FEDERAL COURT OF AUSTRALIA

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Institute of Professional Education Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 3) [2019] FCA 1982

ORDERS

BROMWICH J | |

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The parties furnish, by email to the associate to Justice Bromwich, agreed or competing orders arising from the reasons for judgment within 14 days, or such further time as may be allowed.

2. A case management hearing be listed on a date to be fixed.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

BROMWICH J:

1 The first applicant in this proceeding is the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). The second applicant is the Commonwealth of Australia. The respondent is the Australian Institute of Professional Education Pty Ltd (in liq) (ACN 126 628 215) (AIPE). The applicants allege that the respondent breached the Australian Consumer Law (ACL) in connection with the supply or possible supply of vocational education courses, including by engaging in a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour that was unconscionable, and by engaging in conduct that was false or misleading or deceptive.

2 The applicants commenced this proceeding against AIPE on 31 March 2016, before it went into liquidation. Later that year, on 6 October 2016, the directors of AIPE resolved to wind up the company, and liquidators were appointed on the same date. On 16 May 2017, over the opposition of the liquidators, I granted conditional leave under s 500 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) to the applicants to bring this proceeding against AIPE as a company in liquidation: Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Australian Institute of Professional Education Pty Ltd (in liq) [2017] FCA 521.

3 From 1 May 2013 up to 1 December 2015 (relevant period), AIPE conducted a business which included marketing and providing online vocational education training (VET) courses. Those courses were eligible for Commonwealth funding by way of a scheme of student loans under the Higher Education Support Act 2003 (Cth) (HES Act) known as the Vocational Education and Training Fee Higher Education Loan Program (VET FEE-HELP). Upon confirmation of a student’s enrolment in an eligible course, the Commonwealth paid the course fee directly to the VET provider, in this case, AIPE. The student incurred a corresponding debt of 120% of that course fee. That debt was payable through the income tax system once the student’s taxable income reached a certain threshold (between just over $51,000 to just over $54,000 per annum over the relevant period).

4 The VET FEE-HELP scheme was deliberately and significantly liberalised by the government in 2012 for the express purpose of addressing low participation rates of disadvantaged people, including those with a disability, living in regional and remote areas, coming from lower socio-economic backgrounds, from non-English speaking backgrounds, not in paid employment, and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples. Prior requirements of progression to study at a higher education institution were removed, making vocational training an independent objective.

5 Each person had a lifetime assistance cap, at that time of less than $100,000. Money expended on any given course, whether completed successfully or not, reduced the government assistance available to that person in the future.

6 This proceeding is not about the quality of teaching provided by AIPE to consumers who were bona fide or genuine students and participated as such in the courses it provided, but about the enrolment of consumers whom the applicants contend did not meet that description. The label “student” can only safely be applied to those consumers who enrolled for AIPE’s online VET FEE-HELP funded courses and were suitable to be so enrolled. In these reasons, I therefore refer in a neutral way to “consumers enrolled as students”.

7 The applicants’ case turns on:

(1) the way in which AIPE marketed to and enrolled consumers as students in its online VET courses, including through the use of recruiter organisations (agents) paid by substantial commissions, with employees in the field (recruiters); and

(2) how it dealt with consumers who had been enrolled as students, especially in relation to a census date after which the debt to the Commonwealth was incurred.

8 The agency arrangement was confined to recruitment leading to enrolment, and did not extend to being able to bind AIPE in relation to the final step of entering into an enrolment agreement, that taking place between the prospective student and AIPE, albeit apparently with active involvement or assistance on the part of the recruiter. The agent’s role, via their recruiters, who were also thereby recruiters for AIPE, may be seen to be somewhat akin to a real estate agent, who facilitates a sale, but leaving the sale contract to take place between the vendor and purchaser. AIPE preferred to refer to agents as “service providers”, being a term introduced into policy documentation that was stated to take effect from 1 September 2015 for the final four months of the relevant period. However, that term does not usefully convey the nature of the agent’s role and accordingly they will be referred to as agents in these reasons.

9 There was only one such agent for most of the first year of the relevant years, Acquire Learning Pty Ltd, with other agents commencing to be engaged from about November 2013.

10 By mid-2014, AIPE had entered into contracts with 35 agents, although the evidence reveals that almost 80% of consumers enrolled as students during the relevant period were recruited by four of those agents. Neither AIPE, nor the applicants, called any evidence from any agent or any recruiter. The evidence concerning their activities comes from AIPE’s business records, key former AIPE employees and a small number of consumers approached by recruiters as described in the following paragraph.

11 The evidence of only 13 consumers who were, or were sought to be, enrolled as students, comprising a small fraction of the total numbers of consumers enrolled as students (in excess of 15,000 if the period is counted from 1 January 2013), is relied upon by the applicants to give direct evidence of what happened to them in an illustrative, rather than representative way, in the context of the rest of the evidence. In these reasons the term “consumer witnesses” is therefore used to refer to the 13 consumers who gave affidavit evidence of their enrolment experiences at the hands of recruiters from a number of different agents. They are not referred to as “students” because, as will be readily apparent when their evidence is considered in detail, it is clear that none of them were suitable to be enrolled as a student by AIPE.

12 The outcome that an overwhelming majority of consumers enrolled by AIPE as VET FEE-HELP funded students were not suitable to be enrolled in the first place and so were not genuine or bona fide students, while formally disputed, was a conclusion that is difficult to avoid. It is a conclusion that I ultimately reach on the balance of probabilities based on, inter alia, the disputed enrolment data relied upon by the applicants and the vast number, in excess of 11,000, who incurred VET FEE-HELP debts who failed to complete their courses, with many never being active students. The live question is whether this outcome was the product of unconscionable conduct, or only, for example, a consequence that flowed naturally from an education loan funding scheme that made this likely to occur no matter what, and therefore for which AIPE could not and did not bear any legal responsibility.

13 This posited alternative is not the complete universe of alternatives to the conclusion urged upon the Court by the applicants, but it adequately illustrates the nature of the binary determination required to be made between finding that unconscionable conduct has been made out as a matter of a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour, and a finding that this has not been made out. It is in the nature of the determination required to be made that reasonable alternative explanations for what took place to that posited by the applicants need to be considered in an evaluative sense. In that context, the evidence of the 13 consumer witnesses, while not led as a representative sample, served to illustrate how AIPE’s enrolment practices were able to be, or were even permitted and encouraged to be, implemented, rather than leaving that only to a process of judicial evaluation, including by processes such as inference.

14 The remaining and greater bulk of the evidence the applicants rely upon came from AIPE records, Commonwealth records, analysis of both kinds of records, and a number of key former AIPE employees. A report prepared by a social scientist, Dr Matthew Ericson, was rejected after his cross-examination, although certain demographic tables that he produced were admitted without objection. AIPE adduced affidavit evidence of one of its three joint and several liquidators, Mr Morgan Kelly, who was not cross-examined.

THE PLEADED POSITION AND CASE FOR THE PARTIES

Overview of the applicants’ case and AIPE’s response

15 The applicants seek to establish a “system of conduct or pattern of behaviour, whether or not a particular individual is identified as having been disadvantaged by the conduct or behaviour” that was, in all the circumstances, unconscionable, contrary to s 21(1) via s 21(4)(b) of the ACL. Section 21 of the ACL, which is in schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA) provided as follows:

21 Unconscionable conduct in connection with goods or services

(1) A person must not, in trade or commerce, in connection with:

(a) the supply or possible supply of goods or services to a person (other than a listed public company); or

(b) the acquisition or possible acquisition of goods or services from a person (other than a listed public company);

engage in conduct that is, in all the circumstances, unconscionable.

(2) This section does not apply to conduct that is engaged in only because the person engaging in the conduct:

(a) institutes legal proceedings in relation to the supply or possible supply, or in relation to the acquisition or possible acquisition; or

(b) refers to arbitration a dispute or claim in relation to the supply or possible supply, or in relation to the acquisition or possible acquisition.

(3) For the purpose of determining whether a person has contravened subsection (1):

(a) the court must not have regard to any circumstances that were not reasonably foreseeable at the time of the alleged contravention; and

(b) the court may have regard to conduct engaged in, or circumstances existing, before the commencement of this section.

(4) It is the intention of the Parliament that:

(a) this section is not limited by the unwritten law relating to unconscionable conduct; and

(b) this section is capable of applying to a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour, whether or not a particular individual is identified as having been disadvantaged by the conduct or behaviour; and

(c) in considering whether conduct to which a contract relates is unconscionable, a court’s consideration of the contract may include consideration of:

(i) the terms of the contract; and

(ii) the manner in which and the extent to which the contract is carried out;

and is not limited to consideration of the circumstances relating to formation of the contract.

16 The Court, in deciding whether s 21 has been contravened, may also have regard to the following non-exhaustive considerations set out in s 22(1) of the ACL:

Without limiting the matters to which the court may have regard for the purpose of determining whether a person (the supplier) has contravened section 21 in connection with the supply or possible supply of goods or services to a person (the customer), the court may have regard to:

(a) the relative strengths of the bargaining positions of the supplier and the customer; and

(b) whether, as a result of conduct engaged in by the supplier, the customer was required to comply with conditions that were not reasonably necessary for the protection of the legitimate interests of the supplier; and

(c) whether the customer was able to understand any documents relating to the supply or possible supply of the goods or services; and

(d) whether any undue influence or pressure was exerted on, or any unfair tactics were used against, the customer or a person acting on behalf of the customer by the supplier or a person acting on behalf of the supplier in relation to the supply or possible supply of the goods or services; and

(e) the amount for which, and the circumstances under which, the customer could have acquired identical or equivalent goods or services from a person other than the supplier; and

(f) the extent to which the supplier’s conduct towards the customer was consistent with the supplier’s conduct in similar transactions between the supplier and other like customers; and

(g) the requirements of any applicable industry code; and

(h) the requirements of any other industry code, if the customer acted on the reasonable belief that the supplier would comply with that code; and

(i) the extent to which the supplier unreasonably failed to disclose to the customer:

(i) any intended conduct of the supplier that might affect the interests of the customer; and

(ii) any risks to the customer arising from the supplier’s intended conduct (being risks that the supplier should have foreseen would not be apparent to the customer); and

(j) if there is a contract between the supplier and the customer for the supply of the goods or services:

(i) the extent to which the supplier was willing to negotiate the terms and conditions of the contract with the customer; and

(ii) the terms and conditions of the contract; and

(iii) the conduct of the supplier and the customer in complying with the terms and conditions of the contract; and

(iv) any conduct that the supplier or the customer engaged in, in connection with their commercial relationship, after they entered into the contract; and

(k) without limiting paragraph (j), whether the supplier has a contractual right to vary unilaterally a term or condition of a contract between the supplier and the customer for the supply of the goods or services; and

(l) the extent to which the supplier and the customer acted in good faith.

17 The applicants assert that AIPE breached s 21 of the ACL in various ways. Its sales representatives, the applicants allege, visited low socio-economic communities to enrol consumers in its courses, including by calling on consumers in their homes, making representations that they could receive a free laptop computer or tablet by signing up to an AIPE course, and by offering these items as inducements. Additionally, the applicants allege that the recruiters told consumers that its courses were free, and failed to adequately explain the nature of the VET FEE-HELP scheme. The respondents are said to have provided financial incentives to its sales representatives in order to maximise the number of consumers enrolled in its course. These persons enrolled included those who could not use or access the Internet or a computer, had inadequate literacy or numeracy skills, or were otherwise unsuitable. These actions, it is said, were done in order to maximise AIPE’s revenue from payments by the Commonwealth under the VET FEE-HELP scheme.

18 The applicants contend that as a result of that asserted system of conduct or pattern of behaviour, a significant proportion of the enrolments should not have taken place, corresponding payments should not have been made by the Commonwealth to AIPE, and related debts should not have been incurred by the consumers concerned. In total, VET FEE-HELP payments were made by the Commonwealth to AIPE in excess of $210 million, although the sums potentially affected by this proceeding are only a presently unidentified portion of that amount.

19 The applicants also assert, as a much lesser part of their case, contraventions of ss 18, 29(1)(g), 29(1)(i), 76 and 78 of the ACL, which respectively proscribe misleading or deceptive conduct, making different types of false or misleading representations, and failing to comply with particular statutory obligations in relation to unsolicited consumer agreements. In the greater part, the conduct established by the evidence is only faintly defended by AIPE in terms of reliability, with appropriate concessions as to certain findings that are properly open to be made.

20 By a further amended originating application (in part amended to reflect injunctive relief no longer sought against AIPE due to it being in liquidation):

(1) both applicants seek numerous declarations of contravention and a mandatory injunction requiring AIPE to refund to the Commonwealth amounts that were paid in purported discharge of any consumer’s VET liability as specifically identified that has not been repaid;

(2) the ACCC seeks pecuniary penalties, a sealed copy of the reasons for judgment be kept on the Court file for the purposes of s 137H(3) of the CCA, orders seeking to rectify the position of consumers by way of non-party redress, ineligibility to VET FEE-HELP and annulment of liability to the Commonwealth and directions expunging enrolment references; and

(3) the Commonwealth seeks a further declaration as to the effect of the non-party consumer redress orders sought by the ACCC.

21 There can be no enforcement of any pecuniary penalty, refund or costs order without the leave of the Court, because that was a condition of the Court granting the applicants’ leave to proceed under s 500 of the Corporations Act.

22 AIPE:

(1) specifically denies that it engaged in a pattern of behaviour for marketing and enrolling consumers as students that was generally or specifically unconscionable, noting as discussed below that the case was conducted also upon the basis of a system of conduct which was also denied;

(2) no longer denies that it engaged in conduct that was misleading or deceptive, or likely to mislead or deceive, or that it made false or misleading representations in relation to certain of the individual consumers;

(3) instead admits that, in the context of enrolling students in VET courses, failing to explain the nature of the VET FEE-HELP scheme and offering inducements can amount to misleading or deceptive conduct, but submits that the applicants’ evidence is inadequate on this point;

(4) does not admit contravening ss 76 and 78 of the ACL in relation to unsolicited consumer agreements as alleged;

(5) does not maintain a prior denial that “service providers” were agents or sub-agents of AIPE, but states that any loss or damage proven arose from conduct of unauthorised sub-contractors or sub-sub-contractors who were not acting as agents for AIPE;

(6) denies that the individual consumers suffered loss or damage; and

(7) does not admit that the Commonwealth is entitled to any repayments.

23 AIPE in substance denies that any real or substantial wrongdoing has been shown to have taken place beyond isolated events concerning the individual consumer witnesses. It attributes, in substance, if not in terms, what happened to the very nature of the post-2012 VET FEE-HELP scheme in opening up VET to disadvantaged members of the community. To put the substance of AIPE’s opposing case in simple terms, it contends that the applicants’ evidence failed to bridge the gap between:

(1) on the one hand, consumers who may have been vulnerable and ripe for exploitation as the legislative target group for the post-2012 VET FEE-HELP scheme, and the recruitment practices that had the effect of encouraging enrolments that included consumers who might have had those characteristics; and

(2) on the other hand, there being enough evidence to prove any system of conduct or pattern of behaviour that established unconscionable conduct in relation to that category of consumers.

Admissions as to background facts

24 It is convenient to reproduce the background facts that are admitted by AIPE, before turning to the allegations that are denied, in order to identify the area of dispute calling for an adjudication as to whether or not the applicants have discharged their burden and onus of proof. AIPE, in its further amended response to the applicants’ concise statement, specifically admits the following (at [1]-[13]):

[1] The respondent, Australian Institute of Professional Education Pty Ltd (AIPE), has carried on the business of supplying online courses, including Diplomas in Travel and Tourism, Business, and Hospitality, since 2013. Each of these courses required at least approximately 6 months’ full-time study (and in the case of Diplomas in Hospitality, 12 months).

[2] An eligible student who enrolled in an AIPE online course, each of which consisted of several units of study, was entitled to a Commonwealth student loan called VET FEE-HELP for each of those units of study. Under the VET FEE-HELP program, the Commonwealth paid eligible students’ course fees directly to AIPE in discharge of the student’s liability to pay course fees. Further, the students’ entitlement to a loan from the Commonwealth, the second applicant, was set by criteria determined by the Higher Education Support Act 2003 (Cth) (HESA) and by the Commonwealth.

[3] Once a student’s annual threshold income has been exceeded the student may be required to make repayments as stipulated by the Commonwealth. There are circumstances where repayments would not need to be made even where the threshold is met, in accordance with criteria set by the Commonwealth.

[4] There were 15,932 enrolments of students in AIPE’s courses between 1 January 2013 and 1 December 2015 and AIPE has received $210,890,848.80 for these enrolments.

[5] Between 1 July 2013 and 25 August 2016, AIPE re-credited the amount of $24,660,402 in funding to the Commonwealth as part of its withdrawal of 1,681 of the enrolments specified in (4) above.

[6] The Commonwealth has not paid the sum of $20,833,332.20 to AIPE pursuant to the advance payment determination made on 18 December 2014 for the period November – December 2015. The advance payment determination made on 18 December 2014 was revoked on about 9 March 2016.

[7] Between 1 May 2013 and 1 December 2015 (the Relevant Period) AIPE entered into contracts with 35 service providers (Service Providers) to enrol students in its vocational education training (VET) courses. The Service Providers are listed in Attachment A to the Schedule to the Concise Statement filed on 10 May 2016.

[8] AIPE has no knowledge of the total number of sub-contractors or other entities (together subcontractors) engaged by the Service Providers. The vast majority of AIPE’s contracts with its respective Service Providers prohibited the Service Provider from engaging sub-contractors without AIPE’s consent.

[9] AIPE has consented to certain Service Providers engaging sub-contractors (Authorised Sub-Contractors), from particular dates, as set out in Annexure A to this amended response, for the purposes of marketing to and enrolling students in VET courses with AIPE.

[10] During the Relevant Period AIPE accepted enrolments of students from both Service Providers and their Authorised Sub-Contractors through an online portal.

[11] AIPE paid Service Providers a commission for referring students:

(a) once the census date had been reached without the student having withdrawn, and in some of those cases the payment was reversible if AIPE “re-credited” the student and reversed the student’s debt; or

(b) in respect of a small number of Service Providers, a service fee was paid before the census date but in those cases the service fee was repayable, or the Service Provider was required to provide AIPE with a credit equal to the amount of the service fee, if the student withdrew before the census date.

[12] Some of AIPE’s contracts with Service Providers contained clauses describing a minimum number of students to be referred each month. The number of students was arrived at based on the Service Providers’ capabilities and having regard to the requirement set by the Commonwealth to estimate VET FEE-HELP requirements and other matters.

[13] In terminating AIPE’s arrangements with [a] certain number of the Service Providers it stated as a reason for termination that the Service Provider had not met its minimum monthly student referrals but that for many of its Service Providers, over the course of the term of its contract with the Service Providers, it did not terminate Service Providers where that Service Provider did not achieve minimum referral of students for a particular month.

25 In addition to the above admissions, AIPE does not take issue, in its further amended response, in its opening submissions or in its closing submissions, with the conduct of its contracted agents and their recruiters being conduct properly able to be attributed to it. This is sensible, in light of Gleeson J’s conclusions about agency in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Cornerstone Investment Aust Pty Ltd (in liq) (No 4) [2018] FCA 1408 (Empower, because that is the name of the college involved), discussed below.

26 In response to requests by AIPE for further details of the facts and allegations made in the concise statement, the applicants filed a schedule to that concise statement. The schedule lists, in three attachments, the details of the contractual arrangements established by the evidence in relation to 35 agents who had contracts with AIPE, and a list of the recruiters of those agents. The schedule additionally pleads (at [7] and [8]):

[7] Agents who were contracted to market courses on behalf of AIPE were not trained or given directions by AIPE staff in 2014 as to how its courses should be marketed to individual students so as to ensure that:

• the enrolment of unsuitable students in its courses was avoided;

• each potential student was informed of the financial obligations that arose from pursuing a course of study with AIPE;

• each potential student was aware of the range of withdrawal opportunities without penalty if the student elected not to proceed with a course of study;

• compliant practices were promoted among the agents contracted by AIPE.

Prior to January 2015 agents were not required by AIPE to attend training sessions offered by AIPE staff.

[8.1] Agents and sub-agents [i.e. recruiters] visited the areas identified in paragraph 8.1 and recruited students in those locations.

AIPE sometimes gave agents leads as to particular locations in which students might be recruited.

At all material times, AIPE was aware of the locations from which its students were being recruited because:

(i) At the time the agent and AIPE entered into the Student Enrolment Agreement, the agent and AIPE agreed the geographical areas in which the agent or sub-agent would recruit students; and

(ii) Agents were required to give 2 weeks’ notice of any changes to those agreed areas;

(iii) In regional locations, agents were required by AIPE to notify it of the suburbs to be visited by agents and sub-agents at least 2 weeks in advance; and

(iv) AIPE was provided with the addresses of potential students by agents and sub-agents before they were formally enrolled into courses by AIPE.

Notwithstanding the knowledge of AIPE, it continued to enrol students from low socio-economic communities into its courses.

[8.3] The representations were oral. The specific representations relied upon will be set out in the evidence.

[8.4] The use of the word “including” in the paragraph is deliberate. The paragraph indicates the facts that the Applicants are aware of to date. In the event that additional facts come to light at the time when the Applicants serve their evidence, the Applicants will inform AIPE of those additional facts.

[8.5] Due to the vulnerabilities of the students whom AIPE enrolled into its courses, and the relatively high cost of the courses offered, there was a heightened obligation on AIPE to ensure that students were aware of their VET FEE-HELP obligations before they were enrolled. The evidence of the individual students recruited on behalf of AIPE will demonstrate that the agents and sub-agents did not explain the nature of their VET FEE-HELP obligations to them and that the students were ignorant of their debt to the Commonwealth. The evidence will demonstrate that the Agents and Sub-Agents often represented that the courses were free, or, if they were not free, that the students would never have to repay the debt. Further they often represented to students that, if they enrolled in a course, they would be given a free laptop computer or tablet, when in fact the laptop was provided on loan.

[8.6] As above, this is a matter for evidence, which will be provided by students enrolled into AIPE courses.

27 In the further amended response, AIPE pleads as follows (at [14A], [14B] and [15A]):

[14A] AIPE admits that certain Service Providers and Authorised Sub-Contractors, on its behalf, and for the purposes of recruiting and enrolling students in VET courses of study:

a. visited, in addition to suburban and urban areas, low socio-economic communities, including rural towns, remote communities and communities with Aboriginal populations:

b. conducted face-to-face marketing by calling on consumers in their homes, telephoned potential students and conducted group marketing sessions at public venues, such as careers and education exhibitions and school presentations.

[14B] AIPE admits that it provided to students enrolled in VET courses who requested a learning device, laptops, on loan, which had been configured with relevant course material for the course in which the student was enrolled and which were required to be returned by the student at the completion of their course of study.

[15A] AIPE admits that in the context of enrolling students in VET courses:

a. a failure to explain in plain and clear terms the VET FEE-HELP scheme and that it would leave a person with a debt to the Commonwealth: or

b. offering a free laptop to poorly educated or illiterate persons on the basis that the person signs up to a VET FEE-HELP course without explaining in plain terms the VET FEE-HELP scheme:

can amount to misleading and deceptive conduct.

28 With regards to the agency issue, s 139B(2) of the CCA, which is deliberately in similar terms to s 84 of the CCA (and s 84 of the predecessor Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth)), provides as follows:

Any conduct engaged in on behalf of a body corporate:

(a) by a director, employee or agent of the body corporate within the scope of the actual or apparent authority of the director, employee or agent; or

(b) by any other person:

(i) at the direction of a director, employee or agent of the body corporate; or

(ii) with the consent or agreement (whether express or implied) of such a director, employee or agent;

if the giving of the direction, consent or agreement is within the scope of the actual or apparent authority of the director, employee or agent;

is taken, for the purposes of this Part or the Australian Consumer Law, to have been engaged in also by the body corporate.

29 In Empower, Gleeson J, in dealing with the application of s 139B(2)(a) and the attribution of the conduct of agents and their recruiters in marketing a VET provider’s courses to such a provider said as follows (at [282] to [287]):

The term “agent” is not defined in the Act or in the ACL. It is thus appropriate to have regard to the meaning(s) of agent at common law.

It has been observed that the word “agent” is one that can cause difficulty because of its potentially wide and varying meaning: Tonto Home Loans Australia Pty Ltd v Tavares [2011] NSWCA 389 (“Tonto”) at [170] per Allsop P (Bathurst CJ and Campbell JA agreeing); NMFM at [512] per Lindgren J; see also Dal Pont, Law of Agency (3rd ed, LexisNexis, 2014) at [1.1].

The key feature of an agency relationship is that the agent acts on behalf of the principal. That this is the key characteristic of agency explains why, in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Maritime Union of Australia [2001] FCA 1549; (2001) 114 FCR 472, Hill J at [81] observed that s 84(2) appeared – by its reference to “on behalf of” in addition to “agent” – to have a “double requirement” of agency. In Tonto, Allsop P (with whom Bathurst CJ and Campbell JA agreed) said, at [177]:

Agency is a consensual relationship, generally (if not always) bearing a fiduciary character, in which by its terms A acts on behalf of (and in the interests of) P and with a necessary degree of control requisite for the purpose of the role. Central is the conception of identity or representation of the principal.

His Honour said further at [177]:

It is sufficient to recognise that the essential characteristic is that one party (A) acts on the other’s (P’s) behalf, and that this will generally be in circumstances of a requirement or duty not to act otherwise than in the interests of P in the performance of the consensual arrangement.

It is well established that where a question arises as to whether two persons have a relationship of agency, the label they apply to the relationship, or expressly disclaim, is not determinative of the nature of their relationship. As a result, a term in a written contract between the persons that their relationship is not one of agency will not determine the matter, although such a term must be given proper weight: South Sydney District Rugby League Football Club Ltd v News Ltd [2000] FCA 1541; (2000) 177 ALR 611 at [134]-[135] per Finn J.

As Allsop P observed in Tonto at [178], it should not be controversial that the concept of agency may properly extend to persons whose roles may be described as “canvassers” or “introducing agent”. There, his Honour quoted, with apparent approval, a passage from Bowstead and Reynolds on Agency (19th ed, Street & Maxwell, 2010) at [1-019], where the authors observed that such agents may only introduce a third party to the principal and leave them to enter a contract between themselves. However, such agents often “have authority to receive and communication information on their principals’ behalf, and in so doing have the capacity to alter their principals’ legal position”.

30 After considering the particular contractual terms and arrangements, Gleeson J at [298] to [300] considered, by reference to long-standing authority, whether the conduct of the agents (including via their recruiters) was engaged in on behalf of the VET provider, and concluded (at [301]):

In general, and subject to the question of conduct which might be outside the scope of the agents’ authority, the conduct of the agents in selling and promoting services provided by Empower was conduct engaged in on behalf of Empower because it occurred:

(1) in the course of their respective agency relationships with Empower;

(2) when the agents were acting as representatives of Empower; and

(3) for the benefit of Empower, that is, to build the business of Empower.

31 On the topic of the scope of the agents’ actual or apparent authority, Gleeson J said the following (at [302] to [308]):

In the law of agency, the liability of the principal for an agent’s defaults can be explained by the principal’s ability to stipulate an agent’s authority: Dal Pont, Law of Agency [22.15].

The expressions “actual authority” and “apparent authority” are not defined in the Act or ACL. It is therefore useful to have regard to the general law in determining their meaning.

At common law, the principal is civilly liable for an agent’s torts committed by the agent while acting within the scope of his or her actual or apparent (also called “ostensible”) authority: Ex parte Colonial Petroleum Oil Pty Ltd (1944) 44 SR (NSW) 306 at 308. As to the latter, Jordan CJ repeated the following statement from his decision in Bonette v Woolworths Ltd (1937) 37 SR (NSW) 142 at 151:

If an agent is authorised to do a particular class of acts, the principle is liable if the agent does an act of the class authorised notwithstanding that it is done mistakenly, negligently or wrongfully; and a principle cannot escape liability by expressly prohibiting his agent from making mistakes or being careless in carrying out his duties …

Concluding:

A principal is not, of course, responsible, either civilly or criminally, for anything done by a person who is in fact his agent, if it is done by that person on his own behalf and not in the course of the performance of his duties as agent or within the scope of his general authority as agent.

As a matter of interpretation, these principles apply under s 139B so that the conduct of Empower’s agents in selling and promoting Empower’s courses (being conduct of the authorised class) is taken, for the purposes of the ACL, to also have been engaged in by Empower.

This conclusion is consistent with cases in which the principal has been found liable for the misleading or deceptive conduct of its agent: see, for example, Aliotta v Broadmeadows Bus Service Pty Ltd (1988) 10 ATPR 40-873, Transport Accident Commission v Treloar (1991) ATPR 41-123 at 52,819 and Havyn Pty Ltd v Webster [2005] NSWCA 182; (2005) ATPR (Digest) 46-266.

It follows that the conduct of the agents in using any of the alleged marketing methods is, by s 139B, taken to have also been engaged in by Empower.

It also follows that the conduct of the agents the subject of the evidence given in relation to the Consumers below is, by s 139B, also taken to have been engaged in by Empower.

32 I am satisfied, as was Gleeson J in Empower that, generally speaking, the activities of the agents and recruiters were agents of AIPE within the meaning of that term in s 139B, extending to the conduct of the recruiters in selling and promoting education services by AIPE. This conduct plainly occurred in the course of the agency relationship between the agents and AIPE, including the conduct of the recruiters. The agents and recruiters were generally acting as representatives of AIPE and were doing so for the benefit of AIPE, building its business by the recruitment of consumers to become enrolled as students. Except for extreme or aberrant behaviour, such as making overtly false statements, which would likely fall outside their authority, I accept that the recruiters were ordinarily acting within the scope of their actual or apparent authority on behalf of AIPE.

33 In any event, the applicants submit, and I accept, that even if the conduct of some of the recruiters was not the conduct of AIPE under s 139B(1)(a), it does not follow that such conduct is outside or irrelevant to the system of conduct or pattern of behaviour alleged. AIPE’s enrolment system involved the implementation of its decisions and actions, which facilitated and encouraged conduct in the field by reference to the structure of the written contracts with the agents, the payment of large commissions and the lack of processes identified in some detail below to ensure that only consumers who were suitable were enrolled as students.

34 The core disputed allegations relied upon by the applicants are sufficiently succinct to reproduce rather than summarise. At [6]-[13] of the concise statement, the applicants allege as follows:

[6] AIPE paid the Agents a commission (representing between 15-25% of the course fee) for each student enrolled into a course, thus giving them a financial incentive to maximise the number of students enrolled. Some of the agency contracts contained clauses stipulating a minimum number of students to be recruited each month. AIPE monitored the success of its Agents in meeting sales targets by organising monthly or bi-monthly meetings with them, and in some instances, AIPE terminated the contracts of Agents who did not meet the minimum monthly requirement for recruitments.

[7] AIPE failed to provide any, or adequate, training or instruction to the Agents or Sub-Agents [i.e. recruiters] to ensure that their conduct on behalf of AIPE complied with the requirements of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), which is Schedule 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (CCA).

[8] During the Relevant Period, AIPE engaged in a pattern of behaviour for marketing and enrolling students in its courses. This pattern of behaviour involved certain Agents and Sub-Agents (the Applicants do not allege that this conduct was engaged in by all Agents and Sub-Agents):

8.1 visiting low socio-economic communities, including rural towns, remote communities and communities with Aboriginal populations, to recruit disadvantaged or vulnerable students.

8.2 conducting face-to-face marketing by calling on consumers uninvited in their homes or the homes of relatives or friends, telephoning potential students at their homes and conducting group marketing sessions at public venues, including clubs.

8.3 making false or misleading representations to prospective students that:

(a) the courses were free, when in fact a student immediately incurred a lifetime debt to the Commonwealth;

(b) if the prospective students elected to sign up for VET FEE-HELP, the debt would never have to be repaid, when this was not the case;

(c) the courses were specifically designed for Aboriginal people, when it was not; and/or

(d) if the prospective students enrolled in a course they would be given a free laptop computer or tablet, when in fact the laptop or tablet was provided on loan.

8.4 using unfair tactics, including offering inducements to prospective Aboriginal students to enrol in a course, including Wi-Fi access and mobile phone credits, and paying Aboriginal people (in cash) to assist in recruiting other Aboriginal people to enrol in courses.

8.5 failing to explain to prospective students the nature of their VET FEE-HELP obligations if they enrolled in a course, so that most of the students did not know that they had incurred a debt to the Commonwealth or when that debt would have to be repaid.

8.6 not undertaking any or any adequate assessment of the literacy, numeracy or computer skills of the prospective student, although after March 2015 Agents and Sub-Agents assisted the students to complete their learning, literacy and numeracy tests which were ostensibly designed to determine the student’s ability to undertake a course.

8.7 not assessing whether students had the necessary skills to complete the courses, and as a result, AIPE enrolling students into courses that were not suitable for them, having regard to their limited education, reading, writing and education skills.

8.8 not considering whether students had access to the internet, and as a result, AIPE enrolling students for online courses when they did not have access to the internet; and

8.9 not informing prospective students of the fact that they could withdraw from a course, and that any withdrawal had to be prior to the Census Date, nor how the agreement could be terminated, and not providing students with a copy of the agreement.

[9] During the Relevant Period, AIPE’s pattern of behaviour, set out in paragraph 8, was implemented at least in Queensland, Western Australia and New South Wales. Specific examples of the conduct include the conduct leading to the enrolment of nine students set out in Annexure A to this Concise Statement.

[10] After receiving a student enrolment application from an Agent, AIPE did not routinely make a call to the student to verify whether he or she had the necessary skills to undertake the course, wanted to do the course, was aware of his or her VET FEE-HELP obligations, was aware that the course was not free, or advise that the student could withdraw from the course prior to the Census Date.

[11] AIPE knew that each student would incur a debt to the Commonwealth regardless of whether he or she was capable of undertaking or completing the course.

[12] AIPE enrolled students in courses for its own financial gain, knowing that few if any of them would actually commence the course, or take steps to withdraw from the course before incurring the debt. AIPE would therefore receive VET FEE-HELP payments for each student without, in most cases, having to provide any teaching services.

[13] During 2014 and 2015, AIPE received complaints about the conduct of its Agents, both from students themselves who had been enrolled into courses and from other agencies representing students who had signed up for courses. Despite AIPE being aware of these complaints, it did not immediately terminate its contracts with those Agents, if at all, during the Relevant Period, nor instruct those Agents to cease the engagement of Sub-Agents to recruit students and did not seek to prevent those Agents from conducting door-to-door sales.

35 While the chapeau to [8] and the text of [9] of the concise statement reproduced above refer only to “pattern of behaviour”, the entire hearing of this proceeding, including opening and closing submissions, was conducted upon the dual basis of the applicants’ case being based upon establishing unconscionable conduct, beyond the consumer witnesses, by reliance upon the s 21(4)(b) concept of a “system of conduct or pattern of behaviour”. AIPE’s understanding that this was the case it had to meet was made explicit in AIPE’s closing written submissions at [25] to [26]. Thus, a pleading problem of the kind identified in Australian Building and Construction Commissioner v Hall [2018] FCAFC 83; 277 IR 75 at [25]-[26], and raised but not found to be a problem in Parker v Australian Building and Construction Commissioner [2019] FCAFC 56; 365 ALR 402 at [220]-[222], did not arise.

36 The applicants’ pleaded case is that AIPE exploited the vulnerabilities of the liberalised VET FEE-HELP scheme in a manner that was unconscionable. In opening written submissions dated 6 September 2018, prior to the first trial day on 17 September 2018, the applicants framed their characterisation of AIPE’s model for marketing to and enrolling consumers as students as follows (at [5]-[7], excluding footnotes, omitting parts not maintained in closing submissions, and emphasising points squarely going to the VET FEE-HELP scheme):

[5] In the period from 20 February 2013 to 16 October 2015, AIPE received $211,002,401 in VET FEE-HELP payments from the Commonwealth in respect of students it enrolled in its online courses.

[6] … AIPE had 6,057 students that were enrolled in 2015 and, of those, only 77 (1.3%) finished their course. All students enrolled in AIPE’s courses who did not withdraw before the census date and who were not subsequently withdrawn, or otherwise had their debt remitted, have been left with significant debts.

[7] It is the Applicants’ case that AIPE recruited such a large number of students through its unconscionable business practices in marketing and enrolling students in its courses and failing to identify and withdraw unsuitable students before they incurred permanent debts to the Commonwealth. AIPE’s unconscionable business practices included the following key elements:

(a) AIPE used third party recruiters to identify and recruit students on its behalf for enrolment in its courses. AIPE admits that it does not know how many sub-agents were recruiting students on its behalf …

(b) AIPE incentivised its recruiters to sign up as many students as possible by paying them commissions of up to 40 per cent of the cost of the course per student (up to $8,376). AIPE required some agents to achieve a minimum number of student recruitments per month and monitored the performance of its agents in meeting their targets.

(c) For a significant part of the Relevant Period, AIPE failed to provide any, or any adequate, training to its recruiters as to how to lawfully perform their role, including on matters such as ensuring that prospective students understood their obligations under the VET Scheme if they were enrolled in an AIPE course.

(d) AIPE did not provide any ACL training to its employees or to the recruiters before August 2015.

(e) AIPE enrolled students who were unlikely to be able, or inclined, to undertake and complete its diploma and advanced diploma level courses.

(f) AIPE’s recruiters conducted face-to-face marketing by calling on prospective students uninvited in their homes and conducting sign-ups in public venues, including public bars. At least one of AIPE’s recruiters engaged in tele-marketing by cold calling prospective students for recruitment.

(g) AIPE’s recruiters made false and misleading representations to prospective students including that AIPE’s courses were free, or were free unless students earned over a certain amount, that students would receive a free laptop for signing up to a course, or that the courses were specifically designed for Aboriginal people. AIPE’s recruiters offered prospective students inducements to enrol in a course, including cash and mobile phone credits. AIPE’s recruiters paid Aboriginal people (in cash) to assist in recruiting other Aboriginal people to enrol.

(h) AIPE’s recruiters were ignorant of their legal obligations and failed to adequately explain (or explain at all) to students the VET FEE-HELP scheme and their obligations if they signed up to a course and received VET FEE-HELP assistance, including that they would incur a significant debt to the Commonwealth.

37 The underlying issue in this proceeding is whether the applicants have proven that this was what in fact took place, and if so, whether there was anything unconscionable in doing this, in the manner alleged.

38 AIPE characterises the key dispute as being whether, by reason of what is pleaded by the applicants at [8] to [13] of the concise statement (reproduced above), its system of conduct or pattern of behaviour in enrolling consumers as students during the relevant period was unconscionable in the broad and pervasive way alleged by the applicants. By its pleaded response to those paragraphs, AIPE effectively seeks to confine any possible success by the applicants to contraventions (and thereby remedies) in relation only to the small number of individual consumers who were witnesses. In substance, AIPE admits to at least the possibility of isolated contraventions in relation to those consumers, but maintains that the applicants have not discharged the burden of showing even that took place, let alone that something more than that had taken place.

39 On the third day of the trial, the Full Court decision in the VET FEE-HELP case of Unique International College Pty Ltd v Australian Competition and Consumer Commission [2018] FCAFC 155; 362 ALR 66 was handed down. Unique had features in common with this case, thereby giving significant guidance to the approach required to be taken. In Unique, the primary judge’s unconscionable conduct findings based on a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour were overturned. An important point to emerge from Unique is that unconscionable conduct cases, especially within the framework of the VET FEE-HELP scheme, turn on their own facts and evidence, including the forensic approach taken in bringing such a case.

40 The applicants in substance contend that this case has been brought in a materially different way to Unique. They contend that the evidence goes further than in Unique to permit the necessary findings to be made. AIPE aligns this case more closely to Unique and maintains the applicants’ case should therefore similarly fail, albeit that the resistance to much more limited findings concerning individual consumers is less emphatic. On any view, the evidence of the applicants’ system of conduct or pattern of behaviour case, and what conclusions should be drawn from that evidence, is the most important part of this proceeding.

Divergent views on what needs to be established and how

41 For the most part, the evidence was not disputed or made the subject of cross-examination. Limited rulings were required as to admissibility or restrictions on use (apart from the exclusion of Dr Ericson’s report, confining his evidence to tables containing limited demographic analysis). Nor was there very much dispute about the facts established by that evidence, as opposed to what to make of it, and what the evidence was capable of establishing. AIPE did not take any substantial issue in relation to what had happened to the 13 consumer witnesses relied upon by the applicants, although it cautioned about relying upon their account of what was said to them. In the end, the defence of the applicants’ individual consumer case was somewhat muted.

42 The greater part of AIPE’s case turned on arguments that the applicants’ evidence simply did not go far enough to make good their system or pattern case, especially when regard is had to the quality of evidence that is required, even on the balance of probabilities, when serious allegations are made. Reliance is placed on the practical effect of s 140(2) of the Evidence Act 1995 (Cth) as a legislative manifestation of the principles in Briginshaw v Briginshaw (1938) 60 CLR 336 per Dixon J at 362.

43 The applicants, however, state that it is sufficient that they demonstrate that the marketing and enrolment process and AIPE’s business practices in relation to consumers was unconscionable, as a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour. They do not, they submit, bear an evidentiary burden of proving each instance of conduct in relation to all consumers enrolled as students during the relevant period, nor even a large representative sample. This is on the basis that AIPE’s marketing and enrolment process was a widespread system of conduct or pattern of behaviour, geographically and temporally, and that this conduct necessarily involved conduct in respect of individual consumers affected by it.

44 In summary, the bulk of the ACCC’s case relies upon evidence of the systems and patterns of behaviour, with the evidence related to individual consumers enrolled as students intending to illustrate, by way of detailed examples, the outcomes these unconscionable systems and patterns of behaviour were likely to produce, and, by reference to enrolment data and other evidence, did produce.

45 In addition to differing positions on how a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour might be evidenced, the parties diverged on how much variation is permitted in order to constitute “a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour”. The applicants’ closing written submissions state that “AIPE’s recruitment and enrolment processes varied somewhat” over the course of the three-year relevant period. Those submissions then assert that:

In broad terms, AIPE’s enrolment processes involved unsolicited door-to-door contact by recruiters at prospective students’ homes and recruitment in public areas such as in public bars. Recruiters carried iPads and had students complete the AIPE enrolment form on the iPad. One of AIPE’s agents (Acquire Learning) made unsolicited telephone calls to prospective students, generally chosen from among people who had responded to online job advertisements.

46 AIPE seizes upon the reference to “varied somewhat”, and the way the submission on this topic is developed by the applicants (as described further below) to submit that this highlights a “troubling aspect” of the applicants’ case. AIPE asserts that because the central allegation is that AIPE engaged in “a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour” during the relevant period that was unconscionable, and because only one such system is pleaded in the concise statement, the applicants’ submission referring to the processes varying somewhat was at odds with the pleaded case. AIPE contends that it is incumbent upon the applicants to establish the features of the enrolment process alleged to have been engaged in by AIPE, that the enrolments process was deployed “in… such [a] manner or on a sufficient number of occasions” to constitute “a system of conduct or pattern of behaviour”, and that a system of that kind can be characterised as unconscionable.

47 AIPE points out that there is no pleaded allegation that the system changed during the relevant period, and submits that a variation in the enrolment process “may well be” inconsistent with the notion that a single enrolment process can amount to a system or pattern capable of being characterised as unconscionable, as pleaded. In this context, AIPE asserts that it made admissions in relation to the way in which service providers visited low socio-economic communities and conducted marketing face-to-face by home visits, telephone calls and group marketing sessions. However, it asserts that those admissions do not amount to an enrolment process that “in broad terms” had the characteristics described by the applicants. AIPE submits that the Court should be cautious in accepting such “broad brush” submissions upon the basis that they overstate the effect of the evidence and admissions. AIPE submits that:

The precise features of the enrolment process, whether those features were deployed in a systemic way and whether that system was unconscionable is the pivotal issue which is to be addressed and the Court is not assisted by broad brush summaries of the process.

48 The applicants respond in reply to the effect that AIPE operated a marketing and enrolment process in a number of States that had common features during the relevant period, and that while there may have been some variation in the detail, common features were present at all times and are asserted to be at all times unconscionable. These common features include, but are not limited to, the use of third party recruiters, the payment of large commissions to recruiters, the use of inducements to encourage consumers to enrol and a lack of systems and processes at the operational level to ensure that the respondent only recruited suitable consumers who were capable of completing the courses. The applicants contend that remains so, even though some limited improvements were introduced, including in relation to training, which are described by the applicants as cursory. The applicants therefore submit that none of those changes were such as to alter the asserted unconscionable nature of AIPE’s enrolment system overall.

49 In support of their argument, the applicants assert that an unconscionable system of conduct or pattern of behaviour can continue to exist as proscribed even where key features that constitute it vary or evolve over time. The applicants rely upon what was said by Rangiah J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v ABG Pages Pty Ltd [2018] FCA 764 at [37]. His Honour there observed:

While different elements of the system were used at different times in relation to different customers, the same system existed throughout this period and it was continuously applied by ABG Pages in relation to its dealings with customers and potential customers.

50 Rangiah J in ABG Pages characterised the systemic and unconscionable conduct that his Honour found had been established as forming part of an “ongoing, single episode of wrongdoing”. The applicants also cite Moshinsky J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Harrison [2016] FCA 1543 at [10], where his Honour took a similar approach in describing the key elements of the system of conduct or pattern of behaviour found to be unconscionable. Moshinsky J in Harrison, albeit in dealing with a very different case concerning telecommunications consumer contracts, took a reasonably broad and general view of the conduct, rather than descending into variations in the fine detail that was involved in the execution of the single overall system that was alleged and proven.

51 The applicants therefore submit that there is no authority of which they are aware (and none is cited by AIPE) to the effect that an alleged system must be shown to have been “created at a particular point in time with all of its constituent elements identified and operating in a fixed manner over time”. Rather, the applicants submit, a system may evolve over time, which is consistent with the broad remedial approach which should be taken in interpreting and applying s 21 of the ACL. The applicants submit that the approach urged by AIPE would unduly confine the operation of s 21(4)(b) to a very narrow class of conduct, which would be at odds with both business practice and a sensible understanding of the overall legislative regime and proscription. They submit that the approach that they contend for allows for a system to adapt and evolve incrementally over time, yet still be found overall to fall within the proscribed concept, provided the essential elements relied upon do not materially change. I prefer and accept the applicants’ submissions on this topic. The suggestion of a single, narrowly drawn, system case is not reflective of the case that has been brought, and sought to be proven.

52 AIPE assert a number of other weaknesses in the ACCC’s evidence in support of its system or pattern case. First, it submits that the ACCC conceded that the recruitment methods of Acquire Learning do not form part of the system of conduct or pattern of behaviour alleged. This is said to present an issue as Acquire Learning was by far the most prolific recruiter agent for AIPE, and were indeed the only recruiter agent for AIPE from before the beginning of the relevant period until November 2013. AIPE submits that any non-party redress orders made on the basis of a finding of an unconscionable system or pattern of behaviour therefore need to exclude the approximately 40% of enrolments that were procured by Acquire Learning.

53 AIPE also submits that the substantial sums received by it are insufficient to evidence a “real motive” for enrolling students, and that nor is there any other evidence going to motive.

54 Evidence of the individual consumer witnesses is said by AIPE not to assist the applicants’ system or pattern of behaviour case, for the following reasons:

(1) the 13 consumer witnesses were not relied upon to prove the case on a representative or sample basis;

(2) the allegations are of a widespread system or pattern, despite:

(a) it being conceded by the applicants that the impugned conduct was not engaged in by all recruiter agents;

(b) noting the concession attributed to the applicants regarding Acquire Learning’s individual recruitment method not forming part of the system alleged, there being no other recruiter agent up until about September 2013;

(c) the individual consumers are examples of conduct by only seven of the 35 recruiter agents used by AIPE; and

(d) in a similar vein, the absence of evidence of what took place by way of oral representations or omissions by individual recruiters, or the practices put in place by their employer agents; and

(3) an asserted lack of correlation between what happened to the 13 consumer witnesses and the system pleaded, having regard to the diverse locations that they came from, an asserted lack of clarity as to where those individuals fit into the pleaded case, and significant differences in the manner in which each of them was approached and enrolled, such that they cannot be relied upon to establish any uniform or consistent enrolment process; and

(4) the evidence of the consumer witnesses does not cover the whole of the relevant period, with the first in time consumer witness giving evidence of events beginning February 2014.

55 The evidence of the employee witnesses was similarly attacked on the basis that none of them gave evidence as to AIPE’s practices prior to January 2014. This and other objections related to employee evidence are dealt with in greater detailed below.

56 The further alleged deficiencies of the applicants’ systems case noted above are misconceived or overstated for a range of reasons. First, the impugned conduct does not need to be proven, letter and verse, with regards to each and every agent. Nearly 80% of enrolments came from the four biggest recruiters, and the evidence of former AIPE employees concerned the system overall without that degree of parsing. Second, the concession made by the applicants as to Acquire Learning’s conduct not forming part of the system alleged was confined to its unique practice of using job seeker advertisements to target consumers to seek to enrol them in VET FEE-HELP courses, which was not of itself of any great moment on the applicants’ case. Other conduct of Acquire Learning, for example its language, literacy and numeracy (LLN) test, was expressly relied upon as illustrative of what the AIPE enrolment system permitted and even encouraged.

57 The suggestion of an absence of evidence of motive is also misplaced. Motive does not require confession. It can amply be established by circumstances, as it was in this case.

58 As to the criticism of the evidence not covering all of the relevant period, that is only so if inference is excluded. The key features of the enrolment scheme were demonstrated with sufficient clarity to support an inference that they were at least no better earlier in time, although it is reasonably clear that the problems escalated as the level of enrolments rose, a fact directly proven by the employee witnesses.

59 Ultimately, and most importantly, AIPE’s criticisms fail to appreciate that it is AIPE’s system that is under scrutiny. Other evidence relied upon, such as enrolment data or consumer witnesses, helps to prove what the system allowed or even encouraged to take place. To demand more granular evidence of particular transactions or individuals would defeat the strengths of s 21(1) via s 21(4)(b) of the ACL in not requiring proof of individual disadvantage, or requiring pervasive evidence for all points in time. Similarly, to demand evidence of the conduct of each and every agent is to mistake the focus of the inquiry to be made.

60 The approach urged by the applicants should generally be preferred to that asserted by AIPE, but with the following qualification when it comes to the assessment of what has taken place. The more general or abstract the system or behaviour that is alleged and proven, the harder it may be to establish that it has the character of being unconscionable for want of necessary detail to show that is so, or that it has the necessary pervasive and proscribed character. By contrast, too granular an approach may more readily demonstrate isolated instances of contravening conduct, but may fall short of showing that any overall proscribed system or behaviour took place. That process of characterisation forms part of the evaluative exercise required to be carried out, reflecting in substance the crux of some of the key competing arguments. That is because AIPE submits that the evidence relied upon by the applicants is not sufficiently granular at the enrolment systems level, and that any contravening conduct that is shown to have taken place in respect of individual consumers was isolated, even if repeated from time to time, and that this does not establish that its enrolment system overall had the proscribed character of being unconscionable. By contrast, the applicants rightly seek to draw all of the threads of evidence together, with the individual instances being illustrative of the way in which the system worked overall in an unconscionable way as alleged.

61 A problem with the approach taken by AIPE in its final submissions was, quite understandably in light of the evidence considered in some detail below, to focus on what was not to be found in the evidence, and to pick holes in the evidence that was there, but not to engage in detail with the accumulated and combined effect of the evidence that the applicants rely upon, nor to confront the inferential reasoning processes properly available to the Court. While the applicants had an onus to discharge, and while the seriousness of the allegations required that the evidence be of a quality sufficient to establish that those allegations were proved by more than (per Briginshaw) “inexact proofs, indefinite testimony, or indirect inferences”, it remained at all times a civil case to be proven on the balance of probabilities. This aspect is discussed below in some detail when considering the Full Court Unique decision. The wide ambit of s 21(1) of the ACL, via s 21(4)(b), enabling unconscionable conduct to be established by proving a “system of conduct or pattern of behaviour, whether or not a particular individual is identified as having been disadvantaged by the conduct or behaviour”, must also be kept steadily in mind.

62 The key questions ultimately to be answered, beyond the individual consumer witnesses, were:

(1) was it more probable than not that the conduct alleged by the applicants had taken place beyond that proven by direct evidence, such as by relying on the totality of the evidence and inferences able to be drawn; and

(2) if so, did it have the requisite proscribed legal character of being unconscionable?

63 Given the gulf between the parties, it is necessary to consider a substantial volume of evidence, albeit a relatively small subset of the digital court book containing the equivalent of some 40 or so lever arch folders of documents, including affidavits, reports and AIPE business records, as well as limited viva voce evidence, mostly in cross-examination, in a methodical way. This was not the subject of any contrary view expressed by AIPE going to the detail of the arguments advanced by the applicants.

64 In conducting this evaluative exercise, the case pleaded by the applicants is of course central and important. However, a pleading does not and cannot contain every nuance and detail revealed by the evidence. This made the applicants’ oral and written submissions, both opening and closing, important to understanding the totality of their case, and to aid in the detailed consideration of the evidence. I consider that I am required to conduct my own assessment of the evidence within that broad framework, and am not restricted to every detail in the case as presented, nor on the other hand to express a view on every argument advanced. That is especially so as the parties relied only upon written closing submissions, which by necessity could not address every nuance in the evidence, nor require a response to everything that was thereby argued. The focus must be on what is determinative.

65 In order to understand the significance of key parts of the evidence, and the use that the applicants seek to make of it, it is necessary to outline the essential features of the VET FEE-HELP scheme. It was a scheme to assist eligible consumers to undertake higher level VET courses. The scheme is detailed in Sch 1A of the HES Act as it applied in the relevant period. AIPE was an approved “VET provider” under that Act.

66 An introduction to the overall way in which the VET FEE-HELP scheme operated was helpfully summarised by Perram J in Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Unique International College [2017] FCA 727. While his Honour’s ultimate conclusion as to unconscionable conduct was overturned by the Full Court on the particular facts and evidence in that case (as noted above at [39]), his Honour’s summary of the essential features of the VET FEE-HELP scheme was not affected. His Honour said (at [5]):

VET FEE-HELP is a shorthand for Vocational Education and Training FEE Higher Education Loan Program. … the VET FEE-HELP scheme had these pertinent features:

• it was available to Australian citizens or holders of a permanent humanitarian visa who were resident in Australia, provided that they were enrolled in a full fee paying course approved for VET FEE-HELP (as Unique’s four courses were);

• the Commonwealth would pay in full whatever the tuition fee was for each unit of the approved course and would treat the combined amounts as a loan to the student;

• the loan would be repayable through the tax system once the student began to earn more than the ‘minimum repayment income’ ($53,345 for the period 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2015; $54,126 for the period 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2016) on the income above that amount at a sliding scale of between 4% to 8%. The highest rate became applicable at $99,070 during the relevant period;

• each person had a maximum lifetime amount which could be borrowed through this and other related schemes (such as HECS). This amount was indexed and was $97,728 for the 2015 financial year. The amount which the student had at any time borrowed was specified in an account maintained by the Commonwealth called the FEE-HELP balance;

• there was a 20% loan fee on top of the tuition fee which was also payable to the Commonwealth and which was debited to the student’s FEE-HELP balance; and

• the amount of the student’s FEE-HELP balance was indexed to the Consumer Price Index (‘CPI’).

67 The relevant period in Unique was from 1 July 2014 to 30 September 2015, being in the latter part of the relevant period in this proceeding from 1 May 2013 to 1 December 2015.

68 In order to access a VET FEE-HELP loan, a student had to complete, sign and return a request for Commonwealth assistance (Assistance Request Form), in a form approved by the Minister, and return it to the VET provider on or before the census date for that unit of study: Sch 1A, cl 43(1)(h) and cl 88(3) of the HES Act. The version of the Assistance Request Form used by AIPE on its face had five check or tick boxes by which the person seeking a loan was required to declare that they had read the VET FEE-HELP information booklet, and were aware of their obligations to the Commonwealth if they received such assistance.

69 The applicants, in their closing submissions, draw specific attention to the terms of the Assistance Request Form. The design of the VET FEE-HELP scheme meant this form was plainly intended to be a very important part of the enrolment process. It was evidently intended to ensure, as much as possible, that consumers as prospective students understood the legal and financial obligations they were assuming by becoming enrolled in a course to which VET FEE-HELP applied. The contents of that form are therefore of importance in assessing the evidence going to the issue of AIPE’s enrolment practices and conduct, including by agents of AIPE. Specifically, the applicants point out that the Assistance Request Form required consumers to declare that they understood that:

(1) they were requesting a loan from the Commonwealth in the amount of their VET tuition fees, whereupon the Commonwealth would pay the student’s tuition fees to the VET provider on the student’s behalf, and the student would incur a debt to the Commonwealth;

(2) if they were a full fee-paying student, a loan fee of 20% would be applied to the amount of the VET FEE-HELP assistance provided;

(3) the student would repay the Australian Tax Office the amount loaned plus the 20% loan fee; and

(4) the student could cancel their request for VET FEE-HELP assistance at any time, but would become liable to pay a debt to the Commonwealth if they did so after the census date, regardless of whether they had withdrawn from or cancelled their enrolment in the VET unit of study.

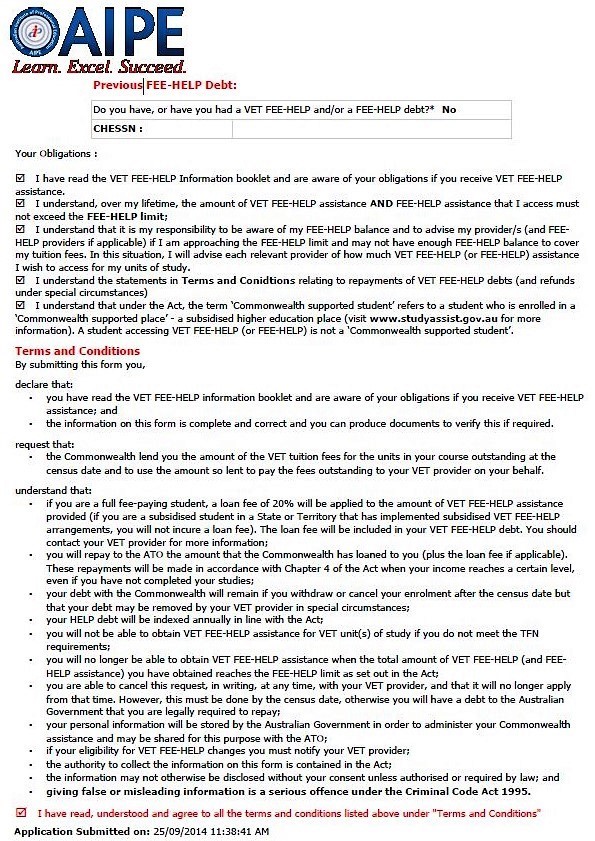

70 It is helpful to reproduce the second page of an AIPE Assistance Request Form in evidence:

The above reproduction of the form gives a sense of the font size and density (although not a perfect reproduction as to overall size, but largely to scale), as well as the typographical and grammatical errors contained within (such as the first listed obligation switching from the first to the second person, and the spelling of “Conditions” as “Conidtions”).

71 As the discussion above shows, the integrity of the VET FEE-HELP scheme, and in particular the protection of the financial interests of the Commonwealth and of consumers, depended on each and every consumer enrolled as a student being aware of, and understanding, the vitally important features of that scheme as set out in the Assistance Request Form. It was a critical and mandatory safeguard, intended to prevent consumers who were unsuitable for VET study from becoming enrolled and incurring VET FEE-HELP debts. Doubtless that was why consumers were, by lodging that form, taken to declare that they aware of the obligations they were assuming if they received VET FEE-HELP assistance.

The VET FEE-HELP scheme and its potential for abuse

72 There were two inherently vulnerable features of the VET FEE-HELP scheme that were ripe for exploitation. The first is that an eligible student incurred a VET FEE-HELP debt to the Commonwealth of 120% of the fee even if he or she did not complete any part of the unit of study for which enrolment had taken place. If a person who had been approved for a VET FEE-HELP debt was enrolled as a student with a VET provider as at the census date, but did not in fact ever partake in the course, that provider would get the revenue benefit of the course fees from the Commonwealth, but would not have to incur the variable costs of providing the course to that person, including any related support. That would happen irrespective of whether the person who was enrolled was a bona fide or genuine student or not.

73 To the extent that the outcome of enrolling consumers who were not bona fide or genuine students was able to be maximised across a large enough pool of individuals, the VET provider would obtain revenue for those consumers without needing to employ staff to provide the services that were needed for bona fide or genuine students who did partake of study. This feature therefore created a significant, and reasonably obvious, windfall profit opportunity to a VET provider who wished to exploit it, or was even prepared to let it occur without correction.