FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Clark v Minister for the Environment [2019] FCA 2027

ORDERS

First Applicant MERIKI ONUS Second Applicant LORRAINE SANDRA ONUS (and another named in the Schedule) Third Applicant | ||

AND: | THE MINISTER FOR THE ENVIRONMENT Respondent | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The decision of the respondent made on 16 July 2019 not to make declarations under s 10 and s 12 of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth) is set aside from the date it was made.

2. The applicants’ application dated 17 June 2018 be referred to the respondent for further consideration according to law.

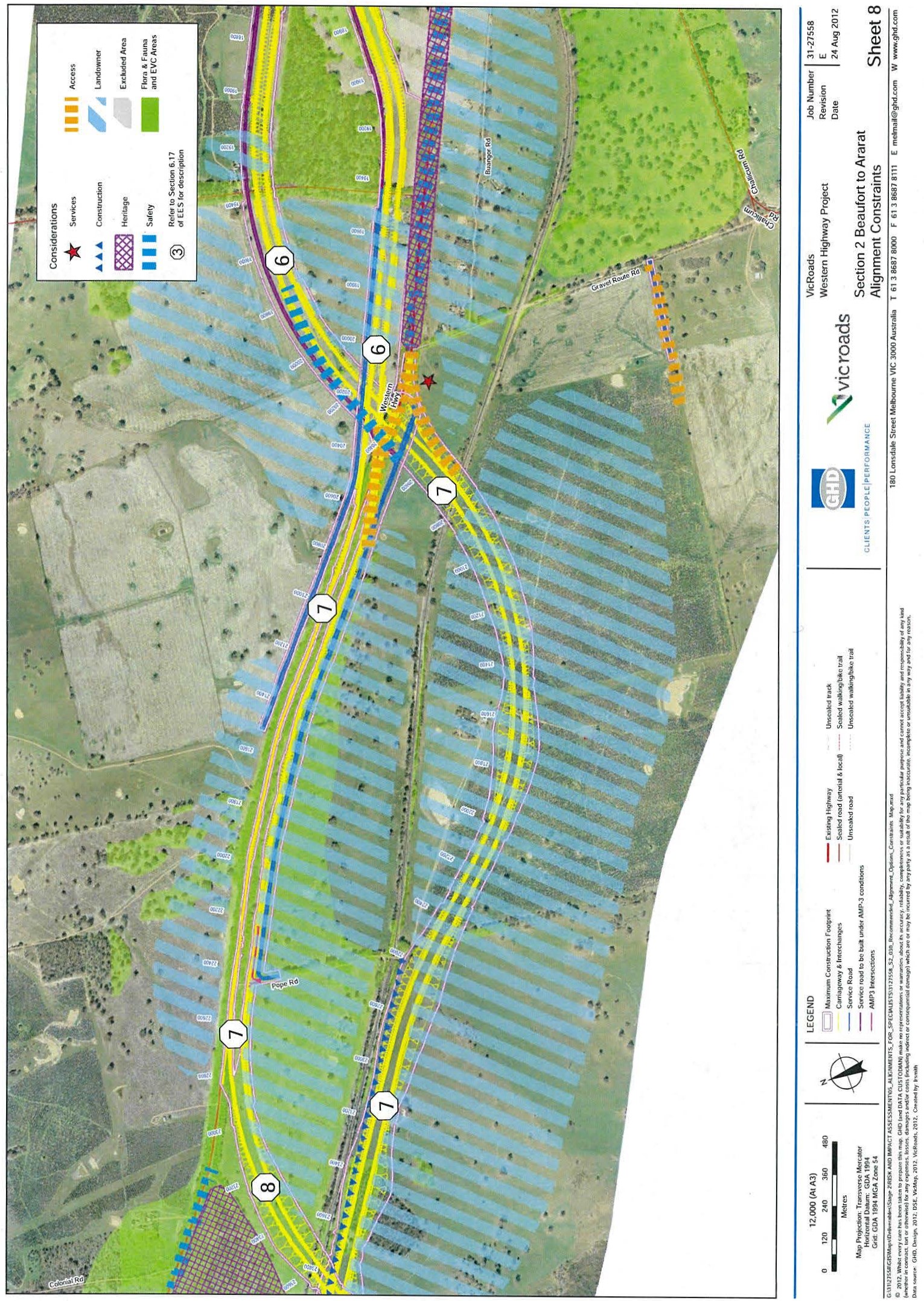

3. The respondent pay the applicants’ costs of the application, excluding the costs of the applicants’ interlocutory application dated 8 November 2019, as agreed or assessed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

ROBERTSON J:

Introduction

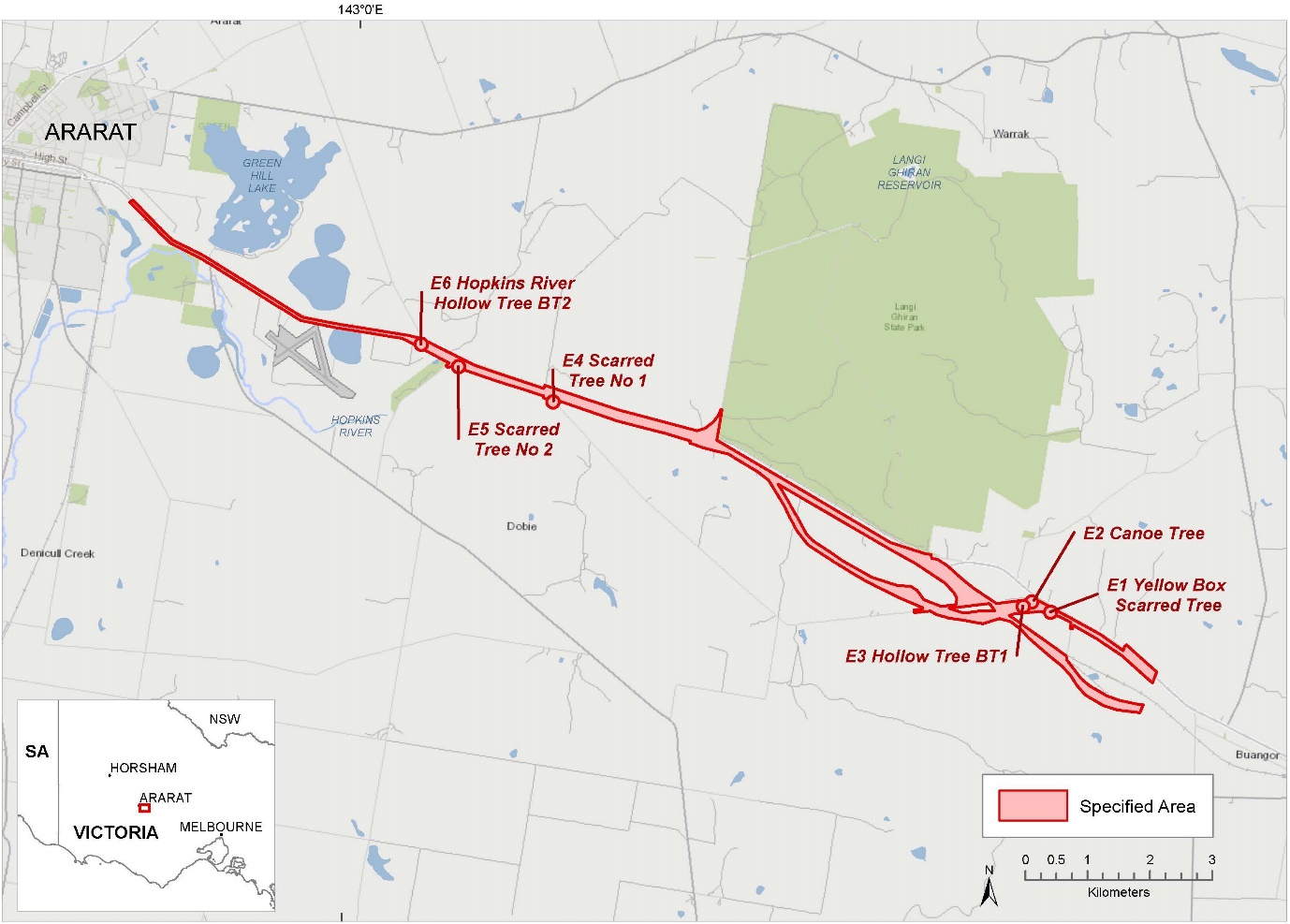

1 On 16 July 2019 the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment decided not to make declarations under s 10 and under s 12 of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth). Application had been made to the Minister by Jidah Clark, Tracey Bamblett Onus, Meriki Onus, Lorraine Sandra Onus, Tameen Onus-Williams, Eileen Austin, Geoff Clark, Monica McDonald and Marjorie Thorpe, who identified themselves as Djab Wurrung traditional owners, seeking protection of a Specified Area of Djab Wurrung Country near Ararat, in Victoria, and six trees located in the Specified Area. The threat of injury or desecration was attributed to an upgrade of the Western Highway proposed by the Roads Corporation of Victoria (VicRoads), particularly what is known as “Section 2B”.

2 The six trees were identified by the Minister as follows:

a. E1 (Yellow Box Scarred Tree) [GDA94 Coordinates: (688430E

5864681N)];

b. E2 (Canoe Tree) [GDA94 Coordinates: (688126E 5864844N)];

c. E3 (Hollow Tree BT1) [GDA94 Coordinates: (687991 E 5864773N)];

d. E4 (Scarred Tree No 1) [GDA94 Coordinates: (680435E 5868058N)];

e. E5 (Scarred Tree No 2) [GDA94 Coordinates: (678917E 5868624N)]; and

f. E6 (Hopkins River Hollow Tree BT2) [GDA94 Coordinates: (678320E 5868983N)].

3 The following map illustrates the location of the six trees and the Specified Area of Djab Wurrung country:

4 The applicants seek an order quashing the decision and remitting the matter to the Minister for reconsideration in accordance with law.

5 The applicants also seek consequential relief against the State of Victoria (the State). The State resists being joined as a party to these proceedings because it resists the relief claimed against it. That aspect of the matter is dealt with in a separate judgment also delivered today: Clark v Minister for the Environment (No 2) [2019] FCA 2028.

6 On 18 July 2018, the then Minister (the Hon Josh Frydenberg MP) nominated Ms Susan Phillips, barrister, as the Reporter for the purposes of the Application under s 10 of the Heritage Protection Act. On 7 September 2018, the Reporter submitted her report to the Minister.

7 On 12 September 2018, the then Minister (the Hon Melissa Price MP) decided not to make an emergency declaration under s 9 of the Heritage Protection Act.

8 On 19 December 2018, the then Minister decided not to make declarations under ss 10 and 12 of the Heritage Protection Act in relation to the Specified Area and the six trees. The applicants sought judicial review of that decision, which was set aside by consent orders made by Mortimer J on 12 April 2019, the matter being remitted to the Minister for reconsideration according to law.

9 The planned works in Section 2B of the Western Highway between Ballarat and Stawell (WHDP) comprise a section between Buangor and Ararat approximately 12.5km long.

10 Before July 2018, VicRoads was responsible for delivery of the WHDP. On 13 June 2018, to take effect on 1 July 2018, the Major Road Projects Authority (MRPA) was established as an administrative office in relation to the Victorian Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources. On 1 January 2019, the MRPA was abolished and its responsibilities transferred to Major Road Projects Victoria (MRPV), an Administrative Office in relation to the Department of Transport. The MRPA had the responsibility for delivering the WHDP and that responsibility was later transferred to MRPV.

The relevant statutory provisions

11 The statutory provisions of the Heritage Protection Act are as follows:

10 Other declarations in relation to areas

(1) Where the Minister:

(a) receives an application made orally or in writing by or on behalf of an Aboriginal or a group of Aboriginals seeking the preservation or protection of a specified area from injury or desecration;

(b) is satisfied:

(i) that the area is a significant Aboriginal area; and

(ii) that it is under threat of injury or desecration;

(c) has received a report under subsection (4) in relation to the area from a person nominated by him or her and has considered the report and any representations attached to the report; and

(d) has considered such other matters as he or she thinks relevant; he or she may, by legislative instrument, make a declaration in relation to the area.

(2) Subject to this Part, a declaration under subsection (1) has effect for such period as is specified in the declaration.

(3) Before a person submits a report to the Minister for the purposes of paragraph (1)(c), he or she shall:

(a) publish, in the Gazette, and in a local newspaper, if any, circulating in any region concerned, a notice:

(i) stating the purpose of the application made under subsection (1) and the matters required to be dealt with in the report;

(ii) inviting interested persons to furnish representations in connection with the report by a specified date, being not less than 14 days after the date of publication of the notice in the Gazette; and

(iii) specifying an address to which such representations may be furnished; and

(b) give due consideration to any representations so furnished and, when submitting the report, attach them to the report.

(4) For the purposes of paragraph (1)(c), a report in relation to an area shall deal with the following matters:

(a) the particular significance of the area to Aboriginals;

(b) the nature and extent of the threat of injury to, or desecration of, the area;

(c) the extent of the area that should be protected;

(d) the prohibitions and restrictions to be made with respect to the area;

(e) the effects the making of a declaration may have on the proprietary or pecuniary interests of persons other than the Aboriginal or Aboriginals referred to in paragraph (1)(a);

(f) the duration of any declaration;

(g) the extent to which the area is or may be protected by or under a law of a State or Territory, and the effectiveness of any remedies available under any such law;

(h) such other matters (if any) as are prescribed.

…

12 Declarations in relation to objects

(1) Where the Minister:

(a) receives an application made orally or in writing by or on behalf of an Aboriginal or a group of Aboriginals seeking the preservation or protection of a specified object or class of objects from injury or desecration;

(b) is satisfied:

(i) that the object is a significant Aboriginal object or the class of objects is a class of significant Aboriginal objects; and

(ii) that the object or the whole or part of the class of objects, as the case may be, is under threat of injury or desecration;

(c) has considered any effects the making of a declaration may have on the proprietary or pecuniary interests of persons other than the Aboriginal or Aboriginals referred to in paragraph (1)(a); and

(d) has considered such other matters as he or she thinks relevant;

he or she may, by legislative instrument, make a declaration in relation to the object or the whole or that part of the class of objects, as the case may be.

(2) Subject to this Part, a declaration under subsection (1) has effect for such period as is specified in the declaration.

(3) A declaration under subsection (1) in relation to an object or objects shall:

(a) describe the object or objects with sufficient particulars to enable the object or objects to be identified; and

(b) contain provisions for and in relation to the protection and preservation of the object or objects from injury or desecration.

(3A) A declaration under subsection (1) cannot prevent the export of an object if there is a certificate in force under section 12 of the Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act 1986 authorising its export.

(4) A declaration under subsection (1) in relation to Aboriginal remains may include provisions ordering the delivery of the remains to:

(a) the Minister; or

(b) an Aboriginal or Aboriginals entitled to, and willing to accept, possession, custody or control of the remains in accordance with Aboriginal tradition.

12 The following provisions in s 3 are also important:

(1) In this Act, unless the contrary intention appears:

Aboriginal tradition means the body of traditions, observances, customs and beliefs of Aboriginals generally or of a particular community or group of Aboriginals, and includes any such traditions, observances, customs or beliefs relating to particular persons, areas, objects or relationships.

…

significant Aboriginal object means an object (including Aboriginal remains) of particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal tradition.

(2) For the purposes of this Act, an area or object shall be taken to be injured or desecrated if:

(a) in the case of an area:

(i) it is used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition;

(ii) by reason of anything done in, on or near the area, the use or significance of the area in accordance with Aboriginal tradition is adversely affected; or

(iii) passage through or over, or entry upon, the area by any person occurs in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition; or

(b) in the case of an object—it is used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition;

and references in this Act to injury or desecration shall be construed accordingly.

(3) For the purposes of this Act, an area or object shall be taken to be under threat of injury or desecration if it is, or is likely to be, injured or desecrated.

13 The applicants also relied on the following provision in relation to the claimed failure to consult:

13 Making of declarations

(1) In this section:

declaration means a declaration under this Division.

(2) The Minister shall not make a declaration in relation to an area, object or objects located in a State or the Northern Territory unless he or she has consulted with the appropriate Minister of that State or Territory as to whether there is, under a law of that State or Territory, effective protection of the area, object or objects from the threat of injury or desecration.

(3) The Minister may, at any time after receiving an application for a declaration, whether or not he or she has made a declaration pursuant to the application, request such persons as he or she considers appropriate to consult with him or her, or with a person nominated by him or her, with a view to resolving, to the satisfaction of the applicant or applicants and the Minister, any matter to which the application relates.

(4) Any failure to comply with subsection (2) does not invalidate the making of a declaration.

(5) Where the Minister is satisfied that the law of a State or of any Territory makes effective provision for the protection of an area, object or objects to which a declaration applies, he or she shall revoke the declaration to the extent that it relates to the area, object or objects.

(6) Nothing in this section limits the power of the Minister to revoke or vary a declaration at any time.

The Minister’s reasons

14 The Minister provided reasons for her decision, dated 16 July 2019.

15 As to Tree E1, the Minister concluded, at [5.25]:

In circumstances where there are differing views from Aboriginal groups that may speak for Country as to the significance of Tree E1 and where commissioned experts have not provided detail about the uses or beliefs centred around the tree (in contrast to the other trees subject to the Application), I am not satisfied that Tree E1 is a significant Aboriginal object for the purposes of the ATSIHP Act [Heritage Protection Act].

16 As to Trees E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6, the Minister said, at [5.26]:

After considering the available evidence, I am satisfied that there is a cultural connection that renders five of the Six Trees (namely Trees E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6) particularly significant, with a degree of antiquity, involving Aboriginal traditions, observances, customs and beliefs that are passed down from generation to generation through spirituality, culture and traditional interaction.

17 At [5.30], the Minister said:

As I am not satisfied that Tree E1 is a significant Aboriginal object, I have considered whether the remaining Six Trees, being Trees E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6, are under threat of injury or desecration.

18 The Minister continued:

5.31 The Applicants have described the nature and the extent of the threat of injury to the objects as severe injury and desecration of the trees caused by activities relating to the planned upgrade to the Western Highway. The threat as outlined in the Application was that ‘VicRoads intends to physically destroy and remove these ancient trees.’

5.32 However, MRPV [Major Road Projects Victoria] and EMAC [Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation] have since come to an agreement regarding how MRPV will undertake the Western Highway upgrade. MRPV will avoid Trees E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6 as part of the upgrade and has developed a draft framework for identifying and monitoring trees (Framework).

5.33 I note that the Applicants’ views that the trees are still under threat because:

a. MRPV’s arborist’s recommendations as set out in their Arborist’s report may not accord with Australian Standard AS4790-2009 Protection of trees on development sites; and

b. there can be no legally binding agreement between MRPV and EMAC.

5.34 I note that that the Framework provides that the ‘extent of the exclusion zone will be determined with the Ecologist/Arborist and in consultation with EMAC’. While the Framework is not as prescriptive as AS4790-2009 (as described by the Applicants), the two standards are compatible and I therefore do not consider them to be inconsistent.

5.35 While I agree with the Applicants that the agreement between MRPV and EMAC is not likely to be legally binding, I note that both MRPV and EMAC have publicly referred to MRPV’s commitment. I consider that given the public standing of MRPV and the scrutiny that has been attracted to the potential impact of the proposed Western Highway upgrade on Djab Wurrung country, MRPV can be expected to act in good faith in giving effect to its commitment (albeit not necessarily legally binding) to not remove the trees.

5.36 The Applicants have also raised concerns about how the agreement was reached. I consider this matter to be secondary to the existence of the agreement.

5.37 I am therefore not satisfied that the trees that I have found to be significant Aboriginal objects (E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6) are under threat of injury or desecration.

19 The Minister then made findings on whether the Specified Area is a significant Aboriginal area. At [5.38], the Minister set out the definitions of “significant Aboriginal area” and “Aboriginal tradition” from the Heritage Protection Act and said that based on these definitions, to be satisfied that the Specified Area was a “significant Aboriginal area” for the purposes of s 10(1)(b)(i), she must be satisfied that the Specified Area is of particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with a relevant body of traditions, observances, customs and beliefs of Aboriginals generally or of a particular community or group of Aboriginals.

20 The Minister’s statement of reasons then set out the conclusion of the Reporter that “it is clear that the trees … are situated in a landscape in which Djab Wurrung people maintain certain traditions. The existence of those traditions has been identified in work done with local Aboriginal people since and before the current controversy. The Applicants follow those traditions which have been handed down to the present generation by their forebears”.

21 The Minister then said:

5.42 To determine whether the Specified Area is a significant Aboriginal area, I considered and evaluated the evidence and material listed at paragraph 4.1 of this statement of reasons to gain an appreciation of the claimed significance of the Specified Area and the relevant Aboriginal tradition.

5.43 In particular, I considered:

a. the basis upon which the Specified Area was claimed by the Applicants to be an area of particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal tradition, especially regarding the cultural significance of the trees to women and the broader cultural landscape of the greater area; and

b. the evaluation of the Application and representations by Ms Phillips in the Section 10 Report.

5.44 I note the Reporter’s view that Djab Wurrung Country is a significant Aboriginal area for the purposes of section 10(1)(b)(i) of the ATSIHP Act due to the local Aboriginals having a close, spiritual association with the Specified Area. Further, I noted broad agreement from persons who have made representations that Djab Wurrung Country is of particular significance. Djab Wurrung Country also has a close relationship with:

a. the songlines and stories that reach from Langi Ghiran, the Djab Wurrung people’s black cockatoo dreaming site.

b. the Hopkins River, which is connected to the Djab Wurrung people’s eel dreaming.

c. the trees within the Djab Wurrung Country area that embody key stories specific to Djab Wurrung traditions.

5.45 I note that in the additional information provided on 5 July 2019 by the Applicants, they sought protection under section 10 for the ‘Maximum Construction Footprint’. While I accept that there is a broader cultural landscape which encompasses the Specified Area, I note that the Application and representations made to the Reporter focused heavily on the cultural significance of the Specified Area as deriving from the Six Trees.

5.46 I note that the Reporter found in her conclusions about the significance of the Specified Area:

It is clear that the trees, many culturally modified by their ancestors, are situation in a landscape in which Djab Wurrung people maintain certain traditions. The existence of those traditions has been identified in work done with local Aboriginal people since before the current controversy. The Applicants follow those traditions which have been handed down to the present generation by their forebears. The Applicants feel obliged by those traditions to seek protection of the trees which form an integral part of those traditions and enduring creation stories.

The particular traditions identified by the Applicants, (as elaborated by Jidah Clark and corroborated by investigation of the areas by Dr Builth, On Country Heritage and Consulting and the Langi Ghiran State Park Management Plan) include the belief in the trees as personifying their ancestors being Ancient Trees, Ancestor Trees, or Guardian Trees … These spiritual beliefs, which are connected to other stories in the landscape and the cultural modification of some of the trees in the specified area, demonstrate the particular significance of both trees and area under Djab Wurrung traditions.

22 The Minister then continued:

5.47 While under the ATSIHP Act significant Aboriginal objects and significant Aboriginal areas are distinct considerations, in the context of the Application the significance of the Specified Area derives cultural significance from the trees (i.e. objects) situated in that area and interconnectedness of those trees to other stories.

5.48 Noting that I am not satisfied that Tree E1 is a significant Aboriginal object, after considering the available evidence, I am satisfied that there is a cultural connection that renders the Specified Area particularly significant, with a degree of antiquity, involving Aboriginal traditions, observances, customs and beliefs that are passed down from generation to generation through dreaming stories, songlines, spirituality, culture and traditional interaction with the cultural landscape comprised by, and within, the Specified Area, (except to the extent of the vicinity of Tree E1 eastwards).

5.49 Therefore, I am satisfied that the Specified Area is a significant Aboriginal area for the purposes of section 10(1)(b)(i) of the ATSIHP Act, except to the extent of the vicinity of Tree E1 eastwards.

23 The Minister then turned to whether she was satisfied that the Specified Area was under threat of injury or desecration. The Minister said:

5.50 Under section 10(1)(b)(ii) of the ATSIHP Act, in order to make a declaration, I must be satisfied that the Specified Area is under threat of injury or desecration.

5.51 I note the Applicants’ view that even if the trees were not considered under threat, the surrounding area will be destroyed by the works and therefore the Specified Area is under threat of injury.

5.52 However, as set out above, I have found that the significance of the Specified Area derives from the culturally significant trees contained in the area. In circumstances where the trees will not be removed, I am not satisfied that the Specified Area is under threat of injury or desecration.

24 The Minister said at [5.53] that notwithstanding that she was not satisfied that the preconditions to make a declaration were not met under ss 10 and 12, she had considered the other matters set out in those sections. The Minister said:

5.55 In reaching my decision I considered the following matters:

a. the extent to which the area is protected under State legislation;

b. the effects on proprietary and pecuniary interests of third parties; and

c. social and economic benefits, particularly relating to community safety.

25 In relation to the first of these matters, the Minister concluded:

5.65 I am satisfied that the measures under the Aboriginal Heritage Act, in particular the CHMP [the Cultural Heritage Management Plan], and the Victorian Government’s commitment to continue working with EMAC provides effective protection of the Six Trees and Specified Area.

26 In relation to the second of these matters, the Minister concluded:

5.68 After considering all the material before me, I am satisfied that, based on the information received from the Victorian Government, the building of an alternate route (the Northern Route) will have a significant economic cost impact.

27 In relation to the third of these matters, the Minister concluded:

5.74 Having considered the information before me, I find that there are likely to be community road safety benefits in the construction of the Western Highway upgrade. I find that there is likely to be safer road conditions associated with the duplication works.

28 Under the heading “Reasons for decision”, the Minister said as follows:

6.1 To make a declaration under section 10 of the ATSIHP Act in relation to the Specified Area, I must be satisfied that the Specified Area is a significant Aboriginal area and is under threat of injury or desecration. While I have found the Specified Area is a significant Aboriginal area (except to the extent of the vicinity of Tree E1 eastwards), I am not satisfied that it is under threat of injury or desecration. Consequently, I am not empowered to make a declaration under section 10 of the ATSIHP Act.

6.2 To make a declaration under section 12 of the ATSIHP Act in relation to the Six Trees, I must be satisfied that the Six Trees are significant Aboriginal objects and are under threat of injury or desecration. I am not satisfied that one of the trees (E1) is a significant Aboriginal object. I am satisfied that the remaining five of the Six Trees are significant Aboriginal objects. However, I am not satisfied that the five trees (E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6) that are significant Aboriginal objects are under threat of injury or desecration as MRPV has agreed not to remove them as part of the construction work for the upgrade and will be monitored under the Framework. Consequently, I am not empowered to make a declaration under section 12 of the ATSIHP Act in relation to the five trees that I have found to be significant Aboriginal objects.

6.3 Notwithstanding that I am not satisfied that the preconditions to make a declaration under section 10 and section 12 of the ATSIHP Act have been met, I note that if I had been so satisfied I would not have made declarations under section 10 and 12 of the ATSIHP Act for the following reasons.

6.4 In making a decision under section 10 or section 12 of the ATSIHP Act, in addition to considering the purpose of the ATSIHP Act set out in section 4, and the matters set out in section 10 and 12, I may only make a declaration after I have considered such other matters as I think are relevant. The ATSIHP Act does not expressly specify or limit the considerations that may be included those other matters. These matters can include a wide range of policy and public interest considerations.

6.5 I note that while the purpose of the ATSIHP Act is to preserve and protect from injury or desecration areas and objects in Australia that are of particular significance for Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal traditions, the ATSIHP Act provides a discretion.

6.6 I consider it relevant that the consultation between MRPV and EMAC that has occurred following the making of the Application has led to the protection of five trees which I consider to be significant Aboriginal objects under the ATSIHP Act. The protection now provided to these trees furthers the purpose of the ATSIHP Act.

6.7 In exercising the discretion in sections 10 and 12 of the ATSIHP Act, I am required to weigh up the competing views expressed and evidence provided to me for consideration. In this respect, I have given greater weight to the positive impact on community safety that the Western Highway upgrade will provide, given that it is extensively used, with the upgrade potentially saving lives. This would have a positive impact on a broad section of the community.

6.8 While I have also taken into account the proprietary and pecuniary interests of third parties presented, I have placed less weight on this.

Based on the material presented to me and for reasons set out above, I found that, for the purposes of the ATSIHP Act:

a. I have received an application for the purposes of section 10(1)(a) and section 12(1)(a) of the ATSIHP Act;

b. I am satisfied that the five trees: E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6 are significant Aboriginal objects for the purposes of section 12(1)(b)(i) of the ATSIHP Act;

c. I am not satisfied that Tree E1 is a significant Aboriginal object for the purposes of section 12(1)(b)(i) of the ATSIHP Act;

d. I am not satisfied that there is a threat of injury or desecration to the five trees: E2, E3, E4, E5 and E6 for the purposes of section 12(1)(b)(ii) of the ATSIHP Act;

e. I am satisfied that part of the Specified Area is a significant Aboriginal area for the purposes of section 10(1)(b)(i) of the ATSIHP Act;

f. I am not satisfied that there is a threat of injury or desecration to the Specified Area that is a significant Aboriginal area for the purposes of section 10(1)(b)(ii) of the ATSIHP Act; and

g. in consideration of other matters that are relevant prior to making a decision for the purposes of section 10(1)(d) of the ATSIHP Act I have found that, based on the evidence available there are likely to be community road safety benefits in the construction of the Western Highway upgrade. I find that that there is likely to be safer road conditions associated with the duplication works.

6.9 In light of these findings, and for the reasons above, I decided not to make declarations under section 10 and section 12 of the ATSIHP Act.

The grounds of the application for judicial review

29 The grounds of the application under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 (Cth) (ADJR Act) in the applicants’ “Substituted further amended originating application” were as follows, the strikethrough showing the grounds which were not pressed. (It is also to be noted that the application referred to the Minister as the “First Respondent”, although at the time that application was filed there was only one respondent.)

ADJR Act section 5(1)(a), (b), (f), (h) or (j)

The area

A. The First Respondent failed to make the Decision in accordance with the Act in that she failed to have proper regard to:

a) the definition of Aboriginal tradition in s 3(1) of the Act;

b) the circumstances in which an area would be taken to be injured or desecrated for the purposes of the Act, as set out in s 3(2) of the Act;

c) the circumstances in which an area would be taken to be under threat of injury or desecration for the purposes of the Act, as set out in s 3(3) of the Act;

with the consequence that the First Respondent asked herself the wrong question in considering her state of satisfaction as prescribed by s 10(1)(b)(ii) of the Act.

B. Having correctly determined that the Specified Area was a significant Aboriginal area for the purposes of s 10(1)(b)(i) of the Act (save in respect of the area east of Tree E1), the First Respondent was required by the definition of Aboriginal tradition in s 3(1) and ss 3(2)(i) and 3(3) of the Act to consider whether on the material before her she was satisfied that the Specified Area was, or was likely to be, used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition, but she failed to approach the Decision on that basis.

C. Having correctly determined that the Specified Area was a significant Aboriginal area for the purposes of s 10(1)(b)(i) of the Act (save in respect of the area east of Tree E1), the First Respondent was required by the definition of Aboriginal tradition in s 3(1) and ss 3(2)(ii) and 3(3) of the Act to consider whether on the material before her she was satisfied that by reason of anything done or proposed to be done in, on or near the Specified Area, it was likely the use or significance of the Specified Area in accordance with Aboriginal tradition would be adversely affected, but she failed to approach the Decision on that basis.

D. Having correctly determined that the Specified Area was a significant Aboriginal area for the purposes of s 10(1)(b)(i) of the Act (save in respect of the area east of Tree E1), the First Respondent was required by the definition of Aboriginal tradition in s 3(1) and ss 3(2)(iii) and 3(3) of the Act to consider whether on the material before her it was likely that passage through or over, or entry upon, the Specified Area by any person would occur in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition, but she failed to approach the Decision on that basis.

E. In making the Decision, the First Respondent misconstrued the Act and unlawfully approached the question of whether she was satisfied as to the matters prescribed by s 10(1)(b)(ii) solely by reference to whether the Trees were to be injured, destroyed or otherwise physically damaged.

F. In so far as the Decision was that the area was a significant Aboriginal area save for the area east of Tree E1:

a) a breach of the rules of natural justice or procedural fairness occurred in connection with the making of the Decision in that the Applicants were not put on notice of that possibility and given an opportunity to comment;

b) there was no evidence or other material to justify it (and no reasons were given to justify it).

G. Procedures that were required by law to be observed in connection with the making of the Decision were not observed.

Particulars

Section 10(1)(c) of the Act required the respondent to consider the report received under section 10(4) of the Act.

The respondent did not consider the report; the respondent was not provided with the Executive Summary and introductory maps forming part of the report (being pages 110 – 134 of the material previously before former Minister Price, one page of which comprised “Map 2” annexed to this amended originating application).

The objects

H. The First Respondent failed to make the Decision in accordance with the Act in that she failed to have proper regard to:

a) the definition of Aboriginal tradition in s 3(1) of the Act;

b) the circumstances in which an object would be taken to be injured or desecrated for the purposes of the Act as set out in s 3(2) of the Act;

c) the circumstances in which an object would be taken to be under threat of injury or desecration for the purposes of the Act as set out in s 3(3) of the Act;

with the consequence that the First Respondent asked herself the wrong question in considering her state of satisfaction as prescribed by s 12(1)(b)(ii) of the Act.

I. Having correctly determined that Trees E2 to E6 were significant Aboriginal objects for the purposes of s 12(1)(b)(i) of the Act, the First Respondent was required by the definition of Aboriginal tradition in s 3(1) and ss 3(2) and 3(3) of the Act to consider whether on the material before her she was satisfied that Trees E2 to E6 were, or were likely to be, used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition, but failed to approach the Decision on that basis.

J. In making the Decision, the First Respondent misconstrued the Act and unlawfully approached the question of whether she was satisfied as to the matters required by s 12(1)(i)(b) solely by reference to whether Trees E2 to E6 were liable to be injured, destroyed or otherwise physically damaged, without having regard to whether Trees E2 to E6 were, or were likely to be, used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition.

The consultation process

K. In making the Decision, the First Respondent failed to comply with the scheme of the Act and the obligations imposed upon her by section 13(2) of the Act, in that the First Respondent:

a) failed to consult with the appropriate Victorian Minister (being the Victorian Minister with responsibility for Aboriginal affairs) as to whether there was, under a law of Victoria, effective protection of the Specified Area or Trees from the threat of injury or desecration;

b) purported to consult with:

i. the Victorian Minister for Roads and Road Safety and Ports; and

ii. the MRPV;

as to whether there was, under a law of Victoria, effective protection of the Specified Area or Trees from the threat of injury or desecration.

Particulars

Letter from the First Respondent to the Hon Luke Donnellan MP dated 25 October 2018 (DW-1 p 1627);

Letter from the Hon Luke Donnellan MP to the First Respondent dated 30 October 2018 (DW-1 p 1629);

Letter from MRPV to Ms R Halliday Director of Indigenous Heritage, Department of Environment and Energy dated 7 November 2018 (DW-1 p 1631).

Letter from MRPV to Ms R Halliday Director of Indigenous Heritage Department of Environment and Energy dated 29 May 2019 (DW-1 p 2715).

EMAC Compromise

L. In making the Decision, the First Respondent failed to comply with the scheme of the Act and the obligations imposed upon her by the Act, in that the First Respondent:

a) failed to have regard to a relevant consideration under each of ss. 10 and 12 of the Act being whether making a declaration would advance the purpose of the Act and would benefit the Applicants, Aboriginal people more generally and the broader Australian community;

b) failed to take into account the detriment to the Applicants, Aboriginal people more generally and the broader Australian community of failing to make a declaration; and

c) made the Decision to facilitate the EMAC Compromise.

Particulars

The Applicants repeat the particulars set out under paragraph U below.

Procedural fairness

M. A breach of the rules of natural justice or procedural fairness occurred in that in making the Decision the First Respondent had before her a briefing from the Department that contained credible and relevant material adverse to the Applicants which material was not shown to the Applicants.

ADJR Act section 5(1)(e)

The area

N. The Decision constituted an improper exercise of power in that the First Respondent failed to take into account a relevant consideration, namely whether on the material before her she was satisfied that the Specified Area was, or was likely to be, injured or desecrated for the purposes of s 3(2) of the Act.

O. The Decision constituted an improper exercise of power in that the First Respondent failed to take into account a relevant consideration, namely a representation by the Applicants that, even if trees E2 to E6 would not be injured or desecrated by the Section 2B Upgrade (as contended by MRPV), the Specified Area was, or was likely to be, injured or desecrated for the purposes of s 3(2) of the Act.

Particulars

The representation was made in a letter dated 13 June 2019 from the Applicants’ solicitor to the Mr David Williams at pages 2823 and 2824 of DW-1 (paragraphs D(viii)(e) and D(viii)(f)).

P. The Decision constituted an improper exercise of power in that, having been satisfied that the Specified Area was a significant Aboriginal area for the purpose of s 10(1)(b)(i) (save in respect of the area east of Tree E1), the First Respondent’s failure to be satisfied that the Specified Area was, or was likely to be, under threat of injury or desecration based on the material before her was so unreasonable that no reasonable person could have so exercised the power.

Q. The Decision constituted an improper exercise of power in that the First Respondent failed to take into account a relevant consideration, namely the actual area in respect of which the Applicants sought a protection declaration.

Particulars

The area in respect of which the Applicants sought a protection declaration was described in the Application, as clarified by material provided to the Minister on 5 July 2018 including maps.

The respondent did not consider all of the material provided to the Minister on 5 July 2018; the respondent was not provided with the clarifying maps (being the maps at pages 55 – 69 of the material previously before former Minister Price).

The objects – Trees E2 to E6

R. The Decision constituted an improper exercise of power in that the respondent (sic) failed to take into account a relevant consideration, namely whether on the material before her she was satisfied that the Trees were, or were likely to be, injured or desecrated for the purposes of s 3(2) of the Act.

S. The Decision constituted an improper exercise of power in that, having been satisfied that Trees E2 to E6 were significant Aboriginal objects for the purpose of s 12(1)(b)(i) of the Act, the First Respondent’s failure to be satisfied that Trees E2 to E6 were, or were likely to be, under threat of injury or desecration based on the material before her was so unreasonable that no reasonable person could have so exercised the power.

The objects – Tree E1

T. In so far as the Decision was that the First Respondent was not satisfied that Tree E1 was a significant Aboriginal object, the Decision constituted an improper exercise of power in that the Reporter having been satisfied that Tree E1 was a significant Aboriginal object for the purpose of s 12(1)(b)(i) of the Act, the First Respondent’s failure to be satisfied that Tree E1 was a significant Aboriginal object based on the material before her was so unreasonable that no reasonable person could have so exercised the power.

Particulars

The Applicants rely on:

a) Dr Heather Builth’s reports of 2017, 2018 and 2019.

b) The On Country Report of 23 July 2018.

c) The fact the Reporter expressed the view that Tree E1 was a significant Aboriginal object.

d) The fact Minister Price determined that Tree E1 was a significant Aboriginal object.

e) The fact the respondent gave weight to the views of Martang and EMAC when Martang and EMAC did not represent the Applicants.

f) The fact the respondent relied on and gave weight to what was said to have been concluded during the Walk-through on 29 April 2019 as described in the letter from EMAC dated 29 May 2019 to MRPV to which reference is made at pp. 4-5 in the Applicants’ submission dated 13 June 2019 which is included in Attachment R (pages 2807-2844 DW1), when the Walk-through did not include the Applicants.

Purpose inconsistent with Act

U. In making the Decision, the First Respondent purported to exercise her powers under the Act for a purpose other than a purpose for which the powers were conferred, namely in order to facilitate the EMAC Compromise.

Particulars

The purpose alleged can be inferred from:

a) the fact that the First Respondent failed to find that Tree E1 was a significant Aboriginal object for the purposes of the Act, notwithstanding that the Reporter and former Minister Price had found to the contrary;

b) the fact that the First Respondent failed to find that the area east of Tree E1 was a significant Aboriginal Area when there was no proper basis for that conclusion and the conclusion was inconsistent with the First Respondent’s conclusion as to the balance of the Specified Area;

c) the fact that it was necessary for Tree E1 and the area east of tree E1 to be destroyed in order to give effect to the EMAC Compromise;

d) the fact that prior to making the Decision the First Respondent consulted with MRPV;

e) the fact that the respondent did not seek the views of, or otherwise consult with a Victorian Minister with responsibility for Aboriginal affairs prior to making the Decision;

f) the fact that the Decision gave effect to and facilitated the EMAC Compromise;

g) the matters alleged in grounds P and S;

h) the fact that the conclusions said to be unreasonable by reason of the matters alleged in grounds P and S can be rationally explained, and can only be rationally explained, on the basis that the First Respondent intended to give effect to the EMAC Compromise.

The evidence

30 The applicants relied on two affidavits of Michael Kennedy, solicitor, sworn on 1 October 2019 and 30 October 2019.

31 The Minister relied on two affidavits affirmed by David Williams, Assistant Secretary in the Minister’s Department, dated 16 September 2019 and 4 October 2019.

32 There was no cross-examination. The purpose of the affidavits was to annex or exhibit documents.

The submissions of the parties

Applicants’ submissions

33 The applicants made clear that they did not contend that there should not be a road but that there ought to be protection of the Aboriginal cultural heritage in the area and that that could be accommodated. Their submissions were as follows.

34 The applicants submitted that the principal error made by the Minister was her conclusion that she lacked jurisdiction to make protection declarations under the Heritage Protection Act because she was not satisfied that the Specified Area or the six trees were under threat of injury or desecration by the Section 2B upgrade. The applicants contended that in failing to be so satisfied the Minister:

(a) failed to have proper regard to the definition of Aboriginal tradition in s 3(1) of the Heritage Protection Act;

(b) failed to have proper regard to the circumstances in which an area or object will be taken to be injured or desecrated for the purposes of the Heritage Protection Act, as set out in s 3(2) of that Act; and

(c) failed to have proper regard to the circumstances in which an area or object will be taken to be under threat of injury or desecration for the purposes of the Heritage Protection Act, as set out in s 3(3) of that Act.

35 The applicants submitted that it was evident from her reasons that the Minister misunderstood her statutory obligation. This caused her to identify the wrong issue, and to ask herself the wrong question, the applicants submitted.

36 The concepts in issue in Northern Territory v Griffiths [2019] HCA 7; 364 ALR 208 and in the definition of Aboriginal tradition identified in s 3 of the Heritage Protection Act were essentially the same, the applicants submitted.

37 The applicants submitted that the s 10 application was always about the significance of the area, and the cultural landscape including the tree landscape along the Western Highway. They submitted that it was never put, and indeed there was much material to the contrary, that the only reason that the area was significant was because the six trees were significant, such that if the six trees remained standing there could be no desecration of the area. The area was significant beyond the significance of the six trees, the applicants submitted, and the issue was about cultural heritage more widely than simply the six trees.

38 The Minister made several errors in connection with the decision, the applicants submitted. Most related to her claimed failure properly to construe the Heritage Protection Act. In particular, the applicants submitted, she failed properly to construe or appreciate the definition of Aboriginal tradition; she also failed to have regard to the requirements of ss 3(2) and 3(3), with the consequence that she asked herself the wrong questions, and thereby erred in purporting to assess whether she had reached the state of satisfaction required by ss 10(1)(b) and 12(1)(b) of the Heritage Protection Act.

39 The applicants submitted that the Heritage Protection Act was directed at the preservation and protection of significant areas and objects. Section 3(2) defined broadly and expansively what would constitute injury or desecration for the purposes of the Heritage Protection Act, and the concept of threat was also broadly defined in s 3(3), the applicants submitted.

40 The applicants submitted that the Heritage Protection Act did not permit the Minister, in assessing the significance of an area, to adjust the significance because of the way the Application was put. The Heritage Protection Act had provisions which prescribed the way the Minister identified and approached the question of what is Aboriginal cultural heritage, the applicants submitted. The Minister’s finding about the way the trees were significant did not reflect the material before her about what Aboriginal tradition is and the Minister misunderstood the application of the test, they submitted. The notion that the significance of the area derived from the trees was not reconcilable with the finding at [5.48] of the reasons that there was a cultural connection that rendered the Specified Area particularly significant, with a degree of antiquity, related to the dreaming stories, the songlines, the spirituality and traditional interaction with the cultural landscape comprised by, and within, the Specified Area. The applicants submitted that this disconnect meant that the Minister erred, when considering the question of injury or desecration, in reasoning that because the six trees were not going to be destroyed it followed that the Specified Area was not under threat. The Minister had not applied the test in s 3(2)(a) which applied in the case of an area, the applicants submitted.

41 The applicants also submitted that the Minister took an eccentric approach to reaching the states of satisfaction required by ss 10(1)(b) and 12(1)(b); she looked first at the 12(1)(b) issue. There was nothing in the legislation that suggested that was the correct approach. In fact, that approach led to serious error, the applicants submitted.

42 In approaching the s 12(1)(b) issue, the Minister determined that she was not satisfied that any of Trees E2 to E6 were under threat of injury or desecration for the purpose of the Heritage Protection Act. The basis for this conclusion was her acceptance of a representation from MRPV that it would “avoid” Trees E2 to E6.

43 That approach asked the wrong question, the applicants submitted. The question for the Minister was not whether these six trees would be “avoided”; that is, whether they would be clear-felled or otherwise destroyed by the Section 2B upgrade. The correct question was that posed by ss 3(2) and 3(3), namely, whether it was “likely” that Trees E2 to E6 would be “used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition” as a consequence of the Section 2B upgrade.

44 The question posed to herself by the Minister was fundamentally different to the question required to be asked by the Heritage Protection Act, the applicants submitted. The Minister approached the question of her satisfaction under s 12(1)(b)(ii) on the basis that she could be satisfied there was no relevant threat of injury or desecration if there was no physical destruction of or injury to Trees E2 to E6. The Heritage Protection Act called for a much broader inquiry about whether the threatened conduct would be likely to lead to use or treatment that was inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition, the applicants submitted, and the Minister’s approach constituted error of a fundamental sort.

45 The applicants submitted that the error by the Minister in relation to the discharge of her obligations under s 10(2)(b), regarding the threat to the Specified Area, was even more acute. Sections 10(2)(b)(ii), 3(2) and 3(3) required the Minister to ask herself three questions, they submitted:

(a) first, whether it was likely that as a consequence of the Section 2B Upgrade the Specified Area would be used or treated in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition (s 3(2)(a)(i));

(b) secondly, whether it was likely that anything done in, on or near the Specified Area as a consequence of the Section 2B Upgrade would adversely affect the use or significance of the Specified Area in accordance with Aboriginal tradition (s 3(2)(a)(ii)); and

(c) thirdly, whether it was likely, as a consequence of the Section 2B Upgrade, that passage through or over, or entry upon, the Specified Area by any person would occur in a manner inconsistent with Aboriginal tradition (s 3(2)(a)(iii)).

46 The applicants submitted that her reasons showed that the Minister did not ask herself these questions. Accordingly, the analysis performed by the Minister in purporting to reach the necessary state of satisfaction did not comply with the statutory requirement cast on her.

47 The Minister’s analysis appeared in [5.51]-[5.52] (see [23] above) of the reasons: she “noted” the view of the applicants to the Application that “even if the trees were not considered under threat, the surrounding area will be destroyed by the works and therefore the Specified Area is under threat of injury”. However, she dismissed that view summarily.

48 Several errors were apparent, the applicants submitted. First, and most fundamentally, the Minister failed to ask herself the questions prescribed by ss 3(2) and 3(3) and instead asked a different, much narrower, question. The question posed by the Minister was whether the six trees would be “removed”.

49 Second, the applicants submitted, the conclusion expressed in this passage, that the significance of the Specified Area “derives from” the culturally significant trees, reflected a misreading of “Aboriginal tradition” as defined in s 3(1) of the Heritage Protection Act. The Aboriginal heritage values called within the scope of the Heritage Protection Act by the definition of Aboriginal tradition must be understood as a “scheme of things in which the spirit ancestors, the people of the clan, particular land and everything that exists on and in it, are organic parts of one indissoluble whole”, the applicants submitted, citing Griffiths: see [36] above. That understanding of Aboriginal tradition was at odds with the model of Aboriginal tradition adopted by the Minister, the applicants submitted, which was one in which the significance of the area derived from, and solely from, the presence of the trees; and while the trees stood, no inconsistency with the traditional use of the Specified Area – not even the total destruction of the area and the construction of a multi-lane highway through the Specified Area – would be found to threaten the use of the Specified Area in accordance with Aboriginal tradition. The Minister’s approach was plainly at odds with the scheme of the Heritage Protection Act, the applicants submitted. They submitted it was wrong as a matter of law, for the reasons explained in Tickner v Bropho (1993) 40 FCR 183 and Griffiths.

50 Even if that were not so, the applicants submitted, there was no material available to the Minister that would support her analysis of the relevant Aboriginal tradition working in the way suggested. The Reporter concluded at [224]-[225] of her report that “the trees, many culturally modified by their ancestors, are situated in a landscape in which Djab Wurrung people maintain certain traditions … The particular traditions … include the belief in the trees as personifying their ancestors … These spiritual beliefs, which are connected to other stories in the landscape and the cultural modification of some of the trees in the specified area, demonstrate the particular significance of both trees and area under Djab Wurrung traditions.” Further, the Minister’s analysis of Aboriginal tradition was inconsistent with her own determination that there was “a cultural connection that rendered the Specified Area particularly significant, with a degree of antiquity, involving Aboriginal traditions, observances, customs and beliefs that are passed down from generation to generation through dreaming stories, song lines, spirituality, culture and traditional interaction with the cultural landscape”. That determination and the Aboriginal tradition it described was impossible to reconcile with the later conclusion that the Specified Area was not threatened by the Section 2B upgrade, the applicants submitted.

51 Finally, the Minister’s analysis failed, even in its own terms, the applicants submitted. The Minister found there was no threat of injury to the area because “the trees will not be removed”. In fact, the decision relied on an arrangement made between the Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation (EMAC) and MRPV that involved Tree E1 being destroyed.

52 The applicants submitted that MRPV set about reaching a compromise with EMAC (EMAC Compromise) that would permit the Section 2B upgrade to be constructed largely on the planned alignment, with adjustments that would avoid the need to destroy five of the six trees.

53 Notably, the applicants submitted, MRPV chose to negotiate with EMAC but not the applicants who had asserted that cultural heritage existed. The elements of the EMAC Compromise were also notable; it involved MRPV committing to “additional incentives” in return for EMAC supporting the existing alignment of the Section 2B upgrade. The incentives MRPV committed to were in part financial, the applicants submitted: “1% of procurement spend being obtained from Aboriginal owned businesses” and an “‘Aboriginal Employment Target’ of 2.5% for the Western Highway Duplication”.

54 Additionally, the applicants submitted, there was a commitment by MRPV to “undertaking a cultural values assessment for the additional projects planned for the Western Highway” that would include “both tangible and intangible Aboriginal heritage values” and “consultation with Traditional Owners”.

55 Lastly, the applicants submitted, MRPV agreed to install “interpretative signs to acknowledge the cultural significance of the land”. In summary, the applicants submitted, by offering financial advantages for some unidentified Aboriginal businesses and people, changes in the route alignment that would avoid destruction of five of the six trees and the other measures identified, MRPV procured EMAC to withdraw its opposition to the works to upgrade the Western Highway.

56 The EMAC Compromise was formally notified to the Minister’s Department on 29 May 2019. On the same day the Department sent a letter to the applicants, in which the Department foreshadowed the reasoning later adopted by the Minister in the decision; namely, the conclusions that Tree E1 was not significant, and that none of the other trees, nor the Specified Area, were threatened by the Section 2B upgrade. The timing and content of this letter obviously suggested co-ordinated action, the applicants submitted.

57 These events suggested several errors that impugned the lawfulness of the decision, the applicants submitted.

58 First, as part of the statutory machinery the Heritage Protection Act created in aid of the purposes of that Act, it contemplated communication between the Minister and the “appropriate” State Minister about whether State law provided effective protection to the relevant area or objects, the applicants submitted, referring to s 13(2). They submitted that it was to be inferred that the “appropriate” State Minister was the person with responsibility for administering the State law which might provide the relevant protection. That consultation did not take place, the applicants submitted. Instead, the Minister wrote to the Victorian Minister for Roads, with responsibility for the Western Highway upgrade, Minister Donnellan. Minister Donnellan invited the Minister to consult directly with the MRPA (the predecessor to MRPV). The applicants submitted that an obligation to consult with the appropriate State Minister was a duty that should be implied into s 13(3) as necessary or “proper” for the discharge of a statutory function set up by the Heritage Protection Act. The applicants submitted that what occurred undermined the scheme of that Act because the Minister conducted her consultation with the statutory entity responsible for development of the project said to threaten the Specified Area and the trees (namely, MRPV), and not with the Victorian Minister charged with protecting Aboriginal interests.

59 Second, the Heritage Protection Act was enacted with the express purpose of preserving and protecting from injury or desecration areas and objects in Australia that are of particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal tradition. Informing its enactment was the idea that it would be used as a protective mechanism of last resort where State or Territory legislation was ineffective or inadequate to protect heritage areas or objects, the applicants submitted. The events described above undermined this protective purpose, they submitted. By consulting with MRPV, the developer, and not the Victorian Minister charged with protecting Aboriginal heritage, the Minster and her Department, implicitly or expressly, became participants in the EMAC Compromise, which had as its sole objective the advancement of the Section 2B upgrade along its existing alignment, the applicants submitted.

60 The EMAC Compromise was not directed at protecting the Specified Area or the trees, but was a bargain, struck on the basis of incentives offered by the developer to EMAC, expressly intended to allow the project to be built notwithstanding its impact on the Specified Area, the applicants submitted. They submitted that by its conduct, the Department set the Minister upon a course that failed to give effect to her statutory obligations: she failed to consider the Application in good faith by reference to the statutory criteria; she allowed the exercise of her statutory powers to be fettered and constrained by the need to bring her decision within the framework contemplated by the EMAC Compromise; and she failed to give proper and appropriate consideration to the material before her. In all the circumstances, the decision was properly characterised as the purported exercise of the powers under ss 10 and 12 of the Heritage Protection Act other than for the purposes for which they were conferred.

61 Finally, and most fundamentally, in adopting the analysis of the Department and the draft reasons provided to her, the Minster erred in concluding that she lacked jurisdiction to make declarations under ss 10 and 12 of the Act, the applicants submitted. At [6.1]-[6.2] of her reasons, the Minister determined that by reason of not being satisfied about the threat to the Specified Area or the six trees, she was not empowered to make the declarations sought by the Application. The applicants relied on their earlier submission that, in assessing her state of satisfaction about the alleged threat, the Minister failed to apply the statutory criteria in s 3(2). That occurred because the process miscarried at an earlier stage. Instead of applying the Heritage Protection Act in good faith, the Minister engaged in an artificial process and adopted contrived reasons, the applicants submitted, which were crafted by the Department to bring about a predetermined result. The applicants submitted that the Minister did not, as the Heritage Protection Act required, engage with the desirability of making declarations that would protect significant Aboriginal cultural heritage for the benefit of the applicants, the Djab Wurrung people and all Australians; instead, she adopted reasons calculated solely to reach a conclusion that would facilitate and give effect to the EMAC Compromise.

62 For these reasons, the applicants submitted, the Minister also failed to take into account whether on the material before her she was satisfied that the Specified Area was, or was likely to be, injured or desecrated for the purposes of s 3(2) of the Heritage Protection Act. She also failed to apply the criterion in s 3(2) in assessing the threat to the six trees (or at least Trees E2 to E6). The failure to have regard to this important issue was (inter alia) a failure to have regard to a relevant consideration.

63 In addition, the applicants submitted, the Minister failed to take into account a representation made by the applicants that expressly identified the errors in the Minister’s approach. In a letter dated 13 June 2019 to the Department, the applicants submitted, they had contended that:

(a) the suggestion that there was a ‘nexus between a significant aboriginal area and significant aboriginal Objects’ so that preservation of the Trees meant the Specified Area may not be under threat was wrong and unjustified; and

(b) even if it were correct that there was no threat to the Trees (which the applicants did not accept), because ‘the area surrounding [the] trees will be destroyed by the proposed works’ there was no basis for the Minister to find that the Specified Area was not under threat of injury and desecration.

The reasons showed that the Minister failed to consider these representations, the applicants submitted.

64 As to unreasonableness, the applicants submitted that the Court was required to consider the quality of the decision by reference to the statutory source of the power exercised in making the decision and, thus, assess whether the decision was lawful, having regard to the scope, purpose and objects of the statutory source of the power. In making that assessment the Court was concerned mostly with the existence of justification, transparency and intelligibility within the decision-making process. It also considered whether the decision fell within a range of possible, acceptable outcomes which were defensible in respect of the facts and law. On either test, the decision by the Minister may be impugned, the applicants submitted.

65 For these reasons, the purposes and objects of the Heritage Protection Act were not given effect by the decision. Additionally, the determination that the significance of the Specified Area derived from, and implicitly solely from, the culturally significant trees totally lacked evidence to support it or any other justification, the applicants submitted. It was inconsistent with both the material before the Minister and her own conclusions about why the area was significant for the purposes of the Heritage Protection Act. Even if these errors were not expressly apparent in the reasons, the decision was not “within a range of possible, acceptable outcomes”. The conclusion that construction of a four-lane highway through an area of significant Aboriginal cultural heritage did not threaten to injure or desecrate that heritage, needed only be articulated for it to be seen to be indefensible. That was true based on an ordinary analysis of the concepts of injury, desecration and threat. When the extended definitions of those concepts in s 3 of the Heritage Protection Act were accounted for, the decision was revealed clearly to be legally unreasonable, the applicants submitted.

66 As to procedural fairness, the applicants submitted that between 12 April 2019 and 29 May 2019, the Department radically changed its approach to the consideration of the Application. The Department’s letter to the applicants dated 17 April 2019 had suggested that the Minister, like the former Minister, was contemplating refusing the Application based on the benefits that the Section 2B upgrade was said to achieve. The 29 May 2019 letter from the Department to the applicants alerted them to “new information” but did not put them on notice of the complete change in the Department’s approach to the Application. In the context, to understand the significance of “new information” required the applicants to have access to the Department’s analysis as provided to the Minister (Departmental Analysis), the applicants submitted. In the circumstances, the provision of this information was necessary to accord procedural fairness. Despite requests, the Departmental Analysis was not provided to the applicants.

67 As to the grounds relating to Tree E1 considered by itself, the applicants noted that the Minister was satisfied that the Specified Area was a significant Aboriginal area for the purposes of s 10(1)(b)(i) of the Heritage Protection Act “except to the extent of the vicinity of Tree E1 eastwards”.

68 The applicants submitted that the conclusion regarding the area “[in] the vicinity of Tree E1 eastwards” was unexplained, and that nowhere in her reasons did the Minister articulate a basis for “excising” this area. Nor did the reasons define, or depict on a map, the boundaries of the area “[in] the vicinity of Tree E1 eastwards”. The area was unknown and therefore uncertain, and one was left to speculate about where the area was, and for what reason the Minister excised it, the applicants submitted.

69 The applicants challenged this aspect of the decision on two bases. First, the applicants submitted that they were not given notice of the possibility that the Minister might treat the area “[in] the vicinity of Tree E1 eastwards” differently from the Specified Area as a whole, and thus were given no opportunity to comment. This was claimed to be a breach of the rules of natural justice.

70 Second, the applicants submitted that there was no evidence to support the conclusion that the area “[in] the vicinity of Tree E1 eastwards” was not significant. There was much evidence to support the conclusion that the Specified Area (as a whole) was “significant”. But the evidence did not address the area “[in] the vicinity of Tree E1 eastwards” separately from, or in any different way to, the Specified Area (as a whole). In terms of s 5(3) of the ADJR Act, the applicants submitted that:

(a) the Minister was required by law to reach a decision (namely, that she lacked jurisdiction to make a protection declaration under the Heritage Protection Act) only if a particular matter was established (namely, that she was not satisfied that the area “[in] the vicinity of Tree E1 eastwards” was significant), and, having determined that the Specified Area was significant, there was no evidence or other material (including facts of which she was entitled to take notice) from which she could reasonably be satisfied that the matter was established; and

(b) the Minister based the decision on the existence of a particular fact (namely, that the area “[in] the vicinity of Tree E1 eastwards” lacked the characteristics that she had found pertained to the remainder of the Specified Area), but that fact did not exist.

71 The applicants also contended that the Minister’s failure to be satisfied that Tree E1 was a significant Aboriginal object based on the material before her was so unreasonable that no reasonable person could have so exercised the power.

72 The applicants observed that the Heritage Protection Act (in s 3(1)) relevantly provided that significant Aboriginal object meant an object (including Aboriginal remains) of particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal tradition. The question for the Minister therefore was whether she was satisfied that Tree E1 was an object “of particular significance to Aboriginals in accordance with Aboriginal tradition”.

73 The applicants noted that on the basis of the Builth 2017 and 2018 reports, the Sanders 2018 report and Ms Phillips’ report, the former Minister had been satisfied that Tree E1 was a significant Aboriginal object.

74 The Minister’s justification for coming to a contrary decision on Tree E1 spanned [5.17]-[5.25] of the reasons. The Minister started by referring to views expressed by Martang Aboriginal Corporation and, later, EMAC, that Tree E1 bears a “European scar”. The applicants submitted that the source of the views ascribed to Martang and EMAC was not clear from the reasons; neither made a representation to the Reporter (or to the Minister).

75 The Minister then noted the Reporter’s conclusion that all six trees were significant Aboriginal objects. But, the applicants submitted, the Minister effectively disregarded or downplayed the Reporter’s conclusion on Tree E1 by characterising her report as “focussed on Trees E3 and E6”.

76 The Minister went on to consider the expert material from Dr Builth and Natasha Sanders. In relation to Ms Sanders, the Minister noted that her report “included information on the cultural values of some of the Six Trees”. The applicants submitted that characterisation disregarded or downplayed Ms Sanders’ actual conclusion (namely, that the tree was “culturally modified”) and Ms Sanders’ overall conclusion, quoted in terms by the Reporter:

All of the old trees, both within the focus areas and the broader area, were identified as having cultural significance even if there were no clear or visible markings from modification. These old trees were often referred to throughout the consultation as Ancient Trees, Ancestor Trees, or Guardian Trees highlighting the relationship between the trees and the ancestors that live within them.

77 In relation to Dr Builth, the Minister referred to all three of her reports. The Minister summarised aspects of Dr Builth’s reports, the applicants submitted, but omitted to refer to the key evidence and conclusions in Dr Builth’s reports concerning Tree E1.

78 The applicants contended that the Minister reached her conclusion at [5.25] (see [15] above) by a process that:

(a) ignored the statutory definition of “significant Aboriginal object” (the Minister did not mention it, but instead appeared to approach the question by considering that the question for her was whether Tree E1 was as significant as Trees E3 and E6);

(b) presented and relied on a highly selective subset of the evidence before her, and disregarded or downplayed “unhelpful” evidence or conclusions that had been placed before her;

(c) gave equal weight to the beliefs of the applicants (supported both by the expert evidence they adduced from Dr Builth, and the “independent” expert evidence from Ms Sanders), and the unascribed hearsay views of Martang and EMAC (who did not represent the applicants);

(d) relied on and gave weight to what was said to have been concluded during the Walk-through on 29 April 2019, when the Walk-through did not include the applicants.

79 The process of reasoning followed by the Minister in respect of Tree E1 was the opposite of a process of justification, transparency and intelligibility, the applicants submitted. The decision was indefensible in light of the whole of the evidence before the Minister; it only had the appearance of defensibility when presented in the reasons in a way that ignored or downplayed “unhelpful” evidence or conclusions. In light of the whole of the evidence before the Minister, the applicants submitted that the Minister’s decision was so unreasonable that no reasonable person could have reached it.

Minister’s submissions

80 The respondent Minister submitted that none of the grounds alleged in the application for review were established. The Minister made nine points by way of summary.

81 First, it was submitted, the Minister correctly had regard to and applied the relevant provisions of the Heritage Protection Act, including the statutory definition of “Aboriginal tradition” in s 3(1), the concept of “injury or desecration” in s 3(2), and the concept of “threat of injury or desecration” under s 3(3) of the Act.

82 Second, on the material before the Minister, it was submitted that it was open to her to find that five of the trees (Trees E2 to E6) located within the Specified Area were significant Aboriginal objects, and that one of the trees (Tree E1) was not a significant Aboriginal object. It was also open to the Minister to find that part of the Specified Area was a significant Aboriginal area and that, in the context of the Application, the cultural significance of that area was relevantly derived from the trees and their interconnectedness to other stories.

83 Third, on the material before the Minister, it was submitted that it was open to her to find that she was not satisfied that the significant Aboriginal objects (ie, Trees E2 to E6) or the relevant part of the Specified Area comprising the significant Aboriginal area were under threat of injury or desecration within the meaning of ss 10 or 12 of the Heritage Protection Act.

84 Fourth, it was submitted that the Minister properly had regard to factual developments in relation to the agreement reached between MRPV and the EMAC, which were relevant to her consideration of whether the trees and surrounding area were under threat of injury or desecration within the meaning of the Heritage Protection Act.

85 Fifth, it was submitted that there was no basis on which to infer that the Minister made the decision for reasons other than those set out in the written statement of reasons, and in particular the Minister did not act for an improper purpose of facilitating or giving effect to the agreement reached between MRPV and EMAC in order to carry out the planned upgrade works. Nor did the Minister (or the Department) engage in an “artificial” process in order to bring about a “pre-determined result”, she submitted: the applicants did not rely on any evidence in support of this assertion, and moreover had not properly pleaded any allegation of actual bias on the part of the Minister.

86 Sixth, it was submitted that there was proper consultation by the Minister with relevant Victorian Ministers (including the Minister for Roads and Road Safety). In circumstances where she did not make a declaration under the Heritage Protection Act, the Minister submitted she was not obliged by s 13(2) to consult with the appropriate Victorian Minister as to whether there was effective protection of the area or objects under the law of Victoria. Further or alternatively, any failure to consult with the appropriate Victorian Minister would not result in invalidity of the decision, it was submitted.

87 Seventh, it was submitted on behalf of the Minister that the applicants were given a reasonable opportunity to be heard on all issues relevant to the decision, and to comment on and respond to the substance of any adverse material. Procedural fairness did not entitle the applicants to be given a copy of the Departmental brief to the Minister which summarised and analysed the material relevant to the decision, the Minister submitted.

88 Eighth, the decision was within the bounds of legal reasonableness. The Minister’s reasons, she submitted, provided an intelligible basis on which she was not satisfied that significant Aboriginal objects or areas were under threat of injury or desecration, and why in any event she would not have exercised the discretion to make a declaration under ss 10 or 12 of the Heritage Protection Act.

89 Ninth, in any event, it was submitted that even if the applicants could establish that there was legal error affecting the Minister’s findings that she was not satisfied that the significant Aboriginal objects or the significant Aboriginal area were under threat of injury or desecration for the purposes of ss 10(1)(b)(ii) and 12(1)(b)(ii) of the Heritage Protection Act, any such error was not material to the Minister’s decision to refuse to make declarations under ss 10 and 12 of the Act. In circumstances where the Minister would not have exercised her discretion to make declarations even if she had been satisfied that the preconditions under ss 10 and 12 had been met, the applicants had not been deprived of any possibility of a different outcome on their Application, the Minister submitted.