and Skoda-branded vehicles.

9 On 1 September 2016, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) commenced a proceeding against VWAG and VW Australia (NSD 1462 of 2016) in which it sought declaratory relief, pecuniary penalties, corrective advertising and other relief in respect of allegedly false and misleading conduct and false representations concerning 57,605 VW-branded diesel vehicles sold in Australia in the period from 1 January 2011 to 3 October 2015. All of the vehicles the subject of this proceeding were powered by a version of Volkswagen’s EA189 diesel engine—either 1.6 L or 2.0 L. The allegations made in this proceeding all relate to the emissions issue. VW Australia is a wholly-owned subsidiary of VWAG. The number of vehicles the subject of proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016 was later revised downwards slightly to 57,082.

10 On 8 March 2017, the ACCC commenced a similar proceeding against VWAG, Audi AG and Audi Australia in respect of 12,368 Audi diesel vehicles sold in Australia in the period from 1 January 2011 to 3 October 2015 (NSD 322 of 2017) in which it claimed relief against those corporations in substantially the same terms as it had claimed against VWAG and VW Australia in proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016. All of the vehicles the subject of proceeding NSD 322 of 2017 were powered by a version of the EA189 diesel engine. All of the allegations made in this proceeding also relate to the emissions issue. Audi AG is a subsidiary of VWAG. VWAG holds more than 99% of the issued capital of Audi AG. Audi Australia is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Audi AG.

11 The total number of vehicles covered by the two proceedings brought by the ACCC to which I have referred at [9] and [10] above (the regulatory proceedings) is 69,450. The difference between that number of vehicles and the number of vehicles covered by the five class actions is explained by the fact that the class actions include Skoda vehicles whereas the regulatory proceedings do not and by the additional fact that the class actions cover vehicles manufactured and sold over a period which is longer than that pleaded in the regulatory proceedings.

12 In these Reasons, I shall refer to the 69,450 Volkswagen and Audi vehicles the subject of the regulatory proceedings as “the affected vehicles”. Schedule 2 to each of the pleadings filed in the regulatory proceedings contains particulars of the VW and Audi models in which the impugned software had been installed. In those schedules, the ACCC also specified the number of each model so affected.

13 Until quite recently, the seven proceedings referred to at [6]–[10] above have been case managed together.

14 In addition to the above proceedings, Complete Taxi Management Pty Limited and others instituted a separate proceeding against VW Australia in the Supreme Court of Queensland involving some of the same issues as had been raised in the seven proceedings commenced in this Court. That proceeding was transferred to this Court on 7 March 2017 and became proceeding NSD 510 of 2017 in this Court. It was dismissed by consent on 15 September 2017.

15 In all of the class actions, the applicants allege that:

(a) The software in the EA189 diesel engines installed in the vehicles covered by those actions is a “defeat device” within the meaning of the Australian Design Rules applicable to those vehicles and within the meaning of the Australian Vehicle Emissions Standards; and

(b) The vehicles covered by those actions failed to comply with the requirements of the Australian Vehicle Emissions Standards, which prohibit the use of “defeat devices” to cause vehicles to operate an emission control system differently in the test environment from the way in which that system functions when operating in normal use on the road.

16 The applicants in all of the class actions allege that the respondents in those actions engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct and made false and misleading representations in respect of the vehicles covered by those actions by representing that those vehicles complied with the applicable Australian Vehicle Emissions Standards when, in truth, they did not comply with those Standards. They also allege that the vehicles were not of acceptable quality and did not comply with applicable safety standards.

17 The applicants in the three Maurice Blackburn class actions make additional allegations to the effect that the European and Australian companies named as respondents in those actions engaged in unconscionable conduct, deceit and general law misrepresentation and also failed to comply with an express warranty provided to their customers.

18 The applicants in the class actions seek, among other things, compensation on behalf of the owners of and interest holders in the vehicles covered by those actions for the alleged diminution in value of those vehicles which they contend has been caused by the respondents’ conduct.

19 The respondents in the class actions deny all of the above allegations on various grounds.

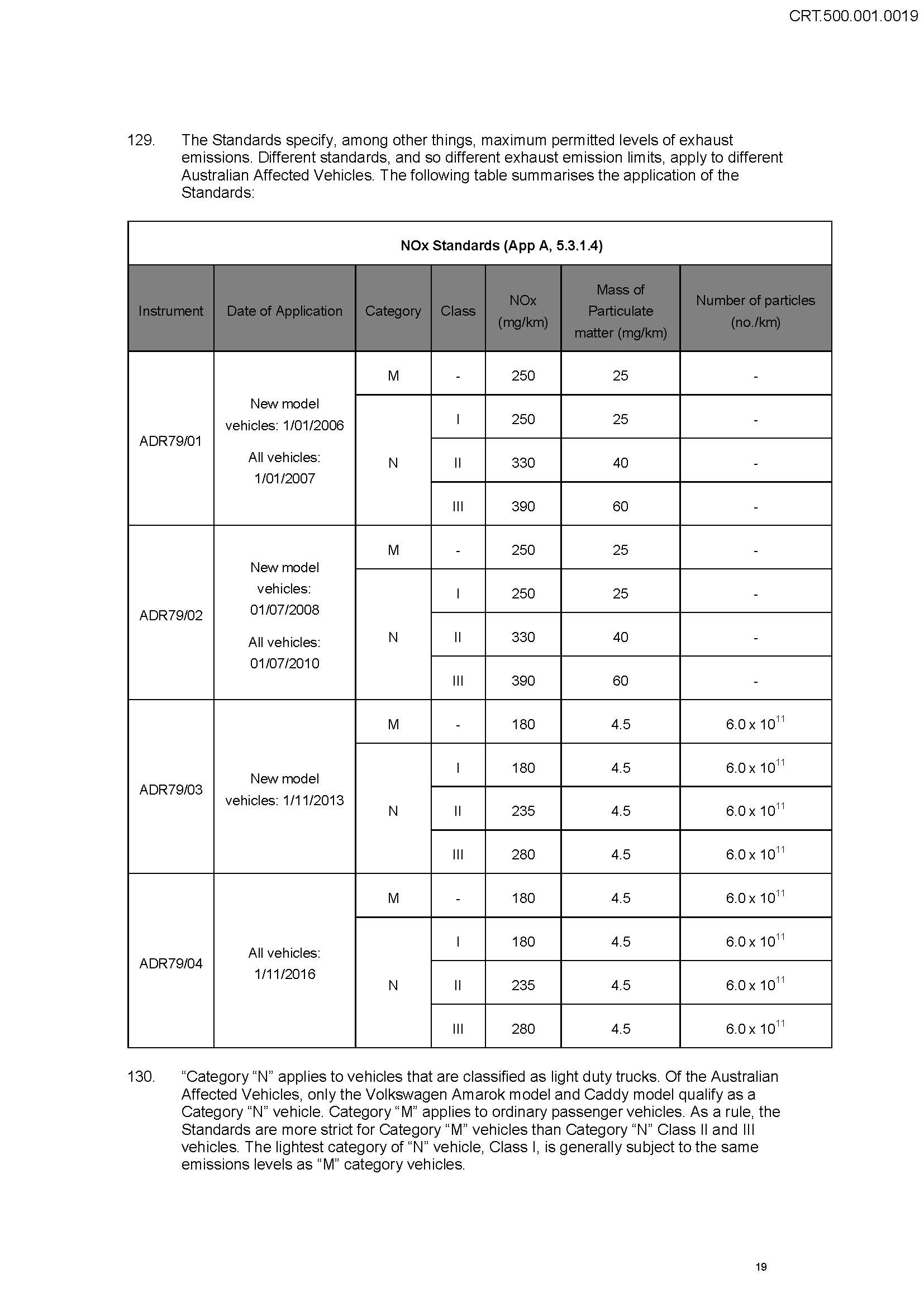

20 In February 2017, in an endeavour to hear and determine all of the above proceedings (except proceeding NSD 322 of 2017 which had not been commenced by then) expeditiously, efficiently and fairly, I ordered that eight important separate questions which arose in all of the first six proceedings be determined separately from and before all other questions in those proceedings. Those common questions were later amended and supplemented and proceeding NSD 322 of 2017 was included in this separate questions approach. Ultimately, twelve separate questions went to trial in all seven proceedings. These twelve separate questions are set out in Orders made by me on 10 November 2017. A question of central importance was whether the diesel engines installed in the vehicles covered by all seven proceedings had been fitted with a “defeat device” within the meaning of the relevant Australian Design Rules and Emissions Standards.

21 In addition, soon after the class actions were commenced, I took steps to require the parties to agree upon the terms of a detailed Technical Document in which the workings of the EA189 diesel engines would be explained. Particular emphasis was to be placed in that document upon the design and functionality of the software to which I have referred at [3] above.

22 In March and May 2018, I conducted a hearing of the twelve separate questions to which I have referred at [20] above (Stage 1 Hearing). At the conclusion of the Stage 1 Hearing, I reserved my judgment in respect of those questions. In light of the settlements to which I will shortly refer, the parties to all seven proceedings no longer require that judgment to be delivered. The need for the judgment has been overtaken by subsequent events.

23 Shortly before the commencement of the Stage 1 Hearing, the parties finalised the Agreed Technical Document. That document became Exhibit A in the Stage 1 Hearing and was given the following electronic exhibit number (CRT.500.001.0001) at that hearing. I shall refer to that document as “the ATD”. A copy of the main text of the ATD without appendices is annexed to these Reasons for Judgment and marked as “Attachment A”.

24 Throughout 2018 and 2019 (up to mid-September 2019), the parties prepared for a further joint hearing of most of the issues remaining in all seven proceedings. That further hearing was called “the Stage 2 Hearing”. The Stage 2 Hearing was fixed to commence on Monday 23 September 2019 with an estimate of six weeks. Further dates in December 2019 were also allocated to the Stage 2 Hearing.

25 The issues to be determined at the Stage 2 Hearing were, for the most part, again common to all seven proceedings.

26 It was envisaged by the Court and by the parties that there would be one final set of hearings after the Stage 2 Hearing which would most likely require the remaining issues in the five class actions to be dealt with separately from the remaining issues in the regulatory proceedings.

27 On 6 September 2019, my Associate was informed by the parties to the five class actions that those proceedings had settled in principle. Subsequently, the parties to the class actions have informed the Court that VWAG has agreed to pay group members a figure in a range between $87 million and $127.1 million, depending upon the number of members who register for the purposes of the settlement. The $87 million is a minimum payment and the $127.1 million is the maximum payment which VWAG will be liable to make. The payment of the class actions settlement amount is on a “without admissions” basis. VWAG has also agreed to pay the applicants’ costs.

28 On 16 September 2019, with the consent of all parties in all seven proceedings, I vacated the Stage 2 Hearing. As at that date, I had been informed that the ACCC and VWAG were still negotiating a settlement of the regulatory proceedings and that a settlement of those proceedings was likely to be reached in the near future.

29 Subsequently, on 23 September 2019, I was informed that the regulatory proceedings had also settled in principle. On the same day, I fixed 10.15 am on 3 October 2019 for the hearing of a joint application to be made by the parties to the regulatory proceedings for the making of declarations and the imposition of an appropriate pecuniary penalty in proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016. For reasons which I will explain below, on 27 September 2019, I vacated that date and re-fixed the hearing of that application at 10.15 am on 16 October 2019. That hearing proceeded on 16 October 2019. A further hearing took place on 13 November 2019.

30 Under the settlement of the regulatory proceedings, the ACCC and VWAG have agreed to the making of certain declarations, to the payment to the Commonwealth of a pecuniary penalty of $75 million and to the payment of the ACCC’s costs agreed between the ACCC and VWAG at $4 million. It has also been agreed between the ACCC and VWAG that these declarations and orders are all to be made in proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016. In effect, VWAG, as the parent corporation and as the entity where the misconduct mostly occurred, is to take sole responsibility for all VW obligations under the settlement. As part of the overall settlement, the ACCC, VWAG, Audi AG and Audi Australia have agreed that the Audi regulatory proceeding (NSD 322 of 2017) is to be dismissed with no order as to costs. This is so notwithstanding that the Audi vehicles the subject of that proceeding were all fitted with a variant of the EA189 diesel engine in which the software to which I have referred at [3] above had been installed. As I have already mentioned, Audi AG is a subsidiary of VWAG which is almost wholly-owned by VWAG.

31 At subsequent listings of the class actions, the Court has been informed that the settlement of those actions is proceeding. Arrangements have been made for the hearing of an application by the parties to those actions for orders approving that settlement, for orders approving the mechanisms for effecting that settlement and for other ancillary orders.

32 By these Reasons for Judgment, I determine the appropriate pecuniary penalty to be imposed upon VWAG in proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016, the appropriate declarations and other orders to be made against VWAG in that proceeding and the appropriate orders to be made in the proceeding brought by the ACCC against VWAG, Audi AG and Audi Australia (NSD 322 of 2017) in light of the relief granted in proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016 and in light of the settlement reached between the ACCC, VWAG, VW Australia, Audi AG and Audi Australia in respect of both of the regulatory proceedings.

33 I will address the settlement of the five class actions in a separate judgment in due course.

The Hearing of the Joint Settlement Application

34 At the hearing before me on 16 October 2019, the following materials were tendered and admitted into evidence on that occasion:

(a) The text of the ATD without the appendices thereto (Exhibit A).

(b) Rule 11 Plea Agreement dated 11 January 2017 filed in proceeding No 16-CR-20394 in the United States District Court, Eastern District of Michigan between the United States of America, as plaintiff, and VWAG, as defendant (the US plea agreement or the plea agreement) (Exhibit B).

(c) A Statement of Agreed Facts dated 15 October 2019 (SOAF) (Exhibit C). A complete copy of the SOAF (including all six Annexures thereto) with a small number of redactions for confidentiality is attached to these Reasons as “Attachment B”.

(d) Press release issued by VWAG in which reference is made to the imposition of a fine upon VWAG by the Braunschweig District Court, Germany, in 2018 (Exhibit D).

35 In the SOAF, VWAG has made a number of express admissions of contraventions of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) and the parties have set out with particularity an agreement between the ACCC and VWAG as to certain relevant facts for the purposes of s 191 of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth).

36 The SOAF is not signed by the ACCC or by VWAG or by the legal representatives of either of them. For this reason, s 191(3)(a) (which provides that the benefits specified in s 191(2) do not apply unless the agreed facts are stated in an agreement in writing signed by the parties or their lawyers) is not engaged. However, the SOAF was tendered by consent at the hearing before me on 16 October 2019 in circumstances which probably engage s 191 by reason of the operation of s 191(3)(b) which refers to facts being stated in open court with the agreement of all parties. In any event, both parties proceeded at that hearing upon the basis that I should treat the document as containing agreed facts having the status of s 191 “agreed facts” for the purposes of proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016. That is, the facts in the SOAF are to be regarded as facts which the parties have agreed are not, for the purposes of proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016, to be disputed. In addition, the parties have agreed that they are not required to adduce evidence to prove the existence of any of the agreed facts specified in the SOAF. They have also agreed that neither party is permitted to adduce evidence to contradict or qualify any of those agreed facts. I shall proceed in accordance with the parties’ agreement as to these matters.

37 In the SOAF, at pars 6, 42, 43 and 44 in particular, VWAG made clear that it accepts that it is liable in law for the conduct of its supervisors, employees and engineers more particularly described in the SOAF which constituted the contravening conduct the subject of the admissions as to liability specified in pars 3, 68, 69, 70 and 71 of the SOAF. That is the conduct which must now be the subject of appropriate relief.

38 Although the executives employed by VWAG who devised and implemented the installation of the Two Mode Software had a status or employment standing below the Board of Management of VWAG, they were nonetheless very senior employees. This is made clear by the description of the culprits set out at pars 7 to 13 of the Statement of Agreed Facts forming part of the US plea agreement to which I will refer in detail later in these Reasons. In particular, Supervisor A referred to in that plea agreement was a very senior employee with significant managerial responsibilities.

39 The evidence which I have described at [34] above was supplemented on 13 November 2019. On that occasion, VWAG was given leave to re-open its case and to read and rely upon an affidavit of Jens Heinemann sworn on 28 October 2019. The ACCC did not oppose VWAG being given leave to re-open its case for the purpose of reading and relying upon that affidavit. The ACCC did not object to any part of that affidavit. The ACCC did not seek to cross-examine Mr Heinemann. Mr Heinemann’s evidence was intended to provide to the Court evidence of the aggregate value in Australian dollars of the net profit earned by the relevant business units of VWAG from the sale in Australia of the Volkswagen-branded affected vehicles during the relevant period.

40 The parties also relied upon a Joint Written Submission dated 15 October 2019 and oral submissions made on 16 October 2019 and on 13 November 2019. That Joint Written Submissions document has been filed and, subject to several words and figures being redacted, is available for inspection.

VW’s EA189 Diesel Engine and the Relevant Emissions Standards

41 The evidence as to the design and operation of VW’s EA189 diesel engine is found in the text of the ATD (Attachment A to these Reasons), in pars 26 to 28 and 34 to 44 of the SOAF and in the US plea agreement which is referred to in detail later in these Reasons (at [101]–[132]). A version of this engine was installed in all of the vehicles sold in Australia which were affected by the emissions issue. This engine is the only engine with which the Australian litigation is concerned.

42 The description of VW’s EA189 diesel engine which follows in this section of these Reasons is taken from Attachment A. I have quoted from Attachment A from time to time, not for the sake of repetition but rather in order to ensure that important material from that Attachment is appropriately included in the text of these Reasons. That is not to say that the balance of Attachment A is not important. Attachment A should be carefully studied and considered by all those who read these Reasons as it contains a detailed (and agreed) exposition of the design and operation of VW’s EA189 diesel engine an understanding of which is a vital part of gaining an accurate and adequate appreciation of the Two Mode Software described in that document, in the SOAF and in these Reasons, and of the purpose for which that software was created and deployed in the engines installed in the affected vehicles.

43 A diesel engine is a combustion engine powered by the combustion of diesel fuel.

44 With the combustion of the fuel in the combustion chamber of the engine, gases are created. These combustion gases are appropriately described as combustion gases until there is a material change in their chemical composition such as the change produced by an after-treatment device. Combustion gases are primarily nitrogen, carbon dioxide, water and oxygen with small amounts of pollutants such as NOx, carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons and particulate matter (combustion gases).

45 NOx is the collective term for the sum of the chemical compounds, nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2). NOx is created in the combustion chamber of the engine by the reaction of nitrogen with surplus oxygen at high pressure and high temperature.

46 Particulates (fine dust or soot) are also created during the combustion process.

47 Once created, combustion gases and particulates must exit the combustion chamber.

48 The engine control unit (ECU) in vehicles fitted with the EA189 diesel engine is a computer that controls the vehicle’s engine and exhaust function.

49 One system that can be adjusted by the ECU is the exhaust gas recirculation system (EGR system). Exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) involves recirculating combustion gases produced in an engine during the combustion process back into the combustion chamber.

50 VWAG has consistently used EGR systems in its turbo charged direct injection (TDI) diesel engines to prevent or impede the creation of NOx. The EGR system deployed in the engines installed in the affected vehicles is one variant of such EGR systems.

51 The EGR system in the Australian affected vehicles is the same as the EGR system in the corresponding European vehicles manufactured by VWAG.

52 There is an EGR cooler in the EGR system. That hardware component in the engine reduces the temperature of the recirculated gas with the use of a heat exchanger.

53 The software component of the EGR system is contained in the ECU and affects the functioning of the EGR system. The ECU also controls other aspects of the engine’s operations, for example, the common rail diesel injection system which regulates the air-fuel mixture formation in the combustion chamber by controlling the fuel rail pressure, the timing of fuel injection and the number of fuel injection events per stroke (injection characteristics).

54 NOx forms when a mixture of nitrogen and oxygen is subjected to high temperature. The lower combustion temperature caused by EGR cooling reduces the amount of NOx created during combustion. As a result of the temperature drop, a greater mass of combustion gas can be fed back into the combustion process. This allows the combustion temperatures and consequently the creation of NOx during the engine warm-up phase to be reduced further. This leads to the same volume of combustion gas but more mass.

55 The “EGR Rate” is used as a means of quantifying the extent to which the EGR system is used by the engine. However, it is not a value that is measured by the engine or in vehicle testing at any point in time. Rather, it is a theoretical target value that, in its most general terms, refers to the amount of recirculated gases in place of fresh air in the combustion chamber. A high EGR Rate indicates that there is more recirculated gas and less fresh air being used by the EGR system at any given point in time and a low EGR Rate indicates that there is less recirculated gas and more fresh air at any given point in time.

56 The EGR Rate is controlled according to various engine operating maps in the ECU.

57 The software of the EGR system is part of the ECU and consists of input values (mainly RRP/revolutions per minute, torque, intake air temperature, coolant temperature, boost pressure, atmospheric temperature and current air mass) and output values (the EGR vent position).

58 The EGR Rate, together with the fuel injection timing, charge air pressure (and other engine variables) affects the amount of combustion gases and particulates created in the combustion chamber.

59 A higher EGR Rate reduces the temperature of the combustion zone. At lower temperatures, less NOx is created in the combustion chamber but more particulates are created.

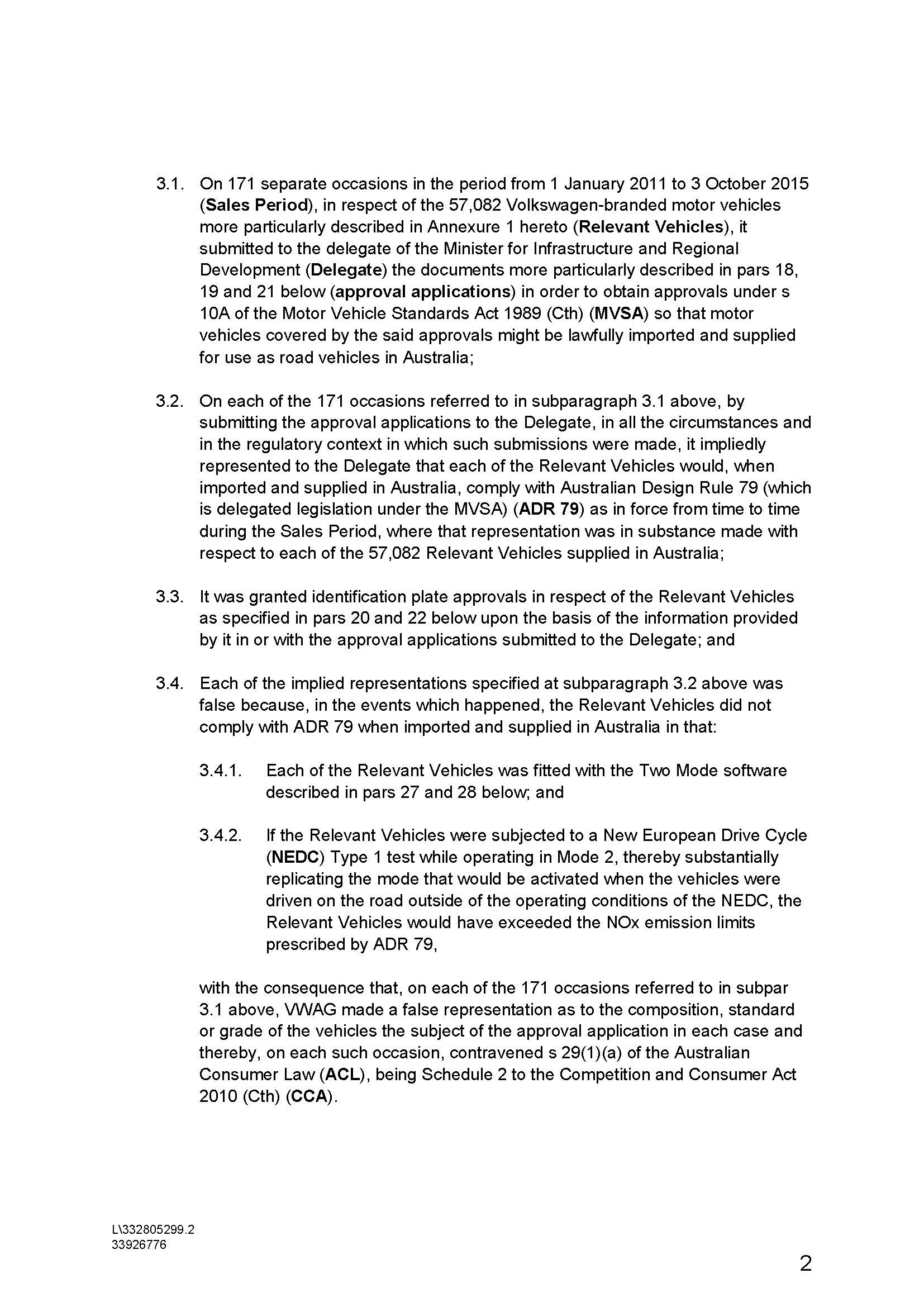

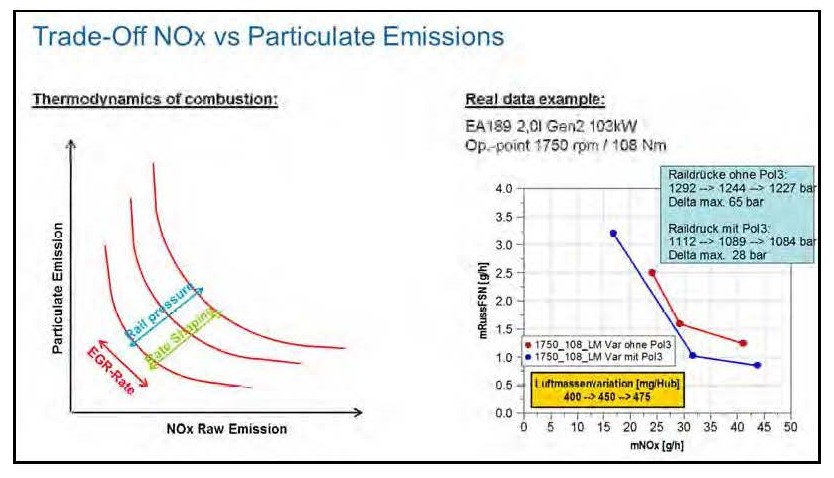

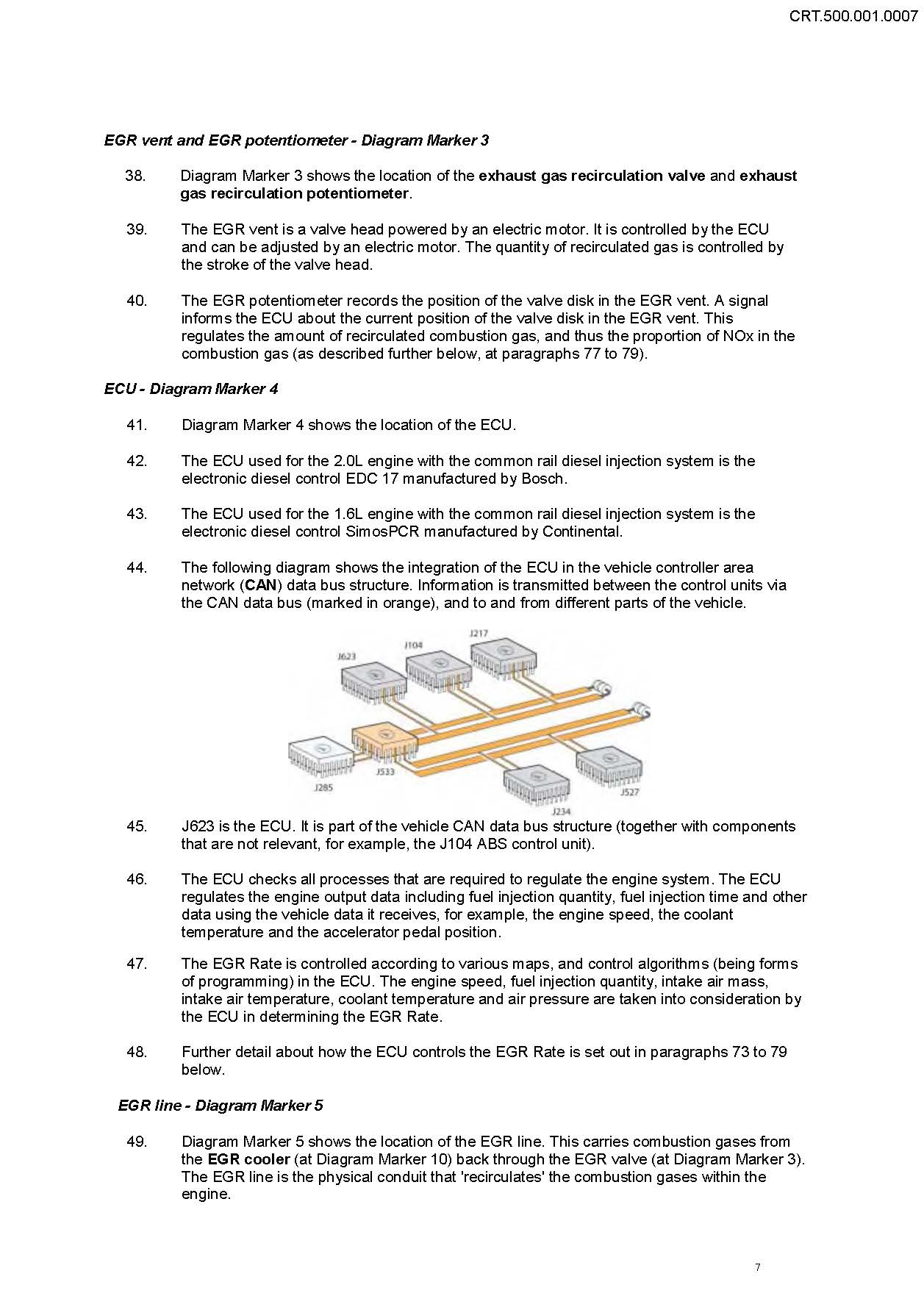

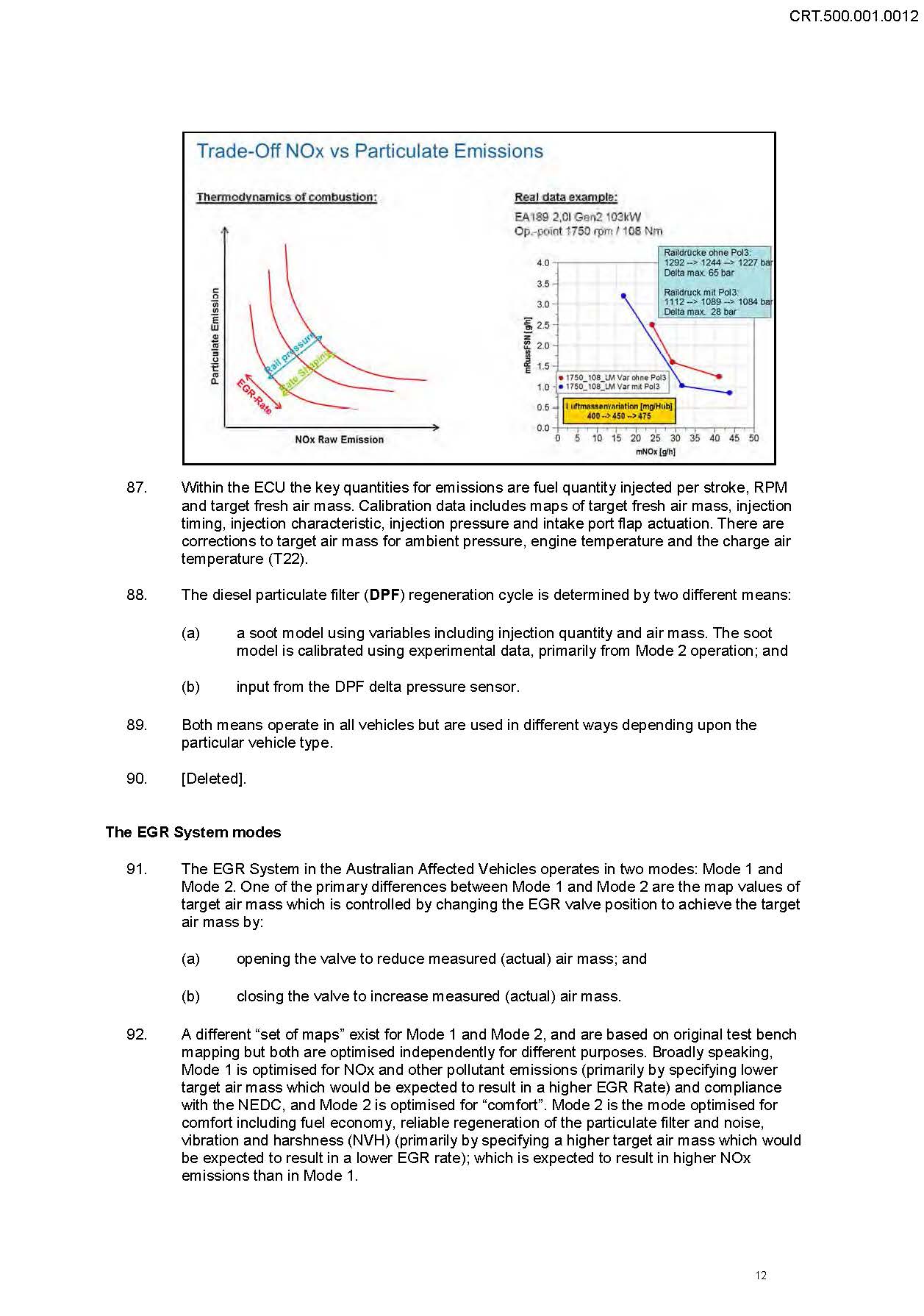

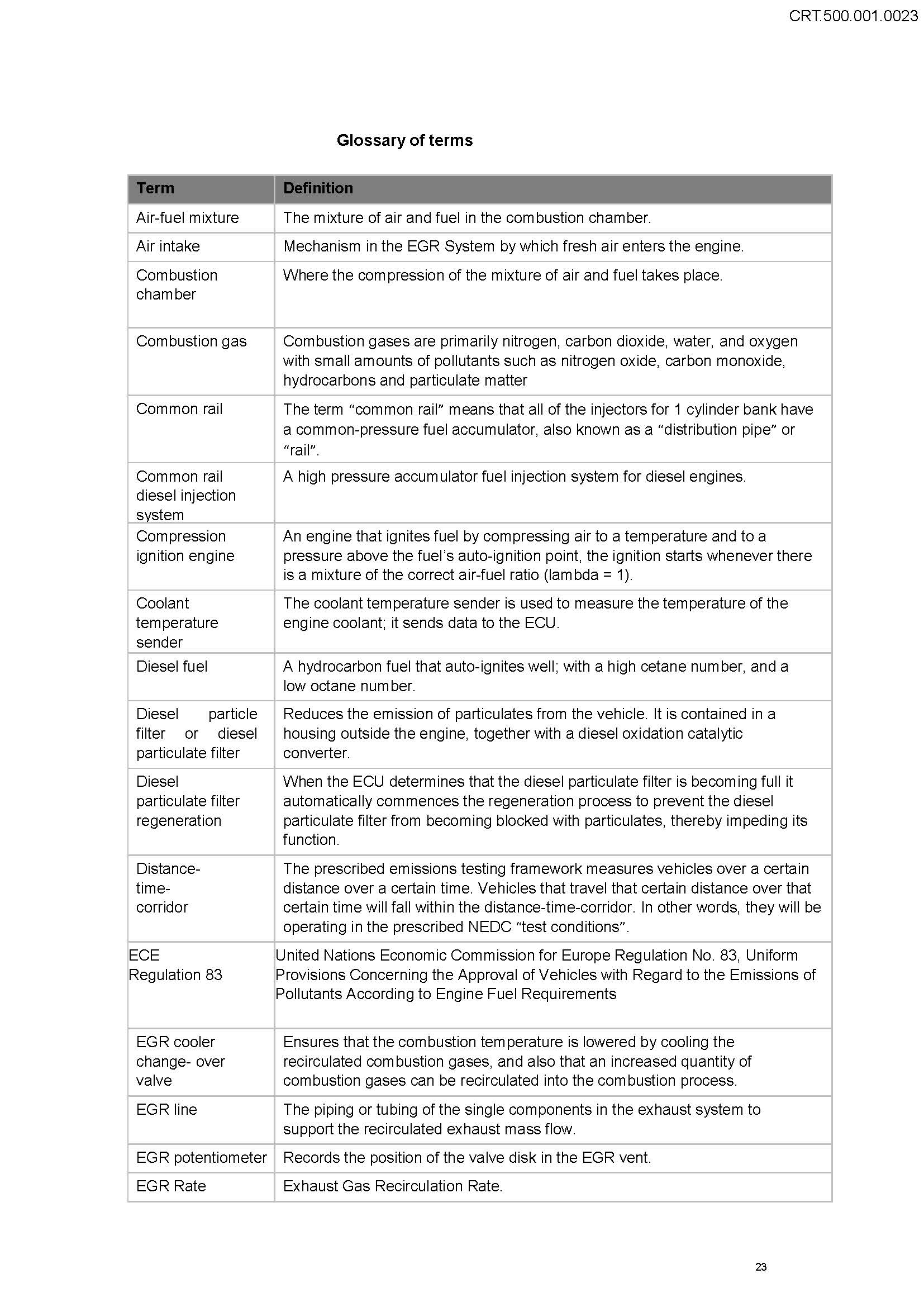

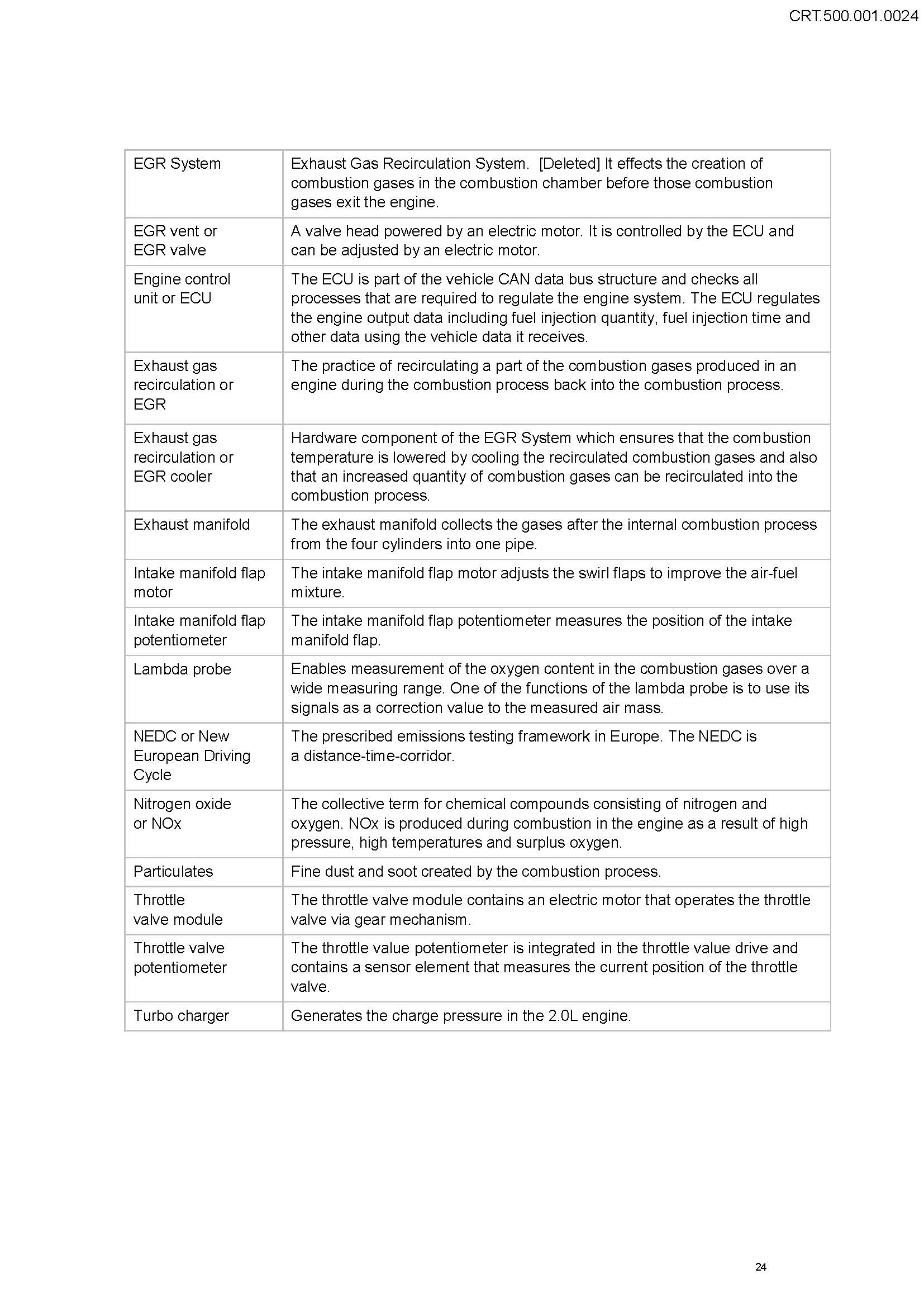

60 On the other hand, a lower EGR Rate, or no EGR, results in a higher temperature in the combustion zone. At higher temperatures, more NOx is created in the combustion chamber but fewer particulates are created. This is illustrated in the following diagram:

61 Within the ECU, key quantities for emissions are fuel quantity injected per stroke, RPM and target fresh air mass. Calibration data include maps of target fresh air mass, injection timing, injection characteristic, injection pressure and intake port flap actuation. There are corrections to target air mass for ambient pressure, engine temperature and the charge air temperature (T22).

62 The diesel particulate filter (DPF) regeneration cycle is determined by two different means:

(a) A soot model using variables including injection quantity and air mass. The soot model is calibrated using experimental data, primarily from Mode 2 operation; and

(b) Input from the DPF delta pressure sensor.

63 The two mode operation of the EGR system is addressed in detail at pars 91 to 108 of the ATD. The effect of those paragraphs is summarised at pars 26 to 28 of the SOAF which are in the following terms:

26. The operation of the Two Mode Software was described in more detail in the Agreed Technical Document dated 17 February 2017 tendered and admitted into evidence in the stage 1 hearing (CRT.500.001.0001).

27. In summary, simplifying the description in that document:

27.1. All of the Relevant Vehicles contained an exhaust gas recirculation system (EGR System).

27.2. In all Relevant Vehicles, the EGR System was controlled by the Engine Control Units (ECU).

27.3. All of the Relevant Vehicles contained software in their ECU which, subject to certain operating conditions, caused the EGR System to operate in one of two modes (Two Mode Software):

27.3.1. Mode 1 was optimised for NOx and other pollutant emissions (primarily by specifying a lower target air mass which would be expected to result in a higher Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR) Rate than in Mode 2 and compliance with applicable emissions limits).

27.3.2. Mode 2 was the mode optimised for comfort including fuel economy, reliable regeneration of the particulate filter and noise, vibration and harshness (primarily by specifying a higher target air mass which would be expected to result in a lower EGR Rate and thus higher NOx emissions than in Mode 1).

27.4. The Two Mode Software caused Mode 1 to operate when the Relevant Vehicles were being driven after start-up according to the Type 1 emissions test (which used the NEDC), which is the primary legislated emissions test in Australia. At all other times, the Two Mode Software caused the Relevant Vehicles to operate in Mode 2.

28. During the Sales Period, if the Relevant Vehicles were subjected to an NEDC Type 1 Test, while operating in Mode 2, thereby substantially replicating the mode that would be activated when the vehicles were driven on the road outside of the operating conditions of the NEDC, they would have exceeded the NOx emissions limits prescribed by ADR 79.

64 The presence of this Two Mode software in the ECU of the relevant engines was consciously and deliberately concealed by VWAG from the relevant Australian regulatory authorities, from the public and from Australian consumers.

65 I shall refer to this concealed software as the “Two Mode Software”.

66 To the above summary, the following may be added:

(a) Generally, the EGR Rate is higher in Mode 1 than in Mode 2 (see par 100 of the ATD);

(b) Because the EGR Rate influences the level of NOx and the level of particulates produced in the engine:

(i) When the EGR Rate is higher, as in Mode 1, less NOx is produced in the engine but more particulates are produced in the engine; and

(ii) Correlatively, when the EGR rate is lower, as in Mode 2 (the mode engaged for normal driving conditions on the road), more NOx is produced in the engine and fewer particulates are produced in the engine;

(see par 101 of the ATD);

(c) The EGR System for Australian Affected Vehicles (as defined in the ATD) operates in Mode 1 when the vehicles are driven in a manner that accords with the prescribed emissions testing framework, including the New European Drive Cycle (NEDC) Type 1 test distance-time corridor, cold start, and ambient pressure requirements (see par 103 of the ATD);

(d) The NEDC Type 1 test is a distance-time-corridor. This means that it measures vehicles over a certain distance across a certain time. Vehicles that travel a specified distance over a certain time will fall within the distance-time-corridor. In other words, they will be operating in the prescribed NEDC Type 1 test “test conditions” (see par 104 of the ATD);

(e) The Australian Affected Vehicles start in Mode 1, and continue to operate in Mode 1 as long as they are driven in a manner which accords with the NEDC Type 1 test (that is, as long as they stay within the NEDC distance-time-corridor) (see par 105 of the ATD); and

(f) If the vehicles are driven in a manner that is not in accordance with the NEDC Type 1 test (that is, they do not stay within the NEDC distance-time-corridor), the mapping (programming) in the ECU directs the EGR System to operate in Mode 2 (see par 106 of the ATD).

67 The parties addressed the applicable emissions standards for NOx at pars 122 to 149 of the ATD.

68 At pars 129 and 130 of the ATD, the parties set out a summary of the maximum permitted levels of exhaust emissions for the affected vehicles when driven in Australia.

69 Throughout the relevant period, the approval of vehicles imported into Australia by VWAG and its associated companies for sale and use in Australia generally occurred via “ECE Approval”. That is, for the purposes of the Australian market, the Australian authorities recognised the authorised use of such vehicles in Europe (see par 131 of the ATD).

70 At pars 132 to 134 of the ATD, the parties described the relevance of European test results to the Australian testing requirements in the following terms:

132. For each vehicle and engine gearbox variant there is a separate ECE approval with all relevant exhaust emission values.

133. Testing determines whether a vehicle meets the Standards. The vehicle runs with a defined speed curve while the exhaust emission values are measured. Compliance with the numerical emission limits is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for type approval.

134. If a model fulfils the required specifications during its testing type, then every vehicle in the series is certified for the relevant emission standard.

71 At pars 135 to 149 of the ATD, the parties described in some detail the NEDC Type 1 test environment and its relationship to the way in which motor vehicles will generally behave in ordinary driving conditions or conditions of normal use. Those paragraphs are in the following terms:

NEDC emissions testing, “ordinary driving conditions” and “normal use”

135. [Deleted]

136. The prescribed testing environment for ECE approval is the NEDC, described in paragraphs 103 to 107 above. The NEDC is a driving cycle, where vehicle speed is specified as a function of time (also known as a distance-time-corridor). It measures vehicle performance over a certain distance over a certain time. This is so regardless of whether or not the vehicles are in a laboratory, on a dynamometer, in ‘test conditions’, or on the road.

137. Individual vehicles of identical models do not exhibit uniform test results, including exhaust emissions test results, even when operating in the NEDC test.

138. The Standards prescribe requirements for how a vehicle must be operated during testing. By way of example, this includes:

(a) requirements for how the vehicle is placed on the chassis dynamometer;

(b) detailed descriptions and provisions for the test procedure for exhaust emissions on the dynamometer, for example, test cell temperature, humidity and atmospheric pressure, dilution and sampling system temperatures, exhaust dilution system and a large number of other ambient and test conditions;

(c) a requirement to drive in accordance with the NEDC. The NEDC is a vehicle based test that is performed in a purpose built vehicle emissions laboratory. The laboratory consists of a chassis dynamometer (also known as a “roller bench”). The vehicle is secured onto the dynamometer which provides a controlled load onto the driven wheels. The vehicle is then driven over a defined distance-time-corridor which is known as the NEDC. All exhaust emissions are collected and analysed to give a cycle result of grams per kilometre for a range of pollutants, including NOx. The driver must drive in accordance with a synthetic driving cycle with a running time of 19.66 minutes (where Part 1 is 4 x 195 seconds and Part 2 is 1 x 400 seconds).

(i) Part 1 of the NEDC involves 15 elementary urban cycles (idling, acceleration, steady speed and deceleration). They consist of four identical operating curves with a duration of 195 seconds, each of which must be driven four times in a row with a specified pause in between. For each operating curve there are then three separate operating curves with precisely specified time and speed: the first up to 15 km/h, the second up to 40 km/h, the third up to 50 km/h and, with decreasing speed, some seconds at 35 km/h. The distance covered is 4.052 kilometres, the maximum speed is 50 km/h and the total running time is 13 minutes.

(ii) Part 2 of the NEDC involves 13 extra-urban cycles (idling, acceleration, steady speed and deceleration). First, the driver accelerates to 70 km/h and continues at that speed for a specified number of seconds. Then the driver reduces the speed according to the driving line displayed on the monitor to 50 km/h and continues at that speed for a period again specified to the second. The driver then accelerates again to 70 km/h, remains at the line displayed on the monitor for 42 seconds, then further accelerates to 100 km/h and, after a short time, to 120 km/h, and then rapidly reduces speed to 0 km/h. The distance covered is 6.955 kilometres, the maximum speed is 120 km/h and the total running time is 6.66 minutes.

139. There are tolerances in the Standards that relate to how a vehicle must be operated during testing. For example, the Standards stipulate that:

A tolerance of plus or minus 2 km/hr shall be allowed between the indicated speed and the theoretical speed during acceleration, during steady speed, and during deceleration when the vehicle’s brakes are used…speed tolerances greater than those prescribed shall be accepted during phase changes provided that the tolerances are never exceeded for more than 0.5 s on any one occasion.

140. The Standards also contain tolerances relating to the test conditions (including factors such as ambient temperature and humidity) and test equipment (including factors such as measurement accuracy of laboratory equipment).

141. Conducting the NEDC in a laboratory has two principle [sic] advantages: repeatability and comparability of results. Laboratory conditions mean that various sources of variability, such as temperature and air pressure can be controlled. This means that the results of the NEDC are highly reproducible and, because the NEDC is consistent, the exhaust emissions values of one vehicle are directly comparable to the exhaust emissions values of every other vehicle under test conditions.

142. [Deleted]

143. On the road, if the same vehicle is driven in the same manner, over the same distance-time-corridor, and the conditions are the same as those under which it is tested in the laboratory, the exhaust emissions, including engine NOx emissions, will be similar. However, because you cannot control every variable affecting engine performance and emissions, the results of any two tests will never be identical.

144. Given the highly specific nature of the NEDC requirements, it is unlikely that a vehicle driven in normal use will be driven at the same speeds, for the same time and in the same conditions as the conditions specified by the Standards.

145. Relevant factors that may influence fuel consumption and exhaust emissions are:

(a) related to the driver: the driver’s fitness on the day, acceleration behaviour, switching point/gear-shifting speed and driving dynamics.

(b) related to traffic: amount of traffic/traffic jams, traffic light stops (quantity, duration), speed profile, and acceleration profile.

(c) related to external conditions: temperature, wind, rain and road conditions (wet, dry etc.); and

(d) related to the vehicle condition: correction of quantity of fuel injection according to software update (new training), DPF regeneration in a cycle, use of heating/air condition, and consumer comforts (fan, windscreen wipers etc.).

146. [Deleted]

147. [Deleted]

148. The difference between vehicle emissions under normal driving conditions and laboratory conditions is attributable to 4 main factors:

(a) the NEDC testing procedures were first developed in the 1970s and were designed to represent typical driving conditions of busy European cities at that time. The NEDC was last updated in 1990 to try to better represent more demanding, high speed driving modes. There is currently an initiative to further update the testing procedures. In 2007, a working group of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UN/ECE) began to develop a worldwide harmonized test procedure for light vehicles that has become known as the “Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure” (the WLTP). The WLTP includes a new test cycle that is designed to be more representative of average modern-day driving behaviour and limits the tolerances in and related to the NEDC. It is expected that the WLTP will replace in the NEDC in 2017;

(b) there are tolerances in the current procedures regarding the assessment of vehicles before they are tested under the NEDC. Before a vehicle can be tested under the NEDC, and in order to simulate normal driving conditions, the level of resistance of the dynamometer must be set to simulate the level of resistance the vehicle would experience if driven on the road. This resistance setting, known as the “road load” is adjusted for each specific vehicle that is tested and can be determined using different methods;

(c) there are tolerances in the current procedures regarding the testing of vehicles under the NEDC. This may include things such as the reference mass of the vehicle, the choice of wheels and tyres, how the laboratory instruments are calibrated, the temperature of the test cell, use of higher gears and the driving technique of the individual driver; and

(d) factors relating to vehicle operation. This includes the use of on-board electrical equipment, such as air conditioning and entertainment systems as well as other external factors such as driving style, fuel quality, weather conditions and road surface.

149. For example, a diesel engine vehicle operating in the NEDC distance-time-corridor must be operated in an environment with a temperature between 20 and 30 degrees Celsius. If the same vehicle is operated in a 10 degrees centigrade environment, even if it otherwise remains within the parameters of the NEDC test, its exhaust emissions will be different

The Identification Plate System in Australia

72 New motor vehicles can only be supplied in or imported into Australia if those vehicles comply with the vehicle standards made under s 7 of the Motor Vehicle Standards Act 1989 (Cth) (MVSA), which is legislation administered by the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (as that Department was called at all relevant times) (DIRD). Section 5 of the MVSA defines these vehicle standards as “national standards”. Where new vehicles of a particular type comply with the national standards, the Minister must, under s 10A of the MVSA, give written approval for identification plates to be placed on the relevant vehicles. In order for a motor vehicle to be lawfully imported into and supplied in Australia, it must be the subject of an approval to affix an identification plate pursuant to s 10A.

73 At all material times during the relevant period between 1 January 2011 and 3 October 2015, it was an offence to supply a new vehicle to the market that was either “nonstandard” (by which is meant that the vehicle did not comply with national standards) or which did not have an identification plate affixed to it (see s 14 of the MVSA). Section 18 of the MVSA similarly made it an offence to import a road vehicle into Australia that was either “nonstandard” or which did not have an identification plate affixed to it.

74 Vehicle Standard (Australian Design Rule 79—Emission Control for Light Vehicles) (ADR 79) is and was at all material times a vehicle standard made under s 7 of the MVSA and was therefore a “national standard” as defined in s 5 of the MVSA. ADR 79 prescribed at all material times a maximum emissions of NOx that vehicles could emit while undergoing a standardised testing procedure, namely the NEDC Type 1 test.

The ACCC’s Pleaded Cases

75 In the current iteration of its Originating Application in proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016 viz the Further Amended Originating Application filed on 18 September 2017, the ACCC claims seven specific declarations that VWAG and VW Australia in a number of particular ways contravened ss 18(1), 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g), 33 and 106 of the ACL. It also claims orders for pecuniary penalties pursuant to s 224 of the ACL, corrective advertising pursuant to s 246 of the ACL and other relief.

76 In the current iteration of its Statement of Claim in proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016 viz the Second Further Amended Statement of Claim filed on 15 March 2019, the ACCC alleges that engines in the VW-branded affected vehicles had been fitted with software (the Two Mode Software) which constituted a “defeat device” within the meaning of the various applicable versions of ADR 79, which is delegated legislation under the MVSA; that VWAG engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct by concealing the existence of that defeat device from the Commonwealth of Australia and its various regulatory emanations, the public and consumers; that it made false and misleading representations in relation to ADR 79 and the applicable motor vehicle emissions limits; and that, by supplying, manufacturing or possessing the VW-branded affected vehicles, it contravened a safety standard as defined in Pt 3.3 of the ACL. Substantially the same allegations were made against VWAG, Audi AG and Audi Australia in proceeding NSD 322 of 2017.

77 In all relevant versions of ADR 79, the use of a defeat device in a motor vehicle is prohibited. In cl 2.16 of Appendix A to all relevant versions of ADR 79, “defeat device” is defined as follows:

2.16 “Defeat device” means any element of design which senses temperature, vehicle speed, engine rotational speed, transmission gear, manifold vacuum or any other parameter for the purpose of activating, modulating, delaying or deactivating the operation of any part of the emission control system, that reduces the effectiveness of the emission control system under conditions which may reasonably be expected to be encountered in normal vehicle operation and use. Such an element of design may not be considered a defeat device if:

2.16.1. The need for the device is justified in terms of protecting the engine against damage or accident and for safe operation of the vehicle; or

2.16.2. The device does not function beyond the requirements of engine starting; or

2.16.3. Conditions are substantially included in the Type I or Type VI test procedures.

78 The definition of “defeat device” in ADR 79 reproduces the definition of “defeat device” found in UNECE Reg 83. In that instrument, the use of a “defeat device” in a motor vehicle is also prohibited.

79 The full title of UNECE Reg 83 is United Nations Economic Commission for Europe Regulation 83, Uniform Provisions Concerning the Approval of Vehicles with Regard to the Emission of Pollutants According to Engine Fuel Requirements, which is an international instrument given legal effect in Australia through ADR 79.

80 In both regulatory proceedings, in addition to claiming that the Two Mode Software constituted a defeat device, the ACCC also alleges that:

(a) The affected vehicles did not comply with the applicable NOx limits set by par 5.3.1.4 of Appendix A to ADR 79 and UNECE Reg 83 (and s 5.3.1.4 of Annex 1 to Euro 4 and Art 10 and Table 1 of Annex 1 to Euro 5), except by reason of the use of a “defeat device”, which was prohibited by par 5.1.2.1 of Appendix A to ADR 79 and UNECE Reg 83 (and s 5.1.1 of Annex 1 of Euro 4 and Art 5(2) of Euro 5);

(b) The components of the affected vehicles liable to affect the emission of pollutants from those vehicles were not so designed, constructed and assembled as to enable them, in normal use, to comply with the provisions of ADR 79 as required by par 5.1.1 of Appendix 1 to ADR 79, and to comply with Euro 5, as required by Art 5(1) of Euro 5; and

(c) In the alternative, the Two Mode Software constituted a defeat device equivalent which defeated the objectives of ADR 79 and UNECE Reg 83.

81 Euro 4 and Euro 5 are particular European regulatory instruments prescribing limits for the emission of pollutants from motor vehicles when driven in certain specific parts of Europe.

82 The particular allegations pleaded against VWAG, VW Australia, Audi AG and Audi Australia in the regulatory proceedings were adequately and accurately summarised by the ACCC at pars 27 to 31 of its Closing Written Submissions filed and relied upon by it at the Stage 1 Hearing in the following terms (footnotes omitted):

It is also alleged that from 2008 to 2015, VWAG and Audi AG sought inclusion of the Vehicles in the Green Vehicle Guide at the time of seeking Identification Plate Approval. During that period, the GVG rating system scored a higher rating out of 10 (being a rating of 6 out of 10) to vehicles that complied with Euro 5 emission limits, including NOx emissions limits. Under the GVG rating system, the applicant [here VWAG and/or VW Australia, Audi AG and/or Audi Australia] was required to report results from the Type 1 Test showing compliance with Euro 5 emission limits. VWAG and Audi AG sought this rating and submitted Type 1 test results to the Commonwealth, which were Euro 5 type approvals. It is alleged that VWAG and Audi AG submitted these results stating that the Vehicles met the Euro 5 NOx emissions limits even though the results were obtained by reason of the Defeat Software.

So far as VWAG is concerned, six categories of conduct are alleged against it:

(a) Prior to and during the Sales Period, VWAG deliberately concealed from the Commonwealth and the public certain matters, including the existence and effect of the Defeat Software, and that the Vehicles failed to comply with applicable legal requirements for road vehicles (including ADR 79), giving rise to contraventions of ss.18 and 33 of the ACL.

(b) VWAG represented to the Commonwealth in respect of each Vehicle type that all Vehicles of that type (i) had been properly approved in accordance with the requirements of UNECE Reg 83 (“VWAG UNECE Approval Representation”); (ii) complied with ADR 79 (“VWAG ADR 79 Representation”); and/or (iii) had not been modified to operate in a different mode from that used in normal driving conditions when undergoing testing for compliance with emissions standards (“VWAG Non-Modification Representation”); and further/alternatively, (iv) complied with NOx emissions limits in Euro 5 (“VWAG Euro 5 Representation”), all of which were not the case, giving rise to contraventions of s.18(1), s.29(1)(a) (goods were of a particular standard, quality, grade or composition), and s.29(1)(g) of the ACL (goods had approval, performance characteristics, uses or benefits which they did not have).

(c) VWAG represented to consumers that the Vehicles (i) complied with all applicable legal requirements for road vehicles, including ADR 79; (ii) had properly been given Identification Plate Approvals; and (iii) did not contain a Defeat Device or Defeat Device Equivalent, when this was not the case (“VWAG Compliance Conduct”), giving rise to contraventions of ss.18(1), 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33.

(d) VWAG represented to consumers that the Vehicles (i) complied with the NOx emissions limits specified by Euro 5; (ii) in normal use, or when driving in normal driving conditions, would produce NOx emissions at levels at or below the limits specified in Euro 5; and/or (iii) did not contain a Defeat Device or Defeat Device Equivalent (“VWAG GVG Conduct”), giving rise to contraventions of ss.18(1), 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL.

(e) VWAG contravened s.106 of the ACL during the Sales Period by supplying, offering to supply, manufacturing, possessing and controlling the Vehicles when those Vehicles did not comply with a safety standard (being ADR 79).

(f) VWAG was knowingly concerned in VWA’s [referring to VW Australia] contraventions.

So far as VWA [VW Australia] is concerned, four categories of conduct are pleaded against it:

(a) VWA represented to consumers that the Vehicles (i) complied with all applicable legal requirements for road vehicles, including ADR 79; (ii) had properly been given Identification Plate Approvals; and (iii) did not contain a Defeat Device or Defeat Device Equivalent, when this was not the case (“VWA Compliance Conduct”), giving rise to contraventions of ss.18(1), 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL.

(b) Through advertising material VWA represented to consumers that the Vehicles were (i) environmentally friendly, environmentally responsible or sustainable; (ii) had clean burning diesel engines; (iii) produced low emissions; (iv) complied with Euro 4 or Euro 5; and/or (v) in normal use, or when driven in normal driving conditions, would produce NOx emissions at levels at or below the limits specified by Euro 4 and/or Euro 5, when these matters were false and/or were misleading in view of the non-disclosure of the existence of the Defeat Software and related matters (“VWA Advertising Representations”), giving rise to contraventions of ACL ss.18(1), 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33.

(c) VWA represented to consumers that the Vehicles (i) complied with the NOx emissions limits specified by Euro 5; (ii) in normal use, or when driving in normal driving conditions, would produce NOx emissions at levels at or below the limits specified in Euro 5; and/or did not contain a Defeat Device or Defeat Device Equivalent (“VWA GVG Conduct”), which gave rise to contraventions of ss.18(1), 29(1)(a), 29(1)(g) and 33 of the ACL.

(d) VWA contravened s.106 of the ACL during the Sales Period by supplying, offering to supply, possessing and controlling the Vehicles when those Vehicles did not comply with a safety standard (being ADR 79).

The contraventions are alleged to have occurred during the “Sales Period”, which is defined as the period 1 January 2011 to 3 October 2015. In this period, VWA’s authorised dealers sold 57,605 Vehicles in Australia, and additionally, second-hand Vehicles were bought and sold. The position for Audi Australia is the same save that Audi Australia’s authorised dealers sold 12,368 vehicles during the Sales Period.

Contraventions essentially paralleling those against VWAG and VWA are alleged in proceedings NSD332/2017 against Audi AG and Audi Australia respectively, and in addition the Audi proceedings concern the SCR as another form of defeat device.

83 VWAG is also alleged to have been knowingly involved in the contraventions pleaded against VW Australia, Audi AG and Audi Australia.

84 All of the main allegations made by the ACCC against VWAG and VW Australia in proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016 were denied in those companies’ Defence, the latest version of which being the Further Amended Defence filed on 15 April 2019. VWAG, Audi AG and Audi Australia similarly denied all of the main allegations made against them in proceeding NSD 322 of 2017.

The Admitted Contraventions

85 At par 3 of the SOAF, VWAG admitted for the purposes of proceeding NSD 1462 of 2016 only, that:

3.1. On 171 separate occasions in the period from 1 January 2011 to 3 October 2015 (Sales Period), in respect of the 57,082 Volkswagen-branded motor vehicles more particularly described in Annexure 1 hereto (Relevant Vehicles), it submitted to the delegate of the Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development (Delegate) the documents more particularly described in pars 18, 19 and 21 below (approval applications) in order to obtain approvals under s 10A of the Motor Vehicle Standards Act 1989 (Cth) (MVSA) so that motor vehicles covered by the said approvals might be lawfully imported and supplied for use as road vehicles in Australia;

3.2. On each of the 171 occasions referred to in subparagraph 3.1 above, by submitting the approval applications to the Delegate, in all the circumstances and in the regulatory context in which such submissions were made, it impliedly represented to the Delegate that each of the Relevant Vehicles would, when imported and supplied in Australia, comply with Australian Design Rule 79 (which is delegated legislation under the MVSA) (ADR 79) as in force from time to time during the Sales Period, where that representation was in substance made with respect to each of the 57,082 Relevant Vehicles supplied in Australia;

3.3. It was granted identification plate approvals in respect of the Relevant Vehicles as specified in pars 20 and 22 below upon the basis of the information provided by it in or with the approval applications submitted to the Delegate; and

3.4. Each of the implied representations specified at subparagraph 3.2 above was false because, in the events which happened, the Relevant Vehicles did not comply with ADR 79 when imported and supplied in Australia in that:

3.4.1. Each of the Relevant Vehicles was fitted with the Two Mode software described in pars 27 and 28 below; and

3.4.2. If the Relevant Vehicles were subjected to a New European Drive Cycle (NEDC) Type 1 test while operating in Mode 2, thereby substantially replicating the mode that would be activated when the vehicles were driven on the road outside of the operating conditions of the NEDC, the Relevant Vehicles would have exceeded the NOx emission limits prescribed by ADR 79,

with the consequence that, on each of the 171 occasions referred to in subpar 3.1 above, VWAG made a false representation as to the composition, standard or grade of the vehicles the subject of the approval application in each case and thereby, on each such occasion, contravened s 29(1)(a) of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), being Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA).

86 In addition to the above admissions, the parties agreed at par 29 of the SOAF that:

VWAG did not disclose at any time prior to or during the Sales Period to the Delegate:

29.1. the existence of the Two Mode Software; or

29.2. that if the Relevant Vehicles were subjected to an NEDC Type 1 Test, while operating in Mode 2, thereby substantially replicating the mode that would be activated when the vehicles were driven on the road outside of the operating conditions of the NEDC, they would have exceeded the NOx emissions limits prescribed by ADR 79.

87 The context in which the above admissions are made is further explained at pars 7 to 25 of the SOAF. At pars 18 to 25 of the SOAF, the parties stated:

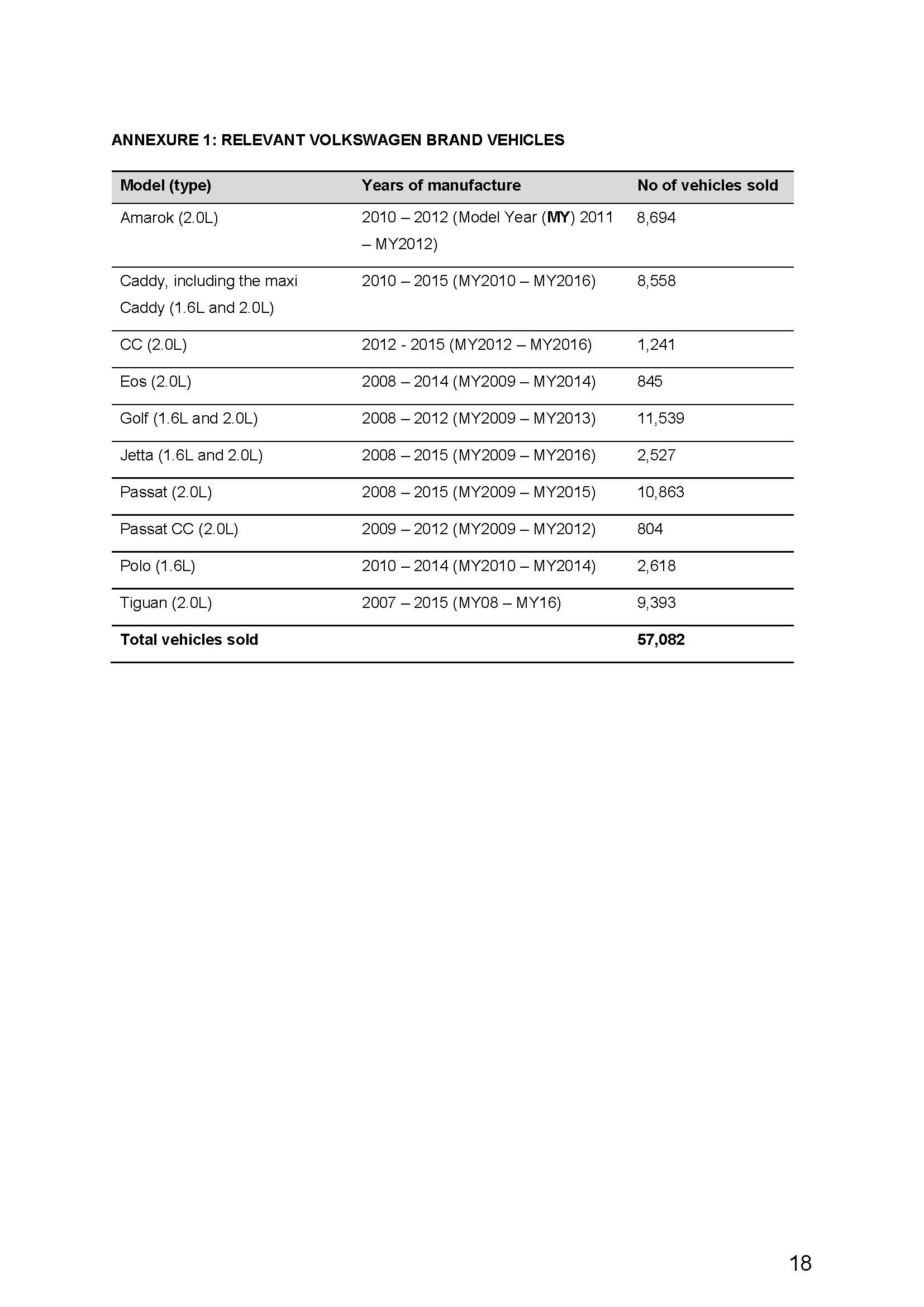

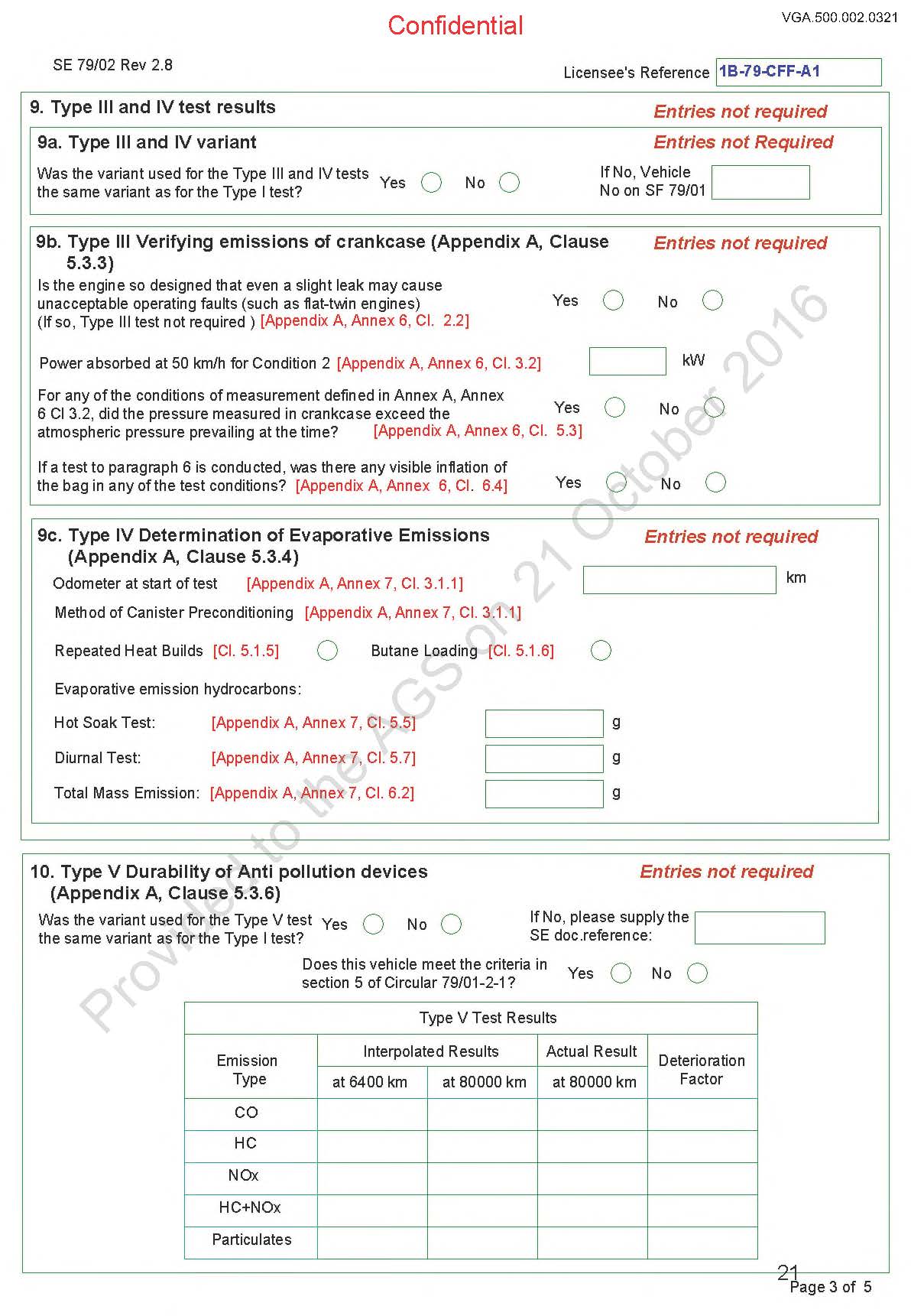

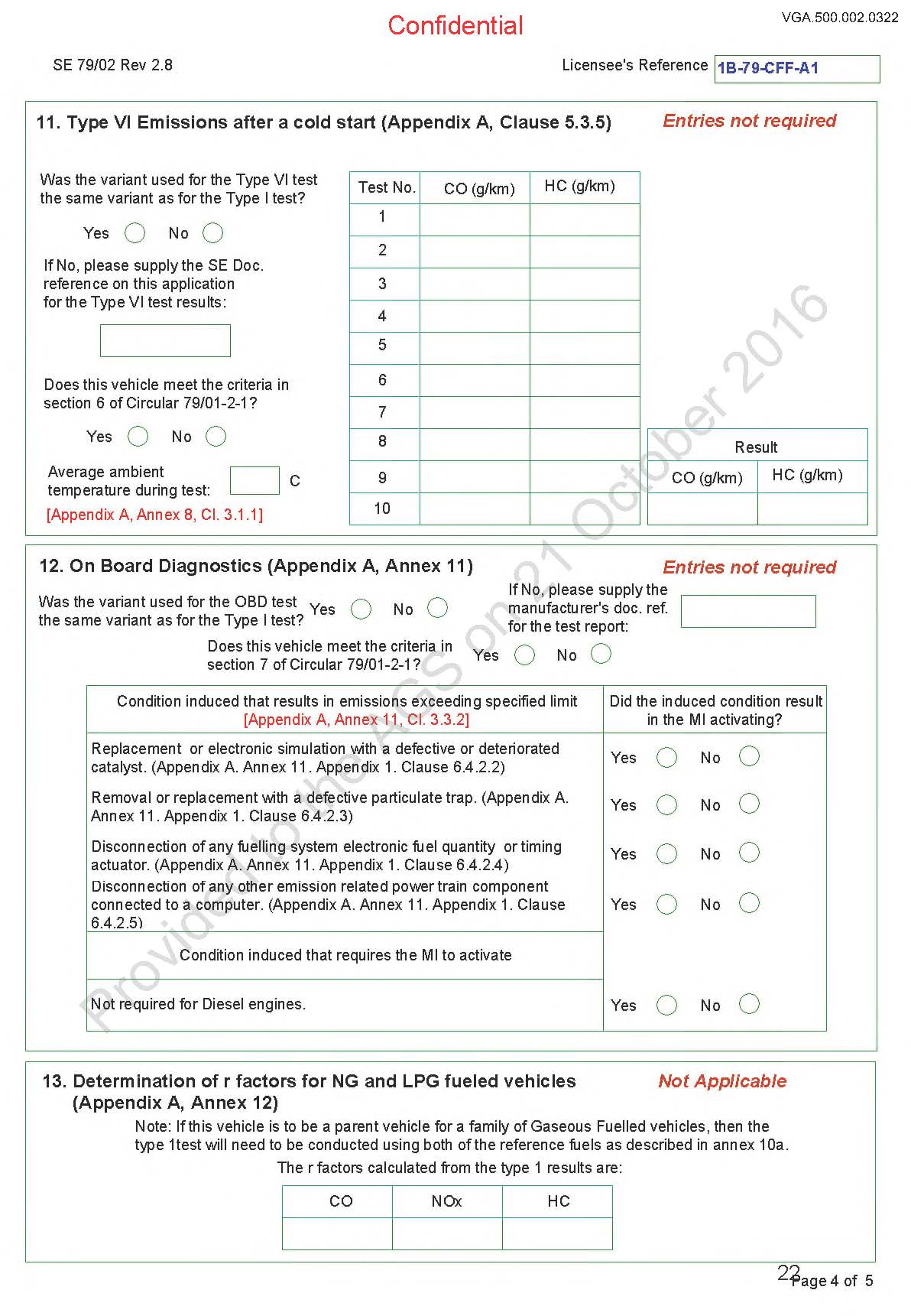

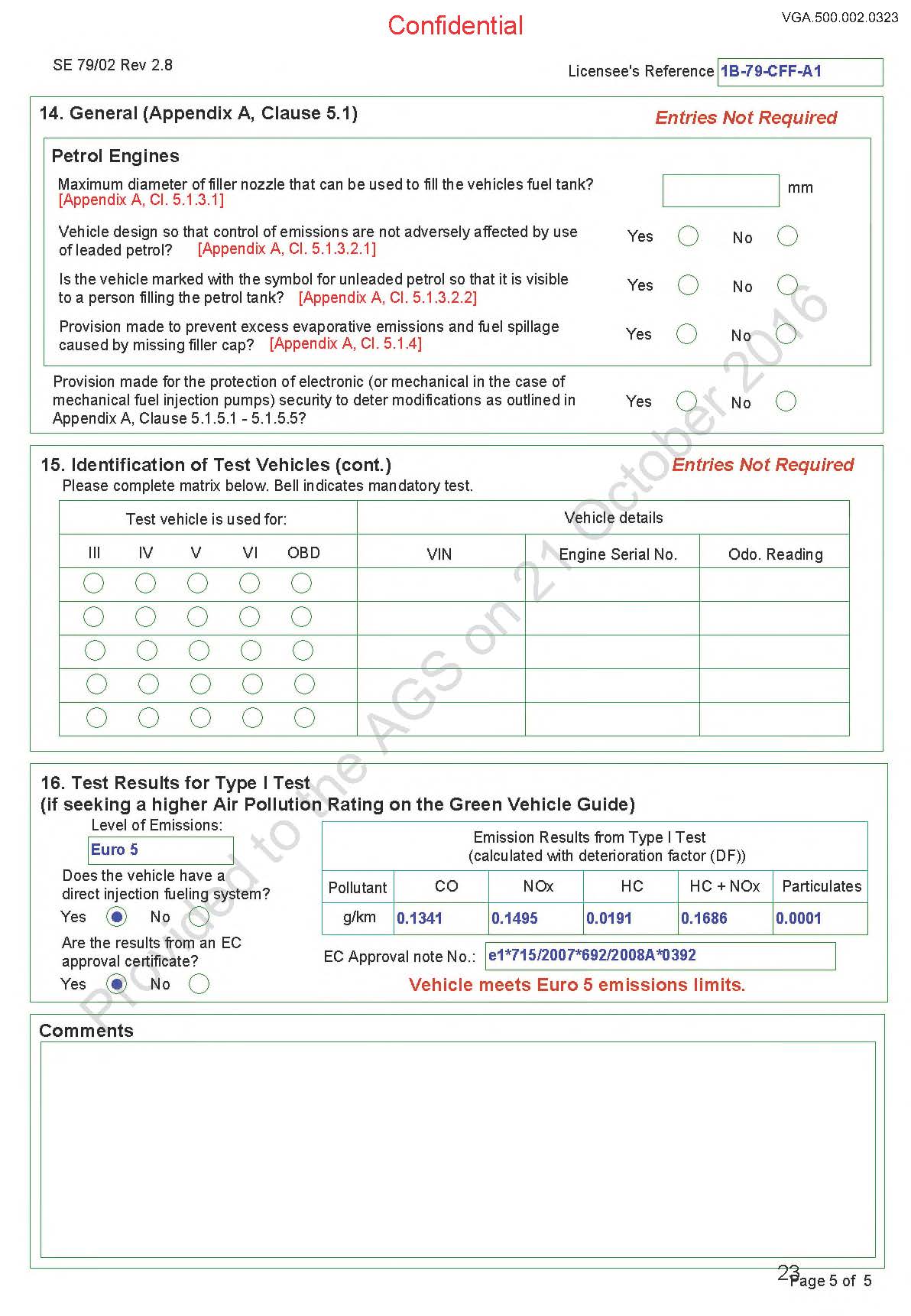

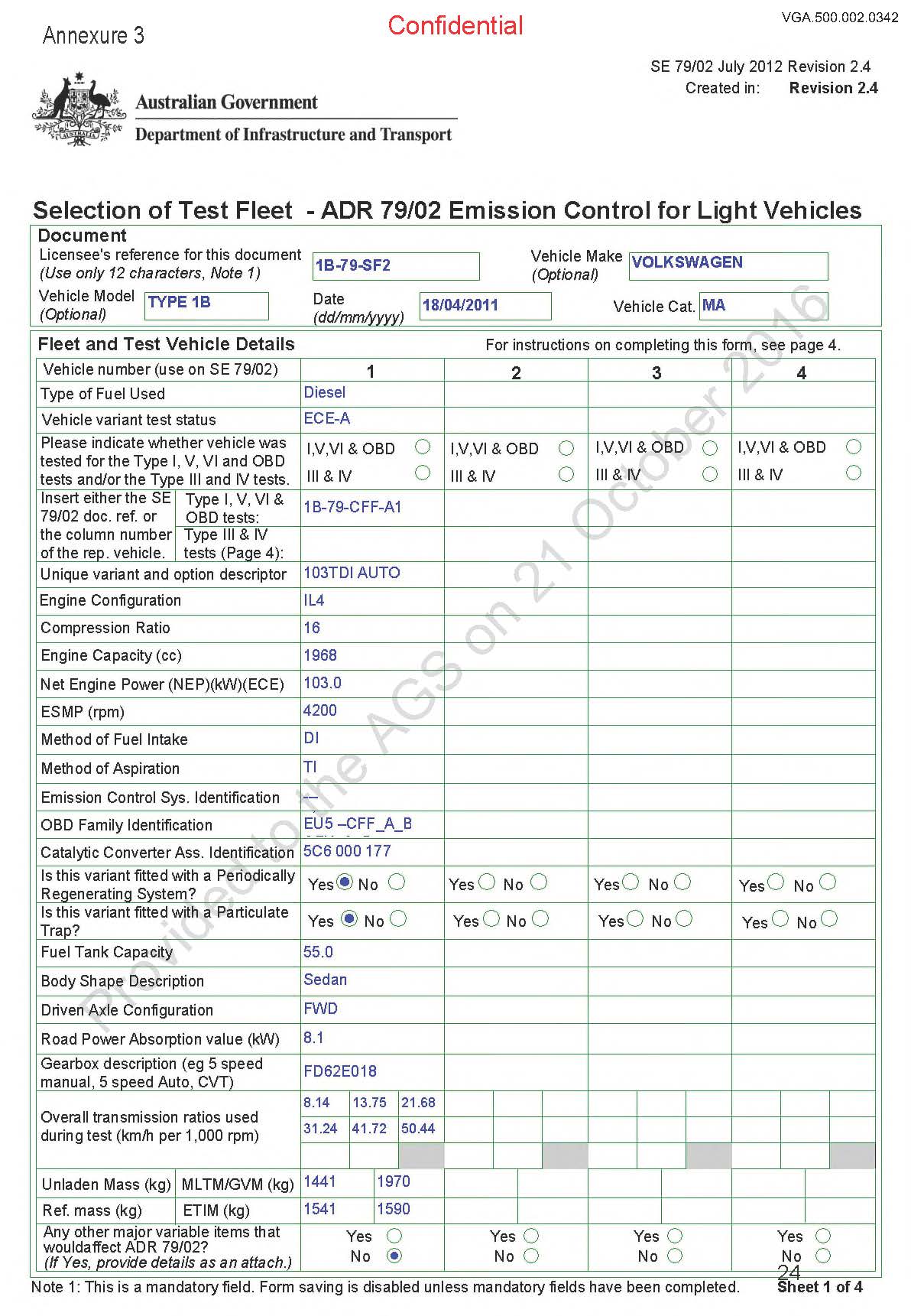

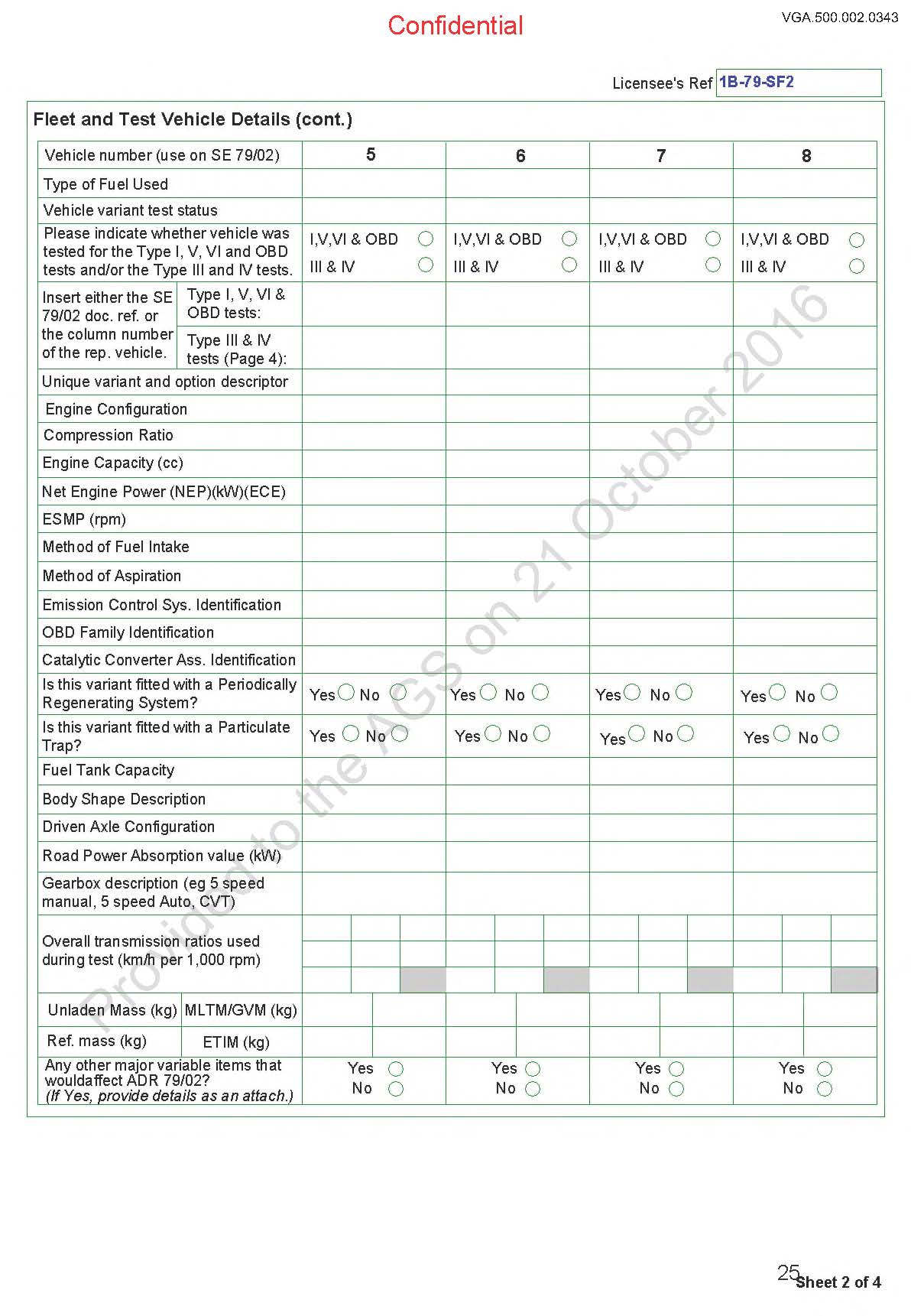

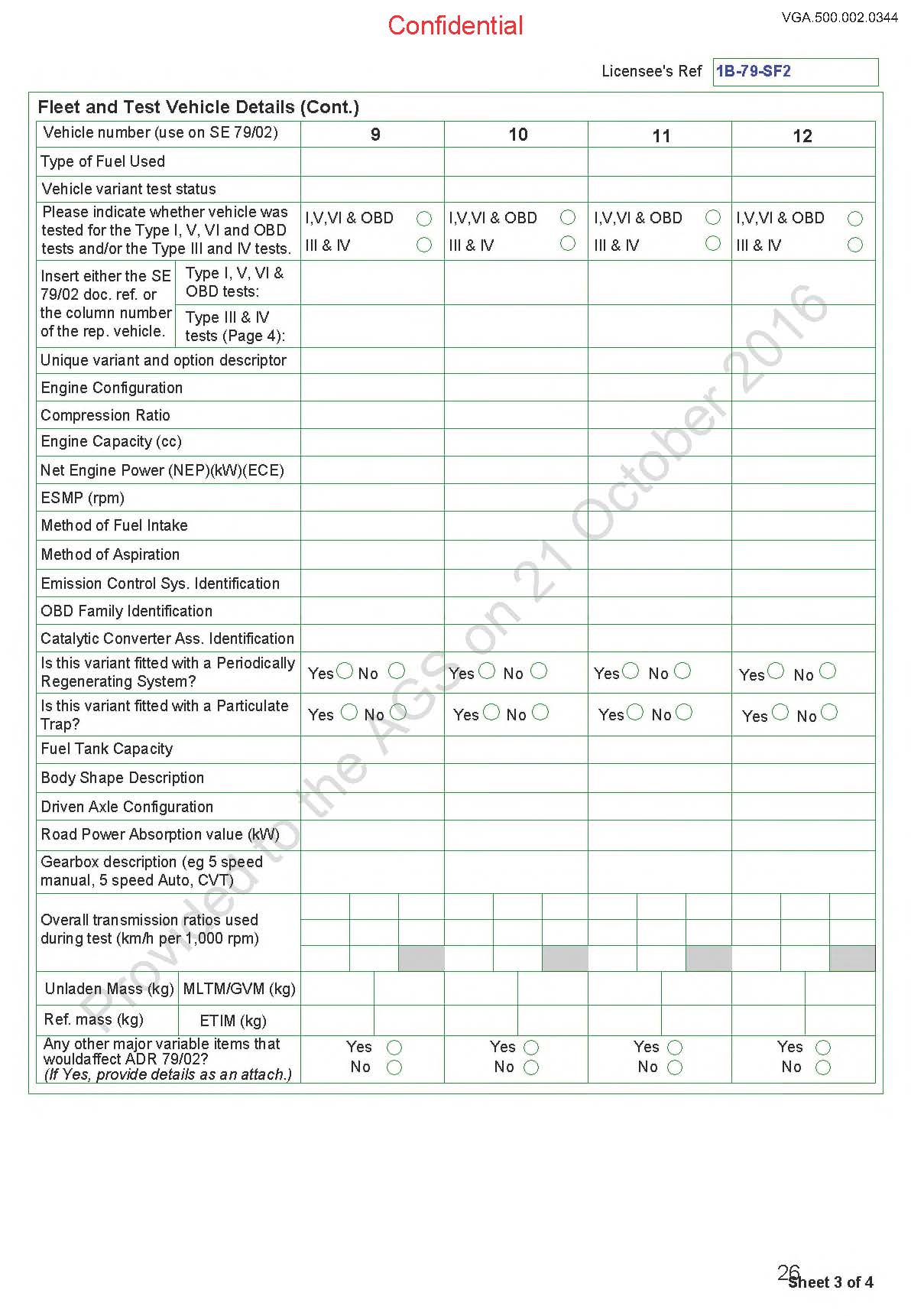

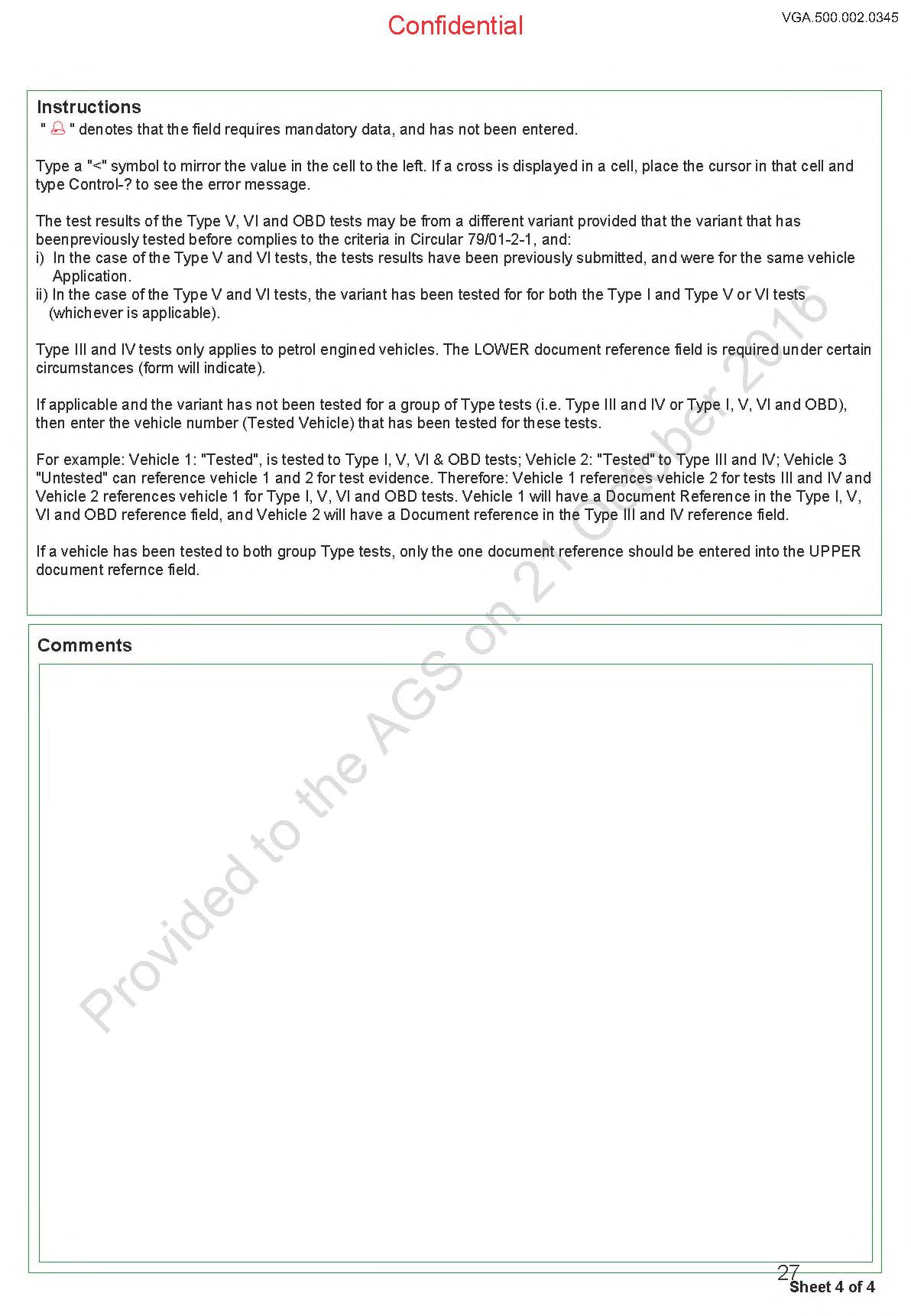

18. VWAG submitted the following information to the Delegate from time to time in the ordinary course of business in accordance with the procedure established by the Minister under s 10 of the MVSA:

18.1. an Application for Compliance Approval form

18.2. for some ADRs, including ADR 79, a Selection of Test Fleet form

18.3. a Summary of Evidence form for each ADR applicable to the vehicle type

in order to obtain approvals under s 10A for identification plates to be placed on VW branded vehicles of various types.

19. In submitting the forms set out at paragraph 18 above, VWAG submitted UNECE approval numbers as evidence of compliance with ADR 79.

20. On the basis of the information submitted to the Delegate identified in paragraphs 18 and 19 above VWAG was granted identification plate approvals under s 10A in respect of the Relevant Vehicles imported into and sold in Australia in the Sales Period.

21. From time to time, VWAG submitted further Summary of Evidence and Selection of Test Fleet Forms with UNECE approval numbers to the Delegate to amend the identification plate approvals, including to make them referable to a newer ADR 79 standard.

22. On the basis of the information submitted to the Delegate identified in paragraph 21 above VWAG was granted amended identification plate approvals under s 10A in respect of certain of the Relevant Vehicles imported into and sold in Australia in the Sales Period.

23. There were 171 relevant submissions by VWAG of the information which is referred to in paragraphs 18, 19 and 21 above. Representative examples of each of a Summary of Evidence form and Selection of Test Fleet form are Annexure 2 and Annexure 3.

24. The Commonwealth, through DIRD, published the identification plate approvals issued under s 10A in respect of the Relevant Vehicles on the publically available RVCS website along with certain other information about the Relevant Vehicles, including their vehicle specifications.

25. During the Sales Period, each identification plate approval issued to VWAG in respect of the Relevant Vehicles came with conditions that included:

The Licensee must not place Identification Plates on vehicles which do not comply with all of the Australian Design Rules specified in Schedule 4.

The Licensee shall not without the prior approval of the Administrator affix the Identification Plate to a vehicle that is in any way different from the vehicle described in the final form of the application for this Approval. The application includes reports and other documents relating to the application.

The Licensee shall by detailed quality control and test ensure continuing compliance with such of the Australian Design Rules specified in Schedule 4.

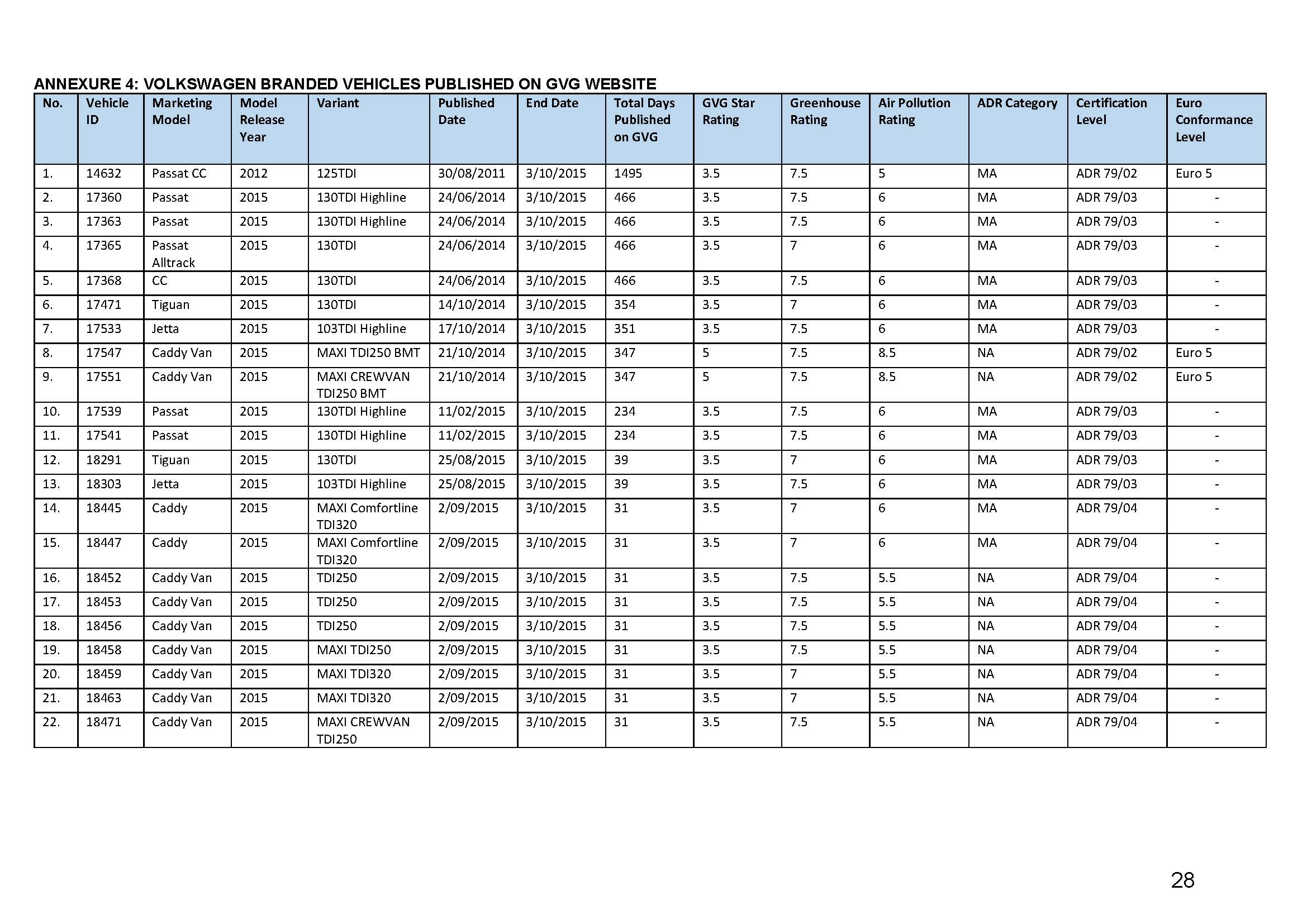

88 VWAG also admitted that, by making applications to have many of its diesel powered vehicles included in the Commonwealth’s Green Vehicle Guide (GVG) website, it made additional false representations to the Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (Commonwealth) (DIRD) in the terms of the admissions set out at pars 68 to 71 of the SOAF as follows:

68. During the Sales Period, VWAG applied:

68.1. on at least 162 occasions, for certain Volkswagen branded vehicles identified in the spreadsheets at Annexures 4 and 5 to be published on the GVG Website; and

68.2. on at least 140 occasions, for certain Volkswagen branded vehicles identified in the spreadsheet at Annexure 5 to be published on the GVG Website with a higher air pollution rating.

and in so doing, provided information regarding the Relevant Vehicles to DIRD for publication on the GVG Website.

69. During the Sales Period, the GVG Website was accessed by approximately 500,000 distinct users (noting that such access was not necessarily directed at obtaining information pertaining to the Relevant Vehicles).

70. By making the applications specified in paragraph 68.1 above through the online administration portal on the GVG Website administered by DIRD, VWAG falsely represented to DIRD on at least 162 occasions in respect of the Volkswagen-branded vehicles identified in Annexures 4 and 5 to this Statement of Agreed Facts that the motor vehicles the subject of each such application complied with ADR 79 as in force at the relevant time when those vehicles did not so comply because:

70.1. Each of the said vehicles was fitted with the Two Mode software described above; and

70.2. If the said vehicles were subjected to an NEDC Type 1 test while operating in Mode 2, thereby substantially replicating the mode that would be activated when the vehicles were driven on the road outside of the operating conditions of the NEDC, the said vehicles would have exceeded the NOx emission limits prescribed by ADR 79

resulting in the said vehicles obtaining ratings on the GVG Website which they would not have obtained had the said false representations not been made with the consequence that, on each of the 162 occasions referred to above, VWAG made a false representation as to the composition, standard or grade of the said vehicles the subject of the listing application in each case and thereby, on each such occasion, contravened s 29(1)(a) of the ACL.

71. By making the additional applications specified in paragraph 68.2 above through the online administration portal on the GVG Website, VWAG falsely represented to DIRD on at least 140 occasions in respect of the Volkswagen-branded vehicles identified in Annexure 5 to this Statement of Agreed Facts that the motor vehicles the subject of each such application complied with a later, more stringent version of ADR 79 than was applicable to the vehicles at the relevant time when those vehicles did not so comply with that more stringent version because:

71.1. Each of the said vehicles was fitted with the Two Mode software described above; and

71.2. If the said vehicles were subjected to an NEDC Type 1 test while operating in Mode 2, thereby substantially replicating the mode that would be activated when the vehicles were driven on the road outside of the operating conditions of the NEDC, the said vehicles would have exceeded the NOx emission limits prescribed by ADR 79

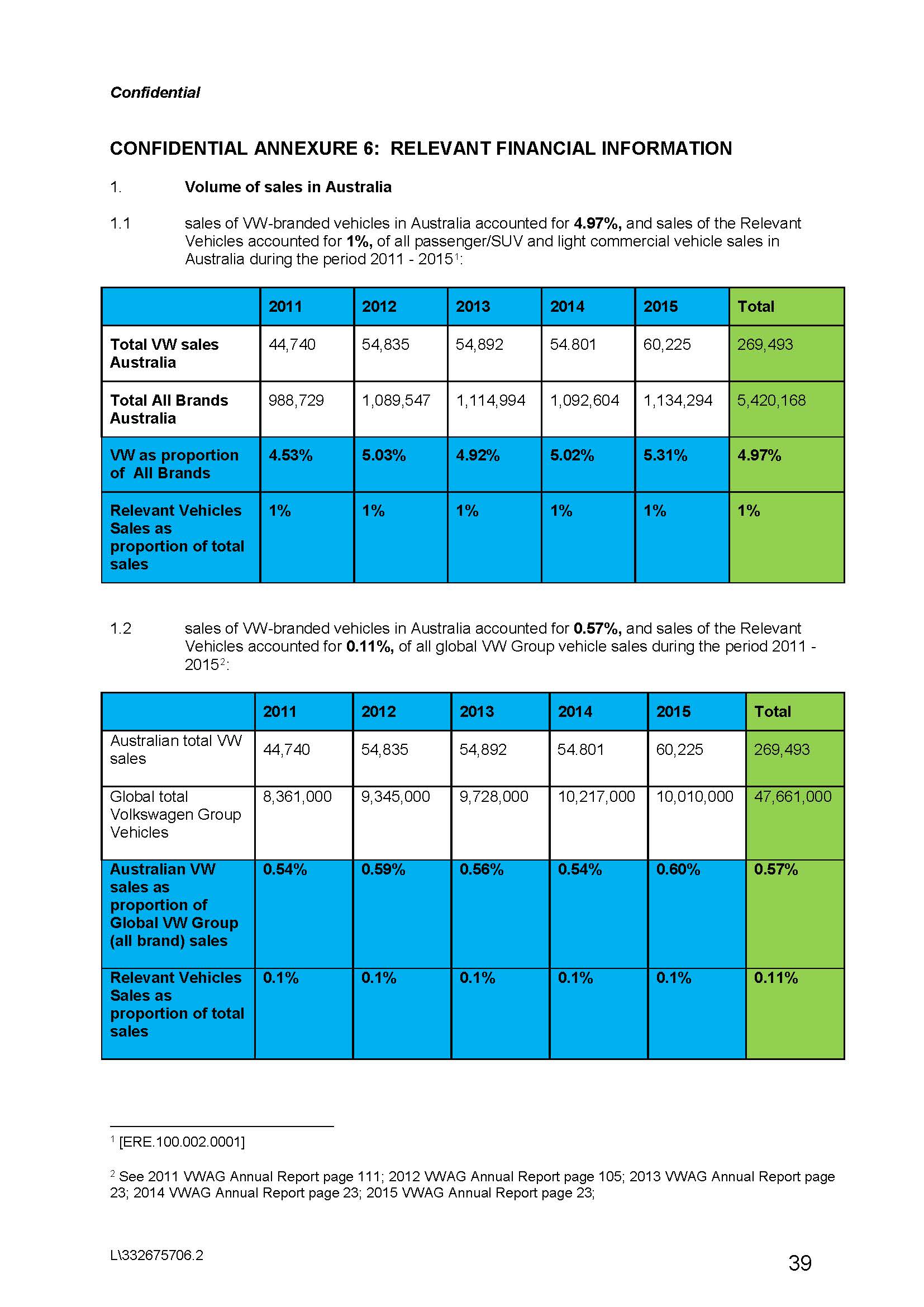

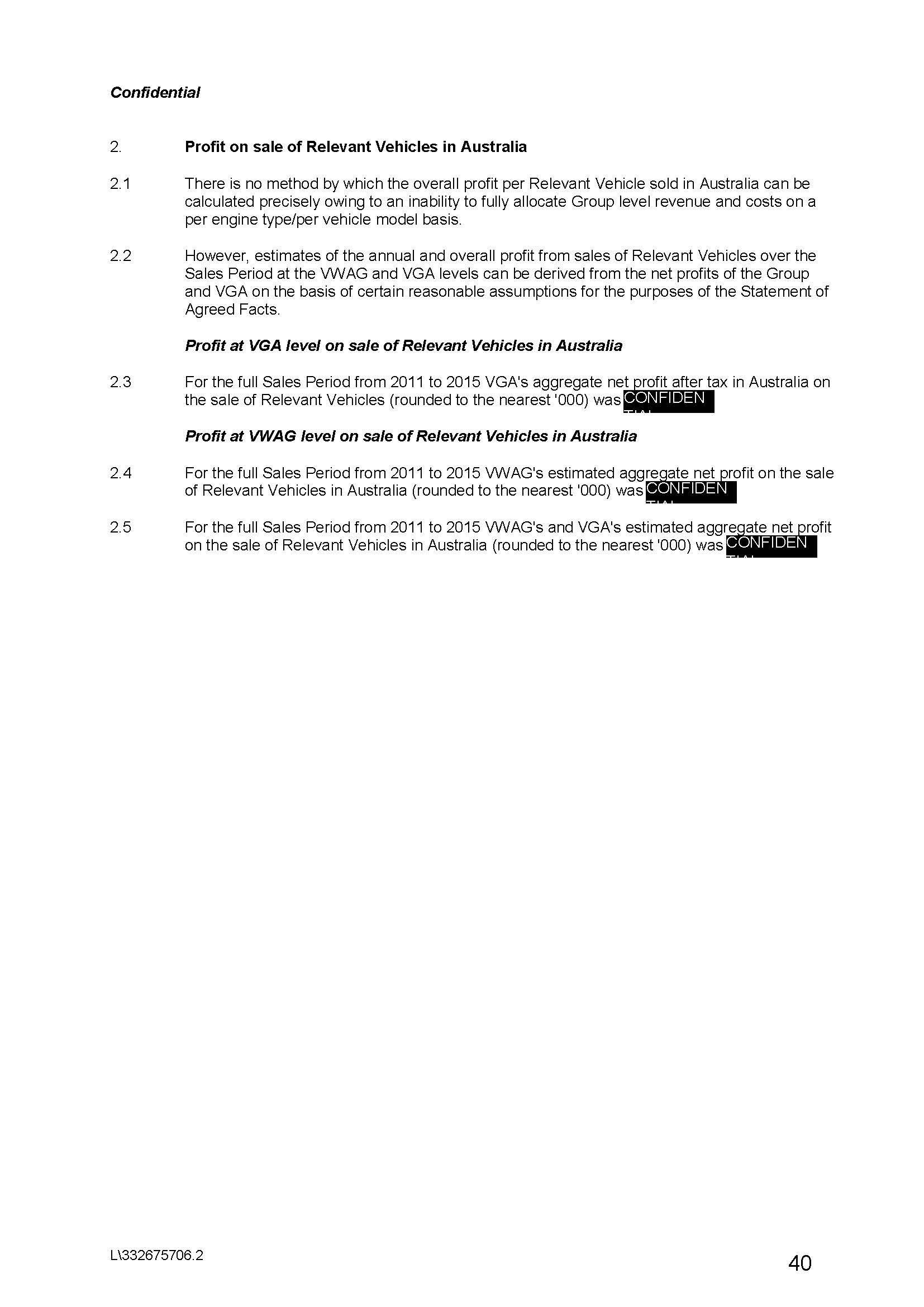

resulting in the said vehicles obtaining higher air pollution ratings on the GVG Website than they would have obtained had the said false representations not been made with the consequence that, on each of the 140 occasions referred to above, VWAG made a false representation as to the composition, standard or grade of the said vehicles the subject of the listing application in each case and thereby, on each such occasion, contravened s 29(1)(a) of the ACL.