FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Findex Group Limited v McKay [2019] FCA 2129

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The proceeding be dismissed.

2. The applicants pay the first respondent’s costs.

3. The parties be granted leave to apply to vary order 2 by filing and serving submissions (of no more than 5 pages) in support of any variation they contend for within 7 days of these orders.

4. In the event that a party applies to vary order 2 by filing and serving submissions under order 3:

(a) The opposing party or parties is/are to file and serve any submissions in response (of no more than 5 pages) within 7 days of service on them of the submissions under order 3;

(b) The party or parties served with submissions under paragraph (a) of this order are to file and serve any submissions in reply (of no more than 3 pages) within 5 days of service on them of the first mentioned submissions.

5. The days from 21 December 2019 to 26 January 2020 (inclusive) are not to count in the calculation of the periods mentioned in orders 3 and 4.

6. The submissions referred to in Orders 3 and 4 should be easily legible using a font size of at least 12 points and one and a half line spacing throughout, including in any footnotes and annexures.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

STEWART J:

[1] | |

[11] | |

[11] | |

[21] | |

[27] | |

[30] | |

[36] | |

[38] | |

[45] | |

[47] | |

[49] | |

[52] | |

[52] | |

[60] | |

[82] | |

[88] | |

[89] | |

[89] | |

[97] | |

[99] | |

[101] | |

[103] | |

[120] | |

[127] | |

[134] | |

[144] | |

The reasonableness of the restraint provisions as between the parties | [153] |

[153] | |

[163] | |

[171] | |

Mr McKay’s additional contentions against the restraint provisions | [179] |

[187] | |

[188] | |

[206] | |

[209] | |

[225] | |

[232] | |

[241] | |

[245] |

1 The essential issues in this case concern alleged breaches by the first respondent, Mr McKay, of restraints in a shareholders’ agreement that governed the relationship between the shareholders of the second applicant, Civic Financial Planning Pty Ltd. For reasons that will shortly become apparent, I will refer to that company as New Civic.

2 Mr McKay was not himself a shareholder of New Civic. Rather, a trust that he controlled through its corporate trustee, Vandaman Pty Ltd (now in liquidation), was a shareholder. Vandaman is the second respondent. The claim against Vandaman is that Mr McKay’s alleged conduct was in breach of a contractual undertaking by Vandaman that he would not breach the restraints.

3 The applicants seek damages, declarations and injunctive relief.

4 The first applicant, Findex Group Ltd (previously Findex Australia Pty Ltd), is the owner of the shares in a number of other companies including the second to fourth applicants all or some of which operate, amongst other things, financial services businesses in Australia.

5 As indicated, the second applicant is New Civic.

6 The third applicant is Findex Services Pty Ltd. It served as a ‘service’ entity to the Findex group. Employees working across the group were employed by Findex Services, and it was the named entity in various service contracts across the group such as telephone and internet contracts and lease agreements.

7 The fourth applicant is Financial Index Australia Pty Ltd. It held the relevant Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL) through which financial services could be provided by authorised representatives.

8 At the commencement of the trial I gave the applicants leave to proceed with the proceeding against Vandaman under s 500(2) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) despite it being in voluntary liquidation: Findex Australia Pty Limited v McKay [2019] FCA 335. Vandaman did not appear at the final hearing, by its liquidator or otherwise.

9 There are eight issues requiring resolution:

Issue 1: was Mr McKay personally bound by the restraint provisions? That issue raises further issues. Did Mr McKay in signing the relevant agreement sign only for Vandaman or did he also sign it for himself personally? Alternatively, did Mr McKay by the conduct of the parties become bound to the terms of the shareholders’ agreement? Or, as a further alternative, is Mr McKay estopped from denying that he was bound by the shareholders’ agreement?

Issue 2: are the restraint provisions enforceable?

Issue 3: did Mr McKay breach the restraint provisions? This also raises an issue whether New Civic conducted the relevant business.

Issue 4: did the applicants suffer any loss? This is related to the issue that arises under issue 3, namely whether New Civic conducted the relevant business.

Issue 5: was all or part of the loss avoidable?

Issue 6: what loss, if any, did the applicants suffer?

Issue 7: did Mr McKay breach s 183(1) of the Corporations Act and should an injunction be ordered to prevent further breaches?

Issue 8: is there any liability of Vandaman?

10 Before turning to each of the issues it is convenient to address some of the background.

11 Mr McKay began working as a financial planner in about 1999.

12 In about February 2003, Mr McKay became one of five principals of Civic Financial Planning Pty Ltd ACN 103 941 313 (Old Civic). Old Civic was the trustee for the Civic Financial Planning Unit Trust. The other principals and the entities through which they held their units in the unit trust were William Waller (through Waller Pty Ltd), Dianne Dash (through DBDash Pty Ltd), Thomas Dawes (through Livengal Pty Ltd) and Howard Kemp (through Blarch Nominees Pty Ltd).

13 Mr McKay held his stake in Old Civic through Vandaman. Also in February 2003, Vandaman was registered in the ACT. Initially, the directors of Vandaman were Mr McKay and Ms Denise May McKay. Ms McKay ceased to be a director of Vandaman on 1 March 2013. Mr McKay was the sole director of Vandaman thereafter. Mr McKay and Ms McKay each own half of Vandaman’s shares.

14 The principals of Old Civic, in their capacity as financial advisers, were each authorised corporate representatives of Securitor Financial Group Ltd and provided financial advice under Securitor’s AFSL. Securitor was not a related body corporate of Old Civic. The business of Old Civic was conducted from premises in Fyshwick in Canberra. It was a financial planning and advisory business catering to private clients. Old Civic’s clientele were largely, though not exclusively, members of Commonwealth government superannuation schemes who were in or close to retirement.

15 In 2007, the principals of Old Civic made a decision to prepare the business for sale.

16 After several years of negotiations wfith different organisations, a decision was made to begin negotiations with Findex for the sale of the business. On or about 14 July 2009, a document titled “Non Binding Heads of Agreement Joint Venture Transaction” was signed by all the principals of Old Civic, including Mr McKay, on behalf of their stakeholder companies and Findex.

17 By March 2010, Findex was to be the buyer of the shares of a new company incorporated in the ACT to which the business of Old Civic was first to be transferred.

18 On 16 March 2010, the new company, Vandaman, Mr McKay and others executed a share sale agreement (which, for reasons that will become apparent, I will refer to as the first SSA). Mr McKay signed the first SSA twice, once as director of Vandaman and separately on his own behalf. Also on 16 March 2010, the new company, Vandaman, Mr McKay and others executed a shareholders agreement (which I will refer to as the first SHA). Again, Mr McKay signed the first SHA twice, once as director of Vandaman and separately on his own behalf.

19 That arrangement was subsequently abandoned and a new arrangement was agreed. On 21 May 2010, the new company, Findex, Vandaman, Mr McKay and others executed a deed of rescission pursuant to which the first SSA was rescinded.

20 Pursuant to the new arrangement, New Civic was incorporated in Victoria in April 2010 with a view to the business of Old Civic being transferred to that company prior to the shares of that company being transferred to Findex. The contractual arrangements that were put in place to effect the transaction are set out in detail below.

21 On 21 May 2010, each of the shareholding entities of the five principals of Old Civic, including Mr McKay’s Vandaman, as vendors and Findex as purchaser concluded a share sale agreement (SSA). Each of the five principals of Old Civic, including Mr McKay, and Old Civic itself were also parties to the SSA.

22 Under the terms of the SSA, immediately prior to completion the vendors would procure that New Civic acquired the legal and beneficial ownership of the business and assets (including all rights to receive the recurring income streams of the business) from Old Civic. The “Business” meant the business carried on as at the date of the agreement by Old Civic under the name “Civic Financial Planning” of providing “Financial Services” and selling “Financial Products”.

23 Further, the vendors warranted that the assets to be purchased by New Civic from Old Civic would include the “Clients”, the “Client Files”, the “Records”, and any “Work In Progress”. “Clients” meant all of the financial planning clients of the business as at completion including those persons identified on the “Client Register” (being the list of clients in Schedule 3 to the SSA), including all right, title and interest of Old Civic.

24 The arrangement was that prior to completion, the vendors would be the owners of the share capital of New Civic. The vendors (including Vandaman) would sell 60% of the share capital of New Civic to Findex on completion for a purchase price of $11 million (less certain amounts).

25 Clause 5.4 of the SSA was in the following terms:

5.4 Shareholders Agreement

At Completion, each of the parties must execute the Shareholders Agreement in counterparts so that the Vendors, the Company and the Purchaser are each provided with a duly executed version of the Shareholders Agreement.

26 “Shareholders Agreement” as referred to in that clause was defined in the SSA to mean “the shareholders agreement in the form set out in Schedule 6, or such other form as the parties agree in writing”. The execution page of the prospective shareholders’ agreement in Schedule 6 to the SSA had a specific place for the director of each of the Old Civic shareholdings entities, including Vandaman, to sign, but did not contain a further and separate place for each of the principals of those entities, including Mr McKay in respect of Vandaman, to sign on their own behalf.

27 On 31 May 2010, Old Civic as vendor, New Civic as purchaser, each of the shareholding entities in Old Civic (i.e. including Vandaman) and each of their principals (i.e. including Mr McKay) concluded a business sale agreement (BSA). Under the BSA, Old Civic sold its financial planning business to New Civic for a purchase price of $18 million. “Business” was defined to mean the business conducted by Old Civic from an address in the ACT that was known as Civic Financial Planning and included the goodwill of the business and the “Clients”. Completion of the sale occurred on 31 May 2010.

28 On or about 31 May 2010, Vandaman became the owner of 200 ordinary shares in New Civic of $18,000 each (total of $3,600,000). The other former shareholding entities in Old Civic held the balance of the shares.

29 On 1 June 2010, pursuant to the SSA outlined above, Findex acquired 60% of the share capital of New Civic. One-hundred and twenty of Vandaman’s 200 shares in New Civic were transferred to Findex, and in return Vandaman received consideration of approximately $2,152,647.40. Similar transfers were made by the other former shareholding entities in Old Civic to Findex.

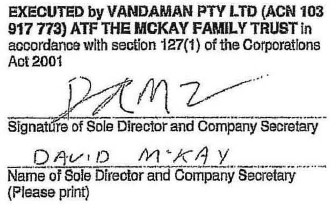

30 Also on 1 June 2010, New Civic and the shareholders of New Civic (i.e. Findex as to 60% and each of the shareholding entities in Old Civic as to the remainder) executed a shareholders’ agreement (SHA). As indicated, a central issue in the case is whether Mr McKay was bound personally as a party to the SHA. That arises, as will be seen, because the attestation provision to which he put his signature was expressed to be on behalf of Vandaman and was not expressed to be also on his own behalf.

31 I will return to some of the detail of the provisions of the SHA. For present purposes it suffices to identify that the SHA included two put/call options which provided for the transfer of the remaining 40% of the shares in two tranches of 20% each. The first option could be exercised two years and 60 days after the SHA was concluded, and the second option could be exercised three years and 60 days after the SHA was concluded.

32 The formula for determining the price of the shares under the second put/call option was amended in August 2011 by a written variation that was signed by Mr McKay expressly “in his own capacity and on behalf of Vandaman”. The applicants rely on this for their contention that even if Mr McKay was not initially personally bound to the SHA by his signature, then he became bound to it by his conduct.

33 It is not in dispute that the total consideration paid for all Vandaman’s shares in New Civic by the applicants was $2,991,586.80. The consideration was paid in part directly to Vandaman and in part to a third party at the direction and for the benefit of Vandaman. The total consideration was paid on the following dates:

As indicated, on 1 June 2010, $2,152.647.40 was paid for 120 shares;

On 1 August 2012, and following the exercise of the first put option in the SHA by the vendors, $400,000 was paid for 40 shares; and

On 29 August 2013, and following the exercise of the second put option in the SHA by the vendors, $438,939.40 was paid for 40 shares.

34 Clause 20 of the SHA contains the restraint provisions on which the applicants rely.

35 The total price that Findex paid for all the shares in New Civic was approximately $15 million of which approximately 85% was ascribed to the client list of Old Civic and 15% to goodwill.

36 Also on 1 June 2010, Financial Index entered into a licensee agreement with New Civic under which Financial Index appointed New Civic to provide “Financial Planning Services” to “Clients” through “Authorised Representatives” subject to Financial Index giving New Civic and each other authorised representative a “Letter of Authority”.

37 At this time, the relevant licensing entity for the principals changed from Securitor to Financial Index.

Mr McKay’s employment by Findex Services

38 On 1 June 2010, Mr McKay entered into an employment agreement with Findex Services and was employed as a financial adviser. He was appointed “branch manager” of New Civic. The evidence about the extent of Mr McKay’s duties as an employee and his performance in the role was an issue that took on some prominence during the trial but ultimately came to little in the parties’ closing submissions (see [185]-[186] below).

39 The employment agreement included a restraint in cl. 10 which was stated to protect Findex Services’ interests in, amongst other things, confidential information acquired during the course of the employment as well as client relationships. The restraint was, however, in favour of “Findex Group” which was defined as Findex Services and its affiliated entities including its related bodies corporate as defined in the Corporations Act. By it, Mr McKay was bound, amongst other things, not to interfere with the relationship between the Findex Group and its clients or to solicit any clients away from Findex Group. The restraint was said to operate for cascading periods of 12 months, six months and three months from the termination of Mr McKay’s employment and to be applicable in the cascading areas of Australia, the Australian Capital Territory and, finally, within 50 km of the Canberra GPO.

40 On 4 September 2012, Mr McKay was informed by way of letter from Tony Roussos, Chief Operations Officer of Financial Index, that he was to be made redundant and the effective date of termination of his employment with Findex Services was to be 7 September 2012. At the time of Mr McKay’s redundancy, Vandaman was a 4% minority shareholder in New Civic, and Vandaman was not permitted to sell those shares until August 2013 at the earliest – being the earliest time that the second put option could be exercised under the SHA.

41 Mr McKay did not provide any financial planning services anywhere from after his redundancy in September 2012 until he started doing so using the resources of StrategyOne Advice Network Pty Ltd. Mr McKay’s LinkedIn social media profile in August 2016 stated that he commenced as a senior financial planner with StrategyOne in October 2013, but he denies that that is correct. It is common ground that at least from January 2014 Mr McKay offered financial planning from an office at Chatswood in Sydney through StrategyOne and continued to do so between January 2014 and June 2015. He commuted weekly between his home in Canberra and his office at Chatswood in this period.

42 StrategyOne was a corporate authorised representative of Fitzpatrick’s Dealer Group which held the relevant AFSL. Mr McKay thus became an authorised representative of Fitzpatrick’s under whose licence he conducted his financial planning or advisory business.

43 From June 2015, Mr McKay commenced operating his financial planning business from Canberra. That was 2 years and 9 months after he was made redundant by Findex and 1 year and 10 months after Mr McKay (and the other vendors) exercised the put option which was when he no longer had any interest in the business.

44 From February 2014, Mr McKay started receiving letters on behalf of one or other of the Findex entities in which he was warned not to breach his restraint obligations and threats of litigation were made.

45 In the period from completion of the SSA (i.e. 1 June 2010) until Findex acquired all the shares in New Civic after the exercise of the second put option (i.e. August 2013), Financial Index collected all payments earned or received by New Civic, and Findex Services paid all of New Civic’s expenses such as employee salaries, rent and other operational costs. Findex then remitted the net revenue back to New Civic less the relevant operational expenses which it credited to Findex Services. This was the arrangement provided for in the SHA.

46 After the second put option had been exercised and Findex came to own all of the shares in New Civic, that arrangement ceased. Rather than make the net payments to New Civic each month, the funds were simply transferred directly from Financial Index to Findex.

47 The applicants contend that from at least January 2014, Mr McKay began communicating with a number of his former clients to lure them away from New Civic to StrategyOne by criticising Findex and offering to provide cheaper financial planning services. As a result of this conduct, the applicants allege that between July 2015 and August 2016, 29 clients ceased their business with New Civic causing the applicants to suffer financial loss. Mr McKay admits that from January 2014 he commenced financial planning in Chatswood in Sydney, but he denies any wrongdoing by that conduct.

48 In their second further amended statement of claim, the applicants allege that through his conduct during the relevant period, Mr McKay was in breach of the restraint provisions of the SHA as well as s 183 of the Corporations Act. The applicants also allege that Vandaman covenanted and undertook that Mr McKay would not engage in the conduct prohibited by the restraint provisions and was therefore also in breach of that undertaking and covenant. Consequently, the applicants say that they have suffered loss and damage and the respondents are liable to pay damages for loss suffered by them as a consequence of the conduct pleaded.

ISSUE 1: Was Mr McKay personally bound by the SHA?

49 The first issue to be dealt with is the question of whether Mr McKay was personally bound by the SHA and therefore obliged to comply with the restraint provisions contained in cl. 20.2 of the SHA. The question arises from the fact that Mr McKay did not sign the SHA expressly on his own behalf. He signed the SHA only once, as follows:

50 As with Mr McKay, each of the other principals of Old Civic signed only once, being expressly on behalf of their shareholding entity and not expressly on their own behalf.

51 As indicated, the applicants rely on three independent bases in submitting that Mr McKay was bound personally to the SHA. First, they say that he signed on his own behalf. Secondly, and alternatively, they say that he became bound to the SHA by conduct. Thirdly, and further alternatively, they say that he is estopped from denying that he was personally bound to the SHA.

Did Mr McKay sign for himself?

The applicable legal principles

52 Prima facie, the execution of the SHA by Mr McKay was as agent for Vandaman and not for himself. That arises from the express wording of the attestation provision, in particular the words “EXECUTED by VANDAMAN” and “Signature of Sole Director and Company Secretary”. The question is whether this is to be interpreted as being an attestation also by Mr McKay for himself.

53 In Scottish Amicable Life Assurance Society v Reg Austin Insurances Pty Ltd (1985) 9 ACLR 909 in the New South Wales Court of Appeal, an agency agreement between the appellant insurer and the first respondent company contained a personal indemnity provision for the directors of the company. The provision was mistakenly executed by the company in the same way as the main agreement was executed, and the question arose whether the indemnity constituted an indemnity given by the directors in their personal capacity.

54 Mahoney JA held (at 922) that the concept of execution would be satisfied by two things: the intention that, as the result of what is done, the document shall be operative as the document of the parties concerned; and that there be a sufficient authentication of the document as their document. The terms of the document which included the provision for the personal indemnity by the directors satisfied the first requirement, and the signatures on the document satisfied the second.

55 McHugh JA (at 923) held that the case depended on what the parties did and not what they intended to do when they signed the document. And what they did depends on the construction to be placed on the document which they signed. His Honour held that in some cases the contents of a document may indicate that the signatory is bound even though a qualification attaches to their signature. Expressly or by implication the body of the document may make it plain that the signatory is a party to the contract. As with Mahoney JA, McHugh JA found that the terms of the document made it clear that the directors were taken to have executed the document also in their personal capacity.

56 A possible difference between the approaches of Mahoney JA and McHugh JA is with regard to the inquiry into the signatories’ intention; is it a subjective enquiry or an objective enquiry? Giles J in Clark Equipment Credit of Australia Ltd v Kiyose Holdings Pty Ltd (1989) 21 NSWLR 160 (at 174B-D) understood the approach of Mahoney JA to also involve an objective enquiry with reference to the documents and the relevant surrounding circumstances. His Honour concluded that:

the proper approach is to inquire whether there is to be found an intention that the signatory be personally bound to the contract evidenced in the document, meaning thereby not a subjective intention but an intention to be found objectively, notwithstanding a qualification attached to the signature. That intention, or lack thereof, is to be found upon the construction of the document as a whole, including but not being limited to the qualification attached to the signature, in the light of the surrounding circumstances to the extent to which evidence thereof is permissible. The inquiry is not limited to consideration of the signature and its qualification in order to determine whether or not the signature indicates an assent to be personally bound.

57 That approach has been followed in numerous subsequent cases: Deeks v Little Moreton Trading Pty Ltd (1995) 14 WAR 58 at 62-63 per Rowland J and 67 per Steytler J; Follacchio v Harvard Securities (Aust) Pty Ltd [2002] FCA 1067 at [7] per Finkelstein J; Harris v Burrell & Family Pty Ltd [2010] SASCFC 12 at [20] per Doyle CJ, Bleby and Sulan JJ agreeing; Padstow Corporation Pty Ltd v Fleming (No 2) [2011] NSWSC 1572; 86 ACSR 636 at [20] per Gzell J; Alonso v SRS Investments (WA) Pty Ltd [2012] WASC 168 at [51]-[52] per Edelman J; Singh v De Castro; Dhaliwal v De Castro; Brar v De Castro [2017] NSWCA 241 at [86] per Sackville AJA; Macfarlan and Gleeson JJA agreeing.

58 It is uncontroversial that interpreting a commercial document requires attention to the language used by the parties, the commercial circumstances which the document addresses, and the objects which it is intended to secure: McCann v Switzerland Insurance Australia Ltd [2000] HCA 65; 203 CLR 579 at [22] per Gleeson CJ. Preference is given to a construction supplying a congruent operation to the various components of the whole: Wilkie v Gordian Runoff Ltd [2005] HCA 17; 221 CLR 522 at [16] per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow and Kirby JJ.

59 Further, the meaning of the terms of a commercial contract is to be determined by what a reasonable businessperson would have understood those terms to mean. That approach requires consideration of the language used by the parties, the surrounding circumstances known to them and the commercial purpose or objects to be secured by the contract. Appreciation of the commercial purpose or objects is facilitated by an understanding of the genesis of the transaction, the background, the context and the market in which the parties are operating: Electricity Generation Corporation v Woodside Energy Ltd [2014] HCA 7; 251 CLR 640 at [35] per French CJ, Hayne, Crennan and Kiefel JJ.

60 There is no doubt that Mr McKay appended his signature to the SHA and thereby authenticated the document. The question is whether, objectively speaking, it is to be concluded that he intended that in signing in the restricted way in which he did he nevertheless signed for himself.

61 There are a number of indications within the SHA itself that it was intended that each of the principals, including Mr McKay, would be personally bound.

62 First, Mr McKay is named as a “party” to the SHA, as is each of the other principals. Together they are defined and referred to in the SHA as “the Covenantors”. This is a strong factor: Mr McKay signed a document which explicitly states that it is an agreement and that he is a party to that agreement in his personal capacity. In the absence of an unequivocal restriction to the signature, such as “Signed only for the company and not for himself” or similar, that goes a long way to establishing that in signing the agreement Mr McKay signed it also on his own behalf.

63 Second, recital E in the SHA states that “[t]he Covenantors are associated with the Non-Findex Shareholders and have agreed to enter into certain obligations in favour of other parties to this agreement”. Then, as anticipated by recital E, cl. 6 of the SHA places certain express obligations on each Covenantor – essentially obligations of cooperation and best endeavours and also not to use any confidential information or intellectual property of New Civic in a way which does or is reasonably likely to damage New Civic or the shareholders. Thus, not only was Mr McKay a named party, but the document places express obligations on him as a party.

64 Third, under cl. 20.2 of the SHA, which contains the restraint provisions, “each of the applicable Shareholders and the Covenantors covenants with and undertakes to, the Other Parties” not to do various specified things. The details of the restraint provisions and their enforceability will be dealt with further below, but in the meantime it is merely that they expressly purport to restrain Mr McKay from doing various things that is relevant because it shows the intention of the Covenantors that he be personally bound by the agreement.

65 Fourth, Mr McKay was a party to the SSA, being listed as one of the parties defined as the “Vendors” in Schedule 1, and he signed it unequivocally for himself. As indicated above, cl. 5.4 of the SSA provided that “each of the parties must execute the Shareholders Agreement in counterparts so that the Vendors, the Company [i.e. New Civic] and the Purchaser [i.e. Findex] are each provided with a duly executed version of the Shareholders Agreement”. “Shareholders Agreement” was in turn defined as the agreement in the form set out in Schedule 6 “or such other form as the parties agree in writing”. That draft SHA set out in Schedule 6 provided for each of the principals including Mr McKay to be parties to it.

66 On behalf of Mr McKay, attention was drawn to the fact that that draft, like the ultimate version that was signed, did not make express provision for each of the principals including Mr McKay to sign it. However, that does not seem to me to be significant. What is significant in this case and those like it is the attestation to which the signature in question is actually applied, including its manner of application and any qualifications stated. As the draft SHA that was Schedule 6 to the SSA was not actually signed, no particular significance can be given to the provisions for attestation. Principal significance must be given to the operative terms of the draft, which provide for Mr McKay to be a party in his personal capacity. Moreover, as indicated, under cl. 5.4 of the SSA he became contractually obliged to execute, on his own behalf, the SHA, indicating the intention of the relevant parties that he would be personally bound to the SHA.

67 The different parts of the SHA that was signed would be quite incongruent, contrary to the principles of construction identified above, if it was to be construed in such a way that there were express provisions by which Mr McKay would be a party to the agreement and he undertook contractual obligations if the attestation provision meant that only his company, Vandaman, was a party and not him.

68 Thus, the express provisions of the SHA make it very clear that it was intended that Mr McKay would be personally bound to the SHA.

69 Mr McKay relied on certain events during the process of negotiation of the SHA which, he says, demonstrate that it was the deliberate choice of the parties that he (and, presumably, the other principals) would not be personally bound to the SHA.

70 In that regard, there was a time during the drafting process when there were attestation provisions for each of the principals to sign twice, once for themselves and once on behalf of their shareholding entities. That must have been a draft subsequent to the draft that was Schedule 6 to the SSA. However, on 23 April 2010 a solicitor acting for Findex in the negotiation and settlement of the SHA sent by email a copy of the then draft SHA to a solicitor acting for the vendors, i.e. Mr McKay and the other principals. The email was copied to Matthew Games, the Chief Financial Officer of Findex. The email stated that the solicitor had “amended the execution pages for your clients where they have only one director”.

71 However, the draft SHA showed that the following two changes were made. First, where previously each of the shareholding entities had a place for two signatures, one by a director and the other by a “Director/Company Secretary”, the new draft provided for only one signature being that of the “Sole Director and Company Secretary”. Secondly, where previously there was a place for each of the principals, including Mr McKay, to sign in their own capacities, the new draft had those signature provisions deleted.

72 It is only the first of the above two amendments that addresses the point that was raised in the covering email from the solicitor.

73 The amended form of the signature pages is the form in which they were ultimately signed.

74 I do not accept the submission that the above facts show that it was the conscious and deliberate intention of the parties that Mr McKay (and the other principals) would not be personally bound to the SHA. It is apparent that the amendments that were made to the draft went beyond what was indicated in the email. The intention was apparently merely to change the provisions for the companies’ attestation in respect of the companies that had only one director, whereas the provisions for the principals’ attestation were also deleted. That deletion is more consistent with simple error than it is with conscious choice because if the principals were not going to be parties that would be incongruent with the express provisions of the document, as I have said.

75 In any event, it is the version of the contract actually executed that is determinative; the earlier drafts merge in the executed version. It is not to the point to scrutinise earlier drafts in search of the parties’ subjective intentions and expectations. As it was put in Byrnes v Kendle [2011] HCA 26; 243 CLR 253 at [53] per Gummow and Hayne JJ, the question to be answered is “What is the meaning of what the parties have said?”, rather than “What did the parties mean to say?” French CJ agreed with and adopted the reasons of Gummow and Hayne JJ at [17]. Heydon at Crennan JJ said at [98]:

A contract means what a reasonable person having all the background knowledge of the ‘surrounding circumstances’ available to the parties would have understood them to be using the language in the contract to mean. But evidence of pre-contractual negotiations between the parties is inadmissible for the purpose of drawing inferences about what the contract meant unless it demonstrates knowledge of ‘surrounding circumstances’.

(Citations omitted.)

76 On behalf of Mr McKay reliance was placed on the conclusion in Clark Equipment that the directors were not personally bound. That was said to be because of (1) the form of the signing clause, (2) the fact that the same form of words had been used for a person who no one contended was personally bound, (3) the addition of the common seal of the company in question which pointed to the directors having signed simply in that capacity, and (4) the same form of words and the same signatures being found in a separate document where there was no provision for personal responsibility. The difficulty for Mr McKay, however, is that only the first of those four elements is present in the present case. Little analogy can accordingly be drawn with the case of Clark Equipment.

77 The point was also made that Mr McKay was not asked any questions in cross-examination regarding the non-execution of the SHA in his personal capacity. However, given that the relevant enquiry is an objective one and not a subjective one, there is nothing in this: any questions as to Mr McKay’s actual intention would have been liable to be disallowed on grounds of relevance.

78 The same is true of Mr McKay’s reliance on the evidence of Mr Games that he was entrusted by the board of Findex to ensure that the contractual documentation was completed properly and that the accuracy of contractual documents is a critical part of any successful acquisition. None of that assists in construing the SHA itself, and neither does it form part of the surrounding circumstances known to the parties. Mr Games’ subjective understanding of what was intended is simply irrelevant. See Codelfa Construction Pty Ltd v State Rail Authority of NSW [1982] HCA 24; 149 CLR 337 at 352 per Mason J.

79 Mr McKay also relied on cl. 28.7(b) of the SHA which provided that the agreement “is not binding on any party unless one or more counterparts have been duly executed by, or on behalf of, each person named as a party to this agreement and those counterparts have been exchanged.” Mr McKay relied on Equity Nominees Ltd v Tucker [1967] HCA 22; 116 CLR 518 which considered whether a deed of guarantee executed by a company had been duly executed. However, that case turned on the requirements of the corporate guarantor’s articles of association which prescribed the manner in which deeds were to be executed. This is not such a case.

80 Consideration of cl. 28.7(b) of the SHA merely directs one back to the question of whether the SHA was “duly executed by” Mr McKay. It does not assist in answering that question.

81 Mr McKay also submitted that there was no consideration in return for any promise by Mr McKay to be personally bound to the SHA. However, as correctly submitted on behalf of the applicants, it is not necessary that any consideration move to Mr McKay; the considerable consideration paid by the applicants to the shareholding entities fulfils the requirement for consideration. That is because the rule is that consideration must move from the promisee, but it need not move to the promisor: Pico Holdings Inc v Wave Vistas Pty Ltd (formerly Turf Club Australia Pty Ltd) [2005] HCA 13; 214 ALR 392 at [66] per Gleeson CJ, McHugh, Gummow, Hayne and Heydon JJ.

82 In view of my conclusion that Mr McKay is personally bound as a party to the SHA, and hence to the restraint provisions, on account of the fact that he is to be taken as having signed it for himself, it is not necessary to consider in any detail the other bases on which the applicants say that Mr McKay is bound personally by the SHA. However for completeness, it is sufficient to say that I find both of the applicants’ alternative arguments persuasive.

83 In particular, the applicants’ first alternative ground argues that it is to be inferred from the parties’ conduct that Mr McKay was a party to the SHA either at the time he signed it or by no later than 4 August 2011, being the date on which he executed a variation to the SHA expressly in his own capacity and on behalf of Vandaman (see [32] above).

84 It is uncontroversial that post contractual conduct may not be used to aid the construction of a contract: Agricultural and Rural Finance Pty Limited v Gardiner [2008] HCA 57; 238 CLR 570 at [35] per Gummow, Hayne and Kiefel JJ. However, post contractual conduct is admissible on the question of whether a contract was formed, and who the parties are to a contract: Brambles Holdings Ltd v Bathurst City Council [2001] NSWCA 61 at 163-164 per Heydon JA.

85 In Tomko v Palasty [2007] NSWCA 258, Einstein J (Mason P agreeing) said at [68]:

subsequent communications may legitimately be used against a party as an admission by conduct of the existence or non-existence, as the case may be, of a subsisting contract, where an issue concerns whether a particular person was a party to that contract.

86 In Palasty, the appellant had made “clear and unequivocal statements which constitute admissions” and which supported the conclusion that a particular company was a party to the loan contract. Similarly, Mr McKay made a clear and unequivocal statement that he was a party to the SHA when he signed the agreement to vary that contract on 15 August 2011 “in his own capacity and on behalf of Vandaman”. This conduct clearly demonstrates Mr McKay’s adoption of the SHA for himself as a party.

87 In their second alternative argument, the applicants rely on the principle of estoppel in pais (conventional estoppel) and, alternatively, equitable estoppel to say that even if as a matter of contract law Mr McKay was not a party to the SHA, he ought to be estopped from denying that he is bound by the restraint provisions. There is clear evidence that all parties to the SHA, including Mr McKay, adopted the assumption that he was a party the SHA and the detriment to the applicants if Mr McKay was now permitted to depart from that assumption is substantial.

ISSUE 2: Are the Restraint Provisions enforceable?

88 As indicated above, Mr McKay says that in the event that he is bound to the restraint provisions, they are in any event unenforceable. It is to that issue that I now turn.

Principles governing the enforceability of restraints

General principles on enforceability

89 Borrowing from McHugh v Australian Jockey Club Ltd [2014] FCAFC 45; 314 ALR 20 at [4], the relevant principles governing the question of whether a restraint of trade is enforceable are the following.

90 At common law all interferences with individual liberty of action in trading and all restraints of trade themselves, if there is nothing more, are contrary to public policy and therefore void: Nordenfelt v Maxim Nordenfelt Guns & Ammunition Co Ltd [1894] AC 535 at 565 per Lord Macnaghten.

91 Such a restraint will nevertheless be valid if: (1) it affords no more protection than is reasonably necessary to protect the interests of the party in whose favour it is imposed; and (2) it is reasonable having regard to the interests of the public: Nordenfelt at 565; Amoco Australia Pty Ltd v Rocca Bros Motor Engineering Co Pty Ltd [1973] HCA 40; 133 CLR 288 at 315-316 per Gibbs J.

92 Reasonableness in those contexts is to be judged at the date the restraint was first imposed: Adamson v New South Wales Rugby League Ltd [1991] FCA 550; 31 FCR 242 at 285-286 per Gummow J with Sheppard J agreeing (at 245).

93 The onus of showing that the restraint is no more than what is reasonably necessary to protect the interests of the party having the benefit of the restraint is on that party: Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Harper’s Garage (Stourport) Ltd [1968] AC 269 at 319 per Lord Hodson; Herbert Morris Ltd v Saxelby [1916] 1 AC 688 at 700 and 707-708 per Lord Atkinson and Lord Parker. There are judgments of individual Justices of the High Court to similar effect: see Lindner v Murdock’s Garage [1950] HCA 48; 83 CLR 628 at 646 per McTiernan J and 653 per Kitto J; Amoco at 317 per Gibbs J.

94 The onus of showing that a contract in restraint of trade is injurious to the public lies on the party making that allegation: Herbert Morris at 700 and 707-708; Esso Petroleum at 319; Amoco at 317.

95 What is to be proved in both cases are facts, but the question of whether those facts make good the proposition that the restraint is reasonable is a question of law: Esso Petroleum at 319; Amoco at 317.

96 In assessing what is reasonable the court may take into account future probabilities that could have been foreseen: Adamson at 285-286. Also, in assessing what is reasonable, facts occurring after the restraint’s inception may, but need not, throw light on circumstances existing at the relevant date: Amoco at 318.

97 The first task is to ascertain the proper construction of the restraint because the ultimate questions is: Did the clause provide at the time it was given no more than reasonable protection of the interests of those in whose favour it was entered into, bearing in mind its possible operation according to its terms properly construed? See Geraghty v Minter [1979] HCA 42; 142 CLR 177 at 179 per Barwick CJ.

98 The exercise of construction is undertaken for the purpose of ascertaining the real meaning of the restraint, independently of the rules prescribing tests of reasonableness for the purpose of ascertaining its validity: Butt v Long [1953] HCA 76; 88 CLR 476 at 487 per Dixon CJ.

99 Where a covenant in restraint of trade is in some material particular unreasonable and on that basis unenforceable, the whole restraint will fail unless severance of the unreasonable part is justified. Severance is only possible if the restraint clause is not really a single covenant but is in effect a combination of several distinct covenants, some of which are too wide. In that event, the invalid covenants may be severed subject to three conditions.

100 First, the impugned covenants must be capable of simply being removed as if struck through with a blue pencil, i.e. without rewriting the restraint clause. Second, the covenant to be severed must be an independent covenant capable of being removed without affecting the remaining part. Third, the clause must be a genuine attempt to establish reasonable protection for the legitimate interests of the covenantee as courts are otherwise reluctant to engage in “curial disentanglement” and sever the unenforceable parts of unreasonably wide restraint clauses. See Just Group Limited v Peck [2016] VSCA 334; 344 ALR 162 at [39] and the authorities there cited.

101 As indicated, the restraint of trade provisions that are the subject of this proceeding are contained in cl. 20 of the SHA. Clause 20 is divided into eight sub-clauses that cover three pages of single-spaced approximately 10pt font. The point is that the clause is lengthy, complex, and even intricate.

102 The restraints themselves are contained in cl. 20.2 which is relevantly as follows:

For the sole purpose of protecting the interest of the Company [i.e. New Civic] and the other Shareholders (Other Parties) in respect of the goodwill of the Company and the Business, subject to the express exclusions set out below, each of the applicable Shareholders and the Covenantors covenants with, and undertakes to, the Other Parties that they will not, nor will any Affiliate of the Non-Findex Shareholders/ Shareholders/ Covenantors (as applicable), do any of the following for so long as the Shareholder remains a Shareholder, and during any of the Restraint Periods, within any of the Restraint Areas, directly or indirectly:

…

(b) solicit any person who is or was or would otherwise have been a supplier or customer or client to not do business or cease doing business with the Company, any of its Controlled Entities or any authorised representative or corporate authorised representative of any of them, or to reduce the amount of business which the supplier or customer or client would have done or would normally do with the Company, any of its Controlled Entities or any authorised representative or corporate authorised representative of any of them;

(c) (in relation to each of the Non-Findex Shareholders and Covenantors only, (but without prejudice to clause 20.2(b))), accept from a customer or client any business of the kind ordinarily forming part of the Business;

…

(f) interfere with the Business or disclose to any person any Confidential Information concerning the Business or concerning the Other Parties or any of their respective dealings, transactions or affairs (except in the circumstances allowed in c1ause 21.2(b)); or

…

The restrained conduct and the restrained parties

103 Although cl. 20.2 has another four sub-clauses covering such conduct as being engaged or concerned in a competing business (subclause (a)), soliciting any employee (subclause (d)), soliciting any authorised representative (subclause (e)) and representing any connection with or interest in the business (subclause (g)), senior counsel for the applicants put their case as relying on subclauses (b), (c) and (f) only.

104 The applicants’ case for breach of the restraint provisions is relatively narrow and omits not only the four subclauses identified above but also omits various permutations that arise within the chapeau and the subclauses that they rely on from the various defined terms. The applicants, in effect, contend that each “Covenantor” (i.e., relevantly, Mr McKay and Vandaman) covenanted and undertook to “the Other Parties” (i.e. New Civic and Findex and each of the other shareholders in New Civic) “during the Restraint Periods, within any of the Restraint Areas, directly or indirectly” that they and any “affiliate” would not:

“solicit” any “customer or client” of New Civic “not to do business or cease doing business with [New Civic]… or to reduce the amount of business which the… customer or client would have done or would normally do with [New Civic]” [cl. 20.2(b)];

“accept from a customer or client any business of the kind ordinarily forming part of the Business” [cl. 20.2(c)]; or

“interfere with the Business” [cl. 20.2(f)].

105 At this stage, the task is to construe the restraints as a whole. It is not appropriate to only have regard to the limited wording on which the applicants ultimately seek to rely.

106 The restraints are said to be applicable to the conduct not only of the relevant parties to the SHA, being Mr McKay and Vandaman in this case, but also to any “Affiliate” of theirs. That term is given a very broad definition in the dictionary in Schedule 1 to the SHA as follows:

Affiliate means, in relation to a person (Principal), any person who:

(a) is Controlled by the Principal;

(b) Controls the Principal;

(c) is Controlled by a person who Controls the Principal;

(d) is a related entity (as that term is defined in Section 9 of the Corporations Act substituting the word Principal for the words body corporate); or

(e) is a partner or joint venturer of the Principal.

107 In Schedule 1 to the SHA, “Control” is defined to mean the following:

(a) In relation to any body corporate (including without limitation, a body corporate in the capacity as trustee of any trust property), the ability of any person to exercise control over the body corporate by virtue of the holding of voting shares in that body corporate or by any other means including, without limitation, the ability to directly or indirectly remove or appoint all or a majority of the directors of the body corporate; and

(b) In relation to an individual, the ability of any person to direct that person to act in accordance with their instructions whether by operation of any law, agreement, arrangement or understanding, custom or any other means.

108 By item 1.1(e) of Schedule 2 to the SHA, the definition of “related entity” in s 9 of the Corporations Act is to be taken as that definition as at the time that the SHA was concluded. It was as follows:

related entity, in relation to a body corporate, means any of the following:

(a) a promoter of the body;

(b) a relative of such a promoter;

(c) a relative of a spouse of such a promoter;

(d) a director or member of the body or of a related body corporate;

(e) a relative of such a director or member;

(f) a relative of a spouse of such a director or member;

(g) a body corporate that is related to the first-mentioned body;

(h) a beneficiary under a trust of which the first-mentioned body is or has at any time been a trustee;

(i) a relative of such a beneficiary;

(j) a relative of a spouse of such a beneficiary;

(k) a body corporate one of whose directors is also a director of the first-mentioned body;

(l) a trustee of a trust under which a person is a beneficiary, where the person is a related entity of the first-mentioned body because of any other application or applications of this definition.

109 “Relative” was defined in the Corporations Act at that time to mean, in relation to a person, the spouse, parent or remoter lineal ancestor, child or remoter issue, or brother or sister of the person.

110 The consequence of these definitions is that the restraint provisions are remarkably complex to follow, and even more remarkably broad in application. Notably, it is not just the non-Findex shareholders and their principals who made the covenants in question in respect of their own conduct, but they did so also in relation to the conduct of any “Affiliate” of theirs. Whether or not another party is an affiliate largely turns on notions of “control” as defined, which in relation to a natural person includes the ability to give instructions including by “arrangement or understanding, custom or any other means”. But it also includes “related entities”, which includes, for example, the relative of a spouse of a director or member of the relevant covenantor including the spouse’s siblings and children and grandchildren, and so on, and parents and grandparents and so on.

111 Turning to the prohibited conduct, as opposed to whose conduct it is, the first point to note is that it is not only direct conduct that is proscribed, but also indirect conduct which leaves some doubt as to just what is covered.

112 Focussing on subclauses (b) and (c), one notices that both proscribe conduct relating to a “customer or client” – subclause (b) proscribes soliciting a customer or client and subclause (c) proscribes accepting “Business” of a customer or client. In cl. 20.1(c), “customer or client” is defined to mean “any person who was, in the twelve (12) month period before the date of retirement, a customer or client of [New Civic], any of its Controlled Entities, or of any authorised representative or corporate authorised representative of [New Civic] or its Controlled Entities.”

113 Confusingly, “client” is also defined in the SHA. That is in Schedule 1 where “Client means all of the financial planning clients of the Business from time to time”. Trying to make sense of these definitions together, it may be that clients are restricted to being financial planning clients whereas customers may not be restricted in that way, although there is no evidence as to the common understanding of the parties at the time that they concluded the SHA as to what business New Civic or any of its “Controlled Entities” might have in the future other than financial planning business/es.

114 Controlled Entity in relation to a party is defined in Schedule 1 as meaning any entity “Controlled” by that party. That refers back to the definition of “Control” dealt with above.

115 “Business” is defined in Schedule 1 as follows:

Business means in respect of the Company (including its Controlled Entitles) the business of the Company from time to time (as conducted in accordance with the Business Plan (if applicable)) including providing Financial Services and the sale of Financial Products (including without limitation the sale of insurance products), and promoting the ‘Pinnacle’ superannuation and managed fund product to retail investors.

116 “Business Plan” then has its own definition, and “Financial Product” and “Financial Services” are defined with reference to the definitions of those terms in the Corporations Act.

117 Even leaving aside the definition of the business, the result is that, for example, Mr McKay by the covenant undertook not to accept – or, indeed, that no grandchild of his would accept – business of the kind ordinarily forming part of the business (as defined) from someone who had, in the 12 months before he sold his remaining shares in New Civic, been a client of an authorised representative of a company in respect of which New Civic or Findex had the ability to indirectly remove or appoint a majority of the directors.

118 The restraint in cl. 20.2(b) is also said to operate in respect of customers or clients not only of New Civic, but also any of its “Controlled Entities” or any authorised representative or corporate authorised representative of any of them. In fact, that provision is in any event merely repetitious of the definition of “customer or client” so serves no purpose.

119 The applicants do not rely on any so-called Controlled Entity, whether on the basis that any customers or clients said to have been solicited by Mr McKay were customers or clients of such an entity or on the basis of any protection said to be provided to a business of a Controlled Entity under cl. 20.1. Nevertheless, the restraints must be construed with the protection of Controlled Entities within them.

120 The “Restraint Areas” are defined under cl. 20.1 as “any of the following”:

(a) “the Australian Capital Territory”;

(b) “within a 200 km radius of the Premises” (being at an address in Fyshwick, ACT); or

(c) “Canberra (Metropolitan)”.

121 The “Restraint Period” is defined under clause 20.1(f) as five cascading periods of time of five years, four years, three years, two years and one year from the “date of retirement”. The “date of retirement” was defined (in cl. 20.1(d)) to mean the date upon which a shareholder disposed of the last of its shares in New Civic or, in the case of the Covenantors, the date upon which a shareholder associated with a particular Covenantor disposed of the last of their shares in New Civic.

122 In the case of Mr McKay, the date of retirement was 29 August 2013. In the result, the “Restraint Period” was the following:

(a) 29 August 2013 to 29 August 2018;

(b) 29 August 2013 to 29 August 2017;

(c) 29 August 2013 to 29 August 2016;

(d) 29 August 2013 to 29 August 2015; or

(e) 29 August 2013 to 29 August 2014.

123 In the task of construing the restraint provisions those dates are not relevant because Mr McKay’s retirement date was not known at the time that the SHA was concluded. I record the dates here only for illustrative purposes.

124 Self-evidently, the purpose behind the cascading periods was so that if a court was to find that the restraint was unreasonable beyond a particular period of time then simply by striking out with a blue pencil the periods beyond that time the remaining period would be left intact without the court having to remake the contract for the parties. The same is true of the different areas in which the restraint was to operate.

125 In that regard, cl. 20.5 provides as follows:

Each of the restraints in clause 20.2 resulting from the various combinations of the Restraint Periods and the Restraint Areas is a separate, severable and independent restraint and the invalidity or unenforceability of any of the restraints in clause 20.2 does not affect the validity or enforceability of any other restraints in that clause.

126 Notably, cl. 20.5 does not identify that there are “separate, severable and independent” restraints other than with reference to the restraint periods of time and the restraint areas. As will be seen, that has some significance.

Possible severance of unused subclauses

127 The principal difficulty in the restraints arises from the many defined terms and the effect that the incorporation of the definitions has on the breadth of the restraints.

128 The applicants’ approach of focusing on and seeking to defend only those parts of the restraint provisions on which they rely could obviate the need to consider the many parts of the many permutations of the restraint provisions on which they do not rely, but only if the test for severance is met. I refer to paragraphs [99]-[100] above.

129 In that regard, the subclauses of cl. 20.2 which are not relied on may be able to be severed from the rest of the clause.

130 First, there is no difficulty in applying the apocryphal blue pencil to each subclause without changing the meaning of what remains and without needing to add anything.

131 Secondly, each subclause proscribes different conduct and could thus be understood as a separate restraint.

132 Thirdly, in so far as the question arises as to whether the restraint provisions as a whole can be seen as a genuine attempt to establish reasonable protection for the legitimate interests of the covenantee, in my view it is significant that by cl. 20.4 Mr McKay acknowledged that each of the restraints is reasonable in its extent having regard to the interests of each party to the SHA, and that it goes no further than is reasonably necessary to protect New Civic. Whilst that acknowledgement will have limited relevance to the question of whether the restraints are, objectively, reasonable, which is the test in respect of their enforceability, it is relevant to the subjective question of whether the restraints constitute a genuine attempt to establish reasonable protection. Also relevant in that regard is that the parties to the restraint were legally represented and there was no apparent inequality of bargaining power; this was an arms-length commercial transaction.

133 The point is that I do not intend at this stage exploring the meaning of each of the four subclauses of cl. 20.2 that the applicants do not rely on. Each has its own permutations and complexity. I am prepared to assume for present purposes that they can be severed. That assumption obviates the need for me to consider them further.

The purpose and character of the restraints

134 As expressed in cl. 20.2, the purpose of the restraint provisions was solely to protect the interest of New Civic and the other “Shareholders” in respect of the goodwill of New Civic and “the Business”.

135 Essentially, the goodwill that was sought to be protected by the restraint provisions was the goodwill in the business formerly conducted by Old Civic and then transferred to New Civic under the BSA. It was the business that was conducted under the name Civic Financial. As New Civic was incorporated specifically for the purpose of transferring the business of Old Civic to it, it had no other business at the time of that transfer and at the time of the execution of the SHA. Thus the goodwill that was sought to be protected was, initially at least, the goodwill of the business that was transferred; there was no goodwill attaching to any pre-existing or independent business of New Civic because there was no such business.

136 “Goodwill” has an established and wide meaning. With reference to Inland Revenue Commissioners v Muller & Co’s Margarine Ltd [1901] AC 217 at 235, cited in Federal Commissioner of Taxation v Murry [1998] HCA 42; 193 CLR 605 at [16]-[17], it includes “whatever adds value to a business by reason of situation, name and reputation, connection, introduction to old customers, and agreed absence from competition”. Also, “[i]t is the benefit and advantage of the good name, reputation, and connection of a business. It is the attractive force that brings in custom. It is the one thing that distinguishes an old established business from a new business at its first start.”

137 In JD Heydon, The Restraint of Trade Doctrine (LexisNexis Butterworths, 4th ed, 2018) at 214, it is said that the goodwill protected by a restraint includes “the propensity of existing customers to continue to resort to the business” and “the propensity of new customers to do so on the recommendation of old customers”.

138 Although there is some debate as to the frontiers of the restraint of trade doctrine (see Heydon chapter 3), there is no doubt that it applies to employee restraints and to restraints to protect goodwill. Also, employee restraints are regarded more strictly than restraints on the sale of goodwill: Heydon at 93; Peters American Delicacy Co Ltd v Patricias Chocolates & Candies Pty Ltd [1947] HCA 62; 77 CLR 574 at 590-591 per Dixon J; Geraghty at 185 per Gibbs J.

139 Because of that difference in treatment, it is important to characterise the relevant restraint. The applicants say that it is a goodwill restraint as it is to protect the goodwill of the business on its sale from vendor to purchaser. In that regard, the fact that Mr McKay is not himself a vendor, or that the subject of the SHA is in fact the shares rather than the business, does not change the analysis. That is because one must look to the whole set of transactions to determine what is being done, and clearly what was being done was the transfer of the business from one set of interests to another set of interests over a period of time. The restraint would arise, in respect of a particular original shareholder and principal, when that shareholding was fully transferred.

140 In Pioneer Concrete Services Ltd v Galli [1985] VR 675 at 693, Brooking J observed that where the sale of a business carried on by a company is effected by means of a sale, not of the business itself, but of the issued capital of the company, it is commonplace to require that promises on the part of the vendors be given, not only to the purchaser, but also to the company whose shares are the subject of the sale. This is done, in part, in an endeavour to avoid difficulties which may arise in relation to damages if the business is injured or found to be less valuable and the only covenantee is, not the owner of the business, but the parent of the owner.

141 The opposite is also true in that the interest in protecting the goodwill of a business is capable of supporting covenants not only from the vendors of the business, but also from shareholders in a company carrying on the relevant business transferring their shares to the purchaser as part of the transaction in which shares are sold, and from persons who were the controlling hands and minds of the company carrying on the business: Heydon at 216; Del Casale v Artedomus (Aust) Pty Ltd [2007] NSWCA 172; 73 IPR 326 at [56] per Hodgson JA. A covenant by the vendor company not to compete with the purchaser would in general be useless as a protection as the vendor would in due course be wound up, and the most serious competition might be expected to come from those who had been actively engaged in managing and carrying on its affairs: Connors Bros Ltd v Connors [1940] 4 All ER 179 at 190H per Viscount Maugham.

142 In this case, as will be seen, Mr McKay was also subject to restraints under an employment contract. Those restraints would be characterised as employee restraints. However, the restraints that the applicants rely on are clearly of a different class. They are properly characterised as goodwill restraints.

143 In order to judge the reasonableness of the restraint provisions with reference to their subject matter (i.e. what is restrained), area and duration of operation it is necessary to enquire further into the nature of the business that the restraint provisions seek to protect.

144 It will be recalled that Schedule 3 to the SSA contained a list of the clients of the business that was conducted by Old Civic and which was sold to New Civic. That list is more than 100 pages and contains thousands of names. The list does not indicate the addresses of the clients.

145 However, a list of Mr McKay’s clients at the time of the transfer of the business from Old Civic to New Civic was also tendered. There are 128 entries in the list, of which 86 (i.e. 67%) have addresses in the ACT, 23 (i.e. 18%) have addresses in NSW and 9 (i.e. 7%) have addresses in Queensland. The remainder are scattered across the other states and one has an address abroad. The significant point is that 85% of the clients were in the ACT and NSW and, of those, the vast majority were in the ACT. Moreover, of those in NSW a substantial number were in suburbs of Sydney.

146 In evidence, Mr McKay accepted that his clients were to be found throughout metropolitan Canberra. He also said that that is the same as the ACT in the sense that the people living in the ACT are in metropolitan Canberra as “the ACT that’s not metropolitan is bush”. He also accepted that he had clients up to 200km away from the business premises. He did not accept that he held himself out as being prepared to visit clients where they were and maintained his position that the clients would come to the offices to see him.

147 As indicated above, Old Civic’s clientele was largely, though not exclusively, comprised of members of Commonwealth government superannuation schemes who were in or close to retirement. They had a particular interest in the short to medium term performance of their investments as well as a concern to keep fees low. I accept Mr McKay’s evidence that he developed strong relationships with the clients of Old Civic and worked hard to develop and maintain their trust. He had advised most of them for many years and had strong relationships built on trust.

148 Mr McKay’s evidence under cross-examination was that success in this type of business requires the maintenance of close contact with one’s clients, including keeping up to date with their financial position, goals, needs and objectives. He accepted that it was necessary to keep up to date with a client’s appetite for risk and, to a lesser extent, their family and personal circumstances. As one would expect, Mr McKay accepted that the client list is a valuable asset of a financial planning business, and that the most important component of the value of such a business is its client list and the income stream derived from that list.

149 Mr Wilkins, a director of Findex, gave evidence. Speaking in March 2018, being the date of his relevant affidavit, he said that approximately 70% to 80% of the clients of the business are in what he refers to as the “pension phase”, meaning that they are not accumulating assets but rather that they have retired and are living off their superannuation. He did not address the position at the time that the SHA was concluded, some eight years earlier, but I infer that the position was similar at that time. That is consistent with Mr McKay’s evidence, referred to above, that most of Old Civic’s clientele were either in or close to retirement.

150 Mr Wilkins’s evidence was that personal relationships between client and adviser or planner are extremely important to the retention of clients in that type of business. He said that all the clients who are closer to retirement age, or retired, prefer more face-to-face contact with their adviser, and will take longer to transition to a new advisor. He said that the vast majority of the clients physically meet with their financial adviser only once per year. Thus, he said, it takes longer for a new advisor to form a relationship with clients as opportunities for face-to-face contact, which is essential to building trust and rapport especially with older clients, arise far less frequently.

151 There are a few things to be said about this at this stage. First, as will be seen, given that the restraints in question are goodwill restraints rather than employment restraints, the nature of the connection between Mr McKay and his clients, or the business and its clients, is perhaps not as significant as it may have been. That is because it is legitimate to protect the goodwill that has been purchased from the subsequent predations of the vendor for a long period of time regardless of whether the clients’ custom, which substantially makes up the goodwill, is easily enticed away, or otherwise.

152 Secondly, and for the same reason, it is not necessary to resolve two competing contentions. The one is that the clients are likely to have found a new financial advisor and built up a relationship with that new financial advisor within, say, two years of a previous financial advisor departing, with the result that a period of restraint longer than that would not be justified. The other is that the departed financial advisor will have a long-lasting ability to attract clients back again because of close and trusted relationships built up over time, even if the clients have in the meantime engaged a new advisor, with the result that a long period of time is justified. Those considerations are more relevant in the context of employment restraints. (See the discussion at [173]-[174] below.)

The reasonableness of the restraint provisions as between the parties

153 As I have indicated, the applicants only rely on three of the seven subclauses of cl. 20.2. It is those three subclauses on which I will focus.

154 From what I have said above (paras [103]-[119]) with regard to the construction, meaning and reach of subclauses (b) and (c) of cl. 20.2, it is apparent that they have extraordinary reach and complexity. They extend well beyond any justifiably protected interest of the applicants in the goodwill of the business – they do not afford no more protection than is reasonably necessary to protect the interests of the party in whose favour they are imposed.

155 The same is true of subclause (f). Although the wording of the subclause taken on its own is simpler and uncomplicated by incorporated defined terms when compared to subclauses (b) and (c), all the breadth and complexity of the chapeau nevertheless applies to it. Thus, the Covenantors covenant not only that they will not “interfere” with the business, but also that no “Affiliate” of theirs will do so which in turn brings any “related entity” within the restraint.

156 For example, through paragraphs (h) and (j) of the definition of “related entity” in s 9 of the Corporations Act and the definition of “Affiliate” in the SHA, Mr McKay and Vandaman covenanted that the relative (which can be, for example, a great-grandchild) of a spouse of a beneficiary of a trust of which Vandaman is or has been at any time a trustee would not solicit any person who is a client or potential client of a controlled entity of New Civic from doing business with that controlled entity. It was also covenanted that such a remotely related or interested person would not “interfere” with the business. The applicants did not come anywhere even close to justifying the breadth of the restraints. Indeed, the applicants did not attempt to justify such breadth, but rather sought to avoid it by focusing on the wording on which they sought to rely.

157 The restraint provisions were clearly the work of lawyers, each with one eye on drafting the greatest possible protection for the applicants and with the other eye firmly shut to the limits that the law places on such restraints by requiring them to be the least necessary to protect the applicants’ interests in the business of New Civic. The result is restraint provisions that are impossibly convoluted and complex and unjustifiably broad.

158 I therefore conclude that the restraints are too broad with respect to the conduct that is restrained with reference to the people and entities whose conduct is caught by the restraints. They are in this respect unreasonable and therefore unenforceable, unless they can be saved by severance.

159 The principal difficulty with regard to severance is the extraordinary complexity of the restraints with their interlinking and overlapping definitions; it is simply not possible to identify an independent covenant capable of being removed without affecting the remaining part as required by the second part of the test referred to above (at [100]).

160 For example, should a blue pencil be put through the words “nor will any Affiliate of the Non-Findex Shareholders/ Shareholders/ Covenantors (as applicable)” in the chapeau? Or, perhaps through paragraph (d) of the definition of “Affiliate” so that all the complexities and breadth of the incorporation of the definition of “related entity” are removed? But why one rather than the other?

161 The point is that the Court will not embark on the task of redrafting the restraint provisions for the parties. That is made clear by the authorities: Lloyd’s Ships Holdings Pty Ltd v Davos Pty Ltd [1987] FCA 70; 17 FCR 505 at 523-524; Just Group at [39]. Severance must be the act of the parties, not the Court: Just Group at [57(d)]. To attempt to sever parts of the applicable definitions in this fashion would be “to reason backwards from allegation of breach to construction and evaluation of the contract, rather than by an assessment of validity of the restraints at the time the contract was made”: Just Group at [57(d)].

162 In that regard, it is not without significance that cl. 20.5 (quoted at [125] above) identifies “separate, severable and independent” restraints with reference to the cascading provisions with regard to area and time, and not with reference to the intersecting, overlapping and cumulative definitions provisions. That counts against it being concluded, objectively speaking, that the parties intended the different permutations of the definitions provisions to be severable.

163 The general rule is that the area of the covenant must not be more extensive than that of the business sold: Heydon at 222 citing British Reinforced Concrete Engineering co Ltd v Schelff [1921] 2 Ch 563 and D Bates & Co v Dale [1937] 3 All ER 650. It is not necessary for a covenantee to prove that the business was conducted throughout the whole of that area: Connors Bros at 194.

164 In the present case, there is certainly no difficulty with regard to the areas of the ACT and Canberra. The business was based in Canberra and, as indicated, most of its clients were located in the ACT. However, based on Mr McKay’s client list it is reasonable to infer that a significant proportion of the clients were also in various places in New South Wales including a not insignificant number in suburbs of Sydney.

165 Mr Konings, an expert witness called by Mr McKay, gave evidence of the population over the age of 18 years in 2011 in the three areas covered by the restraints. He concluded that they were as follows:

(a) Canberra: 274,358

(b) ACT: 275,052

(c) Within 200 km of Fyshwick: 887,473.

166 Even if I could not otherwise take judicial notice of it, from this it can be seen that Sydney is not within 200 km of Fyshwick – if it was the number of people within 200km of Fyshwick would have to be far larger. Thus, a not insignificant number of existing clients were outside of the biggest of the geographic areas. In any event, Mr McKay accepted in cross-examination that the restraint was limited to the area in which the business actually operated.

167 From this it is apparent that even the area within a radius of 200 km from the business premises at Fyshwick is not broader than the area in which the business actually operated and attracted clients.

168 It was submitted on behalf of Mr McKay that it is not reasonable for the restraint to extend well into NSW and to cover almost 900,000 people. It was submitted that the area goes well beyond whatever protectable interest the applicants may have in protecting the goodwill of the business. But this submission overlooks that the restraint applies to actual or potential clients or customers within the area; the number of people in the area who might be or potentially become clients of the business is not a relevant consideration. What is most relevant is that the business was actually conducted in that area.

169 On this basis I conclude that the widest area of the restraint is not bigger or more extensive that what was reasonably required to protect the legitimate interests of the purchasers of the business.

170 Mr McKay did not submit, or establish as he would have been required to do in the circumstances, that the restraints were unreasonable having regard to the interests of the public.

The time periods of the restraints