FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Perera v Australian Securities and Investments Commission, in the matter of Hodder Rook & Associates Pty Limited [2019] FCA 2015

Table of Corrections | |

Date of Judgment and Date of Orders have been amended from 3 November 2019 to 3 December 2019. |

ORDERS

IN THE MATTER OF HODDER ROOK & ASSOCIATES PTY LIMITED ACN 003 936 141

| ||

Plaintiff | ||

AND: | AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES AND INVESTMENTS COMMISSION Defendant | |

DATE OF ORDER: | 3 December 2019 |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating process filed on 13 September 2019 be dismissed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

MARKOVIC J:

1 By an originating process filed on 13 September 2019 Madura Perera seeks an order pursuant to s 601AH(2) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Act) that the defendant, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), reinstate the registration of Hodder Rook & Associates Pty Limited (HRA), an order pursuant to s 482(1) of the Act that the liquidation of HRA be terminated and the following ancillary orders:

6 Any other order that the court pleases

a. Order that the Hodder Rook & Associates Pty. Limited ACN 003 936 141 pay any liability including wages and super to the Director Madura Perera only once all other outstanding liabilities are been paid.

b. Order that the outstanding employee super excluding the Directors super paid as the first payment by Hodder Rook & Associates Pty. Limited ACN 003 936 141

c. Order that the outstanding employee wages excluding the Directors wages paid as the second payment by Hodder Rook & Associates Pty. Limited ACN 003 936 141

d. Order that the outstanding ATO debt is paid as the third payment by Hodder Rook & Associates Pty. Limited ACN 003 936 141

e. Order that all other outstanding creditors are paid as the fourth payment by Hodder Rook & Associates Pty. Limited ACN 003 936 141

2 In his affidavit in support of the application affirmed on 17 October 2019 Mr Perrera seeks two additional orders: first, that upon termination of the winding up, the directors of the company take office of HRA; and secondly, that the costs of the application not be costs in HRA.

3 For the reasons that follow I am not satisfied that the orders sought by Mr Perera should be made and the originating process should be dismissed.

background facts

4 Mr Perera relies on four affidavits sworn by him and an affidavit sworn by Walter Guan, an accountant, annexing a report about HRA’s solvency in support of his application.

5 Mr Perera’s affidavits referred to proceedings involving HRA, interactions he had with the liquidator of HRA and the service of the originating process commencing this proceeding. Those affidavits also annexed a number of other documents to which no express reference was made. Set out below is a summary of the facts insofar as they are relevant to the application now before me.

6 HRA was a property valuation company. In June 2008 Mr Perera acquired all of the shares in HRA and since that time was its sole shareholder and director.

7 Mr Perera deposed that in July 2008 he was informed that Genworth Financial and Mortgage Insurance Pty Limited (Genworth) had filed a claim in the Supreme Court of New South Wales (Supreme Court) against HRA alleging negligence in relation to eight valuations completed by it (Supreme Court Proceeding). DLA Philips Fox (DLA) had been retained to act for HRA in that proceeding on behalf of HRA’s professional indemnity insurers, DUAL Australia Pty Ltd, for three of the valuations and Dexta Corporation Ltd (Dexta) for five of the valuations.

8 The evidence disclosed that the following occurred in and in connection with the Supreme Court Proceeding:

(1) on 9 July 2009 Genworth was informed by DLA that Dexta had refused to indemnify HRA in relation to the five valuations for which it was the relevant insurer;

(2) on 5 August 2009 Mr Perera informed DLA that he intended to terminate DLA’s retainer in relation to the uninsured claims. In a letter dated 9 August 2009, addressed to Mr Perera at HRA, DLA noted that as at that date HRA owed it $110,789.37 in outstanding fees which DLA required to be paid in full in order to facilitate the handover of files to HRA’s new lawyers;

(3) from at least 1 October 2009 until about late March 2010 Carneys Lawyers acted for HRA in the Supreme Court Proceeding. According to a schedule titled “Carneys Lawyers Accounts to Hodder Rook” included in the evidence before me, Carneys billed a total amount of $65,438.73 in the period 1 October 2009 to 26 March 2010 of which $46,913.68 remained outstanding;

(4) on 19 November 2009 Mr Perera was advised that Genworth had discontinued the proceeding in relation to two of the valuations with costs reserved, leaving three in dispute. The transcript of the Supreme Court Proceeding on 6 September 2010, the first day of the hearing, discloses that counsel for Genworth informed the court that three valuations remained in dispute in the proceeding, each of which was prepared and signed by Mr Perera, the proceeding originally concerned eight valuations but that the claims in relation to three of those valuations were resolved at a mediation which took place in July 2009 and since November 2009 Genworth had not pursued two of the valuations;

(5) on 22 September 2010 the Supreme Court made orders including that:

(a) there be judgment for Genworth in the sum of $410,495.77 inclusive of interest pursuant to s 100 of the Civil Procedure Act 2005 (NSW);

(b) HRA to pay Genworth’s costs of the proceedings except for the costs solely incurred in relation to the “Excluded Claims” (identified below) to be assessed as follows:

(i) in respect of costs incurred in the period up to and including 3 August 2010, Genworth’s costs to be assessed on the standard basis; and

(ii) in respect of costs occurred in the period 4 August 2010 to 15 September 2010, Genworth’s costs to be assessed on the indemnity basis;

(c) the “Excluded Claims” are the claims in relation to the valuation of the properties at:

(i) 86 Copeland Road, Beecroft and 60 Bulli Road, Toongabbie which were not pursued following amendments to the commercial list summons pursuant to leave granted on 19 November 2009;

(ii) 2/4 Beresford Road, Greystanes and 108 of 437 Burke Street, Surry Hills which were resolved at mediation on 9 July 2009; and

(iii) 2/40-42 Dutton Street, Bankstown which was not pursued from the commencement of the hearing on 6 September 2010; and

(d) there be no order as to the costs of the “Excluded Claims”.

9 HRA appealed the orders made in the Supreme Court Proceeding (Appeal Proceeding).

10 On 7 February 2011 the New South Wales Court of Appeal (Court of Appeal) made orders in the Appeal Proceeding that pursuant to s 1335 of the Act HRA provide security for Genworth’s costs of the Appeal Proceeding in the sum of $24,000 (Security Amount) within 28 days; the Appeal Proceeding be stayed if security is not paid; and that HRA pay Genworth’s costs of its notice of motion seeking security for its costs (February 2011 Costs Order).

11 There was evidence before me that the Security Amount was paid into court on behalf of HRA and that on 1 March 2011 an amount equal to the Security Amount was withdrawn by bank cheque from an account with St George Bank in the names of Mr Perera and Hui Chun Chang (St George Account).

12 On or about 8 April 2011 HRA paid $15,833.56 to Genworth in satisfaction of the February 2011 Costs Order (Genworth Payment). There was evidence before me that on 7 April 2011 the sum of $15,833.56 was withdrawn by bank cheque from the St George Account.

13 The Appeal Proceeding was listed for hearing before the Court of Appeal on 4 August 2011. At the conclusion of the hearing the Court of Appeal reserved its judgment.

14 On or about 12 August 2011 HRA was wound up and Brian Silvia was appointed as its liquidator (Liquidator).

15 On 15 September 2011 the Court of Appeal made the following orders:

(1) grant leave to HRA to appeal, such order to have effect as at 4 August 2011;

(2) fix 30 September 2011 (or such other date about that time as suits counsel) for the making of formal orders and encourage the parties to reach a settlement in the meantime,

and published its reasons: see Hodder Rook & Associates Pty Ltd v Genworth Financial Mortgage Insurance Pty Ltd [2011] NSWCA 279 (Hodder Rook v Genworth).

16 The effect of the Court of Appeal’s decision was to allow the appeal. In Hodder Rook v Genworth at [76] Young JA (with whom Beazley JA and Handley AJA agreed) said:

However, this commercial case has limped on from 2008. Many aspects of it appear to have been settled through mediation or otherwise. The costs have apparently been vast. I believe that it would be prudent to delay making formal orders to allow the parties to have one more opportunity to settle their differences. It may be that the above reasons will assist in this process. Accordingly, I would further propose that the only order that should be made now is an order noting that reasons have been published today and that formal orders will be made on 30 September 2011.

17 There was an attempt on the part of the Liquidator to settle the Appeal Proceeding. Mr Perera’s evidence is that on 12 September 2011 he was informed by the Liquidator’s office that the Liquidator would be settling the Supreme Court Proceeding on the basis that the Security Amount that had been paid into court would be released to the Liquidator. Mr Perera said that he told the Liquidator that this would not be acceptable because he had funded the trial with his own funds but that he was informed that the Liquidator was proceeding with the settlement.

18 On 12 September 2011 Nacho Rojo of the Liquidator’s office sent an email to Mr Perera in the following terms:

As discussed, we accept your offer of $25,000 to not settle the Genworth proceedings 2008/00290472 in the Court of Appeal of the Supreme Court of NSW. The payment by you is made pursuant to an agreement and will be used to assist with the Liquidation of Hodder Rook & Associates PL (in Liquidation). You will not be entitled to make a claim for this payment in the liquidation or against the liquidator. This acceptance is subject to payment being made by 1 pm tomorrow. You may either deliver a bank cheque to our office or EFT the funds (same day transfer) to our bank account by 1 pm tomorrow. The account details are:

…

If payment is made by EFT, you must send up a copy of the EFT transfer confirmation or receipt also by 1pm tomorrow. If payment or confirmation of payment is not received by 1pm, this agreement will be cancelled and have no effect. The liquidator then may proceed to settle or not settle the proceedings as advised.

This agreement is confidential until judgment is handed down and you are not to disclose this agreement to any other parties without our prior written consent.

19 On 13 September 2011 an amount of $25,000 was withdrawn by bank cheque from the St George Account and a bank cheque in the sum of $25,000 was received by the Liquidator.

20 On 30 September 2011 the Court of Appeal made the following orders in the Appeal Proceeding:

(1) grant leave to HRA to appeal, such order to have effect as of 4 August 2011;

(2) appeal allowed;

(3) orders of the primary judge be set aside;

(4) the matter is remitted to the Equity Division for retrial by a judge other than the primary judge;

(5) Genworth pay HRA’s costs of the appeal;

(6) the costs of the Supreme Court Proceeding be referred to the judge who conducts the subsequent trial; and

(7) the order to remit and the order with reference to the costs of the Supreme Court Proceeding do not dispense with the necessity for leave to proceed against the company in liquidation with further proceedings in the matter.

21 Included in the evidence relied on by Mr Perera is an affidavit sworn by Roderick Stuart Cameron on 6 March 2017 and filed in the Supreme Court Proceeding. Mr Cameron is a partner in the firm of Hicksons, the solicitors for Genworth in the Supreme Court Proceeding. In that affidavit Mr Cameron deposes to a number of matters including that:

(1) in about November 2011 the Liquidator alleged that the Genworth Payment, which was paid in satisfaction of the February Costs Order, was an unfair preference, which Genworth denied; and

(2) the Liquidator’s unfair preference claim was resolved on the basis that the Liquidator would recoup the Security Amount held in the Supreme Court and in exchange agree not to pursue recovery of the Genworth Payment. A letter dated 10 September 2012 from the Liquidator reflecting that agreement was annexed to Mr Cameron’s affidavit.

22 On 17 October 2012 an order was made by consent in the Appeal Proceeding that the Security Amount together with any interest thereon be released and paid forthwith to HRA, care of its solicitors.

23 The following correspondence which passed between Mr Cameron and Paul Bard of Paul Bard Lawyers, solicitors for the Liquidator, in relation to the Supreme Court Proceeding was in evidence before me:

(1) on 21 December 2012 Mr Cameron sent an email to Mr Bard offering to settle the Supreme Court Proceeding on the basis that the Supreme Court Proceeding be discontinued and there be no order as to costs, with the intention that each party pay its own costs and all costs orders in respect of which payment had not already been made be vacated;

(2) by email dated 24 December 2012 Mr Bard acknowledged Genworth’s offer and indicated that he would discuss it with the Liquidator in early January 2013;

(3) by email dated 13 March 2013 Mr Cameron followed up Genworth’s offer made on 21 December 2012;

(4) by email dated 22 July 2013 Mr Bard made a counter offer to the effect that the Liquidator would be prepared to settle the Supreme Court Proceeding on the basis proposed by Genworth provided Genworth paid HRA’s out of pocket costs incurred in the Appeal Proceeding comprising the filing fee and hearing allocation fee totalling $8,903;

(5) by email dated 31 July 2013 Mr Cameron asked for evidence that HRA had paid the filing and hearing allocation fees; and

(6) on 31 July 2013 Mr Bard responded noting that who paid the charges was irrelevant, those charges were recoverable if paid by or on behalf of the party who is the beneficiary of the costs order and thus they were recoverable by HRA.

24 There are two further emails in evidence before me in relation to attempts to settle the Supreme Court Proceeding, dated 30 May 2014 and 28 November 2014. In those emails first Mr Cameron and then another solicitor from Hicksons followed up with Mr Bard in relation to Genworth’s offer to settle the Supreme Court Proceeding by the filing of a notice of discontinuance, on the basis that there be no order as to costs, with the intention that each party pay their own costs.

25 On 2 December 2016 the Liquidator lodged a form 578 “Deregistration request (liquidator not acting/affairs fully wound up)” with ASIC.

26 On 13 December 2016 ASIC published a “Notice of proposed deregistration-ASIC initiated under s 601AB(2) and s 601AB(3)” in relation to HRA in which it noted that it “may deregister [HRA] when two months have passed since publication of [the] notice”.

27 On or about 6 February 2017 Genworth filed a notice of motion in the Supreme Court Proceeding seeking leave to discontinue that proceeding with no order as to costs, with the intent that each party pay its own costs.

28 On 28 March 2017, pursuant to leave granted on that day, Mr Perera filed an amended notice of motion in the Supreme Court Proceeding seeking an order that he be added as second defendant and an order under s 471A of the Act that he be granted approval to perform or exercise a function or power as an officer of HRA in respect of the Supreme Court Proceeding by representing HRA in the proceeding.

29 On 28 March 2017 orders were made in the Supreme Court Proceeding including orders that:

(1) Genworth have leave to discontinue the Supreme Court Proceeding with no order as to costs (with the intent that each party bear its own costs) as and from 12 August 2011; and

(2) Mr Perera’s notice of motion filed 16 January 2017 and his amended notice of motion filed 28 March 2017 be dismissed with Mr Perera to pay the costs of and incidental to those notices of motion as agreed and as assessed.

30 On 4 April 2017 Genworth filed a notice of discontinuance in the Supreme Court Proceeding.

31 Mr Perera has corresponded with ASIC in relation to this application. By letter dated 25 September 2019 ASIC informed Mr Perera that it would not oppose the application for reinstatement of HRA subject to satisfaction of the following conditions:

1. The order sought for reinstatement is in the terms of section 601AH(2) of the Corporations Act, requiring ASIC to reinstate the registration of the company;

2. The previous Liquidator, Brian Silvia, be notified of this application;

3. Previous unpaid creditors be notified of this application to both reinstate and terminate the winding up;

4. The company (if ordered to be reinstated only) continues to be in liquidation (section 601AH(5) of the Act) and the previous Liquidator resumes his role or the Court appoints a new Liquidator;

5. The Court order is lodged with ASIC (see notes below) so that the company may be reinstated;

6. If 4, the Liquidator notifies ASIC upon conclusion of the winding up.

32 There was evidence before me that Mr Perera had advised the Liquidator and, with one exception, those creditors of HRA “listed as informal or formal proof received by the liquidator” of this application. The exception in relation to one creditor, Honuka Pty Limited, for whom Mr Perera could not locate any contact details.

33 There were two responses from the creditors of HRA:

(1) by letter dated 22 October 2019 from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) to Mr Perera, the ATO informed Mr Perera that HRA was indebted to it in the amount of $151,660.21 and that the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation would only consent to the orders sought in the application if that debt was paid before the application was heard; and

(2) by email dated 18 October 2019 Westpac Banking Corporation (Westpac) informed Mr Perera that there were no accounts in the name of HRA held with Westpac, St George Bank, Bank SA or Bank of Melbourne.

Solvency report

34 In his affidavit Mr Guan annexed a report in which he considered the solvency of HRA. Mr Guan concludes, based on the financial analysis set out in his report, that HRA “had net financial position of $12,015.73 as of 4th April 2017, that position remains until today” and that HRA “was solvent on 12th August 2017, and is solvent today”.

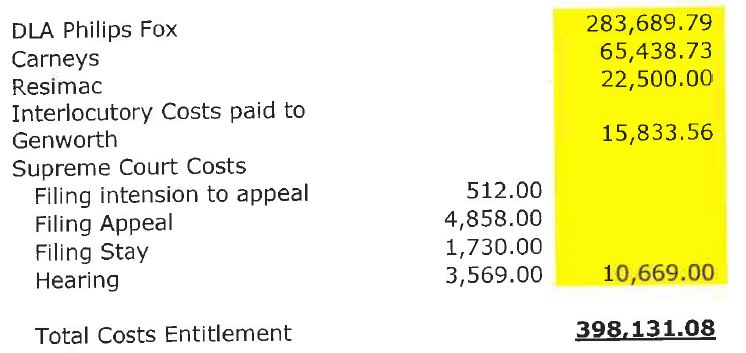

35 Mr Guan’s report includes the following under the heading “financial analysis”:

• The other party had filed Notice of Discontinuance on 4th April 2017, the presiding judge had inserted the term of “No order as to costs (with the intent that each party bear its own costs) as and from 12 August 2011”. That effects cost entitlements of the following items:

• These entitlements thus became Assets of the Said Company as of the date of 4th April 2017.

• As the other party Genworth not to continue their claim through Court, and became liable to the above mentioned costs under the term inserted by Her Honor, Genworth would be no longer a creditor to the said Company, instead they become now a debtor of $398,131.08.

• The liabilities of the Said Company as of the date of 4th April 2017 were consisted of following items as listed on Form 524 and adjustment made as above mentioned

• Net Financial Position of the Said Company as of 4th April 2017 was $12,015.73.

• This Financial Position remains unchanged passing 12th August 2017 until the current date.

36 In other words, Mr Guan has treated the items which he classifies as “cost entitlements” as assets of HRA and has deducted from the total “costs entitlements” the amount which he has assessed as owing to creditors leaving a net positive balance of $12,015.73.

37 At this stage I note the following in relation to Mr Guan’s analysis:

(1) Mr Guan does not refer to, and I infer did not have before him, the correspondence between the Liquidator and the solicitors for Genworth by which those parties agreed that, in consideration of Genworth’s consent to payment of the Security Amount to the Liquidator, the Liquidator would not pursue the Genworth Payment (see [21] above);

(2) the monies paid to Resimac were for its costs of compliance with a subpoena served on it by HRA. It is not clear how Mr Guan has concluded that HRA would have any entitlement to recover those costs given that Resimac was a third party to the litigation. If the recovery would be as a disbursement then there may be an issue as to whether HRA could recover all of those costs; and

(3) the amounts included against the entries for “DLA Phillips Fox” and “Carneys” seem to be the total amounts billed by those firms, in the case of DLA as at 31 July 2009, and in the case of Carneys, as at 26 March 2010. Mr Guan’s analysis assumes that those costs will be recovered in their entirety and ignores the rules as to costs recovery. For example r 42.2 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 (NSW) provides that “unless the court orders otherwise or these rules otherwise provide, costs payable to a person under … these rules are to be assessed on the ordinary basis”. The amount that would likely be recovered by HRA was not the subject of any evidence before me.

Should HRA’s registration be reinstated?

Statutory framework and legal principles

38 Section 601AH(2) of the Act provides:

(2) The Court may make an order that ASIC reinstate the registration of a company if:

(a) an application for reinstatement is made to the Court by:

(i) a person aggrieved by the deregistration; or

(ii) a former liquidator of the company; and

(b) the Court is satisfied that it is just that the company’s registration be reinstated.

39 In Yeo v Australian Securities and Investments Commission, in the matter of Ji Woo International Education Centre Pty Ltd (deregistered) [2017] FCA 1480 at [11]-[13] Gleeson J said the following about the Court’s approach to an application for reinstatement of a deregistered company:

11 In Deputy Commissioner of Taxation; re James Hardie Australia Finance Pty Ltd (Deregistered) [2008] FCA 1181; (2008) 170 FCR 545; (“James Hardie”), Lindgren J said (at [13]):

An application under s 601AH for reinstatement of the registration of a company may be made by “a person aggrieved by the deregistration”. According to s 601AH(2)(b), it is a condition of the enlivening of the Court’s power to order reinstatement that the Court be “satisfied that it is just that the company’s registration be reinstated”. The Court has a residual discretion whether to make an order. These three matters will need to be considered.

12 On an application for reinstatement, the Court is concerned with the justice of reinstating the company, not the justice of any proceedings which it is proposed that the reinstated company might institute: Re ERB International Pty Ltd (deregistered) [2014] NSWSC 200 (“ERB International”) at [10].

13 In Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Australian Securities and Investments Commission; re Civic Finance Pty Limited (Deregistered) [2010] FCA 1411; (2010) 81 ATR 456 at [14], Jagot J noted that it is “often not appropriate in an application for reinstatement to go into factual matters which may be the subject of dispute”. At [16], her Honour noted that it was not the case that the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation was denied status as a person aggrieved because he had not shown any possibility of benefit from reinstatement of the relevant complaints. Her Honour accepted, in effect, that such a requirement would involve an attempt to second guess the outcome of a prospective winding up, including the liquidators’ investigation of the relevant companies’ affairs. Similarly in Pilarinos v Australian Securities & Investments Commission [2006] VSC 301; (2006) 24 ACLC 775 at [22], Gillard J rejected a submission that the Court should resolve disputed factual questions concerning whether it would futile to reinstate the relevant company.

40 An issue for the purposes of this application is who is a “person aggrieved” for the purposes of s 601AH(2)(a)(i) of the Act. In Arnold World Trading Pty Ltd v ACN 133 427 335 Pty Limited (2010) 80 ACSR 670; [2010] NSWSC 1369 at [43] Barrett J said:

The question whether an applicant under s 601AH(2) is “a person aggrieved by the deregistration” is considered by reference to legal rights and legal interests. It must be seen that the applicant has a genuine grievance that the dissolution of the company affected his or her interests because, for example, a right of some value or potential value has gone out of existence: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2000) 174 ALR 688; 34 ACSR 232; [2000] NSWSC 316 at [24]–[26]. Under analogous English legislation, the applicant was expected to have “an interest of a proprietary or pecuniary nature in resuscitating the company”: Re Wood & Martin (Bricklaying Contractors) Ltd [1971] 1 All ER 732; [1971] 1 WLR 293 and see Re GA & RJ Elliott Pty Ltd (1978) 3 ACLR 523.

41 In Bell Group Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2018) 128 ACSR 247; [2018] FCA 884 (Bell Group) McKerracher J said at [47]:

The expression ‘person aggrieved’ in s 601AH should not be construed narrowly: Yeo v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2017] FCA 1480 at [14]–[16] per Gleeson J and the authorities therein cited). For a person to be aggrieved for the purposes of s 601AH(2)(a)(i), an applicant for reinstatement must be able to show that the deregistration deprived the applicant of something, or injured or damaged the applicant in a legal sense, or if the applicant became entitled, in a legal sense, to regard the deregistration as a cause of dissatisfaction: Danich at [32] per Barrett J.

42 At [49]-[50] his Honour continued:

49. There is no temporal restriction in the description ‘person aggrieved’ as long as there is a causal link between the grievance and the deregistration. A person can become aggrieved after the time of deregistration: see the discussion by Gillard J in Pilarinos v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2006] VSC 301 (Pilarinos) at [49]. In Pilarinos, where his Honour said:

The question arises whether a person can be aggrieved as a result of events which occur after the deregistration. In my opinion, there is nothing in the legislation which requires that the applicant must have been aggrieved at the time of the deregistration. Indeed, the history of the legislation, and in particular, the widening of the category of persons who could be aggrieved and, further, the removal of any time limit, supports that view. The actual words of the sub-section themselves do not restrict the application to the grievance being in existence at the date of deregistration. The sub-section requires a causal link between the grievance and the deregistration, but no temporal restriction.

50. There needs, however, to be some connection other than simply being a shareholder or a director of a company that is deregistered in order to be a person aggrieved. An applicant must demonstrate that his or her interests have been, or are likely to be, prejudicially affected by the deregistration of the company. A mere dissatisfaction with an event will not render someone a ‘person aggrieved’; they must be a person who has been damaged or injured in a legal sense: Callegher v Australian Securities and Investments Commission (2007) 218 FCR 81; 239 ALR 749; 98 ALD 1; [2007] FCA 482 (Callegher) at [50] per Lander J and the authorities therein cited). For example, a shareholder demonstrating that he or she is a creditor of the company, or that there will be a surplus of assets and rights to dividends if the company were to be reinstated: Vukasin v Australian Securities and Investments Commission [2007] NSWSC 1341.

43 In Bell Group McKerracher J also addressed the requirement that the Court be satisfied that it is “just” that the registration be reinstated. At [72] his Honour noted that whether that was so was not constrained by any legislative parameters but, relying on Wedgewood Hallam Pty Ltd v Australian Securities and Investments Commission, in the matter of Combined Building Consultants Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 439 at [5], that regard should be had to:

(a) the circumstances in which the companies came to be deregistered;

(b) the future activities of the companies, if an order for reinstatement is made; and

(c) whether any particular person is likely to be prejudiced by the reinstatement.

44 At [73] his Honour noted that a further consideration raised in the case law was that of public policy.

Is Mr Perera a person aggrieved?

45 Mr Perera claims to be a person aggrieved for the purposes of s 601AH(2)(a)(i) because he is a creditor of HRA. He relies on the Genworth Payment and the Security Amount, both of which he says he paid on behalf of HRA, to support that submission. However, I note that in his report Mr Guan classifies Mr Perera as a creditor only on the basis of the Genworth Payment which he says was a loan to HRA.

46 Mr Perera contended that HRA had a costs order made in its favour in the Appeal Proceeding. He said that that in turn would entitle HRA to recover the Genworth Payment as well as the costs of the Appeal Proceeding. Mr Perera relies on Mr Guan’s quantification of those costs. Mr Perera also relied on the notice of discontinuance filed by Genworth in the Supreme Court Proceeding to contend that it entitled HRA to its costs incurred prior to 12 August 2011 in that proceeding which comprised amounts paid by HRA to DLA, Carneys and Resimac.

47 Mr Perera submitted that if HRA was reinstated then it could enforce the costs orders in its favour against Genworth either by negotiating the payment of an agreed amount or seeking an assessment of its costs which, according to Mr Perera, would also entitle HRA to at least two years interest on the assessed amount. Once that occurred, HRA’s creditors, including Mr Perera, would receive a return. To date they have not received a dividend.

48 Mr Perera also submitted that he acquired HRA for approximately $360,000 but that it “has disappeared” and with it his investment. He said that if reinstated HRA can trade and generate income in order to provide a return on his investment.

49 Mr Perera is listed as a creditor in a list of persons present at a creditors’ meeting of HRA which took place on 27 January 2012 and there is evidence of payments made on behalf of HRA from the St George Account. I accept for the purposes of this application that Mr Perera is a creditor of HRA, although the amount for which he could prove in HRA’s liquidation was, on the basis of the evidence before me, never quantified.

50 I accept that HRA has, in effect, two costs orders in its favour which have not been enforced and which if enforced may result in a return for HRA’s creditors including Mr Perera. The costs order in the Appeal Proceeding was in existence prior to deregistration of HRA but, given that HRA had no legal representation in the Appeal Proceeding, is of relatively low value. The entitlement to costs in the Supreme Court Proceeding only arose at about the time of or shortly after HRA’s deregistration, assuming that occurred as foreshadowed in ASIC’s notice of proposed deregistration (see [26] above).

51 The amount that might be recovered and the costs of that recovery are unknown. As to the former, Mr Guan’s analysis of the recoverable amount is deficient for at least the reasons set out at [37] above and likely overstates the recoverable amount. There is no evidence before me as to the likely recovery on an assessment including the likelihood and quantum of an award of interest.

52 Putting that to one side, it seems to me that as a creditor of HRA who, on balance, may have an entitlement to a dividend if the company is reinstated, Mr Perera has established that he is a person aggrieved. That is, the right of which Mr Perera has been deprived is his right to a dividend from the amount recovered following enforcement of the costs orders in HRA’s favour.

Is reinstatement just?

53 I turn then to consider whether reinstatement is just. There are no prescribed matters to be taken into account in considering this issue but the factors referred to by McKerracher J in Bell Group (see [43] above) provide a convenient starting point.

54 HRA was deregistered following its winding up. A request was made by the Liquidator to ASIC for HRA’s deregistration on the basis that its affairs had been fully wound up and there was no or insufficient property to pay the costs of obtaining an order for its dissolution. I would infer that the Liquidator had undertaken all of the prescribed matters in relation to HRA, had gathered in and liquidated any assets, carried out required investigations and complied with his reporting obligations.

55 Mr Perera submitted that the primary purpose of the reinstatement is to enable HRA to recover its costs of the Supreme Court Proceeding and the Appeal Proceeding but also suggested that HRA would trade and seeks ancillary orders to enable it to do so.

56 On the basis of the evidence before me it is apparent that the negotiations to settle the Supreme Court Proceeding were never concluded and it seems that the Liquidator’s attempts to obtain payment of the disbursements made by HRA in the Appeal Proceeding were unsuccessful.

57 It follows that the costs order made in HRA’s favour in the Appeal Proceeding remains unsatisfied. However, that order is not of significant value, Mr Guan estimates it at $10,669 while the Liquidator sought an amount of $8,903 for those costs. Given the agreement between the Liquidator and Genworth (see [21] above), the Genworth Payment is unlikely to be recoverable. That being so, even if all of the costs estimated by Mr Guan are recovered as a result of enforcement of the costs order made in the Appeal Proceeding, that recovery of itself would either result in no return or an insignificant return to creditors, given the likely associated costs of recovery.

58 The recoverable costs in the Supreme Court Proceeding are of a higher magnitude. However there are a number of imponderables associated with the proposal that HRA would, if reinstated, take steps to recover those costs:

(1) firstly, as I have already observed there is no evidence from a person with the requisite experience of the amount that would likely be recovered by HRA on an assessment;

(2) secondly, there is no evidence of the availability of HRA’s records to enable it to take steps to recover its costs, for example, via an assessment. According to a list of creditors both DLA and Carneys are creditors of HRA and, in the case of DLA, as at August 2009 it threatened to exercise a lien over its file unless HRA made a substantial payment in reduction of the amount then owing. Further, given the passage of time since these costs were incurred (in excess of seven years) it is unknown if the files still exist;

(3) thirdly, there is no evidence of an estimate of the cost of costs recovery; and

(4) fourthly, there is no evidence of how HRA would propose to or could fund the costs associated with taking steps to recover its costs in the Supreme Court Proceeding (or the Appeal Proceeding).

59 Putting these issues to one side, I note that it is only Mr Perera who seeks an order for reinstatement. Despite notification to other creditors, with the exception of the matters set out at [32] above, no creditor has come forward to support or join in the application. If costs were recovered, despite the hurdles identified above, Mr Perera would only recover a relatively small amount given the amount of the debt said to be owing by HRA to him relative to other creditors.

60 Mr Perera did not point to any matters of public policy that might bear upon my consideration. In my opinion the possibility of a return to creditors is a matter that might be relevant in that regard. However, given the inaction of the creditors, the length of time since HRA was wound up and the potential difficulties associated with the recovery process, I would not conclude that this factor weighs in favour of making the order sought.

61 Finally there is the issue of delay. Although the exact date is unknown, based on the evidence before me HRA was deregistered about two and a half years ago. The entitlement to costs in the Supreme Court Proceeding arose in March 2017. It was only in recent months that Mr Perera took steps to reinstate its registration, commencing this proceeding on 13 September 2019, with some urgency, although the reason for the urgency was never properly explained. In oral submissions, Mr Perera explained that the delay was caused by his involvement in another proceeding which consumed his time. That proceeding is now complete, allowing him time to focus on making this application. While I am sympathetic to Mr Perera’s difficulties in pursuing various proceedings at the same time without legal assistance, in my opinion, that is not a satisfactory explanation for the delay which has added to the difficulties identified above.

62 For those reasons I am not satisfied that, in the circumstances of this case, it is just that HRA be reinstated.

63 I should add that even if I was persuaded otherwise I would not accede to the orders sought by Mr Perera. As presently framed Mr Perera seeks an order that HRA be reinstated, that its liquidation be terminated and that in effect he would continue as a director of HRA which would then trade and pay out HRA’s creditors in accordance with the ancillary orders sought. However, Mr Perera’s contention that HRA would return to trading is not tenable. That in turn depends on the liquidation being terminated, an issue which I address below.

64 If I had been satisfied that it was just that HRA be reinstated, given the state of the company at the time of its deregistration with no creditors having received a dividend, the only basis on which such an order could be made would be that it remain in liquidation and the Liquidator continue as liquidator or another liquidator be appointed, which is not an order sought. In any event, Mr Perera does not propose that form of order and there is no indication from the Liquidator or any other person that they would be prepared to act in that role.

Should the winding up of HRA be terminated?

Statutory framework and legal principles

65 Section 482(1) of the Act provides that at any time during the winding up of a company the Court may make an order staying the winding up or terminating the winding up on a date specified in the order. An application may be made, in any case, relevantly, by a creditor.

66 In Doolan, in the matter of MIH Company Pty Ltd (in liq) v MIH Company Pty Ltd (in liq) [2015] FCA 1130 at [9]-[11] Edelman J summarised the principles relevant to an exercise of the power in s 482(1) of the Act as follows:

9. This power is discretionary and the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) does not restrict the exercise of the power by reference to any particular criteria. However, eight of the most common factors were described by Master Lee QC in Re Warbler Pty Ltd (1982) 6 ACLR 526 (Warbler) at 533. These factors have become well accepted: see, for example, Benedict v Olde; in the matter of ATS (Asia Pacific) Pty Ltd [2011] FCA 1008 [5] (Jacobsen J); Judson, in the matter of Maneroo Pty Ltd (in liq) [2015] FCA 783 [21]–[22] (Gleeson J) and the authorities cited in those cases. As Gleeson J explains, the factors described in Warbler, are as follows:

(1) The grant of a stay is a discretionary matter, and there is a clear onus on the applicant to make out a positive case for a stay: Re Calgary & Edmonton Land Co Ltd (in liq) (1975) 1 WLR 355, 358-359 per Megarry J.

(2) There must be service of notice of the application for a stay on all creditors and contributories, and proof of this: Re South Barrule Slate Quarry Co (1869) LR 8 Eq 688; Re Bank of Queensland Ltd (1870) 2 QSCR 113.

(3) The nature and extent of the creditors must be shown, and whether or not all debts have been or will be discharged: Krextile Holdings Pty Ltd v Widdows [1974] VR 689; Re Data Homes Pty Ltd [1972] 2 NSWLR 22.

(4) The attitude of creditors, contributories, and the liquidator is a relevant consideration: Re Calgary.

(5) The current trading position and general solvency of the company should be demonstrated. Solvency is of significance when a stay of proceedings in the winding-up is sought: Re a Private Company [1935] NZLR 120; Re Mascot Home Furnishers Pty Ltd [1970] VR 593, 598.

(6) If there has been non-compliance by directors with their statutory duties as to the giving of information or furnishing a statement of affairs, a full explanation of the reasons and circumstances should be given: Re Telescriptor Syndicate Ltd [1963] 2 Ch 174.

(7) The general background and circumstances which led to the winding-up order should be explained: Krextile.

(8) The nature of the business carried on by the company should be demonstrated, and whether or not the conduct of the company was in any way contrary to “commercial morality” or the “public interest”: Krextile.

10. The most significant of all of these factors is usually the question of solvency of the company: see, for instance, In the matter of Glass Recycling Pty Ltd [2014] NSWSC 439 [18] (Brereton J). This is usually because where the winding up was on the grounds of insolvency, it will be necessary for the company to demonstrate that it is solvent in order to show that the state of affairs that required the company to be wound up no longer exists. Hence, an order terminating the winding up will usually be made if all creditors are paid out, the liquidators’ costs and expenses are covered, and the members agree to terminate the winding up: see In the matter of Glass Recycling Pty Ltd [18]; Apostolou v VA Corporation of Australia Pty Ltd [2010] FCA 64; (2010) 77 ACSR 84, 96 [58] (Finkelstein J); Re Kitchen Dimensions Pty Ltd (in liq) [2012] VSC 280 [25] (Judd J).

11. The concept of “commercial morality” includes whether there has been any serious impropriety in the conduct of the company’s affairs, or any other matter which poses a risk to future creditors. Further, the Court must usually be satisfied that it will be reasonable to entrust the affairs of the company to the directors under whose management the company had previously been subjected to an order for winding up: see Re Glass Recycling Pty Ltd [19] (Brereton J).

Consideration

67 This part of Mr Perera’s application proceeds on the basis that an order for reinstatement of HRA is made. I have declined to make that order. Notwithstanding that I will briefly explain why, had I come to a different view about the application pursuant to s 601AH(2) of the Act, I would in any event have declined to make an order terminating the winding up of HRA.

68 The application is made by Mr Perera. For the reasons set out at [49] above I am satisfied that he is a creditor of HRA and thus has standing to bring this application. Mr Perera bears the onus of making out his case for termination of HRA’s winding up. In my opinion he has failed to discharge this onus for the following reasons:

(1) there is no complete explanation of how it is that HRA came to be wound up. The only evidence relevant to that issue is the inclusion in one of Mr Perera’s affidavits of an affidavit deposing to service of a creditor’s statutory demand issued by the Deputy Commissioner of Taxation and an accompanying affidavit in support on HRA on 22 February 2011;

(2) the nature and extent of the creditors of HRA has not been shown in any detail. Nor is it apparent how their debts will be discharged;

(3) there is no evidence upon which I could be satisfied that it will be reasonable to entrust the company to Mr Perera as director. He does not explain how the company will operate in the future, whether there is to be any capital injected into it to pay current creditors and meet future operating costs and how there will not be a recurrence of the state of affairs that led to its winding up; and

(4) most critically I cannot be satisfied on the evidence before me that HRA is solvent or will be solvent. Mr Guan’s report suffers from the deficiencies identified at [37] above. Further the recovery of any costs, which is said to be the basis upon which the company will become solvent, will take some time and be at a cost. There is no evidence of how HRA will meet that cost or its operating costs in the interim.

conclusion

69 For those reasons Mr Perera’s application should be dismissed and I will make an order to that effect.

70 As no party appeared on the application the question of costs of the application does not arise.

I certify that the preceding seventy (70) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment herein of the Honourable Justice Markovic. |

Associate: